Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a type of

noninfectious chronic gastrointestinal inflammation disease that

includes Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) and is

characterized by chronic or intermittent inflammation of the

intestinal mucosa (1). Globally,

in 2019, 405,000 (95% UI 361,000 to 457,000) new cases of IBD and

41,000 (95% UI 35,000 to 45,000) deaths from IBD have been reported

(2). It is projected that the

age-standardized mortality rate from IBD may continue to decline

from 2020 to 2050 (2). The results

of clinical trials have indicated primary non-response rates of up

to 40%, and a significant challenge is the inability to predict

which treatment will benefit individual patients (3). The investigation of preclinical human

IBD mechanisms is one of the key concerns (4).

The mucus layer of the intestines is the first

interface to insulate the complex microbial environment, and the

integrity of the mucus layer directly affects intestinal barrier

function and the development of IBD (5). Mucus is a dilute, aqueous and

viscoelastic secretion that contains 90–95% water, 1–2% lipids,

electrolytes, 29 core proteins and other substances; mucins are the

primary structural and functional components in mucus and are

present at concentrations of 1–5% (6). Mucus separates the epithelium and

millions of antigens from food, the environment and the microbiome

while permitting nutrient absorption and gas exchange (7).

Goblet cells secrete large polymers of gel-forming

mucin 2 (MUC2), which compose the structural backbone of the mucus

that coats the epithelial surface (8). The MUC2 mucus barrier plays important

roles in the response to changes in dietary patterns, MUC2 mucus

barrier dysfunction, contact stimulation with colonic epithelial

cells, and mucosal and submucosal inflammation during the

occurrence and development of IBD (9,10).

MUC2 gene expression is reduced or absent in patients with CD,

whereas MUC2 protein expression and secretion are decreased in

active UC, resulting in a thin mucus layer and increased intestinal

absorption (11). The absence of

MUC2 expression in the mucus layer renders animals vulnerable to

intestinal inflammation, which leads to the development of

spontaneous colitis and predisposes them to the development of

colorectal cancer (12).

MUC2-knockout mice present clinical signs of colitis along with

mucosal thickening, increased proliferation, and superficial

erosion (13).

The present review aimed to explore the importance

of MUC2 in the mucus barrier and the novel UPR pathway to provide

new ideas for future research on IBD.

The human MUC gene family encodes 19 typical

mucin-type glycoproteins, which are recognized by the Human Genome

Organization Gene Nomenclature Committee (http://www.genenames.org) and can be divided into

three subgroups, membrane-bound (including MUC1, MUC3A and MUC3B),

secreted gel-forming (including MUC2, MUC5AC and MUC5B) and

secreted non-gel-forming (MUC7 and MUC8) (Table I). Among these, MUC2 is the most

important secreted and gel-forming component of the intestinal

mucus in the human intestine and provides a first line of defense

against pathogens in the gut immune system (20).

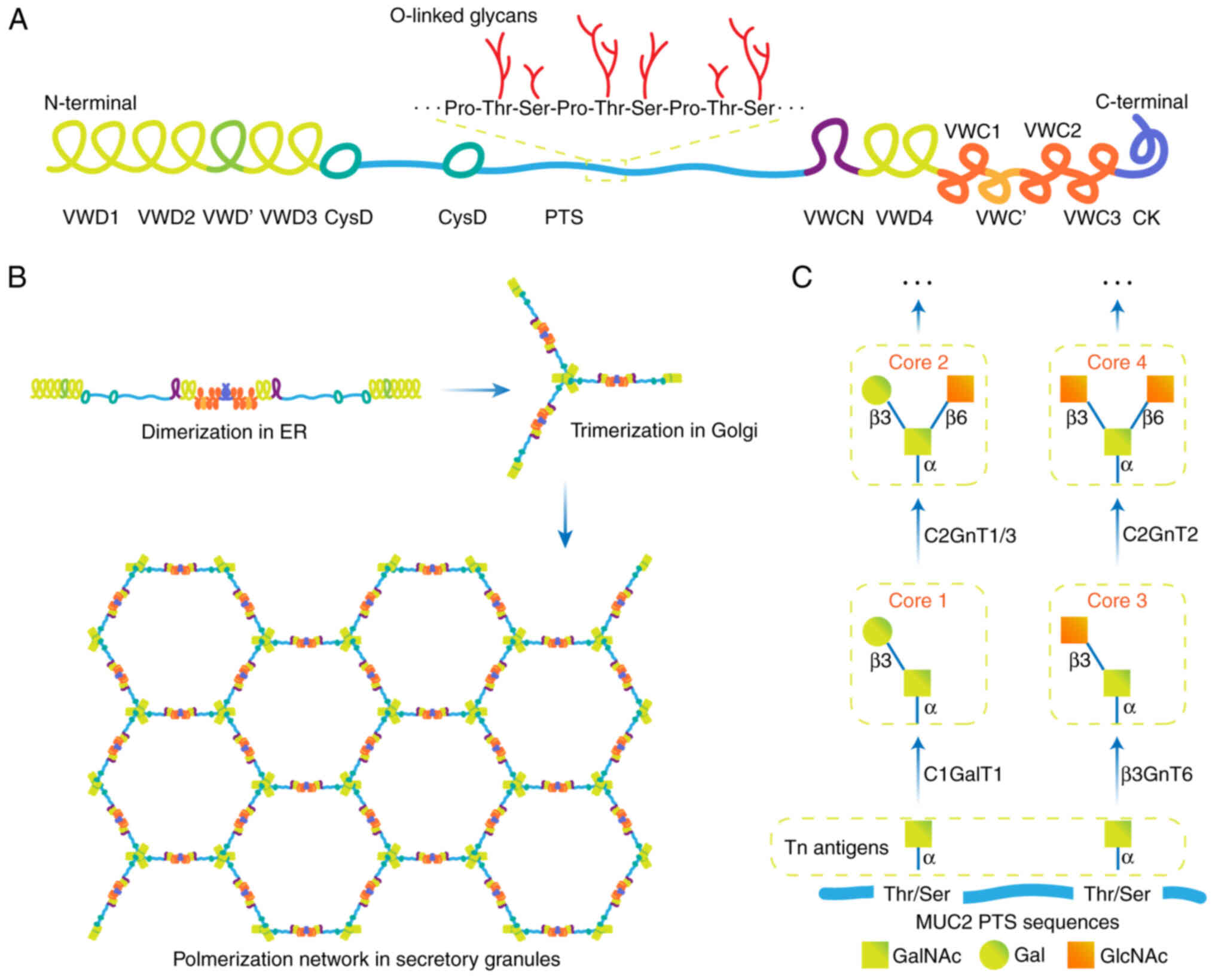

Cysteine residues located at the N- and C-termini of

MUC2 are highly glycosylated, which increases the hydrophilicity of

MUC2 and allows lubrication of the intestinal mucosa (25). MUC2 contains 215 cysteine amino

acids that make up >10% of the total amino acids outside the PTS

mucin domains (26). As all

cysteines need to be interlinked (oxidized) to exit the ER, the

correct assembly of MUC2 is a formidable challenge (26). A MUC2 monomer contains up to 1,600

O-glycans and 30 N-glycans, resulting in more than 3,300 terminal

sugar residues (27).

