Introduction

Acute carbon monoxide poisoning (ACOP) is one of the

most common acute poisoning incidents globally. In the United

States, ACOP is associated with 50,000-100,000 emergency visits and

1,500-2,000 fatalities each year (1). The pathophysiological mechanism of

ACOP is complex, and can eventually lead to the dysfunction of

multiple organs, which is occasionally life-threatening in severe

cases. The kidneys are a highly metabolic and oxygen-dependent

organ, rendering them sensitive to hypoxia and oxidative stress.

Therefore, acute renal injury (AKI) is a notable complication of

ACOP (2). It has been reported

that ~18% of patients with ACOP experience AKI, which not only

markedly increases short-term mortality, but is also associated

with the development of chronic renal disease (CKD) (3). Therefore, investigating the causes of

ACOP could promote the development of targeted therapies to prevent

or alleviate AKI, thus improving patient outcomes and reducing the

risk of progression to CKD.

Evidence has suggested that the mechanisms of

ACOP-induced AKI (ACOP-AKI) involve several interrelated factors,

such as decreased oxygen transport, mitochondrial respiratory

inhibition, reperfusion injury, oxidative stress and the activation

of abnormal inflammatory signal pathways (4–7). CO

exposure may also trigger autophagy by inducing the formation of

mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (8). These findings underscore the

complexity of the molecular pathways involved in ACOP-AKI and

emphasize the need for further studies to uncover these

mechanisms.

Previous advances in RNA sequencing (RNA-seq)

technology have enabled comprehensive analysis of transcriptional

alterations in complex tissues (9–12).

This technique is applied to identify changes in gene expression

and their functional significance, thus offering a novel approach

for understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying the

development of complicated diseases. However, to date,

transcriptional modifications associated with ACOP-AKI remain yet

to be fully elucidated.

The present study aimed to assess the molecular

mechanisms underlying ACOP-AKI using RNA-seq technology. The

present study hypothesized that ACOP-AKI was associated with the

abnormal activation of important factors and signaling pathways. To

assess this hypothesis, an ACOP mouse model was established, and

RNA-seq was employed to comprehensively analyze gene expression

profiles in renal tissues following exposure to CO, mainly focusing

on important components and signaling pathways associated with

inflammation and apoptosis. The primary objective of the present

study was to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying ACOP-AKI

and establish a theoretical basis for the development of targeted

therapeutic interventions.

Materials and methods

Animals

A total of 60 adultC57BL/6 mice (male; age, 8–12

weeks; weight, 22–26 g) were obtained from the Animal Experimental

Center of Zunyi Medical University. All experimental protocols were

approved by the Animal Care Committee of Zunyi Medical University

(approval no. zyfy-an-2024-0710/0358) and supervised by the Ethics

Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University.

Mice were maintained under controlled environmental conditions

(temperature, 22–25°C; humidity, 55–60%; 12-h light/dark cycle)

with free access to food and water. All procedures adhered to

China's guidelines for animal research, with efforts made to

minimize animal use and alleviate potential distress, thus

complying with ethical standards.

Animal models

The ACOP mouse model was established as previously

described (13). Briefly, mice

were placed in a transparent plastic chamber at 22–24°C. To monitor

CO levels, two CO detectors were positioned, one at the center and

another near the edge of the chamber. The chamber was then

gradually filled with CO gas. The exposure protocol involved an

initial phase of 1,000 ppm CO for 40 min, followed by a higher

concentration of 3,000 ppm CO for 20 min, or until the mice

displayed signs of unconsciousness. Following exposure to CO, the

animals were promptly transferred to fresh ambient air and observed

until they fully regained consciousness. Mice were anesthetized

with 2% isoflurane in air (2–3 l/min) on days 1, 3 and 7.

Subsequently, ~0.5–1 ml of whole blood was collected via the

retro-orbital venous plexus equally divided into anticoagulant and

plain tubes for the preparation of plasma and serum. Both plasma

and serum were isolated following centrifugation at 1,000 × g for

10 min at 4°C. Following blood collection, deep anesthesia was

maintained with 2% isoflurane, and the mice were sacrificed

directly. Different euthanasia methods were selected according to

different experimental purposes: In the experiments exploring the

time course of ACOP-induced renal injury and conducting

transcriptome analysis, to minimize animal suffering and preserve

the overall morphological structure of tissues, the experimental

animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation under isoflurane

anesthesia. The collected renal tissues were mainly used for

phenotypic observation studies. In the inhibitor intervention

experiments, under the same isoflurane anesthesia, sacrifice was

performed by transcardiac perfusion with ice-cold 0.1 M

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to harvest renal tissues, which was

mainly to meet the higher tissue quality requirements for mechanism

research.

Experimental groups and process

design

To explore the temporal changes in kidney injury

subsequent to ACOP, a total of 24 mice were randomly divided into

four groups (n=6): The control, ACOP 1-day, ACOP 3-day and ACOP

7-day groups. The degree of kidney injury was evaluated at each

time point by histopathological and biochemical analyses. Follow-up

experiments were performed at the time point exhibiting the most

severe injury (determined by the highest tubular injury score).

Total RNA was extracted from the renal tissue of both the control

and ACOP model groups for RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis. Raw

reads were quality-checked and adapter-trimmed using Fastp

(v0.23.2, github.com/OpenGene/fastp). The resulting high-quality

clean reads were then aligned to the reference genome using HISAT2

(v2.2.1, http://daehwankimlab.github.io/hisat2/). Gene-level

read counts were generated from the alignment files using

FeatureCounts (v2.0.3, http://subread.sourceforge.net/). Finally,

differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the control and model

groups were identified using the DESeq2 (v1.40.2, http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html)

package, with a significance threshold set at an absolute fold

change ≥2 and an adjusted P-value <0.05.

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)

pathway enrichment analysis was then performed to identify key

signaling pathways involved in kidney injury. Based on the KEGG

results, representative upregulated genes were selected as

candidate targets and validated using western blotting. An in

vivo intervention utilizing the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 was

performed to assess the functional role of specific signaling

pathways in ACOP-AKI. A total of 36 mice were randomly allocated

into four groups (n=9) in the inhibitor experiments. The control

group consisted of mice housed in identical transparent plastic

cages as those in the experimental groups without CO treatment or

injection. The ACOP group consisted of mice exposed to CO to

establish an ACOP model.

Subsequently, mice were subject to intraperitoneal

injections with varying components depending on their group. For

the ACOP + LY294002 group, LY294002 was initially dissolved in DMSO

at a concentration of <0.1% and was subsequently diluted in 0.9%

NaCl, resulting in a final injection dose of 10 mg/kg body weight.

Mice in the ACOP group were treated with an intraperitoneal

injection of an equivalent volume of 0.9% NaCl solution without

DMSO, matching the injection volume of LY294002 in the ACOP +

LY294002 group. In the ACOP + vehicle group, mice were also exposed

to CO and then received an intraperitoneal injection of a 0.9% NaCl

solution containing 0.1% DMSO. The first injection was administered

within 2 h post-modeling via CO exposure, followed by daily

injections until the designated experimental endpoint. Mice were

then sacrificed for subsequent analysis.

Measurement of blood CO

concentration

The concentration of CO in blood was measured using

CO assay kit (cat. no. A101-3-1; Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering

Institute), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total

hemoglobin (Hb) concentration was determined. The optical density

(OD) was measured at a wavelength of 540 nm (A540) using a

microplate reader (Varioskan Flash; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). The Hb concentration was calculated as follows:

Hb=A540×73.54. Subsequently, the percentage of carboxyhemoglobin

(COHb) was determined. The ODs of test and control samples were

measured at 568 nm (A568) and 581 nm (A581). The ΔOD value was

calculated using the following formula: ΔOD=ΔOD of test sample

(A568-A581)-ΔOD of control sample (A568-A581). The COHb was then

calculated using the following equation: COHb (%)=(0.822× ΔOD +

0.001) ×100. The final blood CO concentration was calculated as

follows: CO concentration=[COHb (%) × Hb (g/l)

×106x4]/64456.

Kidney function assessment

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine (SCr)

were measured with commercially available assay kits (C013-2-1 and

C011-2-1; both Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineer Institute, China),

according to the manufacturer's protocols. The OD was measured at a

wavelength of 450 nm, and the concentrations of BUN and SCr were

calculated based on a standard curve.

Histopathological analysis

Renal tissue samples were fixed in 4%

phosphate-buffered formaldehyde for 24–48 h at room temperature and

subsequently embedded in paraffin. The embedded tissues were sliced

into 5 µm-thick sections and were then subjected to hematoxylin and

eosin (H&E) as well as periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining.

Specifically, hematoxylin staining was performed for 5–8 min at

room temperature, followed by eosin staining for 1–2 min under the

same conditions. For the PAS staining, sections were oxidized in

periodic acid solution for 5–10 min at room temperature and then

stained with Schiff's reagent for 15–30 min at room temperature.

After staining, the sections were incubated with diaminobenzidine

for 5 min at room temperature, counterstained with hematoxylin for

1–2 min at room temperature, and observed under a light microscope.

Tubular injury was assessed according to a five-tier grading system

that evaluated the extent of brush border loss, tubular dilation,

cast formation, and cellular necrosis, as referenced in (14). The specific grading scheme was

defined as: 0, no pathological changes; 1, less than 10%

involvement; 2, 10–25% involvement; 3, 26–50% involvement; 4,

51–75% involvement; and 5, >75% involvement.

Immunohistochemical staining

Renal tissue samples were fixed in 4%

phosphate-buffered formaldehyde for 24–48 h at room temperature.

