Introduction

Sepsis represents a serious medical condition marked

by the sudden failure of multiple organ systems due to an

inappropriate response to infection by the host (1). Sepsis has become one of the primary

contributors to severe illness and mortality worldwide (2). Based on a 2020 research report

involving the Intensive Care Units (ICUs) of 44 hospitals

nationwide, the Chinese Expert Consensus on Early Prevention and

Blockade of Sepsis in Emergency Medicine indicated that the

incidence rate in ICUs was 20.6%, with a 90-day mortality rate of

35.5% (3). Notably, nearly 60% of

these patients experience co-infection of the lungs (4), indicating that the lungs may be the

most susceptible and severely affected organ in sepsis. Acute lung

injury (ALI) impacts 25–50% of patients suffering from sepsis and,

if not treated promptly and effectively, can progress to acute

respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), a more severe condition

(5). Effective sepsis-induced

acute lung injury (SALI) therapies remain limited, prompting urgent

translational research. The pathological characteristics of ALI

involve extensive inflammation resulting in harm to alveolar

epithelial cells (AECs), breakdown of the pulmonary vascular

endothelial barrier and subsequent accumulation of protein-rich

inflammatory edema fluid within the alveolar spaces, ultimately

causing diffuse alveolar damage (6). Apoptosis and necrosis directly

contribute to epithelial and endothelial cell damage in sepsis, as

demonstrated Jiang et al (7). Consequently, modulating apoptosis and

alleviating lung inflammation are promising therapeutic strategies

for managing ALI.

The inflammatory response serves as the body's

defense mechanism against various stimuli, including infections,

pathogenic microorganisms, trauma and metaplasia. In the context of

sepsis-induced ALI, this response is primarily triggered by the

activation of lung macrophages and the infiltration of neutrophils.

The overactive engagement of these immune cells leads to the

increased release of pro-inflammatory substances, which further

exacerbates inflammation and ultimately causes tissue injury.

Apoptosis, often known as programmed cell death, is a genetically

controlled mechanism of systematic and self-directed cell death

that removes damaged, older or excess cells. During infection,

apoptosis serves a key role in limiting pathogen replication,

preventing the spread of infection and maintaining tissue

homeostasis (8). However,

dysregulated apoptosis and excessive apoptotic activity may also

contribute to the pathogenesis of ALI.

The present review examines the combined influence

of apoptosis and inflammation in SALI to offer a thorough

theoretical foundation for a deeper understanding of the mechanisms

underlying this condition.

Activation and regulation of the

inflammatory response of ALI in sepsis

Recruitment and activation of

inflammatory cells

Mechanisms of neutrophil infiltration in lung

tissue

Neutrophils serve as essential elements of the

innate immune system, contributing to the defense against pathogens

that invade the body. During sepsis, neutrophils become activated

and are released into the circulation in large numbers, where they

accumulate in endothelial cells (ECs) at the site of infection

(9,10). Intercellular cell adhesion

molecules (ICAMs) are upregulated under inflammatory conditions

through pro-inflammatory signaling, facilitating the migration of

neutrophils to lung tissue and their firm adhesion to ECs. A

previous study has demonstrated that ICAM-1 levels in lung

capillary cells are markedly elevated within 24 h of the onset of

infection (11). P-selectin on ECs

further mediates neutrophil aggregation and rolling adhesion,

resulting in substantial neutrophil accumulation in the pulmonary

microcirculation and excessive adhesion to the endothelium. This

aberrant alteration contributes to the activation of

pro-inflammatory chemokines [including IL-1, TNF-α and

lipopolysaccharide (LPS)], which further recruit neutrophils to

infected tissues.

Within neutrophils, phagosomes fuse with lysosomes

to form phagolysosomes, which are key in the defense against

invading pathogens. However, during phagocytosis, the contents of

neutrophil granules may be released into the extracellular

environment, particularly hydrolytic enzymes released by lysosomes.

This leakage can lead to local tissue damage and amplify acute

inflammatory signals, ultimately exacerbating inflammatory lung

injury (12). Additionally,

neutrophils can traverse the alveolar epithelium into the lumen and

adhere to the epithelial surface using β2-integrins. In the

inflammatory state, the migration of numerous neutrophils results

in increased alveolar epithelial permeability. Neutrophils that

have been activated secrete various cytokines, such as proteases,

reactive oxygen species (ROS), pro-inflammatory molecules and

agents that facilitate coagulation. Additionally, these harmful

mediators undermine the structural integrity of the tight junctions

(TJs) located between the epithelial cells.

In the context of sepsis, neutrophils migrate from

the intravascular space to inflamed tissues through the

transendothelial migration (TEM) cascade. Previous research

indicates that, during inflammation, the levels of ECs and

extracellular vesicles (EVs) in human blood notably increase

(13). EC-derived EVs facilitate

the reverse TEM (rTEM) of neutrophils from tissues back into the

vasculature. Neutrophils returning to the circulatory system

through rTEM can carry inflammatory signals and pathogen components

acquired from local tissues, thereby promoting the spread of

inflammation to distant organs and exacerbating distal lung injury.

Zi et al (10) demonstrated

that the proportion of rTEM neutrophils in the peripheral blood of

patients with sepsis was elevated, particularly in those who

developed ARDS.

A previous study found that activated neutrophils

can recruit and degrade pathogens by producing neutrophil

extracellular traps (NETs) (14).

NETs are primarily composed of nuclear DNA, histones, antimicrobial

peptides and enzymes such as myeloperoxidase (MPO) and elastase.

The process by which neutrophils form NETs is known as NETosis, a

novel form of programmed neutrophil death. In previous years,

increasing researchs have demonstrated that NETosis is closely

associated with sepsis-induced lung injury and exhibits a complex

dual role (15,16). On the one hand, in the early stages

of sepsis, NETs can help clear pathogens and limit their spread by

capturing and killing bacteria. However, excessive NETosis can lead

to lung tissue damage. Pathogen-associated molecular patterns such

as LPS, induce neutrophils to release NETs by activating toll-like

receptor 4 (TLR4). Meanwhile, MPO and hydrogen peroxide

(H2O2) produced by NETs can further activate

the NF-κB signaling pathway through the TLR signaling pathway of

epithelial cells, thereby enhancing the pro-inflammatory response

of ECs, upregulating the expression of adhesion molecules such as

ICAM-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 and promoting the

secretion of pro-inflammatory factors, leading to EC damage

(17). Furthermore, the histones

in NETs can directly cause lung epithelial cell and EC death due to

their cytotoxicity, thereby compromising the integrity of cell

membranes. Consequently, histone levels can serve as a clinical

marker for the severity of sepsis-induced lung injury. On the other

hand, the DNA in NETs is associated with coagulation, providing a

scaffold for platelet binding and stimulating platelet aggregation,

activating the extrinsic coagulation pathway, promoting

microthrombus formation and leading to pulmonary microcirculation

disorders and ventilation/perfusion mismatch, thereby exacerbating

lung injury (18).

