Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a prevalent metabolic and

endocrine disorder characterized by the persistent elevation of

blood sugar levels, termed hyperglycemia, occurring as a result of

impaired insulin secretion and/or function (1). It is estimated that >10.5% of the

global adult population now have this condition (2). DM is a major public health burden

associated with high health care and societal costs, early death

and serious morbidity. Sustained hyperglycemia gradually induces

and aggravates damage to the nervous system, cardiovascular,

kidneys, eyes, and other systemic tissues and organs, resulting in

complications such as cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease,

diabetic kidney disease (DKD), diabetic retinopathy (DR) and

diabetic neuropathy (DN) (1,3).

Diabetic eye complications mainly include DR,

diabetic cataract and diabetic keratopathy (DK), the latter of

which has historically been neglected. DK is classified as either

primary and secondary, with primary DK developing due to chronic

hyperglycemia, and secondary DK occurring due to diabetic trauma

and following surgery (4). Chronic

hyperglycemia leads to progressive damage to multiple organ

systems, including corneal tissues (5). DK has been reported to occur in

47–64% of diabetic patients (6,7). The

clinical manifestations of DK include dry eye, persistent corneal

epithelial erosion, superficial punctate keratopathy, delayed

epithelial regeneration and decreased corneal sensitivity (8,9). In

more advanced stages, corneal ulceration and scarring may occur,

leading to corneal opacity, and ultimately impaired vision or

permanent vision loss (10).

Nuclear proteins (NPs) are synthesized in the

cytoplasm and specifically targeted to the nucleus of a cell

(11). They include histones and

non-histone proteins, such as structural proteins of the nuclear

matrix and lamina, RNA and DNA polymerases, and gene regulatory

proteins (12). The transport of

NPs from the cytoplasm into the nucleus is mediated by nuclear

localization signals (NLSs), which induce the NPs to pass through

the nuclear pore complex (NPC) (13). NPs play important roles in the

transmission of genetic information, such as in DNA replication,

RNA transcription and processing, and DNA damage repair (14). Certain NPs have been implicated as

mediators of pathological conditions affecting the eye, including

DR, DK and optic neuropathy; examples include peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) (15,16),

high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) (17) and enhancer of zeste homolog 2

(EZH2) (18). Therefore, the roles

of NPs in DK are of considerable research interest. In the present

review, the pathogenesis of DK is described and the roles of

various NPs in the pathophysiological processes of DK are

discussed.

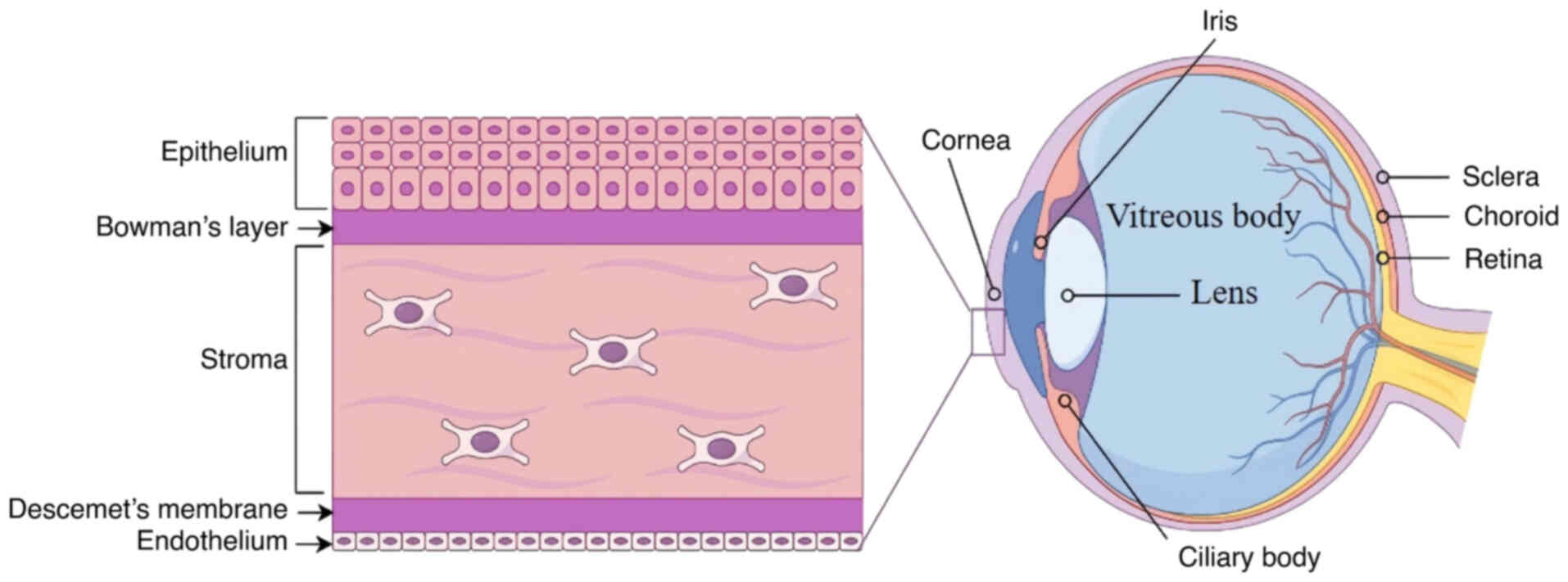

Structure and function of the cornea

The eye is a sensory organ responsible for visual

perception, transmitting light-derived information to the brain to

generate visual images. The eyeball consists of three distinct

anatomical layers: The outer layer including the cornea and sclera;

the middle layer consisting of the iris, ciliary body and choroid;

and the inner neural layer known as the retina. The intraocular

cavity contains the anterior chamber, posterior chamber and

vitreous cavity, and the major intraocular contents include the

aqueous humor, lens and vitreous body (15,19).

The cornea, forming the anterior portion of the eye,

is an avascular, transparent tissue that allows light to enter the

visual system. It not only protects the inner eye but also provides

approximately two-thirds of the total refractive power of the eye

(20–22). The cornea is a convex structure

composed of five distinct layers, which are, in order from the

anterior to the posterior surface: Epithelium, Bowman's layer,

stroma, Descemet's membrane and endothelium (23). Its anterior surface is covered by

the tear film, which provides lubrication, protection through

soluble immune factors, and a smooth optical surface (24,25).

The epithelium is ~53 µm thick and consists of 5–7

cellular layers composed of three distinct cell types, namely

squamous cells, wing cells and basal epithelial cells that adhere

to the underlying basement membrane (26). The basal epithelial cells have

proliferative capacity, which is important for cell renewal and

repair (27). Bowman's layer,

located posterior to the epithelial basement membrane, is 8–12 µm

thick, acellular and lacks the ability to regenerate (28). It is composed of randomly arranged

type I, III, V and XII collagen fibrils together with proteoglycans

(29).

Beneath Bowman's layer lies the corneal stroma,

constituting ~90% of the corneal thickness (30). The stroma primarily consists of

extracellular matrix (ECM) and a small number of keratocytes. The

keratocytes produce type I and type V collagen, along with

proteoglycans, to assemble collagen fibrils and maintain the ECM

(31). The stroma is highly

organized, to ensure both mechanical strength and light

transparency. The subepithelial nerve plexus, located between

Bowman's layer and the anterior stroma, comprises stromal nerve

branches that perforate Bowman's layer and form the sub-basal

epithelial nerve plexus that supplies the corneal epithelium

(32).

Underlying the stroma is Descemet's membrane, a

3-µm, acellular fibrous layer secreted by the underlying

endothelial cells (33).

Descemet's membrane not only provides an ‘adhesive scaffold’ and

barrier protection for corneal endothelial cells, but also

maintains the shape and hydration of the cornea (33). The corneal endothelium, located on

the posterior surface of the cornea, consists of a single layer of

flat, hexagonal cells that are connected in a mosaic honeycomb

pattern (15). These cells

preserve corneal clarity and visual acuity by maintaining the

relatively dehydrated status of the stroma through high-density

ionic pumps in their basolateral membranes (27). Since the corneal endothelium has

very limited regenerative capacity, damage to the endothelial cells

results in permanent loss, leading to corneal edema and blindness

(Fig. 1).

