Introduction

Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is

newly approved nomenclature intended to expand the diagnostic

criteria and avoid the stigma associated with the condition

previously known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). This

condition includes a range of liver conditions, from simple fatty

liver (hepatic steatosis), which can be detected using imaging or

histological methods, to metabolic-associated steatohepatitis

(MASH), which is associated with inflammation and can result in

more severe liver damage (1–3). The

development of MAFLD is related to lipid accumulation,

lipotoxicity, oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress

(ERS) (4), and the mechanism is

complex. The US Food and Drug Administration approved resmetirom as

a therapeutic drug for MASH in March 2024 (5), marking a major breakthrough in the

treatment of MASH. However, the mechanism of MAFLD needs to be

further explored to lay the foundation for developing more

effective treatment strategies and preventive measures for

MAFLD.

The excessive accumulation of lipid droplets (LDs)

is a specific characteristic of MAFLD. Triglycerides (TGs)

accumulate in hepatic LDs, which regulate intracellular fatty acid

flux by storing and releasing fatty acids for oxidation or

re-esterification into TGs or other complex lipids, thus preventing

cytotoxic events (6,7). Perilipin (PLIN)5 is a member of the

PLIN protein family, which has been reported to be positively

associated with TG storage, fatty acid oxidation, lipotoxicity and

metabolic dysfunction (8). PLIN5

is predominantly expressed in tissues with high oxidative

metabolism, such as the liver, heart, skeletal muscle and brown

adipose tissue (BAT) (9). The

absence of PLIN5 can protect against liver injury in MAFLD by

reducing inflammasome activation (10). Furthermore, our previous studies

have shown that knockout of PLIN5 can attenuate high-fat

diet (HFD)-induced MAFLD in mice (11,12);

however, its underlying molecular mechanism remains unclear.

Ferroptosis is a form of iron-dependent,

non-apoptotic cell death characterized by lipid peroxidation. This

unique mode of cell death is regulated by several cellular

metabolic pathways, including iron metabolism and ERS, as well as

various disease-related signaling pathways, such as

glucose-regulated AMPK signaling (13). Notably, ferroptosis has gained

attention in the field of liver disease as the liver is susceptible

to oxidative damage, and excessive iron accumulation is a major

feature in most primary liver diseases (14). Iron overload accelerates the

dysfunction of lipid metabolism and liver injury in MAFLD, and

inhibition of ferroptosis can be used to prevent and protect

against various chronic liver injuries caused by iron deposition

and abnormal lipid metabolism (15). MAFLD alters iron metabolism in the

body and MAFLD progression is accompanied by extensive lipid

accumulation (16–18). Therefore, ferroptosis is considered

an emerging strategy in MAFLD therapeutics.

Activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) belongs to

the ATF/cAMP response element-binding (CREB) transcription factor

protein family, which controls the expression of target genes by

attaching to the specific DNA sequence TGACGTCA (19). ATF3 sensitizes gastric cancer cells

to cisplatin through the induction of ferroptosis by blocking

Nrf2/Keap1/xCT signaling (19). In

addition, it has been shown that ATF3 has the ability to suppress

the transcriptional activity of SLC7A11, a crucial gene

involved in ferroptosis, thereby triggering the process of

ferroptosis (20). Furthermore,

ATF3-dependent induction of RIPK3 causes a modal shift in

hepatocellular death from apoptosis to necroptosis, and has an

important role in MASH (21).

Therefore, it could be hypothesized that ATF3 may participate in

the regulation of ferroptosis in MAFLD.

This present study aimed to investigate the

involvement of PLIN5 in MAFLD progression and to determine if its

role is related to ferroptosis. Comprehensive experiments were

conducted to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms using

both cellular and animal models.

Materials and methods

Animal models

A total of 20 C57BL/6J mice were obtained from

Beijing Huafukang Biotechnology Co., Ltd. In addition, 20

PLIN5−/− mice were generated at the Nanjing

Biomedical Research Institute of Nanjing University (Nanjing,

China) and were identified via gene expression.

PLIN5−/− mice were generated using a CRISPR/Cas9

system in the C57BL/6 background. In vitro transcribed guide

RNA (gRNA) was co-injected with Cas9 protein into mouse fertilized

eggs. Guided by the gRNA, the Cas9 protein binds to the target

genomic site and induces double-strand breaks. These breaks are

subsequently repaired via non-homologous end joining, leading to

deletion mutations and ultimately resulting in gene knockout. Four

single gRNAs (sgRNA1, sgRNA2, sgRNA3 and sgRNA4, listed in Table SI) targeting PLIN5 exon 4

were designed using an online CRISPR design tool (http://chopchop.cbu.uib.no/). The genotypes of the

PLIN5−/− mice were amplified by PCR analysis with

the knockout (PLIN5−/−) and wild-type (WT) primer

pairs (Table SII). The PCR was

performed using the system and program detailed in Tables SIII and SIV by the Nanjing Biomedical Research

Institute of Nanjing University (data not shown). Mice were housed

in a specific pathogen-free-grade rodent facility, with the

temperature maintained at 20–26°C, relative humidity controlled at

40–70%, and under a 12-h light/dark cycle. Specific

pathogen-free-grade C57BL/6J male mice and

PLIN5−/− male mice (age, 6–7-weeks; weight, ~20

g) were randomly divided into groups fed a normal diet ad

libitum (ND) or a HFD (n=10/group; n=40 mice total). Mice in

the ND group were given a normal chow diet and ultrapure water,

whereas those in the HFD group were given a diet high in fat with a

45% fat-supplied ratio (cat. no. H10045; Beijing HFK Bioscience

Co., Ltd.) and sugar water for 20 weeks (14). All mice were housed at the Animal

Center of Zhengzhou University (Zhengzhou, China) under suitable

conditions. For the investigations, the mice were anesthetized via

inhalation of isoflurane, employing an initial induction

concentration of 4% followed by a maintenance concentration of

1.5%. Once the mice had been fed for 20 weeks, liver specimens were

collected and the mice were immediately sacrificed by cervical

dislocation under deep anesthesia. Death was confirmed by the

cessation of vital signs, including the absence of a palpable

heartbeat, fixed and dilated pupils, and unresponsiveness to

mechanical stimuli. The Animal Ethics Committee of Zhengzhou

University approved the protocols for the animal experiments

(approval no. KY2023006). The animals received humane care

according to the criteria outlined in the Guide for the Care and

Use of Laboratory Animals prepared by the National Academy of

Sciences and published by the National Institutes of Health

(22).

Cell culture

The murine hepatocyte AML12 cell line was purchased

from CHI Scientific, Inc., and was cultured in DMEM/F-12 (1:1)

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal

bovine serum (cat. no. F8318; MilliporeSigma), 40 ng/ml

dexamethasone (to maintain the mature phenotype and specific

function of liver cells; cat. no. D4902-25MG; MilliporeSigma) and

100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (cat. no. 15140122; Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and incubated at 37°C with a constant

supply of 5% CO2. To establish a hepatic steatosis model

in vitro, AML12 cells were stimulated with palmitic acid

(PA; 0.5 mM; cat. no. KC002) and oleic acid (OA; 1.0 mM; cat. no.

KC006) (both from Kun Chuang Biotechnology) [dissolved in 0.5%

fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA); cat. no. KC002; Kun

Chuang Biotechnology] at the indicated concentrations for 48 h. The

control group was treated with 0.5% fatty acid-free BSA (21).

Biochemical analysis

To assess the antioxidant capacity of the mouse

liver samples from five mice per group and AML12 cells, commercial

assay kits (Wuhan Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) were used to

measure the levels of glutathione (GSH; cat. no. E-BC-K030-M) and

malondialdehyde (MDA; cat. no. E-BC-K025-M), according to the

manufacturer's instructions. To measure the levels of ferroptosis

in mice, the Cell Ferrous Iron (Fe2+) Fluorometric Assay Kit (cat.

no. E-BC-F101; Wuhan Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was used

to detect levels of Fe2+, according to the

manufacturer's instructions.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and

bioinformatics analysis

When the AML12 cell density reached ~70% confluence,

the cells were stimulate with PA (0.5 mM) and OA (1.0 mM) at 37°C

for 48 h, and continuously supply 5% CO2. Following

treatment, the cells were lysed with TRIzol® reagent

(cat. no. 15596026; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

homogenized via repetitive pipetting. Total RNA was isolated using

chloroform phase separation followed by isopropanol precipitation.

RNA integrity was verified using an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system

(RNA integrity number >8.0; Agilent Technologies, Inc.), and

purity was confirmed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (A260/A280

ratio ≥1.9; NanoDrop; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). RNA-seq

library preparation and paired-end sequencing (150 bp) were

performed by Shanghai OE Biotech Co., Ltd., using an Illumina

NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, Inc.) with the NovaSeq 6000 S4

Reagent Kit (300 cycles; cat. no. 20027466; Illumina, Inc.), The

loading concentration of the final library was adjusted to 10–20

pM, according to standardized protocols. The raw RNA-seq data

generated in the current study have been deposited in the NCBI

Sequence Read Archive under accession number PRJNA1295086

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1295086/).

Using the GeneCards database (https://www.genecards.org/), an association between

PLIN5 and ferroptosis was searched for using the key words ‘PLIN5’

and ‘ferroptosis’. Gene set enrichment analysis was performed using

the Gene Ontology (GO; http://geneontology.org/) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of

Genes and Genomes (KEGG; http://www.kegg.jp//) databases. Protein-protein

interaction (PPI) network analysis was carried out using the STRING

database (https://string-db.org/).

Single-cell RNA-seq

Once the mice had been fed for 20 weeks, liver

tissues from five randomly selected mice in each group were used

for single-cell RNA-seq. Livers were perfused with collagenase

IV/DNase I and incubated at 37°C for 15–30 min. Cells were then

filtered through a 40-µm strainer and viable cells were enriched

via flow cytometry (CytoFLEX S V4-B2-Y4-RO; Beckman Coulter, Inc.).

Single-cell capture, cDNA library construction and sequencing were

performed by Shanghai Bohao Biotechnology Co., Ltd., using the 10×

Genomics Chromium platform (targeting 5,000-10,000 cells/sample;

10× Genomics, Inc.) with the 10× Genomics Chromium Next GEM Single

Cell 3′Reagent Kit v3.1 (cat. no. 1000268; 10× Genomics, Inc.),

according to standardized protocols. An Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100

System (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) was used to detect sample

integrity. The final loading concentration of the library was ≥10

pM, and the sequencing was performed using a paired-end strategy

with a read length of 150 bp. Raw sequencing data were deposited in

the China National Center for Bioinformation under accession number

CRA018673 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/search?searchTerm=CRA018673).

The DESeq2 package (1.34.0; http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html)

was used to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs); genes

with a P-value <0.05 and |log2 fold-change (FC)|>1

were defined as DEGs. A volcano map of the DEGs was generated using

the ggplot2 (https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/) in R. DEGs and

ferroptosis-related genes from the FerrDb database (http://www.zhounan.org/ferrdb) were collated into

Venn diagrams; overlapping DEGs were selected for subsequent

analyses.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

RNA extraction from AML12 cells and mouse liver

tissue from five mice per group was performed using a Cell/Tissue

Total RNA Rapid Extraction Kit (Novogene Co., Ltd.), according to

the manufacturer's instructions. The extracted RNA was then

reverse-transcribed into cDNA using an RT kit (Toyobo Co., Ltd.)

according to the manufacturer's protocol. Subsequently, cDNA,

primers and SYBR Green Master Mix (Toyobo Co., Ltd.) were combined

in the appropriate proportions, and PCR amplification was carried

out using the LightCycler 480 system (Roche Diagnostics). qPCR was

performed using a three-step protocol, as follows: Initial

denaturation at 95°C for 10 min for 1 cycle; 35 cycles of

denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec, annealing at 60°C for 15 sec and

extension at 72°C for 45 sec; and a final extension step at 72°C

for 7 min for 1 cycle. The relative abundance of mRNA was

normalized to GAPDH mRNA. Gene expression levels were

calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method. The data are

expressed as the ratio of the mean of three independent repeats,

and each experiment was repeated at least three times. The primers

used for qPCR are listed in Table

SV.

Western blotting (WB)

Total protein was extracted from AML12 cells and

mouse liver tissues from three mice per group using high-efficiency

radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer containing protease

inhibitors (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.).

Protein concentrations were measured using a BCA Protein Assay Kit

(Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.).

Subsequently, proteins (20 µg/lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE on

10% gels and were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Pall

Life Sciences), which were blocked with 8% skim milk in

Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) for 2 h at

room temperature. The membranes were then incubated overnight at

4°C with primary antibodies, and after washing with TBST, the

membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated AffiniPure Goat

Anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) secondary antibodies at room temperature

for 2 h, before being washed in TBST. The target proteins were

detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection reagent

(Epizyme; Ipsen Pharma) and signal intensities were captured using

an ECL western-blotting analysis system (Tanon Science and

Technology Co., Ltd.). Semi-quantitative analysis was performed

using ImageJ version 1.8.0t software (National Institutes of

Health). All primary and secondary antibodies used are listed in

Table SVI.

