Introduction

Cardiac developmental toxicity refers to harmful

effects induced by external factors, including chemical substances,

pharmaceuticals, environmental pollutants or infectious agents,

which impair normal cardiac morphogenesis, cellular differentiation

or functional maturation during key phases of embryonic or fetal

heart development (1). This

disruption may result in structural cardiac anomalies (such as

ventricular septal defects or patent ductus arteriosus) or

functional impairments (such as cardiac arrhythmias and impaired

cardiac function). Epidemiological studies demonstrate that

congenital heart disease (CHD) affects >1% of live births and

accounts for the majority of prenatal miscarriages (2–4). In

the United States alone, ~500,000 adults currently live with CHD

(5). Notably, although >80,000

chemical substances are commercially available in the United

States, the cardiac teratogenic potential of the majority of these

substances remains uncharacterized, creating notable gaps in

prenatal exposure risk assessment. Beyond genetic predispositions,

maternal exposure to cardiac teratogens during the key cardiac

morphogenesis period, spanning 3 months pre-conception to

gestational weeks 2–7, markedly elevates the risk for developmental

cardiac defects (6). Therefore,

elucidating the molecular mechanisms of xenobiotic-induced cardiac

developmental toxicity is important for developing targeted

clinical surveillance programs and formulating evidence-based

preventive public health measures.

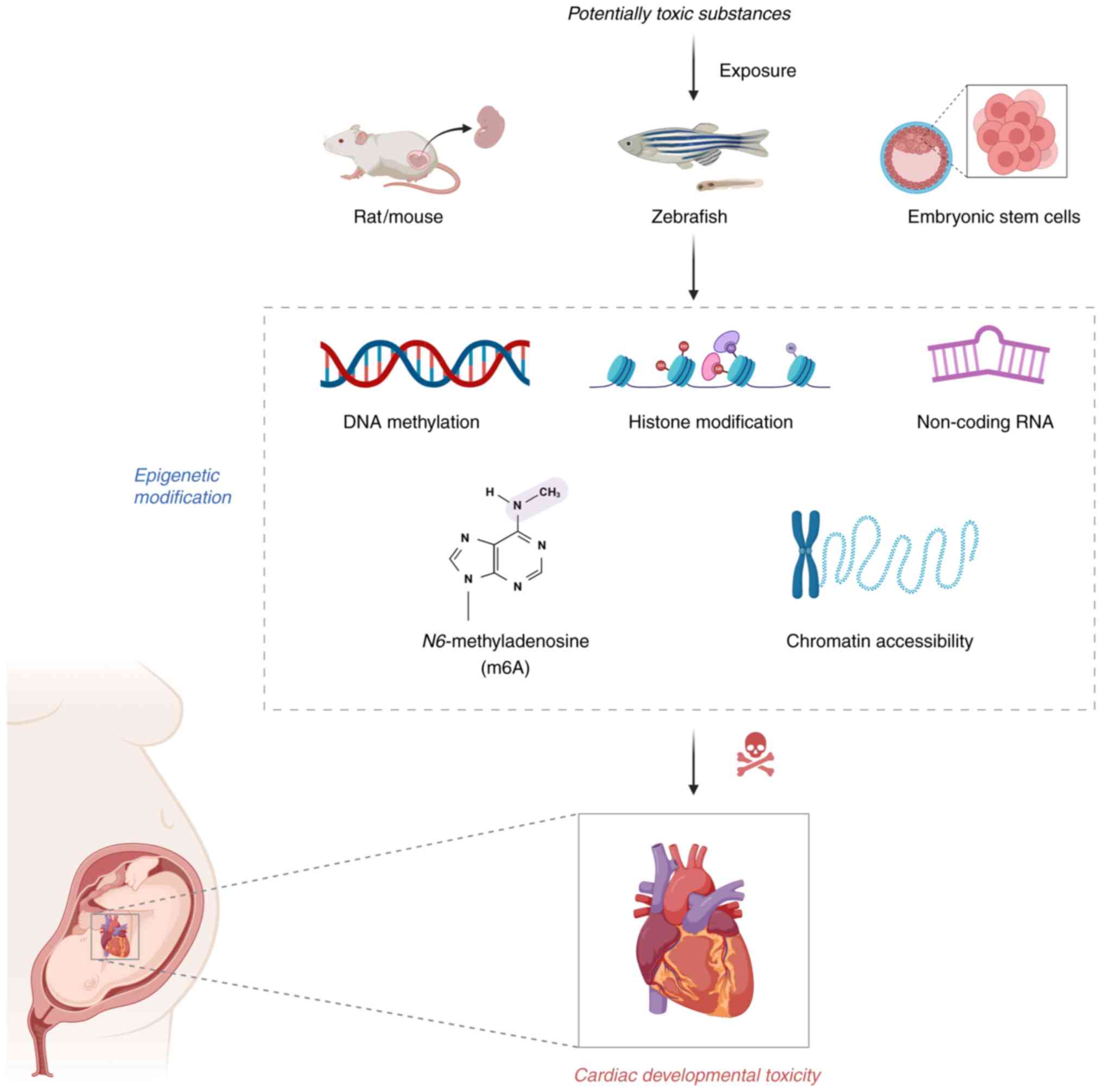

Epigenetic regulation controls transcriptional

activity through stable but reversible chromatin modifications that

occur independently of DNA sequence alterations (7). Key epigenetic mechanisms, including

DNA methylation, histone modifications (acetylation and

methylation), regulatory non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), RNA methylation

and chromatin remodeling, act synergistically to precisely modulate

gene expression while preserving the underlying genetic sequence

(8,9). These modifications demonstrate

plasticity in response to diverse extrinsic factors, encompassing

dietary composition, physical activity, pathogenic challenges,

environmental toxicants, senescence processes and psychosocial

stressors (10,11). Maternal exposure to pharmaceuticals

or environmental contaminants during pregnancy may disrupt cardiac

development through epigenetic mechanisms, leading to dysregulation

of cardiac morphogenesis-related genes and impaired cardiac

differentiation. Such perturbations ultimately contribute to

congenital heart defects. The present review summarizes emerging

evidence regarding epigenetic regulation of cardiac developmental

toxicity (Fig. 1), offering

potential avenues for early detection and prevention of

chemical-induced cardiac malformations.

DNA methylation

DNA methylation represents a key epigenetic

mechanism involving the addition of methyl groups to the fifth

carbon position of cytosines, generating 5-methylcytosine (5mC)

(12,13). This reaction is catalyzed by DNA

methyltransferases (DNMTs), with DNMT3A and DNMT3B primarily

mediating de novo methylation at unmethylated CpG sites

(14,15). DNMT1, as the principal maintenance

methyltransferase, serves a key role in preserving epigenetic

patterns during DNA replication. This enzyme specifically

recognizes hemimethylated CpG dinucleotides, ensuring accurate

methylation inheritance from parent to daughter strands and thereby

maintaining epigenetic memory throughout cellular proliferation

(16). The enzymatic transfer of

methyl moieties to the fifth carbon of cytosines induces

conformational constraints in genomic DNA, creating steric

occlusion that competitively inhibits transcription factor docking.

This biochemical blockade constitutes a fundamental paradigm of

epigenetic gene silencing (17,18).

DNA demethylation proceeds through two

mechanistically distinct pathways. Namely, passive

replication-dependent dilution, followed by active enzymatic

removal. Passive demethylation results from the gradual loss of

methylation marks during successive rounds of DNA replication,

whereas active demethylation involves direct enzymatic erasure of

methyl groups independent of DNA synthesis (19). The ten-eleven translocation (TET)

family of dioxygenases (TET1, TET2 and TET3) drive active DNA

demethylation through iterative oxidation reactions, progressively

modifying 5mC to form 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, subsequently

advancing to 5-formylcytosine and concluding with the generation of

5-carboxylcytosine (20).

Following oxidative modification, thymine DNA glycosylase

selectively binds and cleaves these epigenetic intermediates,

enabling their replacement with canonical cytosine through base

excision repair-mediated nucleotide substitution (21). Alternatively, non-oxidative

demethylation pathways exist whereby deaminases such as

activation-induced deaminase/apolipoprotein B mRNA editing

catalytic polypeptide family enzymes can directly convert 5mC to

thymine (22). This initiates

distinct repair processes that ultimately result in

demethylation.

With regard to DNA methylation dysregulation-induced

cardiac developmental toxicity, recent methodological advances in

whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS), coupled with newly

developed single-cell methylome analysis technologies, now

facilitate genome-wide DNA methylation profiling with unprecedented

resolution and comprehensiveness (23,24).

Mounting evidence indicates that DNA methylation serves as a key

epigenetic regulator governing embryonic development, cellular

differentiation and responses to environmental toxicants (25–27).

Notably, aberrant alterations in DNA methylation are associated

with a number of birth defects and developmental disorders, such as

cardiac malformations and abnormal heart rates, highlighting its

importance in developmental toxicity. Table I summarizes the mechanisms by which

potential toxic substances induce cardiac developmental toxicity

through abnormal DNA methylation.

| Table I.DNA methylation dysregulation-induced

cardiac developmental toxicity. |

Table I.