DK

Diabetes induces morphological and functional

alterations in the cornea. Continuous hyperglycemia can affect all

corneal layers, including the epithelium, nerves, stroma and

endothelium, with the nerves and epithelial cells being

particularly vulnerable (10). DK

exhibits several clinical manifestations, including persistent

corneal epithelial erosion, superficial punctate keratopathy,

delayed epithelial regeneration, corneal edema and decreased

corneal sensitivity (8,34). Persistent corneal epithelial

defects can progress to corneal scarring and ulceration, ultimately

leading to corneal opacity and the risk of decreased visual acuity

or permanent vision loss (35,36).

Diabetic corneal epitheliopathy

Corneal epitheliopathy is one of the most common and

long-term complications of DM (37). The rapid repair ability of the

epithelium is essential for the maintenance of corneal transparency

and homeostasis, particularly in the event of injury or infection

(8). However, DM can increase

susceptibility to spontaneous corneal trauma, and epithelial

lesions take longer to heal in patients with DM. Disrupted

epithelial cell junctions, cellular edema and reduced microvilli

have been observed in the corneas of diabetic rats by scanning

electron microscopy (38).

Hyperglycemia can disrupt the tight-junction

complexes of corneal epithelial cells, leading to epithelial

dysfunction and stromal edema (39,40).

The density of corneal basal epithelial cells has been found to be

significantly reduced in patients with both type 1 DM (T1DM) and

type 2 DM (T2DM), which impairs the ability of the endothelium to

regulate the corneal fluid balance, leading to corneal edema

(41).

Hyperglycemia has been demonstrated to impair

epidermal growth factor receptor signaling in corneal epithelial

cells, ultimately contributing to delayed wound healing (42). The activity of proteolytic enzymes

such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) is increased during the

wound-healing process in corneal epithelial cells exposed to high

glucose (HG) and in the corneal epithelium of diabetic rats,

thereby interfering with wound healing and tissue remodeling

(43). Moreover, Di et al

(44) reported that an excessive

inflammatory response resulted in increased levels of

proinflammatory cytokines and delayed corneal epithelial wound

healing in diabetic model mice.

Diabetic corneal neuropathy (DCN)

The cornea is the most richly innervated structure

in the human body. Corneal nerves provide protective and trophic

functions, including the maintenance of corneal sensitivity and the

regulation of corneal wound healing through the release of

neuropeptides, neurotrophins and growth factors (8). DCN results from trigeminal nerve

impairment caused by chronic hyperglycemia, primarily affecting the

small Aδ and C nerve fibers. This condition leads to structural

abnormalities and reduced corneal innervation, which causes corneal

epithelial breakdown, delayed wound healing, and progression to

corneal ulceration, melting and perforation (5,45).

Corneal confocal microscopy has become the standard

method of assessing the cornea at a cellular level in vivo

(46). Studies using this

technique have shown that corneal nerve parameters, including

subbasal nerve fiber density, fiber length and number of fibers,

are reduced in patients with T1DM or T2DM, and exhibit an

association with diabetic peripheral neuropathy (47–51).

Furthermore, corneal sensitivity in patients with diabetes is

significantly lower compared with that in non-diabetic controls

(52). Notably, these changes are

inversely associated with the duration of DM (53).

Diabetic corneal stroma lesions

DM can cause both structural and functional changes

in the corneal stroma, leading to a loss of corneal transparency

and threatening vision (54). The

accumulation of advanced glycosylation end products (AGEs) promotes

non-enzymatic crosslinking between collagen molecules and

proteoglycans, resulting in corneal sclerosis and thickening. The

levels of collagen I and III in the corneal stroma of patients with

DM have been observed to be significantly increased compared with

those in healthy controls, which is consistent with fibrosis and

disruption of the matrix structure, leading to thickening and

scarring (55). In addition,

Ossabaw mini pigs with T2DM exhibit disorganized stromal collagen

fibrils, with decreased levels of collagen IV and upregulated

expression levels of MMP-9 (56).

In addition, Kalteniece et al (57) found that anterior, mid and

posterior stromal keratocyte density was significantly reduced in

diabetic patients with and without diabetic peripheral neuropathy

compared with those in non-diabetic controls, suggesting an

association with corneal sub-basal plexus nerve damage in patients

with DM. However, Gad et al (58) observed downregulations in corneal

nerve fiber density and anterior and mid-stromal keratocyte

densities in children with T1DM, but no correlation between nerve

and keratocyte loss.

Diabetic corneal endotheliopathy

The corneal endothelium plays a critical role in the

maintenance of appropriate stromal hydration via tight junctions

and Na+/K+-ATPase pump activity (59). In diabetes, structural and

functional impairments in the corneal endothelium reduce

endothelial pump efficiency, leading to stromal edema, which can be

detected clinically as increased central corneal thickness (CCT).

These impairments are exacerbated with disease progression, and can

manifest as corneal haze and decreased vision (60,61).

Numerous studies on the effects of DM on the corneal endothelium

have reported that patients with DM exhibit a higher CCT, reduced

corneal endothelial cell density (ECD), decreased percentages of

hexagonal cells, and increased cell area variation coefficients

compared with those in controls (62–67).

Furthermore, a multivariate analysis of patients with DM

demonstrated that a low ECD is significant associated with elevated

glycated hemoglobin levels, longer DM duration and more advanced DR

(68).

DK results from prolonged hyperglycemia, which

induces severe morphological and functional alterations in the

cornea. Chronic hyperglycemia activates multiple pathological

mechanisms, such as the accumulation of AGEs, oxidative stress,

activation of the polyol pathway and protein kinase C pathways,

chronic inflammation, immune cell activation, and reduced

neurotrophic innervation (9).

These mechanisms complement each other and jointly promote the

development of DK.

NPs

NPs are proteins that localize to the cell nucleus,

and include structural proteins, transcription factors and other

functional proteins. They are synthesized in the cytoplasm and are

transported into the nucleus through NPCs (69). This transport relies on NLSs and

nuclear export signals within the primary structure of the NP. The

NPC, composed of ~30 different protein components called

nucleoporins, regulates the movement of molecules across the

nuclear envelope (70). Small

molecules such as ions, metabolites and <40-kDa proteins can

diffuse freely though the NPC, whereas larger molecules require

specific carrier proteins for transport into and out of the nucleus

(69).

There are numerous regulatory NPs that interact with

DNA, RNA, nucleosomes and other proteins to form biomolecular

condensates, thereby functionally impacting gene expression. These

NPs include DNA- and RNA-binding proteins, as well as transcription

factors (14).

Deoxyribonucleoproteins are involved in the regulation of DNA

replication and transcription (14), whereas ribonucleoproteins

participate in post-transcriptional regulatory processes (71). Some NPs also mediate

post-translational modifications, such as acetylation and

methylation, which regulate the physiological activities of cells

and influence cell transformation and progression (72). For example, EZH2, a histone

methyltransferase of the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2)

complex, promotes the trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 27

(H3K27me3), which alters the chromatin structure and represses gene

transcription (73,74). PEST-containing nuclear protein

(PCNP) is a small NP of only 178 amino acids that contains two PEST

sequences, rich in proline, glutamic acid, serine and threonine.

PCNP is involved in vital cellular processes such as cell

proliferation and has been implicated in tumorigenesis (75).

Role of NPs in DK

In the cell nuclei of the cornea, NPs regulate gene

expression and modulate cellular responses. DK is associated with

the dysregulation of NPs, leading to molecular and cellular

alterations. Certain NPs have been well studied, including PPAR,

HMGB1, EZH2, phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) and sirtuin 1

(SIRT1); however, these proteins have not been systematically

analyzed in relation to DK in previous reviews.

PPARs

PPARs are a group of ligand-activated transcription

factors belonging to the nuclear hormone receptor family (76). The PPAR family comprises three

isotypes: PPARα, PPARγ and PPARδ (also known as PPARβ or PPARβ/δ),

with genes located on human chromosomes 22, 3 and 6, respectively

(77,78). PPARs play crucial roles in glucose

and lipid metabolism, and are involved in cell proliferation and

differentiation, inflammation, angiogenesis and insulin sensitivity

(79). PPARs have been

investigated as therapeutic targets, and PPAR agonists represent a

promising treatment approach for metabolic diseases such as

diabetes, diabetic complications and neurodegeneration (80–82).

