Introduction

The thioredoxin (Trx) system constitutes a pivotal

intracellular antioxidant defense network that plays an essential

role in maintaining cellular redox homeostasis and modulating

signaling cascades, impacting numerous cellular processes such as

proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis (1–3).

Recent advances in redox biology have highlighted the Trx system's

involvement not only in redox regulation (4–6) but

also in the modulation of complex cell death pathways (4,7–9).

Despite considerable progress, comprehensive reviews elucidating

the mechanistic underpinnings of Trx's role in programmed cell

death remain scarce, particularly in relation to autophagy and

ferroptosis. Autophagy, an intracellular degradation process, is a

well-recognized double-edged sword, wherein it can both mitigate

oxidative stress damage by removing oxidized biomolecules and

promote cell death under certain conditions (10). Ferroptosis, a recently identified

form of iron-dependent programmed cell death, has garnered

increasing attention due to its pathophysiological relevance in a

variety of diseases, including neurodegeneration, cancer and

ischemic organ injury (11,12).

Autophagy and ferroptosis are distinct yet intimately linked cell

death modalities, with redox status playing a crucial role in their

regulation (13,14). The precise mechanisms through which

the Trx system influences these processes, however, are not fully

elucidated, highlighting a significant area for further

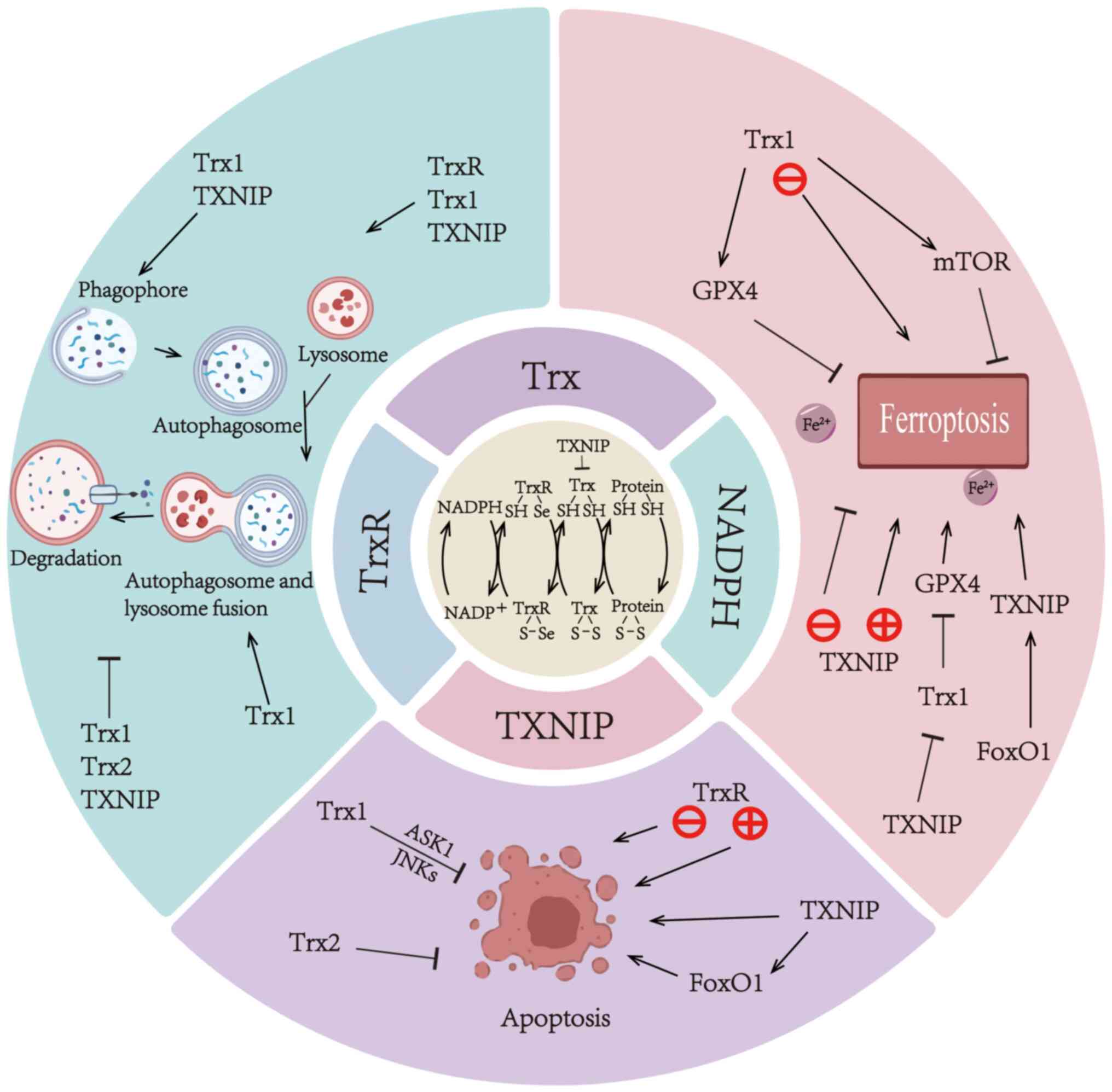

investigation. This review aims to provide an overview of recent

findings on the regulatory roles of the Trx system in cell death

pathways (Fig. 1), with a

particular focus on its interactions with autophagy and

ferroptosis, across various disease contexts. By integrating the

latest research, we aim to provide a conceptual framework for

future studies and therapeutic strategies targeting Trx-mediated

regulation of cell death.

Trx system

The Trx system consists of Trx-interacting protein

(TXNIP), Trx, Trx reductase (TrxR) and NADPH, which serve an

important role in growth promotion, apoptosis, inflammation

regulation, antioxidant defense and maintenance of redox state

homeostasis (15). In a study by

Laurent et al (16) in

1964, Trx was isolated from Escherichia coli. Three

different Trx isoforms were found in mammalian cells, categorized

as Trx1, Trx2 and Trx3 (17).

Trx1, a 105-amino-acid redox protein with a molecular mass of 12

kDa, is an important component of the Trx system and is mainly

localized in the cytoplasm and nucleus (10,18).

Trx2 is present in mitochondria, whereas Trx3 is found only in germ

cells (17).

Trx exhibits broad phylogenetic conservation

spanning prokaryotic to eukaryotic systems. Trx has different

isoforms in different organisms with distinct subcellular

localization patterns, including cytoplasmic, mitochondrial,

endoplasmic reticular, membranous and extracellular distributions.

Notably, these various isoforms have different functions (5). Structural analyses have revealed

conserved architecture across family members, comprising three

α-helical elements encircling a central four-stranded β-sheet core,

with higher eukaryotes demonstrating supplementary secondary

structure elements (19). In

Homo sapiens, the molecular configuration manifests as a

quintuple β-sheet assembly interspersed with four α-helical domains

(20). Evolutionary preservation

is notably observed in the catalytic domain, characterized by a

Cys-Gly-Pro-Cys sequence maintaining redox function across taxa

(18). Trx undergoes a redox

reaction through cysteine residues in its active site. It has been

shown that active site cysteines form disulfide bonds in the

oxidized state, while in the reduced state they exist as thiols

(19). Trx reduces disulfide bonds

in target proteins through this redox exchange, thereby regulating

their activity and function (21).

This shift is important for its catalytic function. The process of

electron transfer through the reversible transformation of active

site sulfhydryl-disulfide (−SH/-S-S-) is the core mechanism of the

Trx system (21).

Biological structure of Trx1 and

Trx2

In addition to the two catalytic cysteine residues

(Cys32 and Cys35) in the catalytic site, human Trx1 contains three

key non-catalytic cysteine residues: Cys62, Cys69 and Cys73. Cys62

and Cys69 are amenable to S-nitrosylation, whereas Cys73 undergoes

multiple modifications, including S-nitrosylation and

glutathionylation (22,23). Given that all these cysteine

residues are subject to post-translational modifications, Trx1

exhibits diverse functional roles.

Trx1 can be proteolytically cleaved by monocytes

in vivo into a truncated form, Trx80, which exhibits

distinct functional properties compared with Trx1 (24,25).

Structurally, Trx1 comprises only a Trx-fold domain containing an

active CXXC motif, whereas Trx2 includes an N-terminal zinc-finger

domain with two additional CXXC motifs alongside the Trx-fold

domain. This structural difference renders Trx2 more complex than

Trx1 (26).

Biological structure of TrxR

As the central enzymatic constituent of the Trx

system, TrxR is classified within the pyridine nucleotide-disulfide

oxidoreductase family (27). TrxR

is a dimer with an N-terminal structural domain that contains the

FAD cofactor, which is responsible for accepting electrons from

NADPH, and a C-terminal structural domain that contains the

conserved selenocysteine (Sec) active site, which is the end-site

for electron transfer (28).

