Introduction

Lung cancer remains one of the leading causes of

tumor-related deaths worldwide, accounting for ~25% of global

cancer fatalities (1,2). It is primarily classified into two

histological types: Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-SCLC

(NSCLC) (3,4). NSCLC, which includes adenocarcinoma,

squamous cell carcinoma and large cell lung cancer, represents ~85%

of all lung cancer cases (5).

Currently, chemotherapy is the first-line treatment for SCLC and

stage IV NSCLC (6); however,

chemotherapy often involves administering the maximum tolerated

intravenous dose of the relevant drug, which can display result in

marked toxicity to healthy tissues. Furthermore, despite the

initial effectiveness of chemotherapy, drug resistance and toxicity

notably limit its long-term clinical success (7). Despite progress in early detection

and treatment strategies, the overall 5-year survival rate for lung

cancer remains at <20% (8).

Therefore, developing new therapeutic agents with improved efficacy

and safety profiles for lung cancer treatment is of substantial

importance.

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent form of regulated

cell death driven by the accumulation of lipid peroxidation

products and reactive oxygen species (ROS) (9). Unlike apoptosis, a process that is

characterized by notable morphological changes such as cell

membrane rupture and nuclear fragmentation (10), ferroptosis is marked by

iron-dependent lipid peroxidation that causes cellular damage and

death. This process involves excessive ROS accumulation and the

disruption of antioxidant defense systems, distinguishing it from

traditional apoptotic pathways. Notably, induction of ferroptosis

has emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy, particularly for

malignancies resistant to conventional treatments, positioning

ferroptosis as a novel approach to induce cancer cell death

(11–13).

System Xc−, composed of the subunits

solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11/xCT) and solute carrier

family 3 member 2, functions as a cystine/glutamate antiporter that

imports cystine into cells while exporting glutamate (14,15).

Inhibition of SLC7A11 by compounds such as erastin blocks cystine

uptake, leading to depletion of intracellular L-cysteine and

reduced synthesis of glutathione (GSH) (16). GSH is an important cofactor for GSH

peroxidase 4 (GPX4), which detoxifies lipid peroxides by converting

them into non-toxic lipid alcohols (17,18).

When L-cysteine is depleted, GPX4 activity is inhibited, resulting

in excessive lipid peroxide accumulation and triggering ferroptosis

(16). Studies have detected the

upregulation of xCT in patients with NSCLC, and targeting xCT has

been shown to suppress tumor growth both in vitro and in

vivo (19,20).

Panax notoginseng, a member of the Araliaceae

family, has been widely used as a traditional Chinese medicine for

thousands of years. Notoginsenoside R1 (NG-R1), one of the primary

bioactive compounds extracted from the root of Panax

notoginseng, exhibits diverse pharmacological activities,

including cardiovascular protection (21), neuroprotection (22) and anticancer effects (23). NG-R1 has been shown to reduce the

incidence of lung cancer in a urethane-induced mouse model by

improving lung barrier permeability and ameliorating

histopathological changes (24).

Additionally, the ethanol extract of Panax notoginseng

inhibits migration, invasion, adhesion and metastasis of colorectal

cancer cells by modulating the expression of key regulatory

molecules (25). Despite numerous

reports on the antitumor efficacy of NGs, to the best of our

knowledge, no studies have investigated NG-induced ferroptosis in

tumor cells. The present study aimed to explore the effects of

NG-R1 on NSCLC using the human NSCLC cell line A549.

Materials and methods

Cell line, reagents and

antibodies

Human NSCLC A549 cells were obtained from Shanghai

Fuheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (cat. no. FH0045). NG-R1 was

purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (cat. no.

N814983). The ROS detection kit (cat. no. S0033), YF 594 Click-iT

EdU Kit (cat. no. C0078S), BCA protein concentration assay kit

(cat. no. P0012S), 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA;

cat. no. S1105S), RIPA lysis buffer (cat. no. P0013B) and

protease-phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (cat. no. P1045) were all

sourced from Beyotime Biotechnology. Primary antibodies against

GPX4 (cat. no. ab125066), ferritin heavy chain 1 (FTH1) (cat. no.

ab183781), transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1) (cat. no. ab214039) and

SLC7A11 (cat. no. ab175186) were purchased from Abcam. GAPDH

monoclonal antibody (cat. no. AF7021), secondary antibody (goat

anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-conjugated; cat. no. S0001) and ECL

luminescent substrate (cat. no. K002) were obtained from Affinity

Biosciences. Cell culture plates including 96-well (cat. no. 3599),

24-well (cat. no. 3527) and 6-well (cat. no. 3516), as well as

Matrigel® and Transwell inserts (cat. no. 3422), were

purchased from Corning, Inc. Crystal Violet Staining Solution

(0.1%; cat. no. G1063) was supplied by Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd. Fetal bovine serum (FBS; cat. no.

A5256701) and Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; cat. no.

11965092) were purchased from Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.

Equipment used included a CO2 incubator (model XD-101;

SANYO), precision balance (model AUW-220D; Shimadzu Corporation),

refrigerated centrifuge (model MicroCL 21R; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), inverted biological light microscope (model

IX73; Olympus Corporation), microplate reader (model ×800; Tecan

Group, Ltd.), electrophoresis and protein transfer system (model

041BR121667; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.), gel imaging system (model

Tanon-4600, Tanon Science and Technology Co., Ltd.) and flow

cytometer (CytoFLEX V2-B2-R2; Beckman Coulter, Inc.).

Cell culture

Human NSCLC A549 cells were cultured in high-glucose

DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin

at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Cells were passaged at a 1:3 ratio every 3 days upon reaching ~90%

confluency. Regular mycoplasma contamination tests were performed

and yielded negative results.

