Introduction

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is a prevalent and severe

complication of diabetes mellitus, and it is the main cause of

chronic kidney disease worldwide (1,2). Due

to the complex and multifactorial pathogenesis of DN, the treatment

of patients with DN is challenging (3,4).

Notably, renal fibrosis is essential for the pathological process

of DN (5,6), and epithelial-to-mesenchymal

transition (EMT), which refers to the differentiation of epithelial

cells into migratory and invasive mesenchymal cells, is considered

a critical step in the development of renal fibrosis (7–10).

Therefore, inhibiting EMT and renal fibrosis may contribute to

suppressing the progression of DN.

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma

translocation protein 1 (MALT1) is a scaffold protein and protease

regulating downstream signaling pathways (11–13).

Previous studies have indicated that the inhibition of MALT1 has a

suppressive effect on EMT and organ fibrosis (14,15).

For example, a study suggested that MALT1 could facilitate EMT

through regulation of EMT-transcription factors (14). Another study revealed that the

inhibition of MALT1 reduces fibrosis, and this may be attributed to

suppression of the NF-κB signaling pathway (15). Therefore, the inhibition of MALT1

could be considered a potential treatment target for DN. MI-2 is an

irreversible small molecule inhibitor that combines with MALT1 and

disrupts its protease function (16). However, to the best of our

knowledge, the role of MI-2 in attenuating the EMT of kidney cells

or renal fibrosis to mitigate DN has not yet been demonstrated.

Therefore, the current study aimed to investigate the effect of

MALT1 inhibition by MI-2 on high glucose-induced EMT and fibrosis

in HK-2 cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

HK-2 cells were purchased from Xiamen Yimo

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The cells were cultured in a special HK-2

culture medium (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) containing

5.6 mM D-glucose (MedChemExpress), pre-supplemented with 10% fetal

bovine serum (FBS; Wuhan Pricella Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and 1%

penicillin/streptomycin solution (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.,

Ltd.).

Glucose treatment

HK-2 cells were cultured to 80% confluence in

standard medium. Subsequently, the cells were treated with fresh

medium plus either 15 mM D-glucose [low-concentration glucose (LG)

group] or 30 mM D-glucose [high-concentration glucose (HG) group].

The negative control (NC) group consisted of cells cultured only

with the standard medium. After being treated for 48 h at 37°C, the

cells were harvested for wound healing and invasion assays,

immunofluorescence staining and western blotting.

MI-2 treatment

MI-2 (MedChemExpress), a MALT1 inhibitor, was used

to suppress the protease function of MALT1. HK-2 cells were treated

with medium containing 30 mM D-glucose and either 0, 1, 2 or 4 µM

MI-2, and were named as the HG group, the low concentration MI-2

(LC-MI-2) group, the medium concentration MI-2 (MC-MI-2) group and

the high concentration MI-2 (HC-MI-2) group, respectively. The

wound healing and invasion assays, immunofluorescence staining and

western blotting were performed after 48 h of treatment at

37°C.

Cell viability

Cell viability was assessed using the Cell Counting

Kit-8 (CCK-8; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.). Briefly,

4×103 cells were plated and treated with high glucose

and/or MI-2 as aforementioned for 24 h, followed by incubation with

10% CCK-8 solution for 2 h. Subsequently, the optical density (OD)

value was detected using a microplate reader (Nanjing Huadong

Electronics Information & Technology Co., Ltd.).

Wound healing assay

The cell migration rate following treatment was

assessed using a wound healing assay. Briefly, after treatment, the

cells were plated and cultured to achieve 90% confluence.

Subsequently, a 10 µl sterile pipette tip was used to create a

straight wound across the cell monolayer. After washing, medium

containing 1% FBS was added and images of the wound area were

captured as baseline (0 h). The cells were then cultured for

another 6 h, and images of the wound area were captured again with

a light microscope (Motic Industrial Group Co., Ltd.). The width of

the wound at 0 and 6 h was measured to calculate the cell migration

rate as follows: (Area of wound at 0 h - area of wound at 6 h)/area

of wound at 0 h × 100%.

Cell invasion assay

Cell invasion was measured after treatment using a

Transwell assay. Briefly, following treatment, the HK-2 cells

(2×104) were resuspended in serum-free medium and were

plated in the upper chamber of pre-coated Transwell inserts (0.8

µm, Corning, Inc.). The Transwell inserts were pre-coated with

Matrigel matrix (Corning, Inc.) at 37°C for 1 h. The lower chamber

was filled with the standard medium. After 24 h of incubation at

37°C, the invasive cells were counted after staining with crystal

violet solution (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) at room

temperature for 5 min. Images of the invasive cells were captured

with an inverted light microscope (Motic Industrial Group Co.,

Ltd.).

Immunofluorescence staining

After treatment, the HK-2 cells were washed and

fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution (Wuhan Servicebio Technology

Co., Ltd.) at room temperature for 20 min to preserve cell

morphology. The cells were then permeabilized using 0.3% Triton

X-100 (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) and blocked with

bovine serum albumin (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) at 37°C

for 1 h. The anti-α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) antibody (1:1,000;

cat. no. GB111364-50; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) was

incubated with the cells at 4°C overnight, and then a Alexa Fluor

488 labeled secondary antibody (1:1,000; cat. no. GB25303; Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) was incubated with the cells at

37°C for 30 min, followed by staining with DAPI (Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd.) at room temperature for 5 min. An inverted

fluorescence microscope (Motic Industrial Group Co., Ltd.) was used

to collect images. Relative fluorescence intensity was measured

using ImageJ (V1.8.0; National Institutes of Health).

Western blotting

After treatment, the HK-2 cells were washed and the

RIPA Kit (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) was added to the

cells for lysis. Subsequently, the cell lysates were harvested and

proteins were isolated after centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 5 min

at 4°C. The protein concentration was quantified using a BCA Kit

(Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.). Subsequently, western

blotting was performed according to standard procedures, including

electrophoresis, electrophoretic transfer, blocking and antibody

incubation. Briefly, 20 µg protein was separated by a 4–20% precast

gel (Shanghai Willget Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and transferred to a

polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Merck KGaA). The membrane was

blocked with 5% BSA (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) at 37°C

for 1 h. Afterwards, the membrane was incubated with primary

antibodies overnight at 4°C and with secondary antibody at 37°C for

1.5 h. Finally, the signal was detected using an enhanced

chemiluminescence kit (Dalian Meilun Biology Technology Co., Ltd.).

The antibodies used included: Anti-vimentin (1:50,000; cat. no.

10366-1-AP), anti-inhibitor of κB α (IκBα; 1:10,000; cat. no.

10268-1-AP), anti-phosphorylated (p)-p65 (1:5,000; cat. no.

82335-1-RR) and anti-p65 (1:20,000; cat. no. 80979-1-RR) (all from

Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology); anti-E-cadherin (1:2,000; cat. no.

AF0131), anti-fibronectin (FN; 1:1,500; cat. no. AF5335) and

anti-collagen I (1:2,000; cat. no. AF7001) (all from Affinity

Biosciences); and anti-MALT1 (1:1,000; cat. no. GB11790-100),

anti-β-actin (1:5,000; cat. no. GB15003-100) and HRP-linked

secondary antibodies (1:10,000; cat. no. GB23303) (all from Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.). The intensity of target bands was

assessed using ImageJ software V1.8.0, and the expression levels of

the target proteins were normalized to β-actin.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad

(version 9.0; Dotmatics). The Shapiro-Wilk test of normality was

initially performed. Subsequently, group comparisons of normal data

were carried out using one-way analysis of variance, followed by

Tukey's multiple comparisons test. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

