Introduction

Osteosarcoma is the most common primary malignant

bone tumor, which predominantly affects young adults and

individuals aged >60 years old. Osteosarcoma typically arises in

the metaphyseal regions of long bones, including the distal femur,

proximal tibia and proximal humerus (1). Despite advancements in treatment, the

5-year survival rate remains at ~60% for localized cases and 20%

for metastatic disease (2,3). Conventional treatment involves a

combination of surgery and chemotherapy. Surgery aims to achieve

complete resection of the tumor, and chemotherapy is administered

both preoperatively (as a neoadjuvant) to shrink the tumor and

postoperatively (as an adjuvant) to eliminate residual disease

(4). However, chemotherapy for

osteosarcoma faces notable challenges, including drug resistance

and the capacity of cancer cells to evade apoptosis (5). Cancer cells can evade apoptosis

through various mechanisms, including the upregulation of

anti-apoptotic proteins (such as Bcl-2), mutations in pro-apoptotic

genes (including p53) and activation of survival pathways (6). These factors contribute to the

limited long-term efficacy of chemotherapy and highlight the

necessity for novel therapeutic approaches (7,8).

Ferroptosis is a programmed form of cell death that

is driven by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation. Unlike apoptosis or

necrosis, ferroptosis is characterized by the accumulation of

lethal lipid reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the depletion of

glutathione (a crucial antioxidant) (9). Key markers of ferroptosis include the

suppression of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), elevated levels of

lipid peroxides and the presence of iron-dependent ROS (10,11).

In cancer treatment, ferroptosis offers a promising therapeutic

strategy, particularly for overcoming drug resistance. Cancer cells

often develop resistance to conventional therapies by evading

apoptosis; however, inducing ferroptosis can bypass these

resistance mechanisms (9).

Ferroptosis inducers, such as erastin and RSL3, have demonstrated

effectiveness in triggering ferroptosis in various cancer cell

lines, including those resistant to apoptosis (12). Additionally, ferroptosis can

improve the effectiveness of treatments such as chemotherapy,

radiotherapy and immunotherapy by sensitizing cancer cells to these

modalities (13). Therefore,

identifying natural compounds that can induce ferroptosis in cancer

cells is crucial; these compounds may function as chemotherapy

drugs or adjuncts, potentially improving treatment outcomes and

overcoming drug resistance.

Shikonin and acetylshikonin are naphthoquinone

derivatives extracted from the roots of the plant Lithospermum

erythrorhizon (14). Shikonin

has been extensively studied for its anticancer properties; it has

been shown to induce apoptosis, necroptosis and ferroptosis in

various cancer cell lines by generating ROS, inhibiting the EGFR

and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways, and suppressing angiogenesis

(15). Via these mechanisms,

shikonin also enhances the efficacy of conventional therapies such

as chemotherapy and radiotherapy by sensitizing cancer cells to

these treatments (15).

Acetylshikonin shares similar anticancer mechanisms, but has shown

distinct advantages in certain contexts. The acetylation of

shikonin enhances its stability and bioavailability, facilitating

more effective delivery and sustained action within the body

(15). This modification enhances

its ability to induce apoptosis and inhibit cancer cell

proliferation. Additionally, acetylshikonin has been identified as

a novel tubulin polymerization inhibitor, demonstrating marked

antitumor activity in hepatocellular carcinoma (16). Furthermore, ROS production from

acetylshikonin is associated with upregulation of apoptosis

pathways in osteosarcoma cells (17). These properties indicate that

acetylshikonin may be a promising candidate for cancer treatment,

with potential applications in overcoming drug resistance and

improving the efficacy of existing therapies. However, the

mechanism underlying the ability of acetylshikonin to induce cell

death in osteosarcoma remains poorly understood. The present study

aimed to investigate whether acetylshikonin induces ferroptosis in

osteosarcoma cells and to elucidate the underlying mechanisms,

thereby assessing its potential as a novel therapeutic agent.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Primary antibodies against GPX4 (cat. no. GTX03194),

Bcl-2 (cat. no. GTX100064), Bcl-xl (cat. no. GTX637939), Bak (cat.

no. GTX100063), Bax (cat. no. GTX109683) and β-actin (cat. no.

GTX109639) were acquired from GeneTex, Inc. The secondary

HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit monoclonal (cat. no. sc-2357) antibody

was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. The other

chemicals and reagents used in the present study were obtained from

MilliporeSigma, unless otherwise specified.

Cell culture

U2OS is an epithelial-like osteosarcoma cell line

originally derived from the tibial tumor of a 15-year-old Caucasian

female patient. This cell line exhibits a hypertriploid karyotype

with extensive chromosomal rearrangements, including stable marker

chromosomes involving chromosomes 1, 7, 9 and 17. HOS is a

fibroblast- and epithelial-like cell line established from the

osteosarcoma lesion of a 13-year-old Caucasian female patient. This

cell line displays a flat morphology, low saturation density and is

highly sensitive to transformation. MG63 is a fibroblast-like

osteosarcoma cell line derived from the bone of a 14-year-old

Caucasian male patient. This cell line is hypotriploid with a modal

chromosome number of 66, and it consistently exhibits 18–19 marker

chromosomes. All cell lines were authenticated using short tandem

repeat profiling. The human osteosarcoma cell lines (U2OS, HOS and

MG63) and normal human osteoblasts (hFOB 1.19) were sourced from

the American Type Culture Collection. Osteosarcoma cells were

maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented

with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml

streptomycin. hFOB 1.19 cells were cultured in a 1:1 mixture of

Ham's F-12 Medium and DMEM supplemented with 2.5 mM L-glutamine

(without phenol red), as per the supplier recommendations. All

cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5%

CO2.

Cell viability assays

The hFOB 1.19, U2OS, HOS and MG63 cells were seeded

in 48-well plates at a density of 1×104 cells/well and

were allowed to adhere overnight. The U2OS, HOS and MG63 cells were

then exposed to various concentrations (0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 3, 10

and 20 µM) of acetylshikonin (cat. no. HY-N2181; MedChemExpress)

for 24 or 48 h at 37°C. The hFOB 1.19 cell line was exposed to

different concentrations (0, 0.1, 0.5, 1 and 3 µM) of

acetylshikonin for 24 h at 37°C. Untreated cells were used as

controls. Cell viability was determined using the Cell Counting

Kit-8 (CCK-8; cat. no. 96992; MilliporeSigma), according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm

using a microplate reader (BioTek; Agilent Technologies, Inc.).

In addition, U2OS, HOS, and MG63 cells were seeded

at 5×104 cells/well on glass coverslips in 24-well

plates and treated with acetylshikonin. (0, 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5 and 10

µM) for 24 h at 37°C. After treatment, the cells were stained with

Hoechst 33342 (5 µg/ml), Calcein-AM (2 µM) and propidium iodide

(PI; 1 µg/ml) at 37°C for 30 min. Hoechst 33342 stained all nuclei

(blue fluorescence), Calcein-AM stained viable cells (green

fluorescence), and PI identified dead cells with compromised

membranes (red fluorescence). Untreated cells were used as

controls. Furthermore, cells treated with acetylshikonin (0 and 3

µM) for 24 h at 37°C were observed using a Nikon Eclipse Ti

fluorescence microscope (Nikon Corporation) to evaluate changes in

morphology and cell density.

To validate the involvement of ferroptosis, U2OS,

HOS and MG63 cells were pretreated with ferrostatin-1 (1 µM; a

ferroptosis inhibitor; cat. no. SML0583; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA)

or liproxstatin-1 (1 µM; a ferroptosis inhibitor; cat. no. SML1414;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 1 h, followed by treatment with

acetylshikonin (3 µM) for 24 h at 37°C. Cell viability was assessed

using the CCK-8 assay, as aforementioned. For comparative analysis,

cells were also treated with erastin (3 µM; a ferroptosis inducer;

cat. no. E7781; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) or RSL3 (3 µM; a

ferroptosis inducer; cat. no. SML2234; Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 h at

37°C, and cell viability was measured using the same method. To

differentiate ferroptosis from apoptosis and necroptosis,

osteosarcoma cells (MG63, HOS and U2OS) were pretreated with the

caspase-3 inhibitor z-DEVD-FMK (10 µM; cat. no. 264155;

Sigma-Aldrich), the RIPK1 inhibitor necrostatin-1 (10 µM; cat. no.

480065; Sigma-Aldrich) or the necrosis inhibitor IM-54 (10 µM; cat.

no. SML0412; Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h prior to treatment with

acetylshikonin (3 µM) for 24 h at 37°C. Untreated cells were used

as controls. Cell viability was subsequently assessed using the

CCK-8 assay, as aforementioned. All experiments were conducted in

quadruplicate (n=4) to ensure reproducibility.

DNA fragmentation analysis

TUNEL enzymatically labels the 3′-ends of fragmented

DNA, a hallmark of apoptosis, using a fluorophore-conjugated

nucleotide (18,19). DNA damage was analyzed using the

TUNEL assay (BD Biosciences). Briefly, cells were treated with

acetylshikonin (0, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1 and 3 µM) for 24 h at 37°C,

followed by fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) for

60 min at room temperature and permeabilization with 0.1% Triton

X-100 in 0.1% sodium citrate on ice for 2 min. TUNEL labeling was

then performed with the reaction mixture containing

fluorescein-dUTP at 37°C for 60 min in a humidified dark chamber.

Finally, DNA strand breaks were detected using a flow cytometer

(Accuri C5; BD Biosciences), and flow cytometry data were acquired

and analyzed using BD Accuri C6 Software (version 227.4; BD

Biosciences).

