Introduction

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common

vascular tumor in children, with an incidence of 3–10% (1). Due to its rapid growth, some IHs lead

to long-term residual permanent skin damage and might affect the

physical and mental health of children (2). Although a number of studies have

focused on the mechanisms underlying IH progression, the detailed

regulatory mechanisms are still not fully understood.

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), with a length of

>200 nucleotides, have crucial roles in hemangioma cell

proliferation and invasion (3,4). A

recent study reported that CTBP1-AS2 sponges microRNA (miR)-335-5p,

upregulates C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 and subsequently enhances

hemangioma angiogenesis and progression (5). MIR4435-2HG, which is secreted by M2

macrophages, targets Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 and

promotes IH progression (4). Most

notably, our previous study revealed that knocking down lncRNA

NEAT1 repressed IH progression by sponging miR-33a-5p and

regulating the downstream hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit α

(HIF1α)/NF-κB pathway (6).

Additional studies have further reported that in hemangioma, lncRNA

NEAT1 is positively regulated by alkB homolog 5, RNA demethylase in

an m6A modification-dependent manner and promotes hemangioma

development by regulating the miR-361-5p/VEGFA pathway (7,8).

However, the exact regulatory roles of lncRNA NEAT1 in hemangioma

progression are still largely unknown.

Histone lactylation (addition of a lactyl group to a

lysine residue) by P300 and KAT8 is a protein modification newly

discovered in 2019 that affects transcription (9,10),

and has been found to widely participate in disease progression

including cancer, atrial fibrillation and keloids (11,12).

Recent studies have shown that H3 lysine 18 lactylation (H3K18la)

can activate gene transcription (13,14).

However, the roles of protein lactylation in hemangioma development

are still unclear.

In the present study, the effects of the lncRNA

NEAT1/H3K18la/β-catenin signaling pathway on the colony formation

ability and viability of hemangioma cells were investigated.

Additionally, the detailed mechanism by which NEAT1 regulates

β-catenin in hemangioma cells was further investigated.

Materials and methods

Tissue sample information

IH tissues (proliferating stage; median age, 7

months; n=10, Table I) and normal

adjacent subcutaneous tissues (n=10) were collected from the

Kunming Children's Hospital (Kunming, China) between February 2022

and September 2024. Samples were kept at −80°C until analysis.

Informed consent was obtained from the parents/legal guardians of

each patient. The patients received no treatment before surgery.

The Ethics Committee of Kunming Children's Hospital approved the

present study (approval no. 2021-03-181-K01). The inclusion

criteria were as follows: i) The patients were diagnosed with IH

(proliferating stage); ii) age of <1 years old; and iii) The

hemangioma lesion was located in concealed areas such as the trunk

and limbs, and the parents voluntarily opted for surgical removal.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: i) Multiple hemangiomas;

ii) vascular malformation; and iii) the patients had received any

other treatment.

| Table I.Clinical features of the patients

with infantile hemangioma included in the present study. |

Table I.

Clinical features of the patients

with infantile hemangioma included in the present study.

| Patient no. | Sex | Age (months) | Location of

tumor | Growth phase |

|---|

| 1 | Male | 9 | Abdominal wall | Proliferating |

| 2 | Female | 4 | Waist | Proliferating |

| 3 | Female | 3 | Neck | Proliferating |

| 4 | Male | 6 | Abdominal wall | Proliferating |

| 5 | Female | 7 | Abdominal wall | Proliferating |

| 6 | Male | 7 | Neck | Proliferating |

| 7 | Female | 9 | Waist | Proliferating |

| 8 | Female | 4 | Neck | Proliferating |

| 9 | Male | 8 | Abdominal wall | Proliferating |

| 10 | Female | 8 | Waist | Proliferating |

Cell culture and treatments

Hemangioma endothelial cells (HemECs) were prepared

following the protocol described in a previous study (15) using the hemangioma sample from

patient no. 4 in Table I. The

HemECs were cultured in human endothelial serum-free medium (Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 5% CO2 and 37°C.

Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

was used to transfect small interfering RNAs (siRNA; 50 nM;

Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd.) into the cells at 37°C for 48 h.

Then, the cells were collected for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR), western blotting,

chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-PCR and cell viability assays.

Table SI lists the sequences of

the siRNAs.

2-Deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG), oxamate, lactate, MG132,

bafilomycin A1 (BafA1), cycloheximide (CHX) and A-485 were

purchased from Selleck Chemicals. In the present study, 10 mM 2-DG,

20 mM oxamate and 10 mM lactate were used to treat the HemECs

(16–19) (RT-qPCR, western blotting, ChIP-PCR

and cell viability assays: 37°C for 48 h; colony formation assay:

37°C for 7–9 days), and the protein lactylation was inactivated

(2-DG and oxamate) and activated (lactate). At 46.5 and 46 h after

transfection of NEAT1 siRNA, 20 µM MG132 (treatment: 1.5 h at 37°C)

and 100 nM BafA1 (treatment: 2 h at 37°C) were used to suppress the

proteosome and lysosome, respectively (20), and the cells were harvested for

western blotting after a total time of 48 h of transfection with

NEAT1 siRNA. At 33, 36, 39, 42 and 45 h after transfection of NEAT1

siRNA (corresponding to the 15, 12, 9, 6 and 3 h treatment group),

100 µg/ml CHX was used to treat the cells (20), and the cells were harvested for

western blotting after a total time of 48 h of transfection with

NEAT1 siRNA. Additionally, 5 µM A-485 (RT-qPCR, western blotting,

cell viability assays: 37°C for 48 h; colony formation assay: 37°C

for 7–9 days) were applied to block p300 (21).

RT-qPCR assay

Total RNA from tissues and cells was extracted using

RNAiso Esay Plus (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) according

to the manufacturer's instructions. First-strand cDNA synthesis and

qPCR were performed using the HifiScript cDNA Synthesis Kit

(Cwbiotech) and PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), respectively, according to the manufacturer's

protocol. The qPCR program was as follows: 95°C for 2 min, followed

by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min. The

2−ΔΔcq method was used to calculate the relative

expression of the genes (22).

GAPDH was used for normalization. Table SII lists the primer sequences.

Colony formation and cell viability

assays

A total of 500 cells per well were plated in 12-well

plate and then incubated for 7–9 days [lactate dehydrogenase B

(LDHB)-knock down cells: cells were seeded after transfection for

24 h; 2-DG/oxamate/lactate/A-485 treated cells: drugs were used to

treat after seeding for 24 h]. At the end of the experiment, the

cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room

temperature and then stained with 0.1% crystal violet (Beyotime

Biotechnology) for 30 min at room temperature. Colonies (>50

cells) were visualized and quantified by light microscopy. The cell

viability was detected using Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo

Laboratories, Inc.) assays as previously described (6).

RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP)

assay

According to the protocol previously described

(23), the hemangioma cells were

harvested and washed twice with ice-cold PBS. The hemangioma cells

were suspended in RIP buffer (1 ml) containing 50 mmol/l Tris pH

7.4, 0.5% NP-40, 1X RNasin plus (Promega Corporation), 150 mmol/l

NaCl, 2 mmol/l ribonucleoside vanadyl complex (New England BioLabs,

Inc.), 1X protease inhibitor cocktail (MilliporeSigma) and 1 mmol/l

PMSF. After brief sonication, cell lysates were centrifuged at

10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C and the supernatants were precleared

using 10 µl Dynabeads Protein G (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

The precleared supernatants were divided into two equal parts, and

one part was incubated with 1 µg LDHB antibody (cat. no.

14824-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and 20 µl Protein A/G Magnetic

Beads (cat. No. HY-K0202; MedChemExpress) overnight at 4°C. The

other part was incubated with 1 µg IgG control antibody (cat. no.

30000-0-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and 20 µl Protein A/G Magnetic

Beads overnight at 4°C. After washing the beads three times with

RIP buffer, the samples were decrosslinked by proteinase K buffer

(50 mmol/l Tris pH 7.4, 150 mmol/l NaCl, 1X RNasin plus, 0.5% SDS

and 200 µg/ml proteinase K) at room temperature for 30 min. Then,

the RNA was extracted and RT-qPCR was performed.

ChIP-PCR

The SimpleChIP Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit (Magnetic

Beads) (cat. no. CST-9003; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) were

used to analyze the H3K18 lactylation level of the promoter of the

β-catenin gene (CTNNB1) following the manufacturer's

protocol. The 2-DG/oxamate-treated cells, lactate-treated cells,

NEAT1-knockdown cells and LDHB-knockdown cells were crosslinked

with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, then collected

after washing twice using PBS (containing 0.5 mM EDTA). The cell

pellet was lysed with 0.3 ml of cell lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl

pH 8.1, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS and protease inhibitor) and incubated

for 10 min on ice. The cell lysates were sonicated (sonication for

15 sec, with a 10-sec interval, totaling 3 min of sonication) to

obtain DNA fragments (150–900 base pair in length) and ~50 µg of

cross-linked sheared chromatin solution was then used for

immunoprecipitation. The L-lactyl-histone H3 (Lys18) antibody (cat.

no. PTM-1427RM; PTM BIO LLC; 6 µg/5×106 cells) was

incubated with the sample overnight at 4°C on a rotating shaker.

