Introduction

Osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH) is a

degenerative hip joint disease that worsens over time (1). ONFH is characterized by bone cell

death due to a lack of blood supply, which can lead to joint

collapse and hip dysfunction (1).

The causes of ONFH are complex and involve mechanical injury,

genetic predisposition and biochemical imbalances (2,3).

Among these factors, steroid use is reported in ~51% of ONFH cases

(4). Prolonged or high-dose

steroid therapy markedly increases the risk of ONFH, leading to

steroid-induced ONFH (SONFH) (1).

For example, in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, the

corticosteroid dosage is positively associated with the occurrence

of ONFH. Daily doses as low as 10 mg have been associated with a

3.6% increase in risk, while doses >40 mg greatly increase the

chance of developing ONFH (5).

Steroids damage bone and blood vessel health through various

mechanisms, including endothelial cell dysfunction and reduced

angiogenesis, ultimately impairing blood flow supply (3,6).

Endothelial cells serve an important role in angiogenesis, as their

growth, migration and tube formation are important for repairing

bone tissue (6,7). When angiogenesis is impaired, bone

regeneration often fails (8).

VEGF, a key factor that promotes angiogenesis, has been shown to

enhance bone repair by stimulating angiogenesis, making it a

potential treatment for ONFH (9–11).

Angiogenesis and osteogenesis are closely linked processes that

occur throughout bone development, maturation, aging and disease

progression (12). Notably,

activation of the VEGF-Notch signaling pathway has been reported to

restore the proliferation of mesenchymal stem cells in aplastic

anemia (13), while the mTOR/AP-1

complex subunit µ-1/VEGF axis regulates endothelial cell growth

(14). Additionally, increasing

hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α/VEGF levels can help to protect

against bone loss in models of nasal obstruction (15). Therefore, understanding the

molecular mechanisms of angiogenesis and endothelial cell function

is important for advancing treatments for ONFH.

Ubiquitination has become an important

post-translational modification for regulating protein stability,

signal transduction and cellular homeostasis (16–19).

Neural precursor cell expressed developmentally downregulated

protein 4 (NEDD4) is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that facilitates

substrate ubiquitination and degradation, thereby influencing

multiple biological processes such as cell proliferation,

migration, angiogenesis and endothelial cell protection (20–22).

NEDD4 has been demonstrated to promote endothelial cell

proliferation, migration and angiogenesis (23). In addition to its role in

endothelial regulation, NEDD4 also affects macrophage autophagy and

tumor cell proliferation, highlighting its versatile function in

maintaining the cellular balance (21,24).

NEDD4 subfamily influences osteogenesis and bone

cell biology (25). By mediating

PTEN degradation, NEDD4 activates the PI3K/AKT pathway, which

promotes cell proliferation and survival. This pathway also

supports angiogenesis through PTEN inactivation and VEGF

upregulation (26–29). Additionally, NEDD4 boosts osteocyte

proliferation and is associated with improved outcomes in

postmenopausal osteoporosis (30,31).

Overall, these findings emphasize the potential of NEDD4 as a

regulator of both angiogenesis and osteogenesis, making it a

promising target in ONFH therapy. The present study was based on

the concept that NEDD4 may serve a role in SONFH. To explore this,

the present study observed how overexpression of NEDD4 affected the

viability, migration and tube formation of bone microvascular

endothelial cells (BMECs). The present study also investigated how

glucocorticoids influenced NEDD4 expression and promoter

methylation, shedding light on how NEDD4 contributes to

angiogenesis and repair in SONFH.

Materials and methods

Construction of the NEDD4

overexpression (OE) vector

Plasmids pcDNA3.1-NEDD4-3×HA (cat. no. HG-HO284338;

HonorGene Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and the negative control (NC)

were transformed into competent E. coli cells (AoLu

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). A total of 2 µl plasmid was combined with

100 µl competent cells, on ice for 30 min. The mixture was

heat-shocked at 42°C for 90 sec and cooled on ice for 3 min.

Subsequently, 700 µl LB (Luria-Bertani) medium (cat. no. L3022;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was added, and the mixture was

incubated at 37°C with shaking at 200 × g for 1 h. This was

followed by plating 60 µl cells onto LB agar containing ampicillin

(Amp) and incubation at 37°C for 12–14 h. A single colony was

selected and inoculated into 20 ml LB medium with 50 µg/ml Amp,

followed by incubation overnight at 37°C. Subsequently, the culture

was scaled up in 50 ml LB/Amp medium and incubated for 12–16 h.

Plasmids were extracted using the HiBind DNA plasmid extraction kit

(Omega Bio-Tek, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. DNA

concentration was determined using an Implen NanoPhotometer (Implen

GmbH) and the sequence was verified by Sanger sequencing (performed

by AoNuo Gene Technology Co., Ltd.). The purified plasmids were

used for cell transfection at a final amount of 2 µg DNA per well

in a 6-well plate, mixed with 6–8 µl PEI-40K transfection reagent

(Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) and incubated at room

temperature for 15 min before being added to BMECs. Cells were

cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 5 h, then refreshed with

complete medium and harvested 48 h post-transfection for subsequent

experiments. OE-NC consisted of the corresponding empty vector

backbone (pcDNA3.1 empty vector; cat. no. V79020; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), ensuring that any observed effects were

specifically attributable to NEDD4 OE. siRNA sequences, including

the NC, are listed in Table SI.

The purified plasmids were used for transfection at a final amount

of 2 µg DNA per well in a 6-well plate.

Transient transfection of BMECs

For the present study, BMECs were obtained from AoLu

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (cat. no. ORC0562). BMECs were seeded at a

density of 6×105 cells per well in 6-well plates. BMECs

were cultured in complete Endothelial Cell Medium (ScienCell

Research Laboratories) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum

(FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (100 U/ml and 100 µg/ml,

respectively; all Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C.

After washing with PBS twice, cells were cultured in 1.8 ml

serum-free basal medium (Endothelial Cell Medium). To prepare the

transfection complexes, solution A, consisting of 100 µl serum-free

medium with 20 nM siRNA, was mixed with solution B comprising 100

µl serum-free medium with 6–8 µl PEI 40K (Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd.). Subsequently, this mixture was added

dropwise to each well. The cells were incubated at 37°C for 5 h.

The cells were harvested 48 h after transfection for subsequent

experiments. Cells were centrifuged at 200 × g for 5 min at 4°C,

resuspended in Cell Freezing Medium; Gibco; cat. no. 12648010),

transferred to cryovials and stored at −80°C overnight before being

transferred to liquid nitrogen for long-term storage.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

BMECs were divided into eight groups: OE-NC,

OE-NEDD4, control, si-NEDD4, si-mTOR-1, si-mTOR-2, si-mTOR-3 and

si-NEDD4 + si-mTOR. Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). according to the manufacturer's

protocol. The quality and concentration of the RNA were then

determined spectrophotometrically. First-strand cDNA synthesis was

performed using the SureScript First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit

(Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.). qPCR was performed with

SYBR Green Master Mix (Takara Bio, Inc.) on a StepOnePlus™

Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). RT was performed

at 42°C for 15 min, followed by 85°C for 5 sec. qPCR thermocycling

conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 30

sec, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 30 sec.

Relative mRNA expression was calculated using the

2^-ΔΔCq method (32).

The primers used are listed in Table

SII. GAPDH was used as the reference gene.

Western blot analysis of NEDD4

expression

Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection with

si-NEDD4, pcDNA3.1-NEDD4-3×HA or the respective controls. Total

proteins were extracted using RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime

Biotechnology) supplemented with protease inhibitors (cat. no.

78430; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Protein concentrations were

quantified using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (cat. no. 23225; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Equal quantities of protein (20–30

µg/lane) were separated via 8–10% SDS-PAGE and subsequently

transferred onto PVDF membranes (MilliporeSigma). Membranes were

blocked with 5% BSA (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by overnight incubation

at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: Anti-NEDD4 (1:2,000;

cat. no. AF4636; Affinity Biosciences) and anti-β-actin (1:25,000;

cat. no. 66009-1-Ig; Proteintech Group, Inc.) as the loading

control. After washing with TBST (0.1% Tween-20), membranes were

incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies: Goat

anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (1:3,000; cat. no. GB23303; Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd.) and goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (1:5,000; cat.

no. GB23301; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) for 1 h at room

temperature. Protein bands were visualized using the Pierce ECL

Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

band intensities were semi-quantified using ImageJ software

(version 1.53; National Institutes of Health).

MTT assay

Cells were incubated in 90 µl DMEM/F12 (Meilunbio)

supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin with 10 µl

5 mg/ml MTT solution (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.) for 4 h. The supernatants were then removed, and 110 µl

DMSO formazan solubilization solution was added. The absorbance was

measured at 560 nm using a Bio-Rad microplate reader.

5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU)

proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was evaluated using the EdU Cell

Proliferation Kit (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) according

to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, cells from various

experimental groups were seeded into 24-well plates at a density of

1×105 cells/well and incubated with EdU working solution

for 2 h at 37°C. After fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde (Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) at room temperature

for 15 min and permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100, cells were

stained using the Apollo® 567 fluorescent dye at room

temperature for 30 min, according to the manufacturer's

instructions.. Images were captured using a Nikon fluorescence

microscope (Nikon Corporation) Cells that incorporated nuclear EdU

exhibited green fluorescence. The percentage of EdU-positive cells

was calculated from five randomly chosen fields per group and the

data were statistically analyzed using ImageJ software (version

1.53; National Institutes of Health).

Tube formation assay

Matrigel® (150 µl/well; Corning, Inc.)

was added to 48-well plates and allowed to solidify at 37°C for 30

min. Cells (1×105/well) were then seeded and incubated

at 37°C for 4 h. Cells were stained with Calcein-AM (2 µM; Beyotime

Biotechnology) at 37°C for 30 min to visualize the tubular network.

The formation of tubes was observed and images were captured under

an inverted fluorescence microscope (Motic Biological Technology

Co., Ltd.).

Wound healing assay

BMECs were seeded into 6-well plates in triplicate

and cultured until reaching 100% confluence. Cells were

serum-starved overnight prior to the assay. Cells were cultured in

DMEM/F12 with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, USA) and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin. A linear scratch was created across the

cell monolayer using a sterile 200-µl pipette tip. Detached cells

were removed by rinsing the wells three times with PBS, after which

fresh culture medium containing NEDD4 overexpression plasmid,

si-NEDD4 and their respective negative controls. Images were

captured at 0, 24 and 48 h using an inverted light microscope

(Motic Biological Technology Co., Ltd.). The scratch width was

measured in pixels using ImageJ software (version 1.53; National

Institutes of Health), with the width at 0 h defined as 100%

(baseline); the widths at subsequent time points were expressed as

a percentage relative to this baseline. The mean value from three

independent experiments was used for analysis.

Methylation-specific PCR

Genomic DNA was extracted from BMECs using a DNA

extraction kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Inc.) and then converted to

bisulfite using the EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit (Zymo Research

Corp.). The methylation status was detected through PCR using Taq

DNA Polymerase (Takara Bio, Inc.) with the following primers:

NEDD4-M (methylated): Forward, 5′-ATTTTTTGTAGAAAGATTTGAAGGC-3′ and

reverse, 5′-CGCAACTCTATAATTAAATTTAACGAT-3′; NEDD4-U (unmethylated):

Forward, 5′-TTTTTGTAGAAAGATTTGAAGGTGT-3′ and Reverse,

5′-CACAACTCTATAATTAAATTTAACAAT-3′. The thermocycling conditions

were as follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed

by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 58°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 30

sec and final extension at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were

separated on 2% agarose gels and visualized using an E-Gel Imager

system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with ethidium bromide

staining The experiment included five groups as follows: i)

H2O (blank negative control); ii) BMECs treated with PBS

(vehicle control); iii) BMECs treated with 1 µM methylprednisolone

(MePr; MedChemExpress); iv) BMECs treated with 5 µM 5-azacytidine

(5-AZA; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA); and v) BMECs co-treated with

MePr (1 µM) and 5-AZA (5 µM). All treatments were performed at 37°C

for 48 h under standard cell-culture conditions.