Plasmid transfection

PLIN5 overexpression and ATF3

knockdown plasmids, along with their corresponding negative

controls, were commercially obtained from Suzhou GenePharma Co.,

Ltd. The PLIN5 overexpression plasmid was constructed using

the pcDNA3.1(+) backbone, while the ATF3 short hairpin

(sh)RNA and its scrambled negative control were cloned into the

pGPU6/GFP/Neo plasmid. For transient transfection, AML12 cells were

seeded at a density of 2.5×105 cells/well in 6-well

plates and cultured for 24 h to reach 70–80% confluence.

Transfection was performed using Lipofectamine® 3000

reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to

the manufacturer's instructions. Specifically, 2.5 µg plasmid DNA

and 5 µl Lipofectamine 3000 reagent were diluted separately in

Opti-MEM (cat. no. 31985070; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), then combined and incubated for 15 min at room temperature

to form transfection complexes. The complexes were added dropwise

to the cells, which were then incubated at 37°C in a 5%

CO2 environment. The culture medium was replaced with

fresh medium at 6 h, and after 48 h of total incubation, the cells

were harvested for subsequent experiments. The sequences of shRNAs

are listed in Table SVII. The

negative control used for overexpression consisted of an empty

pcDNA3.1(+) vector, whereas a non-targeting scrambled shRNA was

used as the control for knockdown experiments. Following

transfection, the cells were treated with PAOA for 48 h. In

addition, in the pcDNA3.1 PLIN5 + ferrostatin-1 (FER-1)

group, the cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1 PLIN5,

pretreated with 2 µM FER-1 (cat. no. HY-100579; MedChemExpress) at

37°C in a 5% CO2 cell culture incubator for 1 h, and

then treated with PAOA for an additional 48 h.

Oil red O (ORO) staining

AML12 cells were cultured in a 6-well plate and then

fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 30 min,

followed by staining with ORO staining solution for 30 min at room

temperature (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute), according

to the manufacturer's instructions. Subsequently, the cells were

thoroughly rinsed with distilled water to remove unbound dye and

images were acquired using a light microscope (Nikon Corporation).

Quantification of the staining results was conducted using ImageJ

(version 1.8.0).

FerroOrange staining

AML12 cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at

room temperature for 15 min. After washing, the nuclei were stained

with the nuclear dye green cyanine SYTO (Jiangsu Kaiji

Biotechnology) for 10 min at room temperature. Subsequently,

Fe2+ was detected by incubating the cells with

FerroOrange dye (Tocris Bioscience) for 30 min at 37°C in the dark.

Cellular nuclei and Fe2+ signals were visualized using a

confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 900; Carl Zeiss AG). All

experimental procedures were carried out according to the

instructions provided with the reagents.

H&E staining

Histological analysis was performed on liver tissues

from three mice per group fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h at

room temperature, followed by paraffin embedding and slicing into

5-µm sections. The sections were then deparaffinized in xylene and

rehydrated through a graded ethanol series (100, 95, 85 and 70%) to

distilled water. Subsequently, nuclei were stained with Harris

hematoxylin for 5 min at room temperature, differentiated in 1%

acid alcohol and blued in Scott's tap water. The cytoplasm and

extracellular matrix were counterstained with eosin Y for 2 min at

room temperature. Finally, sections were dehydrated through a

graded ethanol series, cleared in xylene and mounted with neutral

balsam. Histopathological examination was conducted using a light

microscope (Nikon Corporation).

Masson's trichrome staining

Histological analysis was performed on liver tissues

from three mice per group fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h at

room temperature, followed by paraffin embedding and slicing into

5-µm sections. All staining procedures were carried out at room

temperature. Sections were stained with Weigert's hematoxylin (5–10

min), 1% eosin ethanol (5 min) and Masson composite solution (5

min), followed by differentiation in 1% hydrochloric acid ethanol

(30 sec) and 2% acetic acid (30 sec). Dehydration was performed

using graded ethanol series (70, 85, 95 and 100%). Finally,

histopathological images were acquired using a light microscope

(Nikon Corporation).

TG analysis

The concentration of TGs of mouse liver tissues from

five mice per group was quantified using a commercial TG assay kit

(cat. no. BC0625; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. TG was

extracted with isopropanol and subsequently saponified using KOH to

release glycerol and free fatty acids. The liberated glycerol was

oxidized by iodine to generate formaldehyde, which then underwent

condensation with acetylacetone in the presence of chloride ions to

yield a yellow-colored product. This chromophore displays a

distinct absorption peak at 420 nm, and the absorbance intensity is

proportional to the original TG concentration. This

well-established method allows accurate and reproducible

determination of TG levels.

Total cholesterol (TC) analysis

The concentration of TC in mouse liver tissues from

five mice per group was determined using a commercial TC assay kit

(cat. no. BC1985; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The extracted

cholesterol esters were first hydrolyzed to free cholesterol by

cholesterol esterase. The free cholesterol was then oxidized by

cholesterol oxidase to generate hydrogen peroxide. In the presence

of peroxidase, hydrogen peroxide reacted with 4-aminoantipyrine and

phenol to form a red quinoneimine dye. The absorbance of this

colored product was measured at 500 nm, and its intensity is

proportional to TC concentration.

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT)

analysis

The concentration of ALT was determined using a

commercial ALT assay kit (cat. no. BC1555; Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. After mouse anesthesia, as aforementioned, whole

blood (~500 µl/mouse) was collected from the retro-orbital plexus

of the 40 mice using sterile glass capillary tubes (cat. no.

71900-10; KIMBLE®; DWK Life Sciences) and immediately

transferred to 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes. The mice were

subsequently sacrificed by cervical dislocation under deep

anesthesia. The blood was allowed to clot at room temperature for

30 min and the clots were then pelleted by centrifugation at 2,000

× g for 15 min at 4°C. Subsequently, the supernatant (serum) was

carefully aspirated, aliquoted and stored at −80°C until further

analysis.

The serum samples from five mice per group were

diluted with physiological saline at a ratio of 1:10. A total of 5

µl serum was mixed with 290 µl working reagent containing Tris

buffer (pH 7.8), L-alanine, α-ketoglutarate, NADH and lactate

dehydrogenase. The samples were incubated at 37°C for 30 min to

allow the enzyme to fully react with the substrate. After the

reaction was complete, 50 µl NADH chromogenic reagent was added to

each well, and the OD value change was measured at a wavelength of

505 nm. ALT activity in the sample was calculated based on the

standard curve.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of

mean of at least three independent experiments. All statistical

analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software version 9.5.1

(Dotmatics), and data were analyzed using one-way analysis of

variance followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

PLIN5 deficiency inhibits ferroptosis

in lipotoxic hepatocytes in vitro and in vivo

First, an in vitro PAOA-induced hepatocyte

steatosis model was constructed by treating AML12 cells with PAOA

for 48 h. RNA was collected for transcriptome sequencing, and gene

set enrichment analysis with GO and KEGG was performed to analyze

the cell signaling pathways involved in lipid accumulation and

inflammation. The results revealed that PAOA treatment activated

signaling pathways associated with lipid accumulation and

inflammation, such as ‘fatty acid metabolic process’, ‘response to

lipopolysaccharide’, ‘response to fatty acid’, ‘immune response’,

‘inflammatory response’, ‘innate immune response’, ‘IL-17 signaling

pathway, ‘NF-kappa B signaling pathway’ and ‘TNF signaling pathway’

(Fig. S1B and D). In addition,

using ORO staining to assess LD content, followed by statistical

analysis with ImageJ, the LD content was markedly increased in

PAOA-treated AML12 cells compared with that in the BSA control

group (Fig. S1A). These data

indicated that the lipotoxic cell model was successfully

constructed. Furthermore, the expression levels of PLIN5 were

increased in AML12 cells treated with PAOA compared with those in

the BSA group (Fig. S1E and

F).

To investigate the impact of PLIN5 on ferroptosis

under lipotoxic conditions, the key words ‘PLIN5’ and ‘ferroptosis’

were searched in the GeneCards database to determine their

association. A total of 113 genes were identified to be associated

with both PLIN5 and ferroptosis. According to GO enrichment

analysis, the significantly regulated terms were primarily related

to ferroptosis and lipid metabolism signaling, such as

‘ferroptosis’, ‘PPAR signaling pathway’ and ‘fatty acid

biosynthesis’, indicating that these genes were not only associated

with ferroptosis, but were also closely related to biological

processes such as lipid metabolism (Fig. S1C). The primary changes in

biochemical characteristics associated with ferroptosis are iron

overload and decreased activity of the ferroptosis marker gene GSH

peroxidase 4 (GPX4) in MAFLD development (23,24).

In the present study, PPI analysis revealed an indirect association

between PLIN5 and GPX4 (Fig.

S1G).

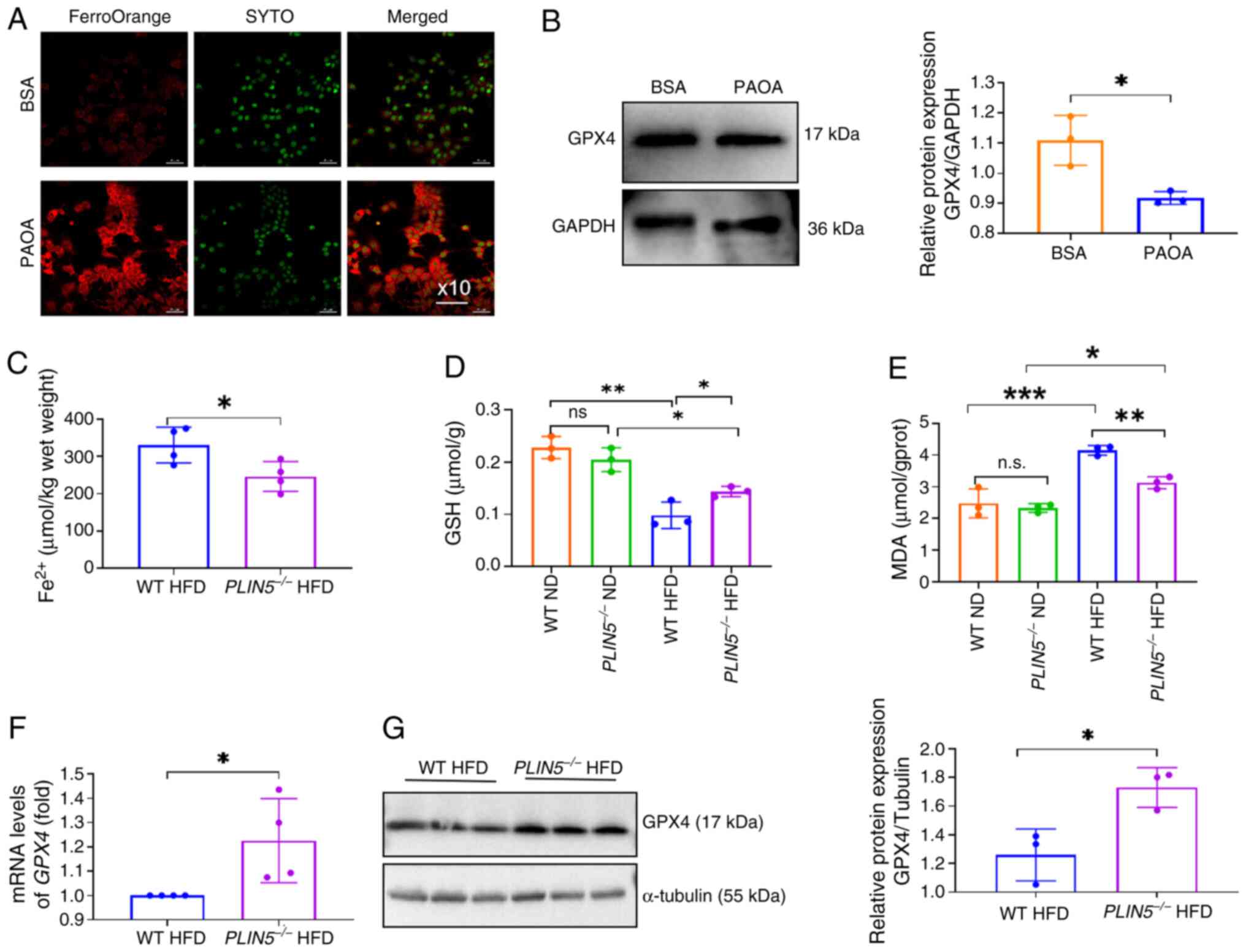

The present study revealed that PAOA-treated AML12

cells exhibited elevated Fe2+ and significantly reduced

GPX4 expression under lipotoxic conditions compared with those in

the BSA group (Fig. 1A and B),

indicating that PAOA treatment induced ferroptosis in vitro.