During catalysis, electrons from NADPH are transferred to FAD and

subsequently relayed through a Cys59-Cys64 disulfide bridge to the

Sec residue within the C-terminal domain. This electron flux

culminates in the reduction of oxidized Trx (Trx-S2) to

its dithiol state [Trx-(SH)2], a biochemical process

important for sustaining cellular redox equilibrium (28). Due to the high reactivity of Sec

residues and the accessible position of the C-terminal active site,

TrxR has broad substrate specificity (29).

Human TrxR is a selenoprotein (27). Selenium deficiency leads to

impaired TrxR activity, which disturbs cellular redox homeostasis

and is closely associated with the pathogenesis of multiple

disorders, such as cancer and inflammatory diseases (30,31).

Three isoforms of TrxR exist in humans-TrxR1, TrxR2 and TrxR3-which

are encoded by the TXNRD1, TXNRD2 and TXNRD3 genes, respectively

(32,33). TrxR1 is localized in the cytoplasm

and nucleus, TrxR2 in the mitochondria and TrxR3 in testicular

tissue (34).

Biological structure of NADPH

NADPH, a key coenzyme, comprises three structural

components: i) A reduced nicotinamide ring carrying two hydrogen

atoms, which serves as an electron carrier; ii) an adenine

nucleotide linked to nicotinamide mononucleotide via a

pyrophosphate bond; and iii) a 2′-phosphate group that confers

specificity in enzyme binding, for example to TrxR (35). In the Trx system, NADPH acts as the

primary electron donor, transferring electrons to Trx-S2

via TrxR, thereby driving its reduction to the active form

[Trx-(SH)2] (36).

In addition to its role in the Trx system, NADPH

provides reducing power to enzymes such as glutathione reductase

and glutathione peroxidase (GPX), enabling the regeneration of

antioxidant molecules (37,38).

It also serves as a key coenzyme in fatty acid and cholesterol

synthesis (39). The

NADPH/NADP+ ratio regulates cell proliferation,

apoptosis and inflammatory responses through the modulation of Trx,

nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 and other pathways (40).

Biological structure of TXNIP

TXNIP is an α-arrestin family member encoded by the

TXNIP locus (41). Originally

designated vitamin D3 upregulated protein 1 following

identification in HL-60 promyelocytic cells under

1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 treatment (42), TXNIP was subsequently characterized

as Trx-binding protein-2 through yeast two-hybrid screening

(43). Structural characterization

revealed two conserved PPxY motifs that serve as docking platforms

for WW domains of E3 ubiquitin ligases, enabling targeted

ubiquitination-mediated proteolysis (44). TXNIP is able to bind to Trx through

a disulfide bond exchange mechanism, forming a disulfide bond of

TXNIP Cys247-Trx Cys32. This binding results in a structural

rearrangement of TXNIP, unlike other α-arrestin family proteins

(44). This interaction may

explain the negative regulatory effect of TXNIP on Trx

activity.

Translocation of TXNIP

The functional dynamics of TXNIP are intrinsically

linked to its subcellular compartmentalization. Under basal

conditions, TXNIP predominantly localizes to nuclear compartments

and exhibits restricted cytoplasmic translocation (45). Oxidative challenge induces atomic

export of TXNIP to membranous or mitochondrial domains (45). Mechanistically, TXNIP functions as

a Trx1 antagonist, suppressing its redox-regulatory capacity

through direct binding (46).

Cytosolic TXNIP-Trx1 complexes dissociate the Trx1-apoptosis

signal-regulated kinase 1 (ASK1) interaction, triggering the p38

mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade activation, thereby

potentiating oxidative stress responses, cellular damage, apoptotic

execution and senescence pathways (46–48).

Under oxidative stress conditions, mitochondrial-localized TXNIP

further engages Trx2 via analogous binding, liberating

Trx2-conjugated ASK1 to initiate apoptosis through ASK1 activation

(49).

TXNIP is also transcriptionally regulated in a cell

type-specific manner by nuclear receptors such as peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR), farnesol X receptor,

vitamin D receptor and glucocorticoid receptor (50).

TXNIP translocation has been observed under

high-glucose conditions. Elevated intracellular glucose induces

TXNIP translocation to the cytoplasmic membrane, where it promotes

the endocytosis of glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1), reduces GLUT1

expression and consequently decreases GLUT1 abundance on the cell

membrane, thereby reducing glucose uptake into the cell (51). Nephrotic syndrome is characterized

by notable proteinuria or albuminuria. Albuminuria can induce

endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS), during which TXNIP translocates

from the nucleus to mitochondria, promoting mitochondrial reactive

oxygen species (ROS) production and activating NOD-like receptor

pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasomes (52). Beyond these mechanisms, TXNIP

demonstrates mitochondrial translocation in hyperuricemic

inflammation, where its interaction with NLRP3 induces inflammasome

assembly and subsequent pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion

(53). Furthermore, under

high-glucose conditions, elevated levels of translocated TXNIP in

retinal Müller cells suggest that the TXNIP-Drp1-Parkin axis may be

involved in mediating mitophagy in retinal cells under diabetic

conditions (54).

TXNIP serves multifaceted roles in cancer

metastasis, closely linked to its subcellular localization and

disease context. In renal cancer, nuclear TXNIP in tumor-supporting

endothelial cells is associated with elevated ROS and favorable

prognosis, whereas cytoplasmic TXNIP is associated with abnormal

angiogenesis, necrosis and recurrence (55). Functionally, TXNIP may promote or

suppress metastasis depending on cancer type and cellular

metabolism. For example, TXNIP upregulation enhances migration in

hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) by increasing ROS levels (56). By contrast, decreased TXNIP

expression is associated with enhanced migration, invasion and

metastatic potential in colorectal cancer, cervical cancer,

melanoma and pancreatic cancer (56).

Furthermore, TXNIP shows context-dependent

subcellular localization and expression changes under conditions

such as high-glucose exposure, proteinuria-induced ERS, and uric

acid-mediated inflammation, which in turn modulate oxidative

stress, inflammation and cell fate (51–53).

These disease-specific localization and expression patterns not

only offer mechanistic insights but also highlight promising

avenues for therapeutic targeting. Modulating TXNIP or its

associated pathways may serve as a novel strategy for treating

tumor metastasis and a broad spectrum of other diseases (56).

Mechanisms of the Trx system involved in

ferroptosis in different diseases

Ferroptosis constitutes a distinctive cell death

modality characterized by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation

(57). A recent study has revealed

the three key processes in the pathogenesis of ferroptosis

following cerebral ischemia: Iron deposition, the accumulation of

lipid peroxides and inhibition of the anti-ferroptosis pathway,

with the GPX4-mediated antioxidant system serving a central role

(58). As a selenoprotein, GPX4

catalyzes the reduction of lipid hydroperoxides, establishing its

enzymatic centrality in ferroptosis regulation (59). This cell death paradigm manifests

distinct ultrastructural features, including mitochondrial volume

reduction with cristae diminution and elevated membrane electron

density, while the nuclear architecture remains unaltered.

Concomitant biochemical alterations involve progressive

accumulation of lipid peroxides and the elevation of ROS (60). The resultant oxidative milieu leads

to protein modification and lipid peroxidation, resulting in

cellular dysfunction, which is associated with numerous diseases

(61).

Linkage between Trx1, TrxR and

ferroptosis

Trx1 functions as an antioxidant factor, maintaining

redox homeostasis and regulating ferroptosis across diverse

pathological conditions. Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1

(Keap1) serves as an important regulatory component in cellular

redox homeostasis (62,63). The cited pharmacological study has

demonstrated that curdione modulates redox complexes by disrupting

Keap1-Trx1 interactions while enhancing Trx1-GPX4 binding, thereby

attenuating post-infarction ferroptosis through Keap1/Trx1/GPX4

axis regulation (64).

Complementary mechanistic evidence has emerged from

neurodegenerative research: In Parkinson's disease (PD) models

characterized by substantia nigra dopaminergic neuron loss, Trx1

exerts ferroptosis inhibition via the modulation of GPX4 activity

and glutathione (GSH) (65).

Ferroptosis is also closely associated with cancer

development, progression and suppression. The apoptotic resistance

of malignant cells underscores the therapeutic value of

non-apoptotic death modalities, with ferroptosis induction emerging

as a promising oncological intervention strategy (66–68).

