Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), including heart

failure (HF), hypertension, coronary heart disease (CHD), vascular

calcification and others, are among the primary causes of health

deterioration in humans worldwide. The Global Health Assessment

2019 report by the World Health Organization (1) indicated that heart disease has

remained the leading cause of mortality globally for the past two

decades. Improving the prognosis and course of treatment for CVDs

requires early detection and diagnosis. Every year, there is an

increase in the prevalence of CVDs despite advancements in therapy

for controlling traditional risk factors. Furthermore, the number

of CVD-associated mortalities is predicted to increase to ~23.6

million by 2030 as a result of aging and changing lifestyles

(2,3). Thus, in-depth studies to broaden the

current understanding of CVDs mechanisms, diagnosis and treatment

are imperative.

Research on exosomes is part of a newly emerged

field, which has attracted great attention due to their role in

regulating intercellular communication. Exosomes are a subtype of

extracellular vesicles with a typical size of ~100 nm, which can

carry a range of lipids, carbohydrates, nucleic acids and proteins

(4). Numerous CVDs are directly

impacted by different circular RNAs (circRNAs), long noncoding RNAs

(lncRNAs), messenger RNAs, short nucleolar RNAs and microRNAs

(miRNA) transported by exosomes. Due to these properties, exosomes

have also been proposed as potential diagnostic and/or prognostic

biomarkers for CVD, as well as novel potential therapeutic

modalities (5). Epigenetics

regulates the function and expression levels of CVD-associated

genes primarily through ncRNA regulation and DNA methylation,

thereby influencing the progression of CVD (6). Exosome-mediated epigenetic regulation

participates in the interaction between blood vessels and

circulating cells, as well as in intercellular communication

processes, and exosomes serve as biomarkers of cell activation

(7).

The aim of the present study was to examine the

molecular mechanism behind exosome-mediated epigenetic regulation

in the development of CVDs, and to explore the potential roles of

exosome-mediated epigenetic regulation in the diagnosis and

treatment of CVDs.

Epigenetics is considered chromosomal changes that

lead to stable genetic phenotypes in the absence of changes in the

DNA sequence (8). Epigenetic

markers are typically present in the first stages of CVD, and are

valuable molecular markers for the diagnosis, evaluation and

prediction of CVD response to treatment (9). Controlling these changed genes and

proteins could also provide a novel focus for the management of

heart disease, which is of considerable relevance for certain

diseases that are becoming more common as the population ages and

are yet challenging to treat clinically. This is because epigenetic

modifications are reversible. In CVDs, through DNA methylation and

ncRNA regulation, epigenetics primarily controls the function and

expression level of associated genes, thus influencing the

development of CVD (6,10).

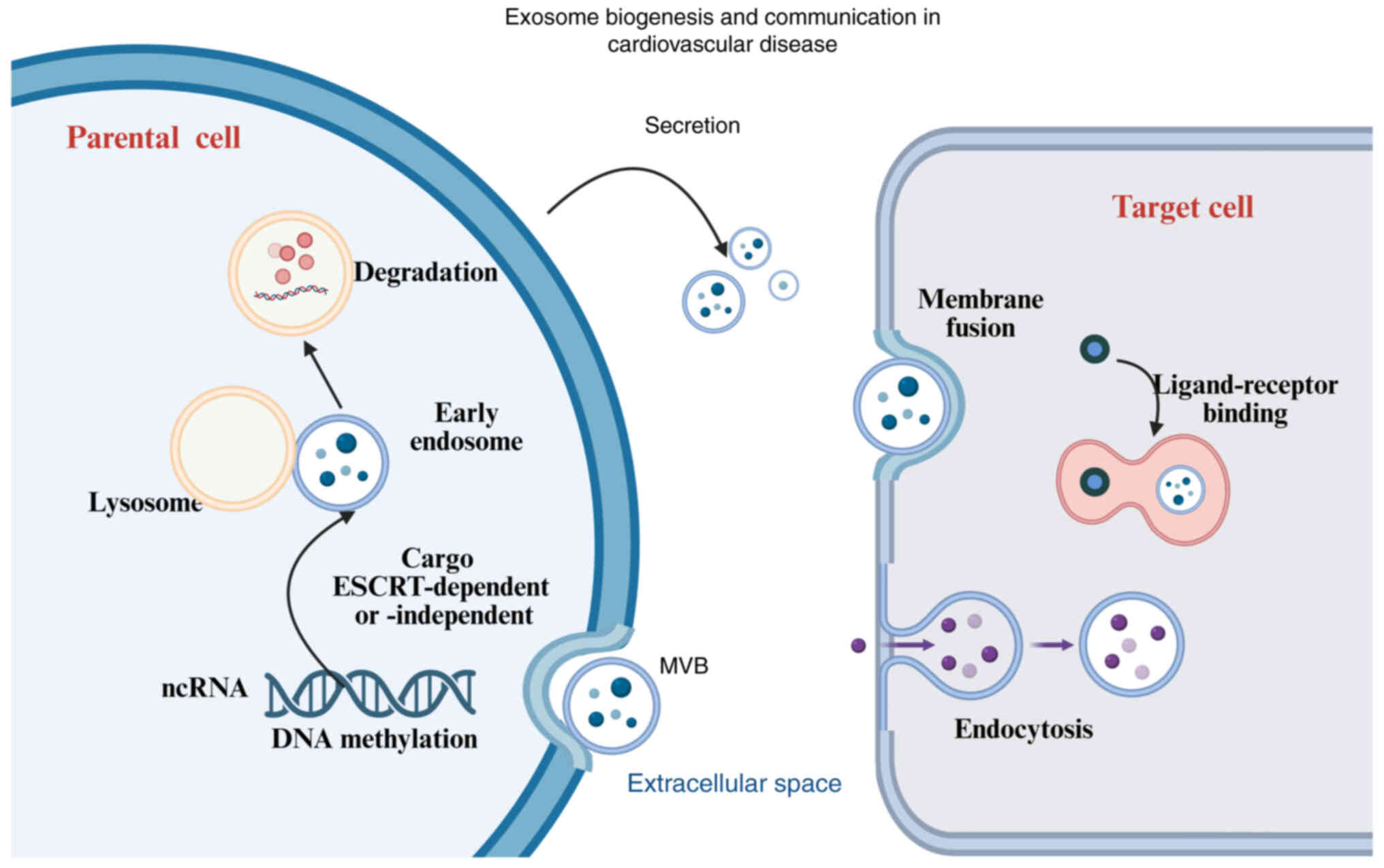

Exosomes participate in intercellular communication

among cells via direct communication with neighboring cells or via

secretion of soluble factors under physiological and pathological

conditions, which can extend the interaction over long distances

(11,12). Exosome formation involves a number

of processes, including synthesis of intraluminal vesicles,

secretion and fusion with target cells, and cargo loading. The

process of exosomal biogenesis commences with endosomal membrane

invagination, resulting in the formation of multivesicular bodies

(MVBs) in vivo (13).

During this step, MVBs integrate proteins and cytoplasmic nucleic

acids (14). On the one hand, when

MVBs fuse with lysosomes, the encapsulated contents are degraded.

When endosomes fuse with parental cell membranes, they are secreted

in exosomes (15), as illustrated

in Fig. 1. Since endosomes are the

result of plasma membrane budding, the membrane protein orientation

of the exosomes generated by this second invagination process is

identical to that of the parental cells (16). Cargo sorting to exosomes is

generally handled by endosomal sorting complexes required for

transport (ESCRT) or sphingolipids (ESCRT-dependent or

ESCRT-independent pathways). Cargo, such as proteins and RNA, can

remain in the extracellular space unbroken if it is not part of the

exosome lipid bilayer. Depending on the source, target and

environment, target cells absorb exosomes through a variety of

methods, such as membrane fusion, ligand receptor binding and

endocytosis. Exosomes can enter adjacent target cells and bodily

fluids, and even reach distant cells once they are secreted

(8,9). This diagram illustrates the process

of exosome biogenesis, including endosomal invagination,

multivesicular body formation, cargo sorting, and exosome release.

Exosomes facilitate intercellular communication by transferring

genetic material (such as ncRNAs) to target cells through fusion,

receptor binding or endocytosis. This process plays a key role in

regulating gene expression and epigenetic changes in CVDs.

LncRNAs, circRNAs and miRNAs are examples of ncRNAs,

which are generally not translated into proteins but function

through the regulation of gene expression. Instead, they carry out

their specific biological roles at the RNA level (6). MiRNAs are ~22 nucleotides in length,

and are mainly transcribed by large primary miRNAs that are

involved in the post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression,

and are produced by RNA polymerase II. Pri-miRNAs comprise one or

more hairpin (stem-loop) structures, each of which is consists of

~70 nucleotides (17). In addition

to being the targets of epigenetic changes such as DNA methylation,

miRNAs also function as histone deacetylase and DNA

methyltransferase (DNMT) regulators (18). LncRNAs are noncoding RNAs that

control gene expression patterns by modifying the accessibility of

DNA and the structure of chromatin via molecular mechanisms such as

scaffolding, decoy, guiding and signal transduction (19). CircRNAs are long, noncoding

endogenous RNA molecules that have no 5′cap or 3′cluster (A) end,

and have single-stranded covalently closed RNA rings that can be

used as templates for protein synthesis. CircRNAs interact with

miRNAs to regulate target gene expression and mRNA translation, and

bind to functional proteins or RNA-binding proteins in order to

control their transport and function (20,21),

as illustrated in Table I.

