Introduction

Among solid tumors, colorectal cancer (CRC) ranks

among the most common causes of morbidity and mortality, and its

prevalence continues to rise (1).

The 5-year survival rate of patients with early-stage localized CRC

is >90%, whereas that of patients with metastatic CRC is only

14% (2). There is evidence to

suggest that CRC development is influenced by both intrinsic and

extrinsic factors. In particular, dysregulated gut microbiota

composition has been demonstrated to influence the immune

microenvironment and promote distant metastases, and gut microbiota

are increasingly recognized as pathogenic contributors to CRC

metastasis (3).

Patients with cancer often have a poor prognosis and

experience ongoing psychological distress following cancer

diagnosis, surgery, chemotherapy and other cancer-related

complications (4). Prolonged

stress can impair the immune system by changing the metabolic

characteristics and composition of the gut microbiota (5), and is a major risk factor that can

accelerate CRC development (6). In

addition, long-term stress in patients with cancer may reduce their

ability to respond to treatments that rely on antitumor immune

activity, particularly immunotherapies (7). Therefore, strategies to reduce the

effect of psychological stress and depression on treatment outcomes

are crucial.

The association between long-term stress and the

growth of tumors is becoming increasingly evident, particularly

through neuroimmune interactions (6). Aside from cancer, chronic stress has

been shown in numerous studies to stimulate the sympathetic nervous

system (8,9), leading to the release of

neurotransmitters or hormones that regulate the activity of

macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs) and cytotoxic T lymphocytes

(10). DCs are immune cells that

play a key role in influencing the tumor microenvironment (TME),

processing and transmitting antigens, and activating

tissue-specific T-cell responses (11). In mice, prolonged psychological

stress causes the significant dysregulation of T-cell functions,

including reduced cytokine production and impaired cytotoxicity

(12), ultimately contributing to

metastasis. Disturbances of the microbiota-gut-brain axis and gut

microbial balance have been implicated in both depression and CRC

pathogenesis. This axis has emerged as a novel target for

depression since it mediates communication between the brain and

intestinal flora (13).

Traditional Chinese medicine has been widely used to

treat CRC, where it may reduce treatment resistance and adverse

effects, promote cancer cell death and inhibit metastasis (14). Ginseng, which is widely used in

traditional Chinese medicine, contains a variety of active

components, including polyacetylenes, ginsenosides and

polysaccharides (15). Among

these, ginsenosides have been shown to strengthen resistance to

stress, boost immunity, and protect the nervous system, with

ginsenoside Rh1 (Rh1) having been shown to improve memory and

learning by promoting cell viability in the hippocampal region

(16). Rh1 is the main metabolite

of protopanaxatriol-type ginsenoside Rg1 (17). Rg1 is a natural steroidal saponin

extracted from Panax ginseng with potent neuroprotective,

anti-inflammatory and antidepressant effects (18,19).

Notably, Rh1 exhibits stronger effects than its precursor Rg1 in

the enhancement of memory and hippocampus excitability (20). These findings suggest that the

antidepressive ability of Rh1 is closely associated with the in

vivo metabolism of Rg1.

Rh1 has demonstrated anti-inflammatory and antitumor

properties, mediated by the inhibition of angiogenesis and

metastasis (15,21). In particular, Rh1 has been reported

to prevent the growth of colon and breast cancers (22,23).

However, few studies have investigated the mechanisms by which Rh1

impacts CRC via modulation of the gut microbiota or immune

responses, and the impact of Rh1 on CRC under chronic stress

conditions remains unclear. In the present study, a CRC mouse model

subjected to chronic restraint stress (CRS) was used to explore the

antidepressant effect of Rh1, and to evaluate the relationship

between Rh1 treatment and the microbial composition of the gut.

Furthermore, the study aimed to determine whether the underlying

mechanism involves the promotion of DC maturation, thereby

activating T cells and enhancing the antitumor immune response to

retard CRC progression.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection of The

Chinese Academy of Sciences supplied the CT26 murine colon

adenocarcinoma cell line (cat. no. SCSP-523). The cells were

cultivated in RPMI-1640 complete medium containing 10% fetal bovine

serum (both Jiangsu KeyGEN BioTECH Co., Ltd.), supplemented with 1%

penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Animal care

A total of 90 male SPF BALB/c mice (age, ~8 weeks;

weight, 20–22 g) were purchased from Shanghai SLAC Laboratory

Animal Co., Ltd. The mice were kept in a climate-controlled

environment at a temperature of 22±2°C and a relative humidity of

50±10%, with a 12-h light/dark cycle and free access to food and

water. Humane endpoints were established, including >20% weight

loss, tumor volume >2,000 mm3, ulceration, necrosis

or infection on the surface of the tumor, abnormal posture or

dyspnea. However, no mice were humanely sacrificed or found dead

during the study. The maximum weight loss observed was 6.1%. At the

end of the experiment, all mice were anesthetized with an

intraperitoneal injection of 50 mg/kg pentobarbital sodium. Then,

300 µl blood was collected from the mice by retro-orbital puncture.

Afterwards, the mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and

death was confirmed by the absence of breathing and heartbeat for

>5 min.

Experimental design and drug

administration protocols

The CRS model was used to induce depression-like

behaviors in mice (24). All mice

were randomly assigned to five groups on day 0, following 7 days of

adaptation (n=5/group): i) Control group (CRC); ii) model group

(CRC + CRS); iii) low dose Rh1 group (CRC + CRS + Rh1 10 mg/kg);

iv) high dose Rh1 group (CRC + CRS + Rh1 20 mg/kg); and v)

fluoxetine group (CRC + CRS + fluoxetine 10 mg/kg). The doses of

Rh1 (Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) were selected on the

basis of a preliminary experiment, in which it was found that 10

and 20 mg/kg Rh1 are able to inhibit both tumor growth and

depression. Fluoxetine (Sigma-Aldrich) was employed as a positive

antidepressant control. The 10 mg/kg dose of fluoxetine

hydrochloride powder was administered by gavage following dilution

with distilled water (25). CRS

was used to induce depression in the mice prior to tumor

implantation. The mice subjected to CRS endured physical

restriction for 8 h/day (from 9:00 to 17:00), starting 21 days

prior to the start of CT26 cell injection and continued for a total

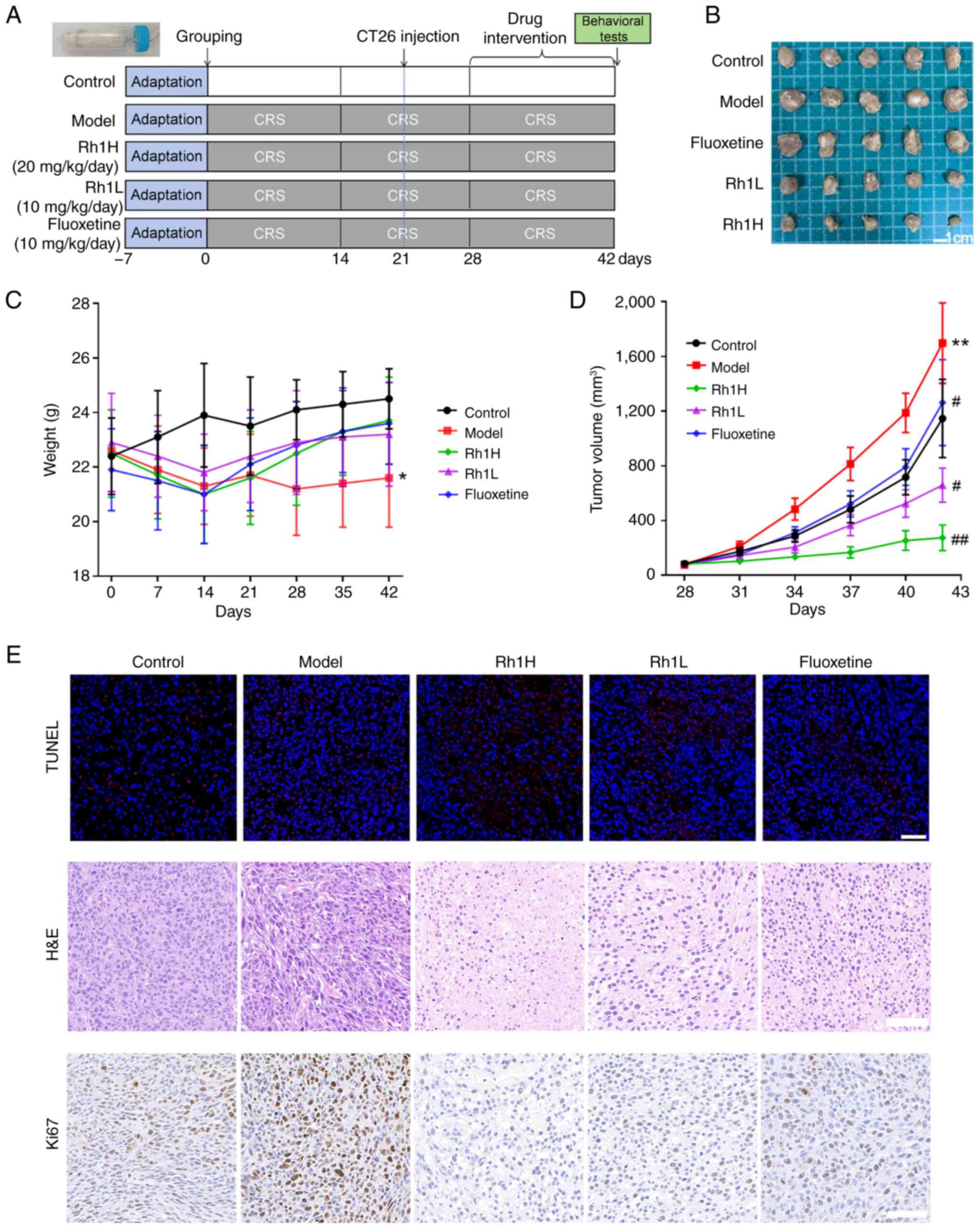

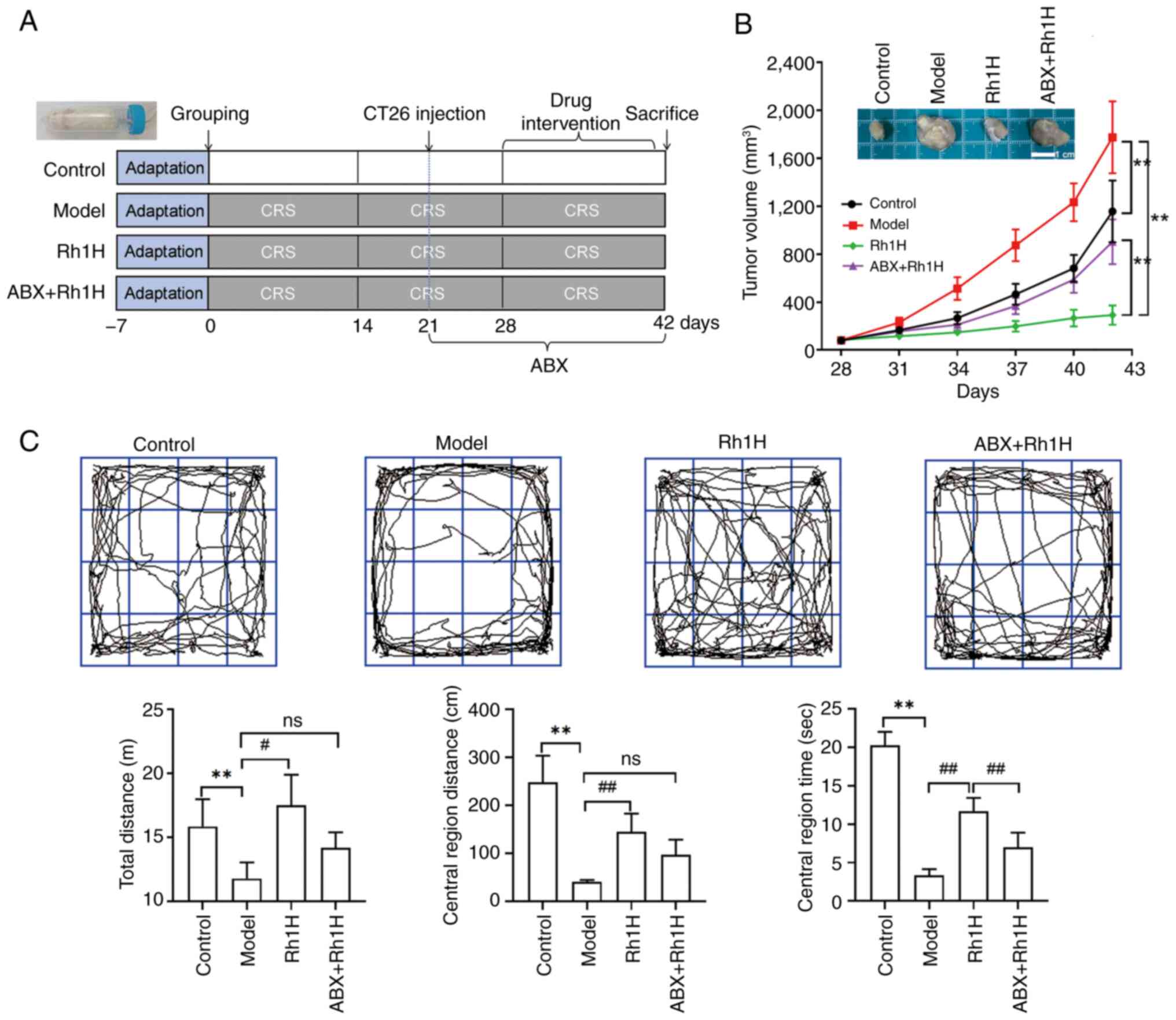

of 42 days (Fig. 1A).

