Introduction

Osteoporosis (OP) is a systemic skeletal disorder

characterized by reduced bone mass and deterioration of bone

microarchitecture, resulting in increased bone fragility and a

higher risk of fractures. This condition markedly impairs the

quality of life of affected patients and may even lead to increased

mortality rates (1). As the global

population ages at an accelerating rate, the incidence of OP

continues to increase. In China alone, the number of individuals

aged ≥60 years is >210 million, posing considerable challenges

for the prevention and management of OP (2). Therefore, the development of

effective therapeutic strategies is of substantial clinical

importance.

Currently, clinical treatments for OP primarily

include pharmacological therapy, exercise interventions and

physical therapies (3,4). However, each of these approaches

presents notable limitations. For example, while bisphosphonates

effectively inhibit bone resorption, long-term use has been

associated with adverse effects such as osteonecrosis of the jaw

and gastrointestinal disturbances (5). Similarly, hormone replacement therapy

may increase the risk of cardiovascular events and breast cancer in

certain patient populations (6,7).

Therefore, the development of novel and safer therapeutic

strategies remains an important focus in current OP research.

In previous years, oxidative stress has emerged as a

notable contributor to the pathogenesis of OP. Factors such as

aging, iron overload and estrogen deficiency can disrupt the

balance between oxidative and antioxidant systems in the body,

leading to excessive accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)

(8,9). These elevated ROS levels cause

oxidative damage to key macromolecules including DNA, lipids and

proteins, thereby accelerating cellular apoptosis (10). In the context of OP, oxidative

stress modulates signaling pathways, cytokine expression and

protein activity in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs),

osteoblasts and osteoclasts (11).

Oxidative stress impairs the osteogenic differentiation potential

of BMSCs, inhibits osteoblast mineralization, and promotes the

activation, proliferation and maturation of osteoclasts (12,13).

This leads to a disrupted balance between bone formation and

resorption, impairs bone remodeling and ultimately accelerates the

progression of OP (14).

The research on natural drugs for the treatment of

OP has recently attracted widespread attention (15,16).

Hyperoside (Hyp), as a natural flavonoid compound existing in

various plants, such as Crataegus, Apocynum venetum and

Hypericum perforatum, exhibits multiple pharmacological

activities. Previous studies have demonstrated that Hyp has a

protective effect on the cardiovascular and nervous systems

(17,18). However, the therapeutic effect and

mechanism of Hyp on OP remain insufficiently characterized.

Therefore, the present study aimed to explore the therapeutic

effect and molecular mechanism of Hyp on OP, providing new ideas

and a theoretical basis for the treatment of OP through a

combination of in vivo and in vitro experiments.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Hyp (cat. no. HY-N0452) and LY294002 (cat. no.

HY-10108) were purchased from MedChemExpress with a purity of

99.5%. The RNA extraction kit (cat. no. AG21207) was selected from

Hunan Accurate Bio-Medical Technology Co., Ltd. Primer synthesis

was completed by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. The Cell Counting Kit-8

(CCK-8) (cat. no. C0037), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining kit

(cat. no. C3206) and Alizarin red S (ARS) staining kit (cat. no.

C0148S) were all purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology. The primary

antibodies runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2) (cat. no.

AF5186, rabbit), Osterix (cat. no. DF7731, rabbit), β-actin (cat.

no. AF7018, rabbit), phosphorylated (p)-PI3K (cat. no. AF3242,

rabbit), PI3K (cat. no. AF6241, rabbit), AKT (cat. no. AF0832,

rabbit), p-AKT (cat. no. AF0016, rabbit), as well as the

corresponding HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary

antibody (cat. no. S0001), were all purchased from Affinity

Biosciences. Isoflurane (cat. no. R510-22-10) was purchased from

Shenzhen Ruiwode Life Science Co., Ltd.

Animal experimentation

A total of 40 female C57BL/6J mice were purchased

from the Guangdong Provincial Medical Experimental Center [license

no. SCXK(YUE)2022-0002]. Female mice (age, 8 weeks; weight, 20–25

g) were randomly divided into control, model, low-concentration and

high-concentration groups (n=10 each) and housed in the specific

pathogen-free-grade Experimental Animal Center of The First

Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine

(Guangzhou, China). The housing conditions were as follows:

22–25°C; 40–60% humidity; 12-h light/dark cycle; ad libitum

access to food/water. After 1 week of acclimation, except for the

control group, bilateral ovariectomy (OVX) was performed under

isoflurane inhalation anesthesia (5% for induction and 2% for

maintenance via precision vaporizer), with depth confirmed by loss

of pedal reflex. At 1-week post-surgery, the low- and

high-concentration groups were intragastrically administered 40 and

80 mg/kg Hyp, respectively, and the control and model groups

received an equal volume of vehicle (0.9% NaCl containing <0.1%

DMSO), once daily for 8 weeks. The selected doses were based on a

previous study reporting osteoprotective effects of Hyp in

ovariectomized mice (19). Humane

endpoints were defined as >20% weight loss, inability to access

food or water, severe distress or moribund state; health and

behavior were monitored daily. Euthanasia was performed by deep

anesthesia with 5% isoflurane followed by cervical dislocation,

with death confirmed by absence of heartbeat, respiration and

corneal reflex. The total experimental duration was 10 weeks. No

unexpected deaths occurred, and all procedures were approved by the

Animal Experiment Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital

of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (approval no.

GZTCMF1-202403241).

Micro-CT scanning

The lower limbs of mice were positioned on the

scanning table of the MicroCT scanner (SkyScan 1276;

Bruker-Michrom, Inc.), with scanning parameters set to appropriate

values, including a voltage of 50 kV, a current of 200 µA and a

scanning resolution of 9 µm. The scan was subsequently performed.

After the scan was completed, specific reconstruction algorithms in

the scanning software were used to reconstruct the two-dimensional

projection images into three-dimensional images. Subsequently,

CT-analyser (CTAn) software (version 1.17.7.2; Bruker-Michrom,

Inc.) was used for data analysis. Initially, the scan data were

imported into the CTAn software, the appropriate region of interest

(ROI) was selected, typically starting with the distal femoral

growth plate, and 150 slices were analyzed upwards of this ROI

(Fig. S1). Using the standard

analysis function in CTAn, parameters such as trabecular thickness

(Tb.Th), trabecular separation (Tb.Sp), trabecular number (Tb.N)

and bone volume fraction (BV/TV) were calculated. Based on set

threshold values, the software automatically identified bone and

non-bone tissues and generated data for the aforementioned bone

structure parameters. Finally, the analysis results were exported

and the parameters compared between different groups to further

analyze trends and variations.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and

tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining

The mouse lower limb bone tissue samples were rinsed

with PBS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and then fixed in

4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 24 h. Subsequently, they were

immersed in the decalcification solution for 2 weeks for

decalcification, followed by rinsing with distilled water. After

that, the samples were dehydrated with successive concentrations of

alcohol and treated with xylene for permeabilization. Subsequently,

the bone tissues were embedded in paraffin, trimmed and cut into

5-µm sections. The sections were placed in a 63°C constant

temperature oven for baking for 2 h. During the H&E staining

process, the sections were first dewaxed and hydrated, then stained

with hematoxylin solution for 5 min at room temperature (22–25°C).

After differentiation with hydrochloric acid alcohol and bluing

with tap water, the sections were stained with eosin solution for 2

min at room temperature. Finally, the sections were dehydrated with

a gradient alcohol series, permeabilized with xylene and sealed

with neutral balsam. Images were then captured using a light

microscope (CX43; Olympus Corporation).

For TRAP staining, the sections were similarly

dewaxed and rehydrated. TRAP staining was performed using a

commercial TRAP staining kit (cat. no. G1492; Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Briefly, the sections were incubated in TRAP working

solution containing naphthol AS-BI phosphate and Fast Red Violet LB

salt in the presence of sodium tartrate at 37°C for 1 h in the

dark. After washing with distilled water, the sections were

counterstained lightly with hematoxylin, then dehydrated, cleared

in xylene and sealed with neutral balsam. TRAP-positive osteoclasts

appeared as red or purplish-red multinucleated cells located along

the trabecular bone surface. Representative images were obtained

under a light microscope, and osteoclast number was

semi-quantitatively evaluated by counting the number of

TRAP-positive cells per field under standardized magnification.

Acquisition of Hyp action targets

The structure of Hyp was obtained from the PubChem

database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and then imported

into the SwissTargetPrediction (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/), PharmMapper

(http://www.lilab-ecust.cn/pharmmapper/), Super-Pred

(https://insilico-cyp.charite.de/SuperCYPsPred/) and

TargetNet (http://targetnet.scbdd.com/) databases to predict its

potential protein targets. After removing duplicates and

unannotated targets, all candidate targets were imported into the

UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/) using the parameters

‘reviewed’, ‘Homo sapiens’ and ‘gene name primary’ to

standardize the target names into official gene symbols. This

approach has been widely applied in previous network pharmacology

studies (20,21).

Prediction of OP targets and

differential gene analysis

The Gene Expression Omnibus database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) was searched

using ‘osteoporosis’ as the key word, and the species ‘Homo

Sapiens’ was selected to obtain the GSE35956 (22) gene chip dataset and the GSE80614

(23). gene chip dataset. In R

software (version 4.3.1; The R Foundation for Statistical

Computing), the parameters P<0.05 and |log (fold change) |>2

were set to screen for differential genes and draw a volcano plot.

Subsequently, searches and screenings were conducted in the

GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) and

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man databases (https://www.omim.org/) using the aforementioned key

word. Finally, the datasets were integrated and duplicates were

removed to obtain the disease-target dataset.

Acquisition of potential action

targets of Hyp for treating OP

To conduct an in-depth study and elucidate the

interaction mechanisms of the active ingredients of Hyp in the

intervention and treatment of OP, a Venn analysis was performed

between the action targets of the active ingredients of Hyp and

OP-related targets. The overlapping region represents the potential

targets of the Hyp for treating OP. Subsequently, a Venn diagram

was generated to visualize these intersecting targets.

Construction of the protein-protein

interaction (PPI) network and screening of core targets

The intersecting targets between the OP and the Hyp

were imported into the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting

Genes/Proteins (STRING) database (https://string-db.org/) for PPI analysis. Briefly, the

intersecting target proteins were imported into the STRING

database, the organism was set to Homo sapiens, and the

database query was performed to generate the PPI network. This

process was used to construct a PPI network model, thereby

facilitating the understanding of cellular functional interactions

between protein expression profiles and enabling a deeper

comprehension of protein functions at the cellular level. Following

retrieval, the PPI network diagram was exported and its

corresponding ‘.tsv’ format file was downloaded. The ‘.tsv’ file

was then imported into Cytoscape (version 3.9.1; http://cytoscape.org/) and the topological parameters

of each node in the network were analyzed using the CytoNCA plugin.

Target importance within the network was evaluated from three

dimensions: Node connectivity, betweenness centrality and closeness

centrality. Finally, a core target screening network was

constructed to identify the core targets.

Enrichment analysis of Gene Ontology

(GO) biological functions and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes (KEGG) information transmission pathways of core

targets

The Metascape database (https://metascape.org) enables enrichment of target

genes into their associated genomes and signaling pathways,

annotates gene functions, visualizes enrichment analysis results

and standardizes genes with different identification codes. To

further elucidate the gene functions of the screened targets and

their involvement in signaling pathways, these targets were

imported into the Metascape database for GO functional enrichment

analysis and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis. The Metascape

database was used to visualize the enrichment analysis results.

Based on ascending P-values, the top 10 results from each GO

category and the top 20 KEGG pathways were selected and visualized

using the platform.

