Introduction

Fluid and blood transfusion-based resuscitation

after hemorrhagic shock (HSR) can result in damage to multiple

organs (1,2). Acute lung injury (ALI) is common and

severe (3,4). However, the treatment options for

managing lung injury are currently limited and primarily involve

ventilation volume and positional changes (5,6).

Thus, effective pharmacological treatments are limited (6–8). Our

previous research demonstrated an increase in inflammatory

cytokines and exacerbated apoptosis in the HSR-ALI model (9,10).

In patients with HSR, tissue hypoxia induces an early inflammatory

response characterized by the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines

such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). This promotes neutrophil

infiltration and vascular endothelial disruption. During

reperfusion, the reintroduction of oxygen leads to the generation

of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS), which further

exacerbate inflammation and apoptosis (11). These findings suggest that

targeting inflammation, apoptosis, and ROS/RNS might offer

potential therapeutic strategies for mitigating HSR-induced lung

injury.

After hemorrhagic shock (HS), patients are exposed

to a hyper-catecholaminergic state characterized by enhanced

sympathetic nervous system activity (12). In particular, β1 adrenergic

receptor activation leads to increased heart rate and myocardial

contractility, which consequently elevates metabolic demand and

causes an imbalance between oxygen supply and demand. This

imbalance may exacerbate ischemia-reperfusion injury and trigger

systemic inflammation (13).

β1-adrenergic receptor stimulation has been reported to enhance the

secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines in human monocytes and

induce apoptosis when stimulated by β1-selective agonists (14,15).

Therefore, β1-blockade is considered a promising strategy for

suppressing these detrimental responses. Notably, the β2 receptor

pathway is preserved even with the use of β1 blockers. The β2

receptor pathway includes the 5′ adenosine monophosphate-activated

protein kinase (AMPK) pathway, which contributes to sustaining

homeostasis; reducing oxidative stress, mitigating mitochondrial

dysfunction, suppressing inflammatory responses, and activating

autophagy to maintain normal bodily functions (13,16,17).

Landiolol hydrochloride, a highly selective β1

blocker, has been employed to manage tachycardia and reduce the

risk of atrial fibrillation during the perioperative phase and

cardiac decompensation. The β1/β2 receptor selectivity ratio of

landiolol (255) is substantially higher than those of commonly used

β-blockers such as esmolol (33),

atenolol (4.3), metoprolol (2.3), and propranolol (0.68), as shown

in Table I (18,19).

It also exhibits approximately eightfold greater β1-selectivity

than does esmolol, with minimal activity on β2 receptors (18). Owing to this pharmacological

profile, landiolol was selected in this study to evaluate its

effects on lung injury following HSR. Although primarily used as an

anti-arrhythmic drug, recent studies have reported that β1 blockers

offer organ protection, including lung protection (20–25).

These findings have been primarily observed in sepsis and

ischemia-reperfusion models. In the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) model,

landiolol treatment has been shown to enhance serum levels of

TNF-α, interleukin (IL)-6, and high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1),

along with reducing TNF-α expression in the liver (20,24).

Conversely, some studies have reported no alterations in serum

levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, or in TNF-α and IL-6 expression

in the lungs, resulting in inconsistent findings (21,25).

| Table I.β1/β2 receptor selectivity ratios of

commonly used β-blockers. |

Table I.

β1/β2 receptor selectivity ratios of

commonly used β-blockers.

| β-blocker | β1/β2 selectivity

ratio |

|---|

| Landiolol | 255 |

| Esmolol | 33 |

| Atenolol | 4.3 |

| Metoprolol | 2.3 |

| Propranolol | 0.68 |

In this study, landiolol was administered following

HSR. To our knowledge, no prior research has examined the effects

of landiolol on inflammatory cytokines and lung apoptosis in the

HSR-ALI model. The study aimed to explore the potential of

landiolol treatment after HSR for protecting lung tissue by

decreasing inflammatory responses and apoptosis.

Materials and methods

Animals

This research received approval from the Department

of Animal Resources at the Advanced Science Research Center,

Okayama University (OKU-2021247 on April 1, 2021 and OKU-2023436 on

April 24, 2023; Okayama, Japan) and adhered to the Guidelines for

the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals based on ARRIVE (26) and the 2020 AVMA euthanasia

guidelines (27). Male

Sprague-Dawley rats, weighing 350–430 g (Clea Japan, Inc., Tokyo,

Japan), were kept in temperature-regulated rooms (25°C) with a 12-h

light/dark cycle and had unrestricted access to water and food

prior to the experiments. A total of sixty-nine rats were used in

this study. Five rats were assigned to a control group without

undergoing any procedures. Since there was no statistically

significant difference between the control and sham groups, data of

the control group were excluded from statistical analysis.

Twenty-four rats were excluded from the analysis. Of these

twenty-four rats, nineteen were excluded due to technical issues

encountered during the HS procedure. These issues included failure

to monitor blood pressure due to thrombosis, inability to achieve

the target hypotensive state due to insufficient bleeding, or

catheter dislodgement that prevented continuation of the

experiment. All of these complications occurred during the HS

procedure, and animals that could not proceed with the study were

promptly euthanized. The other five rats died naturally from

worsening hypotension during the HS procedure, despite attempts at

resuscitation. The remaining forty rats successfully completed the

experimental protocol and their data were included in the final

analysis. These were divided equally into two groups: twenty in the

3-h model (n=5 each, four groups) and twenty in the 24-h model (n=5

each, four groups). All animals that successfully underwent the HSR

procedure survived. The sample size was decided based on previous

studies (28,29).

All rats were numbered sequentially upon arrival and

housed under identical conditions in uniformly sized cages placed

in the same location. All experimental procedures were consistently

performed under the same environmental conditions and followed a

predetermined order. Group assignment and drug preparation were

carried out by H. Shimizu. R. Sakamoto was responsible for

performing the HSR and sham procedures. Both R. Sakamoto and H.

Shimizu jointly conducted sampling and data analysis. Information

on group assignments was disclosed to R. Sakamoto only after sample

collection completion. The rats were euthanized for sampling under

2–3% isoflurane anesthesia by performing a laparotomy and

exsanguination via the abdominal aorta.

All rats included were confirmed to be healthy and

alive before starting the experiment. Isoflurane was used

throughout all procedures to provide adequate sedation and

analgesia. Humane endpoints were predefined based on criteria such

as ≥20% body weight loss or a marked decrease in physical activity.

However, none of the animals that successfully completed the HSR

procedure met these exclusion criteria during the study course. No

special housing conditions were required.

Drug preparation

Prior to administration, landiolol (Landiolol

Hydrochloride, Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) was

dissolved in saline and tailored to the correct dosage (100

µg/kg/min per body weight in 2 ml of saline). The dosage of

landiolol used in this study was determined with reference to

previously published studies (20,21,24,25).

Hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation

(HSR) protocol

During the experiments, the rats were anesthetized

with isoflurane (0.8–2%) and underwent either sham or HSR surgery.

Inhalational anesthesia was performed in a chamber containing

isoflurane (4–5%) for induction. After confirming loss of both the

righting reflex and the tail pinch reflex, anesthesia was

maintained at a dosage of 0.8–2% via a face mask, in accordance

with the approved animal experiment protocol (OKU2023436), with the

most common concentrations being 5% for induction and 1.3 or 1% for

maintenance, during which anesthetic depth was assessed by the

absence of spontaneous movements. The vaporizer setting was reduced

to below 1% only when marked bradycardia (approximately half of the

normal heart rate) was observed. In the five rats that eventually

died, this bradycardia was followed within several minutes by

persistent hypotension, cardiac arrest and respiratory arrest.

During these events, the isoflurane concentration was initially

lowered and blood reinfusion was subsequently initiated in an

attempt to stabilize the hemodynamic condition. Although euthanasia

was also considered in these critical situations, it was difficult

to perform because the progression from bradycardia to cardiac and

respiratory arrest occurred within a very short period of time. The

concentration of isoflurane was verified using a vaporizer. The HSR

model was created as previously described (9,10,30,31).