Analysis of apoptotic and necrotic

cells

To assess apoptotic and necrotic cell populations,

Annexin V/PI staining was performed using an apoptosis detection

kit (cat. no. APOAF; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). Briefly, cells

were seeded at a density of 5×105 cells/well in 6-well

plates and treated with acetylshikonin at 0, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1 or 3

µM for 24 h at 37°C. Cells were then stained with 1 µg/ml PI and

0.5 µg/ml FITC-conjugated Annexin V for 15 min at 37°C, and

analyzed by flow cytometry (Accuri C5; BD Biosciences). Flow

cytometry data were acquired and analyzed using BD Accuri C6

Software (version 227.4; BD Biosciences). For ferroptosis

inhibition experiments, cells were pretreated with ferrostatin-1

(10 µM) for 1 h at 37°C prior to acetylshikonin treatment (3 µM)

for 24 h at 37°C.

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of

5×105 cells/well and treated with acetylshikonin (0,

0.1, 0.5, 1 and 3 µM) for 24 h at 37°C. After treatment, the cells

were fixed with 75% ethanol at −20°C for ≥2 h. After washing, the

cells were stained with PI solution (0.1% Triton X-100, 0.2 mg/ml

RNase A (cat. no. 70856; Merck KGaA), 10 µg/ml PI (cat. no. P4170;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 30 min at 37°C and analyzed using

flow cytometry (Accuri C5; BD Biosciences). Untreated cells were

used as controls. Flow cytometry data were acquired and analyzed

using BD Accuri C6 Software (version 227.4; BD Biosciences).

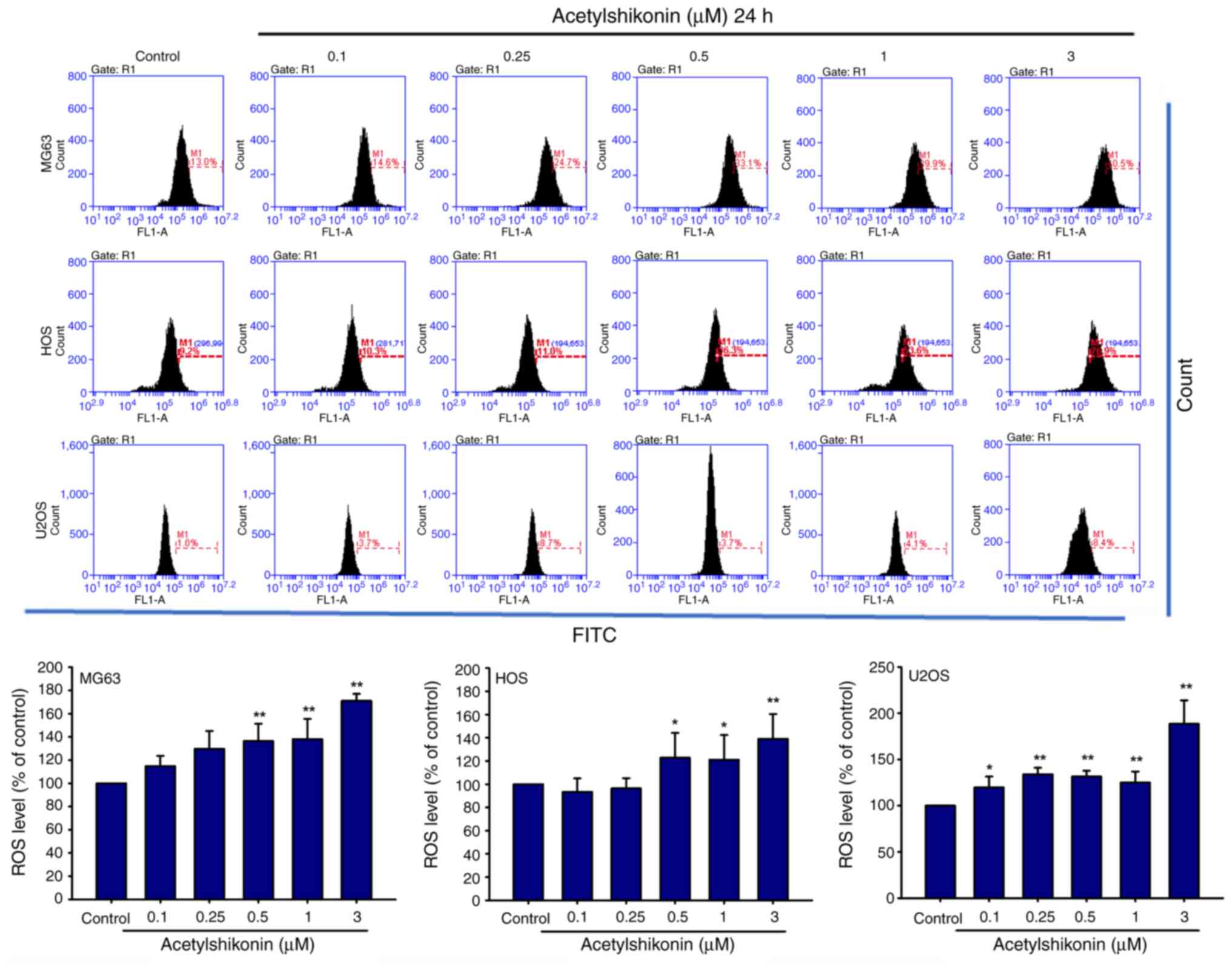

Cellular ROS assay

H2DCFDA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

is a non-fluorescent compound that, after intracellular

deacetylation, emits green fluorescence upon oxidation by ROS

(excitation ~511 nm, emission ~533 nm). Intracellular ROS levels

were determined using H2DCFDA in the present study.

Cells (5×105) were treated with acetylshikonin (0, 0.1,

0.25, 0.5, 1 and 3 µM) for 1 h at 37°C, followed by incubation with

1 µM H2DCFDA at 37°C for 30 min. Untreated cells were

used as controls. ROS levels were analyzed via flow cytometry

(Accuri C5; BD Biosciences). Flow cytometry data were acquired and

analyzed using BD Accuri C6 Software (version 227.4; BD

Biosciences).

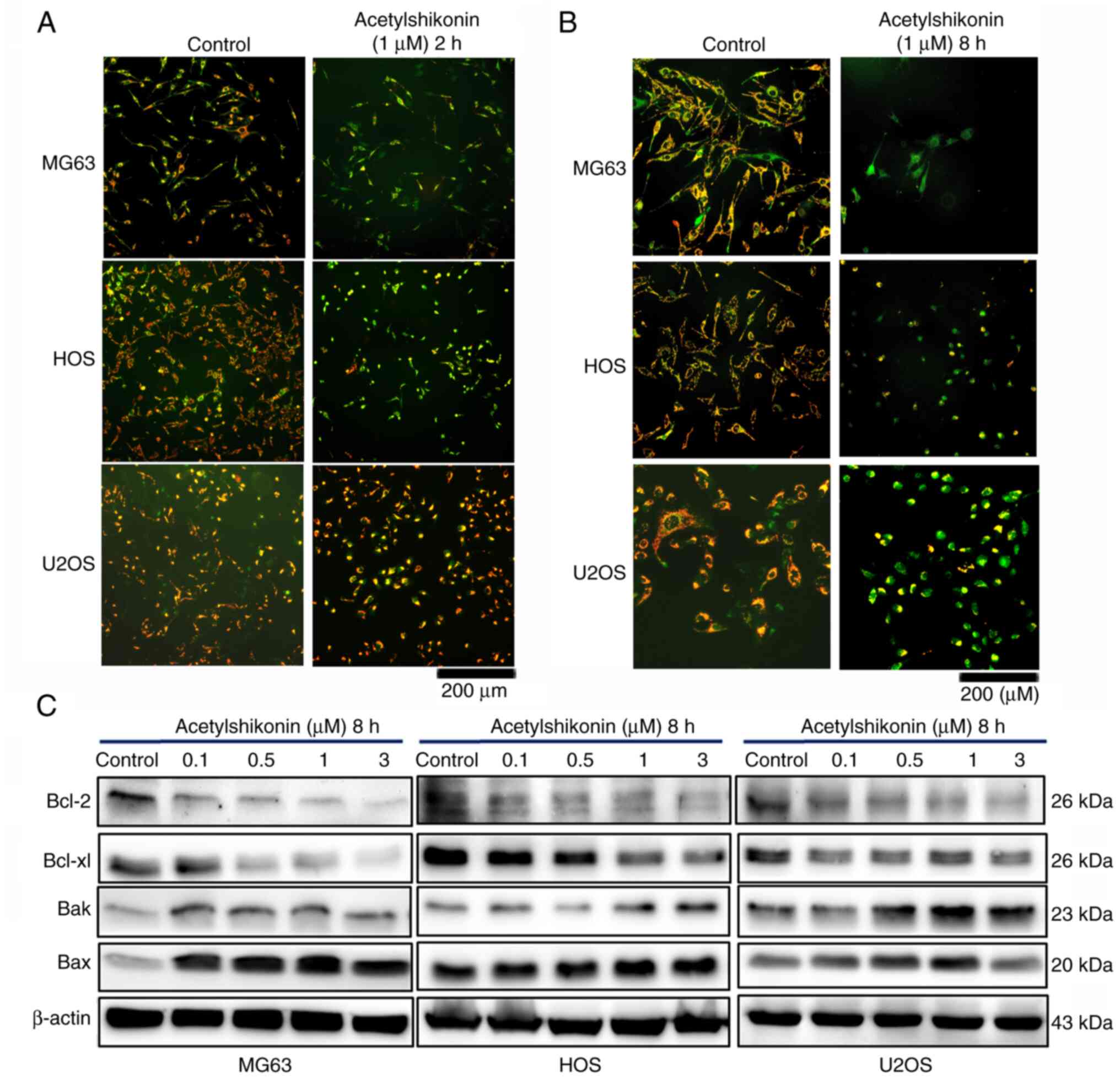

Analysis of mitochondrial membrane

potential

Mitochondrial membrane potential was assessed using

the cationic dye JC-1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.); in healthy

mitochondria, it forms red-fluorescent J-aggregates, whereas in

depolarized or apoptotic mitochondria, JC-1 remains in a monomeric

form, emitting green fluorescence. Briefly, cells were incubated

with acetylshikonin (0 and 1 µM) for 2 or 8 h and were subsequently

stained with JC-1 (5 µg/ml) for 30 min at 37°C. Untreated cells

were used as controls. Fluorescence intensity was observed using a

Nikon Eclipse Ti fluorescence microscope (Nikon Corporation).

