Introduction

Endometriosis is a frequent benign gynecological

disease that occurs in 10–15% of women of childbearing age. It is

typically characterized by endometrial cells and stroma implanting

and growing outside the endometrial cavity (1). Endometriosis has been associated with

~50% of women with infertility receiving assisted reproductive

technology (2,3). Moreover, women with endometriosis

treated with in vitro fertilization (IVF) have a lower

pregnancy rate and a higher miscarriage rate relative to those

without the condition (4,5).

The pathogenesis of endometriosis is not well

understood, but several hypotheses have been proposed, including

retrograde menstruation, hematogenous/lymphatic dissemination of

endometrial cells, coelomic metaplasia, migration of endometrial

stem cells, epigenetic modifications promoting inflammation and

endocrine disruption due to environmental toxins (6). A key feature of endometriosis is

elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in the pelvic cavity,

coupled with reduced antioxidant defenses, suggesting that

oxidative stress serves a critical role in disease progression

(7). ROS, primarily generated as

byproducts of mitochondrial metabolism (8), contributes to cellular senescence,

which is a state of irreversible cell cycle arrest accompanied by

active metabolic activity and the secretion of

senescence-associated secretory phenotypes (SASP). Emerging

evidence, including our unpublished data and other studies

(9,10), has indicated that cellular

senescence is notably associated with endometriotic lesions

(9). Furthermore, previous

research using cellular and murine models reported that excessive

ROS-induced senescence in ovarian granulosa cells contributed to

endometriosis-associated infertility (10). However, the precise molecular

mechanisms by which peritoneal ROS impair folliculogenesis remain

elusive, largely due to ethical constraints limiting functional

ovarian studies in young women with endometriosis.

Given that peritoneal fluid surrounds the ovaries

(11), we hypothesized that

excessive ROS in the pelvic cavity induces ovarian senescence,

disrupting follicular maturation and leading to infertility. A

hallmark of cellular senescence is the activation of the pro-growth

signaling pathway, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), in

non-proliferating cells (12).

Rapamycin, as an mTOR inhibitor, has been theorized to inhibit

cellular senescence, suppress SASP and prolong lifespan (13). Supporting this, a recent clinical

study demonstrated that rapamycin administration prior to IVF in

women with endometriosis reduced senescence markers in follicular

fluid and markedly improved pregnancy and live birth rates

(14).

A growing body of evidence has also reported an

association between proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) and

cellular senescence. During aging, PPARα expression or activity was

reported to decrease in tissues such as the kidney, heart and

spleen (15–17). Insulin-like growth factor-binding

protein 2 (IGFBP-2), a target protein of PPARα (18,19),

is dynamically regulated in follicular fluid during follicular

growth and maturation (20).

Notably, IGFBP-2 expression was reported to be reduced in granulosa

cells from polycystic ovaries (21) and was upregulated in response to

gonadotropin stimulation during final oocyte maturation (22).

Therefore, the present study aimed to assess whether

downregulation of the PPARα/IGFBP2 pathway in senescent ovarian

tissue impairs follicular development, and whether rapamycin can

restore fertility in endometriosis by modulating this signaling

axis.

Materials and methods

Animals

A total of 50 8-week-old female 18–22 g BALB/c mice

were purchased from Shanghai JST Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd., of

which 20 were recipient mice, 20 were donor mice and 10 were

control mice. All mice were subjected to controlled conditions

under a 12 h light/dark cycle with a temperature of 22±2°C and

relative humidity of 50±10%, as well as free access to food and

water. All experiments were performed under the guidelines of the

National Research Council Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory

Animals and were approved by the Institutional Laboratory Animal

Review Board of Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital

(Shanghai, China; approval no. TJBG28625103).

Induction of endometriosis and

rapamycin treatment

A mouse model of endometriosis was established by

intraperitoneal injection of endometrial debris (23). Briefly, after 1 week of adaptation,

20 donor mice were injected intramuscularly with 100 mg/kg

estradiol 2–3 times per week (Hangzhou Animal Pharmaceutical

(Hangzhou) Co., Ltd.). Euthanasia was performed after 1 week by

cervical dislocation. The uteri were removed and collected, and the

uterine tissue was cut up and injected intraperitoneally into the

abdominal cavity of the recipient mice. The uterine horns of one

donor mouse were injected into one recipient mouse. A total of 30

mice (20 recipient mice and 10 control mice) were randomly divided

into three groups: i) Control group (CTL group), in which 10 mice

received an intraperitoneal injection of saline in equal amounts to

the mice in the established mouse endometriosis groups; ii)

endometriosis with rapamycin treatment group (EM-R group), in which

10 mice received an intraperitoneal injection of endometrial debris

and 250 µg rapamycin/mouse once per week at one 1 after

endometriosis induction; and iii) endometriosis group (EM group),

in which 10 mice received an intraperitoneal injection of

endometrial debris only. Rapamycin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich

(Merck KGaA; cat. no. 553210). The present study referred to the

study by Ren et al (24)

for the dose of rapamycin used in mice. Body weight was measured

and the hotplate test was performed in all mice at 1, 2, 3 and 4

weeks after endometriosis induction, and mice were executed 4 weeks

after endometriosis induction by cervical dislocation.

Hotplate test

The hotplate test was performed using a commercial

hotplate analgesia meter (BME-480; Institute of Biomedical

Engineering, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences) to assess the

degree of discomfort caused by endometriosis, as previously

described (25). In summary, mice

were given 10 min to acclimate before the test. The mouse had to

hop on the hotplate or shake or lick its rear paws during 1 min of

being placed within the cylinder to assess the withdrawal latencies

to thermal stimulation. Over the course of 1 h, the latency was

measured twice and then averaged by the two test results.

Peritoneal fluid collection and ROS

detection in mice

After the mice were executed, they were placed in a

supine position with their limbs unfolded and fixed on a dissecting

board. The abdomen was disinfected with 75% alcohol, the lower

abdominal skin was lifted with ophthalmic forceps and a 2-cm

incision was made along the abdominal midline with scissors. A

total of 3–5 ml of sterile saline was injected into the abdominal

cavity of the mice and the abdominal cavity of the mice was opened

under aseptic conditions. The abdominal fluid was rinsed three

times and the rinsed fluid was collected into centrifuge tubes for

the detection of oxidative stress-related substances. Superoxide

dismutase (SOD), malondialdehyde (MDA), glutathione peroxidase

(GSH-PX) and 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) were detected as the

oxidative and antioxidant markers in the peritoneal fluid of mice.

The SOD assay kit (cat. no. A001-3-2; WST-1 method), MDA assay kit

(cat. no. A003-1-2; TBA method), GSH-PX assay kit (cat. no.

A005-1-2; colorimetric method) and mouse 8-OHdG ELISA kit (cat. no.

H165-1-2) were purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering

Institute. The peritoneal fluid of PPARα and IGFBP2 in mice were

detected using an ELISA kit (cat. nos. MM-0249M1 and MM-0029H2,

respectively; Meimian Industry; Jiangsu ELISA Industrial Co.,

Ltd.). All operations are strictly in accordance with the kit

instructions.

Immunohistochemistry of mouse ovarian

tissue

Ovarian tissue samples were fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde for 24 h at 4°C and embedded in paraffin. Sections

(4 µm) were used for subsequent staining. The first section was

stained with hematoxylin and eosin to confirm the pathological

diagnosis, and subsequent sections were stained with

senescence-related markers such as p16, p21 and Lamin B1. Tissue

sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through a

graded ethanol series. Antigen retrieval was performed in EDTA

buffer (pH 9.0; Shanghai Sun Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) or citric

acid solution (pH 6.0; Shanghai Sun Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) using

a microwave heating method, then allowed to cool to room

temperature. Following antigen retrieval and cooling, sections were

washed three times with PBS. To block non-specific binding,

sections were incubated in a solution of PBS containing 5% normal

goat serum (cat. no. G1208; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.)

for 1 h at room temperature. The following antibodies were used in

this experiment: p16 (1:50; cat. no. ab51243), p21 (1:1,000; cat.

no. ab188224) and Lamin B1 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab16048). All

antibodies were purchased from Abcam. All sections were incubated

with the aforementioned primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The

sections were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labeled

secondary antibody detection reagent (1:300; cat. no. A0303;

Beyotime Biotechnology) for 1 h at room temperature. The bound

antibody complexes were stained with diaminobenzidine for 3–5 min

at room temperature, followed by hematoxylin for nuclear staining

at room temperature. The development time was monitored under a

microscope (typically between 3 to 5 min) and stopped immediately

when optimal staining intensity was achieved with minimal

background. Images were captured under a microscope (BX51; Olympus

Corporation) equipped with a digital camera (DP70; Olympus

Corporation). According to the manufacturer's instructions,

distinct tissue slides were utilized for several antibodies as

positive control. For negative controls, tissue samples were

treated with mouse or rabbit serum (Wuhan Servicebio Technology

Co., Ltd.) in lieu of primary antibodies.