Functional shifts in macrophages and

inflammatory amplification

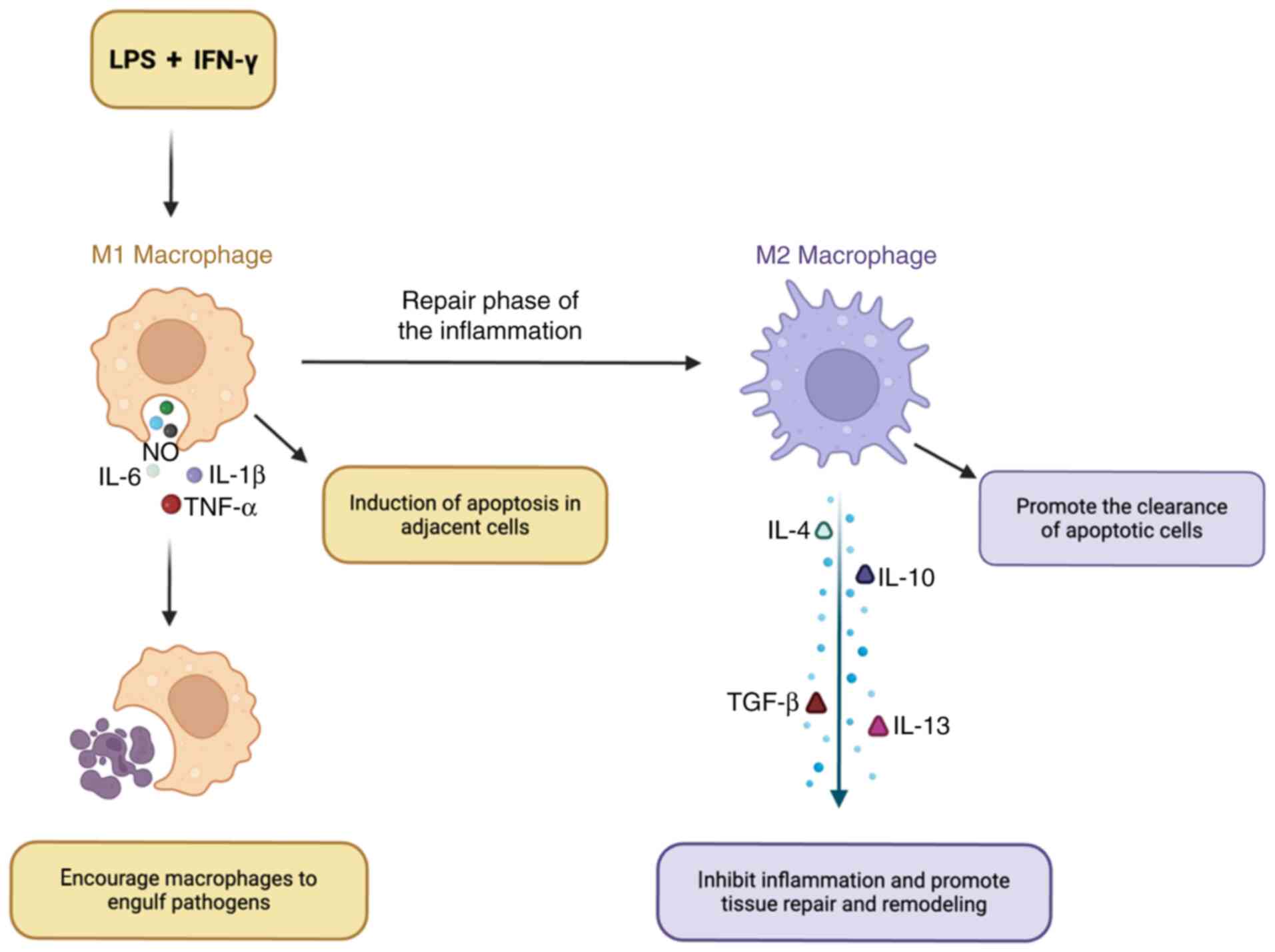

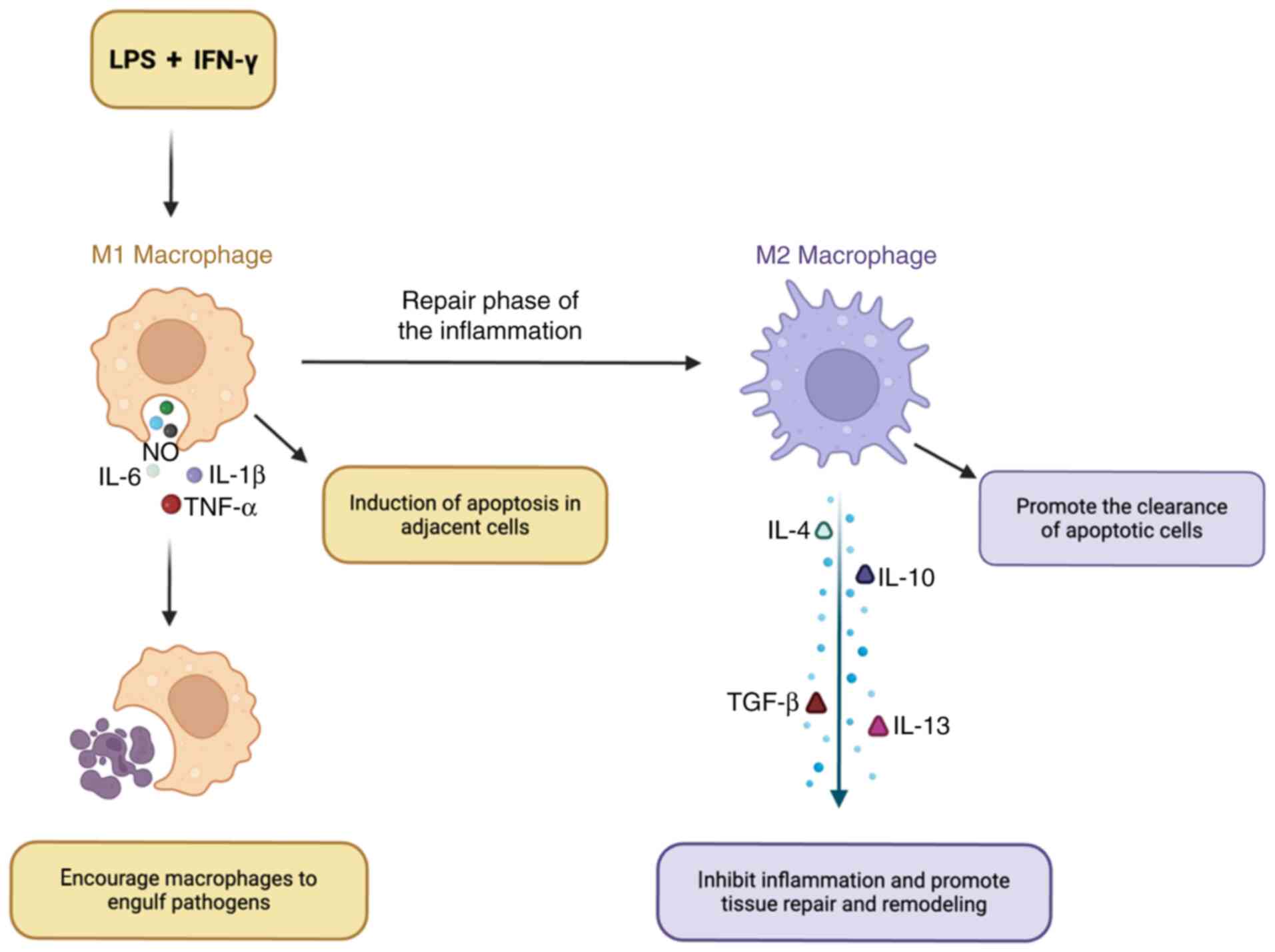

Macrophages represent a highly heterogeneous class

of immune cells that serve a pivotal role in the body's immune

system. Macrophages can polarize into different phenotypes

depending on stimuli from various tissue microenvironments. The

primary phenotypes are inflammatory or classically activated

macrophages (M1) and alternatively activated macrophages (M2) that

promote healing. In response to inflammatory stimuli, the actions

of LPS or interferon, whether alone or synergistically, promote

macrophage polarization towards the M1 phenotype, thereby

increasing the release of pro-inflammatory factors [such as TNF-α,

nitric oxide (NO), IL-1β and IL-6], which are essential for

pathogen elimination and defense (19). During the repair phase of late

inflammation, M1 macrophages polarize toward M2 macrophages,

secreting anti-inflammatory factors (including IL-4, IL-10, IL-13

and TGF-β) to inhibit the inflammatory response and facilitate

tissue repair and remodeling (Fig.

1). Dang et al (20)

noted that macrophage polarization within the lungs has a notable

influence on the onset of, and recovery from, septic lung injuries.

An imbalance in the shift between M1 and M2 macrophages, which

leads to ongoing production of pro-inflammatory mediators, can

result in tissue harm. It has previously been reported that, in

cases of SALI, M1 macrophages exacerbate lung damage due to

unchecked inflammatory responses (21). Additionally, Li et al

(22) demonstrated that in

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), the compound Lianhua Qingdian

effectively alleviates SALI by enhancing the infiltration of M2

macrophages. This mechanism may involve promoting the

transformation of macrophages from the M1 to the M2 phenotype by

activating the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

signaling pathway, inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway and

alleviating inflammatory responses. However, it is important to

note that these results were obtained from a mouse model of

LPS-induced ALI and there is still an overall lack of supporting

clinical data in humans.

| Figure 1.Functional shifts in macrophages. LPS

or IFN promotes the polarization of macrophages toward the M1

phenotype, resulting in an increased release of pro-inflammatory

factors such as TNF-α, NO, IL-1β and IL-6. In the later stages of

inflammatory repair, M1 macrophages transition into M2 macrophages,

which secrete anti-inflammatory factors such as IL-4, IL-10, IL-13

and TGF-β, thereby suppressing the inflammatory response and

facilitating tissue repair and remodeling. LPS, lipopolysaccharide;

NO, nitric oxide. |

M2 macrophages possess anti-inflammatory and tissue

repair properties, thus serving a key role in the recovery process

of patients with ARDS. Yang et al (23) found that, in LPS-induced ARDS mouse

models, the M2/M1 alveolar macrophage ratio notably decreased as

the severity of lung injury increased. Conversely, the

intratracheal administration of exogenous M2 alveolar

macrophage-derived EVs markedly improved LPS-induced ARDS yet

reduced the levels of inflammatory factors in bronchoalveolar

lavage fluid. Similarly, in patients with ARDS who underwent

continuous mechanical ventilation or succumbed to disease within 28

days, there was found to be a persistent M1 phenotype and

insufficient M2 transformation (24). It may be inferred that the

anti-inflammatory and pro-repair effects mediated by M2 macrophages

are key for alveolar epithelial cell reconstruction and pulmonary

function recovery in patients with ARDS during the recovery

phase.

Release of inflammatory mediators and

signaling pathways

Formation and role of cytokine networks

Cytokines are a class of small proteins with diverse

biological activities. During inflammation, these cytokines can

activate immune cells to synthesize and secrete pro-inflammatory

factors, with the overproduction of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 being

characteristic of systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

Excessive release of cytokines leads to mutual stimulation among

other different cytokines, forming a complex network. These

cytokines bind to target cells through cell surface receptors,

activating signal transduction pathways and initiating a series of

inflammatory cascade responses, with NF-κB having been identified

as a key target (25). In healthy

cells, NF-κB resides in the cytoplasm, forming a complex with IκB

that then inhibits further NF-κB activity. Upon stimulation by

cytokines, IκB undergoes phosphorylation through the activation of

the inhibitor of κB kinase, followed by its ubiquitination and

degradation. This sequence of events leads to the relocation of

NF-κB into the nucleus. Consequently, this mechanism enhances the

expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-1β and

TNF-α, thereby intensifying the inflammatory responses.

Synergistic effects of chemokines and

lipid mediators

Chemokines are a class of small molecular weight

cytokines produced by leukocytes in response to external stimuli.

During the inflammatory response, chemokines facilitate the

migration of circulating leukocytes to injured tissues by

recruiting and activating immune cells, thereby forming a

concentration gradient, which is further established by the binding

of chemokines to glycosaminoglycans in the extracellular matrix and

endothelium (26). Neutrophils

tend to be the first immune cells to reach the site of infection,

where they serve a key role in engulfing pathogens and clearing

cellular debris through phagocytosis. Subsequently, monocytes

migrate to the infection, where they transform into macrophages,

continuing the fight against pathogens while releasing various

cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, prostaglandins and

leukotrienes. The chemokine family is generally divided into four

categories: Two primary subfamilies (CXC and CC) and two secondary

subfamilies (CX3C and C). The distinct chemokine groups interact

with specific receptors found on various cell types and are

coordinated with the adhesion molecules present, thus contributing

to the inflammatory response (27).

Chemokine receptors are part of the heptameric

transmembrane guanosine triphosphate-binding G protein-coupled

receptor superfamily, which trigger an intracellular signaling

cascade through the associated trimeric G proteins. This mechanism

promotes the adhesion of target cells to the endothelial lining and

directs their migration toward the infection site (28). Among these, monocyte

chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) (29), also known as CC chemokine ligand 2,

is classified within the CC subfamily of chemokines. In the early

stages of inflammation, MCP-1 attaches to the CC motif chemokine

receptor 2 receptor, stimulating the accumulation of monocytes and

their transformation into macrophages (30). MCP-1 serves a key role in directing

the appropriate immune response associated with infection and

inflammation (31). A different

category of CXC chemokines, such as macrophage inflammatory protein

2 [also referred to as C-X-C motif chemokine ligand (CXCL) 2] and

CXCL8 (often called IL-8), are able to promote the infiltration of

innate immune cells and work in conjunction with lipid signaling.

Additionally, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and leukotriene B4, produced

by ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid, serve as pro-inflammatory lipid

mediators that activate inflammatory vesicles and initiate the

endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response (32). These processes serve a key role in

the onset, progression and resolution of inflammation.

