Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the most

common malignant tumor in the maxillofacial region; globally, there

are 380,000 new cases of OSCC diagnosed and 180,000 OSCC-associated

deaths recorded in 2022 (1).

Although surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy have shown efficacy

in early-stage OSCC, the high invasiveness and metastatic tendency

of OSCC often lead to local recurrence and distant dissemination

(2). Therefore, identifying the

molecular mechanisms underlying the malignant progression of OSCC

and developing novel therapeutic strategies is required.

Recently, liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) has

emerged as a fundamental paradigm for regulating cellular

functions. Through weak interactions between intrinsically

disordered regions (IDRs), multivalent proteins or nucleic acid

scaffolds, biomacromolecules dynamically undergo LLPS to form

membraneless organelles, and precisely regulate key biological

processes such as transcription, epigenetic modification and signal

transduction (3,4). Accumulating evidence has suggested

that abnormal LLPS contributes to various oncogenic processes,

including the evasion of tumor cell senescence, stemness

maintenance and metastatic spread (5,6). For

example, cancer cells can evade senescence and death by activating

telomerase or via alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT)

(7). After telomeric DNA damage in

cancer stem cells, ALT-associated proteins undergo LLPS through

interactions between small ubiquitin-like modifiers (SUMOs) and

SUMO-interacting motifs, forming ALT-associated promyelocytic

leukemia bodies that mediate telomere repair (8). Additionally, Lu et al

(9) reported that the

transcriptional coactivator TAZ forms nuclear condensates through

IDR-mediated LLPS, colocalizing with transcriptional complexes such

as TEAD4 and BRD4. Notably, the loss of the phase separation

ability of TAZ can inhibit target gene expression and tumor

metastasis. Beyond transcriptional regulation, LLPS also serves an

important role in post-transcriptional modification. In acute

myeloid leukemia, the m6A reader protein YTHDC1 interacts with

m6A-modified mRNA through LLPS to form nuclear condensates,

regulating RNA splicing and transport (10). Furthermore, LLPS has reshaped the

understanding of signal transduction mechanisms. Tulpule et

al (11) demonstrated that

receptor tyrosine kinases can form membraneless protein granules

through LLPS, enriching the GRB2/SOS1 complex and activating the

RAS/MAPK pathway, challenging the traditional lipid

membrane-dependent signal transduction model.

Notably, LLPS drives biomolecular condensation in

cancer progression, with LLPS-related genes (LLPSRGs) establishing

prognostic value in ovarian (12),

breast (13) and bladder cancer

(14). However, OSCC, a tumor

shaped by unique etiological factors (use of tobacco and alcohol,

human papillomavirus infection) and frequent recurrence, lacks

systematic investigation into LLPS dysregulation. The following

critical gaps in the knowledge persist: i) No specific research has

been conducted to clarify the prognostic value of LLPSRGs in OSCC;

ii) mechanistic links between LLPSRG-mediated dysregulation and

aggressive OSCC phenotypes are undefined. These gaps hinder

therapeutic targeting of LLPS vulnerabilities in this molecularly

complex carcinoma.

The present study aimed to establish the first

dedicated investigation of LLPS in OSCC, with the following

objectives: i) To identify OSCC-specific LLPSRGs through

multi-omics integration; and ii) to elucidate the mechanistic role

of biomolecular condensates in driving OSCC invasion. Ultimately,

by connecting LLPS dynamics to the molecular landscape of OSCC, the

current study intended to discover novel phase separation-derived

biomarkers and therapeutic targets for precision oncology.

Materials and methods

Acquisition of public datasets

LLPSRGs (n=3,633) were retrieved from the Data

Resource of LLPS (DrLLPS; http://llps.biocuckoo.cn/). Transcriptomics profiles

and clinical records from an OSCC cohort (n=302), whose primary

lesion sites were the tongue, base of the tongue, buccal mucosa,

oral cavity, floor of the mouth and gingiva, were obtained from The

Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; http://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga).

The GSE213862 dataset from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO;

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) was

also acquired, comprising transcriptomics data from 47 pairs of

OSCC tissues and normal mucosal tissues (15).

Identification of two distinct

LLPS-associated molecular clusters

Consensus clustering analysis was conducted using

the R package ‘ConsensusClusterPlus’ (16) to stratify TCGA-OSCC samples into

distinct molecular clusters (C1 and C2) based on the expression

profiles of LLPSRGs. Cluster stability was evaluated by analyzing

the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the consensus matrix

across multiple k-values. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs)

between C1 and C2 were identified using the R package ‘DESeq2’

(17), based on the criteria of

|log2 fold change (FC)|>1 and P<0.05. Survival analysis

between C1 and C2 were conducted using the R package ‘survival’

(https://github.com/therneau/survival).

Construction of a prognostic

prediction model based on LLPSRGs for OSCC

TCGA-OSCC cohort was randomly divided into training

and validation subsets at a ratio of 7:3. Univariate Cox regression

and LASSO regression analyses (implemented via the R packages

‘survival’ and ‘glmnet’ (https://glmnet.stanford.edu) were applied to the

training cohort to screen seven LLPSRGs significantly associated

with OSCC prognosis. A risk score model was established using

LASSO-derived coefficients, and patients in both the training and

validation cohorts were stratified into high- or low-risk groups

based on the median risk score. Model performance was evaluated

through Kaplan-Meier curve analysis with Wilcoxon test,

time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves,

principal component analysis (PCA) and t-distributed stochastic

neighbor embedding (t-SNE) using ‘survival’, ‘timeROC’ (https://github.com/cran/timeROC), ‘Rtsne’

(https://github.com/jkrijthe/Rtsne)

and the related visualization tool ‘ggplot2’ (https://github.com/tidyverse/ggplot2).

The prognostic nomogram was constructed by integrating the

continuous risk score with established clinical variables:

Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) stage, histological grade and age,

using R package ‘rms’ (https://github.com/harrelfe/rms).

Differential expression analysis and

gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

Differential expression analysis between the high-

and low-risk groups was conducted using the R package ‘DESeq2’

(16) and ‘limma’ (https://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/limma), based on the

criteria of P<0.05 and |log2FC|>1. The Minus-vs.-Add (MA)

plot visualizing differential expression patterns between risk

groups was generated using the R package ‘limma’. Gene Ontology

(GO), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment

analyses and Hallmark GSEA based on the Molecular Signatures

Database (MsigDB; http://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb) of DEGs was

conducted using R packages ‘enrichplot’ (https://github.com/YuLab-SMU/enrichplot) and

‘clusterProfiler’ (https://github.com/YuLab-SMU/clusterProfiler).

Public single-cell RNA sequencing

(scRNA-seq) data collection and analysis

The scRNA-seq data analyzed in the present study

were accessible via the GEO accession number, GSE234933 (18). Based on clinical metadata from

GSE234933, samples were categorized into the primary lesion (sample

count, 19; cell count, 123,094) and metastatic lesion (sample

count, 8; cell count, 38,987) groups. The R package ‘Seurat’

(https://github.com/satijalab/seurat;

version 4.3.0) was used for initial quality control removing cells

with <200 detected genes. Validated cell data were integrated

into a Seurat object for downstream analysis. Distinctly expressed

genes were detected with single-cell resolution using the

FindAllMarkers tool implemented in Seurat.

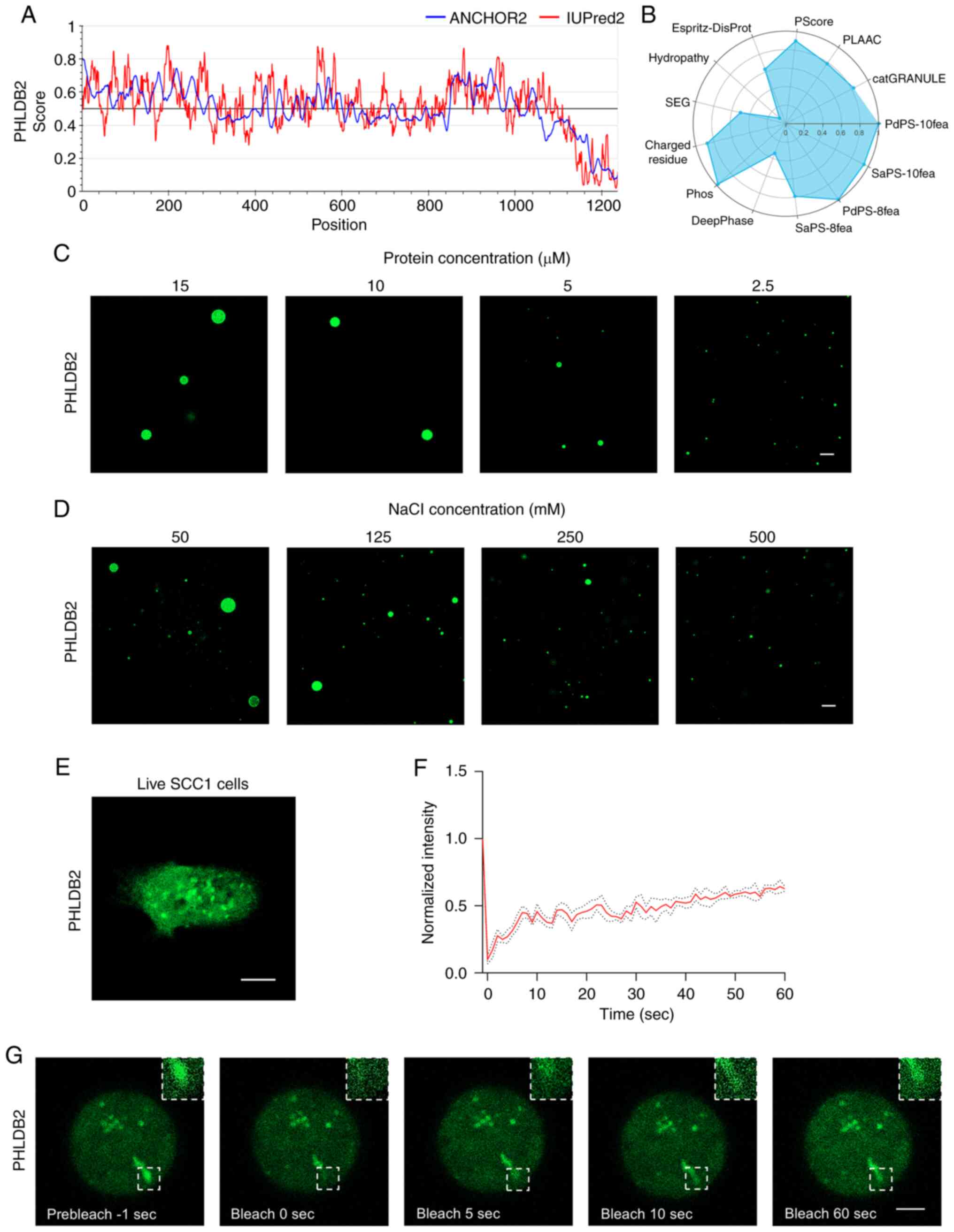

LLPS potential evaluation for model

genes

The GEPIA2 website (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/) (19) was used to compare the relative

expression of model genes in TCGA-OSCC. The IDRs of model genes

were identified using IUPred2, while their disordered binding

regions were characterized via ANCHOR2 analysis through the

IUPred2A platform (https://iupred2a.elte.hu/) (20). LLPS propensity scoring of the model

genes was performed using PhaSePred (http://predict.phasep.pro/) (21), incorporating the following

computational algorithms: catGRANULE, PdPS-10fea, SaPS-10fea,

PdPS-8fea, SaPS-8fea, DeepPhase, Phos, Charged residue, SEG,

Hydropathy, ESpritz-DisProt, PScore and PLAAC.

In vitro droplet formation assay

PHLDB2 protein solutions (cat. no. Ag27331;

Proteintech Group, Inc.) was conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (cat.

no. ab236553; Abcam). Fluorescently labeled recombinant PHLDB2

protein was purified and reconstituted in NaCl solutions at

physiologically relevant concentration gradients, ranging from 50

to 500 mM. Subsequently, the preparations were immediately combined

with a phase separation buffer containing 10% glycerol, 50 mM

Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1 mM DTT and 10% PEG-8000, serving as a

molecular crowding agent. After incubation at room temperature for

5 min, the mixture was pipetted onto glass slides prepared with

coverslips secured by double-sided adhesive spacers. Imaging was

performed using a confocal microscope (LSM980; Zeiss AG) equipped

with a 63X objective lens.

Cell lines and culture conditions

The present study employed two human OSCC lines:

SCC1 and HSC3, obtained from the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor,

MI, USA). HSC3 cells were cultured in DMEM (cat. no. C11995500BT;

Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and SCC1 cells were cultured

in DMEM/F-12 medium (cat. no. C11330500BT; Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Both media were supplemented with 10% FBS (cat.

no. 10099-141C; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin (cat. no. 15140122; Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified

incubator containing 5% CO2.