HG facilitates EMT and fibrosis and

enhances MALT1 expression in HK-2 cells

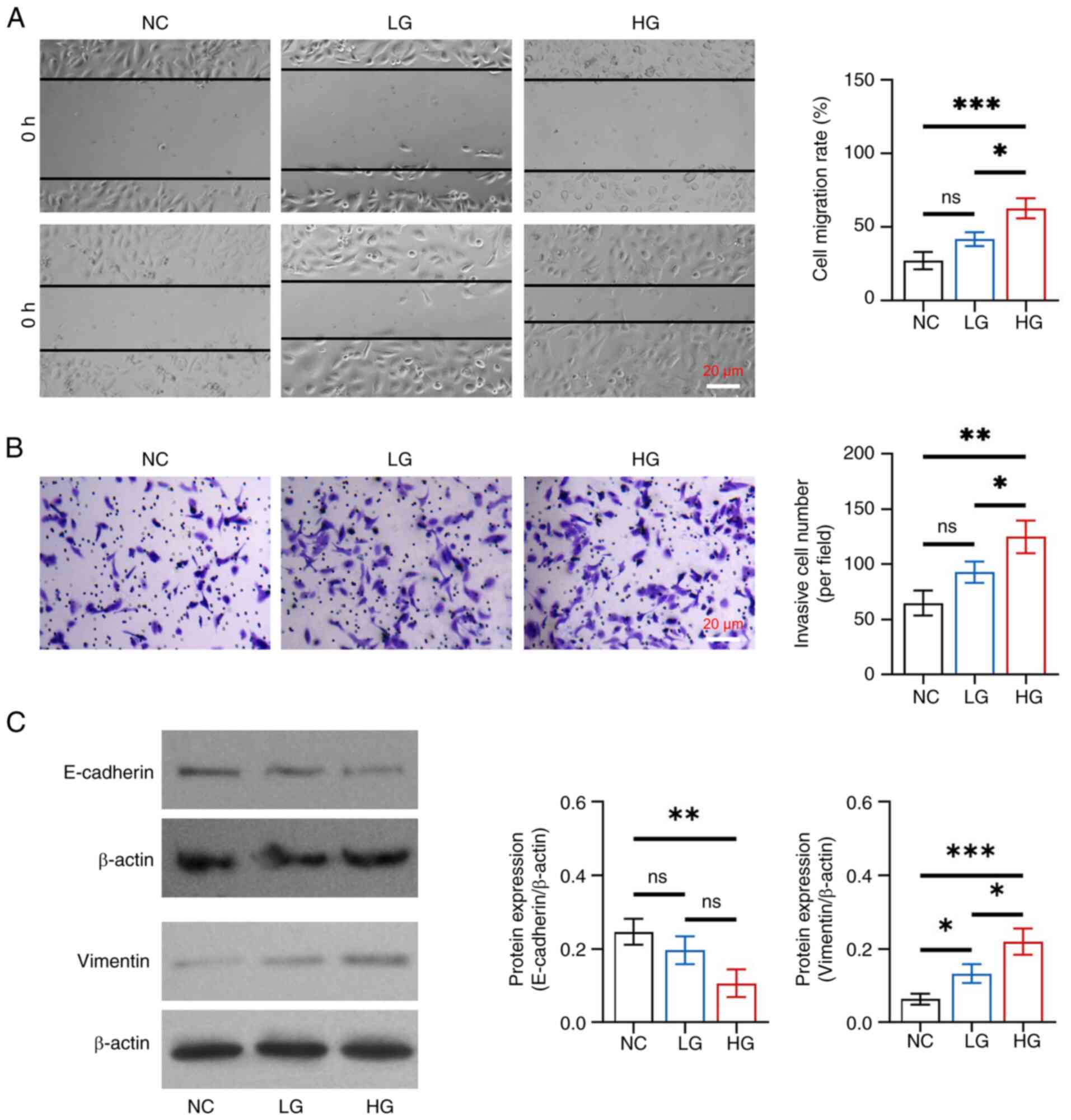

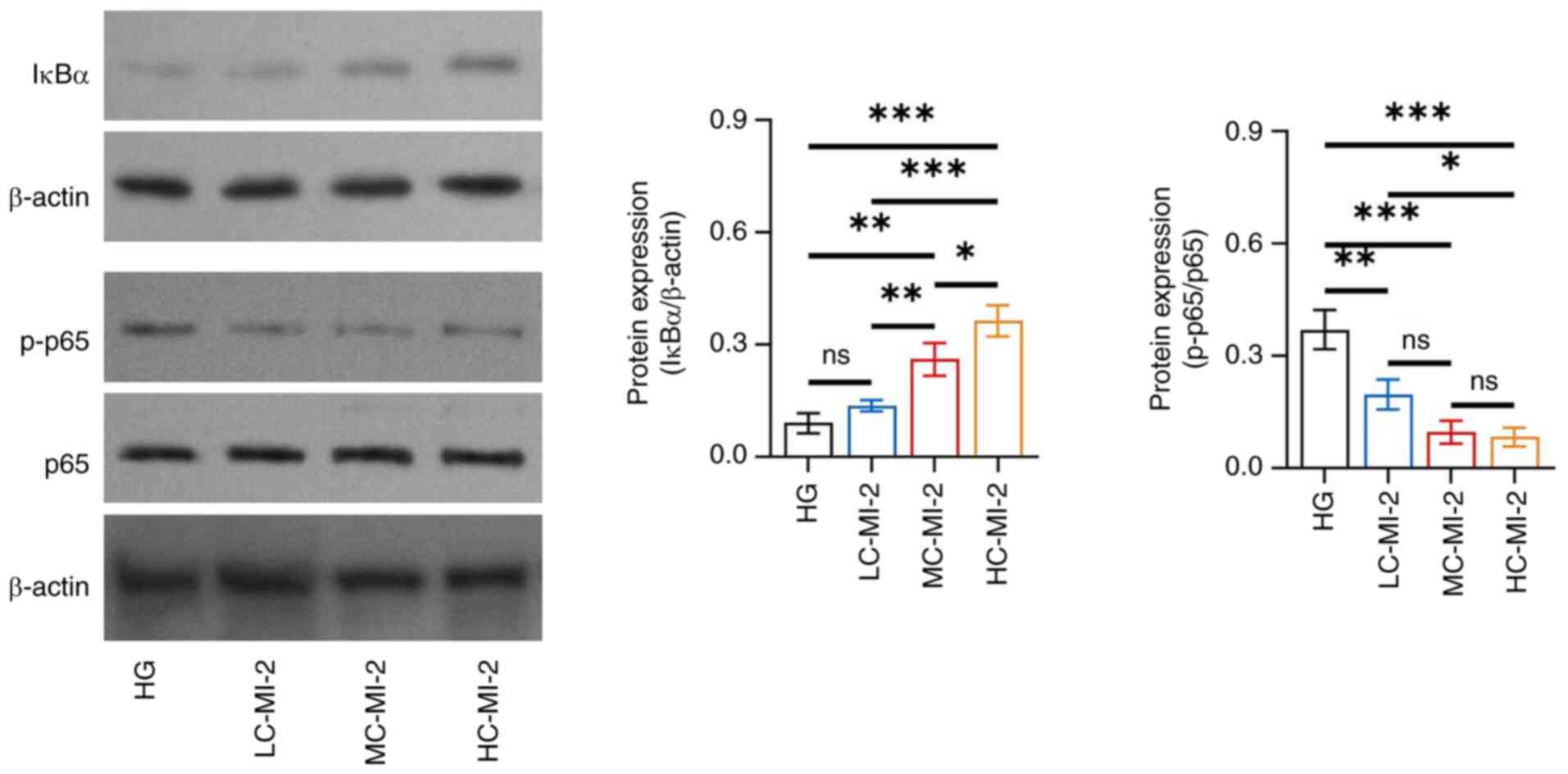

In detail, cell migration rate and invasive cell

number were increased in the HG group compared with those in the NC

and LG groups (all P<0.05), whereas there was no change between

the LG and NC groups (both P>0.05) (Fig. 1A and B). Furthermore, E-cadherin

protein expression levels were reduced in the HG group compared

with those in the NC group (P<0.01), whereas they did not differ

between the HG and LG groups, or between the LG and NC groups (both

P>0.05) (Fig. 1C). By contrast,

elevated vimentin protein expression was observed in the HG group

compared with that in the NC (P<0.001) and LG (P<0.05)

groups, as well as in the LG group compared with that in the NC

group (P<0.05). These results indicated that glucose promoted

EMT with gradient concentration effects in HK-2 cells.

| Figure 1.Effect of different concentrations of

glucose on epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in HK-2 cells. (A)

Comparison of cell migration rate among the NC, LG and HG groups,

between the NC and LG groups, between the NC and HG groups, and

between the LG and HG groups. (B) Comparison of invasive cell

number among the NC, LG and HG groups, between the NC and LG

groups, between the NC and HG groups, and between the LG and HG

groups. (C) Comparison of the protein expression levels of

E-cadherin among the NC, LG and HG groups, between the NC and LG

groups, between the NC and HG groups, and between the LG and HG

groups; and comparison of the protein expression levels of vimentin

among the NC, LG and HG groups, between the NC and LG groups,

between the NC and HG groups, and between the LG and HG groups.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; ns, not significant;