Paraffin-embedded tissue sections (thickness, 5 µm) were

deparaffinized and rehydrated through a descending series of

ethanol to water. Antigen retrieval was performed using citrate

buffer (pH 6.0) at 95°C for 20 min. Endogenous peroxidase activity

was blocked following tissue incubation with 3% hydrogen peroxide

for 10 min at room temperature. Subsequently, sections were blocked

with 10% normal goat serum (cat. no. AR0009, Boster Biological

Technology) for 1 h at room temperature. The sections were then

incubated at 4°C overnight with a primary antibody against

neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL; rabbit; dilution,

1:200; cat. no. ab125075; Abcam). Sections were washed three times

with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) and incubated with an

HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (dilution

1:500; cat. no. ab6721; Abcam) for 30 min at room temperature.

Following secondary antibody incubation, the sections were washed

again with PBS. The tissues were then counterstained with

hematoxylin for 1–2 min at room temperature. Images were captured

under an optical microscope and analyzed with ImageJ software

(v1.8. National Institutes of Health).

TUNEL assay

The kidney tissue samples were fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 24–48 h prior to paraffin

embedding. Paraffin-embedded sections (5 µm) were deparaffinized

and rehydrated as aforementioned, followed by antigen retrieval

with citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 95°C for 20 min. The tissue

sections were then incubated with a TUNEL reaction mixture (One

Step TUNEL Apoptosis Assay Kit, Beyotime, C1089) for 1 h at 37°C.

Subsequently, the sections were counterstaining with hematoxylin

(0.1% w/v, Sigma-Aldrich, H9627) for 1–2 min at room temperature,

and mounted with antifade mounting medium (Beyotime, P0126).

Finally, to assess cell apoptosis, images from five randomly

selected fields of view/section were captured under a light

microscope.

RNA-seq analysis

Total RNA was extracted using a TRIzol®

reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., cat. no.

15596026). RNA integrity and concentration were determined using

the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc.).

Subsequently, for library preparation, high-quality RNA samples

(RNA integrity number ≥7.0) were further analyzed using the NEBNext

Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit (New England BioLabs, Inc., cat. no.

E7530L). The final libraries were quantified using the

Qubit™ dsDNA HS Assay kit (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc., cat. no. Q32851) and diluted to a loading

concentration of 1.8 nM. Paired-end sequencing (2×150 bp) was

performed on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform with the NovaSeq

6000 S4 Reagent kit (300 cycles; Illumina, Inc., cat. no.

20028312). Then the data were processed and analyzed using Fastp

(v0.23.2, github.com/OpenGene/fastp). High-quality reads were then

aligned to the reference genome using HISAT2 (v2.2.1, http://daehwankimlab.github.io/hisat2/),

followed by gene read counting using FeatureCounts (v2.0.3,

http://subread.sourceforge.net/).

Differential expression analysis was ultimately performed using the

DESeq2 (v1.40.2, http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html)

software.

Candidate gene selection

A panel of candidate genes, including cytokine

signaling 6 (SOCS6), mesothelin (MSLN), glutathione-specific

γ-glutamylcyclotransferase 1 (CHAC1) and C-C motif chemokine ligand

4 (CCL4), was preselected for initial screening based on their

previously reported associations with drug-induced organ injury,

cell stress response, inflammation or immune regulation pathways

(14–17). CCL4 was prioritized for detailed

reporting in the present study because it demonstrated the most

consistent and significant dysregulation trends in our preliminary

assessments (data not shown).

ELISA

The serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β were

quantified according to the manufacturer's instructions using Mouse

TNF-α ELISA Kit (Order NO. D721217, Sangon Biotech, Shanghai,

China), Mouse IL-6 ELISA Kit (Order NO. D721022, Sangon Biotech,

Shanghai), and Mouse IL-1β ELISA kit (Order NO. D721017, Sangon

Biotech, Shanghai, China).

Western blot analysis

Total proteins were extracted from kidney tissue

using RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology),

supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Protein

concentration was measured using a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Equal amounts of protein extracts (50 µg

per lane) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, depending on the

molecular weight of each target protein, and were then transferred

onto PVDF membranes (MilliporeSigma). Following blocking with 5%

non-fat milk in TBS-Tween-20 for 1 h at room temperature, the

membranes were incubated at 4°C overnight with primary antibodies

against NGAL (rabbit; dilution, 1:5,000; cat. no. ab125075; Abcam),

C-C motif chemokine ligand 4 (CCL4; rabbit; dilution, 1:800; cat.

no. 26614–1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), phosphorylated

(p)-protein kinase B (p-Akt; rabbit; dilution, 1:3,000; cat. no.

28731-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), Akt (rabbit; dilution,

1:5,000; cat no. 10176-2-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), NF-κB p65

(Ser536) (rabbit; dilution, 1:5,000; cat. no. 80379-2-RR;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), NF-κB p65 (rabbit; dilution, 1:3,000; cat

no. 10745-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), IL-6 (mouse; dilution,

1:3,000; cat. no. 66146-1-Ig; Proteintech Group, Inc.), IL-1β

(rabbit; dilution, 1:1,000; cat. no. 26048-1-AP; Proteintech Group,

Inc.), TNF-α (rabbit; dilution, 1:1,000; cat. no. 17590-1-AP;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), Bax (rabbit; dilution, 1:8,000; cat no.

50599-2-Ig; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and Bcl-2 (mouse; dilution,

1:1,000; cat. no. 26593-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.). Membranes

were washed three times with TBST (0.05% Tween-20), and incubated

with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (cat. no. SA00001-2) or goat

anti-mouse (1:5,000; cat. no. SA00001-1; Proteintech) secondary

antibodies (dilution, 1:5,000; Proteintech Group, Inc.) for 1 h at

room temperature. GAPDH (rabbit; dilution 1:20,000; cat. no.

10494-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and β-actin (rabbit; dilution,

1:20,000; cat. no. 66009-1-Ig; Proteintech Group, Inc.) served as

internal loading controls. The proteins were visualized using the

WesternBright® ECL detection kit (Advansta Inc.)

combined with the ChemiDoc XRS+ imaging system (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.). The signal intensity of each band was

subsequently quantified using ImageLab software v6.1 (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.).

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± SD. All

statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp.).

The differences between two groups were compared by unpaired

Student's t-test, while those among multiple groups were compared

by one-way ANOVA. For multiple comparisons following ANOVA,

Bonferroni correction was applied. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