Transient small interfering RNA

(siRNA) and PHLDB2-EGFP plasmid transfection

The oligonucleotide sequences for siRNA and the

PHLDB2-EGFP plasmid are provided in Table SI. SCC1 and HSC3 OSCC cells at

60–80% confluence were transfected with PHLDB2-targeting siRNAs or

control siRNAs (50 nM) and the PHLDB2-EGFP plasmid (1 µg/ml) using

Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX (cat. no. 13778150; Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's

protocol. Transfection was performed at 37°C for 48 h and

subsequent experiments were conducted 24 h post-transfection.

Fluorescence recovery after

photobleaching (FRAP) analysis

FRAP analysis was performed using an LSM980 confocal

microscope (Zeiss AG). SCC1 cells expressing EGFP-tagged PHLDB2

were visualized with a 63X oil-immersion objective. Phase-separated

condensates were selectively bleached using a 488-nm laser at 98%

intensity. Post-bleaching recovery was tracked by capturing

sequential images at 1-sec intervals for 100 sec. Droplet

fluorescence intensities were analyzed using ZEN Microscopy

Software (version 3.0; Carl Zeiss AG), and recovery kinetics were

plotted with GraphPad Prism 9.0 (Dotmatics).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA isolation was carried out using

TRIzol® reagent (cat. no. 15596018; Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), followed by cDNA synthesis using the

PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (cat. no. RR047A; Takara Bio, Inc.)

according to the manufacturer's protocol. qPCR was conducted on a

Roche LightCycler 96 platform (Roche Diagnostics) employing SYBR

Green PCR Master Mix (cat. no. 11201ES08; Shanghai Yeasen

Biotechnology, Co., Ltd.). The qPCR amplification protocol

consisted of an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 5 min,

followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10 sec, annealing

at 60°C for 20 sec and extension at 72°C for 20 sec. GAPDH was used

as the reference gene for normalization. Relative gene expression

was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method (22). Primer sequences, designed against

GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank) reference data,

are compiled in Table SII.

Western blotting

Protein extraction was performed with ice-cold RIPA

lysis buffer (cat. no. CW2333S; Jiangsu CoWin Biotech Co., Ltd.)

containing protease inhibitor cocktail. Protein concentrations were

determined using a BCA quantification kit (cat. no. CW0014S;

Jiangsu CoWin Biotech Co., Ltd.) according to standardized

protocols. The lysates (control-si 5.26 mg/ml; PHLDB2si-1 4.94

mg/ml; PHLDB2si-2 5.04 mg/ml) were electrophoretically separated by

SDS-PAGE on 10% gels, followed by semi-dry transfer to PVDF

membranes (cat. no. ISEQ00010; MilliporeSigma). The membranes were

then subjected to blocking with 5% milk in TBS with 0.05% Tween at

room temperature for 1 h, and incubated with primary antibodies at

4°C for 16 h. After washing and incubation with HRP-conjugated

secondary antibodies at 25°C for 1 h, immunoreactive bands were

detected using ECL substrate (cat. no. WBKLS0500; MilliporeSigma)

and semi-quantified with a GeneGnome XRQ imaging system (Syngene;

software version, GeneSys 2023). The following primary antibodies

were used: Rabbit polyclonal anti-PHLDB2 (cat. no. ab234885;

1:1,000; Abcam), E-cadherin (cat. no. ab231303; 1:2,000; Abcam),

N-cadherin (cat. no. ab76011; 1:5,000; Abcam), vimentin (cat. no.

ab92547; 1:1,000; Abcam) and mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH (cat. no.

ab8245; 1:5,000; Abcam). The following secondary antibodies were

used: Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (HRP) (cat. no. ab205718;

1:10,000; Abcam) and Goat Anti-Mouse IgG H&L (HRP) (cat. no.

ab205719; 1:10,000; Abcam).

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) cell

proliferation assay and colony formation assay

Cell proliferation was assessed using the CCK-8

assay. HSC3 and SCC1 cells (2×103 cells/well) were

plated and treated with 10% CCK-8 reagent (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA) in DMEM. Absorbance was measured after a 2 h-incubation to

determine cell viability. For colony formation analysis, after 1

week of culturing cells seeded at an initial density of 1,000 cells

per well in 6-well plates, colonies were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde for 20 min and stained with 0.5% crystal violet

(cat. no. C3886; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 20 min at room

temperature, and images were then captured. Colonies defined as

cell aggregates containing ≥50 cells within a 0.3–1.0 mm diameter

were quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.54p; National

Institutes of Health).

Spheroid formation assay and limiting

dilution assay

Cells were plated in ultra-low attachment 96-well

plates at graded densities (1×103, 5×102,

2×102, 1×102 and 5×10¹ per well) using

serum-free DMEM/F-12 containing 2% B27 (cat. no. 17504044; Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 20 ng/ml hEGF (cat. no. 105-04;

PrimeGene) and 10 ng/ml hFGF (cat. no. 104-02; PrimeGene). Cultures

were maintained under 5% CO2 at 37°C with quintuplicate

wells/density. After a 10-day incubation, images of spheroids were

captured using an inverted light microscope (Zeiss Axio Observer;

Carl Zeiss AG), and quantified using ImageJ software (version

1.54p; National Institutes of Health). Cancer stem cell frequency

was determined using ELDA computational analysis (http://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/software/elda/).

Wound healing assay and invasion

assay

For wound healing evaluation, OSCC cells were

cultured to 90% confluence in 6-well plates, and a linear wound was

introduced to monolayers using a 200-µl pipette tip. Migration

progression was documented at 0, 12, 16 and 24 h intervals through

phase-contrast light microscope (Zeiss Axio Observer; Carl Zeiss

AG), with wound closure quantified using ImageJ software (version

1.54p; National Institutes of Health). For Transwell invasion

assays, the upper chambers were precoated with Matrigel (cat. no.

354234; Corning, Inc.) at 4°C and incubated at 37°C for 30 min.

Subsequently, 2×104 cells/well were loaded into

Matrigel-precoated upper chambers (cat. no. 354234; Corning, Inc.)

in serum-free medium. The lower chambers contained 10% FBS as a

chemoattractant. After a 48-h incubation at 37°C, cells on the

membrane were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature

for 20 min and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 20 min at room

temperature. Invasive cells were counted under bright-field

microscopy.

RNA-seq

RNA was extracted from SCC1 cells, with RNA purity

quantified by Nanodrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

integrity assessed using an Agilent 4200 TapeStation (Agilent

Technologies, Inc.). Libraries were constructed from 1 µg RNA using

the TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit (cat. no. 20020594;

Illumina, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly,

mRNA underwent fragmentation using divalent cations, followed by

first-strand cDNA synthesis with reverse transcriptase and

second-strand synthesis using DNA polymerase I/dNTPs.

Double-stranded cDNA was processed through end repair, A-tailing

and adapter ligation (200–300 bp size selection). Libraries were

size-selected (200–300 bp) using AMPure XP beads. After 12 cycles

of PCR amplification, final libraries were purified and

quality-controlled using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer High

Sensitivity DNA Assay (cat. no. 5067-4626; Agilent Technologies,

Inc.). The loading concentration of the final library was 14 nM for

control-si group and 15 nM for PHLDB2-si group. Quality-controlled

libraries were pooled and diluted to 1.8 nM in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH

8.5) based on Qubit dsDNA HS Assay measurements (cat. no. Q32854;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Paired-end sequencing (2×150 bp)

was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 system using the NovaSeq

6000 SP Reagent Kit v1.5 (100 cycles; cat. no. 20027464) (both from

Illumina, Inc.). Bioinformatics analysis identified DEGs between

the control group and the PHLDB2-knockdown group using DESeq2

(|log2FC|>1; P<0.05), followed by functional enrichment

analysis to characterize biological pathways using the R package

‘clusterProfiler’ (https://github.com/YuLab-SMU/clusterProfiler). Core

PI3K-Akt signaling components were retrieved from the KEGG PI3K-Akt

signaling pathway gene set. Differential expression of these

components between control and PHLDB2 knockdown groups was analyzed

with the R package ‘limma’, followed by visualization as a heatmap

using the R package ‘ggplot2’.

Patients and specimens

The Sun Yat-sen University (SYSU)-OSCC cohort

retrospectively analyzed clinicopathological data from 51

treatment-naïve patients treated between June 2016 and June 2018.

The cohort comprised 35 men and 16 women, with a mean age of 52

years (range: 26–77 years). These data were used for validation in

the present study. All participants underwent surgical resection of

primary tumors with cervical lymph node dissection at the Hospital

of Stomatology, SYSU (Guangzhou, China) with no presurgical

adjuvant therapy. Clinicopathological parameters and survival data

were retrieved through clinical documentation and structured

telephone follow-ups. Tumor staging followed the Union for

International Cancer Control 8th edition TNM guidelines (23). The present study received approval

from the ethics committee of the Hospital of Stomatology, SYSU

(approval no. KQEC202013) and all participants provided written

informed consent.

Immunohistochemical (IHC)

staining

IHC staining was performed on 4-µm-thick

paraffin-embedded tissue sections. Sections were blocked with 10%

goat serum (cat. no. SL038; Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) in PBS for 30 min at room temperature.

Primary antibodies were diluted as follows: Anti-PHLDB2 (1:50; cat.

no. ab234885; Abcam) and IgG isotype control antibody (1:100; cat.

no. ab172730; Abcam), and incubated overnight at 4°C. Following

primary antibody incubation, sections were incubated with the

appropriate secondary antibody (1:100 dilution) for 30 min at room

temperature. IHC staining was then conducted with anti-rabbit/mouse

HRP/DAB (ABC) detection kits (cat. nos. ab64261 and ab64259; Abcam)

according to the manufacturer's protocol. Secondary antibodies were

diluted as follows: Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (1:5,000; cat. no.

ab205718; Abcam) and Goat Anti-Mouse IgG H&L (1:5,000; cat. no.

ab205719; Abcam). Tissue section images were acquired using an

Aperio AT2 scanner (Leica Biosystems) with its integrated

microscope and analyzed with ImageJ software (version 1.54p;

National Institutes of Health). IHC scoring followed a four-tier

system based on the staining intensity: 0, Negative; 1, weakly

positive; 2, positive; and 3, strongly positive.

Statistical analysis

Data were processed and analyzed with R (v4.2.2;

http://www.r-project.org) and GraphPad Prism 9.0.

Statistical significance was evaluated via two-tailed tests.

Comparisons between two groups were performed using unpaired

Student's t-test for normally distributed data or Mann-Whitney U

tests for non-normally distributed data. Paired comparisons between

two groups employed paired Student's t-test for normally

distributed data or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for non-normally

distributed data. Multi-group comparisons were analyzed by one-way

ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc testing for normally distributed data

with equal variance or Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's post-hoc

correction for non-normally distributed data. Normality was

assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test and homogeneity of variance was

verified using Levene's test. Continuous variables were examined by

Pearson's correlation, and categorical variables were evaluated by

Spearman's correlation. Analysis of paired tumor-normal tissues in

TCGA-OSCC was conducted using the R package ‘TCGAplot’ (https://github.com/tjhwangxiong/TCGAplot). P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Establishment of two LLPS-related