MUC2 monomers are N-glycosylated within the ER, a

process that enables correct MUC2 folding, stable dimer formation

and maturation (22). The CK

domain in the C-terminus of MUC2 forms a dimer via disulfide bonds

between three cysteine amino acids via the ER machinery (Fig. 1B) (28). The correct folding of MUC2 is

assisted by various molecular chaperones that prevent the

misfolding and aggregation of proteins in the ER, such as binding

immunoglobulin protein (BiP, GRP78), anterior gradient 2 (AGR2),

calnexin and calreticulin (29).

Next, MUC2 dimers are transported to the Golgi, and

the hydroxy amino acids (Ser and Thr) of the PTS domains become

O-glycosylated, in which >80% of all Ser and Thr residues carry

O-linked glycans (30). The

typically O-glycosylated compounds are largely concentrated in the

PTS domains, which resemble bottle brushes with protein cores at

their centers and oligosaccharides as their bristles (31). In the trans-Golgi network, the

glycosylated dimers are then trimerized via disulfide bonding in

VWD3, and a net-like structure is generated (Fig. 1B) (32). The glycosylated MUC2 monomer has a

mass of ~2.5 MDa and the polymer may have a mass of >100 MDa

(33). An important function of

O-glycans is to cover the protein backbone and thus protect the

mucin from proteolytic enzymes while simultaneously binding water

to generate a gel (33). Glycans

also act as attachment sites for bacteria, as they are important

food sources (34). An increase in

the number of small glycans is found in most patients with active

UC, and a decrease in the number of more complex compounds has been

detected (31).

The distribution of glycosyltransferases (GalNAc-Ts)

throughout the Golgi apparatus is not homogenous, and each

compartment has a distinct composition of GalNAc-Ts (35). To achieve controlled, sequential

extension, the GalNAc-Ts are spatially arranged according to the

order of monosaccharide addition (27). First, O-glycosylation is a covalent

linkage initiated by 1 of the 20 GalNAc-Ts that add

N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) to the Ser or Thr amino acid

residues in the MUC2 PTS sequence (36). The Pro amino acids in the PTS

ensure a non-folded structure allowing the GalNAc-Ts of the Golgi

apparatus to access the protein core (37). The structures formed during this

initial stage of modification are known as Tn antigens. Next, the

glucan chains are further extended to form four core structures

known as Core 1–4 (Fig. 1C)

(38). The addition of galactose

(Gal) by Core 1 β1-3-galactosyltransferase (C1GalT1) is known as

core 1 (39). The addition of

N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) by Core 3

β1-3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (β3GnT6) to peptide-bound

GalNAc is known as Core 3 (40).

Core 2 is formed by the addition of β1-6GlcNAc to the GalNAcs of

Core 1 through Core 2 β1,6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase 1/3

(C2GnT1/3) (41). Core 4 is formed

by the addition of β1-6GlcNAc to the GalNAc of Core 3 through Core

2 β1,6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase-2 (C2GnT2) (38). Groups that can be attached to core

structures include galactose, sialic acid, sulfate and fucose

(42). The order in which the

glycans interact with different GalNAc-Ts plays a critical role in

O-glycosylation since specific monosaccharides, such as fucose or

N-acetylneuraminic acid, can limit further elongation (27). There are large differences in MUC2

characteristics between animal species, such as mouse colonic MUC2,

which largely contains Core 2 and minor amounts of Core 3 and Core

4, whereas human MUC2 predominantly contains Core 3 structures,

Core 4 to a lesser extent, and essentially lacks Core 1 (42).

MUC2 forms large net-like structures that are

densely packed in the secretory granules of goblet cells (43). Fully synthesized MUC2 is released

from goblet cells through baseline secretion or via

Ca2+−dependent stimulated secretion (44). The pH along the secretory pathway

shifts gradually from 7.2 in the ER to 6.0 in the trans-Golgi

network, and to 5.2 in the secretory granule (45). Moreover, the intragranular

Ca2+ concentration increases, suggesting that the

packing of MUC2 may be pH- and Ca2+-dependent (45). The N-terminal trimers spontaneously

form concatenated rings with long-extended mucin domains standing

perpendicular to this structure and joining to other MUC2 molecules

end-to-end through their C-terminus (46).

In addition, the hydrolytic activities of some

proteases also play a role in the process of MUC2 volume expansion

(50). Calcium-activated chloride

channel regulator 1 is highly abundant in intestinal mucus, with an

N-terminal metalloprotease domain, a central von Willebrand A

domain and a C-terminal fibronectin type III domain that likely has

both metallohydrolase activity and structural roles and can process

N-terminal MUC2 via proteolysis (51). Transglutaminase 3, the dominant

cross-linking enzyme in the mouse colon, catalyzes cross-linking of

the MUC2 protein and increases the resistance of MUC2 to

degradation (52). Under the

synergistic effects of numerous factors, MUC2 forms a net-like

structure and establishes a sturdy mucus barrier.

In response to environmental factors, such as

pathogenic bacterial infection, there is an increased demand for

MUC2 synthesis, resulting in a significant protein folding and

modification burden on the ER of goblet cells (53). Additionally, owing to the large

size (~2.5 MDa of a monomer) and complex structure of MUC2, it is

prone to misfolding, which may result in the accumulation of

misfolded proteins within the ER lumen, thereby triggering ER

stress (54). Abnormal synthesis

of MUC2 induces a unique model of IBD caused by ER stress (55). In the Winnie and Eeyore mouse

models (which carry single missense MUC2 mutations), misfolded MUC2

proteins heavily accumulate in membranous structures, and

quantitative PCR reveals a two- to threefold increase in the

expression of BiP mRNA (an ER stress marker) in the proximal and

distal colon (16). Winnie and

Eeyore mice develop mild spontaneous inflammation of the colon

accompanied by goblet cell ER stress (16). Winnie mice exhibit altered mucus

production as early as 4 weeks of age, after which colonic

inflammation begins (56).

ER stress aggravates MUC2 synthesis abnormalities

and causes a series of chain reactions (57). The synthesis of MUC2 begins in the

ER, where it must be properly folded and bound to a molecular

chaperone before it can be transported to the Golgi apparatus

(58). Once abnormal MUC2 folding

occurs, it is difficult to perform glycosylation, sulfation and

other modifications, which are performed in the Golgi apparatus,

leading to further functional defects in MUC2 (31). For example, the O-glycosylation

patterns of MUC2 are significantly altered in patients with IBD,

especially in patients with UC; these patterns include

O-glycosylation reduction, a reduction in the length of the

O-glycan chains of MUC2 and genetic defects in GalNAc-Ts enzymes

(59). Sulfation is catalyzed

mainly by sulfotransferases located in the Golgi apparatus, and

sulfotransferase adds sulfuric acid groups to the sugar chains of

MUC2, resulting in the formation of negatively charged molecules

whose hydration and viscosity properties are increased (11). Since the presence of a sugar chain

is necessary for sulfation, the obstruction of MUC2 glycosylation

reduces the number of sulfation sites, thus affecting the addition

and distribution of sulfuric acid groups and resulting in changes

in the charge and viscosity properties of MUC2 (60). Moreover, delayed transport or

misfolding of MUC2 due to ER stress can affect the recognition

sites of proteolytic enzymes, resulting in the failure of MUC2 to

undergo proper hydrolysis and extracellular secretion of MUC2,

further impairing intestinal barrier function (61).

