Introduction

Gram-positive bacteria are a major class of

pathogens that trigger the host's innate immune response,

predominantly through their surface component lipoteichoic acid

(LTA), a potent immunostimulatory agent (1–3).

Alveolar macrophages are the resident immune cells in the alveolar

space, where they serve as the first line of defense against

inhaled pathogens and as key drivers of pulmonary immune responses

(4). LTA activates alveolar

macrophages through its interaction with Toll-like receptor 2

(TLR2), producing inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen

species (ROS). Although both mediators play a role in the host's

defensive response to infection, they can also contribute to lung

tissue injury (5,6). Given their central role in lung

immune surveillance, alveolar macrophages are uniquely vulnerable

to redox perturbations induced by microbial insults (7). Prolonged oxidative stress disrupts

redox balance and amplifies inflammatory signaling, causing

cellular dysfunction and damaging pulmonary tissue (8). Given that alveolar macrophages can be

both sources and targets of oxidative stress, careful regulation of

redox balance is required to sustain pulmonary homeostasis during

infection (7,9).

Cells combat oxidative injury through endogenous

antioxidant systems, which are predominantly mediated through the

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway

(10–12). When Nrf2 is activated in response

to oxidative signals, it dissociates from its cytoplasmic

repressor, Keap1 and translocates to the nucleus, where it induces

transcription of antioxidant and cytoprotective genes such as heme

oxygenase-1 (HO-1) (12,13). Studies have demonstrated that the

Nrf2/HO-1 axis contributes to numerous oxidative injury models and

it may have protective effects against inflammatory lung diseases

(14,15). Although LTA induced macrophage

activation is well established, the extent to which Nrf2/HO-1

signaling contributes in alveolar macrophages remains unclear.

Additionally, whether pharmacological agents or naturally derived

products can induce protective effectors through this

redox-sensitive pathway under LTA-induced stress is unknown

(16).

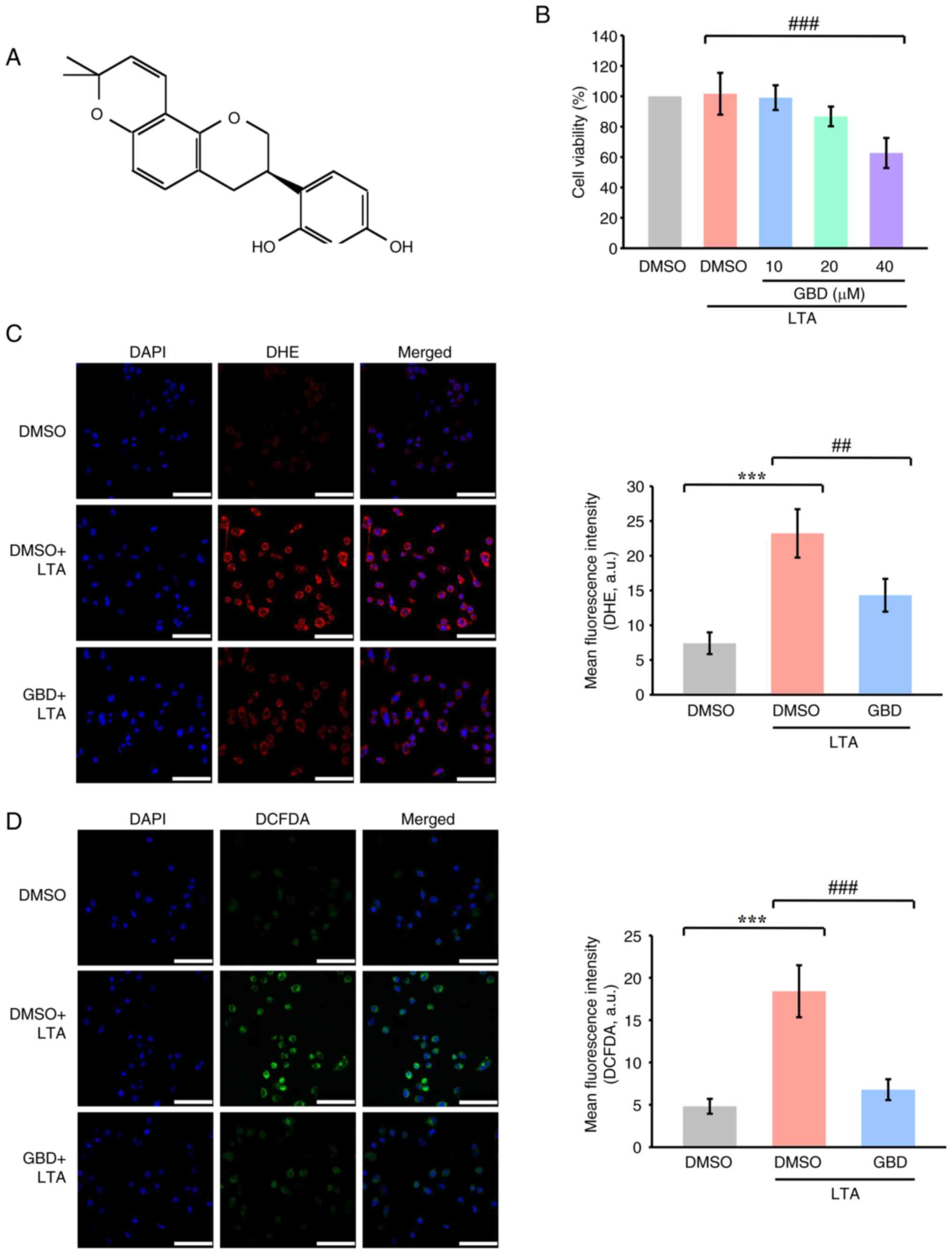

Glabridin (GBD; Fig.

1A), a prenylated isoflavan derived from Glycyrrhiza

glabra (licorice root), has been reported to exhibit

antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties in variouS cellular

models (17). These properties

take effect in part through the activation of Nrf2-dependent

pathways (18). However, whether

GBD can mitigate LTA-induced oxidative stress in alveolar

macrophages and restore redox balance through Nrf2/HO-1 signaling

remains to be elucidated. Moreover, the potential influence of this

pathway on macrophage migration under inflammatory conditions has

not been studied. The present study therefore investigated the

protective effects of GBD on LTA-induced oxidative stress and

macrophage migration, focusing on the potential involvement of

Nrf2/HO-1 signaling.

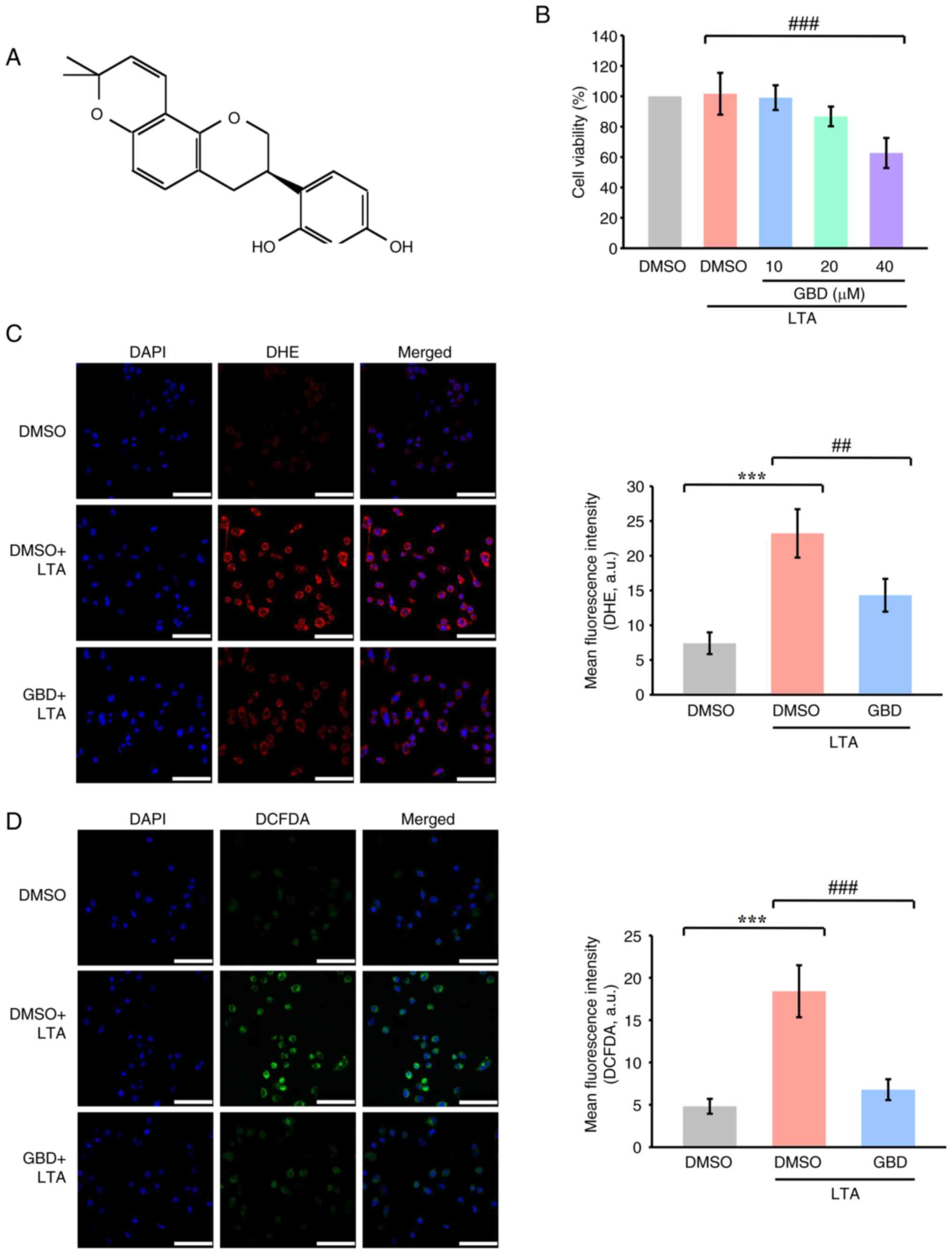

| Figure 1.GBD reduces LTA-induced ROS

production in MH-S cells. (A) Chemical structure of GBD. (B) MTT

assay of cell viability. Cells were pretreated with various

concentrations of GBD (10, 20 and 40 µM) or 0.1% DMSO for 30 min

and then stimulated with LTA (10 µg/ml) for 24 h. (C)

Representative fluorescence images and quantification of DHE

staining in MH-S cells. (D) Representative fluorescence images and

quantification of DCFDA staining. Cells were pretreated with GBD

(20 µM) for 1 h and then stimulated with LTA (10 µg/ml) for 30 min.