molecular clusters and construction of a novel prognostic

prediction model based on LLPSRGs for OSCC

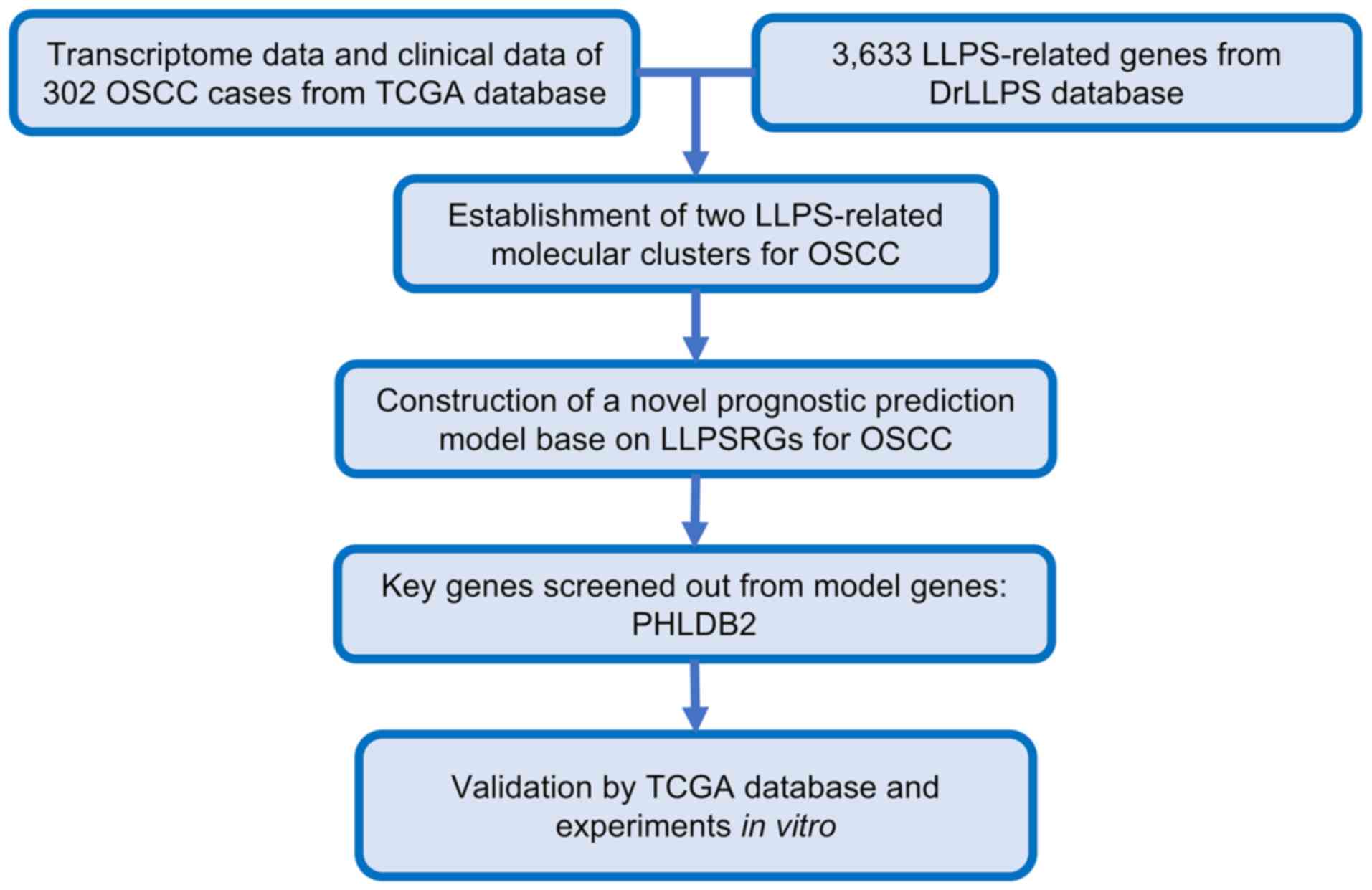

The workflow of the present study is illustrated in

Fig. 1. Through consensus

clustering analysis of 3,633 LLPSRGs from the DrLLPS database of

transcriptomics data from 302 OSCC cases in TCGA, the samples were

successfully stratified into two biologically distinct molecular

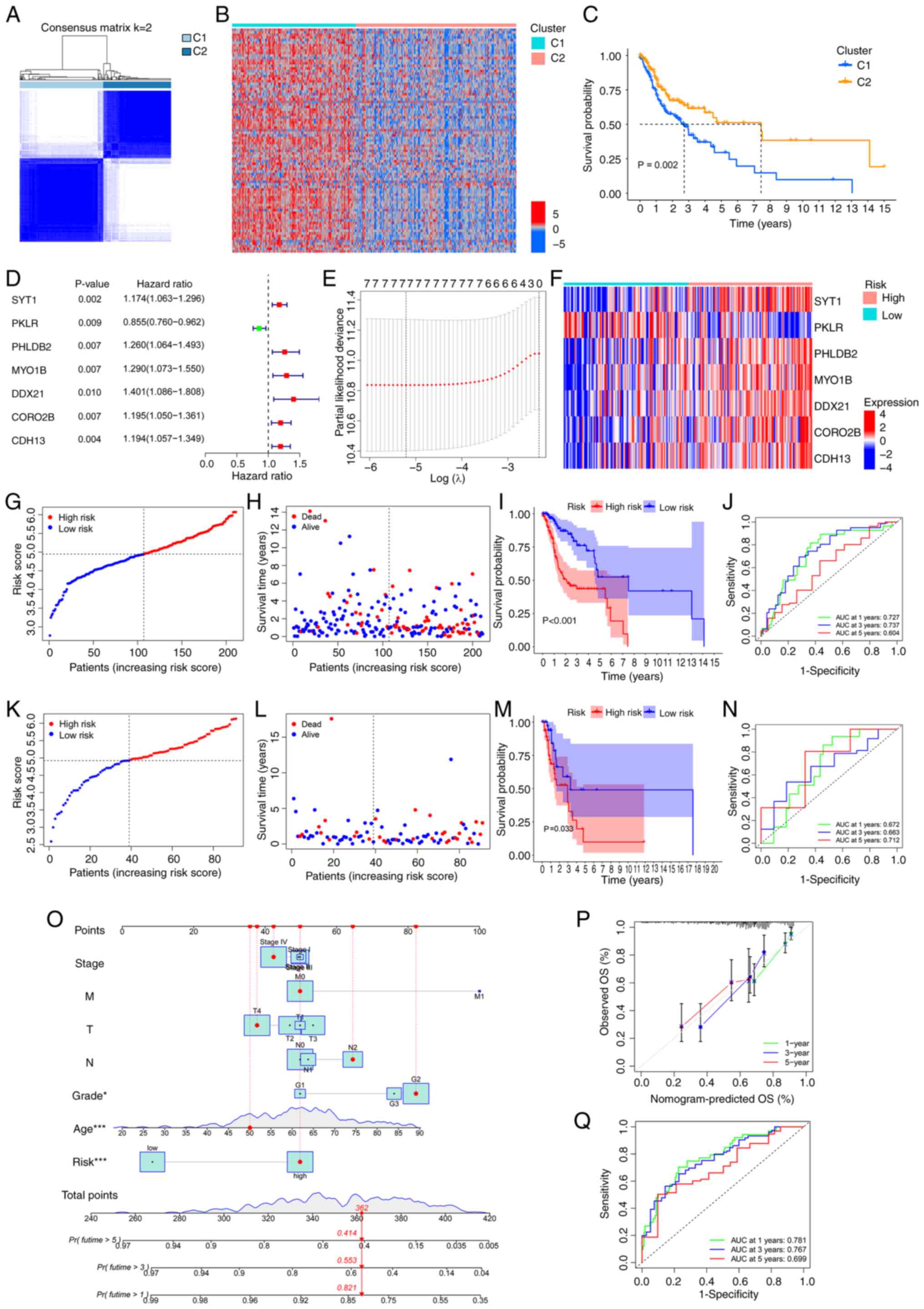

clusters, C1 and C2 (Fig. 2A).

Evaluation of the CDF curve confirmed optimal consistency and

cluster stability at k=2 (Fig.

S1A). Further analysis revealed that LLPSRGs were significantly

upregulated in C1 compared with in C2 (Fig. 2B), and C1 patients exhibited

significantly shorter overall survival (OS; Fig. 2C). GO and KEGG enrichment analyses

demonstrated that DEGs in the C1 cluster were predominantly

enriched in biological processes associated with tumor progression,

including ‘cell junction assembly’, ‘PI3K-Akt signaling pathway’

and ‘Wnt signaling pathway’ (Fig. S1B

and C). These findings suggested that dysregulated LLPSRGs may

influence OSCC prognosis by modulating key oncogenic pathways.

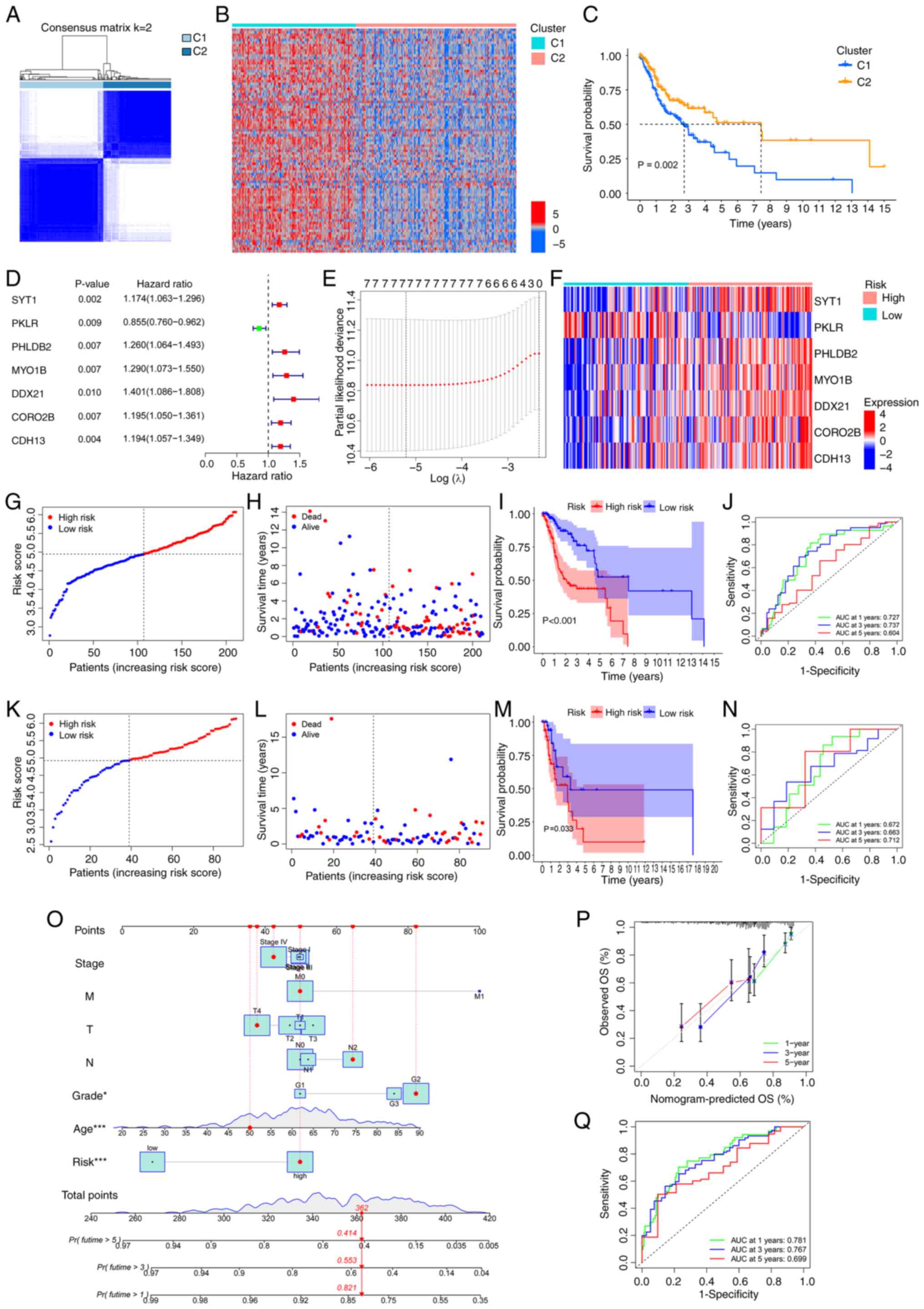

| Figure 2.Establishment of two LLPS-related

molecular clusters and construction of a novel prognostic

prediction model based on LLPSRGs for OSCC. (A) Consensus

clustering matrix heatmap illustrating optimal partitioning (k=2)

of TCGA-OSCC samples based on LLPSRG expression patterns. (B)

Expression profile heatmap of differential genes between C1 and C2

clusters. (C) Kaplan-Meier curves for OS of C1 and C2 clusters. (D)

Univariate Cox regression screening identifying seven

prognostically significant LLPSRGs. (E) Construction of a

prognostic prediction model through LASSO coefficient trajectories

with a vertical line indicating optimal λ selection through 10-fold

cross-validation. (F) Expression profile heatmap of the seven model

genes. Training cohort validation including (G) risk stratification

by median cut-off, (H) survival distribution mapping, (I)

Kaplan-Meier curves for OS of the high- and low-risk groups, and

(J) time-dependent ROC analysis demonstrating predictive accuracy

(AUC values for 1, 3 and 5-year survival). Testing cohort

validation including (K) risk stratification by median cutoff, (L)

survival distribution mapping, (M) Kaplan-Meier curves for OS of

the high- and low-risk groups, and (N) time-dependent ROC analysis

demonstrating predictive accuracy (AUC values for 1, 3 and 5-year

survival). (O) Construction of a prognostic nomogram model

integrating risk score with clinical parameters

(Tumor-Node-Metastasis stage, histological grade and age). (P)

Calibration plots showing concordance between predicted and

observed survival probabilities at 1, 3 and 5-year intervals. (Q)

Time-dependent ROC analysis demonstrating predictive accuracy (AUC

values for 1, 3 and 5-year survival). *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001

by multivariate Cox regression analysis. AUC, area under the curve;

LLPS, liquid-liquid phase separation; LLPSRG, LLPS-related gene;

OS, overall survival; OSCC, oral squamous cell carcinoma; ROC,

receiver operating characteristic; TCGA, The Cancer Genome

Atlas. |

Based on these insights, seven LLPSRGs significantly

associated with OSCC prognosis were identified using Cox

proportional hazards regression (Fig.

2D) and their predictive efficacy was further validated via

LASSO regression (Fig. 2E). To

establish a robust model, TCGA-OSCC cohort was randomly divided

into training (n=211) and validation (n=91) groups at a 7:3 ratio.

