Introduction

Diabetes mellitus has emerged as a major global

health concern, with its prevalence steadily rising. According to

the International Diabetes Federation, the global prevalence of

diabetes was estimated at 10.5% (536.6 million people) in 2024, and

projections indicate that it will increase to 12.2% (783.2 million

people) by 2045 (1). Diabetic

osteoporosis (DOP), a notable complication of diabetes, is becoming

increasingly prevalent (2).

Epidemiological data reveals the gravity of the situation. A

meta-analysis of 21 studies involving 11,603 patients with type 2

diabetes mellitus (T2DM) found a high osteoporosis prevalence of

27.67% (95% confidence interval, 21.37-33.98%) (3). Another study reported that >35% of

patients with diabetes experience bone loss, with ~20% meeting the

diagnostic criteria for osteoporosis (4). The incidence of fractures, a severe

consequence of DOP, is also notably high. In patients with type 1

diabetes mellitus, the relative risk for hip fracture was reported

as 4.93 (95% confidence interval, 3.06-7.95), while in patients

with T2DM the risk was 1.33 (95% confidence interval, 1.19-1.49)

(5).

The pathogenesis of DOP is primarily attributed to

either absolute or relative insulin deficiency, which leads to the

formation and accumulation of advanced glycation end products

(AGEs) (6,7). These AGEs disrupt the cross-linking

of collagen in the bone matrix, resulting in alterations to bone

microstructure, decreasing bone density per unit volume, decreasing

bone strength and increasing bone fragility, thereby compromising

bone quality in diabetic patients and elevating the risk of

fractures (8,9). In current medical practice, the

traditional medical treatment of DOP has certain limitations

(10). For instance, drugs such as

thiazolidinediones may affect bone metabolism and increase the risk

of fractures. Although insulin has the effect of promoting bone

synthesis, observational studies have shown that the fracture risk

also increases in insulin users (11). The therapeutic effects of some

drugs are not satisfactory, and the efficacy of these drugs in

treating related complications and the applicable population remain

unclear. Further research is needed to clarify these aspects

(12). Over the years, numerous

animal models have been established to study the pathophysiology of

T2DM-associated osteoporosis. For instance, the combination of a

high-fat diet and streptozotocin (STZ) in rodents has been widely

used to induce T2DM-like conditions, which are then associated with

subsequent development of osteoporosis-like bone changes (13,14).

These models have shown characteristic features such as reduced

bone mineral density (BMD), deteriorated bone microstructure and

imbalanced bone remodeling, closely mimicking the human DOP

phenotype (15,16).

Zinc carnosine (ZnC), also known as polaprezinc, is

an orally available biochelate composed of L-carnosine and zinc

ions (17). ZnC is broken down

during intestinal absorption into two compounds: L-carnosine and

zinc. Carnosine, a naturally active dipeptide, is abundant in

mammalian skeletal muscle and brain, and is synthesized in the body

from β-alanine and L-histidine. Zinc exhibits a range of beneficial

properties, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-aging,

antitumor and immune regulatory effects, the scavenging of oxygen

free radicals, prevention of AGEs, chelation of bivalent metal ions

(such as zinc2+ and copper2+), and

anti-protein carboxylation and anti-glycosylation effects (18–20).

Studies have confirmed that carnosine can effectively reduce

reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in chondrocytes injured by

hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), thereby inhibiting

chondrocyte degeneration and bone loss (21,22).

Zinc is an important trace element necessary for the growth,

development and maintenance of bone health, and it is considered a

key factor in bone metabolism (23). Additionally, zinc ions exhibit

anti-glycosylation and anti-oxidation effects (24,25).

Research has shown that zinc ions can promote the differentiation

of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and mouse bone marrow

monocytes into osteoblasts and osteoclasts (26). By mediating the receptor activator

of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL)/RANK/osteoprotegerin (OPG) and

Wnt signaling pathways, zinc ions positively influence bone

metabolism by upregulating the expression of key genes involved in

bone formation (20,27,28).

In the latest review by Yudhani et al(29), zinc was summarized to play a

notable role in alleviating obesity, particularly in lipid

metabolism, appetite regulation, insulin signaling and inflammatory

responses.

The present study aims to fill this research gap by

focusing on ZnC. The originality of the present study lies in

comprehensively evaluating the potential of ZnC in ameliorating

DOP. To the best of our knowledge, previous studies have not

examined the effects of ZnC in its chelated form on DOP, and did

not conduct a thorough investigation into the complex

pathophysiological processes of DOP. The present study explores the

effects of ZnC on bone loss and bone quality in a T2DM mouse model

through a multi-parameter assessment, including imaging,

biomechanics, histology and molecular biology analysis. By doing

so, the present study aims to provide novel insights into the

treatment of DOP and potentially identify ZnC as a new therapeutic

option.

In conclusion, AGEs induced by T2DM trigger

oxidative stress, stimulate the production of inflammatory

cytokines and ROS, and provoke an inflammatory response in

osteoblasts and osteoclasts. This cascade of events induced by AGEs

enhances the bone resorption activity of osteoclasts, thereby

contributing to the development of DOP (30,31).

Both L-carnosine and zinc ions exhibit notable antioxidation and

anti-glycosylation effects and are closely associated with bone

metabolism. The chelation of carnosine with trace element zinc ions

forms ZnC, which may inhibit the accumulation of AGEs in the bone

microenvironment by clearing ROS. The removal of ROS could reduce

the persistent progression of chronic low-level inflammation in a

high-glucose environment, lower the expression of inflammatory

factors that induce insulin resistance and decrease osteoblast

apoptosis, thereby ameliorating osteoporosis both directly and

indirectly (32,33). The present study employed a T2DM

mouse model to investigate the impact and mechanism of oral ZnC

supplementation on DOP. The present investigation was based on

evidence of bone loss and deteriorating bone quality in diabetic

mice and assessed various parameters, including imaging,

biomechanics, histology and molecular biology analysis results.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

All experimental protocols were conducted in

compliance with the requirements of the Animal Ethics Committee and

have been approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of

North China University of Science and Technology (Tangshan, China;

approval no. 2023-SY-230). A total of 24 specific pathogen-free

(SPF) C57BL/6J 6-week-old male mice were purchased from Beijing

Huafukang Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The mice were housed under

standard conditions at a temperature of 22±2°C and a humidity of

50±5%, with a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle, ensuring access to

adequate water. The mean body weight of the mice was ~18±3 g and

they were fed with a standard diet for 1 week to allow for

adaptation.

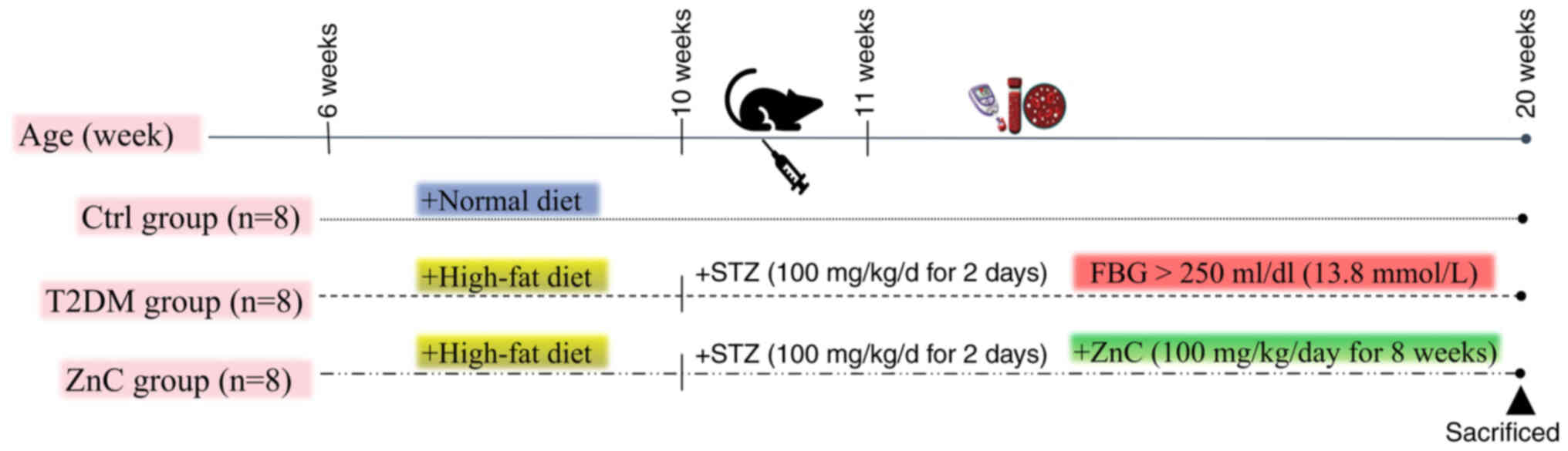

Animal modeling and grouping

A total of 24 6-week-old SPF male C57BL/6J mice were

used in the experiment. The mice were randomly divided into 3

groups, with 8 mice in each group. During the experiment, general

observations were conducted on the animals every day, including

appearance, behavior and activity status. A detailed examination

was performed once a week, including measuring body weight,

observing eating and drinking habits, and checking for any disease

symptoms. If abnormal behaviors were observed in the animals, such

as lethargy, reduced activity or diarrhea, the observation

frequency was increased. In the present experiment, anesthetic

agents were not administered during the observation and handling

procedures, as these did not involve invasive interventions. All

mice survived until the end of the experiment and no mice died.