Mouse ovarian tissue PCR assay

Mouse ovarian tissues were cut into small pieces

(soybean size), placed in a pre-cooled homogenizer, 1 ml RNA

extract (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) was added per 100

mg of tissue, and the tissues were homogenized until no visible

pieces were present. A total of 200 µl chloroform was added per 1

ml RNA extract, and the mixture was vortexed and mixed or shaken

upside down vigorously for 15 sed, let stand at room temperature

for 3–5 min, then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The

upper colorless aqueous phase was carefully transferred to a new

centrifuge tube, aspirating 500–550 µl per ml of extract. A total

of 500 µl isopropanol was added to the collected aqueous extract

tube, which was centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min at 12,000 × g. The

white precipitate visible at the bottom of the tube was the total

RNA, and so supernatant was discarded. A total of 1 ml of 75%

ethanol was then added, which was then mixed upside down (until the

white precipitate floats) and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 5 min

at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, then centrifugation was

performed briefly at high speed (3–5 sec at 5,000 × g at 4°C) and

the liquid was carefully aspirated with a micropipette. The

centrifuge tube with RNA precipitate was left open for 3–5 min to

allow the RNA to dry slightly, and then 20–50 µl DEPC-treated water

(Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) was added to fully dissolve

the RNA. The NanoDrop™ Microvolume UV–Vis

spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to

assess the quality control and quantification of total RNA. RNA

with good integrity and purity (OD260/OD280 values of 1.8–2.0) was

used for further analysis. Mouse tissue RNA was reverse transcribed

and quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using forward and reverse

primers. The cDNA synthesis was performed using a reverse

transcription kit (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.) at 42°C for 30 min.

To evaluate the abundance of mRNA, real-time PCR was conducted

using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara Bio, Inc.). The thermocycling

protocol consisted of an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 30

sec, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 30 sec.

GAPDH was used as a housekeeping gene. The sequences of

senescence-related markers (p16, p21 and γH2AX), gonadotropin

receptor [follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR) and

luteinizing hormone receptor (LHR)] and PPARα and IGFBP2 primers

are listed in Table I. All primers

were designed by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. The relative

gene expression levels were calculated as ΔCq values (Cq ‘target

gene’ minus Cq ‘housekeeping gene’) and 2−ΔΔCq ratios

indicated fold changes (26).

| Table I.Names and sequences of all primers

used in the present study. |

Table I.

Names and sequences of all primers

used in the present study.

| Gene name | Direction | Sequence

(5′-3′) |

|---|

| p16 (human) | Forward |

AGGCCGATCCAGGTCATGATGA |

|

| Reverse |

ACCACCAGCGTGTCCAGGAA |

| p21 (human) | Forward |

GACCTGTCACTGTCTTGTACCCTTG |

|

| Reverse |

TTGGAGTGGTAGAAATCTGTCATG |

|

|

| CTG |

| FSHR (human) | Forward |

TCCCTCCTTGTGCTCAATGTC |

|

| Reverse |

GATGTTGGGGTTCCGCACT |

| LHR (human) | Forward |

TTCTGTCTACACCCTCACCG |

|

| Reverse |

AAAAGAGCCATCCTCCAAGC |

| γH2AX (human) | Forward |

CAGTGCTGGAGTACCTCAC |

|

| Reverse |

GATGATTCGCGTCTTCTTGTTG |

| PPARα (human) | Forward |

TCGGCGAGGATAGTTCTGGAAGC |

|

| Reverse |

ACCACAGGATAAGTCACCGAGGAG |

| IGFBP2 (human) | Forward |

ACAGTGCAAGATGTCTCTGAACGG |

|

| Reverse |

GCCTCCTGCTGCTCATTGTAGAAG |

| GAPDH (human) | Forward |

GCACCGTCAAGGCTGAGAAC |

|

| Reverse |

TGGTGAAGACGCCAGTGGA |

| p16 (mouse) | Forward |

CGCAGGTTCTTGGTCACTGT |

|

| Reverse |

TGTTCACGAAAGCCAGAGCG |

| p21(mouse) | Forward |

CCTGGTGATGTCCGACCTG |

|

| Reverse |

CCATGAGCGCATCGCAATC |

| FSHR (mouse) | Forward |

CCTTGCTCCTGGTCTCCTTG |

|

| Reverse |

CTCGGTCACCTTGCTATCTTG |

| LHR (mouse) | Forward |

CAGCTGCCTTCAAAGTACCC |

|

| Reverse |

TTGGCACAAGAATTGACAGG |

| γH2AX (mouse) | Forward |

GGTGCTCGAGTACCTCACTG |

|

| Reverse |

CTTGTTGAGCTCCTCGTCGT |

| PPARα (mouse) | Forward |

CAAGGCCTCAGGGTACCACT |

|

| Reverse |

TTGCAGCTCCGATCACACTT |

| IGFBP2 (mouse) | Forward |

CCTTGCCAGCAGGAGTTG |

|

| Reverse |

TCCGTTCAGAGACATCTTGC |

| GAPDH (mouse) | Forward |

GGTTGTCTCCTGCGACTTCA |

|

| Reverse |

TGGTCCAGGGTTTCTTACTCC |

Ovarian tissue follicle counting in

mice

A total of 30 mice were sacrificed 4 weeks after

endometriosis induction. After fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde in

phosphate buffer at 4°C for 24 h, the tissues were embedded in

paraffin and sectioned at 4 µm thickness. Ovarian tissue sections

were stained with HE at room temperature and the number of

follicles at different stages was counted for each mouse. The

method of follicle counting involved 5-µm continuous sections, with

1/5 sections stained and counted (27). A total of five types of follicles

were counted: i) Primordial follicles; ii) primary follicles; iii)

secondary follicles; iv) antral follicles; and v) corpus luteum.

Primordial follicles were defined as oocytes surrounded by a layer

of squamous (flattened) granulosa cells; primary follicles were

defined as one follicle containing several or all oocytes

surrounded by a single layer of cuboidal granulosa cells; secondary

follicles were defined as a follicle surrounded by >1 layer of

cuboidal granulosa cells with no visible lumen; a follicle was

identified as a antral follicle if it had a well-defined lumen and

a layer of cumulus granulosa cells; and the corpus luteum was a

post-ovulatory structure, which was filled with lutein cells that

form only after ovulation (28).

Images were captured using a microscope (BX51; Olympus Corporation)

fitted with a digital camera (DP70; Olympus Corporation).

Granulosa cell culture

Mouse primary granulosa cells were extracted and

cultured with reference to the study by Tian et al (29). Mouse ovaries were washed with

sterile PBS and transferred to DMEM/F12 (cat. no. 11330-057;

Invitrogen™; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Follicles

were punctured with a 31-gauge needle under a dissecting

microscope, and granulosa cells were released from the follicles,

centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature, resuspended

in fresh DMEM/F12 with 10% FBS, and incubated at 37°C and 5%

CO2. Cells were passaged every other day.

The granulosa KGN cell line was purchased from

Shanghai Kanglang Biotechnology Co., Ltd. and cultured in DMEM/F12

supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were

passaged every 5–6 days, and the number of passages was <15 for

the experiments.

Transient transfection for knockdown

and overexpression of PPARα

Small interfering (si)RNA of the human PPARα gene

(siRNA-PPARα) and non-specific control siRNA (siRNAc) were

purchased from Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. and were transfected

into cells at room temperature using Lipofectamine™ 3000

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 48 h at a final

concentration of 30 nM, according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Subsequent experiments were conducted 48 h after cell

transfection. The following siRNA sequences were used: siRNA-PPARα,

5′-GCUUUACGGAAUACCAGUAUU-3′; and siRNAc, (forward)

5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUdTdT-3′ and (reverse)

5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAAdTdT-3′.

The PPARα overexpression plasmid [pCDNA3.1(+)

plasmid vector Asian Vector Biotechnology Co., Ltd.] was

transfected into granulocyte cells for 48 h using Lipofectamine

3000 and an empty plasmid (Asian Vector Biotechnology Co., Ltd.)

was used as a negative control. Cells were transfected with 1.0 µg

of either the PPARα overexpression plasmid or the empty control

plasmid using 2.0 µl of Lipofectamine 3000 reagent per well in a

12-well plate, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Subsequent experiments were conducted 48 h after cell

transfection.

To demonstrated the effects of PPARα knockdown or

overexpression on cellular senescence, cells were treated with

H2O2 following knockdown or overexpression.

