Introduction

Osteoporosis is a disease characterized by changes

in bone microstructure, including thinning of trabeculae and an

increased susceptibility to brittle fractures (1). Osteoporosis primarily results from an

imbalance in bone metabolism, where bone formation is weakened

while bone resorption increases, leading to a loss of bone mass

(2). Factors such as aging,

inflammation and hormonal changes lead to a reduction in bone

formation (3); however, the

specific reasons have not yet been fully elucidated.

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) are a

type of pluripotent stem cell with the ability to differentiate

into three lineages: Osteoblasts, adipocytes and chondrocytes

(4). It has previously been shown

that the differentiation strength of BMSCs is markedly associated

with bone changes in vivo (5). Research using tissue engineering

functional scaffolds has demonstrated that increasing the

osteogenic differentiation ability of BMSCs leads to a notable

increase in bone formation in vivo (6). Therefore, BMSCs are considered an

important target and functional cell for treating diseases

characterized by reduced bone formation (7,8).

However, the specific regulatory mechanism underlying the

osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs has not yet been fully

elucidated and requires further investigation.

Forkhead box (FOXJ3) possesses DNA-binding

transcriptional activation activity, RNA polymerase II specificity

and sequence-specific double-stranded DNA-binding activity.

Notably, FOXJ3 participates in the positive regulation of RNA

polymerase II transcription. Previous studies have shown that FOXJ3

is related to the progression of various diseases, such as

rheumatoid arthritis (9), and

spermatogenesis (10).

Furthermore, it has been reported to serve an important role in the

disease evolution process in cancer (11,12).

At the metabolic level, it has been reported that FOXJ3 can promote

the thermogenic effect of fat (13). In addition, FOXJ3 can promote the

formation of osteoclasts (14).

Fat metabolism and osteoclastogenesis in the bone marrow are

associated with bone formation and other processes. Given the

important role of BMSCs in bone formation, it is crucial to clarify

whether FOXJ3 affects the osteogenic differentiation function of

BMSCs and its role in bone metabolic diseases. However, to the best

of our knowledge, no relevant studies have yet been published.

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is a crucial pathway that

serves important roles in various cell functions, including cell

proliferation (15) and

differentiation (16). It has

previously been shown that this pathway can promote the osteogenic

differentiation of BMSCs (17).

After activation of the Wnt/β-catenin protein and its entry into

the nucleus, it can activate the expression of osteogenic-related

molecules, promote the secretion of extracellular matrix proteins,

and the synthesis of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and other

substances by BMSCs, thereby promoting mineralization (18). Therefore, the present study aims to

investigate whether FOXJ3 is involved in the osteogenic

differentiation of BMSCs and whether it exerts its regulatory

function through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, thereby providing a new

therapeutic target for bone metabolic diseases.

Materials and methods

BMSC Treatment

Rat BMSCs were obtained from Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd. Since BMSCs from passages 3–6 exhibit a

homogeneous population, consistent morphology and robust osteogenic

differentiation functionality, all experiments were conducted using

cells within this passage range. Adherent BMSCs were cultured in

DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10%

fetal bovine serum (FBS; Zhejiang Tianhang Biotechnology Co., Ltd.)

in a humidified incubator maintained at 37°C with 5%

CO2.

Osteoblast differentiation

BMSCs were seeded at a density of 1×105

cells/well in 12-well plates. Following medium renewal on day 2,

the BMSCs were induced to differentiate by culturing them in

low-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 10−8 M

dexamethasone (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA; cat: D4902), 50 µg/ml

ascorbic acid 2-phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich, cat: 49752) and 10 mM

β-glycerophosphate (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA; cat. no. G9422). The

culture medium was refreshed every 3 days. Osteogenic

differentiation medium was supplemented with 5 µM SB216763

(19–21) or 10 µM XAV939 (22,23)

(both from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd.) to

activate or inhibit the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway during BMSC

culture in 37°C, respectively. The DMSO group was supplemented with

the same volume of DMSO as the groups treated with SB216763 or

XAV939.

ALP activity assay

BMSCs were seeded at a density of 1×10 cells/well in

12-well plates. ALP activity was assessed following 10 days of

osteogenic differentiation, in accordance with the manufacturer's

protocol, using an ALP activity assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology,

cat: C3206). Total protein concentrations in the lysates (Beyotime

Biotechnology, cat: P0013) were determined using the bicinchoninic

acid assay (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Results were

normalized to total protein content and expressed relative to the

control condition.

Alizarin Red S (ARS) staining

The degree of mineralization was determined by ARS

staining. BMSCs were seeded at a density of 1×105

cells/well in 12-well plates. After osteogenic differentiation, the

cells were fixed with 95% ethanol at 25°C for 30 min, followed by

incubation with 0.1% ARS solution (pH 4.2; Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.) for 20 min at room temperature. To

quantify mineralization, the calcium-bound dye was solubilized

using 10% cetylpyridinium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for

1 h in 25°C, and the eluate was assayed spectrophotometrically at

562 nm. Staining intensity was captured in light microscope and

normalized to total protein content and reported relative to the

undifferentiated control.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from BMSCs using

TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), followed by cDNA synthesis via RT with random primers and an

M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase kit (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) according to manufacturer's protocol.

Subsequently, qPCR analyses were performed using a SYBR Green PCR

kit (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Thermocycling conditions were

as follows: 94°C, 30 sec; 55°C, 30 sec. Step 3: 72°C, 1 min). GAPDH

expression was used for normalization. The ΔCq values were

calculated relative to GAPDH, and relative quantification of gene

expression was determined using the 2−ΔΔCq method

(24). Each sample was assessed in

triplicate. The primers used are shown in Table I.

| Table I.Primer sequences. |

Table I.

Primer sequences.

| Gene | Primer sequence,

5′-3′ |

|---|

| GAPDH | F:

AACCCTCAACAGGGATGCTT |

|

| R:

GTTCACACCGACCTTCACCA |

| FOXJ3 | F:

TTCTCTGGCATTGGGGCAAA |

|

| R:

CTGGCATAGCTGTACGGAGG |

| RUNX2 | F:

CAACCGAGTCAGTGAGTGCT |

|

| R:

CAAACCATACCCAGTCCCTGT |

| OCN | F:

CCGTTTAGGGCATGTGTTGC |

|

| R:

CCGTCCATACTTTCGAGGCA |

Western blotting

Cell protein was obtained using lysis buffer

(Beyotime Biotechnology, cat: P0013) and quantified by BCA method.