Notably, Fe2+ levels were significantly decreased in the

livers of mice in the PLIN5−/− HFD group compared

with those in the WT HFD group (Fig.

1C). The successful knockout of PLIN5 is shown in

Fig. S2A and B. It has previously

been reported that patients with MAFLD have elevated levels of the

lipid peroxidation marker MDA (25). The current study also measured the

redox markers MDA and GSH in the liver tissues from WT and

PLIN5−/− mice fed a ND or HFD for 20 weeks. After

HFD feeding, MDA was increased and GSH was significantly decreased

in mice from both groups; by contrast, MDA levels were

significantly decreased and GSH levels were significantly increased

in the PLIN5−/− HFD group compared with those in

the WT HFD group (Fig. 1D and

E).

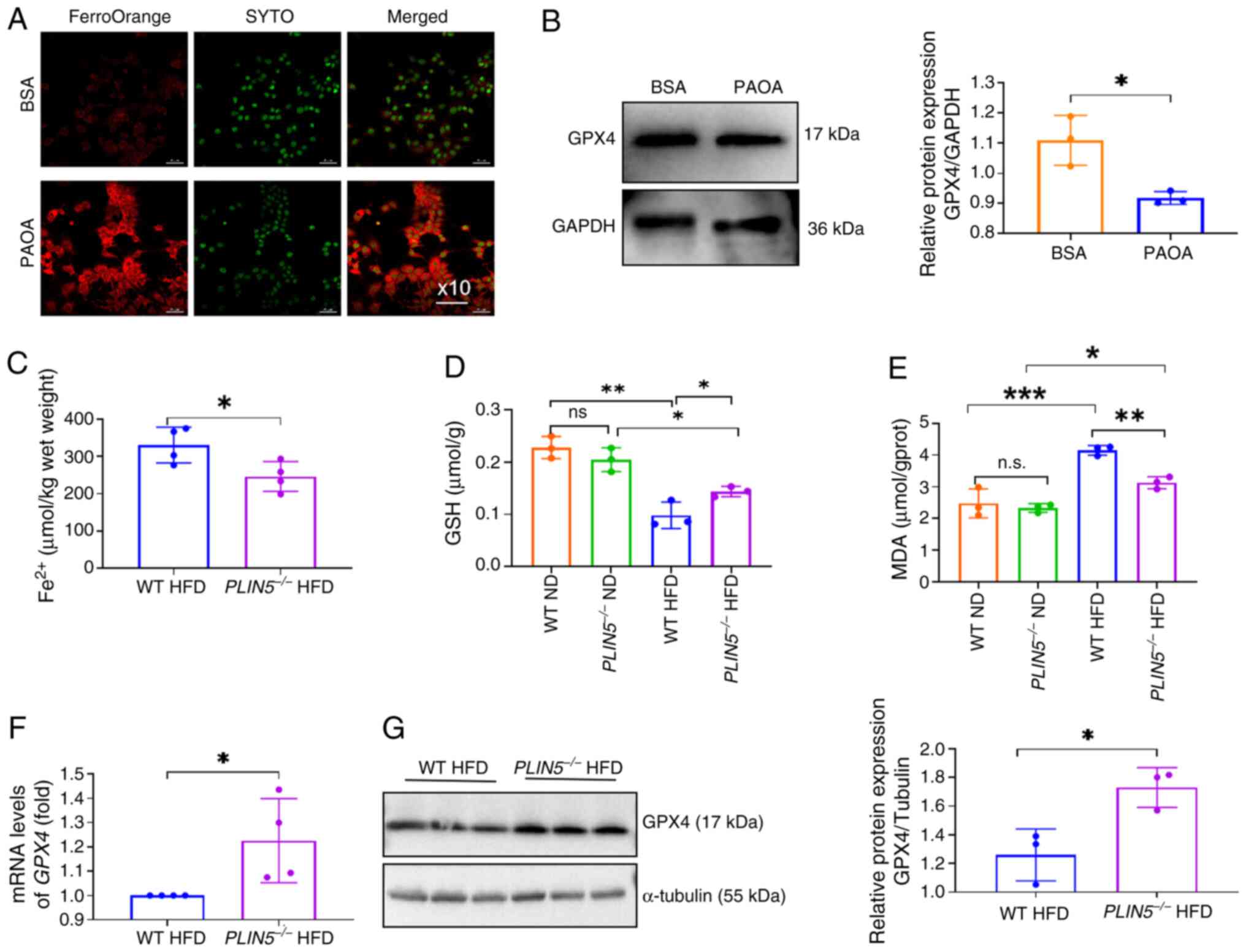

| Figure 1.PLIN5 deficiency inhibits

ferroptosis in lipotoxic hepatocytes in vitro and in

vivo. (A) Fe2+ fluorescence intensity in AML12 cells

observed using a fluorescence microscope (magnification, ×10), with

red indicating Fe2+ fluorescence and green indicating

nuclei. (B) Western blot analysis of GPX4 protein expression in

BSA- or PAOA-treated cells was performed, with GAPDH used as an

internal control. (C) Fe2+ content in the livers of mice

in the WT HFD group and PLIN5−/− HFD group was

measured (n=5 mice/group). (D) Liver GSH content of mice in each

group was detected (n=5 mice/group). (E) Liver MDA content of mice

in each group was detected (n=5 mice/group). (F) mRNA levels of

GPX4 in the liver tissues of mice in the WT HFD and

PLIN5−/− HFD groups were analyzed by quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (n=5 mice/group). (G) Western blot

analysis of GPX4 protein expression in the liver tissues of mice

from the WT HFD and PLIN5−/− HFD groups was

performed, with tubulin used as an internal control (n=3

mice/group). All experiments were repeated at least three times

(n=3). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, n.s., not

significant. Fe2+, ferrous ion; GSH, glutathione; GPX4,

GSH peroxidase 4; HFD, high-fat diet; MDA, malondialdehyde; PAOA,

palmitic acid and oleic acid; PLIN5, perilipin 5; WT,

wild-type. |

Notably, GPX4 expression levels were significantly

higher in the liver tissues of the PLIN5−/− HFD

group compared with those in the WT HFD group (Fig. 1F and G). Consistent with our

previous reports (10,11). H&E staining revealed a marked

reduction in lipid droplets in the PLIN5−/− group

compared with those in the WT group (Fig. S2C). Furthermore, Masson's

trichrome staining indicated a decrease in liver fibrosis in

PLIN5−/− mice (Fig.

S2D), and TG and TC levels were significantly reduced compared

with those in the WT group (Fig. S2E

and F). Additionally, serum ALT levels were lower in the

PLIN5−/− group compared with those in the WT

group (Fig. S2G). These findings

indicated that PLIN5 knockout could attenuate hepatic

steatosis and injury, and suggested that PLIN5 deficiency

may delay the progression of MAFLD in mice by inhibiting

ferroptosis.