To demonstrated the anti-senescence effects of rapamycin, cells

were treated with (50 nM) rapamycin (Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd.).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using

GraphPad Prism 8 (Dotmatics). For comparisons among ≥3 groups,

one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed, followed by

Tukey's post hoc test for multiple comparisons when ANOVA indicated

statistical significance (P<0.05). Unless otherwise stated,

continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation for

normally distributed data. All tests were two-tailed, and P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Rapamycin reduces ectopic lesions

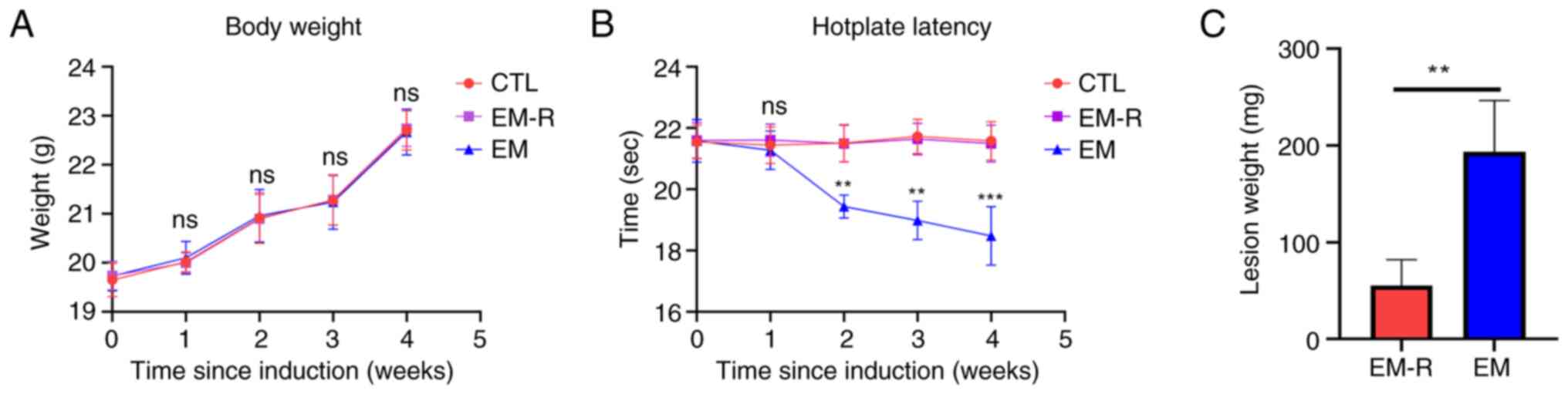

The findings demonstrated that there was no

significant difference in body weight among the 3 groups of mice

before the induction of endometriosis and their death (Fig. 1A). However, the results of the

hotplate test were significantly different between the EM group and

EM-R group, and the hotplate time from week 2 post-endometriosis

induction was significantly lower in the mice of the EM group than

in the EM-R group. There is no difference in hotplate test between

CTL group and EM-R group (Fig.

1B). No lesions of endometriosis were found in the mice of the

CTL group; however, obvious ectopic lesions were observed in the

peritoneal cavity of mice in the EM-R and EM groups. Moreover, the

weight of endometriotic lesions in mice in the EM group were

significantly higher than that in the EM-R group (193.4±53.22 and

55.4±26.69 mg, respectively; P<0.01; Fig. 1C). This indicates that rapamycin

may inhibit endometriosis.

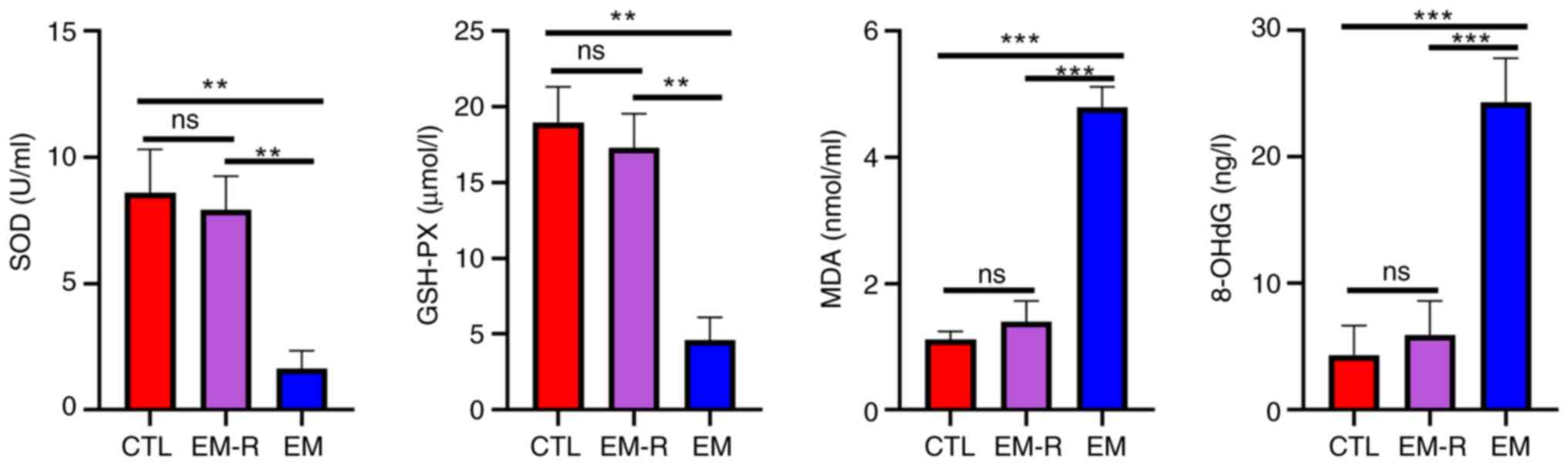

Rapamycin decreases expression of

markers associated with oxidative stress in mouse peritoneal

fluid

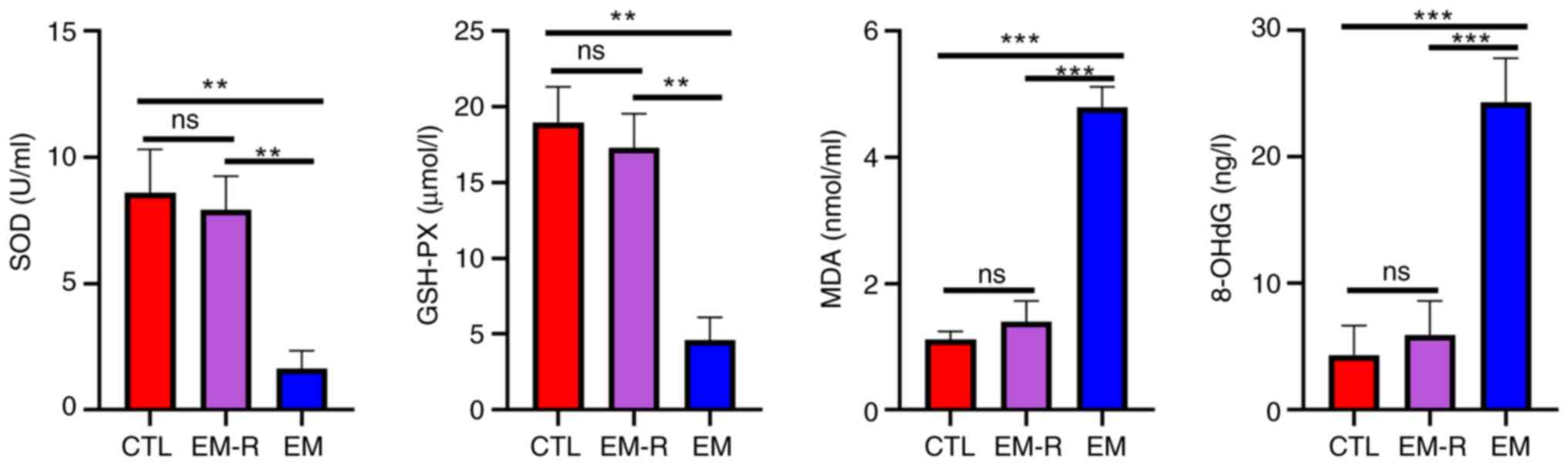

There was no significant difference between the CTL

and EM-R groups for the levels of oxidative stress-related

molecules, SOD (8.60±1.71 and 7.93±1.32 U/ml, respectively;

P=0.49), GSH-PX (18.99±2.32 and 17.30±2.25 µmol/l, respectively;

P=0.17), MDA (1.11±0.13 and 1.39±0.32 nmol/ml, respectively;

P=0.06) and 8-OHdG (4.34±2.31 and 5.91±2.68 ng/l, respectively;

P=0.45). The antioxidant molecules, SOD and GSH-PX, in mouse

peritoneal fluid were significantly lower in the EM group compared

with in the EM-R group (SOD, 1.65±0.69 vs. 7.93±1.32 U/ml; GSH-PX,

4.62±1.48 vs. 17.30±2.25 µmol/l; both P<0.01). By contrast, the

markers of increased oxidative capacity, MDA and 8-OHdG, were

significantly higher in the EM group than in EM-R group (MDA,

4.79±0.32 vs. 1.39±0.32 nmol/ml; 8-OHdG, 24.31±3.48 vs. 5.91±2.68

ng/l; both P<0.001) (Fig. 2).