DNA methylation dysregulation-induced

cardiac developmental toxicity.

| First author,

year | Toxicant | Embryo model | Methylation

status | Potential

mechanism | Cardiac toxicity

manifestations | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Jiang et al,

2019 | PM2.5 | Zebrafish | Widespread

methylation dysregulation (both hyper- and hypomethylation) | Dysregulated

cardiac developmental gene expression | Increased incidence

of cardiac malformations and decreased heart rate | (25) |

| Mu et al,

2020 | Phthalates | Zebrafish | Hypomethylation of

NPPA and cTnT, hypermethylation of TBX5b | Dysregulated

cardiac developmental gene expression | Abnormal heart rate

and pericardial edema | (30) |

| Ma et al,

2012 | Selenite | Zebrafish | Early

hypomethylation, late hypermethylation | Dysregulated

proliferation-apoptosis homeostasis | Bradycardia,

pericardial edema and reduced cardiac chamber volume with

morphological abnormalities | (39) |

| Li et al,

2009 | Arsenite | Zebrafish | Early

hypomethylation, late hypermethylation | Dysregulated

proliferation-apoptosis homeostasis | Bradycardia and

altered ventricular shape | (42) |

| Jiao et al,

2023 | Cyhexatin | Zebrafish | Global DNA

hypomethylation | Apoptosis,

oxidative stress and endocrine disruption | Abnormal heart rate

and pericardial edema | (44) |

| Chatterjee et

al, 2021 | CMIT/MIT | Zebrafish | Global DNA

hypermethylation | Dysregulated

cardiac developmental gene expression | Abnormal heart rate

and pericardial edema | (48) |

Phthalates, a class of ubiquitous industrial

chemicals, are recognized endocrine-disrupting compounds associated

with potential cardiovascular impairment, reproductive dysfunction

and developmental toxicity (28,29).

Mu et al (30) discovered

through methylated DNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (MeDIP-Seq)

that exposure to di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate and di-butyl phthalate

could alter DNA methylation patterns of cardiac development-related

genes, thereby modulating gene expression and subsequently inducing

cardiac developmental defects in zebrafish embryos. This study

observed that reduced DNA methylation at the natriuretic peptide A

(NPPA) and cardiac troponin T2 (cTnT) gene loci was frequently

associated with higher transcriptional activity. By contrast,

increased methylation levels in the T-box transcription factor 5

(TBX5)-b promoter region tended to be associated with decreased

expression, suggesting transcriptional repression. These

methylation-expression relationships support the possibility that

DNA methylation serves as an important epigenetic mechanism

influencing cardiac developmental toxicity following phthalate

exposure.

Particulate matter (PM) represents a heterogeneous

mixture of airborne contaminants comprising chemical components

derived from numerous emission sources, including vehicle

emissions, industrial processes and biomass burning, with PM2.5

specifically referring to fine particulate matter with an

aerodynamic diameter of ≤2.5 µm (31). Accumulating epidemiological

evidence demonstrates that prenatal exposure to particulate matter

is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, particularly preterm

delivery, reduced birth weight and impaired neurodevelopment

(32–34). Emerging research highlights the

role of DNA methylation alterations as a key mechanism underlying

PM-induced cardiac developmental toxicity. Genome-wide DNA

methylation profiling revealed that exposure to PM2.5 extracts

induces widespread methylation dysregulation (both hyper- and

hypomethylation) in zebrafish embryonic hearts, leading to

developmental defects (25). This

process is associated with abnormal folate metabolism, suggesting

that PM2.5 may disrupt folate metabolic homeostasis through DNA

methylation modifications, thereby contributing to cardiac

developmental toxicity.

Selenium, while recognized as a key micronutrient

important in maintaining normal physiological functions, such as

development and immune responses, poses marked toxicological risks

due to the narrow therapeutic margin it exhibits between

nutritional adequacy and toxicological thresholds, thereby

warranting serious consideration of environmental exposure hazards

(35,36). As the primary selenium source for

selenoprotein biosynthesis in mammalian cells, selenite has been

demonstrated to induce developmental toxicity and neurobehavioral

abnormalities in zebrafish embryos (37,38).

Ma et al (39) revealed

that selenite induces cardiac developmental toxicity in zebrafish

embryos by disturbing DNA methylation dynamics, manifesting as

aberrant early-stage hypomethylation followed by late-stage

hypermethylation, concomitant with ventricular/atrial morphological

defects and impaired cardiac function. In addition, folate notably

alleviated cardiac defects by rescuing methylation imbalance,

demonstrating that selenite-induced cardiac developmental toxicity

depends on the disruption of DNA methylation dynamics. Similarly,

arsenic is a widely distributed naturally occurring element that

poses hazards to living organisms (40). Particularly in its trivalent form

as arsenite, arsenic has been demonstrated to cause notable harm to

humans through multiple biochemical pathways, including

mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, due to its

potent carcinogenicity and toxicity (41). A previous study demonstrated that

exposure to 2.0 mM arsenite induced cardiac developmental defects

in zebrafish embryos at 48 h post-fertilization (hpf),

characterized by reduced ventricular volume, morphological

alterations and a markedly increased atrioventricular angle

(42). Concurrent global DNA

hypermethylation was observed, suggesting that this epigenetic

dysregulation may contribute to arsenite-mediated cardiotoxicity.

These findings provide experimental evidence for understanding the

DNA methylation mechanisms underlying the cardiac developmental

toxicity of heavy metals/metalloids.

Cyclohexylltin (CYT), an organotin compound, is

often employed as a broad-spectrum pesticide in modern agricultural

practices for pest management (43). However, its potential cardiotoxic

effects during embryonic development remain to be systematically

elucidated. In a zebrafish model, CYT exposure was shown to induce

genome-wide DNA hypomethylation, characterized by decreased

S-adenosylmethionine (SAM)/S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) ratios and

suppressed DNMTs expression, along with cardiac malformations such

as bradycardia and pericardial edema (44). These findings suggest that CYT

disrupts DNA methylation dynamics, potentially resulting in

aberrant transcriptional regulation of genes key to cardiac

development.

5-Chloro-2-methyl-4-isothiazolin-3-one/2-methyl-4-isothiazolin-3-one

(CMIT/MIT) is an isothiazolinone-based biocide that is commonly

formulated in numerous aqueous consumer products, with extensive

applications in disinfectants and cosmetics (45,46).

Previous research has indicated the potential neurotoxic effects of

CMIT/MIT (47), and due to its

extensive commercial applications and consequent exposure risks,

research has shifted focus toward investigating its developmental

toxicity. Chatterjee et al (48) investigated the developmental

toxicity of CMIT/MIT in zebrafish embryos and found that exposure

to this compound markedly upregulated the expression of DNMTs,

including DNMT1, DNMT3a2, DNMT3b1 and DNMT3b4, leading to global

DNA hypermethylation The observed cardiac malformations, including

pericardial edema and bradycardia, were associated with concurrent

epigenetic modifications, indicating that CMIT/MIT-induced

developmental cardiotoxicity may occur through DNMT-dependent

dysregulation of DNA methylation.

Studies utilizing advanced sequencing technologies

have demonstrated that multiple toxicants can disrupt DNA

methylation patterns, inducing gene-specific alterations or

genome-wide epigenetic instability. These modifications impair key

developmental processes such as cardiogenesis, potentially

culminating in developmental cardiotoxicity (25,30).

However, existing research has predominantly identified associative

relationships between DNA methylation changes and developmental

toxicity, without direct experimental validation of causality

between specific epigenetic modifications and toxicological

outcomes. In addition, the mechanistic pathways through which

aberrant DNA methylation influences downstream gene expression to

confer toxicity remain only partially characterized. Despite

intricate crosstalk between DNA methylation and other epigenetic

modifications such as histone modifications and ncRNAs, the precise

regulatory mechanisms governing these interactions remain

incompletely characterized (49,50).

Integrating multi-omics approaches and employing targeted DNA

methylation editing technologies to validate the functional roles

of key methylation sites could advance the understanding of how DNA

methylation influences cardiac developmental toxicity (51).

Histone modification

Histones constitute the key protein subunits that

form octameric nucleosome complexes, creating the structural

scaffold necessary for DNA compaction. These include four core

histone variants (H3, H4, H2A and H2B), which coordinately assemble

to establish the basic repeating unit of chromatin (52). In addition to their structural

function, histones undergo diverse covalent post-translational

modifications, including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation,

ubiquitination and small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO)-ylation,

that serve as key epigenetic regulators modulating transcriptional

activity (53,54). Such modifications frequently target

flexible histone N-terminal domains, whereby genetic activity would

be modulated through the dual mechanisms of directly changing

histone-DNA interaction dynamics or serving as docking sites for

chromatin-associated regulatory proteins (55).

Among the diverse number of histone modifications,

methylation and acetylation constitute two of the most extensively

characterized epigenetic marks. The addition of methyl moieties to

specific lysine or arginine amino acids is enzymatically

facilitated by histone methyltransferases, utilizing

S-adenosylmethionine as the methyl donor molecule (56). Counteracting this process, histone

demethylases catalyze the elimination of these methyl groups

through oxidative reactions. Simultaneously, the acetylation

process introducing acetyl functional groups through histone

acetyltransferases induces chromatin decondensation, creating a

permissive environment for transcriptional machinery (57). This modification is dynamically

reversible through the enzymatic activity of histone deacetylases,

which leads to chromatin compaction associated with gene silencing

(58). These reversible

modifications collectively constitute a sophisticated regulatory

network of histone modifications.

