Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a serious

progressive disorder and a major public health concern, with a

global prevalence of 8–14%, affecting an estimated 700–840 million

individuals worldwide (1–3). The disease typically manifests with

subtle symptoms in its early stages. However, as it progresses,

patients experience a gradual deterioration of kidney function,

which establishes it as the third most rapidly increasing cause of

mortality globally. In parallel, the economic burden of CKD has

increased markedly (4).

CKD is a multifactorial chronic condition

characterized by structural damage and dysfunction of the kidney

(5). The renal unit is the

fundamental structural and functional unit of the kidney,

comprising two principal components: The glomerulus and the renal

tubule. The key factors accelerating CKD progression include the

loss of renal units, chronic inflammation, myofibroblast activation

and extracellular matrix deposition (6). In addition, mitochondrial dysfunction

and the disruption of cellular redox homeostasis play important

roles in CKD pathogenesis (7).

The treatment of CKD involves lifestyle

modifications and pharmacological interventions. Standard

treatments include renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors,

sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and glucagon-like

peptide-1 receptor agonists. However, these medications have

limited clinical efficacy in preventing disease progression

(8,9). Therefore, the development of drugs

targeting mitochondrial dysfunction and redox imbalance may be of

considerable value for the improvement of CKD outcomes.

The primary function of mitochondria is adenosine

triphosphate (ATP) synthesis, which is essential for the

maintenance of various cellular functions and the regulation of

critical processes, including cell growth, senescence and

apoptosis. Impairment of this crucial function substantially

affects renal physiology, contributing to the development of renal

diseases (10). The kidney is

among the most mitochondria-rich organs and is highly vulnerable to

mitochondrial damage. Such damage compromises ATP production,

causes cellular energy deficiency, and ultimately results in

tubular epithelial cell atrophy or dedifferentiation (11).

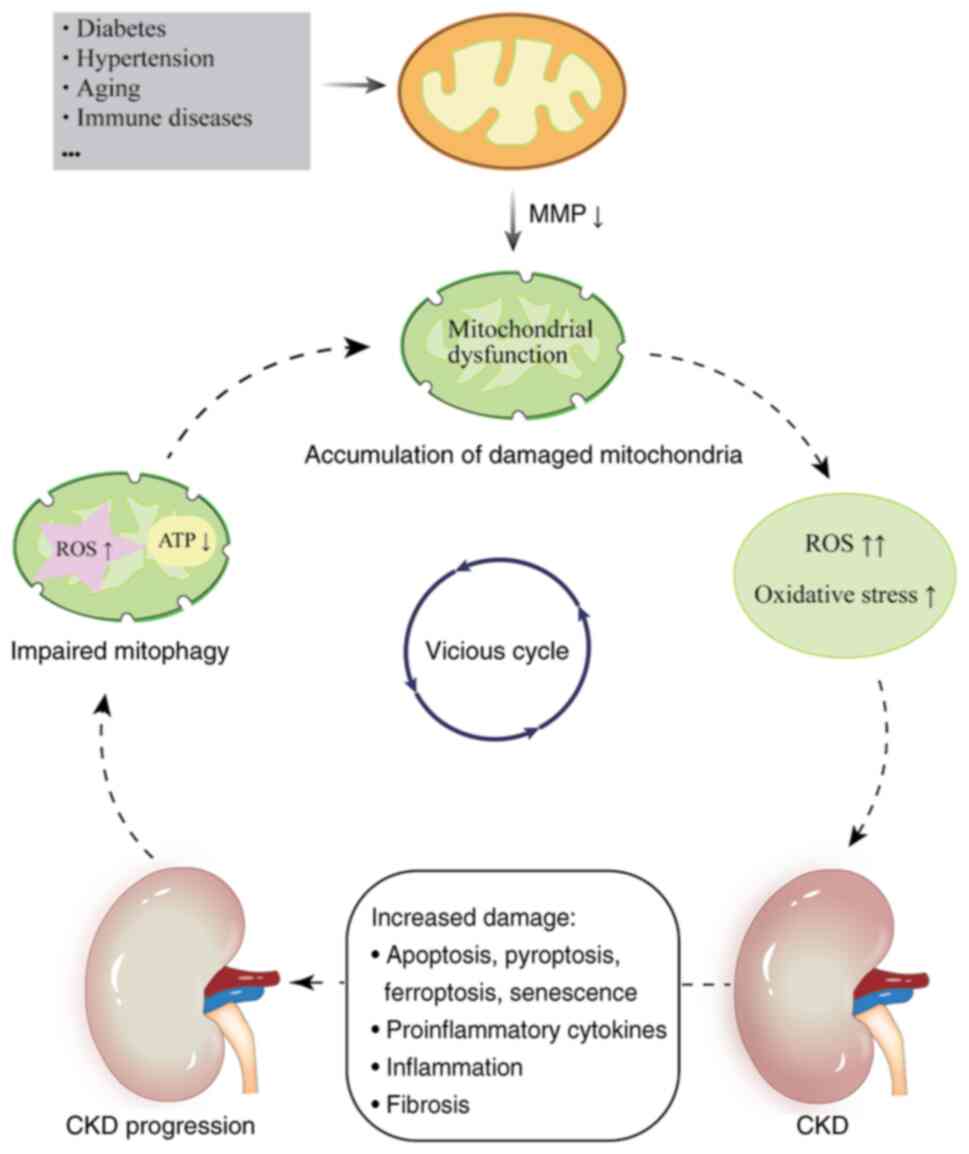

Damaged mitochondria undergo depolarization, which

results in a reduction of the mitochondrial membrane potential

(MMP) (12). Several mechanisms,

including abnormalities in mitochondrial dynamics, mutations in

nuclear or mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), nutrient deficiencies and

bursts of reactive oxygen species (ROS), contribute to CKD

progression, as do certain systemic conditions, such as diabetes,

hypertension, aging and immune diseases (13). Mitochondrial dysfunction disrupts

multiple cellular processes, leading to increased oxidative stress,

chronic inflammation and fibrosis. It also triggers renal

epithelial cell death and promotes microvascular damage, which

collectively impair kidney function (14). Mitochondrial homeostasis and

function are critically dependent on tightly regulated

mitochondrial dynamics (15).

Disruption of these dynamics may reduce the activity of the

mitochondrial respiratory chain complex, diminish ATP generation

and increase mitochondrial ROS (mROS) levels, thereby inducing

oxidative damage (16).

Beyond their role as energy producers, mitochondria

serve as critical regulators of immunity (17). Elevated ROS levels directly induce

oxidative damage in mitochondria via the activation of

proinflammatory signaling molecules, including Toll-like receptors

and the NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, thereby

contributing to renal injury (18). Mitochondrial dysfunction regulates

multiple programmed pathways, including apoptosis, pyroptosis and

ferroptosis, thereby promoting tubular cell loss, inflammation and

kidney dysfunction. Apoptosis is the predominant mechanism of cell

death in renal tubular epithelial cells (RTECs) and podocytes

(11). In addition, mitochondrial

dysfunction promotes cellular senescence and influences the

downstream senescence-associated phenotype (19). Senescent RTECs lose their capacity

for self-repair and secrete proinflammatory cytokines, the

continuous accumulation of which substantially contributes to CKD

progression (20) (Fig. 1).

Mitochondria play a key role in essential cellular

processes, including the tricarboxylic acid cycle, electron

transport system, fatty acid β-oxidation and calcium homeostasis.

These activities inherently lead to ROS generation (21). At physiological levels, ROS

function as signaling molecules in various signaling pathways,

while high levels are toxic to mitochondria and cells (22). Elevated ROS activate multiple

inflammatory factors, and excessive inflammation promotes further

ROS production, creating a mutually reinforcing cycle that

accelerates CKD progression (23).

Oxidative stress results from an imbalance in redox homeostasis

between oxidative and antioxidant systems, which adversely affects

all renal components (24). A

primary source of oxidative stress is the overproduction of

strongly oxidizing free radicals, such as ROS and reactive nitrogen

species. Mitochondria serve as predominant intracellular producers

of ROS and as one of their main targets, making them important in

oxidative injury (25). Under

oxidative stress conditions, ROS activate mitophagy, a process that

removes damaged or excessive mitochondria. This helps to reduce

further ROS production, thereby mitigating oxidative stress and

safeguarding cellular components against oxidative injury (26). Although oxidative stress, mitophagy

and ROS have been studied in the context of renal diseases, their

interdependent roles in modulating the progression of CKD are not

fully understood. By synthesizing current evidence, the present

review aims to offer novel insights into the pathophysiological

crosstalk among these mechanisms and to explore promising

therapeutic strategies targeting these processes to ameliorate

CKD.

Mitophagy: An overview

Definition of mitophagy

As the ‘power station’ of the cell, mitochondria

orchestrate multiple intracellular signaling pathways,

participating in amino acid metabolism, pyridine nucleotide

synthesis and phospholipid modifications, which collectively

influence cell survival, senescence and death (27,28).

Mitochondria are dynamic organelles with a high degree of

plasticity, and this adaptability is encompassed by the concept of

mitochondrial dynamics. Mitochondria continuously undergo

coordinated cycles of biogenesis, fusion, fission and autophagy.

Mitophagy is a selective form of autophagy that eliminates damaged

or superfluous mitochondria. These processes determine the

morphology, quality, quantity, distribution and function of

mitochondria within cells (29).

The primary structural components of mitochondria are the outer

mitochondrial membrane (OMM), inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM)

and intermembrane space (IMS). The IMM surrounds the mitochondrial

matrix and folds into invaginated cristae, markedly increasing the

surface area of IMM, thereby efficiently generating ATP (28). The key mediators of mitophagy are

PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1), Parkin and ubiquitin chains, which

promote the engulfment of damaged mitochondria by autophagosomes

for lysosomal degradation (30).