Protein lysates (30 µg/lane) underwent electrophoretic separation

on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels followed by wet transfer to PVDF

membranes (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). Membranes were then blocked

for 1 h in 0.1% TBS-Tween (TBST) containing 5% non-fat dry milk at

room temperature. Primary antibody (FOXJ3: Solarbio, Cat: K008825P.

active β-catenin: Solarbio, Cat: K009589P. β-catenin: Solarbio,

Cat: K008788P. AKT: Solarbio, Cat: K109232P. p-AKT: Solarbio, Cat:

Cat:K000186M. ERK: Solarbio, Cat: K200062M. p-ERK: Solarbio, Cat:

K009730P. GAPDH: Solarbio, cat. no. K200057M) incubation was

performed overnight at 4°C (1:1,000). After washing, the blots were

incubated for 1 h at room temperature with a HRP-linked goat

anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:1,000) (Solarbio, Cat. no. SE132

and SE134). Following three 5-min TBST washes, protein bands were

treated by ECL kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, cat: P0018S) and

detected by enhanced chemiluminescence after substrate application.

GAPDH blotting served as the normalization control. ImageJ software

(National Institutes of Health, V1.47) is used for protein

quantification.

Lentivirus production and

infection

A lentiviral vector encoding FOXJ3 (lentiviral

vector backbone: pCDH-EF1a-MCS-IRES-puro; OE-FOXJ3) was generated

by Guangzhou iGene Biotechnology Co., Ltd. In short, 293T cells

(Guangzhou iGene Biotechnology Co.) were co-transfected using a

third-generation lentiviral system, with plasmid ratios of 4 µg

(target plasmid): 3 µg (psPAX2): 1 µg (pMD2.G). Virus supernatants

were collected in batches at 48 and 72 h after transfection and

filtered through a 0.45 µm filter membrane. The virus particles

were concentrated by ultracentrifugation (~70,000-100,000 × g, 2 h)

in 4°C, and the precipitate was resuspended in a 500 µl of buffer.

Finally, the samples were aliquoted and stored at −80°C. When cells

reached 80–90% confluency, lentiviral transduction was performed

for 24 h at 37°C. The viral supernatant was diluted in complete

medium to achieve a multiplicity of infection of 10 and was applied

to cells supplemented with polybrene (8 µg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA) in 24 h. The negative control was prepared by transducing the

cells with the lentiviral vector backbone lacking the target gene.

Transduction efficiency was assessed by RT-qPCR analysis of FOXJ3

mRNA levels. Subsequent experiments were performed in 24 h

later.

Small interfering (si)RNA

transfection

Gene silencing was performed using FOXJ3-targeting

siRNAs (Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd.), with a non-targeting

scrambled siRNA (Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd.) used as a negative

control. Transfection of 1×105 BMSCs was carried out

using 50 nM siRNA with Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to standard

procedures in 37°C in 6 h. Subsequent experiments were performed in

6 h later. The siRNA sequences are shown in Table II.

| Table II.siRNA sequences. |

Table II.

siRNA sequences.

| siRNA | siRNA sequence,

5′-3′ |

|---|

| siControl | Sense:

UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT |

|

| Antisense:

ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGA |

|

| ATT |

| siFOXJ3-1 | Sense:

CGGGCCUCAACUCCAUAUATT |

|

| Antisense:

UAUAUGGAGUUGAGGCCC |

|

| GTT |

| siFOXJ3-2 | Sense:

GGGAAGUGUACAUAGUUA |

|

| UTT |

|

| Antisense:

AUAACUAUGUACACUUCC |

|

| CTT |

| siFOXJ3-3 | Sense:

CUGGAGAGCAGCCUAACAUTT |

|

| Antisense:

AUGUUAGGCUGCUCUCCA |

|

| GTT |

Statistical analysis

All data were obtained from experiments repeated at

least three times. Results are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 18.0

(IBM Corp.). Paired Student's t-test was used for two-group

comparisons, whereas one-way ANOVA with Tukey's HSD post hoc

multiple comparisons test applied for multi-group analyses. The

Pearson correlation test was performed for correlation analyses.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

FOXJ3 expression is positively

associated with BMSC osteogenic differentiation

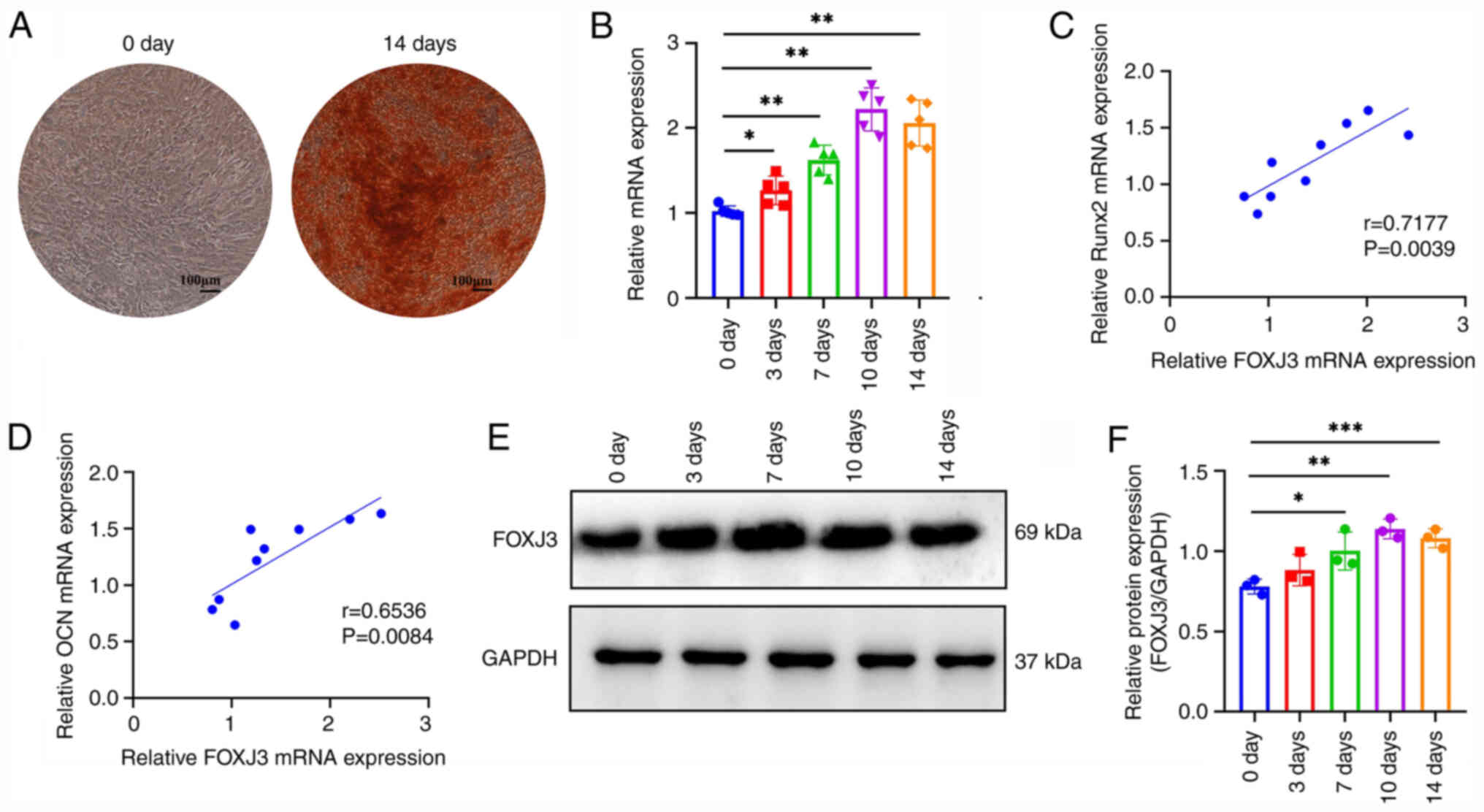

Firstly, osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs was

induced and dynamic changes in FOXJ3 expression were detected

during this differentiation process. The results of ARS staining

indicated that BMSCs were effectively differentiated into

osteoblasts after a 14-day culture in osteogenic induction medium

(Fig. 1A). RT-qPCR results

demonstrated that FOXJ3 expression progressively increased with

prolonged osteogenic induction time, reaching peak levels on day 10

of induction with a ~2-fold increase compared with that in the

non-induced group (Fig. 1B).

