Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune

disease characterized by immune dysregulation, persistent synovial

inflammation and progressive joint destruction. The pathological

hallmarks of RA include uncontrolled synovial inflammation,

abnormal proliferation of fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLSs) and

bone erosion. The disease primarily involves small joints, such as

those of the hands and wrists, typically presenting with

symmetrical inflammation and can also manifest with systemic

symptoms, including anemia and fever (1). Despite extensive research, the

molecular mechanisms driving immune-mediated inflammation and bone

damage in RA remain incompletely understood. Epigenetic alterations

may provide a key link between genetic predisposition,

environmental triggers and RA pathogenesis (2,3).

Among epigenetic regulators, microRNAs (miRNAs or miRs), short,

non-coding RNAs that modulate gene expression by binding mRNA and

promoting its degradation or suppressing translation, have

attracted considerable attention (4,5).

miRNAs influence key cellular processes such as differentiation,

proliferation and apoptosis (6,7).

Dysregulation of miRNAs and their downstream

signaling cascades contributes to the disruption of gene networks

that regulate immune responses and skeletal remodeling in RA

(8). Mounting (9,10)

evidence suggests that miRNAs act through dual mechanisms in the

pathophysiology of RA. First, they modulate immune-driven

inflammation. For instance, miR-146a promotes STAT1 activation,

shifting Treg cells toward pro-inflammatory phenotypes (11). Paeonol inhibits TNF-α-induced FLS

proliferation and cytokine release by downregulating miR-155 and

increasing FOXO3 expression (12).

Tocilizumab alters angiogenic pathways by regulating EMMPRIN and

miR-146a-5p (13). Similarly,

miR-155 promotes NF-κB activation via SOCS1 targeting, enhancing

Th17 differentiation and aggravating synovitis (14), while miR-125a-5p decreases

TNF-α-driven osteoclast differentiation and suppresses inflammatory

signaling through the MAPK pathway (15).

Second, miRNAs are implicated in bone metabolism

abnormalities associated with RA. Elevated miR-22-3p improves bone

formation by activating the SOSTDC1-PI3K/AKT pathway (16). The long non-coding RNA MEG3

facilitates osteogenesis in human bone marrow mesenchymal stem

cells by regulating the miR-21-5p/SOD3 pathway (17). Furthermore, miR-21-5p has been

identified as a potential modulator of osteogenesis (18). Although dysregulated miRNAs are

strongly associated with RA-FLS pathogenicity (19), the specific contributions of

individual miRNAs in orchestrating the interplay between synovial

inflammation and bone remodeling remain poorly defined. In

addition, miR-369-3p has been reported as a critical

immunometabolic regulator in inflammatory disorders (20,21);

however, its involvement in RA-related osteoimmunology has not been

explored. It is hypothesized that miR-369-3p functions as a key

epigenetic switch by directly targeting spectrin β,

non-erythrocytic 1 (SPTBN1), a scaffold protein known to inhibit

Wnt/β-catenin signaling through cytoplasmic sequestration of

β-catenin. Aberrant expression of miR-369-3p may suppress SPTBN1,

allowing β-catenin to translocate into the nucleus, where it

amplifies inflammatory cytokine production and promotes

osteoclastogenesis via RANKL activation. This mechanism positions

miR-369-3p at the intersection of synovial inflammation and

subchondral bone erosion, suggesting its potential as a therapeutic

target for interrupting the link between immune dysregulation and

structural joint damage in RA.

A deeper investigation of the molecular pathways

regulating immune inflammation and bone degradation in RA is,

therefore, crucial. Uncovering the role of miR-369-3p may not only

establish it as a biomarker for RA diagnosis but also provide a

rationale for developing miR-369-3p mimics as novel targeted

therapies to alleviate inflammation and prevent joint destruction

by modulating the SPTBN1/Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

Materials and methods

Cell co-cultivation

RA fibroblast-like synoviocytes (RA-FLSs; Hunan

Fenghui Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. FHHUM195) were maintained

in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS)

and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (100 U/ml each). Cultures were

incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5%

CO2 and the medium was refreshed every 72 h. Once cell

confluence reached 80–90%, the cultures were washed twice with PBS

and digested with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA. Trypsinization was monitored

under an inverted microscope to ensure proper detachment, after

which enzymatic activity was neutralized with complete medium.

Cells in the logarithmic growth phase were collected for subsequent

experiments.

For the Transwell co-culture system, RA-FLSs were

seeded into the lower chambers, while peripheral blood mononuclear

cells (PBMCs) were isolated from the peripheral blood of 10

patients (three male, seven female; age, 35–58 years) with RA

(November 2024; approval number: 2023AH-52,) and plated onto the

upper chamber membrane (BIOFIL; TCS-001-006). When cell confluence

reached ~60%, RA-FLSs and PBMCs were harvested separately from the

lower and upper compartments, respectively. Total RNA and protein

were then extracted from each cell population for downstream

reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-q) PCR and western blot

analyses. To establish optimal stimulation conditions, including

concentration and exposure time, RA-FLS viability was assessed

using the CCK-8 assay, with PBMCs derived from RA patients serving

as the stimulating cells.

Cell transfection

Cells were digested with trypsin, seeded at a

density of 5×105 cells per well in five wells of a

six-well plate and cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 24 h

until reaching ~70% confluence. The miR-369-3p sequence:

AAUAAUACAUGGUUGAUCUUU; mimic: Sense, AAUAAUACAUGGUUGAUCUUU and

antisense, AAAGAUCAACCAUGUAUUAUU (both 20 µM; General Biosystems).

A total of 5 µl mimic or negative control (NC; both 20 µM; General

Biosystems) was diluted in 0.25 ml of serum-free medium. Meanwhile,

10 µl of Lipo8000 (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) reagent was

diluted separately in 0.5 ml of serum-free medium. The two

solutions were gently vortexed and allowed to stand at room

temperature for 5 min. The transfection reagent was then divided

into two portions, each combined with the mimic solution and

incubated for 20 min to enable complex formation. For the

miR-369-3p inhibitor, (AAAGAUCAACCAUGUAUUAUU; 20 µM; General

Biosystems), and 5 µl was prepared following the same procedure as

the mimic. Transfection was performed at room temperature Prior to

transfection, cells were rinsed 2–3 times with serum-free medium to

remove residual serum. Then, 500 µl of the prepared complexes were

added to each well, gently swirled for 1–2 min and supplemented

with serum-free medium to a final volume of 2 ml. After 4 h of

incubation, the medium was replaced with complete culture medium.

The total transfection duration was 48 h, and subsequent

experiments were performed immediately.

Grouping and model preparation

The RA-FLSs in the logarithmic growth phase were

randomly allocated into six experimental groups using a random

number table to ensure comparable cell density and growth

conditions before treatment. When cultures reached ~60% confluence,

cells were divided into the following groups: Group A (Control):

Normal FLSs co-cultured with PBMCs from healthy donors.

Group B (Model): RA-FLSs co-cultured with PBMCs

derived from RA patients.

Group C (Model + miR-369-3p mimics):

RA-FLSs/RA-PBMCs treated with miR-369-3p mimics.

Group D (Model + mimic-NC): RA-FLSs/RA-PBMCs

treated with mimic negative control.

Group E (Model + miR-369-3p inhibitor):

RA-FLSs/RA-PBMCs treated with miR-369-3p inhibitor; F (Model

+ inhibitor-NC): RA-FLSs/RA-PBMCs treated with inhibitor negative

control.

CCK-8 assay

Cell viability was evaluated by measuring metabolic

activity using the CellTiter-Glo 8 Assay Kit (Promega Corporation;

cat. no. BL1055B). Cells were seeded into 96-well flat-bottom

plates at a density of 5×103 cells per well and allowed

to adhere overnight. Following treatment, 10 µl of CCK-8 reagent

was added directly to each well without removing the culture

medium. Plates were then incubated for 2 h at 37°C under humidified

5% CO2 conditions. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm

using a Rayto RT6100 microplate reader (Rayto Life and Analytical

Sciences Co., Ltd.). All assays were performed in six independent

replicates for each group.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from 1×106 cells

using total RNA extraction reagent (ShareBio; cat. no. SB-MR009)

and reverse-transcribed according to the manufacturer's protocol.

RT-qPCR was performed using SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (iScience;

cat. no. EG20117M) with specific primers on a real-time PCR

detection system. Thermocycling conditions were as follows: initial

denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec; followed by 40 cycles of

denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec and annealing/extension at 60°C for

30 sec. For normalization, U6 small nuclear RNA served as the

internal reference for miR-369-3p, while β-actin was used as the

housekeeping control for mRNAs, including SPTBN1, Wnt and

β-catenin. Relative expression levels of miR-369-3p, SPTBN1, Wnt

and β-catenin were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method

(22). Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd.

synthesized primers and their sequences are listed in Table I. Each experiment was conducted

independently three times, with one technical replicate per

group.

| Table I.List of primer sequences. |

Table I.

List of primer sequences.

| Gene | Amplicon size

(bp) | Forward primer

(5′→3′) | Reverse primer

(5′→3′) |

|---|

| Hu-β-actin | 96 |

CCCTGGAGAAGAGCTACGAG |

GGAAGGAAGGCTGGAAGAGT |

| Hu-U6 | 94 |

CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA |

AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT |

| Hu-SPTBN1 | 112 |

CCCTGGAAAGGCTGACTACA |

TCCTCTGAAACCTTCGTGCT |

| Hu-wnt | 154 |

ATCTTCGCTATCACCTCCGC |

GGCCGAAGTCAATGTTGTCG |

| hsa-miR-369-3p |

|

CCGCGCAATACATGGTTG |

AGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATT |

| hsa-miR-369-3p

RT |

|

GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACAAAGAT |

| Hu-β-catenin | 100 |

ATGTCTGAGGACAAGCCACA |

CAGCAGTCTCATTCCAAGCC |

Western blot analysis

Cell pellets were lysed on ice for 30 min in 100 µl

RIPA buffer (Biosharp Life Sciences; cat. no. BL504A) supplemented

with 1 mM PMSF. Lysates were centrifuged at 13,780 g for 15 min at

4°C and the supernatants were collected as total protein extracts.

