Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) comprise chronic

as well as recurrent gastrointestinal conditions. A recent study

has reported on the notable increase in the global prevalence of

IBD, predominantly characterized by Crohn's disease (CD) and

ulcerative colitis (UC) (1).

Impaired intestinal barrier integrity is a contributing factor in

the pathogenesis of IBD and is closely associated with its

pathophysiology (2,3). Despite this, there is a

characteristic lack of therapeutic options that specifically

enhance mucosal barrier function and promote its regeneration in

IBD, which is likely owing to a limited understanding of the

underlying biological pathways and regulatory molecules involved

(4). Although various potential

therapeutic approaches have been developed for improving mucosal

barrier function (4,5), to the best of our knowledge, no

regenerative strategies have yet been developed specifically for

IBD.

Glycosylation is a post-translational modification

affecting proteins, lipids and RNA, which can profoundly influence

the structural and functional characteristics of the modified

molecules (6–8). This modification is important for

regulating a variety of biological mechanisms, including protein

maturation, transport and immune modulation (9). Glycosylation is also implicated in

the pathophysiology of severe diseases, such as during

carcinogenesis, and inflammation; a previous study also

demonstrated its association with IBD (10). In healthy individuals, protein

glycoforms exhibit substantial stability over time; however, they

tend to undergo notable alterations in response to pathological

conditions, particularly during inflammatory states. For example,

patients diagnosed with IBD exhibit increased expression levels of

short-chain O-glycans in the intestine compared with healthy

individuals, accompanied by alterations in the expression of

terminal glycan structures (for example, increased sialylation,

enhanced fucosylation, reduced sulfation and dysregulated Lewis

antigens). These changes adversely affect the integrity of the

intestinal mucus layer, impede glycan-lectin interactions, disrupt

the dynamic balance of the intestinal microbiota and impair the

functionality of the intestinal mucosal immune system (11).

Different sialylation modifications are catalyzed by

various sialyltransferases. However, any alterations in the

expression levels of sialyltransferases change their physiological

functions. For example, a decrease in sialyltransferase ST6GalNAc1

(ST6)-catalyzed α2,6-sialylation in mice results in impaired mucus

barrier function, gut microbiota dysbiosis and increased

susceptibility to intestinal inflammation (12). The α2,6-sialylation catalyzed by

ST6Gal1 promotes the activation of CD4+ T cells and

induces the development of UC (13), whereas α2,8-sialylation catalyzed

by ST8Sia4 facilitates the metastasis of breast cancer cells

(14). However, the role of

ST3Gal1-catalyzed α2,3-sialylation in intestinal inflammation

remains to be fully elucidated.

The upregulation of ST3Gal1 augments the sialylation

of O-glycan Tn and catalyzes its conversion into sialyl-Tn. This

modification introduces an α2,3-linkage between Gal and

β1,3-GalNAc, which is frequently observed in various cancer types,

including breast cancer and hematological malignancies, where the

upregulation of sialyltransferases leads to premature termination

of aberrant mucin-type O-glycan chains (15,16).

Notably, mucin-type O-linked glycosylation is not restricted to

mucins; this modification also occurs in an array of cell-surface

glycoproteins (17). Emerging

evidence has highlighted that glycosylation in intestinal

epithelial cells (IECs) is associated with specific

glycosyltransferases; however, the functional role of

ST3Gal1-catalyzed α2,3-sialylation, a key glycosylation event

mediated by this glycosyltransferase, in the regulation of

intestinal barrier function has often been neglected in relevant

research. Dysregulation of glycosylation exacerbates intestinal

inflammation by damaging the intestinal barrier integrity,

interfering with glycan-lectin interactions, disrupting intestinal

microbiota dynamics and impairing mucosal immunity (18–20).

Given that ST3Gal1-catalyzed α2,3-linkage formation

at the end of N-glycan or O-glycan is associated with

carcinogenesis, as well as a host of other diseases, it is

necessary to evaluate prognostic factors, identify predictive

biomarkers and explore possible therapeutic targets associated with

ST3Gal1 activity, particularly in IBD (15,21).

However, there is limited research on ST3Gal1 and its impact on the

function of the intestinal barrier.

The present study aimed to explore the potential

role of ST3Gal1-catalyzed α2,3-linkage in IBD, along with its

underlying mechanisms. The present experimental study employed an

in vitro triple-cell co-culture system to replicate both the

healthy and inflamed states of the human intestine to investigate

the impact of ST3Gal1-mediated α2,3-sialylation on the integrity of

intestinal mucosal barrier function. Notably, in the present model,

each cell type embodied distinct roles: i) Caco-2 cells formed a

monolayer that mimicked IECs; ii) HT29-MTX-E12 cells secreted mucus

and acted as a surrogate for intestinal goblet cells; and iii)

THP-1 cells, upon induction with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

(PMA), differentiated into macrophage-like cells, simulating

intestinal inflammatory cells (22–24).

The present model adhered to the principles of the 3R framework,

which are replacement, reduction and refinement of animal model

usage, thus underscoring the increasing importance of in

vitro models in intestinal health research (25).

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The colorectal cancer cell line HT-29-MTX was

sourced from Beijing Bohui Innovation Biotechnology Co., Ltd.,

whereas the THP-1 human monocytic leukemia and Caco-2 human

colorectal adenocarcinoma cell lines were obtained from The Cell

Bank of Type Culture Collection of The Chinese Academy of Sciences.

All cells were authenticated by short tandem repeat profiling and

were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Merck KGaA) supplemented with

10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HyClone™; Cytiva). Cell

cultures were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5%

CO2.

Cell culture model

To establish an IEC monolayer, Caco-2 and

HT29-MTX-E12 cells were co-seeded at a total density of

8×104 cells/well into the apical compartment of 24-well

Transwell inserts (pore size, 0.4 µm; Wuxi NEST Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.) at a ratio of 9:1, based on this ratio and total cell

density, the seeding number of Caco-2 cells was 7.2×104

cells/well, and that of HT29-MTX-E12 cells was 8×103

cells/well, followed by a differentiation period of 19 days.

Concurrently, the culture medium was replaced three times a week to

maintain optimal growth conditions. Additionally, THP-1 cells were

stimulated to differentiate into macrophage-like cells by applying

PMA (100 ng/ml; Beyotime Biotechnology) at 37°C with 5%

CO2 for 48 h in 24-well plates. Subsequently, the

differentiated macrophage-like THP-1 cells were cultured in the

basolateral compartment of the same Transwell plate. The IEC

monolayer and macrophage-like THP-1 cells were co-cultured for 24 h

under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO2) to simulate the

intestinal mucosa in vitro.

ST3Gal1 overexpression (ST3Gal1-OE)

assay

Lentiviral vectors designed for the overexpression

of ST3Gal1 were procured from Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. The

ST3Gal1-OE lentiviral vector was constructed using the

LV5(EF-1α/CopGFP&Puro) backbone, based on the 3rd-generation

lentiviral system, with a working concentration of

1×1010 plaque-forming units (PFU)/ml. The lentiviral

particles were produced by transfecting 293T cells (American Type

Culture Collection). For transfection, a total of 10 µg plasmids

was used, and the molar ratio of lentiviral expression plasmid

(ST3Gal1-OE)/packaging plasmid/envelope plasmid was 4:3:1. The

transfection was performed using Lipofectamine® 3000

Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

according to the manufacturer's instructions, under the conditions

of 37°C and 5% CO2 for a duration of 48 h to facilitate

lentivirus production. The negative control for overexpression

experiments was an empty LV5 vector (Shanghai GenePharma Co.,

Ltd.), used at the same concentration (1×1010

PFU/ml).

Following the precise guidelines set forth by the

manufacturer, infection of the cells in the triple co-culture model

was performed within the Transwell system, with lentiviral vectors

added to both the upper and lower chambers. For lentiviral

transduction, polybrene (Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd.) was added

to the culture medium at a final concentration of 5 µg/ml to

enhance infection efficiency, and the lentiviral particles were

used at a multiplicity of infection of 10. The infected cells were

then incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Subsequently, 4 µg/ml puromycin

(MilliporeSigma; Merck KGaA) was used for the initial selection of

stably infected cell lines for 7 days, followed by maintenance with

2 µg/ml puromycin thereafter. These cell lines were subsequently

classified as OE-Ctr/IEC (negative control group) and

ST3Gal1-OE/IEC groups. Cells were collected on day 9 post-infection

(after the completion of the 1-day infection plus a 7-day selection

process), and the successful overexpression of ST3Gal1 was

confirmed through reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

and western blot analysis.

ST3Gal1 interference assay

Adenoviral particles designed for interfering with

the ST3Gal1 enzyme were obtained from Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd.

The adenoviral constructs were based on the ADV1(U6/CMV-GFP) vector

(2nd-generation adenoviral expression system), which separately

harbored three distinct ST3Gal1-targeting short hairpin RNA (shRNA;

ST3Gal1-sh) inserts or a non-targeting scrambled negative control

shRNA (sh-Ctr). The specific interference target sequences and

full-length sense/antisense shRNA fragments were as follows:

ST3Gal1 sh1, target sequence 5′-GCACCATTTCCCACACCTACA-3′, sense

strand′-AATTCGCACCATTTCCCACACCTACATTCAAGAGATGTAGGTGTGGGAAATGGTGCTTTTTTG-3′,

antisense strand

5′-GATCCAAAAAAGCACCATTTCCCACACCTACATCTCTTGAATGTAGGTGTGGGAAATGGTGCG-3′;

ST3Gal1 sh2, target sequence 5′-GCATCCTCTCGGTCATCTTCT-3′, sense

strand

5′-AATTCGCATCCTCTCGGTCATCTTCTTTCAAGAGAAGAAGATGACCGAGAGGATGCTTTTTTG-3′,

antisense strand

5′-GATCCAAAAAAGCATCCTCTCGGTCATCTTCTTCTCTTGAAAGAAGATGACCGAGAGGATGCG-3′;

ST3Gal1 sh3, target sequence 5′-GGTTCGATGAGAGGTTCAACC-3′, sense

strand

5′-AATTCGGTTCGATGAGAGGTTCAACCTTCAAGAGAGGTTGAACCTCTCATCGAACCTTTTTTG-3′,

antisense strand

5′-GATCCAAAAAAGGTTCGATGAGAGGTTCAACCCTCTCTTGAAGGTTGAACCTCTCATCGAACCG-3′;

and sh-Ctr, target sequence 5′-GTTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′, sense

strand

5′-GATCCGTTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTTTCAAGAGAACGTGACACGTTCGGAGAACTTTTTTG-3′,

antisense strand

5′-AATTCAAAAAAGTTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTTCTCTTGAAACGTGACACGTTCGGAGAACG-3′.

The adenoviral particles were produced by transfecting 293T cells.

For transfection, 10 µg plasmids were used per 10-cm culture dish,

and the molar ratio of adenoviral expression plasmid (ST3Gal1-sh or

sh-Ctr)/packaging plasmid/envelope plasmid was 1:1:1. The

transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 3000 Transfection

Reagent, according to the manufacturer's instructions, at 37°C in a

humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 48 h before

collecting the adenoviral supernatant.

The triple co-culture cells cultured within the

Transwell system were infected with these adenoviral particles in

accordance with the manufacturer's guidelines, with adenoviral

particles added to both the upper and lower chambers of the

Transwell system. The infection procedure was consistent with that

used for the infection of overexpression lentiviral vectors

aforementioned. These cell lines were subsequently classified as

sh-Ctr/IEC and ST3Gal1-sh/IEC groups. The working concentration of

adenovirus particles carrying interfering fragments was

1×1010 PFU/ml, and that of negative control adenovirus

particles was 1×1010 PFU/ml. For adenoviral infection,

the MOI was set at 40. Specifically, cells were collected at 48 h

post-infection, and the efficiency of the interference was assessed

through RT-qPCR and western blot analysis.

Induction of inflammation in the IEC

monolayer

To establish an in vitro UC cell model,

ST3Gal1-sh/IEC or ST3Gal1-OE/IEC and their controls were treated

with 2% DSS (MilliporeSigma) and incubated in a cell culture

incubator at 37°C for 4 days (26,27).

The supernatants were collected by centrifuging the cell cultures

at 3,000 × g and 4°C for 10 min, and were employed for subsequent

experiments.