Western blotting

Cells were seeded at a density of 5×105

cells/well in 6-well plates and treated with acetylshikonin (0,

0.1, 0.5, 1, and 3 µM) for 24 h at 37°C. After treatment, the cells

were lysed with RIPA buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl,

1% NP-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1–2% SDS], supplemented with

a protease inhibitor mix (1 mM PMSF, 10 ng/ml leupeptin, 1 ng/ml

aprotinin). Protein concentration was determined using the BCA

Protein Assay Kit (cat. no. 71285-M; Merck KGaA). Equal amounts of

protein (50 µg/lane) were loaded and separated by SDS-PAGE on 15%

gels, followed by transfer to PVDF membranes (MilliporeSigma).

Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in TBS-0.05% Tween-20

for 1 h at room temperature and incubated overnight at 4°C with

primary antibodies (1:1,000 dilution). After washing, the membranes

were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:10,000

dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were

visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system

(Analytik Jena US, LLC).

Transmission electron microscopy

analysis

Following treatment with acetylshikonin (0 and 3 µM)

for 24 h at 37°C, HOS cells (5×105) were collected,

fixed in 70% Karnovsky fixative at 4°C, and processed for

ultrastructural examination. Samples were dehydrated through a

graded ethanol series, embedded in Epon 812 resin (polymerized at

60°C for 48 h) and sectioned into ultrathin slices (70–90 nm) using

an ultramicrotome. Sections were stained with 2% uranyl acetate for

20 min at room temperature, followed by Reynolds's lead citrate for

10 min at room temperature. Images were obtained using a JEOL

JEM-1400 transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Ltd.).

Analysis of lipid peroxidation

C11-BODIPY™ 581/591 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

is a lipid peroxidation sensor dye that shifts its fluorescence

from red (~590 nm) to green (~510 nm) upon oxidation. Imaging and

quantification of C11-BODIPY 581/591 staining were performed using

fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry in the current study.

Briefly, cells (5×104) were incubated with

acetylshikonin (0, 0.1, 0.3, 1 and 3 µM for 30 min at 37°C and C11

BODIPY dye at 37°C for 30 min. Lipid peroxidation was subsequently

determined based on fluorescence shifts from 591 nm (non-oxidized)

to 510 nm (oxidized) using fluorescence microscopy and flow

cytometry (Accuri C5; BD Biosciences). Untreated cells were used as

controls. Flow cytometry data were acquired and analyzed using BD

Accuri C6 Software (version 227.4; BD Biosciences).

Analysis of intracellular ferrous ion

(Fe2+) concentrations

Osteosarcoma cells (HOS, MG63 and U2OS) were treated

with acetylshikonin (0 and 3 µM) for 24 h at 37°C. After treatment,

the cells were lysed with the buffer solution provided in the

Fe2+ Colorimetric Assay Kit (cat. no. E-BC-K881-M;

Elabscience Bionovation Inc.), which contains Tris-based buffer

components, according to the manufacturer's protocol. For each

assay, 1×106 cells were lysed in 200 µl buffer on ice

for 10 min with gentle mixing every 5 min. Lysates were centrifuged

at 15,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was incubated

with the Fe2+ detection reagent for 30 min at room

temperature. Untreated cells were used as controls. Absorbance was

measured at 593 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SD from at least

four independent experiments. Statistical comparisons between

groups were conducted using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's

post-hoc test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

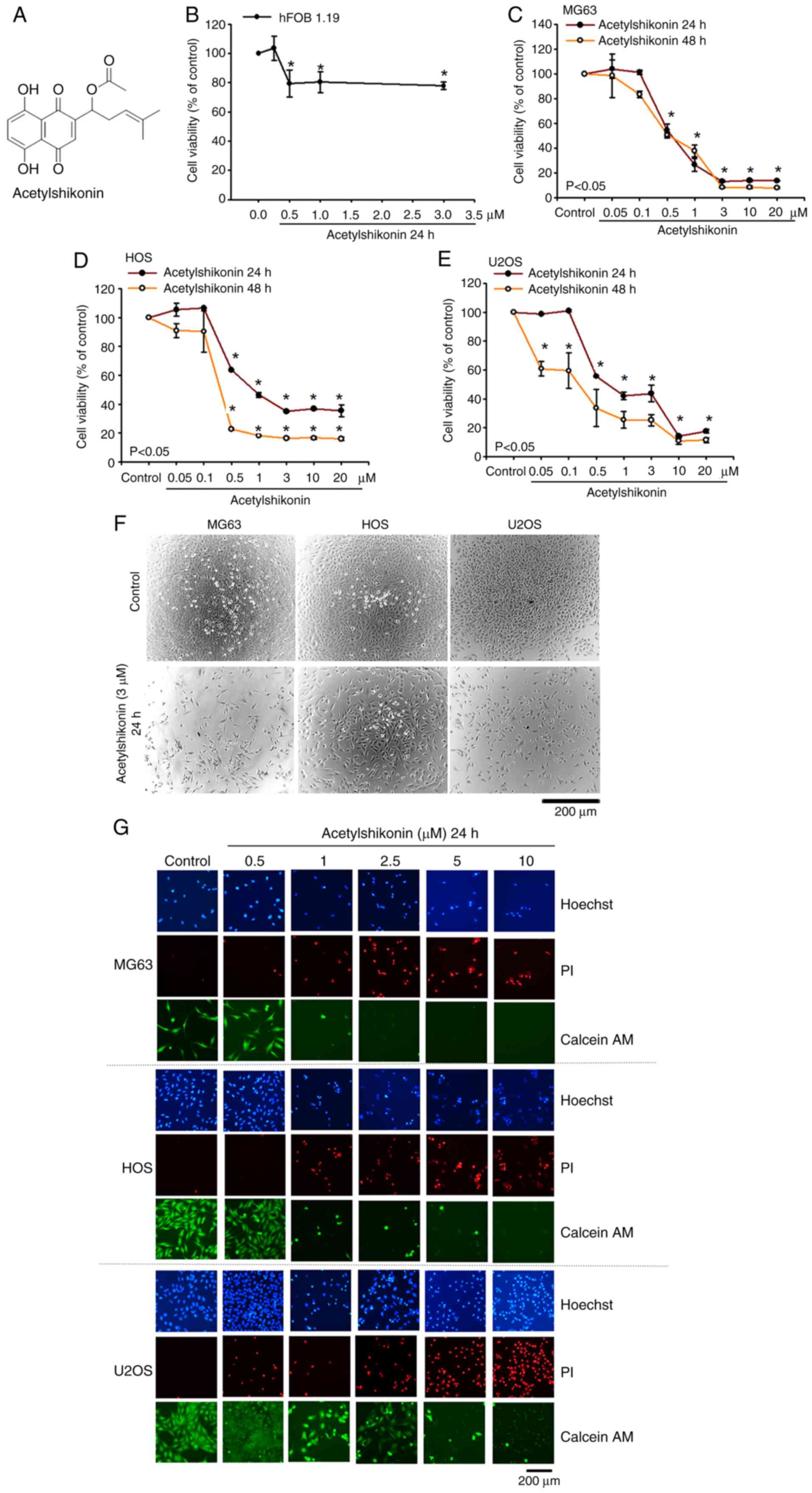

Acetylshikonin reduces the viability

of osteosarcoma cell lines and enhanced membrane permeability

The present study first assessed the effect of

acetylshikonin (Fig. 1A) on the

viability of both normal osteoblasts (hFOB 1.19) and osteosarcoma

cells. After treating hFOB 1.19 cells with acetylshikonin (0.5–3

µM) for 24 h, cell viability remained at ~80% (Fig. 1B), indicating low toxicity in

normal cells. By contrast, the IC50 values for MG63, HOS

and U2OS osteosarcoma cells after 24 h of treatment with

acetylshikonin (0.5–20 µM) were 0.45, 0.83 and 0.69 µM,

respectively (Fig. 1C-E). After 48

h of treatment, the IC50 values decreased to 0.40, 0.28

and 0.17 µM, respectively. In addition, phase-contrast microscopy

revealed a marked reduction in the confluence of osteosarcoma cell

lines following acetylshikonin (3 µM) treatment (Fig. 1F). Hoechst 33342 staining also

showed a marked decrease in the number of MG63, HOS and U2OS cells

after treatment with acetylshikonin (0.5–10 µM). Hoechst 33342

staining revealed dose-dependent increases in apoptotic nuclear

condensation (brighter, punctate nuclei) in U2OS cells treated with

acetylshikonin, which is associated with reduced cell viability

(Fig. 1G). Additionally,

acetylshikonin enhanced the uptake of PI dye into cells in a

dose-dependent manner, indicating compromised cell membrane

integrity. Calcein-AM staining further confirmed that

acetylshikonin notably reduced the viability of osteosarcoma cells.

