Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease caused by

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) infection. Globally, there

are ~10 million new cases of TB and 1.6 million TB-related deaths

annually, making it the leading source of infection and one of the

top ten causes of death. Notably, China is one of 30 countries with

a high morbidity rate of TB (1).

The Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention has shown

that the geographical distribution of TB epidemics in China is

characterized by low incidence in the eastern region and high

prevalence in the western region, and the incidence rate of TB is

higher in the Xinjiang region than in other provinces (2,3). The

average rate of culture-positive TB is 119/100,000 people in China,

whereas it is 433/100,000 in the Xinjiang region (4). The high prevalence rate of TB in

Xinjiang may be due to unique climatic, geographic and demographic

characteristics (5), as well as

the high incidence of HIV infection, the growing floating

population, unhealthy habits and poor living conditions in rural

areas; however, the exact reason is unclear.

MTB is an intracellular pathogen and macrophages are

major innate immune cells, which are the first line of defense

against MTB infection and the primary effector cells for clearing

this pathogen (6,7). To avoid becoming reservoirs of MTB,

host macrophages have evolved a number of defense mechanisms,

including autophagy (8) and

apoptosis (9), to kill or prevent

the growth of MTB. Immune cell apoptosis is an important mechanism

against bacterial and viral infections, and some studies have

suggested that macrophage apoptosis induced by MTB infection can

kill MTB (10,11). However, other studies have

suggested that excessive apoptosis is conducive to MTB survival

(12,13). Thus, a clear understanding of the

interaction of MTB with host macrophages may help develop targeted

strategies for controlling TB.

Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) is a member of the

CDK protein family, and it controls all aspects of cell division,

including cell cycle entry from quiescence, G1/S phase

transition, DNA replication in the S phase, nuclear rupture,

chromosome cohesion and segregation, and cytoplasmic division

(14–16). CDK1 is a proline-directed kinase

that phosphorylates a large number of proteins to drive cell cycle

progression and specific processes associated with different cell

cycle phases (15). Huang et

al (17) showed that CDK1 can

regulate the degree of cell cycle arrest during the G2/M

phase. Furthermore, previous studies have shown a close association

between CDK1 and tumor cell apoptosis in glioblastoma (18), human hepatocellular carcinoma

(19), cervical carcinoma

(20), colorectal carcinoma

(21,22) and ovarian carcinoma (23). However, the role of CDK1 in the

immune response of macrophages after TB infection is unclear.

The transcription factor p53, once activated by

phosphorylation and acetylation, binds directly to specific DNA

sequences in the promoter region of target genes to regulate their

expression (24,25). Notably, p53 target genes are

involved in the regulation of apoptosis, DNA repair, cell cycle

arrest, senescence and programmed cell death (25–27).

It has been shown that promoting phosphorylation of the p53 protein

can enhance macrophage apoptosis and suppress the survival of

MTB-infected macrophages (28).

The present study utilized bioinformatics analysis

to investigate the effects of the CDK1 gene on the apoptosis and

cell cycle progression of macrophages infected with different

sources of MTB in vitro. The current study aimed to reveal

the specific immune response involving CDK1 and phosphorylated

(p)-p53 in macrophages after infection with MTB clinical isolates,

as well as the mechanism by which CDK1 and p-p53 regulate

macrophage cycle arrest and apoptosis after infection with MTB from

Xinjiang (XJMTB). CDK1 and p-p53 may be considered novel treatment

targets for TB in Xinjiang and lay the foundation for formulating

TB treatment strategies.

Materials and methods

Sample collection, and MTB

resuscitation, isolation and culture

The sputum samples of 20 cases were derived from 103

patients with sputum smear-positive TB in the Xinjiang region

during a previous epidemiological survey conducted by the

cooperative team (29). All cases

were diagnosed according to China's national diagnostic criteria

(30). Demographic,

epidemiological and clinical data were obtained from the medical

records of the patients using a unified epidemiological survey

methodology. Table I provides the

details of the 20 patients.

| Table I.Patient's basic information. |

Table I.

Patient's basic information.

| Number | Sex | Age, years | Ethnicity | Separation and

amplification | TCH | PNB |

|---|

| L1 | Male | 35 | Han | Yes | + | + |

| L2 | Male | 32 | Uighur | Yes | - | - |

| L3 | Male | 25 | Uighur | Yes | + | - |

| L4 | Female | 52 | Han | Yes | + | - |

| L5 | Female | 38 | Han | Yes | + | - |

| L6 | Male | 42 | Uighur | Yes | + | - |

| L7 | Male | 56 | Han | Yes | + | - |

| L8 | Female | 43 | Uighur | Yes | + | - |

| L9 | Male | 44 | Uighur | Yes | + | - |

| L10 | Male | 47 | Han | No | / | / |

| L11 | Female | 37 | Uighur | No | / | / |

| L12 | Male | 55 | Uighur | Yes | + | - |

| L13 | Female | 28 | Uighur | No | / | / |

| L14 | Male | 37 | Han | Yes | + | - |

| L15 | Female | 45 | Han | No | / | / |

| L16 | Male | 29 | Uighur | Yes | + | - |

| L17 | Female | 26 | Han | Yes | + | - |

| L18 | Male | 53 | Han | Yes | + | - |

| L19 | Male | 28 | Uighur | Yes | - | - |

| L20 | Female | 57 | Han | Yes | + | - |

The sputum was mixed with 1–3 times the volume of a

4% NaOH (Beijing Chemical Works) solution, shaken well until

dissolved and maintained at room temperature for 20 min. Once the

sample was completely liquefied, 100 µl sample was aspirated and

dropped evenly on the slant of modified acidic Roche's medium

(Celnovte Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Each sample was inoculated

three times and placed in a 37°C incubator. After a single white

colony was grown, it was picked off, placed in a 37°C incubator

containing 40 ml Mycobacterium liquid medium (Shanghai

Jingnuo Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and shaken at 120 rpm for

amplification. In addition, 50–100 µl frozen H37Rv (cat. no. 27294;

American Type Culture Collection) bacterial solution was aspirated,

added to 40 ml Mycobacterium liquid medium and amplified by

shaking at 120 rpm.

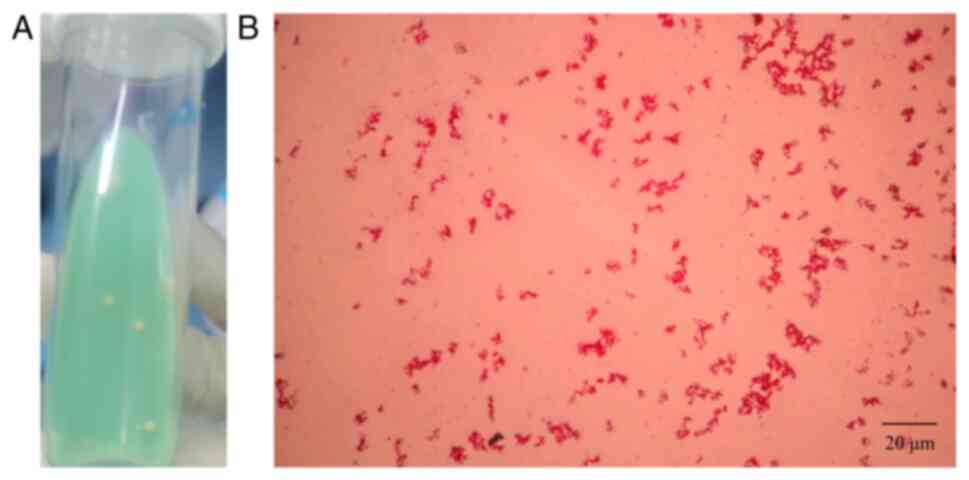

Acid-fast staining

An inoculation loop was dipped into the XJMTB

amplified bacterial solution, applied onto a slide and fixed by

heating alone. Subsequently, carbol fuchsin was added dropwise to

the solution, the solution was slowly heated (but not boiled) for

3–5 min and washed with water. Hydrochloric acid-ethanol solution

(3%) was then added dropwise to the solution to decolorize it for

30 sec. Finally, methylene blue was added dropwise to the solution

for 0.5–1 min, after which the slide was washed, dried and observed

under an optical microscope with oil immersion.

Strain typing and identification of

clinical isolates of MTB

Briefly, 100 µl amplified bacilli were dropped

evenly onto para-nitrobenzoic acid (PNB) and thiophene-2-carboxylic

acid hydrazide (TCH) media (Celnovte Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), with

each sample inoculated three times, and cultured at 37°C with 5%

CO2. Observations were made weekly, and the results were

determined after 4 weeks. A single colony growing on the culture

medium indicates a positive result, with negative PNB and positive

TCH considered MTB infection.

For strain typing, the DNA of MTB was extracted

using a bacterial DNA extraction kit (cat. no. R0017S; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology), and the MIRU 26 fragment was amplified

using a PCR kit with Taq (cat. no. D7232; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). The PCR thermocycling conditions were as follows:

i) 94°C for 3 min (1 cycle); ii) 30 cycles at 94°C for 30 sec, 55°C

for 30 sec and 72°C for 60 sec; iii) 72°C for 10 min (1 cycle), iv)

maintained at 4°C. The MIRU 26 primer sequences were: Forward

primer 5′-3′: TAGGTCTACCGTCGAAATCTGTGAC, reverse primer 5′-3′:

CATAGGCGACCAGGCGAATAG. Agarose (cat. no. ST118; Beyotime Institute

of Biotechnology) and Gel-Green (cat. no. D0143; Beyotime Institute

of Biotechnology) were used to prepare 1% agarose gel, and the PCR

products were electrophoresed at 130 V and observed using a

Tanon-1600 Gel Image system (Tianneng Science and Technology Co.,

Ltd.).

Cell culture and modeling of MTB

infection

The THP-1 human monocyte cell line was purchased

from The Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection of The Chinese

Academy of Sciences. The cells were inoculated at a concentration

of 1×106 cells/ml in 6-well plates (1 ml cell

suspension/well) in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and serum-free RPMI 1640 medium

with an equal amount of phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA;

MedChemExpress) at a concentration of 400 ng/ml was added to induce

cell differentiation into macrophages for 24 h. After removing the

culture medium containing PMA, an equal volume of fresh RPMI 1640

complete culture medium was added. H37Rv and XJMTB were diluted to

an OD600 of 0.6 in Mycobacterium liquid medium, and 100 µl

of the fluid was added to each well to infect cells for 12, 24 and

36 h. Finally, MTB samples isolated from the sputum samples of

patients numbered L3-L6 (Beijing family) were used for L group

modeling in the current study. H37Rv was used for V group modeling

in the current study. THP-1 cells used for transcriptome sequencing

were divided into three groups: XJMTB clinical isolate-infected

group (L group), H37Rv standard strain-infected group (V group) and

blank control group not infected with any bacteria (C group). All

cell culture conditions were as follows: 37°C, 5%

CO2.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

(ELISA)

Culture supernatants were centrifuged at 300 × g for

10 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the secretion levels of

cytokines in the cell culture supernatants were measured using

sandwich ELISA detection kits for IL-12p70 (cat. no. EK112), TNF-α

(cat. no. EK182), IL-6 (cat. no. EK1153), IL-1β (cat. no. EK101B)

and IL-10 (cat. no. EK110) [Multisciences (Lianke) Biotech, Co.,

Ltd.]. All operations were performed according to the

manufacturer's protocol. The absorbance was measured using a

microplate reader at 450 nm and compared to a standard curve.

Nitric oxide (NO) measurement

assay

To evaluate NO levels during MTB infection, cell

culture supernatants were analyzed using the Griess assay. Culture

supernatants were centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 min at room

temperature. Subsequently, the supernatant (100 µl) was incubated

with Griess reagent (cat. no. G4410; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA)

(100 µl) at room temperature for 10 min, and the absorbance was

then measured at 541 nm. Sodium nitrite was used to create a

standard concentration curve.

RNA isolation and library

preparation

Total RNA was extracted from the aforementioned

three groups of THP-1 cells using Trizol reagent (cat. no. R0016;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The extracted RNA was

quantified and assessed for purity and integrity using a NanoDrop

2000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

and an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc.).

Subsequently, library construction was performed using TruSeq

Stranded Total RNA Library Prep Kit with Ribo-Zero Gold (cat. no.

RS-122-2301; Illumina, Inc.). The amount of RNA used to construct

the library was 1 µg. Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) removal was performed

using the Ribo-Zero Gold rRNA Removal Kit (Illumina, Inc.).

Subsequently, sequencing libraries were constructed using

rRNA-depleted samples. Finally, products were purified (Agencourt

AMPure XP; Beckman Coulter, Inc.), and library quality was assessed

using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer system.

Transcriptome sequencing and

differentially expressed gene (DEG) analysis

The libraries were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq X

Ten platform (Illumina, Inc.) to produce 150 bp paired-end reads.

In this step, clean data (clean reads) were obtained by removing

reads containing adapters and ploy-N (sequencing errors or

insufficient sequencing quality) or low-quality reads from the raw

data. Sequencing reads were mapped to the human genome (GRCh38)

using HISAT2 (31). For mRNA, FPKM

was calculated for each gene using Cufflinks (1.2) (32), and read counts were obtained for

each gene using HTSeq-Count (0.12.3) (33). RNA expression profiling data were

analyzed using the R (3.6.3) (https://www.r-project.org/) software package DESeq2

(1.26.0) (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html).

The package pheatmap (1.0.12) (https://cran.r-project.org/package=pheatmap) in R

(3.6.3) was used to create heat maps, whereas the package ggplot2

(3.3.5) (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/index.html)

was used to create volcano maps. Bioinformatics & Evolutionary

Genomics (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/) was

used for creating Venn diagrams. Principal component analysis (PCA)

was performed using the OECloud tools at https://cloud.oebiotech.com. The |log2 fold change|≥1

and P≤0.05 were used as criteria to screen significant DEGs for

subsequent analysis. STRING (https://cn.string-db.org/cgi/input?sessionId=bTEPyYc5wXuA&input_page_show_search=off)

was used to perform the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network

analysis, and Cytoscape (3.8.1) (https://cytoscape.org/) and its MCODE plugin (34) was used to perform subnetwork

screening and confirmation.

Gene ontology (GO) and kyoto

encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses

The Database for Annotation, Visualization, and

Integrated Discovery (https://davidbioinformatics.nih.gov/) was used for

functional analysis of DEGs. The significant GO biological

processes and KEGG pathways with an adjusted P<0.05 were

selected to analyze their biological function. The significant

enrichment results were visualized using the ggplot2 (3.3.5)

(https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/index.html)

package of R software (3.6.3).

