Introduction

Neuroblastoma (NB), the most common extracranial

solid tumor in infants and young children, accounting for 8–10% of

childhood malignancies (1).

Childhood NB is difficult to treat and has a poor prognosis with

single treatment. Although the 5-year survival rate of

neuroblastoma patients has increased from <20–50% in the past

few decades, it still accounts for ~15% of all childhood cancer

deaths (2). Current treatment

approaches aim to improve the effectiveness of treatment by adding

immunotherapy and targeted therapy to standard regimens (3).

Autophagy is the main intracellular material

transport mechanism, responsible for transporting various

intracellular substances to lysosomes for degradation and

recycling. Recent studies have focused not only on the function of

autophagy in tumor cells themselves, but also on the role of

autophagy in the tumor microenvironment and the functions of

related immune cells. There is increasing evidence showing how

autophagy and its related processes affect the development and

progression of cancer, which helps guide the design of anticancer

therapeutics based on inhibiting or promoting autophagy (4). In the tumor microenvironment,

autophagy of tumor cells can be induced by a combination of

intracellular and extracellular stress signals, including metabolic

stress, hypoxia, redox stress and immune signals (5). In response to metabolic stress, tumor

cells rewire their own metabolic pathways by upregulating nutrient

transporters and activating autophagy (6). Mechanistically, 5′-AMP-activated

protein kinase (AMPK) and mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) are two opposing

regulatory kinases. After target phosphorylation in the

pre-autophagy initiation complex, AMPK is located at the activation

site and mTORC1 is located at the inhibition site (7,8). To

initiate autophagy, AMPK phosphorylates six different sites of

unc-51-like kinase 1 (ULK1) and S91/S94 of Beclin 1 (9). Wang et al (10) predicted a risk signature of four

autophagy-related genes for neuroblastoma survival that was

associated with tumor immunity. Bishayee et al (11) demonstrated that the RNA-binding

protein HuD promotes autophagy and tumor stress survival by

inhibiting mTORC1 activity and increasing ARL6IP1 levels.

Ugun-Klusek et al (12)

found that monoamine oxidase-A promotes protective autophagy in

human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells through Bcl-2 phosphorylation.

These results suggest that autophagy can promote apoptosis of

neuroblastoma cells.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is involved in a

number of cellular functions, including protein synthesis, calcium

homeostasis or phospholipid synthesis. Under stressful situations,

the ER environment is disrupted and protein maturation is impaired,

leading to the accumulation of misfolded proteins and a

characteristic stress response called the unfolded protein

response. ER stress and the unfolded protein response (UPR) can

mediate toxic consequences through various pathogenic mechanisms

(including cell death, fibrosis and inflammatory signaling

pathways) (13). Activation of

PerK can also promote the production of pro-inflammatory IL-6 and

IL-8 by increasing p38 and PerK signaling pathways, while CHOP can

regulate the transcription of cytokines including IL-6. In certain

types of cancer, ER stress leads to the release of proinflammatory

cytokines, including IL-6 and TNFα, each of which contains XBP1s

binding sites in its promoter. These cytokines can promote

pathology by driving inflammation and, in some cases, cancer cell

proliferation (14). A number of

studies have demonstrated that ER stress can trigger the autophagy

process (15). Celesia et

al (16) demonstrated that

reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent ER stress and autophagy

play an important role in the mechanism of action of TBT-F in colon

cancer cells. The antitumor drug ABTL0812 impairs the growth of

neuroblastoma cells through ER stress-mediated autophagy and

apoptosis (17). Therefore, the

relationship between autophagy and altered oxidative stress is

evident, following the pathway of ER stress and/or mitochondrial

changes.

Melatonin regulates circadian rhythms and is

associated with improved sleep, scavenging of ROS, anti-aging

effects, and seasonal and circadian rhythms. There is a mutual

relationship between melatonin and autophagy. Ge et al

(18) found that autophagy has a

potential role in regulating melatonin synthesis in rat pineal

cells. At the same time, the therapeutic potential of melatonin in

cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, viral infections and obesity is

related to its role as an autophagy regulator, in which melatonin

regulates ER stress, autophagy and apoptosis (19,20).

Zhang et al (21) found

that melatonin increased cardiomyocyte autophagy by regulating the

VEGF-BGRP78PERK signaling pathway, thereby alleviating diabetic

cardiomyopathy. In preclinical studies, fetal hypoxia caused

autophagy and mitochondrial damage in ovarian granulosa cells,

which was alleviated by melatonin supplementation (22). In terms of anti-inflammatory

effects, melatonin alleviates sepsis-induced small intestinal

damage by upregulating SIRT3-mediated oxidative stress, inhibiting

mitochondrial protection and inducing autophagy (23). However, the therapeutic effect of

melatonin on neuroblastoma and its underlying mechanism remain to

be elucidated.

The present study investigated whether melatonin

reduces ER stress and impairs neuroblastoma tumor growth, enabling

cytotoxic autophagy and apoptosis. Specifically, it investigated

whether melatonin induces the transcription of glucose-regulated

protein (GRP)78 and GRP94 and CHOP in neuroblasts and alleviates ER

stress. In addition, it also explored how melatonin regulates

p21-activated kinase 2 (Pak2) and its mediated signaling pathway to

alleviate ER stress in neuroblastoma. This provided a new treatment

option for patients with high-risk neuroblastoma.

Materials and methods

Cell recovery and passaging

Neuro-2a cells (N2a cells; cat. no. CL0383; Hunan

Fenghui Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) were used for cell studies. A tube

of N2a cells were placed on −80°C ice and the cryopreservation tube

placed in a 37°C water bath until the cryopreservation solution

melted into liquid. Then, 1 ml of the solution was transferred to a

15 ml centrifuge tube, and 1 ml of 10% DMEM was added, mixed and

centrifuged (room temperature, 1,000 × g for 5 min). After the

cells were resuspended, they were transferred to a T25 culture

flask and 5 ml DMEM was added. The cells were observed under a

microscope to be single cells and evenly distributed. The cells

were then transferred to a cell culture incubator at 37°C, and 5%

CO2 for culture. At 24 h after cell recovery, the

adhesion and cell density of N2a cells were observed and fresh 5 ml

DMEM was replaced. At this time, it was observed that 70–80% of the

cells were round, with a small number of spindle-shaped cells, and

the cell density accounted for ~60% of the T25 flask. When the cell

density in the T25 flask reached ~90%, the cell culture was

passaged using the 1-to-2 method to avoid growth inhibition.

Cell proliferation

Since N2a cells proliferate rapidly, neuroblastoma

cells were plated at 3×105 cells/well in 6-well plates

with 1.5 ml of culture medium added, so that the cell confluence of

each well was 60–70% and observed after 24 h. After the cells

adhered, new culture medium was replaced and designated drugs were

used for intervention treatment.

Reagents and instruments

Melatonin reagent, ER stress inhibitor

4-phenylbutyric acid (4-PBA) and AMPK inhibitor Dorsomorphin

(Dorso) were purchased from Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.; ER-related protein GRP78 was purchased from

Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.; Beclin1 was purchased from

BIOSS; GRP94, CHOP, autophagy-related protein P62,

autophagy-related protein 5 (ATG5), LC3, β-Actin, mTOR,

phosphorylated (p)-mTOR, ULK1, phosphorylated (p)-ULK1 and Pak2

were provided by Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology. The PAK2

overexpression lentivirus packaging and PAK2 interference

lentivirus packaging were provided by Beyotime Biotechnology. The

experimental instruments and equipment are as follows: fluorescence

microscope (Olympus Corporation), transmission electron microscope

(Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation), chemiluminescence imager

(Tanon4800 Multi; Tanon Science and Technology Co., Ltd.), and

constant temperature cell culture incubator (Thermo Scientific

Forma Series II; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

PAK2 overexpression and knockdown

The PAK2 overexpression lentivirus packaging and

PAK2 interference lentivirus packaging were provided by Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology (3rd-generation lentiviral packaging

system). PAK2 overexpression lentivirus: The mouse PAK2

interference lentivirusAK2 gene sequence (accession no.

NM_008779.3; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NM_008779.3/)

is available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information

database. The PAK2 overexpression lentivirus was packaged using the

pLOV-UbiC-EGFP vector and then 293T cells (cat. no. CRL-3216;

American Type Culture Collection) were transfected with the

expression vectors. To construct stable PAK2 overexpression and

knockdown cell lines, lentiviruses were packaged using a

three-plasmid system. In brief, HEK293T cells were co-transfected

with 8 µg pLOV-UbiC-EGFP plasmid, 6 µg psPAX2 plasmid and 2 µg

pMD2.G plasmid at a mass ratio of 4:3:1. Viral supernatant was

collected 48 and 72 h after transfection and concentrated to obtain

high titer virus solution. The optimal multiplicity of infection

(MOI) was determined to be 20. Screening was performed 48 h after

infection, using puromycin at a concentration of 2 µg/ml for 7 days

to remove uninfected cells. Subsequently, the concentration of

puromycin was reduced to 0.5 µg/ml for maintenance culture, and

stable cell lines were finally obtained. The PAK2 overexpression

lentivirus was harvested, filtered and concentrated. To establish

short hairpin (sh)RNA-mediated PAK2 knockdown, pLKO.1-puro

lentiviral plasmids were used containing the validated mouse PAK2

shRNA Seq [TRCN0000023619; mRNA Target: GCUGAUGAAGUUGCUGAGUAU.

Constructing the full shRNA Transcript with U bases:

5′-(GCUGAUGAAGUUGCUGAGUAU)-[CUCGAG)-(AUACUCAGCAACUUCAUCAGC)-3′].

The PAK2 shRNA lentiviral plasmid was co-transfected with the

packaging constructs psPAX2 and pMD2.G by Lipofectamine®

2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) into the human

293T cells. After 24 and 48 h, virus particles were collected,

filtered through a 0.45-µm PES filter and then used to infect the

N2a cells. The lentivirus without the transgene was used as the

negative control (NC) and was produced in the same manner as the

inhibitor vector. Transfection efficiency was confirmed by RT-qPCR

and western blot analysis.

Melatonin intervention and protein

extraction

Different concentrations of melatonin, 1, 5, 10, 20

and 0 µm (control group) were placed into the proliferating N2a

cells and cultured in a cell culture incubator at 37°C and 5%

CO2 for 48 h. Then the old culture medium was discarded,

each well washed with 1 ml PBS, 300 ml RIPA lysis buffer + PMSF

protease inhibitor (100:1) mixture added and lysed on ice for 5

min. Then, the cells in the well plate were scraped and transferred

into a new 1.5 ml tube for further lysis on ice for 30 min with

shaking every 10 min. The tube was placed at 4°C and 10,000 × g for

15 min, and 280 µl of the supernatant was aspirated. After

quantification of sample proteins by BCA analysis, each sample was

mixed with loading buffer and denatured in a high-temperature water

bath. Finally, divide into 3 tubes and store at −20°C.