Cell culture

Mouse primary BMSCs (cat. no. MIC-BIOSPECIES-s018)

were purchased from Guangzhou Xinyuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The

cells were cultured in α-Minimum Essential Medium (Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin. Cultures were maintained in a humidified

incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. The medium was refreshed

every 2 days. Once the cells reached 80–90% confluence, they were

detached using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA and passaged at a ratio of 1:3.

Cells at passages 3–6 were used for all subsequent experiments.

CCK-8 assay

The cells were seeded into a 96-well plate at a

density of 5×103 cells/well and cultured overnight to

allow adherence. For the Hyp cytotoxicity assay, the cells were

treated with different concentrations of Hyp (0, 10, 20, 40 and 80

µM) for 24 h at 37°C. For the oxidative stress model, the cells

were exposed to H2O2 at concentrations of 50,

100, 200 or 400 µM for 24 h at 37°C to evaluate the dose-dependent

cytotoxicity. To assess the protective effects of Hyp, the cells

were pretreated with different concentrations of Hyp (10, 20 and 40

µM) for 24 h, followed by exposure to 200 µM

H2O2 for 4 h at 37°C. After each treatment,

10 µl CCK-8 solution (Beyotime Biotechnology) was added to each

well and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Finally, a microplate reader

was used to measure the absorbance at 450 nm.

5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EDU)

assay

An EDU incorporation assay (cat. no. C0075S;

Beyotime Biotechnology) was performed to evaluate the proliferation

of BMSCs. Briefly, BMSCs were pretreated with Hyp (20 or 40 µM) for

24 h at 37°C, followed by exposure to H2O2

(200 µM) for 4 h at 37°C. After treatment, the cells were washed

three times with PBS. Then, BMSCs were incubated with EDU for 2 h

at 37°C. The EDU working solution was prepared by diluting 10 mM

EDU stock with culture medium to a final concentration of 10 µM.

Following EDU incubation, the cells were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. Cells were then

washed three times with PBS for 5 min each. After fixation, the

cells were permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min

and were subsequently washed again with wash buffer. EDU

incorporation was detected using an EDU detection kit, and the

proliferating cells were analyzed using a fluorescence

microscope.

ALP staining and ARS staining

BMSCs were seeded into 12-well plates. After cell

attachment to the surface, they were categorized into groups and

subjected to the respective interventions. Osteogenic induction was

initiated using an osteogenic induction medium containing 10 nM

dexamethasone, 50 µg/ml vitamin C and 10 mM β-sodium

glycerophosphate. The cells were divided into: i) A control group;

ii) a model group treated with 200 µM H2O2;

iii) a low-concentration group treated with 20 µM Hyp and 200 µM

H2O2; and iv) a high-concentration group

treated with 40 µM Hyp and 200 µM H2O2. The

culture medium was refreshed every 3 days. ALP staining was

performed on day 7. The cells were rinsed three times with PBS,

fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature, and

then stained using an ALP staining kit at 37°C for 30 min. ARS

staining was conducted on day 14. The cells were washed three times

with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room

temperature, and then stained with ARS at room temperature for 30

min. To quantitatively evaluate the degree of mineralization, the

ARS stain was eluted with 10% w/v cetylpyridinium chloride for 1 h,

and the OD value at 570 nm was measured using a microplate reader.

All images were captured under a light microscope (Olympus

Corporation), and quantitative analysis of mineralization intensity

was performed using ImageJ software (version 1.8.0; National

Institutes of Health).

Measurement of ROS level

The present study employed DCFH-DA to detect

intracellular ROS levels. After the aforementioned cell

intervention was completed, DCFH-DA (cat. no. S0033S; Beyotime

Biotechnology) was diluted to a final concentration of 10 µM in

serum-free medium and incubated at 37°C in the dark for 30 min. The

cells were then rinsed three times with PBS, and images were

captured under a fluorescence microscope. For flow cytometric

detection of ROS, after the incubation, the cells were gently

washed once with PBS to remove any excess fluorescent probe that

had not entered the cells. The cells were then digested with

trypsin and collected into centrifuge tubes. Following

centrifugation (300 × g, 5 min, 4°C), the supernatant was discarded

and 500 µl of PBS was added to resuspend the cells. The resulting

cell suspension was transferred into flow cytometry tubes and

analyzed on a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data

were processed using FlowJo software (version 10.8.1; BD

Biosciences).

Measurement of superoxide dismutase

(SOD) and malondialdehyde (MDA)

The BMSCs were seeded into 6-well plates. Once the

cells had adhered to the well surface, they were subjected to

intervention according to the aforementioned grouping for a

duration of 24 h. Upon completion of the intervention, cell samples

from each group were harvested. For the determination of

intracellular SOD level, the working solution was prepared

according to the protocol of the SOD activity detection kit (cat.

no. S0101; Beyotime Biotechnology). After incubation at 37°C for 30

min, the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate

reader. The SOD activity in the cell samples of each group was then

calculated based on the standard curve. For the detection of MDA

levels, the working solution was prepared according to the

instructions of the MDA detection kit (cat. no. S0131; Beyotime

Biotechnology). After thorough mixing with the samples, the mixture

was heated at 100°C for 15 min, cooled to room temperature in a

water bath and centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min at room

temperature. A total of 200 µl supernatant was transferred into a

96-well plate, and the absorbance was measured at 532 nm using a

microplate reader. The MDA content in the cell samples of each

group was then calculated based on the standard curve.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

The cell treatments were performed as

aforementioned, and total RNA was extracted from BMSCs using an RNA

extraction kit (cat. no. AG21207; Hunan Accurate Bio-Medical

Technology Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

After measuring the concentration, the RNA was reverse transcribed

into cDNA using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (cat. no. RR047A;

Takara Bio, Inc.) with the following temperature protocol: 37°C for

15 min, 85°C for 5 sec, and hold at 4°C. qPCR was performed using a

SYBR® Green qPCR Mix (cat. no. AG11761; Hunan Accurate

Bio-Medical Technology Co., Ltd.). Using the cDNA of each group as

the template, and after adding the buffer and primers, PCR

amplification was performed according to the following parameters

described in the instruction manual: Initial denaturation at 95°C

for 30 sec, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 5 sec

and annealing/extension at 60°C for 40 sec, in accordance with the

manufacturer's instructions. With 18S rRNA as the internal

control, the relative mRNA expression levels were calculated using

the 2−ΔΔCq method (24). The primer pair sequences for 18S

rRNA, Runx2, Alp, Osterix and type I collagen (Col1) are

listed in Table I.

| Table I.Primer sequences. |

Table I.

Primer sequences.

| Gene | Forward

(5′-3′) | Reverse

(5′-3′) |

|---|

| 18s |

TGGTTGCAAAGCTGAAACTTAAAG |

AGTCAAATTAAGCCGCAGGC |

| Runx2 |

GCCGGGAATGATGAGAACTA |

GGACCGTCCACTGTCACTTT |

| Alp |

CCAGAAAGACACCTTGACTGTGG |

TCTTGTCCGTGTCGCTCACCAT |

| Col1 |

CCTCAGGGTATTGCTGGACAAC |

CAGAAGGACCTTGTTTGCCAGG |

| Osterix |

GGCTTTTCTGCGGCAAGAGGTT |

CGCTGATGTTTGCTCAAGTGGTC |

Western blot analysis

The BMSCs were treated as aforementioned. Total

proteins were extracted from BMSCs using RIPA lysis buffer (cat.

no. P0013B; Beyotime Biotechnology) supplemented with a protease

and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (cat. no. P1005; Beyotime

Biotechnology). Proteins were quantified by BCA assay and 30 µg

total protein was loaded per lane. Proteins were separated by

SDS-PAGE on 10% gels, then transferred to PVDF membranes (cat. no.

IPVH00010; MilliporeSigma). After blocking with 5% skim milk in TBS

containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) for 2 h at room temperature, the

membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies:

Runx2 (1:1,000), Osterix (1:1,000), PI3K (1:1,000), p-PI3K

(1:1,000), AKT (1:1,000), p-AKT (1:1,000) and β-actin (1:5,000).

Following three washes with TBST, membranes were incubated with

HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5,000) for 1.5 h at room

temperature. After further TBST washes, protein bands were

visualized using ECL Chemiluminescence Detection Kit (cat. no.

170-5061; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Band densities were

semi-quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.8.0; National

Institutes of Health).

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded mouse femur sections, prepared as

aforementioned for H&E and TRAP staining, were used for

immunohistochemical analysis. Briefly, the femurs were fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde for 24 h at room temperature, decalcified in 10%

EDTA solution (pH 7.4) for 2 weeks, dehydrated, embedded in

paraffin and cut into 5-µm sections. After the sections had been

dewaxed, antigen retrieval was performed. The sections were then

treated with 3% H2O2 to block endogenous

peroxidase activity, followed by blocking with 5% normal goat serum

(cat. no. C0265; Beyotime Biotechnology) for 30 min at room

temperature. The sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with the

following primary antibodies: p-PI3K (cat. no. AF3242; 1:200) and

p-AKT (cat. no. AF0016; 1:200) (all from Affinity Biosciences). The

primary antibody was applied and incubated overnight at 4°C. On the

following day, after thorough washing with PBS, the corresponding

secondary antibody (1:200; cat. no. S0001; Affinity Biosciences)

was applied and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. The sections

were subsequently developed using a DAB chromogenic agent (cat. no.

P0203; Beyotime Biotechnology), counterstained with hematoxylin for

3 min at room temperature, dehydrated, cleared and mounted. The

staining results were observed and analyzed under a light

microscope (Olympus Corporation), and five random non-overlapping

fields per section were selected for semi-quantitative analysis

using ImageJ software (version 1.8.0; National Institutes of

Health).

Inhibitor treatment

To investigate the protective effects of Hyp and the

involvement of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, BMSCs were divided

into four groups: Control, model (H2O2), Hyp

and Hyp + LY294002. Cells in the control group were cultured under

standard conditions without any treatment. Cells in the model group

were exposed to 200 µM H2O2 for 4 h at 37°C

to induce oxidative stress. In the Hyp group, cells were pretreated

with Hyp (40 µM) for 24 h at 37°C, followed by 200 µM

H2O2 treatment for 4 h. To verify the role of

the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, cells in the Hyp + LY294002 group

were pretreated with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (10 µM;

MedChemExpress) for 2 h at 37°C before Hyp intervention. After

pretreatment, the cells were exposed to Hyp (40 µM) for 24 h and

were subsequently treated with H2O2 (200 µM)

for 4 h at 37°C. LY294002 was dissolved in DMSO, and the final DMSO

concentration in the culture medium did not exceed 0.1% (v/v).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

version 25.0 (IBM Corp.). Data are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation. Each experiment was independently repeated at least

three times. Differences among multiple groups were evaluated by

one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). When significant differences

were detected by ANOVA, Tukey's honestly significant difference

post hoc test was applied for pairwise comparisons. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

