Introduction

Cervical cancer is one of the most common types of

gynecological cancer and ranks as the fourth leading cause of

cancer-related mortality among women, and 14th overall among all

types of cancer (1,2). According to the GLOBOCAN 2022 report,

~660,000 new cases of cervical cancer were diagnosed, with ~340,000

mortalities attributed to the disease (3). Extensive evidence suggests that

cervical cancer is primarily caused by human papillomavirus

infection, with additional contributing factors associated with

social factors (such as income, education and region) and

individual behaviors (such as age, sex, smoking status, nutrition,

activity level) (4,5). This is exemplified by the obvious

regional differences in the incidence and mortality of cervical

cancer within China. Surveillance data from the Chinese cancer

registry shows that incidence and mortality rates in rural areas

are consistently higher than those in urban areas. This disparity

is attributed to inequalities in health education, access to HPV

screening, and availability of vaccination programs. Furthermore,

it is estimated that among younger women, this gap in incidence

rates between urban and rural populations is likely to widen

further, highlighting the critical role of socioeconomic factors in

disease outcomes (4). Excessive

cell division and proliferation are central to the development of

cervical cancer (6,7), making the inhibition of cancer cell

proliferation and the induction of apoptosis key therapeutic

strategies.

Endophytic fungi, which reside within the tissues of

medicinal plants and co-evolve with their hosts (8), produce a diverse array of natural

products (9,10). These products exhibit a range of

biological activities, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory,

antibacterial, antiviral and anticancer properties (11). Anti-tumor natural products have

been classified into several structural groups, such as alkaloids

(12), terpenoids (13), steroids (14), quinones (15) and esters (10).

Taxus wallichiana var. mairei, a rare

and endangered plant native to southern China, is well-known for

producing the anti-cancer drug paclitaxel (16). Fungal endophytes isolated from

Taxus wallichiana var. mairei include species such as

Phoma medicaginis (17),

Diaporthe phaseolorum (18)

and Nigrospora oryzae (19). The genus Alternaria (family

Dematiaceae) consists of globally distributed filamentous fungi and

plant pathogens (20,21), known for producing a variety of

secondary metabolites (22).

Dihydroalterperylenol (DAP) is a perylenequinone

metabolite characterized by a highly conjugated pentacyclic core. A

previous study has reported that DAP does not exhibit cytotoxicity

(23). The present study

demonstrated the potent cytotoxic activity of DAP isolated from the

plant endophytic fungus Alternaria semiverrucosa in HeLa

cells and explored its apoptosis-inducing mechanism through

transcriptome analysis, molecular docking and molecular dynamics

(MD) simulations studies.

Materials and methods

Materials and instruments for chemical

separation

Silica gel (200–300 mesh; Qingdao Haiyang Chemical

Co. Ltd.), Sephadex LH-20 gel (Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co.

Ltd.), Octadecylsilyl-bonded (ODS) silica gel (cat. no. RP-18;

Merck KGaA) and organic solvents (methanol, CAS No: 67-56-1;

dichloromethane, CAS No: 75-09-2; petroleum ether, CAS No:

8032-32-4; ethyl acetate, CAS No: 141-78-6; All the aforementioned

reagents are analytical grade; Tianjin Fuyu Fine Chemical Co. Ltd.)

were used for column chromatography. Thin-layer chromatography was

monitored using silica gel plates (type H; Qingdao Dingkang

Silicone Co. Ltd.). One-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance

(NMR) spectra were recorded using Bruker Avance-500 and 600

spectrometers (Beijing Obel Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd.).

Fungal material and fermentation

All specimens of Taxus chinensis var.

mairei were obtained through artificial propagation and

exclusively sourced from the Wanshun Seedling Farm Guiyang, China.

Voucher specimens of the host plant have been deposited at the

Engineering Research Center for Utilization of Characteristic

Bio-Pharmaceutical Resources in Southwest China, Ministry of

Education, Guizhou University, with the accession number ZZ-HJ-13.

The endophytic fungus Alternaria semiverrucosa was isolated

from the healthy branches of Taxus chinensis var.

mairei. The fungal isolate Alternaria semiverrucosa

was preserved at the Guizhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences under

strain code (dried culture; holotype no. GZAAS 22-2029; ex-type

living culture, no. GZCC 22-2029). The fungus was cultured on

potato dextrose agar plates for 10 days. The mycelia were then

sliced and incubated in 300 ml Yeast extract-Peptone-Starch (YPS)

medium (glucose 20.0 g, peptone 10.0 g, yeast extract 5.0 g,

KH2PO4 1.0 g, MgSO4 1.0 g and 1 l

distilled water) for 3 days at 28°C. A 15 ml aliquot of the seed

culture was transferred to 400 × 1 l Erlenmeyer flasks, each

containing 300 ml of YPS culture medium. The flasks were shaken on

a rotary shaker (140 rpm) at 28°C for 3 days, followed by static

cultivation for 30 days.

Extraction and isolation

After cultivation, the broth and mycelia were

separated by gauze. The broth was extracted with ethyl acetate

(EtOAc) three times. The EtOAc extract was collected and

concentrated under vacuum to yield 120.0 g of extract, while the

mycelia were extracted with methanol to obtain a 250.0 g extract

after evaporation under reduced pressure. Both the EtOAc and

methanol extracts were subjected to silica gel column

chromatography with a step gradient of

CH2Cl2-MeOH (1:0 → 0:1 v/v), yielding 28

fractions (Fr.1-Fr.28) from the EtOAc extract and 22 fractions

(Fr.A-Fr.V) from the methanol extract. Fr.11 was separated on an

ODS column, eluting with a CH3OH/H2O

gradient, yielding five subfractions (Fr.11.1-Fr.11.5). Fr.11.2 was

further purified using a silica gel column, resulting in compound 1

(11.9 mg). Fr.11.3 was purified by Sephadex LH-20 and silica gel

column chromatography to yield compound 4 (27.9 mg). Fr.16 was

separated on an ODS column, eluted with a methanol-water gradient

(10–100%), yielding six subfractions (Fr.16.1-Fr.16.6). Fr.16.3 was

further purified on silica gel and Sephadex LH-20 to obtain

compound 2 (9.8 mg) and Fr.16.6 was chromatographed on an ODS

column to yield compound 3 (7.2 mg). Fr.13 was purified by ODS

column chromatography, followed by repeated silica gel column

purification, yielding compounds 5 (27.9 mg) and 6 (18.4 mg).

Compound 7 (21.8 mg) was obtained by repeated Sephadex LH-20 and

silica gel column chromatography. Fr.8 was separated on an RP-C18

column using a methanol-water gradient to yield six subfractions

(Fr.8.1-Fr.8.6). Fr.8.1 was purified by repeated Sephadex LH-20

chromatography to yield compound 8 (18.9 mg). Fr.I was separated by

RP-C18 column chromatography with a methanol-water gradient

(20–80%), yielding five subfractions (Fr.I.1-Fr.I.5). Fr.I.2 was

further purified by Sephadex LH-20, resulting in compound 9 (18.8

mg). Fr.I.3 was purified by silica gel column chromatography to

yield compound 10 (31.5 mg).

Cell culture and cytotoxicity

assay

A total of six human cancer cell lines (PC3 cat. no.

CRL-1435; LNCaP, cat. no. CRL-1740; HeLa, cat. no. CCL-2; SiHa,

cat. no. HTB-35; K562, cat. no. CCL-243; and HEL, cat. no. TIB-180)

were purchased from Typical Cultures Depository of the United

States of America and are currently maintained in the Key

Laboratory of Chemistry for Natural Products of Guizhou, Chinese

Academy of Sciences in Guiyang, China. Human gingival fibroblasts

(HGF-1) were provided by Guiyang Stomatological Hospital in

Guiyang, China. The inhibitory effects of the compounds on tumor

cells were assessed using the MTT assay, as described in a previous

study (24). A volume of 20 µl 5

mg/ml 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazolyl-2)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

(MTT; M158055, Aladdin) solution was added to each well and

incubated for 4 h at 37°C. After centrifugation at 20 × g for 10

min at room temperature to remove the supernatant, 150 µl DMSO was

added, followed by shaking on a shaker for 15 min. Absorbance at

490 nm was measured using a microplate reader to calculate the cell

proliferation inhibition rate. Inhibition rate of the

proliferation=1-(Average optical density of experimental

group/Average optical density of control group) ×100%. The cells

were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (cat. no. A-CSH807-500ml;

Biogradetech, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (cat.

no. C0230; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin solution, in an incubator for 24 h at 37°C

under 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cell viability was calculated

as a percentage relative to control wells. The half-maximal

inhibitory concentration (IC50) values were determined

using MTT viability curves, and the data were analyzed with

GraphPad Prism 8.0 (Dotmatics). Doxorubicin (cat. no. D1515; Merck

KGaA) was used as a positive control and was applied at

concentrations of 0.0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 4.0 µM. Cells were

treated for 24 h at 37°C under 5% CO2 atmosphere,

consistent with standard protocols for cytotoxicity assessment.

Flow cytometric analysis of cell cycle

and apoptosis

Cell cycle progression was analyzed using the BD

Cycletest Plus DNA Reagent Kit (cat. no. 340242; Becton, Dickinson

and Company), and apoptosis was assessed with the BD Annexin V-FITC

Apoptosis Detection Kit I (cat. no. 556547; Becton, Dickinson and

Company). Cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of

3×105/well. After 24 h, the cells were treated with 0.1%

DMSO (negative control), compound 1 (3.0, 6.0 and 9.0 µM) for 48 h

at 37°C. The cells were washed twice with cold PBS and then

resuspended in 100 µl of binding buffer. Annexin V PE (5 µl) and

7-AAD (5 µl) were added, and the mixture was incubated in the dark

at 37°C for 15 min. Apoptosis and cell cycle distribution were

analyzed using flow cytometry (NovoCyte 2040R; ACEA Biosciences,

Inc.) (24).

RNA-Sequencing (RNA-seq) and data

analysis

HeLa cells were pretreated with compound 1 at 6.0 µM

for 24 h at 37°C and then cells were washed with PBS and

subsequently lysed directly in the culture dish using 1.5 ml of

Trizol™ reagent (cat. no. 15596026CN; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The lysis process was allowed to proceed for 10

min at room temperature. Following lysis, the lysate was

transferred to a 2.0 ml sterile centrifuge tube and stored at −80°C

for subsequent RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted using

Trizol™ reagent following the manufacturer's protocol. RNA

concentration was measured using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and RNA integrity was assessed

using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). RNA

libraries were constructed and the sequencing was performed using

the NovaSeq 6000 S4 Reagent Kit (300 cycles; cat. no. 20028315;

Illumina, Inc.) and sequences using the Illumina HiSeq platform

(New England Biolabs, Inc.). The library loading concentration was

0.5 nM, and quantification was conducted using qPCR. Paired-end

sequencing with a read length of 150 bp (PE150) was carried out.

The mRNA reads were mapped to the reference genome using HISAT2

software (version 2.2.1; http://ccb.jhu.edu/software/hisat/index.shtml). Gene

expression was quantified as fragments per kilobase of exon model

per million mapped reads, based on the number of uniquely mapped

reads. Differential expression analysis was carried out using edgeR

software (version 3.32.1; parameters: P<0.05; fold change ≥1.5).