The experiment lasted for 20 weeks, starting from

week 1 and ending at week 20. In the first 4 weeks, 16 mice were

fed a high-sugar and high-fat diet to induce metabolic disorders of

sugar, fat and insulin resistance. Subsequently, starting from week

5, 12 h of fasting was followed by intraperitoneal injections of

STZ at a dose of 100 mg/(kg/day) for 2 consecutive days. STZ was

dissolved in 0.1 mol/l citrate-sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.5). This

treatment was designed to damage pancreatic β cells and establish a

model of T2DM. The control group received standard food and was

intraperitoneally injected with citrate-sodium citrate buffer (0.1

mol/l; pH 4.5) as a pH-matched control vehicle at week 5 (34–36).

This ensured that any observed differences could be attributed to

the effects of STZ or ZnC (33,37,38).

After completion of the STZ injections, the fasting blood glucose

(FBG) levels of the mice were monitored on designated days. Mice

with FBG levels >250 mg/dl (13.8 mmol/l) on 3 consecutive days

were confirmed as T2DM models. After the successful construction of

the model, the ZnC group and the T2DM group underwent corresponding

treatments for 8 weeks. The ZnC group was orally administered 100

mg/(kg/day) ZnC, while the T2DM group was orally administered 1

ml/(kg/day) 0.9% sodium chloride solution once daily. At the end of

week 20 in the experiment, all mice were euthanized via cervical

dislocation. After performing the cervical dislocation, signs such

as cessation of breathing, disappearance of heartbeat and dilation

of pupils were observed to confirm the death of the animals. At the

same time, all experimental mice underwent autopsy to further

confirm the death status, ensuring the accuracy of the experimental

data and the reliability of the experimental results, and for the

collection of tissue samples for subsequent experiments (Fig. 1).

Micro-computed tomography (micro-CT)

analysis

The right tibia of each mouse was scanned using

high-resolution micro-CT (SkyScan1176; Bruker Corporation) to

assess BMD and microstructural parameters. The scanned images were

reconstructed and analyzed using Avatar software [version 1.7.4.0;

Pingseng Medical Technology (Kunshan) Co., Ltd.]. For trabecular

bone, the region of interest (ROI) was defined as starting at 0.2

mm distal to the growth plate and extending 5% of the tibial length

distally, thereby excluding the growth plate and primary spongy

body. The following parameters were obtained: BMD

(g/cm3) bone volume/tissue volume (BV/TV; %), number of

bone trabeculae (Tb.N; 1/mm), bone trabecular thickness (Tb.Th;

µm), bone trabecular separation (Tb.Sp; mm) and structural model

index (SMI). For cortical bone, the ROI for selected scans

commenced at 40% of the tibia length distal to the proximal growth

plate and extended 10% of the tibia length distally. Within this

ROI, thickness of cortical bone (Ct.Th; µm), area of cortical bone

(Ct.Ar, %) and cortical porosity (Ct.Po, %) were calculated. Ct.Ar

refers to the absolute cortical bone area within the ROI, while

total bone area was not measured in this study.

Determination of biomechanical

properties

The right femurs were utilized for biomechanical

testing using a universal electronic testing machine (cat. no.

MMT-250NV-10; Shimadzu Corporation). The load-measuring accuracy of

the testing instrument was 0.01 N, with a span length of 6 mm and a

loading speed of 2 mm/min. Based on the load-displacement curve,

the maximum load (Max-Load; N) and the maximum bending stress

(Max-Stress; N/mm2) were obtained.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)

staining and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP)

staining

Left tibial tissues were processed for histological

examination using H&E staining and TRAP staining. For bone

tissue decalcification, the left tibia was initially fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde at room temperature (25°C) for 24 h, followed by

decalcification in a 17% EDTA solution at room temperature (25°C)

12 weeks, with the solution being changed weekly. Section

preparation involved a series of steps: Dehydration, clearing,

paraffin embedding and embedding utilizing an automatic embedding

machine. Paraffin blocks were sectioned at a thickness of 5 µm

using a rotary microtome (Leica RM2235, Leica Biosystems). The

trimmed wax blocks were subjected to continuous sectioning. First,

the sections were pre-cooled on an ice stage to prevent tissue

fragmentation, followed by fine trimming. Subsequently, the

sections were spread in warm water at 45°C to obtain flat and

wrinkle-free sections. Next, the sections were picked up and placed

in a 60°C oven for overnight drying to ensure tight adhesion.

Finally, the dried sections were stored at room temperature for

subsequent staining and immunohistochemical experiments.

The tissue sections were placed in an oven at 60°C

and baked for 2 h to remove the wax. Successive immersions were

performed in 100% xylene I, 100% xylene II, and 100, 95, 80, 70 and

60% ethanol, with each solution applied for 10 min, to complete the

dewaxing and rehydration process. Staining and immunohistochemical

experiments were then performed.

H&E staining was performed, which included

hematoxylin (cat. no. BL702B; Biosharp Life Sciences) staining at

room temperature for 3–5 min, differentiation using a 1%

hydrochloric acid solution in ethanol for 20 sec, bluing with 1%

ammonia for 5 min, eosin staining (cat. no. BA4098; Zhuhai Beisuo

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for 30 sec and sealing with neutral gum

following dehydration and clearing.

For TRAP staining, a staining solution composed of

0.1 M acetic acid buffer, 1 mg/ml hexazo para-fuchsin and naphthol

AS-BI phosphate (all from Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was prepared.

Sections were dewaxed, hydrated, stained and incubated for 3 h,

after which they were washed, counterstained, differentiated,

dehydrated, cleared and sealed to ensure optimal staining quality

for subsequent observation and analysis. Histological sections were

examined using a BX53 optical microscope (Olympus Corporation) at

×40 and ×100 magnification. The osteoclast number was obtained by

counting the number of TRAP-positive cells (39).

Immunohistochemical staining

After sections that had been dewaxed to water were

washed with phosphate buffered saline [PBS; cat. no. AC08L033;

Life-iLab; Heyuan Liji (Shanghai) Biotechnology Co., Ltd.] for 10

min, antigen repair was performed by incubation with 0.05% trypsin

[cat. no. AC15L821; Life-iLab; Heyuan Liji (Shanghai) Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.] at 37°C for 30 min. To block endogenous peroxidase

activity, 3% H2O2 was incubated at room

temperature for 10 min. The sections were then incubated with the

corresponding primary antibody at 4°C overnight. The primary

antibodies used and their dilution ratios are as follows: Type I

collagen (COL-I; 1:200; cat. no. AF7001; Affinity Biosciences),

osteocalcin (OCN, 1:200; cat. no. 16157-1-AP; Proteintech Group,

Inc.) and OPG (1:200; cat. no 31766-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.).

The next day, after the sections were rinsed with PBS, they were

incubated with secondary antibody (cat. no. 2414D1020; Beijing

Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), and diaminobenzidine

(cat. no. ZLI-9018; Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.) was used for color development, which was terminated by

washing with PBS. After counterstaining with hematoxylin for 1 min,

differentiation was performed with 1% hydrochloric acid ethanol for

3 sec, followed by rinsing with tap water for 15 min to return to

blue. Subsequently, dehydration was carried out with gradient

ethanol at 60, 70, 80, 90 and 100% for 5 min each in sequence,

followed by 100% xylene clearing for 5 min and finally mounting

with resin. All sections were imaged under an optical microscope

(Olympus BX53; Olympus Corporation) at a magnification of ×200. The

region under the growth plate was selected as the ROI, and Image J

software (National Institutes of Health) was used to analyze the

average optical density (AOD) within the ROI of each section.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

For RT-qPCR, femurs were ground and lysed using

Trizol (cat. no. DP424; Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.) reagent, at room

temperature (25°C) for 5 min. Chloroform (MilliporeSigma) was

added, and the mixture was vortexed for 15 sec and incubated at

room temperature for 3 min, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 ×

g for 15 min at 4°C to separate the aqueous phase containing RNA.

RNA was precipitated by adding isopropyl alcohol, incubated at room

temperature for 10 min, and pelleted by centrifugation at 12,000 ×

g for 10 min at 4°C. The RNA pellet was washed with 70% ethanol,

centrifuged at 7,500 × g for 5 min at 4°C and air-dried before

resuspension in RNase-free water. The purified RNA was dissolved in

nuclease-free water, and its concentration and purity were assessed

using a UV spectrophotometer (cat. no. SLAN-96S; Shanghai Hongshi

Medical Technology Co., Ltd.). A 20-µl reaction mixture was

prepared, and first-strand cDNA was synthesized using a reverse

transcription kit (cat. no. ZR103; Beijing Zhuangmeng International

Biogene Technology Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's

protocol. The cDNA was subsequently subjected to qPCR in a 20-µl

reaction volume using the SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II kit

(cat. no. ZR103-1; Beijing Zoman Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) with SYBR

Green as the fluorophore. With β-actin as the internal reference

gene, the 2−∆∆Cq method (40) was used to calculate the relative

mRNA expression levels of the target genes relative to the control

group. The genes analyzed included OPG, OCN and RANKL, which were

selected since they are key regulators of bone metabolism and

remodeling, serving as important markers of osteogenic

differentiation and bone turnover. The primer synthesis was

completed by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. The primer sequences used are

shown in Table I. The PCR

conditions were as follows: 94°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles

of 94°C for 30 sec, 52–58°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 30 sec.

| Table I.Primer sequences of selected

genes. |

Table I.