This suggests the presence of oxidative stress, decreased

antioxidant capacity and increased oxidative function in the

peritoneal cavity of endometriosis mice without rapamycin

treatment. Moreover, levels of activation of intraperitoneal

oxidative stress were reduced in rapamycin-treated endometriosis

mice.

| Figure 2.Detection of oxidative stress-related

markers in peritoneal fluid of mice. Comparison of

antioxidant-related molecules, SOD, GSH-PX and oxidative

capacity-related molecules MDA and 8-OHdG in peritoneal fluid of

three groups. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. SOD, superoxide

dismutase; GSH-PX, glutathione peroxidase; MDA, malondialdehyde;

8-OHdG, 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine; CTL, control group; EM-R,

endometriosis + rapamycin group; EM, endometriosis group; ns, not

statistically significant. |

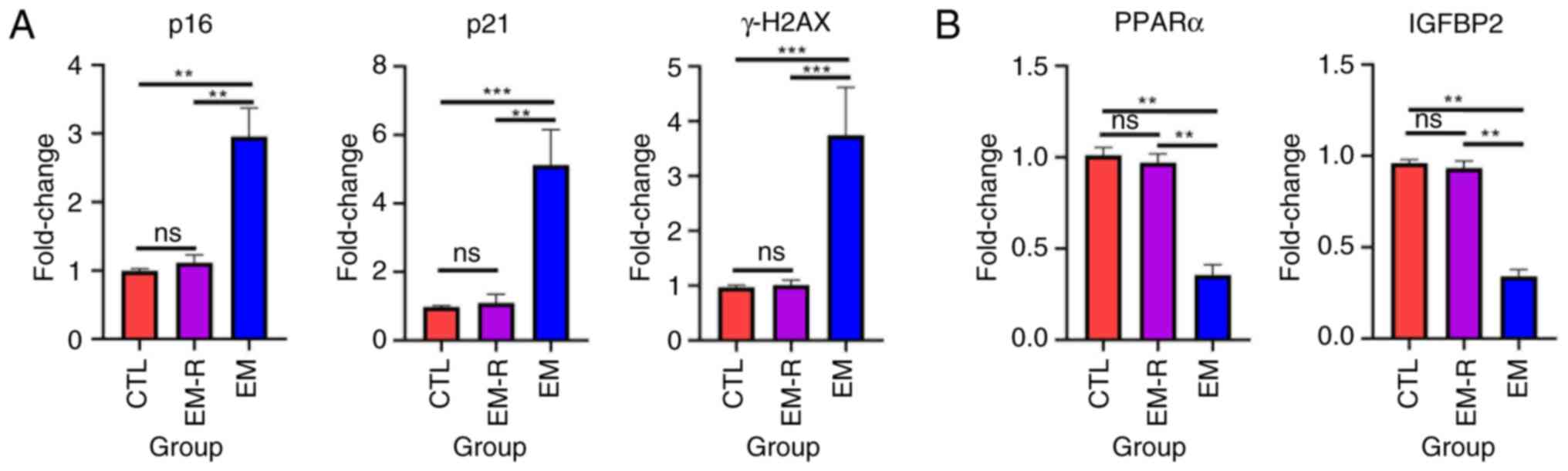

Rapamycin reduces senescence markers

and increases gonadotropin receptors in mouse ovaries

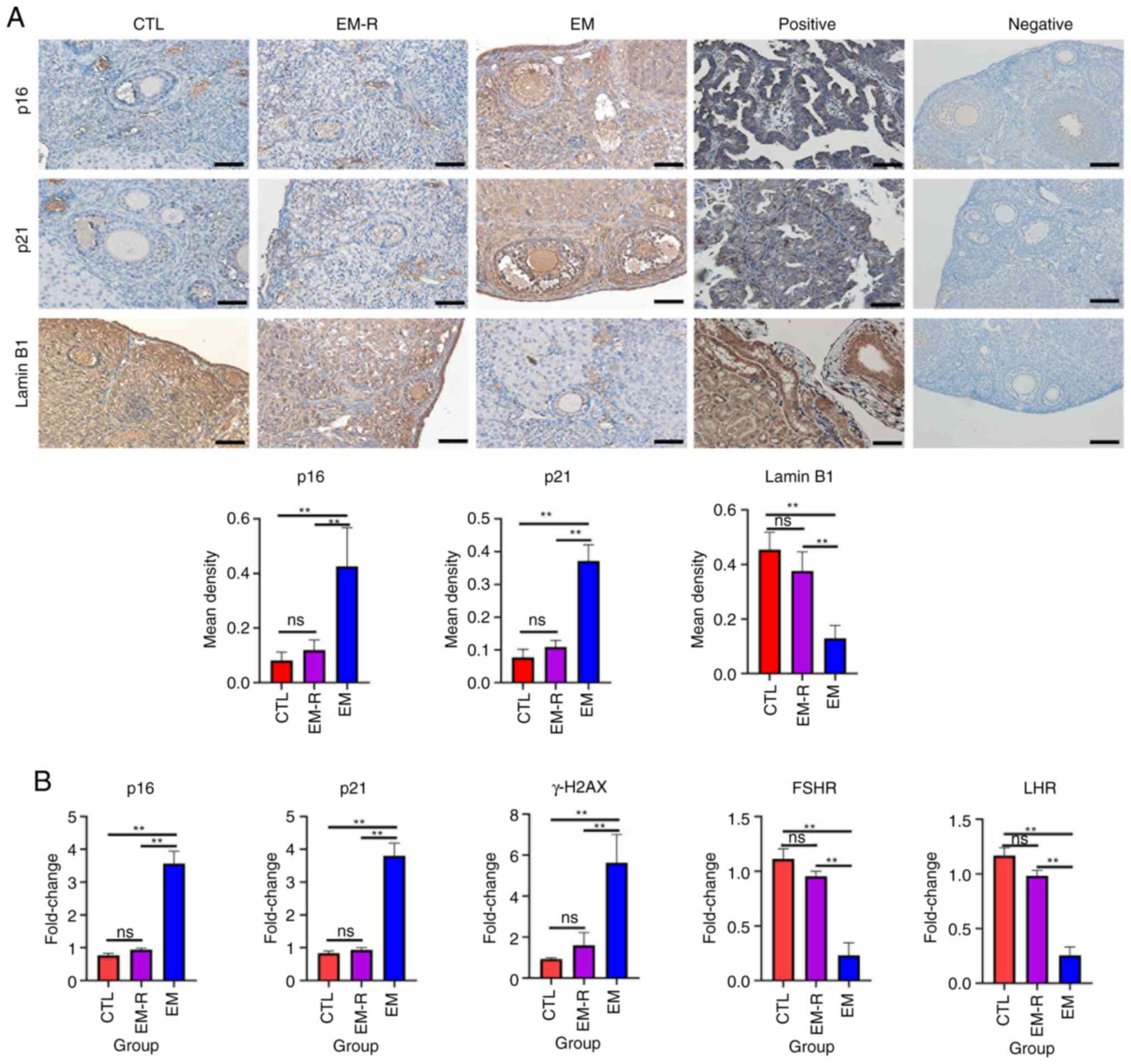

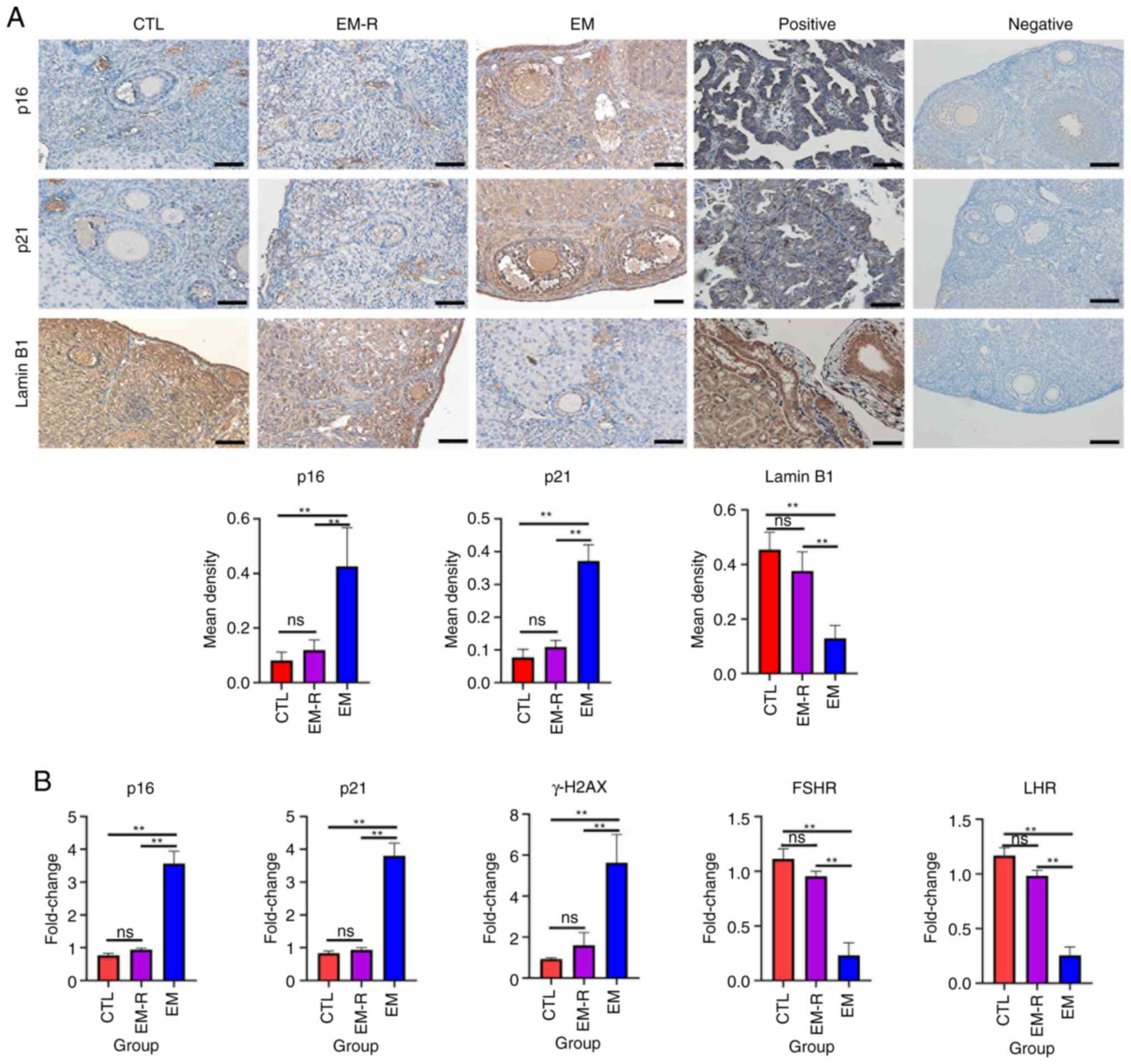

Increased expression of senescence-associated

markers, p16, p21 and γH2AX, and decreased expression of Lamin B1

suggest that tissue or cellular senescence is occurring (30). The immunohistochemical experiments