CRS model establishment

All mice except those in the control group were put

in a 50-ml conical tube with adequate ventilation to enable easy

breathing for 8 h daily, continuously for 42 days in a row, thereby

establishing the CRS model. By contrast, the mice in the control

group were undisturbed in their cages, without food and water, over

the same time periods. After the CRS procedure, the animals were

returned to their home cages. At the end of the experiment, on day

42, behavioral assessments were performed, namely the open field

test (OFT), the sucrose preference test (SPT) and the elevated plus

maze test (EPMT).

CRC tumor model establishment

To establish the CRC model, 1×106 CT26

cells suspended in 0.1 ml PBS were subcutaneously injected into the

right flank of each mouse on day 21. The tumors reached ~100

mm3 in volume 7 days after CT26 cell inoculation. The

mice were then subjected to treatment with 10 or 20 mg/kg Rh1, or

10 mg/kg fluoxetine. Both Rh1 and fluoxetine were orally

administered for 2 weeks, from day 28 to 42. The control and model

groups both received the vehicle orally over the same time period.

A caliper was used to measure the volume of the tumor every 3 days,

and the tumor volume was calculated using the following formula:

V=(L × W2)/2, where V, L and W represent the volume,

length and width of the tumor, respectively. Photographs of the

tumors were captured after immersion in formalin.

OFT

The OFT was conducted as described previously

(26). Mice were placed in a

50×50×50-cm open-field arena with a black floor and blue Plexiglas

walls. Each mouse was allowed to spontaneously explore the arena

for 5 min. Following each trial, 75% ethanol was used to clean the

apparatus to remove odors. The following parameters were measured:

Total distance traveled, distance traveled in the central area and

dwelling time in the central area (27).

EPMT

The EPMT was performed as previously described, with

refinements (28). The plus-maze

apparatus consisted of four arms arranged in a cross, elevated 90

cm above the floor. Two of the arms were closed and two were open.

Mice were placed on the central platform facing an open arm and

allowed to explore the apparatus for 5 min. During this period, the

behavior of the mice was recorded, and the time spent and distance

traveled in the open arms was examined.

SPT

The SPT was conducted as previously described

(29). Mice were individually

housed in a cage containing two bottles of 1% sucrose solution for

24 h. This was followed by 24 h of food and water deprivation.

After adaption, the mice were given free access to two identical

bottles, one containing a 1% sucrose solution and the other

containing water. The volumes of water and sucrose solution

consumed were measured, and the percentage of sucrose solution to

total fluid consumed was calculated to indicate sucrose

preference.

Antibiotics (ABX) treatment

Pseudo germ-free BALB/c mice were established by the

administration of ABX solution to depleting the endogenous gut

microbiota and to investigate the causal role of gut microbiota.

The ABX solution contained neomycin (1 g/l), ampicillin (1 g/l),

metronidazole (1 g/l) and vancomycin (500 mg/l) in autoclaved water

(30). This combination was

selected for its broad-spectrum activity (covering Gram-positive

and -negative bacteria, and anaerobes) to ensure maximal depletion

of gut microbial communities. The ABX solution was orally

administered to the mice for consecutive 21 days starting on day

21, with replacement of the drinking water every 2 days. The ABX

treatment was designed to establish a causal link between gut

microbiota and the Rh1 treatment response and to explore whether

the effect of Rh1 was microbiota-dependent.

Assessments of inflammatory factors

and hormones

The blood collected by retro-orbital puncture was

centrifuged 3,500 × g for 12 min at 4°C to isolate the serum. In

addition, mouse brains were collected, homogenized in saline on

ice, and the homogenates were centrifuged 6,000 × g for 15 min at

4°C. The supernatant was carefully transferred to a sterile tube

and stored at −20° until required for analysis. Noradrenaline (NE),

adrenaline, cortisol (CORT), corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH),

interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and C-X-C

motif chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1) in the serum and

5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) in the brain were measured using the

following ELISA kits: NE (cat. no. E-EL-0047; Wuhan Elabscience

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), adrenaline (cat. no. E-EL-0045; Wuhan

Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), CORT (cat. no. AD3213Mo; Andy

Gene Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), CRH (cat. no. E-EL-M0351; Wuhan

Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), IL-6 (cat. no. PI326;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), TNF-α (cat. no. PT512;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), CXCL1 (cat. no. PC173;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and 5-HT (cat. no. E-EL-0033;

Wuhan Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.).

Histopathological analysis and

immunohistochemical staining

Tumors were excised from the animals and immediately

fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 48 h. For

hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, deparaffinized and

rehydrated 4-µm-thick sections were stained with hematoxylin

solution at room temperature for 5 min. Sections were stained with

0.5% eosin Y solution at room temperature for 3 min. After

staining, sections were dehydrated, cleared in xylene, and mounted

with neutral balsam. Immunohistochemical staining was also

performed. The 4-µm-thick tumor sections were blocked with 3% BSA

(Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at 37°C, subjected to peroxidase

quenching with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min at room temperature

and then incubated with an anti-Ki67 primary antibody (cat. no.

ab15580; Abcam, 1:500) overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, the sections

were incubated with HRP-labeled secondary antibody (cat. no.

ab6721; Abcam, 1:1,000 dilution) for 1 h at 37°C, and then

counterstained with hematoxylin (5 min at room temperature). Both

H&E and Ki67 staining were observed under a bright-field light

microscope (Olympus BX53).

TUNEL assays

Paraffin sections (3 µm thick) were prepared from

the tumors. An In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (cat. no.

11684817910; Roche Diagnostics GmbH) was used to detect apoptotic

cells in the sections. A total of 50 µl TUNEL reaction mixture was

added at 37°C for 45 min. After incubation, sections were washed

with PBS. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (cat. no. ab104139;

Abcam) at a concentration of 2 µg/ml at room temperature for 8 min,

while red fluorescence indicated the apoptotic nuclei. Tissue

sections were visualized under a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss

Axio Imager Z2, Carl Zeiss AG). For quantification, four random

fields were chosen from each section and the average percentage of

positive cells in each field was calculated.

Immunofluorescence staining

3 µm-thick tumor sections were subjected to

deparaffinization and rehydration. Sections were immersed in 0.01 M

sodium citrate buffer, and heated in a microwave. Endogenous

peroxidase activity was quenched with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10

min at room temperature. Sections were then covered with 5% goat

serum (cat. no. GB25004; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) to

block non-specific binding at room temperature for 30 min. For

CD11c/CD80 dual staining, tumor sections were first incubated with

anti-CD11c antibody (cat. no. ab254183; Abcam, 1:200) at 4°C

overnight, followed by anti-mouse IgG H&L (HRP) (cat. no.

GB23301; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd., 1:500 dilution) at

room temperature for 1 h. Cyanine 3 tyramide (cat. no. G1233;

Servicebio, 1:50 dilution) was then incubated at room temperature

for 10 min to amplify the HRP signals, producing red fluorescence.

Sections were subsequently incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-CD80

antibody (cat. no. ZB115640; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.,

1:100 dilution) at room temperature for 1 h, which generated green

fluorescence. For CD8 staining, sections were incubated with

anti-CD8 antibody (cat. no. GB115692; Wuhan Servicebio Technology

Co., Ltd., 1:200 dilution) at 4°C overnight, followed by

FITC-conjugated IgG (H+L) secondary antibody (cat. no. GB22303;

Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd., 1:500) at room temperature

for 1 h. After staining, all sections were counterstained with DAPI

(working concentration: 2 µg/ml, cat. no. ab104139; Abcam) at room

temperature for 8 min. The stained sections were observed using a

fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axio Imager Z2, Carl Zeiss AG).

16S rRNA sequencing and data

analysis

Mice fecal samples were collected on day 42, at the

end of the experiment, and were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and

stored at −80°C until use. Total DNA was extracted from the fecal

samples using the FastPure Feces DNA Isolation Kit (Shanghai Major

Yuhua Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA

concentration and purity were assessed using a NanoDrop2000

spectrophotometer (Themo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The V3-V4

variable region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using PrimeSTAR

Max DNA Polymerase (cat. no. R045A; Takara Bio Inc., Shiga,

Japan),with the universal bacterial primer pair: Forward primer

(338F): 5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′; Reverse primer (806R):

5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′. The thermocycling condition was set as

follows: Pre-denaturation: 98°C for 3 min; Denaturation: 98°C for

10 sec, 55°C for 30 sec; Extension: 72°C for 45 sec; Steps 2–4

repeated for 30 cycles; Final extension: 72°C for 5 min. Amplicon

visualization was verified by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis

stained with 0.5 µg/ml ethidium bromide (cat. no. E1510;

Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Amplified products were

purified using the AMPure XP Beads (cat. no. A63881; Beckman

Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA, USA). Then, the Nextera XT DNA Library

Prep Kit (cat. no. FC-131-1096; Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA)

was used to construct sequencing libraries. Sequencing was then

performed using the MiSeq PE250 system (Illumina, Inc.) with 250 bp

paired-end (PE250) sequencing. The MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (600

cycles, cat. no. MS-102-3003; Illumina, Inc.) was used. After

library quality control, qualified libraries were pooled and

diluted to a loading concentration of 6 pM. Raw sequencing reads

were quality-controlled using FastQC (Version 0.11.9; Babraham

Bioinformatics, Cambridge, UK). Paired-end reads were merged into

full-length sequences using FLASH (Version 1.2.11). Amplicon

sequence variations were generated using Deblur-denoised sequences

(Version 1.1.0; github.com/biocore/deblur. The Simpson (measuring

community evenness), abundance-based coverage estimator (ACE,

estimating species richness) and Shannon (combining richness and

evenness) indices (31–33) were determined to evaluate α

diversity of the data and principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was

performed to evaluate the b diversity of the data. PCoA

visualization was performed using the q2-emperor plugin in QIIME 2

(qiime2.org).

Flow cytometry analysis

The spleen and tumor-draining lymph nodes were each

mechanically filtered using a 200-mesh screen. Red blood cells in

the resulting cell suspensions were lysed using ACK lysis buffer

(cat. no. C3702; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Tumor

tissues were mechanically minced and digested in RPMI-1640 medium

containing DNase, collagenase IV and hyaluronidase (Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C for 1 h. The tissues were filtered

through a sieve to prepare a single-cell suspension. Isolated cells

were plated and cultured for 4 h in a medium containing Cell

Activation Cocktail (cat. no. 423303; BioLegend, Inc.) to analyze

the release of cytokines by tumor-infiltrating T cells. Cells were

then aliquoted into tubes and surface stained in the dark for 30

min at 4°C with Fixable Viability Dye eFluor 780 (cat. no. 2633409;

eBioscience; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), anti-CD3-PE-cy7 (cat.

no. 552774; BD Biosciences), anti-CD4-APC (cat. no. 100412;

BioLegend, Inc.), anti-CD45-Percy-cy5 (cat. no. 103131; BioLegend,

Inc.) and anti-CD8-FITC (cat. no. 100706; BioLegend, Inc.). The

anti-CD45 antibody is used to gate the ‘leukocyte population’, and

the anti-CD3 antibody is used to identify T cells from the

CD45+ leukocyte population. For intracellular staining,

cells were fixed with fixation buffer (4% paraformaldehyde, cat.

no. 420801; BioLegend, Inc.) in the dark for 30 min at room

temperature and washed with permeabilization buffer (cat. no.