Primer sequences of selected

genes.

| Gene | Primer sequence

(5′-3′) |

|---|

| OCN |

|

|

Forward |

GAGGGCAATAAGGTAGTGAA |

|

Reverse |

CATAGATGCGTTTGTAGGC |

| OPG |

|

|

Forward |

CAGAGCGAAACACAGTTTG |

|

Reverse |

CACACAGGGTGACATCTATTC |

| RANKL |

|

|

Forward |

TGTACTTTCGAGCGCAGATG |

|

Reverse |

CCACAATGTGTTGCAGTTCC |

| β-actin |

|

|

Forward |

GATCAGCAAGCAGGAGTACGA |

|

Reverse |

GGTGTAAAACGCAGCTCAGTAAC |

Statistical analysis

All data are presented in the form of mean ±

standard deviation. The present study used SPSS 22.0 software (IBM

Corp.) for all statistical analyses. For the differences between

groups that follow a normal distribution, a one-way analysis of

variance (ANOVA) was first used to confirm the overall group

differences. If the ANOVA results showed a statistically

significant difference (P<0.05), then the LSD (least significant

difference) post-hoc test was further used to conduct pairwise

comparisons between each group to clearly identify which groups had

differences. Each group had a sample size of 8 mice (n=8), and

comparisons were made between groups. The significance level α was

set at 0.05. During the analysis, the actual P-value of each test

was clearly indicated. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference; if P≥0.05, it indicated that

there was no statistically significant difference between the

groups.

Results

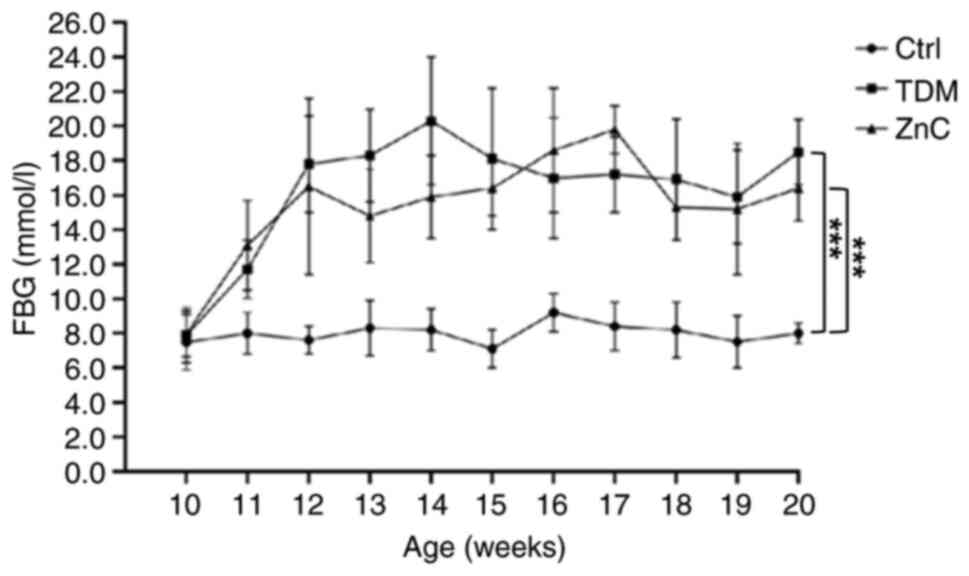

Changes in FBG in each group of

mice

Notable differences in blood glucose concentrations

were observed in the T2DM model group and the ZnC intervention

group when compared with the control group. However, there was no

notable difference in blood glucose concentration between the ZnC

group and the T2DM group, indicating a lack of a substantial

hypoglycemic effect following the ZnC intervention (Fig. 2).