n=3/group. NC, negative control; LG, low-concentration glucose; HG,

high-concentration glucose. |

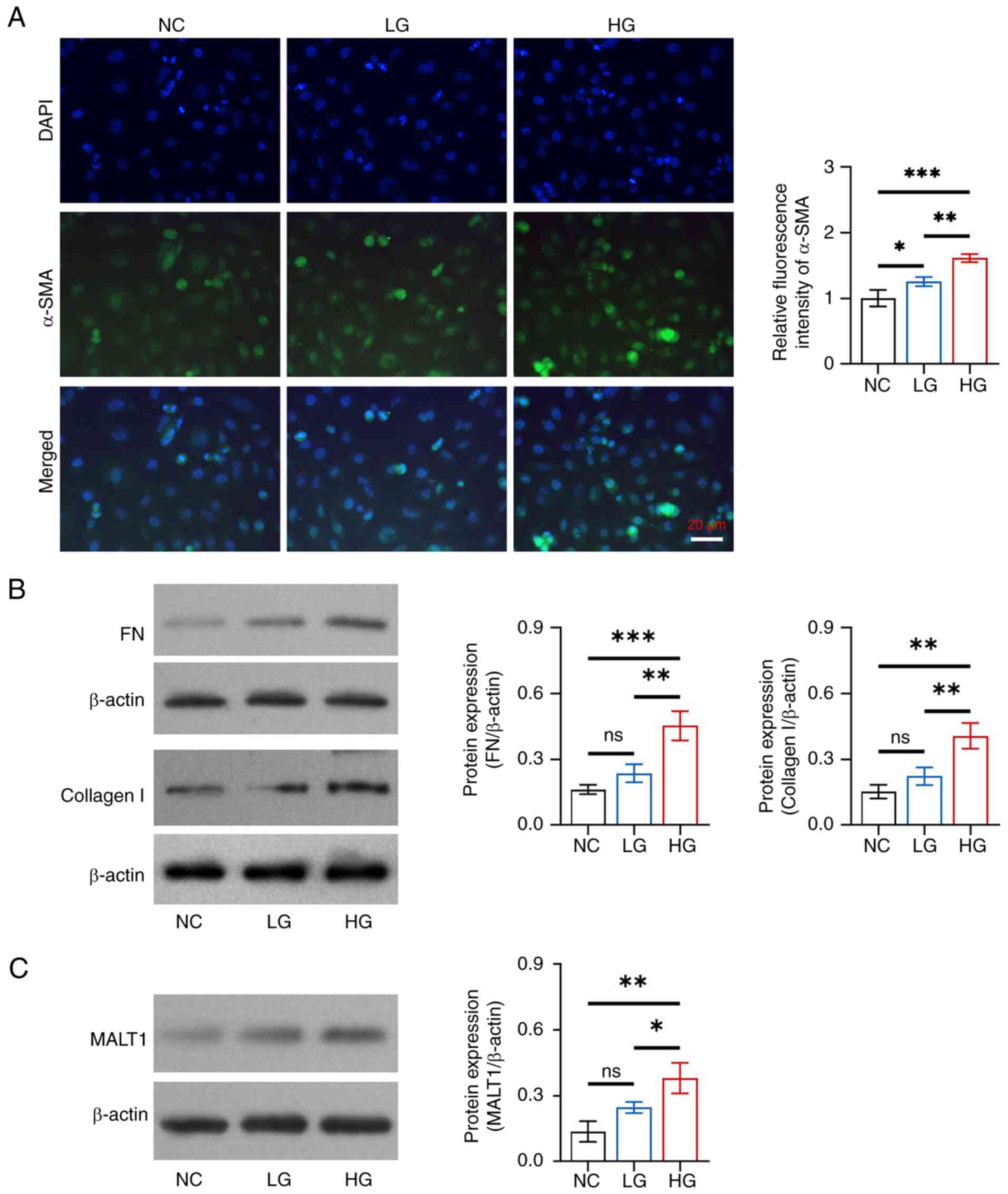

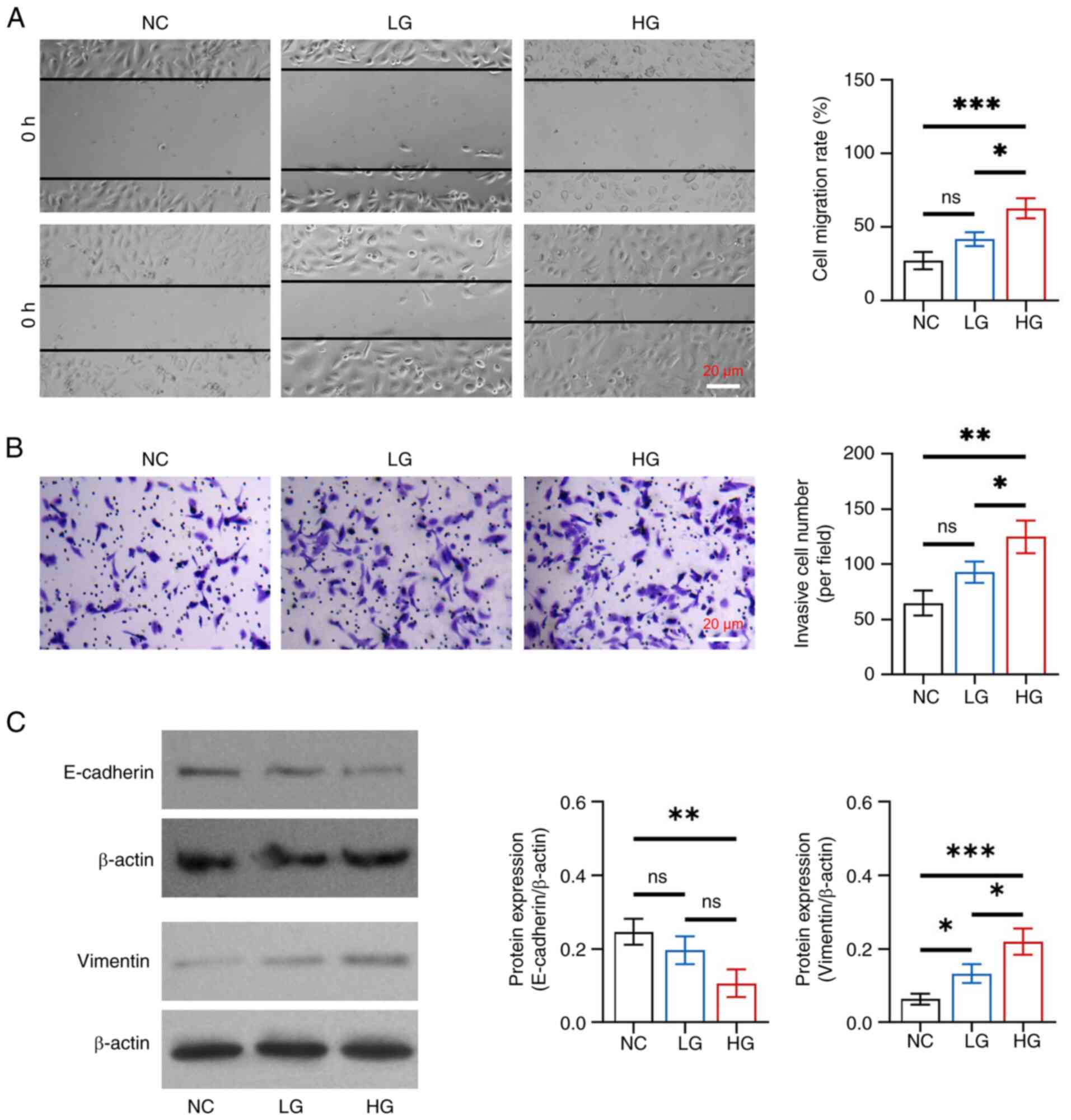

Glucose promoted fibrosis in HK-2 cells in a

dose-dependent manner. The relative fluorescence intensity of α-SMA

was increased in the HG group compared with that in the NC

(P<0.001) and LG (P<0.01) groups, as well as in the LG group

compared with in the NC group (P<0.05) (Fig. 2A). In addition, the protein

expression levels of FN and collagen I were increased in the HG

group compared with those in the NC and LG groups (all P<0.05),

but there was no difference in expression between the LG and NC

groups (both P>0.05) (Fig.

2B).

| Figure 2.Effects of different concentrations

of glucose on fibrosis and MALT1 expression in HK-2 cells. (A)

Comparison of the relative fluorescence intensity of α-SMA among

the NC, LG and HG groups, between the NC and LG groups, between the

NC and HG groups, and between the LG and HG groups. (B) Comparison

of the protein expression levels of FN among the NC, LG and HG

groups, between the NC and LG groups, between the NC and HG groups,

and between the LG and HG groups; and comparison of the protein

expression levels of collagen I among the NC, LG and HG groups,

between the NC and LG groups, between the NC and HG groups, and

between the LG and HG groups. (C) Comparison of the protein

expression levels of MALT1 among the NC, LG and HG groups, between

the NC and LG groups, between the NC and HG groups, and between the

LG and HG groups. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; ns, not

significant; n=3/group. MALT1, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue

lymphoma translocation protein 1; α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; NC,

negative control; LG, low-concentration glucose; HG,

high-concentration glucose; FN, fibronectin. |

Additionally, glucose facilitated MALT1 expression

in a dose-dependent manner in HK-2 cells. Specifically, the protein

expression levels of MALT1 were increased in the HG group compared

with those in the NC (P<0.01) and LG (P<0.05) groups, whereas

there was no difference between the LG and NC groups (P>0.05)

(Fig. 2C).