Immunoprecipitation (IP) assay

Proteins were extracted from the cells using RIPA

buffer (Beyotime Biotechnology; cat. no. P0013B) that contained a

protease inhibitor cocktail (cat. no. 04693132001; Roche

Diagnostics). The cell lysates were then cleared by centrifugation

at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The protein concentrations were

measured using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (cat. no. 23225; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). A total of 500 µg lysate (300 µl) was

incubated with Protein A/G magnetic beads (50 µl; cat. no. 88802;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) prebound to anti-ubiquitin antibody

(2 µg; 1:2,000; cat. no. ER65617; Hangzhou HuaAn Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.) overnight at 4°C. Beads were washed three times with cold PBS

containing 0.1% Tween-20, followed by centrifugation at 2,000 × g

for 3 min at 4°C. The immunocomplexes were eluted by boiling for 5

min in SDS loading buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology).

Subsequently, 30 µg of total protein per lane was separated using

8–10% SDS-PAGE, transferred onto PVDF membranes, and blocked with

5% BSA (Servicebio) for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were

incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, followed by 1 h

incubation with secondary antibodies at room temperature, and then

incubated with the following primary antibodies:, anti-mTOR (1:20;

cat. no. AF6308; Affinity Biosciences); anti-ubiquitin (1:2,000;

cat. no. ER65617; Hangzhou HuaAn Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). This was

followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG

(H+L) (1:3,000; cat. no. GB23303; Servicebio);Goat anti-mouse IgG

(H+L) (1:5,000; cat. no. GB23301; Servicebio), and visualization

using ECL reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Images of

bands were captured the ChemiDoc™ Touch Imaging System (cat. no.

1708370; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) and band intensities were

semi-quantified using ImageJ software version 1.54 (National

Institutes of Health). Statistical analysis was carried out using

GraphPad Prism 8 (Dotmatics). Western blotting was performed as

aforementioned.

Bioinformatics analysis

The GSE123568 dataset (33) from the Gene Expression Omnibus

(GEO) database (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), which includes gene

expression profiles from 30 patients with SONFH and 10 controls,

was analyzed. Differential expression analysis was performed using

the ‘limma’ package (v3.58.1; bioconductor.org/packages/limma/) in

R software (version 4.3.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing,

Vienna, Austria), with the cut-off criteria of |log2FC| ≥1 and

adjusted P<0.05. Additional analyses included weighted gene

co-expression network analysis (WGCNA; version 1.72–5;

horvath.genetics.ucla.edu/html/CoexpressionNetwork/), single-sample

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (ssGSEA; GSVA version 1.46.0;

http://bioconductor.org/packages/GSVA/), and random

forest and support vector machine (SVM) modeling (MetaboAnalyst

version 4.0.0; http://www.metaboanalyst.ca/). Principal component

analysis (PCA) was performed using the ‘FactoMineR’ package

(version 2.8; http://cran.r-project.org/package=FactoMineR) to

visualize sample clustering. Enrichment analysis was conducted

using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Orthology

Based Annotation System (http://bioinfo.org/kobas/) Gene Ontology (GO)

annotation. Protein–protein interaction networks were constructed

using STRING (version 12.0; string-db.org/). Pathway enrichment

analysis was performed using the REACTOME database (reactome.org/).

All data visualization was performed in R using the ‘ggplot2’

package (version 3.5.1; cran.r-project.org/package=ggplot2).

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve

analysis was performed using the pROC package in R to evaluate the

diagnostic performance of key ubiquitination-related genes and

multivariate predictive models.

Gene selection frequencies were calculated as the

number of times each gene was identified as an important variable

across repeated resampling steps during model training.

The present study retrieved the gene expression

dataset GSE123568 from the GEO database, a publicly available

functional genomics repository. This dataset was created using the

GPL15207 Affymetrix Human Gene Expression Array platform (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and contained peripheral blood mononuclear

cell samples from 40 individuals, including 30 patients with SONFH

and 10 controls without SONFH. For more details on clinical

information and experimental protocols, please refer to the

original submission. In the present study, the dataset was used to

analyze differential gene expression and then subjected to

bioinformatics techniques such as functional enrichment and network

analysis to pinpoint candidate genes and signaling pathways

associated with SONFH.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of

the mean. The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8

(Dotmatics). For comparisons between two groups, unpaired Student's

t-tests were used. For comparisons among multiple groups, one-way

ANOVA was performed followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test

as the post hoc test. Pearson's correlation test was performed to

evaluate association between gene expression levels. All

experiments were independently repeated ≥3 times to ensure

reproducibility. All statistical analyses included the necessary

corrections for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg false

discovery rate method. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Changes in gene expression after SONFH

are closely associated with ubiquitination in terms of functional

enrichment

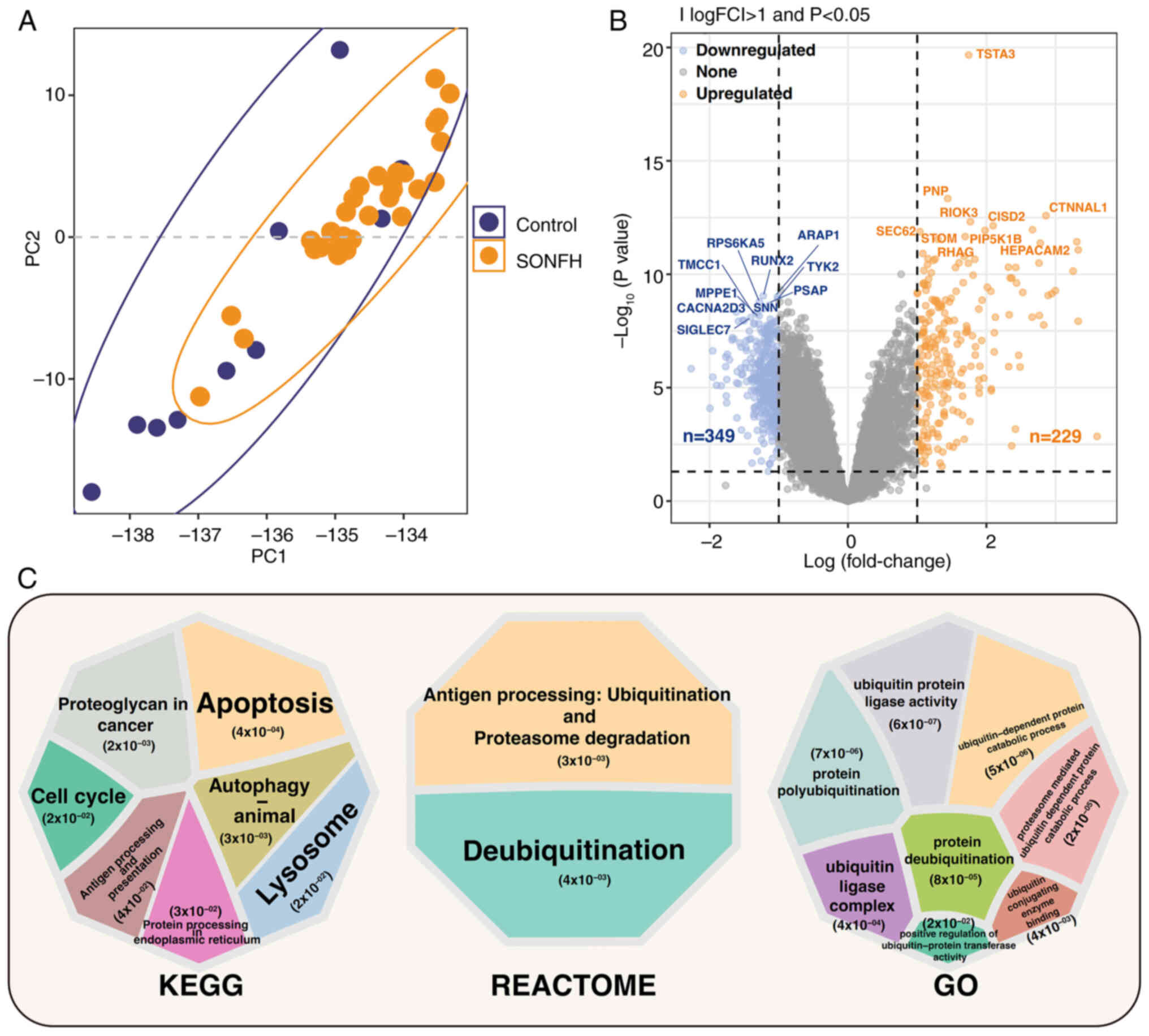

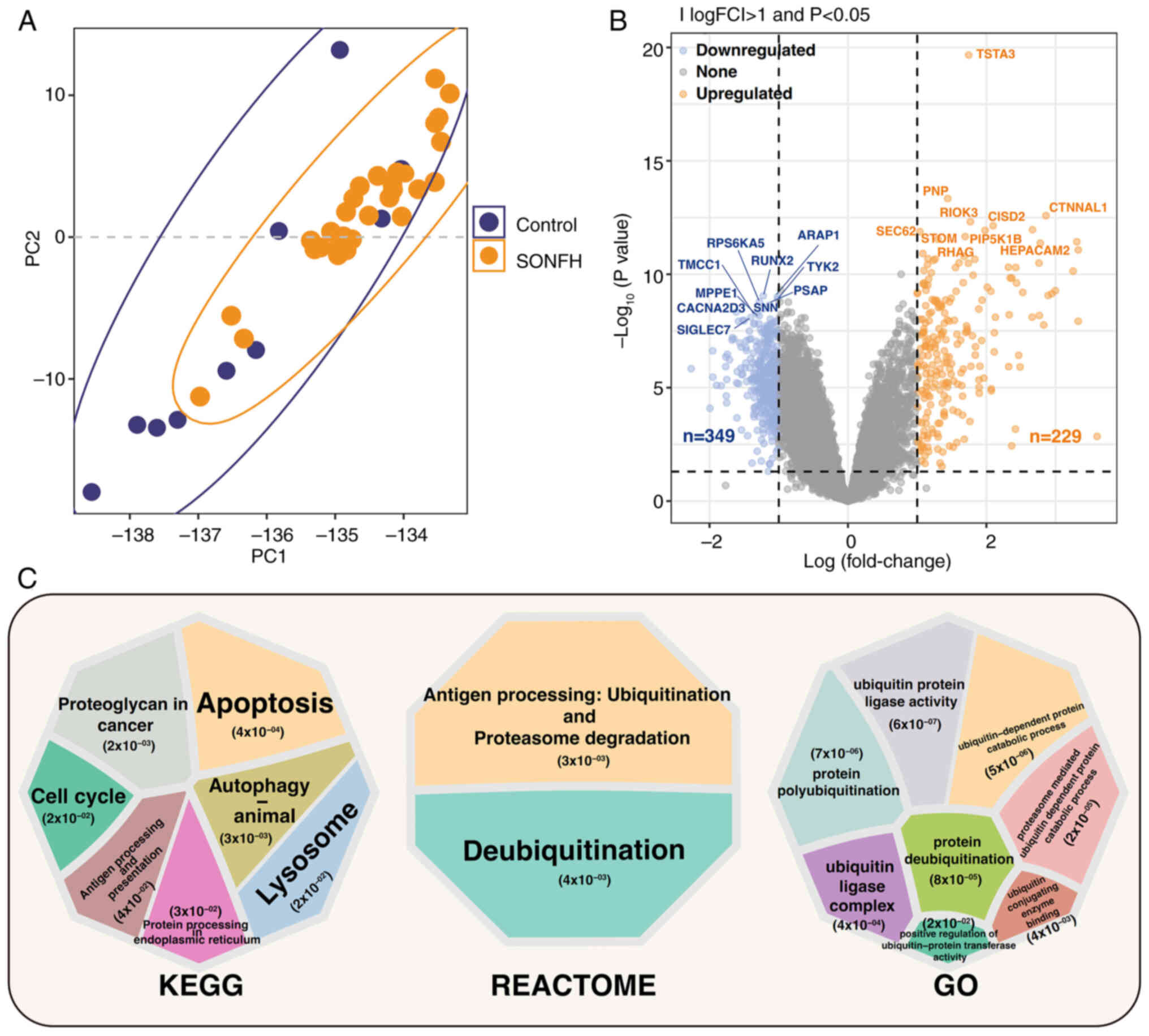

The principal component (PC) analysis performed on

the GSE123568 dataset revealed partial separation between the

control group and the SONFH group, with notable separation in PC1

and PC2, highlighting notable differences in gene expression

patterns (Fig. 1A). Analysis of

differential gene expression revealed 229 upregulated genes and 349

downregulated genes, with significant differences in TSTA3, RIOK3,

STOM, HEPACAM2, RUNX2, ARAP1, TYK2 and SIGLEC7 (Fig. 1B). KEGG enrichment analysis

revealed pathways that were significantly enriched, including,

‘protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum’, ‘lysosome’, ‘cell

cycle’ and ‘autophagy-animal’. The enriched REACTOME pathways

included ‘Deubiquitination’ and ‘Antigen processing: Ubiquitination

& Proteasome degradation’. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment

analysis showed significant enrichment in processes related to

ubiquitination, such as ‘proteasome mediated ubiquitin dependent

protein catabolic process’, ‘ubiquitin protein ligase activity’,

‘ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process’, ‘protein

polyubiquitination’, ‘ubiquitin ligase complex’, ‘ubiquitin

conjugating enzyme binding’, ‘positive regulation of

ubiquitin-protein transferase activity’ and ‘protein

deubiquitination’. These findings indicated significant differences

in gene expression and biological functions between the SONFH and

control groups, particularly in pathways related to ubiquitination

(Fig. 1C).

| Figure 1.Differential gene and pathway

enrichment analysis between the control and SONFH groups. (A) PC

analysis showing the separation between control and SONFH groups.