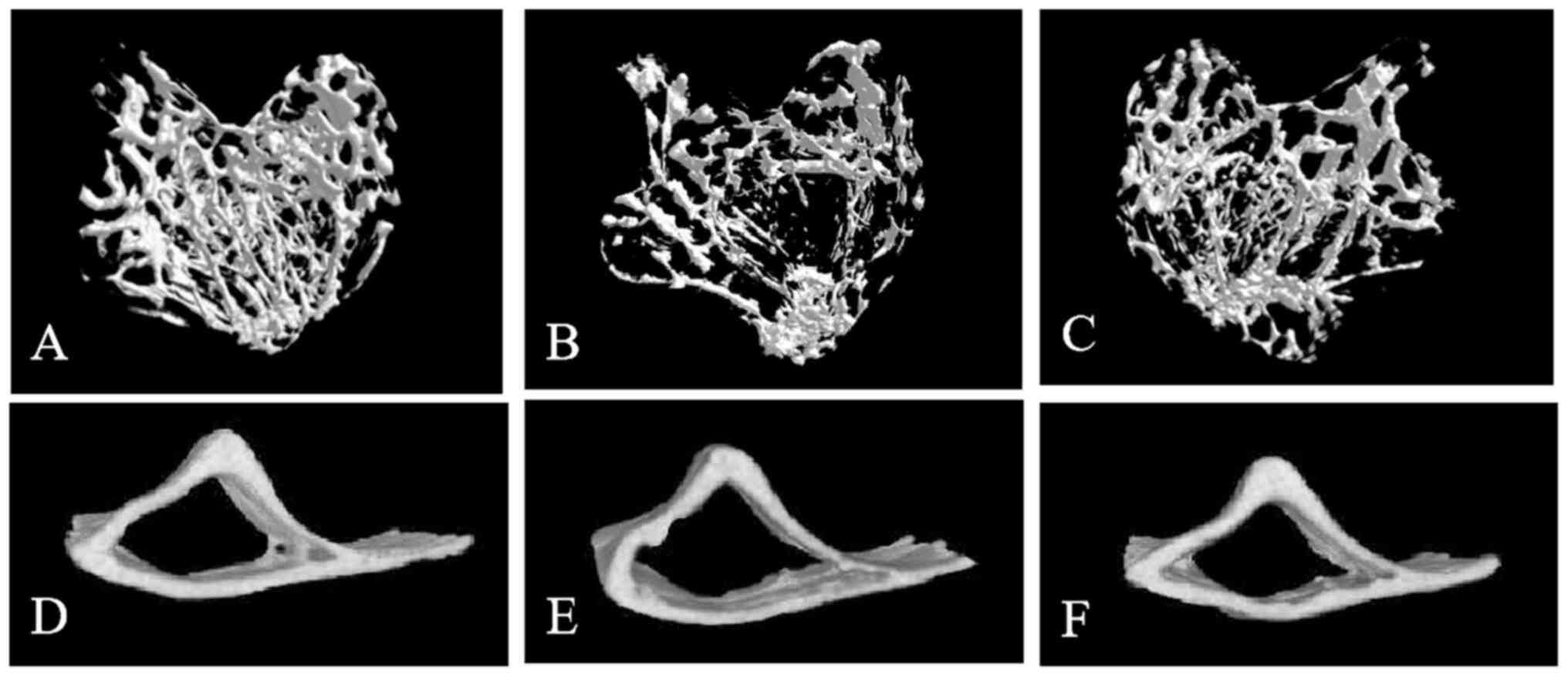

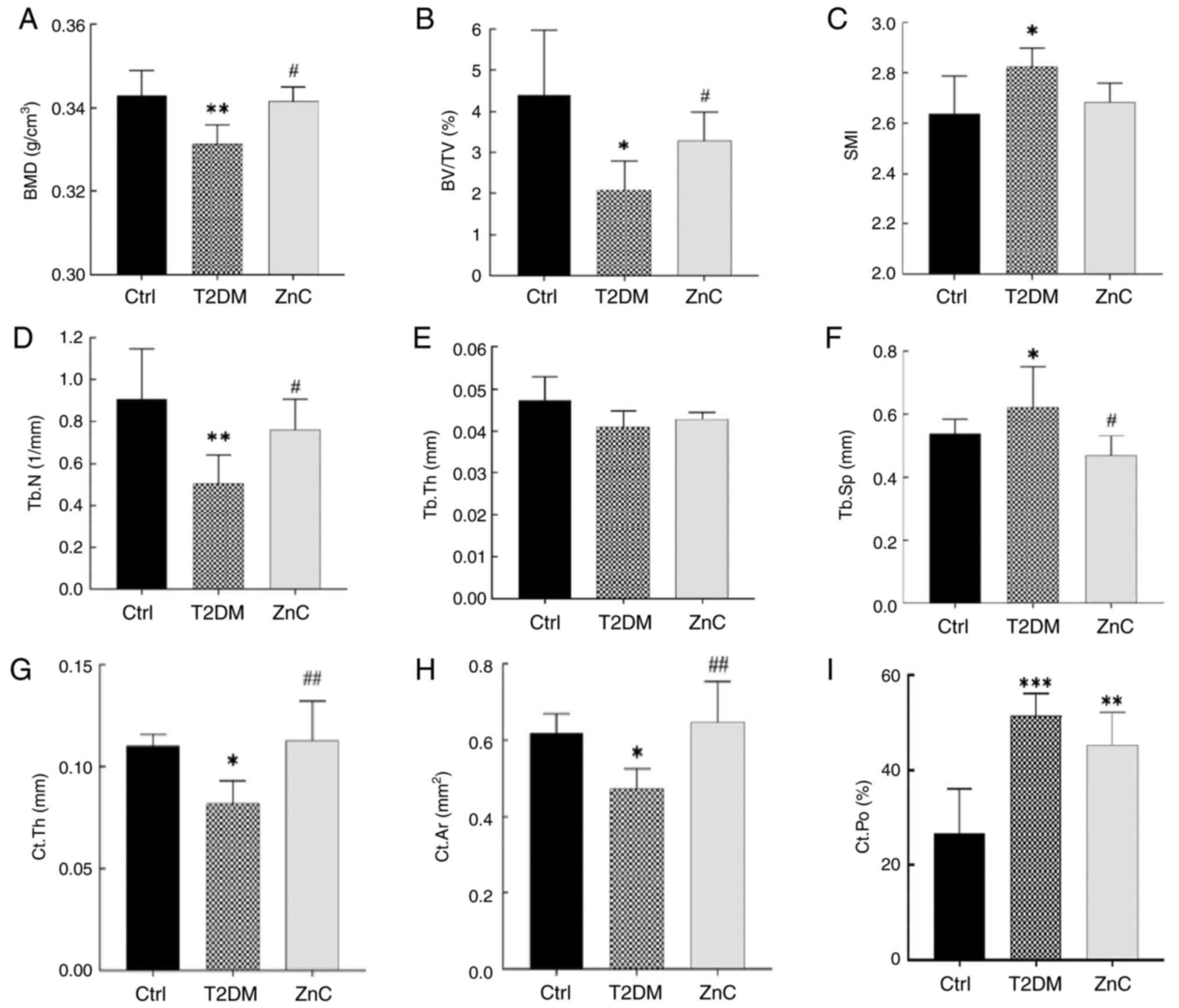

Micro-CT analysis of cancellous and

cortical bone parameters

The tibial bone tissue of mice was examined using

micro-CT, and the three-dimensional reconstruction images revealed

the microstructure of both cancellous and cortical bone. The bone

microstructure in the control group appeared generally normal. By

contrast, the cancellous bone microstructure in the T2DM model

group exhibited significant alterations compared with that of the

control group, including thinning of the proximal growth plate, a

reduction in the number of trabeculae beneath the growth plate,

decreased trabecular thickness, increased trabecular spacing, and

enhanced separation and thinning of the cortical bone. Quantitative

analysis of tibial bone parameters further validated osteoporosis

in the T2DM model. Notably, the microstructural changes observed in

the tibia of the T2DM model group were significantly mitigated in

the ZnC intervention group.

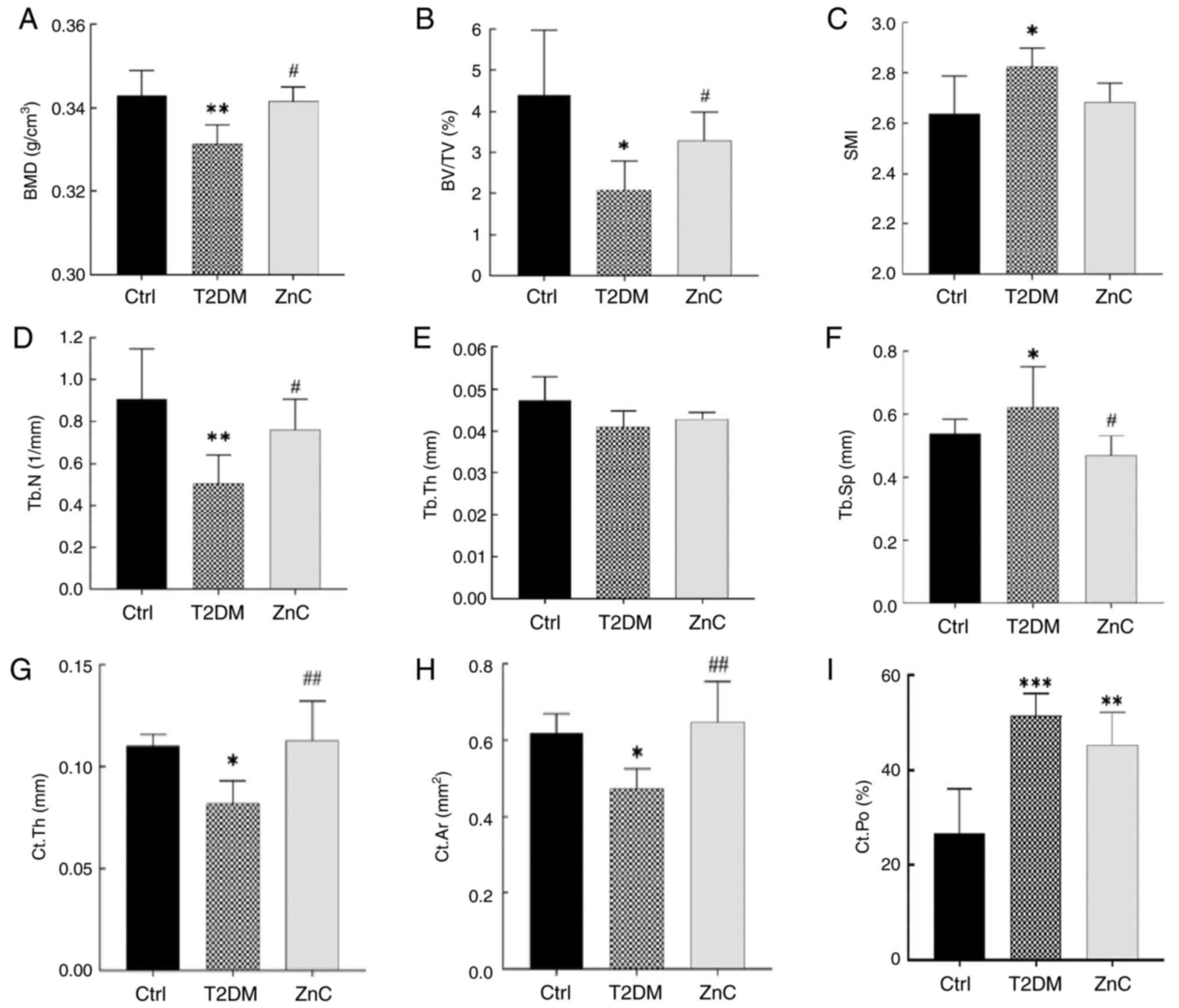

Further analysis of tibial BMD and bone

microstructure parameters revealed that compared with the Control

group, the BMD, BV/TV, Tb.N, Ct.Th and Ct.Ar in the T2DM model

group were significantly decreased (P<0.05). Notably, there were

no significant differences in SMI, Tb.Th and Ct.Po between the ZnC

group and the T2DM model group (P>0.05). However, compared with

the T2DM model group, the BMD, BV/TV, Tb.N, Ct.Th and Ct.Ar in the

ZnC group were significantly increased, and Tb.Sp was significantly

decreased (P<0.05) (Figs. 3 and

4).

| Figure 4.Analysis of tibial BMD and bone

microstructure parameters in mice. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. Ctrl group; #P<0.05 and

##P<0.01 vs. T2DM model group. (A) BMD, bone mineral

density; (B) BV/TV, bone volume/tissue volume; (C) SMI, structural

model index; (D) Tb.N, number of bone trabeculae; (E) Tb.Th, bone

trabecular thickness; (F) Tb.Sp, bone trabecular separation; (G)

Ct.Th, thickness of cortical bone; (H) Ct.Ar, area of cortical

bone; (I) Ct.Po, porosity of cortical bone. Ctrl, control; T2DM,

type 2 diabetes mellitus; ZnC, zinc carnosine. |

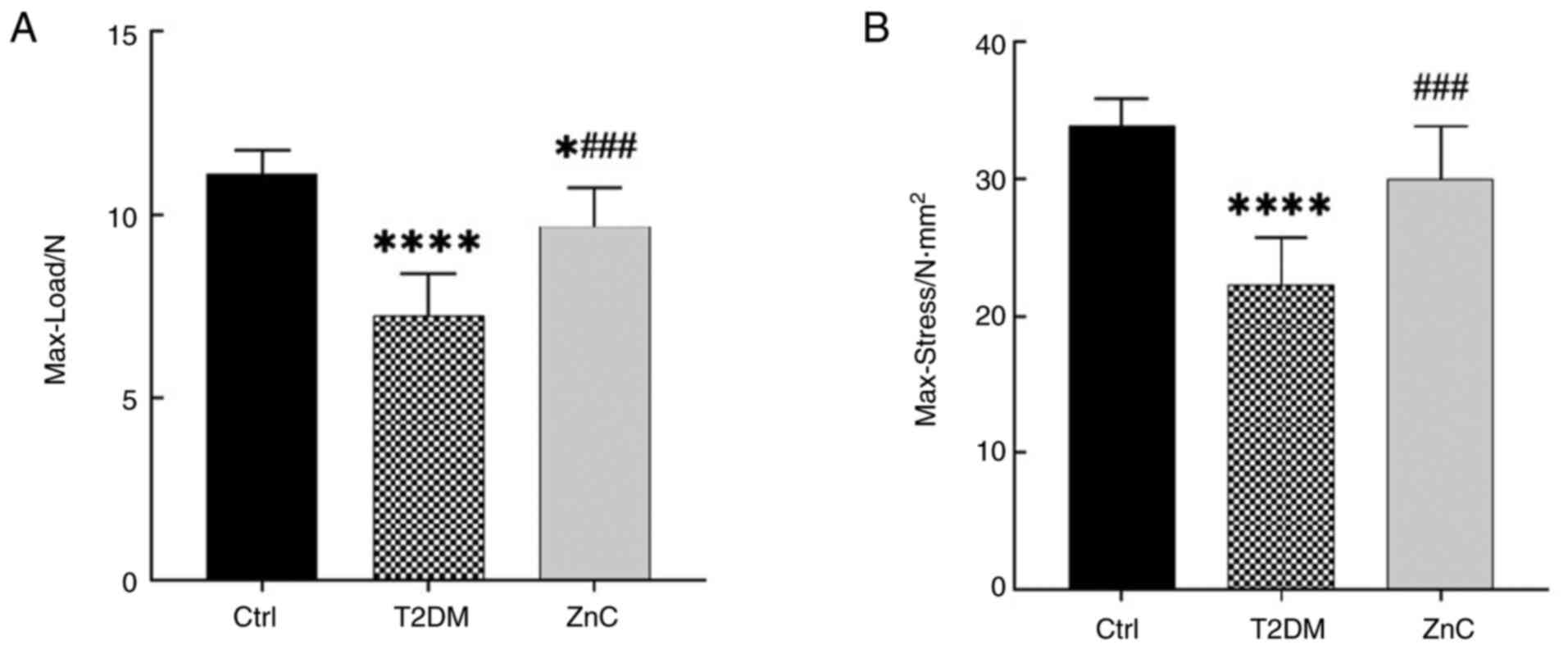

Three-point bending test

The biomechanical properties of the femur were

assessed using a three-point bending test (Fig. 5). When compared with the control

group, the Max-Load in both the T2DM model group and the ZnC

intervention group was significantly reduced (P<0.05). However,

compared with the T2DM model group, the Max-Load and Max-Stress in

the ZnC intervention group were significantly increased

(P<0.05).