A novel prognostic prediction model was developed through LASSO

regression analysis using the training set data, ultimately

yielding the following mathematical formula: RiskScore=Exp(SYT1) ×

0.126671488410991 + Exp(MYO1B) × 0.116232649674581 + Exp(PHLDB2) ×

0.111345681109828 + Exp(CORO2B) × 0.0992669799054353 + Exp(CDH13) ×

0.0701283734822018 + Exp(DDX21) × 0.0342177920472229 + Exp(PKLR) ×

−0.202003545600354. After stratifying TCGA-OSCC patients into high-

and low-risk groups, the gene expression heatmap reveals distinct

expression patterns of model genes demonstrating clear distinctions

between the two subgroups (Fig.

2F).

To validate the predictive performance of the

developed model, risk scores were calculated for all patients, with

samples stratified into high- and low-risk groups based on median

values (Fig. 2G and K). PCA and

t-SNE revealed distinct spatial separation between the two groups

in gene expression profiles (Fig.

S2A-D), confirming the biological discriminative power of the

model. Survival analysis demonstrated markedly higher mortality in

the high-risk group (Fig. 2H and

L) and significantly reduced OS rates compared with those in

the low-risk group (Fig. 2I and

M). Time-dependent ROC curves showed area under the curve (AUC)

values of 0.727, 0.737 and 0.604 for 1-, 3- and 5-year survival

predictions in the training set, and 0.672, 0.663 and 0.712 in the

validation set, indicating high sensitivity and specificity

(Fig. 2J and N).

To enhance clinical applicability, the risk score

was integrated with traditional clinicopathological parameters (TNM

stage, histological grade and age) to construct a nomogram model

(Fig. 2O). Calibration curves

demonstrated strong concordance between predicted and observed

survival probabilities at 1, 3 and 5 years (Fig. 2P). The nomogram model exhibited

significantly improved AUC values compared with the risk score

alone (Fig. 2Q), highlighting its

superior accuracy in individualized prognosis prediction. These

results underscore the potential of the LLPSRG-based prognostic

model to refine clinical risk stratification and inform targeted

therapeutic strategies for OSCC.

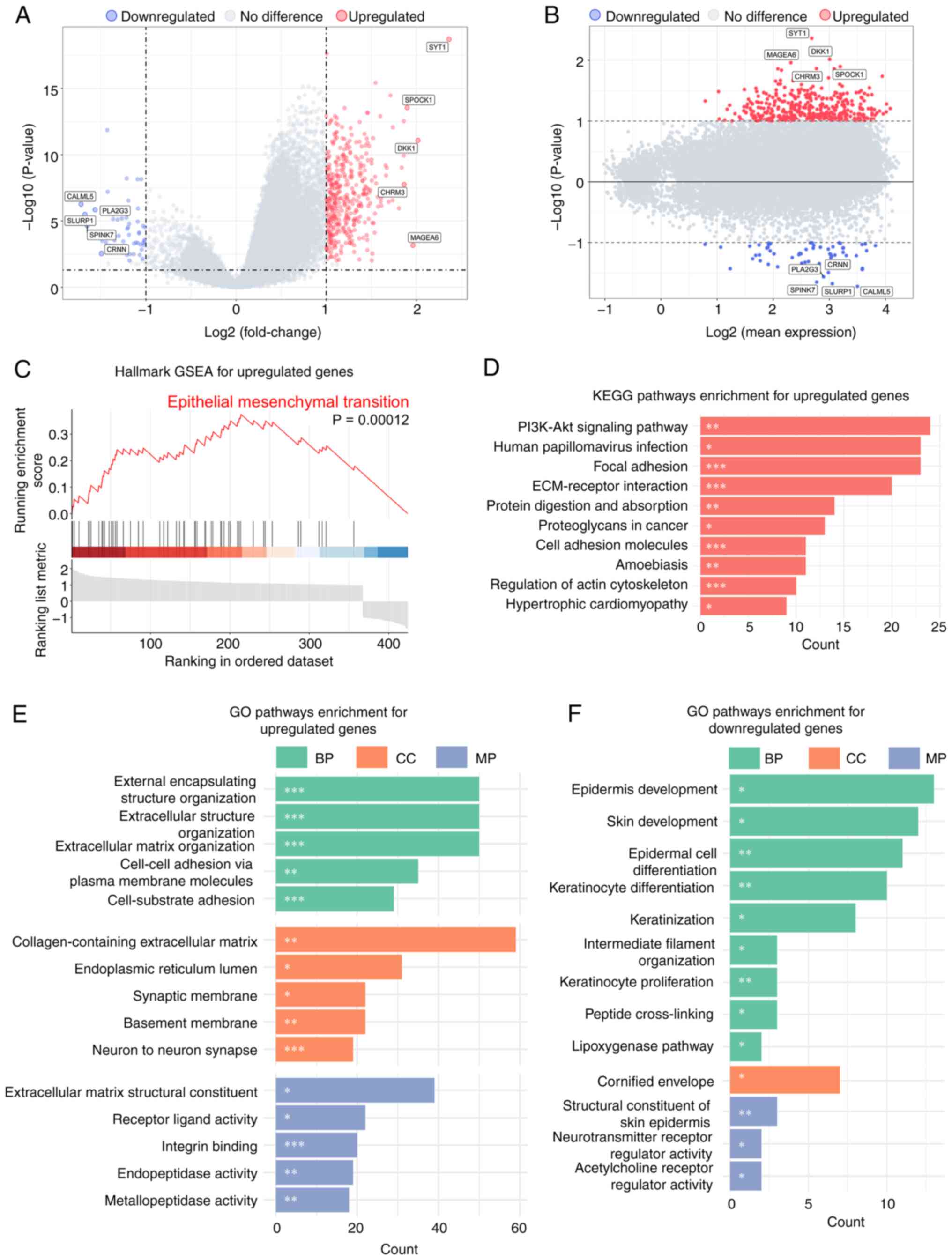

Functional enrichment analysis of DEGs

between high- and low-risk groups

To investigate the mechanistic basis of survival

disparities between the high- and low-risk cohorts, comparative

expression profiling of LLPSRGs across both groups was conducted.

The results revealed 401 significantly upregulated genes and 60

downregulated genes in the high-risk group (P<0.05;

|log2FC|>1; Fig. 3A). The MA

plot demonstrated no significant association between gene

expression levels and fold changes (Fig. 3B), ruling out technical bias as a

cause of false-positive results for highly expressed genes.

According to the core characteristics of LLPS, proteins capable of

phase separation require local critical concentrations and rely on

IDRs to promote droplet-like condensate formation. Therefore, the

functional properties of upregulated genes were focused on.

Hallmark GSEA based on the MsigDB confirmed that EMT

was significantly enriched [normalized enrichment score (NES),

2.45; Fig. 3C]. KEGG pathway

analysis further demonstrated significant enrichment of these genes

in the ‘PI3K-Akt signaling pathway’, ‘ECM-receptor interaction’ and

‘focal adhesion’ (Fig. 3D),

suggesting their potential role in promoting cell migration and

invasion through ECM remodeling.

Consistent with the aforementioned findings, GO

analysis revealed significant enrichment of upregulated genes in

biological processes involving ECM remodeling and cell adhesion

regulation (Fig. 3E). Notably, GO

enrichment analysis of downregulated genes revealed pronounced

enrichment in pathways governing epithelial differentiation and

keratinization processes (Fig.

3F), underscoring the suppression of epithelial lineage

commitment, which corroborates the previously observed EMT pathway

activation.

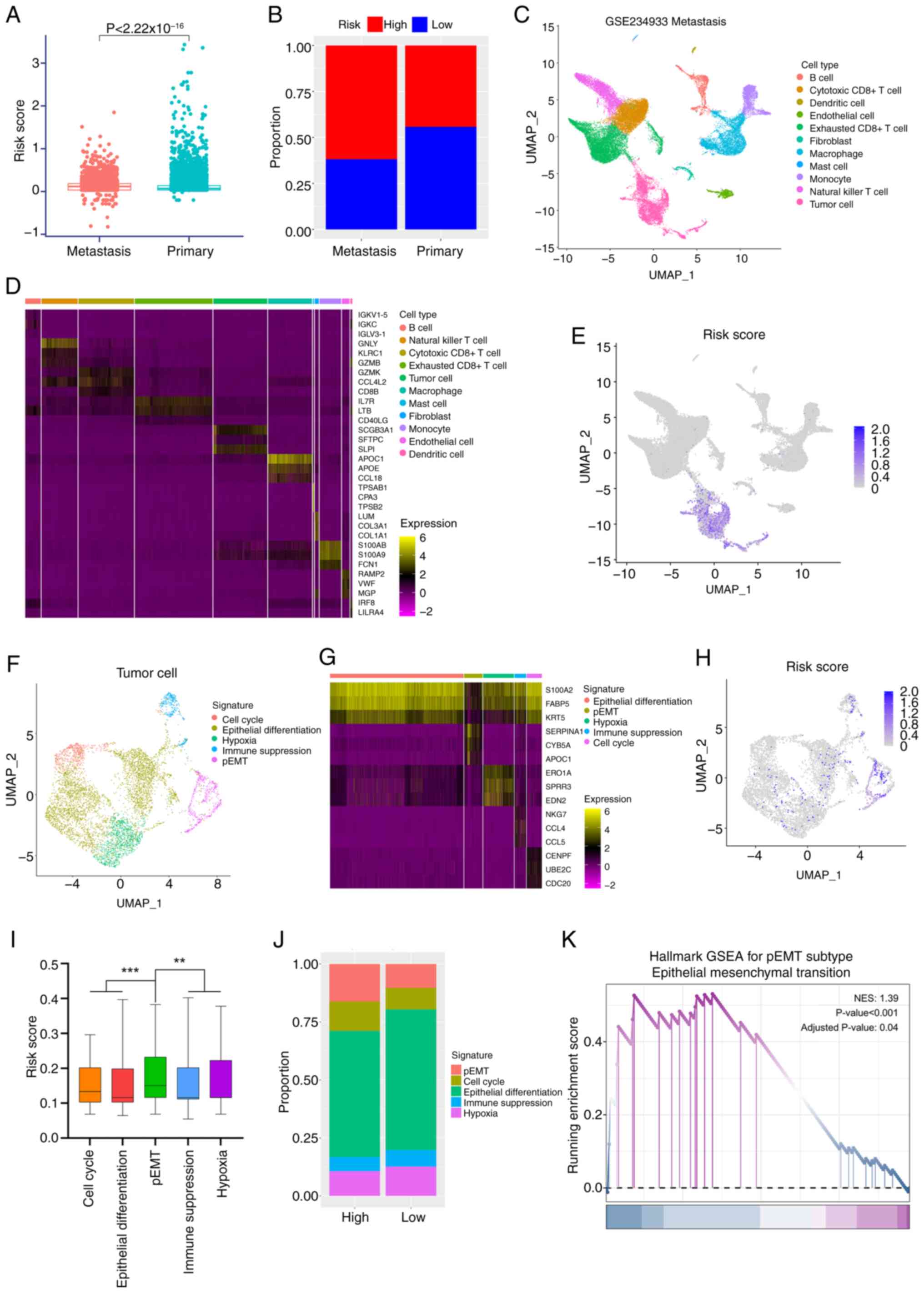

Expression profile of prognostic model

genes in OSCC at a single cell level

To investigate the impact of the seven LLPSRGs in

the prognostic model on the malignant progression of OSCC at a

single cell level, systematic analyses were conducted using the

public scRNA-seq dataset, GSE234933. Primary tumor samples (n=19,

total cells=123,094) and metastatic tumor samples (n=8, total

cells=38,987) were selected based on clinical information. Risk

scores for all cells were calculated using the established

prognostic model formula. Results revealed significantly higher

risk scores in metastatic tumor cells compared with primary tumor

cells (Fig. 4A). When stratifying

cells into high- and low-risk groups based on the median risk

score, the metastatic tumor group exhibited a significantly higher

proportion of high-risk cells (Fig.

4B; 61.9 vs. 44.2% in primary tumors).

Given the aggressive phenotype and elevated risk

scores of metastatic cells, subsequent analyses focused on the

metastatic cell population. Unsupervised clustering and canonical

marker genes were used to annotate major cell types (Fig. 4C), with marker gene expression

heatmaps (such as fibroblast marker COL1A1 and cytotoxic T cell

marker CD8B) confirming accurate classification (Fig. 4D). Risk profiling across all cell

clusters through computing risk model algorithms revealed

pronounced risk score enrichment within Uniform Manifold

Approximation and Projection (UMAP)-defined tumor cell niches

(Fig. 4E), guiding subsequent

investigations to focus on tumor cell subpopulations.

Tumor cells were subdivided into the following five

functional subtypes: i) Cell cycle; ii) epithelial differentiation;

iii) hypoxia; iv) immune suppression; and v) partial (p)EMT, based

on canonical markers (Fig. 4F).

Heatmaps of subtype marker genes (such as CDC20 marking the cell

cycle subtype and KRT5 marking epithelial differentiation)

validated classification accuracy (Fig. 4G). Risk scores were calculated

across tumor cell subpopulations (Fig.