421002; BioLegend, Inc.) twice. Cells were incubated with

anti-granzyme B-BV421 (cat. no. 396413; BioLegend, Inc.) and

anti-IFN-γ-PE (cat. no. 505807; BioLegend, Inc.) in the dark for 30

min at 4°C.

After blocking with anti-mouse CD16/32 (Fc block,

cat. no. 553141, BD Pharmingen), MDSC was examined by staining with

Fixable Viability Dye eFluo 780 (eBioscience), anti-CD45-Percy-cy5

(cat. no. 103131; BioLegend, Inc.), anti-CD11b-FITC (cat. no.

101206; BioLegend, Inc.) and anti-Gr-1-APC (cat. no. 108411;

BioLegend, Inc.) in the dark for 30 min at 4°C. After blocking with

anti-mouse CD16/32, M-MDSCs was examined by staining with Fixable

Viability Dye eFluo 780 (eBioscience), anti-CD45-Alexa Fluor700

(cat. no. 103127; BioLegend, Inc.), anti-CD11b-FITC (cat. no.

101206; BioLegend, Inc.), anti-Ly-6C-PerCP cy5.5 (cat. no. 128011;

BioLegend, Inc.) and anti-Ly-6G-PE (cat. no. 127607; all BioLegend,

Inc.) in the dark for 30 min at 4°C. After blocking with anti-mouse

CD16/32, DC maturation was examined by staining with Fixable

Viability Dye eFluo 780 (eBioscience, USA), anti-CD45-Percy-cy5,

anti-CD11c-APC (cat. no. 117309; BioLegend, Inc.), and

anti-MHCII-FITC (cat. no. 107605; BioLegend, Inc.) antibodies, or

an isotype IgG control (cat. no. 400605; BioLegend, Inc.) in the

dark for 30 min at 4°C. Flow cytometry analysis was performed using

an Beckman CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter Inc.). The flow

cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo software V10.8.1 (BD

Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation

for normally distributed data. Non-normally distributed data are

presented as the median and 25th and 75th percentile). Statistical

analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software

(Dotmatics). When the data displayed a normal distribution and

homogeneous variance, one-way ANOVA was employed, followed by

Bonferroni post-hoc multiple comparisons tests. When the data

displayed a normal distribution and heterogeneous variance, Welch

ANOVA was used; no post-hoc test was performed as the results were

not statistically significant. When the data were non-normally

distributed, Kruskal-Wallis H test was applied, followed by

post-hoc pairwise comparisons using Bonferroni-corrected

Mann-Whitney U tests. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Rh1 inhibits tumor growth in mice with

CRC and CRS

The experimental plan is displayed in Fig. 1A. CRS was applied to induce

depression in all mice, with the exception of those in the control

group. A CT26 cell-bearing tumor model was established after 3

weeks of CRS. The mean body weight of the mice in the model group

at the end of the study was significantly less than that of mice in

the control group. Although mean body weight exhibited an ascending

tendency in the Rh1 and fluoxetine treatment groups compared with

that in the model group, the difference between these groups was

not found to be statistically significant (Fig. 1C). Tumor growth in the model group

was greater than that in the control group (Fig. 1B). By day 42, the tumor volume in

the stressed mice of the model group was significantly higher than

that in the non-stressed mice of the control group, but

significantly lower in the two Rh1 groups compared with the model

group (Fig. 1D).

H&E staining revealed that the tumor cells in

the model group were densely packed, exhibiting irregular

morphologies, nuclear dimorphism and mitotic figures. In the Rh1

and fluoxetine groups, features of cell necrosis and apoptosis were

observed. Necrosis was indicated by dispersed lower-density cells,

cytoplasmic leakage, cellular rupture and multiple vacuolar

structures, while apoptosis was characterized by nuclear

condensation, fragmentation and dissolution (Fig. 1E). In addition, the number of TUNEL

positive cells in the Rh1 groups was increased markedly compared

with that in the model group (Fig.

1E). Furthermore, Rh1 treatment clearly reduced Ki67 expression

in tumors to lower levels than those observed in the model group.

These findings indicate that Rh1 attenuates tumor development in

mice with CRC and CRS.

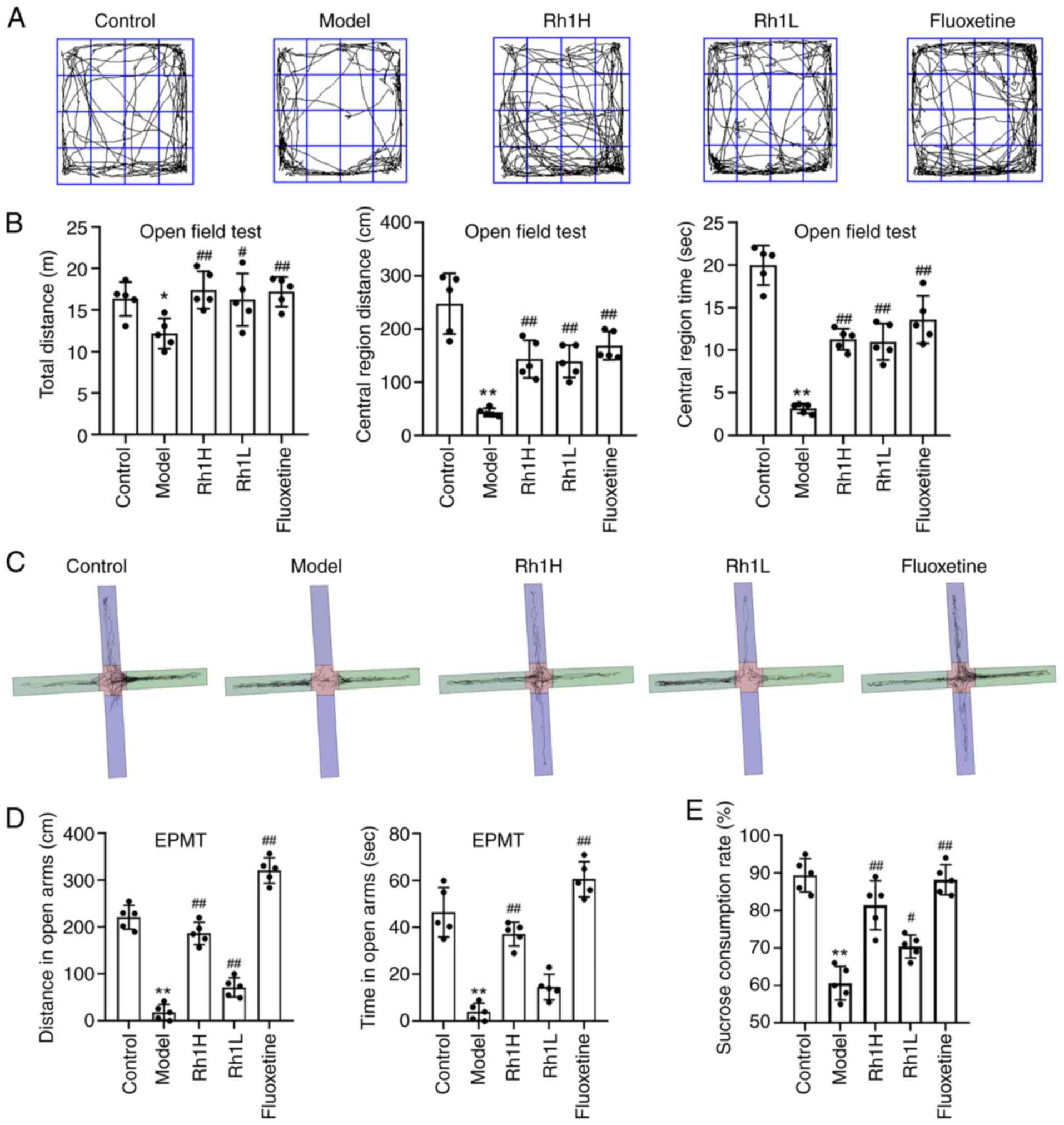

Rh1 ameliorates depressive-like behaviors and

enhances cognitive function in mice with CRC and CRS. The

therapeutic impact of low and high dosages of Rh1 was assessed

using the stress-associated cancer model mice (Fig. 2). Depression- and anxiety-like

behaviors were evaluated using the SPT, EPMT and OFT. In the OFT,

the depressed mice in the model group exhibited a reduced capacity

for spontaneous exploration and tended to remain in the corners and

edges of the field (Fig. 2A). The

total distance traveled, distance traveled in the central area and

dwelling time in the central area of the model mice were

significantly decreased compared with those of the control group

(Fig. 2B). However, these measures

were significantly increased in the mice treated with fluoxetine or

Rh1 compared with those in the model group.

The results of the EPMT assay revealed that the time

spent and distance traveled in the open arms by the model mice were

significantly lower compared with those of the control mice

(Fig. 2C and D). However,

following Rh1 or fluoxetine intervention, significant increases in

the time spent and distance traveled in the open arms were

observed.

The SPT is regarded as an index of anhedonia.

Sucrose preference decreased significantly in model group compared

with that in the control group. However, the Rh1H and fluoxetine

groups exhibited significantly increase sucrose preference rates

compared with that of the model group (Fig. 2E). These results indicate that Rh1

treatment attenuated the abnormal behaviors of CRS rats in the SPT,

EPMT and OFT, and suggest that both fluoxetine and Rh1 alleviate

depression-like behaviors in mice.

