Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is one of the most prevalent

malignancies among men worldwide, making it a significant public

health concern (1). According to

the Global Cancer Observatory, PCa accounted for ~1.4 million new

cases and 375,000 deaths in 2020, ranking it as the second leading

cause of cancer-related mortality in men (1). The incidence of PCa varies by

geographic region, with higher rates observed in North America and

Europe compared with Asia and Africa (2). Despite advances in early detection

and treatment strategies, such as radical prostatectomy and

androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), the pathophysiology of PCa

remains complex and multifactorial and a deeper understanding of

its underlying mechanisms is needed to improve therapeutic outcomes

(3).

Recent studies have illuminated the importance of

the gut microbiota in human health, highlighting its role in

various physiological and pathological processes (4,5). The

gut microbiota, defined as the collective community of

microorganisms residing in the gastrointestinal tract, includes

bacteria, archaea, viruses and fungi (6). A diverse gut microbiota plays a

crucial role in the synthesis of nutrients, metabolism of drugs,

regulation of immune responses and protection against pathogenic

organisms (7). Dysbiosis, or an

imbalance in gut microbiota composition, has been implicated in a

wide range of diseases, including obesity, diabetes, inflammatory

bowel disease and even various forms of cancer (8). The gut-brain and gut-liver axes

further underscore the systemic effects of the microbiota,

suggesting that microbial composition can influence distant organ

systems (9,10).

The rationale for exploring the role of gut

microbiota in PCa stems from emerging evidence linking gut health

with cancer risk and progression (11). Several studies have identified a

distinctive microbial signature in patients with PCa compared with

healthy individuals, suggesting that alterations in gut microbiota

may influence cancer development (12,13).

The mechanisms through which gut microbiota may exert their

influence on prostate carcinogenesis are multifaceted, encompassing

modulation of local and systemic inflammation, alteration of

hormone metabolism and impacts on drug metabolism and efficacy

(14). Given that inflammation and

hormonal factors are well-established contributors to PCa

development, understanding how microbial populations affect these

pathways is critical (15,16).

Furthermore, the interplay between diet, lifestyle

factors and the gut microbiota presents an intriguing opportunity

for research (17). Dietary

patterns have been shown to markedly alter gut microbiota

composition, with Western diets, characterized by high fat and low

fiber intake, being associated with increased dysbiosis (18). This suggests a potential link

between dietary habits, gut health and PCa risk that warrants

further investigation. Additionally, the growing interest in

microbiome-targeted therapies, such as probiotics and dietary

interventions, raises the prospect of novel prevention and

treatment strategies in PCa (19).

Despite the promising associations established

between gut microbiota and PCa, the field remains nascent, with

significant gaps in our understanding. Studies on this topic often

present conflicting results, stemming from variations in

methodology, sample sizes and population diversity (20). Some research suggests specific

microbial taxa may be associated with increased cancer risk, while

others highlight protective microbial profiles. Such discrepancies

highlight the need for a critical appraisal of existing literature

to elucidate consistent findings and bounding contradictions

(21). The present review aimed to

synthesize the current evidence and propose directions for future

research, with the hope of fostering an improved understanding of

how gut microbiota may serve as both a modulator of PCa risk and a

potential target for therapeutic intervention.

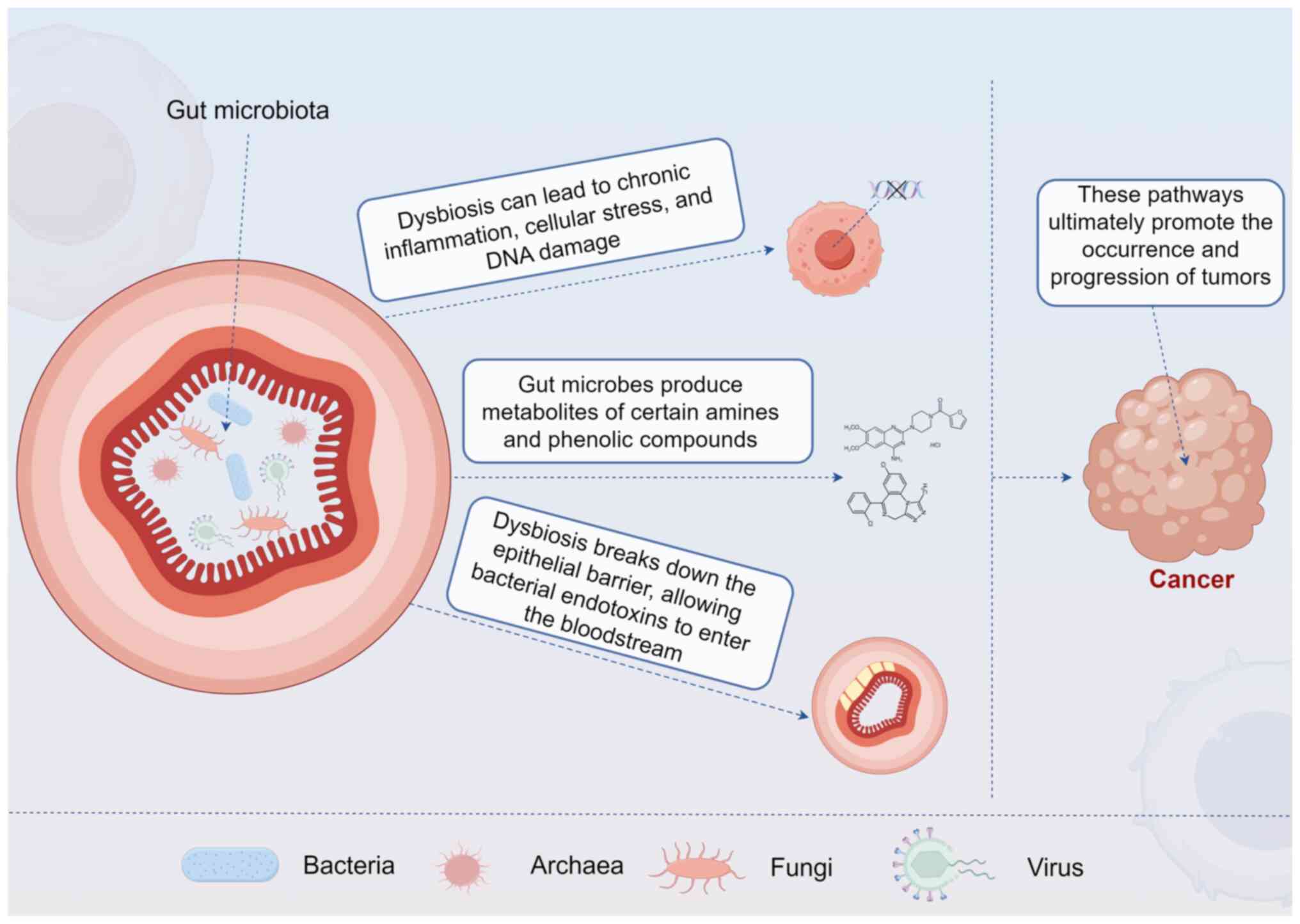

Gut microbiota and cancer

Description of gut microbiota

composition and diversity

The gut microbiota is an intricate consortium of

microorganisms, including bacteria, archaea, fungi and virus, that

inhabit the gastrointestinal tract (22) (Fig.

1). The human gut harbors ~100 trillion microbial cells,

outnumbering human cells by a factor of ten (23). These microorganisms predominantly

belong to two major phyla: Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, along with

smaller representations from Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria and

Verrucomicrobia (23). The

composition and diversity of the gut microbiota can be influenced

by various factors, including diet, age, genetics and antibiotic

use (24).

A diverse gut microbiota is indicative of a healthy

gastrointestinal ecosystem, playing a crucial role in nutrient

metabolism, barrier integrity and immune system function (25). Dysbiosis, or an imbalance in

microbiota composition, has been associated with various diseases,

including inflammatory bowel disease, obesity and cancer (8,26,27).

Recent advances in high-throughput sequencing technologies have

enabled a more nuanced understanding of microbial communities and

have revealed specific microbial signatures associated with

specific health conditions, including malignancies (28).