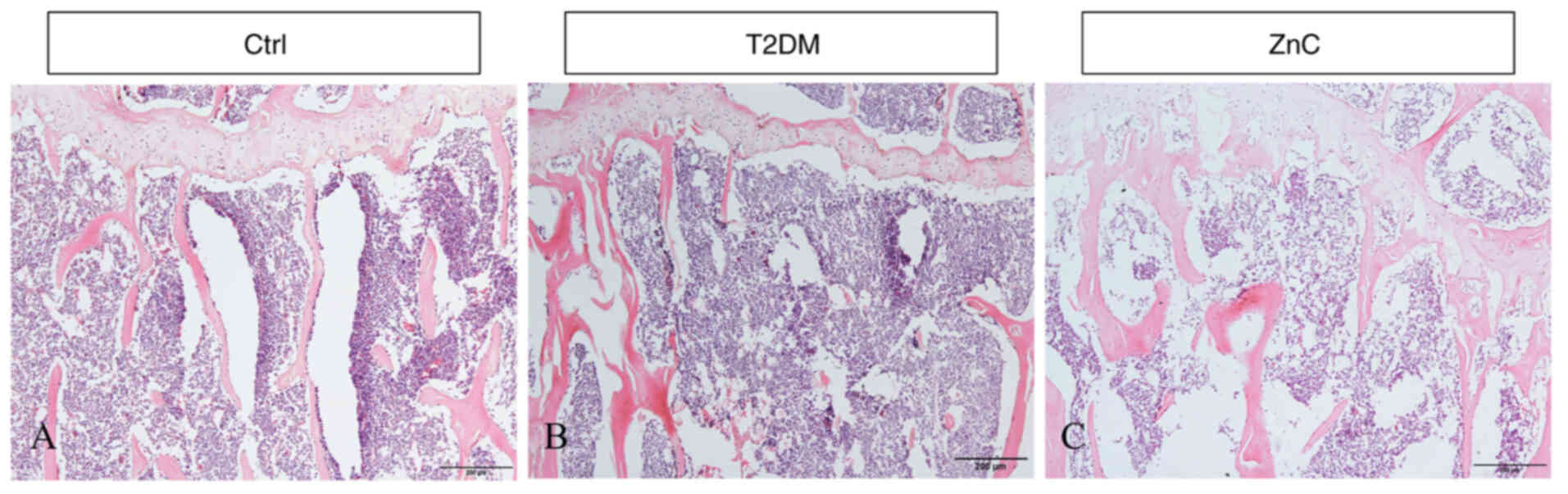

Histological staining results

Compared with that in the control group, the growth

plate in the T2DM model group exhibited a notable reduction in

thickness, with considerable damage to the lamellar trabecular

structure in the lower bone marrow cavity. The distance between

trabeculae increased and the presence of lipid vacuoles was noted.

Additionally, the marginal cortical bone was thinner, resulting in

a more pronounced loss of total bone mass. By contrast, the ZnC

intervention group showed an increase in growth plate thickness, a

reduction in the extent of partial destruction of both trabecular

and cortical bone and a decrease in total bone mass loss when

compared with the T2DM model group (Fig. 6). This is consistent with the

results shown in Fig. 4: that is,

compared with the control group, BMD, BV/TV, Tb.N, Ct.Th and Ct.Ar

in the T2DM model group were all significantly decreased

(P<0.05); while ZnC intervention could significantly reverse

these indicators (P<0.05).

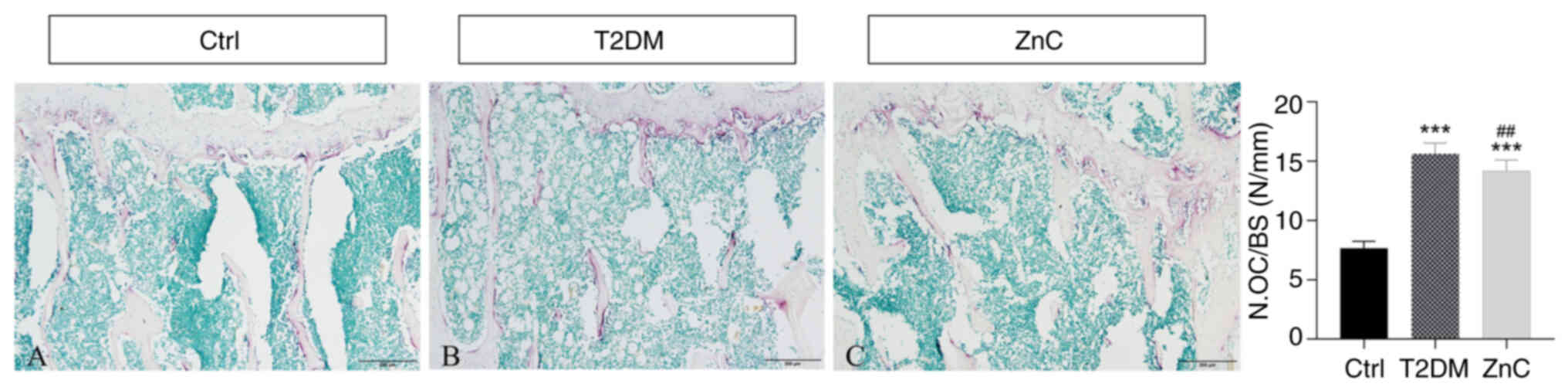

TRAP staining

Compared with the control group, the T2DM model

group exhibited a significantly higher density of TRAP-positive

multinucleated cells (≥3 nuclei/cell) (P<0.01) localized

predominantly in osteoclast-active regions; specifically, beneath

the growth plate and adjacent to the medullary cavity along

trabecular surfaces (P<0.05). This pattern indicated enhanced

osteoclast-mediated bone resorption in diabetic conditions.

Conversely, ZnC intervention significantly suppressed

osteoclastogenesis, evidenced by a marked reduction in

TRAP-positive cell density relative to the T2DM model group

(P<0.05), as quantified by histomorphometric parameter of

measuring osteoclast number/bone surface (41,42)

(Fig. 7).