The concentration of total protein was determined using the BCA

Protein Assay For SDS-PAGE, proteins were denatured by mixing

samples with 5X loading buffer at a 1:4 ratio, boiled for 10 min

and 30 µg of protein was loaded per well. Gels consisted of a 5%

stacking layer (2 ml) and a 10% resolving layer (5 ml).

Electrophoresis was carried out at 80 V for 30 min (stacking) and

120 V for 1 h (resolving). Proteins were transferred onto PVDF

membranes (MilliporeSigma; cat. no. IPVH00010) that had been

pre-activated in methanol, using a current of 300 mA. Membranes

were blocked with 5% non-fat milk at room temperature for 2 h and

subsequently incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies:

β-actin (1:1,000; Zs-BIO; cat. no. TA-09), SPTBN1 (1:500) (HUABIO,

HA500014), Wnt5 (1:1,000) (Proteintech, 55184-1-AP) and β-catenin

(1:500) (Affinity, AF6266). After washing, membranes were incubated

with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:10,000) (Zs-BIO,

ZB-2301) for 2 h. Protein bands were visualized using enhanced

chemiluminescence reagent (GLPBIO; cat. no. GK10008). Band

intensities were quantified with ImageJ software (National

Institutes of Health), with β-actin serving as the internal

control. All experiments were performed independently and repeated

three times.

Assay of dual-luciferase reporter

genes

293T cells were seeded into 12-well plates at a

density of 2×105 cells per well 24 h before

transfection. When cell confluence reached 70–80%,

triple-transfection assays were performed with the following

groups: NC-mimics + SPTBN1-wt, miR-369-3p mimics + SPTBN1-wt,

NC-mimics + SPTBN1-Mut and miR-369-3p mimics + SPTBN1-Mut (all

General Biosystems). Transfections were carried out using

Lipofectamine 8000® (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

diluted in serum-free DMEM. After 6 h, the transfection medium was

replaced with antibiotic-free DMEM containing 10% FBS and cells

were cultured for another 48 h. Cells were then washed three times

with PBS, lysed on ice for 10 min in 300 µl lysis buffer and

centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Luciferase activity

was measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit (Beyotime

Biotechnology; cat. no. RG027). A 50 µl aliquot of cell lysate was

used to sequentially measure firefly luciferase activity (560 nm)

followed by Renilla luciferase activity (465 nm). All

experiments were performed independently in triplicate.

Flow cytometry detection of cell

cycle

Cells were harvested, washed with pre-chilled PBS

and digested with trypsin. After centrifugation at 382 × g for 5

min at 4°C, the supernatant was reduced to ~50 µl and the pellet

was resuspended in 0.3 ml PBS to obtain a single-cell suspension.

While vortexing, 2.7 ml of ice-cold absolute ethanol was added

dropwise to achieve a final ethanol concentration of 90%. The cells

were fixed at 4°C for 18–24 h or at −20°C for 1 h. Following

fixation, the cells were centrifuged again 382 g, 5 min, 4°C),

washed twice with cold PBS and then resuspended in 0.5 ml of PBS.

The suspension was transferred into a 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube

and gently dispersed. Next, 100 µl of RNase A reagent

(ready-to-use, provided with the cell cycle detection kit) was

added and samples were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Cells were

then stained with 400 µl propidium iodide (PI) solution (50 µg/ml,

light-protected, kit-provided) at 4°C for 30–60 min. Within 24 h,

samples were filtered through a 200-mesh strainer and analyzed on a

NovoCyte flow cytometer (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) using

NovoExpress software (version 1.5.6.0) (Agilent Technologies,

Inc.). Each experiment was conducted independently in

triplicate.

Detection of cell proliferation by Edu

staining

Cells were incubated with 10 µM EdU labeling medium

at 37°C for 2 h, followed by fixation, permeabilization and the

Click reaction, as per the manufacturer's instructions (Elabscience

Bionovation Inc.; cat. no. E-CK-A376). After nuclear

counterstaining with 500 µl DAPI working solution at room

temperature for 5–10 min in the dark) and washing (1 ml PBS

containing 3% BSA (Biosharp; cat. no. BS114) per well, washed 3

times for 5 min each), images were captured using an inverted

fluorescence microscope (OLYMPUS; CKX53). Each experiment was

independently repeated three times. EdU-positive cells were

quantified by two blinded observers to minimize bias.

Scratch wound healing assay to detect

cell migration

Horizontal reference lines were drawn on the back of

6-well plates with a marker, spaced 0.5–1 cm apart, with at least

five lines per well. Cells were seeded at a density of

1×106 per well and allowed to reach confluence

overnight. A scratch was made across the cell layer using a 200-µl

pipette tip, perpendicular to the reference lines. Detached cells

were removed by washing three times with PBS and serum-free medium

was added. Plates were then incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2

and wound closure was images captured at 0 and 24 h using an

inverted light microscope (Olympus Corporation; cat. no. CKX53) to

assess migration. Cell migration rate (%) was quantified using

ImageJ software, and the calculation formula was as follows:

[(Wound area at 0 h-Wound area at 12/24 h)/Wound area at 0 h]

×100%. All experiments were independently repeated three times.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS

Statistics 26.0 (IBM Corp.), while figures were prepared with

GraphPad Prism 10.1.2 (Dotmatics). Data were expressed as mean ±

standard deviation (SD). Normality of the datasets was assessed

using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test in SPSS. For normally distributed

data, comparisons between two groups were performed using Student's

t-test, whereas one-way ANOVA was applied for comparisons involving

more than two groups. To minimize type I error from multiple

testing, Tukey's post hoc test was used following ANOVA for

pairwise comparisons. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

A targeted interaction exists between

miR-369-3p and SPTBN1

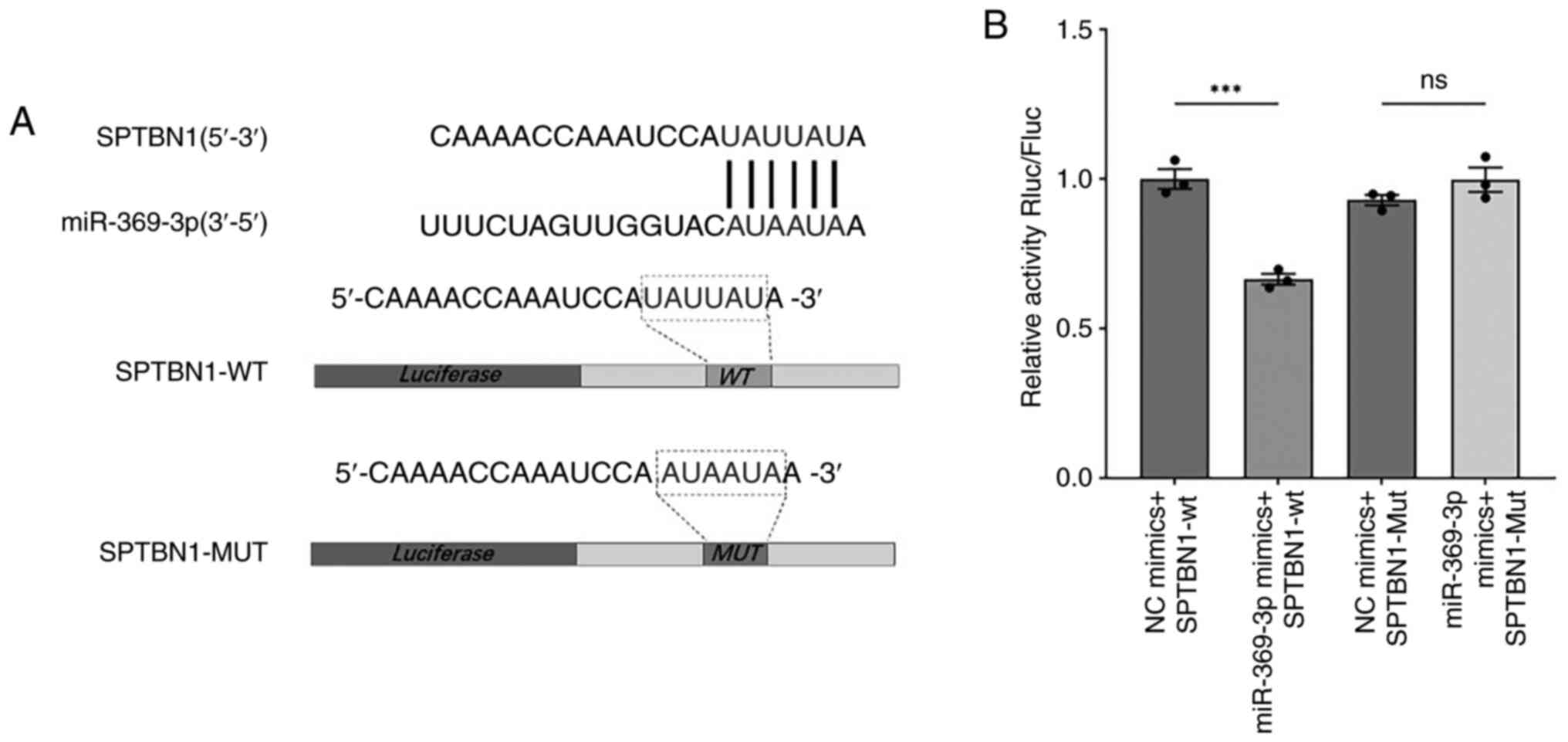

From our previous bioinformatics analysis, a

potential binding site between miR-369-3p and the 3′UTR of SPTBN1

was predicted. To validate this interaction, wild-type (WT) and

mutant (Mut) sequences of the predicted binding region were

synthesized and cloned into a dual-luciferase reporter vector.