Western blotting

After collecting cells from each group for protein

extraction, the denatured proteins were loaded onto the gel (40 µg

per well) for electrophoresis using separation and concentration

gels. After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to a

PVDF membrane of the appropriate size. Each antibody was detected

using a constant current of 290 mA, followed by a quick blocking

solution (cat. no. G2052-500ML; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.,

Ltd.) for 10 min, washed twice with TBS +0.05% Tween (TBST) at room

temperature for 3 min each and incubated with the primary antibody

after blocking. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C, then the

secondary antibody was applied at room temperature for 1 h and

washed three times with TBST for 5 min each. An ECL

chemiluminescence substrate kit (ultra-sensitive; cat. no. BL520A;

Biosharp Life Science) was used, and the developer was added.

Luminol and HRP were used to form luminous images. Developer was to

allow chemiluminescence imaging (Tanon4800 Multi; Tanon Science and

Technology Co., Ltd). The membranes were washed with antibody

eluent (cat. no. G2079-100M; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd)

to remove bound primary antibody at room temperature, and then

washed twice with TBST, each time for 5 min. The membranes were

incubated with the internal control antibody at room temperature in

2 h, using mouse β-actin (1:10,000; cat. no. 66009-1-Ig; Wuhan

Sanying Biotechnology). Following which the membranes were

incubated with a secondary antibody and developed in room

temperature 1 h again. The experiment was repeated twice. The

antibodies used in this experiment were as follows: Rabbit resist

grp94 (1:8,000; cat. no. 14700-1-AP; Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology),

CHOP (1:20,000; cat. no. 15204-1-AP; Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology),

LC3 (1:20,000; cat. no. 14600-1-AP; Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology),

ATG5 (1:5,000; cat. no. 10181-2-AP; Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology),

Beclin1 (1:5,000; cat. no. bs-1353R; BIOSS), P62(1:5,000; cat. no.

18420-1-AP; Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology), PAK2 (1:10,000; cat. no.

21401-1-AP; Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology), ULK1 (1:10,000; cat. no.

68445-1-Ig; Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology), p-ULK1(1:50,000; cat. no.

80218-1-RR; Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology), mouse resist grp78

(1:10,000; cat. no. GB15098; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd),

mTOR (1:10,000; cat. no. 66888-1-Ig; Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology)

and p-mTOR (1:5,000; cat. no. 67778-1-Ig; Wuhan Sanying

Biotechnology). Secondary antibodies were used as follows:

HRP-conjugated Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) (1:6,000; cat. no.

SA00001-2; Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology) and HRP-conjugated Goat

Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) (1:6,000; cat. no. SA00001-1; Wuhan Sanying

Biotechnology).

Immunofluorescence

N2a cells were seeded into 24-well plates, with

1×105 cells per well. After 24 h, cells were treated

with the indicated treatments and 48 h later, immunofluorescence

was performed. First, cells were washed twice with pre-cooled PBS,

then fixed with anhydrous ethanol in room temperature for 15 min,

washed three times for 5 min each time with PBST and then blocked

with 10% blocking solution, 20 µl bovine serum (cat. no.

S12012-100g; Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) + 180 µl

0.25% Triton X-100, at room temperature for 45 min. The blocking

solution was discarded and the primary antibody, 200 µl rabbit LC3

(1:200; cat. no. 14600-1-AP; Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology) was added

and incubated at 4°C overnight, followed by secondary antibody

CoraLite488-conjugated Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) (1:200; cat. no.

SA00013-2; Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology) at room temperature in the

dark for 1 h. The cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (5

mg/ml) at room temperature for 10 min, washed and mounted with an

anti-fluorescence quencher, and then images captured with a

fluorescent microscope (200X).

Transmission electron microscopy

observation of autophagosomes

Culture medium was discarded, 1 ml of PBS was added

to each well for washing, and then 1 ml of trypsin was added for

digestion, followed by the addition of 10% DMEM to terminate the

digestion and the cells incubated at 300 × g for 5 min at room

temperature. After discarding the supernatant, when the cell pellet

was ~5 mm3, 2.5% glutaraldehyde fixative was used at

room temperature in the dark for 30 min and then transferred to 4°C

for storage. The cells were stained with 2% uranyl acetate

saturated alcohol solution for 8 min in the dark; 2.6% lead citrate

solution was used to avoid carbon dioxide staining for a further 8

min. Following which infiltration embedding was performed as

follows: i) Acetone:812 embedding agent (1:1) at 37°C for 2–4 h;

ii) acetone:812 embedding agent (1:2) at 37°C for overnight

infiltration; and iii) pure 812 embedding agent at 37°C for 5–8 h.

The pure 812 embedding agent was poured into the embedding plate,

and the samples were inserted into the embedding plate and oven at

37°C overnight. Subsequently, the embedding plate was transferred

to the oven at 60°C for polymerization for 48 h and the resin block

was removed. The fixed precipitates were sectioned (thickness, 60

nm) and images captured using a transmission electron microscope

(cat. no. HT7800; Hitachi, Ltd.).

Construction of PAK2 overexpression

and inhibition N2a cell model

N2a cells were digested with 0.25% trypsin digestion

solution (cat. no. G4004-100 ml; Servicebio) for 1 min, centrifuged

at 300 × g for 5 min, and resuspended. The resuspended N2a cells

were added to 6-well plates, and 3×105 N2a cells were

added to each well. After 24 h, when the cell confluence reached

50–70%, 6 µl of PAK2 overexpression lentivirus stock solution

(1×109 TU/ml) was added. When MOI=20, 6 µl of PAK2

inhibition lentivirus stock solution and polybrene were added to

make the final concentration of 5 µg/ml. After 48 h, 1, 5, 10 and

20 µm of melatonin were added to the corresponding groups, and cell

protein was extracted after 48 h.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from homogenized the cell

pellets using an RNA extraction buffer (AgBio, Inc.) following the

manufacturer's guidelines. Subsequently, mRNA was reverse

transcribed into cDNA using a cDNA synthesis kit (Takara Bio,

Inc.). A mixture of 1 µl of synthetic cDNA and specific primers was

used to amplify inflammatory cytokine target genes by SYBR Premix

Ex Taq2 (Takara Bio, Inc.). The primers used in the present study

were as follows: Pak2 forward (F), 5′-ACACCAGCACTGAACACCAA-3′, and

reverse (R), 5′-CAATCTGCGCTTCGTCCATG-3′; and GAPDH F,

5′-AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG-3′ and R, 5′-TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA-3′.

The following thermocycling conditions were used for qPCR: initial

step at 50°C for 2 min; 95°C for 10 min; 45 cycles of 95°C for 10

sec, 60°C for 10 sec and 72°C for 15 sec. GAPDH was used as a

housekeeping and internal control gene to assess the relative

expression of target genes. The comparative Cq method

(2−ΔΔCq) was used to calculate the expression change of

the target gene relative to the reference gene (24). Data analysis was performed using

the software CFX Manager™ (BioRadCFXManager; version 2.2; Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad

Prism 8.0 (Dotmatics). All values are presented as mean ± SD.

Multiple comparisons were performed with one-way analysis of

variance followed by Bonferroni post hoc test. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Melatonin reduces ER stress in N2a