The left femoral artery and vein were dissected using aseptic

procedures, and 22- and 24-gauge catheters were inserted,

respectively. The left femoral artery catheter was used to measure

blood pressure, whereas the left femoral vein catheter was used for

inducing HSR. After measuring the baseline blood pressure,

hemorrhage was initiated for over 15 min, aiming to maintain a mean

arterial blood pressure of 30 mmHg, which was achieved by bleeding

into a heparinized syringe (10 units/ml). The animals were

maintained at this blood pressure (30±5 mmHg) for 45 min through

additional blood withdrawal or shed blood infusion. Subsequently,

resuscitation was performed for 15 min by administering all the

shed blood until the pressure was restored to baseline levels. The

rats were kept under anesthesia for 2 h, during which only the

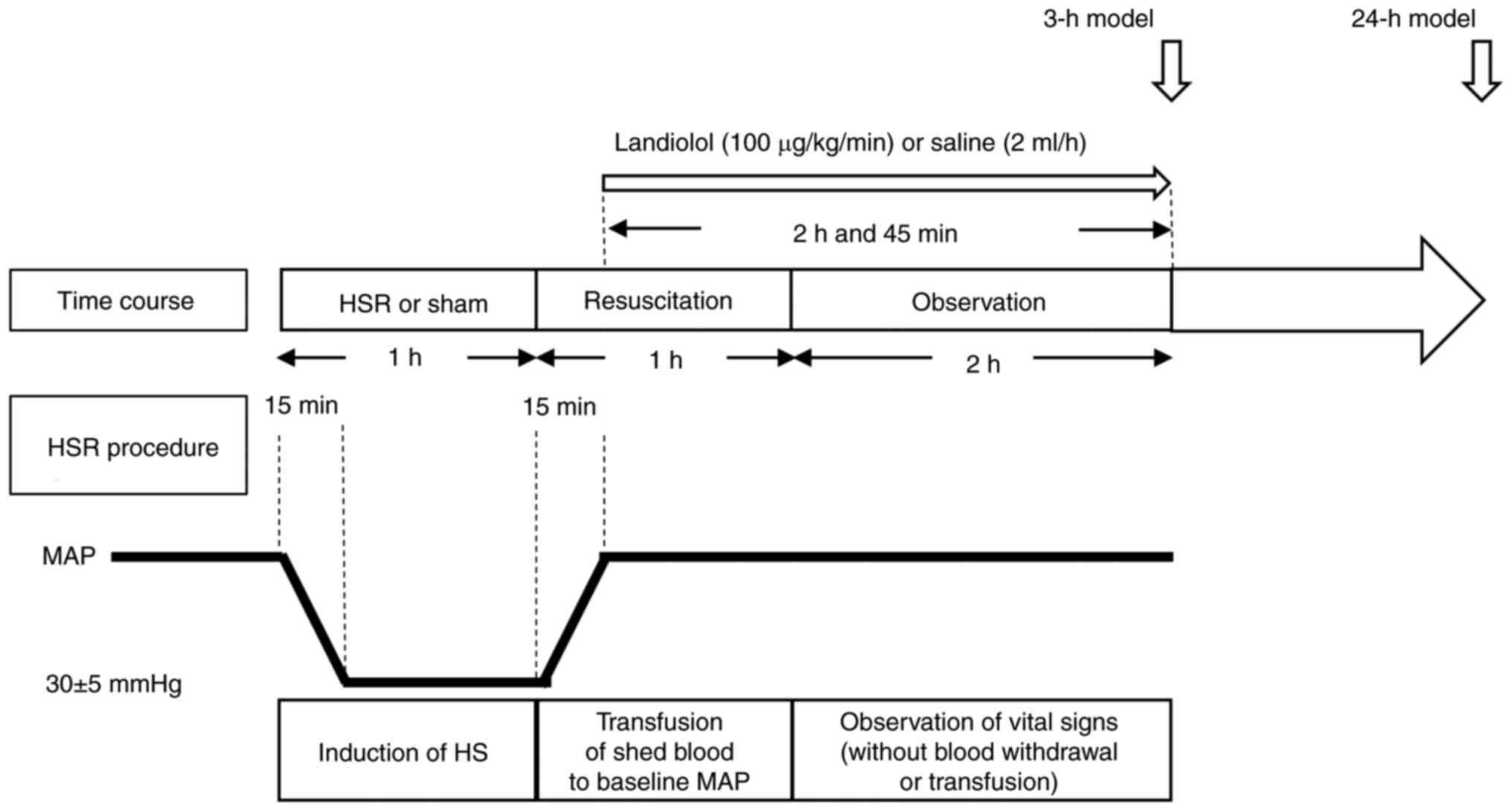

blood pressure and pulse rate were monitored (Fig. 1). The sham group underwent

identical procedures, except for bleeding. All rats maintained

spontaneous breathing throughout the experiment. All procedures

were performed on a heating pad, with continuous monitoring and

regulation to maintain the rectal temperature within the

physiological range.

Experimental design

To examine the effects of landiolol administration

on HSR-induced lung injury, the rats were randomly divided into the

following four groups: sham/saline (n=10), sham/landiolol (n=10),

HSR/saline (n=10), and HSR/landiolol (n=10). Landiolol (100

µg/kg/min) or vehicle (saline 2 ml/h) was injected into the tail

vein after HSR induction or sham surgery (Fig. 1). Continuous infusion was initiated

15 min after starting resuscitation and continued for 2 h and 45

min. The duration of administration was the same in both the 3 and

24-h models. At specific time points (3 h or 24 h) after

resuscitation, the animals were euthanized by phlebotomy under

isoflurane inhalation (2–3%). In our previous study, we found that

TNF-α mRNA expression peaked at 3 h after resuscitation in the rat

HSR-ALI model, supporting this time point for evaluating early

inflammatory gene expression (31). Meanwhile, previous studies have

shown that histological lung injury, lung wet/dry ratio, and

apoptosis markers such as cleaved caspase-3 are most prominent at

24 h post-insult in related ischemia-reperfusion injury models

(32,33). Therefore, the 24-h time point was

selected for assessing lung tissue damage and apoptosis. The left

lung was removed to determine the pulmonary wet-to-dry weight

ratio. The right upper lung was excised, quickly and gently rinsed

with saline, fixed in formalin, and stained for histological

analysis. Regarding the preparation of RNA and proteins, the right

middle and lower lungs were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen

and stored at −80°C until further use.

Measurement of hemodynamic parameters

(blood pressure and heart rate)

To record the arterial pressure, an arterial

catheter was connected to a pressure transducer (Meritrans

DTSPlus® SCK-7874, Merit Medical Japan K.K, Shinjuku-ku,

Tokyo, Japan) attached to a bridge amplifier

(LifeScopeI® BSM-2303, Nihon Kohden Corporation,

Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, Japan). The blood pressure and heart rate were

continuously recorded. The data were measured every 5 min and

saved.

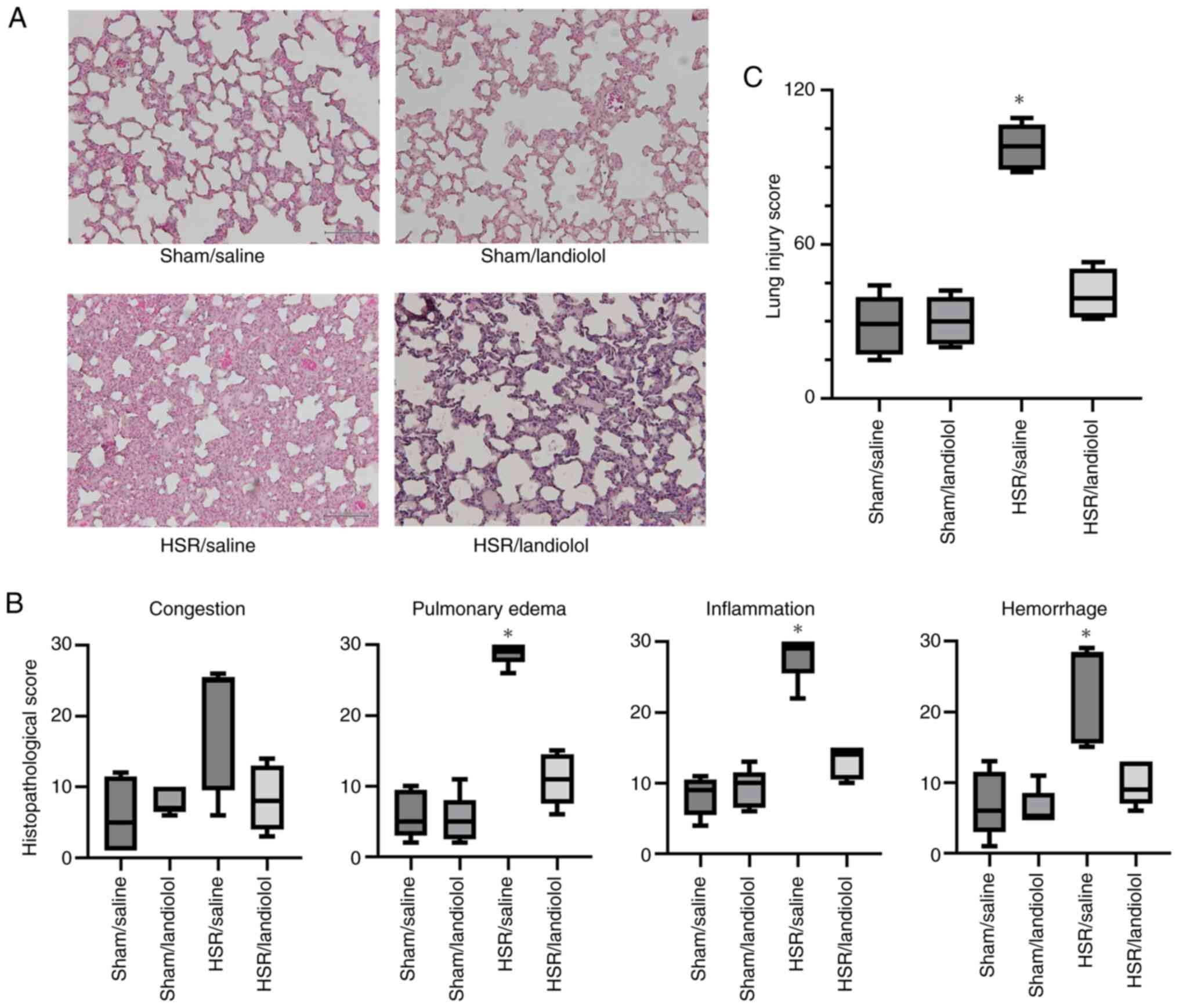

Histopathological examination

After 24 h of resuscitation, the rats were

euthanized using the aforementioned method. Subsequently, the right

upper lobe of the lungs was excised and fixed in 10% neutral

buffered formalin, followed by paraffin embedding and sectioning at

a thickness of 5 µm for histological examinations. Following

deparaffinization and dehydration, the sections were stained with

hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. The lung histological

changes were evaluated using blinded evaluation by five observers

using a light microscope in accordance with previously described

methods (34–36). In each rat, ten regions of lung

parenchyma were assessed on a scale from 0 (normal) to 3 (severe)

for four parameters: intravascular congestion, pulmonary edema,

inflammatory cell infiltration, and intra-alveolar hemorrhage. The

final results were reported as the median total score across these

parameters, with a maximum score of 30 for each parameter and 120

for the combined lung injury score.

