Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a prevalent etiology of

central neuropathic pain (NP), with an estimated 40–70% of

individuals with SCI experiencing this condition (1,2). NP

represents a frequent and multifaceted secondary complication

associated with SCI (3). The

pathophysiological mechanisms underlying SCI-induced NP are

complex, encompassing neuroplastic changes within the central

nervous system, activation of immune cells, and the release of

inflammatory mediators and cytokines (4–6). The

manifestation of NP subsequent to SCI markedly influences patient

outcomes, imposing notable psychological and economic burdens

(2). Contemporary clinical

approaches for the management of NP resulting from SCI

predominantly encompass pharmacological interventions, including

antiepileptic drugs, antidepressants and opioids, alongside

neuromodulation techniques such as spinal cord stimulation,

transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and transcranial

direct-current stimulation (tDCS) (7–9).

Nonetheless, the mechanisms underlying the initiation and

progression of NP post-SCI remain inadequately elucidated, and

therapeutic strategies to mitigate SCI-induced NP remain

insufficient.

Previous studies have shown that small molecules

from traditional Chinese medicine could positively impact various

diseases, with quercetin (Que) specifically exhibiting

pain-relieving effects in NP (10,11).

Animal models have demonstrated that Que can ease pain in a

dose-dependent manner (12–14).

Being a member of the flavonoid family, Que is found in fruits and

vegetables such as apples, grapes and onions, and possesses

antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-aging and neuroprotective

qualities (15–18). Research has demonstrated that Que

can reduce oxidative stress and protect cells from

inflammation-related damage, thus enhancing its neuroprotective

properties (19,20). Although research on the impact of

Que on NP following SCI is limited, exploring its therapeutic

potential and understanding the mechanisms involved in the

interactions of Que with NP is important.

Consequently, an integrative analysis was performed

in the present study utilizing the largest available genome-wide

association study (GWAS) summary data on NP, employing the

summary-based Mendelian randomization (SMR) method. By conducting a

further examination of publicly accessible RNA sequencing datasets,

gene modules associated with SCI were identified. This methodology

enabled genes common to both SCI and NP to be identified.

Subsequently, by employing machine learning (ML) algorithms,

molecular biomarkers that were indicative of NP subsequent to SCI

were identified. In the present study, network pharmacology was

utilized to predict the potential targets of Que, followed by

molecular docking to assess the interaction between Que and these

target proteins. The resulting protein-ligand complexes were

further examined through molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to

identify viable therapeutic targets for SCI-induced NP. This

methodological approach offered novel insights and directions for

future research on the biological mechanisms of SCI-induced NP and

the development of targeted therapeutic strategies.

Materials and methods

Data acquisition and

preprocessing

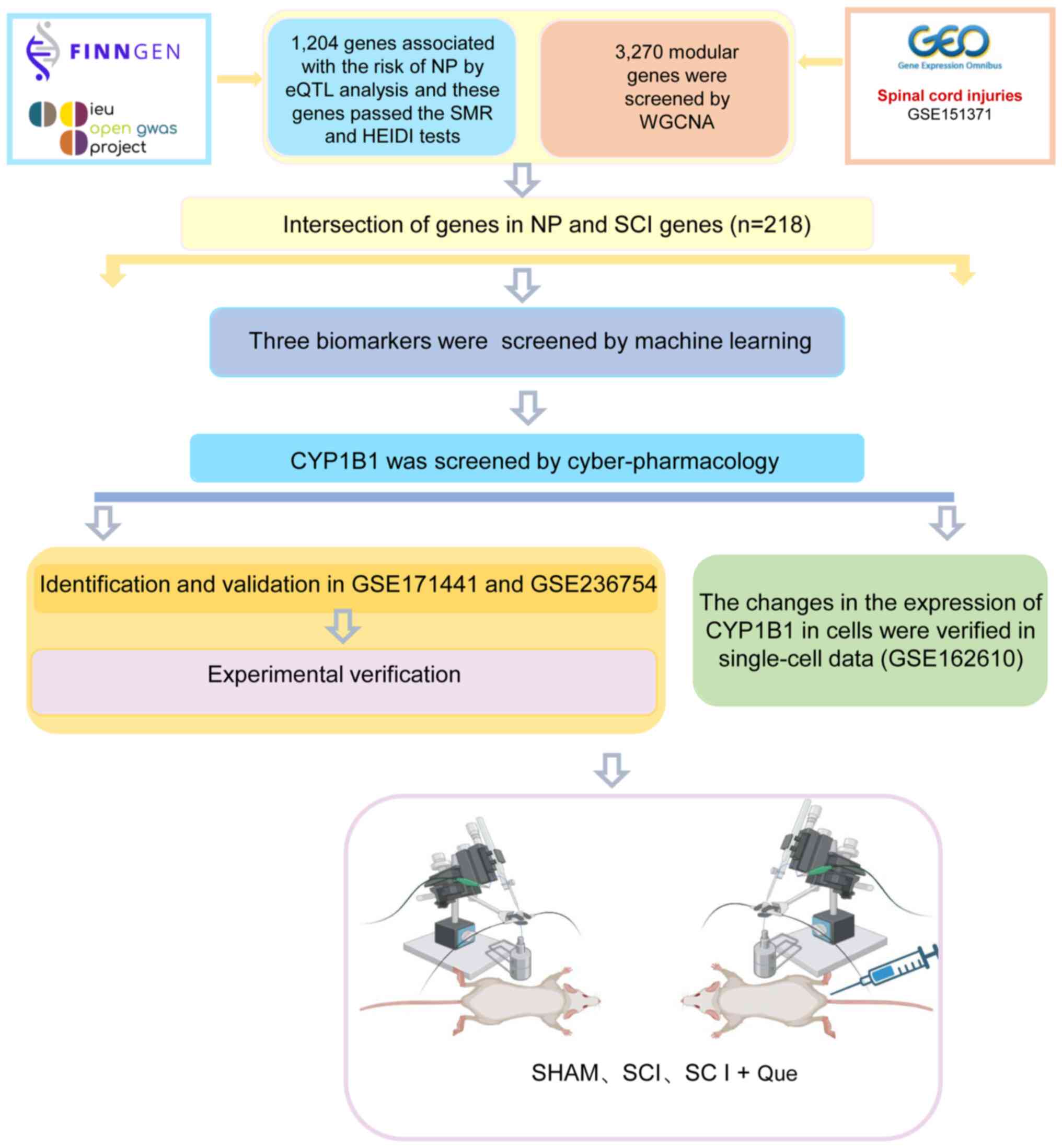

Fig. 1 illustrates

the design of the present study. The present study was centered on

trigeminal neuralgia (TN) and postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), two

conditions that exemplify NP (1).

The relevant datasets for these diseases were sourced from IEU

OPENGWAS and FINNGEN (21,22). The GWAS identifiers for these

datasets were finn-b-G6_POSTZOST and finn-b-G6_TRINEU, both of

which are accessible for public download. Pooled statistics of

blood expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) were derived from

the EQTLGEN dataset, which predominantly comprised blood samples

from healthy European individuals. The EQTLGEN dataset included

expression data for 16,987 genes, with gene expression quantified

at the transcriptional level in peripheral blood (23).

A total of four publicly accessible transcriptome

datasets were procured from the Gene Expression Omnibus database

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

These datasets included: i) A human SCI dataset (GSE151371), which

comprises blood samples from patients with SCI and healthy controls

(24); ii) a single-cell SCI

(ScSCI) dataset for mouse models (GSE162610) (25); iii) a mouse SCI model RNA dataset

(GSE171441) (26); and iv) an RNA

dataset from a mouse NP model using the spared nerve injury (SNI)

model (GSE236754) (27). The

downloaded raw RNA data were subjected to data quality control,

processing and normalization in R (version 4.2.1; R Foundation for

Statistical Computing; http://www.R-project.org/).

Screening of candidate genes

SMR and heterogeneity in dependent instruments

(HEIDI) tests detect polytropic associations

The SMR test was employed to examine the association

between exposure and outcome using instrumental variables (IVs),

typically SNPs, as previously described (28). In summary, the study utilized

cis-acting eQTL (cis-eQTL) genetic variation as an IV, with gene

expression serving as the exposure factor, and PHN and TN as the

outcomes. The Mendelian randomization (MR) approach was employed to

estimate the effect of gene expression on NP. This estimation was

derived by calculating the ratio of the estimated effect of

cis-eQTL genetic variation on NP to its estimated effect on gene

expression. This methodology was applied to integrate GWAS and eQTL

pooled statistics, thereby facilitating the examination of

pleiotropic associations between gene expression and NP. In the

present SMR analysis, the main SNP selection criteria were based on

the data processing procedures outlined on the official SMR website

(https://yanglab.westlake.edu.cn/software/smr/#Overview).

After downloading the data, the first step was to exclude SNPs with

missing values according to these procedures, and the filtered data

were then subjected to SMR analysis. The default settings in SMR

were utilized, which included selecting SNPs within a 2 Mb distance

from each individual probe as cis-eQTL, applying a PeQTL threshold

of <5×10−8 and excluding SNPs exhibiting very strong

linkage disequilibrium (r2>0.9) with the

top-associated eQTL. The heterogeneity in dependent instruments

(HEIDI) test was conducted to assess the presence of cascading

relationships within the associations (28). A PHEIDI-value >0.05

indicated that the original hypothesis was valid, suggesting the

existence of a single causal variant among the observed

associations. The F-statistic in the SMR analysis was computed

using the formula

(beQt1/seeQt1)2.

IVs exhibiting an F-statistic >10 were chosen for further

evaluation. The SMR results, encompassing trajectory plots and

effect plots, are accessible through the SMR webpage (https://yanglab.westlake.edu.cn/software/smr/#Overview).

Genes related to TN and PHN were screened by SMR, and genes related

to NP were identified by intersection.

Weighted gene co-expression network

analysis (WGCNA) and modular gene selection

WGCNA is a systems biology approach employed to

identify modules of highly correlated genes and to compute module

membership measures. Utilizing the R package ‘WGCNA’ (version

1.73), co-expression networks were constructed and filtered based

on an R2 value >0.85. The appropriate ‘soft’

thresholding power (β), ranging from 1 to 20, was selected to

ensure that the constructed co-expression networks conformed more

closely to the characteristics of scale-free networks. Finally,

utilizing Pearson's correlation coefficient and the P-value for

each module trait, the network of SCI co-expression modules was

derived and visualized to identify the shared genes within its key

modules (29). Additionally, an

online Venn diagram tool was employed to determine the intersecting

genes between SCI and NP (30).

Functional enrichment analysis

Both the Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia

of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases are accessible for the

investigation of gene functions (31,32).

To further investigate the role of genes implicated in NP following

SCI, an online Venn diagram tool was utilized to identify

intersecting genes between NP-related candidate genes and key

module genes associated with SCI. Subsequently, GO and KEGG

functional enrichment analyses were conducted using the

‘clusterProfiler’ package (version 4.14.6), with a significance

threshold set at P<0.05. Both the visualization of enrichment

analysis results and the generation of the Upset plot were

performed using the Hiplot (ORG) (https://hiplot.org) (33).

Protein-protein interaction (PPI)

network construction and identification of hub genes

Based on the identified intersecting genes, a

minimum interaction score of 0.400 was established using the STRING

database (version 12.0) to investigate protein-coding gene

interactions (34). Subsequently,

the visualization of PPI networks was performed using Cytoscape

(version 3.9.1) (35). To evaluate

and identify hub genes, seven commonly used algorithms, ‘maximal

clique centrality’, ‘measurement coefficient network’, ‘degree’,

‘embedding pathway components’, ‘closeness’, ‘radiality’ and

‘stress’, were employed using the cytoHubba plug-in in

Cytoscape.

Immune infiltration analysis

The immune infiltration analysis utilized single

sample gene set enrichment analysis to assess the relative

abundance of specific immune cell types in each sample. Enrichment

scores for a reference set of 28 unique immune cell types were

calculated to reveal infiltration patterns across the samples

(36,37). The associations between genes and

immune cells were subsequently visualized utilizing the ‘ggplot2’

(version 3.5.1; http://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/) and ‘ggExtra’ (version

0.10.1; http://cran.r-project.org/package=ggExtra) R packages,

facilitating a comprehensive depiction of gene-immune cell

relationships.

Identification of disease marker genes

through ML

Gene screening for disease diagnosis can be enhanced

through the combined application of ML algorithms, including least

absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO), support vector

machine recursive feature elimination (SVM-RFE) and random forest

(RF) algorithms, for feature selection. LASSO is a regression

technique that selects variables to enhance both the predictive

accuracy and interpretability of statistical models (38). In the current investigation, a

10-fold cross-validation approach was employed, guided by the

‘lambda.min’ criterion, to derive the final gene set utilizing the

‘lambda.min’ value. SVM-RFE, an ML algorithm, was employed for gene

selection by ordering features using a linear support vector

machine (SVM) (39). The RF

algorithm is classified under supervised learning models and

functions as an ensemble tree-based ML tool that enhances

prediction accuracy by averaging values from a subset of each tree

(40). In the RF algorithm, the

total ‘ntree’ value was configured to be 500. Additionally, the

Boruta feature selection significance threshold was established at

a P-value of 0.01, with a maximum of 300 iterations. Furthermore,

the proportion of training datasets for the purpose of database

segmentation was determined through the utilization of the

‘createDataPartition’ function. SVM-RFE, LASSO regression and RF

analyses were conducted utilizing the R function packages ‘glmnet’

(version 4.1–8) (41),

‘randomForest’ (version 4.7–1.2) (42) and ‘e1071’ (version 1.7–16)

(43). Genes identified through

SVM, LASSO and RF analyses were deemed to be potential key markers

for SCI diagnosis. To assess the association between candidate hub

genes implicated in SCI diagnosis and NP, the Comparative

Toxicogenomics Database (CTD) (https://ctdbase.org/) was utilized to extract genes

associated with NP importance scores. Consequently, the hub genes

most pertinent to NP in the context of SCI diagnosis were

identified.

