Introduction

Cell migration is a fundamental process in cell

biology and refers to the movement of cells from one location to

another. During cell migration, a series of elongated tubular

structures are produced at the trailing edge of the cell. Notably,

cell migration serves a key role in various biological processes,

including embryonic development, wound healing, immune response,

tissue regeneration and tumor metastasis (1). Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are

important mediators of intercellular communication, having notable

roles in various physiological and pathological processes; for

example, cancer cell-derived EVs can modulate the tumor

microenvironment, and EVs from endothelial progenitor cells can

induce a proangiogenic phenotype in terminally differentiated

endothelial cells and promote angiogenesis. Therefore, EVs exhibit

potential as novel biomarkers for diseases, therapeutic agents and

drug delivery vehicles (2,3). Previous studies have revealed that

EVs, including exosomes, microvesicles and apoptotic bodies, serve

important roles in a number of biological processes, including

intercellular communication, tissue homeostasis, cell

differentiation, organ development and remodeling (2–5). In

2015, a study by Ma et al (6) discovered a new type EV-like structure

and proposed the concept of migrasomes as novel cellular

organelles. Compared with other EVs, migrasomes exhibit distinct

structural, compositional and functional characteristics. With

diameters typically >1 µm, migrasomes are substantially larger

than exosomes, which have diameters of 30–150 nm. Unlike the

biogenesis of conventional EVs, such as exosomes derived from the

endosomal pathway or microvesicles generated via plasma membrane

budding, migrasome biogenesis is closely associated with cellular

migration (6). This unique

biogenesis mechanism suggests that migrasomes may serve as

migration trail markers, whereas exosomes predominantly facilitate

long-range intercellular communication (Table I). The discovery of migrasomes

provides a new perspective on how cells transport materials and

transmit information through extracellular structures (Fig. 1) (6–14).

| Table I.Comparison of migrasomes with other

extracellular vesicles. |

Table I.

Comparison of migrasomes with other

extracellular vesicles.

| Feature | Migrasomes | Exosomes | Microvesicles | Apoptotic

bodies | Oncosomes |

|---|

| Structure | Pomegranate-like

with intraluminal vesicles (0.5–3 µm) | Single-membrane

vesicles (30–150 nm) | Single-layered

lipid bilayer vesicles with irregular morphology (100 nm-1 µm) | Irregular large

vesicles (1–5 µm) | Heterogeneous large

vesicles (1–10 µm) |

| Biogenesis | Cell

migration-dependent, formed at retraction fibers | Multivesicular

body-plasma membrane fusion | Plasma membrane

budding | Apoptotic

process | Tumor cell membrane

budding |

| Key components | TSPAN4, TSPAN7,

integrin α5β1 | Tumor

susceptibility gene 101 protein, programmed cell death

6-interacting metalloproteinases protein, CD63, CD81 | Annexin A1, Annexin

A2 | Annexin V, caspase

3 | Tumor-associated

antigens, matrix |

| Lipid

composition | Enriched in

sphingolipids, including sphingomyelin cholesterol |

Sphingolipid-rich |

Phosphatidylserine-rich rich |

Phosphatidylserine-sphingolipids | Cholesterol, and

ceramide, and |

| Functions | Intercellular

communication, migration positioning, mitochondrial quality

control, disease association | Intercellular

communication, immune regulation | Intercellular

communication, inflammatory response | Intercellular

communication, debris clearance | Tumor metastasis,

microenvironment remodeling |

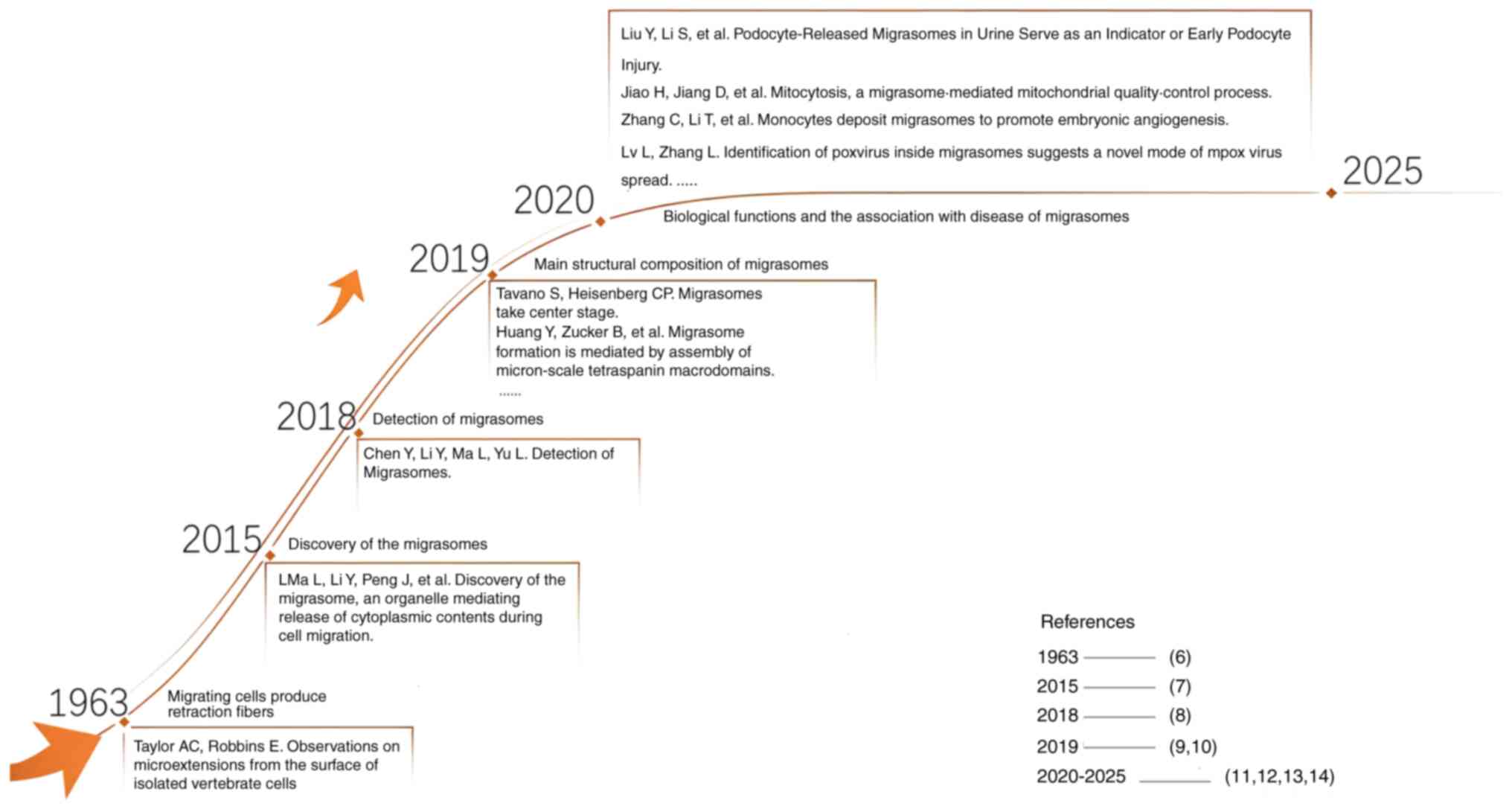

Discovery of migrasomes

The concept of migrasomes was first introduced

through observations of elongated tubular structures located at the

rear of migrating cells. In early studies of migrating cells,

Taylor and Robbins (7) discovered

and documented that elongated tubular structures formed when

migrating cells retracted from a substrate. They designated these

structures ‘retraction fibrils’, which were later named ‘retraction

fibers’ (RFs). Despite the initial lack of interest in these

structures from researchers, in 2012, a study at Tsinghua

University (Beijing, China) led by Yu (15) used transmission electron microscopy

to reveal the migration process of rat kidney cells. The study

revealed that cells leave behind RFs, which, upon further study,

are associated with vesicular structures ranging in diameter from

0.5 to 3 µm (6,15). These structures, situated behind

migrating cells that attach to the RFs left behind during cell

migration (6), were termed

pomegranate-like structures (PLSs) due to their resemblance to

pomegranate seeds. By purifying these structures, tetraspanin

(TSPAN)4, a distinct marker protein for PLS, was identified via

mass spectrometry, which served as a robust reference for future

migrasome research. Through knockdown of the negative regulator

Shank-associated RH domain interacting protein and treatment with

cell migration inhibitors, it was demonstrated that the formation

of PLSs is dependent on cell migration (6). Consequently, PLSs were renamed

‘migrasomes’, being defined as annular organelles formed at the

tips or intersections of RFs, or at the rear edge of migrating

cells (6).

Biological characteristics of

migrasomes

Structural features and main

components

The process of migrasome production can be

visualized dynamically via time-lapse imaging techniques (6,16).