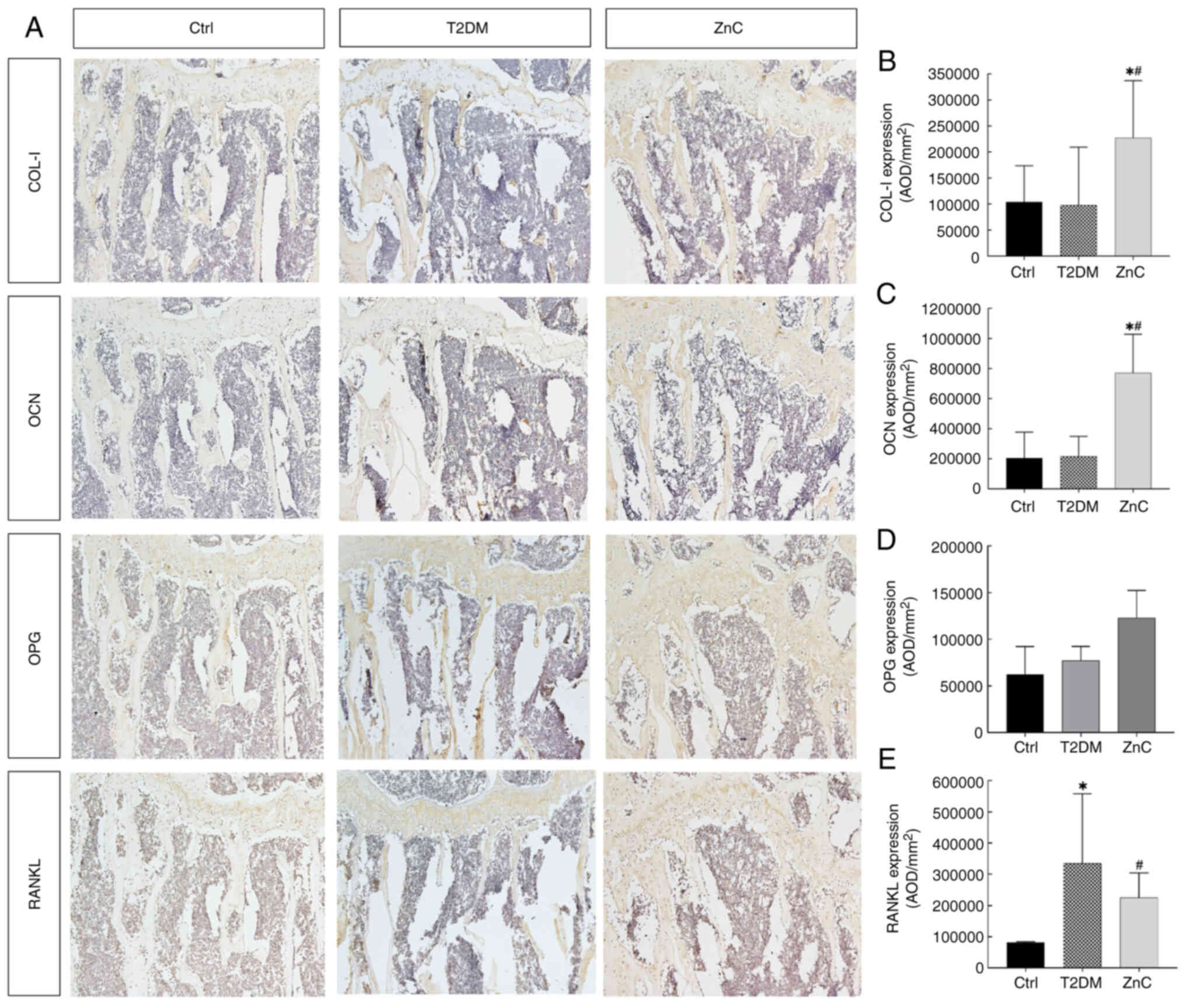

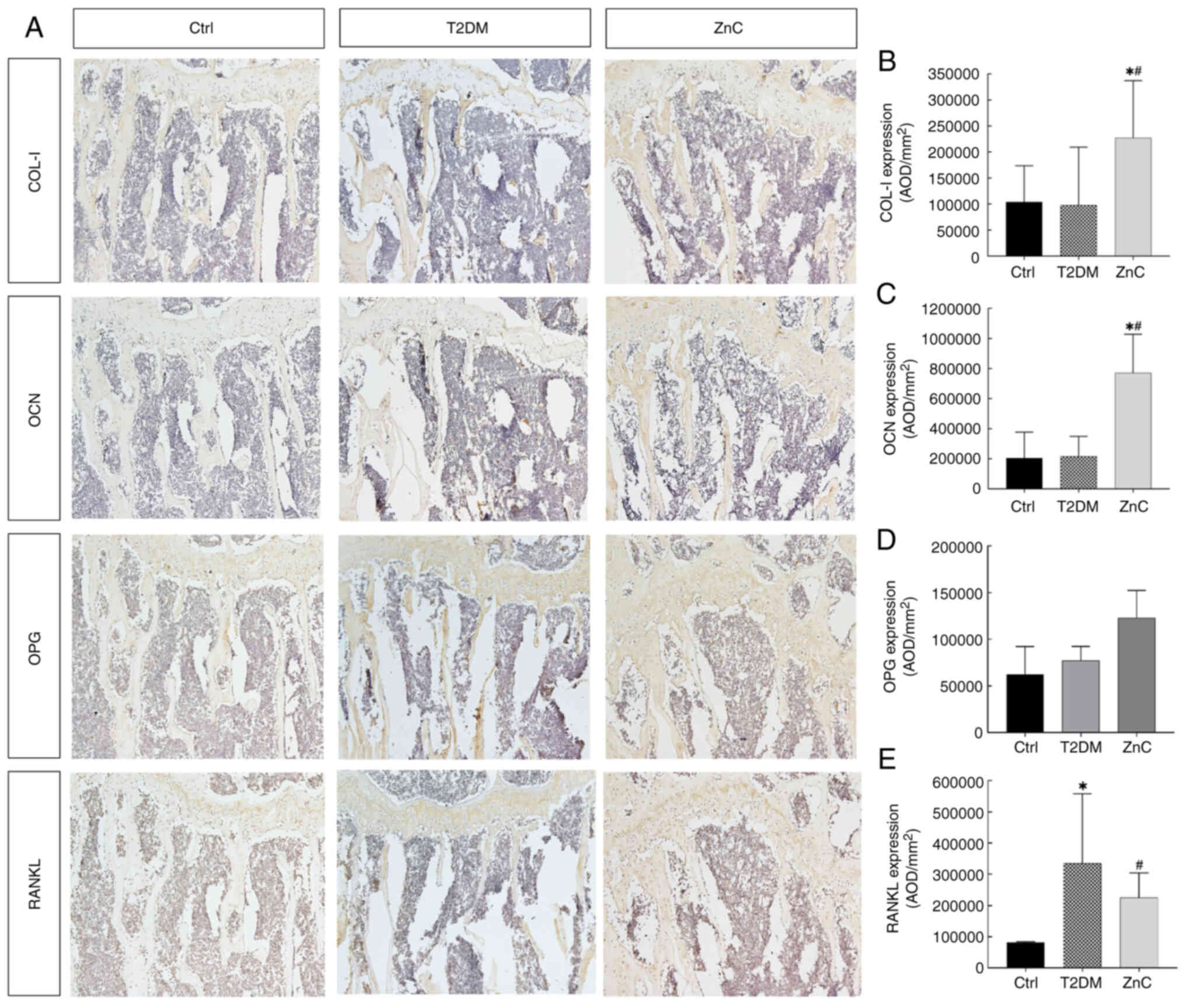

Immunohistochemical detection of

protein expression of bone metabolism-related factors in each

group

Protein expression of bone metabolism-related

factors was evaluated in each group via immunohistochemistry.

Quantitative analysis of histochemical staining images revealed no

significant differences in the expression levels of bone formation

markers type I collagen (COL-I), osteocalcin (OCN) and OPG between

the T2DM group and the control group (all P>0.05). By contrast,

the AOD of RANKL, a key osteoclast-activating factor, was

significantly elevated in the T2DM group compared with that in the

control group (P<0.05).

Following ZnC intervention, the AOD of osteogenic

genes COL-I and OCN increased significantly compared with that in

both the control and T2DM groups (all P<0.05), indicating

enhanced bone formation. Meanwhile, OPG expression remained

unchanged (P>0.05). Notably, ZnC treatment significantly

suppressed RANKL expression compared with that in the T2DM model

group (P<0.05), suggesting inhibition of osteoclast-mediated

bone resorption (Fig. 8).

| Figure 8.COL-I, OCN, OPG and RANKL protein

expression levels in each group after 8 weeks of intervention. (A)

COL-I, OCN, OPG and RANKL protein expression level of each

treatment group. Average optical density of (B) COL-I, (C) OCN, (D)

OPG and (E) RANKL in each group. *P<0.05 vs. Ctrl group;

#P<0.05 vs. T2DM model group. COL-I, type I collagen;

OCN, osteocalcin; OPG, osteoprotegerin; RANKL, receptor activator

of nuclear factor-κB ligand; Ctrl, control; T2DM, type 2 diabetes

mellitus; ZnC, zinc carnosine; AOD, average optical density

value. |

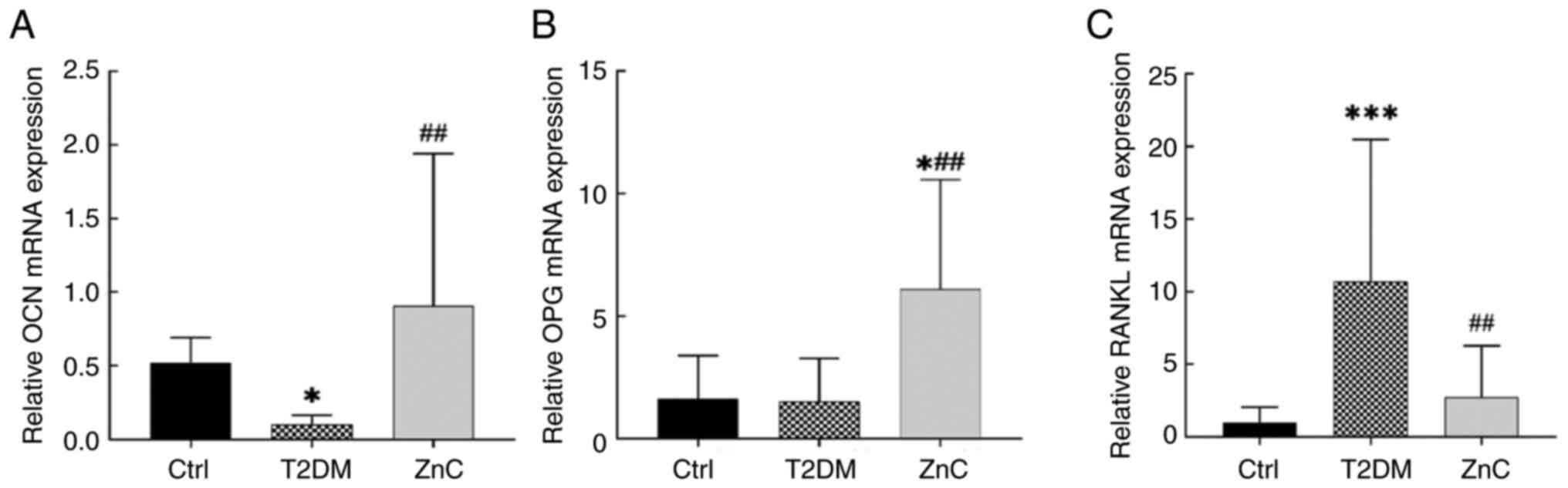

mRNA expression levels of bone

metabolism-related factors

Compared with the control group, the mRNA expression

of OCN in mice of the T2DM model group was significantly decreased

(P<0.05), while the difference in the expression level of OPG

was not statistically significant (P>0.05); however, the

expression level of RANKL was significantly increased (P<0.05).

When compared with the T2DM group, the ZnC group exhibited

significant upregulation of OCN and OPG mRNA expression

(P<0.05), and downregulation of RANKL mRNA expression

(P<0.05) (Fig. 9).

Discussion

ZnC is a zinc peptide that is widely used in the

treatment of peptic ulcers, gastrointestinal tumors, Alzheimer's

disease, diabetes complications and other diseases, and its safety

and lack of toxicity have been demonstrated (43,44).