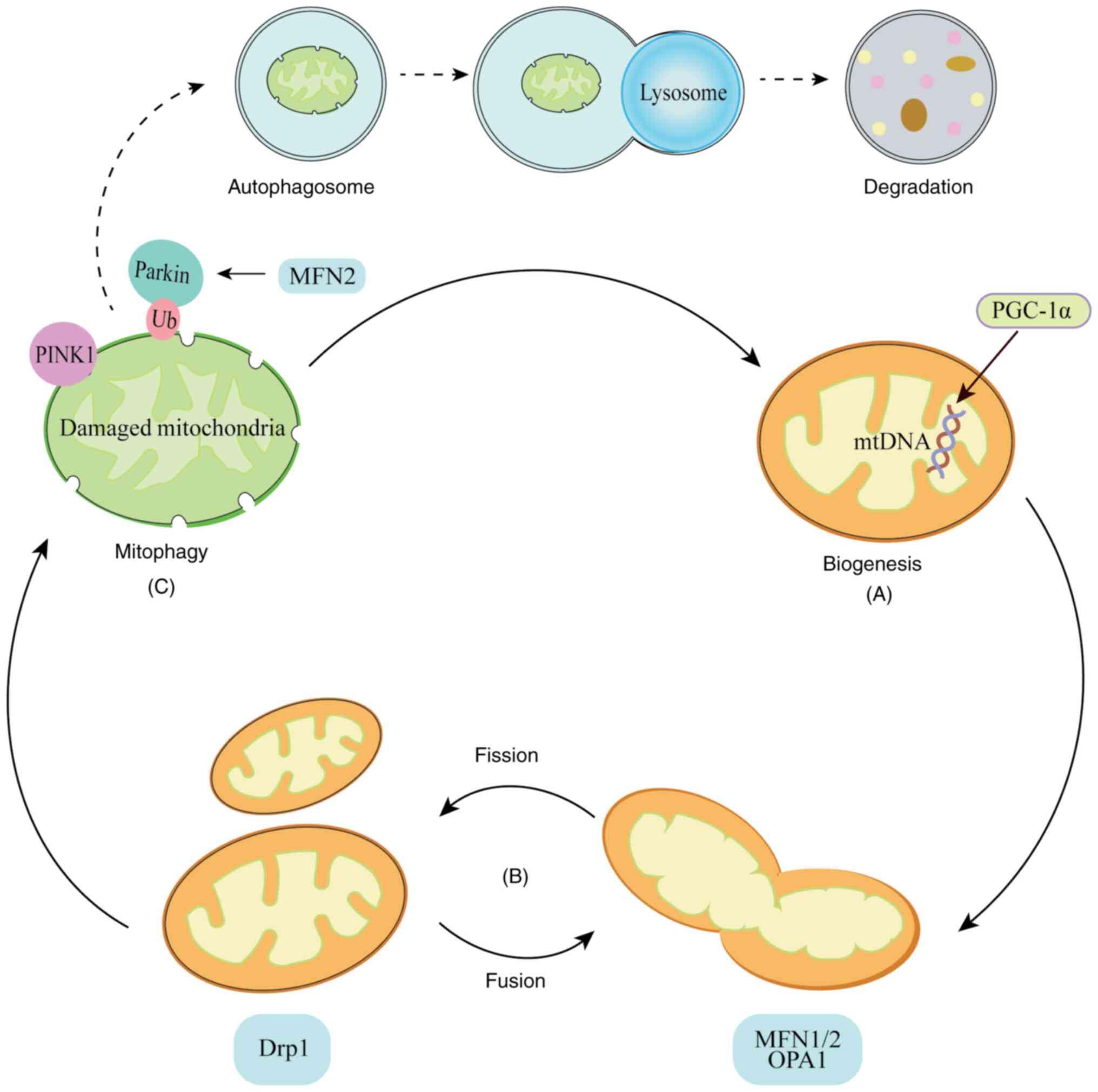

By contrast, mitochondrial biogenesis, a complex biological process

essential for mitochondrial self-renewal, is primarily regulated by

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-g coactivator-1 a; this

process protects mtDNA and promotes dynamic cellular homeostasis

(31). Mitochondrial fusion is

mediated by mitofusin 1 or 2 (MFN1/2) and optic atrophy protein 1.

This fusion process involves the merging of the OMM and IMM from

adjacent mitochondria to create an enlarged organelle.

Dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) is the primary regulator of

mitochondrial fission, a process in which the OMM and IMM of a

single mitochondrion are constricted and divided to produce two

daughter mitochondria (32).

Notably, MFN2 functions as a mitochondrial fusion protein in its

non-phosphorylated state, whereas PINK1-mediated phosphorylation

converts MFN2 into a key mediator of the translocation of Parkin to

damaged mitochondria (30).

Mitochondrial fusion is a process of repair and renewal for the

retention of mitochondria, whereas mitophagy ensures the removal of

irreparably damaged mitochondria. Therefore, mitophagy, rather than

mitochondrial fission, is considered the biological antithesis of

mitochondrial fusion (33). The

aforementioned processes of mitochondrial dynamics do not function

independently; they are tightly interconnected and dynamically

regulated as adaptations to cellular life activities. This

integrated network of mitochondrial dynamics is essential for

mitochondrial-cellular interactions and homeostasis (Fig. 2).

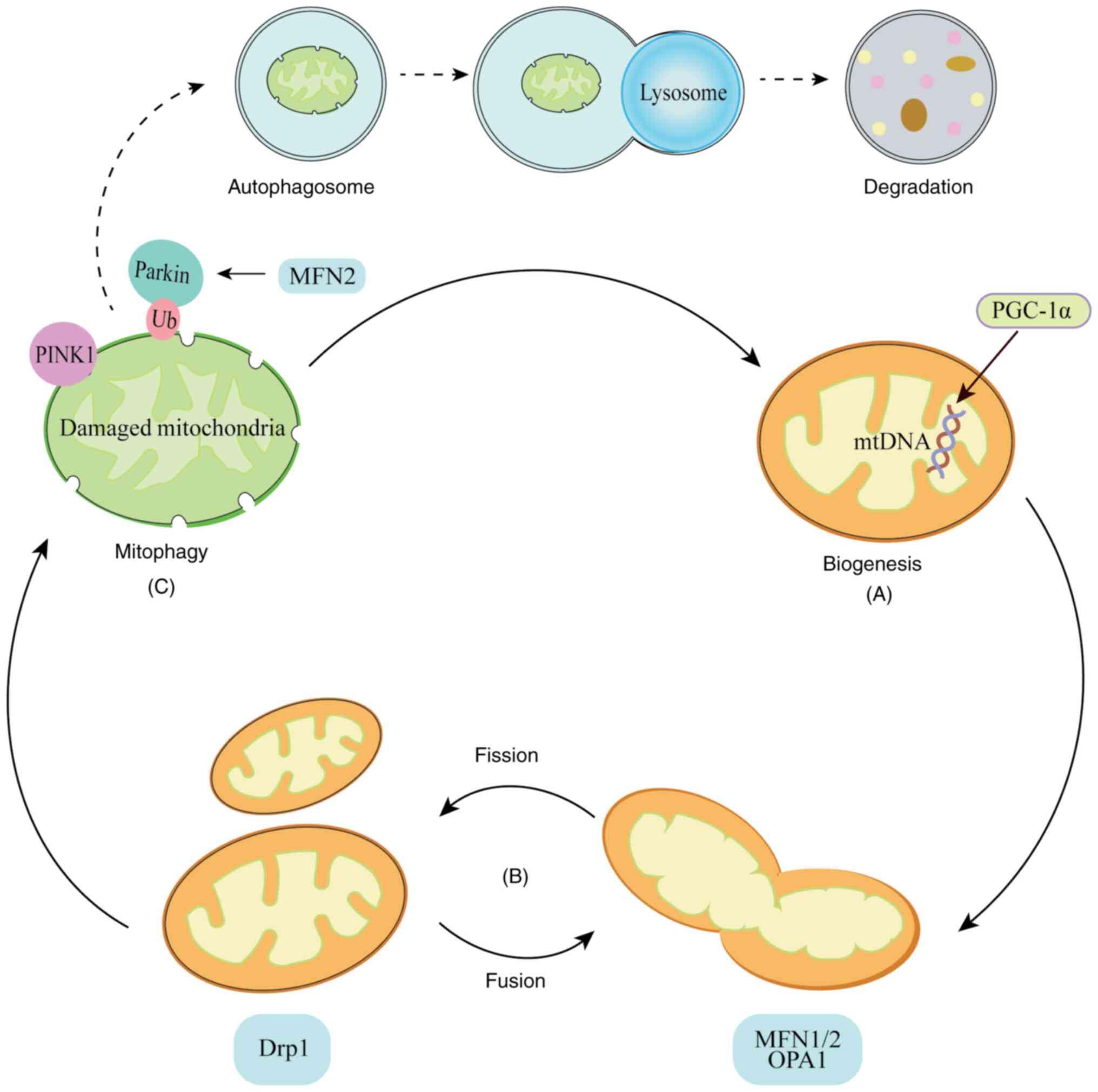

| Figure 2.Schematic diagram of mitochondrial

dynamics. (A) Mitochondrial biogenesis. PGC-1α is a master

regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, which controls mitochondrial

self-renewal and protects mtDNA. (B) Mitochondrial fission and

fusion. Fission is mainly mediated by Drp1, which severs the outer

and inner mitochondrial membranes, resulting in division of the

organelle into two daughter mitochondria. The primary mediators of

mitochondrial fusion are MFN1, MFN2 and OPA1. (C) Mitophagy.

Autophagosomes engulf the damaged mitochondria, which are targeted

by PINK, Parkin and Ub, and then delivered to lysosomes for

degradation. MFN2 promotes the translocation of Parkin to damaged

mitochondria when it is phosphorylated by PINK1. PGC-1α, peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α; mtDNA,

mitochondrial DNA; Drp1, dynamin-related protein l; MFN1/2,

mitofusin 1/2; OPA1, optic atrophy protein l; PINK1, PTEN-induced

kinase 1; Ub, ubiquitin. |

Autophagic processes can be categorized into three

forms: Macroautophagy, microautophagy and chaperone-mediated

autophagy (34). In the present

review, the term autophagy refers specifically to macroautophagy,

the most extensively studied form. In this process, cargo proteins

are sequestered within a double-membraned autophagosome, either

non-selectively, termed bulk autophagy, or through the precise

elimination of specific cellular components, termed selective

autophagy. Subsequently, the autophagosome is transported to the

lysosomal compartment for degradation and recirculation of its

contents. This process plays a crucial role in the maintenance of

cellular and organismal homeostasis via a complex molecular pathway

(35).

Under several pathological conditions, including

elevated ROS levels, nutrient deficiencies and cellular senescence,

intracellular mitochondria may undergo depolarization, a feature of

mitochondrial dysfunction. To eliminate dysfunctional or excess

mitochondria and maintain intracellular homeostasis, mitophagy is

initiated as a cytoprotective mechanism. As discussed above,

mitophagy is a selective form of autophagy in which impaired

mitochondria are translocated to the lysosomal compartment, where

they undergo degradation. This prevents the accumulation of

dysfunctional mitochondria and downstream molecular events that

lead to disease progression, including oxidative stress (36).