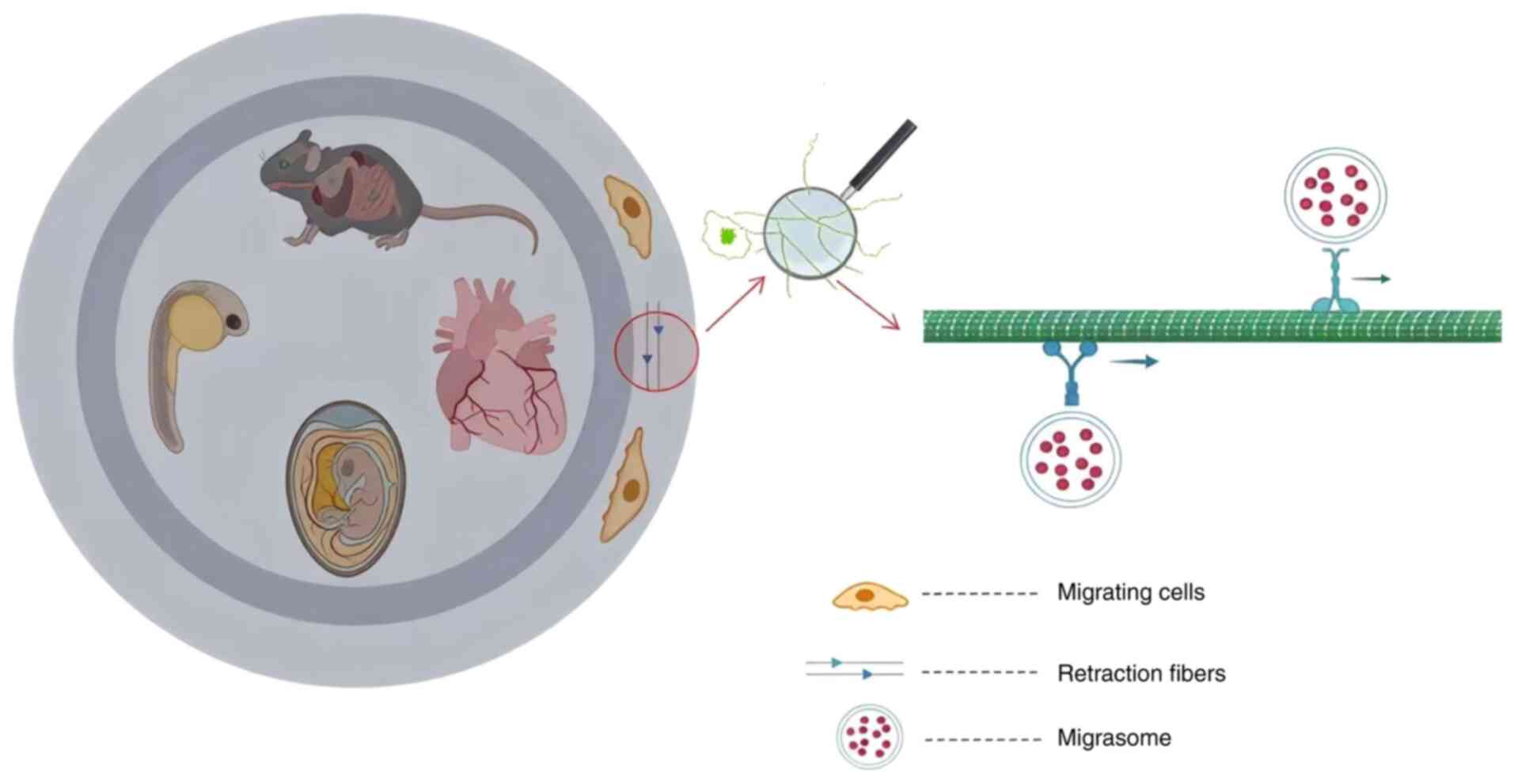

Subsequent studies have confirmed the widespread presence of

migrasomes across a variety of species, tissues, organs and cell

types, including rat eyes, lungs, intestines, zebrafish embryos,

chick chorioallantoic membranes and human coronary artery

endothelial cells (6,11,17–20)

(Fig. 2). As a novel type of

organelle, migrasomes are characterized as membrane-bound vesicles

with an ellipsoidal shape that harbor numerous smaller vesicles.

Their composition primarily comprises proteins, lipids and nucleic

acids (6,21). Notably, migrasomes exhibit a

distinctive protein profile, which includes membrane proteins,

contractile proteins, cytoskeletal proteins, chaperones, vesicular

trafficking proteins and cell adhesion proteins, >50% of which

are membrane-related (6,21,22).

These proteins are engaged predominantly in biological processes,

including cell migration, cell matrix adhesion, lipid degradation,

protein glycosylation and glycoprotein metabolism (21).

In comparison with the cell membrane and overall

lipid composition of the cell, migrasomes are notably enriched in

sphingolipids, such as sphingomyelin (SM), ceramide,

monosialodihexosylgangliosides and glycosphingolipids, including

monoglycosylceramide, diglycosylceramide and triglycosylceramide.

In a study by Liang et al (23), it was demonstrated that ceramide

and SM are essential for the formation and maintenance of

migrasomes. Furthermore, filipin III staining and quantitative

analysis revealed that migrasomes are enriched in cholesterol, an

important component for the physical properties and structural

integrity of the migrasome membrane; notably, TSPAN4, TSPAN7 and

cholesterol assemble into TSPAN-enriched microdomain (TEMs), the

enrichment of which stiffens the plasma membrane, facilitating

migrasome initiation (9). Ongoing

lipidomics analysis of migrasomes anticipates the discovery of

additional lipid components, thereby verifying the growing profile

of known biological characteristics and functions of

migrasomes.

Migrasomes are rich in nucleic acids. A study by Zhu

et al (24) employed

SYTO™ 14 fluorescence staining to demonstrate the

presence of RNA within migrasomes. Sequencing analyses revealed

that migrasomes predominantly contain long-chain mRNAs associated

with cell metabolism, intracellular membrane transport, cell

adhesion, vesicle fusion and the assembly of subcellular membrane

structures. These mRNAs can be translated into proteins within

recipient cells, participating in the biological responses of

recipient cells and regulating their life processes. For example,

the phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) mRNA delivered from

migrasomes to recipient cells is translated into the PTEN protein,

which inhibits the proliferation of the recipient cells (24). Nonetheless, the mechanisms of

migrasome RNA sorting and transport have yet to be elucidated, as

does the presence of DNA within migrasomes, necessitating further

investigation.

Markers of migrasomes

TSPAN4/7, and integrins α1, α3, α5 and β1, which are

expressed on the migrasome membrane, serve as important structural

markers of migrasomes, with TSPAN4 being the most distinguishing

marker, which exhibits the clearest expression when examined by

confocal microscopy (6).

Nonetheless, the detection of migrasomes using fluorescently

labeled marker proteins presents limitations, including complex

procedures, extended experimental duration and difficulty (25). Consequently, Chen et al

(25) investigated

fluorescently-labelled wheat germ agglutinin (WGA), which is a more

rapid, straightforward and less invasive marker than TSPAN4.

However, WGA may non-specifically bind to structures containing

sialic acid and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine, and its fluorescence

intensity can be influenced by various factors; for example, it may

also enter the cell and bind to intracellular components, leading

to enhanced nonspecific signals. In addition, different cell lines

or tissue types naturally exhibit variations in the glycosylation

levels of their cell membrane surfaces, which can also interfere

with the results, potentially limiting its application in

quantitative migrasome analysis (25). Additional specific protein markers

include N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase 1,

phosphatidylinositol glycan anchor biosynthesis class K,

carboxypeptidase Q and epidermal growth factor domain-specific

O-linked N-acetylglucosamine transferase; however, due to

marked variations in protein content across different cell types,

these markers are not uniformly present in migrasomes derived from

the same cell source (21,22). Furthermore, migrasome-associated

mRNAs can be labelled with the nucleic acid stain SYTO 14, making

them secondary markers for migrasomes (24,26).

Mechanisms of migrasome formation

During cell migration, RFs are extended from the

posterior end of the cell, with migrasomes situated at the termini

or bifurcations of these fibers (6). When RFs break, migrasomes may leak or

rupture, thereby releasing their contents into the extracellular

space (6). The formation of

migrasomes is a complex process that involves the regulation of

multiple molecules and signaling pathways.

Migrasome formation depends on cell

migration

The formation of migrasomes is contingent upon

cellular migration, a finding initially presented by Ma et

al (6). A study revealed that,

among 563 compounds capable of reducing migrasome numbers in

cultured cells, 507 also decreased RF formation, reinforcing the

association of migrasome production with cell migration (27). Subsequent research conducted by Fan

et al (28) revealed a

lower migrasome count in turning cells compared with those

migrating in a straight line, highlighting the importance of

migration continuity and speed in migrasome formation. Directional

changes during migration lead to fewer RFs and migrasomes, with the

removal of vimentin from cells having been shown to impair

migration and reduce migrasome numbers (29,30).

In conclusion, these findings suggested that the formation of

migrasomes is markedly regulated by cell migration behavior.

