Introduction

The occurrence of renal cell carcinoma (RCC), one of

the most prevalent malignant tumors of the urinary system, is

becoming increasingly common in numerous countries, with high

incidence and mortality rates (1).

RCC encompasses three subtypes [papillary, chromophobe and clear

cell RCC (ccRCC)], with ccRCC being the most prevalent (2). Although early surgical or ablative

interventions can improve patient survival, approximately one-third

of patients develop metastases, and a quarter of them experience

recurrent metastasis following treatment (3). Unlike other types of cancer, ccRCC is

resistant to chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Advancements in

targeted therapies, immunotherapy and combination therapies have

extended the survival of patients with advanced ccRCC to a certain

extent (4). However, not all

patients respond well to these treatments, and the majority of them

will develop resistance due to the immune microenvironment and

immune escape mechanisms of the tumor (5). Patients with early-stage ccRCC have

been shown to benefit from immediate surgical intervention,

although the 5-year survival rate for advanced cases is only 23%

(6). Consequently, there is an

urgent need to deepen the understanding of RCC. Both exploring

novel molecular targets and developing personalized treatment

strategies are crucial for improving survival and treatment

outcomes, especially for patients with advanced disease.

Alternative splicing (AS) is a critical regulatory

mechanism in eukaryotic gene expression, enabling the generation of

protein diversity through spliceosome-mediated exon-intron

rearrangement (7). This process

allows a single gene to produce multiple mRNA variants that encode

distinct proteins, thereby fulfilling vital roles in cellular

development. Dysregulation of AS is a hallmark of tumorigenesis,

contributing to therapeutic resistance (8–10).

Splicing factor 3a subunit 2 (SF3A2), an essential component of the

spliceosome, has emerged as a key regulator in oncogenic processes

and non-neoplastic diseases, functioning through the control of

alternative splicing (AS) networks and protein-protein interactions

(11). In myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion injury, a previous study showed that the

ginsenoside Rb2 mitigated cardiomyocyte damage by inhibiting

p300-mediated SF3A2-K10 acetylation, thereby promoting AS of fascin

actin-bundling protein 1 (FSCN1) and enhancing mitochondrial

respiration (12). These findings

highlighted the role of SF3A2 in cardiovascular pathophysiology,

suggesting that its acetylation status serves as a potential

prognostic biomarker. SF3A2 exhibits context-dependent functions in

various malignancies; for example, in Ewing sarcoma (ES), its

interaction with DExH-box helicase 9 (DHX9) suppresses tumor

progression through splicing modulation (13), whereas in triple-negative breast

cancer (TNBC), SF3A2 overexpression drives cisplatin resistance

through the activation of makorin ring finger protein 1 (MKRN1)

splicing and ubiquitin protein ligase E3 component N-recognin 5

feedback reinforcement (14).

Considered altogether, these dual roles underscore the multifaceted

regulatory potential of SF3A2 across different diseases.

To the best of our knowledge, the role of SF3A2 in

ccRCC progression has not yet been elucidated. The present study

integrated bioinformatics analyses with experimental validation to

characterize the functional involvement of SF3A2 in ccRCC

pathogenesis, thereby providing a basis for exploring SF3A2 as a

potential therapeutic target.

Materials and methods

Open-access data utilization

The present study employed a multimodal analytical

framework to explore the functional dynamics of SF3A2 in ccRCC.

Multi-omics clinical data were sourced from The Cancer Genome Atlas

Kidney Renal Clear Cell Carcinoma (TCGA-KIRC) dataset [n=539 tumor

specimens with RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) profiles; http://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga] and the

Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) portal (n=73 normal renal

transcriptomes; http://www.gtexportal.org/). Differential expression

profiling was performed using Gene Expression Profiling Interactive

Analysis 2 (http://gepia2.cancerpku.cn/#index), applying

predefined thresholds (|log2 fold change| >1; false

discovery rate <0.05). Prognostic relevance was assessed using

Kaplan-Meier methodology and log-rank testing for overall survival

(OS). Protein-level validation was achieved by assessing

immunohistochemical data from the Human Protein Atlas repository

(https://www.proteinatlas.org/) (15).

Cell culture systems and viral

transduction

Experimental models included renal tubular

epithelial cells (HK-2) and RCC cell lines (786-O, ACHN, 769-P,

OSRC-2 and A498; all cell lines were purchased from The Cell Bank

of Type Culture Collection of The Chinese Academy of Sciences and

authenticated by short tandem repeat profiling). HK-2 cells were

cultured in DMEM. 786-O, 769-P and OSRC-2 cells were maintained in

RPMI-1640 medium, ACHN cells were grown in MEM, and A498 cells were

cultured in EMEM (or MEM when EMEM was unavailable). All media were

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (cat. no. A5256701; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and all

cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing

5% CO2.