(B) Results of differential analysis. The x-axis represents

log(fold change) and the y-axis represents-log10

(P-value). Differentially expressed genes are categorized as

upregulated, downregulated or not significantly changed. Genes with

|log(FC)|>1 and P<0.05 were considered significantly

differentially expressed (orange for upregulated, blue for

downregulated and gray for not significantly changed). (C) KEGG,

REACTOME and GO enrichment results, with significant pathways

highlighted. The pathways were selected based on P<0.05 and

|log(FC)| >1). Each circle represents one pathway; the size of

the circle corresponds to the number of genes, while the color

indicates-log10 (P-value), with darker colors

representing higher significance. SONFH, steroid-induced

osteonecrosis of the femoral head; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of

Genes and Genomes; GO, Gene Ontology; FC, fold change; PC,

principal component. |

Association of ubiquitination with

SONFH

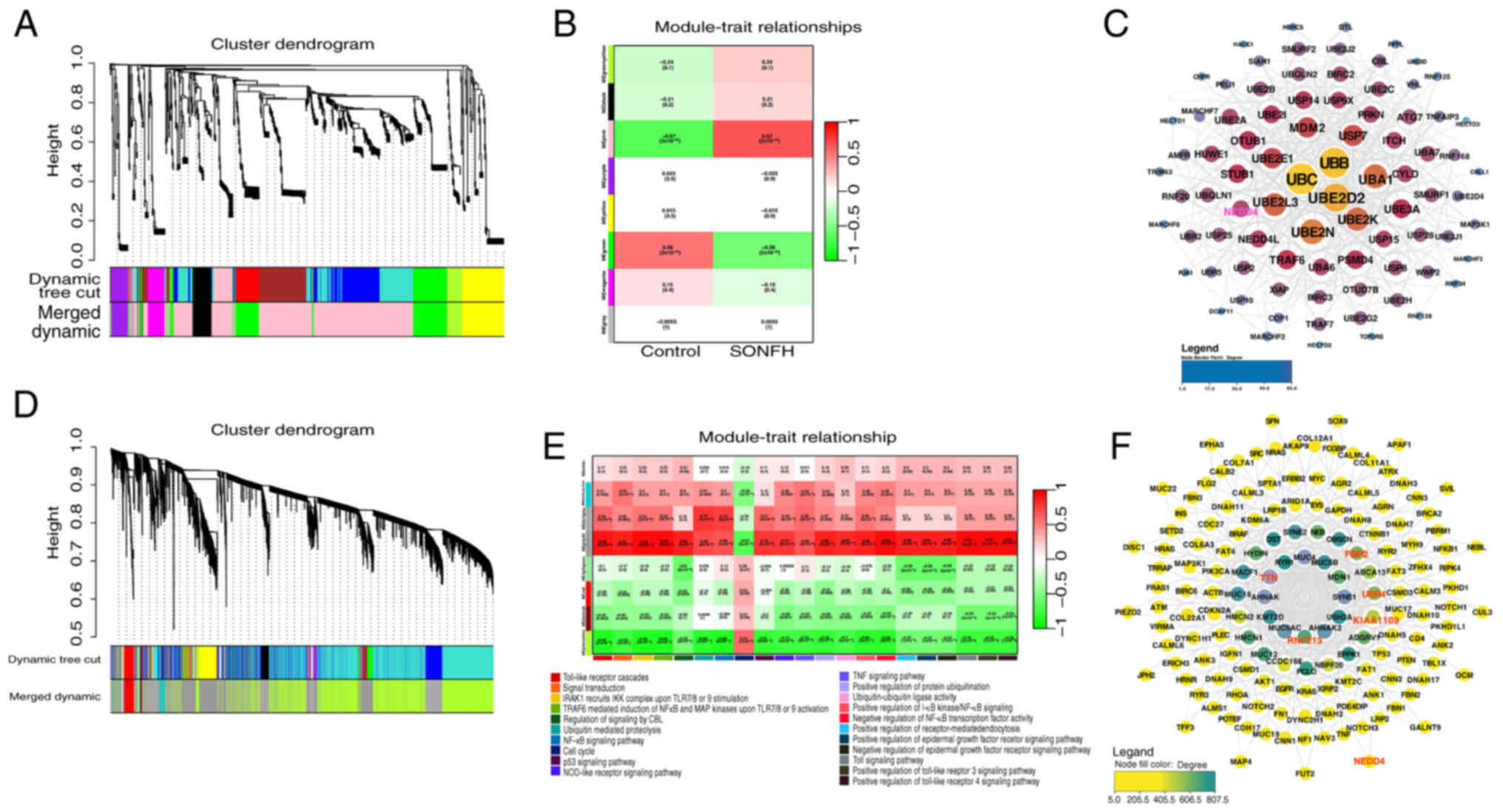

To investigate the role of ubiquitination in SONFH,

ssGSEA was first performed on pathways related to ubiquitination,

cell proliferation and the cell cycle using the KEGG, GO and

REACTOME databases. This revealed marked differences in scores

between the control and SONFH groups (Fig. S1). Subsequently, key

ubiquitination-related pathway ssGSEA scores were chosen for

co-expression network analysis, using control and SONFH as

phenotypes in WGCNA. Numerous module pathways, including those

associated with ubiquitination, angiogenesis and cell

proliferation, exhibited significant differences between the SONFH

and control phenotypes (Fig. 2A and

B). Genes from 489 pathways in the ME (module eigengene (ME)

pink module were selected for network interaction analysis,

identifying UBB and UBC at the core of the network (Fig. 2C). Further analysis showed the

effect of ubiquitination on SONFH. Using ssGSEA scores from

ubiquitination-related pathways as phenotypes, WGCNA was performed

again, revealing significant roles for these pathways in different

gene modules. In the MEdarkgrey module, pathways such as ‘positive

regulation of protein ubiquitination’ (R=0.47), ‘ubiquitin mediated

proteolysis’ (R=0.77) and ‘ubiquitin-ubiquitin ligase activity’

(R=0.41) exhibited significant correlations with module genes

(Fig. 2D and E). Network

interaction analysis revealed the interactions between these genes

in the context of ubiquitination, with RNF213, TTN, FSIP2, KIAA1109

and UBR4 at the network center (Fig.

2F), and demonstrated that the E3 ubiquitin ligase NEDD4 was

connected to two core network genes, RNF213 and FSIP2, within the

ubiquitination-associated network.

Role of NEDD4 in ubiquitination

related to SONFH

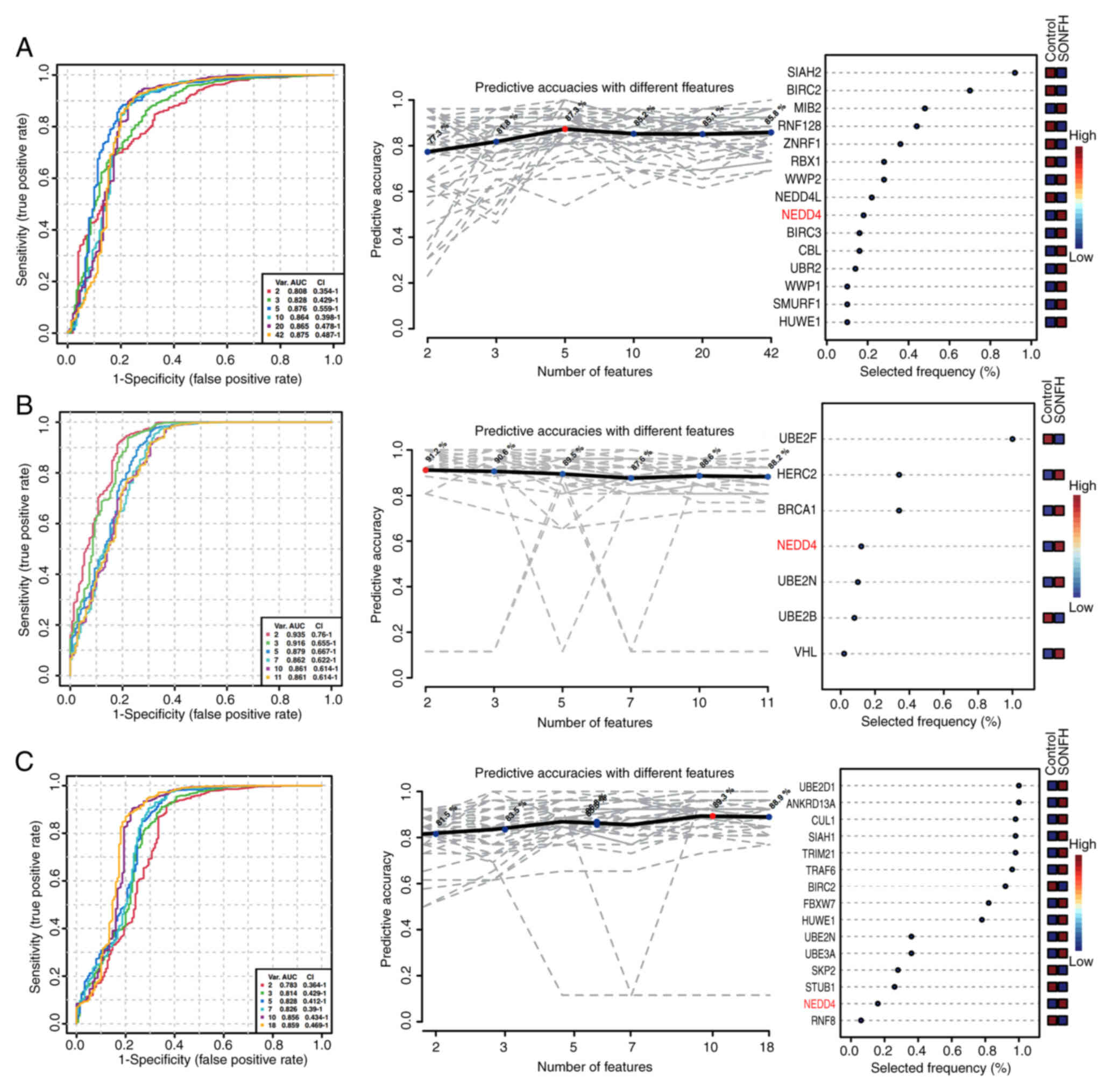

The next step was to investigate genes closely

associated with ubiquitination pathways in SONFH. The present study

used multivariate exploratory receiver operating characteristic

(ROC) analysis on specific pathway genes to achieve this. In the

ubiquitin-ubiquitin ligase activity pathway, the two-factor model

achieved an AUC of 0.876 and a predictive accuracy of 87.3%

(Fig. 3A, right), indicating a

strong ability to distinguish between the control and SONFH groups.

