Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the 14th most

frequently diagnosed cancer during 2022, Globally in 2022, RCC

accounted for an estimated 434,000 newly diagnosed cases,

corresponding to age-standardized incidence rates of 5.9 per

100,000 males and 3.0 per 100,000 females (1). A major clinical challenge in RCC is

its high metastatic potential. It has been reported that ~30% of

patients have distant metastasis at the time of the first diagnosis

and the most common sites of metastasis are the lungs, bones, liver

and brain (2). The prognosis for

patients with metastatic RCC is generally unfavorable, therefore

suggesting the key clinical importance of understanding the

metastatic mechanisms in the development of effective therapeutic

strategies for RCC in the future. RCC originates from the

epithelium of the proximal convoluted tubule and accounts for

80–90% of kidney cancer cases (3).

The etiology of RCC is not fully understood and the risk factors

that can be identified include smoking, obesity, hypertension,

chronic kidney disease and certain hereditary diseases, such as von

Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease and hereditary papillary renal

carcinoma (4). Understanding these

mechanisms is key for developing targeted therapies to improve

patient outcomes.

The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a

fundamental biological process, by which epithelial cells organized

in tight junctions can transform into mesenchymal cells with

increased motility and invasiveness. Through this process, RCC

cells acquire mesenchymal stem cell-like features, which enhance

their metastatic potential and invasive capacity, thereby

facilitating entry into the bloodstream and colonization of distant

organs to form secondary tumors. Furthermore, EMT has been

implicated in drug resistance (5,6) and

serves a key role in renal fibrosis (7), which is a common pathological

manifestation of chronic kidney disease and is an independent risk

factor for RCC. In summary, EMT is one of the primary mechanisms of

distant metastasis in RCC and its activation is frequently

associated with poor prognosis.

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are functional RNA

molecules that do not encode proteins. Although a limited number of

ncRNAs have recently been reported to encode peptides or proteins,

the majority of these RNAs perform their biological functions

through other functions (8,9).

Major types of ncRNAs include microRNAs (miRNAs/miR), long ncRNAs

(lncRNAs), circular RNAs (circRNAs), small interfering RNAs

(siRNAs) and small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs). ncRNAs serve key roles

in regulating gene expression and are involved in diverse

biological processes, including growth, development, organ function

and EMT. ncRNAs are reported to be associated with various human

diseases such as cardiac hypertrophy and spinal motor neuron

disease (10), particularly

cancer, including RCC (11).

Decades of research have reported that ncRNAs can regulate EMT and

affect the occurrence, progression and metastasis of RCC through

multiple pathways (12–15). For example, downregulation of the

miR-200 family promotes EMT and enhances the invasive and

metastatic potential of cancer cells (16).

Unlike previous reports that have only partially

addressed the roles of individual ncRNA species in EMT (17) of miscellaneous cancer types like

breast cancer (18) and colorectal

carcinoma (19), to the best of

our knowledge, the present review introduces the first integrated

analysis of miRNAs, lncRNAs, circRNAs, transcribed-ultra conserved

regions and pseudogenes specifically within RCC context By

synthesizing evidence published until March 2025, the present

review reports an updated regulatory landscape that highlights

ncRNA crosstalk, most notably miRNA-lncRNA-circRNA axes, and

clarifies how these interactions drive both EMT and emerging

therapy resistance (20,21). Furthermore, the present review

translates these mechanistic insights into clinically actionable

prospects, notably evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of

circulating ncRNA signatures and the therapeutic potential of

circRNA-based vaccines together with exosome-directed

interventions, aspects that previous reviews have, to the best of

our knowledge, rarely contemplated (22,23).

Therefore, the present review comprehensively

summarizes current advances in understanding how ncRNAs regulate

EMT in RCC and explores their clinical potential as diagnostic

biomarkers and therapeutic targets to improve the prognosis of

patients with RCC in the future.

Literature search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted using

the PubMed database (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) to identify all

relevant studies published up to March 2025. The search strategy

was designed to encompass three key concepts: ncRNAs, RCC and EMT.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh) terms were primarily

used to ensure retrieval of high-quality, relevant studies.

The core search strategy that yielded the most

comprehensive results was: [‘RNA, Untranslated’ (Mesh)] AND

‘Carcinoma, Renal Cell’(Mesh) AND ‘Epithelial-Mesenchymal

Transition’ (Mesh). This search returned 88 results. These results

were sorted by publication date to prioritize the most recent

evidence. To ensure comprehensiveness, a broader search without the

EMT term [‘RNA, Untranslated’ (Mesh)] AND ‘Carcinoma, Renal Cell’

(Mesh) was also executed, which returned 1,501 results.

Furthermore, a filter for systematic reviews was applied to the

core search string, which returned 0 results, confirming the

novelty of the synthesis approach in the present review. The

reference lists of all retrieved articles and relevant reviews were

manually screened to identify any additional publications that the

electronic search might have missed.

Inclusion criteria for the studies were as follows:

i) Original research articles or reviews focusing on ncRNAs

regulating EMT in RCC; and ii) studies published in English.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: i) Studies

not associated with RCC; ii) studies not investigating EMT or

ncRNAs; and iii) conference abstracts, editorials and letters

without original data.

Due to the predominantly mechanistic nature of the

studies reviewed, which address molecular rather than clinical

endpoints, an objective evidence hierarchy analogous to that

employed in large-scale clinical research could not be rigorously

applied; therefore, formal evidence grading akin to meta-analytical

methodology was not feasible. Although the present review is

structured as a narrative review rather than a systematic review or

meta-analysis, the present review adopted a comprehensive search

strategy with clearly defined exclusion criteria to minimize

selection bias. The present analysis incorporated all relevant

studies identified by the search, with the exception of retracted

publications. Therefore, it can be considered that the potential

for selection bias in the present review is minimal. However, the

present review acknowledges that the scope and emphasis of the

synthesis may be influenced by the current research focus within

the field, which inherently shapes the available evidence.

Overview of EMT

EMT is a biological process in which epithelial

cells undergo morphological and functional transformation into

mesenchymal cells. EMT underlies key biological processes such as

embryonic development and wound healing, and also serves a key role

in the metastasis of malignant tumors (24).

Epithelial cells are usually present in the

superficial layers of the skin or lumen, such as the small

intestinal epithelium, lung epithelium and renal tubular

epithelium. Common features of epithelial cells include abundant

intercellular connections, intercellular communication through

tight junctions and desmosomes and adhesion to each other and

tightly latch onto the basement membrane (25). In cancer, epithelial cells lose

their tissue structure and cell polarity, which suppress cancer

malignancy by controlling asymmetric cell division and the

integrity of the apical junctional complex (26). The main biomarkers of epithelial

cells are E-cadherin, β-catenin and other key proteins for

inter-epithelial cell junctions and epithelial cell adhesion

molecule (27). By contrast,

mesenchymal stem/stromal cells are extensively distributed in

various types of tissues, including bone marrow, adipose and blood.

These cells are non-polarized, often exhibit an irregular

morphology and are loosely arranged with connections mediated by

cytoplasmic protrusions. They also possess certain stem cell

properties such as self-renewal (28), CSC-marker expression (29), multi-lineage potential (28) and enhanced tumorigenicity (30). The main markers of mesenchymal

stromal cells include N-cadherin and vimentin (VIM) (31).

The EMT process in tumors typically does not occur

spontaneously but is triggered by various internal and external

factors, including growth factors such as fibroblast growth factor

(FGF), epidermal growth factor and hepatocyte growth factor.

Furthermore, several signaling pathways, including the TGF-β,

Wnt/β-catenin, NF-κB, Notch and PI3K-AKT pathways, can regulate EMT

(32). The regulatory network of

EMT is highly complex, involving multiple transcription factors

[for example, Twist, Snail and zinc finger E-box binding homeobox

(ZEB)], ncRNAs and epigenetic factors such as EZH2 (33) and HOTAIR. Numerous studies have

demonstrated that ncRNAs serve a notable role in regulating the EMT

process in cancer (8,10,11).

During EMT, epithelial cells detach from the

basement membrane and acquire a partial mesenchymal phenotype to

varying degrees, entering an intermediate state between epithelium

and mesenchyme. This transition endows cells with enhanced invasive

and migratory capabilities. Throughout this process, cells undergo

multiple changes, including cytoskeletal remodeling and

downregulation of adhesion molecules. Morphologically, epithelial

cells transform from a homogeneous, tightly packed structure to

various irregular shapes, such as spindle-like and elongated forms.

The apical-basal polarity of cells is lost and the cytoskeleton

shifts to be dominated by VIM, a wave-like protein. These changes

confer a stronger capacity for locomotion and migration,

facilitating entry into the bloodstream and subsequent colonization

of distant organs (34). However,

there is ongoing debate regarding the necessity of the EMT process

for tumor metastasis. Some studies suggest that EMT may not be key

to metastasis but can markedly enhance chemoresistance. For

instance, research using spontaneous breast-to-lung metastasis

models and genetically engineered mouse models of pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma has indicated that EMT is not a prerequisite for

metastasis but can contribute to drug resistance in tumor cells

(5,35). These findings highlight the complex

role of EMT in tumor biology, where its primary function may extend

beyond facilitating metastasis to enhancing therapeutic resistance.

The resistance mechanisms associated with EMT are considered to

involve increased drug efflux, reduced cell proliferation and the

evasion of apoptosis signaling pathways (36). Furthermore, numerous clinical

studies have reported that EMT is associated with immunosuppression

within the tumor microenvironment (TME), with immune cells in the

TME facilitating the progression of EMT in tumor cells (37–39).

