Introduction

Hyperlipidemia is a common metabolic disorder, which

has been recognized as an independent risk factor for

cardiovascular disease (CVD) (1).

Individuals with hyperlipidemia have approximately twice the risk

of developing CVD compared with those with normal lipid profiles

(2). Increasing evidence has

suggested that hyperlipidemia causes cardiac damage through

oxidative stress, inflammation, pyroptosis and other mechanisms,

leading to lipid load-induced dysfunction characterized by

myocardial cell death, remodeling, impaired contractility and

autophagy-dependent cell death (3–5).

Despite the benefits of statins in lowering blood cholesterol

levels and preventing CVD, a large number of patients remain at

residual risk of CVD events due to intolerance or side effects

associated with lipid-lowering medications. Statins and other

lipid-lowering agents (e.g., ezetimibe, PCSK9 inhibitors, fibrates,

and niacin) can cause adverse effects such as myopathy, liver

enzyme elevation, gastrointestinal discomfort, and, in rare cases,

new-onset diabetes, which limit their widespread use and patient

adherence (6,7). Therefore, further research is needed

to identify drugs that can alleviate hyperlipidemia-induced cardiac

damage.

As a key intermediate in cellular energy metabolism,

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) participates in

numerous biochemical reactions in vivo and has garnered

widespread scientific interest (8). Studies have shown that

NAD+ serves a pivotal role in maintaining redox

homeostasis, mitochondrial function and cellular metabolism

(9–11). In metabolic syndrome,

NAD+ deficiency impairs insulin sensitivity and promotes

lipid accumulation (12,13). In heart failure and

ischemia-reperfusion injury, NAD+ enhances mitochondrial

biogenesis and limits oxidative stress through the activation of

sirtuin (SIRT)1 and SIRT3 (9,14).

In arrhythmia, NAD+ influences calcium handling and

electrophysiological stability (15), and in hypertension, it modulates

vascular tone by improving endothelial function and reducing

inflammation (16). Notably,

NAD+ imbalance is associated with a number of diseases,

and is considered a pathogenic factor in numerous human genetic and

acquired conditions, including metabolic disorders such as obesity

and type 2 diabetes, neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's

and Parkinson's disease, cardiovascular diseases such as heart

failure and atherosclerosis, as well as certain cancers (17). Supplementation with NAD+

has been shown to alleviate the development of heart failure and to

potentially influence lifespan through mitochondrial redox

regulation (18). NAD+

also serves a key role in energy metabolism by acting as an

essential electron carrier in glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid

cycle, and in cellular repair processes by serving as a substrate

for SIRTs and PARPs, which regulate mitochondrial function, DNA

repair and stress resistance. Exercise promotes aerobic metabolism

and enhances NAD+ biosynthesis through increased

oxidative phosphorylation (14,19).

In addition, increased NAD+ activates signaling pathways

related to cardiac protection, such as SIRT1, which promotes the

expression of antioxidant enzymes, and decreases oxidative stress

and inflammatory responses (20).

Furthermore, mitofusin2 (MFN2), an important protein in

mitochondrial outer membrane fusion, interacts with SIRT1 to reduce

cardiomyocyte autophagy by inhibiting oxidative stress (21). Collectively, these mechanisms

facilitate cardiomyocyte repair and regeneration, thereby providing

a robust foundation for recovery from cardiac injury.

Exercise of varying intensities induces different

levels of NAD+ enhancement (22). The present study conducted a

comparative analysis of moderate-intensity continuous training

(MICT) and high-intensity interval training (HIIT) in promoting

NAD+ levels, aiming to elucidate the underlying

molecular mechanisms involved. Furthermore, exogenous

NAD+ was administered to explore its mechanism of

action. The results of the current study may contribute to an

improved understanding of the role and mechanism of aerobic

exercise in hyperlipidemia-induced cardiac damage in apolipoprotein

E-deficient (ApoE−/−) mice by regulating NAD+

levels.

Materials and methods

Exercise model in mice with

hyperlipidemic cardiac damage

A total of 32 male ApoE−/− mice (age, 8

weeks; body weight, 21–25 g) were obtained from Liaoning Changsheng

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The mice were randomly assigned to the

following four groups (n=8/group): The control group received a

standard chow diet; the high-fat diet (HFD) group was fed HFD

alone; the HFD + MICT group received the HFD combined with MICT;

and the HFD + HIIT group received the HFD combined with HIIT. The

HFD consisted of 60% fat energy from fat feed [cat. no. XSYT-HFD60;

Xiaoshu Youtai (Beijing) Biotechnology Co., Ltd.], and the HFD

feeding lasted for 12 weeks, followed by 12 weeks of exercise

training. All animals were housed in a controlled environment

maintained at 24–26°C with 40–60% relative humidity and a 12-h

light/dark cycle, with ad libitum access to food and water

throughout the study. At the end of the experiment, or when humane

endpoints (e.g., severe weight loss >20%, inability to eat or

drink, or signs of severe distress), were reached, the mice were

euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium at

a dose of 150 mg/kg. Death was verified by confirming the complete

cessation of heartbeat and respiratory movement, as well as the

absence of corneal reflex, in accordance with institutional ethical

guidelines. Blood was collected by orbital sinus puncture under

anesthesia before sacrifice, with a total volume of ~0.3 ml/mouse,

and stored at −80°C for subsequent analyses. After sacrifice, heart

tissues were collected. Some samples were fixed in 10%

neutral-buffered formalin at room temperature for 24 h for

histological assessment and paraffin embedding, whereas additional

samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for subsequent protein

expression analysis via western blotting. All experimental animal

procedures were performed in accordance with the Guide for the

Management and Use of Laboratory Animals (23) and were approved by the Animal

Experiment Committee of the Central Hospital of Dalian University

of Technology (Dalian, China; approval no. YN2023-057-55).

Exercise training regimen

ApoE−/− mice in the MICT and HIIT group

underwent a treadmill running test to determine maximum running

speed using the XR-PT-10B treadmill (Shanghai XinRuan Information

Technology Co., Ltd.). The test began at 10 m/min with a 0° incline

for 20 min, with speed increasing by 4 m/min each min until the

mice exhibited signs of exhaustion. In the present study,

exhaustion was defined as either i) the mouse remaining stationary

on the shock grid for 3 consecutive seconds, or ii) the mouse

accumulating a total of 100 electrical stimulations during the

running session, regardless of whether it resumed running

afterward. This criterion was adopted to avoid excessive exposure

to electrical stimulation and to ensure animal welfare by setting a

strict upper limit for the number of shocks (24–26).

The maximum velocity achieved during exercise was defined as the

peak running speed. Before formal training, both groups underwent a

standardized 5-min warm-up at 40% of their respective maximum

running velocities. The HFD + HIIT group underwent nine sets of

high-intensity treadmill exercises, each lasting 1.5 min, with a

1-min rest between sprints, totaling 21.5 min/session at ~85% of

maximum running speed. The HFD + MICT group engaged in continuous

endurance training at 60% of maximum running speed until matching

the HFD + HIIT group distance. After training, both groups had a

5-min flat recovery period at 40% maximum running speed, repeated

five times a week for 12 weeks.

NAD+ therapy model in mice

with hyperlipidemic cardiac damage

Male ApoE−/− mice (age, 8

weeks; body weight, 20–25 g) were obtained from Liaoning Changsheng

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. A total of 32 mice were used in this study,

and these mice were obtained separately from those described in the

first subsection. The mice were housed under standard laboratory

conditions (24–26°C, 40–60% humidity, 12-h light/dark cycle). The

animals were randomly assigned to the following four experimental

groups (n=6/group): i) Normal diet (ND); ii) ND + NAD+

(4 mg/kg/day, intraperitoneally); iii) HFD; and iv) HFD +

NAD+ (4 mg/kg/day, intraperitoneally). The intervention

period lasted for 16 weeks, during which NAD+ was

administered to the designated groups. HFD was formulated using a

commercially available mouse diet enriched with 45%fat Kcal% energy

feed (cat. no. MD12032; Jiangsu Medisen Biomedical Co., Ltd.), HFD

feeding was continued for 12 weeks followed by 16-week

NAD+ intraperitoneal injection (27). NAD+ (cat. no. 53-84-9)

was purchased from Merck KGaA. Anesthesia was induced using 4%

isoflurane in oxygen and maintained at 1.5–2% isoflurane throughout

the orbital sinus puncture procedure; all anesthetic protocols were

performed in accordance with institutional animal care guidelines.

Blood samples were collected from the orbital venous sinus (0.5–0.8

ml/mouse) into serum tubes and immediately centrifuged, with the

resulting serum stored at −80°C for subsequent analysis. At the end

of the experiment or when humane endpoints were reached, the mice

were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital

sodium at a dose of 150 mg/kg. Death was verified by cessation of

heartbeat and respiratory movement, as well as the absence of

corneal reflex, in accordance with institutional ethical

guidelines. Some of the heart tissues were fixed in 10% formalin

for 24 h at room temperature and subsequently embedded in paraffin

for histological evaluation. The remaining heart tissue was frozen

in liquid nitrogen for western blot analysis. Mice were monitored

daily for general health and behavior. Humane endpoints were

established to minimize animal suffering, including >20% body

weight loss, persistent hunched posture, reduced activity,

inability to access food or water, labored breathing or

unresponsiveness to stimuli. Animals reaching any of these criteria

were humanely euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of

pentobarbital sodium. All experimental animal procedures were

performed in accordance with the Guide for the Management and Use

of Laboratory Animals (23) and

were approved by the Animal Experiment Committee of the Central

Hospital of Dalian University of Technology (ethics approval no.

YN2023-057-55).

Assessment of biochemical

parameters

Blood samples were collected from the orbital venous

plexus and centrifuged at 854 × g for 10 min at 4°C using an

Eppendorf 5424R centrifuge (Eppendorf SE) to obtain serum. The

resulting supernatant (serum) was used for the quantification of a

series of biochemical markers. The serum levels of total

cholesterol (T-C; cat. no. A111-1-1), triglycerides (TG; cat. no.

A110-1-1), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C; cat. no.

A113-1-1) were measured using colorimetric assay kits (Nanjing

Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) according to

the manufacturer's instructions, and their optical densities (ODs)

were read at 500 nm. Oxidative stress parameters were also

evaluated using serum samples with the following commercial kits

(Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China),

according to the manufacturer's instructions: superoxide dismutase

(SOD; cat. no. A001-3-2; OD at 450 nm) and malondialdehyde (MDA;

cat. no. A003-1-2; OD at 532 nm). In addition, Levels of coenzyme I

NAD(H) were assessed using a specific enzymatic cycling method

(cat. no. A114-1-1; Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute,

Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and

the OD was measured at 570 nm.

In addition, parameters were additionally measured

in vitro with the following commercial kits (Nanjing

Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China), according to

the manufacturer's instructions: Reduced glutathione (GSH; cat. no.

A006-2-1; OD at 405 nm), superoxide dismutase (SOD; cat. no.

A001-3-2; OD at 450 nm), total cholesterol (T-C; cat. no.

A111-1-1), triglycerides (TG; cat. no. A110-1-1), and low-density

lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C; cat. no. A113-1-1) were measured

using colorimetric assay kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering

Institute) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and

optical densities were read at 500 nm.

All measurements were performed using a calibrated

microplate reader and absorbance values were recorded at the

specified wavelengths according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The use of wavelength-specific detection for each analyte ensured

optimal sensitivity and accuracy of the biochemical assays.

Histopathological assessment

Heart tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered

formalin at 4°C overnight, followed by sequential dehydration in a

graded ethanol series (50, 75, 85, 95 and 100%; 1 h each). Samples

were then cleared twice in xylene (12 min each) and embedded in

paraffin. Paraffin-embedded cardiac tissues were sectioned at a

thickness of 5 µm, and the sections were deparaffinized with xylene

(twice for 10 min), rehydrated through a descending ethanol

gradient (100, 95, 85 and 75%; 10 min each), and rinsed in PBS

three times, with each rinse lasting 5 min.

Subsequently, the sections underwent hematoxylin and

eosin (H&E) staining (cat. no. G1120; Beijing Solarbio

Technology Co. LTD, Beijing, China), Masson's trichrome staining

(cat. no. G1340; Beijing Solarbio Technology Co. LTD.), fluorescein

isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated wheat germ agglutinin (WGA)

staining (cat. no. I3300; Beijing Solarbio Technology Co. LTD,

Beijing, China) and TUNEL assay [One-step TUNEL In Situ

Apoptosis Kit (Green, FITC); cat. no. E-CK-A320; Wuhan Elabscience

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.] to evaluate morphological alterations,

fibrosis, cell membrane boundaries and apoptosis, respectively. All

experiments were performed in accordance with the manufacturers'

instructions. After staining, the sections were dehydrated through

an ascending ethanol series (75, 85, 95 and 100%; 10 min each),

cleared with xylene (twice for 12 min) and mounted with neutral

resin. Sections stained with H&E and Masson's trichrome were

observed under a BX40 upright light microscope (Olympus

Corporation). WGA and TUNEL images were acquired using a STELLARIS

5 laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH).

Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)

staining

PAS staining was performed using Glycogen PAS

staining kit (with hematoxylin); cat. no. G1281; Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). Heart tissue fixation and

dehydration were performed in the same manner as described above.

Sections were then treated with periodic acid solution (0.5%) at

room temperature for 5 min to oxidize polysaccharides, followed by

two washes in distilled water (1 min each). Slides were incubated

with Schiff reagent for 15 min in the dark and washed with

distilled water for 1 min. Nuclei were counterstained with

hematoxylin for 1 min. Sections were briefly differentiated in acid

alcohol (5 s) and then blued in running water for 10 min or in 1×

PBS for 5 min. Sections were dehydrated through a graded ethanol

series (75, 85, 95, 100%, 10 min each), cleared in xylene (2×1

min), and mounted with neutral resin. PAS-positive areas,

representing polysaccharides, glycogen, mucosubstances, and

glycoproteins, appear magenta under light microscopy. Slides were

observed and imaged using a BX40 upright light microscope. Staining

intensity was graded on a scale of 0–3 (0=negative, 1=weak,

2=moderate, 3=strong), and the percentage of PAS-positive area was

graded on a scale of 0–4 (0=<5%, 1=5–25%, 2=26–50%, 3=51–75%,

4=>75%). The final PAS score was obtained by multiplying the two

scores, yielding a total score ranging from 0 to 12. Quantitative

evaluation was performed by two independent blinded observers in

five randomly selected fields of view/section.

Western blotting

Mouse heart tissues frozen at −80°C were removed

from the freezer, and an appropriate amount of tissue was placed in

1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube containing a pre-cooled mixture of

protease [and phosphatase inhibitors]. The tissues were cut up on

ice, and then broken and cracked by ultrasound with 4°C ultrasonic

crushing for 3 sec and then stop for 3 seconds, a total of 20 sec;

power, 30% and 4°C overnight to extract total proteins. The next

day, the samples were centrifuged at 13,700 × g for 10 min at 4°C,

the resulting supernatant was carefully transferred to a fresh

1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube and the volume was recorded. Protein

concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid assay kit

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) in a 96-well plate, alongside

a series of gradient standard protein solutions (2, 1, 0.5, 0.25,

0.125 and 0.0625 mg/ml). The absorbance at 562 nm was measured

using a microplate reader, and a standard calibration curve was

generated for quantification. Equal amounts of protein were then

aliquoted into clean 1.5-ml tubes, denatured in a boiling water

bath for 5 min, and stored at −80°C for subsequent use. Equal

amounts of protein (10 µg/lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE (10%)

and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Immobilon;

MilliporeSigma). The membranes were blocked for 1 h at room

temperature in 5% skim milk diluted in Tris-buffered saline-0.1%

Tween-20 (TBST) and were subsequently incubated overnight at 4°C

with the following primary antibodies: Rabbit anti-SOD2 (1:5,000;

cat. no. K106586P; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.), rabbit anti-heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1; 1:5,000; cat. no.