Experimental groups for C and D: CTRL, DMSO+LTA, and GBD+LTA. Scale

bar, 50 µm. Data are presented as means±SD (n=4). ***P<0.001 vs.

DMSO; ##P<0.01, and ###P<0.001 vs.

DMSO+LTA. GBD glabridin; LTA, lipoteichoic acid; ROS, reactive

oxygen species; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; DHE, dihydroethidium

staining; DCFDA. 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate. |

Materials and methods

Reagents and materials

GBD (≥98%; cat. no. 11843) and dihydroethidium (DHE;

cat. no. 12013) were purchased from Cayman Chemical Company. LTA

(cat. no. L2515), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; cat. no. D8418), bovine

serum albumin (BSA; cat. no. A5611), 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin

diacetate (DCFDA; cat. no. D6883), phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride

(PMSF; cat. no. P7626), sodium orthovanadate (cat. no. S6508),

sodium pyrophosphate (cat. no. S6422), aprotinin (cat. no. A1153),

leupeptin (cat. no. L2884), sodium fluoride (NaF; cat. no. 201154),

and paraformaldehyde (PFA; cat. no. P6148) were purchased from

MilliporeSigma. Anti-Nrf2 (cat. no. GTX103322) polyclonal

antibodies (pAb) were purchased from GeneTex, Inc. Anti-HO-1 (cat.

no. 10701-1-AP) pAb and β-actin (cat. no. 60008-1-Ig) monoclonal

antibodies were purchased from Proteintech Group, Inc. Hybond-P

polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (cat. no. GE10600023)

and enhanced chemiluminescence Western blotting detection reagent

(cat. no. GERPN2232) were obtained from Cytiva. Horseradish

peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G

(IgG; cat. no. AP182P), and sheep anti-mouse IgG (cat. no.

SAB3701093) were obtained from MilliporeSigma. GBD was dissolved in

DMSO, stored at 4°C, and diluted to the working concentration in

cell culture medium before use. DMSO (0.1%) served as the vehicle

control for all experiments.

Cell culture

MH-S cells, a murine alveolar macrophage cell line,

were obtained from ATCC (cat. no. CRL-2019) and cultured in

RPMI-1640 medium (cat. no. A1049101; Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS;

cat. no. 26140079; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5%

CO2 humidified atmosphere. Cells were used for

experiments between passages 4 and 8. The cell line was confirmed

to be free of mycoplasma contamination using a Mycoplasma Detection

Kit (cat. no. rep-mys-10; InvivoGen).

Cell viability assay

The MH-S cells were seeded in 24-well culture plates

at a density of 1×105 cells per well and cultured in

RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS for 24 h. Once the cells

reached the required confluence, they were treated with varying

concentrations of GBD (10–40 µM) or 0.1% DMSO for 30 min and then

subjected to LTA stimulation (10 µg/ml) for 24 h at 37°C. An MTT

assay (cat. no. AM0815-0005; Bionovas Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was

performed to assesS cell viability, with results expressed as a

percentage calculated using the following formula:

Measurement of intracellular ROS

Intracellular ROS production was assessed with DCFDA

and DHE. Cells were cultured on coverslips in 6-well plates at a

density of 5×104 cells/well and treated with 0.1% DMSO

or 20 µM GBD. The cells then underwent LTA stimulation for 30 min

followed by incubation with DCFDA (10 µM) or DHE (5 µM) for 30 min

at 37°C in the dark. The cells were washed twice with

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the coverslips were mounted

onto glass slides with Fluoroshield medium containing DAPI (cat.

no. ab104139; Abcam). A DM6 CS confocal microscope (Leica

Microsystems GmbH) with a ×63 oil immersion objective was used for

immediate fluorescence signal visualization. Fluorescence intensity

was quantified using ImageJ software, version 1.54g (NIH).

Immunofluorescence staining assay

Cells were cultured on coverslips at a density of

5×104 per well and pretreated with 0.1% DMSO, 20 µM GBD,

or 5 µM ML385 (cat. no. 21114; Cayman Chemical Company) for 30 min.

The cells were subsequently stimulated with LTA for 3 or 6 h and

fixed after treatment in 4% PFA for 10 min at room temperature. The

fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, followed by

blocking in 5% BSA for 30 min. The prepared cells were incubated

with target-specific primary antibodies (1:100) overnight at 4°C.

After thorough PBS washing, the specimens were exposed to Alexa

Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody

(1:2,000; cat. no. ab150077; Abcam) for 1 h at room temperature.

Following three additional PBS washes, the coverslips were mounted

onto glass slides with Fluoroshield medium containing DAPI.

Cell imaging was performed with the aforementioned

confocal microscope system. ImageJ software was used to analyze

fluorescence intensity. For Nrf2 nuclear translocation, nuclear

regions of interest (ROIs) were identified through DAPI staining.

For HO-1 analysis, ROIs were selected around individual cells to

calculate the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the whole cell

was calculated after background subtraction.

Cell transfection

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of

2×105 cells/well and cultured until 80% confluence.

Cells were then transfected with either a small interfering (si)RNA

targeting Nrf2 [Nfe2l2 siRNA: 5′-AGCAUUUUAACAUGUUAACAG-3′

(sense) and 5′-GUUAACAUGUUAAAAUGCUAU-3′ (antisense)] or a negative

control siRNA [si-Ctrl: 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′ (sense) and

reverse 5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3′ (antisense); cat. no.

HY-RS09246; MedChemExpress], using a transfection reagent (cat. no.

HY-K2017, MedChemExpress) and 50 nM siRNA diluted in serum-free

medium, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Following 6 h

incubation at 37°C, the transfection mixture was replaced with

complete medium, and cells were further cultured for 24 h before

subsequent treatments. Knockdown efficiency was verified by reverse

transcription-quantitative (RT-q) PCR.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from MH-S cells

(5×106 cells) with a NucleoSpin RNA Kit (cat. no.

740955.50; Macherey-Nagel) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. RNA purity and concentration were assessed with a

NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Complementary DNA was synthesized from 2 µg total RNA with the

SuperScript IV First-Strand Synthesis System (cat. no. 18091050;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). RT-qPCR was performed with Fast

SYBR Green Master Mix (cat. no. 4385612; Applied Biosystems; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Amplification was performed with a

StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) with an initial hot-start activation at 95°C for

1 min, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 5 sec and

annealing/extension at 60°C for 1 min. The following primers were

used: Nrf2, forward 5′-AGCAGGACATGGAGCAAGTT-3′ and reverse

5′-TTCTTTTTCCAGCGAGGAGA-3′; HO-1, forward

5′-GCACTATGTAAAGCGTCTCC-3′ and reverse 5′-GACTCTGGTCTTTGTGTTCC-3′;

and GAPDH, forward 5′-GAACATCATCCCTGCATCCA-3′ and reverse

5′-GCCAGTGAGCTTCCCGTTCA-3′. GAPDH was used as the internal control.

The primer sequences used for IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6 and SOD1 are

listed in Table SI. Relative gene

expression levels were calculated according to the

2−ΔΔCq method (19).

All experiments were independently repeated ≥4 times.

Determination of nitric oxide and malondialdehyde

levels. The detailed procedures for the determination of nitric

oxide (NO) and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels are described in the

Supplementary Methods.

Western blot analysis

MH-S cells (8×105 per ml) were cultured

and preincubated with DMSO, GBD, or ML385 for 30 min at 37°C. Cells

underwent LTA stimulation or were left untreated for 3 or 6 h. The

cells were lysed in lysis buffer containing aprotinin (10 µg/ml),

PMSF (1 mM), leupeptin (2 µg/ml), NaF (10 mM), sodium orthovanadate

(1 mM), and sodium pyrophosphate (5 mM) for 1 h at 4°C.

Subsequently, the samples were centrifuged at 13,500 × g for 30

min, and protein concentration was determined through a Bradford

protein assay (cat. no. 5000006; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Equal

amounts of total protein (50 µg) were separated through 10%

SDS-PAGE and then transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride

membranes (MilliporeSigma). Membranes were blocked in 5% BSA in

Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) at room temperature

for 1 h and incubated with primary antibodies (anti-Nrf2, cat. no.

GTX103322, GeneTex; anti-HO-1, cat. no. 10701-1-AP and

anti-β-actin, cat. no. 60008-1-Ig, Proteintech) diluted 1:1,000 in

TBST overnight at 4°C. The membranes were then washed and incubated

with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (donkey anti-rabbit IgG,

cat. no. AP182P; and sheep anti-mouse IgG, cat. no. SAB3701093,

MilliporeSigma) diluted 1:5,000 in TBST for 1 h at room

temperature. Protein bands were quantified with a video

densitometer and BioProfil BioLight software (v2000.01; Vilber

Lourmat).

Wound healing assay

Cell migration was assessed through a wound healing

assay performed in 24-well plates. A sterile 20-µl pipette

tip was used to create a scratch in the confluent cell monolayer.

Cells were incubated in serum-free medium with or without

treatment. Images were captured at 0, 6, and 24 h after the scratch

was created. Wound width was analyzed with ImageJ software, version

1.54g (NIH). The wound closure percentage was calculated according

to the following formula:

Transwell migration assay

Cell migration was assessed using Transwell inserts

with 8 µm pore size (SPL Life Sciences, FL, USA) in 24-well

plates. MH-S cells (1×105) were resuspended in medium

containing 2% FBS and seeded into the upper chamber in 200

µl medium. The lower chambers were also filled with 600

µl of medium containing 2% FBS, and the plates were

incubated at 37°C for 30–60 min to allow cell

attachment. Cells in the upper chamber were then treated with DMSO,

GBD, or ML385 for 30 min in medium containing 2% FBS at

37°C. After treatment, the medium in the lower chambers was

replaced with fresh medium containing 2% FBS, with or without LTA

(10 µg/ml), to serve as the chemoattractant.