4H), revealing a pronounced risk elevation in the pEMT

subpopulation (Fig. 4I).

Consistently, when tumor cells were stratified by median risk

score, high-risk tumor cells exhibited a higher proportion of the

pEMT subtype (Fig. 4J; 16.2 vs.

10.3% in low-risk), a subtype strongly associated with tumor

invasion and metastatic potential (19). Mechanistically aligning with prior

pathway enrichment findings, specific activation of the EMT

signature pathway was also observed in the pEMT subpopulation

(Fig. 4K; NES, 1.39), indicating

that the EMT activation detected in bulk transcriptomics analyses

predominantly originates from the pEMT subpopulation within tumor

cells.

In summary, single-cell analyses demonstrated that

high-risk cell populations foster a pro-metastatic environment in

OSCC through activation of pEMT tumor cell subpopulations.

LLPS phenomenon of PHLDB2 in OSCC

To delineate core oncogenic drivers among the seven

prognostic model genes that drive the malignant progression of

OSCC, the GEPIA2 website (20) was

used to compare the relative expression of the seven LLPSRGs in

TCGA-OSCC (Fig. S3A),

prioritizing four highly expressed candidates, MYO1B, DDX21, CDH13

and PHLDB2. RT-qPCR of the seven genes in the OSCC cell lines

verified the aforementioned results (Fig. S3B and C). Subsequently,

integrative prognostic mapping for TCGA-OSCC by GEPIA2 (Fig. S3D) further refined the key

regulator candidates to MYO1B, CDH13 and PHLDB2.

To evaluate their phase separation potential, the

amino acid sequences of these proteins were obtained from the

UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/) and uploaded to the IUPred2A

platform (17) to analyze their

IDR propensity. The prediction revealed markedly higher phase

separation potential for PHLDB2 compared with MYO1B and CDH13

(Figs. 5A, S3E and S3F). In addition, LLPS scoring for

PHLDB2, MYO1B and CDH13 by PhaSePred (18) supported the aforementioned results

(Figs. 5B, S3G and S3H), prompting further in-depth

investigation of PHLDB2.

To validate whether PHLDB2 undergoes LLPS, its

ability to form condensates in vitro was first examined. In

LLPS buffer containing 50 mM NaCl, Alexa Fluor 488-labeled PHLDB2

protein formed phase-separated droplets ranging 2.5–15 µm in

diameter, with droplet size positively associated with protein

concentration (2.5–15 µM; Fig. 5C)

and inversely associated with NaCl concentration (50–500 mM;

Fig. 5D). Notably, live-cell

imaging of the SCC1 OSCC cell line transfected with PHLDB2-EGFP

plasmids demonstrated the formation of cytoplasmic droplets

(Fig. 5E). FRAP assays further

confirmed the liquid-like properties of these condensates, with

fluorescence recovering to 31.4% at 5 sec, 52.6% at 30 sec and

62.7% at 60 sec post-bleaching (Fig.

5F and G). These results conclusively demonstrated that PHLDB2

forms LLPS condensates in OSCC cells.

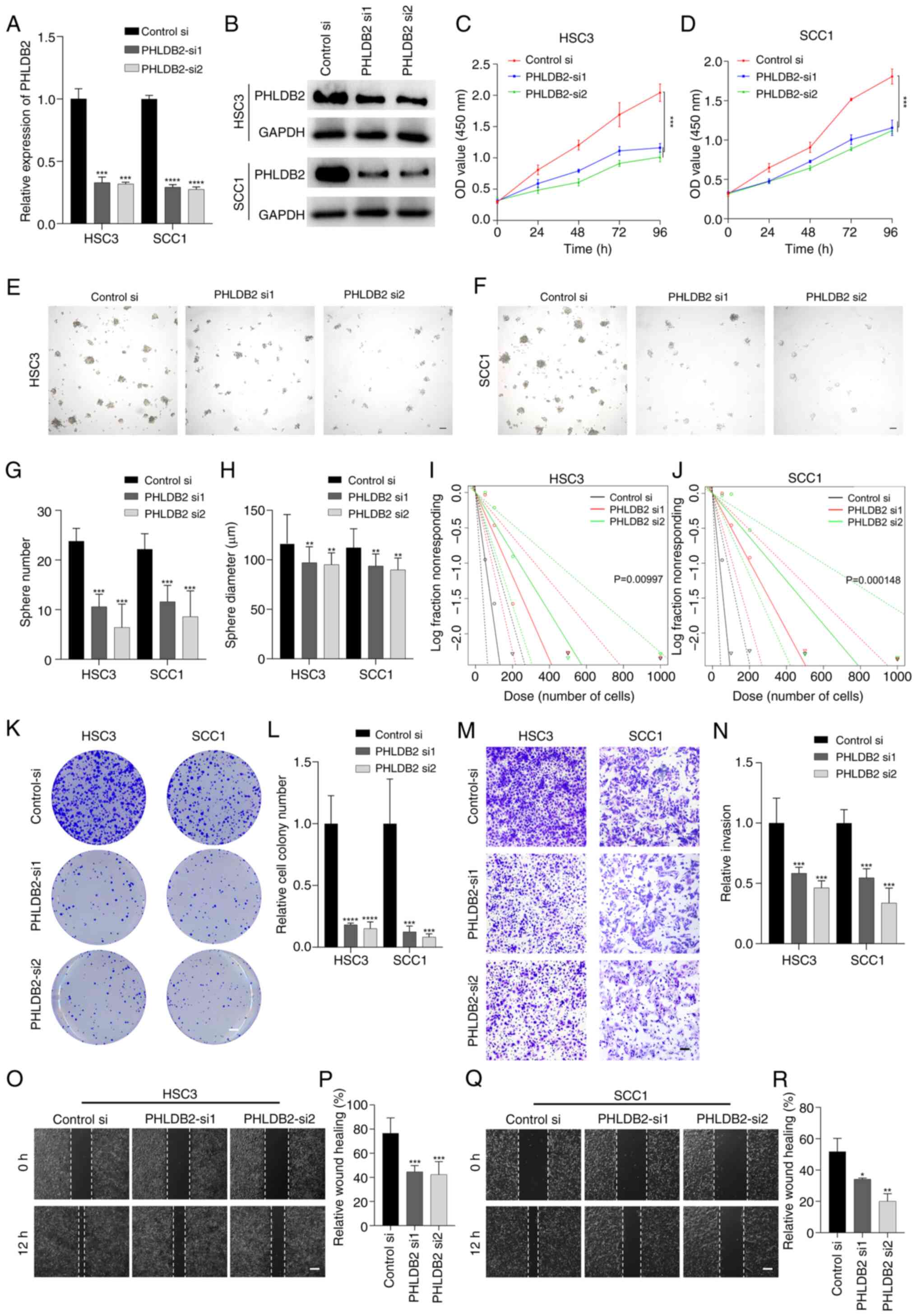

Promoting effects of PHLDB2 on

proliferation, stemness and invasion in OSCC cell lines

To investigate the regulatory role of PHLDB2 in the

biological behavior of OSCC cells, two sequence-specific siRNAs

were designed to knockdown PHLDB2 expression in SCC1 and HSC3 cell

lines via transient transfection. RT-qPCR and western blotting

results demonstrated that both siRNAs significantly reduced PHLDB2

mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 6A and

B), confirming the high efficiency and specificity of the

knockdown system.

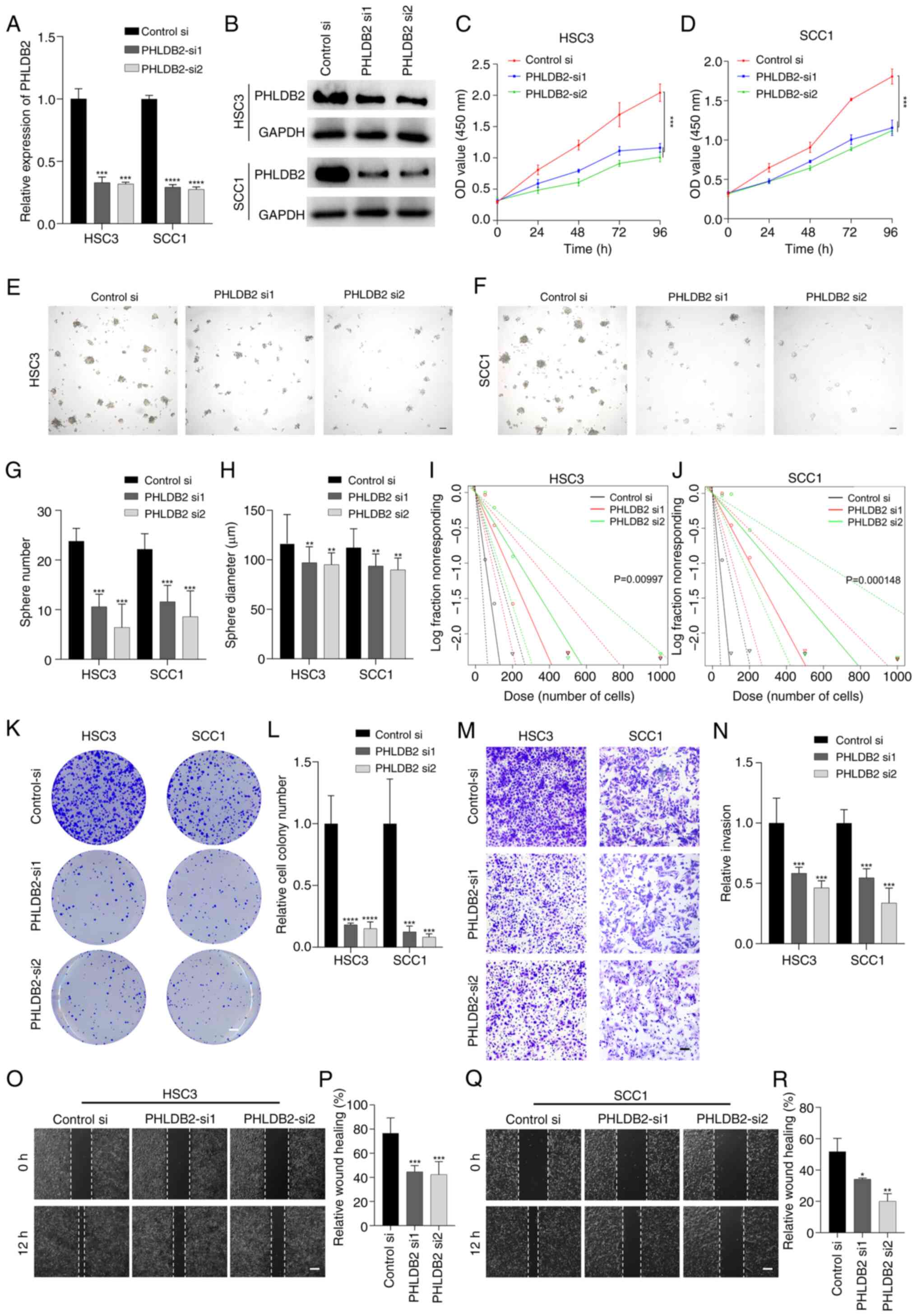

| Figure 6.Promoting effects of PHLDB2 on

proliferation, stemness, invasion and metastasis in OSCC cell

lines. (A) PHLDB2 mRNA levels were decreased in OSCC cells

transfected with PHLDB2-targeting siRNAs (si1/si2). ***P<0.001,

****P<0.0001 vs. control-si. (B) Western blotting confirmed

PHLDB2 protein knockdown following siRNA transfection. OD values

demonstrated changes in (C) HSC3 cells and (D) SCC1 cells upon

PHLDB2 depletion. ***P<0.001. Tumor spheres formed in (E) HSC3

cells and (F) SCC1 cells. Scale bar, 100 µm. (G) Sphere number

decreased in PHLDB2-knockdown HSC3/SCC1 cells. ***P<0.001 vs.

control-si. (H) Sphere diameter decreased in PHLDB2-knockdown

HSC3/SCC1 cells. **P<0.01 vs. control-si. Sphere-forming

capacity decreased in (I) HSC3 cells and (J) SCC1 cells with PHLDB2

knockdown. (K) Representative image of colony formation assays

showed reduction in PHLDB2-knockdown HSC3/SCC1 cells vs. control.

Scale bar, 3 mm. (L) Quantification of colony formation assays

showed reduction in PHLDB2-knockdown HSC3/SCC1 cells.

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 vs. control-si. (M) Representative

image of invasion assays indicated suppression in PHLDB2-knockdown

HSC3/SCC1 cells. Scale bar, 50 µm. (N) Quantification of invasion

assays indicated suppression in PHLDB2-knockdown HSC3/SCC1 cells.

***P<0.001 vs. control-si. (O) Representative image of wound

healing assays indicated depletion of migratory capacity in

PHLDB2-knockdown HSC3 cells vs. control. Scale bar, 100 µm. (P)

Wound healing assays indicated depletion of migratory capacity in

PHLDB2-knockdown HSC3 cells. ***P<0.001 vs. control-si. (Q)

Quantification of wound healing assays indicated depletion of

migratory capacity in PHLDB2-knockdown SCC1 cells vs. control.