Nucleation: SM synthase (SMS)2 foci

are the starting point of migrasome biogenesis

SM, synthesized from ceramide by SMS, is a key

component of the plasma membrane, and is involved in signaling and

membrane transport (23). A

previous study has shown that SM and ceramide are enriched on

migrasomes and are present at the sites of migrasome formation;

furthermore, ceramide is unevenly distributed on different

migrasomes, and as migrasome biogenesis proceeds, SM levels

continuously increase, indicating that ceramide can be converted

into SM on migrasomes (23).

Hydrolyzing SM on migrasomes or knocking out ceramide synthase 5 to

reduce SM synthesis severely impairs the formation of migrasomes,

demonstrating the importance of SM for migrasome formation

(23).

Mammalian cells contain two principal types of SMS:

i) SMS1, which is localized in the Golgi apparatus; and ii) SMS2,

which is located in both the Golgi apparatus and the plasma

membrane (31). SMS2 synthesizes

SM from ceramide in the plasma membrane (23,31).

Consequently, it is plausible that SMS2 modulates migrasome

formation by facilitating SM production. Experimental evidence,

including the knockout of SMS2 and treatment with SMS2 inhibitors

that hinder SM synthesis, has demonstrated that migrasome formation

and growth are impeded in SM-depleted conditions, whereas the

reintroduction of SM restores migrasome production (23). Furthermore, impaired SM synthesis

reduces cholesterol recruitment, thereby affecting TEM assembly,

since TSPAN4, TSPAN7 and cholesterol assemble into TEMs, the

enrichment of which stiffens the plasma membrane, which is an

important condition for migrasome formation (9).

Research has revealed that SMS2 localizes to foci on

the basal membrane at the leading edge of a cell, which predestines

migrasome formation sites (23).

These foci mature into migrasomes during cell migration (23). Intracellular SMS2 foci initially

adhere to the section of the membrane of the migrating cell that is

interacting with a substrate to generate motility, resembling focal

adhesions (FAs), which are the sites where cells are linked to the

ECM in which integrins are highly enriched. However, previous

studies have failed to detect FA markers within migrasomes, and

active forms or markers of FA components such as integrin α5,

integrin β1 or the FA kinase paxillin do not colocalize with

intracellular SMS2 foci, underscoring that SMS2 focus formation is

independent of FAs (23,32). To elucidate the role of SMS2 foci

in migrasome formation, researchers identified an SMS2 mutant,

S217A, that cannot form foci. The formation of migrasomes in cells

expressing this mutation has been shown to be markedly diminished

(23). Notably, the inability to

form SMS2 foci prevents migrasome formation, even when exogenous SM

is added (23). These findings

suggest that SMS2 foci not only regulate migrasome formation by

synthesizing SM, but may also be involved in other important

intracellular signaling processes that are required for migrasome

biosynthesis and function. Future investigations should explore the

precise mechanisms of SMS2 focus assembly, the selection of

assembly sites and the adhesive mechanisms of SMS2 foci to fully

elucidate the contribution of SMS2 foci to migrasome formation and

function.

Expansion: TSPAN4 and cholesterol

mediate migrasome formation

TSPANs constitute a family of small hydrophobic

proteins characterized by four transmembrane domains, comprising a

total of 33 distinct members in mammalian cells. These proteins

facilitate the organization of functional higher-order protein

complexes on the cell membrane through interactions with adhesion

molecules, enzymes and signaling proteins, thereby forming the

structures known as TEMs (33,34).

Initial research identified TSPAN4 as a marker of migrasomes;

however, subsequent investigations have suggested that the roles of

TSPAN family members may extend beyond this initial

characterization. By establishing a stable normal rat kidney (NRK)

cell line that expresses various levels of TSPAN4 and green

fluorescent protein (GFP), a study by Huang et al (9) demonstrated that the overexpression of

14 types of TSPAN family members enhances migrasome formation in a

dose-dependent manner, with TSPAN4 exhibiting the most pronounced

effect. Conversely, knockout of the TSPAN4 gene was shown to

markedly reduce the number of migrasomes, underscoring the

importance of TSPAN4 for migrasome formation. During the migrasome

formation process, the signal from TSPAN4-GFP during the growth

phase of migrasomes rapidly re-emerges on their surface, whereas no

such recovery occurs when migrasomes tend to mature and stabilize

(9). Furthermore, high-speed

imaging revealed that TSPAN4-GFP forms rapidly-moving-discrete

spots on RFs and migrasomes that assemble on the surface of

migrasomes during their growth phase. Taken together, these

findings suggest that TSPAN4 is recruited to migrasomes

specifically during the growth phase (9).

By developing an in vitro system to simulate

migrasome formation, researchers have demonstrated that TSPAN4 and

cholesterol are sufficient to reconstitute migrasome-like

structures, further validating their role in this process (9). To elucidate how the assembly of TEMs

promotes migrasome formation, a theoretical model was proposed,

identifying three key energetic drivers: i) The bending energy of

the migrasome and RF membranes; ii) the membrane tension energy;

and iii) the boundary energy at the migrasome-RF interface

(9). A subsequent study using a

biomimetic system divided migrasome growth into two phases: i) A

local swelling phase, driven by membrane tension and potentially

other cellular factors (such as the cytoskeleton, specific lipids,

ion fluxes, mechanosensitive signaling and adhesion complexes); and

ii) a TSPAN4 migration-enrichment phase mediated by TSPAN family

proteins (35). Notably, the

biomimetic system lacks cytoskeletal components, which may regulate

migrasome formation in vivo; therefore, discrepancies

between artificial and cellular systems may exist (6,17,21,22).

TSPAN4, TSPAN7 and cholesterol assemble into TEMs, whose enrichment

stiffens the plasma membrane, facilitating migrasome initiation.

Changes in TSPAN4 curvature will affect the swelling of the plasma

membrane, the reduced intrinsic curvature of TSPAN4 directs TEMs to

low-curvature membrane swellings, stabilizing these protrusions and

promoting migrasome maturation (9,10,18,35,36).

In summary, TEMs composed of TSPAN4 and cholesterol are important

for migrasome biogenesis.

Maturation

Integrin and extracellular matrix (ECM) protein

pairing determines migrasome formation

Integrins are transmembrane receptors that bind ECM

proteins and link to the cytoskeleton via intracellular adapters.

These heterodimeric proteins, which are composed of α and β chains,

are important for cell adhesion, spreading, migration and matrix

remodeling (37). Migrasomes,

which adhere to ECM sites during cell migration, are enriched with

integrin α5β1, as revealed by mass spectrometry (32). Fluorescence staining confirms that

integrin β1 in migrasomes is in an activated, ligand-bound state,

demonstrating direct ECM binding. Three-dimensional imaging and

total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy have further

revealed the localization of integrins α5 and β1 at the migrasome

base, supporting their role in migrasome anchorage (32).

Although FAs also contain high integrin

concentrations, FA markers are absent in migrasomes, indicating a

distinct adhesion mechanism (32,38).

A functional study has revealed that NRK cells produce markedly

more migrasomes on fibronectin-coated surfaces than on laminin 511-

and collagen I-coated surfaces, with minimal migrasome formation on

uncoated coverslips. This increase in migrasome formation on

fibronectin-coated surfaces compared with other ECM components is

associated with an elevated integrin α5 expression in NRK cells, as

α5 knockout impairs migrasome production on fibronectin but not on

other ECM components (32).

Conversely, integrin α3 overexpression increases the number of

migrasomes on laminin 511. Similarly, integrin α1 overexpression

enhances migrasome formation on collagen IV in Chinese hamster

ovarian cells without affecting formation on other ECM components

(32). These findings demonstrate

that migrasome formation depends on specific integrin-ECM

pairings.

Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

(PIP2)-Rab35 axis regulates migrasome formation

PIP2, a plasma membrane lipid synthesized by

phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase type-1α kinases,

regulates key subcellular processes, including the regulation of

ion channels and transporters, clathrin-dependent and -independent

endocytosis, exocytosis regulation, actin polymerization, efficient

FA turnover and the regulation of cell-cell contacts) (39,40).

PIP2 localizes to migrasomes, as confirmed by phospholipase Cγ-PH

domain-GFP fusion protein probes and antibody staining (41). Kinetic experiments have revealed

that PIP2 recruitment precedes TSPAN4 and integrin α5 recruitment,

both of which are important for migrasome biogenesis.

Phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase type-1α (PIP5K1A)

inhibition disrupts migrasome formation, implicating PIP2 synthesis

in this process (41).

PIP2 likely functions by recruiting binding

partners, such as Rab35, a GTPase involved in organelle biogenesis,

endosomal trafficking and actin regulation (42). Rab35 is recruited to migrasome

formation sites in a PIP2-dependent manner, and its depletion

disrupts RF elongation and migrasome assembly (41). Rab35 also interacts with integrin

α5 via the GFFKR motif, recruiting integrins α5 to migrasome sites,

although the direct binding mechanism remains unconfirmed (41,43).

Thus, the PIP2-Rab35 axis orchestrates migrasome formation by

coupling lipid signaling with integrin trafficking. Future studies

should address PIP5K1A recruitment dynamics, Rab35-integrin α5

interactions and the clinical relevance of the PIP2-Rab35 signaling

axis in cancer and migration-associated diseases.