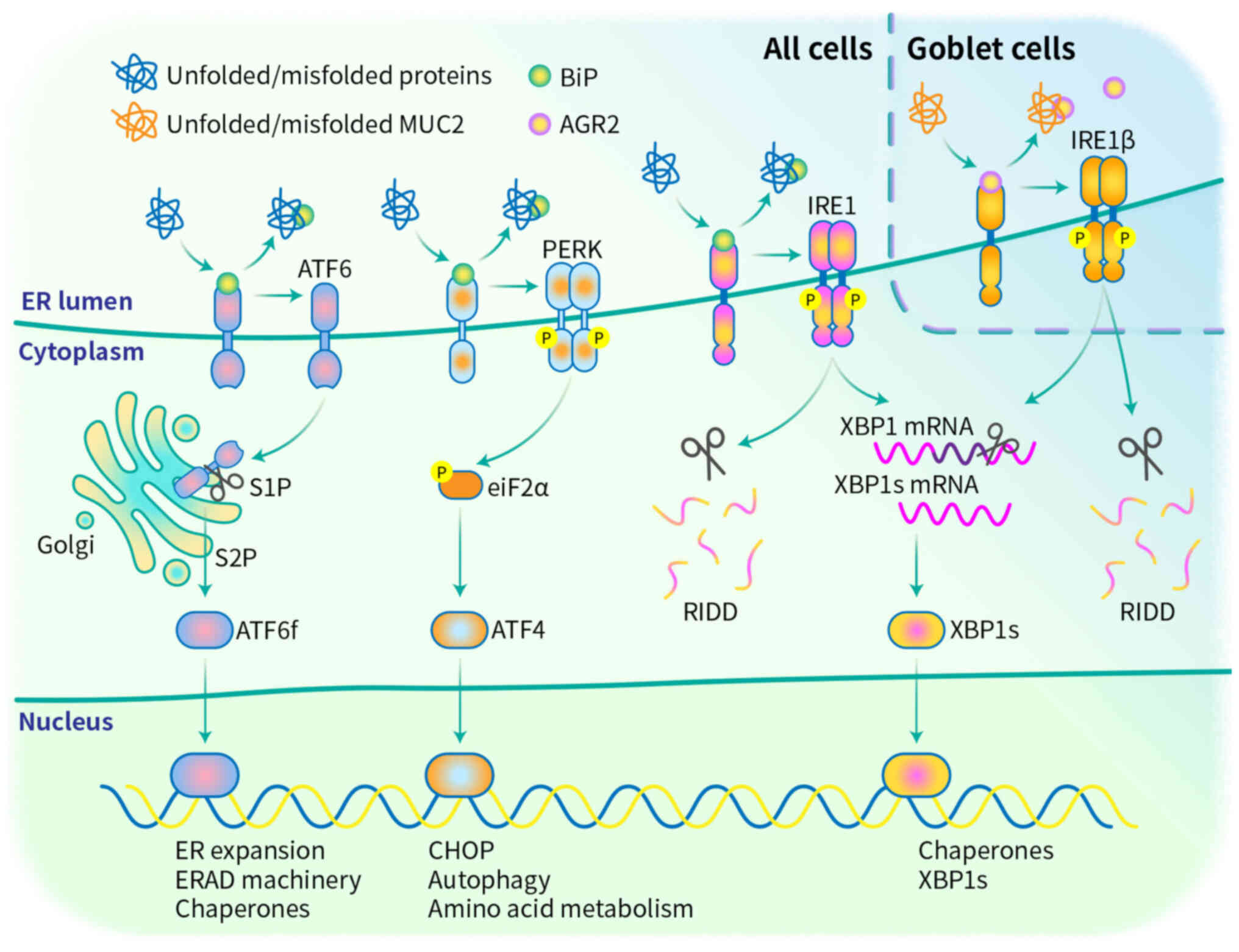

UPR signaling pathways are activated to stop

improper translation, refold unfolded proteins, and degrade

irreversible unfolded proteins via the ER-associated degradation

(ERAD) pathway, in which unfolded/misfolded proteins that have

accumulated in the ER are transported to the cytosol for

degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome system (62). UPR sensors monitor ER protein

folding capacity, and their effectors balance protein synthesis,

folding, trafficking, and degradation to alleviate ER stress

(62). The mammalian UPR has three

known signaling branches: Pancreatic ER kinase (PERK), ER

transmembrane inositol-requiring enzymes 1α and β (IRE1α and IRE1β)

and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) (Fig. 2). These transmembrane sensor

proteins have an ER luminal sensor domain and a cytosolic effector

domain, thereby transmitting the protein folding status inside the

ER to other cellular compartments via intracellular signaling

pathways (63). In the absence of

misfolded proteins in the ER lumen, these cascades are usually

maintained in an inactivated state by the chaperone BiP (64). However, under elevated ER stress,

unfolded proteins compete for BiP binding, thereby detaching BiP

from the sensing molecules, which activates the signaling cascade

to overcome the stress environment and sustain homeostasis

(64). Moreover, under protracted

and acute ER stress, the UPR initiates cascades that can trigger

apoptosis in goblet cells, which are essential for the production

of MUC2 (65). Thus, maintaining

the balance of the UPR is very important.

IRE1 proteins, which include IRE1α and IRE1β,

possess both an ER luminal sensor domain and a cytosolic

endoribonuclease (RNase) domain and show kinase activity (66). Kinase activity enables

trans-autophosphorylation, which activates RNase activity (67). Activated IRE1 splices X-Box Binding

Protein 1 (XBP1) mRNA and removes an inhibitory 26-nucleotide

intron from the XBP1 transcript (68). The mRNA is subsequently re-ligated

by RNA terminal phosphorylase B, generating a functionally active

isoform of XBP1 (XBP1s) (69).

XBP1s bind to ER stress response element (ERSE), ER stress response

element II (ERSE II) and UPR element sequences (70). This process upregulates the

expression of genes that encode proteins that promote protein

refolding (ER chaperone proteins), aid in the destruction of

proteins that are beyond repair (components of the ERAD machinery)

and encode proteins that facilitate the expansion of the ER, thus

increasing protein folding capacity (71). In addition to splicing XBP1, IRE1

RNase activity can cleave other RNA targets in a process known as

regulated IRE1-dependent decay (72).

PERK is a transmembrane protein located in the ER,

and its N-terminal regulatory motif is located in the lumen and

adjoins the cytosolic eIF2α kinase domain (73). PERK is maintained in an inactive

state by the interaction of its ER luminal domain with BiP

(74). Once a misfolded protein is

produced, BiP dissociates from PERK due to its preferential binding

to hydrophobic residues of misfolded proteins (75). Once disassociated, following

phosphorylation at Thr980 by autophosphorylation, PERK dimerizes to

form an active homodimer (76).

The activation of PERK leads to the phosphorylation of eukaryotic

initiation factor 2 (eIF2α) at Ser51 (77). Phosphorylated eIF2α perturbs 80S

ribosome assembly inhibiting protein translation, thus blocking the

production of an additional influx of nascent polypeptides that

could worsen the ER stress (78).