Magnetic beads were added to the solution, incubated at 4°C for 1 h

and then washed with washing buffer. The cross-linking was reversed

by adding NaCl at a final concentration of 200 mM and heating at

65°C for 30 min. The DNA fragments were purified using a spin

column and qPCR was performed. The sequences of the primers used

were as follows: CTNNB1 promoter forward primer,

5′-CCTAGTGACAAGTGGAACCAGA-3′; and reverse primer,

5′-GAACTCTCCGTAGAACGGGC-3′.

Western blot assay

The western blot procedure was described in our

previous study (6). The primary

antibodies used were LDHB (cat. no. 14824-1-AP; 1:5,000), β-catenin

(cat. no. 51067-2-AP; 1:5,000), alanyl-tRNA synthetase 1 (AARS1;

cat. no. 17394-1-AP; 1:2,000), P300 (cat. no. 20695-1-AP; 1:1,000)

and GAPDH (cat. no. 60004-1-Ig; 1:50,000) from Proteintech Group,

Inc., and L-lactyl-Histone H3 (Lys18) (cat. no. PTM-1406RM;

1:1,000), L-lactyl lysine (pan-lac; cat. no. PTM-1401RM; 1:1,000)

and Histone H3 (cat. no. PTM-1002RM; 1:1,000) from PTM BIO LLC. All

primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C. The secondary

antibodies used were HRP-conjugated Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) (cat.

no. SA00001-1; 1:10,000; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and

HRP-conjugated Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) (cat, no. SA00001-2;

1:10,000; Proteintech Group, Inc.), which were incubated for 1 h at

room temperature.

Cellular lactate detection

The cellular lactate concentrations were detected

using a Lactic Acid assay kit (cat. no. BC2230; Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's

protocol.

Bioinformatics analysis

The NEAT1-interacting proteins were predicted using

catRAPID software (http://s.tartaglialab.com/page/catrapid_group;

accessed on September 5, 2024). Based on the NEAT1-interacting

proteins (predicted by catRAPID; Interaction Propensity >50),

Gene Oncology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

(KEGG) analyses were performed using the DAVID platform (24,25).

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 10 software (Dotmatics) was used for

data analysis. The quantitative data are shown as the mean ± SD and

were analyzed via one-way with Tukey's multiple comparisons test

(multiple groups) or unpaired Student's t-test (two groups).

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Identification of lncRNA

NEAT1-interacting proteins

Our previous study reported that NEAT1 was highly

expressed in IH tissues (6). In

the present study, to investigate the regulatory mechanisms

underlying NEAT1-affected hemangioma progression, the proteins that

interact with NEAT1 were analyzed using catRAPID software. In

total, 2,064 proteins (such as HSP90B1 and CDK11B) were predicted

to interact with NEAT1. GO and pathway enrichment analyses of these

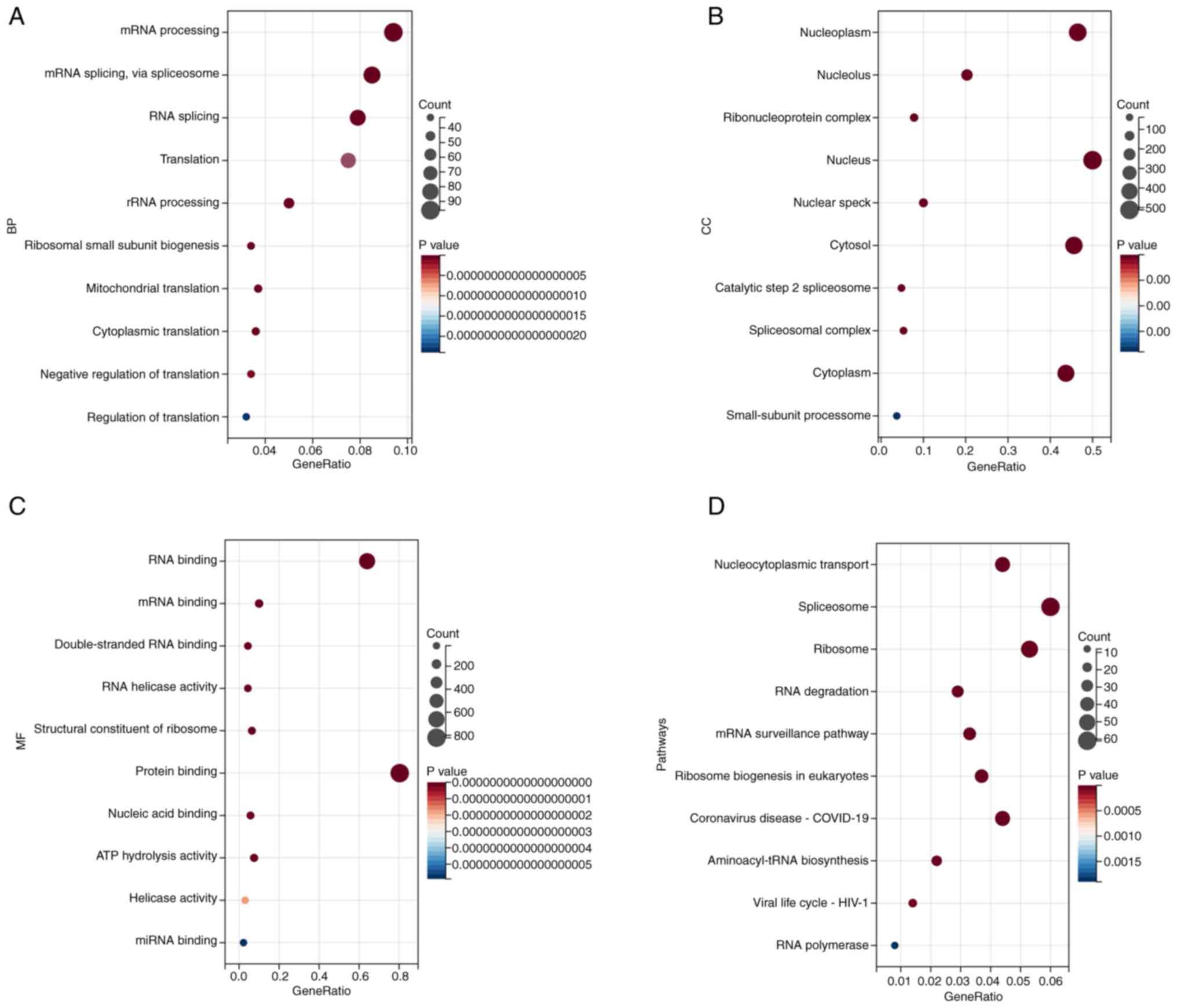

genes were subsequently performed using DAVID. The biological

process enrichment analysis revealed that NEAT1-interacting

proteins were associated with processes such as ‘mRNA processing’,

‘mRNA splicing, via spliceosome’, ‘RNA splicing’, ‘Translation’ and

‘rRNA processing’ (Fig. 1A).

Cellular component enrichment analysis revealed that

NEAT1-interacting proteins were associated with components such as

‘Nucleoplasm’, ‘Nucleolus’, ‘Ribonucleoprotein complex’, ‘Nucleus’

and ‘Nuclear speck’ (Fig. 1B).

Molecular function enrichment analysis revealed that

NEAT1-interacting proteins were associated with functions such as

‘RNA binding’, ‘mRNA binding’, ‘Double-stranded RNA binding’, ‘RNA

helicase activity’ and ‘Structural constituent of ribosome’

(Fig. 1C). KEGG enrichment

analysis revealed that NEAT1-interacting proteins were associated

with ‘Nucleocytoplasmic transport’, ‘Spliceosome,’ ‘Ribosome’, ‘RNA

degradation’ and ‘mRNA surveillance pathway’ (Fig. 1D).

