Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic and

recurrent inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract,

which mainly includes Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis

(UC) (1–4). UC is an idiopathic chronic

inflammatory condition affecting the colonic mucosa, characterized

by alternating periods of flare-ups and remission. The disease

typically originates in the rectum and extends continuously

throughout the colon (5). Lesions

are predominantly confined to the colonic mucosa, with ulcers

manifesting as the primary symptom, alongside diarrhea, abdominal

pain and weight loss, among which bloody diarrhea is a hallmark of

UC (6). CD is a progressive

chronic inflammatory disease that can affect any part of the

gastrointestinal tract. The most commonly affected parts are the

terminal ileum and colon. In addition to symptoms such as diarrhea

and abdominal pain, complications such as stenosis, fistula or

abscesses may occur over time (7,8). The

incidence of IBD is higher in developed countries. According to

recent epidemiological evidence, ~3 million individuals in the USA

are affected by IBD (9). The

majority of patients experience symptom onset aged 20–39 years,

with a lower incidence rate observed in individuals aged >50

years (3). The pathogenesis of IBD

involves multifactorial interactions, including environmental

triggers, genetic susceptibility, immune dysregulation and gut

microbiota alterations. Available evidence suggests that abnormal

immune responses, including both innate and adaptive immune

response, are important causes of chronic intestinal inflammation

in patients with IBD (10,11). Chronic, persistent inflammation is

a hallmark of IBD and is associated with an increased risk of

intestinal malignancies (12,13).

Notably, liver X receptor (LXR), as a cholesterol sensor, has

recently been shown to mitigate inflammation-driven carcinogenesis

by restoring immune-metabolic balance (14). Long-term inflammation can induce

damage and dysregulated proliferation of colonic mucosal cells,

ultimately leading to the development of cancer, such as colorectal

cancer (CRC) and colitis-associated cancer (15,16).

Therefore, a major challenge in controlling IBD and colon cancer is

managing the occurrence and development of intestinal inflammation,

which may be an effective method to treat digestive system diseases

linked to intestinal inflammation.

LXR is a ligand-activated transcription factor

belonging to the nuclear hormone receptor family, comprising two

subtypes: LXRα and LXRβ (17).

LXRα is highly expressed in metabolically active tissues, including

the liver, small intestine, kidney, adipose tissue and macrophages,

while LXRβ is ubiquitously expressed throughout the body (17,18).

LXR has been identified to function as a heterodimer with retinoid

X receptor (RXR). The LXR/RXR heterodimer can be activated by

ligands or agonists of LXR or RXR individually, or by both

simultaneously, resulting in a synergistic effect (19,20).

The activation of LXR has been reported to regulate the expression

of a series of genes associated with cholesterol transport, glucose

metabolism and the modulation of inflammatory responses (21,22).

LXR regulates cholesterol metabolism by inducing the expression of

a series of target genes, including adenosine triphosphate

(ATP)-binding cassette transporter family members such as

ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1), ATP-binding cassette

subfamily G member (ABCG)1, ABCG5 and ABCG8, which promote the

absorption, transport and excretion of cholesterol in the intestine

(23,24). The LXR/RXR heterodimer has been

identified as a key regulator of ABCA1 expression in vivo

(25). In addition, the genes

involved in the LXR-induced regulation of the cholesterol

metabolism pathway include sterol regulatory element-binding

protein (SREBP)2, which can activate cholesterol biosynthesis and

uptake pathways at low cholesterol levels. These mechanisms work

together to maintain the balance of cholesterol in the body

(26–28). Although the most widely studied

function of LXR is to regulate cholesterol metabolism, previous

studies have shown that LXR is also involved in the regulation of

inflammatory responses and tumor progression, particularly in

enteritis and intestinal cancer (29,30).

Existing studies have shown that LXR can reduce inflammatory

response and intestinal mucosal injury by reducing inflammatory

cell infiltration, inhibiting the secretion of pro-inflammatory

cytokines and enhancing the integrity of the intestinal mucosal

barrier (14,31,32).

For example, LXR activation can reduce the release of inflammatory

mediators by promoting macrophage polarization to anti-inflammatory

phenotypes and can enhance the phagocytosis of macrophages toward

tumor-related inflammatory cells (33–36).

In addition, the activation of LXR can directly inhibit the

proliferation or promote the apoptosis of intestinal tumor cells by

regulating cholesterol metabolism or related genes, thus inhibiting

tumor growth (37–39). The present review summarizes the

pleiotropic effects of LXR on IBD and CRC pathogenesis, focusing on

three interconnected axes: i) Intestinal barrier preservation; ii)

immune cell reprogramming; and iii) metabolic regulation.

Therapeutic opportunities and challenges in targeting LXR signaling

are further discussed.

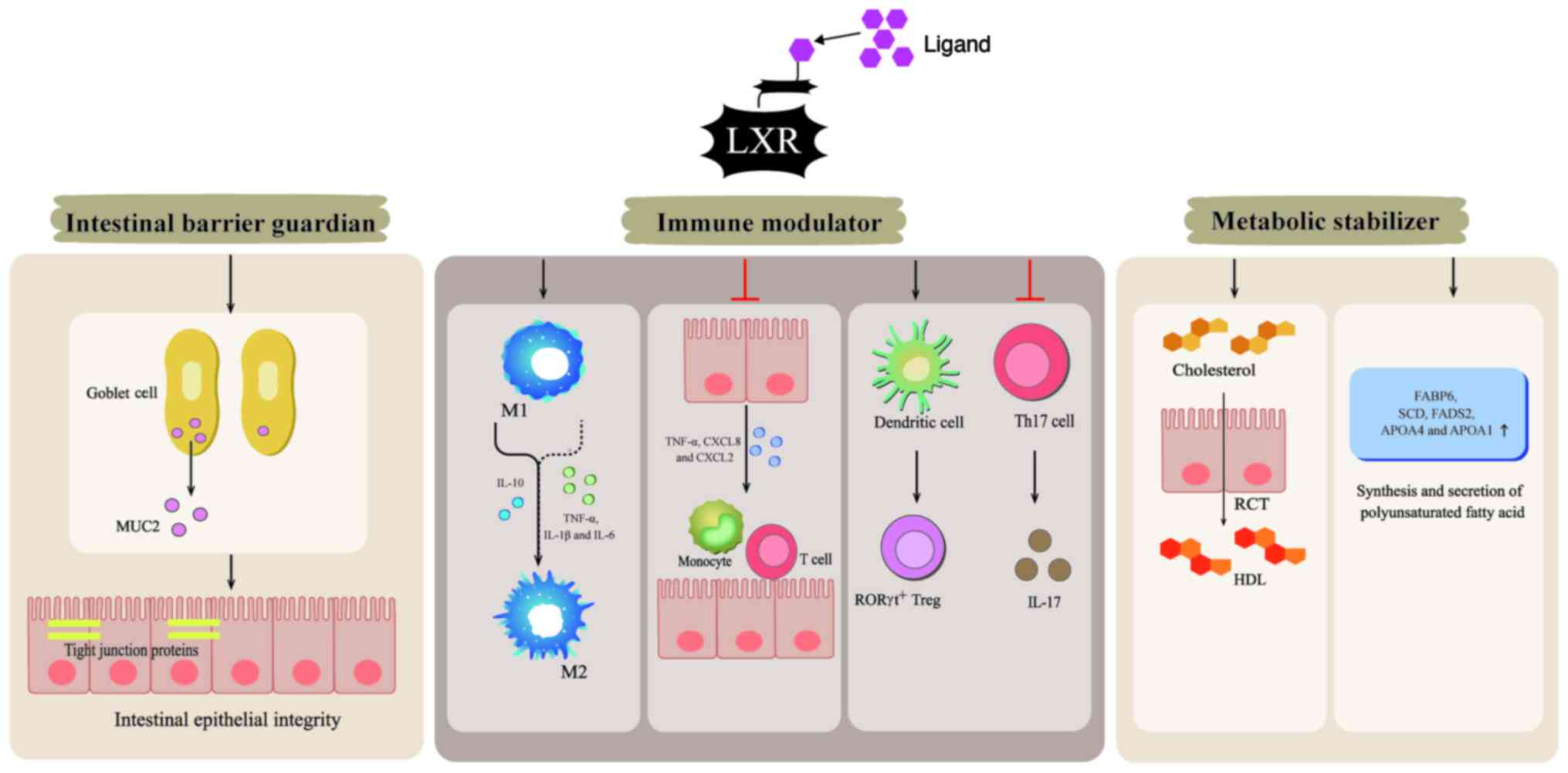

As a nuclear receptor superfamily member, LXR has

emerged as a central regulator of intestinal homeostasis through

its dual roles in metabolic regulation and immune modulation

(29,40). LXR maintains mucosal integrity

through dual mechanisms: The intestinal barrier serves as the first

line of defense in maintaining intestinal homeostasis and it is

mainly composed of the mucus layer on the surface of intestinal

epithelial cells, which is formed by the synthesis and secretion of

large amounts of mucin 2 (MUC2) by goblet cells. MUC2 serves a key

role in protecting the intestinal tract from harmful substances and

numerous microorganisms. By contrast, defects in the synthesis and

secretion of MUC2, as well as alterations in its glycosylation

structure, may lead to intestinal diseases (41–43).