RT-qPCR

RNA was isolated and PCR was carried out following

the methodologies detailed in our earlier study (28). Briefly, total RNA was extracted

from triple co-culture cells, including ST3Gal1-sh, ST3Gal1-OE and

their respective negative control cells, using the RNA Isolation

Kit (MilliporeSigma; Merck KGaA). RNA purity was assessed by

evaluating the A260/A280 ratio (1.8–2.0) with a NanoDrop 2000

spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). RNA integrity

was verified through 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and by using an

Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc.), obtaining an

RNA integrity number >8.0. cDNA synthesis was performed using

the PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara Bio Inc.,

Japan), according to the manufacturer's protocol. For qPCR, the

SYBR® Green Premix Pro Taq HS qPCR Kit (Hunan Accurate

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was used, with SYBR Green as the PCR

fluorophore. Thermocycling conditions were as follows:

Pre-denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C

for 30 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. β-actin was used as the internal

reference gene for normalization. Quantification of the qPCR

results was performed using the 2−ΔΔCq method (29), and result analysis was performed

using Bio-Rad CFX Manager software (version 3.1; Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.). Table I

displays the sequences of PCR primers utilized in the present

experimental investigation.

| Table I.Primer sequences used in reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. |

Table I.

Primer sequences used in reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Primer | Sequence | Product length,

bp |

|---|

| ST3Gal1 |

| 74 |

|

Forward |

5′-TTCCGGGAGCTGGGAGATAA-3′ |

|

|

Reverse |

5′-CTCACCACCCACTCCAAGTC-3′ |

|

| MUC2 |

| 165 |

|

Forward |

5′-GGGGAGTGCTGTAAGAAGTGTGA-3′ |

|

|

Reverse |

5′-GTTGGAGACGGACGAGATGAG-3′ |

|

| TFF3 |

| 143 |

|

Forward |

5′-CTCCAGCTCTGCTGAGGAGT-3′ |

|

|

Reverse |

5′-CAGGGATCCTGGAGTCAAAG-3′ |

|

| CDX2 |

| 85 |

|

Forward |

5′-CAGGACGAAAGACAAATATC-3′ |

|

|

Reverse |

5′-GATGTAGCGACTGTAGTG-3′ |

|

| β-actin |

| 132 |

|

Forward |

5′-GTGATCTCCTTCTGCATCCTGT-3′ |

|

|

Reverse |

5′-CCACGAAACTACCTTCAACTCC-3′ |

|

| IL-1β |

| 153 |

|

Forward |

5′-CAGAAGTACCTGAGCTCGCC-3′ |

|

|

Reverse |

5′-AGATTCGTAGCTGGATGCCG-3′ |

|

| IL-6 |

| 166 |

|

Forward |

5′-TACCCCCAGGAGAAGATTCC-3′ |

|

|

Reverse |

5′-AGTGCCTCTTTGCTGCTTTC-3′ |

|

| IL-8 |

| 210 |

|

Forward |

5′-GTGCAGTTTTGCCAAGGAGT-3′ |

|

|

Reverse |

5′-ACTTCTCCACAACCCTCTGC-3′ |

|

| STAT3 |

| 237 |

|

Forward |

5′-CATCCTGAAGCTGACCCAGG-3′ |

|

|

Reverse |

5′-TCCTCACATGGGGGAGGTAG-3′ |

|

Western blotting

The procedures for protein extraction and detection

were carried out in accordance with the methodologies outlined in

our previous publication (26).

Briefly, total protein was isolated from the triple co-culture

cells, including ST3Gal1-sh cells, ST3Gal1-OE cells and their

corresponding negative control cells. Table II presents the information

regarding the manufacturer, cat. no. and dilution ratios for the

primary and secondary antibodies utilized in the present study.

| Table II.Antibodies used for western

blotting. |

Table II.

Antibodies used for western

blotting.

| A, Primary

antibodies |

|---|

|

|---|

| Name | Company | Cat. no. | Dilution |

|---|

| Rabbit polyclonal

IgG to ST3Gal1 | Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher | PA5-42726 | 1:1,000 |

|

| Scientific,

Inc. |

|

|

| Rabbit monoclonal

IgG to CDX2 | Abcam | ab76541 | 1:1,000 |

| Rabbit monoclonal

IgG to p-STAT3 | Abcam | ab76315 | 1:1,000 |

| Mouse monoclonal

IgG to MUC2 | Abcam | ab11197 | 1:1,000 |

| Rabbit Polyclonal

IgG to TFF3 | Proteintech Group,

Inc. | 23277-1-AP | 1:1,000 |

| Rabbit polyclonal

IgG to STAT3 | Proteintech Group,

Inc. | 10253-2-AP | 1:500 |

| Rabbit polyclonal

IgG to α-tubulin | Proteintech Group,

Inc. | 11224-1-AP | 1:1,000 |

|

| B, Secondary

antibodies |

|

| HRP-conjugated

Affinipure Goat | Proteintech Group,

Inc. | SA00001-2 | 1:10,000 |

| Anti-Rabbit IgG

(H+L) |

|

|

|

| HRP-conjugated

Affinipure Goat | Proteintech Group,

Inc. | SA00001-1 | 1:10,000 |

| Anti-Mouse IgG

(H+L) |

|

|

|

ELISA

Cell culture supernatants from each group were

collected by centrifuging the cell cultures at 3,000 × g and 4°C

for 10 min. The levels of multiple inflammatory mediators, such as

IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8, present in the harvested cell supernatants

were measured in accordance with the instructions outlined in the

ELISA kits specific to these inflammatory factors (Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.): IL-1β (cat. no. SEKH-0002),

IL-6 (cat. no. SEKH-0013), and IL-8 (cat. no. SEKH-0016).

Trans-epithelial electrical resistance

(TEER) assay

Cells from each group were plated at a density of

1×105 cells/well into the upper chambers of a 24-well

Transwell plate with a polyester membrane (pore size, 0.4 µm;

Costar; Corning, Inc.). For the Transwell co-culture assay, both

the upper and lower chambers were initially supplemented with DMEM

containing 10% FBS. Cells were co-cultured at 37°C with 5%

CO2 for 14 days, and 2 days before TEER measurement, the

media in both chambers were replaced with serum-free DMEM. The

resistance values of different cell models, including inflammatory

and non-inflammatory cell models, as well as their ST3Gal1

knockdown or overexpression cell models, were measured using a

resistance meter. The relative TEER values were calculated for each

group by comparison with the control.

FITC-dextran permeability assay

Subsequently, the permeability of different cell

models was studied. Notably, the setup of Transwell inserts used in

this permeability assay (other than the addition of FITC-dextran)

was consistent with that of the aforementioned protocol for TEER

measurement. FITC-dextran (4 kDa; MilliporeSigma) was added to the

apical compartment of Transwell inserts, with a final concentration

of 1 mg/ml. These cell models were incubated at 37°C for 2 h.

Subsequently, a 100-µl aliquot was aspirated from the lower

chamber, and the fluorescence value was measured using a microplate

reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) at an excitation wavelength of

492 nm and an emission wavelength of 520 nm. The relative

fluorescence values were calculated for each group by comparison

with the control.

Bioinformatics analysis

For ST3Gal1 expression analysis, datasets including

human normal samples and UC samples (GDS3119) (30), as well as UC lesional and

non-lesional samples (GSE107499) were obtained from the Gene

Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geoprofiles/?term=) and

analyzed. To investigate the relationship between ST3Gal1 and the

severity score of UC, relevant clinical data were extracted from

the GEO dataset GSE92415 (31) for

analysis. The GEO dataset GDS3859 (32) was used to analyze changes in the

mRNA levels of ST3Gal1 in DSS-treated mice. Additionally, the GEO

dataset GSE107499 was used to analyze the expression changes of

ST3Gal1, as well as the expression profiles of inflammatory

mediators, intestine-associated secretory proteins and signaling

pathway-related proteins in lesional and non-lesional tissues of

UC. Furthermore, the relationships among these factors and proteins

in the GSE107499 dataset, specifically within the lesional tissues

of UC, were investigated. Dataset processing and statistical

analysis were performed using GEO2R (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/geo2r/), an official

GEO tool. In the present study, this tool was specifically utilized

to extract and compare the expression levels of pre-specified

target genes (including ST3Gal1, MUC2, TFF3, CDX2, IL-1β, IL-6,

IL-8 and STAT3) between experimental groups (for example, UC

lesional mucosa vs. UC non-lesional mucosa, and healthy human colon

mucosa vs. UC colon mucosa).

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 6.0 software (Dotmatics) was utilized