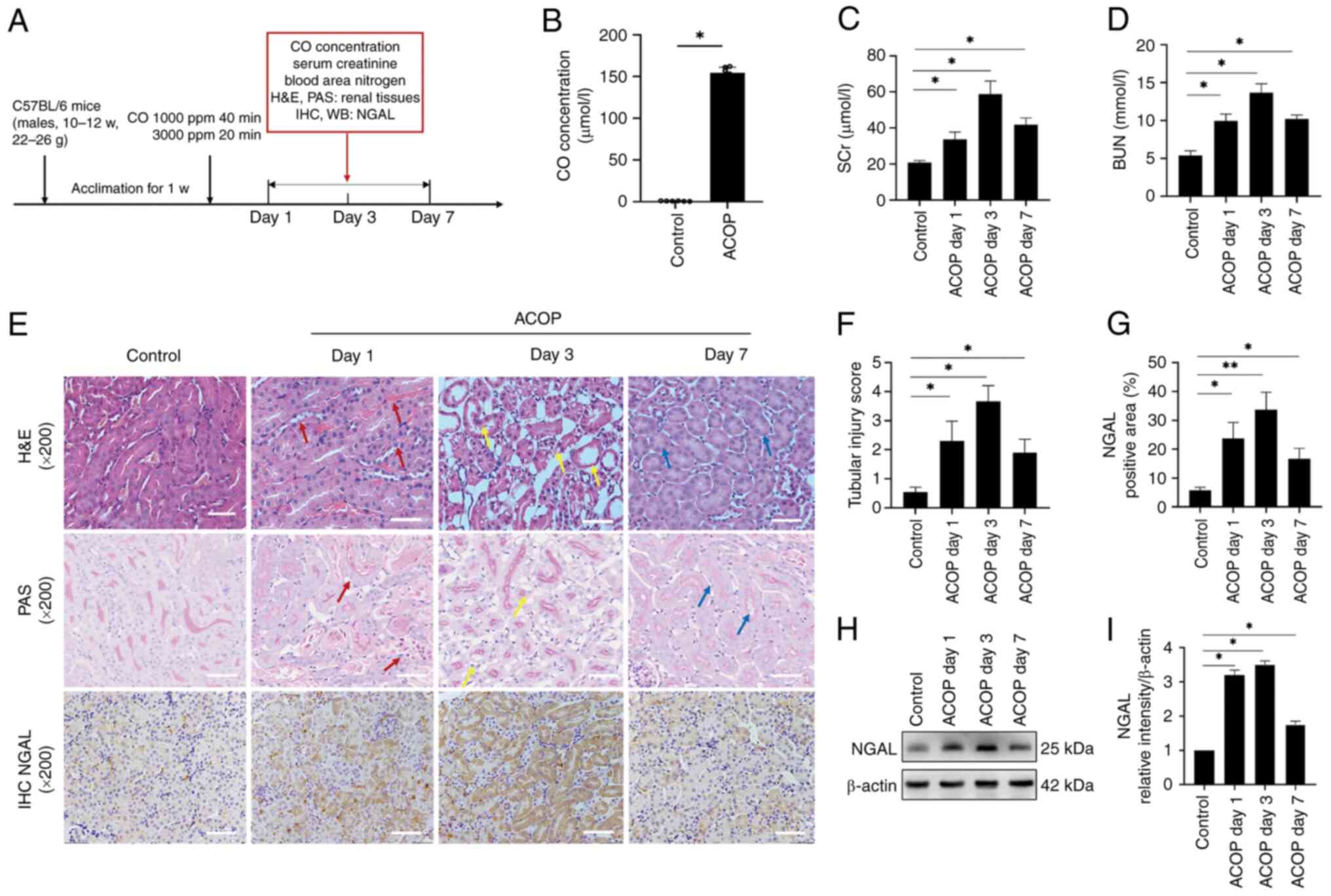

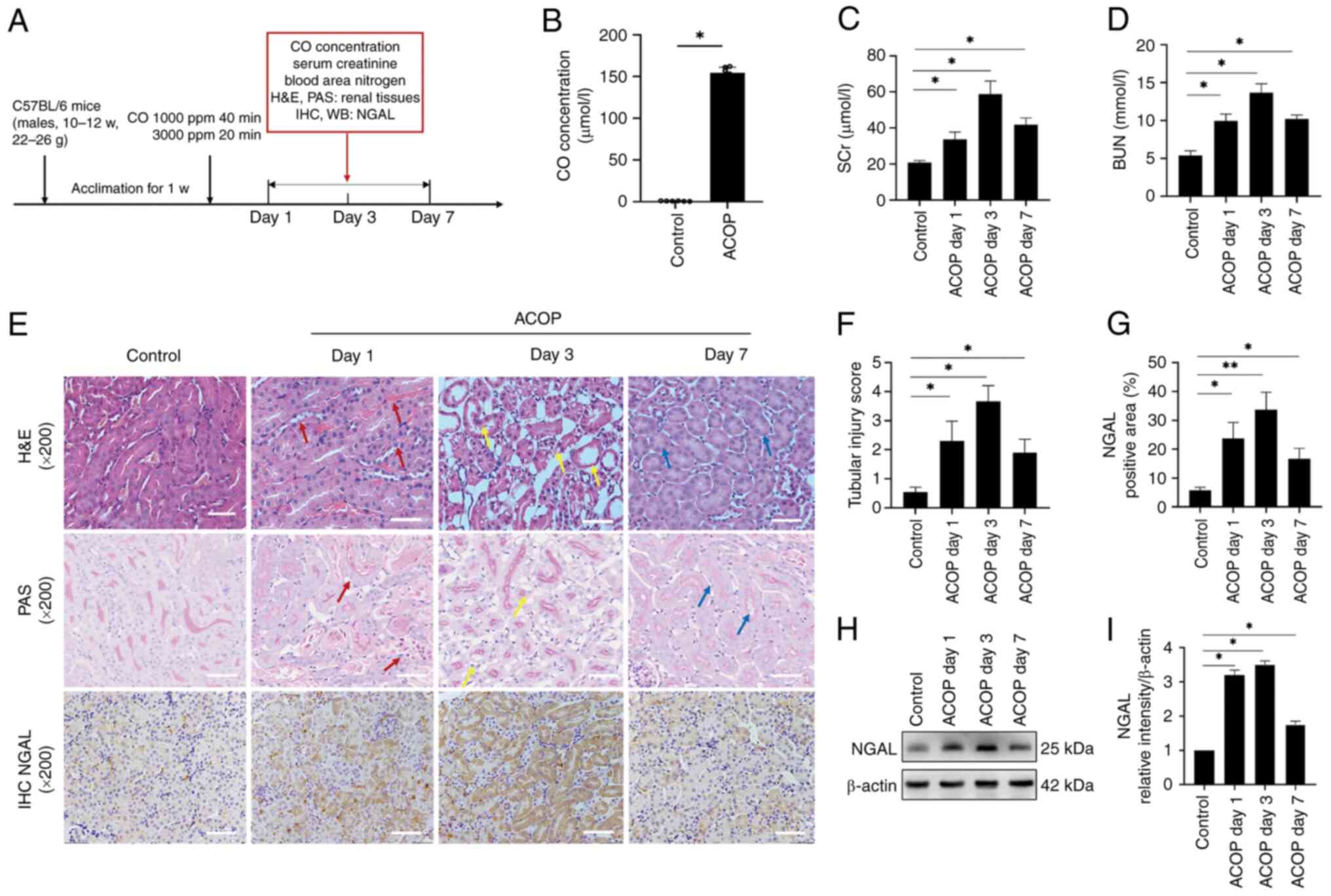

ACOP induces AKI in mice

To evaluate whether ACOP treatment induces kidney

injury in mice, a mouse model of ACOP exposure was established, and

blood samples were collected at 1, 3 and 7 days following CO

exposure to assess blood CO levels, renal function parameters and

renal histopathology (Fig. 1A).

The results demonstrated that blood CO levels were markedly

elevated in ACOP-treated mice compared with control mice, thus

verifying the successful establishment of the mouse model (Fig. 1B). In addition, SCr and BUN levels

were markedly increased at all time points following ACOP treatment

compared with the control group, thus indicating substantial renal

dysfunction (Fig. 1C and D).

Histological analysis, using H&E and PAS staining, revealed

that the glomerular structure remained intact, although mild

mesangial matrix expansion and prominent tubular injury were

observed in the ACOP group (Fig.

1E). On day 1 post-ACOP exposure, renal tubular epithelial

cells displayed marked swelling, peritubular capillary congestion,

cytoplasmic dissolution and nuclear loss (red arrows). On day 3,

severe vacuolar degeneration, tubular dilation, brush border

disruption and extensive nuclear detachment were evident (yellow

arrows). However, on day 7, partial tubular regeneration was

observed, although vacuolar changes, tubular dilation and brush

border damage persisted (blue arrows). To assess tubular injury,

the tubular injury scoring method was applied (18), which showed a significant increase

in injury scores in ACOP treated mice compared with control mice,

with the highest injury scores observed on day 3. This finding was

consistent with the morphological one (Fig. 1F). In addition, the expression

levels of NGAL, an early biomarker of AKI, were detected.

Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated markedly widespread NGAL

expression in renal tubules in mice in the ACOP group compared with

the control group (Fig. 1E and G).

Western blot analysis further verified that NGAL was markedly

upregulated in the ACOP group compared with the control group; this

was most noticeable on days 1 and 3, followed by a decrease on day

7 (Fig. 1H and I). Collectively,

the aforementioned results suggested that exposure of mice to ACOP

could successfully induce AKI.

| Figure 1.ACOP induces acute kidney injury in

mice. (A) Schematic illustration of the ACOP mouse model and

experimental design. (B) Bar graph showing CO concentrations in the

blood of mice in the control and ACOP groups. (C) SCr and (D) BUN

levels at different time points after ACOP exposure are shown. (E)

Representative H&E, PAS and NGAL immunohistochemical staining

of kidney tissues at different time points after mice exposure to

ACOP exposure. On day 1, tubular epithelial cells displayed marked

swelling, peritubular capillary congestion and cytoplasmic

dissolution with nuclear loss, as indicated by the red arrows. On

day 3, extensive vacuolar degeneration, tubular dilation, brush

border disruption and nuclear shedding were observed (yellow

arrows). By day 7, signs of tubular regeneration, with persisted

vacuolar degeneration, tubular dilation and brush border damage

(blue arrows), were observed. Scale bar, 100 µm. (F) Quantification

of tubular injury scoring. (G) Quantification of NGAL protein

expression in renal tissue detected by immunohistochemistry. (H)

Expression of NGAL based on immunoblot bands. (I) Semi-quantitation

of NGAL expression. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n=6).

*P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. control. ACOP, acute carbon monoxide

poisoning; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; SCr,

serum creatinine; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CO, carbon monoxide; w,