lncRNA NEAT1 interacts with and

positively regulates LDHB in hemangioma cells

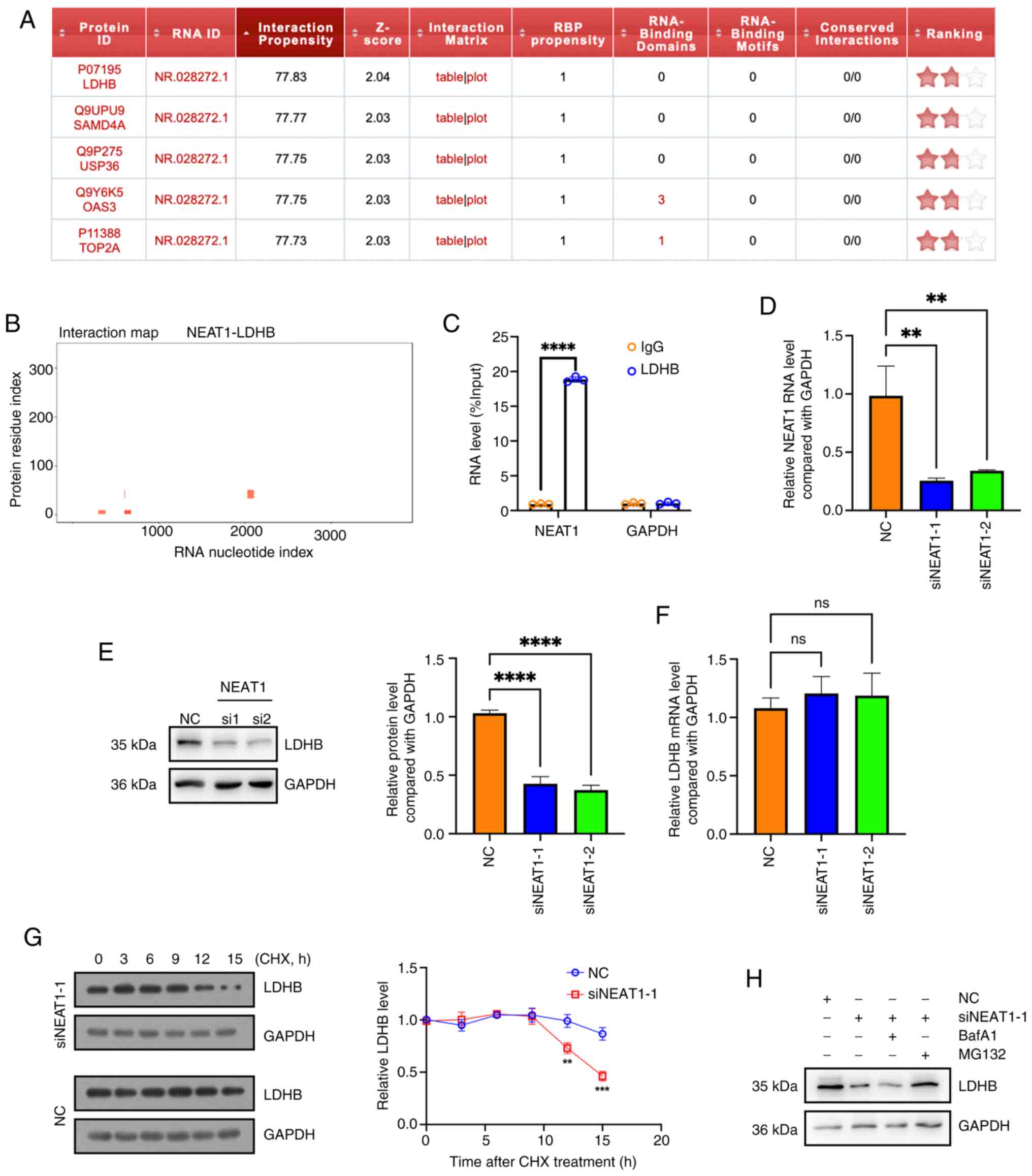

Notably, it was found that LDHB was predicted to

bind with NEAT1 using catRAPID software (Fig. 2A and B). The interaction between

NEAT1 and LDHB in hemangioma cells was validated using a RIP assay

(Fig. 2C). Additionally, after

knocking down NEAT1 expression (Fig.

2D), the protein level (Fig.

2E) but not the mRNA level of LDHB (Fig. 2F) was reduced, indicating that

NEAT1 may regulate LDHB at the protein level. After protein

translation was inhibited via CHX, LDHB degradation occurred faster

in NEAT1-knock down cells than in the negative control cells

(Fig. 2G). The proteasome

inhibitor MG132, but not the lysosome inhibitor BafA1, reversed the

effect of NEAT1 knockdown on the protein level of LDHB, indicating

that NEAT1 knockdown reduced the LDHB protein levels via activation

of the proteasome activity (Fig.

2H). These results suggested that the lncRNA NEAT1 interacted

with and positively regulated LDHB in hemangioma cells.

Knockdown of lncRNA NEAT1 inhibits

cellular protein lactylation and downregulates β-catenin in

hemangioma cells

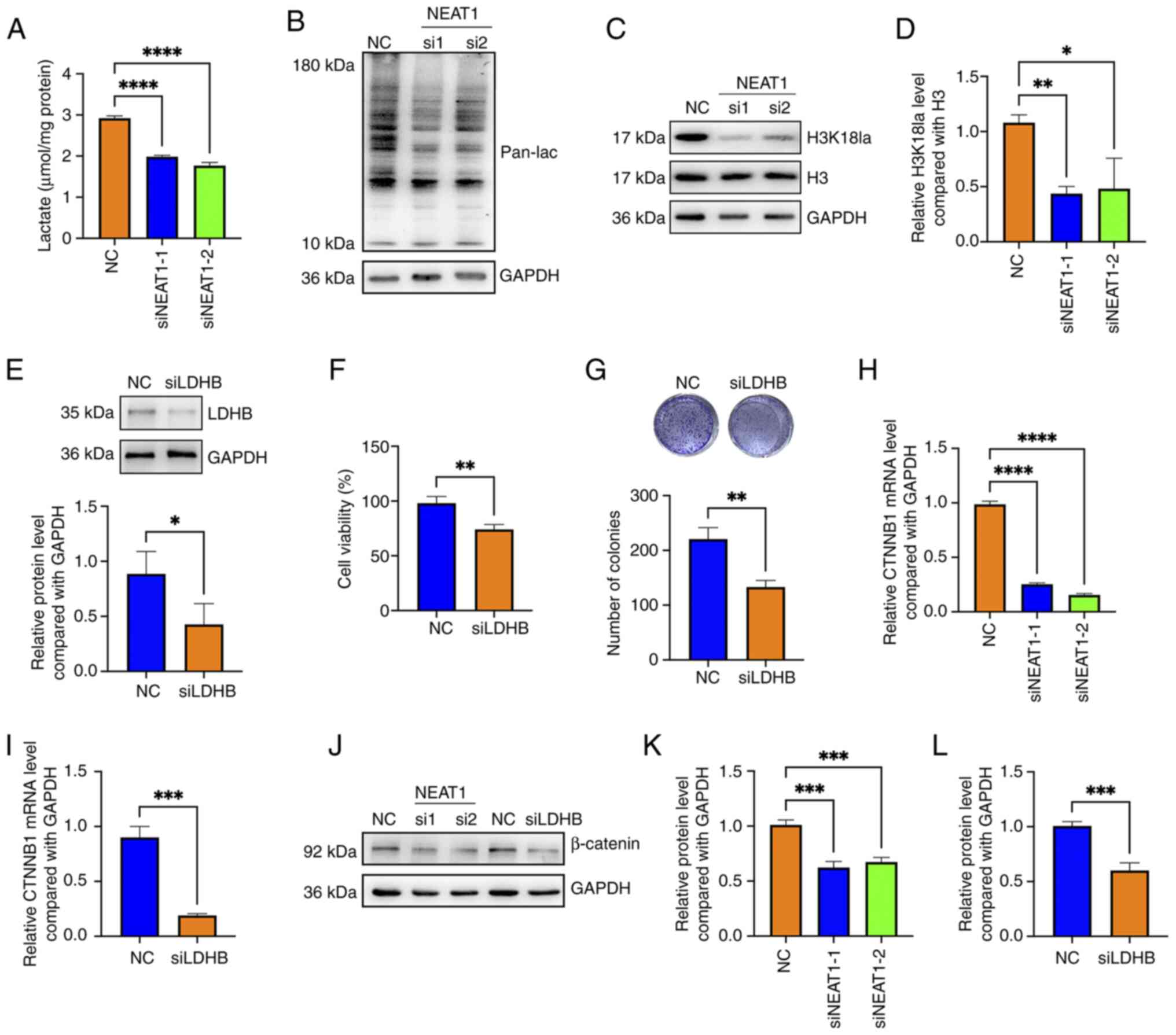

LDHB and LDHA have critical roles in converting

pyruvate to lactate during glycolysis and are involved in

regulating protein lactylation (26,27).

In the present study, the knockdown of NEAT1 reduced the cellular

lactate concentration and attenuated the levels of both pan

lactylation (pan-lac) and H3K18 lactylation in HemECs (Fig. 3A-D). After LDHB expression was

knocked down (Fig. 3E), the

viability and colony formation ability of HemECs was decreased

(Fig. 3F and G).

Activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway potentiates

the invasion, migration, proliferation and epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (EMT) of HemECs (28,29).

Therefore, it was next evaluated whether lncRNA NEAT1 promotes the

colony formation and viability of HemECs by regulating the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. The results revealed that knocking

down NEAT1 downregulated β-catenin at both the mRNA and protein

levels, and that knocking down LDHB also reduced the mRNA and

protein levels of β-catenin in HemECs (Fig. 3H-L). These data revealed that

knocking down of lncRNA NEAT1 inhibited cellular protein

lactylation and downregulated β-catenin in hemangioma cells.