Roles of Rho-associated protein kinase

(ROCK)1 and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) in migrasome

formation

Through a chemical genetic screen designed to

identify compounds and protein targets that disrupt migrasome

formation, a study by Lu et al (27) identified SAR407899, an inhibitor of

ROCK1 and ROCK2, which stably suppresses migrasome biogenesis.

ROCK1 and ROCK2 are serine/threonine kinases that act downstream of

the small GTPase Ras homolog family member A (RhoA), regulating

diverse cellular processes, including actin cytoskeleton

organization, cell adhesion and migration, via the ROCK-Rho

signaling pathway (44). Although

ROCK2 knockdown does not affect migrasome formation, ROCK1

depletion markedly reduces the migrasome abundance per cell

(27). Notably, ROCK1 knockdown

also impairs cell migration. To distinguish the effects of RFs and

migration from migrasome formation, researchers have quantified the

number of migrasomes per 100 µm RFs (27). The findings of this experiment

revealed that ROCK1-depleted cells generate notably weaker traction

forces than healthy cells, supporting the premise that migrasome

formation depends on ROCK1-mediated traction and other ECM

components (such as fibronectin) adhesion (27).

PD-L1 is best known as an immune checkpoint molecule

that facilitates cancer cell migration (45). Emerging evidence has indicated that

PD-L1 has an intrinsic capability to facilitate sustained cellular

migration, a process important for migrasome biogenesis.

High-resolution time-lapse microscopy has demonstrated that PD-L1

accumulates at the trailing edge of migrating cancer cells, where

it forms distinct structures that move directionally during

retraction (46). Given that RFs

form at the rear of the cell during migration, a subsequent study

demonstrated that PD-L1 localizes not only in RFs, but also in

migrasomes. Notably, PD-L1 enhances migrasome formation

independently of cell migration (46). PD-L1 closely associates with

integrin β4, co-localizing at the rear of the cell, and later in

RFs and migrasomes. A further investigation revealed that PD-L1

recruits integrin β4 to the trailing edge; this recruitment

stimulates contractility via the dynamics of the cell, a mechanism

by which PD-L1 maintains rear polarity and reduces membrane tension

(46). Additionally, PD-L1

activates RhoA by coupling integrin β4 to the cytoskeleton, further

promoting rear contraction (actin cytoskeleton-mediated

contractility) (46). Taken

together, these findings underscore the dual role of PD-L1 in

facilitating cell migration and migrasome formation. However, the

precise mechanisms of PD-L1 in migrasome biogenesis, and its

broader functional implications, warrant further exploration.

Other factors affecting migrasome

formation

Regarding the formation mechanisms of migrasomes in

different cell types, the universal core mechanism involves the

following sequence of events: i) Cell migration initiation; ii) the

formation of TEMs; and subsequently iii) the recruitment, fusion

and maturation of microvesicles (the precursors of migrasomes)

(6,9). However, migrasome formation is a

complex biological process influenced by multiple factors, and the

underlying mechanisms may vary across cell types. Some examples are

as follows: i) Triggering signals vary, for example monocytes and

macrophages may initiate migrasome generation through tissue damage

and clearance signals, with these migrasomes potentially

participating in angiogenesis regulation or damaged mitochondrial

clearance, whereas cancer cells may trigger migrasome formation via

oncogenic or metastasis-driving signals to promote cancer

progression; and ii) regulatory factors may be cell type-specific.

For example, normal human dermal fibroblasts exhibit modulated

migrasome formation through peptide-modified matrices, which affect

contractile fiber quantity and length (different peptide-modified

substrates influence the strength of cell migration, such as

migration distance and duration, thereby affecting the number and

length of RFs) (47). Mouse

embryonic stem cells exhibit calcium ion and synaptotagmin-1

(Syt1)-regulated migrasome production, where calcium promotes

migrasome formation via Syt1 (48). Furthermore, in H4 human glioma

cells, osmotic regulation may control migrasome formation, as

hypotonic conditions induce the formation of TSPAN4-enriched

migrasome-like vesicles on RFs. These cholesterol-dependent

vesicles exhibit migrasome characteristics but originate from

osmotic stress rather than from cell migration (49). While conclusive identification of

these cholesterol-dependent vesicles as migrasomes requires further

evidence, these observations provide valuable perspectives on

cellular osmoregulation and migrasome biophysical responses in

tissues. A previous report indicated that high-salt diets

exacerbate ischemic brain injury by promoting excessive migrasome

formation in microglia and macrophages, reducing their

post-ischemic populations alongside astrocytes (17).

Migrasomes from different cell types participate in

distinct biological activities. Nevertheless, research on most

cell-type-specific migrasomes remains preliminary, and the

generation mechanisms of these migrasomes have not been fully

elucidated. Currently, evidence confirms only their existence and

functional roles in various biological responses. For example,

migrasomes produced by zebrafish embryonic cells can regulate the

formation of zebrafish embryonic organs; migrasomes derived from

adipose stem cells serve a key role in adipose tissue regeneration;

and migrasomes from neutrophils affect the coagulation function of

the body (18,50). Specialized investigations into

cell-type-specific formation mechanisms remain lacking, preventing

targeted discussion of these mechanisms at present. Exploring these

heterogeneous-origin migrasomes and their impacts on cellular

functions and disease pathogenesis constitute an important future

research direction.

Biological functions of migrasomes

Migrasomes, notable organelles in cell migration,

are increasingly recognized for their roles in cellular physiology

and pathology. Their formation and function are closely associated

not only with cellular-migratory capacity, but also with

intercellular communication, tissue remodeling and immune

regulation. These microvesicles serve as carriers for the

intercellular transfer of biomolecules, such as proteins, mRNAs and

microRNAs, thereby modulating the gene expression and functional

states of recipient cells. The present section elucidates the

biological functions of migrasomes in organ morphogenesis,

angiogenesis, mitochondrial quality control and immune regulation,

highlighting their notable roles in maintaining tissue homeostasis

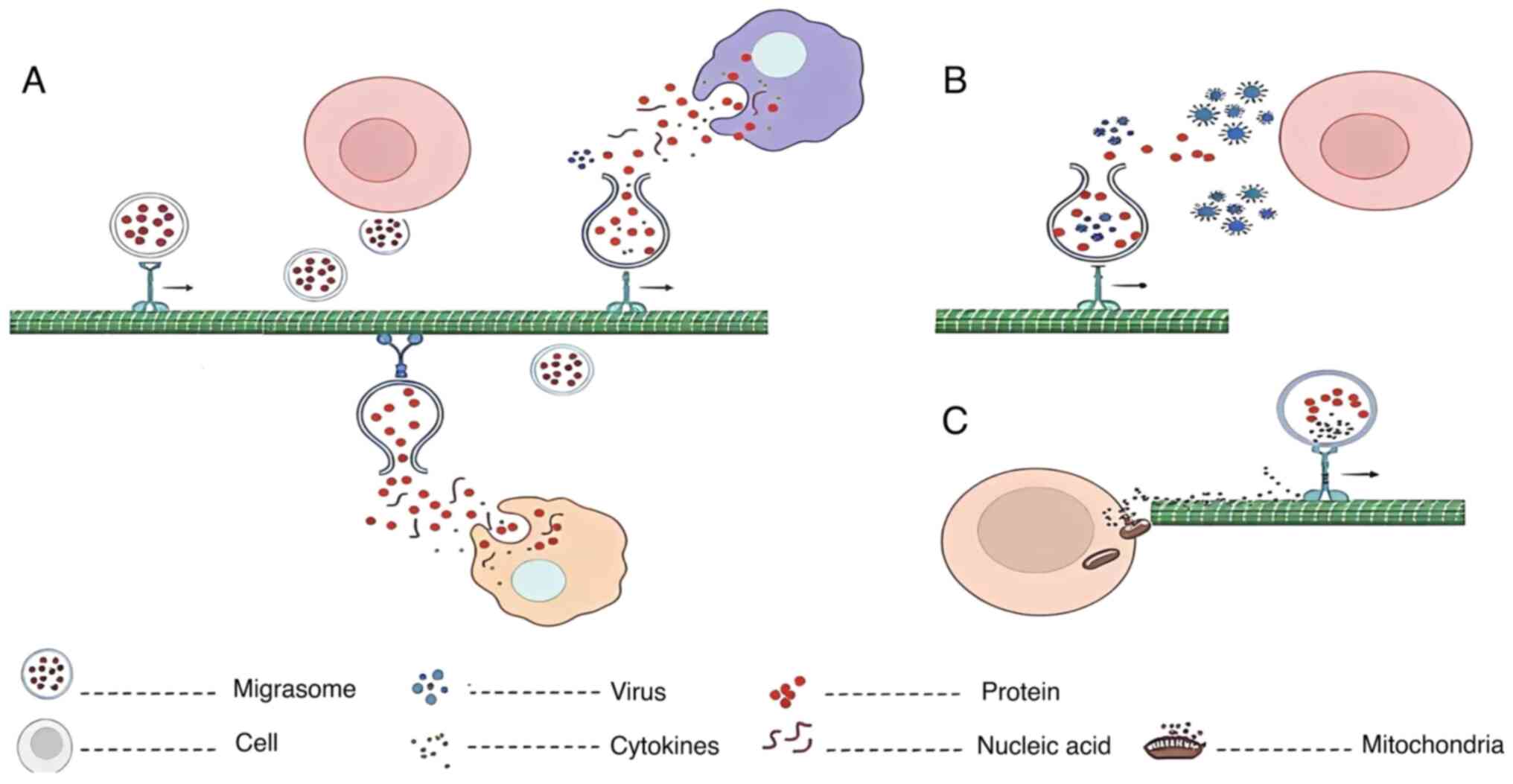

and contributing to disease pathogenesis (Fig. 3). A deeper understanding of these

functions underscores the complexity and diversity of migrasomes in

biological systems and their potential as therapeutic targets in

medical research.