After 6 or 24 h of incubation at 37°C

in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator, non-migrated cells on

the upper surface of the membrane were gently removed with cotton

swabs. Cells that migrated to the lower surface were fixed with 4%

PFA for 15 min at room temperature, washed twice with PBS,

and stained with 0.2% crystal violet for 3 min at room

temperature. Excess stain was removed by washing twice with PBS.

Migrated cells were imaged and counted under an inverted microscope

at ×100 magnification. Relative migration was calculated as the

ratio of the number of migrated cells in each treatment group to

that in the DMSO group, which was defined as 1.

Statistical analysis

At least four independent replicates were performed

for all experiments. Data are expressed as means±standard deviation

(SD). Significance was determined through one-way analysis of

variance followed by a Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test. For

datasets containing >3 groups, Tukey's post hoc test was used.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

GBD attenuates LTA-induced oxidative

stress in MH-S cells

An MTT assay was performed to assess GBD

cytotoxicity in MH-S cells. MH-S cells were treated with 10, 20 and

40 µM of GBD in the presence of LTA (10 µg/ml) for 24 h. Whereas 40

µM of GBD reduced cell viability below 80%, 10 and 20 µM had no

significant cytotoxic effects (Fig.

1B). To determine the effective concentration, cells were

treated with 0, 5, 10, 20, and 30 µM GBD for 24 h. Increasing

concentrations of GBD reduced proliferation, with an

IC50 of ~18 µM (Fig.

S1). Based on both of these findings, 20 µM was selected as the

working concentration for subsequent experiments.

LTA stimulation markedly increased intracellular ROS

production, as indicated by elevated fluorescence in both DCFDA and

DHE staining (Fig. 1C and D),

which suggests the oxidative environment in the MH-S cells was

enhanced. Pretreatment with 20 µM GBD markedly suppressed

LTA-induced ROS accumulation. Quantitative analysis revealed

markedly reduced fluorescence intensity in GBD-treated cells

compared with the LTA group, as measured by DHE and DCFDA staining,

indicating that GBD effectively mitigated LTA-induced oxidative

stress.

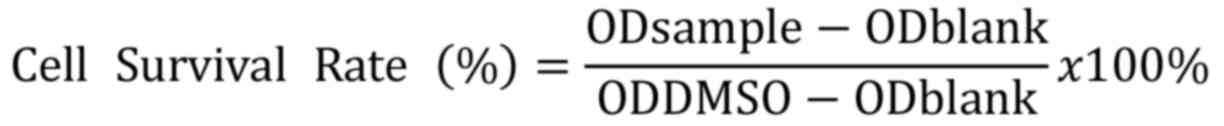

GBD activates Nrf2 signaling in

LTA-stimulated MH-S cells

The present study investigated whether Nrf2

signaling contributed to the antioxidative effects of GBD. Confocal

microscopy revealed that LTA stimulation alone resulted in minimal

Nrf2 nuclear localization, whereas GBD pretreatment markedly

increased Nrf2 nuclear accumulation (Fig. 2A).

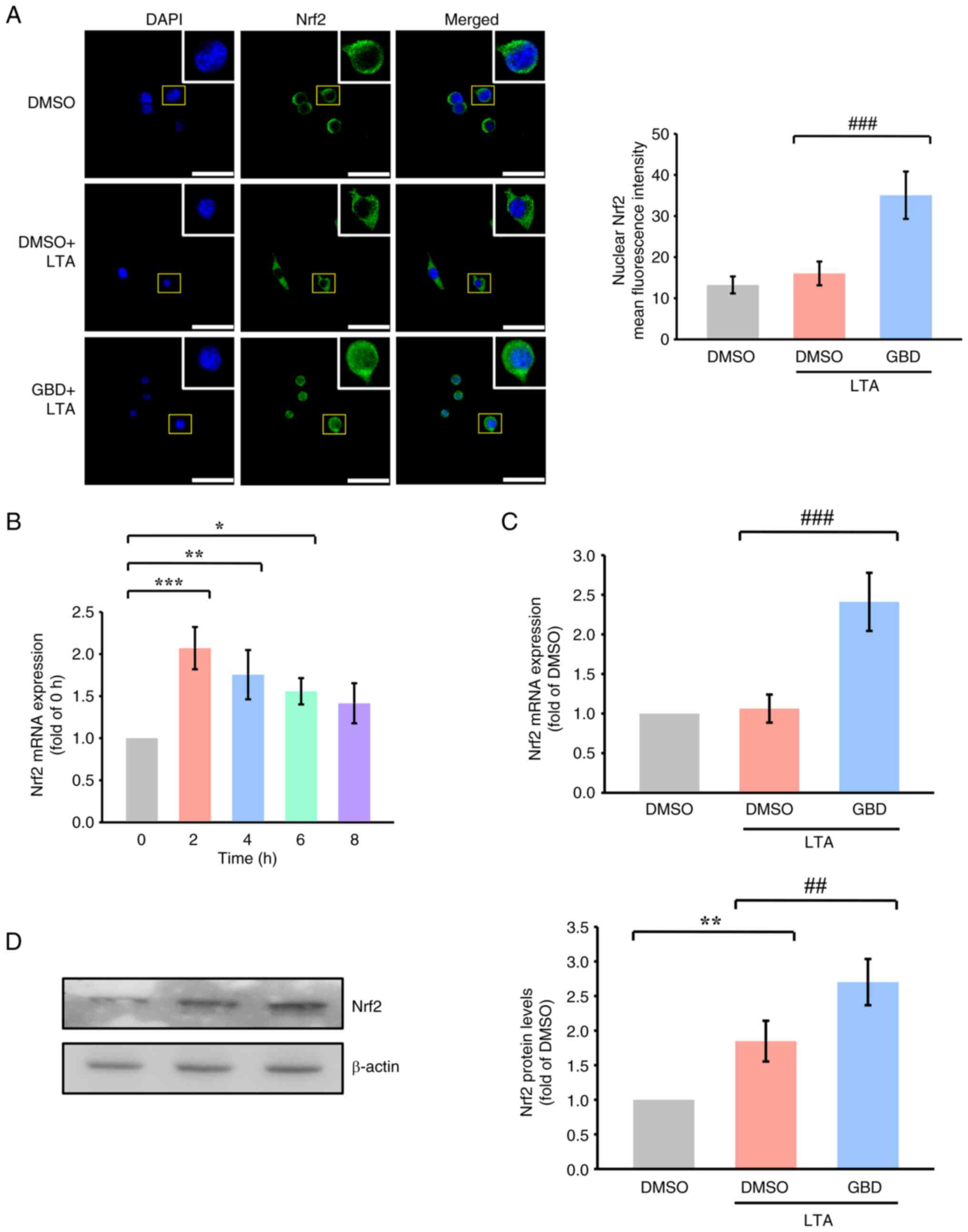

| Figure 2.GBD activates Nrf2 signaling in

response to LTA. MH-S cells were pretreated with GBD for 30 min and

then stimulated with LTA. (A) Confocal images indicating Nrf2

nuclear translocation 3 h poststimulation. Scale bar, 50 µm. (B)

Time-course of Nrf2 mRNA expression after LTA stimulation (0, 2, 4,

6, and 8 h). (C) Nrf2 mRNA expression was determined through

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR 2 h poststimulation, as

described in the materials and methods section. (D) Western blot

analysis of Nrf2 protein levels 3 h after LTA stimulation. Data are

presented as means±SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001

vs. 0 h or DMSO; ##P<0.01 and

###P<0.001 vs. DMSO+LTA. GBD glabridin; Nrf2, nuclear

factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; LTA, lipoteichoic acid; DMSO,

dimethyl sulfoxide. |

Time-course analysis indicated that Nrf2 mRNA peaked

2 h after LTA stimulation (Fig.

2B); thus, 2 h was selected as the representative time point

for mRNA analysis. Nrf2 mRNA levels were markedly elevated in the

GBD+LTA group compared with in the DMSO+LTA group (Fig. 2C). Western blot analysis performed

at 3 h post-LTA stimulation showed that Nrf2 protein levels were

increased following GBD treatment (Fig. 2D).