Scale bar, 100 µm. (R) Wound healing assays indicated depletion of

migratory capacity in PHLDB2-knockdown SCC1 cells. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 vs. control-si. OSCC, oral squamous cell carcinoma; si,

small interfering. |

CCK-8 assays revealed a significant decline in

proliferation rates over time in the PHLDB2 knockdown groups

(Fig. 6C and D). Tumor-sphere

formation assays further showed that the number of tumor-spheres

and their average diameter were significantly reduced in the

knockdown groups compared with those in the control groups

(Fig. 6E-H). Limiting dilution

assays confirmed impaired self-renewal capacity of tumor stem cells

following PHLDB2 knockdown (Fig. 6I

and J). Additionally, colony formation assays indicated a

significant decrease in colony numbers in the knockdown groups

(Fig. 6K and L), suggesting the

critical role of PHLDB2 in maintaining tumor stemness.

For tumor invasion, Transwell assays showed a

significant reduction in matrix gel-penetrating cells in the PHLDB2

knockdown groups (Fig. 6M and N).

Wound healing assays further revealed decreased wound closure rates

in knockdown cells (Fig. 6O-R).

These results systematically demonstrated that PHLDB2 promotes OSCC

malignant progression by enhancing cell proliferation, stemness

maintenance and invasive potential.

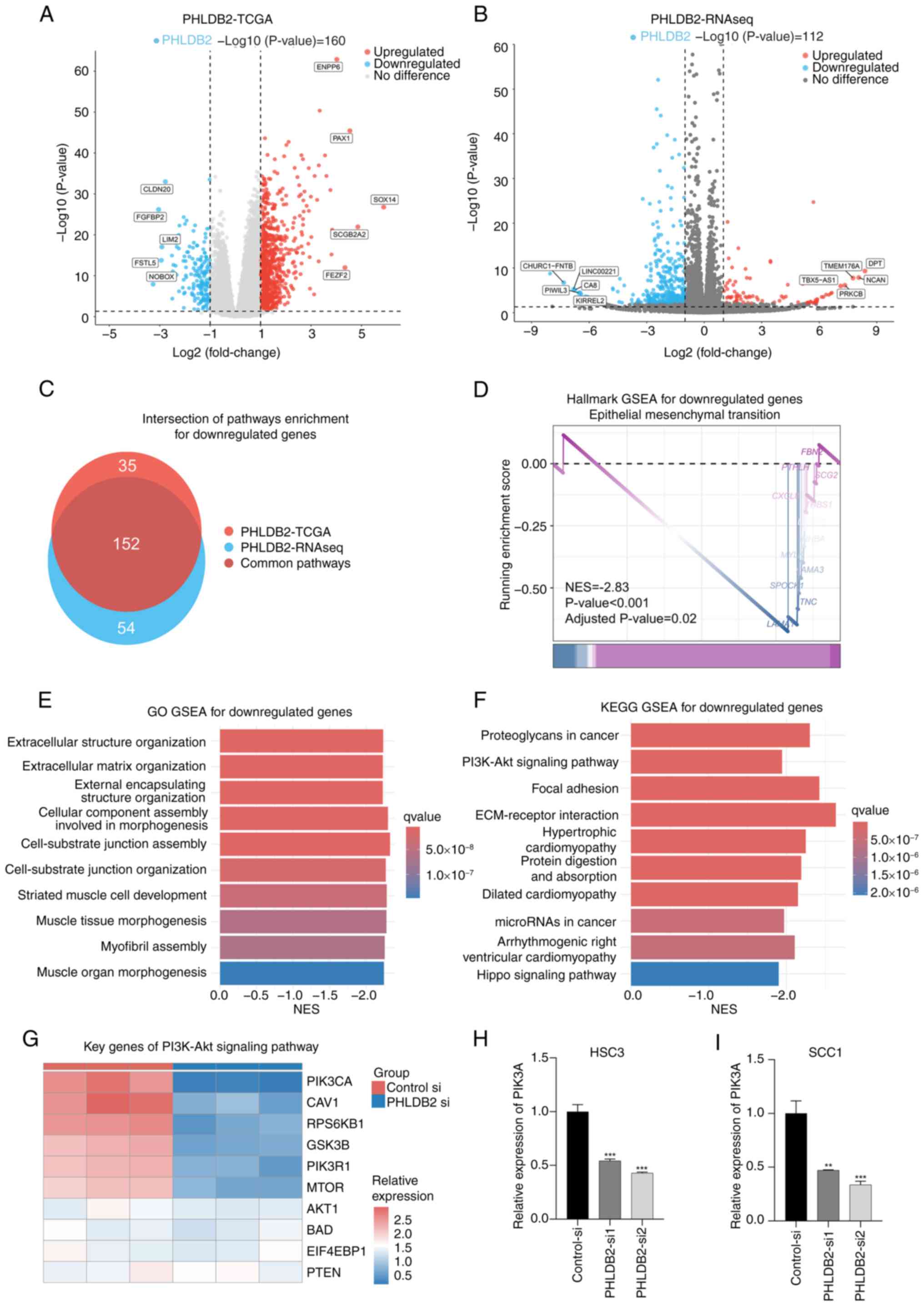

Exploration of the molecular

mechanisms of PHLDB2 promoting the malignant characteristics of

OSCC

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms by which

PHLDB2 promotes malignant phenotypes in OSCC cells, a

multi-dimensional data cross-validation strategy was employed that

systematically compared RNA-seq data from PHLDB2 knockdown

experiments with transcriptomics data from TCGA-OSCC cohort. For

TCGA-OSCC public data, patients were stratified into high- and

low-expression groups based on PHLDB2 levels, followed by

differential gene analysis identifying 3,147 distinctively

upregulated genes and 15,398 distinctively downregulated genes in

the PHLDB2 low-expression group (Fig.

7A). Subsequent Hallmark and GO GSEA based on MsigDB were

performed on these DEGs, collectively named the PHLDB2-TCGA pathway

enrichment results (Fig. 7C). SCC1

cells were transiently transfected with PHLDB2-si1 siRNA to

knockdown PHLDB2 expression, and three biological replicates were

conducted for both the experimental group (PHLDB2-si) and the

control group (control-si), followed by RNA-seq. Differential

expression analysis (thresholds, P<0.05 and |log2FC|>1)

confirmed reliable knockdown efficiency of PHLDB2-si, identifying

80 distinctively upregulated genes and 360 distinctively

downregulated genes in the PHLDB2 knockdown group (Fig. 7B). Subsequent Hallmark and GO GSEA

based on MsigDB were performed on these DEGs, collectively named

the PHLDB2-RNAseq pathway enrichment results (Fig. 7C).

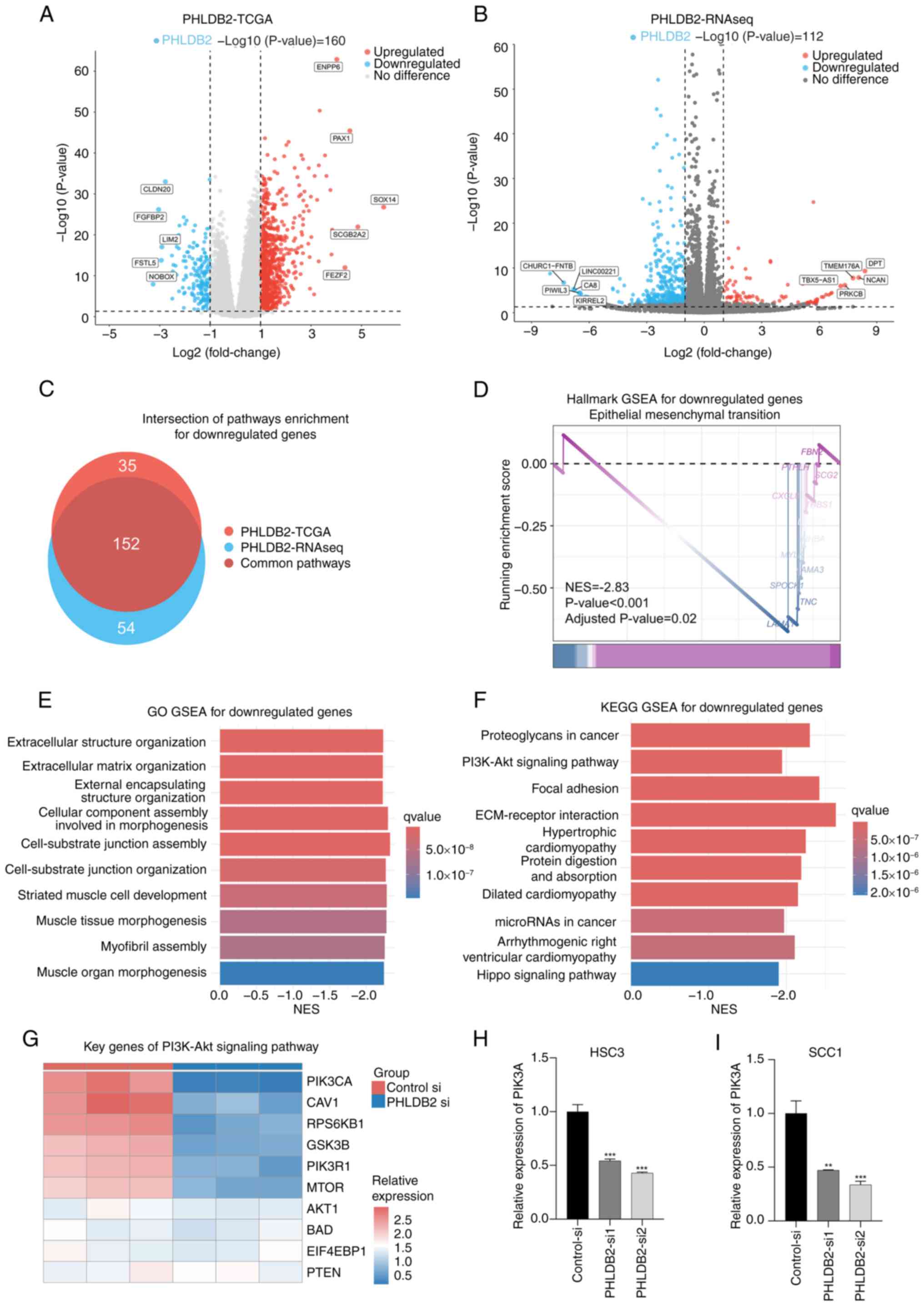

| Figure 7.Exploration of the molecular

mechanisms of PHLDB2 promoting the malignant characteristics of

OSCC. (A) Differential gene analysis identified differentially

expressed genes between PHLDB2 low- and high-expression groups in

TCGA-OSCC cohort. Threshold: P<0.05 and |log2FC|>1. (B)

Differential gene analysis identified differentially expressed

genes between the PHLDB2 knockdown group and the control group.

Thresholds: P<0.05 and |log2FC|>1. (C) Intersection analysis

revealed downregulated pathways shared between PHLDB2-RNAseq and

PHLDB2-TCGA enrichment profiles. (D) Integrated Hallmark pathway

analysis demonstrated enriched pathway for downregulated genes. (E)

Integrated GO pathway analysis identified enriched biological terms

for downregulated genes. (F) Integrated KEGG pathway analysis

showed enriched pathways for downregulated genes. (G) Heatmap

displayed expression patterns of PI3K-Akt signaling pathway genes

in PHLDB2-knockdown vs. control groups. Reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR indicated reduced PIK3CA expression

in PHLDB2-depleted (H) HSC3 and (I) SCC1 cells. **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 vs. control-si. GO, Gene Ontology; GSEA, gene set

enrichment analysis; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes;

NES, normalized enrichment score; OSCC, oral squamous cell

carcinoma; RNAseq, RNA sequencing; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas;

MsigDB, Molecular Signatures Database; si, small interfering. |

To delineate core pathway convergence in

PHLDB2-deficient molecular contexts, a cross-dataset intersection

of the PHLDB2-RNAseq and PHLDB2-TCGA pathway enrichment results was

performed (Fig. 7C). Consensus

pathway analysis of the intersecting 152 molecular signatures

demonstrated significant suppression of the Hallmark EMT gene set

in PHLDB2-depleted samples (NES, −2.833; false discovery rate,

0.023; Fig. 7D), consistent with

the Hallmark enrichment results from prognostic model genes

(Fig. 3C). Western blot validation

of core EMT markers confirmed these findings (Fig. S4), showing decreased N-cadherin

and vimentin protein levels accompanied by increased E-cadherin

expression in the PHLDB2-si groups compared with those in the

control-si groups. GO enrichment analysis further demonstrated that

pathways related to ECM remodeling and the cell-substrate junction

including ‘extracellular structure organization’, ‘extracellular

matrix organization’, ‘cell-substrate junction assembly’ and

‘cell-substrate junction organization’, were markedly downregulated

(Fig. 7E), mechanistically

implicating that PHLDB2 depletion impaired EMT activation dynamics

in OSCC.