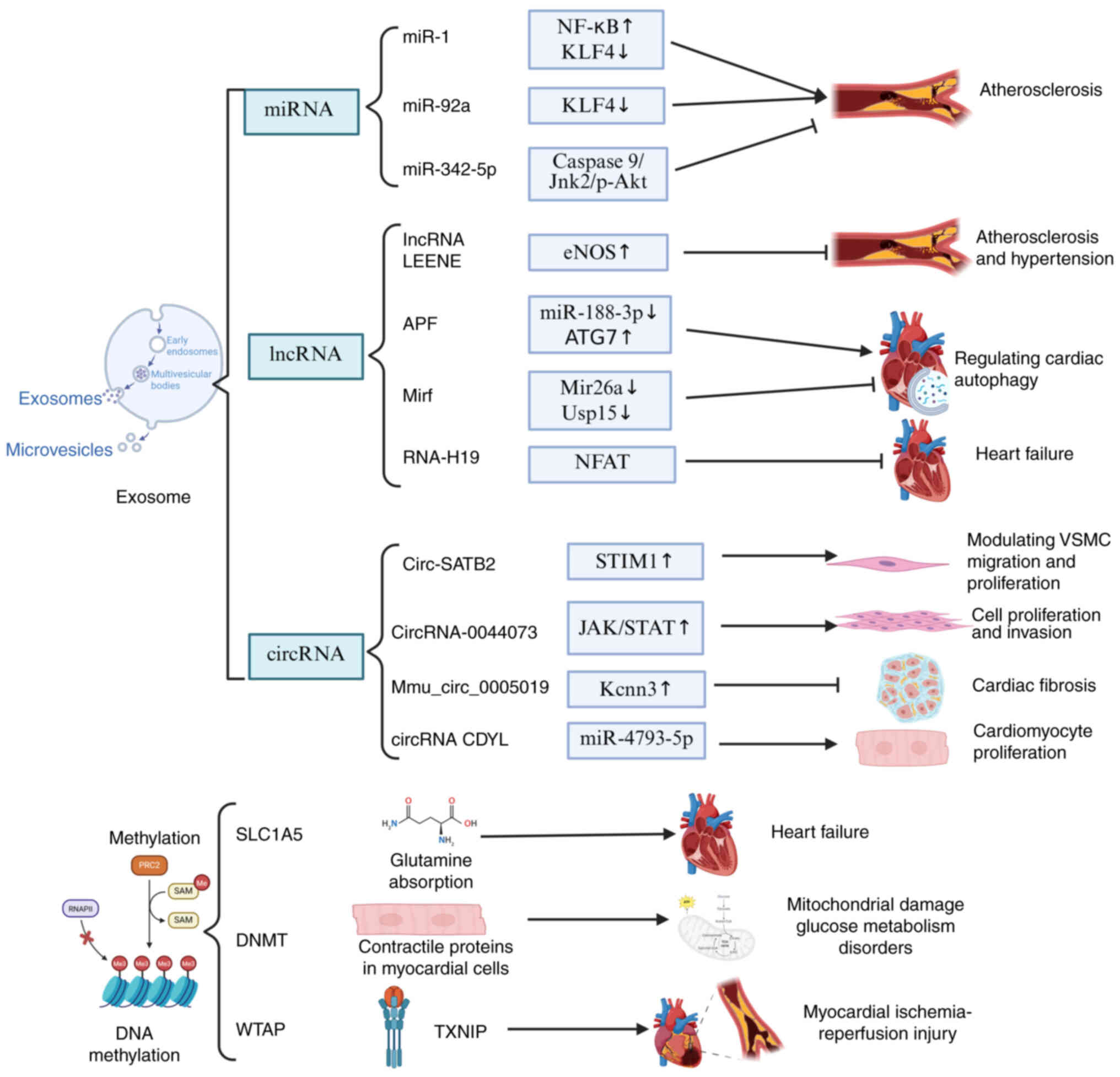

The role of ncRNAs in CVDs has attracted great

attention, particularly due to their potential in early disease

detection and prevention. MiRNAs, lncRNAs and circRNAs offer new

perspectives for understanding the progression of CVDs. Notably,

lncRNAs can exert both protective and detrimental effects in CVD,

and this dual regulatory role makes them a key focus on

cardiovascular research, as illustrated in Fig. 2. First, miRNAs act as essential

regulatory factors in diseases such as coronary heart disease,

myocardial infarction and vascular calcification (22,23).

Furthermore, miRNAs also play a critical role in atherosclerosis.

In endothelial cells (ECs), miR-342-5p exerts an

anti-atherosclerotic effect by suppressing inflammatory responses

(24), whereas miR-92a promotes

the progression of atherosclerosis (25). Similarly, in pulmonary arterial

hypertension, miR-181a-5p and miR-324-5p confer protective effects

by inhibiting pulmonary vascular remodeling, thereby slowing

disease progression (26). Similar

to miRNAs, lncRNAs in CVDs can exert both protective effects and

promote disease progression. For instance, lncRNA LEENE has been

shown to inhibit atherosclerosis in vitro through its

interaction with miR-1 (23,27).

In addition, specific lncRNAs, including APF, CAIF and Mirf, have

been demonstrated to regulate cardiac autophagy, which may play a

critical role during myocardial infarction-induced injury (28,29).

Additionally, lncRNAs RNA-H19, LIPCAR and COL1A1 have been proposed

as biomarkers for risk assessment and prediction of HF (30–32).

Furthermore, circRNAs, as novel regulatory molecules, also play an

important role in CVDs. For example, circRNAs can modulate the

migration and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs)

by interacting with miRNAs such as miRNA-939 and miRNA-221, thereby

contributing to the development of atherosclerosis (33,34).

In cardiomyocytes, circRNAs also play a crucial role, and are

considered novel regulatory elements involved in hypertrophy,

fibrosis, autophagy and apoptosis (35). Among them, mmu_circ_0005019 and

circRNA CDYL have been identified as key regulators in the

progression of HF (36,37). Notably, the overexpression of

certain miRNAs may also lead to adverse effects. For example,

excessive levels of miRNA-765, miRNA-483-3p and miRNA-143/145 can

disrupt the renin-angiotensin system and increase the blood

pressure (38). Similarly,

circACTA2 interacts with miRNA-548F-5p, which targets the

3′-untranslated region of α-SMA mRNA to promote VSMC contraction

and regulate vascular tone, thereby contributing to the development

of hypertension (39). In summary,

miRNAs, lncRNAs and circRNAs play multifaceted roles in CVDs.

In-depth research on these RNA molecules may offer novel insights

and potential biomarkers for the early diagnosis, treatment and

prevention of CVDs.

miRNAs are the most abundant ncRNAs packaged within

exosomes. Exosomal miRNAs derived from the heart and vascular

system exhibit distinct expression patterns under various

pathophysiological conditions. Their abundance and composition

depend not only on the state of CVD but also on specific stimuli

(40). The incorporation of miRNAs

into exosomes relies on distinct selective packaging mechanisms, a

process that is critical for their functional roles within the

cardiovascular system (41).

Previous studies in mouse models have further advanced the

understanding of the role of miRNAs in cardiac development.

Notably, cardiac-specific downregulation of the Dicer gene markedly

disrupts miRNA synthesis in neonatal mice, resulting in atrial

hypertrophy, cardiac dysfunction, ventricular remodeling and

dilation, and ultimately early mortality (42,43).

These findings underscore the critical importance of miRNAs in

cardiac development and functional regulation. Among the numerous

cardiac-specific miRNAs (44),

miR-1 is particularly abundant, representing ~24% of the total

miRNA population in the human heart and exhibiting pronounced

enrichment in cardiac tissue (45). The miR-1 sequence is composed of

two almost identical transcripts known as miR-1-1 and miR-1-2.

While the loss of both transcripts results in mortality, the

deletion of any of these transcripts causes defective cardiomyocyte

differentiation and impaired cardiac electrical conduction

(42,46). These findings indicate that miR-1

plays an indispensable role in normal cardiac development and

functional maintenance. However, dysregulated expression of miRNAs,

particularly abnormal levels within exosomes, may contribute to the

onset of CVDs. For instance, excessive expression of certain

miRNAs, such as miR-195 and miR-208, in vitro can lead to

concentric ventricular hypertrophy and the development of heart

failure (47,48). Therefore, measuring circulating

miRNA levels and identifying specific exosomal miRNA signatures may

provide critical information for the early diagnosis, monitoring

and treatment of CVDs. Dysregulation of specific miRNAs, such as

upregulation of miR-21 and miR-155 (49,50),

or downregulation of miR-126 (51), is closely associated with the

progression of cardiac atherosclerosis, and these miRNAs hold

promise as potential biomarkers for cardiac defects, as summarized

in Table I.