With regard to histone modification

dysregulation-induced cardiac developmental toxicity, existing

evidence has demonstrated that dysregulated histone modifications

can destabilize genomic integrity and dysregulate gene

transcription, ultimately driving multiorgan toxicity

manifestations, particularly hepatotoxicity, neurotoxicity and

reproductive toxicity (59–62).

Furthermore, histone modification-mediated regulatory mechanisms

have become a key focus in developmental toxicity research, as

their dynamic alterations may influence embryonic development and

organogenesis, garnering notable scientific interest (63–65).

The experimental evidence linking toxicant-induced histone

modifications to cardiac developmental toxicity is summarized in

Table II.

| Table II.Histone modification

dysregulation-induced cardiac developmental toxicity. |

Table II.

Histone modification

dysregulation-induced cardiac developmental toxicity.

| First author,

year | Toxicant | Embryo model | Histone

modification | Potential

mechanism | Cardiac toxicity

manifestations | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Zhang et al,

2024 | Fenbuconazole | Zebrafish | H3K9Ac↓

H3K14Ac↓ | Dysregulated

cardiac developmental gene expression | Cardiac arrhythmia

and cardiac morphological defects | (68) |

| Cheng et al,

2016 | Cigarette

smoke | mESCs | Global H3

hypoacetylation | Dysregulated

cardiac developmental gene expression | Decreased cardiac

contraction rate | (75) |

| Wu et al,

2022 | Cadmium | Two-dimensional

cardiac differentiation model and three-dimensional EBs and cardiac

organoid models derived from hESCs | H3K27me3

H3K4me3↓ | Inhibition of

mesoderm formation and suppression of cardiomyocyte differentiation

and cardiac induction | Decreased cardiac

contraction rate | (79) |

Fenbucoonazole (FBZ), a triazole-class fungicide, is

extensively employed in agricultural and horticultural applications

(66). A previous study has

demonstrated that FBZ exposure induces abnormal transcription of

specific genes, thereby compromising cardiac development and

function in larvae (67). However,

the involvement of histone modifications in this process remains

poorly understood. Zhang et al (68) revealed that zebrafish embryos

exposed to FBZ showed markedly decreased acetylation levels of

histone H3K9 and H3K14 (H3K9Ac and H3K14Ac) in the hearts of both

filial (F)0 and F1 generation adult fish. This epigenetic

repression directly downregulated the transcription of core cardiac

developmental genes [GATA binding protein 4 (GATA4), TBX5 and NK2

homeobox 5 (NKX2-5)] and calcium homeostasis-related genes,

resulting in cardiac abnormalities including arrhythmia and

morphological defects. Notably, these adverse effects were

transgenerationally transmitted to the F2 generation. These

findings offer mechanistic insights into histone

acetylation-mediated cardiotoxicity during embryogenesis, while

providing evidence to support transgenerational epigenetic

inheritance.

According to official reports from the U.S. Surgeon

General, tobacco smoke exposure represents a notable environmental

health hazard, accounting for ~480,000 annual mortalities and

constituting one of the most notable pathogenic environmental

factors (69,70). Prenatal exposure to tobacco

pollutants induces embryotoxicity, characterized by growth

restriction, structural anomalies including craniofacial

malformations, congenital heart defects and skeletal abnormalities,

as well as embryonic lethality (71–74).

Cheng et al (75)

demonstrated that both mainstream smoke and sidestream smoke (SS)

exposure during cardiac differentiation of mouse embryonic stem

cells (ESCs) markedly reduced global histone H3 acetylation (H3ac)

levels in developing cardiomyocytes. This study revealed that SS

specifically diminished H3ac enrichment at the promoter region of

GATA4 (a key cardiac transcription factor), leading to its

transcriptional downregulation. The observed epigenetic

modifications suppressed (bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-SMAD

family member 4 signaling, a key pathway regulating cardiac

morphogenesis. These results demonstrate that dysregulated histone

acetylation constitutes a primary molecular mechanism driving

developmental cardiotoxicity induced by tobacco smoke exposure.

Cadmium (Cd), a highly toxic heavy metal, poses

escalating global health risks due to its environmental persistence

and good aqueous solubility (76).

Studies have demonstrated that Cd exposure exhibits both direct

embryogenic regulatory disruption and association with multiple

pathologies, including developmental cardiotoxicity, establishing

its developmental toxicity as a key concern in mechanistic

toxicology (77,78). Wu et al (79) employed human ESCs (hESCs) in

two-dimensional differentiation models, three-dimensional embryoid

bodies and cardiac organoids as experimental systems. Cd exposure

was found to markedly elevate the levels of repressive histone mark

H3K27me3 while reducing the levels of active histone mark H3K4me3.

This epigenetic dysregulation was associated with the

downregulation of mesoderm markers (including heart and neural

crest derivatives expressed 1 and HOP homeobox) and

cardiac-specific genes (including NKX2-5 and GATA4), ultimately

impairing mesoderm-to-cardiomyocyte differentiation. The

experimental results demonstrate that Cd-induced cardiac

developmental toxicity is regulated by histone methylation,

particularly during mesoderm specification, a developmental phase

exhibiting heightened vulnerability.

Histone ubiquitination regulates diverse

chromatin-associated processes, including transcriptional

regulation, DNA repair and chromatin structure remodeling, with

this regulatory mechanism having attracted growing research

attention in recent years (80–82).

Although direct evidence linking toxicant-induced developmental

cardiotoxicity to histone ubiquitination pathways remains limited,

existing studies have provided a number of theories (83,84).

The cullin-RING E3 ubiquitin ligase (CRL) family has been

demonstrated to regulate cardiac morphogenesis and tissue

maturation through ubiquitin-dependent modifications (83). As a key member of the CRL family,

cullin 4A (CUL4A) serves a key role in heart development by

mediating ubiquitin-dependent degradation of target proteins. A

previous study has shown that CUL4A deficiency induces pericardial

edema, abnormal cardiac looping and pectoral fin defects in

zebrafish embryos, phenotypes associated with impaired

cardiomyocyte proliferation and increased apoptosis (84). These findings suggest that

dysregulation of ubiquitination pathways may contribute to

developmental cardiotoxicity. Given the role of histone

ubiquitination in DNA damage response and cell fate determination,

the present review proposes it may regulate cardiac developmental

toxicity, representing a promising research avenue.

Aberrant histone modifications disrupt cardiac

developmental gene expression through alterations in methylation

and acetylation marks, demonstrating direct mediation of

teratogenic effects. Current research has primarily focused on

histone acetylation and specific methylation events, whereas other

key modifications, including phosphorylation, ubiquitination and

SUMOylation, remain poorly characterized. This knowledge gap limits

comprehensive understanding of the diverse mechanistic

contributions of histone modifications to developmental toxicity

(68,75,79).

While numerous current studies demonstrate associative

relationships between histone modification alterations and toxic

phenotypes, the key molecular mechanisms, particularly how

toxicants precisely regulate histone-modifying enzyme activity

within upstream regulatory networks, remain inadequately elucidated

(68,75,79).

Subsequent investigations should aim to focus on delineating

temporal alterations in histone marks and their interactions with

additional epigenetic regulators to elucidate underlying

pathological mechanisms (55).

NcRNAs

NcRNAs constitute transcriptionally active, yet

untranslated, genetic elements predominant in eukaryotic systems,

with three principal subtypes prevailing, namely long ncRNAs

(lncRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs) and circular RNAs (circRNAs)

(85,86). Despite their protein-coding

deficiency, these RNA molecules exert comprehensive regulatory

control over important biological processes, including chromatin

remodeling, transcriptional modulation, post-translational

modifications and signal transduction (87,88).

As key regulatory molecules, ncRNAs have been demonstrated to

participate in the mechanisms underlying toxicity induced by

numerous environmental pollutants and pharmaceutical compounds,

such as crude oil and ribavirin (89,90).

With regard to ncRNA dysregulation-induced cardiac

developmental toxicity, emerging scientific evidence has

established ncRNAs as key molecular mediators orchestrating

toxicological responses throughout embryogenesis (91,92).

These discoveries not only offer promising biomarker candidates for

developmental toxicity assessment but also improve the mechanistic

understanding of the epigenetic regulatory circuitry underlying

developmental toxicity. The dysregulation of ncRNA-mediated cardiac

developmental toxicity is summarized in Table III.

| Table III.NcRNAs dysregulation-induced cardiac

developmental toxicity. |

Table III.