Within the eye, PPARα and PPARγ are expressed in the

cornea, conjunctiva, retina, meibomian glands and lacrimal glands,

whereas PPARδ is located in the cornea, retina and lacrimal glands

(15). Matlock et al

(83) demonstrated that in both

human diabetic corneas and the corneas of diabetic rats, the

expression of PPARα was significantly downregulated. In addition,

experiments using PPARα−/− mice revealed a marked

decline in corneal nerve densities, accompanied by an increased

incidence of epithelial lesions in the central cornea. These

findings suggest that PPARα plays a protective role against

diabetes-induced corneal nerve degeneration, potentially by

maintaining neuronal integrity and modulating pathological

processes associated with diabetes (83). The PPARα agonist fenofibrate has

been shown to alleviate mitochondrial dysfunction and promote

corneal wound healing in diabetic mice (84). Furthermore, a study of 30 patients

with T2DM revealed that oral treatment with fenofibrate for 30 days

significantly improved corneal nerve regeneration, reduced nerve

edema, and improved the density and width of corneal nerve fibers

(85). In addition, both topical

and oral fenofibrate are able to ameliorate DCN in diabetic mice,

with topical fenofibrate significantly reducing neuroinflammation

(86). These findings highlight

the therapeutic potential of PPARα agonists in the treatment of

DK.

Selective agonists to PPARγ, including

thiazolidinedione class drugs such as troglitazone, can decrease

insulin resistance and inhibit inflammation, fibrosis and corneal

scarring (87). PPARγ

downregulates the expression of TGF-β1-induced connective tissue

growth factor, thereby exerting anti-fibrogenic effects that

inhibit the development of corneal scarring (88). Rosiglitazone, a PPARγ agonist, was

shown to alleviate ocular surface damage, enhance corneal

sensitivity and increase tear production in a mouse model of

diabetes-related dry eye. These effects were accompanied by the

upregulation of antioxidant enzyme expression, indicating that

oxidative stress was reduced in the lacrimal glands of the diabetic

mice (89). Furthermore, the

PPARβ/δ agonist GW501516 was reported to suppress inflammatory

cytokine release, promote neovascularization by promoting the

expression of VEGF-α, and increase the infiltration of M2

macrophages and vascular endothelial cells into the corneal wound

area (90).

HMGB1

A ubiquitously expressed and evolutionarily

conserved chromosomal protein, HMGB1 plays diverse roles in the

mediation of inflammation. It is the most abundant and well-studied

member of the HMG superfamily. HMGB1 was first identified in bovine

thymus in 1973 by Goodwin and Johns (91), and its name reflects its high

migration ability in polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. It is

mainly located in the nucleus, wherein it binds to DNA and

regulates chromatin remodeling, gene transcription and DNA damage

repair (92). The HMGB1 protein

comprises a single polypeptide chain of 215 amino acids, which

contains binding sites for DNA as well as for Toll-like receptor 4

(TLR4) and receptor for AGEs (RAGE), which promote inflammation

(93). HMGB1 can be passively

released by necrotic cells or actively secreted by activated immune

cells into the extracellular milieu (94). By interacting with its receptors,

RAGE and TLR, HMGB1 ultimately activates NF-κB and stimulates the

production of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-1β and

TNF-α, while also inducing its own expression and that of its

receptors, creating a positive feedback loop of inflammation

(95). HMGB1 has been implicated

in numerous diseases, including cancer, arthritis (96), diabetes and autoimmune diseases

(97,98).

It has been reported that HMGB1 levels are

associated with diabetic complications, with increased levels of

HMGB1 being observed in both diabetic patients and animal models of

diabetes (99,100). HMGB1 promotes insulin resistance

and inflammation by upregulating the expression of RAGE, activating

the TLR4/JNK/NF-κB pathway and reducing activation of the insulin

receptor substrate-1 signaling pathway (101). Studies have also demonstrated the

involvement of HMGB1 in the occurrence and development of DR

(102,103). Furthermore, HMGB1 exacerbates

neuronal apoptosis and autophagy defects in DN by binding to TLR4,

with increased HMGB1 and TLR4 levels promoting apoptosis and

impairing autophagy (104). Hou

et al (17) reported that

the corneas of diabetic mice with DK exhibit significantly

upregulated protein expression levels of HMGB1 and its receptors,

indicating that HMGB1 and its receptors play a key role in the

development of DK. In another study, a dipotassium

glycyrrhizinate-based micelle formulation encapsulating genistein

blocked HMGB1 signaling, which promoted diabetic corneal and nerve

wound healing (105). These

studies suggest that targeting HMGB1 may be a promising therapeutic

strategy to enhance corneal and nerve repair in patients with

diabetes.

EZH2

EZH2 is a protein that contributes to the regulation

of gene activity in cells. The EZH2 gene is located on chromosome

7q35 and comprises 20 exons, encoding a protein comprising 746

amino acids (106). Acting as a

catalytic subunit of PRC2, EZH2 promotes transcriptional silencing

through H3K27me3 (73,74). EZH2 also forms complexes with

transcriptions factors or directly binds to the promoters of target

genes to regulate gene transcription. As a key regulator in DNA

damage repair, the cell cycle, cell differentiation, autophagy,

apoptosis and immunological modulation, EZH2 has been implicated in

a variety of diseases, including cancer and ocular disorders

(18). Notably, the upregulation

of EZH2 expression has been reported in ocular tumors (107), corneal injury (108), cataracts (109) and DR (110).

Studies suggest that EZH2 is actively involved in

the pathogenesis of DK. Myofibroblast transdifferentiation induced

by TGF-β plays an important role in corneal wound healing but can

cause cornea scarring fibrosis when excessively activated (111). In a mouse model of corneal

injury, EZH2 expression was upregulated, and the EZH2 inhibitor

EPZ-6438 suppressed corneal myofibroblast activation and ECM

protein synthesis (112). Corneal

neovascularization is another key process in wound healing. In a

mouse model of alkali burn-induced corneal neovascularization, the

EZH2 inhibitor 3-deazaneplanocin A reduced EZH2 expression and the

release of proangiogenic factors, thereby alleviating oxidative

stress and abnormal neovascularization in the cornea (113). These findings suggest that EZH2

promotes corneal injury and may serve as a novel and valuable

therapeutic target. In addition, in human corneal endothelial cells

cultured in vitro, EZH2 promoted apoptosis by mediating the

H3K27me3-dependent suppression of heme oxygenase-1 gene

transcription, further supporting the potential of EZH2 as a target

for the treatment of corneal apoptosis (108).

EZH2 has also been implicated in DR. Upregulated

expression of EZH2 has been detected in HG-induced human retinal

endothelial cells and in diabetic animal models, and the inhibition

of EZH2 activity has been shown to reduce MMP-9 and VEGF levels

both in vitro and in vivo (110,114).

PTEN

PTEN is a tumor suppressor gene located at 10q23. It

encodes a 403-amino acid protein containing five main functional

domains: An N-terminal phosphatidyl-inositol-4,5-diphosphate

(PIP2)-binding domain, a phosphatase domain, a

membrane-targeting C2 domain, a C-terminal tail, and a PDZ binding

motif (115). PTEN is normally

present in the nucleus and cytoplasm of cells in normal tissue, but

absent from neoplastic tissues (115). Nuclear PTEN contributes to genome

stability by regulating damage repair, cell-cycle progression, DNA

replication and chromatin organization (116).

PTEN was the first tumor suppressor gene with

phosphatase function identified in humans, and plays a role in

tumor inhibition by regulating cell-cycle progression, apoptosis

and cell migration (117). The

PTEN protein exhibits both lipid- and protein-phosphatase activity.

Its lipid-phosphatase function dephosphorylates

phosphatidyl-inositol-3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3) to form

PIP2, which antagonizes PI3K signaling and blocks the

activation of AKT to inhibit tumorigenesis, while its

protein-phosphatase activity dephosphorylates various protein

substrates, influencing various signaling pathways (118,119). It has been identified that PTEN

has three alternative translational isoforms: PTENα, PTENβ and

PTENε, which each have tumor-suppressive functions (118). Consequently, the dysfunction of

PTEN due to genetic mutation, epigenetic silencing or

post-translational modifications contributes to the development and

progression of numerous cancers.

