Introduction

Esophageal cancer (EC) is the seventh most common

cancer globally, with ~470,000 new cases diagnosed annually; In

addition, EC ranks among the top in terms of incidence among upper

gastrointestinal tumors (1). It

has been reported that ~90% of EC cases are squamous cell

carcinoma, with most of the remaining cases being adenocarcinoma

(2). Owing to the absence of

early-stage clinical manifestations, EC is frequently diagnosed in

the advanced stages. Despite notable advancements in cancer

diagnostics and treatment, with a 5-year survival rate of <30%,

the clinical prognosis of EC remains poor (3). Therefore, the discovery of effective

targets for the treatment and early diagnosis of EC is of great

importance.

Zinc finger proteins (ZNFs), encoded by ~5% of the

human genome, form the largest family of transcription factors in

humans. Characterized by their finger-like DNA-binding motifs, ZNFs

exert important biological functions across multiple cellular

processes (4). Zinc finger motifs

are currently categorized into eight major types: C2H2, TAZ2

domain-like, zinc ribbon, treble clef, Zn2/Cys6 (5), zinc-binding loop, Gag knuckle and

metallothionein (6). A notable

body of literature has documented the biological processes

associated with ZNFs in various types of cancer. For example,

ZNF322A promotes cell proliferation, motility and invasive ability

in lung cancer through transcriptional activation of cyclin D1 and

α-adducin, coupled with inhibition of p53. Furthermore,

multivariate Cox regression analysis has revealed that ZNF322A has

a notable impact on the prognosis of lung cancer (7). Moreover, activating the PI3K/AKT

pathway induces the ZNF139-mediated promotion of bladder cancer

cell proliferation, motility and invasion (8). ZNF148 promotes breast cancer

progression by activating microRNA-335 and superoxide dismutase 2

to enhance the production of reactive oxygen species, which further

triggers pyroptotic cell death (9). To the best of our knowledge, no

studies have yet reported on the prognostic relevance of ZNF514 in

pan-cancer and EC analyses. Therefore, the impact of ZNF514 on the

development of EC warrants further investigation.

The impact of ZNF514 on the proliferation, motility

and invasiveness of EC cells was evaluated through knockdown and

overexpression experiments using Kyse-150 and Kyse-510 cells. By

using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis, followed by Gene Ontology

(GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses,

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) and Ingenuity Pathway Analysis

(IPA), the potential mechanisms underlying the functions of ZNF514

were further explored in the present study. The present study aimed

to explore the pro-tumorigenic role of ZNF514 upregulation in EC,

aiming to identify new therapeutic targets for EC and provide novel

strategies for the diagnosis and subsequent treatment of EC.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatics analysis

The Tumor Immune Estimation Resource (TIMER;

http://cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer/)

database was used to detect ZNF514 upregulation across multiple

malignancies. Data from patients with EC were obtained from TCGA

(https://gdc-portal.nci.nih.gov),

including RNA-seq data from 197 samples (184 EC tissues and 13

normal esophageal tissues). From these, 13 normal tissue samples

and their paired 13 cancer tissue samples were selected, and

Wilcoxon signed-ranks analysis were used to evaluate the

differential expression between the two groups, and data

visualization was performed using the ‘ggplot2’ (v3.5.1;

ggplot2.tidyverse.org) package in R (v4.2.2) (https://cran.r-project.org/src/base/R-4/R-4.2.2.tar.gz).

The frequency of ZNF514 gene alterations was analyzed using the

cBioPortal database (www.cbioportal.org). Data and samples were retrieved

from the esophageal carcinoma section of two TCGA-derived

databases: Firehose legacy) (gdac.broadinstitute.org/) and TCGA

(Nature 2017) (10).

Patients and specimens

Between November 2024 and January 1, 2025, six pairs

of EC samples and their corresponding adjacent non-cancerous

tissues were collected at Jinan Central Hospital (Jinan, China).

The inclusion criteria in the present study were as follows: i)

Pathological biopsy confirms esophageal cancer); ii) patients had

complete pathological data; iii) patients provided written informed

consent; and iv) patients did not receive any radiotherapy,

immunotherapy or chemotherapy before surgery. The six pairs of

cancerous samples and their corresponding adjacent non-cancerous

tissues were immediately frozen to preserve freshness for

subsequent western blot analysis. The protocol for the present

study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Jinan Central

Hospital (Jinan, China), under ethical approval number 20241120027.

All procedures were conducted following applicable guidelines and

regulations.

Cell lines and cell culture

The Het-1a, Kyse-30, Kyse-450, Kyse-150 and Kyse-510

cells were supplied by Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to

Shandong First Medical University (Jinan, China). Het-1a cells were

cultured in DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) containing

10% FBS (Hysigen). 10% FBS was added to RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for the remaining cell culture. All

cell cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator

with 5% CO2.

Transfection

Kyse-150 (interference) and transfected

overexpression plasmids into the Kyse-510 (overexpression) cell

line, which were pre-cultured in 6-well plates with suitable growth

medium. ZNF514 small interfering (si)RNA (Beijing Tsingke Biotech

Co., Ltd.) or overexpression plasmids (Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd.)

were transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and p3000 (Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd.).

siRNA was transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 alone, while

plasmids were transfected using both Lipofectamine 3000 and p3000.

A total of 2.5 µg siRNA was mixed with 5 µl Lipofectamine 3000 to

form a Lipofectamine-siRNA complex. Alternatively, 2.5 µg of

plasmid was mixed with 5 µl of Lipofectamine 3000 and 5 µl P3000 to

prepare a Lipofectamine-P3000-ZNF514 plasmid complex. After

incubating the complexes at room temperature for 15 min, they were

added to the cells. Following transfection at 37°C for 8 h, the

medium was replaced. The cells were then further incubated at 37°C

for 24–48 h before RNA or protein extraction was performed. siRNA

sequences targeting ZNF514 were as follows: si-ZNF514-1: Forward

5′-CCCUUAGCAGAGAUUAUAA-3′ and Reverse 5′-UUAUAAUCUCUGCUAAGGG-3′;

si-ZNF514-2: Forward 5′-GGUCACACUUCAUCCCUUA-3′ and Reverse

5′-UAAGGGAUGAAGUGUGACC-3′ and si-ZNF514-3: Forward

5′-GGGCCUUCUAGUAUCCAAA-3′ and Reverse 5′-UUUGGAUACUAGAAGGCCC-3′.

The negative control sequences were: Forward

5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′ and reverse

5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3′. The negative control for siRNA

transfection is non-targeting siRNA. In the overexpression

experiment, both the ZNF514 overexpression plasmid and the control

plasmid (empty pcDNA3.1 plasmid) used pcDNA3.1 as the vector

backbone.

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from Het-1a, Kyse-30,

Kyse-450, Kyse-150 and Kyse-510 cells using TRIzol®

reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). RT of 1 µg

mRNA into cDNA was performed using the Evo M-MLVRT Mix Kit Ver.2

(Hunan Accurate Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Gene expression was quantified with

SYBR Green PCR (Hunan Accurate Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) using 10 ng

cDNA as the template. Thermocycling conditions were as follows:

Initial pre-denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, followed by 40 cycles

of a denaturation step at 95°C for 30 sec, an annealing step at

55°C for 30 sec, and extension step at 72°C for 30 sec. The primers

used were as follows: ZNF514, forward 5′-ACAAATCTGCCACCACCCTTA-3′,

reverse 5′-TGTTTCCCCCTAAAGTCTGCC-3′; and GAPDH, forward

5′-GCACCGTCAAGGCTGAGAAC-3′ and reverse 5′-TGGTGAAGACGCCAGTGGA-3′

(Azenta US, Inc.). Expression levels were normalized to GAPDH and

analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCq method (11).

Western blotting

Het-1a, Kyse-30, Kyse-450, Kyse-150 and Kyse-510

cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) containing protease/phosphatase inhibitors.

Protein concentration was determined using a BCA kit (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) to ensure equal loading and the protein

samples were mixed with sample buffer and heated at 98°C for 5 min.

25 µg quantified protein lysate per lane was separated by 10%

SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis and transferred to PVDF membranes. The

membranes were blocked in 0.1% TBST containing 5% non-fat milk for

1 h at room temperature, then incubated overnight at 4°C with

primary antibodies diluted in 0.1% TBST buffer. The primary

antibodies used included rabbit polyclonal anti-ZNF514 antibody

(1:2,000; cat. no. YT6669; ImmunoWay Biotechnology Company) and

rabbit polyclonal anti-GAPDH antibody (1:10,000; cat. no. bs-2188R;

Beijing Biosynthesis Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Subsequently, the

membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit

secondary antibody (1:10,000; cat. no. bs-0295G-HRP Beijing

Biosynthesis Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) at room temperature for 1 h

and detected using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents

(MilliporeSigma). Immunoreactive bands were visualized using a

Tanon 5200 imaging system (Molecular Devices, LLC) and analyzed

with ImageJ software (version 1.8.0; National Institutes of

Health).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Esophageal cancer tissue samples collected were

fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 24 h, then

embedded in paraffin and cut into 3-µm-thick paraffin sections. The

sections were deparaffinized with xylene, followed by rehydration

in a graded ethanol series. Subsequently, the sections were

immersed in 1× citrate buffer (pH 6.0), heated to boiling using a

pressure cooker, and then cooled to room temperature. Next, the

sections were washed 3 times with PBS, 5 min each time. They were

then placed in 3% hydrogen peroxide solution and incubated at room

temperature for 25 min in the dark, followed by 3 washes with PBS

(5 min per wash). 3% BSA (cat. no. GC305010; Servicebio) was added

dropwise to cover the tissue evenly, and the sections were blocked

at room temperature for 30 minutes. The sections were incubated

overnight at 4°C with rabbit polyclonal anti-ZNF514 antibody

(1:200; cat. no. YT6669; ImmunoWay Biotechnology Company). After

that, HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:200;

cat. no. GB23303; Servicebio) was added at room temperature for 50

min. Thereafter, the slides were stained with DAB (cat. no. G1212;

Servicebio) and counterstained with hematoxylin at room temperature

for 3 min. The sections were dehydrated, cleared, and mounted with

neutral mounting medium. Finally, observations were made under a

light microscope.

EdU assay

Kyse-150 and Kyse-510 cells were plated into 96-well

plates at a density of 2×104 cells/well and incubated

for 24 h. Cell proliferation was evaluated using the EdU assay kit

(cat. no. C0071S; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) according to

the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were treated with

10 µM EdU at 37°C for 3 h, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room

temperature for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 at

room temperature for 10 min, and sequentially stained with Azide

488 for 30 min and Hoechst 33342 for 10 min at room temperature.

Fluorescence imaging was performed using a fluorescence microscope

(Olympus Corporation) to visualize EdU-positive (proliferating)

cells and total nuclei.

Cell Counting Kit (CCK)-8 cell

proliferation assay

Kyse-150 and Kyse-510 cells in the exponential

growth phase were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 2,000

cells per well. At 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after cell adhesion, 10 µl

of CCK-8 reagent (cat. no. BA00208; Beijing Biosynthesis

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was added to each well, respectively.

After incubation at 37°C for 2 h, the optical density (OD) values

were measured at a wavelength of 450 nm using a microplate reader

(Model Spectra Max i3×; Molecular Devices).

Wound healing assay

Kyse-150 and Kyse-510 cells were seeded into 6-well

plates and cultured in medium containing 10% FBS until reaching 95%

confluence. Uniform scratches were created using sterile pipette

tips, after which the cells were incubated in serum-free medium at

37°C. Images were captured via phase-contrast microscope at 0 and

24 h to monitor scratch healing. Quantitative analysis of scratch

healing was performed using ImageJ software [(version 1.8.0); NIH,

USA], and the cell migration rate (%) was calculated using the

formula: [(initial scratch width-final scratch width)/initial

scratch width] ×100. Finally, observations were made under a light

microscope.

Colony formation assay

Kyse-150 and Kyse-510 cells were plated in 6-well

plates at a density of 2×103 cells/well. The culture

medium was replaced every 3 days; after 14 days of incubation, the

colonies were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room

temperature, stained with hematoxylin (Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.) for 20 min at room temperature, scanned

and counted manually. Clones were defined as colony composed of

>50 cells.

Transwell assays

Transwell assays were performed in 24-well plates.

For the migration assay, 2×104 Kyse-150 or Kyse-510

cells were resuspended in serum-free medium and seeded into

uncoated Transwell chambers (pore size, 8 µm; Corning, Inc.), with

the lower chamber containing medium supplemented with 10% FBS. In

the invasion assay, Transwell chambers were pre-coated with

Matrigel and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Subsequently,

2×104 cells were seeded into the upper chamber, while

the lower chamber was filled with medium supplemented with 10% FBS.

After incubation at 37°C for 24–48 h, non-migrated/non-invaded

cells on the upper surface of the membrane were removed. Cells that

had invaded to the lower surface were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.1% crystal violet at room

temperature for 15 min. Finally, observations were made under a

light microscope.