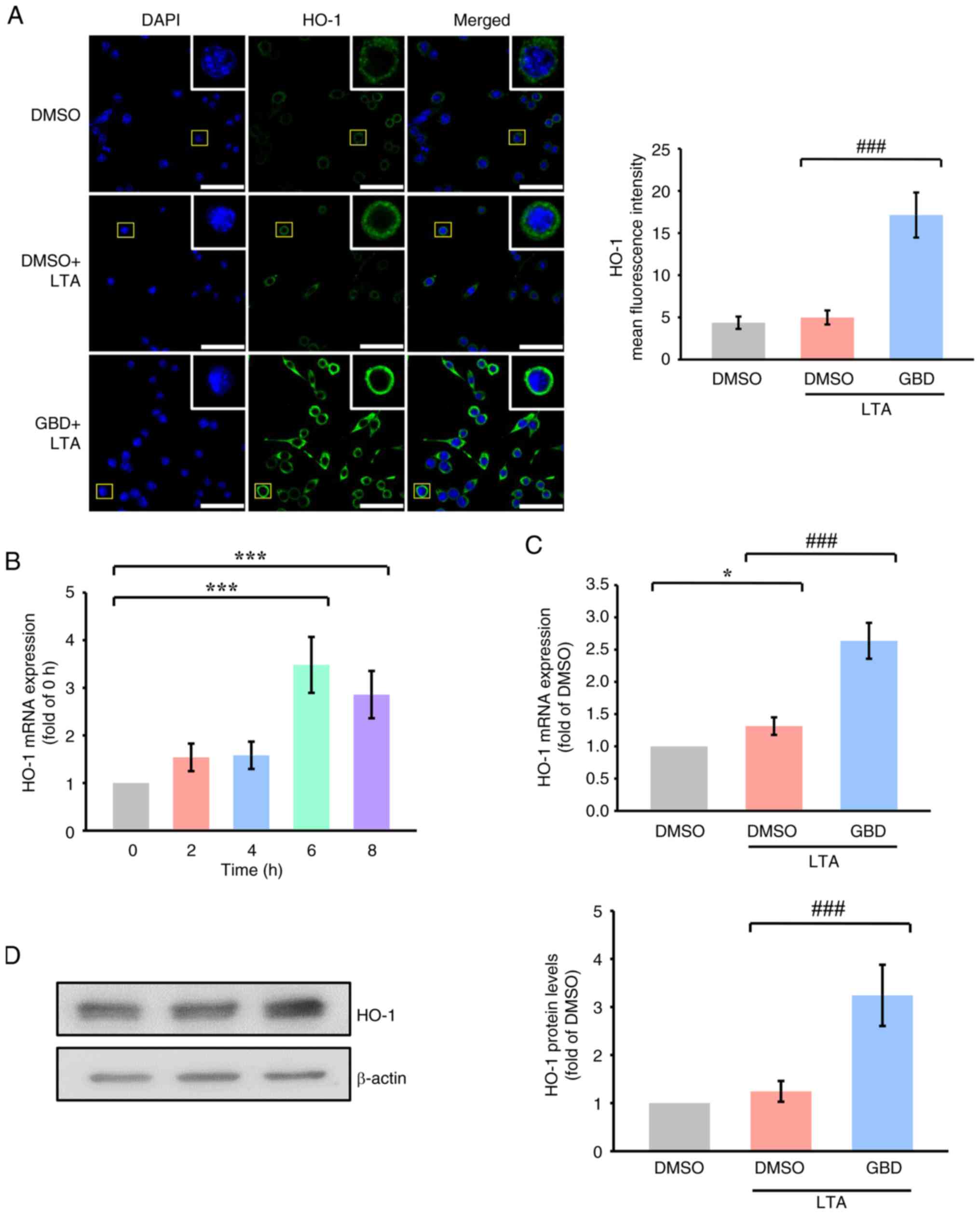

GBD upregulates HO-1 expression

following Nrf2 activation

HO-1 expression was further examined as a downstream

target of Nrf2. Confocal imaging revealed that GBD increased HO-1

fluorescence intensity 6 h after LTA stimulation relative to LTA

treatment alone (Fig. 3A).

Time-course analysis revealed that HO-1 mRNA expression peaked 6 h

following LTA stimulation (Fig.

3B); thus, 6 h was selected as the representative time point

for subsequent analysis. GBD also markedly upregulated HO-1 mRNA

and protein levels 6 h after treatment (Fig. 3C and D), confirming its downstream

activation of Nrf2. HO-1 is a cytoprotective enzyme with

antioxidant properties. Its upregulation by GBD may represent one

mechanism through Nrf2 activation contributes to redox homeostasis.

These results align with the observed decrease in ROS accumulation

and support the role of HO-1 as a key effector in GBD-mediated

regulation of oxidative stress.

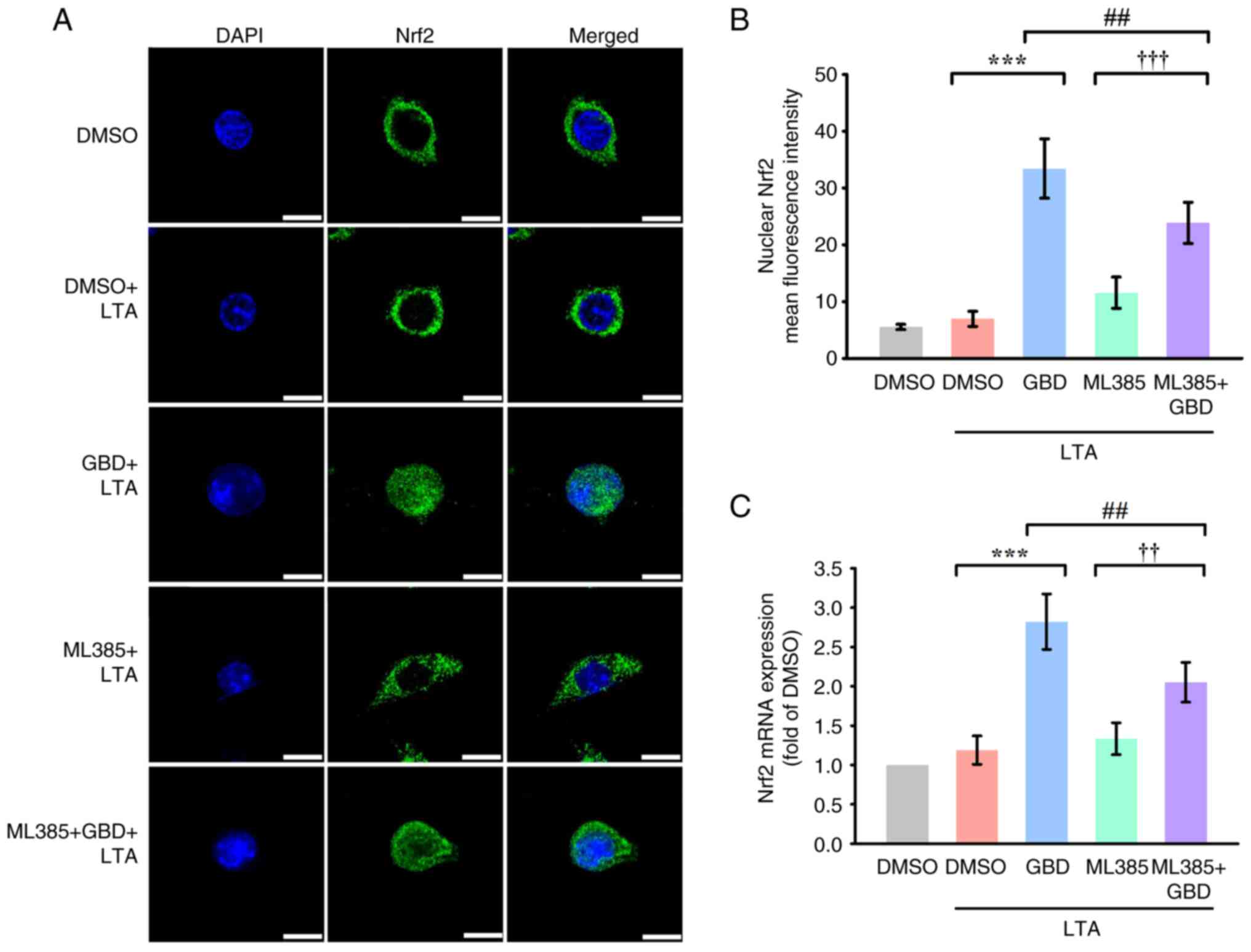

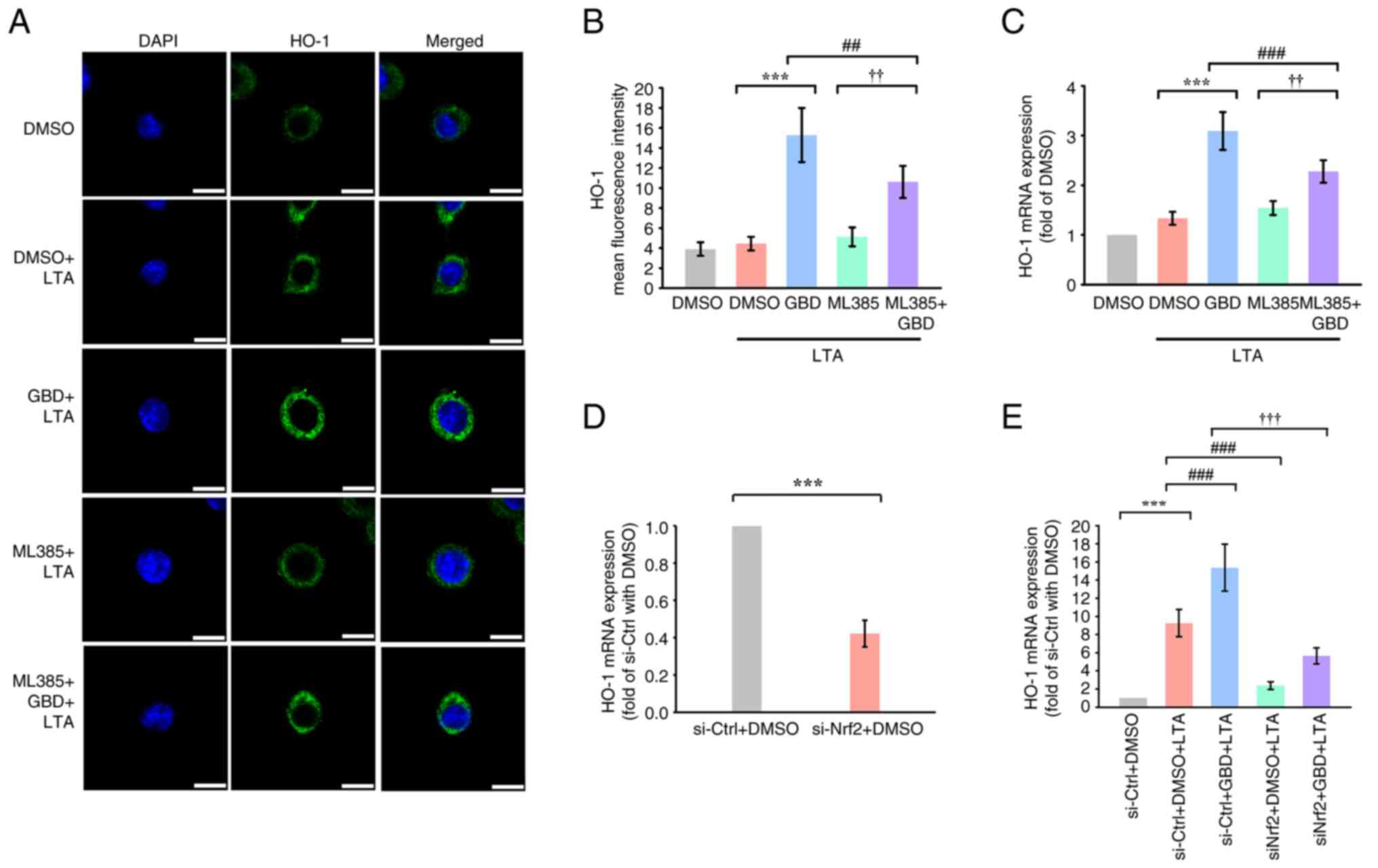

ML385 attenuates GBD-induced

activation of Nrf2 and HO-1

The selective inhibitor ML385 (5 µM) was used to

investigate the Nrf2-dependence of GBD-induced activation of Nrf2

and HO-1. Confocal microscopy indicated that ML385 markedly reduced

the nuclear accumulation of Nrf2 in GBD-treated cells at 3 h

(Fig. 4A and B). Additionally,

RT-qPCR analysis revealed that ML385 suppressed GBD-induced

expression of Nrf2 mRNA (Fig. 4C),

indicating transcriptional inhibition.