Variability in gut microbiota profiles has been

observed across populations, suggesting environmental and lifestyle

factors play significant roles in shaping these communities

(29). For instance, populations

consuming a Western diet rich in fats and sugars often exhibit

decreased microbial diversity, which has been linked to increased

cancer risk (30,31). Comparatively, traditional diets

that emphasize plant-based foods are associated with a higher

diversity of beneficial gut microbes, which may provide protective

effects against various cancers (32).

Mechanisms by which gut microbiota may

influence cancer pathogenesis

The influence of gut microbiota on cancer

pathogenesis occurs through several mechanisms, which can markedly

affect the initiation, promotion and progression of tumors

(33). Among these mechanisms are

immunomodulation, metabolic processes and the production of

bioactive compounds (33).

Immunomodulation: The gut microbiota plays a pivotal

role in shaping the immune system, promoting both innate and

adaptive immune responses (34).

Commensal bacteria stimulate the production of immune cells,

including regulatory T cells (Tregs) and dendritic cells, which in

turn influence systemic immune responses (34). Dysbiosis can lead to an altered

immune landscape, characterized by chronic inflammation, which is

recognized as a risk factor for cancer development (35). For instance, chronic inflammation

driven by microbial imbalances can result in cellular stress, DNA

damage and ultimately tumorigenesis (35) (Fig.

1).

Metabolism of xenobiotics and nutrients: The gut

microbiota is crucial in metabolizing dietary and environmental

xenobiotics, converting them into bioactive compounds that can

influence cancer risk (7). For

example, certain gut bacteria can metabolize dietary fiber into

short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as butyrate, which possesses

anti-cancer properties (36).

Butyrate has been shown to inhibit tumor cell proliferation and

promote apoptosis in colorectal cancer models (37). Conversely, the metabolism of

certain amines and phenolic compounds by gut microbes can yield

carcinogenic metabolites, increasing cancer susceptibility

(38) (Fig. 1).

Alteration of Gut Barrier Function: A healthy gut

microbiota helps maintain intestinal barrier integrity, preventing

translocation of pathogens and toxins into the systemic circulation

(39). Dysbiosis can disrupt the

epithelial barrier, allowing bacterial endotoxins to enter the

bloodstream and provoke systemic inflammation, contributing to

cancer risk (40) (Fig. 1).

The association of gut microbiota with tumors,

including PCa. Significant evidence suggests that gut microbiota is

implicated in the pathogenesis of various cancers, including

colorectal, breast and liver cancers (41). A notable study by Kang et al

(42) observed distinct microbial

profiles in colorectal cancer patients characterized by a reduction

in butyrate-producing bacteria. Similarly, research has indicated

that specific phylotypes, such as Fusobacterium nucleatum,

are enriched in colorectal tumors and may promote tumor growth

through inflammatory pathways (43). In the context of breast cancer,

several studies have reported associations between gut microbiota

composition and tumor development. Caleça et al (44) found that women with breast cancer

exhibited specific dysbiotic features compared with healthy

controls. Furthermore, gut microbiota modulation through dietary

interventions showed promise in altering the risk of breast cancer

through immune system reprogramming (45).

The relevance of gut microbiota to PCa is a

burgeoning area of research. Wang et al (46) reported a significant correlation

between gut microbiota composition and PCa risk, indicating that

distinctive microbial communities may be associated with tumor

presence. Notably, studies employing fecal microbiota

transplantation have highlighted the potential for gut microbiota

to influence host tumor immunology and responses to therapeutic

interventions (47,48). Despite these findings, there are

inconsistencies and limitations in the current literature linking

gut microbiota to PCa. Some studies report significant

associations, while others fail to demonstrate a clear connection,

suggesting that variations in methodology, sample size and

environmental factors may influence outcomes (49,50).

Furthermore, the geographic and dietary contexts in which studies

are conducted may contribute to discrepancies in microbial

composition and cancer susceptibility (51,52).

Clinical evidence linking gut microbiota to

PCa

Accumulating clinical evidence supports the

association between gut microbiota and PCa pathogenesis and

progression (53–63). Key studies have identified distinct

microbial signatures in patients with PCa compared with healthy

controls, with variations observed across disease stages and

treatment modalities. These findings are summarized in Table I, which highlights study designs,

patient cohorts and principal outcomes.

| Table I.Clinical studies of gut microbiota

and PCa. |

Table I.

Clinical studies of gut microbiota

and PCa.

| First author/s,

year | Study type | Number of

patients | Patient type | Findings | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Golombos et

al, 2018 | Prospective pilot

study | 32 | Men diagnosed with

PCa vs. healthy controls | Significant

differences in gut microbiota composition | (53) |

| Liu and Jiang,

2020 | Retrospective

study | 21 | Hormone-sensitive

vs. castration-resistant patients with PCa | Compositional

differences with enrichment in specific taxa in

castration-resistant disease | (54) |

| Newton et

al, 2019 | Randomized

controlled trial | 60 | Individuals

undergoing ADT for PCa | Exercise

intervention led to modifications in the gut microbiota | (55) |

| Matsushita et

al, 2021 | Case-control

study | 152 | Patients with

high-Gleason PCa | Unique microbial

signature associated with aggressive cancer phenotypes | (56) |

| Li et al,

2021 | Cross-sectional

study | 86 | Patients with PCa

undergoing prostatectomy or ADT | Significant changes

in gut microbiota profiles with more pronounced dysbiosis in ADT

patients | (57) |

| Takezawa et

al, 2021 | Case-control

study | 128 | Patients with

prostate enlargement | Potential

association between gut microbiota composition and urological

conditions | (58) |

| Matsushita et

al, 2022 | Cohort study | 54 | Elderly men with

PCa | Firmicutes

correlations with blood testosterone levels | (59) |

| Fernandes et

al, 2022 | Pilot case series

study | 5 | Patients with PCa

treated with Radium-223 | Significant shifts

in microbial populations post-treatment | (60) |

| Huang et al,

2024 | Systematic review

and meta-analysis | 442 | Patients with PCa

vs. healthy individuals | Significant

differences in gut microbiota profiles | (61) |

| Smith et al,

2021 | Randomised

controlled trial | 44 | Breast and PCa

cases vs. matched cancer-free controls | Gut microbial

differences | (62) |

| Reichard et

al, 2022 | Prospective

analysis of a cohort | 692 | Patients at risk of

lethal PCa | Gut

microbiota-dependent metabolic pathways and risk of lethal PCa | (63) |

The role of the gut microbiota in PCa pathology has

gained traction, as illustrated by Golombos et al (53) in their prospective pilot study. The

authors observed significant differences in gut microbiota

composition among men diagnosed with PCa compared with healthy

controls, highlighting alterations in specific microbial profiles

that may be relevant to cancer development (53). However, the small sample size and

the lack of diverse demographics limit the generalizability of

these findings. In another study conducted by Liu and Jiang

(54), compositional differences

were noted between hormone-sensitive and castration-resistant

patients with PCa. This study found that specific microbial taxa

were enriched in patients with castration-resistant disease,

suggesting that gut microbiota may influence disease progression

and therapeutic resistance. However, the design was retrospective

and causality could not be firmly established.

A randomized controlled trial has also provided

valuable insights. Newton et al (55) explored the effect of exercise on

gut microbiota composition in individuals undergoing ADT for PCa.

The authors reported that the exercise intervention led to

modifications in the gut microbiota, which may correlate with

improved patient outcomes. While this study provides promising

evidence on lifestyle interventions, the results must be

interpreted with caution due to potential confounding factors

related to exercise types and patient adherence. Moreover,

Matsushita et al (56)

assessed gut microbiota in relation to high-Gleason PCa. The

authors identified a unique microbial signature associated with

aggressive cancer phenotypes, thus emphasizing the potential of

microbiota profiling for risk stratification in clinical practice.

The findings contribute to our understanding but warrant further

validation in larger cohorts.

Li et al (57) conducted a cross-sectional study

among patients with PCa undergoing prostatectomy or ADT,

demonstrating significant changes in gut microbiota profiles. The

study revealed that patients undergoing ADT experienced more

pronounced dysbiosis, which correlated with therapy outcomes. While

these findings are useful, the cross-sectional nature of the study

limits causal inferences. Takezawa et al (58) also investigated the

Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in connection with prostate

enlargement, establishing a potential association between gut

microbiota composition and urological conditions. However, the

specific relevance to cancer remains unclear and needs to be

contextualized within a broader oncological framework.

Emerging longitudinal studies have further

illuminated the relationship between gut microbiota and PCa.