DNA methylation is a common modification in

eukaryotic cells, which, by controlling DNA methyltransferases

(DNMT), can transfer genetic information to the DNA of the

offspring (52). Accumulating

evidence has suggested that aberrant methylation status of

candidate genes, such as AHRR (53), F2RL3 (54) and CDKN2B-AS1 (55), can be used as indicators to assess

the progression of cardiovascular disorders, as illustrated in

Fig. 2. The expression of

potential genes linked to CHD, HF hypertension and other CVDs has

been reported to be strongly correlated with DNA methylation

(56), as illustrated in Table II.

Specifically, alterations at multiple gene

methylation sites have been demonstrated to be strongly associated

with CVDs. Previous studies have identified that three DNA

methylation areas, including the SLC9A1 (57), SLC1A5 (58) and TNRC6C genes (59), are associated with CVDs. Among

them, the methylation of one CpG (CG22304262) in SLC1A5 is strongly

associated with incident CHD, and shows significant associations

with diabetes, blood pressure and all-cause mortality (60–62).

The primary role of SLC1A5 in the heart is to regulate glutamine

uptake. However, in patients with HF, reduced SLC1A5 expression

leads to impaired glutamine absorption, resulting in disrupted

cardiac glutamine storage and an imbalance in glutamine

homeostasis, which ultimately compromises myocardial function and

health (63). In addition to

SLC1A5 methylation, previous epigenomic studies revealed broader

associations between differential DNA methylation patterns and

atherosclerosis as well as CHD (64). For instance, specific loci such as

AHRR (cg05575921) and F2RL3 (cg03636183) in blood-derived DNA have

been linked to both smoking exposure and increased risk of incident

CHD (65,66). Similarly, epigenome-wide studies

have identified methylation signatures related to chronic

inflammation and lipid metabolism that correlate with

atherosclerosis progression (67,68).

Importantly, these epigenetic markers (e.g., methylation of AHRR

and LINE-1 elements) have been shown to provide greater predictive

value for CHD than traditional risk factors alone (69). Additionally, alterations in the

methylation levels of genes associated with acute myocardial

infarction (AMI), such as Csf1r, Ptpn6, Map3k14 and Col6a1, further

support the mechanistic role of DNA methylation in cardiovascular

pathophysiology (70). Previous

studies have shown that upregulation of thioredoxin-interacting

protein is associated with myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (MI/R)

injury (71), potentially through

aberrant activation of the m6A methyltransferase complex component

WTAP (72). In vivo

experiments further demonstrated that exosome-mediated delivery of

WTAP small interfering RNA effectively alleviated MI/R injury

(73).

Furthermore, DNA methylation mediated by DNMT3a

plays a critical role in maintaining the structural and metabolic

homeostasis of human cardiomyocytes (74), thus underscoring its relevance in

CVDs. Previous research has shown that DNMT3a deficiency alters the

expression of contractile protein genes in cardiomyocytes, leading

to mitochondrial damage and glucose metabolism disorders (75), which may represent a critical

therapeutic target for cardiac diseases. Furthermore, extracellular

vesicles in the circulation of patients with acute coronary

syndrome are enriched in DNMTs, particularly showing markedly

increased expression of the de novo methyltransferases

DNMT3A and DNMT3B. These enzymes can modulate the methylome and

signaling pathways of recipient cells, thereby contributing to CVDs

(76). Further in vitro

studies revealed that downregulation of DNMTs not only participates

in the physiological regulation of cardiomyocytes but also plays a

crucial role in pathological conditions such as cardiac hypertrophy

(77). Notably, the DNMT inhibitor

RG108 has been shown to attenuate pressure overload-induced cardiac

hypertrophy in animal models, possibly by modulating epigenetic

mechanisms in non-myocyte cells (78). A previous study showed that

selenium supplementation exerts beneficial effects in alleviating

HF symptoms (79). By reducing

cardiomyocyte death and reactive oxygen species production,

selenium not only helps mitigate HF, but also indirectly improves

the epigenetic state of cardiomyocytes by inhibiting the

DNMT2-mediated methylation of the glutathione peroxidase 1 gene

promoter (80).

Beyond genes that directly affect cardiac health,

DNA methylation also plays a critical role in other physiological

systems. In mouse models, the loss of the Wnt receptor LRP6 in

aortic VSMCs leads to increased methylation of GTPase-activating

protein-binding proteins, which may be linked to the

transcriptional responses that trigger arterial calcification

(81). Furthermore, DNA

methylation patterns in the placenta have also been found to be

associated with maternal blood pressure and CVDs. A previous study

revealed that mothers with a family history of hypertension

exhibited lower global placental DNA methylation levels in

placental samples, which as accompanied by higher mean arterial

pressure, thus highlighting the potential role of placental

epigenetics in the development of CVDs (82). Additionally, in the field of cancer

research, DNMTs have been shown to play a crucial role in mediating

tumor drug resistance and progression through exosome-based

delivery mechanisms (83–85).

In summary, DNA methylation, as a key epigenetic

regulatory mechanism, is likely to play an important role in the

onset and progression of CVDs. However, the mechanisms underlying

exosome-mediated DNA methylation in the cardiovascular system

remain to be fully elucidated. Although these pathways have been

extensively studied in cancer, such as hepatocellular carcinoma

(86), colorectal cancer (87) and acute myeloid leukemia (88), as well as in other diseases

including Alzheimer's disease (89), type 2 diabetes (90) and systemic lupus erythematosus

(91), direct evidence in CVDs is

relatively limited, highlighting the urgent need for systematic

investigations to clarify their specific roles and clinical

implications. Future research focusing on the role of exosomes in

epigenetic regulation may provide novel insights into the

pathogenesis of CVDs.

The homeostasis of the cardiovascular system is

maintained through the interplay of various cell types, including

cardiac fibroblasts, ECs, VSMCs, cardiomyocytes, immune cells and

resident stem cells (92). These

cells release exosomes that mediate intercellular signaling,

thereby contributing to tissue repair, remodeling and the

regulation of pathological responses in the cardiovascular system.

Notably, exosomes are not merely structural vesicles, but

functional carriers that transport epigenetic information and

influence gene expression in recipient cells. Consequently,

exosome-mediated epigenetic regulatory mechanisms are increasingly

recognized as critical contributors to the onset and progression of

CVDs. Previous studies have demonstrated that exosomes of different

cellular origins, such as ECs, erythrocytes, platelets and

leukocytes, exhibit donor cell-specific profiles of RNAs, proteins

and modifying enzymes, thereby reflecting the physiological or

pathological state of their source cells (93,94).

For example, exosomes derived from ECs are essential for the

phenotypic transition of VSMCs (95), while exosomal miRNA profiles in the

plasma of atherosclerotic patients have been investigated as

potential early biomarkers (59,60).

These findings suggest that pathological alterations in the

cellular microenvironment not only influence exosome abundance and

secretion dynamics, but also profoundly reshape their epigenetic

regulatory cargo.

CVDs, including HF, hypertension, atherosclerosis,

atrial fibrillation and AMI, continue to be the primary causes

worldwide rates of morbidity and mortality, despite continuous

advancements in the clinical diagnosis and treatment of heart

disease. Exosomes are involved in the movement and interchange of

molecules that signal, which makes them a crucial component in

controlling the course of CVDs, as shown in Table III. Furthermore, ncRNAs found in

exosomes function as novel regulators in dyslipidemia, which raises

the risk of CVD caused by atherosclerosis. For example, miR-26a is

markedly downregulated in exosomes from obese mice and overweight

individuals, and its restoration reverses multiple markers

associated with dysregulated lipid metabolism, suggesting a pivotal

role for exosomal miRNAs in the cardiometabolic axis. Importantly,

exosome-mediated epigenetic mechanisms exhibit substantial

heterogeneity across different CVD subtypes. For instance, in HF,

exosomal ncRNAs may contribute to the regulation of myocardial

autophagy and fibrosis, whereas, in atherosclerosis, they are more

likely to influence inflammatory cell infiltration and endothelial

repair processes. Exosomes associated with hypertension are often

enriched in miRNAs involved in vascular tone regulation, whereas

those related to AMI tend to carry factors that modulate

cardiomyocyte apoptosis and stress responses. These differences

underscore the importance of analyzing exosomal epigenetic

functions in a disease-specific context, which represents a

promising direction for precision cardiovascular therapy.

Accordingly, the following section aimed to systematically explore

the roles of exosomal ncRNAs and DNA methylation-related factors in

the pathophysiological mechanisms of four major CVD subtypes,

namely HF, hypertension, atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction,

with the aim of providing a theoretical basis for understanding

their regulatory networks and clinical potential.