EMT transcription factors (EMT-TF) such as Twist, Snail and ZEB are

activated, leading to the accumulation of immunosuppressive cells

within the TME (40). Furthermore,

EMT-TF inducers, including TGF-β, also contribute to the

immunosuppressive milieu of the TME (41). Therefore, it is widely recognized

that the EMT process enables cancer cells to acquire stem cell-like

properties, which not only promote the proliferation of metastatic

foci but also increase resistance to targeted therapies and

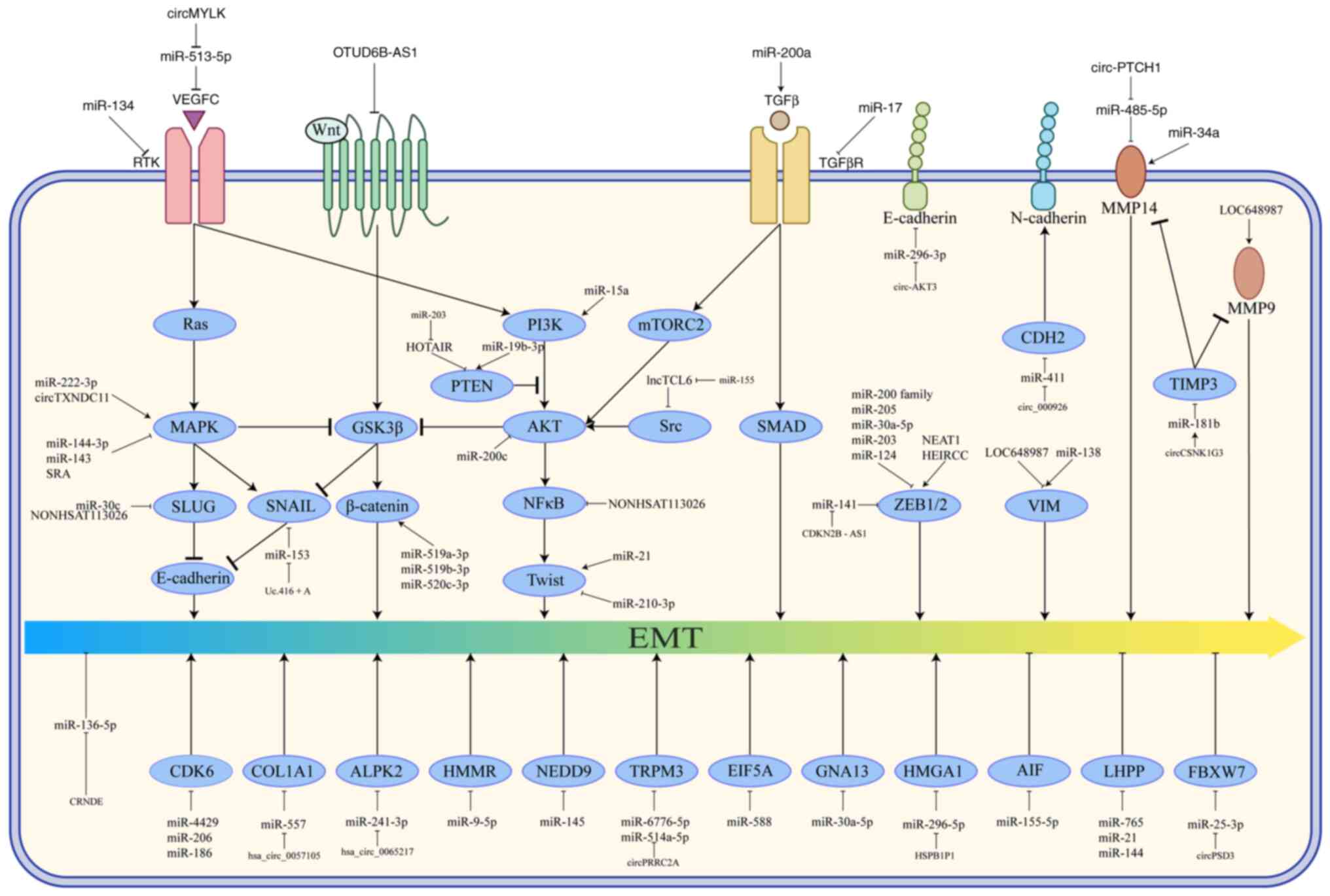

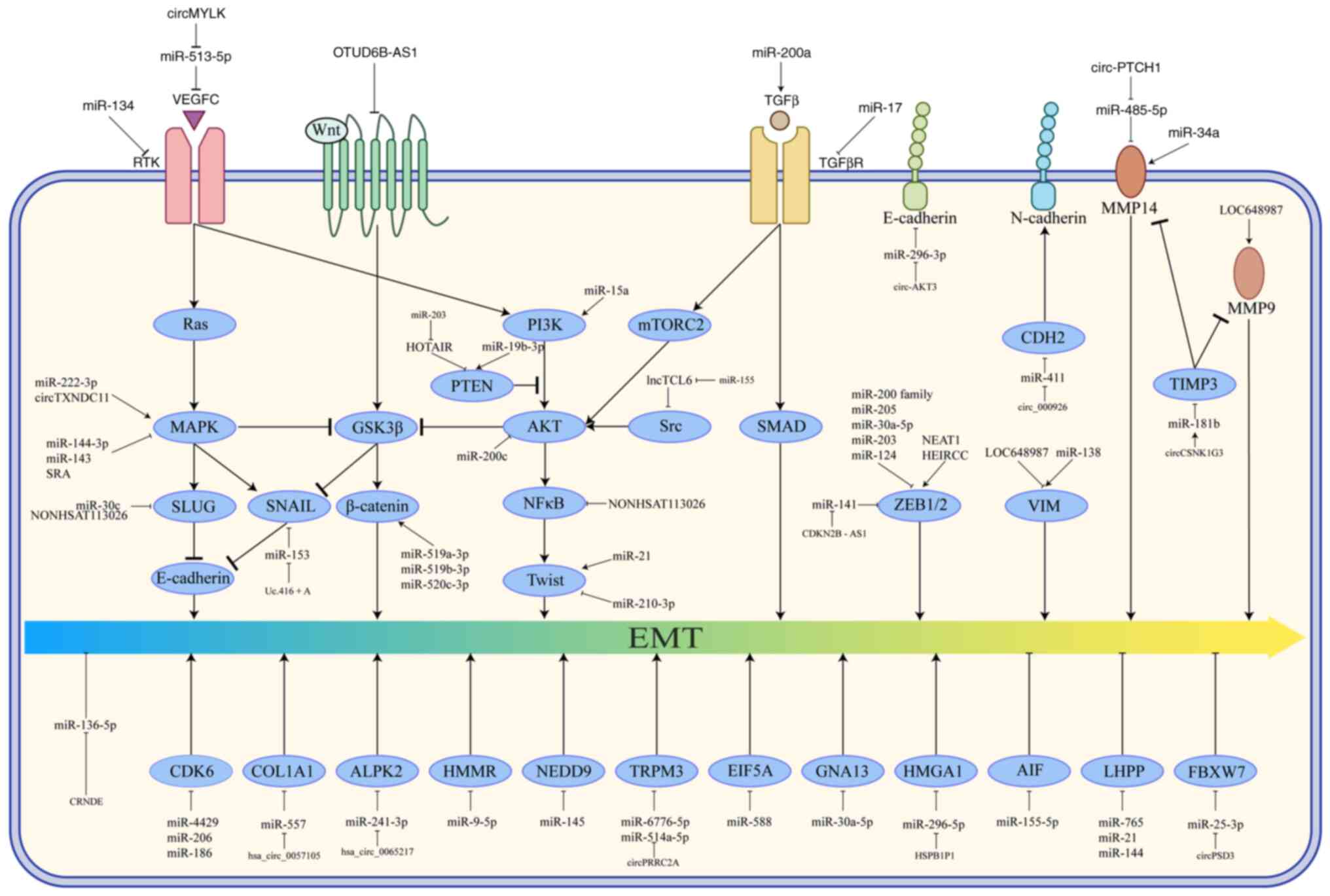

immunotherapy (42). The major

regulatory mechanisms governing EMT and the functional roles of the

ncRNAs highlighted in this review are schematically depicted in

Fig. 1.

| Figure 1.Regulatory mechanisms of EMT

progression associated with ncRNA in RCC. A complex regulatory

network of ncRNAs modulates EMT in cancer cells through selective

activation or inhibition of key signaling pathway components. →,

promotion; ⊥, inhibition; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition;

ncRNA, non-coding RNA; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; miRNA, microRNA;

circRNA, circular RNA; HOTAIR, HOX transcript antisense intergenic

RNA; NEAT1, nuclear enriched abundant transcript 1; SNHG, small

nuclear RNA host gene; CDKN2B-AS1, CDK inhibitor 2B-antisense RNA

1; OTUD6B, ovarian tumor domain deubiquitinase 6B. |

Therefore, the EMT process represents a key

mechanism by which cancer cells gain increased invasiveness and

metastatic potential. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the

cell populations in advanced epithelial tumors and metastatic

cancer exhibit varying degrees of mesenchymal characteristics when

compared with early-stage cancer (24,43),

suggesting that epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is a key step

and hallmark event in cancer metastasis. Furthermore, EMT is a

reversible process and cells can undergo reversion to an epithelial

phenotype through the mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET).

This MET process after metastasis may facilitate the colonization

of tumors in distant organs (7).