10701-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), rabbit anti-SIRT3 (1:1,000;

cat. no. 10099-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), mouse anti-SIRT1

(1:5,000; cat. no. 60303-1-Ig; Proteintech Group, Inc.), rabbit

anti-MFN2 (1:5,000; cat. no. 12186-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.),

rabbit anti-PI3K p85 (1:1,000; cat. no. 20584-1-AP; Proteintech

Group, Inc.), rabbit anti-phosphorylated (p)-PI3K p85 (1:1,000;

cat. no. AF3242; Affinity Biosciences), anti-AKT (1:1,000; cat. no.

AF0836; Affinity Biosciences), rabbit anti-LC3 II (1:500; cat. no.

GB115766; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.), rabbit anti-P62

(1:5,000; cat. no. 18420-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), rabbit

anti-p-AKT (1:1,000; cat. no. AF0016; Affinity Biosciences), rabbit

anti-mTOR (1:1,000; cat. no. AF6308; Affinity Biosciences), rabbit

anti-p-mTOR (1:1,000; cat. no. AF3308; Affinity Biosciences),

rabbit anti-tubulin β (1:2,000; cat. no. AF7011; all Affinity

Biosciences) and mouse anti-β-actin (1:10,000; cat. no. sc-8432;

Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). The next day, the membranes were

washed three times in TBST (10 min each) and then incubated for 1 h

at room temperature with the appropriate horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies: Anti-rabbit IgG

(1:5,000; cat. no. SA00001-2; Proteintech Group, Inc.) or

anti-mouse IgG (1:10,000; cat. no. SA00001-1; Proteintech Group,

Inc.). Protein bands were visualized [High-sensitivity ECL

chemiluminescence detection kit; cat. no. SW134-01; Seven

Innovation (Beijing) Biotechnology Co., LTD,] and semi-quantified

using ImageJ software (version 1.53t; National Institutes of

Health). Tubulin β and β-actin were used as internal loading

controls, and relative protein expression levels were normalized

accordingly.

Immunohistochemistry

Coronal heart tissue sections were fixed in 10%

neutral buffered formalin overnight at 4°C. The following day, the

samples were sequentially dehydrated through a graded ethanol

series (50, 70, 85, 90, 95 and 100%, 1 h each), cleared in xylene

(twice for 12 min) and embedded in paraffin for histological

analysis. Paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned at a thickness

of 5 µm, and were dewaxed twice in xylene (12 min each), rehydrated

through a descending ethanol series (100, 95, 85 and 75%, 10 min

each), and rinsed in PBS three times for 5 min each. For antigen

retrieval, slides were immersed in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and

heated in a microwave oven at high power for 3–5 min, followed by

1–2 min on low power. The slides were then allowed to cool at room

temperature for 40 min and rinsed again with PBS (three times, 5

min each). Immunohistochemistry was conducted using a commercial

immunohistochemical kit (cat. no. KIT-9720; Fuzhou Maixin Biotech

Co., Ltd.). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by

incubating the sections with a peroxidase blocking solution for 10

min, followed by three washes with PBS (5 min each). Non-specific

binding was blocked by incubating the slides in 5% sheep serum

(cat. no. FSP 500; Suzhou Excellent Biotechnology Co., LTD; Suzhou,

China) at room temperature for 1 h. After blocking, the sections

were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary

antibodies: Rabbit anti-SOD (1:100; cat. no. K106586P; Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.), rabbit anti-HO-1

(1:100; cat. no. 10701-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), rabbit

anti-SIRT3 (1:100; cat. no. K008232P; Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.), rabbit anti-TGF-β1 (1:300; cat. no.

81746-2-RR; Proteintech Group, Inc.), mouse anti-collagen I

(1:3,000; cat. no. 67288-1-Ig; Proteintech Group, Inc.), rabbit

anti-collagen III (1:1,000; cat. no. 22734-1-AP; Proteintech Group,

Inc.), mouse anti-SIRT1 (1:300; cat. no. 60303-1-Ig; Proteintech

Group, Inc.), and rabbit anti-MFN2 (1:300; cat. no. 12186-1-AP;

Proteintech Group, Inc.).

The following day, the sections were washed three

times in PBS (5 min each), then incubated at room temperature for 1

h with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody

provided in the N-Histofine Simple Stain Kit (cat. no. KIT-9720;

Fuzhou Maixin Biotech Co., Ltd.). Signal development was performed

using the metal-enhanced DAB substrate kit (cat. no. DA1015;

Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) for 10 min at

room temperature, followed by rinsing in distilled water. Sections

were counterstained with hematoxylin for 1–2 min with room

temperature and washed under running tap water for 30 min.

Differentiation was carried out in 1% hydrochloric acid ethanol for

3 sec, followed by an additional rinse under running water for 3

min. The stained slides were then dehydrated in ascending

concentrations of ethanol (75, 85, 95 and 100%, 10 min each),

cleared in xylene twice (12 min each) and mounted with neutral

resin. All stained sections were examined using an Olympus BX40

upright light microscope (Olympus Corporation) for morphological

analysis was performed using ImageJ software (version 1.53,

National Institutes of Health).

KEGG Pathway Analysis

Differentially expressed genes identified from our

experiments were subjected to pathway enrichment analysis using the

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database (kegg.jp/

using the default parameters. Pathways with a P-value <0.05 were

considered significantly enriched.

Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI)

Network Analysis

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks were

constructed to explore the potential interactions of SIRT1 with

other proteins involved in mitochondrial dynamics and oxidative

stress. Analyses were performed using the STRING database

(string-db.org/). The list of relevant proteins was uploaded, and

interaction scores were calculated using the default medium

confidence threshold (0.4). The resulting network was visualized to

identify central nodes and functional connections. The potential

interactions among PI3K, AKT, and mTOR were investigated using the

STRING database (Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting

Genes/Proteins; string-db.org/). The analysis was performed by

inputting the respective gene symbols, with the species limited to

Mus musculus. A high-confidence interaction score (0.7) was

applied as the cutoff. The resulting network was visualized to

identify functional associations relevant to myocardial

protection.

Tissue-specific expression analysis of

MFN2

Tissue-specific expression analysis of MFN2 was

performed using publicly available transcriptomic data from the

Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) database (accession no.

phs000424.v9.p2; gtexportal.org/) and validated with the Human

Protein Atlas (HPA; accession no. ENSG00000116688; http://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000116688-MFN2).

Immunofluorescence

Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were

deparaffinized, subjected to antigen retrieval and blocked

according to the aforementioned standard immunohistochemical

procedures. For immunofluorescence staining, the following primary

antibodies were applied to the tissue sections: Rabbit anti-SIRT1

(1:100; cat. no. BF0189; Affinity Biosciences) was used for cell

staining, mouse anti-SIRT1 (1:300; cat. no. 60303-1-Ig; Proteintech

Group, Inc.) was used for double immunofluorescence staining and

rabbit anti-MFN2 (1:300; cat. no. 12186-1-AP; Proteintech Group,

Inc.). The slides were incubated overnight at 4°C and washed three

times with PBS (5 min each). In the dark, the following appropriate

fluorescent secondary antibodies were added for 1 h at room

temperature: Alexa Fluor® 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG

(H+L), F(ab')2 fragment (1:800; cat. no. 4412S; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.) and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated

anti-mouse IgG (H+L), F(ab')2 fragment (1:800; cat. no.

8890S; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). The slides were then

washed three times with PBS (5 min each). For nuclear

counterstaining, the sections were treated with DAPI (Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.); the slides were washed with PBS

three times (5 min each), stained with DAPI for 1 min and rinsed

again three times with PBS in the dark. After staining, the

sections were mounted using an anti-fade fluorescence mounting

medium (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.), and fluorescence

signals were visualized and captured using a Leica TCS SP8 confocal

laser scanning microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH).

Cell culture

The HL-1 mouse cardiomyocyte cell line (cat. no.

MYC-TCM783; Dalian Yiran Mingyu Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was

authenticated using short tandem repeat (STR) profiling upon

receipt. The STR results confirmed that the cell line used

corresponds to HL-1 and does not match the STR profile of C2C12 or

any known contaminant cell lines. HL-1 cells exhibit adherent

growth characteristics and were cultured in DMEM with high glucose

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal

bovine serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin (all Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). The cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C

with 5% CO2 and 70% relative humidity. Subculturing was

performed at a 1:3 ratio when cells reached 80–90% confluence,

using standard enzymatic dissociation with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Cell passage

Cells were maintained in complete growth medium

(DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere

containing 5% CO2. When cultures reached 80–90%

confluency, cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline

(PBS), detached using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA solution, and collected by

centrifugation at 300 × g for 5 min. Cells were resuspended in

fresh medium and seeded at an appropriate density for subsequent

experiments. Passages were performed every 2–3 days, and only cells

within passages 3–10 were used for experiments.

Palmitic acid (PA) Treatment in HL-1

Cells

HL-1 cells were treated with PA; MedChemExpress,

Cat. No. HY-N0830) to induce lipotoxicity and mimic metabolic

stress in vitro. PA was prepared as a 5 mM stock solution in 0.1 M

NaOH and complexed with 10% fatty-acid free bovine serum albumin

(BSA) to a final working concentration of 200 µM. Cells were

incubated with PA at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 24

h. Following treatment, autophagy markers LC3 II and p62 were

assessed by western blotting to evaluate autophagic flux under

lipotoxic conditions.

ROS detection

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in adherent

cells were measured using the fluorescent probe CM-H2DCFDA (cat no.

S0035S, Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). CM-H2DCFDA was diluted

(1:1,000 in PBS to a final concentration of 5 µM. Culture medium

was removed, and cells were incubated with sufficient volume of the

diluted CM-H2DCFDA to fully cover the cell layer at 37°C in a

CO2 incubator for 30 min. After incubation, cells were

washed three times with PBS to remove excess probe that had not

entered the cells. For positive control of ROS production, cells

can be stimulated for 20–30 min to achieve a detectable increase in

ROS levels. Fluorescence images were captured immediately using a

laser-scanning confocal microscope (Leica TCS STELLARIS 5), and

signal quantification was performed using ImageJ software (version

1.53).

JC-1 staining for mitochondrial

membrane potential

Mitochondrial membrane potential in adherent cells

was assessed using the JC-1 fluorescent probe kit ((cat no. C2006,

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were washed with PBS

and incubated with JC-1 staining solution at 37°C for 20–30 min.

Following incubation, cells were washed twice with JC-1 buffer to

remove excess dye. Fluorescence images were immediately acquired

using a confocal microscope (Leica TCS STELLARIS 5) with

excitation/emission settings for JC-1 monomers (green, ~514/529 nm)

and aggregates (red, ~585/590 nm). The ratio of red to green

fluorescence intensity was quantified using ImageJ software

(version 1.53) to assess changes in mitochondrial membrane

potential.

EX-527 treatment

HL-1 cardiomyocytes were seeded at a density of

1×105 cells/cm2 in 10 cm culture dishes and

cultured under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO2) until

reaching the desired confluency for subsequent experiments. To

inhibit SIRT1 activity, cells were treated with 10 µM EX-527 (cat.

no. HY-15452; MedChemExpress) for 24 h (37°C, 5% CO2).

After treatment, the cells were collected for subsequent

assays.

Gene silencing via RNA

interference

Cells were seeded in 6-cm dishes as in the passage

procedure, and the cell confluence was ~60% at the time of

transfection. According to the manufacturer's instructions, the

ApoE small interfering (si)RNA was used to silence ApoE expression

in HL-1 cells using a transfection reagent kit (Lipofectamine 8000;

cat no. C0533, Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Cells were

transfected with siRNA (20 µM, 37°C) for 48 h. Culture medium was

replaced with fresh medium containing NAD+, and the

cells were incubated for 48 h under standard conditions before

subsequent experiments. The efficiency of ApoE knockdown in HL-1

cells was verified by western blotting. Three siRNAs targeting

SIRT1 were designed (sequences provided in Table I). HL-1 cells were transfected with

20 µM of each siRNA using Lipofectamine 8000 (Thermo Fisher

Scientific) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Knockdown

efficiency was assessed by western blot, and ApoE-Mus-415 was used

for subsequent experiments. A non-targeting scramble siRNA was used

as a negative control. The siRNA target sequences are shown in

Table I.

| Table I.Small interfering RNA target

sequences. |

Table I.

Small interfering RNA target

sequences.

| Name | Forward, 5′→3′ | Reverse, 5′→3′ |

|---|

| ApoE-Mus-217 |

GCCGUGCUGUUGGUCACAUTT |

AUGUGACCAACAGCACGGCTT |

| ApoE-Mus-415 |

GCACUGAUGGAGGACACUATT |

UAGUGUCCUCCAUCAGUGCTT |

| ApoE-Mus-1052 |

GCCAGUGGGCAAACCUGAUTT |

AUCAGGUUUGCCCACUGGCTT |

| Negative

control |

UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT |

ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT |

MTS colorimetric cell viability

assay

Logarithmic-phase HL-1 cells were collected and

resuspended in complete growth medium. Cell concentration was

determined using a Cell counter instrument after trypan blue

staining to assess cell viability. Based on the counted cell

number, the suspension was adjusted to a concentration of

1×105 cells/ml. Subsequently, 100 µl cell suspension was

seeded into each well of a 96-well flat-bottom plate. The plate was

placed in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 for

24 h. When cells had adhered to the well surface, the medium within

each insert was gently aspirated following a 4-h incubation in

serum-free medium. Subsequently, NAD+ solutions at

varying concentrations (0, 1, 5, 7 and 10 mM) (cat. no. HY-B0445;

MedChemExpress) were added to the wells, and the cells were

incubated for 48 h in a humidified cell incubator at 37°C with 5%

CO2. Following treatment, 20 µl MTS reagent (cat. no.

G3582; Promega Corporation) was added to each well in the dark.

After an additional 2-h incubation, absorbance was measured at 490

nm using a microplate reader. Cell viability under different

NAD+ concentrations was calculated based on OD values at

490 nm. Each experimental condition was performed in triplicate,

and all assays were independently repeated three times. Statistical

analysis was conducted to evaluate differences between groups.