Sequence alignment confirmed complementarity between miR-369-3p and

SPTBN1 (Fig. 1A). The

dual-luciferase reporter assay demonstrated that luciferase

activity in the SPTBN1-WT group was markedly reduced following

transfection with miR-369-3p mimics compared with the NC mimic

group (Fig. 1B).

The crosstalk between RA-FLSs and

RA-PBMCs enhances cell viability, determining the optimal

co-culture conditions

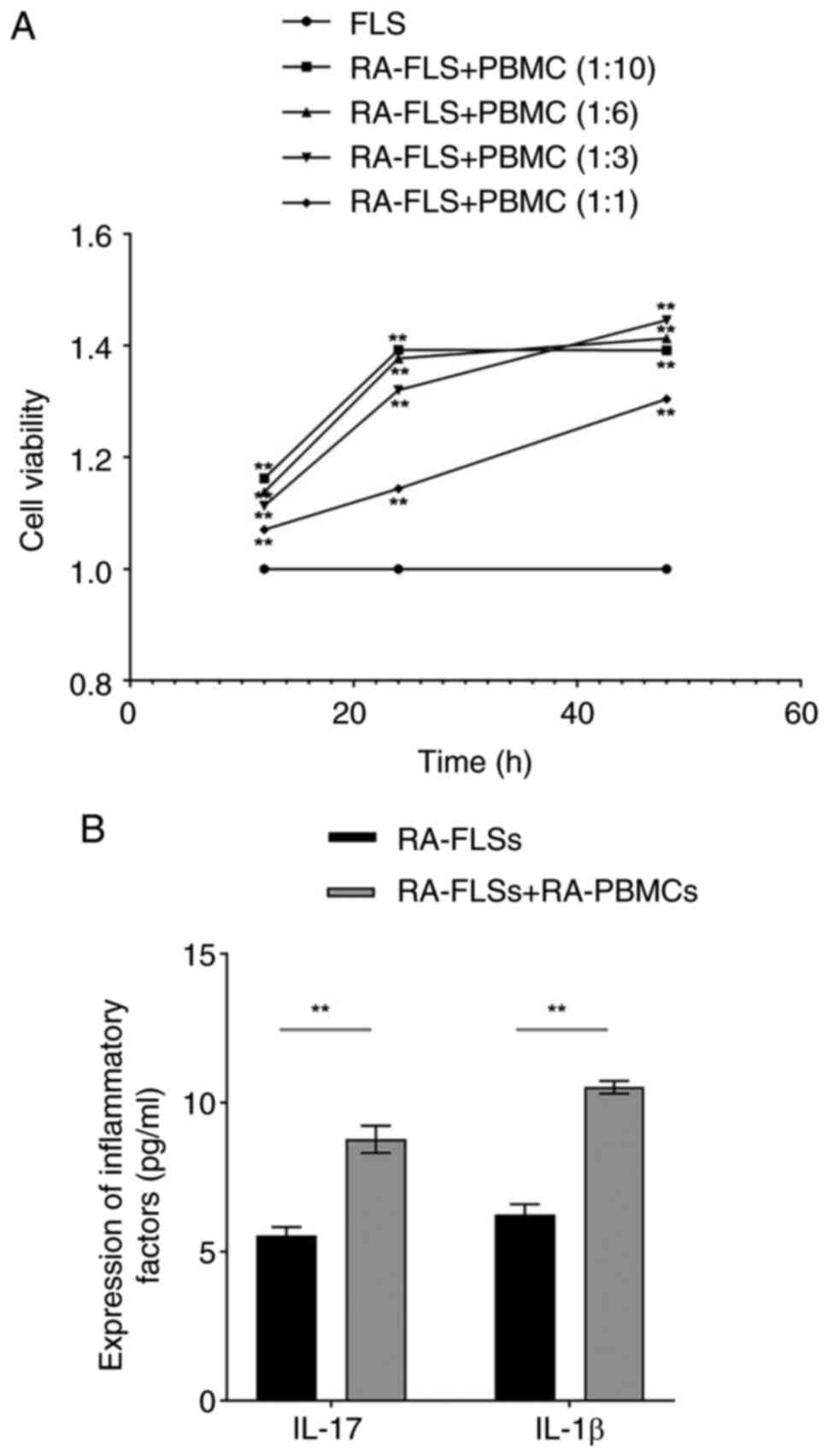

To investigate the interaction between RA-FLSs and

RA-PBMCs, a dual-cell co-culture system was developed to mimic the

synovial inflammatory microenvironment of RA. RA-FLSs and RA-PBMCs

were co-cultured at different ratios (1:10, 1:6, 1:3 and 1:1) and

cell viability was measured at 12, 24 and 48 h. CCK-8 analysis

revealed a time-dependent increase in cell viability across all

groups, with the 1:3 ratio showing the greatest viability at 48 h

(Fig. 2A). Accordingly, the

RA-FLSs + RA-PBMCs co-culture model was established at a 1:3 ratio

with 48 h as the optimal activation time for subsequent

experiments. To further assess the inflammatory profile, ELISA was

used to measure cytokine secretion. Compared with RA-FLSs cultured

alone, the co-culture model showed markedly higher levels of IL-17

and IL-1β (Fig. 2B). These

findings indicated that crosstalk between RA-FLSs and RA-PBMCs

promotes cell viability and amplifies inflammatory signaling within

the RA immune microenvironment.

Effect of miR-369-3p modification on

cell viability and cell cycle dynamics

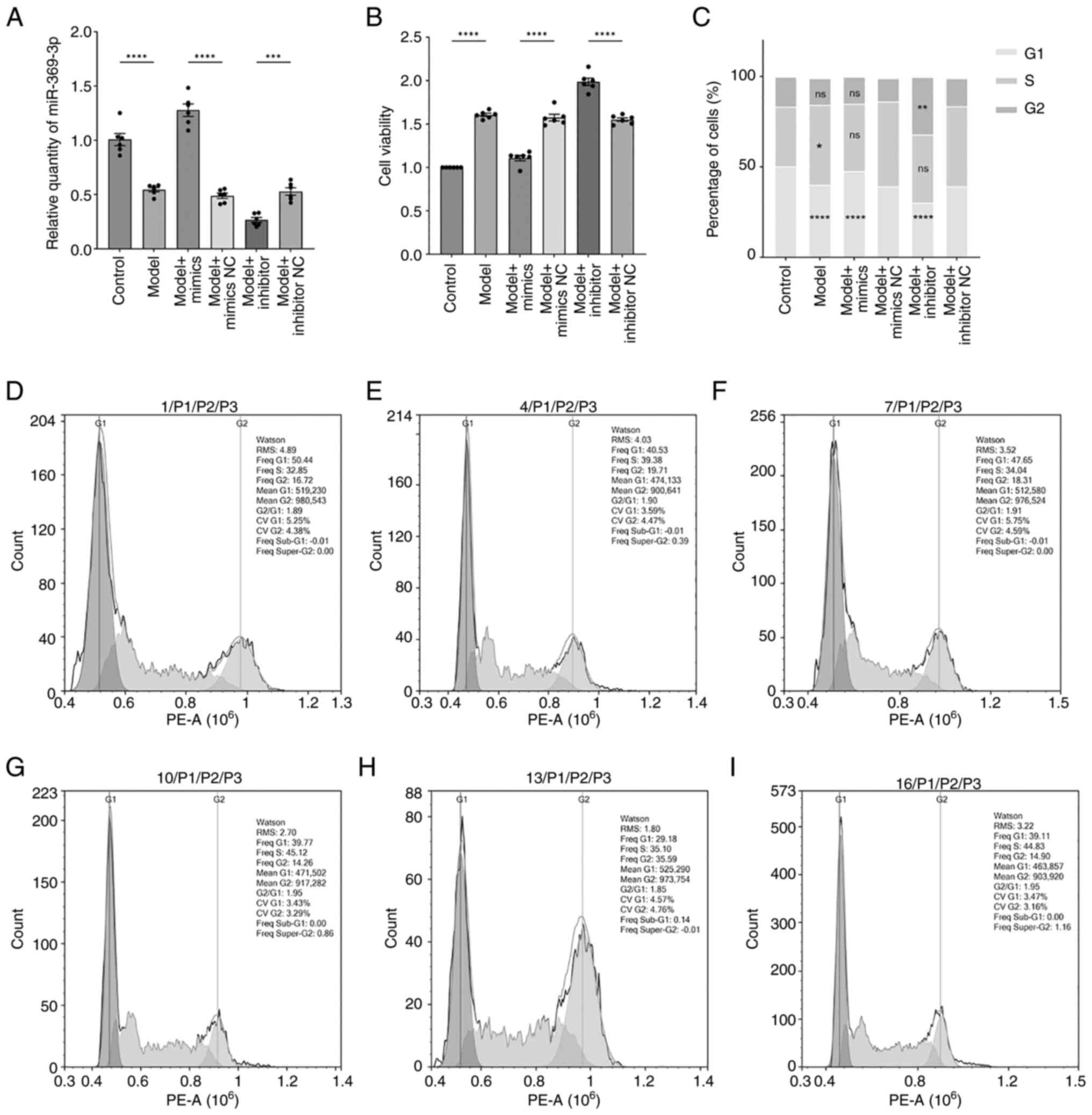

Cells were transfected with miR-369-3p mimics, mimic

negative control (mimic-NC), inhibitors and inhibitor negative

control (inhibitor-NC) (Fig. 3A).

RT-qPCR confirmed altered expression of miR-369-3p across groups.

Compared with the model mimic-NC group, miR-369-3p expression was

markedly upregulated in the model mimic group. At the same time, it

was markedly reduced in the model inhibitor group relative to the

inhibitor-NC group. Model groups displayed lower miR-369-3p

expression compared with control groups.