NcRNAs dysregulation-induced cardiac

developmental toxicity.

| First author,

year | Toxicant | Embryo model | ncRNAs | Target | Potential

mechanism | Cardiac toxicity

manifestations | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Ye et al,

2020 | Ribavirin | hiPSCs | lncRNA GAS5↑ lncRNA

HBL1↑ | p53 | ROS accumulation

and DNA damage | Pericardial edema,

incomplete cardiac looping and ventricular/atrial enlargement | (96) |

| Xu et al,

2019 | Crude oil | Red drum

(Sciaenops ocellatu) | MiR-18a↓ miR-27b↑

miR-203a↓ | - | Disruption of

cardiac developmental pathways | Pericardial

edema | (101) |

| Magnuson et

al, 2022 | Phenanthrene | Zebrafish | miR-203a↓ | VEGFA | Dysregulated

cardiac developmental gene expression | Abnormal heart rate

and pericardial edema | (110) |

| Guo et al,

2024 | MC-LR | Mice | miR-377-3p | NR6A1 | Macrophage

polarization imbalance | Ventricular

dilation and myocardial thinning | (111) |

LncRNAs represent a distinct class of ncRNAs

characterized by lengths of >200 nucleotides, with certain

transcripts extending to hundreds of kilobases. These RNA molecules

regulate key cellular processes such as proliferation, apoptosis

and cellular migration through multiple molecular mechanisms

(93–95). Notably, dysregulation of lncRNAs

has been implicated in drug-induced developmental toxicity, as

exemplified by antiviral drugs (96). Ribavirin, as a broad-spectrum

antiviral drug, may induce adverse effects in clinical

applications, such as rashes, hemolytic anemia and teratogenicity

(97). However, its potential

cardiotoxicity and underlying mechanisms during cardiac development

remain elusive. Ye et al (96) found that ribavirin upregulates the

expression of lncRNAs growth arrest specific 5 and Heart Brake

lnRNA 1, which inhibits the differentiation of human induced

pluripotent stem cells into cardiomyocytes, triggering DNA damage

and p53 pathway activation. This finding establishes novel

perspectives on the teratogenic mechanisms of ribavirin while

decoding the functional importance of lncRNAs in heart

development.

MiRNAs constitute a class of endogenous small ncRNAs

(~22 nucleotides in length) that post-transcriptionally regulate

gene expression by binding to complementary mRNA sequences,

ultimately inducing mRNA degradation or translational repression

(98). The integration of

high-throughput sequencing technologies with sophisticated

bioinformatics tools has advanced miRNA research, driving

developments in mechanistic studies and translational applications

within this field (99).

Increasing evidence suggests that environmental toxicant exposure

can disrupt normal developmental processes by interfering with

epigenetic regulatory mechanisms, particularly through modulating

miRNA expression profiles. These findings provide novel insights

into toxicological pathway mechanisms (100–102).

Trichloroethylene (TCE), a volatile organic solvent,

is distributed in environmental media including soil, groundwater

and air, posing marked contamination risks (103). A growing body of evidence

indicates that TCE exposure may induce cardiac developmental

abnormalities in humans and other organisms (103–106). Huang et al (91) found that TCE exposure downregulates

miR-133a in zebrafish embryonic hearts, leading to heart

developmental defects by increasing ROS generation and excessive

cell proliferation, yet miR-133a agonists effectively mitigated

this toxic effect. This study demonstrates that miR-133a serves a

key mediating role in TCE-induced cardiac developmental toxicity,

suggesting its potential as a biomarker for cardiotoxicity

assessment.

Crude oil and its chemical components represent

common environmental contaminants in aquatic systems, with their

long-term toxicological impacts remaining an active area of

investigation (107–109). Xu et al (101) employed red drum (Sciaenops

ocellatus) larvae to investigate miRNA-mediated cardiotoxicity

through integrated mRNA-miRNA sequencing analysis. This study

revealed that Deepwater Horizon crude oil exposure altered the

expression of miR-18a, miR-27b and miR-203a and this was

concentration-dependent. Specifically, miR-27b upregulation

promoted physiological/pathological cardiac hypertrophy, while

downregulation of miR-18a and miR-203a impaired heart rate

regulation and cardiac valve morphogenesis, respectively.

Mechanistically, these dysregulated miRNAs disrupted key cardiac

developmental pathways, including calcium signaling and

hypertrophic responses, by modulating their target genes, thereby

providing a novel miRNA-dependent mechanism underlying polycyclic

aromatic hydrocarbon (PAHs)-induced developmental cardiotoxicity in

marine fish. Similarly, another study conducted on larvae mahi-mahi

revealed that exposure to PAHs in crude oil resulted in

dose-dependent upregulation of miR-34b and miR-23b, as well as

downregulation of miR-203a (102). These miRNAs dysregulated cardiac

developmental genes, including components of calcium signaling and

regulators of cardiac hypertrophy, leading to pericardial edema,

bradycardia and other morphological abnormalities. Additionally,

the activation of p53 signaling further exacerbated developmental

cardiac impairments. These findings provide evidence for the

central regulatory role of miRNA-mRNA interactions in crude

oil-induced cardiotoxicity during fish development. The

developmental toxicity mediated by miR-203a in PAHs has garnered

notable research attention. Magnuson et al (110) demonstrated that inhibition of

miR-203a in zebrafish embryos led to heart rate reduction and

pericardial edema, cardiac defects that mimic the developmental

toxicity induced by typical PAHs found in crude oil. This study

elucidated the molecular mechanism wherein miR-203a contributes to

cardiac developmental impairment by regulating key factors such as

VEGFA and fibrosis-associated genes including Krüppel-like factor

4.

As a key metabolic and immunomodulatory organ at the

maternal-fetal interface, the placenta serves indispensable roles

in mediating developmental toxicity through xenobiotic metabolism

and cytokine signaling networks. A study by Guo et al

(111) revealed that the

environmental toxin microcystin-leucine arginine can deliver

miR-377-3p through trophoblast cell-derived extracellular vesicles,

targeting and suppressing the nuclear receptor subfamily 6 group A

member 1 gene in macrophages. This suppression activates the

mammalian target of the mTOR/ribosomal protein S6 kinase β-1/sterol

regulatory element-binding protein signaling pathway, leading to M1

polarization and metabolic disruption in placental macrophages,

ultimately resulting in CHDs in future offspring. To the best of

our knowledge, this study was the first to elucidate the role of

miRNA-mediated placenta-heart axis signaling in environmentally

induced cardiac developmental toxicity, providing novel evidence

for miRNA-regulated transgenerational mechanisms in heart

development.

NcRNAs have been demonstrated to serve as key

regulatory molecules in cardiac developmental toxicity induced by

numerous toxicants, exhibiting marked potential as biomarkers and

therapeutic targets (96,101,110,111). However, current research exhibits

notable limitations. As on the one hand, studies have predominantly

focused on miRNAs, while investigations into the mechanisms of

lncRNAs, circRNAs, small interfering RNAs and Piwi-interacting RNAs

in cardiac developmental toxicity remain markedly insufficient. On

the other hand, the interaction networks and synergistic regulatory

mechanisms among different ncRNA classes are yet to be elucidated,

hindering a comprehensive understanding of ncRNA-mediated

developmental toxicity. Future studies should aim to broaden the

scope of ncRNA research and deepen the exploration of regulatory

relationships among numerous ncRNAs to achieve a more systematic

mechanistic understanding.

m6A methylation

N6-methyladenosine (m6A), initially identified in

eukaryotic messenger RNAs in 1974, represents the methylation of

adenine at the N6 position (112). As the primary internal RNA

modification in eukaryotes, m6A occurs at an average frequency of

1–2 modifications per 1,000 nucleotides (113). Among >170 identified RNA

modifications, m6A is the most abundant and dynamically reversible

epigenetic mark in eukaryotic mRNAs, constituting approximately

one-half all methylated ribonucleotides (114).

The m6A modification system achieves dynamic and

reversible regulation through three functionally distinct classes

of regulatory proteins, namely writers, erasers and readers

(115). Methyltransferases such

as the methyltransferase-like (METTL)-3/METTL14 complex act as

‘writers’, catalyzing m6A RNA modifications (116). In 2011, two demethylases, fat

mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) and AlkB homolog 5

(ALKBH5), were discovered as ‘erasers’ that remove these methyl

groups (117,118). This finding revealed the dynamic

reversibility of m6A modifications. Notably, both FTO and ALKBH5

belong to the α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase AlkB homolog

family, highlighting their conserved role in regulating RNA

methylation plasticity (119).

Simultaneously, m6A reader proteins, functioning as recognition

factors, regulate RNA metabolism processes (including splicing,

folding, transport, degradation and translation) through their

specific recognition of m6A-modified sites (114). Together, these core regulatory

components form an integrated m6A modification network, serving not

only as key tools for studying RNA methylation mechanisms but also

emerging as a key research focus in molecular biology due to their

important roles in diverse physiological and pathological

processes.

With regard to m6A methylation dysregulation-induced

cardiac developmental toxicity, the developmental toxicity mediated

by m6A methylation has gradually attracted researchers' attention

(120,121). m6A methylation dynamically

regulates post-transcriptional processes (such as mRNA stability

and translation efficiency) of myocardial development genes.