The PI3K/Akt signaling pathway is a major network

activated in response to insulin or insulin-like growth factor 1

(120). As a negative regulator

of this pathway, PTEN also serves as an inhibitor of insulin

signaling. It dephosphorylates PIP3 to PIP2,

which suppresses insulin-induced PI3K signaling, ultimately leading

to decreased insulin sensitivity and insulin resistance, a key

pathogenic process in T2DM (117). The tissue-specific deletion of

PTEN improves insulin sensitivity and protects against systemic

insulin resistance, suggesting a potential strategy for therapeutic

intervention in both cancer and DM (117).

During the development of DR, hyperglycemia induces

the dysregulation of mitophagy, which causes the accumulation of

dysfunctional mitochondria and activation of the inflammasome,

processes that are mainly regulated by the PTEN-induced putative

kinase protein 1/parkin pathway (121).

The role of PTEN in keratopathy has been

investigated in a number of studies. One study demonstrated that in

hyperglycemia-induced diabetic mice, neuropeptide FF (NPFF) levels

were significantly reduced, while the application of NPFF promoted

corneal nerve injury recovery and epithelial wound healing, and

downregulated PTEN expression (122). Another study found that PTEN mRNA

and protein expression levels were upregulated in diabetic cornea,

which hindered corneal epithelial regeneration and Akt activation,

while the inhibition of PTEN by the topical administration of

dipotassium bisperoxo(picolinato)oxovanadate (V) dihydrate

[bpV(pic)] or potassium bisperoxo (1,10-phenanthroline) oxovanadate

(V) trihydrate [bpV(phen)] facilitated corneal epithelial

regeneration by reactivating Akt signaling. These treatments also

improved the recovery of corneal nerve fiber density and

sensitivity (123). Similarly,

Zhang et al (124)

demonstrated that the intracameral injection of bpV(pic) promoted

the proliferation and migration of corneal endothelial cells, and

enhanced corneal endothelial wound healing in a rat model.

Furthermore, human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived

small extracellular vesicles overexpressing miR-21 were shown to

enhance the recovery of corneal epithelial wounds by suppressing

PTEN expression (125).

SIRTs

SIRTs are a family of NAD+-dependent

lysine deacetylases that act on histones and other proteins,

thereby regulating diverse cellular processes such as

proliferation, apoptosis and metabolism (126). Seven subtypes of SIRTs, namely

SIRT1-7, have been identified in mammals (127). They are involved in numerous

physiological and pathological processes, including energy

metabolism, oxidative stress responses, inflammation and

carcinogenesis (126).

Accordingly, the SIRT family has emerged as a potential therapeutic

target for various types of pathologies, including cancer,

cardiovascular disease and respiratory disease (128). SIRT1 and SIRT2 exist in the cell

nucleus and cytoplasm, while SIRT3-5 are predominantly

mitochondrial, and SIRT6 and SIRT7 are primarily located in the

cell nucleus (129). SIRT1 is the

most well studied member of the SIRT family.

Numerous studies have reported that SIRTs,

particularly SIRT1-6, are associated with biological processes

involved in the development and progression of DM (130). SIRTs participate in the onset and

development of DM by regulating glucose metabolism and maintaining

insulin homeostasis. Most evidence suggests that SIRT1-4 and SIRT6

have protective effects against the development of DM, while SIRT5

promotes DM progression. However, downregulation of SIRT1 and SIRT2

has been reported to improve DM in some contexts, likely due to

cell- and tissue-specific effects (128).

In terms of DM complications, SIRT1 and SIRT3 have

been shown to exert protective effects against DKD (131), DR (132), DN (133) and diabetic cardiomyopathy

(134). Mechanistically, studies

indicate that SIRT1 mediates its protective effects by inhibiting

endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS) and suppressing the NF-κB

inflammatory signaling pathway (135). Furthermore, SIRT1 activators have

been demonstrated to exert a beneficial impact by reversing

T2DM-related complications and promoting diabetic wound healing,

underscoring their therapeutic potential in T2DM (136,137).

In DR, SIRT1, SIRT3, SIRT5 and SIRT6 play important

roles by regulating insulin sensitivity, inflammatory responses and

glucose metabolism (138). More

specifically, in DK, Wei et al (139) reported that SIRT1 alleviates

disease progression by regulating ERS and decreasing the apoptosis

of corneal epithelial cells in diabetic rat corneal tissues.

Furthermore, another study found that SIRT1 expression was

downregulated in the trigeminal sensory neurons of diabetic mice.

However, the overexpression of SIRT1 led to the upregulation of its

downstream effector miR-182, which mitigated the harmful effects of

hyperglycemia by stimulating diabetic corneal nerve regeneration.

These findings suggest that targeting SIRT1 may be a potential

therapeutic approach for diabetic sensory nerve regeneration and DK

(140). Similarly, Hu et

al (141) demonstrated that

HG (25 mM D-glucose) reduced SIRT3 expression and impaired

mitophagy in both TKE2 cells and corneal tissues from

Ins2Akita/+mice. Conversely, the overexpression of SIRT3

has been shown to promote wound healing by upregulating mitophagy

under HG conditions (142). These

results indicate that SIRT3 may positively impact corneal repair in

DK (Table I).

| Table I.Nuclear proteins involved in diabetic

keratopathy. |

Table I.

Nuclear proteins involved in diabetic

keratopathy.

| Nuclear

proteins | Protein class | Isotypes | Genes | Biological

effects | Agonists and

inhibitors |

|---|

| PPARs | Nuclear receptors,

transcription factors (77) | PPARα, PPARγ, PPARδ

(77) | PPARA (22q13.31),

PPARG (3p25.2), PPARD (6p21.31) (78) | Protects the

corneal nerve (83);

anti-fibrogenic (87) |

Fenofibratea (84–86),

thiazolidinedione class drugsa (87,89),

GW501516a (90) |

| HMGB1 | Chromosomal protein

(92,93) | - | HMGB1 (93) | Promotes the

development of diabetic keratopathy (17) and diabetic neuropathy | Dipotassium

glycyrrhi zinate-based micelle formulation encapsulating active

agentsb (105) |

| EZH2 | Catalytic subunit

of polycomb repressive complex 2 (73,74) | - | EZH2 (7q35)

(106) | Promotes corneal

scarring and fibrosis (111,112), corneal oxidative stress and

neovascularization (113) and

human corneal endothelial cell apoptosis (108) |

EPZ-6438b (112), 3-deazaneplanocin Ab (113) |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and

tumor suppressor gene (115,117) | PTENα, PTENβ, PTENε

(118) | PTEN (10q23)

(115) | Decreases insulin

sensitivity and causes insulin resistance (117); inhibits corneal epithelium and

nerve regeneration (122,123) |

BpV(pic)b and BpV(Phen)b (123); BpV(Pic)b (124); HUMSC-sEVsb (125) |

| SIRTs |

NAD+-dependent lysine

deacetylases (126) | SIRT1, SIRT2,

SIRT3, SIRT4, SIRT5, SIRT6, SIRT7 (128) | SIRT1 (10q21.3),

SIRT2 (19q13.3), SIRT3 (11p15.5), SIRT4 (12q24.31), SIRT5 (6p23),

SIRT6 (19p13.3), SIRT7 (17q25.3) (127) | Regulates

endoplasmic reticulum stress and decreases corneal epithelial cell

apoptosis (139); stimulates

diabetic corneal nerve regeneration (140); promotes wound healing (141,142) | - |

Conclusions and prospects

DM is a global public health problem, and its

complications seriously impact quality of life. Although DK has a

high prevalence it has long been overlooked (2). Clinically, it is characterized by dry

eye, corneal epithelial erosions, superficial punctate keratopathy

and delayed epithelial regeneration, which in severe cases may

result in impaired vision or permanent vision loss.