Cellular redox homeostasis is jointly maintained by two

thiol-dependent antioxidant systems, the GSH and Trx systems, which

exhibit redundant functions via inter-system electron transfer

capabilities (69). Malignant

cells exhibit marked elevation of redox regulators including Trx1

and GSH, creating therapeutic barriers by neutralizing ROS-mediated

cytotoxicity and impairing Fenton reaction-driven ferroptosis

(34,69). The Fenton process, wherein

Fe2+ catalyzes H2O2 conversion to

hydroxyl radicals, initiates lipid peroxidation cascades that can

be exploited for targeted tumor ferroptosis induction (70,71).

Trx1 demonstrates marked upregulation across

multiple solid malignanciesand is associated with poor cancer

prognosis (72). Radiotherapeutic

interventions potentiate ferroptosis through ionizing

radiation-generated ROS that drive lipid peroxidation cascades

(73). Therapeutic synergy is

achieved when combining radiotherapy with a Trx1 inhibitor, which

enhances tumor-selective ferroptosis induction (74).

Similarly, in chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML),

co-inhibition of Trx1 and glutamate-cysteine ligase may serve as a

therapeutic strategy for both imatinib-sensitive and drug-resistant

patients by triggering ferroptosis (75).

Notably, in other diseases such as PD and myocardial

infarction, Trx1 upregulation inhibits ferroptosis to confer

cellular protection (64,65). By contrast, in tumors such as CML,

Trx1 inhibition promotes ferroptosis, enhancing therapeutic

efficacy and overcoming treatment resistance (74,75).

Therapeutic induction of ferroptosis through radiotherapy,

chemotherapy and immunotherapeutic regimens demonstrates

synergistic augmentation of oncological treatment efficacy

(68,73,76,77).

Overall, Trx1 may negatively regulate ferroptosis; however,

ferroptosis exhibits opposite effects in different diseases. This

dichotomy likely arises from variations in cell type, metabolic

state and pathological microenvironment (78,79).

Furthermore, the diversity and complexity of Trx1

target proteins are highlighted by the identification of 112 Trx1

target proteins in mouse primary cortical neurons, with 77 of these

Trx1-interacting proteins being modulated by rapamycin (80). Among these, the mechanistic target

of rapamycin (mTOR) is a major downstream target of Trx1, together

with AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), nuclear factor κB (NF-κB)

and histone deacetylase 4 (75).

mTOR serves as a regulatory kinase governing cellular

proliferation, metabolic programming and survival signaling

(81). Oxidative stress promotes

direct interactions between Trx1 and mTOR, inducing intermolecular

disulfide bond formation within mTOR kinase and thereby leading to

its functional inhibition (81,82).

Overexpression of Trx1 prevents mTOR oxidation and preserves its

catalytic activity, whereas Trx1 knockdown conversely promotes mTOR

oxidation and suppresses mTOR signaling (81,83).

However, the C1483F mutation in mTOR confers resistance to

oxidation-mediated inactivation even under Trx1-deficient

conditions (82). Emerging

evidence has further demonstrated that exosomal Trx1 derived from

hypoxic human stem cells activates mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1)

signaling upon cellular internalization, exhibiting

anti-ferroptotic and cardioprotective effects against

doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity (84). These findings collectively

establish the Trx1-mTOR axis as an important regulatory mechanism

in ferroptosis suppression. Complementary studies have revealed

that pharmacological inhibition of TrxR induces ferroptosis in

malignant cells, suggesting its therapeutic potential in cancer

treatment (85,86).

Summarily, Trx1 inhibits ferroptosis primarily

through its antioxidative capacity and regulation of

redox-sensitive signaling cascades. In the context of ferroptosis,

Trx1 supports GPX4 activity and GSH synthesis, and protects mTOR

function under oxidative stress, supporting its role as a negative

regulator of lipid peroxidation and cell death. In various tumor

settings, inhibition of Trx1-mediated suppression of ferroptosis

may enhance the efficacy of anticancer therapies.

Linkage between TXNIP and

ferroptosis

TXNIP has been characterized as a

ferroptosis-associated gene across multiple pathological contexts,

including oncogenesis (87,88),

osteonecrosis of the femoral head (89) and hepatic dysfunction (90).

Functionally, TXNIP acts as a tumor suppressor

through its downregulation in malignant cells, where it

concurrently suppresses proliferation and metastatic potential and

promotes apoptotic pathways (91–93).

In HCC models, the protein inhibitor of activated

STAT3 potentiates ferroptosis through activation of the TGF-β

pathway, which is mechanistically linked to TXNIP transcriptional

upregulation (94). Complementary

multi-omics investigations by Zheng et al (95), employing RNA sequencing and liquid

chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry in lung tumor cell

populations, revealed TXNIP as a ferroptosis-associated prognostic

biomarker. Experimental validation further demonstrated that TXNIP

expression was markedly downregulated in lung cancer stem cells and

correlated with advanced disease progression (95).

While TXNIP downregulation exhibits

ferroptosis-suppressive effects across both neoplastic and

non-neoplastic pathologies, disease-specific regulatory mechanisms

govern its activity.

In high-fructose-induced nephropathy,

carbohydrate-responsive element-binding protein-β-mediated

transcriptional activation of TXNIP leads to lipid peroxidation and

drives ferroptosis in renal tubular epithelial cells, thereby

exacerbating renal injury (96).

By contrast, in diabetic retinopathy, 1,8-eudesmol alleviates

retinal ferroptosis by suppressing TXNIP expression in a

PPAR-γ-dependent manner, thereby reducing oxidative stress and

restoring the integrity of the blood-retinal barrier (97). Mechanistically, TXNIP may inhibit

both Trx1 and Trx2, disrupting redox homeostasis and promoting

ferroptosis. Forkhead box O1 (FoxO1) further exhibits

context-dependent regulation by promoting TXNIP transcription and

GSH metabolic disruption, thereby inducing satellite cell

ferroptosis and contributing to sarcopenia. Notably, TXNIP

silencing rescues these ferroptotic phenotypes, alleviating muscle

atrophy (98). Furthermore,

hypothermic hypoxia-reoxygenation stress elevates TXNIP expression

in ex vivo liver transplantation models. This ferroptosis

cascade is pharmacologically mitigated by dexmedetomidine-argon

co-administration, which blocks TXNIP mitochondrial translocation

to preserve redox homeostasis (99). These findings position TXNIP as a

conserved positive regulator of ferroptosis across multiple

diseases.

TXNIP demonstrates prognostic predictive capacity as

a ferroptosis-related biomarker across malignancies. HCC specimens

exhibit notable TXNIP downregulation, with diminished expression

levels associated with adverse clinical outcomes in HCC progression

(100). In lung adenocarcinoma

stem cell models, this multifunctional regulator serves dual roles

in ferroptosis modulation and prognostic prediction, where reduced

expression patterns are associated with three notable

clinicopathological parameters: Immunosuppressive tumor

microenvironment establishment, advanced tumor, node and metastasis

staging, and impaired histodifferentiation status (95). TXNIP is identified as a

prognostically notable ferroptosis-associated gene implicated in

the pathogenesis of bladder cancer and femoral-head necrosis,

offering potential biomarkers for precision medicine applications

(89,101).

As a negative regulator of the antioxidant protein

Trx1, TXNIP is an important modulator of cellular redox homeostasis

(102,103). Experimental evidence has

demonstrated that TXNIP inhibits Trx1 activity, thereby promoting

ferroptosis. In a neonatal rat model of hypoxic-ischemic injury,

hippocampal neuron ferroptosis was shown to be triggered via

TXNIP/Trx1/GPX4 pathway activation, which was directly associated

with hypoxic-ischemic brain damage severity (104). Similarly, curcumin inhibits

ferroptosis by inhibiting the TXNIP/Trx1/GPX4 pathway, thereby

attenuating septic lung injury (105).

In summary, TXNIP serves an important regulatory

role in ferroptosis across diverse pathological conditions,

underscoring its potential as a therapeutic target.

Mechanistically, TXNIP antagonizes Trx1 by forming a disulfide bond

with its Cys32 residue, leading to Trx1 inactivation and increased

ROS levels, thereby facilitating lipid peroxidation and ferroptotic

signaling. In addition, TXNIP contributes to ferroptosis by

disrupting GSH metabolism and destabilizing redox homeostasis.

TXNIP demonstrates notable prognostic associations across multiple

malignancies, with expression patterns showing potential utility as

a biomarker for cancer diagnosis and prognostic stratification.