The results were visualized using a volcano plot, revealing

differentially expressed metabolism-related genes and lncRNAs in

cervical cancer and adjacent samples. Gene ontology (GO) enrichment

and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway

enrichment analyses were conducted using the clusterProfiler R

package and the iDEP 1.1 web tool (https://bioinformatics.sdstate.edu/idep96/) (25). Heatmap analysis was performed using

TBtools 2.200 (26), red

represents upregulated gene expression.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR) for transcriptomics

HeLa cells were seeded in 12-well plates overnight

and pretreated with compound 1 at different concentrations (3.0,

6.0 and 9.0 µM) at 37°C for 24 h. Total RNA was extracted from the

cells using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and cDNA was synthesized using the HiScript cDNA

Synthesis Mix kit (Jiangsu CoWin Biotech Co., Ltd.). RT-qPCR was

carried out using the UltraSYBR Mixture (With ROX) kit (Jiangsu

CoWin Biotech Co., Ltd.). GAPDH was used as the internal reference

gene. The primer sequences for TGIF2, ID1 and BMP2 were obtained

from previous publications (Table

SI). The PCR reaction mixture contained 2.0 µl cDNA template,

21.0 µl DNase-free ddH2O, 1.0 µl forward and reverse

primers, and 25.0 µl Ultra SYBR Mixture. The relative mRNA

expression levels were measured using the Real-Time PCR Detection

System (CFX Connect; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). qPCR was

performed using the following thermocycling protocol: Initial

pre-denaturation at 95°C for 5 min; 35 cycles consisting of

denaturation at 95°C for 45 sec, annealing at 56°C for 50 sec, and

extension at 72°C for 40 sec; followed by a final extension step at

72°C for 5 min. The relative expression ratio was using the

2−ΔΔCq method (27).

Molecular docking studies

Crystal structures of TGIF2 [Protein Data Bank (PDB)

code, 2dmn], ID1 (PDB code, 6mgn) and BMP2 (PDB code, 1rew) were

obtained from the Research Collaboratory for Structural

Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/). The docking parameters were

calculated using PyMOL 2.2.0 (https://github.com/schrodinger/pymol-open-source;

center and size for the docking box were defined as follows, TGIF2:

Center_x, −3.094; center_y, −3.281; center_z, 3.948 with size_x,

65.45; size_y, 65.45; size_z, 65.45; ID1: Center_x, 18.573;

center_y, 14.631; center_z, 12.395 with size_x, 46.55; size_y,

46.55; size_z, 46.55; BMP2: Center_x, −28.157; center_y, 67.095;

center_z, 21.448 with size_x, 65.45; size_y, 65.45; size_z, 65.45).

Molecular docking studies were carried out to explore the binding

modes of compound 1 with TGIF2, ID1 and BMP2 using AutoDock Vina

1.2.3 (https://github.com/ccsb-scripps/AutoDock-Vina/releases/tag/v1.2.3).

The best-scoring docking poses were selected based on the Vina

docking scores and further analyzed visually using PyMOL 2.2.0 and

Discovery Studio 2021 software (Version 21.1.0.20298; https://www.3ds.com/products-services/biovia/products/molecular-modeling-simulation/biovia-discovery-studio/).

Molecular dynamics simulation

MD simulations were carried out using the Amber24

software suite (version 2024; http://ambermd.org/) (28), applying the ff19SB force field

(29,30) and the OPC water model (31). The complex was placed in a cubic

water box, with electrostatic and van der Waals interactions having

cut off distances set to 1.0 nm. A time step of 2 fs was used for

the integration and long-range electrostatic interactions were

handled using the Particle Mesh Ewald method (32). The system was maintained at a

temperature of 300 K and a pressure of 1 bar. Initial energy

minimization was carried out (33), followed by 200 ps of constant

number of particles, volume, and energy equilibration and 100 ps of

constant number of particles, pressure, and temperature

equilibration dynamics. Temperature control was achieved using the

V-rescale method (34), while

pressure control was applied using the Parrinello-Rahman approach

(35). Following the

equilibration, 200 ns of production dynamics were carried out. Key

metrics such as root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square

fluctuation (RMSF), radius of gyration (Rg) and hydrogen bond

counts were calculated using Amber's built-in Cpptraj tool.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was carried out using SPSS Statistics

21.0 (IBM Corp.) and GraphPad Prism 7.0 (Dotmatics). Results are

presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

Statistical analysis was conducted using the unpaired Student's

t-test or the one-way or two-way ANOVA, followed by Šídák's

multiple comparisons test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Compounds from Alternaria

semiverrucosa and cytotoxic activity assay

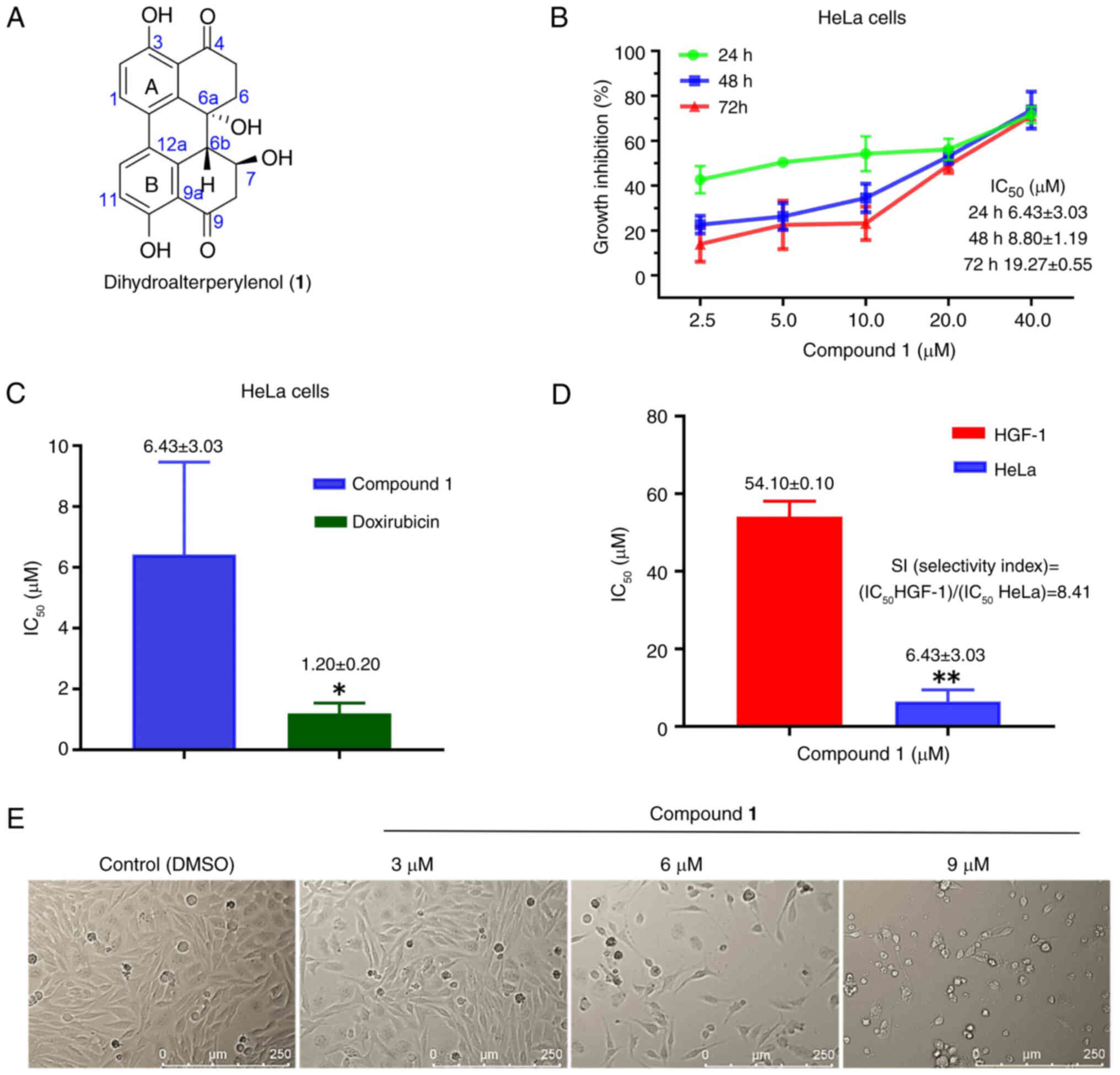

Structures of the ten known compounds were

identified (Fig. S1) as i) DAP

(Figs. 1A, S2 and B) (36), ii) Fonsecinone A (Fig. S3A and iii) (37), Aurasperone A (Fig. S4A-B) (38), iv)

3β,5α,9α-trihydroxy-(22E,24R)-ergosta-7,22-diene-6-one (Fig. S5A and B) (30), v) Gargalol B (Fig. S6A and B) (39), vi)

(22E,24R)-ergosta-7,22-dien-3β,5α,6β,9α-tetraol (Fig. S7A and B) (40), vii)

11-[(6-Deoxy-α-L-mannopyranosyl)oxy]-3-hydroxyhexadecanoic acid

(Fig. S8A and B), viii)

Penisochroman A (Fig. S9A and B)

(41), viiii) β-adenosine

(Fig. S10A and B) (42) and x) uridine (Fig. S11A and B) (43), by comparing their 1H, 13C NMR

(Data S1) and mass spectrometry

data with those in the literature.

The aforementioned compounds were tested for

cytotoxicity in vitro against human tumor cell lines (PC3,

LNCaP, HeLa, SiHa, K562, and HEL). As shown in Table SII, compound 1 exhibited an

inhibition rate of 49.48% against HeLa cells, and demonstrated the

most potent inhibitory effect. HeLa cells were exposed to varying

concentrations of 2.5, 5.0, 10.0, 20.0 and 40.0 µmol/l for 24, 48

and 72 h. As illustrated in Fig.

1B, within the same time frame, the inhibitory effect on cell

proliferation became progressively more pronounced with increasing

treatment concentration. However, when considering the duration of

exposure, the inhibitory effect diminished over time. Statistical

analysis indicated IC50 values of 6.43±3.03 µmol/l at 24

h, 8.80±1.19 µmol/l at 48 h and 19.27±0.55 µmol/l at 72 h (Fig. 1B). This was significantly higher

when compared with the positive control (IC50=1.20±0.20

µM; Fig. 1C) at 24 h

(P=0.0310).

Compound 1 was also tested in normal HGF-1 cells as

a reference, and exhibited a markedly reduced inhibitory effect

when compared with the HeLa cells (P=0.0055), with an

IC50 value of 54.10±0.10 µmol/l (Fig. 1D), suggesting limited cytotoxic

activity. The safety profile of a drug is typically assessed using

the selectivity index (SI), which is defined as: SI=IC50

(normal cells)/IC50 (tumor cells), with a SI value of

8.41. An increased SI value indicates a broader therapeutic window

and reduced cytotoxicity towards normal cells. Morphological

changes in the cells became apparent after 24 h of treatment

compared with the control group (Fig.

1E). As drug concentration increased, intercellular spaces

widen, cellular morphology becomes more rounded, and the presence

of cell debris becomes increasingly evident.