Triggering and regulation of apoptosis in

ALI in sepsis

Activation of apoptosis-related

signaling pathways

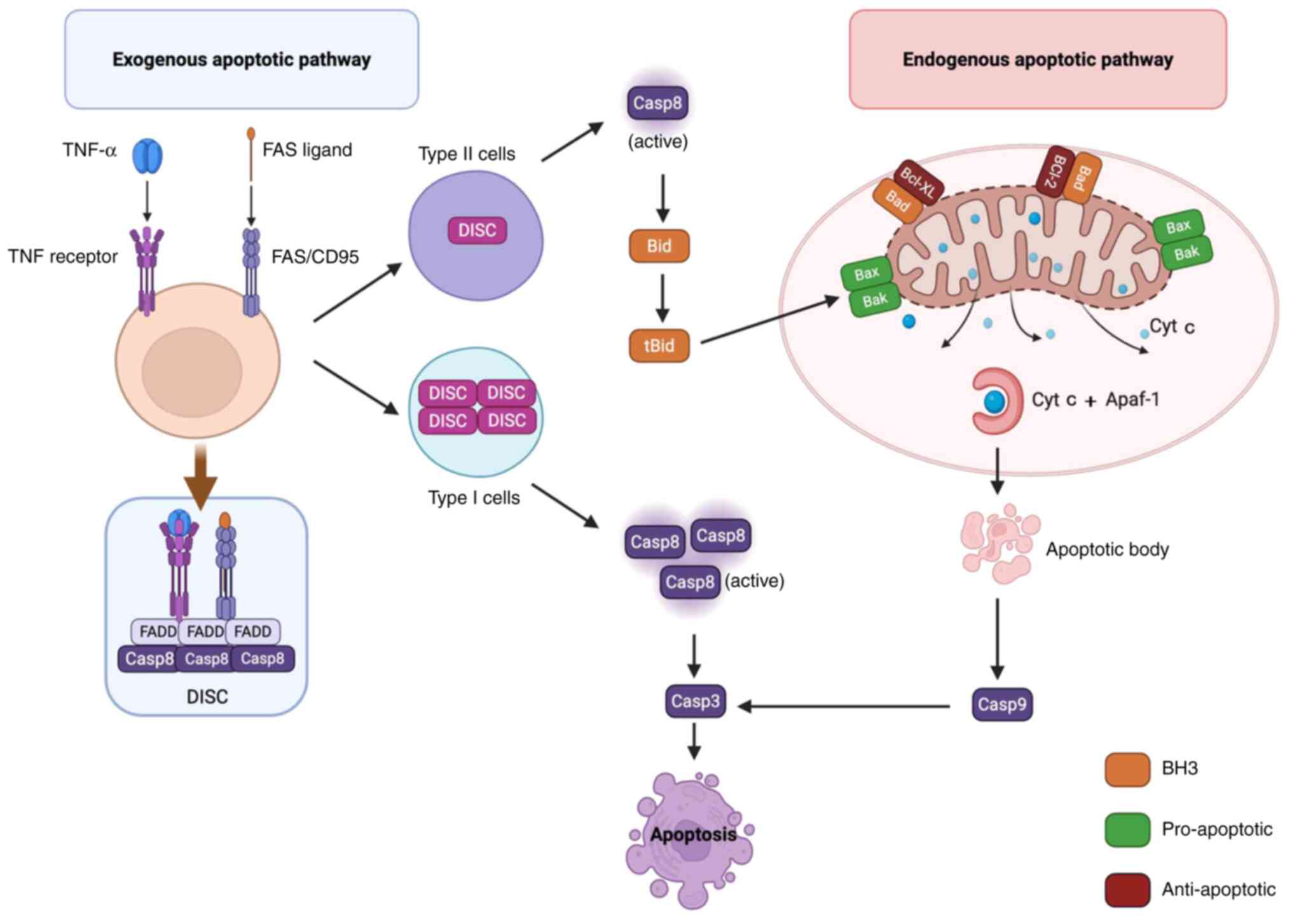

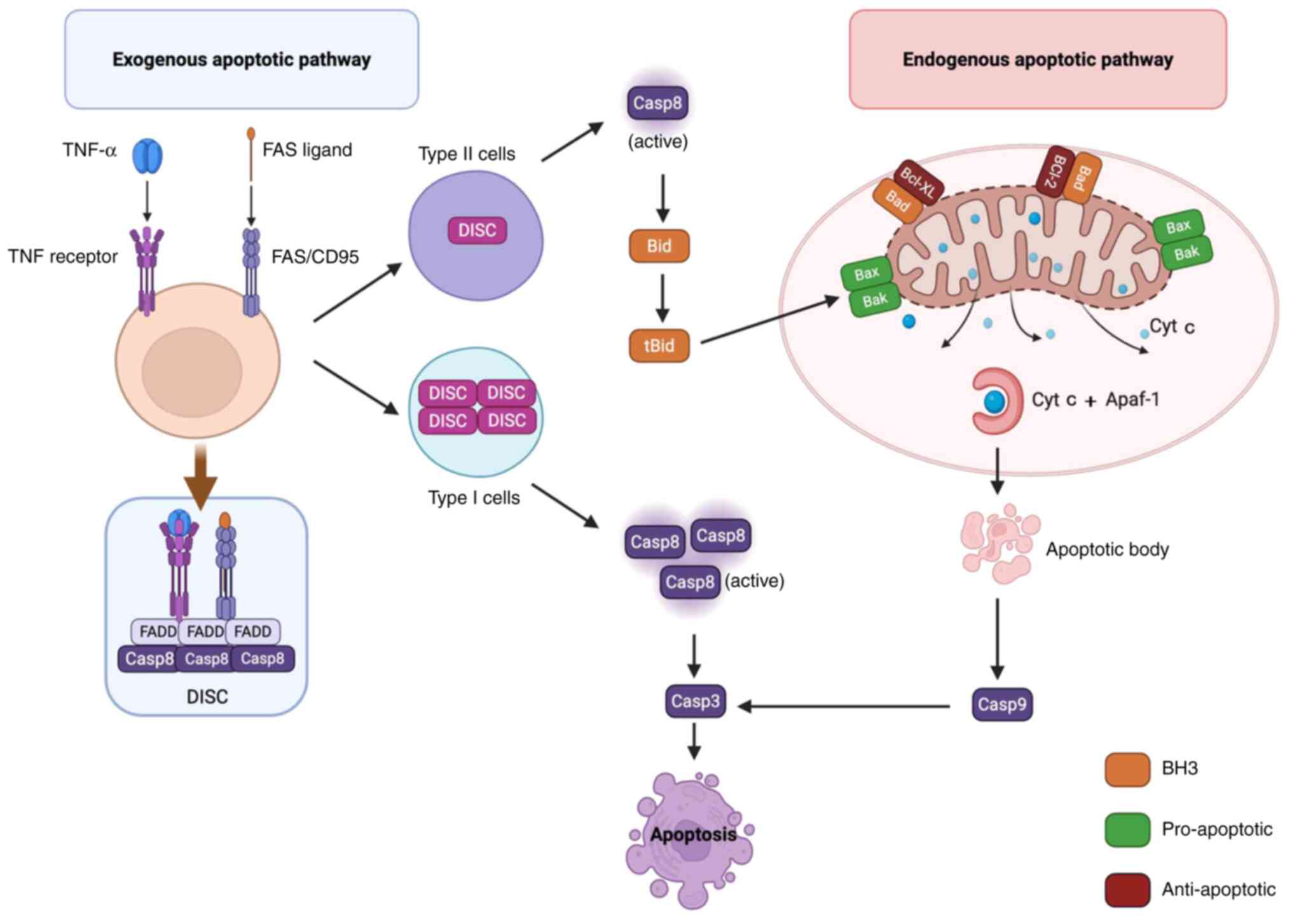

Death receptor-mediated apoptosis pathway

Death receptor pathways involve specific proteins on

cell membranes binding to ligands that carry apoptotic signals,

subsequently transducing these signals into the cell and ultimately

inducing apoptosis. The activation of the death receptor pathway

mainly occurs through death receptors located on the cell surface,

including the Fas cell surface and TNF receptors. These receptors

initiate the apoptotic process by recruiting junctional proteins,

including Fas-associated via death domain and promoting cysteine

aspartyl proteases, such as caspase-8, upon binding with specific

death ligands such as Fas ligands and TNF-α. Subsequently,

caspase-8 activates downstream effector enzymes, including

caspase-3 and caspase-7, ultimately leading to apoptosis (Fig. 2).

| Figure 2.Activation of apoptosis-related

signalling pathways. The activation of the extrinsic apoptotic

pathway is primarily mediated by the binding of specific ligands to

the Fas receptor and TNF receptor on the cell surface, which is

followed by the recruitment of FADD to form the DISC. Notably,

there are marked differences in the formation of DISC between type

I and II cells. In type I cells, the DISC is formed efficiently and

stably, resulting in the production of a substantial amount of

Casp8. This enzyme directly activates downstream effector enzymes,

including Casp3, thereby triggering apoptosis. Conversely, in type

II cells, DISC formation is inefficient and unstable, yielding only

a limited amount of Casp8, which subsequently cleaves Bid into

tBid. tBid then translocates to the outer mitochondrial membrane,

activating Bax/Bak, which leads to the disruption of mitochondrial

membrane integrity, the release of Cyt c and subsequent binding

with Apaf-1 to form the apoptosome. This process further activates

Casp9, which triggers downstream Casp3 to initiate apoptosis. DISC,

death-inducing signaling complex; Bid, BH3 interacting domain death

agonist; tBid, truncated Bid; Bak, Bcl-2 homologous antagonist

killer; Cyt c, cytochrome c; Apaf-1, apoptotic protease activating

factor 1; FADD, Fas-associated death domain; Casp, caspase; Bad,

Bcl-2-associtaed death protein. |

Caspases, which are cysteine-specific cysteine

proteases, serve a pivotal role in the regulation of apoptosis.

Caspases can be categorized into two groups: i) Initiating caspases

(including caspases-2, −8, −9 and −10); and ii) executioner

caspases (including caspases-3, −6 and −7) (33). When an initiating caspase becomes

activated, it processes and triggers the downstream executioner

caspases, which subsequently cleave cellular proteins at particular

aspartate residues, thus facilitating the process of apoptosis

(34). These executioner caspases

are key in shaping the distinctive characteristics of apoptotic

cells by cleaving a multitude of cellular proteins (including, but

not limited to, caspase-activated inhibitor of DNase, aggrecan and

Pac21), ultimately resulting in DNA fragmentation. This cascade of

events leads to observable apoptotic traits such as nuclear

condensation, shrinkage of the cell and blistering of the membrane.

Generally, caspase enzymes are synthesized as inactive zymogens and

their activation pathways include both exogenous and endogenous

mechanisms, with the death receptor pathway being classified as

exogenous (35).

In the exogenous pathway, caspase-8 not only

activates the execution of caspases, but also facilitates the

cleavage of BH3 interacting domain death agonist (Bid), leading to

its translocation to the mitochondria (25). The CD95 signaling model proposed by

Algeciras-Schimnich et al (36) suggests that the involvement of the

mitochondrial pathway in apoptosis is determined through a

dual-threshold mechanism. As a death receptor, CD95, upon binding

with its ligand, induces the formation of the death-inducing

signaling complex (DISC), the efficiency of which directly

determines the levels of caspase-8 produced. However, there are

notable differences in DISC formation between types I and II cells.

In type I cells, DISC formation is highly efficient and stable,

further generating a substantial quantity of caspase-8 that exceeds

the higher threshold, directly activating caspase-3 to trigger

apoptosis. In type II cells, the formation of DISC is inefficient

and unstable, resulting in only a minimal quantity of caspase-8

that only just exceeds the lower threshold. Apoptosis initiation

can only be triggered by amplifying the cell death signal through

the mitochondrial pathway through the cleavage of Bid (36). Consequently, the process of

apoptosis requires participation from the mitochondrial apoptotic

pathway, wherein Bid acts as a key connection between the death

receptor and mitochondrial apoptotic pathways.

Initiation of the mitochondrial

apoptotic pathway

The mitochondrial apoptotic pathway is endogenous.

When triggered by factors such as DNA damage, metabolic stress, ER

stress or growth factor deprivation, the integrity of the

mitochondrial membrane is disrupted (37,38).

Increased mitochondrial membrane permeability leads to the release

of cytochrome c (Cyt c) from the mitochondria into the cytoplasm.

Cyt c interacts with apoptosis-activating factor 1 to create an

ATP-dependent apoptotic complex. This complex activates caspase-9,

which subsequently triggers the activation of downstream caspases-3

and −7, consequently initiating a cascade of caspase reactions that

leads to apoptosis (Fig. 2).

Furthermore, once released from the mitochondria, Cyt c can bind to

inositol triphosphate receptors located in the ER. This binding

results in an elevation of local calcium levels, which then

enhances the release of Cyt c and triggers the initiation of

apoptosis (39). Conversely,

protein tyrosine phosphatase, which is located between the inner

and outer membranes of the mitochondria, can facilitate the

creation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP),

permitting the movement of molecules of ≤1.5 kDa in size. Abnormal

MPTP opening has been found to impair mitochondrial function and

promote apoptosis (40).

Mitochondria serve as the primary source of cellular

energy and are also the principal site for the production of

intracellular ROS. During apoptosis, mitochondrial damage and ROS

production exacerbate each other, resulting in a vicious cycle

(41). ROS can compromise both the

integrity and functionality of the mitochondrial membrane,

resulting in the release of apoptotic factors, which in turn,

further enhances ROS production, aggravating mitochondrial

impairment (42). Wang et

al (43) induced oxidative

stress in Hepa1-6 cells through the application of fluorine (F),

which led to increased levels of intracellular ROS and

propane-1,2-diol and mitochondrial injury. The oxidative stress

induced by F resulted in marked elevations in intracellular ROS,

malondialdehyde (MDA) and NO concentrations. Furthermore, there was

a notable upregulation in the protein expression of Cyt c,

caspase-9 and caspase-3, along with a considerable increase in

apoptotic cell count and extensive mitochondrial vacuolation, as

evidenced by transmission electron microscopy. This demonstrated

that ROS mediates mitochondrial damage, thereby exacerbating

apoptotic injury.

