Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune

inflammatory disorder primarily characterized by symmetrical,

multi-joint pain and swelling, often accompanied by local joint

destruction. The underlying pathogenesis remains incompletely

understood, but it involves a complex interplay of genetic,

environmental, and immune factors, ultimately leading to the

breakdown of immune tolerance and systemic immune dysregulation

(1). RA markedly impairs the

quality of life of patients. Over the past three decades, its

global prevalence has steadily increased, with the 2020 RA Global

Burden of Disease Study reporting an estimated prevalence of ~0.2%,

placing a substantial burden on the global economy (2).

Despite significant advances in the treatment of RA,

outcomes remain unsatisfactory. Due to its complex pathogenesis, no

drug or therapy can fully halt RA progression, and most treatments

are associated with notable side effects (3). Epidemiological and translational

studies have increasingly emphasized the critical role of mucosal

interactions with symbiotic bacteria in RA development (4–6).

Research on high-risk RA populations has revealed lung mucosal

inflammation, as well as the production of local anti-citrullinated

protein antibodies (ACPAs) and rheumatoid factor, supporting the

‘mucosal origin hypothesis’ (7,8).

Further investigations have identified distinct mucosal mechanisms,

including those of the intestinal mucosa, that drive RA progression

(9). The intestine, home to the

largest concentration of innate and adaptive immune cells, forms a

vital interface between the internal environment and external

factors, linking environmental influences to systemic immunity

(10,11). Alterations in the gut microbiota,

which may respond to external environmental and changes or be

driven by systemic inflammation can occur before the onset of

arthritis. Emerging research increasingly highlights the critical

role of the ‘gut-joint axis’ in the transition from preclinical to

clinical RA.

The relationship between intestinal microecological

imbalance and RA involves complex physiological and pathological

mechanisms. Studies from RA animal models and preclinical RA

(PreRA) populations indicate that gut alterations may precede the

onset of the disease and potentially serve as latent triggers of

systemic inflammation (12–16).

Conversely, a reverse ‘gut-joint axis’ mechanism may also exist,

although further research is required to substantiate this

hypothesis. For example, increasing levels of inflammatory factors

in the joints may spread peripherally, contributing to or

exacerbating damage to the intestinal mucosal barrier and

microbiota dysbiosis (17,18). Additionally, pain may alter the

metabolic products of gut microbiota and intestinal hormones

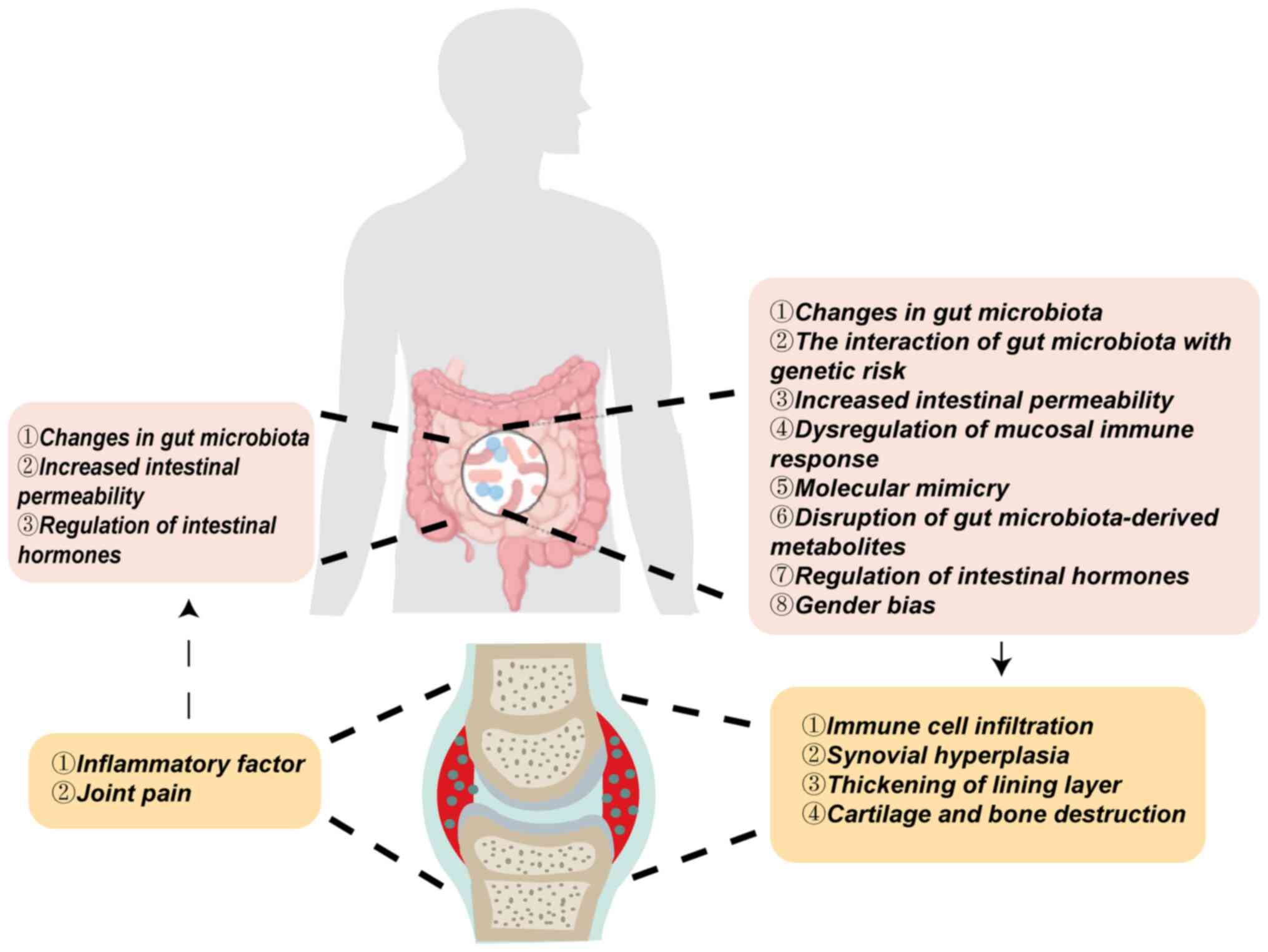

(19,20). The present review summarized the

‘gut-joint axis’ mechanism in RA, highlighting changes in gut

microbiota, interactions between microbiota and genetic risks,

alterations in intestinal permeability, dysregulated mucosal immune

responses, molecular mimicry, disruption of microbial-derived

metabolites, gut hormone regulation and sex bias. These factors,

alone or in combination, contribute to the onset and progression of

RA (Fig. 1).

