Introduction

Bone homeostasis is maintained through the dynamic

balance between osteoblast-mediated bone formation and

osteoclast-mediated bone resorption (1). The disruption of this balance results

in bone loss, contributing to a variety of skeletal disorders,

including osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, periodontitis and

bone metastases (2–4). Among these disorders, osteoporosis is

the most prevalent, particularly in aging populations, and is

marked by decreased bone mass and a higher risk of fractures

(5). Current therapeutic

strategies for bone loss primarily target osteoclast function,

including bisphosphonates, denosumab and selective estrogen

receptor modulators (SERMs) (6).

However, these treatments are often associated with side effects,

including osteonecrosis of the jaw, atypical femoral fractures and

impaired bone remodeling (7),

highlighting the need for the identification of novel therapeutic

targets with improved safety profiles.

Bone loss typically results from dysregulated

osteoclastogenesis and increased osteoclast-mediated resorption.

Osteoclasts are multinucleated cells derived from macrophage

progenitors, which are important for physiological bone remodeling

and pathological bone resorption (8). The differentiation and activity of

osteoclasts are tightly regulated by a range of signaling

molecules, among which receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL)

serves a central role (9). The

binding of RANKL to receptor activator of NF-κB (RANK) on

osteoclast precursors initiates multiple intracellular signaling

cascades, including the MAPK and NF-κB pathways, which converge to

activate transcription factors such as nuclear factor of activated

T-cells 1 (NFATc1) and c-Fos (10). These events drive the fusion of

mononuclear precursors into multinucleated osteoclasts capable of

bone resorption. Given the central role of RANKL signaling in

osteoclastogenesis, the inhibition of its downstream pathways has

been considered a promising therapeutic approach for mitigating

pathological bone loss.

Apelin (APLN) is an endogenous peptide and an

adipokine implicated in various physiological processes (11). APLN exerts its effects through

binding to the G protein-coupled receptor APLN receptor, and is

known to regulate angiogenesis, energy homeostasis and

cardiovascular function (12–14).

For example, studies have demonstrated that APLN promotes the

expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1, VEGF and VEGF receptor 2,

thereby enhancing endothelial cell proliferation and migration, and

ultimately facilitating new blood vessel formation (12,15).

APLN has also been reported to promote inflammatory responses by

upregulating the expression of IL-1β in human synovial fibroblasts,

an effect linked to microRNA (miRNA)-144-3p suppression, and

activation of the PI3K and ERK signaling pathways (16). Emerging evidence has indicated that

adipokines may influence bone metabolism. Leptin is known to

influence bone formation through central and peripheral pathways

(17), whereas adiponectin has

been demonstrated to inhibit osteoclastogenesis and enhance

osteoblast differentiation (18).

Previous evidence has suggested a regulatory role for APLN in

skeletal homeostasis, as APLN deficiency in mice leads to increased

trabecular and cortical bone mass along with elevated osteoblast

activity and bone formation. APLN promotes osteoblast proliferation

but does not enhance mineralized nodule formation, suggesting a

potential disruption of osteoblast maturation. These findings

indicate that APLN may act as an antianabolic factor and contribute

to bone metabolic imbalance (19).

However, the potential influence of APLN on osteoclast lineage

cells, which are primarily responsible for bone resorption, remains

ambiguous. Elucidating whether APLN contributes to osteoclast

formation and function is important for understanding its broader

role in bone remodeling.

To address this, the present study examined the

effects of APLN on RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis using the

murine RAW264.7 cell model. Specifically, the present study

evaluated the role of APLN in promoting osteoclast differentiation,

regulating cytoskeletal organization and modulating intracellular

signaling pathways associated with osteoclast activation. The

results of the current study may provide new perspectives on the

involvement of APLN in bone metabolism and suggest that the

inhibition of APLN may represent a novel therapeutic strategy for

suppressing excessive bone resorption in osteolytic diseases.

Materials and methods

Materials and reagents

Recombinant APLN was purchased from MyBiosource,

Inc., and recombinant RANKL was obtained from PeproTech, Inc.

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The ERK inhibitor FR180204, and

antibodies against phosphorylated (p)-ERK (cat. no. sc-7383), p-JNK

(cat. no. sc-6254) and p-p38 (cat. no. sc-166182), and total ERK

(cat. no. sc-1647), JNK (cat. no. sc-7345) and p38 (cat. no.

sc-7972) were acquired from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. The JNK

inhibitor SP600125 was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences, Inc.

whereas the p38 inhibitor SB203580 and NF-κB inhibitor

pyrrolidinedithiocarbamate ammonium (PDTC) were obtained from

MilliporeSigma.

Antibodies against IKK (cat. no. GTX52348), IκB

(cat. no. GTX110521), p65 (cat. no. GTX102090) and β-actin

(1:10,000; cat. no. GT5512) were purchased from GeneTex

International Corporation. Antibodies for p-IKK (cat. no. 2697S)

were from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., antibodies for p-IκB

(cat. no. sc-8404) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology,

Inc. and antibodies targeting p-p65 (cat. no. AP0124) were obtained

from ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.

Cells and cell cultures

RAW264.7 murine macrophage-like cells were purchased

from the American Type Culture Collection, and were maintained in

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco, Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% characterized fetal bovine

serum (FBS; HyClone™; Cytiva) and the standard antibiotics

penicillin/streptomycin (100 IU/ml). Cells were maintained at 37°C

in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator.

Osteoclast differentiation and

treatment

RAW264.7 cells (2×103/well) were seeded

into 24-well plates and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS.

For osteoclast differentiation, cells were treated with RANKL (50

ng/ml), either alone or in combination with APLN (1, 3 or 10

ng/ml), for 5 days at 37°C with 5% CO2. For the

neutralization group, cells were pre-incubated with APLN antibody

(1 µg/ml; cat. no. NBP3-12282; Novus Biologicals; Bio-Techne) for

30 min before the addition of RANKL and APLN. The culture medium

was refreshed every 2 days. The optimal concentration of APLN (10

ng/ml) was determined from a preliminary dose response assay in

RAW264.7 cells, in which this concentration induced maximal

osteoclast differentiation without affecting cell viability. A

previous study also reported that pyroglutamyl-APLN-13, a distinct

peptide fragment of the APLN molecule, at the same concentration

modulated macrophage functions in RAW264.7 cells (20).

For tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP)

staining, cells were fixed with 10% paraformaldehyde for 5 min at

room temperature, followed by incubation with the TRAP Staining Kit

(cat. no. PMC-AK04-COS; Cosmo Bio Co., Ltd.) at 37°C for 60 min.

TRAP staining was conducted using a commercial TRAP kit (Cosmo Bio

Co., Ltd.), and TRAP-positive multinucleated cells, defined as

cells containing three or more nuclei, were identified by light

microscopy (KimForest Enterprise Co., Ltd.). Images were analyzed

using ImageJ software (v1.8.0; National Institutes of Health). The

TRAP-positive area in each well was quantified and mean values were

calculated from three independent experiments. For each well,

images from three randomly selected microscopic fields were

captured and averaged. For comparative analysis, TRAP-positive

areas were normalized to the RANKL-only group (100%), which served

as the positive control. All images include a scale bar of 100

µm.

For pathway inhibition, RAW264.7 cells

(1×105/well) were seeded into 6-well plates and

pretreated with specific pathway inhibitors for 30 min at 37°C with

5% CO2 before stimulation with RANKL (50 ng/ml) + APLN

(10 ng/ml) for 5 days. The culture medium was refreshed every 2

days. The final inhibitor concentrations were as follows: ERK

inhibitor FR180204 (10 µM), JNK inhibitor SP600125 (10 µM), p38

inhibitor SB203580 (10 µM) and NF-κB inhibitor PDTC (20 µM).

Immunofluorescence staining

RAW264.7 cells (2×103/well) were seeded

directly into 24-well plates and treated with RANKL (50 ng/ml) with

or without APLN (10 ng/ml) for 5 days at 37°C. Following treatment,

the cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and

permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room

temperature. F-actin staining was performed by incubating the cells

overnight at 4°C with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated phalloidin (cat.

no. A12379; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; diluted 1:300 in PBS).

Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Fluorescence images were

captured using an ImageXpress Pico imaging system (Molecular

Devices, LLC). The F-actin ring area was quantified using ImageJ

software (v1.8.0) and expressed relative to the RANKL-only group.

All images include a scale bar of 100 µm.

Transcriptome analysis

RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data from the GSE21639

dataset were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus database

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE21639)

(21). Differentially expressed

genes (DEGs) between control and RANKL-treated RAW264.7 cells on

days 2 and 5 were identified using GEO2R (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/info/geo2r.html)

(22), applying a threshold of

absolute log2(fold change)≥2 and an adjusted

P-value≤0.05. Boxplot and uniform manifold approximation and

projection (UMAP) analyses were performed using R software (version

4.2.2) (https://cran.r–project.org/bin/windows/base/old/4.2.2/)

with the GEOquery (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/GEOquery.html),

limma (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/limma.html)

and UMAP packages (https://cran.r–project.org/web/packages/umap/index.html)

to evaluate the quality of the GSE21639 dataset, and to confirm

consistent overall gene expression distributions and clustering

patterns. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses were performed using the

Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery

v.6.8 (https://davidbioinformatics.nih.gov) (23).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Cellular RNA was obtained from RAW264.7 cells using

TRIzol® reagent according to the manufacturer's

instructions (cat. no. 12183555; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), and cDNA was generated using the M-MLV Reverse

Transcriptase Kit (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in

accordance with the manufacturer's recommendation. SYBR Green-based

qPCR was performed using SYBR™ Green PCR Master Mix (Applied

Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) on a StepOnePlus

Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), with GAPDH as the reference gene. The cycling conditions

were as follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 20 sec, followed

by 40 cycles at 95°C for 3 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. Subsequently, a

melt curve analysis was performed. Expression levels were

normalized and calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method

(24). The mouse primer sequences

used were as follows: Cathepsin K (CTSK), forward

5′-AGTAGCCACGCTTCCTATCC-3′, reverse 5′-CCATGGGTAGCAGCAGAAAC-3′;

acid phosphatase 5, tartrate resistant (ACP5), forward

5′-ATGGGCGCTGACTTCATCAT-3′, reverse 5′-GGTCTCCTGGAACCTCTTGT-3′;

matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9), forward

5′-GGACCCGAAGCGGACATTG-3′, reverse 5′-CGTCGTCGAAATGGGCATCT-3′;

NFATc1, forward 5′-GACCCGGAGTTCGACTTCG-3′, reverse

5′-TGACACTAGGGGACACATAACTG-3′; and GAPDH, forward

5′-TGTGTCCGTCGTGGATCTGA-3′, reverse 5′-TTGCTGTTGAAGTCGCAGGAG-3.