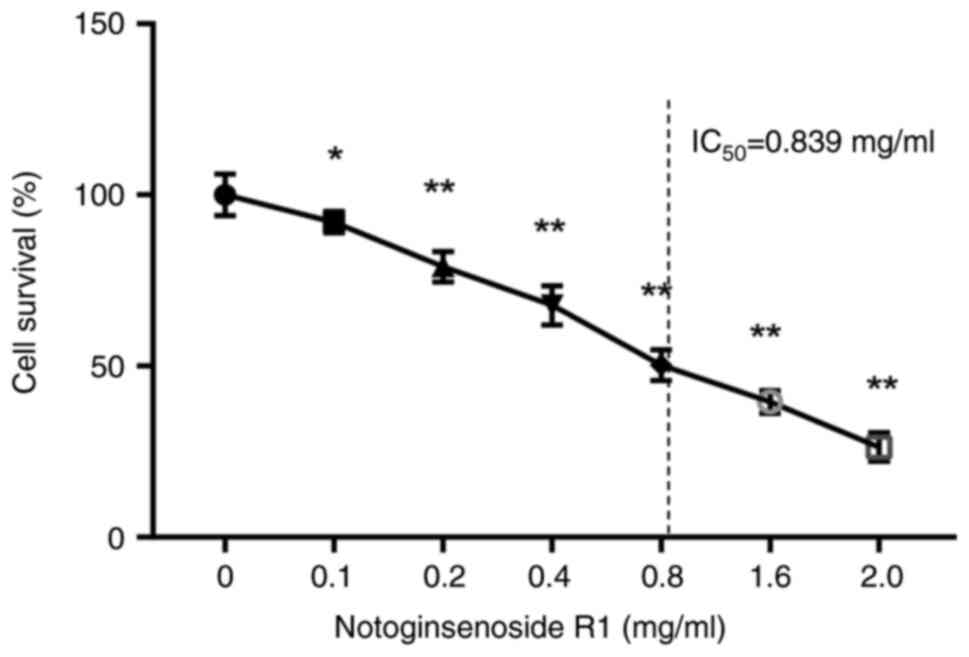

Cell viability test

A549 cells in the logarithmic growth phase were

seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 5×103

cells/well and allowed to adhere for 24 h at 37°C. Subsequently,

the cells were treated with various concentrations of NG-R1 (0,

0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 1.6 and 2.0 mg/ml) for 72 h at 37°C. Following

treatment, 20 µl MTT solution (0.5 mg/ml) was added to each well

and incubated for 4 h at 37°C. The supernatant was then carefully

removed, and 150 µl DMSO was added to each well to dissolve the

formazan crystals. Plates were gently shaken for 10 min at room

temperature, and absorbance (A) was measured at 570 nm using a

microplate reader; cell viability was calculated using the formula:

Cell viability (%)=(Adrug group/Ablank control

group) ×100. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration

(IC50) was determined using the IC50

calculator, an online tool provided by AAT Bioquest (https://www.aatbio.com/tools/ic50-calculator).

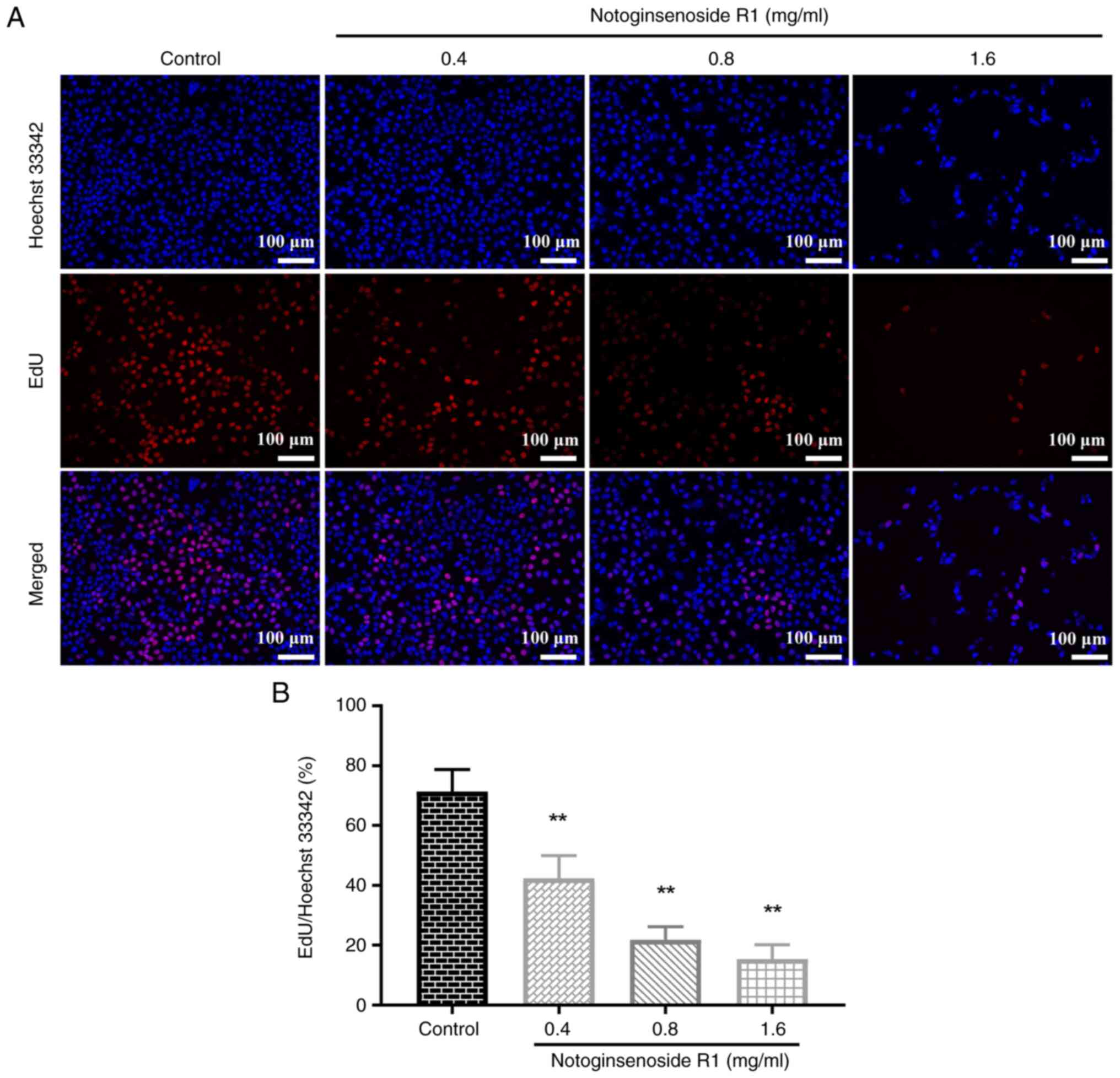

Cell proliferation detection

A549 cells in the logarithmic growth phase were

seeded into 24-well plates at a density of 2.5×104

cells/well and allowed to adhere for 24 h at 37°C. Subsequently,

the cells were treated with varying concentrations of NG-R1 (0,

0.4, 0.8 and 1.6 mg/ml) for 72 h at 37°C. Following treatment, the

supernatant was discarded and 10 µM EdU solution was added to each

well for a 2-h incubation at 37°C. EdU staining was performed using

the YF 594 Click-iT EdU Kit, followed by nuclear counterstaining

with Hoechst 33342, according to the manufacturer's protocol,

including three PBS washes before microscopic imaging. Images were

captured using an inverted fluorescence microscope and subsequently

analyzed with ImageJ software (version 1.53k; National Institutes

of Health).