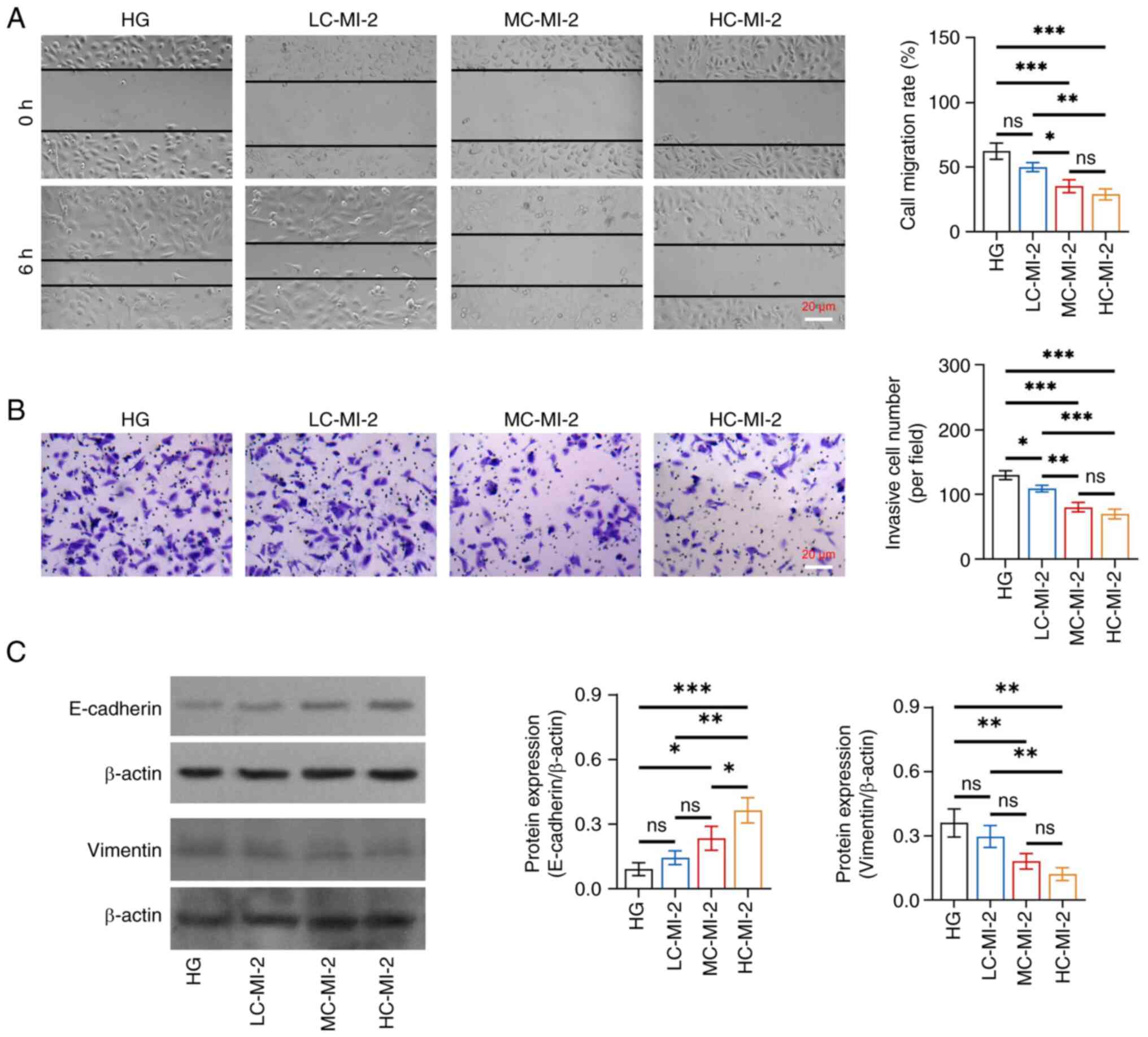

MI-2 inhibits cell viability and EMT

in HG-treated HK-2 cells

No difference was found in the protein expression

levels of MALT1 among the HG, LC-MI-2, MC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2 groups

(all P>0.05; Fig. S1),

indicating that MI-2 functions by inhibiting MALT1 activity but not

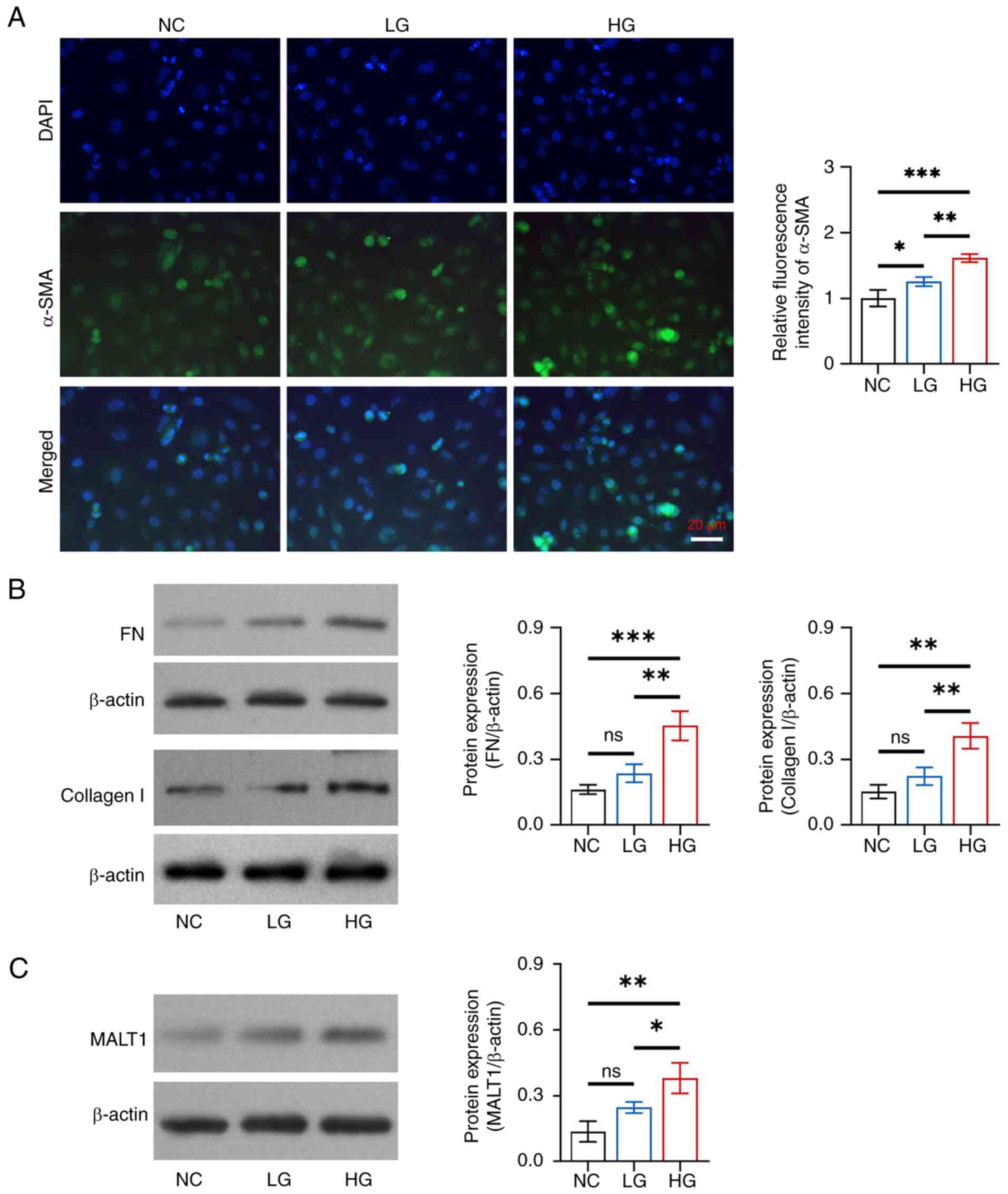

its direct expression. However, MI-2 dose-dependently reduced cell

viability in HG-treated HK-2 cells, and HC-MI-2 exhibited the best

effect. In detail, the OD value was reduced in the HC-MI-2 group

compared with that in the HG, LC-MI-2, and MC-MI-2 groups (all

P<0.01; Fig. S2). The effect

of MI-2 on the inhibition of EMT was dose-dependent in HG-treated

HK-2 cells and HC-MI-2 showed the best inhibitory effect. In

detail, the cell migration rate and invasive cell number were

reduced in the HC-MI-2 group compared with those in the HG and

LC-MI-2 groups (all P<0.05), whereas there was no significant

difference between the HC-MI-2 group and the MC-MI-2 group (both

P>0.05) (Fig. 3A and B).

Furthermore, the protein expression levels of E-cadherin were

elevated, whereas those of vimentin were reduced in the HC-MI-2

group compared with those in the HG group and the LC-MI-2 group

(all P<0.01) (Fig. 3C).

Moreover, the protein expression of E-cadherin was elevated in the

HC-MI-2 group compared with that in the MC-MI-2 group (P<0.05),

but the reduction in vimentin protein expression between the

HC-MI-2 and MC-MI-2 groups was not statistically significant

(P>0.05).

| Figure 3.Effect of different concentrations of

MI-2 on epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in HG-treated HK-2

cells. (A) Comparison of cell migration rate among the HG, LC-MI-2,

MC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2 groups, between the HG and LC-MI-2 groups,

between the HG and MC-MI-2 groups, between the HG and HC-MI-2

groups, between the LC-MI-2 and MC-MI-2 groups, between the LC-MI-2

and HC-MI-2 groups, and between the MC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2 groups. (B)

Comparison of invasive cell number among the HG, LC-MI-2, MC-MI-2

and HC-MI-2 groups, between the HG and LC-MI-2 groups, between the

HG and MC-MI-2 groups, between the HG and HC-MI-2 groups, between

the LC-MI-2 and MC-MI-2 groups, between the LC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2

groups, and between the MC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2 groups. (C) Comparison

of the protein expression levels of E-cadherin among the HG,

LC-MI-2, MC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2 groups, between the HG and LC-MI-2

groups, between the HG and MC-MI-2 groups, between the HG and

HC-MI-2 groups, between the LC-MI-2 and MC-MI-2 groups, between the

LC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2 groups, and between the MC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2

groups; and comparison of the protein expression levels of vimentin

among the HG, LC-MI-2, MC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2 groups, between the HG

and LC-MI-2 groups, between the HG and MC-MI-2 groups, between the

HG and HC-MI-2 groups, between the LC-MI-2 and MC-MI-2 groups,

between the LC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2 groups, and between the MC-MI-2 and

HC-MI-2 groups. HK-2 cells in the LC-MI-2, MC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2

groups were treated with HG. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001; ns, not significant; n=3/group. HG,

high-concentration glucose; LC-MI-2, low concentration MI-2;