Furthermore, tight junction proteins in intestinal epithelial

cells, such as tight junction protein 1 and claudins, are an

important part of the intestinal barrier (44,45).

Under physiological conditions, LXR, with its function primarily

mediated by LXRβ, maintains MUC2 secretion from goblet cells and

sustains the expression of tight junction proteins (46).

The activation of LXR has emerged as a potent

protective mechanism in intestinal inflammatory diseases. It is

worth noting that the distinct LXR subtypes have different roles:

LXRα primarily governs immune responses in myeloid immune cells,

such as macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs), whereas LXRβ

orchestrates immune responses within the intestinal epithelium

(47). Among them, LXRα serves a

notable role in modulating macrophage polarization, shifting their

phenotype from pro-inflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory M2

subtypes, which is important for resolving intestinal inflammation

and maintaining immune homeostasis (29,48).

LXRβ effectively mediates the initiation and progression of

inflammatory responses by suppressing the transcription of

inflammatory factors and chemokines in intestinal epithelial cells,

thereby reducing immune cell infiltration (47). Furthermore, an imbalance between T

helper 17 (Th17) and regulatory T (Treg) cells is an important

factor in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases, such as

rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus and IBD

(49,50). The activation of LXRα and LXRβ

alleviates the occurrence and progression of intestinal

inflammatory diseases by regulating the balance of Th17/Treg cells

in the intestine through distinct mechanisms. The excessive

activation of Th17 cells or excessive immunosuppressive activity

induced by Treg cells may contribute to the development of cancer,

such as colorectal, breast and ovarian cancer. Therefore, the

activation of LXR is important for regulating the balance of

Th17/Treg cells, and inhibiting tumor immune escape and growth

(51).

LXR, which acts as a cholesterol sensor, has been

reported to regulate cholesterol transport to the liver and its

excretion as bile acids, so as to maintain cholesterol homeostasis.

In particular, LXR is involved in reverse cholesterol transport

(RCT), which refers to the transport of cholesterol from peripheral

tissues to the liver, where it is excreted in the form of bile acid

(52–54). In the intestine, LXRα is

predominantly expressed in fully differentiated cells of the

colonic epithelium and ileal villi, mediating the reverse excretion

of cholesterol, while LXRβ is typically expressed in the intestinal

mucosal epithelium, promoting cholesterol absorption. The relative

distribution and interaction of these two subtypes jointly regulate

the absorption and excretion of intestinal cholesterol (55).

Furthermore, the activation of LXR, particularly

LXRα, promotes fatty acid desaturation and storage by upregulating

fatty acid-binding protein 6, stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) and

fatty acid desaturase 2, thereby facilitating dynamic lipid

buffering within intracellular lipid droplets. Complementing these

processes, LXR stimulates the synthesis and secretion of

apolipoprotein (APO)A4 and APOA1, which are important for

chylomicron assembly and basolateral trafficking of dietary lipids

(56–58). These synergistic mechanisms

maintain the homeostatic equilibrium of intestinal lipid

absorption, metabolism and excretion. Therefore, the activation of

LXR can regulate intestinal cholesterol homeostasis, thus

preventing the occurrence of metabolic diseases. Notably, the

intestinal vs. hepatic tissue-specific effects of LXR agonists

warrant further investigation, as systemic activation of LXR may

lead to hepatic steatosis, a key challenge for therapeutic

development (30).

Briefly, the activation of LXR inhibits intestinal

inflammation and tumorigenesis by enhancing intestinal barrier

function and immune regulation, as well as regulating cholesterol

metabolism (Fig. 1).

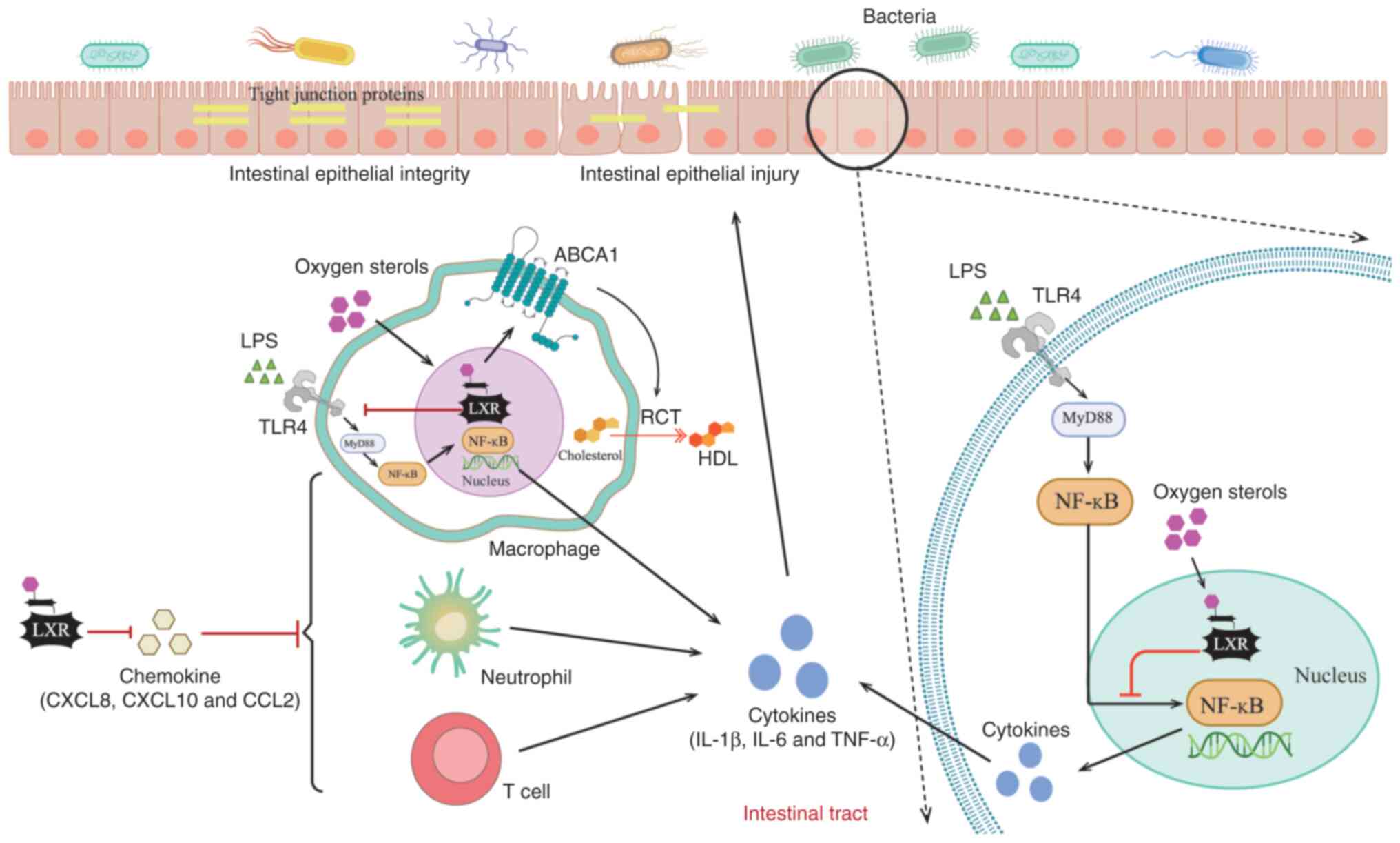

In the pathological process of IBD, as a nuclear

receptor and transcriptional regulator, LXR ameliorates colonic

pathology and intestinal inflammation by maintaining the intestinal

barrier function, inhibiting the release of inflammatory mediators

and modulating immune cell function. In terms of CRC, LXR

activation in tumor cells is responsible for apoptosis or

pyroptosis by blocking the cell cycle and regulating cholesterol

metabolism, thus inhibiting tumor cell proliferation. In addition,

the activation of LXR within the tumor microenvironment (TME) also

inhibits tumor progression by fostering a robust antitumor immune

response. The role of LXR in IBD and CRC pathogenesis is summarized

as follows.

Various immune factors contribute to the development

of IBD. These include immune cells, such as macrophages,

neutrophils and lymphocytes, as well as the inflammatory cytokines

and chemokines they produce (47,59–61).

Furthermore, epithelial cells can secrete a variety of cytokines

and chemokines, which promote the migration and infiltration of

other immune cells, thus aggravating the inflammatory response

(47,59,62).

Current evidence has indicated that the activation of LXR can

inhibit the inflammatory response by regulating the differentiation

and infiltration of lymphocytes. LXRβ activation suppresses

pro-inflammatory cytokine release and CD4+ T-cell

infiltration, thereby preventing aberrant Th17 cell

differentiation. In parallel, LXRα activation mitigates

inflammation by driving DC-dependent Treg cell differentiation.

Together, these mechanisms reduce the production of inflammatory

mediators, such as TNF-α (46,47,63–66).

Previous studies in mice with colitis have revealed that impaired

oxysterol-LXR signaling disrupts the Th17/Treg cell balance through

increased Th17 polarization and diminished Treg cell populations.