The five-factor model was demonstrated to be the most accurate

predictor, with an AUC value of 0.876. Here, gene selection

frequency reflects the relative stability and importance of each

gene during model construction. Gene selection frequencies were

ranked from highest to lowest as follows: SIAH2, BIRC2, MIB2,

RNF128, ZNRF1, RBX1, WWP2, NEDD4L, NEDD4, BIRC3, CBL, UBR2, WWP1,

SMURF1 and HUWE1 (Fig. 3A). Within

the ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis pathway, all AUC values were

>0.8, with the two-factor model yielding the highest AUC at

0.935. Gene selection frequencies, ranked from highest to lowest,

were: UBE2F, HERC2, BRCA1, NEDD4, UBE2N, UBE2B and VHL (Fig. 3B). In the positive regulation of

protein ubiquitination pathway, ROC curves exhibited AUC values

>0.75, indicating high sensitivity. The 10-factor model

demonstrated high specificity and accuracy, with an AUC of 0.893.

Gene selection frequencies, ranked from highest to lowest, were:

UBE2D1, ANKRD13A, CUL1, SIAH1, TRIM21, TRAF6, BIRC2, FBXW7, HUWE1,

UBE2N, UBE3A, SKP2, STUB1, NEDD4 and RNF8 (Fig. 3C). ROC analysis revealed that NEDD4

had high AUC values and high selection frequencies across multiple

pathways, especially in the ubiquitin-ubiquitin ligase activity and

ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis pathways. This suggested a

significant role for NEDD4 in distinguishing between control and

SONFH groups. Gene contribution analysis, random forest analysis

and SVM analyses also supported this finding (Fig. S2). NEDD4 consistently ranked among

the top genes by feature importance, accuracy contribution and

selection frequency, underscoring its robust predictive value.

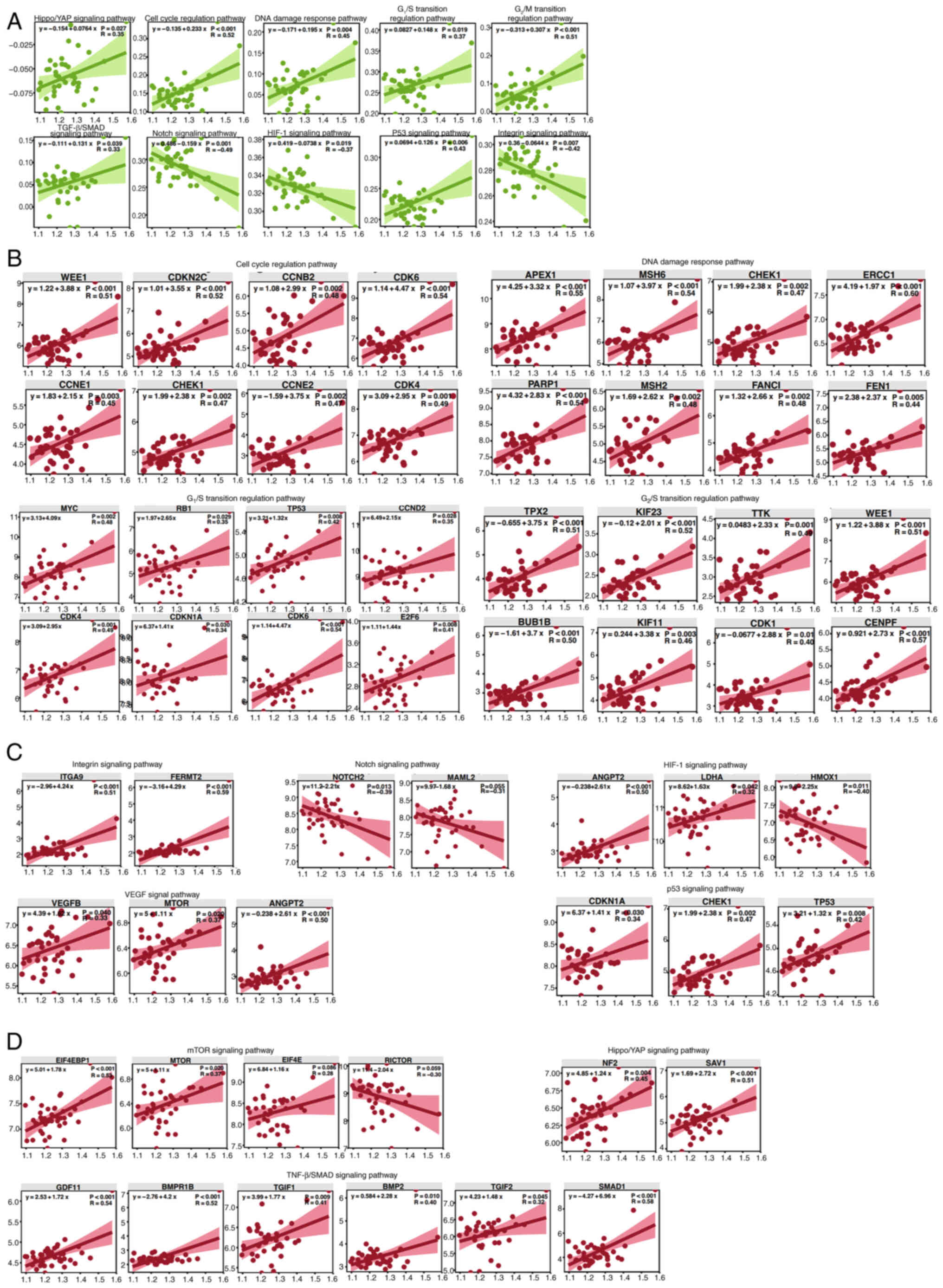

NEDD4 potentially regulates the cell

cycle, angiogenesis and cell proliferation in SONFH

Based on the analyses showing the potential

regulatory role of NEDD4 in SONFH, correlation analyses were

performed. The results of the present study revealed significant

associations between NEDD4 and pathways related to the cell cycle,

angiogenesis and cell growth. Specifically, NEDD4 was negatively

correlated with key pathways, including the ‘HIF-1 signaling

pathway’ (R=−0.37), ‘integrin signaling pathway’ (R=−0.42) and

‘Notch signaling pathway’ (R=−0.49). Additionally, NEDD4 was

positively correlated with multiple pathways, including the ‘p53

signaling pathway’ (R=0.43), ‘DNA damage response pathway’ (R=0.45)

and the ‘G2/M transition regulation pathway’ (R=0.51;

Fig. 4A). Among cell cycle-related

genes, NEDD4 showed significant positive correlations with key

genes such as WEE1 (R=0.51), CCNE1 (R=0.45), MSH6 (R=0.54), ERCC1

(R=0.60), CDK6 (R=0.54) and CENPF (R=0.57), further supporting the

role of NEDD4 in regulating the cell cycle (Figs. 4B and S3). NEDD4 also showed positive

correlations with multiple angiogenesis-associated genes, including

ANGPT2 (R=0.50), VEGFB (R=0.33) and FERMT2 (R=0.59), suggesting a

potential role for NEDD4 in regulating angiogenesis (Figs. 4C and S3). Within cell proliferation-related

pathways, NEDD4 displayed significant positive correlations with

multiple genes, including EIF4EBP1 (R=0.53), SAV1 (R=0.51), GDF11

(R=0.54) and MTOR (R=0.37), further highlighting the key role of

NEDD4 in cell proliferation and metabolic regulation (Figs. 4D and S3). These findings indicated that NEDD4

serves an important role in regulating the cell cycle, angiogenesis

and cell proliferation in SONFH.