Neutrophils in the lungs were stained using a

naphthol AS-D chloroacetate esterase staining kit (Sigma

Diagnostics, St. Louis, MO, USA) on sections adjacent to those used

for the histopathological analysis (30). An observer, blinded to the groups,

counted the positively stained cells in five nonconsecutive

sections per rat at ×400 magnification.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl

transferase-mediated dUTP-fluorescein isothiocyanate nick-end

labeling staining

Transferase-mediated dUTP-fluorescein isothiocyanate

(FITC) nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining was conducted using the

MEBSTAIN Apoptosis TUNEL Kit Direct (No. 8445; MBL, Nagano, Japan)

following the manufacturer's instructions. The sections were

briefly incubated with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase and

FITC-labeled dUTP, then counterstained with 0.5 µg/ml propidium

iodide. TUNEL-positive cells were counted in five non-consecutive

sections per rat at ×400 magnification by a blinded observer using

a Zeiss LSM510 confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss, Jena,

Germany).

Lung wet weight to dry weight

(wet/dry) ratio

The left lung tissue samples were collected 24 h

after resuscitation, weighed for their wet weight, and then dried

at 110°C for 24 h to obtain the dry weight. The wet-to-dry weight

ratio, calculated by dividing the wet weight by the dry weight, was

used as an indicator of pulmonary edema (9,31,37).

RNA isolation and reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

The total RNA was isolated from the lung tissues at

3 h after HSR using TRI REAGENT® (Molecular Research

Center, Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA) following the manufacturer's

instructions. The total RNA was purified using the

RNeasy® Mini kit (Qiagen Sciences, Germantown, MD, USA).

After removing potentially contaminating DNA with DNase I

(RNase-Free DNase set; Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany), reverse

transcription of the total RNA was performed using a

QuantiTect® Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen GmbH) to

generate first-strand cDNA. The PCR mixture was prepared using the

SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan).

PCR was performed using StepOnePlus (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.,

Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The

primer sequences for TNF-α, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS),

and β-actin were as follows: 5′-GCCCTGGTATGAGCCCATGTA-3′ and

5′-CCTCACAGAGCAATGACTCCAAAG-3′ for TNF-α;

5′-CAAACTGTGTGCCTGGAGGTTC-3′ and 5′-AAGTAGGTGAGGGCTTGCCTGA-3′ for

iNOS; and 5′-AACCCTAAGGCCAACCGTGAA-3′ and

5′-CAGGGACAACACAGCCTGGA-3′ for β-actin, respectively. PCR

specificity was confirmed using melting curve analysis and DNA

sequencing. Quantification of gene expression was performed using a

standard curve method, as previously described (38,39).

The mRNA levels of TNF-α and iNOS were normalized to the mRNA level

of β-actin.

Protein extraction

The total proteins were extracted from a portion of

the right lung lobe collected 24 h after establishing the HSR

model, using Tissue Protein Extraction Reagent (T-PER) (Thermo

Fisher Scientific Inc.), according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Lung tissue was briefly homogenized in T-PER containing 5 mM

dithiothreitol, 5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, a protease

inhibitor (cOmplete; Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Sigma-Aldrich, St.

Louis, MO, USA), and phosphatase inhibitors (PhosSTOP; Roche

Diagnostics GmbH, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The sample

was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C, after which the

supernatants were collected and stored for later analysis. Protein

concentrations in the lung homogenates were measured using the

Pierce BCA™ Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) following

the manufacturer's instructions, with readings taken on a Nivo 5

Multimode Microplate Reader (PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT, USA).

Western blot analysis

Samples with approximately 50 µg of protein were

loaded onto sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels (10, 12, or

15% concentration) for electrophoresis, followed by the transfer of

proteins onto Amersham Hybond-PVDF membranes (GE Healthcare Life

Sciences, Chicago, IL, USA). The membranes were blocked at 25°C for

1 h using 4% (w/v) BlockAce (DS Pharma Biomedical Co., Ltd., Osaka,

Japan) or Blocking One-P (NACALAI TESQUE, Inc., Kyoto, Japan).

Subsequently, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with

primary antibodies: cleaved caspase-3 [rabbit anti-cleaved

caspase-3 (Asp175), Cell Signaling, #9661, 1:500], Caspase-3

(rabbit anti-caspase-3, Cell Signaling, #9662, 1:1,000), GAPDH

[rabbit anti-GAPDH (FL 335), Santa Cruz, sc-25778, 1:5,000], pAMPKα

[rabbit anti-phosphorylated-AMPKα (Thr172)(40H9), Cell Signaling,

#2535, 1:1,000], and AMPKα (rabbit anti-AMPKα, Cell Signaling,

#2532 1:1,000). After washing in Tris-buffered saline with Tween

20, the membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies (goat

anti-rabbit IgG-HRP, Abcam, ab6721, 1:20,000 and anti-rabbit

IgG-HRP conjugate, Promega, W401B, 1:20,000) for 1 h at 25°C. The

membranes were then treated with Clarity Western ECL Substrate

(Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's

guidelines. Imaging was done with the ChemiDoc XRS Plus System

(Bio-Rad), with automatic exposure settings, and densitometry

analysis was conducted using Image Lab Version 5.0 software

(Bio-Rad).

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± standard error

of the mean (SEM) or as the median (interquartile range), as

appropriate. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired

Student's t-test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with

Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons, or Kruskal-Wallis test followed

by Dunn's post hoc test for non-parametric data, as appropriate. A

two-sided P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically

significant. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 10

(GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Landiolol administration does not

adversely affect the hemodynamic status after HSR

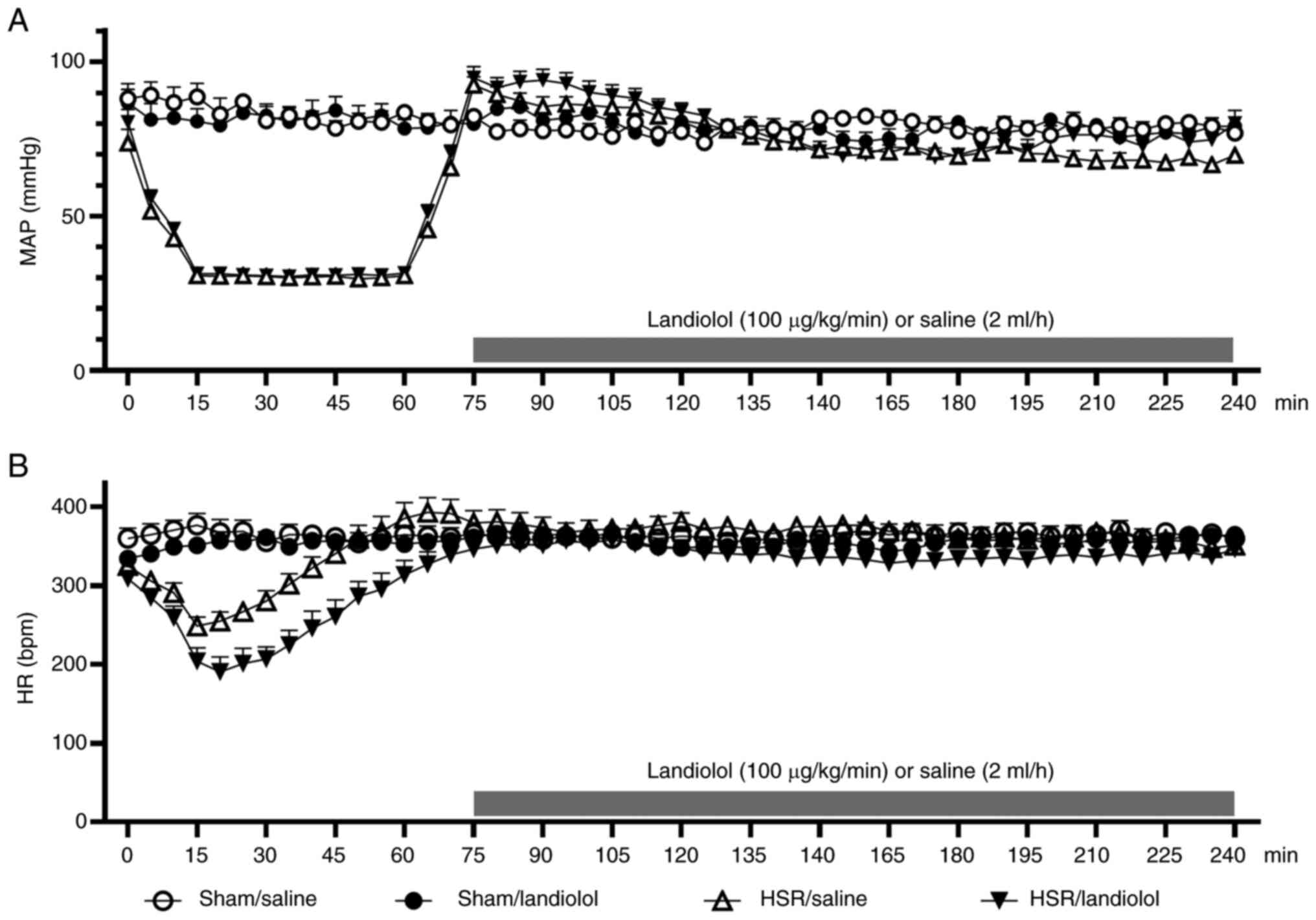

During the HS period, the mean arterial blood

pressure in the HSR groups was maintained within the target range

(30±5 mmHg) (Fig. 1). During the

subsequent resuscitation period, the heart rate and mean blood

pressure did not differ between the sham and HSR groups (Fig. 2A and B). However, during the

observation period after resuscitation, the HSR/saline group

exhibited a tendency toward decreased mean blood pressure compared

with that by the sham/saline group. In contrast, the HSR/landiolol

group showed no significant difference or tendency toward lower

blood pressure compared with that in the HSR/saline group. This

observation suggests that the HSR procedure could cause hypotension

after the procedure; however, landiolol administration did not

induce harmful blood pressure reduction. Regarding the heart rate,

no significant differences were observed among the four groups

after landiolol administration. No significant difference in blood

loss was observed between the HSR/saline and HSR/landiolol groups

(Fig. S1).