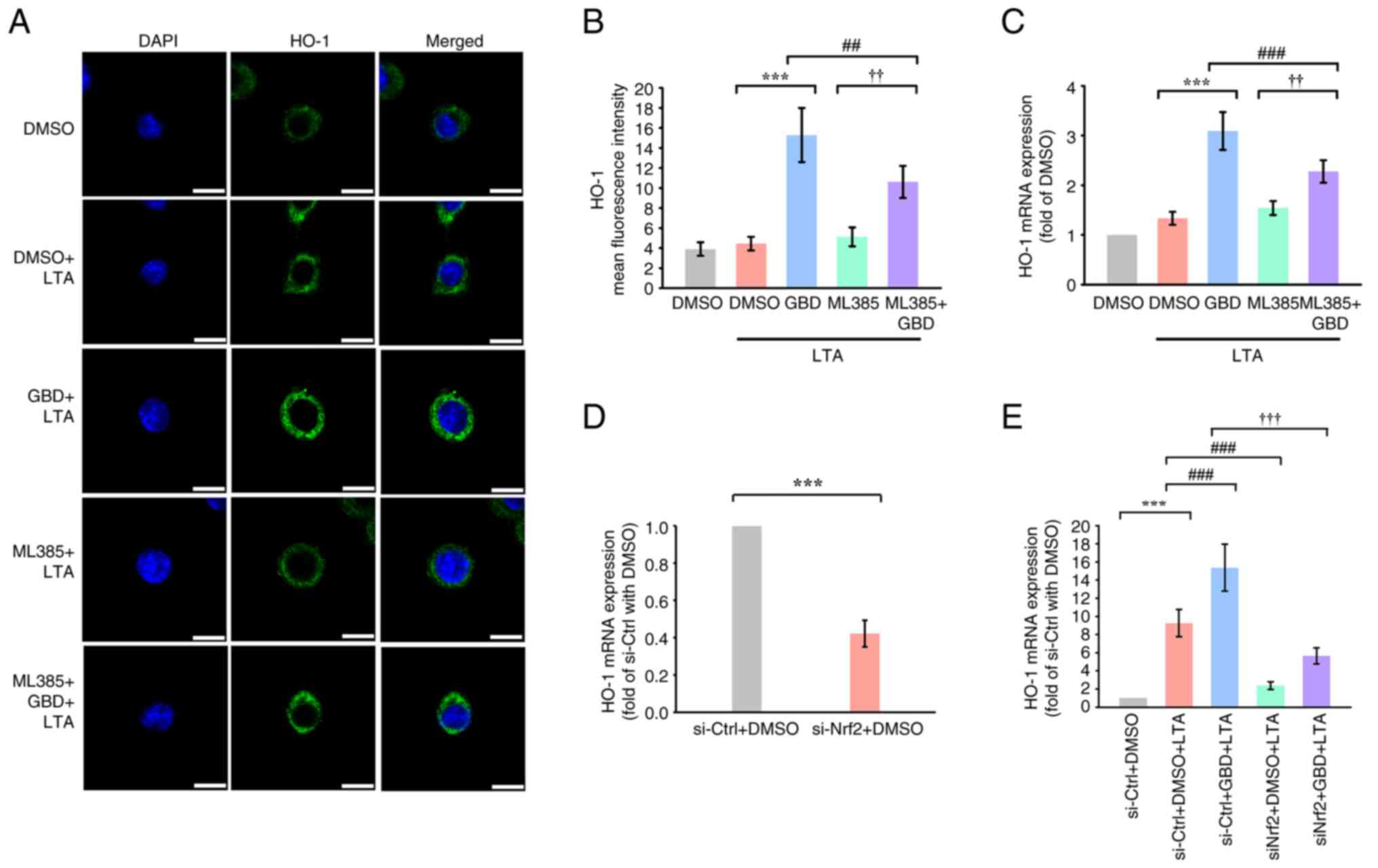

ML385 attenuated HO-1 fluorescence intensity at 6 h,

as confirmed through confocal imaging (Fig. 5A and B), and markedly decreased

HO-1 mRNA levels in GBD-treated cells (Fig. 5C). These findings suggested that

GBD-mediated upregulation of the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway is substantially

dependent on Nrf2 activity, given that pharmacological inhibition

of Nrf2 impaired both nuclear localization and downstream gene

expression.

| Figure 5.Pharmacological and genetic

inhibition of Nrf2 attenuates GBD-induced HO-1 expression. MH-S

cells were pretreated with the indicated compounds for 30 min and

then stimulated with LTA. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis of HO-1

expression 6 h poststimulation. Scale bar, 10 µm. (B)

Immunofluorescence image evaluation of HO-1 mean fluorescence

intensity. (C) HO-1 mRNA expression 6 h poststimulation, determined

through RT-qPCR. (D and E) Effect of Nrf2 knockdown on GBD-induced

HO-1 expression. MH-S cells were transfected with control siRNA

(siNC) or Nrf2 siRNA (siNrf2) for 6 h, followed by the indicated

treatments. HO-1 mRNA levels were measured by RT-qPCR. Data are

presented as means ± SD. ***P<0.001 vs. DMSO+LTA (B-C) or

si-Ctrl+DMSO (D and E); ##P<0.01 and

###P<0.001 vs. GBD+LTA (B-C) or si-Ctrl+DMSO+LTA (E);

††P<0.01 and †††P<0.001 vs. ML385+LTA

(B-C) or si-Ctrl+GBD+LTA (E). Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid

2-related factor 2; GBD, glabridin; LTA, lipoteichoic acid; HO-1,

heme oxygenase-1; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR;

si, short interfering; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide. |

Genetic inhibition of Nrf2 reduces

GBD-induced HO-1 expression

To further validate the role of Nrf2 in mediating

GBD's effects, the present study performed siRNA knockdown

experiments. Transfection with siRNA targeting Nrf2 (siNrf2)

markedly reduced Nrf2 mRNA expression under basal conditions

compared with a negative control siRNA (si-Ctrl; Fig. S2). Furthermore, Nrf2 knockdown

markedly attenuated the GBD-induced upregulation of HO-1 mRNA

(Fig. 5D and E). These results,

together with the pharmacological inhibition by ML385, supported

the involvement of Nrf2 in GBD-mediated HO-1 induction.

In addition to the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, GBD also

influenced inflammatory and oxidative stress-related factors in

LTA-stimulated MH-S cells. GBD significantly decreased the mRNA

expression of IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6, while the expression of SOD1

remained unchanged at 6 h (Fig.

S3). Furthermore, GBD reduced MDA and NO levels at 24 h. These

findings provide additional evidence supporting the antioxidative

and anti-inflammatory potential of GBD.

