Diabetic kidney disease (DKD), recognized as a

severe chronic microvascular complication of diabetes, has emerged

as the leading cause of chronic kidney disease, surpassing chronic

glomerulonephritis in incidence (1). Clinically, DKD is characterized by

progressive proteinuria, edema and hypertension. Pathologically, it

affects multiple renal structures, including glomeruli, tubules and

microvessels, ultimately culminating in end-stage renal disease

(2). DKD diagnosis is performed

through biopsy; however, the filtration rate and albumin excretion

rate enable initial identification (3). Notably, accumulating evidence has

underscored pre-biopsy biomarker screening as important for curbing

disease progression (4–6). Therefore, the identification of

important therapeutic targets and molecular biomarkers in

early-stage DKD holds notable clinical implications. Shifting away

from established DKD research models, the present review identified

endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress (ERS) as a prospective

therapeutic focus, including a systematic dissection of its role in

disease progression and a thorough re-evaluation of herbal

treatment approaches.

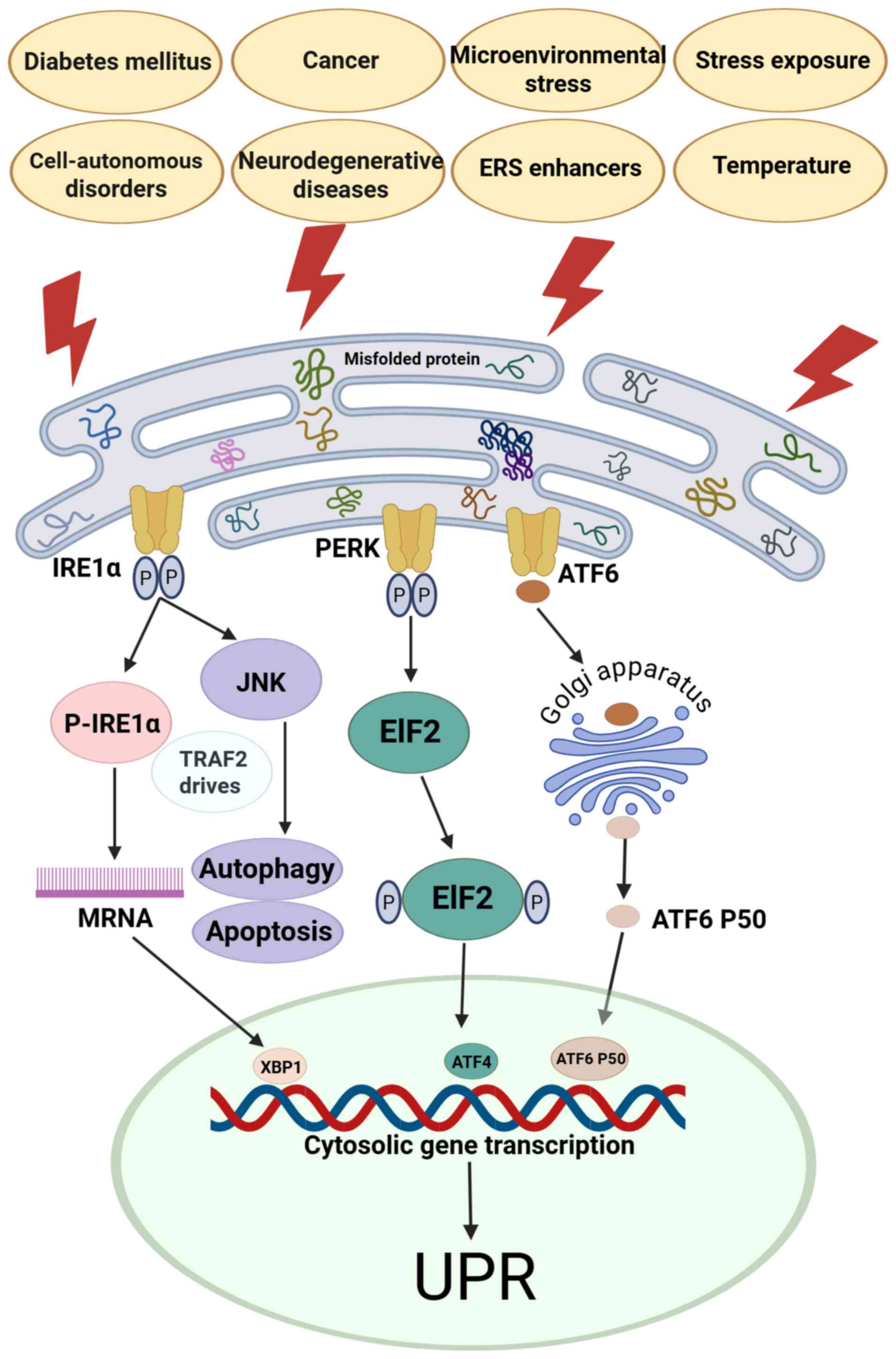

The ER, a notable cellular organelle, orchestrates

polypeptide folding and protein processing, functions that underpin

its roles in calcium storage and regulation, lipid metabolism, and

glucose homeostasis (7). ERS can

be initiated by two distinct mechanisms: i) Endogenous factors such

as cancer and neurodegenerative diseases, which disrupt cellular

processes (8); and ii) exogenous

stressors such as microenvironmental alterations and chemical

insults that induce ERS responses (9). Microenvironmental perturbations and

diverse stressors, including metabolic dysregulation,

cancer-associated stress, drug toxicity and radiation, elicit the

unfolded protein response (UPR) in the ER, a hallmark of ERS

(10). ERS serves as one of the

fundamental mechanisms underlying metabolic dysfunction across

renal organs and tissues. As a trophic signaling hub in metabolic

disorders such as obesity and type 2 diabetes, the ER integrates

inflammation, autophagy and apoptosis pathways, while modulating

cytokine release (11). ERS

induces dynamic changes in the expression of inositol-requiring

enzyme 1α (IRE1α), PKR-like ER kinase (PERK), activating

transcription factor (ATF)6 and glucose-regulated protein

(GRP)78/binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP). Following energy

metabolism fluctuations, these metabolism sensors (IRE1α, PERK and

ATF6) dissociate from GRP78/BiP, triggering increased metabolic

activity and protective responses such as autophagy (10). Failure to restore homeostasis via

translational arrest and chaperone upregulation leads to the

initiation of CHOP-dependent apoptosis, a determinant of stressed

cell fate (2,12).

ERS-related protective responses activate three

stress protein pathways. First, starting with the IRE1α-spliced

X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1s) pathway, phosphorylated (p-)IRE1α

dimerization catalyzes XBP1 mRNA splicing, generating

nuclear-translocated XBP1 that activates ER-associated degradation

(ERAD) or promotes mRNA decay during adaptive UPR. Concurrently,

tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2)-mediated

JNK activation contributes to dual-function UPR signaling,

balancing adaptive and apoptotic responses. Second, p-PERK

dimerization in the PERK/eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2)

pathway drives eIF2 phosphorylation, which enhances ATF4

translation to elicit adaptive UPR. During severe ERS, ATF4 induces

CHOP expression, activating the apoptotic arm of the UPR. Third, in

the ATF6 axis, chaperone dissociation of GRP78/BiP promotes Golgi

trafficking, where proteolytic processing generates ATF6 p50. This

nuclear effector drives the adaptive UPR via chaperone and foldase

transcription or the apoptotic UPR via ERAD activation (13).

Collectively, the IRE1α/XBP1s, PERK/eIF2 and ATF6

pathways balance ERS-induced survival and apoptosis through UPR

modulation: Moderate UPR restores homeostasis, while persistent ERS

activates apoptotic signals such as caspase-12, leading to cell

death (Fig. 1) (8–14).

Preclinical and clinical investigations have

consistently revealed ERS marker upregulation in renal tissues of

patients with DKD and relevant animal models (15–17).

Pathological changes in DKD tend to start early with thickening of

the basement membrane, gradually spreading to glomeruli,

microvessels and tubules. By contrast, changes in glomerular

hyaluronan appear in the late stages of DKD (18,19).

Persistent urinary protein abnormalities stem predominantly from

four sources: i) Renal filtration barrier defects, including those

affecting the basement membrane, podocytes and associated cells

(20); ii) damage across renal

tubular segments (21); iii) renal

interstitial functional impairment (22); and iv) immune cell population

dysregulation (23). In

conclusion, renal histopathology reveals that ERS impacts DKD in

three notable manners: Glomerular filtration membrane injury, renal

tubular reabsorptive dysfunction and renal interstitial remodeling

with immune cell dysregulation (24).

Studies in DKD model mice have revealed that ERS

contributes to glomerular injury, as demonstrated by increased

GRP78/caspase-12 expression and reduced Bcl-2 levels (25–27)

Notably, genetic deletion of ER protein 44 in db/db mice

upregulated ATF6, XBP1 and CHOP, further indicating ERS involvement

in glomerular filtration membrane injury (28). Composed of endothelial cells,

basement membrane and podocytes, the glomerular filtration membrane

is important for blood filtration. Damage to these components

drives early DKD progression and proteinuria (27). Surface-bound GRP78 drives

extracellular matrix (ECM) accumulation through PI3K/Akt

activation, while the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)/mTOR

pathway promotes late-stage PERK/CHOP upregulation to enhance

autophagy, and the IRE1/NF-κB pathway mediates ERS-induced

inflammation in podocytes (29–31).