Effect of landiolol on HSR-Induced

lung histological damage

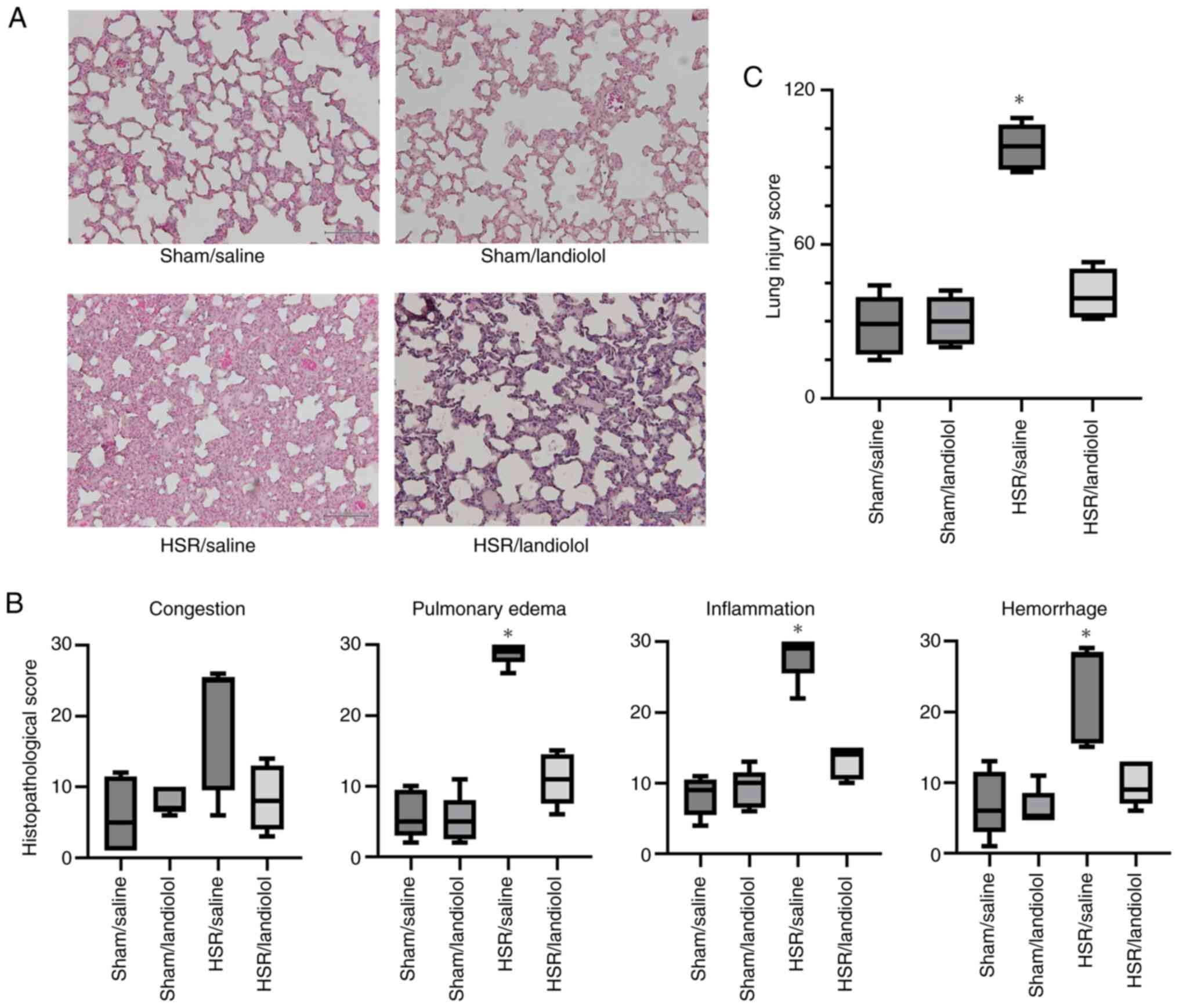

In this study, we examined the effect of landiolol

treatment on lung injury induced by HSR following HS.

Histopathological analysis showed that lung sections from the sham

group appeared approximately normal. In contrast, the HSR/saline

group displayed interstitial edema, marked by noticeable alveolar

septal thickening and inflammatory cell infiltration, 24 h after

HSR (Fig. 3A). Although there was

no statistically significant difference between the HSR/saline and

HSR/landiolol groups, the histopathological score in the

HSR/landiolol group was reduced to a level comparable with that of

the sham/saline group. Landiolol treatment after HSR tended to

attenuate these pathological changes, such as edema, inflammation,

and hemorrhage (Fig. 3A and B).

The impact of landiolol was further validated through

histopathological scoring by an independent, blinded researcher,

showing a decrease in the histopathological score (Fig. 3C).

| Figure 3.Histological assessment of lung

injury following HSR. Lungs were collected from HSR model rats,

treated with or without landiolol, 24 h after resuscitation for

histological analysis. (A) Representative images from four

independent experiments (H&E staining; original magnification,

×200; scale bar, 100 µm). (B) The severity of histopathological

alterations in the lungs was scored for congestion, edema,

inflammation, and hemorrhage. Ten areas of lung parenchyma per rat

were rated on a scale from 0 (normal) to 3 (severe) for each

parameter, resulting in a maximum of 30 points per parameter.

Scoring was performed independently by five blinded observers, and

data are presented as median (interquartile range) and analyzed

using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's post hoc test. (C)

The total histopathological score was calculated by summing scores

across the four parameters, with a maximum possible score of 120.

Again, scoring was performed by five blinded observers, and the

median values (interquartile range) were analyzed using the

Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's post hoc test. The sum score

reflects the extent of lung tissue injury for each group.

*P<0.05 vs. sham/saline. Sham/saline and sham/landiolol groups

received sham surgery with saline or landiolol; HSR/saline and

HSR/landiolol groups underwent HSR with saline or landiolol

administration. HSR, hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation. |

Effect of landiolol administration on

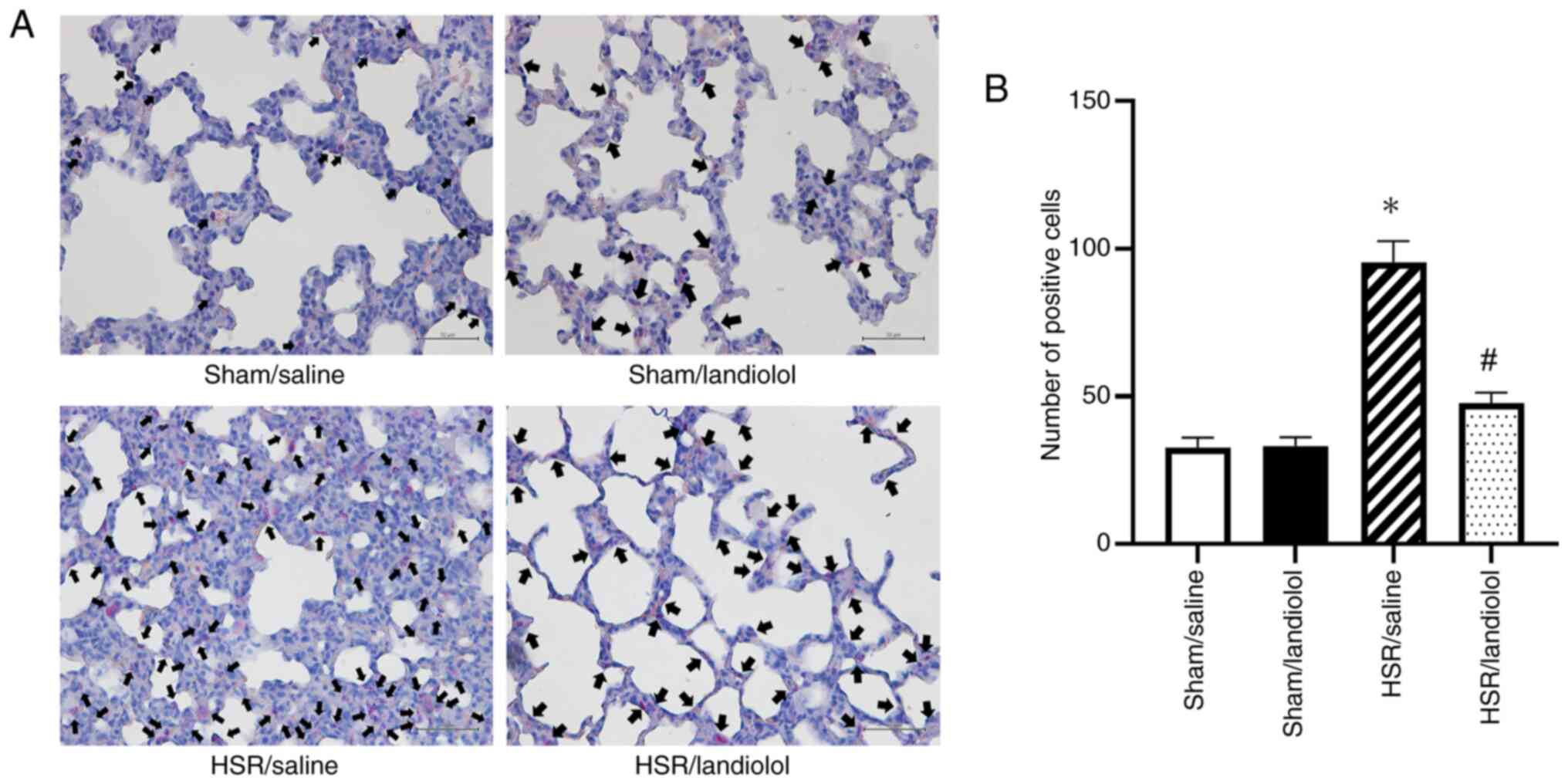

neutrophil accumulation in HSR-induced lung injury

To provide additional visual and quantitative

evidence of lung inflammation, neutrophils in the lung tissue were

stained and counted (Fig. 4A).