NPs regulate gene expression and cellular

physiological activities in the cell nucleus, and their

dysregulation is closely associated with the development of

multiple diseases. In DK, the aberrant expression or dysfunction of

NPs such as PPARs, HMGB1, EZH2, PTEN and SIRT1 has been implicated

in the pathological process of keratopathy. PPAR agonists have

shown therapeutic potential in DK by ameliorating corneal

neuropathy and enhancing wound healing, while the blockade of HMGB1

suppresses inflammatory responses and promotes corneal healing.

EZH2 contributes to corneal scar formation, and its inhibition may

prevent corneal fibrosis. PTEN negative regulates the PI3K/Akt

pathway, and its inhibition helps to promote corneal epithelial

regeneration and nerve repair. Conversely, SIRT1 exerts protective

effects by attenuating ERS and inflammation. Collectively, these

findings suggest novel targets and strategies for the treatment of

DK.

While other reviews have broadly summarized the

corneal complications of DM, the present review is the first to

specifically examine the functional interplay between specific NPs,

namely PPARs, EZH2 and SIRTs, in all corneal layers in DK. However,

research on NPs in DK is at an early stage, and numerous questions

remain to be addressed. For example, the specific molecular

mechanisms underlying the functions of NPs in DK have not yet been

fully elucidated, and their interactions with other cell signaling

pathways merit further exploration. In addition, the clinical

application of NPs as potential biomarkers or therapeutic targets

requires validation in additional clinical studies to establish

their safety and efficacy.

In conclusion, NPs play complex and diverse roles in

DK. Investigating these mechanisms contributes to an in-depth

understanding of the pathophysiological process of DK, and also

provides an important theoretical basis for the development of

novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Continued research in

this field may be expected to provide more effective solutions for

DK and improve the quality of life of diabetic patients.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Henan Provincial

Science and Technology Development Program of China (grant no.

232102310104), and Cultivation Project for Innovation Team in

Teachers' Teaching Proficiency by Zhengzhou Health College (grant

no. 2024jxcxtd01).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

HX and ZJ were responsible for conceptualization,

methodology, investigation, formal analysis and writing the

original draft of the manuscript. YW collected and collated

clinical literature on DK phenotypes and classification, assisted

in analyzing clinical evidence of corneal confocal microscopy for

DK, and verifying key clinical data such as DK prevalence to ensure

the review's clinical conclusions were evidence-based. XH and WD

made contributed to data analysis and interpretation by designing

key figures, conducting statistical analysis of visualized data,

drafting the “Structure and Function of the Cornea” section and

figure legends, and critically revising the manuscript. YC and QZ

contributed to data acquisition by curating and verifying

experimental resources and to data interpretation by optimizing

figure layouts and cross-validating visualized data, while also

revising figure descriptions and approving the final version. XJ,

SJ and YD contributed to conceptualization, resources, supervision,

funding acquisition, and the review and editing of the manuscript.

Data authentication is not applicable. All authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

DK

|

diabetic keratopathy

|

|

DM

|

diabetes mellitus

|

|

NPs

|

nuclear proteins

|

|

PPARs

|

peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptors

|

|

HMGB1

|

high-mobility group box 1

|

|

EZH2

|

enhancer of zeste homolog 2

|

|

PTEN

|

phosphatase and tensin homolog

|

|

SIRT

|

sirtuin

|

|

DR

|

diabetic retinopathy

|

|

NLSs

|

nuclear localization signals

|

|

NPC

|

nuclear pore complex

|

|

CCT

|

central corneal thickness

|

|

ECD

|

endothelial cell density

|

|

AGEs

|

advanced glycosylation end

products

|

|

PCNP

|

PEST-containing nuclear protein

|

|

DCN

|

diabetic corneal neuropathy

|

|

PRC2

|

polycomb repressive complex 2

|

References

|

1

|

Bodke H, Wagh V and Kakar G: Diabetes

mellitus and prevalence of other comorbid conditions: A systematic

review. Cureus. 15:e493742023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M,

Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, Stein C, Basit A, Chan JCN, Mbanya JC, et

al: IDF diabetes atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes

prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes

Res Clin Pract. 183:1091192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Cole JB and Florez JC: Genetics of

diabetes mellitus and diabetes complications. Nat Rev Nephrol.

16:377–390. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Zhu L, Titone R and Robertson DM: The

impact of hyperglycemia on the corneal epithelium: Molecular

mechanisms and insight. Ocul Surf. 17:644–654. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zhao H, He Y, Ren YR and Chen BH: Corneal

alteration and pathogenesis in diabetes mellitus. Int J Ophthalmol.

12:1939–1950. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Lyu Y, Zeng X, Li F and Zhao S: The effect

of the duration of diabetes on dry eye and corneal nerves. Cont

Lens Anterior Eye. 42:380–385. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Teo ZL, Tham YC, Yu M, Chee ML, Rim TH,

Cheung N, Bikbov MM, Wang YX, Tang Y, Lu Y, et al: Global

prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and projection of burden through

2045: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology.

128:1580–1591. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Priyadarsini S, Whelchel A, Nicholas S,

Sharif R, Riaz K and Karamichos D: Diabetic keratopathy: Insights

and challenges. Surv Ophthalmol. 65:513–529. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Han SB, Yang HK and Hyon JY: Influence of

diabetes mellitus on anterior segment of the eye. Clin Interv

Aging. 14:53–63. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Buonfiglio F, Wasielica-Poslednik J,

Pfeiffer N and Gericke A: Diabetic keratopathy: Redox signaling

pathways and therapeutic prospects. Antioxidants (Basel).

13:1202024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Pelley JW: 17-Protein synthesis and

degradation. Elsevier's Integrated Biochemistry. Pelley JW: Mosby,

Philadelphia: pp. 147–158. 2007, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Goodman SR: Chapter 5-regulation of gene

expression. Medical Cell Biology. (Third Edition). Goodman SR:

Academic Press; San Diego, CA: pp. 149–190. 2008

|

|

13

|

Bernhofer M, Goldberg T, Wolf S, Ahmed M,

Zaugg J, Boden M and Rost B: NLSdb-major update for database of

nuclear localization signals and nuclear export signals. Nucleic

Acids Res. 46:D503–D508. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Li W and Jiang H: Nuclear protein

condensates and their properties in regulation of gene expression.

J Mol Biol. 434:1671512022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Escandon P, Vasini B, Whelchel AE,

Nicholas SE, Matlock HG, Ma JX and Karamichos D: The role of

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in healthy and diseased

eyes. Exp Eye Res. 208:1086172021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Khatol P, Saraf S and Jain A: Peroxisome

proliferated activated receptors (PPARs): Opportunities and

challenges for ocular therapy. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst.

35:65–97. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hou Y, Lan J, Zhang F and Wu X: Expression

profiles and potential corneal epithelial wound healing regulation

targets of high-mobility group box 1 in diabetic mice. Exp Eye Res.

202:1083642021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Peng Y, Bui CH, Zhang XJ, Chen JS, Tham

CC, Chu WK, Chen LJ, Pang CP and Yam JC: The role of EZH2 in ocular

diseases: A narrative review. Epigenomics. 15:557–570. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Rocher N: Anatomy and physiology of the

human eye. Soins. 30–31. 2010.(In French). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Mobaraki M, Abbasi R, Omidian Vandchali S,

Ghaffari M, Moztarzadeh F and Mozafari M: Corneal repair and

regeneration: Current concepts and future directions. Front Bioeng

Biotechnol. 7:1352019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Meek KM and Knupp C: Corneal structure and

transparency. Prog Retin Eye Res. 49:1–16. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lavker RM, Kaplan N, Wang J and Peng H:

Corneal epithelial biology: Lessons stemming from old to new. Exp

Eye Res. 198:1080942020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Doughty MJ and Jonuscheit S: Corneal

structure, transparency, thickness and optical density

(densitometry), especially as relevant to contact lens wear-a

review. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 42:238–245. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Luke RA, Braun RJ, Driscoll TA, Begley CG

and Awisi-Gyau D: Parameter estimation for evaporation-driven tear

film thinning. Bull Math Biol. 82:712020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Braun RJ, King-Smith PE, Begley CG, Li L

and Gewecke NR: Dynamics and function of the tear film in relation

to the blink cycle. Prog Retin Eye Res. 45:132–164. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Wilson SL, El Haj AJ and Yang Y: Control

of scar tissue formation in the cornea: Strategies in clinical and

corneal tissue engineering. J Funct Biomater. 3:642–687. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Melnyk S and Bollag WB: Aquaporins in the

cornea. Int J Mol Sci. 25:37482024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Sridhar MS: Anatomy of cornea and ocular

surface. Indian J Ophthalmol. 66:190–194. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wilson SE: Bowman's layer in the

cornea-structure and function and regeneration. Exp Eye Res.