Communication and regulatory

functions

Migrasomes constitute a notable secretory pathway in

migrating cells, encapsulating diverse cytoplasmic contents

(6,51). Migrasomes form and mature on RFs of

migrating cells before they detach, rupture and release their

contents (6) (Fig. 3A). Migrasomes can also be

internalized by neighboring cells, or adhere to cell surfaces or

the ECM without being engulfed. For example, interactions with the

ECM enable migrasomes to attach to specific cell surfaces or

tissues, facilitating intercellular communication (32). These vesicles transport

intracellular biomolecules, including proteins, mRNAs and

microRNAs. Recent studies have indicated that secretory proteins,

such as signaling molecules, are actively transported from

migrating cells into migrasomes via kinesin-mediated carriers, akin

to targeted neurotransmitter release in neuronal systems (51). These molecules can be transferred

to adjacent or distant cells, altering recipient cell-gene

expression and function. For example, Zhu et al (24) added purified migrasomes derived

from L929 cells to U87-MG, MDA-MB-468 and PC3 cells that do not

express the PTEN protein, and demonstrated that migrasomes mediate

the transfer of PTEN mRNA and protein, inhibiting proliferation in

recipient cells.

Migrasomes are enriched with cytokines, including

chemokines and morphogens, which enables them to act as signaling

molecule-carriers, and thereby influence cell behavior. In

zebrafish embryos, gastrula-derived migrasomes contain high levels

of C-X-C motif chemokine ligand (CXCL)12a (18). These migrasomes, produced during

mesoderm and endoderm cell gastrulation, regulate organ

development. Mutations that reduce migrasome numbers lead to severe

developmental defects, which can be rescued by migrasome

supplementation, underscoring their role in organogenesis (18). Further studies have revealed that

CXCL12 in migrasomes interacts with C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4

(CXCR4) on dorsal precursor cells (DFCs), inducing chemotaxis and

ensuring typical organ morphogenesis (35). Migrasomes thus spatially and

temporally distribute signaling molecules, releasing CXCL12 upon

rupture to modulate DFC behavior. Similarly, adipose-derived stem

cells produce CXCL12-enriched migrasomes that promote adipose

tissue regeneration via CXCR4/RhoA signaling (50).

A study by Zhang et al (11) identified migrasome-producing

monocytes in the chorioallantoic membrane of chicken embryos, where

these vesicles are rich in proangiogenic factors, including TGF-β3,

VEGFA and CXCL12. In this context, migrasomes induce endothelial

tube formation; their depletion via monocyte clearance or TSPAN4

knockout inhibits angiogenesis, whereas supplementation restores

monocyte recruitment and capillary formation (11). Monocytes leverage migrasomes to

deliver angiogenic factors, thereby creating a microenvironment

conducive to blood vessel growth. Notably, migrasome-derived CXCL12

recruits additional monocytes, forming a positive feedback loop

(11,52).

Multipotent mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are

precursors to various cell types, with the ability to support

tissue homeostasis, promote hematopoiesis and interact with cancer

cells. Previous research on MSCs has focused on MSC-derived EVs

(MSC-EVs), indicating that MSC-EVs have functions similar to those

of MSC (53–58). A recent investigation demonstrated

that MSCs generate migrasomes that attract leukemia KG-1a cells and

CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells via the CXCR4-CXCL12 axis

(59). These migrasomes, enriched

in TSPANs, including CD166 and TSPAN4, and endosomal markers, such

as Rab7 and CD63, are influenced by ECM components such as

fibronectin and laminins. In addition to influencing cell migration

and thereby affecting the formation of retraction fibers, ECM

components can also impact the process of TEM formation (59). Migrasomes produced by MSCs attract

leukemia KG-1a cells and CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells

through the CXCR4-CXCL12 axis, thereby facilitating communication

between the MSCs and these cells, thus highlighting the role of

migrasomes in MSC-hematopoietic cell interactions, offering

insights into their functions in health and disease.

Neutrophil-derived migrasomes adsorb coagulation

factors from the plasma; migrasomes actively bind and enrich

coagulation factors on their surface by virtue of their unique

membrane composition, particularly cholesterol esters, and then

localize to injury sites and modulate coagulation by activating

platelets (60). These migrasomes

also regulate immune responses by delivering cytokines and

chemokines to injury sites, enhancing immune cell recruitment

during inflammation (60).

Conversely, migrasomes have been shown to suppress immunity by

transporting immunosuppressive molecules, thereby maintaining

immune tolerance (46).

Participation in maintaining cellular

homeostasis

Mitochondria, the cellular ‘powerhouses’, maintain

homeostasis through energy production and quality control

mechanisms, such as mitophagy (61,62).

A previous study demonstrated that migrasomes mediate mitocytosis,

a process in which damaged mitochondria are selectively expelled to

sustain cellular health (12)

(Fig. 3C). Under stress

conditions, such as carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone

treatment, mitochondria undergo fragmentation via kinesin-5B

(KIF5B)-mediated transport and myosin head domain-containing

protein 1 (MYO19)/density-regulated protein 1-dependent fission,

accumulating at the cell periphery for subsequent migrasome

encapsulation. Knocking out TSPAN9 or taking other measures to

block the formation of migrasomes has been shown to cause migrating

cells to lose their mitocytosis capability, leading to the

accumulation of damaged mitochondria within the cells and affecting

cell viability (12,63,64).

Although both mitocytosis and mitophagy contribute

to cellular homeostasis, their mechanisms differ markedly.

Mitocytosis, which is mediated by migrasomes, selectively removes

mildly damaged mitochondria from migrating cells. In this process,

damaged mitochondria selectively bind to intracellular dynein to

facilitate their transport out of the cell, they are then

transported towards the cell periphery by outwards motor proteins,

such as KIF5B. MYO19 further facilitates this process by anchoring

mitochondria to cortical actin, thereby promoting their

incorporation into migrasomes (12,63,64).

By contrast, mitophagy primarily degrades damaged mitochondria via

the autophagy pathway. Upon mitochondrial damage, PTEN-induced

kinase 1 accumulates on the outer mitochondrial membrane, where it

recruits parkin to ubiquitinate outer membrane proteins. This

ubiquitination marks the mitochondria for autophagosomal

engulfment, and subsequent lysosomal degradation (61,62).

Mitocytosis complements mitophagy by incrementally

clearing mildly damaged mitochondria. Migrasomes may also transfer

mitochondrial components, including mitochondrial DNA and

mitochondrial microRNAs, to recipient cells, influencing their

function.

Migrasomes mediate virus spread

Migrasomes facilitate viral dissemination,

facilitating the evasion of antiviral therapies (Fig. 3B). Vaccinia virus induces

migrasomes containing viral particles, enabling their spread

despite tecovirimat treatment (13,65).

Similarly, herpes simplex virus-2 exploits migrasomes as ‘Trojan

horses’ for intercellular transmission (66). Taken together, these findings

illuminate novel viral spread mechanisms and suggest potential

targets for antiviral strategies.