in the present study demonstrated that senescence-related markers

expression in ovarian granulosa cells and oocyte did not differ

significantly between the CTL and EM-R group. However, the

expression of senescence-related markers, p16 and p21, in ovarian

granulosa cells and oocytes was significantly higher in the EM

group than in the EM-R group (p16, 0.42±0.14 vs. 0.12±0.03; p21,

0.37±0.04 vs. 0.11±0.02; both P<0.01). Another

senescence-related marker, Lamin B1, was significantly lower in

ovarian granulosa cells and oocytes of the EM group compared with

the EM-R group (0.13±0.05 vs. 0.37±0.07; P<0.01) (Fig. 3A). This suggests that ovarian

tissues in endometriosis mice without rapamycin treatment undergo

senescence, and rapamycin could decrease expression of senescence

markers in ovaries. Similarly, ovarian tissue PCR experiments

revealed significantly higher gene expression of p16, p21 and γH2AX

in mice in the EM group than in mice in the EM-R group (p16,

3.57±0.36 vs. 0.94±0.04; p21, 3.80±0.39 vs. 0.93±0.06; γH2AX,

5.63±1.37 vs. 1.61±0.61; all P<0.01). Moreover, gonadotropin

receptor (FSHR and LHR) gene expression was significantly higher in

the EM-R group than the EM group (FSHR, 0.95±0.04 vs. 0.23±0.11;

LHR, 0.98±0.04 vs. 0.25±0.07; both P<0.01) (Fig. 3B).

| Figure 3.Detection of senescence-related

markers and gonadotropin receptor in mice ovarian tissues. (A)

Representative immunohistochemical images and the corresponding

statistical results of senescence-related markers, p16, p21 and

Lamin B1 in the ovarian tissues of three groups, as well as

positive and negative controls for immunostaining of p16, p21 and

Lamin B1. For positive controls, human endometrial adenocarcinoma

tissues were used for p16, human lung tissues were used for p21 and

human kidney tissues were used for Lamin B1. p16, p21, Lamin B1

showed positive staining in the nuclei. For negative controls,

mouse ovarian tissues were used. The controls all showed negative

staining. Scale bar, 50 µm. (B) Gene expression of p16, p21, γH2AX,

FSHR and LHR in mice ovarian tissues among the three groups.

**P<0.01. FSHR, follicle-stimulating hormone receptor; LHR,

luteinizing hormone receptor; CTL, control group; EM-R,

endometriosis + rapamycin group; EM, endometriosis group; ns, not

statistically significant. |

Rapamycin improves follicular

development

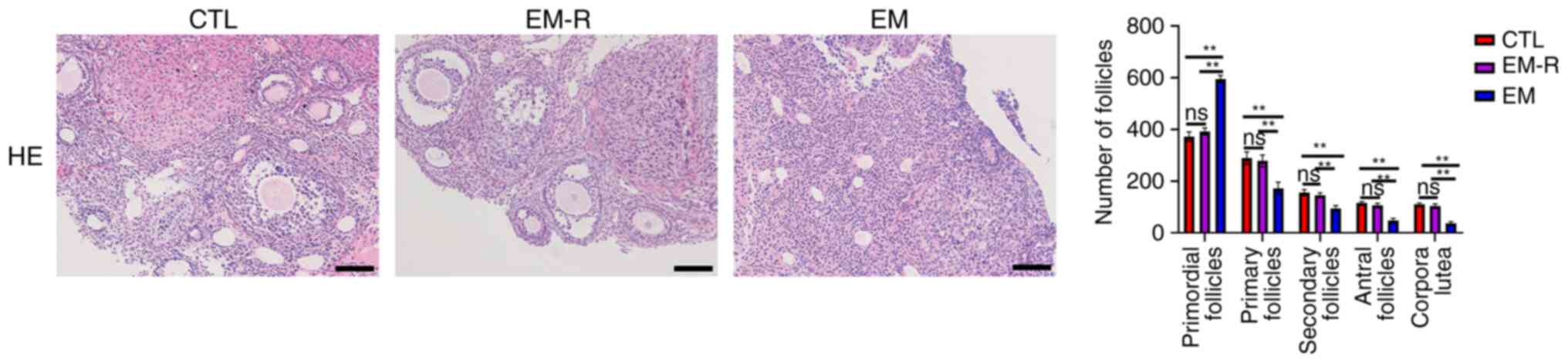

The number of follicles at different stages was not

significantly different between the CTL and EM-R groups. However,

primordial follicles of the EM group were significantly higher than

in the EM-R group (595.6±13.66 vs. 392.1±13.89; P<0.01), whilst

primary follicles, secondary follicles, antral follicles and corpus

luteum were significantly lower in the EM group than in the EM-R

group (primary follicles, 172.2±24.15 vs. 278.6±23.08; secondary

follicles, 94.9±10.62 vs. 145.3±9.81; antral follicles, 48±8.56 vs.

106.2±7.88; corpus luteum, 37.8±5.73 vs. 103.6±8.5; All P<0.01).

This suggests that endometriosis mice follicles undergo senescence

in response to oxidative stress, which leads to impaired

development and significant increase in the number of mature

follicles in endometriosis mice treated with rapamycin (Fig. 4).

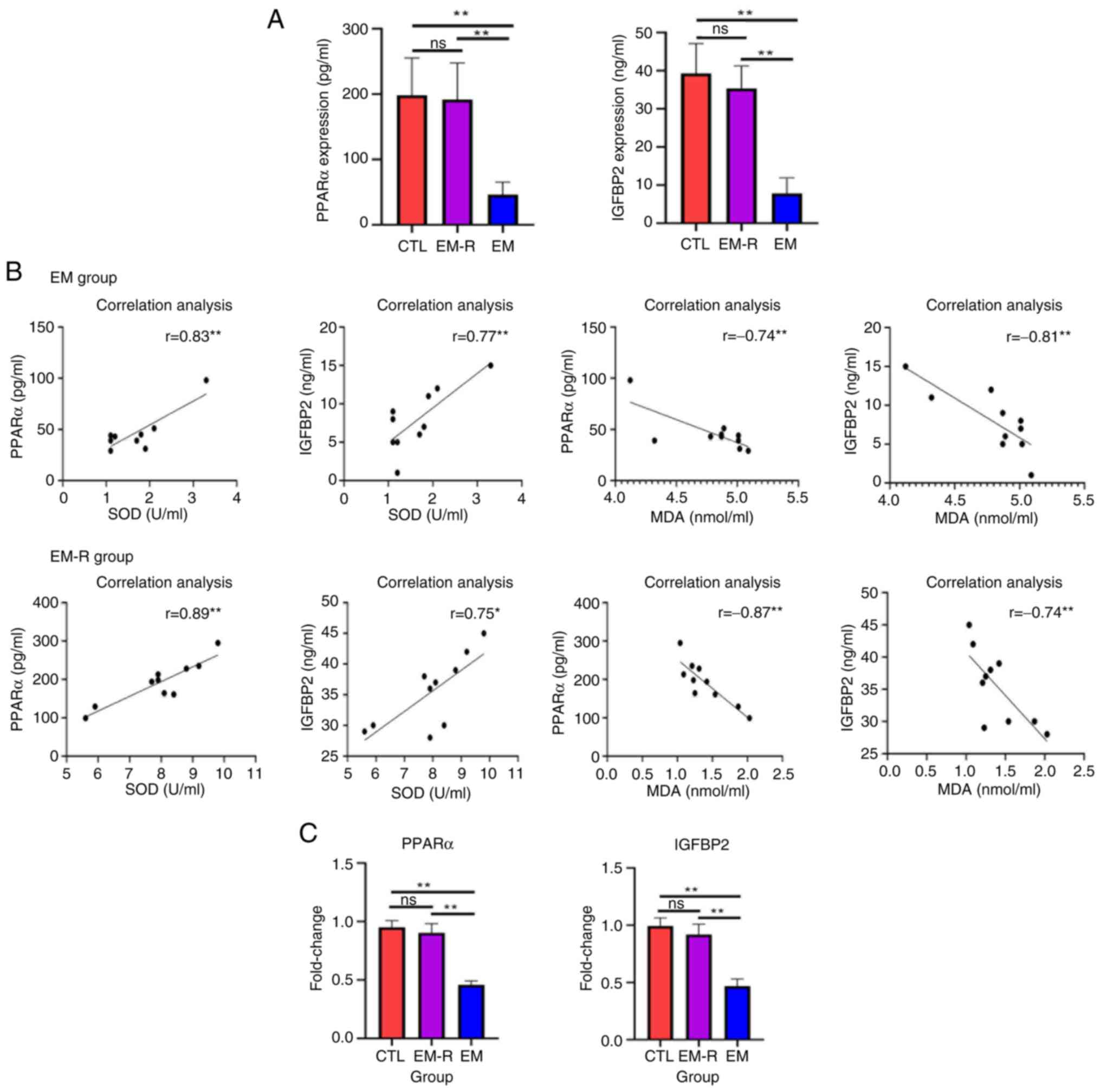

Activation of PPARα and IGFBP2 in the

ovaries of endometriosis mice treated with rapamycin

The concentration of PPARα and IGFBP2 in the

peritoneal fluid of mice in the CTL group were not significantly

different from those of the EM-R group; however, the concentration

of PPARα and IGFBP2 in the EM group were significantly lower than

those in the EM-R group (PPARα, 46.2±19.33 vs. 191.6±56.37 pg/ml;