neuroblastoma cells

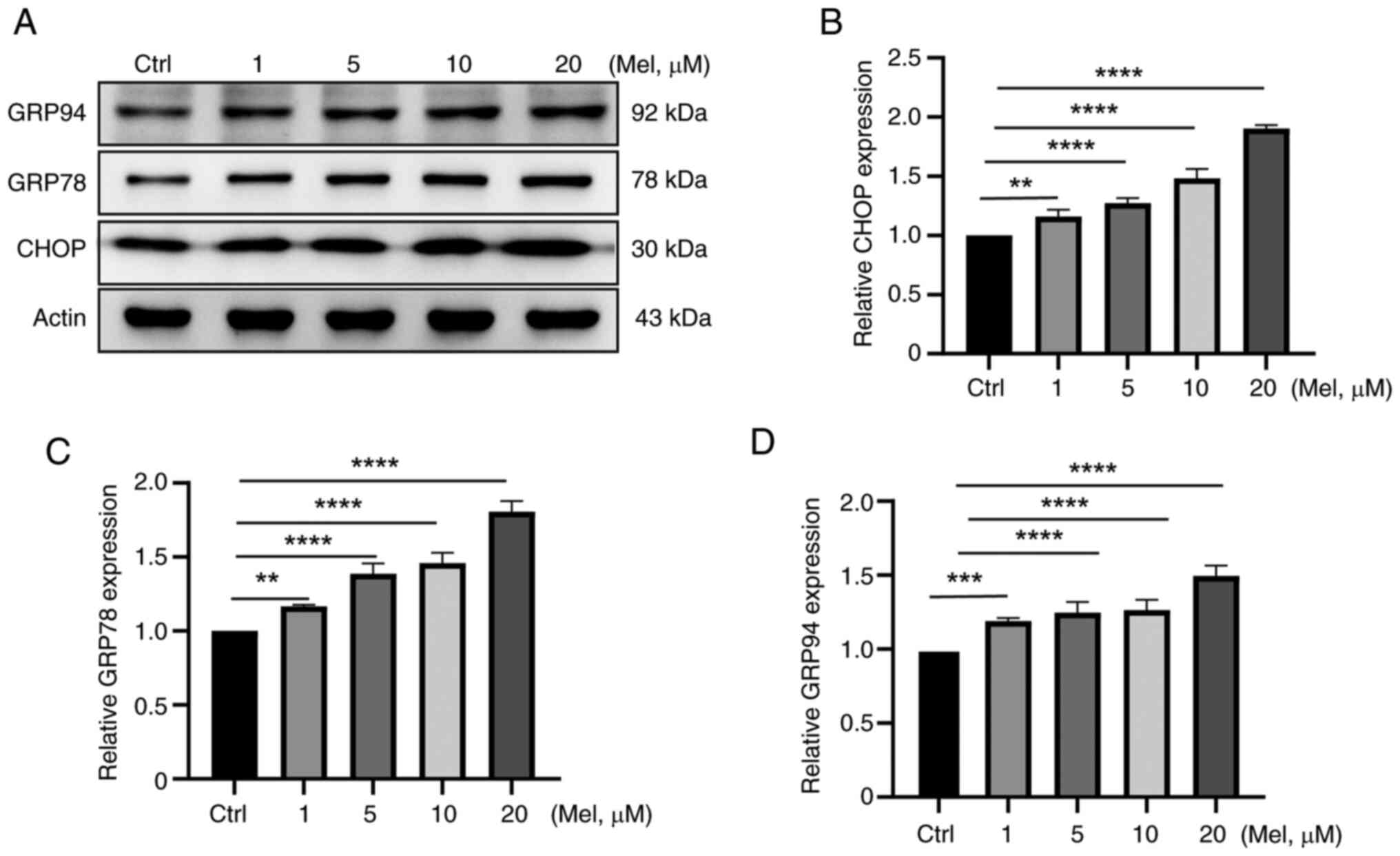

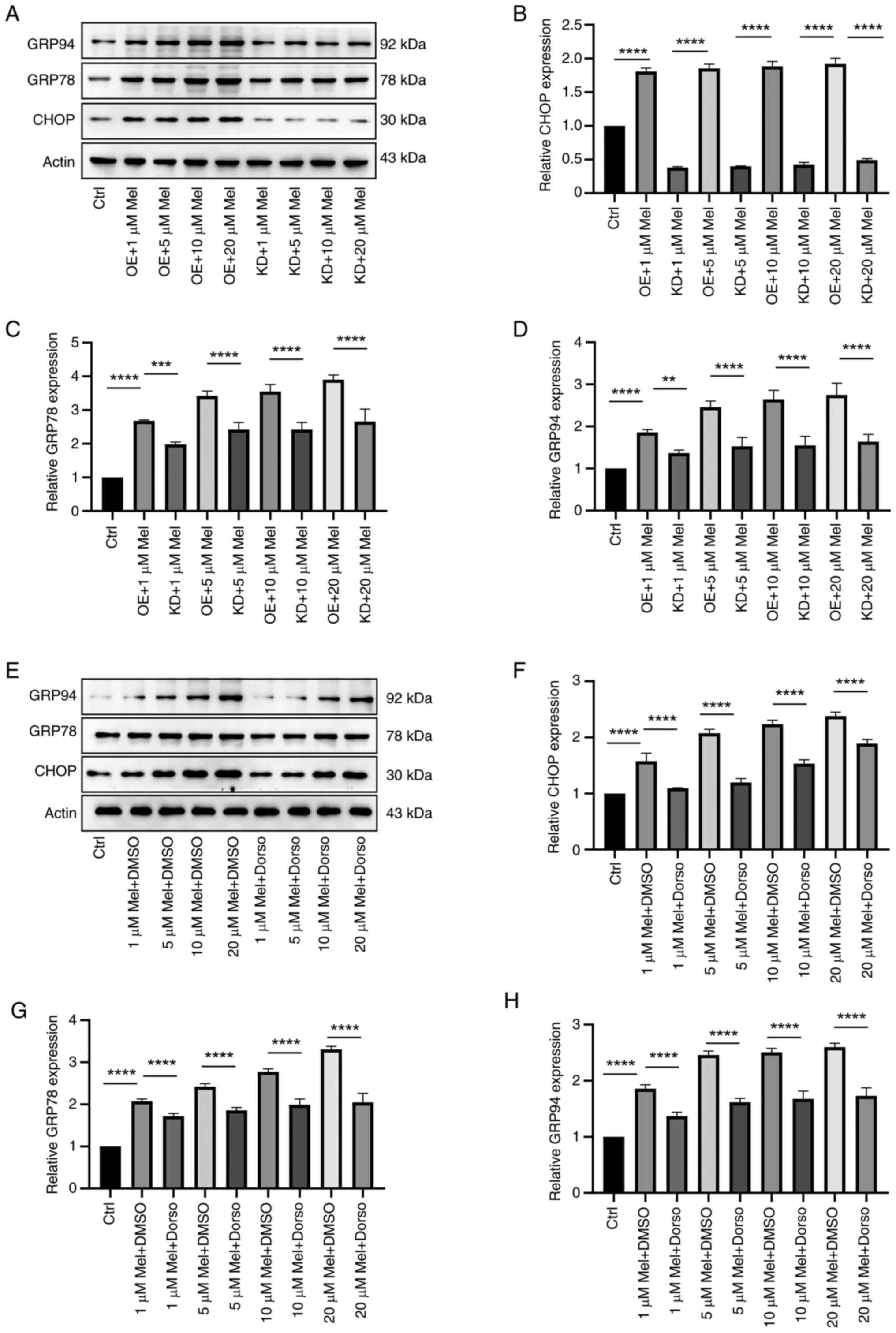

Melatonin has been shown to play a role in ER stress

in various diseases and can directly or indirectly interfere with

ER-related sensors and downstream targets of UPR, but there are

currently no studies on ER stress in N2a neuroblastoma cells

(25). The present study used the

UPR to drive the increased expression of the ER chaperones GRP78

and GRP94 and the Perk downstream protein CHOP to verify that

melatonin alleviates ER stress in N2a neuroblastoma cells (26,27).

After N2a cells were treated with melatonin at different

concentrations for 48 h, western blotting showed that the

expression of GRP94, GRP78 and CHOP proteins increased (Fig. 1A). The rapid proliferation of N2a

cells caused the accumulation of misfolded and unfolded proteins in

the ER lumen, triggering the ER stress response. At the N2a cell

level, after melatonin treatment, the expression of CHOP (Fig. 1B), GRP78 (Fig. 1C) and GRP94 (Fig. 1D) proteins increased, which can

help accelerate the processing of misfolded and unfolded proteins

in the ER, thereby alleviating ER stress and maintaining the

homeostasis of the intracellular environment.

| Figure 1.Melatonin reduces ER stress in N2a

neuroblastoma cells. N2a cells were treated with melatonin at 1, 5,

10, 20 µM concentrations for 48 h. (A) Western blotting detection

showed that the expression of (B) CHOP, (C) GRP78 and (D)

GRP94proteins increased. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001,