Furthermore, RT-qPCR analysis revealed a positive correlation

between FOXJ3 expression and the expression of osteogenesis-related

genes Runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) (Fig. 1C) and osteocalcin (OCN) (Fig. 1D). Additionally, western blotting

demonstrated a progressive elevation in FOXJ3 protein expression

with extended osteogenic induction, reaching a maximum on day 10 of

induction (Fig. 1E and F). These

findings collectively suggested that FOXJ3 may be positively

associated with osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs and could serve

a regulatory role in BMSCs osteogenic differentiation

processes.

Loss of FOXJ3 in vitro inhibits the

osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs

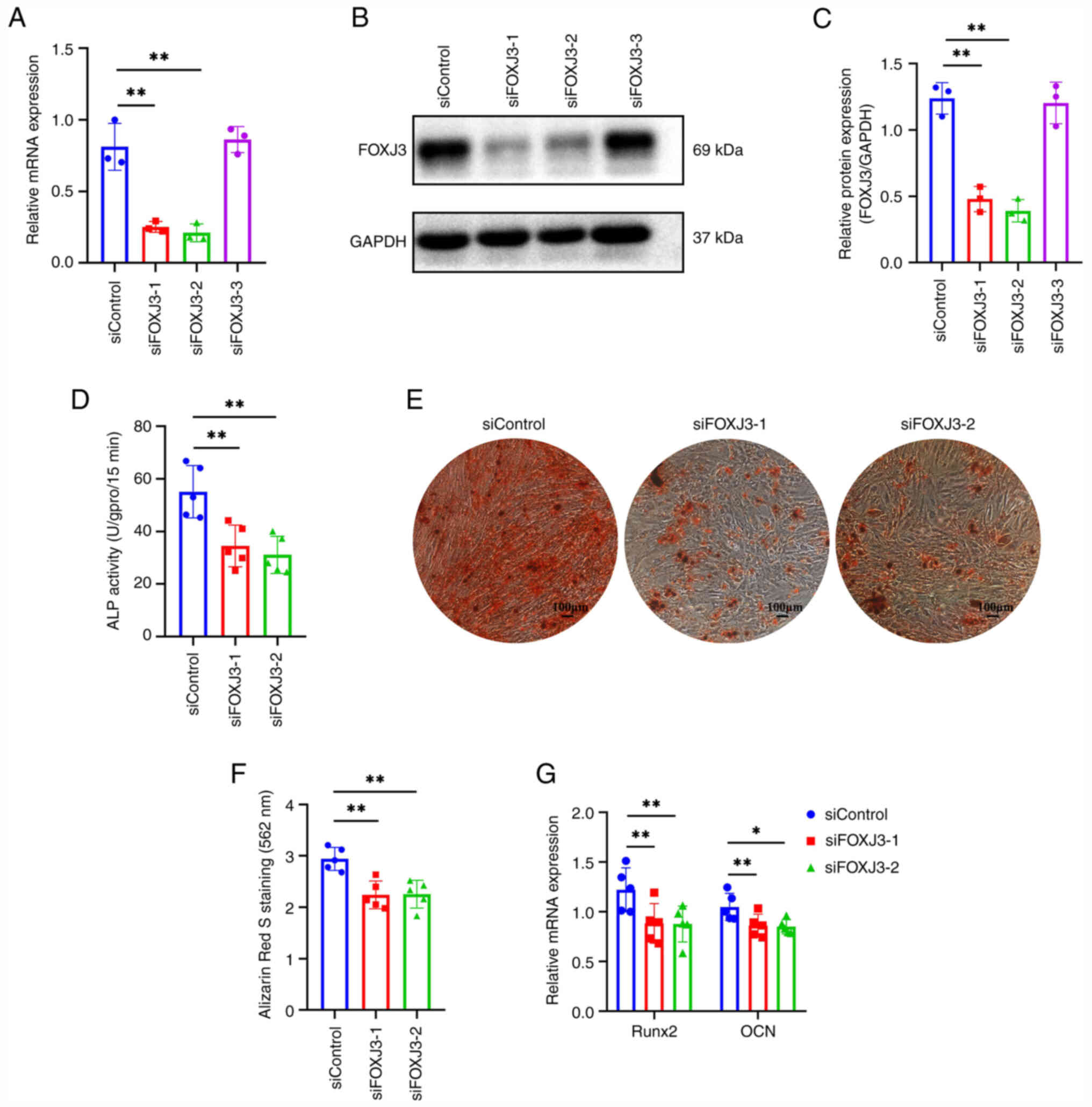

To investigate the regulatory role of FOXJ3 in BMSCs

osteogenic differentiation, BMSCs were transfected with siRNA to

knock down FOXJ3 expression. The results of RT-qPCR demonstrated

that siFOXJ3-1 and siFOXJ3-2 exhibited significant knockdown

efficiencies, whereas siFOXJ3-3 showed no substantial effect

compared to the siControl group (Fig.

2A). Western blotting further confirmed that siFOXJ3-1 and

siFOXJ3-2 effectively reduced FOXJ3 protein expression in BMSCs

(Fig. 2B and C). Therefore,

siFOXJ3-1 and siFOXJ3-2 for the subsequent experiments. Following

FOXJ3 knockdown, osteogenic differentiation was induced in BMSCs.

Quantitative ALP analysis revealed decreased ALP activity in both

siFOXJ3-1 and siFOXJ3-2 groups compared with that in the control,

indicating that FOXJ3 knockdown suppressed ALP activity in BMSCs

(Fig. 2D). ARS staining showed

that the numbers of osteogenic nodules in the siFOXJ3-1 and

siFOXJ3-2 groups were markedly reduced compared with those in the

control group (Fig. 2E).

Quantitative analysis of ARS staining further confirmed that

knockdown of FOXJ3 expression inhibited osteogenic differentiation

of BMSCs (Fig. 2F). RT-qPCR

demonstrated that the expression of osteogenic

differentiation-related genes RUNX2 and OCN was suppressed

following FOXJ3 knockdown (Fig.