RNA-seq

Total RNA was extracted from Kyse-150 cells using

the MJzol Animal RNA Extraction kit (cat. no.T102096; MagBeads) in

accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. RNA integrity was

assessed by determining the RNA Integrity Number using an Agilent

4200 TapeStation (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Qualified total RNA was purified using the RNAClean XP Kit (cat.

no. A63987, Beckman Coulter, Inc.) and the RNase-Free DNase Set

(cat. no. 79254, QIAGEN, GmbH). Subsequently, the purified total

RNA underwent mRNA isolation, fragmentation, first-strand cDNA

synthesis, second-strand cDNA synthesis, end repair, 3′-end

adenylation, adapter ligation, and enrichment steps, following the

protocol provided with the Dual-mode mRNA Library Prep Kit (cat.

no. 12310ES96, YEASen). The resulting products were purified using

HieffNGS DNA Selection Beads (cat. no. 12601ES56, YEASen). Library

concentration was quantified using the ExKubit dsDNA HS Assay kit

(cat. no. NGS00-3012, Excell) and a Qubit® 2.0

Fluorometer, while library size was determined using an Agilent

4200 TapeStation (Agilent Technologies) and diluted to 2 nM loading

concentration. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000

platform using a paired-end 150 bp mode.

Data analysis for gene expression

Raw sequencing reads underwent preprocessing to

remove ribosomal RNA reads, sequencing adapters, short-fragment

sequences and other low-quality reads. The cleaned reads were then

mapped to the human hg38 reference genome using HISAT2 (version

2.0.4; http://daehwankimlab.github.io/hisat2/), allowing for

up to two mismatches. Following genome alignment, StringTie

(version 1.3.0; http://ccb.jhu.edu/software/stringtie/) was employed

with reference annotation to calculate fragment per kilobase of

transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) values for known gene

models. Differential gene analysis between samples was performed

using edgeR (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/edgeR.html)

(12). After obtaining P-values,

multiple hypothesis testing correction was conducted. The threshold

for P-values was determined by controlling the False Discovery Rate

(FDR) (13), and the corrected

P-values were referred to as q-values, with fold-changes estimated

based on FPKM values across samples. Significant DEGs were

identified as those with a FDR value above the threshold

(Q<0.05) (When the total number of DEGs in all comparisons is

less than 50, the threshold will be automatically adjusted to a

P-value ≤0.05) and fold-change >2 (or

|log2(fold-change)|>1). DEGs with a

|log2(Fold-change)|>2 and P<0.05 were uploaded to

the STRING database (string-db.org/) to construct protein-protein

interaction (PPI) networks. A high-confidence threshold, indicated

by an interaction score of >0.9, was applied to filter

significant protein interactions and generate the PPI network. To

identify the enriched biological processes, molecular functions,

and cellular components, Gene Ontology analysis (GO; http://www.geneontology.org/) was conducted. Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes analysis (KEGG; clusterProfiler

3.10.1; https://biocon

ductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/clusterProfiler.html) was

applied to detect cellular biochemical processes closely associated

with the DEGs. To identify signaling pathways significantly

associated with ZNF514 expression levels, we performed Gene Set

Enrichment Analysis (GSEA; http://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp).

IPA

Canonical pathway analysis and upstream regulator

analysis for various DEGs were performed using IPA. (QIAGEN Inc.;

http://digitalinsights.qiagen.com/IPA). In enrichment

analysis, we use the z-score to quantify the degree of deviation in

the overall activation/inhibition trend of a pathway. The

formula:

where X represents the raw data, µ denotes the mean,

and σ is standard deviation. The direction of the z-score indicates

the activation or inhibition trend of the pathway, while the

absolute value of the z-score reflects the significance level.

Additionally, we use -log(P-value) to enhance the visual

distinguishability of ‘significant differences’. Specifically, a

larger -log(P-value) corresponds to a smaller P-value, which in

turn means the statistics are more reliable.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation

of at least three independent experiments. A paired-samples t-test

was used to compare differences between two paired groups, while an

unpaired t-test was applied to analyze differences between two

independent samples. For comparisons involving more than two

groups, a one-way analysis of variance was employed, followed by

Dunnett's post-hoc test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference. All analyses were performed

using Prism v8.0 software (Dotmatics). To quantify the linear

association between two continuous variables, the Pearson

correlation coefficient was calculated following standard

statistical protocols. For two variables X and Y with

a total sample size of n, the Pearson correlation

coefficient was computed using the formula:

Results

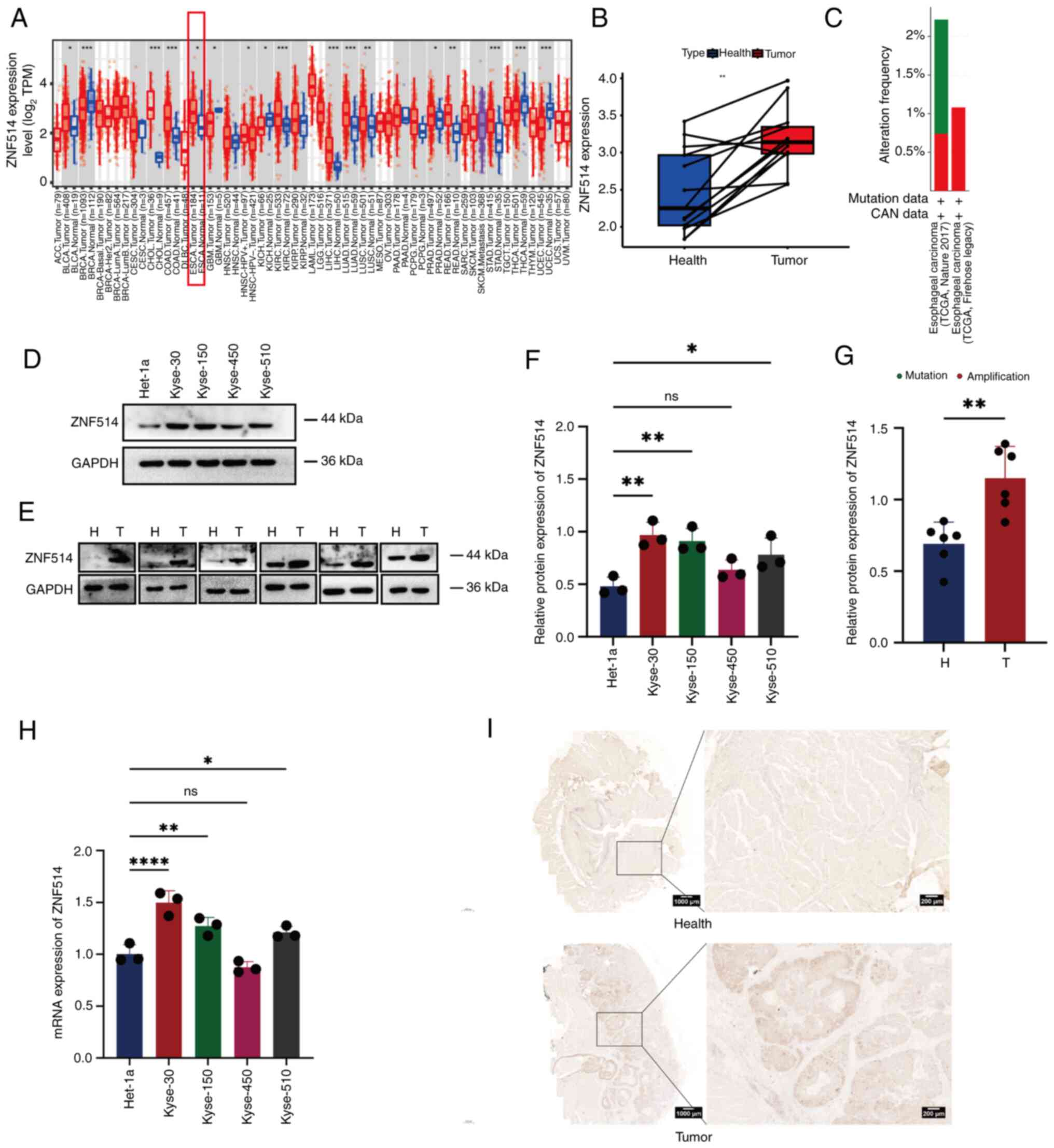

ZNF514 is upregulated in EC

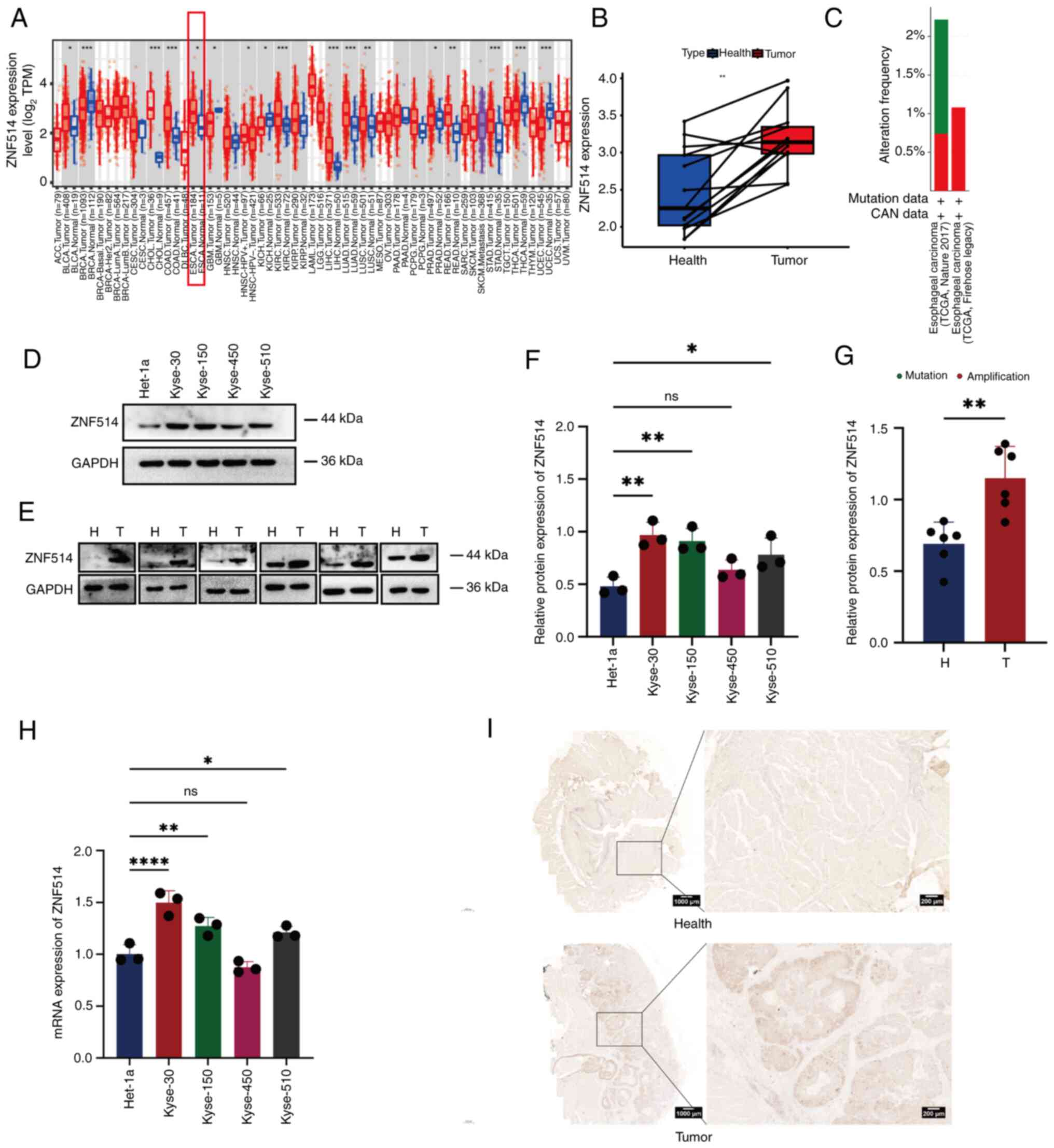

The TIMER database was used to investigate ZNF514

expression across different tumor types (Fig. 1A) and it was revealed that ZNF514

was commonly upregulated in various types of cancer, including EC,

bladder urothelial carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma and colon

adenocarcinoma. Additionally, a quantitative comparison of ZNF514

expression using Log2(TPM+1) normalization across EC

samples and matched healthy tissue revealed that ZNF514 was

upregulated in most EC samples vs. healthy tissues (Fig. 1B). Additionally, the cBioPortal

database was utilized to analyze the alteration types and

frequencies of ZNF514 in EC from two different data sources from

TCGA database (Nature 2017/Firehose Legacy). The analysis revealed

that, among the 541 patients in the Nature 2017 data source, 8

patients had mutations (1.48%), 4 patients had amplifications

(0.74%) and the gene alteration frequency was 2.22% (Fig. 1C). Among 185 patients in the

Firehose legacy dataset, 0 patients had mutations (0%), while two

patients had amplifications (1.08%), and the gene alteration

frequency was 1.08% (Fig. 1C).