In the present study, a mouse model of DOP was

established by administering a high-fat diet in conjunction with

intraperitoneal injections of a moderate dose of STZ (45,46).

Continuous monitoring of FBG levels and body mass changes confirmed

the onset of insulin resistance after 4 weeks of high-fat diet

feeding. Following two consecutive injections of moderate doses of

100 mg/(kg/day) STZ, blood glucose levels gradually increased over

the course of 1 week, successfully establishing the T2DM model. In

the present study, it was observed that the FBG levels of mice

receiving ZnC intervention for 8 weeks were lower than those of the

diabetes model group without ZnC intervention; however, this

difference was not statistically significant, suggesting that ZnC

does not have a notable hypoglycemic effect. Previous meta-analyses

have indicated that ZnC may possess therapeutic potential in

diabetes, as it can reduce glycated hemoglobin and FBG levels

(47,48). Further studies are necessary to

conclusively determine whether ZnC has a hypoglycemic effect.

ZnC has been demonstrated to markedly alleviate bone

mass loss associated with postmenopausal osteoporosis, senile

osteoporosis, apraxia osteoporosis, autoimmune osteoporosis and

secondary osteoporosis resulting from vitamin D or calcium

deficiency (49–52). In the present study, micro-CT

analysis revealed that BMD, BV/TV, Tb.N, Ct.Th and Ct.Ar were

significantly reduced in the diabetes model group, whilst Tb.Sp,

SMI and the Ct.Po were significantly increased compared with the

control group. After ZnC intervention, these parameters were

partially restored toward control group levels, showing significant

improvement compared with the T2DM group. The data of the

three-point bending mechanics test indicated that the Max-Load and

Max-Stress of the diabetic model group were significantly reduced

compared with those of the control group. No significant

differences were observed between the ZnC intervention group and

the T2DM model group, indicating that ZnC treatment did not

significantly improve femoral biomechanical properties. The

aforementioned results showed that STZ injection combined with a

high-fat diet for 8 weeks could induce a significant DOP phenotype

in mice and that the associated osteoporosis was significantly

improved after ZnC intervention. ZnC intervention partially

mitigated diabetic bone mass loss, as evidenced by improvements in

bone microstructure and histological parameters, although

biomechanical properties were not significantly restored.

ZnC, a bidirectional modulator, may help to treat

osteoporosis and other bone diseases. By increasing the expression

levels of protein kinase and protein phosphatase in osteoblasts,

ZnC stimulates newly synthesized bone proteins in osteoblasts,

enhances the activity of zinc-activated aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase

in translation, and stimulates bone formation and calcification

(51,53–55).

ZnC can also upregulate the OPG/RANKL ratio and block the

RANKL/RANK interaction between osteoclast precursors and

osteoclasts, thereby effectively inhibiting the formation,

differentiation and apoptosis of osteoclasts, and mitigating

DOP-associated bone loss (56–60).

In the present study, immunohistochemical and histological analyses

demonstrated that oral supplementation of 100 mg/(kg/day) ZnC

alleviated diabetes-induced bone loss, improved high sugar-induced

abnormalities in bone microstructure, and regulated bone

metabolism-related factors by increasing osteogenic proteins

(COL-I, OCN and OPG) and decreasing the osteoclast-related factor

RANKL, accompanied by a reduction in TRAP-positive cells, which may

reduce the stimulating effect of diabetes on osteoclast

differentiation by promoting osteoblast differentiation, and

inhibiting osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption function,

and exhibits a protective role in cortical bone and cancellous bone

during abnormal bone loss.

In conclusion, ZnC effectively alleviated the DOP

phenotype in diabetic mice, improved bone homeostasis and mitigated

the abnormal osteoclast activity under the high glucose-metabolic

state. ZnC was shown to inhibit bone resorption and promote bone

formation by suppressing osteoclast activity and enhancing

osteoblast differentiation, demonstrating its potential as a

therapeutic drug for bone remodeling-related diseases (including

osteoporosis). However, the present study also had certain

limitations, as follows: i) The present study was conducted only in

mouse models, and the animal-based experimental results exhibit a

level of uncertainty when extrapolated to humans; and ii) although

the present study explored the effects of ZnC on bone

metabolism-related factors and initially revealed its mechanism of

action, the specific molecular signaling pathways have not been

fully clarified. Future research should consider conducting

clinical studies to verify the efficacy and safety of ZnC in

humans; at the same time, in-depth explorations of its mechanism of

action at the cellular and molecular levels can provide a

theoretical basis for developing more effective osteoporosis

treatment strategies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Central Government-Guided

Local Science and Technology Development Foundation of Hebei

Province (grant nos. 226Z7709G and 246Z7744G), the Natural Science

Foundation of Hebei Province (grant no. H2022209054) and the Basic

Scientific Research Foundation of Universities in Hebei Province

(grant no. JYG2021005).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

FT and JG conceived and designed the study,

supervised the project, interpreted the data, critically revised

the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the

final manuscript. FT and JG are responsible for the overall

integrity of the work. HY made substantial contributions to the

conception of the work, performed all experiments, analyzed and

interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript and approved the final

version. JG and HY confirm the authenticity of all raw data. QL and

YH made substantial contributions to data acquisition, performed

the statistical analysis, interpreted the results and approved the

final manuscript. ZY contributed to data collection, validation of

the experimental results and approval of the final manuscript. LX,

YX and XH performed the H&E and TRAP staining experiments,

contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the histological

data, and approved the final manuscript. DH secured funding for the

study, provided methodological guidance, contributed to the

critical review of the manuscript and approved the final version.

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript, and agree

to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All experiments were approved by the Institutional

Animal Care and Use Committee of North China University of Science

and Technology (Tangshan, China; approval no. 2023-SY-230).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

ZnC

|

zinc carnosine

|

|

DOP

|

diabetic osteoporosis

|

|

T2DM

|

type 2 diabetes mellitus

|

|

STZ

|

streptozotocin

|

|

micro-CT

|

micro-computed tomography

|

|

BMD

|

bone mineral density

|

|

BV/TV

|

bone volume/tissue volume

|

|

Tb.N

|

number of bone trabeculae

|

|

Ct.Th

|

thickness of cortical bone

|

|

Ct.Ar

|

area of cortical bone

|

|

Tb.Sp

|

bone trabecular separation

|

|

Ct.Po

|

porosity of cortical bone

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

|

ROI

|

region of interest

|

|

Tb.Th

|

bone trabecular thickness

|

|

SMI

|

structural model index

|

|

Max-Load

|

maximum load

|

|

COL-I

|

type I collagen

|

|

OCN

|

osteocalcin

|

|

AOD

|

average optical density value

|

|

FBG

|

fasting blood glucose

|

References

|

1

|

Gao HX, Regier EE and Close KL:

International diabetes federation world diabetes Congress 2015. J

Diabetes. 8:300–302. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Carballido-Gamio J: Imaging techniques to

study diabetic bone disease. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes.

29:350–360. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Liu X, Chen F, Liu L and Zhang Q:

Prevalence of osteoporosis in patients with diabetes mellitus: A

systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMC

Endocr Disord. 23:12023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Schacter GI and Leslie WD: Diabetes and

osteoporosis: Part I, epidemiology and pathophysiology. Endocrinol

Metab Clin North Am. 50:275–228. 20215. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Vilaca T, Schini M, Harnan S, Sutton A,

Poku E, Allen IE, Cummings SR and Eastell R: The risk of hip and

non-vertebral fractures in type 1 and type 2 diabetes: A systematic

review and meta-analysis update. Bone. 137:1154572020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Asadipooya K and UY EM: Advanced glycation

end products (AGEs), receptor for AGEs, diabetes, and bone: Review

of the literature. J Endocr Soc. 3:1799–1818. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Yamagishi S: Role of advanced glycation

end products (AGEs) in osteoporosis in diabetes. Curr Drug Targets.

12:2096–2102. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lee HS and Hwang JS: Impact of type 2

diabetes mellitus and antidiabetic medications on bone metabolism.

Curr Diab Rep. 20:782020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Napoli N, Chandran M, Pierroz DD,

Abrahamsen B, Schwartz AV and Ferrari SL; IOF Bone and Diabetes

Working Group, : Mechanisms of diabetes mellitus-induced bone

fragility. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 13:208–219. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Jankovic J: Complications and limitations

of drug therapy for Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 55 (12 Suppl

6):S2–S6. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Pietschmann P, Patsch JM and Schernthaner

G: Diabetes and bone. Horm Metab Res. 42:763–768. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Holstege A: Long-term drug treatments to

improve prognosis of patients with liver cirrhosis and to prevent

complications due to portal hypertension. Z Gastroenterol.

57:983–996. 2019.(In German). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Huang KC, Chuang PY, Yang TY, Tsai YH, Li

YY and Chang SF: Diabetic rats induced using a high-fat diet and

low-dose streptozotocin treatment exhibit gut microbiota dysbiosis

and osteoporotic bone pathologies. Nutrients. 16:12202024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Boyar H, Turan B and Severcan F: FTIR

spectroscopic investigation of mineral structure of streptozotocin

induced diabetic rat femur and tibia. Spectroscopy. 17:627–633.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Lu R, Zheng Z, Yin Y and Jiang Z:

Genistein prevents bone loss in type 2 diabetic rats induced by

streptozotocin. Food Nutr Res. 64:10.29219/fnr.v64.3666. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Wu X, Gong H, Hu X, Shi P, Cen H and Li C:

Effect of verapamil on bone mass, microstructure and mechanical

properties in type 2 diabetes mellitus rats. BMC Musculoskelet

Disord. 23:3632022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ghodsi R and Kheirouri S: Carnosine and

advanced glycation end products: A systematic review. Amino Acids.