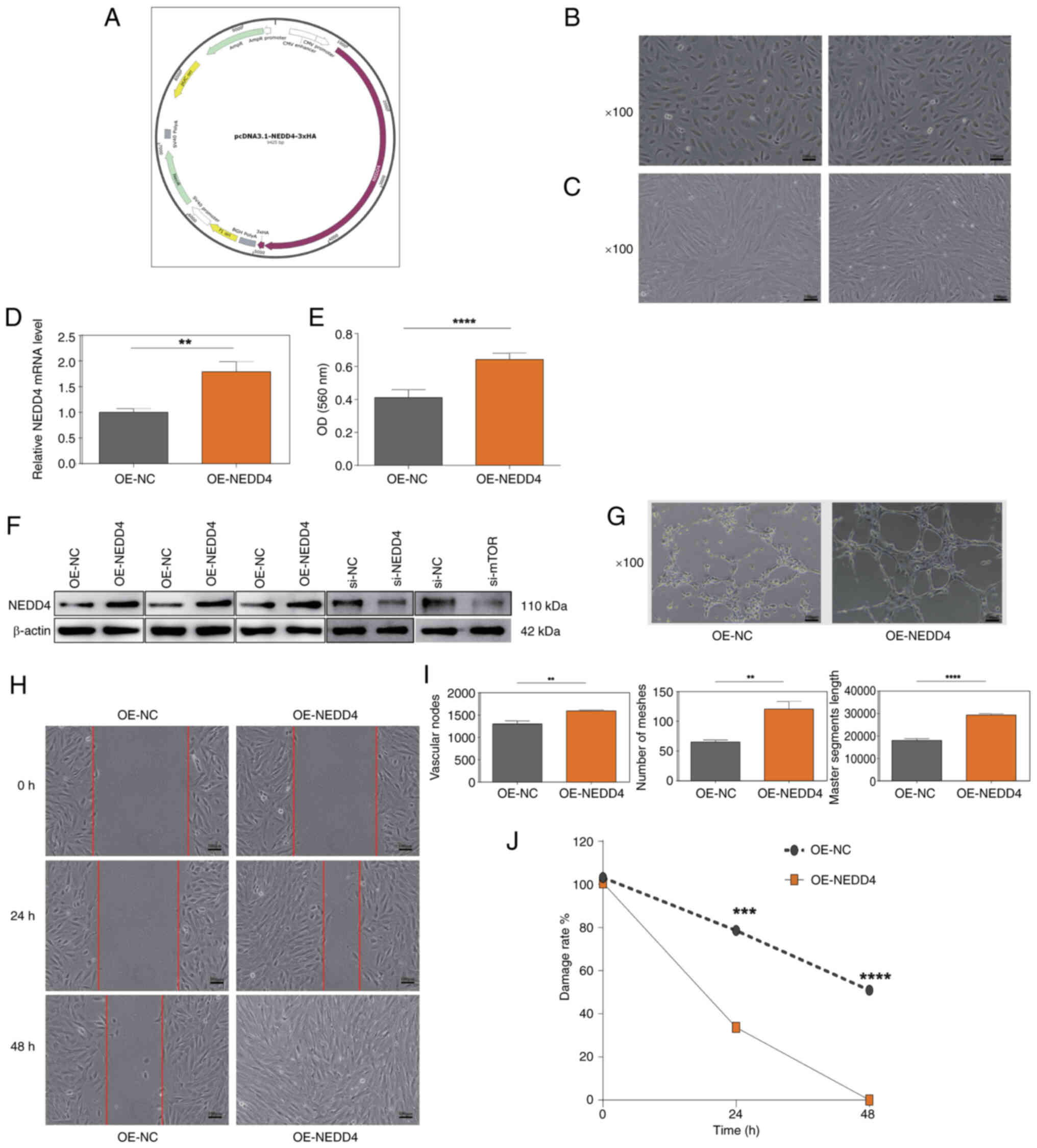

OE of NEDD4 promotes proliferation,

angiogenesis and wound healing in BMECs

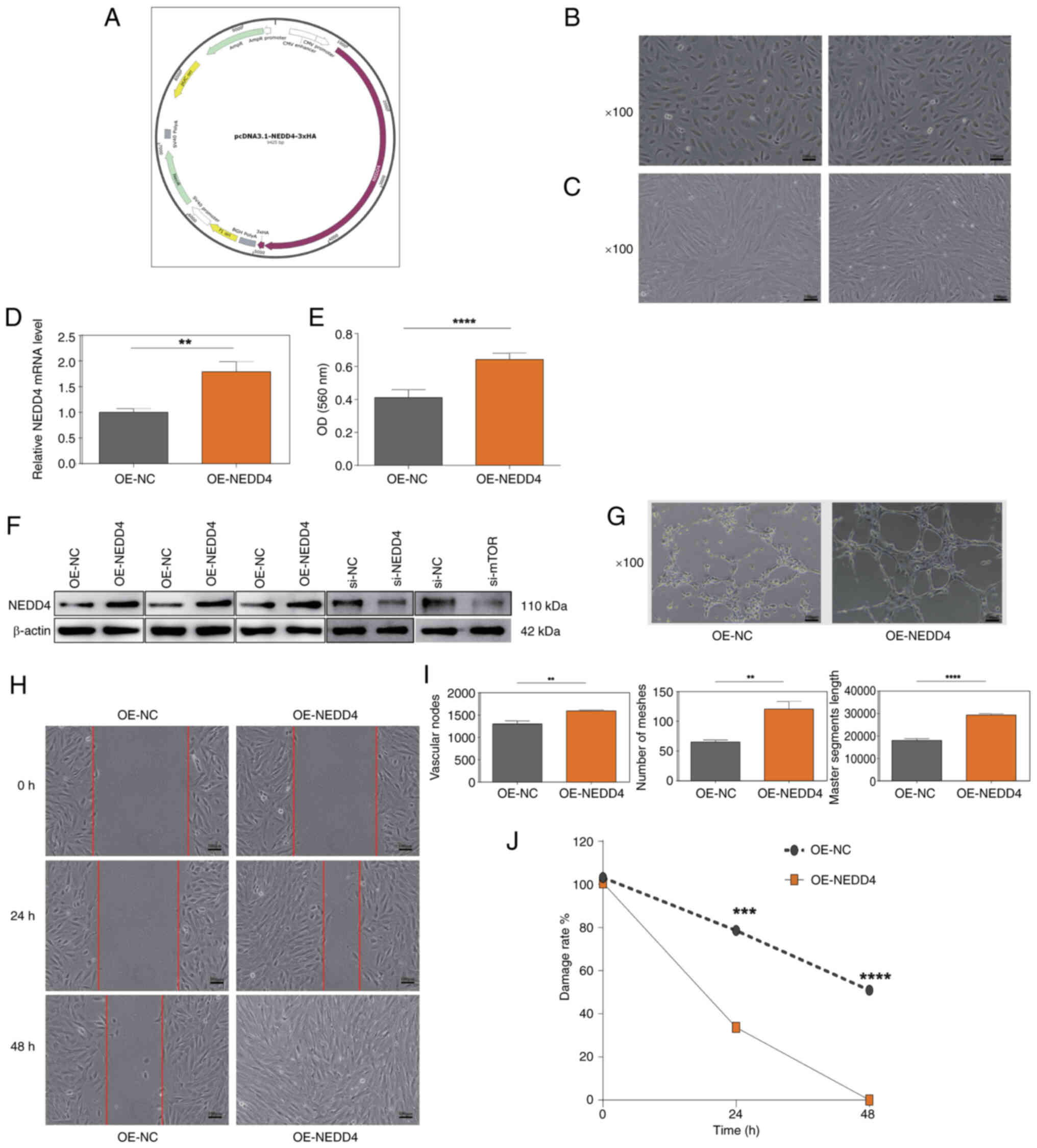

To determine the role of NEDD4 in SONFH, a NEDD4 OE

vector was created and tested in BMECs. BMECs displayed clear

boundaries, no trailing and appeared healthy (Fig. 5A and B), following transfection

with si-NEDD4 or si-NC. BMECs also remained in healthy condition,

characterized by intact cell morphology, clear cell-cell boundaries

and absence of cytoplasmic blebbing, following transient

overexpression of NEDD4 (pcDNA3.1-NEDD4-3×HA) compared with the

OE-NC group (Fig. 5C). RT-qPCR

demonstrated significantly increased NEDD4 mRNA levels in the

OE-NEDD4 group compared with the OE-NC group, indicating successful

transfection (Fig. 5D). After 48

h, the optical density (OD)560 values of BMECs in the OE-NEDD4

group were significantly increased compared with those in the

control group (Fig. 5E). Western

blot analysis supported notable OE of NEDD4 in

pcDNA3.1-NEDD4-3×HA-transfected BMECs compared with controls and

effective knockdown of NEDD4 and mTOR in si-NEDD4- and

si-mTOR-transfected cells, respectively. (Fig. 5F). The tube formation assay

revealed a significant increase in the total tube length and number

of junctions and meshes in BMECs in the OE-NEDD4 group compared

with the control group (Fig. 5G and

I). The wound healing assay indicated a significant decrease in

wound area in the OE-NEDD4 compared with the control group at 24

and 48 h (Fig. 5H). Subsequently,

the present study evaluated how NEDD4 affected the viability of

BMECs using an MTT assay; OE-NEDD4 group exhibited significantly

higher OD (560 nm) values compared with the control group,

indicating enhanced cell viability (Fig. 5J).

| Figure 5.Effects of NEDD4 overexpression on

BMECs. (A) Morphology of BMECs in the control group showing normal

cell boundaries and morphology. (B) Morphology of BMECs in the

OE-NEDD4 group showing no visible damage. (C) BMECs maintained good

condition after transient NEDD4 transfection. Magnification, ×100.

(D) Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR confirmed significantly

elevated NEDD4 mRNA expression in the OE-NEDD4 group. (E) An MTT

assay showed increased viability of BMECs after NEDD4

overexpression. (F) Western blot analysis demonstrating efficient

NEDD4 overexpression and knockdown in OE-NEDD4- and

siRNA-2-transfected cells, respectively. (G) Quantitative analysis

of tube formation indicating increased number of meshes, greater

master segment length, and more vascular nodes in the OE-NEDD4

group. (H) Representative wound-healing assay showing smaller

scratch areas in the OE-NEDD4 group. Magnification, ×100; scale

bar, 100 µm. (I) Quantitative analysis of wound-healing rates,

indicating significantly improved migration capacity in the

OE-NEDD4 group. (J) Decreased scratch area in the OE-NEDD4 group at

0, 24 and 48 h, consistent with enhanced migration ability.

Magnification, ×100. OE, overexpression; NC, negative control; si,

small interfering RNA; NEDD4, neural precursor cell expressed

developmentally downregulated protein 4; BMEC, bone microvascular

endothelial cell; OD, optical density. *P<0.05; **P<0.01;

***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001 vs. OE-NC or 0 h. |

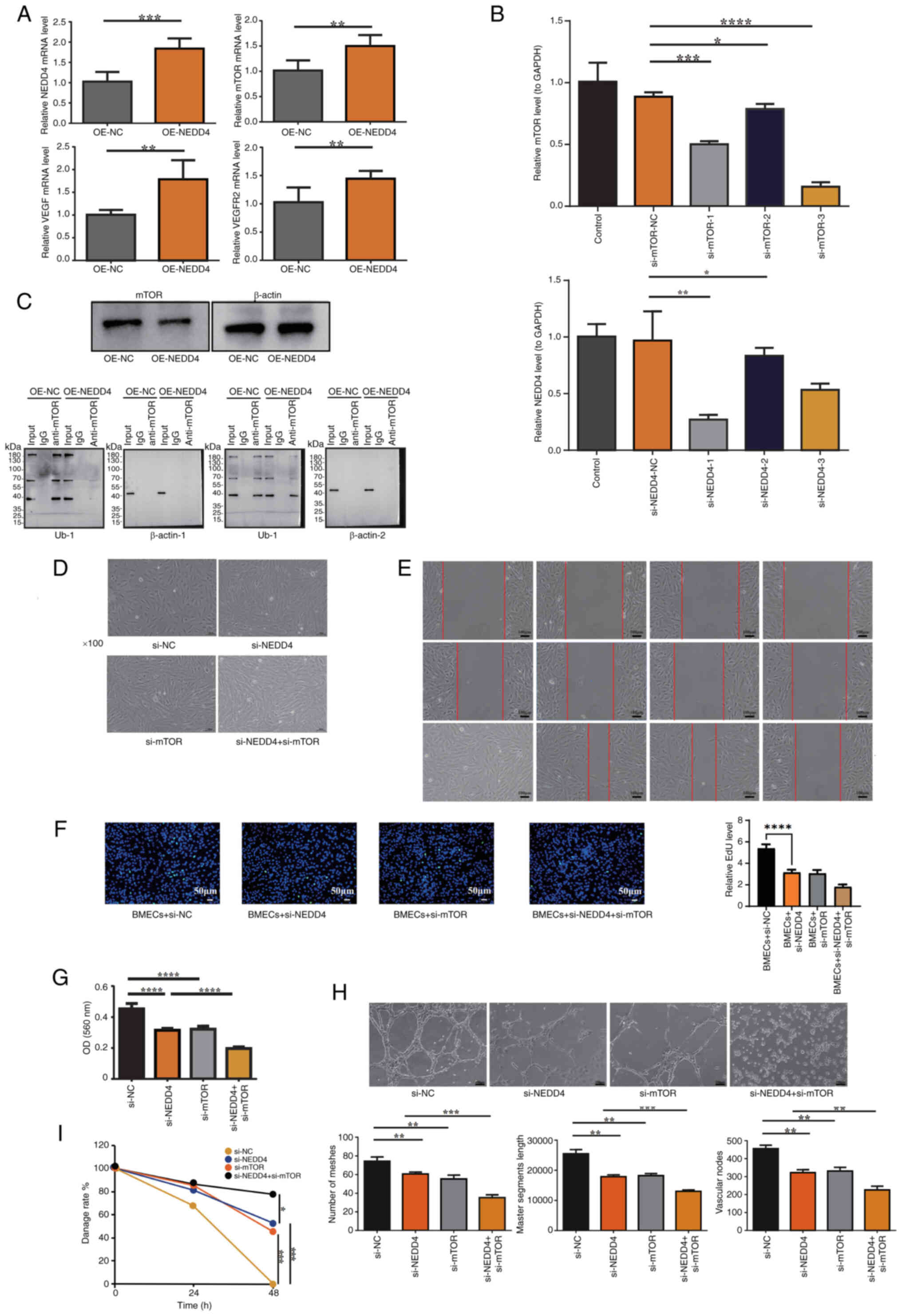

NEDD4 regulates vascular endothelial

cell function by activating the VEGF signaling pathway while

functionally interacting with mTOR signaling in BMECs

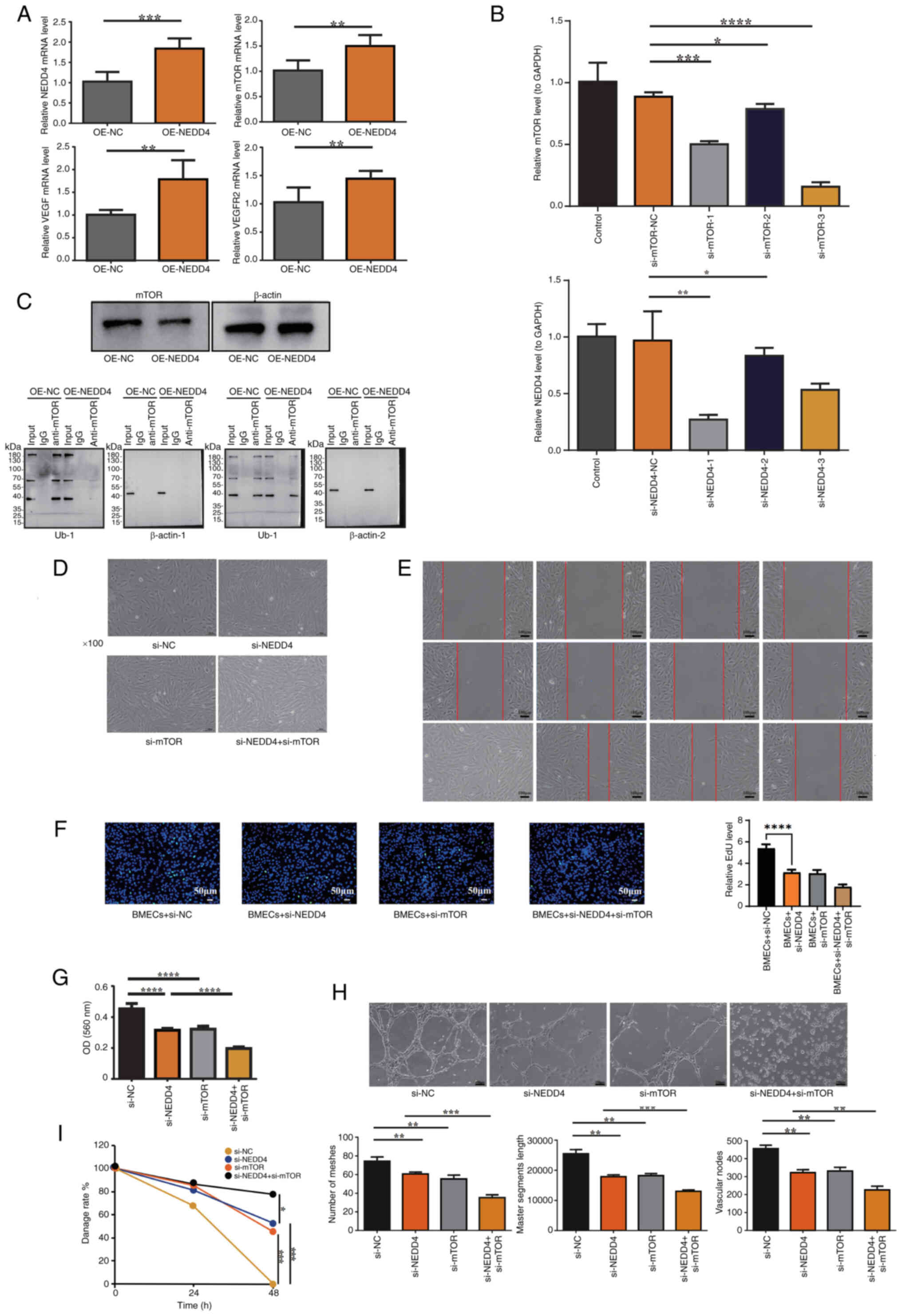

To verify the associations between NEDD4, mTOR and

the VEGF signaling pathway, the present study used RT-qPCR to

measure the mRNA levels of mTOR, VEGF and VEGFR2. NEDD4 OE

significantly increased the mRNA levels of mTOR, VEGF and VEGFR2

(Fig. 6A). To explore the role of

NEDD4 in BMEC function via mTOR regulation, siRNA transfection was

performed to generate si-NEDD4- and si-mTOR-transfected BMECs.