This imbalance is associated with elevated levels of

pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-17 and IL-23 (44,64,67).

However, specific drug treatments, such as Si-Ni-San, can target

oxysterol/LXR signaling, which helps to restore the balance of

Th17/Treg cells, thus protecting the body from intestinal diseases

caused by inflammatory response (44).

In addition, experimental models have shown that LXR

deficiency exacerbates colitis by increasing the infiltration of

immune cells and the release of inflammatory mediators into the

colon (46,47). The activation of LXR, primarily of

the isoform LXRα, reduces the accumulation of immune cells at

inflammatory sites and inhibits the release of pro-inflammatory

mediators, including IL-17, TNF-α, IL-1β, C-X-C motif chemokine

(CXCL)8, CXCL10 and C-C motif chemokine (CCL)2, thus alleviating

intestinal inflammation and injury (68–70).

Additionally, the activation of LXR attenuates the recruitment of

MyD88, an innate immune signal transduction adaptor, and TNF

receptor associated factor 6 via ABCA1-dependent changes in

membrane lipid tissue; furthermore, LXR activation inhibits the

Toll-like receptor (TLR)2, TLR4 and TLR9 signaling pathways,

particularly TLR4 signaling and the NF-κB axis, and reduces the

release of pro-inflammatory factors, such as TNF-α and IL-1β

(32,71). These anti-inflammatory effects

following LXR activation are observed not only in immune cells,

such as macrophages and DCs, but also in intestinal epithelial

cells (71–74).

The anti-inflammatory effect of epithelial LXR

activation is mediated through two primary mechanisms. Primarily,

in response to high intracellular cholesterol, LXRα activation in

intestinal epithelial cells orchestrates cholesterol homeostasis by

upregulating efflux transporters, such as ABCA1 and ABCG1, and

inhibiting the uptake mediator NPC1-like intracellular cholesterol

transporter 1 (75). This promotes

RCT and high-density lipoprotein synthesis, thereby preventing

excessive accumulation of cholesterol in enterocytes and exerting

an anti-inflammatory effect (56,76–79).

It has been shown that the activation of LXR can regulate lipid

metabolism by increasing the expression of ABCA1 and promoting the

outflow of cholesterol (75,80),

thus inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway and the release of

pro-inflammatory factors (72,76,81,82).

Similarly, LXRβ expression in colonic epithelial cells exerts

anti-inflammatory effects. The activation of LXRβ markedly

suppresses the expression of inflammatory and chemotactic factors,

such as TNF-α, CXCL8 and CXCL2, thereby reducing the recruitment of

immune cells, including macrophages and T cells, and ultimately

curbing the propagation of inflammation (47).

Intestinal barrier homeostasis is important for

preventing IBD. Compromise of the mucosal barrier can initiate IBD

and even the development of CRC. Both LXRα and LXRβ are expressed

in colonic epithelial cells and work cooperatively to maintain

intestinal barrier integrity (46,72).

A study has shown that LXRβ deletion leads to the development of

higher severity colitis than LXRα deletion (47). Further mechanistic analysis has

suggested that LXRβ may directly regulate goblet cell

differentiation and sustain MUC2 expression, whereas loss of LXRβ

can lead to reduced goblet cell numbers and disruption of the mucus

layer, thereby impairing the intestinal mucosal barrier (46). Notably, LXRα/β double knockout mice

have been shown to exhibit a loss of estrogen receptor β (ERβ),

which leads to the dysfunction of goblet cell secretion and the

notable downregulation of the hemidesmosomal protein plectin,

resulting in mucosal damage and the deterioration of epithelial

cell connections, suggesting that LXRα indirectly regulates

epithelial structure integrity through ERβ expression (46,47).

These findings in LXR-deficient mice suggest that LXR contributes

to intestinal barrier integrity not only in its activated state but

also through basal expression in the absence of ligand binding.

Nonetheless, the specific regulatory mechanisms of LXR isoforms in

intestinal barrier function remain to be fully elucidated. Further

investigations using subtype-selective genetic knockout models are

required to elucidate their distinct roles in cellular

differentiation.

LXR also serves as an important regulator of

intestinal stem cell proliferation, differentiation dynamics and

epithelial repair processes (30).

In dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis models, treatment with

the LXR agonist GW3965 hydrochloride was shown to promote the

proliferation of crypt cells, rather than directly mitigating

damage. Upon intestinal injury, LXR activation enhances epithelial

regeneration and tissue repair through modulation of cholesterol

homeostasis and induction of amphiregulin expression (30,83,84).

Although these findings highlight the regenerative role of LXR, the

precise molecular mechanisms governing LXR-mediated intestinal

regeneration require further elucidation. Additionally, one study

demonstrated that LXR agonists such as T0901317 promote fecal

cholesterol excretion by promoting RCT and intestinal cholesterol

excretion in diabetic and obese mice, thus preventing excessive

accumulation of cholesterol in intestinal epithelial cells

(24).

Briefly, LXR serves an important role in regulating

intestinal inflammation by maintaining the integrity of the

intestinal barrier, regulating the release of chemokines and

mediating the function of immune cells. Notably, chronic

inflammation in IBD establishes a tumor-promoting microenvironment

through sustained cytokine signaling and oxidative stress (85,86).

Given the anti-inflammatory function of LXR, it is plausible that

LXR activation may attenuate chronic inflammation-driven

tumorigenesis during IBD progression. Therefore, LXR is not only a

key molecule in the development of human intestinal inflammation

and experimental colitis, but also a potential target for the

treatment of intestinal cancer (Fig.

2).

CRC is a prevalent malignancy of the

gastrointestinal tract, which mainly occurs in the colon (87,88).

At present, CRC is one of the most common types of cancer worldwide

and the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality (89,90).

The incidence and mortality of CRC vary according to ethnicity and

its incidence is usually closely associated with diet, such as a

high consumption of red meat and processed meat, and lifestyle,

including a lack of physical activity, smoking, obesity and heavy

drinking (91–93). In previous years, the overall

incidence of CRC, particularly rectal cancer and distal colon

cancer, has decreased in individuals aged >50 years old, but

increased in those aged <50 years old (94). Notably, surgery, radiotherapy,

chemotherapy and other cancer treatment methods cannot cure

advanced or metastatic CRC, thus identifying a target for the

treatment of colon cancer is important (90,95).

Recent research has demonstrated that LXR activation within tumor

cells and the TME controls CRC progression, indicating that

elucidating the mechanisms of LXR activity could offer promising

new targets for clinical therapy (96,97).

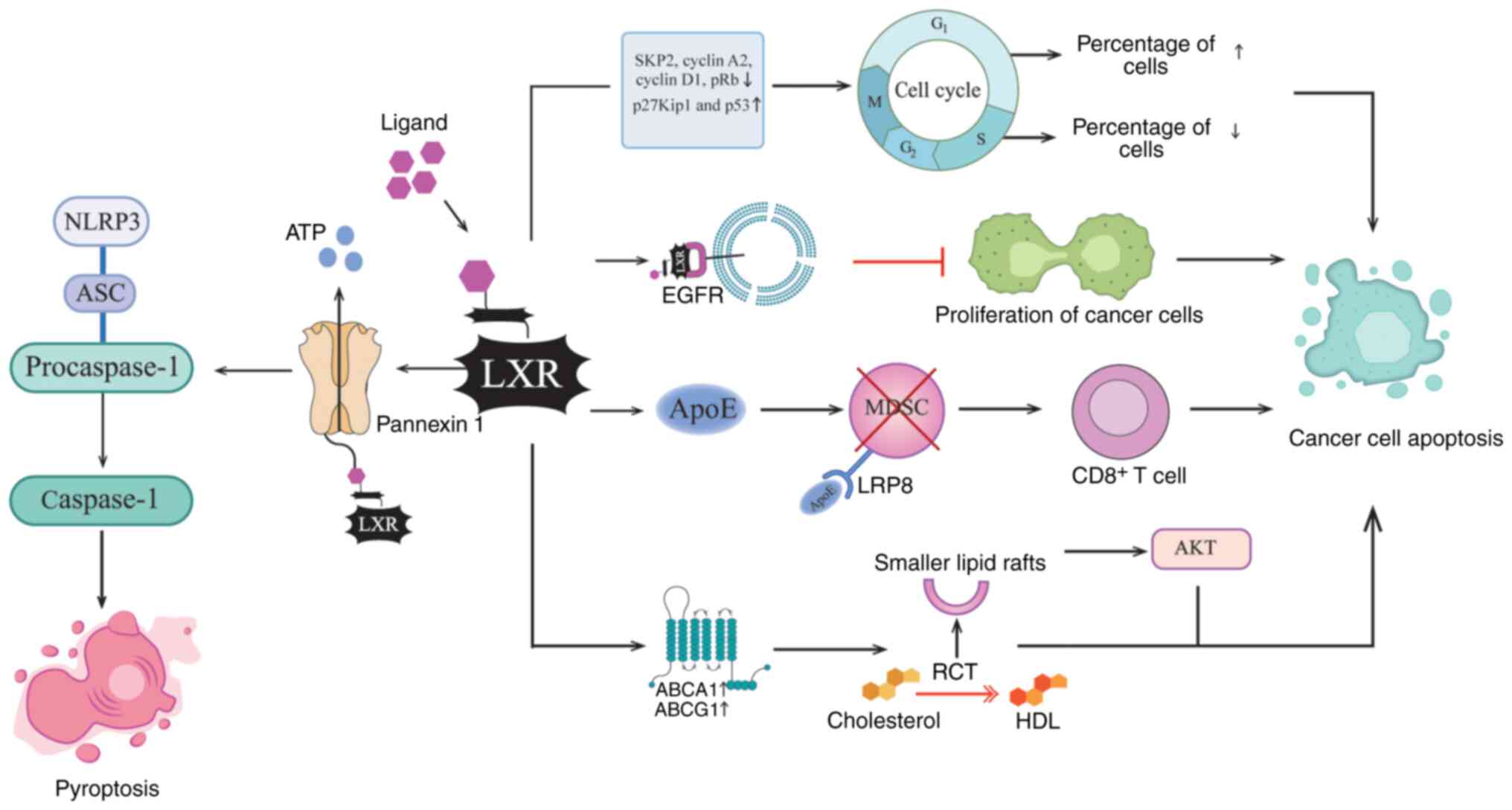

Studies have shown that the occurrence of intestinal

tumors is associated with the loss of control of cell proliferation

and with cholesterol metabolism disorders (98–100). During cell proliferation, the