MC-MI-2, medium concentration MI-2; HC-MI-2; high concentration

MI-2. |

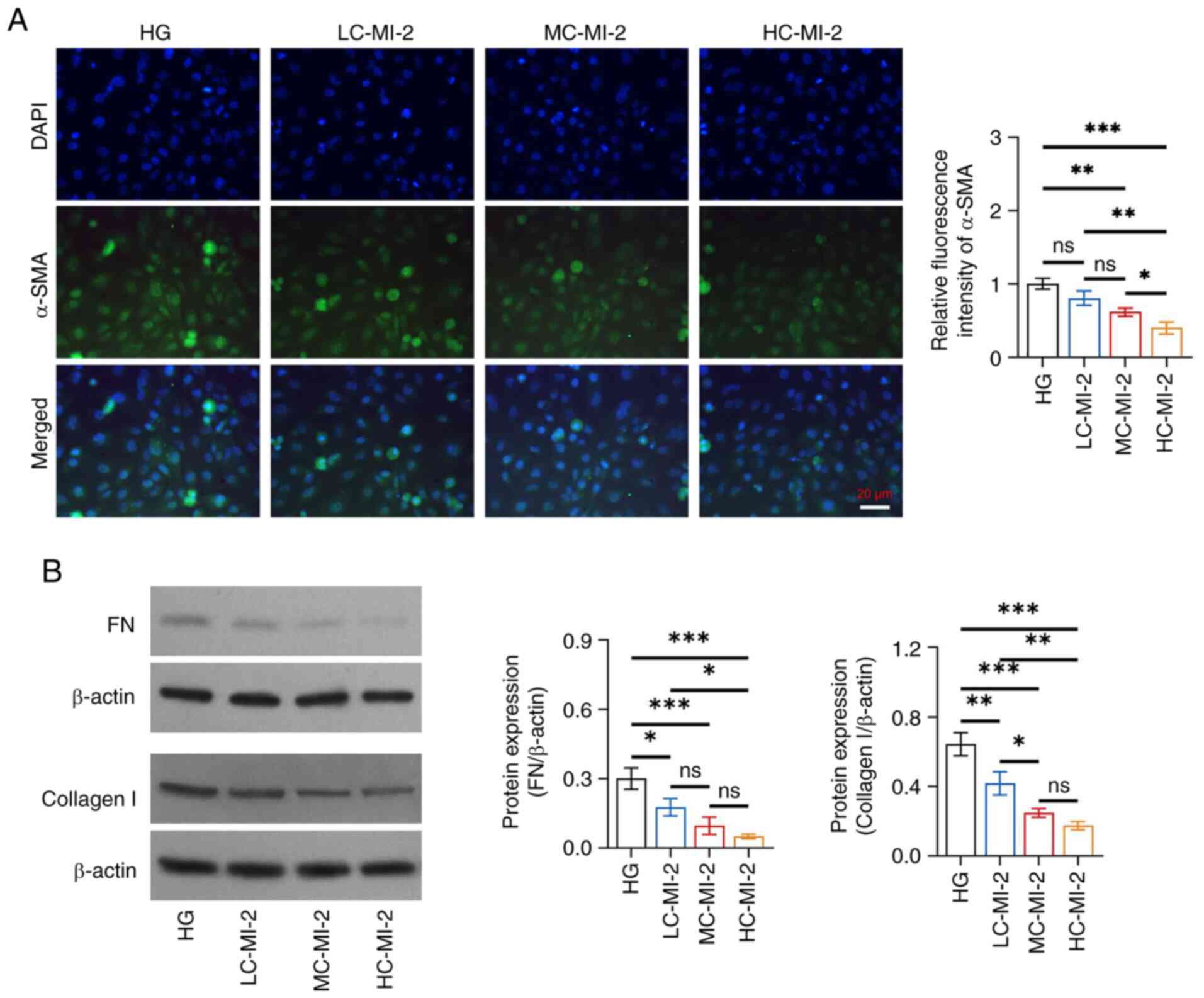

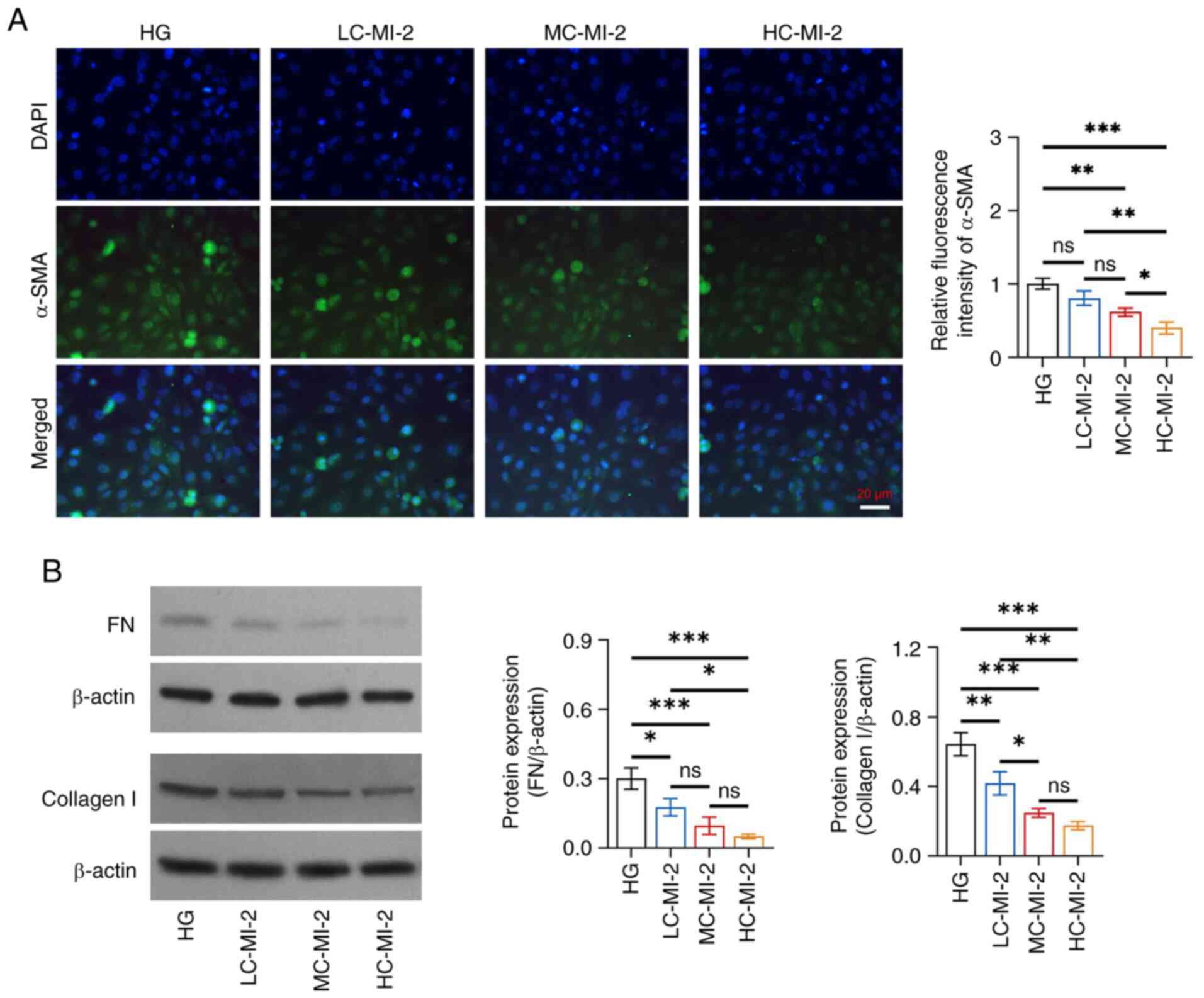

MI-2 inhibits fibrosis in HG-treated

HK-2 cells

MI-2 dose-dependently reduced fibrosis in HG-treated

HK-2 cells and HC-MI-2 exhibited the best effect. Specifically, the

relative fluorescence intensity of α-SMA was reduced in the HC-MI-2

group compared with that in the HG, LC-MI-2 and MC-MI-2 groups (all

P<0.05; Fig. 4A). Furthermore,

the protein expression levels of FN were reduced in the HC-MI-2

group compared with those in the HG and LC-MI-2 groups (both

P<0.05), but there was no significant difference between the

HC-MI-2 group and the MC-MI-2 group (P>0.05) (Fig. 4B). Collagen I protein expression

was also decreased in the HC-MI-2 group compared with that in the

HG (P<0.001) and LC-MI-2 (P<0.01) groups, but it did not

differ statistically between the HC-MI-2 and MC-MI-2 groups

(P>0.05).

| Figure 4.Effect of different concentrations of

MI-2 on fibrosis in HG-treated HK-2 cells. (A) Comparison of the

relative fluorescence intensity of α-SMA among the HG, LC-MI-2,

MC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2 groups between the HG and LC-MI-2 groups,

between the HG and MC-MI-2 groups, between the HG and HC-MI-2

groups, between the LC-MI-2 and MC-MI-2 groups, between the LC-MI-2

and HC-MI-2 groups, and between the MC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2 groups. (B)