Dysregulation of this epigenetic mechanism may contribute to

congenital heart malformations. Bisphenol A (BPA) is a

representative industrial chemical used in the production of

polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins (122). It has been established that BPA

exposure is associated with numerous health disorders, including

metabolic dysregulation, reproductive impairment, cardiovascular

abnormalities, developmental malformations and mammary

tumorigenesis (123). Given the

potential hazards of BPA, bisphenol C (BPC) has been adopted as an

alternative in industrial applications. The presence of BPC is

commonly identified in multiple human biospecimens, particularly

infant urine, indicating a potential exposure hazard for young

children (124). However, whether

BPC exerts toxic effects on embryonic development remains poorly

characterized, highlighting the need for further toxicological

evaluations. Su et al (125) demonstrated that BPC disrupts m6A

modification homeostasis by suppressing the expression of m6A

methyltransferase METTL3. This leads to decreased m6A methylation

levels in mRNAs encoding key cardiac developmental regulators,

including acyl-CoA oxidase 1 involved in fatty acid metabolism and

troponin T2d, key in myocardial contraction. The impaired m6A

modification compromises transcript recognition and stabilization

by m6A reader protein insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding

protein 2b, ultimately causing structural and functional cardiac

abnormalities in zebrafish. This work reveals environmental

pollutants can interfere with cardiac development by subverting

m6A-mediated epitranscriptomic regulation, identifying novel

molecular targets for evaluating developmental toxicity of

bisphenol analogs.

In addition to the aforementioned DNA methylation

alterations discussed, PM2.5 exposure-induced cardiac developmental

toxicity may also involve dysregulation of m6A methylation. A study

by Ji et al (126) using a

zebrafish larval model revealed that extractable organic matter

from PM2.5 activates the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR), leading

to direct suppression of m6A methyltransferase transcripts METTL14

and METTL3. This resulted in global reduction of cardiac m6A

methylation levels, consequently decreasing m6A modifications while

increasing expression of apoptosis-related genes (TNF receptor

associated factor 4 and BCL2 binding component 3), ultimately

triggering excessive ROS production, apoptosis and cardiac

developmental malformations. These results establish that

AHR-mediated disruption of m6A methylation constitutes a central

mechanism underlying PM2.5-induced cardiac developmental toxicity.

Importantly, supplementation with the methyl donor betaine or

overexpression of METTL14 and METTL3 was found to restore m6A

homeostasis and ameliorate PM2.5-induced cardiotoxicity, thereby

providing key experimental evidence for therapeutic interventions

against environmental pollutant-associated cardiac developmental

defects.

Notable knowledge gaps persist in understanding the

functional mechanisms of m6A RNA methylation during cardiac

developmental toxicity. Although existing studies have established

the critical roles of ‘writers’ such as METTL3/METTL14 in

toxin-induced cardiac malformations, the target-specific

recognition mechanisms of ‘readers’ (such as the insulin-like

growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein family) and the dynamic

regulatory functions of ‘erasers’ (such as FTO/ALKBH5) remain

poorly understood (125,126). Furthermore, the upstream

molecular mechanisms by which environmental pollutants (including

BPC and PM2.5) specifically interfere with m6A-modifying enzyme

activities are yet to be elucidated, although proteomics and

co-immunoprecipitation techniques may help identify their direct

molecular targets. Additionally, the interactions between m6A and

other RNA modifications, such as 5-methylcytosine (m5C) and

N7-methylguanosine (m7G), and their synergistic effects in cardiac

developmental toxicity warrant further investigation (127). Future research should aim to

integrate high-throughput sequencing technologies to

comprehensively delineate the spatiotemporal dynamics of m6A

methylation in cardiac developmental toxicity.

Chromatin accessibility

Chromatin is a dynamic nucleoprotein complex

residing in eukaryotic nuclei, comprising three core components,

namely genomic DNA, histone proteins and non-histone proteins, with

the additional potential association of small RNA molecules

(128). As the organizational

form of eukaryotic genetic material, chromatin facilitates genetic

information storage and transcriptional regulation through its

distinctive three-dimensional architecture, while demonstrating

dynamic spatiotemporal variations in both molecular composition and

structural organization. Chromatin accessibility allows genomic DNA

regions to be recognized and bound by nuclear factors. This

biochemical characteristic is principally governed by local

nucleosome positioning dynamics and competitive binding

interactions among DNA-associated proteins (129–131). Key cellular activities, including

transcription factor-dependent gene regulation, scheduled DNA

replication and repair of genomic damage, all depend on proper

chromatin accessibility (132,133). Research findings demonstrate that

fluctuating chromatin accessibility patterns serve key regulatory

functions across multiple biological pathways, encompassing

senescence, immune system regulation and embryogenesis (134–136). The Assay for

Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq)

enables efficient detection of cell type-specific chromatin

accessibility features and their dynamic alterations under

perturbations or disease conditions, while simultaneously

facilitating genome-wide analysis of transcription factor binding

sites and comparative assessment of chromatin landscapes across

biological contexts (137).

With regard to chromatin accessibility

dysregulation-induced cardiac developmental toxicity, as advances

in epigenetics have occurred, research on the association between

chromatin accessibility and cardiac developmental toxicity is

gradually emerging. A previous study demonstrated that parental

zebrafish exposure to 10 µg/l perfluorobutane sulfonate (PFBS)

disrupts the maternal transmission of transcripts related to

histone-DNA interactions in offspring oocytes, suggesting that this

contaminant may impair transcription factor accessibility to DNA by

altering chromatin compaction (138). Notably, exposure to 100 µg/l PFBS

further results in reduced embryonic heart rates, providing

evidence for PFBS-induced dysregulation of chromatin accessibility

to be associated with cardiac developmental toxicity. Unlike the

mechanistic inference from zebrafish models, experiments in human

stem cells directly demonstrated the chromatin accessibility

alterations that lead to cardiac developmental defects through

ATAC-seq analysis. Liu et al (139) employed ATAC-seq in human induced

pluripotent stem cells and hESCs, demonstrating that

13-cis-retinoic acid (isotretinoin; INN) disrupts cardiac

development by altering chromatin accessibility. This perturbation

leads to aberrant enhancement of transcription factor binding

activities, including hepatocyte nuclear factor 1β, SRY-box

transcription factor 10 and nuclear factor I C. This subsequently

disrupts the normal function of TGF-β and Wnt signaling pathways

and dysregulates the expression of key mesodermal differentiation

genes, such as Eomesodermin, Mix paired-like homeobox 1 and

Dickkopf WNT signaling pathway inhibitor 1. These findings

systematically elucidate the epigenetic mechanisms underlying

INN-induced cardiac developmental toxicity at the human stem cell

level, providing key evidence for drug safety evaluation.

Investigations into toxin-induced perturbations of

cardiac development mediated through chromatin accessibility are

only just emerging. Contemporary research proposes that exposure to

environmental toxicants can disrupt physiological transcription

factor binding to chromatin, potentially inducing aberrant

expression of cardiac developmental gene programs (139). However, these findings only

indicate associations, lacking direct experimental validation

regarding the functionality of open chromatin regions or the

regulatory roles of upstream mechanisms, such as DNA methylation

and histone modifications, in shaping chromatin accessibility.

Furthermore, existing studies predominantly rely on static, in

vitro models at single time-points, failing to capture the

dynamic progression from cardiac mesoderm to cardiomyocyte

differentiation. Limitations in multi-omics approaches [such as

underutilization of WGBS, chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by

sequencing (ChIP-seq)] further hinder systematic dissection of the

epigenetic regulatory network (140). Integrating gene-editing

technologies with model organisms such as zebrafish will enable

more precise elucidation of the mechanisms by which potential

toxicants disrupt cardiac development through chromatin

remodeling.

Epigenetic crosstalk in cardiac

developmental toxicity

Advancements in epigenetic research, particularly

regarding DNA methylation and histone modifications, have

highlighted their intricate interplay and well-coordinated

regulatory networks (141–143).

Although direct evidence concerning the crosstalk among epigenetic

modifications in cardiac developmental toxicity remains scarce,

emerging studies provide key mechanistic theories (144–146). Epidemiological data demonstrate a

dose-dependent association between maternal caffeine intake and

adverse pregnancy outcomes, including spontaneous abortion, low

birth weight and congenital cardiac/genital anomalies (147). Experimental investigations

consistently reveal that in utero caffeine exposure disrupts

embryonic cardiac function, leading to developmental cardiotoxicity

(144,145). Of note, Fang et al

(146) demonstrated that

gestational caffeine exposure markedly altered both DNA methylation

patterns and the expression of histone modification regulators in

murine embryonic ventricles, concurrent with the dysregulation of

cardiac-specific miRNAs (miR-208a/b and miR-499). These findings

collectively suggest that synergistic interactions among DNA

methylation, histone modifications and ncRNAs may drive cardiac

maldevelopment through disruption of epigenetic homeostasis.

However, further systems-level investigations integrating

multi-omics profiling and functional validation are key for

delineating precise molecular interactions underpinning this

regulatory hierarchy and establish a comprehensive epigenetic

framework for cardiac developmental toxicity.