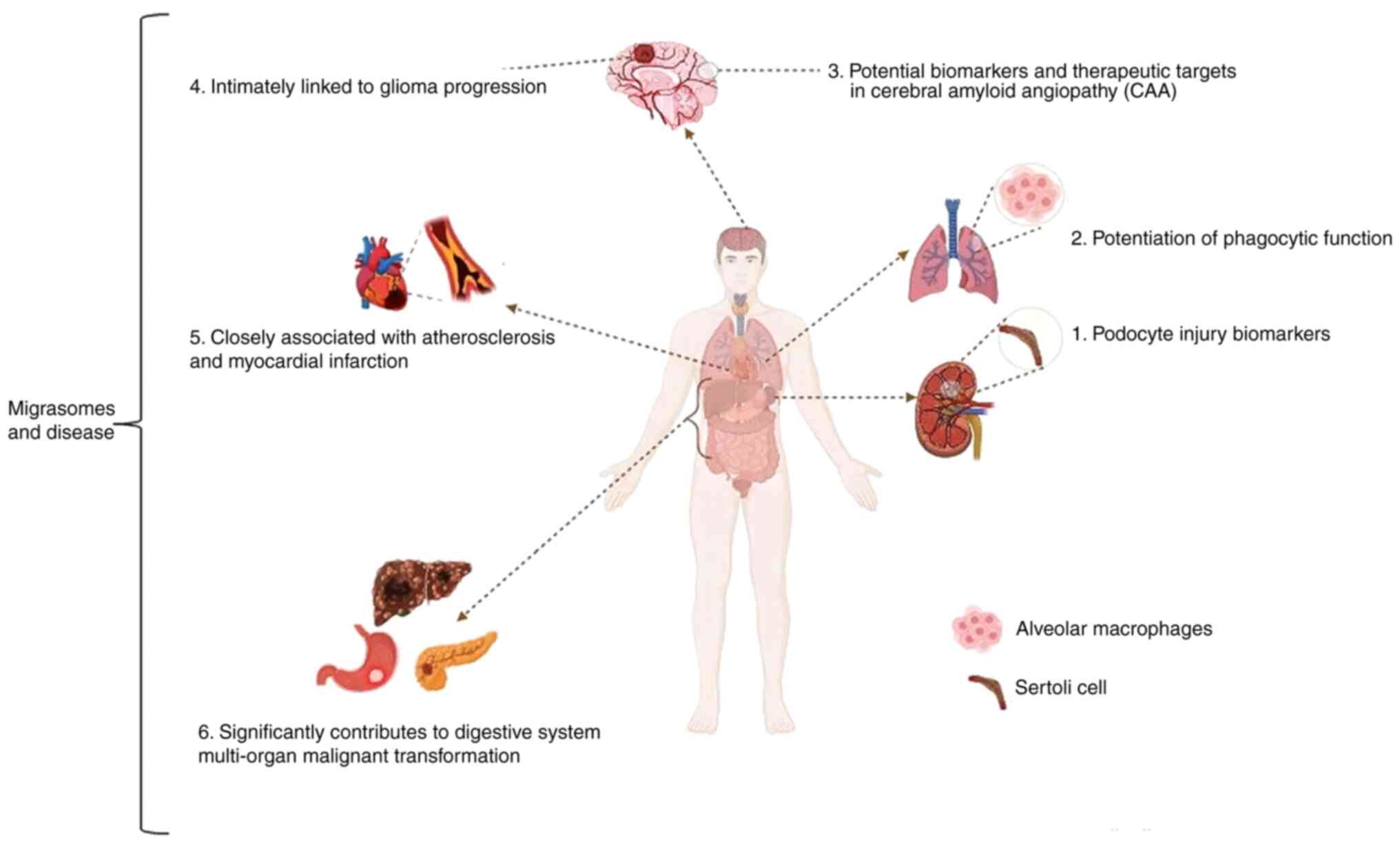

Migrasomes and disease

As research advances, the understating of migrasomes

is improving, with their structure and physiological functions

becoming increasingly elucidated. Studies have demonstrated that

migrasomes perform notable roles in intercellular communication and

signal transduction, as well as in the pathogenesis of various

diseases (Fig. 4). These findings

highlight the potential of migrasomes for clinical applications in

disease diagnosis and treatment.

The association between migrasomes and kidney

disease is particularly notable. Studies have identified

podocyte-derived migrasomes in urine as early biomarkers of

podocyte injury (14,67). Podocytes, which regulate glomerular

permeability, are terminally differentiated cells incapable of

regeneration; therefore, early detection of their injury is

important for managing glomerular diseases (14). Research indicates that podocytes

generate migrasomes during migration, with their numbers markedly

increasing during kidney injury. Furthermore, Rac-1 inhibitors that

target a small Rho family GTPase that is overactivated in podocyte

injury dose-dependently suppress lipopolysaccharide-induced

migrasome release, underscoring the diagnostic potential of the

urinary presence of podocyte migrasomes (14).

Migrasomes also exhibit therapeutic relevance for

post-stroke pneumonia. Bone marrow (BM)-MSC-derived migrasomes,

which are packed with dermcidin, display dual effects that reduce

pulmonary bacteria load and enhance LC3-associated phagocytosis

(LAP) of macrophages (68). These

migrasomes not only exert antibacterial effects, but also augment

LAP in macrophages, facilitating bacterial clearance. Consequently,

BM-MSC-derived migrasomes represent a promising alternative to

conventional antibiotics for preventing and treating post-stroke

pneumonia.

In neurodegenerative disorders, migrasomes have been

implicated in cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). β-amyloid protein

40-induced macrophage-derived migrasomes adhere to the vasculature

in biopsies from patients with CAA and mouse models, delivering the

protein CD5L to vascular walls and triggering complement-dependent

cytotoxicity, thereby compromising the blood-brain barrier

(69). These observations suggest

that macrophage-derived migrasomes and complement activation are

potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets for CAA.

Emerging evidence further links migrasomes to

atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction and malignancies. TSPAN4, a

migrasome-forming protein, is strongly associated with

atherosclerosis regression-associated macrophages according to

single-cell sequencing, Gene Expression Omnibus datasets and The

Cancer Genome Atlas analyses, and is also associated with plaque

hemorrhage and rupture (70). In

another study, low-intensity pulsed ultrasound has been shown to

mitigate myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury via

migrasome-mediated mitochondrial quality control; the possible

mechanism involves promoting the formation of migrasomes,

potentially by enhancing cell motility, which enables migrasomes to

exert mitocytosis activity, facilitating the removal of damaged

mitochondria from cells (71).

TSPAN4 is also upregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma, gastric

cancer and glioblastoma (GBM), where it influences tumor-associated

macrophages (72). In

hepatocellular carcinoma, migrasomes guide cancer cell invasion

(73); in pancreatic cancer,

pancreatic cancer cell-derived migrasomes modulate

immunosuppressive factors in the tumor microenvironment, thereby

accelerating progression (74). In

GBM, TSPAN4 promotes the progression of GBM by regulating epidermal

growth factor receptor stability, whereas migrasome-autophagosome

crosstalk alleviates endoplasmic reticulum stress and

migrasome-mediated GBM-microenvironment communication may drive

recurrence (75–77). Collectively, these findings

underscore the therapeutic potential of targeting TSPAN4 and

migrasomes in severe diseases.

Summary and outlook

Migrasomes, a novel class of EVs, have attracted

considerable attention in the field of cell biology, with their

important roles in cellular processes gradually being elucidated.

Research on migrasomes has advanced markedly, from structural

characterization to functional exploration. These vesicles not only

serve important roles in normal physiological processes, but also

modulate cell behavior and disease progression under pathological

conditions, highlighting their potential as biomarkers and

therapeutic targets.

The field of migrasome research is rapidly evolving,

but still faces substantial challenges. Firstly, a deeper

mechanistic understanding of migrasome biogenesis and its

regulatory networks, particularly the contributions of lipid and

protein components, is important. Secondly, further experimental

validation is needed to clarify how migrasome-derived biomolecules,

such as RNAs and proteins, influence recipient cell functions and

mediate intercellular communication. Additionally, investigating

migrasome heterogeneity across cell types and tissues, as well as

their functional alterations in disease states, remains a key

research direction. Advances in single-cell sequencing and

high-resolution imaging technologies are expected to provide deeper

insights into the biology and disease-related functions of

migrasomes.

Clinically, migrasome research may offer novel

strategies for early disease diagnosis and therapy (Table II). For example, migrasomes could

serve as biomarkers for monitoring kidney or neurodegenerative

diseases, or their formation and function could be therapeutically

targeted. Furthermore, migrasome involvement in viral transmission

suggests their potential applications in infectious disease

research. As knowledge on the function of migrasomes expands, their

impact on research and clinical therapeutics is expected to grow.

In summary, migrasome research presents both challenges and

opportunities, with future discoveries poised to further elucidate

the complexity of cellular processes while advancing diagnostic and

therapeutic innovations.

| Table II.Dual roles of migrasomes in

diseases. |

Table II.