Matsushita et al (59)

conducted a detailed examination of firmicutes correlations and

blood testosterone levels in elderly men with PCa, supporting the

concept that microbiota could influence hormonal pathways that are

critical in cancer progression. While insightful, the study's

retrospective nature poses challenges to establishing direct

causative relationships. The case series exploring the effects of

Radium-223 on gut microbiota reported significant shifts in

microbial populations post-treatment, suggesting that certain

therapies might modulate the microbiome, which in turn could

influence cancer dynamics (60).

The limited sample size and lack of controls temper the broader

applicability of these findings, highlighting the need for further

robust studies.

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Huang et

al (61) synthesized data from

various studies, confirming that significant differences exist in

gut microbiota profiles between patients with PCa and healthy

individuals. This comprehensive review underscores the

reproducibility of observed dysbiosis across different populations

and study designs. Nevertheless, the heterogeneity of study

methodologies and microbiota analyses complicates direct

comparisons. Moreover, a Mendelian randomization study by Wang

et al (46) suggested a

causal relationship between gut microbiota and PCa. The authors'

findings advocate for the gut-prostate axis by demonstrating

potential microbiome-driven mechanisms influencing prostate disease

pathology. This strengthens the biologic plausibility of the gut

microbiota's role in PCa, although the models require rigorous

validation. In addition, prospective cohort analyses have shown

that gut microbiome-dependent metabolic pathways may be associated

with the risk of developing lethal prostate cancer, further

supporting the clinical relevance of microbial metabolism in PCa

pathogenesis (63).

In summary, clinical evidence consistently reports a

state of gut microbiota dysbiosis in patients with PCa compared

with healthy controls (53,61).

Key findings include distinct microbial signatures associated with

PCa presence (53,56), differences between disease states

such as hormone-sensitive and castration-resistant PCa (54) and modulations induced by therapies

such as ADT (57) or Radium-223

(60). Furthermore, interventions

such as exercise have been shown to alter the gut microbiota in

patients with PCa (55). Despite

this accumulation of evidence, significant inconsistencies remain

regarding the specific microbial taxa associated with increased or

decreased risk. For instance, the roles of Bacteroides,

Streptococcus and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, as well as the

Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio, are not consistently reported

across studies (58,62,64,65).

These discrepancies are likely attributable to methodological

variations (such as sequencing techniques, bioinformatic pipelines)

and profound inter-individual and geographic heterogeneity in

microbiome composition (49,51).

Therefore, while a consensus confirms the involvement of gut

microbiota in PCa, future multi-center studies with standardized

protocols are essential to identify robust, generalizable microbial

signatures for clinical application.

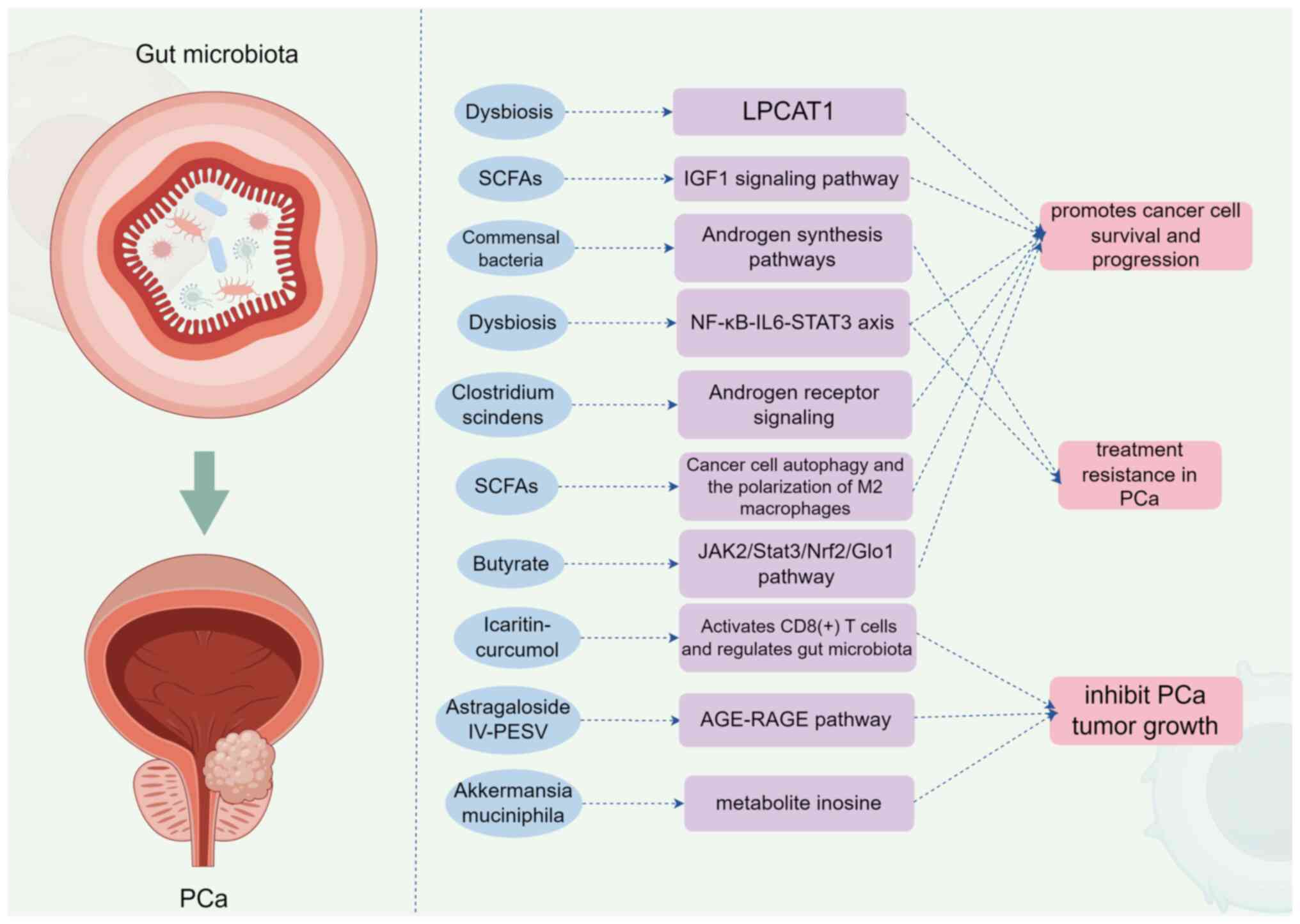

Mechanisms of action

The gut microbiota influences PCa through multiple

interconnected mechanisms, including metabolic regulation, immune

modulation and hormonal signaling. Major pathways involve microbial

metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs),

inflammation-related axes (such as NF-κB-IL6-STAT3) and androgen

metabolism (66), and key

mechanistic pathways are illustrated in Fig. 2. A summary of these mechanisms and

supporting studies is provided in Table II.

| Figure 2.Mechanism of action of gut microbiota

on prostate cancer (generated with Figdraw; www.figdraw.com; ID: RWTIA8dd77). SCFAs, short-chain

fatty acids; LPCAT1, lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase; IGF1,

insulin-like growth factor 1; NF-κB, nuclear factor

kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; IL-6,

interleukin-6; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of

transcription 3; JAK2, Janus kinase 2; Nrf2, nuclear factor

erythroid 2-related factor 2; Glo1, glyoxalase 1; LPCAT1,

lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 1; AGE, advanced glycation

end-product; RAGE, receptor for advanced glycation end-products;

PCa, prostate cancer; CRPC, castration-resistant prostate

cancer. |

| Table II.Key mechanisms of gut microbiota

influence on PCa progression. |

Table II.