****P<0.0001, ns, not significant; ER, endoplasmic reticulum;

N2a, Neuro-2a; GRP, glucose-regulated protein; Mel, melatonin. |

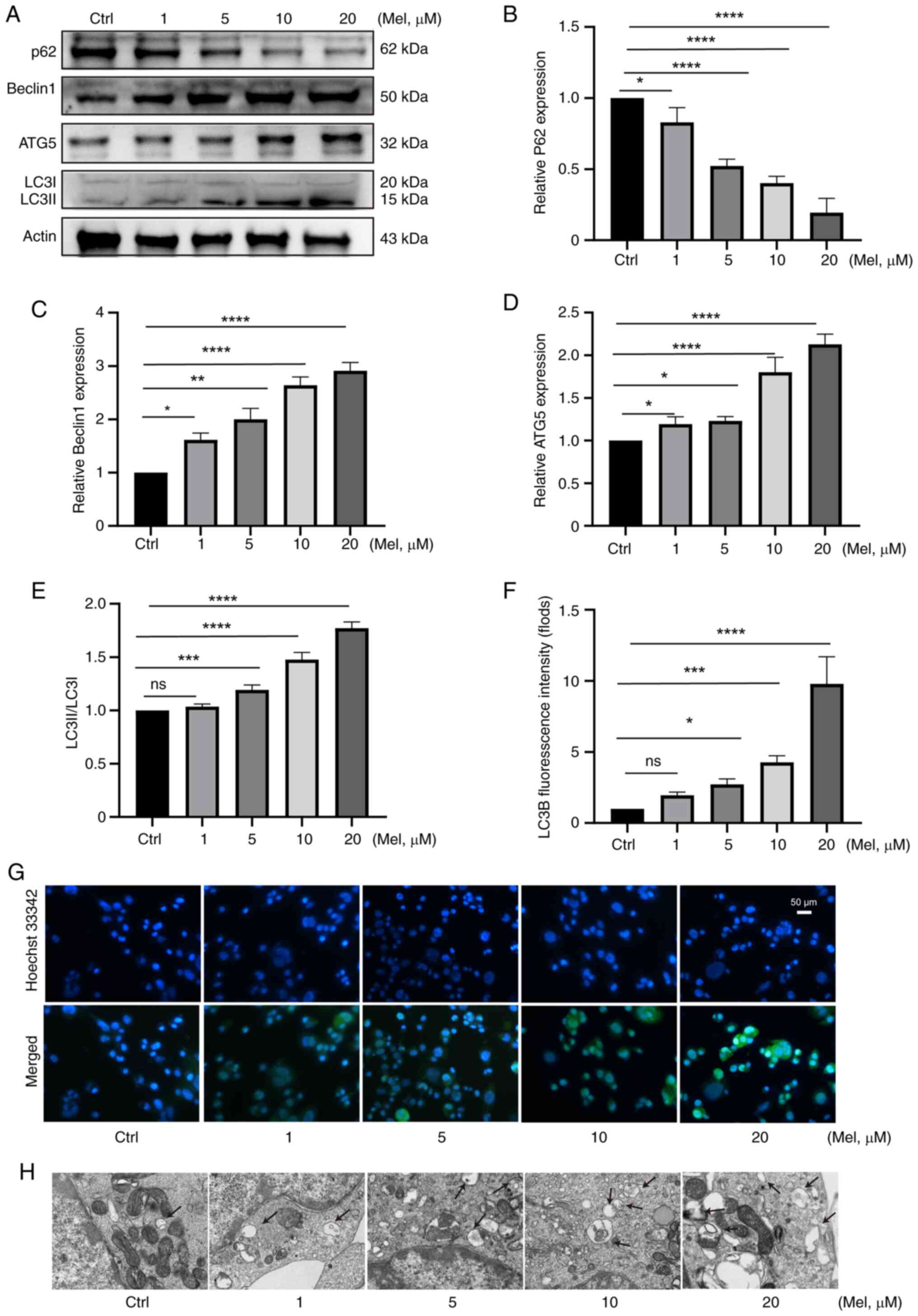

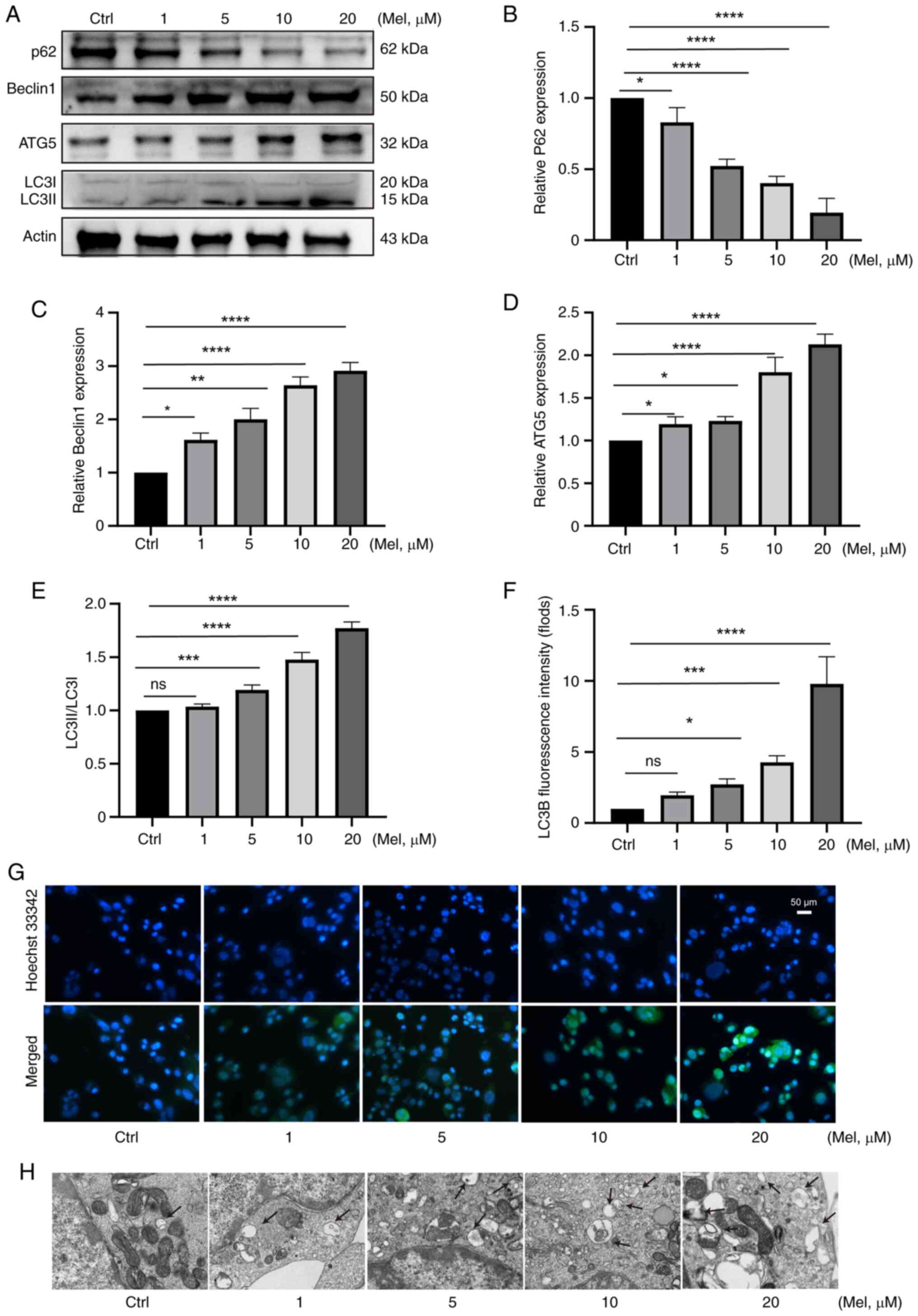

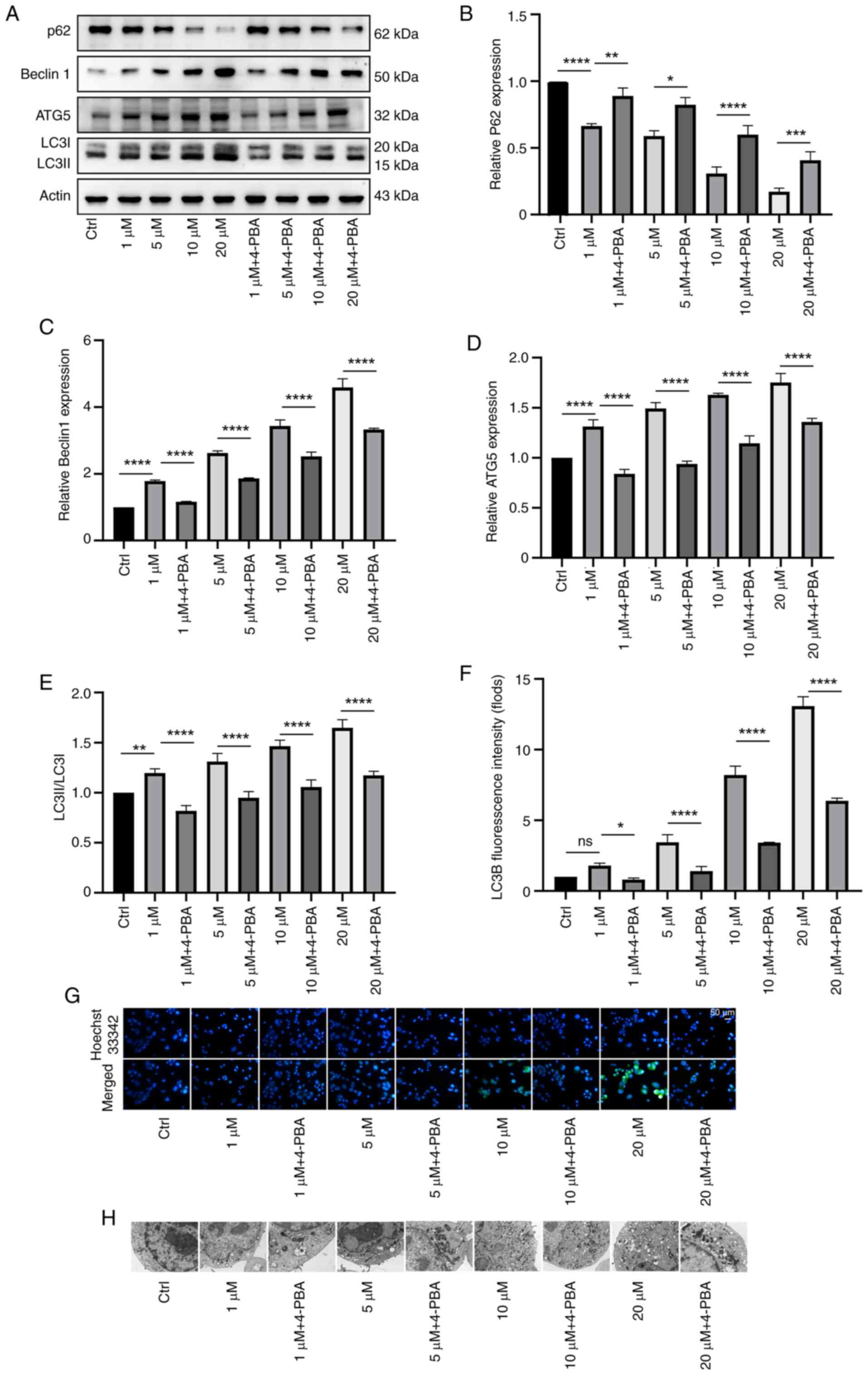

Melatonin can induce autophagy in N2a

neuroblastoma cells

To evaluate the effect of melatonin on autophagy in

N2a neuroblastoma cells, the present study used western blotting to

detect autophagy-related proteins ATG5, P62, BECLIN1, LC3BI/LC3BII

and electron microscopy to observe the formation of autophagosomes

and immunofluorescence for verification (28). The western blotting results of N2a

cells treated with melatonin for 48 h showed that the ratio of

protein LC3II/LC3I increased, the expression of ATG5 and Beclin1

proteins increased, and the expression of p62 protein decreased.

There was a negative association between p62 and autophagy levels,

and a positive association between Beclin1 and autophagy levels

(Fig. 2A-E). The results showed

that as the concentration of melatonin increased, the expression of

autophagy-related proteins also increased, indicating that cellular

autophagy was enhanced.

| Figure 2.Melatonin can induce autophagy in N2a

neuroblastoma cells. N2a cells were treated with melatonin at 1, 5,

10, 20 µM concentrations for 48 h. (A) western blotting detection

showed (B) the expression of p62 protein decreased, (C) the

expression of Beclin1 proteins and (D) ATG5 increased and (E) the

ratio of protein LC3II/LC3I increased. (F and G) As the

concentration of melatonin increased, the intensity of LC3 staining

(green) gradually increased. (H) As the concentration of melatonin

increased, the number of autophagosomes gradually increased.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001; ns, not

significant; N2a, Neuro-2a; ATG5, autophagy-related protein 5; Mel,

melatonin. |

Regarding LC3B-green fluorescence, the fluorescence

signal of positive samples should show a bright and uniform

morphology, which indicates strong autophagic activity. Conversely,

weak or absent fluorescence signal represent that autophagy

activity is weak or not occurring. As the concentration of

melatonin increased, the LC3B-green fluorescence intensity

gradually increased (Fig. 2F and

G).

The cell pellets collected after melatonin treatment

were examined by transmission electron microscopy. There are three

types of autophagy markers: Isolation membrane, autophagosome and

autolysosome. The present study experiment mainly observed the

autophagosome. As the concentration of melatonin increased, the

number of autophagosomes gradually increased (Fig. 2H).

Therefore, through western blotting detection,

transmission electron microscopy and immunofluorescence, it can be

concluded that as the concentration of melatonin increased, the

ability of N2a neuroblastoma to undergo autophagy increased.

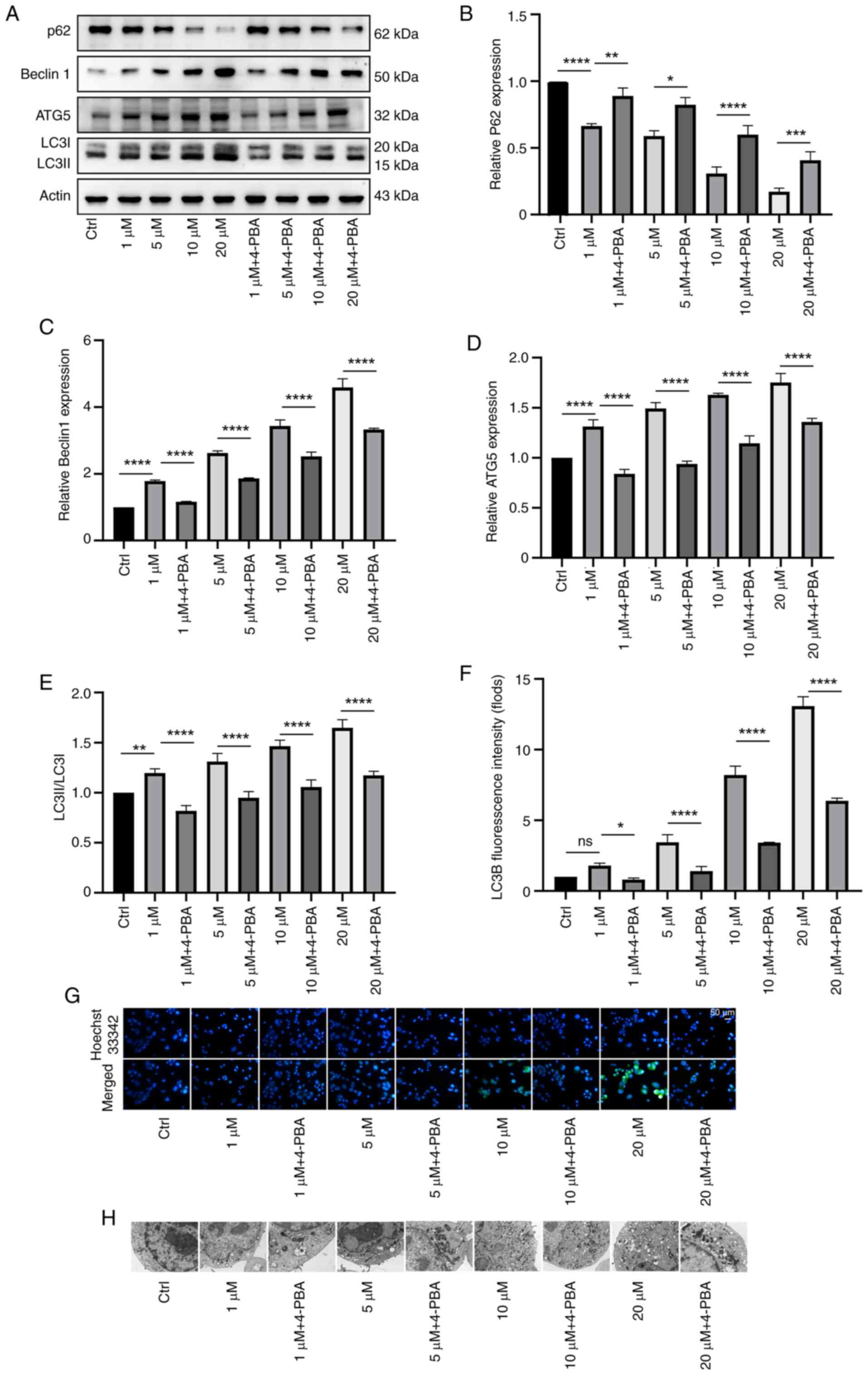

Effects of different concentrations of

melatonin on autophagy in N2a neuroblastoma cells via ER

stress

In order to further verify the relationship between

melatonin and ER stress and autophagy in neuroblastoma cells, the

effects of different concentrations of melatonin on autophagy in

neuroblastoma cells were detected by western blotting after

treatment with the ER stress inhibitor 4-PBA (Fig. 3A). The expression of p62 protein is

