Hirschsprung disease (HSCR) is a congenital

neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by the absence of enteric

ganglion cells in the distal bowel, leading to dysmotility and

functional obstruction (1). Its

most severe complication, Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis

(HAEC), occurs in 17–50% of patients with HSCR. The preoperative

incidence of HAEC peaks at 60% in unscreened cohorts, while

postoperative rates range from 25–37% (2,3). In

total, >95% of cases occur in children <5 years of age in

multicenter studies (4). Asian

cohorts report lower postoperative rates (5,6) than

Western populations with HRSC (7),

with HAEC representing the leading cause of mortality in this

population. Clinically, HAEC manifests as fulminant diarrhea

progressing to sepsis, driven by mucosal barrier failure, dysbiosis

and immune hyperactivation (7,8).

Central to this pathophysiology is tight junction (TJ) dysfunction,

a ‘leaky epithelium’ phenotype that facilitates systemic pathogen

dissemination and fluid loss (9,10),

although its molecular underpinnings remain elusive.

The intestinal epithelial barrier is governed by

TJs, which orchestrate selective permeability to balance nutrient

absorption and pathogen exclusion (11). TJs are assembled from transmembrane

proteins, including claudins, occludin and junctional adhesion

molecules, cytoplasmic scaffolds, such as zonula occludens protein

1 (ZO-1) and cingulin, and the actomyosin cytoskeleton comprising

filamentous-actin (F-actin) and myosin II (12). Claudins form charge-selective

pores, as is the case with claudin-2, or barrier strands, such as

claudin-4, while occludin regulates macromolecular transport via

lipid raft-dependent endocytosis (13,14).

Notably, mechanical coupling between TJ proteins and the actomyosin

cytoskeleton is important for maintaining TJ ultrastructural

stability (15). Dysregulation of

this dynamic assembly system directly precipitates barrier collapse

(16).

Studies have shown that in bowel segments lacking

ganglion cells, intestinal barrier function is impaired and

exhibits decreased expression of ZO-1 and increased expression of

claudin-3 (17). These alterations

in TJ gene expression may result in increased epithelial

permeability, further promoting the development of HAEC. Compared

with other HSCR subgroups and patients with anorectal

malformations, patients with postoperative HAEC exhibit

significantly increased paracellular permeability during radical

surgery (18). Additionally, the

interaction between TJ proteins and the cytoskeleton, composed of

F-actin and myosin, is important for maintaining TJ structure and

function (13,15).

M1-polarized pro-inflammatory macrophages secrete

IL-1β and TNF-α, downregulating occludin and ZO-1 expression and

disrupting actomyosin-TJ coupling (19). This cytokine storm activates the

RhoA/Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) axis, which induces

pathological stress fiber assembly. The formation of these stress

fibers dismantles TJ architecture and accelerates luminal toxin

influx, propelling HAEC progression toward toxic megacolon

(20,21).

The pathogenesis of HAEC involves synergistic

defects in tight junction regulation (22) and actomyosin contractility

(23). Targeting TJ dynamic

assembly or modulating cytoskeletal remodeling may offer precision

therapeutic strategies to reverse the ‘leaky barrier’ phenotype,

thereby improving clinical outcomes in HAEC.

The claudin family consists of at least 27 members

that serve as important components of TJs, where they determine

paracellular ion permeability and charge selectivity. Claudins

exhibit tissue-specific expression patterns; for instance,

claudin-5 and −6 are predominant in renal podocytes, claudin-2, −4,

−8, −12 and −13 in bladder urothelium, claudin-2 to −5 in gastric

epithelium and claudin-1 to −19 in murine intestinal epithelium,

while human sigmoid colon primarily expresses claudin-1 to −5, −7

and −8. These proteins collectively contribute to barrier formation

and function (24).

Functionally, claudins are categorized as either

barrier-forming, such as claudin-1, −3 and −4, or pore-forming,

such as claudin-2 (16).

Disruption of this balance is implicated in intestinal pathologies.

For instance, in a benzalkonium chloride (BAC)-induced HSCR model,

claudin-3 is upregulated, compromising barrier integrity (17). Conversely, decreased claudin-4

expression is observed in postoperative patients with HAEC

(22). Although claudin-1 and −2

have been studied in necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) (25,26),

their roles in HAEC remain to be fully elucidated.

Given their established importance in intestinal

barrier regulation, with claudin-1 enhancing barrier tightness,

claudin-2 modulating fluid and cation flux (27) and the demonstrated dysregulation of

claudin-3 and −4 in HAEC and HSCR, the present study focused on

claudin-1 to −4 to systematically investigate their collective and

individual roles in HAEC pathogenesis.