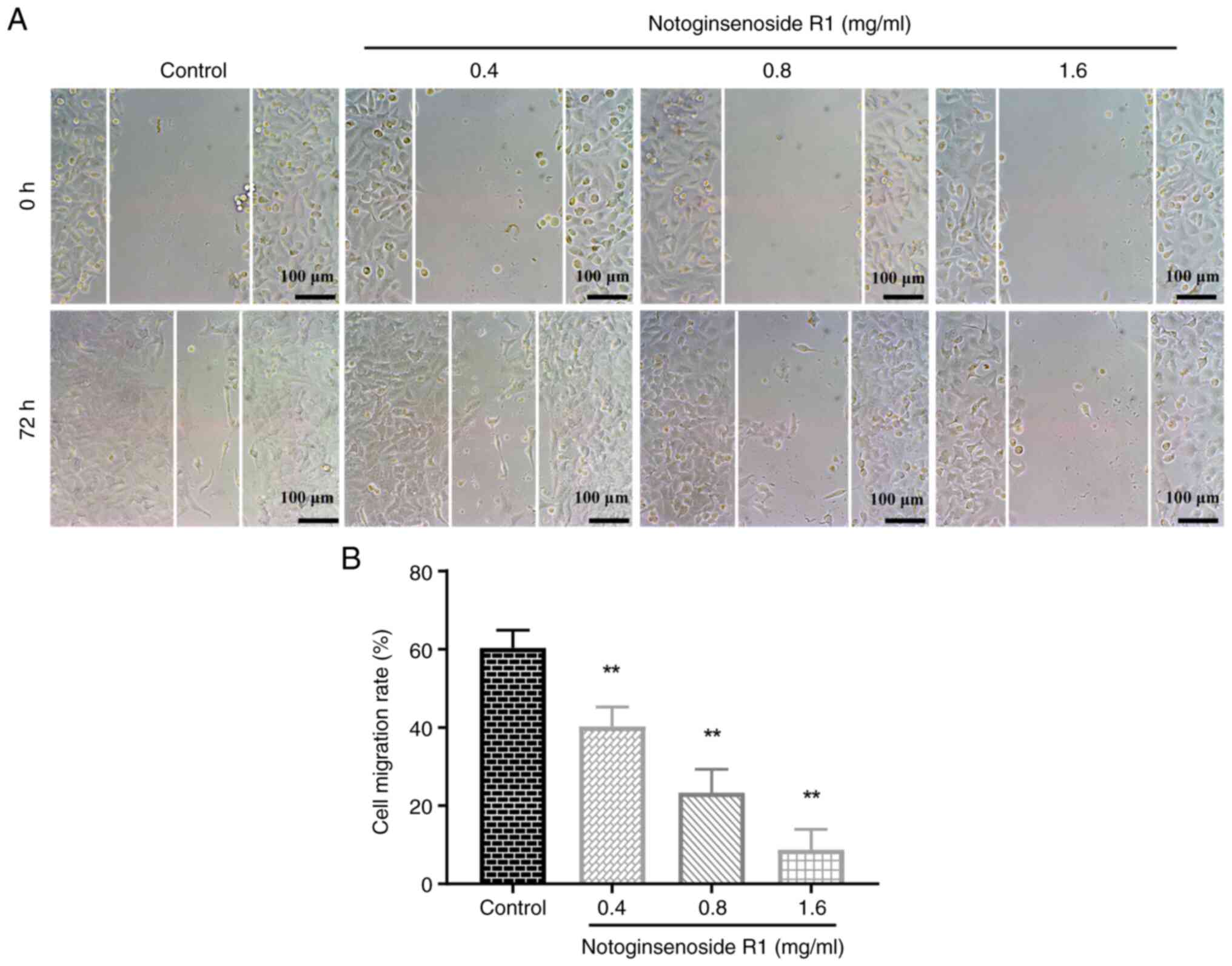

Wound healing assay

A549 cells in the logarithmic growth phase were

seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 1.0×106

cells/well and cultured in medium containing 10% FBS for 24 h at

37°C to allow adhesion. Subsequently, a 10-µl pipette tip was used

to create three straight scratches per well. Floating cells were

removed by washing with PBS and images of the scratch area at 0 h

(W0 h) were captured using an inverted biological light

microscope. Subsequently, cells were treated with different

concentrations of NG-R1 (0, 0.4, 0.8 and 1.6 mg/ml) in medium

containing 2% FBS and incubated for 72 h at 37°C before images were

captured again. Images were analyzed using ImageJ software and the

cell migration rate was calculated using the formula: Cell

migration rate (%)=[(W0 h-W72

h)/W0 h] ×100.