inversely proportional to the intensity of autophagy, so after the

inhibitor treatment, its expression increased, indicating that the

intensity of autophagy was weakened (Fig. 3B). Compared with the group treated

with the same concentration of melatonin, the expression of

autophagy-related proteins (ATG5, BECLIN1, LC3B) in the group

treated with 4-PBA was relatively reduced (Fig. 3C-E).

| Figure 3.Effects of different concentrations

of melatonin on autophagy in N2a neuroblastoma cells via ER stress.

(A) N2a cells were treated with melatonin at 1, 5, 10 and 20 µM

concentration and with the ER stress inhibitor 4-PBA. (B) The

expression of p62 protein was inversely proportional to the

intensity of autophagy, its expression increases. Compared with the

group treated with the same concentration of melatonin, the

expression of autophagy-related proteins (C) ATG5, (D) Beclin1, (E)

LC3B in the group treated with 4-PBA was relatively reduced. (F and

G) Immunofluorescence of LC3B (green) revealed that autophagy was

weakened after treatment with 4-PBA, and the green fluorescence was

reduced compared with that of the same concentration of melatonin.

(H) Electron microscopy revealed that the number of vacuolar

autophagosomes after treatment with 4-PBA was reduced compared with

that after treatment with the same concentration of melatonin.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. N2a,

Neuro-2a; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; 4-PBA, 4-phenylbutyric acid;

ATG5, autophagy-related protein 5; Mel, melatonin. |

Similarly, immunofluorescence (LC3B) revealed that

autophagy was weakened after treatment with 4-PBA, and the green

fluorescence was reduced compared with that of the same

concentration of melatonin (Fig. 3F

and G).

Electron microscopy revealed that the number of

vacuolar autophagosomes after treatment with 4-PBA was also reduced

compared with that after treatment with the same concentration of

melatonin (Fig. 3H).

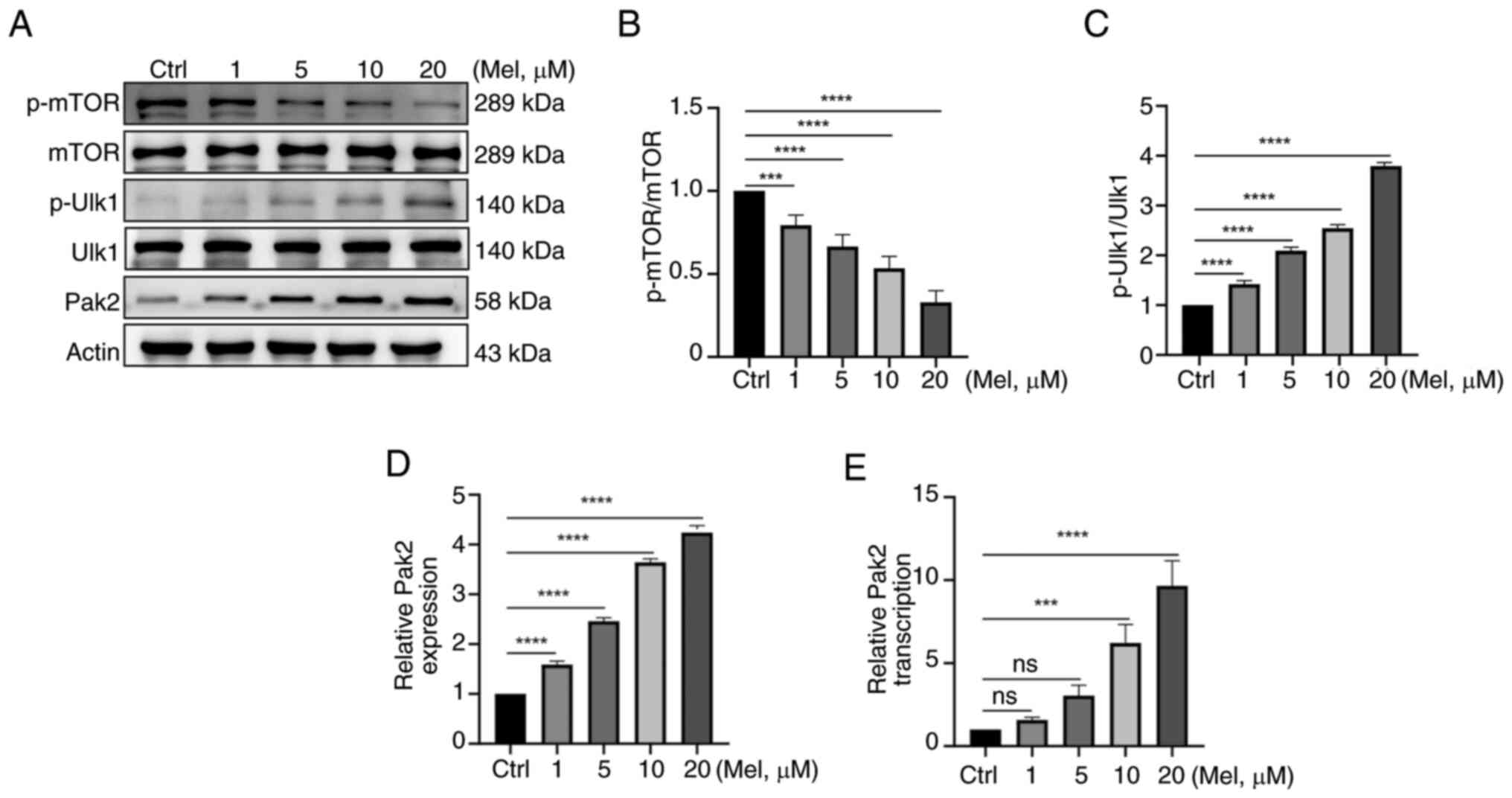

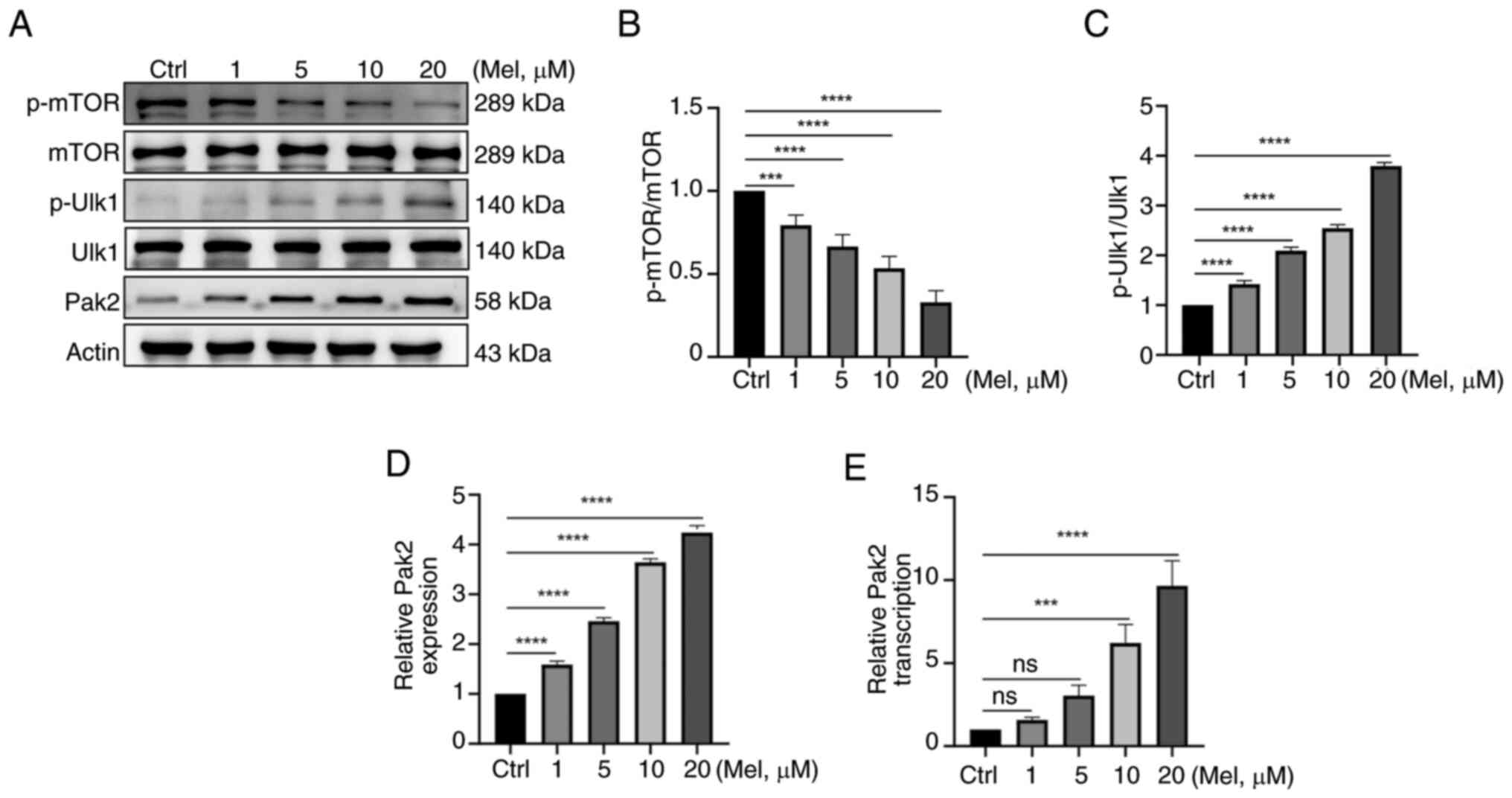

Melatonin regulates Pak2 expression

and detects the activation of the downstream AMPK signaling pathway

of Pak2

Pak2 was tested by western blotting to detect

whether melatonin could regulate Pak2 expression, and the

activation of the AMPK signaling pathway downstream of Pak2 was

detected by western blotting. With the increase of melatonin

concentration, the expression of PAK2 protein gradually increased,

indicating that melatonin can regulate Pak2 expression. For all

shRNA and overexpression vector transfections, it was confirmed

that the transfection was successful (Fig. S1). In the detection of AMPK

signaling pathway: the total protein of MTOR and ULK1 remained

basically unchanged, but the expression of phosphorylated protein

of MTOR decreased, and the expression of phosphorylated protein of

ULK1 increased. This indicated that after melatonin treatment, the

MTOR activity in the AMPK signaling pathway was inhibited,

resulting in a decrease in the MTOR phosphorylation level. It

promoted the activity of ULK1, indicating that the expression of

Pak2 can affect the activation of the downstream AMPK signaling

pathway, thereby participating in regulating the initiation and

progress of cellular autophagy (Fig.