The inflammatory microenvironment reprograms the

expression of claudins through cytokines, directly disrupting the

homeostasis of TJ. For example, IL-1β activates multiple

transcription factors, such as NF-κB p50/p65, activating

transcription factor-2 and ETS domain-containing protein Elk-1, and

through the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase

kinase 1, the catalytic subunit of IKKβ, binds to the minimal

promoter region of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK). This

synergistically activates the MLCK gene and increases the

permeability of TJs (28), thereby

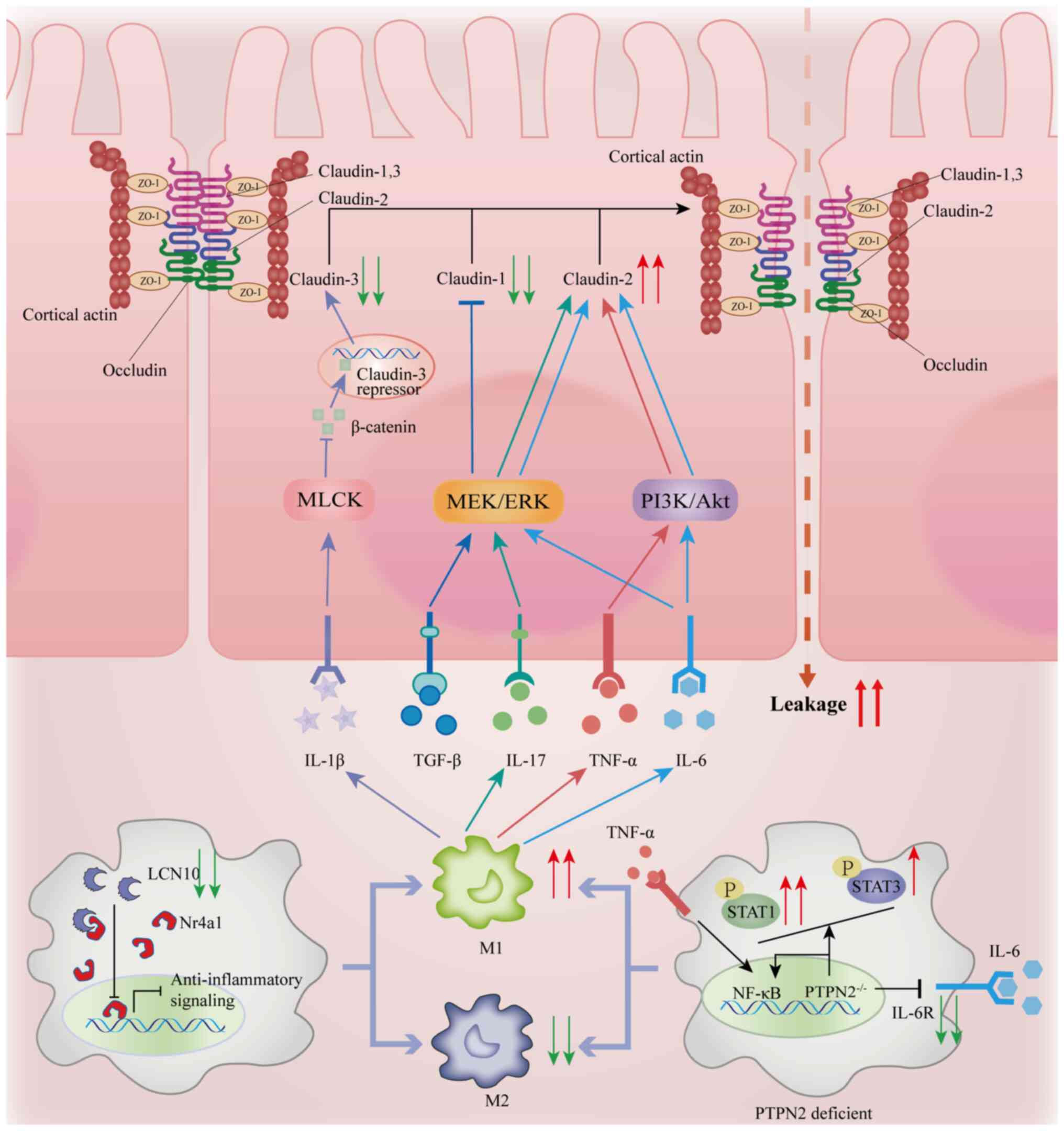

promoting intestinal inflammation (Fig. 1) (29). However, regarding the effect of

IL-1β on claudins, current research results remain inconsistent. A

study by Maria-Ferreira et al (30) found that the increase in TJ

permeability of Caco-2 cells induced by IL-1β is related to a

decrease in claudin-1 expression. By contrast, other studies have

shown that IL-1β activates β-catenin via the Wnt signaling pathway

or through an MLCK-dependent mechanism, thus downregulating the

expression of claudin-3 and leading to an increase in intestinal

permeability (31,32).

The increase in macrophages and the imbalance of the

M1/M2 macrophage ratio can affect intestinal barrier function by

influencing TJ proteins. Classically activated M1 macrophages

usually infiltrate the intestine during infection or inflammation

(37), and an increase in their

proportion has been observed during HAEC episodes (38,39).

M1 macrophages exacerbate intestinal barrier breakdown through a

dual mechanism: i) They secrete TNF-α and IL-6 (Fig. 1), promoting the expression of

claudin-2 and inducing the endocytosis and degradation of claudin-4

(40); and ii) M1 macrophages

activate heparanase to degrade heparan sulfate within the basement

membrane, altering the expression levels of TJ proteins, such as

occludin and ZO-1, and disrupting the TJ-extracellular matrix

interaction (TJ-ECM) anchoring, thus exacerbating intestinal

hyperpermeability (36–38). In macrophages with protein tyrosine

phosphatase non-receptor type 2 deficiency, the overactive

STAT1/NF-κB signaling pathway drives M1 macrophage polarization and

inhibits STAT3-mediated M2 macrophage differentiation by reducing

the expression of the IL-6 receptor (35,39).

The deficiency of lipocalin 10 (LCN10) further enhances this

process by inhibiting the nuclear receptor 4A1 pathway,

exacerbating M1 polarization (41)

and directly disrupting TJ-cytoskeleton coupling, which leads to

barrier leakage (Fig. 1) (42).

Based on the aforementioned mechanisms, multimodal

intervention strategies show clinical promise. In the BAC pig

model, specific small interfering RNA interference of claudin-3 can

reduce intestinal permeability and decrease the release of

inflammatory factors IL-1β and TNF-α (17). The heparanase inhibitor PG545

restores TJ-ECM anchoring and preclinical trials have shown that

the mucosal homeostasis of pediatric patients with HAEC is restored

upon treatment (43). The LCN10

protein increases the TER by regulating macrophage polarization

(41). These findings not only

reveal the multi-level pathogenic mechanisms of HAEC but also

provide a theoretical framework for the development of precise

therapies targeting the TJ network.

Occludin is a four-pass transmembrane protein

consisting of 522 amino acids, and its structural features

determine its dynamic regulatory function in TJs (44). The two extracellular loops mediate

cell-cell adhesion, while the cytoplasmic occludin/ELL (OCEL)

domain comprising 107 amino acids engages in interactions with

ZO-1, actin and kinases such as MLCK, imparting mechanical

stress-response capability to TJs (41,45).

Functional studies have demonstrated that occludin specifically

regulates the paracellular flux of macromolecules (46) without affecting the fundamental

structure of TJs; occludin knockout mice retain intact TJ

morphology (43,44), indicating that the core role of

occludin is as a ‘permeability regulator’ rather than a ‘structural

scaffold.’

The dynamic regulation of occludin in the membrane

is a key mechanism in the plasticity of the intestinal barrier.

Under inflammation or mechanical stress stimuli, occludin can be

directly internalized via vesicle-mediated endocytosis, leading to

the dissociation of the TJ supramolecular structure (47). This process is precisely regulated

by the lipid raft-scaffolding protein caveolin-1, which has an

N-terminus that forms a stable complex with the OCEL domain in the

cytoplasmic tail of occludin and modulates its membrane trafficking

cycle by altering its phosphorylation pattern (46,48).

Inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1β, trigger

hyperphosphorylation of occludin at Ser408 (49). This dysregulation promotes

clathrin-mediated endocytic internalization of occludin while

disrupting ZO-1 anchoring to the actin cytoskeleton,

synergistically increasing paracellular permeability in aganglionic

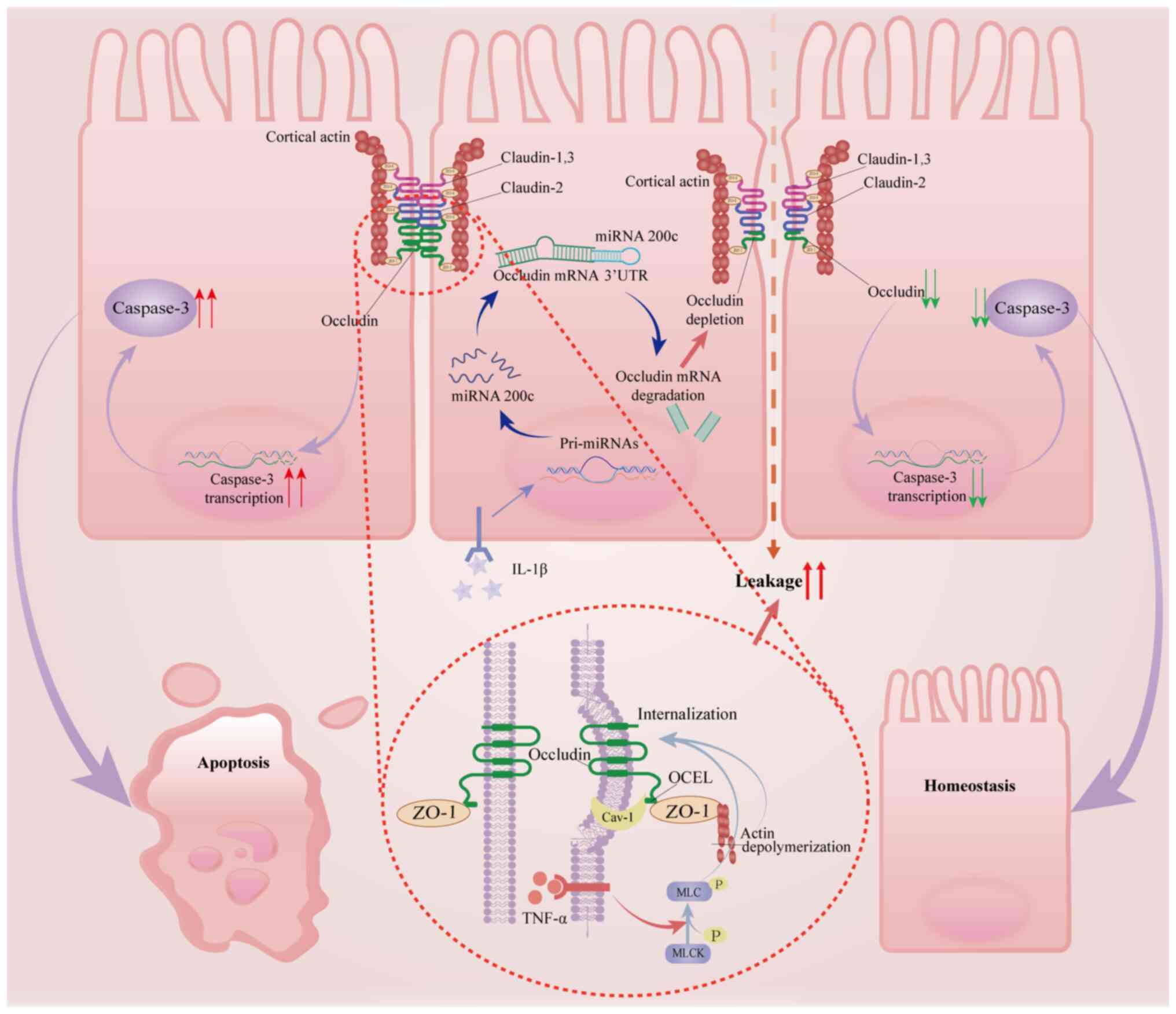

bowel segments (Fig. 2) (50). A study reported by Van Itallie

et al (51) revealed that

knockout of either occludin or caveolin-1 in Madin-Darby canine

kidney cells attenuated the disruption of the tight junction

barrier induced by inflammatory factors such as TNF-α. In

vivo experiments support that the absence of caveolin-1

significantly reduces the changes in TJ permeability mediated by

TNF-α, suggesting that the pathological function of occludin

depends on caveolin-1-mediated lipid raft-signaling microdomain

remodeling (51).

Notably, TNF-α triggers a caveolin-1-dependent

endocytic cascade by activating the MLCK pathway, a necessary

condition for TNF-α regulation of TJ structure and function

(50,52). Furthermore, actin depolymerization

can exacerbate intestinal barrier breakdown by promoting the

clathrin-mediated endocytosis of TJ components, including occludin,

and further destabilizing the barrier (53). IL-1β activates microRNA-200c-3p

through the MLCK/NF-κB pathway, which binds to the 3′UTR of

occludin mRNA and induces its degradation. This degradation results

in reduced occludin protein levels, thereby increasing intestinal

permeability (Fig. 2) (29). These cooperative mechanisms

together form the molecular basis of HAEC (54,55),

suggesting that targeting the caveolin-1-occludin axis or the MLCK

signaling network could be a potential new strategy for reversing

barrier damage.

Dysregulated expression of occludin is a common

feature of various intestinal diseases. During the active phase of

inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), occludin expression is reduced in

the colonic epithelium, which negatively correlates with barrier

permeability (56). A decrease in

occludin protein levels has also been observed in intestinal

samples from pediatric patients with NEC (57). In response to this pathological

mechanism, ROCK inhibitors can stabilize occludin membrane

localization and increase its expression, improving intestinal

barrier resistance in the BAC rat model (58).

As a representative member of the

membrane-associated guanylate kinase protein family, ZO-1 mediates

multidimensional regulation of TJs through its modular structure:

i) Three PDZ domains guide the topological localization of

claudin/occludin; ii) the SRC homology 3 (SH3) domain recruits

signaling kinases to regulate downstream pathways; and iii) the

actin-binding region (ABR) at the carboxyl terminus forms the

physical-functional coupling interface between TJs and the

cytoskeleton (60,61). Notably, in ZO-1 knockout models,

although TJ ultrastructure can spontaneously assemble (62), its maturation is significantly