Identification of SCI subtypes was performed by

non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) clustering of pain-related

genes. The NMF algorithm is an innovative ML algorithm that

identifies and clusters molecular function patterns from

high-throughput data (44). The

NMF approach was applied to samples using the ‘NMF’ R package

(version 0.26) (45) to identify

subtypes of SCI within various NP-related gene expression profiles

derived from SMR.

Column chart construction and

assessment of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve

The construction of column graphs is important in

the clinical diagnosis of SCI. In the present study, the ‘rms’ R

package (version 7.0–0; http://cran.r-project.org/package=rms) was utilized to

generate a column chart based on candidate genes. The ‘Points’

denote the scores assigned to each candidate gene, while the ‘Total

Points’ represent the aggregate score of all candidate genes.

Subsequently, the ‘pROC’ R package (version 1.18.5; http://github.com/xrobin/pROC) was employed to

construct a ROC curve (46), which

was used to evaluate the diagnostic efficacy of the candidate genes

in SCI diagnosis. The diagnostic value was quantified by

calculating the area under the curve (AUC) along with its 95% CI.

Typically, an AUC >0.7 is regarded as an acceptable diagnostic

threshold.

Network pharmacology

Screening for potential targets of Que

The Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System

notation for Que constituents was obtained from the PubChem

database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and entered into

the Swiss Target Prediction tool to identify potential targets with

a probability of ≥0.4 (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/) (47).

Molecular docking

CYP1B1 was selected as the receptor for Que. The

molecular structure and ‘MOL2’ format of Que were obtained from the

Chinese Traditional Medicine Systems Pharmacology database

(https://old.tcmsp-e.com/tcmsp.php),

while the protein structure and Protein Data Bank (PDB) format of

CYP1B1 were obtained from the PDB database (https://www.rcsb.org/). Finally,

ligand-receptor-related file formats were imported into the

AutoDock software (version 1.5.7) to perform docking, thereby

generating docking fractions and facilitating the analysis of

protein active sites (48,49). Subsequently, these results were

imported into the PYMOL software (version 2.6.0a0; http://pymol.org/) for the visualization, display and

detailed analysis of molecular structures (50).

MD simulation

MD simulations of the Que-CYP1B1 complex were

conducted utilizing the Groningen machine for chemical simulations

software version 2020.6 (https://www.gromacs.org/). The simulations employed

the ‘AMBER99SB’ force field in conjunction with the simple point

charge water model, maintaining the system at a temperature of 300

K over a duration of 40 nsec. Initially, energy minimization was

achieved through the application of the conjugate gradient method,

which was followed by a canonical ensemble equilibration step to

ensure system stabilization. The MD simulation was then executed to

completion. The resulting simulation data were analyzed and

visualized using Qtgrace software (version 0.2.6; http://sourceforge.net/projects/qtgrace/).

Validation

Validation of external datasets pertaining to

diagnostic hub genes and single-cell sequencing analysis

The mRNA expression of the identified NP-associated

key SCI diagnosis genes was validated using the GSE171441 and

GSE236754 datasets. The GSE171441 dataset comprised 3 control

samples and 3 SCI samples, while the GSE236754 dataset included 12

control samples and 12 SNI samples. An unpaired t-test-test was

used to compare control and trial group data, and P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Additionally, to identify potential targets of Que and assess the

relevance of NP-related hub genes and cells in the context of SCI,

the single-cell GSE162610 dataset was analyzed using the ‘Seurat’ R

package (version 5.2.1; http://satijalab.org/seurat/) (51). Initially, the

‘PercentageFeatureSet’ function was employed to calculate the

proportion of mitochondrial genes in each cell. The cells were then

filtered by creating separate objects for each sample, retaining

only those cells with <10% mitochondrial gene content and >50

gene expression counts. Subsequently, multiple samples were

integrated using canonical correlation analysis (52,53).

A total of 3,000 highly variable genes were selected for analysis,

and appropriate principal component values and resolution

parameters were chosen to obtain cell clusters, which were

subsequently visualized using the ‘uwot R package (version 0.2.3;

http://cran.r-project.org/package=uwot). Subsequently,

the analyzed clusters were annotated by integrating the results of

the corresponding marker genes from the PanglaoDB database

(54) and the CellMarker database

(55). Finally, the ‘ggplot2’ R

package (version 3.5.1; http://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/) was employed for the

subsequent visualization of the single-cell sequencing analysis

results.

Construction of the SCI model

The study was in compliance with the Guidelines for

the Care and Use of Experimental Animals (https://portal.smu.edu.cn/sydwzx/fgbz/3.htm) and

approved by the Ethics Committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital

of Southern Medical University and the Animal Experimental

Committee of the Daoke Pharmaceutical Technology (Guangdong) Co.,

Ltd. (approval no. IACUC-DK-2024-04-10-01). Male C57BL6J mice (6–8

weeks old; mean body weight, 25 g; Huaxia Cage Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.), underwent standardized rearing in an SPF animal house

(temperature, 22±2°C; relative humidity, 55±5%; 12-h light-dark

cycle) with daily monitoring of environmental parameters,

replacement of litter and replenishment of food and water every

48–72 h. The mice were randomly allocated into three experimental

groups, each consisting of 20 subjects (n=20 per group): The

sham-operated (SHAM) control group, which underwent anesthesia,

laminectomy and all surgical procedures except for the induction of

SCI, the SCI group and the SCI combined with Que treatment group

(SCI + Que). In the present study, C57BL/6J strain mice were

anesthetized by intraperitoneal administration of a 1.25% solution

of tribromoethanol (commercially known as Avertin (cat. no.

75-80-9; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) at a dose of 250 mg/kg. In the

present study, Avertin was used only prior to model construction

and euthanasia. The mice were anesthetized using Avertin™ and

subjected to a laminectomy at the T10 vertebral level to expose the

T9-T10 segment of the spinal cord. SCI was induced via a controlled

contusion at the T9 segment, utilizing a spinal impactor with the

following parameters: i) Impact velocity of 1.5 m/sec; ii) impact

depth of 0.2 mm; iii) dwell time of 0.5 sec; and iv) hammer

diameter of 1.3 mm. Post-surgical procedures involved suturing the

skin and muscle, followed by placing the mice on a heating pad to

promote recovery. Manual bladder expression was conducted twice

daily for a duration of 2 weeks to aid in urination. Furthermore,

all mice were administered intraperitoneal injections of the

antibiotic cefotaxime (cat. no. 64485-93-4; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA) at a dosage of 16 mg/kg, administered twice daily over a

period of 7 days. Mice in the SCI + Que group received Que (cat.

no. hy-18085; MedChemExpress) injections twice daily at a dose of

7.5 mg/kg for 14 days. This dose was specifically selected based on

previous studies (56,57). Motor function was evaluated using

the Basso Mouse Scale (BMS) on postoperative days 1, 3, 7, 10 and

14. The BMS scoring system categorizes motor function as follows:

i) A score of 0 signifies total paralysis; ii) scores ranging

between 1 and 3 reflect mild movement capabilities; iii) scores of

4–5 denote the presence of a plantigrade gait; iv) scores from 6 to

8 indicate coordinated walking abilities; and v) a score of 9

represents normal motor function (58). Additionally, on postoperative day

14, the mechanical paw withdrawal threshold (MWT) and thermal paw

withdrawal latency (TWL) were assessed in the hind paws of mice

from each experimental group. MWT was determined using a set of

calibrated Von Frey aesthesiometers (KW-CT-1; KEW BASIS; Nanjing

Calvin Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), and the TWL was measured using the

Plantar Test (Hargreaves method) with heated glass (part no. 390G;

IITC, Inc.). The mice were anesthetized with 250 mg/kg of Avertin

and then euthanized by cervical dislocation. Death was confirmed by

the absence of cardiac or respiratory activity for at least 5 min

post-mortem, along with no response to painful stimuli.

Cell culture

Fibroblasts of the NRK-49F cell line (cat. no.

CL-0854; Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) were

maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine

serum (FBS; FSP500; Shanghai ExCell Biology, Inc.) and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin under standard conditions at 37°C with 5%

CO2. The fibroblasts were seeded at a density of

2×105 cells/ml and allocated into three experimental

groups (n=4 per group): i) Control (Con) group; ii) group treated

with 10 ng/ml TGF-β; and iii) group treated with 10 ng/ml TGF-β in

combination with 10 µmol/ml Que (TGF-β + Que). Each group was

subjected to the respective treatments for a duration of 24 h.

Western blotting

NRK-49F cells and mouse spinal cord tissue samples

were lysed using a lysis buffer containing a protease inhibitor

cocktail (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Protein

concentration was determined using the BCA protein assay kit (cat.

no. 23227; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The protein samples

were then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes, which

were subsequently blocked for 1 h at room temperature., washed with

TBST solution and incubated with the following primary antibodies:

CYP1B1 (1:500; cat. no. 18505-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.),

Fibronectin (Fn) (1:1,000; cat. no. ab2413; Abcam) and GAPDH

(1:50,000; cat. no. 1E6D9; Proteintech Group, Inc.). The membrane

was incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The

following day, after washing, it was incubated with horseradish

peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:5,000; cat. no.

ab205718; Abcam) and goat anti-mouse IgG (1:5,000; cat. no.

ab150113; Abcam) for 1 h at room temperature. Protein detection was

performed using the Biodlight™ ECL Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate

(High Sensitivity) (cat. no. BLH01S100; Bioworld Technology, Inc.)

and a TANON-5200 Chemiluminescent Imaging System (Tanon Science and

Technology Co., Ltd.). Results analysis was performed using ImageJ

software (version 1.54 g; National Institutes of Health) and Prism

(version 9.0.0; Dotmatics).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from spinal cord tissue and

fibroblasts utilizing Trizol reagent (cat. no. bs258A; Biosharp

Life Sciences). After verifying RNA purity, complementary DNA

(cDNA) synthesis was performed using the HiScript II Q RT SuperMix

for qPCR kit (cat. no. R222-01; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) according

to the manufacturer's instructions. The reverse transcription

procedure was carried out under the following conditions: 50°C for

15 min, 85°C for 5 sec, followed by a hold at 4°C. qPCR was

subsequently performed with the ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master

Mix kit (cat. no. Q711-02; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.). The

amplification protocol consisted of an initial phase for 1 min at

95°C, followed by 50 cycles for 15 sec at 95°C and 30 sec at 50°C.

The relative mRNA expression levels of the target genes were

normalized to GAPDH expression levels and analyzed using the

2−ΔΔCq method (59).

Details of the primer sequences are shown in Table SI, and the rat primers included in

the table are for cell experiments only.

Immunofluorescence

After euthanasia, the spinal cords were removed and

washed in PBS. The spinal cords were immersed in a 4%

glutaraldehyde solution at 4°C for 24 h for fixation, followed by

cryoprotection in a sucrose solution for 48 h at 4°C. Using a

cryostat, the spinal cords were manually sectioned into 10-µm-thick

slices for immunofluorescence staining. The slides were allowed to

equilibrate at room temperature for 1 h. Subsequently, 0.5% Triton

X-100 permeabilization solution (cat. no. 9036-19-5; Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA) was applied to the sections and incubated at 4°C for 5

min. Ready-to-use goat serum blocking buffer (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) was then applied, followed by incubation at room

temperature for 1 h. The sections were incubated overnight at 4°C

with the following primary antibodies: CYP1B1 (1:100 dilution; cat.

no. 18505-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and PDGF-D (1:100

dilution; cat. no. 14075-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.). Afterward,

the sections were stained for 1 h with the following secondary

antibodies: Goat anti-mouse IgG H&L (1:500; cat. no. ab150113;

Abcam) and goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (1:500; cat. no. ab150080;

Abcam). Finally, cell nuclei in the tissue sections were labeled

using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (cat. no. F6057; Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA). The stained samples were visualized under an upright

fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation), and images were

analyzed using ImageJ software. Three replicates were conducted for

the immunofluorescence experiments to ensure the reliability and

reproducibility of the results of the present study. Furthermore,

spinal cord tissues were collected from six independent mice per

group to account for inter-individual variability. Additionally,

serial sections from the same tissue block were stained separately

on different days to control for batch effects. Furthermore, ImageJ

(National Institutes of Health) was used to quantify fluorescence

intensity by measuring the mean pixel intensity of the regions of

interest. To ensure accuracy, the fluorescence intensity data were

normalized to sham group samples to account for variations in

imaging conditions.

Statistical analysis

In the present study, R (version 4.2.1, R Foundation

for Statistical Computing; http://www.R-project.org/) was used as the core

analysis tool, and Prism 9.0 was used for all data statistics. The

data presented are from three independent experiments. During

hypothesis testing, each value is presented as mean ± SEM. For

comparative analysis of different data structures, two groups were

compared using an independent samples t-test. Multiple groups were

compared using one-way ANOVA, followed by the Tukey's honest

significant difference post hoc test. The Kruskal-Wallis test was

applied for the BMS scores, followed by Dunn's post hoc test. The

resulting figure was visualized using Adobe Illustrator (version

24.0; http://www.adobe.com/products/illustrator.html).

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

NP-related genes identified using SMR,

and the key module genes associated with SCI determined through

WGCNA

Prioritization was achieved through WGCNA, utilizing

the SMR and HEIDI methods to identify pleiotropic associations

between gene expression and both TN and PHN. To mitigate the

effects of pleiotropy and improve the precision of causal

inference, cis-eQTLs were exclusively used as genetic instruments.