Western blot analysis

RAW264.7 cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (cat. no.

P0013; Beyotime Biotechnology) containing protease and phosphatase

inhibitors. Protein levels were measured by BCA assay, and total

proteins (30 µg) were separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% gels and were

subsequently transferred to PVDF membranes. Blocking was performed

with 5% non-fat milk for 1 h at room temperature, followed by

overnight incubation with primary antibodies (1:1,000 for

p-proteins and 1:2,000 for total proteins) at 4°C, and detection

with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit IgG,

cat. no. sc-2004 for IKK, IκB, p65, p-IKK, p-IκB, and p-p65;

1:2,000; goat anti-mouse IgG, cat. no. sc-2302 for p-ERK, p-JNK,

p-p38, ERK, JNK, and p38; 1:2,000; both from Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by

western chemiluminescent HRP substrate (ECL) detection

(MilliporeSigma). Band intensities were measured using ImageJ

software (v1.8.0).

NF-κB reporter assay

NF-κB luciferase reporter assays were conducted

using the pNF-κB-Luc plasmid from the NF-κB cis-Reporting System

(cat. no. 219077; Agilent Technologies, Inc.). The vector contains

five tandem NF-κB response elements upstream of a minimal promoter

driving luciferase expression. RAW264.7 cells were transfected with

NF-κB luciferase constructs using Lipofectamine® 2000

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and treated with RANKL

(50 ng/ml) or RANKL (50 ng/ml) + APLN (10 ng/ml) 24 h after

transfection for an additional 24 h at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Luciferase activity was assessed using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter

assay (Promega Corporation) and measured with a Fluoroskan Ascent

Microplate Luminometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The

relative NF-κB luciferase activity was normalized to the control

group and expressed as a percentage of the control value (% of

control).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by

the Bonferroni post hoc test for pairwise comparisons between

selected groups. All data are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation, and P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference. Analyses were performed using GraphPad

Prism 9.0 (Dotmatics).

Results

APLN promotes RANKL-induced osteoclast

differentiation and enhances F-actin ring formation

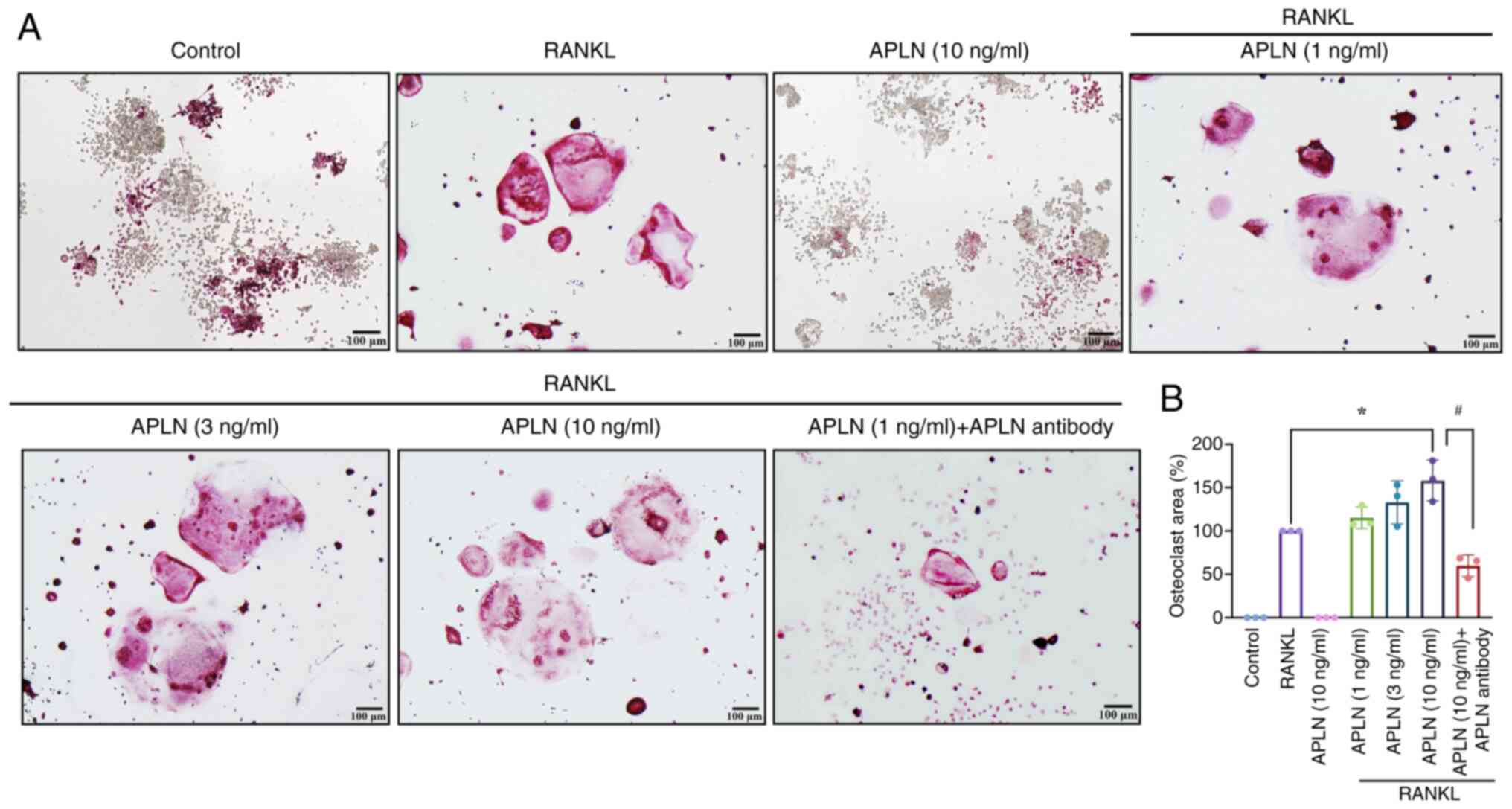

The ability of RANKL to induce osteoclast

differentiation in RAW264.7 cells has been extensively validated

in vitro (25). In the

present study, RAW264.7 cells were stimulated with RANKL (50 ng/ml)

in the presence of increasing concentrations of APLN (1, 3 or 10

ng/ml) for 5 days to assess whether APLN modulated

osteoclastogenesis. TRAP staining revealed a marked increase in the

size of multinucleated osteoclasts in cells co-treated with APLN

and RANKL compared with RANKL alone (Fig. 1A). By contrast, APLN treatment

alone did not induce osteoclast formation (Fig. 1A), indicating that APLN enhanced

RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis as opposed to initiating the

differentiation process independently.

In addition, quantitative analysis of the mature

osteoclast area supported that APLN co-treatment with RANKL

significantly increased the osteoclast area in a

concentration-dependent manner, with the 10 ng/ml treatment group

having exhibited the most pronounced effect (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, to functionally

validate whether the pro-osteoclastic effect of APLN was

reversible, an APLN-neutralizing antibody was co-administered

together with RANKL and APLN (10 ng/ml). TRAP staining results

demonstrated that the enhanced osteoclast formation observed in the

APLN + RANKL group was markedly attenuated by the addition of APLN

antibody (Fig. 1A). Quantitative

analysis showed a significant reduction in osteoclast area, not

only reversing the APLN-mediated enhancement but further

suppressing osteoclastogenesis, resulting in an osteoclast area

lower than that induced by RANKL alone (Fig. 1B). These findings suggested that

APLN may serve an important modulatory role in osteoclast

differentiation and that its effects could be effectively

neutralized by targeted-antibody blockade.

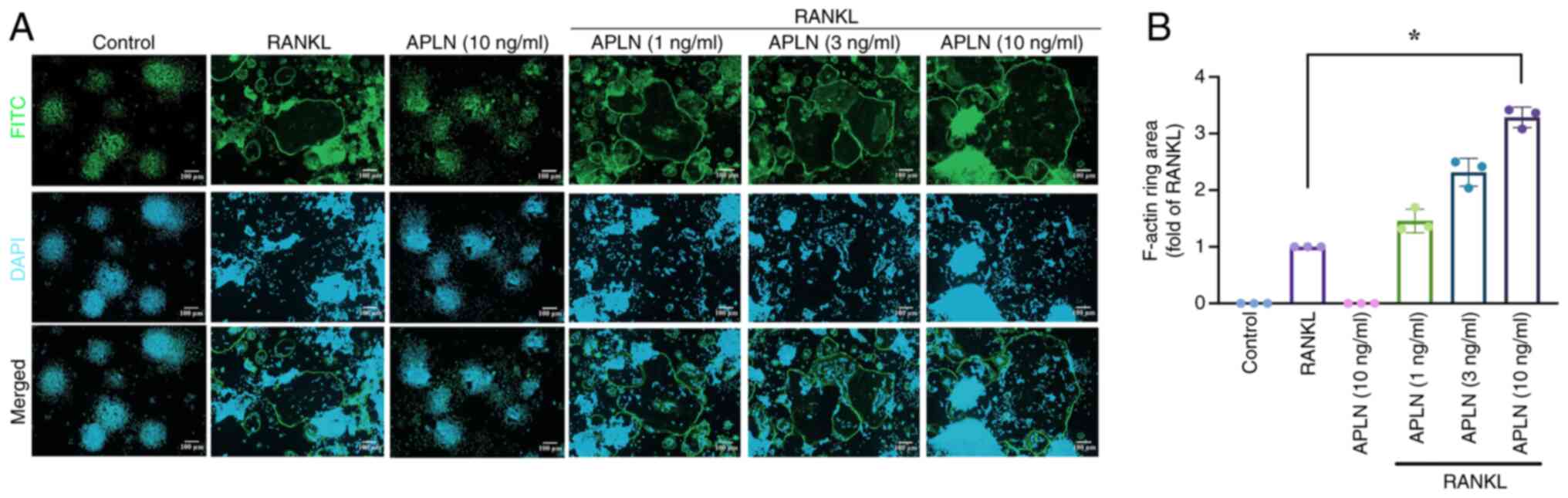

To further investigate whether APLN also affected

the functional activity of mature osteoclasts, the present study

evaluated F-actin ring formation using immunofluorescence staining,

which specifically reflects cytoskeletal organization and the

resorptive capacity of osteoclasts. RAW264.7 cells treated with

RANKL alone exhibited F-actin ring formation. By contrast,

co-treatment with APLN led to a concentration-dependent increase in

the size of F-actin rings (Fig.