delayed and accompanied by increased macromolecular transmembrane

leakage (63), suggesting that

ZO-1 is not a rigid scaffold for TJ assembly. Rather, ZO-1

dynamically regulates the liquid-liquid phase transition of protein

complexes through a phase separation mechanism. ZO-1 phase

separation, mediated through PDZ-SH3 domain-driven biomolecular

condensate formation, orchestrates rapid TJ assembly by

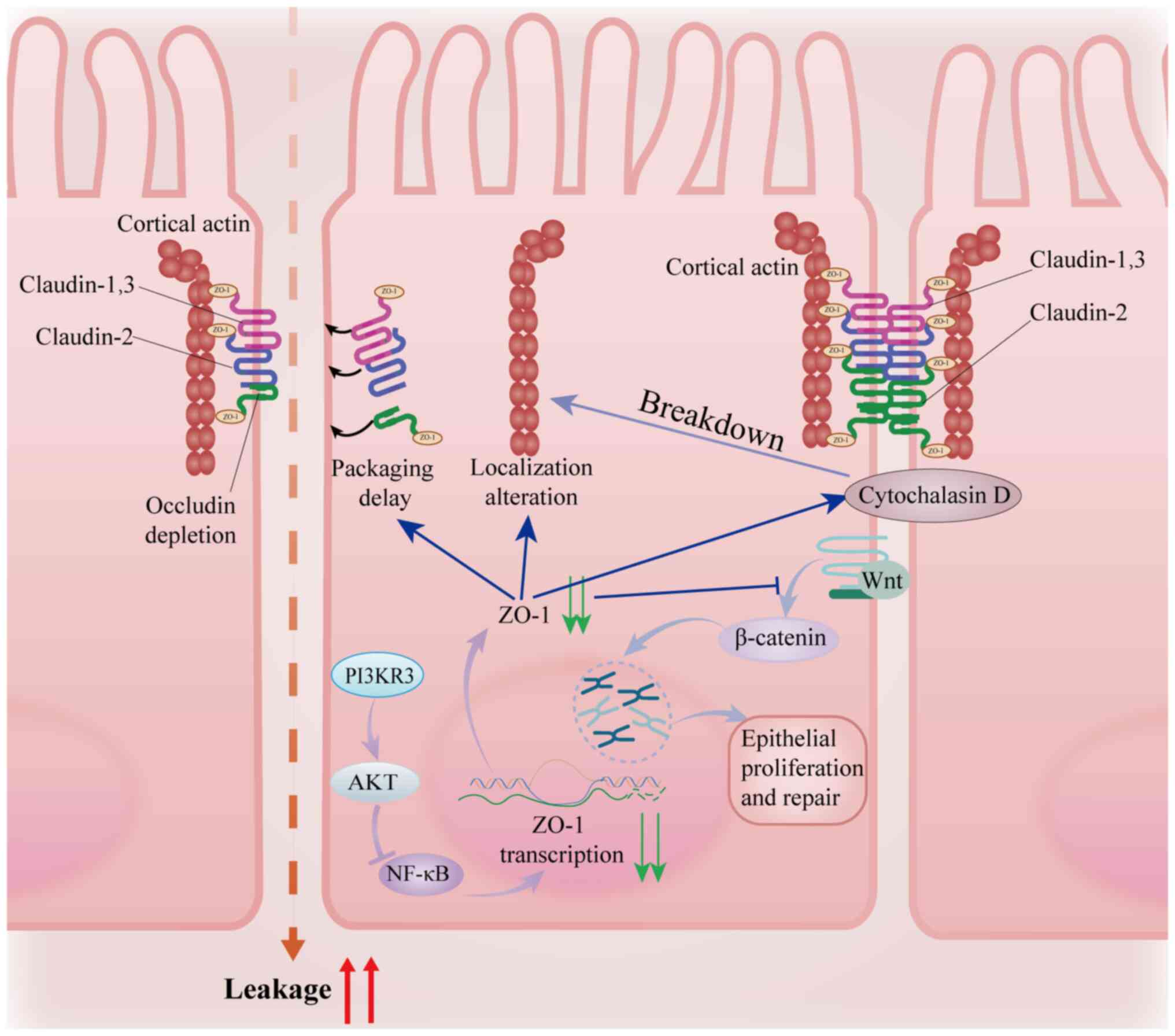

concentrating scaffolding proteins (Fig. 3) (60). Notably, pro-inflammatory cytokines

such as TNF-α disrupt this process by inducing hyperphosphorylation

of the intrinsically disordered regions of ZO-1, thereby dissolving

condensates and impairing barrier repair (64). In intestinal epithelia, TNF-α

reduces ZO-1 expression while increasing phosphorylation of its

intrinsically disordered regions, directly impairing barrier

function through delayed TJ assembly (65). This multifaceted

structural-functional characteristic positions ZO-1 as both a

molecular adapter and a signaling hub, with conformational changes

potentially regulating barrier plasticity through allosteric

effects.

ZO-1 regulates TJ plasticity through two synergistic

axes: i) ZO-1 directly interacts with claudin proteins and guides

the localization of their polymerization sites (66), coordinating the assembly of

transmembrane proteins; and ii) ZO-1 couples TJs to the

cytoskeletal network via its ABR, with actin depolymerization

having been shown to significantly increase paracellular

permeability (67). It is worth

noting that although ZO-1 deletion does not alter the total actin

content of the cell, it disrupts its spatial organization (68), highlighting the role of ZO-1 in the

topological regulation of the cytoskeleton rather than providing

only mechanical anchorage. This dual regulatory mechanism may

provide insights into how ZO-1 coordinates acute barrier remodeling

and chronic fibrosis during mucosal repair.

Upon injury, ZO-1 coordinates epithelial repair

through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (Fig. 3) (69). ZO-1 knockdown reduces β-catenin

nuclear translocation and impairs wound healing (69). Clinical cohort studies have shown a

strong positive correlation between ZO-1 expression in intestinal

epithelium and endoscopic healing scores in patients with IBD

(69), while ZO-1 mRNA levels in

exosomes from fecal samples of neonates with NEC can predict the

risk of intestinal perforation (57). These findings collectively suggest

that ZO-1 not only mediates barrier integrity but also acts as an

important node linking homeostasis maintenance and regenerative

repair through mechanical-chemical signaling. Its functional

depletion may trigger a cycle of barrier defect-induced chronic

inflammation.

Although ZO-1 plays a central role in barrier

regulation, its pathological mechanism in congenital

megacolon-associated fatal complications, such as HAEC, remains yet

to be fully elucidated. Given that HAEC is characterized by the

disruption of TJ structures (17),

targeting the regulation of ZO-1 interactions offers a promising

avenue for therapeutic innovation. Future research may explore the

spatiotemporal analysis of ZO-1 dynamics in HAEC models to identify

important nodes of dysfunction, for example ABR-actin uncoupling

and other pathological processes. Furthermore, peptides derived

from the ABR could be designed to selectively block pathological

cytoskeletal remodeling while preserving barrier integrity. The

systematic integration of these research strategies will drive

translational medical progress from mechanism elucidation to

precise intervention in HAEC.

The plasticity of the intestinal epithelial cell

barrier relies on the spatiotemporal reorganization of the actin

cytoskeleton. The steady-state conversion between globular-actin

monomers and F-actin polymers is finely regulated by the

phosphorylation cycle of cofilin. LIM kinase (LIMK) mediates

cofilin phosphorylation, thereby inhibiting its activity, while the

phosphatase slingshot homologue 1 (Ssh1) activates cofilin through

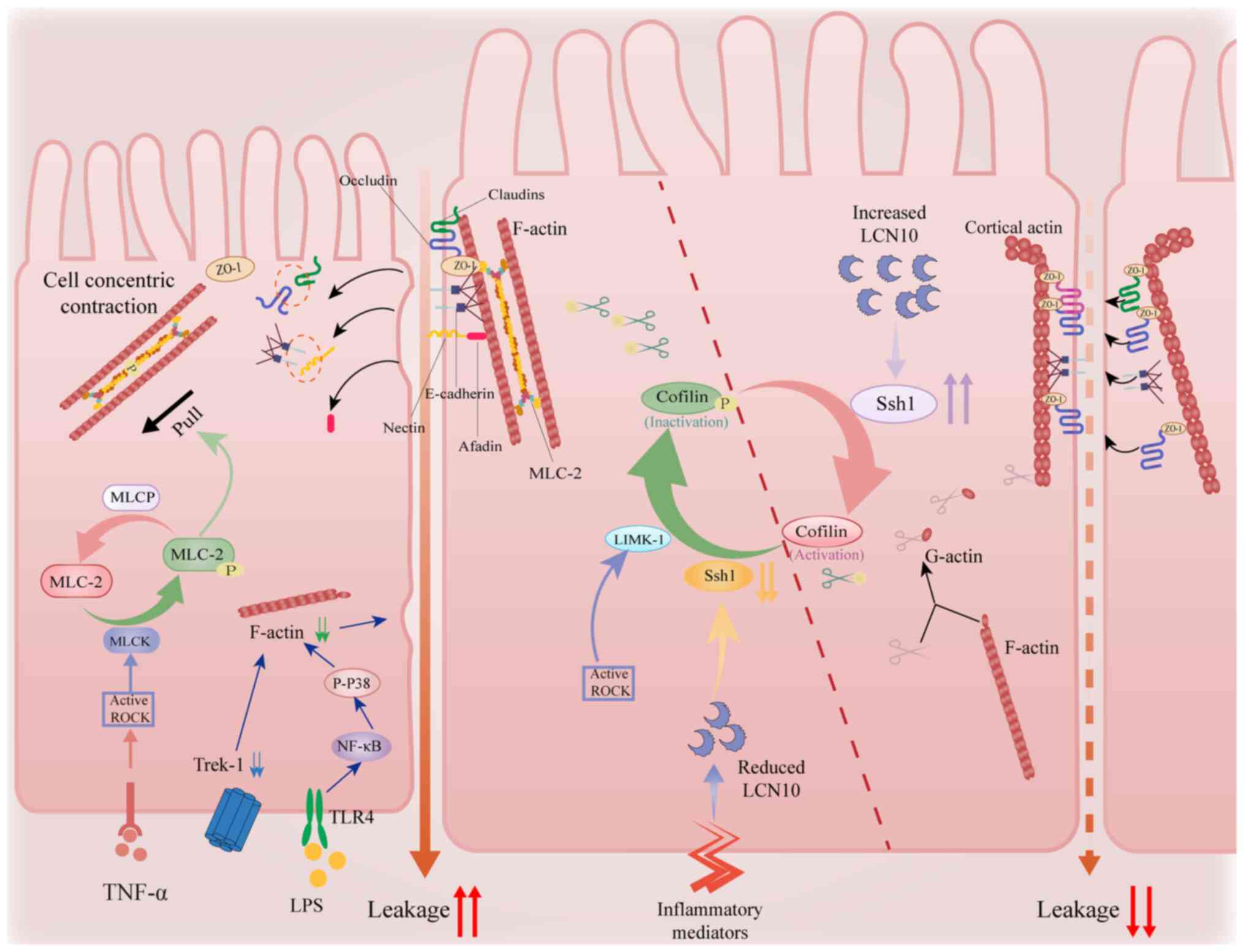

dephosphorylation, promoting the disassembly of F-actin (Fig. 4) (70,71).

Imbalance in this system can directly disrupt the membrane

localization of TJ proteins, such as ZO-1 and occludin, leading to

an increase in paracellular permeability (23,72).

ZO-1 forms a mechanical coupling interface with

F-actin through its carboxy-terminal ABR. Loss of ZO-1 function

results in the disruption of actin filament integrity (68). MLCK and ROCK mediate actomyosin

contraction through phosphorylation of myosin light chains, which,

in turn, dissociates the ZO-1 ABR from F-actin, ultimately

triggering the opening of the paracellular pathway (73–75).

Notably, MLCK inhibitors completely reverse the ZO-1

internalization phenotype, while ROCK inhibitors partially restore

barrier function, indicating the signaling pathway specificity of

the ZO-1/F-actin interaction (76,77).

This mechanical transduction property positions ZO-1 as a molecular

sensor linking the mechanical microenvironment with barrier

plasticity.

Pro-inflammatory factors exacerbate barrier damage

via multifaceted regulation of actin dynamics: i) IFN-γ enhances

actomyosin contractility via a ROCK-dependent pathway, leading to

the internalization of ZO-1 and occluding (78); ii) a dynamic interaction exists

between Twik-related K+ channel-1 (Trek-1) and the actin

cytoskeleton. In colonic epithelia, Trek-1 stabilizes cortical

actin via direct binding to F-actin. Trek-1 deficiency reduces

F-actin density, increasing paracellular permeability (79). Hypoganglionic segments in HSCR show

lower Trek-1 expression compared with normoganglionic bowels. This

deficit impairs mechanotransduction in the neurogenic

microenvironment, exacerbating barrier dysfunction during HAEC

flares (Fig. 4) (80). Similarly, activation of the

Toll-like receptor 4/phosphorylated p38/NF-κB signaling pathway

also results in reduced F-actin expression (81), influencing the opening of

intercellular gaps (Fig. 4); and

(iii) lipopolysaccharides (LPS) inhibit EGFR phosphorylation,

thereby hindering its activity in protective actin reorganization

(82). Collectively, these

pathways form a positive feedback loop of inflammatory

signals/cytoskeletal remodeling/barrier breakdown, providing a

mechanistic explanation for the chronic progression of IBD.

The lipid carrier protein LCN10, a secreted protein

expressed in macrophages, endothelial and epithelial cells

(64), serves as an important

regulator of cytoskeletal dynamics. Mechanistically, LCN10

activates Ssh1 phosphatase to dephosphorylate cofilin, thereby

enhancing F-actin depolymerization, a process important for TJ

protein redistribution in barrier dysfunction (42,83).

Notably, this LCN10/Ssh1/cofilin pathway-dependent regulation is

conserved across vascular and intestinal barriers, where LCN10

deficiency exacerbates inflammation-induced permeability (42). Pathologically, pro-inflammatory

stimuli, such as LPS and IFN-γ, suppress LCN10 expression by

>80% in intestinal macrophages (41), which may drive HAEC progression by

disrupting actin-mediated TJ stability.

Furthermore, in cohorts of pediatric patients with

HAEC (n=75), stenotic bowel segments exhibit 73% lower

phosphorylated cofilin levels vs. controls (84,85).

Mechanistically, LCN10 activates Ssh1 via high-affinity binding to

low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 2, restoring

cofilin-mediated actin dynamics to reduce barrier leakage (42). These findings nominate the

LCN10/Ssh1/cofilin axis as a theragnostic target for HAEC. Based on

these findings, small molecule agonists targeting LCN10 may

overcome the current lack of cytoskeletal targets in HAEC

therapies. Furthermore, we hypothesize that combinatory strategies

involving ZO-1 ABR stabilizers could produce synergistic barrier

repair effects.

The present study elucidates the molecular

pathogenesis of HAEC, revealing that intestinal barrier dysfunction

stems from TJ protein dysregulation, including claudin-2/4

imbalance, occludin endocytosis via the MLCK/NF-κB pathway and

ZO-1-cytoskeleton uncoupling, coupled with inflammatory

mediator-driven actin remodeling through the cofilin

phosphorylation cycle. The identification of the LCN10/Ssh1/cofilin

axis and TJ-cytoskeleton interactions provides mechanistic insights

into HAEC pathogenesis and potential therapeutic targets. The

scarcity of targeted research on TJ and cytoskeletal proteins in

HAEC underscores the translational significance of the present

study. Future studies should investigate subcellular TJ protein

dynamics, develop small-molecule modulators of the LCN10/Ssh1

pathway, validate their pharmacokinetic and toxicological profiles

and explore combination therapies targeting both barrier repair and

inflammation, ultimately translating these findings into clinical

strategies for HAEC prevention and treatment.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 81700497 and 81873848) and the

Hubei Natural Science Foundation (grant nos. 2024AFB668 and

2021CFB264).

Not applicable.

ST, YW and LL contributed to the conception and

design of the study, and provided administrative support. LZ, ShaC,

YZ, DY, KL, YL and ShuC participated in data analysis and

visualization, including the creation and interpretation of

graphical figures. SL and CW were major contributors in drafting

and revising the manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Montalva L, Cheng LS, Kapur R, Langer JC,

Berrebi D, Kyrklund K, Pakarinen M, de Blaauw I, Bonnard A and

Gosain A: Hirschsprung disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 9:542023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Gosain A, Frykman PK, Cowles RA, Horton J,

Levitt M, Rothstein DH, Langer JC and Goldstein AM; American

Pediatric Surgical Association Hirschsprung Disease Interest Group,

: Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of

Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis. Pediatr Surg Int.

33:517–521. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Nakamura H, Tomuschat C, Coyle D, O'Donnel

AM, Lim T and Puri P: Altered goblet cell function in

Hirschsprung's disease. Pediatr Surg Int. 34:121–128. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Lewit RA, Veras LV, Cowles RA, Fowler K,

King S, Lapidus-Krol E, Langer JC, Park CJ, Youssef F, Vavilov S

and Gosain A: Reducing Underdiagnosis of Hirschsprung-Associated

Enterocolitis: A Novel Scoring System. J Surg Res. 261:253–260.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Feng W, Zhang B, Fan L, Song A, Hou J, Die

X, Liu W, Wang Y and Guo Z: Clinical characteristics and influence

of postoperative Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis:

Retrospective study at a tertiary children's hospital. Pediatr Surg

Int. 40:1062024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wu L, Gao Y, Zhou R, Xiao P, Zhang Z, Li

B, Pierro A, Li L, Jiang Q and Li Q: Predictive value of plasma

zonulin for postoperative Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis.

World J Pediatr Surg. 8:e0010572025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Hagens J, Reinshagen K and Tomuschat C:

Prevalence of Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis in patients

with Hirschsprung disease. Pediatr Surg Int. 38:3–24. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Li S, Zhang Y, Li K, Liu Y, Chi S, Wang Y

and Tang S: Update on the pathogenesis of the

hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis. Int J Mol Sci. 24:46022023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Jiao CL, Chen XY and Feng JX: Novel

Insights into the Pathogenesis of Hirschsprung's-associated

Enterocolitis. Chin Med J (Engl). 129:1491–1497. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Cong X and Kong W: Endothelial tight

junctions and their regulatory signaling pathways in vascular

homeostasis and disease. Cell Signal. 66:1094852020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Chelakkot C, Ghim J and Ryu SH: Mechanisms

regulating intestinal barrier integrity and its pathological

implications. Exp Mol Med. 50:1–9. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Suzuki T: Regulation of intestinal

epithelial permeability by tight junctions. Cell Mol Life Sci.

70:631–659. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

König J, Wells J, Cani PD, García-Ródenas

CL, MacDonald T, Mercenier A, Whyte J, Troost F and Brummer RJ:

Human intestinal barrier function in health and disease. Clin

Transl Gastroenterol. 7:e1962016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Tsukita S, Furuse M and Itoh M:

Multifunctional strands in tight junctions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

2:285–293. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Van Itallie CM and Anderson JM:

Architecture of tight junctions and principles of molecular

composition. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 36:157–165. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Garcia-Hernandez V, Quiros M and Nusrat A:

Intestinal epithelial claudins: Expression and regulation in

homeostasis and inflammation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1397:66–79. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Arnaud AP, Hascoet J, Berneau P, LeGouevec

F, Georges J, Randuineau G, Formal M, Henno S and Boudry G: A

piglet model of iatrogenic rectosigmoid hypoganglionosis reveals

the impact of the enteric nervous system on gut barrier function

and microbiota postnatal development. J Pediatr Surg. 56:337–345.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Dariel A, Grynberg L, Auger M, Lefèvre C,

Durand T, Aubert P, Le Berre-Scoul C, Venara A, Suply E, Leclair

MD, et al: Analysis of enteric nervous system and intestinal

epithelial barrier to predict complications in Hirschsprung's

disease. Sci Rep. 10:217252020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Chen X, Meng X, Zhang H, Feng C, Wang B,

Li N, Abdullahi KM, Wu X, Yang J, Li Z, et al: Intestinal

proinflammatory macrophages induce a phenotypic switch in

interstitial cells of Cajal. J Clin Invest. 130:6443–6456. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Pall H: Advances in pediatric

gastroenterology. Pediatr Clin North Am. 68:xix–xx. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Roorda D, Oosterlaan J, van Heurn E and

Derikx JPM: Risk factors for enterocolitis in patients with

Hirschsprung disease: A retrospective observational study. J

Pediatr Surg. 56:1791–1798. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Abe K, Takeda M, Ishiyama A, Shimizu M,

Goto H, Iida H, Fujimoto T, Ueda-Abe E, Yamada S, Fujiwara K, et

al: Impact of epithelial claudin-4 and leukotriene B4 receptor 2 in

normoganglionic hirschsprung disease colon on post pull-through

enterocolitis. J Pediatr Surg. 60:1619002025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Perrin L and Matic Vignjevic D: The

emerging roles of the cytoskeleton in intestinal epithelium

homeostasis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 150-151:23–27. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Günzel D and Yu AS: Claudins and the

modulation of tight junction permeability. Physiol Rev. 93:525–569.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Bu C, Hu M, Su Y, Yuan F, Zhang Y, Xia J,

Jia Z and Zhang L: Cell-permeable JNK-inhibitory peptide regulates

intestinal barrier function and inflammation to ameliorate

necrotizing enterocolitis. J Cell Mol Med. 28:e185342021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Gunasekaran A, Eckert J, Burge K, Zheng W,

Yu Z, Kessler S, de la Motte C and Chaaban H: Hyaluronan 35 kDa

enhances epithelial barrier function and protects against the

development of murine necrotizing enterocolitis. Pediatr Res.

87:1177–1184. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Ganapathy AS, Saha K, Suchanec E, Singh V,

Verma A, Yochum G, Koltun W, Nighot M, Ma T and Nighot P: AP2M1

mediates autophagy-induced CLDN2 (claudin 2) degradation through

endocytosis and interaction with LC3 and reduces intestinal

epithelial tight junction permeability. Autophagy. 18:2086–2103.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Al-Sadi R, Ye D, Said HM and Ma TY:

Cellular and molecular mechanism of interleukin-1β modulation of

Caco-2 intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier. J Cell Mol

Med. 15:970–982. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Rawat M, Nighot M, Al-Sadi R, Gupta Y,

Viszwapriya D, Yochum G, Koltun W and Ma TY: IL1B increases

intestinal tight junction permeability by Up-regulation of

MIR200C-3p, which degrades occludin mRNA. Gastroenterology.

159:1375–1389. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Maria-Ferreira D, Nascimento AM, Cipriani

TR, Santana-Filho AP, Watanabe PDS, Sant Ana DMG, Luciano FB,

Bocate KCP, van den Wijngaard RM, Werner MFP and Baggio CH:

Rhamnogalacturonan, a chemically-defined polysaccharide, improves

intestinal barrier function in DSS-induced colitis in mice and

human Caco-2 cells. Sci Rep. 8:122612018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Haines RJ, Beard RS Jr, Chen L, Eitnier RA

and Wu MH: Interleukin-1β mediates β-Catenin-driven downregulation

of claudin-3 and barrier dysfunction in caco2 cells. Dig Dis Sci.

61:2252–2261. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Ahmad R, Kumar B, Chen Z, Chen X, Müller

D, Lele SM, Washington MK, Batra SK, Dhawan P and Singh AB: Loss of

claudin-3 expression induces IL6/gp130/Stat3 signaling to promote

colon cancer malignancy by hyperactivating Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

Oncogene. 36:6592–6604. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Mankertz J, Amasheh M, Krug SM, Fromm A,

Amasheh S, Hillenbrand B, Tavalali S, Fromm M and Schulzke JD:

TNFalpha up-regulates claudin-2 expression in epithelial HT-29/B6

cells via phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase signaling. Cell Tissue Res.

336:67–77. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Barmeyer C, Fromm M and Schulzke JD:

Active and passive involvement of claudins in the pathophysiology

of intestinal inflammatory diseases. Pflugers Arch. 469:15–26.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Lee SH: Intestinal permeability regulation

by tight junction: Implication on inflammatory bowel diseases.

Intest Res. 13:11–18. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Raju P, Shashikanth N, Tsai PY,

Pongkorpsakol P, Chanez-Paredes S, Steinhagen PR, Kuo WT, Singh G,

Tsukita S and Turner JR: Inactivation of paracellular

cation-selective claudin-2 channels attenuates immune-mediated

experimental colitis in mice. J Clin Invest. 130:5197–5208. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Bain CC, Scott CL, Uronen-Hansson H,

Gudjonsson S, Jansson O, Grip O, Guilliams M, Malissen B, Agace WW

and Mowat AM: Resident and pro-inflammatory macrophages in the

colon represent alternative context-dependent fates of the same

Ly6Chi monocyte precursors. Mucosal Immunol. 6:498–510. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Meng X, Xiao J, Wang J, Sun M, Chen X, Wu

L, Feng C, Zhuansun D, Yang J, Wu X, et al: Mesenchymal stem cells

attenuates hirschsprung diseases-associated enterocolitis by

reducing M1 macrophages infiltration via COX-2 dependent mechanism.

J Pediatr Surg. 59:1498–1514. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zheng Z, Lin L, Lin H, Zhou J, Wang Z,

Wang Y, Chen J, Lai C, Li R, Shen Z, et al: Acetylcholine from tuft

cells promotes M2 macrophages polarization in

Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis. Front Immunol.

16:15599662025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Spalinger MR, Sayoc-Becerra A, Santos AN,

Shawki A, Canale V, Krishnan M, Niechcial A, Obialo N, Scharl M, Li

J, et al: PTPN2 regulates interactions between macrophages and

intestinal epithelial cells to promote intestinal barrier function.

Gastroenterology. 159:1763–1777.e14. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Li Q, Li Y, Huang W, Wang X, Liu Z, Chen

J, Fan Y, Peng T, Sadayappan S, Wang Y and Fan GC: Loss of

lipocalin 10 exacerbates diabetes-induced cardiomyopathy via

disruption of Nr4a1-mediated anti-inflammatory response in

macrophages. Front Immunol. 13:9303972022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhao H, Wang P, Wang X, Du W, Yang HH, Liu

Y, Cui SN, Huang W, Peng T, Chen J, et al: Lipocalin 10 is

essential for protection against inflammation-triggered vascular

leakage by activating LDL receptor-related protein 2-slingshot

homologue 1 signalling pathway. Cardiovasc Res. 119:1981–1996.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Capozzi A, Riitano G, Recalchi S,

Manganelli V, Costi R, Saccoliti F, Pulcinelli F, Garofalo T,

Misasi R, Longo A, et al: Effect of heparanase inhibitor on tissue

factor overexpression in platelets and endothelial cells induced by

anti-β2-GPI antibodies. J Thromb Haemost. 19:2302–2313. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Furuse M, Hirase T, Itoh M, Nagafuchi A,

Yonemura S and Tsukita S and Tsukita S: Occludin: A novel integral

membrane protein localizing at tight junctions. J Cell Boil. 123((6

Pt 2)): 1777–1788. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Tugal D, Liao X and Jain MK:

Transcriptional control of macrophage polarization. Arterioscler,

Thromb, Vasc Biol. 33:1135–1144. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Buckley A and Turner JR: Cell biology of

tight junction barrier regulation and mucosal disease. Cold Spring

Harb Perspect Biol. 10:a0293142018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Shimizu Y, Shirasago Y, Kondoh M, Suzuki

T, Wakita T, Hanada K, Yagi K and Fukasawa M: Monoclonal antibodies

against occludin completely prevented hepatitis C virus infection

in a mouse model. J Virol. 92:e02258–17. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Nusrat A, Chen JA, Foley CS, Liang TW, Tom

J, Cromwell M, Quan C and Mrsny RJ: The coiled-coil domain of

occludin can act to organize structural and functional elements of

the epithelial tight junction. J Biol Chem. 275:29816–29822. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Srivastava AK, Venkata BS, Sweat YY, Rizzo

HR, Jean-François L, Zuo L, Kurgan KW, Moore P, Shashikanth N, Smok

I, et al: Serine 408 phosphorylation is a molecular switch that

regulates structure and function of the occludin α-helical bundle.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 119:e22046181192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Buschmann MM, Shen L, Rajapakse H, Raleigh

DR, Wang Y, Wang Y, Lingaraju A, Zha J, Abbott E, McAuley EM, et

al: Occludin OCEL-domain interactions are required for maintenance

and regulation of the tight junction barrier to macromolecular

flux. Mol Biol Cell. 24:3056–3068. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Van Itallie CM, Fanning AS, Holmes J and

Anderson JM: Occludin is required for cytokine-induced regulation

of tight junction barriers. J Cell Sci. 123:2844–2852. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Marchiando AM, Shen L, Graham WV, Weber

CR, Schwarz BT, Austin JR II, Raleigh DR, Guan Y, Watson AJ,

Montrose MH and Turner JR: Caveolin-1-dependent occludin

endocytosis is required for TNF-induced tight junction regulation

in vivo. J Cell Biol. 189:111–126. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Shen L and Turner JR: Actin

depolymerization disrupts tight junctions via caveolae-mediated

endocytosis. Mol Biol Cell. 16:3919–3936. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Budianto IR, Kusmardi K, Maulana AMuh,

Arumugam S, Afrin R and Soetikno V: Paneth-like cells disruption

and intestinal dysbiosis in the development of enterocolitis in an

iatrogenic rectosigmoid hypoganglionosis rat model. Front Surg.

11:14079482024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Nakamura H, O'Donnell AM, Tomuschat C,

Coyle D and Puri P: Altered expression of caveolin-1 in the colon

of patients with Hirschsprung's disease. Pediatr Surg Int.

35:929–934. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Zeissig S, Bürgel N, Günzel D, Richter J,

Mankertz J, Wahnschaffe U, Kroesen AJ, Zeitz M, Fromm M and

Schulzke JD: Changes in expression and distribution of claudin 2, 5

and 8 lead to discontinuous tight junctions and barrier dysfunction

in active Crohn's disease. Gut. 56:61–72. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Zhang X, Zhang Y, He Y, Zhu X, Ai Q and

Shi Y: β-glucan protects against necrotizing enterocolitis in mice

by inhibiting intestinal inflammation, improving the gut barrier,

and modulating gut microbiota. J Transl Med. 21:142023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Grothaus JS, Ares G, Yuan C, Wood DR and

Hunter CJ: Rho kinase inhibition maintains intestinal and vascular

barrier function by upregulation of occludin in experimental

necrotizing enterocolitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol.

315:G514–G528. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Kuo WT, Shen L, Zuo L, Shashikanth N, Ong

MLDM, Wu L, Zha J, Edelblum KL, Wang Y, Wang Y, et al:

Inflammation-induced Occludin Downregulation Limits Epithelial

Apoptosis by Suppressing Caspase-3 Expression. Gastroenterology.

157:1323–1337. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Spadaro D, Le S, Laroche T, Mean I, Jond

L, Yan J and Citi S: Tension-dependent stretching activates ZO-1 to

control the junctional localization of its interactors. Curr Biol.

27:3783–3795.e8. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Rouaud F, Sluysmans S, Flinois A, Shah J,

Vasileva E and Citi S: Scaffolding proteins of vertebrate apical

junctions: Structure, functions and biophysics. Biochim Biophys

Acta Biomembr. 1862:1833992020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Umeda K, Matsui T, Nakayama M, Furuse K,

Sasaki H, Furuse M and Tsukita S: Establishment and

characterization of cultured epithelial cells lacking expression of

ZO-1. J Biol Chem. 279:44785–44794. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Otani T, Nguyen TP, Tokuda S, Sugihara K,

Sugawara T, Furuse K, Miura T, Ebnet K and Furuse M: Claudins and

JAM-A coordinately regulate tight junction formation and epithelial

polarity. J Cell Biol. 218:3372–3396. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Sun S and Zhou J: Phase separation as a

therapeutic target in tight junction-associated human diseases.

Acta Pharmacol Sin. 41:1310–1313. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Zhang J, Lei H, Hu X and Dong W:

Hesperetin ameliorates DSS-induced colitis by maintaining the

epithelial barrier via blocking RIPK3/MLKL necroptosis signaling.

Eur J Pharmacol. 873:1729922020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Umeda K, Ikenouchi J, Katahira-Tayama S,

Furuse K, Sasaki H, Nakayama M, Matsui T and Tsukita S, Furuse M

and Tsukita S: ZO-1 and ZO-2 independently determine where claudins

are polymerized in tight-junction strand formation. Cell.

126:741–754. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Bentzel CJ, Hainau B, Ho S, Hui SW,

Edelman A, Anagnostopoulos T and Benedetti EL: Cytoplasmic

regulation of tight-junction permeability: Effect of plant

cytokinins. Am J Physiol. 239:C75–C89. 1980. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Van Itallie CM, Fanning AS, Bridges A and

Anderson JM: ZO-1 stabilizes the tight junction solute barrier

through coupling to the perijunctional cytoskeleton. Mol Biol Cell.

20:3930–3940. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Kuo WT, Zuo L, Odenwald MA, Madha S, Singh

G, Gurniak CB, Abraham C and Turner JR: The tight junction protein

ZO-1 is dispensable for barrier function but critical for effective

mucosal repair. Gastroenterology. 161:1924–1939. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Grintsevich EE and Reisler E: Drebrin

inhibits cofilin-induced severing of F-actin. Cytoskeleton

(Hoboken). 71:472–483. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Suzuki K, Lareyre JJ, Sánchez D, Gutierrez

G, Araki Y, Matusik RJ and Orgebin-Crist MC: Molecular evolution of

epididymal lipocalin genes localized on mouse chromosome 2. Gene.

339:49–59. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Van Itallie CM, Tietgens AJ, Krystofiak E,

Kachar B and Anderson JM: A complex of ZO-1 and the BAR-domain

protein TOCA-1 regulates actin assembly at the tight junction. Mol

Biol Cell. 26:2769–2787. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Yu D, Marchiando AM, Weber CR, Raleigh DR,

Wang Y, Shen L and Turner JR: MLCK-dependent exchange and actin

binding region-dependent anchoring of ZO-1 regulate tight junction

barrier function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 107:8237–8241. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Turner JR, Rill BK, Carlson SL, Carnes D,

Kerner R, Mrsny RJ and Madara JL: Physiological regulation of

epithelial tight junctions is associated with myosin light-chain

phosphorylation. Am J Physiol. 273:C1378–C1385. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Walsh SV, Hopkins AM, Chen J, Narumiya S,

Parkos CA and Nusrat A: Rho kinase regulates tight junction

function and is necessary for tight junction assembly in polarized

intestinal epithelia. Gastroenterology. 121:566–579. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Odenwald MA, Choi W, Kuo WT, Singh G,

Sailer A, Wang Y, Shen L, Fanning AS and Turner JR: The scaffolding

protein ZO-1 coordinates actomyosin and epithelial apical

specializations in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 293:17317–17335.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Kuo W, Odenwald MA, Turner JR and Zuo L:

Tight junction proteins occludin and ZO-1 as regulators of

epithelial proliferation and survival. Ann N Y Acad Sci.

1514:21–33. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Ma TY, Boivin MA, Ye D, Pedram A and Said

HM: Mechanism of TNF-{alpha} modulation of Caco-2 intestinal

epithelial tight junction barrier: Role of myosin light-chain

kinase protein expression. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol.

288:G422–G430. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Roan E, Waters CM, Teng B, Ghosh M and

Schwingshackl A: The 2-pore domain potassium channel TREK-1

regulates stretch-induced detachment of alveolar epithelial cells.

PLoS One. 9:e894292014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Tomuschat C, O'Donnell AM, Coyle D, Dreher

N, Kelly D and Puri P: Altered expression of a two-pore domain

(K2P) mechano-gated potassium channel TREK-1 in Hirschsprung's

disease. Pediatr Res. 80:729–733. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Zheng Z, Gao M, Tang C, Huang L, Gong Y,

Liu Y and Wang J: E.coli JM83 damages the mucosal barrier in Ednrb

knockout mice to promote the development of Hirschsprung-associated

enterocolitis via activation of TLR4/p-p38/NF-κB signaling. Mol Med

Rep. 25:1682022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Samak G, Aggarwal S and Rao RK: ERK is

involved in EGF-mediated protection of tight junctions, but not

adherens junctions, in acetaldehyde-treated Caco-2 cell monolayers.

Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 301:G50–G59. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Krndija D, El Marjou F, Guirao B, Richon

S, Leroy O, Bellaiche Y, Hannezo E and Matic Vignjevic D: Active

cell migration is critical for steady-state epithelial turnover in

the gut. Science. 365:705–710. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Lappalainen P, Kotila T, Jégou A and

Romet-Lemonne G: Biochemical and mechanical regulation of actin

dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 23:836–852. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Zhou WK, Qu Y, Liu YM, Gao MJ, Tang CY,

Huang L, Du Q and Yin J: The abnormal phosphorylation of the Rac1,

Lim-kinase 1, and Cofilin proteins in the pathogenesis of

Hirschsprung's disease. Bioengineered. 13:8548–8557. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|