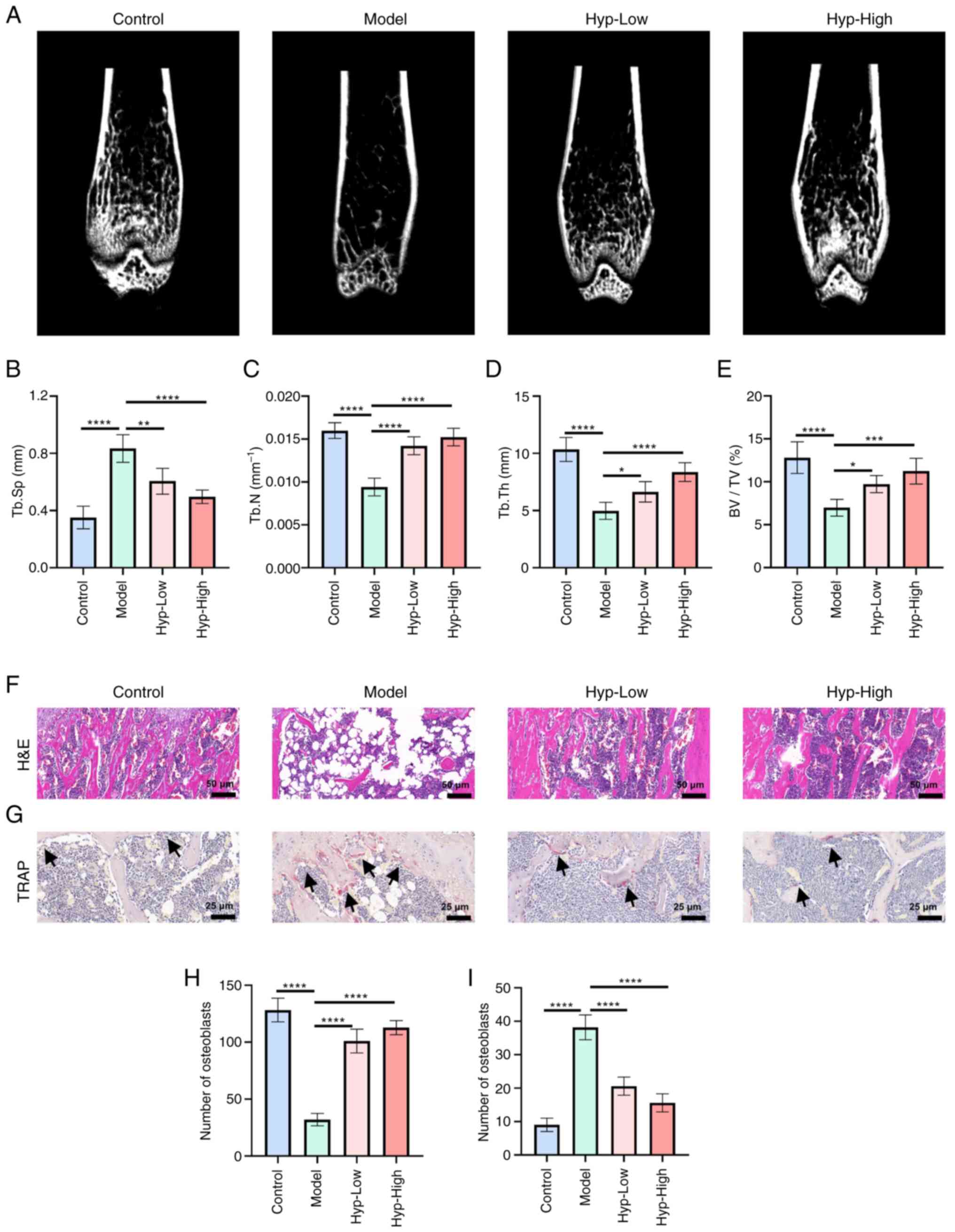

Hyp alleviates OP in mice induced by

OVX

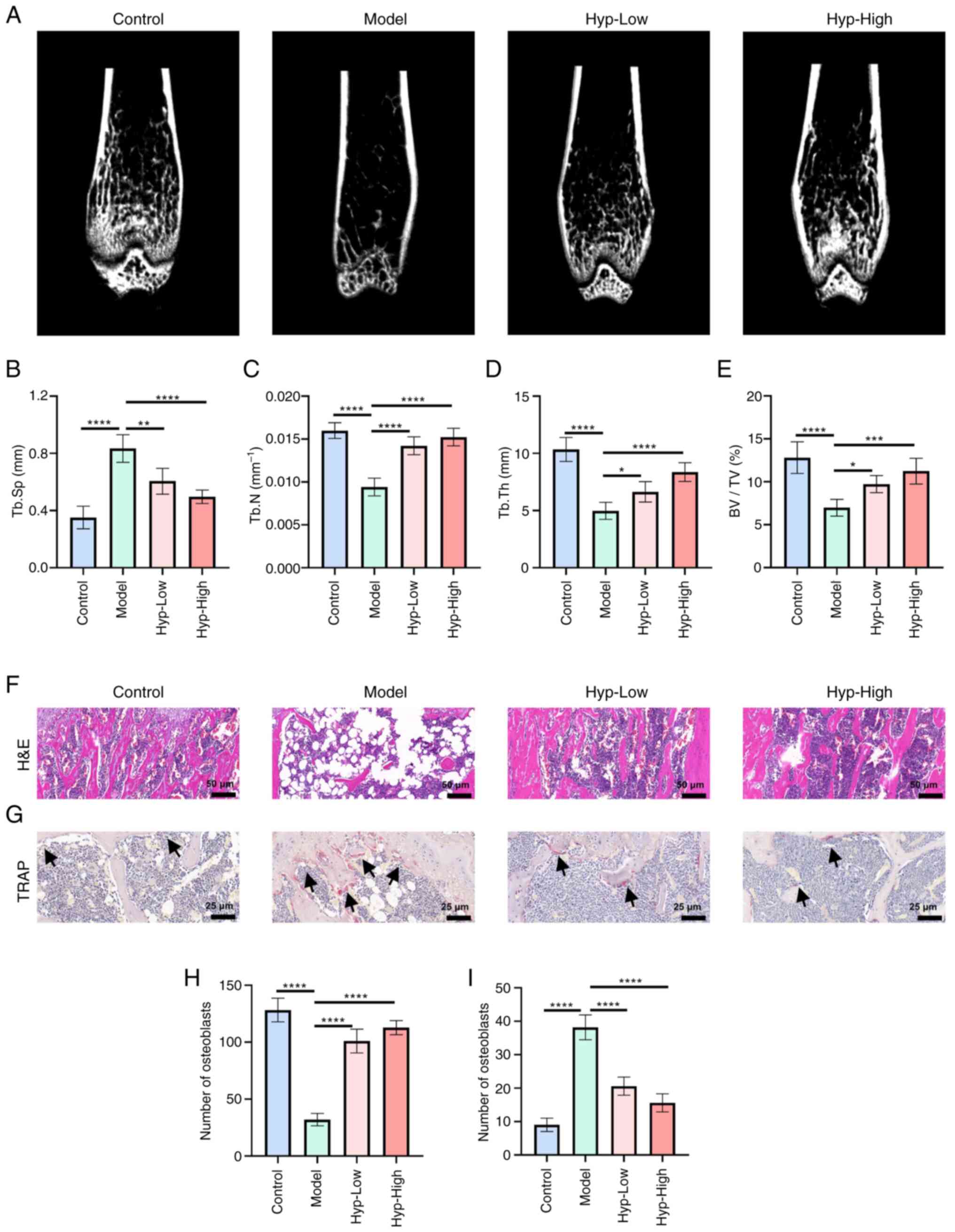

The present study utilized micro-CT and H&E

staining to comprehensively assess structural alterations in the

lower limb bones of mice. Compared with in the control group, the

model group exhibited significant reductions in Tb.N, Tb.Th and

BV/TV, alongside a significant increase in Tb.Sp (Fig. 1A-E). These findings validated the

successful establishment of the OP model. Following Hyp

administration, these parameters significantly improved in a

dose-dependent manner, indicating that Hyp effectively promoted

trabecular bone formation, mitigated OVX-induced bone loss and

contributed to the restoration of bone microarchitecture.

| Figure 1.Hyp alleviates ovariectomy-induced

osteoporosis in mice. (A) Representative micro-CT three-dimensional

reconstruction images of the mouse femur. Quantitative analyses of

(B) Tb.Sp, (C) Tb.N, (D) Tb.Th and (E) BV/TV (n=5). (F)

Representative H&E staining images of femoral sections (n=5;

×20 magnification). (G) Representative TRAP-stained sections

showing osteoclasts (indicated by black arrows) (n=5; ×40

magnification). (H) Quantification of osteoblast number per bone

surface (n=5). (I) Quantification of osteoclast number per bone

surface (n=5). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001. Tb.Sp,

trabecular separation; Tb.N, trabecular number; Tb.Th, trabecular

thickness; BV/TV, bone volume fraction; TRAP, tartrate-resistant

acid phosphatase; Hyp, hyperoside. |

Histological evaluation by H&E staining further

corroborated these observations. In the OVX group, trabeculae were

sparse and attenuated, the marrow cavity was markedly expanded,

osteocyte density was reduced and cell morphology appeared

irregular (Fig. 1F). Additionally,

the number of empty lacunae was markedly elevated. By contrast,

bone sections from Hyp-treated mice exhibited more intact and

compact trabeculae, an increased number of osteocytes with

normalized morphology and a reduction in empty lacunae.

To further investigate cellular changes, the present

study quantitatively analyzed osteoblast and osteoclast

populations. The number of osteoblasts per bone surface was

significantly decreased in the OVX model mice but was restored in a

dose-dependent manner following Hyp treatment (Fig. 1H). Meanwhile, TRAP staining

revealed a substantial increase in TRAP-positive multinucleated

osteoclasts in the OVX group, indicative of enhanced bone

resorption (Fig. 1G and I).

Notably, Hyp significantly reduced osteoclast numbers per bone

surface compared with those in the OVX group. These results

underscored the dual modulatory effects of Hyp on bone regulation,

having simultaneously enhanced osteoblast activity and inhibited

osteoclastogenesis, thereby contributing to the maintenance of bone

homeostasis. Collectively, the present findings demonstrated that

Hyp not only ameliorated microarchitectural deterioration

associated with OP but also regulated key cellular mediators of

bone remodeling, supporting its therapeutic potential in the

management of OP.