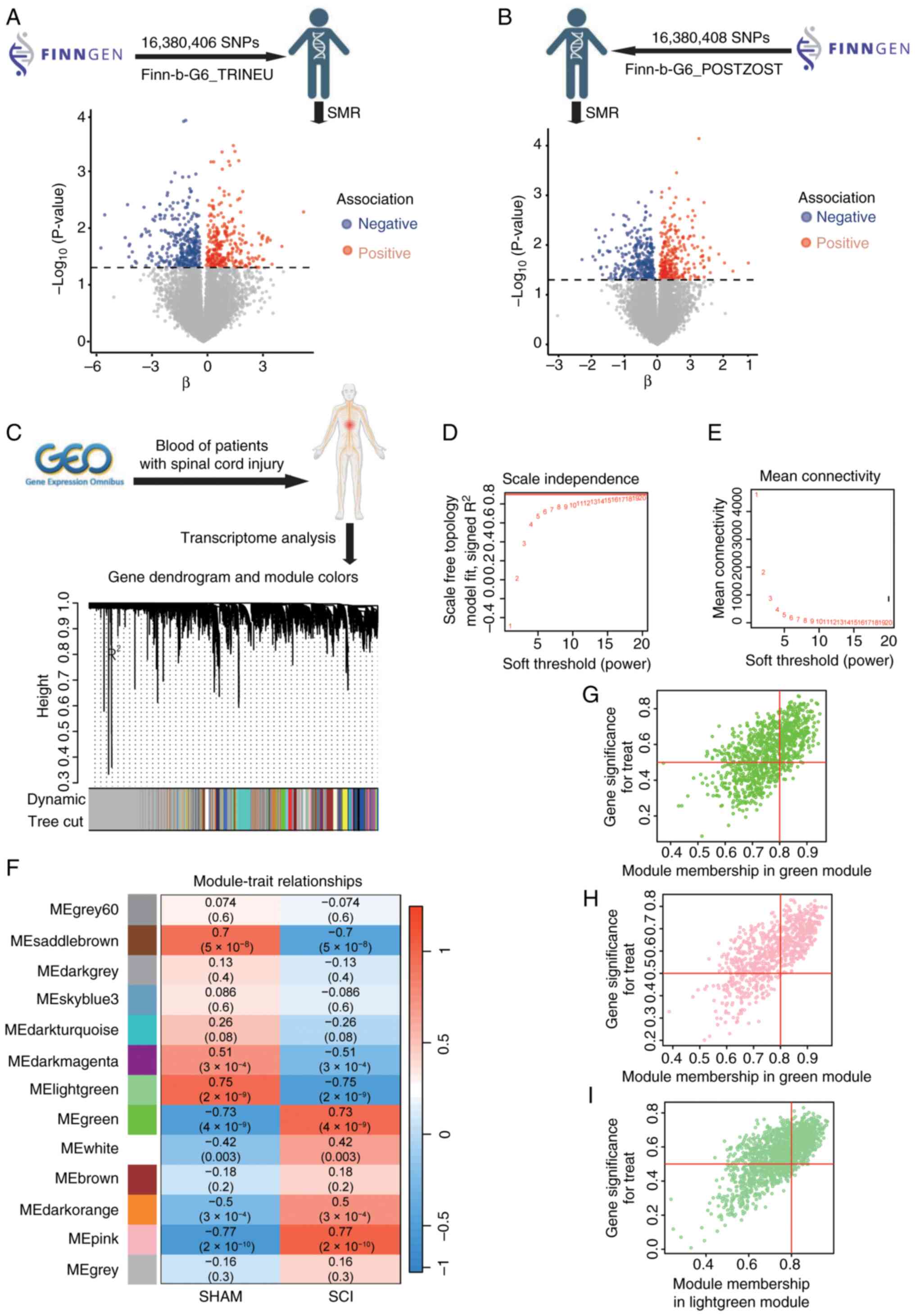

The SMR results, following HEIDI testing, revealed associations

with 610 genes for TN (Fig. 2A)

and 619 genes for PHN (Fig. 2B).

In the present study, the most pertinent modules related to SCI

were analyzed using WGCNA. Based on this threshold, 13 distinct

gene co-expression modules were identified, with each module

represented by a different color (Fig.

2C). The analysis revealed that selecting a ‘soft’ thresholding

power β of 20 (scale-free R2, 0.85) resulted in gene

associations that most closely adhered to a scale-free distribution

(Fig. 2D and E). Pearson's

correlation analysis revealed that the MEpink module (correlation

coefficient r, 0.77), the MElightgreen module (correlation

coefficient r, −0.75) and the MEgreen module (correlation

coefficient r, 0.73) exhibited strong correlations with SCI

(Fig. 2F). Consequently, modules

with correlation coefficients >0.70 were identified as key

modules for subsequent SCI analyses. This selection process

resulted in a total of 3,243 genes identified across the three key

modules (Fig. 2G-I).

Core gene screening and immune

infiltration analysis

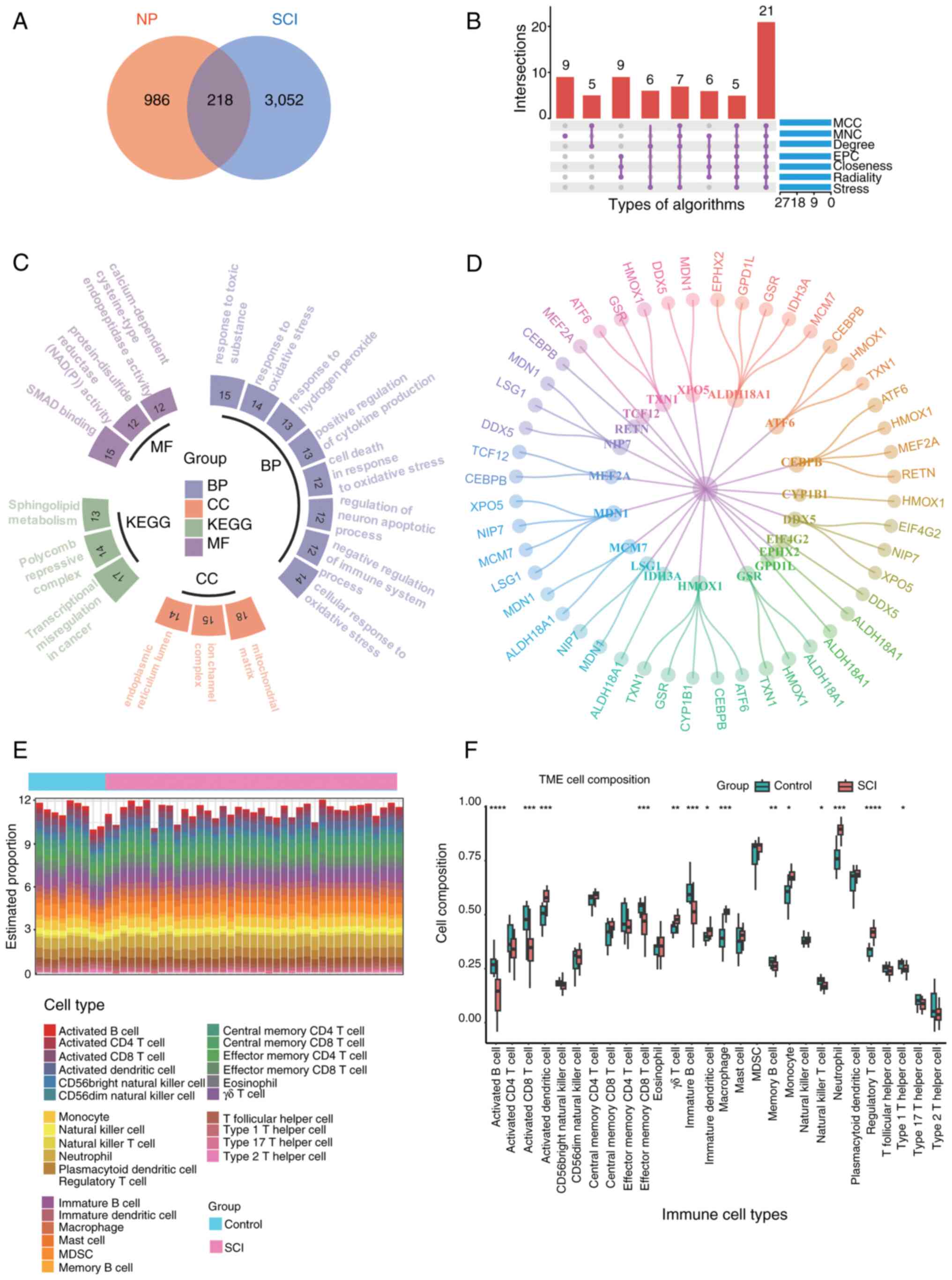

The aforementioned NP-related candidate genes were

cross-referenced with key module genes associated with SCI,

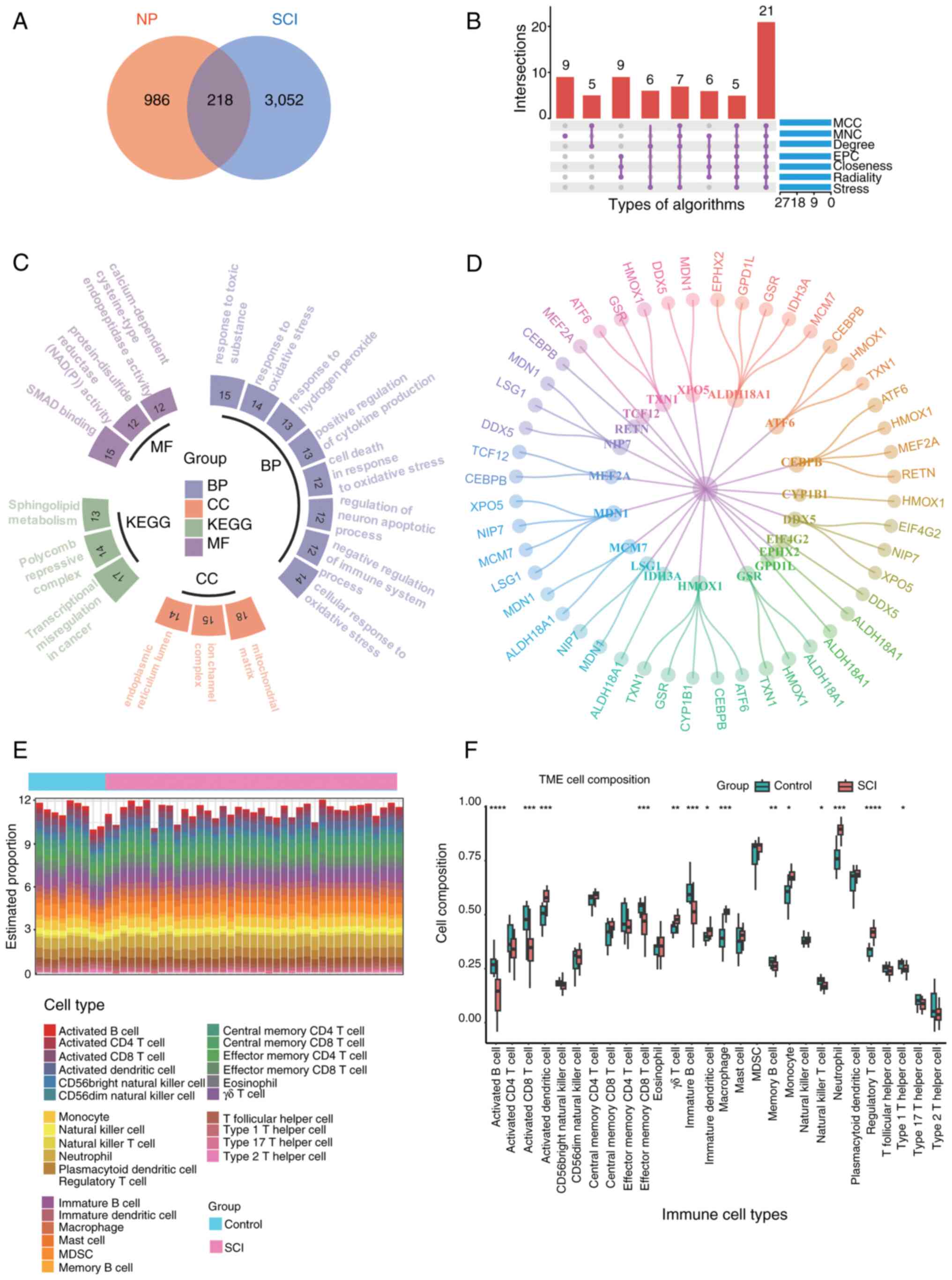

resulting in the identification of 218 intersecting genes (Fig. 3A). By applying seven different

algorithms implemented by the cytoHubba plug-in in Cytoscape, the

top 45 genes for each algorithm's respective score were identified.

Following the intersection analysis using a Upset plot, 21 hub

genes were identified (Fig. 3B).

These 218 genes subsequently underwent GO and KEGG enrichment

analyses (Fig. 3C). The GO

enrichment analysis revealed that the intersecting genes were

predominantly associated with biological processes such as

‘response to toxic substance’, ‘response to oxidative stress’ and

‘regulation of neuron apoptotic process’. In the context of

cellular component ontology, notable enrichment was observed in the

‘mitochondrial matrix’ and ‘ion channel complex’. Molecular

function analyses indicated that the intersecting genes were

predominantly enriched in ‘protein-disulfide reductase (NAD(P))

activity’, ‘SMAD binding’ and ‘calcium-dependent cysteine-type

endopeptidase activity’. Regarding the KEGG pathway analysis,

notable enrichment was found in ‘transcriptional misregulation in

cancer’, ‘polycomb repressive complex’ and ‘sphingolipid

metabolism’. The 218 intersecting genes were subsequently analyzed

to determine potential interactions among their encoded proteins

using the STRING database. In order to explore the protein-protein

interaction of these 21 genes, PPI interaction experiments were

carried out (Fig. 3D). The

observations of the analysis indicated that genes associated with

NP were implicated in the pathogenesis of SCI. Enrichment analysis

revealed notable involvement in immune system regulation.

Consequently, immune infiltration analysis may provide deeper

insights into the immune regulatory mechanisms underlying SCI. The

bar graph in Fig. 3E illustrates

the proportion of 28 immune cell types in each sample for both

patients with SCI and control subjects in the GSE151371 dataset.