These results indicated that acetylshikonin has a potent cytotoxic

effect on osteosarcoma cell lines, primarily through mechanisms

associated with cell permeability. Notably, acetylshikonin

demonstrates low toxicity to normal cells, highlighting its

potential as a promising therapeutic agent for osteosarcoma

treatment.

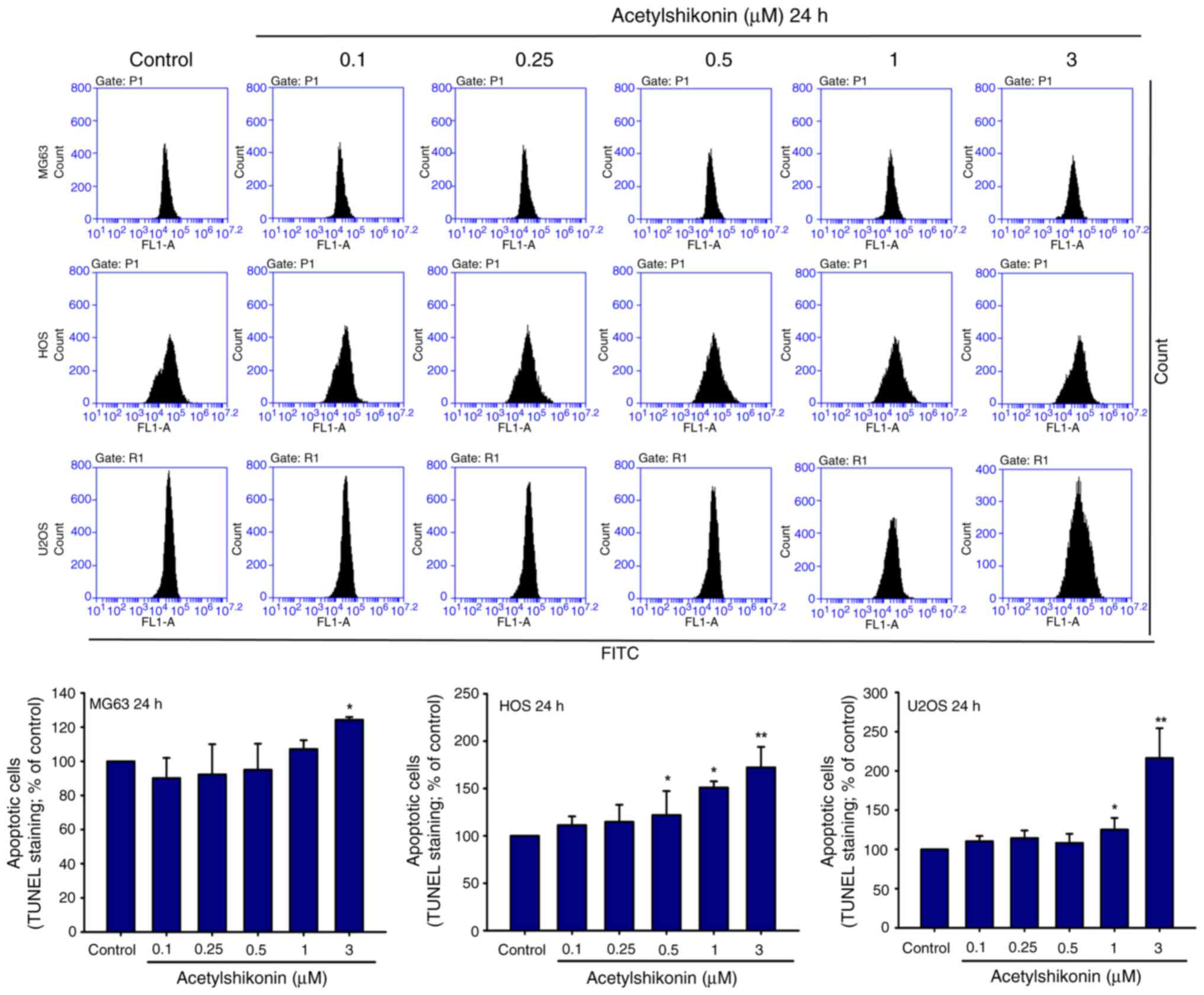

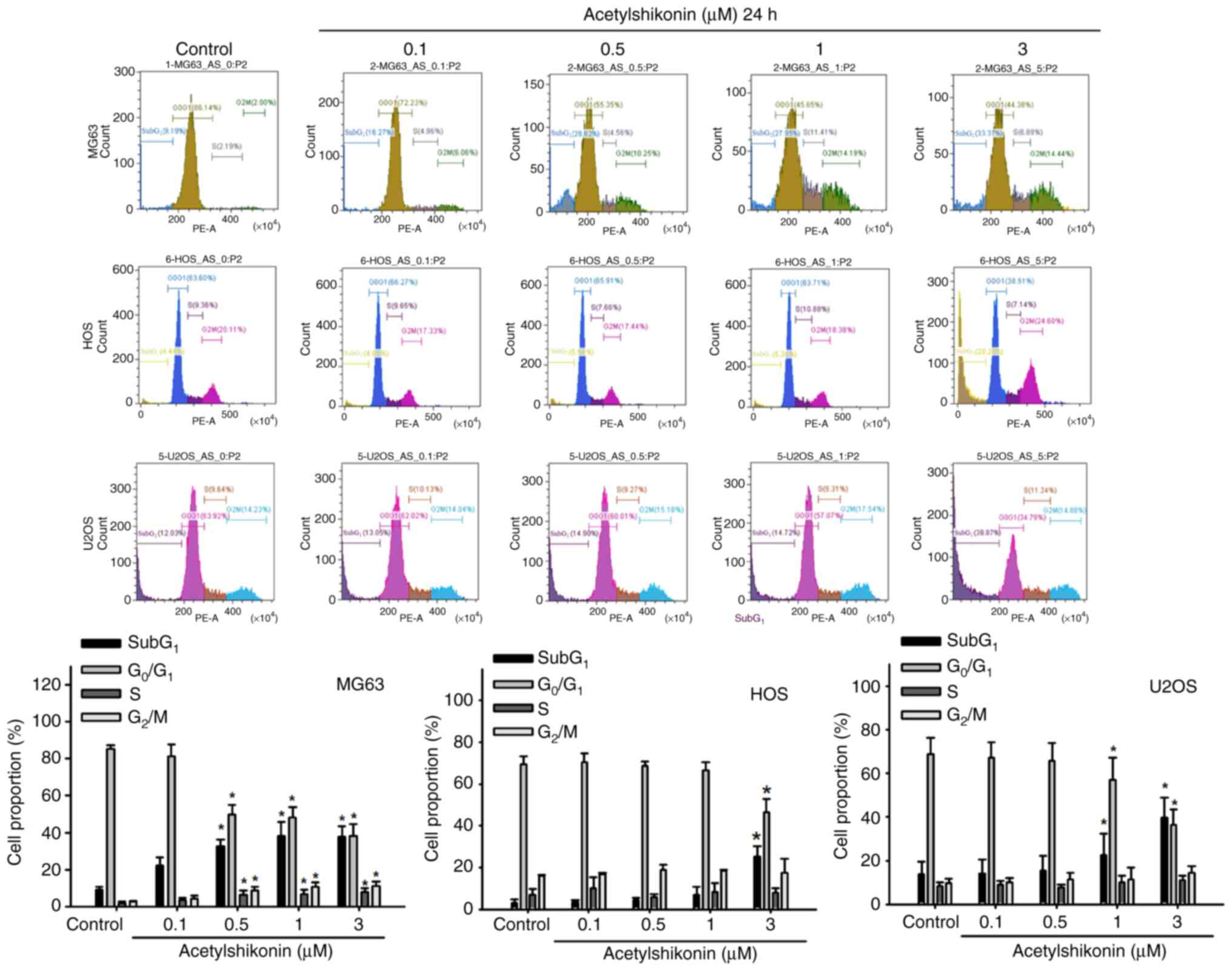

Acetylshikonin induces DNA

fragmentation and cell death in osteosarcoma cells

To elucidate the mechanism by which acetylshikonin

affects osteosarcoma cell viability, MG63, HOS and U2OS cells were

treated with acetylshikonin (0.1–3 µM) for 24 h, and DNA

fragmentation was assessed using the TUNEL assay. A significant

increase in DNA fragmentation was observed in all three cell lines

following treatment with acetylshikonin (Fig. 2). Treatment with 3 µM

acetylshikonin significantly increased the percentage of

TUNEL-positive cells compared with that in the untreated control

group.

Flow-cytometric apoptosis profiling after 24 h of

acetylshikonin treatment (0.0-0.5 µM) showed increases in

upper-right (UR; Annexin V+/PI+) and

upper-left (UL; PI+ only) quadrant populations. In

particular, following treatment with 0.5 µM acetylshikonin, in MG63

cells, the percentage of UL quadrant cells increased from 0.7 to

9.8% and UR quadrant cells increased from 4.0 to 5.7%); in HOS

cells the percentage of UL quadrant cells increased from 2.4 to

10.4% and UR quadrant cells increased from 0.1 to 1.0%; and in U2OS

cells the percentage of UL quadrant cells increased from 3.1 to

12.6% and UR quadrant cells increased from 3.4 to 3.8%, these

findings indicated that the cells were undergoing apoptosis. By

contrast, at higher doses (1–3 µM), the major population shifted to

PI+/Annexin V− cells in the UL quadrant, with

a concomitant decrease in Annexin V+/PI+

cells in the UR quadrant, indicating a dose-dependent increase in

necrotic cell death rather than late apoptosis/secondary necrosis

(Fig. 3). Quantification in

Fig. 3 was performed by combining

Annexin V+/PI+ and Annexin

V−/PI+ populations. Statistical analysis

showed that acetylshikonin treatment at 1–3 µM significantly

increased the proportion of PI+ cells, mainly due to the

enhanced Annexin V−/PI+ population.