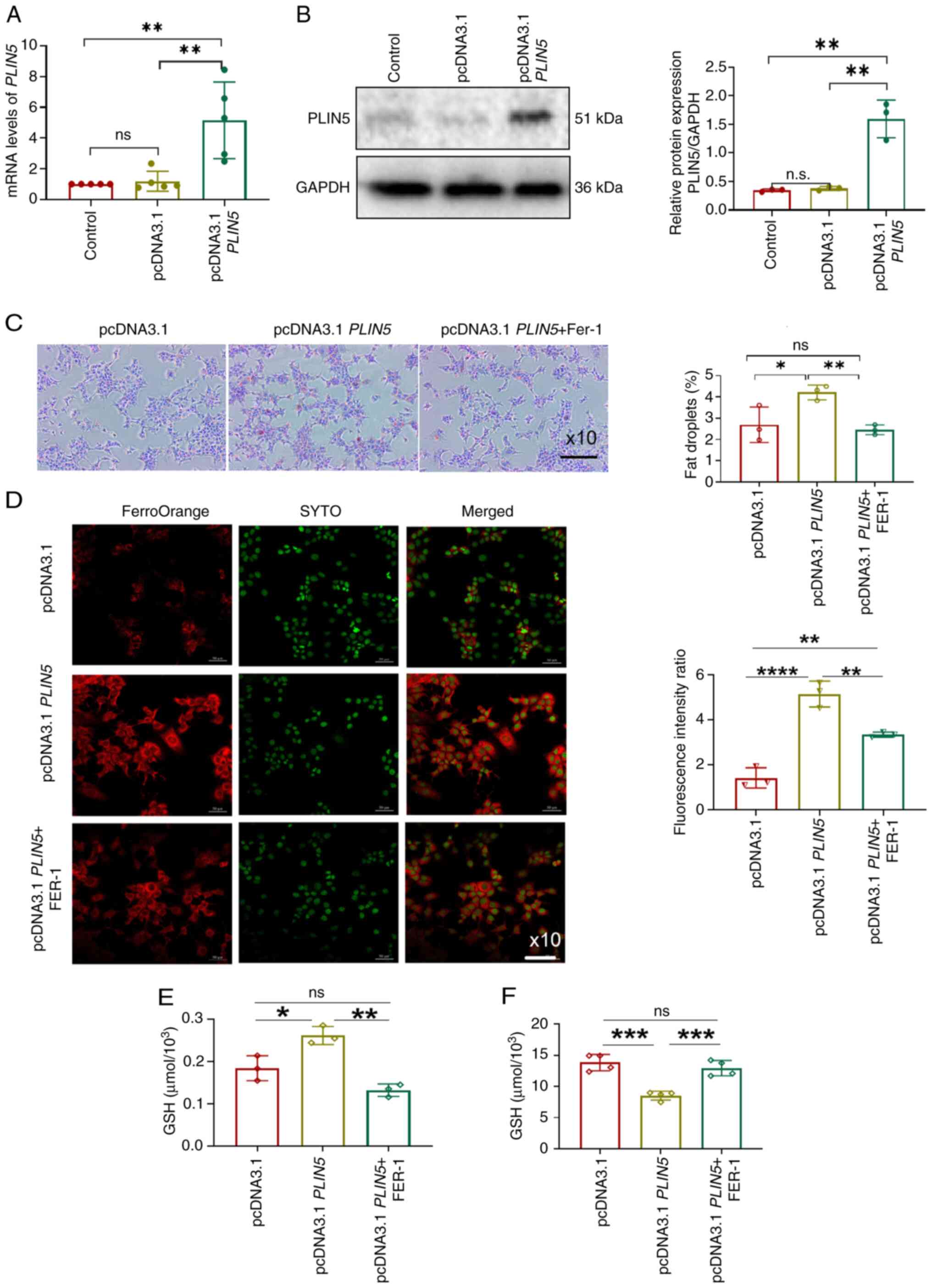

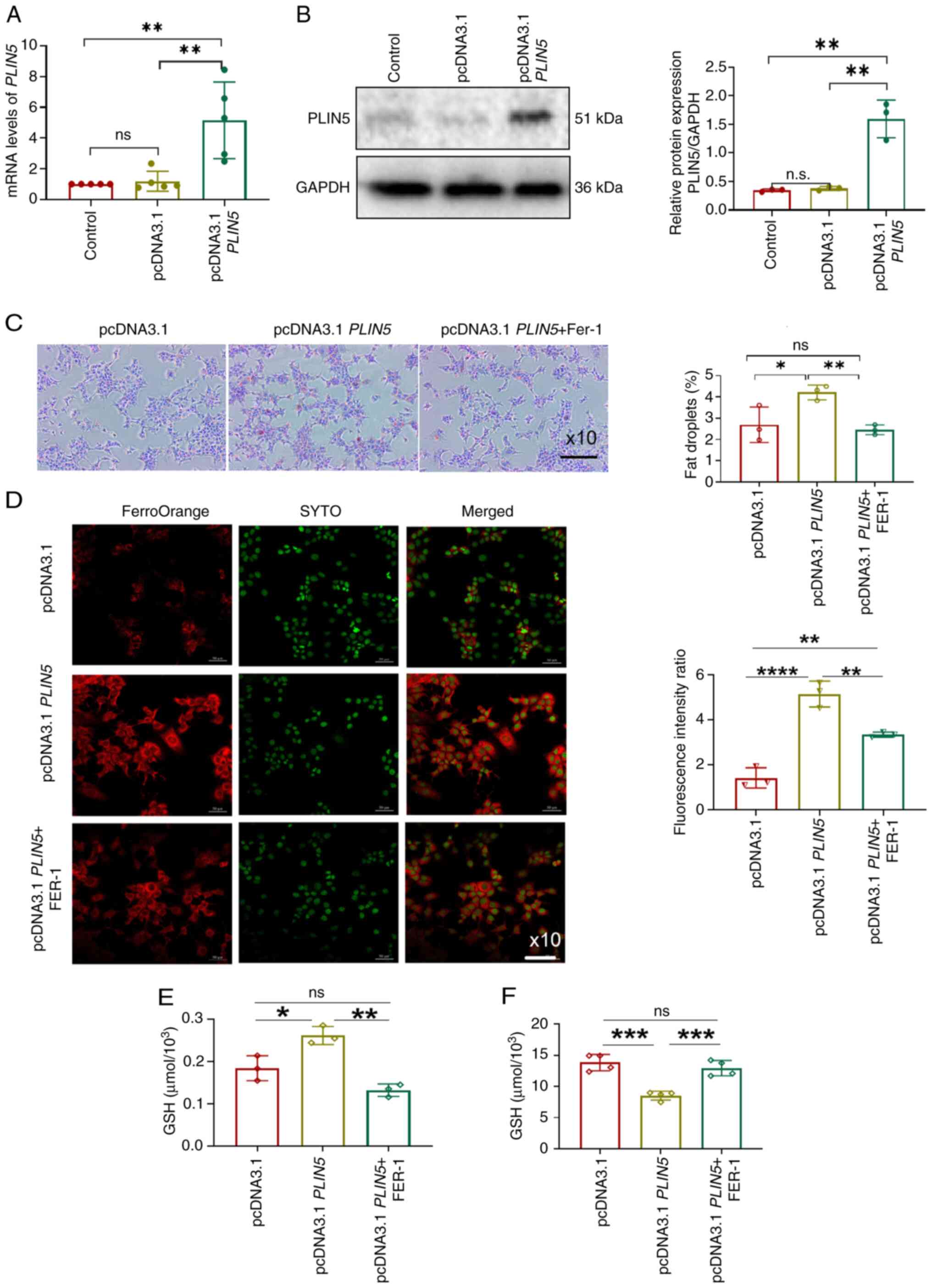

Overexpression of PLIN5 promotes lipid

accumulation and ferroptosis in hepatocytes

To further explore how PLIN5 affects ferroptosis, a

PLIN5 overexpression cell model was established (Fig. 2A and B).

PLIN5-overexpressing cells were pretreated with FER-1, a

selectively effective inhibitor of ferroptosis, and all cell groups

were treated with PAOA. The results showed that LD accumulation was

significantly increased in the pcDNA3.1-PLIN5 group compared

with that in the pcDNA3.1 group, which was reversed by the addition

of FER-1 (Fig. 2C). Furthermore,

Fe2+ fluorescence intensity was significantly enhanced

in the pcDNA3. 1-PLIN5 group treated with PAOA, which was

reversed by the addition of FER-1 (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, the MDA content was

increased and GSH levels were significantly decreased in

pcDNA3.1-PLIN5 cells treated with PAOA, which was reversed

by treatment with FER-1 (Fig. 2E and

F). These findings revealed that PLIN5 overexpression

could promote lipid accumulation and ferroptosis in PAOA-treated

hepatocytes, and that the ferroptosis inhibitor FER-1 could

partially alleviate lipid accumulation, oxidative damage and

FE2+ content caused by PLIN5 overexpression.

| Figure 2.Overexpression of PLIN5

promotes lipid accumulation and ferroptosis in hepatocytes. (A)

mRNA levels of PLIN5 levels were detected via quantitative

polymerase chain reaction. (B) PLIN5 protein expression was

detected via western blotting. (C) LD changes in cells were

observed using a microscope (magnification, ×10), with nuclei

stained blue and LDs stained red. Quantitative analysis was

performed using ImageJ. (D) Fe2+ fluorescence intensity

in cells was observed using a fluorescence microscope

(magnification, ×10), with nuclei stained green and Fe2+

fluorescence stained red, followed by quantitative analysis. (E)

MDA levels were detected in the three cell groups. (F) GSH levels

were detected in the three groups of cells. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001, n.s., not significant.

Fe2+, ferrous ion; GSH, glutathione; LD, lipid droplet;

MDA, malondialdehyde; PLIN5, perilipin 5; FER-1, ferrostatin-1. |

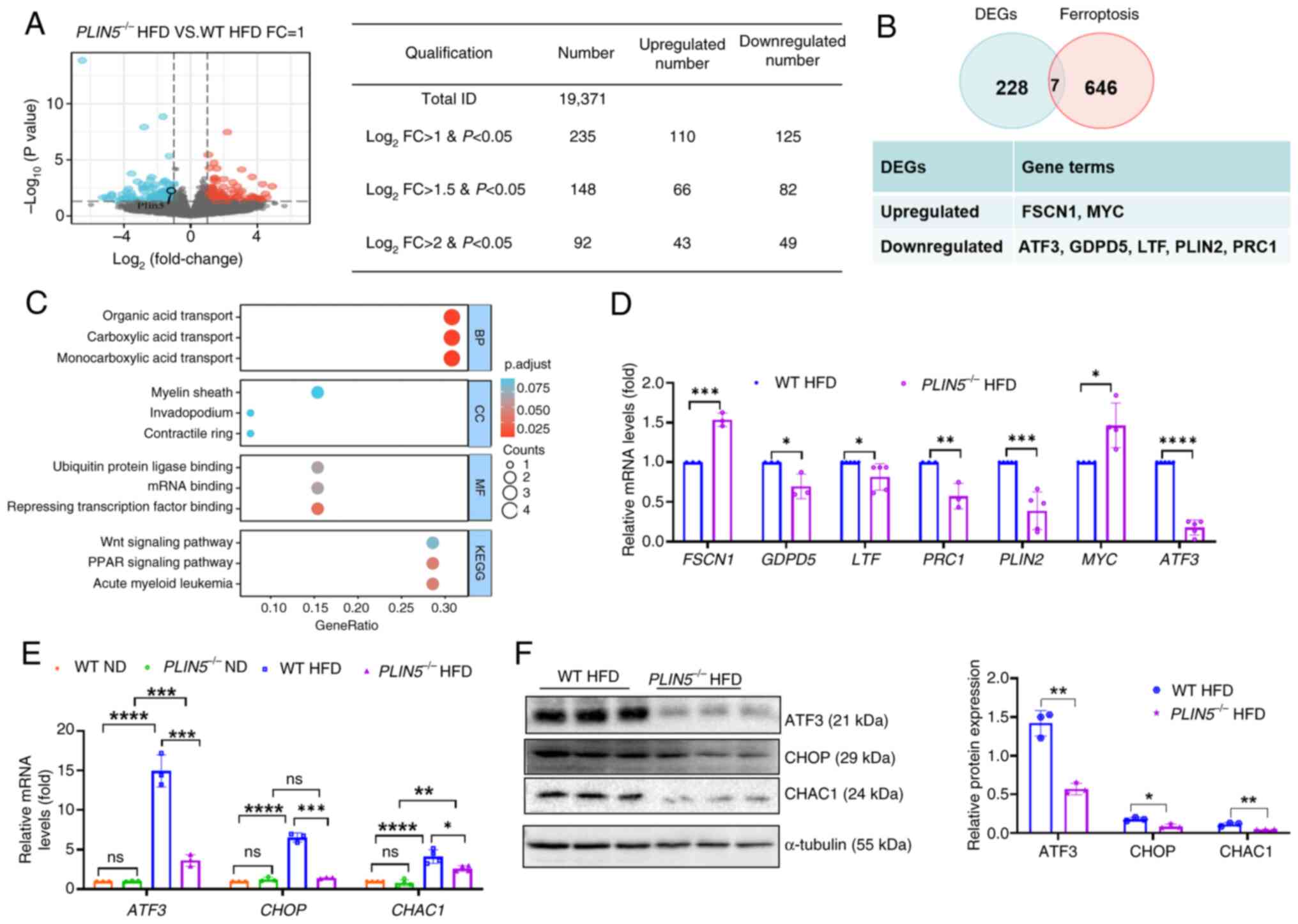

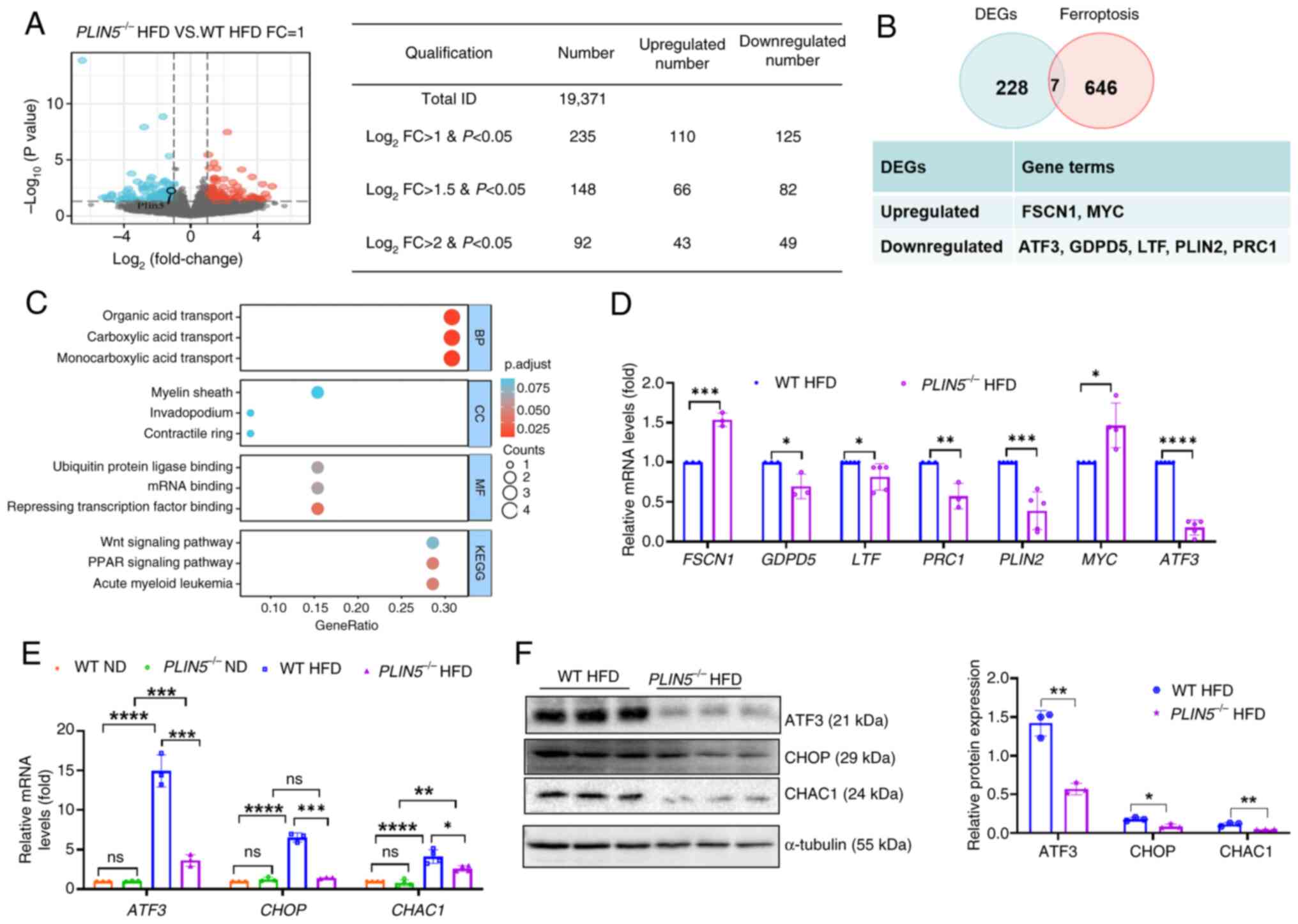

PLIN5-induced ferroptosis is

associated with ATF3

As aforementioned, the present study initially

discovered that PLIN5 may modulate ferroptosis both in vivo

and in vitro. To further elucidate how PLIN5 affects

ferroptosis signaling, an in-depth analysis was subsequently

performed by mining single-cell RNA-seq data. This strategy enabled

identification of cell type-specific ferroptosis regulators

downstream of PLIN5. The current study analyzed single-cell RNA-seq

data obtained from the liver tissues from 5 mice from the

PLIN5−/− HFD group and 5 mice from the WT HFD

group to elucidate the functional genes involved in regulating the

effects of PLIN5 knockout in MAFLD. The results revealed

that there were 235 DEGs (log2 FC>1, P<0.05)

between the PLIN5−/− HFD and WT HFD groups, with

110 upregulated and 125 downregulated genes (Fig. 3A). Notably, these genes were

intersected with the FerrDb database and seven ferroptosis-related

DEGs were identified, including two upregulated genes: Fascin

actin-bundling protein 1 (FSCN1) and MYC, and five

downregulated genes: ATF3, glycerophosphodiester

phosphodiesterase domain containing 5 (GDPD5),

lactotransferrin (LTF), PLIN2 and protein regulator

of cytokinesis 1 (PRC1) (Fig.