In HF, exosomal miRNAs play a pivotal role in

regulating myocardial remodeling, and exhibit potential as both

biomarkers and therapeutic targets, as shown in Table III. In a rat model of chronic HF,

exosomal miR-124 derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem

cells was found to target PRSS23 and suppress associated fibrotic

signaling pathways, thereby reducing the expression of the

endothelial marker CD31, alleviating myocardial ischemic injury,

and promoting angiogenesis and cellular repair (96). A clinical study also highlighted

the critical role of exosomal miRNAs in HF (97). Previous studies have shown that

patients with HF and reduced ejection fraction exhibit elevated

levels of exosomal miR-92b-5p (97,98).

This miRNA correlates positively with left atrial diameter,

systolic blood pressure and left ventricular end-diastolic

diameter, while it correlates negatively with fractional shortening

and left ventricular ejection fraction (97), suggesting its potential involvement

in the structural and functional remodeling of the left-side of the

heart. In addition, miR-425 and miR-744 have also exhibited

beneficial effects in mitigating myocardial fibrosis. In

angiotensin-induced models, overexpression of these two miRNAs

effectively suppresses collagen production and fibrotic processes

in fibroblasts, whereas their downregulation is accompanied by

significant upregulation of α-SMA and COL1, further confirming

their critical regulatory role in cardiac fibrosis (99). Therefore, miR-425 and miR-744, as

exosome-delivered epigenetic regulators, represent promising

therapeutic targets and potential novel tools for reversing cardiac

remodeling in HF. Notably, the regulatory effects of exosomal

miRNAs may be bidirectional. Previous research has reported that

serum exosomal miR-27a levels are significantly reduced in patients

with HF, and this decrease is closely associated with poor

prognosis (100). Additionally,

aberrant expression of miR-126 in peripheral blood mononuclear

cells of patients with chronic HF has been shown to exacerbate

cardiac injury (101).

Collectively, exosomal miRNAs modulate myocardial fibrosis through

multiple targets and mechanisms, thus playing a critical role in

the structural and functional remodeling of the heart.

Hypertension is a major risk factor for

cardiovascular events such as coronary artery disease, HF, stroke

and myocardial infarction (102,103). In addition, its onset and

progression are also governed by a variety of molecular and

cellular processes. In recent years, exosome-mediated ncRNA

signaling has been recognized as a key epigenetic regulatory

mechanism linking these pathological processes (104,105). According to previous studies,

numerous cellular and molecular processes, such as the

renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, endothelial dysfunction,

vascular remodeling, oxidative stress, angiogenesis, VSMC

proliferation and inflammation, are regulated by a number of

exosomal ncRNAs, which ultimately lead to the development of

hypertension (77,106).

Exosomal miRNAs can influence the development and

occurrence of hypertension in a positive or negative manner. In

spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs), compared with Wistar-Kyoto

rats, 23 exosomal miRNAs were upregulated and 4 were downregulated,

indicating a systemic alteration in circulating exosomal miRNA

profiles under hypertensive conditions (107). For example, miR-155-5p was

significantly downregulated in exosomes derived from adventitial

fibroblasts of SHR aortas (1).

This miRNA could suppress ACE/Ang II signaling, reduce oxidative

stress and inflammation, and thereby inhibit VSMCs migration in

SHRs (108). On the other hand,

certain exosomal miRNAs have been shown to exert pro-hypertensive

effects. Exosomal miR-27a derived from THP-1 monocytes could

inhibit the phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in

mesenteric arteries, and reduce Mas receptor expression in ECs,

thereby impairing vasodilation and elevating blood pressure

(109). Following Ang II

treatment, the levels of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in THP-1

cells increased, whereas exosomal miR-17 could downregulate its

expression, thus modulating endothelial inflammatory responses and

indirectly affecting the vascular tone (110). In addition, exosomal miR-106b-5p,

released from macrophages, could be transferred to glomerular

mesangial cells, where it suppressed the transcription factors

Pde3b and E2f1, thus mediating tissue responses associated with

inflammatory hypertension (111).

A previous epidemiological study reported that extracellular

vesicle-derived miRNAs, particularly miR-199a/b and miR-223-3p,

exhibited significant interactions with elevated systolic blood

pressure, thus potentially contributing to hypertension through

mechanisms involving vascular function, inflammatory responses and

oxidative stress (112). In

summary, miRNAs play a critical regulatory role in the onset and

progression of hypertension. They modulate vascular tone and

remodeling through multiple pathways, such as exosomal miR-155

(113), which impairs endothelial

nitric oxide signaling and promotes vascular inflammation, and

exosomal miR-505 (114), which

enhances vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration,

reflecting their unique and complex functional characteristics in

hypertensive pathology. However, current research on miRNAs in

hypertension remains largely preclinical (115), with a lack of systematic

validation in large populations and limited progress in

translational applications.

Atherosclerosis is a long-term immunoinflammatory

disease characterized by the accumulation of lipid-rich particles

in arterial plaques, which is one of the main causes of CVDs, with

serious clinical consequences such as myocardial infarction and

stroke. In recent years (116,117), exosome-mediated regulation of

ncRNAs has been recognized as one of the key epigenetic mechanisms

driving the development and progression of atherosclerosis (AS), as

shown in Table III. Exosomal

ncRNAs primarily regulate lipid metabolism, vascular inflammation

and cell survival, which have crucial regulatory functions in the

onset and advancement of atherosclerosis.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that, in both

patients and animal models of atherosclerosis, miRNAs, serving as

key epigenetic molecules within exosomes, can significantly

influence the pathological progression of AS through changes in

their expression levels (116,118). In patients with unstable angina,

28 miRNAs were upregulated, among which miR-19b showed the most

pronounced increase. This miRNA may inhibit the transcriptional

activity of the STAT3 signaling pathway, thereby suppressing the

proliferation, migration and angiogenesis of ECs, ultimately

delaying the formation and progression of unstable plaques

(41). Dysfunction of ECs can lead

to atherosclerosis by causing EC senescence, inflammation,

hyperpermeability, oxidative stress and vasodilation abnormalities

(119). Previous studies have

shown that exosomal ncRNAs play a major role in this process. Human

smooth muscle cells in the aorta produce miR-221/222, which

inhibits autophagy in these cells by regulating the PTEN/Akt axis

(120,121). Thrombin-stimulated platelet

exosomes showed enhanced miR-21, miR-339 and miR-223 levels, and

miR-223 could inhibit the expression of intercellular adhesion

molecule-1 (ICAM-1) in inflammatory processes by regulating the

MAPK/NF-κB axis (122). In

addition, exosomal miR-146a modulates inflammatory responses in ECs

by inhibiting interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 (123), whereas miR-4532 exacerbates EC

injury through its interaction with SP1 (124). A previous study showed that

upregulation of miR-155 can regulate the interaction between ECs

and VSMCs, inhibiting EC migration, proliferation and

reendothelialization (113).

This, in turn, weakens the endothelial barrier, increases vascular

wall permeability and promotes the progression of atherosclerotic

plaque (125).

In addition, the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis

is regulated by exosomal miRNAs derived from non-cardiomyocyte cell

types, such as endothelial cell-derived exosomal miR-92a that

promotes vascular inflammation (126), macrophage-derived exosomal

miR-146a that modulates inflammatory signaling (127), and vascular smooth muscle

cell-derived exosomal miR-221/222 that enhances cell proliferation

and migration (128). Macrophages

in particular possess the unique ability to engulf aggregated and

oxidized low-density lipoprotein via micropinocytosis and scavenger

receptor-mediated uptake, subsequently transforming into

lipid-laden foam cells that constitute the core of atherosclerotic

plaques. Exosomal miR-33a-5p, secreted by these cells, can regulate

ABCA1 expression and promote apoA1-mediated cholesterol efflux,

thereby affecting foam cell formation (129). miR-16-5p accelerates inflammation

and oxidative stress in atherosclerosis by downregulating SMAD7,

and promotes apoptosis (130),

thereby facilitating the progression of atherosclerotic lesions.

Endothelial dysfunction is one of the key initiating factors in the

early stages of atherosclerosis. Previous in vitro studies

have shown that circ_0124644 promotes endothelial injury by

modulating the miR-149-5p/PAPP-A axis, highlighting its pathogenic

role in the progression of AS and its potential as a target for

clinical intervention (131). In

addition, the miR-203-3p/cathepsin S pathway, which functions along

the p38/MAPK axis, has been shown to reverse atherosclerosis

(132). Neutrophil extracellular

traps (NETs) have also been identified as contributors to the

amplification of immune-inflammatory responses in AS (133,134). NETs are a network of densified

chromatin, nuclear histones and granular antimicrobial proteins

that are released by neutrophils in response to microbial antigens

(135). Exosomal miR-146a

released from macrophages upon oxidized low-density lipoprotein

(oxLDL) stimulation can induce the formation of NETs and promote

the progression of atherosclerosis (136). Following oxLDL treatment, human

umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) exhibit enhanced NF-κB pathway

activation, which upregulates miR-505 expression. MiR-505 then

targets SIRT3, leading to increased reactive oxygen species

production and elevated NET formation (88). VSMCs participate in plaque

formation during the early stages of AS and contribute to plaque

stability in the later stages.