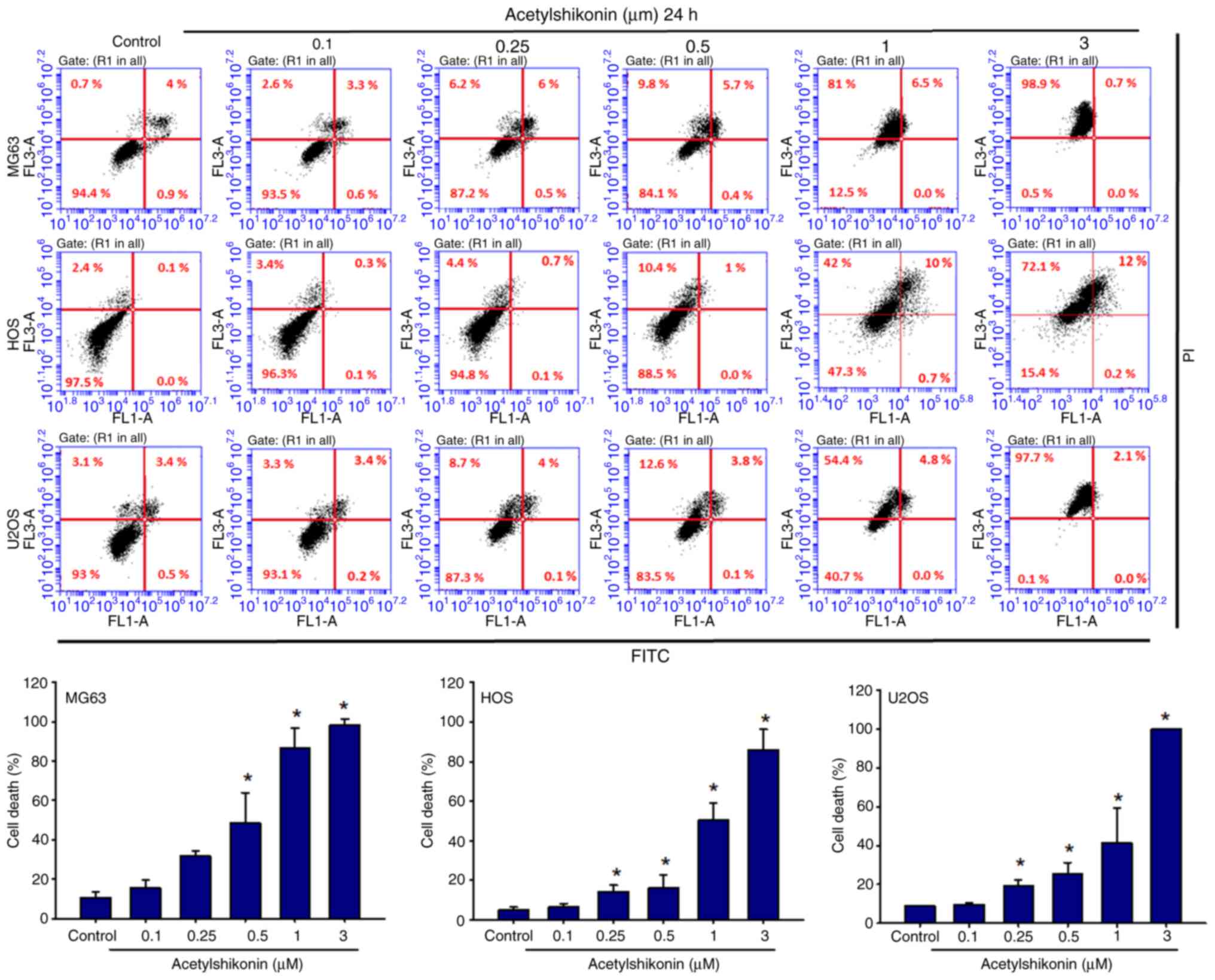

The current study also examined the effect of

acetylshikonin on cell cycle distribution. Acetylshikonin treatment

significantly increased the number of sub-G1 cells,

indicative of DNA fragmentation, and decreased the number of

G0/G1 cells in osteosarcoma cell lines

(Fig. 4). A significant increase

in the sub-G1 population was observed in all cell lines

following 3 µM acetylshikonin treatment. Taken together, the

increase in DNA fragmentation (TUNEL assay), the predominance of

PI+ cells at higher doses (Annexin V/PI analysis), and

the accumulation of sub-G1 cells (cell cycle analysis)

indicated that acetylshikonin may disrupt cellular integrity and

induce cell death in osteosarcoma cells through mechanisms that may

differ from conventional apoptosis.

Acetylshikonin induces ROS production

and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential

Given the established anticancer effects of ROS

generation induced by shikonin and acetylshikonin in various cancer

cells (15,17), the current study investigated the

effect of acetylshikonin on intracellular ROS levels in

osteosarcoma cells. Treatment with acetylshikonin at 0.5–3 µM

resulted in a significant increase in ROS production in

osteosarcoma cell lines (Fig. 5).

Acetylshikonin at 3 µM significantly increased intracellular ROS

levels compared with those in the untreated control group

(P<0.01). This increase in ROS may be strongly associated with

cell death and mitochondrial dysfunction (20,21).

The present study next examined how acetylshikonin influences

mitochondrial membrane potential in osteosarcoma cells to further

elucidate its effects on mitochondrial function. Administration of

acetylshikonin (1 µM) disrupted the mitochondrial membrane

potential, assessed by fluorescence microscopy, as indicated by a

reduction in JC-1 red fluorescence (Fig. 6A and B). A marked reduction in

mitochondrial membrane potential, indicated by the JC-1 red/green

fluorescence ratio, was observed after acetylshikonin

treatment.

Furthermore, western blot analysis revealed that

acetylshikonin treatment increased the levels of pro-apoptotic

proteins Bax and Bak, which regulate mitochondrial membrane

permeability, while decreasing the expression levels of

anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl (Fig. 6C). These results suggested that

acetylshikonin induces osteosarcoma cell death through ROS

generation and the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, which

may be associated with apoptosis. However, additional experimental

data are required to fully elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

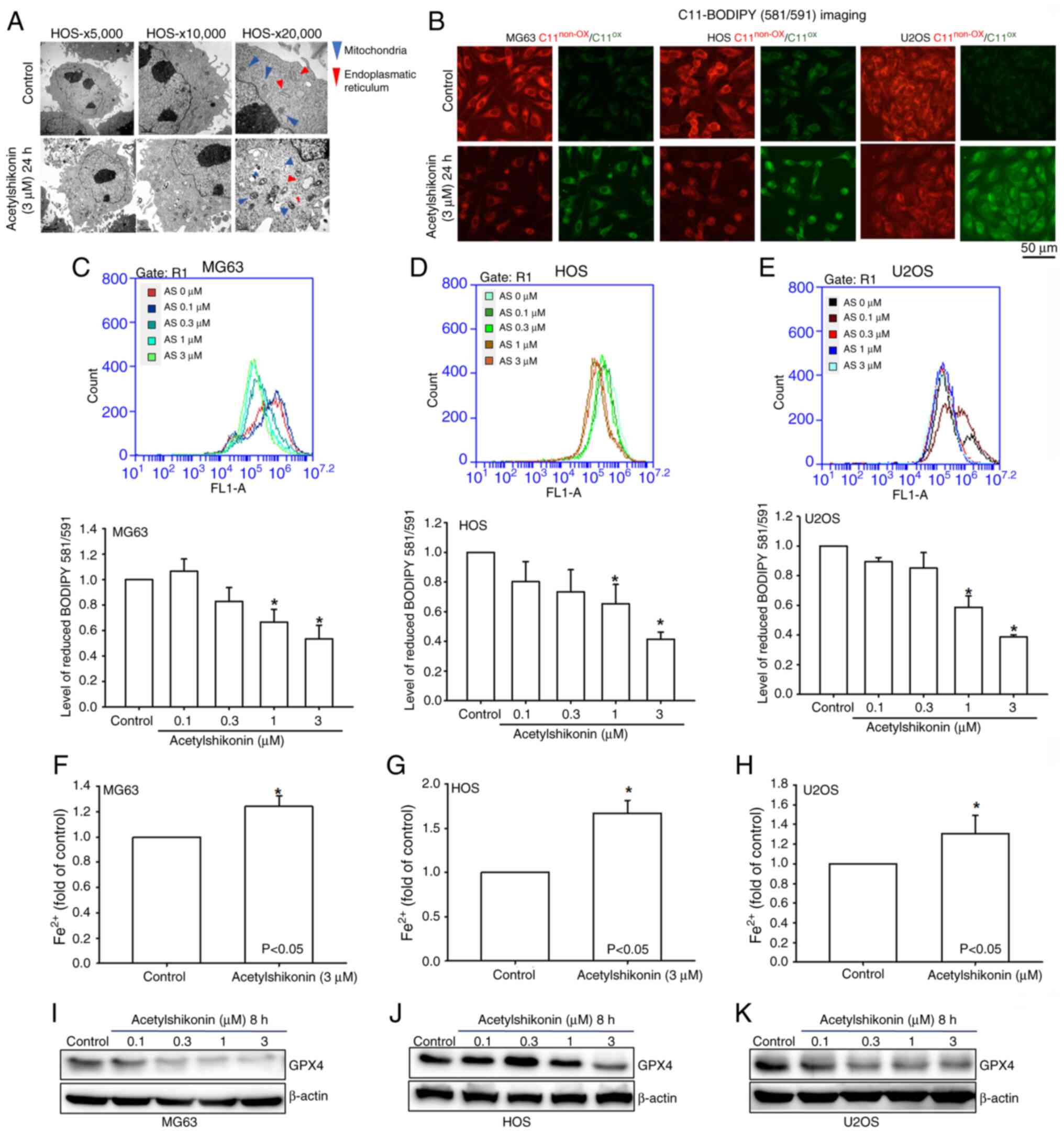

Acetylshikonin induces ferroptosis in

osteosarcoma cells

Mitochondria are the primary generators of

intracellular ROS and serve a crucial role in regulating iron

homeostasis (22). Using

transmission electron microscopy, the effect of acetylshikonin on

mitochondrial morphology was observed in osteosarcoma cells.