Compared with individuals without DKD, renal biopsy analyses of

patients with DKD have revealed increased GRP78 and caspase-12

expression in human glomerular podocytes (28,32).

The elevation of ATF6 and PERK in human podocytes triggers lipid

metabolism disorders and inflammation, which are suppressed by

JNK-mediated insulin activity (33). Mechanistically, the high

glucose-induced elevation of PERK, ATF6 and IRE1α in rat podocytes

is linked to protein arginine methyltransferase 1 (PRMT1) (34). Concurrently, the activation of

XBP1s in glomerular mesangial cells triggers histone-lysine

N-methyltransferase SETD7-mediated histone methylation, leading to

the upregulation of DKD-associated monocyte chemoattractant protein

1 (35,36). These findings indicate that ERS

influences the expression of UPR-induced transcription factors,

which in turn contribute to fibrotic and inflammatory pathological

changes, thereby regulating the balance between adaptive and

apoptotic states in podocytes.

The depletion of terminally differentiated

podocytes, which form the glomerular filtration barrier, is

characteristic of chronic kidney diseases, including DKD. Numerous

studies have revealed an association between ERS and podocyte

injury in DKD, as ERS markers are upregulated in human and murine

podocytes exposed to high glucose; this process is induced by the

dysregulation of hyperglycemia, lipid metabolism and insulin

signaling (37,38). In mouse podocytes, the accumulation

of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) and high-glucose exposure

activate GRP78, CHOP and caspase-12 through distinct pathways,

ultimately driving podocyte apoptotic processes (39). PERK-eIF2α activation induces

CHOP-mediated podocyte apoptosis, and PERK phosphorylation triggers

a CHOP-reticulon 1A (RTN1A) positive feedback loop for synergistic

apoptotic enhancement (40).

Dysfunction in the insulin PI3K/Akt pathway may underlie

GRP78/CHOP-mediated ERS and podocyte apoptosis. Reduced activity of

PTEN, a downstream inhibitory regulator, exacerbates ERS, while

MEK/ERK signaling counteracts this pathological effect (41). The GRP78-mediated modulation of the

MEK kinase 1 (MEKK1)/JNK signaling cascade induces podocyte

apoptosis through MEKK1-dependent Ser280 phosphorylation (42).

The ERAD pathway is a specialized mechanism within

the ER that employs the ubiquitin-proteasome system to degrade

misfolded or aberrantly modified proteins, serving an important

role in eliminating these faulty proteins from cells (43). Derlin-2 expression is elevated in

podocytes from patients with DKD biopsies, triggering ERAD to

sustain the cellular balance (44,45).

Similarly, ERS serves an important role in balancing podocyte

survival and apoptosis through autophagy, given that compared with

DKD, podocytes inherently exhibit a higher basal autophagic

activity (46) High glucose levels

increase eIF2α, CHOP, caspase-3/12, GRP78, ATF6 and PERK levels in

podocytes through the inhibition of autophagy, whereas

sarcoendoplasmic reticulum calcium-ATPase (SERCA)2b-mediated ERS

attenuation is associated with AMPKα-induced autophagy (46,47).

The intercellular transmission of ERS signals, coupled with

podocyte-intraglomerular cell interactions, suppresses ERAD through

derlin-2 downregulation, inducing podocyte apoptosis in DKD

(48). Additional evidence has

shown that GRP78/CHOP activation in endothelial cells drives

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (49), implying a potential role for

glomerular endothelial cells in DKD pathogenesis, although the

underlying mechanisms remain ambiguous.

UPR-activated transcription factors drive fibrosis

and inflammation in glomerular podocytes at the early stage of

diabetic kidney injury. Three ERS pathways collectively influence

disease progression, including: i) Regulation of podocyte apoptosis

through the PI3K/Akt, PTEN and MEK/ERK signaling pathways; ii)

maintenance of cellular homeostasis through the activation of ERAD;

and iii) modulation of podocyte autophagy via AMPK (50,51).

In addition, key ERS factors also contribute to the DKD process by

affecting intraglomerular mesangial cells and podocytes (52).

Composed of Henle's loop, proximal and distal

tubules and collecting ducts, renal tubules reabsorb small

molecules and lipids, with their epithelium serving as a key

DKD-targeted cell type susceptible to injury (53,54).

Extensive research has established that ERS contributes to

DKD-related renal tubular injury, as evidenced by the upregulation

of differential ERS markers in human biopsies, animal tissues and

in vitro models (15,55–57).

This process is driven by the AGE/receptor for AGEs (RAGE) axis,

PRMT1 and histone H4 deacetylation (15,58,59),

while it is alleviated by calbindin-D28k, transmembrane BAX

inhibitor motif-containing protein 6, sestrin 2 and dapagliflozin

(60,61). Renal tubular ERS markers (notably

including GRP78) can modulate the autophagic processes and drive

inflammatory responses by regulating mitochondrial function and

reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation (62,63).

Saturated fatty acid-associated factors, such as

carbohydrate-responsive element-binding protein, cholesterol and

palmitic acid (PA), promote ERS marker upregulation in renal

tubular cells, causing lipid accumulation and apoptotic cell death

(64,65). Therefore, the comprehensive role of

ERS in renal tubules is closely intertwined with autophagy,

inflammation and lipid peroxidation.

In the renal tubular system, the proximal tubule

reabsorbs glucose, amino acids, HCO3−,

Cl− and Na+, while secreting H+.

By contrast, the distal tubule and collecting ducts mainly mediate

Na+ and water reabsorption alongside K+

secretion. The proximal and distal tubule of the kidney functional

distinction partially explain the structural variations in ERS

signaling, with GRP78-governed ATF4/p16/p21 axes promoting

AGE/RAGE-driven premature cellular senescence in mouse proximal

tubular cells (66). GRP78 and

protein disulfide isomerase exhibit distinct regulatory dynamics

between proximal and distal tubules, varying across early and late

stages of diabetes-induced ERS. Early-stage diabetes triggers PERK

activation, while late-stage disease promotes ATF6 activation in

renal tubules, resulting in stage-dependent differential ERS

responses between proximal and distal segments in DKD (67).

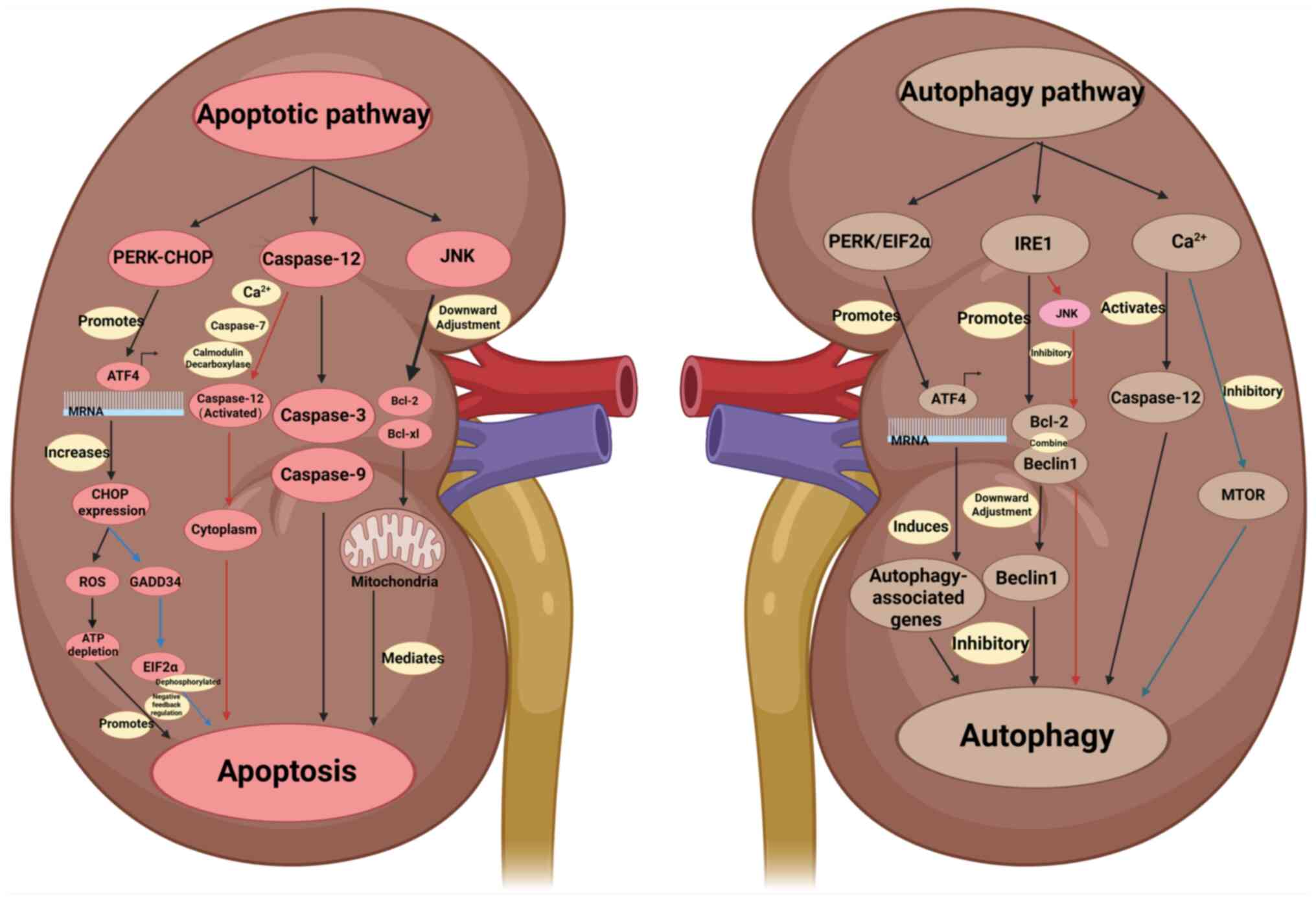

ERS notably regulates renal cell function by

suppressing inflammation, inhibiting abnormal proliferation and

fibrosis, and combating oxidative damage through the precise

modulation of DKD pathways, including the PERK/CHOP and caspase-12

pathways (53,68,69).

The mechanistic exploration of ERS in DKD pathway regulation sheds

light on DKD pathogenesis and facilitates the identification of

novel therapeutic targets (Fig.

2).

The PERK/CHOP pathway regulates ERS and contributes

to DKD. The core aspects of the PERK/CHOP pathway comprise the

following mechanisms: Initially, ERS is triggered when high glucose

levels, oxidative stress and inflammation lead to misfolded protein

accumulation in the ER, prompting GRP78/BiP dissociation from PERK

and subsequent kinase activation (70). Subsequently, the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4

axis is activated; PERK phosphorylates eIF2α, globally inhibiting

translation to reduce ERS burden. Simultaneously, p-eIF2α

selectively promotes ATF4 translation, leading to CHOP expression

(71) Finally, CHOP-mediated

apoptotic signaling occurs (72)

CHOP, a transcription factor, upregulates pro-apoptotic genes, such

as Bcl-2-interacting mediator of cell death (Bim), p53 upregulated

modulator of apoptosis and Bax, and downregulates Bcl-2, ultimately

inducing apoptosis (73).

The PERK/CHOP pathway mediates DKD podocyte injury

through high glucose-activated PERK/eIF2α/ATF4/CHOP signaling,

inducing apoptosis, foot process effacement, proteinuria and

glomerulosclerosis, which are exacerbated by pathway

hyperactivation (74). The

PERK/CHOP pathway drives mesangial cell proliferation, fibrosis and

ECM deposition, mediated via pathways such as the TGF-β1/connective

tissue growth factor pathway, in DKD, additionally serving as a

central mediator of proteinuria and glomerulosclerosis (75). In DKD, the CHOP pathway mediates

renal tubular injury. High glucose-induced ERS promotes tubular

apoptosis through the PERK/CHOP axis and activates pro-inflammatory

cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α to exacerbate renal interstitial

inflammation (68). Renal

tubulointerstitial fibrosis is an important step in the progression

of DKD to end-stage renal disease. Sustained PERK activation

enhances ATF4 transcription to upregulate CHOP, which downregulates

Bcl-2 and promotes apoptosis through ROS production and ATP

depletion (76). Concurrently,

CHOP triggers growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible 34 activation

to facilitate eIF2α dephosphorylation, a negative feedback

mechanism that restores transiently-arrested protein synthesis in

the PERK pathway (77).

The PERK/CHOP regulatory axis balances adaptive and

apoptotic responses to ERS through integrated positive and negative

feedback mechanisms (78). PERK

and its downstream effector CHOP exhibit segment-specific

regulation across different regions of the renal tubule. Renal

tubular cells secrete CHOP-induced fibronectin, driving mesenchymal

fibrosis in DKD, a process implying that PERK/CHOP signaling

controls the synthesis and release of ECM proteins in these cells

(79). The RTN1A/PERK/CHOP

positive feedback loop exacerbates ERS-induced podocyte apoptosis,

highlighting the dual role of the PERK/CHOP pathway in maintaining

ERS balance and promoting pathological cell death (80).

Caspase-12 acts as a key executor of apoptotic

signaling, with its activation closely linked to ERS-induced cell

death (81). Upon ER misfolded

protein accumulation, for example, due to high blood glucose

levels, oxidative stress or calcium dyshomeostasis, GRP78/BiP

dissociates from ER membrane sensors such as PERK, IRE1 and ATF6 to

bind misfolded proteins, triggering the activation of caspase-12 as

a downstream responder to ERS signals (82,83).

In non-stressed cells, GRP78 associates with pro-caspase-12 to

suppress its activity. During ERS, GRP78 dissociation exposes the

active site for proteolytic processing by upstream enzymes,

including IRE1α and calpain, generating active caspase-12 (p35/p12

subunits) that cleaves caspase-3 to initiate apoptosis (84,85).

In patients with DKD, high glucose induces ERS,

which activates caspase-12 and promotes the apoptosis of podocytes

and tubular epithelial cells, accelerating proteinuria and renal

interstitial fibrosis (86). In

the DKD mouse model, CHOP overexpression upregulates caspase-12 to

promote apoptosis, whereas caspase-12 inhibition attenuates high

glucose-induced renal cell injury (87). ERS also induces calcium

dyshomeostasis and mitochondrial calcium overload, indirectly

activating the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway via the

ER-mitochondrial axis (88).

ER-released Ca2+ activates peripheral calpains,

prompting their translocation to the cytoplasm. Calpain activation

results in translocation to the ER outer membrane, triggering

caspase-7 translocation and activation (87,89).

Both factors process pro-caspase-12 into an active form that

translocates to the cytoplasm, activates caspase-9 and −3 through

the cytochrome c (CytC)-independent pathway and induces

apoptosis (90). In addition, the

IRE1α-TRAF2 complex activates caspase-12 through calmodulin

decarboxylase, thereby initiating the caspase-mediated apoptotic

pathway (91).

Caspase-12-dependent signaling contributes to severe podocyte and

tubular cell injury in DKD. Therapeutic targeting of this pathway

mitigates ERS-mediated apoptosis, slowing DKD progression (92,93).

Therefore, caspase-12 signaling is important for ERS-induced

apoptosis. Despite genetic polymorphisms limiting its activity in

humans, caspase-12 retains diagnostic and therapeutic value for ERS

(94). Targeting the caspase-12

pathway may provide novel targets for the treatment of DKD.

JNK, originally identified in its capacity to

phosphorylate the amino terminus of the transcription factor c-Jun

(95), is also referred to as

stress-activated protein kinase. Extracellular stimuli, such as

stress signals, cytokines and growth factors, activate JNK, with

the activation relying on the cellular microenvironment. JNK

inhibition reduces podocyte apoptosis and matrix deposition, and

combination with PERK/CHOP inhibitors may enhance therapeutic

efficacy (96,97). As an important branch of the MAPK

cascade, the JNK pathway orchestrates multiple physiological

processes (98). During ERS,

activated IRE1α engages TRAF2 to trigger apoptosis

signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) activation, generating a trimeric

complex that sequentially activates JNK, CHOP and pro-apoptotic

factors such as BH3-interacting domain death agonist and Bim, a

process that suppresses anti-apoptotic genes, including Bcl-2 and

Bcl-xL, and initiates mitochondrial apoptotic pathways (99–102). In addition, phosphorylation at

the MEKK1 Ser280 residue activates the JNK signaling pathway,

thereby promoting ERS-induced podocyte apoptosis (38,103). High glucose triggers JNK

activation in renal cells, inducing apoptosis and fibrosis. These

processes are alleviated by JNK inhibitors, which reduce

CHOP/caspase-3-dependent apoptosis in ERS-impaired podocytes to

mitigate DKD-related renal injury (33). Acting as a central stress response

hub, the JNK pathway integrates external stimuli with intracellular

signaling to govern inflammation and disease progression, with

functional complexity emerging from stimulus subtype specificity,

stimulus intensity and cellular context (104,105). Despite the challenges of drug

development targeting JNK (such as poor specificity and high

concentrations required to inhibit c-Jun phosphorylation), its

potential applications in areas such as DKD and neurodegenerative

diseases make it a promising therapeutic target (106–109).

The PERK/eIF2α signaling axis, a key branch of ERS

signaling, maintains intracellular proteostasis by regulating

protein synthesis and gene expression (110). Following the accumulation of

misfolded or unfolded proteins in the ER, this pathway is activated

to promote either stress adaptation or apoptosis through global

translation inhibition and induction of stress-responsive genes

(111). The key component of this

pathway, PERK, is an ER transmembrane protein with a kinase domain

on the cytoplasmic side, while only its stress-sensing domain is

present within the lumen of the ER) (112). In unstressed cells, PERK stays

inactive by associating with the ER chaperone BiP that has

dissociated from GRP78 (113). By

contrast, eIF2α is a key factor in the initiation of protein

translation, and phosphorylation at its Ser51 site is a central

event in the activation of the PERK/eIF2α pathway. This pathway

coordinates cellular homeostasis through multifaceted mechanisms,

such as translation repression for energy conservation, amino acid

transporter induction for survival and proteostasis regulation

through reduced synthesis, enhanced folding through mechanisms such

as BiP upregulation, or misfolded protein degradation, for example,

via ERAD (72).

The PERK/eIF2α branch of the UPR signaling pathway

induces autophagy-associated gene expression through the

transcriptional regulation of ATF4, thereby promoting the

transcription of autophagy-associated genes (114). Downstream genetic effectors

include beclin-1, which mediates autophagosome biogenesis and

maturation, the ubiquitin-like system and transport receptor genes

such as p62 and next to BRCA1 gene 1 protein (115). These transport receptor genes

undergo selective degradation via ubiquitinated cargoes. Vaspin, a

serine protease inhibitor, suppresses p62 aggregation by forming

complexes with GRP78 and heat shock 70 kDa protein 1L (116,117). This mechanism protects organelles

from metabolic stress-induced damage through endocytosis-driven

autophagy facilitation, maintaining cellular homeostasis under

stress (118). The PERK/eIF2α

pathway is a ‘regulatory hub’ for ERS through precise regulation at

the translational level and reprogramming of gene expression to

maintain a balance between cell adaptation and death (119).

The IRE1 signaling cascade acts as a core ERS

effector, governing adaptive or apoptotic cell fates predominantly

by modulating mRNA splicing and gene transcription (120,121). The pathway is highly

evolutionarily conserved from yeast to mammals and is a key

mechanism for maintaining ER protein homeostasis. The IRE1/XBP1

axis preserves cellular homeostasis during acute stress by boosting

protein folding, degradation and transport, while governing the

activity of secretory cells, such as plasma and pancreatic β-cells,

for efficient antibody and insulin production (122,123). Conversely, chronic ERS in

pancreatic β-cells engages the IRE1/JNK pathway, causing β-cell

death and diminishing insulin release (124,125).

The IRE1 pathway engages in crosstalk with the other

two UPR arms: The PERK/eIF2α and ATF6 pathways. The PERK branch

suppresses global translation through eIF2α phosphorylation to

reduce protein synthesis load, while ATF6 activates BiP, ERAD and

other chaperone genes through nuclear translocation (126,127). The IRE1 pathway promotes protein

folding and degradation through XBP1 splicing, concurrently

regulating cell fate through JNK activation and the regulated

IRE1-dependent decay (RIDD) pathway (111,128). Collectively, these three pathways

dictate cellular outcomes during stress, promoting survival under

acute stress conditions and triggering apoptosis under prolonged or

severe stress (129). In the ERS

state, IRE1/XBP1 signaling directly promotes the expression of

Bcl-2, increases the binding of Bcl-2 to beclin-1 and downregulates

the activity of beclin-1, thus inhibiting autophagy (2). During early ERS, IRE1α assembles with

TRAF2 and ASK1 to activate the downstream JNK signaling cascade,

which phosphorylates Bcl-2 to promote its dissociation from

beclin-1 and encourages subsequent autophagy initiation (92,93).

In addition, XBP1, a downstream effector of IRE1α, promotes

autophagy through beclin-1 activation (43). Blocking the kinase and RNase

activities of IRE1α has been shown to intensify PA-induced

cytotoxicity in renal tubular cells, indicating that IRE1α protects

against PA-mediated kidney injury in DKD (130). The IRE1 signaling pathway is a

‘multifunctional hub’ of the ERS response, responsible for shutting

down and splicing of the mRNA that encodes secretory proteins in a

process called regulated RIDD to decrease ER protein load and

spliced mRNA of XBP1 that activated the transcription of ER

hemostatic factors as chaperone and endoplasmic

reticulum-associated degradation components that degraded unfolded

and misfolded proteins in an attempt to resolve endoplasmic

reticulum stress; if this stress was unresolved, XBP1 upregulated

the expression of JNK that activated podocytes, tubular apoptosis,

and inflammation (131), and its

aberrant activation is closely associated with a variety of

diseases(such as Sepsis, DKD, breast cancer et.) (131–133).

Calcium channels are the core molecular machinery

regulating the intracellular flow of Ca2+ across the

membrane (129). DKD marked by

glomerular mesangial matrix dilation, basement membrane thickening,

tubulointerstitial fibrosis and renal unit loss involves

Ca2+ as a key signaling molecule; calcium homeostatic

imbalance markedly drives disease pathogenesis (134,135). The ER functions as a primary

intracellular Ca2+ store, regulating calcium homeostasis

(136). During stress,

Ca2+ influx sustains cellular homeostasis by activating

the MAPK pathway, thereby promoting intracellular protein folding

(137,138). Excessive release of

Ca2+ into the cytoplasm initiates ERS, thereby

activating caspase-12-dependent autophagy (139). The transient ER surface calcium

concentration is a key signal that determines the activation of ER

autophagy (140). In addition,

ATP and other Ca2+ mobilizers antagonize mTOR-mediated

autophagy inhibition via Ca2+-dependent pathways,

thereby promoting beclin-1- or autophagy-related gene 7-dependent

autophagosome biogenesis (141,142). In addition, Ca2+ can

activate both protein kinase C (PKC) and death-associated protein

kinase (DAPK). PKC induces autophagy through an mTOR-independent

pathway, whereas DAPK promotes beclin-1 phosphorylation and

disrupts the beclin-1/Bcl-2 complex, thereby activating autophagy

(143,144). The ERS-associated inhibition of

PERK and IRE1 protects against kidney injury, mitochondrial

dysfunction and renal cell apoptosis by maintaining Ca2+

homeostasis, which blocks cytosolic release of CytC and

apoptosis-inducing factor, inhibits caspase-9 activation and

restores mitochondrial membrane integrity, thereby suppressing

pathological cell death pathways (145). Calcium channels are ‘signaling

hubs’ for cellular functions, and their diversity and sophisticated

regulatory mechanisms serve key roles in physiological and

pathological processes (129,134).

Research on AS modulation of DKD through ERS

intervention has primarily focused on DKD rodent models and

meta-analyses (26,47,150–152). In DKD rat models (47,150) induced by a high-fat diet combined

with streptozotocin (STZ), intragastric administration of AS-IV

effectively mitigated apoptosis in renal tubular epithelial cells.

This protective effect involved two primary mechanisms: i)

Downregulation of ERS-associated proteins, including p-PERK, ATF4

and CHOP; and ii) restoration of the homeostatic balance between

the pro-apoptotic protein Bax and anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2

(47,150). In STZ-induced DKD rats (26,151,152), AS-IV alleviated ERS-driven

podocyte apoptosis through three coordinated pathways: i)

Suppression of the PERK/ATF4/CHOP signaling cascade; ii) inhibition

of oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 150 (ORP150) and GRP78

expression; and iii) reduction of phosphorylation levels of PERK,

eIF2α and JNK (26,151). Similarly, in db/db mice and

podocytes exposed to high glucose or PA, two important pathological

stimuli in DKD, AS-IV mitigated ERS and reduced podocyte apoptosis

by restoring SERCA2 expression and activity (152). Collectively, AS-IV exerted

anti-ERS effects through a multi-targeted strategy: Blocking three

important ERS signaling pathways, including the PERK/ATF4/CHOP,

PERK/eIF2α and IRE1/JNK pathways, increasing SERCA2 expression and

decreasing ORP150 and GRP78 expression (Table I) (26,151,152).

Huangkui is a TCM approved by the Chinese National

FDA for nephritis treatment. Its therapeutic effect on DKD is

primarily mediated by active ingredients, particularly flavonoid

derivatives such as quercetin glycosides and kaempferol glycosides.

These components intervene in the core pathological mechanisms of

DKD, including ERS, oxidative stress, the inflammatory response,

apoptosis and renal interstitial fibrosis, thereby forming a

multi-dimensional protective network (159–164). Huangkui (158,159) can restore ER protein homeostasis:

The upregulation of molecular chaperone proteins GRP78 and GRP94

promotes correct protein folding, enhances ERAD of misfolded

proteins, and attenuates ER loading (165).

In summary, Huangkui capsules exert protective

effects against both glomerular and tubular injuries by regulating

multiple mechanisms, including signal transduction pathways,

nuclear receptor activities, inflammatory responses, mitochondrial

function and gut microbiota, thus providing novel drugs and

approaches for the treatment of kidney disease. Ge et al

(33) demonstrated that Huangkui

ameliorated renal damage by attenuating ERS in DKD model rats.

Through its multi-targeted mechanism, encompassing ERS inhibition,

and antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic and

podocyte-protective effects, Huangkui mediates multi-level

regulatory effects in DKD progression, with notable promise in

proteinuria control and delaying renal interstitial fibrosis

(33,171,172). The natural medicinal properties

of Huangkui provide a novel strategy for early intervention in DKD,

and the combination of Chinese and Western medicine, which is

particularly suitable for the long-term management of patients with

mild to moderate proteinuria (170)

OA, as a monounsaturated fatty acid, serves an

important role in the development of DKD, and its involvement in

kidney injury through the regulation of ERS has attracted

increasing attention. OA is naturally found in fruits and

vegetables. Podocytes, early DKD targets, exhibit dose-dependent OA

responses: Low-dose OA mitigates injury, while high-dose OA

triggers ERS-PERK-mediated apoptosis, impairing podocyte protein

synthesis and filtration barrier integrity. Mechanistically, CHOP

upregulation inhibits Bcl-2, activating mitochondrial apoptotic

cascades, such as the caspase-3-mediated cascade (173,174). OA also exerts context-dependent

effects on tubular fibrosis: Low ERS inhibits fibrosis, while

OA-induced ERS activates ATF6/CHOP to upregulate TGF-β1/α-smooth

muscle actin (α-SMA), driving EMT (175). Excessive OA drives mesangial cell

proliferation and ECM accumulation through ERS-hyperactivated mTOR

signaling, contributing to glomerulosclerosis (176). This underscores OA concentration

modulation as a promising DKD therapeutic strategy.

In preclinical models, OlA exhibits antioxidant,

antiglycation, anti-inflammatory and bactericidal activity, notably

ameliorating DKD by reducing ERS. In diabetic rats, OlA treatment

enhances the renal protein expression of p-AMPK/AMPK and peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1-α (PGC-1α), while

concurrently decreasing the expression of CD68, collagen-IV, TLR4,

NF-κB and TGF-β1 (177). By

regulating lipid metabolism and inflammation through the

AMPK/PGC-1α and TLR4/NF-κB pathways, OlA mitigates renal injury in

diabetic rats. In DKD model mice, OlA administration notably

reduces the ALB-creatinine ratio (ACR). The marked DKD-induced

elevation in ERS markers, such as p-PERK, p-eIF2α, ATF-6, BiP and

CHOP, was notably decreased following OlA treatment, accompanied by

marked reductions in ROS and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related

factor 2 levels in glomerular mesangial cells (177,178). Furthermore, OlA administration

reduces TGF-β/Smad2/3 signaling and α-SMA expression, repairs renal

damage, alleviates albuminuria and suppresses diabetes-induced

renal fibrosis by inhibiting ERS and apoptosis (179). In combination with

N-acetylcysteine, OlA further attenuates oxidative stress and

reduces the ERS-induced activation of TGF-β/Smad2/3 signaling

(180).

Quercetin, a widely distributed natural polyphenol,

exhibits potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and multi-target

regulatory effects, making it a focal point of interdisciplinary

research in disease prevention (181,182). Quercetin exhibits efficacy in

treating metabolic diseases, including diabetes and its

complications. Quercetin enhances cell-mediated immunity by

upregulating IFN-γ secretion from Th1 lymphocytes and reduces

inflammation by downregulating IL-4 secretion from Th2 lymphocytes

(183). The protective effects of

quercetin are mediated through multiple mechanisms, including

inhibition of ROS production and mitochondrial permeability

transition-pore opening, suppression of lipid peroxidation,

elevation of glutathione and superoxide dismutase levels (184), inhibition of NF-κB, TNF-α and

IL-6 signaling (185), reduction

of inflammatory mediator release, suppression of

angiotensin-converting enzyme and NF-κB activity, and enhancement

of endothelial-dependent vasodilation (184,185). These actions collectively

regulate blood pressure and reduce urinary protein excretion.

Quercetin may improve glucose homeostasis by

modulating the expression of the microRNA-29 family, thereby

increasing glucose transporters and insulin-like growth factor 1

gene expression, ultimately mitigating diabetic complications

(186). In STZ-induced diabetic

male Wistar rats, quercetin exhibited hypoglycemic effects,

restored pancreatic morphology and β-cell function, reduced ERS

markers such as CHOP and endothelin-1, inhibited lipid

peroxidation, and enhanced antioxidant enzyme activities (183,187). Consequently, it lowered blood

glucose levels, protected pancreatic tissues, alleviated ERS and

improved oxidative status. Quercetin also inhibits platelet

aggregation, hypertension and lipid peroxidation (188). In metabolic disorders, quercetin

ameliorates diabetic endothelial dysfunction by targeting ERS,

highlighting its role in metabolic-endothelial crosstalk (189).

As metabolic disease therapy, the renin-angiotensin

system (RAS) inhibitors aliskiren (193,194) and valsartan (195,196) reduce DKD proteinuria by lowering

glomerular pressure, with evidence showing that ERS pathway

regulation contributes to their renoprotective effects in

RAS-driven DKD.

ACEIs and ARBs such as aliskiren and valsartan

inhibit renal ERS in DKD, and dual therapy yields cumulative

renoprotective effects via synergistic RAS blockade and ERS control

(193). Valsartan is recommended

by several guidelines, including the Kidney Disease: Improving

Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines (197), as the preferred ARB for DKD with

hypertension, and its nephroprotective effect is partly attributed

to ERS modulation. The clinical use of aliskiren is currently

limited due to early clinical trials, such as the ALTITUDE study

(72,198), showing an increased risk of

hyperkalemia and renal injury when used in combination with an ARB,

but its single-agent modulation of ERS remains worth studying

(199–201). Aliskiren and valsartan exert

anti-apoptotic, anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects in DKD

by inhibiting RAS overactivation and modulating upstream or

downstream ERS. Valsartan, as a classical ARB, has been clinically

validated as an ERS regulator, particularly in the context of DKD

treatment. However, the ERS-targeting effect of aliskiren (a direct

renin inhibitor) remains to be further evaluated and balanced in

terms of its efficacy and safety (193). Basic research has confirmed that

angiotensin II exacerbates ERS in renal tubular epithelial cells by

activating the PERK/eIF2α/CHOP pathway, while ACEIs and ARBs

downregulate stress markers such as GRP78 and CHOP in renal tissue

(196,202). However, clinical studies have yet

to incorporate assessments of ERS-related biomarkers, thus direct

clinical evidence of ACEI and ARB exerting effects via inhibition

of ERS is lacking (193,196). The 2024 KDIGO guidelines

recommend RAS inhibitors for patients with DKD with proteinuria,

emphasizing blood pressure and proteinuria management but omitting

the discussion of ERS-related mechanisms (202).

CB1R, a notable cannabinoid receptor, is widely

distributed in renal vascular endothelial, mesangial, tubular and

immune cells (203,204). In DKD, hyperglycemia, oxidative

stress and inflammation activate CB1R, inducing renal inflammation,

fibrosis and metabolic dysfunction, including insulin resistance

(205–207). CB1R antagonists, such as

rimonabant and AM251, have been shown to improve glucose-lipid

metabolism in metabolic disorders through the blockade of CB1R

signaling, and their protective mechanism against DKD has been

demonstrated to be closely associated with modulation of the ERS

pathway (208,209). The protective effect of CB1R

inhibition in DKD is linked to ERS pathway modulation, with CB1R,

abundantly expressed in diabetic rats kidneys, mediating ERS and

apoptosis in rat mesangial Cells) under high glucose. CB1R

regulates palmitic acid-induced apoptosis in human renal proximal

tubular cells through the ERS pathway (210,211). CB1R antagonists are not

recommended in DKD guidelines; rimonabant has been withdrawn

globally due to severe psychiatric side effects such as depression

and anxiety (212). Subsequent

candidate CB1R antagonists, such as AM6545, remain in preclinical

research for DKD and have not yet been incorporated into guidelines

(213,214).

Endogenous cannabinoids activating CB1R may serve a

notable role in the pathogenesis of diabetic cardiomyopathy by

promoting MAPK activation, type-1 angiotensin II receptor

expression and signaling, AGE accumulation, oxidative and

nitrosative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis (215,216). Conversely, CB1R antagonists exert

anti-diabetic effects by increasing pancreatic β-cell glucokinase

and glucose transporter (GLUT)-2 expression, improving β-cell

insulin signaling and proliferation (for example, mitigating β-cell

loss in male Zucker diabetic obese rats, independent of weight

loss) (216,217). CB1R antagonists also upregulate

skeletal muscle GLUT-4 to ameliorate intermittent hypoxia-induced

insulin resistance, whereas CB1R agonists interfere with insulin

signaling pathways (218,219). CB1R antagonists modulate the ERS

pathway by blocking high-glucose- or inflammation-induced CB1R

signaling on several levels: i) Inhibiting oxidative stress and

calcium disruption (211); and

ii) attenuating inflammation and fibrosis, thereby improving renal

cell survival and renal function (220). The use of CB1R antagonists is

subject to notable limitations. Currently, to the best of our

knowledge, no human studies using CB1R antagonists have been

conducted, and the risk of psychiatric side effects remains to be

assessed (221,222). Consequently, clinical advancement

cannot proceed at this stage (223). However, it holds potential and

may provide a basis for DKD treatment following future animal

studies and clinical trials.

Chemical chaperones, such as TUDCA and 4-PBA, are

small molecules responsible for stabilizing protein conformation,

enhancing ER folding and promoting mutant protein transport. TUDCA,

a secondary bile acid, exhibits beneficial effects in various

disorders, including diabetes, obesity and neurodegenerative

disease (224). The

cytoprotective mechanisms of chemical chaperones primarily involve

the alleviation of ERS. 4-PBA, a small-molecule chaperone employed

in urea-cycle disorders, mitigates ERS to normalize hyperglycemia

and insulin resistance (225–227). Preclinical study has demonstrated

the efficacy of 4-PBA in preventing podocyte apoptosis in type 2

diabetes (228). In addition,

three widely used ERS inducers, clindamycin, dithiothreitol and

carbobenzoxy-Leu-Leu-leucinal, have been applied to assess ERS in

animal models and cell lines. 4-PBA was shown to alleviate

drug-induced ERS (229), while

drugs targeting PERK, IRE1α, eIF2α and ATF4, such as GSK2606414,

MKC-3946, salubrinal and trazodone, offer promise for ERS-related

disorder management (230,231).

In rats fed a high-salt diet, damage to the glomeruli and proximal

tubules was exacerbated, accompanied by increased urinary protein

excretion. Following treatment with TUDCA, the levels of proximal

tubular giant cells increased and urinary protein levels were

markedly decreased (232). TUDCA

and 4-PBA are not formally included in clinical guidelines for DKD.

However, the Chinese Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of

Diabetic Kidney Disease (2021 Edition) mention in the section on

‘Novel Therapeutic Targets for DKD’ that ‘chemical companions may

improve renal injury by alleviating ERS’, listing TUDCA as a

potential candidate drug (233).

Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors,

such as empagliflozin and dapagliflozin, currently represent

first-line therapies for DKD. Their regulation of ERS involves

indirect multi-pathway interventions, and the direct association

between their renal protective effects and ERS inhibition requires

validation through mechanistic clinical trials (244,245). The 2024 KDIGO guidelines classify

SGLT2 inhibitors as a first-line therapy with Class 1A

recommendation for patients with DKD with an estimated glomerular

filtration rate (eGFR) ≥20 ml/min/1.73 m2, emphasizing

their role in delaying renal progression (246,247). However, ERS-related mechanisms

are not addressed. Existing large-scale clinical trials have

primarily focused on definitive renal endpoints, such as eGFR

decline and end-stage kidney disease, without systematic assessment

of ERS biomarkers (202,248–251). Thus, attention to ERS treatment

is warranted for kidney disease.

The aforementioned drugs exhibit pleiotropic

effects, indicating their lack of specificity for ERS inhibition;

thus, development of ERS-targeted therapeutics is warranted.

Notably, ERS exhibits dual effects: Moderate ERS restores

intracellular homeostasis, while sustained ERS drives renal damage

in DKD, meaning that human-targeted ERS research is warranted

(252–254). A deeper understanding of the

mechanisms underlying this process will help improve the treatment

of DKD.

As a major microvascular complication of diabetes

mellitus, DKD is closely associated with aberrant activation of

ERS. Factors such as hyperglycemia and oxidative stress trigger an

imbalance of protein folding in renal podocytes, tubular epithelial

and renal capsule cells, which activates the three core pathways of

the UPR, namely the IRE1α/XBP1, PERK/eIF2α/ATF4 and ATF6 pathways

(50,255). Short-term ERS maintains cellular

homeostasis by promoting protein folding and degradation, whereas

sustained overactivation induces pro-apoptotic factor expression,

such as CHOP expression, exacerbating inflammatory responses

through NF-κB pathway activation and mesangial fibrosis via

TGF-β1/Smad3 pathway dysregulation, which ultimately leads to

glomerulosclerosis and renal failure. Several stimuli disrupting

cellular homeostatic function induce ERS (58,256) (Fig.

1). The present review discusses ERS-related experimental

agents, preclinical models and clinical data, alongside an analysis

of the three UPR pathways in DKD renal histopathology.

Phase I and II clinical trials are underway for

ERS-modulating compounds such as alginate and TUDCA (257). Pharmacological interventions

against ERS have focused on blocking the excessive stress response.

However, although the aforementioned RAS inhibitors, SGLT2

inhibitors, 4-PBA and CB1R antagonists may regulate ERS through

indirect pathways, existing guidelines do not provide specific

recommendations based on this mechanism (258–260). Clinical trials lack ERS-related

endpoint data, and the causal relationship between medications for

the treatment of DKD, ERS) requires further validation through

targeted research. Western drugs, such as PERK inhibitors, IRE1α

endonuclease inhibitors and CHOP antagonists, have demonstrated

potential in attenuating apoptosis and fibrosis in animal models

(203,261–263); however, challenges associated

with target specificity and long-term safety remain.

ERS inhibitors commonly used in laboratory studies,

such as the chemical chaperone 4-PBA or the pathway-specific PERK

inhibitor GSK2606414, generally exhibit good tolerability in rodent

DKD models (264,265), but their clinical safety

assessments present significant challenges. Primarily, ERS is a

fundamental physiological mechanism enabling cellular responses to

abnormal protein folding, which is important in metabolically

active tissues such as pancreatic β-cells and hepatocytes. While

4-PBA alleviates ERS in renal tissues of rat models (266–268), its prolonged clinical application

may cause hyperammonemia and gastrointestinal mucosal irritation.

Furthermore, suppressing ERS responses in pancreatic β-cells can

impair insulin synthesis, potentially exacerbating glycemic

dysregulation (225). Secondly,

the risk of kidney-specific toxicity may be underestimated. Animal

models commonly involve young, healthy rats, whereas clinical

patients with DKD typically present with comorbidities such as

hypertension, cardiovascular disease and renal insufficiency,

markedly reducing drug metabolism capacity. In addition, drug

interactions remain unclear: Patients with DKD frequently require

concomitant hypoglycemic, antihypertensive and lipid-lowering

medications (269,270). Furthermore, ERS inhibitors may

compete with SGLT2 inhibitors for renal tubular excretion pathways

or affect the renal metabolism of ACEIs, increasing the risk of

adverse reactions such as hyperkalemia (271). Such interactions are challenging

to detect in controlled, single-factor laboratory settings.

Additionally, the complex multi-pathway regulatory nature of ERS,

coordinated by PERK, IRE1α and ATF6, combined with individual

heterogeneity among patients with DKD makes ‘precision targeting’ a

translational challenge. Laboratory studies often target single

pathways, whereas clinical ERS activation patterns vary notably

among patients with DKD: Some cases of DKD primarily involve

activation of the PERK/eIF2α pathway, accompanied by extensive

tubular epithelial apoptosis, while others predominantly involve

activation of the ATF6 pathway, accompanied by inflammatory

mediator release (for example, elevated IL-6 and TNF-α levels)

(71). Furthermore, ERS in DKD

involves glomerular mesangial cells, podocytes and tubular

epithelial cells; however, existing drugs exhibit systemic

distribution, complicating precise delivery to specific renal cell

subpopulations (18,19).

Addressing these bottlenecks requires further

research. Safety evaluations should incorporate multiple animal

models with renal insufficiency to more accurately replicate drug

metabolism characteristics observed in clinical populations. For

target optimization, kidney-specific drug formulations could be

developed to enhance renal tissue accumulation. Only through these

approaches can ERS inhibition strategies transition from being

mechanistically effective in laboratory settings to being safe and

beneficial in clinical practice.

The active constituents of TCM, such as AS and

Huangkui total flavonoids, exert multi-target modulatory effects on

ERS, including the downregulation of CHOP and inhibition of IRE1α

phosphorylation (47,166). These compounds also exert

antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and podocyte-protective effects,

supporting clinical evidence of reduced proteinuria and delayed

renal function decline in DKD. Such findings underscore the

potential of TCM-Western medicine integration as a promising

research avenue for DKD management. The development and translation

of ER-specific reagents targeting protein folding, UPR signaling

and ER calcium homeostasis hold promise for novel therapeutic

strategies (7).

In future research, it is important to investigate

ERS biomarkers for early DKD diagnosis by elucidating the

underlying ERS mechanisms. BiP/GRP78, as a sentinel protein for ERS

activation, exhibits increased expression levels that signal early

ERS and are directly associated with the severity of renal

pathological damage in DKD, thereby providing a foundational

reference for assessing disease progression (112). Concurrently, p-PERK, p-eIF2α and

ATF4 from the PERK pathway, p-IRE1α and XBP1s from the IRE1α

pathway and ATF6f (a type II transmembrane protein that under ER

stress is translocated to the Golgi apparatus where it is

proteolytically processed, releasing the cytoplasmic fragment of

ATF6) (77). from the ATF6 pathway

indicate the activation status of the three principal UPR branches,

accurately reflecting the ERS-mediated pathological transition from

adaptive protection to apoptosis initiation. The comprehensive

assessment of these markers not only clarifies the molecular

mechanisms of ERS in DKD but also provides molecular evidence for

staging disease progression (16).

These biomarkers thus hold potential for translation into early

diagnostic tools and therapeutic efficacy-monitoring indicators for

DKD, enabling precise clinical interventions. Simultaneously, the

development of inhibitors targeting specific pathways, such as

IRE1α-specific inhibitors, is important, offering novel therapeutic

strategies for DKD management. Given the growing potential of

ERS-targeted therapies, focused clinical studies are required to

deepen the current understanding of DKD pathogenesis and refine

targeted interventions. Collectively, these efforts will advance

DKD treatment and provide insights that are relevant to broader

ERS-associated disorders.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the Jilin Province Science

and Technology Development Program (grant no. 20210101201JC).

Not applicable.

PZ contributed to writing the manuscript and

prepared the figures. YZ made substantial contributions to the

conception and design of the study, conducting a comprehensive and

systematic literature review to identify key studies and ensuring

the research was grounded in relevant and current findings in the

field of DKD. YZ also played a crucial role in the analysis and

interpretation of data, particularly in understanding the

mechanisms of ERS in DKD. Additionally, YZ contributed to drafting

significant portions of the manuscript and critically revised it

for important intellectual content. YZ approved the final version

of the manuscript and takes full responsibility for the integrity

and accuracy of the work, ensuring all aspects of the research were

thoroughly addressed. CC, YC, FL, SZ and CL revised the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Zhang L, Long J, Jiang W, Shi Y, He X,

Zhou Z, Li Y, Yeung RO, Wang J, Matsushita K, et al: Trends in

chronic kidney disease in China. N Engl J Med. 375:905–906. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Cybulsky AV: Endoplasmic reticulum stress,

the unfolded protein response and autophagy in kidney diseases. Nat

Rev Nephrol. 13:681–696. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

American Diabetes Association: 11

Microvascular complications and foot care: Standards of medical

care in diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care. 43 (Suppl 1):S135–S151. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Pena MJ, Mischak H and Heerspink HJ:

Proteomics for prediction of disease progression and response to

therapy in diabetic kidney disease. Diabetologia. 59:1819–1831.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bustamante P, Tsering T, Coblentz J,

Mastromonaco C, Abdouh M, Fonseca C, Proença RP, Blanchard N, Dugé

CL, Andujar RAS, et al: Circulating tumor DNA tracking through

driver mutations as a liquid biopsy-based biomarker for uveal

melanoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 40:1962021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Tang M, Sun J and Cai Z: PCK2 inhibits

lung adenocarcinoma tumor cell immune escape through oxidative

stress-induced senescence as a potential therapeutic target. J

Thorac Dis. 15:2601–2615. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Almanza A, Carlesso A, Chintha C,

Creedican S, Doultsinos D, Leuzzi B, Luís A, McCarthy N,

Montibeller L, More S, et al: Endoplasmic reticulum stress

signalling - from basic mechanisms to clinical applications. FEBS

J. 286:241–278. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Tilija Pun N, Lee N, Song SH and Jeong CH:

pitavastatin induces cancer cell apoptosis by blocking autophagy

flux. Front Pharmacol. 13:8545062022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Çiftçi YC, Yurtsever Y and Akgül B: Long

non-coding RNA-mediated modulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress

under pathological conditions. J Cell Mol Med. 28:e185612024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kober L, Zehe C and Bode J: Development of

a novel ER stress based selection system for the isolation of

highly productive clones. Biotechnol Bioeng. 109:2599–2611. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Hotamisligil GS: Endoplasmic reticulum

stress and the inflammatory basis of metabolic disease. Cell.

140:900–917. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Shahzad K, Ghosh S, Mathew A and Isermann

B: Methods to detect endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis in

diabetic nephropathy. Methods Mol Biol. 2067:153–173. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hetz C and Papa FR: The unfolded protein

response and cell fate control. Mol Cell. 69:169–181. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Guzmán Mendoza NA, Homma K, Osada H, Toda

E, Ban N, Nagai N, Negishi K, Tsubota K and Ozawa Y:

Neuroprotective effect of 4-phenylbutyric acid against photo-stress

in the Retina. Antioxidants (Basel). 10:11472021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Chen YY, Peng XF, Liu GY, Liu JS, Sun L,

Liu H, Xiao L and He LY: Protein arginine methyltranferase-1

induces ER stress and epithe-lial-mesenchymal transition in renal

tubular epithelial cells and contributes to diabetic nephropathy.

Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 1865:2563–2575. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Liu H and Sun HL: LncRNA TCF7 triggered

endoplasmic reticulum stress through a sponge action with miR-200c

in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci.

23:5912–5922. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Chen N, Song S, Yang Z, Wu M, Mu L, Zhou T

and Shi Y: ChREBP deficiency alleviates apoptosis by inhibiting

TXNIP/oxidative stress in diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes

Complications. 35:1080502021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Tervaert TW, Mooyaart AL, Amann K, Cohen

AH, Cook HT, Drachenberg CB, Ferrario F, Fogo AB, Haas M, de Heer

E, et al: Pathologic classification of diabetic nephropathy. J Am

Soc Nephrol. 21:556–563. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Oshima M, Shimizu M, Yamanouchi M, Toyama

T, Hara A, Furuichi K and Wada T: Trajectories of kidney function

in diabetes: A clinicopathological update. Nat Rev Nephrol.

17:740–750. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Garg P: A review of podocyte biology. Am J

Nephrol. 47 (Suppl 1):S3–S13. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

O'Toole JF: Renal manifestations of

genetic mitochondrial disease. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 7:57–67.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Nath KA: Tubulointerstitial changes as a

major determinant in the progression of renal damage. Am J Kidney

Dis. 20:1–17. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Tang J, Yao D, Yan H, Chen X, Wang L and

Zhan H: The role of MicroRNAs in the pathogenesis of diabetic

nephropathy. Int J Endocrinol. 2019:87190602019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Bazzi C, Bakoush O and Gesualdo L:

Proteinuria: From molecular to clinical applications in

glomerulonephritis. Int J Nephrol. 2012:4249682012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Edirs S, Jiang L, Xin X and Aisa HA: Kursi

Wufarikun Ziyabit improves the physiological changes by regulating

endoplasmic reticulum stress in the type 2 diabetes db/db mice.

Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021:21001282021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Guo H, Cao A, Chu S, Wang Y, Zang Y, Mao

X, Wang H, Wang Y, Liu C, Zhang X and Peng W: Astragaloside IV

attenuates podocyte apoptosis mediated by endoplasmic reticulum

stress through upregulating sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase

2 expression in diabetic nephropathy. Front Pharmacol. 7:5002016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Wang D, Wang YS, Zhao HM, Lu P, Li M, Li

W, Cui HT, Zhang ZY and Lv SQ: Plantamajoside improves type 2

diabetes mellitus pancreatic β-cell damage by inhibiting

endoplasmic reticulum stress through Dnajc1 up-regulation. World J

Diabetes. 16:990532025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zhang HX, Yuan J and Li RS: Thalidomide

mitigates apoptosis via endoplasmic reticulum stress in diabetic

nephropathy. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 22:787–794.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Van Krieken R, Mehta N, Wang T, Zheng M,

Li R, Gao B, Ayaub E, Ask K, Paton JC, Paton AW, et al: Cell

surface expression of 78-kDa glucose-regulated protein (GRP78)

mediates diabetic nephropathy. J Biol Chem. 294:7755–7768. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zhang MZ, Wang Y, Paueksakon P and Harris

RC: Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition slows progression

of diabetic nephropathy in association with a decrease in

endoplasmic reticulum stress and an increase in autophagy.

Diabetes. 63:2063–2072. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Chen J, Hou XF, Wang G, Zhong QX, Liu Y,

Qiu HH, Yang N, Gu JF, Wang CF, Zhang L, et al: Terpene glycoside

component from Moutan Cortex ameliorates diabetic nephropathy by

regulating endoplasmic reticulum stress related inflammatory

responses. J Ethnopharmacol. 193:433–444. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Yao F, Li Z, Ehara T, Yang L, Wang D, Feng

L, Zhang Y, Wang K, Shi Y, Duan H and Zhang L: Fatty acid-binding

protein 4 mediates apoptosis via endoplasmic reticulum stress in

mesangial cells of diabetic nephropathy. Mol Cell Endocrinol.

411:232–242. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ge J, Miao JJ, Sun XY and Yu JY: Huangkui

capsule, an extract from Abelmoschus manihot (L.) medic, improves

diabetic nephropathy via activating peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-α/γ and attenuating

endoplasmic reticulum stress in rats. J Ethnopharmacol.

189:238–249. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Park MJ, Han HJ and Kim DI:

Lipotoxicity-Induced PRMT1 exacerbates mesangial cell apoptosis via

endoplasmic reticulum stress. Int J Mol Sci. 18:14212017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Khoi CS, Xiao CQ, Hung KY, Lin TY and

Chiang CK: Oxidative stress-induced growth inhibitor (OSGIN1), a

Target of X-Box-Binding Protein 1, protects palmitic acid-induced

vascular lipotoxicity through maintaining autophagy. Biomedicines.

10:9922022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Jeon HY, Moon CH, Kim EB, Sayyed ND, Lee

AJ and Ha KS: Simultaneous attenuation of hyperglycemic

memory-induced retinal, pulmonary, and glomerular dysfunctions by

proinsulin C-peptide in diabetes. BMC Med. 21:492023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Jiao Y, Liu X, Shi J, An J, Yu T, Zou G,

Li W and Zhuo L: Unraveling the interplay of ferroptosis and immune

dysregulation in diabetic kidney disease: A comprehensive molecular

analysis. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 16:862024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Liu F, Yang Z, Li J, Wu T, Li X, Zhao L,

Wang W, Yu W, Zhang G and Xu Y: Targeting programmed cell death in

diabetic kidney disease: from molecular mechanisms to

pharmacotherapy. Mol Med. 30:2652024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Cao Y, Hao Y, Li H, Liu Q, Gao F, Liu W

and Duan H: Role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in apoptosis of

differentiated mouse podocytes induced by high glucose. Int J Mol

Med. 33:809–816. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Tian N, Gao Y, Wang X, Wu X, Zou D, Zhu Z,

Han Z, Wang T and Shi Y: Emodin mitigates podocytes apoptosis

induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress through the inhibition of

the PERK pathway in diabetic nephropathy. Drug Des Devel Ther.

12:2195–2211. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Garner KL, Betin VMS, Pinto V, Graham M,

Abgueguen E, Barnes M, Bedford DC, McArdle CA and Coward RJM:

Enhanced insulin receptor, but not PI3K,signalling protects

podocytes from ER stress. Sci Rep. 8:39022018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhang Y, Gao X, Chen S, Zhao M, Chen J,

Liu R, Cheng S, Qi M, Wang S and Liu W: Cyclin-dependent kinase 5

contributes to endoplasmic reticulum stress induced podocyte

apoptosis via promoting MEKK1 phosphorylation at Ser280 in diabetic

nephropathy. Cell Signal. 31:31–40. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Cybulsky AV: The intersecting roles of

endoplasmic reticulum stress, ubiquitin-proteasome system, and

autophagy in the pathogenesis of proteinuric kidney disease. Kidney

Int. 84:25–33. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Dong Z, Liu N and Sun M: The distinct

biological role of JAML positions it as a promising target for

treating human cancers and a range of other diseases. Front

Immunol. 16:15584882025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Feng Z, Tang L, Wu L, Cui S, Hong Q, Cai

G, Wu D, Fu B, Wei R and Chen X: Na+/H+ exchanger-1 reduces

podocyte injury caused by endoplasmic reticulum stress via

autophagy activation. Lab Invest. 94:439–454. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Fang L, Li X, Luo Y, He W, Dai C and Yang

J: Autophagy inhibition induces podocyte apoptosis by activating

the proapoptotic pathway of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Exp Cell

Res. 322:290–301. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Guo H, Wang Y, Zhang X, Zang Y, Zhang Y,

Wang L, Wang H, Wang Y, Cao A and Peng W: Astragaloside IV protects

against podocyte injury via SERCA2-dependent ER stress reduction

and AMPKα-regulated autophagy induction in streptozotocin-induced

diabetic nephropathy. Sci Rep. 7:68522017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Kato M: Intercellular transmission of

endoplasmic reticulum stress through gap junction targeted by

microRNAs as a keystep of diabetic kidney diseases? Ann Transl Med.

9:8272021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Liang X, Duan N, Wang Y, Shu S, Xiang X,

Guo T, Yang L, Zhang S, Tang X and Zhang J: Advanced oxidation

protein products induce endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in

human renal glomerular endothelial cellsthrough induction of

endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Diabetes Complications. 30:573–579.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Ma X, Ma J, Leng T, Yuan Z, Hu T, Liu Q

and Shen T: Advances in oxidative stress in pathogenesis of

diabetic kidney disease and efficacy of TCM intervention. Ren Fail.

45:21465122023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Cao Y, Chen Z, Hu J, Feng J, Zhu Z, Fan Y,

Lin Q and Ding G: Mfn2 regulates high glucose-induced MAMs

dysfunction and apoptosis in podocytes via PERK pathway. Front Cell

Dev Biol. 9:7692132021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Mega C, Teixeira-de-Lemos E, Fernandes R

and Reis F: Renoprotective effects of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4

inhibitor sitagliptin: A review in type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Res.

2017:51642922017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Feng A, Yin R, Xu R, Zhang B and Yang L:

An update on renal tubular injury as related to glycolipid

metabolism in diabetic kidney disease. Front Pharmacol.

16:15590262025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Bondue T, van den Heuvel L, Levtchenko E

and Brock R: The potential of RNA-based therapy for kidney

diseases. Pediatr Nephrol. 38:327–344. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Zhang J, Dong XJ, Ding MR, You CY, Lin X,

Wang Y, Wu MJ, Xu GF and Wang GD: Resveratrol decreases high

glucose-induced apoptosis in renal tubular cells via suppressing

endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Med Rep. 22:4367–4375.

2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Zhang J, Cao P, Gui J, Wang X, Han J, Wang

Y and Wang G: Arc-tigenin ameliorates renal impairment and inhibits

endoplasmic reticulum stress in diabetic db/db mice. Life Sci.

223:194–201. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Han J, Pang X, Shi X, Zhang Y, Peng Z and

Xing Y: Ginkgo biloba extract EGB761 ameliorates the extracellular

matrix accumulation and mesenchymal transformation of renal tubules

in diabetic kidney disease by inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum

stress. Biomed Res Int. 2021:66572062021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Huang KH, Guan SS, Lin WH, Wu CT, Sheu ML,

Chiang CK and Liu SH: Role of calbindin-D28k in diabetes-associated

advanced glycation end-products-induced renal proximal tubule cell

injury. Cells. 8:6602019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Sun X, Sun Y, Lin S, Xu Y and Zhao D:

Histone deacetylase inhibitor valproic acid attenuates high

glucoseinduced endoplas-mic reticulum stress and apoptosis in

NRK52E cells. Mol Med Rep. 22:4041–4047. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Shibusawa R, Yamada E, Okada S, Nakajima

Y, Bastie CC, Maeshima A. Kaira K and Yamada M: Dapagliflozin

rescues endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated cell death. Sci Rep.

9:98872019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Wu L, Wang Q, Guo F, Ma X, Wang J, Zhao Y,

Yan Y and Qin G: Involvement of miR-27a-3p in diabetic nephropathy

via affecting renal fibrosis, mitochondrial dysfunction, and

endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Cell Physiol. 236:1454–1468. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Fang L, Xie D, Wu X, Cao H, Su W and Yang

J: Involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress in albuminuria

induced inflam-masome activation in renal proximal tubular cells.

PLoS One. 8:e723442013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Kang JM, Lee HS, Kim J, Yang DH, Jeong HY,

Lee YH, Kim DJ, Park SH, Sung M, Kim J, et al: Beneficial effect of

Chloroquine and Amodiaquine on type 1 Diabetic Tubulopathy by

attenuating mitochondrial Nox4 and endoplasmic reticulum stress. J

Korean Med Sci. 35:e3052020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Sun H, Yuan Y and Sun Z: Update on

mechanisms of renal tubule injury caused by advanced glycation end

products. Biomed Res Int. 2016:54751202019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Iwai T, Kume S, Chin-Kanasaki M, Kuwagata

S, Araki H, Takeda N, Sugaya T, Uzu T, Maegawa H and Araki SI:

Stearoyl-CoA Desaturase-1 protects cells against

lipotoxicity-mediated apoptosis in proximal tubular cells. Int J

Mol Sci. 17:18682016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Liu J, Yang JR, Chen XM, Cai GY, Lin LR

and He YN: Impact of ER stress-regulated ATF4/p16 signaling on the

premature senescence of renal tubular epithelial cells in diabetic

nephropathy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 308:C621–C630. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Barati MT, Powell DW, Kechavarzi BD,

Isaacs SM, Zheng S, Epstein PN, Cai L, Coventry S, Rane MJ and

Klein JB: Differential expression of endoplasmic reticulum

stress-response proteins in different renal tubule subtypes of

OVE26 diabetic mice. Cell Stress Chaperones. 21:155–166. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Liu Y, Chen DQ, Han JX, Zhao TT and Li SJ:

A review of traditional Chinese medicine in treating renal

interstitial fibrosis via endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated

apoptosis. Biomed Res Int. 2021:66677912021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Wang J, Lu L, Chen S, Xie J, Lu S, Zhou Y

and Jiang H: PERK overexpression-mediated Nrf2/HO-1 pathway

alleviates hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced injury in neonatal murine

cardiomyocytes via improving endoplasmic reticulum stress. Biomed

Res Int. 2020:64580602020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Chen Z, Feng H, Peng C, Zhang Z, Yuan Q,

Gao H, Tang S and Xie C: Renoprotective effects of tanshinone IIA:

A literature review. Molecules. 28:19902023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Nakka VP, Prakash-Babu P and Vemuganti R:

Crosstalk between endoplasmic reticulum stress, oxidative stress,

and autophagy: Potential therapeutic targets for acute CNS

injuries. Mol Neurobiol. 53:532–544. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Qiu M, Li S, Jin L, Feng P, Kong Y, Zhao

X, Lin Y, Xu Y, Li C and Wang W: Combination of chymostatin and

aliskiren attenuates ER stress induced by lipid overload in kidney

tubular cells. Lipids Health Dis. 17:1832018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Chai H, Yao S, Gao Y, Hu Q and Su W:

Developments in the connection between epithelial-mesenchymal

transition and endoplasmic reticulum stress (Review). Int J Mol

Med. 56:1022025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Wang WW, Liu YL, Wang MZ, Li H, Liu BH, Tu

Y, Yuan CC, Fang QJ, Chen JX, Wang J, et al: Inhibition of renal

tubular epithelial mesenchymal transition and endoplasmic reticulum

stress-induced apoptosis with shenkang injection attenuates

diabetic tubulopathy. Front Pharmacol. 12:6627062021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Wang W, Ke B, Wang C, Xiong X, Feng X and

Yan H: Targeting ion channel networks in diabetic kidney disease:

from molecular crosstalk to precision therapeutics and clinical

innovation. Front Med (Lausanne). 12:16077012025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Jo HJ, Yang JW, Park JH, Choi ES, Lim CS,

Lee S and Han CY: Endoplasmic reticulum stress increases DUSP5

expression via PERK-CHOP pathway, leading to hepatocyte death. Int

J Mol Sci. 20:43692019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Hu H, Tian M, Ding C and Yu S: The C/EBP