RT-qPCR identified si-NEDD4-1 and si-mTOR-3 as the most effective

interference sequences (Fig. 6B).

IP was performed to assess the ubiquitination level of mTOR,

revealing a notable decrease in mTOR ubiquitination in

NEDD4-overexpressing cells compared with the control group

(Fig. 6C).. The morphology and

fluorescence of BMECs following siRNA transfection confirmed

successful transfection efficiency (Fig. 6D). Wound healing assay results

showed a significant reduction in wound healing rates in the

si-NEDD4 and si-mTOR groups compared with the control group, with a

greater decrease observed in the si-NEDD4 + si-mTOR group at 48 h,

aligning with the results from the MTT and EdU assays, where

si-NEDD4 and si-NEDD4 + si-mTOR groups showed significantly reduced

proliferation while the si-mTOR group exhibited a non-significant

downward trend (Fig. 6E-G). In the

tube formation assay, total tube length and number of junctions and

meshes were significantly decreased in the si-NEDD4 and si-mTOR

groups compared with the control group, with further significant

reductions observed in the si-NEDD4 + si-mTOR group compared with

the si-NEDD4 group, consistent with the findings from the MTT and

scratch assays (Fig. 6H). In the

MTT assay, OD560 values were significantly decreased in the

si-NEDD4- and si-mTOR-transfected groups compared with the control

group, and further decreased in the si-NEDD4 + si-mTOR compared

with the si-NEDD4 group (Fig.

6I).

| Figure 6.Functional validation of NEDD4 in the

VEGF signaling pathway. (A) RT-qPCR showed increased mTOR, VEGF and

VEGFR2 mRNA levels after NEDD4 overexpression. (B) RT-qPCR

identified si-NEDD4-1 and si-mTOR-3 as the most effective

interference sequences. (C) Immunoprecipitation analysis showing

that NEDD4 overexpression decreased the ubiquitination level of

mTOR. (D) Validation of transfection efficiency in BMECs.

Representative microscopic images show cells transfected with

si-NEDD4, si-mTOR and their respective controls (si-NC). BMECs

maintained a normal morphology and healthy growth state after

transfection, without observable cytotoxicity or detachment,

confirming that the transfection was effective and did not

adversely affect cell viability. Magnification, ×100. (E) Scratch

assay showing decreased wound closure rates in the si-NEDD4 and

si-mTOR groups compared with the control group, with the lowest

migration observed in the si-NEDD4 + si-mTOR group. Scale bar, 100

µm. (F) Representative images from the EdU proliferation assay

demonstrating reduced EdU-positive nuclei in the si-NEDD4 and

si-mTOR groups, with further reductions in the si-NEDD4 + si-mTOR

group. Scale bar, 50 µm. (G) MTT assay showed reduced viability in

si-NEDD4 and si-mTOR groups, with the greatest reduction in the

si-NEDD4 + si-mTOR group. (H) Tube formation assay demonstrating

reduced angiogenesis parameters in the si-NEDD4 and si-mTOR groups,

with further reductions in the si-NEDD4 + si-mTOR group.

Magnification, ×100. (I) Quantitative analysis of wound-healing

rates, indicating significantly reduced migration ability in the

si-NEDD4 and si-mTOR groups, with further reduction in the si-NEDD4

+ si-mTOR group. NC, negative control; si, small interfering RNA;

NEDD4, neural precursor cell expressed developmentally

downregulated protein 4; OE, overexpression; RT-qPCR, reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR; BMEC, bone microvascular

endothelial cell; OD, optical density; Ub-1, first ubiquitination

site assay. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and

****P<0.0001. |

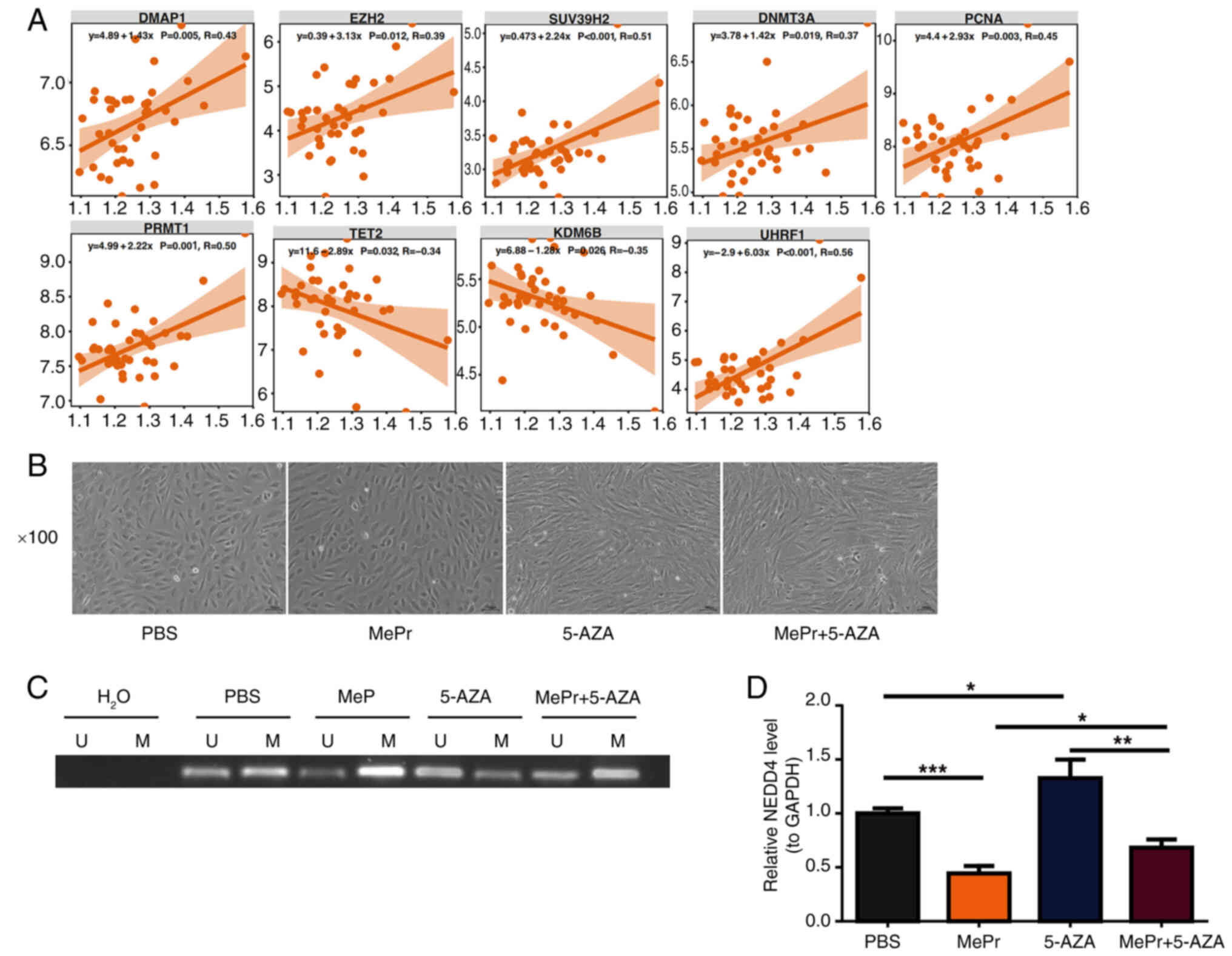

Glucocorticoids inhibit NEDD4

expression by upregulating methylation levels in its promoter

region

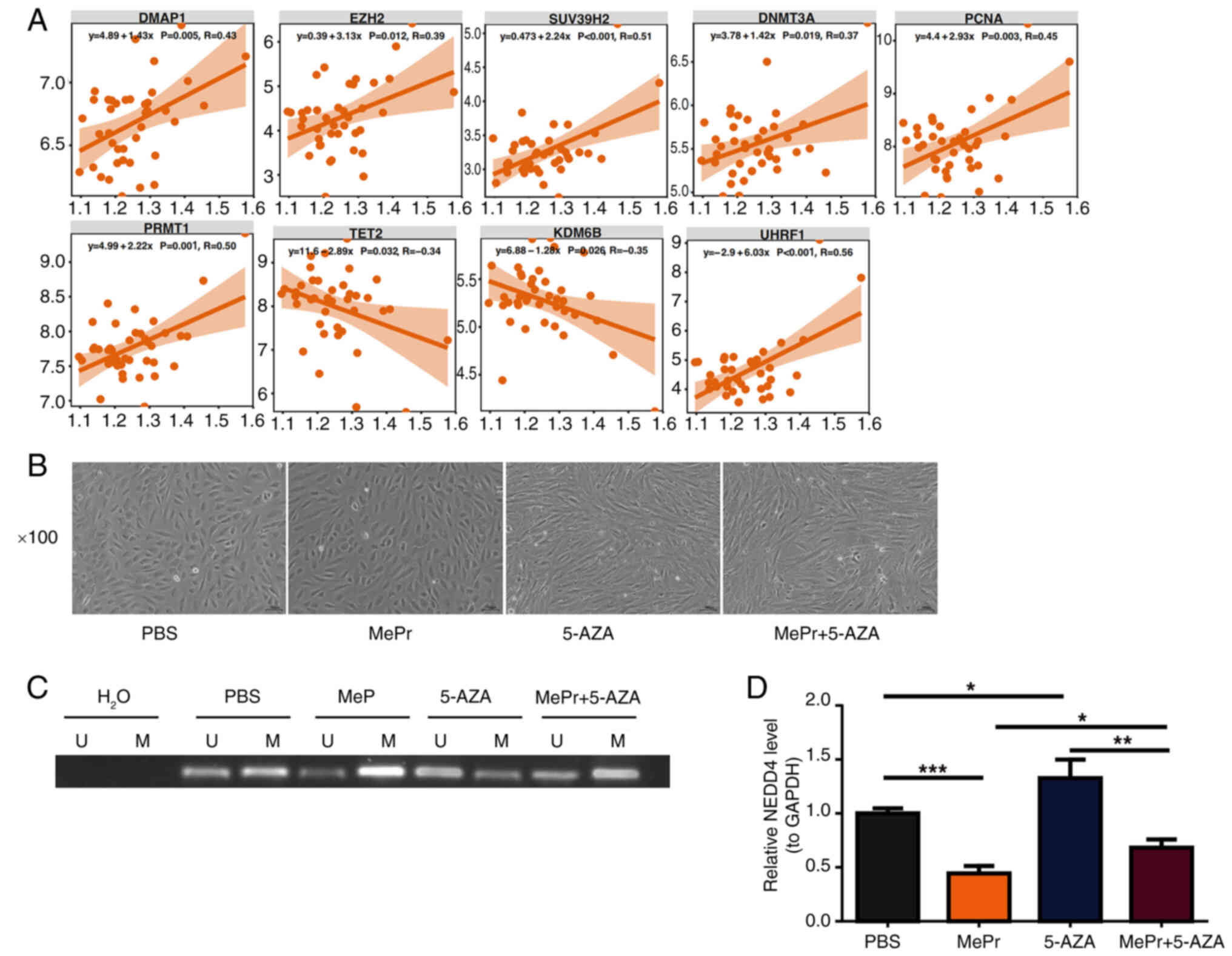

Correlation analysis of NEDD4 and

methylation-related genes showed significant positive and negative

correlations with genes such as KDM6B, PCNA, DNMT3A, SUV39H2,

UHRF1, EZH2, TET2, DMAP1 and PRMT1, further highlighting the

complex role of NEDD4 in methylation regulation (Fig. 7A). BMECs exhibited healthy

proliferation after treatment with PBS, MePr, 5-AZA, or MePr +

5-AZA (Fig. 7B).