Potential mechanism underlying the

effects of Hyp on the treatment of OP

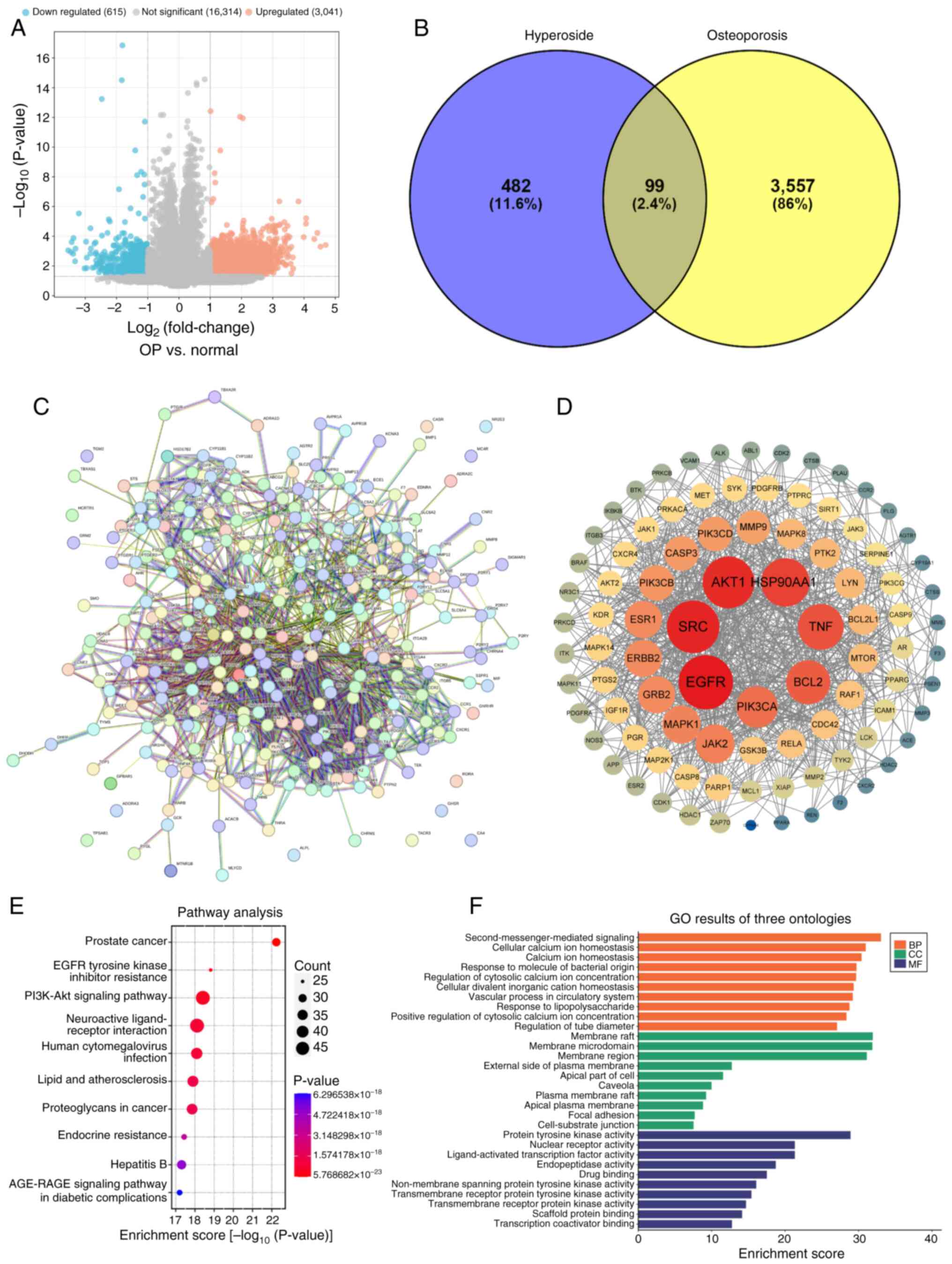

A volcano plot of the GSE35956 and GSE80614 gene

expression datasets are shown in Fig.

2A. A total of 581 drug targets and 3,565 disease targets

(Fig. 2B) were retrieved through

online databases. By conducting an intersection analysis with a

Venn diagram, 99 common target genes were determined and

subsequently designated as potential therapeutic targets for

further in-depth investigation (Fig.

2B). Subsequently, the STRING database was used to explore the

potential associations among these 99 common genes. Subsequently,

the analysis outcomes were imported into the Cytoscape software to

generate a PPI network for Hyp in OP (Fig. 2C and D). In the degree value

analysis of the PPI network, it was ascertained that the top 10

genes, namely Src, Hsp90aa1, Akt1, Egfr, Tnf, Pik3ca, Bcl2,

Grb2, Jak2 and Erbb2, were highly likely to assume a

central role in the therapeutic process of Hyp for OP. Further GO

molecular function analysis divulged that the top 5 functions of

Hyp encompassed ‘second-messenger-mediated signaling’, maintenance

of ‘cellular calcium ion homeostasis’, regulation of ‘calcium ion

homeostasis’, ‘response to molecule of bacterial origin’ and

‘regulation of cytosolic calcium ion concentration’ (Fig. 2F). This implied that Hyp may have

influenced intracellular signal transduction and ionic equilibrium

by regulating these molecular functions, thereby exerting a

beneficial effect on OP. Simultaneously, the KEGG enrichment

analysis results demonstrated that pathways such as ‘Prostate

cancer’, ‘EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance’, ‘PI3K-Akt

signaling pathway’, ‘Neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction’ and

‘Human cytomegalovirus infection’ held significant implications in

the treatment of OP with Hyp (Fig.

2E).

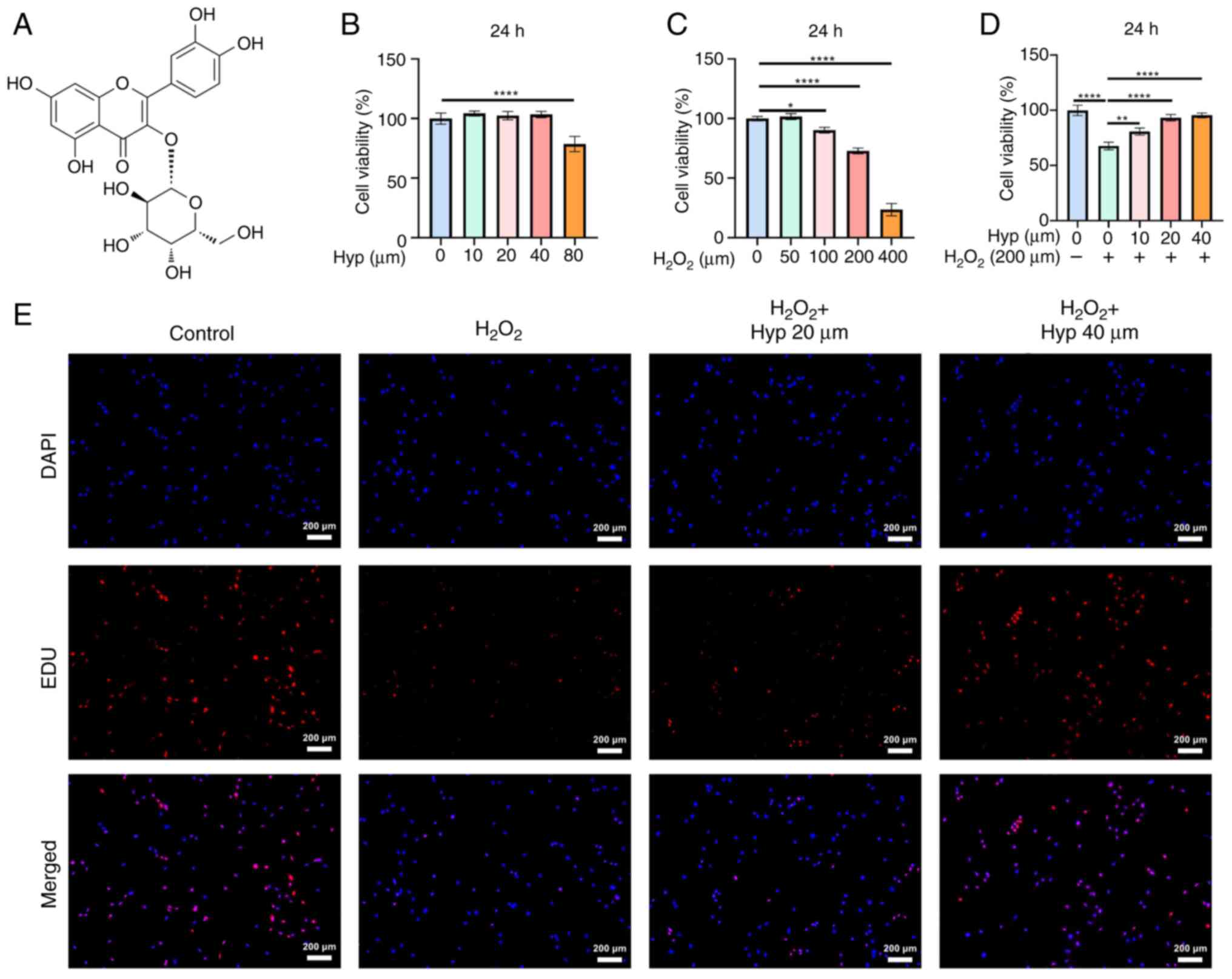

Effect of Hyp on the viability of

BMSCs

The chemical structure of Hyp is shown in Fig. 3A. The CCK-8 assay demonstrated that

Hyp concentrations ≤40 µM did not exhibit significant cytotoxicity

on BMSCs, with 20 and 40 µM selected for subsequent experiments

(Fig. 3B).

H2O2 at concentrations >100 µM

significantly inhibited BMSC proliferation, and 200 µM

H2O2 was chosen for inducing oxidative stress

in BMSCs (Fig. 3C). Notably, Hyp

effectively alleviated the inhibitory effect of

H2O2 on BMSC proliferation (Fig. 3D). Further analysis using EDU

labeling supported these findings. H2O2

treatment resulted in a reduced number of proliferating cells, as

indicated by lower EDU incorporation (Fig. 3E). By contrast, Hyp treatment

notably increased EDU-positive cells, suggesting its potential to

promote BMSC proliferation under oxidative stress.

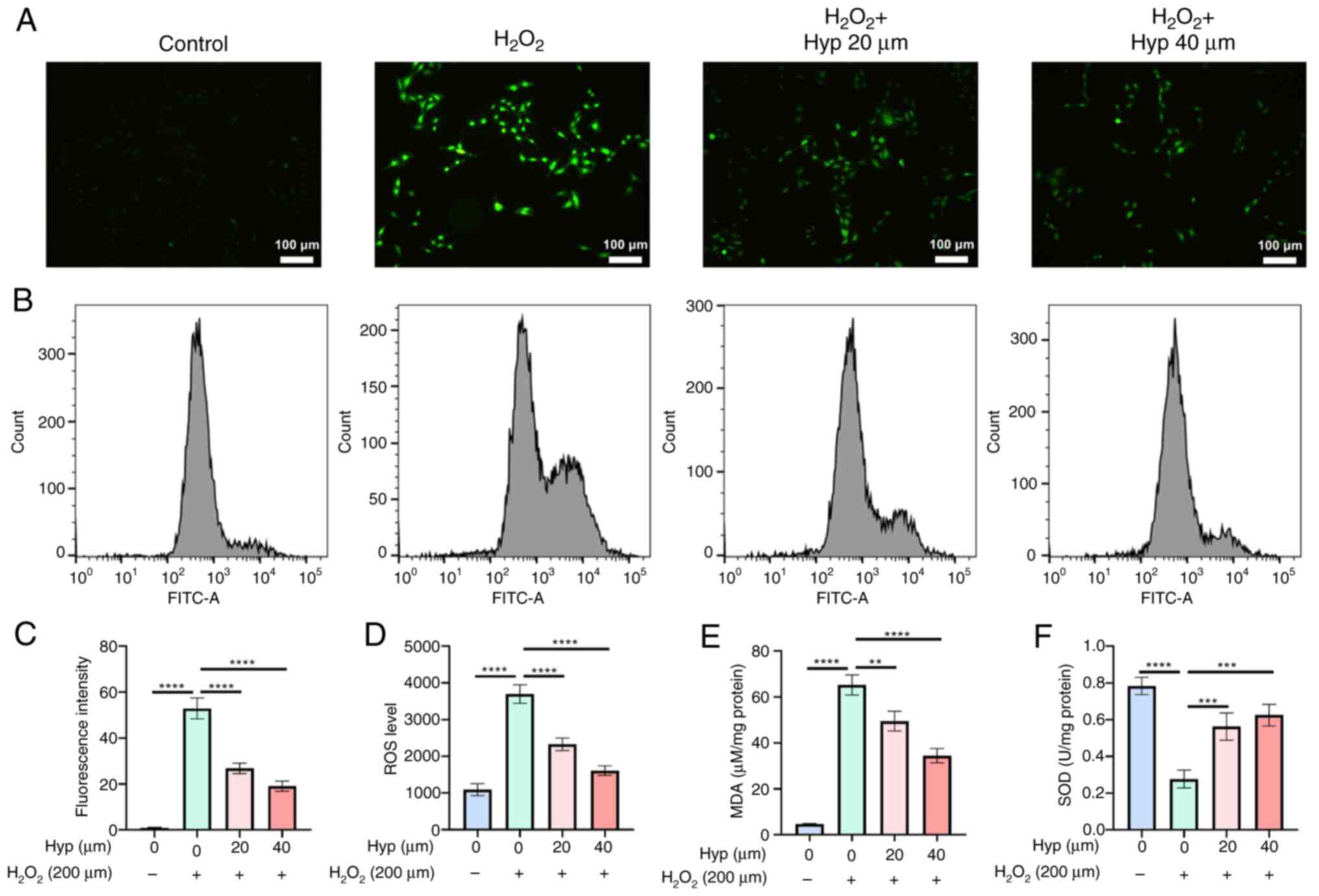

Hyp is capable of alleviating the

oxidative stress induced by H2O2

The DCFH-DA staining outcomes manifested that upon

the administration of H2O2, a conspicuous

augmentation in fluorescence intensity was observed, signifying a

pronounced elevation in the ROS levels within the cells (Fig. 4A and C). By contrast, when Hyp was