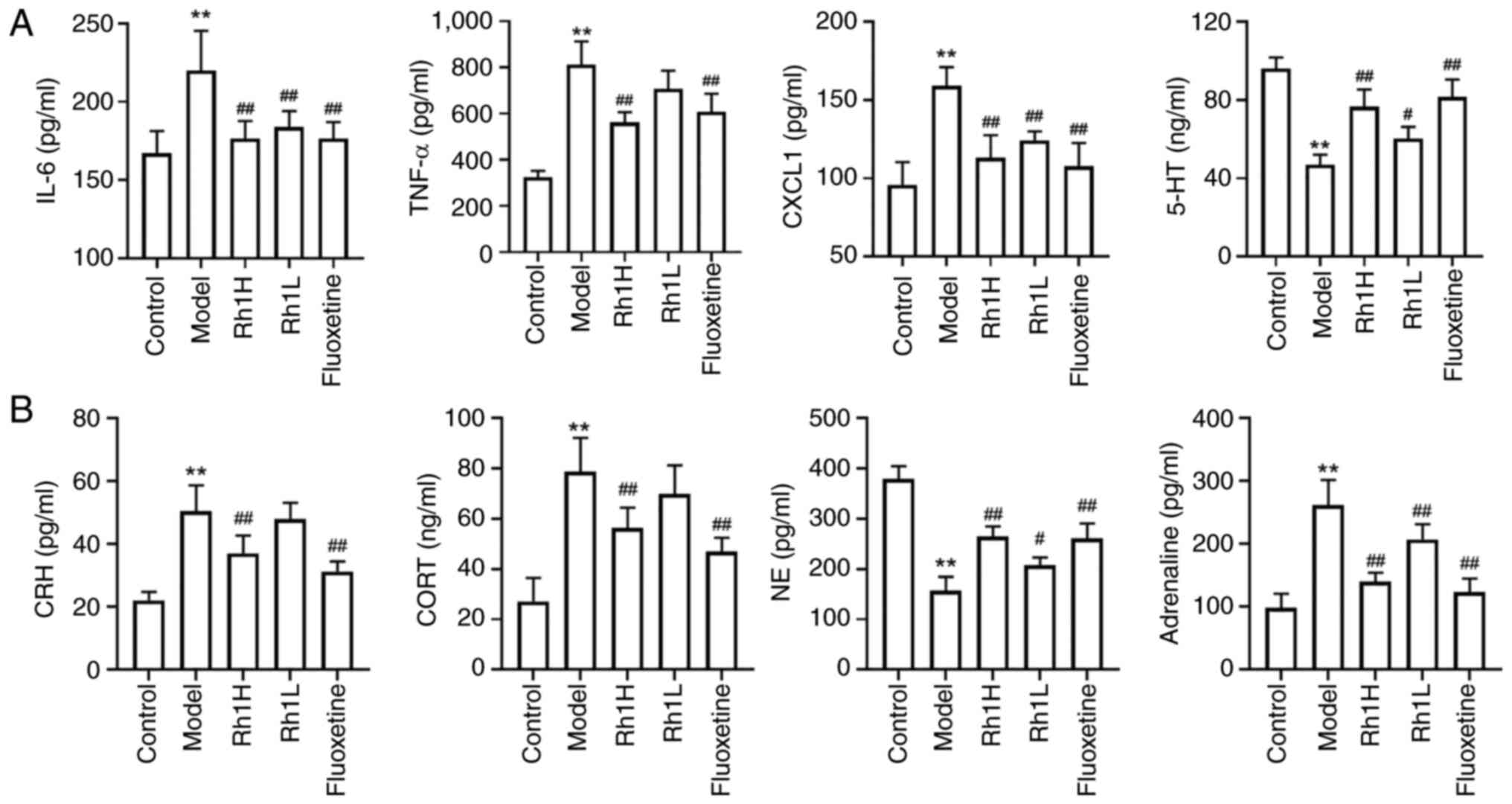

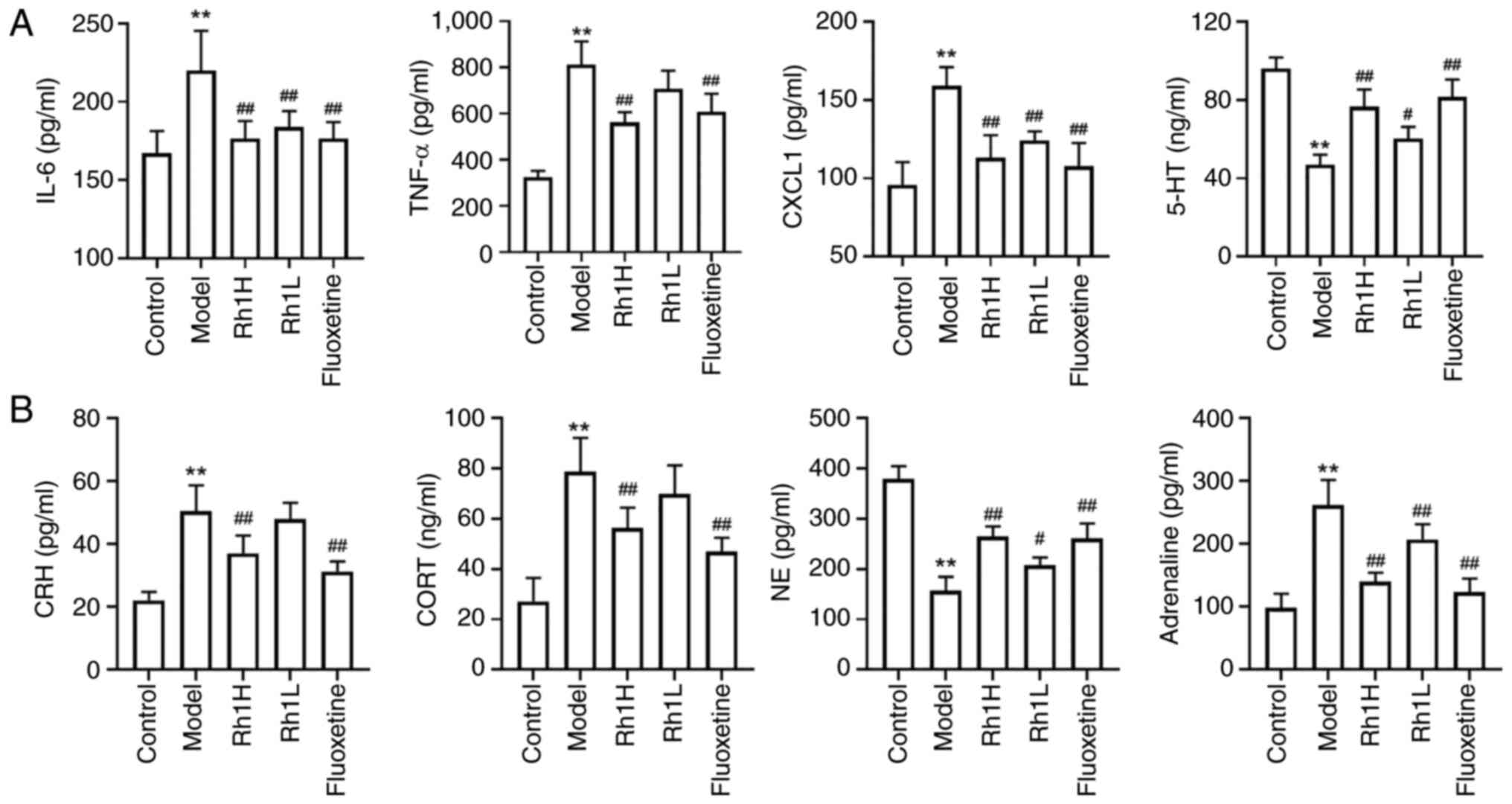

Rh1 regulates cytokine expression and hormone

levels in mice with CRC and CRS. Cytokines are essential

contributors to the regulation of inflammatory processes. ELISA

results revealed that the levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and CXCL1 were

significantly higher in CRS-exposed mice with CRC compared with

those in control mice with CRC, indicating that CRS increased the

inflammatory response in mice with CT26 tumors (Fig. 3A). The levels of TNF-α, CXCL1 and

IL-6 in the Rh1 and fluoxetine groups were considerably lower

compared with those in the model group. Reductions in the levels of

the monoamine neurotransmitters 5-HT and NE, and increases in CORT

levels are associated with depression (34). In particular, alterations in the

release or reuptake of 5-HT are associated with depressive

disorder. Mice in the CRS-stimulated CRC-bearing model group

exhibited significantly lower brain 5-HT and serum NE levels

compared with those in the control group, indicating that CRS

stimulation disrupts monoamine neurotransmitter homeostasis.

Treatment with Rh1 or fluoxetine resulted in significant increases

in these levels (Fig. 3).

Adrenaline is a key catecholamine hormone released during stress

and may influence cancer progression (35). The serum levels of adrenaline, CRH

and CORT in the model group were significantly higher compared with

those in the control group; however, treatment with a high dose of

Rh1 or fluoxetine resulted in a significant reduction in these

levels (Fig. 3B).

| Figure 3.Rh1 regulates the levels of hormones

and inflammatory factors in the brain and serum of mice bearing

colorectal tumors and subjected to chronic restraint stress. (A)

Brain levels of 5-HT and serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and CXCL1. (B)

Serum levels of adrenaline, NE, CRH and CORT. Results are presented

as the mean ± SD (n=5). **P<0.01 vs. the control group;

#P<0.05 and ##P<0.01 vs. the model

group. Rh1, ginsenoside Rh1; Rh1H, high dose Rh1; Rh1L, low dose

Rh1; IL-6, interleukin-6; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; CXCL1,