Methylation-specific PCR results revealed increased methylation

levels following MePr addition and decreased levels following 5-AZA

treatment. Compared with the 5-AZA group, combined treatment with

MePr and 5-AZA increased methylation levels in the NEDD4 promoter

region (Fig. 7C). RT-qPCR results

indicated that combined treatment with MePr + 5-AZA significantly

suppressed NEDD4 mRNA expression compared with 5-AZA treatment

alone (Fig. 7D).

| Figure 7.Glucocorticoids inhibit NEDD4

expression by increasing promoter methylation levels in BMECs. (A)

Correlation between NEDD4 and methylation-related genes, with

significance and correlation marked. (B) BMEC culture, including

PBS, MePr, 5-AZA and MePr + 5-AZA groups. Magnification, ×100. (C)

Methylation PCR, with H2O as the system negative control

to exclude contamination. (D) NEDD4 mRNA expression level, with

significant differences marked. U, unmethylated control; M,

methylated sample; NEDD4, neural precursor cell expressed

developmentally downregulated protein 4; BMEC, bone microvascular

endothelial cell; MePr, methylprednisolone; 5-AZA, 5-azacytidine.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. |

Discussion

Research highlights the important role of NEDD4 in

ONFH. The p53 signaling pathway is important for regulating the

cell cycle and apoptosis by slowing down cell proliferation and

killing abnormal cells, while protecting healthy cells (34). P53 is controlled by

post-translational modifications such as ubiquitination,

phosphorylation, acetylation and methylation (34). The positive link between NEDD4 and

the p53 signaling pathway, as well as tumor protein p53, suggests

that NEDD4 may impact the cell cycle and apoptosis by affecting p53

activity (34). The DNA damage

response (DDR) pathway is important for fixing DNA damage and

preserving genome stability. When cellular DNA is harmed, the DDR

pathway is activated, triggering cellular responses such as DNA

repair (35,36). Important genes such as APEX1, MSH6,

CHEK1, ERCC1, PARP1, MSH2, FANC and FEN1 are involved in DNA

repair, influencing the cell cycle and apoptosis (37–42).

The positive link between NEDD4 and key DDR genes suggests that

NEDD4 may be involved in DNA repair and cell cycle control through

its association with these genes. Additionally, CCNE1 and CCNE2 are

regulatory subunits of CDK2 that control promote the re-entry of

quiescent (G0-phase) cells into the cell cycle and regulate the

G1/S phase transition (43). WEE1

encodes a kinase that negatively regulates the G2/M

transition of the cell cycle (44). Upregulation of this protein helps

to strengthen the G2/M DNA damage checkpoint (45). CHEK1 serves an important role in

maintaining and restoring spermatogonial cells during mitosis

(44). In meiosis, CHK1

selectively weakens the DNA damage signal on autosomes at specific

stages, ensuring the normal progression of meiosis (46). The positive correlation between

NEDD4 and cell cycle regulatory genes such as CCNE1, CCNE2, WEE1

and CHEK1 highlights its important role in the G1/S and

G2/M transitions, as well as in mitosis and meiosis. In

the present study, the significance of NEDD4 in cell cycle

regulation and apoptosis was emphasized through its positive

association with multiple key genes and signaling pathways. These

results suggested that NEDD4 may serve an important role in the

cell cycle and DNA damage repair in ONFH.

Integrins, as transmembrane receptors, can detect

the physical properties of the extracellular matrix and organize

the cytoskeleton while transmitting bidirectional cellular signals.

They mediate signaling pathways such as the TGF-β, Hippo, Wnt and

Notch pathways, thereby serving important roles in biological

processes such as cell adhesion, spreading, migration and

mechanotransduction (47,48). The Notch signaling pathway could

have therapeutic benefits for bone regeneration and osteoporosis

treatment (49). The analysis in

the present study showed that NEDD4 expression was positively

correlated with ssGSEA scores of the TGF-β/SMAD and

Hippo/yes-associated protein (YAP) pathways but negatively

correlated with the Notch signaling pathway. Although NEDD4

expression was positively correlated with ITGA9 and FERMT2

expression in the integrin pathway, the ssGSEA score for this

pathway was negative, suggesting that the regulatory role of NEDD4

is complex and this may influence pathways through different

mechanisms. As an E3 ubiquitin ligase, NEDD4 may serve a key role

in the progression and repair of ONFH. NEDD4 may contribute to bone

tissue repair and remodeling by boosting the activity of the

TGF-β/SMAD and Hippo/YAP signaling pathways (25,31).

For example, NEDD4 may promote the growth and differentiation of

bone cells by stabilizing TGF-β receptors or SMAL proteins

(31). At the same time, by

enhancing the Hippo/YAP pathway, it may help regulate the

mechanical adaptability and repair of bone tissue (25). Conversely, the negative correlation

between NEDD4 and the Notch signaling pathway genes such as NOTCH2

and MAML2 indicated that NEDD4 may affect the pathological process

of SONFH by inhibiting the Notch pathway and influencing osteoblast

differentiation (49). The

interaction of the integrin signaling pathway with NEDD4 could

impact the regulation of these pathways, further affecting the

progression and repair of SONFH (47). In summary, the regulatory roles of

NEDD4 in the integrin, TGF-β/SMAD, Hippo/YAP and Notch signaling

pathways highlighted its complex function in cell signal

transduction. This diverse regulatory mechanism offers important

insights for further exploring the functions and mechanisms of

NEDD4 in SONFH.

Research has shown that ANGPT2 serves an important

role in the vascular niche within the bone marrow, helping to

maintain the balance and regeneration of hematopoietic stem cells

(50). Although VEGFB does not

directly contribute to angiogenesis, it indirectly supports

vascular growth and cell survival by affecting the actions of VEGFA

(51). Bone morphogenetic protein

receptor type-1B (BMPR1B) also serves a role, as it can prevent

chondrocyte hypertrophy and act as a stabilizer for cartilage

during joint development (52).

mTOR is involved in tissue regeneration across neurons, muscles,

liver and intestines, helping restore tissue homeostasis (53). In the present study, NEDD4

expression was positively associated with the expression of genes

involved in angiogenesis, such as ANGPT2, VEGFB, MTOR and BMPR1B.

This finding further emphasizes the notable role of NEDD4 in

regulating both angiogenesis and bone tissue homeostasis. Notably,

the positive correlation between NEDD4 and ANGPT2 supported the

role of ANGPT2 in coordinating hematopoietic stem cell homeostasis

within the vascular niche (50).

Additionally, this correlation suggested that NEDD4 may indirectly

affect the function of VEGFA through interactions with VEGFB and

mTOR, thereby encouraging vascular growth, and cell proliferation

and survival (51,53). The positive correlation between

NEDD4 and BMPR1B suggested that NEDD4 may prevent chondrocyte

hypertrophy and support cartilage health and stability (52).

The present study demonstrated that NEDD4 OE

promoted the viability, migration and angiogenesis of BMECs,

indicating its key role in endothelial cell function, and

maintaining angiogenesis and homeostasis. NEDD4 regulates processes

such as proliferation and angiogenesis via ubiquitination (23). Glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of

BMECs promotes the onset and progression of ONFH (54). The present research sheds light on

the role and mechanism of NEDD4 in ONFH. The present study found

that NEDD4 enhanced the cell function of BMECs by activating the

VEGF signaling pathway and working with mTOR. When NEDD4 was

overexpressed, the mRNA levels of mTOR, VEGF and VEGFR2 were

significantly increased, demonstrating that NEDD4 promoted

angiogenesis by triggering the VEGF signaling pathway. Notably,

overexpression of NEDD4 did not markedly affect the ubiquitination

level of mTOR, suggesting that NEDD4 did not directly mediate the

ubiquitination of mTOR but instead affected it by activating the

mTOR signaling pathway. In the siRNA transfection experiments, a

synergistic effect of NEDD4 and mTOR on BMEC proliferation and

migration was observed. Additionally, glucocorticoids inhibited the

expression of NEDD4 by increasing the methylation level of the

NEDD4 promoter region. After adding the methylation inhibitor

5-AZA, the methylation levels of the NEDD4 promoter notably

decreased, while glucocorticoid MePr treatment markedly increased

the methylation level of the NEDD4 promoter and significantly

suppressed NEDD4 mRNA expression. This further supported the

important role of NEDD4 in methylation regulation and showed the

substantial influence of glucocorticoids on NEDD4 expression.

In conclusion, the present study revealed the

diverse roles of NEDD4 in SONFH, particularly in angiogenesis,

cellular homeostasis, cell cycle regulation and DNA damage repair.

NEDD4 enhanced BMEC function by activating the VEGF signaling

pathway and working with mTOR, with its expression regulated by

methylation. This offers novel insights into NEDD4 as a potential

therapeutic target for SONFH. Further research into the functions

of NEDD4 in bone pathology and angiogenesis will provide valuable

insights for developing novel treatment strategies. These findings

not only add to the existing literature but also provide novel

perspectives on the multiple roles of NEDD4 in SONFH and

angiogenesis, indicating that NEDD4 may affect angiogenesis, bone

tissue repair and bone regeneration through various mechanisms.

NEDD4 may represent a promising therapeutic target

for SONFH. By mediating PTEN degradation and activating the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, NEDD4 promoted cell proliferation and

survival, while also enhancing VEGF signaling to support

angiogenesis and bone repair (26,31).

These dual effects on osteogenesis and angiogenesis highlight its

translational potential, and future studies on pharmacological or

genetic modulation of NEDD4 could lead to novel treatment

strategies.

The present study had several limitations.

Primarily, the bioinformatics analysis was based on a single

publicly available dataset without external validation, which may

limit the generalizability of the present findings. Secondly,

although the present study validated key molecular alterations

in vitro, in vivo animal experiments were not performed,

which reduced the translational value of the results. Furthermore,

the relatively small sample size and limited types of control may

weaken the conclusions of the present study. Additionally, the

present study did not explore how NEDD4 regulates the mTOR and VEGF

pathways at a mechanistic level. Finally, the present study did not

include clinical relevance data, and thus, future studies should

incorporate patient samples and correlation analyses to increase

the translational significance of the present work. Overall, future

research with larger cohorts, more comprehensive controls, in

vivo validation, more in-depth mechanistic studies and clinical

correlation analyses is needed to confirm and extend the findings

of the present study.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by The Guizhou Provincial Natural

Science Foundation [grant no. Qiankehebasis-ZK (2024) general 241],

the Start-up Fund for Doctoral Research at the Affiliated Hospital

of Guizhou Medical University (grant no. gyfybsky-2022-38), the

National Natural Science Foundation of China Cultivation Program of

Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University [grant no.

gyfynsfc(2023)-62], the Key Medical Discipline Construction Project

of Guizhou Provincial Health Commission during 2025–2026, and the

2025 Annual Hospital-Level Scientific Research Fund of Guizhou

Hospital of Beijing Jishuitan Hospital [grant no.

JGYYK(2025)-24].