Molecular mechanisms of mitophagy

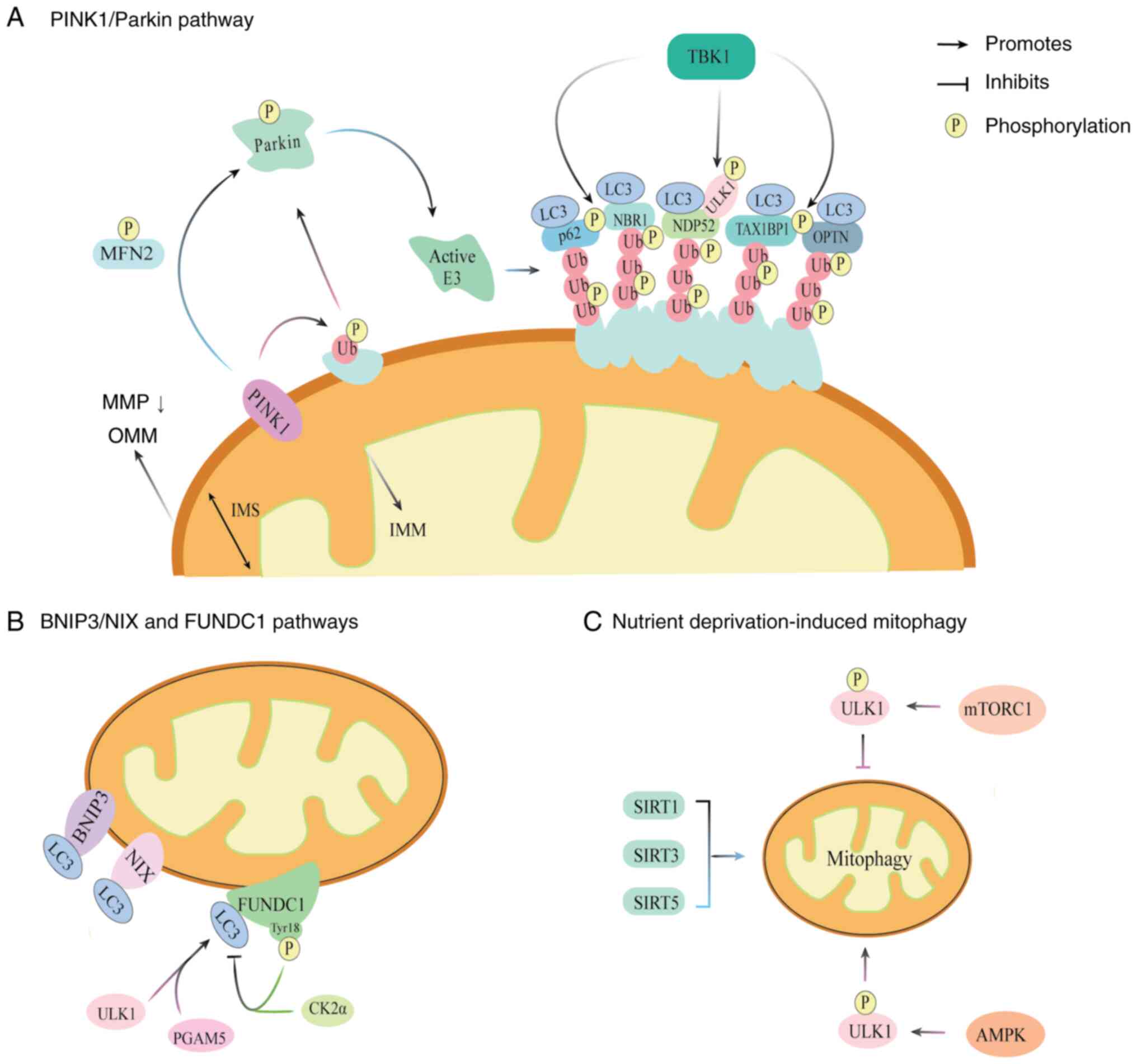

PINK1/Parkin pathway

In 2008, Narendra et al (37) discovered that Parkin, an E3

ubiquitin ligase, is involved in mitochondrial depolarization and

recruited to accelerate mitochondrial autophagic degradation.

Subsequent studies identified key mitophagy receptors involved in

this process, including sequestosome 1 (also known as p62),

optineurin (OPTN) and nuclear dot protein 52 (NDP52) (36). Parkin, encoded by PRKN, functions

in conjunction with PINK1, a mitochondrial-targeted serine kinase.

Upon mitochondrial depolarization, Parkin is recruited to scavenge

damaged mitochondria and promote mitophagy. This finding is

considered a landmark discovery in mitophagy research (38). The PINK1/Parkin pathway is the most

extensively studied mechanism of mitophagy, and comprises three

main components: PINK1 as the mitochondrial damage sensor, Parkin

as the signal amplifier and ubiquitin chains as the signal

effectors (39). Upon

mitochondrial damage, PINK1 accumulates at the OMM and

phosphorylates ubiquitin. This phosphorylated ubiquitin activates

Parkin, which subsequently adds more ubiquitin chains to OMM

proteins. These chains serve as labels for autophagy receptors in

damaged mitochondria, thereby triggering selective autophagy

(40) (Fig. 3).

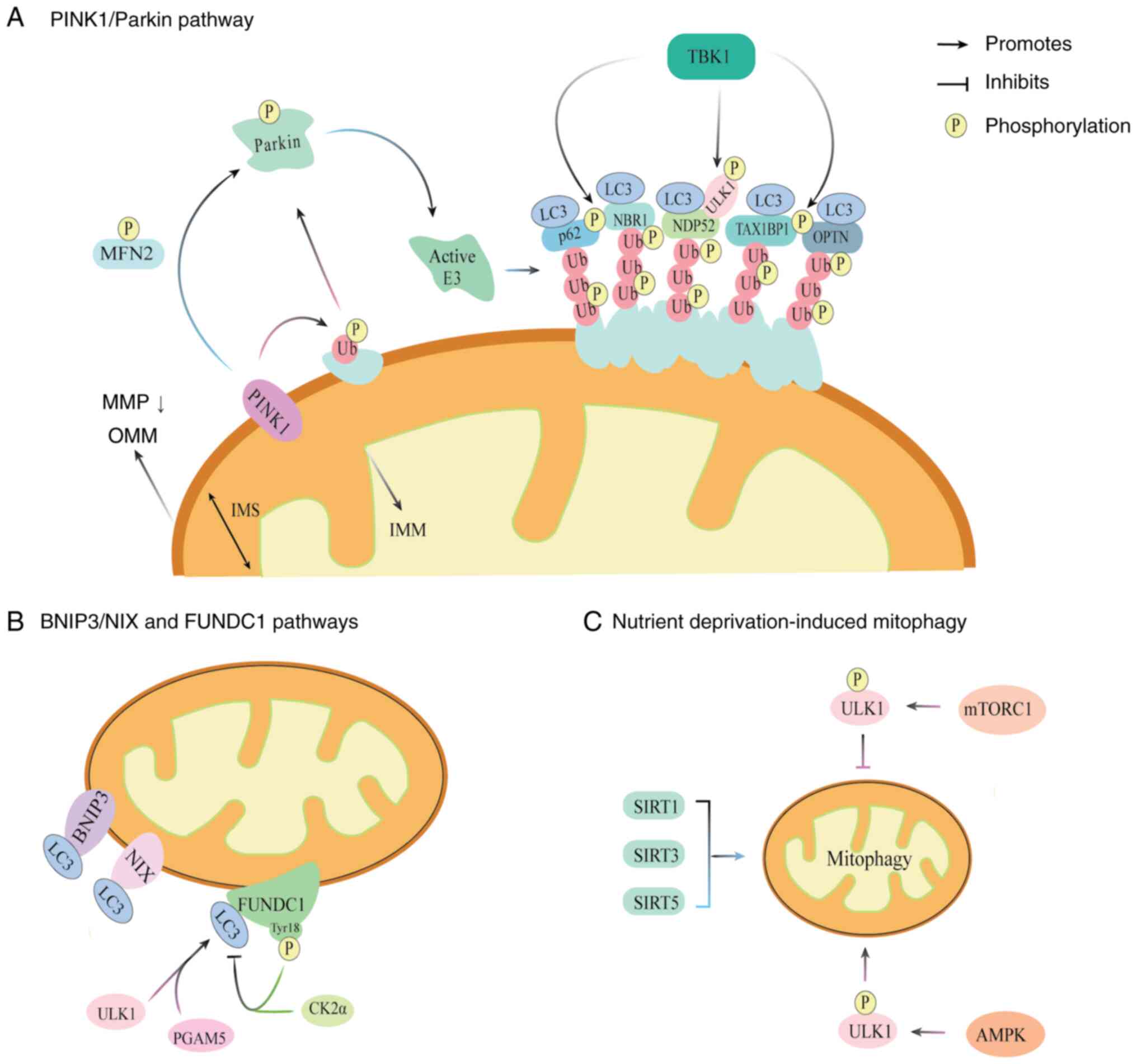

| Figure 3.Molecular mechanisms of mitophagy.

(A) PINK1/Parkin pathway. Among the various mitophagy pathways, the

PINK1/Parkin pathway is the most well-characterized. Loss of MMP

causes PINK1 to accumulate on the OMM of the depolarized

mitochondria. and the recruitment of Parkin. PINK1 phosphorylates

Ub and Parkin, which converts Parkin into an active E3 Ub ligase.

PINK1 also phosphorylates MFN2, further promoting the recruitment

of Parkin to damaged mitochondria. Ub chains are tethered to

autophagy receptors, including p62, NBR1, NDP52, TAX1BP1 and OPTN,

that interact with LC3 on the autophagosome. NDP52 also binds to

the ULK1 complex, a process that is facilitated by the

TBK1-mediated phosphorylation of autophagy receptors. (B) BNIP3/NIX

and FUNDC1 pathways. The receptors BNIP3, NIX and FUNDC1 bind to

LC3, to induce mitophagy. Phosphorylation of the Tyr18 residue of

FUNDC1 by CK2α weakens the binding between LC3 and FUNDC1. By

contract, PGAM5 and ULK1 enhance the interaction of FUNDC1 with LC3

to promote mitophagy. (C) Nutrient deprivation-induced mitophagy.

Mitophagy induced by nutrient deprivation is primarily regulated by

mTOR, AMPK and SIRTs. Active mTORC1 suppresses mitophagy by

phosphorylating ULK1 while AMPK directly activates ULK1 through

phosphorylation. SIRT1, SIRT3 and SIRT5 have been shown to promote

mitophagy in animal models. PINK1, PTEN induced kinase l; MMP,

mitochondrial membrane potential; OMM, outer mitochondrial

membrane; Ub, ubiquitin; MFN2, mitofusin 2; p62, sequestosome 1;

NBR1, neighbor of BRCA1 gene l; NDP52, nuclear dot protein 52;

TAX1BP1, T-cell leukemia virus type I binding protein 1; OPTN,

optineurin; LC3, microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3;

ULK1, Unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase l; TBK1, TANK-binding

kinase 1; IMM, inner mitochondrial membrane; IMS, intermembrane

space; BNIP3, BCL2 interacting protein 3; NIX, Nip3-like protein X;

FUNDC1, FUN14 domain-containing protein l; Tyr18, tyrosine 18;

CK2α, casein kinase 2α; PGAM5, phosphoglycerate mutase family

member 5; mTOR, serine/threonine protein kinase mammalian target of

rapamycin; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; SIRT, sirtuin

mTORC1, mTOR complex 1. |

PINK1 acts as a mitochondrial damage sensor. Its

levels on mitochondria are regulated by voltage-dependent

proteolysis, which ensures low expression on healthy, polarized

mitochondria (41). PINK1

functions upstream of Parkin translocation and Parkin-mediated

mitophagy. In dysfunctional mitochondria with low MMP, the

selective accumulation of PINK1 on the OMM recruits Parkin, which

initiates a series of degradation processes to clear the damaged

mitochondria (41). The

translocase of the outer membrane (TOM) complex, a multimeric

protein assembly at the OMM, mediates the mitochondrial targeting

of PINK1 (42). Under

physiological conditions, TOM20 recognizes the mitochondrial

targeting sequence of PINK1 and facilitates its import into the

TOM40-formed translocation pore, with assistance from TOM22 and

TOM70. PINK1 is ultimately delivered to the translocase of inner

mitochondria membrane 23 complex at the IMM (43). Once inside, PINK1 undergoes

sequential cleavage by mitochondrial processing peptidase and

presenilin-associated rhomboid-like, followed by ubiquitin

proteasome system-mediated degradation via the N-end rule pathway

(44,45). Due to a steady balance between

PINK1 import and degradation, healthy mitochondria maintain an

extremely low or undetectable level of PINK1 accumulation (46). However, mitochondrial dysfunction,

such as the loss of MMP induced by mtDNA mutations, mitochondrial

depolarization, protein misfolding and increased ROS production,

impairs the degradation process, resulting in the accumulation of

PINK1 on the depolarized OMM and Parkin recruitment (47). PINK1 also phosphorylates MFN2,

Parkin and ubiquitin, leading to further Parkin activation

(48).

Parkin, a signal amplifier in mitophagy and a member

of the RING-between-RING E3 ligase family, participates in the

ubiquitin-mediated degradation and trafficking of proteins. It

includes a C-terminal ubiquitin ligase domain and an N-terminal

ubiquitin-like (UBL) domain (49).

In healthy mitochondria, Parkin remains in an inactive conformation

as a self-inhibiting dormant enzyme in the cytosolic compartment.

Following mitochondrial damage, PINK1 accumulates on the OMM and

phosphorylates the serine (Ser)65 residue of ubiquitin, even when

present at low levels (50).