In addition to the aforementioned miRNAs, lncRNAs

are also important epigenetic regulators, and have been shown to be

significantly upregulated in both animal models and patients with

atherosclerosis. Previous studies have shown that exosomal lncRNA

LIPCAR regulates CDK2 and participates in the phenotypic

transformation of VSMCs (137,138). MiR-106a-3p modulates apoptosis by

targeting CASP9 (139), and the

LINC01005/miR-128-3p/KLF4 axis influences VSMC migration and

proliferation (140). These

lncRNAs mediate intercellular communication via exosomes, and serve

as key regulatory nodes in the evolution and stability of

atherosclerotic plaques. In THP-1 cells, lncRNA GAS5 can induce and

regulate apoptosis in both THP-1 monocytes and ECs (141). By contrast, EC-derived lncRNA

MALAT1 exhibits bidirectional effects: On one hand, it promotes M2

macrophage polarization and protects against atherosclerosis

(142), while, on the other hand,

it may also facilitate the formation of NETs, thereby accelerating

the progression of atherosclerosis (143). In addition, several studies have

found that exosomal circRNA-0006896 is closely associated with the

pathogenesis of atherosclerosis (144,145). It is significantly upregulated in

patients with unstable atherosclerotic plaques, and its levels are

positively correlated with triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein

and C-reactive protein. Mechanistically, circRNA-0006896 may

promote EC proliferation and migration by activating the NF-κB

signaling pathway (144,146). Previous in vitro studies

have shown that exosome levels are significantly elevated in the

serum of patients with coronary artery disease, which can

exacerbate inflammatory responses and apoptosis in HUVECs, thereby

promoting endothelial injury and atherosclerosis progression

(147,148). Conversely, exosomal circ_0001785

can alleviate endothelial damage through the miR-513a-5p/TGFBR3

axis, thus exhibiting a protective effect (149).

In summary, exosome-derived miRNAs, lncRNAs and

circRNAs in atherosclerosis profoundly participate in immune

inflammation, apoptosis, lipid metabolism and plaque stability by

targeting multiple key signaling pathways, including MAPK, NF-κB,

STAT3 and p38. These epigenetic factors not only hold promise as

diagnostic biomarkers for AS, but also offer new strategies for

intervening in plaque progression and enhancing therapeutic

precision.

AMI is typically caused by sudden coronary artery

occlusion and is characterized by myocardial cell necrosis and loss

of function, which can have severe clinical consequences (150). Previous studies have shown that

exosomal miRNAs play a pivotal regulatory role in the onset and

progression of myocardial infraction (MI) by modulating a variety

of pathological processes, including autophagy, inflammation,

angiogenesis and apoptosis (151,152), as shown in Table III.

Multiple studies have found that the exosomal miRNA

expression profile derived from cardiomyocytes is significantly

altered in patients with MI. Notably, exosomal miR-125b, miR-499,

miR-133, miR-22, miR-21 and miR-301, which originate from

cardiomyocytes, are markedly upregulated following MI (153,154). These miRNAs are encapsulated

within cardiomyocyte-derived exosomes and are broadly expressed in

damaged myocardial regions. By inhibiting cardiomyocyte death,

modulating local inflammatory responses and promoting ischemic

tissue repair, they help alleviate pathological injury following MI

and may partially contribute to the prevention of complications

such as atherosclerosis (155,156). Furthermore,

inflammation-associated miRNAs, such as miR-146a and miR-25-3p, are

upregulated in the immune environment induced by MI. Notably,

exosomal miR-301 is also elevated and has been shown to suppress

autophagy in cardiomyocytes (109,157). At the translational level,

exosomal miR-499 and miR-133a are significantly elevated in

patients with MI compared to those with stable coronary artery

disease or acute coronary syndrome, demonstrating their potential

utility for clinical diagnosis and disease stratification (94). In addition, miR-26b-5p promotes

ferroptosis by targeting SLC7A11, and its downregulation in

exosomes from patients with AMI helps attenuate myocardial injury

(158), thus offering new

perspectives for anti-ferroptosis therapies.

In addition to those derived from cardiomyocytes,

exosomal ncRNAs from other cell types also play important roles in

the pathology of MI. For example, during ischemic episodes, the

expression of miR-22 in mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes is

reduced (159); however, in

vivo supplementation of this miRNA can significantly attenuate

cardiac fibrosis (160),

highlighting its therapeutic potential after AMI. High expression

of miR-21 in mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes can

significantly inhibit EC apoptosis and promote angiogenesis,

thereby exerting a protective effect on cardiomyocytes (161). In addition, lncRNAs are involved

in the epigenetic regulation of MI. LncRNA BC002059 has been shown

to reduce infarct size in mice with coronary artery ligation

(162). Mechanistically, BC002059

exerts its cytoprotective effects by influencing the downstream

target gene ABHD10 and subsequently regulating the expression of

miR-19b-3p (163). The roles of

other lncRNAs in the process of MI should not be overlooked, such

as MALAT and H19 (164,165). After AMI, the levels of MALAT1 in

exosomes released from cardiomyocytes are significantly increased

under hyperoxic conditions. MALAT1 enhances neovascularization by

suppressing miR-92a expression (117), thereby contributing to ischemic

tissue repair. Atorvastatin treatment has been shown to induce an

increase in lncRNA H19 release from mesenchymal stem cells

(118). By contrast, under

hypoxic conditions, cardiomyocyte-derived exosomal lncRNA AK139128

regulates cardiac fibrosis by affecting the proliferation,

migration and apoptosis of cardiac fibroblasts (165). These findings suggest that

exosomal lncRNAs not only play functional roles in response to

ischemic injury, but may also serve as important molecular targets

for the treatment of MI.

Overall, exosomal ncRNAs play critical roles in

myocardial infarction as well as other CVDs, including

hypertension, atherosclerosis and HF. Previous research in both

animal models and clinical samples has identified numerous

potential therapeutic targets, such as exosomal miR-92b-5p

regulating cardiomyocyte apoptosis (166), lncRNA H19 enhancing the efficacy

of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes in myocardial infarction

(167). However, there is

considerable heterogeneity in the mechanisms, target pathways and

functional roles of ncRNAs among different types of CVDs. In HF,

exosomal miRNAs primarily regulate fibroblast activity and

influence myocardial remodeling, demonstrating potential for

anti-fibrotic effects and cardiac structural modulation. By

contrast, exosomal ncRNAs associated with atherosclerosis are more

focused on regulating endothelial function and lipid metabolism,

reflecting microenvironment-specific regulatory characteristics

within atherosclerotic lesions. By comparison, those involved in

hypertension predominantly participate in the regulation of

vascular tone and remodeling.

Although these findings reveal distinct mechanisms

by which exosomal ncRNAs act in different CVDs, as shown in

Table III, their clinical

translation still faces important challenges. The majority of

previous studies rely on animal models and in vitro

experiments, with a lack of validation in large-scale human

samples. Future research urgently requires multicenter clinical

data to further clarify the specific mechanisms of exosomal ncRNAs

in cardiovascular pathology.

Prognostic biomarkers may be employed for

identification of diseases and/or prognostic indicators. The most

crucial and essential qualities of effective biomarkers are their

sensitivity, specificity, stability and relative noninvasive

detection. Notably, recent studies (166,168) are focusing on exosomes as

possible biomarkers due to their easy and affordable detection in

multiple bodily fluids, and their ability to function as a

protective transport system against enzymatic degradation. Exosomes

possess the capacity to serve as helpful biomarkers for the early

detection of CVDs, since their cargo for epigenetic pathways varies

depending on the type of CVD (169,170). Therefore, exosomes may be used as

biomarkers to assist diagnosis according to their abnormal

manifestations in different CVDs.

Previous studies have shown that exosomal ncRNAs

exhibit diverse biological functions within the cardiovascular

system. Dicer's heart-specific downregulation in young mice

degrades miRNAs, particularly miR-1, miR-133a, miR-208 and miR-499

(171,172), resulting in atrial expansion,

ventricular remodeling and enlargement, reduced cardiac function,

and early mortality (173,174).

By contrast, overexpression of certain specific miRNAs in

vitro can induce cardiac hypertrophy and HF (44,45),

indicating that the balance of miRNA expression is essential for

maintaining cardiac homeostasis (173). Therefore, exosomal miRNAs and

other epigenetic cargos not only reflect disease states but may

also serve as potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

As therapeutic agents, exosomes hold promise as

viable delivery vehicles due to a range of advantages, including

minimal immunogenicity and toxicity, high biocompatibility,

efficient bio-barrier permeability and natural availability

(174). It has been attempted to

alter exosomes through genetic engineering for medicinal uses

(175,176). The potential to use exosomes as

carriers to deliver certain cargo to particular tissues or organs

is made possible by the capacity to change isolated and purified

exosomes with target molecules and surface-loaded mimics or

inhibitors of epigenetic payload (172,177). This gene regulation points to

exosome epigenetic cargo as a potentially effective treatment

strategy for a range of human diseases.