4A-D).

| Figure 4.Melatonin regulates Pak2 expression

and detects the activation of the downstream AMPK signaling pathway

of Pak2. (A) Pak2 and AMPK signaling pathway was tested by western

blotting. The total protein of mTOR and ULK1 remained unchanged;

(B) however, the expression of phosphorylated protein of mTOR

decreased and (C) the expression of phosphorylated protein of ULK1

increased. This indicated that after melatonin treatment, the mTOR

activity in the AMPK signaling pathway is inhibited. (D) With the

increase of melatonin concentration (1, 5, 10 and 20 µM), the

expression of Pak2 protein gradually increased. (E) Quantitative

PCR was used to detect the ability to regulate Pak2 expression

increases with the enhancement of melatonin concentration.

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. ns, not significant; Pak2,

p21-activated kinase 2; AMPK, 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase;

ULK1, unc-51-like kinase 1; Mel, melatonin. |

RNA was isolated from N2a cells treated with

different concentrations of melatonin and the ability to express

Pak2 was measured by qRT-PCR analysis. As the dose of melatonin

increased, especially when the melatonin concentration was ≥10 µm,

the ability of relative Pak2 transcription was significantly

increased (Fig. 4E).

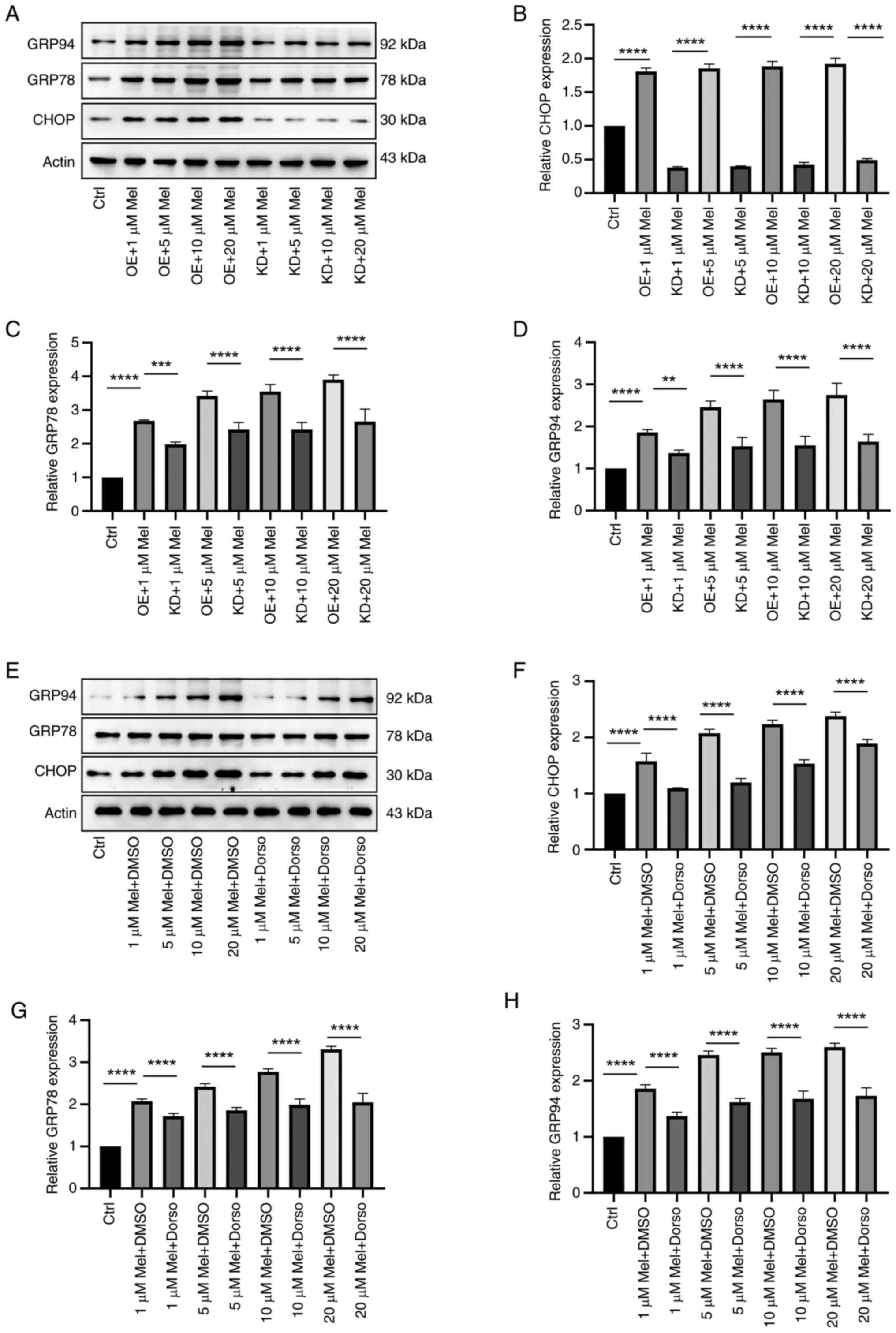

Effects of different concentrations of

melatonin on ER stress and autophagy in N2a neuroblastoma

cells

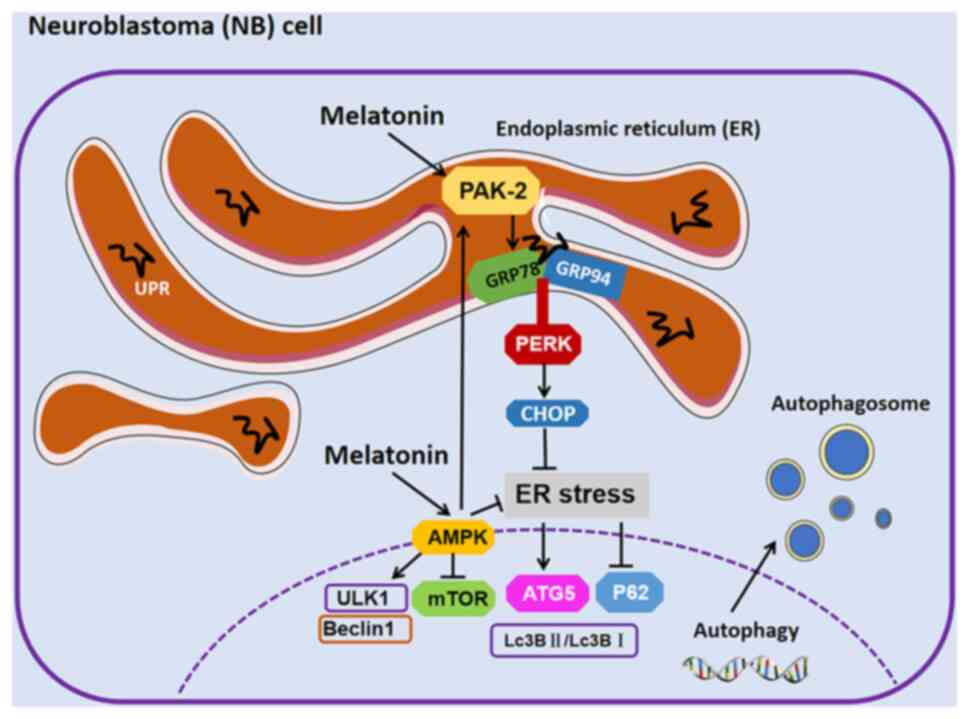

A neuroblastoma cell model of Pak2 overexpression

and expression inhibition was constructed and western blotting was

used to detect the effects of different concentrations of melatonin

on ER stress in neuroblastoma cells. After constructing the Pak2

overexpression model, different concentrations of melatonin were

added and it was found that the expression of GRP94, GRP78 and CHOP

proteins increased compared with the Pak2 overexpression and Pak2

inhibition groups with the same concentration of melatonin. This

indicated that overexpression of Pak2 increased the level of

melatonin in alleviating ER stress in neuroblastoma; conversely,

inhibition of Pak2 expression reduces the level of melatonin in

alleviating ER stress in neuroblastoma (Fig. 5A-D).

| Figure 5.Effects of different concentrations

of melatonin on ER stress and autophagy in N2a neuroblastoma cells.

(A) The model of Pak2 overexpression and expression inhibition was

constructed, and western blotting was used to detect the effects of

different concentrations of melatonin on ER stress in neuroblastoma

cells. (B-D) The expression of GRP94, GRP78 and CHOP proteins

increased compared with the Pak2 overexpression and Pak2 inhibition

groups with the same concentration of melatonin. (E) For the groups

of AMPK signaling pathway inhibitors and DMSO solvent at the same

melatonin concentration, the protein levels of GRP94, GRP78 and

CHOP were detected via Western blot analysis. Compared with the

AMPK signaling pathway inhibitor and DMSO solvent groups with the

same concentration of melatonin, the expression of (F) CHOP, (G)

GRP78 and (H) GRP94 proteins was weakened (F-H). **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. ER, endoplasmic reticulum; N2a,

Neuro-2a; Pak2, p21-activated kinase 2; GRP, glucose-regulated

protein; AMPK, 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase; Mel, melatonin; OE,

Pak2 overexpression; KD, Pak2 knockdown; Dorso, dorsomorphin; DMSO,

solvent control group. |

To verify the accuracy, AMPK signaling pathway

inhibitors were added into neuroblastoma cells and western blotting

used to detect the effects of different concentrations of melatonin

on ER stress in neuroblastoma cells. The expression of GRP94, GRP78

and CHOP was compared by different concentrations of melatonin in

Dorso and DMSO. This indicates that inhibition of the AMPK

signaling pathway reduces the level of melatonin in alleviating ER

stress in neuroblastoma (Fig.