Treatment with acetylshikonin reduced mitochondrial volume without

inducing cell swelling or shrinkage, which are morphological

characteristics of ferroptosis (Fig.

7A) (22). The current study

further investigated whether acetylshikonin induces lipid

peroxidation in osteosarcoma cell lines. Fluorescence microscopy

and flow cytometry revealed that acetylshikonin (1–3 µM)

significantly induced lipid peroxidation, as evidenced by the shift

in BODIPY dye fluorescence from red to green (Fig. 7B-E). Treatment with 3 µM

acetylshikonin significantly increased lipid peroxidation, as

indicated by enhanced green fluorescence of C11-BODIPY compared

with that in the control group. Additionally, treatment with

acetylshikonin (3 µM) significantly increased intracellular

Fe2+ concentrations in osteosarcoma cells compared with

those in untreated cells (Fig.

7F-H). The present study also observed a reduction in GPX4

protein expression in acetylshikonin-treated osteosarcoma cells

compared with that in the untreated control group, as shown by

western blotting (Fig. 7I-K).

These findings suggested that acetylshikonin induces osteosarcoma

cell death through mechanisms involving mitochondrial size

reduction, lipid peroxidation and a decrease in GPX4 levels, which

are indicative of ferroptosis.

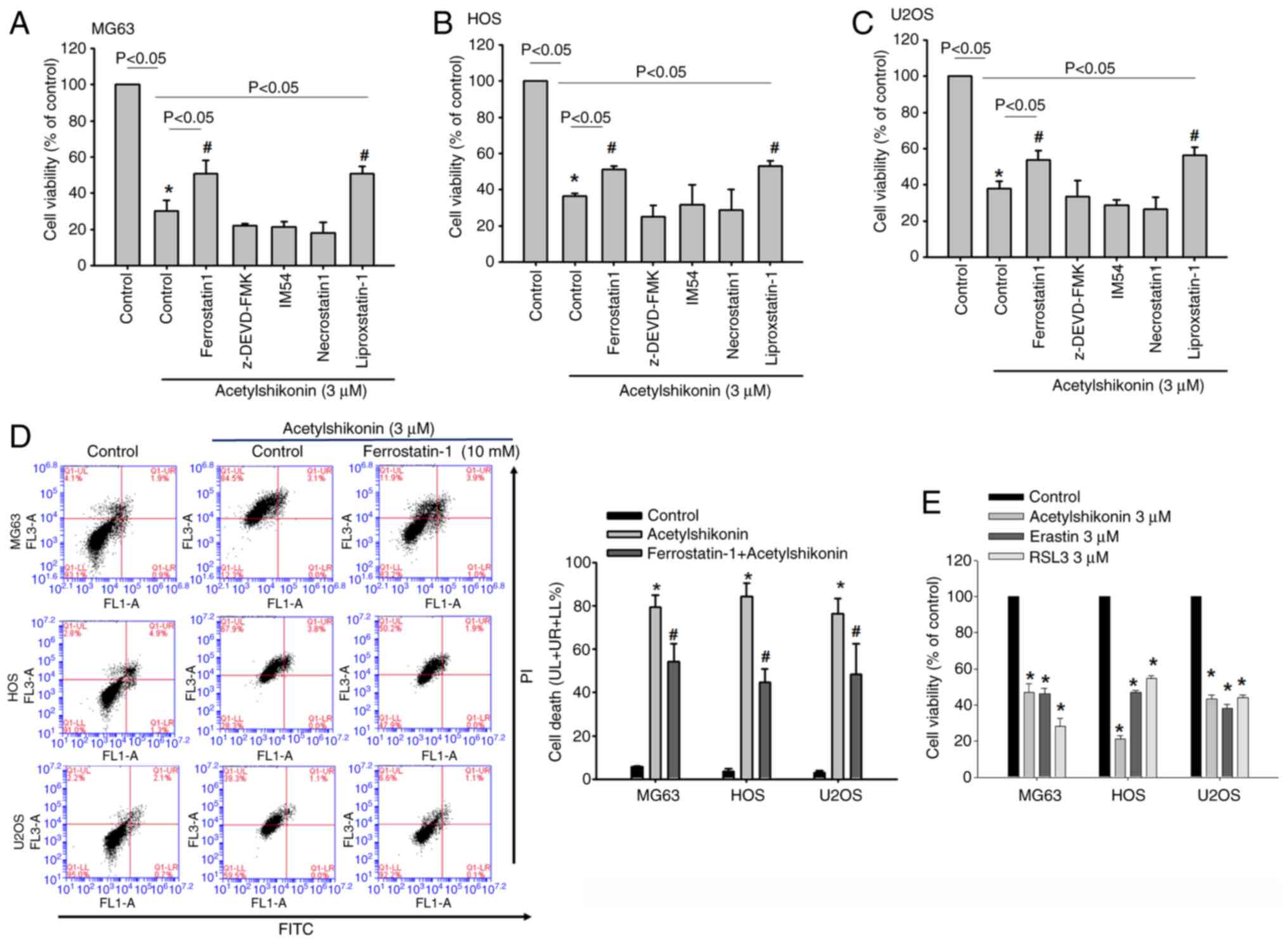

To further confirm that acetylshikonin-induced cell

death is ferroptosis-dependent, the current study compared the

protective effects of two ferroptosis inhibitors, ferrostatin-1 and

liproxstatin-1. Pretreatment with either ferrostatin-1 (1 µM) or

liproxstatin-1 (1 µM) for 1 h significantly reversed the reduction

in cell viability caused by acetylshikonin (3 µM) in osteosarcoma

cells (Fig. 8A-C). To rigorously

exclude apoptosis and necroptosis as alternative cell-death

pathways, cells were treated with the caspase-3 inhibitor

z-DEVD-FMK, the RIPK1 inhibitor necrostatin-1 and the necrosis

inhibitor IM-54. None of these inhibitors rescued

acetylshikonin-induced cytotoxicity (Fig. 8A-C). These results provide

additional pharmacological evidence that the cell death induced by

acetylshikonin is mediated through ferroptosis. Similar results

were observed in flow cytometry with Annexin V/PI staining.

Treatment with acetylshikonin markedly increased the proportion of

PI+ cells, calculated as the combined Annexin

V+/PI+ and Annexin

V−/PI+ populations, whereas pretreatment with

ferrostatin-1 significantly reduced this PI+ population

in osteosarcoma cell lines (Fig.

8D). Although the reduction was mainly attributable to a

decrease in Annexin V−/PI+ cells, this subset

was not analyzed statistically on its own. Additionally, the

cytotoxic potency of acetylshikonin was compared with two classical

ferroptosis inducers, erastin and RSL3. Treatment with erastin (3

µM) or RSL3 (3 µM) for 24 h resulted in a significant decrease in

cell viability, similar in magnitude to that caused by

acetylshikonin (Fig. 8E). These

findings indicated that acetylshikonin exhibits

ferroptosis-inducing activity comparable to established inducers,

further reinforcing its potential as a therapeutic ferroptosis

activator in osteosarcoma cells. These results experimentally

demonstrated that acetylshikonin induces ferroptosis in

osteosarcoma cells. This form of cell death is distinct from

classic necrosis and apoptosis, highlighting the potential of

acetylshikonin as a novel therapeutic agent targeting ferroptosis

in osteosarcoma cells.

Discussion

The present study investigated the potential of

acetylshikonin to induce cell death in osteosarcoma cells. The

results demonstrated that acetylshikonin significantly reduced the

viability of osteosarcoma cell lines while exhibiting low toxicity

to normal cells. Mechanistically, acetylshikonin induced ROS

production, disrupted the mitochondrial membrane potential and

promoted lipid peroxidation, ultimately leading to ferroptosis.

Additionally, treatment with acetylshikonin resulted in decreased

levels of GPX4 and increased intracellular Fe2+

concentrations, further supporting its role in the induction of

ferroptosis. These findings suggested that acetylshikonin may

address the limitations of conventional chemotherapy by targeting

ferroptosis, a unique form of cell death. This highlights the

potential of acetylshikonin as a promising therapeutic agent for

osteosarcoma, offering a novel treatment option that could enhance

patient outcomes and address the limitations of current

chemotherapy.