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying

PHLDB2-mediated EMT regulation, KEGG GSEA was conducted for

downregulated genes in PHLDB2-depleted samples, which revealed

significant enrichment of the ‘PI3K-Akt signaling pathway’

(Fig. 7F), recapitulating the

pathway convergence pattern observed in prior prognostic model gene

signatures. Subsequent expression profiling of core PI3K-Akt

signaling components in PHLDB2-knockdown models demonstrated marked

downregulation of PIK3CA (Fig.

7G). Further validation through RT-qPCR in PHLDB2-knockdown

OSCC cell lines confirmed the transcriptional repression of PIK3CA

(Fig. 7H and I). Previous research

has identified PIK3CA as a critical molecular regulator of EMT

activation (24,25). Integrated analysis of the

multidimensional datasets in the present study revealed that

PHLDB2-mediated upregulation of PIK3CA may constitute a novel

mechanistic axis driving EMT progression in OSCC pathogenesis.

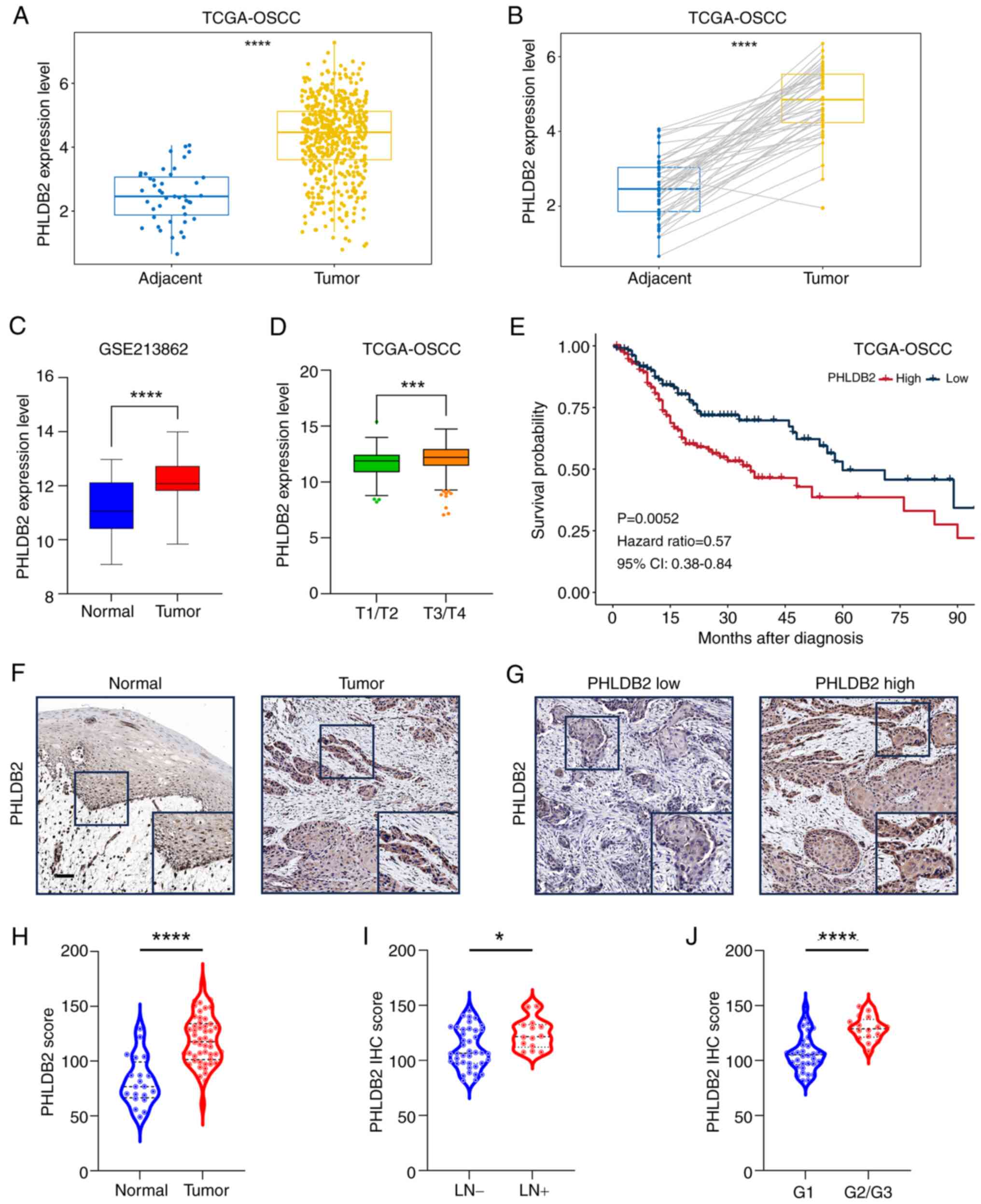

High expression of PHLDB2 is

associated with a poorer prognosis for patients with OSCC

To clarify the expression characteristics and

clinical significance of PHLDB2 in OSCC clinical samples,

multicenter data were systemically integrated. Analysis of TCGA

database revealed that PHLDB2 mRNA expression was significantly

higher in OSCC tumor tissues (n=302) compared with that in adjacent

tissues (n=67; Fig. 8A), with

consistent differences observed in paired tumor-adjacent samples

(Fig. 8B). This trend was further

validated in the independent cohort GSE213862 (n=43), where PHLDB2

expression in OSCC tissues was significantly elevated compared with

that in normal mucosal tissues from healthy individuals (Fig. 8C). Notably, analysis of TCGA-OSCC

cohort demonstrated that PHLDB2 expression was significantly higher

in advanced-stage tumors (T3/T4) compared with that in early-stage

tumors (T1/T2) (Fig. 8D), and

patients with high PHLDB2 expression had significantly shorter OS

compared with that in the patients with low PHLDB2 expression

(Fig. 8E).

To further validate protein-level expression

characteristics, IHC analysis was performed on an OSCC cohort

(n=51) from the Hospital of Stomatology, SYSU. Negative control

experiments using non-specific IgG demonstrated assay specificity

(Fig. S5). Results indicated

significantly higher PHLDB2 protein expression in tumor tissues

compared with those in adjacent normal tissues (Fig. 8F-H). Additionally, high PHLDB2

expression was significantly associated with lymph node metastasis

(Fig. 8I) and poor tumor

differentiation (G2/3 vs. G1; Fig.

8J). These data collectively suggested that elevated PHLDB2

expression may be closely linked to malignant progression and poor

prognosis in OSCC.

Discussion

Previous studies on LLPSRGs and OSCC have primarily

focused on characterizing phase separation phenomena of established

oncogenes (such as FOSL1 and DAZAP1) (26,27);

however, to the best of our knowledge, the systematic exploration

of their prognostic value remains unreported. Notably, prognostic

models based on LLPSRGs have demonstrated efficacy in stratifying

patient survival in ovarian (12),

breast (13) and bladder cancer

(14), yet this strategy remains

unexplored in OSCC. The present study innovatively integrated LLPS

mechanism exploration with prognostic model construction,

establishing the first OSCC-specific LLPSRG prognostic prediction

model, by conducting Cox and LASSO regression analyses on LLPSGs

and survival rate of TCGA-OSCC cohort. Through rigorous

bioinformatics screening and experimental validation, the

independent prognostic value of the key gene PHLDB2 was

investigated, and to the best of our knowledge, the first

experimental evidence that the PHLDB2 protein exhibits spontaneous

LLPS in OSCC cells was provided. This discovery addresses the

research gap regarding LLPSRGs in OSCC prognostic assessment

systems.

It is critical to emphasize the screening strategy

of the present study. Although the DrLLPS database provides 3,633

proteins predicted to have LLPS potential, these predictions

require experimental validation of their biological functions

(28). To enhance result

reliability, genes with high scores across multiple phase

separation prediction platforms [such as IUPred2A (19) and PhaSepDB (20)] were prioritized during the

selection of key model genes, ultimately identifying PHLDB2.

Notably, as well as PHLDB2, the other six core genes (SYT1, MYO1B,

CORO2B, CDH13, DDX21 and PKLR) included in the present prognostic

model have partial functional annotations in tumor biology, but

their LLPS-related mechanisms and roles in OSCC malignant

progression have not yet been elucidated.

Specifically, SYT1 was associated with poor

prognosis as a high-risk gene in the present model, contradicting

its tumor-suppressive role observed by Shi et al (29) in colorectal cancer. Considering the

canonical function of SYT1 in neurotransmitter release regulation

as a synaptotagmin family member, and previous findings that neural

pathways influence tumor progression through diverse mechanisms

(30–32), it was hypothesized that SYT1 may

activate pro-oncogenic signaling via phase-separated condensates at

neural synapse-related sites. This hypothesis requires validation

through co-localization experiments and neural co-culture models.

MYO1B has been linked to poor prognosis in head and neck squamous

cell carcinoma (HNSCC), glioma and colorectal cancer (33–36).

Its oncogenic role in HNSCC has been shown to involve regulation by

microRNA (miRNA)-145-3p (33), yet

whether miRNA-MYO1B interactions involve LLPS warrants further

investigation. While CORO2B and CDH13 exhibit oncogenic properties

in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (37) and renal cancer (38), their molecular mechanisms remain

unconnected to LLPS, offering new research directions. Notably, the

high-risk association of DDX21 in the present model aligns with its

function in colorectal cancer. Specifically, Gao et al

(39) demonstrated that DDX21

activates EMT pathways through LLPS-dependent chromatin remodeling,

suggesting a conserved metastatic mechanism in OSCC. By contrast,

the negative association between the low expression and poor

prognosis (negative risk coefficient) of PKLR contradicts the

majority of reports (40–42), potentially attributable to the

unique metabolic microenvironment of OSCC or dynamic changes in the

phase-separated states of PKLR, necessitating further

investigation. While SYT1, CORO2B, CDH13, DDX21 and PKLR lack

extensive prior links to OSCC, their strong prognostic value in the

present analysis warrants further mechanistic exploration.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is

the first to reveal the critical role of PHLDB2 as an LLPS driver

in OSCC, yet the molecular mechanisms by which it regulates

downstream signaling via LLPS require deeper exploration. Notably,

the findings of the present study do not directly establish a

causal relationship between PHLDB2-mediated LLPS and EMT/invasive

phenotypes, which requires validation, potentially through the

following mechanistic studies: i) Generation of LLPS-deficient

PHLDB2 mutants (targeting IDRs/key domains) and validation of the

loss of potential condensate formation outside and in cells,

followed by assessment of the effects of wild-type vs. mutant

PHLDB2 on EMT markers and biofunction in OSCC cells. ii)

Identification of proteins specifically recruited into PHLDB2

condensates using proximity labeling and co-immunoprecipitation

coupled with mass spectrometry, and assessment of the functional

roles of identified partners and oncogenic pathways activated by

LLPS. iii) Comparison of tumor growth/metastasis of cells

expressing wild-type vs. mutant PHLDB2 in mouse models.

As a pleckstrin homology domain protein family

member, PHLDB2 has been reported to participate in tumor metastasis

by regulating cytoskeletal rearrangement and focal adhesion

dynamics, with established links to EMT in OSCC (43,44),

colorectal cancer (45) and

gastric cancer (46). Building on

the discovery of the spontaneous LLPS condensate formation of

PHLDB2 in OSCC cells, the following novel hypothesis was proposed:

PHLDB2 may enhance EMT and metastatic efficacy through a phase

separation-dependent ‘molecular condensation’ mechanism, locally

enriching and activating cytoskeletal regulators and PI3K-Akt

signaling effectors in microenvironments, such as leading-edge

pseudopodia or invasive protrusions. This mechanism could explain

why traditional gene expression analysis inadequately captures the

oncogenic effects of PHLDB2, as its biological impact may depend

heavily on spatiotemporally specific protein interaction networks

mediated by LLPS. To address these scientific questions, subsequent

research should focus on the following: i) Interactome validation

whereby core interacting proteins within PHLDB2 condensates are

systematically screened using co-immunoprecipitation coupled with

mass spectrometry, emphasizing co-localization patterns of

cytoskeletal regulators and PI3K-Akt pathway components. ii) Phase

separation domain analysis whereby IDR deletion or phosphorylation

site mutants are constructed, combined with FRAP and in

vitro reconstitution experiments, to define the necessity of

the phase separation capability of PHLDB2 for its pro-metastatic

function and PI3K-Akt pathway activation. iii) Spatiotemporal

dynamics tracking whereby super-resolution live-cell imaging is

employed to observe real-time formation-dissolution kinetics of

PHLDB2 condensates at migration fronts and their co-evolution with

cytoskeletal regulators and PI3K-Akt pathway components. iv)

PI3K-Akt condensate crosstalk involving validation of whether

PHLDB2 scaffolds PI3K-Akt complexes via LLPS by assessing

co-condensation with PIP3-Akt using dual-color imaging, testing

functional rescue of EMT phenotypes upon PI3K-Akt inhibition in

PHLDB2-overexpressing cells, and mapping PIK3CA-binding capacity of

PH domain mutants with impaired phase separation. These

investigations could uncover the novel role of LLPS as a ‘molecular

accelerator’ in tumor cell plasticity regulation, providing a

theoretical foundation for developing anti-metastatic therapies

targeting phase separation processes.