Lentivirus-mediated stable transduction enabled

bidirectional genetic modification: SF3A2 knockdown was achieved

using validated short hairpin (sh)RNAs (shRNAs/shs; sequences of

shRNAs 1–2, respectively: 5′-ACATCAACAAGGACCCGTACT-3′ and

5′-CAAAGTGACCAAGCAGAGAGA-5′). A non-targeting shRNA

(5′-CAACAAGATGAAGAGCACCAA-3′) was used as the negative control. For

overexpression assays, SF3A2 was introduced using an OriGene

LentiORF™ lentiviral expression vector (cat. no. RC201244L4;

Origene Technologies, Inc.), which is based on the

pLenti-CMV-ORF-Puro backbone. The corresponding empty

vector(pLenti-CMV-Puro; cat. no. PS100093V; Origene Technologies,

Inc.) was used as the negative control. Viral particles were

packaged in 293T cells through co-transfection with psPAX2 (cat.

no. #12260; Addgene, Inc.) and pMD2.G (cat. no. #12259; Addgene,

Inc.), and cell supernatant was harvested at 48 h

post-transfection, and subsequently sterile-filtered (0.45-µm

filters). SF3A2 knockdown was performed using pLKO.1-based shRNA

lentiviral plasmids (shRNA-1 and shRNA-2; Shanghai GeneChem Co.,

Ltd.), with a non-targeting pLKO.1 shRNA serving as the control.

Lentiviruses were produced using a third-generation packaging

system in 293T cells (ATCC CRL-3216, obtained from the Cell Bank of

the Chinese Academy of Sciences). 293T cells at 60–70% confluence

were transfected using Lipofectamine® 3000 (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with 4 µg transfer plasmid (pLKO.1-shRNA

or pCMV-SF3A2), 3 µg psPAX2, and 1 µg pMD2.G (total 8 µg DNA per

10-cm dish; 4:3:1 ratio). After 6–8 h at 37°C, the medium was

replaced, and viral supernatants were collected at 48 and 72 h,

filtered through a 0.45-µm membrane, and used immediately or stored

at −80°C. Target cells (786-O, OSRC-2) were infected at 40–50%

confluence with virus supplemented with 8 µg/ml polybrene for 24 h,

followed by medium replacement and recovery for 48–72 h. Stable

knockdown or overexpression lines were established using puromycin

selection (1.5–2.0 µg/ml for selection; 0.5–1.0 µg/ml for

maintenance) for 3–5 days, and cells were expanded for an

additional 3–5 days before downstream experiments. Target cells

were transduced at a multiplicity of infection of 5, followed by

selection with puromycin (2 µg/ml; cat. no. P8833; Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA) over a 14-day period to establish stable lines.

Finally, the genetic perturbation efficiency was validated using

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) and western blot

analyses, as described subsequently.

RT-qPCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cellular samples using

TRIzol® reagent (cat. no. 15596026CN; Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and RNA purity was quantified using a

NanoDrop2000™ spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. RT) was performed

using the ReverTra Ace® qPCR RT Kit (Toyobo Co., Ltd.)

at 37°C for 15 min (cDNA synthesis), 98°C for 5 min (enzyme

inactivation), hold at 4°C. qPCR was performed using

SYBR® Green qPCR Mix (TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd.) on a

QuantStudio™ real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The

thermocycling conditions were: 95°C for 30 s (initial

denaturation); 40 cycles of: 95°C for 5 s; 60°C for 30 sec

(annealing/extension); Melt curve analysis: 65–95°C, increment

0.5°C every 5 s; SYBR Green®-based qPCR analysis

(TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd.) was performed using the

2−ΔΔCq method. β-actin acted as the endogenous control

(16).

The forward primer sequence for SF3A2 was

5′-GATTGACTACCCTGAGATCGCC-3′, and the sequence of the reverse

primer was 5′-CTCCCGGTTCCAGTGTGTC-3′. The sequences of the primers

for the reference gene, β-actin, were as follows: Forward,

5′-CATGTACGTTGCTATCCAGGC-3′ and reverse,

5′-CTCCTTAATGTCACGCACGAT-3′.

Western blot analysis

Protein lysates from cultured cells were prepared

using RIPA buffer with 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (cat. no.

P8340; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). Protein concentrations were

determined using a BCA assay (Jiangsu CoWin Biotech Co., Ltd.).