for the graphical representation and statistical evaluation of

diverse data obtained during the experiment. Data are presented as

box and whisker plots (displaying median and interquartile range),

scatter plots or as the mean ± SD from at least three independent

replicates, with unpaired two-tailed t-test used for comparisons

between two groups and Pearson's correlation test used for

assessing linear correlations. In addition, one-way ANOVA with

Tukey's HSD post hoc multiple comparisons test was applied for

multi-group analyses. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

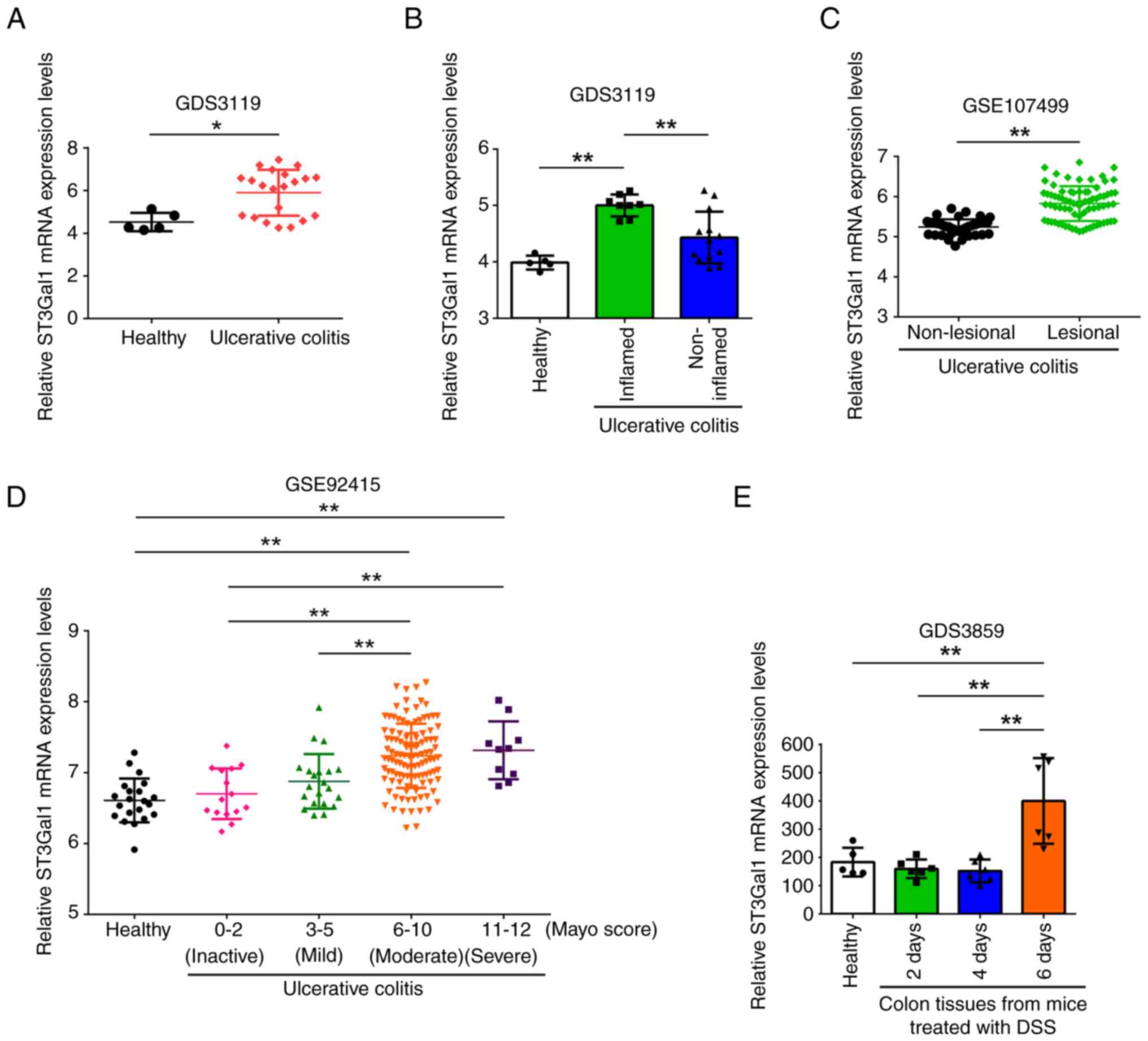

ST3Gal1 expression in intestinal

mucosa from patients with UC and the mouse DSS-induced colitis

model is related to the inflammatory status of colitis

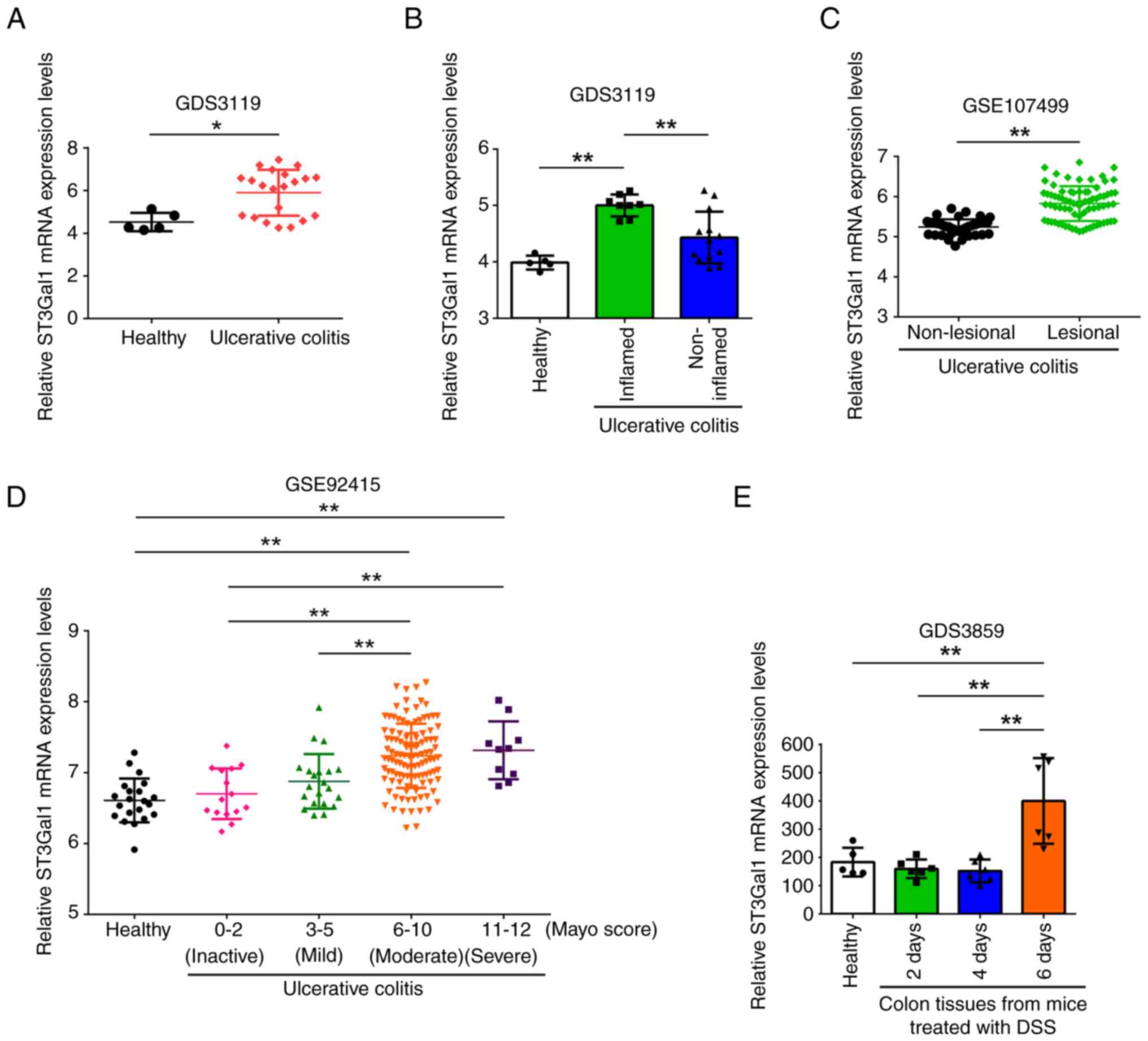

The present study compared the mRNA levels of

ST3Gal1 in normal human colon mucosa and the mucosa from patients

with UC obtained from the GDS3119 dataset in the GEO. The mRNA

expression levels of ST3Gal1 in the mucosal tissue of individuals

diagnosed with UC were significantly higher than those in healthy

colon mucosa (derived from healthy control individuals) (P<0.05;

Fig. 1A). Furthermore, mRNA levels

of ST3Gal1 in the inflamed mucosal regions of patients with UC were

significantly higher than those observed in normal colon mucosa.

Additionally, ST3Gal1 expression levels were significantly higher

in inflamed UC intestinal mucosa than in non-inflamed UC intestinal

mucosa (P<0.01; Fig. 1B).

Furthermore, the mRNA expression levels of ST3Gal1 in non-lesional

mucosa were significantly lower than those in lesional mucosa

(GSE107499; P<0.01; Fig. 1C).

Additionally, in patients with UC, ST3Gal1 mRNA within the inflamed

mucosa exhibited progressive, mostly significant upregulation

associated with an increasing modified Mayo score (GSE92415;

P<0.01; Fig. 1D).

| Figure 1.ST3Gal1 mRNA levels in intestinal

mucosa from patients with UC and a mouse DSS-induced colitis model

are associated with inflammatory states. (A) Comparison of ST3Gal1

mRNA levels between human normal colon mucosa from healthy controls

(n=5) and colonic mucosa from patients diagnosed with UC (n=21) in

the GDS3119 dataset from the GEO database. (B) ST3Gal1 mRNA levels

in human normal colonic tissues from healthy controls (n=5),

inflamed colonic tissues from patients with UC and visible

macroscopic inflammation (n=8), and non-inflamed colonic mucosal

tissues from patients with UC without macroscopic signs of

inflammation (n=13) in the GEO dataset GDS3119. (C) ST3Gal1 mRNA

levels in non-lesional mucosa (n=44) and lesional mucosa (n=75)

from different patients with UC, obtained from the GEO dataset

GSE107499. (D) ST3Gal1 mRNA levels in the normal mucosa (n=21) from

healthy controls and the inflamed mucosa (n=162) from patients with

UC with varying modified Mayo scores in the GEO dataset GSE92415.

(E) ST3Gal1 mRNA levels in colon tissues from mice treated with DSS

to induce colitis (independent, non-overlapping mice) divided into

four groups: Before DSS administration (n=5), and at 2, 4 and 6

days post-DSS treatment (n=6/group). Data were obtained from the

GEO dataset GDS3859. Data in A, C and D are presented as box and

whisker plots, whereas data in B and E are presented as the mean ±

SD. Statistical significance was determined using specific tests

for each subpart based on group comparisons: (A and C) Unpaired

t-test and (B, D and E) one-way analysis of variance followed by

Tukey's post-hoc test. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. DSS, dextran

sulfate sodium; GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; UC, ulcerative

colitis. |

The present study further analyzed the mRNA levels

of ST3Gal1 in the mucosa of the DSS-induced mouse colitis model.

The obtained ST3Gal1 mRNA levels were classified into four groups

based on DSS usage: The normal group, classified as mRNA levels

obtained prior to DSS administration, and those obtained 2, 4 and 6

days after DSS feeding. ST3Gal1 mRNA expression in the mucosa of

mice 6 days after DSS feeding was significantly higher than that in

all other groups analyzed (GDS3859; P<0.01; Fig. 1E).

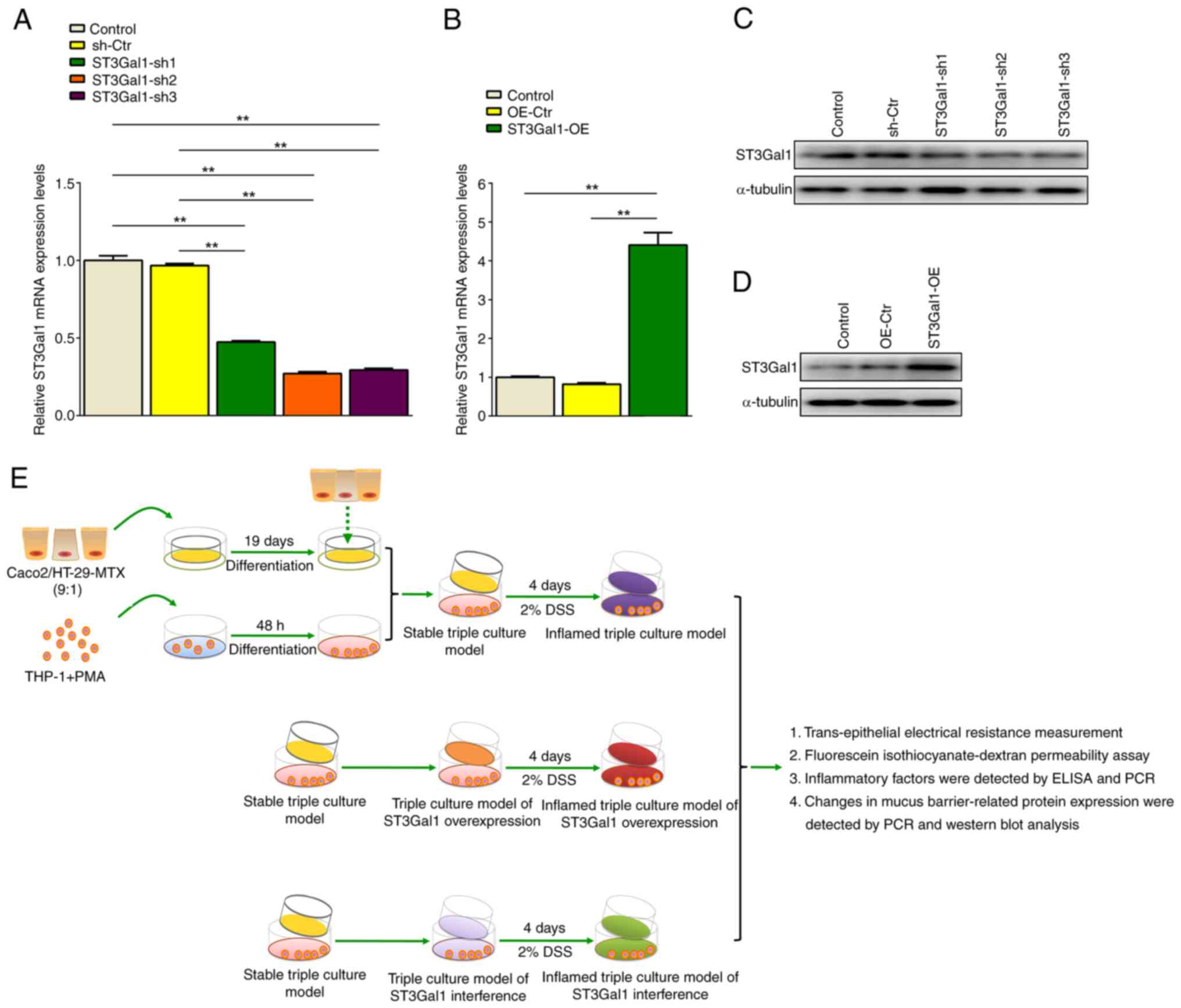

Establishment of an IEC monolayer and

ST3Gal1-knockdown or ST3Gal1-OE models

The present study first prepared an IEC monolayer

model through a co-culture of three distinct cell types, and then

obtained ST3Gal1-knockdown and ST3Gal1-OE IEC monolayer cell models

using either an ADV1(U6/CMV-GFP) vector and an ST3Gal1 interference

sequence insert or a ST3Gal1-OE lentiviral vector. The third

interference sequence (ST3Gal1-sh3) had the most efficient

inhibitory effect on ST3Gal1 expression in the IEC monolayer model,

named ST3Gal1-sh3/IEC for further experiments (P<0.01; Fig. 2A and C). A ST3Gal1-OE assay showed

that the ST3Gal1-OE group exhibited a significant increase in

ST3Gal1 expression at both mRNA and protein levels in the IEC

monolayer model compared with those in the untreated and

overexpression control groups (P<0.01; Fig. 2B and D). This model was designated

ST3Gal-OE/IEC for further experiments.