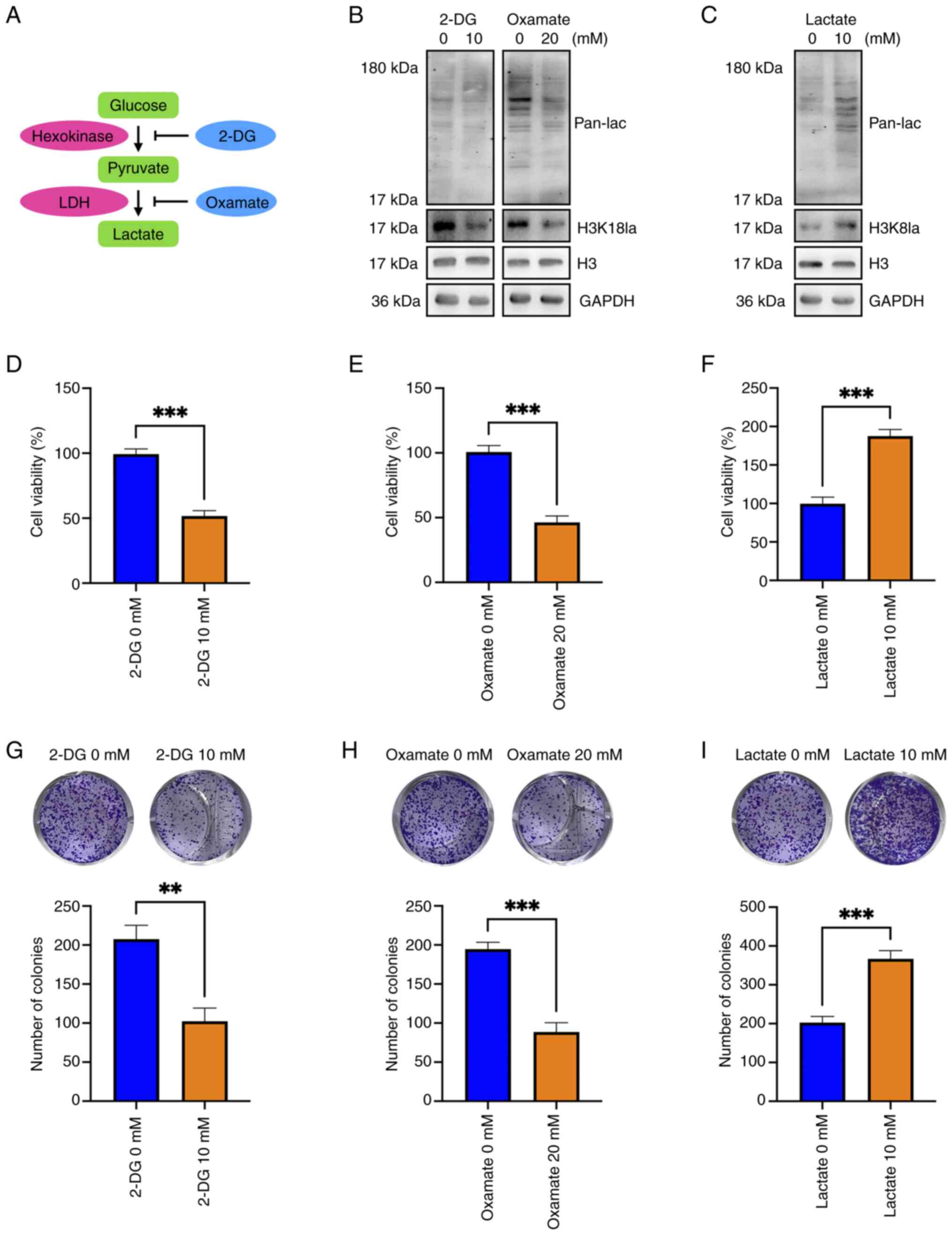

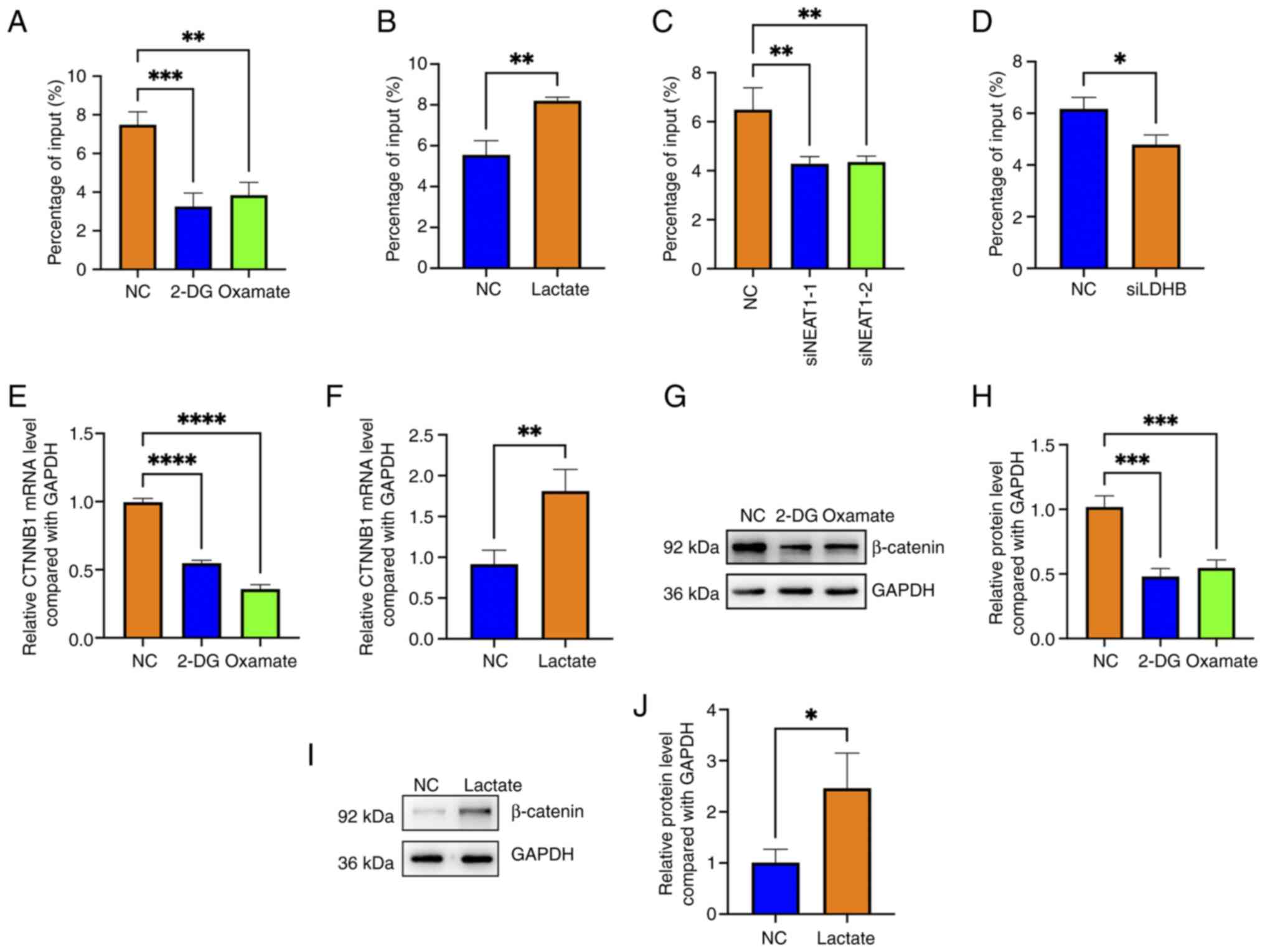

Blockade of lactylation using 2-DG and

oxamate attenuates the viability and colony formation of hemangioma

cells and lactate treatment has the opposite effects

Oxamate suppressed cellular protein and H3K18

lactylation in hemangioma cells and 2-DG slightly reduced the H3K18

lactylation level and inhibited cellular protein lactylation in

hemangioma cells (Fig. 4A and B).

Conversely, lactate addition markedly increased cellular protein

lactylation and H3K18 lactylation in hemangioma cells (Fig. 4C). Both 2-DG and oxamate

significantly impeded the viability and colony formation of

hemangioma cells (Fig. 4D, E, G and

H), and lactate significantly enhanced the viability and colony

formation of hemangioma cells (Fig. 4F

and I). These data indicated that inhibition of lactylation

suppressed the viability and colony formation of hemangioma cells

and that promotion of lactylation exhibited promotive effects.

lncRNA NEAT1 promotes H3K18

lactylation of the CTNNB1 promoter and the blockade of lactylation

downregulates β-catenin in hemangioma cells

Lactylation of promoters or enhancers is an

indication of transcription activation (13); hence, whether NEAT1 regulates

β-catenin by affecting lactylation of the CTNNB1 promoter

was investigated. The results showed that both 2-DG and oxamate

treatment reduced the H3K18 lactylation level of the CTNNB1

promoter; conversely, lactate addition increased the H3K18

lactylation level (Fig. 5A and B).

Notably, knocking down NEAT1 or LDHB inhibited the H3K18

lactylation of the CTNNB1 promoter (Fig. 5C and D).