Cell viability, assessed by CCK-8 assay (Fig. 3B), was markedly higher in model

groups than in controls. However, the introduction of miR-369-3p

mimics suppressed cell viability, whereas the inhibitor group

demonstrated increased proliferation. These results suggested that

upregulation of miR-369-3p inhibits cell proliferation. To further

investigate the role of miR-369-3p in cell proliferation, cell

cycle distribution was analyzed using flow cytometry. The results

were consistent with the CCK-8 findings. Cell cycle analysis

(Fig. 3C-H) showed that RA-FLSs in

the model group had a reduced proportion of cells in the

G1 phase compared with controls. Transfection with

miR-369-3p mimics increased the G1-phase population

relative to mimic-NC, while transfection with the inhibitor

elevated the G2-phase fraction compared with

inhibitor-NC. These findings suggested that inhibiting miR-369-3p

promotes cell cycle progression and accelerates proliferation,

whereas overexpressing miR-369-3p exerts a suppressive effect.

Effects of modifying miR-369-3p on

cellular proliferation and migratory capacity

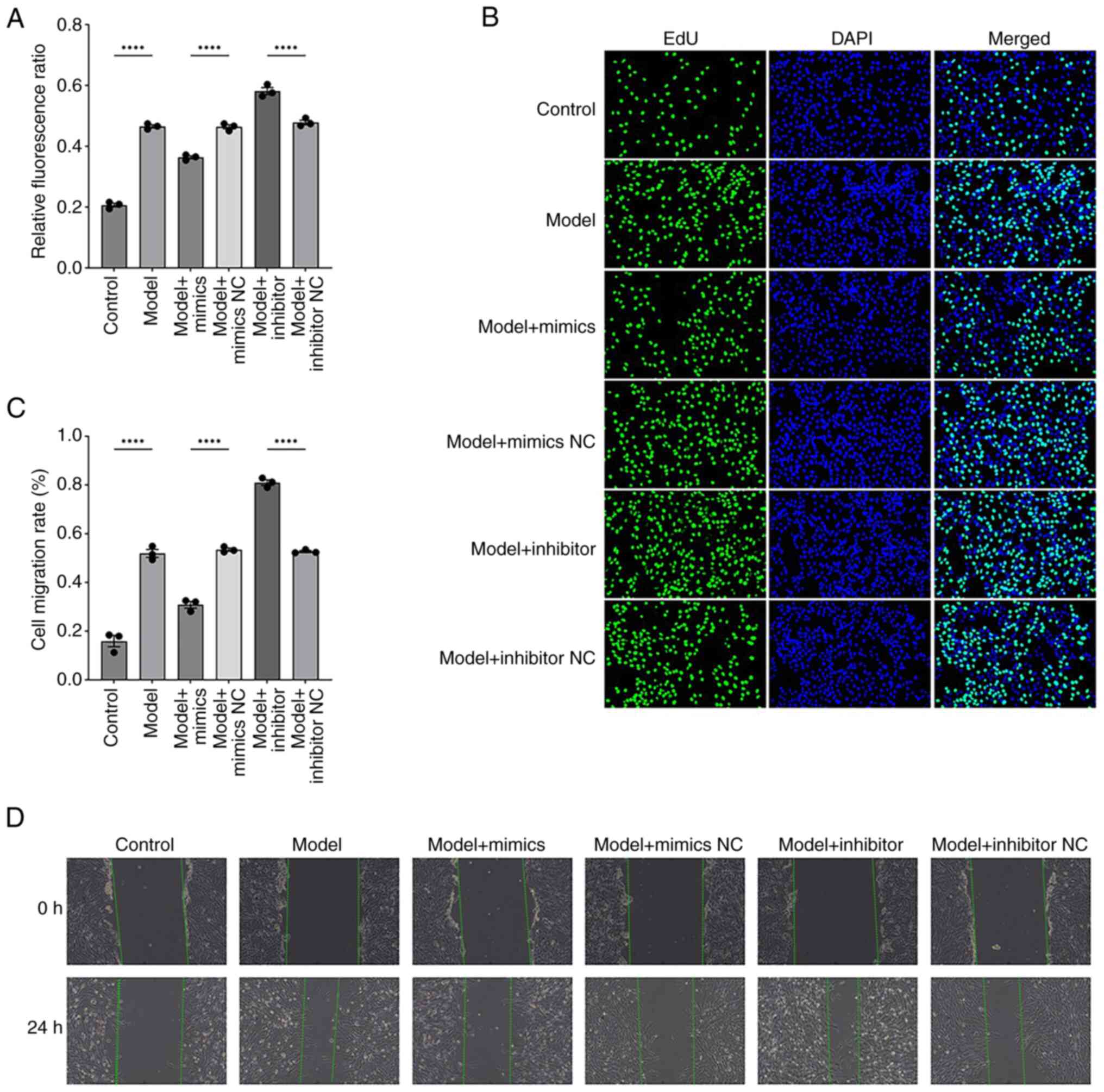

To further visualize the effect of miR-369-3p on

cell proliferation and migration, EdU and scratch assays were

performed. The EdU assay results were consistent with previous

findings, showing that transfection with miR-369-3p mimics markedly

reduced cell proliferation, whereas the inhibitor group showed the

opposite trend (Fig. 4A and B).

Similarly, scratch assays demonstrated that the mimic group

displayed a significant reduction in migration capacity, while the

inhibitor group showed enhanced migratory activity (Fig. 4C and D).

miR-369-3p can regulate SPTBN1 and

Wnt/β-catenin gene expression levels

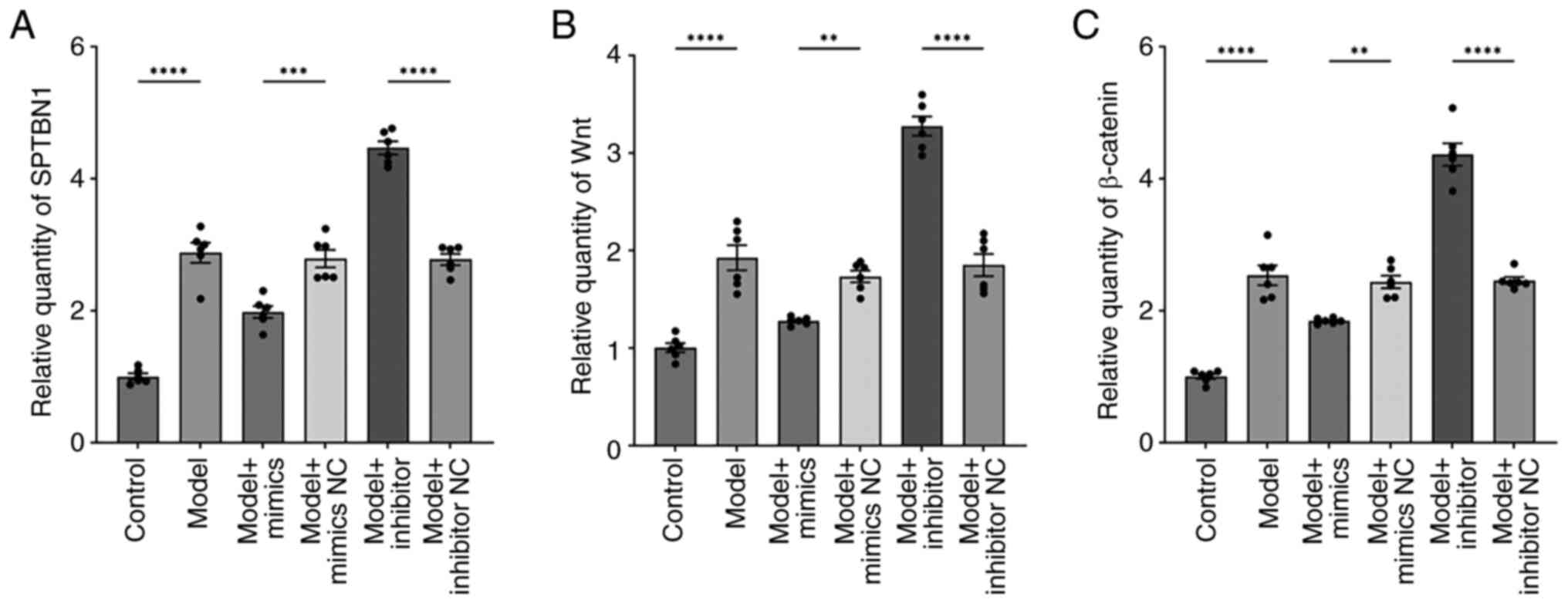

RT-qPCR (Fig. 5A-C)

revealed that the expression levels of SPTBN1, Wnt and β-catenin

were markedly higher in the model group compared with the control

group. Relative to the model mimics-NC group, these gene

expressions were markedly reduced in the model mimics group. In

comparison, the model inhibitor group showed a pronounced increase

in SPTBN1, Wnt and β-catenin expression compared with the model

inhibitor-NC group. These findings indicated that miR-369-3p

overexpression suppresses, while its inhibition enhances, the

expression of SPTBN1, Wnt and β-catenin in the co-culture

system.