Mechanisms of the Trx system involved in

autophagy in different diseases

The autophagic process comprises four

mechanistically distinct phases: Autophagosome

nucleation/maturation, cargo sequestration, autolysosomal fusion

and lysosomal degradation (106,107). Notably, microtubule-associated

protein light chain 3 (LC3) undergoes conjugation with

phosphatidylethanolamine during autophagosome biogenesis, leading

to the conversion of LC3 to its lipidated form LC3-II, which serves

as a principal biomarker for autophagic flux quantification

(108–110). Mechanistically, p62 orchestrates

selective autophagy execution through ubiquitinated cargo

recognition and autophagosomal translocation, ultimately enabling

substrate proteolysis (111,112). Lysosome-associated membrane

proteins (LAMPs), particularly LAMP1 and LAMP2, are important for

maintaining lysosomal acidity and facilitating autophagic flux

(113,114). Reduced LAMP2 expression impairs

autophagosome clearance through lysosomal dysfunction (115). LAMP2 dysregulation disrupts

lysosomal homeostasis, and also impairs the activity of Cathepsin D

(CTSD), a key protease for autophagosomal cargo degradation

(116,117).

Mitophagy, a selective autophagy subtype,

specifically regulates mitochondrial quality control via targeted

organelle degradation (118). The

PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1)/Parkin axis constitutes an important

mitophagy regulatory mechanism. PINK1 selectively accumulates on

depolarized mitochondrial membranes, orchestrating Parkin

recruitment and activating its E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase activity

to initiate ubiquitin-dependent organelle tagging (119). Subsequent recognition of

ubiquitinated mitochondria by p62 facilitates autophagosomal

engulfment and lysosomal elimination of defective organelles

(120). PINK1 and Parkin are also

key proteins associated with PD (121).

The mechanisms by which the Trx system regulates

autophagy in various diseases are summarized in Table I, highlighting its molecular

interactions and bidirectional regulatory effects on autophagy.

| Table I.Effect of the Trx system on

autophagy. |

Table I.

Effect of the Trx system on

autophagy.

| A, Trx1 |

|---|

|

|---|

| First author,

year | Autophagy

regulation | Effects on

autophagy | Diseases | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Gu, 2024 | Positive | Trx1 upregulation

improves autophagic flux and promotes clearance of damaged

mitochondria by regulating autophagy-lysosomal processes. | Parkinson's

disease | (125) |

| Ren, 2022 | Positive | Trx1 activates

autophagy and ameliorates impaired autophagic flux. | Diabetic

retinopathy | (126) |

| Hu, 2023 | Positive | Trx1 promotes

autophagy induction mainly at the initiation stage of autophagy and

protects LECs from oxidative damage. | Cataracts | (127) |

| Ren, 2021 | Positive | Trx1 upregulation

activates autophagy and improves autophagic flux by inhibiting

TXNIP. | Diabetes-induced

hearing impairment | (128) |

| Sánchez-Villamil,

2016 | Positive | Trx1 may promote

mitochondrial autophagy, but it remains yet to be fully elucidated

whether autophagic flux is blocked. | Sepsis-induced

myocardial injury | (129) |

| Nagarajan,

2023 | Positive | Trx1 enhances

myocardial ischemia-induced autophagy through ATG7

transnitrosylation, thereby playing an important role in mediating

protection of the heart. | Myocardial

ischemia | (141) |

| Wang, 2020 | Negative | Trx1 antagonizes

the induction of autophagy by acrylamide. | Acrylamide-induced

neurotoxicity | (132) |

| Ren, 2018 | Negative | Trx1 inhibits

autophagy and improves retinal function through the TXNIP/mTOR

pathway. | Diabetic

retinopathy | (133) |

|

| B, Trx2 |

|

| First author,

year | Autophagy

regulation | Effects on

autophagy |

Diseases | (Refs.) |

|

| He, 2021 | Negative | Trx2 knockdown

causes excessive mitochondrial autophagy and accelerates disease

progression. | Type 2

diabetes | (143) |

| Li, 2017 | Negative | Trx2 may inhibit

ROS-mediated autophagy through the Akt/mTOR and AMPK/mTOR signaling

pathways. | Myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion injury in vitro | (144) |

| Li, 2017 | Negative | Trx2 overexpression

reduces cell death via ASK1-dependent mitochondrial apoptosis and

inhibits autophagy through the mTOR pathway. | Myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion injury in vivo | (145) |

|

| C, TrxR |

|

| First author,

year | Autophagy

regulation | Effects on

autophagy |

Diseases | (Refs.) |

|

| Lei, 2018 | Positive | TrxR inhibitors

induce ROS-independent autophagy inhibition and exhibit anticancer

effects. | Hepatocellular

carcinoma | (147) |

| Nagakannan,

2016 | Positive | TrxR inhibition

leads to impaired autophagic flux by interrupting the

autophagy-lysosomal degradation pathway, which in turn inhibits

autophagy. | Neurodegenerative

disease | (148) |

|

| D,

TXNIP |

|

| First author,

year | Autophagy

regulation | Effects on

autophagy |

Diseases | (Refs.) |

|

| Ren, 2018 | Positive | Inhibition of TXNIP

may lead to autophagy inhibition and improved retinal

function. | Diabetic

retinopathy | (133) |

| Gao, 2020 | Positive | TXNIP can stimulate

autophagy by interacting with DNA damage-inducible transcript 4

protein, causing an excessive accumulation of autophagosomes. | Myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion injury | (154) |

| Ao, 2021 | Positive | TXNIP upregulation

positively regulates autophagy and enhances autophagic flux by

inactivating PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling. | Diabetic

retinopathy | (155) |

| Park, 2021 | Positive | TXNIP induces

autophagy by directly binding to phosphorylated protein kinase

AMP-activated catalytic subunit α and regulating mTOR complex 1 and

TFEB. |

Steatohepatitis | (156) |

| Huang, 2016 | Negative | TXNIP deficiency

stimulates autophagy by inhibiting mTOR activation, attenuates

diabetes-induced autophagic flux blockage and enhances

mitochondrial autophagy. | Diabetic

nephropathy | (149) |

| Huang, 2014 | Negative | Silencing TXNIP

enhances autophagic flux and reduces autophagosome

accumulation. | Diabetic

nephropathy | (150) |

| Du, 2024 | Negative | TXNIP knockdown

attenuates mTOR activation and restores nuclear translocation of

TFEB, thereby stimulating autophagy and ameliorating impaired

autophagic flux. | Diabetic

nephropathy | (153) |

Linkage between Trx1 and

autophagy

PD develops an abnormal accumulation of α-synuclein

(α-syn) (122). Pathological

α-syn aggregates exhibit dual neurotoxic effects: Synaptic

transmission impairment (123)

and autophagic-lysosomal system dysfunction that promotes cytotoxic

substrate accumulation (124).

Autophagy-lysosomal pathway impairment induces

molecular signatures, including elevated LC3-II expression with

concomitant LC3-II/LC3-I ratio upregulation, p62 accumulation and

reduced histone D levels (125).

Trx1 enhances α-syn clearance in

1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3, 6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-induced PD

models by modulating autophagic-lysosomal degradation pathways.

Furthermore, MPTP exposure upregulates PINK1 and Parkin expression

to activate mitophagy. Notably, Trx1 overexpression attenuates this

MPTP-induced overaccumulation of damaged mitochondria,

demonstrating that Trx1 may restore autophagic flux to eliminate

dysfunctional mitochondria (125).

Multiple studies have corroborated the role of Trx1

in enhancing autophagic flux. LC3 accumulation in diabetic

retinopathy (DR), accompanied by p62 upregulation, indicates

lysosomal dysfunction and subsequent autophagosome accumulation.

Trx1 activates autophagy and restores impaired flux by accelerating

lysosomal degradation and suppressing excessive autophagosome

formation, as demonstrated by autophagic flux assays (126). Furthermore, Trx1 overexpression

protects human lens epithelial cells (LECs) from damage by

promoting beneficial autophagy under normal conditions while

preventing its excessive activation during mild oxidative stress

(127). Similarly, Trx

upregulation mitigates diabetes-induced hearing loss by preserving

cochlear hair cells through TXNIP inhibition and autophagy

activation. Elevated LC3-II and reduced p62 expression further

support the ameliorating effect of Trx1 on autophagic flux

(128).

Cardiac-specific Trx1 expression increases the

LC3-II/LC3-I ratio and PPAR-γ coactivator 1-α levels, indicating

enhanced mitochondrial autophagy to eliminate dysfunctional

mitochondria and mitigate sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction

(129). However, whether

autophagic flux is blocked remains yet to be fully elucidated, as

the elevated LC3-II/LC3-I ratio may reflect either autophagic

activation or impaired flux leading to autophagosome accumulation

(130). Further investigation is

warranted to clarify these mechanisms.

Evidence indicates that pharmacological inhibition

of autophagosome-lysosome fusion with bafilomycin A1, combined with

blockade of autophagosome formation using wortmannin, reveals Trx1

primarily regulates autophagy at the initiation stage and promotes

its induction (127). This

parallels TXNIP-mediated autophagic flux regulation at the

initiation phase of autophagy (131).