2G). These findings collectively demonstrated that FOXJ3

knockdown may impair the osteogenic differentiation potential in

BMSCs.

In vitro overexpression of FOXJ3

promotes BMSCs osteogenic differentiation

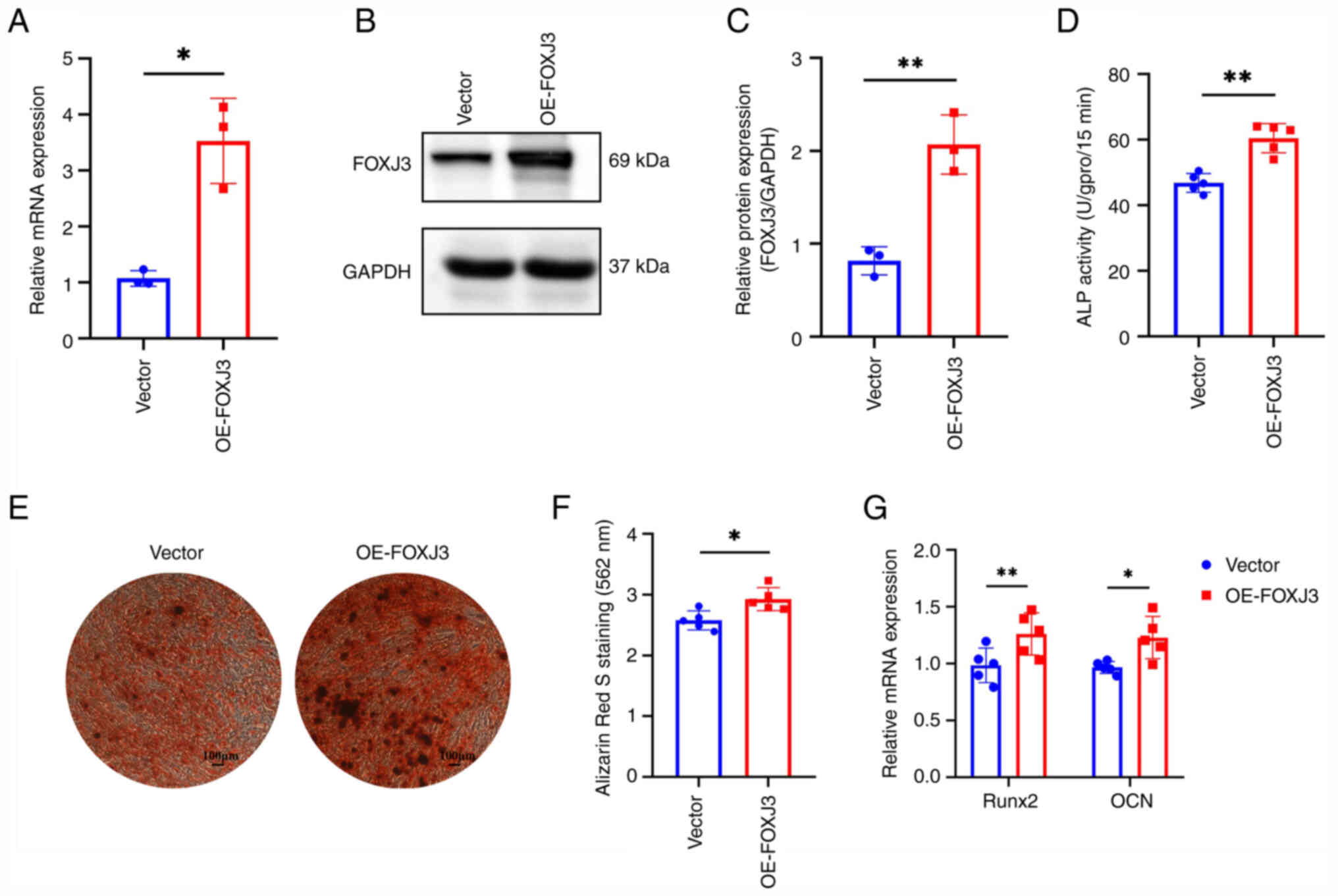

To further elucidate the regulatory role of FOXJ3 in

osteogenic differentiation, lentiviral infection was used to

overexpress FOXJ3 in BMSCs. The results of RT-qPCR showed that the

expression levels of FOXJ3 in BMSCs were significantly increased

after lentiviral infection (Fig.

3A). Western blotting also revealed that FOXJ3 protein

expression was elevated in the OE-FOXJ3 group compared with that in

the control group (Fig. 3B).

Protein semi-quantification demonstrated a ~2-fold increase in

protein expression in the OE-FOXJ3 group relative to the control

group (Fig. 2C). Following FOXJ3

OE, osteogenic differentiation was further induced in BMSCs.

Quantitative detection of ALP revealed that ALP activity in the

OE-FOXJ3 group was significantly increased compared with that in

the control group (Fig. 3D). ARS

staining results demonstrated a marked increase in osteogenic

nodules within the OE-FOXJ3 group relative to the control group

(Fig. 3E), and quantitative

analysis of ARS staining further confirmed that FOXJ3

overexpression enhanced osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs

(Fig. 3F). Additionally, RT-qPCR

revealed that the expression levels of the osteogenic

differentiation-related genes RUNX2 and OCN were upregulated

following FOXJ3 overexpression (Fig.

3G). These findings collectively demonstrated that FOXJ3

gain-of-function may promote osteogenic differentiation in

BMSCs.