Key mechanisms of gut microbiota

influence on PCa progression.

| First author/s,

year | Mechanism

category | Key

elements/microbial factors | Proposed effect on

PCa | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Matsushita et

al, 2021; Liu et al, 2023 | Metabolic

Regulation | SCFAs | Activate IGF1

signaling, promoting cell proliferation and survival. Promote

autophagy and M2 macrophage polarization, facilitating a

tumor-promoting environment. | (68,74) |

| Hsia et al,

2024 | Metabolic

Regulation | Microbial

modulation of methylglyoxal | Butyrate increases

methylglyoxal production via JAK2/Stat3/Nrf2/Glo1 pathway in

CRPC. | (75) |

| Zhong et al,

2022 | Immune Modulation

and Inflammation | NF-κB-IL6-STAT3

axis activation | Dysbiosis activates

this inflammatory axis, promoting PCa progression and docetaxel

resistance. | (72) |

| Xu et al,

2024 | Immune Modulation

and Inflammation | CD8 (+) T cell

activation | Compounds such as

Icaritin-curcumol can activate CD8 (+) T cells and regulate gut

microbiota, suppressing cancer. | (76) |

| Pernigoni et

al, 2021 | Hormonal

Signaling | Androgen

biosynthesis | Commensal bacteria

can alter androgen synthesis pathways, promoting endocrine

resistance. | (69) |

| Bui et al,

2023 | Hormonal

Signaling | Androgen receptor

signaling | Metabolites from

Clostridium scindens can trigger PCa progression via

androgen receptor signaling. | (73) |

| Liu et al,

2021 | Other Pathways | LPCAT1

upregulation | Gut dysbiosis can

increase LPCAT1 expression, enhancing DNA repair pathways and

promoting cancer cell survival. | (67) |

| You et al,

2024 | Other Pathways | AGE-RAGE

pathway | Restoration of gut

microbiota and metabolic homeostasis via this pathway can inhibit

tumor growth (such as Astragaloside IV-PESV). | (77) |

| Yu et al,

2024 | Other Pathways | Bacterial

metabolites (e.g., Inosine) | Akkermansia

muciniphila metabolite inosine inhibits castration

resistance. | (78) |

Dysbiosis and PCa progression

A growing body of evidence suggests that alterations

in gut microbiota composition, referred to as dysbiosis, are

closely associated with PCa progression (61,67).

Liu et al (67) found that

specific taxa, when disrupted, lead to increased levels of LPCAT1,

a lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase involved in membrane

repair, which promotes cancer cell survival and progression. In

this context, the study highlights a critical intersection between

microbial metabolism and cancer biology. Another study by

Matsushita et al (68)

emphasizes the role of SCFAs derived from gut microbiota in

promoting PCa growth. The authors' research revealed that SCFAs

activate the insulin-such as growth factor 1 (IGF1) signaling

pathway, which is well-known for its role in cell proliferation and

survival . Hence, the microbial production of SCFAs offers a

potential oncogenic pathway that merits further exploration.

Androgen biosynthesis and resistance

mechanisms

Studies have illuminated the role of gut microbiota

in modulating androgen biosynthesis, a crucial factor in PCa

development. Pernigoni et al (69) demonstrated that commensal bacteria

could promote endocrine resistance by altering androgen synthesis

pathways, potentially leading to treatment resistance in PCa. This

finding underlines the necessity of considering microbial

influences in both hormonal regulation and therapeutic strategies

against PCa. Furthermore, Matsushita et al (70) also reported that high-fat diets,

which can alter gut microbiota composition, enhance histamine

signaling and foster an environment conducive to PCa progression.

The dual role of diet and gut microbiota in cancer dynamics

highlights the complexity of interactions and the importance of

holistic approaches in cancer management.

Inflammatory pathways involved in PCa

progression

Dysbiosis has been linked to chronic inflammation,

which is a precursor in a number of cancers, including PCa

(71). Zhong et al

(72) established that gut

microbiota dysbiosis activates the NF-κB-IL6-STAT3 axis, promoting

not only PCa progression but also docetaxel resistance. This

finding suggests that therapies targeting the gut microbiota could

enhance the efficacy of conventional treatments by modulating the

inflammatory milieu associated with PCa. Moreover, Bui et al

(73) highlighted Clostridium

scindens metabolites as triggers of PCa progression through

androgen receptor signaling. This indicates that specific microbial

metabolites can directly affect cancer biology, suggesting possible

intervention strategies aimed at microbial pathway

manipulation.

Autophagy and immune response

modulation

Gut microbiota-derived molecules have also been

implicated in regulating autophagy and immune responses in PCa. Liu

et al (74) reported that

SCFAs promote cancer cell autophagy and the polarization of M2

macrophages, facilitating a tumor-promoting environment. As immune

evasion is a critical hallmark of cancer, understanding how gut

microbiota influences immune modulation could pave the way for

innovative therapeutic strategies (34). In a related study, Hsia et

al (75) demonstrated that

butyrate, a major SCFAs, increases methylglyoxal production via the

JAK2/Stat3/Nrf2/Glo1 pathway in castration-resistant PCa cells,

further implicating metabolic interplay in cancer progression.

These findings emphasize the multifaceted roles of gut-derived

metabolites in shaping tumor biology.

Mechanisms of cancer suppression via

gut microbiota

Notably, research has also shown that certain

natural compounds can restore gut microbiota homeostasis,

potentially suppressing PCa progression (61). Xu et al (76) explored the action of

Icaritin-curcumol, which activates CD8 (+) T cells and regulates

gut microbiota, demonstrating a dual effect on immune enhancement

and cancer suppression. This highlights promising avenues for

therapeutic strategies that incorporate microbiota modulation

alongside conventional treatments. Furthermore, You et al

(77) presented evidence

indicating that Astragaloside IV-PESV can inhibit PCa tumor growth

through gut microbiota restoration and metabolic homeostasis, which

is mediated via the AGE-RAGE pathway. Such findings contribute to a

growing body of literature supporting the significance of gut

microbiota in cancer therapeutics. Lastly, Yu et al

(78) investigated Akkermansia

muciniphila and its metabolite inosine, which inhibits

castration resistance in PCa. This research reinforces the notion

that specific microbial taxa could serve as therapeutic targets or

biomarkers, further integrating gut microbiota research into PCa

clinical practice.

The intricate interplay between gut microbiota and

PCa progression underscores the necessity for further research in

this burgeoning field (79).

Studies consistently highlight that dysbiosis not only contributes

to the pathogenesis of PCa but also influences the efficacy of

various treatment modalities (52,72).

As we continue to unravel these complex relationships, it is vital

to incorporate gut microbiota considerations into PCa management

strategies, paving the way for personalized therapeutic approaches

that target the microbiome for improved outcomes. The ongoing

exploration of microbial metabolites, signaling pathways and

dietary factors will undoubtedly provide new insights into the

mechanisms of PCa progression and resistance, ultimately benefiting

patient care and treatment efficacy.

Microbiota as a therapeutic target

Modulating gut microbiota presents a promising

avenue for influencing PCa pathogenesis and treatment outcomes

(11). Interventions, including

probiotics, prebiotics and dietary changes, aim to restore

microbiota balance and enhance immune function (19). However, the variability in

individual microbiome compositions and the specificities of

intervention effects necessitate careful evaluation of available

studies and clinical trials to establish effective and personalized

therapeutic strategies (52).

Role of microbiota in modulating

responses to PCa treatments

Emerging evidence suggests that the composition of

gut microbiota can markedly influence the effectiveness of various

PCa treatments, specifically immunotherapies and chemotherapies

(52,72). For instance, it has been shown that

specific gut bacteria can enhance the efficacy of immune checkpoint

inhibitors by modulating systemic immune responses (80). A study found that patients with

colorectal cancer who had a higher abundance of certain gut

bacteria experienced improved responses to immunotherapy, raising

the possibility that similar principles could apply to PCa

treatment (81). Conversely,

dysbiosis may lead to decreased effectiveness of chemotherapy.

Antibiotic exposure during treatment can disrupt microbiota

balance, potentially diminishing therapeutic outcomes and

increasing susceptibility to adverse effects (67). Thus, understanding how gut

microbiota interact with therapeutic modalities could inform

approaches to enhance treatment efficacy and minimize toxicity.

Exploration of potential interventions

targeting gut microbiota

Probiotics, defined as live microorganisms that

confer health benefits, have been shown to restore gut microbiota

balance (82). Specific strains,

such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus, have been demonstrated to

enhance immune modulation, which may inhibit tumor growth and

progression. However, the efficacy of probiotics can vary markedly

by strain and individual response due to unique host microbiota

compositions (83). For instance,

while certain strains may exert beneficial effects, others may not

confer the same advantages, raising questions about strain

specificity and the need for personalized approaches (84).