Dual roles of migrasomes in

diseases.

| Disease type | Functional

mechanism | Potential

applications |

|---|

| Developmental

defects | Loss of

CXCL12+ migrasomes leads to abnormal organ morphogenesis

in zebrafish embryos (18) | Early intervention

targets for developmental disorders |

| Tumor

microenvironment | MSC-derived

migrasomes recruit leukemia cells; pancreatic cancer migrasomes

enrich immunosuppressive factors (59,74) | Blocking

migrasome-mediated tumor metastasis |

| Ischemic

injury | Adipose stem

cell-derived migrasomes activate Ras homolog family member A via

CXCL12, promoting vascular regeneration (50) | Tissue engineering

and regenerative medicine |

| Inflammation and

infection | Neutrophil-derived

migrasomes enhance coagulation or antibacterial functions, such as

releasing dermcidin in post-stroke pneumonia (68) | Novel

anti-infection strategies |

| Autoimmune

diseases | Migrasomes deliver

immunosuppressive molecules, such as interleukin-10, to maintain

immune tolerance (46) | Immunomodulatory

therapies for autoimmune disorders |

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Jiangsu Provincial Key

Medical Discipline (grant no. ZDXK202227) and the Wuxi Taihu Talent

Program (grant no. WX0302B010507200065).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

YC and QW wrote the manuscript. YC, XL, BZ and HZ

revised the manuscript. XL supervised the present review and guided

each author who participated in writing the article. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

EV

|

extracellular vesicle

|

|

RF

|

retraction fiber

|

|

PLS

|

pomegranate-like structure

|

|

TSPAN

|

tetraspanin

|

|

SM

|

sphingomyelin

|

|

WGA

|

wheat germ agglutinin

|

|

SMS

|

sphingomyelin synthase

|

|

TEM

|

tetraspanin-enriched microdomain

|

|

FA

|

focal adhesion

|

|

NRK

|

normal rat kidney

|

|

ECM

|

extracellular matrix

|

|

PIP2

|

phosphatidylinositol

4,5-bisphosphate

|

|

GFP

|

green fluorescent protein

|

|

PIP5K1A

|

phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate

5-kinase type-1α

|

|

PD-L1

|

programmed death-ligand 1

|

|

ROCK

|

Rho-associated protein kinase

|

|

RhoA

|

Ras homolog family member A

|

|

PTEN

|

phosphatase and tensin homolog

|

|

CXCL

|

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand

|

|

CXCR4

|

C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4

|

|

DFC

|

dorsal precursor cell

|

|

MSC

|

mesenchymal stem cell

|

|

KIF5B

|

kinesin-5B

|

|

MYO19

|

myosin head domain-containing protein

1

|

|

BM-MSCs

|

bone marrow mesenchymal stem

cells

|

|

Syt1

|

synaptotagmin-1

|

|

CAA

|

cerebral amyloid angiopathy

|

|

GBM

|

glioblastoma

|

References

|

1

|

Trepat X, Chen Z and Jacobson K: Cell

migration. Compr Physiol. 2:2369–2392. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ratajczak J, Wysoczynski M, Hayek F,

Janowska-Wieczorek A and Ratajczak MZ: Membrane-derived

microvesicles: Important and underappreciated mediators of

cell-to-cell communication. Leukemia. 20:1487–1495. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Bruno S, Chiabotto G, Favaro E, Deregibus

MC and Camussi G: Role of extracellular vesicles in stem cell

biology. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 317:C303–C313. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Hopkin K: Core concept: Extracellular

vesicles garner interest from academia and biotech. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 113:9126–9128. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kang T, Atukorala I and Mathivanan S:

Biogenesis of extracellular vesicles. Subcell Biochem. 97:19–43.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Ma L, Li Y, Peng J, Wu D, Zhao X, Cui Y,

Chen L, Yan X, Du Y and Yu L: Discovery of the migrasome, an

organelle mediating release of cytoplasmic contents during cell

migration. Cell Res. 25:24–38. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Taylor AC and Robbins E: Observations on

microextensions from the surface of isolated vertebrate cells. Dev

Biol. 6:660–673. 1963. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Chen Y, Li Y, Ma L and Yu L: Detection of

migrasomes. Methods Mol Biol. 1749:43–49. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Huang Y, Zucker B, Zhang S, Elias S, Zhu

Y, Chen H, Ding T, Li Y, Sun Y, Lou J, et al: Migrasome formation

is mediated by assembly of micron-scale tetraspanin macrodomains.

Nat Cell Biol. 21:991–1002. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Tavano S and Heisenberg CP: Migrasomes

take center stage. Nat Cell Biol. 21:918–920. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhang C, Li T, Yin S, Gao M, He H, Li Y,

Jiang D, Shi M, Wang J and Yu L: Monocytes deposit migrasomes to

promote embryonic angiogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 24:1726–1738. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Jiao H, Jiang D, Hu X, Du W, Ji L, Yang Y,

Li X, Sho T, Wang X, Li Y, et al: Mitocytosis, a migrasome-mediated

mitochondrial quality-control process. Cell. 184:2896–2910.e13.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Lv L and Zhang L: Identification of

poxvirus inside migrasomes suggests a novel mode of mpox virus

spread. J Infect. 87:160–162. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Liu Y, Li S, Rong W, Zeng C, Zhu X, Chen

Q, Li L, Liu ZH and Zen K: Podocyte-released migrasomes in urine

serve as an indicator for early podocyte injury. Kidney Dis

(Basel). 6:422–433. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yu L: Migrasomes: The knowns, the known

unknowns and the unknown unknowns: A personal perspective. Sci

China Life Sci. 64:162–166. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wu J, Lu Z, Jiang D, Guo Y, Qiao H, Zhang

Y, Zhu T, Cai Y, Zhang X, Zhanghao K, et al: Iterative tomography

with digital adaptive optics permits hour-long intravital

observation of 3D subcellular dynamics at millisecond scale. Cell.

184:3318–3332.e17. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Schmidt-Pogoda A, Strecker JK, Liebmann M,

Massoth C, Beuker C, Hansen U, König S, Albrecht S, Bock S, Breuer

J, et al: Dietary salt promotes ischemic brain injury and is

associated with parenchymal migrasome formation. PLoS One.

13:e02098712018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Jiang D, Jiang Z, Lu D, Wang X, Liang H,

Zhang J, Meng Y, Li Y, Wu D, Huang Y, et al: Migrasomes provide

regional cues for organ morphogenesis during zebrafish

gastrulation. Nat Cell Biol. 21:966–977. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Gagat M, Zielińska W, Mikołajczyk K,

Zabrzyński J, Krajewski A, Klimaszewska-Wiśniewska A, Grzanka D and

Grzanka A: CRISPR-based activation of endogenous expression of tpm1

inhibits inflammatory response of primary human coronary artery

endothelial and smooth muscle cells induced by recombinant human

tumor necrosis factor α. Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:6680322021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ardalan M, Hosseiniyan Khatibi SM, Rahbar

Saadat Y, Bastami M, Nariman-Saleh-Fam Z, Abediazar S, Khalilov R

and Zununi Vahed S: Migrasomes and exosomes; different types of

messaging vesicles in podocytes. Cell Biol Int. 46:52–62. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhao X, Lei Y, Zheng J, Peng J, Li Y, Yu L

and Chen Y: Identification of markers for migrasome detection. Cell

Discov. 5:272019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhang Y, Wang J, Ding Y, Zhang J, Xu Y, Xu

J, Zheng S and Yang H: Migrasome and tetraspanins in vascular

homeostasis: Concept, present, and future. Front Cell Dev Biol.

8:4382020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Liang H, Ma X, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Liu N,

Zhang W, Chen J, Liu B, Du W, Liu X and Yu L: The formation of

migrasomes is initiated by the assembly of sphingomyelin synthase 2

foci at the leading edge of migrating cells. Nat Cell Biol.

25:1173–1184. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhu M, Zou Q, Huang R, Li Y, Xing X, Fang

J, Ma L, Li L, Yang X and Yu L: Lateral transfer of mRNA and

protein by migrasomes modifies the recipient cells. Cell Res.

31:237–240. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Chen L, Ma L and Yu L: WGA is a probe for

migrasomes. Cell Discov. 5:132019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Gustafson CM, Roffers-Agarwal J and

Gammill LS: Chick cranial neural crest cells release extracellular

vesicles that are critical for their migration. J Cell Sci.

135:jcs2602722022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Lu P, Liu R, Lu D, Xu Y, Yang X, Jiang Z,

Yang C, Yu L, Lei X and Chen Y: Chemical screening identifies ROCK1

as a regulator of migrasome formation. Cell Discov. 6:512020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Fan C, Shi X, Zhao K, Wang L, Shi K, Liu

YJ, Li H, Ji B and Jiu Y: Cell migration orchestrates migrasome

formation by shaping retraction fibers. J Cell Biol.

221:e2021091682022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ivaska J, Pallari HM, Nevo J and Eriksson

JE: Novel functions of vimentin in cell adhesion, migration, and

signaling. Exp Cell Res. 313:2050–2062. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Jiu Y, Peränen J, Schaible N, Cheng F,

Eriksson JE, Krishnan R and Lappalainen P: Vimentin intermediate

filaments control actin stress fiber assembly through GEF-H1 and

RhoA. J Cell Sci. 130:892–902. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Huitema K, van den Dikkenberg J, Brouwers

JF and Holthuis JC: Identification of a family of animal

sphingomyelin synthases. EMBO J. 23:33–44. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wu D, Xu Y, Ding T, Zu Y, Yang C and Yu L:

Pairing of integrins with ECM proteins determines migrasome

formation. Cell Res. 27:1397–1400. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zuidscherwoude M, Göttfert F, Dunlock VM,

Figdor CG, van den Bogaart G and van Spriel AB: The tetraspanin web

revisited by super-resolution microscopy. Sci Rep. 5:122012015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Hemler ME: Tetraspanin proteins mediate

cellular penetration, invasion, and fusion events and define a

novel type of membrane microdomain. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol.