IGFBP2, 7.90±4.04 vs. 35.4±5.89 ng/ml; both P<0.01) (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, the results

revealed a positive correlation between SOD and PPARα, and between

SOD and IGFBP2, compared with a negative correlation between MDA

and PPARα, and between MDA and IGFBP2 in both the EM-R and EM

groups (Fig. 5B). In addition, the

gene expression of PPARα and IGFBP2 in the ovaries of mice in the

EM-R group was not significantly different from that of mice in the

CTL group; however, the expression of PPARα and IGFBP2 in the

ovaries of mice in the EM group was significantly lower than that

of mice in the EM-R group (PPARα, 0.90±0.07 vs. 0.45±0.03; IGFBP2,

0.91±0.09 vs. 0.46±0.06; both P<0.01). This indicated that the

expression of PPARα and IGFBP2 in the ovaries of endometriosis mice

was significantly decreased, and treatment with rapamycin activated

PPARα and IGFBP2 expression (Fig.

5C).

Rapamycin decreases the expression of

senescence markers and increases PPARα and IGFBP2 expression in

primary mouse granulosa cells

Granulosa cells, which closely surround the oocyte,

are essential for supporting oocyte development (31). To assess cellular senescence in

these cells, primary granulosa cells were isolated from three

experimental groups of mice. PCR analysis revealed that granulosa

cells from the EM group exhibited significantly elevated levels of

senescence-associated markers, including p16, p21 and γH2AX,

compared with in the EM-R group (p16, 2.95±0.41 vs. 1.11±0.11; p21,

5.13±1.02 vs. 1.09±0.25; γH2AX, 3.74±0.87 vs. 1.01±0.09; all

P<0.01; Fig. 6A). Notably, the

expression of these markers in the EM-R group was comparable with

that of the CTL group, with no statistically significant

differences observed between them (Fig. 6A). By contrast, the expression

levels of PPARα and IGFBP2 were significantly reduced in the EM

group compared with the EM-R group (PPARα, 0.35±0.55 vs. 0.97±0.04;

IGFBP2, 0.34±0.03 vs. 0.93±0.04; both P<0.01; Fig. 6B).