Role of apoptosis-regulating genes and

proteins

Imbalance in the regulation of Bcl-2 family

proteins

Bcl-2 family proteins are the primary regulators of

the release of mitochondria-associated apoptotic factors and can be

classified into three primary categories based on their biological

functions: i) Anti-apoptotic proteins, such as Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, Bcl-w

and myeloid cell leukemia 1 (Mcl-1); ii) pro-apoptotic proteins,

such as Bax and Bcl-2 homologous antagonist killer (Bak); and iii)

BH3-only proteins, such as Bad, Bid, Bcl-2-interacting mediator of

cell death (Bim), phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate-induced protein 1

and p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis (Puma). In healthy

cells, a balance is sustained between anti-apoptotic and

pro-apoptotic proteins. However, in a septic state, the

concentration of free Bad in the cytoplasm increases, allowing Bad

to bind to Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL. This binding leads to the dissociation

of Bax and Bak and the formation of pore-protein complexes through

interactions with other Bax or Bak proteins. These complexes can

insert into the outer mitochondrial membrane, disrupting its

integrity and ultimately resulting in the release of intracellular

apoptosis-inducing factors (Cyt c) and triggering apoptosis

(44).

Bax is a crucial pro-apoptotic protein. Upon

receiving apoptotic signals, Bax, which initially exists as a

monomer in the cytosol, translocates to the mitochondrial surface,

where it forms trans-mitochondrial membrane pores, resulting in

increased membrane permeability and further facilitating the

release of apoptotic factors (45). Simultaneously, when the Bcl-2/Bax

imbalance disrupts the TJ proteins between alveolar epithelial

cells, it directly or indirectly induces the apoptosis of alveolar

epithelial cells, leading to the destruction of the alveolar

epithelial barrier and increased permeability, which ultimately

causes alveolar edema, alveolar collapse and refractory hypoxemia.

Previous research has shown that polydeoxyribonucleotide (PDRN)

extracted from salmon sperm is able to promote tissue healing and

reduce apoptosis and inflammation. An et al (46) treated a rat model of LPS-induced

lung injury with intraperitoneal injections of PDRN and observed a

notable reduction in lung injury scores. In addition, the ratio of

the pro-apoptotic protein Bax relative to the anti-apoptotic

protein Bcl-2 was reduced, suggesting that PDRN treatment

alleviated lung damage through the inhibition of apoptosis.

Regulation of apoptosis by p53

The p53 protein functions as a transcription factor,

triggering the expression of various target genes and serving a key

role in maintaining genomic stability, regulating the cell cycle,

facilitating DNA repair and promoting apoptosis. Under standard

physiological circumstances, p53 is targeted for degradation by

murine double minute 2 homolog (MDM2) and murine double minute X

(MDMX), which ubiquitinate it, thereby keeping its intracellular

levels low through proteasomal degradation. By contrast, when cells

face stressors such as DNA damage, hypoxia or infection, the

process of p53 ubiquitination is suppressed, causing a rapid

increase in its cellular concentrations (47). Various sensor proteins, such as the

ataxia-telangiectasia-mutated protein, ataxia-telangiectasia and

Rad3-related protein, checkpoint kinase 1, checkpoint kinase 2,

DNA-dependent protein kinase and the p14ARF protein, become

activated and p53 stability is enhanced through post-translational

modifications, including acetylation, methylation and

phosphorylation. Stabilized p53 proteins form tetramers in the

nucleus that bind to p53 response elements on target DNA, thereby

regulating gene transcription (48). On one side, p53 is involved in

apoptosis mediated by mitochondria through activating the

transcription of pro-apoptotic proteins such as Bax, Puma and Bid.

Conversely, p53 can trigger apoptosis without relying on

transcription. The p53 protein, in a manner that does not depend on

its transcriptional functions, translocates to the mitochondria,

where it competes with Mcl-1 for binding to Bak through protein

interactions, leading to the release of Bak from Mcl-1 and

initiates Bak oligomerization (49). Furthermore, p53 interacts with

Bcl-XL, prompting the detachment of Bax from the Bax/Bcl-XL

complex, subsequently enhancing oligomerization. The

oligomerization of Bax and Bak modifies the permeability of the

outer mitochondrial membrane, allowing the release of Cyt c into

the cytoplasm, which then activates caspase proteases, ultimately

prompting apoptosis (50).

In addition, the activation of p53 can lead to the

disruption of the EC cytoskeleton, increased vascular permeability

and the induction of apoptosis in alveolar type II epithelial

cells, severely affecting the synthesis and secretion of pulmonary

surfactant (PS). This results in increased alveolar surface

tension, alveolar collapse and ventilator-associated lung injury.

Previous research has found that MDM2 promotes the degradation of

p53 protein through the ubiquitination pathway, maintaining p53 at

low levels. When MDM2 function is lost, uncontrolled activation of

p53 leads to apoptosis, barrier disruption and amplification of

inflammation, ultimately exacerbating lung injury (51).

Mechanisms of synergy between inflammation

and apoptosis

Induction of apoptosis by inflammatory

mediators

Molecular crosstalk of cytokines to apoptotic

signaling pathways

When sepsis manifests, there is an enhanced release

of pro-inflammatory agents in the body (such as TNF-α, IL-1β and

IL-6) and the NF-κB pathway is dysregulated, which exacerbates the

inflammatory response or transcriptionally activates the Bcl-2

family, thus inducing apoptosis through an ‘inflammatory storm’.

Conversely, activation of NF-κB further induces the production of

TNF-α and IL-1β, forming a positive feedback loop. Furthermore,

elevated levels of activated cytokines such as IL-6 attach to the

membrane-associated IL-6 receptor (IL-6R), resulting in the

formation of the IL-6/IL-6R complex. This complex then associates

with glycoprotein 130 (gp130) to establish a signaling complex that

triggers the MAPK cascade through the recruitment of gp130.

Similarly, locally released cytokines (such as IL-1β or TNF-α) have

been shown to activate MAPK pathways, including JNK and ERK

(52,53). Abnormal activation of these

signaling pathways further promotes the activation of inflammatory

cells and disrupts the stress response, thus inducing cell

apoptosis, ultimately leading to tissue injury.

Inflammation-induced oxidative stress

and apoptosis

Oxidative stress influences apoptosis through

various pathways. An important component of this process is the

action of ROS, which function as ‘redox messengers’ and are crucial

for redox regulation and cellular signaling. Generally, ROS are

understood to encompass free radicals derived from oxygen

(O2), including superoxide anion

(O2−), hydroxyl radical (HO−),

peroxyl radical and alkoxyl radical, along with non-free radical

O2 derivatives such as hydrogen peroxide

(H2O2). However, ROS, once produced in

excess, may lead to oxidative modification of cellular

macromolecules, which in turn may cause notable damage to cellular

proteins and DNA. Mokrá (54)

suggested that oxidative stress is not only an important causative

factor in ALI but may also contribute to extensive damage to lung

tissues and worsening inflammatory responses through activation of

apoptotic pathways.

Mitochondria serve as the primary location for the

production of ROS, with 1–2% of the O2 consumed by

mitochondria being utilized for the generation of ROS, particularly

during the electron transfer process to O2 within the

electron transport chain. In the presence of inflammation and

tissue injury, a marked increase in the release of mitochondrial

ROS (mtROS) occurs. This increase may result in mitochondrial

membrane depolarization that relies on the pore-forming protein

gasdermin D (GSDMD). Consequently, there is a reduction in the

mitochondrial membrane potential, prompting GSDMD to associate with

the mitochondrial membrane, thereby forming a pore. This process

ultimately enhances the permeability of the mitochondrial membrane,

facilitates the release of apoptotic factors and triggers the

activation of mitochondrial apoptotic pathways. In addition, it has

been found that ROS can also inhibit the degradation and transport

of mitochondrial proteins, which is the main cause of mitochondrial

dysfunction (55). In addition,

oxidative stress can trigger the activation of transcription

factors such as NF-κB and p53 (56), influencing the expression and

functionality of proteins associated with apoptosis (such as

Bcl-2). Previous research has demonstrated that, in cells treated

with H2O2, there is a marked reduction in

Bcl-2 protein levels (57),

thereby modulating the apoptotic process.