195:1080332020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

DelMonte DW and Kim T: Anatomy and

physiology of the cornea. J Cataract Refract Surg. 37:588–598.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Hassell JR and Birk DE: The molecular

basis of corneal transparency. Exp Eye Res. 91:326–335. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Marfurt CF, Cox J, Deek S and Dvorscak L:

Anatomy of the human corneal innervation. Exp Eye Res. 90:478–492.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

de Oliveira RC and Wilson SE: Descemet's

membrane development, structure, function and regeneration. Exp Eye

Res. 197:1080902020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Ljubimov AV: Diabetic complications in the

cornea. Vision Res. 139:138–152. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Mukhija R, Gupta N, Vashist P, Tandon R

and Gupta SK: Population-based assessment of visual impairment and

pattern of corneal disease: Results from the CORE (corneal opacity

rural epidemiological) study. Br J Ophthalmol. 104:994–998. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Chang YS, Tai MC, Ho CH, Chu CC, Wang JJ,

Tseng SH and Jan RL: Risk of corneal ulcer in patients with

diabetes mellitus: A retrospective large-scale cohort study. Sci

Rep. 10:73882020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Yeung A and Dwarakanathan S: Diabetic

keratopathy. Dis Mon. 67:1011352021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Huang C, Liao R, Wang F and Tang S:

Characteristics of reconstituted tight junctions after corneal

epithelial wounds and ultrastructure alterations of corneas in type

2 diabetic rats. Curr Eye Res. 41:783–790. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Shih KC, Lam KS and Tong L: A systematic

review on the impact of diabetes mellitus on the ocular surface.

Nutr Diabetes. 7:e2512017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Alfuraih S, Barbarino A, Ross C, Shamloo

K, Jhanji V, Zhang M and Sharma A: Effect of high glucose on ocular

surface epithelial cell barrier and tight junction proteins. Invest

Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 61:32020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Liu T, Sun DP, Li DF, Bi WJ and Xie LX:

Observation and quantification of diabetic keratopathy in type 2

diabetes patients using in vivo laser confocal microscopy. Zhonghua

Yan Ke Za Zhi. 56:754–760. 2020.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Xu KP, Li Y, Ljubimov AV and Yu FS: High

glucose suppresses epidermal growth factor

receptor/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway and

attenuates corneal epithelial wound healing. Diabetes.

58:1077–1085. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Lan X, Zhang W, Zhu J, Huang H, Mo K, Guo

H, Zhu L, Liu J, Li M, Wang L, et al: dsRNA induced IFNβ-MMP13 axis

drives corneal wound healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 63:142022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Di G, Du X, Qi X, Zhao X, Duan H, Li S,

Xie L and Zhou Q: Mesenchymal stem cells promote diabetic corneal

epithelial wound healing through TSG-6-dependent stem cell

activation and macrophage switch. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci.

58:4344–4354. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Bikbova G, Oshitari T, Baba T, Bikbov M

and Yamamoto S: Diabetic corneal neuropathy: Clinical perspectives.

Clin Ophthalmol. 12:981–987. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Liu YC, Lin MT and Mehta JS: Analysis of

corneal nerve plexus in corneal confocal microscopy images. Neural

Regen Res. 16:690–691. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Kaplan H, Yüzbaşıoğlu S, Vural G and

Gümüşyayla Ş: Investigation of small fiber neuropathy in patients

with diabetes mellitus by corneal confocal microscopy. Neurophysiol

Clin. 54:1029552024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Mokhtar SBA, van der Heide FCT, Oyaert

KAM, van der Kallen CJH, Berendschot TTJM, Scarpa F, Colonna A, de

Galan BE, van Greevenbroek MMJ, Dagnelie PC, et al: (Pre)diabetes

and a higher level of glycaemic measures are continuously

associated with corneal neurodegeneration assessed by corneal

confocal microscopy: The maastricht study. Diabetologia.

66:2030–2041. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Carmichael J, Fadavi H, Ishibashi F,

Howard S, Boulton AJM, Shore AC and Tavakoli M: Implementation of

corneal confocal microscopy for screening and early detection of

diabetic neuropathy in primary care alongside retinopathy

screening: Results from a feasibility study. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 13:e8915752022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Banerjee M, Mukhopadhyay P and Ghosh S,

Basu M, Pandit A, Malik R and Ghosh S: Corneal confocal microscopy

abnormalities in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes.

Endocr Pract. 29:692–698. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

De Clerck EEB, Schouten JSAG, Berendschot

TTJM, Koolschijn RS, Nuijts RMMA, Schram MT, Schaper NC, Henry RMA,

Dagnelie PC, Ruggeri A, et al: Reduced corneal nerve fibre length

in prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: The maastricht study. Acta

Ophthalmol. 98:485–491. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Mvilongo C, Akono ME, Nkoudou D, Nanfack

C, Nomo A, Dim R and Eballé AO: Clinical profile of corneal

sensitivity in diabetic patients: A case-control study. J Fr

Ophtalmol. 47:1042122024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Schiano Lomoriello D, Abicca I, Parravano

M, Giannini D, Russo B, Frontoni S and Picconi F: Early alterations

of corneal subbasal plexus in uncomplicated type 1 diabetes

patients. J Ophthalmol. 2019:98182172019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Torricelli AA and Wilson SE: Cellular and

extracellular matrix modulation of corneal stromal opacity. Exp Eye

Res. 129:151–160. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Priyadarsini S, McKay TB, Sarker-Nag A,

Allegood J, Chalfant C, Ma JX and Karamichos D: Complete metabolome

and lipidome analysis reveals novel biomarkers in the human

diabetic corneal stroma. Exp Eye Res. 153:90–100. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Sinha NR, Balne PK, Bunyak F, Hofmann AC,

Lim RR, Mohan RR and Chaurasia SS: Collagen matrix perturbations in

corneal stroma of Ossabaw mini pigs with type 2 diabetes. Mol Vis.

27:666–678. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Kalteniece A, Ferdousi M, Azmi S, Marshall

A, Soran H and Malik RA: Keratocyte density is reduced and related

to corneal nerve damage in diabetic neuropathy. Invest Ophthalmol

Vis Sci. 59:3584–3590. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Gad H, Al-Jarrah B, Saraswathi S, Mohamed

S, Kalteniece A, Petropoulos IN, Khan A, Ponirakis G, Singh P,

Khodor SA, et al: Corneal confocal microscopy identifies a

reduction in corneal keratocyte density and sub-basal nerves in

children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Br J Ophthalmol.

106:1368–1372. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Eghrari AO, Riazuddin SA and Gottsch JD:

Overview of the cornea: Structure, function, and development. Prog

Mol Biol Transl Sci. 134:7–23. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

El-Agamy A and Alsubaie S: Corneal

endothelium and central corneal thickness changes in type 2

diabetes mellitus. Clin Ophthalmol. 11:481–486. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Goldstein AS, Janson BJ, Skeie JM, Ling JJ

and Greiner MA: The effects of diabetes mellitus on the corneal

endothelium: A review. Surv Ophthalmol. 65:438–450. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Yalcın SO, Kaplan AT and Sobu E: Corneal

endothelial cell morphology and optical coherence tomography

findings in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Eur J

Ophthalmol. 33:1331–1339. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Amador-Muñoz DP, Conforti V, Matheus LM,

Molano-Gonzalez N and Payán-Gómez C: Diabetes mellitus type 1 has a

higher impact on corneal endothelial cell density and pachymetry

than diabetes mellitus type 2, independent of age: A

meta-regression model. Cornea. 41:965–973. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Chowdhury B, Bhadra S, Mittal P and Shyam

K: Corneal endothelial morphology and central corneal thickness in

type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Indian J Ophthalmol.