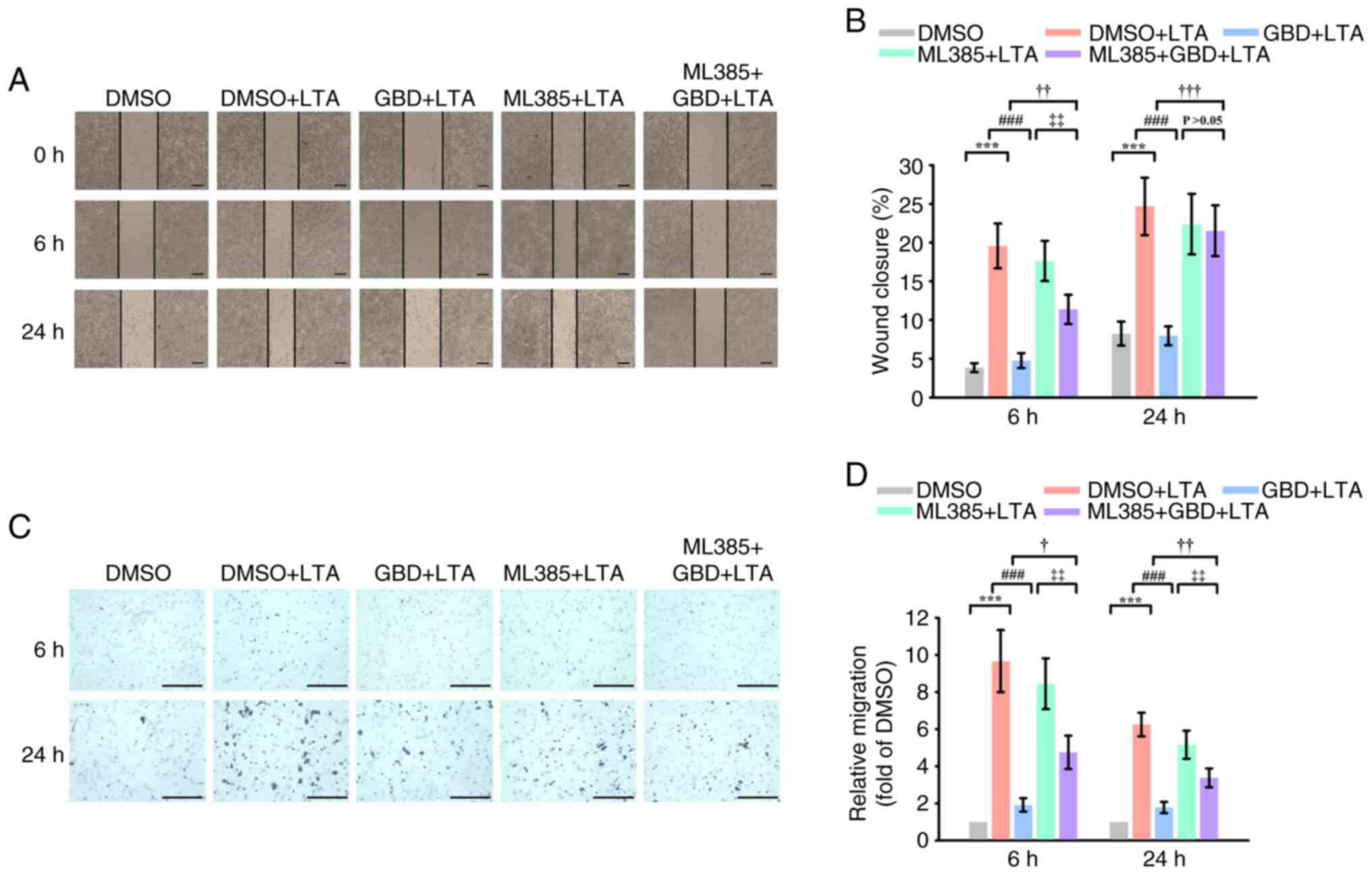

Nrf2 contributes to the inhibitory

effect of GBD on LTA-induced macrophage migration

Wound healing assays revealed that LTA markedly

promoted MH-S cell migration at 6 and 24 h. GBD pretreatment

suppressed this effect at both time points (Fig. 6A and B). Notably, cotreatment with

Nrf2 inhibitor ML385 attenuated the antimigratory effects of GBD,

as evidenced by markedly higher closure in the ML385+GBD+LTA group

than in the GBD+LTA group at 6 and 24 h. In addition, migration in

ML385+GBD+LTA group remained lower than in ML385+LTA group at 6 h,

although this difference was not sustained at 24 h. These findings

suggested that activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 axis at least partially

mediates the inhibitory effects of GBD.

To further validate the antimigratory effects of

GBD, Transwell assays were performed to assess directional cell

migration. LTA stimulation markedly enhanced macrophage migration

at both 6 and 24 h compared with the DMSO group (Fig. 6D). GBD pretreatment markedly

attenuated this increase. Consistent with Nrf2 involvement, ML385

treatment in combination with LTA promoted migration, and

importantly, cotreatment with ML385 partially reversed the

inhibitory effect of GBD. These results corroborated the

wound-healing findings and indicated that the antimigratory effects

of GBD were mediated, at least in part, by Nrf2.

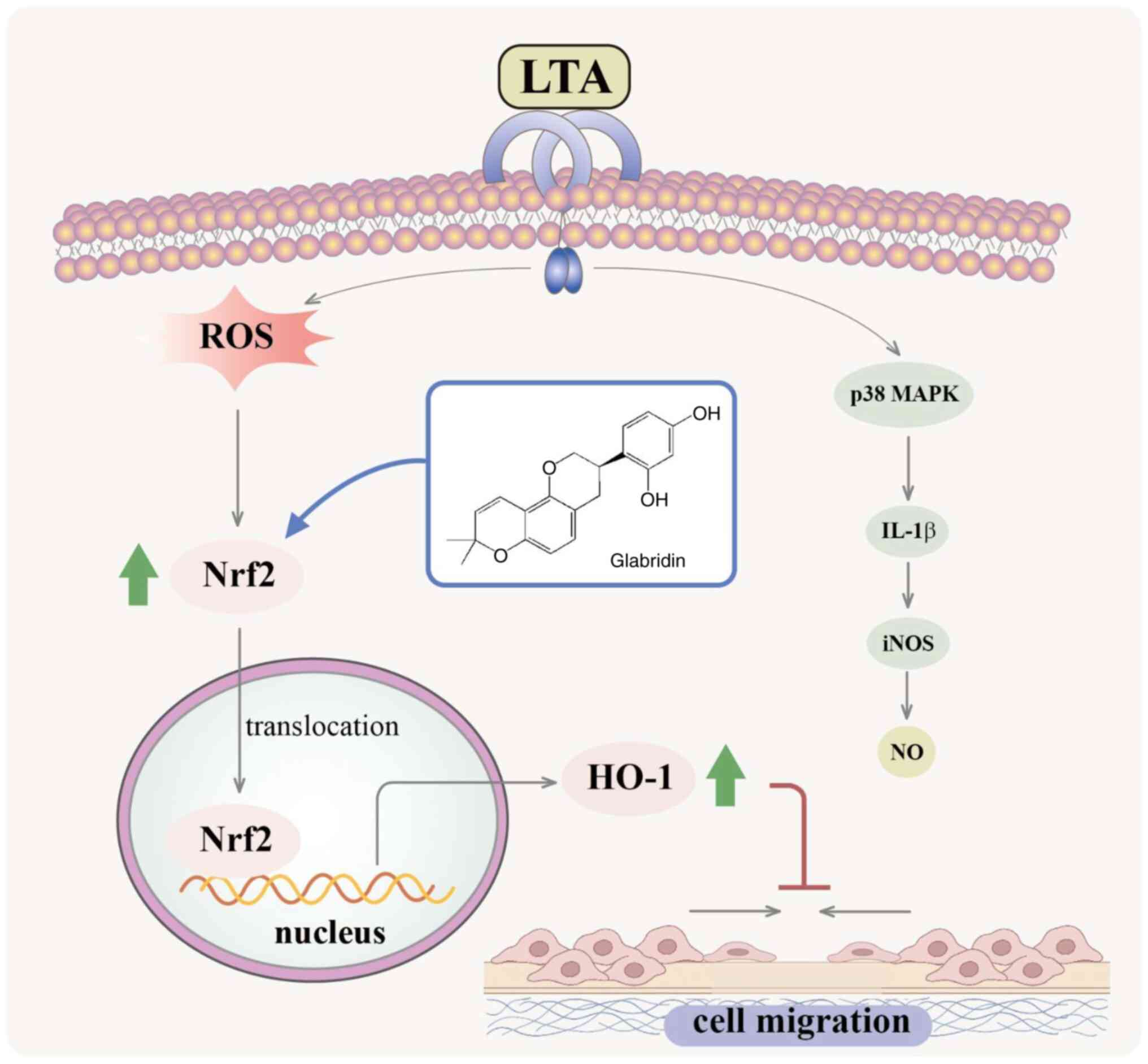

Discussion

Regulation of macrophage migration has gained

increasing attention in inflammatory contexts, given that the

aberrant migratory behavior of activated macrophages contributes to

tissue damage and disease progression (20). Control over immune cell movement

could limit excessive inflammatory responses and promote resolution

(21). Although several studies

have demonstrated the involvement of oxidative and inflammatory

signaling in macrophage motility (22,23),

the specific modulatory role of natural compounds remains

uncertain. The findings of the present study suggested that GBD

suppresses macrophage migration following LTA stimulation and that

this effect was associated with the activation of the Nrf2/HO-1

pathway (Fig. 7). Thus, GBD may be

a novel avenue for therapies targeting macrophage dynamics in

inflammation-related conditions.

Notably, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which is derived

from Gram-negative bacteria, primarily activates TLR4 signaling.

Although both LTA and LPS initiate innate immune responses, their

receptor engagement, downstream signaling profiles and temporal

dynamics differ. Clinically, LPS-related endotoxemia is commonly

associated with sepsis caused by Gram-negative infections, such as

Escherichia coli or Pseudomonas aeruginosa. By

contrast, LTA is implicated in Gram-positive bacterial infections,

including Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae,

and Enterococcus species, which contribute to pneumonia,

endocarditis, and skin and soft tissue infections (24). In research on pulmonary diseases,

both LPS and LTA have been employed as experimental stimuli to

mimic bacterial infection and elicit innate immune responses in

lung models. In animal studies, LPS is widely used to induce acute

lung injury or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) because

of its potent ability to activate neutrophils, disrupt endothelial

barriers, and promote cytokine storms through TLR4-dependent

signaling (25,26). By contrast, LTA activates alveolar

macrophages, modulates surfactant expression, and contributes to

the development of Gram-positive pneumonia (27). Although LTA-induced responses are

generally less systemically severe than LPS-induced responses are,

evidence increasingly suggests that chronic or repeated exposure to

LTA can provoke sustained lung inflammation, epithelial damage, and

macrophage-driven remodeling (27,28).

These differential effects underscore a need to distinguish between

Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial stimuli in evaluations of

pulmonary immune responses and corresponding therapeutic

strategies. In the present study, LTA stimulation induced a marked

increase in alveolar macrophage migration, elevated ROS levels and

activated the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. These findings indicated that

Gram-positive bacterial components influence macrophage behavior

through stress-responsive mechanisms, providing novel insights into

cell dynamics during bacterial exposure.

Alveolar macrophages are specialized tissue-resident

immune cells located within the alveolar lumen, where they play a

critical role in maintaining pulmonary homeostasis and coordinating

immune surveillance (29). Unlike

circulating monocytes or recruited inflammatory macrophages,

alveolar macrophages originate from fetal monocytes and their

population is self-renewing (30,31).

Under steady-state conditions, they exhibit a relatively quiescent

phenotype, clearing inhaled particles, apoptotic cells and

pathogens without eliciting excessive inflammation (32). Due to their position at the

interface between the airway epithelium and the external

environment, their activity must be tightly regulated to avoid

compromising alveolar barrier integrity (33). In the present study, MH-S cells

were employed as an in vitro model because of their

established relevance in studies of pulmonary innate immunity

(34). This model provided a

suitable framework to investigate the regulatory effects of GBD on

alveolar macrophage migration.