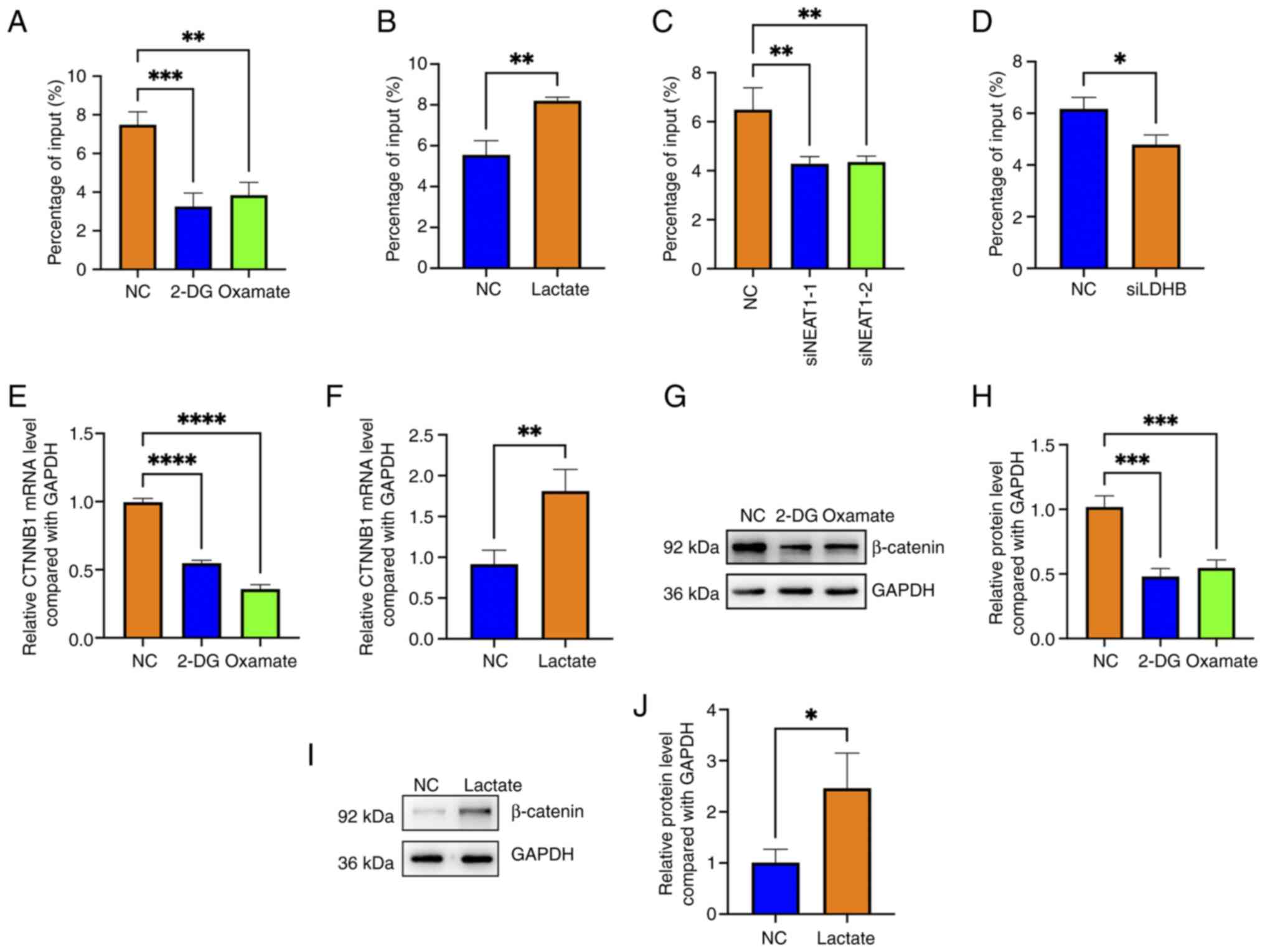

| Figure 5.Long non-coding RNA NEAT1 promotes

the H3K18 lactylation of the CTNNB1 promoter and the

blockade of lactylation downregulates β-catenin in hemangioma

cells. H3K18 lactylation levels of the CTNNB1 promoter in

(A) 2-DG- or oxamate-treated cells and (B) lactate-treated, (C)

NEAT1-knock down and (D) LDHB-knock down hemangioma cells were

evaluated using ChIP-PCR; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

vs. NC (n=3). The CTNNB1 mRNA levels in (E) 2-DG- and

oxamate-treated cells as well as (F) lactate-treated cells were

detected by RT-qPCR; **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001 vs. NC (n=3). The

protein levels of β-catenin in (G) 2-DG- and oxamate-treated cells

were detected by western blotting (n=3). (H) Semi-quantitative

analysis of the levels of β-catenin in 2-DG and oxamate-treated

cells detected by western blotting; ***P<0.001 vs. NC (n=3). (I)

The protein levels of β-catenin in lactate-treated cells were

detected by western blotting (n=3). (J) Semi-quantitative analysis

of the levels of β-catenin in lactate-treated cells detected by

western blotting; *P<0.05 vs. NC (n=3). 2-DG, 2-Deoxy-D-glucose;

NC, negative control; CTNNB1, β-catenin gene; LDHB, lactate

dehydrogenase B; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; RT-qPCR,

reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction; si,

small interfering (RNA). |

Both 2-DG and oxamate treatment reduced the

CTNNB1 mRNA level; by contrast, lactate increased

CTNNB1 mRNA expression (Fig. 5E

and F). Additionally, western blotting revealed that 2-DG and

oxamate treatment downregulated β-catenin at the protein level

(Fig. 5G and H) and that lactate

upregulated β-catenin at the protein level (Fig. 5I and J). These findings suggested

that NEAT1 promoted H3K18 lactylation of the CTNNB1 promoter

and that blocking lactylation downregulated β-catenin expression in

hemangioma cells.