Exacerbation of the inflammatory

response by apoptotic cells

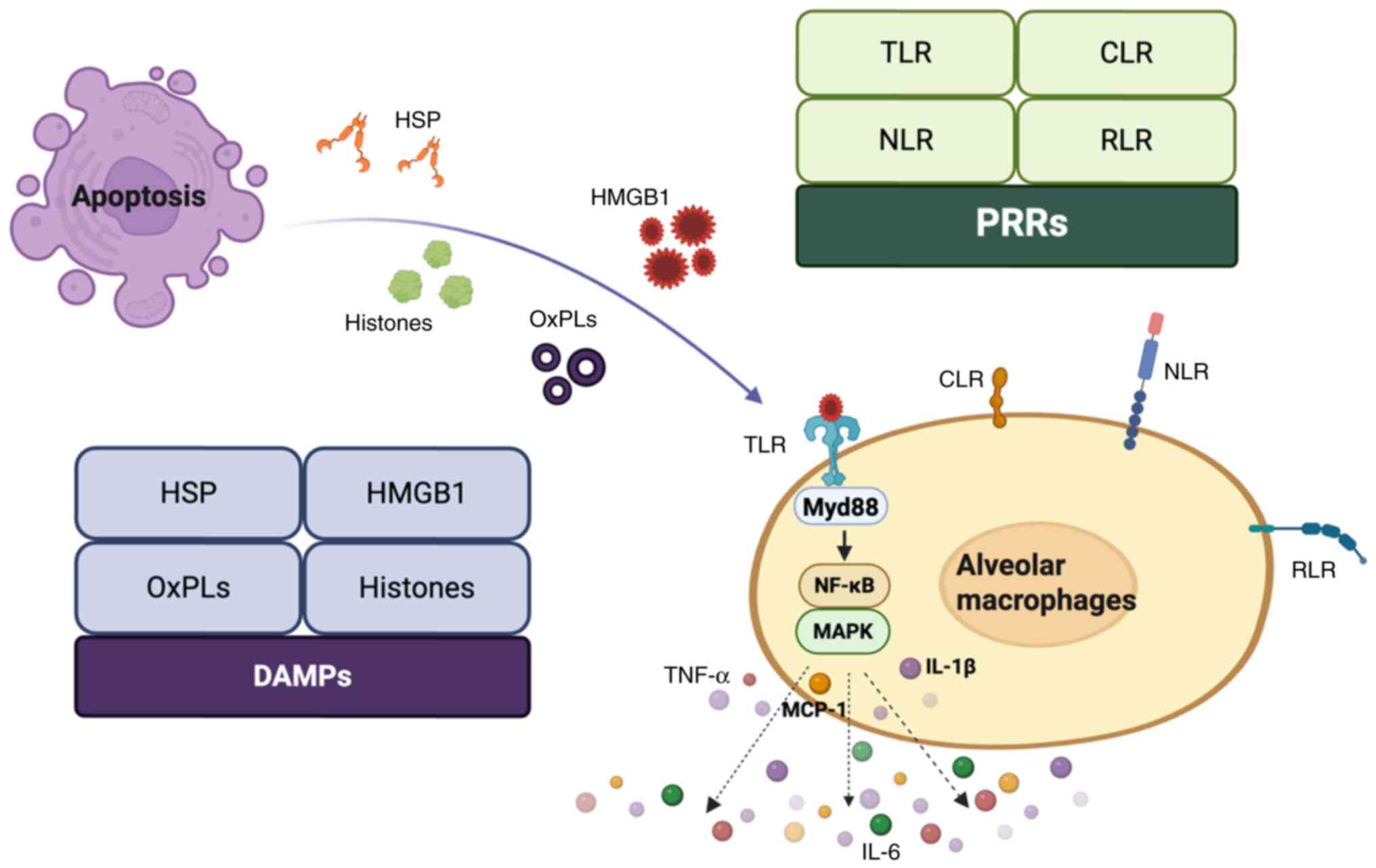

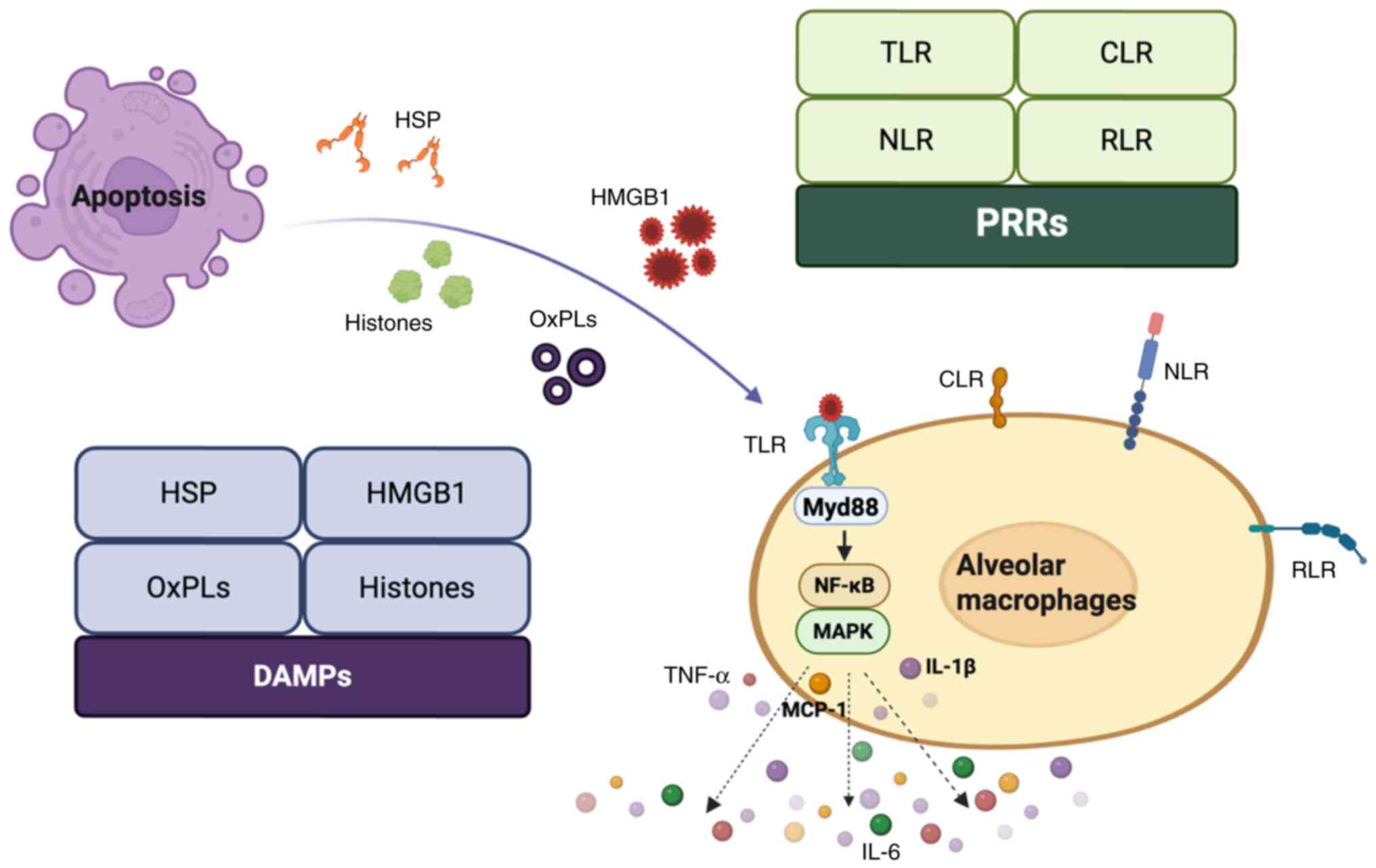

Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs)

released by apoptotic cells

Alveolar macrophages, as the primary immune cells in

the lungs, encounter infections, injuries and stress, leading to

the transformation of specific endogenous molecules into DAMPs.

These DAMPs can activate the immune system and exhibit

pro-inflammatory characteristics. In a steady-state environment,

endogenous molecules, including nucleic acids, proteins, ions,

glycans and metabolites, usually do not initiate an immune

response. However, during stress, these molecules can be

transformed into DAMPs through three mechanisms: i) Positional

substitution; ii) alterations in properties; or iii) changes in

concentration, with positional substitution being the predominant

mechanism (58). It is evident

that, during infection or stress, the mitochondrial membrane

sustains damage, leading to increased membrane permeability and the

release of intracellular substances that can induce apoptosis.

Proteins or peptides released into the extracellular space by

apoptotic cells can be converted into DAMPs such as nuclear

proteins like high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) (59), histones (60), heat shock proteins (HSPs) (61) and oxidized phospholipids (62). Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs)

identify these molecules, leading to the subsequent release of

chemokines and pro-inflammatory factors that initiate and worsen

the inflammatory response (63,64).

PRRs are a class of innate immune receptors that detect endogenous

molecules released following tissue injury and serve as sensors for

DAMPs, including TLRs, C-type lectin receptors, retinoic

acid-inducible gene I-like receptors, nucleotide-binding

oligomerization domain-like receptors and DNA sensors (65,66).

For example, HMGB1 is recognized by TLR2 and TLR4, while HSPs are

recognized by TLR2. Stimulation of TLR2 or TLR4 triggers the

activation of downstream MAPK and NF-κB pathways through the

intermediary protein myeloid differentiation primary response 88

(Myd88), which subsequently enhances the activation of inflammatory

cells and the secretion of inflammatory mediators (Fig. 3). Furthermore, oxidized lipids

serve as important DAMPs involved in the inflammatory response by

interacting with immune and ECs. For example, high concentrations

of cyclopentenone prostaglandins can activate NLR family pyrin

domain containing 3 inflammatory vesicles, which form a protein

complex with the articulin ASC and pro-caspase-1, thereby mediating

caspase-1-dependent IL-1β production, which in turn exacerbates the

inflammatory response (58). Thus,

inflammation can induce the onset of apoptosis and, conversely,

apoptosis can further exacerbate the inflammatory response, with

the two interacting, resulting in a vicious cycle (Table I).

| Figure 3.DAMPs released by apoptotic cells.

Proteins or peptides released from apoptotic cells into the

extracellular space can be transformed into DAMPs, including

nuclear proteins such as HMGB1, histones, HSPs and oxidized

phospholipids. These DAMPs can be recognized by PRRs, which

subsequently activate downstream MAPK and NF-κB pathways through

the adaptor protein Myd88, resulting in the secretion of

inflammatory mediators. DAMPs, damage-associated molecular

patterns; HMGB1, high mobility group box 1; HSPs, heat shock

proteins; PRRs, pattern recognition receptors; MAPK,

mitogen-activated protein kinase; Myd88, myeloid differentiation

primary response 88; OxPLs, oxidized phospholipids; TLR, toll-like

receptors; CLR, C-type lectin receptors; MCP-1, monocyte

chemoattractant protein 1; RLR, RIG-I-like receptors; NLR, NOD-like

receptors. |

| Table I.Key DAMPs and their clinical

significance in ALI/ARDS. |

Table I.

Key DAMPs and their clinical

significance in ALI/ARDS.

| First author,

year | DAMP | Release

mechanism | Recognition

receptors | Clinical relevance

(ALI/ARDS in sepsis) | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Deng et al,

2022 | HMGB1 | Nucleoprotein

leakage from necrotic cells | TLR2/4 | HMGB1 levels are

notably elevated in serum and BALF from patients with sepsis, but

their association with the extent of lung injury and prognosis

remains controversial | (59) |

| Dutta et al,

2025 | Histone | Neutrophil

NETosis | NLRP3 | Extracellular

histones associate with ARDS severity and mortality and are

expected to be early diagnostic markers of ARDS. In particular,

histones H3 and H4 may serve as effective biomarkers and

therapeutic targets in inflammatory diseases | (60) |

| Pei et al,

2022 | HSP70 | Stress cell

cytoplasmic protein release | TLR2 | Enhanced HSP70

expression attenuates sepsis-induced lung injury by inhibiting

inflammation and apoptosis | (61) |

| Karki et al,

2023 | Oxidized

phospholipids | Apoptotic cell

membrane lipid peroxidation | NLRP3 | Oxidized

phospholipids levels are elevated in patients with sepsis and ARDS,

which can be used for early identification of high-risk patients

and guide clinical decision-making | (62) |

Impaired clearance of apoptotic cells

and persistence of inflammation

Under normal physiological conditions, apoptotic

cells are cleared through phagocytosis, primarily by macrophages,

thereby preventing the initiation of an inflammatory response.

Effective clearance of apoptotic cells is key for managing

inflammatory diseases, preventing secondary necrosis and restoring

normal tissue function. Phagocytes are guided by chemokine

‘find-me’ signals in order to migrate towards apoptotic cells

(67). The current four identified

signals that facilitate locating cells are chemokine C-X3-C motif

ligand 1 (CX3CL1; fractalkine), nucleotide triphosphates [including

ATP and uridine triphosphate (UTP)], sphingosine-1 phosphate (S1P)

and lysophosphatidylcholine (LysoPC). Among these, the release of

ATP, UTP and CX3CL1 occurs during the early stages of apoptosis,

while LysoPC and S1P are lipid chemokines produced in the later

stages of apoptosis (67).

Phagocytes near apoptotic cells recognize specific

ligands on their surface, referred to as ‘eat-me’ signals,

including cell-surface calreticulin, ICAM-1 and complement

component 1q, which activate signal transduction pathways and

facilitate the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells (68). Following phagocytosis, apoptotic

cells undergo cytosolic burial, maturing gradually and secreting

anti-inflammatory and pro-tissue healing factors. However, when the

clearing process is hindered, apoptosis can advance to necrotic

apoptosis, which is marked by the rupture of the cell membrane and

a marked release of intracellular DAMPs, thereby intensifying

inflammation and causing tissue injury.

In normal lung tissue, the process of cytosolic

burial helps to avert tissue injury and regulate the inflammatory

response, largely facilitated by alveolar macrophages. Compared

with other macrophage types, alveolar macrophages exhibit a longer

lifespan and an enhanced self-renewal capacity. Under steady-state

conditions, even during acute lung inflammation, the efficient

cellular clearance of alveolar macrophages results in a minimal

presence of apoptotic cells in the airways. When the function of

alveolar macrophages is compromised and when apoptotic cells are

generated in large quantities and cannot be rapidly cleared through

cytosolic burial, a sustained release of DAMPs is prompted,

perpetuating the inflammatory response (69). In certain patients with bacterial

pneumonia, failure to resolve inflammation promptly or the

occurrence of an inflammatory storm, results in impaired lung

function and the subsequent development of ALI or ARDS, which

further prolongs the inflammatory response in the lungs (70). A previous study has indicated that

an increased quantity of uncleared apoptotic cells is found in the

airways of patients with ARDS, respiratory failure or chronic lung

inflammation, all of which are conditions frequently marked by

impairments in the cellular clearance capabilities of alveolar

macrophages (71). Therefore, the

timely and effective clearance of apoptotic cells is key in

modulating the inflammatory response and protecting lung

function.

Effects of inflammation and apoptosis:

Pathophysiological functions of lung tissue

Alveolar epithelial cell damage and

dysfunction

Alveolar epithelial barrier disruption

Alveolar epithelial cell damage is a key determinant

of the severity of ALI and ARDS. Therefore, protecting the function

and barrier integrity of AECs is of great importance (72). AECs, the structural components of

the lung, comprise alveolar type I and II epithelial cells. Type I

epithelial cells, which serve as the main location for gas

exchange, experience higher vulnerability to inflammation,

oxidative stress and various injuries (mechanical injury, chemical

injury, hyperoxic injury, etc.), resulting in an increased

likelihood of cell death. Conversely, type II epithelial cells

exhibit greater resilience, possessing the ability to proliferate

and convert into type I epithelial cells, thus serving a role in

the repair and preservation of alveolar epithelial barrier

integrity (73). Furthermore, AECs

regulate ion transport through the

Na+/K+-ATPase on the cell surface,

establishing an osmotic gradient between the intracellular and

extracellular environments. This regulates the alveolar fluid

clearance process, preventing the accumulation of alveolar edema

fluid (74).