Subsequently, RT-qPCR and western blotting were employed to examine

the mRNA and protein expression levels of ZNF514 in Het-1a and

multiple EC cell lines (Kyse-30, Kyse-150, Kyse-450 and Kyse-510).

The results demonstrated that, with the exception of Kyse-450, both

the protein (Fig. 1D and F) and

mRNA expression levels (Fig. 1H)

of ZNF514 were significantly elevated in these EC cell lines

compared with those in the Het-1a cell line. To further assess the

expression of ZNF514 in tissues, surgically resected EC tissues and

adjacent healthy tissues were collected and analyzed through

western blotting (Fig. 1E and G)

and IHC (Fig. 1I). The results

showed that ZNF514 expression levels were higher in EC tissues than

those in adjacent healthy tissues. These findings suggested that

ZNF514 was upregulated in EC tissues and cells, indicating a close

relationship between ZNF514 and the development and progression of

EC.

| Figure 1.ZNF514 is significantly upregulated

in EC tissues and cells. (A) Analysis of RNA expression differences

of ZNF514 in normal and cancer tissues across various types of

cancer using the Tumor Immune Estimation Resource database. (B) RNA

expression differences between H and paired cancer tissues in

patients with EC. (C) Gene alteration frequency of ZNF514 in EC.

(D) Western blot analysis of ZNF514 protein expression differences

in Het-1a and EC cell lines. (E) Western blot analysis of ZNF514

protein expression differences in the tumors and adjacent tissues

of patients with EC. Semi-quantitative analyses of ZNF514 protein

expression in (F) Het-1a and EC cell lines, and (G) tumor and

adjacent tissues of patients with EC normalized to GAPDH. (H)

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR analysis of ZNF514

expression levels in Het-1a and EC cell lines. (I) Representative

images of immunohistochemical staining for ZNF514 in the tumors and

adjacent tissues of patients with EC. Scale bar, 1000 µm.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001. H,

Healthy; T, tumor; ZNF514, zinc finger protein 514; EC, esophageal

cancer; ns, not significant; CNA, copy number alteration; TCGA, The

Cancer Genome Atlas. |

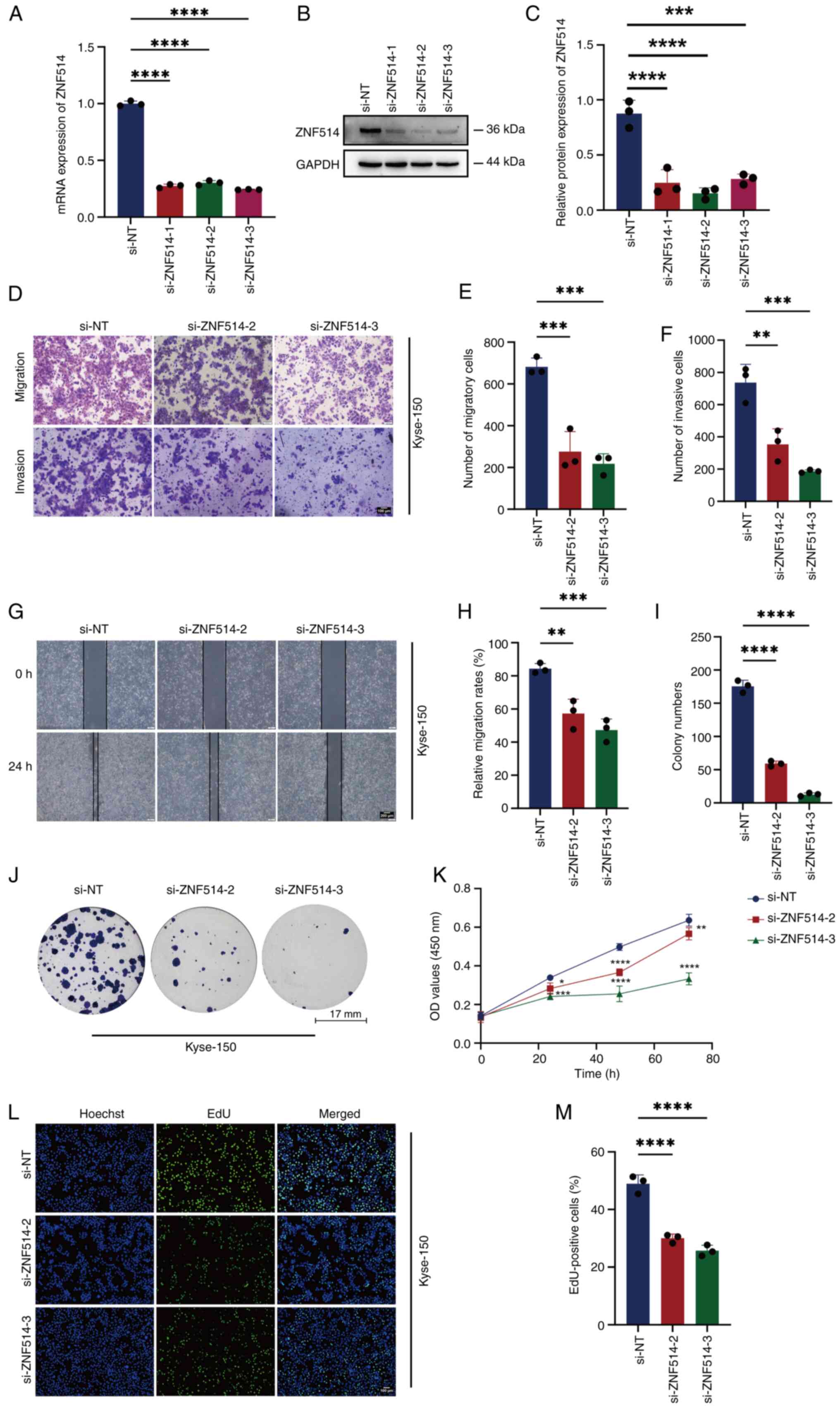

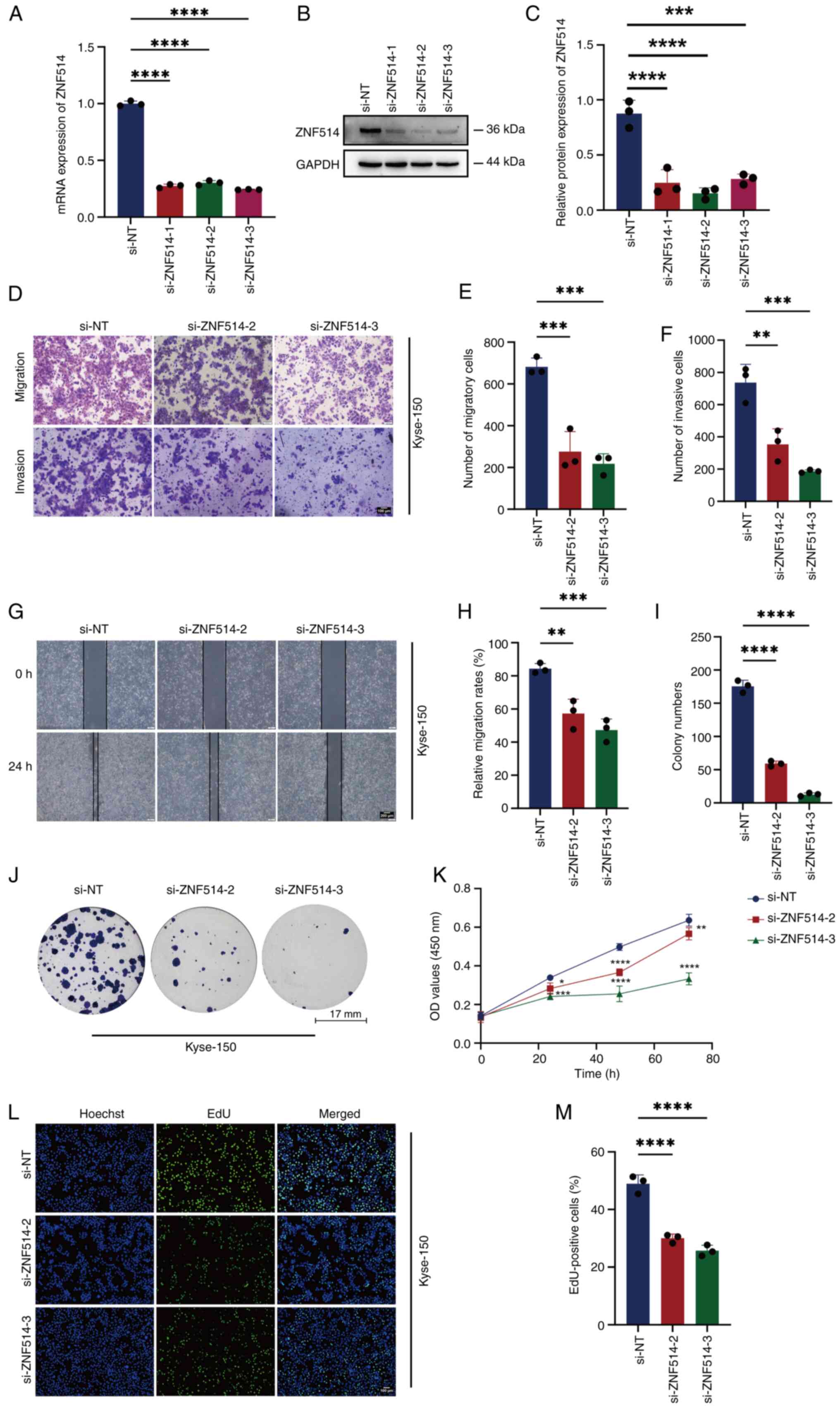

Silencing ZNF514 leads to suppression

of EC cell migration, invasion and proliferation

To investigate the functional role of ZNF514 in EC

progression, phenotypic assays were performed following ZNF514

knockdown in Kyse-150 cells. First, the transfection efficiency of

three ZNF514-specific siRNAs (siZNF514-1, siZNF514-2 and

siZNF514-3) was validated using RT-qPCR (Fig. 2A) and western blotting (Fig. 2B and C). Based on these results,

siZNF514-2 and siZNF514-3 were selected for subsequent functional

analyses. Transwell migration and invasion assays (Fig. 2D-F), wound healing assay (Fig. 2G and H), colony formation assay

(Fig. 2I and J), CCK-8

proliferation assay (Fig. 2K) and

EdU assay (Fig. 2L and M)

collectively showed that compared with the si-NT group, ZNF514

knockdown significantly inhibited migration, invasion and

proliferation in EC cells. These findings indicated that silencing

ZNF514 exerted a tumor-suppressive effect by restricting the

migratory, invasive and proliferative capacities of EC cells.

| Figure 2.Downregulation of ZNF514 inhibits

proliferation, migration and invasion of Kyse-150 cells. ZNF514

mRNA and protein expression levels in Kyse-150 cells transfected

with targeted siRNAs were analyzed using (A) reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR and (B) western blot analysis,

alongside (C) semi-quantitative analysis of ZNF514 protein levels.