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JL conceived and designed the experiments, performed

the experiments, analyzed the data, authored and reviewed drafts of

the article, and approved the final draft. DZ performed the

experiments. YQ analyzed and interpreted data CG supervised the

study and interpreted data. All authors read and approved the final

version of the manuscript, JL and CG confirm the authenticity of

all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The use of primary human cells in the present study

was conducted in accordance with The Declaration of Helsinki. The

protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Jishuitan

Hospital Guizhou Hospital (approval no. KT2025022804; Guiyang,

China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Zhang W, Du H, Liu Z, Zhou D, Li Q and Liu

W: Worldwide research trends on femur head necrosis (2000–2021): A

bibliometrics analysis and suggestions for researchers. Ann Transl

Med. 11:1552023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Wang T, Azeddine B, Mah W, Harvey EJ,

Rosenblatt D and Séguin C: Osteonecrosis of the femoral head:

Genetic basis. Int Orthop. 43:519–530. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Shao W, Wang P, Lv X, Wang B, Gong S and

Feng Y: Unraveling the role of endothelial dysfunction in

osteonecrosis of the femoral head: A pathway to new therapies.

Biomedicines. 12:6642024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Fukushima W, Fujioka M, Kubo T, Tamakoshi

A, Nagai M and Hirota Y: Nationwide epidemiologic survey of

idiopathic osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Clin Orthop Relat

Res. 468:2715–2724. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Mont MA, Pivec R, Banerjee S, Issa K,

Elmallah RK and Jones LC: High-dose corticosteroid use and risk of

hip osteonecrosis: Meta-analysis and systematic literature review.

J Arthroplasty. 30:1506–1512.e5. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Radke S, Battmann A, Jatzke S, Eulert J,

Jakob F and Schütze N: Expression of the angiomatrix and angiogenic

proteins CYR61, CTGF, and VEGF in osteonecrosis of the femoral

head. J Orthop Res. 24:945–952. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Shao W, Li Z, Wang B, Gong S, Wang P, Song

B, Chen Z and Feng Y: Dimethyloxalylglycine attenuates

steroid-associated endothelial progenitor cell impairment and

osteonecrosis of the femoral head by regulating the HIF-1α

signaling pathway. Biomedicines. 11:9922023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Huard J: Stem cells, blood vessels, and

angiogenesis as major determinants for musculoskeletal tissue

repair. J Orthop Res. 37:1212–1220. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wang Y, Xia CJ, Wang BJ, Ma XW and Zhao

DW: The association between VEGF-634C/G polymorphisms and

osteonecrosis of femoral head: A meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med.

8:9313–9319. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hang D, Wang Q, Guo C, Chen Z and Yan Z:

Treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head with VEGF165

transgenic bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in mongrel dogs.

Cells Tissues Organs. 195:495–506. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Grosso A, Burger MG, Lunger A, Schaefer

DJ, Banfi A and Di Maggio N: It takes two to tango: Coupling of

angiogenesis and osteogenesis for bone regeneration. Front Bioeng

Biotechnol. 5:682017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Portal-Núñez S, Lozano D and Esbrit P:

Role of angiogenesis on bone formation. Histol Histopathol.

27:559–566. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Deng S, Xiang JJ, Shen YY, Lin SY, Zeng YQ

and Shen JP: Effects of VEGF-notch signaling pathway on

proliferation and apoptosis of bone marrow MSC in patients with

aplastic anemia. Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 27:1925–1932.

2019.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wang S, Lu J, You Q, Huang H, Chen Y and

Liu K: The mTOR/AP-1/VEGF signaling pathway regulates vascular

endothelial cell growth. Oncotarget. 7:53269–53276. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Liu Z and Li Y: Expression of the

HIF-1α/VEGF pathway is upregulated to protect alveolar bone density

reduction in nasal-obstructed rats. Histol Histopathol.

39:1053–1063. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Gao L, Zhang W, Shi XH, Chang X, Han Y,

Liu C, Jiang Z and Yang X: The mechanism of linear ubiquitination

in regulating cell death and correlative diseases. Cell Death Dis.

14:6592023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Popovic D, Vucic D and Dikic I:

Ubiquitination in disease pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Med.

20:1242–1253. 2014. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wang Y, Huang S, Xu P and Li Y: Progress

in atypical ubiquitination via K6-linkages. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue

Bao. 38:3215–3227. 2022.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Yan J, Qiao G, Yin Y, Wang E, Xiao J, Peng

Y, Yu J, Du Y, Li Z, Wu H, et al: Black carp RNF5 inhibits

STING/IFN signaling through promoting K48-linked ubiquitination and

degradation of STING. Dev Comp Immunol. 145:1047122023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Xu J, Sheng Z, Li F, Wang S, Yuan Y, Wang

M and Yu Z: NEDD4 protects vascular endothelial cells against

Angiotensin II-induced cell death via enhancement of XPO1-mediated

nuclear export. Exp Cell Res. 383:1115052019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Eide PW, Cekaite L, Danielsen SA,

Eilertsen IA, Kjenseth A, Fykerud TA, Ågesen TH, Bruun J, Rivedal

E, Lothe RA and Leithe E: NEDD4 is overexpressed in colorectal

cancer and promotes colonic cell growth independently of the

PI3K/PTEN/AKT pathway. Cell Signal. 25:12–18. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Huang ZJ, Zhu JJ, Yang XY and Biskup E:

NEDD4 promotes cell growth and migration via PTEN/PI3K/AKT

signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 14:2649–2656.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Guo Y, Wang Y, Liu H, Jiang X and Lei S:

High glucose environment induces NEDD4 deficiency that impairs

angiogenesis and diabetic wound healing. J Dermatol Sci.

112:148–157. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Sun W, Lu H, Cui S, Zhao S, Yu H, Song H,

Ruan Q, Zhang Y, Chu Y and Dong S: NEDD4 ameliorates myocardial

reperfusion injury by preventing macrophages pyroptosis. Cell

Commun Signal. 21:292023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Xu K, Chu Y, Liu Q, Fan W, He H and Huang

F: NEDD4 E3 Ligases: Functions and mechanisms in bone and tooth.

Int J Mol Sci. 23:99372022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Drinjakovic J, Jung H, Campbell DS,

Strochlic L, Dwivedy A and Holt CE: E3 ligase Nedd4 promotes axon

branching by downregulating PTEN. Neuron. 65:341–357. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Han X, Zhang G, Chen G, Wu Y, Xu T, Xu H,

Liu B and Zhou Y: Buyang huanwu decoction promotes angiogenesis in

myocardial infarction through suppression of PTEN and activation of

the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 287:1149292022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zhou YJ, Xiong YX, Wu XT, Shi D, Fan W,

Zhou T, Li YC and Huang X: Inactivation of PTEN is associated with

increased angiogenesis and VEGF overexpression in gastric cancer.

World J Gastroenterol. 10:3225–3229. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Lindberg ME, Stodden GR, King ML, MacLean

JA II, Mann JL, DeMayo FJ, Lydon JP and Hayashi K: Loss of CDH1 and

Pten accelerates cellular invasiveness and angiogenesis in the

mouse uterus. Biol Reprod. 89:82013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Jeon SA, Lee JH, Kim DW and Cho JY:

E3-ubiquitin ligase NEDD4 enhances bone formation by removing

TGFβ1-induced pSMAD1 in immature osteoblast. Bone. 116:248–258.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Zheng HL, Xu WN, Zhou WS, Yang RZ, Chen

PB, Liu T, Jiang LS and Jiang SD: Beraprost ameliorates

postmenopausal osteoporosis by regulating Nedd4-induced Runx2

ubiquitination. Cell Death Dis. 12:4972021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Liang XZ, Luo D, Chen YR, Li JC, Yan BZ,

Guo YB, Wen MT, Xu B and Li G: Identification of potential

autophagy-related genes in steroid-induced osteonecrosis of the

femoral head via bioinformatics analysis and experimental

verification. J Orthop Surg Res. 17:862022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Liu Y, Su Z, Tavana O and Gu W:

Understanding the complexity of p53 in a new era of tumor

suppression. Cancer Cell. 42:946–967. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Chatterjee N and Walker GC: Mechanisms of

DNA damage, repair, and mutagenesis. Environ Mol Mutagen.

58:235–263. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Ciccia A and Elledge SJ: The DNA damage

response: Making it safe to play with knives. Mol Cell. 40:179–204.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Li J, Zhao H, McMahon A and Yan S: APE1

assembles biomolecular condensates to promote the ATR-Chk1 DNA

damage response in nucleolus. Nucleic Acids Res. 50:10503–10525.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Provasek V, Kodavati M, Kim B, Mitra J and

Hegde ML: TDP43 Interacts with MLH1 and MSH6 Proteins in A DNA

Damage-Inducible Manner. Mol Brain. 17:322024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Pfeiffer C, Grandits AM, Asnagli H,

Schneller A, Huber J, Zojer N, Schreder M, Parker AE, Bolomsky A,

Beer PA and Ludwig H: CTPS1 is a novel therapeutic target in

multiple myeloma which synergizes with inhibition of CHEK1, ATR or

WEE1. Leukemia. 38:181–192. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Li WH, Wang F, Song GY, Yu QH, Du RP and

Xu P: PARP-1: A critical regulator in radioprotection and

radiotherapy-mechanisms, challenges, and therapeutic opportunities.

Front Pharmacol. 14:11989482023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Olazabal-Herrero A, He B, Kwon Y, Gupta

AK, Dutta A, Huang Y, Boddu P, Liang Z, Liang F, Teng Y, et al: The

FANCI/FANCD2 complex links DNA damage response to R-loop regulation

through SRSF1-mediated mRNA export. Cell Rep. 43:1136102024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zheng L, Jia J, Finger LD, Guo Z, Zer C

and Shen B: Functional regulation of FEN1 nuclease and its link to

cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:781–794. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Sonntag R, Giebeler N, Nevzorova YA,

Bangen JM, Fahrenkamp D, Lambertz D, Haas U, Hu W, Gassler N,

Cubero FJ, et al: Cyclin E1 and cyclin-dependent kinase 2 are

critical for initiation, but not for progression of hepatocellular

carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 115:9282–9287. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Ghelli Luserna di Rorà A, Cerchione C,

Martinelli G and Simonetti G: A WEE1 family business: Regulation of

mitosis, cancer progression, and therapeutic target. J Hematol

Oncol. 13:1262020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Sokhi S, Lewis CW, Bukhari AB, Hadfield J,

Xiao EJ, Fung J, Yoon YJ, Hsu WH, Gamper AM and Chan GK: Myt1

overexpression mediates resistance to cell cycle and DNA damage

checkpoint kinase inhibitors. Front Cell Dev Biol. 11:12705422023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Abe H, Alavattam KG, Kato Y, Castrillon

DH, Pang Q, Andreassen PR and Namekawa SH: CHEK1 coordinates DNA

damage signaling and meiotic progression in the male germline of

mice. Hum Mol Genet. 27:1136–1149. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Li S, Sampson C, Liu C, Piao HL and Liu

HX: Integrin signaling in cancer: Bidirectional mechanisms and

therapeutic opportunities. Cell Commun Signal. 21:2662023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Huveneers S and Danen EH: Adhesion

signaling-crosstalk between integrins, Src and Rho. J Cell Sci.

122:1059–1069. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Nobta M, Tsukazaki T, Shibata Y, Xin C,

Moriishi T, Sakano S, Shindo H and Yamaguchi A: Critical regulation

of bone morphogenetic protein-induced osteoblastic differentiation

by Delta1/Jagged1-activated Notch1 signaling. J Biol Chem.

280:15842–15848. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Rafii S and Lis R: Angiocrine ANGPTL2

executes HSC functions in endothelial niche. Blood. 139:1433–1434.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Lal N, Puri K and Rodrigues B: Vascular

endothelial growth factor B and its signaling. Front Cardiovasc

Med. 5:392018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Mang T, Kleinschmidt-Doerr K, Ploeger F,

Schoenemann A, Lindemann S and Gigout A: BMPR1A is necessary for

chondrogenesis and osteogenesis, whereas BMPR1B prevents

hypertrophic differentiation. J Cell Sci. 133:jcs2469342020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Wei X, Luo L and Chen J: Roles of mTOR

signaling in tissue regeneration. Cells. 8:10752019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zhang F, Wei L, Wang L, Wang T, Xie Z, Luo

H, Li F, Zhang J, Dong W, Liu G, et al: FAR591 promotes the

pathogenesis and progression of SONFH by regulating Fos expression

to mediate the apoptosis of bone microvascular endothelial cells.

Bone Res. 11:272023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|