Statistical analysis

All quantitative data are presented as the mean ±

standard error of the mean. Statistical analyses were conducted

using SPSS software (version 23.0; IBM Corp.). Intergroup

differences were assessed by one-way analysis of variance, followed

by Tukey's post hoc test for multiple comparisons. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

HIIT enhances NAD+

metabolism and decreases oxidative stress in ApoE−/−

hyperlipidemic mice

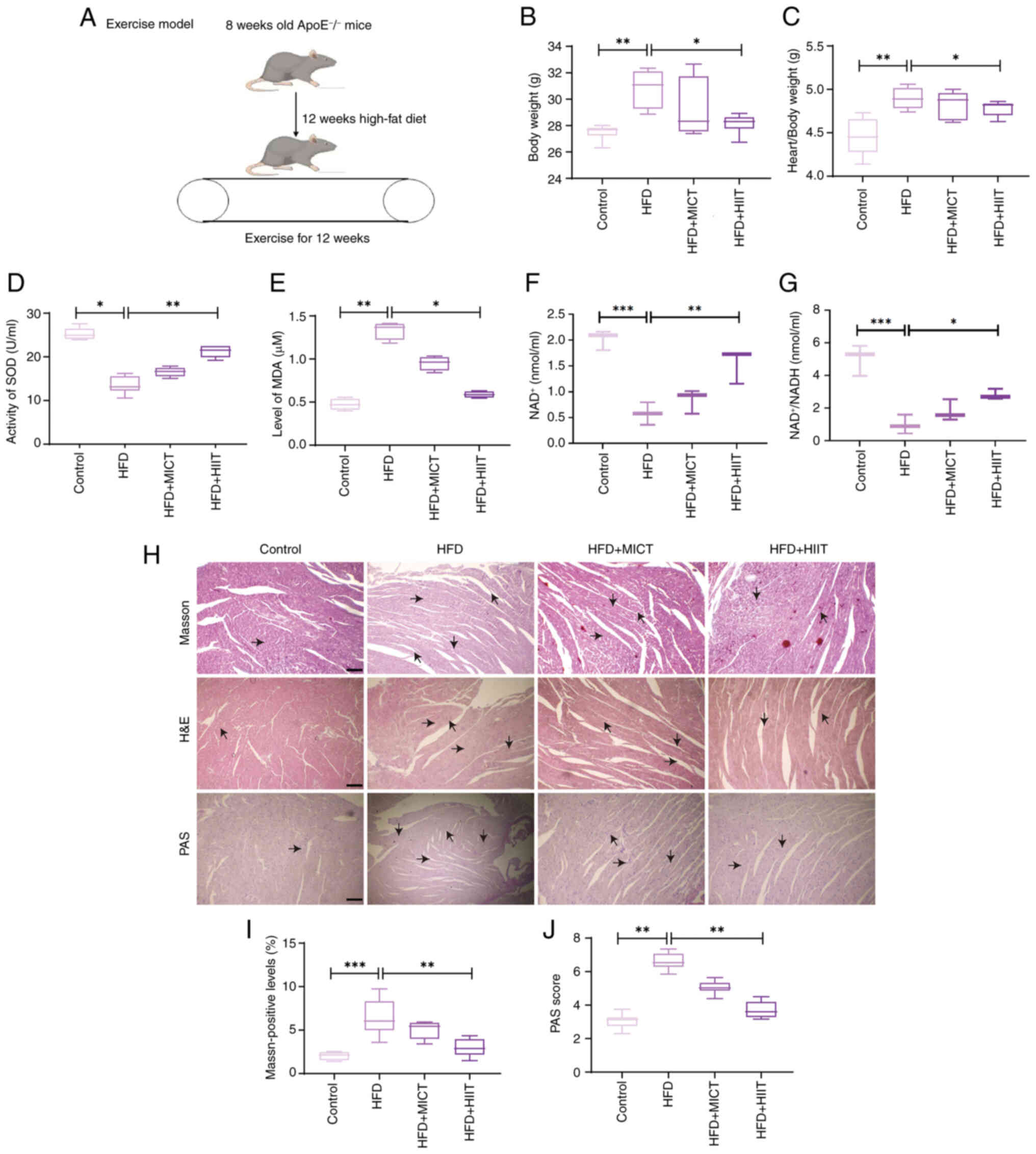

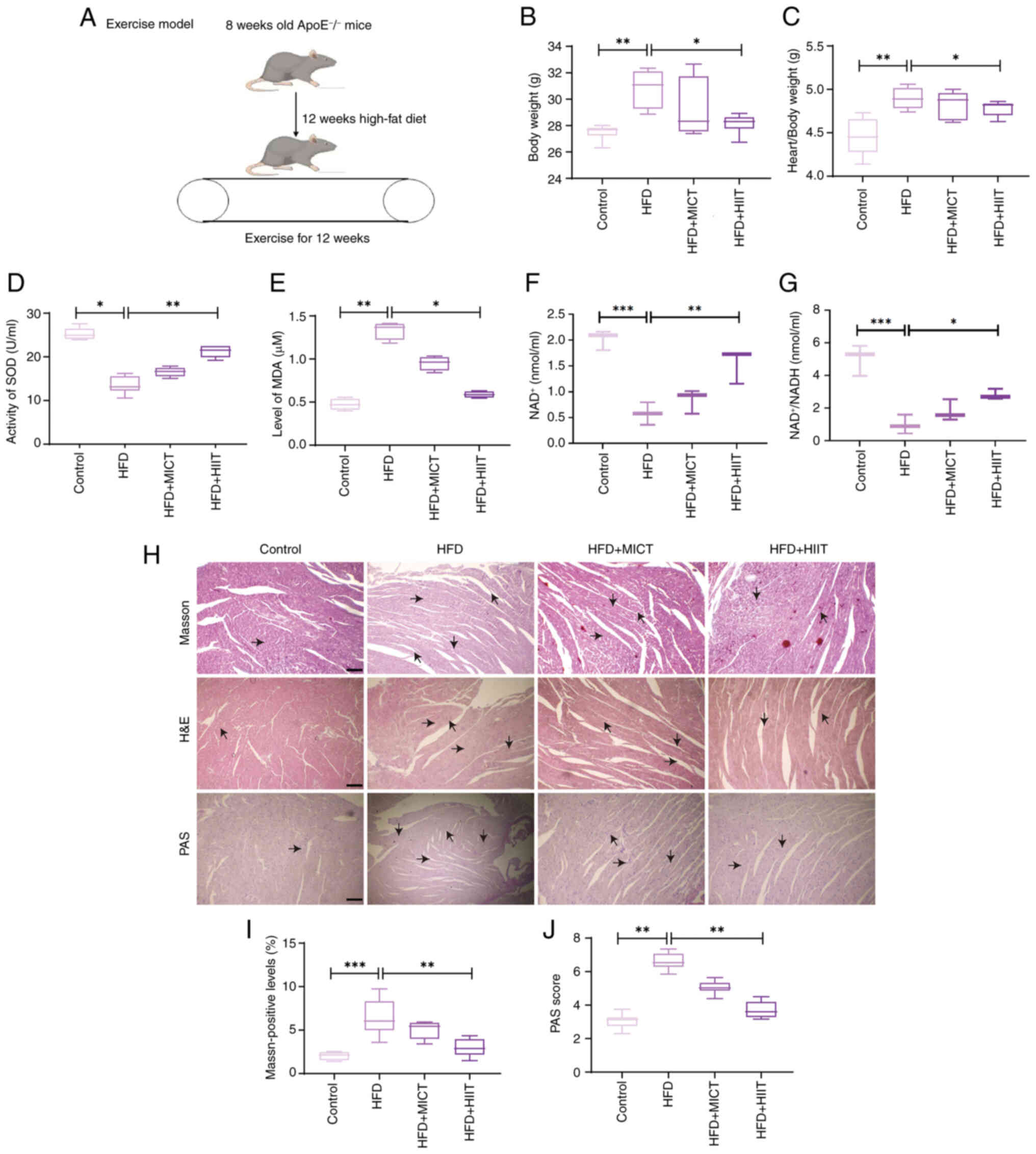

The experimental design is shown in Fig. 1A. Significant differences in body

weight and heart-to-body weight ratio were observed among the

groups (Fig. 1B and C). Mice in

the HFD group exhibited the highest body weight and heart-to-body

weight ratio, whereas both the HFD + MICT and HFD + HIIT groups

demonstrated reductions in these parameters, with the HFD + HIIT

group showing the most pronounced improvement. These findings

suggested that HIIT may alleviate HFD-induced obesity and cardiac

hypertrophy. Serum analysis showed a significant decrease in SOD

activity in the HFD group, which was partially reversed by exercise

interventions, with HIIT demonstrating the greatest effect

(Fig. 1D). Conversely, MDA levels,

which were elevated in the HFD group, were significantly reduced by

exercise, particularly following HIIT (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, in

ApoE−/− mice, Exercise increased the

NAD+/NADH ratio in both cardiac tissue and serum, with

HIIT exerting the most pronounced effect (Fig. 1F and G). Myocardial hypertrophy and

fibrosis induced by HFD) were alleviated by exercise, particularly

in the HFD + HIIT group, as evidenced by histological analyses.

Heart sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)

for general morphology, Masson's trichrome for fibrosis, and

periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) for glycogen deposition (Fig. 1H and I). PAS staining showed

decreased glycogen accumulation in both exercise groups, with the

most notable reduction in the HFD + HIIT group (Fig. 1H and J). These results indicated

that HIIT provided more pronounced protection against HFD-induced

myocardial hypertrophy, fibrosis and glycogen accumulation compared

with MICT.

| Figure 1.Metabolic data in each group after 12

weeks of exercise training. (A) Schematic diagram of the

experimental model. (B) Changes in the body weight of mice. (C)

Quantitative analysis of heart/body weight ratio in each group. (D)

SOD levels in the serum of mice in each group (n=6). (E) MDA levels

in the serum of mice in each group (n=4). Serum (F) NAD+

and (G) NAD+/NADH levels in each group of mice (n=3).

(H) H&E, Masson and PAS staining heart tissue sections, with

arrows indicating positively stained cells. Scale bar, 100 µm;

magnification, ×40 (n=3). (I) Masson's trichrome staining of

myocardial tissue showing collagen deposition. (J) PAS) staining of

myocardial tissue showing glycogen deposition. Data are presented

as the mean ± standard error of the mean; statistical analysis was

performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. ApoE−/−,

apolipoprotein E-deficient; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; HFD,

high-fat diet; HIIT, high-intensity interval training; MDA,

malondialdehyde; MICT, moderate-intensity continuous training;

NAD+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; PAS, Periodic

acid-Schiff; SOD, superoxide dismutase. |

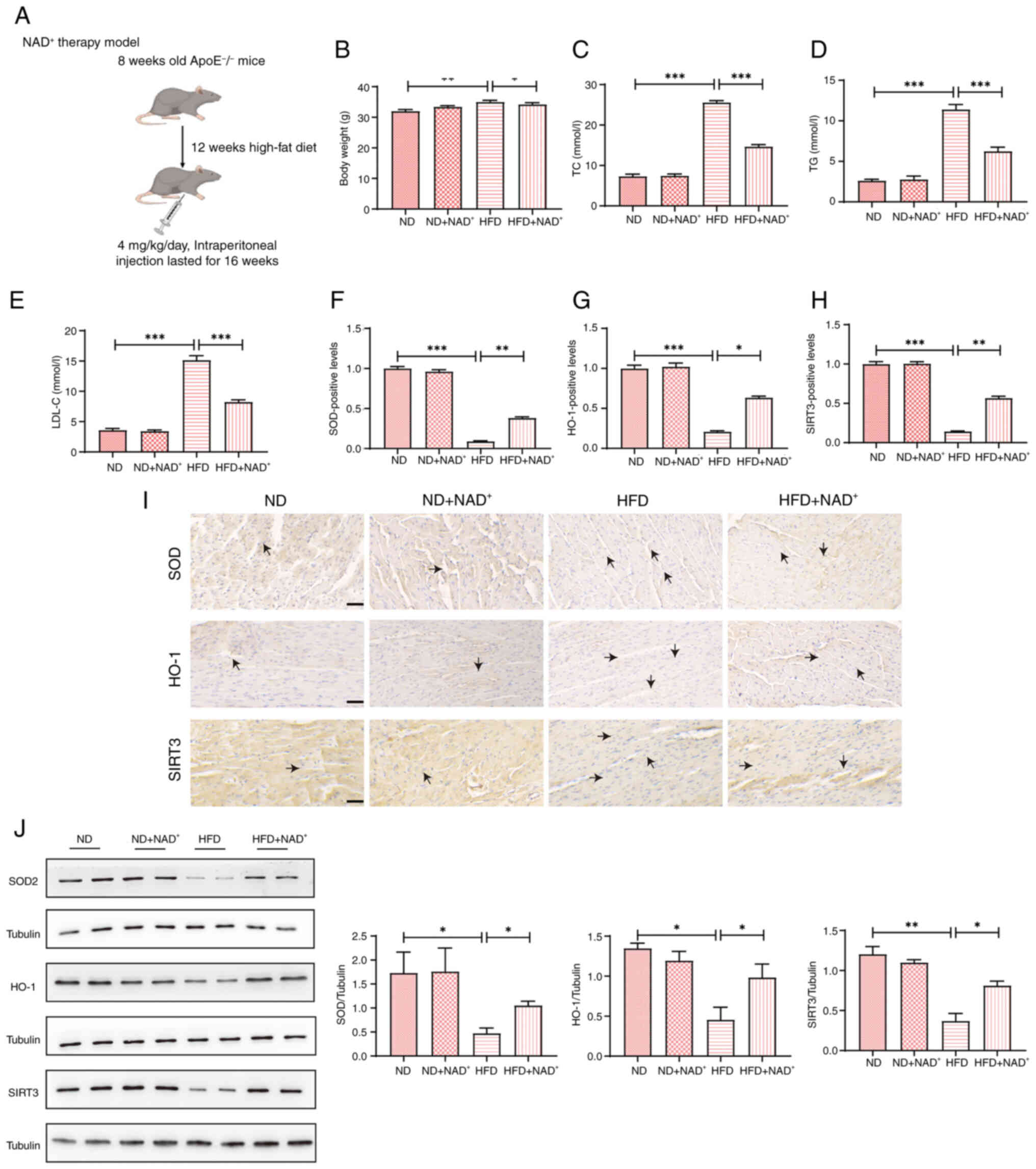

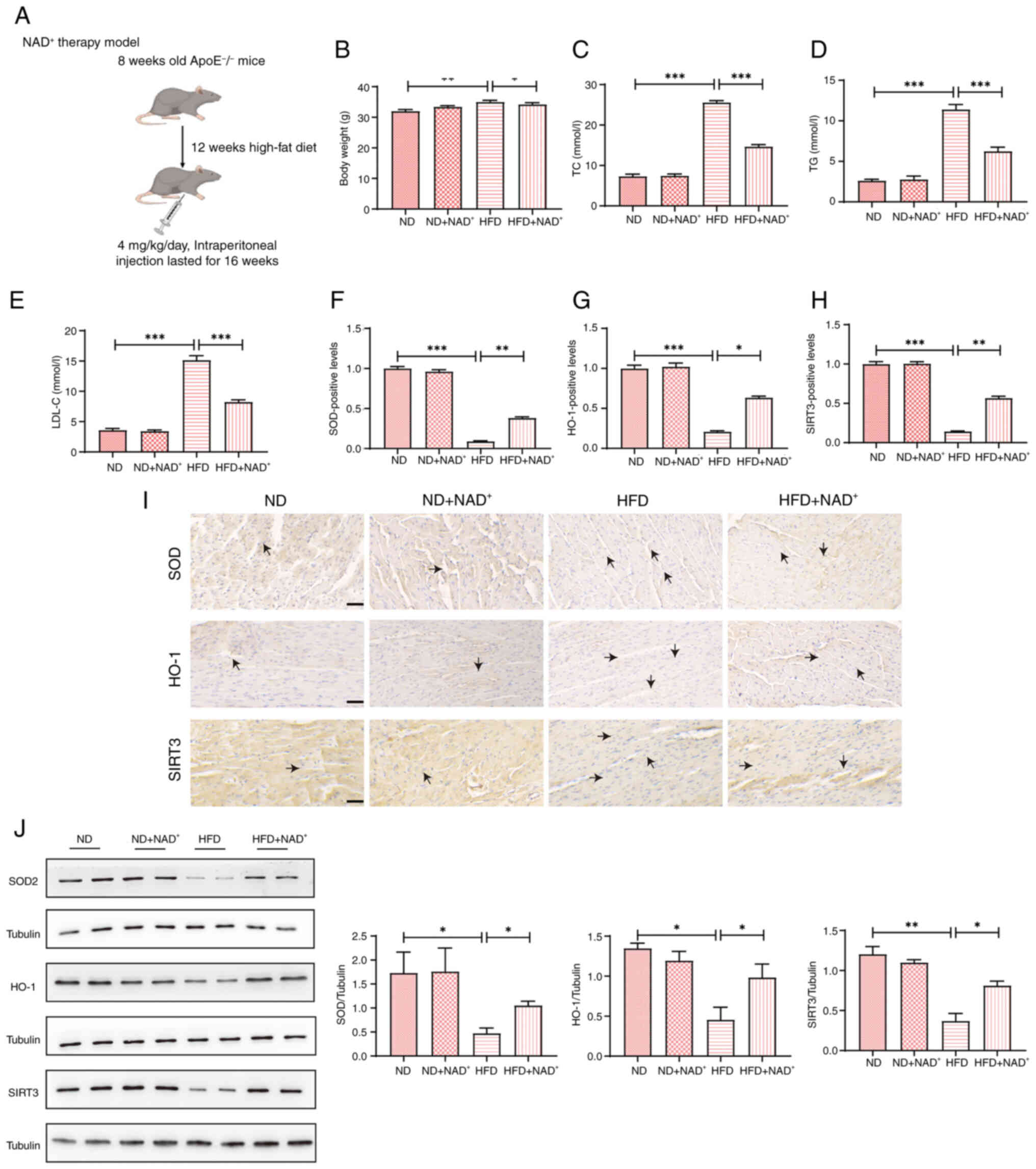

NAD+ supplementation

ameliorates HFD-induced obesity, dyslipidemia and oxidative

stress

The experimental design is shown in Fig. 2A. Significant differences in body

weight and lipid profiles were observed among the groups (Fig. 2B-E). The HFD group showed a

pronounced increase in body weight compared with that in the ND

group, whereas NAD+ supplementation (HFD +

NAD+) significantly lowered body weight, nearing that of

the ND group (Fig. 2B). In terms

of lipid levels, the HFD group had significantly higher TC, TG, and

LDL-C levels compared with those in the ND group. NAD+

supplementation in the HFD + NAD+ group led to a

significant decrease in serum lipid levels, including TC), (TG),

and (LDL-C), compared with the HFD group (Fig. 2C-E). Immunohistochemistry analysis