5E-H).

Discussion

Melatonin is an important immunomodulatory molecule

and exhibits inhibitory effects on cancer growth. Its anti-tumor

mechanism is complex and extensive, mainly including the regulation

of the estrogen action pathway, affecting the cell cycle,

regulating growth factors, interfering with calmodulin and tubulin

functions, increasing intercellular gap junctions, affecting cell

metabolism and antioxidant and immune-enhancing effects (29). The present study explored whether

melatonin could reduce ER stress in N2a neuroblastoma cells and

induce autophagy in N2a cells. It studied the relationship between

ER stress and autophagy in N2a cells under the action of melatonin,

observed the regulation of Pak2 expression by melatonin, detected

the activation of AMPK signaling pathway downstream of Pak2 and

constructed N2a cell models of Pak2 overexpression and expression

inhibition. In contrast to Xing et al (30), who applied the

hypoxia-reoxygenation (HR) model, proven that melatonin alleviates

ER stress in HR injury through the AMPK-Pak2 pathway, the present

study applied the tumor microenvironment stress model; the end

point of Xing et al (30)

was cell survival/apoptosis inhibition, whereas the present study

focused on autophagy activation. Xing et al (30) focused their analysis on apoptosis

inhibition, whereas the present study revealed autophagy

initiation. Hence, the present study aimed to demonstrate that

melatonin induces neuroblastoma autophagy by alleviating

Pak2-mediated ER stress, thereby inhibiting the growth of N2a

neuroblastoma cells.

Early studies have found that physiological

concentrations of melatonin can inhibit human neuroblastoma cells,

suggesting that melatonin has anti-proliferation and

pro-differentiation effects (31,32).

These studies support the present findings that low concentrations

of melatonin have the function of promoting differentiation and

inducing autophagy. High concentrations of melatonin could induce

cell cycle arrest at G2/M phase, activate caspase-3 and

lead to 75% cell apoptosis (33).

In a study of Alzheimer's disease, Singrang et al (34) found that melatonin was able to

inhibit hypoxia-induced amyloid-producing pathway, thereby

alleviating Alzheimer's disease-related pathological changes in

SH-SY5Y cells. This evidence confirms that melatonin triggers

downstream autophagy or apoptosis by alleviating ER stress and that

Pak2 is a key regulator. Melatonin upregulates Pak2 through AMPK,

which in turn inhibits mTOR and activates ULK1 to determine cell

fate (autophagy or apoptosis). In particular, Lee et al

(32) found that melatonin

promoted differentiation through HAS3-mitophagy, while the present

study found that melatonin inhibited tumor growth through Pak2-ER

stress-autophagy, both pointing to autophagy as a bridge between

differentiation and tumor suppression.

In the tumor microenvironment, multiple stressors

are enriched to dynamically perturb the protein folding capacity of

the ER of malignant tumor cells and stromal cells. In addition to

the adverse environmental conditions created by tumors, genetic

alterations in cancer cells can exacerbate ER stress and promote

sustained activation of the UPR pathway. Co-ordination of the ER

stress response is a highly dynamic process that can result in both

pro-survival and pro-apoptotic outputs. The intensity and duration

of UPR have decisive effects on the fate of cells and a previous

study has revealed the role of the ER stress response pathway in

the occurrence and development of cancer (35). GRP94 and GRP78 are UPR-driven ER

molecular chaperones whose purpose is to clear unfolded proteins

and restore ER homeostasis. A previous study has demonstrated that

melatonin reduces ER stress by activating ER-associated protein

degradation (36). Melatonin

inhibits the expression of GRP78 and GRP94 through

receptor-mediated mechanisms, blocks the excessive activation of

the ER stress signaling pathway and ultimately alleviates

BPA-induced testicular cell apoptosis and ER homeostasis imbalance

(37). Under conditions of

myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury or HR stress, the protein

and mRNA levels of GRP78 are markedly upregulated. Melatonin can

markedly reduce the expression of GRP78 by activating Pak2

(38). Based on previous studies,

the present study used different concentrations of melatonin to act

on N2a cells and found that the expression of GRP94, GRP78 and CHOP

proteins increased, proving for the first time to the best of the

authors' knowledge that melatonin is also effective in controlling

ER stress response in N2a neuroblasts.

Autophagy is a key part of the way tumor cells

metabolize. Liu et al (39)

observed that autophagic degradation of CDK4 was responsible for

G0G1 cell cycle arrest in NVP-BEZ235-treated neuroblastoma cells,

and Liu et al (40) found

that Aβ(1–42) ginsenosides Rg1 and Rg2 activated autophagy and

alleviated oxidative stress in neuroblastoma cells overexpressing

Aβ(1–42). Melatonin also induces autophagy in neuroblastoma cells.

Lee et al (32) found that

melatonin promotes neuroblastoma cell differentiation by activating

hyaluronan synthase 3-induced mitochondrial autophagy. The present

study detected autophagy-related proteins ATG5, P62, BECLIN1 and

LC3BI/LC3BII by western blotting and observed the formation of

autophagosomes and immunofluorescence by electron microscopy and

found that autophagic activity increased with the increase of

melatonin concentration. At the same time, it used western blotting

to detect the effect of different concentrations of melatonin on

autophagy of neuroblastoma cells after treatment with the ER stress

inhibitor 4-PBA, and found that melatonin induces autophagy of

neuroblastoma cells by alleviating ER stress.

Pak2 is a novel stress response kinase localized to

the ER membrane. A study found that Pak2 is a new therapeutic

target for ER stress response (41). Xing et al (30) found that melatonin regulates the

expression of Pak2 through the AMPK pathway and that inhibition of

the AMPK pathway can inhibit melatonin-mediated Pak2 upregulation

and promote N2a cell death. The present study observed that with

the increase of melatonin concentration, the expression of PAK2

protein gradually increased and after melatonin treatment, although

the total protein of MTOR and ULK1 remained basically unchanged,

the expression of MTOR phosphorylated protein decreased and the

expression of ULK1 phosphorylated protein increased. The

aforementioned confirms that in neuroblastoma cells, the expression

of Pak2 following melatonin treatment can affect the activation of

the downstream AMPK signaling pathway, thereby participating in

regulating the initiation and progress of cellular autophagy. The

present study simultaneously constructed neuroblastoma cell models

with Pak2 overexpression and expression inhibition and added AMPK

signaling pathway inhibitors to neuroblastoma cells. It

demonstrated for the first time that inhibition of the AMPK

signaling pathway reduced the level of melatonin in alleviating ER

stress in neuroblastoma.

The present study is a preliminary exploration of

the effects of melatonin on autophagy in neuroblastoma cells. It

revealed for the first time its novel therapeutic effects in in

vitro experiments on neuroblastoma cells and delineated its

mechanism by alleviating the ER stress pathway. However, the

present study has its limitations. The results were only verified

in in vitro tumor cell experiments and further related

research is needed to confirm its effectiveness and safety in

clinical applications. In addition, although the present study

confirmed the therapeutic effect of melatonin on neuroblastoma

cells, the specific therapeutic mechanism still needs to be

verified through further research in animal models and clinical

trials.

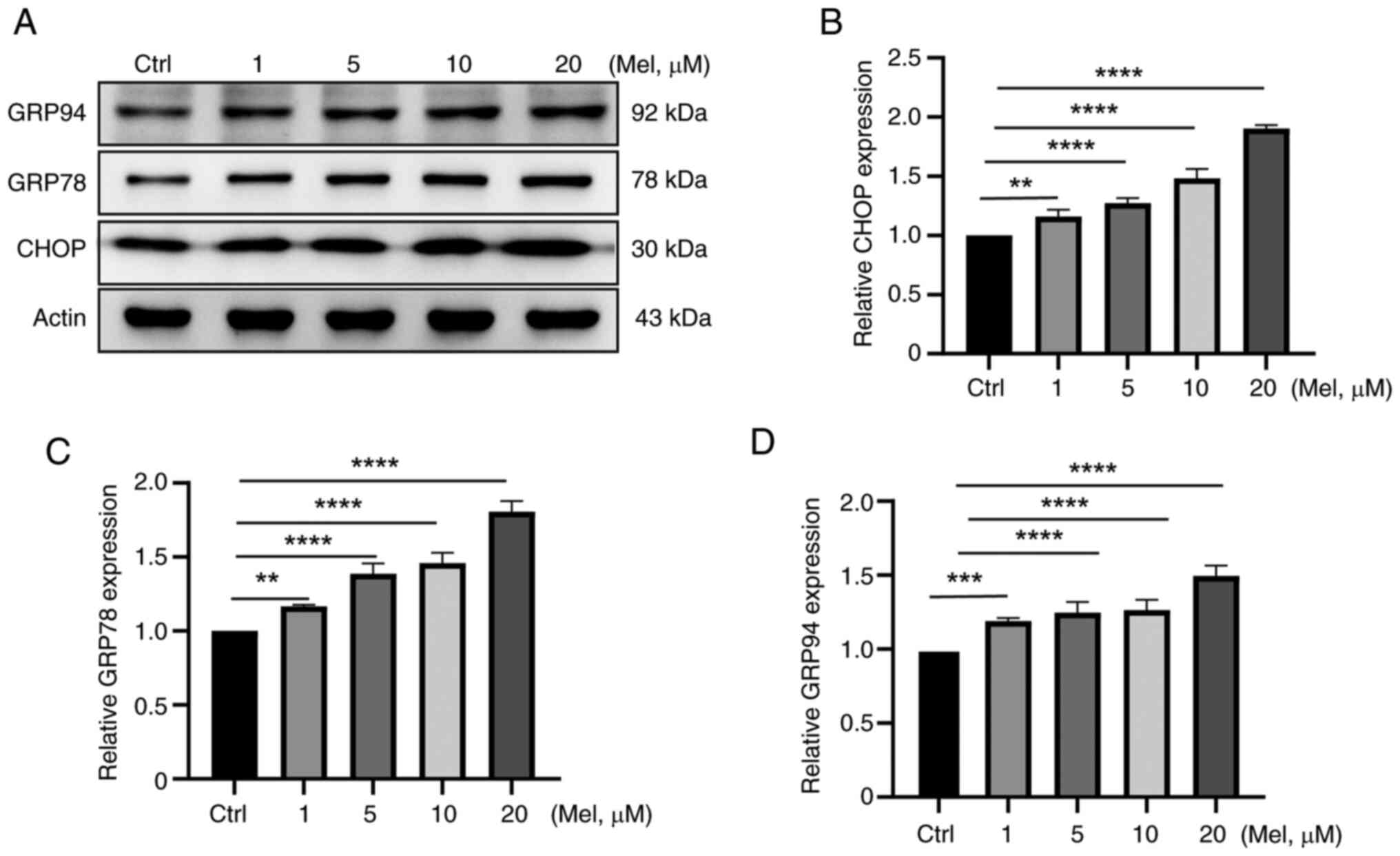

Taken together, the present study concluded that

melatonin induced autophagy in neuroblastoma by alleviating

Pak2-mediated ER stress (Fig.