In conclusion, the present study pioneered the

integration of LLPS mechanistic investigation with prognostic model

development, establishing the first LLPSRG prognostic prediction

model specifically for OSCC. By combining comprehensive

bioinformatics screening with experimental validation, the

independent prognostic significance of the key gene PHLDB2 was

confirmed and the first experimental evidence demonstrating the

spontaneous LLPS behavior of the PHLDB2 protein in OSCC cells was

provided. This discovery fills a critical knowledge gap regarding

LLPSRGs within OSCC prognostic evaluation frameworks.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was funded by The National Natural Science Foundation

of China (grant nos. 82373015 and 82403204).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author. The RNA-seq generated in

the present study may be found in the NCBI SRA database, under

accession number PRJNA1274177 or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1274177,

with data of control-si group in SRX29112934 at the following URL:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/SRX29112934[accn] and

data of PHLDB2-si group in SRX29112935 at the following URL:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/SRX29112935[accn].

Authors' contributions

KC and YW conceptualized and validated the present

study, performed the study investigation and methodology, and wrote

the original draft of the manuscript. JC performed data acquisition

and validation, and performed the investigation. QL performed the

formal analysis and obtained the resources. XL performed data

acquisition and validation. WW conceptualized and supervised the

study, acquired the funding and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

JH conceptualized and supervised the study, acquired the funding,

performed project administration, and reviewed and edited the

manuscript. KC and YW confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study received approval from the ethics

committee of the Hospital of Stomatology, Sun Yat-sen University

(Guangzhou, China; approval no. KQEC202013) and all participants

provided written informed consent.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Cramer JD, Burtness B, Le QT and Ferris

RL: The changing therapeutic landscape of head and neck cancer. Nat

Rev Clin Oncol. 16:669–683. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Alberti S, Gladfelter A and Mittag T:

Considerations and challenges in studying liquid-liquid phase

separation and biomolecular condensates. Cell. 176:419–434. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Tong X, Tang R, Xu J, Wang W, Zhao Y, Yu X

and Shi S: Liquid-liquid phase separation in tumor biology. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 7:2212022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Mehta S and Zhang J: Liquid-liquid phase

separation drives cellular function and dysfunction in cancer. Nat

Rev Cancer. 22:239–252. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zheng LW, Liu CC and Yu KD: Phase

separations in oncogenesis, tumor progressions and metastasis: A

glance from hallmarks of cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 16:1232023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Blackburn EH: Structure and function of

telomeres. Nature. 350:569–573. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zhang H, Zhao R, Tones J, Liu M, Dilley

RL, Chenoweth DM, Greenberg RA and Lampson MA: Nuclear body phase

separation drives telomere clustering in ALT cancer cells. Mol Biol

Cell. 31:2048–2056. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Lu Y, Wu T, Gutman O, Lu H, Zhou Q, Henis

YI and Luo K: Phase separation of TAZ compartmentalizes the

transcription machinery to promote gene expression. Nat Cell Biol.

22:453–464. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Cheng Y, Xie W, Pickering BF, Chu KL,

Savino AM, Yang X, Luo H, Nguyen DT, Mo S, Barin E, et al:

N6-methyladenosine on mRNA facilitates a phase-separated

nuclear body that suppresses myeloid leukemic differentiation.

Cancer Cell. 39:958–972.e8. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Tulpule A, Guan J, Neel DS, Allegakoen HR,

Lin YP, Brown D, Chou YT, Heslin A, Chatterjee N, Perati S, et al:

Kinase-mediated RAS signaling via membraneless cytoplasmic protein

granules. Cell. 184:2649–2664.e18. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Qiu Y, Pan M and Chen X: A liquid-liquid

phase separation-related gene signature as prognostic biomarker for

epithelial ovarian cancer. Front Oncol. 11:6718922021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yu-Qing H, Peng-Ping L, Ke S, Ke-Xing Y,

Wei-Jun Z and Zhen-Yu W: Comprehensive analysis of liquid-liquid

phase separation-related genes in prediction of breast cancer

prognosis. Front Genet. 13:8344712022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Sun L, Liu XP, Yan X, Wu S, Tang X, Chen

C, Li G, Hu H, Wang D and Li S: Identification of molecular

subtypes based on liquid-liquid phase separation and cross-talk

with immunological phenotype in bladder cancer. Front Immunol.

13:10595682022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Chatterjee A, Chaudhary A, Ghosh A, Arun

P, Mukherjee G, Arun I, Maitra A, Biswas N and Majumder PP:

Overexpression of CD73 is associated with recurrence and poor

prognosis of gingivobuccal oral cancer as revealed by transcriptome

and deep immune profiling of paired tumor and margin tissues.

Cancer Med. 12:16774–16787. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wilkerson MD and Hayes DN:

ConsensusClusterPlus: A class discovery tool with confidence

assessments and item tracking. Bioinformatics. 26:1572–1573. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Love MI, Huber W and Anders S: Moderated

estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with

DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15:5502014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Bill R, Wirapati P, Messemaker M, Roh W,

Zitti B, Duval F, Kiss M, Park JC, Saal TM, Hoelzl J, et al:

CXCL9:SPP1 macrophage polarity identifies a network of cellular

programs that control human cancers. Science. 381:515–524. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Tang Z, Kang B, Li C, Chen T and Zhang Z:

GEPIA2: An enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling

and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 47:W556–W560. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Mészáros B, Erdos G and Dosztányi Z:

IUPred2A: context-dependent prediction of protein disorder as a

function of redox state and protein binding. Nucleic Acids Res.

46:W329–W337. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Hou C, Wang X, Xie H, Chen T, Zhu P, Xu X,

You K and Li T: PhaSepDB in 2022: Annotating phase

separation-related proteins with droplet states, co-phase

separation partners and other experimental information. Nucleic

Acids Res. 51:D460–D465. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Lydiatt WM, Patel SG, O'Sullivan B,

Brandwein MS, Ridge JA, Migliacci JC, Loomis AM and Shah JP: Head

and Neck cancers-major changes in the American Joint Committee on

cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin.

67:122–137. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Coussy F, El Botty R, Lavigne M, Gu C,

Fuhrmann L, Briaux A, de Koning L, Dahmani A, Montaudon E, Morisset

L, et al: Combination of PI3K and MEK inhibitors yields durable

remission in PDX models of PIK3CA-mutated metaplastic breast

cancers. J Hematol Oncol. 13:132020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jeong YG, Katuwal NB, Kang MS, Ghosh M,

Hong SD, Park SM, Kim SG, Kim TH and Moon YW: Combined PI3K

inhibitor and eribulin enhances anti-tumor activity in preclinical

models of paclitaxel-resistant, PIK3CA-mutated endometrial cancer.

Cancers (Basel). 15:48872023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhang J, Ni Z, Zhang Y, Guo Y, Zhai R,

Wang M, Gong Z, Wang M, Zeng F, Gu Z, et al: DAZAP1 phase

separation regulates mitochondrial metabolism to facilitate

invasion and metastasis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer

Res. 84:3818–3833. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Wang W, Yun B, Hoyle RG, Ma Z, Zaman SU,

Xiong G, Yi C, Xie N, Zhang M, Liu X, et al: CYTOR facilitates

formation of FOSL1 phase separation and super enhancers to drive

metastasis of tumor budding cells in head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma. Adv Sci (Weinh). 11:e23050022024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Ning W, Guo Y, Lin S, Mei B, Wu Y, Jiang

P, Tan X, Zhang W, Chen G, Peng D, et al: DrLLPS: A data resource

of liquid-liquid phase separation in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res.

48(D1): D288–D295. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Shi J, Li W, Jia Z, Peng Y, Hou J, Li N,

Meng R, Fu W, Feng Y, Wu L, et al: Synaptotagmin 1 suppresses

colorectal cancer metastasis by inhibiting ERK/MAPK

signaling-mediated tumor cell pseudopodial formation and migration.

Cancers (Basel). 15:52822023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Balood M, Ahmadi M, Eichwald T, Ahmadi A,

Majdoubi A, Roversi K, Roversi K, Lucido CT, Restaino AC, Huang S,

et al: Nociceptor neurons affect cancer immunosurveillance. Nature.

611:405–412. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Zhang Y, Lin C, Liu Z, Sun Y, Chen M, Guo

Y, Liu W, Zhang C, Chen W, Sun J, et al: Cancer cells co-opt

nociceptive nerves to thrive in nutrient-poor environments and upon

nutrient-starvation therapies. Cell Metab. 34:1999–2017.e10. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Qiao N, Dai X, Chen J, Cao H, Hu G, Guo X,

Liu P, Xing C and Yang F: Single nucleus RNA sequencing reveals

cellular and molecular responses to vanadium exposure in duck

kidneys. J Hazard Mater. 480:1364922024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Yamada Y, Koshizuka K, Hanazawa T, Kikkawa

N, Okato A, Idichi T, Arai T, Sugawara S, Katada K, Okamoto Y and

Seki N: Passenger strand of miR-145-3p acts as a tumor-suppressor

by targeting MYO1B in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J

Oncol. 52:166–178. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Zhou X, Wang R, Li X, Yu L, Hua D, Sun C,

Shi C, Luo W, Rao C, Jiang Z, et al: Splicing factor SRSF1 promotes

gliomagenesis via oncogenic splice-switching of MYO1B. J Clin

Invest. 129:676–693. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Chen YH, Xu NZ, Hong C, Li WQ, Zhang YQ,

Yu XY, Huang YL and Zhou JY: Myo1b promotes tumor progression and

angiogenesis by inhibiting autophagic degradation of HIF-1α in

colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis. 13:9392022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Wang H, Yang F, Ye J, Dai X, Liao H, Xing

C, Jiang Z, Peng C, Gao F and Cao H: Ginkgo biloba extract

alleviates deltamethrin-induced testicular injury by upregulating

SKP2 and inhibiting Beclin1-independent autophagy. Phytomedicine.

135:1562452024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhang D, Qian C, Wei H and Qian X:

Identification of the prognostic value of tumor

microenvironment-related genes in esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma. Front Mol Biosci. 7:5994752020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Shao Y, Li W, Zhang L, Xue B, Chen Y,

Zhang Z, Wang D and Wu B: CDH13 is a prognostic biomarker and a

potential therapeutic target for patients with clear cell renal

cell carcinoma. Am J Cancer Res. 12:4520–4544. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Gao H, Wei H, Yang Y, Li H, Liang J, Ye J,

Zhang F, Wang L, Shi H, Wang J and Han A: Phase separation of DDX21

promotes colorectal cancer metastasis via MCM5-dependent EMT

pathway. Oncogene. 42:1704–1715. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Wang S, Zhang Y, Cai Q, Ma M, Jin LY, Weng

M, Zhou D, Tang Z, Wang JD and Quan Z: Circular RNA FOXP1 promotes

tumor progression and Warburg effect in gallbladder cancer by

regulating PKLR expression. Mol Cancer. 18:1452019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Chen WY, Thuy Dung PV, Yeh HL, Chen WH,

Jiang KC, Li HR, Chen ZQ, Hsiao M, Huang J, Wen YC and Liu YN:

Targeting PKLR/MYCN/ROMO1 signaling suppresses neuroendocrine

differentiation of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Redox

Biol. 62:1026862023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Peng J, Dai X, Zhang T, Hu G, Cao H, Guo

X, Fan H, Chen J, Tang W and Yang F: Copper as the driver of the

lncRNA-TCONS-6251/miR-novel-100/TC2N axis: Unraveling ferroptosis

in duck kidney. Int J Biol Macromol. 282:1367972024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Li H, Wang Z, Liang H, Liu X, Liu H,

Zhuang Z and Hou J: Depletion of PHLDB2 suppresses

epithelial-mesenchymal transition and enhances anti-tumor immunity

in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Biomolecules. 14:2322024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Chen J, Dai X, Xing C, Zhang Y, Cao H, Hu

G, Guo X, Gao X, Liu P and Yang F: Cooperative application of

transcriptomics and ceRNA hypothesis: lncRNA-00742/miR-116 targets

CD74 to mediate vanadium-induced mitochondrial apoptosis in duck

liver. J Hazard Mater. 480:1359042024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Chen G, Zhou T, Ma T, Cao T and Yu Z:

Oncogenic effect of PHLDB2 is associated with

epithelial-mesenchymal transition and E-cadherin regulation in

colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 19:1842019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Kang W, Zhang J, Huang T, Zhou Y, Wong CC,

Chan RCK, Dong Y, Wu F, Zhang B, Wu WKK, et al: NOTCH3, a crucial

target of miR-491-5p/miR-875-5p, promotes gastric carcinogenesis by

upregulating PHLDB2 expression and activating Akt pathway.

Oncogene. 40:1578–1594. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|