Chemotherapeutic agents have long been a cornerstone

of cancer treatment, which primarily function by inducing apoptosis

in cancer cells. However, their efficacy is frequently hindered by

substantial challenges, including drug resistance and severe side

effects (23,24). The development of drug resistance

and the ability of cancer cells to evade apoptosis represent key

adaptations that ultimately result in treatment failure and disease

progression (23,24). Ferroptosis, a form of programmed

cell death that is distinct from apoptosis, presents a promising

alternative target for cancer therapy. Characterized by elevated

lipid peroxides dependent on iron, the production of ROS and the

suppression of GPX4, ferroptosis circumvents the conventional

mechanisms associated with apoptosis (9,12,25,26).

Inducing ferroptosis in cancer cells can help overcome drug

resistance and enhance the effectiveness of existing treatments,

including chemotherapy, radiotherapy and immunotherapy (9,12).

The current findings are consistent with these concepts, and

notably, acetylshikonin-induced ferroptosis was further confirmed

by the reversal of cell death following treatment with

ferrostatin-1, underscoring the critical involvement of ferroptosis

processes in acetylshikonin-mediated cytotoxicity.

To further distinguish ferroptosis from other forms

of regulated cell death, inhibitor rescue assays were performed

using the caspase-3 inhibitor z-DEVD-FMK (apoptosis), the RIPK1

inhibitor necrostatin-1 (necroptosis) and the necrosis inhibitor

IM-54 across three osteosarcoma cell lines. None of these

inhibitors significantly reversed the cytotoxic effects of

acetylshikonin. By contrast, ferrostatin-1 conferred substantial

protection. These findings strengthen the conclusion that

acetylshikonin-induced cell death is mediated through a

ferroptosis-specific mechanism rather than apoptosis or

necroptosis. These findings suggest that acetylshikonin may address

the limitations of conventional chemotherapy by targeting

ferroptosis, thereby providing a novel approach for treating

osteosarcoma.

Shikonin, a naphthoquinone derivative derived from

Lithospermum erythrorhizon, has demonstrated notable

anticancer properties against various types of cancer, including

breast, lung and colorectal cancer (15). Its mechanisms of action include the

induction of apoptosis, necroptosis and immunogenic cell death, as

well as the inhibition of angiogenesis and key signaling pathways,

such as EGFR and PI3K/Akt (27,28).

Shikonin also enhances the efficacy of conventional therapies by

sensitizing cancer cells to chemotherapy and radiotherapy (28,29).

However, its clinical application is limited by poor stability, low

bioavailability and potential toxicity to normal cells (29). Acetylshikonin, a shikonin

derivative, overcomes these limitations and demonstrates potential

as a more effective candidate for cancer treatment. The acetylation

of shikonin enhances its stability and bioavailability,

facilitating more effective delivery and sustained action within

the body (15). Acetylshikonin has

been reported to trigger ROS-dependent apoptosis in hepatocellular

carcinoma and to activate necroptosis via the RIPK1/RIPK3 signaling

axis in lung cancer cells (16,30).

However, most of these studies have predominantly focused on

classical cell death pathways, and the role of acetylshikonin in

ferroptosis has remained largely unexplored. The present findings

provide novel evidence that acetylshikonin selectively induces

ferroptosis in osteosarcoma cells by promoting lipid peroxidation,

increasing intracellular Fe2+ levels and suppressing

GPX4 expression. These results highlight a previously unrecognized

mechanism for acetylshikonin, which could have important

therapeutic implications in overcoming therapeutic resistance in

osteosarcoma.

Although the present study primarily focused on the

in vitro anticancer effects of acetylshikonin, several

previous investigations have provided valuable insights into its

pharmacokinetic characteristics. In radiolabeled mouse studies,

[3H]-acetylshikonin became detectable in plasma within

15 min of oral administration, with peak concentrations occurring

at ~1 h. Notably, the compound showed widespread tissue

distribution, particularly in the gastrointestinal tract and liver;

however, it exhibited poor systemic absorption, with >80% of the

administered dose recovered in feces within 48 h, suggesting

limited bioavailability (31).

Furthermore, acetylshikonin has demonstrated high plasma protein

binding, and in mice, its parent form was reported to be

undetectable in circulation, complicating direct pharmacokinetic

analysis (30). In a non-human

primate model, Sun et al (32) employed a derivatization-based

liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass

spectrometry assay, and revealed that oral administration of

acetylshikonin resulted in a terminal half-life of 12.3±1.6 h and a

mean residence time of 10.2±0.7 h, indicating prolonged systemic

exposure. In terms of chemical stability, acetylshikonin has been

reported to be relatively stable under acidic aqueous-organic

conditions. For example, in pH 3.0 glycine buffer containing 50%

ethanol, its half-life was measured as 67.0±9.6 h at 40°C and

31.3±3.3 h at 70°C (33). These

findings suggest that while acetylshikonin demonstrates favorable

chemical stability and residence time, its limited oral

bioavailability remains a key limitation. Future in vivo

studies should therefore focus on formulation strategies and

structural modifications to enhance its absorption and therapeutic

potential in osteosarcoma models.

The present study utilized U2OS, HOS and MG63

osteosarcoma cell lines, which represent diverse genetic profiles

of osteosarcoma. In the HOS cell line, a TP53 mutation has been

confirmed, classifying it as a p53-mutated cell line. Therefore,

HOS represents a model of p53-mutated osteosarcoma with a

functional RB pathway (34). The

U2OS cell line is classified as p53 wild-type or expressing,

maintaining functional p53 expression. It harbors a heterozygous

BRCA2 mutation, with likely preservation of one intact allele, and

shows reduced or absent RB1 protein expression, suggesting a

defective RB pathway. Thus, U2OS exhibits partial BRCA2 deficiency

combined with a compromised RB pathway (34,35).

MG63 cells are characterized by a complete absence of TP53

(classified as p53-null), and markedly reduced or absent RB1

protein expression. This cell line demonstrates genomic

instability, homologous recombination deficiency, loss of

heterozygosity and a ‘BRCAness’ phenotype, typical of

BRCA1/2-mutant tumors, marked by disruptive alterations in DNA

repair pathways (34,35). While these cell lines model varying

degrees of tumor aggressiveness and genetic alterations, they may

not fully capture the molecular diversity of clinical osteosarcoma

subtypes, particularly those with metastatic or drug-resistant

phenotypes. To address this limitation, future studies should

include additional cell lines, such as SJSA-1 (TP53-mutated, highly

invasive) and 143B (a metastatic HOS derivative with enhanced

migratory capacity), to better evaluate the therapeutic potential

of acetylshikonin across diverse osteosarcoma subtypes.

From a clinical perspective, the present findings

suggest that acetylshikonin could serve as a promising

complementary agent in osteosarcoma treatment. In traditional

Chinese medicine, natural compounds are often used alone or in

combination with Western therapies to enhance antitumor efficacy

and reduce treatment-related toxicity. The integration of natural

products into conventional treatment regimens is gaining increasing

attention in oncology (36–38).

Given the substantial side effects and the frequent emergence of

drug resistance associated with current standard chemotherapies for

osteosarcoma, including doxorubicin, cisplatin and high-dose

methotrexate, the introduction of a ferroptosis-inducing agents

such as acetylshikonin may provide synergistic benefits (39,40).

Specifically, combining acetylshikonin with standard

chemotherapeutic agents could enhance therapeutic effectiveness by

simultaneously activating multiple, non-redundant cell death

pathways. Moreover, the minimal toxicity of acetylshikonin toward

normal osteoblasts, as observed in the present study, supports its

feasibility as an adjunctive treatment strategy.

To provide a broader context, the present findings

may be compared with those of previous studies on the anticancer

effects of acetylshikonin. Prior studies have demonstrated that

acetylshikonin induces apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma and

triggers necroptosis through the RIPK1/RIPK3 pathway in lung cancer

cells (15,30). However, its role in ferroptosis has

remained largely uncharacterized. The current study is among the

first to show that acetylshikonin may promote ferroptosis in

osteosarcoma cells by enhancing lipid peroxidation, increasing

intracellular Fe2+ concentrations and downregulating

GPX4 expression, representing a novel mechanistic contribution to

the understanding of this compound (10,11,41).

To assess clinical feasibility, previous reports have highlighted

the limitations of high-dose MAP regimens (methotrexate,

doxorubicin and cisplatin) in metastatic or recurrent osteosarcoma,

and have identified iron metabolism as a targetable vulnerability

associated with ROS production and tumor resistance (39,42,43).

Furthermore, curcumin enhances methotrexate efficacy by suppressing

the Hedgehog signaling pathway, thereby overcoming resistance and

reducing proliferation (39).

Based on these insights, acetylshikonin may represent a potential

complementary agent to activate non-redundant cell death pathways,

warranting future investigation into its synergistic potential with

conventional chemotherapeutics.