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cultured cells using

TRIzol reagent. mRNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the

HiScript II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Vazyme Biotech Co.,

Ltd.), according to manufacturer's protocol. qPCR was performed to

measure mRNA using the ABI 7300 Plus Real-Time PCR System (Applied

Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) using the FastStart

Universal SYBR Green Master Mix (Roche Diagnostics). The qPCR

thermocycling conditions were as follows: i) 50°C for 2 min (1

cycle); ii) 95°C for 10 min (1 cycle); iii) 40 cycles of

denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec, and annealing and extension at

60°C for 60 sec. β-actin was used as the endogenous control for

mRNA expression and relative fold changes were calculated using the

2−ΔΔCq method (35).

Each RT-qPCR assay was repeated three times. The primer sequences

used are shown in Table II.

| Table II.Primer sequences used for reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. |

Table II.

Primer sequences used for reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

| Primer name | Forward primer

5′-3′ | Reverse primer

5′-3′ |

|---|

| CCNA2 |

AGAAACAGCCAGACATCACTAA |

TTCAAACTTTGAGGCTAACAGC |

| CDK1 |

CACAAAACTACAGGTCAAGTGG |

GAGAAATTTCCCGAATTGCAGT |

| β-actin |

GGCCAACCGCGAGAAGATGAC |

GGATAGCACAGCCTGGATAGCAAC |

Western blotting

Cells were lysed using RIPA buffer (MilliporeSigma)

supplemented with EDTA-Free 1× Halt™ protease and phosphatase

inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The cell lysate was

then centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C and the protein

concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid assay kit

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Proteins (30 µg) were

separated by SDS-PAGE on 12% gels and transferred to PVDF

membranes. After blocking at room temperature for 20 min with

protein-free blocking solution (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) and incubating overnight with antibodies against the

target proteins at 4°C, as follows: BCL2 (1:2,000; cat. no.

ab182858; Abcam), BAX (1:2,000; cat. no. ab32503; Abcam), caspase 3

(1:5,000; cat. no. ab32351; Abcam), cleaved-caspase 3 (1:500; cat.

no. ab32042; Abcam), PARP (1:1,000; cat. no. ab191217; Abcam),

cleaved-PARP (1:1,000; cat. no. ab32561; Abcam), β-actin (1:500;

cat. no. ab205; Abcam), CDK1 (1:10,000; cat. no. ab133327; Abcam),

p-CDK1 (Thr161) (1:1,000; cat. no. ab47329; Abcam), p53 (1:1,000;

cat. no. ab32049; Abcam), p-p53 (Ser315) (1:1,000; cat. no.

WL02504; Wanleibio Co., Ltd.). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated

AffiniPure goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (1:1,000; cat.

no. A0277; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and goat anti-mouse

IgG (1:1,000; cat. no. A0216; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology)

were used as the secondary antibody and incubated at room

temperature for 1 h. Primary antibody diluent (cat. no. P0023A) and

secondary antibody diluent (cat. no. P0023D) were from Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology. Subsequently, after adding an

appropriate amount of electrochemiluminescence chromogenic

substrate (BeyoECL Star; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), a

chemiluminescence imaging system (GeneGnome XRQ; Syngene) was used

to detect the chemiluminescence, and the intensity was measured

using ImageJ software (1.54f; National Institutes of Health).

Inhibitors and activators

Ro3306 (cat. no. SC6673; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) was used as a CDK1 inhibitor at a working

concentration of 20 nM. Pifithrin-α (pft-α; cat. no. S1816;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was employed as a p53

phosphorylation inhibitor at a working concentration of 10 µM. TC11

(cat. no. HY-129478; MedChemExpress) was used as a CDK1 activator

at a concentration of 5 µM. These were dissolved in DMSO (cat. no.

ST038; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Briefly, after

inducing THP-1 cells to differentiate into macrophages and adhere

to the bottom of 6-well plates, the culture medium containing PMA

was removed, and the same volume of fresh RPMI 1640 complete

culture medium containing the aforementioned concentrations of the

inhibitors and activator was added, followed by the addition of the

bacterial solution for infection for 24 h at 37°C and 5%

CO2.

Cell cycle analysis

The modeling of MTB cell infection was performed as

described previously (using ~1×106 cells/well).

Subsequently, the cells were collected, washed twice with PBS and

fixed in 70% ethanol at 4°C for 24 h. The cells were then stained

with 500 µl propidium iodide/RNase staining buffer (BD Biosciences)

at 37°C for 15 min and cell cycle progression was detected by flow

cytometry (BD FACSVerse; BD Biosciences). FlowJo (10.0.7r2; BD

Biosciences) was used to analyze the results.

Apoptosis analysis

The apoptosis detection kit (cat. no. 556547; BD

Biosciences) was used to assess the apoptosis of THP-1 cells. The

modeling of MTB cell infection was performed as described

previously (using ~1×106 cells/well). Briefly, the cells

were collected, washed twice with pre-cooled PBS, and resuspended

in 1X binding buffer. Subsequently, a 100-µl cell suspension

(~1×105 cells) was incubated with 5 µl Annexin V-FITC

and 5 µl propidium iodide at room temperature in the dark for 15

min, followed by resuspension in 400 µl 1X binding buffer and flow

cytometry (BD FACSVerse; BD Biosciences). FlowJo (10.0.7r2) was

used to analyze the results.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

THP-1-derived macrophages infected with XJMTB were

homogenized in 0.5% Triton X-100 (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) with 1X Halt™ Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor

SingleUse Cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The cell

lysate was centrifuged at 4°C and 13,680 × g for 20 min to obtain a

clear lysate. For IP, 5 µg rabbit IgG antibody (cat. no. HY-P80879;

MedChemExpress), 5 µg rabbit CDK1 antibody (cat. no. HY-P80611;

MedChemExpress) and 5 µg rabbit p53 antibody (cat. no. HY-P86169;

MedChemExpress) were mixed with 500 µg protein solution, and

incubated overnight at 4°C. The protein A/G magnetic beads (Merck

KGaA) were washed with 500 µl Cell Lysis Buffer for Western or IP

(cat. no. P0013; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) three times.

Afterwards, the mixture was mixed with 50 µl protein A/G magnetic

beads and the antibody-protein A/G magnetic beads complex was

gently shaken for 4 h at 4°C, and 500 µl Cell Lysis Buffer for

Western or IP was then added to the precipitate. The precipitate

was then eluted with 100 µl 1X SDS loading buffer at 100°C for 10

min. Finally, SDS-PAGE was performed with eluent and whole cell

lysate (input), and western blotting was conducted as

aforementioned.

Survival analysis of MTB in cells

Briefly, XJMTB-infected macrophage specimens were

prepared according to the aforementioned method. The XJMTB

specimens were washed with PBS to remove the extracellular

bacteria. Subsequently, PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 was added

to the cell culture dish to lyse the XJMTB-infected macrophages,

and PBS containing the lysate of XJMTB-infected macrophage was

diluted for 10, 100, 1,000 and 10,000 times, and inoculated onto

7H10 agar plates. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 2–3 weeks,

after which the colonies were counted.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated three times. Data are

presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were performed

using two-way ANOVA or one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's post hoc

test, or using unpaired Student's t-test. All statistical analyses

were conducted using SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp.). P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Study subjects

The isolation results in the modified acidic Roche's

medium are shown in Fig. 1A, and

the results of acid-fast staining are shown in Fig. 1B. The specific information and

sputum features of the 20 patients are shown in Table I, including 12 male patients and

eight female patients, aged 25–57 years old, with a median age of

40 years old. All patients had no history of smoking or other lung

diseases, and tested negative for HIV. As shown in Table I, among the 20 patients, samples

were successfully isolated and amplified from 16 patients. After

PNB and TCH medium identification, 13 of them were isolated as MTB.

A previous study conducted multiple-locus variable-number tandem

repeat analysis strain typing and cluster analysis on the strains

isolated from 103 sputum samples collected in the epidemiological

survey (29), and it was revealed

that most of the MTB strains prevalent in Xinjiang belonged to the

Beijing MTB family (29,36,37).

Rao et al (38) reported

that Beijing family strains have seven repeat fragments at the MIRU

26 site (the size of the seven repeated segments is ~642 bp);

therefore, this locus can be used for rapid identification of

Beijing family strains. Fig. S1A

shows the agarose gel electrophoresis patterns of the 13 MTB

samples isolated after PCR of the MIRU 26 site, and Fig. S1B shows the cluster analysis of

all strains collected by the collaborative team during the

aforementioned epidemiological investigation.

Infection with MTB leads to increased

secretion of inflammatory cytokines and NO

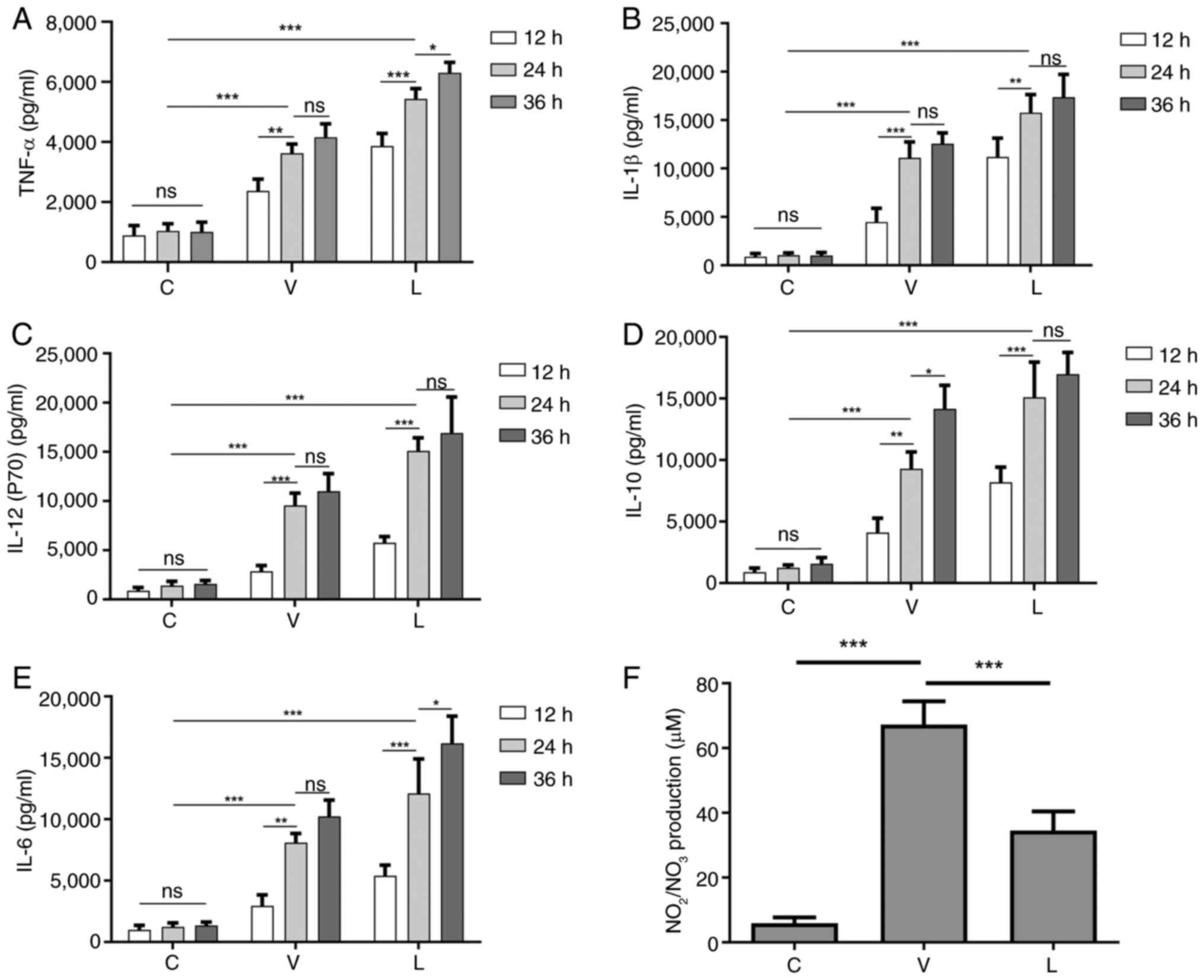

The induction of NO and pro-inflammatory cytokines

produced by macrophages infected with MTB can lead to DNA damage,

oxidative stress and persistent inflammation (28). Therefore, the current study

detected the secretion of the cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10

and IL-12 in macrophages infected with different MTB strains at 12,

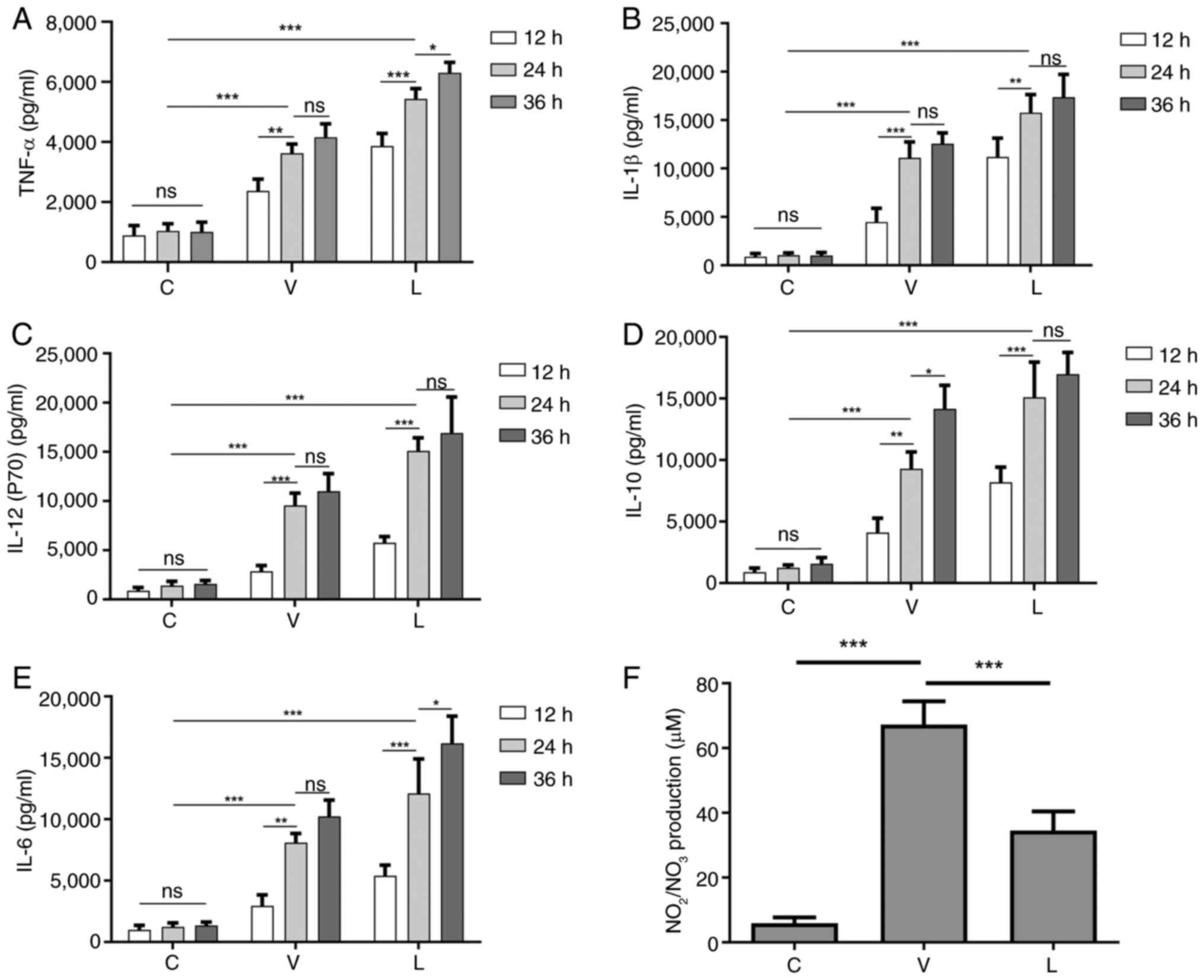

24 and 36 h. As shown in Fig. 2,

compared with those in the C group without any MTB infection, the

secretion levels of these cytokines in the V and L groups were

significantly increased in a dose-dependent manner. After

comprehensively observing the secretion levels of cytokines at

various time points, 24 h was ultimately selected as the infection

time for subsequent experiments, since there was no significant

difference in the secretion of most cytokines between 24 and 36 h

after infection.