6).

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated for

the first time to the best of the authors' knowledge that melatonin

has a therapeutic effect on neuroblastoma by alleviating

Pak2-mediated ER stress and inducing autophagy. Therefore, the

present study hypothesized that melatonin is a promising new drug

candidate for the treatment of neuroblastoma. In the future, more

effective combined treatment methods can be explored by combining

melatonin with other drugs or treatments, thereby improving the

comprehensive treatment effect of neuroblastoma.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by Guangzhou Health Science and

Technology Project (grant no. 20241A011036) and The Key R&D

Program of Guangzhou (grant no. 202206010006).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

QQ and XS designed the study. QQ, NZ, YX, JQ, GY and

XS performed the literature review, experiments and statistical

analysis. QQ, NZ and XS edited the manuscript. QQ and XS confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved

the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Del Bufalo F, De Angelis B, Caruana I, Del

Baldo G, De Ioris MA, Serra A, Mastronuzzi A, Cefalo MG, Pagliara

D, Amicucci M, et al: GD2-CART01 for relapsed or refractory

High-risk neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 388:1284–1295. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Qiu B and Matthay KK: Advancing therapy

for neuroblastoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 19:515–533. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Abbasi J: Mixed findings in pediatric

neuroblastoma CAR-T therapy trial. JAMA. 325:1212021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Debnath J, Gammoh N and Ryan KM: Autophagy

and autophagy-related pathways in cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

24:560–575. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Xia H, Green DR and Zou W: Autophagy in

tumour immunity and therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 21:281–297. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Bian Y, Li W, Kremer DM, Sajjakulnukit P,

Li S, Crespo J, Nwosu ZC, Zhang L, Czerwonka A, Pawłowska A, et al:

Cancer SLC43A2 alters T cell methionine metabolism and histone

methylation. Nature. 585:277–282. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B and Guan KL:

AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of

Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol. 13:132–141. 2011. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Egan DF, Shackelford DB, Mihaylova MM,

Gelino S, Kohnz RA, Mair W, Vasquez DS, Joshi A, Gwinn DM, Taylor

R, et al: Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP-activated protein

kinase connects energy sensing to mitophagy. Science. 331:456–461.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kim J, Kim YC, Fang C, Russell RC, Kim JH,

Fan W, Liu R, Zhong Q and Guan KL: Differential regulation of

distinct Vps34 complexes by AMPK in nutrient stress and autophagy.

Cell. 152:290–303. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wang Y, Zhao W, Xiao Z, Guan G, Liu X and

Zhuang M: A risk signature with four autophagy-related genes for

predicting survival of glioblastoma multiforme. J Cell Mol Med.

24:3807–3821. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Bishayee K, Habib K, Nazim UM, Kang J,

Szabo A, Huh SO, Sadra A, et al: RNA binding protein HuD promotes

autophagy and tumor stress survival by suppressing mTORC1 activity

and augmenting ARL6IP1 levels. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 41:182022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ugun-Klusek A, Theodosi TS, Fitzgerald JC,

Burté F, Ufer C, Boocock DJ, Yu-Wai-Man P, Bedford L and Billett

EE: Monoamine oxidase-A promotes protective autophagy in human

SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells through Bcl-2 phosphorylation. Redox

Biol. 20:167–181. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Marciniak SJ, Chambers JE and Ron D:

Pharmacological targeting of endoplasmic reticulum stress in

disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 21:115–140. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Clarke HJ, Chambers JE, Liniker E and

Marciniak SJ: Endoplasmic reticulum stress in malignancy. Cancer

Cell. 25:563–573. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yang R, Ma S, Zhuo R, Xu L, Jia S, Yang P,

Yao Y, Cao H, Ma L, Pan J and Wang J: Suppression of endoplasmic

reticulum stress-dependent autophagy enhances cynaropicrin-induced

apoptosis via attenuation of the P62/Keap1/Nrf2 pathways in

neuroblastoma. Front Pharmacol. 13:9776222022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Celesia A, Morana O, Fiore T, Pellerito C,

D'Anneo A, Lauricella M, Carlisi D, De Blasio A, Calvaruso G,

Giuliano M and Emanuele S: ROS-Dependent ER stress and autophagy

mediate the anti-tumor effects of tributyltin (IV) ferulate in

colon cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci. 21:81352020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

París-Coderch L, Soriano A, Jiménez C,

Erazo T, Muñoz-Guardiola P, Masanas M, Antonelli R, Boloix A, Alfón

J, Pérez-Montoyo H, et al: The antitumour drug ABTL0812 impairs

neuroblastoma growth through endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated

autophagy and apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 11:7732020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Ge W, Yan ZH, Wang L, Tan SJ, Liu J,

Reiter RJ, Luo SM, Sun QY and Shen W: A hypothetical role for

autophagy during the day/night rhythm-regulated melatonin synthesis

in the rat pineal gland. J Pineal Res. 71:e127422021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Boga JA, Caballero B, Potes Y,

Perez-Martinez Z, Reiter RJ, Vega-Naredo I and Coto-Montes A:

Therapeutic potential of melatonin related to its role as an

autophagy regulator: A review. J Pineal Res. 66:e125342029.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Fernández A, Ordóñez R, Reiter RJ,

González-Gallego J and Mauriz JL: Melatonin and endoplasmic

reticulum stress: Relation to autophagy and apoptosis. J Pineal

Res. 59:292–307. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhang S, Tian W, Duan X, Zhang Q, Cao L,

Liu C, Li G, Wang Z, Zhang J, Li J, et al: Melatonin attenuates

diabetic cardiomyopathy by increasing autophagy of cardiomyocytes

via regulation of VEGF-B/GRP78/PERK signaling pathway. Cardiovasc

Diabetol. 23:192024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhang L, Liu K, Liu Z, Tao H, Fu X, Hou J,

Jia G and Hou Y: In pre-clinical study fetal hypoxia caused

autophagy and mitochondrial impairment in ovary granulosa cells

mitigated by melatonin supplement. J Adv Res. 64:15–30. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Xu S, Li L, Wu J, An S, Fang H, Han Y,

Huang Q, Chen Z and Zeng Z: Melatonin attenuates sepsis-induced

small-intestine injury by upregulating SIRT3-Mediated

oxidative-stress inhibition, mitochondrial protection, and

autophagy induction. Front Immunol. 12:6256272021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

De Almeida Chuffa LG, Seiva FRF, Silveira

HS, Cesário RC, da Silva Tonon K, Simão VA, Zuccari DAPC and Reiter

RJ: Melatonin regulates endoplasmic reticulum stress in diverse

pathophysiological contexts: A comprehensive mechanistic review. J

Cell Physiol. 239:e313832024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lebeau PF, Wassef H, Byun JH, Platko K,

Ason B, Jackson S, Dobroff J, Shetterly S, Richards WG, Al-Hashimi

AA, et al: The loss-of-function PCSK9Q152H variant increases ER

chaperones GRP78 and GRP94 and protects against liver injury. J

Clin Invest. 131:e1286502021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Cubillos-Ruiz JR, Bettigole SE and

Glimcher LH: Tumorigenic and immunosuppressive effects of

endoplasmic reticulum stress in cancer. Cell. 168:692–706. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Vargas JNS, Hamasaki M, Kawabata T, Youle

RJ and Yoshimori T: The mechanisms and roles of selective autophagy

in mammals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 24:167–185. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Li M, Hao B, Zhang M, Reiter RJ, Lin S,

Zheng T, Chen X, Ren Y, Yue L, Abay B, et al: Melatonin enhances

radiofrequency-induced NK antitumor immunity, causing cancer

metabolism reprogramming and inhibition of multiple pulmonary tumor

development. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 6:3302021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Xing J, Xu H, Liu C, Wei Z, Wang Z, Zhao L

and Ren L: Melatonin ameliorates endoplasmic reticulum stress in

N2a neuroblastoma cell hypoxia-reoxygenation injury by activating

the AMPK-Pak2 pathway. Cell Stress Chaperones. 24:621–633. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Cos S, Verduga R, Fernández-Viadero C,

Megías M and Crespo D: Effects of melatonin on the proliferation

and differentiation of human neuroblastoma cells in culture.

Neurosci Lett. 216:113–136. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Lee WJ, Chen LC, Lin JH, Cheng TC, Kuo CC,

Wu CH, Chang HW, Tu SH and Ho YS: Melatonin promotes neuroblastoma

cell differentiation by activating hyaluronan synthase 3-induced

mitophagy. Cancer Med. 8:4821–4835. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

García-Santos G, Antolín I, Herrera F,

Martín V, Rodriguez-Blanco J, del Pilar Carrera M and Rodriguez C:

Melatonin induces apoptosis in human neuroblastoma cancer cells. J

Pineal Res. 41:130–135. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Singrang N, Nopparat C, Panmanee J and

Govitrapong P: Melatonin inhibits Hypoxia-induced Alzheimer's

disease pathogenesis by regulating the amyloidogenic pathway in

human neuroblastoma cells. Int J Mol Sci. 25:52252024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Chen X and Cubillos-Ruiz JR: Endoplasmic

reticulum stress signals in the tumour and its microenvironment.

Nat Rev Cancer. 21:71–88. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Choi SI, Lee E, Akuzum B, Jeong JB, Maeng

YS, Kim TI and Kim EK: Melatonin reduces endoplasmic reticulum

stress and corneal dystrophy-associated TGFBIp through activation

of endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation. J Pineal

Res. 632017.doi: 10.1111/jpi.12426.

|

|

37

|

Qi Q, Feng L, Liu J, Xu D, Wang G and Pan

X: Melatonin alleviates BPA-induced testicular apoptosis and

endoplasmic reticulum stress. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed).

29:952024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Wang S, Bian W, Zhen J, Zhao L and Chen W:

Melatonin-mediated Pak2 activation reduces cardiomyocyte death

through suppressing hypoxia reoxygenation Injury-induced

endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 74:20–29.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Liu Z, Wang XY, Wang HW, Liu SL, Zhang C,

Liu F, Guo Y and Gao FH: Autophagic degradation of CDK4 is

responsible for G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in NVP-BEZ235-treated

neuroblastoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 25:23855172024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Liu Z, Cecarini V, Cuccioloni M, Bonfili

L, Gong C, Angeletti M and Eleuteri AM: Ginsenosides Rg1 and Rg2

activate autophagy and attenuate oxidative stress in neuroblastoma

cells overexpressing Aβ(1–42). Antioxidants (Basel). 13:3102024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Binder P, Binder P, Wang S, Radu M, Zin M,

Collins L, Khan S, Li Y, Sekeres K, Humphreys N, et al: Pak2 as a

novel therapeutic target for cardioprotective endoplasmic reticulum

stress response. Circ Res. 124:696–711. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|