week; ppm, parts per million; H&E, Hematoxylin and Eosin; PAS,

periodic acid-Schiff; IHC, immunohistochemistry; WB, western blot

analysis. |

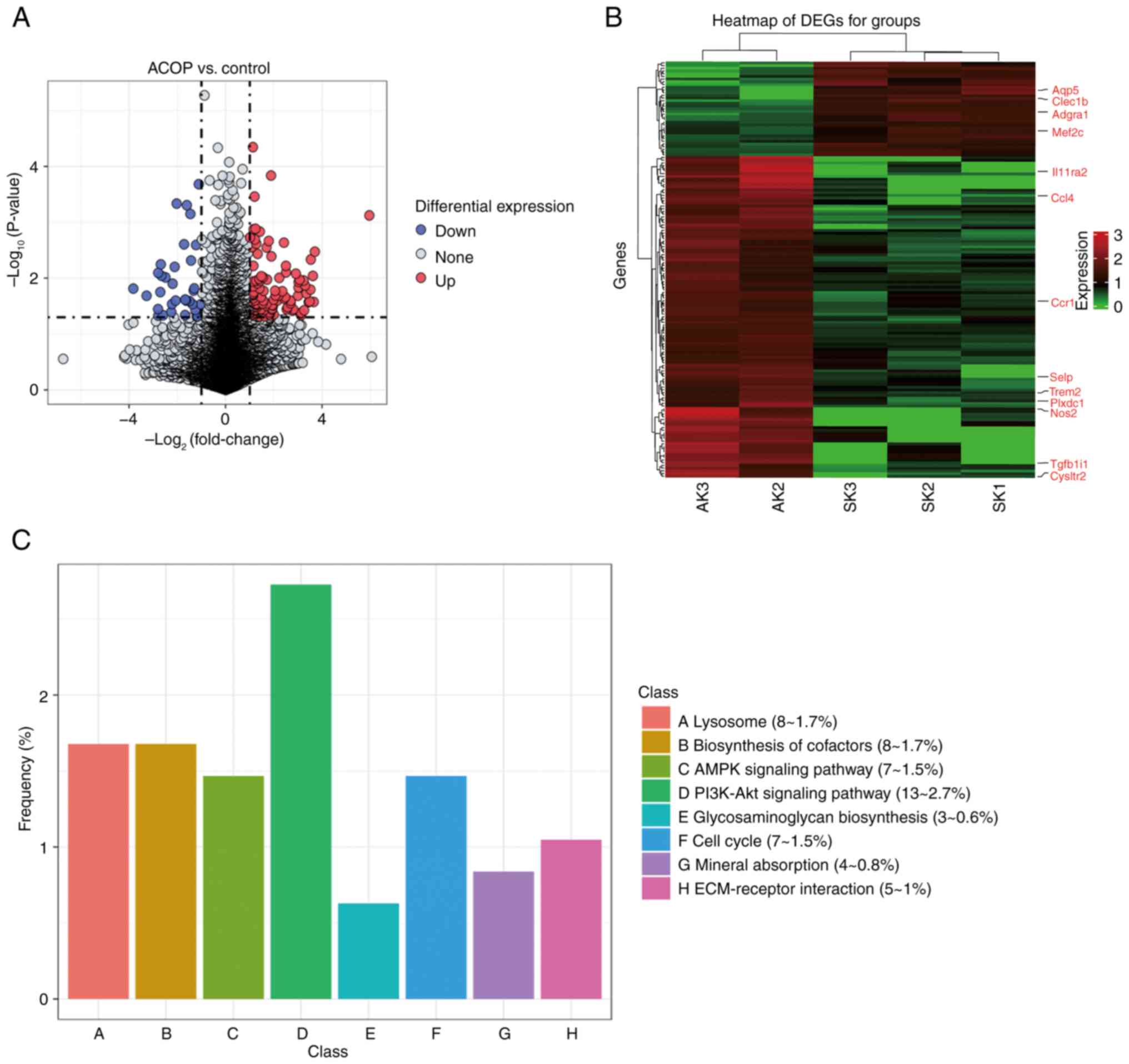

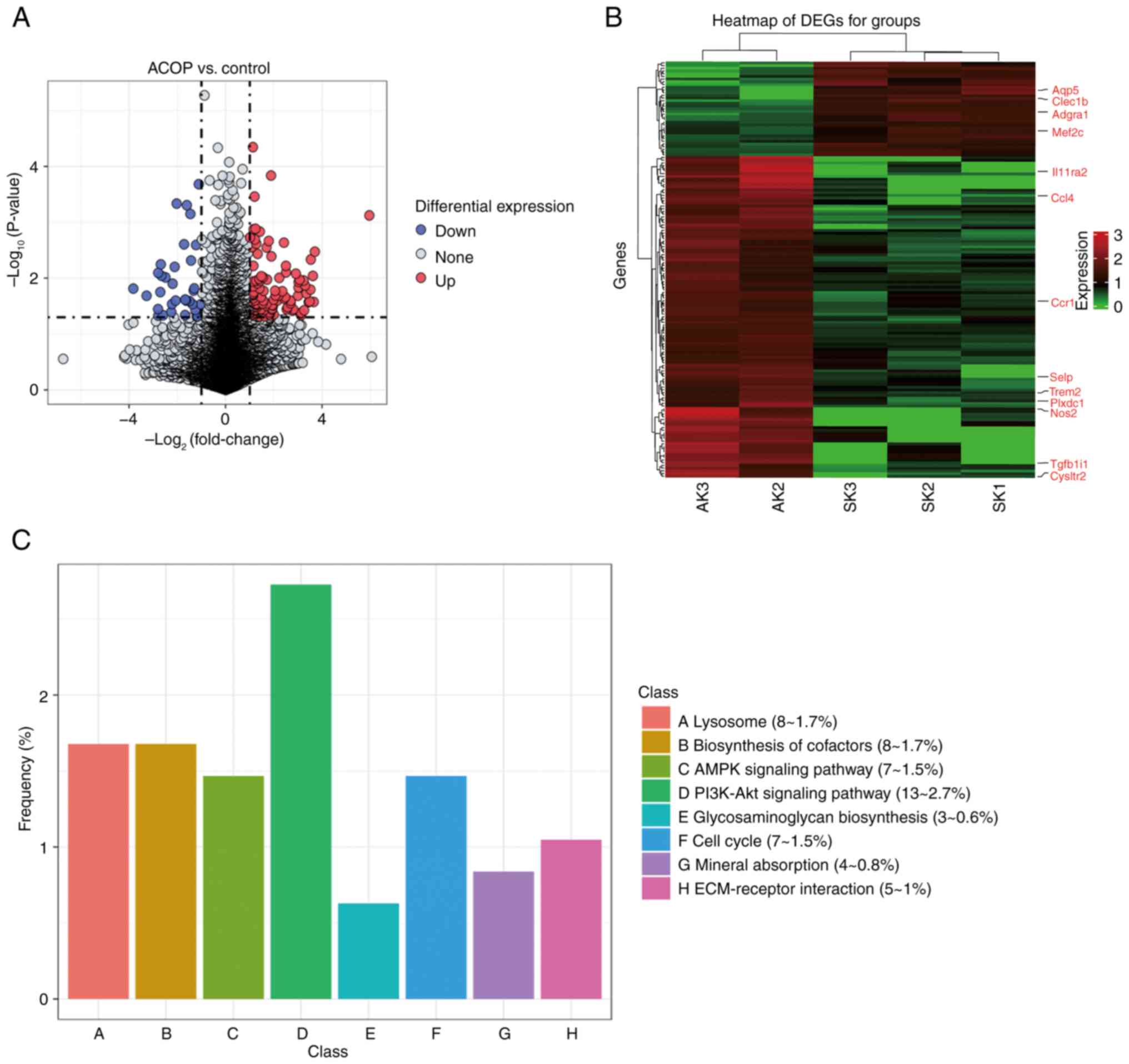

DEGs and signaling pathways in

ACOP-AKI

To further explore the molecular mechanism of

ACOP-AKI, RNA-seq analysis was carried out on the kidney tissue

samples from the ACOP model and control groups on day 3, identified

as the peak of kidney injury. Based on the analysis of differential

gene expression, the top 20 DEGs with the highest average

expression levels were presented in Table SI, including log2(fold

change) and P-value. The volcano plot in Fig. 2A depicts the distribution of DEGs,

revealing significant up- and downregulation trends, whereas the

heatmap in Fig. 2B focuses on

genes functionally linked to the PI3K/Akt pathway. A KEGG pathway

enrichment analysis of DEGs revealed that the ‘PI3K/Akt signaling

pathway’ was markedly enriched in the ACOP group (Fig. 2C).

| Figure 2.C-C motif chemokine ligand 4 is

upregulated in ACOP-treated mice via the PI3K/Akt signaling

pathway. (A) Volcano plots showing identified DEGs. Red and blue

dots indicate markedly upregulated and downregulated genes,

respectively, while gray dots represent genes that do not meet the

differential expression criteria. (B) Heatmap of DEGs. Red and

green indicate the upregulated and downregulated genes,

respectively. (C) Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway

enrichment analysis of DEGs. DEG, differentially expressed genes;

ACOP, acute carbon monoxide poisoning; AMPK, AMP-activated protein

kinase; ECM, extracellular matrix; AK, acute kidney; SK, sham

kidney Aqp5, aquaporin 5; Clec1b, C-type lectin domain family 1

member B; Adgra1, adhesion G protein-coupled receptor A1; Mef2c,

myocyte enhancer factor 2C; Il11ra2, interleukin 11 receptor

subunit α2; Ccl4, C-C motif chemokine ligand 4; Ccr1, C-C motif

chemokine receptor 1; Selp, selectin P; Trem2, triggering receptor

expressed on myeloid cells 2; Plxdc1, plexin domain containing 1;