miR-369-3p regulates the

immuno-inflammatory microenvironment in RA

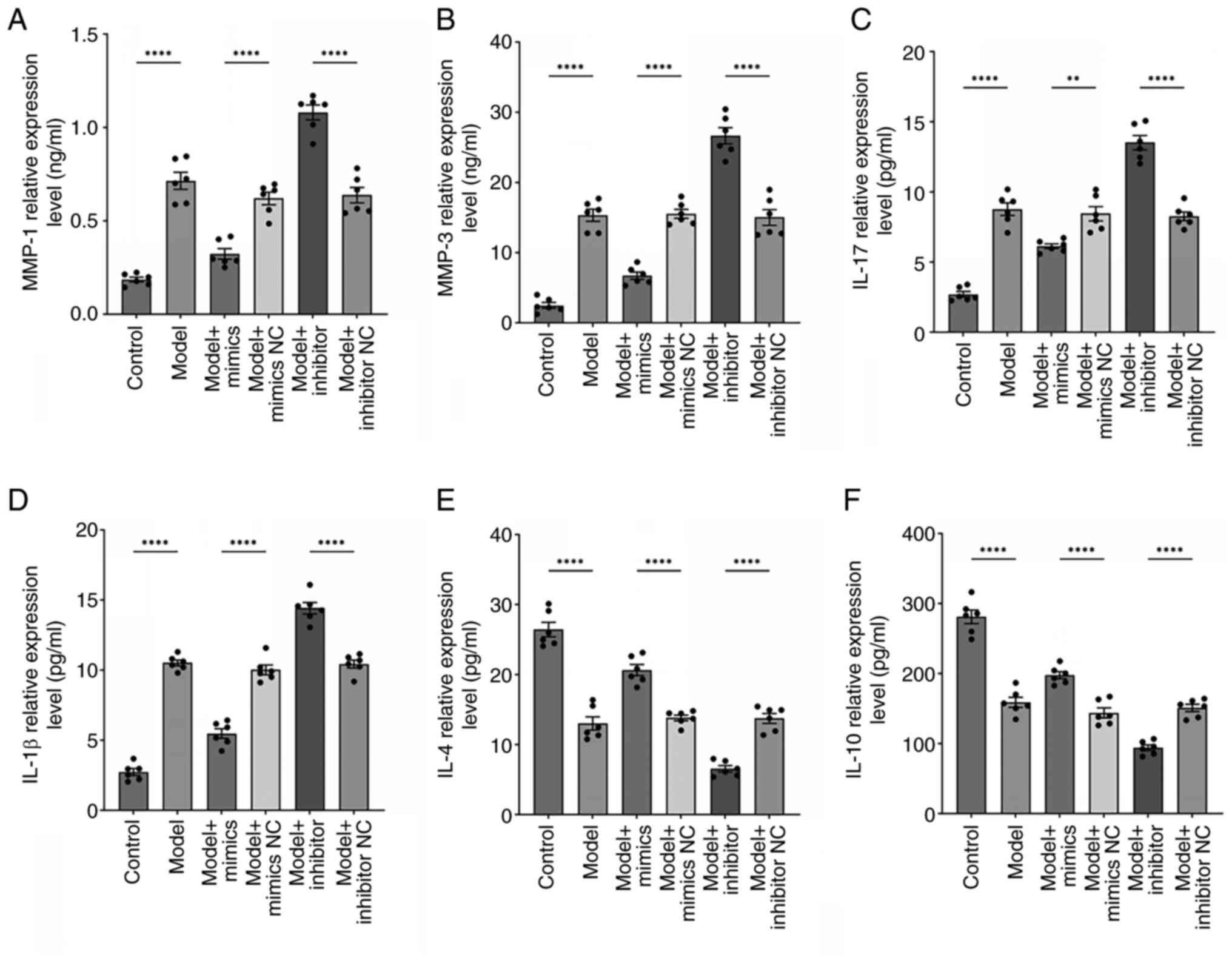

Previous research has highlighted a tightly

regulated pathological network involving FLSs, matrix

metalloproteinases (MMPs) and inflammatory mediators in RA, which

collectively drive synovial inflammation, cartilage destruction and

disease progression (23,24). In the present study, the expression

profiles of two key MMPs (MMP-1 and MMP-3) were investigated and

both pro-inflammatory (IL-17, IL-1β) and anti-inflammatory (IL-4,

IL-10) cytokines were analyzed. ELISA results (Fig. 6A and B) showed that MMP-1 and MMP-3

expression were markedly elevated in the model group compared with

the controls. Transfection with miR-369-3p mimics markedly reduced

MMP-1 and MMP-3 levels relative to the mimic-NC group

(P<0.0001), whereas the inhibitor group showed the opposite

effect compared with its negative control (P<0.0001). Likewise,

model group cells secreted higher levels of IL-17 and IL-1β and

lower levels of IL-4 and IL-10 compared with controls

(P<0.0001). miR-369-3p mimics increased IL-4/IL-10 expression

and suppressed IL-17/IL-1β, while inhibition of miR-369-3p reversed

this pattern (P<0.0001; Fig.

6C-F). These findings suggested that the upregulation of

miR-369-3p mitigates the inflammatory environment in the co-culture

system, whereas its inhibition exacerbates inflammatory

responses.

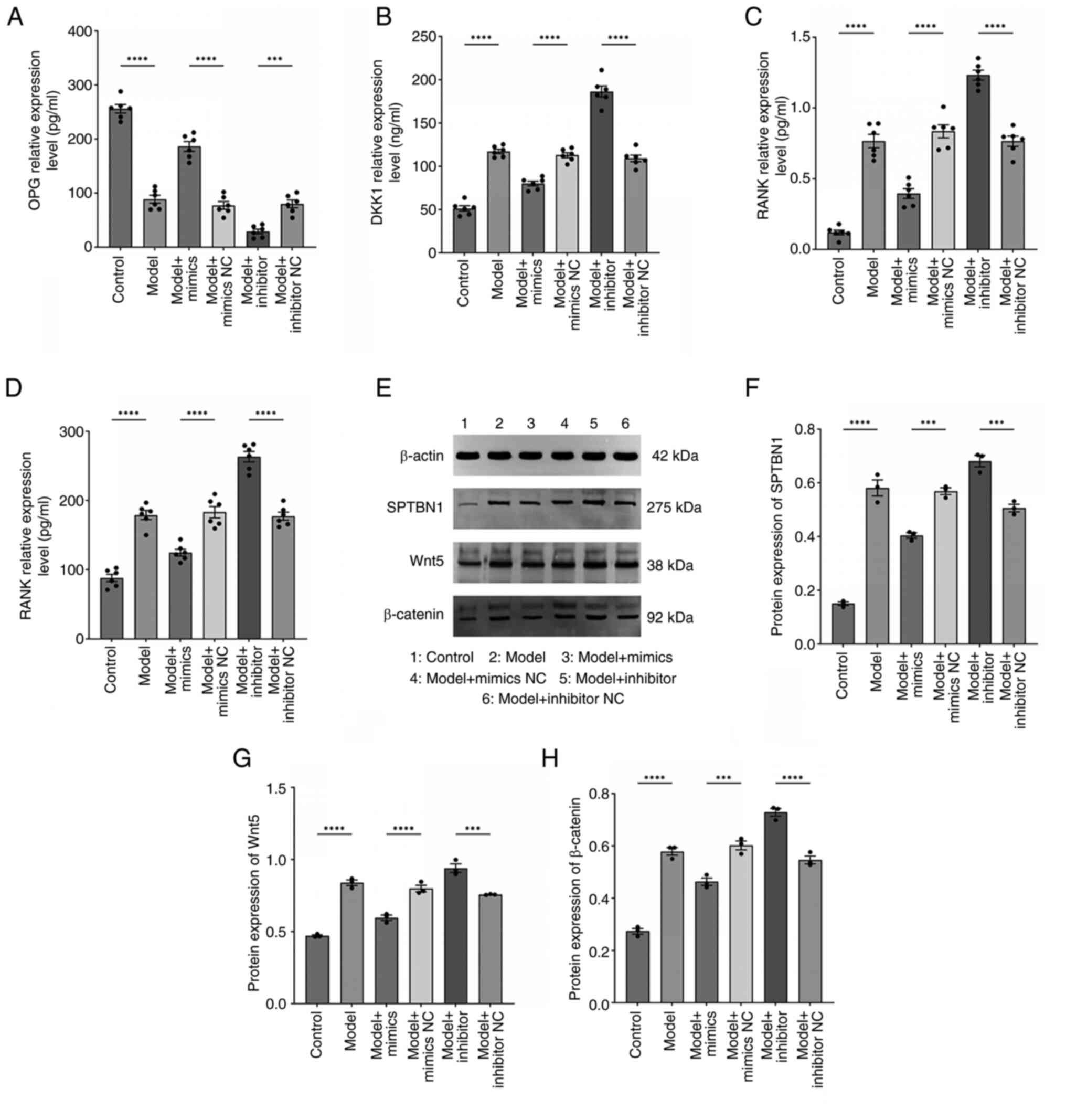

miR-369-3p ameliorates bone

destruction indicators in RA by regulating the SPTBN1/Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway expression