Previous animal studies have demonstrated the

therapeutic potential of exosomes in various CVD models (168,178,179). Engineered exosomes enriched with

low-density lipoprotein receptor mRNA have been shown to

effectively alleviate hypercholesterolemia in mice (180). Additionally, mesenchymal

stem/stromal cell (MSC)-derived exosomes can reduce cardiomyocyte

apoptosis after myocardial infarction by suppressing SOCS2

signaling via miRNA-185 (181–183). A previous study further confirmed

that pharmacological agents can modulate exosomes to intervene in

the development and progression of CVDs (165). Furthermore, a previous study

found that phenol can attenuate inflammatory responses in HUVECs,

which deaccelerates the progression of atherosclerosis, and

decreases the expression levels of STAT3 and phosphorylated STAT3

in HUVECs by increasing the quantity of exosome miR-223 in HUVECs

treated with THP-1 and exosomes (184). In an I/R injury model in mice,

the injection of cortical diaphysial-derived exosomes decreased the

size of the infarct (185). On

the contrary, chrysin reduced miR-92a expression in HCAEC cells and

accelerated the progression of atherosclerosis (186). Furthermore, exosomal miR-21-3p

derived from nicotine-treated macrophages could bind to PTEN,

thereby promoting VSMC migration and proliferation, and

exacerbating the progression of atherosclerosis (187). In addition, exosomes have shown a

promising potential in promoting cardiac regeneration. Multiple

studies using models of ischemic heart disease have demonstrated

that injection of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes can

effectively improve myocardial remodeling, enhance cardiomyocyte

survival (188,189), and promote EC proliferation,

thereby partially restoring cardiac function (190,191). This ‘cell-free therapy’ offers a

safer and more controllable alternative to traditional cell

transplantation.

In recent years, exosome-based therapeutic

strategies have attracted increasing attention for the treatment of

CVDs (192). Exosomes are

nanoscale, membrane-bound vesicles secreted by cells, and their

unique structural and functional properties make them highly

promising as therapeutic carriers (176,193). The bilayer lipid membrane of

exosomes effectively protects encapsulated bioactive molecules,

such as miRNAs and proteins, enhancing their stability and

biological activity in vivo (194). For example, compared with free

curcumin, curcumin encapsulated in exosomes exhibits higher plasma

concentrations and greater anti-inflammatory effects (195). Furthermore, as non-living

particulate structures, exosomes offer greater controllability

compared to viral vectors or live cell systems, and lack

tumorigenic potential (196). In

multiple studies, exosomes have demonstrated a favorable safety

profile (197,198).

However, despite the numerous advantages of

exosomes as therapeutic tools, their clinical application still

faces notable challenges. First, safety concerns cannot be ignored.

While exosomes derived from autologous cells are generally

considered to have low immunogenicity, artificially engineered

exosome delivery systems may still pose immunogenic risks, follow

unintended pathways away from target recipient cell types, and

result in unexpected off-target effects (199). More importantly, exosomes lack

specific biodistribution in vivo. Once cleared from the

bloodstream, exosomes tend to accumulate in organs such as the

lungs, spleen and liver (200,201), which can result in off-target

effects, reduced therapeutic efficacy and even potential toxicity.

Due to the tendency of RNA to aggregate or degrade, loading

specific RNA cargos into exosomes using conventional

electroporation or sonication techniques presents remarkable

technical challenges, and the efficacy of these approaches remains

uncertain (202). In addition,

there may be a risk of infection when these particles enter the

human bloodstream. More challenging is the substantial variability

in exosomal drug loading capacity and the lack of uniformity,

making it difficult to optimize exosome dosing (140). Furthermore, the optimal

therapeutic time window for exosome administration in vivo

has not yet been determined, which further increases the

uncertainty of clinical translation (203). Therefore, before advancing

exosomes as RNA delivery vehicles for clinical use, it is essential

to ensure their safety in vivo and to minimize immune

responses or off-target effects. In addition, optimization of

loading techniques is needed to improve RNA stability and achieve a

uniform cargo distribution.

Furthermore, the industrialization and clinical

translation of exosomes face important technical bottlenecks.

Currently, ultracentrifugation is the most commonly used isolation

method for exosomes; however, it is labor-intensive, inefficient,

and has limited yield, thus making it difficult to meet the demands

of large-scale clinical applications. On one hand, there is still a

lack of unified and standardized Good Manufacturing Practice-grade

manufacturing processes (204).

On the other hand, exosomes derived from different cell sources

show significant variations in composition, function and efficacy,

leading to poor batch-to-batch reproducibility and substantial

challenges in quality control. Furthermore, delivery efficiency

remains one of the most critical issues. Exosomes are commonly

administered for the treatment of CVDs via intravenous,

intracoronary or intramyocardial injection; however, these

approaches are often associated with procedural complexity or low

cardiac retention rates in clinical practice. Although surface

engineering modifications can enhance targeted delivery (205), exosomes still face challenges

such as off-target effects, rapid clearance and the need for

rigorous safety validation in the complex human physiological

environment.

In summary, exosomes hold great therapeutic promise

for CVDs, particularly due to their advantages in targeting

specificity, delivery efficiency and epigenetic regulation.

However, several key issues must be addressed before exosome-based

therapies can be translated into clinical practice, including

ensuring safety, improving manufacturing processes and enhancing

consistency in therapeutic efficacy.

The present study aimed to review in detail the

exosome-mediated epigenetic mechanisms, such as exosomal ncRNAs and

exosome-mediated DNA methylation, and their role in CVDs.

Concurrently, the present study examined the function of exosomal

phylogenetic pathways in CVD detection and treatment. The miRNA

cargo of exosomes is of particular importance, as these molecules

have the capacity to control the expression of proteins. At

present, research on the mechanisms by which exosomes influence

cardiovascular epigenetics is still ongoing, with current studies

mainly focusing on exosomal ncRNAs. Targeted approaches for the

treatment of CVDs are feasible, as exosomes are capable of

delivering therapeutic agents directly to damaged cells and

tissues. The application of exosomes as delivery vehicles for CVD

therapy is highly promising. Both animal studies and preliminary

clinical trials have shown encouraging results, suggesting that

exosome-based therapies could represent a breakthrough in CVD

treatment. Given that CVD remains a leading cause of mortality

worldwide, this strategy is particularly meaningful for high-risk

populations, including those with comorbidities such as diabetes

and hypertension, or individuals with a history of angina or

myocardial infarction.

However, the clinical application of exosomes still

faces multiple challenges. First, there is a lack of standardized

protocols for exosome isolation, characterization and cargo

detection, resulting in poor reproducibility of experimental

results and efficacy validation across studies, which limits

translational progress. Second, the low loading efficiency and

instability of functional RNAs compromise the stability and

controllability of exosome-based delivery systems. In addition, the

non-specific biodistribution of exosomes in vivo leads to

risks of rapid clearance and off-target effects, which highlights

the need for improved delivery strategies such as surface

modification and magnetic guidance to enhance targeting.

Particularly in the cardiovascular field, achieving safe, stable

and effective therapeutic delivery in complex microenvironments

requires further systematic research and validation.

However, as research on exosomes continues to

advance, their prospects in precision medicine remain highly

promising. In particular, exosomes offer novel insights into

epigenetic regulation and intercellular communication underlying

the pathogenesis and progression of CVDs. Future studies should

focus on both mechanistic exploration and the establishment of

technical standards to facilitate the critical transition from

laboratory research to clinical application.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the Jilin Province Science

and Technology Development Plan Project (grant no.

YDZJ202201ZYTS209); the Regional Joint Fund Project of National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. U24A20779); and the

Science and Technology Development Plan of Jilin Province (grant

no. YDZJ202301ZYTS337).

Not applicable.

Conceptualization and study design: LZ and JL.

Writing of the first manuscript draft: YZ. Literature search,

figure reparation (created with BioRender) and manuscript editing:

WJ and YL. Data curation, writing, reviewing and editing: YZ and

SZ. Supervision and project administration: LZ and JL. All authors

contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript, read and

approved the final version of the manuscript. Data authentication

is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

GBD 2019 Viewpoint Collaborators, . Five

insights from the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet.

396:1135–1159. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Shah R, Patel T and Freedman JE:

Circulating extracellular vesicles in human disease. N Engl J Med.

379:958–966. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Théry C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, Alcaraz JM,

Anderson JD, Andriantsitohaina R, Antoniou A, Arab T, Archer F,

Atkin-Smith GK, et al: Minimal information for studies of

extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A position statement of

the international society for extracellular vesicles and update of

the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles. 7:15357502018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Sahoo S, Adamiak M, Mathiyalagan P,

Kenneweg F, Kafert-Kasting S and Thum T: Therapeutic and diagnostic

translation of extracellular vesicles in cardiovascular diseases.