Parkin is activated by two key steps. First, its UBL domain is

phosphorylated at Ser65 by PINK1 kinase. Second, it binds to

phosphorylated ubiquitin, These modifications induce substantial

conformational changes, wherein the ubiquitin-E2 binding site of

Parkin is repositioned on the RING1 domain proximal to the cysteine

(Cys)431 acceptor site on the RING2 domain. This structural

remodeling transforms Parkin into an active E3 ligase (51). Activated Parkin ubiquitinates

various OMM proteins, which are subsequently phosphorylated by

PINK1 to form phospho-ubiquitin chains that recruit autophagy

receptors to induce mitophagy (52). At present, ubiquitin and the UBL

domain of Parkin are the only known direct substrates of PINK1

(53).

Ubiquitin chains function as signal effectors in

autophagy. When these chains are attached to OMM proteins, they are

recognized by autophagy receptors, which mediate the encapsulation

of damaged mitochondria into autophagosomes for lysosomal

degradation. The ubiquitin chains also stimulate PINK1 kinase

activity, creating an efficient feedforward loop that ensures

effective mitophagy (46). Lazarou

et al (40) demonstrated

that p62 and neighbor of BRCA1 gene 1 (NBR1) are not essential for

Parkin-mediated mitophagy. Instead, OPTN and NDP52 are the primary,

yet redundant receptors in this pathway. Knockout of NDP52 or OPTN

alone causes no defect in mitophagy. Since ubiquitin chains cannot

directly bind to autophagic membranes or their associated

autophagy-related protein 8 (ATG8) family proteins, molecular

bridges are required to physically connect them (54). The ATG8 autophagy-related

ubiquitin-like protein family includes microtubule-associated

protein 1 light chain 3 (MAP1LC3, most commonly referred to as LC3)

and γ-aminobutyric acid receptor-associated protein (GABARAP)

subfamilies (55). LC3 shows

binding affinity for multiple proteins containing a LC3-interacting

region (LIR) motif, which marks ubiquitinated protein aggregates

and binds to LC3 to facilitate autophagosome recruitment (56). These receptors contain a

ubiquitin-binding domain to recognize ubiquitin-labeled

mitochondria and a LIR motif to interact with ATG8 family proteins,

forming a functional bridge between damaged mitochondria and the

autophagic structures (57).

Among selective autophagy receptors, p62 was the

first to be identified as playing an important role in

Parkin-mediated mitophagy. Its accumulation at

polyubiquitin-positive mitochondrial clusters is dependent on

Parkin (36). For effective

degradation, cargo proteins must be clustered into discrete

compartments to enable their encapsulation by autophagosomes. p62

promotes this in vivo by forming droplets in which ubiquitin

chains are sequestered, thereby mediating the concentration of

autophagic cargo proteins and facilitating association with LC3 for

delivery to lysosomes (58). While

early research (59) indicated

that deletion of p62 completely blocked the final clearance of

damaged mitochondria, Lazarou et al (40) later demonstrated that p62 is

dispensable for Parkin-mediated mitophagy. NBR1 is an autophagy

receptor that is structurally similar to p62 and assists p62 in

this process (60). The Kelch-like

ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1)-NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)

system is essential for protection against oxidative and

electrophilic insults (61). p62

directly interacts with Keap1 and competitively inhibits the

Keap1-Nrf2 interaction, which stabilizes Nrf2 and promotes its

accumulation in the nucleus. The nuclear accumulation of Nrf2

activates the transcription of numerous cytoprotective genes,

including antioxidants (61,62).

NBR1 is stress-inducible and indispensable for activation of the

p62-Keap1-Nrf2 system (63). It

induces the phase separation of p62, thereby enhancing the

formation of p62 liquid droplets, while Nrf2 increases p62

transcription, establishing a positive feedback loop that

continuously regulates p62 levels (63). The ATG8-binding capacity of NDP52

and OPTN is weaker than that of p62 and NBR1 (40). OPTN consists of several structural

domains, including two coiled-coil (CC) domains, a leucine zipper,

an LIR, a ubiquitin-binding domain and a zinc finger (ZF) domain

(64). The accumulation of

ubiquitin chains on damaged mitochondria triggers the activation of

TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1), which physically associates with p62,

OPTN and NDP52, and phosphorylates sites in the ubiquitin-binding

domain of p62 and residues of OPTN neighboring the LIR motifs,

thereby strengthening the ability of p62 and OPTN to interact with

LC3 (65,66). NDP52 is a multi-domain autophagy

receptor, with a N-terminal SKIP carboxyl homology (SKICH) domain,

central CC region and C-terminal ZF ubiquitin-binding domain

(67). The SKICH domain binds to

the Unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1 (ULK1) complex

subunit RB1-inducible coiled-coil protein 1, also known as FAK

family kinase-interacting protein of 200 kDa (FIP200), thereby

activating cargo recruitment and autophagosome formation. TBK1

facilitates NDP52-ULK1 complex formation, further supporting the

activation of mitophagy (68).

Notably in addition to the four aforementioned

receptors, there is a fifth autophagy receptor, human T-cell

leukemia virus type I binding protein 1 (TAX1BP1), which is a

paralog of NDP52 (53). Both NDP52

and TAX1BP1 have an atypical C-LIR motif located between the SKICH

and CC domains. The atypical C-LIR motif in NDP52 preferentially

binds with LC3C (69). Following

OMM protein ubiquitination, TAX1BP1 is recruited to damaged

mitochondria, where it interacts with LC3 via its LIR motif to

initiate autophagosome formation and mitochondrial clearance

(70). It has been revealed that

TAX1BP1 and NBR1 colocalize, with TAX1BP1 serving as a critical

organizer that directs the recruitment of upstream autophagy

factors, including FIP200 and TBK1, to form autophagosomes around

NBR1-marked cargo. Via these interactions, TAX1BP1 helps to tether

ubiquitinated mitochondria to autophagic membranes via LC3, thereby

ensuring efficient degradation (71).

BCL2 interacting protein 3

(BNIP3)/Nip3-like protein X (NIX) pathway

A secondary mitophagy mechanism, regulated by the

expression thresholds of BNIP3 and NIX (also known as BNIP3 like),

is known to contribute substantially to mitophagy across multiple

tissues (72). Unlike other BCL2

family members, BNIP3 and NIX contain a divergent BH3 domain that

is not essential for inducing apoptosis (73).

BNIP3 is an OMM protein consisting of a large

N-terminal region containing an LIR motif and a characteristic

C-terminal transmembrane (TM) domain (74). Bruick (75) identified that BNIP3 acts as a

hypoxia-responsive gene. Under hypoxic conditions, BNIP3 promotes

mitophagy by triggering mitochondrial depolarization (76). BNIP3 also interacts with PINK1 to

enhance the accumulation of full-length PINK1 on the OMM, whereas

the inhibition of BNIP3 promotes PINK1 proteolytic processing and

suppresses PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy (77). In addition, BNIP3 actively

suppresses Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fusion, thereby facilitating

the fragmentation and segregation of damaged mitochondria (78).

NIX is structurally similar to BNIP3, and is a

single-pass OMM protein whose TM domain is essential for correct

OMM targeting (79). During

erythroid differentiation, NIX expression is upregulated at the

transcriptional level. The deletion of NIX disrupts erythroid

maturation, resulting in anemia, reticulocytosis and

erythroid-myeloid hyperplasia (80). It also plays essential roles in

retinal ganglion cell differentiation and in the reprogramming of

somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (81,82).

NIX participates in mitophagy induced by hypoxia and elevated

oxidative phosphorylation activity (83). It acts as a substrate of Parkin and

functions downstream of the PINK1/Parkin pathway to promote

mitophagy (84).

In resting cells, low levels of NIX and BNIP3 are

maintained by ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation through an

OMM-localized protein called SCFFBXL4 E3 ubiquitin

ligase complex (85). Their

activity in mitophagy is regulated by phosphorylation: The

phosphorylation of BNIP3 at Ser17 and Ser24 within its LIR motif is

essential for LC3B interaction (86), while the phosphorylation of NIX at

Ser34 and Ser35 enables it to bind with GABARAP family proteins

(87). Generally, the BNIP3/NIX

pathway demonstrates stronger associations with development and

differentiation than other mitophagy pathways (88).

FUN14 domain-containing protein 1

(FUNDC1) pathway

FUNDC1 is an integral OMM protein with a C-terminus

that extends into the mitochondrial IMS and a cytosolic N-terminus

containing a typical LIR (89).

Under hypoxic conditions, FUNDC1 is dephosphorylated, which

enhances its binding to LC3 through its typical LIR and promotes

mitophagy (90), while

phosphorylation inhibits this binding. Therefore, the dynamic

balance between FUNDC1 phosphorylation and dephosphorylation

functions as a critical switch that controls its LC3 binding

capacity and subsequent regulation of mitophagy (36). A key regulatory site of FUNDC1 is

tyrosine (Tyr)18, which is phosphorylated by Src kinase. This

weakens the binding between LC3 and FUNDC1 due to electrostatic

repulsion, thereby inhibiting mitophagy (91).

In addition to Tyr18 phosphorylation, three

potential regulators of FUNDC1 activity are currently known. These

are phosphoglycerate mutase family member 5 (PGAM5) and ULK1, which

promote mitophagy, and casein kinase 2α (CK2α), which inhibits

mitophagy (92–94). CK2α, a constitutive Ser/threonine

(Thr) kinase, is a suppressor of FUNDC1 that promotes its

phosphorylation at Ser13, thus effectively preventing its

association with LC3 and inhibiting mitophagy (92). Chen et al (93) demonstrated that PGAM5, a

mitochondrial phosphatase, dephosphorylates the Ser13 residue of

FUNDC1, resulting in an increased association with LC3 during

hypoxia or after treatment with a mitochondrial oxidative

phosphorylation uncoupler (FCCP). FUNDC1 is a novel substrate of

ULK1. ULK1 directly phosphorylates FUNDC1 at Ser17 under hypoxic

conditions or FCCP exposure, following its recruitment to damaged

mitochondria. This promotes the interaction of ULK1 with LC3,

forming a bridge that links damaged mitochondria to autophagosomes

(94).

Nutrient deprivation-induced

mitophagy

Under conditions of nutrient or energy deprivation,

mitophagy is predominantly regulated by three key pathways: Ser/Thr

protein kinase mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), AMP-activated

protein kinase (AMPK) and sirtuins (SIRTs) (95). AMPK and mTOR function as nutrient

sensors in the kidney. In addition, mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) serves

as the primary negative modulator of mitophagy, while AMPK and

SIRTs are positive regulators (95,96).

As a key regulator of anabolism, mTORC1 promotes

cell growth and proliferation while concurrently inhibiting

mitophagy. Under nutrient-abundant conditions, it phosphorylates

ULK1 to suppress mitophagy, whereas under nutrient-limited

conditions, mTORC1 is inactivated, allowing AMPK to activate ULK1

by phosphorylation, thereby inducing mitophagy (97). AMPK is a heterotrimeric complex

comprising a catalytic α-subunit and regulatory β and γ subunits

(98). During glucose deprivation,

AMPK directly activates ULK1 via the phosphorylation of Ser317 and

Ser777, to enhance mitophagy (99).

SIRTs play major roles in various physiological

functions of the kidney, including DNA repair, mitochondrial

metabolism, mitophagy, oxidative stress control and inflammation.

SIRT dysfunction contributes to CKD pathophysiology and progression

(100). Reduced SIRT1 expression

or activity is associated with diminished mitophagy and exacerbated

kidney disease (101,102). SIRT3, the primary mitochondrial

deacetylase, is transformed from an inactive 44-kDa enzyme

precursor to an active 28-kDa protein that translocates to

mitochondria (103). In a sepsis

model created by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) in mice,

decreased SIRT1 and SIRT3 activity was associated with

mitochondrial damage (104).