Neutrophil infiltration remained mild in the sham group, without

notable difference between the sham/saline and sham/landiolol

groups. However, in the HSR/saline group, the number of

infiltrating neutrophils was significantly higher 24 h after HSR

compared with the sham/saline and sham/landiolol groups. In

contrast, neutrophil infiltration was substantially lower in the

HSR/landiolol group than in the HSR/saline group (Fig. 4B). These neutrophil staining

results indicated that landiolol administration alleviated tissue

injury and decreased neutrophil infiltration.

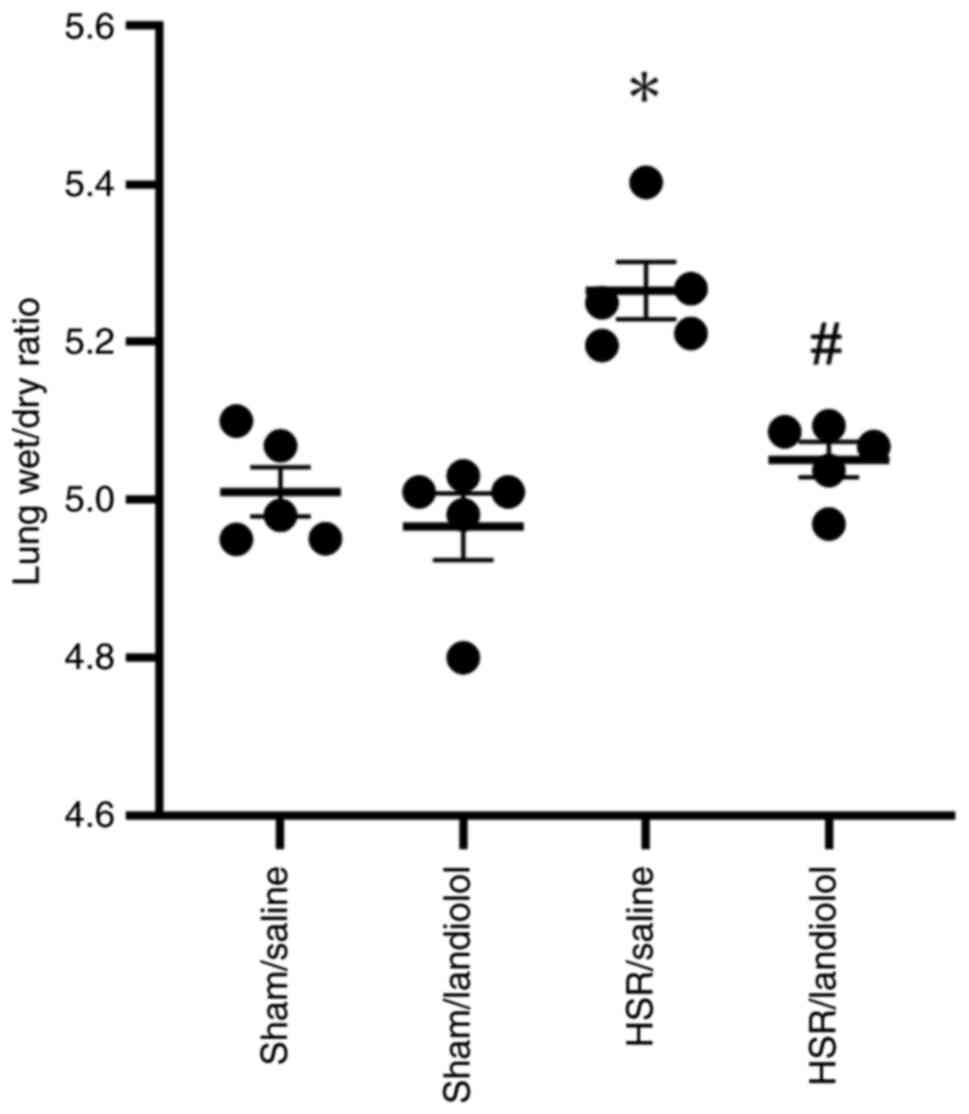

Effect of landiolol on lung wet/dry

weight ratio in HSR model rats

The lung wet/dry ratio, a parameter of lung edema,

was assessed in the 24 h models. Compared with those in the sham

groups, no differences were observed; the wet/dry ratio in the

sham/saline group was 5.01±0.03 and 4.97±0.04 in the sham/landiolol

group. The lung wet/dry ratio in the HSR/saline group significantly

increased compared with that in the sham groups (5.27±0.04).

However, landiolol administration significantly attenuated

HSR-induced lung edema, and the wet/dry ratio of HSR/landiolol was

statistically comparable to the sham groups (5.05±0.02) (Fig. 5). These results suggest that

landiolol administration could reduce lung edema in HSR model

rats.

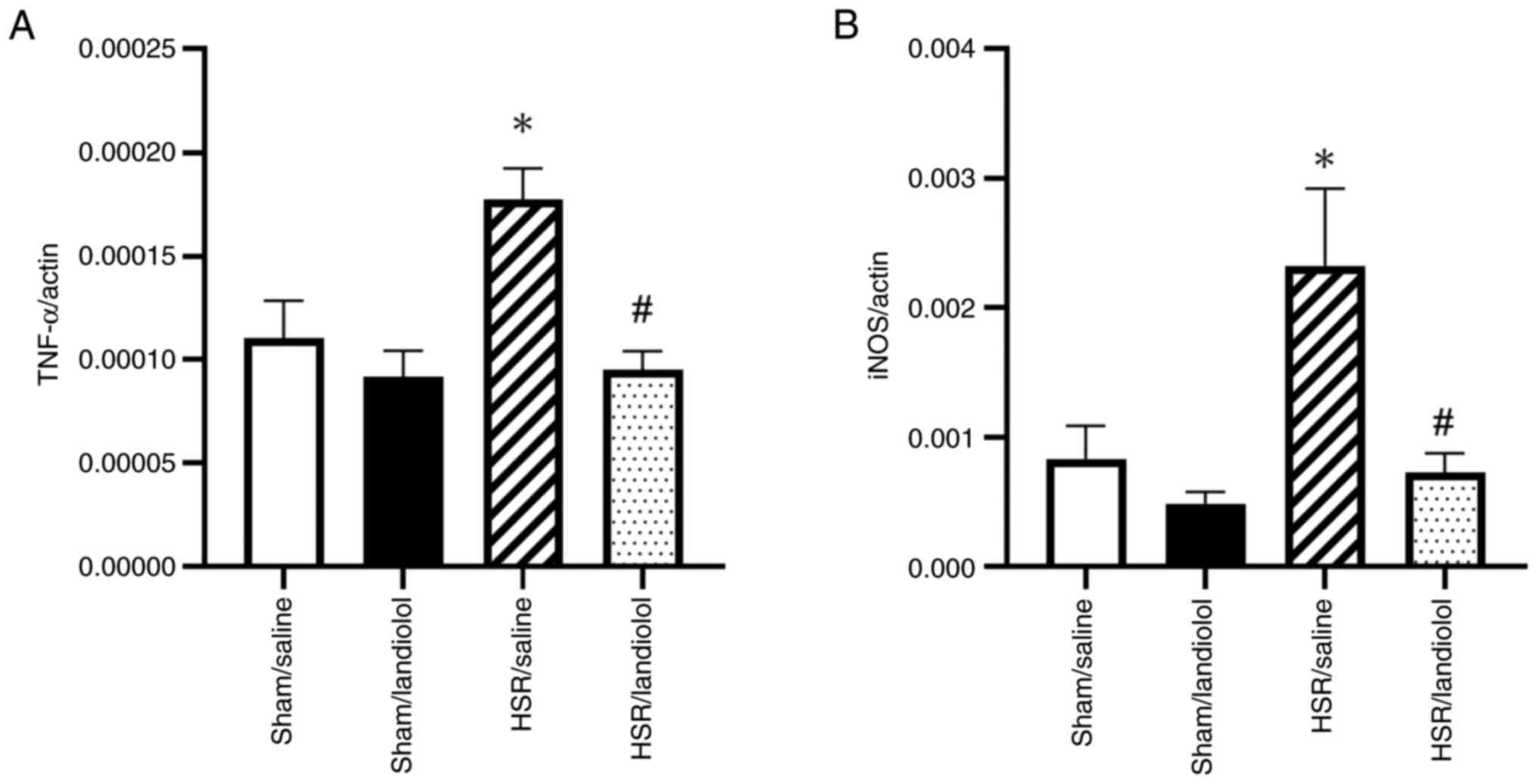

Effect of landiolol on gene

expressions of inflammatory mediators in HSR-induced lung

injury

To assess the anti-inflammatory effects of

landiolol, we analyzed the mRNA expression of TNF-α and iNOS in the

lungs 3 h after HSR using RT-qPCR. There were no statistically

significant differences in the levels of these inflammatory markers

between the sham groups. However, the HSR/saline group demonstrated

a significant increase in the TNF-α and iNOS expression compared

with that in the sham group. In contrast, landiolol administration

reduced the mRNA levels of TNF-α and iNOS by roughly 50 and 30%,

respectively, bringing them close to the levels observed in the

sham groups (Fig. 6A and B). These

findings indicate that landiolol administration lowered

inflammatory mRNA expression in the lungs of HSR model rats.