(Fig. 2F-I) revealed that the ND

group exhibited significantly higher expression of SOD, HO-1, and

SIRT3 compared with the HFD group. The HFD group showed decreased

expression of these markers, whereas the HFD + NAD+

group exhibited increased staining for SOD, HO-1 and SIRT3, similar

to the ND group. Semi-quantification of immunohistochemistry

results (Fig. 2F-H) confirmed the

significantly increased expression of these proteins in the HFD +

NAD+ group compared with that in the HFD group. Western

blot analysis (Fig. 2J) further

supported these findings, showing a marked increase in SOD, HO-1

and SIRT3 expression in the HFD + NAD+ group compared

with those in the HFD group. Semi-quantitative analysis of western

blotting data confirmed the enhanced expression of these proteins

in the NAD+ supplemented group. Notably, NAD+

supplementation did not produce significant effects in mice fed a

ND.

| Figure 2.Effects of NAD+

supplementation on body weight, lipid profiles and antioxidant

proteins in HFD-induced mice. (A) Schematic diagram of the

experimental model. (B) Body weight changes in the ND, ND +

NAD+, HFD and HFD + NAD+ groups. Lipid

profiles of the mice in all groups, including (C) TC, (D) TG and

(E) LDL-C (n=6). Semi-quantification of immunohistochemical results

showing significant upregulation of (F) SOD, (G) HO-1 and (H) SIRT3

in the HFD + NAD+ compared with in the HFD group (n=4).

(I) Immunohistochemical staining of the antioxidant proteins SOD,

HO-1 and SIRT3 in heart tissue; arrows indicate positively stained

cells. Magnification, ×40; scale bar, 100 µm (n=3). (J) Western

blot analysis of SOD, HO-1 and SIRT3 expression in heart tissue,

and semi-quantification of western blotting data, confirming

increased expression of SOD, HO-1 and SIRT3 in the HFD +

NAD+ group. Data are presented as the mean ± standard

error of the mean; statistical analysis was performed using one-way

ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001. ApoE−/−, apolipoprotein E-deficient; HFD,

high-fat diet; HO-1, heme oxygenase 1; LDL-C, low-density

lipoprotein cholesterol; NAD+, nicotinamide adenine

dinucleotide; ND, normal diet; SIRT3, sirtuin 3; SOD, superoxide

dismutase; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides. |

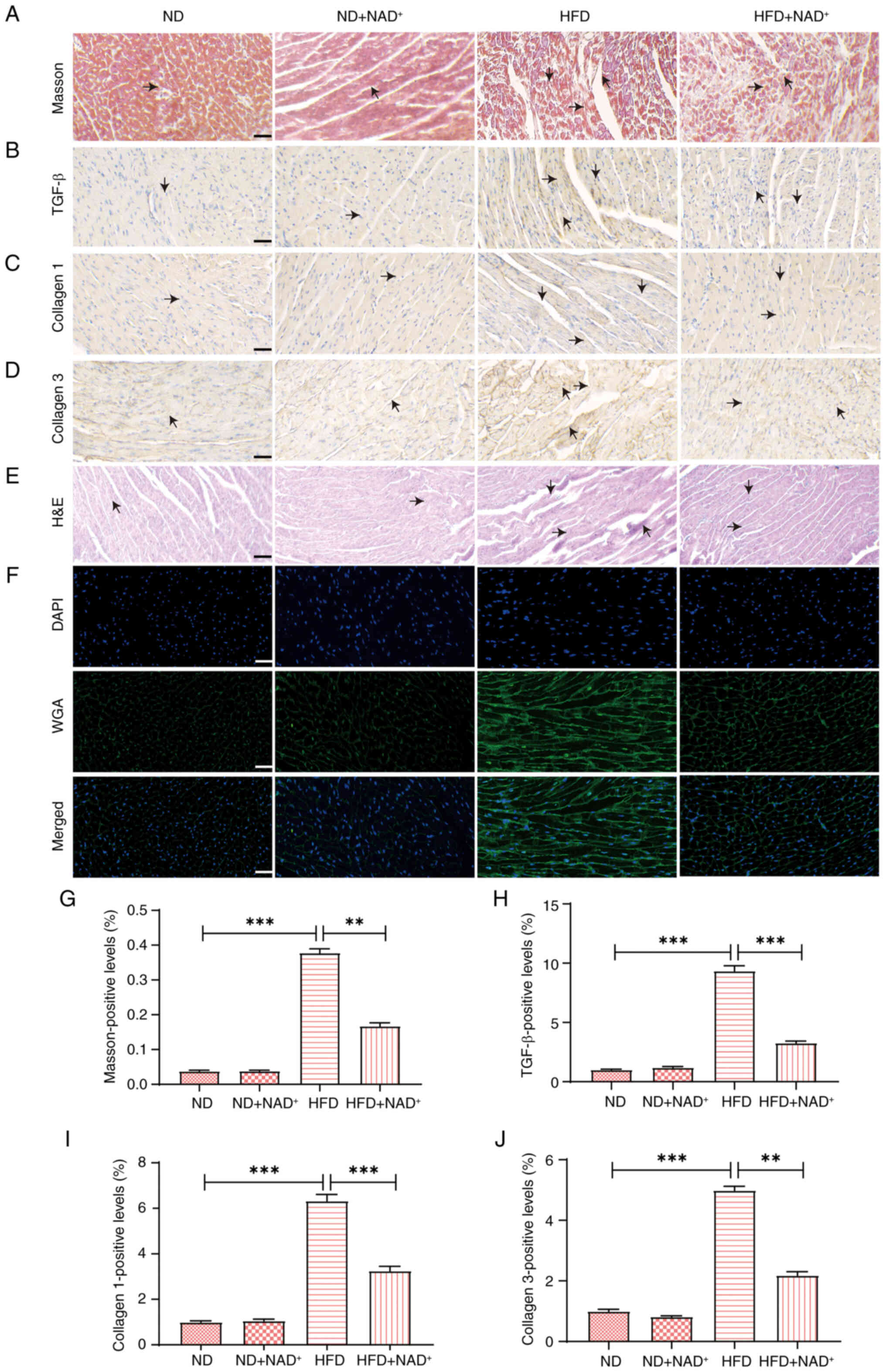

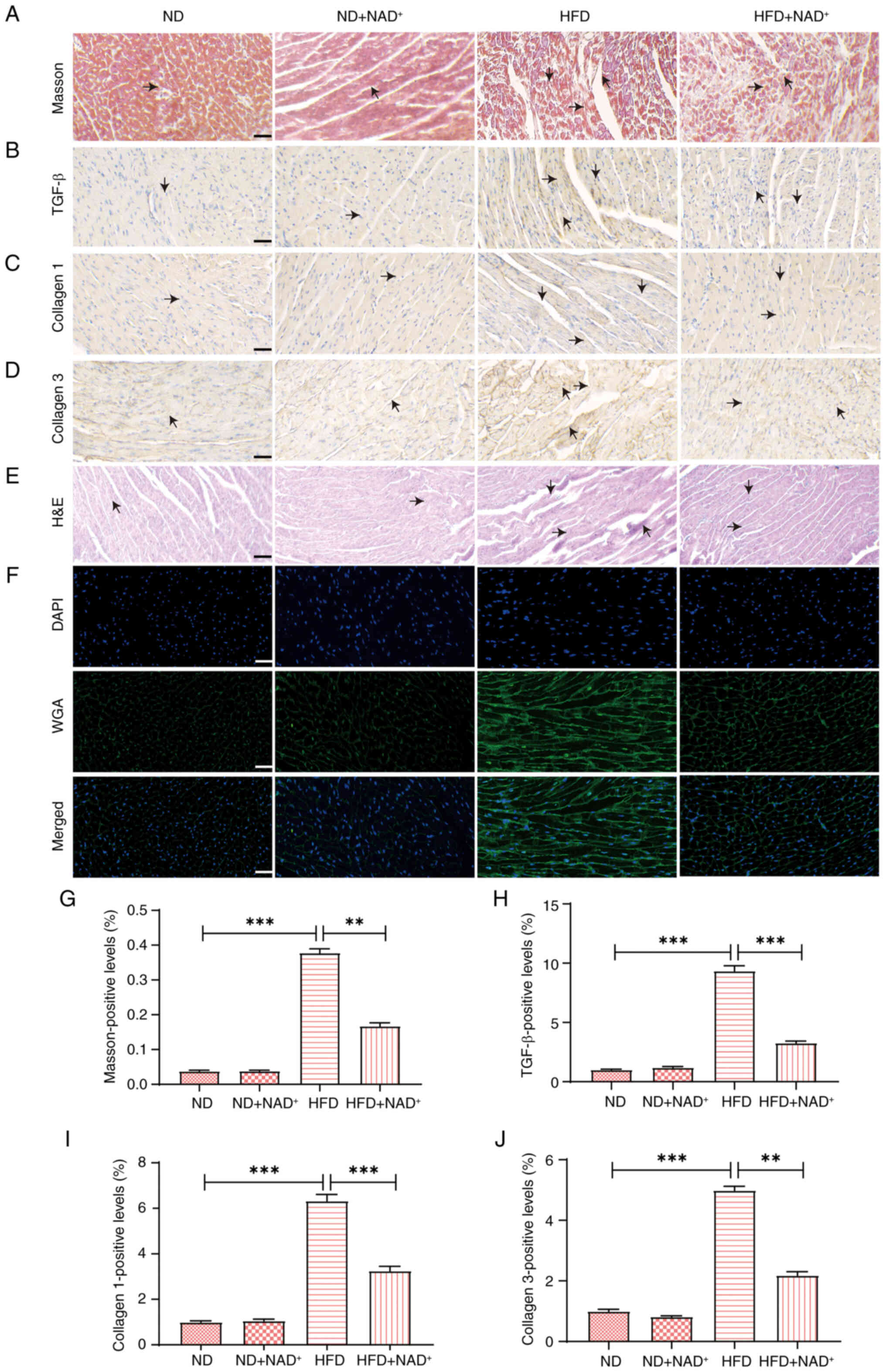

NAD+ supplementation

attenuates myocardial fibrosis and extracellular matrix (ECM)

remodeling in HFD-induced mice

Masson's trichrome staining (Fig. 3A) revealed substantial collagen

deposition in the HFD group, indicative of fibrosis, while

NAD+ supplementation (HFD + NAD+) reduced

this deposition to levels similar to those in the ND group.

Immunohistochemical staining of the fibrosis-related markers TGF-β,

collagen I and III (Fig. 3B-D)

exhibited elevated expression in the HFD group, which was markedly

reduced in response to NAD+ supplementation, approaching

the levels observed in the ND group. H&E staining (Fig. 3E) demonstrated structural

disorganization and injury in the HFD group, whereas

NAD+ supplementation improved myocardial architecture,

especially in the HFD + NAD+ group. WGA staining

(Fig. 3F) confirmed enhanced

myocardial cell integrity in both the ND + NAD+ and HFD

+ NAD+ groups. Semi-quantitative analysis further

confirmed that NAD+ supplementation significantly

reduced the Masson-positive area, and TGF-β, collagen I and

collagen III expression (Fig.

3G-J) levels, indicating a protective effect against myocardial

fibrosis and ECM remodeling in the HFD + NAD+ group.

Notably, NAD+ supplementation did not induce significant

changes in the ND group, suggesting that its protective effects are

specific to pathological conditions such as HFD-induced cardiac

injury.

| Figure 3.NAD+ supplementation

attenuates myocardial fibrosis and ECM remodeling in HFD-induced

mice. (A) Masson's trichrome staining of myocardial tissue.

Blue-stained regions indicate collagen deposition (fibrotic areas),

and red indicates myocardial fibers. Black arrows point to areas of

increased collagen accumulation. Scale bar, 100 µm.

Immunohistochemical staining of fibrosis-related markers: (B)

TGF-β, (C) collagen I, and (D) collagen III. Brown staining

indicates positive expression, and black arrows highlight regions

with enhanced marker expression. Scale bar, 100 µm. (E) H&E

staining of myocardial tissue showing general histological

structure. Black arrows indicate areas of myocardial hypertrophy or

structural abnormalities. Scale bar, 100 µm. (F) WGA staining

showing improved myocardial cell integrity in the HFD +

NAD+ group. Scale bar, 100 µm. Semi-quantification of

the (G) Masson-positive area, and (H) TGF-β, (I) collagen I and (J)

collagen III levels. NAD+ supplementation significantly

reduced fibrosis and ECM remodeling in the HFD + NAD+

group compared with in the HFD group. Data are presented as the

mean ± standard error of the mean, n=3; statistical analysis was

performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test.