DAP induced apoptosis and cell cycle

G1/S arrest in HeLa cancer cells

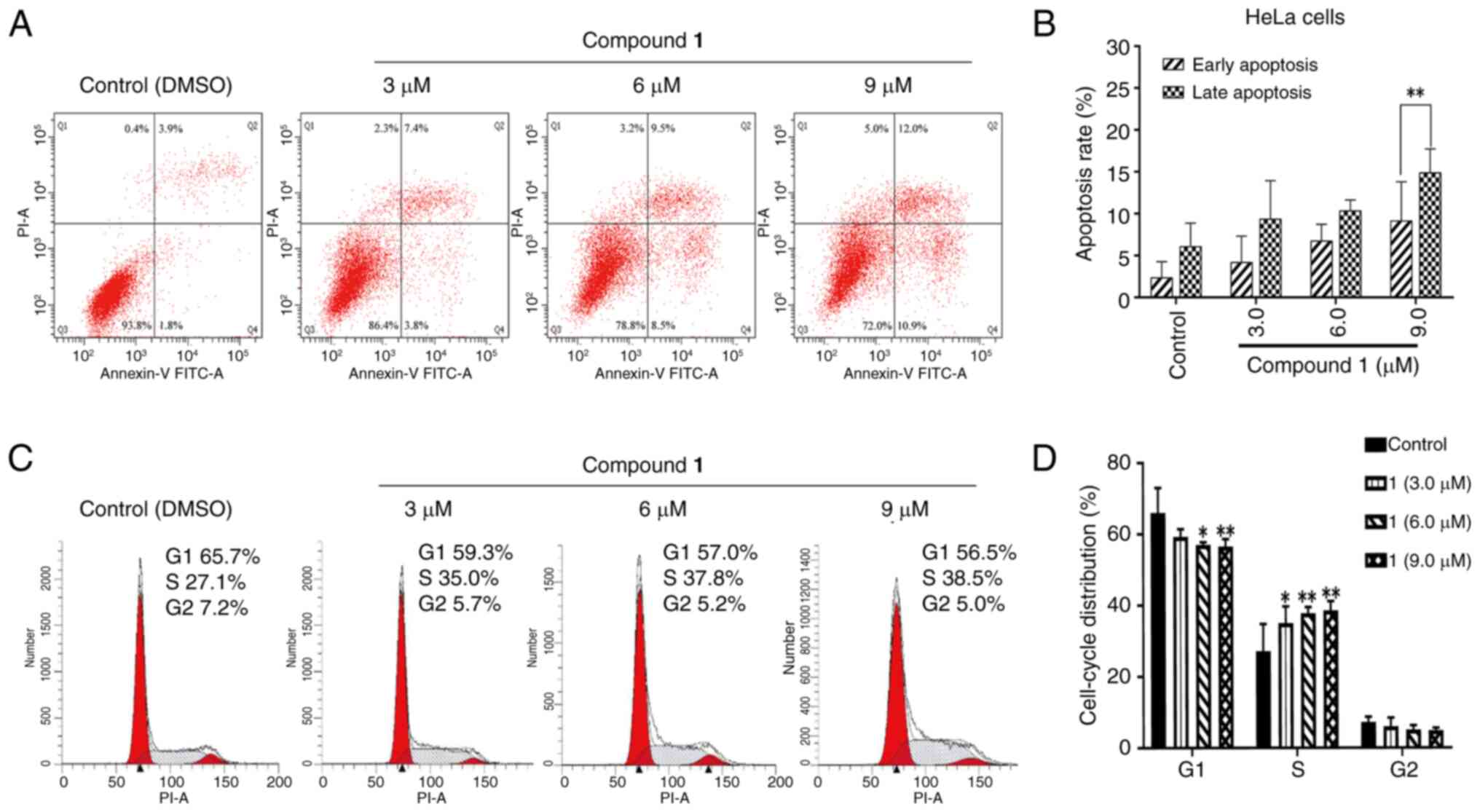

Compound 1 was subsequently evaluated for its

effects on the cell cycle and apoptosis. As shown in Fig. 2A and B, these findings suggest that

compound 1 induces apoptosis in HeLa cells. Notably, the proportion

of early apoptotic cells was reduced compared with that of late

apoptotic cells after a 24 h treatment with compound 1 (P=0.0065),

indicating that the majority of the cytotoxic effects of compound 1

on HeLa cells are due to the induction of late-stage apoptotic cell

death. The impact of compound 1 on cell cycle distribution was

evaluated using flow cytometry. As illustrated in Fig. 2C, compared with the control group,

alterations in the G1 and S phases were observed with increasing

concentrations of compound 1. Statistical analysis (Fig. 2D) revealed that when the

concentration of compound 1 reached 6.0 µmol/l, the proportion of

HeLa cells in the G1 phase was significantly reduced compared with

the control group (P=0.0126), with a significant decrease observed

at 9.0 µmol/l (P=0.0090). By contrast, cell accumulation was

evident in the S phase. A significant increase in the S phase

population was detected at a concentration of 3.0 µmol/l

(P=0.0280), which further increased markedly at 6.0 µmol/l

(P=0.0043). No notable changes were observed in the G2/M phase.

These findings suggest that the growth inhibitory effect of

compound 1 on HeLa cells is associated with cell cycle arrest in

the S phase.

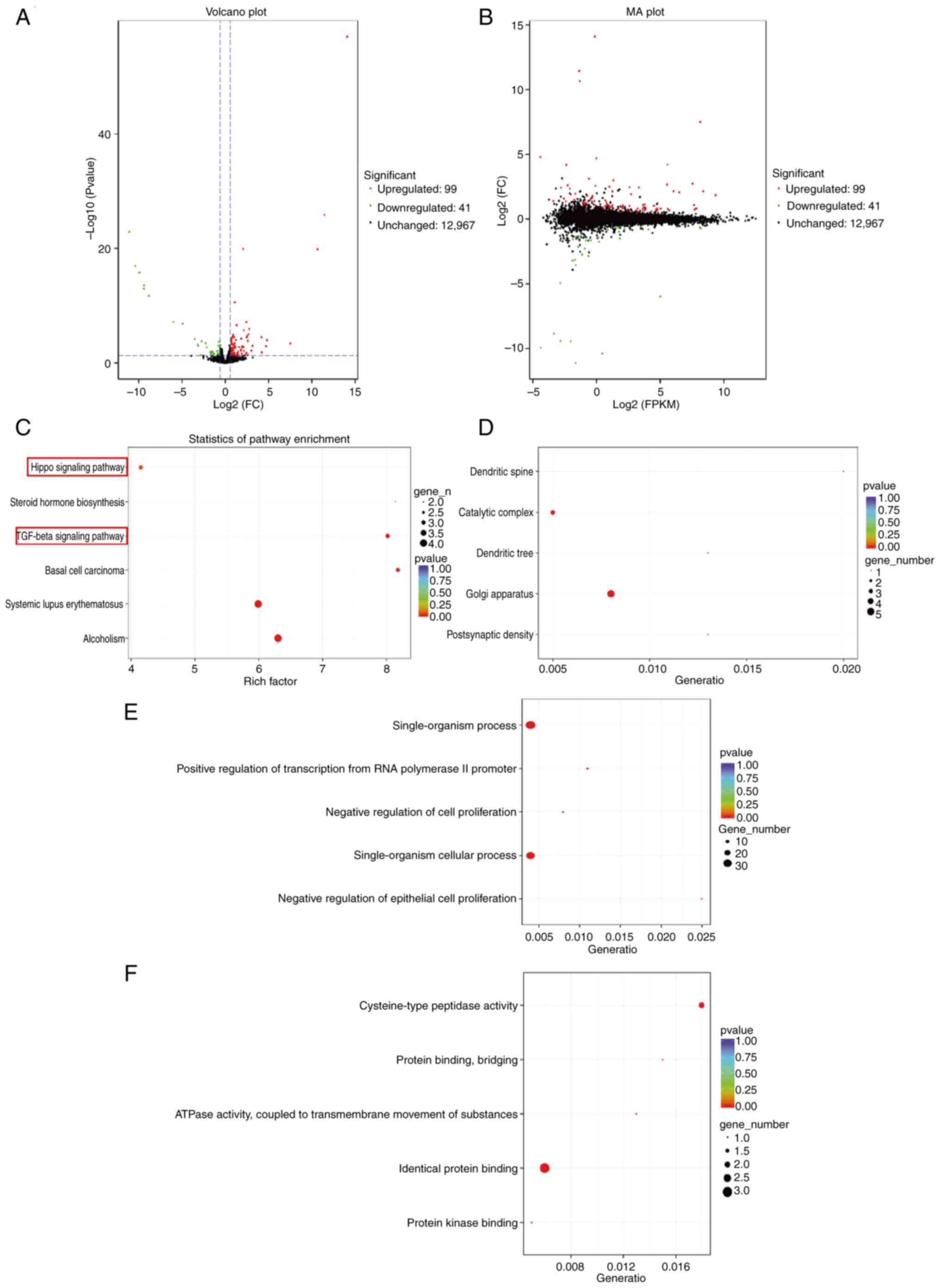

Transcriptome analysis

To further investigate the molecular mechanisms

underlying the effects of DAP, transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq)

was carried out in HeLa cells. This analysis identified 140

differentially expressed genes (DEGs), including 99 upregulated and

41 downregulated genes (Fig. 3A and

B). GO and KEGG enrichment analyses revealed significant

enrichment in pathways associated with tumor cell proliferation,

particularly the Hippo signaling and TGFβ signaling pathways

(Fig. 3C) have been implicated in

the regulation of cell apoptosis. Among the pathways enriched with

a P<0.05 (Fig. 3C), two

apoptosis-related signaling pathways, specifically the TGF-β

signaling pathway and the Hippo signaling pathway, were identified.

Within the TGF-β signaling pathway, the differentially expressed

genes were TGIF2, BMP2, and ID1; in contrast, the Hippo signaling

pathway exhibited differential expression of TGIF2 and BMP2.

Collectively, three distinct differentially expressed genes (TGIF2,

BMP2, and ID1) were observed across both signaling pathways. GO

analysis was conducted on DEGs to elucidate the molecular

mechanisms underlying their regulation. In the cellular component

category (Fig. 3D), significant

enrichment was observed for postsynaptic density (P=0.00052), Golgi

apparatus (P=0.00099), dendritic tree (P=0.00162), catalytic

complex (P=0.00294) and dendritic spine (P=0.00392). In the

biological process category (Fig.

3E), notable terms included ‘negative regulation of epithelial

cell proliferation’ (P=7.20×−06), ‘single-organism

cellular process’ (P=1.90×−05), ‘negative regulation of

cell proliferation’ (P=2.50×−05), ‘positive regulation

of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter’

(P=3.30×−05) and ‘single-organism process’ (P=0.00012).

In the molecular function category (Fig. 3F), enriched terms were ‘protein

kinase binding’ (P=0.00032), ‘identical protein binding’

(P=0.00125), ‘ATPase activity coupled to transmembrane movement of

substances’ (P=0.00131), ‘protein binding, bridging’ (P=0.0042) and

‘cysteine-type peptidase activity’ (P=0.0043). The GO analysis

indicated that the inhibitory effect of compound 1 on HeLa cell

proliferation was primarily associated with the regulation of

cellular proliferation processes.