expression of LXRα and LXRβ is upregulated. Activation of LXR

downregulates key cell cycle promoters including S-phase

kinase-related protein 2, cyclin A2 and cyclin D1, while

upregulating cell cycle inhibitors p27Kip1 and p53. These changes

lead to G1 phase cell cycle arrest and inhibit cell

cycle progression in cancer cells (81,97,101). The antitumor effect of LXR is

also dependent on inducing apoptosis by activating the caspase-3

pathway (102). A study has shown

that ergosterol, as an agonist of both LXR subtypes, can induce the

apoptosis of CRC cells by upregulating pro-apoptotic proteins Bax

and cleaved caspase-3, downregulating the anti-apoptotic protein

Bcl-2, and synergistically inhibiting pathways such as the PI3K/AKT

and Ras/MAPK signaling pathways (97). In addition, the homeostatic

regulation of cholesterol mediated by LXR demonstrates potent

anti-neoplastic activity by inhibiting the growth of colon cancer

and other tumors, as research has found that the activation of LXR

can inhibit the survival of cancer cells by regulating

intracellular cholesterol levels (103–107). Specifically, the activation of

LXR, predominantly LXRα, mediates the upregulation of the ABCA1 and

ABCG1 genes, which stimulates the reverse transport and efflux of

cholesterol and damages the structure of lipid rafts, making them

smaller and thinner. The decrease of the plasma membrane

cholesterol steady-state level leads to the downregulation of AKT

phosphorylation in the lipid layer and promotes cancer cell

apoptosis (104,108).

Notably, LXR activation induces not only apoptosis

but also pyroptosis in cancer cells. Specifically, in colon cancer,

LXR promotes caspase-1 activation to trigger pyroptosis (107). The primary mechanism involves

LXRβ activation, which facilitates the opening of the pannexin 1

channel on the cell membrane, leading to ATP release. Extracellular

ATP activates P2X purinoceptor 7, thereby inducing the assembly of

the NOD-like-receptor pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3)

inflammasome and subsequent caspase-1 activation. This process

ultimately results in pyroptosis of colon cancer cells (109,110). This mechanism establishes NLRP3

inflammasome activation as a novel LXR-dependent antitumor

modality, which has important clinical relevance for targeting LXR

in colon cancer therapies.

Furthermore, studies have revealed that LXR

activation can influence tumor progression by modulating antitumor

immunity within the TME. During the development of malignant

tumors, immunosuppressive cells such as myeloid-derived suppressor

cells (MDSCs) expand and inhibit the antitumor immune response,

thereby promoting tumor cell proliferation and metastasis (111–114). Studies have revealed that the

LXRβ-selective agonist abequolixron (RGX-104) inhibits tumor growth

by reducing the survival of immunosuppressive cells within the TME.

Specifically, LXRβ activation upregulates the transcription of

ApoE, which binds to LDL receptor-related protein 8 (LRP8) on

MDSCs. This interaction impairs MDSC survival, enhances

CD8+ T-cell activation and potentiates antitumor

immunity in vivo (18,111,115–117). Furthermore, in zearalenone

(Zen)-induced Sprague-Dawley rats, intestinal injury,

immunosuppression and dysregulated lipid metabolism have been

observed. Zen can markedly reduce the level of the LXR endogenous

agonist 27-hydroxycholesterol, downregulate LXRα and LXRβ, and

inhibit the expression of ApoE (118). ApoE deficiency promotes the

proliferation of intestinal MDSCs and inhibits T-cell function,

thus increasing the risk of immunosuppressive TME formation

(18,118,119). Notably, administration of either

LXR or ApoE agonists can reverse T-cell suppression, restoring the

core activity of this pathway in preventing tumorigenesis (118).

LXRα, as a transcription factor, can regulate the

expression of several cancer-related genes (120,121). Epidermal growth factor receptor

(EGFR) is highly expressed in several types of cancer, and is

closely associated with the proliferation, invasion and metastasis

of tumors (122–124). Previous studies have shown that

LXRα can directly bind to the promoter region of EGFR and inhibit

its transcription, thus blocking the downstream signaling pathway

mediated by EGFR and inhibiting the proliferation of CRC cells

(122,125). This transcriptional regulation

mechanism unveils an epigenetic dimension of LXR-mediated tumor

suppression, providing a possible novel target for the treatment of

CRC. In addition, emerging research has revealed a

context-dependent duality of LXR signaling in colorectal

carcinogenesis. A recent study demonstrated that ATPase

H+ transporting V0 subunit A1 (ATP6VOA1), an intrinsic

regulator in tumor cells, promotes the synthesis of cholesterol

metabolite 24-hydroxycholesterol (24-OHC) by enhancing both

exogenous cholesterol uptake and intracellular cholesterol

accumulation in CRC cells (96).

As a natural agonist of LXR, 24-OHC simultaneously activates both

LXRα and LXRβ subtypes. In contrast to the conventional view of

LXR-mediated tumor suppression, this activation of the LXR pathway

promotes CRC cell secretion of elevated levels of TGF-β1 into the

TME in a paracrine manner. The released TGF-β1 subsequently

activates SMAD family member 3 signaling in CD8+ T

cells, ultimately suppressing their antitumor cytotoxicity.

Notably, the pharmacological inhibition of the ATP6VOA1/24-OHC

pathway blocks LXR activation and prevents immunosuppressive

reprogramming, thereby attenuating CRC tumor growth (96,126,127). These findings demonstrate that

context-specific LXR inhibition can exert antitumor effects,

expanding the paradigm of LXR function in oncogenesis and

highlighting the context-dependent duality of LXR activity in tumor

regulation. These insights establish a novel therapeutic strategy

for CRC through the precise modulation of LXR signaling pathways.

Emerging evidence has suggested that the circadian regulation of

LXR activity may influence therapeutic efficacy. Previous studies

have demonstrated diurnal oscillation of LXRα expression in colonic

epithelium, with peak activity coinciding with lipid absorption

phases. This chronobiological dimension introduces new

considerations for optimizing dosing schedules of LXR-targeted

therapies (128–130).

In summary, LXR activation exerts multifaceted

antitumor effects by inducing cell cycle arrest, promoting

apoptosis and pyroptosis via NLRP3 inflammasome activation, and

suppressing cholesterol metabolism in cancer cells. LXR also

enhances antitumor immunity by inhibiting MDSCs and dampening

EGFR-mediated proliferation. It is worth noting that all

aforementioned pleiotropic effects are contingent upon LXR

activation status and cellular context. However, emerging evidence

has suggested a context-dependent dual role for LXR: The activation

of LXR may also promote the secretion of immunosuppressive factors

by tumor cells, thereby undermining antitumor immunity. These

pleiotropic actions highlight the therapeutic potential of

targeting LXR in CRC, although its precise mechanisms require

further elucidation. Continued research is important to fully

exploit LXR as a novel therapeutic target or agent (Fig. 3).

Given the notable role of the LXR pathway in

combating IBD and CRC, the discovery and development of LXR

agonists holds considerable therapeutic potential for intestinal

diseases. As a nuclear transcription factor, LXR is activated by

its natural ligand oxysterol, a cholesterol derivative that

regulates the transcription of target genes (131). Commonly used synthetic agonists,

such as T0901317 and GW3965 hydrochloride, activate the downstream

pathway of LXR by simulating the activity of oxysterols, the

natural ligands for LXR, subsequently regulating immune function

and lipid homeostasis (31,72).

For example, the synthetic ligand GW3965 hydrochloride promotes

RCT, inhibits the NF-κB signal cascade by activating the LXR/ABCA1

pathway and inhibits the production of pro-inflammatory factors,

such as IL-8 and CCL28 (72).

T0901317 inhibits the proliferation of colon cancer stem cells by

activating LXR signaling, and upregulates ABCA1, ABCG5 and ABCG8,

disrupting membrane integrity in CRC cells and inducing apoptosis

(58). Subtype-selective agonists

offer improved safety profiles compared with general LXR agonists.