Regulatory mechanisms of ncRNAs

There are various types of ncRNAs, such as miRNAs,

lncRNAs, circRNAs, siRNAs, transfer RNAs, ribosomal RNAs, snoRNAs

and small nuclear RNAs. However, due to the extensive research on

the regulatory roles of miRNAs, lncRNAs and circRNAs in RCC, the

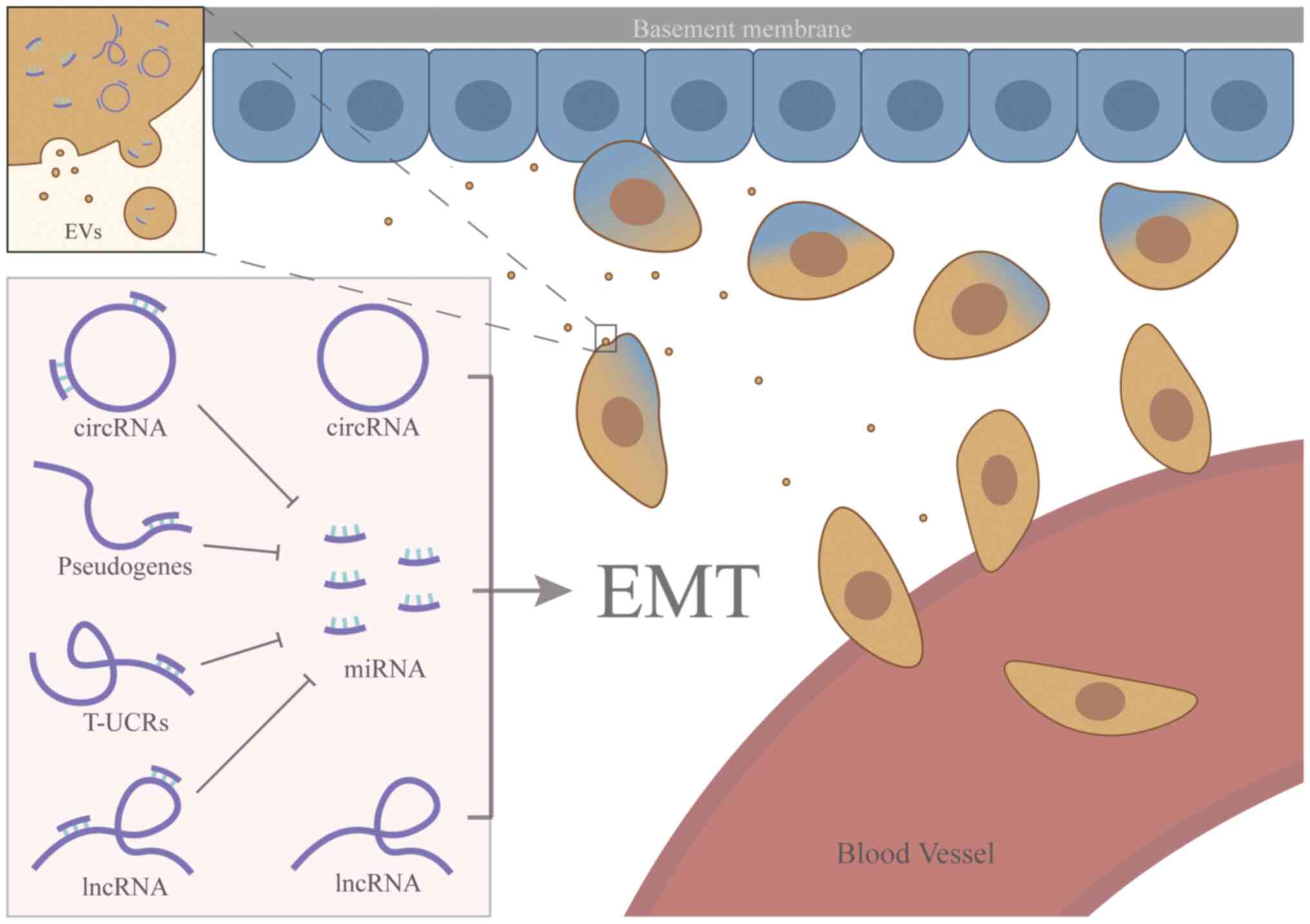

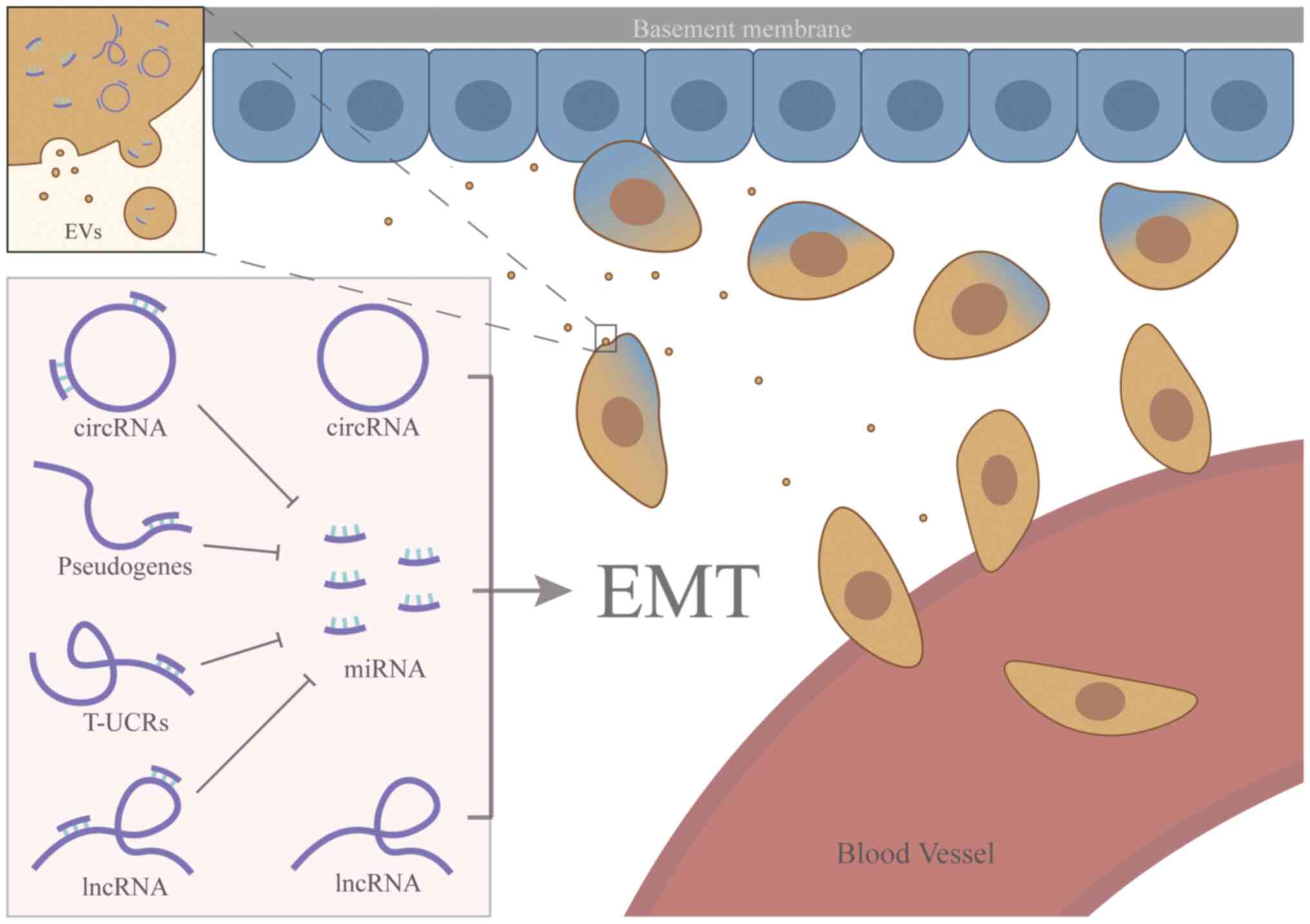

present review primarily focused on their roles. As shown in

Fig. 2, several ncRNAs influence

the progression of renal cancer by regulating the EMT process.

miRNAs constitute the hub of this regulatory network; all other

ncRNAs exert their effects principally by modulating these miRNAs,

whereas select circRNAs and lncRNAs can additionally regulate the

EMT programme directly in the absence of a downstream miRNA

intermediate.

| Figure 2.ncRNAs regulate EMT in RCC. ncRNAs

regulating the EMT progression and miRNAs are the center of this

system. Pseudogenes, circRNAs, lncRNAs and T-UCRs can exert their

downstream effects by sequestering miRNAs, which establishes miRNAs

as the central hub of this regulatory network. However, certain

circRNAs and lncRNAs may also regulate EMT directly, independent of

the miRNA pathway. RNAs can be located in the cytoplasm and

extracellular vesicles of RCC. Certain tumor cells release various

EVs, including exosomes and microparticles containing ncRNAs, which

further promote the EMT process and facilitate tumor metastasis.

After EMT, the carcinoma cells become more invasive and spread to

distant organs through the circulation. EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal

transition; ncRNA, non-coding RNA; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; EVs,

extracellular vesicles; miRNA, microRNA; circRNA, circular RNA;

T-UCRs, transcribed-ultra conserved regions; lncRNA, long

non-coding RNA. |

miRNAs

miRNAs are a family of single-stranded ncRNA

molecules, ~22 nucleotides in length. These small RNAs are

ubiquitously present in eukaryotes and primarily function in

regulating gene expression in plants, animals and humans.

Dysregulation of miRNAs has been observed in nearly all types of

cancer cells such as A549 (44)

and 786-O (45), highlighting

their key role in cancer pathogenesis (46).

The primary biological function of miRNAs is to

regulate post-transcriptional gene expression. A single miRNA can

regulate multiple mRNAs, while several miRNAs can target the

expression of a single mRNA, creating a ‘many-to-many’

relationship. miRNAs interact with argonaute and other functional

proteins to form the miRNA-induced silencing complex, which is key

to their function (47). miRNAs

can influence mRNA translation through several mechanisms. If a

miRNA is complementary to its target mRNA, it will induce direct

cleavage of the transcript. This mechanism is common in plants but

rarely occurs in animals and humans, as the complementarity between

miRNAs and target mRNAs is often insufficient. In animals and

humans, miRNAs typically exert their effects by binding to

sequences in the 3′-untranslated region of mRNAs, thereby

preventing ribosome-mediated translation or promoting mRNA

destabilization (48).

Occasionally, miRNAs directly enter the nucleus and enhance the

expression of target genes. In addition, miRNAs can interact with

other ncRNAs, such as circRNAs, lncRNAs and other miRNAs (49).

lncRNAs

lncRNAs are a class of ncRNAs typically longer than

200 nucleotides. Most of the lncRNAs possess an mRNA-like

structure, including a 5′-end cap, a poly(A) tail and exon-intron

organization. However, they generally lack open reading frames of

sufficient length to encode proteins, representing a fundamental

distinction between lncRNAs and mRNAs. Despite their inability to

be translated into proteins, several lncRNAs still exert notable

biological functions. lncRNAs are involved in nearly all stages of

gene expression, including transcription, post-transcriptional

regulation and epigenetic modifications. In cancer cells, lncRNAs

regulate genes with specific functions, thereby influencing

biological processes such as proliferation, invasion and

metastasis. The mechanisms underlying these actions are complex and

diverse, including miRNA sponging, RNA-protein scaffolding,

recruitment of specific proteins, chromatin remodeling and the

production of micropeptides (50,51).

lncRNAs can function as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) when

they contain specific miRNA binding sites. Therefore, lncRNAs

inhibit the activity of their target mRNAs by sequestering miRNAs

(52). Furthermore, lncRNAs

modulate transcriptional activation or repression by influencing

chromatin topology. Certain lncRNAs can recruit various

chromatin-modifying enzymes such as PRC2 and G9a to specific loci

or directly bind to chromatin structural proteins (53), thereby altering chromatin structure

and influencing gene expression at those sites. A subset of lncRNAs

is transcribed from cis-regulatory elements, such as promoters and

enhancers, and regulate the expression levels of downstream genes

(50).

circRNAs

circRNAs are a class of ncRNAs that form covalently

closed continuous loops, with covalent bonds at both ends, thus

lacking 3′- and 5′-ends (54).