introduced, a reduction in the fluorescence intensity of BMSCs

ensued, implying a reduced ROS level. This was further corroborated

by flow cytometry, wherein the average ROS levels were

significantly elevated post-H2O2 treatment

and subsequently decreased after Hyp treatment (Fig. 4B and D). Furthermore, the results

of MDA detection assays indicated that H2O2

intervention led to a significant upsurge in MDA levels, whereas

Hyp treatment effectively mitigated these levels (Fig. 4E). Similarly, the SOD detection

assays revealed that H2O2 treatment induced a

significant decline in SOD levels, which were significantly

augmented following Hyp treatment (Fig. 4F). In summary, these comprehensive

findings demonstrated that Hyp possessed the capacity to alleviate

H2O2-induced oxidative stress levels in

BMSCs. This not only holds promise for safeguarding cells against

oxidative damage but also for maintaining cellular homeostasis,

potentially providing new options for therapeutic interventions

aimed at combating oxidative stress-related cellular

dysfunctions.

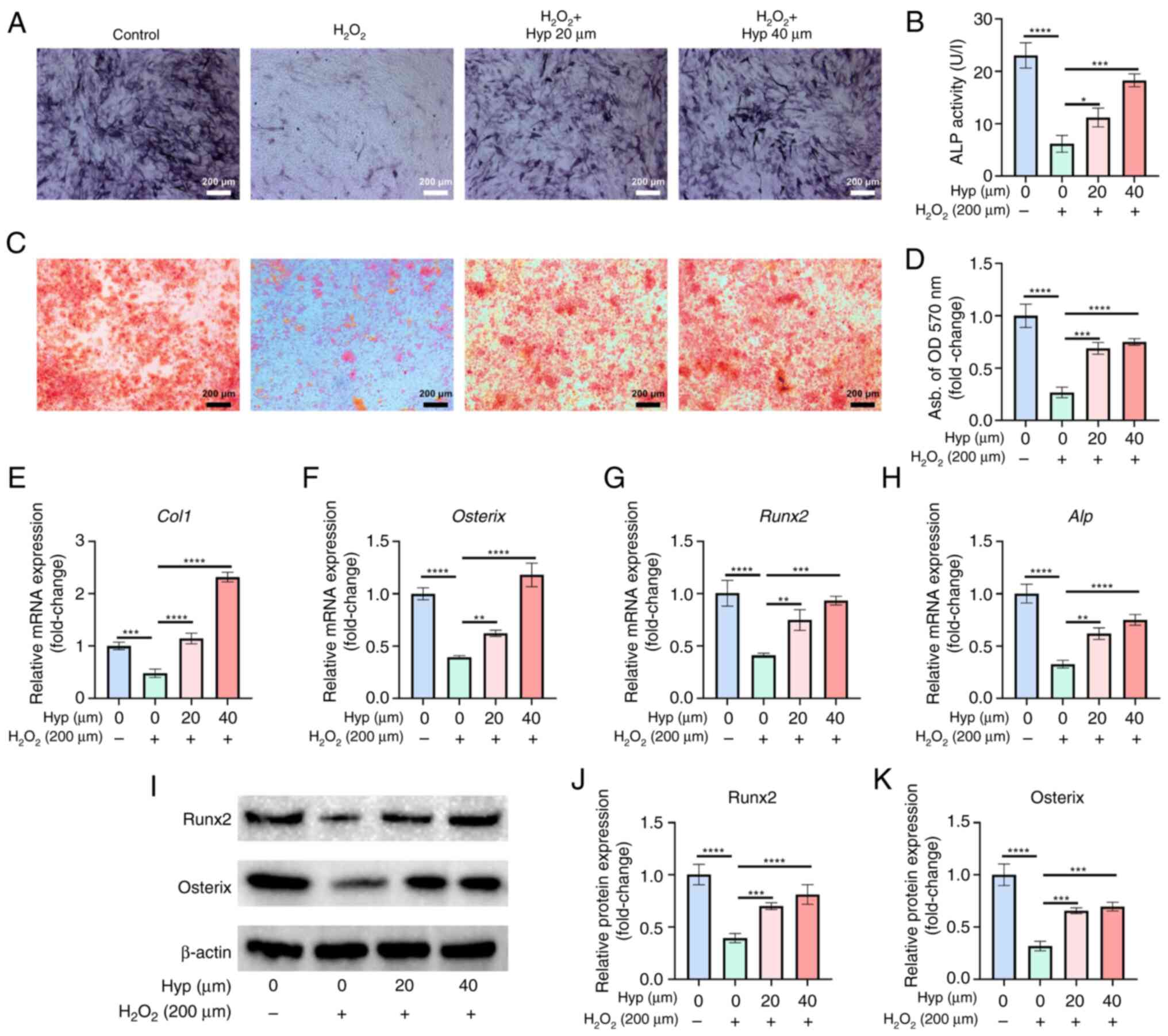

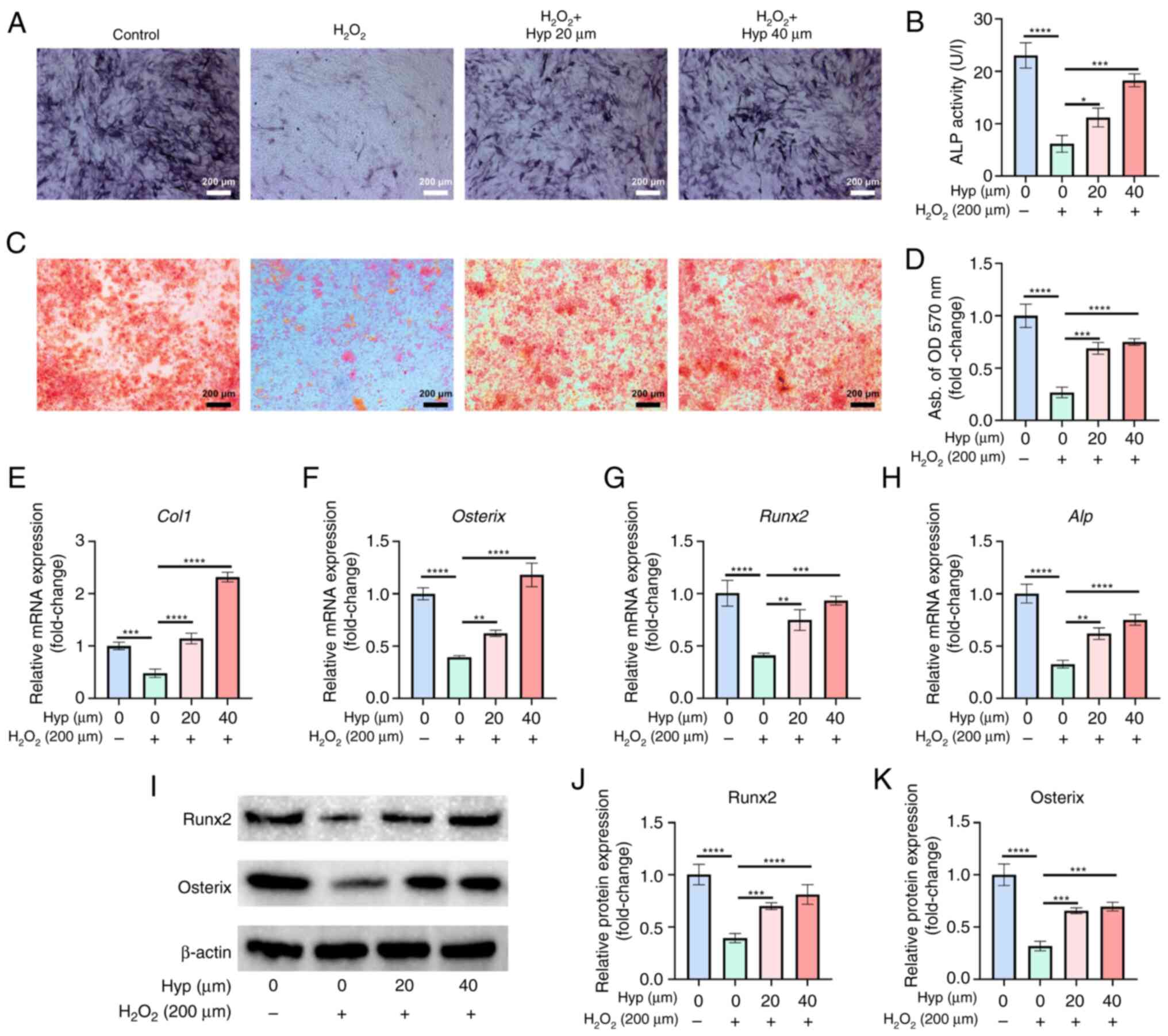

Hyp protects the osteogenic

differentiation ability of BMSCs

In the present study, the effect of Hyp on the

osteogenic differentiation ability of BMSCs was investigated under

oxidative stress conditions. The results of ALP and ARS staining

assays demonstrated that the osteogenic differentiation capacity of

BMSCs was significantly reduced after H2O2

intervention (Fig. 5A-D). However,

treatment with Hyp significantly enhanced the osteogenic

differentiation of BMSCs, as evidenced by the increased ALP

activity and the greater number of calcium nodules detected by ARS

staining. Furthermore, RT-qPCR analysis revealed that the

expression levels of Col1, Osterix, Runx2 and Alp

were significantly decreased upon H2O2

exposure (Fig. 5E-H). By contrast,

Hyp treatment led to a significant upregulation of these genes,

indicating its positive regulatory role in osteogenic gene

expression. Consistent with the RT-qPCR results, the results of

western blot analysis also showed that Hyp treatment significantly

increased the protein expression levels of Osterix and Runx2

(Fig. 5I-K). Collectively, these

results provided compelling evidence that Hyp effectively protected

the osteogenic differentiation ability of BMSCs under oxidative

stress conditions, suggesting its potential therapeutic application

in bone-related disorders associated with oxidative stress.

| Figure 5.Hyperoside rescues the osteogenic

differentiation function of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. (A)

Representative images of ALP staining and (B) quantification of ALP

activity (n=3; ×5 magnification). (C) Representative images of ARS

staining and (D) quantification of ARS staining (n=3; ×5

magnification). The mRNA expression levels of (E) Col1, (F)

Osterix, (G) Runx2 and (H) Alp (n=3). (I)

Representative western blot images, and semi-quantification of the

protein expression levels of (J) Runx2 and (K) Osterix (n=3). Data

are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001. OD, optical

density; Hyp, Hyperoside; Col1, type-I collagen; Runx2,

runt-related transcription factor 2; ARS, Alizarin red S;