The Nrf2/HO-1 pathway is a central regulator of

cellular homeostasis under stress (35–37).

Upon activation, the transcription factor Nrf2 translocates to the

nucleus to induce cytoprotective genes (38). HO-1 was chosen as the canonical

marker because it is not only a robustly induced Nrf2 target in

macrophages (39), but also

because its enzymatic products actively regulate inflammation and

macrophage migration (40,41), positioning it at the mechanistic

nexus of GBD's effects. While this pathway is known to modulate

immune cell behavior, including migration (42,43),

its role in response to specific bacterial components such as LTA

was unclear.

To further refine the mechanistic profile, the

present study also examined additional inflammatory and oxidative

stress markers. GBD displayed a selective pattern of activity. GBD

markedly suppressed LTA-induced IL-1β mRNA expression, yet had no

effect on TNF-α or IL-6 levels. Similarly, while the steady-state

antioxidant enzyme SOD1 remained unchanged, GBD markedly reduced

later-stage oxidative markers, including 24-h lipid peroxidation

(MDA) and nitric oxide (NO) production. These supplementary

findings suggested that HO-1 is likely to be a prominent downstream

effector of GBD in this setting, consistent with reports that the

Nrf2/HO-1 axis can provide real-time protection against oxidative

insults (37,38). and that HO-1 products can modulate

inflammatory cell migration (44,45).

Dysregulated macrophage migration has been

implicated in inflammatory lung diseases, contributing to both

excessive inflammation and impaired pathogen clearance (46). While alveolar macrophages are

generally sessile under homeostatic conditions (4), they can adopt a migratory phenotype

upon microbial stimulation to support immune surveillance (33,47).

To assess GBD's effect on this process, the present study employed

two complementary approaches: The wound-healing assay a

well-established method for assessing collective motility and the

Transwell assay for directional chemotaxis. In both systems, LTA

stimulation increased macrophage migration, whereas GBD treatment

reduced this response. The inhibitory effect was attenuated by the

Nrf2 inhibitor ML385, suggesting that Nrf2 signaling contributes to

this regulation. Consistent outcomes from both assays supported the

reliability of these findings and provided a rationale for further

validation of the underlying mechanism.

To rigorously validate the essential role of Nrf2,

the present study employed both pharmacological inhibition and

genetic knockdown approaches. The Nrf2 inhibitor ML385 partly

reversed the anti-migratory effects of GBD, while silencing Nrf2

with siRNA markedly attenuated the GBD-induced upregulation of HO-1

mRNA. This convergence of evidence from two distinct methodologies

supported the involvement of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling in mediating the

effect of GBD. Furthermore, the specific downstream effectors

mediating this anti-migratory response remain to be elucidated.

Future studies should therefore examine additional Nrf2 targets,

including other cytoprotective enzymes beyond HO-1, such as NQO1,

as well as proteins directly involved in cell motility,

particularly matrix metalloproteinases (such as MMP-2 and MMP-9),

which are functionally linked to macrophage migration (48).

The present study offered novel mechanistic insights

regarding how GBD affects macrophage behavior under LTA

stimulation. LTA exposure was sufficient to induce pronounced

migratory activity in alveolar macrophages, highlighting its

capacity to modulate innate immune cell motility. GBD pretreatment

markedly reduced macrophage migration, possibly because of the

increased nuclear accumulation of Nrf2 and elevated HO-1

expression. Pharmacological inhibition with ML385 and genetic

knockdown with siRNA both attenuated the antimigratory effects of

GBD, supporting the involvement of Nrf2 activation in mediating

this response. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first

study to demonstrate that GBD modulated LTA-induced alveolar

macrophage migration through mechanisms involving the Nrf2/HO-1

pathway. These findings revealed a novel functional aspect of GBD

in controlling macrophage dynamics, suggesting it holds potential

relevance in preventing dysregulated cell migration associated with

pulmonary inflammation.

The clinical implications of modulating macrophage

migration are extensive. Aberrant cell motility is a recognized

pathological feature in a wide range of diseases; for instance,

excessive macrophage infiltration drives pulmonary conditions such

as COPD and ARDS, while insufficient migration can impair pathogen

clearance and tissue repair (46,49–52).

Beyond the lung, macrophage trafficking is also pivotal in the

progression of cancer, atherosclerosis and autoimmune diseases

(53). The present study thus

positioned GBD as a potential modulator in these contexts. Notably,

the temporal dynamics of GBD's antimigratory effects have important

therapeutic implications. The rapid onset of action suggested

potential utility in acute inflammatory conditions where early

intervention is critical. However, the attenuated long-term effects

indicated that sustained therapeutic benefits may require optimized

dosing regimens or combination approaches. This nuanced profile

supported the strategy of using pharmacological agents to modulate,

rather than abolish, macrophage migration to restore immune

balance. Therefore, GBD may hold potential as a modulator for

diseases involving immune cell dysregulation.

Macrophage migration and polarization are

functionally interlinked, particularly under inflammatory

conditions where M1-polarized cells exhibit enhanced motility

(54–56). This relationship is often

bidirectional, as migration into a pro-inflammatory

microenvironment can further reinforce M1 polarization (57). In this context, the LTA-induced

migration observed may reflect a shift toward an activated,

pro-inflammatory M1-like state. Measurement of nitric oxide (NO)

production, a marker often associated with M1 activation, supported

this notion. However, a more comprehensive assessment using

canonical polarization markers (such as iNOS, CD86 and Arg1) will

be valuable in future studies to further establish this link.

While the present study established a mechanistic

link between GBD, Nrf2/HO-1 activation and suppressed macrophage

migration, several limitations should be acknowledged. One

limitation is that the investigation was confined to in

vitro models. Future in vivo studies are necessary to

validate the physiological relevance of the findings and to assess

downstream pathophysiological implications, such as the effect of

GBD on alveolar-capillary barrier integrity. Another limitation is

that the mechanistic focus was restricted to the Nrf2/HO-1 axis.

The role of other critical components of cell motility,

particularly adhesion molecules (such as integrins, selectins), was

not assessed and represents an important avenue for future

research. A further limitation is that the analysis of oxidative

stress was not exhaustive. Future work should therefore include a

more comprehensive profiling of oxidative stress parameters; for

instance, by measuring protein carbonyl formation and assessing the

cellular glutathione antioxidant system. Finally, for GBD to

advance as a pharmacologically viable compound, its pharmacokinetic

profile, particularly bioavailability and metabolic stability, will

require comprehensive evaluation (58). The observed time-dependent

attenuation of GBD's effects in the present study also highlighted

the need to investigate optimal dosing regimens for sustained

therapeutic efficacy.

The present study demonstrated that GBD attenuated

LTA-induced alveolar macrophage migration by activating the

Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. It integrated molecular, cellular and

functional analyses to reveal a regulatory mechanism by which GBD

affected macrophage motility in response to bacterial stimulation.

These findings broadened the current understanding of the

biological effects of GBD and suggested its potential as a

modulatory agent of immune cell behavior in disease contexts.

Future in vivo investigations and pharmacological profiling

are required to further validate the therapeutic utility and

translational applicability of GBD to inform the development of

novel therapeutic strategies for inflammatory lung diseases.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Science and

Technology Council, Taiwan, R.O.C. (grant nos. NSTC

112-2320-B-038-037-MY3 and NSTC 113-2320-B341-002-MY3), Shin Kong

Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital (grant no. 2025SKHAND011) and Chi Mei

Medical Center-Taipei Medical University (grant no.

111CM-TMU-07).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

JRS designed the study. CHH and CMY wrote the

manuscript. CHH, CMY, CCC, TLY, AGD and CCH performed the

experiments. CCC, TLY and AGD analyzed the data. CMY and JRS

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read

and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Takeuchi O, Hoshino K, Kawai T, Sanjo H,

Takada H, Ogawa T, Takeda K and Akira S: Differential roles of TLR2

and TLR4 in recognition of gram-negative and gram-positive

bacterial cell wall components. Immunity. 11:443–451. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Pai AB, Patel H, Prokopienko AJ, Alsaffar

H, Gertzberg N, Neumann P, Punjabi A and Johnson A: Lipoteichoic

acid from staphylococcus aureus induces lung endothelial cell

barrier dysfunction: Role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species.

PLoS One. 7:e492092012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Percy MG and Gründling A: Lipoteichoic

acid synthesis and function in gram-positive bacteria. Annu Rev

Microbiol. 68:81–100. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Hussell T and Bell TJ: Alveolar

macrophages: Plasticity in a tissue-specific context. Nat Rev

Immunol. 14:81–93. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Boyd AR, Shivshankar P, Jiang S, Berton MT

and Orihuela CJ: Age-related defects in TLR2 signaling diminish the

cytokine response by alveolar macrophages during murine

pneumococcal pneumonia. Exp Gerontol. 47:507–518. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Liu CF, Drocourt D, Puzo G, Wang JY and

Riviere M: Innate immune response of alveolar macrophage to house

dust mite allergen is mediated through TLR2/-4 co-activation. PLoS

One. 8:e759832013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Aggarwal S, Dimitropoulou C, Lu Q, Black

SM and Sharma S: Glutathione supplementation attenuates

lipopolysaccharide-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis

in a mouse model of acute lung injury. Front Physiol. 3:1612012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Birben E, Sahiner UM, Sackesen C, Erzurum

S and Kalayci O: Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense. World

Allergy Organ J. 5:9–19. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Malainou C, Abdin SM, Lachmann N, Matt U

and Herold S: Alveolar macrophages in tissue homeostasis,

inflammation, and infection: Evolving concepts of therapeutic

targeting. J Clin Invest. 133:e1705012023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Harvey CJ, Thimmulappa RK, Sethi S, Kong

X, Yarmus L, Brown RH, Feller-Kopman D, Wise R and Biswal S:

Targeting Nrf2 signaling improves bacterial clearance by alveolar

macrophages in patients with COPD and in a mouse model. Sci Transl

Med. 3:78ra322011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Itoh K, Chiba T, Takahashi S, Ishii T,