This unique structure grants circRNAs higher stability and makes

them more resistant to degradation by ribonuclease R (55,56).

Initially, circRNAs were considered byproducts of transcriptional

errors, but recent studies have revealed their notable regulatory

functions as ncRNAs.

The main mechanisms of circRNA action are as

follows: i) circRNAs can inhibit miRNA activity by binding large

numbers of miRNAs. A single circRNA may contain multiple miRNA

binding sites, allowing it to sequester numerous miRNAs. Once

bound, these miRNAs are unable to exert their regulatory effects,

thereby influencing their downstream targets. CircRNAs are often

referred to as ‘molecular sponges’ due to this function (57). Since miRNAs typically exert their

functions by binding to mRNAs, circRNAs act as ceRNAs, competing

with mRNAs for miRNA binding and thereby indirectly regulating gene

expression (58). This is the

predominant mechanism by which circRNAs function (22).

ii) In addition to miRNA binding, circRNAs can also

function as ‘protein sponges’. By binding to RNA-binding proteins,

circRNAs prevent the proper functioning of these proteins (59). Furthermore, recent studies

indicated that certain circRNAs bind to proteins and form

circRNA-protein complexes (60,61).

These complexes can serve as scaffolds facilitating interactions

between proteins and mRNAs or other proteins or participate in

subcellular protein trafficking. The various ways in which circRNAs

interact with proteins warrant further research (19,62).

iii) Although most circRNAs do not encode proteins,

a small subset of circRNAs has been reported to serve a role in

biological functions through translation into proteins (63).

miRNAs in EMT of RCC

Among all ncRNAs, miRNAs are the most extensively

studied class, with several regulatory processes of EMT involving

the participation of miRNAs. Based on their roles in the EMT

process of RCC, miRNAs can be broadly classified into several

categories: One category includes miRNAs that are downregulated

during EMT, typically functioning as tumor suppressors (6,12,13,64–88).

Another category comprises miRNAs that are upregulated during EMT,

generally promoting cancer progression. There are also miRNAs with

more complex mechanisms of action, which can simultaneously exert

both pro-tumor and antitumor effects; these will be discussed

separately. Based on the extant literature accessible to date, the

preponderance of reported miRNAs fall into the first category.

Tumor suppressor miRNAs

Numerous miRNAs are closely associated with EMT,

with the earliest identified miRNA being the miRNA-200 family

(miR-200a, miR-200b, miR-200c, miR-141, miR-429 and miR-205)

(16,64–66).

The roles of the miR-200 family in various cancer types such as

lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) (89),

endometrial cancer (EC) (90) and

RCC (16) have been extensively

documented and they are among the most well-established miRNAs

associated with EMT. This family can be categorized into two groups

based on the chromosomal regions where it is located:

miR-200b/c/429 and miR-200a/141 (91).

It has been observed that all six of the

aforementioned miRNAs are markedly downregulated in RCC cells.

Reintroducing miRNA clusters consisting of these miRNAs inhibits

EMT development. These findings suggest a strong association

between these miRNAs and the EMT process (16,64–66).

Mechanistically, these miRNAs inhibit the expression of ZEB1/ZEB2

genes, which are direct targets of miR-200c and miR-200b,

respectively. ZEB1/2 functions to downregulate E-cadherin and

β-catenin expression by reducing inter-epithelial cell adhesion and

the interaction between epithelial cells and the basement membrane,

thereby promoting EMT (64,66).

Under normal conditions, miR-200a, miR-200b and miR-205 work

synergistically to suppress ZEB1/2 expression (64,67).

The underlying mechanism may be associated with chromosome

instability triggered by telomere shortening (92).

It is worth noting that RNAs from this family may

have distinct roles in different cancer types. For instance,

miR-200c expression is upregulated in pancreatic cancer and

non-small cell lung cancer, although the exact mechanism remains to

be elucidated. High expression of miR-144 in prostate cancer may

also indicate a relatively poor prognosis (93). Numerous other miRNAs exhibit

similar behaviors, performing different functions across various

tumors, for example, miR-106b-5p is oncogenic in gastric cancer

(GC), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and RCC, yet

tumor-suppressive in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and

colorectal cancer (CRC) (94).

However, in RCC, this family is still considered oncogenic.

In addition to the classical ZEB pathway, other

mechanisms of action for the miR-200 family have been identified

through studies in RCC. In RCC, the miR-200 family can also

modulate the PI3K/AKT pathway by regulating AKT proteins, which in

turn influences the production of E-cadherin, thereby affecting the

EMT process (66). miR-429 can

directly target B-cell-specific Moloney murine leukemia virus

integration region 1 (BMI1) and E2F transcription factor 3, leading

to their downregulation. BMI1 inhibits E-cadherin expression and

the reduced levels of miR-429 in RCC result in the loss of its

inhibitory effect, thus promoting EMT (68). A previous study on disease-free

survival and overall survival in patients with clear cell RCC

(ccRCC) suggested that low miR-429 levels are associated with a

relatively poor prognosis (69).

In the context of RCC, miR-200a directly targets TGF-β2 to inhibit

RCC progression (65). miR-141 has

been reported to reverse the EMT process and enhance the

sensitivity of tumor cells to hypoxia. Furthermore, miR-141

promotes resistance to sunitinib in tumor cells (6).

Another miRNA family markedly associated with EMT is

the miR-30 family (miR-30a, miR-30b, miR-30c, miR-30a-5p,

miR-30a-3p, miR-30e and miR-30e-3p), which is also notably

downregulated in renal tumors (95). Low expression level of miR-30a-5p,

which targets ZEB2, is associated with poor patient survival and,

under normal conditions, this miRNA markedly reduces ZEB2

expression. Furthermore, this miRNA may be regulated by

lncRNA-deleted in lymphocytic leukemia 2, although this requires

further verification (70).

Compared with normal renal tissues, miR-30b-5p is downregulated in

both RCC cell lines and tissue samples. Upregulation of miR-30b-5p

in vitro markedly inhibits the proliferation and metastasis

of RCC cells. Mechanistically, miR-30b-5p directly targets and

inhibits the expression of guanine nucleotide-binding protein α 13,

which is upregulated in RCC and promotes tumor cell proliferation

and metastasis; its tumorigenic role has been validated in a

variety of other cancer types (71). miR-30c is typically an oncogenic

miRNA, serving a key role in various cancer types, including

endometrial, ovarian and breast cancer (96). In RCC, the downregulation of

miR-30c expression reduces its inhibitory effect on Snail family

transcriptional repressor 2 (SLUG), leading to increased SLUG

expression and excessive production of E-cadherin, which triggers

the EMT process. The decrease in miR-30c expression is induced by

hypoxia, a process dependent on hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) and

VHL deficiency in RCC hampers HIF degradation, resulting in

excessive HIF accumulation (97).

Similar to the aforementioned RNAs, miRNAs with

inhibitory effects on cancer are typically downregulated in RCC and

a notable proportion of them decrease with the progression of tumor

stage. Specifically, their expression is lower in advanced and

metastatic cancer types compared with early-stage and primary

cancer types (6,12,13,64–88).

The specific RNA names and targets are presented in Table I.

| Table I.EMT-associated miRNAs in RCC. |

Table I.

EMT-associated miRNAs in RCC.