(D) Effects of ZNF514 knockdown on the migration and invasion of

Kyse-150 cells was assessed using Transwell assays; (E)

quantitative analysis of the migration assay, (F) quantitative

analysis of the invasion assay. Scale bar, 100 µm. (G) Wound

healing assays were conducted to evaluate the effect of ZNF514

knockdown on the migration of Kyse-150 cells; (H) quantitative

analysis of cell migration rate. Scale bar, 200 µm. (I)

Quantitative analysis of colony formation, (J) colony formation,

(K) Cell Counting Kit −8, (L) EdU assays, and (M) quantitative

analysis of the EdU assay were utilized to evaluate the effects of

ZNF514 knockdown on the proliferation of Kyse-150 cells. Scale bar,

100 µm. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001

vs. si-NT. NT, non-targeting; ZNF514, zinc finger protein 514;

CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; si, small interfering; EdU,

5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine. |

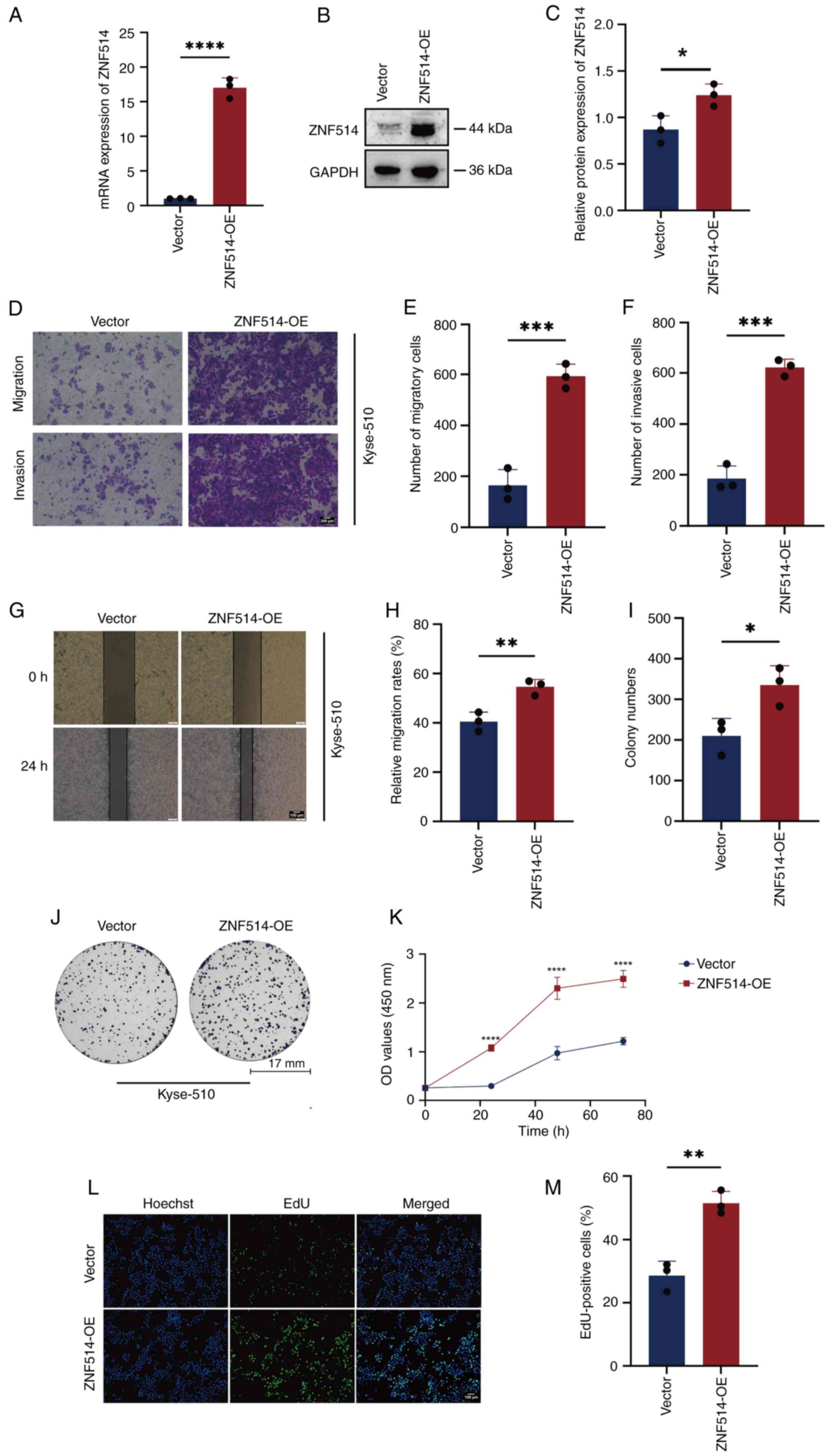

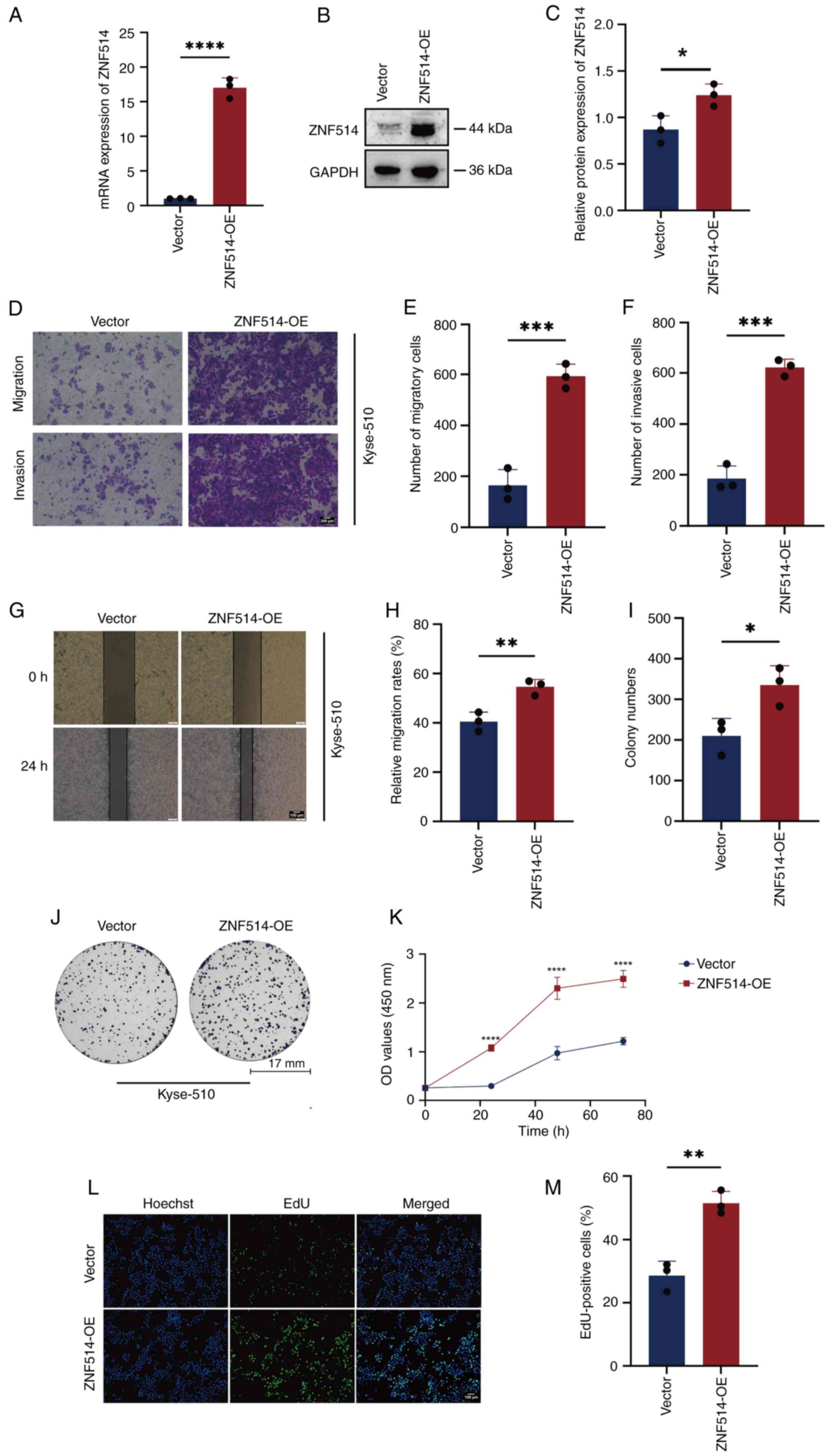

Overexpression of ZNF514 increases

migration, invasion and proliferation of EC cells

To explore the oncogenic role of ZNF514 in EC,

phenotypic analyses were conducted following ZNF514 overexpression

in Kyse-510 cells. First, the transfection efficiency of the ZNF514

overexpression plasmid was validated using RT-qPCR (Fig. 3A) and western blotting (Fig. 3B and C). Cells with stable

overexpression then underwent functional assays. Transwell

migration and invasion assays (Fig.

3D-F), wound healing assay (Fig.

3G and H), colony formation assay (Fig. 3I and J), CCK-8 proliferation assay

(Fig. 3K) and EdU assay (Fig. 3L and M) revealed that

ZNF514-overexpressing EC cells exhibited significantly enhanced

migration, invasion and proliferative capacity compared with

control EC cells transfected with empty vector plasmids. These

results indicated that ZNF514 may act as an oncogene to facilitate

EC progression by enhancing tumor cell motility and proliferative

potential.

| Figure 3.OE of ZNF514 promotes proliferation,

migration and invasion of Kyse-510 cells. Analysis of ZNF514 mRNA

and protein expression in Kyse-510 cells transfected with targeted

OE plasmid using (A) reverse transcription-quantitative PCR and (B)

western blot analysis, along with (C) semi-quantification of ZNF514

protein. (D) Transwell assays were performed to evaluate the

effects of ZNF514 OE on the migration and invasion of Kyse-510

cells; (E) quantitative analysis of the migration assay, (F)

quantitative analysis of the invasion assay. Scale bar, 200 µm. (G)

Wound healing assays were conducted to assess the impact of ZNF514

OE on the migration of Kyse-510 cells. (H) quantitative analysis of

cell migration rate. Scale bar, 100 µm. (I) Quantitative analysis

of colony formation, (J) Colony formation, (K) Cell Counting Kit-8,

(L) EdU assays, and (M) quantitative analysis of the EdU assay were

utilized to evaluate the effects of ZNF514 OE on the proliferation

of Kyse-510 cells. Scale bar, 100 µm. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 vs. vector. ZNF514, zinc finger