According to the vioplot analysis, patients with SCI exhibited

elevated levels of activated dentritic cell, γδ T cells, immature

dendritic cells, macrophages, monocytes, neutrophils and regulatory

T cells compared with controls. Conversely, the levels of activated

B cells, activated CD8 T cells, effector memory CD8 T cells,

immature B cells, memory B cells, natural killer cells and type 1 T

helper cells were found to be lower in patients with SCI than in

controls (Fig. 3F).

| Figure 3.(A) Venn diagram obtained by crossing

NP-related candidate genes with SCI key module genes, with a total

of 218 common genes. (B) Upset plot depicting the intersection of

the top 45 genes produced by each of the seven algorithms to get 21

genes. (C) Results of GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of 218 common

genes. Different colors represent the classification of different

enrichment pathways, including KEGG, and BP, CC and MF in GO, with

P<0.05 for all enriched pathways, and the number of each bar

cell represents the Count. (D) Protein-protein interaction network

diagram of the 21 core genes (there are only 20 gene interactions

in the image as the gene ALOX5AP cannot be identified by the SRING

database). (E) Proportions of 28 immune cell types in different

samples are shown in the bar graph. (F) Comparison of the

proportions of 28 immune cell types in SCI and control groups.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 vs.

control. BP, biological processes; CC, cellular component; GO, Gene

Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encylopedia of Genes and Genomes; MF,

molecular function; NP, neuropathic pain; SCI, spinal cord injury;

TME, tumor microenvironment; MCC, maximal clique centrality; MNC,

measurement coefficient network; EPC, embedding pathway

components. |

Identification of the diagnostic

marker gene CYP1B1

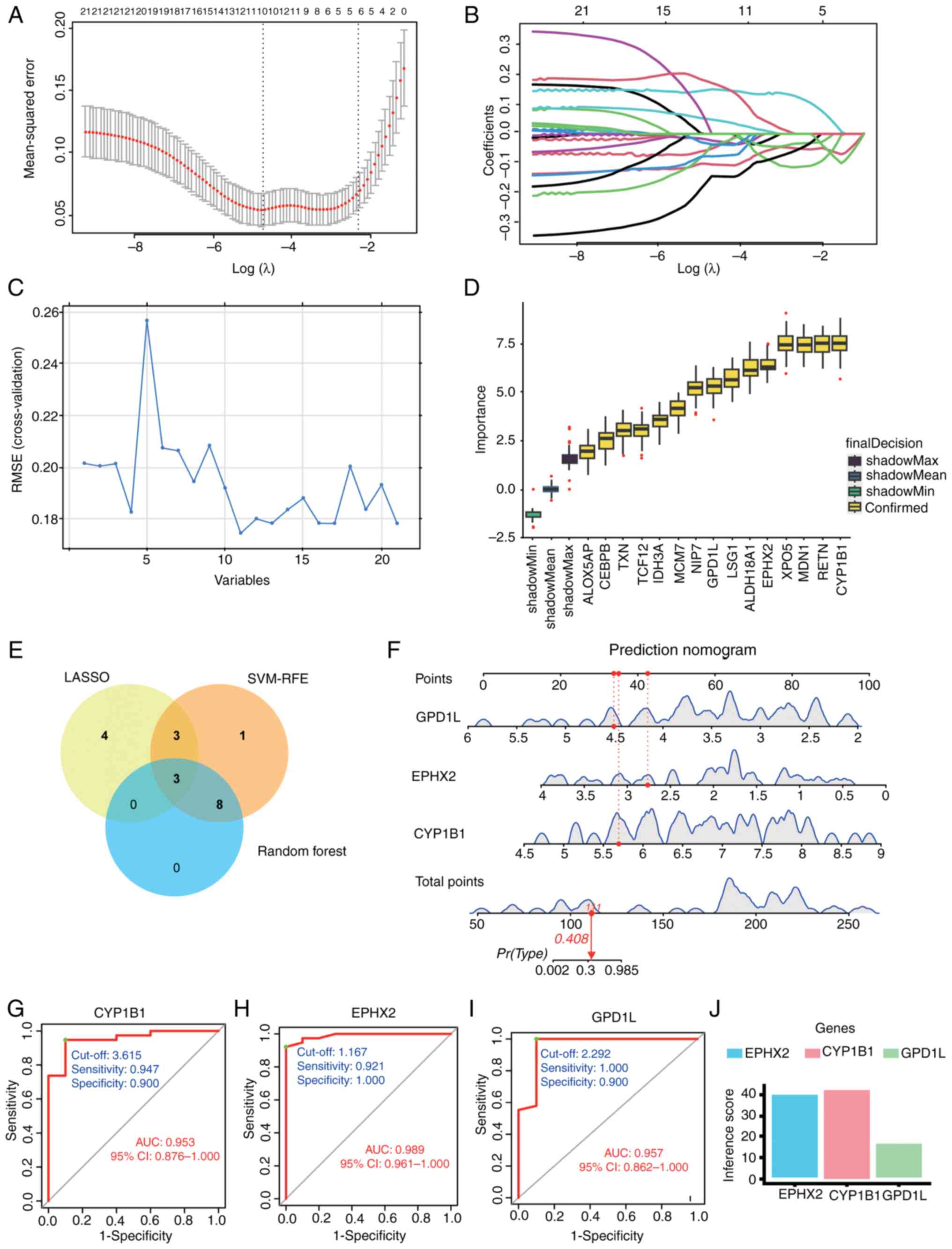

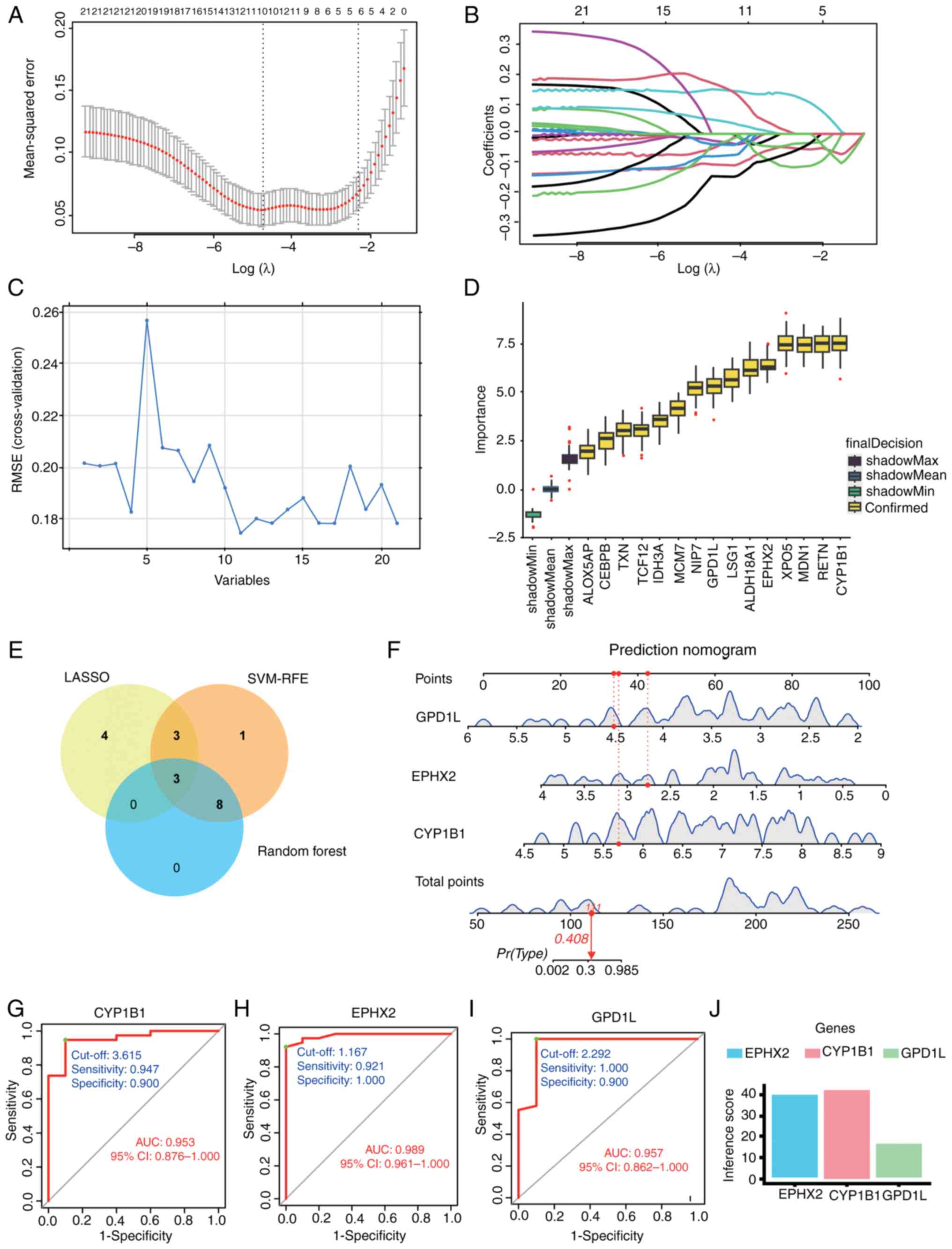

The pivotal genes were identified through the

application of LASSO regression, SVM-RFE and RF ML algorithms,

which facilitated the construction of column-line diagrams and the

assessment of diagnostic value. LASSO regression identified 10

potential diagnostic candidate genes (Fig. 4A and B), while the SVM-RFE

algorithm identified 11 potential diagnostic candidate genes

(Fig. 4C). The RF algorithm ranked

the 21 genes identified at the intersection of seven algorithms.

From this ranking, the top 15 most diagnostic candidate genes were

selected. (Fig. 4D). The potential

diagnostic candidate genes identified through three ML algorithms

were visualized using a Venn diagram (Fig. 4E), leading to the selection of

three genes, CYP1B1, EPHX2 and GPD1L, for further investigation.

Subsequently, a nomogram was developed (Fig. 4F) utilizing these three diagnostic

candidate genes. ROC curves were constructed for the aforementioned

genes to evaluate their diagnostic specificity and sensitivity. The

AUC of CYP1B1 was 0.953 with a CI of 0.876–1.000 and an optimal

cut-off of 3.615 (Fig. 4G), the

AUC of EPHX2 was 0.989 with a CI of 0.961–1.000 and an optimal

cut-off of 1.167 (Fig. 4H), and

the AUC of GPD1L was 0.957 with a CI of 0.862–1.000 and an optimal

cut-off of 2.292 (Fig. 4I). These

findings suggest that CYP1B1, EPHX2 and GPD1L possess significant

diagnostic value for SCI. The association between three identified

candidate genes for SCI diagnosis and neuralgia disease was

investigated by using the inference score of neuralgia disease with

CTD (https://ctdbase.org/). Among them, CYP1B1

exhibited the highest inference score, suggesting a stronger

association with pain (Fig. 4J).

As a result, CYP1B1 was selected as a target gene in the blood for

further investigation of its association with NP risk through MR

analysis. Additionally, the gene CDC42 effector protein 3, located

within a 2 Mb window of CYP1B1, was identified to be associated

with NP risk (Fig. 5A and B).

| Figure 4.(A) Screening of diagnostic marker

genes in the LASSO model. This panel shows the cross-validated

mean-squared error plotted against Log(λ). The number of genes

corresponding to the lowest point of the curve (n=10) was most

suitable for the diagnosis of SCI. (B) This panel displays the

number of features (variables) retained in the model at different

values of Log(λ). (C) Characteristic gene selection using the

SVM-RFE technique. A total of 11 characteristic genes were

identified from the 21 core genes. (D) The 15 trait genes were

ranked according to the importance score. (E) Venn diagram of

diagnostic candidate genes identified by three machine algorithms.

(F) Predicted nomograms of candidate genes for SCI diagnosis. To

use it, locate the value for each biomarker (GPD1L, EPHX2, CYP1B1)

on its respective scale and draw a line upward to the ‘Points’ axis

to determine the score for each variable. Sum all the points to get

the ‘Total points’. (G) ROC curve of CYP1B1 in GSE151371 with an

AUC value of 0.953. (H) ROC curve of EPHX2 in GSE151371 with an AUC

value of 0.989. (I) ROC curve of GPD1L in GSE151371 with an AUC

value of 0.957. (J) Visualization of SCI diagnostic candidate genes

based on CTD pain inference scores. AUC, area under the curve; CTD,

Comparative Toxicogenomics Database; CYP1B1, cytochrome P450 family

1 subfamily B member 1; EPHX2, epoxide hydrolase 2; GPD1L,

glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1-like; LASSO, least absolute

shrinkage and selection operator; RMSE, root mean square error;

ROC, receiver operating characteristic; SCI, spinal cord injury;