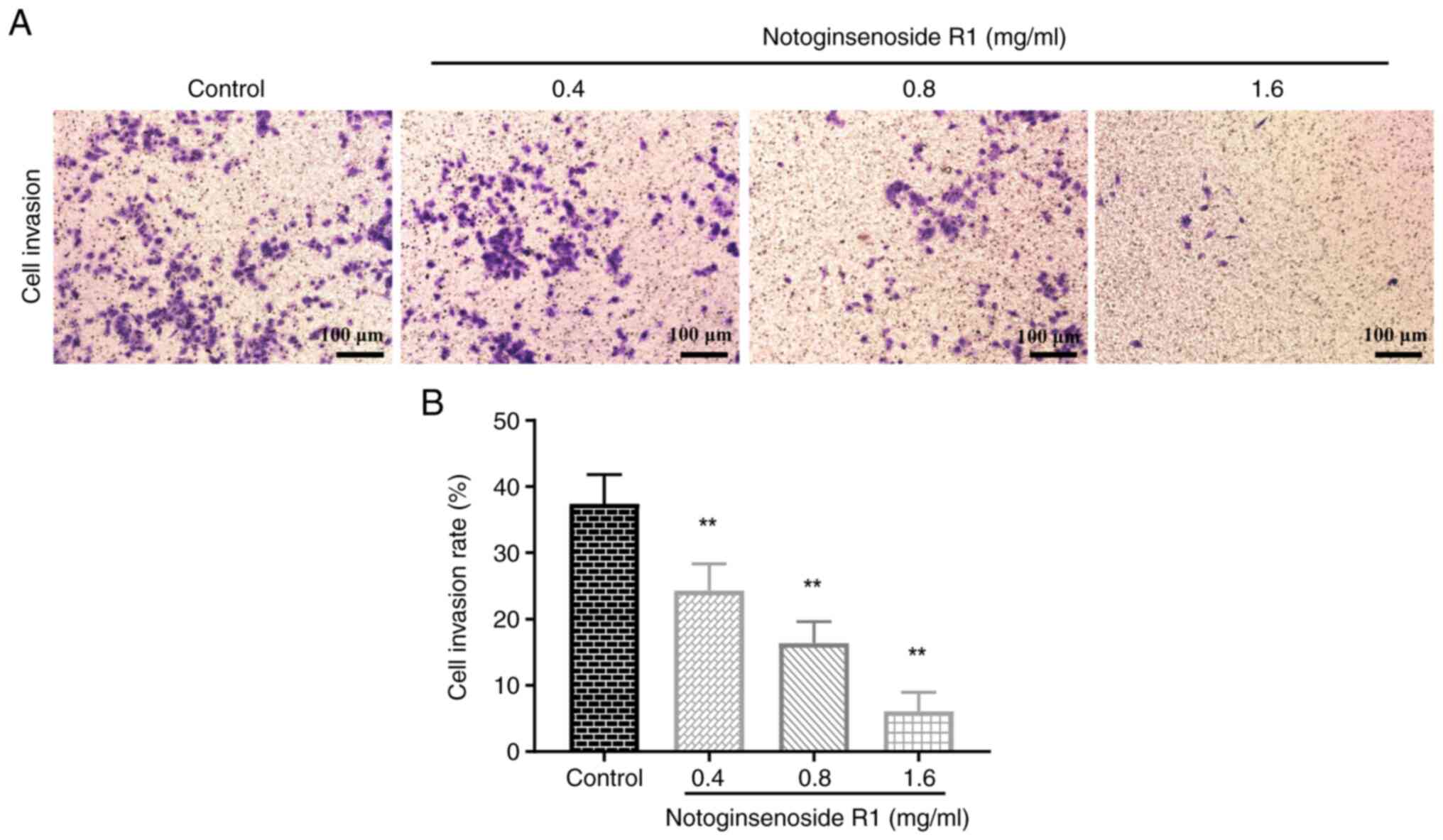

Cell invasion detection

Serum-free high-glucose DMEM was used to dilute

Matrigel basement membrane matrix at a ratio of 1:8. Then, 50 µl

diluted Matrigel was added to the upper chamber of each Transwell

insert and incubated at 37°C for 1 h to allow gelation, after which

any residual liquid was carefully aspirated. A549 cells were

suspended in serum-free high-glucose DMEM at a density of

1×105 cells/ml. A volume of 200 µl of this cell

suspension was added per well to the upper chamber coated with

Matrigel. The lower chamber was filled with 600 µl high-glucose

DMEM containing 10% FBS and different concentrations of NG-R1 (0,

0.4, 0.8 and 1.6 mg/ml) and the setup was incubated for 72 h at

37°C. After incubation, non-invasive cells on the upper surface of

the membrane were gently removed with a cotton swab. The invasive

cells on the lower membrane surface were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature, washed twice with

PBS, stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 10 min at room

temperature and washed twice with PBS. Once dried, images of the

invaded cells were captured using an inverted biological light

microscope and analyzed using ImageJ software.