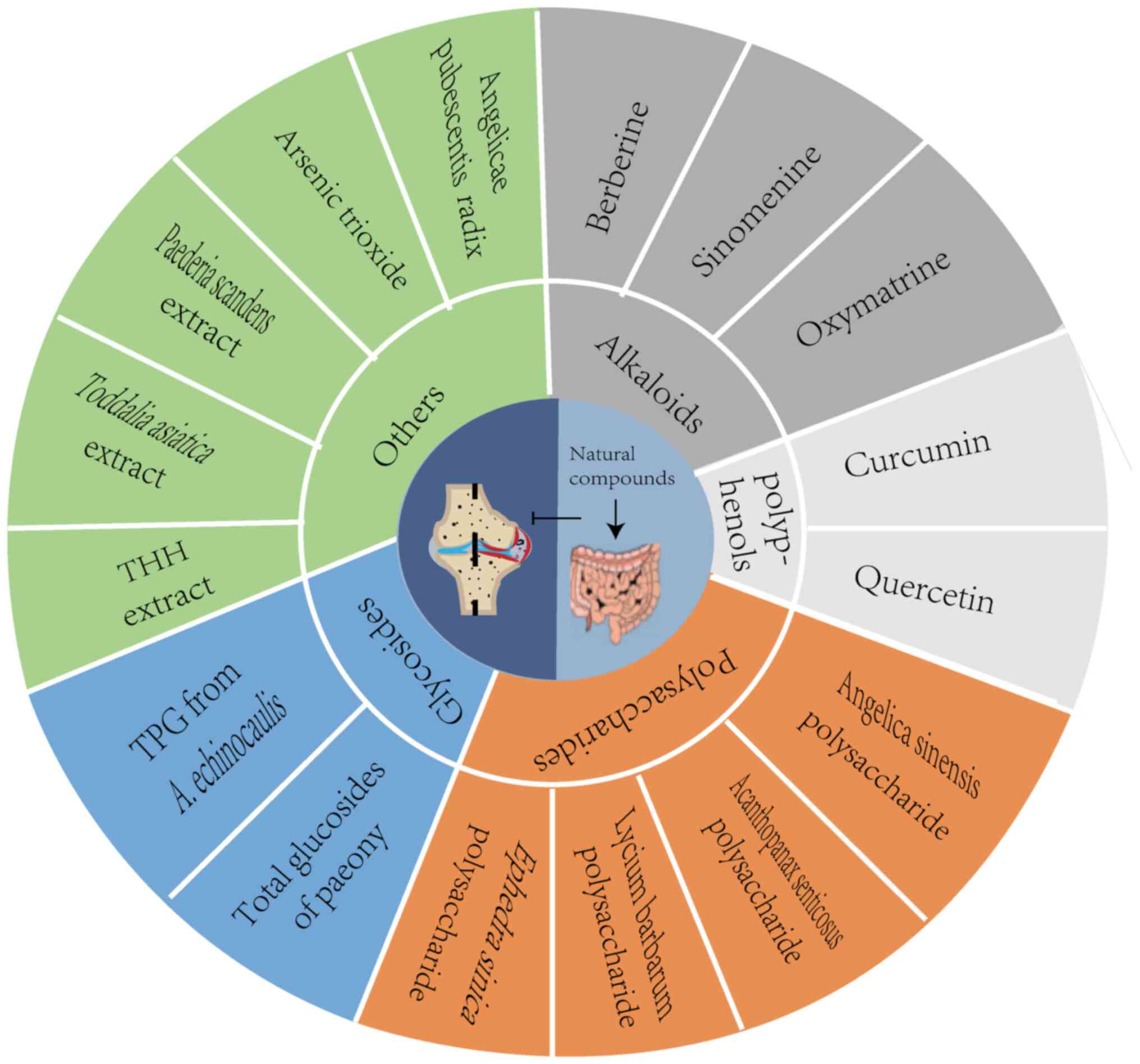

Natural compounds, biologically active substances

derived from natural sources, have garnered significant attention

due to their diverse biological effects, including antioxidant,

anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrotic, anti-tumor and anti-angiogenesis

properties. Given the limitations of current RA treatments, the

present review explored several natural compounds that exert

anti-RA effects through the ‘gut-joint axis’ mechanism, offering

new insights and potential strategies for innovative RA therapies

(Fig. 2).

The gut microbiota plays a pivotal role in

regulating host immunity and influencing the progression of RA

through various mechanisms (21,22).

Several recurring patterns have been identified in the intestinal

microbiota of patients with RA, including an increase in the

abundance of Prevotella and Lactobacillus and a

decrease in Faecalibacterium and Bacteroidetes

(14,23–27).

Among these, the pathogenic role of Prevotella in RA has

been extensively studied. Prevotella is closely associated

with the RA risk gene human leukocyte antigen

(HLA)-DRB1 and is involved in the disease's adaptive

immune response (12). Notably,

antibodies against Prevotella copri (P. copri) are specific

to patients with RA, with antibody levels to other symbiotic

bacteria in patients with RA are similar or lower compared with

those in other patients with arthritis or healthy controls

(28,29). Moreover, when P. copri

enters the systemic circulation, it can selectively accumulate in

the joints, potentially inducing synovial hyperplasia and

deformation by promoting synovial tissue growth (30). P. copri is one of several

intestinal microbiota species with pathogenic effects on RA and

their mechanisms have been comprehensively reviewed (31,32).

Genome-wide association studies have identified

several RA susceptibility alleles, including HLA-DRB1,

PTPN22, and PADI4 genes (33,34).

Alleles within the class II loci of HLA, particularly those

in DRB1, show a strong association with RA risk in

individuals positive for autoantibodies, with >70% of

ACPA-positive patients with RA carrying the HLA-DRB1 allele

(35). Environmental factors may

serve as significant triggers for individuals with a genetic

predisposition to develop RA. Notable microbiome changes have been

observed in the intestines of healthy individuals carrying the RA

risk allele HLA-DRB1, including an increase in

Lachnospiraceae, Clostridiaceae and Bifidobacterium

longum species (36). Wells

et al (12) classified

Prevotella species based on predicted types and assigned

numerical names according to the SILVA database. The authors cohort

study found that, even in the absence of clinically detectable

disease, the genetic risk of RA was associated with specific gut

microbiota. The Prevotella_7 strain (whose predicted type

remains uncertain) was particularly strongly linked to the RA

genotype.

The intestine plays a critical role as a conduit

between the body's internal environment and external factors. When

the intestinal mucosal barrier is compromised, non-self antigens

can penetrate and invade the body, triggering and exacerbating

systemic inflammatory responses. This can lead to the breakdown of

self-immune tolerance and the disruption of immune homeostasis

(37). Additionally, increased

intestinal permeability allows immune cells to migrate beyond the

intestine, potentially causing extraintestinal inflammation

(38,39). Clinical studies have shown that

intestinal permeability is elevated in both preclinical and

established patients with RA (24,39–42).

Individuals with high zonulin levels (>10 ng/ml) during the

early stages of RA are at greater risk of developing the disease

within a year (39). Furthermore,

persistent arthritis may further compromise intestinal

permeability, facilitating the invasion of joint synovial fluid by

intestinal microorganisms in the IV stage of RA (17). In vitro studies have also

indicated that intestinal bacteria from PreRA subjects directly

modulate the expression of zonula occludens-1 in Caco-2 cells at

both the transcriptional and protein levels (5). Collinsella, a genus within the

Actinobacteria phylum, is markedly enriched in the gut microbiota

of patients with RA. Its overgrowth disrupts intestinal barrier

function and is independently associated with disease-related

inflammatory activity (14,43).

In collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) mice, serum zonulin levels and

intestinal permeability are elevated prior to arthritis onset, with

this barrier dysfunction being microbiota-driven. Transfer of

CIA-derived gut microbiota to germ-free (GF) recipients results in

increased gut permeability. Moreover, pre-arthritic administration

of a zonulin antagonist selectively restores epithelial integrity

and reduces subsequent joint inflammation (39). Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) plays

a pivotal role in regulating tight junction proteins such as

claudin-1, thereby orchestrating adaptive barrier responses in the

mucosa (44,45). HIF-2α, specifically expressed in

the mucosal epithelium, is essential for maintaining gut barrier

integrity and regulating intestinal iron absorption. Certain

bacterial metabolites, such as 1,3-diaminopropane, reuterin, and

short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), suppress HIF-2α, influencing

intestinal barrier function (46).

Wen et al (42)

demonstrated that inhibiting intestinal HIF-2α preserves epithelial

barrier integrity by selectively downregulating claudin-15, thereby

reducing arthritis severity. Consequently, restoring intestinal

tight junctions may be a key intervention in the prevention and

treatment of RA.

Studies suggest that the initiation of autoimmune

responses in RA begins in gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT),

distant from the joints, involving both innate and adaptive immune

responses (5,39,47,48).

Increased intestinal permeability facilitates the transport of

intestinal immune cells to the joints. Takahashi et al

(49) performed cell transport

analysis using KikGR mice and observed that both follicular helper

T (Tfh) cells and B cells migrated from the colonic patch to the

draining lymph nodes following immunization. In the CIA model, it

has been confirmed the distal GALT is a primary site for initiating

the autoimmune response. The intestinal lamina propria is

recognized as the main source of T helper 17 (Th17) cells, and

during the immune initiation phase in CIA mice, an increase in Th17

cell content in intestinal lamina propria correlates strongly with

arthritis severity (47,50,51).

In transgenic K/BxN arthritis mice, a population of α4β7-expressing

Th17 cells was found in the spleen, where they assist in the

generation of autoantibodies against glucose-6-phosphate isomerase

(52). Another potential source of

α4β7+ Th17 cells in the spleen is the migration of

intestinal CD103+ dendritic cells (DCs) to the spleen.

Marietta et al (38)

demonstrated that CD103+ DCs, located in the intestinal

lamina propria, migrate to the spleen in CIA mice, suggesting that

these DCs may have originated from the intestine.

Molecular mimicry, a process in which microbial

antigens share structural similarities with autoantigens, can lead

to the cross-activation of autoreactive T or B cells, thereby

triggering autoimmunity. Certain gut microbiota have been

implicated in causing autoimmune responses and systemic

inflammation through molecular mimicry, resulting in joint tissue

damage (53). For instance,

Escherichia coli heat-shock protein (DnaJ) shares a

molecular mimicry mechanism with the HLA-DRB1*0401 molecule,

as both exhibit the amino acid sequence QKRAA (54). Preclinical RA studies have

identified potential epitopes in Citrobacter, Clostridium,

Bacteroides and Eggerthella that resemble collagen XI

and HLA-DRB1*0401 epitopes (12,13,55,56).

Additionally, Bacteroides fragilis 3_1_12, a strain from the

Bacteroidaceae family, may mimic the collagen II peptide

(57–59). Similarly, Prevotella

epitopes show high sequence homology with T-cell epitopes of

N-acetylglucosamine-6-sulfonamide and serpin A, presented by

HLA-DR (60–62). These microorganisms may trigger

autoimmune responses and antibody production via molecular

mimicry, thereby accelerating RA progression. Thus, molecular

mimicry may represent a key mechanism by which the gut microbiota

influences the pathogenesis and development of RA.