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine; CRH,

corticotropin-releasing hormone; CORT, cortisol; NE,

noradrenaline. |

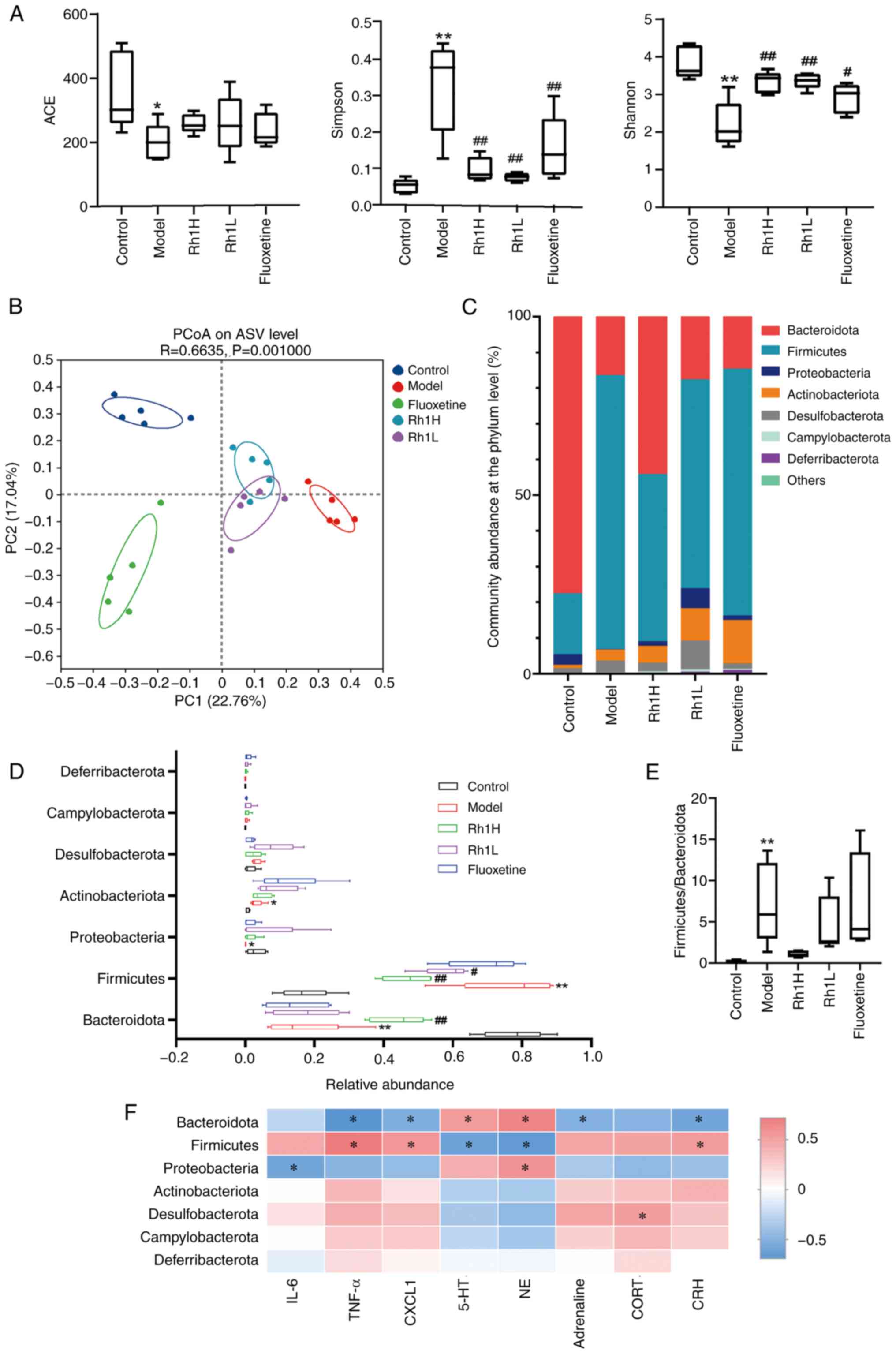

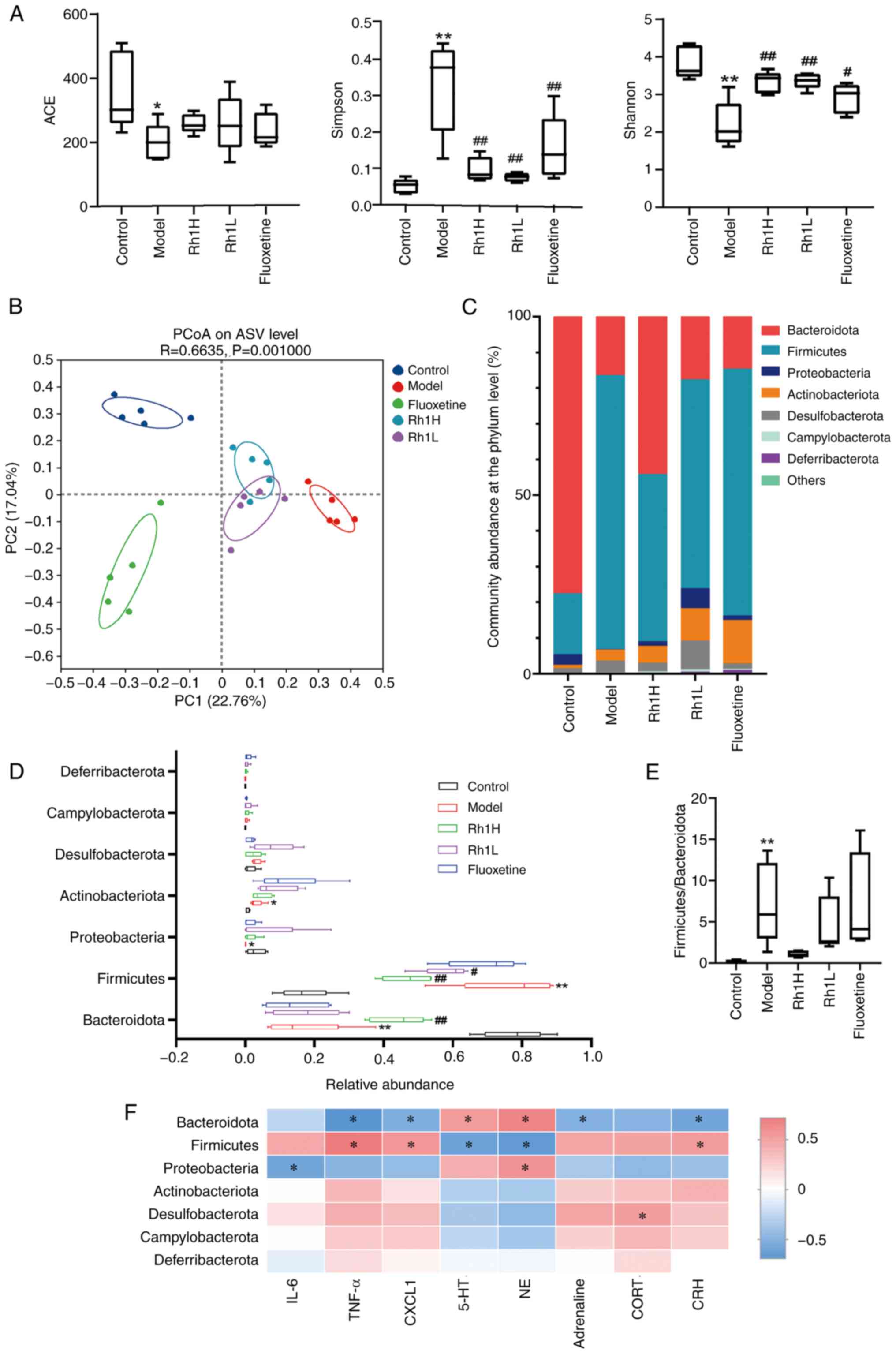

Rh1 rebalances gut dysbiosis in mice with CRC and

CRS. The results of α-diversity analyses indicated that the gut

microbial communities in all five groups were rich and diverse. In

the model group, the Simpson index was significantly higher and the

ACE and Shannon indices were significantly lower compared with

those in the control group. ACE indices in the Rh1 or fluoxetine

groups were not significantly different from that of the model

group. The Simpson indices of the Rh1 and fluoxetine groups were

significantly lower than that of the model group. The Shannon

indices of the Rh1 and fluoxetine groups were significantly higher

than the Shannon index of the model group (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, b diversity was

analyzed using PCoA based on various distance measures, including

Bray-Curtis distances. When plotted against the relative

contributions of each group to each principal component (PC), the

first two principal components, which together accounted for 39.80%

of the total microbial factor loadings (PC1, 22.76%; PC2, 17.04%),

revealed notable differences in the gut microbiota communities

among the groups. In the Rh1-treated groups, clear shifts in

bacterial composition towards that of the control group were

observed (Fig. 4B), indicating

partial restoration of the gut microbial community. Proteobacteria,

Firmicutes, Bacteriodota, Actinobacteriota and Desulfobacterota

accounted for the majority of the sequencing reads among the phyla

that were detected (Fig. 4C). When

compared with the microbial composition of the control group, the

model group exhibited a significantly higher abundance of

Firmicutes and Actinobacteriota, lower abundance of Bacteroidota

and Proteobacteria (Fig. 4D), and

a higher Firmicutes/Bacteroidota ratio (Fig. 4E). Exposure to a high dose of Rh1

significantly increased the abundance of Bacteroidota and reduced

the abundance of Firmicutes. Mice treated with a low dose of Rh1

also exhibited a significantly reduced abundance of Firmicutes.

| Figure 4.Rh1 treatment regulates the gut

microbial balance in mice bearing colorectal tumors and subjected

to chronic restraint stress. (A) ACE, Simpson and Shannon indices

of α-diversity and (B) PCoA analysis of the β-diversity of the gut

microbiota. (C) Community distribution and (D) richness of the

intestinal flora at the phylum level. (E) Firmicutes/Bacteroidota

ratios. (F) Heat map showing the Spearman correlation coefficients

for hormone or inflammatory factors with phylum abundance. n=5).

*P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. the control group;

#P<0.05 and ##P<0.01 vs. the model

group. Rh1, ginsenoside Rh1; Rh1H, high dose Rh1; Rh1L, low dose

Rh1; ACE, abundance-based coverage estimator; PCoA, principal

coordinate analysis; PC, principal component; ASV, amplicon

sequence variant; IL-6, interleukin-6; TNF-α, tumor necrosis

factor-α; CXCL1, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1; 5-HT,

5-hydroxytryptamine; NE, noradrenaline; CORT, cortisol; CRH,

corticotropin-releasing hormone. |

A Spearman correlation heatmap revealed that

Bacteroidota abundance positively correlated with 5-HT and NE

(Fig. 4F), and negatively

correlated with TNF-α, CXCL1, adrenaline and CRH. It also revealed

that Firmicutes abundance negatively correlated with 5-HT and NE,

and positively correlated with TNF-α, CXCL1 and CRH. In addition,

the inflammatory factor IL-6 and Proteobacteria exhibited a

negative correlation, while the endocrine hormone CORT and

Desulfobacterota exhibited a positive correlation.

Gut microbiota mediates the antitumor

effect of Rh1 in mice with CRC and CRS

We hypothesized that the efficacy of Rh1 in treating

cancer comorbid with depression may be mediated by gut bacteria,

given the importance of intestinal flora in both carcinogenesis and

depression (36). ABX treatment

was administered to decrease the resident microbiota in mice

subjected to CRS during Rh1 intervention (Fig. 5A). The amelioration of

depression-like behaviors observed in the OFT for the high dose Rh1

group was attenuated when the mice also received ABX treatment

(Fig. 5C). No significant

differences were observed between the mice in the model group and

those treated with both ABX and high dose Rh1 with regard to the

total distance traveled and the distance traveled in the central

area. The time in the central region in ABX + Rh1H group were

considerably lower than that of Rh1H group. The antitumor effect of

Rh1 in mice with CRS and CRC may be weakened by the reduction of

gut flora, as suggested by the significantly larger mean tumor

volume in the mice treated with ABX and high dose Rh1 compared with

that in mice treated with high dose Rh1 alone (Fig. 5B).

Rh1 improves T-cell activation in mice

with CRC and CRS

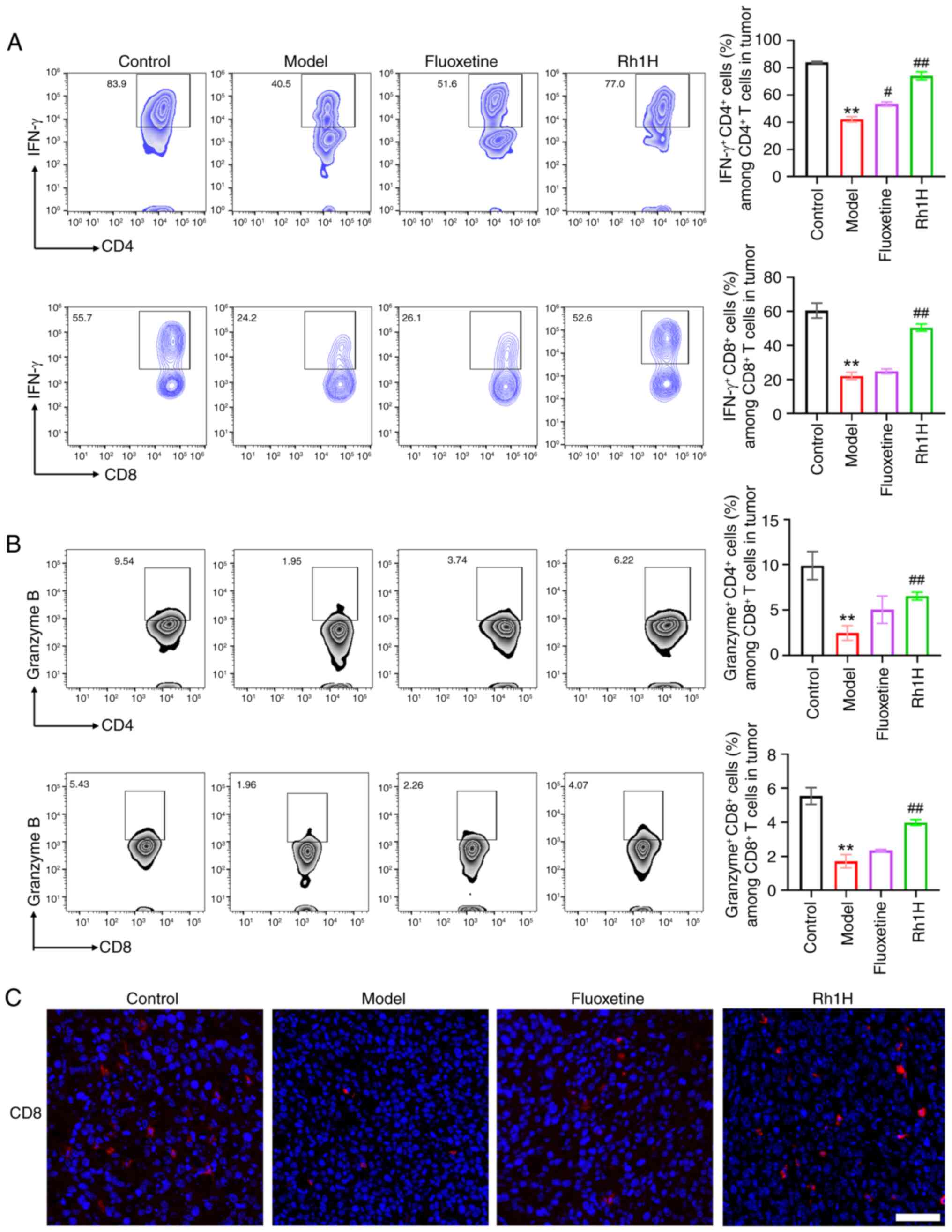

The effect of Rh1 on immune cell infiltration and

activation in mice with CRC and CRS was investigated (Fig. 6). Examination of CD8+T

and CD4+T cell subsets in the tumors revealed that mice

in the high dose Rh1 group had a significantly higher population of

effector T cells (IFN-γ+CD8+T cells and

IFN-γ+CD4+T cells) compared with that in the

model group (Fig. 6A). These data

indicate that increased activation of CD8+ and

CD4+ T cells increases IFN-γ production in tumor

tissues, which may serve as a key mediator of the tumor rejection

response. In addition, by significantly increasing the percentage

of granzyme B+ cells within the CD8+T and

CD4+T cell population, Rh1 may restore the functional

activity of tumor-infiltrating CD8+T and

CD4+T cells (Fig. 6B).