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. ECM, extracellular matrix; H&E,

hematoxylin and eosin; HFD, high-fat diet; NAD+,

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; ND, normal diet; WGA, what germ

agglutinin. |

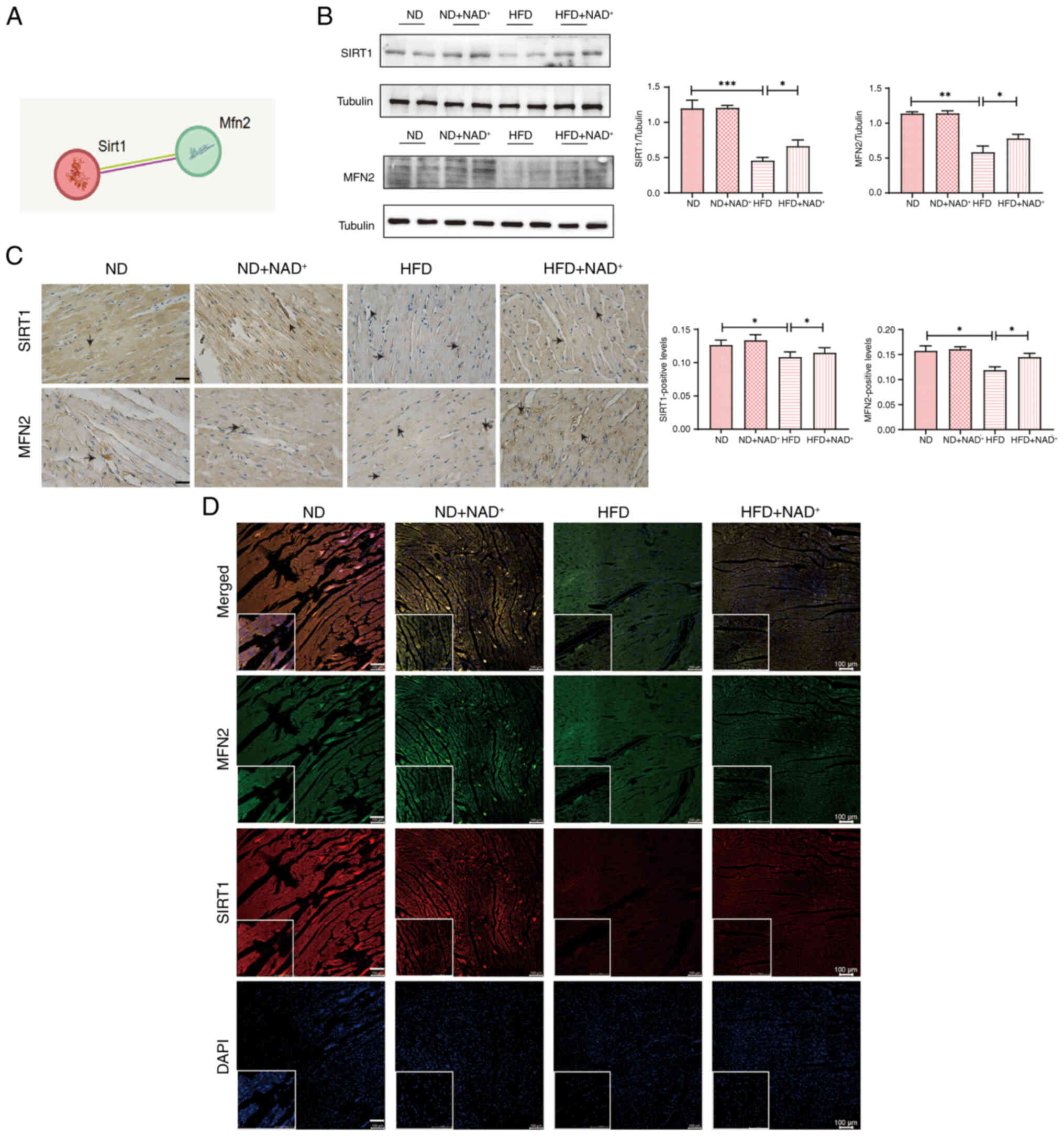

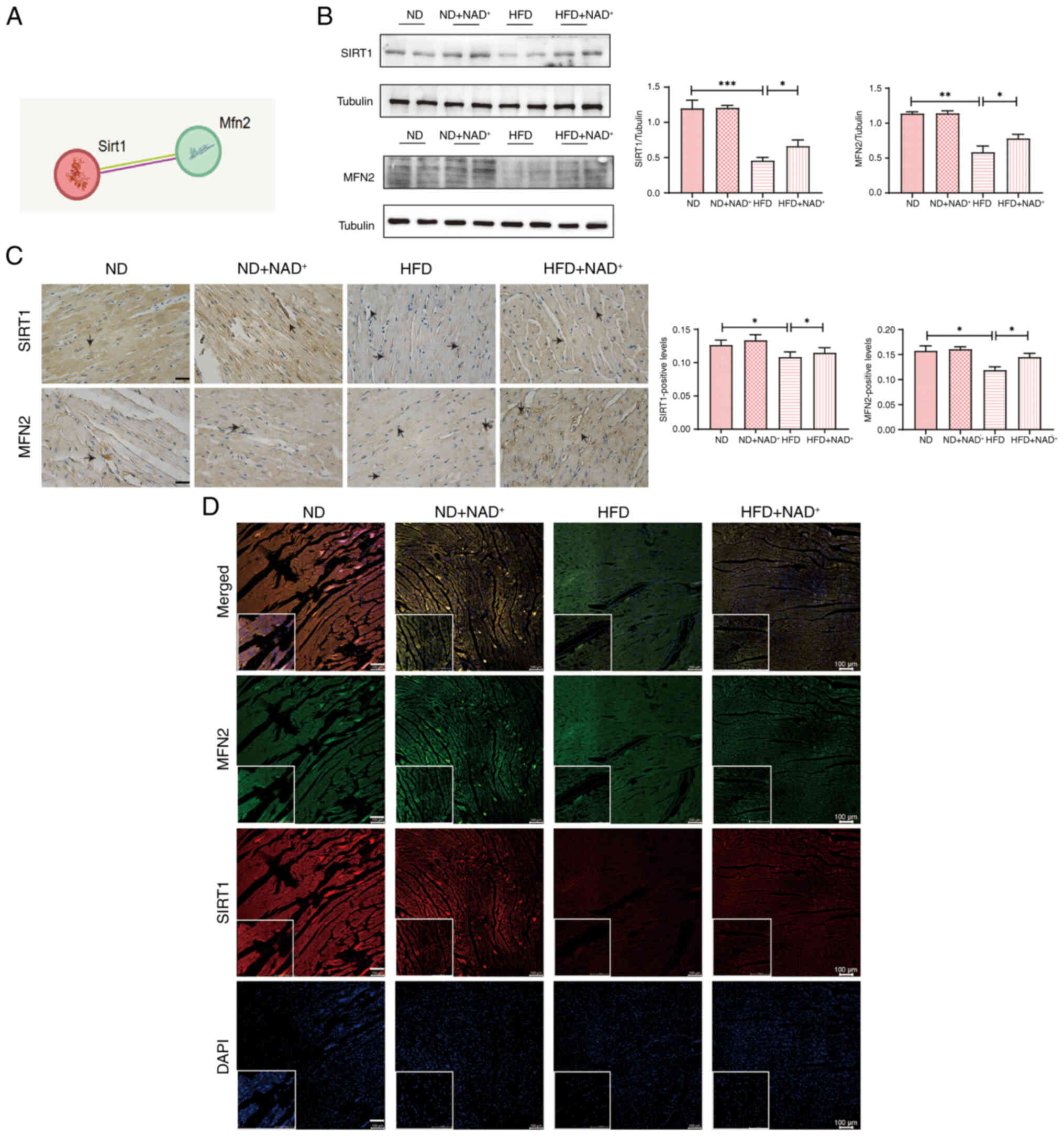

NAD+ ameliorates cardiac

damage in hyperlipidemic mice via the SIRT1/MFN2 pathway

KEGG pathway analysis (Fig. S1) indicated that SIRT1 serves a

central role in regulating key pathways involved in cellular

metabolism and stress response. Protein interaction analysis

(Fig. 4A) highlighted potential

interactions between SIRT1 and MFN2 involved in mitochondrial

dynamics and oxidative stress. Tissue specificity analysis of MFN2

(Fig. S2) revealed its

predominant expression in myocardial tissue, suggesting its

critical role in cardiac function. Western blot analysis (Fig. 4B) showed that SIRT1 and MFN2

protein expression levels were significantly reduced in the HFD

group compared with those in the ND group. However, NAD+

supplementation (HFD + NAD+) restored the expression of

both SIRT1 and MFN2 to levels comparable with the HFD group,

suggesting that NAD+ exerts protective effects by

modulating these proteins. Immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 4C) further confirmed that SIRT1 and

MFN2 expression levels were reduced in the HFD group, with marked

restoration in the HFD + NAD+ group. The arrows in the

staining images indicate areas of stained cells, illustrating the

cellular localization of these proteins in myocardial tissue.

Additionally, immunofluorescence double-labeling colocalization

staining (Fig. 4D) showed clear

colocalization of SIRT1 and MFN2 in the heart tissue, confirming

that NAD+ supplementation enhanced the expression of

both proteins in myocardial cells. Notably, NAD+

administration did not significantly affect SIRT1 or MFN2

expression in the ND group, reinforcing that its modulatory effects

are specific to pathological conditions such as HFD-induced cardiac

stress.

| Figure 4.NAD+ ameliorates cardiac

damage in hyperlipidemic mice by modulating the SIRT1/MFN2 pathway.

(A) Protein interaction analysis. (B) Expression levels of SIRT1

and MFN2 proteins in the heart tissues of mice. (C) Representative

immunohistochemistry images showing the expression of SIRT1 and

MFN2 in myocardial tissue. The arrows indicate areas of stained

cells. Scale bar, 100 µm; magnification, ×40. (D) SIRT1 and MFN 2

were detected by immunofluorescence double staining to assess

colocalization. Scale bars, 100 and 50 µm; magnification, ×40. Data

are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n=3);

statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by

Tukey's post hoc test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. HFD,

high-fat diet; MFN2, mitofusin 2; NAD+, nicotinamide

adenine dinucleotide; ND, normal diet; SIRT1, sirtuin 1. |

HIIT regulates the myocardial

PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway through NAD+-induced regulation of

the SIRT1/MFN2 pathway

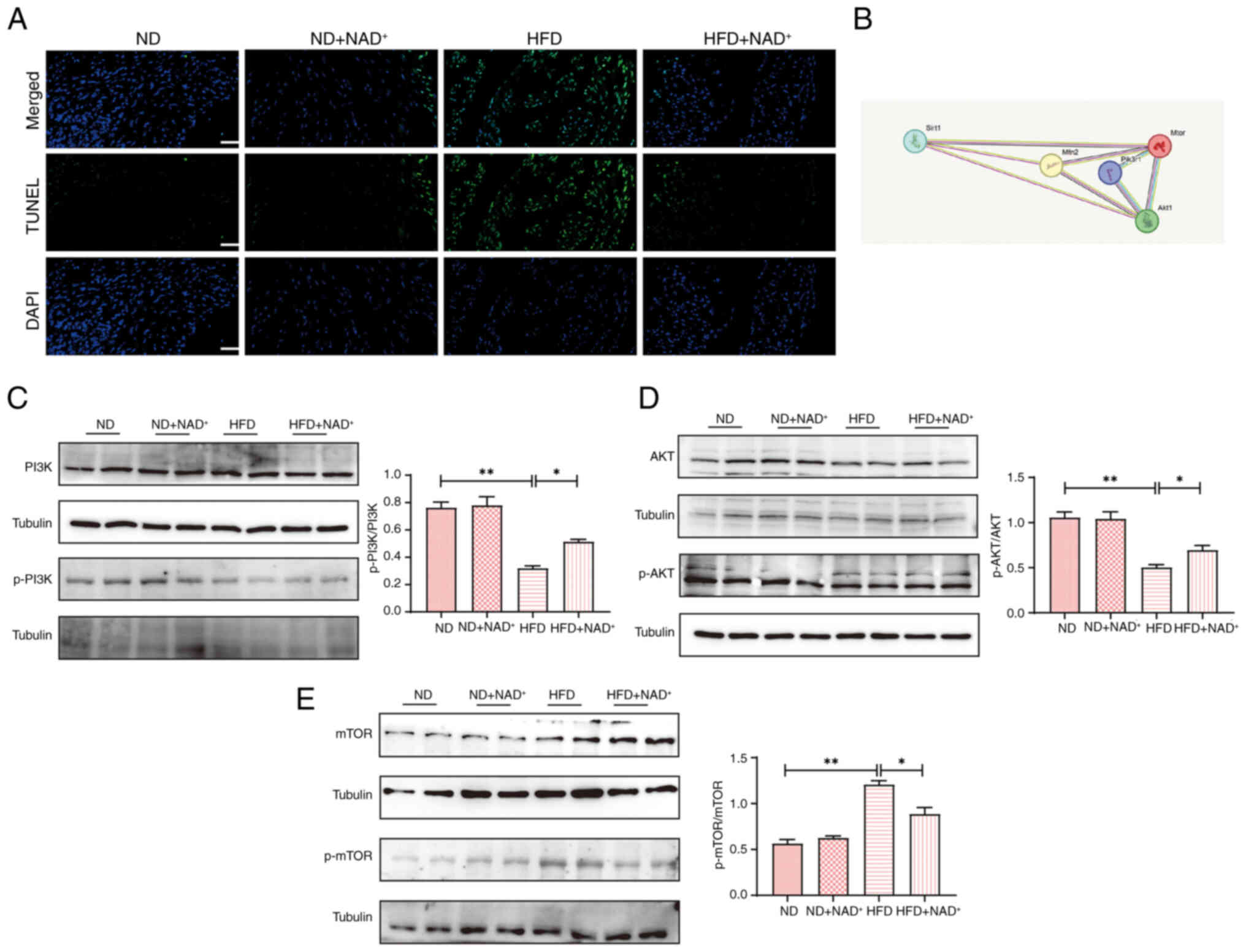

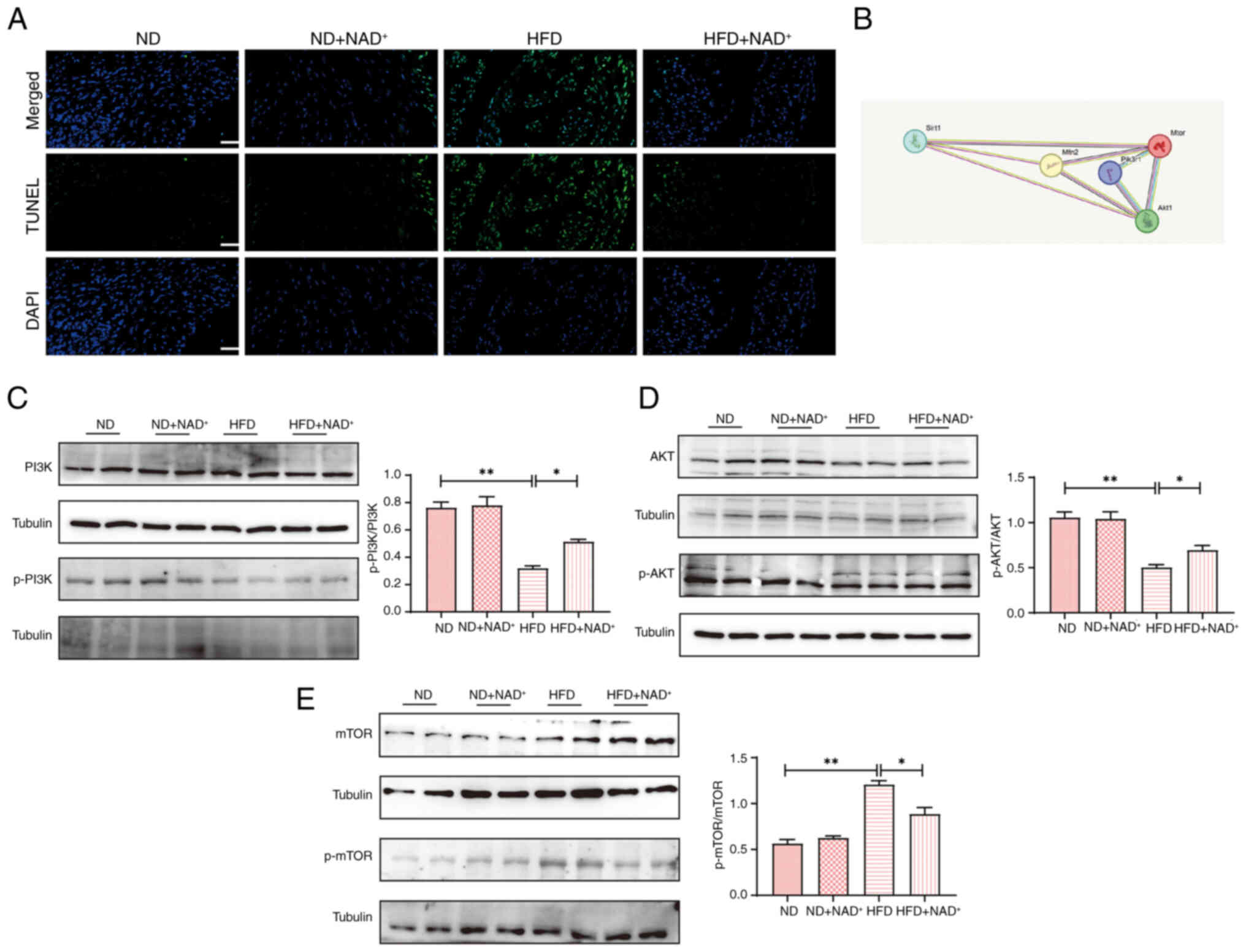

TUNEL staining (Fig.