Another study revealed that the activation of SIRT3 preserves

mitophagy and maintains mitochondrial homeostasis in both CLP model

mice and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-treated RTECs (105). SIRT5 expression in the kidney is

minimal. Polletta et al (106) demonstrated that the main function

of SIRT5 in non-hepatic cells is the regulation of glutamine

metabolism, which controls ammonia production and ammonia-induced

mitophagy.

Mitophagy in CKD

Mitophagy is as a key mechanism for mitochondrial

quality control that helps to maintain cellular homeostasis and

protects cells by enabling them to adapt to external environmental

changes. It plays a pivotal role in CKD by modulating factors

associated with inflammation and fibrosis (107). Renal tubule injury is a major

contributor to CKD progression (108). As the primary cellular

constituents of renal tubules, RTECs are essential for both kidney

repair and CKD progression, and critically determine the overall

condition of the kidneys. Their innate immune functions allow them

to recognize diverse stimuli and produce biologically active

mediators that drive interstitial inflammation and fibrosis

(108).

The unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) model is

commonly used to study tubulointerstitial fibrosis and CKD

(109). In this model, PINK1 or

Parkin deficiency disrupts mitophagy, resulting in excessive mROS

production, mitochondrial damage, increased TGF-β1 expression and

Drp1 recruitment in RTECs, all of which promote renal fibrosis.

Hypoxia-induced damage to RTECs and renal fibrosis in the UUO model

are ameliorated by Drp1-Parkin-dependent mitophagy, highlighting

the essential role of this process (110). In another study, it was reported

that PINK1 or Parkin knockout in macrophages leads to the

accumulation of damaged mitochondria and promotes their conversion

to a profibrotic phenotype, which aggravates kidney fibrosis

(111). In the kidneys of

patients with CKD, the expression levels of the mitophagy-related

proteins PINK1, Parkin and MFN2 are downregulated, which inhibits

mitophagy. Furthermore, the circulating levels of C-C motif

chemokine ligand 2 are increased, which recruits macrophages and

exacerbates renal fibrosis. UUO models have also shown that Parkin

and MFN2 expression levels are downregulated during kidney fibrosis

(111). Together, these findings

underscore the anti-fibrotic role of mitophagy in the repair of

kidney injury and its potential to slow CKD progression.

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a major risk factor for

the development and progression of CKD (112). Following AKI, the maladaptive

repair of injured tubules typically results in a sparse

microvascular bed, persistent inflammation, tubular cell loss and

renal fibrosis, leading to the transition of AKI to CKD (113). Proximal tubular cells contain

abundant mitochondria, the dysfunction of which is a major

contributor to AKI pathogenesis. Regardless of etiology, mitophagy

is a vital protective mechanism in AKI (36). If mitochondrial dysfunction

persists after AKI, it promotes progression to CKD via inflammatory

and fibrotic pathways (114).

Cisplatin is a commonly prescribed alkylating

chemotherapeutic agent that demonstrates broad-spectrum anticancer

activity; however, its therapeutic potential is limited by

nephrotoxic, neurotoxic and ototoxic side effects. In particular,

AKI is a recognized complication of cisplatin-based chemotherapy

(115). Mapuskar et al

(116) revealed that

cisplatin-induced pathological changes in mitochondrial metabolism

occur during the repair phase. These are characterized by

superoxide anion radical (O2•−) accumulation,

which predisposes the kidney to future injury and contribute to CKD

progression. In vitro, Zhao et al (117) demonstrated that in human renal

proximal tubular cells the knockdown of PINK1 or Parkin exacerbates

mitochondrial dysfunction by impairing mitophagy, resulting in the

accumulation of damaged mitochondria and increased cellular injury.

By contrast, the overexpression of PINK1 or Parkin activates

mitophagy, which alleviates cisplatin-induced mitochondrial

dysfunction and cellular injury.

The NLRP3 inflammasome plays a key role in renal

inflammation and pyroptosis (118). In both UUO models and hypoxic

conditions, elevated mROS levels, increased accumulation of damaged

mitochondria, activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and

significantly increased expression of α-SMA and TGF-β1 are

observed. These changes are further intensified following BNIP3

gene deletion or silencing (119).

The activation of mitophagy can reduce pyroptosis in

renal cells (120). For instance,

Zn2+ has been shown to enhance Parkin expression by

inhibiting SIRT7 activity, thereby promoting mitophagy, suppressing

NLRP3 inflammasome activation and pyroptosis, and consequently

protecting against sepsis-induced AKI (121).

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α) is upregulated

in UUO models, and functions as an upstream regulator of BNIP3.

Knockout of HIF1α leads to impaired mitophagy, aggravated apoptosis

and increased ROS production (122). These findings suggest that

HIF1α-BNIP3-mediated mitophagy protects renal tubular cells against

hypoxia-induced injury and fibrosis by reducing mROS and inhibiting

NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

In the context of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity,

Zhou et al (123) observed

the downregulation of PINK1 and Parkin and upregulation of NIX in

the kidney, indicating that the BNIP3/NIX pathway may be

particularly important in cisplatin-induced mitophagy. The study

also indicated that PINK1 knockout ameliorated cisplatin-induced

kidney injury in rats.

Another key mitophagy pathway involves FUNDC1, which

protects against mitochondrial dysfunction, cell death and renal

fibrosis in CKD. In end-stage renal disease, chronic inflammation

and renal injury suppress FUNDC1-mediated mitophagy, resulting in

defective mitochondrial clearance, aggravated renal fibrosis and

deteriorating renal function (124). Notably, the balance of mitophagy

homeostasis is preserved when FUNDC1 alone is deficient, while the

concurrent deficiency of both FUNDC1 and Parkin disrupts the

homeostasis. Parkin compensates for the lack of FUNDC1 via

compensatory upregulation, thereby sustaining basal mitophagy,

which explains why baseline FUNDC1 knockout alone has little impact

on renal function (125).

Oxidative stress: An overview

Definition of oxidative stress

The term oxidative stress was first coined by Sies

and Cadenas (126) in 1985, and

later defined as an imbalance between oxidants and antioxidants in

favor of oxidants, leading to a disruption in redox signaling and

metabolic regulation (127).

Oxidative stress contributes to disease through two distinct but

interrelated mechanisms. The first involves the generation of

reactive species that directly oxidize macromolecules, such as

membrane lipids, structural proteins, functional enzymes and

nucleic acids, resulting in abnormal cellular function or death.

The second is non-physiological redox signaling, particularly

involving the aberrant production of hydrogen peroxide

(H2O2), which can disrupt redox signaling

(128). Sustained oxidative

stress in the kidney initiates a cascade of cellular damage,

including renal ischemia, glomerular lesions, cell death, fibrosis

and exacerbated inflammation. These processes are also associated

with multiple CKD comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes

and atherosclerosis (129).

Mitochondria-related oxidative

stress

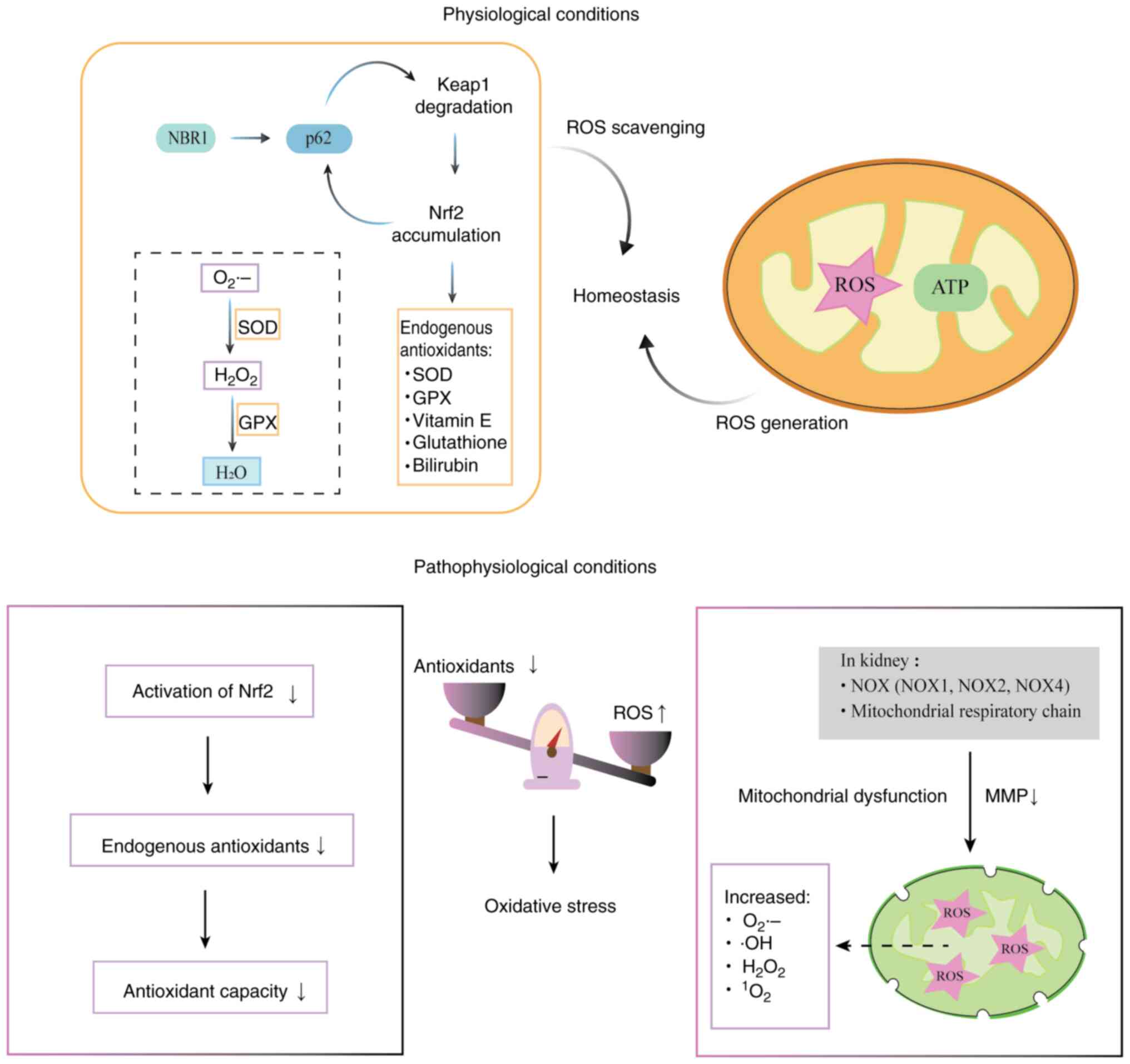

Oxidative stress involves chemical reactions

triggered by various reactive species, with ROS exerting the

greatest biological impact and intracellular ROS predominantly

originating from mitochondria (130). The kidney has high mitochondrial

density, which renders it particularly vulnerable to oxidative

stress-induced damage (11). Under

physiological conditions, ROS generation and scavenging are

strictly balanced. At low levels, ROS are known to affect specific

signaling pathways to regulate cell proliferation, differentiation

and death (129). However, ROS

are generated at high levels when mitochondrial function is

impaired, which creates a signal for the self-elimination of

mitochondria via mitophagy. The excessive production of ROS and

inability of endogenous antioxidants to remove them leads to

oxidative stress (131).

The ROS family includes radical species such as

O2•− and hydroxyl radicals (•OH),

and non-radical oxidants, including H2O2 and

singlet oxygen. Among these, O2•− and

H2O2 are central to redox signaling and can

exert beneficial effects at controlled levels (22,131,132). In the kidney, the major sources

of ROS are NADPH oxidases (NOXs) and the mitochondrial respiratory

chain (133). NOX enzymes

catalyze the transfer of electrons from NADPH to molecular oxygen,

which produce ROS. In addition to NOX4, which serves as a major

source of ROS in the kidney, NOX1 and NOX2 contribute to vascular

dysfunction and fibrosis in CKD by increasing oxidative stress

(134). Furthermore, angiotensin

II (AngII) serves as an early key mediator of kidney disease, which

induces tubular hypertrophy and apoptosis in RTECs through

ROS-mediated molecular mechanisms (135).