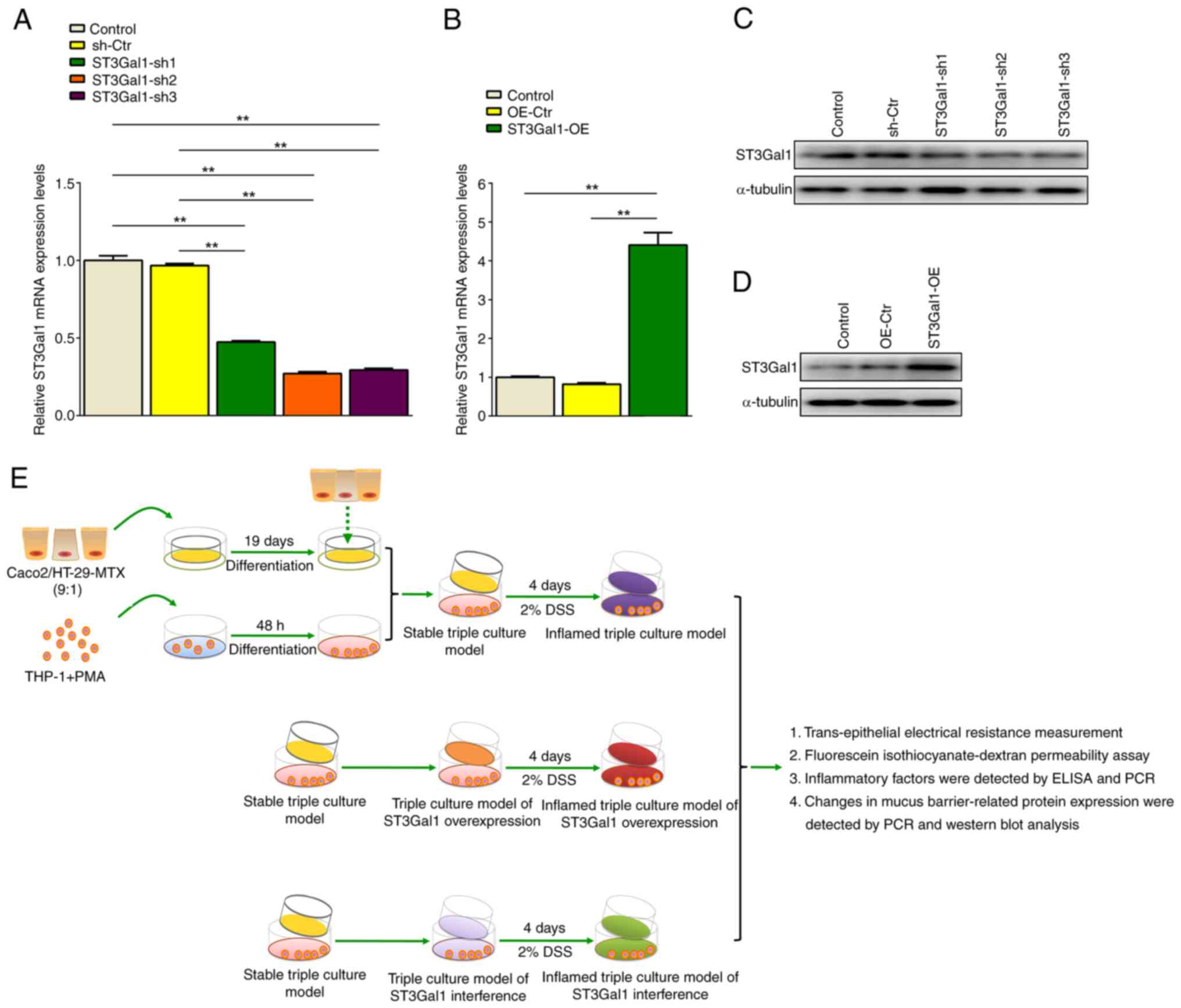

| Figure 2.Establishment of ST3Gal1-interfered

IEC and ST3Gal1-overexpressed IEC models, and the schematic

representation of IEC monolayer grouping. (A) ST3Gal1 mRNA levels

in IEC, sh-Ctr/IEC and ST3Gal1-interfered IEC groups 1–3. (B)

ST3Gal1 mRNA levels in IEC, OE-Ctr/IEC and ST3Gal1-OE/IEC groups.

(C) ST3Gal1 protein levels in IEC, sh-Ctr/IEC and

ST3Gal1-interfered IEC groups. (D) ST3Gal1 protein levels in IEC,

OE-Ctr/IEC and ST3Gal1-OE/IEC groups. (E) Establishment of IEC

monolayers containing sh-Ctr, ST3Gal1-sh3, OE-Ctr and ST3Gal1-OE.

The stable triple culture models were treated with fresh complete

medium supplemented with 2% DSS for 4 days to obtain inflamed

models. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Statistical

significance was assessed using one-way analysis of variance

followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. **P<0.01. IEC, intestinal

epithelial cell; sh, short hairpin; Ctr, control; OE,

overexpression; PMA, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate; DSS, dextran

sulfate sodium. |

The present study used IEC monolayer models to

replicate both healthy and inflamed states of the human intestine.

To establish an inflamed IEC monolayer model, the aforementioned

infection models were administered fresh complete medium enriched

with 2% DSS for 4 days. The resulting inflamed IEC monolayer model

was employed for investigating intestinal barrier integrity and

inflammatory mediator secretion (Fig.

2E).

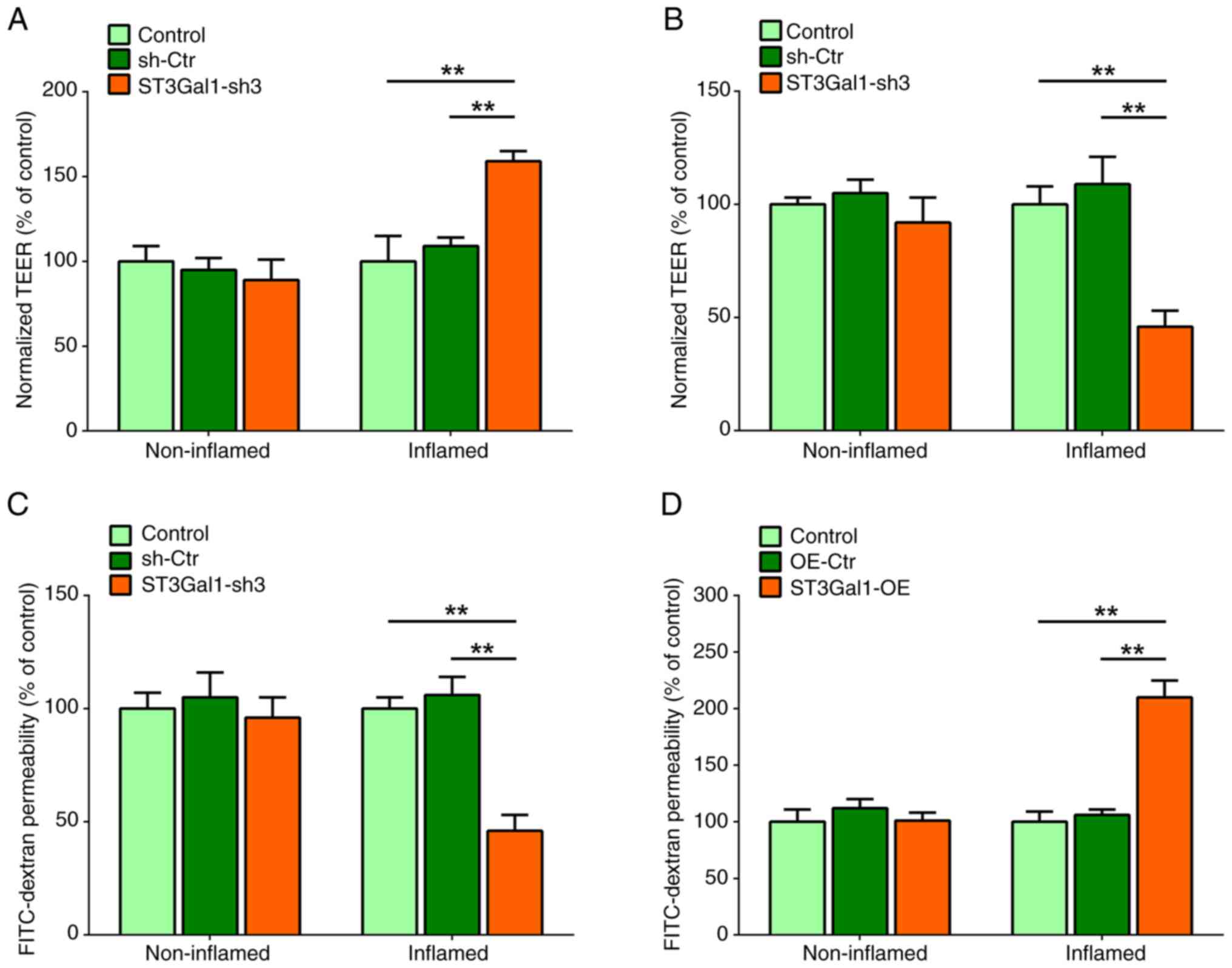

ST3Gal1 alters the barrier function of

the IEC monolayer

The IEC monolayer barrier was assessed by measuring

TEER. The TEER levels in the ST3Gal1-sh3/IEC group were

significantly higher than those in the IEC and sh-Ctr/IEC groups

after stimulation with 2% DSS (P<0.01; Fig. 3A). By contrast, no notable

differences in the TEER levels were observed among the non-inflamed

IEC monolayers of the stable triple culture models without 2% DSS

treatment (P>0.05; Fig. 3A).

The TEER levels of the inflamed ST3Gal1-OE/IEC group were

significantly lower compared with those in the IEC or Ctr/IEC

groups (P<0.01; Fig. 3B). By

contrast, no notable differences were observed among the

non-inflamed IEC monolayers of the stable triple culture models

(P>0.05; Fig. 3B). The impact

of modifications in ST3Gal1 expression on the permeability of IEC

monolayers was measured by performing a trans-epithelial

permeability assay using FITC-dextran. The assays demonstrated a

notable decrease in the FITC-dextran permeability of the inflamed

ST3Gal1-sh3/IEC population compared with that in the IEC and

sh-Ctr/IEC groups (P<0.01; Fig.

3C). However, no significant difference was observed among the

non-inflamed stable triple culture models (P>0.05; Fig. 3C). Notably, a significant increase

in the permeability of the inflamed ST3Gal1-OE/IEC group was noted

compared with that in the IEC and Ctr/IEC groups (P<0.01;

Fig. 3D). By contrast, the

non-inflamed triple culture models did not show any significant

differences in permeability (P>0.05; Fig. 3D). Therefore, it may be suggested

that ST3Gal1 interference in IECs enhanced the barrier function of

the IEC monolayer. However, enforced expression of the ST3Gal1 gene

in IECs damaged the barrier function of the IEC monolayer.