Prebiotics, which are non-digestible food components

that promote beneficial bacteria growth, have also gained attention

(85). They can selectively

increase populations of SCFAs-producing bacteria, such as

Faecalibacterium, linked to anti-inflammatory properties

(86). Dietary modifications

focused on increasing fiber intake may support these beneficial

communities while simultaneously mitigating dysbiosis and

inflammation (87). Nevertheless,

the challenge lies in establishing standardized guidelines on

effective prebiotic intake, given the variability in individual gut

microbiota responses.

Further, dietary interventions are increasingly seen

as viable approaches to alter gut microbiota (88). Studies suggest that Mediterranean

diets rich in fruits, vegetables and whole grains can enhance

microbial diversity and reduce cancer progression risk (89,90).

However, a number of these studies are observational and require

causal evidence to substantiate claims regarding dietary impact on

PCa outcomes.

Emerging clinical trials and

studies

The gut microbiota has emerged as a potential

therapeutic target in the management of PCa, with recent studies

highlighting its role in disease progression and response to

treatment (91). The modulation of

gut microbiota through dietary interventions, prebiotics,

probiotics and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has shown

promise in enhancing treatment efficacy and mitigating adverse

effects associated with standard therapies such as chemotherapy,

immunotherapy and hormone therapy (19,92).

Critical evaluation of the literature reveals a

growing body of evidence supporting the impact of gut microbiota on

PCa. For instance, Liss et al (93) identified specific bacterial species

associated with PCa, suggesting a role for microbiota in disease

pathogenesis. Furthermore, Matsushita et al (56) reported that gut microbiota

metabolites, particularly SCFAs, promote PCa growth, indicating a

potential therapeutic avenue through dietary fiber manipulation.

The therapeutic potential of the gut microbiota is further

supported by studies showing that probiotics can enhance the

response to treatment and reduce postoperative infections,

suggesting their utility as an adjuvant therapy (94). FMT has also demonstrated potential

in modifying the gut microbiota to improve treatment responses,

although the clinical efficacy of such interventions requires

further exploration (69).

Despite the promising findings, there is a noted

inconsistency in the results across studies, which may be

attributed to variations in study design, population demographics

and methodology (53). For

example, while some studies report an increase in

Bacteroides and Streptococcus in patients with PCa,

others find a decrease in Faecalibacterium prausnitzii,

highlighting the complexity of the gut microbiota's role in PCa

(64,65).

Notwithstanding the promising potential of

microbiota-targeted therapies, several critical limitations must be

acknowledged. The efficacy of probiotics is highly strain-specific

and beneficial effects observed with one strain, such as

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (83), cannot be generalized to other

strains or probiotic formulations (84). Furthermore, substantial

inter-individual variability in baseline gut microbiota

composition, driven by factors such as genetics, diet and prior

antibiotic exposure (52),

markedly influences responses to interventions, complicating the

development of universal therapeutic recommendations. Patient

heterogeneity also extends to disease status and prior treatments,

which may alter the gut ecosystem and modulate intervention

outcomes (69). Safety

considerations are equally paramount. While probiotics and

prebiotics are generally regarded as safe, the long-term

consequences of microbiota manipulation, especially in

immunocompromised cancer patients, remain inadequately studied.

More invasive approaches, such as FMT, carry risks of pathogen

transmission, unintended microbial engraftment and unpredictable

shifts in microbial communities that could potentially exacerbate

inflammation or promote resistance pathways (92,95).

Therefore, future clinical applications must incorporate rigorous

safety monitoring, strain-level characterization and personalized

strategies that account for individual microbiome profiles and

clinical contexts.

Current limitations and challenges

The gut microbiota has emerged as a significant

player in the pathogenesis and progression of PCa, yet several

limitations and challenges hinder its clinical application as a

therapeutic target (50). One of

the primary challenges is the complexity and variability of the gut

microbiota across individuals. Factors such as diet, genetics, age

and environmental influences contribute to this variability, making

it difficult to establish a standardized microbiome profile that

correlates with PCa risk or treatment response (14,19).

This heterogeneity complicates the interpretation of microbiome

studies and the generalization of findings across diverse

populations.

The interpretation of gut microbiota studies in PCa

is heavily influenced by the diversity of research designs

employed, including observational, interventional, cross-sectional

and longitudinal approaches. Observational studies, such as

case-control and cohort designs, have been instrumental in

identifying associations between specific microbial taxa and PCa

risk or progression (53,56). However, these studies are prone to

confounding factors, including diet, lifestyle and comorbidities,

and cannot establish causality. Interventional studies, such as

randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating probiotics or

dietary modifications (55), offer

stronger evidence for causal relationships but are often limited by

small sample sizes, short durations and heterogeneous intervention

protocols. Cross-sectional studies (57) provide a snapshot of microbial

composition at a single time point, which is useful for hypothesis

generation but cannot capture dynamic changes in the microbiome

over time or in response to disease progression or treatment. By

contrast, longitudinal studies allow for the assessment of temporal

changes and are more suited for evaluating the microbiome's role in

disease progression or treatment response (59). Nevertheless, they are

resource-intensive and may still be affected by unmeasured

confounders. The variability in study designs contributes markedly

to the inconsistency of reported findings and complicates the

comparison and synthesis of results across studies. Therefore,

future research should prioritize well-designed, prospective

longitudinal studies and RCTs with standardized methodologies to

enhance the reliability and generalizability of conclusions.

Moreover, the methodologies employed in microbiome

research often vary markedly, leading to inconsistent results. For

instance, studies utilizing different sampling techniques (for

example, stool vs. urine vs. tissue) and analytical methods (for

example, 16S rRNA sequencing vs. shotgun metagenomics) can yield

divergent microbiome compositions and associations with PCa

(53,56). Such discrepancies highlight the

need for standardized protocols to ensure comparability and

reproducibility of results. Furthermore, the lack of consensus on

the definition of ‘healthy’ compared with ‘dysbiotic’ microbiomes

poses additional challenges in interpreting the implications of

microbiome alterations in patients with PCa (96).

Another significant limitation is the current

understanding of the mechanisms by which gut microbiota influences

PCa. While certain bacterial taxa, such as Bacteroides

massiliensis and Akkermansia muciniphila, have been

implicated in PCa progression, the precise pathways and

interactions involved remain poorly characterized (14,92).

For example, the role of microbial metabolites, such as SCFAs, in

modulating inflammation and hormone levels in the prostate is still

under investigation, necessitating further research to elucidate

these mechanisms (69).

Additionally, the therapeutic potential of

modulating the gut microbiota through interventions such as

probiotics, prebiotics and FMT faces several obstacles (95). The efficacy of these treatments is

often inconsistent, with some studies reporting beneficial effects

while others show no significant impact on PCa outcomes (97,98).

This inconsistency may stem from variations in individual

microbiome composition and the specific strains used in probiotic

formulations, underscoring the need for tailored approaches based

on individual microbiome profiles. Furthermore, the safety and

long-term effects of manipulating the gut microbiota in patients

with PCa are not well understood. Concerns regarding the potential

for adverse effects, such as the introduction of pathogenic

bacteria or the exacerbation of existing conditions, necessitate

careful consideration and monitoring in clinical settings (92).

Future directions

The exploration of the gut microbiota as a potential

modulator of PCa pathogenesis and progression represents an

exciting frontier in cancer research. To translate recent

associative findings into actionable clinical strategies, future

investigations must prioritize several key areas through

coordinated and rigorous scientific approaches.

A primary imperative is the establishment of

large-scale, multiethnic prospective cohorts. Such studies are

essential to account for the profound heterogeneity in gut

microbiota composition influenced by genetics, diet, geography and

lifestyle (14,29,51).

These initiatives should employ standardized methodologies for

sample collection, DNA sequencing (preferentially shotgun

metagenomics) and bioinformatic analysis to minimize technical

variability and enable robust cross-study comparisons. This will

help identify consistent microbial signatures for PCa risk

stratification across diverse populations and clarify the role of

the racial disparities that have been highlighted in preliminary

research (80).

Moreover, a deeper mechanistic dissection of the

gut-prostate axis is crucial. While microbial metabolites such as

SCFAs and their involvement in pathways such as IGF1 signaling and

chronic inflammation (such as the NF-κB-IL6-STAT3 axis) have been

implicated (68,72,99),

the precise cause-and-effect relationships remain incompletely

defined. Future work should utilize gnotobiotic animal models,

organoids and multi-omics integrations (metagenomics, metabolomics,

proteomics) to definitively link specific microbial taxa and their

metabolic outputs (such as SCFAs, polyamines and secondary bile

acids) to molecular events driving PCa initiation, progression and

therapy resistance. The role of bacterial components in modulating

intratumoral immune responses represents a particularly promising

yet underexplored avenue (52).