Comparison of the protein expression levels of FN among the HG,

LC-MI-2, MC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2 groups, between the HG and LC-MI-2

groups, between the HG and MC-MI-2 groups, between the HG and

HC-MI-2 groups, between the LC-MI-2 and MC-MI-2 groups, between the

LC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2 groups, and between the MC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2

groups; and comparison of the protein expression levels of collagen

I among the HG, LC-MI-2, MC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2 groups, between the HG

and LC-MI-2 groups, between the HG and MC-MI-2 groups, between the

HG and HC-MI-2 groups, between the LC-MI-2 and MC-MI-2 groups,

between the LC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2 groups, and between the MC-MI-2 and

HC-MI-2 groups. HK-2 cells in the LC-MI-2, MC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2

groups were treated with HG. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001; ns, not significant; n=3/group. HG,

high-concentration glucose; α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; LC-MI-2,

low concentration MI-2; MC-MI-2, medium concentration MI-2;

HC-MI-2; high concentration MI-2; FN, fibronectin. |

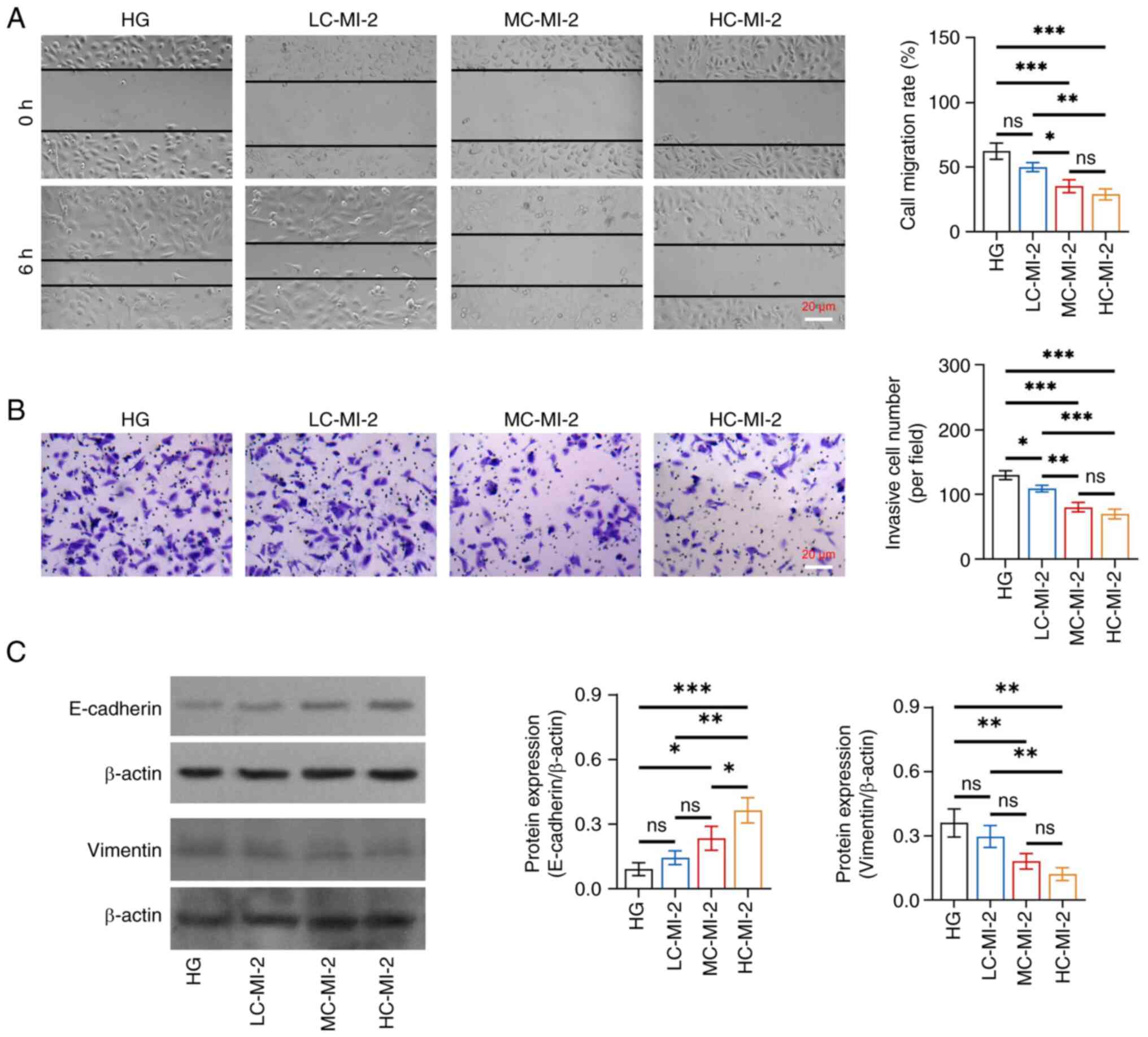

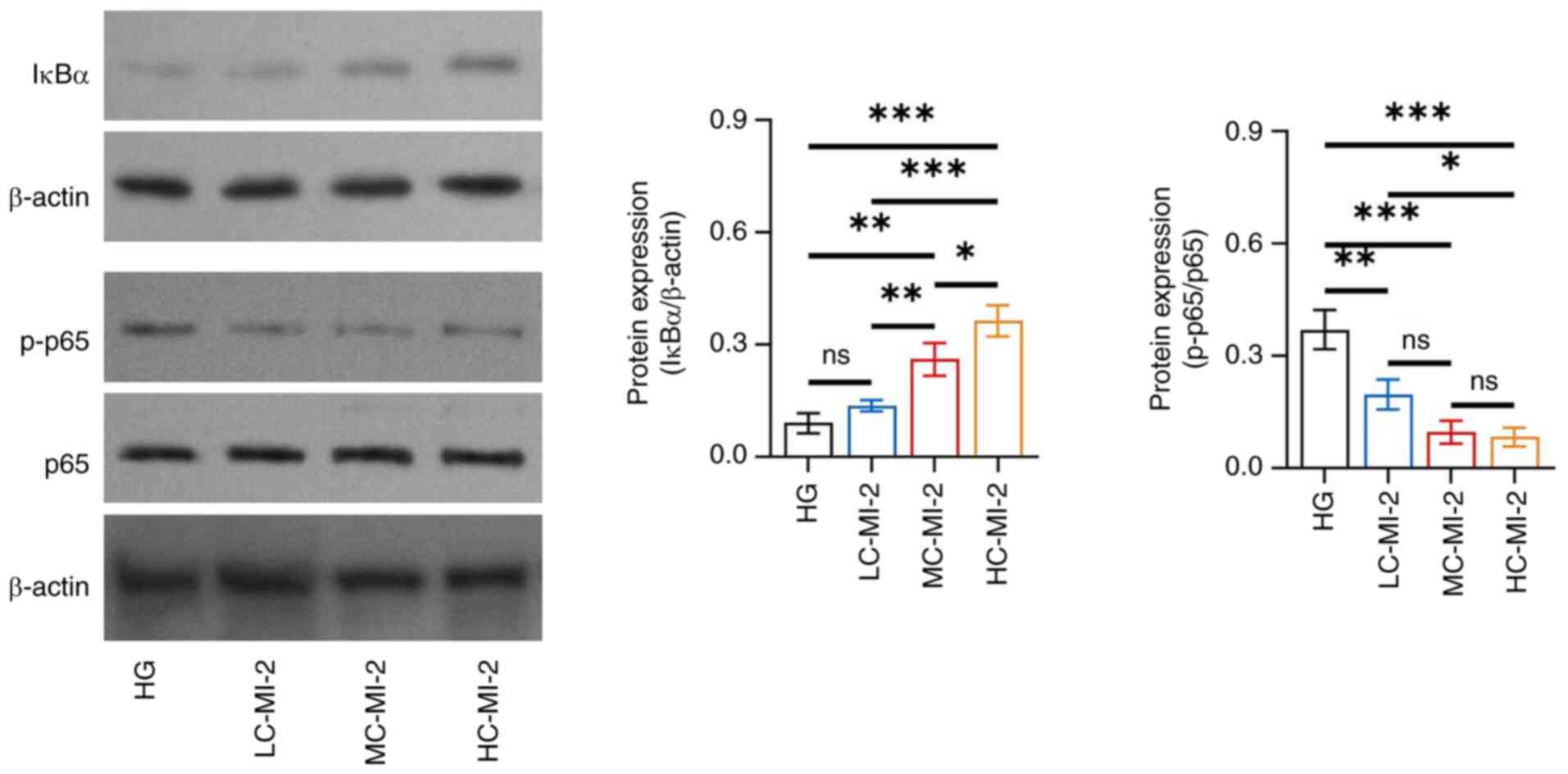

MI-2 inhibits the NF-κB pathway in

HG-treated HK-2 cells

MI-2 inhibited the NF-κB pathway in HG-treated HK-2

cells in a dose-dependent manner and HC-MI-2 had the best

inhibitory effect. In particular, IκBα protein expression was

increased in the HC-MI-2 group compared with that in the HG

(P<0.001), LC-MI-2 (P<0.001) and MC-MI-2 (P<0.05) groups

(Fig. 5). By contrast, the protein

expression ratio of p-p65/p65 was descended in the HC-MI-2 group

compared with that in the HG (P<0.001) and LC-MI-2 (P<0.05)

groups; however, no significant difference was found between the

HC-MI-2 and MC-MI-2 groups (P>0.05).

| Figure 5.Effect of different concentrations of

MI-2 on the NF-κB pathway in HG-treated HK-2 cells. Comparison of

the protein expression levels of IκBα among the HG, LC-MI-2,

MC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2 groups, between the HG and LC-MI-2 groups,

between the HG and MC-MI-2 groups, between the HG and HC-MI-2

groups, between the LC-MI-2 and MC-MI-2 groups, between the LC-MI-2

and HC-MI-2 groups, and between the MC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2 groups; and

comparison of p-p65/p65 among the HG, LC-MI-2, MC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2

groups, between the HG and LC-MI-2 groups, between the HG and

MC-MI-2 groups, between the HG and HC-MI-2 groups, between the

LC-MI-2 and MC-MI-2 groups, between the LC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2 groups,

and between the MC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2 groups. HK-2 cells in the

LC-MI-2, MC-MI-2 and HC-MI-2 groups were treated with HG.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; ns, not significant;

n=3/group. HG, high-concentration glucose; IκBα, inhibitor of κB α;

LC-MI-2, low concentration MI-2; MC-MI-2, medium concentration

MI-2; HC-MI-2; high concentration MI-2; p, phosphorylated. |

Discussion

DN is a burden on healthcare systems that affects

~1/3 of patients with diabetes mellitus (3,17,18).