Advances in epigenetic research methods and

models for cardiac developmental toxicity

Integrative multi-omics studies: From

single-modification analysis to multi-omics convergence

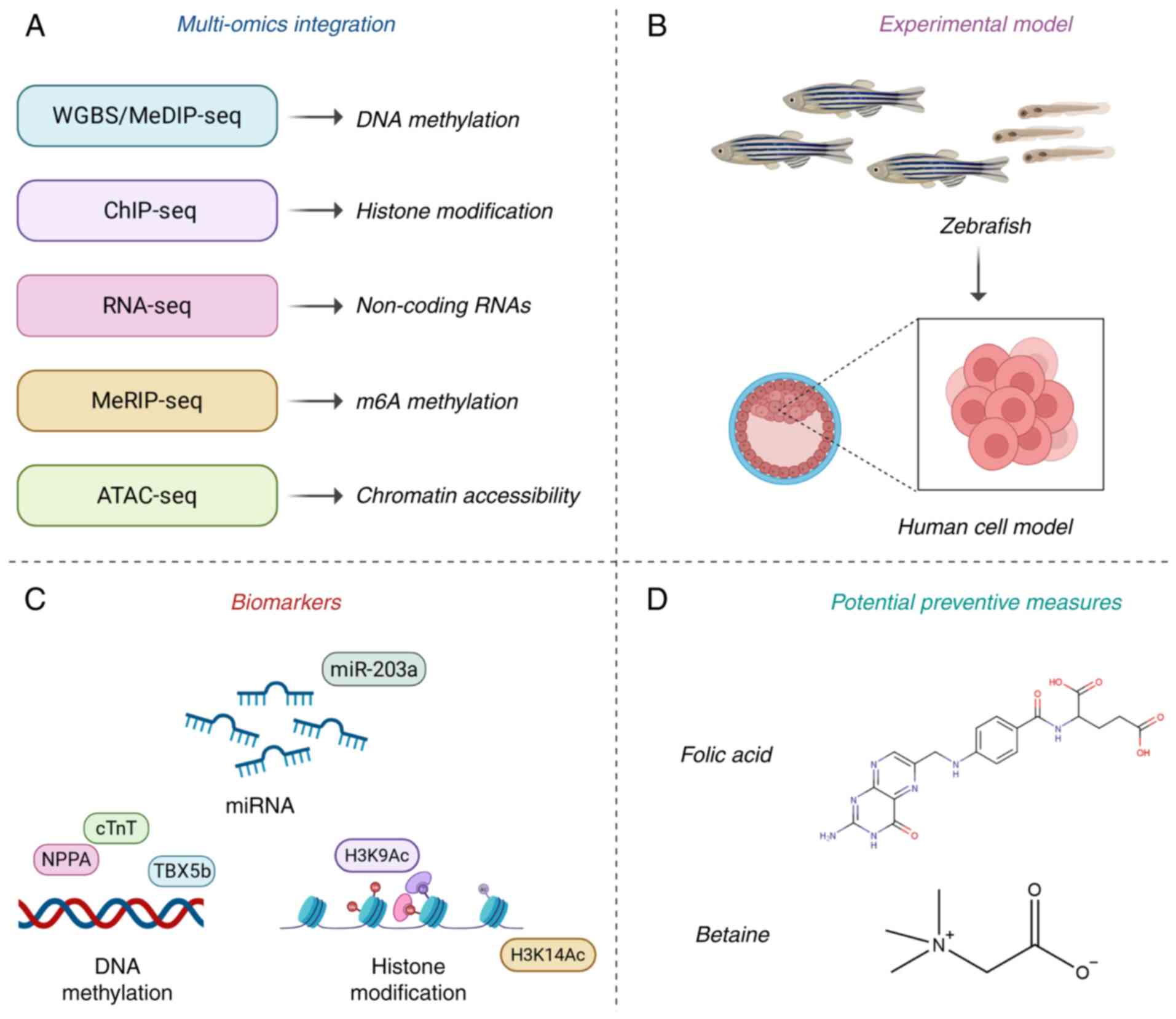

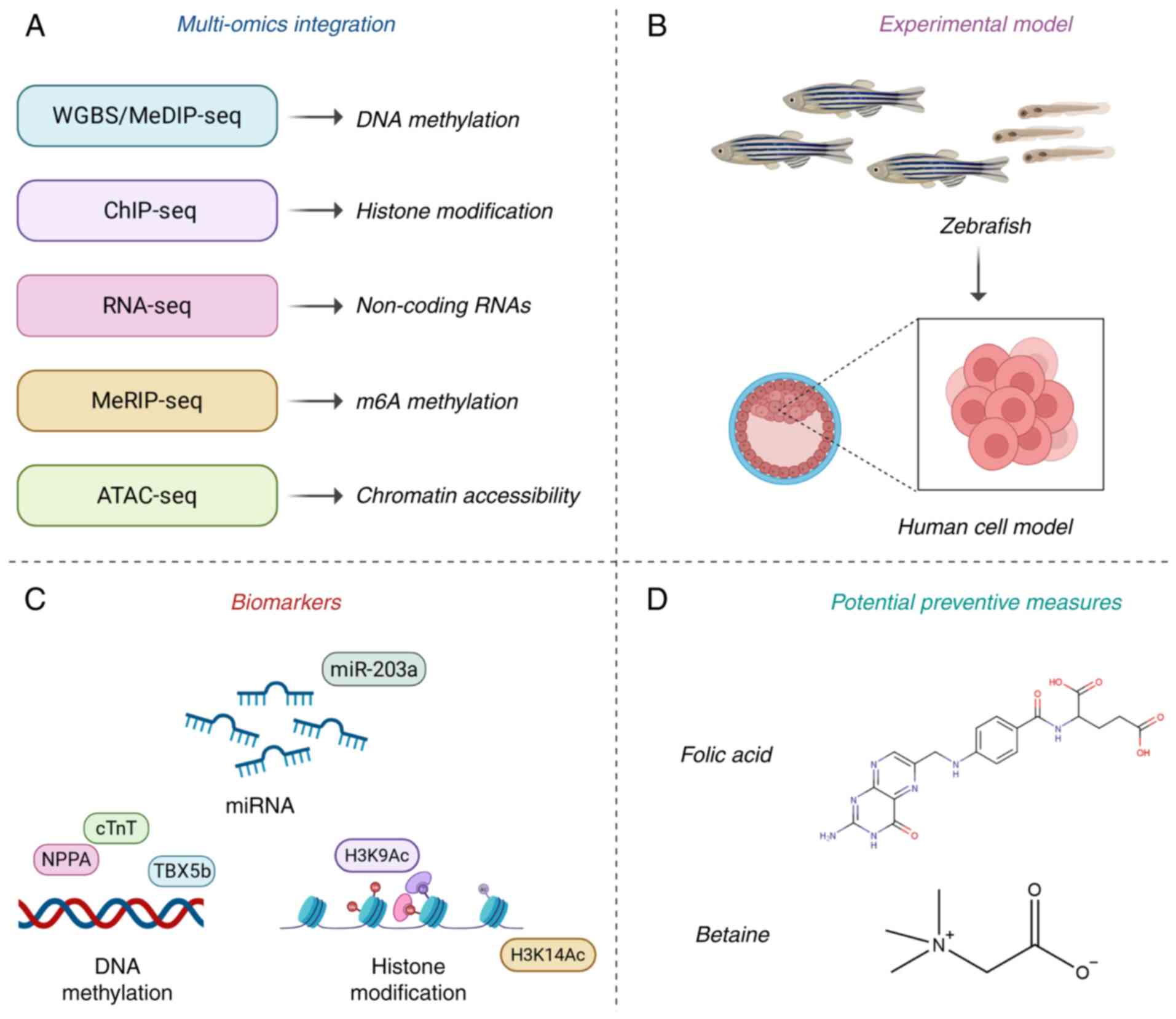

Advancements in high-throughput sequencing now

permit epigenetic evaluation of cardiac developmental toxicity

through multi-omics integration, overcoming the previous

limitations of single-omics analyses. By contrast with traditional

single-epigenetic-marker detection, multidimensional omics

technologies integrating DNA methylation (WGBS/MeDIP-Seq), histone

modifications (ChIP-Seq), chromatin accessibility (ATAC-Seq), m6A

methylation (methylated RNA immunoprecipitation followed by

sequencing) and ncRNAs [RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq)] enable systematic

elucidation of toxicity-induced epigenetic reprogramming networks

and their regulatory effects on cardiac development (Fig. 2A). For instance, the integrated

multi-omics analysis of RNA-Seq and MeDIP-Seq not only enables

simultaneous detection of DNA methylation modifications and gene

expression changes, but also effectively establishes their causal

associations (30). This

methodology conclusively establishes that toxin-induced cardiac

developmental toxicity primarily arises through DNA

methylation-directed modulation of gene transcription processes.

Furthermore, in combined ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq analyses,

researchers can first map the binding sites of cardiac

developmental transcription factors using ChIP-seq, and then

identify functionally active regions within open chromatin at these

binding sites through ATAC-seq (148). This strategy accurately

identifies core regulatory elements disrupted by toxicants,

demonstrating that cardiac developmental impairment occurs through

direct interference with transcription factor binding and

diminished chromatin accessibility. This comprehensive approach

provides novel mechanistic insights into cardiac developmental

toxicity. Furthermore, it enables the advancement of epigenetic

biomarkers from individual markers to diagnostic signature

profiles, thereby potentially improving both the specificity and

sensitivity of toxicity risk assessment.

| Figure 2.Integrative application of

multi-omics technologies and models in cardiac developmental

toxicity studies. (A) Multi-omics integration of epigenetic

regulation in cardiac developmental toxicity research. (B) Research

progress in experimental models of cardiac developmental toxicity.