The maintenance of redox homeostasis is crucial for

cellular function, and its disruption is a major contributor to

human diseases (136). Oxidative

stress in CKD arises not only from excessive ROS production but

also from diminished antioxidant capacity, particularly due to

impaired Nrf2 activation (137).

The antioxidant system is the primary cellular defense against

oxidative damage. It comprises enzymatic antioxidants, including

superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX), and

nonenzymatic antioxidants such as α-tocopherol (vitamin E),

glutathione and bilirubin (138).

These components are largely regulated by the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway.

Keap1 functions as a sensor of oxidative stress, while Nrf2 is the

principal regulator driving the transcription of antioxidant

enzyme-encoding genes. Under oxidative stress, ROS reacts with

redox-sensitive cysteine residues (Cys273 and Cys288) of Keap1

(139), altering its conformation

and preventing it from binding to Nrf2, thereby affecting the

autophagy receptor p62. The affinity between p62 and Keap1 is

enhanced, forming a stable p62-Keap1 complex, which is subsequently

degraded (140). The

p62-Keap1-Nrf2 system is essential for mitophagy. The degradation

of Keap1 disrupts its polyubiquitination and proteasomal

degradation of Nrf2, thereby enabling Nrf2 stabilization and

accumulation, leading to the sustained transcriptional activation

of antioxidant genes (61).

Mitochondria are major sources of ROS due to

electron leakage, primarily from respiratory chain complexes I and

III. This results in incomplete oxygen reduction and the generation

of O2•−, which is rapidly converted into

H2O2 either spontaneously or via SOD-mediated

catalysis (26). The distribution

of SOD is compartment-specific: SOD1 exists in both the cytosol and

IMS, while SOD2 is localized in the mitochondrial matrix (141). GPX converts

H2O2 to water. However, if not neutralized,

H2O2 can form •OH radicals by

reacting with metal ions (142).

Due to its extreme oxidative capacity, •OH is the most

destructive oxidant, which is capable of inducing oxidative DNA

damage (129) (Fig. 4).

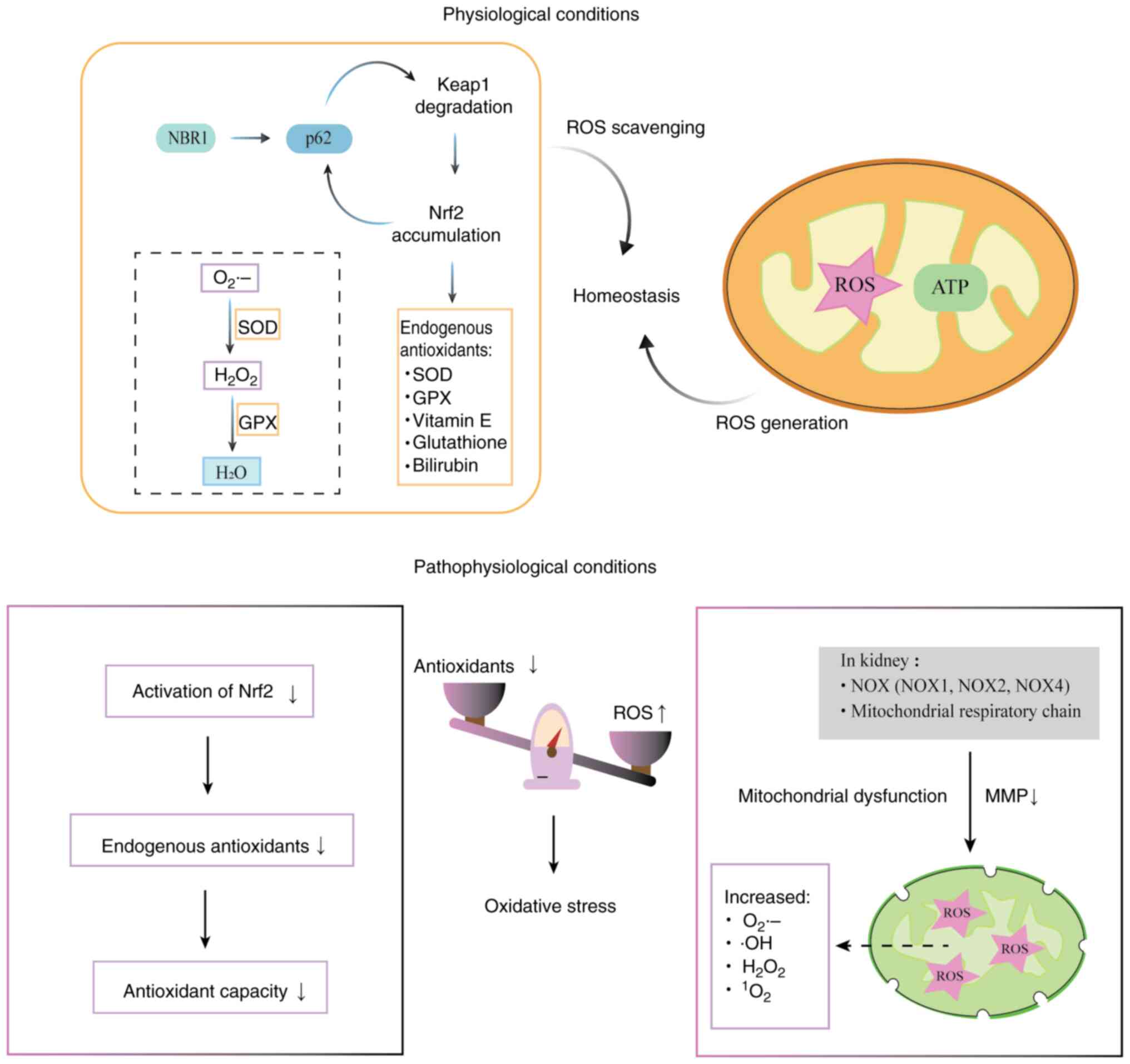

| Figure 4.Diagram of mitochondria-related

oxidative stress. Oxidative stress contributes to disease by two

major mechanisms: ROS overproduction and the disruption of redox

homeostasis. Mitochondria are the primary source of intracellular

ROS. In the kidney, NOXs (NOX1, NOX2 and NOX4) and the

mitochondrial respiratory chain are the major contributors to the

production of ROS, which include O2•−,

•OH, H2O2 and

1O2. Diminished antioxidant capacity, due to

impaired activation of Nrf2, also contributes to oxidative stress.

NBR1 induces the phase separation of p62 and enhances the formation

of p62-containing liquid droplets. A positive feedback mechanism

exists, in which the p62-dependent degradation of Keap1 leads to

the accumulation of Nrf2, which activates the transcription of

antioxidant genes, including p62. The Keap1-Nrf2 pathway regulates

endogenous antioxidants, such as SOD and GPX. SOD rapidly converts

O2•− into H2O2, which

is then converted to water by GPX. However, if unquenched,

H2O2 can generate •OH radicals by reacting

with metal ions. ROS, reactive oxygen species; NOX, NADPH oxidase;

O2•−, superoxide anion radical;

•OH, hydroxyl radical; H2O2,

hydrogen peroxide; 1O2, singlet oxygen; Nrf2,

NF-E2-related factor 2; NBR1, neighbor of BRCA1 gene l; p62,

sequestosome 1; Keap1, Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1; SOD,

superoxide dismutase; GPX, glutathione peroxidase; ATP, adenosine

triphosphate; MMP, mitochondrial membrane potential. |

Redox regulation of mitophagy

pathways

The regulation of mitophagy by redox imbalance is a

dynamic, biphasic and intensity-dependent. A mild redox imbalance

can activate mitophagy. In this process, the activity of the

mitochondrial damage sensor PINK1 is directly regulated and

activates Parkin, which initiates the ubiquitin chain labeling of

outer membrane proteins, enabling them to be recognized by

autophagy receptor proteins. Elevated ROS levels due to

mitochondrial damage promote the oxidation and oligomerization of

NDP52, an autophagy receptor essential for the efficient clearance

of ubiquitin-labeled mitochondria. This enhances the initiation and

efficiency of mitophagy by facilitating the selective clearance of

damaged mitochondria (143).

Oxidative stress activates PGAM5, which promotes the

dephosphorylation of FUNDC1, enabling it to bind to LC3 and induce

mitophagy (124). However, redox

imbalance under sustained oxidative stress suppresses

mitophagy.

In the chronic and intense oxidative stress

environment of CKD, key mitophagy-associated proteins undergo

excessive oxidative modification, which can lead to their

inactivation. For example, PINK1 and Parkin expression is

suppressed, impairing ubiquitin chain formation and consequently

impeding mitophagy. This crosstalk between mitophagy and oxidative

stress establishes a reinforcing cycle of damage.

Evidence from animal experiments and patient samples

indicates that PINK1/Parkin pathway-mediated mitophagy is impaired

in kidney fibrosis (111).

Furthermore, decreased levels of mitophagy mediators, including

PINK1, Parkin, p62, LC3-II and BNIP3, in muscle-derived

mitochondria from patients with CKD, are associated with poor

oxidative capacity (144).

In contrast with the ubiquitin-dependent pathway,

receptor-mediated mitophagy is more directly regulated by oxidative

stress and is independent of Parkin. Under the hypoxic, nutrient

starvation and oxidative stress environment of CKD, the expression

levels of BNIP3 and NIX are significantly upregulated. However,

high expression of BNIP3 and NIX can lead to the formation of

homodimers, which disrupts the permeability of the OMM. This

exacerbates ROS leakage and directly triggers

mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis (73). In proteinuric mice, NIX-dependent

mitophagy is considerably suppressed and associated with increased

mitochondrial fragmentation, tubular epithelial cell apoptosis and

loss of kidney function (145).

While the activation of mitophagy within a tolerable range is

protective by the removal of damaged mitochondria, excessive

mitochondria injury triggers the overactivation of mitophagy and

subsequent cell death.

Notably, honokiol (HKL), a pharmacologically active

component of Magnolia officinalis, exhibits diverse

therapeutic properties. Wei et al (146) discovered that HKL suppresses

BNIP3, NIX and FUNDC1 expression and reduces AMPK activation levels

in CKD models, resulting in the reduction of excessive mitophagy

and induction of protective effects on the kidneys.

Crosstalk between mitophagy and oxidative

stress in CKD.

Considerable evidence supports the crucial role of

mitophagy in CKD progression, particularly in the removal of

impaired mitochondria, reduction of oxidative stress and

alleviation of inflammation and fibrosis in the kidney, all of

which delay CKD progression (147). However, under CKD conditions,

mitophagy is impaired and mitochondrial dynamics shift toward

excessive fission. Antioxidants increase mitophagy flux in animal

models of CKD, supporting the impairment of mitophagy in CKD

(148). In particular, five-sixth

nephrectomy (5/6Nx) model animals, which are commonly used to study

CKD pathophysiology, exhibit increased levels of p62. Since p62

accumulation is regarded as a marker of defective mitophagy, this

further implicates impaired mitophagy in the context of CKD

(149).

Although mitophagy initially acts as an adaptive,

protective mechanism, it becomes dysfunctional under sustained

oxidative stress. Conversely, impaired mitophagy leads to excessive

ROS production. This harmful feedback cycle is a pivotal

intermediary link between various initial pathologies, such as

diabetes, hypertension, aging and immune diseases, and the

progression of CKD (150).