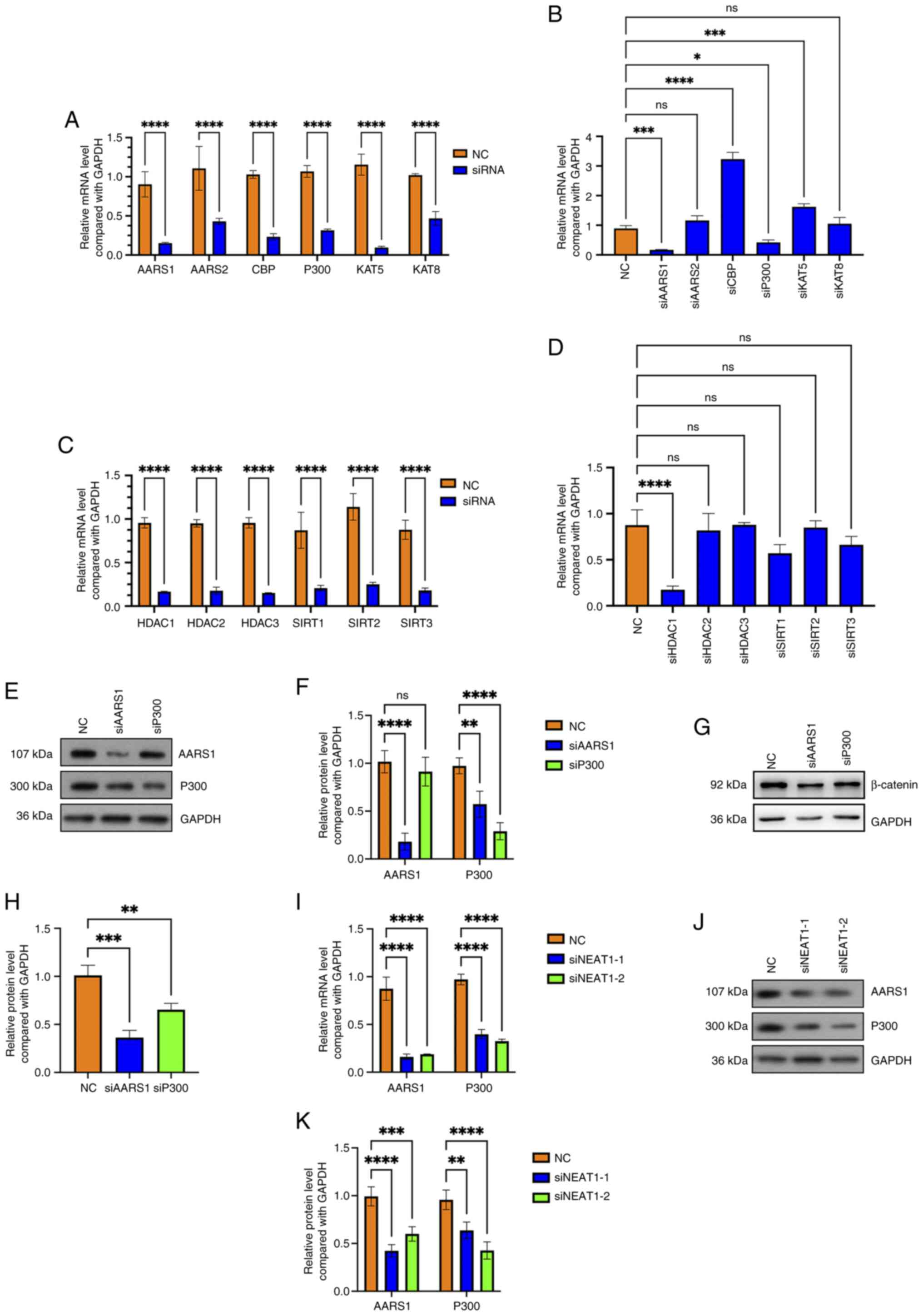

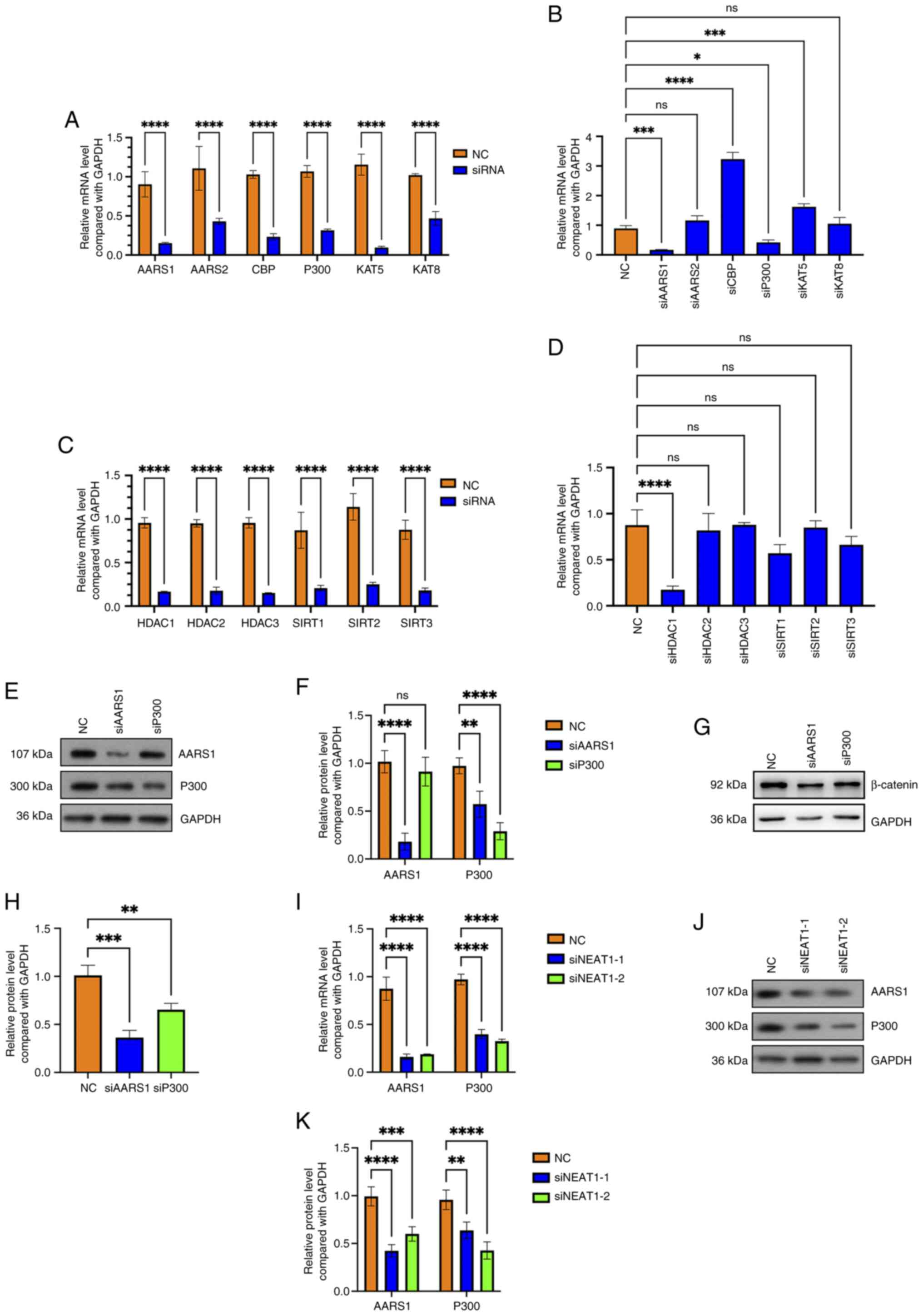

Lactyltransferases AARS1 and P300 are

indirectly regulated by lncRNA NEAT1 and further regulate β-catenin

in hemangioma cells

AARS1, AARS2, CREB binding lysine acetyltransferase

(CBP), lysine acetyltransferase (KAT) 5, KAT8 and P300 are reported

to positively regulate protein lactylation as lactyltransferases,

and Sirtuin (SIRT) 1, SIRT2, SIRT3, Histone deacetylase (HDAC) 1,

HDAC2 and HDAC3 have been found to negatively affect protein

lactylation as delactyltransferases (30). Hence, which molecules regulate

β-catenin in hemangioma cells were screened next. Notably, after

separately knocking down every lactyltransferase (Fig. 6A) and delactyltransferase (Fig. 6C), it was found that the knockdown

of AARS1 and P300 reduced the mRNA level of CTNNB1 (Fig. 6B). Additionally, knocking down

HDAC1 also downregulated CTNNB1 at the mRNA level in

hemangioma cells (Fig. 6D). The

knockdown efficiency of AARS1 and P300 was further confirmed using

western blotting (Fig. 6E and F).

It was subsequently found that the knocking down of AARS1 and P300

in hemangioma cells also downregulated β-catenin at the protein

level (Fig. 6G and H).

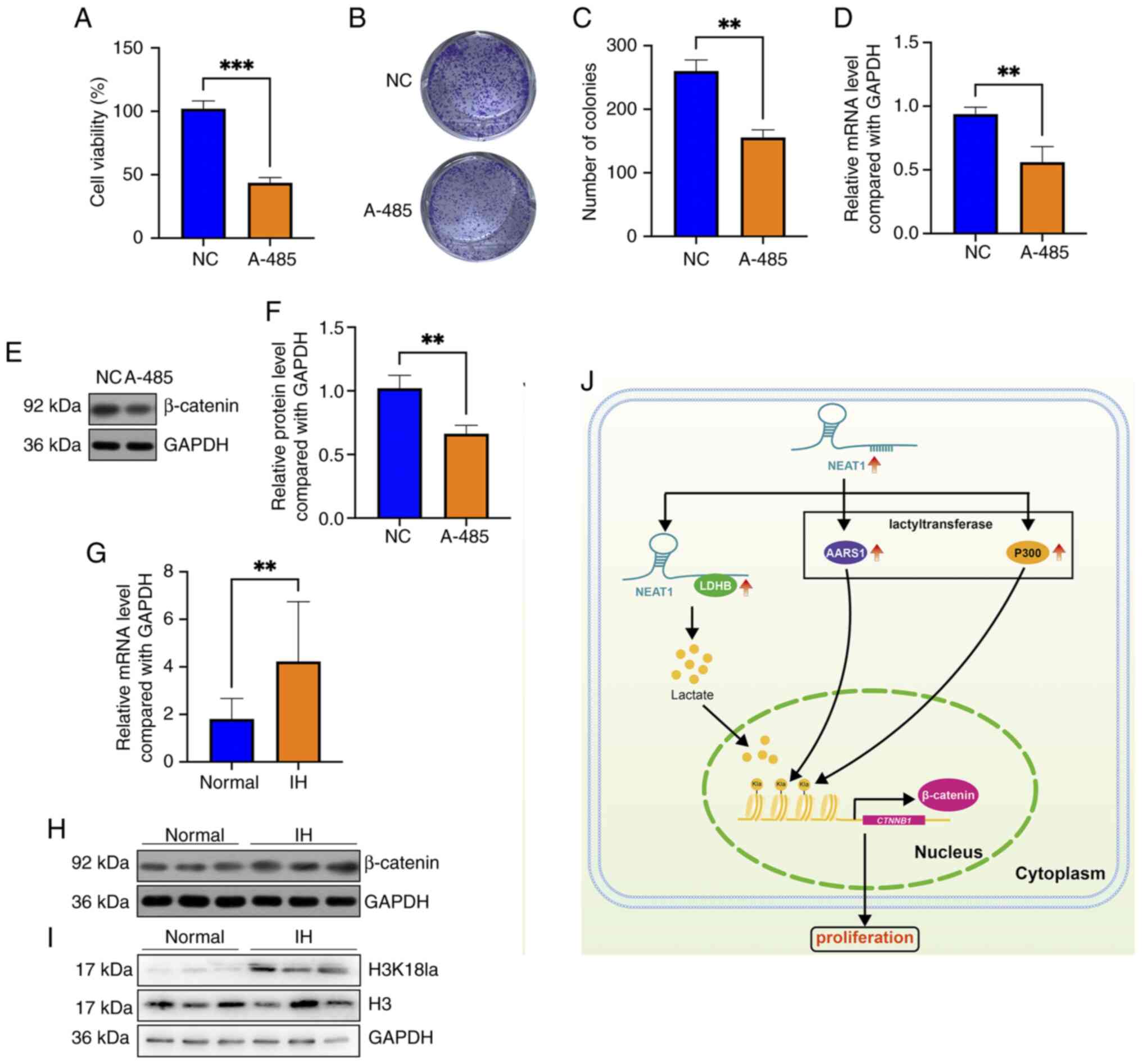

Furthermore, knockdown of NEAT1 significantly decreased the mRNA

and protein levels of AARS1 and P300 (Fig. 6I-K). Notably, blocking P300 using

A-485 suppressed the viability and colony formation of HemECs

(Fig. 7A-C), and A-485 treatment

also decreased the mRNA and protein levels of β-catenin (Fig. 7D-F). These results indicated that

NEAT1 regulates β-catenin in hemangioma cells possibly by

positively affecting the lactyltransferases AARS1 and P300.

| Figure 6.Long non-coding RNA NEAT1 regulates

β-catenin by positively affecting the lactyltransferases AARS1 and

P300 in hemangioma cells. (A) The knockdown efficiencies of AARS1,

AARS2, CBP, KAT5, KAT8 and P300 were confirmed by RT-qPCR;