In summary, the present study highlights

acetylshikonin, a naphthoquinone derivative, as a promising

therapeutic candidate for osteosarcoma. Acetylshikonin reduced

osteosarcoma cell viability and selectively promoted ferroptosis by

increasing ROS production, disrupting mitochondrial function,

enhancing lipid peroxidation, downregulating GPX4 and elevating

intracellular iron levels. These findings suggest that

acetylshikonin may help overcome therapeutic resistance and improve

outcomes in osteosarcoma. Future studies should evaluate its

efficacy in vivo, explore its potential in combination with

standard chemotherapy agents, and assess its pharmacokinetic and

safety profiles to facilitate clinical translation.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the National Science and

Technology Council of Taiwan (NSTC113-2628-B-038-008-MY3).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JYC was responsible for data collection,

conceptualization, methodology development, investigation and

preparation of the original draft. GSW contributed to

conceptualization, project administration, investigation and

software analysis. TMC performed formal analysis, contributed to

methodology and project administration, and conducted software

analysis. JFL conceptualized the study, developed the methodology,

performed investigation, collected data, acquired funding, and

critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. TMC and JFL confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved

the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Ottaviani G and Jaffe N: The epidemiology

of osteosarcoma. Cancer Treat Res. 152:3–13. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Meltzer PS and Helman LJ: New Horizons in

the treatment of osteosarcoma. N Engl J Med. 385:2066–2076. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Belayneh R, Fourman MS, Bhogal S and Weiss

KR: Update on osteosarcoma. Curr Oncol Rep. 23:712021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Lilienthal I and Herold N: Targeting

molecular mechanisms underlying treatment efficacy and resistance

in osteosarcoma: A review of current and future strategies. Int J

Mol Sci. 21:68852020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Haider T, Pandey V, Banjare N, Gupta PN

and Soni V: Drug resistance in cancer: Mechanisms and tackling

strategies. Pharmacol Rep. 72:1125–1151. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Mohammad RM, Muqbil I, Lowe L, Yedjou C,

Hsu HY, Lin LT, Siegelin MD, Fimognari C, Kumar NB, Dou QP, et al:

Broad targeting of resistance to apoptosis in cancer. Semin Cancer

Biol. 35 (Suppl 1):S78–S103. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Wang J, Li M, Guo P and He D: Correction:

Survival benefits and challenges of adjuvant chemotherapy for

high-grade osteosarcoma: A population-based study. J Orthop Surg

Res. 18:8342023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Hiraga H and Ozaki T: Adjuvant and

neoadjuvant chemotherapy for osteosarcoma: JCOG bone and soft

tissue tumor study group. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 51:1493–1497. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Zhang C, Liu X, Jin S, Chen Y and Guo R:

Ferroptosis in cancer therapy: A novel approach to reversing drug

resistance. Mol Cancer. 21:472022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Zhou N and Bao J: FerrDb: A manually

curated resource for regulators and markers of ferroptosis and

ferroptosis-disease associations. Database (Oxford).

2020:baaa0212020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Zhou Q, Meng Y, Li D, Yao L, Le J, Liu Y,

Sun Y, Zeng F, Chen X and Deng G: Ferroptosis in cancer: From

molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 9:552024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Nie Q, Hu Y, Yu X, Li X and Fang X:

Induction and application of ferroptosis in cancer therapy. Cancer

Cell Int. 22:122022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Wu Y, Yu C, Luo M, Cen C, Qiu J, Zhang S

and Hu K: Ferroptosis in cancer treatment: Another way to rome.

Front Oncol. 10:5711272020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Hayashi M: Pharmacological studies of

Shikon and Tooki. (2) Pharmacological effects of the pigment

components, Shikonin and acetylshikonin. Nihon Yakurigaku Zasshi.

73:193–203. 1977.(In Japanese). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Wang Q, Wang J, Wang J, Ju X and Zhang H:

Molecular mechanism of shikonin inhibiting tumor growth and

potential application in cancer treatment. Toxicol Res (Camb).

10:1077–1084. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Hu S, Li Y, Zhou J, Xu K, Pang Y,

Weiskirchen R, Ocker M and Ouyang F: Identification of

acetylshikonin as a novel tubulin polymerization inhibitor with

antitumor activity in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J

Gastrointest Oncol. 14:2574–2586. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Cha HS, Lee HK, Park SH and Nam MJ:

Acetylshikonin induces apoptosis of human osteosarcoma U2OS cells

by triggering ROS-dependent multiple signal pathways. Toxicol In

Vitro. 86:1055212023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Majtnerova P and Rousar T: An overview of

apoptosis assays detecting DNA fragmentation. Mol Biol Rep.

45:1469–1478. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Loo DT: TUNEL assay. An overview of

techniques. Methods Mol Biol. 203:21–30. 2002.

|

|

20

|

Wang B, Wang Y, Zhang J, Hu C, Jiang J, Li

Y and Peng Z: ROS-induced lipid peroxidation modulates cell death

outcome: Mechanisms behind apoptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis.

Arch Toxicol. 97:1439–1451. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Rizwan H, Pal S, Sabnam S and Pal A: High

glucose augments ROS generation regulates mitochondrial dysfunction

and apoptosis via stress signalling cascades in keratinocytes. Life

Sci. 241:1171482020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Battaglia AM, Chirillo R, Aversa I, Sacco

A, Costanzo F and Biamonte F: Ferroptosis and cancer: Mitochondria

meet the ‘Iron Maiden’ cell death. Cells. 9:15052020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Fu B, Lou Y, Wu P, Lu X and Xu C: Emerging

role of necroptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis in breast cancer:

New dawn for overcoming therapy resistance. Neoplasia.

55:1010172024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Sajeev A, Sailo B, Unnikrishnan J,

Talukdar A, Alqahtani MS, Abbas M, Alqahtani A, Sethi G and

Kunnumakkara AB: Unlocking the potential of Berberine: Advancing

cancer therapy through chemosensitization and combination

treatments. Cancer Lett. 597:2170192024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Chen X, Comish PB, Tang D and Kang R:

Characteristics and biomarkers of ferroptosis. Front Cell Dev Biol.

9:6371622021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Chen F, Kang R, Tang D and Liu J:

Ferroptosis: Principles and significance in health and disease. J

Hematol Oncol. 17:412024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Yadav S, Sharma A, Nayik GA, Cooper R,

Bhardwaj G, Sohal HS, Mutreja V, Kaur R, Areche FO, AlOudat M, et

al: Review of shikonin and derivatives: Isolation, chemistry,

biosynthesis, pharmacology and toxicology. Front Pharmacol.

13:9057552022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Iranzadeh S, Dalil D, Kohansal S and

Isakhani M: Shikonin in breast cancer treatment: A comprehensive

review of molecular pathways and innovative strategies. J Pharm

Pharmacol. 76:967–982. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Qi K, Li J, Hu Y, Qiao Y and Mu Y:

Research progress in mechanism of anticancer action of shikonin

targeting reactive oxygen species. Front Pharmacol. 15:14167812024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Lin SS, Chang TM, Wei AI, Lee CW, Lin ZC,

Chiang YC, Chi MC and Liu JF: Acetylshikonin induces necroptosis

via the RIPK1/RIPK3-dependent pathway in lung cancer. Aging (Albany

NY). 15:14900–14914. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Zhang Z, Bai J, Zeng Y, Cai M, Yao Y, Wu

H, You L, Dong X and Ni J: Pharmacology, toxicity and

pharmacokinetics of acetylshikonin: A review. Pharm Biol.

58:950–958. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Sun DX, Tian HF, Meng ZY, Du A, Yuan D, Gu

RL, Wu ZN and Dou GF: Quantitative determination of acetylshikonin

in macaque monkey blood by LC-ESI-MS/MS after precolumn

derivatization with 2-mercaptoethanol and its application in

pharmacokinetic study. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 29:1499–1506. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Cho MH, Paik YS and Hahn TR: Physical

stability of shikonin derivatives from the roots of Lithospermum

erythrorhizon cultivated in Korea. J Agric Food Chem. 47:4117–4120.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Zhang Q, Hao S, Wei G, Liu X and Miao Y:

The p53-mediated cell cycle regulation is a potential mechanism for

emodin-suppressing osteosarcoma cells. Heliyon. 10:e268502024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Engert F, Kovac M, Baumhoer D, Nathrath M

and Fulda S: Osteosarcoma cells with genetic signatures of BRCAness

are susceptible to the PARP inhibitor talazoparib alone or in

combination with chemotherapeutics. Oncotarget. 8:48794–48806.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Wei J, Liu Z, He J, Liu Q, Lu Y, He S,

Yuan B, Zhang J and Ding Y: Traditional Chinese medicine reverses

cancer multidrug resistance and its mechanism. Clin Transl Oncol.

24:471–482. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Miao K, Liu W, Xu J, Qian Z and Zhang Q:

Harnessing the power of traditional Chinese medicine monomers and

compound prescriptions to boost cancer immunotherapy. Front

Immunol. 14:12772432023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Yuan J, Liu Y, Zhang T, Zheng C, Ding X,

Zhu C, Shi J and Jing Y: Traditional Chinese medicine for breast

cancer treatment: A bibliometric and visualization analysis. Pharm

Biol. 62:499–512. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Argenziano M, Tortora C, Pota E, Di Paola

A, Di Martino M, Di Leva C, Di Pinto D and Rossi F: Osteosarcoma in

children: Not only chemotherapy. Pharmaceuticals (Basel).

14:9232021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Giliberti G, Marrapodi MM, Di Feo G, Pota

E, Di Martino M, Di Pinto D, Rossi F and Di Paola A: Curcumin and

methotrexate: A promising combination for osteosarcoma treatment

via hedgehog pathway inhibition. Int J Mol Sci. 25:113002024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Hsu PC, Tsai CC, Lin YH and Kuo CY:

Therapeutic targeting of apoptosis, autophagic cell death,

necroptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis pathways in oral squamous

cell carcinoma: Molecular mechanisms and potential strategies.

Biomedicines. 13:17452025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Ma X, Zhao J and Feng H: Targeting iron

metabolism in osteosarcoma. Discov Oncol. 14:312023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Zhao J, Zhao Y, Ma X, Zhang B and Feng H:

Targeting ferroptosis in osteosarcoma. J Bone Oncol. 30:1003802021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|