Moreover, activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4)

escapes translational attenuation by eIF2α phosphorylation because

ATF4 has upstream open reading frames (ORFs) in its 5′-untranslated

region (79). These upstream ORFs

prevent translation of ATF4 under normal conditions and are

bypassed only when eIF2α is phosphorylated; therefore, ATF4

translation occurs (80). ATF4

translation activates the expression of the transcription factor

CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-homologous protein, a master

regulator of ER stress-induced apoptosis and plays pro-apoptotic

roles in the stress response (81). Chronic or prolonged PERK signaling

can lead to goblet cell apoptosis in IBD (82).

ATF6 proteins are type II transmembrane proteins

that contain basic leucine zipper (bZIP) motifs in their cytosolic

domains and a C-terminus protrudes that into the ER lumen (83). After disassociation from BiP under

ER/oxidative stress conditions, ATF6 translocates from the ER to

the Golgi apparatus, where it is cleaved by site-1 protease (S1P)

and site-2 protease (S2P) to remove the luminal and transmembrane

domains (84). This process

results in the generation of a cytosolic fragment with

transcription factor activity which is designated as ATF6f, the

released ATF6f then translocate to the nucleus and regulates the

expression of genes encoding BiP, XBP1s and ERAD components

(85).

Unlike IRE1α, which plays a broad role in the UPR by

splicing XBP1 mRNA and degrading misfolded proteins, IRE1β has

specialized functions in secretory epithelial cells, especially in

goblet cells (86). Vertebrates

express two IRE1 paralogs, IRE1α, which is universally expressed

and IRE1β, which is specifically expressed within mucus-secreting

cells in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts (87). Single-cell RNA sequencing revealed

that the abundance of IRE1β mRNAs is ~50-fold greater than that of

IRE1α mRNAs in the goblet cells of the small intestinal epithelium

(88). Loss of IRE1β expression

results in the accumulation of misfolded MUC2 precursor proteins in

the ER of immature goblet cells, and defects in MUC2 maturation and

its accumulation in the ER lead to marked ER abnormalities and

signs of ER stress (89).

The role of IRE1β in intestinal mucus barrier

homeostasis can't be replaced by IRE1α (90). The transplantation of microbiota

from conventionally raised mice to germ-free mice restored goblet

cell numbers; this restoration was completely abolished in

IRE1β-deficient mice, despite normal IRE1α expression, but it

failed to compensate for IRE1β function (91). Compared with normal colonic

tissues, the tumor tissues exhibited a significant increase in

XBP1s mRNA expression levels, no significant difference in IRE1α

mRNA expression, and a significant decrease in both IRE1β and MUC2

mRNA and protein levels (92).

Moreover, the expression levels of 23 genes associated with the

mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 signaling pathway were

increased in the IRE1β-knockout intestinal epithelial cells (IECs)

compared with IRE1α knockout IECs in both an ER stress mouse model

treated with tunicamycin, and a colitis mouse model induced by 2.5%

DSS (93). These findings

indicated that, unlike IRE1α, IRE1β exerts a novel non-canonical

splicing target gene unique in IECs.

AGR2 selectively binds to IRE1β, but not IRE1α.

AGR2, a member of the protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) family with

redox and molecular chaperone functions that process and modify

immature mucins into mature mucins, is highly expressed in goblet

cells (94). AGR2 forms disulfide

bonds with the N- and C-terminal cysteine-rich sections of MUC2

(94). Impaired AGR2 function,

such as H117Y mutation and S-glutathiolation modification, directly

suppresses MUC2 biosynthesis, inducing ER stress and driving IBD

pathogenesis (58,95). Bio-Layer Interferometry revealed a

half-maximal binding concentration of 19 µM for binding of the

IRE1β luminal domain (LD) to AGR2, whereas an immobilized IRE1α LD

resulted in significantly weaker binding signals with AGR2

(96). The interaction between

IRE1β and AGR2 does not involve disulfide bonds, and AGR2 binding

favors the formation of IRE1β LD monomers (96). Both the C81S and H117Y mutations in

AGR2 abrogate its ability to bind and inhibit IRE1β activity

(97). Importantly, both the

N-terminus (residues 21–1,397) and the C-terminus (residues

4,198-6,178) of MUC2 have a derepression effect on the IRE1β-AGR2

pair, and the derepression effect on IRE1α is relatively weak under

the same conditions (96).

These results suggest that the IRE1β-mediated UPR

likely works by binding with AGR2 in a manner such as that of BiP

and IRE1α, by antagonizing IRE1β LD dimerization (Fig. 2) (98). The IRE1β-AGR2 pathway may be an

important UPR pathway in goblet cells.

MUC2 dysfunction disrupts intestinal host-commensal

homeostasis. An imbalance in host-microbiota interactions leading

to a thinner mucus layer may be an early sign of IBD (99). The exposed terminal glycans on the

outer surface of MUC2 can be recognized by bacteria and lectins,

providing adhesion binding sites for intestinal commensal bacteria

and utilizing mucin O-glycans as an energy source (27). Escherichia coli secretes the

metalloprotease SslE, Vibrio cholerae secretes the

metalloprotease TagA, and Candida albicans secretes the

aspartyl protease Sap2, which can all degrade mucins, potentially

allowing microbial penetration of the mucosal barrier (100). Decreased MUC2 expression induced

by REGγ gene deficiency in goblet cells leads to dysregulation of

the intestinal flora (101).

ST6GalNAc1 (ST6)-mediated sialylation protects MUC2 from bacterial

proteolytic (such as protease of C1 esterase inhibitor and

O-glycoprotease) degradation to maintain mucus integrity, and ST6

R319Q mutation mice harbor a different microbiome with less

diversity (102).

MUC2 dysfunction leads to an imbalance in the

extracellular matrix (ECM), resulting in ECM remodeling, and

further exacerbating intestinal fibrosis in IBD. The ECM forms a

complex network of multidomain macromolecules composed of collagen,

elastin, fibronectin, laminin, aminoglycans and proteoglycans

(103). ECM provides structural

support to IECs while cooperatively establishing intestinal barrier

function with the mucus layer (103). Upon disruption of the mucus

barrier, bacterial products such as lipopolysaccharides recruit

neutrophils, which release MMPs and elastase, leading to excessive

degradation of ECM components including elastin, collagen,

fibronectin, and proteoglycans (104). Although probiotics generally have

beneficial effects, there is a risk that probiotics (such as

Bacteroides fragilis and Lactobacillus gasseri) may

degrade the ECM components abundant in either the mucosa or

submucosa (collagen I and IV, laminin, fibronectin and hyaluronic

acid) and exacerbate inflammation (105).

Although appropriate UPR have beneficial effects,

chronic and aberrant UPR aggravates ECM remodeling, which in turn

exacerbates MUC2 dysfunction. The IRE1α/XBP1 arm of the UPR

upregulates the expression of integrins, laminins, collagens, MMP1,

MMP10 and MMP9 in epithelial cells, which further leads to the

remodeling of the basement membrane (106). Excessive degradation of the ECM

may inhibit the differentiation of intestinal stem cells into

goblet cells by increasing yes-associated protein 1 (YAP)-dependent

signaling, thereby reducing the MUC2 synthesis (107,108). Moreover, excessive

proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α and

interleukin 13 produced in the ECM upregulate MUC2 mRNA synthesis,

which increases the metabolic load on intestinal cells and causes

ER stress in IECs (109,110).