2A). Quantitative analysis revealed that the F-actin ring area

was significantly greater in the cells co-treated with RANKL and

APLN, particularly in the cells treated with the 10 ng/ml APLN,

compared with the RANKL-only group (Fig. 2B). These findings allowed for the

comprehensive assessment of the functional activity of osteoclasts

in the presence of APLN and provided further insight into its role

in RANKL-mediated osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption.

APLN facilitates RANKL-induced

osteoclastogenic gene expression

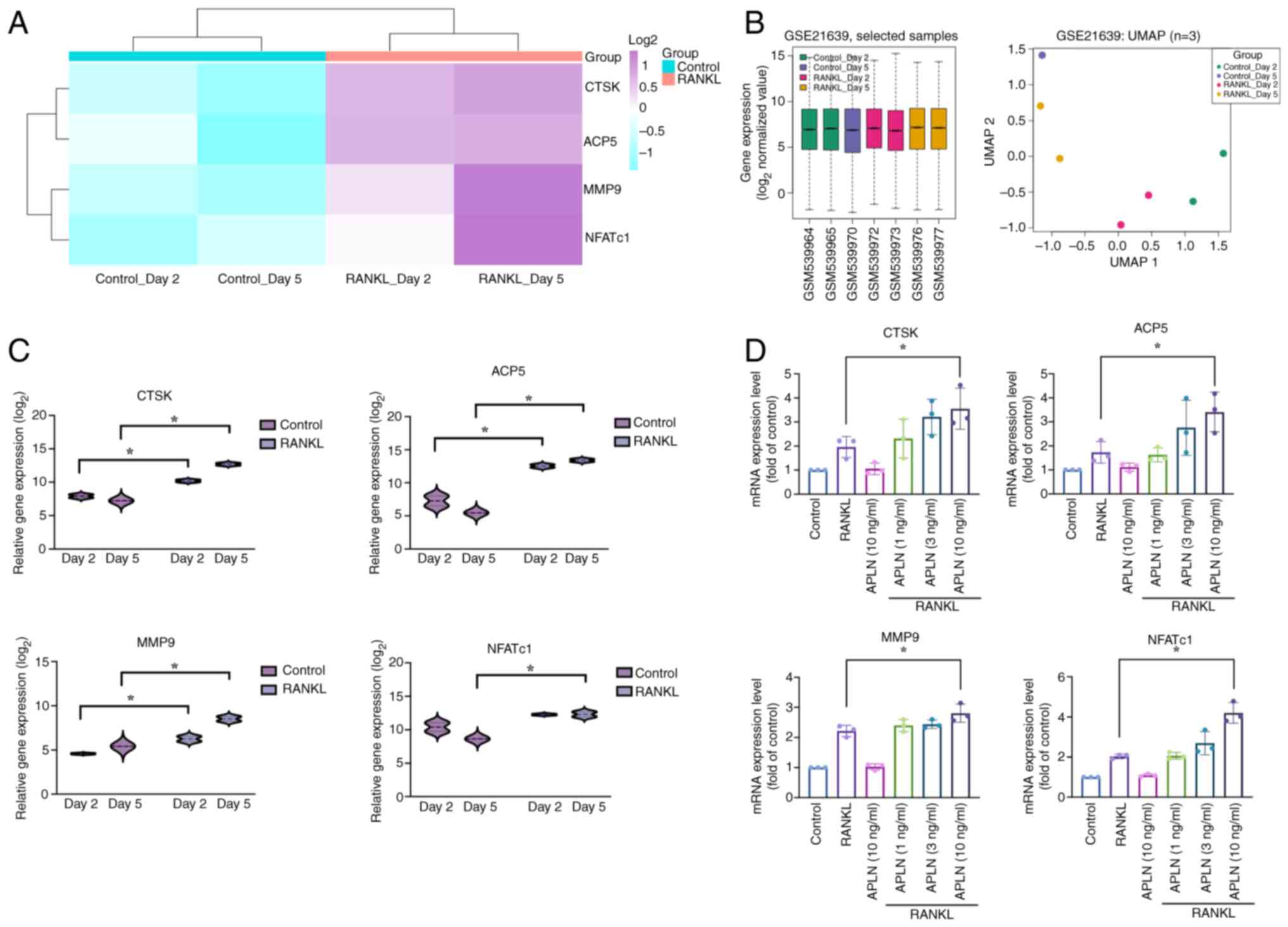

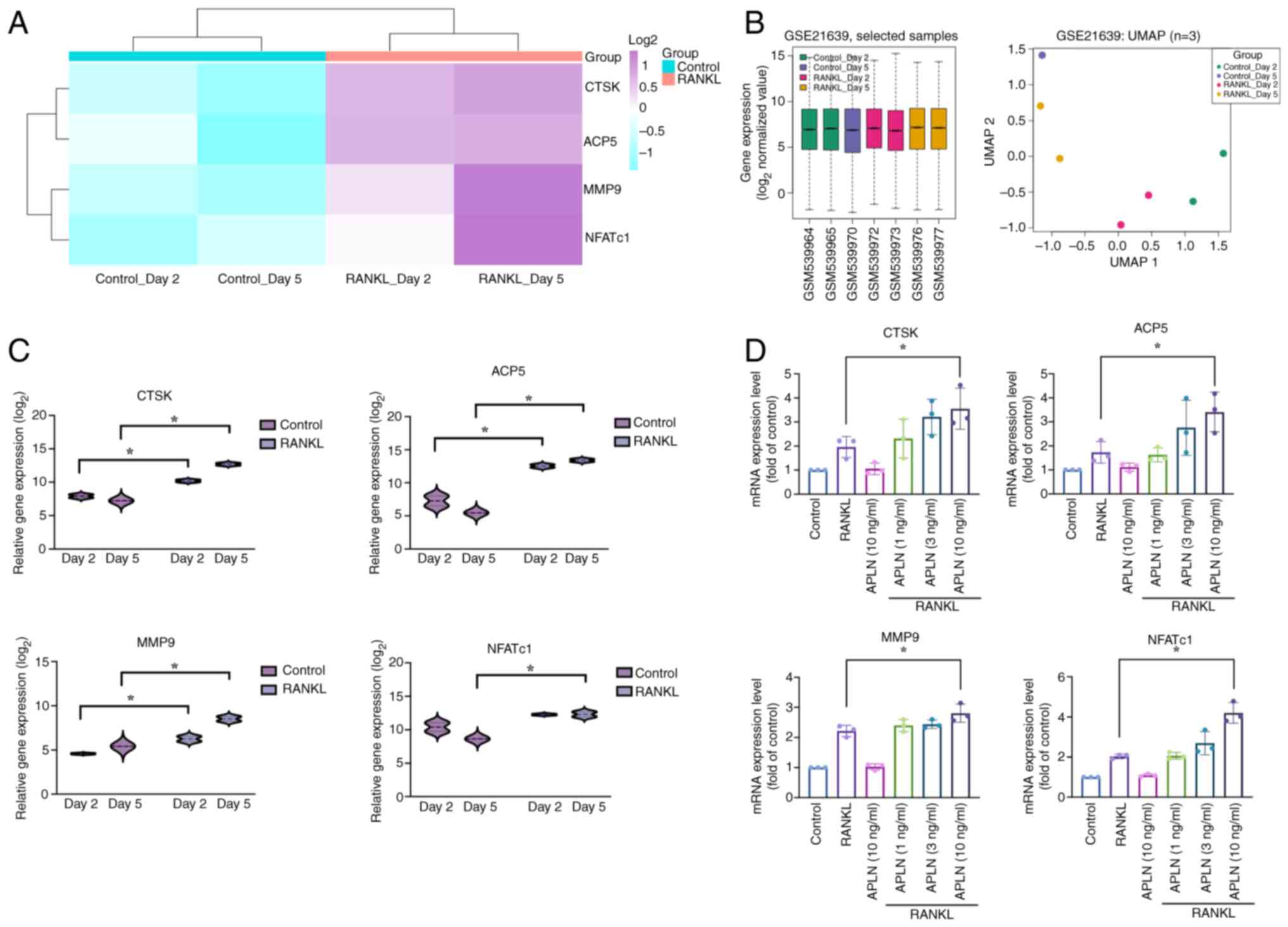

Previous research has demonstrated that osteoclast

marker genes such as ACP5, CTSK, MMP9 and NFATc1 are upregulated

during osteoclast differentiation (26). To support this observation, the

present study analyzed RNA-seq data from the GSE21639 dataset,

which included RAW264.7 cells treated with or without RANKL for 2

and 5 days. The heatmap with hierarchical clustering revealed

increased expression of ACP5, CTSK, MMP9 and NFATc1 in

RANKL-treated groups compared with that in the control groups. Both

control and RANKL groups clustered tightly within their respective

branches, indicating high intra-group consistency and clear

separation between conditions (Fig.