The disruption of metabolites derived from the

intestinal microbiota plays a pivotal role in the ‘gut-joint axis’

of RA. Preclinical high-risk populations have already shown

intestinal microbiota dysbiosis and alterations in metabolomics

(5). Among these metabolites,

SCFAs have been studied most extensively studied and are considered

key immunomodulatory compounds closely associated with RA (63). SCFAs primarily exert their effects

on the immune system by modulating histone acetyltransferases and

deacetylases (64). In patients

with RA, fecal levels of acetate, propionate, butyrate, and

valerate are markedly reduced (49,63,65),

with a characteristic deficiency of butyrate producers and an

enrichment of butyrate consumers in the intestinal microbiota of

these individuals (66,67). The protective role of butyrate in

RA has been widely investigated, particularly its effects on

balancing Th17 and T regulatory (Treg) cells in the intestine

system, as well as its regulation of B cells and autoantibody

production (63,67,68).

Additionally, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)

pathway enrichment analysis has revealed alterations in amino acid

and lipid metabolism in PreRA and established patients with RA

(5,69). A retrospective clinical cohort

study in Sweden found that patients with RA and positive ACPA

exhibited elevated levels of lysophospholipid and tryptophan

metabolism several years before diagnosis, compared with

undiagnosed individuals with RA (70). Following this, Seymour et al

(71) demonstrated in animal

studies that indole, a tryptophan metabolite produced by bacteria

such as P. copri, Collinsella and Ruminococcus, plays

a pivotal role in the development of CIA by enhancing Th17 immunity

both locally in the gut and systemically. Bile acids (BAs) are

vital for immune regulation, particularly in balancing Th17 and

Treg cell populations (72–75),

and contribute to the maintenance of fat metabolism. However, high

concentrations of BAs can have cytotoxic effects on colonic

epithelial cells (76). While

studies on BA levels in RA animal models remain inconclusive

(77–79), accumulating evidence suggests that

BAs play a protective and preventative role in RA (18,80).

The intestine harbors a significant number of

endocrine cells that secrete various intestinal hormones. Hormones

such as vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), somatostatin (SOM),

substance P (SP) and gastrin-releasing peptide are implicated in

the progression of RA (81–83).

VIP can promote the Th1/Th2 balance and enhance the differentiation

of Treg cells and follicular regulatory T (Tfr) cells, thereby

reducing joint inflammation in RA animal models (84–86).

SP has been reported to stimulate the proliferation of synovial

cells (87,88) and serum SP levels are considered

indicative of disease activity and subclinical inflammation in

patients with RA (89). However,

other studies suggest that SP treatment can reduce inflammatory

cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and

interleukin-17 (IL-17), while increasing the expression of the

anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, leading to significant

improvements in RA symptoms (90,91).

Consequently, the exact mechanism by which SP influences RA remains

to be further elucidated.

Significant sex differences exist in RA, with a

prevalence rate in females that is notably higher than in males,

often at a ratio of 4:1 or more (92,93).

The influence of sex hormones on RA has been extensively studied. A

sudden drop in estrogen levels and a decrease in androgen can both

increase RA risk (94). Sex

hormone deficiency enhances intestinal permeability, expands the

Th17 cell pool and upregulates osteoclastogenic factors, such as

TNF-α, RANKL and IL-17, in the bone marrow, with the gut microbiota

playing a central role in this process (95). However, butyrate supplementation

has been shown to prevent estrogen-deficiency-induced bone loss

(96) and alleviate arthritis by

activating the estrogen-related receptor α on Th17 cells,

modulating IL-17 and IL-10 production (68). Sex-specific differences in the gut

microbiota have been well established (97). Compared to women, men have markedly

lower levels of Prevotella (36) and P. copri antibodies, which

are considered specific to RA, exhibit a sex disparity, with a

male-to-female ratio of 1:9. This difference may markedly

contribute to the female predominance observed in RA (28). Additionally, Eggerthella lenta

(E. lenta), a potential pathogenic bacterium in RA, is found in

higher levels in female patients with RA (98). Animal studies have shown that

female mice treated with E. lenta display increased

intestinal permeability, elevated IgG-RF levels, an expansion of

IL-17- and IFN-γ-producing B cells, and higher concentrations of

BAs and succinyl carnitine, indicating a sex-specific immune

response to E. lenta (98).

Despite some evidence, the role of sex-dependent differences in the

human microbiota in RA remains poorly understood. Preclinical and

clinical data are both still limited, and more comprehensive

evidence is needed to support or challenge these findings.

Natural compounds exert a positive effect on human

health by regulating various mechanisms, offering potential

therapeutic benefits for a range of diseases. Several natural

compounds, including sinomenine and Tripterygium wilfordii

are widely used in the clinical treatment of RA in China. Clinical

studies exploring the use of natural compounds for RA treatment

have entered the initial exploration stage (Table I). However, these studies face

challenges such as low quality, weak evidence and small sample

size, necessitating high-quality clinical trials to improved

support the therapeutic effects of these compounds on RA. Basic

research has consistently confirmed the protective effects of

natural compounds on RA, elucidating the underlying mechanisms. For

most high-molecular-weight, low-bioavailability natural compounds,

which accumulate in large quantities in the gastrointestinal tract

after oral administration, the intestine appears to be a key target

for their action in treating RA. This section focuses on natural

compounds that treat or enhance RA therapy through the ‘gut-joint

axis’ (Table II).

Alkaloids, primarily found in plants, are key

components of numerous Chinese herbal medicines. Higher plants from

the Liliaceae, Berberidaceae, Ranunculaceae, Leguminosae,

Amaryllidaceae, Papaveraceae and Solanaceae families are rich in

alkaloids. These compounds are characterized by nitrogen atoms in

their chemical structure, which is a defining feature and their

biological efficacy is attributed to the specific arrangement of

atoms in their molecular structure (99). Alkaloids exhibit significant

biological activities, including antibacterial, antiviral,

anti-inflammatory, and anti-tumor effects, suggesting their

potential medicinal value in the RA treatment (100–102).

Berberine, an isoquinoline alkaloid extracted from

various medicinal plants such as Coptis, Phellodendron and

Berberis, possesses a broad range of pharmacological effects,

including anti-tumor, anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory,

hypoglycemic and lipid-lowering properties. Clinical studies have

reported its therapeutic efficacy in treating conditions such as

cancer, digestive system disorders, and metabolic diseases

(103–107). Due to its ability to inhibit

toxins and bacteria and protect the intestinal mucosal barrier,

berberine has shown significant advantages in the treatment of

digestive disorders (108). A

large portion of orally administered berberine remains in the

intestine, with an extremely low bioavailability of only 0.1%

(109). Oral administration of

200 mg/kg berberine markedly improved CIA in rats, although the

peak drug concentration in the blood was <0.06 µM (110), which is much lower than the in

vitro minimum effective concentration of 1–50 µM (109,111). Additionally, intravenous

berberine did not improve arthritis in rats, suggesting that its

anti-arthritis effects are intestinally dependent (110). Further mechanistic studies

revealed that oral berberine selectively increased cortistatin

levels, a neuropeptide derived from the intestine, both in the

intestines and serum of arthritic rats. It also promoted

cortistatin expression in intestinal nerve and endocrine cells. The

upregulated cortistatin then entered systemic circulation, where it

suppressed the immune response of Th17 cells, alleviating arthritis

symptoms (110). Moreover,

berberine markedly increased the levels of intestinal SCFAs,

particularly butyrate, enhanced the abundance of butyrate-producing

bacteria and stimulated the expression and activity of butyryl-CoA:

Acetate CoA transferase (BUT) (112). When BUT inhibitors or

broad-spectrum antibiotics were applied, the regulatory effect of

berberine on the intestinal internal environment and its

anti-arthritis effects were markedly reduced, indicating that

berberine promotes butyrate production through the intestinal

microbiota, positioning it as a potential therapeutic agent for RA

(112). This effect is highly

dependent on the intestinal microbiota (112).

Matrine, a natural bioactive compound extracted from

the roots of the leguminous plant Sophora flavescens, is one

of its main pharmacologically active components. It possesses a

broad range of pharmacological and biological effects, including

antiviral, anti-tumor, antioxidant and antibacterial properties,

with the added advantage of low toxicity and minimal side effects

(125). A number of studies have

demonstrated that matrine can effectively alleviate arthritis

symptoms in RA model animal by regulating immune responses,

inhibiting synovial vessel formation, and suppressing

fibroblast-such as synovial cell proliferation, among other

mechanisms (126–128). Oxymatrine, a derivative of

matrine with a distinct oxygen structure, exhibits similar

pharmacological effects. Animal studies have shown that oxymatrine

also exerts anti-RA effects (129–131). In CIA mice, oxymatrine treatment

markedly improved arthritis symptoms, reduced the abundance of

Firmicutes in the gut and increased the abundance of

Bacteroidota, Patescibacteria and Campylobacterota,

thereby reshaping the gut microbiota towards more normal levels

(131). Moreover, oxymatrine

treatment corrected the imbalance in CD4+ T cell subsets

in CIA mice, restoring intestinal immune balance by regulating the

Th1/Th2, Treg/Th17 and Tfr/Tfh cell ratios (131). Limited clinical studies also

suggest that adding oxymatrine to routine RA treatment can more

effectively reduce inflammatory markers and balance the immune

response in patients (132,133).