The therapeutic potential of microbiota modulation

demands rigorous evaluation through well-designed interventional

trials. Promising strategies include targeted probiotic and

prebiotic formulations, personalized dietary interventions (such as

Mediterranean, high-fiber, or polyphenol-rich diets) and FMT

(19,69,88,92).

Future clinical trials must move beyond observational correlations

and focus on randomized controlled designs that assess the efficacy

of these interventions in improving responses to standard therapies

(such as ADT, immunotherapy and chemotherapy) and mitigating

treatment-related adverse effects. A critical aspect will be to

develop personalized approaches that consider an individual's

baseline microbiome, ensuring that interventions are tailored for

maximal efficacy (52,84).

Finally, fostering interdisciplinary collaboration

among oncologists, microbiologists, immunologists, nutritionists

and bioinformaticians is paramount. Such synergy is necessary to

unravel the complex interactions between diet, microbiota and host

physiology. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine

learning with microbiome data holds significant promise for

developing predictive models of disease progression and treatment

response (19). By systematically

addressing these priorities, including standardized large-scale

cohorts, mechanistic elucidation, targeted interventional trials

and interdisciplinary collaboration, the field can accelerate the

translation of gut microbiota research into novel diagnostic tools

and personalized therapeutic strategies for PCa, ultimately

improving patient outcomes.

In summary, the gut microbiota represents a

promising, yet complex, modulator in PCa pathogenesis. Future

research should focus on addressing the existing gaps in

understanding microbial diversity, elucidating mechanisms of action

and translating insights into clinical applications. By

prioritizing these future directions, we enhance our potential to

develop innovative strategies that leverage the gut microbiota in

the prevention and treatment of PCa, ultimately contributing to

improved patient outcomes.

Conclusions

The present review highlighted the emerging role of

gut microbiota as a potential modulator in PCa pathogenesis and

progression, underscoring significant associations between

microbial composition and cancer outcomes. While current studies

demonstrate the promise of gut microbiota modulation as a novel

strategy for PCa prevention and treatment, inconsistencies in

methodologies and findings warrant caution. Further investigations

are necessary to establish causative relationships and identify

actionable therapeutic pathways. Continued research will be crucial

in integrating gut microbiota insights into clinical practice,

ultimately enhancing patient management and outcomes in PCa.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by Baiyin Science and Technology

Plan Project (Clinical Application Research on Early Screening of

Prostate Cancer in Baiyin Area: Grant no. 2022-3-6Y) and Baiyin

First People's Hospital Science and Technology Plan Project (grant

no. 2023-2-16Y).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

ZH, YX and QZ contributed to the manuscript

conception. ZH, KC and RZ were involved in drafting the manuscript

and revising it critically for important intellectual content. HS,

LL, YL, JH and JW have revised the article for content and

language. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors read

and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Almeeri MNE, Awies M and Constantinou C:

Prostate cancer, pathophysiology and recent developments in

management: A narrative review. Curr Oncol Rep. 26:1511–1519. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wasim S, Lee SY and Kim J: Complexities of

prostate cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 23:142572022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Perler BK, Friedman ES and Wu GD: The role

of the gut microbiota in the relationship between diet and human

health. Annu Rev Physiol. 85:449–468. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Wang MY, Sang LX and Sun SY: Gut

microbiota and female health. World J Gastroenterol. 30:1655–1662.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Matijašić M, Meštrović T, Paljetak HC,

Perić M, Barešić A and Verbanac D: Gut microbiota beyond

bacteria-mycobiome, virome, archaeome, and eukaryotic parasites in

IBD. Int J Mol Sci. 21:26682020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Pant A, Maiti TK, Mahajan D and Das B:

Human gut microbiota and drug metabolism. Microb Ecol. 86:97–111.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Yang Q, Wang B, Zheng Q, Li H, Meng X,

Zhou F and Zhang L: A review of gut microbiota-derived metabolites

in tumor progression and cancer therapy. Adv Sci (Weinh).

10:e22073662023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Aburto MR and Cryan JF: Gastrointestinal

and brain barriers: unlocking gates of communication across the

microbiota-gut-brain axis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

21:222–247. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hsu CL and Schnabl B: The gut-liver axis

and gut microbiota in health and liver disease. Nat Rev Microbiol.

21:719–733. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Pernigoni N, Guo C, Gallagher L, Yuan W,

Colucci M, Troiani M, Liu L, Maraccani L, Guccini I, Migliorini D,

et al: The potential role of the microbiota in prostate cancer

pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Urol. 20:706–718. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Gut microbiota differs significantly

between men with and without prostate cancer. Cancer. 129:169–170.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kalinen S, Kallonen T, Gunell M, Ettala O,

Jambor I, Knaapila J, Syvänen KT, Taimen P, Poutanen M, Aronen HJ,

et al: Differences in gut microbiota profiles and microbiota

steroid hormone biosynthesis in men with and without prostate

cancer. Eur Urol Open Sci. 62:140–150. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zha C, Peng Z, Huang K, Tang K, Wang Q,

Zhu L, Che B, Li W, Xu S, Huang T, et al: Potential role of gut

microbiota in prostate cancer: Immunity, metabolites, pathways of

action? Front Oncol. 13:11962172023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Porter CM, Shrestha E, Peiffer LB and

Sfanos KS: The microbiome in prostate inflammation and prostate

cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 21:345–354. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Cereda V, Falbo PT, Manna G, Iannace A,

Menghi A, Corona M, Semenova D, Calò L, Carnevale R, Frati G and

Lanzetta G: Hormonal prostate cancer therapies and cardiovascular

disease: A systematic review. Heart Fail Rev. 27:119–134. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Beam A, Clinger E and Hao L: Effect of

diet and dietary components on the composition of the gut

microbiota. Nutrients. 13:27952021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

García-Montero C, Fraile-Martínez O,

Gómez-Lahoz AM, Pekarek L, Castellanos AJ, Noguerales-Fraguas F,

Coca S, Guijarro LG, García-Honduvilla N, Asúnsolo A, et al:

Nutritional components in western diet versus mediterranean diet at

the gut microbiota-immune system interplay. implications for health

and disease. Nutrients. 13:6992021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Pei X, Liu L and Han Y: Advances in human

microbiome and prostate cancer research. Front Immunol.

16:15766792025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Sha S, Ni L, Stefil M, Dixon M and

Mouraviev V: The human gastrointestinal microbiota and prostate

cancer development and treatment. Investig Clin Urol. 61 (Suppl

1):S43–S50. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Han EJ, Ahn JS, Choi YJ, Kim DH, Choi JS

and Chung HJ: Exploring the gut microbiome: A potential biomarker

for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta

Rev Cancer. 1880:1892512025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ling Z, Liu X, Cheng Y, Yan X and Wu S:

Gut microbiota and aging. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 62:3509–3534.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Adak A and Khan MR: An insight into gut

microbiota and its functionalities. Cell Mol Life Sci. 76:473–493.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhang Y, Zhou M, Zhou Y and Guan X:

Dietary components regulate chronic diseases through gut

microbiota: A review. J Sci Food Agric. 103:6752–6766. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

McCallum G and Tropini C: The gut

microbiota and its biogeography. Nat Rev Microbiol. 22:105–118.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Weingarden AR and Vaughn BP: Intestinal

microbiota, fecal microbiota transplantation, and inflammatory

bowel disease. Gut Microbes. 8:238–252. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Boulangé CL, Neves AL, Chilloux J,

Nicholson JK and Dumas ME: Impact of the gut microbiota on

inflammation, obesity, and metabolic disease. Genome Med. 8:422016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zhang Y, Zhu Y, Guo Q, Wang W and Zhang L:

High-throughput sequencing analysis of the characteristics of the

gut microbiota in aged patients with sarcopenia. Exp Gerontol.