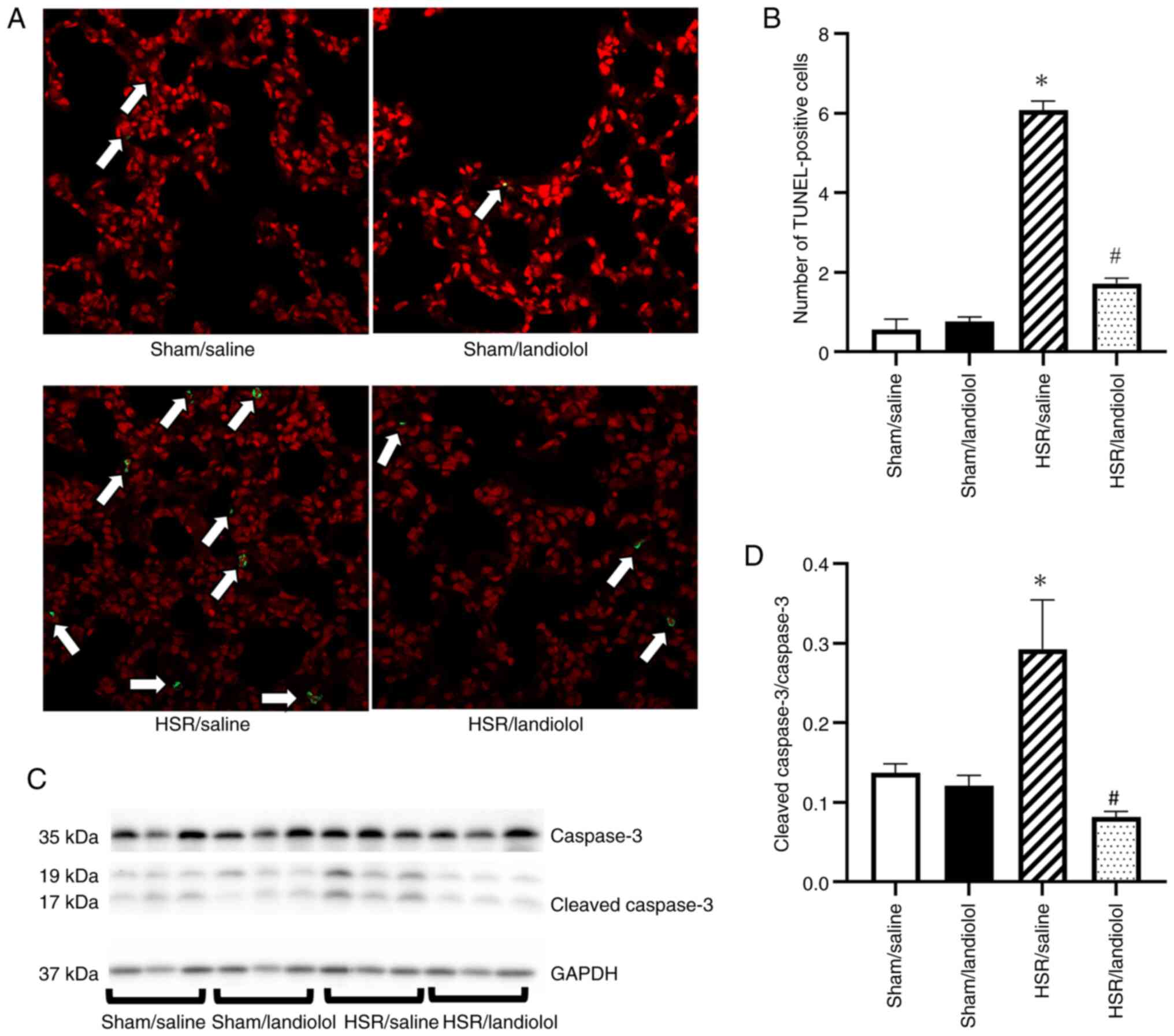

Effect of landiolol on apoptotic cell

death in HSR-induced lung injury

To assess apoptosis, we analyzed the TUNEL-positive

cells and cleaved caspase-3 expression in the lungs 24 h after HSR

using western blotting. The lung sections from the sham group had

very few TUNEL-positive cells, but their numbers increased

following the HSR procedure. In contrast, landiolol treatment

significantly reduced the number of TUNEL-positive cells compared

with the HSR/saline group (Fig. 7A and

B). Similarly, cleaved caspase-3 expression was minimally

detectable in the sham group but increased in the HSR group.

However, landiolol treatment effectively inhibited the increase in

cleaved caspase-3 (Fig. 7C and

D).

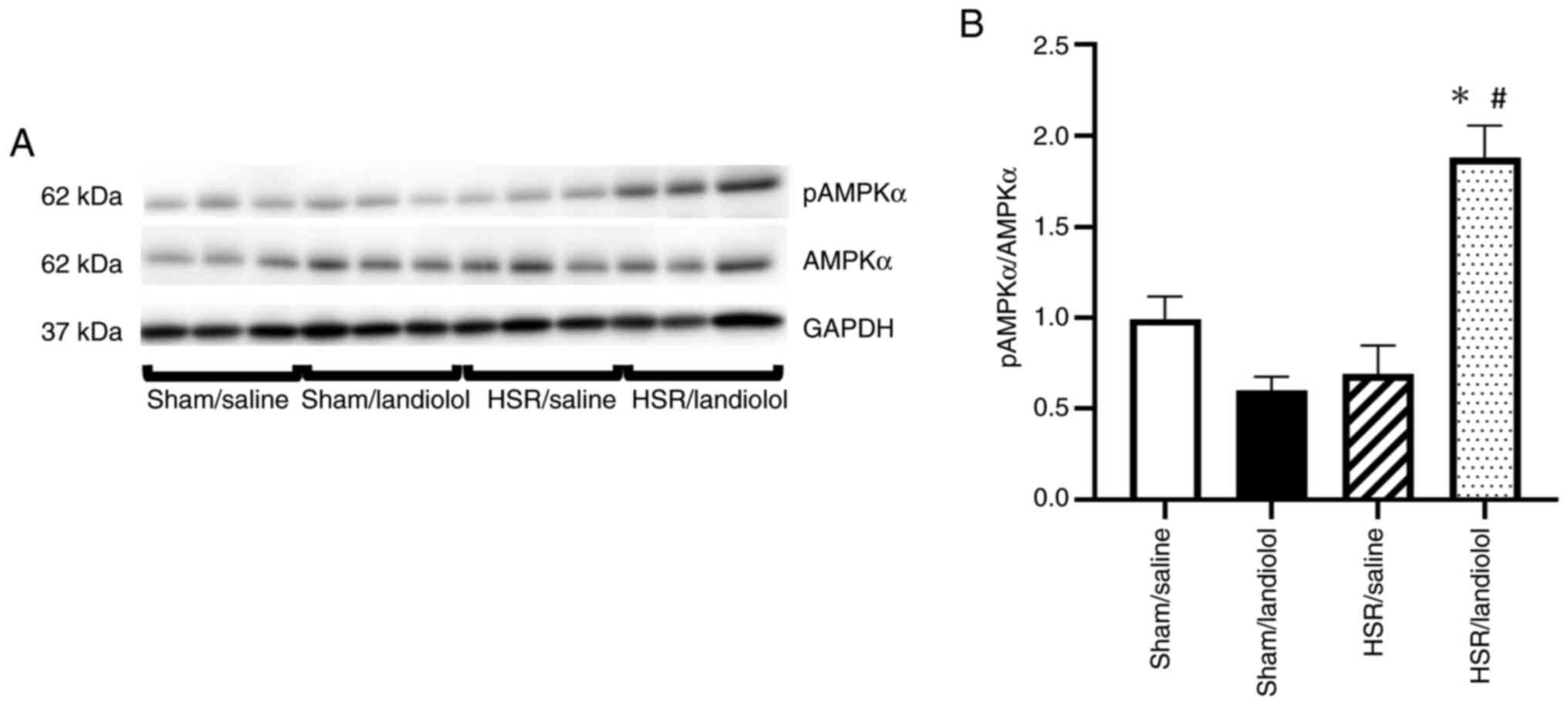

Effect of landiolol on the AMPK

pathway in the lungs following HSR

We examined pAMPKα via western blotting. pAMPKα is a

protein involved in mitochondrial biogenesis, autophagy, and

related processes. Regarding pAMPKα, we found no significant

differences between the sham/saline and sham/landiolol groups. The

HSR/saline group also showed no differences compared with the sham

group. However, landiolol treatment was found to increase pAMPKα

expression compared with the other three groups (Fig. 8A and B).

Discussion

This study showed that intravenous administration of

landiolol at a dose of 100 µg/kg/min following the HSR procedure

substantially alleviated lung injury induced by HSR. This finding

was supported by a trend toward reductions in histological

alterations, and was further substantiated by significant

reductions in neutrophil infiltration and lung edema. Furthermore,

landiolol administration markedly lowered the mRNA expression of

inflammatory mediators, including TNF-α and iNOS. Additionally,

landiolol administration reduced apoptotic cell death, as shown by

a decrease in the TUNEL-positive cells and cleaved caspase-3

expression. We investigated the pAMPKα expression as a mechanism

for the anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects of landiolol

and found by western blotting that pAMPKα expression was increased

when landiolol was administered after HSR procedures. In addition,

landiolol administration following the HSR procedure had no

discernible effect on the mean arterial blood pressure.

TNF-α promotes neutrophil infiltration and increases

vascular permeability, leading to endothelial injury. Neutrophils

act on vascular endothelial cells and produce superoxides and other

ROS, which cause cellular injury and edema (40). This endothelial disruption induces

the expression of iNOS, which generates reactive nitrogen species

such as nitric oxide, thereby exacerbating oxidative injury during

reperfusion (41). Furthermore,

endothelial damage results in vascular leakage, which exacerbates

tissue edema in the lungs (11).