Polyphenols, commonly found in plants such as

vegetables, fruits and soybeans, consist primarily of aromatic

rings and hydroxyl groups. These compounds are renowned for their

potent anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, which offer

significant benefits for human health and the prevention of chronic

diseases. Due to these properties, polyphenols are emerging as

promising candidate drugs for the management of RA.

Curcumin, the main active compound in turmeric,

directly targets the intestines and exhibits potent

anti-inflammatory, immune-regulatory and intestinal

microbiota-modulating effects (134,135). Extensive basic and clinical

studies have confirmed curcumin's significant benefits in improving

RA (136). In clinical settings,

curcumin not only alleviates symptoms and reduces serum

inflammatory markers but also demonstrates a high safety profile

(137–140). However, curcumin is characterized

by poor gastrointestinal absorption and low oral bioavailability,

with an absolute bioavailability of only 1%. In rats, oral

administration of 100 mg/kg curcumin resulted in a plasma peak of

only 0.02 µM, far below the minimum effective concentration of 10

µM needed to inhibit synovial cell and lymphocyte activation in

vitro (141–144). Consequently, curcumin's

therapeutic effects on RA may be primarily mediated through its

extensive pharmacological effect on the intestine. Yang et

al (145) indicated that the

anti-arthritis effects of oral curcumin depend on the intestine.

Curcumin activates the cAMP/PKA and Ca2+/CaMKII

signaling pathways, increasing the number of SOM-positive cells in

the small intestine and raising SOM levels in both the intestine

and serum. This process alleviates inflammation and immune

dysfunction, thereby inhibiting the progression of adjuvant-induced

arthritis (AIA) in rats. However, when a SOM inhibitor is used or

curcumin is administered intraperitoneally, this anti-arthritis

effect is markedly diminished.

Quercetin, a flavonoid commonly found in fruits and

vegetables, possesses multiple biological activities, including

anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-cancer and liver-protective

effects. Clinical studies on quercetin for treating RA are limited.

While quercetin appears to positively affect arthritis symptoms,

its ability to enhance antioxidant capacity and modulate

inflammation in patients with RA remains controversial (146,147). Animal studies, however, have

shown that quercetin's potent antioxidant properties not only

improve RA but also alleviate side effects caused by traditional RA

treatments (148,149). Moreover, research has

demonstrated that RA is associated with enteric neurodegenerative

changes that impair intestinal functions such as absorption,

secretion, and immunity (150,151). Oral administration of quercetin

can increase the expression of glial cell-derived neurotrophic

factor, glial fibrillary acidic protein and VIP in the intestine.

This effect helps reverse the decreased density of intestinal

neurons and glial cells in RA mice, restores the morphological

changes in the myenteric and submucosal plexuses, and alleviates

both intestinal and joint inflammation (152,153).

Natural polysaccharides are macromolecular

substances primarily extracted from plants, algae, animals, fungi

and bacteria. These polysaccharides exhibit a wide range of

important biological activities, including anti-hyperlipidemic,

antioxidant, anti-tumor, anti-hepatotoxicity, and immunomodulatory

effects (154). Several Chinese

herbal medicines, such as Angelica sinensis, wolfberry,

Acanthopanax senticosus and Ephedra, contain natural

polysaccharides that have been shown to alleviate RA by protecting

the intestines and modulating the intestinal microbiota.

LBP, a key active component of wolfberry, is not

directly digested or absorbed by the human body. Instead, it

reaches the large intestine where it is metabolized by the gut

microbiota. LBP is highly valued for its medicinal properties,

including enhancing barrier function, anti-inflammatory,

antioxidant, anti-tumor effects and its ability to regulate the

intestinal microbiota (163–167). LBP exerts an anti-CIA effect

regulates chondrocyte proliferation, reduces the expression of

inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-12 and IL-17 and

restores anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 levels (168–170). Additionally, LBP may alter the

gut microbiota composition, increasing the abundance of microbial

taxa that produce S-adenosylmethionine, which induces DNA

hypermethylation of RA-related genes (such as Dpep3, Gstm6,

Slc27a2, Col11a2, Sycp2, SNORA22) in intestinal epithelial

cells. This suppresses gene expression, reduces inflammatory

cytokine levels, and mitigates inflammation (170). The elimination of LBP's anti-CIA

effect by antibiotics further suggests that its therapeutic action

relies on the intestinal microbiota (171).

Paeony, a traditional Chinese herbal medicine, is

highly regarded for its medicinal properties. TGP, extracted from

the roots of paeony, serves as an immunomodulator and is widely

used in China for RA treatment. Although clinical studies have not

yet conclusively demonstrated that combining TGP with conventional

drugs offers superior efficacy in treating RA, they have shown that

TGP can mitigate liver function damage caused by drug treatments

(175–178). The primary chemical components of

TGP include paeoniflorin, albiflorin, hydroxy-paeoniflorin, paeonin

and benzoylpaeoniflorin, all of which are monoterpene glycosides

with low bioavailability and poor absorption (179,180). These compounds tend to accumulate

in the intestine and can be metabolized by the intestinal

microbiota (181–183). TGP treatment reduces arthritis

severity in CIA rats, restructures the gut microbiota by correcting

78% of differential taxonomic profiles and enriches beneficial

symbionts, thereby restoring intestinal ecological balance.

Additionally, TGP markedly downregulates intestinal IFN-γ and

secretory IgA production, modulates mucosal immunity, induces

autoimmune tolerance and suppressed inflammatory responses

(180). TGP also inhibits the

expression of VEGF in CIA rats, regulating synovial

neovascularization and abnormal synovial cell proliferation

(184). These findings suggest

that the therapeutic effects of TGP on RA may be mediated through

intestinal regulatory mechanisms.

THH is a commonly used drug in China, known for its

immunosuppressive, anti-tumor and anti-inflammatory properties

(187). Numerous studies have

demonstrated that THH extract improves joint indices, reduces

swelling and mitigates joint damage in RA animal models (188,189). Further investigations have

revealed that THH extract markedly elevates the colonic mRNA levels

of tight-junction proteins and mucins in RA mice. It also reduces

the abundance of pathogenic bacteria, such as Marvinbryantia,

Desulfovibrio, Parabobacterides, Bacteroides and

Butyricimonas, while enriching beneficial taxa such as

ifidobacterium, Akkermansia, Lactobacillus and

Roseburia. These alterations help restore microbial balance,

reprogram metabolic pathways, enhance SCFA production, and modulate

BA metabolism (190,191). Additionally, THH treatment

reduces the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-8,

IL-17) and increases anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in the colon

of RA model mice. It also inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation

and blocks the TLR4/MyD88/MAPK signaling pathways in muscles and

plasma, reducing joint inflammation and protecting the joints

(190,191). However, these therapeutic effects

were not observed in RA mice with gut microbiota deficiency,

confirming that a healthy gut microbiota is essential for the

therapeutic efficacy of THH extract (190,191).

RTA, a liana primarily found in China and Southeast

Asia, has anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties, making it

widely used for treating chronic pain and gastrointestinal

disorders (192–194). RTA extract reduces serum

inflammatory markers in RA model animals, increases chondrocyte

survival in inflammatory environments, and improves arthritis

symptoms (194–196). Research by Qin et al

(197) suggests that the

therapeutic the mechanism of RTA extract in RA may involve

modulating intestinal immune responses and restoring microbial

balance. Following RTA treatment, Th17 (IL-17A, RORC, IL-1β and

IL-6) and Treg (IL-10 and FOXP3) cell-related protein and mRNA

levels in the colon tissues of AIA rats were downregulated and

upregulated, respectively, promoting the restoration of the

Th17//Treg balance. Additionally, RTA extract reshaped the

intestinal microbiota of AIA rats, increasing beneficial bacteria

and reducing RA-associated strains, such as Liilactobacillus

and Streptococcus.

ATO, a compound with a long history of use in

treating various diseases, was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug

Administration in 2000 for treating acute promyelocytic leukemia,

eventually emerging as a cutting-edge treatment for lymphoma, solid

tumors, and other conditions (200). Studies suggest that ATO holds

potential in RA treatment by balancing immune cells and inhibiting

angiogenesis (201–203). Additionally, regulating

intestinal microecology and abnormal metabolites may be part of

ATO's therapeutic action in RA (204). Specifically, ATO treatment

increased the richness and diversity of the intestinal microbiota

in CIA mice, restoring the imbalance between the two major phyla,

Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes (204). On a metabolic level, ATO

regulates several metabolites, including (−)-β-pinene, a substrate

involved in lipid metabolism related to RA. ATO may alleviate RA

symptoms by regulating lipid metabolism through the modulation of

(−)-β-pinene levels (204).