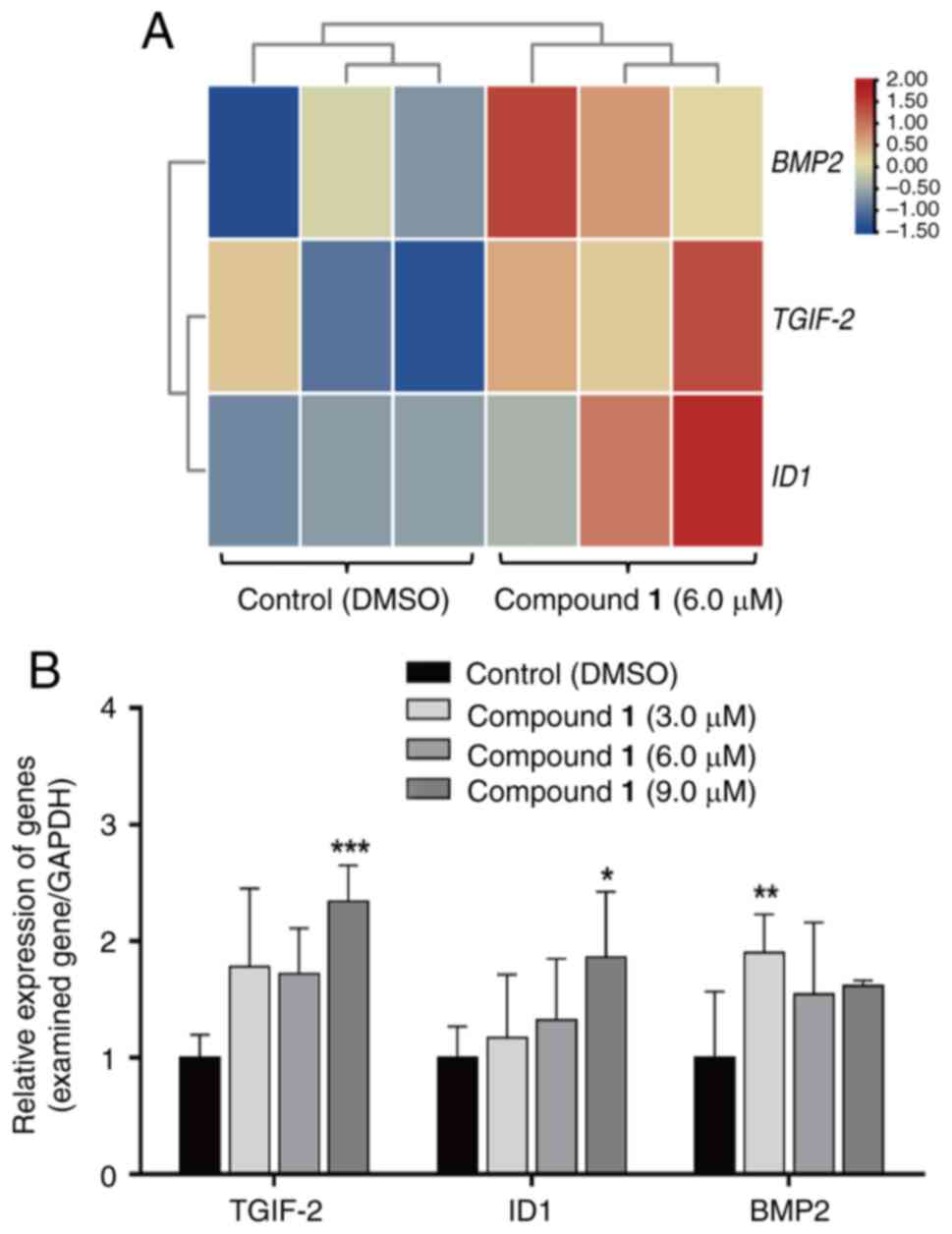

mRNA expression of DAP in HeLa

cells

To investigate the expression patterns of key genes

in the TGFβ signaling pathway and Hippo signaling pathway, TGIF2,

ID1 and BMP2 were selected. Heatmaps were generated using TBtool

(https://gitee.com/an–jiaxin/TBtools), revealing that

all three genes exhibited significant upregulation compared with

the control group (Fig. 4A).

Additionally, RT-qPCR analysis was conducted to evaluate the

expression levels of these genes under treatment with different

concentrations of compound 1. Compared with the control group, the

expression levels of all three genes were increased. Specifically,

the expression of TGIF2 and ID1 showed a significant increase at

9.0 µmol/l compound 1 (P=0.0006 and P=0.0215), while BMP2

expression significantly increased at 3.0 µmol/l Compound 1

(P=0.0035) (Fig. 4B). These

results indicate that the gene expression trends observed in

transcriptome sequencing are consistent with those obtained from

RT-qPCR analysis, verifying that the expression levels of TGIF2,

ID1 and BMP2 are upregulated following compound 1 treatment.

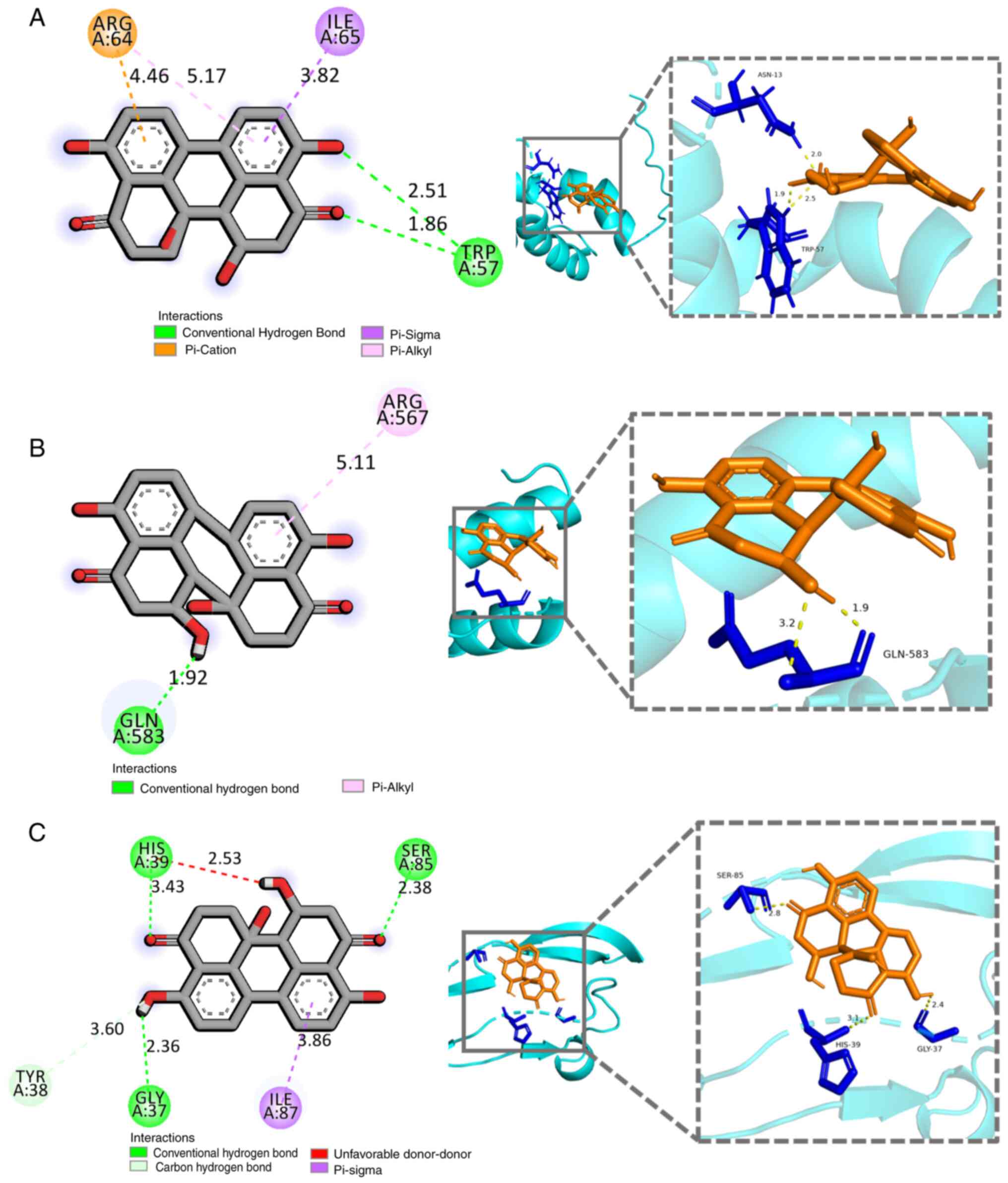

Docking studies of DAP with TGIF2, ID1

and BMP2

Molecular docking studies were conducted to explore

the potential binding sites of compound 1 with TGIF2, ID1 and BMP2.

The docking results revealed that the binding energies between

compound 1 and TGIF2, ID1 and BMP2 were all <-5.0 kcal/mol

(Table SIII). Specifically, a

hydrogen bond was formed between the 7-OH group of compound 1 and

Trp57 of TGIF2 (Fig. 5A).

Additionally, π-Cation and π-Sigma interactions were observed

between the two benzene rings of compound 1 and Arg64 and Ile65.

For ID1, a hydrogen bond was formed between the 7-OH group of

compound 1 and Gln583, while the A-ring of compound 1 interacted

with Arg567 of ID1, with distances of 1.92 Å and 5.11 Å,

respectively (Fig. 5B). As shown

in Fig. 5C, a hydrogen bond

interaction was observed between 7-OH of compound 1 and the

carbonyl group (C-4) of BMP2, with distances of 3.43 Å and 2.53 Å,

respectively. Furthermore, the benzene B-ring of compound 1

interacted with Ile87 of BMP2 via a π-σ bond.

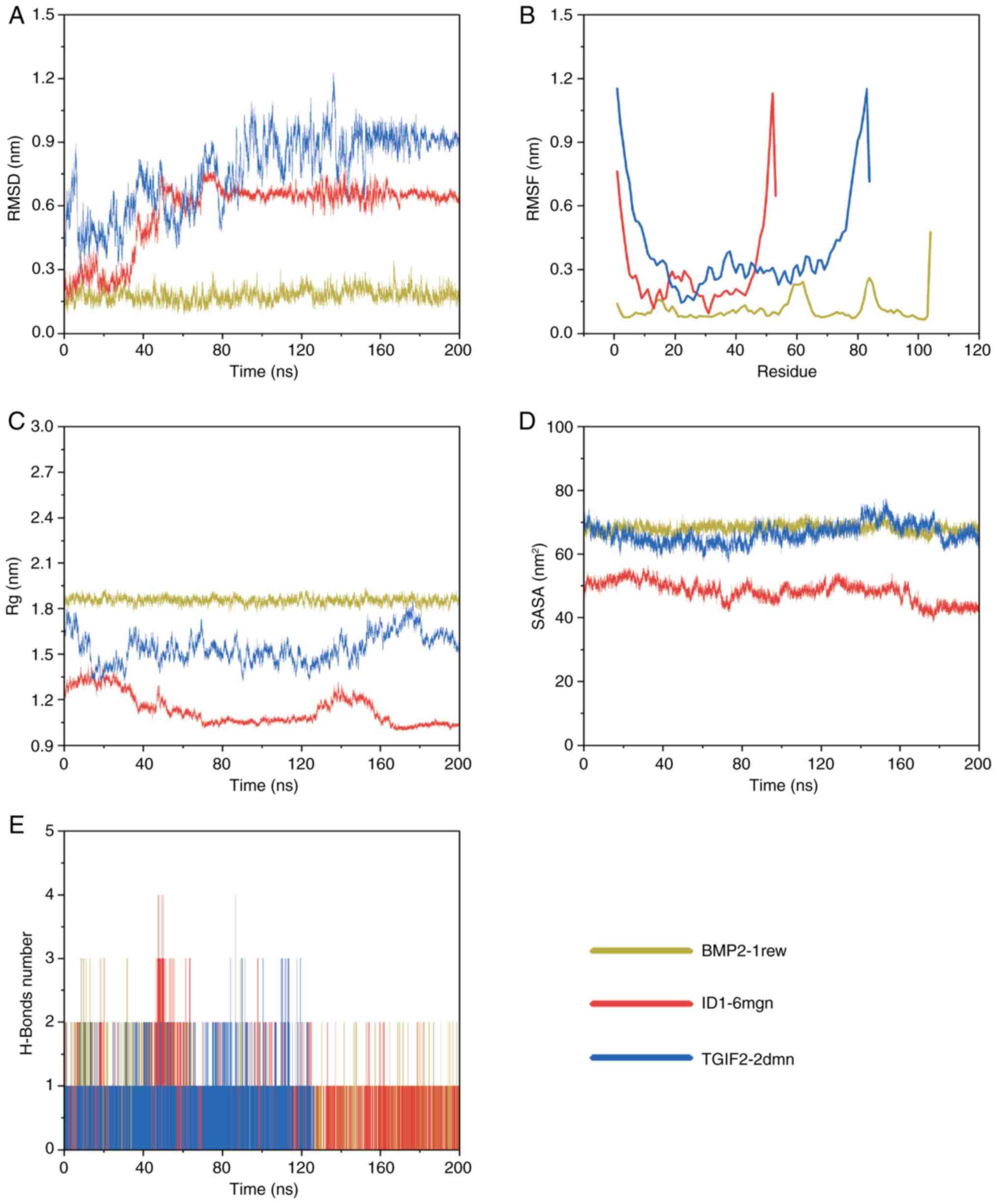

RMSD

RMSD is a key indicator of protein conformational

variability, providing insights into the stability of ligand-target

protein interactions. Higher RMSD values indicate greater

structural alterations within the complex, while lower values

suggest more stable binding configurations (44). As shown in Fig. 6A, the BMP2-1rew complex exhibited

notable fluctuations in RMSD during the initial phase of the

simulation (0–10 ns) before stabilizing between 10 and 200 ns.