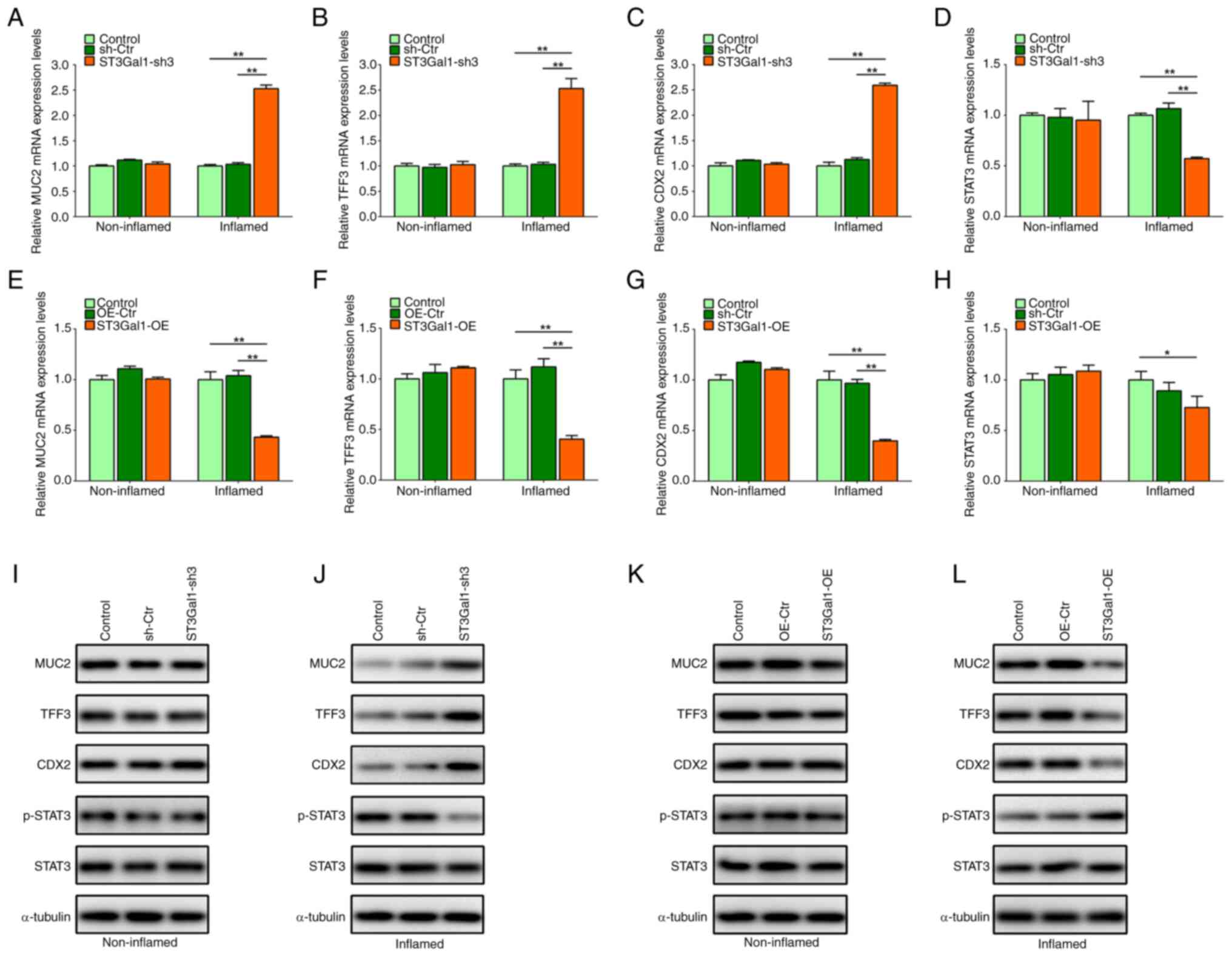

ST3Gal1 expression in the IEC

monolayer alters MUC2, TFF3 and CDX2 expression, as well as STAT3

phosphorylation

Owing to alterations in the intestinal epithelial

barrier caused by altered ST3Gal1 expression in the IEC monolayer,

the present study detected intestinal mucus barrier-associated MUC2

and TFF3, goblet cell differentiation-associated CDX2 expression

and inflammation-associated STAT3 phosphorylation in IEC

monolayers. The present study found that ST3Gal1 knockdown in IECs

significantly increased the mRNA levels of MUC2, TFF3 and CDX2, but

significantly decreased the mRNA levels of STAT3 in the inflamed

stable triple culture model compared with those in the control

groups (P<0.01; Fig. 4A-D). No

significant differences in MUC2, TFF3, CDX2 and STAT3 mRNA levels

were observed among the non-inflamed stable triple culture models

(P>0.05; Fig. 4A-D).

Overexpression of ST3Gal1 in IECs significantly reduced the mRNA

levels of MUC2, TFF3 and CDX2 in the inflamed stable triple culture

model compared with those in the control groups (P<0.05 or

P<0.01; Fig. 4E-H), and the

mRNA expression levels of STAT3 were decreased in the inflamed

stable triple culture model compared with those in the control

groups (P<0.05; Fig. 4H);

however, no significant difference was observed when compared with

the OE-Ctr group (P>0.05; Fig.

4H). No significant differences were observed in the mRNA

levels of MUC2, TFF3, CDX2 and STAT3 among the non-inflamed stable

triple-culture models (P>0.05; Fig.

4E-H).

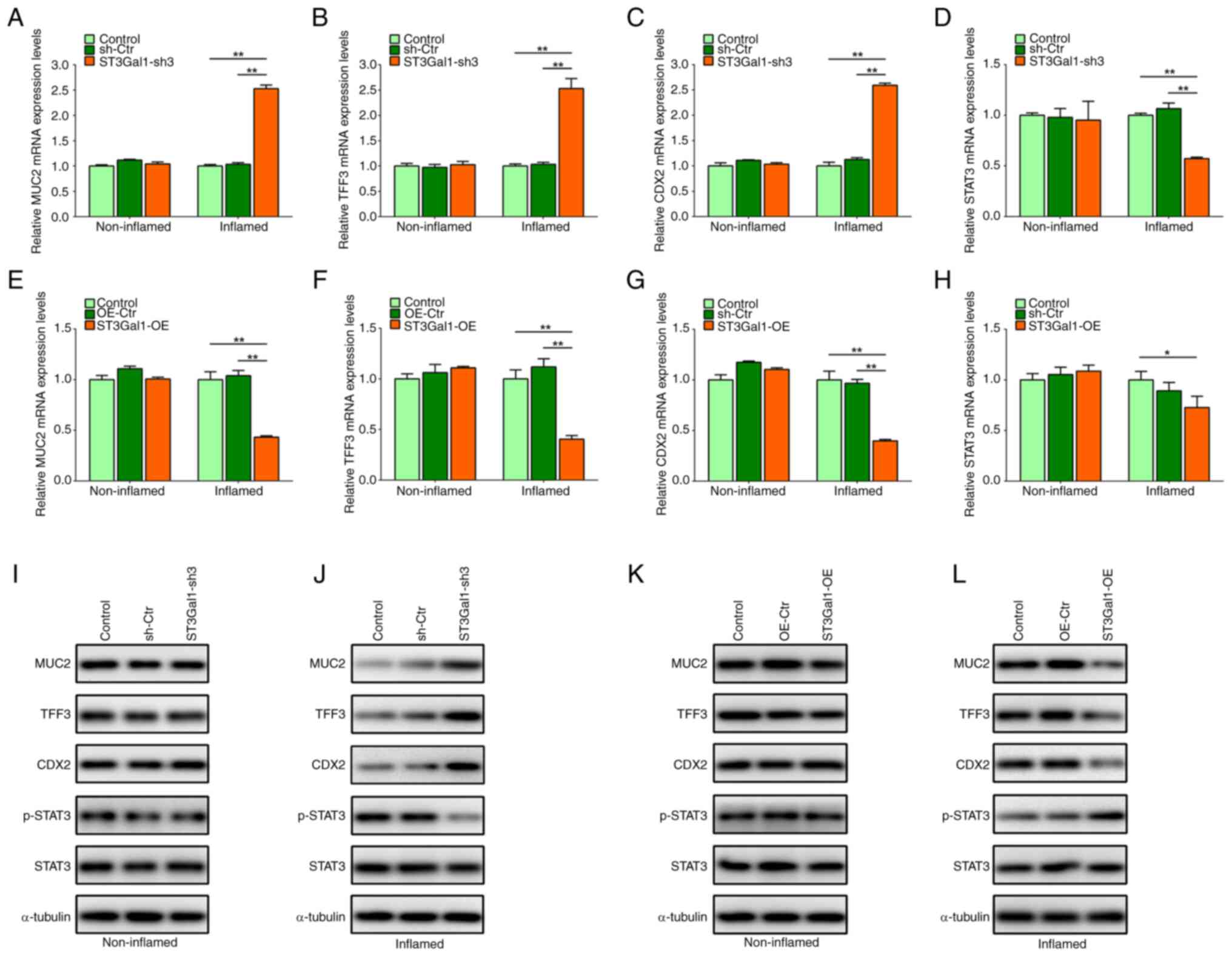

| Figure 4.ST3Gal1 expression in inflamed IEC

monolayers alters MUC2, TFF3, CDX2, STAT3 and p-STAT3 expression.

ST3Gal1 knockdown in ST3Gal1-sh3/IEC significantly increased (A)

MUC2, (B) TFF3 and (C) CDX2, but significantly reduced (D) STAT3

mRNA levels in the inflamed IEC monolayer. ST3Gal1 OE in

ST3Gal1-OE/IEC significantly reduced (E) MUC2, (F) TFF3 and (G)

CDX2 mRNA levels in the inflamed IEC monolayer. (H) ST3Gal1 OE in

ST3Gal1-OE/IEC slightly decreased STAT3 mRNA levels in the inflamed

IEC monolayer. (I) Western blotting showed no changes in protein

expression in non-inflamed knockdown samples. (J) Western blotting

showed that MUC2, TFF3 and CDX2 protein levels were increased, and

p-STAT3 expression was decreased in the inflamed IEC monolayer

comprising ST3Gal1-sh3/IEC. (K) Western blotting showed no notable

changes in protein expression in non-inflamed OE samples. (L)

Western blotting showed that MUC2, TFF3 and CDX2 protein levels

were decreased, and p-STAT3 expression was increased in the

inflamed IEC monolayer comprising ST3Gal1-OE/IEC. Data are

presented as the mean ± SD. Statistical significance was assessed

using one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post-hoc

test. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. IEC, intestinal epithelial cell;

sh, short hairpin; Ctr, control; OE, overexpression; MUC2, mucin 2;

TFF3, trefoil factor 3; CDX2, homeobox protein CDX-2; p-,

phosphorylated. |

The present study also detected the protein

expression levels of MUC2, TFF3, CDX2, phosphorylated (p)-STAT3 and

STAT3 in both the inflamed and non-inflamed stable triple culture

models. In the inflamed stable triple culture model comprising

ST3Gal1-sh3/IEC, the protein levels of MUC2, TFF3 and CDX2 were

increased, whereas p-STAT3 levels were notably decreased compared

with those in the control groups (Fig.

4J). However, no notable difference was noted in the MUC2,

TFF3, CDX2, STAT3 and p-STAT3 protein levels of the non-inflamed

stable triple culture models (Fig.

4I). Additionally, the protein levels of MUC2, TFF3 and CDX2

were notably decreased in the inflamed stable triple culture model

comprising ST3Gal1-OE/IEC, whereas p-STAT3 levels were increased

compared with those in the control groups (Fig. 4L). However, there were no marked

differences observed in the MUC2, TFF3, CDX2, STAT3 and p-STAT3

protein levels of the non-inflamed stable triple culture

overexpression model (Fig.

4K).

ST3Gal1 expression is correlated with

TFF3 and CDX2 mRNA levels in lesional mucosa obtained from patients

with UC

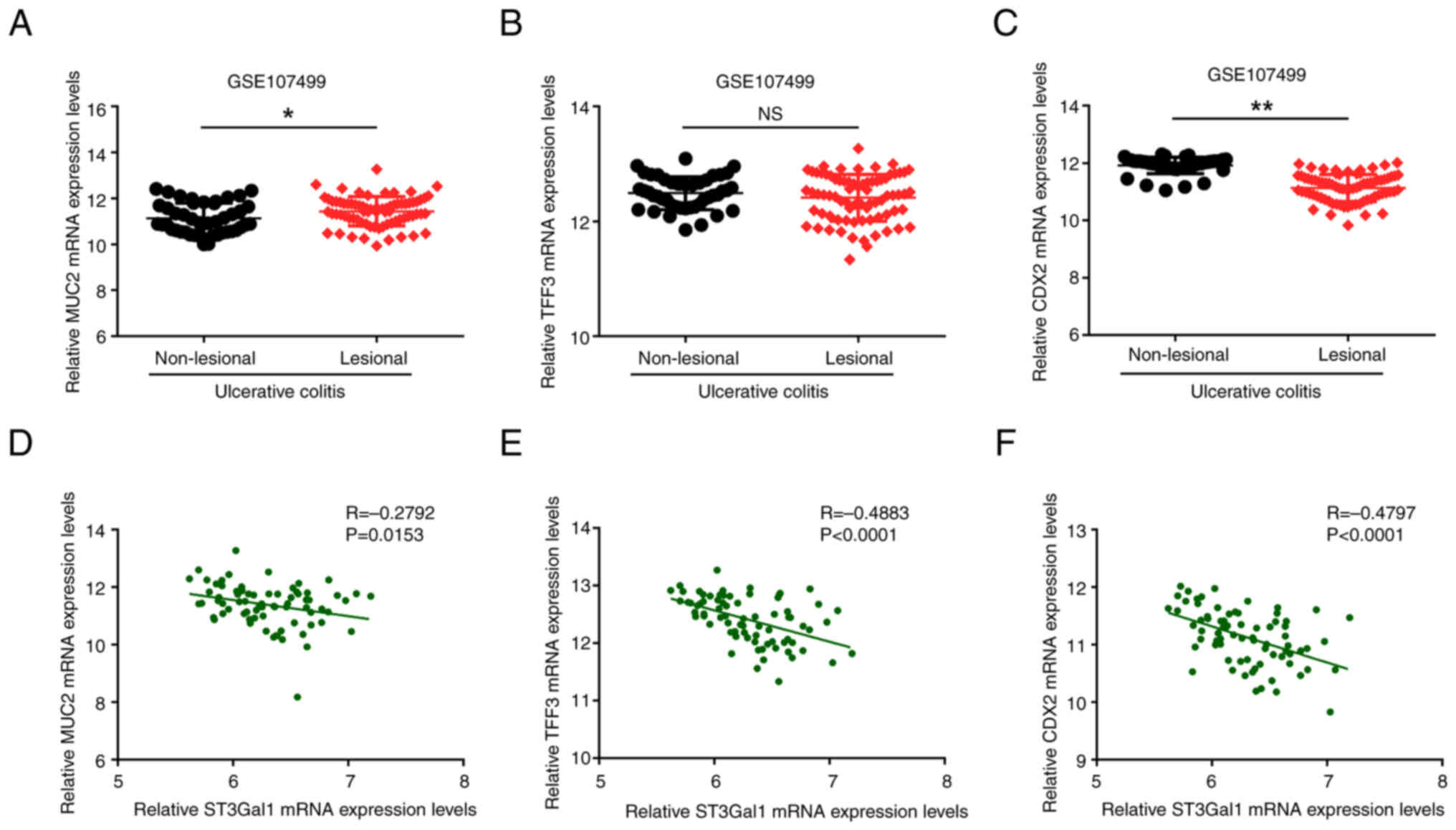

To support the relationship between ST3Gal1

expression and MUC2, TFF3 and CDX2 mRNA levels in patients with UC,

the expression dataset GSE107499 was downloaded, and the mRNA

levels of TFF3 and CDX2 in the non-lesional and lesional mucosa

from patients with UC, as well as their correlations with ST3Gal1

mRNA expression, were subsequently compared. As illustrated in

Fig. 5A, the mRNA expression

levels of MUC2 in the affected lesional mucosal tissue were

significantly elevated compared with those in the non-lesional

mucosa (P<0.05). By contrast, the TFF3 mRNA levels in the

lesional mucosa showed no significant difference when compared with

those in the non-lesional mucosa of patients with UC (P>0.05;