protein 514; OE, overexpression; EdU,

5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine. |

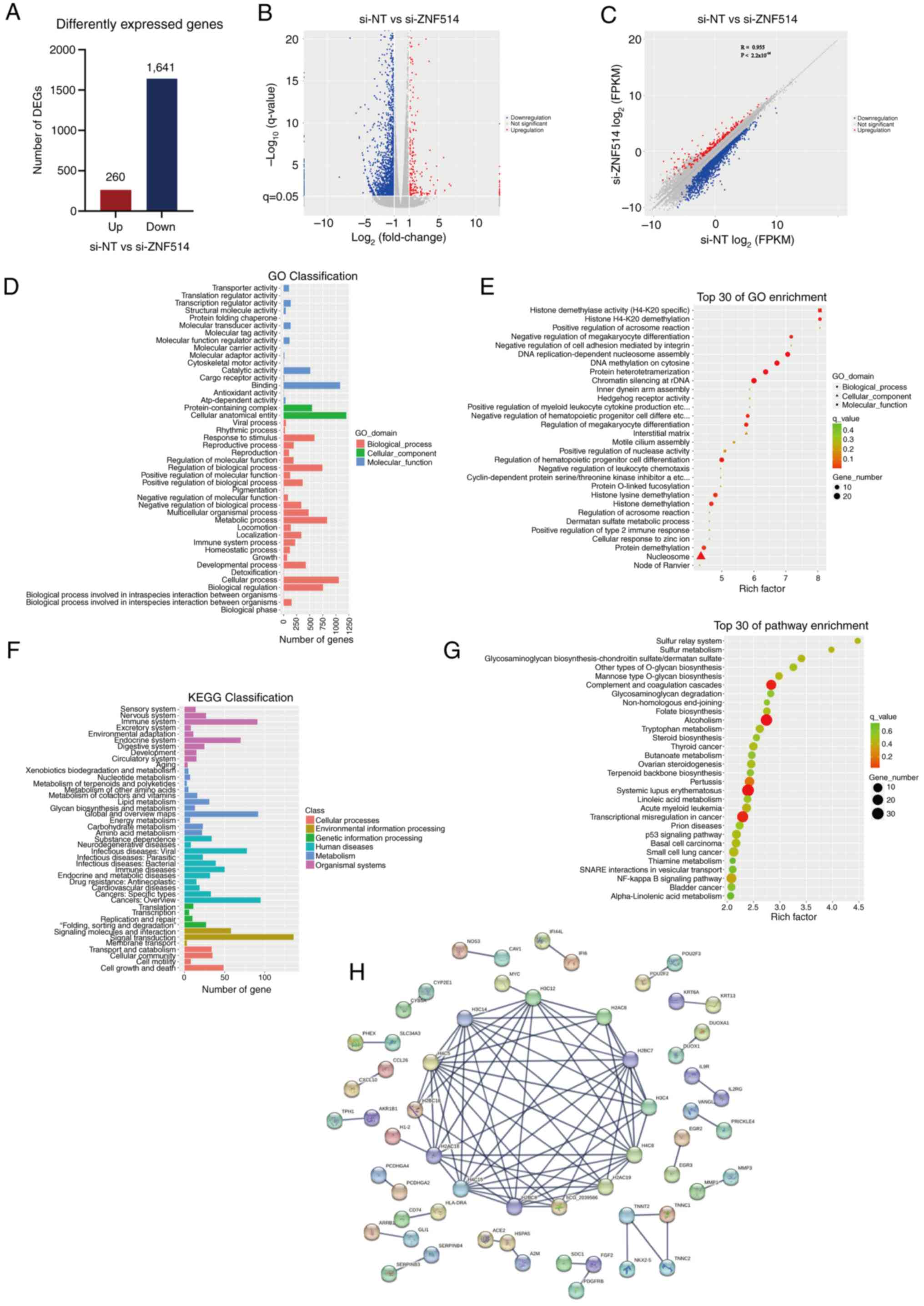

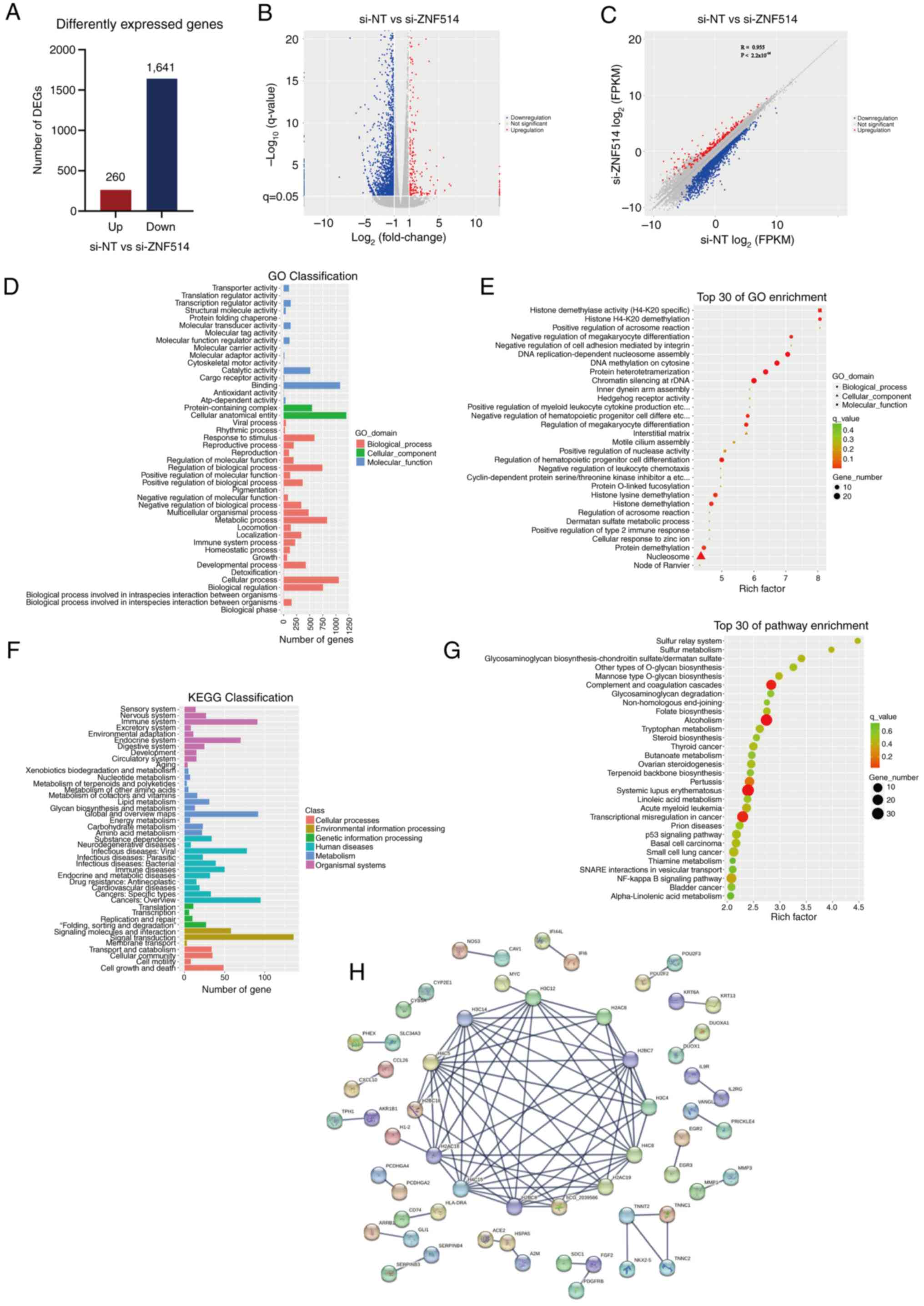

RNA-seq analysis following ZNF514

knockdown in Kyse-150 cells

Building on the previous findings, RNA-seq was

performed on ZNF514-knockdown Kyse-150 150 EC s to explore the

molecular mechanisms underlying ZNF514-mediated promotion of EC

tumorigenesis and progression. Genes displaying significant

expression level changes across various experimental conditions

were termed DEGs. Significant DEGs were identified using the

‘edgeR’ software, with selection criteria including a q<0.05,

fold-change >2 or |log2(fold-change)|>1). This

filtering process resulted in the identification of 1,901 DEGs,

which included 260 upregulated genes and 1,641 downregulated genes

(Fig. 4A and B). Subsequently,

Pearson correlation analysis was performed on the identified DEGs.

The Pearson correlation coefficient was 0.955, indicating an

extremely strong positive correlation between the gene expression

profiles of the si-NT group and the si-ZNF514 group. In terms of

DEGs, red dots represent up-regulated genes, blue dots represent

down-regulated genes, and gray dots represent genes with no

significant differential expression. P<2.2×10−16

(Fig. 4C). To further clarify the

functional enrichment of DEGs, GO enrichment analysis categorized

the DEGs into three primary categories: Biological processes,

cellular components and molecular functions (Fig. 4D). The analysis indicated that

these DEGs were significantly associated with molecular functions,

including ‘histone demethylase activity (H4-K20 specific)’ and

‘hedgehog receptor activity’. (Fig.

4E) Additionally, they were associated with biological

processes such as ‘histone H4-K20 demethylation’ and ‘positive

regulation of acrosome reaction’.

| Figure 4.RNA sequencing analysis of esophageal

cancer cells reveals the mechanisms by which downregulation of

ZNF514 contributes to cancer progression. (A) Bar graph displaying

the number of genes affected by ZNF514 knockdown, selected based on

the criteria of |log2(Fold-change)|>1 and q-value

<0.05. (B) Volcano plot illustrating the expression of DEGs,

with red indicating upregulated genes and blue signifying

downregulated genes. (C) Scatter plot showing the correlation of

DEGs, with red indicating upregulated genes and blue signifying

downregulated genes. (D) GO functional classification of DEGs, (E)

GO enrichment analysis of DEGs, (F) KEGG pathway classification of

DEGs, and (G) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs. (H)

Protein-protein interaction analysis was conducted based on the

DEGs. DEG, differentially expressed gene; ZNF514, zinc finger

protein 514; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes

and Genomes; si-NT, siRNA-non-targeting. |

KEGG pathway analysis was performed to identify key

signaling pathways associated with the DEGs, aiming to clarify the

mechanisms through which these genes impact cancer initiation and

progression. The findings indicated that DEGs exhibited enrichment

in pathways categorized into: Cellular Processes, including

‘Cellular community’, ‘Cell growth and death’ and ‘Transport and

catabolism’; Environmental Information Processing, including

‘Signaling molecules and interaction’, ‘Membrane transport’ and

‘Signal transduction’; Genetic Information Processing including

‘Transcription’, ‘Replication and repair’, ‘folding, sorting and

degradation’ and ‘Translation’; Human Diseases, including

‘Infectious diseases: Viral’, ‘Cancers: Specific types’ and ‘Immune

diseases’; Metabolism, including ‘Energy metabolism’ and

‘Nucleotide metabolism’; and Organismal Systems, including ‘Immune

system’ and ‘Digestive system’ (Fig.

4F). The bubble plot illustrated that DEGs were significantly

enriched in pathways related to ‘Complement and coagulation

cascades’, ‘Alcoholism’, ‘Pertussis’, ‘Systemic lupus

erythematosus’ and ‘Transcriptional misregulation in cancer’

(Fig. 4G). The STRING database was

used for PPI analysis and to build a PPI network of DEGs. The

resulting comprehensive overview revealed that the ZNF514-related

protein network primarily consisted of histone families, which were

structural constituents of chromatin, and associated troponins of

the troponin complex, including histones H2A, H2B, H3 and the

troponin proteins TNNC1, TNNC2, TNNT2 and NKX2-5 (Fig. 4H).

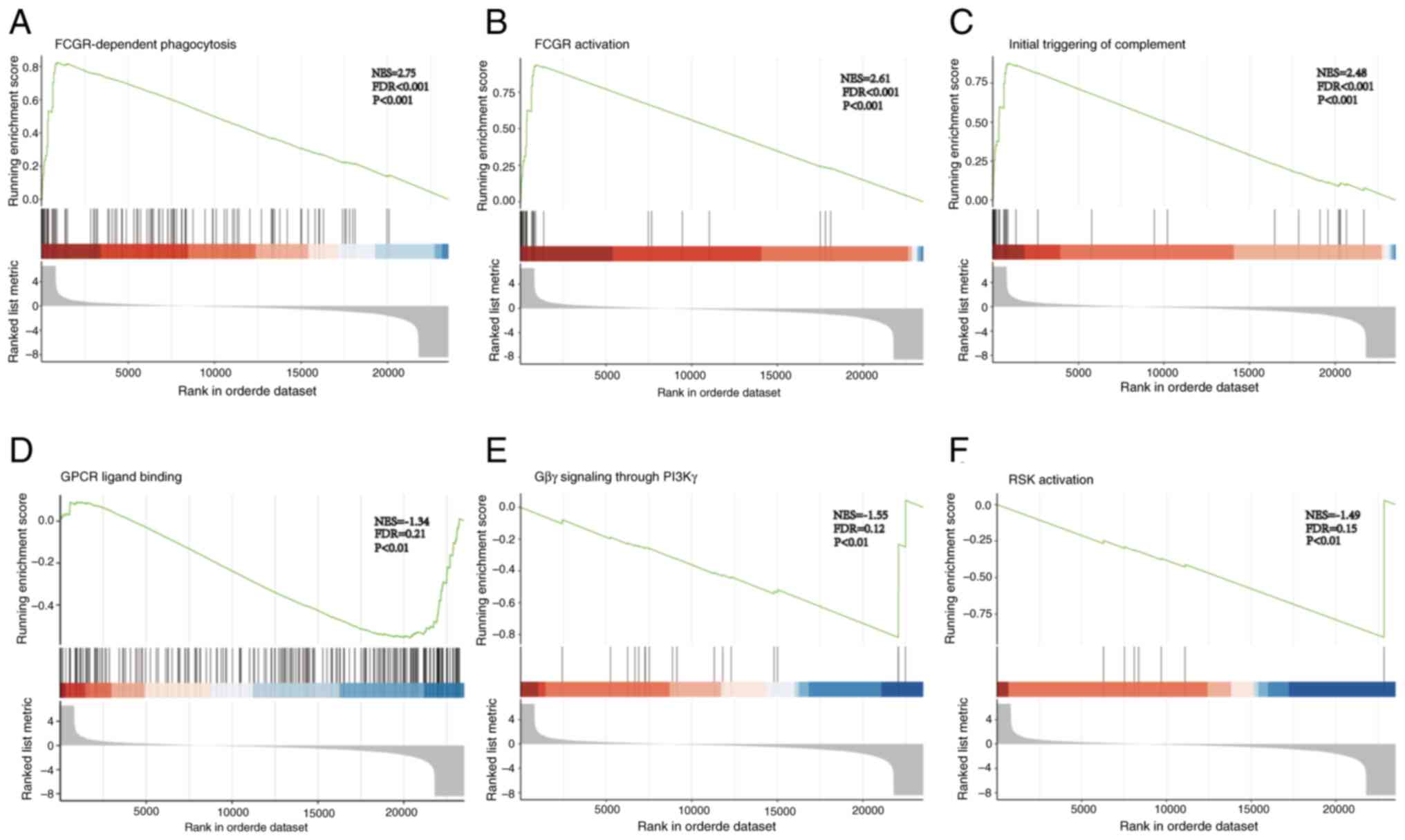

GSEA of the RNA-seq

GSEA was carried out on the DEGs obtained through

RNA-seq analysis. The enrichment score (ES) was calculated and

normalized to produce the normalized ES (NES), thereby

standardizing the gene set data. By calculating the ES and

evaluating its significance, enrichment plots for various pathways

were generated. In the analysis results, the criteria of P<0.05,

|NES|>1 and q-value <0.25 were regarded as significantly

enriched. GSEA revealed that the Fcγ receptor (FCGR)-dependent

phagocytosis (Fig. 5A), FCGR

activation (Fig. 5B) and the

initial triggering of complement (Fig.

5C) were activated. Additionally, G-protein coupled receptor

(GPCR) ligand binding (Fig. 5D),

G-protein βγ (Gβγ) signaling through PI3Kγ (Fig. 5E) and ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK)

activation (Fig. 5F) were

inhibited. These results suggested that ZNF514 regulation may

affect EC immunosurveillance via FCGR-dependent phagocytosis, FCGR

activation, and initial complement triggering; it may also

influence EC occurrence and development by regulating oncogenic

signaling cascades through GPCR ligand binding, Gβγ signaling via

PI3Kγ, and RSK activation.