The development of artificial mucus layer and

small-molecule drugs targeting the UPR signaling pathway have shown

efficacy in IBD. An artificial mucus layer formed from a

thiol-substituted hyaluronic acid derivative excellent protection

against the penetration of Escherichia coli (111). Epithelial cell ER-targeted

protein, a recombinant variant of the cholera toxin B subunit,

induces colon epithelial mucosal healing in colitis by activating

the IRE1α/XBP1 arm of the UPR in colon epithelial cells (112,113). Integrated stress response

inhibitor, a small molecule inhibitor of the UPR, blocks eIF2α

phosphorylation and PERK pathway activation, thereby preserving

intestinal epithelial integrity in IBD by mitigating aberrant

apoptosis (114). The development

of small-molecule drugs targeting the IRE1β-AGR2-MUC2 axis of the

UPR in goblet cells and further elucidating the functional

distinctions between IRE1α and IRE1β may provide new strategies for

mucosal healing in IBD.

The effects of UPR signaling pathways are intricate

and interconnected and involve both positive and negative effects.

The present review emphasizes the positive impact of the UPR on the

synthesis of MUC2 in early-IBD. But its negative effects, such as

the induction of apoptosis and ECM remodeling, cannot be ignored.

Focusing solely on isolated aspects of mucus layer function yields

limited understanding, research and therapeutic strategies should

adopt a holistic approach.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by Three-year Action Plan for

the Construction of the Public Health System of Songjiang

(Shanghai, China; 2023-2025) (grant no. SJGW6-23).

Not applicable.

ZWY and FZ designed and supervised the review. ZX,

LYL and JZX conducted literature organization and revised the

review. ZWY contributed to draft the manuscript. ZWY and FZ

reviewed this manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript

and approved all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved

the final version of the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Gilliland A, Chan JJ, De Wolfe TJ, Yang H

and Vallance BA: Pathobionts in inflammatory bowel disease:

Origins, underlying mechanisms, and implications for clinical care.

Gastroenterology. 166:44–58. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Zhou JL, Bao JC, Liao XY, Chen YJ, Wang

LW, Fan YY, Xu QY, Hao LX, Li KJ, Liang MX, et al: Trends and

projections of inflammatory bowel disease at the global, regional

and national levels, 1990–2050: a bayesian age-period-cohort

modeling study. BMC Public Health. 23:25072023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wyatt NJ, Watson H, Anderson CA, Kennedy

NA, Raine T, Ahmad T, Allerton D, Bardgett M, Clark E, Clewes D, et

al: Defining predictors of responsiveness to advanced therapies in

Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis: protocol for the

IBD-RESPONSE and nested CD-metaRESPONSE prospective, multicentre,

observational cohort study in precision medicine. BMJ Open.

14:e0736392024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Heller C, Moss AC and Rubin DT: Overview

to challenges in IBD 2024–2029. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 30 (Suppl

2):S1–S4. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Gasaly N, Hermoso MA and Gotteland M:

Butyrate and the fine-tuning of colonic homeostasis: Implication

for inflammatory bowel diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 22:30612021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

van der Post S, Jabbar KS, Birchenough G,

Arike L, Akhtar N, Sjovall H, Johansson MEV and Hansson GC:

Structural weakening of the colonic mucus barrier is an early event

in ulcerative colitis pathogenesis. Gut. 68:2142–2151. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Reznik N, Gallo AD, Rush KW, Javitt G,

Fridmann-Sirkis Y, Ilani T, Nairner NA, Fishilevich S, Gokhman D,

Chacón KN, et al: Intestinal mucin is a chaperone of multivalent

copper. Cell. 185:4206–4215.e11. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Tonetti FR, Eguileor A and Llorente C:

Goblet cells: Guardians of gut immunity and their role in

gastrointestinal diseases. eGastroenterology. 2:e1000982024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Leoncini G, Cari L, Ronchetti S, Donato F,

Caruso L, Calafà C and Villanacci V: Mucin expression profiles in

ulcerative colitis: New Insights on the histological mucosal

healing. Int J Mol Sci. 25:18582024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yao D, Dai W, Dong M, Dai C and Wu S: MUC2

and related bacterial factors: Therapeutic targets for ulcerative

colitis. EBioMedicine. 74:1037512021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kang Y, Park H, Choe BH and Kang B: The

role and function of mucins and its relationship to inflammatory

bowel disease. Front Med (Lausanne). 9:8483442022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wu M, Wu Y, Li J, Bao Y, Guo Y and Yang W:

The dynamic changes of gut microbiota in Muc2 deficient mice. Int J

Mol Sci. 19:28092018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Van der Sluis M, De Koning BA, De Bruijn

AC, Velcich A, Meijerink JP, Van Goudoever JB, Büller HA, Dekker J,

Van Seuningen I, Renes IB and Einerhand AW: Muc2-deficient mice

spontaneously develop colitis, indicating that MUC2 is critical for

colonic protection. Gastroenterology. 131:117–129. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Engevik MA, Herrmann B, Ruan W, Engevik

AC, Engevik KA, Ihekweazu F, Shi Z, Luck B, Chang-Graham AL,

Esparza M, et al: Bifidobacterium dentium-derived

y-glutamylcysteine suppresses ER-mediated goblet cell stress and

reduces TNBS-driven colonic inflammation. Gut Microbes. 13:1–21.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Das I, Png CW, Oancea I, Hasnain SZ,

Lourie R, Proctor M, Eri RD, Sheng Y, Crane DI, Florin TH and

McGuckin MA: Glucocorticoids alleviate intestinal ER stress by

enhancing protein folding and degradation of misfolded proteins. J

Exp Med. 210:1201–1216. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Heazlewood CK, Cook MC, Eri R, Price GR,

Tauro SB, Taupin D, Thornton DJ, Png CW, Crockford TL, Cornall RJ,

et al: Aberrant mucin assembly in mice causes endoplasmic reticulum

stress and spontaneous inflammation resembling ulcerative colitis.

PLoS Med. 5:e542008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

López-Cauce B, Puerto M, García JJ,

Ponce-Alonso M, Becerra-Aparicio F, Del Campo R, Peligros I,

Fernández-Aceñero MJ, Gómez-Navarro Y, Lara JM, et al: Akkermansia

deficiency and mucin depletion are implicated in intestinal barrier

dysfunction as earlier event in the development of inflammation in

interleukin-10-deficient mice. Front Microbiol. 13:10838842023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wiseman RL, Mesgarzadeh JS and Hendershot

LM: Reshaping endoplasmic reticulum quality control through the

unfolded protein response. Mol Cell. 82:1477–1491. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Gao H, He C, Hua R, Guo Y, Wang B, Liang

C, Gao L, Shang H and Xu JD: Endoplasmic reticulum stress of gut

enterocyte and intestinal diseases. Front Mol Biosci. 9:8173922022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Fekete E and Buret AG: The role of mucin

O-glycans in microbiota dysbiosis, intestinal homeostasis, and

host-pathogen interactions. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver

Physiol. 324:G452–G465. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Gum JR Jr, Hicks JW, Toribara NW, Siddiki

B and Kim YS: Molecular cloning of human intestinal mucin (MUC2)

cDNA. Identification of the amino terminus and overall sequence

similarity to prepro-von Willebrand factor. J Biol Chem.