Nos2, nitric oxide synthase 2; Tgfb1i1, transforming growth factor

β1 induced transcript 1; Cysltr2, cysteinyl leukotriene receptor

2. |

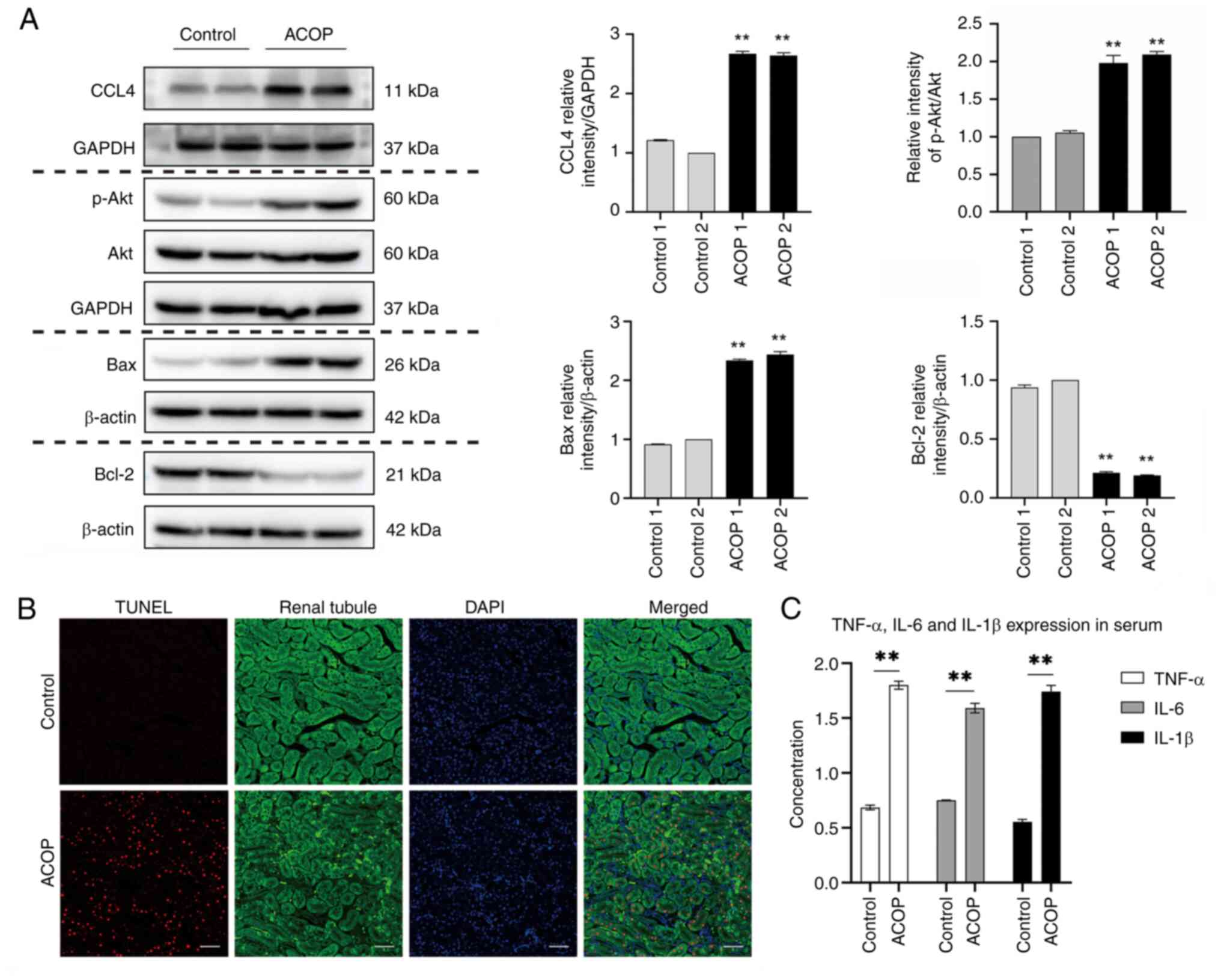

ACOP upregulates CCL4 expression in

renal tissue, activates the PI3K/Akt pathway and elevates renal

cell apoptosis and systemic inflammatory cytokine levels

Through candidate gene screening and validation,

CCL4 exhibited consistent patterns at both the transcriptional and

protein levels in the present model (data not shown), indicating

its potential role in the mechanisms underlying ACOP-AKI. In

addition, the present study observed that in ACOP-exposed mice, the

p-Akt/Akt ratio and Bax protein levels were markedly increased,

whereas Bcl-2 expression was markedly decreased when compared with

control mice (Fig. 3A). TUNEL

staining assays further revealed that the number of TUNEL-positive

cells was notably increased in renal tissues of mice in the ACOP

group compared with the control group. Merged images demonstrated

co-localization of TUNEL signals with DAPI-stained nuclei,

confirming the induction of cellular apoptosis in the renal tissue

following ACOP injury. Furthermore, the apoptosis appeared to be

predominantly localized within the renal tubule (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, the ELISA results

demonstrated markedly elevated serum levels of the systemic

pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β in the ACOP group

compared with the control group (Fig.

3C). The aforementioned data indicated that ACOP may have

upregulated the expression of CCL4, accompanied by activation of

the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Furthermore, ACOP induced

significant inflammatory responses and notable apoptosis.

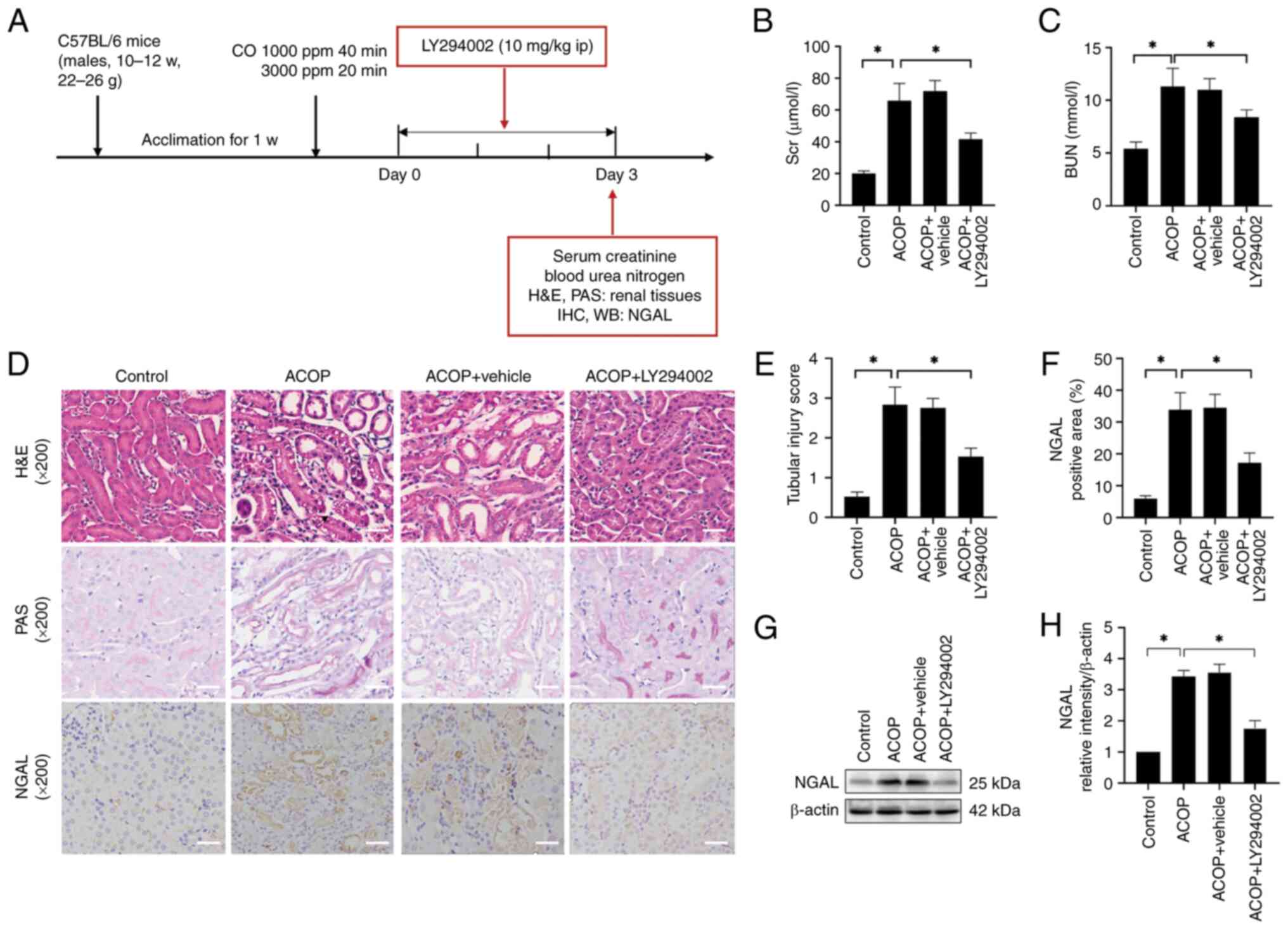

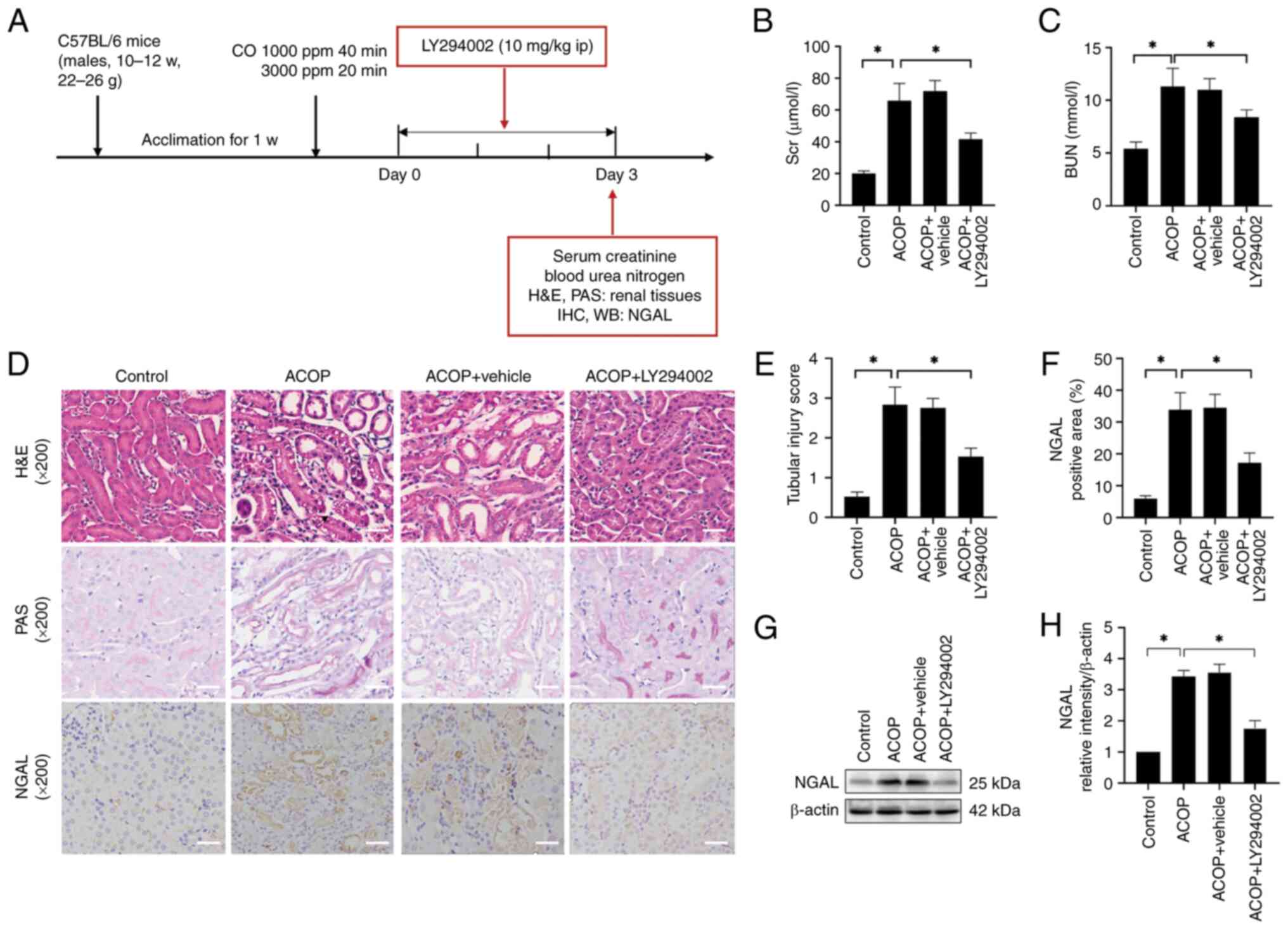

LY294002 attenuates ACOP-AKI

To investigate the role of the PI3K/Akt signaling

pathway in ACOP-AKI, mice were treated with the PI3K inhibitor

LY294002, and renal function and histopathological changes were

evaluated on day 3 (Fig. 4A).