ALP/Alp, alkaline phosphatase. |

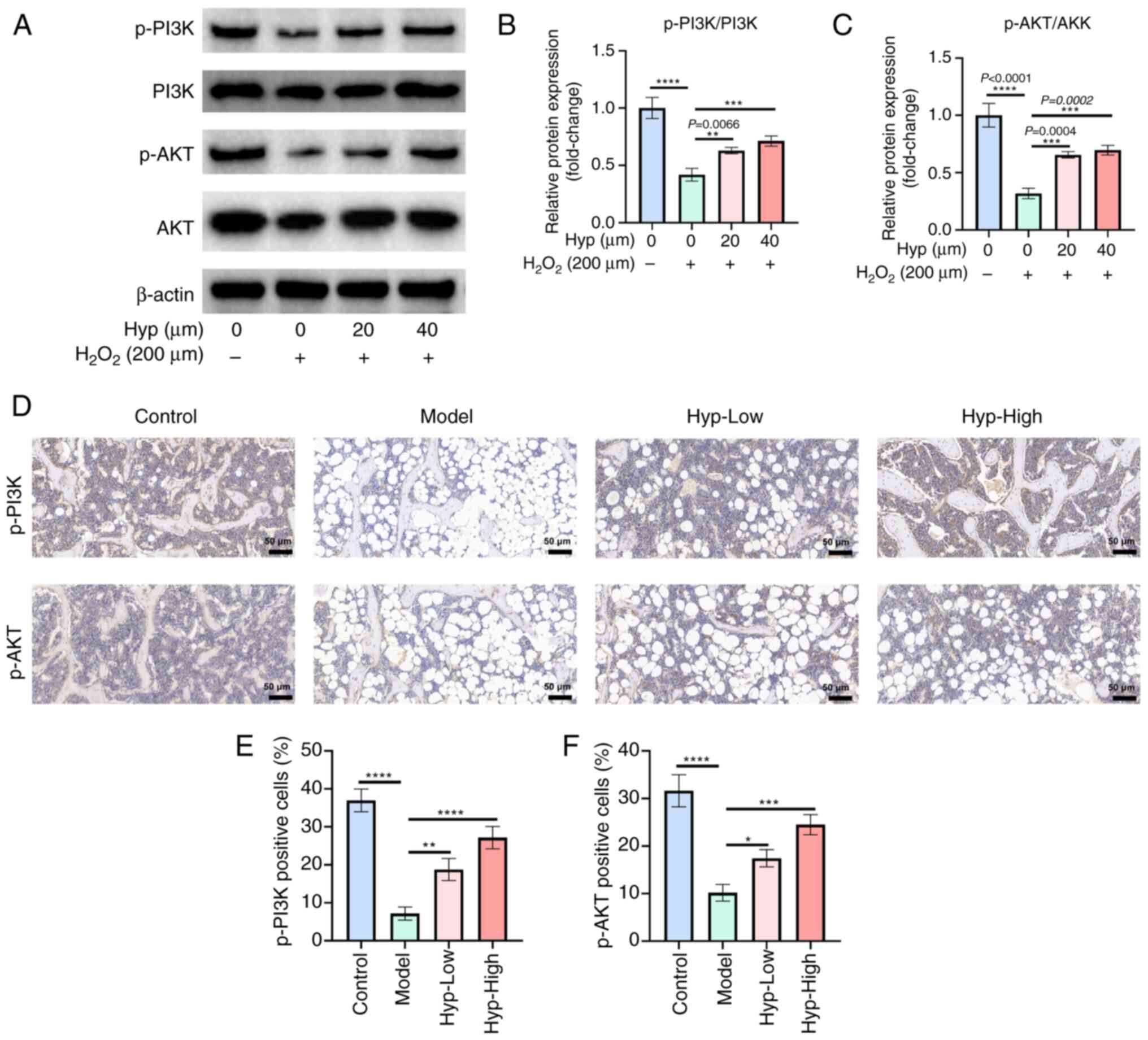

Hyp initiates activation of the

PI3K/AKT signaling pathway

Western blot analysis of BMSCs revealed that

H2O2 intervention led to a significant

decline in the phosphorylation levels of both PI3K and AKT. By

contrast, Hyp treatment effectively reversed this downward trend

and promoted the activation of PI3K and AKT phosphorylation

(Fig. 6A-C). This was further

supported by immunohistochemical analysis of mouse femoral tissues,

which indicated that the expression levels of p-PI3K and p-AKT were

significantly reduced in the model group compared with those in the

control group (Fig. 6D-F).

However, following Hyp intervention, a significant increase in the

expression of p-PI3K and p-AKT was observed.

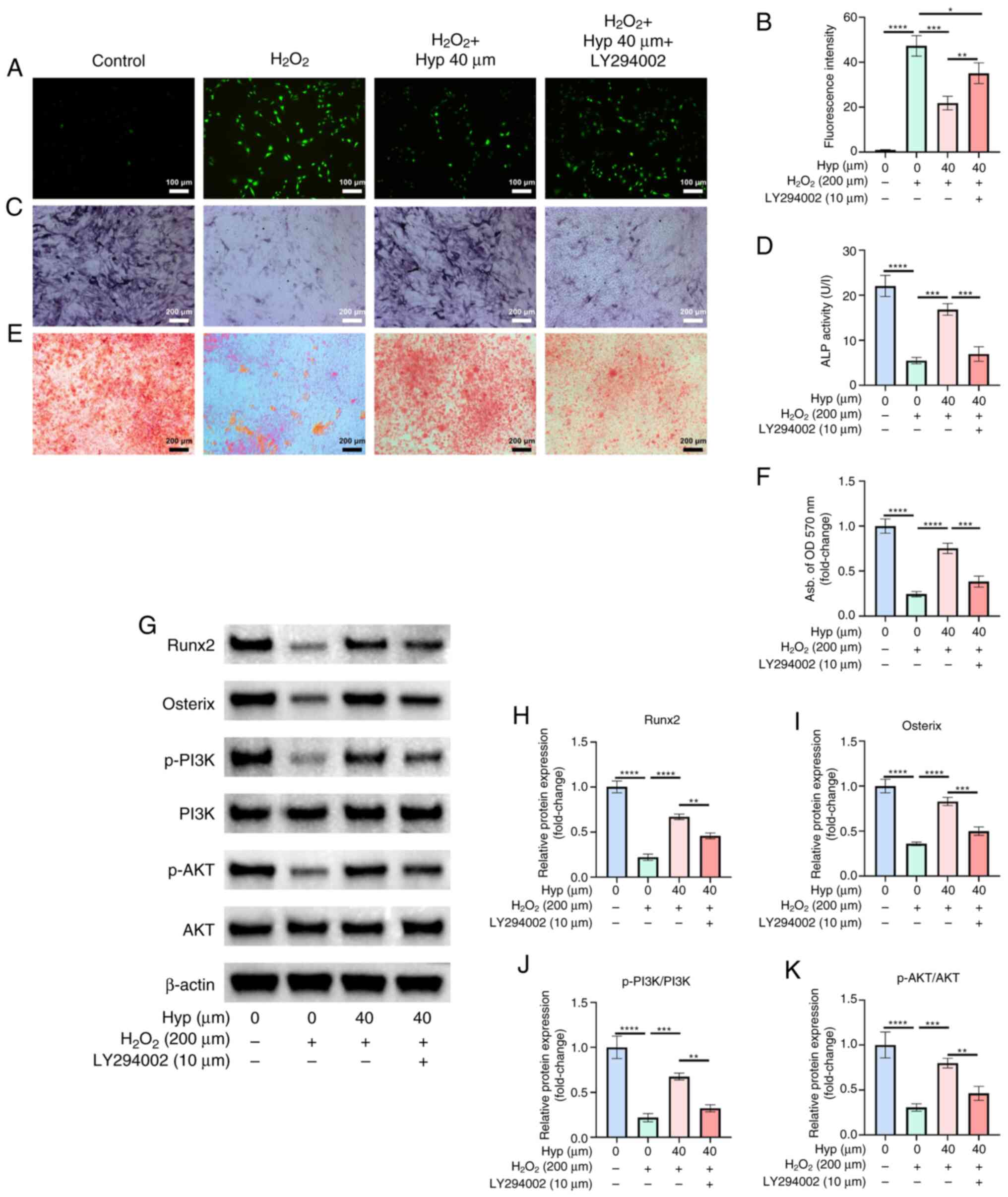

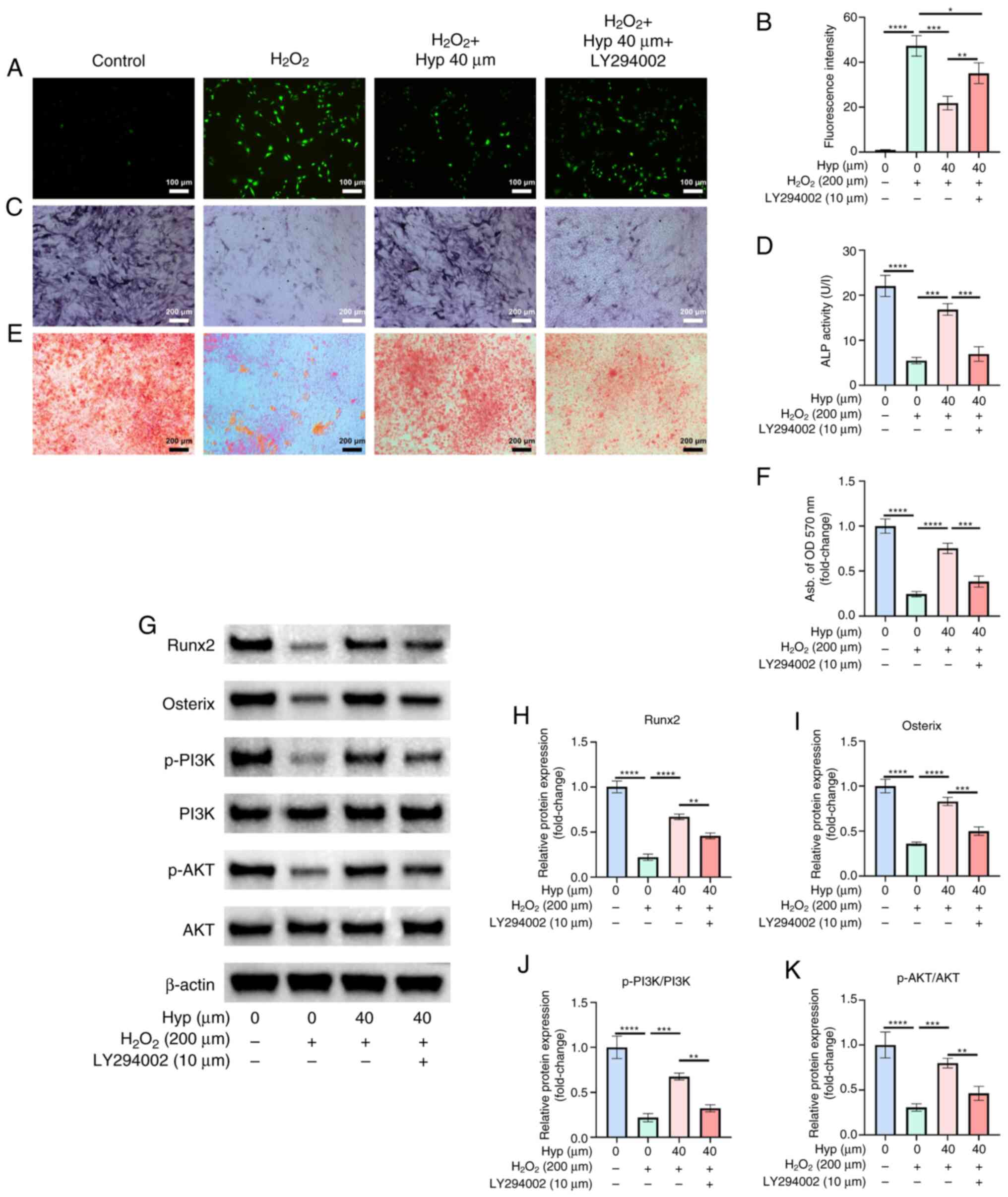

Inhibition of the PI3K/AKT pathway

attenuates the antioxidative and osteogenic effects of Hyp

To investigate the role of the PI3K/AKT signaling

pathway in the antioxidative and osteogenic effects of Hyp, a

series of in vitro experiments were conducted using

LY294002, a specific inhibitor of the PI3K/AKT pathway. LY294002 is

a synthetic flavonoid derivative that acts as a reversible,

ATP-competitive inhibitor of PI3Ks, thereby blocking the

phosphorylation and subsequent activation of AKT and downstream

signaling molecules. DCFH-DA fluorescence staining revealed that

Hyp treatment significantly reduced

H2O2-induced intracellular ROS levels, as

evidenced by decreased green fluorescence intensity (Fig. 7A and B). However, co-treatment with