Circulation. 143:1426–1449. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Martin-Ventura JL, Roncal C, Orbe J and

Blanco-Colio LM: Role of extracellular vesicles as potential

diagnostic and/or therapeutic biomarkers in chronic cardiovascular

diseases. Front Cell Dev Biol. 10:8138852022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Shi Y, Zhang H, Huang S, Yin L, Wang F,

Luo P and Huang H: Epigenetic regulation in cardiovascular disease:

Mechanisms and advances in clinical trials. Signal Transduct Target

Ther. 7:2002022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Khan MI, Alsayed RKME, Choudhry H and

Ahmad A: Exosome-mediated response to cancer therapy: Modulation of

epigenetic machinery. Int J Mol Sci. 23:62222022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Nasir A, Bullo MMH, Ahmed Z, Imtiaz A,

Yaqoob E, Jadoon M, Ahmed H, Afreen A and Yaqoob S: Nutrigenomics:

Epigenetics and cancer prevention: A comprehensive review. Crit Rev

Food Sci Nutr. 60:1375–1387. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Schiano C, Benincasa G, Franzese M, Della

Mura N, Pane K, Salvatore M and Napoli C: Epigenetic-sensitive

pathways in personalized therapy of major cardiovascular diseases.

Pharmacol Ther. 210:1075142020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hulshoff MS, Xu X, Krenning G and Zeisberg

EM: Epigenetic regulation of Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition

in chronic heart disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol.

38:1986–1996. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Chang W and Wang J: Exosomes and their

noncoding RNA cargo are emerging as new modulators for diabetes

mellitus. Cells. 8:8532019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Mathieu M, Martin-Jaular L, Lavieu G and

Théry C: Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and

other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nat

Cell Biol. 21:9–17. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Shao H, Im H, Castro CM, Breakefield X,

Weissleder R and Lee H: New technologies for analysis of

extracellular vesicles. Chem Rev. 118:1917–1950. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Raiborg C and Stenmark H: The ESCRT

machinery in endosomal sorting of ubiquitylated membrane proteins.

Nature. 458:445–452. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhang J, Li S, Li L, Li M, Guo C, Yao J

and Mi S: Exosome and exosomal microRNA: Trafficking, sorting, and

function. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 13:17–24. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kalluri R: The biology and function of

exosomes in cancer. J Clin Invest. 126:1208–1215. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Poddar S, Kesharwani D and Datta M:

Interplay between the miRNome and the epigenetic machinery:

Implications in health and disease. J Cell Physiol. 232:2938–2945.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Petrovic N and Ergun S: miRNAs as

potential treatment targets and treatment options in cancer. Mol

Diagn Ther. 22:157–168. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Quinn JJ and Chang HY: Unique features of

long non-coding RNA biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Genet.

17:47–62. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Lou Z, Zhou R, Su Y, Liu C, Ruan W, Jeon

CO, Han X, Lin C and Jia B: Minor and major circRNAs in virus and

host genomes. J Microbiol. 59:324–331. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yang T, Long T, Du T, Chen Y, Dong Y and

Huang ZP: Circle the cardiac remodeling with circRNAs. Front

Cardiovasc Med. 8:7025862021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Hall IF, Climent M, Viviani Anselmi C,

Papa L, Tragante V, Lambroia L, Farina FM, Kleber ME, März W,

Biguori C, et al: rs41291957 controls miR-143 and miR-145

expression and impacts coronary artery disease risk. EMBO Mol Med.

13:e140602021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Jiang F, Chen Q, Wang W, Ling Y, Yan Y and

Xia P: Hepatocyte-derived extracellular vesicles promote

endothelial inflammation and atherogenesis via microRNA-1. J

Hepatol. 72:156–166. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Hou Z, Qin X, Hu Y, Zhang X, Li G, Wu J,

Li J, Sha J, Chen J, Xia J, et al: Longterm Exercise-derived

exosomal miR-342-5p: A novel exerkine for cardioprotection. Circ

Res. 124:1386–1400. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Chang YJ, Li YS, Wu CC, Wang KC, Huang TC,

Chen Z and Chien S: Extracellular MicroRNA-92a mediates endothelial

Cell-macrophage communication. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol.

39:2492–2504. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Sindi HA, Russomanno G, Satta S,

Abdul-Salam VB, Jo KB, Qazi-Chaudhry B, Ainscough AJ, Szulcek R,

Jan Bogaard H, Morgan CC, et al: Therapeutic potential of

KLF2-induced exosomal microRNAs in pulmonary hypertension. Nat

Commun. 11:11852020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Miao Y, Ajami NE, Huang TS, Lin FM, Lou

CH, Wang YT, Li S, Kang J, Munkacsi H, Maurya MR, et al:

Enhancer-associated long non-coding RNA LEENE regulates endothelial

nitric oxide synthase and endothelial function. Nat Commun.

9:2922018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Wang K, Liu CY, Zhou LY, Wang JX, Wang M,

Zhao B, Zhao WK, Xu S, Fan LH, Zhang XJ, et al: APF lncRNA

regulates autophagy and myocardial infarction by targeting

miR-188-3p. Nat Commun. 6:67792015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Liang H, Su X, Wu Q, Shan H, Lv L, Yu T,

Zhao X, Sun J, Yang R, Zhang L, et al: LncRNA 2810403D21Rik/Mirf

promotes ischemic myocardial injury by regulating autophagy through

targeting Mir26a. Autophagy. 16:1077–1091. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Viereck J, Bührke A, Foinquinos A,

Chatterjee S, Kleeberger JA, Xiao K, Janssen-Peters H, Batkai S,

Ramanujam D, Kraft T, et al: Targeting muscle-enriched long

non-coding RNA H19 reverses pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Eur

Heart J. 41:3462–3474. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Omura J, Habbout K, Shimauchi T, Wu WH,

Breuils-Bonnet S, Tremblay E, Martineau S, Nadeau V, Gagnon K,

Mazoyer F, et al: Identification of long noncoding RNA H19 as a new

biomarker and therapeutic target in right ventricular failure in

pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 142:1464–1484. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Hua X, Wang YY, Jia P, Xiong Q, Hu Y,

Chang Y, Lai S, Xu Y, Zhao Z, Song J, et al: Multi-level

transcriptome sequencing identifies COL1A1 as a candidate marker in

human heart failure progression. BMC Med. 18:22020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Mao YY, Wang JQ, Guo XX, Bi Y and Wang CX:

Circ-SATB2 upregulates STIM1 expression and regulates vascular

smooth muscle cell proliferation and differentiation through

miR-939. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 505:119–125. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Shen L, Hu Y, Lou J, Yin S, Wang W, Wang

Y, Xia Y and Wu W: CircRNA-0044073 is upregulated in

atherosclerosis and increases the proliferation and invasion of

cells by targeting miR-107. Mol Med Rep. 19:3923–3932.

2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Sygitowicz G and Sitkiewicz D: Involvement

of circRNAs in the development of heart failure. Int J Mol Sci.

23:141292022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Wu N, Li C, Xu B, Xiang Y, Jia X, Yuan Z,

Wu L, Zhong L and Li Y: Circular RNA mmu_circ_0005019 inhibits

fibrosis of cardiac fibroblasts and reverses electrical remodeling

of cardiomyocytes. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 21:3082021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhang M, Wang Z, Cheng Q, Wang Z, Lv X,

Wang Z and Li N: Circular RNA (circRNA) CDYL induces myocardial

regeneration by ceRNA after myocardial infarction. Med Sci Monit.

26:e9231882020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Leimena C and Qiu H: Non-Coding RNA in the

pathogenesis, progression and treatment of hypertension. Int J Mol

Sci. 19:9272018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Sun Y, Yang Z, Zheng B, Zhang XH, Zhang

ML, Zhao XS, Zhao HY, Suzuki T and Wen JK: A novel regulatory

mechanism of smooth muscle α-Actin expression by

NRG-1/circACTA2/miR-548f-5p Axis. Circ Res. 121:628–635. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Yang K, Zhou Q, Qiao B, Shao B, Hu S, Wang

G, Yuan W and Sun Z: Exosome-derived noncoding RNAs: Function,

mechanism, and application in tumor angiogenesis. Mol Ther Nucleic

Acids. 27:983–997. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Qian Z, Shen Q, Yang X, Qiu Y and Zhang W:

The role of extracellular vesicles: An epigenetic view of the

cancer microenvironment. Biomed Res Int. 2015:6491612015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Radhakrishna U, Albayrak S, Zafra R, Baraa

A, Vishweswaraiah S, Veerappa AM, Mahishi D, Saiyed N, Mishra NK,

Guda C, et al: Placental epigenetics for evaluation of fetal

congenital heart defects: Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD). PLoS

One. 14:e02002292019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Li S, Geng Q, Chen H, Zhang J, Cao C,

Zhang F, Song J, Liu C and Liang W: The potential inhibitory

effects of miR-19b on vulnerable plaque formation via the

suppression of STAT3 transcriptional activity. Int J Mol Med.