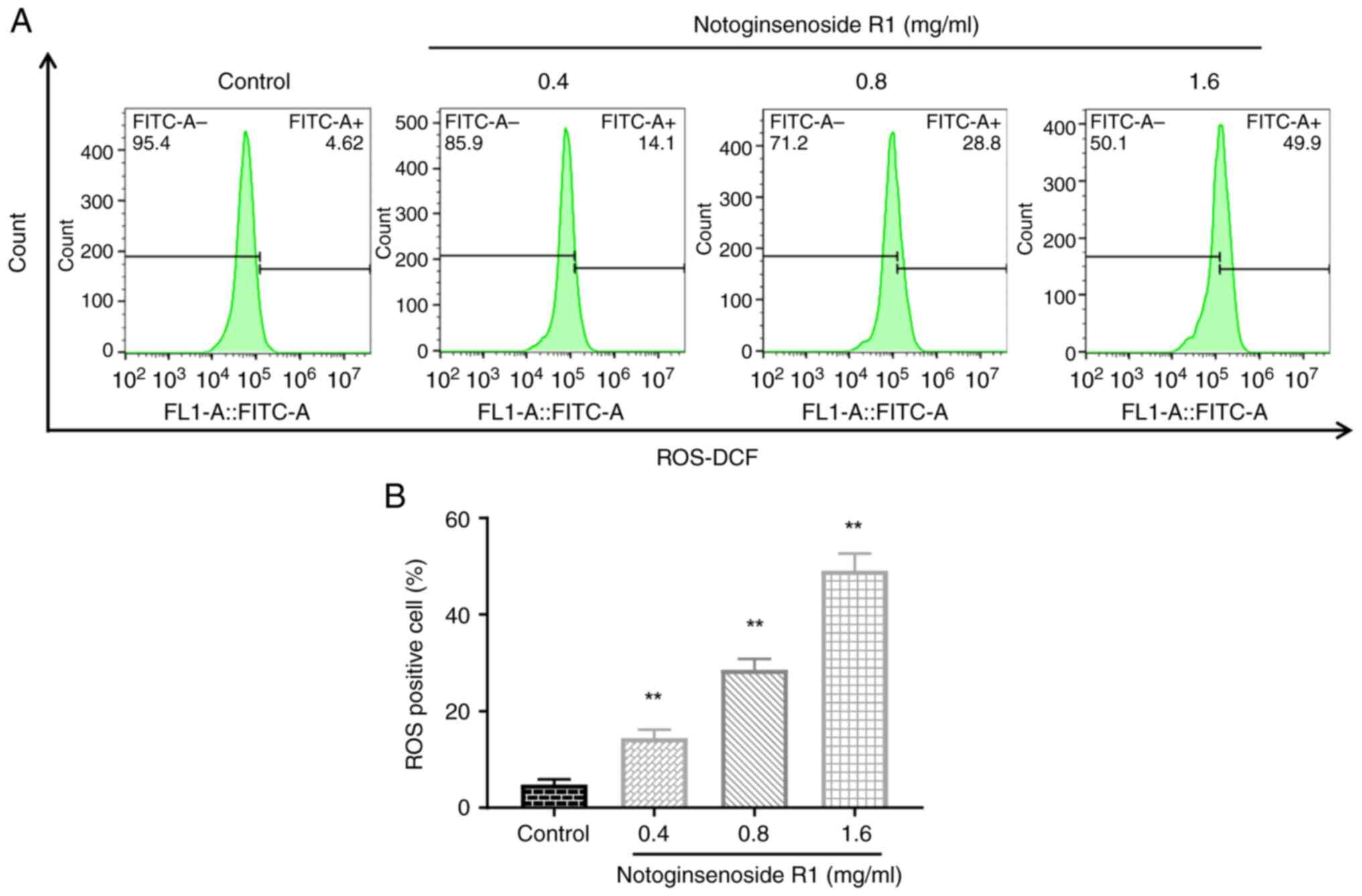

Detection of intracellular ROS

A549 cells in the logarithmic growth phase were

seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 5.0×105

cells/well and allowed to adhere for 24 h at 37°C. Subsequently,

the cells were treated with varying concentrations of NG-R1 (0,

0.4, 0.8 and 1.6 mg/ml) for 72 h at 37°C. The supernatant was then

discarded, and 1 ml DCFH-DA probe (diluted 1:1,000 in serum-free

medium) was added to each well. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 20

min, washed twice with PBS and subsequently digested with 0.05%

trypsin. The cells were collected, resuspended in PBS and analyzed

by flow cytometry recording 10,000 events per sample. Subsequent

data analysis was performed using FlowJo software (version 10.0; BD

Biosciences) to measure DCFH-DA fluorescence intensity, which

reflects intracellular ROS levels.