| Figure 2.Secretion levels of cytokines at

different time points after MTB infection of macrophages and the

secretion level of NO 24 h after infection. Levels of (A) TNF-α,

(B) IL-1β, (C) IL-12 (p70), (D) IL-10 and (E) IL-6 secretion at

different time points after MTB infection in macrophages. (F)

Levels of NO secretion in macrophages infected with MTB for 24 h.

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001. C group, blank control group not infected with any

bacteria; L group, MTB from Xinjang clinical isolate-infected

group; MTB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis; NO, nitric oxide;

ns, not significant; V group, H37Rv standard strain-infected

group. |

NO has a killing effect on MTB (39); therefore, the secretion of NO was

assessed 24 h after infection. As shown in Fig. 2F, NO levels were lower in

macrophages in the L group compared with those in macrophages in

the V group, which may lead to enhanced survival of MTB in the L

group.

CDK1 and cyclin A2 (CCNA2) expression

levels are significantly elevated after MTB infection

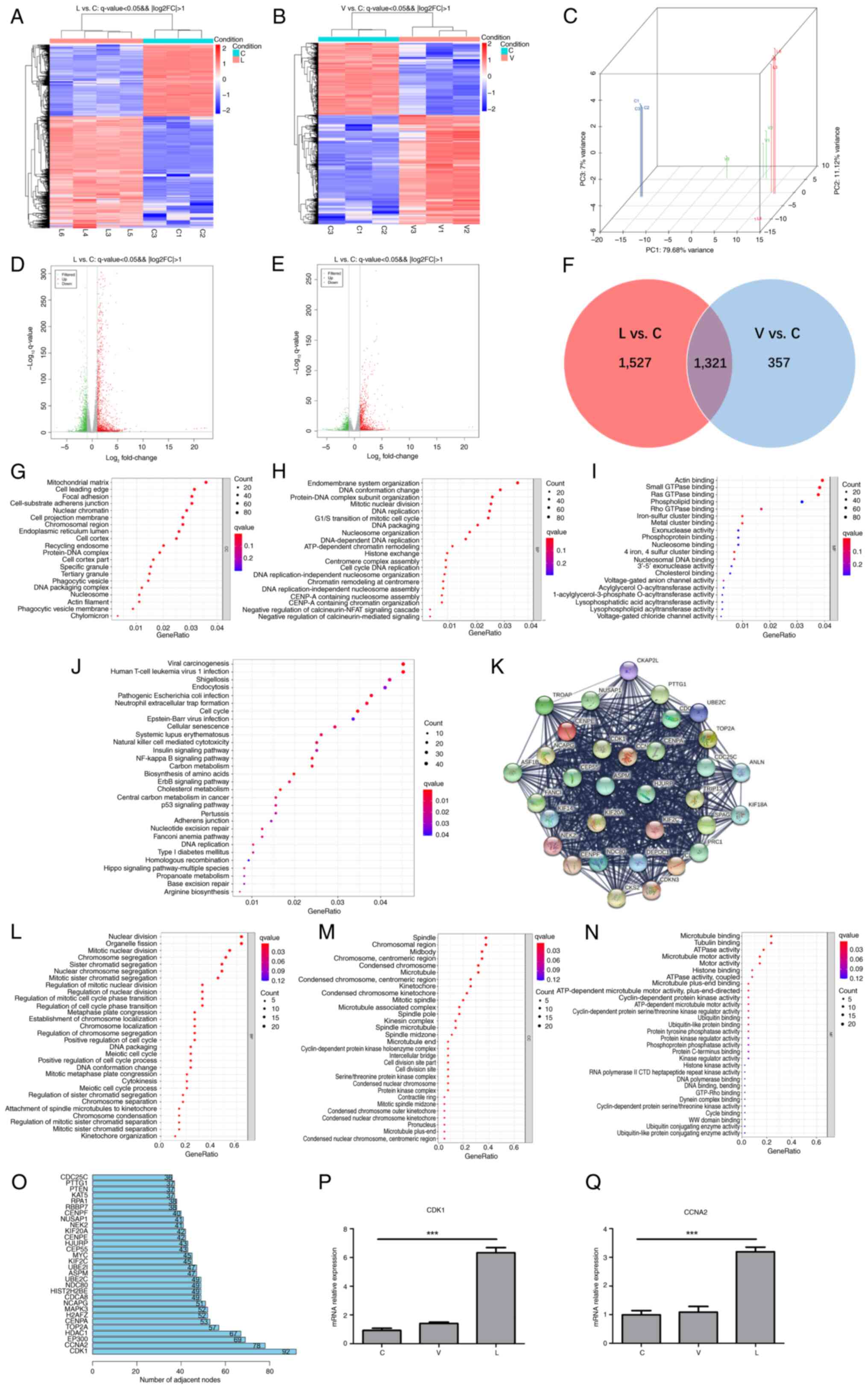

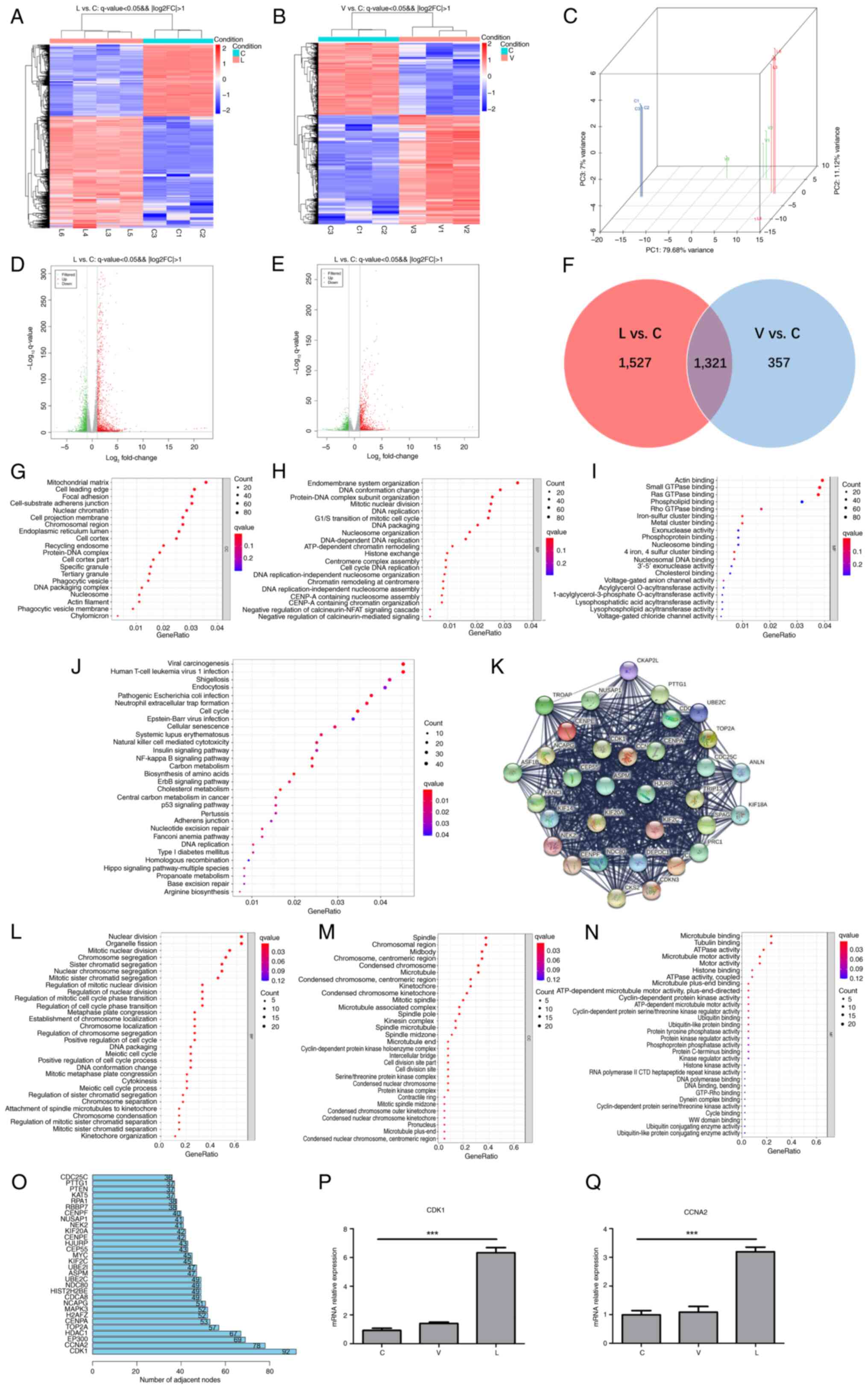

To identify DEGs, transcriptome sequencing data

between groups C, L and V were analyzed. The results showed that

the expression levels of 2,848 mRNAs were significantly altered in

the L group compared with the C group, of which 1,737 mRNAs were

upregulated and 1,111 were downregulated (Fig. 3A and D). In group V compared with

the C group, the expression levels of 1,678 mRNAs were

significantly altered, with 1,011 upregulated and 667 downregulated

mRNAs (Fig. 3B and E). The results

of PCA between the three groups are shown in Fig. 3C. Furthermore, a Venn analysis was

performed on the two sets of DEGs (Fig. 3F) and a follow-up analysis for the

1,527 DEGs between groups L and C was performed, since these unique

1,527 DEGs between groups L and C may reveal the specific

biological processes triggered by XJMTB. GO term (Fig. 3G-I) and KEGG pathway (Fig. 3J) enrichment analyses revealed that

multiple biological functions and pathways enriched by the 1,527

DEGs were associated with MTB infection, such as ‘DNA conformation

change’ (40), ‘phagocytic

vesicle’ (41), ‘phagocytic

vesicle membrane’ (42),

‘exonuclease activity’ (43),

‘endocytosis’ (44,45), ‘neutrophil extracellular trap

formation’ (46–48), ‘cellular senescence’ (49,50),

‘natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity’ (51), ‘p53 signaling pathway’ (28,52)

and ‘nucleotide excision repair’ (53).

| Figure 3.CDK1 expression is upregulated in

response to infection with MTB. Heatmap of DEGs in (A) L and (B) V

groups vs. C group. Red, high expression; blue, low expression. (C)

Principal component analysis of group L, group V and group C.

Volcano plots of DEGs in the (D) L and (E) V groups (|log2 fold

change|≥1; P<0.05). Green, downregulated expression; gray, no

differential expression; red, upregulated expression. (F) Venn

diagram of L vs. C DEGs and V vs. C DEGs. GO functional enrichment

analysis of 1,527 mRNAs: (G) Cellular components, (H) biological

processes and (I) molecular functions. (J) Kyoto Encyclopedia of

Genes and Genomes pathway enrichment analysis of 1,527 mRNAs. (K)

Protein-protein interaction network top-level module containing 35

genes modularized by the plug-in MCODE. GO functional enrichment

analysis of 35 key mRNAs: (L) Biological processes, (M) cellular

components and (N) molecular functions. (O) Top 30 genes of the

1,527 mRNAs contained in the module that interacted most closely

with other genes in the module. Expression of (P) CDK1 and (Q)

CCNA2 in each group was verified through reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Data are

presented as the mean ± SEM. ***P<0.001. C group, blank control

group not infected with any bacteria; CCNA2, cyclin A 2; CDK1,

cyclin-dependent kinase; DEG, differentially expressed gene; GO,

Gene Ontology; L group, MTB from Xinjang clinical isolate-infected

group; MTB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis; V group, H37Rv

standard strain-infected group. |

To further explore the functions of the 1,527 mRNAs

at the protein level, a PPI network (high confidence, 0.7) was

established based on the results of the STRING database analysis,

which consisted of 1,382 nodes and 14,264 edges. Subsequently, the

plug-in MCODE in Cytoscape was used to deeply analyze the network,

and the top module (score=29) was selected for subsequent research

(Fig. 3K). The 33 mRNAs contained

in this top module were regarded as critical mediators, and a

functional analysis was performed. GO functional enrichment

analysis showed that the 33 critical mediators were closely

associated with ‘cell mitosis’ and the ‘cell cycle’ (Fig. 3L-N). R (3.6.3) software was applied

to analyze the core genes in the PPI formed by the 1,527 genes. The

top two genes were found to be CDK1 and CCNA2, and these genes were

also found in the 33 key mRNAs. It has previously been shown that

CDK1 and CCNA2 are closely related to the cell cycle (54). Furthermore, the previous GO and

KEGG enrichment analyses showed that the unique 1,527 DEGs between

groups L and C were enriched in terms of ‘DNA replication’ and

other cell cycle related terms and pathways. Subsequently, RT-qPCR

was used to detect the mRNA expression levels of CDK1 and CCNA2

(Fig. 3P), which showed

significant differences between the L and C groups. Given that the

mRNA expression levels of CDK1 in each group were consistent with

the results of the bioinformatics analysis, and that the number of

interaction nodes between CDK1 and other genes ranked first in

Fig. 3O, CDK1 was identified as

the target gene for subsequent studies.