269:2440–2446. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Liu Y, Yu Z, Zhu L, Ma S, Luo Y, Liang H,

Liu Q, Chen J, Guli S and Chen X: Orchestration of MUC2-The key

regulatory target of gut barrier and homeostasis: A review. Int J

Biol Macromol. 236:1238622023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Gallego P, Garcia-Bonete MJ, Trillo-Muyo

S, Recktenwald CV, Johansson MEV and Hansson GC: The intestinal

MUC2 mucin C-terminus is stabilized by an extra disulfide bond in

comparison to von Willebrand factor and other gel-forming mucins.

Nat Commun. 14:19692023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Stanforth KJ, Zakhour MI, Chater PI,

Wilcox MD, Adamson B, Robson NA and Pearson JP: The MUC2 gene

product: Polymerisation and post-secretory organisation-current

models. Polymers (Basel). 16:16632024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Liu Y, Yu X, Zhao J, Zhang H, Zhai Q and

Chen W: The role of MUC2 mucin in intestinal homeostasis and the

impact of dietary components on MUC2 expression. Int J Biol

Macromol. 164:884–891. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Pelaseyed T, Bergström JH, Gustafsson JK,

Ermund A, Birchenough GM, Schütte A, van der Post S, Svensson F,

Rodríguez-Piñeiro AM, Nyström EE, et al: The mucus and mucins of

the goblet cells and enterocytes provide the first defense line of

the gastrointestinal tract and interact with the immune system.

Immunol Rev. 260:8–20. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Luis AS and Hansson GC: Intestinal mucus

and their glycans: A habitat for thriving microbiota. Cell Host

Microbe. 31:1087–1100. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Arike L and Hansson GC: The densely

o-glycosylated MUC2 mucin protects the intestine and provides food

for the commensal bacteria. J Mol Biol. 428:3221–3229. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

McCool DJ, Okada Y, Forstner JF and

Forstner GG: Roles of calreticulin and calnexin during mucin

synthesis in LS180 and HT29/A1 human colonic adenocarcinoma cells.

Biochem J. 341((Pt 3)): 593–600. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Johansson ME, Larsson JM and Hansson GC:

The two mucus layers of colon are organized by the MUC2 mucin,

whereas the outer layer is a legislator of host-microbial

interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 108 (Suppl 1):S4659–S4665.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Larsson JM, Karlsson H, Crespo JG,

Johansson ME, Eklund L, Sjövall H and Hansson GC: Altered

O-glycosylation profile of MUC2 mucin occurs in active ulcerative

colitis and is associated with increased inflammation. Inflamm

Bowel Dis. 17:2299–2307. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Javitt G, Khmelnitsky L, Albert L, Bigman

LS, Elad N, Morgenstern D, Ilani T, Levy Y, Diskin R and Fass D:

Assembly mechanism of mucin and von willebrand factor polymers.

Cell. 183:717–729.e16. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Bergstrom KS and Xia L: Mucin-type

O-glycans and their roles in intestinal homeostasis. Glycobiology.

23:1026–1037. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Paone P and Cani PD: Mucus barrier, mucins

and gut microbiota: The expected slimy partners? Gut. 69:2232–2243.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Kouka T, Akase S, Sogabe I, Jin C,

Karlsson NG and Aoki-Kinoshita KF: Computational modeling of

o-linked glycan biosynthesis in CHO Cells. Molecules. 27:17662022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Nielsen MI, de Haan N, Kightlinger W, Ye

Z, Dabelsteen S, Li M, Jewett MC, Bagdonaite I, Vakhrushev SY and

Wandall HH: Global mapping of GalNAc-T isoform-specificities and

O-glycosylation site-occupancy in a tissue-forming human cell line.

Nat Commun. 13:62572022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Bennett EP, Mandel U, Clausen H, Gerken

TA, Fritz TA and Tabak LA: Control of mucin-type O-glycosylation: A

classification of the polypeptide GalNAc-transferase gene family.

Glycobiology. 22:736–756. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Brockhausen I, Wandall HH, Hagen KGT and

Stanley P: O-GalNAc Glycans. Essentials of Glycobiology. Varki A,

Cummings RD, Esko JD, Stanley P, Hart GW, Aebi M, Mohnen D,

Kinoshita T, Packer NH, Prestegard JH, Schnaar RL and Seeberger PH:

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York, USA: pp. 117–128.

2022

|

|

39

|

Xia L, Ju T, Westmuckett A, An G, Ivanciu

L, McDaniel JM, Lupu F, Cummings RD and McEver RP: Defective

angiogenesis and fatal embryonic hemorrhage in mice lacking core

1-derived O-glycans. J Cell Biol. 164:451–459. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Bergstrom K, Fu J, Johansson ME, Liu X,

Gao N, Wu Q, Song J, McDaniel JM, McGee S, Chen W, et al: Core 1-

and 3-derived O-glycans collectively maintain the colonic mucus

barrier and protect against spontaneous colitis in mice. Mucosal

Immunol. 10:91–103. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Schwientek T, Yeh JC, Levery SB, Keck B,

Merkx G, van Kessel AG, Fukuda M and Clausen H: Control of O-glycan

branch formation. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel

thymus-associated core 2 beta1, 6-n-acetylglucosaminyltransferase.

J Biol Chem. 275:11106–11113. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Hansson GC: Mucins and the Microbiome.

Annu Rev Biochem. 89:769–793. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Song C, Chai Z, Chen S, Zhang H, Zhang X

and Zhou Y: Intestinal mucus components and secretion mechanisms:

what we do and do not know. Exp Mol Med. 55:681–691. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Wang Z and Shen J: The role of goblet

cells in Crohn's disease. Cell Biosci. 14:432024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Birchenough GM, Johansson ME, Gustafsson

JK, Bergström JH and Hansson GC: New developments in goblet cell

mucus secretion and function. Mucosal Immunol. 8:712–719. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Ambort D, Johansson ME, Gustafsson JK,

Nilsson HE, Ermund A, Johansson BR, Koeck PJ, Hebert H and Hansson

GC: Calcium and pH-dependent packing and release of the gel-forming

MUC2 mucin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 109:5645–5650. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Harrison CA, Laubitz D, Ohland CL,

Midura-Kiela MT, Patil K, Besselsen DG, Jamwal DR, Jobin C, Ghishan

FK and Kiela PR: Microbial dysbiosis associated with impaired

intestinal Na(+)/H(+) exchange accelerates and exacerbates colitis

in ex-germ free mice. Mucosal Immunol. 11:1329–1341. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Ridley C, Kouvatsos N, Raynal BD, Howard

M, Collins RF, Desseyn JL, Jowitt TA, Baldock C, Davis CW,

Hardingham TE and Thornton DJ: Assembly of the respiratory mucin

MUC5B: A new model for a gel-forming mucin. J Biol Chem.

289:16409–16420. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Johansson ME, Phillipson M, Petersson J,

Velcich A, Holm L and Hansson GC: The inner of the two Muc2

mucin-dependent mucus layers in colon is devoid of bacteria. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 105:15064–15069. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Nyström EEL, Birchenough GMH, van der Post

S, Arike L, Gruber AD, Hansson GC and Johansson MEV:

Calcium-activated chloride channel regulator 1 (CLCA1) controls

mucus expansion in colon by proteolytic activity. EBioMedicine.

33:134–143. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Nyström EEL, Arike L, Ehrencrona E,

Hansson GC and Johansson MEV: Calcium-activated chloride channel

regulator 1 (CLCA1) forms non-covalent oligomers in colonic mucus

and has mucin 2-processing properties. J Biol Chem.