5A) revealed increased myocardial apoptosis in the HFD group,

which was markedly reduced by NAD+ supplementation in

the HFD + NAD+ group, indicating enhanced cell survival.

Protein interaction analysis (Fig.

5B) identified key interactions between PI3K, AKT and mTOR,

suggesting their involvement in myocardial protection. Western blot

analysis (Fig. 5C) confirmed these

findings, showing decreased p-PI3K/PI3K and p-AKT/AKT levels but

elevated p-mTOR/mTOR levels in the HFD group. Notably,

NAD+ supplementation restored PI3K and AKT

phosphorylation while suppressing the abnormal increase in p-mTOR

expression. In addition, in the HFD group, both LC3 II and P62

levels were increased, suggesting impaired autophagic flux

(Fig. S3A). By contrast, in the

HFD + NAD+ group, the levels of LC3 II and p62 were

decreased, indicating restoration of autophagic degradation and

enhanced autophagic flux following NAD+ supplementation,

as decreased accumulation of both LC3 II and p62 reflects improved

turnover of autophagosomes rather than impaired autophagosome

formation. These results suggested that NAD+ exerts

cardioprotective effects through activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR

pathway and increased autophagy by promoting autophagic flux.

Notably, NAD+ treatment did not significantly affect

apoptosis markers or autophagy-related proteins in the ND group,

suggesting that its beneficial effects are specific to the

pathological state induced by HFD.

| Figure 5.NAD+ supplementation

activates the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in the myocardium. (A) TUNEL

staining was performed to assess myocardial cell apoptosis in the

heart tissues of mice. Magnification, ×40; scale bar, 100 µm. (B)

Protein interaction analysis. Expression levels of (C) p-PI3K/PI3K,

(D) p-AKT/AKT and (E) p-mTOR/mTOR in the heart tissues of mice.

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n=4);

statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by

Tukey's post hoc test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. HFD, high-fat diet;

Mfn2, mitofusin 2; NAD+, nicotinamide adenine

dinucleotide; ND, normal diet; p-, phosphorylated; Sirt1, sirtuin

1. |

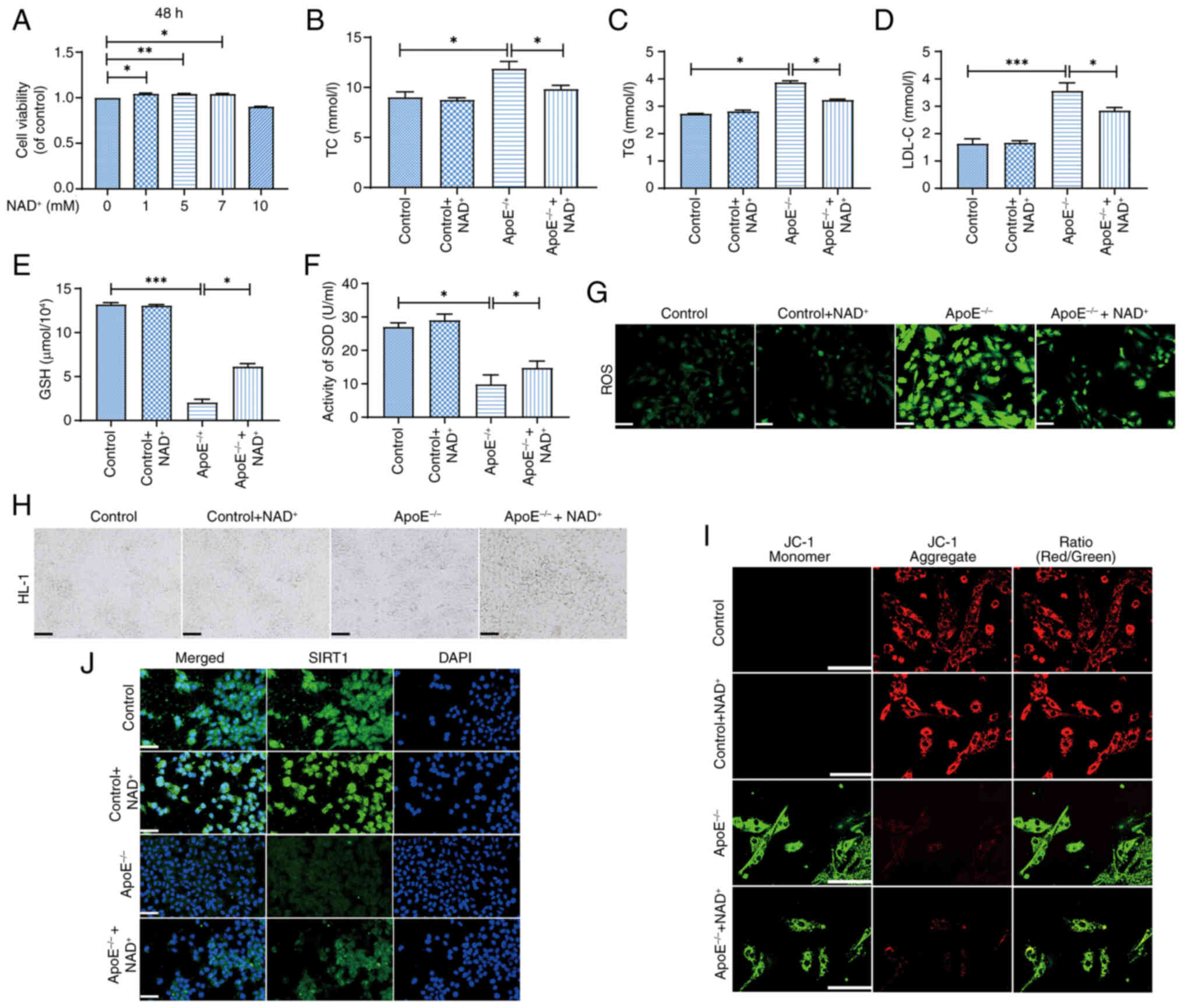

NAD+ protects

ApoE−/− HL-1 cells from lipid accumulation and oxidative

stress

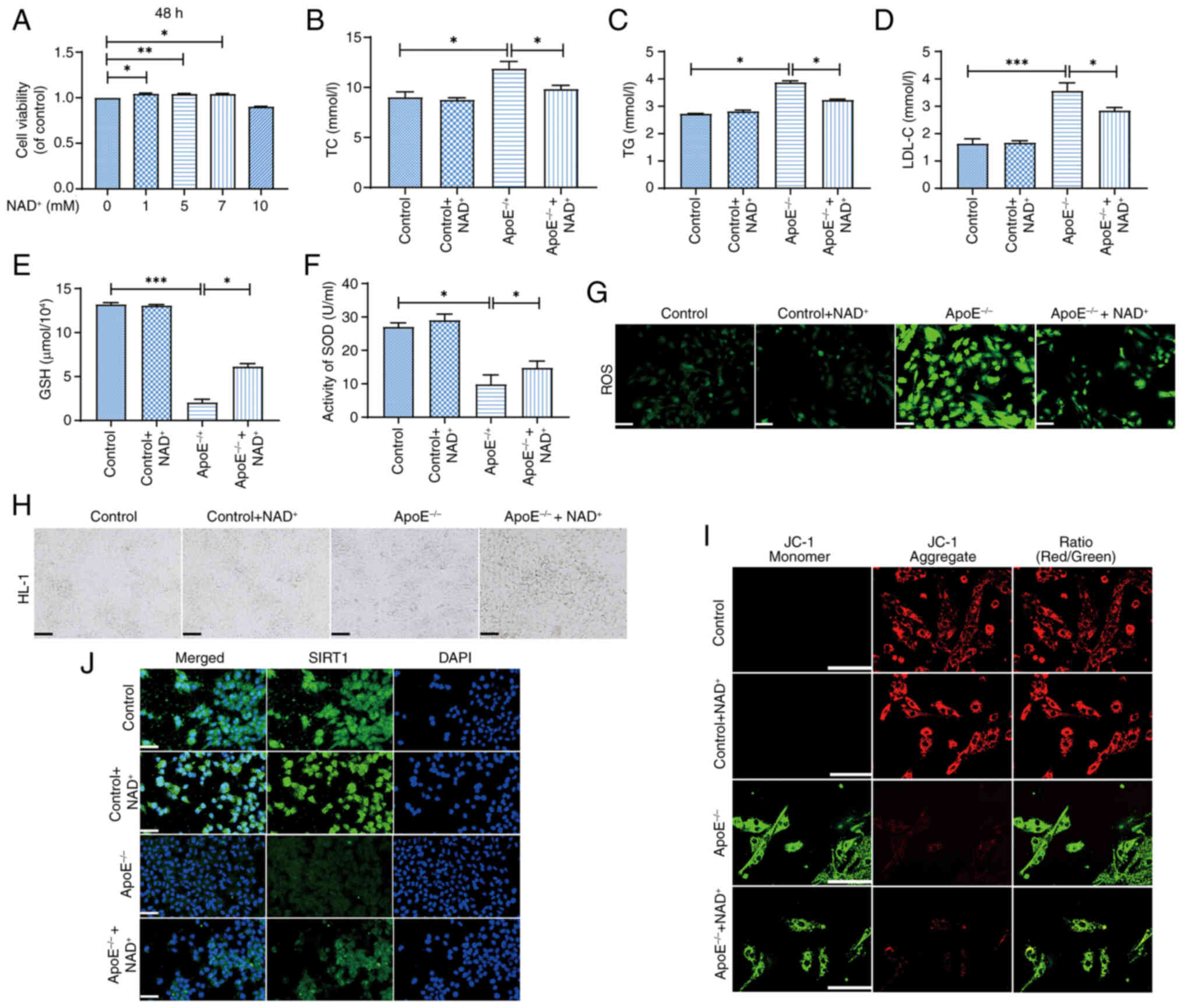

Western blot analysis confirmed successful knockdown

of ApoE expression in HL-1 cardiomyocytes following transfection

with ApoE-specific siRNA (Fig.

S4). NAD+ treatment at concentrations of 1, 5 and 7

µM significantly improved cell viability compared with the control

group, with 5 µM showing the most pronounced effect (Fig. 6A). By contrast, 10 µM

NAD+ did not significantly affect viability compared

with the control. In the ApoE−/− group, lipid

accumulation was evident, as indicated by elevated TC (Fig. 6B), TG (Fig. 6C) and LDL-C (Fig. 6D) levels, which were significantly

reduced by NAD+ supplementation (ApoE−/− +

NAD+ group). Additionally, NAD+ treatment

increased GSH levels (Fig. 6E) and

enhanced SOD activity (Fig. 6F),

indicating improved antioxidant capacity. ROS) staining (Fig. 6G) showed increased ROS accumulation

in the ApoE−/− group, which was mitigated by

NAD+ treatment. Microscopic images (Fig. 6H) confirmed that NAD+

supplementation improved cell morphology and viability, as

evidenced by more uniform cell shape, increased adherence and

reduced cell shrinkage and detachment compared with the untreated

group. Immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 6J) showed increased expression of

SIRT1 in the ApoE−/− + NAD+ group, suggesting

NAD+ activation of the SIRT1 pathway compared with

ApoE−/− group. JC-1 staining (Fig. 6I) revealed improved mitochondrial

membrane potential in the ApoE−/− + NAD+

group compared with ApoE−/− group, indicating enhanced

mitochondrial function with NAD+ treatment. These

findings demonstrate that NAD+ supplementation may

improve cellular function, lipid metabolism and oxidative stress in

HL-1 cells. Notably, NAD+ had minimal effects on lipid

levels, antioxidant capacity and mitochondrial function in

untransfected control cells, suggesting that its beneficial effects

are specific to ApoE−/−-induced cellular stress.

| Figure 6.NAD+ protects

ApoE−/− HL-1 cells from lipid accumulation and oxidative

stress. (A) Cell viability was significantly enhanced in the 5 mM

NAD+ group compared with that in the control group. (B)

NAD+ supplementation reduced TC levels in

ApoE−/−-treated cells. (C) TG levels were also

significantly decreased by NAD+ treatment. (D) LDL-C

levels were also reduced in the ApoE−/− +

NAD+ group, indicating improved lipid metabolism. (E)

NAD+ supplementation increased GSH levels, reflecting

enhanced antioxidant defense. (F) SOD activity was also

significantly elevated in the ApoE−/− + NAD+

group, suggesting improved oxidative stress response. (G) ROS

staining revealed reduced reactive oxygen species in the

ApoE−/− + NAD+ group, indicating a decrease

in oxidative stress. Scale bar, 200 µm. (H) Microscopic images

confirmed improved cell morphology and viability in the

ApoE−/− + NAD+ group. Scale bar, 100 µm. (I)

JC-1 staining showed improved mitochondrial membrane potential in

the ApoE−/− + NAD+ group. Scale bar, 100 µm.