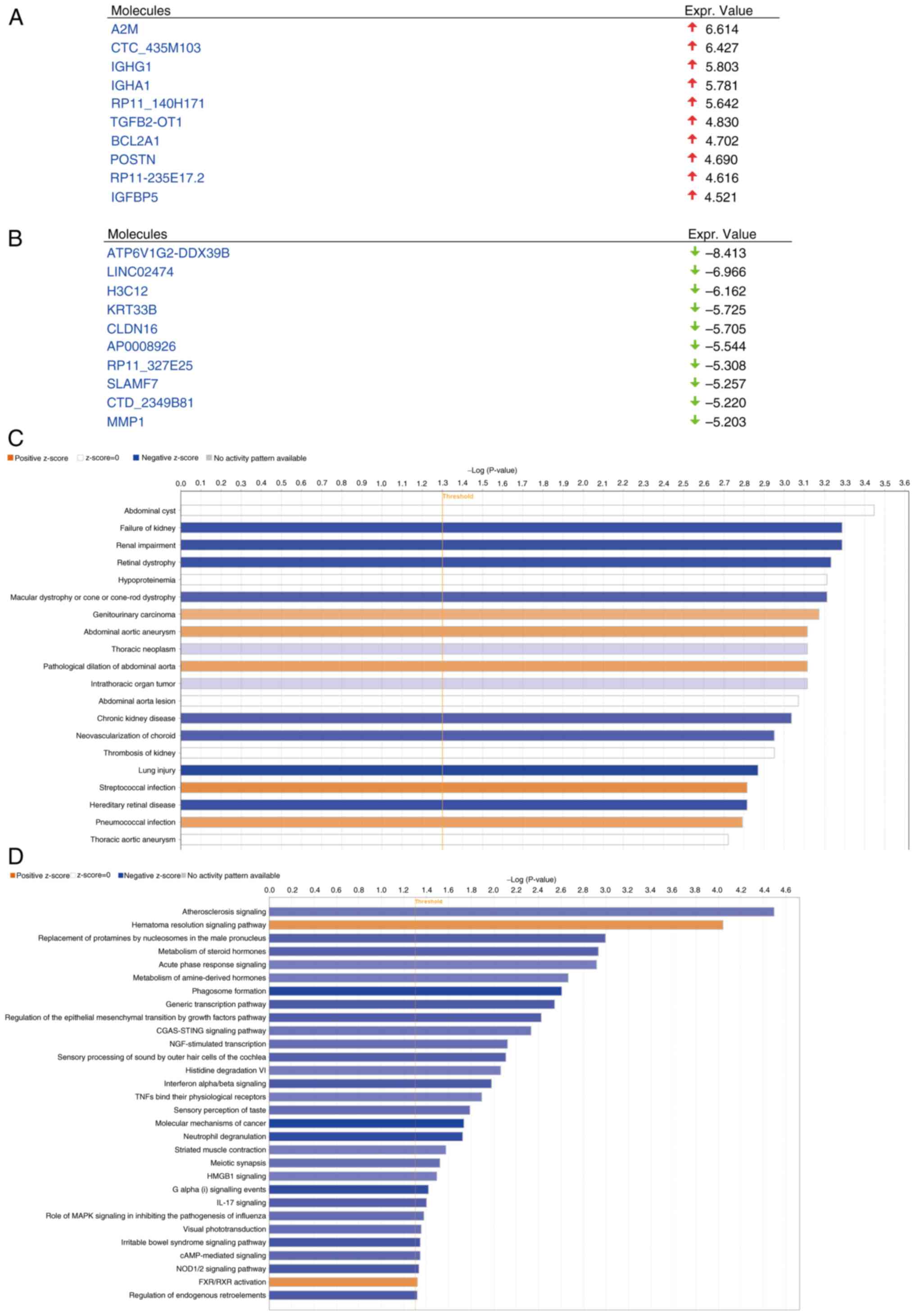

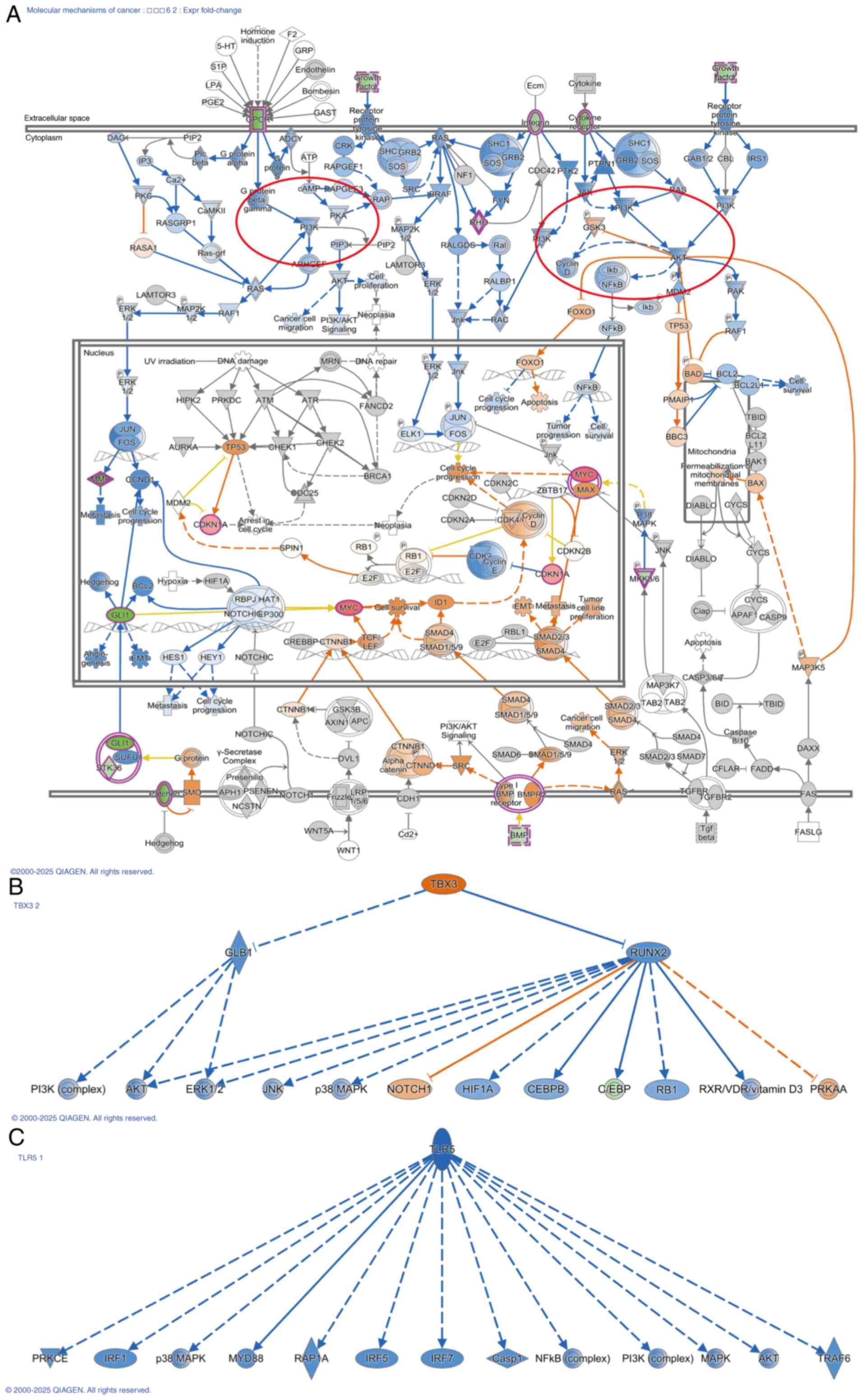

IPA of the DEGs identified by RNA-seq

analysis uncovers their potential mechanisms of influence on EC

progression

To investigate the mechanism by which ZNF514

influences EC progression, IPA of the DEGs was performed. After

ZNF514 knockdown in Kyse-150 cells, significantly upregulated genes

included A2M, CTC_435M103, IGHG1, IGHA1, RP11_140H171, TGFB2-OT1,

BCL2A1, POSTN, RP11-235E17.2 and IGFBP5 (Fig. 6A). Conversely, the significantly

downregulated genes included ATP6V1G2-DDX39B, LINC02474, H3C12,

KRT33B, CLDN16, AP0008926, RP11_327E25, SLAMF7, CTD_2349B81 and

MMP1 (Fig. 6B). Enrichment

analysis indicated that these genes were significantly associated

with multiple pathologies, such as ‘Failure of kidney’, ‘Renal

impairment’, ‘Retinal dystrophy’, ‘Macular dystrophy or cone-rod

dystrophy’, ‘Genitourinary carcinoma’ and ‘Abdominal aortic

aneurysm’. (Fig. 6C).

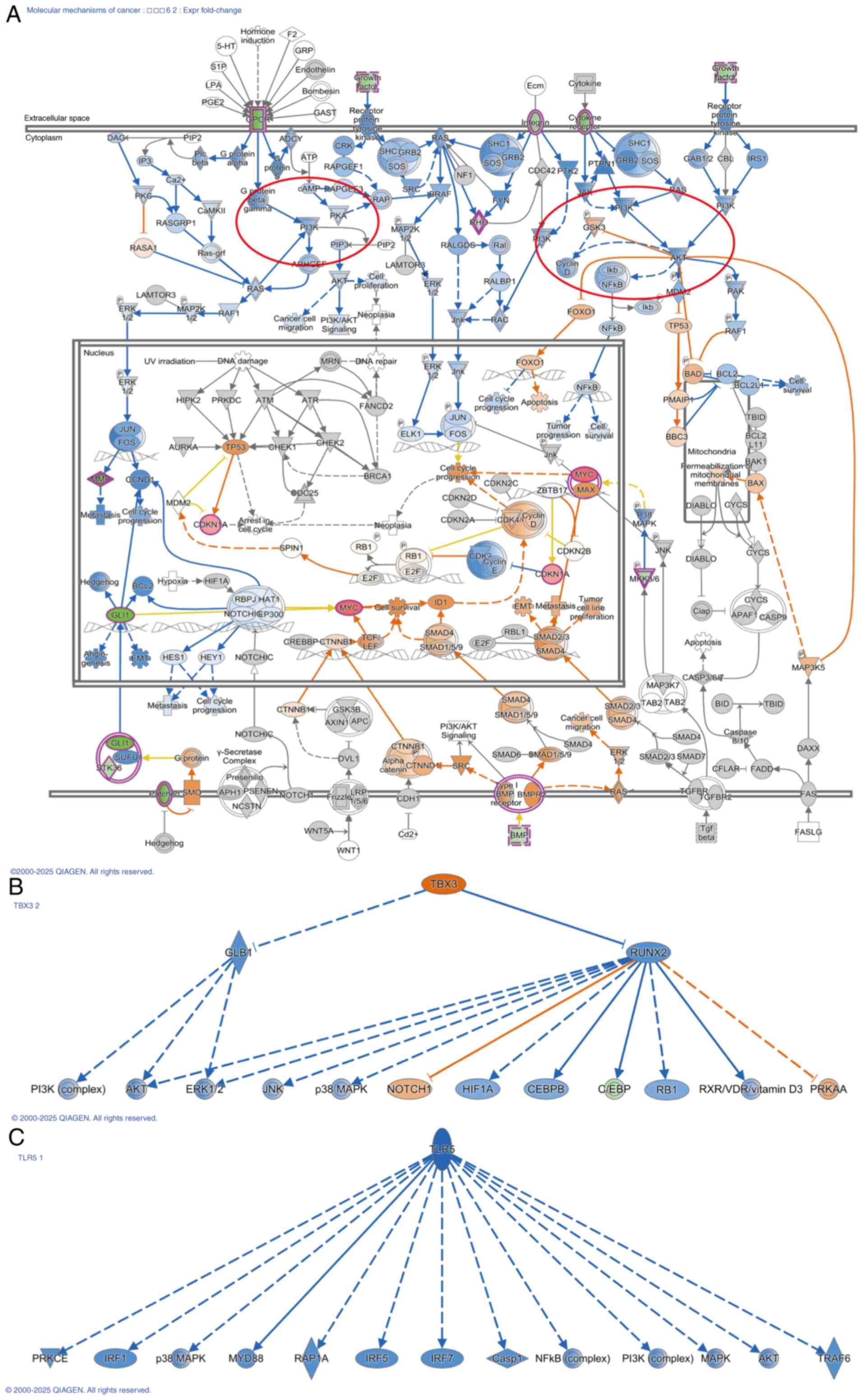

Pathway enrichment analysis identified several

significantly affected pathways (negative Z-score indicates that

the pathway is significantly inhibited, while a positive Z-score

indicates the pathway is significantly activated.), encompassing

the ‘Atherosclerosis Signaling’ pathway, ‘Hematoma Resolution

Signaling Pathway’, ‘Regulation of the Epithelial Mesenchymal

Transition by Growth Factors Pathway’, ‘NOD1/2 Signaling Pathway’,

‘Molecular Mechanisms of Cancer’, ‘IL-17 Signaling’ pathway and

‘CGAS-STING Signaling Pathway’. Based on the Z-value results,

including the following pathways were significantly inhibited:

‘Molecular Mechanisms of Cancer’; ‘Regulation of the Epithelial

Mesenchymal Transition by Growth Factors Pathway’; ‘NOD1/2

Signaling Pathway’ and ‘IL-17 Signaling Pathway’ (Fig. 6D). The present study found that

‘Molecular Mechanisms of Cancer’ was the pathway with the furthest

Z-score from 0 (−4.323), indicating that the pathway was subjected

to the most significant inhibition. Subsequent analysis of the

pathways within ‘Molecular Mechanisms of Cancer’ revealed that the

PI3K/AKT pathway was widely inhibited (Fig. 7A). Therefore, it was highly

plausible that the low expression of ZNF514 exerted its effects on

cellular biological functions by suppressing the upstream PI3K/AKT

pathway, which in turn would lead to the inhibition of multiple

downstream pathways. The ‘Regulation of the Epithelial Mesenchymal

Transition by Growth Factors Pathway’ was implicated in

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) regulation, with multiple

pathways, such as the Ras/MEK and PI3K/AKT pathways, found to be

inhibited following ZNF514 knockdown. Fig. S1 illustrates the key molecules

involved in these pathways. Furthermore, the related molecules in

the ‘STAT3 pathway’ (Fig. S2) and

‘NOD1/2 Signaling Pathway’ (Fig.