The integrity of the AEC barrier is also supported

by the glycocalyx, a layer of glycosaminoglycans and proteoglycans

covering the alveolar surface and the basement membrane shared with

ECs (75). However, during sepsis,

the organism releases a large quantity of pro-inflammatory factors

and chemokines, leading to an exaggerated and dysregulated

inflammatory response. Mitochondria, essential organelles in AECs,

not only generate ATP but also function in intracellular and

extracellular signaling under stress (76). Evidence indicates that sustained

mitochondrial dysfunction serves an important role in the process

of necrotic apoptosis within AECs (77,78).

Inflammatory stimuli activate the mitochondria-associated apoptotic

pathway, which further releases apoptotic factors and upregulates

pro-inflammatory factor levels. This excessive cytokine production

can directly or indirectly induce epithelial cell apoptosis by

recruiting leukocytes to migrate to the lungs and disrupting TJ

proteins (such as connexin, sealin and E-calmodulin) between AECs.

Consequently, this results in damage to epithelial structures,

detachment of the glycocalyx, impairment of the alveolar epithelial

barrier integrity, increased permeability, decreased production of

surface-active substances and reduced ion and fluid transport

capacity from the alveolar lumen. These changes lead to dysfunction

in gas exchange, ultimately causing alveolar edema, alveolar

collapse and refractory hypoxemia. Lei et al (79) demonstrated that the treatment of

SALI mice with 3-methyladenine (3-MA), a drug that regulates

apoptosis, significantly enhanced the integrity of the alveolar

epithelial barrier. This study found that it effectively inhibited

lung inflammation and epithelial cell apoptosis in mice, improved

pulmonary pathological changes and alleviated lung injury.

Conversely, activated epithelial cells contribute to increased

secretion of chemokines and adhesion molecules, leading to cell

death and inflammatory responses, therefore resulting in a vicious

cycle.

Therefore, the repair of the alveolar epithelial

barrier is a critical indicator for the prognosis of lung injury. A

previous clinical study has shown that therapeutic strategies

targeting epithelial repair, such as mesenchymal stem cell

(MSC)-secreted keratinocyte growth factor, can improve the

oxygenation index in patients with ARDS (80).

Abnormal synthesis and secretion of

alveolar surface-active substances

Alveolar type II epithelial cells are capable of

secreting the alveolar surface-active substance pulmonary

surfactant (PS). The functions of PS include reducing alveolar

surface tension, maintaining the relative stability of the alveolar

structure, facilitating the absorption of alveolar fluid,

maintaining fluid balance in the lungs, preventing pulmonary edema

and atelectasis and enhancing the lung's defense function (81,82).

PS is a complex formulation that consists primarily of 90%

phospholipids and 10% proteins (83). It contains four surfactant proteins

(SPs) that are linked to surface-active agents, namely SP-A, SP-B,

SP-C and SP-D. Among these, SP-A and SP-D are hydrophilic proteins

that are part of the collectin family and are key in innate immune

defense. Conversely, SP-B and SP-C are highly hydrophobic

apolipoproteins that are key in the biophysical functionalities of

surfactants (84). A previous

study found that SP-A knockout mice exhibited a higher severity of

lung injury and mortality in a severe acute respiratory syndrome

coronavirus (COVID) 2-induced mouse ALI model, indicating that SP-A

serves a key role in pathogen defense (85).

Under physiological conditions, 80–90% of PS is

distributed in large aggregates (LAs) with high surface activity.

However, during infection, the upregulation of inflammatory

mediators and activation of apoptosis-inducing signals leads to the

disruption or inhibition of PS. The content of PS in LAs is

markedly reduced, shifting to small aggregates with markedly low

surface activity, which are mainly products of PS degradation.

Furthermore, activated immune cells generate ROS, which may disrupt

surfactant functionality by diminishing the synthesis of SP and

phospholipids (86). Additionally,

high levels of NO free radicals and TNF-α produced during

inflammation can directly impede the production of SP-A, SP-B and

SP-C (87). As a result, the

synthesis and activity of alveolar surface-active substances are

reduced, leading to an increase in alveolar surface tension. On the

other hand, the increased alveolar surface tension fails to

maintain the normal alveolar structure, leading to alveolar

collapse. During mechanical ventilation, atelectatic alveoli may be

damaged by the force generated by the cyclic opening and closing of

the ventilator, ultimately exacerbating respiratory failure.

Dargaville et al (88),

through a 2-year follow-up study of preterm infants with ARDS

treated with minimally invasive surfactant application, found that

infants treated with surfactant had a lower incidence of adverse

respiratory outcomes within a period of 2 years. This finding, to

some extent, suggests that alveolar surfactant can improve lung

injury and maintain normal alveolar function.

Pulmonary vascular EC damage and

vascular dysfunction

Vascular endothelial barrier disruption and

increased permeability

The endothelium acts as a physical barrier that

separates blood, gases and stromal tissues, serving a vital role in

preventing inflammation and coagulation, aiding in gas exchange,

controlling vascular tone and engaging in endocrine signaling

(89). In particular, the

pulmonary endothelium functions as a semi-permeable barrier key for

gas exchange at the alveolar-capillary interface and in managing

the flow of fluids and solutes between the blood and the

interstitial compartments of the lungs. The connections among lung

ECs include adherens junctions (AJs), TJs and gap junctions. Among

these, AJs are mainly composed of VE-cadherin, which bind to

intracellular connexins (such as p120-connexin), waveform proteins

and other proteins in the actin cytoskeleton to maintain the

integrity of the pulmonary endothelial barrier. During an

inflammatory response, various factors such as the activation of

pro-inflammatory factors (including TNF-α and IL-1β) and increased

ROS production can lead to the phosphorylation of VE-cadherin and

its associated proteins. This results in the detachment of

VE-cadherin from the actin cytoskeleton and the breakdown of AJ

proteins. At the same time, the contraction of actin stress fibers

creates a pulling force on VE-cadherin, compelling it to dissociate

from the proteins it is bound to. This results in impaired

inter-endothelial connections, increased permeability and damage to

the endothelial barrier. Therefore, VE-cadherin has become an

important biomarker for endothelial barrier disruption and is key

for maintaining the integrity of the endothelial barrier. Previous

research has suggested that the concentration of serum VE-cadherin

in patients with ARDS is notably elevated compared with healthy

controls. With this, its levels are negatively associated with the

pulmonary vascular permeability and oxygenation indexes (90).

In addition, TJ proteins (such as claudin and

occludin) interact with zonula occludens (ZO-1) in the cytoplasm.

ZO-1 binds to α-catenin and the actin cytoskeleton to stabilize

endothelial barrier function (91). When inflammatory mediators such as

histamine are present, TJ proteins experience phosphorylation

dependent on Src and undergo depletion, resulting in a compromised

endothelial barrier function and increased endothelial permeability

(92). Previous research indicates

that the expression levels of TJ proteins are markedly reduced in

the lung endothelium of patients with ARDS (93). Meanwhile, damaged or dead ECs

further release toxic cellular components, allowing more leukocytes

to migrate from the circulation to the site of inflammation, thus

exacerbating the inflammatory response. Additionally, inflammatory

mediators may further activate the apoptotic pathway, leading to EC

damage and death.

Vasodilatory dysfunction and

microthrombosis

A healthy pulmonary endothelium largely suppresses

inflammation, maintains blood flow and prevents thrombosis. Some

studies have shown that various stimuli, including hypoxia,

cytokines, chemokines, thrombin, LPS, DAMPs and apoptosis, can lead

to the activation and damage of ECs (94,95).

On the one hand, ECs produce endothelium-derived diastolic factors

(EDRFs) such as NO and prostacyclin as well as endothelium-derived

contractile factors such as endothelin, epoxyeicosatrienoic acid

and thromboxane A2 to regulate vascular tone (96). Activated ECs exhibit impaired

synthesis or release of EDRFs, resulting in sustained

vasoconstriction, reduced vessel diameter, slowed blood flow and

impaired pulmonary microcirculation. On the other hand, activated

ECs recruit activated neutrophils and form neutrophil extracellular

traps with activated platelets, shifting to a pro-coagulant

phenotype. Anticoagulant molecules such as thrombomodulin (TM) are

other important markers of endothelial injury. Under normal

conditions, TM is expressed on the surface of ECs, where it exerts

anticoagulant effects by activating the protein C system through

binding to thrombin (97). During

endothelial injury, TM is shed from the cell surface into

circulation, forming soluble TM (sTM), exposing collagen fibers and

other subendothelial matrix proteins. The expression of platelet

adhesion molecules is upregulated and platelets are activated and

rapidly adhere to form a microthrombus, initiating the hemostatic

process. Previous research has shown that patients with ARDS who

exhibit high levels of sTM have a 3.5-fold increased risk of 60-day

mortality, which can serve as a biomarker for early prognostic

assessment, and perhaps provide a reference for clinical risk

stratification and treatment decision-making (98).

Coagulation factors interact with tissue factor

(TF), which is present on AECs and macrophages, initiating an

exogenous coagulation cascade. Within the intact vessel wall, TF

remains hidden. Following damage to the vascular endothelium, TF

becomes accessible to blood and can bind directly to coagulation

factor VII to create the TF-VIIa complex, which is capable of

activating clotting factors IX and X in the bloodstream, resulting

in the formation of active enzymes (coagulation factors IXa and Xa)

that subsequently convert plasminogen to thrombin. Thrombin then

cleaves fibrinogen into fibrin, which polymerizes to create a

fibrin network that forms a thrombus, incorporating aggregated

platelets (99). Naderpour et

al (100) studied patients

with COVID-19 during the pandemic and found that the combined use

of tissue plasminogen activator and heparin in patients with severe

respiratory failure improved oxygenation and reduced overall

mortality. Thus, impaired pulmonary microcirculation further

exacerbates tissue ischemia and hypoxia, promoting EC injury,

pro-inflammatory factor release and activation of apoptotic

pathways, thereby exacerbating lung tissue injury.

Advances in therapeutic strategies targeting

the synergistic effects of inflammation and apoptosis

Drug intervention targets and

strategies

Inhibitors of inflammatory and apoptotic

signaling pathways

The activation of essential signaling pathways, such

as NF-κB and MAPK, is closely linked to ALI associated with sepsis,

which subsequently triggers the apoptotic pathway and exacerbates

lung damage. NF-κB, a major regulator of inflammation, serves a

pivotal role in the onset and progression of numerous inflammatory

diseases. Inhibitors of NF-κB reduce the production of inflammatory

factors while also suppressing the expression of apoptosis-related

genes, thus presenting a potential therapeutic avenue for lung

injury driven by synergistic inflammation and apoptosis (Table II). For example, non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory medications (such as aspirin) specifically

prevent the phosphorylation and breakdown of IκBα, which in turn

reduces the activity of NF-κB. In the lung tissue of mice treated

with aspirin, NF-κB activation was notably inhibited, leading to

improved pulmonary edema (101).

Glucocorticoid receptor agonists, such as dexamethasone, can

inhibit NF-κB through direct interaction with its RELA

enhancer-binding protein like arrestin subunit, effectively

blocking its functional activity. Furthermore, fibroblast growth

factor (FGF) 18, which belongs to the FGF family, has demonstrated

the ability to reduce cellular inflammation (102). Previous research has shown that

FGF18 suppresses the phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 and reduces its

translocation to the nucleus in both in vivo and in

vitro settings. This activity consequently inhibits the

activation of the NF-κB pathway, reduces lung injury and supports

lung repair (103). In TCM, it is

considered that numerous herbs are related to this mechanism, among

which quercetin is a well-researched example (104).

| Table II.Inhibitors of inflammatory and

apoptotic signaling pathways. |

Table II.