3B). GO and KEGG analyses were performed on the aforementioned

genes (Fig. 3C). The DEGs

associated with ferroptosis were involved in various biological

processes, including ‘carboxylic acid transport’, ‘organic acid

transport’ and ‘monocarboxylic acid transport’. The genes were

enriched in molecular functions related to ‘repressing

transcription factor binding’, ‘mRNA binding’ and ‘ubiquitin

protein ligase binding’. In addition, these DEGs were enriched in

the following cellular components: ‘Myelin sheath’, ‘contractile

ring’ and ‘invadopodium’. KEGG analysis revealed associations with

‘acute myeloid leukemia’, as well as the ‘PPAR signaling pathway’

and ‘Wnt signaling pathway’. The results of RT-qPCR showed that,

compared with those in the WT HFD group, the mRNA expression levels

of FSCN1 (P<0.001) and MYC (P<0.05) were

significantly higher in the PLIN5−/− HFD group,

whereas the mRNA levels of ATF3, GDPD5 (P<0.05), LTF,

PLIN2 and PRC1 were significantly lower; among these,

the most significant difference was observed in ATF3)

(Fig. 3D). Therefore, PLIN5

knockout-induced inhibition of ferroptosis in MAFLD may be

associated with ATF3.

| Figure 3.PLIN5 affects ferroptosis

through ATF3/CHOP/CHAC1 signaling. (A) DEGs in mouse liver tissues

from the PLIN5−/− HFD group are shown compared to

those in the WT HFD group (red dots represent upregulated genes,

whereas blue dots represent downregulated genes). (B) DEGs

associated with ferroptosis in the PLIN5−/− HFD

and WT HFD groups were analyzed (log2 FC>1,

P<0.05). (C) KEGG pathway and GO term enrichment analyses of

different genes were performed. (D) mRNA levels of PRC1, LTF,

GDPD5, FSCN1, MYC, ATF3 and PLIN2 in the liver tissues

of WT HFD and PLIN5−/− HFD mice were measured

(n=5 mice/group). (E) mRNA levels of ATF3, CHOP and

CHAC1 in the liver tissues of mice in each group were

detected (n=5 mice/group). (F) Western blot analysis of ATF3, CHOP

and CHAC1 protein expression in the liver tissues of mice from the

WT HFD and PLIN5−/− HFD groups was performed,

with tubulin as the internal reference. Semi-quantitative analysis

performed using ImageJ (n=3 mice/group). All experiments were

repeated at least three times (n=3). *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001, n.s., not significant. ATF3,

activating transcription factor 3; CHAC1, cation transport

regulator-like protein 1; CHOP, C/EBP homologous protein; DEGs,

differentially expressed genes; FC, fold-change; FSCN1,

fascin actin-bundling protein 1; GDPD5,

glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase domain containing 5;

GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; HFD, high-fat diet; KEGG,

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; ND, normal diet;

LTF, lactotransferrin; PLIN, perilipin; PRC1,

protein regulator of cytokinesis 1; WT, wild-type; BP, biological

process; CC, cellular component; MF, molecular function. |

ATF3 is a member of the ATF/CREB transcription

factor family and is upregulated in mouse models of non-alcoholic

steatohepatitis (NASH) (26). The

C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) signaling pathway is involved in

the synergistic interaction between ferroptosis and apoptosis

(27). ATF3 and CHOP regulate the

transcription of cation transport regulator-like protein 1 (CHAC1)

(28), and elevated CHAC1 is an

important marker of ferroptosis (29,30).

Notably, the present results showed that the expression levels of

ATF3, CHOP and CHAC1 were significantly lower in the

PLIN5−/− HFD group compared with those in the WT

HFD group, and compared with in the ND group, their expression

levels were significantly increased in the HFD group (Fig. 3E and F). Moreover, single-cell

transcriptome data were analyzed and it was revealed that knocking

out PLIN5 significantly reduced the expression of

ACSL4 in hepatocytes in PLIN5−/− HFD mice

compared with that in the WT HFD group; however, there was no

difference in the expression of SLC7A11 (Fig. S3). These findings suggested that

knocking out PLIN5 can inhibit ferroptosis. Notably,

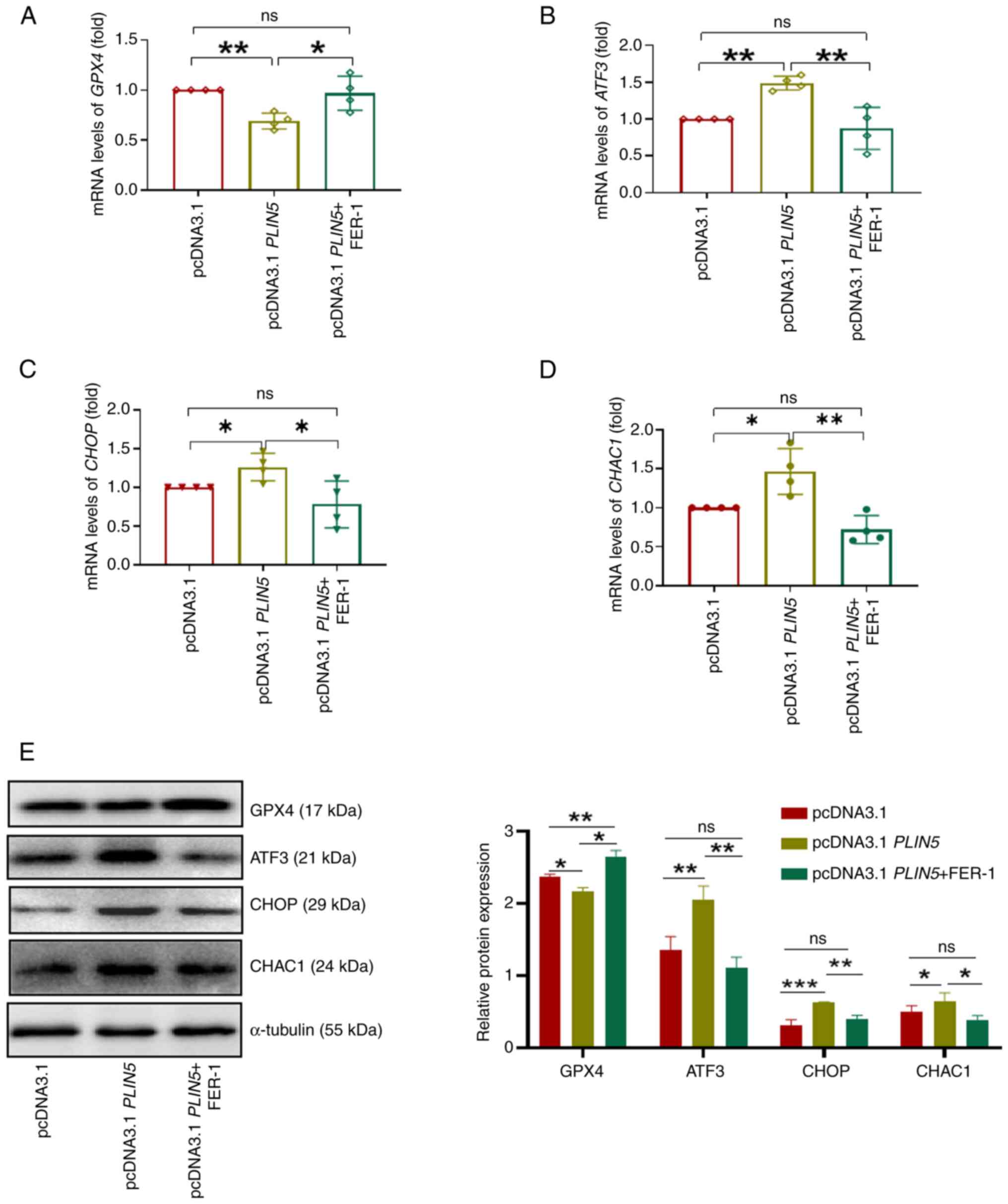

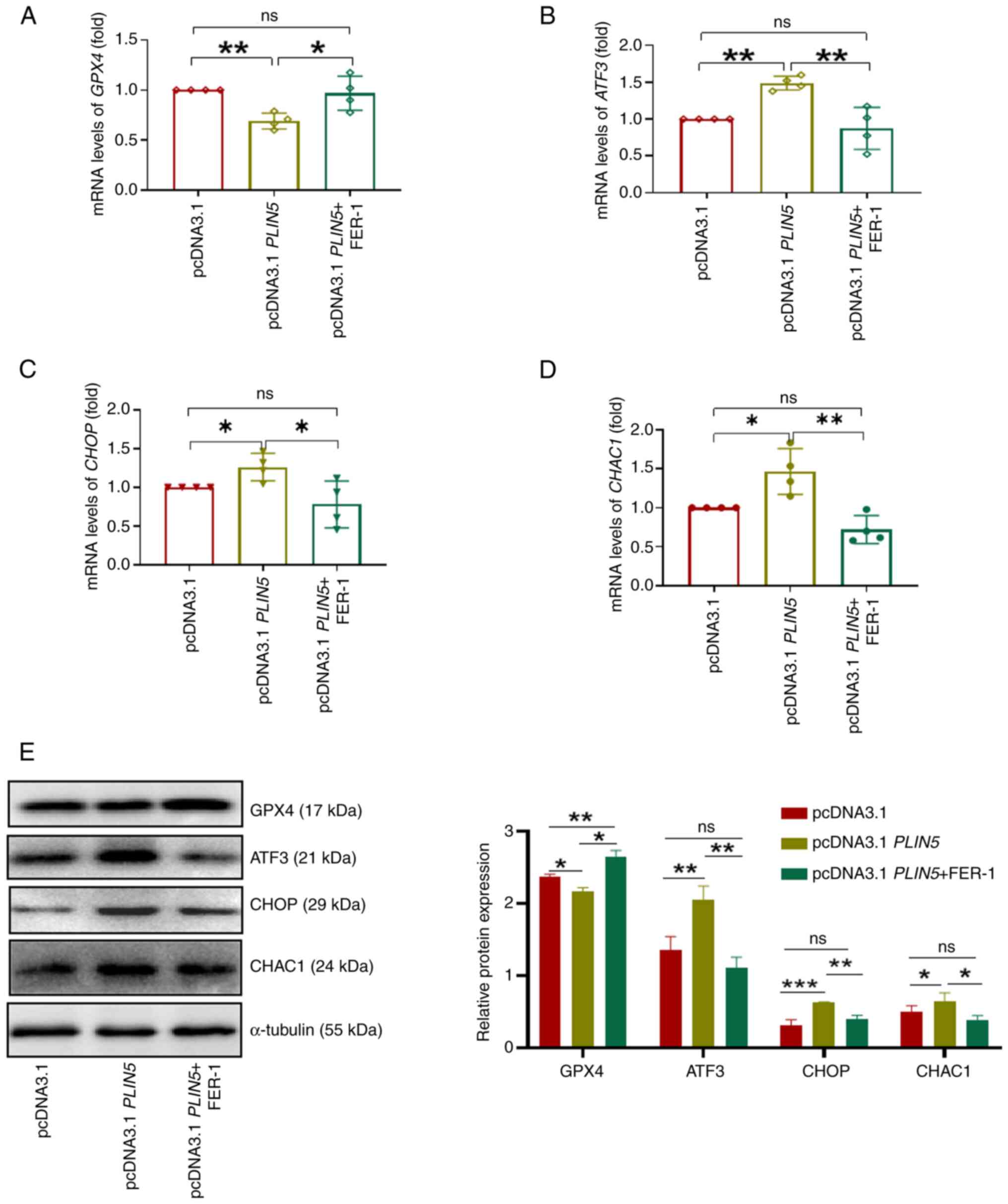

overexpression of PLIN5 could promote the expression of,

ATF3, CHOP and CHAC1 with PAOA treatment compared

with that in the pcDNA3.1 group, which was reversed by FER-1

treatment (Fig. 4B-E). By

contrast, compared with those in the pcDNA3.1 group, GPX4

expression levels were significantly decreased by PLIN5

overexpression; however, GPX4 was significantly enhanced in the

pcDNA3.1 PLIN5 + FER-1 group (Fig. 4A and E). Taken together, these

findings suggested that ATF3 may be involved in the

PLIN5-associated regulation of HFD-induced hepatocyte

ferroptosis.

| Figure 4.PLIN5 affects ferroptosis via

ATF3/CHOP/CHAC1 signaling. The mRNA expression levels of (A)

GPX4, (B) ATF3, (C) CHOP and (D) CHAC1

in cells from each group were measured. (E) Western blot analysis

of GPX4, ATF3, CHOP and CHAC1 protein expression in cells from

different groups was performed, normalized to tubulin as an

internal control. Semi-quantitative analysis was performed using

ImageJ. All experiments were repeated at least three times.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, n.s., not significant.