Similarly, the ID1-6mgn complex displayed considerable RMSD

variations from 0 to 80 ns, followed by stabilization from 80 to

200 ns. The TGIF2-2dmn complex also experienced considerable RMSD

fluctuations during the first 155 ns, ultimately stabilizing from

155 to 200 ns. These results indicate that all three complexes,

BMP2-1rew, ID1-6mgn and TGIF2-2dmn underwent substantial

conformational changes early in the simulation before achieving

stability at different time intervals.

RMSF

RMSF measures the flexibility of individual amino

acid residues during MD simulations. Higher RMSF values indicate

increased flexibility at specific residues (45). As depicted in Fig. 6B, the BMP2-1rew complex exhibited

fluctuations at residues 58–63, 83–85 and 104. The ID1-6mgn complex

revealed marked mobility in residues 1–4 and 48–53, while the

TGIF2-2dmn complex demonstrated considerable movement in residues

1–4 and 79–84. Despite these localized fluctuations, the overall

structural stability of all three complexes, BMP2-1rew, ID1-6mgn

and TGIF2-2dmn, remained relatively intact.

Radius of gyration (Rg)

Rg radius is an important metric for evaluating the

compactness of molecular structures. Higher Rg values suggest a

more extended conformation, while lower values indicate a more

condensed structure (46). As

shown in Fig. 6C, after

equilibration, the BMP2-1rew complex exhibited minimal fluctuations

and stabilized at ~1.86 nm. The ID1-6mgn complex revealed limited

variation, stabilizing at ~1.08 nm. Similarly, the TGIF2-2dmn

complex demonstrated minor fluctuations, stabilizing at ~1.52 nm.

These results suggest that the BMP2-1rew complex adopts a

relatively extended conformation, indicative of weaker

intermolecular interactions. By contrast, the ID1-6mgn complex

adopts a more compact structure, implying stronger intermolecular

interactions. The TGIF2-2dmn complex falls in between, revealing

moderate intermolecular interactions.

Solvent-accessible surface area

(SASA)

SASA quantifies the exposure of protein molecules to

their surrounding water environment, reflecting changes in

hydrophobic and hydrophilic properties (47). As shown in Fig. 6D, SASA values for the entire system

remained relatively stable throughout the simulation. Among the

three complexes, the ID1-6mgn complex exhibited the most compact

structure, followed by TGIF2-2dmn, with BMP2-1rew displaying the

least compact conformation. These findings suggest that the

ID1-6mgn complex likely has the strongest intermolecular

interactions, while the BMP2-1rew complex likely exhibits the

weakest.

Hydrogen bonds

Hydrogen bonds are among the strongest non-covalent

interactions and serve as important indicators of binding strength

during molecular simulations (48). The frequency and number of hydrogen

bonds observed in the simulations reflect the dynamic nature of

protein-ligand interactions. A higher number of hydrogen bonds

typically correlates with greater binding stability (48). As shown in Fig. 6E, the BMP2-1rew complex formed

between 1 and 3 hydrogen bonds, whereas both the ID1-6mgn and

TGIF2-2dmn complexes formed between 1 and 4 hydrogen bonds. These

findings suggest that the interactions within the ID1-6mgn and

TGIF2-2dmn complexes are likely more robust compared with those

observed in the BMP2-1rew complex.

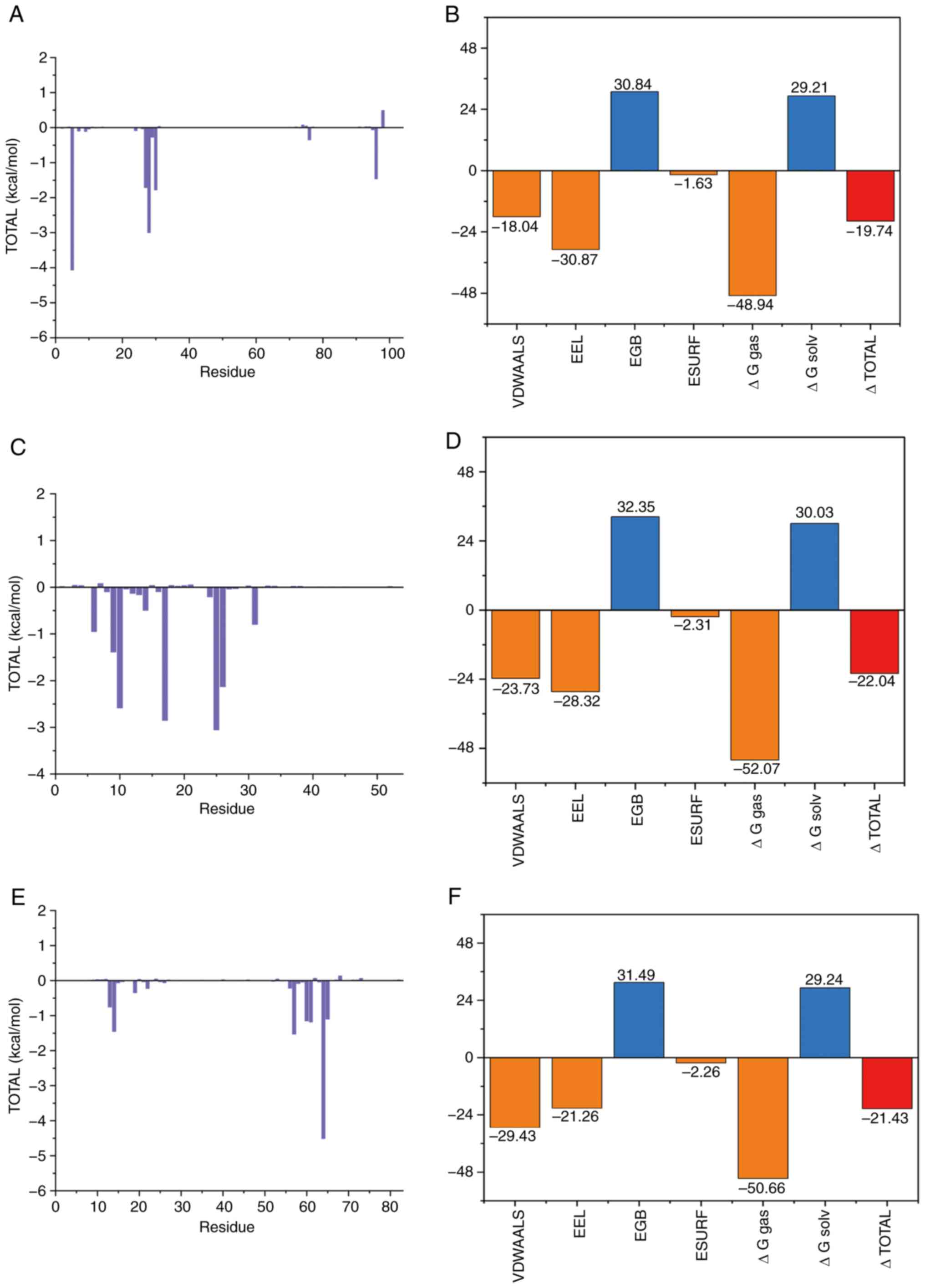

Combination free energy

Molecular mechanics generalized born surface area is

a method (49) that is widely

employed post-simulation to estimate the binding free energy of

molecular complexes, providing insights into their stability. A

lower binding free energy value suggests a stronger binding

affinity (49). As shown in

Fig. 7A, the key residues

contributing to the binding free energy of the BMP2-1rew complex

include ARG-5, HIE-28, PHE-30, TYR-27, VAL-96, ILE-76, ALA-29,

TYR-9, PRO-7 and PRO-24 from the protein. The binding free energy

for this complex is calculated at −19.74 kcal/mol, with

contributions from van der Waals interactions (−18.04 kcal/mol),

electrostatic potential energy (−30.87 kcal/mol) and non-polar

solvation effects (−1.63 kcal/mol; Fig. 7B).

For the ID1-6mgn complex (Fig. 7C), the binding free energy

primarily involves residues ALA-25, GLN-17, ARG-10, GLN-26, PHE-9,

ASN-6, ILE-31, ARG-14, LYS-24 and GLY-13. The calculated binding

free energy is −22.04 kcal/mol, with van der Waals forces

contributing −23.73 kcal/mol, electrostatic potential energy

contributing −28.32 kcal/mol and non-polar solvation energy

contributing −2.31 kcal/mol (Fig.

7D).

For the TGIF2-2dmn complex (Fig. 7E), the binding free energy involves

residues ARG-64, TRP-57, LEU-14, ALA-61, ASN-60, ILE-65, ASN-13,

VAL-19, LEU-22 and ASN-56, with the overall binding free energy

calculated as −21.43 kcal/mol (Fig.

7F). The contributions include van der Waals forces (−29.43

kcal/mol), electrostatic potential energy (−21.26 kcal/mol) and

non-polar solvation energy (−2.26 kcal/mol).

These results indicate that DAP exhibits strong

binding affinities with TGIF2, ID1 and BMP2, with van der Waals and

electrostatic interactions carrying out the most significant roles,

while non-polar solvation energy contributes to a lesser extent.

Polar solvation energy appears to have a less favorable effect on

these interactions.

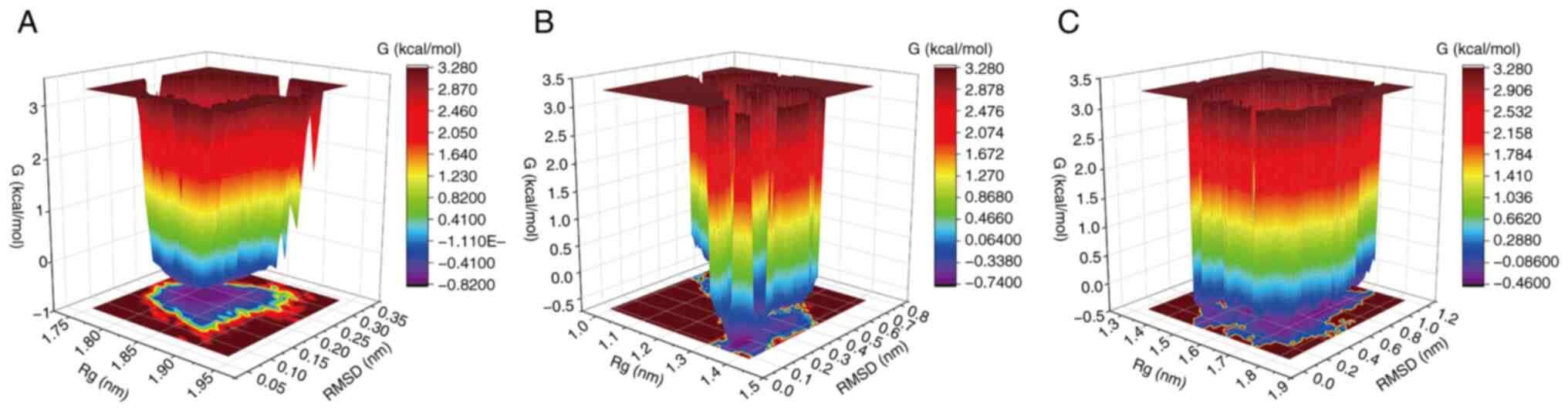

Free energy landscape (FEL)

FEL provides a detailed characterization of the free

energy changes experienced by a molecular system during

simulations. By analyzing the FEL, the characteristic conformations

of a complex can be identified and examined, which serves as an

indicator of conformational stability during the simulation

(50,51). As illustrated in Fig. 8, the BMP2-1rew complex

predominantly adopts a stable conformation within an RMSD range of

0.10–0.30 Å and an Rg range of 1.77–1.90 nm (Fig. 8A). For the ID1-6mgn complex, the

most stable conformation is observed within an RMSD range of

0.0–0.7 Å and an Rg range of 1.0–1.4 nm (Fig. 8B). The TGIF2-2dmn complex

demonstrates two distinct regions of dominant stability: One with

an RMSD of 0.0–1.2 Å and Rg of 1.3–1.8 nm, and another with an RMSD

of 0.8–1.0 Å and Rg of 1.45–1.55 nm (Fig. 8C). These findings indicate that the

BMP2-1rew, ID1-6mgn and TGIF2-2dmn complexes each exhibit stable

conformations within specific RMSD and Rg ranges, which can be

utilized as a basis for understanding the characteristic

conformations and stability of these complexes.