Inhibition of CDK1 alleviates

G2/M cell cycle block and apoptosis caused by MTB

infection

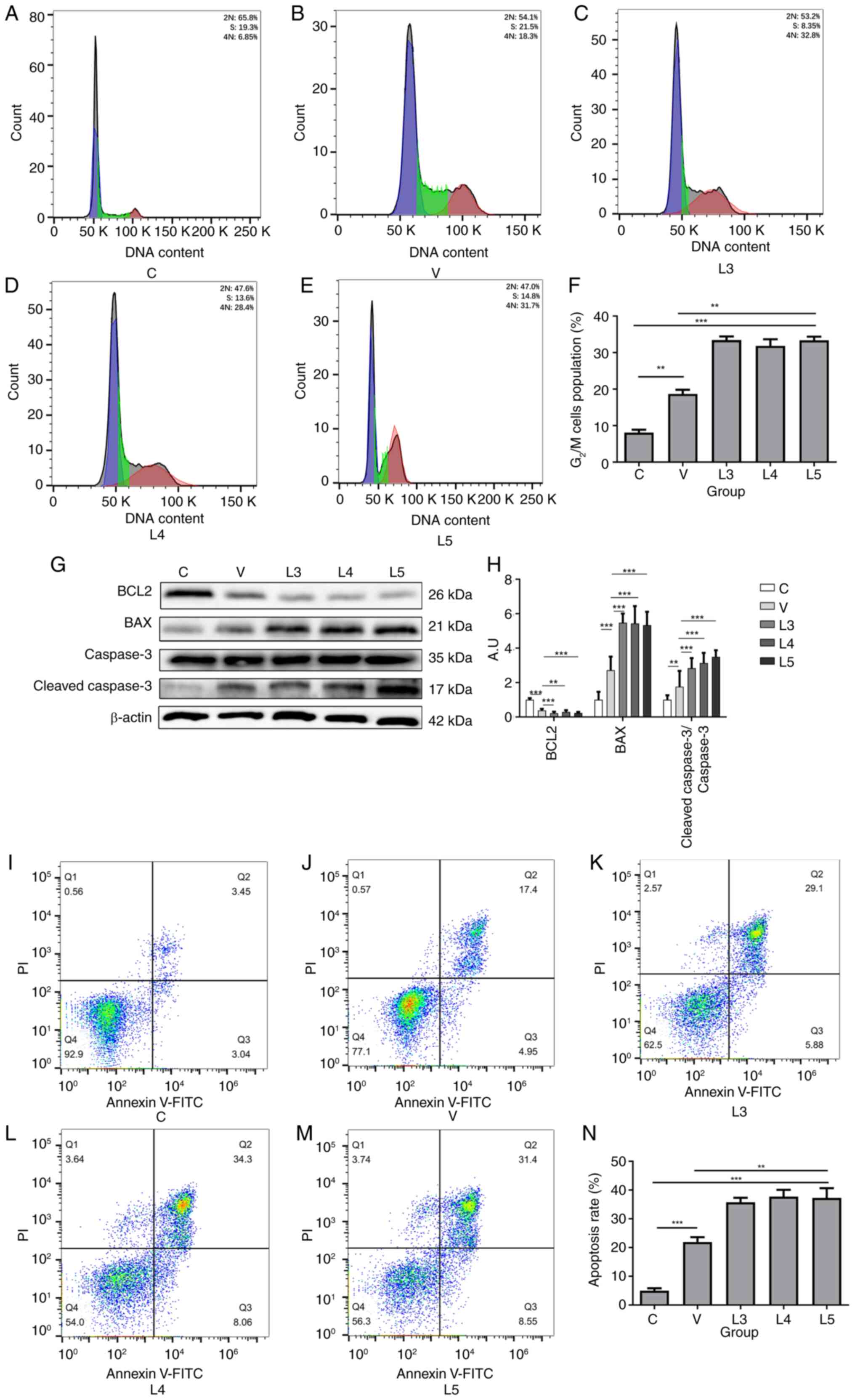

CDK1 is an enzyme necessary for initiating mitosis

after the end of S-phase, and it can regulate the G2/M

checkpoint (17) and is closely

related to apoptosis (18).

Therefore, flow cytometry was performed to detect differential

changes in the cell cycle of macrophages before and after infection

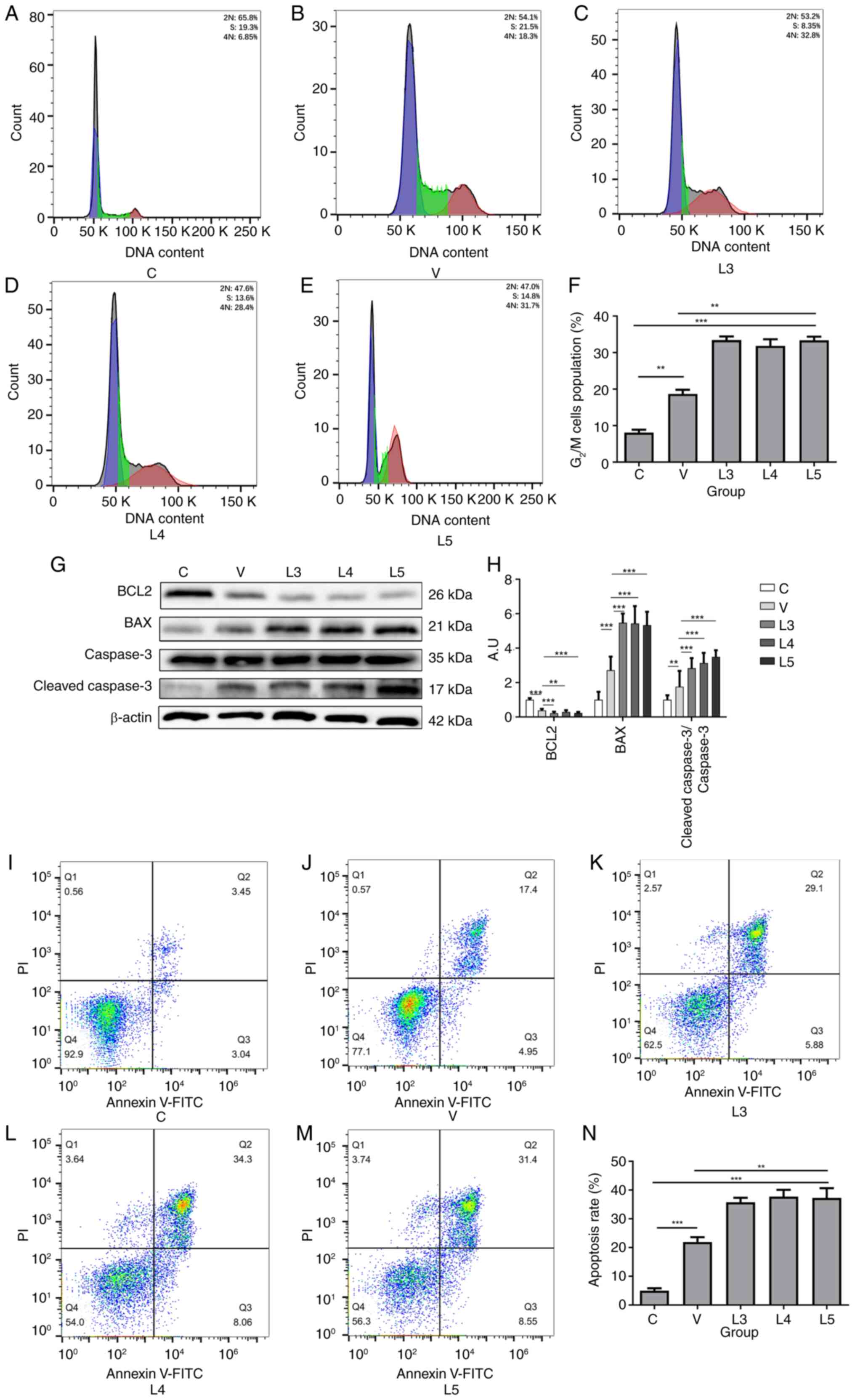

with different sources of MTB. As shown in Fig. 4A-F, compared with in group C,

groups V and L exhibited significantly higher G2/M cell

cycle blockage, and the ratio of cell cycle blockage was

significantly higher in groups L3-5 than that in in group V,

suggesting that macrophages infected with MTB could trigger

G2/M cell cycle block and that different sources of MTB

could induce distinct degrees of cell cycle arrest. Notably,

macrophages infected with XJMTB may trigger a more severe

G2/M cell cycle block compared with those infected with

H37Rv.

| Figure 4.Infection with XJMTB causes stronger

G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis than infection with

H37Rv. Cell cycle profile of macrophages in the (A) C group, (B) V

group, (C) L3 group, (D) L4 group and (E) L5 group. (F)

G2/M cell cycle ratio in each group. (G) Protein

expression levels of BCL2, BAX, BCL-2, caspase 3 and

cleaved-caspase 3 were determined by western blotting. (H)

Statistical analysis of apoptosis-related proteins detected by

western blotting. Apoptosis of macrophages in the (I) C group, (J)

V group, (K) L3 group, (L) L4 group and (M) L5 group. (N) Apoptosis

rate in each group. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. A.U., arbitrary units; C group, blank

control group not infected with any bacteria; L group, XJMTB

clinical isolate-infected group; MTB, Mycobacterium

tuberculosis; V group, H37Rv standard strain-infected group;

XJMTB, MTB from Xinjang. |

The current study next examined the apoptosis of

macrophages after infection with different sources of MTB using

western blotting and flow cytometry. Compared with those in group

C, the protein expression levels of BCL2 were decreased in groups L

and V, whereas the protein expression levels of BAX and

cleaved-caspase 3 (Fig. 4G and H),

and cleaved-PARP (Fig. S2) were

increased. Compared with that in group C (Fig. 4I), groups V (Fig. 4J) and L (Fig. 4K-M) exhibited marked apoptosis,

with the degree of apoptosis being significantly stronger in group

L than that in group V (Fig. 4N).

These findings suggested that MTB could induce macrophage

apoptosis, but the degree of macrophage apoptosis after infection

with different sources of MTB varied, with the proportion of

apoptotic macrophages infected with XJMTB being higher compared

with those infected with H37Rv.