SVM-RFE, support vector machine recursive feature elimination. |

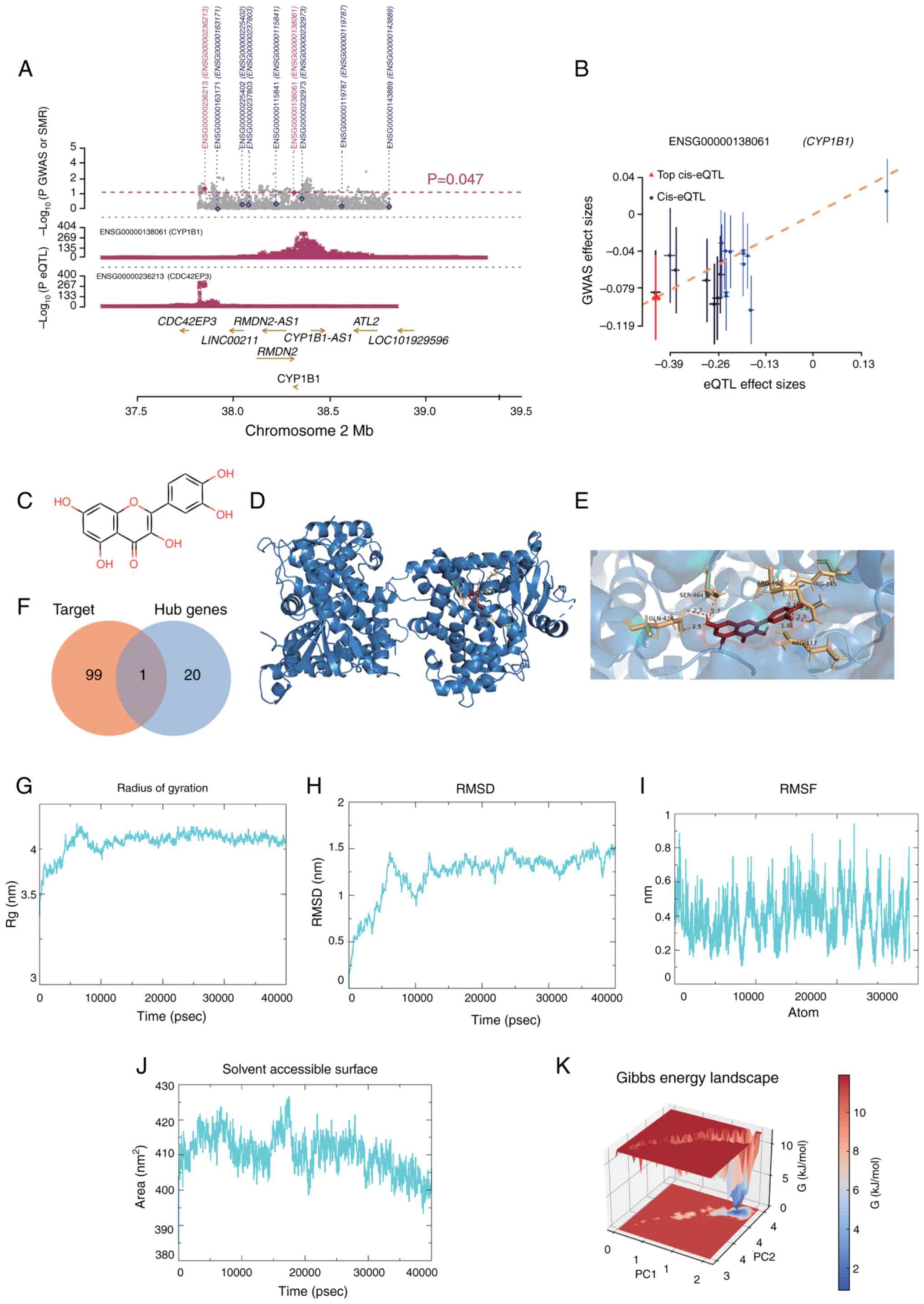

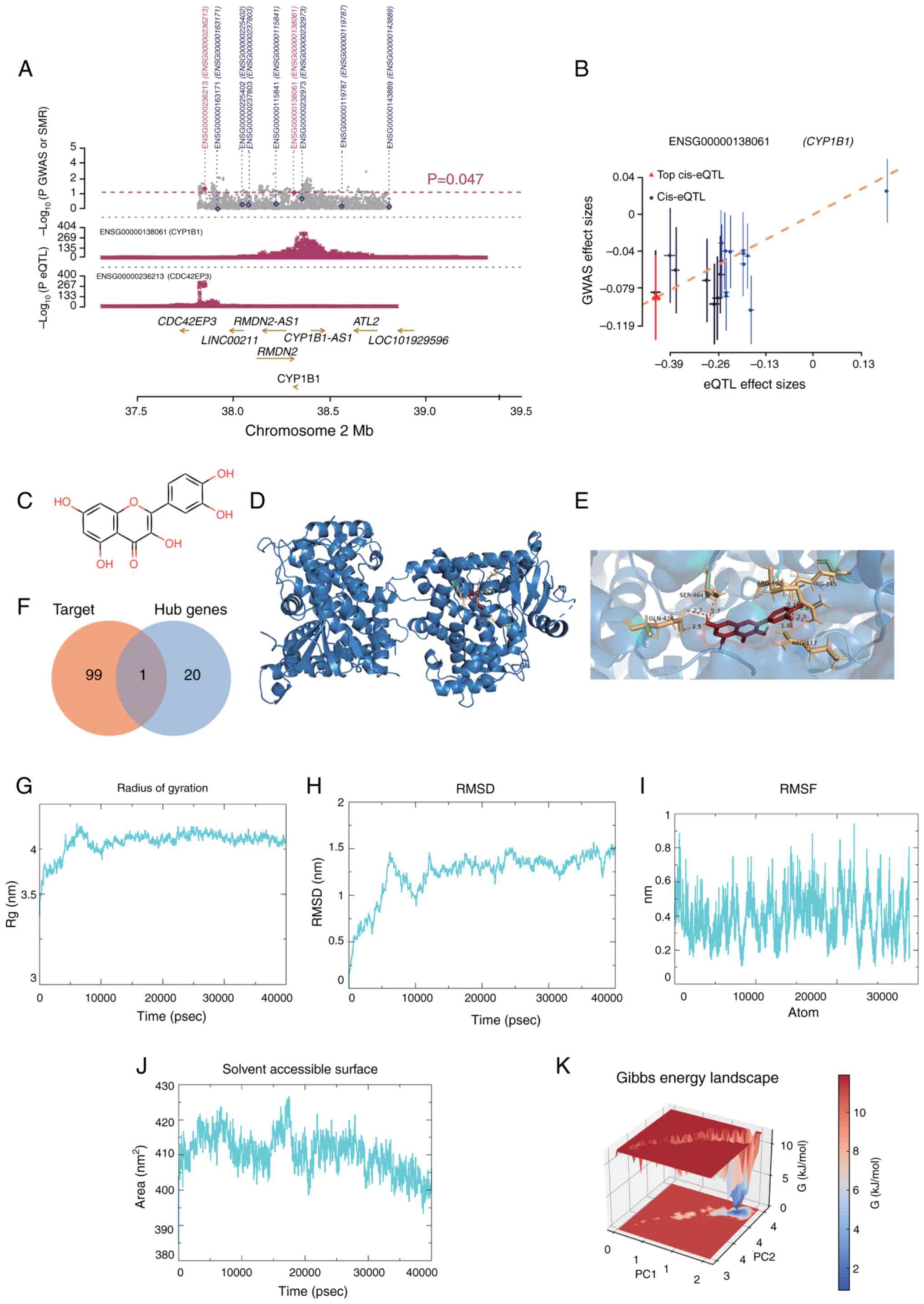

| Figure 5.(A) MR association between CYP1B1

gene expression and trigeminal neuralgia in blood. All SNPs

available in GWAS and eQTL data are shown in. (A) Grey dots

represent the P-values of SNPs for GWAS, and diamonds represent

P-values of probes for SMR tests. (B) P-values for eQTL analyses of

CYP1B1 SNPs from GWAS (used in the heterogeneity in dependent

instruments test) are plotted against effect sizes of SNPs from

eQTL studies. The orange dashed line indicates the effect size

estimate for the MR association at the top cis-eQTL. The error line

is the standard error of the SNP effect. (C) Chemical structure of

Que. (D) Interaction of the CYP1B1 receptor with Que ligands. The

protein is depicted as a blue cartoon (α-helices and β-sheets) with

its molecular surface shown in transparent gray. Que is shown as

red sticks. (E) Detailed view of the local interactions within the

Que-CYP1B1 binding pocket Protein residues are shown as blue

sticks. The ligand, Que, is shown as red sticks. (F) Venn diagram

of potential targets of Que and 21 core genes. (G) Rg of the

Que-CYP1B1 complex. (H) RMSD of the Que-CYP1B1 complex. (I) RMSF of

CYP1B1 protein residues. (J) Solvent accessible surface of the

Que-CYP1B1 complex. (K) Free energy landscape of the Que-CYP1B1

complex. CYP1B1, cytochrome P450 family 1 subfamily B member 1;

eQTL, expression-quantitative trait loci; GWAS, genome wide

association study; MR, Mendelian randomization; PC, principal

component; Que, quercetin; Rg, radius of gyration; RMSD, root mean

square deviation; RMSF, root mean square fluctuation; SMR,

summary-based Mendelian randomization. |

Screening and identification of target

genes for Que

Fig. 5C depicts the

chemical structure of Que. Employing a network pharmacology

methodology, 100 potential gene targets of Que were identified.

This analysis revealed that CYP1B1 was implicated not only in the

pathogenesis of NP following SCI but also as a potential

therapeutic target for Que.

Molecular docking of Que and

CYP1B1

Molecular docking experiments were conducted to

further investigate the interaction between CYP1B1 and Que,

revealing a binding energy of −8.9 kcal/mol for Que with CYP1B1

(Fig. 5D and E). The intersections

of these potential targets with 21 core genes were analyzed using a

Venn diagram (Fig. 5F). The

binding affinity of both entities was determined to be <-5

kcal/mol, indicating a notable affinity of Que for CYP1B1. The

interaction bond between Que and CYP1B1 is represented in Fig. S1A. Furthermore, negative control

substances that exhibit anti-inflammatory properties and possess a

comparable molecular weight to Que, specifically paracetamol,

aspirin and caffeine, were incorporated. In the present

investigation, The aforementioned negative control reagents were

docked with CYP1B1. Although the binding energies of the control

reagents with CYP1B1 were <-5 kcal/mol, Que exhibited the

strongest binding affinity, as indicated by the most negative

binding energy. This is one of the reasons why Que was chosen for

follow-up. The detailed molecular docking results are shown in

Fig. S1B.

MD simulation study of the Que-CYP1B1

complex

To further validate the binding affinity and

stability of Que with CYP1B1, a 40 nsec MD simulation was conducted

to assess the docking results. The root mean square deviation

(RMSD) is a dependable measure for assessing the stability of

protein-ligand conformations, as it indicates changes in atomic

positions compared with the original structure. Greater stability

is indicated by a lower RMSD value. As depicted in Fig. 5G and H, the Que-CYP1B1 complex

achieved equilibrium after 15,000 psec, with RMSD fluctuations

stabilizing at ~1.25 Å, and the radius of gyration (Rg) exhibited

only slight variations during the simulation, suggesting that the

interaction between Que and CYP1B1 is highly stable. The

flexibility of the amino acid residues of the protein was assessed

using the root mean square fluctuation (RMSF). As illustrated in

Fig. 5I, the RMSF values were

relatively low (predominantly <1 Å), indicating high stability.

Additional analysis revealed that the solvent-accessible surface

area fluctuated between 395 and 425 Å2 during the

simulation (Fig. 5J), suggesting

that the structure of the protein remained relatively stable after

ligand attachment. Using RMSD and Rg values, the Gibbs relative

free energy was used to create a free energy landscape, with RMSD,

Rg and Gibbs free energy plotted on the X, Y and Z axes. The free

energy landscape outlines the lowest energy conformations seen

during the MD simulation of the complex, as shown in Fig. 5K. The blue points represent the

lowest energy values, which correspond to the most stable

structural shapes. The Que-CYP1B1 complex demonstrated a nearly

singular and smooth minimum energy cluster. In summary, the

Que-CYP1B1 complex exhibited substantial binding stability,

suggesting that Que effectively binds to CYP1B1.

CYP1B1 genotype identification and

external validation

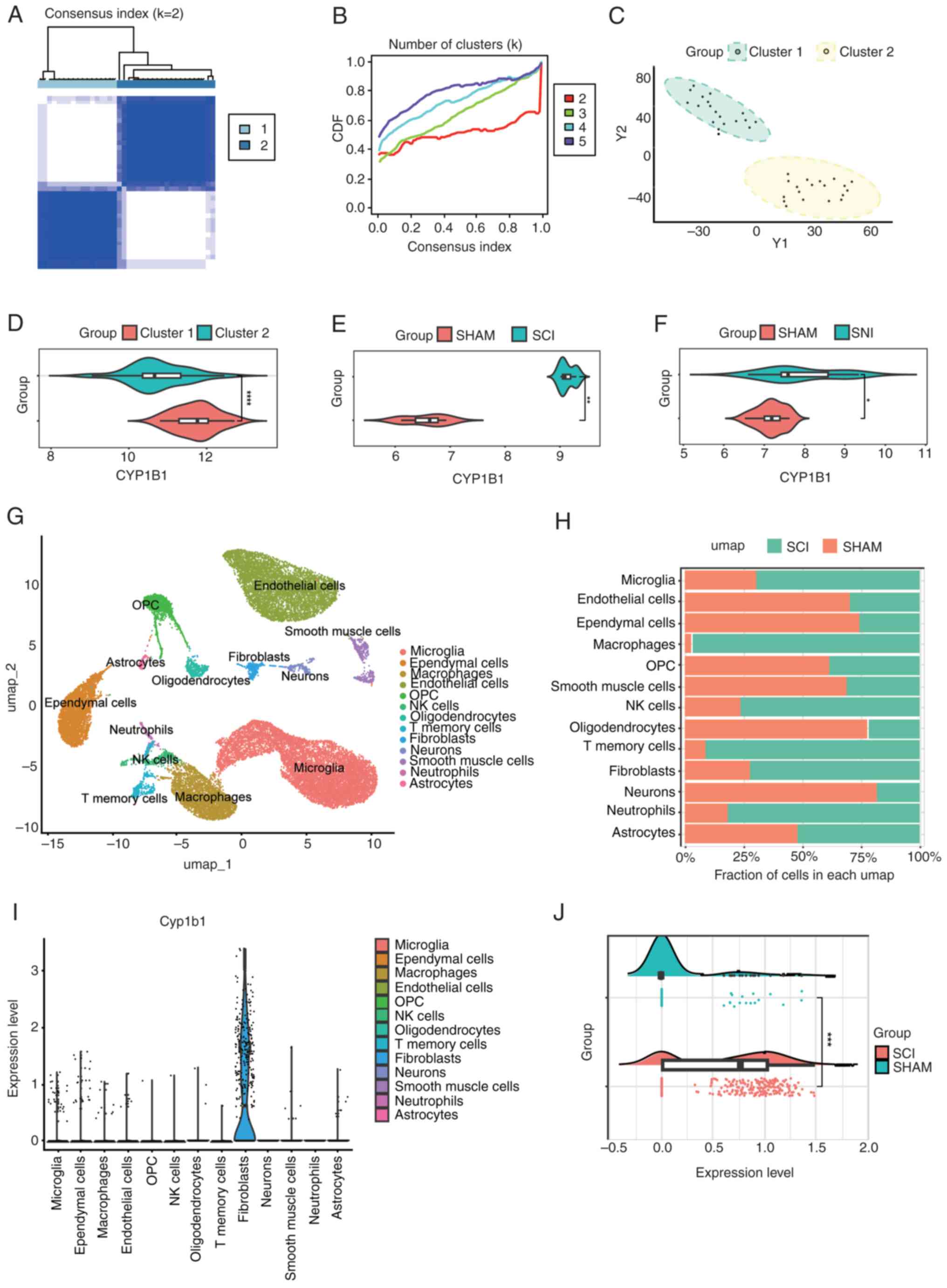

The NMF algorithm was utilized to cluster 38 SCI

samples according to the expression profiles of genes associated

with NP, as identified through the SMR approach. The clustering

analysis exhibited optimal stability when the number of clusters,

K, was designated as 2 (Fig. 6A).