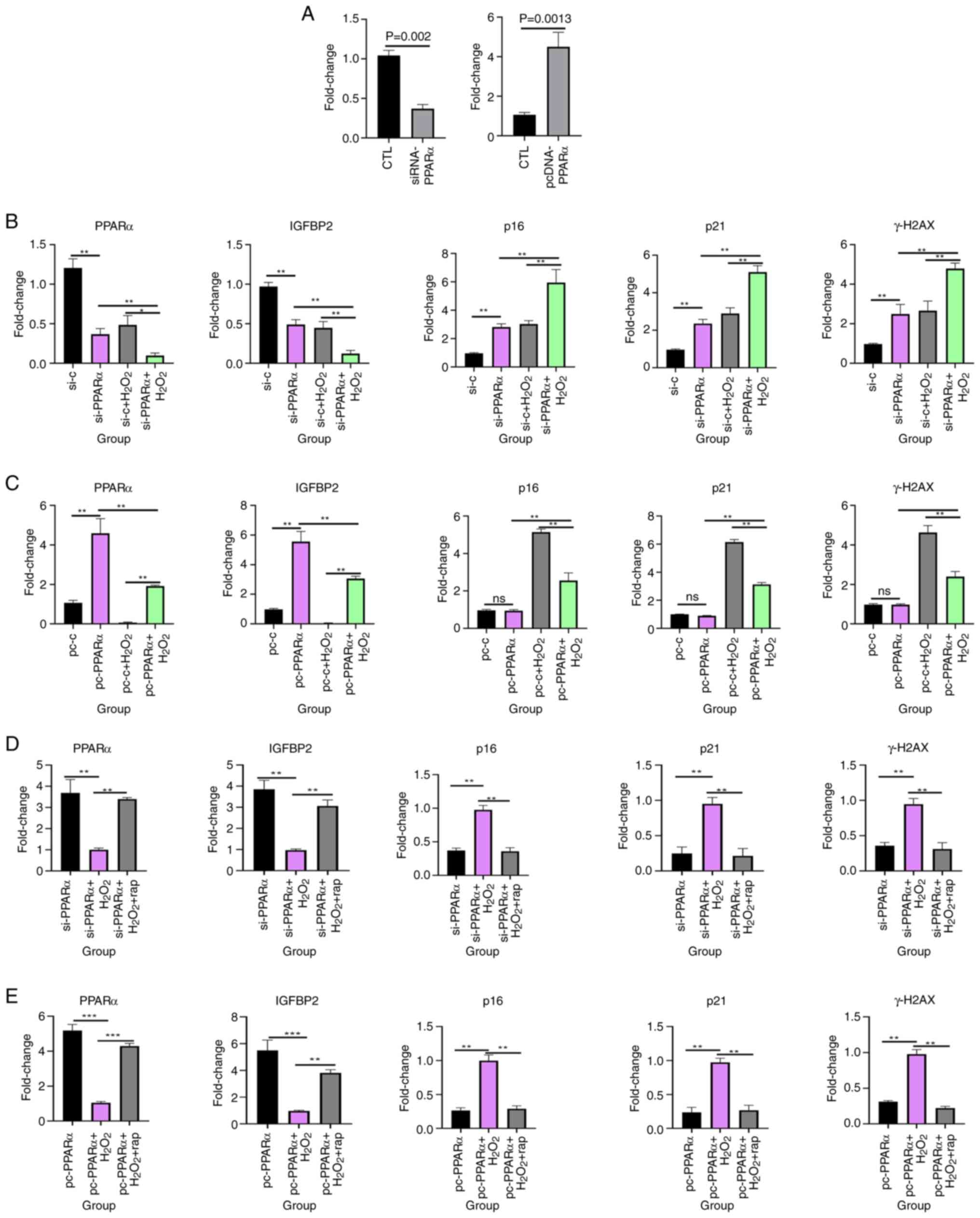

Rapamycin increases PPARα and IGFBP2

expression and inhibits granulosa cell senescence in vitro

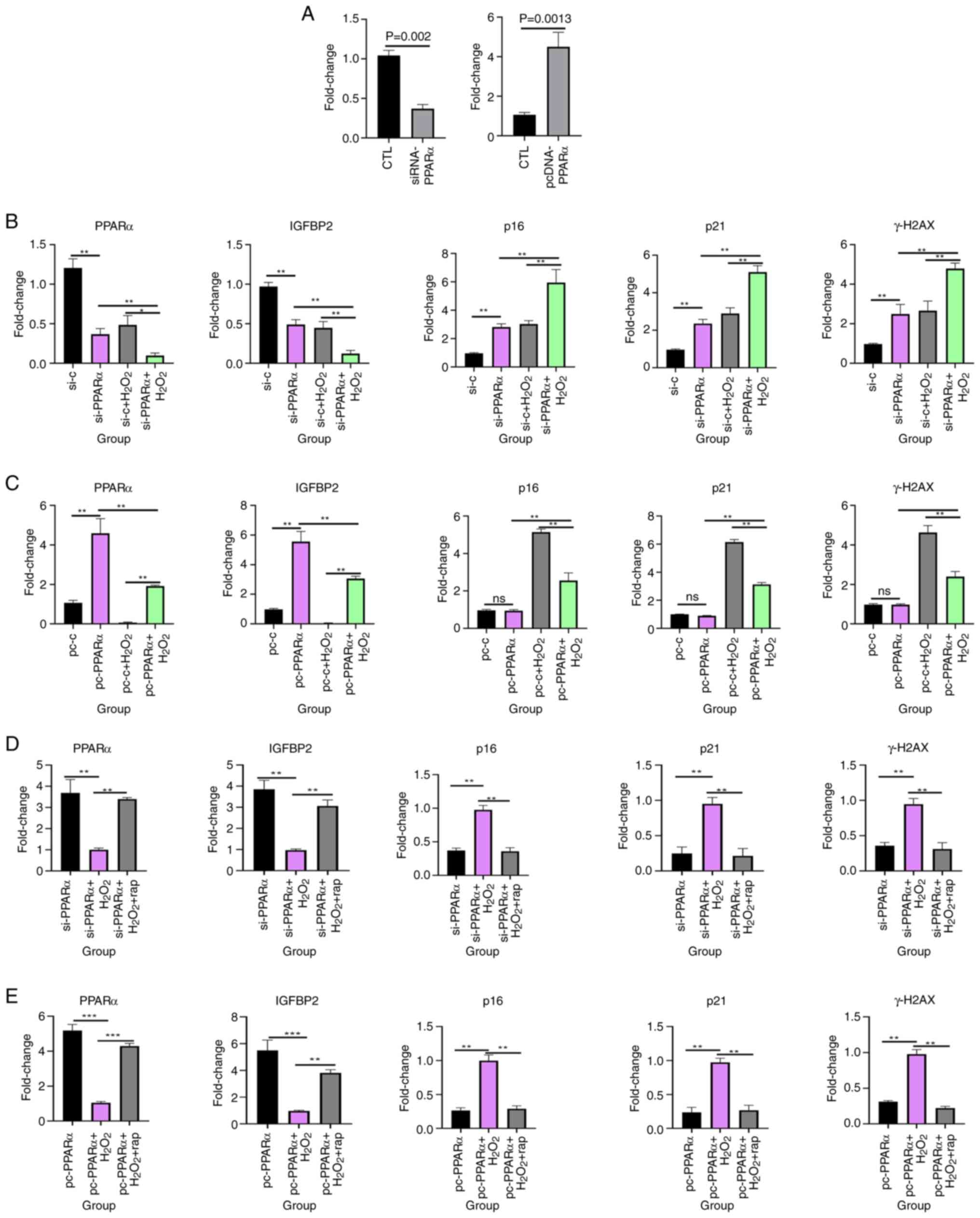

To evaluate the functional relationship between

PPARα and IGFBP2, knockdown and overexpression of PPARα experiments

were performed using KGN cells. First, PCR experiments were

performed to assess the expression of PPARα after transfecting

cells with siRNA and overexpression plasmids. The results

demonstrated that PPARα expression was significantly lower after

siRNA transfection (0.37±0.05 vs. 1.04±0.06; P=0.0002) and

significantly higher after overexpression plasmid transfection

(4.50±0.73 vs. 1.06±0.11; P=0.0013) than in the respective control

groups (Fig. 7A). Notably,

silencing PPARα significantly reduced IGFBP2 expression, whereas

PPARα overexpression significantly increased IGFBP2 levels

(Fig. 7B and C). This indicated

that IGFBP2 is a downstream target of PPARα.

| Figure 7.PPARα modulates oxidative

stress-induced senescence and IGFBP2 expression in KGN cells. (A)

Compared with the blank control group, the PCR results of PPARα

after cell transfection with siRNA and overexpression plasmids.

Gene expression of PPARα, IGFBP2, p16, p21 and γH2AX in KGN cells

treated with H2O2 after (B) knockdown and (C)

overexpression of PPARα. Gene expression of PPARα, IGFBP2, p16, p21

and γH2AX in KGN cells treated with H2O2 and

rapamycin after (D) knockdown and (E) overexpression of PPARα.

**P<0.01; ***P<0.001. PPARα, proliferator-activated receptor

α; IGFBP2, insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 2; si, small

interfering; si-c, non-specific control siRNA; pc, pcDNA; rap,

rapamycin; CTL, control; ns, not statistically significant. |

To assess the role of PPARα in cellular senescence,

granulosa cells were treated with H2O2

following PPARα knockdown or overexpression. The siRNA-PPARα +

H2O2 group exhibited the highest expression

of senescence markers (p16, p21 and γH2AX), significantly exceeding

levels in the siRNA-control + H2O2 group (p16, 5.96±0.90

vs. 3.03±0.23; p21, 5.10±0.34 vs. 2.89±0.30; γH2AX, 4.79±0.27 vs.

2.66±0.48; all P<0.01; Fig.

7B). Conversely, the pcDNA-PPARα + H2O2

group exhibited lower expression of the senescence markers (p16,

p21 and γH2AX) than the pcDNA + H2O2 group,

(p16, 2.56±0.41 vs. 5.13±0.17; p21, 3.13±0.13 vs. 6.15±0.17; γH2AX,

2.40±0.25 vs. 4.63±0.35; all P<0.01; Fig. 7C). PPARα overexpression attenuated

H2O2-induced senescence, further supporting the protective role of

PPARα against cellular aging. Moreover, cells with knockdown or

overexpression of PPARα were treated with

H2O2 for 24 h followed by the addition of 30

µM rapamycin (32) for 48 h,

revealed that rapamycin significantly increased PPARα and IGFBP2

expression and significantly decreased the expression of

senescence-related markers, p16, p21 and γH2AX. The siRNA-PPARα +

H2O2 group exhibited higher expression of the

senescence markers (p16, p21 and γH2AX) than the siRNA-PPARα +

H2O2 + rapamycin group (p16, 0.97±0.06 vs.

0.35±0.05; p21, 0.95±0.09 vs. 0.21±0.10; γH2AX, 0.94±0.08 vs.

0.31±0.09; all P<0.01; Fig.

7D). The pcDNA-PPARα + H2O2 group

exhibited higher expression of the senescence markers (p16, p21 and

γH2AX) than the pcDNA-PPARα + H2O2 +

rapamycin group (p16, 0.99±0.08 vs. 0.29±0.04; p21, 0.97±0.06 vs.

0.26±0.07; γH2AX, 0.98±0.06 vs. 0.22±0.02; all P<0.01; Fig. 7E) These findings suggest that

rapamycin counteracted senescence by upregulating the PPARα-IGFBP2

axis.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that elevated ROS in

the peritoneal fluid of endometriosis mice contributed to ovarian

senescence and impaired follicular development, whilst rapamycin

treatment mitigated these effects by reducing oxidative stress and

activating the PPARα/IGFBP2 pathway.

Endometriosis is characterized by a pro-oxidative

peritoneal environment (33), with

increased ROS levels adversely affecting ovarian function (34,35).

It is well documented that oxidative stress is a major source of

endogenous and exogenous challenges that promotes senescence and

the senescence phenotype (36). A

previous study reported that excessive oxidative stress in cumulus

granulosa cells triggered cellular senescence which contributed to

endometriosis-related infertility (10). Consistent with previous studies

(9,10), the present study demonstrated that

ROS in peritoneal fluid promoted cellular senescence in ovarian

tissues, as shown by elevated senescence-related markers and

reduced expression of gonadotropin receptors (FSHR and LHR),

critical for follicular maturation (37). This senescence phenotype was

associated with a decline in mature follicles and an accumulation

of primordial follicles, suggesting impaired folliculogenesis.

Rapamycin, an established anti-senescence agent (38), reversed these effects, restoring

follicular development and ovarian function.

The mTOR network is an evolutionarily conserved

signaling hub that detects and integrates environmental and

intracellular nutrients, as well as growth factor signals, thereby

orchestrating fundamental cellular and organismal responses such as

cell growth, proliferation, apoptosis and inflammation. Previous

research supports the notion that mTOR signaling influences

lifespan and senescence (39). At

present, the only known pharmacological approach to extend lifespan

in all studied model organisms, to the best of our knowledge, is

the inhibition of the mTOR complex 1 using rapamycin (39). Treatment of hepatocytes with

pterostilbene inhibits mTOR and promotes the expression of its

downstream molecule, PPARα (40).

PPARα serves a crucial role in metabolic homeostasis and aging,

with its deficiency associated with fibrotic and senescent

phenotypes in several tissues (41). Similarly, IGFBP2 has been

implicated in mitigating senescence in pulmonary fibrosis models

(42). The findings of the present

study revealed for the first time, to the best of our knowledge,

that PPARα and IGFBP2 are downregulated in endometriosis-affected

ovaries and are negatively associated with senescence. In

endometriosis, reduced PPARα/IGFBP2 signaling may exacerbate

oxidative stress-induced ovarian damage. Rapamycin restored their

expression, suggesting that this pathway is a key mediator in

counteracting endometriosis-related ovarian dysfunction.

Whilst the present study characterized

folliculogenesis dysfunction in endometriosis-related infertility,

it is acknowledged that direct fertility assessments (such as

ovulation rates, pregnancy outcomes or litter sizes) were not

assessed. These endpoints would provide critical translational

insights into how observed follicular abnormalities impact

reproductive success. Future studies should integrate longitudinal

fertility metrics in murine models, ideally combining hormonal

profiling with timed mating trials, to establish functional

associations between folliculogenesis defects and infertility

phenotypes. Such data would strengthen the clinical relevance of

the findings of the present study for patients with

endometriosis.

Additionally, although the in vitro

experiments in the present study demonstrated the regulatory role

of the PPARα/IGFBP2 axis in granulosa cells, further in vivo

validation is warranted to confirm its causal involvement in

rapamycin-mediated effects. Pharmacological modulation (such as

PPARα agonists/antagonists) or conditional knockout models could

elucidate whether targeting this pathway rescues ovarian function

in endometriosis. These experiments would not only solidify the

mechanistic link, but also explore therapeutic potential, aligning

with the broader goal of developing targeted interventions for

endometriosis-associated infertility.