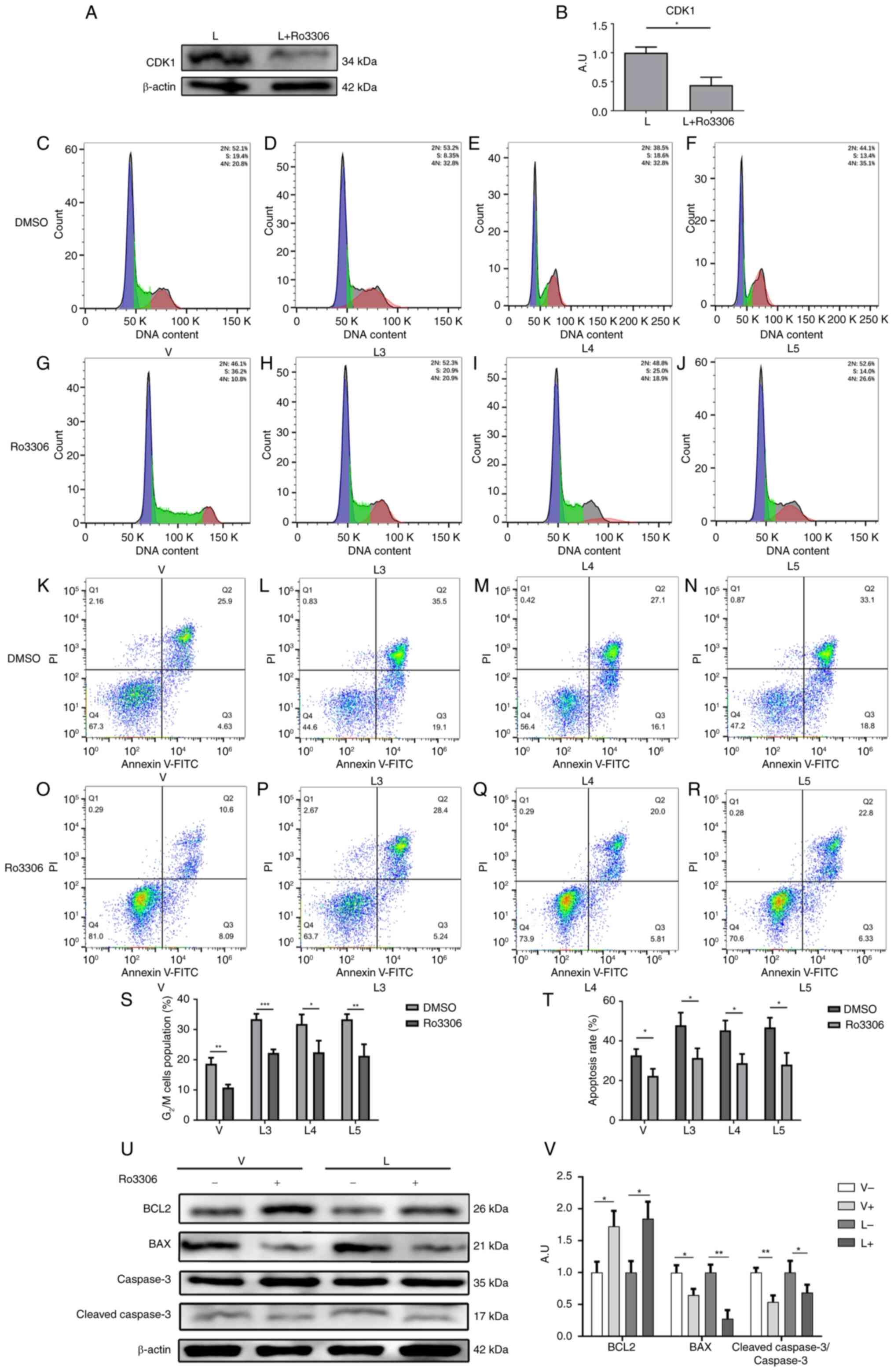

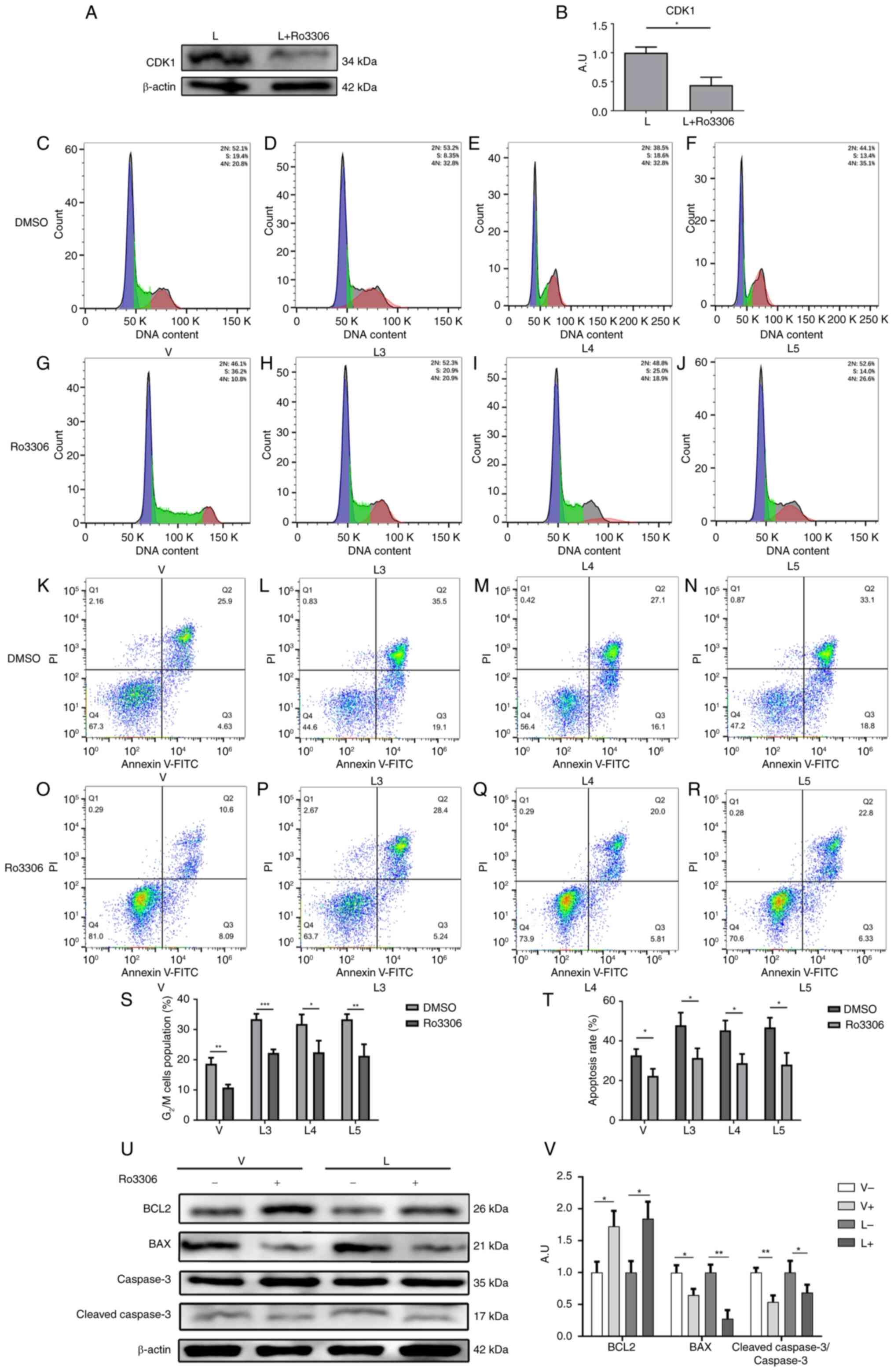

Next, the CDK1 inhibitor Ro3306 was used to inhibit

the expression of CDK1 in macrophages after infection with

different sources of MTB. The expression of CDK1 was first detected

in group L before and after the addition of Ro3306, as shown in

Fig. 5A and B. The findings

indicated that the working concentration provided in the Ro3306

manual could effectively inhibit the expression of CDK1. The

results of the flow cytometric analysis showed that the percentages

of G2/M cell cycle arrest in macrophages in the V group

(Fig. 5C and G), L3 group

(Fig. 5D and H), L4 group

(Fig. 5E and I) and L5 group

(Fig. 5F and J) were significantly

decreased after the addition of Ro3306 (Fig. 5S). These results suggested that

inhibiting CDK1 expression could attenuate the G2/M cell

cycle block of macrophages caused by infection with MTB.

| Figure 5.Inhibition of CDK1 alleviates

macrophage G2/M cycle arrest and apoptosis caused by MTB

infection. (A) Protein expression levels of CDK1 were determined by

western blotting. (B) Statistical analysis of CDK1 protein

expression detected by western blotting. Cell cycle profiles of

macrophages in the (C) V group, (D) L3 group, (E) L4 group and (F)

L5 group when Ro3306 was not added. Cell cycle profiles of

macrophages in the (G) V group, (H) L3 group, (I) L4 group and (J)

L5 group after the addition of Ro3306. Apoptosis of macrophages in

the (K) V group, (L) L3 group, (M) L4 group and (N) L5 group when

Ro33006 was not added. Apoptosis of macrophages in the (O) V group,

(P) L3 group, (Q) L4 group and (R) L5 group after the addition of

Ro3306. (S) G2/M cell cycle ratio and (T) apoptosis rate

in each group before and after the addition of Ro3306. (U) Protein

expression levels of BCL2, BAX, Bcl-2, caspase 3 and

cleaved-caspase 3 were determined by western blotting before and

after the addition of Ro3306. (V) Statistical analysis of

apoptosis-related protein expression detected by western blotting

before and after the addition of Ro3306. Data are presented as the

mean ± SEM. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. A.U., arbitrary

units; CDK1, cyclin-dependent kinase; L group, MTB from Xinjang

clinical isolate-infected group; MTB, Mycobacterium

tuberculosis; V group, H37Rv standard strain-infected

group. |

Similarly, the effects of the CDK1 inhibitor Ro3306

on macrophage apoptosis were examined after infection with

different sources of MTB. The results of flow cytometry showed that

the percentages of apoptotic macrophages in the V group (Fig. 5K and O), L3 group (Fig. 5L and P), L4 group (Fig. 5M and Q) and L5 group (Fig. 5N and R) were significantly

decreased after the addition of Ro3306 (Fig. 5T). Furthermore, the results of

western blotting showed that the protein expression levels of BCL2

were increased by Ro3306, whereas the protein expression levels of

BAX and cleaved-caspase 3 (Fig. 5U and

V), and cleaved-PARP (Fig.

S3) were decreased. These findings suggested that inhibiting

CDK1 expression could attenuate macrophage apoptosis caused by MTB

infection.

The aforementioned results indicated that

macrophages infected with MTB could induce G2/M cell

cycle block and apoptosis, but the degree of cell cycle arrest and

apoptosis induced by different sources of MTB varied. The

proportion of G2/M cell cycle block and apoptosis in

macrophages infected with XJMTB was significantly higher compared

with that in macrophages infected with H37Rv. Furthermore, the

degree of apoptosis and G2/M cell cycle arrest in

macrophages infected with H37Rv or XJMTB was alleviated after

inhibiting CDK1 expression, which was consistent with the predicted

result of the bioinformatics analyses, suggesting that CDK1 may be

a key regulatory gene for G2/M cell cycle arrest and

apoptosis in macrophages with MTB infection.

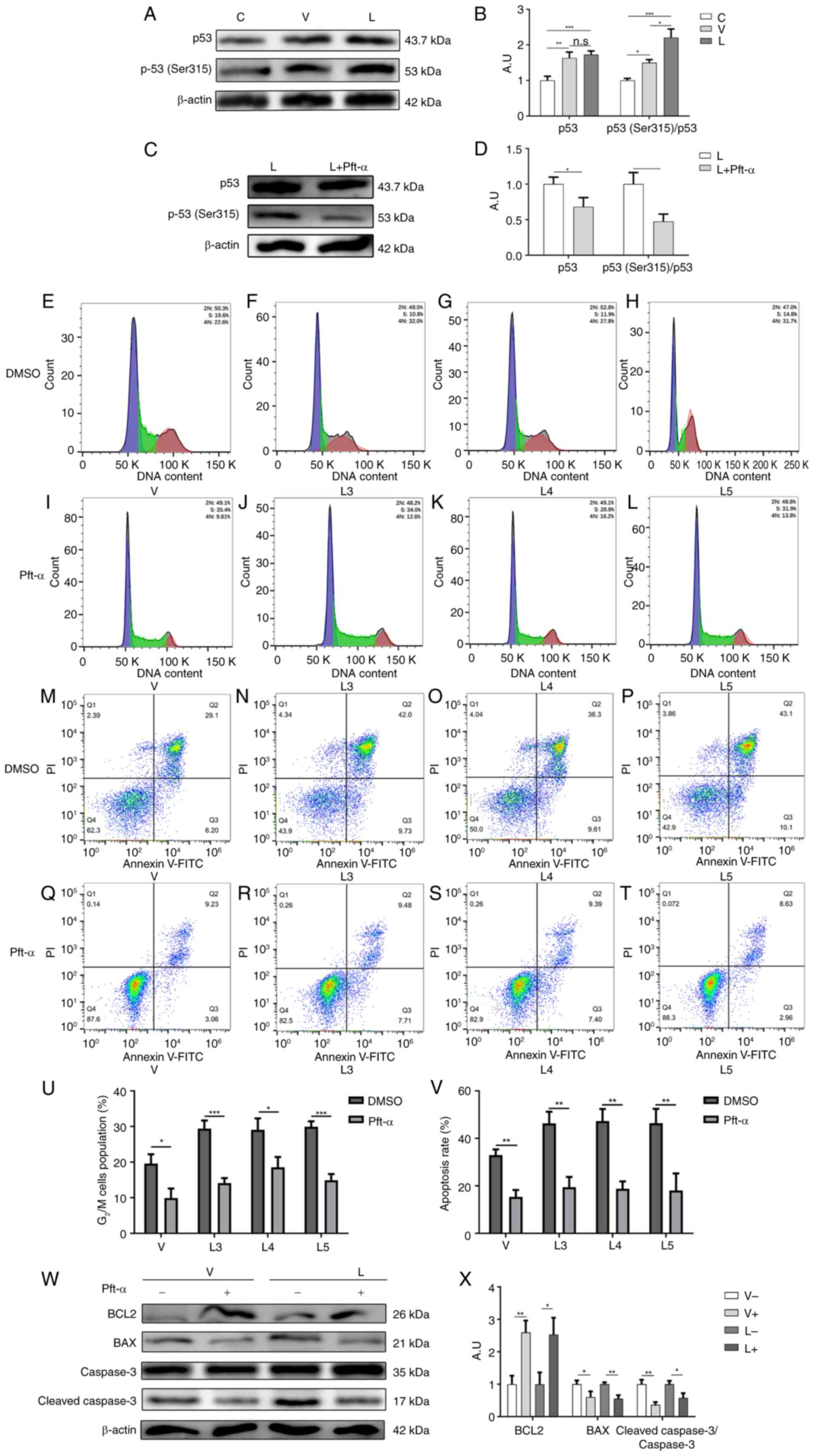

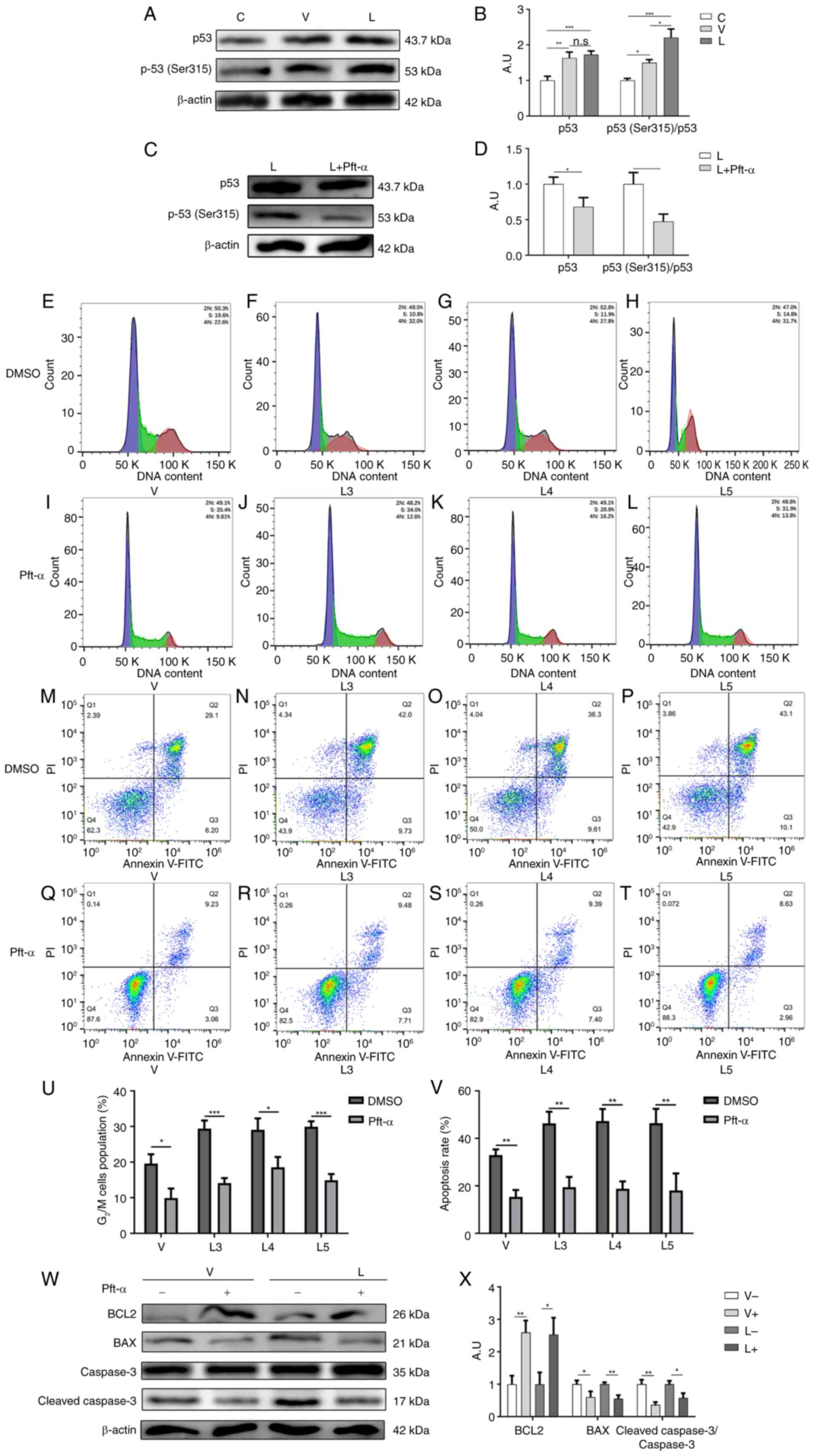

Inhibition of p53 (Ser315)

phosphorylation attenuates G2/M cell cycle arrest and

apoptosis caused by MTB infection

Since the ‘p53 signaling pathway’ was revealed to be

enriched in the aforementioned KEGG analysis, and it is well known

that CDK1 can interact with p53 to affect cell cycle progression

and apoptosis (55), the current

study examined the expression of p53 in macrophages after infection

with different sources of MTB. As shown in Fig. 6A and B, the expression levels of

p53 were significantly elevated after infection with different

sources of MTB, but there was no significant difference between the

two infection groups, suggesting that the G2/M cell

cycle arrest and apoptosis caused by high expression of CDK1 after

MTB infection was not achieved by directly affecting p53

expression.

| Figure 6.Inhibition of p53 (Ser315)

phosphorylation attenuates macrophage G2/M cycle block

and apoptosis caused by MTB infection. (A) Protein expression

levels of total p53 and p-p53 (Ser315) after MTB infection were

determined by western blotting. (B) Statistical analysis of total

p53 and p-p53 (Ser315) expression detected by western blotting

after MTB infection. (C) Protein expression levels of total p53 and

p-p53 (Ser315) were determined by western blotting before and after

the addition of Pft-α. (D) Statistical analysis of total p53 and

p-p53 (Ser315) expression determined by western blotting before and

after the addition of Pft-α. Cell cycle profiles of macrophages in

the (E) V group, (F) L3 group, (G) L4 group and (H) L5 group when

Pift-α was not added. Cell cycle profiles of macrophages in the (I)

V group, (J) L3 group, (K) L4 group and (L) L5 group after the

addition of Pft-α. Apoptosis of macrophages in the (M) V group, (N)

L3 group, (O) L4 group and (P) L5 group when Pft-α was not added.