The cumulative distribution function curve exhibits fluctuations

from 0.3 to 1.0 across the minimum range of the consensus index for

varying values of K (Fig. 6B).

Finally, the 38 SCI samples were classified into two subtypes:

Cluster 1 (n=18) and cluster 2 (n=20). Principal component analysis

demonstrated notable differences between cluster 1 and cluster 2 in

the expression levels of NP-related genes (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, it was observed

that the core gene CYP1B1 was highly expressed in the cluster 1

subtype (Fig. 6D). Validation

using the GSE171441 and GSE236754 datasets demonstrated significant

upregulation of CYP1B1 in both SCI and NP conditions compared with

SHAM (Fig. 6E and F).

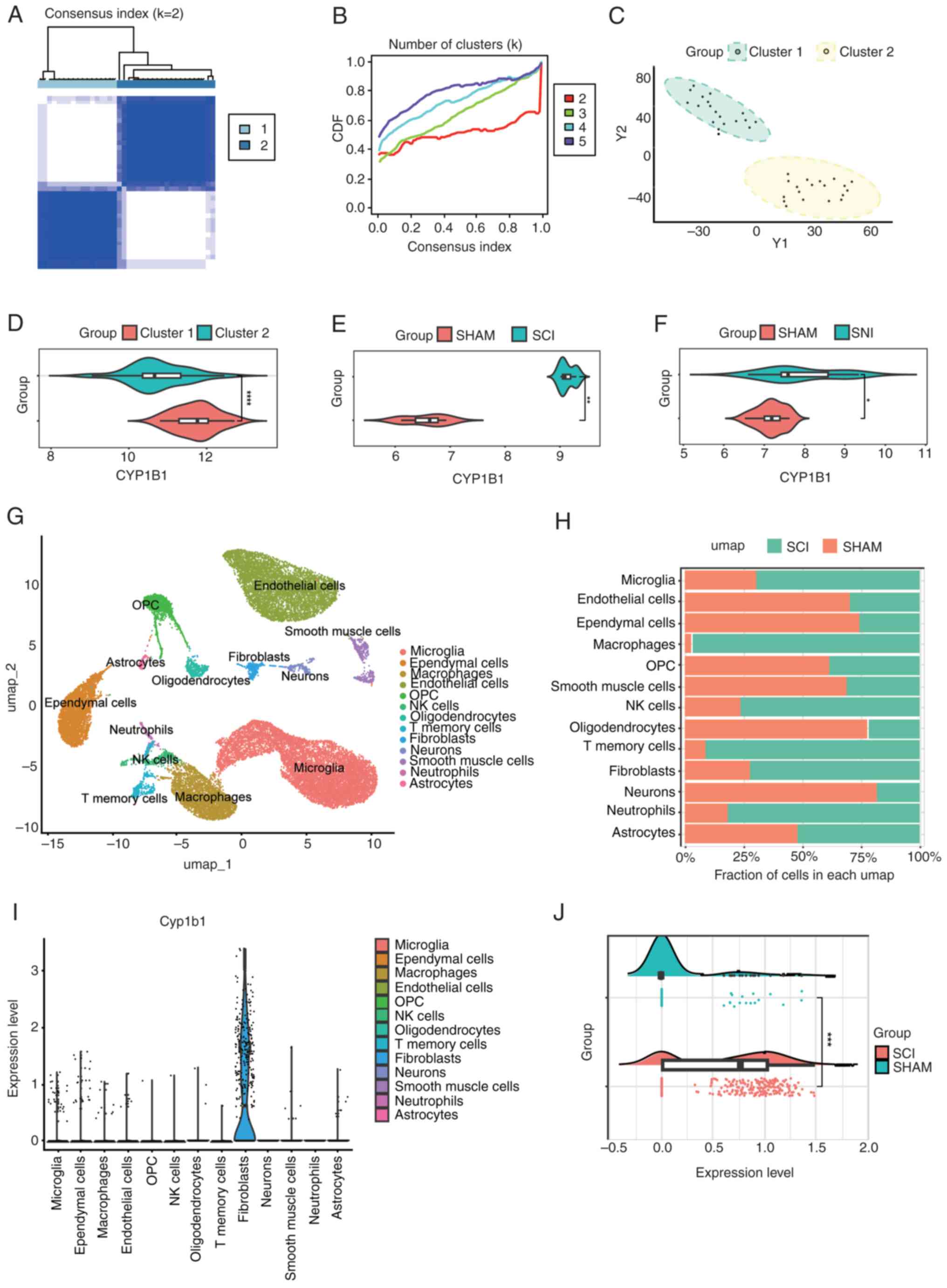

| Figure 6.(A) A clustering heat map of the

samples with the optimal clustering number set to k=2. (B) CDF

curve for various values of k, constrained within the minimum range

of the consensus index. (C) Principal component analysis graphs

with the optimal clustering number set to k=2. (D) Differential

expression of CYP1B1 across two distinct clusters. (E) CYP1B1

expression in the GSE171441 dataset. (F) CYP1B1 expression in the

GSE236754 dataset. (G) A total of 13 cell populations were

identified in the single-cell sequencing data from the GSE162610

dataset. (H) Proportion of the 13 cell populations in the two

groups. (I) CYP1B1 expression in 13 cell populations. (J)

Comparison of changes in CYP1B1 levels in fibroblasts of two

groups. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001.

CDF, cumulative distribution function; CYP1B1, cytochrome P450

family 1 subfamily B member 1; NK, natural killer; OPC,

oligodendrocyte precursor cells; SCI, spinal cord injury; SHAM,

sham surgery group; umap, uniform manifold approximation and

projection; Y1, Principal Component 1; Y2, Principal Component

2. |

Single-cell sequencing analysis

In order to further study cellular infiltration

following SCI and the expression of CYP1B1 in the affected cells,

the single-cell GSE162610 dataset was analyzed, ensuring rigorous

quality control and comprehensive analysis. In the processed ScSCI

dataset, the cell populations were categorized into 13 distinct

clusters (Fig. 6G). The

alterations in the proportions of cells in the SCI group relative

to the Con group were quantified (Fig.

6H). In this analysis, there was an observed increase in

microglia, macrophages, natural killer cells, memory T cells,

fibroblasts, neutrophils and astrocytes in the SCI group compared

with that in the SHAM group. Conversely, there was a relative

decrease in endothelial cells, ependymal cells, oligodendrocyte

precursor cells, oligodendrocytes, smooth muscle cells and neurons.

CYP1B1 exhibited elevated expression levels in fibroblasts compared

with other cell types (Fig. 6I).

Furthermore, compared with that in the SHAM group, the expression

level of fibroblasts in the SCI group was significantly increased

(Fig. 6J).

CYP1B1 expression is elevated in SCI

and activated fibroblasts, with Que effectively inhibiting its

expression

CYP1B1, identified as a prognostic biomarker through

bioinformatics, MR and network pharmacology, and recognized as a

therapeutic target for Que, requires further validation. Upon

successful establishment of the SCI, SCI + Que and SHAM

experimental models, spinal cord tissues were harvested on day 14

post-modeling. The detailed surgical protocol and tissue processing

workflow are schematically illustrated in Fig. 7A. In comparison with the SHAM

group, the SCI and SCI + Que group exhibited decreased MWT and TWLs

on day 14 following surgery. Notably, the MWT and TWL values were

significantly elevated in the SCI + Que group relative to the SCI

group (Fig. 7B and C). The BMS

scores of the Que-treated mice were superior to those of the

SCI-treated mice by day 3 post-SCI surgery, with a statistically

significant difference observed in BMS scores between the two

groups at day 14 (Fig. 7D). These

results suggest that Que may alleviate NP by increasing mechanical

and thermal pain thresholds.