ATF3, activating transcription factor 3; CHAC1, cation transport

regulator-like protein 1; CHOP, C/EBP homologous protein; FER-1,

ferrostatin-1; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; PAOA,

palmitic acid and oleic acid; PLIN5, perilipin 5. |

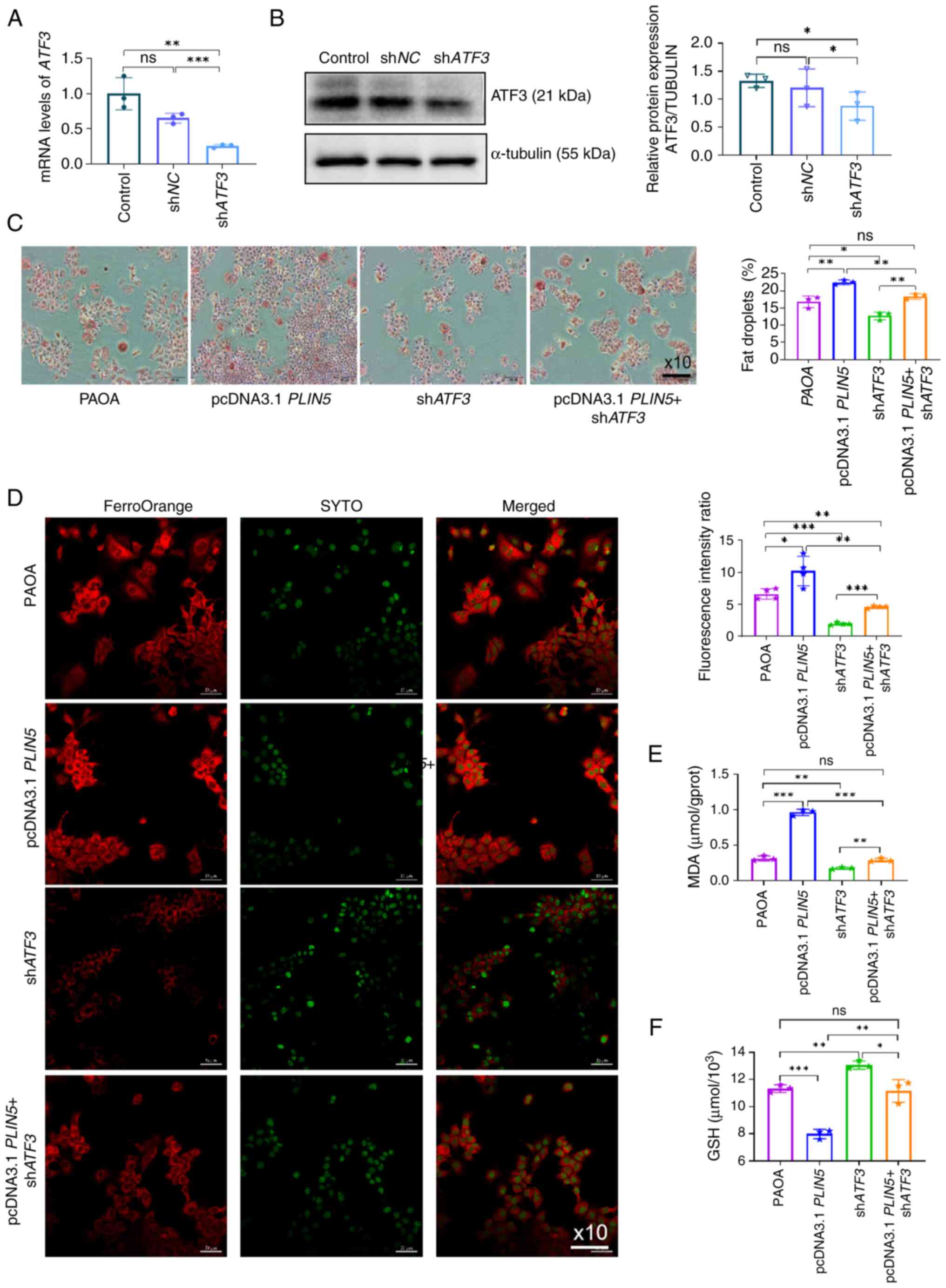

Knockdown of ATF3 alleviates lipid

accumulation and ferroptosis induced by overexpression of

PLIN5

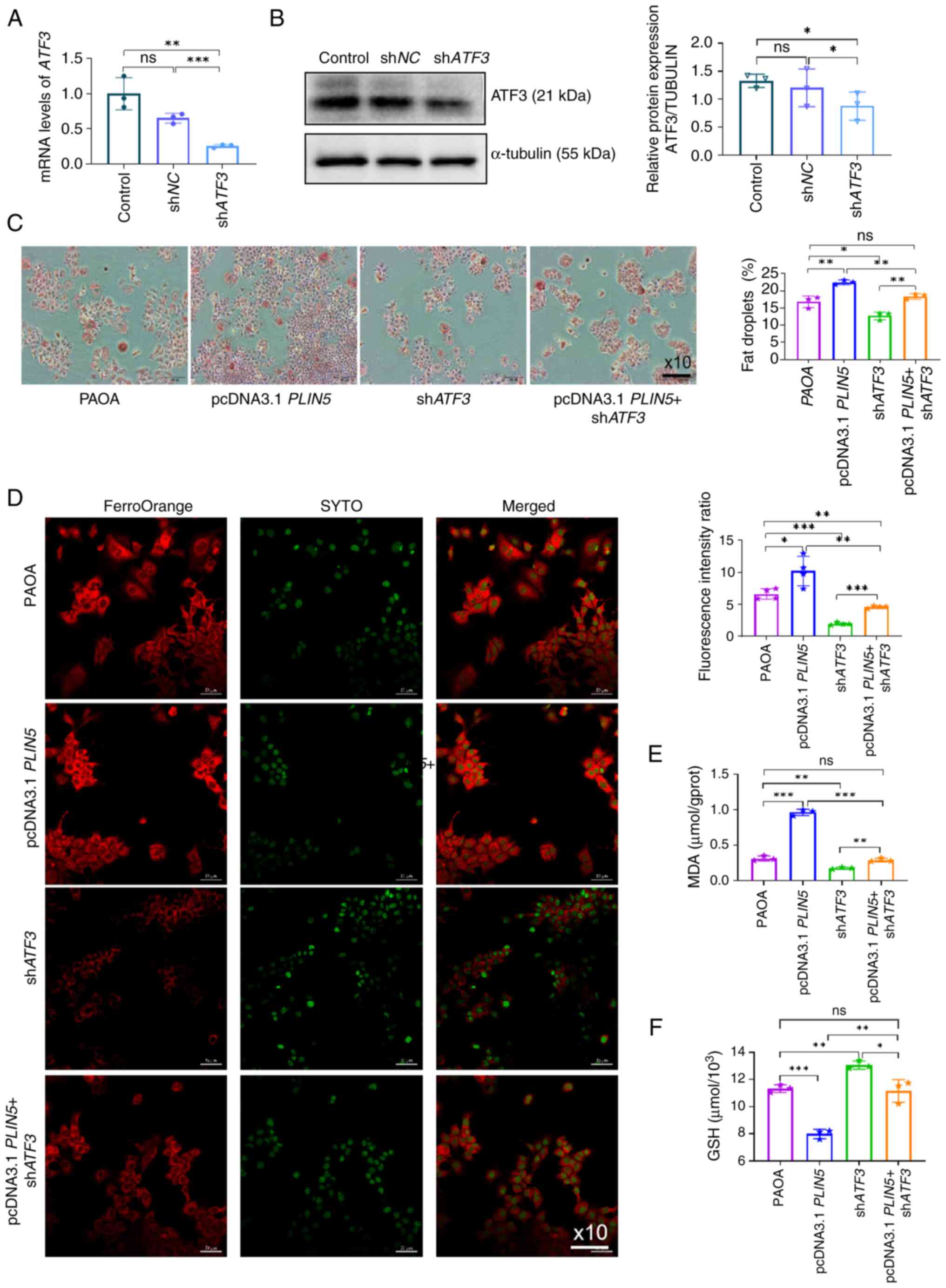

To confirm that ATF3 is involved in the process of

PLIN5-regulated ferroptosis, ATF3 expression was knocked down in

the cells (Fig. 5A and B). PAOA

stimulation was used to establish cell models, and then ORO

staining was performed. The results showed that ATF3

knockdown significantly reduced PAOA-induced lipid accumulation in

hepatocytes and also partially reversed lipid accumulation induced

by PLIN5 overexpression (Fig.

5C). In addition, ATF3 knockdown partially reversed the

Fe2+ fluorescence intensity induced by PLIN5

overexpression, and PAOA-induced oxidative damage was also

alleviated, as determined by MDA and GSH detection (Fig. 5D-F). Collectively, these results

suggested that as a key regulator, PLIN5 could enhance lipid

peroxidation and ferroptosis in hepatocytes.

| Figure 5.Knockdown of ATF3 alleviates

lipid accumulation and ferroptosis induced by overexpression of

PLIN5. (A) ATF3 mRNA expression in AML12 cells was

analyzed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction 48 h after

transfection with shATF3 plasmid. (B) Semi-quantitative analysis of

ATF3 protein expression in AML12 cells 48 h after transfection with

shATF3 plasmid was performed, normalized to tubulin as an internal

control, using ImageJ. (C) LDs were observed in cells from

different intervention groups using a microscope (magnification,

×10), with nuclei stained blue and LDs stained red and quantitative

analysis was performed using ImageJ. (D) Fe2+

fluorescence intensity in cells from different intervention groups

was observed using a fluorescence microscope, with nuclei stained

green and Fe2+ fluorescence stained red, followed by

quantitative analysis. (E) MDA content was measured in cells from

different intervention groups. (F) GSH content was measured in

cells from different intervention groups. All experiments were

repeated at least three times. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, n.s., not significant. ATF3, activating

transcription factor 3; Fe2+, ferrous ion; GSH,

glutathione; LD, lipid droplet; MDA, malondialdehyde; NC, negative

control; PAOA, palmitic acid and oleic acid; PLIN5,

perilipin 5; sh, short hairpin. |

Discussion

Over time, the increasing incidence of MAFLD and

associated complications leading to mortality have become of

increasing concern (31). The

development of MAFLD is associated with lipid accumulation,

oxidative stress, ERS and lipotoxicity (4). The pathogenesis of MAFLD is complex,

and there are currently no specific drugs that can be used to

reverse MAFLD. Notably, different types of hepatocellular death in

MAFLD, including apoptosis, necrosis, necroptosis and pyroptosis,

have been studied extensively (32,33).

Ferroptosis is a form of regulated cell death that is

iron-dependent and non-apoptotic, induced by lipid peroxidation and

controlled by the integration of oxidative and antioxidant systems

(34). Key steps in the formation

of ferroptosis include Fe2+ accumulation and lipid

peroxidation, and ACSL4 and GPX4 positively and negatively regulate

ferroptosis, respectively (24,25).

Previous studies have shown that ferroptosis is

exacerbated in MAFLD, that it serves an important role as a trigger

for the initiation of inflammation in steatohepatitis and that it

affects the progression of NASH (18,35,36).

Given that ferroptosis is critical in regulating the progression of

MAFLD, understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying

ferroptosis and identifying novel targets to inhibit its occurrence

may be an effective approach in the treatment of abnormal

ferroptosis-related MAFLD. The present study provides compelling

evidence demonstrating that the downregulation of PLIN5 can

inhibit the occurrence of ferroptosis. Mechanistically, PLIN5 may

influence the progression of MAFLD and the occurrence of

ferroptosis by regulating ATF3 activation. Knockout of PLIN5

was shown to inhibit expression of the ferroptosis-related genes

ATF3, CHOP and CHAC1; in addition, knockdown of

ATF3 could alleviate PLIN5 overexpression-induced

ferroptosis and lipid accumulation in cells. Notably, it has been

reported that ATF1, ATF3 and ATF4 can bind to the

PLIN5 promoter and induce its expression in hepatocytes

(37). It may thus be speculated

that a positive feedback loop between PLIN5 and ATF3

could contribute to the pathogenesis of MAFLD. Moreover, emerging

evidence has indicated that phosphorylation of PLIN5 by protein

kinase A triggers PLIN5 nuclear translocation and regulates the

transcriptional expression of PPARγ coactivator 1-α (38). However, current evidence

demonstrates that PLIN5 primarily functions as a transcriptional

co-activator or auxiliary factor. It therefore could be

hypothesized that PLIN5 may participate in regulating ATF3

transcriptional expression; however, this requires further

validation in luciferase reporter assays and chromatin

immunoprecipitation experiments. In addition, a previous study

showed that JNK phosphorylation was significantly reduced in a

moues model of MAFLD after loss of PLIN5 (39). In another experiment, the JNK

inhibitor JM-2 was reported to significantly protect mouse livers

from HFD-induced lipid accumulation and apoptosis (40). Therefore, other cell death pathways

regulated by PLIN5 may also contribute to the development of

MAFLD.