However, conflicting evidence exists in the

literature indicating that Trx1 may negatively regulate autophagy,

contradicting the aforementioned findings. Acrylamide (ACR), a

neurotoxic chemical, primarily exerts its effects through ROS

elevation. Trx1 overexpression downregulates ATG4B, LC3-II, histone

D and LAMP2a, and counteracts ACR-induced autophagy, while Trx1

suppression triggers autophagy (132). Consistent with these findings,

Trx1 also suppresses autophagy via the TXNIP/mTOR pathway. DR

represents a severe diabetic complication linked to advanced

glycation end-product (AGE) accumulation (133). Experimental evidence has

demonstrated that Trx upregulation attenuates AGE-mediated

neurodegeneration, potentially through TXNIP/mTOR axis suppression

and subsequent autophagic inhibition (133). Analogously, in Streptococcus

suis serotype 2 models, TrxC modulates AGE-induced

neurotoxicity via phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase

(PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt)/mTOR pathway regulation, thereby

controlling macrophage autophagic responses (134). Streptococcus suis is a

common porcine pathogen (135).

TrxC is a protein that is widely distributed in microorganisms

(134). This evidence indicates

that Trx1 exhibits dual regulatory effects on autophagy,

influencing either initiation or the autophagy-lysosomal pathway,

likely contingent on cellular context and oxidative stress

intensity.

Trx1 may undergo autophagic degradation.

Methylglyoxal (MGO) accumulation, which promotes AGE formation

in vivo, induces neuronal autophagy via AMPK/mTOR pathway

activation. Inhibition of autophagy through bafilomycin treatment

or ATG5 knockdown prevents Trx1 degradation, indicating

AMPK-dependent autophagy mediates Trx1 degradation (136). However, in hyperosmotic

stress-treated neuronal cells, Trx1 reduction occurs independently

of autophagy and AMPK (137),

contrasting with MGO-induced AMPK activation and autophagy

(137). These discrepancies

highlight the need for disease-specific investigation into Trx1

degradation mechanisms.

Autophagy-related proteins ATG4 and ATG7, important

for autophagosome formation, are regulated by Trx (138,139). Yeast ATG4 is activated by Trx

(140), while Trx1 enhances

myocardial ischemia-induced autophagy through ATG7

transnitrosylation (141).

Linkage between Trx2 and

autophagy

Multiple experiments have indicated that Trx2

suppresses mitochondrial ROS generation, preserving organelle

integrity and function (142).

Trx2 knockdown disrupts systemic metabolic homeostasis, exacerbates

hyperglycemia and promotes excessive mitochondrial autophagy

(143). Specifically, Trx2

deficiency in adipocytes triggers NF-κB-dependent p62 accumulation,

which targets damaged mitochondria for excessive autophagy via

polyubiquitination (143).

Consistent with these findings, in vivo and in vitro

experiments have demonstrated that Trx2 reduces myocardial

ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting ROS-mediated autophagy

through the Akt/mTOR and AMPK/mTOR signaling pathways (144,145). Collectively, Trx2 exerts dual

regulatory effects by suppressing both mitochondrial-specific and

general autophagy processes.

Linkage between TrxR and

autophagy

TrxR regenerates functional Trx through reductive

reactivation, establishing a catalytic cycle that drives iterative

redox transitions (146). TrxR

inhibitors not only display antitumor effects by inhibiting

apoptosis in HCC cells but are also capable of inducing

ROS-independent inhibition of autophagy. Pharmacological autophagy

inhibition enhances HCC susceptibility to TrxR suppression,

positioning TrxR as a promising chemotherapeutic target for HCC

management (147). In serum

deprivation models, TrxR is associated with lysosomal maturation

and regulates the terminal stage of autophagy. Specifically, TrxR

inhibition disrupts autophagosome-lysosome fusion, impairing

autophagic flux and blocking autophagic degradation (148). This mechanism parallels the role

of TrxR as a positive regulator of autophagy in HCC.

Linkage between TXNIP and

autophagy

Inhibition of TXNIP enhances autophagy in diabetic

nephropathy models. Elevated LC3 and p62 levels in the kidneys of

patients with diabetic nephropathy and diabetic rats indicate

autophagy dysregulation. TXNIP deficiency stimulates autophagy by

inhibiting mTOR activation, alleviates diabetes-induced tubular

autophagic flux blockage and promotes tubular mitochondrial

autophagy in diabetic rat kidneys (149). Consistently, in vitro

studies have shown that silencing TXNIP reduces autophagic vesicle

accumulation and the expression of LC3-II and p62 in renal tubular

cells exposed to high glucose, thereby enhancing autophagic flux

and resolving autophagic dysfunction (150). Transcription factor EB (TFEB), a

key regulator of autophagy and lysosomal biogenesis (151,152), is negatively regulated by mTOR,

which suppresses TFEB nuclear translocation (152). TXNIP knockdown attenuates mTOR

activation, restoring TFEB nuclear translocation and stimulating

autophagy to improve impaired flux (153).

However, TXNIP may also exert context-dependent

pro-autophagic effects. For example, in DR, TXNIP inhibition

paradoxically suppresses autophagy (133), highlighting the tissue-specific

and disease context-dependent nature of the autophagic regulation

of TXNIP. TXNIP positively modulates autophagic activity via

complex formation with stress sensor DNA damage-inducible

transcript 4 protein (REDD1). This TXNIP-REDD1 interaction

amplifies autophagosome biogenesis, resulting in cytoplasmic

autophagic vesicle overload that precipitates cardiomyocyte death

through excessive autophagy during myocardial ischemia-reperfusion

injury (154).

TXNIP-mediated autophagy regulation extends to mTOR

pathway inhibition through other mediators under metabolic stress

conditions. In DR models, TXNIP upregulation potentiates Müller

glial autophagic flux via PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling suppression

(155). Similarly, TXNIP

ameliorates steatohepatitis through activation of autophagy and

suppression of lipotoxic fatty acid oxidation. Mechanistically,

TXNIP induces autophagy by directly binding to phosphorylated

protein kinase AMP-activated catalytic subunit α. and regulating

mTORC1 and TFEB (156).

Crosstalk between apoptosis and

ferroptosis with autophagy

Multiple studies have documented the interplay

between autophagy and apoptosis (157,158). In pancreatic islet cells, TXNIP

overexpression concurrently drives autophagy and apoptosis, whereas

pharmacological autophagy inhibition via 3-methyladenine attenuates

TXNIP-induced apoptosis (159).

Trx upregulation reduces intracellular ROS levels and suppresses

apoptosis by inhibiting autophagy (133).

Autophagy and ferroptosis also exhibit crosstalk in

various disease contexts (160).

Previous evidence has indicated that TXNIP-mediated autophagy

regulates ferroptosis. Specifically, TXNIP suppresses both

canonical autophagy and mitochondrial autophagy in patients with

diabetes (149). In renal

pathology, PINK1/Parkin-driven mitochondrial autophagy protects

tubular epithelial cells from ferroptotic death through the

ROS/heme oxygenase 1/GPX4 axis (161). In diabetic nephropathy,

upregulation of the epigenetic regulator UHRF1 inhibits TXNIP

expression, thereby promoting PINK1-mediated mitochondrial

autophagy and suppressing ferroptosis (162).

Overall, the regulation of autophagy by TXNIP

exhibits a dual nature, capable of either suppressing or promoting

autophagy. This dichotomy may arise from several factors: i)

TXNIP-mediated regulation of autophagy is context-dependent,

varying across different disease settings (163); ii) the function of TXNIP is

influenced by its subcellular localization and interactions with

distinct intracellular factors, which modulate its effects on

autophagy; and iii) this duality may reflect the inherent dual

nature of autophagy itself, a process that maintains cellular

homeostasis by degrading damaged components but becomes detrimental

when excessive.

Furthermore, whether TXNIP possesses a threshold

mechanism that governs the initiation or suppression of autophagy

remains to be elucidated. Given the complexity of autophagy

regulation and the multifaceted role of TXNIP, further

investigation into these mechanisms is warranted to elucidate the

precise regulatory frameworks governing this relationship.

Notably, the Trx system co-regulates autophagy and

other cell death pathways, such as ferroptosis and apoptosis,

primarily through four key signaling axes: i) The PINK1/Parkin

pathway, linking mitophagy and ferroptosis (161,162); ii) the TXNIP-FoxO1 pathway,

linking autophagy to apoptosis (164); iii) the ASK1/c-Jun N-terminal

kinase (JNK) pathway, mediating redox-sensitive apoptosis and

autophagy (165); and iv) the

Trx1/mTOR pathway, linking Trx1 to ferroptosis suppression

(81–84). Such crosstalk reflects the key

regulatory position of the Trx system in balancing stress signaling

and influencing cell survival outcomes.