****P<0.0001 vs. NC (n=3). (B) After AARS1, AARS2, CBP, KAT5,

KAT8 and P300 were knocked down, the CTNNB1 mRNA level was

detected using RT-qPCR; *P<0.05, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001

vs. NC (n=3). (C) The knockdown efficiencies of SIRT1, SIRT2,

SIRT3, HDAC1, HDAC2 and HDAC3 were confirmed by RT-qPCR;

****P<0.0001 vs. NC (n=3). (D) After SIRT1, SIRT2, SIRT3, HDAC1,

HDAC2 and HDAC3 were knocked down, the CTNNB1 mRNA level was

detected using RT-qPCR; ****P<0.0001 vs. NC (n=3). (E) The

knockdown efficiency of AARS1 and P300 was confirmed by western

blotting (n=3). (F) Semi-quantitative analysis of the levels of

AARS1 and P300 in AARS1-knock down and P300-knock down cells

detected by western blotting; **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001 vs. NC

(n=3). (G) The protein level of β-catenin after AARS1 and P300

knockdown was detected using western blotting (n=3). (H)

Semi-quantitative analysis of the levels of β-catenin in

AARS1-knock down and P300-knock down cells detected by western

blotting; **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. NC (n=3). (I) The mRNA

levels of AARS1 and P300 after NEAT1 knockdown were detected using

RT-qPCR; ****P<0.0001 vs. NC (n=3). (J) The protein levels of

AARS1 and P300 after NEAT1 knockdown were detected using western

blotting (n=3). (K) Semi-quantitative analysis of the levels of

AARS1 and P300 in NEAT1-knock down cells detected by western

blotting; **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 vs. NC (n=3).

ns, not significant; NC, negative control; AARS, alany-tRNA

synthetase; CBP, CREB binding lysine acetyltransferase; KAT, lysine

acetyltransferase; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction; CTNNB1, β-catenin gene; SIRT, sirtuin;

HDAC, histone deacetylase; siRNA, small interfering RNA. |

β-catenin and H3K18 lactylation levels

are elevated in IH tissues

The status of β-catenin expression and H3K18

lactylation levels in IH tissues were further evaluated. The

RT-qPCR and western blotting results revealed that both the mRNA

and protein levels of β-catenin were greater in the IH tissues than

in normal tissues (Fig. 7G and H).

Additionally, western blotting indicated that the H3K18 lactylation

level was greater in IH tissues than in normal tissues (Fig. 7I). In summary, the results revealed

that lncRNA NEAT1, which is upregulated in hemangioma, binds with

and upregulates LDHB, subsequently elevates the levels of cellular

lactate and H3K18 lactylation, potentiates β-catenin transcription

and ultimately enhances the proliferation of hemangioma cells

(Fig. 7G).

Discussion

Our previous study revealed that lncRNA NEAT1 is

highly expressed in IH tissues and promotes the proliferation,

migration and invasion of hemangioma cells by sponging miR-33a-5p

and regulating the downstream HIF1α/NF-κB pathway (6). Nevertheless, the functional roles and

detailed mechanisms of NEAT1 in hemangioma are still not fully

understood.

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway plays critical promotional

roles in hemangioma progression, and inactivation of the

Wnt/β-catenin pathway has therapeutic effects on hemangioma

(28,29). IL13RA2 was overexpressed in IH

tissues, and exogenous expression of IL13RA2 potentiated hemangioma

progression by interacting with and activating the β-catenin

pathway (28). Renin has been

shown to promote the proliferation of IH cells by activating the

Wnt pathway (31). Additionally,

blockade of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway by fucoidan has been shown to

inhibit the proliferation and EMT of hemangioma cells (29). Dai et al (32) reported that luteolin suppresses IH

progression by blocking the Wnt signaling pathway. Notably, the

results of the present study indicated that lncRNA NEAT1, which is

upregulated in IH tissues, upregulated β-catenin expression in an

H3K18 lactylation-dependent manner.

Lactic acid was first discovered in 1780 and was

formerly considered a byproduct of metabolism (33). However, at present, lactate is

considered to act as both a metabolic substance and a signaling

molecule (34,35). In 2019, Zhang et al

(9) discovered protein lysine

lactylation, a new posttranslational modification, and provided a

new insight into the novel function of lactate. H3K18 lactylation

is a critical type of histone lactylation that typically activates

gene transcription (36) and is

recognized as a biomarker for poor prognosis in epithelial ovarian

cancer (37). In non-small cell

lung carcinoma, H3K18 lactylation directly transcriptionally

activates POM121 transmembrane nucleoporin and ultimately induces

programmed cell death protein 1 expression and enhances immune

escape (27). In ovarian cancer,

lactate-induced H3K18 lactylation increases CCL18 expression

(38). In pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma (PDAC), H3K18 lactylation, which is elevated in

PDAC, promotes the transcription of BUB1 mitotic checkpoint

serine/threonine kinase B and TTK protein kinase and eventually

causes tumorigenesis (39). H3K18

lactylation transcriptionally activates SOX9 and facilitates liver

fibrosis development (40).

Notably, the present study revealed that H3K18 lactylation

transcriptionally activates β-catenin in hemangioma.

H3K18 lactylation is typically regulated by

glycolysis, lactyltransferases and delactyltransferases. In breast

cancer, potassium two pore domain channel subfamily K member 1

binds with LDHA and affects histone lysine lactylation (41). In PDAC, HDAC2 and P300 regulate

histone lactylation as the eraser and writer of protein lactylation

(39). The present study revealed

that NEAT1 binds to LDHB and positively regulates LDHB expression

in hemangioma cells. A previous study reported that LDHA was highly

expressed in HemECs compared with human umbilical vein endothelial

cells (42). Another study

revealed that the protein expression of phosphofructokinase-1

(FPK-1) is greater in proliferating IHs than in involuting IHs, and

that suppression of FPK-1 impedes the proliferation and migration

of HemECs and reduces lactate production (43). However, the role of LDHB in

hemangioma progression is still unclear.

The proliferative (first 6–12 months after birth),

involuting (starting at ~13 months) and involuted (4–7 years of

age) phases are the three stages of the self-limiting disease

course in IH (44). Unraveling the

mechanisms underlying IH development from proliferation to

involution is crucial for developing a new therapeutic strategy for

IH. The findings of the present study suggest that the levels of

H3K18la and β-catenin are increased in proliferating IH tissues.

Molecular analysis further revealed that H3K18la-driven

transcriptional activation of CTNNB1 enhances the

proliferation of hemangioma cells. Therefore, blocking this

mechanism might be a benefit for IH therapy.

Taken together, the results of the present study

revealed that lncRNA NEAT1, which is upregulated in hemangioma,

binds with and stabilizes LDHB, subsequently elevates the levels of

cellular lactate and H3K18 lactylation, potentiates CTNNB1

transcription and finally enhances the proliferation of hemangioma

cells. Nevertheless, several limitations of the present study

remain. First, when the candidate lactyltransferases or

delactyltransferases that may regulate β-catenin expression were

screened, the changes in expression were only examined at the mRNA

level and not the protein level. Second, in addition to H3K18

lactylation, NEAT1 also regulates the lactylation of non-histone

proteins; therefore, whether the lactylation of non-histone

proteins is also involved in the NEAT1-affected hemangioma cell

proliferation still needs to be investigated. Third, how NEAT1

regulates AARS1 and P300 requires further exploration.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was funded by the Joint Special Funds for the

Department of Science and Technology of Yunnan Province-Kunming

Medical University (grant no. 202201AY070001-202).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HS conceived and designed the research. LY performed

the experiments and wrote the manuscript. NZ, XLZ, XJP, LX, YJP, LZ

and JNW analyzed the data. All authors read and approved the final

version of the manuscript. HS and LY confirm the authenticity of

all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The Ethics Committee of Kunming Children's Hospital

(Kunming, China) approved this study (approval no.

2021-03-181-K01). Informed consent was obtained from the

parents/legal guardians of each patient.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Liu C, Zhao ZL, Ji ZD, Jiang Y and Zheng

J: MiR-187-3p enhances propranolol sensitivity of hemangioma stem

cells. Cell Struct Funct. 44:41–50. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Acevedo LM and Cheresh DA: Suppressing

NFAT increases VEGF signaling in hemangiomas. Cancer Cell.

14:429–430. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wang Q, Zhao C, Du Q, Cao Z and Pan J:

Non-coding RNA in infantile hemangioma. Pediatr Res. 96:1594–1602.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Li Z, Cao Z, Li N, Wang L, Fu C, Huo R, Xu

G, Tian C and Bi J: M2 macrophage-derived exosomal lncRNA

MIR4435-2HG promotes progression of infantile hemangiomas by

targeting HNRNPA1. Int J Nanomedicine. 18:5943–5960. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Li R, Liu Y, Liu J, Chen B, Ji Z, Xu A and

Zhang T: CCL2 regulated by the CTBP1-AS2/miR-335-5p axis promotes

hemangioma progression and angiogenesis. Immunopharmacol

Immunotoxicol. 46:385–394. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Yu L, Shu H, Xing L, Lv MX, Li L, Xie YC,

Zhang Z, Zhang L and Xie YY: Silencing long non-coding RNA NEAT1

suppresses the tumorigenesis of infantile hemangioma by

competitively binding miR-33a-5p to stimulate HIF1α/NF-κB pathway.