41:859–867. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Small EM and Olson EN: Pervasive roles of

microRNAs in cardiovascular biology. Nature. 469:336–342. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Li Q, Song XW, Zou J, Wang GK, Kremneva E,

Li XQ, Zhu N, Sun T, Lappalainen P, Yuan WJ, et al: Attenuation of

microRNA-1 derepresses the cytoskeleton regulatory protein

twinfilin-1 to provoke cardiac hypertrophy. J Cell Sci.

123:2444–2452. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Heidersbach A, Saxby C, Carver-Moore K,

Huang Y, Ang YS, de Jong PJ, Ivey KN and Srivastava D: microRNA-1

regulates sarcomere formation and suppresses smooth muscle gene

expression in the mammalian heart. Elife. 2:e013232013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Van Rooij E, Sutherland LB, Liu N,

Williams AH, McAnally J, Gerard RD, Richardson JA and Olson EN: A

signature pattern of stress-responsive microRNAs that can evoke

cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

103:18255–18260. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Benzoni P, Nava L, Giannetti F, Guerini G,

Gualdoni A, Bazzini C, Milanesi R, Bucchi A, Baruscotti M and

Barbuti A: Dual role of miR-1 in the development and function of

sinoatrial cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 157:104–112. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Ji R, Cheng Y, Yue J, Yang J, Liu X, Chen

H, Dean DB and Zhang C: MicroRNA expression signature and

antisense-mediated depletion reveal an essential role of MicroRNA

in vascular neointimal lesion formation. Circ Res. 100:1579–1588.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Nazari-Jahantigh M, Wei Y, Noels H, Akhtar

S, Zhou Z, Koenen RR, Heyll K, Gremse F, Kiessling F, Grommes J, et

al: MicroRNA-155 promotes atherosclerosis by repressing Bcl6 in

macrophages. J Clin Invest. 122:4190–202. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Zernecke A, Bidzhekov K, Noels H,

Shagdarsuren E, Gan L, Denecke B, Hristov M, Köppel T, Jahantigh

MN, Lutgens E, et al: Delivery of microRNA-126 by apoptotic bodies

induces CXCL12-dependent vascular protection. Sci Signal.

2:ra812009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Mattei AL, Bailly N and Meissner A: DNA

methylation: A historical perspective. Trends Genet. 38:676–707.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Zhu L, Zhu C, Wang J, Yang R and Zhao X:

The association between DNA methylation of 6p21.33 and AHRR in

blood and coronary heart disease in Chinese population. BMC

Cardiovasc Disord. 22:3702022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zhang Y, Yang R, Burwinkel B, Breitling

LP, Holleczek B, Schöttker B and Brenner H: F2RL3 methylation in

blood DNA is a strong predictor of mortality. Int J Epidemiol.

43:1215–1225. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Guarrera S, Fiorito G, Onland-Moret NC,

Russo A, Agnoli C, Allione A, Di Gaetano C, Mattiello A, Ricceri F,

Chiodini P, et al: Gene-specific DNA methylation profiles and

LINE-1 hypomethylation are associated with myocardial infarction

risk. Clin Epigenetics. 7:1332015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Zhang W, Song M, Qu J and Liu GH:

Epigenetic modifications in cardiovascular aging and diseases. Circ

Res. 123:773–786. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Nakamura TY, Iwata Y, Arai Y, Komamura K

and Wakabayashi S: Activation of Na+/H+ exchanger 1 is sufficient

to generate Ca2+ signals that induce cardiac hypertrophy and heart

failure. Circ Res. 103:891–899. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Chen S, Ma J, Chi J, Zhang B, Zheng X,

Chen J and Liu J: Roles and potential clinical implications of

tissue transglutaminase in cardiovascular diseases. Pharmacol Res.

177:1060852022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Westerman K, Sebastiani P, Jacques P, Liu

S, DeMeo D and Ordovás JM: DNA methylation modules associate with

incident cardiovascular disease and cumulative risk factor

exposure. Clin Epigenetics. 11:1422019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

GTEx Consortium; Laboratory, Data Analysis

& Coordinating Center (LDACC)-Analysis Working Group;

Statistical Methods groups-Analysis Working Group; Enhancing GTEx

(eGTEx) groups; NIH Common Fund; NIH/NCI; NIH/NHGRI; NIH/NIMH;

NIH/NIDA; Biospecimen Collection Source Site-NDRI et al., . Genetic

effects on gene expression across human tissues. Nature.

550:204–213. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Walaszczyk E, Luijten M, Spijkerman AMW,

Bonder MJ, Lutgers HL, Snieder H, Wolffenbuttel BHR and van

Vliet-Ostaptchouk JV: DNA methylation markers associated with type

2 diabetes, fasting glucose and HbA1c levels: A systematic review

and replication in a case-control sample of the Lifelines study.

Diabetol. 61:354–368. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Richard MA, Huan T, Ligthart S, Gondalia

R, Jhun MA, Brody JA, Irvin MR, Marioni R, Shen J, Tsai PC, et al:

DNA methylation analysis identifies loci for blood pressure

regulation. American. J Human Genet. 101:888–902. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Kennel PJ, Liao X, Saha A, Ji R, Zhang X,

Castillero E, Brunjes D, Takayama H, Naka Y, Thomas T, et al:

Impairment of myocardial glutamine homeostasis induced by

suppression of the amino acid carrier SLC1A5 in failing myocardium.

Circ Heart Fail. 12:e0063362019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Fernández-Sanlés A, Sayols-Baixeras S,

Curcio S, Subirana I, Marrugat J and Elosua R: DNA Methylation and

Age-independent cardiovascular risk, an Epigenome-wide approach:

The REGICOR study (REgistre GIroní del COR). Arterioscler Thromb

Vasc Biol. 38:645–652. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Guarrera S, Fiorito G, Onland-Moret NC,

Russo A, Agnoli C, Allione A, Di Gaetano C, Mattiello A, Ricceri F,

Chiodini P, et al: Gene-specific DNA methylation profiles and

LINE-1 hypomethylation are associated with myocardial infarction

risk. Clin Epigenetics. 7:1332015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Shenker NS, Polidoro S, van Veldhoven K,

Sacerdote C, Ricceri F, Birrell MA, Belvisi MG, Brown R, Vineis P

and Flanagan JM: Epigenome-wide association study in the European

Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-Turin)

identifies novel genetic loci associated with smoking. Hum Mol

Genet. 22:843–851. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Zaina S, Heyn H, Carmona FJ, Varol N,

Sayols S, Condom E, Ramírez-Ruz J, Gomez A, Gonçalves I, Moran S

and Esteller M: DNA methylation map of human atherosclerosis. Circ

Cardiovasc Genet. 7:692–700. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Ligthart S, Marzi C, Aslibekyan S,

Mendelson MM, Conneely KN, Tanaka T, Colicino E, Waite LL, Joehanes

R, Guan W, et al: DNA methylation signatures of chronic low-grade

inflammation are associated with complex diseases. Genome Biol.

17:2552016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Navas-Acien A, Domingo-Relloso A, Subedi

P, Riffo-Campos AL, Xia R, Gomez L, Haack K, Goldsmith J, Howard

BV, Best LG, et al: Blood DNA methylation and incident coronary

heart disease: Evidence from the strong heart study. JAMA Cardiol.

6:1237–1246. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Luo X, Hu Y, Shen J, Liu X, Wang T, Li L

and Li J: Integrative analysis of DNA methylation and gene

expression reveals key molecular signatures in acute myocardial

infarction. Clin Epigenetics. 14:462022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Yoshioka J, Imahashi K, Gabel SA, Chutkow

WA, Burds AA, Gannon J, Schulze PC, MacGillivray C, London RE,

Murphy E and Lee RT: Targeted deletion of thioredoxin-interacting

protein regulates cardiac dysfunction in response to pressure

overload. Circ Res. 101:1328–1338. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Dorn LE, Lasman L, Chen J, Xu X, Hund TJ,

Medvedovic M, Hanna JH, van Berlo JH and Accornero F: The

N6-methyladenosine mRNA methylase METTL3 controls cardiac

homeostasis and hypertrophy. Circulation. 139:533–545. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Yin T, Wang N, Jia F, Wu Y, Gao L, Zhang J

and Hou R: Exosome-based WTAP siRNA delivery ameliorates myocardial

ischemia-reperfusion injury. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 197:1142182024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Madsen A, Krause J, Höppner G, Hirt MN,

Tan WLW, Lim I, Hansen A, Nikolaev VO, Foo RSY, Eschenhagen T and

Stenzig J: Hypertrophic signaling compensates for contractile and

metabolic consequences of DNA methyltransferase 3A loss in human