Fig. 5B). Notably, the mRNA levels

of CDX2 in the lesional mucosa were significantly lower than those

in non-lesional mucosa (P<0.01; Fig. 5C). The correlation analysis

revealed that the mRNA expression levels of ST3Gal1 in the lesional

mucosal tissue exhibited a negative correlation with the mRNA

levels of TFF3 (R=−0.4883; P<0.0001; Fig. 5E) and CDX2 (R=−0.4797; P<0.0001;

Fig. 5F) in patients diagnosed

with UC. However, no notable correlation was observed between

ST3Gal1 and of MUC2 expression in lesional tissues of patients with

UC (R=−0.2792; P<0.05; Fig.

5D).

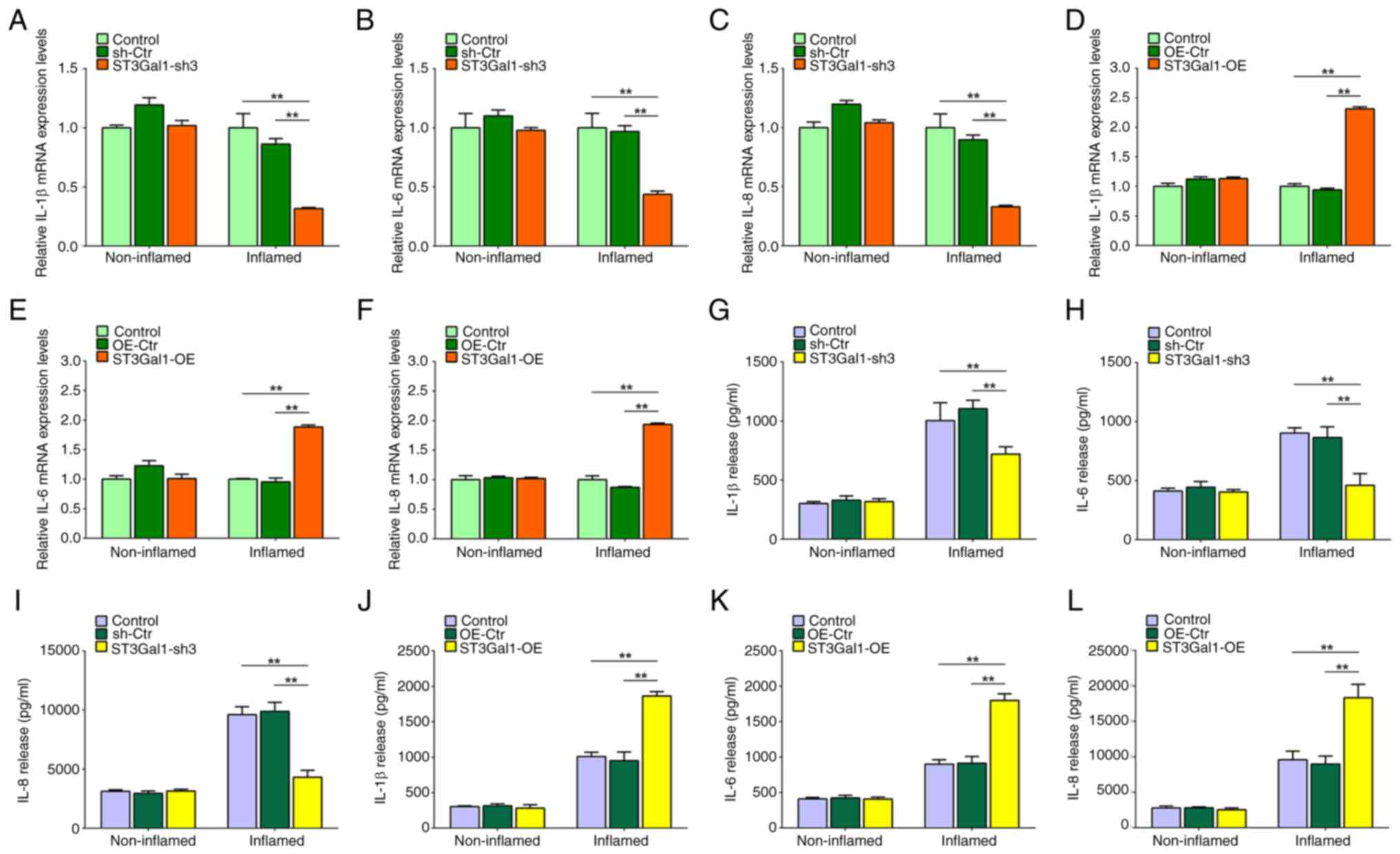

ST3Gal1 expression in the IEC

monolayer alters the expression of inflammatory mediators

Supernatants from the inflamed and non-inflamed

stable triple culture models comprising ST3Gal1-sh3/IEC and

ST3Gal1-OE/IEC were collected to detect the levels of inflammatory

mediators. The protein concentrations of inflammatory mediators

were quantified via ELISA, whereas the mRNA levels of inflammatory

mediators in cell lysates were assessed via RT-qPCR. Notably,

knockdown of ST3Gal1 significantly reduced the mRNA expression

levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 in the inflamed intestinal IEC

monolayer, compared with that in the control groups (P<0.01;

Fig. 6A-C). This analysis,

however, revealed no significant differences in the mRNA levels of

IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 among the non-inflamed IEC monolayers

(P>0.05; Fig. 6A-C). However,

the overexpression of ST3Gal1 in ST3Gal1-OE/IEC cells significantly

elevated the mRNA levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 within the

inflamed IEC monolayer compared with the control groups (P<0.01;

Fig. 6D-F). By contrast, the

non-inflamed IEC monolayer exhibited no significant differences in

the expression of these cytokines (P>0.05; Fig. 6D-F). Additionally, a significant

decrease in the protein concentrations of IL-1β (720.51±61.01

pg/ml), IL-6 (461.20±98.06 pg/ml) and IL-8 (4,325.37±579.25 pg/ml)

was observed in supernatants derived from the inflamed IEC

monolayer containing ST3Gal1-sh3/IEC when compared with the control

groups (P<0.01; Fig. 6G-I). No

significant differences were noted in the protein concentrations of

IL-1β (318.43±24.54 pg/ml), IL-6 (404.52±20.55 pg/ml) and IL-8

(3,151.23±156.78 pg/ml) in ST3Gal1-sh3/IEC compared with in the

control groups in the supernatants obtained from the non-inflamed

IEC monolayer (P>0.05; Fig.

6G-I). In addition, the protein concentrations of IL-1β

(1,863.41±62.25 pg/ml), IL-6 (1,797.57±94.93 pg/ml) and IL-8

(18,319.25±1,893.01 pg/ml) were significantly higher in the

supernatants derived from the inflamed IEC monolayer containing

ST3Gal1-OE/IEC compared with those from the control groups

(P<0.01; Fig. 6J-L). Consistent

with previous observations in the present study, there were no

significant differences in the concentrations of IL-1β

(282.01±48.33 pg/ml), IL-6 (408.14±28.22 pg/ml) and IL-8

(4,203.54±433.62 pg/ml) the aforementioned cytokines in the

supernatants obtained from the non-inflamed IEC monolayer

(P>0.05; Fig. 6J-L). Therefore,

it may be inferred that the expression of ST3Gal1 in IECs markedly

modified the expression, and subsequent release of IL-1β, IL-6 and

IL-8 in inflamed triple culture models.

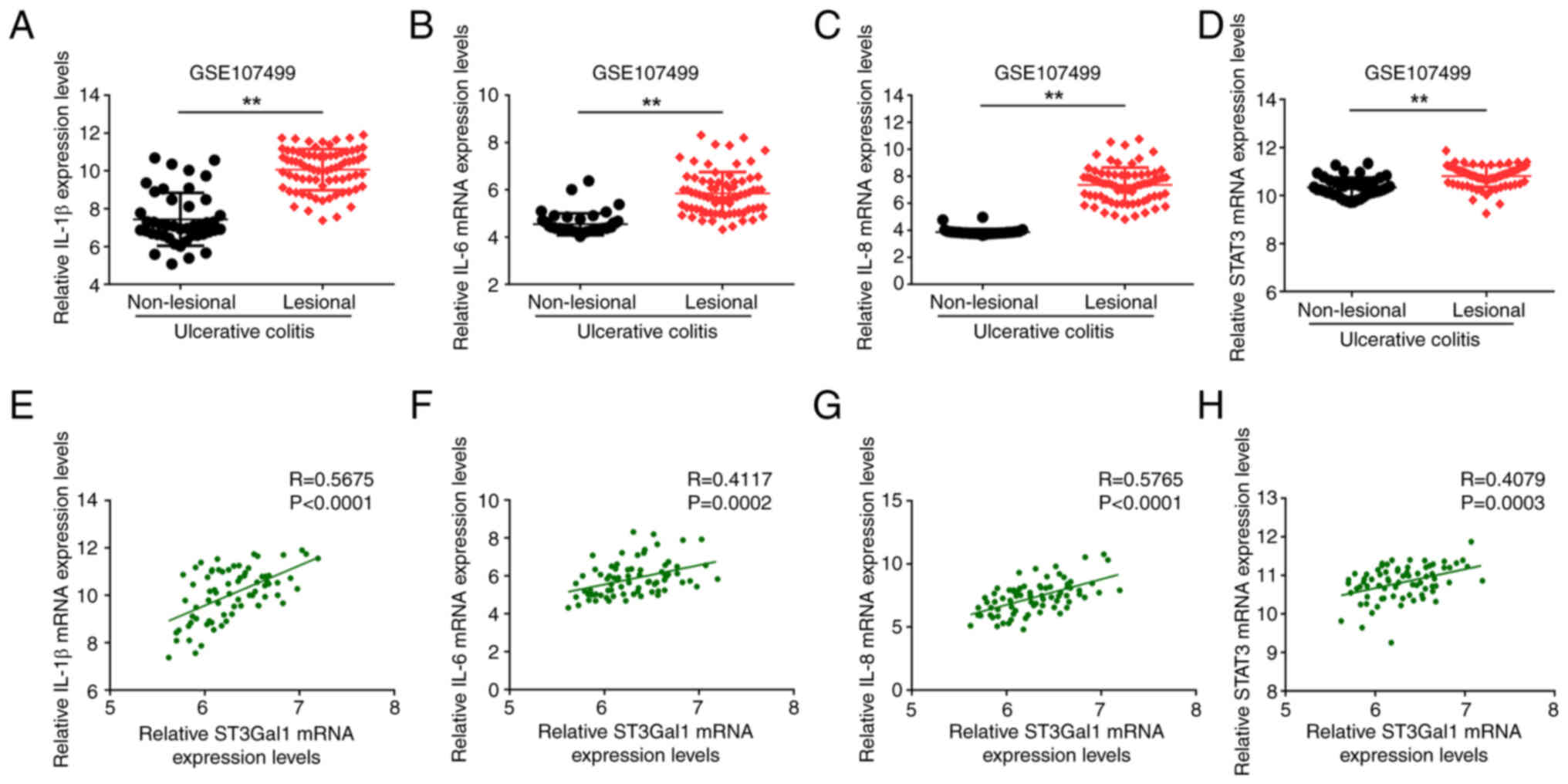

ST3Gal1 levels are correlated with

IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and STAT3 mRNA levels in lesional mucosa obtained

from patients with UC

The present study conducted a comparative analysis

of the mRNA expression levels of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and STAT3

between the non-lesional and lesional mucosal tissues of patients

diagnosed with UC, which was obtained from the GSE107499 dataset,

alongside the relationships of cytokine expression with ST3Gal1

mRNA expression levels. The present results demonstrated that the

mRNA levels of IL-1β (P<0.01; Fig.