Targeting upstream inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α,

iNOS-induced vascular injury, and neutrophil-mediated permeability

enhancement may help attenuate lung damage. For this reason, these

factors were selected as therapeutic targets in our study.

Landiolol is a drug used for treating arrhythmia;

however, previous studies have shown that landiolol treatment has

lung-protective effects. In a rat LPS model, Hagiwara et al

reported that landiolol administration reduced HMGB1 expression in

the lungs and serum and alleviated histological lung injury

(20). Matsuishi et al

reported that landiolol ameliorated histological findings and

PaO2 levels in a rat ALI model of early sepsis by

suppressing elevated levels of pulmonary endothelin-1 (25). Notably, our research is the first

to suggest that landiolol administration may play a protective role

against ALI in a non-septic HSR model. Considering our findings and

those of other studies (20,25),

landiolol appears to be highly effective in protecting the lungs

from ALI.

When investigating the mechanisms underlying the

protective effects of landiolol on ALI following HSR, we observed

that landiolol administration suppressed HSR-induced expression of

inflammatory genes. This finding aligns with those of previous

reports. Hagiwara et al showed that landiolol administration

reduces TNF-α and IL-6 levels in the serum of the LPS rat model

(20). Yoshino showed that

landiolol administration to the LPS rat model improves TNF-α

expression levels in the liver (24). Furthermore, Ackland et al

reported that the β1 adrenergic receptor blocker metoprolol

suppresses the expression of IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-18, and

MCP-1 in the liver when administered to the LPS rat model (42). The findings of our study also

indicated that landiolol administration decreased the expression of

inflammatory genes in the HSR-induced ALI model. Thus, landiolol

exhibits anti-inflammatory effects, representing a key mechanism in

its protective action against lung injury.

Our study demonstrated that landiolol inhibited

apoptosis in HSR-induced lung injury. Previous reports have also

shown that β1-blockers may have anti-apoptotic effects. Zaugg et

al reported that a β1 blocker atenolol suppressed

TUNEL-positive cells and increased the expression of the

anti-apoptotic protein Bcl2 in catecholamine-induced apoptosis

(15). Hashemi et al

reported that atenolol administration increases MEF2

transcriptional activity, which is involved in the anti-apoptotic

effects of catecholamine-induced apoptosis in rat cardiomyocytes

(43). Additionally, Taha et

al reported that the administration of atenolol suppressed the

gene expression of the pro-apoptosis protein caspase 1 and

increases the expression of Bcl2 in a rat intestinal

ischemia-reperfusion model (44).

These reports and our experimental results suggest that β1-blocker

has anti-apoptotic effects. Although the precise mechanism

underlying the anti-apoptotic effects of landiolol could not be

fully elucidated in this study, increased p-AMPKα expression

observed in the HSR/Landiolol group suggests a potential role of

AMPK pathway activation. AMPK is known to suppress oxidative

stress, promote autophagy, and preserve mitochondrial function, all

of which may contribute to the observed reduction in apoptosis

(16,17). In addition, the AMPK/Nrf2 signaling

pathway has been reported as a potential therapeutic target for

treating ALI. Activation of this pathway may upregulate downstream

effectors such as heme oxygenase-1 and modulate macrophage

activity, thereby attenuating inflammation (45). Further investigation into the

upstream and downstream signaling pathways of AMPK is warranted in

future studies. Additionally, in vitro studies have reported

that landiolol can scavenge multiple types of free radicals, which

may also contribute to its anti-apoptotic properties (46).

Our study had some limitations. First, our model

does not comply with the Berlin definition regarding the disuse of

positive end-expiratory pressure and image evaluations, oxygenation

index, pulmonary function indicator (47). However, conforming to this

definition for animal experiments is challenging. Therefore, we

performed the experiments according to the ALI definition for

animal experiments (48). The

severity of ALI for the animals was approximated using H&E

staining, neutrophil staining, and the wet/dry ratio. Second, this

HSR model is difficult to establish, with a mortality rate of

approximately 11% during the HS procedure, and several animals were

excluded due to complications. Third, we lacked survival rate data.

Although the mortality during the HS procedure was relatively high,

all rats that successfully underwent HSR treatment survived,

indicating that this represents a mild lung injury model. Forth,

the primary aim of this study was to assess the lung-protective

effects of landiolol administration; however, the detailed

mechanisms underlying these effects were not fully elucidated.

Previous studies have demonstrated the organ-protective role of

AMPK using Compound C, a specific AMPK inhibitor (49–51).

In the future, we plan to investigate whether the AMPK pathway

contributes to the protective effects observed in this study by

conducting validation experiments using Compound C. This study was

conducted using only male rats to ensure consistency with previous

experiments (9,10,28–31).

The potential influence of sex differences on the outcomes was not

assessed and remains a subject for future investigation.

In conclusion, landiolol administration after HSR

improved HSR-induced ALI through its anti-inflammatory and

anti-apoptotic effects, at least in part, mediated by the

activation of the AMPK pathway without severe hypotension. Further

research is required to elucidate the exact mechanisms and

pharmacological characteristics of landiolol. Thus, landiolol

administration may be a therapeutic approach for acute lung injury

following HSR.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The StepOnePlus and Zeiss LSM510 devices used in

this study were obtained from the Central Research Laboratory,

Okayama University Medical School (Okayama, Japan). The authors

would also like to thank Mr. Kosuke Iguchi, Ms. Misako Yanagita and

Ms. Shukuko Wani (medical students at Okayama University, Okayama,

Japan) for their technical support.

Funding

This work was supported by a Japan Society for the Promotion of

Science Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (grant nos. JP19K09381

and JP23K08360).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

RS, HS and TT designed the study. RS wrote the first

draft of the manuscript. HS and HM critically revised the

manuscript for intellectual content. RS, HS, YLu and EO performed

the experiments. RS and HS confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. RS, HS, YLi, RN and EO performed histological scoring, which

was conducted in a blinded manner. RS, HS, TT and HM analyzed and

interpreted the data. RS and HS performed the statistical analyses.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The animal experimental procedures in the present

study were approved by the Department of Animal Resources, Advanced

Science Research Center, Okayama University (approval no.

OKU-2021247 on April 1, 2021 and approval no. OKU-2023436 on April

24, 2023).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, AI tools

(ChatGPT and Consensus) were used to improve the readability and

language of the manuscript, and subsequently, the authors revised

and edited the content produced by the AI tools as necessary,

taking full responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

ALI

|

acute lung injury

|

|

AMPK

|

5′ adenosine monophosphate-activated

protein kinase

|

|

ANOVA

|

analysis of variance

|

|

iNOS

|

inducible nitric oxide synthase

|

|

H&E

|

hematoxylin and eosin

|

|

HSR

|

hemorrhagic shock and

resuscitation

|

|

MAP

|

mean arterial blood pressure

|

|

RT-qPCR

|

reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction

|

|

SEM

|

standard error of the mean

|

|

TNF-α

|

tumor necrosis factor-α

|

|

IL

|

interleukin

|

|

TUNEL

|

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase

dUTP nick-end labeling

|

|

FITC

|

fluorescein isothiocyanate

|

|

HMGB1

|

high mobility group box 1

|

|

LPS

|

lipopolysaccharide

|

References

|

1

|

Dewar D, Moore FA, Moore EE and Balogh Z:

Postinjury multiple organ failure. Injury. 40:912–918. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ciesla DJ, Moore EE, Johnson JL, Cothren

CC, Banerjee A, Burch JM and Sauaia A: Decreased progression of

postinjury lung dysfunction to the acute respiratory distress

syndrome and multiple organ failure. Surgery. 140:640–648. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Ware LB: Pathophysiology of acute lung

injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Semin Respir

Crit Care Med. 27:337–349. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

ARDS Definition Task Force, . Ranieri VM,

Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E,

Camporota L and Slutsky AS: Acute respiratory distress syndrome:

The Berlin definition. JAMA. 307:2526–2533. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

Network, . Brower RG, Matthay MA, Morris A, Schoenfeld D, Thompson

BT and Wheeler A: Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared

with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute

respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 342:1301–1308. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Tonelli AR, Zein J, Adams J and Ioannidis

JPA: Effects of interventions on survival in acute respiratory

distress syndrome: An umbrella review of 159 published randomized

trials and 29 meta-analyses. Intensive Care Med. 40:769–787. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Adhikari N, Burns KEA and Meade MO:

Pharmacologic therapies for adults with acute lung injury and acute

respiratory distress syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2004:CD0044772004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Peter JV, John P, Graham PL, Moran JL,

George IA and Bersten A: Corticosteroids in the prevention and

treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in adults:

Meta-analysis. BMJ. 336:1006–1009. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kanagawa F, Takahashi T, Inoue K, Shimizu

H, Omori E, Morimatsu H, Maeda S, Katayama H, Nakao A and Morita K:

Protective effect of carbon monoxide inhalation on lung injury

after hemorrhagic shock/resuscitation in rats. J Trauma.

69:185–194. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kumada Y, Takahashi T, Shimizu H, Nakamura

R, Omori E, Inoue K and Morimatsu H: Therapeutic effect of carbon

monoxide-releasing molecule-3 on acute lung injury after

hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation. Exp Ther Med. 17:3429–3440.