(C) Epigenetic biomarkers identified in cardiac developmental

toxicity research. (D) Preliminary measures for preventing cardiac

developmental toxicity through epigenetic regulation. WGBS,

whole-genome bisulfite sequencing; MeDIP-Seq, methylated DNA

immunoprecipitation sequencing; ChIP-Seq, chromatin

immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing RNA-Seq, RNA sequencing;

MeRIP-Seq, methylated RNA immunoprecipitation followed by

sequencing; ATAC-Seq, Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin

using sequencing; NPPA, natriuretic peptide A; cTnT, cardiac

troponin T2; TBX5b, T-box transcription factor 5b; miR, microRNA;

H3K, histone H3 lysine K. The figure was created using

BioRender.com. |

Cardiac developmental toxicity models:

From zebrafish to human cell-based systems

In cardiac developmental toxicity research,

zebrafish and human cell-based models represent widely utilized

experimental systems (Fig. 2B). In

contemporary developmental biology research, zebrafish serve as a

primary animal model for heart formation studies (149). Notably, the cardiac structure in

zebrafish demonstrates marked conservation with mammalian hearts,

displaying ~70% genetic homology to human cardiac genes (150). Embryonic heart development

follows a well-defined chronological sequence. First, cardiac

progenitor cells begin to differentiate by 5 hpf, forming a linear

heart tube by 16 hpf (151–153). Subsequently, key morphological

changes occur, including cardiac looping into an S-shape (~33 hpf),

initiation of regular contractions (~36 hpf) and formation of

primitive valves (~40 hpf). By 2 days post-fertilization (dpf),

distinct inner and outer curvatures become evident in the

ventricular region (154).

Additionally, zebrafish embryos remain optically transparent until

3–4 dpf, enabling non-invasive real-time visualization and dynamic

monitoring of chemical effects on heart development. These

features, combined with high-throughput screening technologies,

markedly enhance the efficiency of developmental toxicity

assessments. Zebrafish exhibit good reproductive capacity, with

adult individuals capable of year-round cyclical spawning,

producing <200 eggs per female weekly (155). From an ethical standpoint, the

early life stages of zebrafish are considered to experience minimal

pain or distress upon chemical exposure, more closely aligning with

animal welfare guidelines and reducing ethical concerns in

experimental studies (156).

However, this model also presents a number of limitations. Compared

with mammalian models (including mice), zebrafish possess fewer

biological resources such as antibodies and gene-editing tools,

restricting their application in protein biochemistry and related

fields. The cardiac architecture of zebrafish is composed of two

distinct chambers (an atrium and ventricle), differing from the

four-chambered organization typical of mammals. This structural

disparity restricts its effectiveness as a model for investigating

cardiac septation processes or sophisticated hemodynamic parameters

(152). Additionally, zebrafish

embryos primarily absorb test compounds through cutaneous exposure,

differing from common human exposure routes such as oral ingestion

or inhalation (157).

Furthermore, the absence of distinct sex differentiation markers

during early developmental stages hinders the assessment of

sex-specific toxicological effects (158).

Overall cardiac organogenesis relies on animal

models to investigate morphogenesis and systemic integration, yet

early key events (such as stem cell differentiation and cardiac

progenitor fate determination) can be effectively studied using

pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) and in vitro models (159). Through directed differentiation

of ESCs or induced PSCs (iPSCs), researchers can systematically

recapitulate key stages of cardiac development. Specifically,

BMP/Wnt signaling activation initially induces mesoderm formation

and then, under defined growth factors (such as activin A and BMP4)

combined with Wnt pathway inhibition, drives further

differentiation into cardiac progenitor cells, ultimately yielding

functionally contractile cardiomyocytes (159). This process closely mimics the

spatiotemporal features of embryonic heart development, providing

an ideal platform for exploring cardiac developmental mechanisms

and drug toxicity screening (79).

However, this technology exhibits inherent limitations. First, the

differentiation efficiency of ESCs/iPSCs into cardiomyocytes

remains relatively low (typically 1–3%) (159), often resulting in heterogeneous

cellular populations containing undesired non-cardiac lineages that

may compromise experimental reliability (160). Second, the in vitro

culture system cannot fully recapitulate the dynamic regulatory

network governing cardiac development in vivo, thereby

constraining its applicability for comprehensive organ-level

studies. Consequently, this model system may be more suited towards

mechanistic investigations at cellular and molecular levels rather

than integrated organ-scale analyses.

Human cardiac organoids (hCOs) represent a

biomimetic three-dimensional culture model that effectively

recapitulates key aspects of heart development and drug toxicity

responses. These systems are composed of multiple cell types,

including cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells and stromal cells,

establishing a physiologically relevant microenvironment that

surpasses conventional two-dimensional cultures in functional

evaluation (161). hCOs exhibit

mature functional properties, such as spontaneous contractility and

stable electrophysiological signals, enabling simultaneous

assessment of drug effects on cardiomyocyte proliferation and

function. However, it should be noted that hCOs more closely mimic

the postnatal cardiac physiology, limiting their applicability for

toxicity prediction during early embryonic development (162). Additionally, challenges remain,

including prolonged culture duration, technical complexity and

insufficient standardization, which warrant further optimization to

enhance the reproducibility and scalability of the hCO model.

Epigenetic discoveries elucidating cardiac

developmental toxicity

Identification of epigenetic

biomarkers in cardiac developmental toxicity

Biomarkers represent measurable biological

parameters that objectively indicate physiological processes,

pathological conditions or pharmacological responses, making them

important tools for disease screening, accurate diagnosis and

reliable prognostic assessment (163). Advances in omics technologies,

particularly high-throughput genomic profiling, have enabled

systematic identification of candidate biomarkers while providing

novel approaches to elucidate disease mechanisms. Epigenetic

markers have gained particular prominence as promising

next-generation biomarkers, given their key role in regulating

disease pathogenesis (7).

In the investigation of cardiac developmental

toxicity, a number of epigenetic biomarkers have been preliminarily

identified as serving as early warning indicators of toxicity

(Fig. 2C). Notably, miR-203a has

been consistently shown to be downregulated during cardiac toxicity

events and zebrafish embryos treated with miR-203a inhibitors

exhibit characteristic cardiac malformations, suggesting its

potential as a biomarker for assessing developmental cardiotoxicity

induced by numerous toxicants (101,102,110). At the DNA methylation level,

hypomethylation of NPPA and cTnT genes, along with hypermethylation

at the TBX5b promoter region, may serve as epigenetic signatures

for phthalate-induced cardiac defects (30). Regarding histone modifications,

reduced H3K9Ac and H3K14Ac levels appear to represent key

epigenetic biomarkers for triazole fungicide (FBZ-induced)

transgenerational cardiotoxicity (68). However, current limitations include

insufficient mechanistic validation of these biomarkers and their

specificity to particular toxicants. This further compromises their

general applicability. Therefore, establishing standardized

epigenetic toxicity assessment systems will markedly facilitate the

identification and application of developmental cardiotoxicity

biomarkers.

Preliminary exploration of potential

preventive measures

Based on current research findings, numerous

candidate drugs have been identified that may exhibit protective

effects against cardiac developmental toxicity (Fig. 2D). Folic acid, a key water-soluble

B vitamin (vitamin B9), cannot be synthesized endogenously and must

be obtained through dietary sources such as leafy green vegetables

and citrus fruits (164). This

biological component has key functions in important cellular

activities such as nucleotide biosynthesis and DNA methylation

processes (165). Research

demonstrates that folic acid, as a vital nutritional factor,

exhibits notable efficacy in preventing cardiac and neurological

developmental defects during embryogenesis (166). Additionally, folic acid has shown

promising potential in exploring epigenetic mechanisms for

preventing cardiac malformations, particularly through DNA

methylation-related pathways. Research has demonstrated that folic

acid supplementation corrects methylation imbalances by restoring

the SAM/SAH ratio and modulating DNMT expression, consequently

ameliorating cardiac malformations (25). This discovery provides a potential

intervention strategy against cardiac developmental toxicity

induced by environmental pollutants such as PM2.5. Similarly,

evidence shows that folate effectively alleviates selenite-induced

genomic methylation disorders and markedly reduces the incidence of

cardiac developmental anomalies, indicating its preventive role

against developmental toxicity through methylation reprogramming

regulation.

Betaine, also known as trimethylglycine, derives its

name from its structural similarity to glycine but with three

additional methyl groups (167).

As a safe and stable natural compound, betaine primarily serves as

a methyl donor in biological systems, participating in

transmethylation reactions and serving a key role in SAM synthesis

(168). SAM, a key cellular

methyl donor, is involved in diverse epigenetic modification

processes, including m6A RNA methylation. By promoting SAM

production, betaine indirectly modulates m6A methylation levels,

thereby influencing gene expression, RNA metabolism, and cellular

functions regulating glucolipid metabolism (168–170). Previous research has demonstrated

that betaine supplementation restores global m6A methylation levels

in the heart, mitigating PM2.5-induced cardiac developmental

toxicity by reducing ROS overproduction, mitochondrial dysfunction

and cell death (126). These

findings provide important evidence for preventing cardiac

developmental toxicity through epigenetic regulatory mechanisms,

although the discussed evidence primarily focuses on DNA

methylation and m6A RNA methylation regulation. Future

investigations should aim to examine more thoroughly the

therapeutic implications of addressing supplementary epigenetic

regulators, such as histone marks, ncRNA-mediated control and DNA

accessibility patterns, in developmental cardiotoxicity contexts.