Apoptosis of macrophages in the (Q), V group, (R) L3 group, (S) L4

group and (T) L5 group after the addition of Pft-α. (U)

G2/M cell cycle ratio and (V) apoptosis rate of each

group before and after the addition of Pft-α. (W) Protein

expression levels of BCL2, BAX, caspase 3 and cleaved-caspase 3

were determined by western blotting before and after the addition

of Pft-α. (X) Statistical analysis of apoptosis-related protein

expression detected by western blotting before and after the

addition of Pft-α. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. A.U., arbitrary units; L

group, MTB from Xinjang clinical isolate-infected group; MTB,

Mycobacterium tuberculosis; n.s., not significant; p-,

phosphorylated; Pft-α, pifithrin-α; V group, H37Rv standard

strain-infected group. |

Fogal et al (56) demonstrated that CDK1 could mediate

the phosphorylation of p53 at the Ser315 site to affect apoptosis,

and indicated that the expression of total p53 may not change

during this process. Therefore, the present study examined the

phosphorylation of p53 at the Ser315 site in macrophages infected

with different sources of MTB. The results showed that the

phosphorylation of p53 at the Ser315 site was higher in macrophages

infected with XJMTB than in those infected with H37Rv (Fig. 6A and B), suggesting that the G2/M

cell cycle arrest and apoptosis caused by high expression of CDK1

after infection with MTB might be mediated by the phosphorylation

of p53 at the Ser315 site.

Subsequently, the p53 inhibitor pft-α was used to

inhibit the phosphorylation of p53. The expression of p53 and the

phosphorylation of p53 (Ser315) before and after the addition of

pft-α is shown in Fig. 6C and D.

The findings indicated that the working concentration recomeded in

the pft-α instruction manual could effectively inhibit the

phosphorylation of p53 (Ser315). The results of flow cytometric

analysis revealed that the percentages of G2/M cell

cycle block in macrophages in the V group (Fig. 6E and I), L3 group (Fig. 6F and J), L4 group (Fig. 6G and K) and L5 group (Fig. 6H and L) were decreased after the

addition of pft-α (Fig. 6U). These

findings indicated that inhibiting the phosphorylation of p53

(Ser315) could attenuate the G2/M cell cycle arrest

caused by MTB infection.

The current study then examined the effect of pft-α

on the apoptosis of macrophages after infection with different

sources of MTB. The results of flow cytometric analysis showed that

the percentages of apoptotic macrophages in the V group (Fig. 6M and Q), L3 group (Fig. 6N and R), L4 group (Fig. 6O and S) and L5 group (Fig. 6P and T) were decreased after the

addition of pft-α (Fig. 6V). The

western blot analysis showed that the protein expression levels of

BCL2 were increased after the addition of pft-α, whereas the

protein expression levels of BAX and cleaved-caspase 3 (Fig. 6W and X), and cleaved-PARP (Fig. S4) were decreased. The two

experiments suggested that inhibiting the phosphorylation of p53

(Ser315) could attenuate macrophage apoptosis due to infection with

MTB.

The aforementioned results indicated that infection

with MTB could induce elevated p53 expression; however, there was

no significant difference in p53 expression among macrophages

infected with different sources of MTB, whereas there was a

difference in the phosphorylation of p53 (Ser315). The degree of

macrophage apoptosis and G2/M cell cycle arrest caused

by infection with different sources of MTB was alleviated by

inhibiting the phosphorylation of p53 (Ser315), which was

consistent with the predicted result of the bioinformatics

analysis, suggesting that p-p53 may be a key regulatory protein for

G2/M cell cycle block and apoptosis in macrophages

infected with MTB. Therefore, it was hypothesized that a regulatory

relationship may exist between CDK1 and p-p53.

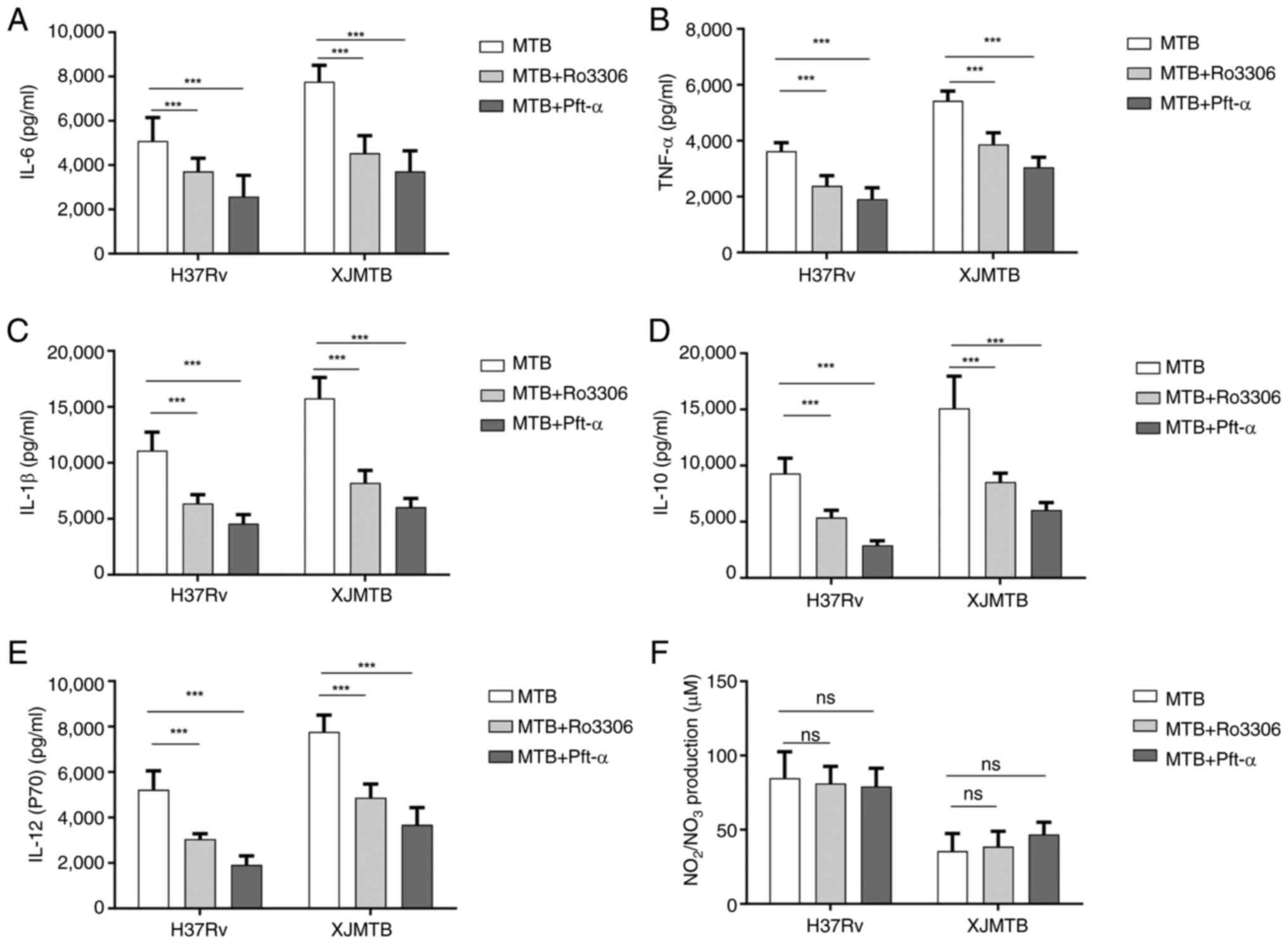

Effect of inhibiting CDK1 expression

or p53 (Ser315) phosphorylation on cytokine and NO secretions in

MTB-infected macrophages

The present study revealed that the secretion levels

of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-12, IL-10 and IL-1β were increased after MTB

infection of macrophages. Therefore, the secretions of TNF-α, IL-6,

IL-12, IL-10, IL-1β and NO were examined before and after

inhibiting CDK1 expression or p53 (Ser315) phosphorylation. As

shown in Fig. 7, in macrophage

models infected with MTB from different sources, inhibition of CDK1

expression (MTB + Ro3306) or p53 (Ser315) phosphorylation (MTB +

Pft-α) resulted in a significant decrease in the secretion of

TNF-α, IL-6, IL-12, IL-10 and IL-1β, but no change in NO secretion.

These results indicated that inhibiting CDK1 expression or p53

(Ser315) phosphorylation may suppress the release of inflammatory

cytokines in THP-1-derived macrophages infected with MTB.