2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Esiobu P and Childs EW: A rat model of

hemorrhagic shock for studying vascular hyperpermeability. Methods

Mol Biol. 1717:53–60. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Peitzman AB, Billiar TR, Harbrecht BG,

Kelly E, Udekwu AO and Simmons RL: Hemorrhagic shock. Curr Probl

Surg. 32:925–1002. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Pérez-Schindler J, Philp A and

Hernandez-Cascales J: Pathophysiological relevance of the cardiac

β2-adrenergic receptor and its potential as a therapeutic target to

improve cardiac function. Eur J Pharmacol. 698:39–47. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Grisanti LA, Evanson J, Marchus E,

Jorissen H, Woster AP, DeKrey W, Sauter ER, Combs CK and Porter JE:

Pro-inflammatory responses in human monocytes are beta1-adrenergic

receptor subtype dependent. Mol Immunol. 47:1244–1254. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zaugg M, Xu W, Lucchinetti E, Shafiq SA,

Jamali NZ and Siddiqui MA: Beta-adrenergic receptor subtypes

differentially affect apoptosis in adult rat ventricular myocytes.

Circulation. 102:344–350. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Aslam M and Ladilov Y: Emerging role of

cAMP/AMPK signaling. Cells. 11:3082022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ding R, Wu W, Sun Z and Li Z:

AMP-activated protein kinase: An attractive therapeutic target for

ischemia-reperfusion injury. Eur J Pharmacol. 888:1734842020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Plosker GL: Landiolol: A review of its use

in intraoperative and postoperative tachyarrhythmias. Drugs.

73:959–977. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Bennett M, Chang CL, Tatley M, Savage R

and Hancox RJ: The safety of cardioselective β1-blockers

in asthma: Literature review and search of global pharmacovigilance

safety reports. ERJ Open Res. 7:00801–2020. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Hagiwara S, Iwasaka H, Maeda H and Noguchi

T: Landiolol, an ultrashort-acting beta1-adrenoceptor antagonist,

has protective effects in an LPS-induced systemic inflammation

model. Shock. 31:515–520. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Kiyonaga N, Moriyama T and Kanmura Y:

Effects of landiolol in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute kidney

injury in rats and in vitro. Shock. 52:e117–e123. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Goyagi T, Kimura T, Nishikawa T, Tobe Y

and Masaki Y: Beta-adrenoreceptor antagonists attenuate brain

injury after transient focal ischemia in rats. Anesth Analg.

103:658–663. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Iwata M, Inoue S, Kawaguchi M, Nakamura M,

Konishi N and Furuya H: Posttreatment but not pretreatment with

selective beta-adrenoreceptor 1 antagonists provides

neuroprotection in the hippocampus in rats subjected to transient

forebrain ischemia. Anesth Analg. 110:1126–1132. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Yoshino Y, Jesmin S, Islam M, Shimojo N,

Sakuramoto H, Oki M, Khatun T, Suda M, Kawano S and Mizutani T:

Landiolol hydrochloride ameliorates liver injury in a rat sepsis

model by down regulating hepatic TNF-A. J Vasc Med Surg.

3:10001942015.

|

|

25

|

Matsuishi Y, Jesmin S, Kawano S, Hideaki

S, Shimojo N, Mowa CN, Akhtar S, Zaedi S, Khatun T, Tsunoda Y, et

al: Landiolol hydrochloride ameliorates acute lung injury in a rat

model of early sepsis through the suppression of elevated levels of

pulmonary endothelin-1. Life Sci. 166:27–33. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Percie du Sert N, Hurst V, Ahluwalia A,

Alam S, Avey MT, Baker M, Browne WJ, Clark A, Cuthill IC, Dirnagl

U, et al: The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for

reporting animal research. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 40:1769–1777.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Leary S, Underwood W, Anthony R, Cartner

S, Grandin T, Greenacre C, Gwaltney-Brant S, McCrackin MA, Meyer R,

et al: AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2020 Edition.

American Veterinary Medical Association; Schaumburg, IL, USA: pp.

1–121. 2020, https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/avma-policies/avma-guidelines-euthanasia-animalsMarch

1–2021

|

|

28

|

Kosaka J, Morimatsu H, Takahashi T,

Shimizu H, Kawanishi S, Omori E, Endo Y, Tamaki N, Morita M and

Morita K: Effects of biliverdin administration on acute lung injury

induced by hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation in rats. PLoS One.

8:e636062013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Li Y, Shimizu H, Nakamura R, Lu Y,

Sakamoto R, Omori E, Takahashi T and Morimatsu H: The protective

effect of carbamazepine on acute lung injury induced by hemorrhagic

shock and resuscitation in rats. PLoS One. 19:e03096222024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Umeda K, Takahashi T, Inoue K, Shimizu H,

Maeda S, Morimatsu H, Omori E, Akagi R, Katayama H and Morita K:

Prevention of hemorrhagic shock-induced intestinal tissue injury by

glutamine via heme oxygenase-1 induction. Shock. 31:40–49. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Maeshima K, Takahashi T, Uehara K, Shimizu

H, Omori E, Yokoyama M, Tani T, Akagi R and Morita K: Prevention of

hemorrhagic shock-induced lung injury by heme arginate treatment in

rats. Biochem Pharmacol. 69:1667–1680. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Yang Z, Zhang XR, Zhao Q, Wang SL, Xiong

LL, Zhang P, Yuan B, Zhang ZB, Fan SY, Wang TH and Zhang YH:

Knockdown of TNF-α alleviates acute lung injury in rats with

intestinal ischemia and reperfusion injury by upregulating IL-10

expression. Int J Mol Med. 42:926–934. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Hassoun HT, Lie ML, Grigoryev DN, Liu M,

Tuder RM and Rabb H: Kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury induces

caspase-dependent pulmonary apoptosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol.

297:F125–F137. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Murakami K, McGuire R, Cox RA, Jodoin JM,

Bjertnaes LJ, Katahira J, Traber LD, Schmalstieg FC, Hawkins HK,

Herndon DN and Traber DL: Heparin nebulization attenuates acute

lung injury in sepsis following smoke inhalation in sheep. Shock.

18:236–241. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zegdi R, Fabre O, Cambillau M, Fornès P,

Tazi KA, Shen M, Hervé P, Carpentier A and Fabiani JN: Exhaled

nitric oxide and acute lung injury in a rat model of extracorporeal

circulation. Shock. 20:569–574. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Jiang H, Meng F, Li W, Tong L, Qiao H and

Sun X: Splenectomy ameliorates acute multiple organ damage induced

by liver warm ischemia reperfusion in rats. Surgery. 141:32–40.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Stephens KE, Ishizaka A, Larrick JW and

Raffin TA: Tumor necrosis factor causes increased pulmonary

permeability and edema. Comparison to septic acute lung injury. Am

Rev Respir Dis. 137:1364–1370. 1988. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Nakatsuka K, Matsuoka Y, Kurita M, Wang R,

Tsuboi C, Sue N, Kaku R and Morimatsu H: Intrathecal administration

of the α1 adrenergic antagonist phentolamine upregulates spinal

GLT-1 and improves mirror image pain in SNI model rats. Acta Med

Okayama. 76:255–263. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

McMillen MA, Huribal M and Sumpio B:

Common pathway of endothelial-leukocyte interaction in shock,

ischemia, and reperfusion. Am J Surg. 166:557–562. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Cinelli MA, Do HT, Miley GP and Silverman

RB: Inducible nitric oxide synthase: Regulation, structure, and

inhibition. Med Res Rev. 40:158–189. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Ackland GL, Yao ST, Rudiger A, Dyson A,

Stidwill R, Poputnikov D, Singer M and Gourine AV:

Cardioprotection, attenuated systemic inflammation, and survival

benefit of beta1-adrenoceptor blockade in severe sepsis in rats.

Crit Care Med. 38:388–394. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Hashemi S, Salma J, Wales S and McDermott

JC: Pro-survival function of MEF2 in cardiomyocytes is enhanced by

β-blockers. Cell Death Discov. 1:150192015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Taha MO, Silva TDMAE, Ota KS, Vilela WJ,

Simões RS, Starzewski A and Fagundes DJ: The role of atenolol in

the modulation of the expression of genes encoding pro-(caspase-1)

and anti-(Bcl2L1) apoptotic proteins in endothelial cells exposed

to intestinal ischemia and reperfusion in rats. Acta Cir Bras.

33:1061–1066. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Huang Q, Ren YX, Yuan P, Huang M, Liu G,

Shi Y, Jia G and Chen M: Targeting the AMPK/Nrf2 pathway: A novel

therapeutic approach for acute lung injury. J Inflamm Res.

17:4683–4700. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Matsumoto S, Tokumaru O, Ogata K,

Kuribayashi Y, Oyama Y, Shingu C, Yokoi I and Kitano T:

Dose-dependent scavenging activity of the ultra-short-acting

β1-blocker landiolol against specific free radicals. J Clin Biochem

Nutr. 71:185–190. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Ferguson ND, Fan E, Camporota L, Antonelli

M, Anzueto A, Beale R, Brochard L, Brower R, Esteban A, Gattinoni

L, et al: The Berlin definition of ARDS: An expanded rationale,

justification, and supplementary material. Intensive Care Med.

38:1573–1582. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Matute-Bello G, Downey G, Moore BB,

Groshong SD, Matthay MA, Slutsky AS and Kuebler WM; Acute Lung

Injury in Animals Study Group, : An official American Thoracic

Society workshop report: Features and measurements of experimental

acute lung injury in animals. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol.

44:725–738. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Escobar DA, Botero-Quintero AM, Kautza BC,

Luciano J, Loughran P, Darwiche S, Rosengart MR, Zuckerbraun BS and

Gomez H: Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

activation protects against sepsis-induced organ injury and

inflammation. J Surg Res. 194:262–272. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Jiang WL, Zhao KC, Yuan W, Zhou F, Song

HY, Liu GL, Huang J, Zou JJ, Zhao B and Xie SP: MicroRNA-31-5p

exacerbates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury via

inactivating Cab39/AMPKα pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2020:88223612020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Chen R, Cao C, Liu H, Jiang W, Pan R, He

H, Ding K and Meng Q: Macrophage Sprouty4 deficiency diminishes

sepsis-induced acute lung injury in mice. Redox Biol.

58:1025132022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|