(J) Immunofluorescence staining demonstrated increased expression

of SIRT1 in the ApoE−/− + NAD+ group,

suggesting activation of the SIRT1 pathway. Magnification, ×40;

scale bar, 50 µm. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error

of the mean (n=3); statistical analysis was performed using one-way

ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001. ApoE−/−, apolipoprotein E-deficient; GSH,

glutathione; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol;

NAD+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; ROS, reactive

oxygen species; SIRT1, sirtuin 1; SOD, superoxide dismutase; TC,

total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides. |

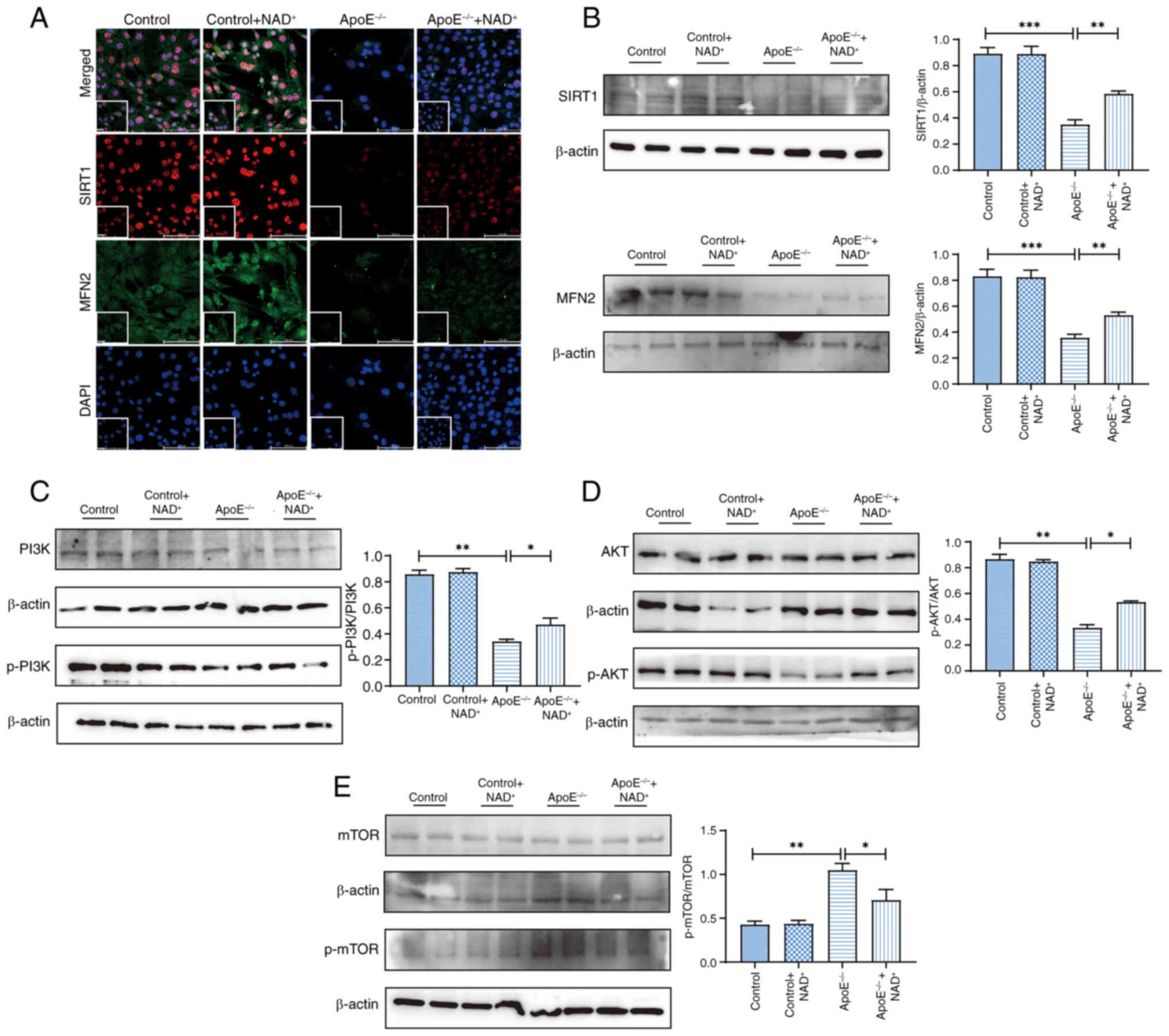

NAD+ enhances the

SIRT1/MFN2 pathway to protect ApoE−/− HL-1 cells through

SIRT1 upregulation

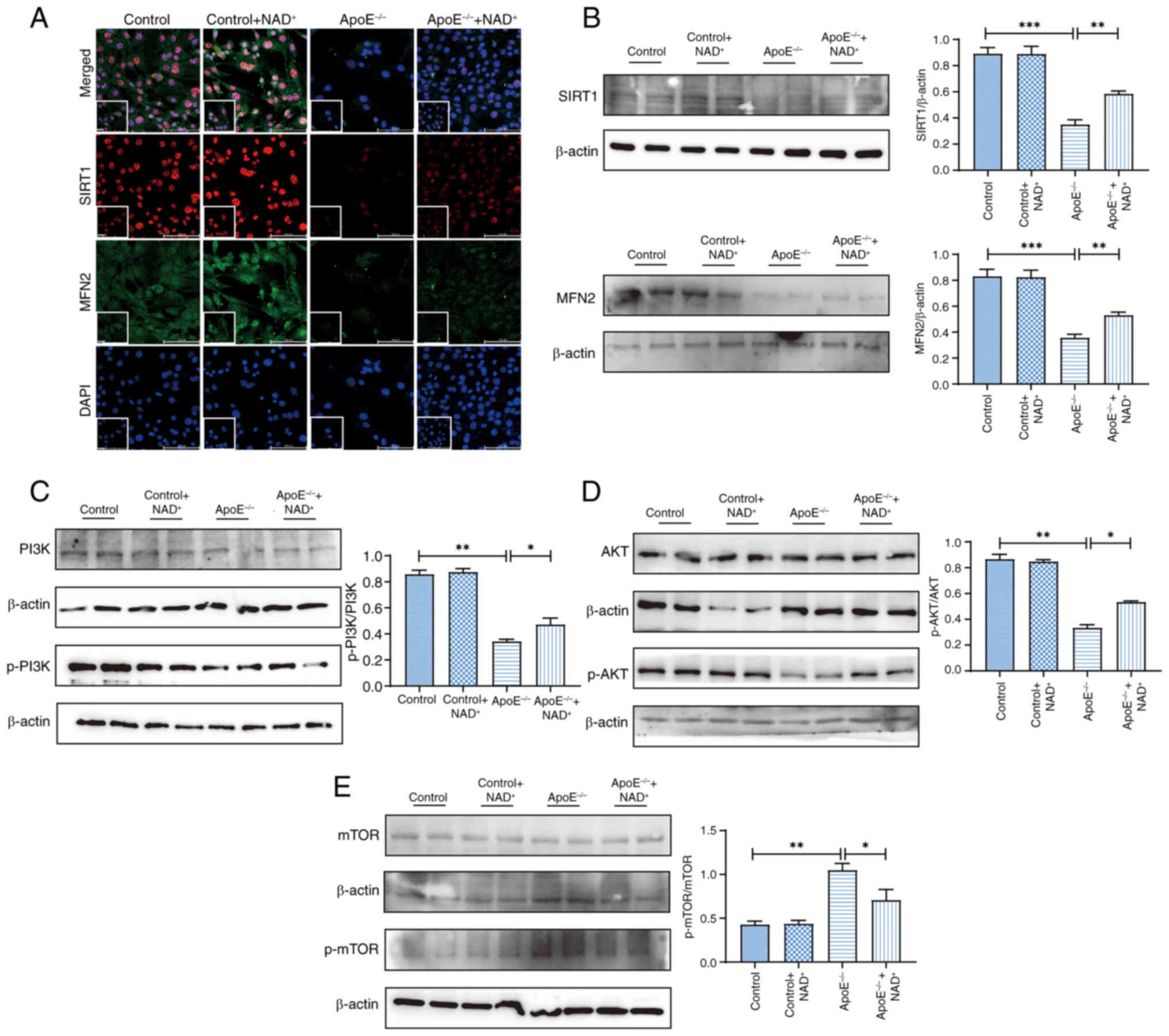

Fig. 7A shows

representative immunofluorescence images of MFN2 and SIRT1 double

staining, with colocalization observed in the cytoplasm of cells,

particularly in the ApoE−/−+NAD+ group,

indicating that NAD+ treatment promoted the

co-expression of these proteins. Furthermore, western blot analysis

showed increased levels of both MFN2 and SIRT1 in the

ApoE−/− + NAD+ group compared with those in

the ApoE−/− group, further supporting the

immunofluorescence results (Fig.

7B). Additionally, activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway was

observed in the ApoE−/− + NAD+

group, indicated by restored phosphorylation of PI3K and AKT and

suppression of the HFD-induced increase in p-mTOR, compared with

the ApoE−/− group. To further validate the

involvement of autophagy in vitro, HL-1 cells were treated

with PA), and the levels of LC3 II and P62 were assessed.

Consistent with the in vivo findings, PA treatment led to a

significant accumulation of both LC3 II and P62, suggesting

impaired autophagic flux (Fig.

S3B). However, NAD+ markedly reduced the levels of

LC3 II and P62 in PA-treated cells, indicating that NAD+

supplementation may restore autophagic degradation and enhance

autophagic flux under lipotoxic stress conditions. To determine

whether NAD+ supplementation activated SIRT1 rather than

merely increased its expression, HL-1 cells were treated with PA

and co-incubated with NAD+ and/or the SIRT1 inhibitor

EX-527. NAD+ treatment significantly increased SIRT1

expression and modulated p-mTOR levels altered by PA, indicative of

enhanced autophagic flux; this effect was abolished by EX-527

Fig. S5). These results suggested

that NAD+ may exert its protective effects through

functional activation of SIRT1.

| Figure 7.NAD+ enhances MFN2/SIRT1

expression and activates the PI3K/AKT pathway in HL-1 cells. (A)

Representative immunofluorescence double staining showing

colocalization of MFN2 and SIRT1 in HL-1 cells. Magnification, ×40;

scale bars, 100 and 50 µm. Protein expression levels of (B) SIRT1

and MFN2, (C) PI3K and p-PI3K, (D) AKT and p-AKT, and (E) mTOR and

p-mTOR in HL-1 cells. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n=4);

statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by

Tukey's post hoc test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

ApoE−/−, apolipoprotein E-deficient; MFN2, mitofusin 2;

NAD+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; p-,

phosphorylated; SIRT1, sirtuin 1. |

The present findings support the notion that

NAD+ could promote autophagy in cardiomyocytes via the

modulation of autophagic flux, potentially contributing to its

cardioprotective effects. In addition, it was suggested that

NAD+ supplementation not only modulated the MFN2/SIRT1

pathway but also activated the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway,

contributing to improved cellular function and mitochondrial

integrity. Notably, NAD+ did not produce significant

effects on autophagy- or metabolism-related markers in untreated

HL-1 cells, indicating that its regulatory role is specific to

lipotoxic or stress-induced conditions (Fig. S6).

Discussion

The present study systematically investigated the

effects of NAD+ supplementation and exercise

intervention on a model of HFD-induced cardiac injury, highlighting

their key roles in alleviating oxidative stress, correcting

metabolic dysfunction and modulating autophagy. ApoE−/−

mice were selected as a model of hyperlipidemia and

atherosclerosis. Owing to the lack of ApoE, these mice develop

spontaneous hypercholesterolemia and exhibit early cardiovascular

alterations under a HFD, closely resembling human cardiometabolic

disorders (28,29). Notably, in the present study

different HFD formulations and suppliers were used for each model;

however, both diets were selected based on their validation in the

literature for reliably inducing hyperlipidemia, obesity and

cardiovascular dysfunction in rodents (30). Moreover, both suppliers are

certified Chinese manufacturers whose products meet national

standards for laboratory animal feed production; although minor

compositional differences (such as fatty acid profiles and

micronutrients) between diet sources could theoretically affect

certain metabolic parameters, consistent phenotypic outcomes were

observed in terms of body weight gain, serum lipid levels and

cardiac pathology. These findings support the reproducibility and

reliability of both models.

The present HFD model offered a sensitive and

reproducible platform for evaluating interventions targeting lipid

metabolism, oxidative stress and myocardial injury. Notably,

ApoE−/− mice represent a hyperlipidemia-prone model with

increased susceptibility to cardiac injury (31). This enabled the present study to

delineate the cardioprotective effects of NAD+ under

metabolic stress, particularly via activation of the SIRT1/MFN2 and

PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Future studies using wild-type mice should

be performed to determine whether NAD+ confers similar

benefits under physiological or less severe metabolic conditions,

thereby assessing its broader translational potential (32,33).

Unlike earlier studies relying on NAD+ precursors, the

approach of the present study directly demonstrated the therapeutic

value of NAD+ in lipid-induced myocardial injury

(34,35).

Exercise is a well-recognized non-pharmacological

intervention that improves metabolic homeostasis and cardiovascular

health, and it has been shown to enhance endogenous NAD+

biosynthesis via AMPK and NAMPT pathways (36,37).