Biochemical analysis showed that mice in the ACOP group exhibited

markedly elevated serum levels of SCr and BUN compared with the

control group. In addition, LY294002 treatment partially yet

markedly ameliorated these increased serum levels (Fig. 4B and C). Morphological assessment

revealed pronounced tubular damage in the kidneys of ACOP-treated

mice, which was markedly alleviated in the ACOP + LY294002 group

(Fig. 4D). Consistently, the

tubular injury score was markedly lower in the ACOP + LY294002

group compared with the ACOP group (Fig. 4E). Immunohistochemical analysis

demonstrated a significant increase in NGAL expression in the ACOP

group compared with the control group, which was markedly reduced

following treatment with LY294002 (Fig. 4F). Finally, western blot analysis

was performed to assess the NGAL protein expression levels

(Fig. 4G), and densitometric

quantification verified that LY294002 markedly suppressed NGAL

expression in the kidneys of ACOP-treated mice (Fig. 4H). These findings suggested that

LY294002 could effectively mitigate ACOP-AKI.

| Figure 4.Effects of LY294002 on kidney injury

in mice exposed to ACOP. (A) Schematic representation of the

establishment of the ACOP + LY294002 mouse model and experimental

design. The experiment was conducted on day 3 after ACOP exposure,

when the injury was most severe. Blood and tissue samples were

subsequently collected for serological, morphological and protein

expression analyses. (B) SCr and (C) BUN levels in control, ACOP,

vehicle-treated ACOP control and LY294002-treated ACOP groups are

shown. (D) Representative H&E, PAS and NGAL immunohistochemical

staining images of kidney tissues in different groups are shown.

Scale bar, 100 µm. (E) Tubular injury scoring is presented. (F)

Quantification of NGAL protein expression in renal tissue detected

by immunohistochemistry. (G) Expression of NGAL based on immunoblot

bands. (H) Semi-quantitation of NGAL expression. Data are expressed

as the mean ± SD (n=3). *P<0.05 vs. control. ACOP, acute carbon

monoxide poisoning; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated

lipocalin; SCr, serum creatinine; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CO,

carbon monoxide; w, week; ppm, parts per million; PAS, periodic

acid-Schiff; IHC, immunohistochemistry; WB, western blot analysis;

ip, intraperitoneal. |

LY294002 inhibits inflammation and

apoptosis in the kidneys of ACOP mice

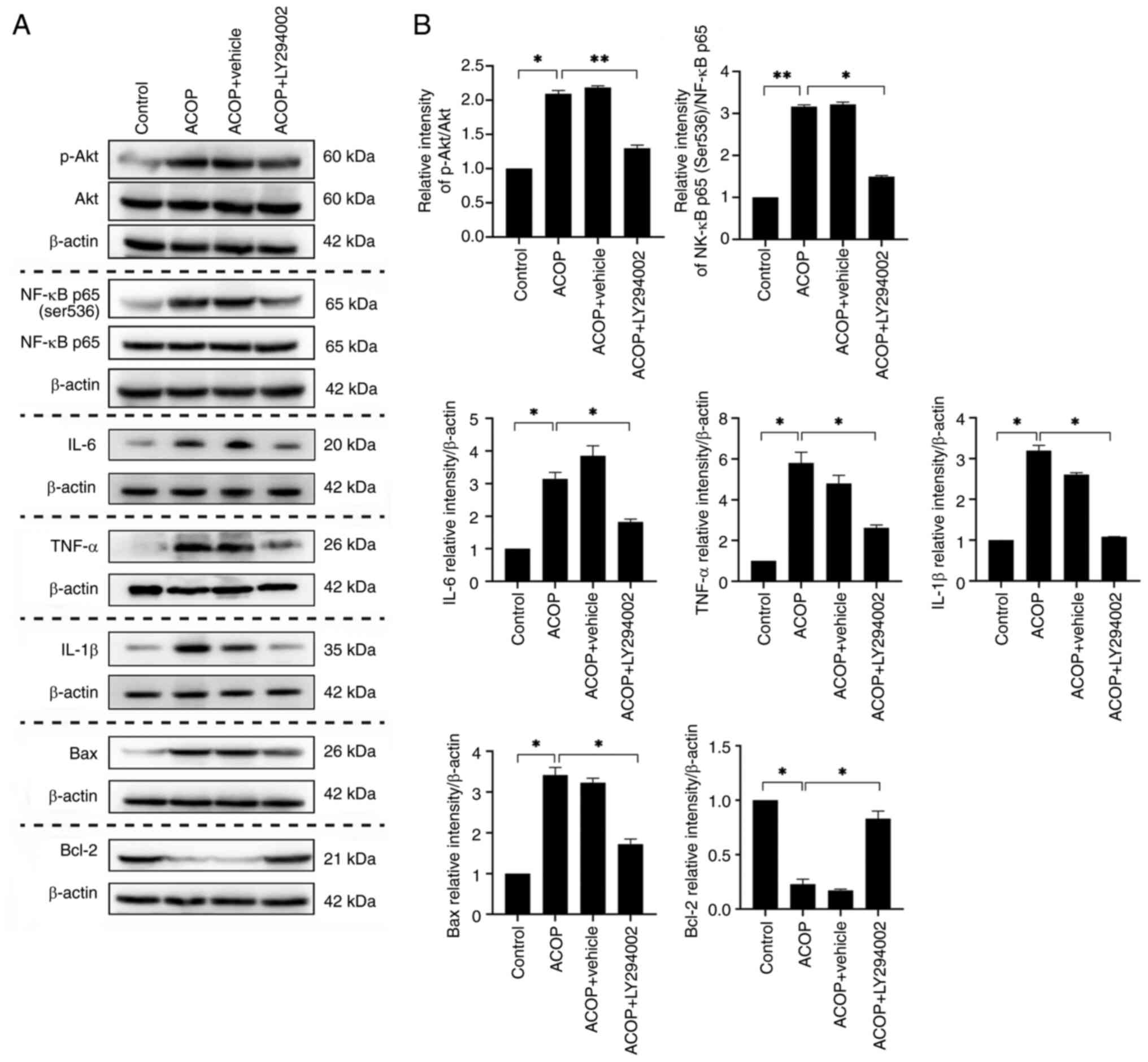

To further investigate the molecular mechanisms

underlying the effects of LY294002 on ACOP-AKI, western blot

analysis was employed to detect the expression levels of

inflammatory factors and apoptosis-related proteins. The results

showed that the ratio of p-Akt/Akt was markedly elevated in the

ACOP-treated group, compared with the control, accompanied by a

significant upregulation of inflammatory factors such as IL-6,

TNF-α and IL-1β. By contrast, treatment with LY294002 markedly

reduced the p-Akt/Akt ratio and the protein expression levels of

IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α compared with the ACOP group, suggesting an

inhibitory effect of LY294002 on the expression of pro-inflammatory

cytokines.

Considering that NF-κB is a key mediator of

pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, the present study further

assessed the ratio of NF-κB p65 (Ser536)/NF-κB p65. The results

revealed that treatment with LY294002 also markedly inhibited the

elevation of this ratio in the kidneys of ACOP-treated mice.

Furthermore, ACOP treatment induced a significant increase in the

expression of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax and a significant

decrease in the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 when

compared with the control group. However, LY294002 treatment

markedly suppressed ACOP-induced Bax expression and restored Bcl-2

levels (Fig. 5). In conclusion,

LY294002 effectively suppressed inflammation and apoptosis in the

kidneys of ACOP-treated mice by modulating key signaling pathways

such as PI3K/Akt and NF-κB, providing a potential pharmacological

target for the treatment of ACOP-AKI.

Discussion

ACOP is one of the most common causes of poisoning

globally and can induce AKI, potentially leading to CKD in severe

cases (19,20). In the present study, the successful

establishment of the ACOP mouse model was verified via measuring

the serum levels of CO. Renal dysfunction was observed on the first

day after exposure of mice to ACOP, which was characterized by

elevated SCr and BUN levels, accompanied by hallmark

histopathological alterations, including tubular dilatation,

epithelial cell detachment, inflammatory infiltration and aberrant

NGAL expression. A clinical study reported that the median time to

the first diagnosis of ACOP-AKI is one day after Emergency

Department (ED) admission, with the majority of patients being

diagnosed at their highest KDIGO stage within three days of ED

admission (3). Notably, renal

injury reached its peak on day 3 and exhibited partial recovery by

day 7, which was consistent with clinical observations (3). While individuals with stage I and II

AKI typically achieved a full recovery, up to 55.6% of those with

stage III AKI progressed to CKD (3,21).

The underlying mechanisms of ACOP-AKI to CKD may involve a burst of

reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and the activation of

downstream signal cascades. ROS not only directly damage cellular

components but also trigger sustained tissue injury via promoting

inflammatory responses and apoptotic signaling, potentially forming

the pathological basis for long-term sequelae of ACOP (22). Histological analyses further

revealed that metabolically active renal tubular epithelial cells

were the primary targets of injury, whereas glomerular structures

remained relatively intact. This may be attributed to the higher

oxygen demand and greater susceptibility to oxidative stress of

tubular epithelial cells (23,24).