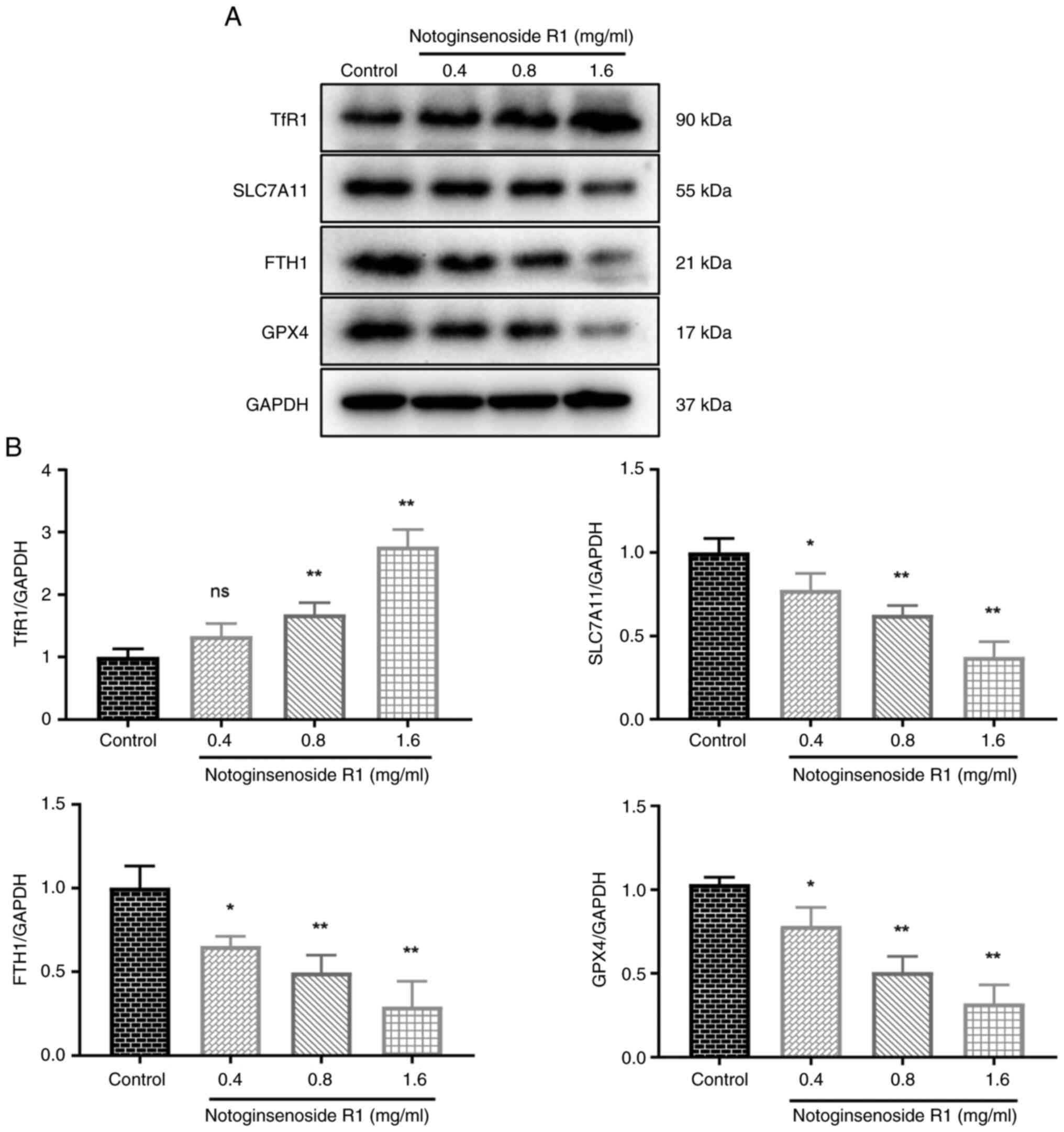

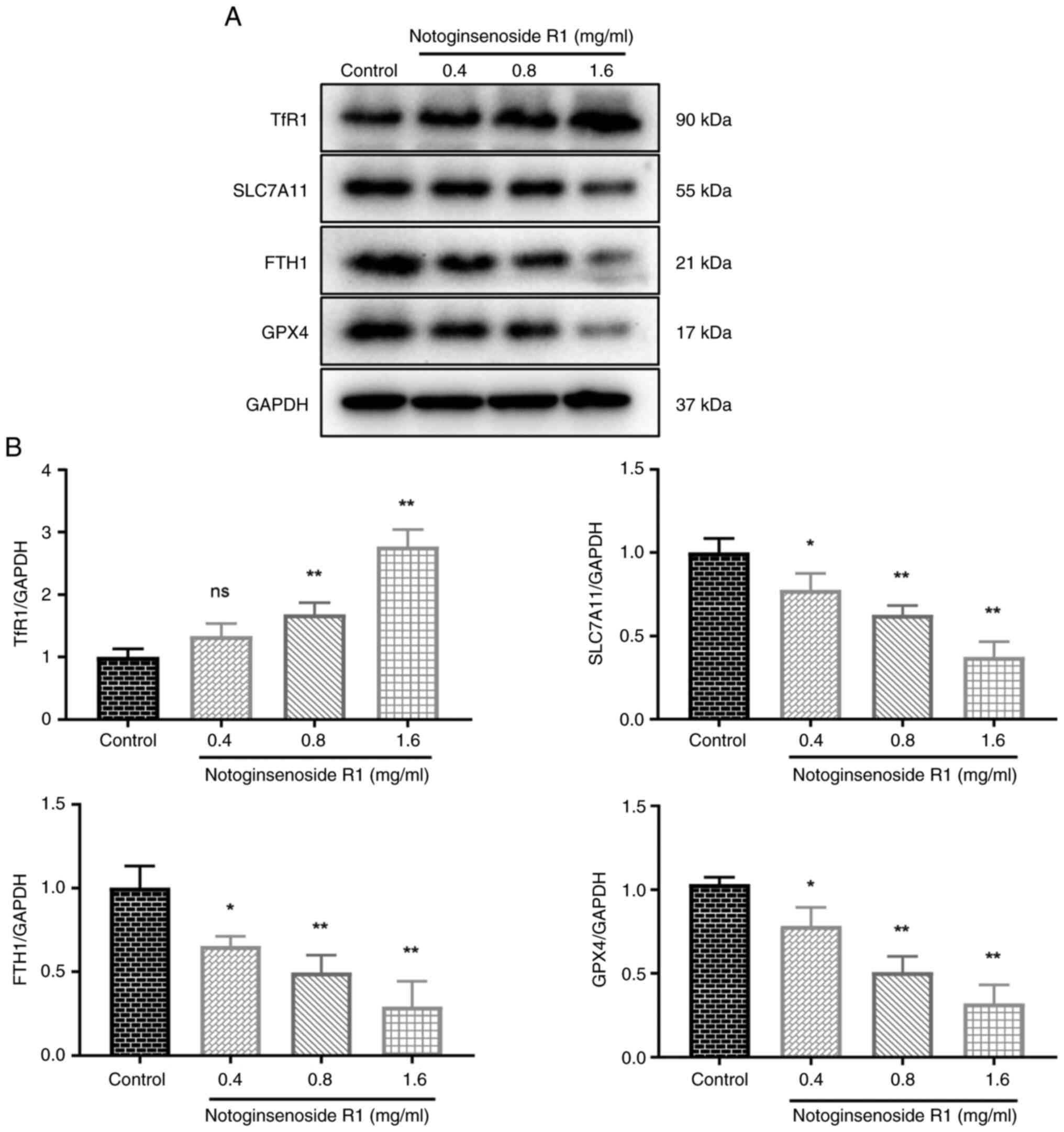

Detection of expression levels of

ferroptosis-related proteins

A549 cells, after being treated with varying

concentrations of NG-R1 (0, 0.4, 0.8 and 1.6 mg/ml) for 72 h at

37°C, were lysed using RIPA buffer supplemented with 1% protease

and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. Protein concentrations were

determined using a BCA assay kit. Subsequently, 20 µg total protein

was mixed with loading buffer and denatured at 100°C for 10 min.

Proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE on 12% gels and

transferred onto PVDF membranes using the wet transfer method.

Thereafter, the membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk at room

temperature for 1 h and the blocked membranes were incubated with

specific primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. The primary

antibodies and their dilutions were as follows: Anti-GPX4

(1:1,000), anti-FTH1 (1:1,000), anti-TfR1 (1:1,000), anti-SLC7A11

(1:1,000), and anti-GAPDH (1:5,000). Following primary antibody

incubation, the membranes were incubated with an HRP-conjugated

secondary antibody (1:5,000) at room temperature for 30 min.

Protein bands were visualized using the aforementioned ECL kit

according to the manufacturer's instructions and images were

captured with the Tanon gel imaging system. Band intensities were

semi-quantified with ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

Experimental results from three independent

experiments are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. All

data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 7.0 software (Dotmatics) by

one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test,

which compared all treatment groups against a single control group.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Effect of NG-R1 on A549 cell

viability

As shown in Fig. 1,

NG-R1 exhibited significant dose-dependent cytotoxicity against

A549 cells. The IC50 value for the inhibitory effect of

NG-R1 was calculated to be 0.839 mg/ml. Therefore, the

concentrations of 0.4, 0.8 and 1.6 mg/ml were selected for

subsequent experiments.

Effect of NG-R1 on A549 cell

proliferation

The BeyoClick EdU-594 cell proliferation detection

kit was used to assess the effect of NG-R1 on A549 cell

proliferation. As shown in Fig. 2,

treatment with 0.4 mg/ml NG-R1 significantly reduced the

proliferation rate of A549 cells compared with that in the control

group (P<0.01). Furthermore, the proliferation rate of A549

cells decreased progressively with increasing concentrations of

NG-R1, indicating that NG-R1 significantly inhibited A549 cell

proliferation in a dose-dependent manner (all P<0.01).

Effect of NG-R1 on A549 cell

migration

The wound healing assay results demonstrated that

the migration rates in the 0.4, 0.8 and 1.6 mg/ml NG-R1 treatment

groups were significantly lower than those in the control group

(all P<0.01; Fig. 3),

indicating that NG-R1 effectively inhibited the migration of A549

cells.

Effect of NG-R1 on A549 cell

invasion

Compared with that in the control group, the

invasion rate of A549 cells was significantly reduced in a

dose-dependent manner following 72 h of treatment with 0.4, 0.8 and

1.6 mg/ml NG-R1 (all P<0.01; Fig.

4), indicating that NG-R1 inhibited the invasive ability of

A549 cells.

Effect of NG-R1 on the ROS levels of

A549 cells

The fluorescent probe DCFH-DA was used to measure

ROS levels in A549 cells following 72 h of treatment with various

concentrations of NG-R1. As shown in Fig. 5, treatment with 0.4, 0.8 or 1.6

mg/ml NG-R1 significantly increased ROS levels in A549 cells (all

P<0.01), which may indicate the induction of ferroptosis.