50:1177–1186. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Corona C, Frazzini V, Silvestri E,

Lattanzio R, La Sorda R, Piantelli M, Canzoniero LM, Ciavardelli D,

Rizzarelli E and Sensi SL: Effects of dietary supplementation of

carnosine on mitochondrial dysfunction, amyloid pathology, and

cognitive deficits in 3×Tg-AD mice. PLoS One. 6:e179712011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Jukić I, Kolobarić N, Stupin A, Matić A,

Kozina N, Mihaljević Z, Mihalj M, Šušnjara P, Stupin M, Ćurić ŽB,

et al: Carnosine, small but mighty-prospect of use as functional

ingredient for functional food formulation. Antioxidants (Basel).

10:10372021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ko EA, Park YJ, Yoon DS, Lee KM, Kim J,

Jung S, Lee JW and Park KH: Drug repositioning of polaprezinc for

bone fracture healing. Commun Biol. 5:4622022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Busa P, Lee SO, Huang N, Kuthati Y and

Wong CS: Carnosine alleviates knee osteoarthritis and promotes

synoviocyte protection via activating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling

pathway: An in-vivo and in-vitro study. Antioxidants (Basel).

11:12092022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Huang T, Yan G and Guan M: Zinc

homeostasis in bone: Zinc transporters and bone diseases. Int J Mol

Sci. 21:12362020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kheirouri S, Alizadeh M and Maleki V: Zinc

against advanced glycation end products. Clin Exp Pharmacol

Physiol. 45:491–498. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Marreiro DD, Cruz KJ, Morais JB, Beserra

JB, Severo JS and de Oliveira AR: Zinc and oxidative stress:

Current mechanisms. Antioxidants (Basel). 6:242017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Brzóska MM and Rogalska J: Protective

effect of zinc supplementation against cadmium-induced oxidative

stress and the RANK/RANKL/OPG system imbalance in the bone tissue

of rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 272:208–220. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Bartmański M, Pawłowski Ł, Knabe A, Mania

S, Banach-Kopeć A, Sakowicz-Burkiewicz M and Ronowska A: The effect

of marginal Zn(2+) excess released from titanium coating on

differentiation of human osteoblastic cells. ACS Appl Mater

Interfaces. 16:48412–48427. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Shiota J, Tagawa H, Izumi N, Higashikawa S

and Kasahara H: Effect of zinc supplementation on bone formation in

hemodialysis patients with normal or low turnover bone. Ren Fail.

37:57–60. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Saito M and Marumo K: Collagen cross-links

as a determinant of bone quality: A possible explanation for bone

fragility in aging, osteoporosis, and diabetes mellitus. Osteoporos

Int. 21:195–214. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Yudhani RD, Pakha DN, Wiyono N and Wasita

B: Molecular mechanisms of zinc in alleviating obesity: Recent

updates (Review). World Acad Sci J. 6:702024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Gao X, Al-Baadani MA, Wu M, Tong N, Shen

X, Ding X and Liu J: Study on the local anti-osteoporosis effect of

polaprezinc-loaded antioxidant electrospun membrane. Int J

Nanomedicine. 17:17–29. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

An Y, Zhang H, Wang C, Jiao F, Xu H, Wang

X, Luan W, Ma F, Ni L, Tang X, et al: Activation of

ROS/MAPKs/NF-κB/NLRP3 and inhibition of efferocytosis in

osteoclast-mediated diabetic osteoporosis. FASEB J.

33:12515–201927. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Li M, Sun Z, Zhang H and Liu Z: Recent

advances on polaprezinc for medical use (Review). Exp Ther Med.

22:14452021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Furman BL: Streptozotocin-induced diabetic

models in mice and rats. Curr Protoc Pharmacol. 70:5.47.1–5.20.

2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Furman BL: Streptozotocin-induced diabetic

models in mice and rats. Curr Protoc. 1:e782021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Islam MS and Loots DT: Experimental rodent

models of type 2 diabetes: A review. Methods Find Exp Clin

Pharmacol. 31:249–261. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Amri J, Alaee M, Babaei R, Salemi Z,

Meshkani R, Ghazavi A, Akbari A and Salehi M: Biochanin-A has

antidiabetic, antihyperlipidemic, antioxidant, and protective

effects on diabetic nephropathy via suppression of TGF-β1 and PAR-2

genes expression in kidney tissues of STZ-induced diabetic rats.

Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 69:2112–2121. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Muhammad HJ, Shimada T, Fujita A and Sai

Y: Sodium citrate buffer improves pazopanib solubility and

absorption in gastric acid-suppressed rat model. Drug Metab

Pharmacokinet. 55:1009952024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Krebs H: Citric acid cycle: A chemical

reaction for life. Nurs Mirror. 149:30–32. 1979.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Sun Q, Tian FM, Liu F, Fang JK, Hu YP,

Lian QQ, Zhou Z and Zhang L: Denosumab alleviates intervertebral

disc degeneration adjacent to lumbar fusion by inhibiting endplate

osteochondral remodeling and vertebral osteoporosis in

ovariectomized rats. Arthritis Res Ther. 23:1522021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Livák F and Petrie HT: Somatic generation

of antigen-receptor diversity: A reprise. Trends Immunol.

22:608–612. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Tsuji-Naito K: Aldehydic components of

cinnamon bark extract suppresses RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis

through NFATc1 downregulation. Bioorg Med Chem. 16:9176–9183. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Matsui S, Hiraishi C, Sato R, Kojima T,

Matoba K, Fujimoto K and Yoshida H: Association of metformin

administration with the serum levels of zinc and homocysteine in

patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study. Diabetol

Int. 16:394–402. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Goyal SN, Reddy NM, Patil KR, Nakhate KT,

Ojha S, Patil CR and Agrawal YO: Challenges and issues with

streptozotocin-induced diabetes-A clinically relevant animal model

to understand the diabetes pathogenesis and evaluate therapeutics.

Chem Biol Interact. 244:49–63. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

El Dib R, Gameiro OL, Ogata MS, Módolo NS,

Braz LG, Jorge EC, do Nascimento P Jr and Beletate V: Zinc

supplementation for the prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus in

adults with insulin resistance. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2015:CD0055252015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Sureshkumar K, Durairaj M, Srinivasan K,

Goh2 KW, Undela K, Mahalingam VT, Ardianto C, Ming LC and Ganesan

RM: Effect of L-carnosine in patients with age-related diseases: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed).

28:182023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Cararo JH, Streck EL, Schuck PF and

Ferreira Gda C: Carnosine and related peptides: Therapeutic

potential in age-related disorders. Aging Dis. 6:369–379. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Yamaguchi M and Ehara Y: Zinc decrease and

bone metabolism in the femoral-metaphyseal tissues of rats with

skeletal unloading. Calcif Tissue Int. 57:218–223. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Sugiyama T, Tanaka H and Kawai S:

Improvement of periarticular osteoporosis in postmenopausal women

with rheumatoid arthritis by beta-alanyl-L-histidinato zinc: A

pilot study. J Bone Miner Metab. 18:335–338. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Kato H, Ochiai-Shino H, Onoder S, Saito A,

Shibahara T and Azuma T: Promoting effect of 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D3

in osteogenic differentiation from induced pluripotent stem cells

to osteocyte-like cells. Open Biol. 5:1402012015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Seo HJ, Cho YE, Kim T, Shin H and Kwun IS:

Zinc may increase bone formation through stimulating cell

proliferation, alkaline phosphatase activity and collagen synthesis

in osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells. Nutr Res Pract. 4:356–361. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Yamaguchi M, Goto M, Uchiyama S and

Nakagawa T: Effect of zinc on gene expression in osteoblastic

MC3T3-E1 cells: Enhancement of Runx2, OPG, and regucalcin mRNA

expressions. Mol Cell Biochem. 312:157–166. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Yang Y, Wang Y, Kong Y, Zhang X, Zhang H,

Gang Y and Bai L: Carnosine prevents type 2 diabetes-induced

osteoarthritis through the ROS/NF-κB pathway. Front Pharmacol.

9:5982018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Yamaguchi M and Uchiyama S: Receptor

activator of NF-kappaB ligand-stimulated osteoclastogenesis in

mouse marrow culture is suppressed by zinc in vitro. Int J Mol Med.

14:81–85. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Thomas S and Jaganathan BG: Signaling

network regulating osteogenesis in mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell

Commun Signal. 16:47–61. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Amarasekara DS, Kim S and Rho J:

Regulation of osteoblast differentiation by cytokine networks. Int

J Mol Sci. 22:28512021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Lin W, Hu S, Li K, Shi Y, Pan C, Xu Z, Li

D, Wang H, Li B and Chen H: Breaking osteoclast-acid vicious cycle

to rescue osteoporosis via an acid responsive organic

framework-based neutralizing and gene editing platform. Small.

20:e23075952024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Amin N, Clark CCT, Taghizadeh M and

Djafarnejad S: Zinc supplements and bone health: The role of the

RANKL-RANK axis as a therapeutic target. J Trace Elem Med Biol.

57:1264172020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Molenda M and Kolmas J: The role of zinc

in bone tissue health and regeneration-a review. Biol Trace Elem

Res. 201:5640–5651. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Ono T, Hayashi M, Sasaki F and Nakashima

T: RANKL biology: Bone metabolism, the immune system, and beyond.

Inflamm Regen. 40:22020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Boyce BF and Xing L: Functions of

RANKL/RANK/OPG in bone modeling and remodeling. Arch Biochem

Biophys. 473:139–146. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|