This observation was consistent with the clinical manifestations of

patients with ACOP-AKI, who primarily present with oliguria,

proteinuria, urinary casts, and disturbances in water and

electrolyte balance (25).

The mechanisms underlying ACOP-AKI are complex,

involving CO-mediated tissue hypoxia and ischemia, mitochondrial

dysfunction, oxidative stress and inflammation. However, the

underlying molecular mechanisms remain yet to be fully elucidated

(2,23). Among the aforementioned mechanisms,

inflammation was considered to be closely related to ACOP-AKI. In

the present study, RNA-seq analysis of renal tissues from mice with

ACOP-AKI revealed a significant upregulation of multiple

inflammation-related genes. During the initial phase of the present

study, candidate genes were preselected, such as SOCS6, MSLN, CHAC1

and CCL4, for further investigation based on prior research.

Notably, CCL4 exhibited consistent trends at both the

transcriptional and protein levels in the present model, suggesting

its potential role in the mechanisms underlying ACOP-AKI. While we

are actively exploring the functional roles of other key candidate

genes, further evidence is required to substantiate these findings.

Given the novelty of CCL4 in ACOP-AKI, we prioritized reporting

these results. Furthermore, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis

indicated that the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway was markedly

activated, thus suggesting that this signaling axis could serve an

important role in the pathogenesis of ACOP-AKI.

In the present study, the RNA-seq results were

further verified at the protein and functional levels by western

blot analysis. The results demonstrated that in ACOP-treated mice,

the expression levels of CCL4 and the p-Akt/Akt ratio were markedly

increased compared with the control group. As a chemotactic factor,

CCL4 is important for immune cell recruitment and initiates local

immune responses, thus promoting inflammation (26). The PI3K/Akt signaling pathway is a

notable axis in cell growth, survival and stress responses, and its

activation can enhance cell survival signals and inhibit apoptosis.

However, chronic or excessive PI3K/Akt signaling activation can

result in an amplified inflammatory response and promote apoptosis

(27). The present study found

that renal tubular cell apoptosis was accelerated in ACOP-treated

mice, accompanied by a significant increase in Bax and decrease in

Bcl-2 expression. In addition, the serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and

IL-1β were also markedly elevated, thus indicating that a systemic

inflammatory response was activated. These findings supported the

involvement of CCL4 upregulation and activation of the PI3K/Akt

pathway in the process of ACOP-AKI, which may play a role in

promoting the inflammatory response and apoptosis.

To further verify the functional involvement of the

PI3K/Akt pathway, mice in the ACOP group were treated with the

LY294002 PI3K inhibitor (28). The

results demonstrated that LY294002 markedly improved renal

dysfunction, as evidenced by the reduced SCr and BUN levels, and

improved the morphological integrity of the renal tubular

structures. Immunohistochemical and western blot analyses further

revealed a significant decrease in the expression levels of NGAL in

the LY294002-treated group compared with the ACOP model group, thus

providing additional evidence for the nephroprotective effects of

PI3K inhibition.

As a key regulatory factor in inflammatory

responses, PI3K has emerged as a potential treatment target for

inflammatory diseases (29).

Previous studies showed that LY294002 could inhibit the PI3K/Akt

pathway, eventually downregulating NF-κB and pro-inflammatory

factors, such as TNF-α and IL-1β, in the spinal cords of bone

cancer pain-model rats (30).

NF-κB is a key transcription factor, which is notably involved in

several inflammatory reactions. The NF-κB-induced release of

downstream inflammatory mediators not only enhances the recruitment

of immune cells but can also lead to cell damage and apoptosis

through various mechanisms, such as generating excessive oxidative

stress or directly activating apoptotic pathways (31,32).

In particular, TNF-α and IL-1β are considered significant

pro-apoptotic factors.

In the present study, the activation of the PI3K/Akt

pathway was associated with the phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 (Ser

536), which may enhance its transcriptional activity and promote

the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators, including TNF-α, IL-6

and IL-1β. These inflammatory mediators further promoted the

expression of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax, while reducing the

expression levels of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2, eventually

aggravating renal cell apoptosis. This mechanism was reversed by

LY294002 treatment. The aforementioned mechanism was consistent

with that reported in a previous study, suggesting that

NF-κB-mediated inflammation could also be involved in CO

poisoning-induced neurological injury (33). However, PI3K/Akt may also have

affected apoptosis via additional downstream targets, such as

mammalian target of rapamycin or forkhead box O. Nevertheless,

further studies are needed to verify the involvement of these

pathways.

However, the present study had some limitations.

Previous studies have demonstrated that CCL4 can activate a variety

of downstream signaling pathways, including the PI3K/Akt pathway

(34), and induce the

phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 via its receptor C-C chemokine

receptor type (CCR)5 (35). This

process promotes cell senescence and dysfunction via increasing ROS

production and activating inflammatory responses (17). Although the results of RNA-seq

showed that CCL4 was markedly upregulated at the transcription

level and was closely associated with the activation of the

PI3K/Akt pathway, the particular role of CCL4 in ACOP-AKI and its

causal association with the PI3K/Akt pathway should be further

verified. Functional experiments, such as gene knockout or

antibody-mediated neutralization are necessary to validate this

association. In addition, other differentially expressed

inflammation-related genes identified through RNA-seq analysis,

such as MSLN, SOCS6, CHAC1, CCR1, nitric oxide synthase 2 and

P-selectin, could also interact with the PI3K/Akt axis, warranting

further exploration into their molecular interaction mechanisms.

Furthermore, clinical data correlating the CCL4/Akt axis with the

severity of AKI in patients with ACOP remains lacking. Therefore,

future studies exploring this potential association should be

performed for improved understanding of its clinical relevance.

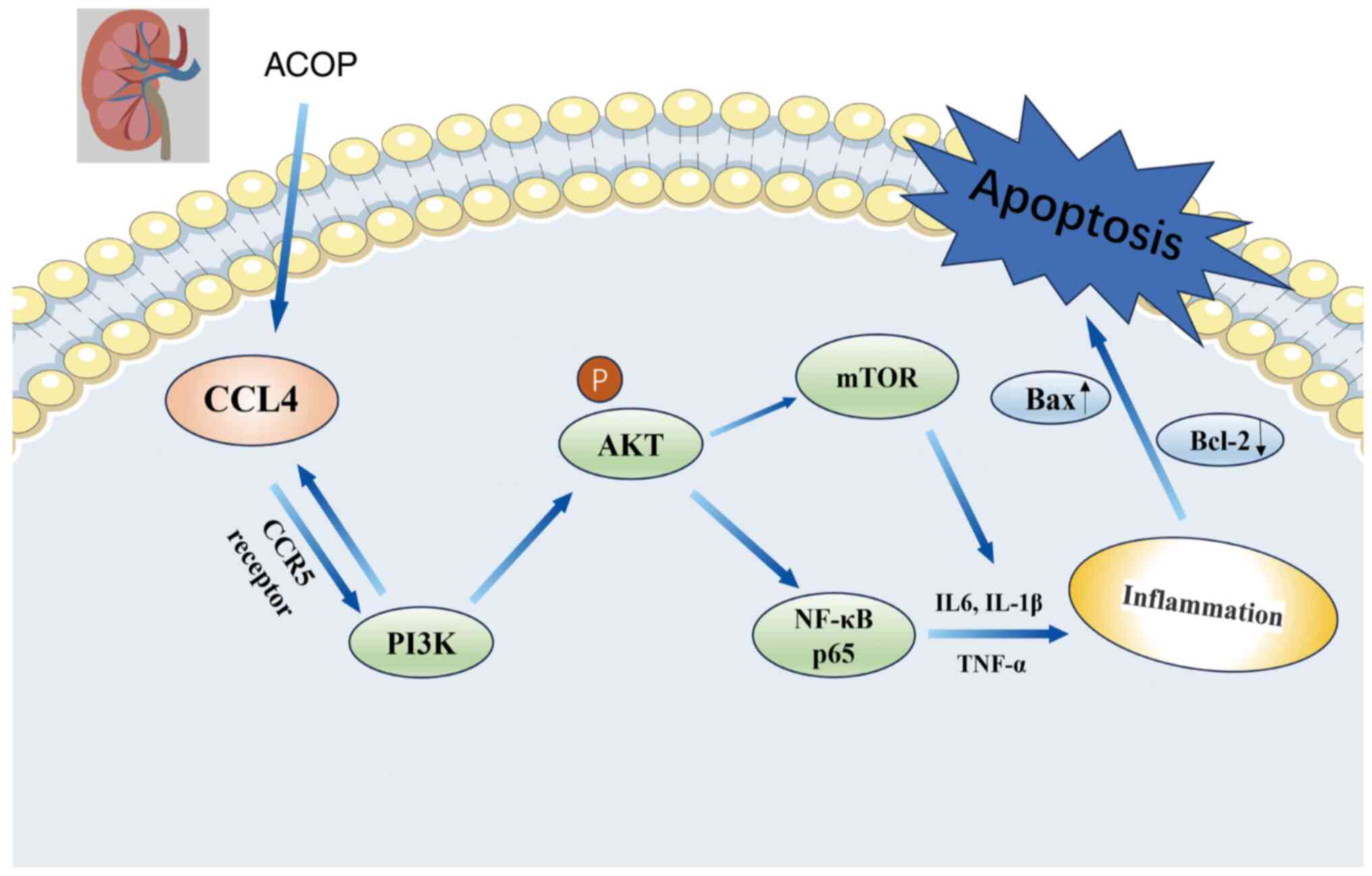

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

during ACOP, CCL4 expression and the PI3K/Akt pathway were

upregulated, resulting in renal dysfunction and promoting

inflammatory responses and apoptosis. Additionally,

LY294002-induced inhibition of the PI3K/Akt pathway attenuated

NF-κB-mediated inflammatory signaling, thus alleviating AKI in ACOP

mice via suppressing inflammatory responses and cell apoptosis

(Fig. 6). To the best of our

knowledge, the present study was the first study to utilize RNA-seq

technology to identify abnormal gene expression and changes in

signaling pathways in the renal tissues of ACOP-exposed mice. These

findings could provide important experimental evidence and

theoretical insights for further elucidating the molecular

mechanisms underlying ACOP-AKI.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82260254), Medical Research Union

Fund for High-quality health development of Guizhou Province (grant

no. 2024GZYXKYJJXM0081), Guizhou Province Basic Research Program

[grant no. (2023)568], Guizhou Province Basic Research

Program-[grant no. (2025)387] and Science and Technology Fund

Project of Guizhou Provincial Health Commission (grant no.