Renal fibrosis, marked by the excessive deposition of extracellular

matrix components, destroys kidney structure and causes loss of

kidney function, which is closely linked to the development and

progression of DN (19). EMT is

one of the major pathogeneses of renal fibrosis (20). In the present study, the HK-2 cell

line was used, a human renal proximal tubule epithelial cell line,

to construct a widely used in vitro model of DN (21–25).

The results revealed that HG promoted EMT and fibrosis in HK-2

cells, which was similar to the findings of previous studies

(22,23). Moreover, previous studies have

revealed that HG can induce the protein expression of MALT1, which

was similar to the findings of the current study (26,27).

In the present study, HG promoted the protein expression levels of

MALT1 in HK-2 cells, which indicated that MALT1 may be a promising

target and a potential biomarker for DN.

Enhanced cell migration and invasion reflect the

development of EMT (28), and the

reduction of epithelial surface markers (such as E-cadherin) and

the elevation of mesenchymal markers (such as vimentin) are the

hallmarks of EMT (29).

Furthermore, the excessive deposition of extracellular matrix

components, such as α-SMA, FN and collagen I are considered

important markers of fibrosis (30). The present study revealed that MI-2

could reverse HG-induced EMT and fibrosis with gradient

concentration effects in HK-2 cells. These findings suggested that

MI-2 might be an effective therapeutic agent for DN. In the wound

healing assay, the choice of time point of cell migration depends

on numerous factors. The main factor is the specific requirements

of the experiment and cell type. In addition, other factors, such

as cell density, scratch width and cell processing methods need to

be taken into account. Due to a comprehensive consideration of

these factors, the present study set multiple evaluation time

points in the preliminary experiments. The time point of 6 h was

eventually selected as the evaluation time point to prevent the

cells from becoming too dense and affecting the migration

evaluation.

The current study suggested that MI-2 did not

significantly affect the protein expression of MALT1 in HG-treated

HK-2 cells. The cause of this phenomenon may be that MI-2 is an

irreversible MALT1 inhibitor, which works by directly combining

with MALT1 and inhibiting MALT1 protease activity (15,31–34);

thus, MI-2 did not directly affect the protein expression of MALT1.

In addition, due to the fact that MALT1 is the key regulator in

activating the NF-κB signaling pathway, the present study further

explored whether the NF-κB signaling pathway was inhibited by MI-2

in HG-treated HK-2 cells. The findings revealed that MI-2 increased

the protein expression levels of IκBα, while reducing the protein

expression ratio of p-p65/p65 in a dose-dependent manner in

HG-treated HK-2 cells. Notably, a previous study showed that MALT1

inhibition by MI-2 can suppress the NF-κB signaling pathway in

mantle cell lymphoma cells (35).

The results of this previous study were similar to the present

results (35), indicating that

MALT1 inhibition by MI-2 may decrease cell viability and migration

via the NF-κB signaling pathway. However, there were some

differences between the previous study and the current study: i)

The previous study focused on mantle cell lymphoma cells, whereas

the present study focused on HK-2 cells (which were used for in

vitro studies of DN) (35).

ii) The previous study highlighted the impact of MI-2 inhibiting

the NF-κB signaling pathway on tumor resistance, while the present

study focused on its impact on EMT and fibrosis (35). iii) The previous study did not

construct MI-2 concentration gradient models; however, the present

study constructed these models, which further indicated that the

inhibitory effect of MI-2 on the NF-κB pathway was dose-dependent

(35). The possible mechanisms

underlying the inhibitory effects of MI-2 on the NF-κB signaling

pathway may be as follows: MI-2 could directly bind to MALT1 and

suppress its protease function, thus disrupting the assembly of the

CARMA1/BCL10/MALT1 (CBM) complex, further inactivating the IκB

kinase complex, inhibiting the phosphorylation of IκB and reducing

NF-κB activation (36,37). However, the current study did not

explore specific molecular interactions or downstream effects,

which require verification in future studies. Overall, the results

indicated that MI-2 inhibited MALT1, further blocking the NF-κB

signaling pathway to suppress HG-induced EMT and fibrosis. Notably,

some other signaling pathways, such as transforming growth

factor-β/SMAD, Wnt/β-catenin and phosphatidylinositol

3-kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of the rapamycin, are

also involved in EMT and fibrosis (38–40).

These signaling pathways could be explored in future studies.

Overall, the aforementioned findings highlighted

that MI-2 might be a promising agent, which could meet the current

clinical needs for the management of DN. However, the CCK-8 cell

viability assay showed that MI-2 dose-dependently reduced the

viability of HG-treated HK-2 cells. This result indicated that

although MI-2 showed a favorable effect on the treatment of DN, its

clinical application may be limited by toxicity. Thus, strict dose

optimization is required to avoid exacerbating toxicity in clinical

practice. Moreover, more clinical studies are required to further

validate the clinical application of MI-2, including the efficacy

and safety assessment of MI-2 in patients with DN.

The current study has the following limitations: i)

The mechanism by which HG promoted the protein expression of MALT1

in HK-2 cells remains unknown. Future studies should explore the

signaling pathways or transcription factors involved in MALT1

upregulation under HG conditions, which may provide deeper insights

into the pathogenesis of DN and potential therapeutic targets. ii)

The study only focused on HK-2 cells. The findings may not be

generalizable to other types of kidney cells, such as podocytes and

mesangial cells, which also serve crucial roles in DN. Thus, future

studies should investigate whether MI-2 has similar effects on

these kidney cells. iii) Due to the lack of experimental

conditions, the current study was entirely based on in vitro

experiments. The results might not fully reflect the complex

interactions and responses in a living organism. Future studies

should conduct in vivo studies using animal models of DN to

validate the findings and assess the therapeutic potential of MI-2

in a more physiologically relevant context. iv) The current study

evaluated the effects of MI-2 treatment after 48 h, and the short

duration might not capture the full spectrum of cellular responses

or long-term effects. Future studies should extend the treatment

and observation periods to evaluate the sustained effects and

potential side effects of MI-2. v) The current study lacked

detailed mechanistic studies to elucidate the specific interactions

and downstream effects of MALT1 inhibition by MI-2 on the NF-κB

pathway. On one hand, MALT1 acts as a scaffolding protein, which

mediates the formation of the CBM complex to drive activation of

the NF-κB pathway (41). Thus,

immunoprecipitation is required to evaluate the effect of MALT1 on

the CBM complex, and western blot analysis should be performed to

assess the effect of MI-2 on downstream proteins of the CBM complex

(such as TRAF6 and TAK1). On the other hand, MALT1 acts as a

protease, which cleaves several proteins directly connected to the

NF-κB pathway, such as CYLD, A20 and RelB (41). Thus, western blotting is required

to assess the effect of MI-2 on these related proteins. However,

considering technical and financial limitations, the detailed

molecular studies were not conducted. vi) Due to financial

limitations, the current study prioritized and only focused on the

NF-κB pathway. Future studies may consider investigating other

relevant signaling pathways to provide a more comprehensive

understanding of the molecular mechanisms. vii) The current study

only used western blotting to measure proteins, whereas dual

measurements of proteins using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

and western blotting assay may enhance the quality of results.

In conclusion, the present study revealed that MALT1

inhibition by MI-2 may attenuate HG-induced EMT and fibrosis in

HK-2 cells, and this attenuation may be attributed to inhibition of

the NF-κB signaling pathway.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the Postdoctoral Foundation of

Heilongjiang Province (grant no. LBH-Z23284), Heilongjiang

University of Chinese Medicine Young Researchers Scientific and

Technological Innovation Capacity Cultivation Project (grant nos.

2024XJJ-QNCX023 and 2024-KYYWF-1392), Heilongjiang University of

Traditional Chinese Medicine ‘Double First Class’ Discipline

Development Assistance Fund (grant no. GJJGSPZDXK31003) and the

NSFC Cultivation Support Program, First Affiliated Hospital,

Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine (grant no.

PYQN202501008).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

NZ contributed to the conception and the design of

the study. YL and JM were responsible for the acquisition and

analysis of the data. HC and CL contributed to data interpretation.