294:17075–17089. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Sharpen JDA, Dolan B, Nyström EEL,

Birchenough GMH, Arike L, Martinez-Abad B, Johansson MEV, Hansson

GC and Recktenwald CV: Transglutaminase 3 crosslinks the secreted

gel-forming mucus component Mucin-2 and stabilizes the colonic

mucus layer. Nat Commun. 13:452022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Ma X, Dai Z, Sun K, Zhang Y, Chen J, Yang

Y, Tso P, Wu G and Wu Z: Intestinal epithelial cell endoplasmic

reticulum stress and inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis: An

update review. Front Immunol. 8:12712017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Verjan Garcia N, Hong KU and Matoba N: The

unfolded protein response and its implications for novel

therapeutic strategies in inflammatory bowel disease. Biomedicines.

11:20662023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Chieppa M, De Santis S and Verna G: Winnie

mice: A chronic and progressive model of ulcerative colitis.

Inflamm Bowel Dis. 31:1158–1167. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Liso M, De Santis S, Verna G, Dicarlo M,

Calasso M, Santino A, Gigante I, Eri R, Raveenthiraraj S,

Sobolewski A, et al: A specific mutation in muc2 determines early

dysbiosis in colitis-prone winnie mice. Inflamm Bowel Dis.

26:546–556. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Kaser A and Blumberg RS: Endoplasmic

reticulum stress in the intestinal epithelium and inflammatory

bowel disease. Semin Immunol. 21:156–163. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Al-Shaibi AA, Abdel-Motal UM, Hubrack SZ,

Bullock AN, Al-Marri AA, Agrebi N, Al-Subaiey AA, Ibrahim NA,

Charles AK; COLORS in IBD-Qatar Study Group, ; et al: Human AGR2

deficiency causes mucus barrier dysfunction and infantile

inflammatory bowel disease. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol.

12:1809–1830. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Kudelka MR, Stowell SR, Cummings RD and

Neish AS: Intestinal epithelial glycosylation in homeostasis and

gut microbiota interactions in IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

17:597–617. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Grondin JA, Kwon YH, Far PM, Haq S and

Khan WI: Mucins in intestinal mucosal defense and inflammation:

Learning from clinical and experimental studies. Front Immunol.

11:20542020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Pelaseyed T and Hansson GC: Membrane

mucins of the intestine at a glance. J Cell Sci. 133:jcs2409292020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Hosomi S, Kaser A and Blumberg RS: Role of

endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagy as interlinking pathways

in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin

Gastroenterol. 31:81–88. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Li H, Wen W and Luo J: Targeting

endoplasmic reticulum stress as an effective treatment for

alcoholic pancreatitis. Biomedicines. 10:1082022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Oikawa D, Kimata Y, Kohno K and Iwawaki T:

Activation of mammalian IRE1alpha upon ER stress depends on

dissociation of BiP rather than on direct interaction with unfolded

proteins. Exp Cell Res. 315:2496–2504. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Deka D, D'Incà R, Sturniolo GC, Das A,

Pathak S and Banerjee A: Role of ER stress mediated unfolded

protein responses and ER stress inhibitors in the pathogenesis of

inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 67:5392–5406. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Le Goupil S, Laprade H, Aubry M and Chevet

E: Exploring the IRE1 interactome: From canonical signaling

functions to unexpected roles. J Biol Chem. 300:1071692024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Ferri E, Le Thomas A, Wallweber HA, Day

ES, Walters BT, Kaufman SE, Braun MG, Clark KR, Beresini MH,

Mortara K, et al: Activation of the IRE1 RNase through remodeling

of the kinase front pocket by ATP-competitive ligands. Nat Commun.

11:63872020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Hetz C, Zhang K and Kaufman RJ:

Mechanisms, regulation and functions of the unfolded protein

response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 21:421–438. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Lu Y, Liang FX and Wang X: A synthetic

biology approach identifies the mammalian UPR RNA ligase RtcB. Mol

Cell. 55:758–770. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Yamamoto K, Yoshida H, Kokame K, Kaufman

RJ and Mori K: Differential contributions of ATF6 and XBP1 to the

activation of endoplasmic reticulum stress-responsive cis-acting

elements ERSE, UPRE and ERSE-II. J Biochem. 136:343–350. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Ong G and Logue SE: Unfolding the

interactions between endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative

stress. Antioxidants (Basel). 12:9812023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Lu M, Lawrence DA, Marsters S,

Acosta-Alvear D, Kimmig P, Mendez AS, Paton AW, Paton JC, Walter P

and Ashkenazi A: Opposing unfolded-protein-response signals

converge on death receptor 5 to control apoptosis. Science.

345:98–101. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Wek RC, Anthony TG and Staschke KA:

Surviving and adapting to stress: Translational control and the

integrated stress response. Antioxid Redox Signal. 39:351–373.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Urra H and Hetz C: Fine-tuning PERK

signaling to control cell fate under stress. Nat Struct Mol Biol.

24:789–790. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Kopp MC, Larburu N, Durairaj V, Adams CJ

and Ali MMU: UPR proteins IRE1 and PERK switch BiP from chaperone

to ER stress sensor. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 26:1053–1062. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Elvira R, Cha SJ, Noh GM, Kim K and Han J:

PERK-Mediated eIF2α phosphorylation contributes to the protection

of dopaminergic neurons from chronic heat stress in drosophila. Int

J Mol Sci. 21:8452020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Gorbatyuk MS, Starr CR and Gorbatyuk OS:

Endoplasmic reticulum stress: New insights into the pathogenesis

and treatment of retinal degenerative diseases. Prog Retin Eye Res.

79:1008602020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Ajoolabady A, Lindholm D, Ren J and

Pratico D: ER stress and UPR in Alzheimer's disease: Mechanisms,

pathogenesis, treatments. Cell Death Dis. 13:7062022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Saito A, Ochiai K, Kondo S, Tsumagari K,

Murakami T, Cavener DR and Imaizumi K: Endoplasmic reticulum stress

response mediated by the PERK-eIF2(alpha)-ATF4 pathway is involved

in osteoblast differentiation induced by BMP2. J Biol Chem.

286:4809–4818. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Vattem KM and Wek RC: Reinitiation

involving upstream ORFs regulates ATF4 mRNA translation in

mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 101:11269–11274. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Hooper KM, Barlow PG, Henderson P and

Stevens C: Interactions between autophagy and the unfolded protein

response: Implications for inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm

Bowel Dis. 25:661–671. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Yin S, Li L, Tao Y, Yu J, Wei S, Liu M and

Li J: The inhibitory effect of artesunate on excessive endoplasmic

reticulum stress alleviates experimental colitis in mice. Front

Pharmacol. 12:6297982021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Lei Y, Yu H, Ding S, Liu H, Liu C and Fu

R: Molecular mechanism of ATF6 in unfolded protein response and its

role in disease. Heliyon. 10:e259372024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Ye J, Rawson RB, Komuro R, Chen X, Davé

UP, Prywes R, Brown MS and Goldstein JL: ER stress induces cleavage

of membrane-bound ATF6 by the same proteases that process SREBPs.