3A). As additional evidence of dataset quality, boxplot and

UMAP analyses showed consistent expression distributions without

outliers and clustering patterns aligned with experimental

conditions (Fig. 3B), indicating

effective normalization, high reproducibility and biological

relevance. Further quantification revealed that the ACP5, CTSK and

MMP9 levels were significantly elevated on both day 2 and 5

following RANKL stimulation compared with those in the control

group. However, NFATc1 exhibited a significant increase in

expression in the RANKL-treated group on day 5 only (Fig. 3C). The present study also validated

the findings of the transcriptome analysis and assessed the effects

of APLN on osteoclast-specific gene expression in RAW264.7 cells.

RT-qPCR analysis demonstrated that co-treatment with RANKL and APLN

increased ACP5, CTSK, MMP9 and NFATc1 mRNA expression relative to

RANKL alone, showing a dose-dependent response, with statistical

significance observed only at 10 ng/ml APLN (Fig. 3D). Notably, APLN treatment alone

had no notable effect. These findings indicated that APLN may

facilitate RANKL-induced osteoclastogenic gene expression, thereby

supporting its functional role as a positive regulator of

osteoclast differentiation.

| Figure 3.APLN enhances osteoclast marker gene

expression under RANKL stimulation. (A) Heatmap analysis of

osteoclast-related gene expression (ACP5, CTSK, MMP9 and NFATc1)

from the GSE21639 dataset. RAW264.7 cells were treated with or

without RANKL for 2 or 5 days. (B) Boxplot and UMAP analyses of the

GSE21639 dataset. The boxplot shows consistent overall gene

expression distributions across all samples without outliers, while

the UMAP plot illustrates the clustering of samples according to

experimental conditions (Control or RANKL treatment on days 2 and

5). These analyses were conducted to assess dataset quality and

comparability prior to differential expression analysis. (C) Violin

plot visualization of the transcript levels of each gene. Data were

log2-transformed and grouped by treatment condition. (D)

RAW264.7 cells were treated with RANKL (50 ng/ml) and increasing

concentrations of APLN (1, 3 or 10 ng/ml) for 5 days. The mRNA

expression of osteoclast markers was determined using reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. *P<0.05 vs. RANKL-treated group.

UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection analyses;

RANKL, receptor activator of NF-κB ligand; APLN, apelin; ACP5, acid

phosphatase 5, tartrate resistant; CTSK, cathepsin K; MMP9, matrix

metalloproteinase 9; NFATc1, nuclear factor of activated T-cells

1. |

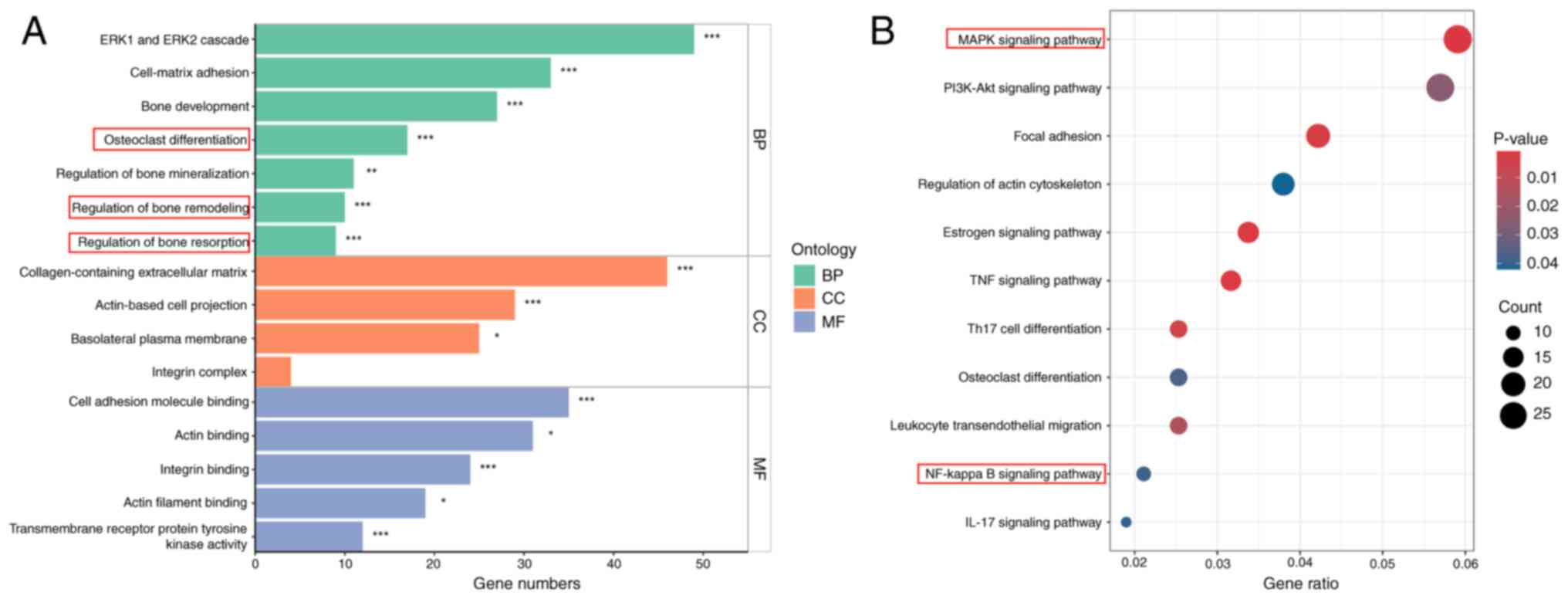

Transcriptome enrichment analysis

reveals osteoclast-related pathways activated by RANKL

To provide further mechanistic insights into the

biological processes and signaling pathways involved in

APLN-enhanced osteoclastogenesis, the present study analyzed DEGs

using RNA-seq data from the GSE21639 dataset. This dataset contains

data on RAW264.7 cells cultured with RANKL for 5 days. DEGs were

defined using thresholds of |log2(fold change)|>2 and

P<0.05. GO enrichment analysis revealed that upregulated DEGs

were significantly associated with biological processes relevant to

osteoclast activity, including ‘osteoclast differentiation’,

‘regulation of bone remodeling’ and ‘regulation of bone resorption’

(Fig. 4A). Furthermore, KEGG

pathway analysis demonstrated significant enrichment in key

signaling cascades, including the ‘MAPK signaling pathway’ and ‘NF-

kappa B signaling pathway’ (Fig.

4B). These findings highlighted the involvement of

osteoclast-related biological processes and signaling pathways in

RANKL-induced differentiation.