19:397–422. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Dharan R, Huang Y, Cheppali SK, Goren S,

Shendrik P, Wang W, Qiao J, Kozlov MM, Yu L and Sorkin R:

Tetraspanin 4 stabilizes membrane swellings and facilitates their

maturation into migrasomes. Nat Commun. 14:10372023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Dharan R, Goren S, Cheppali SK, Shendrik

P, Brand G, Vaknin A, Yu L, Kozlov MM and Sorkin R: Transmembrane

proteins tetraspanin 4 and CD9 sense membrane curvature. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 119:e22089931192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zaidel-Bar R: Job-splitting among

integrins. Nat Cell Biol. 15:575–577. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Wehrle-Haller B: Structure and function of

focal adhesions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 24:116–124. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Kolay S, Basu U and Raghu P: Control of

diverse subcellular processes by a single multi-functional lipid

phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P2]. Biochem J.

473:1681–1692. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Hammond GRV: Does PtdIns(4,5)P2

concentrate so it can multi-task? Biochem Soc Trans. 44:228–233.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Ding T, Ji J, Zhang W, Liu Y, Liu B, Han

Y, Chen C and Yu L: The phosphatidylinositol

(4,5)-bisphosphate-Rab35 axis regulates migrasome formation. Cell

Res. 33:617–627. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Klinkert K and Echard A: Rab35 GTPase: A

central regulator of phosphoinositides and F-actin in endocytic

recycling and beyond. Traffic. 17:1063–1077. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Allaire PD, Seyed Sadr M, Chaineau M,

Seyed Sadr E, Konefal S, Fotouhi M, Maret D, Ritter B, Del Maestro

RF and McPherson PS: Interplay between Rab35 and Arf6 controls

cargo recycling to coordinate cell adhesion and migration. J Cell

Sci. 126:722–731. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Lock FE, Ryan KR, Poulter NS, Parsons M

and Hotchin NA: Differential regulation of adhesion complex

turnover by ROCK1 and ROCK2. PLoS One. 7:e314232012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Yu W, Hua Y, Qiu H, Hao J, Zou K, Li Z, Hu

S, Guo P, Chen M, Sui S, et al: PD-L1 promotes tumor growth and

progression by activating WIP and β-catenin signaling pathways and

predicts poor prognosis in lung cancer. Cell Death Dis. 11:5062020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Wang M, Xiong C and Mercurio AM: PD-LI

promotes rear retraction during persistent cell migration by

altering integrin β4 dynamics. J Cell Biol. 221:e2021080832022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Saito S, Tanaka M, Tatematsu S and Okochi

M: Peptide-modified substrate enhances cell migration and migrasome

formation. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 131:1124952021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Han Y and Yu L: Calcium ions promote

migrasome formation via Synaptotagmin-1. J Cell Biol.

223:e2024020602024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Yoshikawa K, Saito S, Kadonosono T, Tanaka

M and Okochi M: Osmotic stress induces the formation of

migrasome-like vesicles. FEBS Lett. 598:437–445. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Chen Y, Li Y, Li B, Hu D, Dong Z and Lu F:

Migrasomes from adipose derived stem cells enrich CXCL12 to recruit

stem cells via CXCR4/RhoA for a positive feedback loop mediating

soft tissue regeneration. J Nanobiotechnology. 22:2192024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Jiao H, Li X, Li Y, Guo Y, Hu X, Sho T,

Luo Y, Wang J, Cao H, Du W, et al: Localized, highly efficient

secretion of signaling proteins by migrasomes. Cell Res.

34:572–585. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Strzyz P: Migrasomes promote angiogenesis.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 24:842023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Nawaz M, Fatima F, Vallabhaneni KC,

Penfornis P, Valadi H, Ekström K, Kholia S, Whitt JD, Fernandes JD,

Pochampally R, et al: Extracellular vesicles: Evolving factors in

stem cell biology. Stem Cells Int. 2016:10731402016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Rani S, Ryan AE, Griffin MD and Ritter T:

Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles: Toward

cell-free therapeutic applications. Mol Ther. 23:812–823. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Tan X, Gong YZ, Wu P, Liao DF and Zheng

XL: Mesenchymal stem cell-derived microparticles: A promising

therapeutic strategy. Int J Mol Sci. 15:14348–14363. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Bruno S and Camussi G: Role of mesenchymal

stem cell-derived microvesicles in tissue repair. Pediatr Nephrol.

28:2249–2254. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Zhang Y, Chopp M, Meng Y, Katakowski M,

Xin H, Mahmood A and Xiong Y: Effect of exosomes derived from

multipluripotent mesenchymal stromal cells on functional recovery

and neurovascular plasticity in rats after traumatic brain injury.

J Neurosurg. 122:856–867. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Xin H, Li Y, Buller B, Katakowski M, Zhang

Y, Wang X, Shang X, Zhang ZG and Chopp M: Exosome-mediated transfer

of miR-133b from multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells to neural

cells contributes to neurite outgrowth. Stem Cells. 30:1556–1564.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Deniz IA, Karbanová J, Wobus M, Bornhäuser

M, Wimberger P, Kuhlmann JD and Corbeil D: Mesenchymal stromal

cell-associated migrasomes: A new source of chemoattractant for

cells of hematopoietic origin. Cell Commun Signal. 21:362023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Jiang D, Jiao L, Li Q, Xie R, Jia H, Wang

S, Chen Y, Liu S, Huang D, Zheng J, et al: Neutrophil-derived

migrasomes are an essential part of the coagulation system. Nat

Cell Biol. 26:1110–1123. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Sugiura A, McLelland GL, Fon EA and

McBride HM: A new pathway for mitochondrial quality control:

Mitochondrial-derived vesicles. EMBO J. 33:2142–2156. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Poole LP and Macleod KF: Mitophagy in

tumorigenesis and metastasis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 78:3817–3851.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Baumann K: Damaged mitochondria are

discarded via migrasomes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 22:4422021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Mehra C and Pernas L: Move it to lose it:

Mitocytosis expels damaged mitochondria. Dev Cell. 56:2014–2015.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Zhao W, Tang X and Zhang L:

Virus-containing migrasomes enable poxviruses to evade

tecovirimat/ST-246 treatment. J Infect. 88:203–205. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Liu Y, Zhu Z, Li Y, Yang M and Hu Q:

Migrasomes released by HSV-2-infected cells serve as a conveyance

for virus spread. Virol Sin. 38:643–645. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Yang R, Zhang H, Chen S, Lou K, Zhou M,

Zhang M, Lu R, Zheng C, Li L, Chen Q, et al: Quantification of

urinary podocyte-derived migrasomes for the diagnosis of kidney

disease. J Extracell Vesicles. 13:e124602024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Li T, Su X, Lu P, Kang X, Hu M, Li C, Wang

S, Lu D, Shen S, Huang H, et al: Bone marrow mesenchymal stem

cell-derived dermcidin-containing migrasomes enhance LC3-associated

phagocytosis of pulmonary macrophages and protect against

post-stroke pneumonia. Adv Sci (Weinh). 10:e22064322023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Hu M, Li T, Ma X, Liu S, Li C, Huang Z,

Lin Y, Wu R, Wang S, Lu D, et al: Macrophage lineage cells-derived

migrasomes activate complement-dependent blood-brain barrier damage

in cerebral amyloid angiopathy mouse model. Nat Commun.

14:39452023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Zheng Y, Lang Y, Qi B and Li T: TSPAN4 and

migrasomes in atherosclerosis regression correlated to myocardial

infarction and pan-cancer progression. Cell Adh Migr. 17:14–19.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Sun P, Li Y, Yu W, Chen J, Wan P, Wang Z,

Zhang M, Wang C, Fu S, Mang G, et al: Low-intensity pulsed

ultrasound improves myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury via

migrasome-mediated mitocytosis. Clin Transl Med. 14:e17492024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Zhang Z, Zhang T, Zhang R, Zhang Z and Tan

S: Migrasomes and tetraspanins in hepatocellular carcinoma: Current

status and future prospects. Future Sci OA. 9:FSO8902023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Zhang K, Zhu Z, Jia R, Wang NA, Shi M,

Wang Y, Xiang S, Zhang Q and Xu L: CD151-enriched migrasomes

mediate hepatocellular carcinoma invasion by conditioning cancer

cells and promoting angiogenesis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

43:1602024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Zhang R, Peng J, Zhang Y, Zheng K, Chen Y,

Liu L, Li T, Liu J, Li Y, Yang S, et al: Pancreatic cancer

cell-derived migrasomes promote cancer progression by fostering an

immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. Cancer Lett.

605:2172892024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Dong Y, Tang X, Zhao W, Liu P, Yu W, Ren

J, Chen Y, Cui Y, Chen J and Liu Y: TSPAN4 influences glioblastoma

progression through regulating EGFR stability. iScience.

27:1104172024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Lee SY, Choi SH, Kim Y, Ahn HS, Ko YG, Kim

K, Chi SW and Kim H: Migrasomal autophagosomes relieve endoplasmic

reticulum stress in glioblastoma cells. BMC Biol. 22:232024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Köktürk S, Doğan S, Yılmaz CE, Cetinkol Y

and Mutlu O: Expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and

formation of migrasome increases in the glioma cells induced by the

adipokinetic hormone. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 70:e202313372024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|