2024GZWJKJXM1070).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

in the Sequence Read Archive under accession number PRJNA1234475 or

at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1234475.

Authors' contributions

AYY and QL conceived and designed the study. YN,

XHJ, SHW, TP and TTY analyzed and interpreted data. YN, XHJ and SHW

improved the quality of the figures. XHJ, SHW, TTY and YN drafted

the manuscript. TP, AYY and QL revised the manuscript. YN and QL

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All experimental protocols were approved by the

Animal Care Committee of Zunyi Medical University (approval no.

zyfy-an-2024-0710/0358) and supervised by the Ethics Committee of

the Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University. All procedures

adhered to China's guidelines for animal research, ensuring ethical

standards were met by minimizing animal usage and alleviating

potential distress.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Rose JJ, Wang L, Xu Q, McTiernan CF, Shiva

S, Tejero J and Gladwin MT: Carbon monoxide poisoning:

Pathogenesis, management, and future directions of therapy. Am J

Respir Crit Care Med. 195:596–606. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Huang TL, Tung MC, Lin CL and Chang KH:

Risk of acute kidney injury among patients with carbon monoxide

poisoning. Medicine (Baltimore). 100:e272392021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kim YJ, Sohn CH, Seo DW, Oh BJ, Lim KS,

Chang JW and Kim WY: Analysis of the development and progression of

carbon monoxide poisoning-related acute kidney injury according to

the kidney disease improving global outcomes (KDIGO) criteria. Clin

Toxicol (Phila). 56:759–764. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Garrabou G, Inoriza JM, Morén C, Oliu G,

Miró Ò, Martí MJ and Cardellach F: Mitochondrial injury in human

acute carbon monoxide poisoning: The effect of oxygen treatment. J

Environ Sci Health C Environ Carcinog Ecotoxicol Rev. 29:32–51.

2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Rose JJ, Bocian KA, Xu Q, Wang L,

DeMartino AW, Chen X, Corey CG, Guimarães DA, Azarov I, Huang XN,

et al: A neuroglobin-based high-affinity ligand trap reverses

carbon monoxide-induced mitochondrial poisoning. J Biol Chem.

295:6357–6371. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Teksam O, Sabuncuoğlu S, Girgin G and

Özgüneş H: Evaluation of oxidative stress and antioxidant

parameters in children with carbon monoxide poisoning. Hum Exp

Toxicol. 38:1235–1243. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Thom SR, Fisher D and Manevich Y: Roles

for platelet-activating factor and *NO-derived oxidants causing

neutrophil adherence after CO poisoning. Am J Physiol Heart Circ

Physiol. 281:H923–H930. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lee SJ, Ryter SW, Xu JF, Nakahira K, Kim

HP, Choi AM and Kim YS: Carbon monoxide activates autophagy via

mitochondrial reactive oxygen species formation. Am J Respir Cell

Mol Biol. 45:867–873. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wang Z, Gerstein M and Snyder M: RNA-Seq:

A revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat Rev Genet. 10:57–63.

2009. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ozsolak F and Milos PM: RNA sequencing:

Advances, challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Genet. 12:87–98.

2011. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Stark R, Grzelak M and Hadfield J: RNA

sequencing: The teenage years. Nat Rev Genet. 20:631–656. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Conesa A, Madrigal P, Tarazona S,

Gomez-Cabrero D, Cervera A, McPherson A, Szcześniak MW, Gaffney DJ,

Elo LL, Zhang X and Mortazavi A: A survey of best practices for

RNA-seq data analysis. Genome Biol. 17:132016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wang S, Xiong B, Tian Y, Hu Q, Jiang X,

Zhang J, Chen L, Wang R, Li M, Zhou X, et al: Targeting ferroptosis

promotes functional recovery by mitigating white matter injury

following acute carbon monoxide poisoning. Mol Neurobiol.

61:1157–1174. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhang P, Guan P, Ye X, Lu Y, Hang Y, Su Y

and Hu W: SOCS6 promotes mitochondrial fission and cardiomyocyte

apoptosis and is negatively regulated by quaking-mediated miR-19b.

Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022:11213232022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Nishio T, Koyama Y, Liu X, Rosenthal SB,

Yamamoto G, Fuji H, Baglieri J, Li N, Brenner LN, Iwaisako K, et

al: Immunotherapy-based targeting of MSLN+ activated

portal fibroblasts is a strategy for treatment of cholestatic liver

fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 118:e21012701182021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Sun J, Ren H, Wang J, Xiao X, Zhu L, Wang

Y and Yang L: CHAC1: A master regulator of oxidative stress and

ferroptosis in human diseases and cancers. Front Cell Dev Biol.

12:14587162024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Chang TT, Lin LY, Chen C and Chen JW: CCL4

contributes to aging related angiogenic insufficiency through

activating oxidative stress and endothelial inflammation.

Angiogenesis. 27:475–499. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kim MG, Yun D, Kang CL, Hong M, Hwang J,

Moon KC, Jeong CW, Kwak C, Kim DK, Oh KH, et al: Kidney VISTA

prevents IFN-γ/IL-9 axis-mediated tubulointerstitial fibrosis after

acute glomerular injury. J Clin Invest. 132:e1511892022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Mattiuzzi C and Lippi G: Worldwide

epidemiology of carbon monoxide poisoning. Hum Exp Toxicol.

39:387–392. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wei KY, Liao CY, Chung CH, Lin FH, Tsao

CH, Sun CA, Lu KC, Chien WC and Wu CC: Carbon monoxide poisoning

and chronic kidney disease risk: A nationwide, population-based

study. Am J Nephrol. 52:292–303. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ostermann M, Bellomo R, Burdmann EA, Doi

K, Endre ZH, Goldstein SL, Kane-Gill SL, Liu KD, Prowle JR, Shaw

AD, et al: Controversies in acute kidney injury: Conclusions from a

kidney disease: Improving global outcomes (KDIGO) conference.

Kidney Int. 98:294–309. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Dent MR, Rose JJ, Tejero J and Gladwin MT:

Carbon monoxide poisoning: From microbes to therapeutics. Annu Rev

Med. 75:337–351. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Scholz H, Boivin FJ, Schmidt-Ott KM,

Bachmann S, Eckardt KU, Scholl UI and Persson PB: Kidney physiology

and susceptibility to acute kidney injury: Implications for

renoprotection. Nat Rev Nephrol. 17:335–349. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhao ZB, Marschner JA, Iwakura T, Li C,

Motrapu M, Kuang M, Popper B, Linkermann A, Klocke J, Enghard P, et

al: Tubular epithelial cell HMGB1 promotes AKI-CKD transition by

sensitizing cycling tubular cells to oxidative stress: A rationale

for targeting HMGB1 during AKI recovery. J Am Soc Nephrol.

34:394–411. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Weaver LK: Carbon monoxide poisoning.

Undersea Hyperb Med. 47:151–169. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Ozga AJ, Chow MT and Luster AD: Chemokines

and the immune response to cancer. Immunity. 54:859–874. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Glaviano A, Foo ASC, Lam HY, Yap KCH,

Jacot W, Jones RH, Eng H, Nair MG, Makvandi P, Geoerger B, et al:

PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling transduction pathway and targeted therapies

in cancer. Mol Cancer. 22:1382023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Vanhaesebroeck B, Perry MWD, Brown JR,

André F and Okkenhaug K: PI3K inhibitors are finally coming of age.

Nat Rev Drug Discov. 20:741–769. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Castel P, Toska E, Engelman JA and

Scaltriti M: The present and future of PI3K inhibitors for cancer

therapy. Nat Cancer. 2:587–597. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zhao J, Yan Y, Zhen S, Yu L, Ding J, Tang

Q, Liu L, Zhu H and Xie M: LY294002 alleviates bone cancer pain by

reducing mitochondrial dysfunction and the inflammatory response.

Int J Mol Med. 51:422023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Zhang H and Sun SC: NF-κB in inflammation

and renal diseases. Cell Biosci. 5:632015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Dai C, Liu D, Qin C, Fang J, Cheng G, Xu

C, Wang Q, Lu T, Guo Z, Wang J, et al: Guben Kechuan granule

attenuates bronchial asthma by inhibiting NF-κB/STAT3 signaling

pathway-mediated apoptosis. J Ethnopharmacol. 340:1191242025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Arya AK, Sethuraman K, Waddell J, Cha YS,

Liang Y, Bhopale VM, Bhat AR, Imtiyaz Z, Dakessian A, Lee Y and

Thom SR: Inflammatory responses to acute carbon monoxide poisoning

and the role of plasma gelsolin. Sci Adv. 11:eado97512025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Festa BP, Siddiqi FH, Jimenez-Sanchez M

and Rubinsztein DC: Microglial cytokines poison neuronal autophagy

via CCR5, a druggable target. Autophagy. 20:949–951. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Deng H, Xue P, Zhou X, Wang Y and Liu W:

CCL4/CCR5 regulates chondrocyte biology and OA progression.

Cytokine. 183:1567462024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|