|

|

|

| Function |

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| First author,

year | miRNA | Expression | Proliferation | Metastasis | Target | Verified in

vivo | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Gregory et

al, 2008 | miR-200 family | Down | ↓ | ↓ | ZEB1/2 | No | (64) |

| Lu et al,

2015 | miR-200a | Down | ↓ | ↓ | TGFB2 | No | (65) |

| Wang et al,

2013 | miR-200c | Down | NA | ↓ | ZEB1 and AKT | No | (66) |

| Machackova et

al, 2016; | miR-429 | Down | ↓ | ↓ | BMI1/E2F3 | No | (69,68) |

| Qiu et al,

2015 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gregory et

al, 2008; | miR-205 | Down | ↓ | ↓ | ZEB1/2 | No | (64,67) |

| Xu et al,

2018 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yamasaki et

al, 2012 | miR-138 | Down | ↓ | ↓ | VIM | No | (73) |

| Berkers et

al, 2013; | miR-141 | Down | ↓ | ↓ | ZEB, CDKN2B- | No | (6,74) |

| Dasgupta et

al, 2020 |

|

|

|

| AS1, cyclin-D1 and

cyclin-D2 |

|

|

| Huang et al,

2013 | miR-30c | Down | NA | ↓ | SLUG | No | (97) |

| Chen et al,

2017 | miR-30a-5p | Down | ↓ | ↓ | ZEB2 | Yes | (70) |

| Liu et al,

2017 | miR-30b-5p | Down | ↓ | ↓ | GNA13 | No | (71) |

| Lu et al,

2014 | miR-145 | Down | ↓ | ↓ | ANGPT2 and

NEDD9 | No | (75) |

| Lichner et

al, 2015 | miR-17 | Down | ↓ | ↓ | TGFBR2 | Yes | (76) |

| Liu et al,

2015 | miR-134 | Down | ↓ | ↓ | KRAS | No | (77) |

| Liu et al,

2016 | miR-144-3p | Down | ↓ | ↓ | MAP3K8 | No | (78) |

| Chen et al,

2020; | miR-203 | Down | ↓ | ↓ | HOTAIR and | Yes | (13,79,72) |

| Dasgupta et

al, 2018; |

|

|

|

| CAV1 |

|

|

| Han et al,

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Dong et al,

2019 | miR-588 | Down | ↓ | ↓ | EIF5A2 | No | (80) |

| Chen et al,

2020 | miR-124 and

miR-203 | Down | ↓ | ↓ | ZEB2 | No | (13) |

| Pan et al,

2019 | miR-4429 | Down | ↓ | ↓ | CDK6 | No | (81) |

| Guo et al,

2020 | miR-206 | Down | ↓ | ↓ | CDK6 | Yes | (82) |

| Guo et al,

2020; | miR-186 | Down | ↓ | ↓ | CDK6 | Yes | (83,88) |

| Wang et al,

2021 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Xu et al,

2020 | miR-143 | Down | ↓ | ↓ | ABL2 | No | (84) |

| Sekino et

al, 2018 | miR-153 | Down | ↓ | ↓ | Snail | No | (85) |

| Chen et al,

2021 | miR-296-5p | Down | ↓ | ↓ | HMGA1 | No | (87) |

| Niu et al,

2025 | miR-9-5p | Down | ↓ | ↓ | HMMR | Yes | (12) |

| Xue et al,

2019 | miR-296-3p | Up | → | ↑ | E-cadherin | Yes | (86) |

| Cao et al,

2016; | miR-21 | Up | ↑ | ↑ | HIF-1α | No | (102,103) |

| Wu et al,

2019 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Wang et al,

2019 | miR-19b-3p | Up | ↑ | ↑ | PTEN | Yes | (14) |

| Lyu et al,

2020 | miR-222-3p | Up | ↑ | ↑ | TIMP2 and

ERK1/2 | No | (104) |

| Gorka et al,

2021 | miR-519a-3p,

miR-519b-3p and miR-520c-3p | Up | ↑ | ↑ | Wnt pathway

inhibitors (SFRP4, KREMEN1, CXXC4, CSNK1A1 and ZNFR3) | No | (105) |

| Lei et al,

2021 | miR-155-5p | Up | ↑ | ↑ | AIF | Yes | (106) |

| Kulkarni et

al, 2021 | miR-155 | Up | ↑ | ↑ | lncTCL6 | Yes | (15) |

| Li et al,

2021 | miR-15a | Up | ↑ | ↑ | BTG2, PI3K and

AKT | No | (101) |

| Meng et al,

2021 | miR-765, miR-21 and

miR-144 | Up | ↑ | ↑ | LHPP | No | (107) |

| Yoshino et

al, 2017 | miR-210-3p | Up | ↓ | ↓ | TWIST1 | Yes | (109) |

| Landolt et

al, 2017 | miR-34a | Up | NA | NA | MMP14 and AXL | No | (108) |

Certain miRNAs can influence EMT through multiple

pathways. An example of this is a study by Han et al

(72), in which miR-203,

previously described as targeting FGF2, was reported to inhibit the

EMT process by another mechanism: Inactivation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR

signaling pathway via the inhibition of caveolin-1 (CAV1).

In addition to acting individually, miRNAs can

cooperate with each other. Multiple miRNAs can work together to

regulate a common target, as seen in the case of miR-124 and

miR-203. miR-124 is a key miRNA that targets CAV1 and flotillin 1

to promote ccRCC invasiveness and its downregulation can be a

predictor of relatively poor prognosis (98). miR-203 targets FGF2 and reduces

tumor invasiveness (99); it is

regulated by lncRNA snRNA host gene (SNHG) 14 and HOX transcript

antisense intergenic RNA (HOTAIR) and is also considered an

oncogene and indicator of poor prognosis in certain studies

(13). Both miR-124 and miR-203

have been identified to be downregulated in RCC cell lines, where

they have a synergistic effect in regulating EMT, with ZEB2 being

their direct target. When miR-124 and miR-203 were overexpressed in

RCC cell lines, ZEB2 expression was reduced by 11 and 27%,

respectively. Co-overexpression of both miRNAs resulted in a 45%

reduction in ZEB2 expression. Co-transfection of miR-124 and

miR-203 inhibited the invasion and metastasis of RCC cells more

effectively compared with the transfection of either miRNA alone

(13). This study suggested that a

single RNA may lack efficacy, but a synergistic combination of

multiple RNAs can form a regulatory network with notable

effects.

miRNAs can also serve a role in intercellular

communication. Grange et al (100) reported that microvesicles (MVs)

derived from CD105+ RCC cells stimulate angiogenesis and

the formation of a lung premetastatic niche in vitro and

in vivo. These MVs contain miRNAs involved in tumor

progression and metastasis, including miR-19b, miR-29c and miR-151.

These miRNAs were reported to be upregulated in renal carcinomas

compared with normal renal tissue, although the specific roles of

these miRNAs were not further investigated (100). Nevertheless, miRNAs can regulate

the metastasis of RCC via extracellular vesicles, as these MVs are

released from mesenchymal stem cells, where EMT may serve a role.

This was exemplified in the work of Wang et al (14), which demonstrated that exosomes

derived from ccRCC cancer stem cells (CSCs) had higher expression

levels of miR-19b-3p compared with that in normal tissues. This

miRNA can promote the EMT process by targeting PTEN, thus

facilitating distant tumor metastasis. Experiments in vivo

and in vitro have demonstrated that this miRNA markedly

enhances the malignancy of ccRCC (14). Furthermore, exosomal miR-15a from

adenocarcinoma human nasal (ACHN) cells has been reported to

enhance EMT activity and aggravate ccRCC via the B-cell

translocation gene 2/PI3K/AKT axis (101).

Several miRNAs have been identified as promoters of

EMT in kidney cancer. For instance, miR-138 is downregulated in

renal cancer cells and under normal physiological conditions, this

miRNA inhibits the synthesis of VIM, a key component of the

mesenchymal cytoskeleton. The downregulation of miR-138 facilitates

the EMT process in cancer cells (73). Similarly, miR-134 directly targets

KRAS, thereby suppressing the ERK signaling pathway, which enhances

cell proliferation and inhibits EMT in RCC (77). Furthermore, miR-4429 exerts its

effects by inhibiting CDK6 and its downregulation in RCC leads to

relative upregulation of CDK6, which promotes tumor cell

proliferation, invasion and metastasis, thereby predicting a worse

prognosis in patients (81). The

mechanisms underlying the EMT-inhibitory roles of certain miRNAs,

such as miR-145 and miR-17, remain to be elucidated. The latter may

regulate the EMT process through modulation of TGF-β signaling

(75,76).

Oncogenic miRNAs

In comparison with cancer-inhibiting miRNAs, the

number of identified oncogenic miRNAs is relatively limited in

current reports (14,15,86,101–107). miR-21 is known to exhibit

oncogenic properties and can promote the formation of ccRCC tumor

spheres (102). Other oncogenic

miRNAs include miR-34a, although its exact mechanism is not fully

understood. miR-34a may exert its effects by regulating MMP14

(108).

However, oncogenic miRNAs that are highly expressed

in RCC tissues do not always promote the EMT process. For example,

miR-210-3p is highly expressed in RCC cell lines and clinical ccRCC

tissues; however, its expression is lower in high-grade and

advanced ccRCC with metastasis compared with low-grade and

early-stage ccRCC. Knockdown or overexpression of miR-210-3p

promoted or suppressed tumor invasiveness, respectively.

Furthermore, it was reported that miR-210-3p inhibited the EMT

process, as evidenced by changes in cell morphology. Knockdown of

miR-210-3p enhanced Twist-related protein 1 expression, promoting

tumor metastasis. This study suggested that miR-210-3p is necessary

for tumorigenesis and its inhibitory effect on EMT should be

relieved in advanced metastatic stages (109).

lncRNAs in EMT of RCC

lncRNAs are predominantly oncogenic in RCC (74,79,110–118). For example, lncRNA HEIRCC acts as

a positive regulator of EMT by suppressing the production of

E-cadherin through the inhibition of ZEB1. This lncRNA is

upregulated in RCC and its silencing leads to decreased tumor cell

proliferation and increased apoptosis (113).

Several lncRNAs interact with miRNAs. A well-known

example is HOTAIR, which has been implicated in various types of

cancer like breast carcinoma (119) and prostate cancer (120). In RCC, miR-203 exerts an

oncostatic effect by interacting with HOTAIR, inhibiting EMT as

well as tumor cell proliferation, invasion and metastasis, as

demonstrated in both in vivo and in vitro experiments

(79). Similarly, CDK inhibitor 2B

antisense RNA 1 (AS1) is markedly overexpressed in RCC, with its

expression increasing from early to advanced stages of the disease.

This lncRNA can bind to miR-141 and influence its regulation of

cyclin D, subsequently regulating the EMT process (74).

By contrast, certain lncRNAs function through

independent mechanisms. For instance, SNHG15 is highly expressed in

RCC tissues and cell lines compared with that in adjacent non-tumor

tissues and a proximal tubule epithelial cell line. Knockdown of

SNHG15 markedly inhibits tumor cell proliferation. SNHG15 promotes

the expression of Snail family transcriptional repressor 1, SLUG

and ZEB1 through the NF-κB pathway, thereby facilitating the EMT

process and promoting invasion and metastasis in RCC (114). Similarly, nuclear enriched

abundant transcript 1 (NEAT1) is highly expressed in ccRCC samples

and cell lines and is associated with poor patient prognosis

(112). Knockdown or

overexpression of NEAT1 in ccRCC cell lines markedly inhibits or

promotes tumor cell proliferation, invasion and metastasis.

Mechanistically, NEAT1 may act by promoting ZEB1, NEAT1 knockdown

repressed ZEB1 expression in 786-O and Caki-1 cells, thereby

impairing the subsequent epithelial-mesenchymal transition

(112). lncRNA Z38 is highly

expressed in patients with RCC, with its transcriptional level

being higher in late-stage RCC. Z38 promotes tumor invasion and

metastasis through the EMT process in vitro; however, the

upstream and downstream mechanisms remain to be elucidated in

further research (111).

However, certain lncRNAs exert antitumor effects

(15,121–123). lncRNA NONHSAT113026 is markedly

downregulated in RCC and its low expression is associated with poor

prognosis. Upregulation of this RNA inhibits tumor cell

proliferation in vivo and in vitro and suppresses the

EMT process, reducing invasiveness and metastatic potential.