The LXRβ-specific agonist RGX-104 depletes MDSCs through the

LXRβ/ApoE/LRP8 axis, enhances CD8+ T-cell activity and

suppresses tumor growth in CRC models, and has advanced to phase

Ib/II clinical trials (trial no. NCT02922764), suggesting superior

tumor suppression compared with non-selective agonists (18). However, to date, no agonists

specifically targeting LXRα for alleviating IBD or CRC have been

identified. Sterol-based LXR agonists, such as DMHCA and MePipHCA,

have been shown to alleviate intestinal inflammation in DSS-induced

IBD mouse model of IBD by activating ABCA1 and ABCG1, and

inhibiting pro-inflammatory factors, such as IL-1β and CCL2,

without inducing SREBP1c-mediated lipogenic pathways, thereby

avoiding hepatotoxicity (31).

Although LXR synthetic agonists have shown potential

in treating IBD and CRC in preclinical studies, LXR targeted

therapy still faces notable obstacles. Synthetic agonists may

promote hepatic steatosis via lipogenesis mediated by LXRα/SREBP1c

(132), and cholestasis via ABCG5

and ABCG8 upregulation, leading to hepatotoxicity (133). LXRα predominantly regulates lipid

metabolism, while LXRβ mainly regulates immune cells; both LXRα and

LXRβ are widely co-expressed in the body, so the design of

LXR-targeting subtype-selective drugs is complex (120). Furthermore, LXR activation in CRC

may paradoxically promote immunosuppression via the

ATP6V0A1/LXR/TGF-β1 axis, thereby inhibiting CD8+ T-cell

function and undermining antitumor immunity, which complicates the

development of LXR-targeted therapies (96).

Combination strategies represent promising

approaches to enhance LXR-directed therapy. RGX-104 combined with

photosensitizer Ce6-mediated photodynamic therapy depletes MDSCs

and activates the caspase-3/gasdermin-E-dependent cell apoptosis

pathway (119). Further synergy

with anti-programmed cell death-1 antibody treatment could promote

CD8+ T-cell infiltration and activation, amplifying

systemic antitumor immunity, although this strategy remains

unexplored in IBD and CRC contexts (119,134). In addition, the LXR inverse

agonist SR9243 specifically targets CRC stem cells (CSCs) and

inhibits the expression of lipid synthesis genes SCD1 and fatty

acid synthase by specifically binding to the allosteric site of

LXR, resulting in the obstruction of lipid production and

metabolism. However, this inhibitory effect does not affect the

LXR-mediated RCT pathway. This inhibition of lipid metabolism leads

to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species in CSCs, which

eventually induces apoptosis (39,58).

This discovery provides a novel concept for targeted therapy based

on LXR allosteric inhibition.

LXR serves a notable role at the intersection of

lipid metabolism and immune regulation, positioning it as a

promising therapeutic target linking IBD and CRC. Current

understanding of LXR function predominantly depends on animal model

research and no LXR agonist has progressed to phase III clinical

trials of IBD or CRC. Given that LXR is widely expressed in the

body, existing agonists are often accompanied by the risk of

hepatotoxicity. Furthermore, there is insufficient targeted

research on LXR subtypes, which makes it difficult to develop

intestine-specific treatments. Nevertheless, the latest progress in

subtype selection and combination therapy provides a feasible way

forward. Developing intestine-specific agonists and combined

regimens may be key strategies in unlocking the potential of

metabolism and immunotherapy in treating IBD and CRC. However, the

ways in which LXR activation and inhibition affect the progress of

enteritis through interactions with intestinal microflora remain to

be fully elucidated. Clarifying the role of LXR in IBD and CRC may

provide new targets for the treatment of these diseases and broaden

the application prospects of LXR.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 82000525 and 81873883), the Science

and Technology Support Plan for Youth Innovation of Colleges and

Universities of Shandong Province of China (grant no. 2021KJ106)

and the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (grant no.

ZR2023MH359). In addition, the present study was funded by the

Youth Innovation Team Project for Talent Introduction and

Cultivation in Universities of Shandong Province.

Not applicable.

YL, ML and SL conceived the study and edited the

manuscript. MB, JZ, JQ, HZ and XF contributed to the search and

analysis of literature and the review of the manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Guan Q: A comprehensive review and update

on the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. J Immunol Res.

2019:72472382019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Singh N and Bernstein CN: Environmental

risk factors for inflammatory bowel disease. United European

Gastroenterol J. 10:1047–1053. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Bruner LP, White AM and Proksell S:

Inflammatory bowel disease. Prim Care. 50:411–427. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Gilliland A, Chan JJ, De Wolfe TJ, Yang H

and Vallance BA: Pathobionts in inflammatory bowel disease:

Origins, underlying mechanisms, and implications for clinical care.

Gastroenterology. 166:44–58. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Sun Y, Zhang Z, Zheng CQ and Sang LX:

Mucosal lesions of the upper gastrointestinal tract in patients

with ulcerative colitis: A review. World J Gastroenterol.

27:2963–2978. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Voelker R: What is ulcerative colitis?

JAMA. 331:7162024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Dolinger M, Torres J and Vermeire S:

Crohn's disease. Lancet. 403:1177–1191. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Cockburn E, Kamal S, Chan A, Rao V, Liu T,

Huang JY and Segal JP: Crohn's disease: An update. Clin Med (Lond).

23:549–557. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Lewis JD, Parlett LE, Funk MLJ, Brensinger

C, Pate V, Wu Q, Dawwas GK, Weiss A, Constant BD, et al: Incidence,

Prevalence, and Racial and Ethnic Distribution of Inflammatory

Bowel Disease in the United States. Gastroenterology.

165:1197–1205. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Saez A, Herrero-Fernandez B, Gomez-Bris R,

Sánchez-Martinez H and Gonzalez-Granado JM: Pathophysiology of

inflammatory bowel disease: Innate immune system. Int J Mol Sci.

24:15262023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Yue N, Hu P, Tian C, Kong C, Zhao H, Zhang

Y, Yao J, Wei Y, Li D and Wang L: Dissecting innate and adaptive

immunity in inflammatory bowel disease: Immune

compartmentalization, microbiota crosstalk, and emerging therapies.

J Inflamm Res. 17:9987–10014. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Hisamatsu T, Miyoshi J, Oguri N, Morikubo

H, Saito D, Hayashi A, Omori T and Matsuura M:

Inflammation-associated carcinogenesis in inflammatory bowel

disease: Clinical features and molecular mechanisms. Cells.

14:5672025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Fathima A and Jamma T: UDCA ameliorates

inflammation driven EMT by inducing TGR5 dependent SOCS1 expression

in mouse macrophages. Sci Rep. 14:242852024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Endo-Umeda K, Kim E, Thomas DG, Liu W, Dou

H, Yalcinkaya M, Abramowicz S, Xiao T, Antonson P, Gustafsson JÅ,

et al: Myeloid LXR (Liver X Receptor) Deficiency induces

inflammatory gene expression in foamy macrophages and accelerates

atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 42:719–731. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Shah SC and Itzkowitz SH: Colorectal

cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: Mechanisms and management.

Gastroenterology. 162:715–730.e3. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zhou RW, Harpaz N, Itzkowitz SH and

Parsons RE: Molecular mechanisms in colitis-associated colorectal

cancer. Oncogenesis. 12:482023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Griffett K, Hayes M, Bedia-Diaz G,

Appourchaux K, Sanders R, Boeckman MP, Koelblen T, Zhang J,

Schulman IG, Elgendy B and Burris TP: Antihyperlipidemic activity

of gut-restricted LXR inverse agonists. ACS Chem Biol.

17:1143–1154. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Tavazoie MF, Pollack I, Tanqueco R,

Ostendorf BN, Reis BS, Gonsalves FC, Kurth I, Andreu-Agullo C,

Derbyshire ML, Posada J, et al: LXR/ApoE activation restricts

innate immune suppression in cancer. Cell. 172:825–840. e182018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Nishimaki-Mogami T, Tamehiro N, Sato Y,

Okuhira K, Sai K, Kagechika H, Shudo K, Abe-Dohmae S, Yokoyama S,

Ohno Y, et al: The RXR agonists PA024 and HX630 have different

abilities to activate LXR/RXR and to induce ABCA1 expression in

macrophage cell lines. Biochem Pharmacol. 76:1006–1013. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Brahma M, Ghosal S, Maruthi M and Kalangi

SK: Endocytosis of LXRs: Signaling in liver and disease. Prog Mol

Biol Transl Sci. 194:347–375. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Mukwaya A, Lennikov A, Xeroudaki M,

Mirabelli P, Lachota M, Jensen L, Peebo B and Lagali N:

Time-dependent LXR/RXR pathway modulation characterizes capillary

remodeling in inflammatory corneal neovascularization.