S3) were significantly inhibited. Additionally, the related

molecules of NF-κB in the ‘Molecular Mechanisms of Cancer’ were

significantly inhibited. The upstream factors of ZNF514 were also

identified, with TBX3 (Fig. 7B),

and TLR5 (Fig. 7C) being

recognized as significant upstream regulators. Notably, TBX3 was

significantly activated, while TLR5 was significantly

inhibited.

| Figure 7.IPA shows that ZNF514 knockdown

affects multiple cancer-related pathways. (A) The affected PI3K/AKT

pathway, and its upstream and downstream relationships in the

Molecular Mechanisms in Cancer pathway. (B) Activation of TBX3, and

(C) inhibition of TLR5, with the downstream molecules influenced by

these factors shown. Solid line, direct interaction; dashed line,

indirect interaction. Arrow, activation; Blocked arrow, inhibition.

Blue, leads to inhibition; Orange, leads to activation; Yellow,

findings inconsistent with state of downstream molecule; Gray,

effect not predicted. |

In conclusion, the present findings suggested that

the antitumor mechanisms of ZNF514 downregulation might be linked

to the suppression of the PI3K/AKT and Ras/MEK pathways, as well as

the STAT3 pathway, nucleotide oligomerization domain receptor

(NOD)1/2 pathway and NF-κB pathway. Therefore, low expression of

ZNF514 may suppress EC progression by inhibiting these classical

oncogenic pathways, making ZNF514 a notable target for EC

treatment.

Discussion

ZNFs, defined by their conserved zinc finger motifs,

represent one of the largest families of transcription factors in

the human genome and are important in a number of diverse

biological processes, such as differentiation, cell development,

metabolic regulation and apoptosis (14). The C2H2 is the largest class among

all zinc finger types, comprising the sequence CX2CX3FX5LX2HX3H.

Upon interaction with zinc ions, the two cysteine and two histidine

residues fold into a finger-like structure comprising an α-helix

and a double-stranded anti-parallel β-sheet (5). Each C2H2-type ZNF typically contains

KRAB, BTB, SCAN and SET domains, and multiple zinc finger motifs

capable of binding to DNA sequences. ZNF514, a member of the

KRAB-type C2H2 ZNF family, encompasses two core domains: The

N-terminal KRAB domain (residues 74–111), which acts as a key

transcriptional repressor by recruiting corepressors such as

KRAB-associated protein 1 to modulate chromatin states and

facilitate epigenetic regulation; and seven C2H2 zinc finger

domains at the C-terminus (residues 307–400), each featuring a

conserved Cys2/His2 motif that enables sequence-specific DNA

binding and thereby mediates the regulation of gene promoter

regions, underpinning its function as a transcription factor

(15–17).

Studies have shown that ZNF family can perform

distinct functions with various partners, potentially leading to

antagonistic interactions with different partners. For example,

zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 1 is a transcriptional repressor

closely associated with cell differentiation genes, which can

interact with yes-associated protein 1 to promote the invasive

phenotype of cancer (18). ZNF

family exhibit diverse regulatory mechanisms for various downstream

genes by recruiting different chromatin modifiers. For example,

ZNF217 modifies downstream genes by interacting with REST

corepressor 1, lysine demethylase 1, histone deacetylase 2 and

C-terminal binding protein, thereby influencing their expression

(19).

Additionally, post-translational modifications of

ZNF family provide another layer of regulation. Phosphorylation of

serine or threonine residues on ZNF-linked peptides has previously

been reported. During mitosis, ZNFs such as Ikaros, Sp1 and YY1

exhibit high levels of phosphorylation on threonine/serine residues

in the linked peptides of ZNF family, leading to a loss of

DNA-binding ability (5).

Furthermore, research has indicated that ZNFs can affect tumor cell

migration and invasion by regulating the EMT process. The A20

protein belongs to the Cys2/Cys2 ZNF family (20), where it induces the

monoubiquitination of Snail1 at three lysine residues, thereby

decreasing its phosphorylation. Consequently, the monoubiquitinated

Snail1 is stabilized in the nucleus and promotes EMT and basal-like

breast cancer metastasis induced by transforming growth factor-β1

(21). Multiple ZNFs have emerged

as potential biomarkers and effective therapeutic targets in cancer

(22–24). However, research on ZNF514 in EC is

limited and the mechanisms by which it functions in EC remain to be

elucidated.

In the present study, ZNF514 exhibited significant

upregulation in EC tissues. Furthermore, functional assays, such as

siRNA-mediated knockdown experiments, supported the role of ZNF514

in promoting EC cell migration, invasion and proliferation.

Mechanistically, ZNF514 inhibition may suppress tumorigenesis by

disrupting multiple oncogenic pathways, including PI3K/AKT,

Ras/MEK, STAT3, NOD1/2 and NF-κB signaling cascades. Collectively,

the findings of the present study established ZNF514 as a central

regulator of EC progression, highlighting its potential as a

therapeutic target and prognostic biomarker.

In the present study, RNA-seq analysis of Kyse-150

cells after ZNF514 knockdown, followed by GO and KEGG analyses,

GSEA and IPA of the transcriptomics data, indicated that ZNF514

modulated multiple signaling pathways, functioning as an upstream

regulator and consequently impacting EC progression. GSEA further

revealed that ZNF514 knockdown in Kyse-150 cells activated

FCGR-dependent phagocytosis, increased FCGR activation and promoted

early complement triggering compared with normal Kyse-150 cells.

Additionally, GPCR ligand binding, Gβγ signaling via PI3Kγ and RSK

activation were significantly inhibited. Meanwhile, IPA

corroborated the reliability of the GSEA findings, showing that the

Ras/MEK, PI3K/AKT, STAT3, NOD1/2 and NF-κB pathways were inhibited

in the transcriptome following ZNF514 knockdown.

FCGRs are a family of transmembrane glycoproteins

that exert anti-pathogen effects by specifically binding to the Fc

region of IgG antibodies. These receptors are expressed across

diverse immune cell types, establishing a robust defense mechanism

to eliminate invading pathogens (25). Studies have shown that the

bispecific antibody MDX-H210 can target FCGR1 (FcγRI) on cytotoxic

effector cells with upregulated FcγRI expression, thereby

activating these effector cells to target HER2/neu-overexpressing

malignancies (26).

The complement system is part of the innate immune

system and protects the host against pathogen invasion after

activation via the classical, alternative and lectin pathways

(27). The complement system

exerts dual effects on cancer progression. Furthermore, the

interactions of complement components are specific to each cancer

type, and are regulated by tumor cell characteristics and the tumor

microenvironment (28). The

effects of the complement system on malignancies are determined by

a combination of complement-mediated antitumor and cytotoxicity,

along with C5a/C5aR1 axis-mediated protumor chronic inflammation

that hinders antitumor T-cell responses (29). Although the mechanisms by which

complement system activation via ZNF514 downregulation affects

tumor cells are yet to be elucidated, the increase in cytotoxic

effects resulting from FCGR activation suggests that the activation

of the complement system in the present study may have enhanced

immune cell toxicity, thereby inhibiting tumor progression.

Therefore, ZNF514 downregulation may have promoted the activation

of FCGRs and the complement system, thereby enhancing cytotoxic

effects to kill tumor cells.

GPCRs, which constitute ~4% of the human genome,

represent the largest family of cell surface receptors. These

receptors mediate cell communication by transducing external

signals into internal cellular responses (30). By binding to ligands, they activate

various Gα proteins, including Gαs, Gαi, Gαq and Gα12/13,

subsequently triggering downstream signaling cascades. These

signaling cascades regulate cell migration, transcription,

proliferation and survival via kinases and phosphatases, including

MAPK, AKT and mTOR (31). This

indicates that GPCR activation is closely associated with cancer

initiation and progression.

An important step in neutrophil chemotaxis involves

the transformation of PIP2 into PIP3 by PI3Kγ, which is also

important for the metastasis of multiple cancer types (32). The Gβγ heterodimer can recruit

PI3Kγ to the cell membrane and activate the kinase activity of

PI3Kγ via allosteric regulation, enabling PI3Kγ to convert PIP2

into PIP3. This activates the PI3K signaling pathway and

subsequently triggers pro-tumorigenic signaling cascades (32). RSK is a signaling molecule located

downstream of the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway and its activation

promotes cellular biological functions such as proliferation,

growth, motility and survival (33). Thus, downregulation of ‘Gβγ

signaling through the PI3Kγ’ and RSK pathways may inhibit tumor

progression, a finding that the present study emphasizes.

Furthermore, transcriptomic IPA revealed that the

tumor-suppressive mechanisms associated with ZNF514 downregulation

may involve inhibition of the Ras/MEK, PI3K/AKT, STAT3, NOD1/2 and

NF-κB pathways. EGF is important in governing cell growth,

proliferation and differentiation. Additionally, it is linked to

cancer stemness and EMT (34),

with the Ras/Raf/MAPK pathway considered a traditional downstream

signaling pathway of EGF/EGF receptor interactions. The Ras-ERK

signaling cascade is activated by growth factors that bind to

receptor tyrosine kinases (35,36),

leading to the activation of the small G-protein Ras. Subsequently,

MEK, RAF and ERK are activated sequentially in a

phosphorylation-dependent cascade, with ERK1/2 ultimately

phosphorylating downstream effectors which regulate numerous

physiological processes, including proliferation, transcription,

survival, cell adhesion, growth and differentiation (35,37,38).

Aberrant activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway markedly

contributes to carcinogenesis by driving cancer initiation and

progression via its impact on cell proliferation (39,40),

autophagy (41,42), apoptosis (43), angiogenesis (44,45)

and EMT (46,47). Activation of STAT3 is closely

associated with various epithelial (48), mesenchymal (49) and hematological tumors (50), and STAT3 activation is key for the

malignant phenotype (51).

Research indicates that STAT3 binds to the TWIST promoter to

mediate its transcriptional upregulation, consequently triggering

EMT (52).

NOD1 primarily participates in innate inflammatory

immune responses by mediating the NF-κB, MAPK and autophagy-related

pathways. Uncontrolled apoptosis regulated by NOD1 may induce an

immunosuppressive microenvironment that facilitates tumor

progression (53). By contrast,

NOD2 is associated with chronic inflammation and cancer development

(54). The NF-κB pathway has long

been recognized as a prototypical pro-inflammatory signaling

pathway that is frequently overactivated in tumors (55). Additionally, NF-κB activation is

observed in cancer cells and the tumor microenvironment of most

solid tumors and hematological malignancies. This activation

contributes to genetic and epigenetic alterations, metabolic

reprogramming, the acquisition of cancer stem cell traits, EMT,

invasion, angiogenesis and metastasis (55).

Through bioinformatics analyses and in vitro

cell experiments, the present study revealed the important role of

ZNF514 in the progression of EC. ZNF514 may serve a notable role in

regulating cell motility and the invasive potential of EC cells.

The present study aimed to explore the role of high ZNF514

expression in the mechanism of EC progression using EC cell models

and did not perform in vivo experiments. In future research,

it is necessary to establish EC animal models, such as

immunodeficient mouse xenograft models, and combine techniques,

such as in vivo imaging and histopathological analysis, to

further validate the pro-cancer effects and molecular pathways of

ZNF514 in the in vivo environment, and to elaborate its role

in driving EC initiation and progression. Meanwhile, the small

sample size of the present study also constitutes a limitation. In

the future, we aim to expand the sample size, conduct more

comprehensive clinical validations, and further explore the

relationship between ZNF514 expression and the prognosis of

patients with EC. In addition, the lack of validation experiments

based on RNA-seq and pathway analysis was also a limitation of the

present study. The study of the mechanism of ZNF514 in EC remains

in its initial stage and further experimental verification is

needed. This validation will not only establish a solid foundation

for the present conclusions but also provide a scientific rationale

for developing ZNF514-targeted small-molecule compounds and their

clinical translation.