7A), IL-6 (P<0.01; Fig.

7B), IL-8 (P<0.01; Fig. 7C)

and STAT3 (P<0.01; Fig. 7D) in

the lesional mucosa were significantly elevated compared with those

in the non-lesional mucosa. Furthermore, correlation analyses

revealed positive correlations between ST3Gal1 mRNA expression and

the expression levels of the cytokines IL-1β (R=0.5675;

P<0.0001; Fig. 7D), IL-6

(R=0.4117; P=0.0002; Fig. 7E),

IL-8 (R=0.5765; P<0.0001; Fig.

7F) and STAT3 (R=0.4079; P=0.0003; Fig. 7H) in the lesional mucosa of

patients with UC.

Discussion

The results of the present study indicated a strong

relationship between ST3Gal1 expression in the intestinal

epithelium and the barrier function of IECs, as well as with the

secretion of inflammatory mediators within the context of

intestinal inflammation. ST3Gal1 knockdown in the IEC monolayer

increased the barrier function, whereas its overexpression resulted

in intestinal barrier function deterioration. Overexpression of

ST3Gal1 in the IEC monolayer reduced the expression of intestinal

mucus barrier-associated MUC2, TFF3 and CDX2, as well as the

expression of inflammation-associated p-STAT3. By contrast,

overexpression of ST3Gal1 elevated the levels of inflammatory

mediators (IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8), which are important for

maintaining intestinal mucosa homeostasis (33). The DSS-induced colitis model is

linked to the inflammatory status of the colonic tissue, as

evidenced by the dynamic association between disease progression

and the expression profiles of key molecules: Specifically,

inflammatory factors (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8), goblet cell secretory

proteins (MUC2, TFF3) and signaling pathway-related proteins

(STAT3, p-STAT3). This is supported by the bioinformatics analysis

of the GEO dataset GDS3859, where ST3Gal1 mRNA expression in mouse

colonic mucosa was significantly upregulated with prolonged DSS

treatment (peaking at 6 days post-administration), concurrent with

the exacerbation of colonic inflammation. Additionally, in the

in vitro inflamed triple-culture model induced by 2% DSS,

the expression patterns of the aforementioned molecules were

consistently altered in response to ST3Gal1 knockdown or

overexpression, further confirming that the DSS-induced model

recapitulates the intrinsic association between colonic

inflammatory status and the expression of these functional proteins

in UC. ST3Gal1 facilitates the formation of α2,3-sialic acid

residues and contributes to the modification of glycan ends on

proteins that possess α2,3-sialic acid residues (34). Dysregulation of ST3Gal1 within IECs

can result in the abnormal expression of sialic acid, which is a

unique carbohydrate that anchors glycoproteins and glycolipids to

the cell membrane through α2,3-sialic acid residue modifications

(35). The present study

elucidated the role of ST3Gal1 in various IEC monolayers, including

inflamed and non-inflamed states, to identify knowledge gaps, and

explore its potential application as a novel diagnostic and

therapeutic target.

Sialyltransferases are key enzymes in the regulatory

mechanisms of various life processes, including cell signaling,

cellular recognition, interactions between cells and pathogens, and

cancer metastasis (36–38). Among these enzymes, the ST3Gal

family stands out as one of the most important enzyme families,

comprising six distinct members in both mice and humans: ST3Gal1-6

(39). The ST3Gal family catalyzes

the synthesis and attachment of α2,3-linked sialic acid residues to

the terminal galactose residues of glycans in proteins through a

process known as sialylation. The evolution of distinct human

ST3Gal family members, which establish specific α2,3-linkages,

suggests a degree of functional specialization; however, the roles

of α2,3-linkage in health and disease remain insufficiently

investigated (39). Prior research

has documented increased sialylation in IBD, as well as in other

autoimmune conditions and instances of acute inflammation (40). Notably, α2,6- and α2,3-sialylation

of glycans with extensively branched structures appear to escalate

during inflammatory responses in CD and UC, respectively, which are

mediated by α2,6-sialyltransferases and α2,3-sialyltransferases

(41,42). Similarly, ST6 mutations in animal

models have been shown to cause impairment of the intestinal mucus

barrier, dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiota and increased

susceptibility to intestinal inflammation (11,43).

Therefore, it can be suggested that ST6 is important for inhibiting

bacterial translocation and mitigating inflammation within the

intestinal mucus barrier (44).

Consequently, the role of α2,3-linkage, catalyzed by ST3Gal1

sialyltransferases, in the pathogenesis of patients with IBD and

its underlying mechanisms remain largely unexplored.

IBD refers to a persistent inflammatory disorder

affecting the intestines, which is influenced by a combination of

genetic predispositions, immune responses and environmental

elements (45). To facilitate

research on IBD, 66 distinct animal models have been developed at

present, which can be classified into chemical treatment models,

cell migration models, gene mutation models and gene transfer

models (46). However, in some

mouse models with few IBD-related genes, the specific pathogenic

mechanisms of IBD are more complex than previously predicted

(46). To investigate the

pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic approaches of IBD under

healthy conditions and inflammatory microenvironments,

respectively, researchers have established tri-culture cell models

of healthy and inflamed states in vitro. Based on these

models, various complex in vitro culture systems and

derivative systems have been developed, including primary cell

organoid culture systems, multicellular co-culture systems and chip

device systems (24,47,48).

The present study established an in vitro intestinal barrier

simulation model by co-culturing three cell lines: i) HT29-MTX-E12

cells, which exhibit goblet cell characteristics and have a

mucus-secreting ability, can be used to simulate the intestinal

mucus layer in vitro; ii) Caco-2 cells with epithelial cell

properties, which were seeded in the upper layer; and iii)

differentiable THP-1 inflammatory cells, which were seeded in the

basal side. Subsequently, this model was treated with 2% DSS to

induce an inflammatory state. The effect of ST3Gal on the integrity

of the IEC monolayer barrier was then evaluated by measuring TEER

and FITC-dextran permeability. Additionally, as reported in

previous studies, the secretion levels of relevant inflammatory

factors and the expression of intestinal barrier-related proteins

were compared between inflammatory and non-inflammatory states

(49–51). The tri-culture system designed to

simulate intestinal conditions streamlined the present model,

enhancing its robustness and reproducibility (24). The epithelial Transwell cultures

incorporating Caco-2 and HT29-MTX-E12 cell lines exhibited traits

that closely resemble those of human intestinal mucosal epithelium.

Furthermore, the inclusion of immune-competent THP-1 cells

contributed to the immune mechanisms associated with the

development of IBD (21). Notably,

both the presence of these immune effector cells and the

persistence of inflammatory processes substantially influenced the

sensitivity of the IEC monolayer.

However, there remains a lack of

α2,3-sialylation-linked target molecules bridging ST3Gal1 and

intestinal mucus barrier-associated MUC2, TFF3 and CDX2, as well as

inflammation-associated molecules, such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, STAT3

and p-STAT3. Further study is required to identify ST3Gal1-mediated

molecules with post-translation α2,3-sialylation at their glycan

termini. This may help identify novel target molecules to modulate

the intestinal epithelial barrier function important for the

pathogenesis of human IBD.

The present study provided a new direction for the

treatment of UC and other IBDs and showed that ST3Gal1 can act as a

potential therapeutic target. Overexpression of ST3Gal1 was

directly associated with impaired intestinal barrier function,

elevated expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6

and IL-8, and increased disease activity in patients with UC,

supported by in vitro and clinical data: i) In vitro,

ST3Gal1 overexpression in the inflamed triple-culture model showed

significantly reduced TEER, increased FITC-dextran permeability,

downregulated expression of barrier-protective proteins MUC2, TFF3

and CDX2, and upregulated p-STAT3, as well as elevated mRNA and

protein levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8. ii) Clinically,

bioinformatics analysis of GEO datasets (GSE107499 and GSE92415)

revealed that ST3Gal1 mRNA expression was significantly higher in

lesional vs. non-lesional mucosa inpatients with UC, it was

positively associated with modified Mayo scores (a measure of UC

disease activity), and it was positively correlated with the mRNA

levels of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and STAT3 in UC lesional tissues. By

contrast, ST3Gal1 knockdown upregulated the barrier-protective

molecules (MUC2, TFF3 and CDX2) and reduced p-STAT3 expression,

thereby repairing the mucosal barrier and alleviating inflammation.

Compared with traditional broad-spectrum immunosuppressive

therapies, ST3Gal1-targeted interventions may act precisely on the

glycosylation pathway, thereby potentially minimizing off-target

effects. Additionally, the characteristic high expression of

ST3Gal1 in inflamed mucosal tissues enables it to serve as a

potential biomarker for assessing disease activity or treatment

response. Future studies should validate the efficacy of ST3Gal1

inhibitors in animal models or explore their synergistic effects

with existing drugs, such as mesalamine, to provide more precise

therapeutic options for IBD.

While the Caco-2/HT29-MTX-E12/THP-1 triple-culture

model recapitulated key intestinal mucosal features and followed

the 3R principles, it failed to fully replicate the in vivo

intestinal microenvironment, lacking fibroblasts, endothelial cells

and diverse gut microbiota, which are all regulators of mucosal

barrier function and IBD inflammation (52). Furthermore, immortalized cell lines

such as those used in the present study may not reflect the

phenotypes or functions of primary cells of patients with IBD, thus

limiting translational relevance.

The clinical analyses of the present study, which

relied on retrospective GEO data, also had inherent constraints: i)

The lack of access to detailed patient metadata, such as age and

treatment history, or long-term paired samples, which would

preclude ST3Gal1-prognosis/treatment response analyses; and ii)

limited sample sizes of subgroups, such as the UC non-inflamed

mucosa group, reduced the power of the correlation analysis for

ST3Gal1 with MUC2, which as a key intestinal mucosal barrier

component and goblet cell marker, is closely implicated in UC

pathogenesis (53). To address

these limitations, future studies should: i) Validate the findings

of the present study by using primary IEC-organoid models with

microbiota or stromal cells for improved physiological relevance;

ii) use prospective, well-characterized clinical cohorts to clarify

the clinical utility of ST3Gal1; and iii) apply glycoproteomic

methods, such as lectin affinity chromatography-mass spectrometry,

to identify ST3Gal1-mediated α-2,3-sialylation target molecules to

strengthen the mechanistic and translational value of the present

results.

In conclusion, the present study provided evidence

that ST3Gal1-catalyzed α2,3-linkage formation in IEC may be closely

associated with intestinal barrier function. This relationship

could be mediated through the distinct influence of ST3Gal1 on the

expression of intestinal barrier-associated proteins, including

MUC2, TFF3 and CDX2, which are important for preserving the

integrity of the intestinal barrier. Additionally, ST3Gal1

modulated the expression of associated inflammatory mediators and

transcription factors, including the expression of IL-1β, IL-6,

IL-8 and STAT3, which serve important roles in regulating

intestinal mucosal inflammation, thereby further linking ST3Gal1 to

barrier function.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation

of Chongqing (grant no. cstc2020jcyj-msxmX1094).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YT, YL, YS, LR and LL were responsible for

performing the experiments, and collecting and analyzing the data;

specifically, they performed in vitro cell culture

(triple-culture model establishment, ST3Gal1

overexpression/knockdown), functional assays (TEER, FITC-dextran

permeability), molecular experiments (RT-qPCR, western blotting,

ELISA), and bioinformatics data processing (GEO dataset analysis).