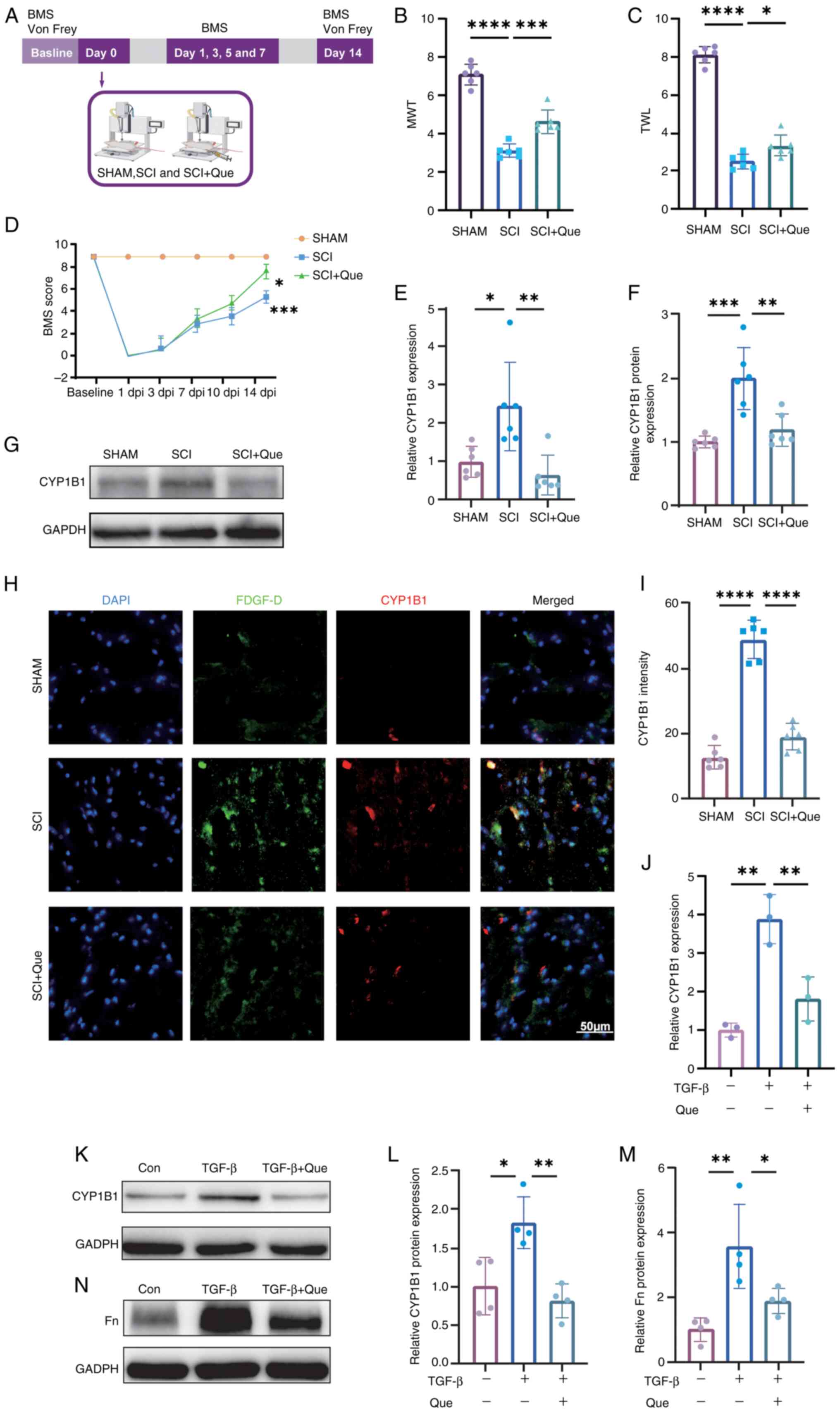

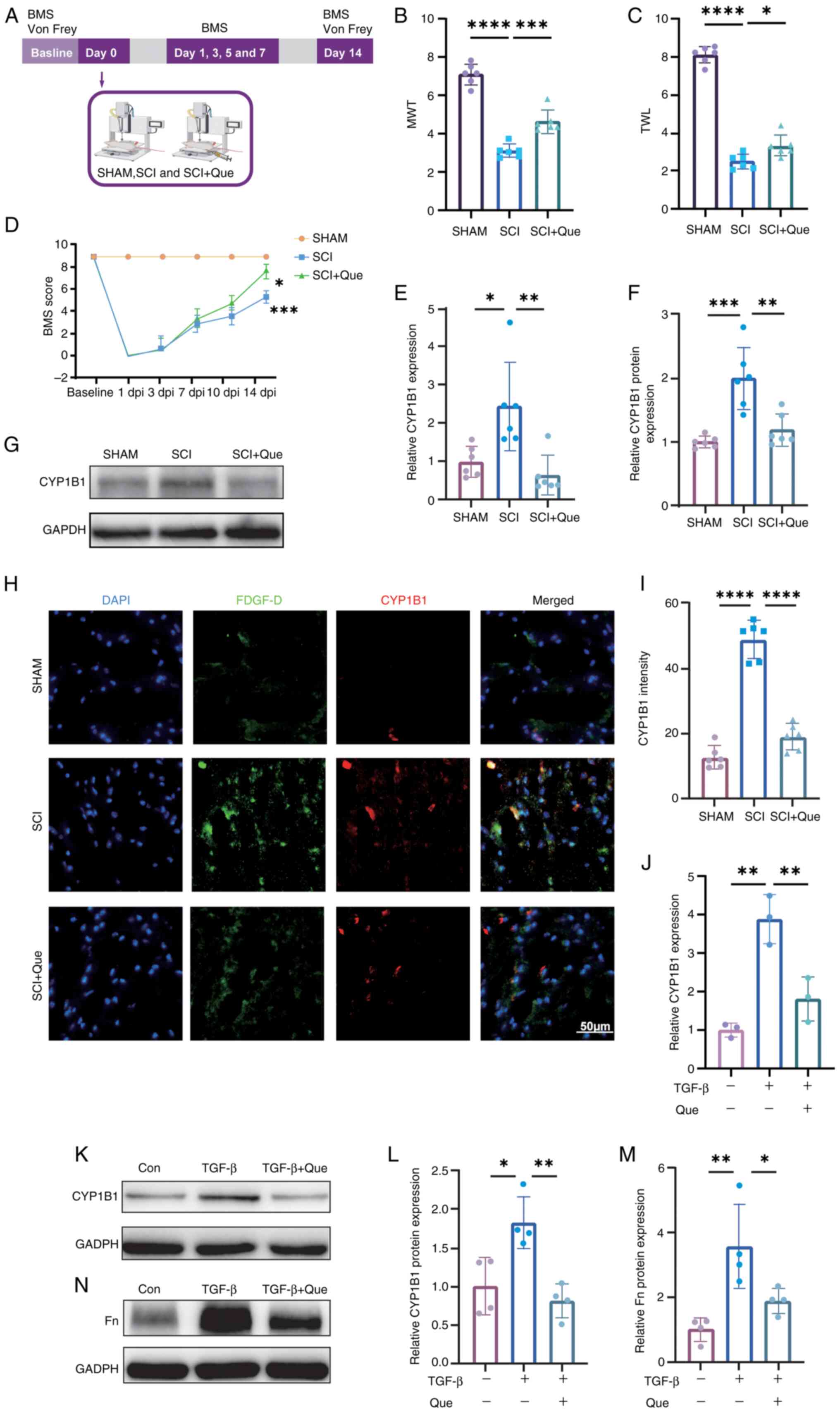

| Figure 7.(A) Flow chart of the animal

experiment. (B) MWT measurements for the SHAM, SCI and SCI + Que

groups were recorded on day 14. (C) TWL for the SHAM, SCI and SCI +

Que groups was also measured on day 14. (D) BMS scores for the

SHAM, SCI and SCI + Que groups were assessed at baseline and on

postoperative days 1, 3, 5, 7, 10 and 14. A statistically

significant difference was observed (***P<0.001) between the SCI

and SHAM groups of mice (n=6 each). Additionally, a significant

difference was noted between the SCI and SCI + Que groups

(*P<0.05), with n=6. (E) RT-qPCR assessment of CYP1B1 mRNA

levels in spinal cord tissues from SHAM, SCI and SCI + Que groups,

with expression levels normalized to GAPDH. (F) Semi-quantitative

analysis of CYP1B1 protein levels in spinal cord tissues from the

SHAM, SCI and SCI + Que groups, with fold-changes normalized to

GAPDH. (G) Western blot analysis was conducted to assess CYP1B1

expression in spinal cord tissues from the SHAM, SCI and SCI + Que

groups on day 14 post-modeling. (H) Immunofluorescence analysis was

performed to assess the expression levels of CYP1B1 and the

fibroblast marker PDGF-D in spinal cord tissues from the SHAM, SCI

and SCI + Que groups, with n=6. Scale bar, 50 µm. (I) Quantitative

fluorescence analysis of CYP1B1 expression was conducted on spinal

cord tissues from the SHAM, SCI and SCI + Que groups. (J) RT-qPCR

evaluation of CYP1B1 mRNA expression in fibroblasts treated under

control conditions, with 10 ng/ml TGF-β and with 10 ng/ml TGF-β +

10 µmol/ml Que, with mRNA levels normalized to GAPDH. (K) Western

blot analysis was performed to evaluate CYP1B1 expression in

fibroblasts subjected to control conditions, 10 ng/ml TGF-β

stimulation or co-treatment with 10 ng/ml TGF-β and 10 µmol/ml Que.

(L) Semi-quantitative evaluation of CYP1B1 protein expression in

fibroblasts subjected to control conditions, treated with 10 ng/ml

TGF-β or treated with 10 ng/ml TGF-β combined with 10 µmol/ml Que,

with protein levels normalized to GAPDH. (M) A semi-quantitative

analysis was conducted on the Fn protein levels in fibroblasts

subjected to control conditions, 10 ng/ml TGF-β treatment or

treatment with a combination of 10 ng/ml TGF-β and 10 µmol/ml Que,

with the resulting fold-changes normalized against GAPDH. (N)

Western blot analysis was utilized to investigate Fn expression in

fibroblasts under control conditions, after treatment with 10 ng/ml

TGF-β or after co-treatment with 10 ng/ml TGF-β and 10 µmol/ml Que.

The data are presented as the mean ± SEM, with sample sizes of n=6

per group for (B, C, D, E, F, G, H and I), n=3 per group for (J)

and n=4 per group for (K, L, M and N). *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001. BMS, Basso Mouse Scale; Con,

control; CYP1B1, cytochrome P450 family 1 subfamily B member 1;

PDGF-D, platelet-derived growth factor D; dpi, days post-injury;

Fn, Fibronectin; MWT, mechanical withdrawal threshold; Que,

quercetin; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; SCI,

spinal cord injury; SHAM, sham surgery group; TWL, thermal

withdrawal latency. |

In the spinal cord tissues of the SCI group, both

the protein and mRNA levels of CYP1B1 were markedly elevated

compared with those in the SHAM group; however, treatment with Que

significantly attenuated this expression (Fig. 7E-G). Furthermore,

immunofluorescence analysis revealed a substantial increase in

CYP1B1 expression within fibroblasts in the SCI group relative to

the SHAM group, which was effectively reduced by Que treatment

(Fig. 7H and I). In vitro

experiments revealed a substantial elevation in CYP1B1 protein and

mRNA levels in activated fibroblasts, which was subsequently

attenuated by Que (Fig. 7J-L).

Furthermore, fibroblasts exhibiting elevated CYP1B1 expression

exhibited significant upregulation of Fn, and this expression was

likewise inhibited by Que (Fig. 7M and

N).

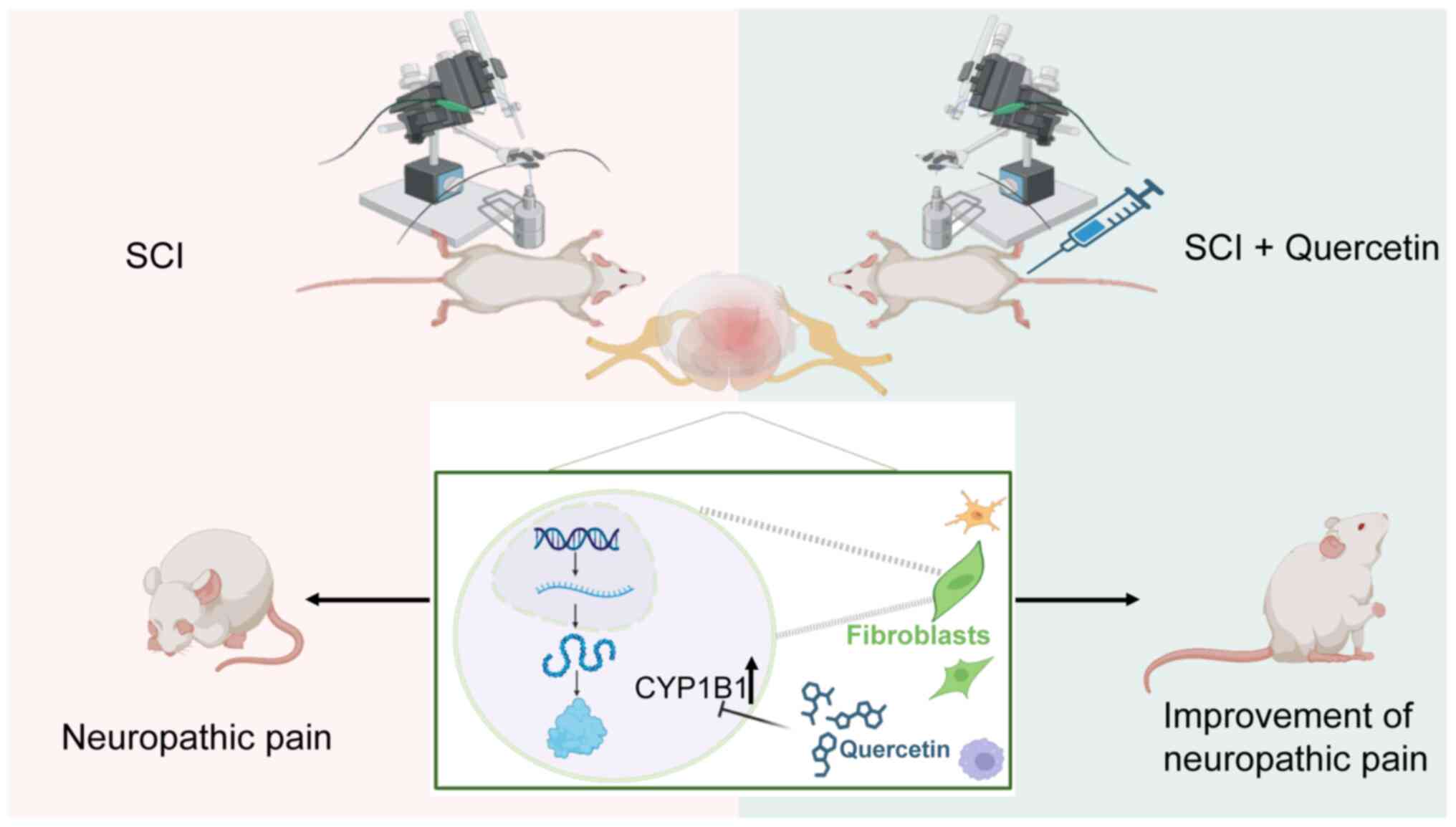

Discussion

In the present study, the SMR approach was utilized

for the integrated analysis of GWAS summaries pertaining to NP, in

conjunction with transcriptome sequencing data from public

databases. The present multiomics investigation facilitated the

synthesis of genomic and transcriptomic analyses. Specifically,

genes associated with NP risk were identified by employing cis-eQTL

gene variants as IVs and gene expression levels as exposure

factors. Subsequently, transcriptome sequencing analysis was

utilized to identify key modular genes associated with SCI, with

the objective of elucidating the molecular mechanisms common to

both SCI and NP. Furthermore, considering previous research that

has demonstrated the beneficial effects of Que in the context of

SCI and NP (60,61), network pharmacology approaches were

incorporated to explore potential targets of Que among the core

genes implicated in both conditions. The present study offers novel

perspectives and identifies potential pathways for improving the

diagnosis and treatment of NP associated with SCI. The mechanism

investigated in this study is that when SCI occurs, neuropathic

pain is associated with an increase in CYP1B1 expression in

fibroblasts. Que alleviates neuropathic pain by inhibiting this

upregulation of CYP1B1 (Fig.

8).

The management of NP poses a considerable clinical

challenge. Despite previous advancements in elucidating the

underlying mechanisms, such as disruptions in afferent pathways due

to alterations in ion channels, elevated levels of spinal

dynorphin, increased glutamate release from spinal primary afferent

endings and the generation of ectopic action potentials, patients

frequently do not receive sufficient analgesia in clinical practice

(62,63). One etiological factor contributing

to NP is SCI, which poses substantial challenges to clinical

management when these conditions occur sequentially. The emergence

of NP in individuals with SCI markedly exacerbates the

deterioration of their quality of life (1,2). The

present study primarily focused on NP following SCI. By comparison,

conditions such as PHN and TN are classified as peripheral

neuropathic pain. Although both PHN and TN are types of NP

(1), the present research

specifically aimed to investigate genes associated with NP in the

context of SCI. Despite differences in etiology between peripheral

and central neuropathic pain, both share common clinical features,

including hyperalgesia and allodynia (63). An SCI mouse model was employed in

the present study. The principal goals were to elucidate the

mechanisms underlying NP after SCI and to identify effective

therapeutic strategies, particularly to determine whether the

specific intervention alleviated NP-related symptoms such as

hyperalgesia and allodynia. Furthermore, both peripheral NP and

central NP share a variety of interconnected cellular and molecular

mechanisms, particularly through interactions among neuroglial

cells and the involvement of neuroinflammatory signaling. While

peripheral NP, exemplified by PHN or TN, and central neuropathic

pain, such as that resulting from SCI, originate from distinct

injury sites, they ultimately engage similar pathways that

culminate in hyperexcitability, sensitization and the chronicity of

pain. A significant mechanism underlying these processes is the

activation of neuroglial cells. Following peripheral nerve damage,

satellite glial cells within the dorsal root ganglia become

activated. These glial cells secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines,

including tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and

adenosine triphosphate, which enhance neuronal excitability and

promote peripheral sensitization. In parallel, SCI induces the

activation of microglia and astrocytes in the central nervous

system. Activated microglia release brain-derived neurotrophic

factor and various cytokines, which disrupt inhibitory mechanisms

and facilitate excitatory signaling. Meanwhile, astrocytes play a

crucial role in sustaining a neuroinflammatory response, thereby

contributing to the ongoing central sensitization (64,65).

TN and PHN represent classical models of NP characterized by

distinct clinical phenotypes. A key aim of the present study was to

investigate the shared molecular networks associated with NP,

rather than narrowing the focus to specific etiological subtypes.

Previous studies have infrequently explored the molecular

mechanisms and pathways within the context of these two

interrelated diseases concurrently. By treating these conditions as

distinct yet interconnected entities and analyzing them

collectively, a deeper and more holistic understanding of the

underlying molecular mechanisms and pathways can be achieved. The

simultaneous consideration of these conditions enables a more

profound insight into the progression of NP, from its initial onset

to its manifestation following SCI.

The onset of NP following SCI is markedly associated

with the recruitment and activation of a substantial number of

immune cells, predominantly from the innate immune system. The

inflammation accompanying NP and SCI constitutes a complex process

involving various cell types and a diverse array of inflammatory

cytokines that interact synergistically (66,67).

While the immune response possesses the ability to modulate

inflammation and mitigate its persistence, it may also facilitate

the transition from acute to chronic pain. Empirical evidence

suggests that the immune response serves a notable role in

sustaining persistent pain, with considerable infiltration of

immune cells acting as a primary catalyst for neurodegeneration

subsequent to SCI (68,69).

Inflammation is an adaptive physiological process

that facilitates tissue healing and regeneration. However, if

neuroinflammatory responses persist after the resolution of the

initial inflammatory event, this may lead to the development of

chronic pain (70). The

involvement of fibroblasts in NP following SCI has been

investigated, with a focus on their roles in scar formation,

extracellular matrix remodeling and the secretion of

pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Fibrotic scars are also

observed following SCI (71,72).