Furthermore, immunofluorescence staining indicated that

CD8-positive T cells exhibited weaker red fluorescence in the model

group compared with that in the control group, while CD8-positive T

cells were markedly increased in the high dose Rh1 group (Fig. 6C).

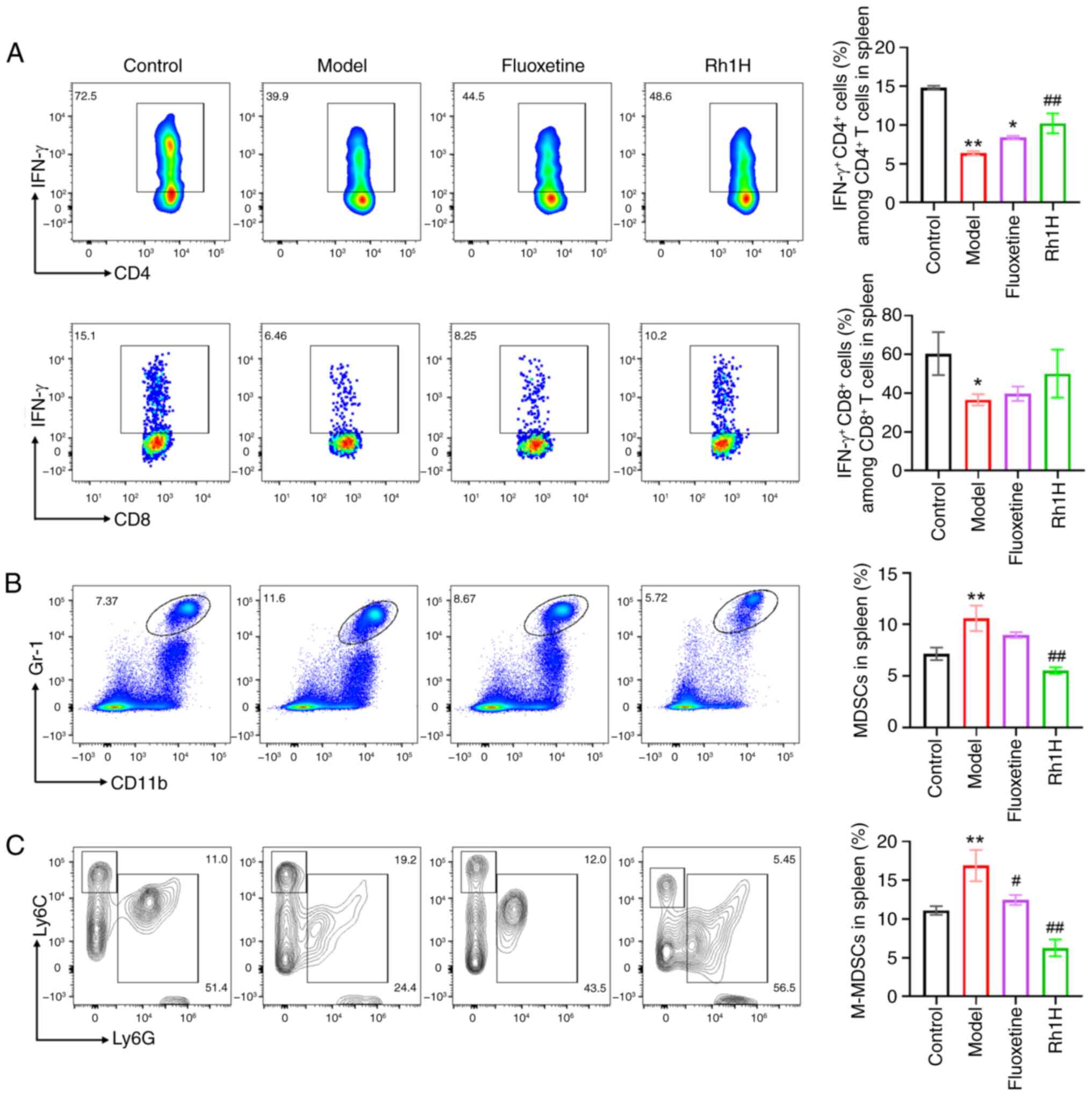

The spleens of mice treated with a high dose of Rh1

had a significantly higher frequency of

IFN-γ+CD4+T cells than that observed in the

model group (Fig. 7A). Treatment

with a high dose of Rh1 also raised the proportion of

CD8+T cells co-expressing IFN-γ; however, this increase

was not statistically significant. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

(MDSCs) isolated from the spleen were also analyzed by flow

cytometry. The number of tumor-infiltrating

CD11b+Gr-1+ cells, considered to represent

MDSCs, was analyzed. As shown in Fig.

7B, Rh1 significantly decreased the proportion of total MDSCs

in the spleen compared with that in the model group (Fig. 7B). Additionally, the percentages of

different MDSC subtypes were evaluated, and the results revealed

that after treatment with a high dose of Rh1, the frequency of

monocytic MDSCs (M-MDSC,

CD11b+Ly6G−Ly6Chigh) cells was

significantly reduced (Fig. 7C).

These findings suggest that CD8+T, CD4+T and

MDSC cells may contribute to the antitumor response of Rh1, with

Rh1 reducing MDSC counts and promoting the recovery of T

cell-dependent antitumor responses.

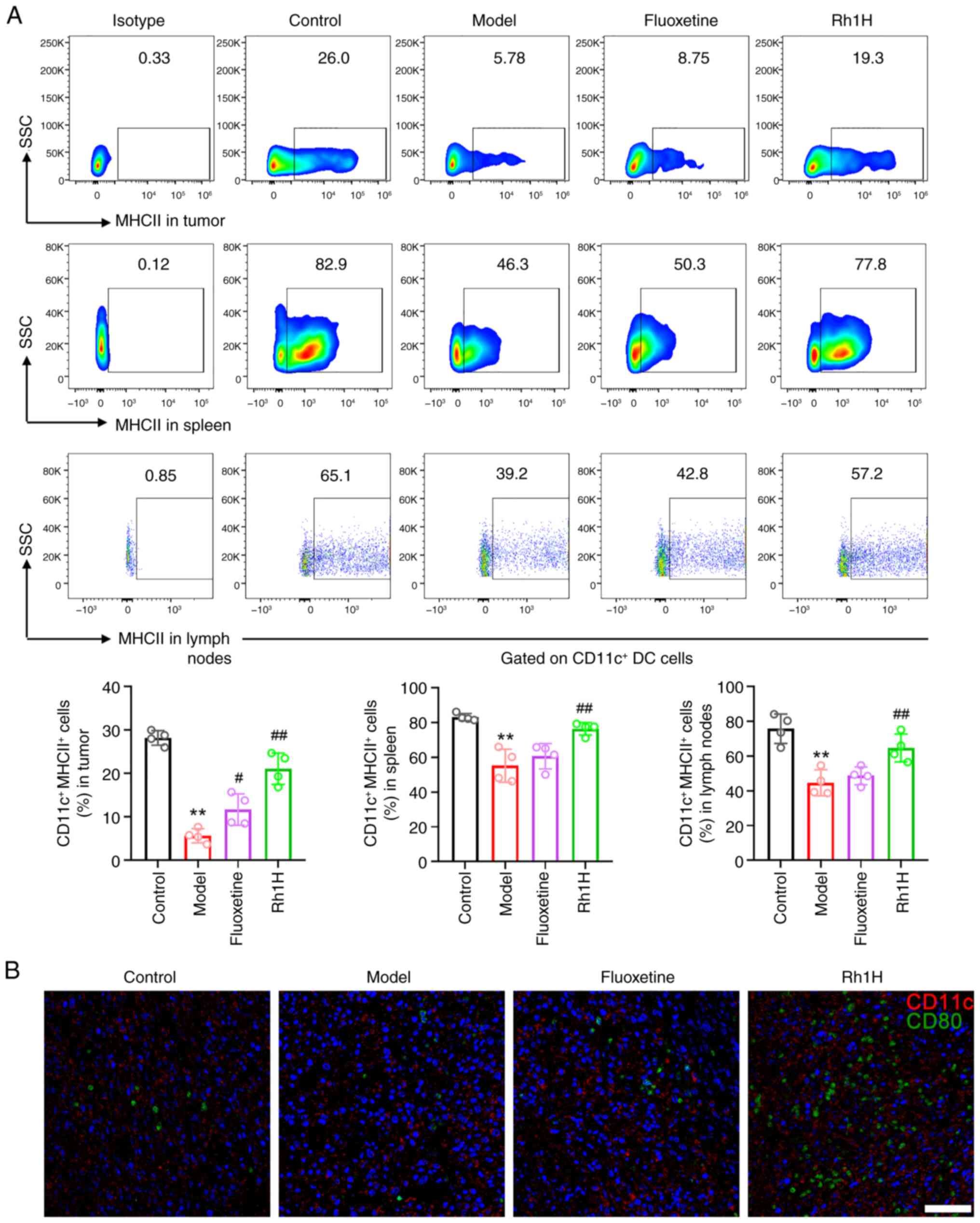

Rh1 promotes DC maturation in mice

with CRC and CRS

Naive or memory CD8+ and CD4+T

cells are exposed to antigens by mature DCs through MHCI and MHCII

molecules, respectively (37). To

verify whether DCs contributed to the immune response, the

maturation of DCs was detected in Rh1-treated CRC tissues,

tumor-draining lymph nodes and the spleen. Flow cytometric analysis

confirmed that the expression of MHCII, a DC maturation marker, was

significantly increased in the spleen, lymph node and tumor tissue

following Rh1 treatment compared with that in the model group

(Fig. 8A), suggesting the robust

accumulation and maturation of DCs in the TME following Rh1

treatment. In addition, immunofluorescence staining indicated that

CD80-positive DCs exhibited only weak green fluorescence in the

model group (Fig. 8B), but

markedly higher green fluorescence in the high dose Rh1 group.

These results demonstrate that Rh1 effectively stimulates DCs to

cross-present antigens, which in turn activate CD8+T

cells to enhance the immune response. In addition, Rh1 may have

markedly boosted the antitumor immune response by increasing the

capacity of activated T cells to eradicate tumor cells.

Discussion

Depression is a prevalent psychological disorder

that is a threat to mental well-being worldwide and has resulted in

a growing suicide rate during the 21st century (38). CRC is the second most common cause

of cancer-related deaths (39).

Depression and chronic psychological stress negatively impact the

quality of life of patients with CRC. In addition, an increased

risk of depression has been observed in patients with CRC following

prognosis (40). Therefore, the

effective management of comorbid depression has attracted

considerable attention.

The Rg1 metabolite Rh1 has demonstrated strong

inhibitory effects on the proliferation of lung and breast cancer

cells (41), and has been reported

to suppress the invasion of CRC and breast cancer cells (22). Research on Rh1 has focused on its

anticancer, anti-inflammatory and immune modulating properties

(11,42). However, its potential

antidepressant effects and the underlying mechanisms remain

unclear. Cognitive impairments and depression-like behaviors have

been noted in mice subjected to CRS, and ginsenoside Rb1 was shown

to prevent these depression-like behaviors (43). Similarly, Rg1 exhibits

antidepressant-like effects in rats subjected to CRS (44). Rb1 also significantly attenuated

azoxymethane/dextran sodium sulfate-induced colon carcinogenesis in

mice (45), while Rg1 demonstrated

antitumor activity in a CT26 CRC xenograft mouse model (46). However, these protective effects of

Rb1 or Rg1 were not evaluated in models combining depression with

cancer. Therefore, the present study investigated the anticancer

and antidepressant potential of Rh1 in CRS-exposed CRC-bearing

mice. Previous studies have shown that Rh1 (20 mg/kg) inhibits

tumor growth in mice bearing gastric cancer and CRC xenografts

(22,47). In addition, fluoxetine (10 mg/kg)

was used as a positive control in a previous study on a combined

CRS and CRC xenograft model (48).

Therefore, it was selected for use as a positive control in the

present study. Notably, Rh1 (20 mg/kg) significantly mitigated the

depression-like behaviors of mice subjected to CRS in the present

study. In addition, the findings of the study indicate that Rh1

prevents CRC tumor growth in mice subjected to CRS.