The ‘gut-joint axis’ is not exclusive to RA but

also occurs in other immune-mediated arthritis diseases, with

distinct mechanisms at play. Studies have shown that ~50% of

patients with spondyloarthritis (SpA) develop subclinical

intestinal inflammation, which can progress to inflammatory bowel

disease (IBD), most commonly Crohn's disease (210,211). By contrast, subclinical

intestinal inflammation in RA predominantly involves the small

intestine and is characterized by lymphocyte and macrophage

infiltration (39,210,211). Furthermore, the composition of

the intestinal microbiota differs between RA and SpA:

Prevotella is markedly and specifically enriched in RA,

whereas no distinct microbial signature has yet been identified for

SpA. However, dysbiosis-driven activation of the IL-23/IL-17 axis

plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of both SpA and IBD

(212). Additionally, whereas

CD4+ T cells that dominate the ‘gut-joint axis’ in RA,

CD8+ T cells bearing identical T-cell receptor

clonotypes are the predominant immune population in both the gut

and joints of SpA patients (210,213).

Overall, alterations in the microbiota are a key

factor in the ‘gut-joint axis’ of RA. These changes not only

influence mucosal and systemic autoimmune responses via

metabolites, molecular mimicry and other mechanisms but are also

closely linked to the efficacy and side effects of RA treatments,

particularly methotrexate (24,214,215). Research focusing on specific

microbiota and metabolomics may offer a more targeted approach to

understanding the ‘gut-joint axis’ in RA. Since the intestinal

microbiota is influenced by numerous factors, broadly studying all

microbiota changes to pinpoint the pathogenesis of diseases may

lead to incorrect conclusions.

Natural compounds possess diverse biological

activities and can improve RA by regulating the intestinal

microecology. Importantly, the anti-RA effects of certain compounds

are dependent on the intestine. The intestinal microbiota

represents a potential target for the treatment of RA, particularly

with high-molecular-weight and low-bioavailability natural

compounds. Although existing reviews have catalogued the potential

mechanisms by which natural compounds ameliorate RA and

occasionally mention the gut-joint axis, the present review

presented a more comprehensive and systematic summary of the

anti-RA effects of natural compounds based on this mechanism

(216–219). The present review highlighted the

protective effects of natural compounds such as alkaloids,

polyphenols, polysaccharides and plant extracts on the intestinal

mucosa and the regulation of intestinal flora homeostasis in RA

model animals, ultimately improving RA symptoms. It explored the

anti-RA potential and mechanisms of these compounds, providing a

scientific foundation and new insights for the development of novel

therapeutic drugs. Several natural compounds have already been

widely used in clinical practice, while others, with solid

scientific support for drug development, should be prioritized. For

example, berberine, a well-studied natural compound, has shown

significant therapeutic effects across various diseases, suggesting

its broad potential in RA drug development. Lycium barbarum

polysaccharides, one of the key active components of L.

barbarum, also exhibit notable efficacy in treating RA.

Moreover, L. barbarum, being a readily available and

low-cost source, could be a valuable candidate for drug

development.

Despite their therapeutic potential, most natural

compounds suffer from low oral bioavailability and tend to

accumulate in the gastrointestinal tract after oral administration.

While this accumulation may be advantageous for RA treatment

through the ‘gut-joint axis’ mechanism, improving the

bioavailability of these compounds could further enhance their

efficacy in disease recovery. Additionally, challenges in

translating natural compounds into clinical drugs include

structural instability, poor solubility and unclear toxic or side

effects. Hence, novel drug discovery remains a protracted,

multi-parameter endeavor that demands rigorous, head-to-toe

optimization and integrated assessment of all pharmacological,

pharmacokinetic and safety attributes. However, as pharmacological

mechanisms of natural compounds are being dissected at ever-greater

depth, our knowledge of these compounds has broadened and their

multifaceted profiles are now improved understood.

At present, new drug delivery methods such as

nanoparticles are developing rapidly. It is expected that in the

future, there will be more basic research and clinical trials on

the treatment of RA using natural compounds through the ‘gut-joint

axis’ pathway. This is precisely what is needed at present.

Not applicable.

Funding: No funding was received.

Not applicable.

WH was responsible for conceptualization, writing

the original draft, writing, reviewing and editing. RL was

responsible for writing, reviewing and editing and providing

illustrations and tables. ZZ was responsible for writing, reviewing

and editing. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors

read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

|

1

|

Di Matteo A, Bathon JM and Emery P:

Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 402:2019–2033. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

GBD 2021 Rheumatoid Arthritis

Collaborators, . Global, regional, and national burden of

rheumatoid arthritis, 1990–2020, and projections to 2050: A

systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021.

Lancet Rheumatol. 5:e594–e610. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Aletaha D and Smolen JS: Diagnosis and

management of rheumatoid arthritis: A Review. JAMA. 320:1360–1372.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Brewer RC, Lanz TV, Hale CR, Sepich-Poore

GD, Martino C, Swafford AD, Carroll TS, Kongpachith S, Blum LK,

Elliott SE, et al: Oral mucosal breaks trigger anti-citrullinated

bacterial and human protein antibody responses in rheumatoid

arthritis. Sci Transl Med. 15:eabq84762023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Luo Y, Tong Y, Wu L, Niu H, Li Y, Su LC,

Wu Y, Bozec A, Zaiss MM, Qing P, et al: Alteration of gut

microbiota in individuals at High-Risk for rheumatoid arthritis

associated with disturbed metabolome and the initiation of

arthritis through the triggering of mucosal immunity imbalance.

Arthritis Rheumatol. 75:1736–1748. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

de Jesus VC, Singh M, Schroth RJ,

Chelikani P and Hitchon CA: Association of bitter taste receptor

T2R38 polymorphisms, oral microbiota, and rheumatoid arthritis.

Curr Issues Mol Biol. 43:1460–1472. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

van Delft MAM and Huizinga TWJ: An

overview of autoantibodies in rheumatoid arthritis. J Autoimmun.

110:1023922020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kronzer VL and Sparks JA: Occupational

inhalants, genetics and the respiratory mucosal paradigm for

ACPA-positive rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 82:303–305.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Holers VM, Demoruelle KM, Buckner JH,

James EA, Firestein GS, Robinson WH, Steere AC, Zhang F, Norris JM,

Kuhn KA and Deane KD: Distinct mucosal endotypes as initiators and

drivers of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 20:601–613.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zhao T, Wei Y, Zhu Y, Xie Z, Hai Q, Li Z

and Qin D: Gut microbiota and rheumatoid arthritis: From

pathogenesis to novel therapeutic opportunities. Front Immunol.

13:10071652022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Jiao Y, Wu L, Huntington ND and Zhang X:

Crosstalk between gut microbiota and innate immunity and its

implication in autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol. 11:2822020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wells PM, Adebayo AS, Bowyer RCE, Freidin

MB, Finckh A, Strowig T, Lesker TR, Alpizar-Rodriguez D, Gilbert B,

Kirkham B, et al: Associations between gut microbiota and genetic

risk for rheumatoid arthritis in the absence of disease: A

cross-sectional study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2:e418–e427. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhang X, Zhang D, Jia H, Feng Q, Wang D,

Liang D, Wu X, Li J, Tang L, Li Y, et al: The oral and gut

microbiomes are perturbed in rheumatoid arthritis and partly

normalized after treatment. Nat Med. 21:895–905. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chen J, Wright K, Davis JM, Jeraldo P,

Marietta EV, Murray J, Nelson H, Matteson EL and Taneja V: An

expansion of rare lineage intestinal microbes characterizes

rheumatoid arthritis. Genome Med. 8:432016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Inamo J: Non-causal association of gut

microbiome on the risk of rheumatoid arthritis: A Mendelian

randomisation study. Ann Rheum Dis. 80:e1032021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Jeong Y, Kim JW, You HJ, Park SJ, Lee J,

Ju JH, Park MS, Jin H, Cho ML, Kwon B, et al: Gut microbial

composition and function are altered in patients with early

rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Med. 8:6932019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Cheng M, Zhao Y, Cui Y, Zhong C, Zha Y, Li

S, Cao G, Li M, Zhang L, Ning K and Han J: Stage-specific roles of

microbial dysbiosis and metabolic disorders in rheumatoid

arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 81:1669–1677. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Sun H, Guo Y, Wang H, Yin A, Hu J, Yuan T,

Zhou S, Xu W, Wei P, Yin S, et al: Gut commensal Parabacteroides

distasonis alleviates inflammatory arthritis. Gut. 72:1664–1677.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Xu X, Zhan G, Chen R, Wang D, Guan S and

Xu H: Gut microbiota and its role in stress-induced hyperalgesia:

Gender-specific responses linked to different changes in serum

metabolites. Pharmacol Res. 177:1061292022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Barton JR, Londregan AK, Alexander TD,

Entezari AA, Covarrubias M and Waldman SA: Enteroendocrine cell

regulation of the gut-brain axis. Front Neurosci. 17:12729552023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Fan L, Xia Y, Wang Y, Han D, Liu Y, Li J,

Fu J, Wang L, Gan Z, Liu B, et al: Gut microbiota bridges dietary

nutrients and host immunity. Sci China Life Sci. 66:2466–2514.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Chen S, Dan L, Xiang L, He Q, Hu D and Gao

Y: The role of gut flora-driven Th cell responses in preclinical

rheumatoid arthritis. J Autoimmun. 154:1034262025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Alpizar-Rodriguez D, Lesker TR, Gronow A,

Gilbert B, Raemy E, Lamacchia C, Gabay C, Finckh A and Strowig T:

Prevotella copri in individuals at risk for rheumatoid

arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 78:590–593. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Scher JU, Sczesnak A, Longman RS, Segata

N, Ubeda C, Bielski C, Rostron T, Cerundolo V, Pamer EG, Abramson

SB, et al: Expansion of intestinal Prevotella copri

correlates with enhanced susceptibility to arthritis. Elife.