Mechanisms of the Trx system involved in

apoptosis in different diseases

Apoptosis, a form of programmed cell death, is

executed through tightly regulated gene activation cascades and

molecular signaling networks, exerting important regulatory

functions in both physiological homeostasis and disease

pathogenesis (166).

Trx1 exerts anti-apoptotic effects across various

diseases, often involving ASK1 and JNKs (167,168). Specifically, Trx1 inhibition

abolishes preconditioning-induced cardioprotection by promoting

apoptosis (169). Additionally,

Trx1 suppresses apoptosis triggered by ERS (170), which arises from redox

environment imbalance and Ca2+ homeostasis disruption in

the ER. ERS activation, in turn, stimulates excessive ROS

production (171). However, the

role of Trx1 in apoptosis regulation varies in tumorigenesis. In

HCC, Trx1 upregulation inhibits arsenide-induced apoptosis,

potentially due to mutations in its active site (172). Similarly, Trx2 has been shown to

negatively regulate apoptosis across multiple studies (173,174).

The relationship between TrxR and apoptosis has

been markedly investigated in cancer research, where TrxR

inhibitors have been shown to induce apoptosis and exert antitumor

effects (86,175,176). Beyond pharmacological inhibition,

the upregulation of TrxR itself can promote apoptosis in

non-neoplastic diseases. For example, selenite alleviates

bleomycin-induced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis by upregulating

TrxR, thereby increasing ROS production and promoting apoptosis in

mouse lung fibroblasts (177).

TXNIP interacts with NLRP3 to activate inflammatory

responses and subsequent pyroptosis (178). Beyond its role in inflammation,

TXNIP markedly contributes to apoptosis induction (179). Specifically, TXNIP upregulation

activates apoptotic pathways (155) and modulates intracellular ROS

generation, which in turn induces oxidative damage and apoptosis

(180). Additionally, TXNIP

upregulates FoxO1 expression via ROS accumulation and enhances

FoxO1 acetylation by inhibiting sirtuin 1 activity, thereby

promoting autophagic apoptosis in diabetic cardiomyopathy (164).

In summary, while the role of the Trx system in

apoptosis regulation is well-documented, its manifestations across

different disease contexts and interactions with other

intracellular mechanisms warrant further in-depth investigation.

TXNIP promotes apoptosis by disrupting the Trx1-ASK1 and Trx2-ASK1

complexes, leading to ASK1 activation, activation of the p38 MAPK

and JNK pathways, and initiation of apoptotic cascades (46,48,49).

TXNIP-induced ROS production further amplifies apoptotic signaling

and activates inflammasomes (52,180). By contrast, Trx1 protects against

apoptosis through ASK1 and JNK inhibition, demonstrating their

opposing regulatory roles in cell fate decisions (167,168). Beyond its roles in autophagy,

ferroptosis and apoptosis, TXNIP has recently emerged as a

modulator of immune responses. Programmed cell death protein 1

(PD-1) and its ligand programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) are

key immune checkpoint regulators that play a pivotal role in

modulating immune activity. Combination regimens incorporating

PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors with modalities such as chemotherapy,

radiotherapy, complementary immunotherapies or targeted agents have

demonstrated enhanced therapeutic efficacy (181). Given its role in shaping the

tumor immune microenvironment and promoting inflammasome

activation, TXNIP-targeted modulation may enhance responses to

immune checkpoint inhibitors such as PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. A recent

study suggests that TXNIP depletion could improve T cell-mediated

immunity and may serve as a promising combinatorial strategy in

immunotherapy, warranting further investigation (182).

Challenges and perspectives of targeting the

Trx system in neurodegenerative diseases

Synergistic and antagonistic

interactions in complex disease networks

The Trx system interacts dynamically with multiple

signaling pathways related to oxidative stress, inflammation,

apoptosis and cell survival. These interactions include both

synergistic and antagonistic effects (183). For example, targeting TXNIP can

suppress NLRP3 inflammasome activation, offering a promising

anti-inflammatory strategy (184). Furthermore, Trx/GSH system

inhibitors have demonstrated synergistic antitumor effects in

cancer therapy (185). Therefore,

therapies targeting the Trx system in isolation may be insufficient

or potentially imbalanced. Trx-based diagnosis and treatment should

preferably be combined with other oxidative stress markers or

standard therapies to improve therapeutic efficacy and ensure

system-level coordination.

Genetic and environmental influences

enabling personalized treatment

The expression and activity of Trx/TXNIP are highly

sensitive to environmental stressors, such as glucose, ROS and ERS,

and are further modulated by genetic polymorphisms and

environmental exposures such as nutrition, metals and toxins. These

factors influence individual responses to redox-targeted

interventions. Therefore, personalized therapeutic strategies

integrating genetic and environmental context may reduce off-target

effects and overcome the risk of systemic redox imbalance (183,186).

Spatial and temporal precision in

delivery and regulation

Jia et al (185) demonstrated that adeno-associated

virus-mediated Trx1 overexpression restricted to the hippocampus in

APP/PS1 mice improved cognitive function without disrupting

systemic redox homeostasis. This may support the notion that

region-specific delivery can confine Trx system modulation to

affected tissues, helping avoid systemic imbalance. In cancer

therapy, Trx-targeted treatments have also been combined with

precision delivery systems, such as nanoparticles or exosomes, to

selectively target diseased tissues or cell populations (49,63).

Additionally, the role of the Trx system may vary across different

disease stages; thus, temporal precision and disease-phase

specificity may also be important for therapeutic success.

These considerations are important for developing

precise and safe Trx-based interventions in complex neurological

conditions.

Conclusion

Being a central regulator of intracellular redox

homeostasis, the Trx system is markedly involved in autophagy,

ferroptosis and apoptosis regulation via its electron transfer

function and diverse signaling pathways. The present review

summarizes the biological structure and function of the Trx system,

with a focus on its dual roles in autophagy and ferroptosis, and

its complex influence on cell fate across different

pathophysiological contexts.

In autophagy regulation, the Trx system exhibits

dual functionality, either inhibiting or enhancing autophagy. It

modulates autophagy at both the initiation and autophagy-lysosome

binding stages, likely contingent on disease-specific environments

and cell types. TXNIP, in particular, achieves bidirectional

autophagy regulation by engaging with distinct target proteins,

such as the metabolic regulators mTOR and AMPK, the stress sensor

REDD1, the master transcription factor TFEB, and by influencing the

PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Notably, when observing autophagy

inhibition, the status of autophagic flux should be carefully

assessed to determine if it is blocked.

Regarding ferroptosis, Trx predominantly exerts

negative regulation. Trx1 inhibition induces ferroptosis in tumors,

offering potential antitumor strategies (86,173,174). Conversely, TXNIP positively

regulates ferroptosis across various diseases, including diabetic

retinopathy, high-fructose-induced nephropathy, sarcopenia and

ex vivo liver transplantation models, and serves as a

ferroptosis-related gene for cancer diagnosis and prognosis

prediction.

In the regulation of apoptosis, Trx and TrxR

generally exhibit anti-apoptotic properties, whereas TXNIP and TrxR

in non-neoplastic diseases show pro-apoptotic effects. Furthermore,

crosstalk between autophagy and ferroptosis, as well as between

autophagy and apoptosis, has gained research attention. These

interplays reflect cellular adaptive strategies to complex stress

conditions, and provide novel therapeutic targets and concepts for

disease intervention.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present review was supported by the Shandong Provincial

Medical and Health Science and Technology Project (grant no.