Research indicates that TGF-β serves a crucial role in promoting

the expression of collagen (73),

a recognized marker of fibroblast activation (74). Consequently, in order to replicate

the unique environment associated with SCI in vivo, the

present study employed TGF-β to conduct a functional validation

analysis aimed at assessing fibroblast activation. Furthermore, the

interactions among fibroblasts, immune cells and neurons have been

acknowledged as potential factors influencing the development and

progression of NP post-SCI (75,76).

Research indicates that Fn is predominantly synthesized and

secreted by fibroblasts, serving a crucial function as an

extracellular matrix protein. The presence of Fn within neurons has

the potential to modify neuronal growth and signal transmission.

Furthermore, Fn engages with cell surface receptors, including

integrins, to modulate the expression of genes associated with

pain. This interaction may facilitate inflammation and enhance the

sensitivity of nerve endings, thereby amplifying pain responses

(77,78).

CYP1B1 is an important enzyme involved in the

metabolism of a wide range of endogenous and exogenous substances

(79). Its role in NP following

SCI includes modulating the inflammatory response and regulating

oxidative stress levels. CYP1B1 functions as a regulator of

reactive oxygen species (ROS) (80), facilitating the in vitro

metabolism of arachidonic acid into various metabolites, including

20-hydroxy-eicosatetraenoic acid, which subsequently stimulates

nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase activity and

promotes ROS generation (81). In

the context of brain tissue, testosterone can induce hypertension

and neuroinflammation through its CYP1B1-derived metabolite,

6β-hydroxytestosterone (82). The

present investigation revealed altered expression levels of CYP1B1

following SCI, with single-cell analysis pinpointing its

localization within fibroblasts, thereby indicating a potential

involvement of CYP1B1 in SCI mechanisms. Nevertheless, the specific

role of CYP1B1 in fibroblasts concerning the onset and progression

of NP following SCI remains to be elucidated. In light of these

observations, the present study suggested that the abnormal

activation of fibroblasts and CYP1B1 subsequent to SCI markedly

contributes to the progression of NP, primarily through the

activation of ROS and inflammation, which are key contributors to

neuronal cell injury and death post-SCI (83).

Current clinical strategies for managing NP

post-SCI encompass pharmacological options such as antiepileptic,

antidepressant and opioid medications, alongside

non-pharmacological conditioning techniques, including spinal cord

electrical stimulation, TMS and tDCS (7,8).

However, the mechanisms driving the onset and progression of NP

following SCI remain inadequately elucidated. The majority of

available drugs primarily address symptomatic relief, with limited

capacity for targeting specific underlying mechanisms;

consequently, there exists a considerable gap in effective

treatments aimed at ameliorating NP following SCI (84). Studies suggest that inhibiting

CYP1B1 activity can reduce the production of ROS, subsequently

decreasing oxidative stress-induced neuronal damage and alleviating

NP following SCI (85,86).

Numerous natural compounds exhibit neuroprotective

and anti-inflammatory properties, with notable examples including

resveratrol, curcumin and Que (19,87,88).

In molecular docking experiments, paracetamol, aspirin and caffeine

served as negative control agents. Beyond its neuroprotective and

anti-inflammatory capabilities, Que is also acknowledged for its

antioxidant properties. Research indicates that Que can markedly

enhance the total antioxidant status in both plasma and spinal cord

tissue following SCI, thereby highlighting its potential

therapeutic role for this ailment (89). Que is recognized for its

anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, with research

suggesting its therapeutic potential for both general inflammation

and SCI. Que also modulates neuronal receptors, including T-type

calcium channels and cyclooxygenase-2, thereby contributing to the

reduction of central sensitization and the alleviation of

hyperalgesia (90). Furthermore,

it inhibits the expression of inflammatory cytokines such as tumor

necrosis factor-α and IL-1β, thereby mitigating

inflammation-associated neuronal damage (91). Its antioxidative properties

facilitate the clearance of free radicals, consequently reducing

oxidative stress levels (92).

Consequently, the present research revealed that CYP1B1 not only

serves as a biomarker for NP following SCI, but it was also

recognized as a potential target of Que in receptor prediction

analysis. This observation implies that Que might mitigate

oxidative stress through the inhibition of CYP1B1, thereby

providing a theoretical foundation for further exploration of the

role of CYP1B1 in NP following SCI and enhancing the understanding

of the underlying mechanisms involved in NP management after SCI.

Nevertheless, the precise molecular pathways through which Que

inhibits CYP1B1-mediated NP necessitate additional research.

The analysis in the present study predominantly

focused on the mouse SCI dataset (GSE171441) during the subacute

phase, specifically at 14 days post-injury. Correspondingly, animal

experiments were performed utilizing a 14-day SCI model for both

model establishment and experimental validation. This emphasis on

the subacute phase is justified, as oxidative stress is intricately

linked to disease progression, and CYP1B1, recognized as a

biomarker for post-SCI NP, functions as a regulator of ROS

(80). Furthermore, oxidative

stress is acknowledged as a distinguishing feature of the subacute

phase following SCI. Thus, the results of the present study

suggested that oxidative stress is an important factor in the

pathogenesis of post-SCI NP and that attenuation of oxidative

stress during this subacute phase could serve as an effective

therapeutic approach (93).

Building on this premise, the 14-day SCI animal model was employed

to investigate the relevant mechanisms and assess the therapeutic

potential of Que intervention. Additional research is warranted to

explore the mechanisms and associated pharmacological interventions

throughout the chronic phase following the onset and progression of

NP subsequent to SCI.

The present study has a number of limitations.

First, the availability of high-quality human datasets pertaining

to NP after SCI is limited and displays considerable variability.

Drawing on the present findings related to conditions such as PHN

and TN, the shared characteristics of NP were examined and a novel

strategy for managing NP after SCI was introduced. Nonetheless,

additional efforts in accumulating datasets specific to NP after

SCI are required for a deeper understanding of the underlying

mechanisms driving the onset and progression of this condition.

Second, the present investigation primarily concentrated on

elucidating and validating the mechanisms and pharmacological

interventions for NP after SCI during the subacute phase. It is

important to further examine the molecular mechanisms and

therapeutic interventions relevant to other stages, including the

acute and chronic phases. Additionally, the significance of the

core biomarker CYP1B1 and the influence of Que during these

distinct phases warrant further inquiry and confirmation. Third,

the present study investigated the therapeutic effect of Que at a

dose of 7.5 mg/kg twice daily. However, the effects of other doses

were not examined. Future studies will evaluate multiple doses of

Que to determine the optimal therapeutic range, providing a

theoretical basis for its clinical application. Fourth, in

single-cell analysis, no further distinction was made between

myofibroblasts or resting fibroblasts, and in future studies, more

single-cell sequencing datasets should be obtained for

comprehensive analysis of fibroblast subsets. Fifth, in the in

vitro component of the present study, the established

fibroblast activator TGF-β was primarily utilized, and the role of

CYP1B1 in fibroblast responses to other NP-associated stimuli, such

as lipopolysaccharide and H2O2, requires

further investigation. In summary, this integrated multi-omics and

experimental study identifies CYP1B1 as a key mediator of

neuropathic pain (NP) following spinal cord injury, specifically

highlighting its role in fibroblast activation and associated

neuroinflammatory and oxidative pathways. We demonstrate that

quercetin exerts analgesic effects, at least in part, by inhibiting

CYP1B1, providing a mechanistic basis for its neuroprotective

properties. Moreover, these findings not only advance our

understanding of central NP pathogenesis but also support the

therapeutic targeting of CYP1B1, thereby opening new translational

avenues for developing treatments for neuropathic pain after

SCI.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding was obtained from the Natural Science Foundation of

Guangdong Province (grant no. 2514050000156), the Research Project

of Guangdong Bureau of Traditional Chinese Medicine (grant no.

20251251), the Special Fund for Clinical Scientific Research of

Guangdong Medical Association (grant no. 2024HY-B4001), the Norman

Bethune Foundation Enzer Pain Management Medical Research Program

(grant no. ezmr2023-080), the Education, Teaching and Research

Project of The Third Affiliated Hospital of The Southern Medical

University (grant no. JXY202408), and the Youth Fund Program of

Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no.

822QN451).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

PZ contributed to the conceptualization,

methodology and data curation of the study. PZ, LL, YC, JiaC, CC,

XZ, JiuC, YD, PS and JZ were responsible for data analysis and

interpretation. PZ, LL, YC, JiaC, ZL, YL, SW, ST, WZ and CC were

responsible for the animal and cell experiments. XZ, JiuC and YD

were responsible for acquiring resources and validation. PZ, ZL and

YL provided administrative oversight. SW, ST and WZ acquired the

funding. PS and JZ supervised the project. PZ, PS and JZ

contributed to the writing, reviewing and editing of the final

manuscript. PZ, LL and YC confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors have read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All experimental procedures involving animals were

carried out in strict accordance with the guidelines for the care

and use of laboratory animals and were approved by the

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Daoke Pharmaceutical

Technology (Guangdong) Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China; approval no.

IACUC-DK-2024-04-10-01).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Finnerup NB, Kuner R and Jensen TS:

Neuropathic Pain: From mechanisms to treatment. Physiol Rev.

101:259–301. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Burke D, Fullen BM, Stokes D and Lennon O:

Neuropathic pain prevalence following spinal cord injury: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Pain. 21:29–44. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Hergenroeder GW, Redell JB, Choi HA,

Schmitt L, Donovan W, Francisco GE, Schmitt K, Moore AN and Dash

PK: Increased levels of circulating glial fibrillary acidic protein

and collapsin response mediator Protein-2 autoantibodies in the

acute stage of spinal cord injury predict the subsequent

development of neuropathic pain. J Neurotraum. 35:2530–2539. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Widerström-Noga E: Neuropathic pain and

spinal cord injury: Phenotypes and pharmacological management.

Drugs. 77:967–984. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Orr MB and Gensel JC: Spinal cord injury

scarring and inflammation: Therapies targeting glial and

inflammatory responses. Neurotherapeutics. 15:541–553. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

O'Shea TM, Burda JE and Sofroniew MV: Cell

biology of spinal cord injury and repair. J Clin Invest.

127:3259–3270. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Boldt I, Eriks-Hoogland I, Brinkhof MW, de

Bie R, Joggi D and von Elm E: Non-pharmacological interventions for

chronic pain in people with spinal cord injury. Cochrane Database

Syst Rev. 2014:CD0091772014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Mehta S, McIntyre A, Janzen S, Loh E and

Teasell R; Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence Team, :

Systematic review of pharmacologic treatments of pain after spinal

cord injury: An update. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 97:1381–1391.e1.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Loh E, Mirkowski M, Agudelo AR, Allison

DJ, Benton B, Bryce TN, Guilcher S, Jeji T, Kras-Dupuis A,

Kreutzwiser D, et al: The CanPain SCI clinical practice guidelines

for rehabilitation management of neuropathic pain after spinal cord

injury: 2021 update. Spinal Cord. 60:548–566. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Liu C, Liu DQ, Tian YK, Mei W, Tian XB, Xu

AJ and Zhou YQ: The emerging role of quercetin in the treatment of

chronic pain. Curr Neuropharmacol. 20:2346–2353. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Yang H, Yang T, Heng C, Zhou Y, Jiang Z,

Qian X, Du L, Mao S, Yin X and Lu Q: Quercetin improves

nonalcoholic fatty liver by ameliorating inflammation, oxidative

stress, and lipid metabolism in db/db mice. Phytother Res.

33:3140–3152. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Gao W, Zan Y, Wang ZJ, Hu XY and Huang F:

Quercetin ameliorates paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain by

stabilizing mast cells, and subsequently blocking PKCε-dependent

activation of TRPV1. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 37:1166–1177. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wang R, Qiu Z, Wang G, Hu Q, Shi N, Zhang

Z, Wu Y and Zhou C: Quercetin attenuates diabetic neuropathic pain

by inhibiting mTOR/p70S6K pathway-mediated changes of synaptic

morphology and synaptic protein levels in spinal dorsal horn of

db/db mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 882:1732662020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Abbey EL and Rankin JW: Effect of

quercetin supplementation on repeated-sprint performance, xanthine

oxidase activity, and inflammation. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab.

21:91–96. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhao L, Wang H and Du X: The therapeutic

use of quercetin in ophthalmology: Recent applications. Biomed

Pharmacother. 137:1113712021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Li Y, Yao J, Han C, Yang J, Chaudhry MT,

Wang S, Liu H and Yin Y: Quercetin, inflammation and immunity.

Nutrients. 8:1672016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Costa LG, Garrick JM, Roquè PJ and

Pellacani C: Mechanisms of neuroprotection by Quercetin:

Counteracting oxidative stress and more. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2016:29867962016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Shao Z, Wang B, Shi Y, Xie C, Huang C,

Chen B, Zhang H, Zeng G, Liang H, Wu Y, et al: Senolytic agent

Quercetin ameliorates intervertebral disc degeneration via the

Nrf2/NF-κB axis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 29:413–422. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Chiang MC, Tsai TY and Wang CJ: The

potential benefits of quercetin for brain health: A review of

Anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci.

24:63282023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Grewal AK, Singh TG, Sharma D, Sharma V,

Singh M, Rahman MH, Najda A, Walasek-Janusz M, Kamel M, Albadrani

GM, et al: Mechanistic insights and perspectives involved in

neuroprotective action of quercetin. Biomed Pharmacother.

140:1117292021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Elsworth B, Lyon B, Alexander T, Liu Y,

Matthews P, Hallett J, Bates P, Palmer T, Haberland V, Smith GD, et

al: The MRC IEU OpenGWAS data infrastructure. bioRxiv. August

10–2020.doi: 10.1101/2020.08.10.244293. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Kurki MI, Karjalainen J, Palta P, Sipilä

TP, Kristiansson K, Donner KM, Reeve MP, Laivuori H, Aavikko M,

Kaunisto MA, et al: FinnGen provides genetic insights from a

well-phenotyped isolated population. Nature. 613:508–518. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Võsa U, Claringbould A, Westra HJ, Bonder

MJ, Deelen P, Zeng B, Kirsten H, Saha A, Kreuzhuber R, Yazar S, et