In the present study, although the focus was on exogenous

NAD+ supplementation, the results revealed that HIIT

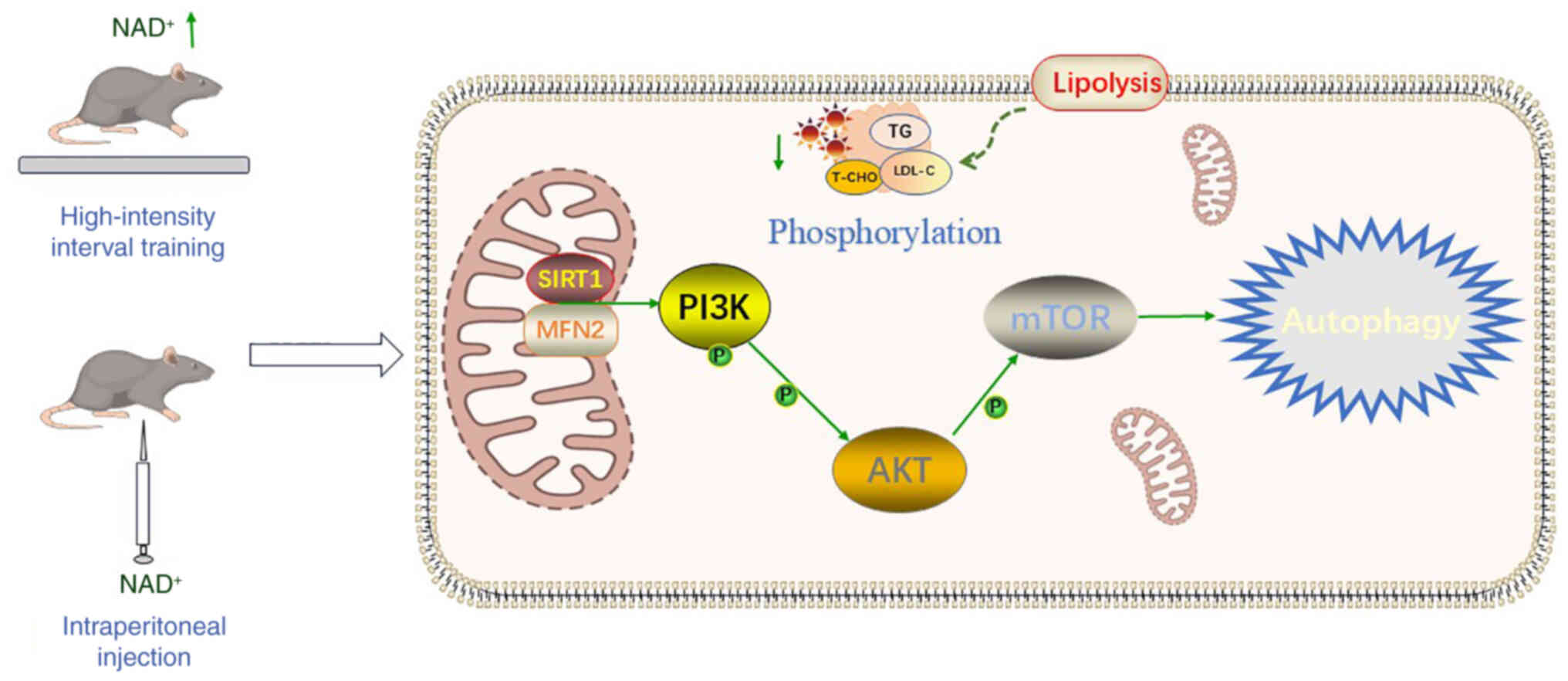

also elevated cardiac NAD+ levels, and alleviated

oxidative stress, fibrosis and myocardial injury in

ApoE−/− mice. These results underscore the potential of

exercise to mitigate hyperlipidemia-induced cardiac damage,

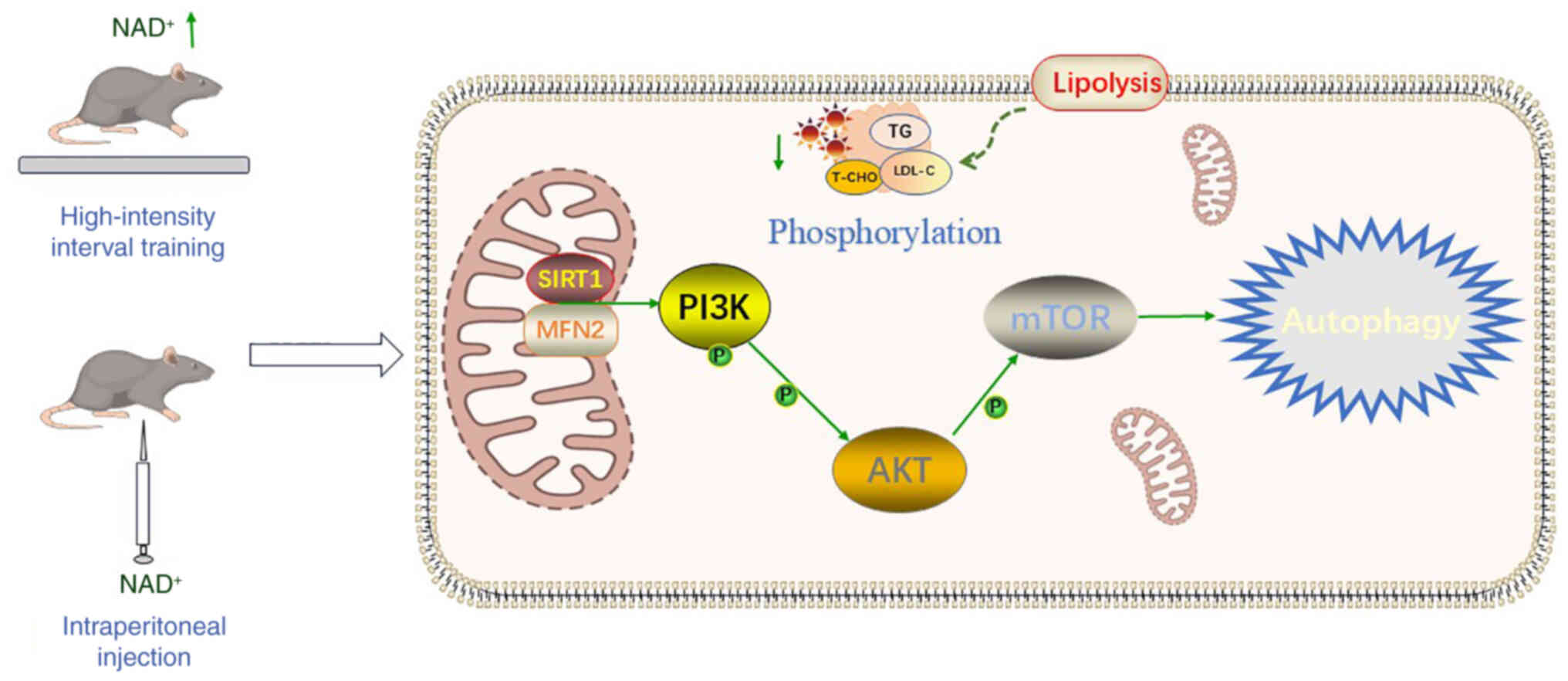

partially through NAD+-related mechanisms. The findings

demonstrated that NAD+ markedly improved mitochondrial

integrity and reduced excessive ROS accumulation potentially by

activating the SIRT1/MFN2 pathway (Fig. 8), thereby protecting cardiomyocytes

from metabolic stress-induced damage. Furthermore, the combination

of NAD+ and HIIT may amplify these protective effects by

enhancing tissue NAD+/NADH ratios and increasing the

phosphorylation levels of PI3K and AKT, thereby modulating the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway and providing a multilayered

cardioprotective mechanism at both molecular and cellular levels.,

providing a multilayered cardioprotective mechanism at both

molecular and cellular levels. Although prior studies have explored

the independent roles of NAD+ and exercise in cardiac

metabolic regulation (38–40), the present study provides

preliminary evidence suggesting that NAD+

supplementation combined with HIIT may exert complementary

protective effects against HFD-induced cardiac damage, offering

potential theoretical insights and therapeutic implications for

metabolic cardiomyopathy.

| Figure 8.Mechanistic overview of

NAD+ in improving HFD-induced cardiac dysfunction.

High-intensity interval training elevates cardiac NAD+

levels, and subsequent intraperitoneal NAD+

supplementation further activates SIRT1/MFN2 signaling. This

enhances PI3K/AKT/mTOR phosphorylation, promoting autophagy and

mitochondrial quality control. Interventions also improve lipid

metabolism, reducing TG, T-CHO, and LDL-C. Together, these

mechanisms mitigate mitochondrial dysfunction, and metabolic

disturbances in HFD-induced cardiac injury. LDL-C, low-density

lipoprotein cholesterol; MFN2, mitofusin 2; NAD+,

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; T-CHO, total cholesterol; TG,

triglycerides; SIRT1, sirtuin 1. |

SIRT1, a NAD+-dependent deacetylase,

serves a central role in regulating mitochondrial function,

oxidative stress and metabolic homeostasis (41). NAD+ supplementation

markedly upregulated SIRT1 expression, thereby attenuating

oxidative damage through enhanced mitochondrial quality control and

reduced ROS generation. Additionally, SIRT1 deacetylates MFN2, a

critical protein in mitochondrial fusion, stabilizing its function

under metabolic stress conditions (42). In addition to the involvement of

the SIRT1/MFN2 pathway, the present study demonstrated that

exercise increased NAD+ levels, which subsequently

activated the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway via SIRT1/MFN2. This

pathway is known to play a crucial role in regulating lipid

accumulation, fibrosis, and metabolic homeostasis (43). Excessive activation of this pathway

in HFD models has been associated with exacerbated cardiac

remodeling. By suppressing this signaling cascade, NAD+

and exercise intervention effectively reduced myocardial fibrosis

and lipid deposition. These findings align with previous metabolic

studies and highlight the beneficial effects of NAD+

supplementation and exercise in improving metabolic cardiomyopathy

(44,45).

The present study highlighted the distinct effects

of HIIT and MICT on cardiac metabolic regulation. HIIT demonstrated

superior benefits in increasing NAD+ levels and reducing

oxidative stress compared with MICT. The acute metabolic stress

induced by HIIT may trigger the activation of NAD+

biosynthetic enzymes such as NAMPT, thereby amplifying NAD

availability and improving mitochondrial function (46,47).

These findings underscore the potential of HIIT as a potent

exercise modality for enhancing cardiac resilience in metabolic

conditions. From a clinical perspective, the specificity of

exercise interventions highlights the importance of tailoring

training regimens to optimize therapeutic outcomes. Future studies

should further explore the dose-response relationship of exercise

intensity and NAD+ supplementation in improving cardiac

function.

The involvement of SIRT1/MFN2 and PI3K/AKT/mTOR

pathways offers mechanistic insights in heart and liver (42,48–50).

The present findings build upon and expand the existing knowledge

on the independent effects of NAD+ and exercise in

cardiac metabolic regulation. Previous studies have predominantly

investigated their individual effects. This dual approach amplifies

the benefits, providing a more comprehensive understanding of how

metabolic and mechanical interventions can jointly enhance cardiac

health. To further validate the signaling relationship, in

vitro experiments were performed using the specific SIRT1

inhibitor EX-527 (51). Treatment

with EX-527 significantly attenuated NAD+-induced

activation of the p-mTOR mTOR pathway, indicating that SIRT1 is an

upstream regulator. These results confirm that the PI3K/AKT/mTOR

pathway functions downstream of the SIRT1/MFN2 pathway. The

additional experiments using EX-527 confirmed that SIRT1 modulates

the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in response to NAD+,

reinforcing the proposed SIRT1/MFN2-PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling cascade

involved in cardioprotection. Moreover, exogenous NAD+

supplementation reduced the levels of LC3 II and P62 in the

hyperlipidemia model, indicating that autophagic degradation may be

restored and autophagic flow enhanced after NAD+

supplementation. Therefore, it could be hypothesized that

NAD+ treatment promotes the maturation of autophagosomes

and enhances the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes, thereby

improving autophagic flow and promoting autophagic degradation in

hyperlipidemia-induced heart injury. These findings establish a

foundation for future translational studies exploring the broader

applications of NAD+ and exercise intervention.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

NAD+ supplementation and exercise, particularly HIIT,

independently protect against HFD-induced cardiac damage by

targeting oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and

metabolic disturbances. The protective effects of NAD+

in HFD-induced cardiac injury were mediated primarily via

activation of the SIRT1/MFN2 pathway and the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway.

These findings provide new insights into the prevention and

treatment of metabolic cardiomyopathy, supporting further research

and potential clinical applications.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by the Central Hospital of Dalian

University of Technology ‘Climbing Plan’ (grant no. 2023ZZ008).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

ZP designed the study. SG and WY performed the

experiments. ZP, SG and WY analyzed the data. ZP and SG confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. SG and WY drafted and wrote the

manuscript. JY and YL analyzed the data and revised the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal experiments were performed in accordance

with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were

approved by the Ethics Committee of Dalian Municipal Central

Hospital (grant no. YN2023-057-55).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Kotseva K, Jennings C, Bassett P, Adamska

A, Hobbs R and Wood D; ASPIRE-3-PREVENT Investigators, : Challenge

of cardiovascular prevention in primary care: Achievement of

lifestyle, blood pressure, lipids and diabetes targets for primary

prevention in England-results from ASPIRE-3-PREVENT cross-sectional

survey. Open Heart. 11:e0027042024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Han S, Kim NR, Kang JW, Eun JS and Kang

YM: Radial BMD and serum CTX–I can predict the progression of

carotid plaque in rheumatoid arthritis: A 3-year prospective cohort

study. Arthritis Res Ther. 23:2582021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zheng L, Than A, Zan P, Li D, Zhang Z,

Leow MKS and Chen P: Mild-photothermal and nanocatalytic therapy

for obesity and associated diseases. Theranostics. 14:5608–5620.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Narasimhulu CA and Singla DK: BMP-7

Attenuates sarcopenia and adverse muscle remodeling in diabetic

mice via alleviation of lipids, inflammation, HMGB1, and

pyroptosis. Antioxidants (Basel). 12:3312023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Aaronson SA, Abrams

JM, Adam D, Agostinis P, Alnemri ES, Altucci L, Amelio I, Andrews

DW, et al: Molecular mechanisms of cell death: Recommendations of

the Nomenclature committee on cell death 2018. Cell Death Differ.

25:486–541. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Shoji S and Mentz RJ: Beyond quadruple

therapy: The potential roles for ivabradine, vericiguat, and

omecamtiv mecarbil in the therapeutic armamentarium. Heart Fail

Rev. 29:949–955. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Bentivegna E, Galastri S, Onan D and

Martelletti P: Unmet needs in the acute treatment of migraine. Adv

Ther. 41:1–13. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Perryman R, Chau TW, De-Felice J, O'Neill

K and Syed N: Distinct capabilities in NAD metabolism mediate

resistance to NAMPT inhibition in glioblastoma. Cancers (Basel).

16:20542024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Abdellatif M, Sedej S and Kroemer G:

NAD+ metabolism in cardiac health, aging, and disease.

Circulation. 144:1795–1817. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Chu X and Raju RP: Regulation of NAD(+)

metabolism in aging and disease. Metabolism. 126:1549232022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Lin Q, Zuo W, Liu Y, Wu K and Liu Q:

NAD(+) and cardiovascular diseases. Clin Chim Acta. 515:104–110.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Yoshino M, Yoshino J, Kayser BD, Patti GJ,

Franczyk MP, Mills KF, Sindelar M, Pietka T, Patterson BW, Imai SI

and Klein S: Nicotinamide mononucleotide increases muscle insulin

sensitivity in prediabetic women. Science. 372:1224–1229. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Cheng L, Deepak RNVK, Wang G, Meng Z, Tao

L, Xie M, Chi W, Zhang Y, Yang M, Liao Y, et al: Hepatic

mitochondrial NAD + transporter SLC25A47 activates AMPKα mediating

lipid metabolism and tumorigenesis. Hepatology. 78:1828–1842. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Lopaschuk GD, Karwi QG, Tian R, Wende AR

and Abel ED: Cardiac energy metabolism in heart failure. Circ Res.

128:1487–1513. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Doan KV, Luongo TS, Ts'olo TT, Lee WD,

Frederick DW, Mukherjee S, Adzika GK, Perry CE, Gaspar RB, Walker

N, et al: Cardiac NAD+ depletion in mice promotes

hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and arrhythmias prior to impaired

bioenergetics. Nat Cardiovasc Res. 3:1236–1248. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Qiu Y, Xu S, Chen X, Wu X, Zhou Z, Zhang

J, Tu Q, Dong B, Liu Z, He J, et al: NAD(+) exhaustion by CD38

upregulation contributes to blood pressure elevation and vascular

damage in hypertension. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8:3532023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Li J, Zhang C, Hu Y, Peng J, Feng Q and Hu

X: Nicotinamide enhances Treg differentiation by promoting Foxp3

acetylation in immune thrombocytopenia. Br J Haematol.

205:2432–2441. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Pei Z, Wang F, Wang K and Wang L:

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide in the development and treatment

of cardiac remodeling and aging. Mini Rev Med Chem. 22:2310–2317.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Fritzen AM, Lundsgaard AM and Kiens B:

Tuning fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle with dietary fat and

exercise. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 16:683–696. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Qi XM, Qiao YB, Zhang YL, Wang AC, Ren JH,

Wei HZ and Li QS: PGC-1α/NRF1-dependent cardiac mitochondrial

biogenesis: A druggable pathway of calycosin against triptolide

cardiotoxicity. Food Chem Toxicol. 171:1135132023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhang H, Wang Y, Wu K, Liu R, Wang H, Yao

Y, Kvietys P and Rui T: miR-141 impairs mitochondrial function in

cardiomyocytes subjected to hypoxia/reoxygenation by targeting

Sirt1 and MFN2. Exp Ther Med. 24:7632022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ji LL and Yeo D: Maintenance of NAD+

homeostasis in skeletal muscle during aging and exercise. Cells.

11:7102022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

National Research Council Committee for

the Update of the Guide for the C. A. Use of Laboratory. The

National Academies Collection, . Reports funded by National

Institutes of Health, in Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory

Animals. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2011

|

|

24

|

Nishida Y, Nawaz A, Kado T, Takikawa A,

Igarashi Y, Onogi Y, Wada T, Sasaoka T, Yamamoto S, Sasahara M, et

al: Astaxanthin stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis in insulin

resistant muscle via activation of AMPK pathway. J Cachexia

Sarcopenia Muscle. 11:241–258. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Brault V, Duchon A, Romestaing C, Sahun I,

Pothion S, Karout M, Borel C, Dembele D, Bizot JC, Messaddeq N, et

al: Opposite phenotypes of muscle strength and locomotor function

in mouse models of partial trisomy and monosomy 21 for the proximal

Hspa13-App region. PLoS Genet. 11:e10050622015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Wang L, Lavier J, Hua W, Wang Y, Gong L,

Wei H, Wang J, Pellegrin M, Millet GP and Zhang Y: High-Intensity

interval training and moderate-intensity continuous training

attenuate oxidative damage and promote myokine response in the

skeletal muscle of ApoE KO mice on high-fat diet. Antioxidants

(Basel). 10:9922021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Pei Z, Li Y, Yao W, Sun F and Pan X:

NAD+ Protects against hyperlipidemia-induced kidney

injury in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Cur Pharm Biotechnol.

25:488–498. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Aravani D, Kassi E, Chatzigeorgiou A and

Vakrou S: Cardiometabolic syndrome: An update on available mouse

models. Thromb Haemost. 121:703–715. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Poledne R and Jurčíková-Novotná L:

Experimental models of hyperlipoproteinemia and atherosclerosis.

Physiol Res. 66 (Suppl 1):S69–S75. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Park Y, Jang I, Park HY, Kim J and Lim K:

Hypoxic exposure can improve blood glycemic control in high-fat

diet-induced obese mice. Phys Act Nutr. 24:19–23. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Zhao Y, Qu H, Wang Y, Xiao W, Zhang Y and