202303070601) and the Weifang Municipal Health Commission

Scientific Research Project (grant no. WFWSJK-2024-160).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

WHW, DLL and SSX were responsible for designing the

study. WHW and YDM both contributed to writing the manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

Trx

|

thioredoxin

|

|

TXNIP

|

thioredoxin-interacting protein

|

|

TrxR

|

thioredoxin reductase

|

|

GPX

|

glutathione peroxidase

|

|

ASK1

|

apoptosis signal-regulated kinase

1

|

|

MAPK

|

mitogen-activated protein kinase

|

|

GLUT1

|

glucose transporter 1

|

|

ERS

|

endoplasmic reticulum stress

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

|

NLRP3

|

NOD-like receptor family pyrin

domain-containing 3

|

|

PPAR

|

peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor

|

|

Keap1

|

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein

1

|

|

PD

|

Parkinson's disease

|

|

CML

|

chronic myeloid leukaemia

|

|

AMPK

|

AMP-activated protein kinase

|

|

NF-κB

|

nuclear factor κB

|

|

mTOR

|

mechanistic target of rapamycin

|

|

mTORC1

|

mTOR complex 1

|

|

HCC

|

hepatocellular carcinoma

|

|

FoxO1

|

forkhead box O1

|

|

LC3

|

microtubule-associated protein light

chain 3

|

|

LAMPs

|

lysosome-associated membrane

proteins

|

|

PINK1

|

PTEN-induced kinase 1

|

|

α-syn

|

α-synuclein

|

|

MPTP

|

1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine

|

|

DR

|

diabetic retinopathy

|

|

LECs

|

lens epithelial cells

|

|

ACR

|

acrylamide

|

|

AGE

|

advanced glycation end-product

|

|

PI3K

|

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate

3-kinase

|

|

Akt

|

protein kinase B

|

|

MGO

|

methylglyoxal

|

|

TFEB

|

transcription factor EB

|

|

JNK

|

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

|

References

|

1

|

Hasan AA, Kalinina E, Tatarskiy V and

Shtil A: The thioredoxin system of mammalian cells and its

modulators. Biomedicines. 10:17572022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Lee S, Kim SM and Lee RT: Thioredoxin and

thioredoxin target proteins: From molecular mechanisms to

functional significance. Antioxid Redox Signal. 18:1165–1207. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Seitz R, Tümen D, Kunst C, Heumann P,

Schmid S, Kandulski A, Müller M and Gülow K: Exploring the

thioredoxin system as a therapeutic target in cancer: Mechanisms

and implications. Antioxidants (Basel). 13:10782024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Muri J and Kopf M: The thioredoxin system:

Balancing redox responses in immune cells and tumors. Eur J

Immunol. 53:e22499482023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Yang B, Lin Y, Huang Y, Shen YQ and Chen

Q: Thioredoxin (Trx): A redox target and modulator of cellular

senescence and aging-related diseases. Redox Biol. 70:1030322024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Dagah OMA, Silaa BB, Zhu M, Pan Q, Qi L,

Liu X, Liu Y, Peng W, Ullah Z, Yudas AF, et al: Exploring immune

redox modulation in bacterial infections: Insights into

thioredoxin-mediated interactions and implications for

understanding host-pathogen dynamics. Antioxidants (Basel).

13:5452024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Lu J and Holmgren A: Thioredoxin system in

cell death progression. Antioxid Redox Signal. 17:1738–1747. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Jiang C, Krzyzanowski G, Chandel DS, Tom

WA, Fernando N, Olou A and Fernando MR: Inhibition of thioredoxin

reductase activity and oxidation of cellular thiols by

antimicrobial agent, 2-bromo-2-nitro-1,3-propanediol, causes

oxidative stress and cell death in cultured noncancer and cancer

cells. Biology (Basel). 14:5092025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Oberacker T, Kraft L, Schanz M, Latus J

and Schricker S: The importance of thioredoxin-1 in health and

disease. Antioxidants (Basel). 12:10782023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yu G and Klionsky DJ: Life and death

decisions-the many faces of autophagy in cell survival and cell

death. Biomolecules. 12:8662022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Jiang X, Stockwell BR and Conrad M:

Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 22:266–282. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Yan HF, Zou T, Tuo QZ, Xu S, Li H, Belaidi

AA and Lei P: Ferroptosis: Mechanisms and links with diseases.

Signal Transduct Target Ther. 6:492021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yang Y, Cheng J, Lin Q and Ni Z:

Autophagy-dependent ferroptosis in kidney disease. Front Med

(Lausanne). 9:10718642023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Liu X, Tuerxun H and Zhao Y, Li Y, Wen S,

Li X and Zhao Y: Crosstalk between ferroptosis and autophagy:

Broaden horizons of cancer therapy. J Transl Med. 23:182025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Mahmood DFD, Abderrazak A, El Hadri K,

Simmet T and Rouis M: The thioredoxin system as a therapeutic

target in human health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal.

19:1266–1303. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Laurent TC, Moore EC and Reichard P:

Enzymatic synthesis of deoxyribonucleotides. IV. isolation and

characterization of thioredoxin, the hydrogen donor from

Escherichia coli B. J Biol Chem. 239:3436–3444. 1964.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Xinastle-Castillo LO and Landa A:

Physiological and modulatory role of thioredoxins in the cellular

function. Open Med (Wars). 17:2021–2035. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Eklund H, Gleason FK and Holmgren A:

Structural and functional relations among thioredoxins of different

species. Proteins. 11:13–28. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Hanschmann EM, Godoy JR, Berndt C,

Hudemann C and Lillig CH: Thioredoxins, glutaredoxins, and

peroxiredoxins-molecular mechanisms and health significance: From

cofactors to antioxidants to redox signaling. Antioxid Redox

Signal. 19:1539–1605. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Forman-Kay JD, Clore GM, Wingfield PT and

Gronenborn AM: High-resolution three-dimensional structure of

reduced recombinant human thioredoxin in solution. Biochemistry.

30:2685–2698. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Collet JF and Messens J: Structure,

function, and mechanism of thioredoxin proteins. Antioxid Redox

Signal. 13:1205–1216. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Barglow KT, Knutson CG, Wishnok JS,

Tannenbaum SR and Marletta MA: Site-specific and redox-controlled

S-nitrosation of thioredoxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

108:E600–E606. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Ungerstedt J, Du Y, Zhang H, Nair D and

Holmgren A: In vivo redox state of human thioredoxin and redox

shift by the histone deacetylase inhibitor suberoylanilide

hydroxamic acid (SAHA). Free Radic Biol Med. 53:2002–2007. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Cortes-Bratti X, Bassères E,

Herrera-Rodriguez F, Botero-Kleiven S, Coppotelli G, Andersen JB,

Masucci MG, Holmgren A, Chaves-Olarte E, Frisan T and Avila-Cariño

J: Thioredoxin 80-activated-monocytes (TAMs) inhibit the

replication of intracellular pathogens. PLoS One. 6:e169602011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

King BC, Nowakowska J, Karsten CM, Köhl J,

Renström E and Blom AM: Truncated and full-length thioredoxin-1

have opposing activating and inhibitory properties for human

complement with relevance to endothelial surfaces. J Immunol.

188:4103–4112. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Kim MK, Zhao L, Jeong S, Zhang J, Jung JH,

Seo HS, Choi JI and Lim S: Structural and biochemical

characterization of thioredoxin-2 from deinococcus radiodurans.

Antioxidants (Basel). 10:18432021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Gencheva R, Cheng Q and Arnér ESJ:

Thioredoxin reductase selenoproteins from different organisms as

potential drug targets for treatment of human diseases. Free Radic

Biol Med. 190:320–338. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Arnér ES and Holmgren A: Physiological

functions of thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase. Eur J Biochem.

267:6102–6109. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Papp LV, Lu J, Holmgren A and Khanna KK:

From selenium to selenoproteins: Synthesis, identity, and their

role in human health. Antioxid Redox Signal. 9:775–806. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Lu J, Zhong L, Lönn ME, Burk RF, Hill KE

and Holmgren A: Penultimate selenocysteine residue replaced by

cysteine in thioredoxin reductase from selenium-deficient rat

liver. FASEB J. 23:2394–2402. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Zeisel L, Felber JG, Scholzen KC, Poczka

L, Cheff D, Maier MS, Cheng Q, Shen M, Hall MD, Arnér ESJ, et al:

Selective cellular probes for mammalian thioredoxin reductase

TrxR1: Rational design of RX1, a modular 1,2-thiaselenane redox

probe. Chem. 8:1493–1517. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Muri J, Heer S, Matsushita M, Pohlmeier L,

Tortola L, Fuhrer T, Conrad M, Zamboni N, Kisielow J and Kopf M:

The thioredoxin-1 system is essential for fueling DNA synthesis

during T-cell metabolic reprogramming and proliferation. Nat

Commun. 9:18512018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Cebula M, Moolla N, Capovilla A and Arnér

ESJ: The rare TXNRD1_v3 (‘v3’) splice variant of human thioredoxin

reductase 1 protein is targeted to membrane rafts by N-acylation

and induces filopodia independently of its redox active site

integrity. J Biol Chem. 288:10002–10011. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Zhang J, Li X, Han X, Liu R and Fang J:

Targeting the thioredoxin system for cancer therapy. Trends

Pharmacol Sci. 38:794–808. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Pollak N, Dölle C and Ziegler M: The power

to reduce: Pyridine nucleotides-small molecules with a multitude of

functions. Biochem J. 402:205–218. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Holmgren A and Lu J: Thioredoxin and

thioredoxin reductase: current research with special reference to

human disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 396:120–124. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Gaber A, Tamoi M, Takeda T, Nakano Y and

Shigeoka S: NADPH-dependent glutathione peroxidase-like proteins

(Gpx-1, Gpx-2) reduce unsaturated fatty acid hydroperoxides in

Synechocystis PCC 6803. FEBS Lett. 499:32–36. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Frasier CR, Moukdar F, Patel HD, Sloan RC,

Stewart LM, Alleman RJ, La Favor JD and Brown DA: Redox-dependent

increases in glutathione reductase and exercise preconditioning:

Role of NADPH oxidase and mitochondria. Cardiovasc Res. 98:47–55.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Koh HJ, Lee SM, Son BG, Lee SH, Ryoo ZY,

Chang KT, Park JW, Park DC, Song BJ, Veech RL, et al: Cytosolic

NADP+-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase plays a key role in lipid

metabolism. J Biol Chem. 279:39968–39974. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Santos CXC, Raza S and Shah AM: Redox

signaling in the cardiomyocyte: From physiology to failure. Int J

Biochem Cell Biol. 74:145–151. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Masutani H: Thioredoxin-interacting

protein in cancer and diabetes. Antioxid Redox Signal.