FOXJ3 regulates the Wnt/β-catenin

pathway

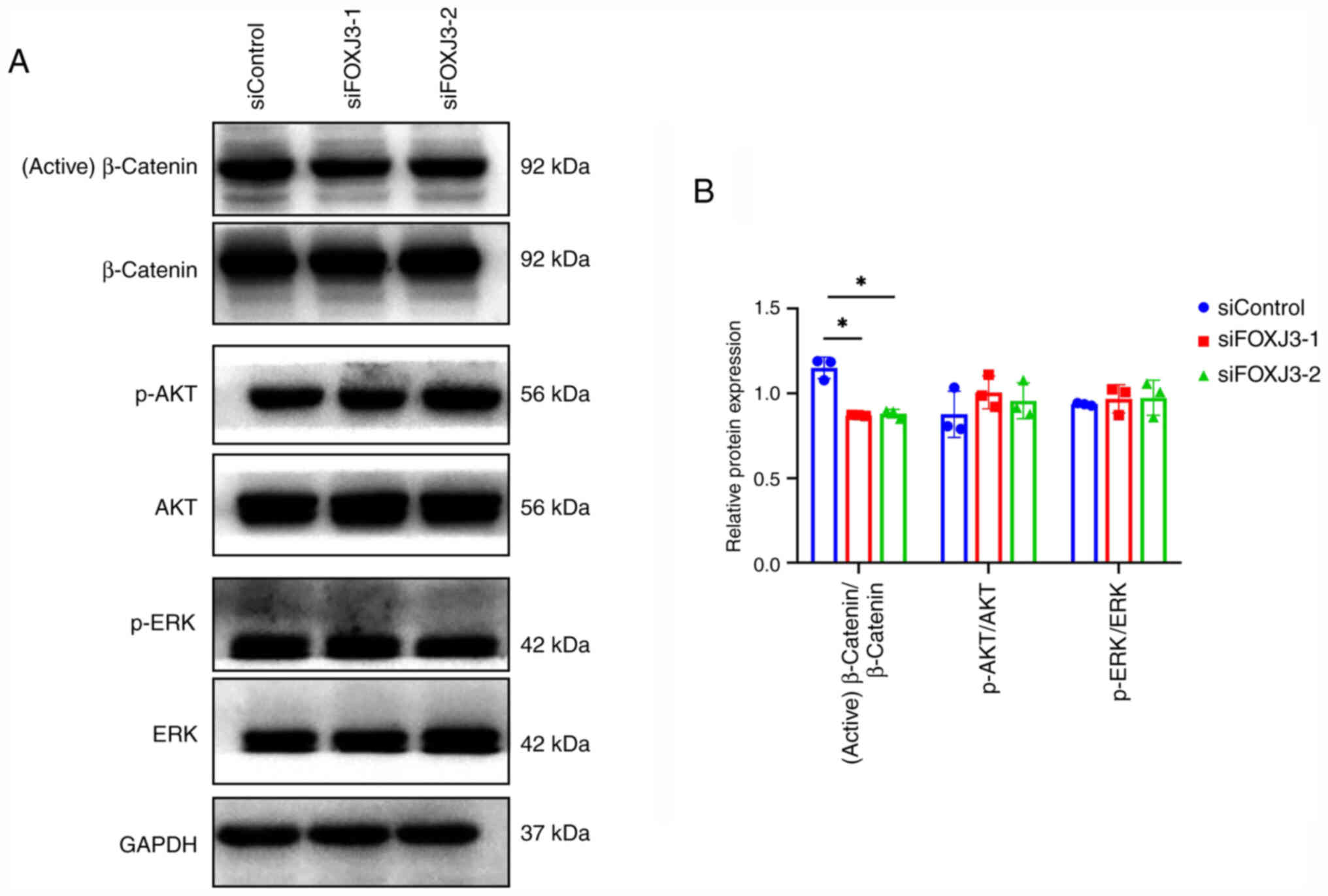

To investigate the mechanism by which FOXJ3

regulates BMSC osteogenic differentiation, osteogenic

differentiation was induced after knocking down FOXJ3 expression,

and the expression levels of proteins in common osteogenic

differentiation pathways, including the Wnt/β-catenin, PI3K/AKT and

MAPK/ERK pathways, were examined via western blotting. The results

revealed that the expression levels of active β-catenin were

decreased in the siFOXJ3-1 and siFOXJ3-2 groups compared with those

in the control group, whereas p-AKT and p-ERK expression showed no

significant differences (Fig. 4A and

B). These results indicated that FOXJ3 may primarily promote

BMSCs osteogenic differentiation by regulating the Wnt/β-catenin

pathway.

FOXJ3 modulates the osteogenic

differentiation of BMSCs through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway

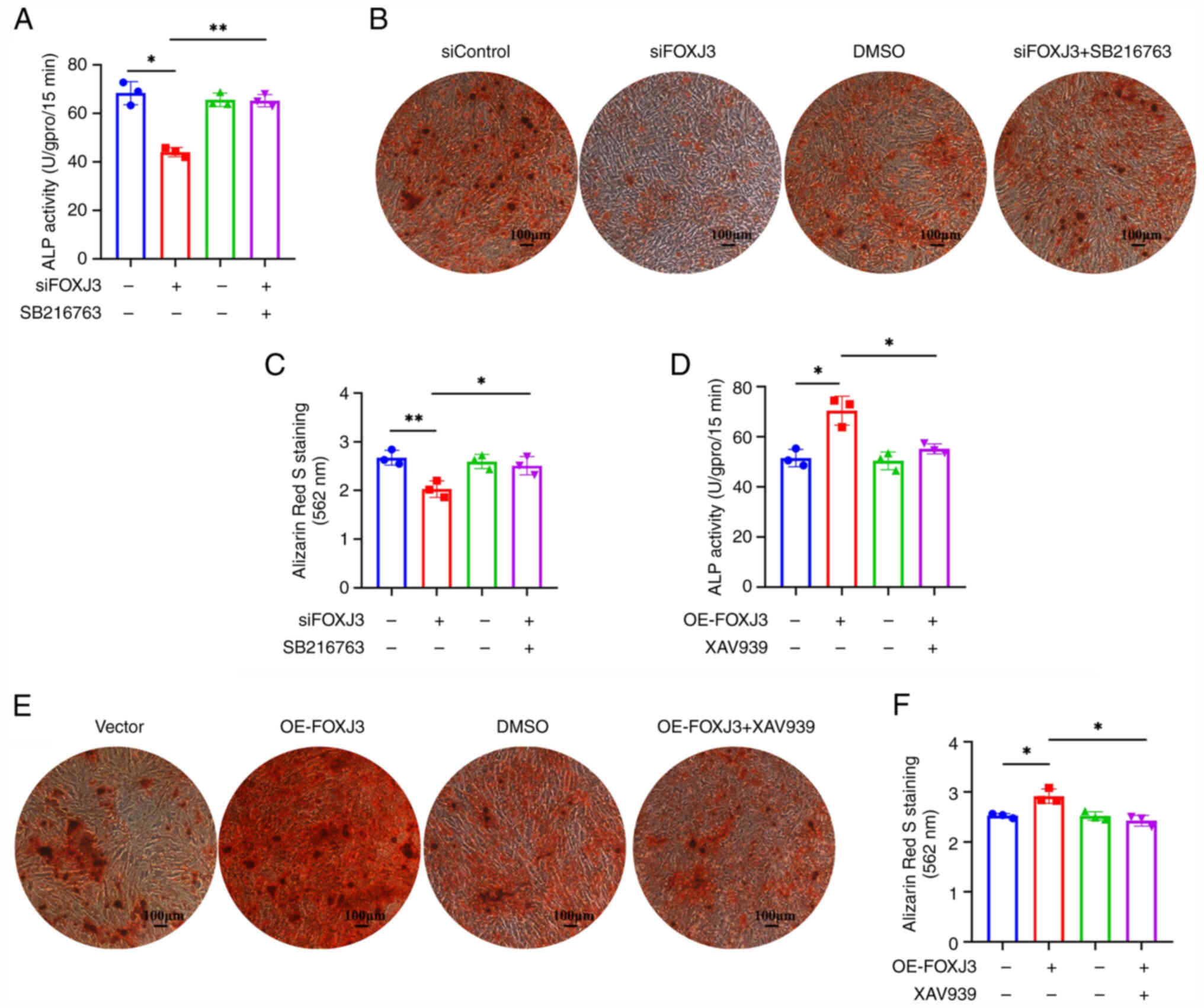

To further elucidate the role of the Wnt/β-catenin

pathway in FOXJ3-mediated regulation of BMSCs osteogenic

differentiation, rescue experiments were performed using

pathway-specific inhibitors or agonists. Western blotting initially

confirmed alterations in the expression levels of proteins

associated with the Wnt/β-catenin pathway following combined FOXJ3

knockdown and treatment with SB216763, a Wnt/β-catenin pathway

agonist. The results showed that the expression of active β-catenin

in the siFOXJ3 group was decreased compared with that in the

siControl group; however, after the addition of the pathway agonist

SB216763, levels of active β-catenin were increased to levels

comparable with the control (Fig. S1A

and B). Quantitative ALP analysis revealed that ALP activity

was reduced in the siFOXJ3 group compared with that in the

siControl group, whereas the addition of the pathway agonist

SB216763 significantly enhanced ALP activity (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, ARS staining and