Mol Cell. 6:1355–1364. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Jin JK, Blackwood EA, Azizi K, Thuerauf

DJ, Fahem AG, Hofmann C, Kaufman RJ, Doroudgar S and Glembotski CC:

ATF6 decreases myocardial ischemia/reperfusion damage and links ER

stress and oxidative stress signaling pathways in the heart. Circ

Res. 120:862–875. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Grey MJ, Cloots E, Simpson MS, LeDuc N,

Serebrenik YV, De Luca H, De Sutter D, Luong P, Thiagarajah JR,

Paton AW, et al: IRE1β negatively regulates IRE1α signaling in

response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Cell Biol.

219:e2019040482020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Luo H, Gong WY, Zhang YY, Liu YY, Chen Z,

Feng XL, Jiao QB and Zhang XW: IRE1β evolves to be a guardian of

respiratory and gastrointestinal mucosa. Heliyon. 10:e390112024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Haber AL, Biton M, Rogel N, Herbst RH,

Shekhar K, Smillie C, Burgin G, Delorey TM, Howitt MR, Katz Y, et

al: A single-cell survey of the small intestinal epithelium.

Nature. 551:333–339. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Cloots E, Simpson MS, De Nolf C, Lencer

WI, Janssens S and Grey MJ: Evolution and function of the

epithelial cell-specific ER stress sensor IRE1β. Mucosal Immunol.

14:1235–1246. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Johansson ME and Hansson GC: Goblet cells

need some stress. J Clin Invest. 132:e1620302022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Grey MJ, De Luca H, Ward DV, Kreulen IA,

Bugda Gwilt K, Foley SE, Thiagarajah JR, McCormick BA, Turner JR

and Lencer WI: The epithelial-specific ER stress sensor ERN2/IRE1β

enables host-microbiota crosstalk to affect colon goblet cell

development. J Clin Invest. 132:e1535192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Dai F, Dong S, Rong Z, Xuan Q, Chen P,

Chen M, Fan Y and Gao Q: Expression of inositol-requiring enzyme 1β

is downregulated in azoxymethane/dextran sulfate sodium-induced

mouse colonic tumors. Exp Ther Med. 17:3181–3188. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Deng R, Wang M, Promlek T, Druelle-Cedano

C, Murad R, Davidson NO and Kaufman RJ: IRE1α and IRE1β protect

intestinal epithelium and suppress colorectal tumorigenesis through

distinct mechanisms. Preprint. bioRxiv [Preprint].

2025.05.01.651751. 2025.

|

|

94

|

Ye X, Wu J, Li J and Wang H: anterior

gradient protein 2 promotes mucosal repair in pediatric ulcerative

colitis. Biomed Res Int. 2021:64838602021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Wu D, Su S, Zha X, Wei Y, Yang G, Huang Q,

Yang Y, Xia L, Fan S and Peng X: Glutamine promotes O-GlcNAcylation

of G6PD and inhibits AGR2 S-glutathionylation to maintain the

intestinal mucus barrier in burned septic mice. Redox Biol.

59:1025812023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Neidhardt L, Cloots E, Friemel N, Weiss

CAM, Harding HP, McLaughlin SH, Janssens S and Ron D: The

IRE1β-mediated unfolded protein response is repressed by the

chaperone AGR2 in mucin producing cells. EMBO J. 43:719–753. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Cloots E, Guilbert P, Provost M, Neidhardt

L, Van de Velde E, Fayazpour F, De Sutter D, Savvides SN, Eyckerman

S and Janssens S: Activation of goblet-cell stress sensor IRE1β is

controlled by the mucin chaperone AGR2. EMBO J. 43:695–718. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Bertolotti A: Keeping goblet cells

unstressed: new insights into a general principle. EMBO J.

43:663–665. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Cadwell K and Loke P: Gene-environment

interactions shape the host-microbial interface in inflammatory

bowel disease. Nat Immunol. 26:1023–1035. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Valle Arevalo A and Nobile CJ:

Interactions of microorganisms with host mucins: A focus on Candida

albicans. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 44:645–654. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Zhu X, Li Y, Tian X, Jing Y, Wang Z, Yue

L, Li J, Wu L, Zhou X, Yu Z, et al: REGγ mitigates

radiation-induced enteritis by preserving mucin secretion and

sustaining microbiome homeostasis. Am J Pathol. 194:975–988. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Yao Y, Kim G, Shafer S, Chen Z, Kubo S, Ji

Y, Luo J, Yang W, Perner SP, Kanellopoulou C, et al: Mucus

sialylation determines intestinal host-commensal homeostasis. Cell.

185:1172–1188.e28. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Vilardi A, Przyborski S, Mobbs C, Rufini A

and Tufarelli C: Current understanding of the interplay between

extracellular matrix remodelling and gut permeability in health and

disease. Cell Death Discov. 10:2582024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Zhu Y, Huang Y, Ji Q, Fu S, Gu J, Tai N

and Wang X: Interplay between extracellular matrix and neutrophils

in diseases. J Immunol Res. 2021:82433782021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Porras AM, Zhou H, Shi Q, Xiao X; JRI Live

Cell Bank, ; Longman R and Brito IL: Inflammatory bowel

disease-associated gut commensals degrade components of the

extracellular matrix. mBio. 13:e02201222022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Zhao Y, Qiao D, Skibba M and Brasier AR:

The IRE1α-XBP1s Arm of the unfolded protein response activates

N-glycosylation to remodel the subepithelial basement membrane in

paramyxovirus infection. Int J Mol Sci. 23:90002022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Onfroy-Roy L, Hamel D, Foncy J, Malaquin L

and Ferrand A: Extracellular matrix mechanical properties and

regulation of the intestinal stem cells: When mechanics control

fate. Cells. 9:26292020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Gjorevski N, Sachs N, Manfrin A, Giger S,

Bragina ME, Ordóñez-Morán P, Clevers H and Lutolf MP: Designer

matrices for intestinal stem cell and organoid culture. Nature.

539:560–564. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Fionda C and Sciumè G: A little ER stress

isn't bad: The IRE1α/XBP1 pathway shapes ILC3 functions during

intestinal inflammation. J Clin Invest. 134:e1822042024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Ren C, Dokter-Fokkens J, Figueroa Lozano

S, Zhang Q, de Haan BJ, Zhang H, Faas MM and de Vos P: Fibroblasts

impact goblet cell responses to lactic acid bacteria after exposure

to inflammatory cytokines and mucus disruptors. Mol Nutr Food Res.

63:e18014272019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Zhang G, Song D, Ma R, Li M, Liu B, He Z

and Fu Q: Artificial mucus layer formed in response to ROS for the

oral treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Sci Adv.

10:eado82222024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Royal JM, Oh YJ, Grey MJ, Lencer WI,

Ronquillo N, Galandiuk S and Matoba N: A modified cholera toxin B

subunit containing an ER retention motif enhances colon epithelial

repair via an unfolded protein response. FASEB J. 33:13527–13545.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Kittle WM, Reeves MA, Fulkerson AE,

Hamorsky KT, Morris DA, Kitterman KT, Merchant ML and Matoba N:

Preclinical long-term stability and forced degradation assessment

of EPICERTIN, a mucosal healing biotherapeutic for inflammatory

bowel disease. Pharmaceutics. 17:2592025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Zheng T, Huang KY, Tang XD, Wang FY and Lv

L: Endoplasmic reticulum stress in gut inflammation: Implications

for ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. World J Gastroenterol.

31:1046712025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|