Mechanistically, NONHSAT113026 functions by binding to the 3′-UTR

of NF-κB/p50 and SLUG in RCC cells, inhibiting their expression

(121). Similarly, lncRNA-ovarian

tumor domain deubiquitinase 6B-AS1 exerts its effects by inhibiting

the aberrantly activated Wnt/β-catenin pathway in tumors (122).

Due to the complex biological mechanisms of lncRNAs,

the targets of certain lncRNAs remain to be elucidated. Certain

lncRNAs exert their effects by targeting downstream miRNAs, such as

SNHG12 and colorectal neoplasia differentially expressed. Others

directly target factors associated with EMT, including

high-expressed in RCC and LOC648987. Further research is warranted

to elucidate the mechanisms through which these RNAs function.

Detailed information on these lncRNAs is provided in Table II.

| Table II.EMT-associated lncRNAs in RCC. |

Table II.

EMT-associated lncRNAs in RCC.

|

|

|

| Function |

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| First author,

year | lncRNA | Expression | Proliferation | Metastasis | Target | miRNA target

genes/proteins | Verified in

vivo | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Xiong et al,

2016 | lncRNA-ATB | Up | ↑ | ↑ | NA | NA | No | (110) |

| Dasgupta et

al, 2018 | HOTAIR | Up | ↑ | ↑ | PTEN | - | Yes | (79) |

| He et al,

2017 | Z38 | Up | ↑ | ↑ | NA | NA | No | (111) |

| Ning et al,

2017 | NEAT1 | Up | ↑ | ↑ | ZEB1 | - | No | (112) |

| Xiong et al,

2017 | HEIRCC | Up | ↑ | ↑ | ZEB1 | - | No | (113) |

| Du et al,

2018 | SNHG15 | Up | ↑ | ↑ | NF-κB | - | No | (114) |

| Dasgupta et

al, 2020 | CDKN2B-AS1 | Up | ↑ | ↑ | miR-141 | cyclin-D1 and

cyclin-D2 | Yes | (74) |

| Su et al,

2021 | LOC648987 | Up | ↑ | ↑ | Vimentin and

MMP-9 | - | Yes | (115) |

| Yu et al,

2021 | SNHG12 | Up | ↑ | ↑ | miR-30a-3p | RUNX2, IGF-1R and

Wnt2 | Yes | (116) |

| Zhang et al,

2021 | CRNDE | Up | ↑ | ↑ | miR-136-5p | NA | No | (117) |

| Shao et al,

2023 |

RP11-367G18.1V2 | Up | ↑ | ↑ | H4K16Ac | - | Yes | (118) |

| Pu et al,

2019 | NONHSAT-113026 | Down | ↓ | ↓ | NF-κB/p50 and

SLUG | - | Yes | (121) |

| Wang et al,

2019 | OTUD6B-AS1 | Down | ↓ | ↓ | Wnt/β-catenin | - | Yes | (122) |

| Zhang et al,

2020 | SRA | Down | ↓ | ↓ | ERK | - | No | (123) |

| Kulkarni et

al, 2021 | lncTCL6 | Down | ↓ | ↓ | Src | Src/AKT | Yes | (15) |

circRNAs in EMT of RCC

As presented in Table

III, circRNAs primarily function as miRNA sponges during EMT in

RCC. The circRNA-miRNA-gene regulatory axis is commonly observed in

circRNA studies (86,124–133). When circRNAs target oncogenic

miRNAs, they exert pro-oncogenic effects and are often upregulated

in tumor cell lines and RCC tissues. For example, circPRRC2A, by

competitively binding to miR-514a-5p and miR-6776-5p, disrupts

their inhibitory effect on the target gene transient receptor

potential melastatin-3, resulting in increased expression of this

oncogene and promotion of EMT, tumor cell proliferation and

metastasis (128). Similarly,

circRNAs that act as sponges for pro-oncogenic miRNAs can exert

oncogenic effects. For instance, circ-AKT3 upregulates the

expression level of its downstream target, E-cadherin, by adsorbing

miR-296-3p, thereby inhibiting the EMT process and suppressing RCC

cell proliferation, invasion and migration both in vitro and

in vivo (86).

| Table III.EMT-associated circRNAs in RCC. |

Table III.

EMT-associated circRNAs in RCC.

|

|

|

| Function |

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| First author,

year | circRNA | Expression | Proliferation | Metastasis | Target | miRNA target

genes/proteins | Verified in

vivo | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Zhang et al,

2019 | circ_000926 | Up | ↑ | ↑ | miR-411 | CDH2 | Yes | (126) |

| Li et al,

2020 | circMYLK | Up | ↑ | ↑ | miR-513a-5p | VEGFC | Yes | (127) |

| Li et al,

2020 | circPRRC2A | Up | ↑ | ↑ | miR-514a-5p and

miR-6776-5p | TRPM3 | Yes | (128) |

| Liu et al,

2020 | circPTCH1 | Up | NA | ↑ | miR-485-5p | MMP14 | Yes | (129) |

| Yan et al,

2021 |

hsa_circ_0065217 | Up | ↑ | ↑ | miR-214-3p | ALPK2 | No | (130) |

| Li et al,

2022 | circCSNK1G3 | Up | ↑ | ↑ | miR-181b | TIMP3 | Yes | (131) |

| Cen et al,

2023 |

has_circ_0057105 | Up | ↑ | ↑ | miR-557 | COL1A1/VDAC2 | Yes | (132) |

| Yang et al,

2021 |

hsa_circ_101705/circTXNDC11 | Up | ↑ | ↑ | p-ERK/p-MEK | - | Yes | (134) |

| Xue et al,

2019 |

hsa_circ_0017252/circ-AKT3 | Down | → | ↓ | miR-296-3p | E-cadherin | Yes | (86) |

| Xie et al,

2022 | circPSD3 | Down | ↓ | ↓ | miR-25-3p | FBXW7 | Yes | (133) |

However, circTXNDC11 regulates EMT through direct

modulation of the ERK/MEK pathway. In this study, the researchers

observed changes in the expression levels of phosphorylated (p)-ERK

and p-MEK proteins without involving any miRNA molecules (134). Further studies on how circRNAs

exert effects on EMT through other mechanisms are warranted.

Although circRNAs have only recently gained notable

research attention, they have been reported to serve key roles in

regulating gene expression. Therefore, future research in this area

has a lot of potential.

Other ncRNAs in EMT of RCC

A number of ncRNAs also contribute to the EMT

process in RCC, such as transcribed-ultra conserved regions

(T-UCRs) and pseudogenes, which require further investigation.

T-UCRs represent a novel class of ncRNAs, typically

located at fragile sites and cancer-associated genomic regions. One

such T-UCR, Uc.416+A, which has been reported to be upregulated in

gastric cancer and downregulated in prostate cancer, exhibits high

expression levels in RCC, particularly in metastatic RCC tissues.

Knockdown of Uc.416+A in RCC cells resulted in reduced cell

proliferation and migration activity, along with notable changes in

EMT biomarker levels. Luciferase reporter assays confirmed that

Uc.416+A is directly regulated by miR-153, a miRNA known to promote

EMT through Snail. Uc.416+A promotes RCC EMT by binding to and

sequestering miR-153, thus preventing its regulatory functions. To

the best of our knowledge, this is the first T-UCR confirmed to

modulate EMT (85).

Pseudogenes, traditionally regarded as ‘junk DNA’,

share sequence similarity with ≥1 paralogous genes but lack

functional protein-coding ability. However, a subset of pseudogenes

can regulate gene expression by acting as decoys or ceRNAs

(135). For instance, Chen et

al (87) identified that the

pseudogene heat shock protein family B (small) member 1 pseudogene

1 promotes RCC proliferation and metastasis by targeting the

miR-296-5p/high mobility group AT-hook 1 axis. This finding has

expanded the understanding of the regulatory functions of ncRNAs in

RCC.

In certain cases, pseudogenes and T-UCRs have been

classified as lncRNAs due to their unique characteristics. However,

due to their distinct features, pseudogenes and T-UCRs were chosen

to be discussed separately in the present review.

Potential of EMT-associated ncRNAs in the

diagnosis and treatment of RCC

RCC is an aggressive carcinoma with a rising

incidence, the age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR) rose from

2.88 to 4.37 per 100,000, an increase of ~52% (136), and 25–30% of patients with RCC

present with metastasis at the time of diagnosis (137,138). Therefore, identifying appropriate

biomarkers and therapeutic targets is of notable importance for the

clinical treatment of RCC.

Currently, it is commonly considered that the EMT

process may be a key step in tumorigenesis and progression

(139,140). After the EMT process in RCC,

cells enhance their invasiveness and metastatic potential and

increase their drug resistance (141). Therefore, the early detection of

ongoing EMT via ncRNA signatures presents a key target for

therapeutic intervention. Halting or reversing the EMT process at

this stage could prevent the acquisition of invasive and metastatic

capabilities, potentially improving patient outcomes in the future

(142).

The EMT process in RCC is heavily regulated by

ncRNAs. Exploring the mechanisms through which ncRNAs modulate EMT

is key to identify novel therapeutic strategies and targets in RCC.

As previously discussed, several EMT-associated ncRNAs are

differentially expressed in tumor tissues compared with normal

tissues, and the expression levels of certain ncRNAs are associated

with tumor stage, malignancy and metastasis. These observations

highlight the potential of using these ncRNAs as diagnostic and

prognostic markers for RCC in the future (112,143). For example, Silva-Santos et

al (144) demonstrated that

miR-141 and miR-200b could effectively distinguish renal tumors

from normal renal tissues and miR-21, miR-141 and miR-155 could

serve as prognostic markers for patients with RCC. Furthermore,

Zhang et al (145)

constructed a risk-scoring system using EMT-associated lncRNAs,

which can predict overall survival and immune microenvironment

status in patients with ccRCC.

Since the EMT process is reversible to a certain

extent, EMT-associated ncRNAs also offer potential as therapeutic

targets for RCC in the future. Approaches such as the synthesis of

mimics of oncogenic ncRNAs or antisense oligonucleotides targeting

oncogenic ncRNAs may prove effective. For example, cerebellar

degeneration-related protein 1 antisense (ciRS-7), an oncogenic RNA

in RCC, is highly expressed in tumors and its expression is

associated with poor prognosis. Researchers have developed

poly(β-amino ester)/si-ci-ciRS-7 nanocomplexes, which can markedly

inhibit its oncogenic effects both in vitro and in

vivo (143). This approach

also illustrates the potential to combine RNA-based therapies with

nanomaterials in RCC treatment. Furthermore, CSCs may induce EMT by

secreting exosomes containing ncRNAs, which contribute to TME

formation and distant metastasis. Removing CD103+ CSC

exosomes may represent a novel strategy for the treatment of

patients with metastatic RCC in the future (14).