LY294002 partially yet significantly restored the fluorescence

signal and elevated ROS levels, suggesting that the antioxidative

capacity of Hyp was impaired when the PI3K/AKT pathway was

inhibited. Regarding osteogenic differentiation, ALP staining and

enzyme activity assays demonstrated that Hyp significantly

increased ALP activity, indicating the promotion of early

osteogenesis (Fig. 7C and D). By

contrast, the ALP activity and staining intensity were

significantly reduced in the Hyp + LY294002 group, approaching the

levels observed in the H2O2 group. These

findings suggested that the PI3K/AKT pathway was involved in

Hyp-induced early osteogenic differentiation. Furthermore, ARS

staining showed a substantial increase in mineralized nodule

formation in the Hyp-treated group, with quantitative analysis

supporting elevated calcium deposition (Fig. 7E and F). However, in the Hyp +

LY294002 group, both the ARS-stained area and calcium content were

markedly decreased, indicating compromised osteogenic

mineralization.

| Figure 7.Inhibition of the PI3K/AKT pathway

attenuates the antioxidative and osteogenic effects of Hyp. (A)

Representative fluorescence images of DCFH-DA staining and (B)

quantification (n=3; ×10 magnification). (C) Representative images

of ALP staining and (D) quantification of ALP activity (n=3; ×5

magnification). (E) Representative images of ARS staining and (F)

quantification of ARS absorbance levels (n=3; ×5 magnification).

(G) Representative western blotting images, and semi-quantification

of the protein expression levels of (H) Runx2, (I) Osterix, (J)

p-PI3K/PI3K and (K) p-AKT/AKT (n=3). Data are presented as the mean

± standard deviation. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and

****P<0.0001. Hyp, Hyperoside; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ARS,

Alizarin red S; Runx2, runt-related transcription factor 2; p-,

phosphorylated. |

Western blot analysis corroborated these findings.

Compared with in the model group, Hyp treatment significantly

upregulated the expression levels of p-PI3K and p-AKT, as well as

the key osteogenic transcription factors Runx2 and Osterix

(Fig. 7G-K). By contrast,

co-treatment with LY294002 resulted in a significant downregulation

of these proteins, demonstrating that LY294002 partially reversed

the effects of Hyp on PI3K/AKT signaling and its downstream

targets. Collectively, these results indicated that Hyp exerted its

antioxidative and pro-osteogenic effects by activating the PI3K/AKT

signaling pathway and that inhibition of this pathway significantly

attenuated its biological functions, highlighting the notable role

of PI3K/AKT signaling in mediating the effects of Hyp.

Discussion

Oxidative stress has been acknowledged to serve an

important role in the pathogenesis of OP, a view that has become

accepted in the current research field (11). With increases in age, alterations

in hormonal levels and the influence of other pathological factors,

the redox balance within the body is disrupted, leading to the

excessive generation of oxidative stress products such as ROS

(10,25) ROS can target intracellular

biomacromolecules, resulting in lipid peroxidation, protein

oxidative modification and DNA damage, thereby impairing the normal

function and viability of cells (26). In the skeletal system, oxidative

stress can markedly enhance the activity and number of osteoclasts,

thereby promoting the bone resorption process. Concurrently, it

inhibits the proliferation, differentiation and mineralization

capacity of osteoblasts, ultimately reducing bone formation. This

disruption in the balance of bone remodeling leads to bone mass

loss, and the occurrence and development of OP (27). A large number of in vivo and

in vitro studies have provided conclusive evidence for this,

prompting researchers to continuously explore effective antioxidant

strategies to combat OP (28,29).

Hyp is a natural flavanol glycoside compound that

has been shown to possess notable antioxidant and anti-inflammatory

activities (30,31). A study conducted by Chen et

al (19) demonstrated that Hyp

can prevent oxidative stress-induced liver injury in rats.

Additionally, Wu et al (32) revealed that Hyp can treat acute

kidney injury by regulating oxidative stress and cell apoptosis.

These findings collectively support the potent antioxidant

therapeutic effects of Hyp.

The present study found that Hyp exhibits a notable

ability to alleviate oxidative stress. The results of DCFH-DA

staining to measure the intracellular ROS levels showed that the

fluorescence intensity of the cells was significantly reduced after

Hyp treatment, indicating that Hyp effectively decreased

intracellular ROS generation. Meanwhile, the detection of MDA

content showed that Hyp reduced the MDA levels, and the detection

of SOD activity indicated that Hyp enhanced SOD activity. This

further supported the role of Hyp in alleviating oxidative stress

from the perspectives of lipid peroxidation levels and the

antioxidant enzyme system. This ability to reduce oxidative stress

is of notable importance for protecting cells from oxidative

damage, especially for cell types such as BMSCs that have a key

role in bone metabolism, thereby providing a favorable

microenvironment for maintaining their normal osteogenic

differentiation ability.

Oxidative stress refers to a state in which the

body, when exposed to various harmful stimuli, produces an

excessive amount of highly reactive molecules such as ROS and

reactive nitrogen species, leading to an imbalance between the

oxidative system and the antioxidant system, and ultimately causing

damage to cells and tissues (33,34).

Excessive oxidative stress can cause a notable accumulation of ROS

within cells, inflicting damage on cellular DNA. DNA damage may

trigger cell cycle arrest, thereby preventing osteoblast precursor

cells from undergoing normal mitosis and differentiation. Severe

DNA damage can also lead to cell apoptosis, reducing the number of

osteoblasts and thus inhibiting osteogenic differentiation

(35). Therefore, enhancing the

antioxidant capacity and osteogenic differentiation ability of

BMSCs is an important research direction for the treatment of

OP.

The results of the present study indicated that Hyp

not only reduced oxidative stress but also had a significant

protective effect on the osteogenic differentiation ability of

BMSCs. In the ALP and ARS staining experiments, the ALP activity of

the Hyp-treated group was significantly enhanced, and the ARS

staining showed a significant increase in the number of calcium

nodules, which are important markers of enhanced osteogenic

differentiation. At the molecular level, RT-qPCR and western blot

analysis revealed that Hyp upregulated the expression of

osteogenic-related genes and proteins, such as Col1, Osterix,

Runx2 and Alp. This series of results clearly

demonstrated the positive role of Hyp in protecting and promoting

the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs. The mechanism of action of

Hyp may have involved reducing the interference of oxidative stress

on intracellular signal pathways, thus maintaining the normal

transduction of osteogenic differentiation-related signals,

enabling BMSCs to differentiate into osteoblasts in a relatively

stable environment and providing a strong cellular basis for bone

formation.

The PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, an important

intracellular signal transduction pathway, serves a central role in

the regulation of oxidative stress and OP, a concept that is widely

accepted in current research (29,36).

The activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway can alleviate

oxidative stress through various mechanisms, including upregulating

the expression of antioxidant enzyme genes, enhancing the synthesis

of intracellular antioxidant substances and inhibiting the activity

of enzymes related to ROS production, thus maintaining the

intracellular redox balance (37,38).

In terms of bone metabolism, the activation of the PI3K/AKT

signaling pathway can promote the proliferation, differentiation

and survival of osteoblasts, while inhibiting osteoclast activity,

thus preserving the normal process of bone remodeling and

regulating OP (39,40). For instance, Wu et al

(41) demonstrated that

7,8-dihydroxyflavone can inhibit oxidative stress and promote bone

formation by activating the tyrosine kinase receptor B/PI3K/AKT

pathway. This pathway enhances the viability and osteogenic

differentiation ability of BMSCs inhibited by

H2O2-induced oxidative stress, thereby

improving OP (28). Several other

natural compounds, such as luteolin and curcumin, have also been

reported to regulate bone metabolism through the PI3K/AKT pathway

(42,43). While luteolin similarly promotes

osteoblast differentiation via the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway,

evidence regarding its role in redox regulation remains limited

(29). Curcumin has been shown to

promote osteogenic differentiation in association with PI3K/AKT and

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) activation,

suggesting a role in both bone formation and antioxidative

responses (43).

By contrast, the present study showed that Hyp

exerted both antioxidative and osteogenic effects in a

PI3K/AKT-dependent manner, highlighting its dual-function

specificity and potential novelty. In the present study, Hyp

significantly activated the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Western

blot analysis revealed that Hyp treatment partially reversed the

H2O2-induced reduction in p-PI3K and p-AKT

levels, and immunohistochemical staining further supported the

upregulation of p-PI3K and p-AKT expression following Hyp

administration. These results suggested that Hyp exerted both

antioxidative and osteogenic effects at least in part through

PI3K/AKT pathway activation.

To validate the specificity of this signaling axis,

the present study employed LY294002, a classical PI3K inhibitor,

and showed that co-treatment with LY294002 significantly attenuated

the beneficial effects of Hyp. Specifically, the reduction of ROS

levels by Hyp, as evidenced by DCFH-DA staining, was partially

reversed by LY294002, indicating a decline in the antioxidative

efficacy of Hyp. Similarly, ALP staining, ALP activity and ARS

staining demonstrated that LY294002 co-treatment inhibited

Hyp-induced early- and late-stage osteogenesis. Western blot

analysis further supported that LY294002 significantly suppressed

the Hyp-induced upregulation of p-PI3K, p-AKT and key osteogenic

transcription factors, such as Runx2 and Osterix. These findings

collectively suggested that the PI3K/AKT pathway was not only

activated by Hyp but was also important for its antioxidative and

osteogenic actions. The use of LY294002 as a pathway-specific

inhibitor provided robust mechanistic evidence supporting the

notable role of PI3K/AKT in mediating the therapeutic effects of

Hyp. These results align with prior studies highlighting the

importance of this pathway in OP treatment and offer a more

comprehensive mechanistic understanding of the pharmacological

profile of Hyp (44,45).

In summary, the results of the present study

indicated that Hyp holds notable promise in the treatment of OP and

suggested that its mechanism of action was multifaceted. The

results indicated that Hyp promoted bone homeostasis through

multiple mechanisms, including mitigating oxidative stress,

preserving osteogenic differentiation capacity and activating the

PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. These findings provide a solid

theoretical basis for further development of Hyp-based therapeutic

strategies for OP.

However, the present study also had certain

limitations. Firstly, the present study was mainly based on cell

and animal experimental models. Although these models can provide

important information regarding the mechanism of Hyp action, the

physiological environment and disease state of the human body are

notably complex. The efficacy, safety and pharmacokinetic

characteristics of Hyp in humans remain to be verified through

further clinical studies. Secondly, although the present study has

preliminarily revealed the association between Hyp and the PI3K/AKT

signaling pathway, the upstream and downstream molecular regulatory

networks of this pathway, as well as its potential crosstalk with

other signaling pathways, remain insufficiently elucidated.