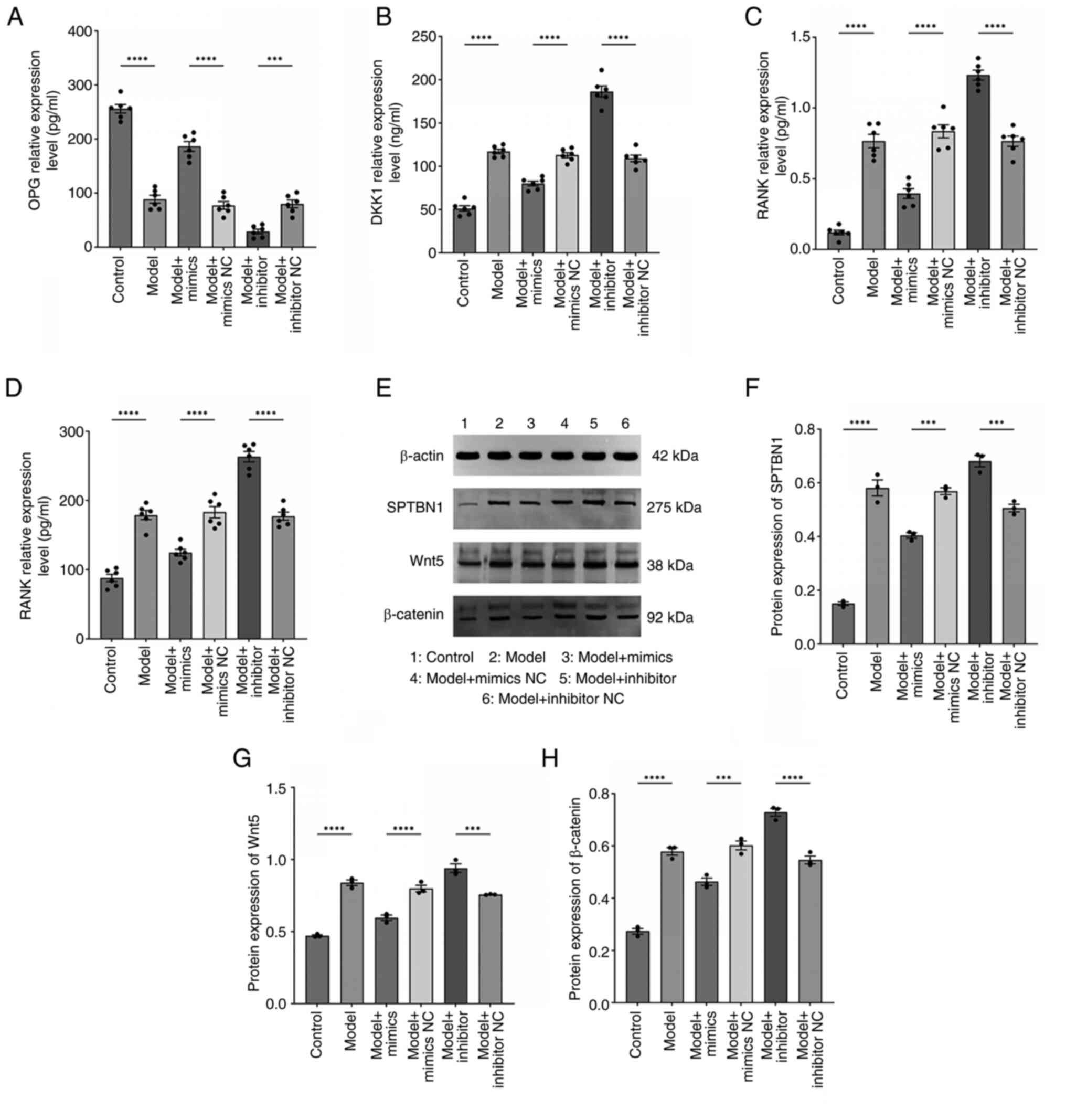

To further investigate the role of miR-369-3p in

regulating bone destruction markers and its involvement in the

SPTBN1/Wnt/β-catenin pathway, bone-related factors were measured

using ELISA and protein expression was evaluated through western

blotting. ELISA results showed that miR-369-3p overexpression

markedly increased osteoprotegerin (OPG) levels, while decreasing

Dickkopf-related protein 1 (DKK1), receptor activator of nuclear

factor κ B (RANK) and RANK ligand (RANKL) expression; however,

miR-369-3p inhibition produced the opposite effect (Fig. 7A-D). Similarly, western blot

analysis (Fig. 7E-H) revealed

higher expression of SPTBN1, Wnt5 and β-catenin proteins in the

model group compared with the control group. In comparison to the

mimic-NC group, cells transfected with miR-369-3p mimics showed

reduced protein expression of SPTBN1, Wnt5 and β-catenin.

Inhibition of miR-369-3p led to increased expression of these

proteins compared with the inhibitor-NC group. These findings

indicated that miR-369-3p overexpression suppresses SPTBN1, Wnt5

and β-catenin protein levels, likely through regulation of the

SPTBN1/Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

| Figure 7.miR-369-3p regulates RA bone

destruction and the expression of the SPTBN1/Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

ELISA employed for the determination of (A) OPG (pg/ml), (B) DKK1

(ng/ml), (C) RANK (pg/ml) and (D) RANKL (pg/ml) expression in all

cell groups. (n=6). ****P<0.0001. ***P<0.001. (E-H) Western

blot employed for the determination of SPTBN1, Wnt and β-catenin

protein expression in all cell groups (n=3). ****P<0.0001.

***P<0.001. miR, microRNA; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SPTBN1,

spectrin β, non-erythrocytic 1; OPG, osteoprotegerin; DKK1,

Dickkopf-related protein 1; RANK, receptor activator of nuclear

factor κ B; RANKL, RANK ligand. |

Discussion

The present study began by establishing a co-culture

system of RA-FLSs and RA-PBMCs to simulate the synovial

microenvironment observed in RA more accurately. Comparison of

inflammatory cytokine levels, specifically IL-17 and IL-1β, between

RA-FLSs cultured alone and those in co-culture revealed markedly

higher concentrations in the co-culture group. These findings

suggested that the crosstalk between RA-FLSs and RA-PBMCs activates

inflammatory signaling pathways, amplifying the inflammatory

cascade. This approach more accurately replicates the pathological

interactions between immune cells and stromal cells within RA

synovial tissue. Using CCK-8 assays showed that a co-culture ratio

of 1:3 (RA-FLSs:RA-PBMCs) with a 48-h incubation period provided

optimal stimulation conditions. In parallel, our bioinformatics

analyses predicted potential binding sites for miR-369-3p on

SPTBN1, which were validated through luciferase reporter

assays.

Focusing on the molecular mechanisms underlying

immune inflammation and bone destruction in RA, the present study

revealed that RA-FLSs exhibited decreased miR-369-3p expression,

accompanied by elevated SPTBN1 levels. It was hypothesized that

miR-369-3p directly targets SPTBN1 and regulates the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway, driving RA-FLS proliferation, intensifying

immune-mediated inflammation and contributing to bone damage. By

modulating miR-369-3p expression and assessing its effect on cell

viability, cell cycle progression, proliferation and migration, it

was found that overexpression of miR-369-3p substantially inhibited

the viability, proliferation and migratory activity of RA-FLS.

Simultaneously, the upregulation of miR-369-3p increased the

secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines while reducing the

production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, MMPs and markers of bone

destruction.