A notable portion of advanced RCC treatment relies

on targeted therapies, such as sunitinib. However, several patients

are either insensitive to these treatments or develop resistance

over time, leading to poor prognosis (146). A previous study reported that the

level of EMT-associated miR-141 can influence the therapeutic

response to sunitinib in patients with RCC (6). Therefore, altering drug resistance by

modulating the EMT process through ncRNAs may offer a promising

adjuvant therapeutic strategy in the future.

Furthermore, as miRNAs can be regulated by other

ncRNAs, such as circRNAs and lncRNAs, these molecules can serve as

natural inhibitors of oncogenic miRNAs. Compared with linear RNAs,

circRNAs have a more stable molecular structure, making them less

susceptible to degradation by RNases and prolonging their half-life

(147). Furthermore, circRNAs

typically contain numerous RNA-binding sites, which allow them to

efficiently sponge miRNAs. Unmodified circRNAs are less immunogenic

compared with linear mRNAs and N6-methyladenosine modification of

exogenous circRNAs almost entirely abrogates their immunogenicity

(148). Furthermore, lipid

nanoparticle-delivered (LNP) circRNAs provoke minimal immune

responses following injection, highlighting their safety profile

(149). These properties make

circRNAs promising candidates for reliable cancer biomarkers in the

future and anticancer drugs with fewer side effects, however, their

clinical translation necessitates further investigation. A

circRNA-based vaccine platform has demonstrated notable efficacy in

B16 orthotopic melanoma and B16 lung metastasis models (150). Thus, it is conceivable that

circRNA-based vaccines targeting EMT could be a viable therapeutic

approach for RCC.

Study limitations and future

perspectives

Despite comprehensively summarizing the regulatory

role of ncRNAs in RCC EMT, the present review also highlighted

several inherent limitations in the current body of literature that

should be addressed in future research.

Firstly, the mechanistic insights discussed in the

present review are predominantly derived from in vitro cell

line experiments and murine xenograft models. Although these

studies were valuable, these models cannot fully recapitulate the

intricate TME, immune cell interactions and physiological pressures

present in human patients. Potential confounding factors, such as

the selective pressure of cell culture and the lack of a fully

functional immune system in immunodeficient mice, may oversimplify

the complex role of ncRNAs in vivo (151). Future studies should prioritize

more physiologically relevant models, such as patient-derived

organoids, orthotopic implantation models and genetically

engineered mouse models of RCC, to validate these findings

(152).

Secondly, there is a notable heterogeneity across

published studies regarding RCC subtypes (for example, ccRCC vs.

papillary), sampling techniques and methodological approaches (for

example, RNA extraction, normalization methods in reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR). This heterogeneity poses a

challenge for direct comparison and meta-analysis. The clinical

translation of ncRNA biomarkers will require rigorous

standardization of protocols and validation in large-scale,

multi-center, prospective patient cohorts to ensure reliability and

reproducibility (153).

Thirdly, to the best of our knowledge, due to the

paucity of data on EMT-associated ncRNAs in RCC, molecules other

than the well-characterized miR-200 family are typically described

in single reports, precluding longitudinal or cross-study

comparisons. As the majority of these publications remain

methodologically constrained, most notably by the absence of in

vivo validation, the present review contended that systematic

re-evaluation of previously identified ncRNAs constitutes a

clinically relevant and underexplored avenue of investigation.

Lastly, while the present review outlined numerous

ncRNAs with therapeutic potential, their delivery to tumor sites

in vivo remains a notable hurdle. Future research should

focus on developing efficient and targeted delivery systems, such

as LNPs or exosome-based vectors, conjugated with ligands specific

to RCC cells to potentially minimize off-target effects and

maximize therapeutic efficacy in the future.

Addressing these limitations will be key to moving

the field forward from descriptive mechanistic studies to the

clinical realization of ncRNA-based diagnostics and therapies for

patients with RCC.

Conclusions

The study of the metastatic mechanisms of RCC is of

notable clinical importance, as a large proportion of patients with

RCC present with metastasis at the time of their initial diagnosis.

EMT serves as a pivotal driver of RCC metastasis and the present

review has systematically elucidated the regulatory roles of

ncRNAs, particularly miRNAs, lncRNAs and circRNAs, in this process.

miRNAs are central to these ncRNA-mediated regulatory networks in

RCC, with the most extensive research conducted in this area. Most

circRNAs, T-UCRs, pseudogenes and certain lncRNAs regulate EMT by

targeting miRNAs, primarily via the ceRNA mechanism.

Beyond summarizing current knowledge, the present

review highlighted the notable clinical potential of EMT-associated

ncRNAs. Their differential expression across tumor stages and

metastatic states positions them as promising diagnostic and

prognostic biomarkers. Furthermore, their involvement in

therapeutic resistance and metastasis underscores their potential

value as novel therapeutic targets. For instance, strategies such

as synthetic miRNA mimics, antisense oligonucleotides or

circRNA-based vaccines offer potential avenues for intervention in

the future. The stability, low immunogenicity and efficient

regulatory capacity of circRNAs, make them promising candidates for

next-generation RNA therapeutics.

In conclusion, RCC can enhance its malignancy

through the EMT process, which is tightly regulated by various

ncRNAs. This highlights the notable potential of these molecules in

RCC diagnosis, prognosis and treatment in the future. Through

further research on these ncRNAs, novel biomarkers for RCC may be

identified and novel therapeutic targets may be revealed that

potentially improve patient outcomes in the future.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Mariya

Rangarajan (International School of Medicine, Zhejiang University,

Yiwu, China) for their review of the language in the

manuscript.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

ZL and HZ conceptualized the present review. ZL

reviewed the data and wrote the manuscript. CZ provided

supervision. CZ, ZL, JS, YQ and XG reviewed and edited the

manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Rouprêt M, Seisen T, Birtle AJ, Capoun O,

Compérat EM, Dominguez-Escrig JL, Gürses Andersson I, Liedberg F,

Mariappan P, Hugh Mostafid A, et al: European association of

urology guidelines on upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma:

2023 Update. Eur Urol. 84:49–64. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Motzer RJ, Jonasch E, Agarwal N, Alva A,

Baine M, Beckermann K, Carlo MI, Choueiri TK, Costello BA, Derweesh

IH, et al: Kidney cancer, version 3.2022, NCCN clinical practice

guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 20:71–90. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Young M, Jackson-Spence F, Beltran L, Day

E, Suarez C, Bex A, Powles T and Szabados B: Renal cell carcinoma.

Lancet. 404:476–491. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zheng X, Carstens JL, Kim J, Scheible M,

Kaye J, Sugimoto H, Wu CC, LeBleu VS and Kalluri R:

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is dispensable for metastasis

but induces chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. Nature.

527:525–530. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Berkers J, Govaere O, Wolter P, Beuselinck

B, Schöffski P, van Kempen LC, Albersen M, Van den Oord J, Roskams

T, Swinnen J, et al: A possible role for microRNA-141

down-regulation in sunitinib resistant metastatic clear cell renal

cell carcinoma through induction of epithelial-to-mesenchymal

transition and hypoxia resistance. J Urol. 189:1930–1938. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Galichon P, Finianos S and Hertig A:

EMT-MET in renal disease: Should we curb our enthusiasm? Cancer

Lett. 341:24–29. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Fu XD: Non-coding RNA: A new frontier in

regulatory biology. Natl Sci Rev. 1:190–204. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Xiao Y, Ren Y, Hu W, Paliouras AR, Zhang

W, Zhong L, Yang K, Su L, Wang P, Li Y, et al: Long non-coding

RNA-encoded micropeptides: Functions, mechanisms and implications.

Cell Death Discov. 10:4502024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Esteller M: Non-coding RNAs in human

disease. Nat Rev Genet. 12:861–874. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Slack FJ and Chinnaiyan AM: The role of

non-coding RNAs in oncology. Cell. 179:1033–1055. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Niu X, Lu D, Zhan W, Sun J, Li Y, Shi Y,

Yu K, Huang S, Ma X, Liu X and Liu B: miR-9-5p/HMMR regulates the

tumorigenesis and progression of clear cell renal cell carcinoma

through EMT and JAK1/STAT1 signaling pathway. J Transl Med.

23:362025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Chen J, Zhong Y and Li L: miR-124 and

miR-203 synergistically inactivate EMT pathway via coregulation of

ZEB2 in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). J Transl Med.

18:692020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wang L, Yang G, Zhao D, Wang J, Bai Y,

Peng Q, Wang H, Fang R, Chen G, Wang Z, et al: CD103-positive CSC

exosome promotes EMT of clear cell renal cell carcinoma: Role of

remote MiR-19b-3p. Mol Cancer. 18:862019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kulkarni P, Dasgupta P, Hashimoto Y,

Shiina M, Shahryari V, Tabatabai ZL, Yamamura S, Tanaka Y, Saini S,

Dahiya R and Majid S: A lncRNA TCL6-miR-155 interaction regulates

the Src-Akt-EMT network to mediate kidney cancer progression and

metastasis. Cancer Res. 81:1500–1512. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Saleeb R, Kim SS, Ding Q, Scorilas A, Lin

S, Khella HW, Boulos C, Ibrahim G and Yousef GM: The miR-200 family

as prognostic markers in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Urol

Oncol. 37:955–963. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zhang ZH, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Zheng SF, Feng

T, Tian X, Abudurexiti M, Wang ZD, Zhu WK, Su JQ, et al: The

function and mechanisms of action of circular RNAs in urologic

cancer. Mol Cancer. 22:612023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Javdani H, Mollaei H, Karimi F, Mahmoudi

S, Farahi A, Mirzaei-Parsa MJ and Shahabi A: Review article

epithelial to mesenchymal transition-associated microRNAs in breast

cancer. Mol Biol Rep. 49:9963–9973. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Chen RX, Chen X, Xia LP, Zhang JX, Pan ZZ,

Ma XD, Han K, Chen JW, Judde JG, Deas O, et al:

N6-methyladenosine modification of circNSUN2 facilitates

cytoplasmic export and stabilizes HMGA2 to promote colorectal liver

metastasis. Nat Commun. 10:46952019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Entezari M, Taheriazam A, Orouei S, Fallah

S, Sanaei A, Hejazi ES, Kakavand A, Rezaei S, Heidari H,

Behroozaghdam M, et al: LncRNA-miRNA axis in tumor progression and

therapy response: An emphasis on molecular interactions and

therapeutic interventions. Biomed Pharmacother. 154:1136092022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chen B, Dragomir MP, Yang C, Li Q, Horst D

and Calin GA: Targeting non-coding RNAs to overcome cancer therapy

resistance. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:1212022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Chen L and Shan G: CircRNA in cancer:

Fundamental mechanism and clinical potential. Cancer Lett.