In summary, the results of the present study

highlight that ROS-induced ovarian senescence contributed to

endometriosis-related infertility, and rapamycin counteracted this

process by activating the PPARα/IGFBP2 pathway. These findings not

only deepen the understanding of endometriosis pathogenesis but

also suggest that targeting senescence pathways may offer a

promising strategy to improve fertility outcomes in affected women.

Future studies should focus on translating these findings into

clinical applications.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JF and QW were responsible for writing the article,

data statistics and data collection. QS was responsible for data

collection. XH conributed to conceptualization, methodology,

writing the original draft and also reviewing and editing,

supervisionand project administration. XH and JF confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present research was approved by the

Institutional Laboratory Animal Review Board of Shanghai First

Maternity and Infant Hospital (approval no. TJBG28625103).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bulun SE, Yilmaz BD, Sison C, Miyazaki K,

Bernardi L, Liu S, Kohlmeier A, Yin P, Milad M and Wei J:

Endometriosis. Endocr Rev. 40:1048–1079. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Harb HM, Gallos ID, Chu J, Harb M and

Coomarasamy A: The effect of endometriosis on in vitro

fertilisation outcome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG.

120:1308–1320. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Sanchez AM, Vanni VS, Bartiromo L, Papaleo

E, Zilberberg E, Candiani M, Orvieto R and Viganò P: Is the oocyte

quality affected by endometriosis? A review of the literature. J

Ovarian Res. 10:432017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

De Hondt A, Peeraer K, Meuleman C, Meeuwis

L, De Loecker P and D'Hooghe TM: Endometriosis and subfertility

treatment: A review. Minerva Ginecol. 57:257–267. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Barnhart K, Dunsmoor-Su R and Coutifaris

C: Effect of endometriosis on in vitro fertilization. Fertil

Steril. 77:1148–1155. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Burney RO and Giudice LC: Pathogenesis and

pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 98:511–519. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ansariniya H, Yavari A, Javaheri A and

Zare F: Oxidative stress-related effects on various aspects of

endometriosis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 88:e135932022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Schieber M and Chandel NS: ROS function in

redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr Biol. 24:R453–R462.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Malvezzi H, Dobo C, Filippi RZ, Mendes do

Nascimento H, Palmieri da Silva E Sousa L, Meola J, Piccinato CA

and Podgaec S: Altered p16Ink4a, IL-1β, and lamin b1

protein expression suggest cellular senescence in deep

endometriotic lesions. Int J Mol Sci. 23:24762022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Lin X, Dai Y, Tong X, Xu W, Huang Q, Jin

X, Li C, Zhou F, Zhou H, Lin X, et al: Excessive oxidative stress

in cumulus granulosa cells induced cell senescence contributes to

endometriosis-associated infertility. Redox Biol. 30:1014312020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Duval C, Wyse BA, Tsang BK and Librach CL:

Extracellular vesicles and their content in the context of

polycystic ovarian syndrome and endometriosis: A review. J Ovarian

Res. 17:1602024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Blagosklonny MV: Cell senescence,

rapamycin and hyperfunction theory of aging. Cell Cycle.

21:1456–1467. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Selvarani R, Mohammed S and Richardson A:

Effect of rapamycin on aging and age-related diseases-past and

future. Geroscience. 43:1135–1158. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Fan J, Chen C and Zhong Y: A cohort study

on IVF outcomes in infertile endometriosis patients: The effects of

rapamycin treatment. Reprod Biomed Online. 48:1033192024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Sung B, Park S, Yu BP and Chung HY:

Modulation of PPAR in aging, inflammation, and calorie restriction.

J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 59:997–1006. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Iemitsu M, Miyauchi T, Maeda S, Tanabe T,

Takanashi M, Irukayama-Tomobe Y, Sakai S, Ohmori H, Matsuda M and

Yamaguchi I: Aging-induced decrease in the PPAR-alpha level in

hearts is improved by exercise training. Am J Physiol Heart Circ

Physiol. 283:H1750–H1760. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Sanguino E, Roglans N, Alegret M, Sánchez

RM, Vázquez-Carrera M and Laguna JC: Atorvastatin reverses

age-related reduction in rat hepatic PPARalpha and HNF-4. Br J

Pharmacol. 145:853–861. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kang HS, Cho HC, Lee JH, Oh GT, Koo SH,

Park BH, Lee IK, Choi HS, Song DK and Im SS: Metformin stimulates

IGFBP-2 gene expression through PPARalpha in diabetic states. Sci

Rep. 6:236652016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Shin M, Kang HS, Park JH, Bae JH, Song DK

and Im SS: Recent insights into insulin-like growth factor binding

protein 2 transcriptional regulation. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul).

32:11–17. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Spitschak M and Hoeflich A: Potential

functions of IGFBP-2 for ovarian folliculogenesis and

steroidogenesis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 9:1192018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Haouzi D, Assou S, Monzo C, Vincens C,

Dechaud H and Hamamah S: Altered gene expression profile in cumulus

cells of mature MII oocytes from patients with polycystic ovary

syndrome. Hum Reprod. 27:3523–3530. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kamangar BB, Gabillard JC and Bobe J:

Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein (IGFBP)-1, −2, −3, −4,

−5, and −6 and IGFBP-related protein 1 during rainbow trout

postvitellogenesis and oocyte maturation: molecular

characterization, expression profiles, and hormonal regulation.

Endocrinology. 147:2399–2410. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Somigliana E, Viganò P, Rossi G, Carinelli

S, Vignali M and Panina-Bordignon P: Endometrial ability to implant

in ectopic sites can be prevented by interleukin-12 in a murine

model of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 14:2944–2950. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ren XU, Wang Y, Xu G and Dai L: Effect of

rapamycin on endometriosis in mice. Exp Ther Med. 12:101–106. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Lu Y, Nie J, Liu X, Zheng Y and Guo SW:

Trichostatin A, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, reduces lesion

growth and hyperalgesia in experimentally induced endometriosis in

mice. Hum Reprod. 25:1014–1025. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Tilly JL: Ovarian follicle counts-not as

simple as 1, 2, 3. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 1:112003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Luo LL, Huang J, Fu YC, Xu JJ and Qian YS:

Effects of tea polyphenols on ovarian development in rats. J

Endocrinol Invest. 31:1110–1118. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Tian Y, Shen W, Lai Z, Shi L, Yang S, Ding

T, Wang S and Luo A: Isolation and identification of ovarian

theca-interstitial cells and granulose cells of immature female

mice. Cell Biol Int. 39:584–590. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Hernandez-Segura A, Nehme J and Demaria M:

Hallmarks of cellular senescence. Trends Cell Biol. 28:436–453.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Fragouli E, Lalioti MD and Wells D: The

transcriptome of follicular cells: biological insights and clinical

implications for the treatment of infertility. Hum Reprod Update.

20:1–11. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Laschke MW, Elitzsch A, Scheuer C,

Holstein JH, Vollmar B and Menger MD: Rapamycin induces regression

of endometriotic lesions by inhibiting neovascularization and cell

proliferation. Br J Pharmacol. 149:137–144. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Augoulea A, Mastorakos G, Lambrinoudaki I,

Christodoulakos G and Creatsas G: The role of the oxidative-stress

in the endometriosis-related infertility. Gynecol Endocrinol.

25:75–81. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Mansour G, Sharma RK, Agarwal A and

Falcone T: Endometriosis-induced alterations in mouse metaphase II

oocyte microtubules and chromosomal alignment: A possible cause of

infertility. Fertil Steril. 94:1894–1899. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Ding GL, Chen XJ, Luo Q, Dong MY, Wang N

and Huang HF: Attenuated oocyte fertilization and embryo

development associated with altered growth factor/signal

transduction induced by endometriotic peritoneal fluid. Fertil

Steril. 93:2538–2544. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Papaconstantinou J: The role of signaling

pathways of inflammation and oxidative stress in development of

senescence and aging phenotypes in cardiovascular disease. Cells.

8:13832019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Kishi H, Kitahara Y, Imai F, Nakao K and

Suwa H: Expression of the gonadotropin receptors during follicular

development. Reprod Med Biol. 17:11–19. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Harrison DE, Strong R, Sharp ZD, Nelson

JF, Astle CM, Flurkey K, Nadon NL, Wilkinson JE, Frenkel K, Carter

CS, et al: Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in

genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature. 460:392–395. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Weichhart T: mTOR as regulator of

lifespan, aging, and cellular senescence: A mini-review.

Gerontology. 64:127–134. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Shen B, Wang Y, Cheng J, Peng Y, Zhang Q,

Li Z, Zhao L, Deng X and Feng H: Pterostilbene alleviated NAFLD via

AMPK/mTOR signaling pathways and autophagy by promoting Nrf2.

Phytomedicine. 109:1545612023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Chung KW, Lee EK, Lee MK, Oh GT, Yu BP and

Chung HY: Impairment of PPARα and the fatty Acid oxidation pathway

aggravates renal fibrosis during aging. J Am Soc Nephrol.

29:1223–1237. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Chin C, Ravichandran R, Sanborn K, Fleming

T, Wheatcroft SB, Kearney MT, Tokman S, Walia R, Smith MA, Flint

DJ, et al: Loss of IGFBP2 mediates alveolar type 2 cell senescence

and promotes lung fibrosis. Cell Rep Med. 4:1009452023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|