All authors contributed to manuscript drafting or critical

revisions of the intellectual content. NZ and YL confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Caramori ML and Rossing P: Diabetic Kidney

Disease. Endotext. Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A,

Chrousos G, Corpas E, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, Hofland

J, Kalra S, Kaltsas G, Kapoor N, Koch C, Kopp P, Korbonits M,

Kovacs CS, Kuohung W, Laferrere B, Levy M, McGee EA, McLachlan R,

New M, Purnell J, Sahay R, Shah AS, Singer F, Sperling MA,

Stratakis CA, Trence DL and Wilson DP: South Dartmouth (MA):

2000

|

|

2

|

Dwivedi S and Sikarwar MS: Diabetic

nephropathy: Pathogenesis, mechanisms, and therapeutic strategies.

Horm Metab Res. 57:7–17. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Hu Q, Chen Y, Deng X, Li Y, Ma X, Zeng J

and Zhao Y: Diabetic nephropathy: Focusing on pathological signals,

clinical treatment, and dietary regulation. Biomed Pharmacother.

159:1142522023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Zac-Varghese S, Mark P, Bain S, Banerjee

D, Chowdhury TA, Dasgupta I, De P, Fogarty D, Frankel A, Goldet G,

et al: Clinical practice guideline for the management of lipids in

adults with diabetic kidney disease: Abbreviated summary of the

Joint Association of British Clinical Diabetologists and UK Kidney

Association (ABCD-UKKA) Guideline 2024. BMC Nephrol. 25:2162024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zeng LF, Xiao Y and Sun L: A glimpse of

the mechanisms related to renal fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy.

Adv Exp Med Biol. 1165:49–79. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Watanabe K, Sato E, Mishima E, Miyazaki M

and Tanaka T: What's new in the molecular mechanisms of diabetic

kidney disease: Recent advances. Int J Mol Sci. 24:5702022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Jonckheere S, Adams J, De Groote D,

Campbell K, Berx G and Goossens S: Epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (EMT) as a therapeutic target. Cells Tissues Organs.

211:157–182. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Chen Y, Zou H, Lu H, Xiang H and Chen S:

Research progress of endothelial-mesenchymal transition in diabetic

kidney disease. J Cell Mol Med. 26:3313–3322. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Balakumar P, Sambathkumar R, Mahadevan N,

Muhsinah AB, Alsayari A, Venkateswaramurthy N and Jagadeesh G: A

potential role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition-induced renal abnormalities:

Mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Pharmacol Res.

146:1043142019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hadpech S and Thongboonkerd V:

Epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in kidney fibrosis. Genesis.

62:e235292024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhang YY, Peng J and Luo XJ:

Post-translational modification of MALT1 and its role in B cell-

and T cell-related diseases. Biochem Pharmacol. 198:1149772022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Afonina IS, Elton L, Carpentier I and

Beyaert R: MALT1-a universal soldier: Multiple strategies to ensure

NF-ĸB activation and target gene expression. FEBS J. 282:3286–3297.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hachmann J and Salvesen GS: The

Paracaspase MALT1. Biochimie. 122:324–338. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Lee JL, Ekambaram P, Carleton NM, Hu D,

Klei LR, Cai Z, Myers MI, Hubel NE, Covic L, Agnihotri S, et al:

MALT1 is a targetable driver of epithelial-to-mesenchymal

transition in claudin-low, triple-negative breast cancer. Mol

Cancer Res. 20:373–386. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Fusco R, Siracusa R, D'Amico R, Cordaro M,

Genovese T, Gugliandolo E, Peritore AF, Crupi R, Di Paola R,

Cuzzocrea S and Impellizzeri D: Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue

lymphoma translocation 1 inhibitor as a novel therapeutic tool for

lung injury. Int J Mol Sci. 21:77612020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Fontan L, Yang C, Kabaleeswaran V, Volpon

L, Osborne MJ, Beltran E, Garcia M, Cerchietti L, Shaknovich R,

Yang SN, et al: MALT1 small molecule inhibitors specifically

suppress ABC-DLBCL in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Cell. 22:812–824.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Elendu C, John Okah M, Fiemotongha KDJ,

Adeyemo BI, Bassey BN, Omeludike EK and Obidigbo B: Comprehensive

advancements in the prevention and treatment of diabetic

nephropathy: A narrative review. Medicine (Baltimore).

102:e353972023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Samsu N: Diabetic nephropathy: Challenges

in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Biomed Res Int.

2021:14974492021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Huang R, Fu P and Ma L: Kidney fibrosis:

From mechanisms to therapeutic medicines. Signal Transduct Target

Ther. 8:1292023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Cao Y, Lin JH, Hammes HP and Zhang C:

Cellular phenotypic transitions in diabetic nephropathy: An update.

Front Pharmacol. 13:10380732022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Huang J, Chen G, Wang J, Liu S and Su J:

Platycodin D regulates high glucose-induced ferroptosis of HK-2

cells through glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4). Bioengineered.

13:6627–6637. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Li J, Shu L, Jiang Q, Feng B, Bi Z, Zhu G,

Zhang Y, Li X and Wu J: Oridonin ameliorates renal fibrosis in

diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway. Ren Fail. 46:23474622024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zeng J and Bao X: Tanshinone IIA

attenuates high glucose-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal

transition in HK-2 cells through VDR/Wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 59:259–270. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Sun Y, Qu H, Song Q, Shen Y, Wang L and

Niu X: High-glucose induced toxicity in HK-2 cells can be

alleviated by inhibition of miRNA-320c. Ren Fail. 44:1388–1398.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Deng J, Zheng C, Hua Z, Ci H, Wang G and

Chen L: Diosmin mitigates high glucose-induced endoplasmic

reticulum stress through PI3K/AKT pathway in HK-2 cells. BMC

Complement Med Ther. 22:1162022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chen ST, Chang KS, Lin YH, Hou CP, Lin WY,

Hsu SY, Sung HC, Feng TH, Tsui KH and Juang HH: Glucose upregulates

ChREBP via phosphorylation of AKT and AMPK to modulate MALT1 and

WISP1 expression. J Cell Physiol. 240:e314782025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Wang X, Gao Y, Sun H, et al: Mechanism of

Tangluoning for alleviating high glucose-induced inflammatory

reaction of Schwann cells by regulating lncRNA MALAT1. Beijing

Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 41:236–239. 2022.(In

Chinese).

|

|

28

|

Yang J, Antin P, Berx G, Blanpain C,

Brabletz T, Bronner M, Campbell K, Cano A, Casanova J, Christofori

G, et al: Guidelines and definitions for research on

epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

21:341–352. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Serrano-Gomez SJ, Maziveyi M and Alahari

SK: Regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition through

epigenetic and post-translational modifications. Mol Cancer.

15:182016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Meran S and Steadman R: Fibroblasts and

myofibroblasts in renal fibrosis. Int J Exp Pathol. 92:158–167.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Zhang H, Sun G, Li X, Fu Z, Guo C, Cao G,

Wang B, Wang Q, Yang S, Li D, et al: Inhibition of MALT1

paracaspase activity improves lesion recovery following spinal cord

injury. Sci Bull (Beijing). 64:1179–1194. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Yan B, Belke D, Gui Y, Chen YX, Jiang ZS

and Zheng XL: Pharmacological inhibition of MALT1

(mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma translocation protein

1) induces ferroptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells. Cell Death

Discov. 9:4562023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Gu H, Qiu H, Yang H, Deng Z, Zhang S, Du L

and He F: PRRSV utilizes MALT1-regulated autophagy flux to switch

virus spread and reserve. Autophagy. 20:2697–2718. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Li Y, Huang X, Huang S, He H, Lei T,

Saaoud F, Yu XQ, Melnick A, Kumar A, Papasian CJ, et al: Central

role of myeloid MCPIP1 in protecting against LPS-induced

inflammation and lung injury. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

2:170662017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Jiang VC, Liu Y, Lian J, Huang S, Jordan

A, Cai Q, Lin R, Yan F, McIntosh J, Li Y, et al: Cotargeting of BTK

and MALT1 overcomes resistance to BTK inhibitors in mantle cell

lymphoma. J Clin Invest. 133:e1656942023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Qian R, Niu X, Wang Y, Guo Z, Deng X, Ding

Z, Zhou M and Deng H: Targeting MALT1 suppresses the malignant

progression of colorectal cancer via miR-375/miR-365a-3p/NF-ĸB

axis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 10:8450482022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Yao Y, Yuan M, Shi M, Li W, Sha Y, Zhang

Y, Yuan C, Luo J, Li Z, Liao C, et al: Halting multiple myeloma

with MALT1 inhibition: suppressing BCMA-induced NF-ĸB and inducing

immunogenic cell death. Blood Adv. 8:4003–4016. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Lee JH and Massague J: TGF-β in

developmental and fibrogenic EMTs. Semin Cancer Biol. 86:136–145.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Hu L, Ding M and He W: Emerging

therapeutic strategies for attenuating tubular EMT and kidney

fibrosis by targeting Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Front Pharmacol.

12:8303402022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Lu Q, Wang WW, Zhang MZ, Ma ZX, Qiu XR,

Shen M and Yin XX: ROS induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition

via the TGF-β1/PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in diabetic nephropathy. Exp

Ther Med. 17:835–846. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Moud BN, Ober F, O'Neill TJ and Krappmann

D: MALT1 substrate cleavage: What is it good for? Front Immunol.

15:14123472024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|