quantification demonstrated fewer osteogenic nodules in the siFOXJ3

group compared with that in the siControl group, whereas the

addition of the pathway agonist SB216763 restored the osteogenic

differentiation capacity of BMSCs (Fig. 5B and C).

Furthermore, after overexpressing FOXJ3, the

findings were further validated using the Wnt/β-catenin pathway

inhibitor XAV939. Western blotting demonstrated that active

β-catenin expression was elevated in the OE-FOXJ3 group compared

with that in the vector group; however, this enhancement was

reversed following treatment with the pathway inhibitor XAV939,

restoring active β-catenin expression to control levels (Fig. S1C and D). ALP activity was

significantly enhanced in the OE-FOXJ3 group relative to the vector

group, whereas this effect was attenuated upon pathway inhibitor

treatment (Fig. 5D). ARS staining

and quantification showed increased osteogenic nodule formation in

the OE-FOXJ3 group compared with that in the vector group, whereas

this pro-osteogenic effect was abolished in the OE-FOXJ3 + XAV939

group, with nodule formation returning to baseline control levels

(Fig. 5E and F). Therefore, these

results indicated that FOXJ3 could regulate the osteogenic

differentiation of BMSCs in a Wnt/β-catenin pathway-dependent

manner.

Discussion

The present study provided compelling evidence

establishing the transcription factor FOXJ3 as a novel and

important positive regulator of osteogenic differentiation in BMSCs

and identified its crucial dependence on the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway. The findings suggested the potential role of

FOXJ3 in in the development of osteoporosis, offering a promising

novel target for therapeutic intervention.

The pivotal role of BMSCs in maintaining bone

homeostasis and their dysfunction in osteoporosis is

well-established (25). As

multipotent progenitors residing in the bone marrow, BMSCs possess

the capacity to differentiate into osteoblasts, the bone-forming

cells essential for skeletal integrity and repair (26,27).

In osteoporosis, an age-related imbalance occurs where the

commitment of BMSCs shifts from osteogenesis towards adipogenesis,

coupled with a general decline in their osteogenic potential and

proliferative capacity (28).

Previous studies have indicated that numerous transcription factors

(including RUNX2 and Osterix/SP7) are master regulators of

osteogenesis (29,30). FOXJ3, a member of the FOX family of

transcription factors, which are characterized by a conserved

winged-helix DNA-binding domain, represents a hitherto unrecognized

regulator of cell differentiation (13). Although FOXJ3 has been implicated

in other biological processes, such as spermatogenesis and cellular

stress responses (12), its

specific functions in bone metabolism and BMSC biology have remain

unexplored. Notably, some other FOX members, such as FOXO1, have

been implicated in the oxidative stress response in bone, and FOXC2

has been shown to be involved in BMP2 signaling (31), thus indicating that FOXJ3 may also

be involved in osteogenesis.

The present study first revealed that FOXJ3 was

upregulated during in vitro osteogenic differentiation, and

further results indicated that a positive association existed

between FOXJ3 and osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs. Furthermore,

the siRNA-mediated knockdown of FOXJ3 resulted in a marked

suppression of the osteogenic potential of BMSCs. Conversely,

lentiviral overexpression of FOXJ3 robustly enhanced osteogenesis.

These findings are important in identifying FOXJ3 as a novel

modulator of BMSCs osteogenesis. While previous studies have

explored factors such as microRNAs (32), long non-coding RNAs (33) and epigenetic regulators (34) in BMSC osteogenesis, the

identification of the role of a transcription factor such as FOXJ3

may provide a novel mechanism and potential target. The present

results demonstrated that manipulating FOXJ3 levels alone was

sufficient to markedly alter the osteogenic differentiation

trajectory of BMSCs, highlighting its potency as a regulator.

FOXJ3, alongside other identified positive regulators of BMSCs

osteogenesis, such as specific isoforms of Dlk1, may expand the

known factors that potentially manipulate bone formation (35). Moreover, investigating FOXJ3

expression in well-characterized human osteoporosis cohorts,

particularly its association with bone mineral density, fracture

history or response to existing therapies, represents a critical

next step to validate its clinical relevance. Such studies could

further establish FOXJ3 as a potential diagnostic biomarker or

therapeutic target in osteoporosis.

The canonical Wnt pathway is a well-established and

powerful promoter of osteoblast differentiation and bone formation

(36). Here, FOXJ3 knockdown

specifically reduced the levels of active (non-phosphorylated)

β-catenin, while leaving the PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK pathways

unaffected. The selective impact of FOXJ3 on Wnt/β-catenin

signaling suggests a focused regulatory mechanism. This finding is

consistent with the results of previous studies emphasizing the

critical role of precise Wnt pathway modulation in bone anabolism

and its therapeutic exploitation (37,38).

For example, romosozumab, an anti-sclerostin antibody that enhances

Wnt signaling, has been shown to exert notable efficacy in treating

patients with osteoporosis (39).

The finding that FOXJ3 acts upstream of β-catenin activation adds a

novel layer to this complex regulatory network. Previous studies

have suggested that FOXJ3 can act as a recruited transcription

factor to promote osteoclast formation (40,41).

If both osteoclasts and osteoblasts exist in vivo, FOXJ3 may

have regulatory effects on both types of cells. Whether it promotes

or inhibits osteoporosis depends on whether its effect on bone

formation is greater than that on bone resorption. This not only

involves the quantity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts, but also the

activity of the cells and their proportion of their roles in bone

formation. The present study lacks animal experiments; therefore,

whether FOXJ3 will aggravate osteoporosis remains unknown. To

assess this, research using high-quality tools, such as gene

knockout mice, is needed.