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is a major contributor to end-stage

kidney failure; however, current treatment strategies for DN are

limited (151). There is evidence

to suggest that mitophagy in tubular cells is defective in the

diabetic kidney. Han et al (152) found that PINK1, Parkin, LC3-II

and ATG5 expression levels are downregulated in the kidneys of

diabetic mice, suggesting impaired mitophagy. Supporting this,

patients with DN exhibit diminished circulating mtDNA levels,

increased mtDNA damage and deficient mitophagy (153). The renal expression of NOX5 is

upregulated in patients with DN, which induces ROS generation in

podocytes and contributes to DN progression (154). Experimental models suggest that

improving mitochondrial quality control can reduce

tubulointerstitial fibrosis and suppress epithelial-to-mesenchymal

transition (EMT)-like phenotype changes in tubular cells (155).

In hypertensive CKD, oxidative stress induces EMT

and renal fibrosis. A study revealed that AdipoRon, an adiponectin

receptor agonist, alleviated renal fibrosis in a mouse model of

hypertension by promoting mitophagy (156). Similarly, Long et al

(157) found that the kidneys of

aging rats exhibited signs of degenerative pathology, increased

oxidative stress and reduced mitophagy. Treatment with a

combination of Epimedium dried leaves and Ligustrum

lucidum fruits improved mitochondrial dynamics and restored

mitophagy via activation of the AMPK/ULK1 pathway. Furthermore, in

rats with passive Heymann nephritis, Fangji Huangqi (FJHQ)

decoction enhanced mitophagy in podocytes by upregulating the

expression of BNIP3, thereby ameliorating membranous nephropathy

(158). In systemic lupus

erythematosus, the mitophagy-inducing agent UMI-77 promoted

mitophagy, suppressed autoimmunity, and reduced renal inflammation

and ROS production, thereby preventing the progression of lupus

nephritis both in patients and model mice (159). However, excessive oxidative

stress can lead to excessive mitochondrial fragmentation, exceeding

the mitophagic clearance capacity and leading to the accumulation

of damaged mitochondria. One study showed that the activation of

Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission promoted fibrogenesis, while

decreased mitochondrial fission attenuated fibrogenesis (160).

Regulated oxidative stress triggers signaling

pathways that promote mitochondrial fission and mitophagy to clear

damaged mitochondria and cells. This process prevents the spread of

damage to neighboring mitochondria and cells. Efficient mitophagy

enables the timely clearance of damaged mitochondria, characterized

by reduced MMP and increased electron leakage, which are primary

intracellular sources of ROS. By eliminating these mitochondria,

mitophagy directly reduces ROS production at its source (161). However, because mitophagy is

impaired in CKD, damaged mitochondria accumulate, leading to

excessive ROS generation. Elevated ROS levels further damage

healthy mitochondria and other organelles, activate inflammasomes,

and promote the expression of pro-fibrotic factors, thereby

exacerbating tubulointerstitial inflammation and fibrosis. This

oxidative damage promotes CKD progression and is associated with a

significant decline in renal function (162).

Li et al (110) demonstrated that mitophagy

protects against uncontrolled oxidative stress in a UUO model.

Whether triggered by acute or chronic injury, mitochondrial damage

results in a decline in mtDNA content, ROS overproduction and

reduced ATP generation, subsequently causing oxidative stress and

cell injury (163).

In summary, oxidative stress can inhibit mitophagy,

while impaired mitophagy exacerbates oxidative stress. This harmful

feedback loop drives CKD progression.

Potential therapeutic strategies

Modulators of mitophagy

Oxidative stress is exacerbated by impaired

mitophagy during CKD progression. Therefore, the simultaneous

targeting of both aspects of this feedback loop presents a novel

therapeutic strategy with potential for the treatment of CKD

(Table I).

| Table I.Therapeutic agents targeting

mitophagy and oxidative stress. |

Table I.

Therapeutic agents targeting

mitophagy and oxidative stress.

| Compound | Experimental

model | Mechanism | Current status | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Quercetin | UUO model mice | Promotes the

expression of SIRT1/PINK1 to attenuate RTEC senescence and kidney

fibrosis | Preclinical | (102) |

| Melatonin | CLP-treated

mice | Enhances the

degradation of p62 via the inhibition of TFAM acetylation and

subsequent SIRT3 activation | Clinical use for

sleep disorders | (105) |

| Honokiol | Rats with

adenine-induced CKD | Suppresses

BNIP3/NIX, FUNDC1 and AMPK expression, reduces excessive mitophagy

and protects the kidneys | Preclinical | (146) |

| Metformin | High-fat and

streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice | Activates AMPK and

promotes mitophagy through the p-AMPK-PINK1-Parkin pathway | Clinical use for

type 2 diabetes | (152) |

| Epimedii

folium and Ligustri lucidi fructus | Aged rats | Delay renal aging

by activating the AMPK/ULK1 pathway | Preclinical

stage | (157) |

| Fangji

huangqi decoction | Passive Heymann

nephritis model rats | Enhances mitophagy

in podocytes by promoting the expression of BNIP3 | Clinical use for

edema and dysuria | (158) |

| UMI-77 | Lupus nephritis

model mice, and clinical samples | Enhances mitophagy,

suppresses autoimmunity and limits renal inflammation | Preclinical | (159) |

| Magnoflorine | High-fat and

high-fructosefed mice | Promotes

Parkin/PINK1-mediated mitophagy and inhibits

NLRP3/caspase-1-mediated pyroptosis | Preclinical | (164) |

| Ruxolitinib | UUO model mice | Activates

Parkin/PINK1 mitophagy, reduces inflammatory responses and

oxidative stress | Clinical use for

myeloproliferative disorders | (165) |

| Chicoric acid | High-fat diet-fed

mice | Activates the Nrf2

pathway and increases PINK1 and Parkin expression, thereby

enhancing mitophagy | Preclinical | (166) |

| Paeoniflorin | RAW264.7 cells

stimulated with lipopolysaccharide | Upregulates PINK1,

Parkin, BNIP3, p62 and LC3, increases mitochondrial membrane

potential and reduces ROS accumulation | Preclinical | (167) |

| Tongluo

yishen decoction | UUO model rats | Modulates

PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy and alleviates renal fibrosis | Clinical use for

CKD | (168) |

| Rapamycin,

everolimus and temsirolimus | UUO model mice | Suppresses mTORC1

and promotes AMPK-induced ULK1 activation to induce mitophagy | Preclinical | (171) |

| Resveratrol | 5/6-nephrectomy and

CLP-treated rats | Activates SIRT1/3

and reduces acetylated SOD2 levels to ameliorate oxidative stress

and mitochondrial function in RTECs | Preclinical | (104, 173) |

| Roxadustat | Rats with renal I/R

injury | Increases HIF1α

protein expression and promotes HIF1α/FUNDC1-mediated

mitophagy | Clinical use for

renal anemia in CKD and dialysis | (174) |

| Uridine | Aged mice | Reduces

intracellular oxidative stress, promotes the synthesis of

high-energy compounds and protects cells from hypoxic damage | Preclinical | (179) |

| Lycopene | Mice with

aristolochic acidinduced nephropathy | Activates the

antioxidant system and mitophagy, upregulates levels of LC3-II and

p62, exerts anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects | Preclinical | (180) |

| Mitoquinone | Mice with I/R

injury, or infused with AngII | Decreases oxidative

damage and reduces the severity of I/R injury to the kidney | Preclinical | (184,185) |

| SS-31 | Uninephrectomy and

streptozotocin-treated mice; mice with cisplatin-induced AKI | Anti-oxidative and

anti-apoptotic action via the inhibition of ROS production | Preclinical | (187,188) |

| Curcumin-loaded

nanodrug delivery system | Cisplatin-induced

AKI | Inhibits oxidation,

activates autophagy and reduces apoptosis | Preclinical | (190) |

Several pharmacological agents have been identified

that modulate mitophagy and thereby attenuate oxidative

stress-induced renal injury. For example, magnoflorine promotes

PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy, thereby inhibiting

NLRP3/caspase-1-mediated pyroptosis. This effects is reversed by

either the genetic deletion of Parkin or use of a chemical

mitophagy inhibitor, confirming that the ability of magnoflorine to

inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome activation depends on mitophagy in

cultured cells (164).

Ruxolitinib also activates PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy, thereby

reducing oxidative stress, inflammation and renal fibrosis

(165). Chicoric acid, a key

bioactive component of chicory, stimulates Nrf2 signaling and

upregulates PINK1 and Parkin expression levels in high-fat diet

(HFD)-fed mice (166). Similarly,

Cao et al (167) revealed

that paeoniflorin (PF) increases the expression levels of PINK1,

Parkin, BNIP3, p62 and LC3, which repairs damaged mitochondria by

restoring the MMP and clearing accumulated ROS. In addition, PF

ameliorates kidney inflammation by inducing the transition of

macrophages to the M2 phenotype and activating mitophagy in

LPS-induced murine RAW264.7 CKD models

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has also been

shown to regulate mitophagy. In addition to the previously

mentioned FJHQ decoction, which exhibited efficacy in the treatment

of membranous nephropathy, Tongluo Yishen decoction was found to

improve mitochondrial dynamics and alleviate renal fibrosis by

modulating PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy and reducing ROS levels

in UUO model rats (168). Unlike

most mitophagy regulators, whose efficacy has been demonstrated

solely in animal and in vitro models, TCMs are the only

mitophagy modulators supported by clinical data.

The inhibition of mTORC1 or activation of the

AMPK/SIRT1 by genetic or pharmacological approaches has shown

protective effects against the progression of DN in animal models

(169,170). Well-known mTORC1 inhibitors

include rapamycin and its analogs, everolimus and temsirolimus

(171). Han et al

(152) demonstrated that the AMPK

activator metformin promotes mitophagy through the

phospho-AMPK-PINK1-Parkin pathway, while concurrently attenuating

oxidative stress and tubulointerstitial fibrosis in the kidneys of

HFD/streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Transcription factor A,

mitochondrial (TFAM) is essential for the initiation of mtDNA

transcription (172). Melatonin

has been identified as a positive regulator of PINK1 and Parkin

expression, which activates upstream mitophagy. Deng et al

(105) demonstrated that

melatonin promotes p62 degradation by suppressing TFAM acetylation

through SIRT3 activation, thereby enhancing mitophagy flux.

Quercetin, an activator of SIRT1, attenuates RTEC senescence and

kidney fibrosis by upregulating the expression of SIRT1 and PINK1

to promote mitophagy in vivo, as shown in an UUO model, and

also enhances mitophagy in AngII-treated RTECs (102). Similarly, resveratrol activates

both SIRT1 and SIRT3 to promote mitophagy (104). In another study, the

administration of resveratrol to rats following 5/6Nx improved

kidney function, as indicated by decreased proteinuria and lower

cystatin C levels (173).

The HIF1α-FUNDC1 mitophagy axis plays a key role in

hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R)-promoted mitophagy in renal tubular

cells. H/R treatment upregulates the expression of FUNDC1, while

the selective inhibition of HIF1α reduces H/R-induced mitophagy

(174). Notably, treatment with

roxadustat further increases the expression of HIF1α in

vivo. Zhang et al (174) suggested that Roxadustat may serve

as a potential therapeutic agent to block the transition of AKI to

CKD in future clinical applications. Currently, roxadustat is used

clinically to treat renal anemia in patients with CKD and those on

dialysis, and shows considerable promise as a novel

mitophagy-targeting therapeutic agent for CKD.