Angiogenesis. 21:395–413. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Hiebl V, Ladurner A, Latkolik S and Dirsch

VM: Natural products as modulators of the nuclear receptors and

metabolic sensors LXR, FXR and RXR. Biotechnol Adv. 36:1657–1698.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Gu Y, Bi X, Liu X, Qian Q, Wen Y, Hua S,

Fu Q, Zheng Y and Sun S: Roles of ABCA1 in chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease. COPD. 22:24937012025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Srivastava RAK, Cefalu AB, Srivastava NS

and Averna M: NPC1L1 and ABCG5/8 induction explain synergistic

fecal cholesterol excretion in ob/ob mice co-treated with PPAR-α

and LXR agonists. Mol Cell Biochem. 473:247–262. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Matsuo M: ABCA1 and ABCG1 as potential

therapeutic targets for the prevention of atherosclerosis. J

Pharmacol Sci. 148:197–203. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Wang B and Tontonoz P: Liver X receptors

in lipid signalling and membrane homeostasis. Nat Rev Endocrinol.

14:452–463. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Aljabban J, Rohr M, Borkowski VJ, Nemer M,

Cohen E, Hashi N, Aljabban H, Boateng E, Syed S, Mohammed M, et al:

Probing predilection to Crohn's disease and Crohn's disease flares:

A crowd-sourced bioinformatics approach. J Pathol Inform.

13:1000942022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Saito H, Tachiura W, Nishimura M, Shimizu

M, Sato R and Yamauchi Y: Hydroxylation site-specific and

production-dependent effects of endogenous oxysterols on

cholesterol homeostasis: Implications for SREBP-2 and LXR. J Biol

Chem. 299:1027332023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

de Freitas FA, Levy D, Reichert CO,

Cunha-Neto E, Kalil J and Bydlowski SP: Effects of oxysterols on

immune cells and related diseases. Cells. 11:12512022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Das S, Parigi SM, Luo X, Fransson J, Kern

BC, Okhovat A, Diaz OE, Sorini C, Czarnewski P, Webb AT, et al:

Liver X receptor unlinks intestinal regeneration and tumorigenesis.

Nature. 637:1198–1206. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Yu S, Li S, Henke A, Muse ED, Cheng B,

Welzel G, Chatterjee AK, Wang D, Roland J, Glass CK and Tremblay M:

Dissociated sterol-based liver X receptor agonists as therapeutics

for chronic inflammatory diseases. FASEB J. 30:2570–2579. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

George M, Lang M, Gali CC, Babalola JA,

Tam-Amersdorfer C, Stracke A, Strobl H, Zimmermann R, Panzenboeck U

and Wadsack C: Liver X receptor activation attenuates

oxysterol-induced inflammatory responses in fetoplacental

endothelial cells. Cells. 12:11862023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Yan C, Zheng L, Jiang S, Yang H, Guo J,

Jiang LY, Li T, Zhang H, Bai Y, Lou Y, et al: Exhaustion-associated

cholesterol deficiency dampens the cytotoxic arm of antitumor

immunity. Cancer Cell. 41:1276–1293.e11. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Lin CY and Gustafsson JÅ: Targeting liver

X receptors in cancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Cancer. 15:216–224.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

de la Aleja AG, Herrero C,

Torres-Torresano M, Schiaffino MT, Del Castillo A, Alonso B, Vega

MA, Puig-Kröger A, Castrillo A and Corbí ÁL: Inhibition of LXR

controls the polarization of human inflammatory macrophages through

upregulation of MAFB. Cell Mol Life Sci. 80:962023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Snodgrass RG, Benatzy Y, Schmid T,

Namgaladze D, Mainka M, Schebb NH, Lütjohann D and Brüne B:

Efferocytosis potentiates the expression of arachidonate

15-lipoxygenase (ALOX15) in alternatively activated human

macrophages through LXR activation. Cell Death Differ.

28:1301–1316. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Sharma B, Gupta V, Dahiya D, Kumar H,

Vaiphei K and Agnihotri N: Clinical relevance of cholesterol

homeostasis genes in colorectal cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol

Cell Biol Lipids. 1864:1314–1327. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Wang Q, Ren M, Feng F, Chen K and Ju X:

Treatment of colon cancer with liver X receptor agonists induces

immunogenic cell death. Mol Carcinog. 57:903–910. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Dianat-Moghadam H, Abbasspour-Ravasjani S,

Hamishehkar H, Rahbarghazi R and Nouri M: LXR inhibitor

SR9243-loaded immunoliposomes modulate lipid metabolism and

stemness in colorectal cancer cells. Med Oncol. 40:1562023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Bhunia AK and Al-Sadi R: Editorial:

Intestinal epithelial barrier disruption by enteric pathogens.

Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 13:11347532023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Liu Y, Yu X, Zhao J, Zhang H, Zhai Q and

Chen W: The role of MUC2 mucin in intestinal homeostasis and the

impact of dietary components on MUC2 expression. Int J Biol

Macromol. 164:884–891. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Yao D, Dai W, Dong M, Dai C and Wu S: MUC2

and related bacterial factors: Therapeutic targets for ulcerative

colitis. EBioMedicine. 74:1037512021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Zhang H, Wang X, Zhao L, Zhang K, Cui J

and Xu G: Biochanin a ameliorates DSS-induced ulcerative colitis by

improving colonic barrier function and protects against the

development of spontaneous colitis in the Muc2 deficient mice. Chem

Biol Interact. 395:1110142024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Wang A, Yang X, Lin J, Wang Y, Yang J,

Zhang Y, Tian Y, Dong H, Zhang Z and Song R: Si-Ni-San alleviates

intestinal and liver damage in ulcerative colitis mice by

regulating cholesterol metabolism. J Ethnopharmacol.

336:1187152025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Klepsch V, Moschen AR, Tilg H, Baier G and

Hermann-Kleiter N: Nuclear Receptors Regulate Intestinal

Inflammation in the Context of IBD. Front Immunol. 10:10702019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Song X, Wu W, Dai Y, Warner M, Nalvarte I,

Antonson P, Varshney M and Gustafsson JÅ: Loss of ERβ in aging

LXRαβ knockout mice leads to colitis. Int J Mol Sci. 24:124612023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Jakobsson T, Vedin LL, Hassan T, Venteclef

N, Greco D, D'Amato M, Treuter E, Gustafsson JÅ and Steffensen KR:

The oxysterol receptor LXRβ protects against DSS- and TNBS-induced

colitis in mice. Mucosal Immunol. 7:1416–1428. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Vassiliou E and Farias-Pereira R: Impact

of lipid metabolism on macrophage polarization: Implications for

inflammation and tumor immunity. Int J Mol Sci. 24:120322023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Yan JB, Luo MM, Chen ZY and He BH: The

function and role of the Th17/Treg cell balance in inflammatory

bowel disease. J Immunol Res. 2020:88135582020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Astier AL and Kofler DM: Editorial:

Dysregulation of Th17 and Treg cells in autoimmune diseases. Front

Immunol. 14:11518362023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Knochelmann HM, Dwyer CJ, Bailey SR, Amaya

SM, Elston DM, Mazza-McCrann JM and Paulos CM: When worlds collide:

Th17 and Treg cells in cancer and autoimmunity. Cell Mol Immunol.

15:458–469. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

King RJ, Singh PK and Mehla K: The

cholesterol pathway: Impact on immunity and cancer. Trends Immunol.

43:78–92. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Korach-André M and Gustafsson JÅ: Liver X

receptors as regulators of metabolism. Biomol Concepts. 6:177–190.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Xu H, Xin Y, Wang J, Liu Z, Cao Y, Li W,

Zhou Y, Wang Y and Liu P: The TICE pathway: Mechanisms and

potential clinical applications. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 25:653–662.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Modica S, Gofflot F, Murzilli S, D'Orazio

A, Salvatore L, Pellegrini F, Nicolucci A, Tognoni G, Copetti M,

Valanzano R, et al: The intestinal nuclear receptor signature with

epithelial localization patterns and expression modulation in

tumors. Gastroenterology. 138:636–648. 648.e1–12. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Willemsen S, Yengej FAY, Puschhof J,

Rookmaaker MB, Verhaar MC, van Es J, Beumer J and Clevers H: A

comprehensive transcriptome characterization of individual nuclear

receptor pathways in the human small intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 121:e24111891212024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Kikuchi T, Orihara K, Oikawa F, Han SI,

Kuba M, Okuda K, Satoh A, Osaki Y, Takeuchi Y, Aita Y, et al:

Intestinal CREBH overexpression prevents high-cholesterol

diet-induced hypercholesterolemia by reducing Npc1l1 expression.

Mol Metab. 5:1092–1102. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Dianat-Moghadam H, Khalili M, Keshavarz M,

Azizi M, Hamishehkar H, Rahbarghazi R and Nouri M: Modulation of

LXR signaling altered the dynamic activity of human colon

adenocarcinoma cancer stem cells in vitro. Cancer Cell Int.

21:1002021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Lazennec G and Richmond A: Chemokines and

chemokine receptors: New insights into cancer-related inflammation.