The rescue experiments in the present study

demonstrated the pathway dependence and enhance the impact of the

study. The use of the specific Wnt/β-catenin agonist SB216763

effectively reversed the inhibitory effects of FOXJ3 knockdown on

β-catenin activation, ALP activity and mineralization. Conversely,

the pro-osteogenic effects of FOXJ3 overexpression were negated by

the Wnt pathway inhibitor XAV939. These experiments indicated that

the ability of FOXJ3 to promote BMSC osteogenic differentiation

requires a functional Wnt/β-catenin pathway, thus integrating FOXJ3

into a well-characterized and therapeutically relevant signaling

axis. However, the exact molecular mechanism by which FOXJ3

regulates β-catenin activation remains to be fully determined,

which is a promising direction for future research.

Placing the current findings within the broader

context of osteoporosis research underscores their potential

importance. Osteoporosis therapies have traditionally focused on

anti-resorptive agents (such as bisphosphonates and denosumab)

(42), however, while they are

effective, these treatments primarily prevent bone loss rather than

robustly rebuild bone. The development of true bone-forming

(anabolic) agents, such as teriparatide [a parathyroid hormone

(PTH) analogue], abaloparatide (a PTH-associated protein analogue)

and the aforementioned romosozumab, represents a major advance

(43). However, limitations

remain, including cost, administration routes and potential side

effects (44). Identifying novel

upstream regulators such as FOXJ3, which positively drives

osteogenesis through a fundamental anabolic pathway

(Wnt/β-catenin), provides novel options for therapeutic

development. Strategies may involve small molecules or biologics

designed to enhance FOXJ3 expression or activity directly within

BMSCs or osteoprogenitors, or gene therapy approaches. This

approach aligns with the growing interest in stem cell-based

therapies and targeting stem cell dysfunction in age-associated

diseases such as osteoporosis (45–47).

Enhancing the intrinsic osteogenic potential of endogenous BMSCs

via FOXJ3 modulation could offer a powerful strategy for bone

regeneration. Moreover, future studies should include in

vivo models, such as FOXJ3-knockout mice or local injection of

FOXJ3-modulating vectors in osteoporotic animal models, to further

validate its role.

In conclusion, the present study advances the

understanding of the molecular control of BMSC osteogenic

differentiation and the pathogenesis of osteoporosis. Robust

mechanistic evidence was provided demonstrating that FOXJ3 exerts

its pro-osteogenic effects primarily, if not exclusively, through

the potent Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. This dependency was

conclusively proven through targeted pathway rescue experiments.

The integration of functional cellular assays and mechanistic

pathway analysis provided a strong foundation for considering FOXJ3

as a promising new molecular target for the development of novel

anabolic therapies aimed at restoring bone formation in

osteoporosis and other bone-deficit conditions. While the present

study provided strong evidence for the role of FOXJ3 in

vitro and its clinical association, certain limitations warrant

mention and guide future research. First, the findings were based

on in vitro models, which may not fully recapitulate the

complex bone microenvironment. Second, the precise molecular

mechanism by which FOXJ3 regulates β-catenin remains unclear.

Third, clinical patient-derived data, to assess the association

between FOXJ3 expression and osteoporosis severity or treatment

outcomes, were not included. Thus, future research focusing on

in vivo validation and detailed mechanistic assessment will

be crucial to fully realize the therapeutic potential of targeting

the FOXJ3-Wnt/β-catenin axis, and to confirm the role of FOXJ3 in

osteoporosis and its translational potential.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Zhuhai Xiangshan Talent

Project (grant no. 2021XSYC-01) and the Supporting Project of

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. PT8217140653).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HX performed the cell experiments and wrote the

initial manuscript and submitted the paper for publication. JL

contributed to some cell experiments. WH conducted the statistical

analysis of the data. YQ conceived the study, supervised the

research and revised the manuscript. HX and JL confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Jin J: Screening for osteoporosis to

prevent fractures. JAMA. 333:5472025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Reid IR and Billington EO: Drug therapy

for osteoporosis in older adults. Lancet. 399:1080–1092. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zhang B, He W, Pei Z, Guo Q, Wang J, Sun

M, Yang X, Ariben J, Li S, Feng W, et al: Plasma proteins,

circulating metabolites mediate causal inference studies on the

effect of gut bacteria on the risk of osteoporosis development.

Ageing Res Rev. 101:1024792024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Yin JQ, Zhu J and Ankrum JA: Manufacturing

of primed mesenchymal stromal cells for therapy. Nat Biomed Eng.

3:90–104. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Dalle Carbonare L, Cominacini M, Trabetti

E, Bombieri C, Pessoa J, Romanelli MG and Valenti MT: The bone

microenvironment: New insights into the role of stem cells and cell

communication in bone regeneration. Stem Cell Res Ther. 16:1692025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zhang L, Yuan X, Song R, Yuan Z, Zhao Y

and Zhang Y: Engineered 3D mesenchymal stem cell aggregates with

multifunctional prowess for bone regeneration: Current status and

future prospects. J Adv Res. Apr 11–2025.doi:

10.1016/j.jare.2025.04.008 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

7

|

Wu KC, Chang YH, Ding DC and Lin SZ:

Mesenchymal stromal cells for aging cartilage regeneration: A

review. Int J Mol Sci. 25:129112024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Artamonov MY and Sokov EL: Intraosseous

delivery of mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of bone and

hematological diseases. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 46:12672–12693. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ban JY, Park HJ, Kim SK, Kim JW, Lee YA,

Choi IA, Chung JH and Hong SJ: Association of forkhead box J3

(FOXJ3) polymorphisms with rheumatoid arthritis. Mol Med Rep.

8:1235–1241. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ni L, Xie H and Tan L: Multiple roles of

FOXJ3 in spermatogenesis: A lesson from Foxj3 conditional knockout

mouse models. Mol Reprod Deve. 83:1060–1069. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Jin J, Zhou S, Li C, Xu R, Zu L, You J and

Zhang B: MiR-517a-3p accelerates lung cancer cell proliferation and

invasion through inhibiting FOXJ3 expression. Life Sci. 108:48–53.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Challagundla KB, Pathania AS, Chava H,

Kantem NM, Dronadula VM, Coulter DW and Clarke M: FOXJ3, a novel

tumor suppressor in neuroblastoma. Mol Ther Oncol. 33:2009142025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Huang J, Zhang Y, Zhou X, Song J, Feng Y,

Qiu T, Sheng S, Zhang M, Zhang X, Hao J, et al: Foxj3 Regulates

thermogenesis of brown and beige fat via induction of PGC-1α.

Diabetes. 73:178–196. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yuan L, Jiang N, Li Y, Wang X and Wang W:

RGS1 Enhancer RNA promotes gene transcription by recruiting

transcription factor FOXJ3 and facilitates osteoclastogenesis

through PLC-IP3R-dependent Ca2+ response in rheumatoid arthritis.

Inflammation. 48:447–463. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Ding Y and Chen Q: Wnt/beta-catenin

signaling pathway: An attractive potential therapeutic target in

osteosarcoma. Front Oncol. 14:14569592024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hosseini A, Dhall A, Ikonen N, Sikora N,

Nguyen S, Shen Y, Amaral MLJ, Jiao A, Wallner F, Sergeev P, et al:

Perturbing LSD1 and WNT rewires transcription to synergistically

induce AML differentiation. Nature. 642:508–518. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Arya PN, Saranya I and Selvamurugan N:

Crosstalk between Wnt and bone morphogenetic protein signaling

during osteogenic differentiation. World J Stem Cells. 16:102–113.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Abhishek Shah A, Chand D, Ahamad S, Porwal

K, Chourasia MK, Mohanan K, Srivastava KR and Chattopadhyay N:

Therapeutic targeting of Wnt antagonists by small molecules for

treatment of osteoporosis. Biochem Pharmacol. 230:1165872024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Gong W, Li M, Zhao L, Wang P, Wang X, Wang

B, Liu X and Tu X: Sustained release of a highly specific GSK3β

inhibitor SB216763 in the PCL scaffold creates an osteogenic niche

for osteogenesis, anti-adipogenesis, and potential angiogenesis.

Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 11:12152332023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Tanthaisong P, Imsoonthornruksa S,

Ngernsoungnern A, Ngernsoungnern P, Ketudat-Cairns M and Parnpai R:

Enhanced chondrogenic differentiation of human umbilical cord

Wharton's jelly derived mesenchymal stem cells by GSK-3 inhibitors.

PLoS One. 12:e01680592017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yao J, Wu X, Qiao X, Zhang D, Zhang L, Ma

JA, Cai X, Boström KI and Yao Y: Shifting osteogenesis in vascular

calcification. JCI Insight. 6:e1430232021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Rong X, Kou Y, Zhang Y, Yang P, Tang R,

Liu H and Li M: ED-71 Prevents Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis

by regulating osteoblast differentiation via notch and

Wnt/β-catenin pathways. Drug Des Devel Ther. 16:3929–3946. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Yang N, Zhang X, Li L, Xu T, Li M, Zhao Q,

Yu J, Wang J and Liu Z: Ginsenoside Rc promotes bone formation in

Ovariectomy-induced osteoporosis in vivo and osteogenic

differentiation in vitro. Int J Mol Sci. 23:61872022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Abdelbaset S, Mohamed Sob MA, Mutawa G,

El-Dein MA and Abou-El-Naga AM: Therapeutic potential of different

injection methods for bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell

transplantation in Buslfan-induced male rat infertility. J Stem

Cells Regen Med. 20:26–46. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Pajarinen J, Lin T, Gibon E, Kohno Y,

Maruyama M, Nathan K, Lu L, Yao Z and Goodman SB: Mesenchymal stem

cell-macrophage crosstalk and bone healing. Biomaterials.

196:80–89. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Sun Y, Wan B, Wang R, Zhang B, Luo P, Wang

D, Nie JJ, Chen D and Wu X: Mechanical stimulation on mesenchymal

stem cells and surrounding microenvironments in bone regeneration:

Regulations and applications. Front Cell Dev Biol. 10:8083032022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Wu Y, Xie L, Wang M, Xiong Q, Guo Y, Liang

Y, Li J, Sheng R, Deng P, Wang Y, et al: Mettl3-mediated m6A RNA

methylation regulates the fate of bone marrow mesenchymal stem

cells and osteoporosis. Nat Commun. 9:47722018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chan WCW, Tan Z, To MKT and Chan D:

Regulation and role of transcription factors in osteogenesis. Int J

Mol Sci. 22:54452021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Komori T: Regulation of skeletal

development and maintenance by Runx2 and Sp7. Int J Mol Sci.

25:101022024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Zhang W, Zhang X, Li J, Zheng J, Hu X, Xu

M, Mao X and Ling J: Foxc2 and BMP2 Induce Osteogenic/odontogenic

differentiation and mineralization of human stem cells from apical

papilla. Stem Cells Int. 2018:23639172018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Hong L, Sun H and Amendt BA: MicroRNA

function in craniofacial bone formation, regeneration and repair.

Bone. 144:1157892021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Jin C, Jia L, Huang Y, Zheng Y, Du N, Liu

Y and Zhou Y: Inhibition of lncRNA MIR31HG promotes osteogenic

differentiation of human Adipose-derived stem cells. Stem Cells.

34:2707–2720. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Liu S, Liu D, Chen C, Hamamura K,

Moshaverinia A, Yang R, Liu Y, Jin Y and Shi S: MSC Transplantation

improves osteopenia via epigenetic regulation of notch signaling in

lupus. Cell Metab. 22:606–618. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Paradise CR, Galvan ML, Kubrova E, Bowden

S, Liu E, Carstens MF, Thaler R, Stein GS, van Wijnen AJ and

Dudakovic A: The epigenetic reader Brd4 is required for osteoblast

differentiation. J Cell Physiol. 235:5293–5304. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Hu L, Chen W, Qian A and Li YP:

Wnt/β-catenin signaling components and mechanisms in bone

formation, homeostasis, and disease. Bone Res. 12:392024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Huybrechts Y, Mortier G, Boudin E and Van

Hul W: WNT signaling and bone: Lessons from skeletal dysplasias and

disorders. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 11:1652020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Maeda K, Kobayashi Y, Koide M, Uehara S,

Okamoto M, Ishihara A, Kayama T, Saito M and Marumo K: The

regulation of bone metabolism and disorders by Wnt signaling. Int J

Mol Sci. 20:55252019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Wu D, Li L, Wen Z and Wang G: Romosozumab

in osteoporosis: Yesterday, today and tomorrow. J Transl Med.

21:6682023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Alexander MS, Shi X, Voelker KA, Grange

RW, Garcia JA, Hammer RE and Garry DJ: Foxj3 transcriptionally

activates Mef2c and regulates adult skeletal muscle fiber type

identity. Dev Biol. 337:396–404. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Chen X, Wang Z, Duan N, Zhu G, Schwarz EM

and Xie C: Osteoblast-osteoclast interactions. Connect Tissue Res.

59:99–107. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Langdahl BL: Overview of treatment

approaches to osteoporosis. Br J Pharmacol. 178:1891–1906. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Khosla S and Hofbauer LC: Osteoporosis

treatment: Recent developments and ongoing challenges. Lancet

Diabetes Endocrinol. 5:898–907. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Shimizu R, Sukegawa S, Sukegawa Y,

Hasegawa K, Ono S, Nakamura T, Fujimura A, Fujisawa A, Nakano K,

Takabatake K, et al: Incidence and risk of Anti-Resorptive

Agent-related osteonecrosis of the jaw after tooth extraction: A

retrospective study. Healthcare (Basel). 10:13322022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Tong Y, Tu Y, Wang J, Liu X, Su Q, Wang Y

and Wang W: Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies linking

mesenchymal stem cells senescence to osteoporosis. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 16:16258062025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Li H and Bai L: Advances in mesenchymal

stem cell and Exosome-based therapies for aging and age-related

diseases. Stem Cell Res Ther. 16:4012025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Liang B, Burley G, Lin S and Shi YC:

Osteoporosis pathogenesis and treatment: Existing and emerging

avenues. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 27:722022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|