There is a significant association between

depression and the brain-gut axis. Therefore, the preservation and

restoration of the normal state of the intestinal flora is

considered beneficial for the prevention and treatment of mental

disorders (49). In the present

study, the results indicated that CRS is positively associated with

the progression of CRC, likely by affecting the balance of

intestinal flora. Consistent with previous reports, Firmicutes and

Bacteroidota were the most common phyla identified across all

groups (50). An increased

abundance of Firmicutes and a decreased proportion of Bacteroidota

were observed in the CRS-exposed xenografted mice in the present

study, which is consistent with previous observations (51). However, treatment with a high dose

of Rh1 attenuated these changes, lowering the abundance of

Firmicutes and increasing that of Bacteroidota compared with the

respective abundances in the CRS model mice.

Due to the complexity of depression, the

relationship between the Firmicutes/Bacteriodota ratio and

depression remains unclear. However, the oral administration of

probiotics or fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has been shown

to restore the microbial balance of the gut and alleviate dysbiosis

(52). For example, the

introduction of a probiotic mixture containing six

Bifidobacteria and Lactobacillus strains to patients

following CRC surgery lead to a significant reduction in the serum

levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and improved the intestinal

microenvironment (53).

The findings of the present study suggest that gut

flora at least partially mediate the effects of Rh1 in mice with

CRS and CRC, supporting the notion that changes in the gut flora

may play a role in the pathophysiology of patients with CRC and

comorbid depression. This aligns with clinical evidence that

dysregulation of the gut microbiota contributes to CRC development,

metastasis and treatment resistance (54). In patients with CRC who have a

bacterial infection and require treatment with antibiotics,

probiotics supplementation or FMT from a healthy donor may

represent a supportive strategy (55). However, future research is

necessary to validate these findings and address current

limitations.

Immunological dysregulation contributes to the

development of depression and can hinder antidepressant treatment

outcomes. A study demonstrated that chronic stress increases the

proportions of tumor-associated macrophages and MDSCs in the TME,

while decreasing the activity of CD8+T cells. In

addition, the study revealed that splenic

CD11b+Gr-1intLy6Chi myeloid cells

induce tolerance in memory CD8+T cells (56). Notably, patients with major

depressive disorder exhibit altered numbers of monocytes,

CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the peripheral

circulation compared with those in healthy individuals (57). The most potent antigen-presenting

cells are DCs, which are crucial components of the adaptive immune

response. During maturation, DCs increase the secretion of

inflammatory or anti-inflammatory cytokines and upregulate MHCII

expression, while mature DCs provide processed antigens to naïve T

cells in adjacent lymphatic organs (58). In the present study, a reduction in

the quantity of CD8+T and CD4+T cells

infiltrating the CRC tissue and producing IFN-γ and granzyme B was

observed, which was attenuated by Rh1 treatment. These findings

suggest that the functions of DC and T cells were suppressed in CRC

tumor-bearing mice subjected to CRS, and that such a repression was

mitigated by treatment with Rh1.

Depression and cancer progression have both been

associated with MDSC proliferation, which suppresses the immune

response (59). Consistent with

this, the CRS model mice in the present study displayed a

significantly elevated percentage of MDSCs than those in the

control group, whereas treatment with Rh1 reduced the frequency of

monocytic MDSCs.

Immune dysregulation and heightened inflammatory

responses are recognized as contributors to depression,

particularly in vulnerable individuals (60). Consistent with this,

anti-inflammatory treatments decrease depressive symptoms (61–63).

Elevated levels of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-1β and

TNF-α have been reported in patients with depression (64); therefore, peripheral blood levels

of these cytokines have been proposed as indicators of depression

(65). In addition, chronically

stressed tumor-bearing animals also exhibit elevated levels of

TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-6, which is consistent with the inflammatory

hypotheses of depression and may accelerate the development of

cancer (66). In the present

study, persistent CRS stress increased the release of IL-6, TNF-α

and CXCL1 into the serum of tumor-bearing mice, potentially

contributing to the progression of CRS. Notably, mice treated with

Rh1 had significantly reduced serum levels of these proinflammatory

cytokines compared with those in the model group, suggesting that

Rh1 exerts anti-inflammatory and antitumor effects under CRS

conditions.

The present study has several limitations. Firstly,

no electroencephalogram (EEG) activity data were collected to

detect if any changes in brain electrical activity associated with

depressive symptoms occurred. In future studies, active

collaboration with an institution equipped with EEG detection

facilities will be sought to investigate the

neuroelectrophysiological mechanisms of Rh1, with the aim of

obtaining more comprehensive evidence for its therapeutic effects.

Second, the 16S rRNA sequencing used to analyze gut microbiota has

a relatively low resolution and cannot distinguish closely related

species. The results revealed differences in the microbiota of

certain groups at the phylum level, as exemplified by the

abundances of Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteriodota and

Actinobacteriota. Some data obtained on bacterial genera displayed

non-normal distributions and heterogeneous variance. After using

appropriate statistical tests, namely Welch's ANOVA or

Kruskal-Wallis, non-significant differences in bacterial genera

were detected among groups for certain genera, including

Bifidobacterium, Romboutsia and Alistipes. In future

studies, the sample size will be expanded and metagenomic

sequencing performed to explore the effect of Rh1 on microorganisms

more deeply. Metagenomic sequencing can also be used to gain

whole-genome information and achieve species- or strain-level

resolution, with high sensitivity in the identification of

low-abundance species.

In conclusion, Rh1 shows promise as an adjunctive

therapy for CRC by reducing tumor growth, alleviating

depression-like behaviors, and restoring intestinal flora and

immunological homeostasis in CRC-xenografted mice under CRS. These

findings reveal a novel bioactivity of Rh1 derived from ginseng,

which has potential as a novel strategy to improve the outcomes of

patients with CRC and associated depressive symptoms. To obtain

direct evidence of its interaction with existing therapies, future

research should prioritize preclinical trials combining Rh1 with

chemotherapy, immunotherapy or targeted agents to evaluate their

potential effects on tumor growth and survival.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the Key Project of TCM Science and

Technology Development Plan of Jiangsu Province (grant nos.

ZD202415 and ZD202320), Nanjing Medical Institution Traditional

Chinese Medicine Preparation Research Project (grant no.

NJCC-ZJ-202426), Key Research Project of Jiangsu Provincial Health

Commission (grant no. K2023033), Jiangsu Clinical Innovation Center

of Digestive Cancer of Traditional Chinese Medicine (grant no.

2021.6), Jiangsu Provincial Association for Maternal and Child

Health Studies (grant no. JSFY202202), Traditional Chinese Medicine

Clinical Transformation of Public Service Platform in Jiangsu

Province (grant no. BM2023005), Postgraduate Research &

Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (grant no.

SJCX24_0881) and Post-subsidy Project for High-Quality Research

Achievements of Jiangsu Province Academy of Traditional Chinese

Medicine (grant nos. HBZ202501 and HBZ202405).

Availability of data and materials

The high-throughput 16S rRNA sequencing data

generated in the present study may be found in the NCBI Sequence

Read Archive under the accession number PRJNA1288220 and may be

accessed using the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1288220.

All other data generated in the present study may be requested from

the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

TD, SS and SL conceived and designed the

experiments. TD, LL and JS performed the experiments. TD, LL and JL

revised the manuscript. JL, TD, XT, XW and YL analyzed and

interpreted the data. LL wrote the manuscript. All authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript. TD and SS confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All experimental procedures were authorized by the

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Jiangsu Province

Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine (approval nos.

AEWC-20230902-327 and AEWC-20240301-391). Jiangsu Province Academy

of Traditional Chinese Medicine is an alternative name for Nanjing

Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine Hospital

Affiliated with Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine. All animal

experiments were performed in compliance with the National

Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory

animals (NIH Publication no. 8023, amended 1978) and described in

compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Salvucci M, Crawford N, Stott K, Bullman

S, Longley DB and Prehn JHM: Patients with mesenchymal tumours and

high Fusobacteriales prevalence have worse prognosis in colorectal

cancer (CRC). Gut. 71:1600–1612. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Zhao N, Lai C, Wang Y, Dai S and Gu H:

Understanding the role of DNA methylation in colorectal cancer:

Mechanisms, detection, and clinical significance. Biochim Biophys

Acta Rev Cancer. 1879:1890962024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zheng Z, Hou X, Bian Z, Jia W and Zhao L:

Gut microbiota and colorectal cancer metastasis. Cancer Lett.

555:2160392023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wang J and Liao ZX: Research progress of

microrobots in tumor drug delivery. Food Med Homol. 1:94200252024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Ye L, Hou Y, Hu W, Wang H, Yang R, Zhang

Q, Feng Q, Zheng X, Yao G and Hao H: Repressed Blautia-acetate

immunological axis underlies breast cancer progression promoted by

chronic stress. Nat Commun. 14:61602023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Yang S, Li Y, Zhang Y and Wang Y: Impact

of chronic stress on intestinal mucosal immunity in colorectal

cancer progression. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 80:24–36. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Otun S, Achilonu I and Odero-Marah V:

Unveiling the potential of Muscadine grape Skin extract as an

innovative therapeutic intervention in cancer treatment. J Funct

Foods. 116:1061462024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Urakami H, Yoshikawa S, Nagao K, Miyake K,

Fujita Y, Komura A, Nakashima M, Umene R, Sano S, Hu Z, et al:

Stress-experienced monocytes/macrophages lose anti-inflammatory

function via β2-adrenergic receptor in skin allergic inflammation.

J Allergy Clin Immunol. 155:865–879. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Globig AM, Zhao S, Roginsky J, Maltez VI,

Guiza J, Avina-Ochoa N, Heeg M, Araujo Hoffmann F, Chaudhary O,

Wang J, et al: The β1-adrenergic receptor links sympathetic nerves

to T cell exhaustion. Nature. 622:383–392. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zhang S, Yu F, Che A, Tan B, Huang C, Chen

Y, Liu X, Huang Q, Zhang W, Ma C, et al: Neuroendocrine regulation

of stress-induced T cell dysfunction during lung cancer

immunosurveillance via the kisspeptin/GPR54 signaling pathway. Adv

Sci (Weinh). 9:e21041322022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wang XH, Fu YL, Xu YN, Zhang PC, Zheng TX,

Ling CQ and Feng YL: Ginsenoside Rh1 regulates the immune

microenvironment of hepatocellular carcinoma via the glucocorticoid

receptor. J Integr Med. 22:709–718. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Sommershof A, Scheuermann L, Koerner J and

Groettrup M: Chronic stress suppresses anti-tumor T(CD8+) responses

and tumor regression following cancer immunotherapy in a mouse

model of melanoma. Brain Behav Immun. 65:140–149. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhou M, Fan Y, Xu L, Yu Z, Wang S, Xu H,

Zhang J, Zhang L, Liu W, Wu L, et al: Microbiome and tryptophan

metabolomics analysis in adolescent depression: Roles of the gut

microbiota in the regulation of tryptophan-derived

neurotransmitters and behaviors in human and mice. Microbiome.

11:1452023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zou Y, Wang S, Zhang H, Gu Y, Chen H,

Huang Z, Yang F, Li W, Chen C, Men L, et al: The triangular

relationship between traditional Chinese medicines, intestinal

flora, and colorectal cancer. Med Res Rev. 44:539–567. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zheng W, Shen P, Yu C, Tang Y, Qian C,

Yang C, Gao M, Wu Y, Yu S, Tang W, et al: Ginsenoside Rh1, a novel

casein kinase II subunit alpha (CK2α) inhibitor, retards metastasis

via disrupting HHEX/CCL20 signaling cascade involved in tumor cell

extravasation across endothelial barrier. Pharmacol Res.