Effect of NG-R1 on the expression

levels of ferroptosis-related proteins in A549 cells

As shown in Fig. 6,

treatment with 0.4 mg/ml NG-R1 did not significantly alter TfR1

protein levels, whereas 0.8 and 1.6 mg/ml concentrations

significantly increased TfR1 expression in A549 cells (all

P<0.01). Additionally, NG-R1 treatment at concentrations of 0.4,

0.8 and 1.6 mg/ml significantly downregulated the protein

expression levels of SLC7A11 (P<0.05, P<0.01), FTH1

(P<0.05 and P<0.01) and GPX4 (P<0.05 and P<0.01). These

results suggested that NG-R1 may modulate ferroptosis-related

proteins and induce ferroptosis in A549 cells.

| Figure 6.Effect of Notoginsenoside R1 on the

expression levels of ferroptosis-related proteins (n=3). (A)

Representative western blot images of the ferroptosis-related

proteins. (B) Protein expression levels of TfR1, SLC7A11, FTH1 and

GPX4 were examined by western blotting. Data are presented as the

mean ± SD. The one-way ANOVA results were as follows: TfR1:

F (3, 8), 41.41; SLC7A11: F (3, 8), 28.67; FTH1:

F (3, 8), 19.68; GPX4: F (3, 8), 32.63. *P<0.05

and **P<0.01 vs. control group. FTH1, ferritin heavy chain 1;

GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; ns, non-significant; SLC7A11,

solute carrier family 7 member 11; TfR1, transferrin receptor

1. |

Discussion

The present study is, to the best of our knowledge,

the first to demonstrate that NG-R1 induces ferroptosis in human

NSCLC A549 cells and to explore its underlying mechanisms. The

results of the present study showed that NG-R1 significantly

inhibited the viability, proliferation, migration and invasion of

A549 cells in a dose-dependent manner. Notably, western blot

analysis revealed that NG-R1 upregulated TfR1 while downregulating

SLC7A11, GPX4 and FTH1, suggesting that its anticancer effects may

have been mediated through ferroptosis in A549 cells (16).

The findings of the present study are consistent

with those of previous studies demonstrating the anticancer effects

of NG-R1 and its analogs, particularly against NSCLC (23,26).

In a similar manner to established ferroptosis inducers such as

erastin, NG-R1 promotes ferroptosis by elevating intracellular ROS

levels (27). The pronounced

inhibition of A549 cell proliferation, migration and invasion

observed in the present study further supports the potential of

NG-R1 as an effective anticancer agent, providing new scientific

evidence for its application in NSCLC treatment (23,26).

To further elucidate the molecular mechanisms

underlying NG-R1-induced ferroptosis, the present study examined

changes in the expression of key ferroptosis-related proteins. The

results of the present study suggested that NG-R1 may regulate iron

metabolism through multiple pathways, thereby activating

ferroptosis, based on the findings from western blot analysis of

related proteins. Notably, NG-R1 significantly downregulated

SLC7A11, an important protein responsible for maintaining

intracellular GSH levels and suppressing lipid peroxidation

(27). SLC7A11 is commonly

upregulated in NSCLC cells, contributing to tumor growth (19), and its downregulation by NG-R1 may

reduce GSH synthesis, leading to increased lipid peroxidation and

ferroptosis induction. The precise regulatory mechanism of NG-R1 on

SLC7A11 warrants further investigation, potentially involving

signaling pathways such as those mediated by nuclear factor

erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), p53 or other transcription

factors (28,29). Additionally, NG-R1 significantly

decreased the expression of GPX4, an important enzyme responsible

for repairing lipid peroxides (21,27).

This reduction may be secondary to GSH depletion following SLC7A11

downregulation, resulting in impaired GPX4 activity and the

accumulation of toxic lipid peroxides, a hallmark of ferroptosis.

Furthermore, NG-R1 could have modulated iron metabolism by

significantly upregulating TfR1 and downregulating FTH1, thereby

increasing the labile iron pool and promoting ferroptosis via

enhanced Fenton reaction-mediated lipid peroxidation (13,27,30).

Collectively, these findings suggest that NG-R1 induced ferroptosis

in NSCLC cells by orchestrating the suppression of antioxidant

defenses and dysregulation of iron homeostasis.

Although the present study provides evidence that

NG-R1 induced ferroptosis in A549 cells, several important

limitations remain. First, the lack of rescue experiments using

ferroptosis-specific inhibitors, such as ferrostatin-1 or

liproxstatin-1, and iron chelators such as deferoxamine, limits the

suggestion that the observed cytotoxicity is primarily due to

ferroptosis. Such experiments are important to exclude other forms

of cell death, including apoptosis and necroptosis (27). Second, while alterations in key

ferroptosis-related proteins were observed, the upstream regulatory

mechanisms by which NG-R1 modulates proteins such as SLC7A11 and

TfR1 remain ambiguous. Future investigations should focus on

elucidating how NG-R1 influences these targets at the

transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels, including the

potential involvement of signaling pathways such as Nrf2, p53 and

activating transcription factor 4 (28,29).

In conclusion, in the present study, NG-R1 was shown

to inhibit the proliferation and migration of A549 cells, while

significantly increasing intracellular ROS levels. Western blot

analysis revealed that treatment with NG-R1 significantly

upregulated TfR1 expression, and downregulated SLC7A11, GPX4 and

FTH1 levels. These findings suggest that NG-R1 may induce

ferroptosis in A549 cells and thus holds potential as an anti-lung

cancer agent.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present work was supported by a grant from the Science and

the Technology Plan Project of Yunnan Provincial Department of

Science and Technology (grant no. 202101BA070001-267).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YZ was responsible for conceptualization, data

curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation,

methodology, project administration, resources, and writing,

reviewing and editing the manuscript. ZM was responsible for data

curation [data collection, cleaning (which involved data inspection

and error correction: examining the collected raw data for

recording errors, anomalies, or clearly illogical inputs)and

validation], formal analysis, investigation, and writing, reviewing

and editing the manuscript. YD was responsible for formal analysis,

investigation and project administration. YZ and ZM confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Dubey AK, Gupta U and Jain S: Epidemiology

of lung cancer, approaches for its prediction: A systematic review

and analysis. Chin J Cancer. 35:712016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I,