APLN promotes RANKL-mediated

osteoclast differentiation through MAPK and NF-κB signaling

pathways

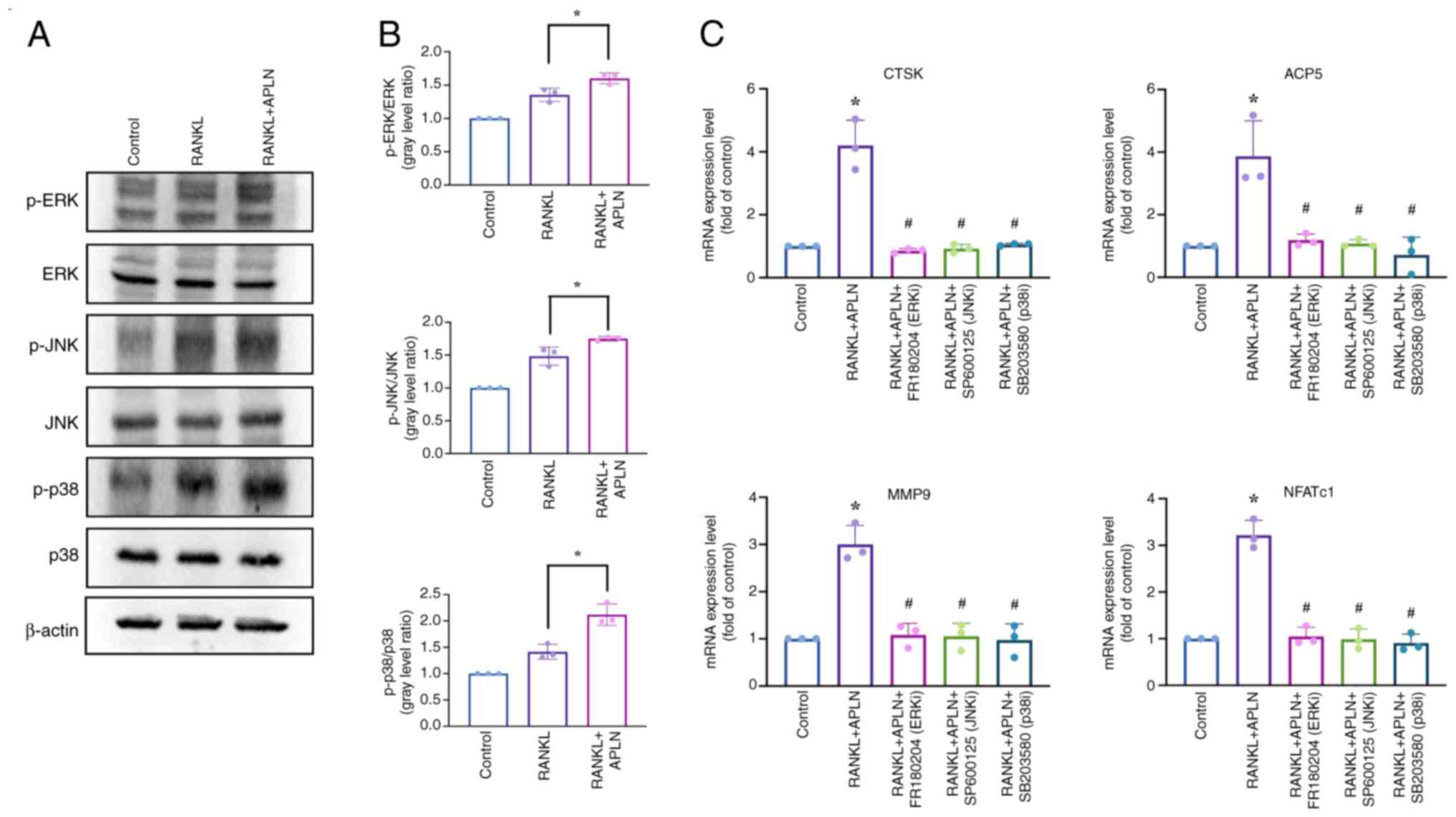

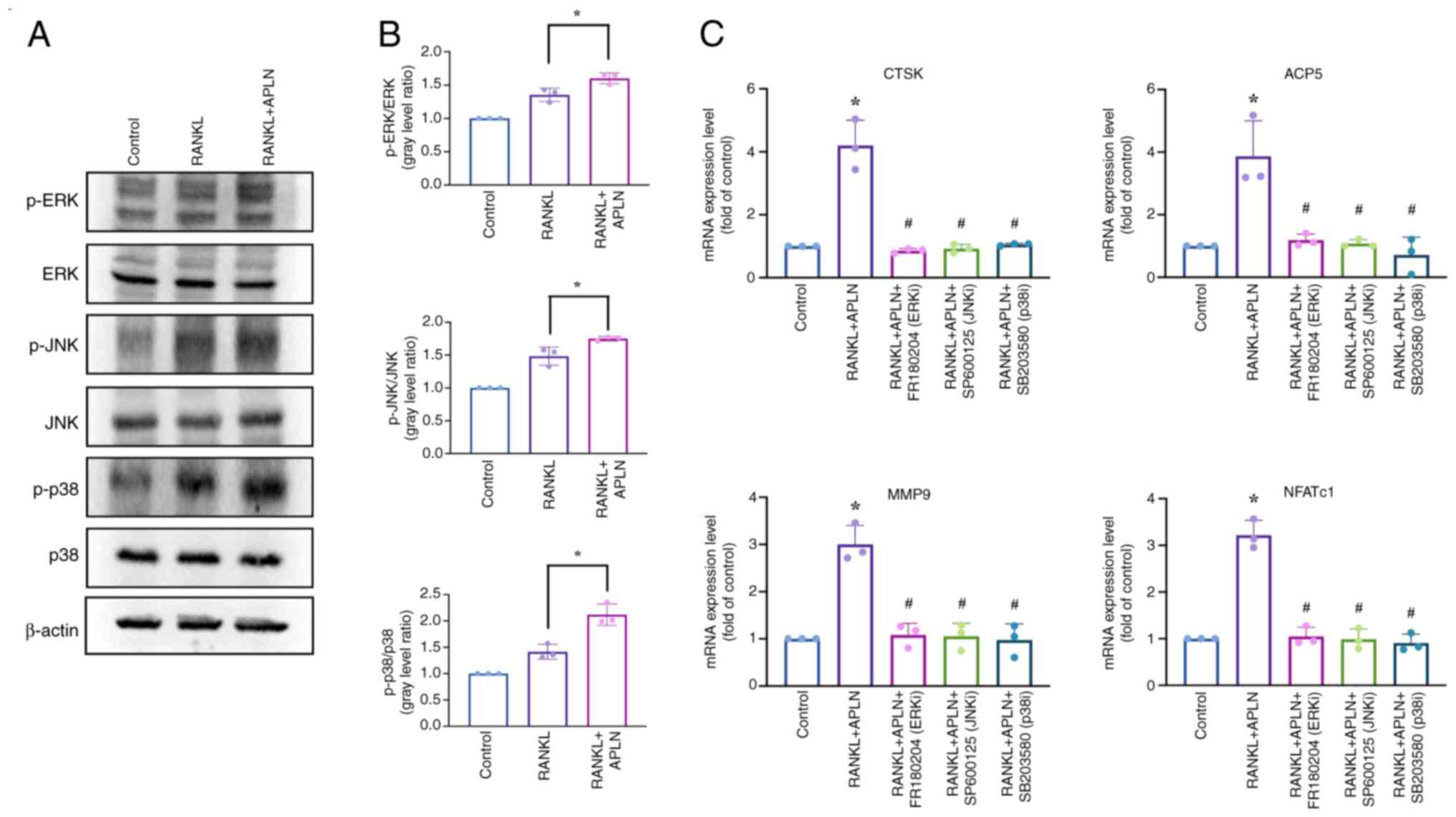

Given the enrichment of MAPK and NF-κB pathways

observed in transcriptome analysis, the present study then

investigated whether these pathways contributed to the

pro-osteoclastogenic effects of APLN. Western blot analysis

revealed that co-treatment with APLN and RANKL markedly enhanced

the phosphorylation of ERK, JNK and p38 compared with RANKL

treatment alone (Fig. 5A).

Quantitative analysis of the western blots revealed that treatment

with RANKL significantly increased the phosphorylation of ERK, JNK

and p38 compared with the control group (Fig. 5B). This phosphorylation was

significantly enhanced by co-treatment with RANKL and APLN. To

determine whether APLN promoted osteoclast differentiation through

MAPK pathway activation, the effects of selective MAPK inhibitors

on APLN-treated cells were assessed. RAW264.7 cells were treated

with APLN and RANKL in the presence of the ERK inhibitor FR180294,

JNK inhibitor SP600125 or p38 inhibitor SB203580, and the

expression levels of osteoclast marker genes were subsequently

assessed by RT-qPCR analysis. As expected, treatment with RANKL and

APLN significantly upregulated the mRNA expression levels of ACP5,

CTSK, MMP9 and NFATc1 compared with those in the control group.

However, this enhanced expression was significantly suppressed upon

treatment with MAPK inhibitors (Fig.

5C), indicating that the activation of MAPK signaling was

important for APLN activity in promoting RANKL-mediated osteoclast

differentiation.

| Figure 5.APLN promotes osteoclast

differentiation through activation of the MAPK pathway. (A)

RAW264.7 cells were exposed to a control medium, RANKL (50 ng/ml)

or RANKL + APLN (10 ng/ml) for 10 min. Cell lysates were subjected

to western blot analysis to assess the phosphorylation of MAPK

family members, including ERK, JNK and p38. (B) Signal intensities

of p-ERK, p-JNK and p-p38 were semi-quantified using ImageJ

software and normalized to their respective total protein levels.

*P<0.05 vs. RANKL-treated group. (C) mRNA expression levels of

osteoclast marker genes (ACP5, CTSK, MMP9 and NFATc1) were assessed

using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR in cells treated with