Inhibitors of inflammatory and

apoptotic signaling pathways.

| Drug class | Representative

drugs | Mechanism of

action | Effect | (Refs.) |

|---|

| NF-κB

inhibitor | Aspirin | Blocks IκBα

phosphorylation and degradation, inhibits NF-κB activation | Reduces pulmonary

edema, inhibits inflammatory factor release | (101) |

|

| FGF18 | Inhibits NF-κB p65

phosphorylation and nuclear translocation | Reduces

inflammatory response, promotes lung repair | (103) |

| MAPK inhibitor | SB203580 (p38

inhibitor) | Inhibits p38 MAPK

phosphorylation | Reduces TNF-α,

IL-1β level, inhibits caspase-3 activation | (105) |

|

| SP600125 (JNK

inhibitor) | Blocks JNK

signaling | Inhibits Bax/Bak

activation, reduces mitochondrial apoptosis | (106) |

| Apoptosis pathway

inhibitor | Soluble Fas | Fas/FasL

inhibitor | Blocks exogenous

apoptotic pathway, attenuates alveolar epithelial cell injury | (107) |

|

| Z-VAD-FMK | Broad-spectrum

caspase inhibitor | Blocks apoptosis

execution stage, attenuates lung tissue damage | (108) |

| Herbal active

ingredient | Quercetin

pathway | Inhibits

NF-κB-related | Attenuates

SALI | (104) |

The MAPK pathway (including p38, JNK and ERK) also

serves a key role in inflammatory responses and apoptosis. Previous

research indicates that p38 inhibitors such as SB203580 can

mitigate LPS-induced lung injury through various mechanisms,

including inhibition of TNF-α and IL-1β release and reduction of

caspase-3 activity (105).

SP600125 is an orally active, reversible ATP-competitive JNK

inhibitor that can influence the expression of key proteins in the

mitochondrial apoptotic pathway, upregulate the expression of the

anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 and downregulate expression of the

pro-apoptotic protein Bax, thereby reducing apoptosis (106).

In addition, specific inhibitors of apoptotic

pathways may also become therapeutic targets for SALI. Fas

receptor/Fas ligand inhibitors (such as soluble Fas), as inhibitors

of the death receptor pathway, can block the extrinsic apoptotic

pathway and reduce alveolar epithelial cell damage (107). As a factor in apoptosis, the

broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor Z-Val-Ala-Asp-fluoromethylketone

can block the execution phase of apoptosis and alleviate lung

tissue damage (108).

Antioxidants and free radical

scavengers

Free radicals serve a key role in intracellular

signal transduction and various physiological processes at optimal

concentrations. However, excess of these free radicals can lead to

oxidative damage to proteins. The body's antioxidant defense system

comprises both endogenous antioxidants and exogenous free radical

scavenging mechanisms. Endogenous antioxidants primarily eliminate

excess free radicals and are categorized into enzymatic and

non-enzymatic ROS scavengers. Enzymatic antioxidants, including

superoxide dismutase (SOD) (109), catalase (CAT) (110) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX)

(111), facilitate the conversion

of O2 radicals into H2O2 and

O2, which are further catalyzed into H2O and

O2. Non-enzymatic ROS scavengers include coenzyme Q10

(also known as ubiquinone) (112,113) and acetylated phospholipids

(plasmalogens) (114), among

others. Coenzyme Q10 is integral to the mitochondrial electron

transport chain, functioning as a component of the mitochondrial

respiratory chain while scavenging lipid peroxidation free radicals

(113,115). Exogenous free radical scavengers,

primarily sourced from dietary intake, encompass hydrophilic

agents, such as vitamin C (116)

and glutathione, as well as lipophilic agents, including vitamin E

(117), flavonoids (118,119) and carotenoids (120), which effectively scavenge

O2− and HO−.

Mitochondria, as the primary site of ROS production,

are often subjected to high levels of ROS, leading to oxidative

damage of mitochondrial DNA. This damage subsequently activates the

mitochondrial-associated apoptotic pathway, thus exacerbating lung

injury. Antioxidants serve a key role in mitigating

inflammation-induced oxidative stress by scavenging free radicals

and maintaining the body's redox balance. This action effectively

inhibits the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway, thereby protecting

lung tissue from the combined detrimental effects of inflammation

and apoptosis. Numerous antioxidant drugs have been employed in

clinical treatments, including recombinant SOD, vitamin C, vitamin

E, α-lipoic acid (121),

bioflavonoids, selenium (122),

glutathione, coenzyme Q10 (123)

and various TCM herbal medicines such as Curcuma longa

(124), Astragalus

(125) and Rhodiola rosea

(126). Curcumin (124), through its β-diketone group and

Astragalus (125), through

active components such as polysaccharides, saponins and flavonoids,

directly scavenge ROS while simultaneously activating the

endogenous antioxidant enzyme system, which includes SOD, CAT and

GPX. This dual action results in a multi-level, multi-target

antioxidant protective effect. Similarly, study has demonstrated

that Rhodiola injection not only exhibits direct ROS

scavenging capabilities, but also protects mitochondrial function,

regulates the AMP-activated protein kinase/mTOR autophagy signaling

pathway and maintains the balance between cell apoptosis and

survival (126). This creates a

comprehensive protective network ranging from oxidative stress

prevention to cellular damage repair.

However, there is currently very few related

clinical trial available (127).

These therapeutic agents face important challenges in clinical

application. Previous research has indicated that vitamin E

supplementation does not reduce all-cause mortality in patients and

high doses of vitamin E may even increase overall mortality

(128). A similar issue is

observed with vitamin C, whereby excessively high levels in the

body can induce oxidative stress-related DNA damage, similar to the

effects of lower levels. Potential limitations of antioxidant

therapy may arise from the need to preserve an equilibrium between

oxidation and reduction. Elevated levels of ROS can activate

endogenous antioxidant defenses to protect damaged tissues.

Notably, scavenging ROS may increase the risk of infection and

disrupt ROS-dependent signaling pathways. Consequently, the timing,

concentration and dosage of antioxidants, along with their

bioavailability and effective targeted delivery to specific organs,

are important factors that are often challenging to regulate in

clinical practice.