PLINs have been recognized as key proteins involved

in lipid accumulation; in particular, the role of PLIN5 in the

liver has been extensively studied (9–12).

Different models of MAFLD have been established in

PLIN5−/− mice and have yielded differing results.

These conflicting findings may be due to differences in the

MAFLD/MASH model and stages of the disease studied. For example,

Mass-Sanchez et al (41)

demonstrated that loss of PLIN5 protects against worsening

of MAFLD by regulating inflammatory signaling, mitochondrial

function and lipid metabolism, while in a mouse model of

MAFLD-induced hepatocellular carcinoma, PLIN5 knockout was

found to suppress phosphorylated-STAT3 and attenuate the

inflammatory response, thereby mitigating severe liver injury.

However, in various NASH models, PLIN5 knockout has been

shown to worsen NASH-associated characteristics in mice given a

high-fat/high-cholesterol (HFHC) diet, such as lipid accumulation,

inflammation and hepatic fibrosis; by contrast, overexpression of

PLIN5 has been shown to ameliorate methionine and

choline-deficient (MCD) diet-induced NASH and ferroptosis (42). In a previous study, key points

reported regarding the major models were reviewed, as well as the

feeding conditions evaluated in each of these models, underpinning

the notion that the role of PLIN5 in metabolism appears to be

tissue-specific (43). In the

current study, PLIN5 was highly expressed in the MAFLD model, and

knockout of PLIN5 could reverse MAFLD. Notably, it was

demonstrated that the loss of PLIN5 could reduce ferroptosis

and upregulate the expression of GPX4; however, these

findings differ from those reported in other studies (42,44),

where knockout of PLIN5 diminished HFHC diet-induced

ferroptosis and overexpression of PLIN5 ameliorated MCD

diet-induced NASH and ferroptosis (42). Furthermore, PLIN5

overexpression has been suggested to ameliorate ferroptosis via the

PIR/NF-κB axis in PA-stimulated HL-1 cells (44). In summary, the regulation of

ferroptosis by PLIN5 varies in different disease models.

A previous study demonstrated that knocking out

PLIN5 enhances insulin resistance in skeletal muscles by

reducing the storage of TGs (45).

Moreover, PLIN5 deletion protects against MAFLD and

hepatocellular carcinoma by modulating lipid metabolism and

inflammatory responses (41).

Gallardo-Montejano et al (46) demonstrated that promoting PLIN5

function in BAT was associated with healthy remodeling of

subcutaneous white adipose tissue, and an improvement in systemic

glucose tolerance, as well as diet-induced hepatic steatosis. These

conflicting results may be attributed to the methods used in

previous PLIN5-related research related to MAFLD, all of which have

focused on systemic rather than local knockout of PLIN5.

Therefore, crosstalk in the biological effects of PLIN5 in

different tissues is possible. Furthermore, systemic knockout may

have off-target metabolic effects. Given that PLIN5 exhibits

distinct biological functions across different tissues and cell

types, liver-specific knockout mice will be essential to further

elucidate the role of PLIN5 in liver metabolism. Furthermore, ex

vivo liver organoid models, with their operational simplicity,

reproducibility and technical accessibility (47,48),

may serve as an ideal platform for elucidating how

microenvironmental factors mediate the regulatory role of PLIN5 in

MAFLD pathogenesis.

ATF3 is a member of the ATF/CREB family of

transcription factors (20).

Recent research has demonstrated that liver macrophage ATF3

simultaneously inhibits hepatocyte lipogenesis and hepatic stellate

cell activation in mice (49).

Basak et al (50) showed

that ATF3 can form a complex with RGS7, which is required for

PA-dependent oxidative stress and cell death. ATF3 has also

been identified as a key gene in ferroptosis following spinal cord

injury (51), and the soy-derived

compound 6j can inhibit liver cancer cell proliferation via

ATF3-mediated ferroptosis (52).

In addition, evidence has suggested that ATF3 is involved in

erastin-induced ferroptosis (53).

Therefore, ATF3 may have a critical role in regulating ferroptosis

during MASH progression. The present study identified a set of

genes associated with ferroptosis, and demonstrated that ATF3

expression was significantly lower in the

PLIN5−/− HFD group compared with that in the WT

HFD group.

The CHOP signaling pathway is also involved in the

synergistic interaction between ferroptosis and apoptosis (28), and ATF3/CHOP/BCL2 signaling can

control ERS-associated apoptosis (54). CHAC1 is the downstream target of

the ATF4/CHOP axis; it possesses γ-glutamyl cyclotransferase

activity and also degrades GSH. Notably, depletion of GSH is a

crucial factor in apoptosis initiation and execution (55). Endoplasmic reticulum-mediated

apoptosis is also activated via the ATF4/CHOP/CHAC1 cascade

(56). Given these findings, it

may be hypothesized that ATF3 is the interacting target of PLIN5,

which affects ferroptosis, oxidative damage and lipid accumulation.

The present study revealed that the expression levels of CHOP and

CHAC1 were reduced in PLIN5−/− HFD mice compared

with those in WT HFD mice. Furthermore, knockdown of ATF3

alleviated lipid accumulation and ferroptosis induced by

PLIN5 overexpression. Emerging evidence has revealed that

PLIN5 not only functions as an LD-coating protein localized on LDs,

but that its phosphorylated form can also translocate into the

nucleus to participate in transcriptional regulation. This dual

functionality markedly enhances the complexity of the reciprocal

regulatory network between PLIN5 and transcription factor ATF3,

warranting further mechanistic investigation (34,57).

Owing to limitations in clinical specimen availability, the current

study was unable to examine the association between PLIN5 and

ferroptosis-related proteins (including ATF3, CHOP and CHAC1) in

human fatty liver tissues. Notably, a previous study reported that

the protein expression of PLIN5 was markedly elevated in the

severely steatotic livers of included patients (58). Moreover, ATF3 has been reported to

be highly expressed in the livers of Zucker diabetic fatty rats and

in human participants with MAFLD and/or type 2 diabetes (59).

As indicated in the current guidelines (AASLD

(60), very few drugs are

recommended for MAFLD treatment. To date, only vitamin E and the

PPARγ ligand pioglitazone have been endorsed for limited patients

by the European-and American Association for the Study of the Liver

(61). Given the central roles of

PLIN5 in LD stabilization and ATF3 in hepatic stress response, as

demonstrated by the present study, pharmacological inhibition of

these targets represents a mechanistically rational strategy for

MAFLD intervention. Patients with hypercholesterolemia routinely

receive statins, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors that block de

novo cholesterol biosynthesis. Previous studies have

demonstrated that statins reduce PLIN5 levels in murine/human

hepatocytes, concomitant with decreased TGs and LD quantity. This

effect is mediated by an atypical sterol-regulatory sequence in the

PLIN5 promoter, where SREBP2 binding confers statin

responsiveness (62,63). Crucially, partial PLIN5

knockdown can mimic statin-induced TG reduction, while PLIN5

overexpression reverses it (62).

Thus, combining PLIN5 inhibitors with statins may yield synergistic

anti-MAFLD effects. Notably, Yu et al (64) proposed targeting ATF3 with

engineered peptide inhibitors, providing a compelling rationale for

developing ATF3-targeted therapies against MAFLD.

In conclusion, the present study identified a link

from PLIN5 to ferroptosis and MAFLD via the ATF3/CHOP/CHAC1 axis,

thereby providing insights into the mechanism of ferroptosis in

MAFLD progression. Knocking down PLIN5 may target the

ATF3/CHOP/CHAC1 signaling axis, which attenuates ferroptosis in

liver cells, eventually alleviating MAFLD. The present findings may

lay the foundation for a promising therapeutic strategy in the

treatment of MAFLD.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by research grants from the

National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31471330),

the Henan Provincial Medical Science and Technology Tackling

Program Co-construction Project (grant nos. LHGJ20210483 and

LHGJ20220557), the Zhengzhou University Discipline Key Special

Project (grant no. XKZDQY202001), the Henan Province Foreign

Intelligence Introduction Program (grant no. GZS2022008), Science

and Technology Projects (grant no. 242102310228), the Zhengzhou

Science and Technology Benefit to the People Project (grant no.

2022KJHM0020) and the Key Research and Development Projects of

Henan Province (grant no. 241111210500).

Availability of data and materials

The raw RNA-seq data generated in the present study

may be found in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under accession

number PRJNA1295086 or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1295086/.

The raw single-cell RNA-seq data generated in the present study may

be found in the China National Center for Bioinformation under

accession number CRA018673 or at the following URL: https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/search?searchTerm=CRA018673.

The other data generated in the present study may be requested from

the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

Experiments were performed by YT, YL, XW and XY,

with the help of LD, WC and YX. Experiments were designed by YL and

XW, with the help of PZ and YW. LD, XZ and LL managed animals and

performed animal experiments. XW, XY and YL analyzed the data. YL

wrote the paper, with assistance from YT, XW and XY in editing and

revisions. PZ and YT supervised the work, and confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors made significant

contributions to the article, and read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The animal study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Zhengzhou University (approval no. KY2023006). The

study was performed in accordance with Institutional Animal Care

and Use Committee guidelines; all procedures were carried out in

accordance with institutional guidelines.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Rinella ME, Neuschwander-Tetri BA,

Siddiqui MS, Abdelmalek MF, Caldwell S, Barb D, Kleiner DE and

Loomba R: AASLD Practice Guidance on the clinical assessment and

management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology.

77:1797–1835. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Yip TCF, Vilar-Gomez E, Petta S, Yilmaz Y,

Wong GL, Adams LA, de Lédinghen V, Sookoian S and Wong VW:

Geographical similarity and differences in the burden and genetic

predisposition of NAFLD. Hepatology. 77:1404–1427. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Syed-Abdul MM: Lipid metabolism in

Metabolic-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Metabolites.

14:122024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Guo X, Yin X, Liu Z and Wang J:

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) pathogenesis and natural

products for prevention and treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 23:154892022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Petta S, Targher G, Romeo S, Pajvani UB,

Zheng MH, Aghemo A and Valenti LVC: The first MASH drug therapy on

the horizon: Current perspectives of resmetirom. Liver Int.

44:1526–1536. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Herker E, Vieyres G, Beller M, Krahmer N

and Bohnert M: Lipid droplet contact sites in health and disease.

Trends Cell Biol. 31:345–358. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Gluchowski NL, Becuwe M, Walther TC and

Farese RV Jr: Lipid droplets and liver disease: From basic biology

to clinical implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

14:343–355. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Najt CP, Khan SA, Heden TD, Witthuhn BA,

Perez M, Heier JL, Mead LE, Franklin MP, Karanja KK, Graham MJ, et

al: Lipid Droplet-derived monounsaturated fatty acids traffic via

PLIN5 to allosterically activate SIRT1. Mol Cell. 77:810–824.e8.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Mason RR and Watt MJ: Unraveling the roles

of PLIN5: Linking cell biology to physiology. Trends Endocrinol

Metab. 26:144–152. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Asimakopoulou A, Engel KM, Gassler N,

Bracht T, Sitek B, Buhl EM, Kalampoka S, Pinoé-Schmidt M, van

Helden J, Schiller J and Weiskirchen R: Deletion of perilipin 5

protects against hepatic injury in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

via missing inflammasome activation. Cells. 9:13462020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ma Y, Yin X, Qin Z, Ke X, Mi Y, Zheng P

and Tang Y: Role of Plin5 deficiency in progression of

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease induced by a High-fat diet in

mice. J Comp Pathol. 189:88–97. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Yin X, Dong L, Wang X, Qin Z, Ma Y, Ke X,

Li Y, Wang Q, Mi Y, Lyu Q, et al: Perilipin 5 regulates hepatic

stellate cell activation and high-fat diet-induced non-alcoholic

fatty liver disease. Animal Model Exp Med. 7:166–178. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Jiang X, Stockwell BR and Conrad M:

Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 22:266–282. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wu J, Wang Y, Jiang R, Xue R, Yin X, Wu M

and Meng Q: Ferroptosis in liver disease: New insights into disease

mechanisms. Cell Death Discov. 7:2762021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhou X, Fu Y, Liu W, Mu Y, Zhang H, Chen J

and Liu P: Ferroptosis in chronic liver diseases: Opportunities and

challenges. Front Mol Biosci. 9:9283212022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wang S, Liu Z, Geng J, Li L and Feng X: An

overview of ferroptosis in Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Biomed Pharmacother. 153:1133742022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zhang H, Axinbai M, Zhao Y, Wei J, Qu T,

Kong J, He Y and Zhang L: Bioinformatics analysis of

Ferroptosis-related genes and immune cell infiltration in

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur J Med Res. 28:6052023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Yin X, Mi Y, Wang X, Li Y, Zhu X, Bukhari

I, Wang Q, Zheng P, Xue X and Tang Y: Exploration and validation of

Ferroptosis-associated genes in ADAR1 Deletion-induced NAFLD

through RNA-seq analysis. Int Immunopharmacol. 134:1121772024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Fu D, Wang C, Yu L and Yu R: Induction of

ferroptosis by ATF3 elevation alleviates cisplatin resistance in

gastric cancer by restraining Nrf2/Keap1/xCT signaling. Cell Mol

Biol Lett. 26:262021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhao X, Wang Z, Wu G, Yin L, Xu L, Wang N

and Peng J: Apigenin-7-glucoside-loaded nanoparticle alleviates

intestinal ischemia-reperfusion by ATF3/SLC7A11-mediated

ferroptosis. J Control Release. 366:182–193. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Inaba Y, Hashiuchi E, Watanabe H, Kimura

K, Oshima Y, Tsuchiya K, Murai S, Takahashi C, Matsumoto M,

Kitajima S, et al: The transcription factor ATF3 switches cell

death from apoptosis to necroptosis in hepatic steatosis in male

mice. Nat Commun. 14:1672023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

National Research Council (US) Institute

for Laboratory Animal Research, . The Development of Science-based

Guidelines for Laboratory Animal Care: Proceedings of the November

2003 International Workshop. National Academies Press; Washington

DC: 2004

|

|

23

|

Hu Y, He W, Huang Y, Xiang H, Guo J, Che

Y, Cheng X, Hu F, Hu M, Ma T, et al: Fatty acid synthase-suppressor

screening identifies sorting Nexin 8 as a therapeutic target for

NAFLD. Hepatology. 74:2508–2525. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ren Y, Mao X, Xu H, Dang Q, Weng S, Zhang

Y, Chen S, Liu S, Ba Y, Zhou Z, et al: Ferroptosis and EMT: Key

targets for combating cancer progression and therapy resistance.