69:1718–1724. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Kim YJ and Kim TG: The effects of type 2

diabetes mellitus on the corneal endothelium and central corneal

thickness. Sci Rep. 11:83242021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Taşlı NG, Icel E, Karakurt Y, Ucak T,

Ugurlu A, Yilmaz H and Akbas EM: The findings of corneal specular

microscopy in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus. BMC

Ophthalmol. 20:2142020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Zhang K, Zhao L, Zhu C, Nan W, Ding X,

Dong Y and Zhao M: The effect of diabetes on corneal endothelium: A

meta-analysis. BMC Ophthalmol. 21:782021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Papadakou P, Chatziralli I, Papathanassiou

M, Lambadiari V, Siganos CS, Theodossiadis P and Kozobolis V: The

effect of diabetes mellitus on corneal endothelial cells and

central corneal thickness: A case-control study. Ophthalmic Res.

63:550–554. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Sekimoto T and Yoneda Y: Intrinsic and

extrinsic negative regulators of nuclear protein transport

processes. Genes Cells. 17:525–535. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Cronshaw JM, Krutchinsky AN, Zhang W,

Chait BT and Matunis MJ: Proteomic analysis of the mammalian

nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol. 158:915–927. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Jeon P, Ham HJ, Park S and Lee JA:

Regulation of cellular ribonucleoprotein granules: From assembly to

degradation via post-translational modification. Cells.

11:20632022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Shen F, Kirmani KZ, Xiao Z, Thirlby BH,

Hickey RJ and Malkas LH: Nuclear protein isoforms: Implications for

cancer diagnosis and therapy. J Cell Biochem. 112:756–760. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Simon JA and Lange CA: Roles of the EZH2

histone methyltransferase in cancer epigenetics. Mutat Res.

647:21–29. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Glancy E, Ciferri C and Bracken AP:

Structural basis for PRC2 engagement with chromatin. Curr Opin

Struct Biol. 67:135–144. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Khan NH, Chen HJ, Fan Y, Surfaraz M,

Ahammad MF, Qin YZ, Shahid M, Virk R, Jiang E, Wu DD and Ji XY:

Biology of PEST-containing nuclear protein: A potential molecular

target for cancer research. Front Oncol. 12:7845972022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Brown JD and Plutzky J: Peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptors as transcriptional nodal points

and therapeutic targets. Circulation. 115:518–533. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Chow BJ, Lee IXY, Liu C and Liu YC:

Potential therapeutic effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptors on corneal diseases. Exp Biol Med (Maywood).

249:101422024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Kim IS, Silwal P and Jo EK: Peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor-targeted therapies: Challenges upon

infectious diseases. Cells. 12:6502023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Mirza AZ, Althagafi II and Shamshad H:

Role of PPAR receptor in different diseases and their ligands:

Physiological importance and clinical implications. Eur J Med Chem.

166:502–513. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Jain N, Bhansali S, Kurpad AV, Hawkins M,

Sharma A, Kaur S, Rastogi A and Bhansali A: Effect of a dual PPAR

α/γ agonist on insulin sensitivity in patients of type 2 diabetes

with hypertriglyceridemia-randomized double-blind

placebo-controlled trial. Sci Rep. 9:190172019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Lin Y, Wang Y and Li PF: PPARα: An

emerging target of metabolic syndrome, neurodegenerative and

cardiovascular diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

13:10749112022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Hu P, Li K, Peng X, Kan Y, Li H, Zhu Y,

Wang Z, Li Z, Liu HY and Cai D: Nuclear receptor PPARα as a

therapeutic target in diseases associated with lipid metabolism

disorders. Nutrients. 15:47722023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Matlock HG, Qiu F, Malechka V, Zhou K,

Cheng R, Benyajati S, Whelchel A, Karamichos D and Ma JX:

Pathogenic role of PPARα downregulation in corneal nerve

degeneration and impaired corneal sensitivity in diabetes.

Diabetes. 69:1279–1291. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Liang W, Huang L, Whelchel A, Yuan T, Ma

X, Cheng R, Takahashi Y, Karamichos D and Ma JX: Peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor-α (PPARα) regulates wound healing

and mitochondrial metabolism in the cornea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

120:e22175761202023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Teo CHY, Lin MT, Lee IXY, Koh SK, Zhou L,

Goh DS, Choi H, Koh HWL, Lam AYR, Lim PS, et al: Oral peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor-α agonist enhances corneal nerve

regeneration in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes.

72:932–946. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Mansoor H, Lee IXY, Lin MT, Ang HP, Xue

YC, Krishaa L, Patil M, Koh SK, Tan HC, Zhou L and Liu YC: Topical

and oral peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α agonist

ameliorates diabetic corneal neuropathy. Sci Rep. 14:134352024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Jeon KI, Kulkarni A, Woeller CF, Phipps

RP, Sime PJ, Hindman HB and Huxlin KR: Inhibitory effects of PPARγ

ligands on TGF-β1-induced corneal myofibroblast transformation. Am

J Pathol. 184:1429–4145. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Jeon KI, Phipps RP, Sime PJ and Huxlin KR:

Inhibitory effects of PPARγ ligands on TGF-β1-induced CTGF

expression in cat corneal fibroblasts. Exp Eye Res. 138:52–58.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Wang J, Chen S, Zhao X, Guo Q, Yang R,

Zhang C, Huang Y, Ma L and Zhao S: Effect of PPARγ on oxidative

stress in diabetes-related dry eye. Exp Eye Res. 231:1094982023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Tobita Y, Arima T, Nakano Y, Uchiyama M,

Shimizu A and Takahashi H: Peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor beta/delta agonist suppresses inflammation and promotes

neovascularization. Int J Mol Sci. 21:52962020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Goodwin GH and Johns EW: Isolation and

characterisation of two calf-thymus chromatin non-histone proteins

with high contents of acidic and basic amino acids. Eur J Biochem.

40:215–219. 1973. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Thomas JO and Stott K: H1 and HMGB1:

Modulators of chromatin structure. Biochem Soc Trans. 40:341–346.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Kang R, Chen R, Zhang Q, Hou W, Wu S, Cao

L, Huang J, Yu Y, Fan XG, Yan Z, et al: HMGB1 in health and

disease. Mol Aspects Med. 40:1–116. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Bell CW, Jiang W, Reich CF III and

Pisetsky DS: The extracellular release of HMGB1 during apoptotic

cell death. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 291:C1318–C1325. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

van Beijnum JR, Buurman WA and Griffioen

AW: Convergence and amplification of toll-like receptor (TLR) and

receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) signaling

pathways via high mobility group B1 (HMGB1). Angiogenesis.

11:91–99. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Zhang S, Zhong J, Yang P, Gong F and Wang

CY: HMGB1, an innate alarmin, in the pathogenesis of type 1

diabetes. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 3:24–38. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Lotze MT and Tracey KJ: High-mobility

group box 1 protein (HMGB1): Nuclear weapon in the immune arsenal.

Nat Rev Immunol. 5:331–342. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Taniguchi N, Kawahara K, Yone K,

Hashiguchi T, Yamakuchi M, Goto M, Inoue K, Yamada S, Ijiri K,

Matsunaga S, et al: High mobility group box chromosomal protein 1

plays a role in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis as a novel

cytokine. Arthritis Rheum. 48:971–981. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Dasu MR, Devaraj S, Park S and Jialal I:

Increased toll-like receptor (TLR) activation and TLR ligands in

recently diagnosed type 2 diabetic subjects. Diabetes Care.

33:861–868. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Skrha J Jr, Kalousová M, Svarcová J,

Muravská A, Kvasnička J, Landová L, Zima T and Skrha J:

Relationship of soluble RAGE and RAGE ligands HMGB1 and EN-RAGE to

endothelial dysfunction in type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Exp

Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 120:277–281. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Wu H, Chen Z, Xie J, Kang LN, Wang L and

Xu B: High mobility group box-1: A missing link between diabetes

and its complications. Mediators Inflamm. 2016:38961472016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Steinle JJ: Role of HMGB1 signaling in the

inflammatory process in diabetic retinopathy. Cell Signal.