Currently, the majority of evidence originates from preclinical

studies (cell-based and animal models), whereas clinical validation

in humans remains limited. Unresolved issues, such as optimal

dosage, administration timing and potential adverse effects,

require systematic investigation before this approach can progress

to clinical application.

Conclusion

Environmental pollutants and pharmaceuticals have

become a growing concern owing to their widespread potential to

induce embryonic cardiac developmental toxicity. Epigenetic marks

demonstrate notable dynamic plasticity during embryonic heart

development, with their modification patterns subject to regulation

by numerous environmental factors such as nutritional status,

maternal exposure to environmental contaminants and pharmacological

agents. The present review focuses on epigenetic regulatory

mechanisms and elucidates the molecular pathways through which

specific pollutants and chemicals mediate cardiac developmental

toxicity through epigenetic modifications. In addition, potential

epigenetic biomarkers and preventive pharmaceuticals are

summarized, which may contribute to monitoring embryonic cardiac

developmental toxicity and implementing preventive interventions

(25,68,110,126).

The current understanding of epigenetic mechanisms

underlying cardiac developmental toxicity remains limited, with

numerous key knowledge gaps yet to be resolved. First, the

establishment of causality remains inadequate. The majority of

studies have only observed associations between epigenetic

modifications (such as DNA methylation) and cardiac malformations,

lacking direct experimental evidence demonstrating that specific

modifications drive the toxic phenotypes (42,44,48).

This gap in causality markedly restricts the translational

applicability of existing findings. Second, systematic research

into epigenetic networks is lacking. Although crosstalk exists

among numerous epigenetic modifications, the mechanisms by which

potential toxicants regulate these interactions to induce cardiac

developmental defects remain poorly understood. In addition,

cardiac development is a continuous and precisely timed process,

yet current studies tend to employ static analytical approaches,

examining epigenetic changes at isolated time-points only.

Consequently, they fail to elucidate how pollutant-induced

epigenetic reprogramming dynamically evolves across different

developmental stages (such as cardiac tube formation and

atrioventricular septation) or its stage-dependent impact on

developmental progression. Furthermore, the number of identified

epigenetic biomarkers remains limited and exhibits insufficient

specificity, hindering their utility in clinical diagnosis and

environmental monitoring (30,68,110). Drug development targeting

epigenetic regulation for the prevention of cardiac developmental

defects is notably underdeveloped. Although methyl donors such as

folate and betaine have demonstrated protective effects in a number

of studies, their actions lack specificity and may inadvertently

interfere with normal epigenetic regulation during development

(23,119).

Future research should aim to integrate multi-omics

and epigenomic profiling technologies with CRISPR-based functional

validation to systematically decipher the molecular mechanisms by

which environmental exposures (such as pharmaceuticals and

pollutants) perturb cardiac development through epigenetic

regulation. Additionally, it is important to strengthen the

‘exposure-epigenetics-phenotype’ evidence chain by precisely

defining key time windows and dose-effect relationships. The

development of AI-driven high-throughput biomarker screening

platforms may help identify diagnostic molecular signatures and

facilitate the exploration of targeted epigenetic interventions.

These strategies will enhance early detection and prevention of

embryonic cardiac developmental toxicity, providing a strong

scientific foundation for translational applications.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present review was supported by the Talent Development

Program of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Tianjin University of

Traditional Chinese Medicine (grant no. YC-FY202303) and the

National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no.

8207141582).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

ZQ and RC drafted the manuscript and prepared the

figures and tables. RC and DS edited and revised the manuscript.

All the authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Mahler GJ and Butcher JT: Cardiac

developmental toxicity. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today.

93:291–297. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hoffman JI and Kaplan S: The incidence of

congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 39:1890–1900. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Hoffman JI: The global burden of

congenital heart disease. Cardiovasc J Afr. 24:141–145. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Hoffman JI: Incidence of congenital heart

disease: II. Prenatal incidence. Pediatr Cardiol. 16:155–165. 1995.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Sun R, Liu M, Lu L, Zheng Y and Zhang P:

Congenital heart disease: Causes, diagnosis, symptoms, and

treatments. Cell Biochem Biophys. 72:857–860. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Jenkins KJ, Correa A, Feinstein JA, Botto

L, Britt AE, Daniels SR, Elixson M, Warnes CA and Webb CL; American

Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, :

Noninherited risk factors and congenital cardiovascular defects:

Current knowledge: A scientific statement from the American heart

association council on cardiovascular disease in the young:

Endorsed by the American academy of pediatrics. Circulation.

115:2995–3014. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

de Oliveira DT and Guerra-Sá R: Uncovering

epigenetic landscape: A new path for biomarkers identification and

drug development. Mol Biol Rep. 47:9097–9122. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Maher N, Maiellaro F, Ghanej J, Rasi S,

Moia R and Gaidano G: Unraveling the epigenetic landscape of mature

B cell neoplasia: Mechanisms, biomarkers, and therapeutic

opportunities. Int J Mol Sci. 26:81322025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Leduque B, Edera A, Vitte C and Quadrana

L: Simultaneous profiling of chromatin accessibility and DNA

methylation in complete plant genomes using long-read sequencing.

Nucleic Acids Res. 52:6285–6297. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Choi SW and Friso S: Epigenetics: A new

bridge between nutrition and health. Adv Nutr. 1:8–16. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Samanta S, Rajasingh S, Cao T, Dawn B and

Rajasingh J: Epigenetic dysfunctional diseases and therapy for

infection and inflammation. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis.

1863:518–528. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Smith ZD and Meissner A: DNA methylation:

Roles in mammalian development. Nat Rev Genet. 14:204–220. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhang H, Lang Z and Zhu JK: Dynamics and

function of DNA methylation in plants. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

19:489–506. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Gowher H, Liebert K, Hermann A, Xu G and

Jeltsch A: Mechanism of stimulation of catalytic activity of Dnmt3A

and Dnmt3B DNA-(cytosine-C5)-methyltransferases by Dnmt3L. J Biol

Chem. 280:13341–13348. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Okano M, Bell DW, Haber DA and Li E: DNA

methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are essential for de novo

methylation and mammalian development. Cell. 99:247–257. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hermann A, Goyal R and Jeltsch A: The

Dnmt1 DNA-(cytosine-C5)-methyltransferase methylates DNA

processively with high preference for hemimethylated target sites.

J Biol Chem. 279:48350–48359. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Bansal A and Pinney SE: DNA methylation

and its role in the pathogenesis of diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes.

18:167–177. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Jones PA: Functions of DNA methylation:

Islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet.

13:484–492. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Bochtler M, Kolano A and Xu GL: DNA

demethylation pathways: Additional players and regulators.

Bioessays. 39:1–13. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Strasenburg W, Borowczak J, Piątkowska D,

Jóźwicki J and Grzanka D: The role of DNA methylation and

demethylation in bladder cancer: A focus on therapeutic strategies.

Front Oncol. 15:15672422025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yu F, Li K, Li S, Liu J, Zhang Y, Zhou M,

Zhao H, Chen H, Wu N, Liu Z and Su J: CFEA: A cell-free epigenome

atlas in human diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 48((D1)): D40–D44.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Wu SC and Zhang Y: Active DNA

demethylation: Many roads lead to rome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

11:607–620. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Li X, Cui J, Zhang X, Wu Y, Xu J, Zhao Y,

Hussain S and Chen L: Integrated analysis of methylomic and

transcriptomic profiles in fetal mouse hypothalamus in response to

maternal gestational exposure to arsenic. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf.

299:1184002025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Demond H, Khan S, Castillo-Fernandez J,

Hanna CW and Kelsey G: Transcriptome and DNA methylation profiling

during the NSN to SN transition in mouse oocytes. BMC Mol Cell

Biol. 26:22025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jiang Y, Li J, Ren F, Ji C, Aniagu S and

Chen T: PM2.5-induced extensive DNA methylation changes in the

heart of zebrafish embryos and the protective effect of folic acid.

Environ Pollut. 255:1133312019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Qiu M, Chen J, Liu M, Shi Y, Nie Z, Dong

G, Li X, Chen J, Ou Y and Zhuang J: Reprogramming of DNA

methylation patterns mediates perfluorooctane sulfonate-induced

fetal cardiac dysplasia. Sci Total Environ. 919:1709052024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Cai J, Zhao Y, Liu P, Xia B, Zhu Q, Wang

X, Song Q, Kan H and Zhang Y: Exposure to particulate air pollution

during early pregnancy is associated with placental DNA

methylation. Sci Total Environ. 607–608. 1103–1108. 2017.

|

|

28

|

Heudorf U, Mersch-Sundermann V and Angerer

J: Phthalates: Toxicology and exposure. Int J Hyg Environ Health.

210:623–634. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wang Y and Qian H: Phthalates and their