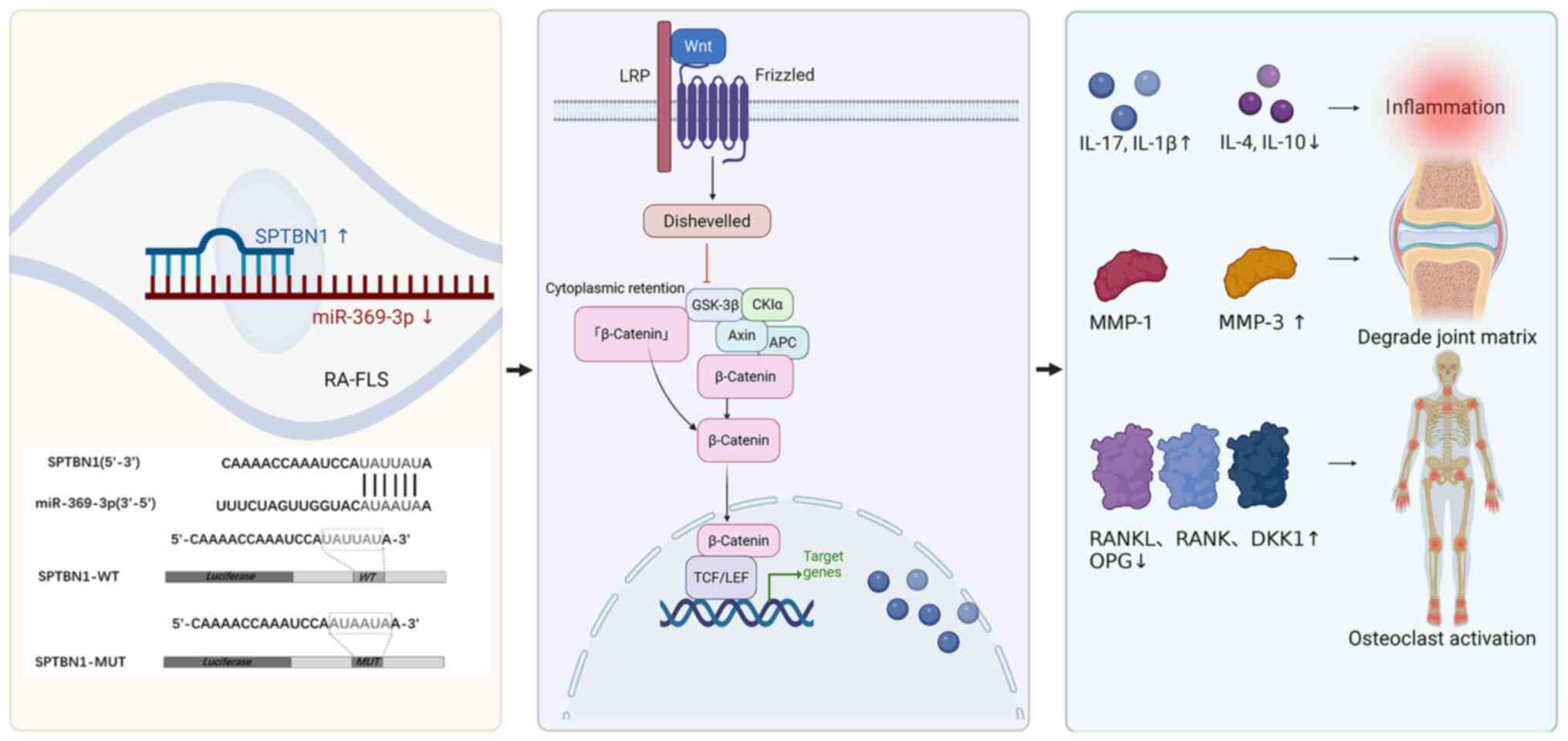

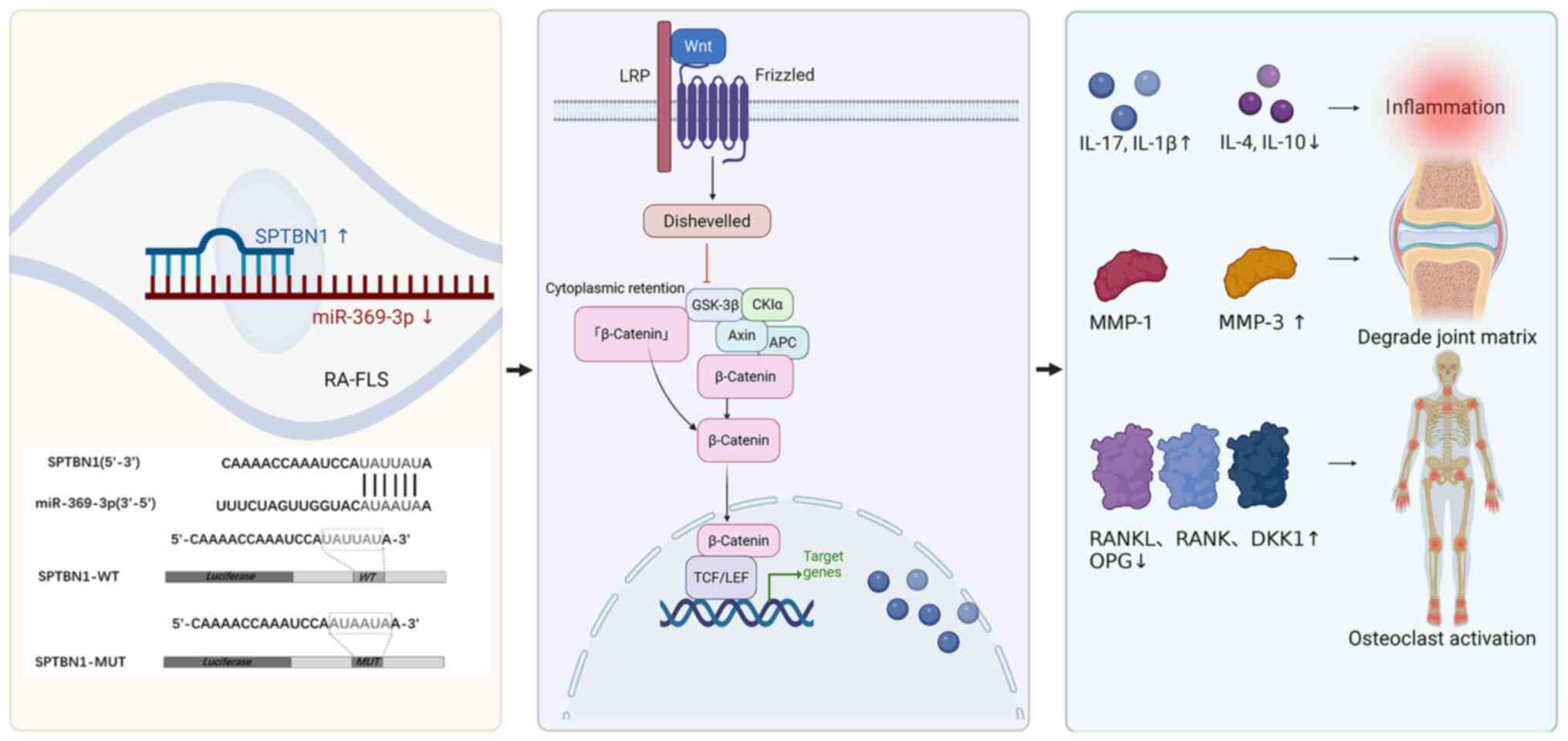

Western blot analyses confirmed that miR-369-3p

modulates immune inflammation and bone destruction through the

SPTBN1/Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. To further illustrate the

hierarchical regulatory relationships of this pathway, a schematic

diagram summarizing the entire mechanism is provided in Fig. 8. These findings demonstrated that

miR-369-3p acts as a key epigenetic regulator linking synovial

inflammation to bone erosion through the SPTBN1/Wnt/β-catenin

pathway, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target for RA.

Furthermore, the miR-369-3p/SPTBN1/Wnt/β-catenin pathway may

constitute a novel post-transcriptional regulatory pathway that

contributes to the epigenetic network governing RA pathogenesis

through miRNA-mediated gene silencing. This pathway may serve a

crucial role in regulating immune inflammation and bone

destruction, underscoring its significance in the molecular

pathogenesis of RA.

| Figure 8.Schematic diagram of the mechanism

through which miR-369-3p regulates inflammation and bone

destruction via SPTBN1/Wnt/β-catenin pathway. miR, microRNA;

SPTBN1, spectrin β, non-erythrocytic 1; MMP, matrix

metalloproteinases; IL, interleukin; DKK1, Dickkopf-related protein

1; RANK, receptor activator of nuclear factor κ B; RANKL, RANK

ligand; LRP, low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein; TCF,

T-Cell Factor; LEF, Lymphoid Enhancer-Binding Factor. |

The FLSs are a key mesenchymal cell population that

serves as a central mediator of joint damage in RA, primarily due

to their secretion of MMPs, which drive bone resorption (25). In addition, FLS-derived chemokines

recruit leukocytes to the synovium, contributing critically to the

initiation and perpetuation of synovitis. Therefore, targeting FLSs

has emerged as a promising strategy for restoring synovial

homeostasis in RA (26). The

miRNAs, as non-coding RNAs, act as molecular switches in autoimmune

diseases by regulating gene expression through targeted mRNA

degradation or translational inhibition (3,27).

Growing evidence suggests that miRNA-mediated dysregulation of FLS

functions, including proliferation, apoptosis and migration, plays

a pivotal role in RA progression through downstream signaling

pathways (28). Among these,

miR-369-3p has been identified as a pleiotropic regulator of

metabolism and inflammation, demonstrating protective effects in

multiple diseases (21). Its

upregulation suppresses lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced

inflammatory responses by downregulating cytokines such as C/EBP-β,

TNF-α and IL-6 and inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation through

modulation of deubiquitination pathways (such as Brcc3

downregulation in macrophages), reducing caspase-1-mediated

secretion of pro-inflammatory mediators, including IL-1β and IL-18

(29–31). Due to the key role of these

inflammatory cascades and cytokine networks in RA pathogenesis, the

dynamic expression of miR-369-3p is likely critical for disease

progression. In line with previous studies, the present study

demonstrated downregulation of miR-369-3p in RA-FLSs. Functional

experiments further reveal that modulation of miR-369-3p markedly

reduced SPTBN1 expression and influenced both immune-mediated

inflammation and bone metabolism via the Wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway.

SPTBN1, which encodes βII-spectrin, is a member of

the spectrin family and serves as an actin-crosslinking

cytoskeletal protein, playing a key role in organizing

transmembrane proteins and cellular organelles (32). Emerging studies have shown that

SPTBN1 modulates disease progression and prognosis by influencing

multiple signaling pathways. For instance, it suppresses primary

osteoporosis by inhibiting osteoblast activity via the Smad3/TGF-β

and STAT1/Cxcl-9 pathways, therefore reducing bone microvascular

blood flow and decreasing VEGF expression (33). In epithelial ovarian cancer, SPTBN1

inhibits tumor progression by regulating the cell cycle through the

suppression of the JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway via SOCS3 (34). Furthermore, SPTBN1 modulates the

Wnt pathway by regulating Kallistatin, a Wnt inhibitor, restraining

the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (35). SPTBN1 has been proposed as a

biomarker to predict therapeutic responses to Wnt/β-catenin pathway

inhibitors.

As a cytoskeletal protein, SPTBN1 has been

recognized for its tumor-suppressive effects in cancer and

osteoporosis, primarily through the inhibition of the Wnt pathway;

however, its role in RA remains largely unexplored. In the present

study, miR-369-3p directly targets SPTBN1, with this miRNA-mediated

regulation affecting β-catenin nuclear translocation. The present

study revealed for the first time, to the best of the authors'

knowledge, that the SPTBN1/Wnt/β-catenin pathway plays a critical

role in RA-related synovial inflammation and bone destruction,

broadening our understanding of Wnt pathway regulation in the

context of autoimmune disease.

Bone destruction in RA results from the synergistic

interplay between synovial inflammation and osteoclast activation,

with the RANKL/RANK/OPG and the Wnt signaling pathway serving as

central regulatory nodes. The present study demonstrated that

miR-369-3p orchestrated the regulation of inflammatory cytokines

and bone metabolism markers through the SPTBN1/Wnt/β-catenin

pathway, highlighting the integrative role of epigenetic factors

within the ‘immunity-bone’ regulatory network. This finding

overcomes the limitations of traditional single-pathway approaches

by revealing the crosstalk between immune regulation and skeletal

homeostasis.

However, the present study has certain limitations.

It relies exclusively on in vitro cell models and lacks

validation in RA animal models or clinical samples. Further

investigations are required to confirm the in vitro

expression patterns and functional relevance of miR-369-3p. In

addition, the upstream regulatory mechanisms of miR-369-3p, such as

transcription factors or inflammatory signals influencing its

promoter, remain unexplored, which limits a comprehensive

understanding of its hierarchical regulation in RA.

Translating miR-369-3p-based therapies into clinical

applications also faces several challenges. First, delivery

efficiency is a major concern: Naked miRNAs are rapidly degraded by

nucleases in vivo and current systemic administration

methods struggle to target RA-affected synovial tissues

effectively, potentially reducing therapeutic impact. Second, miRNA

stability remains an issue, even with delivery vectors. In

addition, the miRNAs may be quickly cleared by the

reticuloendothelial system, necessitating repeated administration

and increasing the risk of off-target effects. Third, the potential

for immune activation cannot be ignored: Exogenous miRNAs or

delivery systems, such as lipid nanoparticles, may provoke innate

immune responses via Toll-like receptors, unintentionally

exacerbating inflammation in RA. Finally, off-target effects are

intrinsic to miRNA therapies because a single miRNA can regulate

multiple mRNAs. For instance, miR-369-3p may influence genes

unrelated to the SPTBN1/Wnt/β-catenin pathway in other tissues,

potentially disrupting normal bone metabolism or immune

homeostasis.

Future studies will aim to validate the therapeutic

efficacy of miR-369-3p mimics in animal models and clinical

cohorts, assessing their capacity to alleviate joint inflammation

and prevent bone erosion. At the same time, efforts will focus on

optimizing delivery strategies, such as the development of

synovial-targeted nanocarriers, to improve the stability and

tissue-specific delivery of miR-369-3p mimics. Furthermore,

bioinformatics-guided target screening, combined with in

vitro validation, will be employed to identify and avoid

off-target genes, while minimizing risks to immune activation.