36:1001–1022. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Chen KS and DeLuca HF: Isolation and

characterization of a novel cDNA from HL-60 cells treated with

1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D-3. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1219:26–32. 1994.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Nishiyama A, Matsui M, Iwata S, Hirota K,

Masutani H, Nakamura H, Takagi Y, Sono H, Gon Y and Yodoi J:

Identification of thioredoxin-binding protein-2/vitamin D(3)

up-regulated protein 1 as a negative regulator of thioredoxin

function and expression. J Biol Chem. 274:21645–21650. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Hwang J, Suh HW, Jeon YH, Hwang E, Nguyen

LT, Yeom J, Lee SG, Lee C, Kim KJ, Kang BS, et al: The structural

basis for the negative regulation of thioredoxin by

thioredoxin-interacting protein. Nat Commun. 5:29582014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Saxena G, Chen J and Shalev A:

Intracellular shuttling and mitochondrial function of

thioredoxin-interacting protein. J Biol Chem. 285:3997–4005. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Chen CL, Lin CF, Chang WT, Huang WC, Teng

CF and Lin YS: Ceramide induces p38 MAPK and JNK activation through

a mechanism involving a thioredoxin-interacting protein-mediated

pathway. Blood. 111:4365–4374. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Li Y, Deng W, Wu J, He Q, Yang G, Luo X,

Jia Y, Duan Y, Zhou L and Liu D: TXNIP exacerbates the senescence

and aging-related dysfunction of β cells by inducing cell cycle

arrest through p38-p16/p21-CDK-Rb pathway. Antioxid Redox Signal.

38:480–495. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Song S, Qiu D, Wang Y, Wei J, Wu H, Wu M,

Wang S, Zhou X, Shi Y and Duan H: TXNIP deficiency mitigates

podocyte apoptosis via restraining the activation of mTOR or p38

MAPK signaling in diabetic nephropathy. Exp Cell Res.

388:1118622020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Pan M, Zhang F, Qu K, Liu C and Zhang J:

TXNIP: A double-edged sword in disease and therapeutic outlook.

Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022:78051152022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Yoshihara E: TXNIP/TBP-2: A master

regulator for glucose homeostasis. Antioxidants (Basel). 9:7652020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Wu N, Zheng B, Shaywitz A, Dagon Y, Tower

C, Bellinger G, Shen CH, Wen J, Asara J, McGraw TE, et al:

AMPK-dependent degradation of TXNIP upon energy stress leads to

enhanced glucose uptake via GLUT1. Mol Cell. 49:1167–1175. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Park SJ, Kim Y, Li C, Suh J, Sivapackiam

J, Goncalves TM, Jarad G, Zhao G, Urano F, Sharma V and Chen YM:

Blocking CHOP-dependent TXNIP shuttling to mitochondria attenuates

albuminuria and mitigates kidney injury in nephrotic syndrome. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 119:e21165051192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Kim SK, Choe JY and Park KY:

TXNIP-mediated nuclear factor-κB signaling pathway and

intracellular shifting of TXNIP in uric acid-induced NLRP3

inflammasome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 511:725–731. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Devi TS, Somayajulu M, Kowluru RA and

Singh LP: TXNIP regulates mitophagy in retinal Müller cells under

high-glucose conditions: Implications for diabetic retinopathy.

Cell Death Dis. 8:e27772017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Meszaros M, Yusenko M, Domonkos L, Peterfi

L, Kovacs G and Banyai D: Expression of TXNIP is associated with

angiogenesis and postoperative relapse of conventional renal cell

carcinoma. Sci Rep. 11:172002021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Deng J, Pan T, Liu Z, McCarthy C, Vicencio

JM, Cao L, Alfano G, Suwaidan AA, Yin M, Beatson R and Ng T: The

role of TXNIP in cancer: A fine balance between redox, metabolic,

and immunological tumor control. Br J Cancer. 129:1877–1892. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Fearnhead HO, Vandenabeele P and Vanden

Berghe T: How do we fit ferroptosis in the family of regulated cell

death? Cell Death Differ. 24:1991–1998. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Tuo QZ and Lei P: Ferroptosis in ischemic

stroke: Animal models and mechanisms. Zool Res. 45:1235–1248. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Xie Y, Kang R, Klionsky DJ and Tang D:

GPX4 in cell death, autophagy, and disease. Autophagy.

19:2621–2638. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Cheng Q, Chen M, Liu M, Chen X, Zhu L, Xu

J, Xue J, Wu H and Du Y: Semaphorin 5A suppresses ferroptosis

through activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling in rheumatoid

arthritis. Cell Death Dis. 13:6082022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Yodoi J, Matsuo Y, Tian H, Masutani H and

Inamoto T: Anti-inflammatory thioredoxin family proteins for

medicare, healthcare and aging care. Nutrients. 9:10812017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Sastre J, Pérez S, Sabater L and

Rius-Pérez S: Redox signaling in the pancreas in health and

disease. Physiol Rev. 105:593–650. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Shen K, Wang X, Wang Y, Jia Y, Zhang Y,

Wang K, Luo L, Cai W, Li J, Li S, et al: miR-125b-5p in adipose

derived stem cells exosome alleviates pulmonary microvascular

endothelial cells ferroptosis via Keap1/Nrf2/GPX4 in sepsis lung

injury. Redox Biol. 62:1026552023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Wang H, Xie B, Shi S, Zhang R, Liang Q,

Liu Z and Cheng Y: Curdione inhibits ferroptosis in

isoprenaline-induced myocardial infarction via regulating

Keap1/Trx1/GPX4 signaling pathway. Phytother Res. 37:5328–5340.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Bai L, Yan F, Deng R, Gu R, Zhang X and

Bai J: Thioredoxin-1 rescues MPP+/MPTP-induced

ferroptosis by increasing glutathione peroxidase 4. Mol Neurobiol.

58:3187–3197. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Bebber CM, Müller F, Prieto Clemente L,

Weber J and von Karstedt S: Ferroptosis in cancer cell biology.

Cancers (Basel). 12:1642020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Ye Z, Liu W, Zhuo Q, Hu Q, Liu M, Sun Q,

Zhang Z, Fan G, Xu W, Ji S, et al: Ferroptosis: Final destination

for cancer? Cell Prolif. 53:e127612020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Su Y, Zhao B, Zhou L, Zhang Z, Shen Y, Lv

H, AlQudsy LHH and Shang P: Ferroptosis, a novel pharmacological

mechanism of anti-cancer drugs. Cancer Lett. 483:127–136. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Lu J and Holmgren A: The thioredoxin

antioxidant system. Free Radic Biol Med. 66:75–87. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta

R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS,

et al: Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell

death. Cell. 149:1060–1072. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Tang Z, Liu Y, He M and Bu W: Chemodynamic

therapy: Tumour microenvironment-mediated fenton and fenton-like

reactions. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 58:946–956. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Mohammadi F, Soltani A, Ghahremanloo A,

Javid H and Hashemy SI: The thioredoxin system and cancer therapy:

A review. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 84:925–935. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Lei G, Mao C, Yan Y, Zhuang L and Gan B:

Ferroptosis, radiotherapy, and combination therapeutic strategies.

Protein Cell. 12:836–857. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Lin Y, Chen X, Yu C, Xu G, Nie X, Cheng Y,

Luan Y and Song Q: Radiotherapy-mediated redox

homeostasis-controllable nanomedicine for enhanced ferroptosis

sensitivity in tumor therapy. Acta Biomater. 159:300–311. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75