RANKL + APLN (10 ng/ml), either alone or in combination with MAPK

inhibitors (FR180204 for ERK, SP600125 for JNK and SB203580 for

p38). *P<0.05 vs. Control group; #P<0.05 vs. RANKL

+ APLN group. APLN, apelin; RANKL, receptor activator of NF-κB

ligand; ACP5, acid phosphatase 5, tartrate resistant; CTSK,

cathepsin K; MMP9, matrix metalloproteinase 9; NFATc1, nuclear

factor of activated T-cells 1; p-, phosphorylated-; ERK/JNK/p38i,

ERK/JNK/p38 inhibitor. |

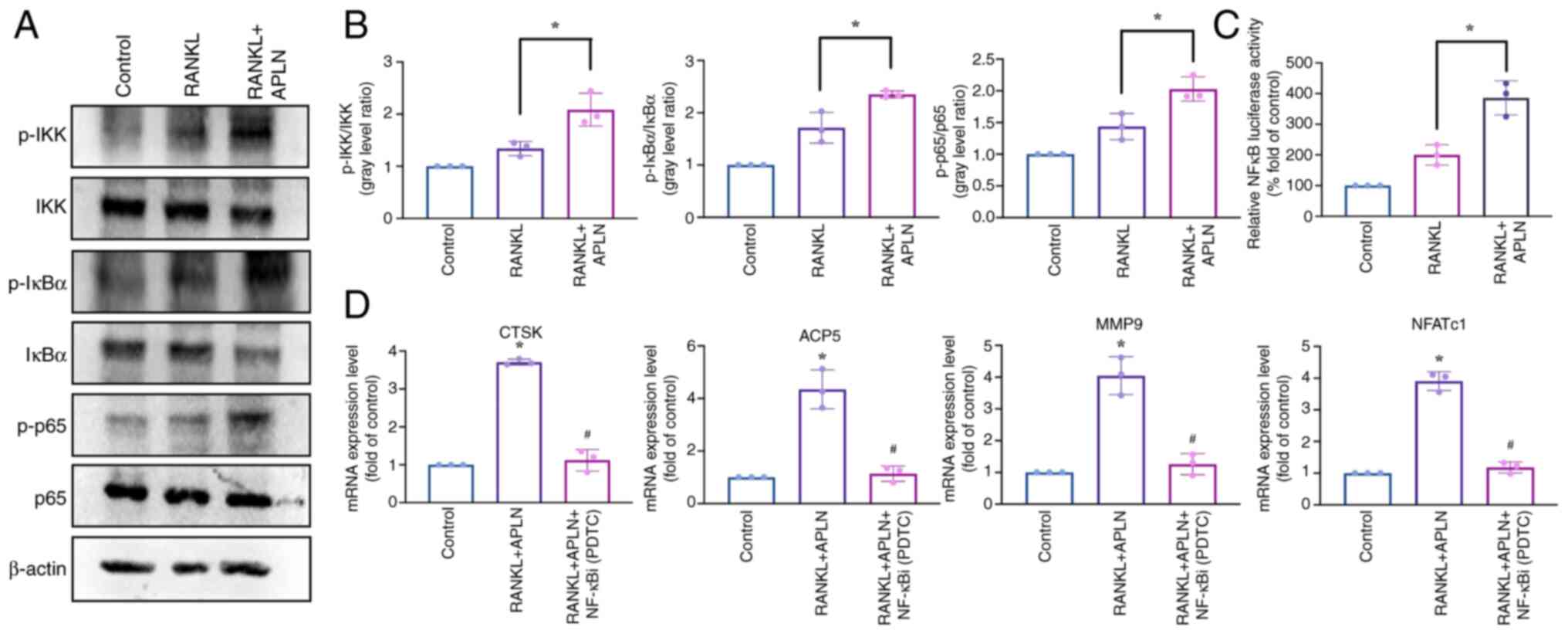

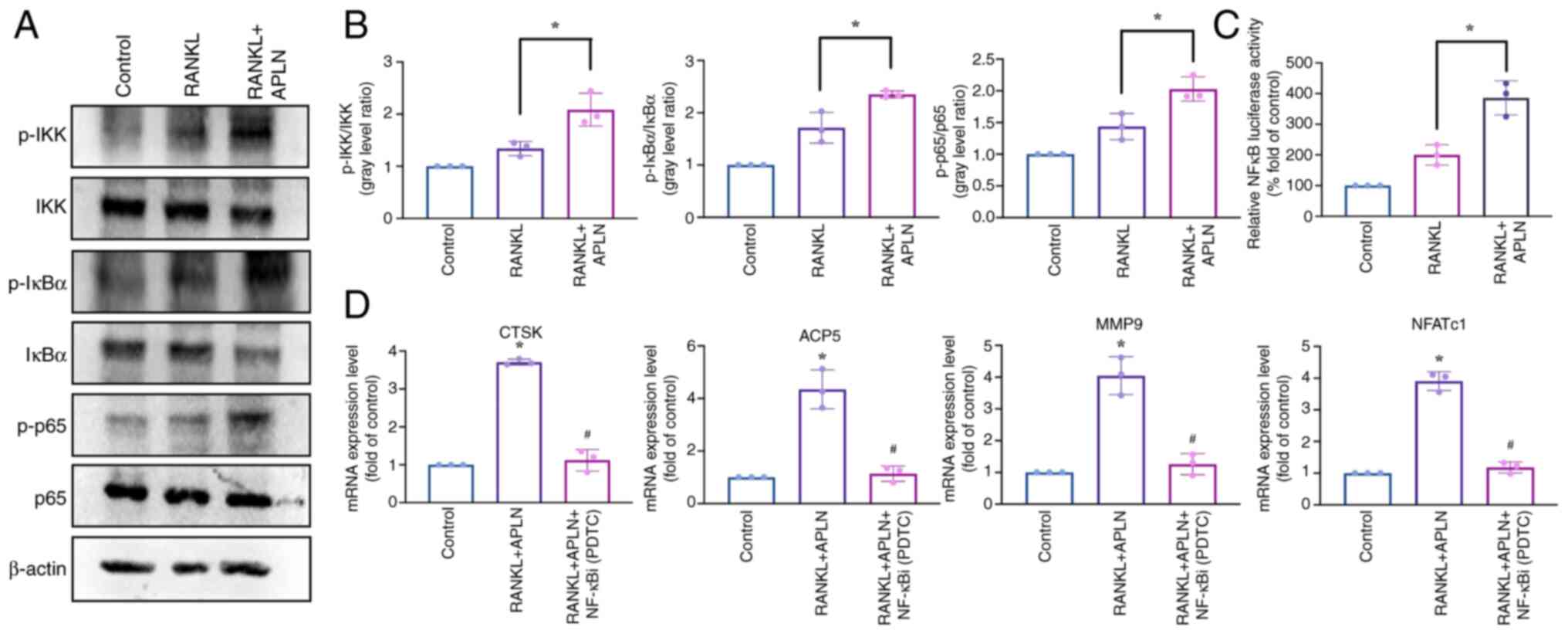

The present study then investigated the role of

NF-κB signaling in APLN-enhanced RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis.

Western blot analysis and signal semi-quantification revealed that

RANKL treatment significantly increased the phosphorylation of IKK,

IκB and NF-κB p65 compared with that in the control group.

Co-treatment with APLN and RANKL significantly enhanced the

phosphorylation levels of these proteins relative to RANKL alone

(Fig. 6A and B). Consistently,

luciferase reporter assays revealed that APLN significantly

enhanced RANKL-induced NF-κB transcriptional activity (Fig. 6C). In addition, RT-qPCR analysis

demonstrated that co-treatment of RAW264.7 cells with APLN and

RANKL significantly upregulated the expression of osteoclast marker

genes compared with the control group; however, this effect was

significantly reduced by the NF-κB inhibitor PDTC (Fig. 6D). Taken together, these results

suggested that APLN may promote RANKL-mediated osteoclast

differentiation by activating the MAPK and NF-κB signaling

pathways.

| Figure 6.APLN enhances RANKL-induced

activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway. (A) Western blot

analysis of RAW264.7 cells treated with control medium, RANKL (50

ng/ml) or RANKL + APLN (10 ng/ml) for 10 min. Protein levels of

p-IKK, p-IκB and p-p65 were detected to evaluate pathway

activation. (B) Semi-quantification of p-IKK, p-IκB and p-p65

levels relative to their corresponding total proteins was performed

using ImageJ software. (C) RAW264.7 cells were transfected with an

NF-κB luciferase reporter construct and treated with RANKL (50

ng/ml) or RANKL + APLN (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. Luciferase activity was

measured using cell lysates and reporter buffer mixed at a 1:1

ratio. NF-κB transcriptional activity is shown as the fold change

relative to the RANKL-only group. *P<0.05 vs. RANKL-treated

group. (D) Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR analysis of

osteoclast marker genes (ACP5, CTSK, MMP9 and NFATc1) in cells

treated with RANKL + APLN (10 ng/ml) with or without the NF-κBi

PDTC (20 µM). *P<0.05 vs. Control group; #P<0.05

vs. RANKL + APLN group. APLN, apelin; RANKL, receptor activator of

NF-κB ligand; ACP5, acid phosphatase 5, tartrate resistant; CTSK,

cathepsin K; MMP9, matrix metalloproteinase 9; NFATc1, nuclear

factor of activated T-cells 1; p-, phosphorylated-; NF-κBi, NF-κB

inhibitor; PDTC, pyrrolidinedithiocarbamate ammonium. |

Discussion

Adipokines are bioactive peptides derived from

adipose tissue that regulate key physiological processes, including

metabolism, inflammation and vascular function. Increasing evidence

has indicated that adipokines exert effects on the musculoskeletal

system and also participate in the regulation of bone remodeling

(27,28). Leptin has been shown to induce the

production of oncostatin M in human osteoblasts, thereby promoting

inflammatory signaling that disrupts osteoblast function and bone

homeostasis (29). The

proinflammatory and catabolic effects of visfatin in gingival

fibroblasts may indirectly promote osteoclast activation, thereby

exacerbating alveolar bone resorption in periodontitis (30). However, the roles of numerous

adipokines in bone homeostasis remain yet to be fully elucidated.

APLN has been identified as an adipokine implicated in

cardiovascular control, glucose metabolism and inflammatory

responses (31–33). Despite its broad biological role,

information on the influence of APLN on osteoclast differentiation

or bone resorption is limited.

The present study demonstrated that APLN enhanced

RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation and function in a

concentration-dependent manner. Co-treatment with APLN

significantly increased TRAP-positive multinucleated cell

formation, F-actin ring size and the expression of osteoclast

marker genes, including ACP5, CTSK, MMP9 and NFATc1. These findings

provided novel insights into the bone-regulatory role of APLN and

suggested that APLN inhibition may serve as a potential strategy to

modulate osteoclast function.

Bone remodeling is a dynamic process that requires

regulation to maintain a balance between osteoblast-mediated bone

formation and osteoclast-mediated bone resorption (1). The disruption of this balance,

particularly when bone resorption outpaces formation, contributes

to the pathogenesis of various skeletal disorders, including

osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis (34–36).

Osteoclast differentiation and activation are primarily driven by

RANKL, which initiates a cascade of intracellular signaling events

upon binding to its receptor RANK on osteoclast precursors

(37). Activated pathways include

the NF-κB and MAPK pathways, both of which are important for the

induction of key osteoclastogenic transcription factors such as

NFATc1 (38). The present study

found that APLN co-treatment with RANKL significantly enhanced the

phosphorylation of ERK, JNK and p38 in the MAPK pathway, as well as

IKK, IκB and NF-κB p65 in the canonical NF-κB pathway. The

inhibition of these signaling pathways significantly attenuated the

APLN-induced upregulation of osteoclast-specific genes, indicating

that APLN promoted osteoclastogenesis through the activation of

classical signaling cascades downstream of RANKL. These findings

suggested that APLN may facilitate pathological bone resorption by

amplifying RANKL-induced signals.

Building on these mechanistic insights, targeting

APLN may represent a promising therapeutic strategy for osteolytic

conditions such as osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis and

periodontitis. However, given that APLN is a multifunctional

adipokine involved in cardiovascular regulation, angiogenesis and

metabolic homeostasis, systemic inhibition may lead to undesirable

off-target effects (39–42). To overcome these limitations,

localized treatment strategies may offer a more favorable

therapeutic strategy. For example, APLN-silencing molecules, such

as small interfering RNAs or miRNA mimics, could be encapsulated

within engineered exosomes for targeted delivery to the bone

microenvironment. This approach may enable site-specific

suppression of APLN activity, thereby attenuating osteoclast

overactivation while minimizing systemic effects. Further

investigations are warranted to evaluate the feasibility and

therapeutic benefit of exosome-mediated APLN inhibition in

bone-resorptive diseases.

Current pharmacological approaches for the treatment

of bone-resorptive diseases mainly focus on inhibiting osteoclast

activity (43). Bisphosphonates,

such as alendronate and zoledronic acid, are used to suppress

osteoclast-mediated bone resorption by inducing osteoclast

apoptosis (44). While effective

in reducing fracture risk, their prolonged use has been shown to be

associated with complications such as atypical femoral fractures

and osteonecrosis of the jaw (45). Denosumab, a monoclonal antibody

against RANKL, provides the potent and reversible suppression of

osteoclastogenesis, but its discontinuation may lead to rapid bone

loss and an increased risk of multiple vertebral fractures

(46). Furthermore, both

treatments broadly suppress bone turnover, potentially impairing

the physiological remodeling process.

Other anti-resorptive agents, including calcitonin,

hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and SERMs such as raloxifene,

have also been used in clinical practice. However, these options

are limited by suboptimal efficacy and potential systemic risks.

For example, calcitonin has been associated with an increased risk

of developing cancer (47); and

HRT has been a subject of concern regarding cardiovascular disease

and hormone-sensitive cancers (48). In addition, SERMs may increase the

risk of thromboembolism (49).

Given these limitations, there is growing interest in identifying

novel osteoclastogenic regulatory pathways complementing current

therapies. A co-therapeutic strategy combining adipokine-targeted

interventions with current anti-resorptive agents may improve

outcomes in osteolytic disease treatment.