The present study represents, to the best of our

knowledge, the first report on the role of ZNF514 in EC,

demonstrating that ZNF514 may be highly expressed in patients with

EC. Its overexpression may drive the proliferation, motility and

invasiveness of EC cells. The present study also revealed that

ZNF514 can modulate the biological behavior of EC cells by engaging

multiple signaling pathways. Its mechanism may predominantly

regulate EC progression via the PI3K/AKT pathway, underscoring its

multifunctional role. The findings of the present study merit

further investigation into the specific molecular mechanisms

underlying the diverse regulatory functions of ZNF514. Furthermore,

the present study established a robust theoretical framework for

exploring the specific mechanisms underlying the multifaceted

function of ZNF514. This not only facilitates the development of

targeted therapies across diverse cancer types, but also

accelerates the advancement of EC diagnosis and treatment in

clinical settings. Notably, the present study has laid an

experimental foundation for the molecular functions of ZNF514 in

EC.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was financially supported by the Shandong

Province Medical and Health Development Plan (grant no.

202304020860) and the Jinan Municipal Health Commission Science and

Technology Development Plan Project (grant no. 2024302003).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author. The RNA sequencing data

generated in the present study have been deposited in the Gene

Expression Omnibus database under accession number GSE301311 or at

the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE301311.

Authors' contributions

LZ and HL conceived and designed the study. LL, GW

and CZ conducted the experiments; LL, XS and HZ performed the

bioinformatics analysis. LZ revised the manuscript. LZ and XS

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the institutional

review board of Jinan Central Hospital (approval no. 20241120027).

All subjects provided written informed consent form before

enrollment in the study.

Patient consent for publication

Patients provided written informed consent regarding

publishing their data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, the AI tool

ChatGPT (https://chatgpt.com) was used to improve

the readability and language of the manuscript, and subsequently,

the authors revised and edited the content produced by the AI tools

as necessary, taking full responsibility for the ultimate content

of the present manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Deboever N, Jones CM, Yamashita K, Ajani

JA and Hofstetter WL: Advances in diagnosis and management of

cancer of the esophagus. BMJ. 385:e0749622024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Smyth EC, Lagergren J, Fitzgerald RC,

Lordick F, Shah MA, Lagergren P and Cunningham D: Oesophageal

cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 3:170482017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Huang FL and Yu SJ: Esophageal cancer:

Risk factors, genetic association, and treatment. Asian J Surg.

41:210–215. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Lin L and Lin DC: Biological significance

of tumor heterogeneity in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

Cancers (Basel). 11:11562019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Jen J and Wang YC: Zinc finger proteins in

cancer progression. J Biomed Sci. 23:532016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Hong K, Yang Q, Yin H, Wei N, Wang W and

Yu B: Comprehensive analysis of ZNF family genes in prognosis,

immunity, and treatment of esophageal cancer. BMC Cancer.

23:3012023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Jen J, Lin LL, Lo FY, Chen HT, Liao SY,

Tang YA, Su WC, Salgia R, Hsu CL, Huang HC, et al: Oncoprotein

ZNF322A transcriptionally deregulates alpha-adducin, cyclin D1 and

p53 to promote tumor growth and metastasis in lung cancer.

Oncogene. 36:52192017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Yao J, Qian K, Chen C, Liu X, Yu D, Yan X,

Liu T and Li S: Correction for: ZNF139/circZNF139 promotes

cell proliferation, migration and invasion via activation of

PI3K/AKT pathway in bladder cancer. Aging (Albany NY).

14:4927–4928. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wang Y, Gong Y, Li X, Long W, Zhang J, Wu

J and Dong Y: Targeting the ZNF-148/miR-335/SOD2 signaling cascade

triggers oxidative stress-mediated pyroptosis and suppresses breast

cancer progression. Cancer Med. 12:21308–21320. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network;

Analysis Working Group; Asan University; BC Cancer Agency; Brigham

and Women's Hospital; Broad Institute; Brown University; Case

Western Reserve University; Dana-Farber Cancer Institute; Duke

University; Greater Poland Cancer Centre, et al, . Integrated

genomic characterization of oesophageal carcinoma. Nature.

541:169–175. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ and Smyth GK:

edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis

of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 26:139–140. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Korthauer K, Kimes PK, Duvallet C, Reyes

A, Subramanian A, Teng M, Shukla C, Alm EJ and Hicks SC: A

practical guide to methods controlling false discoveries in

computational biology. Genome Biol. 20:1182019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ye Q, Liu J and Xie K: Zinc finger

proteins and regulation of the hallmarks of cancer. Histol

Histopathol. 34:1097–1109. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wang J, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, Gonzales

NR, Gwadz M, Lu S, Marchler GH, Song JS, Thanki N, Yamashita RA, et

al: The conserved domain database in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res.

51:D384–D388. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Lu S, Wang J, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK,

Geer RC, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, Hurwitz DI, Marchler GH, Song JS, et

al: CDD/SPARCLE: The conserved domain database in 2020. Nucleic

Acids Res. 48:D265–D268. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Marchler-Bauer A, Bo Y, Han L, He J,

Lanczycki CJ, Lu S, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, Geer RC, Gonzales NR,

et al: CDD/SPARCLE: Functional classification of proteins via

subfamily domain architectures. Nucleic Acids Res. 45:D200–D203.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lehmann W, Mossmann D, Kleemann J, Mock K,

Meisinger C, Brummer T, Herr R, Brabletz S, Stemmler MP and

Brabletz T: ZEB1 turns into a transcriptional activator by

interacting with YAP1 in aggressive cancer types. Nat Commun.

7:104982016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Qin X, Zhou K, Dong L, Yang L, Li W, Chen

Z, Shen C, Han L, Li Y, Chan AKN, et al: CRISPR screening reveals

ZNF217 as a vulnerability in high-risk B-cell acute lymphoblastic

leukemia. Theranostics. 15:3234–3256. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Enesa K and Evans P: The biology of

A20-like molecules. Adv Exp Med Biol. 809:33–48. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Lee JH, Jung SM, Yang KM, Bae E, Ahn SG,

Park JS, Seo D, Kim M, Ha J, Lee J, et al: A20 promotes metastasis

of aggressive basal-like breast cancers through

multi-monoubiquitylation of Snail1. Nat Cell Biol. 19:1260–1273.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Li J, Zhou Q, Zhang C, Zhu H, Yao J and

Zhang M: Development and validation of novel prognostic models for

zinc finger proteins-related genes in soft tissue sarcoma. Aging

(Albany NY). 15:3171–3190. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wu P, Lin Y, Dai F, Wang H, Wen H, Xu Z,

Sun G and Lyu Z: Pan-cancer analysis and experimental validation

revealed the prognostic role of ZNF83 in renal and lung cancer

cohorts. Discov Oncol. 16:13352025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kou H, Jiang S, Wu X, Jing C, Xu X, Wang

J, Zhang C, Liu W, Gao Y, Men Q, et al: ZNF655 involved in the

progression of multiple myeloma via the activation of AKT. Cell

Biol Int. 49:177–187. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Gan SY, Tye GJ, Chew AL and Lai NS:

Current development of Fc gamma receptors (FcγRs) in diagnostics: A

review. Mol Biol Rep. 51:9372024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Rajasekaran N, Chester C, Yonezawa A, Zhao

X and Kohrt HE: Enhancement of antibody-dependent cell mediated

cytotoxicity: A new era in cancer treatment. Immunotargets Ther.

4:91–100. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Omori T, Machida T, Ishida Y, Sekiryu T

and Sekine H: Roles of MASP-1 and MASP-3 in the development of

retinal degeneration in a murine model of dry age-related macular

degeneration. Front Immunol. 16:15660182025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Roumenina LT, Daugan MV, Petitprez F,

Sautès-Fridman C and Fridman WH: Context-dependent roles of

complement in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 19:698–715. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Merle NS and Roumenina LT: The complement

system as a target in cancer immunotherapy. Eur J Immunol.

54:e23508202024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Wess J: Designer GPCRs as novel tools to

identify metabolically important signaling pathways. Front

Endocrinol (Lausanne). 12:7069572021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Inverso D, Tacconi C, Ranucci S and De

Giovanni M: The power of many: Multilevel targeting of

representative chemokine and metabolite GPCRs in personalized

cancer therapy. Eur J Immunol. 54:e23508702024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Chen CL, Syahirah R, Ravala SK, Yen YC,

Klose T, Deng Q and Tesmer JJG: Molecular basis for Gβγ-mediated

activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ. Nat Struct Mol Biol.

31:1198–1207. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Romeo Y and Roux PP: Paving the way for

targeting RSK in cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 15:5–9. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Chatterjee P, Ghosh D, Chowdhury SR and

Roy SS: ETS1 drives EGF-induced glycolytic shift and metastasis of

epithelial ovarian cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res.

1871:1198052024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Nussinov R, Yavuz BR and Jang H: Molecular

principles underlying aggressive cancers. Signal Transduct Target

Ther. 10:422025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Du R, Shen W, Liu Y, Gao W, Zhou W, Li J,

Zhao S, Chen C, Chen Y, Liu Y, et al: TGIF2 promotes the

progression of lung adenocarcinoma by bridging EGFR/RAS/ERK

signaling to cancer cell stemness. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

4:602019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Asghar J, Latif L, Alexander SPH and

Kendall DA: Development of a novel cell-based, In-Cell Western/ERK

assay system for the high-throughput screening of agonists acting

on the delta-opioid receptor. Front Pharmacol. 13:9333562022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Caunt CJ, Sale MJ, Smith PD and Cook SJ:

MEK1 and MEK2 inhibitors and cancer therapy: The long and winding

road. Nat Rev Cancer. 15:577–592. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Tian T, Li X and Zhang J: mTOR signaling

in cancer and mTOR inhibitors in solid tumor targeting therapy. Int

J Mol Sci. 20:7552019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Mangé A, Coyaud E, Desmetz C, Laurent E,

Béganton B, Coopman P, Raught B and Solassol J: FKBP4 connects

mTORC2 and PI3K to activate the PDK1/Akt-dependent cell

proliferation signaling in breast cancer. Theranostics.

9:7003–7015. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Al-Bari MAA and Xu P: Molecular regulation

of autophagy machinery by mTOR-dependent and -independent pathways.

Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1467:3–20. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Nowosad A, Jeannot P, Callot C, Creff J,

Perchey RT, Joffre C, Codogno P, Manenti S and Besson A: Publisher

correction: p27 controls ragulator and mTOR activity in amino

acid-deprived cells to regulate the autophagy-lysosomal pathway and

coordinate cell cycle and cell growth. Nat Cell Biol. 23:10482021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

He K, Zheng X, Li M, Zhang L and Yu J:

mTOR inhibitors induce apoptosis in colon cancer cells via

CHOP-dependent DR5 induction on 4E-BP1 dephosphorylation. Oncogene.

35:148–157. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Karar J and Maity A: PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway

in angiogenesis. Front Mol Neurosci. 4:512011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Kim K, Kim IK, Yang JM, Lee E, Koh BI,

Song S, Park J, Lee S, Choi C, Kim JW, et al: SoxF transcription

factors are positive feedback regulators of VEGF signaling. Circ

Res. 119:839–852. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Herrerias MM and Budinger GRS: Revisiting

mTOR and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Am J Respir Cell Mol

Biol. 62:669–670. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Karimi Roshan M, Soltani A, Soleimani A,

Rezaie Kahkhaie K, Afshari AR and Soukhtanloo M: Role of AKT and

mTOR signaling pathways in the induction of epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (EMT) process. Biochimie. 165:229–234. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Tian F, Yang X, Liu Y, Yuan X, Fan T,

Zhang F, Zhao J, Lu J, Jiang Y, Dong Z and Yang Y: Constitutive

activated STAT3 is an essential regulator and therapeutic target in

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 8:88719–88729.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

D'Amico S, Shi J, Martin BL, Crawford HC,

Petrenko O and Reich NC: STAT3 is a master regulator of epithelial

identity and KRAS-driven tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 32:1175–1187.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Andersson EI, Brück O, Braun T, Mannisto

S, Saikko L, Lagström S, Ellonen P, Leppä S, Herling M, Kovanen PE

and Mustjoki S: STAT3 mutation is associated with STAT3

activation in CD30+ ALK− ALCL. Cancers

(Basel). 12:7022020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Groner B and von Manstein V: Jak Stat

signaling and cancer: Opportunities, benefits and side effects of

targeted inhibition. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 451:1–14. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Sadrkhanloo M, Entezari M, Orouei S,

Ghollasi M, Fathi N, Rezaei S, Hejazi ES, Kakavand A, Saebfar H,

Hashemi M, et al: STAT3-EMT axis in tumors: Modulation of cancer

metastasis, stemness and therapy response. Pharmacol Res.

182:1063112022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Moreno L and Gatheral T: Therapeutic

targeting of NOD1 receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 170:475–485. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zhang W and Wang Y: Activation of

RIPK2-mediated NOD1 signaling promotes proliferation and invasion

of ovarian cancer cells via NF-κB pathway. Histochem Cell Biol.

157:173–182. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Taniguchi K and Karin M: NF-κB,

inflammation, immunity and cancer: Coming of age. Nat Rev Immunol.

18:309–324. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|