Igarashi K, Katoh Y, Oyake T, Hayashi N, Satoh K, Hatayama I, et

al: An Nrf2/small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase

II detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 236:313–322. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ma Q: Role of nrf2 in oxidative stress and

toxicity. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 53:401–426. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Itoh K, Wakabayashi N, Katoh Y, Ishii T,

Igarashi K, Engel JD and Yamamoto M: Keap1 represses nuclear

activation of antioxidant responsive elements by Nrf2 through

binding to the amino-terminal Neh2 domain. Genes Dev. 13:76–86.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ryter SW, Alam J and Choi AM: Heme

oxygenase-1/carbon monoxide: From basic science to therapeutic

applications. Physiol Rev. 86:583–650. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Meng X, Hu L and Li W: Baicalin

ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice by

suppressing oxidative stress and inflammation via the activation of

the Nrf2-mediated HO-1 signaling pathway. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch

Pharmacol. 392:1421–1433. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Luan R, Ding D and Yang J: The protective

effect of natural medicines against excessive inflammation and

oxidative stress in acute lung injury by regulating the Nrf2

signaling pathway. Front Pharmacol. 13:10390222022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Shin J, Choi LS, Jeon HJ, Lee HM, Kim SH,

Kim KW, Ko W, Oh H and Park HS: Synthetic glabridin derivatives

inhibit LPS-induced inflammation via MAPKs and NF-κB Pathways in

RAW264.7 macrophages. Molecules. 28:21352023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Shu L, Zhang Z, Wang N, Yin Q, Chao Y and

Ge X: Glabridin ameliorates hemorrhagic shock induced acute kidney

injury by activating Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol

Basis Dis. 1871:1678102025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Murrey MW, Ng IT and Pixley FJ: The role

of macrophage migratory behavior in development, homeostasis and

tumor invasion. Front Immunol. 15:14800842024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Rodriguez-Morales P and Franklin RA:

Macrophage phenotypes and functions: Resolving inflammation and

restoring homeostasis. Trends Immunol. 44:986–998. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Tran N and Mills EL: Redox regulation of

macrophages. Redox Biol. 72:1031232024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Breßer M, Siemens KD, Schneider L,

Lunnebach JE, Leven P, Glowka TR, Oberländer K, De Domenico E,

Schultze JL, Schmidt J, et al: Macrophage-induced enteric

neurodegeneration leads to motility impairment during gut

inflammation. EMBO Mol Med. 17:301–335. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Gatica S, Fuentes B, Rivera-Asin E,

Ramírez-Céspedes P, Sepúlveda-Alfaro J, Catalán EA, Bueno SM,

Kalergis AM, Simon F, Riedel CA and Melo-Gonzalez F: Novel evidence

on sepsis-inducing pathogens: From laboratory to bedside. Front

Microbiol. 14:11982002023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

He J, Zhao Y, Fu Z, Chen L, Hu K, Lin X,

Wang N, Huang W, Xu Q, He S, et al: A novel tree shrew model of

lipopolysaccharide-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. J

Adv Res. 56:157–165. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhang Y, Han Z, Jiang A, Wu D, Li S, Liu

Z, Wei Z, Yang Z and Guo C: Protective effects of pterostilbene on

lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice by inhibiting

NF-κB and activating Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathways. Front Pharmacol.

11:5918362021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Knapp S, von Aulock S, Leendertse M,

Haslinger I, Draing C, Golenbock DT and van der Poll T:

Lipoteichoic acid-induced lung inflammation depends on TLR2 and the

concerted action of TLR4 and the platelet-activating factor

receptor. J Immunol. 180:3478–3484. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Hoogerwerf JJ, de Vos AF, Bresser P, van

der Zee JS, Pater JM, de Boer A, Tanck M, Lundell DL, Her-Jenh C,

Draing C, et al: Lung inflammation induced by lipoteichoic acid or

lipopolysaccharide in humans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 178:34–41.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Hou F, Xiao K, Tang L and Xie L: Diversity

of macrophages in lung homeostasis and diseases. Front Immunol.

12:7539402021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Guilliams M, De Kleer I, Henri S, Post S,

Vanhoutte L, De Prijck S, Deswarte K, Malissen B, Hammad H and

Lambrecht BN: Alveolar macrophages develop from fetal monocytes

that differentiate into long-lived cells in the first week of life

via GM-CSF. J Exp Med. 210:1977–1992. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Röszer T: Understanding the biology of

self-renewing macrophages. Cells. 7:1032018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Guan F, Wang R, Yi Z, Luo P, Liu W, Xie Y,

Liu Z, Xia Z, Zhang H and Cheng Q: Tissue macrophages: Origin,

heterogenity, biological functions, diseases and therapeutic

targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 10:932025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ahmad S, Nasser W and Ahmad A: Epigenetic

mechanisms of alveolar macrophage activation in chemical-induced

acute lung injury. Front Immunol. 15:14889132024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Mbawuike IN and Herscowitz HB: MH-S, a

murine alveolar macrophage cell line: Morphological, cytochemical,

and functional characteristics. J Leukoc Biol. 46:119–127. 1989.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Loboda A, Damulewicz M, Pyza E, Jozkowicz

A and Dulak J: Role of Nrf2/HO-1 system in development, oxidative

stress response and diseases: An evolutionarily conserved

mechanism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 73:3221–3247. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Li N, Hao L, Li S, Deng J, Yu F, Zhang J,

Nie A and Hu X: The NRF-2/HO-1 signaling pathway: A promising

therapeutic target for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic

liver disease. J Inflamm Res. 17:8061–8083. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Su H, Wang Z, Zhou L, Liu D and Zhang N:

Regulation of the Nrf2/HO-1 axis by mesenchymal stem cells-derived

extracellular vesicles: Implications for disease treatment. Front

Cell Dev Biol. 12:13979542024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

O'Rourke SA, Shanley LC and Dunne A: The

Nrf2-HO-1 system and inflammaging. Front Immunol. 15:14570102024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Alam J and Cook JL: How many transcription

factors does it take to turn on the heme oxygenase-1 gene? Am J

Respir Cell Mol Biol. 36:166–174. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Vijayan V, Wagener FADTG and Immenschuh S:

The macrophage heme-heme oxygenase-1 system and its role in

inflammation. Biochem Pharmacol. 153:159–167. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Wang L and He C: Nrf2-mediated

anti-inflammatory polarization of macrophages as therapeutic

targets for osteoarthritis. Front Immunol. 13:9671932022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Feng R, Morine Y, Ikemoto T, Imura S,

Iwahashi S, Saito Y and Shimada M: Nrf2 activation drive

macrophages polarization and cancer cell epithelial-mesenchymal

transition during interaction. Cell Commun Signal. 16:542018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Han H, Gao Y, Chen B, Xu H, Shi C, Wang X,

Liang Y, Wu Z, Wang Z, Bai Y and Wu C: Nrf2 inhibits M1 macrophage

polarization to ameliorate renal ischemia-reperfusion injury

through antagonizing NF-κB signaling. Int Immunopharmacol.

143:1133102024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Jagadeesh ASV, Fang X, Kim SH,

Guillen-Quispe YN, Zheng J, Surh YJ and Kim SJ: Non-canonical vs.

canonical functions of heme oxygenase-1 in cancer. J Cancer Prev.

27:7–15. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Freitas A, Alves-Filho JC, Secco DD, Neto

AF, Ferreira SH, Barja-Fidalgo C and Cunha FQ: Heme

oxygenase/carbon monoxide-biliverdin pathway down regulates

neutrophil rolling, adhesion and migration in acute inflammation.

Br J Pharmacol. 149:345–354. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Cheng P, Li S and Chen H: Macrophages in

lung injury, repair, and fibrosis. Cells. 10:4362021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Chen S, Saeed AFUH, Liu Q, Jiang Q, Xu H,

Xiao GG, Rao L and Duo Y: Macrophages in immunoregulation and

therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8:2072023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Ngo V and Duennwald ML: Nrf2 and oxidative

stress: A general overview of mechanisms and implications in human

disease. Antioxidants (Basel). 11:23452022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Matthay MA and Zemans RL: The acute

respiratory distress syndrome: Pathogenesis and treatment. Annu Rev

Pathol. 6:147–163. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Barnes PJ: Inflammatory mechanisms in

patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin

Immunol. 138:16–27. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Gordon S and Plüddemann A: Macrophage

clearance of apoptotic cells: A critical assessment. Front Immunol.

9:1272018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Wynn TA and Vannella KM: Macrophages in

tissue repair, regeneration, and fibrosis. Immunity. 44:450–462.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Gordon S, Plüddemann A and Martinez

Estrada F: Macrophage heterogeneity in tissues: Phenotypic

diversity and functions. Immunol Rev. 262:36–55. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Mantovani A, Biswas SK, Galdiero MR, Sica

A and Locati M: Macrophage plasticity and polarization in tissue

repair and remodelling. J Pathol. 229:176–185. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Murray PJ, Allen JE, Biswas SK, Fisher EA,

Gilroy DW, Goerdt S, Gordon S, Hamilton JA, Ivashkiv LB, Lawrence

T, et al: Macrophage activation and polarization: Nomenclature and

experimental guidelines. Immunity. 41:14–20. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Auffray C, Fogg D, Garfa M, Elain G,

Join-Lambert O, Kayal S, Sarnacki S, Cumano A, Lauvau G and

Geissmann F: Monitoring of blood vessels and tissues by a

population of monocytes with patrolling behavior. Science.

317:666–670. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Lawrence T and Natoli G: Transcriptional

regulation of macrophage polarization: Enabling diversity with

identity. Nat Rev Immunol. 11:750–761. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Xie L, Diao Z, Xia J, Zhang J, Xu Y, Wu Y,

Liu Z, Jiang C, Peng Y, Song Z, et al: Comprehensive evaluation of

metabolism and the contribution of the hepatic first-pass effect in

the bioavailability of glabridin in rats. J Agric Food Chem.

71:1944–1956. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|