Trends Mol Med. 16:133–144. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Kobayashi T, Siegmund B, Le Berre C, Wei

SC, Ferrante M, Shen B, Bernstein CN, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L

and Hibi T: Ulcerative colitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 6:742020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Saez A, Gomez-Bris R, Herrero-Fernandez B,

Mingorance C, Rius C and Gonzalez-Granado JM: Innate lymphoid cells

in intestinal homeostasis and inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Mol

Sci. 22:76182021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

dos Santos Ramos A, Viana GCS, de Macedo

Brigido M and Almeida JF: Neutrophil extracellular traps in

inflammatory bowel diseases: Implications in pathogenesis and

therapeutic targets. Pharmacol Res. 171:1057792021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Kiss M, Czimmerer Z and Nagy L: The role

of lipid-activated nuclear receptors in shaping macrophage and

dendritic cell function: From physiology to pathology. J Allergy

Clin Immunol. 132:264–286. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Parigi SM, Das S, Frede A, Cardoso RF,

Tripathi KP, Doñas C, Hu YOO, Antonson P, Engstrand L, Gustafsson

JÅ and Villablanca EJ: Liver X receptor regulates Th17 and RORγt+

Treg cells by distinct mechanisms. Mucosal Immunol. 14:411–419.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Qin T, Yang J, Huang D, Zhang Z, Huang Y,

Chen H and Xu G: DOCK4 stimulates MUC2 production through its

effect on goblet cell differentiation. J Cell Physiol.

236:6507–6519. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Herold M, Breuer J, Hucke S, Knolle P,

Schwab N, Wiendl H and Klotz L: Liver X receptor activation

promotes differentiation of regulatory T cells. PLoS One.

12:e01849852017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Li H, Fan C, Lu H, Feng C, He P, Yang X,

Xiang C, Zuo J and Tang W: Protective role of berberine on

ulcerative colitis through modulating enteric glial

cells-intestinal epithelial cells-immune cells interactions. Acta

Pharm Sin B. 10:447–461. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Lee JW, Wang P, Kattah MG, Youssef S,

Steinman L, DeFea K and Straus DS: Differential regulation of

chemokines by IL-17 in colonic epithelial cells. J Immunol.

181:6536–6545. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Jakobsson T, Treuter E, Gustafsson JÅ and

Steffensen KR: Liver X receptor biology and pharmacology: new

pathways, challenges and opportunities. Trends Pharmacol Sci.

33:394–404. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Delfini M, Stakenborg N, Viola MF and

Boeckxstaens G: Macrophages in the gut: Masters in multitasking.

Immunity. 55:1530–1548. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Xiong T, Zheng X, Zhang K, Wu H, Dong Y,

Zhou F, Cheng B, Li L, Xu W, Su J, et al: Ganluyin ameliorates

DSS-induced ulcerative colitis by inhibiting the enteric-origin

LPS/TLR4/NF-κB pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 289:1150012022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Miranda-Bautista J, Rodríguez-Feo JA,

Puerto M, López-Cauce B, Lara JM, González-Novo R, Martín-Hernández

D, Ferreiro-Iglesias R, Bañares R and Menchén L: Liver X receptor

exerts anti-inflammatory effects in colonic epithelial cells via

ABCA1 and its expression is decreased in human and experimental

inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 27:1661–1673. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Qu Y, Li X, Xu F, Zhao S, Wu X, Wang Y and

Xie J: Kaempferol alleviates murine experimental colitis by

restoring gut microbiota and inhibiting the LPS-TLR4-NF-κB axis.

Front Immunol. 12:6798972021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Li B, Jiang XF, Dong YJ, Zhang YP, He XL,

Zhou CL, Ding YY, Wang N, Wang YB, Cheng WQ, et al: The effects of

Atractylodes macrocephala extract BZEP self-microemulsion based on

gut-liver axis HDL/LPS signaling pathway to ameliorate metabolic

dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease in rats. Biomed

Pharmacother. 175:1165192024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Pang J, Xu H, Wang X, Chen X, Li Q, Liu Q,

You Y, Zhang H, Xu Z, Zhao Y, et al: Resveratrol enhances

trans-intestinal cholesterol excretion through selective activation

of intestinal liver X receptor alpha. Biochem Pharmacol.

186:1144812021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Ito A, Hong C, Rong X, Zhu X, Tarling EJ,

Hedde PN, Gratton E, Parks J and Tontonoz P: LXRs link metabolism

to inflammation through Abca1-dependent regulation of membrane

composition and TLR signaling. Elife. 4:e080092015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Režen T, Rozman D, Kovács T, Kovács P,

Sipos A, Bai P and Mikó E: The role of bile acids in

carcinogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 79:2432022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Breevoort SR, Angdisen J and Schulman IG:

Macrophage-independent regulation of reverse cholesterol transport

by liver X receptors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 34:1650–1660.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Lifsey HC, Kaur R, Thompson BH, Bennett L,

Temel RE and Graf GA: Stigmasterol stimulates transintestinal

cholesterol excretion independent of liver X receptor activation in

the small intestine. J Nutr Biochem. 76:1082632020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Liang L, Xie Q, Sun C, Wu Y, Zhang W and

Li W: Phospholipase A2 group IIA correlates with circulating

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and modulates cholesterol

efflux possibly through regulation of PPAR-γ/LXR-α/ABCA1 in

macrophages. J Transl Med. 19:4842021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Lo Sasso G, Bovenga F, Murzilli S,

Salvatore L, Di Tullio G, Martelli N, D'Orazio A, Rainaldi S, Vacca

M, Mangia A, et al: Liver X receptors inhibit proliferation of

human colorectal cancer cells and growth of intestinal tumors in

mice. Gastroenterology. 144:1497–1507. 1507e1–13. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Zhu X, Lee JY, Timmins JM, Brown JM,

Boudyguina E, Mulya A, Gebre AK, Willingham MC, Hiltbold EM, Mishra

N, et al: Increased cellular free cholesterol in

macrophage-specific Abca1 knock-out mice enhances pro-inflammatory

response of macrophages. J Biol Chem. 283:22930–22941. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Pentinmikko N, Iqbal S, Mana M, Andersson

S, Cognetta AB III, Suciu RM, Roper J, Luopajärvi K, Markelin E,

Gopalakrishnan S, et al: Notum produced by Paneth cells attenuates

regeneration of aged intestinal epithelium. Nature. 571:398–402.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Liebergall SR, Angdisen J, Chan SH, Chang

Y, Osborne TF, Koeppel AF, Turner SD and Schulman IG: Inflammation

triggers liver X receptor dependent lipogenesis. Mol Cell Biol.

40:e00364–19. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Fantini MC, Favale A, Onali S and

Facciotti F: Tumor infiltrating regulatory T cells in sporadic and

colitis-associated colorectal cancer: The red little riding hood

and the wolf. Int J Mol Sci. 21:67442020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Zhang H, Shi Y, Lin C, He C, Wang S, Li Q,

Sun Y and Li M: Overcoming cancer risk in inflammatory bowel

disease: New insights into preventive strategies and pathogenesis

mechanisms including interactions of immune cells, cancer signaling

pathways, and gut microbiota. Front Immunol. 14:13389182024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Tao XY, Li QQ and Zeng Y: Clinical

application of liquid biopsy in colorectal cancer: Detection,

prediction, and treatment monitoring. Mol Cancer. 23:1452024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Dougherty MW and Jobin C: Intestinal

bacteria and colorectal cancer: Etiology and treatment. Gut

Microbes. 15:21850282023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, Arain

MA, Chen YJ, Ciombor KK, Cohen S, Cooper HS, Deming D, Farkas L, et

al: Colon cancer, version 2.2021, NCCN clinical practice guidelines

in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 19:329–359. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Miller KD, Nogueira L, Devasia T, Mariotto

AB, Yabroff KR, Jemal A, Kramer J and Siegel RL: Cancer treatment

and survivorship statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 72:409–436.

2022.

|

|

91

|

Carethers JM: Racial and ethnic

disparities in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Adv

Cancer Res. 151:197–229. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Rawla P, Sunkara T and Barsouk A:

Epidemiology of colorectal cancer: Incidence, mortality, survival,

and risk factors. Prz Gastroenterol. 14:89–103. 2019.

|

|

93

|

Li N, Lu B, Luo C, Cai J, Lu M, Zhang Y,

Chen H and Dai M: Incidence, mortality, survival, risk factor and

screening of colorectal cancer: A comparison among China, Europe,

and Northern America. Cancer Lett. 522:255–268. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Li J, Ma X, Chakravarti D, Shalapour S and

DePinho RA: Genetic and biological hallmarks of colorectal cancer.

Genes Dev. 35:787–820. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

95

|

Wen J, Min X, Shen M, Hua Q, Han Y, Zhao

L, Liu L, Huang G, Liu J and Zhao X: ACLY facilitates colon cancer

cell metastasis by CTNNB1. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 38:4012019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

96

|

Huang TX, Huang HS, Dong SW, Chen JY,

Zhang B, Li HH, Zhang TT, Xie Q, Long QY, Yang Y, et al:

ATP6V0A1-dependent cholesterol absorption in colorectal cancer

cells triggers immunosuppressive signaling to inactivate memory

CD8+ T cells. Nat Commun. 15:56802024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

97

|

Taank Y and Agnihotri N: Exploring the

anticancer potential of ergosterol and ergosta-5,22,25-triene-3-ol

against colorectal cancer: Insights from experimental models and

molecular mechanisms. Biochem Pharmacol. 240:1170612025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Huang B, Song BL and Xu C: Cholesterol

metabolism in cancer: Mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Nat

Metab. 2:132–141. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

99

|

Matthews HK, Bertoli C and de Bruin RAM:

Cell cycle control in cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 23:74–88.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

100

|

Ren YM, Zhuang ZY, Xie YH, Yang PJ, Xia

TX, Xie YL, Liu ZH, Kang ZR, Leng XX, Lu SY, et al: BCAA-producing

Clostridium symbiosum promotes colorectal tumorigenesis through the

modulation of host cholesterol metabolism. Cell Host Microbe.