Antioxidants

Antioxidants prevent oxidative stress by

neutralizing oxidizing agents and blocking harmful oxidation by

converting free radicals into nonreactive compounds (175). Uridine, a pyrimidine nucleoside

composed of uracil and ribose, is important in the maintenance of

cellular function and energy metabolism. It promotes the synthesis

of high-energy compounds and reduces intracellular oxidative

stress, thereby preventing hypoxia-induced cellular damage

(176,177). In animal models of acute ischemia

and ischemia/reperfusion (I/R), uridine administration has been

shown to protect against injury by restoring redox balance and

activating mitochondrial ATP-dependent channels (178). The levels of inflammatory factors

and ROS also decrease significantly following uridine treatment

(179).

Lycopene (LYC), a potent carotenoid antioxidant,

exhibits multiple therapeutic effects, including anti-inflammatory,

anti-apoptotic and mitophagy-modulating properties. Wang et

al (180) demonstrated that

LYC activates the Nrf2 antioxidant system and induces mitophagy to

ameliorate renal fibrosis. The study showed that LYC attenuated the

aristolochic acid I-induced intracellular expression of PINK1,

Parkin and TGF-β; upregulated LC3-II and p62 levels; decreased MMP;

and mitigated renal fibrosis in mice by suppressing mTORC1 and

promoting ULK1 activation.

Mitochondria-targeted

antioxidants

Growing evidence suggests that

mitochondria-targeted antioxidants have substantial therapeutic

potential. Mitoquinone (MitoQ), a mitochondria-targeted

antioxidant, shows therapeutic potential against the oxidative

stress mediated by excessive ROS production (142). MitoQ comprises a ubiquinone

moiety conjugated to a lipophilic triphenyl phosphonium (TPP)

cation, which targets mitochondria. The MMP facilitates efficient

cellular internalization of the TPP cation, leading to its

accumulation in the mitochondrial matrix. Once inside,

mitochondrial complex II reduces ubiquinone to ubiquinol, its

bioactive antioxidant form, thereby counteracting oxidative damage

(181,182). Due to its combination of

extensive mitochondrial uptake, antioxidant recycling and

localization on the matrix-facing surface of the IMM, MitoQ is

substantially more effective than untargeted antioxidants in

preventing oxidative damage (183). Other studies have also confirmed

the ability of MitoQ to prevent MMP reduction and reduce excessive

ROS production (184,185).

SS-31, another mitochondria-targeted antioxidant,

contains dimethyl tyrosine residues that react with oxygen

radicals, forming inactive tyrosine radical species and scavenging

ROS (186). Following its

accumulation on the IMM, SS-31 preserves mitochondrial structure,

promotes ATP production, and inhibits ROS generation and apoptosis

(187). In murine models, SS-31

demonstrates nephroprotective effects against cisplatin-induced

renal damage. It exerts both antioxidant and antiapoptotic

activities by modulating the mROS-NLRP3 signaling axis (188). However, preclinical studies

regarding the effectiveness of SS-31 in the treatment of renal

diseases are limited. Large-scale, multicenter clinical studies

with a diverse range of patients are necessary to assess the

efficacy, safety and tolerability of SS-31 for clinical application

(189).

Nanotechnology-based delivery systems can be used

to encapsulate antioxidants, with surface modifications to enable

their specific uptake by mitochondria. For example, a

curcumin-loaded nanodrug delivery system demonstrated protective

effects on mitochondrial function and kidney tissue by scavenging

excess ROS, reducing apoptosis and activating autophagy (190).

Despite these findings, the therapeutic

applicability of mitochondria-targeted antioxidants in CKD warrants

further investigation. The therapeutic efficacy of these

antioxidants should be evaluated in multiple animal models with

diverse CKD etiologies. Prior to human clinical trials, these

therapies should be tested in models that most closely resemble

human disease to validate their safety and efficacy, providing

robust evidence to support their clinical translation.

Challenges and prospects

CKD is a global health issue with a complex

pathogenesis involving multiple cellular and molecular processes.

Attention has been focused on the roles of mitophagy and oxidative

stress in CKD. A considerable body of evidence emphasizes the

importance of mitophagy and oxidative stress in kidney function in

healthy and disease states. Therefore, targeting mitophagy and

oxidative stress has emerged as a promising approach to improve

renal function and delay CKD progression.

Although targeting mitophagy and oxidative stress

are promising approaches for the treatment CKD, limitations remain,

and multiple challenges must be overcome before these findings can

be translated into clinically effective therapies. Most current

evidence is derived from animal models such as those involving UUO,

I/R injury or aged mice. While these models replicate certain

pathological features of CKD, they cannot fully reproduce the

multifactorial course of human CKD and its long-term progression,

which may involve the complex interplay of hypertension, diabetes

and aging. Differences between animals and humans in drug

metabolism, immune response and renal cell biology may cause

strategies that are effective in animals to be ineffective or even

toxic in humans. In addition, mitophagy and oxidative stress form a

dynamic regulatory cycle. However, clinical methods that can

dynamically and quantitatively monitor mitophagy flux in the kidney

are currently lacking. Therefore, it is not yet possible to

determine the optimal regulatory window for intervention in

mitophagy. The excessive activation of mitophagy may lead to the

unnecessary removal of healthy mitochondria, triggering cellular

energy depletion, while insufficient inhibition of mitophagy fails

to eliminate dysfunctional mitochondria, allowing dysfunction to

persist.

To overcome these challenges, future research

should focus on several aspects. First, to screen drugs and

validate the underlying mechanisms, disease models that more

closely resemble human physiology should be established. Kidney

organoids generated from patient-derived induced pluripotent stem

cells are a promising platform to simulate human-specific CKD

pathological processes in vitro. Second, novel biomarkers

that reflect in vivo mitophagy status and oxidative stress

levels, such as mtDNA or specific mitochondrial proteins detected

in blood or urine exosomes, should be identified and validated. The

development of kidney-targeted nanodelivery systems is also

critical, with the aim of enhancing drug accumulation in the renal

tissue while reducing systemic exposure and off-target effects.

Another area worthy of exploration is the integration of TCM with

modern nanotechnology to design delivery carriers that, according

to TCM theory, have ‘kidney meridian affinity’. Finally, greater

efforts should be made to discover highly specific mitophagy

modulators that precisely regulate specific pathways, providing

more controlled effects than those of broad-spectrum autophagy

inducing agents or antioxidants.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study received support from the following sources: Sichuan

Science and Technology Program (grant no. 2022YFS0621), Southwest

Medical University Technology Program (grant no. 2023QN019),

National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82205002),

Science and Technology Research Special Project of Sichuan

Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (grant no.

2024MS524) and Special Project of Integrated Chinese and Western

Medicine, Southwest Medical University (grant no. 2023ZYQJ04).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

QM was involved in writing, reviewing and editing

the manuscript, and creating visualizations. YT drafted the

original manuscript and worked on visualization. JL contributed to

writing, reviewing and editing, visualization and supervision. YQ

and HF contributed to writing the original draft of the manuscript.

QH and QZ helped to write, review and edit the manuscript, and also

provided supervision and secured funding. Data authentication is

not applicable. All authors read and approved the final version of

the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CKD

|

chronic kidney disease

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

|

mROS

|

mitochondrial ROS

|

|

ATP

|

adenosine triphosphate

|

|

mtDNA

|

mitochondrial DNA

|

|

NLRP3

|

NOD-like receptor protein 3

|

|

Drp1

|

dynamin-related protein l

|

|

MFN1/2

|

mitofusin 1/2

|

|

MMP

|

mitochondrial membrane potential

|

|

OMM

|

outer mitochondrial membrane

|

|

IMM

|

inner mitochondrial membrane

|

|

IMS

|

intermembrane space

|

|

HIF1α

|

hypoxia-inducible factor 1α

|

|

ULK1

|

Unc-51 like autophagy activating

kinase l

|

|

PINK1

|

PTEN-induced kinase l

|

|

p62

|

sequestosome 1

|

|

NBR1

|

neighbor of BRCA1 gene l

|

|

OPTN

|

optineurin

|

|

NDP52

|

nuclear dot protein 52

|

|

LC3

|

microtubule-associated protein 1

light chain 3

|

|

TBK1

|

TANK-binding kinase 1

|

|

BNIP3

|

BCL2 interacting protein 3

|

|

NIX

|

Nip3-like protein X

|

|

FUNDC1

|

FUN14 domain-containing protein l

|

|

mTOR

|

serine/threonine protein kinase

mammalian target of rapamycin

|

|

AMPK

|

AMP-activated protein kinase

|

|

Keap1

|

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein

1

|

|

Nrf2

|

NF-E2-related factor 2

|

|

SOD

|

superoxide dismutase

|

|

GPX

|

glutathione peroxidase

|

|

AKI

|

acute kidney injury

|

|

DN

|

diabetic nephropathy

|

|

RTECs

|

renal tubular epithelial cells

|

|

UUO

|

unilateral ureteral obstruction

|

|

EMT

|

epithelial-to-mesenchymal

transition

|

References

|

1

|

Kovesdy CP: Epidemiology of chronic kidney

disease: An update 2022. Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 12:7–11. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Flythe JE and Watnick S: Dialysis for

chronic kidney failure: A review. JAMA. 332:1559–1573. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Yang W, Wu X, Zhao M, Hu J, Lin C, Mei Z,

Chen J, Zhou XJ, Nie S, Nie J, et al: Kidney function and

cardiovascular disease: Evidence from observational studies and

mendelian randomization analyses. Phenomics. 4:250–253. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Jha V, Al-Ghamdi SMG, Li G, Wu MS,

Stafylas P, Retat L, Card-Gowers J, Barone S, Cabrera C and Garcia

Sanchez JJ: Global economic burden associated with chronic kidney

disease: A pragmatic review of medical costs for the inside CKD

research programme. Adv Ther. 40:4405–4420. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Dan Hu Q, Wang HL, Liu J, He T, Tan RZ,

Zhang Q, Su HW, Kantawong F, Lan HY and Wang L: Btg2 promotes focal

segmental glomerulosclerosis via Smad3-dependent

podocyte-mesenchymal transition. Adv Sci (Weinh). 10:e23043602023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Panizo S, Martínez-Arias L, Alonso-Montes

C, Cannata P, Martín-Carro B, Fernández-Martín JL, Naves-Díaz M,

Carrillo-López N and Cannata-Andía JB: Fibrosis in chronic kidney

disease: Pathogenesis and consequences. Int J Mol Sci. 22:4082021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ho HJ and Shirakawa H: Oxidative stress

and mitochondrial dysfunction in chronic kidney disease. Cells.

12:882022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kushner P, Khunti K, Cebrián A and Deed G:

Early identification and management of chronic kidney disease: A

narrative review of the crucial role of primary care practitioners.

Adv Ther. 41:3757–3770. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zhu HZ, Li CY, Liu LJ, Tong JB, Lan ZH,

Tian SG, Li Q, Tong XL, Wu JF, Zhu ZG, et al: Efficacy and safety

of qingfei huatan formula in the treatment of acute exacerbation of

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A multi-centre, randomised,

double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Integr Med. 22:561–569.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Aranda-Rivera AK, Cruz-Gregorio A,

Aparicio-Trejo OE and Pedraza-Chaverri J: Mitochondrial redox

signaling and oxidative stress in kidney diseases. Biomolecules.

11:11442021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Doke T and Susztak K: The multifaceted

role of kidney tubule mitochondrial dysfunction in kidney disease

development. Trends Cell Biol. 32:841–853. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Lu Y, Li Z, Zhang S, Zhang T, Liu Y and

Zhang L: Cellular mitophagy: Mechanism, roles in diseases and small

molecule pharmacological regulation. Theranostics. 13:736–766.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hoogstraten CA, Hoenderop JG and de Baaij

JHF: Mitochondrial dysfunction in kidney tubulopathies. Annu Rev

Physiol. 86:379–403. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Che R, Yuan Y, Huang S and Zhang A: