Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI), a critical condition

among cardiovascular diseases, is primarily caused by inadequate

blood supply to the myocardium, resulting in ischemia and

subsequent necrosis (1). This

pathology is markedly influenced by numerous risk factors,

including obesity, smoking, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and

poor dietary habits (2).

Clinically, MI is typically manifested through chest pain, along

with symptoms such as chest tightness, dyspnoea, nausea and

vomiting (3). The incidence of MI

varies regionally and by population, typically ranging from a few

hundred to several thousand cases per 100,000 individuals per year

(4,5). The mortality associated with MI is

influenced by several factors, including age, sex, preexisting

cardiac health and the quality of care received (6). Timely and effective interventions,

including emergency resuscitation, anticoagulant and antiplatelet

therapies, vasodilators or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG),

are key and have been revealed to reduce notably mortality

(7). In addition, a previous study

suggested that the use of volatile anaesthetics during CABG may

reduce postoperative MI rates and long-term cardiac mortality

(8).

Mepivacaine, a local anesthetic, is commonly used to

reduce pain during various medical procedures through the

inhibition of sodium channels in nerve cells (9). This function hinders the transmission

of nerve impulses, thereby facilitating local anaesthesia. Although

considered relatively safe, mepivacaine can cause side effects such

as overdose, allergic reactions and nerve damage (10). A protocol study by Dell'Olio et

al (11) suggested that

light-conscious sedation with mepivacaine may effectively manage

postoperative pain in patients with acute MI (AMI). Further

experimental evidence revealed that mepivacaine markedly reduces

calcium transients in adult mouse cardiomyocytes (12). This is achieved through sodium

channel blockade and enhancement of the reverse mode activity of

the sodium-calcium exchanger, suggesting a novel mechanism by which

mepivacaine may reduce myocardial contractility. In addition, a

clinical case report by de Groot-van der Mooren et al

(13) described an infant with

unexplained cardiorespiratory distress and neurological symptoms

shortly after birth, possibly related to maternal exposure to

mepivacaine. This case study raised concerns regarding the possible

function of mepivacaine in the emergence of cardiovascular and

neurological adverse effects.

The calcium voltage-gated channel auxiliary subunit

β1 (CACNB1) gene, located on chromosome 12 of the human

genome, encodes the β1 subunit of the voltage-gated calcium channel

(14). In cardiomyocytes,

voltage-gated calcium channels are essential for controlling

cardiac muscle contraction (15).

The β subunit encoded by the CACNB1 gene forms a complex

with the α1 subunit in cardiomyocytes, contributing to the

functionality of the calcium channel complex (16). Abnormalities in this function of

the complex may affect calcium channel activity, thereby

influencing cardiomyocyte excitability and contractility. Previous

studies have reported that abnormal expression of CACNB1 in

cardiac muscle cells is associated with such as arrhythmias,

myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure (17,18).

A study revealed that the CACNB1 gene encodes the CaVβ1

protein, which regulates T-cell function (17). After infection with the lymphocytic

choriomeningitis virus, deletion of CACNB1 increased T-cell

death and inhibited clonal proliferation. However, CACNB1 is

not necessary for T-cell proliferation, cytokine production or

Ca2+ signal transduction. Xuan et al (18) demonstrated that the levels of

potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily D member 3 (KCND3),

CACNB1 and potassium inwardly rectifying channel subfamily J member

2 (KCNJ2) proteins can be regulated by microRNA 195 through

direct interactions with KCND3, CACNB1 and KCNJ2

genes. Therefore, further exploration of the potential role of

CACNB1 in MI is warranted.

In the context of MI, understanding the molecular

mechanisms of cardiomyocyte injury is key for developing effective

treatment plans. The present study aimed to elucidate the impacts

of mepivacaine on apoptosis, cell viability, cell cycle regulation,

inflammatory responses and oxidative stress in H9c2 cells.

Furthermore, through CACNB1 knockdown experiments, the

protective effect of CACNB1 against mepivacaine- and

hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R)-induced injury was investigated,

highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target to attenuate

myocardial injury. The present study reveals an innovative view

into the pathogenic processes and therapeutic interventions of

mepivacaine in the context of MI.

Materials and methods

Differential expression analysis of

the GSE19339 dataset

The GSE19339 dataset, available in the Gene

Expression Omnibus database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/), was used to

identify genes associated with MI. This data set comprises

transcriptomic data from four patients with MI and four normal

individuals. The ‘limma’ package in the R programming language

(version 3.5.3; http://www.r-project.org/) was used to carry out the

differential expression analysis. The fold change (FC) criterion

was employed to assess differentially expressed genes (DEGs), with

FC ≤0.77 designating downregulated DEGs and FC ≥1.3 designating

upregulated DEGs. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Functional enrichment analysis of DEGs

and expression analysis of CACNB1 in MI

The Database for Annotation, Visualization, and

Integrated Discovery (DAVID) (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/tools.jsp) was employed to

elucidate the functional characteristics of MI-related DEGs.

Analysis also included the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

(KEGG; http://www.kegg.jp/) pathway and Gene

Ontology (GO; http://geneontology.org/) term. GO classification

facilitates the categorization of gene and protein functions into

three hierarchical classifications: Biological Process (BP),

Molecular Function (MF) and Cell Component (CC). Finally, the

CACNB1 gene expression in the MI and normal groups was

assessed using the GSE19339 dataset, which was analyzed using the R

software (version 3.5.3).

Culturing and maintenance of H9c2

cells

H9c2 cells (cat. no. GNR 5, National Collection of

Authenticated Cell Cultures), a rat ventricular cardiomyocyte cell

line, were purchased from the Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry

and Cell Biology. H9c2 cells were cultured under conventional cell

culture conditions, which include a humidified environment at 37°C

with 5% CO2, using DMEM (cat. no. 10566016; Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine

serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The cell culture

solution was refreshed regularly to maintain cell viability and

growth. All experiments were carried out using cells within

passages 3–5 after cell recovery. The H9c2 cell line was

authenticated through short tandem repeat analysis and evaluated

for mycoplasma contamination, with negative results.

Cell transfection and treatment

Transfection was carried out on H9c2 cells utilizing

the following specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting

CACNB1: si-CACNB1-1, sense 5′-CAAGACCAAGCCAGUGGCAUUUGCU-3′ and

antisense, 5′-AGCAAAUGCCACUGGCUUGGUCUUG-3′; si-CACNB1-2 sense,

5′-CAAUGUCCAAAUAGCGGCCUCGGAA-3′ and antisense,

5′-UUCCGAGGCCGCUAUUUGGACAUUG-3′; and negative control siRNA

(si-NC), sense 5′-CAAACCUAUAAGGCGCUCCGGUGAA-3′ and antisense,

5′-UUCACCGGAGCGCCUUAUAGGUUUG-3′. All siRNAs, including CACNB1-siRNA

and negative control siRNA, were purchased from Shanghai GenePharma

Co., Ltd. H9c2 cells were transfected with siRNAs (at a final

concentration of 50 nM) using Lipofectamine® 2000

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) after being cultured

in 24-well plates. Cells were incubated with the transfection

mixture at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2

for 6 h, after which the medium was replaced with fresh DMEM

supplemented with 10% FBS. All transfections were carried out using

the same procedure. At 48 h post-transfection, to explore the

impact of mepivacaine on H9c2 cells, the cells were subjected to

different mepivacaine concentrations (0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 5.0, 7.0 and

10.0 mM; cat. no. HY-B0517; MedChemExpress; CAS No. 96-88-8) at

37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 for 24 h.

After mepivacaine treatment, cells were harvested for subsequent

analyses.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

A CCK-8 assay (cat. no. CK04; Dojindo Laboratories,

Inc.) was employed to measure cell viability. H9c2 cells were

seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 5×103

cells/well. Subsequently, each well was treated with 10 µl CCK-8

reagent and the wells were then incubated at 37°C with 5%

CO2 for 4 h. Subsequently, the absorbance at 450 nm was

measured utilizing a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

H9c2 cells were treated with the TRIzol®

Reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) to extract

total RNA. The purity and concentration of the RNA were evaluated

through spectrophotometric analysis. The SuperScript III

First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) was used for the synthesis of complementary DNA,

with 1 µg of the extracted RNA being reverse-transcribed.

Subsequently, the Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System

(Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was employed

to carry out qPCR analysis using the following primer pairs:

CACNB1, forward, 5′-AGGGCTATGAGGTAACTGAC-3′ and reverse,

5′-GGAAATCCTGCCATCAAACC-3′); Bax forward,

5′-TGAAGACAGGGGCCTTTTTG-3′ and reverse, 5′-AATTCGCCTGAGACACTCG-3′);

Bcl-2 forward, 5′-ATGCCTTTGTGGAACTATATGGC-3′ and reverse,

5′-GGTATGCACCCAGAGTGATGC-3′; Caspase-3 forward,

5′-AGCATTTCCCATAAGCCTCCT-3′ and reverse,

5′-AGCACCAAAAGTATCATTGGC-3′; P21 forward,

5′-ACCCCAGATAACCAAGGATGC-3′ and reverse,

5′-AGAACACCATCTTGCCCTTGT-3′; Cyclin E1 forward,

5′-GACACAGCTTCGGGTACGG-3′ and reverse, 5′-TTGCTGTGGTCCTTCGAGTC-3′;

CDK4 forward, 5′-CTTCCCGTCAGCACAGTTC-3′ and reverse,

5′-GGTCAGCATTTCCAGCAGC-3′; and GAPDH forward,

5′-ACGGGAAACCCATCACCATC-3′ and reverse, 5′-CTCGTGGTTCACACCCATCA-3′.

GAPDH was used as an internal reference. The thermocycling

conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 10

min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec and

annealing/extension at 60°C for 1 min. A melt curve analysis

(60–95°C) was performed to verify amplification specificity. The

expression was examined utilizing the 2−ΔΔCq method

(19).

Western blotting (WB)

Total protein lysates from H9c2 cells were prepared

utilizing RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The BCA Protein Assay Kit (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) was used to measure the protein content. Equal

amounts of protein (30 µg per lane) were separated on 10% gels

using SDS-PAGE and then transferred onto PVDF membranes

(MilliporeSigma). The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk

in TBS-Tween (TBST; 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20) at room temperature for 1

h and then incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary

antibodies: CACNB1 (1:1,000; cat. no. 13039-1-AP; Proteintech

Group, Inc.), Bax (1:20,000; cat. no. 50599-2-Ig; Proteintech

Group, Inc.), Caspase-3 (1:1,000; cat. no. 19677-1-AP; Proteintech

Group, Inc.), Bcl-2 (1:2,000; cat no. 26593-1-AP; Proteintech

Group, Inc.), P21 (1:1,000; cat no. 28248-1-AP; Proteintech Group,

Inc.), CDK4 (1:1,000; cat no. 11026-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.),

Cyclin E1 (1:1,000; cat no. AF0144; Affinity Biosciences), NOD-like

receptor protein 3 (NLRP3; 1:2,000; cat no. 30109-1-AP; Proteintech

Group, Inc.), Caspase-1 (1:2,000; cat no. 31020-1-AP; Proteintech

Group, Inc.), C-Caspase-1 (1:1,000; cat no. AF4005; Affinity

Biosciences), GSDMD (1:2,000; cat no. 20770-1-AP; Proteintech

Group, Inc.), IL-18 (1:2,000; cat no. DF6252; Affinity

Biosciences), ASC (1:5,000; cat no. 30641-1-AP; Proteintech Group,

Inc.), IL-1β (1:2,000; cat no. AF5103; Affinity Biosciences),

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2; 1:1,000; cat no.

AF0639; Affinity Biosciences), GAPDH (1:5,000; cat no. 10494-1-AP;

Proteintech Group, Inc.) and Lamin B (1:2,000, cat no. 12987-1-AP;

Proteintech Group, Inc.). After secondary antibody incubation with

HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:5,000; cat. no. SA00001-2;

Proteintech Group, Inc.) at room temperature for 1 h, bands were

developed using an ECL kit (Cytiva) and captured on ImageJ software

(version 1.8.0; National Institutes of Health).

Flow cytometry analysis

Flow cytometry analysis was carried out to evaluate

apoptosis in H9c2 cells. After being seeded in 24-well plates at a

density of 1×104 cells/well, H9c2 cells were grown for

24 h at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Following

cell detachment with trypsin-EDTA (0.25% trypsin and 0.02% EDTA),

the cells were collected by centrifugation at 300 × g for 5 min at

4°C, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended. Subsequently, the

cells were cultured with 5 µl Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate

and 5 µl of PI solution at ambient temperature for 15 min for

apoptosis analysis. The staining with PI and Annexin V was then

evaluated using a flow cytometer (CyFlow® Cube 6;

Sysmex-Partec; Guangzhou Jiyuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and the

FlowJo program (version 7.4.1; BD Biosciences) was employed to

analyze the data.

Measurement of oxidative stress

biomarkers in H9c2 cells

H9c2 cells were plated in 96-well plates at a

density of 1×104 cells/well and allowed to adhere for 24

h at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. After

adhesion, the cells were rinsed twice with PBS and then lysed. The

supernatants were separated from the lysates through centrifugation

at 10,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. To aid homogeneity, the

supernatants were sonicated on ice at 20 kHz for 3×10 sec bursts

with 10 sec intervals. The prepared samples were utilized to

measure the expression of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity,

reactive oxygen species (ROS), superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity

and malondialdehyde (MDA) content. The assays for SOD and MDA were

conducted utilizing commercial kits (Nanjing Jiancheng

Bioengineering Institute). The ROS assay and LDH activity were

evaluated utilizing a kit from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology.

All measurements were carried out in triplicate and the data were

standardized to protein content in the samples to account for

variations in cell density across wells.

ELISA

In the present study, the secretion of IL-1β, TNF-α

and IL-8 in the culture supernatants of H9c2 cells, either

untreated or treated with mepivacaine (0.5, 1 and 2 mM for 24 h),

was determined using ELISA kits for IL-1β (cat. no. CSB-E08055r;

Cusabio Technology, LLC), TNF-α (cat. no. CSB-E11987r; Cusabio

Technology, LLC), and IL-8 (cat. no. SEKR-0014; Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). The absorbance at 450 nm was

measured using an ELISA reader. The obtained values were compared

with standard curves established using standard titration. The BCA

test was utilized to ascertain the protein content in each culture

bottle. All concentrations were standardized to the respective

cellular protein content and expressed as pg/ml (cellular

protein).

H/R model and treatment in H9c2

cells

After being moved to the cell culture equipment,

H9c2 cells were treated with a hypoxic buffer solution (1%

O2 + 5% CO2 + 94% N2) to exhaust

any remaining oxygen for 2 h at 37°C. Cells were then exposed to 3

h of hypoxia in a constant temperature CO2 incubator at

37°C with 95% humidity. After hypoxic exposure, the cells were

reoxygenated under normal oxygen conditions (21% O2, 74%

N2 and 5% CO2) at 37°C for 2 h following the

replacement of the buffer solution with a standard culture medium.

Cell samples were randomly divided into three groups: i) Control,

with normal incubation (37°C, 5% CO2, 95% humidity) for

6 h; ii) HR, pre-treated with 2 mM mepivacaine for 24 h before H/R

induction, followed by 2 h of reoxygenation after 3 h of hypoxia;

iii) si-CACNB1−1 + HR, pre-treated with 2 mM mepivacaine for

24 h before H/R induction and then transfected with CACNB1-1

siRNA, as described in the ‘Cell transfection and treatment’

section.

Statistical analysis

R software was employed for statistical analysis of

the current dataset. The normality of data distribution was

assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk normality test. P>0.05 indicated

that the data were normally distributed. Comparisons between two

independent groups of normally distributed data were analyzed using

an unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-test. For comparisons involving

more than two groups, a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc

test was applied to control the familywise error rate. All

quantitative data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference. To ensure equal protein loading in western blot

analyses, GAPDH was used as the loading control for cytoplasmic

proteins, while Lamin B was used for nuclear proteins. In the

RT-qPCR analyses, GAPDH was used as the internal reference. Each

experiment was independently repeated at least three times with

separate biological samples to ensure reproducibility and

reliability of statistical analysis.

Results

Functional enrichment analysis of

GSE19339-DEGs and expression verification of CACNB1

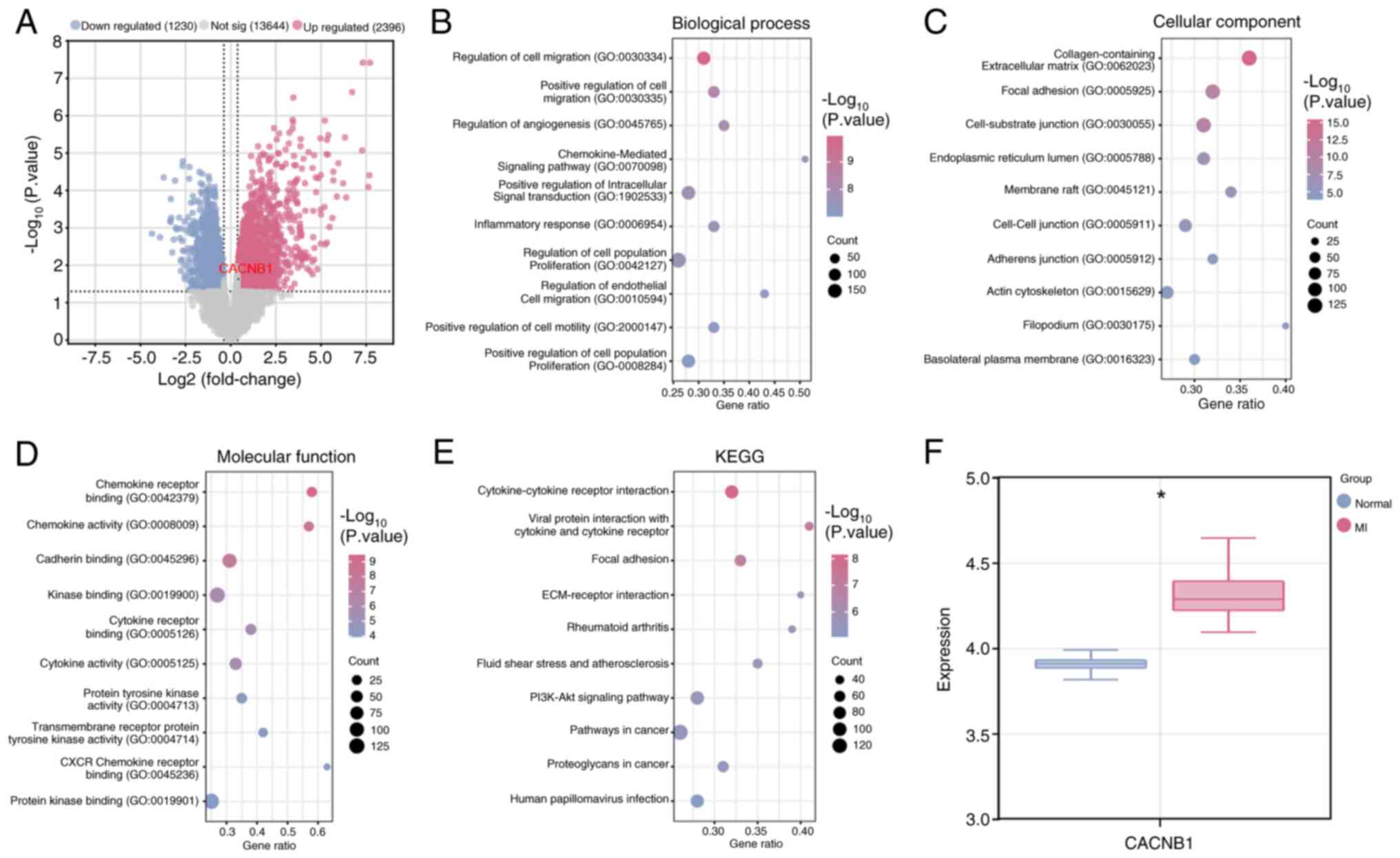

DEG analysis was carried out on samples from the

GSE19339 dataset using the ‘limma’ package, resulting in the

identification of 2,396 upregulated DEGs and 1,230 downregulated

DEGs (Fig. 1A). Subsequently,

functional enrichment analysis was conducted on the DEGs. Analysis

of GO terms revealed significant enrichment of DEGs in BP such as

‘Chemokine-Mediated Signalling Pathway’, ‘Inflammatory Response’

and ‘Regulation Of Cell Migration’ (Fig. 1B). Moreover, in CC terms, DEGs

demonstrated notable enrichment in ‘Endoplasmic Reticulum Lumen’,

‘Adherens Junction’ and ‘Actin Cytoskeleton’ (Fig. 1C). For MF terms, DEGs exhibited

significant enrichment in ‘Protein Kinase Binding’, ‘Protein

Tyrosine Kinase Activity’ and ‘Cadherin Binding’ (Fig. 1D). As depicted in Fig. 1E, in the KEGG pathways, the

majority of DEGs were enriched in pathways such as ‘PI3K-Akt

signalling pathway’, ‘Fluid shear stress and atherosclerosis’ and

‘Proteoglycans in cancer’. Given that CACNB1 has been

previously associated with cardiovascular diseases (20,21)

and encodes the β1 subunit of the voltage-gated calcium channel,

which is essential for regulating calcium influx and modulating

cardiac muscle contraction, CACNB1 was selected as the

target gene. Further investigation revealed that the expression of

CACNB1 was upregulated in MI samples of the GSE19339

dataset, suggesting a potential role of this gene in enhancing

cardiac dysfunction or exacerbating disease pathology in MI

(Fig. 1F).

Mepivacaine induces apoptosis in H9c2

cells in a dose-dependent manner

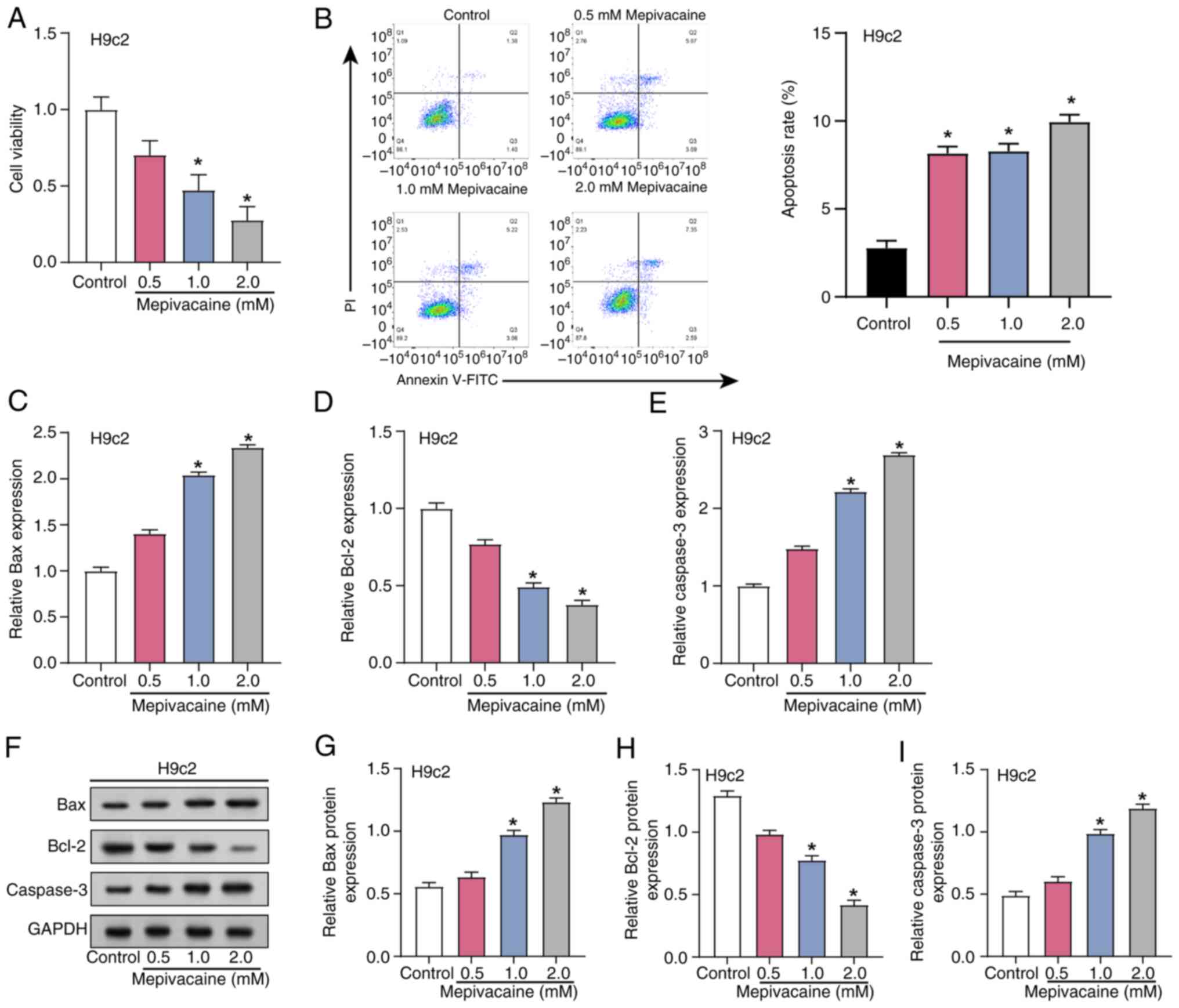

Clinically relevant plasma concentrations of

mepivacaine may vary depending on the specific application and

patient population. For example, in a study on plasma mepivacaine

concentrations in patients undergoing anesthesia, the peak plasma

concentration ranged from 0.77–8.31 µg/ml (22). Based on preliminary experiments

(Fig. S1), the concentrations of

0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 mM for mepivacaine were used (23). Cell viability and apoptosis in H9c2

cells subjected to different concentrations (0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 mM)

of mepivacaine were assessed using flow cytometry, as well as CCK-8

assays (Fig. 2A and B). The

outcomes demonstrated that there was a dose-dependent reduction in

cell viability of H9c2 cells with increasing concentrations of

mepivacaine, while the apoptosis rate increased. Subsequent

analysis using RT-qPCR examined the effects of mepivacaine

treatment on apoptotic factors (caspase-3, Bax and Bcl-2) in H9c2

cells (Fig. 2C-E). Compared with

the control group, levels of Caspase-3 and Bax increased, whereas

the expression of Bcl-2 decreased with increasing concentrations of

mepivacaine. These changes were further confirmed through

semi-quantification of protein expression (Fig. 2F-I). Collectively, these findings

suggested that mepivacaine induces apoptosis in H9c2 cells in a

concentration-dependent manner.

Mepivacaine modulates cell cycle

regulatory factors to induce G1 arrest in H9c2

cells

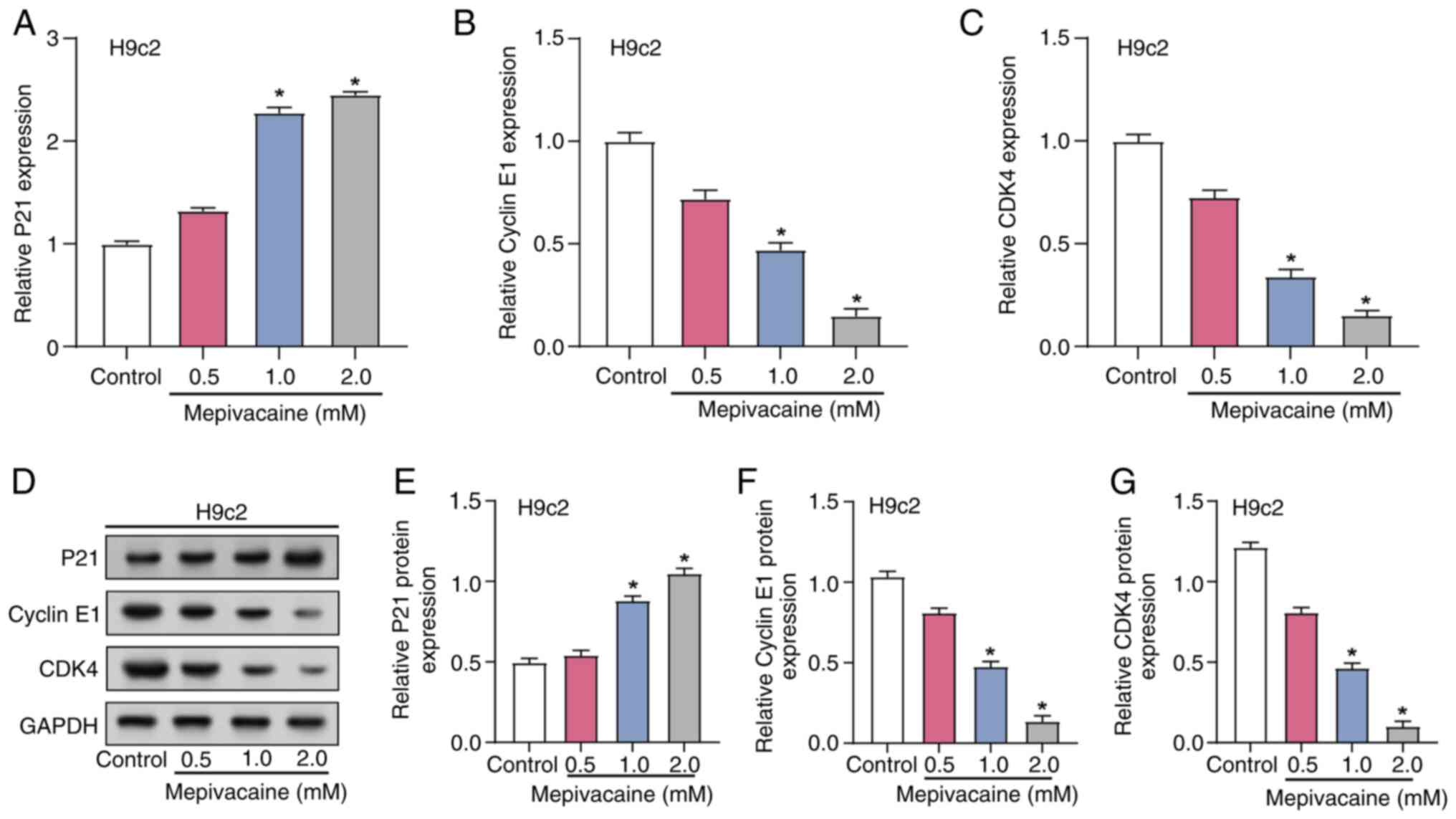

The influence of mepivacaine on cell cycle dynamics

in H9c2 cells was investigated by assessing the expression of key

cell cycle regulators, including Cyclin E1, P21 and CDK4. RT-qPCR

and WB analysis were utilized to measure changes in the levels of

cell cycle regulators after exposure to varying concentrations of

mepivacaine (0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 mM; Fig.

3A-G). The data revealed a dose-dependent increase in P21

expression, with significant elevations at 1 and 2 mM mepivacaine,

suggesting an enhanced inhibitory effect on the cell cycle

(Fig. 3A and E). Conversely, the

levels of CDK4 and Cyclin E1, key promoters of the G1 to

S phase transition, revealed a marked decrease across the same

mepivacaine concentrations (Fig. 3B,

C, F and G). This reciprocal regulation of cell cycle proteins

suggested that mepivacaine induces G1 phase arrest in

H9c2 cells by disrupting the balance of cell cycle regulators

required for progression into the S phase.

Mepivacaine induces oxidative stress

and inflammation in H9c2 cells

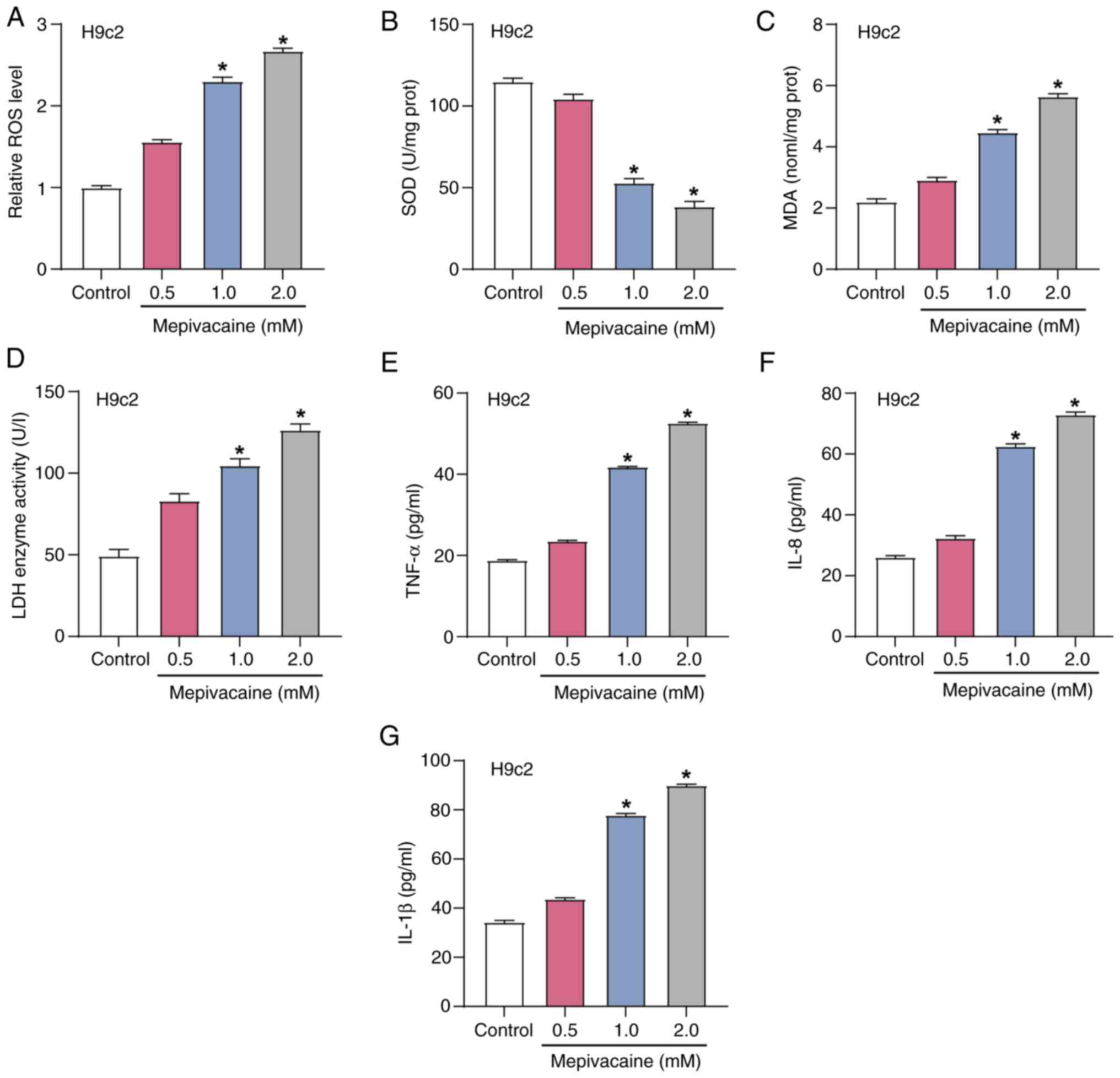

To explore the impact of mepivacaine on oxidative

stress in H9c2 cells, the expression levels of ROS, SOD, MDA and

LDH were assessed using the corresponding assay kits after exposure

to varying concentrations of mepivacaine (Fig. 4A-D). The outcomes indicated that

compared with the control group, the ROS, MDA and LDH levels

increased with increasing concentrations of mepivacaine, while SOD

levels decreased. These findings suggested that mepivacaine induces

oxidative stress and cell damage in H9c2 cells. Subsequently, the

secretion levels of inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-8)

in H9c2 cells after exposure to different concentrations of

mepivacaine were measured using ELISA experiments (Fig. 4E-G). The current findings

demonstrated that, compared with the control group, the expression

levels of IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-8 increased with increasing

concentrations of mepivacaine. This indicated a significant

pro-inflammatory effect of mepivacaine in H9c2 cells.

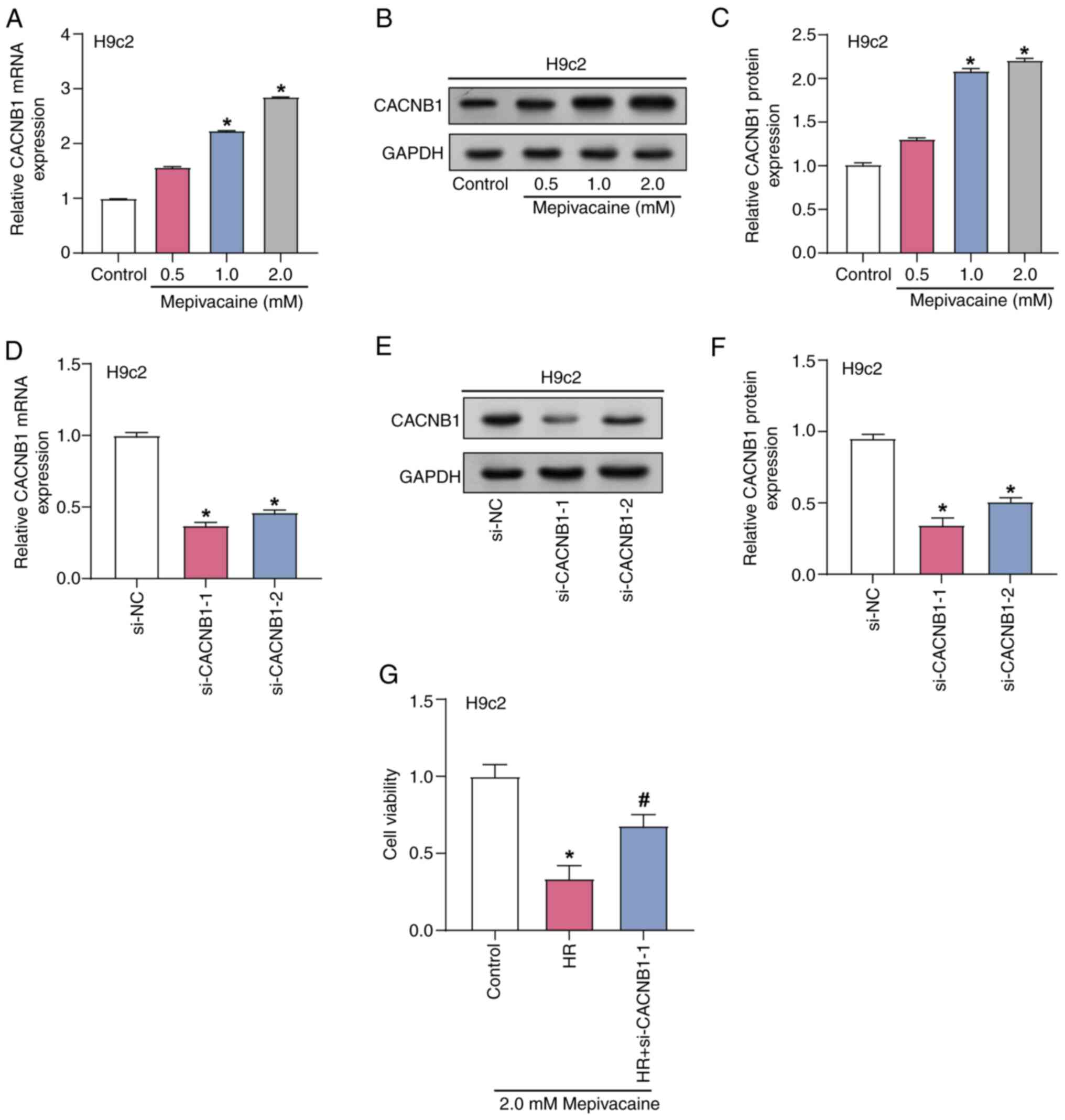

CACNB1 knockdown protects H9c2 cells

from mepivacaine and H/R-induced injury

The effect of mepivacaine treatment at several

concentrations on the expression of CACNB1 in H9c2 cells was

investigated using RT-qPCR and WB analyses (Fig. 5A-C). Analysis revealed that as the

mepivacaine concentration increases, the level of CACNB1 in

H9c2 cells also increases. Furthermore, CACNB1 expression

was highest under treatment with 2 mM mepivacaine; therefore, this

particular concentration was used for further experiments.

Subsequently, the transfection efficiency of CACNB1

knockdown plasmids was assessed with RT-qPCR and WB analyses, with

si-CACNB1−1 demonstrating the greatest efficacy. Therefore,

si-CACNB1−1 was used for knockdown experiments (Fig. 5D-F). The viability of H/R model

H9c2 cells subjected to 2 mM mepivacaine for 24 h, combined with

CACNB1 knockdown, was assessed with the CCK-8 assay

(Fig. 5G). The findings indicated

that the viability of H/R-treated cells was notably reduced

compared with the control group, whereas knockdown of CACNB1

significantly improved cell viability compared with the H/R group.

This suggested that CACNB1 knockdown protects cardiomyocytes

from injury induced by mepivacaine and H/R.

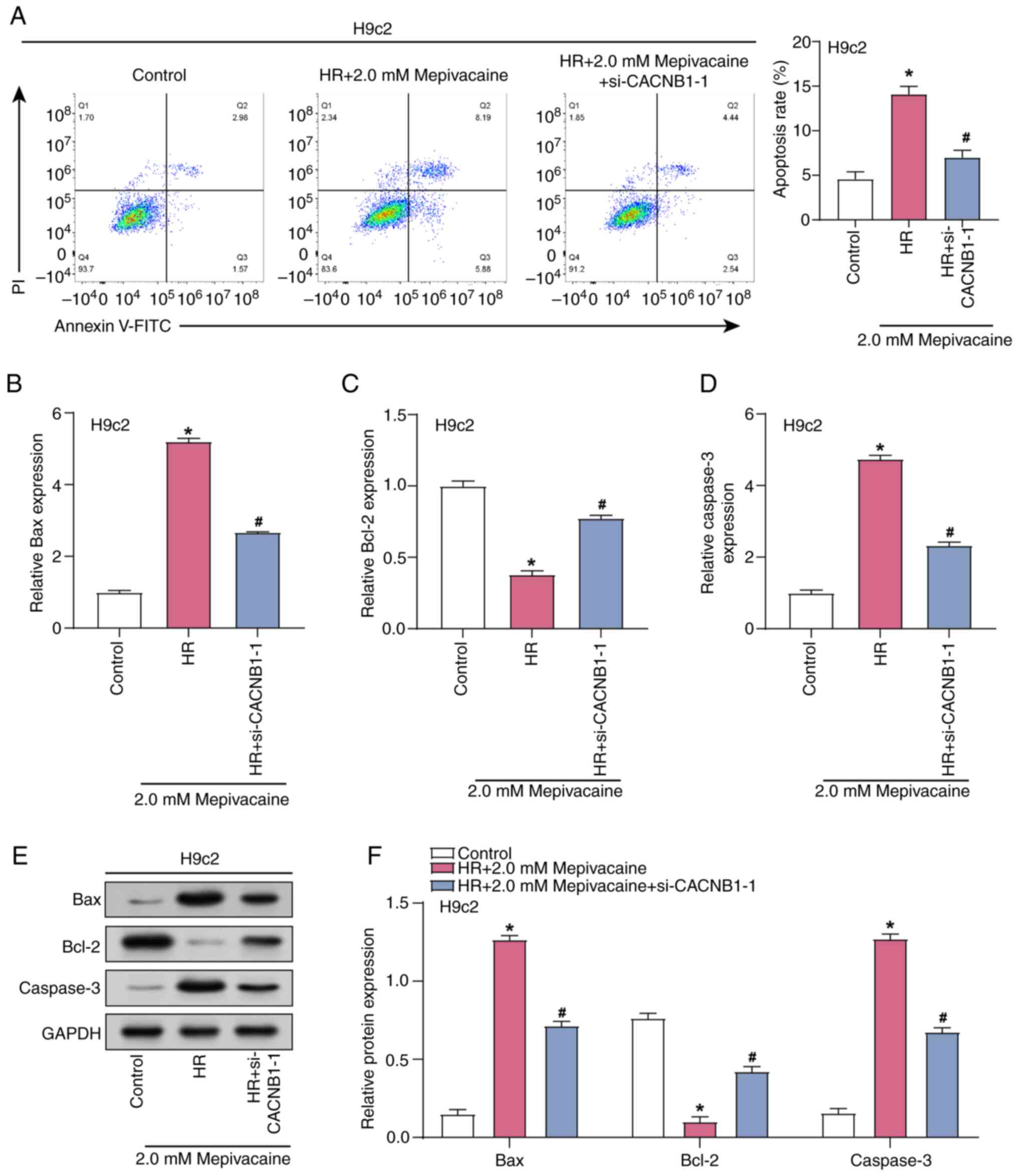

CACNB1 knockdown attenuates apoptosis

in H/R model H9c2 cells treated with mepivacaine

Flow cytometry was used to measure the level of

apoptosis in H/R model H9c2 cells subjected to 2 mM mepivacaine in

combination with CACNB1 knockdown (Fig. 6A). The results indicated a notable

increase in the apoptosis rate in the H/R group in comparison with

the control group, while the apoptosis rate was decreased in the

H/R group with CACNB1 knockdown compared with the H/R group.

Subsequently, RT-qPCR and WB analyses were conducted to examine the

impact of combined treatment with 2 mM mepivacaine and

CACNB1 knockdown on the levels of apoptotic proteins in H/R

model H9c2 cells (Fig. 6B-F).

Analysis revealed that, compared with the Control group, the

expression of Caspase-3 and Bax was upregulated, whereas the

expression of Bcl-2 was downregulated in the H/R group. However,

upon additional CACNB1 knockdown, the expression of

Caspase-3 and Bax decreased, while the expression of Bcl-2

increased compared with the H/R group. These experiments

demonstrated that CACNB1 knockdown exerts anti-apoptotic

effects, alleviating the damage induced by H/R and mepivacaine.

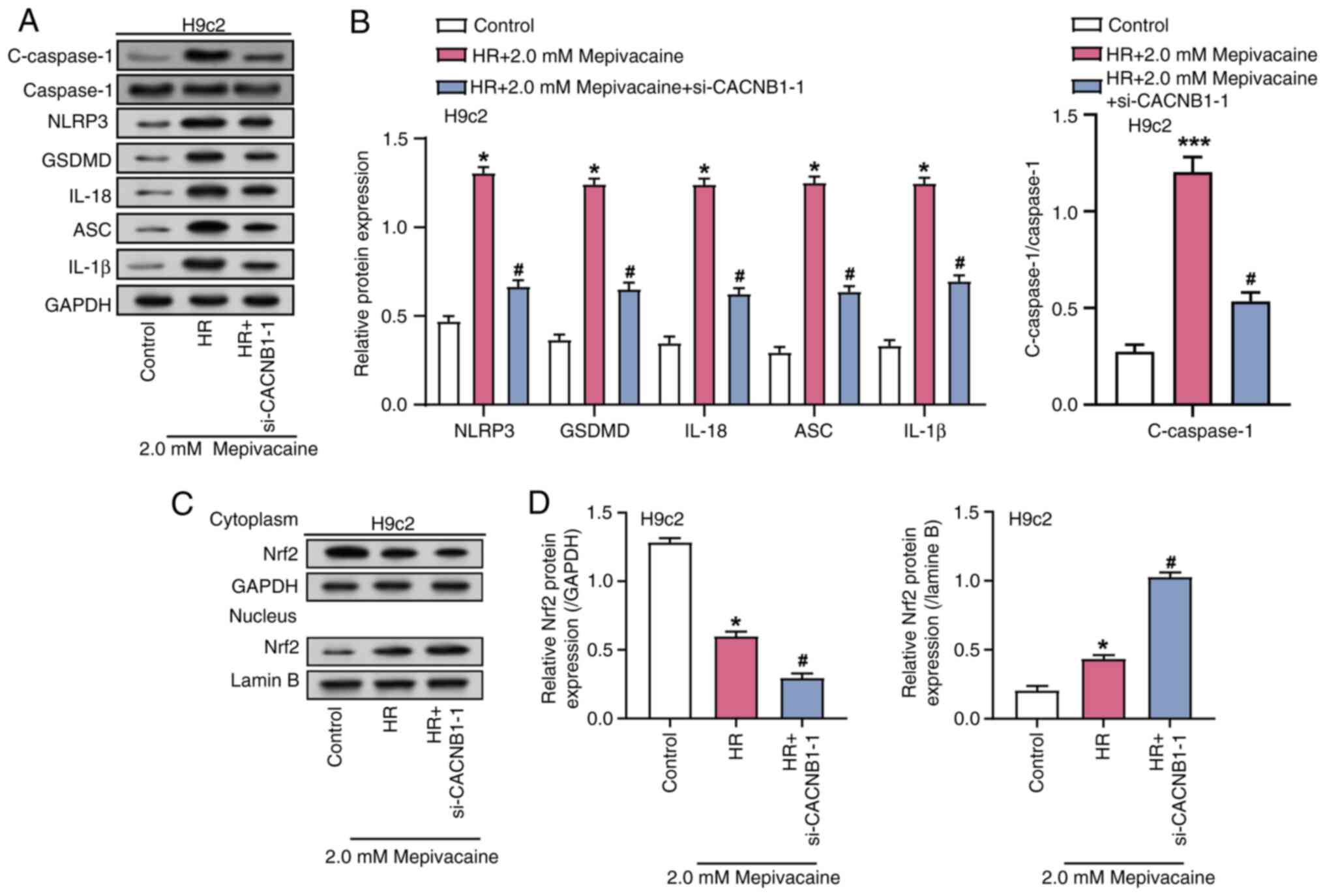

CACNB1 knockdown modulates the

expression of inflammatory mediators and Nrf2 nuclear translocation

in the H/R model treated with mepivacaine

WB analysis was employed to assess the impact of

combined treatment with 2 mM mepivacaine and CACNB1

knockdown on the levels of inflammatory-related factors (NLRP3,

IL-1β, GSDMD, ASC, IL-18, Caspase-1 and C-Caspase-1) in H/R model

H9c2 cells (Fig. 7A and B).

Analysis revealed a noteworthy rise in the level of these

inflammation-related factors in the H/R group, compared with the

control group, while their expression was notably reduced in the

H/R group with CACNB1 knockdown compared with the H/R group.

Previous research suggested that Nrf2 is involved in maintaining

redox homeostasis and exhibits protective effects against MIRI

(24). To investigate whether the

anti-apoptotic effect induced by CACNB1 knockdown is

associated with Nrf2 nuclear translocation, the levels of nuclear

Nrf2 and cytoplasmic Nrf2 proteins were assessed through WB

analysis (Fig. 7C and D). Analysis

revealed that compared with the Control group, the levels of

cytoplasmic Nrf2 decreased, while the levels of nuclear Nrf2

increased in the H/R group. Furthermore, in the H/R group with

CACNB1 knockdown, the level of nuclear Nrf2 increased and the level

of cytoplasmic Nrf2 further decreased. These findings indicated

that CACNB1 knockdown advances the translocation of Nrf2

into the nucleus, indicating that CACNB1 inhibits

inflammation and apoptosis through the CACNB1/NLRP3/Nrf2

axis, thereby alleviating the damage induced by H/R and

mepivacaine.

Discussion

MI, as a globally prevalent and highly lethal

disease, has attracted considerable attention from clinicians and

researchers. Zhao et al (25) identified genes such as IL1R2,

IRAK3 and THBD as diagnostic biomarkers for AMI, which

are associated with immune cell infiltration. Scholars have

summarized signaling pathways associated with MI, including

inflammatory pathways such as TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB and NLRP3/Caspase-1,

oxidative stress and apoptosis-related pathways such as Sonic

hedgehog and Nrf2/HO-1 and key regulators of angiogenesis such as

PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways, all carrying out key roles in the

development of MI (26). The

bioinformatic analysis of the present study, leveraging the

GSE19339 dataset, supported these findings by identifying

significant enrichment of ‘Inflammatory Response’ and ‘PI3K-Akt

signaling pathway’ among the GSE19339-DEGs. Paolisso et al

(27) revealed that patients with

obstructive AMI with hyperglycaemia exhibited increased

inflammation markers and larger infarct areas, whereas patients

with non-obstructive AMI demonstrated less myocardial damage.

Additionally, the hypothesis by Zhao et al (28) that the long non-coding RNA MI

Associated Transcript regulates the PI3K/Akt pathway, which

potentially influences myocardial fibrosis and heart failure,

underscores the complexity of post-MI remodeling processes.

Notably, the findings of the present study also revealed an

upregulation of CACNB1 in MI samples, indicating its pivotal role

in cardiac dysfunction and the progression of disease pathology.

This positions CACNB1 as a potential target for therapeutic

intervention, aiming to modulate cardiac responses to ischemic

stress and improve outcomes in patients with MI.

Mepivacaine, an amide-type local anesthetic known

for its rapid diffusion and brief duration, is widely used in

surgery and dentistry (29,30).

While essential for effective pain management, its potential for

cardiac toxicity requires careful use, especially in patients with

cardiovascular risks (31). The

current research on H9c2 cardiomyocytes revealed that mepivacaine

may exacerbate myocardial injury, characterized by notable cell

cycle arrest and activation of apoptosis. This effect is

characterized by a reduction in the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 and

increases in the pro-apoptotic markers Caspase-3 and Bax,

suggesting that mepivacaine could intensify cell death pathways

that are important under ischemic conditions. Furthermore,

mepivacaine treatment disrupted cell cycle progression by inducing

a G1 phase arrest, as demonstrated by increased P21

expression and decreased levels of Cyclin E1 and CDK4. Importantly,

mepivacaine elevates oxidative stress markers such as ROS and MDA,

indicators of increased oxidative damage (32). Oxidative stress is a major factor

in cellular damage during MI, where it contributes to cell membrane

damage through mechanisms such as lipid peroxidation, evidenced by

elevated MDA levels. This oxidative damage is particularly key

during IR events, characterized by a rapid increase in oxygen that

leads to excessive ROS production. This surge can overwhelm the

antioxidant defenses of a cell, such as SOD, which was observed to

be diminished in the present study. This imbalance between

pro-oxidants and antioxidants exacerbates cellular injury,

underscoring the deleterious impact of mepivacaine on myocardial

health, especially under ischemic conditions. Inflammation is

another key factor in the pathophysiology of MI, with cytokines

such as IL-1β, IL-8 and TNF-α carrying out key roles in mediating

inflammatory responses (33,34).

These cytokines are known to influence the infarct size and

intensity of myocardial injury by promoting further inflammatory

cell infiltration and activating additional cytotoxic pathways

(35). The present study revealed

that mepivacaine elevates these cytokines, potentially increasing

the inflammatory response in myocardial tissues, which could

exacerbate the damage in ischemic conditions. These findings

highlight the ability of mepivacaine to amplify cardiomyocyte

oxidative stress and inflammatory responses.

As an integral component of calcium ion channels,

CACNB1 carries out a key role in regulating calcium ion

permeability across cell membranes and maintaining intracellular

calcium levels (36). In the

present study, CACNB1 expression increased as mepivacaine

concentration increased, suggesting its involvement in the cellular

response to mepivacaine exposure. MIRI is a considerable

pathophysiological component of MI, where, despite the restoration

of blood supply alleviating ischemia, reperfusion itself can induce

further myocardial damage (37).

Reperfusion is known to trigger inflammatory responses, activate

inflammatory cells and release mediators that exacerbate myocardial

damage and remodeling (38). A

recent study by Algoet et al (39) emphasized the intertwined mechanisms

of IR injury and inflammatory changes and explored dual

intervention strategies as potential therapeutic approaches. It is

well-documented that MIRI can lead to calcium overload (40–42),

worsening MIRI. Specifically, myocardial cell-specific loss of the

NBCe1 Na+-HCO3− cotransporter was revealed to

confer cardioprotective effects during IR injury (43). Additionally, disruptions in

Ca2+ homeostasis, commonly observed in cardiac IR and

heart failure, were associated with mitochondrial-associated

membrane between the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria,

affecting Ca2+ transport and suggesting new therapeutic

targets for cardiac diseases (44,45).

In the present study, experiments using the H/R model demonstrated

that knocking down CACNB1 could alleviate cell damage

induced by H/R and mepivacaine, providing novel insights into

myocardial cell protection mechanisms. These results emphasize the

importance of understanding the role of CACNB1 in calcium

regulation and its potential as a focus to lessen myocardial injury

in the setting of IR.

NLRP3 and Nrf2 represent two key regulatory pathways

involved in inflammation and oxidative stress responses (46,47).

The multi-protein complex known as the NLRP3 inflammasome is

primarily produced by immunological cells, including dendritic and

macrophage cells (48).

Conversely, Nrf2 acts as a major regulator of cellular antioxidant

defense mechanisms. Emerging evidence suggests a complex interplay

between the NLRP3 inflammasome and the Nrf2 pathway (49). While triggering the NLRP3

inflammasome promotes inflammation and oxidative stress, activation

of Nrf2 exerts anti-inflammatory and antioxidative effects. Nie

et al (50) revealed that

the SIRT1/NRF2 signaling pathway is the true target of resveratrol

and carries out a key part in the cardioprotective effect against

inflammation induced by resveratrol. Mauro et al (51) highlighted that NLRP3 senses

intracellular danger signals during ischemia and extracellular or

intracellular alarm molecules during tissue injury and highlighted

its role in initiating inflammation and cell death through

activation of caspase-1. Shen et al (52) further emphasized the role of Nrf2

in maintaining redox balance and demonstrated that the

Nrf2/Keap1/ARE pathway is key in reducing the size of MI and

protecting the cardiac function after MIRI.

In line with these insights, the present study

investigated the effects of CACNB1 knockdown in an H/R model

treated with mepivacaine. WB analysis revealed that CACNB1

knockdown modulates inflammatory mediators, such as NLRP3 and

IL-1β, and notably promotes Nrf2 translocation into the nucleus.

This suggested a protective mechanism against H/R-induced

myocardial injury, where CACNB1 knockdown not only reduces

inflammatory and apoptotic signaling but also enhances the

antioxidant response. The decreased expression of cytoplasmic Nrf2

and increased Nrf2 translocation to the nucleus in the H/R model

with CACNB1 knockdown demonstrated a dynamic shift towards

enhancing cellular resilience against oxidative stress. These

findings highlight the CACNB1/NLRP3/Nrf2 axis as a strategic

approach to alleviate inflammation and enhance antioxidant

defenses, offering potential therapeutic pathways to reduce

myocardial injury during IR, particularly in treatments involving

mepivacaine and other stressors.

The use of the H9c2 cell line in the present study

provided a valuable model for investigating the effects of

mepivacaine on cardiomyocytes. However, it is essential to

acknowledge the potential limitations associated with using a

single cell line rather than primary cardiomyocytes. H9c2 cells,

derived from embryonic rat heart tissue, may not fully recapitulate

the mature phenotype and complex physiological responses of adult

cardiomyocytes. Additionally, the genetic homogeneity of the cell

line may limit the generalizability of the current findings to a

broader population. While H9c2 cells offer reproducibility and ease

of use, their response to experimental conditions may differ from

that of primary cardiomyocytes, which are embedded in a native

extracellular matrix and exhibit more diverse genetic backgrounds.

Future studies should aim to validate these findings in primary

cardiomyocytes or in vivo models to further elucidate the

physiological relevance of present observations.

In conclusion, the present study elucidated the

potential cardiotoxic effects of mepivacaine, particularly in the

context of MIRI. CACNB1 was identified as a key player in

mediating mepivacaine-induced cardiomyocyte injury and demonstrated

its involvement in apoptosis and inflammation pathways. Through

CACNB1 knockdown, a notable protection against mepivacaine

and H/R-induced damage was observed, evidenced by improved cell

viability, reduced apoptosis and modulation of inflammatory

mediators. Importantly, the current findings revealed a novel

mechanism involving the CACNB1/NLRP3/Nrf2 axis, wherein

CACNB1 knockdown facilitates Nrf2 nuclear translocation,

thereby mitigating inflammation and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes.

These insights shed light on potential therapeutic targets for

mitigating mepivacaine-induced cardiotoxicity and offer novel

perspectives for the development of cardioprotective strategies,

particularly within the framework of perioperative cardiac care.

Further investigation into the precise molecular mechanisms

underlying CACNB1-mediated cardioprotection is warranted to

fully harness its therapeutic potential in clinical settings.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

QS, JZ and HW contributed to the conception and

design of the present study. QS and JZ contributed to acquisition

of data. QS and JZ contributed to analysis and interpretation of

data. QS contributed to statistical analysis. QS and JZ contributed

to drafting the manuscript. HW contributed to revision of

manuscript for important intellectual content. QS and HW confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. All the authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Katari V, Kanajam LSP, Kokkiligadda S,

Sharon T and Kantamaneni P: A review on causes of myocardial

infarction and its management. World J Pharmaceutical Res.

12:511–529. 2023.

|

|

2

|

Sagris M, Antonopoulos AS, Theofilis P,

Oikonomou E, Siasos G, Tsalamandris S, Antoniades C, Brilakis ES,

Kaski JC and Tousoulis D: Risk factors profile of young and older

patients with myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 118:2281–2292.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Khan IA, Karim HMR, Panda CK, Ahmed G and

Nayak S: Atypical presentations of myocardial infarction: A

systematic review of case reports. Cureus. 15:e354922023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Camacho X, Nedkoff L, Wright FL, Nghiem N,

Buajitti E, Goldacre R, Rosella LC, Seminog O, Tan EJ, Hayes A, et

al: Relative contribution of trends in myocardial infarction event

rates and case fatality to declines in mortality: An international

comparative study of 1 95 million events in 80 4 million people in

four countries. Lancet Public Health. 7:e229–e239. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Fathima SN: An update on myocardial

infarction. Curr Res Trends Med Sci Technol. 1:152021.

|

|

6

|

Dos Santos CC, Matharoo AS, Cueva EP, Amin

U, Ramos AAP, Mann NK, Maheen S, Butchireddy J, Falki VB, Itrat A,

et al: The influence of sex, age, and race on coronary artery

disease: A narrative review. Cureus. 15:e477992023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Radu RI, Ben Gal T, Abdelhamid M, Antohi

EL, Adamo M, Ambrosy AP, Geavlete O, Lopatin Y, Lyon A, Miro O, et

al: Antithrombotic and anticoagulation therapies in cardiogenic

shock: A critical review of the published literature. ESC Heart

Fail. 8:4717–4736. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zangrillo A, Lomivorotov VV, Pasyuga VV,

Belletti A, Gazivoda G, Monaco F, Nigro Neto C, Likhvantsev VV,

Bradic N, Lozovskiy A, et al: Effect of volatile anesthetics on

myocardial infarction after coronary artery surgery: A post hoc

analysis of a randomized trial. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth.

36:2454–2462. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Körner J, Albani S, Sudha Bhagavath

Eswaran V, Roehl AB, Rossetti G and Lampert A: Sodium channels and

local anesthetics-old friends with new perspectives. Front

Pharmacol. 13:8370882022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Gitman M, Fettiplace MR, Weinberg GL, Neal

JM and Barrington MJ: Local anesthetic systemic toxicity: A

narrative literature review and clinical update on prevention,

diagnosis, and management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 144:783–795. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Dell'Olio F, Capodiferro S, Lorusso P,

Limongelli L, Tempesta A, Massaro M, Grasso S and Favia G: Light

conscious sedation in patients with previous acute myocardial

infarction needing exodontia: An observational study. Cureus.

11:e65082019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Mosqueira M, Aykut G and Fink RH:

Mepivacaine reduces calcium transients in isolated murine

ventricular cardiomyocytes. BMC Anesthesiol. 20:102020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

de Groot-van der Mooren M, Quint S, Knobbe

I, Cronie D and van Weissenbruch M: Severe cardiorespiratory and

neurologic symptoms in a neonate due to mepivacaine intoxication.

Case Rep Pediatr. 2019:40135642019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Andrade A, Brennecke A, Mallat S, Brown J,

Gomez-Rivadeneira J, Czepiel N and Londrigan L: Genetic

associations between voltage-gated calcium channels and psychiatric

disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 20:35372019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Gilbert G, Demydenko K, Dries E, Puertas

RD, Jin X, Sipido K and Roderick HL: Calcium signaling in

cardiomyocyte function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol.

12:a0354282020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Shah K, Seeley S, Schulz C, Fisher J and

Gururaja Rao S: Calcium channels in the heart: Disease states and

drugs. Cells. 11:9432022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Erdogmus S, Concepcion AR, Yamashita M,

Sidhu I, Tao AY, Li W, Rocha PP, Huang B, Garippa R, Lee B, et al:

Cavβ1 regulates T cell expansion and apoptosis independently of

voltage-gated Ca2+ channel function. Nat Commun. 13:20332022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Xuan L, Zhu Y, Liu Y, Yang H, Wang S, Li

Q, Yang C, Jiao L, Zhang Y, Yang B and Sun L: Up-regulation of

miR-195 contributes to cardiac hypertrophy-induced arrhythmia by

targeting calcium and potassium channels. J Cell Mol Med.

24:7991–8005. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Lu Y, Zhang Y, Wang N, Pan Z, Gao X, Zhang

F, Zhang Y, Shan H, Luo X, Bai Y, et al: MicroRNA-328 contributes

to adverse electrical remodeling in atrial fibrillation.

Circulation. 122:2378–2387. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Couch LS, Fiedler J, Chick G, Clayton R,

Dries E, Wienecke LM, Fu L, Fourre J, Pandey P, Derda AA, et al:

Circulating microRNAs predispose to takotsubo syndrome following

high-dose adrenaline exposure. Cardiovasc Res. 118:1758–1770. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Scarparo HC, Maia RN, Filho ED, Soares E,

Costa F, Fonteles C, Bezerra TP, Ribeiro TR and Romero NR: Plasma

mepivacaine concentrations in patients undergoing third molar

surgery. Aust Dent J. 61:446–454. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zhou Q and Zhang L: MicroRNA-183-5p

protects human derived cell line SH-SY5Y cells from

mepivacaine-induced injury. Bioengineered. 12:3177–3187. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Cheng L, Zhang H, Wu F, Liu Z, Cheng Y and

Wang C: Role of Nrf2 and its activators in cardiocerebral vascular

disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020:46839432020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhao E, Xie H and Zhang Y: Predicting

diagnostic gene biomarkers associated with immune infiltration in

patients with acute myocardial infarction. Front Cardiovasc Med.

7:5868712020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhang Q, Wang L, Wang S, Cheng H, Xu L,

Pei G, Wang Y, Fu C, Jiang Y, He C and Wei Q: Signaling pathways

and targeted therapy for myocardial infarction. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 7:782022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Paolisso P, Foà A, Bergamaschi L, Donati

F, Fabrizio M, Chiti C, Angeli F, Toniolo S, Stefanizzi A,

Armillotta M, et al: Hyperglycemia, inflammatory response and

infarct size in obstructive acute myocardial infarction and MINOCA.

Cardiovasc Diabetol. 20:332021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zhao X, Ren Y, Ren H, Wu Y, Liu X, Chen H

and Ying C: The mechanism of myocardial fibrosis is ameliorated by

myocardial infarction-associated transcript through the PI3K/Akt

signaling pathway to relieve heart failure. J Int Med Res. Jul

18–2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Burgos EG, García-García LL,

Gómez-Serranillos MP and Oliver FG: Local Anesthetics. Adv

Neuropharmacol. 351–388. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Lottinger C: Local anesthetics in

dentistry. Evidence-Based Oral Surgery. Springer; London: pp.

129–150. 2019

|

|

31

|

Ozbay S, Ayan M and Karcioglu O: Local

anesthetics, clinical uses, and toxicity: Recognition and

management. Curr Pharm Des. 29:1414–1420. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Aladağ N, Asoğlu R, Ozdemir M, Asoğlu E,

Derin AR, Demir C and Demir H: Oxidants and antioxidants in

myocardial infarction (MI): Investigation of ischemia modified

albumin, malondialdehyde, superoxide dismutase and catalase in

individuals diagnosed with ST elevated myocardial infarction

(STEMI) and non-STEMI (NSTEMI). J Med Biochem. 40:2862021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Mitsis A, Kadoglou NP, Lambadiari V,

Alexiou S, Theodoropoulos KC, Avraamides P and Kassimis G:

Prognostic role of inflammatory cytokines and novel adipokines in

acute myocardial infarction: An updated and comprehensive review.

Cytokine. 153:1558482022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Zhang H and Dhalla NS: The role of

pro-inflammatory cytokines in the Pathogenesis of Cardiovascular

Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 25:10822024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Shao L, Shen Y, Ren C, Kobayashi S,

Asahara T and Yang J: Inflammation in myocardial infarction: Roles

of mesenchymal stem cells and their secretome. Cell Death Discov.

8:4522022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Tuluc P, Theiner T, Jacobo-Piqueras N and

Geisler SM: Role of high Voltage-Gated Ca2+ Channel subunits in

pancreatic β-cell insulin release. From structure to function.

Cells. 10:20042021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhang S, Yan F, Luan F, Chai Y, Li N, Wang

YW, Chen ZL, Xu DQ and Tang YP: The pathological mechanisms and

potential therapeutic drugs for myocardial ischemia reperfusion

injury. Phytomedicine. 129:1556492024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zhang D, Wu H, Liu D, Li Y and Zhou G:

Research progress on the mechanism and treatment of inflammatory

response in myocardial Ischemia-reperfusion injury. Heart Surg

Forum. 25:E462–E468. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Algoet M, Janssens S, Himmelreich U, Gsell

W, Pusovnik M, Van den Eynde J and Oosterlinck W: Myocardial

ischemia-reperfusion injury and the influence of inflammation.

Trends Cardiovasc Med. 33:357–366. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Li YW, Liu Y, Luo SZ, Huang XJ, Shen Y,

Wang WS and Lang ZC: The significance of calcium ions in cerebral

ischemia-reperfusion injury: Mechanisms and intervention

strategies. Front Mol Biosci. 12:15857582025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

He J, Liu D, Zhao L, Zhou D, Rong J, Zhang

L and Xia Z: Myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury: Mechanisms of

injury and implications for management. Exp Ther Med. 23:4302022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Trujillo-Rangel WÁ, García-Valdés L,

Méndez-del Villar M, Castañeda-Arellano R, Totsuka-Sutto SE and

García-Benavides L: Therapeutic targets for regulating oxidative

damage induced by ischemia-reperfusion injury: A study from a

pharmacological perspective. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2022:86243182022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Vairamani K, Prasad V, Wang Y, Huang W,

Chen Y, Medvedovic M, Lorenz JN and Shull GE: NBCe1

Na+-HCO3-cotransporter ablation causes reduced apoptosis following

cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury in vivo. World J Cardiol.

10:972018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Wang Y, Zhang X, Wen Y, Li S, Lu X, Xu R

and Li C: Endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria contacts: A potential

therapy target for cardiovascular remodeling-associated diseases.

Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:7749892021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Luan Y, Luan Y, Yuan R-X, Feng Q, Chen X

and Yang Y: Structure and function of mitochondria-associated

endoplasmic reticulum membranes (MAMs) and their role in

cardiovascular diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021:45788092021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Li W, Cao T, Luo C, Cai J, Zhou X, Xiao X

and Liu S: Crosstalk between ER stress, NLRP3 inflammasome, and

inflammation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 104:6129–6140. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Saha S, Buttari B, Panieri E, Profumo E

and Saso L: An overview of Nrf2 signaling pathway and its role in

inflammation. Molecules. 25:54742020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Wang L and Hauenstein AV: The NLRP3

inflammasome: Mechanism of action, role in disease and therapies.

Mol Aspects Med. 76:1008892020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Tastan B, Arioz BI and Genc S: Targeting

NLRP3 inflammasome with Nrf2 inducers in central nervous system

disorders. Front Immunol. 13:8657722022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Nie Q, Zhang J, He B, Wang F, Sun M, Wang

C, Sun W, Guo J, Wen J and Liu P: A novel mechanism of protection

against isoproterenol-induced cardiac inflammation via regulation

of the SIRT1/NRF2 signaling pathway with a natural SIRT1 agonist.

Eur J Pharmacol. 886:1733982020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Mauro AG, Bonaventura A, Mezzaroma E,

Quader M and Toldo S: NLRP3 inflammasome in acute myocardial

infarction. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 74:175–187. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Shen Y, Liu X, Shi J and Wu X: Involvement

of Nrf2 in myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury. Int J Biol

Macromol. 125:496–502. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|