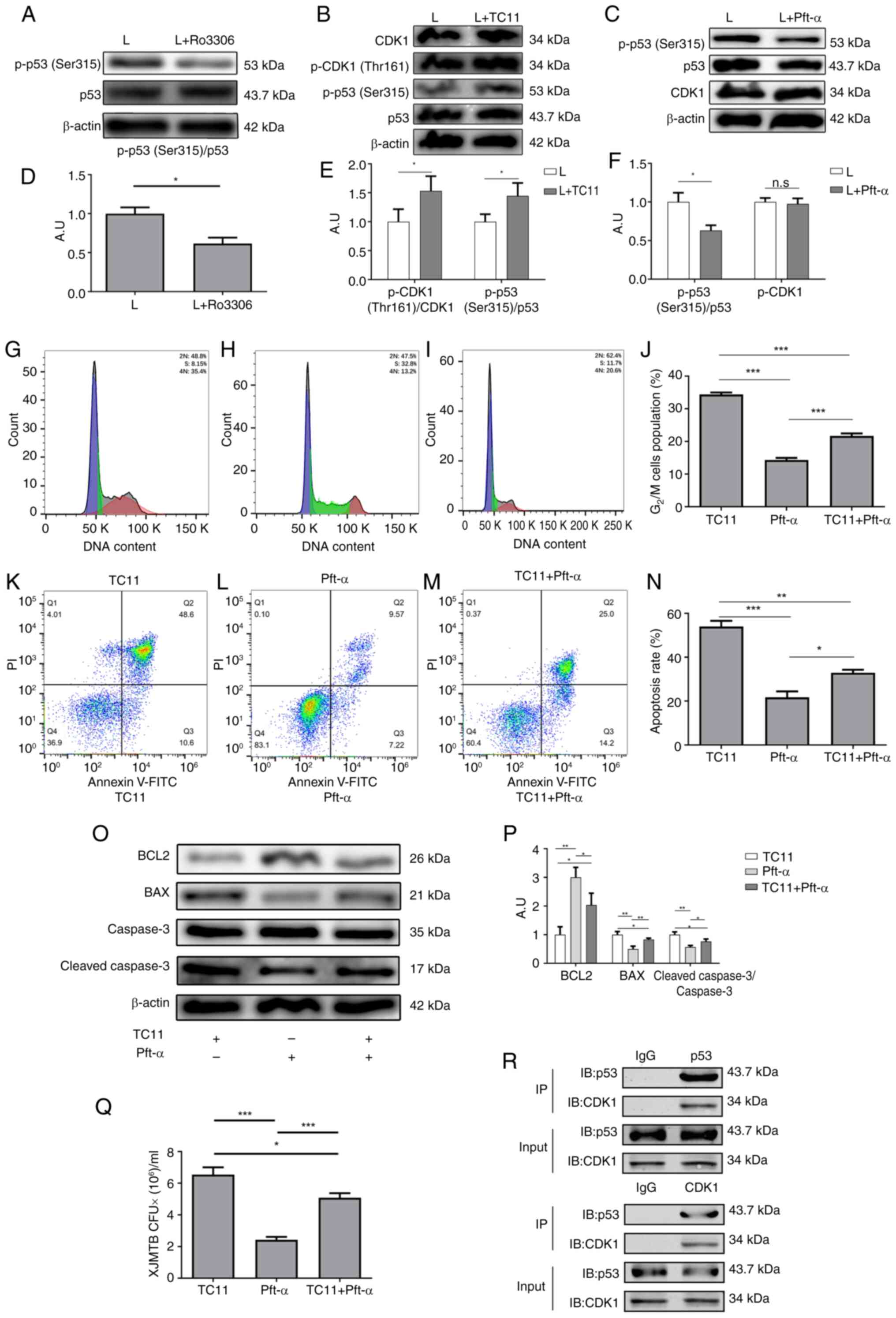

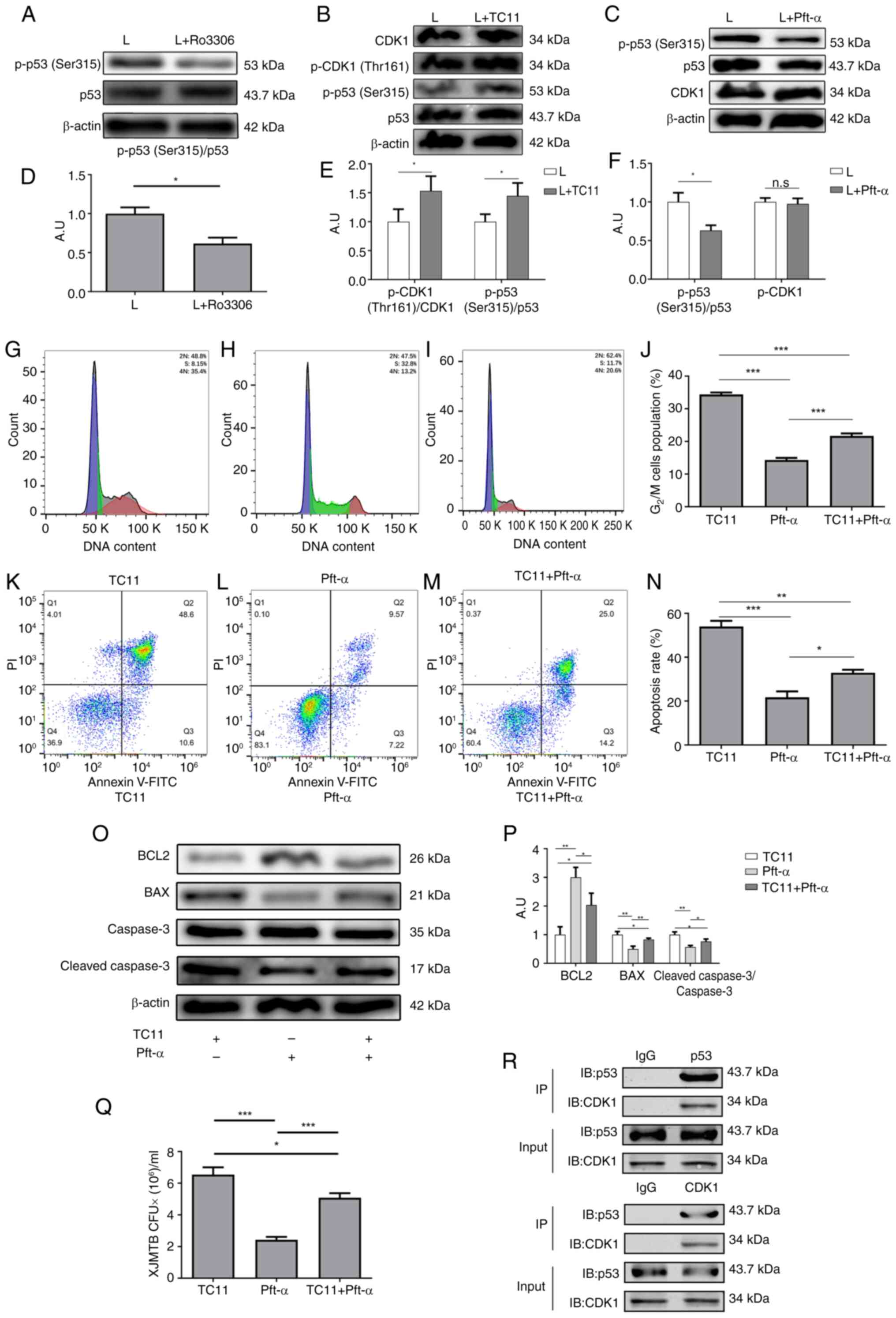

CDK1 mediates G2/M cell

cycle arrest and apoptosis induced by MTB infection and MTB

survival in macrophages by regulating p53 (Ser315)

phosphorylation

To verify whether CDK1 could affect G2/M

cell cycle arrest and apoptosis due to MTB infection by regulating

the phosphorylation of p53 (Ser315), western blotting was performed

to examine the phosphorylation of p53 (Ser315) following the

addition of Ro3306 to XJMTB-infected macrophages to inhibit the

expression of CDK1. As shown in Fig.

8A and D, after the addition of Ro3306, the phosphorylation of

p53 (Ser315) was subsequently decreased.

| Figure 8.CDK1 mediates G2/M cell

cycle arrest and apoptosis caused by infection with XJMTB through

regulation of p53 (Ser315) phosphorylation. (A) Phosphorylation of

p53 (Ser315) after inhibition of CDK1. (B) Phosphorylation of CDK1

(Thr161) and of p53 (Ser315) following treatment with TC11. (C)

Expression of CDK1 after inhibition of p53 (Ser315)

phosphorylation. (D) Statistical analysis of total p53 and p-p53

(Ser315) expression determined by western blotting before and after

the addition of Ro3306. (E) Statistical analysis of total p53,

p-p53 (Ser315), total CDK1 and p-CDK1 (Thr161) expression

determined by western blotting before and after the addition of

TC11. (F) Statistical analysis of total p53, p-p53 (Ser315) and

total CDK1 expressiondetermined by western blotting before and

after the addition of Pft-α. Cell cycle progression of

XJMTB-infected macrophages in the (G) TC11, (H) Pft-α and (I) TC11

+ Pft-α groups. (J) G2/M cell cycle ratio in the various

groups. Apoptosis of XJMTB-infected macrophages in the (K) TC11,

(L) Pft-α and (M) TC11 + Pft-α groups. (N) Apoptosis rate in the

various groups. (O and P) Protein expression levels of BCL2, BAX,

caspase 3 and cleaved-caspase 3 were determined by western blotting

in the TC11, Pft-α and TC11 + Pft-α groups. (Q) CFU analysis was

performed to determine the survival rate of XJMTB in macrophages in

the TC11, Pft-α and TC11 + Pft-α groups. (R) Co-IP results of CDK1

and p53. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. A.U., arbitrary units; CDK1,

cyclin-dependent kinase; CFU, colony-forming unit; IB,

immunoblotting; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IP, immunoprecipitation; L

group, XJMTB clinical isolate-infected group; MTB, Mycobacterium

tuberculosis; n.s., not significant; p-, phosphorylated; Pft-α,

pifithrin-α; XJMTB, MTB from Xinjang. |

Subsequently, TC11 (an activator of CDK1) was used

to activate CDK1. TC11 functions as a phenylacetylamide derivative

and is structurally related to immunomodulatory active drugs, such

as thalidomide, lenalidomide and pomalidomide (57). TC11 can induce MCL1 degradation and

activate caspase 9 and CDK1, leading to cell apoptosis (58,59).

Fig. 8B and E showed that TC11

could enhance the phosphorylation of CDK1 (Thr161), and the

phosphorylation of p53 (Ser315) was also increased. Moreover,

inhibiting the phosphorylation of p53 (Ser315) did not alter CDK1

expression (Fig. 8C and F).

Therefore, it was hypothesized that CDK1 could regulate p53

(Ser315) phosphorylation in macrophages infected with XJMTB.

Next, cell cycle progression and apoptosis were

examined in three situations: i) Activation of CDK1 only; ii)

inhibition of p53 (Ser315) phosphorylation only; iii) and

activation of CDK1 + inhibition of p53 (Ser315) phosphorylation.

The aforementioned results revealed that elevated CDK1 expression

and enhanced p53 phosphorylation levels led to G2/M cell

cycle arrest. TC11 can activate CDK1, whereas pft-α can inhibit p53

(Ser315) phosphorylation. The results of flow cytometry showed that

the proportion of G2/M cell cycle arrest in macrophages

with CDK1 activation and p-p53 (Ser315) inhibition (Fig. 8I) was higher than that in

macrophages with p-p53 (Ser315) inhibition alone (Fig. 8H), but lower than that in those

with CDK1 activation (Fig. 8J).

These findings indicated that the inhibitory ability of pft-α on

p53 (Ser315) phosphorylation was weakened by TC11, thus suggesting

that the CDK1 activation caused by TC11 could reverse the reduction

in the proportion of G2/M cell cycle block caused by the

inhibition of p53 (Ser315) phosphorylation in macrophages infected

with XJMTB.

As expected, flow cytometry results showed that the

proportion of apoptosis in macrophages in which CDK1 was activated

and p53 phosphorylation was inhibited (Fig. 8M) was higher than that in

macrophages in which only p53 phosphorylation was inhibited

(Fig. 8L), but lower than that in

macrophages in which only CDK1 was activated (Fig. 8K). Fig. 8N shows the apoptosis ratio in each

group. Furthermore, the results of western blotting were consistent

with those obtained by flow cytometry (Figs. 8O, P and S5). These findings suggested that

TC11-induced CDK1 activation could reverse the reduction in the

proportion of apoptosis caused by the inhibition of p53 (Ser315)

phosphorylation in macrophages infected with XJMTB.

To clarify whether this regulatory relationship

affected the survival of XJMTB in macrophages, XJMTB survival was

assessed in macrophages under the aforementioned three conditions.

As shown in Fig. 8Q, the survival

rate of XJMTB in macrophages with CDK1 activation and p-p53

(Ser315) inhibition was higher than that in macrophages with p-p53

(Ser315) inhibition, but lower than that in those with CDK1

activation. These data strongly suggested that CDK1 activity

influenced p53 phosphorylation levels.

To clarify the relationship between CDK1 and p53 in

macrophages infected with XJMTB, Co-IP experiments were performed

to observe whether they could interact with each other. The results

showed that there was an interaction between CDK1 and p53 (Fig. 8R). CDK1 is a kinase that can

transfer phosphate groups, thus it may be hypothesized that CDK1

can directly regulate p53 phosphorylation. Based on the

aforementioned results in an in vitro model of XJMTB

infected-macrophages, the high expression of CDK1 could enhance the

phosphorylation of p53 (Ser315), affect the secretion of TNF-α,

IL-6, IL-10, IL-1β and IL-12, promote G2/M cell cycle

arrest and apoptosis of macrophages, and enhance the survival of

XJMTB in macrophages.

Discussion

TB is a complex disease involving multiple

mechanisms (60), and macrophages

are the first immune mechanism against MTB infection and the main

effector cells to eliminate MTB (61). In the early stages of TB, MTB

predominantly adopts an intracellular parasitic mode. The release

of inflammatory factors (62), the

production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (63) and inducible NO synthase (iNOS)

(62), and macrophage autophagy

(64) and apoptosis (65) after MTB infection affect the

ability of macrophages to clear MTB. However, their effects on the

ability of macrophages to clear MTB is not very clear, especially

autophagy and apoptosis. The morbidity of TB in Xinjiang is

markedly higher than the national average (4), bringing great economic pressure to

the majority of patients, and seriously affecting their physical

and mental health. The search for specific immune responses

triggered by XJMTB may help develop targeted control strategies for

TB. Therefore, the present study used transcriptome sequencing to

identify specific immune responses triggered by XJMTB.

Cell cycle progression is tightly regulated by

cyclins and their catalytic partners, CDKs (66–68).

Cyclin and CDKs can regulate the progression of the G1,

S, G2 and M phases of the cell cycle through various

mechanisms, which may include periodic synthesis and degradation,

post-translational modification and subcellular localization

(69). Cyclins are a large class

of proteins characterized by the presence of a CDK-binding domain

called the ‘cyclin box’, of which the cell cycle regulator CCNA2 is

a member. The results of the present bioinformatics analysis showed

that the expression levels of CDK1 and CCNA2 were significantly

elevated in macrophages infected with XJMTB compared with in those

infected with H37Rv, suggesting that XJMTB could lead to more

severe cell cycle arrest, affect macrophage proliferation and

influence the effectiveness of the host immune defense. There have

been numerous reports on the role of CDK1 in various diseases

(70–74); however, to the best of our

knowledge, no reports have described its role in TB. According to

the present results, the number of interaction nodes between CDK1

and other genes ranked higher than CCNA2, and since kinases serve

an important role in the post-translational modification of

proteins CDK1 was selected as the primary research target.

Notably, the regulatory relationship between CDK1

and the cell cycle and apoptosis has been widely reported in a

number of studies (18,75,76).

The present findings suggested that elevated CDK1 expression in

macrophages infected with MTB could lead to the exacerbation of

G2/M cell cycle block and a higher proportion of

apoptotic cells. When the expression of CDK1 was inhibited by

Ro3306, the proportion of G2/M cell cycle block and

macrophage apoptosis was reduced, suggesting that CDK1 may be

essential in MTB infection-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis.

It has previously been shown that p53 can promote cell cycle

arrest, induce DNA repair, and participate in various cell

death-related pathways and metabolic changes (77–79).

Notably, macrophages infected with MTB have been shown to exhibit

increased p53 (Ser315) phosphorylation and enhanced apoptosis

(80). Similarly, the current

study revealed that an increase in p53 (Ser315) phosphorylation led

to G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in MTB-infected

macrophages. Yuan et al (81) showed that circular RNA CEA could

promote CDK1-mediated phosphorylation of p53 at the Ser315 site,

which was in line with the results of the present study, which

revealed that elevated CDK1 expression could regulate p53 (Ser315)

phosphorylation.

Infection with MTB leads to macrophage apoptosis

(82–85), which may be mediated by surface or

secreted proteins. MTB Rv3261 protein can induce ROS production to

inhibit MTB growth in macrophages, activate caspase 3/9-dependent

pathways, and induce macrophage apoptosis (86). Medha et al (87) showed that the C-terminal and

N-terminal sequences of MTB Rv0335c were similar to those of the

BCL2 protein, and in vitro experiments confirmed that it

could lead to apoptosis. The present study observed elevated

cleaved-caspase 3 expression and decreased BCL2 expression

following infection with MTB, and this phenomenon was more

pronounced in samples infected with XJMTB than in those infected

with H37Rv.

There is a view that although apoptosis is usually

a non-inflammatory form of cell death, excessive apoptosis may lead

to the propagation of MTB, which is beneficial for the pathogen

rather than the host (12,13). Host infection can be exacerbated by

the elimination of important host defense cells, penetration of the

epithelial barrier and transmission of pathogens to immature host

phagocytes that engulf apoptotic bodies (88). It has been shown that Fas-mediated

apoptosis does not affect the survival of macrophages and MTB

(89). Kelly et al

(90) showed that infected

macrophages can induce apoptosis of uninfected macrophages in a

cell-to-cell contact-dependent manner, leading to exacerbation of

MTB infection. In addition, Lee et al (91) reported that bacteria released from

apoptotic macrophages infected with MTB were still alive and could

subsequently grow extracellularly. Furthermore, H37Rv has been

reported to induce more cell death compared with H37Ra, and this

mode of death was initially characterized by apoptosis (91–93).