Parkin DM, Piñeros M, Znaor A and Bray F: Cancer statistics for the

year 2020: An overview. Int J Cancer. 149:778–789. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Jurisic V, Obradovic J, Nikolic N, Javorac

J, Perin B and Milasin J: Analyses of P16INK4a gene

promoter methylation relative to molecular, demographic, clinical

parameters characteristics in non-small cell lung cancer patients:

A pilot study. Mol Biol Rep. 50:971–979. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Petrović M, Bukumirić Z, Zdravković V,

Mitrović S, Atkinson HD and Jurišić V: The prognostic significance

of the circulating neuroendocrine markers chromogranin A,

pro-gastrin-releasing peptide, and neuron-specific enolase in

patients with small-cell lung cancer. Med Oncol. 31:8232014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Socinski MA and Pennell NA: Best practices

in treatment selection for patients with advanced NSCLC. Cancer

Control. 23 (4 Suppl):S2–S4. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Zappa C and Mousa SA: Non-small cell lung

cancer: Current treatment and future advances. Transl Lung Cancer

Res. 5:288–300. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Pilkington G, Boland A, Brown T, Oyee J,

Bagust A and Dickson R: A systematic review of the clinical

effectiveness of first-line chemotherapy for adult patients with

locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Thorax.

70:359–367. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Luo YH, Wang C, Xu WT, Zhang Y, Zhang T,

Xue H, Li YN, Fu ZR, Wang Y and Jin CH: 18β-Glycyrrhetinic acid Has

Anti-cancer effects via inducing apoptosis and G2/M cell cycle

arrest, and inhibiting migration of A549 lung cancer cells. Onco

Targets Ther. 14:5131–5144. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Proneth B and Conrad M: Ferroptosis and

necroinflammation, a yet poorly explored link. Cell Death Differ.

26:14–24. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Aaronson SA, Abrams

JM, Adam D, Agostinis P, Alnemri ES, Altucci L, Amelio I, Andrews

DW, et al: Molecular mechanisms of cell death: Recommendations of

the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018. Cell Death Differ.

25:486–541. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Hassannia B, Vandenabeele P and Berghe TV:

Targeting ferroptosis to iron out cancer. Cancer Cell. 35:830–849.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Liang C, Zhang X, Yang M and Dong X:

Recent progress in ferroptosis inducers for cancer therapy. Adv

Mater. 31:19041972019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Bebber CM, Müller F, Clemente LP, Weber J

and Karstedt SV: Ferroptosis in cancer cell biology. Cancers.

12:1642020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Lewerenz J, Hewett SJ, Huang Y, Lambros M,

Gout PW, Kalivas PW, Massie A, Smolders I, Methner A, Pergande M,

et al: The Cystine/glutamate Antiporter system x(c)(−) in health,

disease: From molecular mechanisms to novel therapeutic

opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 18:522–555. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Bridges RJ, Natale NR and Patel SA: System

xc− Cystine/glutamate antiporter: An update on molecular

pharmacology and roles within the CNS. Br J Pharmacol. 165:20–34.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta

R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS,

et al: Ferroptosis: An Iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell

death. Cell. 149:1060–1072. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME,

Shimada K, Skouta R, Viswanathan VS, Cheah JH, Clemons PA, Shamji

AF, Clish CB, et al: Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by

GPX4. Cell. 156:317–331. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Ursini F, Maiorino M, Valente M, Ferri L

and Gregolin C: Purification from pig liver of a protein which

protects liposomes and biomembranes from peroxidative degradation

and exhibits glutathione peroxidase activity on phosphatidylcholine

hydroperoxides. Biochim Biophys Acta. 710:197–211. 1982. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Ji X, Qian J, Rahman SMJ, Siska PJ, Zou Y,

Harris BK, Hoeksema MD, Trenary IA, Heidi C, Eisenberg R, et al:

xCT (SLC7A11)-mediated metabolic reprogramming promotes non-small

cell lung cancer progression. Oncogene. 37:5007–5019. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Koppula P, Zhang Y, Zhuang L and Gan B:

Amino acid transporter SLC7A11/xCT at the crossroads of regulating

redox homeostasis and nutrient dependency of cancer. Cancer Commun

(Lond). 38:122018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Sun B, Xiao J, Sun XB and Wu Y:

Notoginsenoside R1 attenuates cardiac dysfunction in endotoxemic

mice: An insight into oestrogen receptor activation and PI3K/Akt

signalling. British J Pharmacology. 168:1758–1770. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Guo Q, Li P, Wang Z, Cheng Y, Wu H, Yang

B, Du S and Lu Y: Brain distribution pharmacokinetics and

integrated pharmacokinetics of Panax Notoginsenoside R1,

Ginsenosides Rg1, Rb1, Re and Rd in rats after intranasal

administration of Panax Notoginseng Saponins assessed by

UPLC/MS/MS. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci.

969:264–271. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Lee CY, Hsieh SL, Hsieh S, Tsai CC, Hsieh

LC, Kuo YH and Wu CC: Inhibition of human colorectal cancer

metastasis by notoginsenoside R1, an important compound from

Panax notoginseng. Oncol Rep. 37:399–407. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhang W, Shu H, Fang L, Tang N, Li Y, Guo

B and Meng F: Cancer inhibition mechanism of lung cancer mouse

model based on dye trace method. Saudi J Biol Sci. 27:1155–1162.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Hsieh SL, Hsieh S, Kuo YH, Wang JJ, Wang

JC and Wu CC: Effects of Panax notoginseng on the metastasis

of human colorectal cancer cells. Am J Chin Med. 44:851–870. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhou Y, Zhang X, Wang X, Li Y, Liu Z,

Zhang J, Chen L, Xu Y, Yang Y and Wang Z: Ferroptosis in cancer:

From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic applications. Nat Rev

Cancer. 24:1–15. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Xie Y, Hou W, Song X, Yu Y, Huang J, Sun

X, Kang R and Tang D: Ferroptosis: Process and function. Cell Death

Differ. 23:369–79. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Muckenthaler MU, Galy B and Hentze MW:

Systemic iron homeostasis and the iron-responsive

element/iron-regulatory protein (IRE/IRP) regulatory network. Annu

Rev Nutr. 28:197–213. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Yang WS and Stockwell BR: Synthetic lethal

screening identifies compounds activating iron-dependent,

nonapoptotic cell death in oncogenic-RAS-harboring cancer cells.

Chem Biol. 15:234–245. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ganz T and Nemeth E: Hepcidin and iron

homeostasis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1823:1434–1443. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|