Cell Mol Life Sci. 80:2632023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Chen GH, Song CC, Pantopoulos K, Wei XL,

Zheng H and Luo Z: Mitochondrial oxidative stress mediated

Fe-induced ferroptosis via the NRF2-ARE pathway. Free Radic Biol

Med. 180:95–107. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Asghari S, Hamedi-Shahraki S and Amirkhizi

F: Systemic redox imbalance in patients with nonalcoholic fatty

liver disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 50:e132112020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Bathish B, Robertson H, Dillon JF,

Dinkova-Kostova AT and Hayes JD: Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and

mechanisms by which it is ameliorated by activation of the CNC-bZIP

transcription factor Nrf2. Free Radic Biol Med. 188:221–261. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Hong SH, Lee DH, Lee YS, Jo MJ, Jeong YA,

Kwon WT, Choudry HA, Bartlett DL and Lee YJ: Molecular crosstalk

between ferroptosis and apoptosis: Emerging role of ER

stress-induced p53-independent PUMA expression. Oncotarget.

8:115164–115178. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Mungrue IN, Pagnon J, Kohannim O,

Gargalovic PS and Lusis AJ: CHAC1/MGC4504 is a novel proapoptotic

component of the unfolded protein response, downstream of the

ATF4-ATF3-CHOP cascade. J Immunol. 182:466–476. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Stockwell BR: Ferroptosis turns 10:

Emerging mechanisms, physiological functions, and therapeutic

applications. Cell. 185:2401–2421. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Golabi P, Paik JM, AlQahtani S, Younossi

Y, Tuncer G and Younossi ZM: Burden of non-alcoholic fatty liver

disease in Asia, the Middle East and North Africa: Data from global

burden of disease 2009–2019. J Hepatol. 75:795–809. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Li J, Wang T, Liu P, Yang F, Wang X, Zheng

W and Sun W: Hesperetin ameliorates hepatic oxidative stress and

inflammation via the PI3K/AKT-Nrf2-ARE pathway in oleic

acid-induced HepG2 cells and a rat model of high-fat diet-induced

NAFLD. Food Funct. 12:3898–3918. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Tong J, Lan X, Zhang Z, Liu Y, Sun D, Wang

X, Ou-Yang SX, Zhuang CL, Shen FM, Wang P and Li DJ: Ferroptosis

inhibitor liproxstatin-1 alleviates metabolic

dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease in mice: Potential

involvement of PANoptosis. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 44:1014–1028. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Chen X, Li J, Kang R, Klionsky DJ and Tang

D: Ferroptosis: Machinery and regulation. Autophagy. 17:2054–2081.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Tsurusaki S, Tsuchiya Y, Koumura T,

Nakasone M, Sakamoto T, Matsuoka M, Imai H, Yuet-Yin Kok C, Okochi

H, Nakano H, et al: Hepatic ferroptosis plays an important role as

the trigger for initiating inflammation in nonalcoholic

steatohepatitis. Cell Death Dis. 10:4492019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Guan Q, Wang Z, Hu K, Cao J, Dong Y and

Chen Y: Melatonin ameliorates hepatic ferroptosis in NAFLD by

inhibiting ER stress via the MT2/cAMP/PKA/IRE1 signaling pathway.

Int J Biol Sci. 19:3937–3950. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Tan Y, Jin Y, Wang Q, Huang J, Wu X and

Ren Z: Perilipin 5 Protects against cellular oxidative stress by

enhancing mitochondrial function in HepG2 cells. Cells. 8:12412019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Gallardo-Montejano VI, Saxena G, Kusminski

CM, Yang C, McAfee JL, Hahner L, Hoch K, Dubinsky W, Narkar VA and

Bickel PE: Nuclear Perilipin 5 integrates lipid droplet lipolysis

with PGC-1α/SIRT1-dependent transcriptional regulation of

mitochondrial function. Nat Commun. 7:127232016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Fang Z, Xu H, Duan J, Ruan B, Liu J, Song

P, Ding J, Xu C, Li Z, Dou K and Wang L: Short-term tamoxifen

administration improves hepatic steatosis and glucose intolerance

through JNK/MAPK in mice. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8:942023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Jin L, Wang M, Yang B, Ye L, Zhu W, Zhang

Q, Lou S, Zhang Y, Luo W and Liang G: A small-molecule JNK

inhibitor JM-2 attenuates high-fat diet-induced non-alcoholic fatty

liver disease in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 115:1095872023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Mass-Sanchez PB, Krizanac M, Štancl P,

Leopold M, Engel KM, Buhl EM, van Helden J, Gassler N, Schiller J,

Karlić R, et al: Perilipin 5 deletion protects against nonalcoholic

fatty liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma by modulating

lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses. Cell Death Discov.

10:942024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Xu X, Qiu J, Li X, Chen J, Li Y, Huang X,

Zang S, Ma X and Liu J: Perilipin5 protects against Non-alcoholic

steatohepatitis by increasing 11-Dodecenoic acid and inhibiting the

occurrence of ferroptosis. Nutr Metab (Lond). 20:292023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Mass Sanchez PB, Krizanac M, Weiskirchen R

and Asimakopoulos A: Understanding the role of perilipin 5 in

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and its role in hepatocellular

carcinoma: A review of novel insights. Int J Mol Sci. 22:52842021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Shen X, Zhang J, Zhou Z and Yu R: PLIN5

suppresses lipotoxicity and ferroptosis in cardiomyocyte via

modulating PIR/NF-κB Axis. Int Heart J. 65:537–547. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Mason RR, Mokhtar R, Matzaris M,

Selathurai A, Kowalski GM, Mokbel N, Meikle PJ, Bruce CR and Watt

MJ: PLIN5 deletion remodels intracellular lipid composition and

causes insulin resistance in muscle. Mol Metab. 3:652–663. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Gallardo-Montejano VI, Yang C, Hahner L,

McAfee JL, Johnson JA, Holland WL, Fernandez-Valdivia R and Bickel

PE: Perilipin 5 links mitochondrial uncoupled respiration in brown

fat to healthy white fat remodeling and systemic glucose tolerance.

Nat Commun. 12:33202021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Navik U, Singh SK, Khurana A and

Weiskirchen R: Revolutionizing liver fibrosis research: The promise

of 3D organoid models in understanding and treating chronic liver

disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 19:105–110. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Liu Y, Gilchrist AE, Johansson PK, Guan Y,

Deras JD, Liu YC, Ceva S, Huang MS, Navarro RS, Enejder A, et al:

Engineered hydrogels for organoid models of human nonalcoholic

fatty liver disease. Adv Sci (Weinh). 12:e173322025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Hu S, Li R, Gong D, Hu P, Xu J, Ai Y, Zhao

X, Hu C, Xu M, Liu C, et al: Atf3-mediated metabolic reprogramming

in hepatic macrophage orchestrates metabolic dysfunction-associated

steatohepatitis. Sci Adv. 10:eado31412024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Basak M, Das K, Mahata T, Sengar AS, Verma

SK, Biswas S, Bhadra K, Stewart A and Maity B: RGS7-ATF3-Tip60

complex promotes hepatic steatosis and fibrosis by directly

inducing TNFα. Antioxid Redox Signal. 38:137–159. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Kang Y, Li Q, Zhu R, Li S, Xu X, Shi X and

Yin Z: Identification of Ferroptotic genes in spinal cord injury at

different time points: Bioinformatics and experimental validation.

Mol Neurobiol. 59:5766–5784. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Tian K, Wei J, Wang R, Wei M, Hou F and Wu

L: Sophoridine derivative 6j inhibits liver cancer cell

proliferation via ATF3 mediated ferroptosis. Cell Death Discov.

9:2962023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Wang L, Liu Y, Du T, Yang H, Lei L, Guo M,

Ding HF, Zhang J, Wang H, Chen X and Yan C: ATF3 promotes

erastin-induced ferroptosis by suppressing system Xc. Cell Death

Differ. 27:662–675. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Alosaimi M, Abd-Elhakim YM, Mohamed AA,

Metwally MMM, Khamis T, Alansari WS, Eskandrani AA, Essawi WM, Awad

MM, El-Shaer RAA, et al: Green synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles

attenuate acrylamide-induced cardiac injury via controlling

endoplasmic reticulum stress-associated apoptosis through

ATF3/CHOP/BCL2 signaling in rats. Biol Trace Elem Res.

202:2657–2671. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Crawford RR, Prescott ET, Sylvester CF,

Higdon AN, Shan J, Kilberg MS and Mungrue IN: Human CHAC1 protein

degrades glutathione, and mRNA induction is regulated by the

transcription factors ATF4 and ATF3 and a bipartite ATF/CRE

regulatory element. J Biol Chem. 290:15878–15891. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Wang X, He MJ, Chen XJ, Bai YT and Zhou G:

Glaucocalyxin A impairs tumor growth via amplification of the

ATF4/CHOP/CHAC1 cascade in human oral squamous cell carcinoma. J

Ethnopharmacol. 290:1151002022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Drummer C IVth, Saaoud F, Jhala NC, Cueto

R, Sun Y, Xu K, Shao Y, Lu Y, Shen H, Yang L, et al: Caspase-11

promotes high-fat diet-induced NAFLD by increasing glycolysis,

OXPHOS, and pyroptosis in macrophages. Front Immunol.

14:11138832023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Ma SY, Sun KS, Zhang M, Zhou X, Zheng XH,

Tian SY, Liu YS, Chen L, Gao X, Ye J, et al: Disruption of Plin5

degradation by CMA causes lipid homeostasis imbalance in NAFLD.

Liver Int. 40:2427–2438. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Kim JY, Park KJ, Hwang JY, Kim GH, Lee D,

Lee YJ, Song EH, Yoo MG, Kim BJ, Suh YH, et al: Activating

transcription factor 3 is a target molecule linking hepatic

steatosis to impaired glucose homeostasis. J Hepatol. 67:349–359.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Cusi K, Isaacs S, Barb D, Basu R, Caprio

S, Garvey WT, Kashyap S, Mechanick JI, Mouzaki M, Nadolsky K, et

al: American association of clinical endocrinology clinical

practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic

fatty liver disease in primary care and endocrinology clinical

settings: Co-sponsored by the American association for the study of

liver diseases (AASLD). Endocr Pract. 28:528–562. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Paternostro R and Trauner M: Current

treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Intern Med.

292:190–204. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Langhi C, Marquart TJ, Allen RM and Baldán

A: Perilipin-5 is regulated by statins and controls triglyceride

contents in the hepatocyte. J Hepatol. 61:358–365. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Gao X, Nan Y, Zhao Y, Yuan Y, Ren B and

Sun C: Atorvastatin reduces lipid accumulation in the liver by

activating protein kinase A-mediated phosphorylation of perilipin

5. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 1862:1512–1519. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Yu M, Tang TMS, Ghamsari L, Yuen G,

Scuoppo C, Rotolo JA, Kappel BJ and Mason JM: Exponential

Combination of a and e/g intracellular peptide libraries identifies

a selective ATF3 inhibitor. ACS Chem Biol. 19:753–762. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|