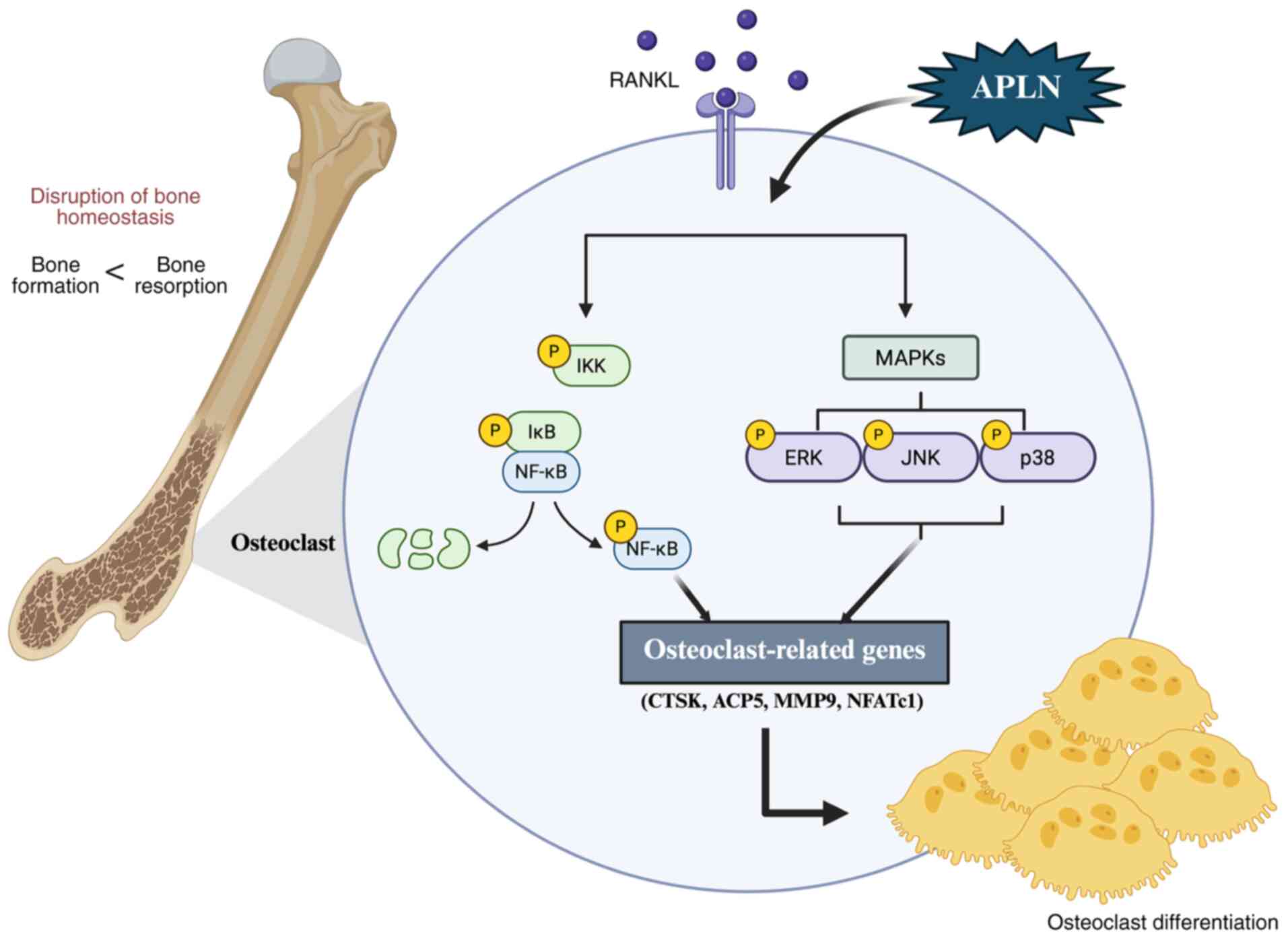

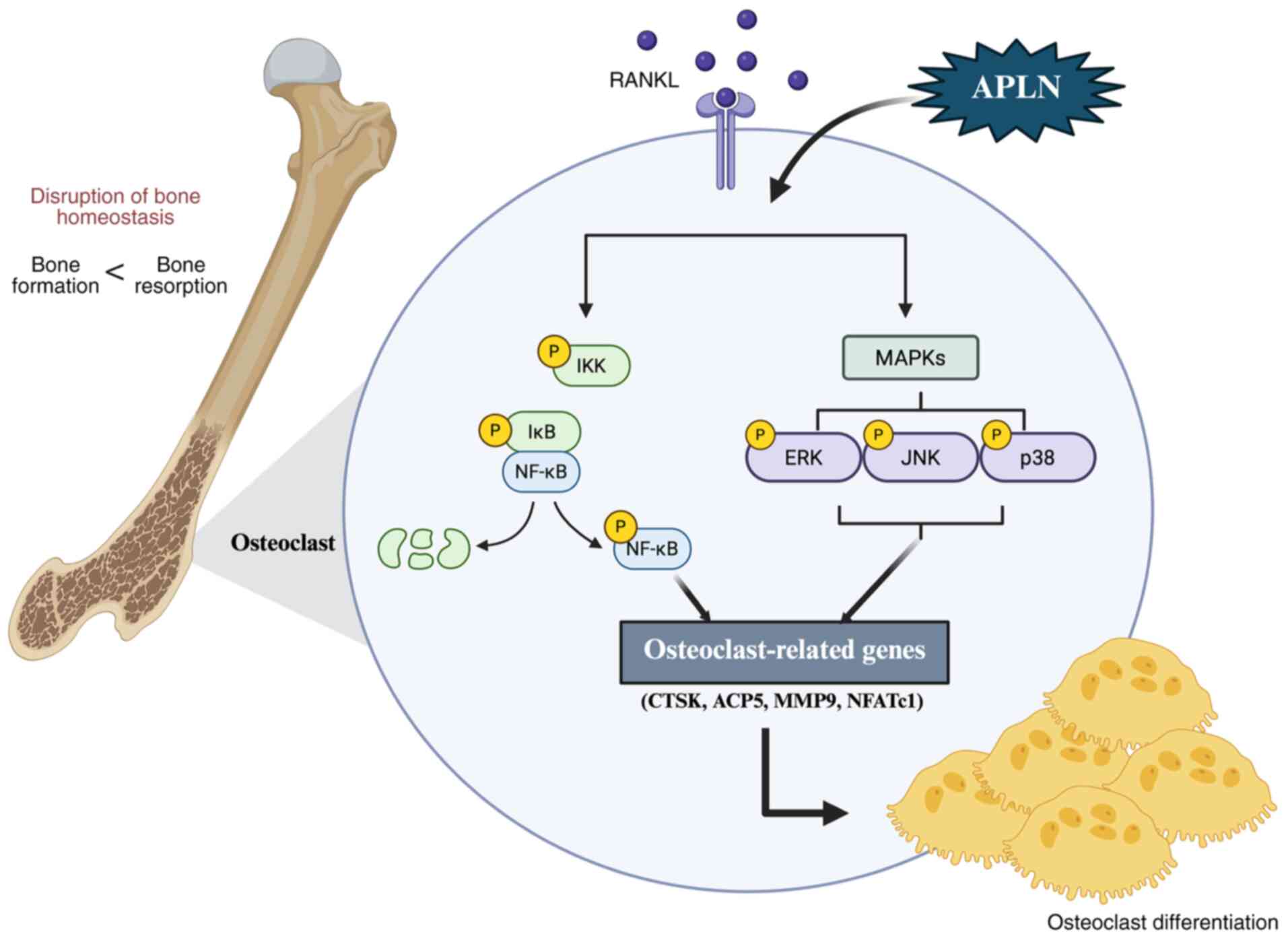

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

APLN may promote RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation and

function, and upregulate the levels of key osteoclast marker genes.

APLN was found to enhance the MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways in

the presence of RANKL, and the inhibition of these pathways

attenuated the ability of APLN to promote osteoclast

differentiation (Fig. 7). These

findings provide a novel perspective into the role of APLN in bone

remodeling and identify APLN as an important enhancer of

osteoclastogenesis. Given these observations, therapeutic

strategies aimed at inhibiting APLN signaling may represent a novel

approach for mitigating pathological bone resorption in conditions

such as osteoporosis, inflammatory arthritis and periodontitis.

| Figure 7.APLN promotes RANKL-mediated

osteoclastogenesis, and activates MAPK and NF-κB signaling

pathways. APLN augmented RANKL-induced phosphorylation of ERK, JNK,

p38 and NF-κB p65, leading to the increased expression of

osteoclast marker genes and enhanced osteoclast differentiation and

function. APLN, apelin; RANKL, receptor activator of NF-κB ligand;

ACP5, acid phosphatase 5, tartrate resistant; CTSK, cathepsin K;

MMP9, matrix metalloproteinase 9; NFATc1, nuclear factor of

activated T-cells 1. |

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors acknowledge financial support from the Ministry of

Science and Technology of Taiwan (grant nos. MOST

110-2320-B-039-022-MY3, NSTC 112-2320-B-039-035-MY3, MOST

111-2314-B-039-048-MY3, NSTC 113-2320-B-039-049-MY3, NSTC

111-2320-B-371-002, NSTC 114-2314-B-039-051-MY3 and NSTC

114-2320-B- 039-016-), the China Medical University Hospital (grant

nos. DMR-114-003 and DMR-114-043) and the China Medical University

(grant no. CMU 113-ASIA-05).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YHW, YYW, CHTs, and CHTa contributed to the

conception and design of the study. YCF, CYK and HTC were

responsible for data acquisition and experimental validation. CHTs

and YYL contributed to data analysis and interpretation. YHW and

CHTa drafted the manuscript and confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data. All authors critically revised the manuscript for

important intellectual content and agreed to be accountable for all

aspects of the work. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bolamperti S, Villa I and Rubinacci A:

Bone remodeling: An operational process ensuring survival and bone

mechanical competence. Bone Res. 10:482022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Zhu L, Zhou C, Chen S, Huang D, Jiang Y,

Lan Y, Zou S and Li Y: Osteoporosis and alveolar bone health in

periodontitis niche: A predisposing factors-centered review. Cells.