Gan et al (92) infected

mice in vivo with the MTB H37Rv strain or attenuated H37Ra

strain, and showed that H37Rv induced a higher macrophage death

rate and notably depleted resident alveolar macrophages, whereas

H37Ra resulted in a marked reduction in cell death and only

partially depleted the resident macrophages. Afriyie-Asante et

al (94) revealed that MTB

inhibited ROS production by decreasing focal adhesion kinase

expression, leading to apoptosis and persistent lung injury. One

hypothesis is that apoptosis in the late stages of infection during

granuloma formation may be a pathogenic process that increases the

persistence and future spread of MTB (95). In addition, macrophage apoptosis

caused by MTB may evolve into macrophage necrosis, which releases

cellular contents and triggers inflammation (96,97),

and sustained inflammation exacerbates tissue damage and leads to

disease progression (98,99). Compared with other forms of cell

death, apoptotic cells may be less likely to activate the specific

immune responses required to control MTB infection (100). As aforementioned, H37Rv can

induce more severe apoptosis than H37Ra, and H37Rv is more

pathogenic than H37Ra. This is consistent with the present findings

that XJMTB, which is more pathogenic, induces stronger macrophage

apoptosis compared with H37Rv. Nevertheless, there is also a view

that activating host cell apoptosis is an important defense

strategy for pathogens that utilize host cell resources for

survival and replication, meaning that the more severe the

apoptosis, the better the bactericidal effect (101). Moreover, the virulence of MTB has

been reported to be negatively associated with the degree of

classical apoptosis, and the attenuated strain H37Ra has been

suggested to induce more apoptosis compared with the highly

virulent strain H37Rv (102).

The aforementioned studies suggest that the

macrophage apoptosis induced by MTB infection can be beneficial for

both the host and MTB, which may be influenced by the viability of

the bacteria and host cells, as well as the duration of the

infection (103). Therefore, it

is hypothesized that apoptosis can be considered as having a dual

role. Apoptosis is a means of controlling the growth of

intracellular pathogens and is capable of killing MTB only under

the appropriate conditions (89,104–108). The fate of cells may depend on

the balance between pro- and anti-apoptotic signals emitted by the

cell or pathogen, as well as other variables, including host

species, origin and state of the host cell differentiation, in

vitro culture conditions, MTB strains and multiplicity of

infection. MTB can induce macrophage apoptosis directly when

objective conditions change (109), regardless of the killing effect

of MTB (110). In addition, in

the presence of large numbers of mycobacteria and when large

numbers of apoptotic cells exceed the local phagocytic clearance

capacity of macrophages, macrophages are considered to be critical

for the clearance of apoptotic vesicles, and thus ineffective

clearance of apoptotic cells may lead to tissue damage (111). Moreover, unabsorbed apoptotic

cells may undergo secondary necrosis, thereby favoring MTB

dissemination (112). These

results suggest that when infected with MTB, the occurrence of

massive apoptosis in macrophages does not necessarily represent

notable clearance of MTB, but rather indicates an exacerbation of

the infection, which explains the phenomenon that clinical isolates

of XJMTB were more likely to induce macrophage apoptosis compared

with clinical isolates of H37Rv.

NO is a free radical mediator that serves an

important role in the immune system. Long et al (39) concluded that exogenous NO has a

time- and dose-dependent killing effect on MTB, and that short-term

exposure of extracellular MTB to low concentrations of NO (<100

ppm) can kill MTB. During macrophage infection, NO may act directly

or combine with superoxide to form peroxynitrite, which kills MTB

in phagosomes (113). NOS

converts L-arginine to NO, which is protective against parasitic

infections and a variety of infectious organisms, such as MTB

(114,115). Mice deficient in iNOS have been

shown to be highly susceptible to MTB infection, permitting MTB

infection and leading to early death (116–118). Furthermore, the expression levels

of iNOS are higher in the peripheral monocytes and alveolar

macrophages of patients with TB compared with those in healthy

individuals (119). These studies

indicated that NO may have a strong bactericidal effect on

MTB-infected macrophages. In the present study, XJMTB induced a

lower secretion of NO than H37Rv, which may explain its enhanced

survival in macrophages.

It has been shown that in the J774.1 macrophage

model of mice infected with Mycobacterium bovis BCG, IFN-γ

and lipopolysaccharide treatment enhance the expression of the

arginine permease MCAT2B; however, this does not explain the

observed increase in L-arginine uptake, suggesting that the

activity of the L-arginine transporter may also be altered in

response to macrophage activation, which in turn affects NO

production (120). In addition,

expression of the solute carrier family 11 member 1 gene affects

the ability of macrophages to produce NO, resulting in differential

susceptibility or resistance to MTB (121). NO production by alveolar

macrophages in patients with TB may have an autoregulatory role,

which can promote proinflammatory cytokine production through

activation of the transcription factor NF-κB (122–124). Upregulation of the inhibitor of

NF-κB has confirmed that the IκBα kinase-NF-κB signaling pathway

enhances IFN-γ- and MTB lipoarabinomannan-induced iNOS promoter

activity and NO expression (124). These studies suggested that NO

production is regulated by multiple factors and does not come from

a single source, which may be one of the reasons why the regulation

of the CDK1-p53 axis had no effect on NO secretion in the current

study.

One limitation of the present study is the

relatively small sample size, with only four strains of XJMTB used

for infection and sequencing, which may limit the generalizability

of the findings. Additionally, the study was conducted using a

single cell line, THP-1, which might not reflect the broader

population. The use of human monocyte-derived macrophages may

enhance the physiological relevance of the study. However, primary

monocyte-derived macrophages are difficult to obtain and isolate.

We previously considered validating the relevant conclusions in the

RAW264.7 cell line, but considering that RAW264.7 cells are

mouse-derived cells, this cell line was not used due to species

differences between humans and mice. In addition, the conclusions

should be verified in animal experiments; however, animal

experiments related to TB require extremely stringent experimental

conditions and environments.

CDK1 was the target of the present study due to its

high bioinformatics score and verifiability, as well as its novelty

in the field of MTB. The identification of the ‘p53 signaling

pathway’ entry in the bioinformatics analysis process attracted

clarification as to whether a regulatory relationship exists

between CDK1 and p53 in the process of MTB infection of

macrophages, thus the upstream molecules that regulate the high

expression of CDK1 were overlooked. Future research should include

larger and more diverse samples to validate these results,

including validating this mechanism in MTBs from other regions.

The present study showed that MTB infection of

macrophages resulted in high CDK1 expression and increased levels

of p53 (Ser315) phosphorylation, and that the level of p53 (Ser315)

phosphorylation increased with CDK1 activation, leading to

increased macrophage G2/M cell cycle arrest and

apoptosis. Compared with H37Rv, XJMTB infection typically led to a

greater elevation of CDK1 and p-p53. Furthermore, Co-IP analysis

showed that there was indeed a protein interaction between CDK1 and

p53. The activation of CDK1 could reverse the reduction of

G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis caused by p-p53

inhibition. These results suggested that the increase in p53

(Ser315) phosphorylation in MTB-infected macrophages may be caused

by elevated CDK1 expression. In an in vitro model of

XJMTB-infected macrophages, high activation of CDK1 can enhance the

phosphorylation of p53 (Ser315), affect the secretion of TNF-α,

IL-6, IL-10, IL-1β and IL-12, promote G2/M cell cycle

arrest and apoptosis of macrophages, and enhance the survival of

XJMTB in macrophages. These findings lay the foundation for

formulating treatment strategies targeting the prognosis of TB in

Xinjiang, China. Future studies should explore the potential of

targeting CDK1 and p53 phosphorylation in clinical settings.

Regulating the macrophage cycle or apoptosis by adjusting the

activity of CDK1 or p53 may be considered a potential treatment for

TB.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. Jing Wang

(Department of Respiratory Medicine, The Second Affiliated Hospital

of Hainan Medical College) for their contribution to specimen

collection.

Funding

The present study received funding from the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81672109).

Availability of data and materials

The sequencing data generated in the present study

may be found in the Gene Expression Omnibus database under

accession number GSE275640 or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE275640.

The other data generated in the present study may be requested from

the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

BS, QM, ZZ and FL conceptualized the study. XJ, SL

and FC collected the data in the study and conducted statistical

analysis. FL acquired funding. BS, QM, LP, ZZ and FL designed the

study. FL conducted project administration. ZZ and FL provided

materials and resources for the study. BS, QM and LP conducted

bioinformatics analysis using software. FL supervised the study.

BS, LP and XJ validated the research results obtained. FC and ZZ

visualized the content and data to be published. BS and ZZ

conducted the initial draft writing. QiM and FL reviewed and edited

the manuscript. BS and FL confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All protocols performed in the present study were

approved by the Ethics Committee of Jilin University (approval no.

2016-057; Changchun, China). Written informed consent for

participation was obtained from the patients.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Abdullah M, Humayun A, Imran M, Bashir MA

and Malik AA: A bibliometric analysis of global research

performance on tuberculosis (2011–2020): Time for a global approach

to support high-burden countries. J Family Community Med.

29:117–124. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Li XX, Zhang H, Jiang SW, Liu XQ, Fang Q,

Li J, Li X and Wang LX: Geographical distribution regarding the

prevalence rates of pulmonary tuberculosis in China in 2010.

Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 34:980–984. 2013.(In Chinese).

PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wubuli A, Xue F, Jiang D, Yao X, Upur H

and Wushouer Q: Socio-demographic predictors and distribution of

pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) in Xinjiang, China: A spatial analysis.

PLoS One. 10:e01440102015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wang L, Zhang H, Ruan Y, Chin DP, Xia Y,

Cheng S, Chen M, Zhao Y, Jiang S, Du X, et al: Tuberculosis

prevalence in China, 1990–2010; a longitudinal analysis of national

survey data. Lancet. 383:2057–2064. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

He X, Cao M, Mahapatra T, Du X, Mahapatra

S, Li Q, Feng L, Tang S, Zhao Z, Liu J and Tang W: Burden of

tuberculosis in Xinjiang between 2011 and 2015: A surveillance

data-based study. PLoS One. 12:e01875922017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Anilkumar U and Prehn JHM: Anti-apoptotic

BCL-2 family proteins in acute neural injury. Front Cell Neurosci.

8:2812014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Behar SM, Divangahi M and Remold HG:

Evasion of innate immunity by Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Is

death an exit strategy? Nat Rev Microbiol. 8:668–674. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Deretic V and Wang F: Autophagy is part of

the answer to tuberculosis. Nat Microbiol. 8:762–763. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Arnett E and Schlesinger LS: Live and let

die: TB control by enhancing apoptosis. Immunity. 54:1625–1627.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Häcker G: Apoptosis in infection. Microbes

Infect. 20:552–559. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ashida H, Mimuro H, Ogawa M, Kobayashi T,

Sanada T, Kim M and Sasakawa C: Cell death and infection: A

double-edged sword for host and pathogen survival. J Cell Biol.

195:931–942. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Hirsch CS, Johnson JL, Okwera A, Kanost

RA, Wu M, Peters P, Muhumuza M, Mayanja-Kizza H, Mugerwa RD,

Mugyenyi P, et al: Mechanisms of apoptosis of T-cells in human

tuberculosis. J Clin Immunol. 25:353–364. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Pagán AJ and Ramakrishnan L: Immunity and

immunopathology in the tuberculous granuloma. Cold Spring Harb

Perspect Med. 5:a0184992014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Malumbres M and Barbacid M: Cell cycle,

CDKs and cancer: A changing paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer. 9:153–166.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Enserink JM and Kolodner RD: An overview

of Cdk1-controlled targets and processes. Cell Div. 5:112010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Morgan DO: Cyclin-dependent kinases:

Engines, clocks, and microprocessors. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol.

13:261–291. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Huang R, Gao S, Han Y, Ning H, Zhou Y,

Guan H, Liu X, Yan S and Zhou PK: BECN1 promotes radiation-induced

G2/M arrest through regulation CDK1 activity: A potential role for

autophagy in G2/M checkpoint. Cell Death Discov. 6:702020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Huang S, Xiao J, Wu J, Liu J, Feng X, Yang

C, Xiang D and Luo S: Tizoxanide promotes apoptosis in glioblastoma

by inhibiting CDK1 activity. Front Pharmacol. 13:8955732022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhang Q, Chen L, Gao M, Wang S, Meng L and

Guo L: Molecular docking and in vitro experiments verified that

kaempferol induced apoptosis and inhibited human HepG2 cell

proliferation by targeting BAX, CDK1, and JUN. Mol Cell Biochem.

478:767–780. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Xu G, Yan X, Hu Z, Zheng L, Ding K, Zhang

Y, Qing Y, Liu T, Cheng L and Shi Z: Glucocappasalin induces

G2/M-phase arrest, apoptosis, and autophagy pathways by targeting

CDK1 and PLK1 in cervical carcinoma cells. Front Pharmacol.

12:6711382021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yang YJ, Luo S and Xu ZL: Effects of

miR-490-5p targeting CDK1 on proliferation and apoptosis of colon

cancer cells via ERK signaling pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci.

26:2049–2056. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Tong Y, Huang Y, Zhang Y, Zeng X, Yan M,

Xia Z and Lai D: DPP3/CDK1 contributes to the progression of

colorectal cancer through regulating cell proliferation, cell

apoptosis, and cell migration. Cell Death Dis. 12:5292021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Huang Y, Fan Y, Zhao Z, Zhang X, Tucker K,

Staley A, Suo H, Sun W, Shen X, Deng B, et al: Inhibition of CDK1

by RO-3306 exhibits anti-tumorigenic effects in ovarian cancer

cells and a transgenic mouse model of ovarian cancer. Int J Mol

Sci. 24:123752023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ozaki T and Nakagawara A: Role of p53 in

cell death and human cancers. Cancers (Basel). 3:994–1013. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Chen J: The cell-cycle arrest and

apoptotic functions of p53 in tumor initiation and progression.

Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 6:a0261042016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zheng SJ, Lamhamedi-Cherradi SE, Wang P,

Xu L and Chen YH: Tumor suppressor p53 inhibits autoimmune

inflammation and macrophage function. Diabetes. 54:1423–1428. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Fischer M: Census and evaluation of p53

target genes. Oncogene. 36:3943–3956. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Lim YJ, Lee J, Choi JA, Cho SN, Son SH,

Kwon SJ, Son JW and Song CH: M1 macrophage dependent-p53 regulates

the intracellular survival of mycobacteria. Apoptosis. 25:42–55.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Gong X, Li Y, Yao L, Aynur M, Liu N, Wang

L and Wang J: Preliminary study on genotype of Mycobacterium

tuberculosis in some areas of Xinjiang by the multiple locus

VNTR analysis. Chin J Lung Dis (Electronic Edition). 10:304–308.

2017.(In Chinese).

|