505:49–57. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Xu Y, Liu H, Zhang Y, Luo J, Li H, Lai C,

Shi L and Heng B: piRNAs and circRNAs acting as diagnostic

biomarkers in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Sci Rep.

15:77742025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Nieto MA: Epithelial plasticity: A common

theme in embryonic and cancer cells. Science. 342:12348502013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Glauert AM, Daniel MR, Lucy JA and Dingle

JT: Studies on the mode of action of excess of vitamin A. VII.

Changes in the fine structure of erythrocytes during haemolysis by

vitamin A. J Cell Biol. 17:111–121. 1963. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Royer C and Lu X: Epithelial cell

polarity: A major gatekeeper against cancer? Cell Death Differ.

18:1470–1477. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Han L, Luo H, Huang W, Zhang J, Wu D, Wang

J, Pi J, Liu C, Qu X, Liu H, et al: Modulation of the EMT/MET

process by E-cadherin in airway epithelia stress injury.

Biomolecules. 11:6692021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Wang SS, Jiang J, Liang XH and Tang YL:

Links between cancer stem cells and epithelial-mesenchymal

transition. OncoTargets Ther. 8:2973–2980. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Banales JM, Marin JJG, Lamarca A,

Rodrigues PM, Khan SA, Roberts LR, Cardinale V, Carpino G, Andersen

JB, Braconi C, et al: Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: The next horizon in

mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

17:557–588. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ, Eaton EN, Ayyanan

A, Zhou AY, Brooks M, Reinhard F, Zhang CC, Shipitsin M, et al: The

epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties

of stem cells. Cell. 133:704–715. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Lan T, Luo M and Wei X: Mesenchymal

stem/stromal cells in cancer therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 14:1952021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Polyak K and Weinberg RA: Transitions

between epithelial and mesenchymal states: Acquisition of malignant

and stem cell traits. Nat Rev Cancer. 9:265–273. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Galassi C, Manic G, Esteller M, Galluzzi L

and Vitale I: Epigenetic regulation of cancer stemness. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 10:2432025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Dongre A and Weinberg RA: New insights

into the mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and

implications for cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 20:69–84. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Fischer KR, Durrans A, Lee S, Sheng J, Li

F, Wong STC, Choi H, El Rayes T, Ryu S, Troeger J, et al:

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is not required for lung

metastasis but contributes to chemoresistance. Nature. 527:472–476.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

De Las Rivas J, Brozovic A, Izraely S,

Casas-Pais A, Witz IP and Figueroa A: Cancer drug resistance

induced by EMT: Novel therapeutic strategies. Arch Toxicol.

95:2279–2297. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Spranger S, Koblish HK, Horton B, Scherle

PA, Newton R and Gajewski TF: Mechanism of tumor rejection with

doublets of CTLA-4, PD-1/PD-L1, or IDO blockade involves restored

IL-2 production and proliferation of CD8(+) T cells directly within

the tumor microenvironment. J Immunother Cancer. 2:32014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Fridlender ZG, Sun J, Kim S, Kapoor V,

Cheng G, Ling L, Worthen GS and Albelda SM: Polarization of

tumor-associated neutrophil phenotype by TGF-beta: ‘N1’ versus ‘N2’

TAN. Cancer Cell. 16:183–194. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zhai L, Spranger S, Binder DC, Gritsina G,

Lauing KL, Giles FJ and Wainwright DA: Molecular pathways:

Targeting IDO1 and other tryptophan dioxygenases for cancer

immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 21:5427–5433. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Taki M, Abiko K, Ukita M, Murakami R,

Yamanoi K, Yamaguchi K, Hamanishi J, Baba T, Matsumura N and Mandai

M: Tumor immune microenvironment during epithelial-mesenchymal

transition. Clin Cancer Res. 27:4669–4679. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhang F, Wang H, Wang X, Jiang G, Liu H,

Zhang G, Wang H, Fang R, Bu X, Cai S and Du J: TGF-β induces

M2-like macrophage polarization via SNAIL-mediated suppression of a

pro-inflammatory phenotype. Oncotarget. 7:52294–52306. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Mittal V: Epithelial mesenchymal

transition in tumor metastasis. Annu Rev Pathol. 13:395–412. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Aparicio LA, Blanco M, Castosa R, Concha

Á, Valladares M, Calvo L and Figueroa A: Clinical implications of

epithelial cell plasticity in cancer progression. Cancer Lett.

366:1–10. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Lin S, Sun JG, Wu JB, Long HX, Zhu CH,

Xiang T, Ma H, Zhao ZQ, Yao Q, Zhang AM, et al: Aberrant microRNAs

expression in CD133+/CD326+ human lung

adenocarcinoma initiating cells from A549. Mol Cells. 33:277–283.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Yuan J, Dong R, Liu F, Zhan L, Liu Y, Wei

J and Wang N: The miR-183/182/96 cluster functions as a potential

carcinogenic factor and prognostic factor in kidney renal clear

cell carcinoma. Exp Ther Med. 17:2457–2464. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Bartel DP: Metazoan MicroRNAs. Cell.

173:20–51. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Seyhan AA: Trials and tribulations of

MicroRNA therapeutics. Int J Mol Sci. 25:14692024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Bartel DP: MicroRNAs: Target recognition

and regulatory functions. Cell. 136:215–233. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Hill M and Tran N: miRNA interplay:

Mechanisms and consequences in cancer. Dis Model Mech.

14:dmm0476622021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Ransohoff JD, Wei Y and Khavari PA: The

functions and unique features of long intergenic non-coding RNA.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 19:143–157. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

McCabe EM and Rasmussen TP: lncRNA

involvement in cancer stem cell function and epithelial-mesenchymal

transitions. Semin Cancer Biol. 75:38–48. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Yoon JH, Abdelmohsen K and Gorospe M:

Post-transcriptional gene regulation by long noncoding RNA. J Mol

Biol. 425:3723–3730. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Wang KC and Chang HY: Molecular mechanisms

of long noncoding RNAs. Mol Cell. 43:904–914. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Kristensen LS, Andersen MS, Stagsted LVW,

Ebbesen KK, Hansen TB and Kjems J: The biogenesis, biology and

characterization of circular RNAs. Nat Rev Genet. 20:675–691. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Mauer C, Paz S and Caputi M: Backsplicing

of the HIV-1 transcript generates multiple circRNAs to promote

viral replication. Npj Viruses. 3:212025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Ma Y, Wang T, Zhang X, Wang P and Long F:

The role of circular RNAs in regulating resistance to cancer

immunotherapy: Mechanisms and implications. Cell Death Dis.

15:3122024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Hansen TB, Jensen TI, Clausen BH, Bramsen

JB, Finsen B, Damgaard CK and Kjems J: Natural RNA circles function

as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature. 495:384–388. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Memczak S, Jens M, Elefsinioti A, Torti F,

Krueger J, Rybak A, Maier L, Mackowiak SD, Gregersen LH, Munschauer

M, et al: Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with

regulatory potency. Nature. 495:333–338. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Thamjamrassri P and Ariyachet C: Circular

RNAs in cell cycle regulation of cancers. Int J Mol Sci.

25:60942024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Hu X, Wu D, He X, Zhao H, He Z, Lin J,

Wang K, Wang W, Pan Z, Lin H and Wang M: circGSK3β promotes

metastasis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by augmenting

β-catenin signaling. Mol Cancer. 18:1602019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Fang L, Du WW, Awan FM, Dong J and Yang

BB: The circular RNA circ-Ccnb1 dissociates Ccnb1/Cdk1 complex

suppressing cell invasion and tumorigenesis. Cancer Lett.

459:216–226. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Fei T, Chen Y, Xiao T, Li W, Cato L, Zhang

P, Cotter MB, Bowden M, Lis RT, Zhao SG, et al: Genome-wide CRISPR

screen identifies HNRNPL as a prostate cancer dependency regulating

RNA splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 114:E5207–E5215. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Yang Y, Fan X, Mao M, Song X, Wu P, Zhang

Y, Jin Y, Yang Y, Chen LL, Wang Y, et al: Extensive translation of

circular RNAs driven by N6-methyladenosine. Cell Res.

27:626–641. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Gregory PA, Bert AG, Paterson EL, Barry

SC, Tsykin A, Farshid G, Vadas MA, Khew-Goodall Y and Goodall GJ:

The miR-200 family and miR-205 regulate epithelial to mesenchymal

transition by targeting ZEB1 and SIP1. Nat Cell Biol. 10:593–601.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Lu R, Ji Z, Li X, Qin J, Cui G, Chen J,

Zhai Q, Zhao C, Zhang W and Yu Z: Tumor suppressive microRNA-200a

inhibits renal cell carcinoma development by directly targeting

TGFB2. Tumour Biol. 36:6691–6700. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Wang X, Chen X, Wang R, Xiao P, Xu Z, Chen

L, Hang W, Ruan A, Yang H and Zhang X: microRNA-200c modulates the

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in human renal cell carcinoma

metastasis. Oncol Rep. 30:643–650. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Xu XW, Li S, Yin F and Qin LL: Expression

of miR-205 in renal cell carcinoma and its association with

clinicopathological features and prognosis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol

Sci. 22:662–670. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Qiu M, Liang Z, Chen L, Tan G, Wang K, Liu

L, Liu J and Chen H: MicroRNA-429 suppresses cell proliferation,