73:1096872020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Feng L, Liang L, Zhang S, Yang J, Yue Y

and Zhang X: HMGB1 downregulation in retinal pigment epithelial

cells protects against diabetic retinopathy through the

autophagy-lysosome pathway. Autophagy. 18:320–339. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Guo X, Shi Y, Du P, Wang J, Han Y, Sun B

and Feng J: HMGB1/TLR4 promotes apoptosis and reduces autophagy of

hippocampal neurons in diabetes combined with OSA. Life Sci.

239:1170202019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Hou Y, Xin M, Li Q and Wu X: Glycyrrhizin

micelle as a genistein nanocarrier: Synergistically promoting

corneal epithelial wound healing through blockage of the HMGB1

signaling pathway in diabetic mice. Exp Eye Res. 204:1084542021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Liu Y and Yang Q: The roles of EZH2 in

cancer and its inhibitors. Med Oncol. 40:1672023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Cao J, Pontes KC, Heijkants RC, Brouwer

NJ, Groenewoud A, Jordanova ES, Marinkovic M, van Duinen S,

Teunisse AF, Verdijk RM, et al: Overexpression of EZH2 in

conjunctival melanoma offers a new therapeutic target. J Pathol.

245:433–444. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Lin Y, Su H, Zou B and Huang M: EZH2

promotes corneal endothelial cell apoptosis by mediating H3K27me3

and inhibiting HO-1 transcription. Curr Eye Res. 48:1122–1132.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Zhang L, Wang L, Hu XB, Hou M, Xiao Y,

Xiang JW, Xie J, Chen ZG, Yang TH, Nie Q, et al: MYPT1/PP1-mediated

EZH2 dephosphorylation at S21 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal

transition in fibrosis through control of multiple families of

genes. Adv Sci (Weinh). 9:e21055392022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Thomas AA, Feng B and Chakrabarti S:

ANRIL: A regulator of VEGF in diabetic retinopathy. Invest

Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 58:470–480. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Wilson SE: Corneal myofibroblasts and

fibrosis. Exp Eye Res. 201:1082722020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Liao K, Cui Z, Zeng Y, Liu J, Wang Y, Wang

Z, Tang S and Chen J: Inhibition of enhancer of zeste homolog 2

prevents corneal myofibroblast transformation in vitro. Exp Eye

Res. 208:1086112021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Wan SS, Pan YM, Yang WJ, Rao ZQ and Yang

YN: Inhibition of EZH2 alleviates angiogenesis in a model of

corneal neovascularization by blocking FoxO3a-mediated oxidative

stress. FASEB J. 34:10168–10181. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Duraisamy AJ, Mishra M and Kowluru RA:

Crosstalk between histone and DNA methylation in regulation of

retinal matrix metalloproteinase-9 in diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol

Vis Sci. 58:6440–6448. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Liu T, Wang Y, Wang Y and Chan AM:

Multifaceted regulation of PTEN subcellular distributions and

biological functions. Cancers (Basel). 11:12472019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Ho J, Cruise ES, Dowling RJO and Stambolic

V: PTEN nuclear functions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med.

10:a0360792020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Li A, Qiu M, Zhou H, Wang T and Guo W:

PTEN, insulin resistance and cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 23:3667–3676.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Liu A, Zhu Y, Chen W, Merlino G and Yu Y:

PTEN dual lipid- and protein-phosphatase function in tumor

progression. Cancers (Basel). 14:36662022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Li X, Yang P, Hou X and Ji S:

Post-translational modification of PTEN protein: Quantity and

activity. Oncol Rev. 18:14302372024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Li YZ, Di Cristofano A and Woo M:

Metabolic role of PTEN in insulin signaling and resistance. Cold

Spring Harb Perspect Med. 10:a0361372020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

D'Amico AG, Maugeri G, Magrì B, Bucolo C

and D'Agata V: Targeting the PINK1/Parkin pathway: A new

perspective in the prevention and therapy of diabetic retinopathy.

Exp Eye Res. 247:1100242024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Dai Y, Zhao X, Chen P, Yu Y, Wang Y and

Xie L: Neuropeptide FF promotes recovery of corneal nerve injury

associated with hyperglycemia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci.

56:7754–7765. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Li J, Qi X, Wang X, Li W, Li Y and Zhou Q:

PTEN inhibition facilitates diabetic corneal epithelial

regeneration by reactivating Akt signaling pathway. Transl Vis Sci

Technol. 9:52020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Zhang W, Yu F, Yan C, Shao C, Gu P, Fu Y,

Sun H and Fan X: PTEN inhibition accelerates corneal endothelial

wound healing through increased endothelial cell division and

migration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 61:192020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

125

|

Liu X, Li X, Wu G, Qi P, Zhang Y, Liu Z,

Li X, Yu Y, Ye X, Li Y, et al: Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem

cell-derived small extracellular vesicles deliver miR-21 to promote

corneal epithelial wound healing through PTEN/PI3K/Akt pathway.

Stem Cells Int. 2022:12525572022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Penteado AB, Hassanie H, Gomes RA, Silva

Emery FD and Goulart Trossini GH: Human sirtuin 2 inhibitors, their

mechanisms and binding modes. Future Med Chem. 15:291–311. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Vassilopoulos A, Fritz KS, Petersen DR and

Gius D: The human sirtuin family: Evolutionary divergences and

functions. Hum Genomics. 5:485–496. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Wu QJ, Zhang TN, Chen HH, Yu XF, Lv JL,

Liu YY, Liu YS, Zheng G, Zhao JQ, Wei YF, et al: The sirtuin family

in health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:4022022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Tao Z, Jin Z, Wu J, Cai G and Yu X:

Sirtuin family in autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol.

14:11862312023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Guarente L: Franklin H: Epstein lecture:

Sirtuins, aging, and medicine. N Engl J Med. 364:2235–2244. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Hong Q, Zhang L, Das B, Li Z, Liu B, Cai

G, Chen X, Chuang PY, He JC and Lee K: Increased podocyte Sirtuin-1

function attenuates diabetic kidney injury. Kidney Int.

93:1330–1343. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Hammer SS, Vieira CP, McFarland D, Sandler

M, Levitsky Y, Dorweiler TF, Lydic TA, Asare-Bediako B,

Adu-Agyeiwaah Y, Sielski MS, et al: Fasting and fasting-mimicking

treatment activate SIRT1/LXRα and alleviate diabetes-induced

systemic and microvascular dysfunction. Diabetologia. 64:1674–1689.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

133

|

Chandrasekaran K, Salimian M, Konduru SR,

Choi J, Kumar P, Long A, Klimova N, Ho CY, Kristian T and Russell

JW: Overexpression of Sirtuin 1 protein in neurons prevents and

reverses experimental diabetic neuropathy. Brain. 142:3737–3752.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

134

|

Li L, Zeng H, He X and Chen JX: Sirtuin 3

alleviates diabetic cardiomyopathy by regulating TIGAR and

cardiomyocyte metabolism. J Am Heart Assoc. 10:e0189132021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

135

|

Zhao K, Zhang H and Yang D: SIRT1 exerts

protective effects by inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress and

NF-κB signaling pathways. Front Cell Dev Biol. 12:14055462024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

136

|

Mihanfar A, Akbarzadeh M, Ghazizadeh

Darband S, Sadighparvar S and Majidinia M: SIRT1: A promising

therapeutic target in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Physiol

Biochem. 130:13–28. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

137

|

Prabhakar PK, Singh K, Kabra D and Gupta

J: Natural SIRT1 modifiers as promising therapeutic agents for

improving diabetic wound healing. Phytomedicine. 76:1532522020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

138

|

Nebbioso M, Lambiase A, Armentano M,

Tucciarone G, Sacchetti M, Greco A and Alisi L: Diabetic

retinopathy, oxidative stress, and sirtuins: An in depth look in

enzymatic patterns and new therapeutic horizons. Surv Ophthalmol.

67:168–183. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

139

|

Wei S, Fan J, Zhang X, Jiang Y, Zeng S,

Pan X, Sheng M and Chen Y: Sirt1 attenuates diabetic keratopathy by

regulating the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. Life Sci.