Cell therapy and biological

agents

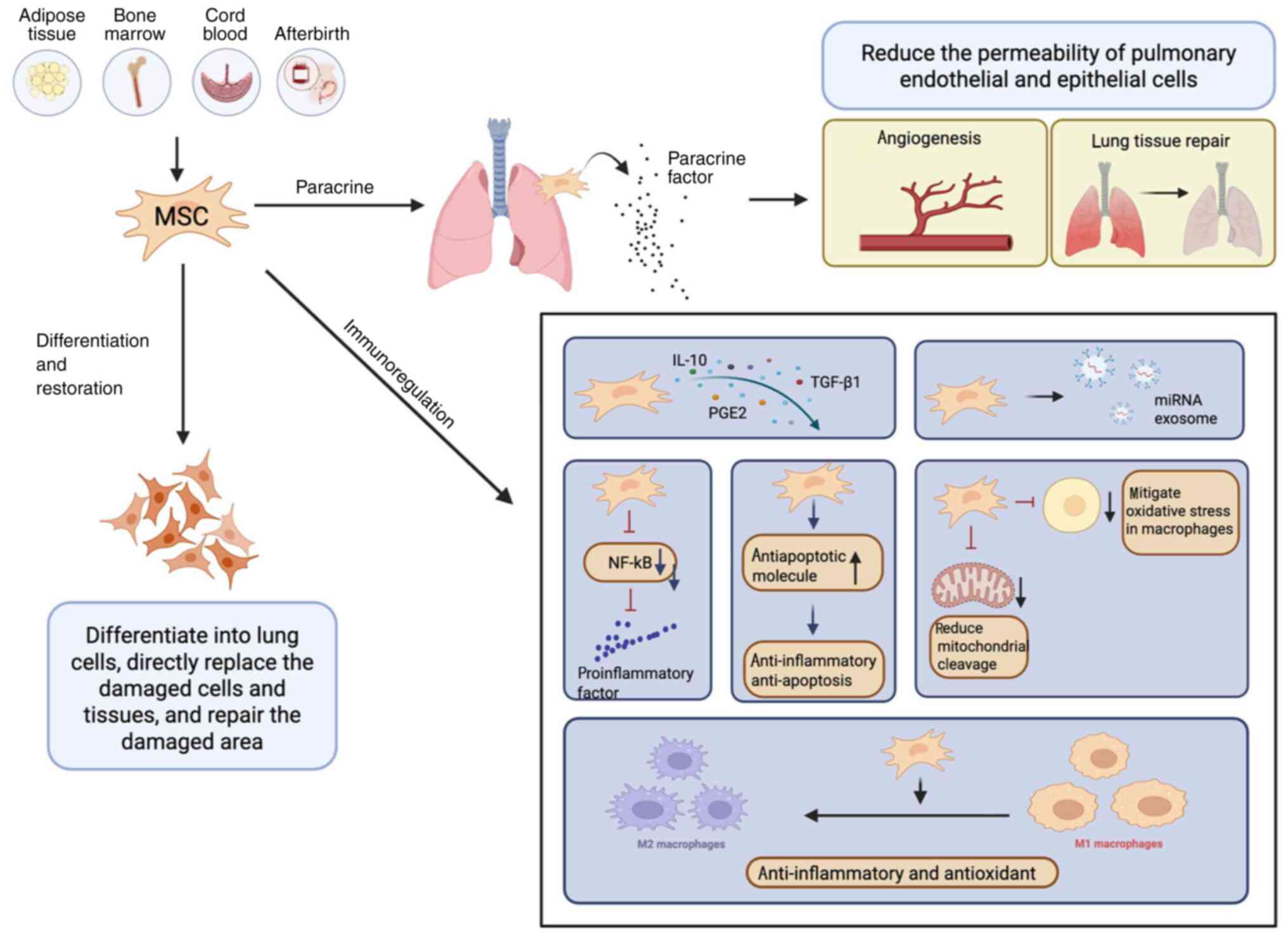

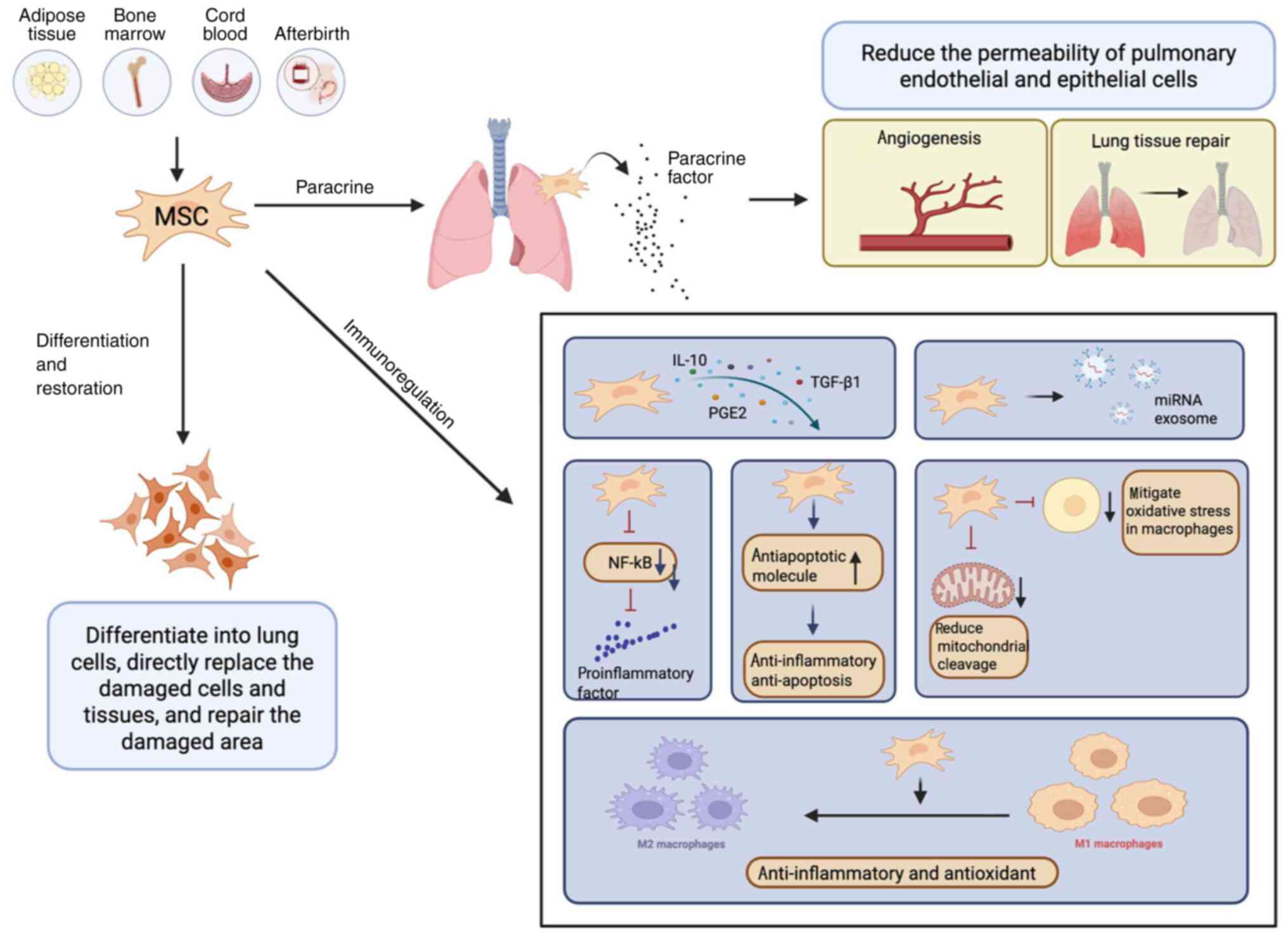

MSC therapy

There is increasing evidence to suggest that therapy

involving MSCs shows considerable potential for treating SALI and

ARDS and it is currently being evaluated in clinical trials

(129,130). MSCs have multiple functions and

originate from various sources including adipose tissue, bone

marrow, umbilical cord blood and placental tissue. These cells are

able to differentiate into a wide variety of cell types belonging

to the mesenchymal lineage (131,132). As a novel therapeutic agent for

ALI, MSCs may exhibit immunomodulatory, angiogenic and regenerative

effects (133–135). Mechanistically, MSCs can

differentiate into lung cells, directly replacing damaged cells and

tissues, thereby facilitating repair at the injury site.

Additionally, MSCs can migrate to damaged lung areas and reduce the

permeability of lung ECs and epithelial cells by secreting various

paracrine factors that promote neoangiogenesis and tissue repair, a

phenomenon validated in multiple preclinical ALI models (136–138).

Furthermore, MSCs possess complex immunomodulatory

functions. In a pro-inflammatory setting, MSCs have the ability to

release anti-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-10, TGF-β1 and

PGE2 (118), release exosomes

with microRNAs with anti-inflammatory effects (136), inhibit the activation of NF-κB,

reduce the release of pro-inflammatory factors (139) and upregulate the expression of

anti-apoptotic molecules, thereby exerting direct anti-inflammatory

and anti-apoptotic effects. Concurrently, MSCs also reduce

mitochondrial division, mitigate oxidative stress damage in

macrophages and induce macrophage polarization towards

anti-inflammatory phenotypes, indirectly contributing to

anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects (140,141) (Fig.

4).

| Figure 4.MSC therapy. MSCs are derived from

various sources, including adipose tissue, bone marrow, umbilical

cord blood and placental tissue. On the one hand, MSCs can

differentiate into lung cells, directly replacing damaged cells and

tissues, thereby promoting the repair of injured sites.

Additionally, MSCs can migrate to the damaged lung area, where they

reduce the permeability of pulmonary endothelial and epithelial

cells by secreting various paracrine factors that promote

angiogenesis and tissue repair. On the other hand, MSCs release

anti-inflammatory cytokines and miRNA exosomes, which inhibit NF-κB

activation, decrease the release of pro-inflammatory factors and

upregulate the expression of anti-apoptotic molecules.

Simultaneously, MSCs also reduce mitochondrial fission, alleviate

oxidative stress damage in macrophages and induce the polarization

of macrophages toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype. MSCs,

mesenchymal stem cells; miRNA, micro-RNA; PGE2, prostaglandin

E2. |

The effects of MSCs on reducing inflammation,

modulating the immune response and promoting tissue repair have

been validated, showing considerable effectiveness in preclinical

studies involving animals. However, the marked individual

variability and prevalence of non-responsive patients observed in

clinical trials pose substantial challenges for the broader

application of MSC therapy in clinical practice (142). An initial clinical study suggests

that MSC therapy is generally safe and does not remain in the body

for a prolonged period of time (143). However, a certain experimental

study has reported the detection of MSCs ≤120 days

post-administration (144). This

persistence raises concerns regarding potential tumorigenesis, an

area where conclusive findings and solutions remain elusive.

Consequently, further accumulation of safety data regarding

long-term treatment and the large-scale application of MSC therapy

is important. Additionally, the optimal therapeutic regimen for

MSCs in treating SALI, including therapeutic dosage, timing of

treatment and route of administration, remains to be established.

Despite the encouraging effectiveness shown by MSCs in preliminary

animal research, it is important to recognize that mouse models

frequently do not accurately mimic human diseases. The quantity of

MSCs utilized in these mouse experiments vary greatly from those

administered to clinical patients, along with there being

considerable individual differences among humans, which could

additionally affect treatment results (144). Therefore, the clinical

therapeutic effects of MSCs are yet to be fully elucidated,

necessitating additional follow-up data to accurately assess their

efficacy.

Anti-apoptotic gene therapy and

biologics

Oxidative stress is a key mechanism in SALI.

Traditional antioxidants, such as vitamin C or vitamin E, have

limited clinical efficacy due to their lack of targeting

specificity and dose-dependent effects. To overcome this

bottleneck, progress has been made in recent years with novel

targeted antioxidants and biologics. For instance, developments

have been made in mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants such as

MitoQ, which has been shown to protect cells from apoptosis and

inhibit H2O2-induced growth factor receptor

signaling. This is primarily achieved through its unique

triphenylphosphonium carrier system, which precisely delivers the

compound to the interior of mitochondria, directly scavenging mtROS

and effectively blocking the

mtROS-Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II-mediated

apoptotic signaling pathway. In an investigation using MitoQ to

intervene in LPS-induced ALI in mice, it was found that, compared

with the model group, MitoQ treatment significantly reduced the

levels of oxidative markers in mouse serum (a 50% decrease in MDA

content; P<0.05), while also improving lung injury in mice

(145).

Edaravone, approved in Japan as a free radical

scavenger for ischemia-reperfusion injury, primarily works by

inhibiting lipid peroxidation and preventing the abnormal opening

of the mitochondrial MPTP, thereby reducing apoptosis in alveolar

epithelial cells. In a randomized clinical trial, edaravone was

used to treat critically ill patients with COVID-19 admitted to the

ICU. Results showed that the edaravone treatment group experienced

a reduction in mechanical ventilation dependency and a shortened

ICU treatment duration (146).

Numerous studies have shown that specific

biological substances can alleviate pulmonary injury by mitigating

inflammatory oxidative stress, offering new avenues for the

clinical management of SALI. For example, the nebulized formulation

of recombinant human SOD can specifically neutralize

O2− within lung tissue, directly targeting

the sites of inflammation. Furthermore, FGF21, which was initially

identified and cloned in 2000, performs various biological roles,

including promoting tissue repair and regulating metabolism

(147). Research conducted by Gao

et al (148) suggested

that the administration of exogenous FGF21 leads to a reduction in

lung inflammation and apoptosis by influencing the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB

signaling pathway, thereby mitigating SALI. As a result, the

relevance of FGF21 in severe conditions such as ALI and ARDS has

gained interest (149).

Conclusion

The present study systematically summarized the

synergistic mechanisms of inflammation and apoptosis in SALI,

emphasizing the pivotal role of signaling pathways such as

NF-κB/MAPK and the cascade of inflammatory factors (TNF-α, IL-1β

and MCP-1) they mediate, which drive oxidative stress and apoptosis

activation, ultimately leading to the disruption of alveolar

epithelial and pulmonary vascular endothelial barriers. Despite

progress in therapeutic strategies targeting synergistic effects

(such as MSC therapy and targeted antioxidants), key research gaps

and translational challenges remain. For example, the detailed

molecular regulatory networks between inflammation and apoptosis,

as well as the impact of individual differences on their

synergistic effects, have not yet been fully elucidated.

Furthermore, there is a lack of targeted specificity regulation

tools, such as precise identification of biomarkers for different

pathological stages of SALI and insufficient targeting of

lung-specific drug delivery systems to acute inflammatory lesion

areas.

Future research should focus on elucidating the

molecular complexity of the synergistic effects between

inflammation and apoptosis to develop more targeted and effective

therapeutic strategies. Additionally, multicenter, large-sample

clinical studies should be conducted to explore the clinical

translation potential of apoptosis/inflammation pathway inhibitors.

Integrating multidisciplinary resources from immunology,

bioengineering, data science and other fields will advance the

synergistic development of regulatory science and technological

innovation. There is an expectation that such initiatives will

generate innovative concepts and approaches to enhance the

prognosis of patients with SALI.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present review was supported by the National Key Research

and Development Program of China (grant no. 2021YFC2501800) and the

6th Shanghai Three-Year Action Plan to Strengthen the Construction

of Public Health System (grant no. GWVI-2.1–3).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

LZ contributed to conceptualization, visualization,

writing the original draft, reviewing and editing. HL contributed

to investigation, writing, reviewing and editing the manuscript. DL

contributed to formal analysis, the software used, writing,

reviewing and editing the manuscript. QD contributed to funding

acquisition, project administration, resources, supervision,

writing, reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors have

read and approved the final manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Gao X, Cai S, Li X and Wu G:

Sepsis-induced immunosuppression: Mechanisms, biomarkers and

immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 16:15771052025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, Antonelli

M, Coopersmith CM, French C, Machado FR, Mcintyre L, Ostermann M,

Prescott HC, et al: Surviving sepsis campaign: International

guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021.

Intensive Care Med. 47:1181–1247. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Xie J, Wang H, Kang Y, Zhou L, Liu Z, Qin

B, Ma X, Cao X, Chen D, Lu W, et al: The epidemiology of sepsis in

Chinese ICUs: A National cross-sectional survey. Crit Care Med.

48:e209–e218. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Dulhunty JM, Brett SJ, De Waele JJ,

Rajbhandari D, Billot L, Cotta MO, Davis JS, Finfer S, Hammond NE,

Knowles S, et al: Continuous vs Intermittent β-lactam antibiotic

infusions in critically Ill patients with sepsis: The BLING III

Randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 332:629–637. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Li W, Li D, Chen Y, Abudou H, Wang H, Cai

J, Wang Y, Liu Z, Liu Y and Fan H: Classic signaling pathways in

alveolar injury and repair involved in sepsis-induced ALI/ARDS: New

research progress and prospect. Dis Markers.

2022:63623442022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Vincent JL, Opal SM, Marshall JC and

Tracey KJ: Sepsis definitions: Time for change. Lancet.

381:774–775. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Jiang J, Huang K, Xu S, Garcia JGN, Wang C

and Cai H: Targeting NOX4 alleviates sepsis-induced acute lung