JY substantially contributed to study conception and design,

provided critical project oversight (experimental direction, data

validation), and led manuscript drafting and critical revision for

key intellectual content. RW critically revised the manuscript by

interpreting the biological significance of core findings (for

example, linking ST3Gal1-mediated α2,3-sialylation to intestinal

barrier dysfunction in UC) and standardizing the academic

expression of results (refining data description and mechanistic

discussion logic). The manuscript was authored by JY and RW, with

JY providing project oversight. JY and YT confirm the authenticity

of all the raw data. All authors have read, critically revised, and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Furfaro F, Ragaini E, Peyrin-Biroulet L

and Danese S: Novel therapies and approaches to inflammatory bowel

disease (IBD). J Clin Med. 11:43742022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Selvakumar B and Samsudin R: Intestinal

barrier dysfunction in inflammatory bowel disease: Pathophysiology

to precision therapeutics. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 31:450–3464. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Marincola Smith P, Choksi YA, Markham NO,

Hanna DN, Zi J, Weaver CJ, Hamaamen JA, Lewis KB, Yang J, Liu Q, et

al: Colon epithelial cell TGFβ signaling modulates the expression

of tight junction proteins and barrier function in mice. Am J

Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 320:G936–G957. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Rader AG, Cloherty APM, Patel KS,

Almandawi DDA, Perez-Vargas J, Wildenberg ME, Muncan V, Schreurs R,

Jean F and Ribeiro CMS: Autophagy-enhancing strategies to promote

intestinal viral resistance and mucosal barrier function in

SARS-CoV-2 infection. Autophagy Rep. 4:25142322025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Wang R, Xie L, Jiang P, Hou Y, Li D and

Wang W: Metformin may improve intestinal mucosal barrier function

and help prevent and reverse colorectal cancer in mice. J Cancer.

16:3703–3711. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Esmail S and Manolson MF: Advances in

understanding N-glycosylation structure, function, and regulation

in health and disease. Eur J Cell Biol. 100:1511862021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Montag N, Gousis P and Wittmann J: The

emerging role of GlycoRNAs in immune regulation and recognition.

Immunol Lett. 276:1070482025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Flynn RA, Pedram K, Malaker SA, Batista

PJ, Smith BAH, Johnson AG, George BM, Majzoub K, Villalta PW,

Carette JE, et al: Small RNAs are modified with N-glycans and

displayed on the surface of living cells. Cell. 188:44702025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

He M, Zhou X and Wang X: Glycosylation:

Mechanisms, biological functions and clinical implications. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 9:1942024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wang G, Yuan J, Luo J, Ocansey DKW, Zhang

X, Qian H, Xu W and Mao F: Emerging role of protein modification in

inflammatory bowel disease. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 23:173–188.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kudelka MR, Stowell SR, Cummings RD and

Neish AS: Intestinal epithelial glycosylation in homeostasis and

gut microbiota interactions in IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

17:597–617. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Yao Y, Kim G, Shafer S, Chen Z, Kubo S, Ji

Y, Luo J, Yang W, Perner SP, Kanellopoulou C, et al: Mucus

sialylation determines intestinal host-commensal homeostasis. Cell.

185:1172–1188.e28. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Fan Q, Li M, Zhao W, Zhang K, Li M and Li

W: Hyper α2,6-Sialylation promotes CD4+ T-Cell activation and

induces the occurrence of ulcerative colitis. Adv Sci (Weinh).

10:e23026072023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Shu X, Li J, Chan UI, Su SM, Shi C, Zhang

X, An T, Xu J, Mo L, Liu J, et al: BRCA1 insufficiency induces a

hypersialylated acidic tumor microenvironment that promotes

metastasis and immunotherapy resistance. Cancer Res. 83:2614–2633.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Fan TC, Yeo HL, Hung TH, Chang NC, Tang

YH, Yu J, Chen SH and Yu AL: ST3GAL1 regulates cancer cell

migration through crosstalk between EGFR and neuropilin-1

signaling. J Biol Chem. 301:1083682025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hong Y, Walling BL, Kim HR, Serratelli WS,

Lozada JR, Sailer CJ, Amitrano AM, Lim K, Mongre RK, Kim KD, et al:

ST3GAL1 and βII-spectrin pathways control CAR T cell migration to

target tumors. Nat Immunol. 24:1007–1019. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Tajadura-Ortega V, Gambardella G, Skinner

A, Halim A, Van Coillie J, Schjoldager KTG, Beatson R, Graham R,

Achkova D, Taylor-Papadimitriou J, et al: O-linked mucin-type

glycosylation regulates the transcriptional programme downstream of

EGFR. Glycobiology. 31:200–210. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zaro BW, Bateman LA and Pratt MR: Robust

in-gel fluorescence detection of mucin-type O-linked glycosylation.

Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 21:5062–5066. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhang Y, Wang L, Ocansey DKW, Wang B, Wang

L and Xu Z: Mucin-Type O-Glycans: Barrier, microbiota, and immune

anchors in inflammatory bowel disease. J Inflamm Res. 14:5939–5953.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Bergstrom K, Shan X, Casero D, Batushansky

A, Lagishetty V, Jacobs JP, Hoover C, Kondo Y, Shao B, Gao L, et

al: Proximal colon-derived O-glycosylated mucus encapsulates and

modulates the microbiota. Science. 370:467–472. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhao Z, Zheng W, Zhang L, Song W and Wang

T: Sialyltransferase ST3GAL1 promotes malignant progression in

glioma. Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi Xue Za Zhi. 41:308–317. 2025.(In

Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Busch M, Kämpfer AAM and Schins RPF: An

inverted in vitro triple culture model of the healthy and inflamed

intestine: Adverse effects of polyethylene particles. Chemosphere.

284:1313452021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Busch M, Ramachandran H, Wahle T, Rossi A

and Schins RPF: Investigating the role of the NLRP3 inflammasome

pathway in acute intestinal inflammation: Use of THP-1 knockout

cell lines in an advanced triple culture model. Front Immunol.

13:8980392022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kämpfer AAM, Busch M, Büttner V, Bredeck

G, Stahlmecke B, Hellack B, Masson I, Sofranko A, Albrecht C and

Schins RPF: Model complexity as determining factor for in vitro

nanosafety studies: Effects of silver and titanium dioxide

nanomaterials in intestinal models. Small. 17:e20042232021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Aske KC and Waugh CA: Expanding the 3R

principles: More rigour and transparency in research using animals.

EMBO Rep. 18:1490–1492. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Deng X, Shang L, Du M, Yuan L, Xiong L and

Xie X: Mechanism underlying the significant role of the

miR-4262/SIRT1 axis in children with inflammatory bowel disease.

Exp Ther Med. 20:2227–2235. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Samak G, Chaudhry KK, Gangwar R, Narayanan

D, Jaggar JH and Rao R: Calcium/Ask1/MKK7/JNK2/c-Src signalling

cascade mediates disruption of intestinal epithelial tight

junctions by dextran sulfate sodium. Biochem J. 465:503–515. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Pan Q, Tian Y, Li X, Ye J, Liu Y, Song L,

Yang Y, Zhu R, He Y, Chen L, et al: Enhanced membrane-tethered

mucin 3 (MUC3) expression by a tetrameric branched peptide with a

conserved TFLK motif inhibits bacteria adherence. J Biol Chem.

288:5407–5416. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Olsen J, Gerds TA, Seidelin JB, Csillag C,

Bjerrum JT, Troelsen JT and Nielsen OH: Diagnosis of ulcerative

colitis before onset of inflammation by multivariate modeling of

genome-wide gene expression data. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 15:1032–1038.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Marano C, Zhang H,

Strauss R, Johanns J, Adedokun OJ, Guzzo C, Colombel JF, Reinisch

W, et al: Subcutaneous golimumab induces clinical response and

remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis.

Gastroenterology. 146:85–95. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Fang K, Bruce M, Pattillo CB, Zhang S,

Stone R II, Clifford J and Kevil CG: Temporal genomewide expression

profiling of DSS colitis reveals novel inflammatory and

angiogenesis genes similar to ulcerative colitis. Physiol Genomics.

43:43–56. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Xu W, Guo Y, Huang Z, Zhao H, Zhou M,

Huang Y, Wen D, Song J, Zhu Z, Sun M, et al: Small heat shock

protein CRYAB inhibits intestinal mucosal inflammatory responses

and protects barrier integrity through suppressing IKKβ activity.

Mucosal Immunol. 12:1291–1303. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Fan J, Huang S, Cao C, Jin X and Su Y: The

roles of ST3Gal1-6 in cancer: Expression profiles and functional

implications. Carbohydr Res. 559:1097402025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Ma X, Li M, Wang X, Qi G, Wei L and Zhang

D: Sialylation in the gut: From mucosal protection to disease

pathogenesis. Carbohydr Polym. 343:1224712024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Al Saoud R, Hamrouni A, Idris A, Mousa WK

and Abu Izneid T: Recent advances in the development of

sialyltransferase inhibitors to control cancer metastasis: A

comprehensive review. Biomed Pharmacother. 165:1150912023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Perez S, Fu CW and Li WS:

Sialyltransferase inhibitors for the treatment of cancer

metastasis: Current challenges and future perspectives. Molecules.

26:56732021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Uslupehlivan M, Şener E and İzzetoğlu S:

Computational analysis of the structure, glycosylation and CMP

binding of human ST3GAL sialyltransferases. Carbohydr Res.

486:1078232019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Hatano K, Miyamoto Y, Nonomura N and

Kaneda Y: Expression of gangliosides, GD1a, and sialyl

paragloboside is regulated by NF-κB-dependent transcriptional

control of α2,3-sialyltransferase I, II, and VI in human

castration-resistant prostate cancer cells. Int J Cancer.

129:1838–1847. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Kelm M, Quiros M, Azcutia V, Boerner K,

Cummings RD, Nusrat A, Brazil JC and Parkos CA: Targeting

epithelium-expressed sialyl Lewis glycans improves colonic mucosal

wound healing and protects against colitis. JCI Insight.

5:e1358432020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Taniguchi M, Okumura R, Matsuzaki T,

Nakatani A, Sakaki K, Okamoto S, Ishibashi A, Tani H, Horikiri M,

Kobayashi N, et al: Sialylation shapes mucus architecture

inhibiting bacterial invasion in the colon. Mucosal Immunol.

16:624–641. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhao T, Liu S, Ma X, Shuai Y, He H, Guo T,

Huang W, Wang Q, Liu S, Wang Z, et al: Lycium barbarum

arabinogalactan alleviates intestinal mucosal damage in mice by

restoring intestinal microbes and mucin O-glycans. Carbohydr Polym.

330:1218822024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Kotlarz D: Mucus sialylation maintains the

peace in intestinal host microbe relations. Gastroenterology.

163:527–528. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Sánchez-Martínez E, Garrido-Romero M and

Moreno FJ: Functional role of ST6GALNAC1-mediated sialylation of

mucins in preserving intestinal barrier integrity and ameliorating

inflammation. Allergy. 77:3697–3698. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Petit C, Rozières A, Boschetti G, Viret C,

Faure M, Nancey S and Duclaux-Loras R: Advances in understanding

intestinal homeostasis: Lessons from inflammatory bowel disease and

monogenic intestinal disorder pathogenesis. Int J Mol Sci.

26:61332025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Mizoguchi A: Animal models of inflammatory

bowel disease. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 105:263–320. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Le NPK, Altenburger MJ and Lamy E:

Development of an Inflammation-triggered in vitro ‘Leaky Gut’ Model

using Caco-2/HT29-MTX-E12 combined with Macrophage-like THP-1 cells

or primary Human-derived macrophages. Int J Mol Sci. 24:74272023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Weber L, Kuck K, Jürgenliemk G, Heilmann

J, Lipowicz B and Vissiennon C: Anti-Inflammatory and

Barrier-stabilising effects of myrrh, coffee charcoal and chamomile

flower Extract in a Co-Culture cell model of the intestinal mucosa.

Biomolecules. 10:10332020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Ma L, Zhang X, Zhang C, Hou B and Zhao H:

FOSL1 knockdown ameliorates DSS-induced inflammation and barrier

damage in ulcerative colitis via MMP13 downregulation. Exp Ther

Med. 24:5512022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Roselli M, Maruszak A, Grimaldi R,

Harthoorn L and Finamore A: Galactooligosaccharide treatment

alleviates DSS-induced colonic inflammation in Caco-2 cell model.

Front Nutr. 9:8629742022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Wang Y, Wen R, Liu D, Zhang C, Wang ZA and

Du Y: Exploring effects of chitosan oligosaccharides on the

DSS-Induced intestinal barrier impairment in vitro and in vivo.

Molecules. 26:21992021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

De Cecco F, Franceschelli S, Panella V,

Maggi MA, Bisti S, Bravo Nuevo A, D'Ardes D, Cipollone F and

Speranza L: Biological response of treatment with saffron petal

extract on Cytokine-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in

the Caco-2/Human leukemia monocytic Co-Culture model. Antioxidants

(Basel). 13:12572024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Yin S, Yang H, Tao Y, Wei S, Li L, Liu M

and Li J: Artesunate ameliorates DSS-induced ulcerative colitis by

protecting intestinal barrier and inhibiting inflammatory response.

Inflammation. 43:765–776. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|