198:1069862023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hou J, Xue J, Lee M, Yu J and Sung C:

Long-term administration of ginsenoside Rh1 enhances learning and

memory by promoting cell survival in the mouse hippocampus. Int J

Mol Med. 33:234–240. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zhang L, Gao X, Yang C, Liang Z, Guan D,

Yuan T, Qi W, Zhao D, Li X, Dong H and Zhang H: Structural

characters and pharmacological activity of protopanaxadiol-type

saponins and protopanaxatriol-type saponins from ginseng. Adv

Pharmacol Pharm Sci. 2024:90967742024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wang H, Yang Y, Yang S, Ren S, Feng J, Liu

Y, Chen H and Chen N: Ginsenoside Rg1 ameliorates neuroinflammation

via suppression of connexin43 ubiquitination to attenuate

depression. Front Pharmacol. 12:7090192021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Han D, Zhao Z, Mao T, Gao M, Yang X and

Gao Y: Ginsenoside Rg1: A neuroprotective natural dammarane-type

triterpenoid saponin with anti-depressive properties. CNS Neurosci

Ther. 30:e701502024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wang YZ, Chen J, Chu SF, Wang YS, Wang XY,

Chen NH and Zhang JT: Improvement of memory in mice and increase of

hippocampal excitability in rats by ginsenoside Rg1′s metabolites

ginsenoside Rh1 and protopanaxatriol. J Pharmacol Sci. 109:504–510.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Nahar J, Boopathi V, Murugesan M, Rupa EJ,

Yang DC, Kang SC and Mathiyalagan R: Investigating the anticancer

activity of G-Rh1 using in silico and in vitro studies (A549 Lung

Cancer Cells). Molecules. 27:83112022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lyu X, Xu X, Song A, Guo J and Zhang Y and

Zhang Y: Ginsenoside Rh1 inhibits colorectal cancer cell migration

and invasion in vitro and tumor growth in vivo. Oncol Lett.

18:4160–4166. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Jin Y, Huynh DTN and Heo KS: Ginsenoside

Rh1 inhibits tumor growth in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells via

mitochondrial ROS and ER stress-mediated signaling pathway. Arch

Pharm Res. 45:174–184. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Jiang Y, Hu Y, Yang Y, Yan R, Zheng L, Fu

X, Xiao C and You F: Tong-Xie-Yao-Fang promotes dendritic cells

maturation and retards tumor growth in colorectal cancer mice with

chronic restraint stress. J Ethnopharmacol. 319((Pt 1)):

1170692024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Olescowicz G, Neis VB, Fraga DB, Rosa PB,

Azevedo DP, Melleu FF, Brocardo PS, Gil-Mohapel J and Rodrigues

ALS: Antidepressant and pro-neurogenic effects of agmatine in a

mouse model of stress induced by chronic exposure to

corticosterone. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry.

81:395–407. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Wang W, Liu L, Yang X, Gao H, Tang QK, Yin

LY, Yin XY, Hao JR, Geng DQ and Gao C: Ketamine improved

depressive-like behaviors via hippocampal glucocorticoid receptor

in chronic stress induced-susceptible mice. Behav Brain Res.

364:75–84. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Wu X, Shetty AK and Reddy DS: Long-term

changes in neuroimaging markers, cognitive function and psychiatric

symptoms in an experimental model of Gulf War Illness. Life Sci.

285:1199712021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Liu L, Liu Y, Li R, Teng Y, Zhao S, Chen

J, Li C, Hu X and Sun L: Identification of critical signature in

post-traumatic stress disorder using bioinformatics analysis and in

vitro analyses. Brain Behav. 15:e702432025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wu J, Zhang T, Yu L, Huang S, Yang Y, Yu

S, Li J, Cao Y, Wei Z, Li X, et al: Zhile capsule exerts

antidepressant-like effects through upregulation of the BDNF

signaling pathway and neuroprotection. Int J Mol Sci. 20:1952019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Sui H, Zhang L, Gu K, Chai N, Ji Q, Zhou

L, Wang Y, Ren J, Yang L, Zhang B, et al: YYFZBJS ameliorates

colorectal cancer progression in Apc(Min/+) mice by remodeling gut

microbiota and inhibiting regulatory T-cell generation. Cell Commun

Signal. 18:1132020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Simpson EH: Measurement of diversity.

Nature. 163:6881949. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Chao A and Lee SM: Estimating the number

of classes via sample coverage. J Am Stat Assoc. 87:210–217. 1992.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Shannon CE: Shannon CE. A mathematical

theory of communication. Bell System Technical Journal. 27:379–423.

1948. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Ren Q, He C, Sun Y, Gao X, Zhou Y, Qin T,

Zhang Z, Wang X, Wang J, Wei S and Wang F: Asiaticoside improves

depressive-like behavior in mice with chronic unpredictable mild

stress through modulation of the gut microbiota. Front Pharmacol.

15:14618732024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zhao L, Zhu X, Ni Y, You J and Li A:

Xiaoyaosan, a traditional Chinese medicine, inhibits the chronic

restraint stress-induced liver metastasis of colon cancer in vivo.

Pharm Biol. 58:1085–1091. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Yan X, Shi L, Zhu X, Zhao Y, Luo J, Li Q,

Xu Z and Zhao J: From microbial homeostasis to systemic

pathogenesis: A narrative review on gut flora's role in

neuropsychiatric, metabolic, and cancer disorders. J Inflamm Res.

18:8851–8873. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Chu Y, Qian L, Ke Y, Feng X, Chen X, Liu

F, Yu L, Zhang L, Tao Y, Xu R, et al: Lymph node-targeted

neoantigen nanovaccines potentiate anti-tumor immune responses of

post-surgical melanoma. J Nanobiotechnology. 20:1902022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Hao Y, Ge H, Sun M and Gao Y: Selecting an

appropriate animal model of depression. Int J Mol Sci. 20:48272019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Ding H, Lin J, Xu Z, Wang HHX, Huang L,

Huang J and Wong MCS: The association between organised colorectal

cancer screening strategies and reduction of its related mortality:

A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 24:3652024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

He L, Tian Y, Liu Q, Bao J and Ding RB:

Antidepressant sertraline synergistically enhances paclitaxel

efficacy by inducing autophagy in colorectal cancer cells.

Molecules. 29:37332024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Huynh DTN, Jin Y, Myung CS and Heo KS:

Ginsenoside Rh1 induces MCF-7 cell apoptosis and autophagic cell

death through ROS-Mediated Akt signaling. Cancers (Basel).

13:18922021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Mathiyalagan R, Wang C, Kim YJ,

Castro-Aceituno V, Ahn S, Subramaniyam S, Simu SY, Jiménez-Pérez

ZE, Yang DC and Jung SK: Preparation of polyethylene

glycol-ginsenoside Rh1 and Rh2 conjugates and their efficacy

against lung cancer and inflammation. Molecules. 24:43672019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Guo Y, Xie J, Zhang L, Yang L, Ma J, Bai

Y, Ma W, Wang L, Yu H, Zeng Y, et al: Ginsenoside Rb1 exerts

antidepressant-like effects via suppression inflammation and

activation of AKT pathway. Neurosci Lett. 744:1355612021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Li J, Gao W, Zhao Z, Li Y, Yang L, Wei W,

Ren F, Li Y, Yu Y, Duan W, et al: Ginsenoside Rg1 reduced

microglial activation and mitochondrial dysfunction to alleviate

depression-like behaviour via the GAS5/EZH2/SOCS3/NRF2 axis. Mol

Neurobiol. 59:2855–2873. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Wang L, Zhang QQ, Xu YY, Zhang R, Zhao Q,

Zhang YQ, Huang XH, Jiang B and Ni M: Ginsenoside Rb1 Suppresses

AOM/DSS-induced colon carcinogenesis. Anticancer Agents Med Chem.

23:1067–1073. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Liu R, Zhang B, Zou S, Cui L, Lin L and Li

L: Ginsenoside Rg1 induces autophagy in colorectal cancer through

inhibition of the Akt/mTOR/p70S6K pathway. J Microbiol Biotechnol.

34:774–782. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Yang Z, Wu X, Shen J, Gudamu A, Ma Y,

Zhang Z and Hou M: Ginsenoside Rh1 regulates gastric cancer cell

biological behaviours and transplanted tumour growth in nude mice

via the TGF-β/Smad pathway. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol.

49:1270–1280. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Zhang Z, Shao S, Zhang Y, Jia R, Hu X, Liu

H, Sun M, Zhang B, Li Q and Wang Y: Xiaoyaosan slows cancer

progression and ameliorates gut dysbiosis in mice with chronic

restraint stress and colorectal cancer xenografts. Biomed

Pharmacother. 132:1109162020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Gao Y: Inflammation and gut microbiota in

the alcoholic liver disease. Food Med Homol. 1:94200202024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Wang J, Fan L, Teng T, Wu H, Liu X, Yin B,

Li X, Jiang Y, Zhao J, Wu Q, et al: Adolescent male rats show

altered gut microbiota composition associated with depressive-like

behavior after chronic unpredictable mild stress: Differences from

adult rats. J Psychiatr Res. 173:183–191. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Shao S, Jia R, Zhao L, Zhang Y, Guan Y,

Wen H, Liu J, Zhao Y, Feng Y, Zhang Z, et al: Xiao-Chai-Hu-Tang

ameliorates tumor growth in cancer comorbid depressive symptoms via

modulating gut microbiota-mediated TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling

pathway. Phytomedicine. 88:1536062021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Xu JY, Liu MT, Tao T, Zhu X and Fei FQ:

The role of gut microbiota in tumorigenesis and treatment. Biomed

Pharmacother. 138:1114442021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Zaharuddin L, Mokhtar NM, Muhammad Nawawi

KN and Raja Ali RA: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled

trial of probiotics in post-surgical colorectal cancer. BMC

Gastroenterol. 19:1312019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Piccinno G, Thompson KN, Manghi P, Ghazi

AR, Thomas AM, Blanco-Míguez A, Asnicar F, Mladenovic K, Pinto F,

Armanini F, et al: Pooled analysis of 3,741 stool metagenomes from

18 cohorts for cross-stage and strain-level reproducible microbial

biomarkers of colorectal cancer. Nat Med. 31:2416–2429. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Jamal R, Messaoudene M, de Figuieredo M

and Routy B: Future indications and clinical management for fecal

microbiota transplantation (FMT) in immuno-oncology. Semin Immunol.

67:1017542023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Ugel S, Peranzoni E, Desantis G, Chioda M,

Walter S, Weinschenk T, Ochando JC, Cabrelle A, Mandruzzato S and

Bronte V: Immune tolerance to tumor antigens occurs in a

specialized environment of the spleen. Cell Rep. 2:628–639. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Foley ÉM, Parkinson JT, Mitchell RE,

Turner L and Khandaker GM: Peripheral blood cellular

immunophenotype in depression: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 28:1004–1019. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Shi H, He J, Li X, Han J, Wu R, Wang D,

Yang F and Sun E: Isorhamnetin, the active constituent of a Chinese

herb Hippophae rhamnoides L, is a potent suppressor of

dendritic-cell maturation and trafficking. Int Immunopharmacol.

55:216–222. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Lu YT, Li J, Qi X, Pei YX, Shi WG and Lin

HS: Effects of Shugan Jianpi Formula () on myeloid-derived

suppression cells-mediated depression breast cancer mice. Chin J

Integr Med. 23:453–460. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Bai Y, Cai Y, Chang D, Li D, Huo X and Zhu

T: Immunotherapy for depression: Recent insights and future

targets. Pharmacol Ther. 257:1086242024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Du Y, Dou Y, Wang M, Wang Y, Yan Y, Fan H,

Fan N, Yang X and Ma X: Efficacy and acceptability of

anti-inflammatory agents in major depressive disorder: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 15:14075292024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Baghdadi LR: Tocilizumab reduces

depression risk in rheumatoid arthritis patients: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 17:3419–3441.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Iyengar RL, Gandhi S, Aneja A, Thorpe K,

Razzouk L, Greenberg J, Mosovich S and Farkouh ME: NSAIDs are

associated with lower depression scores in patients with

osteoarthritis. Am J Med. 126:1017.e11–8. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Drago A, Crisafulli C, Calabrò M and

Serretti A: Enrichment pathway analysis. The inflammatory genetic

background in Bipolar Disorder. J Affect Disord. 179:88–94. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Argue BMR, Casten LG, McCool S, Alrfooh A,

Richards JG, Wemmie JA, Magnotta VA, Williams AJ, Michaelson J,

Fiedorowicz JG, et al: Immune dysregulation in bipolar disorder. J

Affect Disord. 374:587–597. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Dai S, Mo Y, Wang Y, Xiang B, Liao Q, Zhou

M, Li X, Li Y, Xiong W, Li G, et al: Chronic stress promotes cancer

development. Front Oncol. 10:14922020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|