Notably, it remains to be fully elucidated whether Hyp directly

regulates other redox-sensitive pathways such as the ROS/Kelch-like

ECH-associated protein 1/Nrf2 axis, which serves a central role in

maintaining intracellular oxidative balance in bone-related cells.

Therefore, further in-depth studies using targeted molecular

approaches, such as pathway-specific inhibitors, activators or

genetic knockdown models, are necessary to comprehensively uncover

the mechanistic landscape of the biological activity of Hyp.

Thirdly, the present study did not evaluate serum calcium and

estrogen levels. Direct biochemical measurements would provide

stronger support for the pathophysiological relevance and treatment

efficacy of Hyp. Future investigations should incorporate these

assessments to strengthen the comprehensiveness and translational

relevance of findings.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Science and Technology

Projects for Social Development in Dongguan City (grant no.

20221800900102).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

LL and DX designed the study. LL and DX wrote the

manuscript. LL, HD and SZ performed animal experiments. LL and HD

carried out online data information collection. LL, HD, SZ and BW

performed the cell experiments. LL and DX performed the statistical

analysis. DX revised the manuscript. LL and DX confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal experimental procedures were approved by

the Animal Experiment Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated

Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (approval no.

GZTCMF1-202403241) and were performed in accordance with

institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of

laboratory animals. According to the ethics committee, the

commercially purchased mouse primary BMSCs used in the present

study did not require additional ethics approval.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Walker MD and Shane E: Postmenopausal

osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 389:1979–1991. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Tang SS, Yin XJ, Yu W, Cui L, Li ZX, Cui

LJ, Wang LH and Xia W: Prevalence of osteoporosis and related

factors in postmenopausal women aged 40 and above in China.

Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 43:509–516. 2022.(In Chinese).

PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

LeBoff MS, Greenspan SL, Insogna KL,

Lewiecki EM, Saag KG, Singer AJ and Siris ES: The clinician's guide

to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int.

33:2049–2102. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Cosman F, Langdahl B and Leder BZ:

Treatment sequence for osteoporosis. Endocr Pract. 30:490–496.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Eid A and Atlas J: The role of

bisphosphonates in medical oncology and their association with jaw

bone necrosis. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 26:231–237.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Chlebowski RT and Manson JE: Menopausal

hormone therapy and breast cancer. Cancer J. 28:169–175. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Cho L, Kaunitz AM, Faubion SS, Hayes SN,

Lau ES, Pristera N, Scott N, Shifren JL, Shufelt CL, Stuenkel CA,

et al: Rethinking menopausal hormone therapy: For whom, what, when,

and how long? Circulation. 147:597–610. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Luo J, Mills K, le Cessie S, Noordam R and

van Heemst D: Ageing, age-related diseases and oxidative stress:

What to do next? Ageing Res Rev. 57:1009822020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Iantomasi T, Romagnoli C, Palmini G,

Donati S, Falsetti I, Miglietta F, Aurilia C, Marini F, Giusti F

and Brandi ML: Oxidative stress and inflammation in osteoporosis:

Molecular mechanisms involved and the relationship with microRNAs.

Int J Mol Sci. 24:37722023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Marcucci G, Domazetovic V, Nediani C,

Ruzzolini J, Favre C and Brandi ML: Oxidative stress and natural

antioxidants in osteoporosis: Novel preventive and therapeutic

approaches. Antioxidants (Basel). 12:3732023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kimball JS, Johnson JP and Carlson DA:

Oxidative stress and osteoporosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am.

103:1451–1461. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Chen Y, Cai Y, Chen C, Li M, Lu L, Yu Z,

Wang S, Fang L and Xu S: Aroclor 1254 induced inhibitory effects on

osteoblast differentiation in murine MC3T3-E1 cells through

oxidative stress. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 13:9406242022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Tanaka M, Inoue H, Takahashi N and Uehara

M: AMPK negatively regulates RANKL-induced osteoclast

differentiation by controlling oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol

Med. 205:107–115. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhu C, Shen S, Zhang S, Huang M, Zhang L

and Chen X: Autophagy in bone remodeling: A regulator of oxidative

stress. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 13:8986342022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhao Q, Feng J, Liu F, Liang Q, Xie M,

Dong J, Zou Y, Ye J, Liu G, Cao Y, et al: Rhizoma Drynariae-derived

nanovesicles reverse osteoporosis by potentiating osteogenic

differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells via

targeting ERα signaling. Acta Pharm Sin B. 14:2210–2227. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Li B, Wang Y, Gong S, Yao W, Gao H, Liu M

and Wei M: Puerarin improves OVX-induced osteoporosis by regulating

phospholipid metabolism and biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids

based on serum metabolomics. Phytomedicine. 102:1541982022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Rao T, Tong H, Li J, Huang J, Yin Y and

Zhang J: Exploring the role and mechanism of hyperoside against

cardiomyocyte injury in mice with myocardial infarction based on

JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. Phytomedicine. 128:1553192024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhao K, Zhou F, Lu Y, Gao T, Wang R, Xie M

and Wang H: Hyperoside alleviates depressive-like behavior in

social defeat mice by mediating microglial polarization and

neuroinflammation via TRX1/NLRP1/Caspase-1 signal pathway. Int

Immunopharmacol. 145:1137312025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Chen Y, Dai F, He Y, Chen Q, Xia Q, Cheng

G, Lu Y and Zhang Q: Beneficial effects of hyperoside on bone

metabolism in ovariectomized mice. Biomed Pharmacother.

107:1175–1182. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Yan K, Zhang RK, Wang JX, Chen HF, Zhang

Y, Cheng F, Jiang Y, Wang M, Wu Z, Chen XG, et al: Using network

pharmacology and molecular docking technology, proteomics and

experiments were used to verify the effect of Yigu decoction (YGD)

on the expression of key genes in osteoporotic mice. Ann Med.

57:24492252025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yang PH, Wei YN, Xiao BJ, Li SY, Li XL,

Yang LJ, Pan HF and Chen GX: Curcumin for gastric cancer: Mechanism

prediction via network pharmacology, docking, and in vitro

experiments. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 16:3635–3650. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Benisch P, Schilling T, Klein-Hitpass L,

Frey SP, Seefried L, Raaijmakers N, Krug M, Regensburger M, Zeck S,

Schinke T, et al: The transcriptional profile of mesenchymal stem

cell populations in primary osteoporosis is distinct and shows

overexpression of osteogenic inhibitors. PLoS One. 7:e451422012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

van de Peppel J, Strini T, Tilburg J,

Westerhoff H, van Wijnen AJ and van Leeuwen JP: Identification of

three early phases of cell-fate determination during osteogenic and

adipogenic differentiation by transcription factor dynamics. Stem

Cell Reports. 8:947–960. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhang C, Li H, Li J, Hu J, Yang K and Tao

L: Oxidative stress: A common pathological state in a high-risk

population for osteoporosis. Biomed Pharmacother. 163:1148342023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Karthik V and Guntur AR: Energy metabolism

of osteocytes. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 19:444–451. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Shinohara I, Morita M, Chow SK, Murayama

M, Sususki Y, Gao Q and Goodman SB: Pathophysiology of the effects

of oxidative stress on the skeletal system. J Orthop Res.

43:1059–1072. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Li D, Zhao Z, Zhu L, Feng H, Song J, Fu J,

Li J, Chen Z and Fu H: 7,8-DHF inhibits BMSC oxidative stress via

the TRKB/PI3K/AKT/NRF2 pathway to improve symptoms of

postmenopausal osteoporosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 223:413–429.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chai S, Yang Y, Wei L, Cao Y, Ma J, Zheng

X, Teng J and Qin N: Luteolin rescues postmenopausal osteoporosis

elicited by OVX through alleviating osteoblast pyroptosis via

activating PI3K-AKT signaling. Phytomedicine. 128:1555162024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Jang E: Hyperoside as a potential natural

product targeting oxidative stress in liver diseases. Antioxidants

(Basel). 11:14372022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ku SK, Zhou W, Lee W, Han MS, Na M and Bae

JS: Anti-inflammatory effects of hyperoside in human endothelial

cells and in mice. Inflammation. 38:784–799. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wu L, Li Q, Liu S, An X, Huang Z, Zhang B,

Yuan Y and Xing C: Protective effect of hyperoside against renal

ischemia-reperfusion injury via modulating mitochondrial fission,

oxidative stress, and apoptosis. Free Radic Res. 53:727–736. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Lennicke C and Cocheme HM: Redox

metabolism: ROS as specific molecular regulators of cell signaling

and function. Mol Cell. 81:3691–3707. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Gebicki JM: Oxidative stress, free

radicals and protein peroxides. Arch Biochem Biophys. 595:33–39.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Jomova K, Raptova R, Alomar SY, Alwasel

SH, Nepovimova E, Kuca K and Valko M: Reactive oxygen species,

toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: chronic diseases and

aging. Arch Toxicol. 97:2499–2574. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Ren BC, Zhang YF, Liu SS, Cheng XJ, Yang

X, Cui XG, Zhao XR, Zhao H, Hao MF, Li MD, et al: Curcumin

alleviates oxidative stress and inhibits apoptosis in diabetic

cardiomyopathy via Sirt1-Foxo1 and PI3K-Akt signalling pathways. J

Cell Mol Med. 24:12355–12367. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Deng S, Dai G, Chen S, Nie Z, Zhou J, Fang

H and Peng H: Dexamethasone induces osteoblast apoptosis through

ROS-PI3K/AKT/GSK3β signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother.

110:602–608. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Wei L, Chen W, Huang L, Wang H, Su Y,

Liang J, Lian H, Xu J, Zhao J and Liu Q: Alpinetin ameliorates bone

loss in LPS-induced inflammation osteolysis via ROS mediated

P38/PI3K signaling pathway. Pharmacol Res. 184:1064002022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Xin L, Feng HC and Zhang Q, Cen XL, Huang

RR, Tan GY and Zhang Q: Exploring the osteogenic effects of simiao

wan through activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway in osteoblasts. J

Ethnopharmacol. 338:1190232025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Wang D, Liu Y, Tang D, Wei S, Sun J, Ruan

L, He L, Li R, Ren Q, Tian X and Chen Y: Induction of

PI3K/Akt-mediated apoptosis in osteoclasts is a key approach for

buxue tongluo pills to treat osteonecrosis of the femoral head.

Front Pharmacol. 12:7299092021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Wu CH, Hung TH, Chen CC, Ke CH, Lee CY,

Wang PY and Chen SF: Post-injury treatment with

7,8-dihydroxyflavone, a TrkB receptor agonist, protects against

experimental traumatic brain injury via PI3K/Akt signaling. PLoS

One. 9:e1133972014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Liang G, Zhao J, Dou Y, Yang Y, Zhao D,

Zhou Z, Zhang R, Yang W and Zeng L: Mechanism and experimental

verification of luteolin for the treatment of osteoporosis based on

network pharmacology. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 13:8666412022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Xiong Y, Zhao B, Zhang W, Jia L, Zhang Y

and Xu X: Curcumin promotes osteogenic differentiation of

periodontal ligament stem cells through the PI3K/AKT/Nrf2 signaling

pathway. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 23:954–960. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Lu J, Shi X, Fu Q, Han Y, Zhu L, Zhou Z,

Li Y and Lu N: New mechanistic understanding of osteoclast

differentiation and bone resorption mediated by P2X7 receptors and

PI3K-Akt-GSK3beta signaling. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 29:1002024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Jiang Z, Deng L, Li M, Alonge E and Wang Y

and Wang Y: Ginsenoside Rg1 modulates PI3K/AKT pathway for enhanced

osteogenesis via GPER. Phytomedicine. 124:1552842024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|