32:1519–1535. e72024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

101

|

Warns J, Marwarha G, Freking N and Ghribi

O: 27-hydroxycholesterol decreases cell proliferation in colon

cancer cell lines. Biochimie. 153:171–180. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

102

|

Zhang W, Jiang H, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Liu A,

Zhao Y, Zhu X, Lin Z and Yuan X: Liver X receptor activation

induces apoptosis of melanoma cell through caspase pathway. Cancer

Cell Int. 14:162014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

103

|

Dufour J, Viennois E, De Boussac H, Baron

S and Lobaccaro JM: Oxysterol receptors, AKT and prostate cancer.

Curr Opin Pharmacol. 12:724–728. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

104

|

Pommier AJC, Alves G, Viennois E, Bernard

S, Communal Y, Sion B, Marceau G, Damon C, Mouzat K, Caira F, et

al: Liver X Receptor activation downregulates AKT survival

signaling in lipid rafts and induces apoptosis of prostate cancer

cells. Oncogene. 29:2712–2723. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

105

|

Wan W, Hou Y, Wang K, Cheng Y, Pu X and Ye

X: The LXR-623-induced long non-coding RNA LINC01125 suppresses the

proliferation of breast cancer cells via PTEN/AKT/p53 signaling

pathway. Cell Death Dis. 10:2482019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

106

|

Ding X, Zhang W, Li S and Yang H: The role

of cholesterol metabolism in cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 9:219–227.

2019.

|

|

107

|

Piccinin E, Cariello M and Moschetta A:

Lipid metabolism in colon cancer: Role of liver X receptor (LXR)

and Stearoyl-CoA Desaturase 1 (SCD1). Mol Aspects Med.

78:1009332021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

108

|

Kashiwagi K, Sato-Yazawa H, Ishii J, Kohno

K, Tatsuta I, Miyazawa T, Takagi M, Chiba H and Yazawa T: LXRβ

activation inhibits the proliferation of small-cell lung cancer

cells by depleting cellular cholesterol. Anticancer Res.

42:2923–2930. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

109

|

Derangère V, Chevriaux A, Courtaut F,

Bruchard M, Berger H, Chalmin F, Causse SZ, Limagne E, Végran F,

Ladoire S, et al: Liver X receptor β activation induces pyroptosis

of human and murine colon cancer cells. Cell Death Differ.

21:1914–1924. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

110

|

Rébé C, Derangère V and Ghiringhelli F:

Induction of pyroptosis in colon cancer cells by LXRβ. Mol Cell

Oncol. 2:e9700942015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

111

|

No authors listed. LXR agonism depletes

MDSCs to promote antitumor immunity. Cancer Discov. 8:2632018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

112

|

Wang L, Lynch C, Pitroda SP, Piffkó A,

Yang K, Huser AK, Liang HL and Weichselbaum RR: Radiotherapy and

immunology. J Exp Med. 221:e202321012024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

113

|

Wang H, Zhou F, Qin W, Yang Y, Li X and

Liu R: Metabolic regulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in

tumor immune microenvironment: Targets and therapeutic strategies.

Theranostics. 15:2159–2184. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

114

|

Zhao H, Teng D, Yang L, Xu X, Chen J,

Jiang T, Feng AY, Zhang Y, Frederick DT, Gu L, et al:

Myeloid-derived itaconate suppresses cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and

promotes tumour growth. Nat Metab. 4:1660–1673. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

115

|

Killock D: Immunotherapy: Targeting MDSCs

with LXR agonists. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 15:200–201. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

116

|

Liang H and Shen X: LXR activation

radiosensitizes non-small cell lung cancer by restricting

myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

528:330–335. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

117

|

Hinshaw DC and Shevde LA: The tumor

microenvironment innately modulates cancer progression. Cancer Res.

79:4557–4566. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

118

|

Ruan H, Zhang J, Wang Y, Huang Y, Wu J, He

C, Ke T, Luo J and Yang M: 27-Hydroxycholesterol/liver X

receptor/apolipoprotein E mediates zearalenone-induced intestinal

immunosuppression: A key target potentially linking zearalenone and

cancer. J Pharm Anal. 14:371–388. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

119

|

Qiu W, Su W, Xu J, Liang M, Ma X, Xue P,

Kang Y, Sun ZJ and Xu Z: Immunomodulatory-photodynamic

nanostimulators for invoking pyroptosis to augment tumor

immunotherapy. Adv Healthc Mater. 11:e22012332022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

120

|

Pontini L and Marinozzi M: Shedding light

on the roles of liver X receptors in cancer by using chemical

probes. Br J Pharmacol. 178:3261–3276. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

121

|

Wang M, Ma LJ, Yang Y, Xiao Z and Wan JB:

n-3 Polyunsaturated fatty acids for the management of alcoholic

liver disease: A critical review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 59

(sup1):S116–S129. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

122

|

Gabitova L, Restifo D, Gorin A, Manocha K,

Handorf E, Yang DH, Cai KQ, Klein-Szanto AJ, Cunningham D, Kratz

LE, et al: Endogenous sterol metabolites regulate growth of

EGFR/KRAS-dependent tumors via LXR. Cell Rep. 12:1927–1938. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

123

|

Chen T, Xu J and Fu W: EGFR/FOXO3A/LXR-α

axis promotes prostate cancer proliferation and metastasis and

dual-targeting LXR-α/EGFR shows synthetic lethality. Front Oncol.

10:16882020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

124

|

Wu Y, Yu DD, Hu Y, Cao HX, Yu SR, Liu SW

and Feng JF: LXR ligands sensitize EGFR-TKI-resistant human lung

cancer cells in vitro by inhibiting Akt activation. Biochem Biophys

Res Commun. 467:900–905. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

125

|

Liang X, Cao Y, Xiang S and Xiang Z:

LXRα-mediated downregulation of EGFR suppress colorectal cancer

cell proliferation. J Cell Biochem. 120:17391–17404. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

126

|

Trebska-McGowan K, Chaib M, Alvarez MA,

Kansal R, Pingili AK, Shibata D, Makowski L and Glazer ES: TGF-β

alters the proportion of infiltrating immune cells in a pancreatic

ductal adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 26:113–121. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

127

|

Park BV, Freeman ZT, Ghasemzadeh A,

Chattergoon MA, Rutebemberwa A, Steigner J, Winter ME, Huynh TV,

Sebald SM, Lee SJ, et al: TGFβ1-mediated SMAD3 enhances PD-1

expression on antigen-specific T cells in cancer. Cancer Discov.

6:1366–1381. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

128

|

Kovač U, Skubic C, Bohinc L, Rozman D and

Režen T: Oxysterols and gastrointestinal cancers around the clock.

Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 10:4832019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

129

|

Chen R, Zuo Z, Li Q, Wang H, Li N, Zhang

H, Yu X and Liu Z: DHA substitution overcomes high-fat diet-induced

disturbance in the circadian rhythm of lipid metabolism. Food

Funct. 11:3621–3631. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

130

|

Le Martelot G, Claudel T, Gatfield D,

Schaad O, Kornmann B, Lo Sasso G, Moschetta A and Schibler U:

REV-ERBalpha participates in circadian SREBP signaling and bile

acid homeostasis. PLoS Biol. 7:e10001812009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

131

|

Wang Q, Wang J, Wang J and Zhang H:

Molecular mechanism of liver X receptors in cancer therapeutics.

Life Sci. 273:1192872021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

132

|

Nguyen LH, Cho YE, Kim S, Kim Y, Kwak J,

Suh JS, Lee J, Son K, Kim M, Jang ES, et al: Discovery of

N-Aryl-N'-[4-(aryloxy)cyclohexyl]squaramide-based inhibitors of

LXR/SREBP-1c signaling pathway ameliorating steatotic liver

disease: Navigating the role of SIRT6 activation. J Med Chem.

67:17608–17628. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

133

|

Ghosh S, Devereaux MW, Anderson AL, Gehrke

S, Reisz JA, D'Alessandro A, Orlicky DJ, Lovell M, El Kasmi KC,

Shearn CT and Sokol RJ: NF-κB regulation of LRH-1 and ABCG5/8

potentiates phytosterol role in the pathogenesis of parenteral

nutrition-associated cholestasis. Hepatology. 74:3284–3300. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

134

|

Kato Y, Tabata K, Yachie-Kinoshita A,

Ozawa Y, Yamada K, Ito J, Tachino S, Hori Y, Matsuki M, Matsuoka Y,

et al: Lenvatinib plus anti-PD-1 antibody combination treatment

activates CD8+ T cells through reduction of tumor-associated

macrophage and activation of the interferon pathway. PLoS One.

14:e02125132019. View Article : Google Scholar

|