182:1122872023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Zhang X, Zhong H, Li Y, Shi Z, Ren H,

Zhang Z, Zhou X, Tang S, Han X, Lin Y, et al: Sex- and age-related

trajectories of the adult human gut microbiota shared across

populations of different ethnicities. Nat Aging. 1:87–100. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Fajstova A, Galanova N, Coufal S, Malkova

J, Kostovcik M, Cermakova M, Pelantova H, Kuzma M, Sediva B,

Hudcovic T, et al: Diet rich in simple sugars promotes

pro-inflammatory response via gut microbiota alteration and TLR4

signaling. Cells. 9:27012020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Francescangeli F, De Angelis ML and Zeuner

A: Dietary factors in the control of gut homeostasis, intestinal

stem cells, and colorectal cancer. Nutrients. 11:29362019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Li C and Hu Y: Align resistant starch

structures from plant-based foods with human gut microbiome for

personalized health promotion. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr.

63:2509–2520. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Liu Y, Cao Y, Liu P, Zhai S, Liu Y, Tang

X, Lin J, Shi M, Qi D, Deng X, et al: ATF3-induced activation of

NF-κB pathway results in acquired PARP inhibitor resistance in

pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 47:939–950. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Zhou CB, Zhou YL and Fang JY: Gut

microbiota in cancer immune response and immunotherapy. Trends

Cancer. 7:647–660. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Liu Q, Yang Y, Pan M, Yang F, Yu Y and

Qian Z: Role of the gut microbiota in tumorigenesis and treatment.

Theranostics. 14:2304–2328. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Sivaprakasam S, Prasad PD and Singh N:

Benefits of short-chain fatty acids and their receptors in

inflammation and carcinogenesis. Pharmacol Ther. 164:144–151. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka K, Marano L, Merola

E, Roviello F and Połom K: Sodium butyrate in both prevention and

supportive treatment of colorectal cancer. Front Cell Infect

Microbiol. 12:10238062022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Cheng WY, Wu CY and Yu J: The role of gut

microbiota in cancer treatment: friend or foe? Gut. 69:1867–1876.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Jandhyala SM, Talukdar R, Subramanyam C,

Vuyyuru H, Sasikala M and Nageshwar Reddy D: Role of the normal gut

microbiota. World J Gastroenterol. 21:8787–8803. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Liu L, Wang H, Chen X, Zhang Y, Zhang H

and Xie P: Gut microbiota and its metabolites in depression: from

pathogenesis to treatment. EBioMedicine. 90:1045272023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Chen Y, Wang X, Ye Y and Ren Q: Gut

microbiota in cancer: Insights on microbial metabolites and

therapeutic strategies. Med Oncol. 41:252023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Kang J, Sun M, Chang Y, Chen H, Zhang J,

Liang X and Xiao T: Butyrate ameliorates colorectal cancer through

regulating intestinal microecological disorders. Anticancer Drugs.

34:227–237. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Kostic AD, Chun E, Robertson L, Glickman

JN, Gallini CA, Michaud M, Clancy TE, Chung DC, Lochhead P, Hold

GL, et al: Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal

tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment. Cell

Host Microbe. 14:207–215. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Caleça T, Ribeiro P, Vitorino M, Menezes

M, Sampaio-Alves M, Mendes AD, Vicente R, Negreiros I, Faria A and

Costa DA: Breast cancer survivors and healthy women: Could gut

microbiota make a difference?-‘biotacancersurvivors’: A

case-control study. Cancers (Basel). 15:5942023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Arnone AA, Wilson AS, Soto-Pantoja DR and

Cook KL: Diet modulates the gut microbiome, metabolism, and mammary

gland inflammation to influence breast cancer risk. Cancer Prev Res

(Phila). 17:415–428. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Wang L, Zheng YB, Yin S, Li KP, Wang JH,

Bao EH and Zhu PY: Causal relationship between gut microbiota and

prostate cancer contributes to the gut-prostate axis: Insights from

a Mendelian randomization study. Discov Oncol. 15:582024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Ooijevaar RE, Terveer EM, Verspaget HW,

Kuijper EJ and Keller JJ: Clinical application and potential of

fecal microbiota transplantation. Annu Rev Med. 70:335–351. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Chen D, Wu J, Jin D, Wang B and Cao H:

Fecal microbiota transplantation in cancer management: Current

status and perspectives. Int J Cancer. 145:2021–2031. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Yin Z, Liu B, Feng S, He Y, Tang C, Chen

P, Wang X and Wang K: A large genetic causal analysis of the gut

microbiota and urological cancers: A bidirectional mendelian

randomization study. Nutrients. 15:40862023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Matsushita M, Fujita K, Hatano K, De

Velasco MA, Tsujimura A, Uemura H and Nonomura N: Emerging

relationship between the gut microbiome and prostate cancer. World

J Mens Health. 41:759–768. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Fujimoto S, Hatano K, Banno E, Motooka D,

De Velasco MA, Kura Y, Toyoda S, Hashimoto M, Adomi S, Minami T, et

al: Comparative analysis of gut microbiota in hormone-sensitive and

castration-resistant prostate cancer in Japanese men. Cancer Sci.

116:462–469. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Shyanti RK, Greggs J, Malik S and Mishra

M: Gut dysbiosis impacts the immune system and promotes prostate

cancer. Immunol Lett. 268:1068832024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Golombos DM, Ayangbesan A, O'Malley P,

Lewicki P, Barlow L, Barbieri CE, Chan C, DuLong C, Abu-Ali G,

Huttenhower C and Scherr DS: The role of gut microbiome in the

pathogenesis of prostate cancer: A prospective, pilot study.

Urology. 111:122–128. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Liu Y and Jiang H: Compositional

differences of gut microbiome in matched hormone-sensitive and

castration-resistant prostate cancer. Transl Androl Urol.

9:1937–1944. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Newton RU, Christophersen CT, Fairman CM,

Hart NH, Taaffe DR, Broadhurst D, Devine A, Chee R, Tang CI, Spry N

and Galvão DA: Does exercise impact gut microbiota composition in

men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer? A

single-blinded, two-armed, randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open.

9:e0248722019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Matsushita M, Fujita K, Motooka D, Hatano

K, Fukae S, Kawamura N, Tomiyama E, Hayashi Y, Banno E, Takao T, et

al: The gut microbiota associated with high-Gleason prostate

cancer. Cancer Sci. 112:3125–3135. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Li JKM, Wang LL, Wong CYP, Chiu PKF, Teoh

JYC, Kwok HSW, Leung SCH, Wong SH, Tsui SKW and Ng CF: A

cross-sectional study on gut microbiota in prostate cancer patients

with prostatectomy or androgen deprivation therapy. Prostate Cancer

Prostatic Dis. 24:1063–1072. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Takezawa K, Fujita K, Matsushita M,

Motooka D, Hatano K, Banno E, Shimizu N, Takao T, Takada S, Okada

K, et al: The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio of the human gut

microbiota is associated with prostate enlargement. Prostate.

81:1287–1293. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Matsushita M, Fujita K, Motooka D, Hatano

K, Hata J, Nishimoto M, Banno E, Takezawa K, Fukuhara S, Kiuchi H,

et al: Firmicutes in gut microbiota correlate with blood

testosterone levels in elderly men. World J Mens Health.

40:517–525. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Fernandes A, Oliveira A, Guedes C,

Fernandes R, Soares R and Barata P: Effect of radium-223 on the gut

microbiota of prostate cancer patients: A pilot case series study.

Curr Issues Mol Biol. 44:4950–4959. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Huang H, Liu Y, Wen Z, Chen C, Wang C, Li

H and Yang X: Gut microbiota in patients with prostate cancer: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 24:2612024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Smith KS, Frugé AD, van der Pol W, Caston

NE, Morrow CD, Demark-Wahnefried W and Carson TL: Gut microbial

differences in breast and prostate cancer cases from two randomised

controlled trials compared to matched cancer-free controls. Benef

Microbes. 12:239–248. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Reichard CA, Naelitz BD, Wang Z, Jia X, Li

J, Stampfer MJ, Klein EA, Hazen SL and Sharifi N: Gut

microbiome-dependent metabolic pathways and risk of lethal prostate

cancer: Prospective analysis of a PLCO cancer screening trial

cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 31:192–199. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Alanee S, El-Zawahry A, Dynda D, Dabaja A,

McVary K, Karr M and Braundmeier-Fleming A: A prospective study to

examine the association of the urinary and fecal microbiota with

prostate cancer diagnosis after transrectal biopsy of the prostate

using 16sRNA gene analysis. Prostate. 79:81–87. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Hurst R, Meader E, Gihawi A, Rallapalli G,

Clark J, Kay GL, Webb M, Manley K, Curley H, Walker H, et al:

Microbiomes of urine and the prostate are linked to human prostate

cancer risk groups. Eur Urol Oncol. 5:412–419. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Li D, Wang P, Wang P, Hu X and Chen F: The

gut microbiota: A treasure for human health. Biotechnol Adv.