Mol Med Rep. 22:3358–3366. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Yu X, Liu X, Wang R and Wang L: Long

non-coding RNA NEAT1 promotes the progression of hemangioma via the

miR-361-5p/VEGFA pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 512:825–831.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Peng K, Xia RP, Zhao F, Xiao Y, Ma TD, Li

M, Feng Y and Zhou CG: ALKBH5 promotes the progression of infantile

hemangioma through regulating the NEAT1/miR-378b/FOSL1 axis. Mol

Cell Biochem. 477:1527–1540. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zhang D, Tang Z, Huang H, Zhou G, Cui C,

Weng Y, Liu W, Kim S, Lee S, Perez-Neut M, et al: Metabolic

regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature.

574:575–580. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Xiao SY, Zhang SH, Sun K, Huang Q and Hu

C: Lactate and lactylation: Molecular insights into histone and

non-histone lactylation in tumor progression, tumor immune

microenvironment, and therapeutic strategies. Biomark Res.

13:1342025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Fang N, Zhang N, Jiang X, Yan S, Wang Z,

Gao Q, Xu M, Mu L, Li X, Chen J, et al: PFKM-Driven lactate

overproduction promotes atrial fibrillation via triggering cardiac

fibroblasts histone lactylation. Adv Sci (Weinh). 12:e009632025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Gu JJ, Deng CC, An Q, Zhu DH, Xu XY, Fu

ZZ, Zhou ZY, Rong Z and Yang B: Lactate promotes collagen

expression, proliferation and migration through H3K18

lactylation-dependent stimulation of LTBP3/TGF-beta1 axis in keloid

fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol. July 7–2025.(Epub ahead of print).

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Galle E, Wong CW, Ghosh A, Desgeorges T,

Melrose K, Hinte LC, Castellano-Castillo D, Engl M, de Sousa JA,

Ruiz-Ojeda FJ, et al: H3K18 lactylation marks tissue-specific

active enhancers. Genome Biol. 23:2072022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wang H, Xu M, Zhang T, Pan J, Li C, Pan B,

Zhou L, Huang Y, Gao C, He M, et al: PYCR1 promotes liver cancer

cell growth and metastasis by regulating IRS1 expression through

lactylation modification. Clin Transl Med. 14:e700452024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Khan ZA, Melero-Martin JM, Wu X, Paruchuri

S, Boscolo E, Mulliken JB and Bischoff J: Endothelial progenitor

cells from infantile hemangioma and umbilical cord blood display

unique cellular responses to endostatin. Blood. 108:915–921. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kong C, Li R, Wang X, Li L, Kang N, Zhen

X, Dong Y and Yan G: Environmental aminomethylphosphonic acid

(AMPA) exposure increased the risk of spontaneous abortion through

lactate-induced JunB lactylation in trophoblast. Ecotoxicol Environ

Saf. 302:1187432025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Lu Y, Zhu J, Zhang Y, Li W, Xiong Y, Fan

Y, Wu Y, Zhao J, Shang C, Liang H and Zhang W: Lactylation-Driven

IGF2BP3-mediated serine metabolism reprogramming and RNA

m6A-modification promotes lenvatinib resistance in HCC. Adv Sci

(Weinh). 11:e24013992024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhao SS, Liu J, Wu QC and Zhou XL: Lactate

regulates pathological cardiac hypertrophy via histone lactylation

modification. J Cell Mol Med. 28:e700222024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wei S, Zhang J, Zhao R, Shi R, An L, Yu Z,

Zhang Q, Zhang J, Yao Y, Li H and Wang H: Histone lactylation

promotes malignant progression by facilitating USP39 expression to

target PI3K/AKT/HIF-1α signal pathway in endometrial carcinoma.

Cell Death Discov. 10:1212024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Lu G, Yi J, Gubas A, Wang YT, Wu Y, Ren Y,

Wu M, Shi Y, Ouyang C, Tan HWS, et al: Suppression of autophagy

during mitosis via CUL4-RING ubiquitin ligases-mediated WIPI2

polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. Autophagy.

15:1917–1934. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Whitworth CP, Aw WY, Doherty EL, Handler

C, Ambekar Y, Sawhney A, Scarcelli G and Polacheck WJ: P300

modulates endothelial mechanotransduction of fluid shear stress.

Cell Mol Bioeng. 17:507–523. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Chen B, Deng S, Ge T, Ye M, Yu J, Lin S,

Ma W and Songyang Z: Live cell imaging and proteomic profiling of

endogenous NEAT1 lncRNA by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knock-in. Protein

Cell. 11:641–660. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Huang da W, Sherman BT and Lempicki RA:

Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID

bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 4:44–57. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Huang da W, Sherman BT and Lempicki RA:

Bioinformatics enrichment tools: Paths toward the comprehensive

functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res.

37:1–13. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Cai S, Xia Q, Duan D, Fu J, Wu Z, Yang Z

and Yu C: Creatine kinase mitochondrial 2 promotes the growth and

progression of colorectal cancer via enhancing Warburg effect

through lactate dehydrogenase B. PeerJ. 12:e176722024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhang C, Zhou L, Zhang M, Du Y, Li C, Ren

H and Zheng L: H3K18 Lactylation potentiates immune escape of

Non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 84:3589–3601. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Liu Z, Ma T, Li J, Ren W and Zhang Z:

IL13RA2 promotes progression of infantile haemangioma by activating

glycolysis and the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Oncol Res.

32:1453–1465. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Zhu Z, Luo J, Li L, Wang D, Xu Q, Teng J,

Zhou J, Sun L, Yu N and Zuo D: Fucoidan suppresses proliferation

and epithelial-mesenchymal transition process via Wnt/β-catenin

signalling in hemangioma. Exp Dermatol. 33:e150272024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Chen J, Zhao D, Wang Y, Liu M, Zhang Y,

Feng T, Xiao C, Song H, Miao R, Xu L, et al: Lactylated

apolipoprotein C-II induces immunotherapy resistance by promoting

extracellular lipolysis. Adv Sci (Weinh). 11:e24063332024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

van Schaijik B, Tan ST, Marsh RW and

Itinteang T: Expression of (pro)renin receptor and its effect on

endothelial cell proliferation in infantile hemangioma. Pediatr

Res. 86:202–207. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Dai Y, Zheng H, Liu Z, Wang Y and Hu W:

The flavonoid luteolin suppresses infantile hemangioma by targeting

FZD6 in the Wnt pathway. Invest New Drugs. 39:775–784. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Li X, Yang Y, Zhang B, Lin X, Fu X, An Y,

Zou Y, Wang JX, Wang Z and Yu T: Lactate metabolism in human health

and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:3052022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Yu H, Zhu T, Ma D, Cheng X, Wang S and Yao

Y: The role of nonhistone lactylation in disease. Heliyon.

10:e362962024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Brooks GA: Lactate as a fulcrum of

metabolism. Redox Biol. 35:1014542020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Raychaudhuri D, Singh P, Chakraborty B,

Hennessey M, Tannir AJ, Byregowda S, Natarajan SM, Trujillo-Ocampo

A, Im JS and Goswami S: Histone lactylation drives CD8+

T cell metabolism and function. Nat Immunol. 25:2140–2151. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Chao J, Chen GD, Huang ST, Gu H, Liu YY,

Luo Y, Lin Z, Chen ZZ, Li X, Zhang B, et al: High histone H3K18

lactylation level is correlated with poor prognosis in epithelial

ovarian cancer. Neoplasma. 71:319–332. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Sun J, Feng Q, He Y, Wang M and Wu Y:

Lactate activates CCL18 expression via H3K18 lactylation in

macrophages to promote tumorigenesis of ovarian cancer. Acta

Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 56:1373–1386. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Li F, Si W, Xia L, Yin D, Wei T, Tao M,

Cui X, Yang J, Hong T and Wei R: Positive feedback regulation

between glycolysis and histone lactylation drives oncogenesis in

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer. 23:902024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Wu S, Li J and Zhan Y: H3K18 lactylation

accelerates liver fibrosis progression through facilitating SOX9

transcription. Exp Cell Res. 440:1141352024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Hou X, Ouyang J, Tang L, Wu P, Deng X, Yan

Q, Shi L, Fan S, Fan C, Guo C, et al: KCNK1 promotes proliferation

and metastasis of breast cancer cells by activating lactate

dehydrogenase A (LDHA) and up-regulating H3K18 lactylation. PLoS

Biol. 22:e30026662024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Chen J, Wu D, Dong Z, Chen A and Liu S:

The expression and role of glycolysis-associated molecules in

infantile hemangioma. Life Sci. 259:1182152020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Yang K, Zhang X, Chen L, Chen S and Ji Y:

Microarray expression profile of mRNAs and long noncoding RNAs and

the potential role of PFK-1 in infantile hemangioma. Cell Div.

16:12021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Rodriguez Bandera AI, Sebaratnam DF,

Wargon O and Wong LF: Infantile hemangioma. Part 1: Epidemiology,

pathogenesis, clinical presentation and assessment. J Am Acad

Dermatol. 85:1379–1392. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|