2:e012022013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Picchianti-Diamanti A, Panebianco C,

Salemi S, Sorgi ML, Di Rosa R, Tropea A, Sgrulletti M, Salerno G,

Terracciano F, D'Amelio R, et al: Analysis of gut microbiota in

rheumatoid arthritis patients: Disease-related dysbiosis and

modifications induced by etanercept. Int J Mol Sci. 19:29382018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Liu X, Zeng B, Zhang J, Li W, Mou F, Wang

H, Zou Q, Zhong B, Wu L, Wei H and Fang Y: Role of the gut

microbiome in modulating arthritis progression in mice. Sci Rep.

6:305942016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Hu Q, Wu C, Yu J, Luo J and Peng X:

Angelica sinensis polysaccharide improves rheumatoid

arthritis by modifying the expression of intestinal Cldn5, Slit3

and Rgs18 through gut microbiota. Int J Biol Macromol. 209:153–161.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Pianta A, Arvikar S, Strle K, Drouin EE,

Wang Q, Costello CE and Steere AC: Evidence of the immune relevance

of Prevotella copri, a gut microbe, in patients with

rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 69:964–975. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Pianta A, Chiumento G, Ramsden K, Wang Q,

Strle K, Arvikar S, Costello CE and Steere AC: Identification of

novel, immunogenic HLA-DR-Presented Prevotella copri

peptides in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis

Rheumatol. 73:2200–2205. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zhao Y, Chen B, Li S, Yang L, Zhu D, Wang

Y, Wang H, Wang T, Shi B, Gai Z, et al: Detection and

characterization of bacterial nucleic acids in culture-negative

synovial tissue and fluid samples from rheumatoid arthritis or

osteoarthritis patients. Sci Rep. 8:143052018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Peng Y, Huang Y, Li H, Li C, Wu Y, Wang X,

Wang Q, He J and Miao C: Associations between rheumatoid arthritis

and intestinal flora, with special emphasis on RA pathologic

mechanisms to treatment strategies. Microb Pathog. 188:1065632024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Liu Z, Wu Y, Luo Y, Wei S, Lu C, Zhou Y,

Wang J, Miao T, Lin H, Zhao Y, et al: Self-Balance of intestinal

flora in spouses of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Front Med

(Lausanne). 7:5382020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Padyukov L: Genetics of rheumatoid

arthritis. Semin Immunopathol. 44:47–62. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Saevarsdottir S, Stefansdottir L, Sulem P,

Thorleifsson G, Ferkingstad E, Rutsdottir G, Glintborg B,

Westerlind H, Grondal G, Loft IC, et al: Multiomics analysis of

rheumatoid arthritis yields sequence variants that have large

effects on risk of the seropositive subset. Ann Rheum Dis.

81:1085–1095. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Larid G, Pancarte M, Offer G, Clavel C,

Martin M, Pradel V, Auger I, Lafforgue P, Roudier J, Serre G and

Balandraud N: In rheumatoid arthritis patients, HLA-DRB1*04:01 and

rheumatoid nodules are associated with ACPA to a particular fibrin

epitope. Front Immunol. 12:6920412021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Asquith M, Sternes PR, Costello ME,

Karstens L, Diamond S, Martin TM, Li Z, Marshall MS, Spector TD, le

Cao KA, et al: HLA alleles associated with risk of ankylosing

spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis influence the gut microbiome.

Arthritis Rheumatol. 71:1642–1650. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Paray BA, Albeshr MF, Jan AT and Rather

IA: Leaky gut and autoimmunity: An Intricate balance in individuals

health and the diseased State. Int J Mol Sci. 21:97702020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Marietta EV, Murray JA, Luckey DH, Jeraldo

PR, Lamba A, Patel R, Luthra HS, Mangalam A and Taneja V:

Suppression of inflammatory arthritis by human Gut-derived

prevotella histicola in humanized mice. Arthritis Rheumatol.

68:2878–2888. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Tajik N, Frech M, Schulz O, Schälter F,

Lucas S, Azizov V, Dürholz K, Steffen F, Omata Y, Rings A, et al:

Targeting zonulin and intestinal epithelial barrier function to

prevent onset of arthritis. Nat Commun. 11:19952020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Audo R, Sanchez P, Riviere B, Mielle J,

Tan J, Lukas C, Macia L, Morel J and Immediato Daien C: Rheumatoid

arthritis is associated with increased gut permeability and

bacterial translocation which are reversed by inflammation control.

Rheumatology (Oxford). Aug 10–2022.(Epub ahead of print). doi:

10.1093/rheumatology/keac454.

|

|

41

|

Heidt C, Kammerer U, Fobker M, Ruffer A,

Marquardt T and Reuss-Borst M: Assessment of intestinal

permeability and inflammation Bio-markers in patients with

rheumatoid arthritis. Nutrients. 15:23862023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Wen J, Lyu P, Stolzer I, Xu J, Gießl A,

Lin Z, Andreev D, Kachler K, Song R, Meng X, et al: Epithelial

HIF2α expression induces intestinal barrier dysfunction and

exacerbation of arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 81:1119–1130. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Ruiz-Limón P, Mena-Vázquez N,

Moreno-Indias I, Manrique-Arija S, Lisbona-Montañez JM, Cano-García

L, Tinahones FJ and Fernández-Nebro A: Collinsella is associated

with cumulative inflammatory burden in an established rheumatoid

arthritis cohort. Biomed Pharmacother. 153:1135182022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Schwartz AJ, Das NK, Ramakrishnan SK, Jain

C, Jurkovic MT, Wu J, Nemeth E, Lakhal-Littleton S, Colacino JA and

Shah YM: Hepatic hepcidin/intestinal HIF-2α axis maintains iron

absorption during iron deficiency and overload. J Clin Invest.

129:336–348. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Saeedi BJ, Kao DJ, Kitzenberg DA,

Dobrinskikh E, Schwisow KD, Masterson JC, Kendrick AA, Kelly CJ,

Bayless AJ, Kominsky DJ, et al: HIF-dependent regulation of

claudin-1 is central to intestinal epithelial tight junction

integrity. Mol Biol Cell. 26:2252–2262. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Das NK, Schwartz AJ, Barthel G, Inohara N,

Liu Q, Sankar A, Hill DR, Ma X, Lamberg O, Schnizlein MK, et al:

Microbial metabolite signaling is required for systemic Iron

homeostasis. Cell Metab. 31:115–130.e6. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Rogier R, Evans-Marin H, Manasson J, van

der Kraan PM, Walgreen B, Helsen MM, van den Bersselaar LA, van de

Loo FA, van Lent PL, Abramson SB, et al: Alteration of the

intestinal microbiome characterizes preclinical inflammatory

arthritis in mice and its modulation attenuates established

arthritis. Sci Rep. 7:156132017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Chriswell ME, Lefferts AR, Clay MR, Hsu

AR, Seifert J, Feser ML, Rims C, Bloom MS, Bemis EA, Liu S, et al:

Clonal IgA and IgG autoantibodies from individuals at risk for

rheumatoid arthritis identify an arthritogenic strain of

Subdoligranulum. Sci Transl Med. 14:eabn51662022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Takahashi D, Hoshina N, Kabumoto Y, Maeda

Y, Suzuki A, Tanabe H, Isobe J, Yamada T, Muroi K, Yanagisawa Y, et

al: Microbiota-derived butyrate limits the autoimmune response by

promoting the differentiation of follicular regulatory T cells.

EBioMedicine. 58:1029132020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Ivanov II, Atarashi K, Manel N, Brodie EL,

Shima T, Karaoz U, Wei D, Goldfarb KC, Santee CA, Lynch SV, et al:

Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous

bacteria. Cell. 139:485–498. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Tan TG, Sefik E, Geva-Zatorsky N, Kua L,

Naskar D, Teng F, Pasman L, Ortiz-Lopez A, Jupp R, Wu HJ, et al:

Identifying species of symbiont bacteria from the human gut that,

alone, can induce intestinal Th17 cells in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 113:E8141–E8150. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Wu HJ, Ivanov II, Darce J, Hattori K,

Shima T, Umesaki Y, Littman DR, Benoist C and Mathis D:

Gut-residing segmented filamentous bacteria drive autoimmune

arthritis via T helper 17 cells. Immunity. 32:815–827. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Rojas M, Restrepo-Jimenez P, Monsalve DM,

Pacheco Y, Acosta-Ampudia Y, Ramírez-Santana C, Leung PSC, Ansari

AA, Gershwin ME and Anaya JM: Molecular mimicry and autoimmunity. J

Autoimmun. 95:100–123. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Albani S, Keystone EC, Nelson JL, Ollier

WE, La Cava A, Montemayor AC, Weber DA, Montecucco C, Martini A and

Carson DA: Positive selection in autoimmunity: Abnormal immune

responses to a bacterial dnaJ antigenic determinant in patients

with early rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Med. 1:448–452. 1995.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Alcaide-Ruggiero L, Molina-Hernandez V,

Granados MM and Dominguez JM: Main and minor types of collagens in

the articular cartilage: The role of collagens in repair tissue

evaluation in chondral defects. Int J Mol Sci. 22:133292021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Gomez A, Luckey D, Yeoman CJ, Marietta EV,

Berg Miller ME, Murray JA, White BA and Taneja V: Loss of sex and

age driven differences in the gut microbiome characterize

arthritis-susceptible 0401 mice but not arthritis-resistant 0402

mice. PLoS One. 7:e360952012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Zhou C, Zhao H, Xiao XY, Chen BD, Guo RJ,

Wang Q, Chen H, Zhao LD, Zhang CC, Jiao YH, et al: Metagenomic

profiling of the pro-inflammatory gut microbiota in ankylosing

spondylitis. J Autoimmun. 107:1023602020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Miyoshi M and Liu S: Collagen-induced

arthritis models. Methods Mol Biol. 2766:3–7. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Liang B, Ge C, Lönnblom E, Lin X, Feng H,

Xiao L, Bai J, Ayoglu B, Nilsson P, Nandakumar KS, et al: The

autoantibody response to cyclic citrullinated collagen type II

peptides in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford).

58:1623–1633. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Pianta A, Arvikar SL, Strle K, Drouin EE,

Wang Q, Costello CE and Steere AC: Two rheumatoid

arthritis-specific autoantigens correlate microbial immunity with

autoimmune responses in joints. J Clin Invest. 127:2946–2956. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Wang JY and Roehrl MH: Glycosaminoglycans

are a potential cause of rheumatoid arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 99:14362–14367. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Hua R, Ni Q, Eliason TD, Han Y, Gu S,

Nicolella DP, Wang X and Jiang JX: Biglycan and chondroitin sulfate

play pivotal roles in bone toughness via retaining bound water in

bone mineral matrix. Matrix Biol. 94:95–109. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Rosser EC, Piper CJM, Matei DE, Blair PA,

Rendeiro AF, Orford M, Alber DG, Krausgruber T, Catalan D, Klein N,

et al: Microbiota-derived metabolites suppress arthritis by

amplifying Aryl-hydrocarbon receptor activation in regulatory B

cells. Cell Metab. 31:837–851.e10. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Correa-Oliveira R, Fachi JL, Vieira A,

Sato FT and Vinolo MA: Regulation of immune cell function by

short-chain fatty acids. Clin Transl Immunol. 5:e732016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Yao Y, Cai X, Zheng Y, Zhang M, Fei W, Sun

D, Zhao M, Ye Y and Zheng C: Short-chain fatty acids regulate B

cells differentiation via the FFA2 receptor to alleviate rheumatoid

arthritis. Br J Pharmacol. 179:4315–4329. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Wang Y, Wei J, Zhang W, Doherty M, Zhang

Y, Xie H, Li W, Wang N, Lei G and Zeng C: Gut dysbiosis in

rheumatic diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 92

observational studies. EBioMedicine. 80:1040552022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

He J, Chu Y, Li J, Meng Q, Liu Y, Jin J,

Wang Y, Wang J, Huang B, Shi L, et al: Intestinal

butyrate-metabolizing species contribute to autoantibody production

and bone erosion in rheumatoid arthritis. Sci Adv. 8:eabm15112022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Kim DS, Kwon JE, Lee SH, Kim EK, Ryu JG,

Jung KA, Choi JW, Park MJ, Moon YM, Park SH, et al: Attenuation of

rheumatoid inflammation by sodium butyrate through reciprocal

targeting of HDAC2 in osteoclasts and HDAC8 in T cells. Front

Immunol. 9:15252018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Wang M, Huang J, Fan H, He D, Zhao S, Shu

Y, Li H, Liu L, Lu S, Xiao C and Liu Y: Treatment of rheumatoid

arthritis using combination of methotrexate and tripterygium

glycosides Tablets-A quantitative plasma pharmacochemical and

pseudotargeted metabolomic approach. Front Pharmacol. 9:10512018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Surowiec I, Arlestig L, Rantapaa-Dahlqvist

S and Trygg J: Metabolite and lipid profiling of biobank plasma

samples collected prior to onset of rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS One.

11:e01641962016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Seymour BJ, Trent B, Allen BE, Berlinberg

AJ, Tangchittsumran J, Jubair WK, Chriswell ME, Liu S, Ornelas A,

Stahly A, et al: Microbiota-dependent indole production stimulates

the development of collagen-induced arthritis in mice. J Clin

Invest. 134:e1676712023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Cao S, Meng X, Li Y, Sun L, Jiang L, Xuan

H and Chen X: Bile acids elevated in chronic periaortitis could

activate Farnesoid-X-receptor to suppress IL-6 production by

macrophages. Front Immunol. 12:6328642021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Fiorucci S, Biagioli M, Zampella A and

Distrutti E: Bile acids activated receptors regulate innate

immunity. Front Immunol. 9:18532018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Hu J, Wang C, Huang X, Yi S, Pan S, Zhang

Y, Yuan G, Cao Q, Ye X and Li H: Gut microbiota-mediated secondary

bile acids regulate dendritic cells to attenuate autoimmune uveitis

through TGR5 signaling. Cell Rep. 36:1097262021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Zou F, Qiu Y, Huang Y, Zou H, Cheng X, Niu

Q, Luo A and Sun J: Effects of short-chain fatty acids in

inhibiting HDAC and activating p38 MAPK are critical for promoting

B10 cell generation and function. Cell Death Dis. 12:5822021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Ignacio Barrasa J, Olmo N, Perez-Ramos P,

Santiago-Gómez A, Lecona E, Turnay J and Antonia Lizarbe M:

Deoxycholic and chenodeoxycholic bile acids induce apoptosis via

oxidative stress in human colon adenocarcinoma cells. Apoptosis.

16:1054–1067. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Cheng X, Pi Z, Zheng Z, Liu S, Song F and

Liu Z: Combined 16S rRNA gene sequencing and metabolomics to

investigate the protective effects of Wu-tou decoction on

rheumatoid arthritis in rats. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed

Life Sci. 1199:1232492022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Liu M, Li S, Cao N, Wang Q, Liu Y, Xu Q,

Zhang L, Sun C, Xiao X and Yao J: Intestinal flora, intestinal

metabolism, and intestinal immunity changes in complete Freud's

adjuvant-rheumatoid arthritis C57BL/6 mice. Int Immunopharmacol.

125:1110902023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Wang Z, Yu Y, Liao J, Hu W, Bian X, Wu J

and Zhu YZ: S-Propargyl-Cysteine remodels the gut microbiota to

alleviate rheumatoid arthritis by regulating bile acid metabolism.

Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 11:6705932021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Liu J, Peng F, Cheng H, Zhang D, Zhang Y,

Wang L, Tang F, Wang J, Wan Y, Wu J, et al: Chronic cold

environment regulates rheumatoid arthritis through modulation of

gut microbiota-derived bile acids. Sci Total Environ.

903:1668372023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Gonzalez-Rey E, Delgado-Maroto V, Souza

Moreira L and Delgado M: Neuropeptides as therapeutic approach to

autoimmune diseases. Curr Pharm Des. 16:3158–3172. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Delgado M, Pozo D and Ganea D: The

significance of vasoactive intestinal peptide in immunomodulation.

Pharmacol Rev. 56:249–290. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Imhof AK, Gluck L, Gajda M, Lupp A, Bräuer

R, Schaible HG and Schulz S: Differential antiinflammatory and

antinociceptive effects of the somatostatin analogs octreotide and

pasireotide in a mouse model of immune-mediated arthritis.

Arthritis Rheum. 63:2352–2362. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Jimeno R, Leceta J, Martínez C,

Gutiérrez-Cañas I, Pérez-García S, Carrión M, Gomariz RP and

Juarranz Y: Effect of VIP on the balance between cytokines and

master regulators of activated helper T cells. Immunol Cell Biol.

90:178–186. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Jimeno R, Gomariz RP, Gutierrez-Canas I,

Martinez C, Juarranz Y and Leceta J: New insights into the role of

VIP on the ratio of T-cell subsets during the development of

autoimmune diabetes. Immunol Cell Biol. 88:734–745. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Leceta J, Garin MI and Conde C: Mechanism

of immunoregulatory properties of vasoactive intestinal peptide in

the K/BxN mice model of autoimmune arthritis. Front Immunol.

12:7018622021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

O'Connor TM, O'Connell J, O'Brien DI,

Goode T, Bredin CP and Shanahan F: The role of substance P in

inflammatory disease. J Cell Physiol. 201:167–180. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Raap T, Justen HP, Miller LE, Cutolo M,

Scholmerich J and Straub RH: Neurotransmitter modulation of

interleukin 6 (IL-6) and IL-8 secretion of synovial fibroblasts in

patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared to osteoarthritis. J

Rheumatol. 27:2558–2565. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Barbosa-Cobos RE, Lugo-Zamudio G,

Flores-Estrada J, Becerril-Mendoza LT, Rodríguez-Henríquez P,

Torres-González R, Moreno-Eutimio MA, Ramirez-Bello J and Moreno J:

Serum substance P: An indicator of disease activity and subclinical

inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 37:901–908.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Jiang MH, Chung E, Chi GF, Ahn W, Lim JE,

Hong HS, Kim DW, Choi H, Kim J and Son Y: Substance P induces

M2-type macrophages after spinal cord injury. Neuroreport.

23:786–792. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Hong HS and Son Y: Substance P ameliorates

collagen II-induced arthritis in mice via suppression of the

inflammatory response. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 453:179–184.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Galarza-Delgado DA, Azpiri-Lopez JR,

Colunga-Pedraza IJ, Cárdenas-de la Garza JA, Vera-Pineda R,

Wah-Suárez M, Arvizu-Rivera RI, Martínez-Moreno A, Ramos-Cázares

RE, Torres-Quintanilla FJ, et al: Prevalence of comorbidities in

Mexican mestizo patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int.

37:1507–1511. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Castillo-Canon JC, Trujillo-Caceres SJ,

Bautista-Molano W, Valbuena-Garcia AM, Fernandez-Avila DG and

Acuna-Merchan L: Rheumatoid arthritis in Colombia: A clinical

profile and prevalence from a national registry. Clin Rheumatol.

40:3565–3573. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Niu Q, Hao J, Li Z and Zhang H: Helper T

cells: A potential target for sex hormones to ameliorate rheumatoid

arthritis? (Review). Mol Med Rep. 30:2152024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Li JY, Chassaing B, Tyagi AM, Vaccaro C,

Luo T, Adams J, Darby TM, Weitzmann MN, Mulle JG, Gewirtz AT, et

al: Sex steroid deficiency-associated bone loss is microbiota

dependent and prevented by probiotics. J Clin Invest.

126:2049–2063. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Porwal K, Pal S, Kulkarni C, Singh P,

Sharma S, Singh P, Prajapati G, Gayen JR, Ampapathi RS, Mullick A

and Chattopadhyay N: A prebiotic, short-chain

fructo-oligosaccharides promotes peak bone mass and maintains bone

mass in ovariectomized rats by an osteogenic mechanism. Biomed

Pharmacother. 129:1104482020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Dominianni C, Sinha R, Goedert JJ, Pei Z,

Yang L, Hayes RB and Ahn J: Sex, body mass index, and dietary fiber

intake influence the human gut microbiome. PLoS One.

10:e01245992015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Balakrishnan B, Luckey D, Wright K, Davis

JM, Chen J and Taneja V: Eggerthella lenta augments

preclinical autoantibody production and metabolic shift mimicking

senescence in arthritis. Sci Adv. 9:eadg11292023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Bhambhani S, Kondhare KR and Giri AP:

Diversity in chemical structures and biological properties of plant

alkaloids. Molecules. 26:33742021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Ettefagh KA, Burns JT, Junio HA, Kaatz GW

and Cech NB: Goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis L.) extracts

synergistically enhance the antibacterial activity of berberine via

efflux pump inhibition. Planta Med. 77:835–840. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Zhu M, Wang H, Chen J and Zhu H:

Sinomenine improve diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting fibrosis and

regulating the JAK2/STAT3/SOCS1 pathway in streptozotocin-induced

diabetic rats. Life Sci. 265:1188552021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Samra YA, Said HS, Elsherbiny NM, Liou GI,

El-Shishtawy MM and Eissa LA: Cepharanthine and Piperine ameliorate

diabetic nephropathy in rats: Role of NF-kappaB and NLRP3

inflammasome. Life Sci. 157:187–199. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Naz I, Masoud MS, Chauhdary Z, Shah MA and

Panichayupakaranant P: Anti-inflammatory potential of

berberine-rich extract via modulation of inflammation biomarkers. J

Food Biochem. 46:e143892022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Alorabi M, Cavalu S, Al-Kuraishy HM,

Al-Gareeb AI, Mostafa-Hedeab G, Negm WA, Youssef A, El-Kadem AH,

Saad HM and Batiha GE: Pentoxifylline and berberine mitigate

diclofenac-induced acute nephrotoxicity in male rats via modulation

of inflammation and oxidative stress. Biomed Pharmacother.

152:1132252022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Luo R, Liao Z, Song Y, Yin H, Zhan S, Li

G, Ma L, Lu S, Wang K, Li S, et al: Berberine ameliorates oxidative

stress-induced apoptosis by modulating ER stress and autophagy in

human nucleus pulposus cells. Life Sci. 228:85–97. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Samadi P, Sarvarian P, Gholipour E,

Asenjan KS, Aghebati-Maleki L, Motavalli R, Hojjat-Farsangi M and

Yousefi M: Berberine: A novel therapeutic strategy for cancer.

IUBMB Life. 72:2065–2079. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Pirillo A and Catapano AL: Berberine, a

plant alkaloid with lipid- and glucose-lowering properties: From in

vitro evidence to clinical studies. Atherosclerosis. 243:449–461.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Song D, Hao J and Fan D: Biological

properties and clinical applications of berberine. Front Med.

14:564–582. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Liu YT, Hao HP, Xie HG, Lai L, Wang Q, Liu

CX and Wang GJ: Extensive intestinal first-pass elimination and

predominant hepatic distribution of berberine explain its low

plasma levels in rats. Drug Metab Dispos. 38:1779–1784. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Yue M, Xia Y, Shi C, Guan C, Li Y, Liu R,

Wei Z and Dai Y: Berberine ameliorates collagen-induced arthritis

in rats by suppressing Th17 cell responses via inducing cortistatin

in the gut. FEBS J. 284:2786–2801. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Tan XS, Ma JY, Feng R, Ma C, Chen WJ, Sun

YP, Fu J, Huang M, He CY, Shou JW, et al: Tissue distribution of

berberine and its metabolites after oral administration in rats.

PLoS One. 8:e779692013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Yue M, Tao Y, Fang Y, Lian X, Zhang Q, Xia

Y, Wei Z and Dai Y: The gut microbiota modulator berberine

ameliorates collagen-induced arthritis in rats by facilitating the

generation of butyrate and adjusting the intestinal hypoxia and

nitrate supply. FASEB J. 33:12311–12323. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Sun Y, Yao Y and Ding CZ: A combination of

sinomenine and methotrexate reduces joint damage of collagen

induced arthritis in rats by modulating osteoclast-related

cytokines. Int Immunopharmacol. 18:135–141. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Liu W, Zhang Y, Zhu W, Ma C, Ruan J, Long

H and Wang Y: Sinomenine inhibits the progression of rheumatoid

arthritis by regulating the secretion of inflammatory cytokines and

Monocyte/macrophage subsets. Front Immunol. 9:22282018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Huang RY, Pan HD, Wu JQ, Zhou H, Li ZG,

Qiu P, Zhou YY, Chen XM, Xie ZX, Xiao Y, et al: Comparison of

combination therapy with methotrexate and sinomenine or leflunomide

for active rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized controlled clinical

trial. Phytomedicine. 57:403–410. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Chen JJ, Sun Y and Huang CB: Clinical

observation of sinomenine hydrochloride in the treat-to-target

therapy of rheumatoid arthritis and patient-reported outcomes. J

Chin Med Materials. 228–231. 2025.

|

|

117

|

Xiang G, Gao M, Qin H, Shen X, Huang H,

Hou X and Feng Z: Benefit-risk assessment of traditional Chinese

medicine preparations of sinomenine using multicriteria decision

analysis (MCDA) for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. BMC

Complement Med Ther. 23:372023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Li X, He L, Hu Y, Duan H, Li X, Tan S, Zou

M, Gu C, Zeng X, Yu L, et al: Sinomenine suppresses osteoclast

formation and Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra-induced bone loss by

modulating RANKL signaling pathways. PLoS One. 8:e742742013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Chen DP, Wong CK, Leung PC, Fung KP, Lau

CB, Lau CP, Li EK, Tam LS and Lam CW: Anti-inflammatory activities

of Chinese herbal medicine sinomenine and Liang Miao San on tumor

necrosis factor-α-activated human fibroblast-like synoviocytes in

rheumatoid arthritis. J Ethnopharmacol. 137:457–468. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|