34:1210–1224. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Liu Y, Yang C, Zhang Z and Jiang H: Gut

microbiota dysbiosis accelerates prostate cancer progression

through increased LPCAT1 expression and enhanced DNA repair

pathways. Front Oncol. 11:6797122021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Matsushita M, Fujita K, Hayashi T, Kayama

H, Motooka D, Hase H, Jingushi K, Yamamichi G, Yumiba S, Tomiyama

E, et al: Gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids promote

prostate cancer growth via IGF1 signaling. Cancer Res.

81:4014–4026. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Pernigoni N, Zagato E, Calcinotto A,

Troiani M, Mestre RP, Calì B, Attanasio G, Troisi J, Minini M,

Mosole S, et al: Commensal bacteria promote endocrine resistance in

prostate cancer through androgen biosynthesis. Science.

374:216–224. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Matsushita M, Fujita K, Hatano K, Hayashi

T, Kayama H, Motooka D, Hase H, Yamamoto A, Uemura T, Yamamichi G,

et al: High-fat diet promotes prostate cancer growth through

histamine signaling. Int J Cancer. 151:623–636. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Biragyn A and Ferrucci L: Gut dysbiosis: A

potential link between increased cancer risk in ageing and

inflammaging. Lancet Oncol. 19:e295–e304. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Zhong W, Wu K, Long Z, Zhou X, Zhong C,

Wang S, Lai H, Guo Y, Lv D, Lu J and Mao X: Gut dysbiosis promotes

prostate cancer progression and docetaxel resistance via activating

NF-κB-IL6-STAT3 axis. Microbiome. 10:942022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Bui NN, Li CY, Wang LY, Chen YA, Kao WH,

Chou LF, Hsieh JT, Lin H and Lai CH: Clostridium scindens

metabolites trigger prostate cancer progression through androgen

receptor signaling. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 56:246–256. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Liu Y, Zhou Q, Ye F, Yang C and Jiang H:

Gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids promote prostate

cancer progression via inducing cancer cell autophagy and M2

macrophage polarization. Neoplasia. 43:1009282023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Hsia YJ, Lin ZM, Zhang T and Chou TC:

Butyrate increases methylglyoxal production through regulation of

the JAK2/Stat3/Nrf2/Glo1 pathway in castration-resistant prostate

cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 51:712024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Xu W, Li Y, Liu L, Xie J, Hu Z, Kuang S,

Fu X, Li B, Sun T, Zhu C, et al: Icaritin-curcumol activates CD8(+)

T cells through regulation of gut microbiota and the DNMT1/IGFBP2

axis to suppress the development of prostate cancer. J Exp Clin

Cancer Res. 43:1492024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

You X, Qiu J, Li Q, Zhang Q, Sheng W, Cao

Y and Fu W: Astragaloside IV-PESV inhibits prostate cancer tumor

growth by restoring gut microbiota and microbial metabolic

homeostasis via the AGE-RAGE pathway. BMC Cancer. 24:4722024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Yu Y, Li L, Yang Q, Xue J, Wang B, Xie M,

Shangguan W, Zhu Z and Wu P: Akkermansia muciniphila metabolite

inosine inhibits castration resistance in prostate cancer.

Microorganisms. 12:16532024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Li S, Liu R, Hao X and Liu X: The role of

gut microbiota in prostate cancer progression: A Mendelian

randomization study of immune mediation. Medicine (Baltimore).

103:e388252024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Miya TV, Marima R, Damane BP, Ledet EM and

Dlamini Z: Dissecting microbiome-derived SCFAs in prostate cancer:

Analyzing gut microbiota, racial disparities, and epigenetic

mechanisms. Cancers (Basel). 15:40862023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Zhang SL, Cheng LS, Zhang ZY, Sun HT and

Li JJ: Untangling determinants of gut microbiota and tumor

immunologic status through a multi-omics approach in colorectal

cancer. Pharmacol Res. 188:1066332023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Legesse Bedada T, Feto TK, Awoke KS,

Garedew AD, Yifat FT and Birri DJ: Probiotics for cancer

alternative prevention and treatment. Biomed Pharmacother.

129:1104092020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Banna GL, Torino F, Marletta F, Santagati

M, Salemi R, Cannarozzo E, Falzone L, Ferraù F and Libra M:

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG: An overview to explore the rationale of

its use in cancer. Front Pharmacol. 8:6032017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka K,

Skonieczna-Żydecka K, Hupp T, Duchnowska R, Marek-Trzonkowska N and

Połom K: Next-generation probiotics - do they open new therapeutic

strategies for cancer patients? Gut Microbes. 14:20356592022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Yadav MK, Kumari I, Singh B, Sharma KK and

Tiwari SK: Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics: Safe options for

next-generation therapeutics. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol.

106:505–521. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Mahdavi M, Laforest-Lapointe I and Massé

E: Preventing colorectal cancer through prebiotics. Microorganisms.

9:13252021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Holscher HD: Dietary fiber and prebiotics

and the gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes. 8:172–184. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Fernandes MR, Aggarwal P, Costa RGF, Cole

AM and Trinchieri G: Targeting the gut microbiota for cancer

therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 22:703–722. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Jain MG, Hislop GT, Howe GR and Ghadirian

P: Plant foods, antioxidants, and prostate cancer risk: Findings

from case-control studies in Canada. Nutr Cancer. 34:173–184. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Miller PE, Morey MC, Hartman TJ, Snyder

DC, Sloane R, Cohen HJ and Demark-Wahnefried W: Dietary patterns

differ between urban and rural older, long-term survivors of

breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer and are associated with

body mass index. J Acad Nutr Diet. 112:824–31. 831.e12012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Lachance G, Robitaille K, Laaraj J,

Gevariya N, Varin TV, Feldiorean A, Gaignier F, Julien IB, Xu HW,

Hallal T, et al: The gut microbiome-prostate cancer crosstalk is

modulated by dietary polyunsaturated long-chain fatty acids. Nat

Commun. 15:34312024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Yadav A, Kaushik M, Tiwari P and Dada R:

From microbes to medicine: Harnessing the gut microbiota to combat

prostate cancer. Microb Cell. 11:187–197. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Liss MA, White JR, Goros M, Gelfond J,

Leach R, Johnson-Pais T, Lai Z, Rourke E, Basler J, Ankerst D and

Shah DP: Metabolic Biosynthesis Pathways Identified from Fecal

Microbiome Associated with Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol. 74:575–582.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Sfanos KS, Markowski MC, Peiffer LB, Ernst

SE, White JR, Pienta KJ, Antonarakis ES and Ross AE: Compositional

differences in gastrointestinal microbiota in prostate cancer

patients treated with androgen axis-targeted therapies. Prostate

Cancer Prostatic Dis. 21:539–548. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Matzaras R, Nikopoulou A, Protonotariou E

and Christaki E: Gut microbiota modulation and prevention of

dysbiosis as an alternative approach to antimicrobial resistance: A

narrative review. Yale J Biol Med. 95:479–494. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Lv J, Jin S, Zhang Y, Zhou Y, Li M and

Feng N: Equol: A metabolite of gut microbiota with potential

antitumor effects. Gut Pathog. 16:352024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Daisley BA, Chanyi RM, Abdur-Rashid K, Al

KF, Gibbons S, Chmiel JA, Wilcox H, Reid G, Anderson A, Dewar M, et

al: Abiraterone acetate preferentially enriches for the gut

commensal Akkermansia muciniphila in castrate-resistant prostate

cancer patients. Nat Commun. 11:48222020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Kim SJ, Park M, Choi A and Yoo S:

Microbiome and prostate cancer: Emerging diagnostic and therapeutic

opportunities. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 17:1122024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Duan H, Wang L, Huangfu M and Li H: The

impact of microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids on macrophage

activities in disease: Mechanisms and therapeutic potentials.

Biomed Pharmacother. 165:1152762023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|