Discussion

Treatment of cervical cancer currently relies on a

combination of surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and

immunotherapy (52). Early-stage

cervical cancer can often be managed with either radical surgery or

radiation therapy (53). However,

both methods suffer from a lack of specificity for cancer cells,

leading to notable side effects despite their clinical efficacy.

Traditional chemotherapy agents for cervical cancer, such as

nedaplatin, paclitaxel and bleomycin, are associated with harmful

side effects (54,55). Consequently, there is a need for

more effective and safer anticancer drugs. Natural products, known

for their low toxicity and ability to target multiple biological

pathways, have gained attention as promising alternatives to

chemical drugs due to their superior biocompatibility (56). As a result, natural products have

become a key source of novel antitumor agents (57).

DAP also known as Altertoxin I, is a quinone-type

mycotoxin first isolated from Alternaria species. A previous

study reveal that DAP has an ID50 value of 20 µg/ml

against HeLa cells (58). DAP has

been evaluated for cytotoxicity in A549, HeLa, U2OS and HepG2 cell

lines, and the results revealed that DAP exhibited minimal

cytotoxicity at 20 µM in these cell lines (43). DAP has demonstrated selective

cytotoxicity against human colon cancer cells (HCT-8) with an

IC50 of 1.78 µM (59),

highlighting its potential in cancer therapy. Chemotherapy, a

mainstay treatment, is frequently hampered by drug resistance and

dose-limiting toxicities (60).

Cisplatin remains the preferred drug for the chemotherapeutic

treatment of cervical cancer, however, several factors, including

its low selectivity, high toxicity, adverse side effects, tumor

multidrug resistance and propensity for recurrence, ultimately

contribute to treatment failure (61). Chemotherapy failure is primarily

caused by drug resistance mechanisms, such as

P-glycoprotein-mediated efflux of chemotherapeutic agents from

tumor cells. Furthermore, chemotherapy is constrained by

dose-limiting toxicities that adversely affect healthy tissues and

compromise the quality of life of patients (62). Additionally, targeted therapies

encounter obstacles due to tumor heterogeneity and the development

of resistance through compensatory signaling pathways (63). Natural products such as DAP offer a

promising strategy to address these issues. Its structural

complexity enables multi-target mechanisms, potentially overcoming

resistance while minimizing off-target effects. In the present

study, DAP exhibited potent activity against HeLa cells

(IC50±6.43 µM) and transcriptome analysis revealed that

DAP induces apoptosis via the Hippo and TGFβ pathways. This dual

effect may circumvent common drug resistance mechanisms. Notably,

DAP exhibited minimal inhibitory activity against HGF-1 after 24 h

of exposure, with an SI value of 8.41. The safety profile of the

drug was evaluated using the SI value, where a higher SI value

indicates a broader therapeutic window and reduced cytotoxicity

towards normal cells. A previous study has demonstrated that an SI

value >1 is indicative of selective antitumor activity (64).

The findings of the present study demonstrated that

the IC50 of DAP exhibits a time-dependent increase,

indicating that prolonged exposure to drug treatment may enhance

the fitness of a cell population. According to existing research

findings (65), the fitness of a

cell population can be improved through gradual exposure to stress,

as cells epigenetically adapt and fine-tune their stress regulatory

networks, thereby establishing stable adaptive states. Initially,

drug-sensitive cells accumulate transcriptional and epigenetic

changes in response to stress, resulting in more robust responses

upon subsequent stimulation. We hypothesize that a comparable

process occurs when DAP is applied to HeLa cells spanning an

extended period, leading to an increase in IC50 from

6.43 µM at 24 h to 19.27 µM at 72 h.

DAP was applied to HeLa cells at concentrations of

3.0, 6.0 and 9.0 µmol/l for 24 h, inducing apoptosis and cell cycle

arrest in a concentration-dependent manner. At the highest

concentration of 9.0 µmol/l, the apoptosis rate reached 24.13%,

with cell cycle arrest occurring predominantly in the S phase.

These findings suggest that the inhibitory effects of DAP on HeLa

cells are associated with apoptosis induction and cell cycle

arrest. To further elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying

DAP-induced apoptosis, transcriptome sequencing was conducted on

HeLa cells treated with 6.0 µmol/l DAP for 24 h, identifying 140

DEGs. Bioinformatics analysis using KEGG and GO revealed that

significantly enriched pathways were associated with apoptosis,

while GO annotations highlighted terms associated with the

regulation of cell proliferation. Specifically, the TGFβ signaling

pathway and Hippo signaling pathway, both implicated in apoptosis

and enriched in KEGG, were analyzed in detail. Three genes (TGIF2,

ID1 and BMP2) were identified as key mediates in these pathways.

Subsequent RT-qPCR analysis confirmed that the expression trends of

these three genes were consistent with the results from

transcriptome sequencing. This consistency indicates that the

inhibitory effects of DAP on HeLa cells are likely mediated through

the upregulation of TGIF2, ID1 and BMP2.

TGIF2, an important member of the TGIF family,

encodes a DNA-binding transcription factor that carries out a key

role in tumor regulation through multiple mechanisms. The study has

demonstrated that long non-coding RNA SNHG7 upregulates TGIF2

expression by modulating miR-449a, thereby promoting proliferation,

migration, invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in

non-small cell lung cancer (66).

Additionally, non-coding RNA MALAT1 upregulates TGIF2 expression by

negatively regulating miR-129, leading to enhanced proliferation,

migration and invasion in human osteosarcoma MG63 cells (67). In osteosarcoma, TGIF2 serves as a

target gene of miR-34; its upregulation inhibits osteosarcoma tumor

growth in nude mice and promotes apoptosis (68), these findings are consistent with

the upregulation of TGIF2 expression observed in cervical cancer

HeLa cells in the present study.

ID1 is a member of the helix-loop-helix (HLH) family

of transcription factors. ID1 exerts its oncogenic effects by

inhibiting the activity of basic HLH transcription factors, thereby

participating in tumor initiation, progression, cell cycle

regulation and metastasis. It is closely associated with

angiogenesis, tumor differentiation and drug resistance in various

types of cancer (69,70). As a negative regulator of cell

differentiation, ID1 promotes tumorigenesis by activating the MAPK

signaling pathway and inactivating the p16(INK4a)/pRB tumor

suppressor pathway, thus facilitating the growth and proliferation

of prostate cancer cells (71,72).

A study has confirmed that ID1 is highly expressed in ovarian

cancer tissues and its expression associates with the degree of

tumor differentiation, carrying out a key role in ovarian cancer

development (73). Compared with

control cells, SKOV3 cells depleted of ID1 exhibited a notable

reduction in proliferation and invasion capabilities, while

apoptosis was markedly increased (74). The increase in ROS levels following

ID1 overexpression aligns with prior studies revealing ROS inhibits

dendritic cell differentiation and myeloid-derived suppressor cell

expansion in tumor-bearing mice (75), These findings are consistent with

the results of the present study. We hypothesize that DAP

upregulates ID1 expression, increasing ROS levels and inhibiting

cervical cancer cells.

BMP2 is a highly expressed secreted protein in

various types of cancer (76). As

a member of the TGFβ superfamily, BMP2 participates in multiple

biological processes, including normal cell growth and development,

apoptosis, migration, invasion, bone formation and cancer

progression (77). Research

(78) indicates that BMP2 carries

out a key role in the proliferation, migration and differentiation

of neural crest cells. Compared with normal tissues, BMP2 is

considerably upregulated in various cancer tissues, suggesting its

potential as a key biomarker for targeted cancer therapy.

Literature studies have revealed that BMP2 exhibits both pro-cancer

and anti-cancer functions in cancer tissues. For instance, Du et

al (79) demonstrated that

promoter methylation of the BMP2 gene in the breast cancer cell

line MCF-7 downregulates BMP2 expression, enhancing drug resistance

and promoting cancer progression. Conversely, other studies have

revealed that treating the human and mouse breast cancer cell,

MCF-7, with BMP2 inhibits cell migration and proliferation,

revealing its anti-cancer effects (80,81).

In nasopharyngeal carcinoma, the BMP2 promoter

enhances its expression by binding to SOX9, thereby activating the

BMP2-induced mTOR signaling pathway and promoting the

proliferation, migration and invasion of nasopharyngeal carcinoma

cells (77,82). Research reveals that BMP2

suppresses gastric cancer cell proliferation by arresting the cell

cycle via a non-SMAD BMP pathway that downregulates EZH2 (83), consistent with the findings of the

present study. The present study indicates that DAP induces the

upregulation of BMP2 expression, which subsequently influences cell

proliferation. This effect may be attributed to the ability of BMP2

upregulation to activate AMPK, leading to the inhibition of the

mTOR signaling pathway. Specifically, the activation of AMPK

suppresses the activity of the mTORC1 complex via phosphorylation,

thereby disrupting protein synthesis and metabolic processes

essential for cell proliferation (84).

The limited number of DEGs identified at 24 h

post-treatment suggests an early drug response phase rather than

transcriptomic reprogramming. Similar results were seen in other

studies: Only 357 and 455 DEGs were found in two sweet corn

varieties under low-temperature stress (85) and 551 DEGs were detected after

vascular hepatocyte differentiation in pigs (86). The limited number of DEGs observed

in this study may be attributed to three potential factors:

Inadequate drug exposure or low concentrations preventing a

significant transcriptional response, cellular heterogeneity

causing varied drug sensitivities and diluting signals, and the

phenotypic lag effect (87) where

drugs act through early gene activity and protein interactions.

Future work will assess DAP's effects on cervical cancer HeLa cells

by extending treatment time and testing more concentration

levels.

Following DAP treatment, cells exhibited signs of

apoptosis. Transcriptome analysis and RT-qPCR validation confirmed

that this apoptotic response was associated with the upregulation

of three genes: TGIF2, ID1 and BMP2. This finding raises the

question of whether DAP interacts directly with the corresponding

proteins encoded by these genes. To investigate potential

protein-level interactions between DAP and the TGIF2, ID1 and BMP2

proteins, the present study employed molecular docking technology

to evaluate their binding affinities. Molecular docking is based on

the lock-and-key principle, examining how the spatial structure and

electrostatic characteristics of small molecules match the active

sites of their target proteins. The lower the binding energy

between a small molecule and its target protein, the stronger their

interaction. Typically, a binding energy <-4.25 kcal/mol

indicates some degree of binding activity; <-5.0 kcal/mol

suggests good binding activity; and <-7.0 kcal/mol indicates

strong binding activity (88).

While this study elucidated the potential binding

modes of DAP with TGIF2, ID1 and BMP2 proteins using molecular

docking, it is important to acknowledge the intrinsic limitations

of static docking models. Molecular docking generally relies on

rigid or semi-flexible receptor models, which may fail to

adequately capture the conformational dynamics of protein-ligand

complexes under physiological conditions (89). To address these limitations, the

present study incorporated MD simulations for dynamic validation.

To further elucidate the molecular interactions underlying the

anticancer potential of DAP, MD simulations were carried out to

evaluate its binding stability with key regulatory proteins

involved in cervical cancer progression. The simulations analyzed

ligand-protein interactions with TGIF2, ID1 and BMP2 over a

200-nanosecond trajectory. RMSD analysis revealed that all three

complexes exhibited initial structural fluctuations before

achieving stable conformations, suggesting successful ligand

binding. Similarly, RMSF analysis identified key residues

exhibiting flexibility within each protein-ligand complex, further

supporting their dynamic interactions. These computational findings

provide valuable insights into the structural basis of the

biological activity of DAP, reinforcing its potential as a novel

therapeutic candidate for cervical cancer.

The present study provides insights into the

inhibitory mechanisms of DAP on cervical cancer cells but is

limited by using only the HeLa cell line. Initial screening

(Table SII) revealed DAP has

notable activity against HeLa and SiHa cells, however, only 11.9 mg

of purified DAP was available. Due to this limitation, mechanistic

studies focused on HeLa cells. Using a single cell line restricts

the generalizability of the findings, as cervical cancer is

heterogeneous and responses vary across cell lines. Thus, results

obtained with HeLa cells may not fully represent other subtypes.

The proposed mechanisms require further validation for broader

applicability.

Future work will validate key experiments in

additional cell lines such as CaSki and SiHa and, where feasible,

use patient-derived cells or organoids for clinically relevant

models. Simultaneously, this study will establish subcutaneous

xenograft cervical cancer models in immunodeficient nude mice

through the injection of cervical cancer cells. DAP will be

administered subcutaneously at low, medium and high doses to these

models. This study will utilize the untreated models as the control

group, and paclitaxel-treated models as the positive control. In

vivo experiments will evaluate the efficacy of DAP by analyzing

tumor growth, final tumor size, pathological changes and marker

protein expression across all groups. Acute or subchronic toxicity

studies using healthy mice will assess behavioral changes, body

weight, food/water intake, blood profiles, biochemical parameters

and organ histopathology (liver, kidney, spleen, lung, heart and

intestine). These analyses will aim to identify toxic target

organs, determine the maximum tolerated dose and establish a safety

margin. Together, these experiments will provide preclinical data

to assess the clinical potential of DAP and guide its development

as a therapy.

Collectively, a novel endophytic fungal species,

Alternaria semiverrucosa, was isolated from Taxus

chinensis var. marei collected in Guiyang, China. DAP

was subsequently obtained from the fermentation metabolites of

Alternaria semiverrucosa. The inhibitory effects of DAP on

cervical cancer HeLa cells suggest that it exhibits high efficacy

and low toxicity, making it a promising candidate for further

investigation, and warranting further investigation into its

underlying molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Future

studies integrating experimental validation of these molecular

interactions will be key to confirming efficacy and clinical

applicability of DAP.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Heng Luo for

their assistance and guidance with the in vitro experiments

which were conducted at the Key Laboratory of Chemistry for Natural

Products of Guizhou Province, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guiyang,

China. The authors would also like to thank Guiyang Stomatological

Hospital (Guiyang, China) for donating HGF-1 human gingival

fibroblasts.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 32460007, 32170019 and

31670027).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

found in the National Center for Biotechnology Information under

accession number PRJNA1272013, or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1272013/.

Authors' contributions

JK and MY conceptualized the present study. MY and

YL developed the methodology. LH and ZH were responsible for the

application and implementation of the Molecular dynamics simulation

software. MY, YL and JK conducted the analysis of the experimental

data. MY, YL and ZH carried out cell validation experiments. ZH and

YL managed the transcriptome data curation and analysis. MY and LH

wrote the original draft. JK, MY and YL contributed to reviewing

and editing. LH, ZH and YL handled the microscopy images. JK

supervised the project and administered it. MY, YL, ZH and JK

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read

and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Cohen PA, Jhingran A, Oaknin A and Denny

L: Cervical cancer. Lancet. 393:169–182. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Kokhdan EP, Khodavandi P, Ataeyan MH,

Alizadeh F, Khodavandi A and Zaheri A: Anti-cancer activity of

secreted aspartyl proteinase protein from Candida tropicalis on

human cervical cancer HeLa cells. Toxicon. 249:1080732024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Bray F, Jemal A, Soerjomataram I, Siegel

RL, Ferlay J, Sung H and Laversanne M: Global cancer statistics

2022: Globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Luan H: Human papilloma virus infection

and its associated risk for cervical lesions: A cross-sectional

study in Putuo area of Shanghai, China. BMC Womens Health.

23:282023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Wang R, Pan W, Jin L, Huang W, Li Y, Wu D,

Gao C, Ma D and Liao S: Human papillomavirus vaccine against

cervical cancer: Opportunity and challenge. Cancer Lett.

471:88–102. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Xu J, Tan ZC, Shen ZY, Shen XJ and Tang

SM: Cordyceps cicadae polysaccharides inhibit human cervical cancer

hela cells proliferation via apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. Food

Chem Toxicol. 148:1119712021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhang X, Song Z, Li Y, Wang H, Zhang S,

Reid AM, Lall N, Zhang J, Wang C, Lee D, et al: Cytotoxic and

antiangiogenetic xanthones inhibiting tumor proliferation and

metastasis from garcinia xipshuanbannaensis. J Nat Prod.

84:1515–1523. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kusari S, Hertweck C and Spiteller M:

Chemical ecology of endophytic fungi: Origins of secondary

metabolites. Chem Biol. 19:792–798. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zhang HW, Song YC and Tan RX: Biology and

chemistry of endophytes. Nat Prod Rep. 23:753–771. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Bashyal BP, Wijeratne EM, Tillotson J,

Arnold AE, Chapman E and Gunatilaka AA: Chlorinated

dehydrocurvularins and alterperylenepoxide A from Alternaria sp.

AST0039, a fungal endophyte of Astragalus lentiginosus. J Nat Prod.

80:427–433. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Li SJ, Zhang X, Wang XH and Zhao CQ: Novel

natural compounds from endophytic fungi with anticancer activity.

Eur J Med Chem. 156:316–343. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zhu M, Zhang X, Feng H, Dai J, Li J, Che

Q, Gu Q, Zhu T and Li D: Penicisulfuranols A-F, alkaloids from the

mangrove endophytic fungus Penicillium janthinellum HDN13-309. J

Nat Prod. 80:71–75. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Chakravarthi BV, Sujay R, Kuriakose GC,

Karande AA and Jayabaskaran C: Inhibition of cancer cell

proliferation and apoptosis-inducing activity of fungal taxol and

its precursor baccatin III purified from endophytic Fusarium

solani. Cancer Cell Int. 13:1052013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wu LS, Hu CL, Han T, Zheng CJ, Ma XQ,

Rahman K and Qin LP: Cytotoxic metabolites from Perenniporia

tephropora, an endophytic fungus from Taxus chinensis var. mairei.

Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 97:305–315. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Uzor PF, Ebrahim W, Osadebe PO, Nwodo JN,

Okoye FB, Müller WE, Lin W, Liu Z and Proksch P: Metabolites from

Combretum dolichopetalum and its associated endophytic fungus

Nigrospora oryzae-evidence for a metabolic partnership.

Fitoterapia. 105:147–150. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wani MC, Taylor HL, Wall ME, Coggon P and

McPhail AT: Plant antitumor agents. VI. The isolation and structure

of taxol, a novel antileukemic and antitumor agent from Taxus

brevifolia. J Am Chem Soc. 93:2325–2327. 1971. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zaiyou J, Li M, Xu G and Zhou X: Isolation

of an endophytic fungus producing baccatin III from Taxus

wallichiana var. mairei. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 40:1297–1302.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zaiyou J, Li M and Xiqiao H: An endophytic

fungus efficiently producing paclitaxel isolated from Taxus

wallichiana var. mairei. Medicine (Baltimore). 96:e74062017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Fan ZY, Peng J, Lou JQ, Chen Y, Wu XM, Tan

R and Tan RX: Neuroprotective α-pyrones from Nigrospora oryzae, an

endophytic fungus residing in Taxus chinensis var. mairei.

Phytochemistry. 216:1138732023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Hu D, Fan Y, Tan Y, Tian Y, Liu N, Wang L,

Zhao D, Wang C and Wu A: Metabolic profiling on alternaria toxins

and components of Xinjiang Jujubes incubated with pathogenic

alternaria Alternata and Alternaria tenuissima via orbitrap

high-resolution mass spectrometry. J Agri Food Chem. 65:8466–8474.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Andersen B, Nielsen KF, Fernández Pinto V

and Patriarca A: Characterization of Alternaria strains from

Argentinean blueberry, tomato, walnut and wheat. Int J Food

Microbiol. 196:1–10. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yang CL, Wu HM, Liu CL, Zhang X, Guo ZK,

Chen Y, Liu F, Liang Y, Jiao RH, Tan RX and Ge HM: Bialternacins

A-F, aromatic polyketide dimers from an endophytic Alternaria sp. J

Nat Prod. 82:792–797. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Xi J, Tian LL, Xi J, Girimpuhwe D, Huang

C, Ma R, Yao X, Shi D, Bai Z, Wu QX and Fang J: Alterperylenol as a

novel thioredoxin reductase inhibitor induces liver cancer cell

apoptosis and ferroptosis. J Agric Food Chem. 70:15763–15775. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Li L, Yang M, Yu J, Cheng S, Ahmad M, Wu

C, Wan X, Xu B, Ben-David Y and Luo H: A novel L-phenylalanine

dipeptide inhibits the growth and metastasis of prostate cancer

cells via targeting DUSP1 and TNFSF9. Int J Mol Sci. 23:109162022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Liu Y, Xin ZZ, Song J, Zhu XY, Liu QN,

Zhang DZ, Tang BP, Zhou CL and Dai LS: Transcriptome analysis

reveals potential antioxidant defense mechanisms in Antheraea

pernyi in response to zinc stress. J Agric Food Chem. 66:8132–8141.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chen C, Chen H, Zhang Y, Thomas HR, Frank

MH, He Y and Xia R: TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for

interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol Plant.

13:1194–1202. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Case DA, Aktulga HM, Belfon K, Cerutti DS,

Cisneros GA, Cruzeiro VWD, Forouzesh N, Giese TJ, Götz AW, Gohlke

H, et al: Amber Tools. J Chem Inf Model. 63:6183–6191. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Shaw DE, Maragakis P, Lindorff-Larsen K,

Piana S, Dror RO, Eastwood MP, Bank JA, Jumper JM, Salmon JK, Shan

Y and Wriggers W: Atomic-level characterization of the structural

dynamics of proteins. Science. 330:341–346. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Tian C, Kasavajhala K, Belfon KAA,

Raguette L, Huang H, Migues AN, Bickel J, Wang Y, Pincay J, Wu Q

and Simmerling C: ff19SB: Amino-acid-specific protein backbone

parameters trained against quantum mechanics energy surfaces in

solution. J Chem Theory Comput. 16:528–552. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Izadi S, Anandakrishnan R and Onufriev AV:

Building water models: A different approach. J Phys Chem Lett.

5:3863–3871. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wang H, Gao X and Fang J: Multiple

staggered mesh ewald: Boosting the accuracy of the smooth particle

mesh ewald method. J Chem Theory Comput. 12:5596–5608. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Donnelly SM, Lopez NA and Dodin IY:

Steepest-descent algorithm for simulating plasma-wave caustics via

metaplectic geometrical optics. Phys Rev E. 104:0253042021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Bussi G, Donadio D and Parrinello M:

Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J Chem Phys.

126:0141012007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Nosé S and Klein ML: Constant pressure

molecular dynamics for molecular systems. Mol Phys. 50:1055–1076.

1983. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Zhang SY, Li ZL, Bai J, Wang Y, Zhang LM,

Wu X and Hua HM: A new perylenequinone from a halotolerant fungus,

Alternaria sp. M6. Chin J Nat Med. 10:68–71. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Campos FR, Barison A, Daolio C, Ferreira

AG and Rodrigues-Fo E: Complete 1H and 13C NMR assignments of

aurasperone A and fonsecinone A, two bis-naphthopyrones produced by

Aspergillus aculeatus. Magn Reson Chem. 43:962–965. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Xiong HY, Fei DQ, Zhou JS, Yang CJ and Ma

GL: Steroids and other constituents from the mushroom Armillaria

lueo-virens. Chem Nat Compd. 45:759–761. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Wu J, Choi JH, Yoshida M, Hirai H, Harada

E, Masuda K, Koyama T, Yazawa K, Noguchi K, Nagasawa K and

Kawagishi H: Osteoclast-forming suppressing compounds, gargalols A,

B, and C, from the edible mushroom Grifola gargal. Tetrahedron.

67:6576–6581. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Yue JM, Chen SN, Lin ZW and Sun HD:

Sterols from the fungus lactarium volemus. Phytochemistry.

56:801–806. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Ding T, Zhou Y, Qin JJ, Yang LJ, Zhang WD

and Shen YH: Chemical constituents from wetland soil fungus

penicillium oxalicum GY1. Fitoterapia. 142:1045302020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Liu S, Sun C, Ha Y, Ma M, Wang N, Zhou Y

and Zhang Z: Novel antibacterial alkaloids from the mariana

trench-derived actinomycete streptomyces sp. SY2255. Tetrahedron

Lett. 137:1549352024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Wu B, Lin WH, Gao HY, Zheng L, Wu LJ and

Kim CS: Four new antibacterial constituents from Senecio

cannabifolius. Pharm Biol. 44:440–444. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Pitera JW: Expected distributions of

root-mean-square positional deviations in proteins. J Phys Chem B.

118:6526–6530. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Trott O and Olson AJ: AutoDock vina:

Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring

function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput

Chem. 31:455–461. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Fu Y, Wu F, Huang JH, Chen YC and Luo MB:

Simulation study on the extension of semi-flexible polymer chains

in cylindrical channel. Chin J Polym Sci. 37:1053–1060. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Cao X, Hummel MH, Wang Y, Simmerling C and

Coutsias EA: Exact analytical algorithm for the solvent-accessible

surface area and derivatives in implicit solvent molecular

simulations on GPUs. J Chem Theory Comput. 20:4456–4468. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Wang Y and Wang Y: HBCalculator: A tool

for hydrogen bond distribution calculations in molecular dynamics

simulations. J Chem Inf Model. 64:1772–1777. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Jiang D, Du H, Zhao H, Deng Y, Wu Z, Wang

J, Zeng Y, Zhang H, Wang X, Wang E, et al: Assessing the

performance of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods. 10. Prediction

reliability of binding affinities and binding poses for RNA-ligand

complexes. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 26:10323–10335. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Liao Q: Enhanced sampling and free energy

calculations for protein simulations. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci.

170:177–213. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Bai F, Xu Y, Chen J, Liu Q, Gu J, Wang X,

Ma J, Li H, Onuchic JN and Jiang H: Free energy landscape for the

binding process of Huperzine A to acetylcholinesterase. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 110:4273–4278. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Zhang Z, Liu M, An Y, Gao C, Wang T, Zhang

Z, Zhang G, Li S, Li W, Li M and Wang G: Targeting immune

microenvironment in cervical cancer: Current research and advances.

J Transl Med. 23:8882025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Sharma S, Deep A and Sharma AK: Current

treatment for cervical cancer: An update. Anticancer Agents Med

Chem. 20:1768–1779. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Barra F, Lorusso D, Leone Roberti Maggiore

U, Ditto A, Bogani G, Raspagliesi F and Ferrero S: Investigational

drugs for the treatment of cervical cancer. Expert Opin Investig

Drugs. 26:389–402. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Giudice E, Mirza MR and Lorusso D:

Advances in the management of recurrent cervical cancer: State of

the art and future perspectives. Curr Oncol Rep. 25:1307–1326.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Newman DJ and Giddings LA: Natural

products as leads to antitumor drugs. Phytochem Rev. 13:123–137.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Baek SH: Editorial for the special issue

‘Anticancer activity and metabolic pathways of natural products

2.0’. Biomedicines. 13:20832025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Pero RW, Posner H, Blois M, Harvan D and

Spalding JW: Toxicity of metabolites produced by the ‘Alternaria’.

Environ Health Perspect. 4:87–94. 1973. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Fang ZF, Yu SS, Zhou WQ, Chen XG, Ma SG,

Li Y and Qu J: A new isocoumarin from metabolites of the endophytic

fungus Alternaria tenuissima (Nees & T. Nees: Fr.)

Wiltshire. Chinese Chem Lett. 23:317–320. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Ma Y, Lin Q, Yang Y, Liang W, Salamone SJ,

Li Y, Lin Y, Zhao H, Zhao Y, Fang W, et al: Clinical

pharmacokinetics and drug exposure-toxicity correlation study of

docetaxel based chemotherapy in Chinese head and neck cancer

patients. Ann Transl Med. 8:2362020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Yang Z, Liu Z, Ablise M, Jia J, Maimaiti

A, Lv ZY, Mutalipu Z, Yan T, Wang Y, Aihaiti A, et al: Design,

synthesis, and in vitro and in vivo anti-drug resistant cervical

cancer activity of novel licochalcone A derivatives based on dual

targeting of VEGFR-2/P-gp. Bioorg Chem. 163:1086392025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Zafar A, Khatoon S, Khan MJ, Abu J and

Naeem A: Advancements and limitations in traditional anti-cancer

therapies: A comprehensive review of surgery, chemotherapy,

radiation therapy, and hormonal therapy. Discov Oncol. 16:6072025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Raman R, Debata S, Govindarajan T and

Kumar P: Targeting triple-negative breast cancer: Resistance

mechanisms and therapeutic advancements. Cancer Med. 14:e708032025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Li W, Xu F, Shuai W, Sun H, Yao H, Ma C,

Xu S, Yao H, Zhu Z, Yang DH, et al: Discovery of novel

quinoline-chalcone derivatives as potent antitumor agents with

microtubule polymerization inhibitory activity. J Med Chem.

62:993–1013. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

França GS, Baron M, King BR, Bossowski JP,

Bjornberg A, Pour M, Rao A, Patel AS, Misirlioglu S, Barkley D, et

al: Cellular adaptation to cancer therapy along a resistance

continuum. Nature. 631:876–883. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Pang L, Cheng Y, Zou S and Song J: Long

noncoding RNA SNHG7 contributes to cell proliferation, migration,

invasion and epithelial to mesenchymal transition in non-small cell

lung cancer by regulating miR-449a/TGIF2 axis. Thorac Cancer.

11:264–276. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Liu K, Zhang Y, Liu L and Yuan Q:

MALAT1 promotes proliferation, migration, and invasion of

MG63 cells by upregulation of TGIF2 via negatively

regulating miR-129. Onco Targets Ther. 11:8729–8740. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Xi L, Zhang Y, Kong S and Liang W:

miR-34 inhibits growth and promotes apoptosis of

osteosarcoma in nude mice through targetly regulating TGIF2

expression. Biosci Rep. 38:BSR201800782018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Weiler S, Ademokun JA and Norton JD: ID

helix-loop-helix proteins as determinants of cell survival in

B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells in vitro. Mol Cancer.

14:302015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Ruzinova MB and Benezra R: Id proteins in

development, cell cycle and cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 13:410–418.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Ouyang XS, Wang X, Ling MT, Wong HL, Tsao

SW and Wong YC: Id-1 stimu-lates serum independent prostate cancer

cell proliferation through inactivation of p16(INK4a)/pRB pathway.

Carcinogenesis. 23:721–725. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Ling MT, Wang X, Ouyang XS, Lee TK, Fan

TY, Xu K, Tsao SW and Wong YC: Activation of MAPK signaling pathway

is essential for Id-1 induced serum independent prostate cancer

cell growth. Oncogene. 21:8498–8505. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Su Y, Zheng L, Wang Q, Bao J, Cai Z and

Liu A: The PI3K/Akt pathway upregulates Id1 and integrin α4 to

enhance recruitment of human ovarian cancer endothelial progenitor

cells. BMC Cancer. 10:4592010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Sun WZ, Li MH, Chu M, Wei LL, Bi MY, He Y

and Yu LB: Id1 knockdown induces the apoptosis and inhibits the

proliferation and invasion of ovarian cancer cells. Eur Rev Med

Pharmacol Sci. 20:2812–2818. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Papaspyridonos M, Matei I, Huang Y, do

Rosario Andre M, Brazier-Mitouart H, Waite JC, Chan AS, Kalter J,

Ramos I, Wu Q, et al: Id1 suppresses anti-tumour immune responses

and promotes tumour progression by impairing myeloid cell

maturation. Nat Commun. 6:68402015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Wang MH, Zhou XM, Zhang MY, Shi L, Xiao

RW, Zeng LS, Yang XZ, Zheng XFS, Wang HY and Mai SJ: BMP2 promotes

proliferation and invasion of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells via

mTORC1 pathway. Aging (Albany NY). 9:1326–1340. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Lan L, Evan T, Li H, Hussain A, Ruiz EJ,

Zaw Thin M, Ferreira RMM, Ps H, Riising EM, Zen Y, et al: GREM1 is

required to maintain cellular heterogeneity in pancreatic cancer.

Nature. 607:163–168. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Huang S, Wang Y, Luo L, Li X, Jin X, Li S,

Yu X, Yang M and Guo Z: BMP2 is related to Hirschsprung's disease

and required for enteric nervous system development. Front Cell

Neurosci. 13:5232019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Du M, Su XM, Zhang T and Xing YJ: Aberrant

promoter DNA methylation inhibits bone morphogenetic protein 2

expression and contributes to drug resistance in breast cancer. Mol

Med Rep. 10:1051–1055. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Waite KA and Eng C: BMP2 exposure results

in decreased PTEN protein degradation and increased PTEN levels.

Hum Mol Genet. 12:679–684. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Buijs JT, van der Horst G, van den Hoogen

C, Cheung H, de Rooij B, Kroon J, Petersen M, van Overveld PG,

Pelger RC and van der Pluijm G: The BMP2/7 heterodimer inhibits the

human breast cancer stem cell subpopulation and bone metastases

formation. Oncogene. 31:2164–2174. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Xiao B, Zhang W, Kuang Z, Lu J, Li W, Deng

C, He Y, Lei T, Hao W, Sun Z and Li L: SOX9 promotes nasopharyngeal

carcinoma cell proliferation, migration and invasion through BMP2

and mTOR signaling. Gene. 715:1440172019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Chen Z, Yuan L, Li X, Yu J and Xu Z: BMP2

inhibits cell proliferation by downregulating EZH2 in gastric

cancer. Cell Cycle. 21:2298–2308. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Vora M, Mondal A, Jia D, Gaddipati P, Akel

M, Gilleran J, Roberge J, Rongo C and Langenfeld J: Bone

morphogenetic protein signaling regulation of AMPK and PI3K in lung

cancer cells and C. elegans. Cell Biosci. 12:762022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Mao J, Yu Y, Yang J, Li G, Li C, Qi X, Wen

T and Hu J: Comparative transcriptome analysis of sweet corn

seedlings under low-temperature stress. Crop J. 5:396–406. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Chen L, Zhang Y, Chen H, Zhang X, Liu X,

He Z, Cong P, Chen Y and Mo D: Comparative transcriptome analysis

reveals a more complicated adipogenic process in intramuscular stem

cells than that of subcutaneous vascular stem cells. J Agric Food

Chem. 67:4700–4708. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Zhao W, Li J, Chen MM, Luo Y, Ju Z, Nesser

NK, Johnson-Camacho K, Boniface CT, Lawrence Y, Pande NT, et al:

Large-scale characterization of drug responses of clinically

relevant proteins in cancer cell lines. Cancer Cell. 38:829–843.e4.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Istyastono EP, Radifar M, Yuniarti N,

Prasasty VD and Mungkasi S: PyPLIF HIPPOS: A molecular interaction

fingerprinting tool for docking results of autoDock vina and