These approaches aim to improve the safety, specificity and

therapeutic potential of miR-369-3p-based interventions for RA.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by National Administration of

Traditional Chinese Medicine High-Level Key Discipline Construction

Project-Traditional Chinese Medicine Arthralgia and Bi Syndrome

[project no.: (2023)85], Anhui Provincial Clinical Medical Research

Transformation Special Project (grant no. 202304295107020110) and

the Anhui Province Young Leading Talents Support Program, funded by

the Central Government Development Office [grant no. (2022)4].

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

AW was involved in the study conception and protocol

design, the collection and collation of experimental data; drafted

the initial manuscript and revised the paper. YW was responsible

for experimental design, verification and validation. FL and SD

were responsible for the statistical analysis of experimental data.

ZC and MS participated in the experimental process. AW and YW

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The collection and use of peripheral blood samples

from patients with RA were approved by the Ethics Committee of the

First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui University of Chinese Medicine

(approval no.: 2023AH-52). All patients with RA signed the informed

consent form prior to blood sample collection.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Ding Q, Hu W, Wang R, Yang Q, Zhu M, Li M,

Cai J, Rose P, Mao J and Zhu YZ: Signaling pathways in rheumatoid

arthritis: Implications for targeted therapy. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 8:682023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Kmiołek T and Paradowska-Gorycka A: miRNAs

as biomarkers and possible therapeutic strategies in rheumatoid

arthritis. Cells. 11:4522022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Payet M, Dargai F, Gasque P and Guillot X:

Epigenetic regulation (including micro-RNAs, DNA methylation and

histone modifications) of rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic

review. Int J Mol Sci. 22:121702021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Nag S, Mitra O, Tripathi G, Samanta S,

Bhattacharya B, Chandane P, Mohanto S, Sundararajan V, Malik S,

Rustagi S, et al: Exploring the theranostic potentials of miRNA and

epigenetic networks in autoimmune diseases: A comprehensive review.

Immun Inflamm Dis. 11:e11212023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Yao Q, Chen Y and Zhou X: The roles of

microRNAs in epigenetic regulation. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 51:11–17.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Diener C, Keller A and Meese E: The

miRNA-target interactions: An underestimated intricacy. Nucleic

Acids Res. 52:1544–1557. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Sell MC, Ramlogan-Steel CA, Steel JC and

Dhungel BP: MicroRNAs in cancer metastasis: Biological and

therapeutic implications. Expert Rev Mol Med. 25:e142023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Gao B, Sun G, Wang Y, Geng Y, Zhou L and

Chen X: microRNA-23 inhibits inflammation to alleviate rheumatoid

arthritis via regulating CXCL12. Exp Ther Med. 21:4592021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Bao X, Ma L and He C: MicroRNA-23a-5p

regulates cell proliferation, migration and inflammation of

TNF-α-stimulated human fibroblast-like MH7A synoviocytes by

targeting TLR4 in rheumatoid arthritis. Exp Ther Med. 21:4792021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wang X, Liu D, Cui G and Shen H:

Circ_0088036 mediated progression and inflammation in

fibroblast-like synoviocytes of rheumatoid arthritis by

miR-1263/REL-activated NF-κB pathway. Transpl Immunol.

73:1016042022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhou Q, Haupt S, Kreuzer JT, Hammitzsch A,

Proft F, Neumann C, Leipe J, Witt M, Schulze-Koops H and Skapenko

A: Decreased expression of miR-146a and miR-155 contributes to an

abnormal treg phenotype in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann

Rheum Dis. 74:1265–1274. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Liu N, Feng X, Wang W, Zhao X and Li X:

Paeonol protects against TNF-α-induced proliferation and cytokine

release of rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes by

upregulating FOXO3 through inhibition of miR-155 expression.

Inflamm Res. 66:603–610. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zisman D, Safieh M, Simanovich E, Feld J,

Kinarty A, Zisman L, Gazitt T, Haddad A, Elias M, Rosner I, et al:

Tocilizumab (TCZ) decreases angiogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis

through its regulatory effect on miR-146a-5p and EMMPRIN/CD147.

Front Immunol. 12:7395922021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kmiołek T, Rzeszotarska E, Wajda A,

Walczuk E, Kuca-Warnawin E, Romanowska-Próchnicka K, Stypinska B,

Majewski D, Jagodzinski PP, Pawlik A and Paradowska-Gorycka A: The

interplay between transcriptional factors and MicroRNAs as an

important factor for Th17/Treg balance in RA patients. Int J Mol

Sci. 21:71692020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Safari F, Damavandi E, Rostamian AR,

Movassaghi S, Imani-Saber Z, Saffari M, Kabuli M and Ghadami M:

Plasma levels of MicroRNA-146a-5p, MicroRNA-24-3p, and

MicroRNA-125a-5p as potential diagnostic biomarkers for rheumatoid

arthris. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 20:326–337. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wang C, Wang X, Cheng H and Fang J:

MiR-22-3p facilitates bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell

osteogenesis and fracture healing through the SOSTDC1-PI3K/AKT

pathway. Int J Exp Path. 105:52–63. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Wang S, Xiong G, Ning R, Pan Z, Xu M, Zha

Z and Liu N: LncRNA MEG3 promotes osteogenesis of hBMSCs by

regulating miR-21-5p/SOD3 axis. Acta Biochim Pol. 69:71–77.

2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lian F, Zhao C, Qu J, Lian Y, Cui Y, Shan

L and Yan J: Icariin attenuates titanium particle-induced

inhibition of osteogenic differentiation and matrix mineralization

via miR-21-5p. Cell Biol Int. 42:931–939. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Chang C, Xu L, Zhang R, Jin Y, Jiang P,

Wei K, Xu L, Shi Y, Zhao J, Xiong M, et al: MicroRNA-Mediated

epigenetic regulation of rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility and

pathogenesis. Front Immunol. 13:8388842022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Scalavino V, Piccinno E, Labarile N,

Armentano R, Giannelli G and Serino G: Anti-inflammatory effects of

miR-369-3p via PDE4B in intestinal inflammatory response. Int J Mol

Sci. 25:84632024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Rawal S, Randhawa V, Rizvi SHM, Sachan M,

Wara AK, Pérez-Cremades D, Weisbrod RM, Hamburg NM and Feinberg MW:

miR-369-3p ameliorates diabetes-associated atherosclerosis by

regulating macrophage succinate-GPR91 signalling. Cardiovasc Res.

120:1693–1712. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Mahmoud DE, Kaabachi W, Sassi N, Tarhouni

L, Rekik S, Jemmali S, Sehli H, Kallel-Sellami M, Cheour E and

Laadhar L: The synovial fluid fibroblast-like synoviocyte: A

long-neglected piece in the puzzle of rheumatoid arthritis

pathogenesis. Front Immunol. 13:9424172022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Xin PL, Jie LF, Cheng Q, Bin DY and Dan

CW: Pathogenesis and function of interleukin-35 in rheumatoid

arthritis. Front Pharmacol. 12:6551142021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Waltereit-Kracke V, Wehmeyer C, Beckmann

D, Werbenko E, Reinhardt J, Geers F, Dienstbier M, Fennen M,

Intemann J, Paruzel P, et al: Deletion of activin a in mesenchymal

but not myeloid cells ameliorates disease severity in experimental

arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 81:1106–1118. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Nygaard G and Firestein GS: Restoring

synovial homeostasis in rheumatoid arthritis by targeting

fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 16:316–333. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Mirzaei R, Zamani F, Hajibaba M,

Rasouli-Saravani A, Noroozbeygi M, Gorgani M, Hosseini-Fard SR,

Jalalifar S, Ajdarkosh H, Abedi SH, et al: The pathogenic,

therapeutic and diagnostic role of exosomal microRNA in the

autoimmune diseases. J Neuroimmunol. 358:5776402021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Peng Y, Zhang M and Hu J: Non-coding RNAs

involved in fibroblast-like synoviocyte functioning in arthritis

rheumatoid: From pathogenesis to therapy. Cytokine. 173:1564182024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Scalavino V, Liso M, Cavalcanti E, Gigante

I, Lippolis A, Mastronardi M, Chieppa M and Serino G: miR-369-3p

modulates inducible nitric oxide synthase and is involved in

regulation of chronic inflammatory response. Sci Rep. 10:159422020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Galleggiante V, De Santis S, Liso M, Verna

G, Sommella E, Mastronardi M, Campiglia P, Chieppa M and Serino G:

Quercetin-induced miR-369-3p suppresses chronic inflammatory

response targeting C/EBP-β. Mol Nutr Food Res. 63:e18013902019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Scalavino V, Piccinno E, Valentini AM,

Schena N, Armentano R, Giannelli G and Serino G: miR-369-3p

modulates intestinal inflammatory response via BRCC3/NLRP3

inflammasome axis. Cells. 12:21842023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Susuki K, Zollinger DR, Chang KJ, Zhang C,

Huang CY, Tsai CR, Galiano MR, Liu Y, Benusa SD, Yermakov LM, et

al: Glial βII spectrin contributes to paranode formation and

maintenance. J Neurosci. 38:6063–6075. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Xu X, Yang J, Ye Y, Chen G, Zhang Y, Wu H,

Song Y, Feng M, Feng X, Chen X, et al: SPTBN1 prevents primary

osteoporosis by modulating osteoblasts proliferation and

differentiation and blood vessels formation in bone. Front Cell Dev

Biol. 9:6537242021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Chen M, Zeng J, Chen S, Li J, Wu H, Dong

X, Lei Y, Zhi X and Yao L: SPTBN1 suppresses the progression of

epithelial ovarian cancer via SOCS3-mediated blockade of the

JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway. Aging (Albany NY). 12:10896–10911.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zhi X, Lin L, Yang S, Bhuvaneshwar K, Wang

H, Gusev Y, Lee MH, Kallakury B, Shivapurkar N, Cahn K, et al:

βII-Spectrin (SPTBN1) suppresses progression of hepatocellular

carcinoma and Wnt signaling by regulation of Wnt inhibitor

kallistatin. Hepatology. 61:598–612. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|