11:33802022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Ashai S and Harvey NC: Rheumatoid

arthritis and bone health. Clin Med (Lond). 20:565–567. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Park JJ and Wong C: Pharmacological

prevention and management of skeletal-related events and bone loss

in individuals with cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 38:1512762022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Salari N, Ghasemi H, Mohammadi L, Behzadi

MH, Rabieenia E, Shohaimi S and Mohammadi M: The global prevalence

of osteoporosis in the world: A comprehensive systematic review and

meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 16:6092021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Elahmer NR, Wong SK, Mohamed N, Alias E,

Chin KY and Muhammad N: Mechanistic insights and therapeutic

strategies in osteoporosis: A comprehensive review. Biomedicines.

12:16352024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ayers C, Kansagara D, Lazur B, Fu R, Kwon

A and Harrod C: Effectiveness and safety of treatments to prevent

fractures in people with low bone mass or primary osteoporosis: A

living systematic review and network meta-analysis for the American

College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 176:182–195. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Weivoda MM and Bradley EW: Macrophages and

bone remodeling. J Bone Miner Res. 38:359–369. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Campbell MJ, Bustamante-Gomez C, Fu Q,

Beenken KE, Reyes-Pardo H, Smeltzer MS and O'Brien CA:

RANKL-mediated osteoclast formation is required for bone loss in a

murine model of Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis. Bone.

187:1171812024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Park JH, Lee NK and Lee SY: Current

understanding of RANK signaling in osteoclast differentiation and

maturation. Mol Cells. 40:706–713. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Yan J, Wang A, Cao J and Chen L:

Apelin/APJ system: An emerging therapeutic target for respiratory

diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 77:2919–2930. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wang YH, Kuo SJ, Liu SC, Wang SW, Tsai CH,

Fong YC and Tang CH: Apelin affects the progression of

osteoarthritis by regulating VEGF-dependent angiogenesis and

miR-150-5p expression in human synovial fibroblasts. Cells.

9:5942020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hu G, Wang Z, Zhang R, Sun W and Chen X:

The role of apelin/apelin receptor in energy metabolism and water

homeostasis: A comprehensive narrative review. Front Physiol.

12:6328862021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chapman FA, Melville V, Godden E, Morrison

B, Bruce L, Maguire JJ, Davenport AP, Newby DE and Dhaun N:

Cardiovascular and renal effects of apelin in chronic kidney

disease: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover

study. Nat Commun. 15:83872024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wysocka MB, Pietraszek-Gremplewicz K and

Nowak D: The role of apelin in cardiovascular diseases, obesity and

cancer. Front Physiol. 9:5572018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Chang TK, Wang YH, Kuo SJ, Wang SW, Tsai

CH, Fong YC, Wu NL, Liu SC and Tang CH: Apelin enhances IL-1beta

expression in human synovial fibroblasts by inhibiting miR-144-3p

through the PI3K and ERK pathways. Aging (Albany NY). 12:9224–9239.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ducy P, Amling M, Takeda S, Priemel M,

Schilling AF, Beil FT, Shen J, Vinson C, Rueger JM and Karsenty G:

Leptin inhibits bone formation through a hypothalamic relay: A

central control of bone mass. Cell. 100:197–207. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Tu Q, Zhang J, Dong LQ, Saunders E, Luo E,

Tang J and Chen J: Adiponectin inhibits osteoclastogenesis and bone

resorption via APPL1-mediated suppression of Akt1. J Biol Chem.

286:12542–12553. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wattanachanya L, Lu WD, Kundu RK, Wang L,

Abbott MJ, O'Carroll D, Quertermous T and Nissenson RA: Increased

bone mass in mice lacking the adipokine apelin. Endocrinology.

154:2069–2080. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Izgut-Uysal VN, Gemici B, Birsen I, Acar N

and Ustunel I: The effect of apelin on the functions of peritoneal

macrophages. Physiol Res. 66:489–496. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Sharma P, Patntirapong S, Hann S and

Hauschka PV: RANKL-RANK signaling regulates expression of

xenotropic and polytropic virus receptor (XPR1) in osteoclasts.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 399:129–132. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Love MI, Huber W and Anders S: Moderated

estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with

DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15:5502014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Dennis G Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang

J, Gao W, Lane HC and Lempicki RA: DAVID: Database for annotation,

visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Biol. 4:P32003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Lampiasi N, Russo R, Kireev I, Strelkova

O, Zhironkina O and Zito F: Osteoclasts differentiation from murine

RAW 264.7 cells stimulated by RANKL: Timing and behavior. Biology

(Basel). 10:1172021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Sun W, Li Y, Li J, Tan Y, Yuan X, Meng H,

Ye J, Zhong G, Jin X, Liu Z, et al: Mechanical stimulation controls

osteoclast function through the regulation of Ca(2+)-activated

Cl(−) channel Anoctamin 1. Commun Biol. 6:4072023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Greco EA, Lenzi A and Migliaccio S: The

obesity of bone. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 6:273–286. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Armutcu F, McCloskey E and Ince M: Obesity

significantly modifies signaling pathways associated with bone

remodeling and metabolism. J Cell Signal. 5:183–194. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Yang WH, Tsai CH, Fong YC, Huang YL, Wang

SJ, Chang YS and Tang CH: Leptin induces oncostatin M production in

osteoblasts by downregulating miR-93 through the Akt signaling

pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 15:15778–15790. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Park KH, Kim DK, Huh YH, Lee G, Lee SH,

Hong Y, Kim SH, Kook MS, Koh JT, Chun JS, et al: NAMPT enzyme

activity regulates catabolic gene expression in gingival

fibroblasts during periodontitis. Exp Mol Med. 49:e3682017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

de Oliveira AA, Vergara A, Wang X, Vederas

JC and Oudit GY: Apelin pathway in cardiovascular, kidney, and

metabolic diseases: Therapeutic role of apelin analogs and apelin

receptor agonists. Peptides. 147:1706972022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wang Q, Wang B, Zhang W, Zhang T, Liu Q,

Jiao X, Ye J, Hao Y, Gao Q, Ma G, et al: APLN promotes the

proliferation, migration, and glycolysis of cervical cancer through

the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Arch Biochem Biophys. 755:1099832024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Chen L, Tao Y and Jiang Y: Apelin

activates the expression of inflammatory cytokines in microglial

BV2 cells via PI-3K/Akt and MEK/Erk pathways. Sci China Life Sci.

58:531–540. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Tilotta F, Gosset M, Herrou J, Briot K and

Roux C: Association between osteoporosis and periodontitis. Joint

Bone Spine. 92:1058832025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Llorente I, Garcia-Castaneda N, Valero C,

Gonzalez-Alvaro I and Castaneda S: Osteoporosis in rheumatoid

arthritis: Dangerous liaisons. Front Med (Lausanne). 7:6016182020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Sarhan RS, El-Hammady AM, Marei YM, Elwia

SK, Ismail DM and Ahmed EAS: Plasma levels of miR-21b and miR-146a

can discriminate rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis and severity.

Biomedicine (Taipei). 15:30–41. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Takegahara N, Kim H and Choi Y: Unraveling

the intricacies of osteoclast differentiation and maturation:

Insight into novel therapeutic strategies for bone-destructive

diseases. Exp Mol Med. 56:264–272. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Lee NK: RANK signaling pathways and key

molecules inducing osteoclast differentiation. Biomed Sci Lett.

23:295–302. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Castan-Laurell I, Dray C and Valet P: The

therapeutic potentials of apelin in obesity-associated diseases.

Mol Cell Endocrinol. 529:1112782021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Yasir M, Senthilkumar GP, Jayashree K,

Ramesh Babu K, Vadivelan M and Palanivel C: Association of serum

omentin-1, apelin and chemerin concentrations with the presence and

severity of diabetic retinopathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus

patients. Arch Physiol Biochem. 128:313–320. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Gao S and Chen H: Therapeutic potential of

apelin and Elabela in cardiovascular disease. Biomed Pharmacother.

166:1152682023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Couvineau P and Llorens-Cortes C:

Metabolically stable apelin analogs: Development and functional

role in water balance and cardiovascular function. Clin Sci (Lond).

139:131–149. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Liang B, Burley G, Lin S and Shi YC:

Osteoporosis pathogenesis and treatment: Existing and emerging

avenues. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 27:722022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Mbese Z and Aderibigbe BA:

Bisphosphonate-based conjugates and derivatives as potential

therapeutic agents in osteoporosis, bone cancer and metastatic bone

cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 22:68692021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Hussain MA, Joseph A, Cherian VM,

Srivastava A, Cherian KE, Kapoor N and Paul TV:

Bisphosphonate-induced atypical femoral fracture in tandem:

long-term follow-up is warranted. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case

Rep. 2022:2022:22–0249. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Tsourdi E, Zillikens MC, Meier C, Body JJ,

Rodriguez EG, Anastasilakis AD, Abrahamsen B, McCloskey E, Hofbauer

LC, Guañabens N, et al: Fracture risk and management of

discontinuation of denosumab therapy: A systematic review and

position statement by ECTS. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

26:dgaa7562020.

|

|

47

|

Okamoto H, Shibazaki N, Yoshimura T, Uzawa

T and Sugimoto T: Association between elcatonin use and cancer risk

in Japan: A follow-up study after a randomized, double-blind,

placebo-controlled study of once-weekly elcatonin in primary

postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Sarcopenia. 6:15–19. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Vinogradova Y, Coupland C and

Hippisley-Cox J: Use of hormone replacement therapy and risk of

breast cancer: Nested case-control studies using the QResearch and

CPRD databases. BMJ. 371:m38732020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Nordstrom BL, Cai B, De Gregorio F, Ban L,

Fraeman KH, Yoshida Y and Gibbs T: Risk of venous thromboembolism

among women receiving ospemifene: A comparative observational

study. Ther Adv Drug Saf. Nov 19–2022.(Epub ahead of print).

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|