Aliquots (20 µg/lane) were resolved using SDS-PAGE (10% gels; Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) and transferred onto 0.45-µm PVDF

membranes. After blocking the membranes with 5% non-fat milk for 1

h at room temperature, washed with TBST containing 0.1% Tween-20,

and incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary

antibodies: SF3A2 (1:1,000; Abcam, cat. no. ab317408), Actin

(1:5,000; CST Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.; cat. no. 4970),

phosphorylated (p-)AKT (1:2,000; CST Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.

cat. no. 4060) and total AKT (1:2,000; CST Biological Reagents Co.,

Ltd. cat. no. 4691) antibodies. Following washes three times for 10

min each, with TBST. The membrane was incubated with the

HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5,000, Proteintech, cat. no.

SA00001-1 and SA00001-2) in TBST at room temperature for 1 h,

followed by three washes of 10 min each. prior to ECL detection

(Fdbio Science). Band intensities were semi-quantified using Image

Lab software (version 6.1.0, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

Immunohistochemical analysis

For histological examination, tissue samples were

fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at

4°C for 24 h. Following fixation, the tissues were dehydrated

through a graded ethanol series, cleared in xylene, and embedded in

paraffin blocks. Serial sections of 5 µm thickness were cut using a

rotary microtome and mounted onto glass slides. Sections were

deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through a graded ethanol

series to distilled water. The nuclei were stained with Mayer's

hematoxylin for 8 min at room temperature, followed by rinsing in

running tap water for 10 min. Cytoplasmic counterstaining was

performed by immersing the sections in Eosin Y solution for 2 min

at room temperature. Finally, the stained sections were dehydrated

through a graded alcohol series, cleared in xylene, and

coverslipped with a permanent mounting medium. The stained sections

were examined and imaged using a standard light microscope.

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed on paraffin-embedded

specimens as aforementioned. After antigen retrieval in sodium

citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and peroxidase inactivation with 3%

H2O2, sections were incubated overnight at

4°C with anti-SF3A2 (1:200; Abcam, cat. no. ab317408), anti-PCNA

(1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, cat. no. sc-56), phosphorylated

(p-)AKT (1:100; CST Biological Reagents Co., Ltd., cat. no. 4060).

Following three washes with PBS buffer, sections were then

incubated with an anti-mouse/rabbit-specific protein kit (Envision

Plus, Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA) at room temperature. The

chromogen used was 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC, SK-4205, Vector,

Burlingame, CA, USA). The sections were then counterstained with

Meyer's hematoxylin at room temperature for 30–60 sec. Digital

whole-slide images were generated using a domestic high-throughput

slide scanner (PANOVUE VS200 Panoramic Pathology Scanning

System).

Cell proliferation assay

786-O and OSRC-2 cells were seeded at a density of

500 cells/well. After optimized cell seeding in 96-well plates,

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) proliferation assays (cat. no. CK04;

Dojindo Laboratories, Inc.) were performed at 24, 48, 72 and 96 h,

with a 2-h reagent incubation. Absorbance measurements at 450 nm

were subsequently recorded using a BioTek™ Synergy H1 microplate

reader (Agilent Technologies, Inc.), with six technical replicates

per experimental condition.

Colony formation assay

786-O and OSRC-2 cells were seeded at 500 cells per

well in 6-well plates and cultured for 10 days at 37°C in a

humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 with 0.1% DMSO or

SC79 (10 µM). Cells were subsequently fixed with 100% methanol for

15 min at room temperature and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for

15 min. Colonies >50 µm in diameter were counted manually across

three independent biological replicates.

Cell migration and invasion

assays

786-O and OSRC-2 cell migration was assessed using

8-µm Corning® Transwell chambers (Corning, Inc.). Cells

were seeded at 3×104/insert in serum-free medium in the

upper chambers and RPMI-1640 medium containing 20% fetal bovine

serum was added to the lower chambers for 36 h at 37°C. Subsequent

assays were initiated after 36 h, with migrated cells fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature and stained with

0.1% crystal violet for 1 h at room temperature. Non-migrated cells

were removed using a cotton swab. For the invasion assays,

Matrigel™-coated membranes (50 µl/insert; BD Biosciences) were

used, the coated chambers were incubated at 37°C for 1 h in a cell

culture incubator to allow the Matrigel to form a thin gel, and

3×104 cells were seeded per insert and incubated for 36

h at 37°C. The culture conditions for the upper and lower chambers

of the invasion assay, as well as the fixation and crystal violet

staining steps were performed as aforementioned. In both assays,

cellular penetration was quantified by counting cells in five

randomly selected fields per replicate at a magnification of light

microscope in ×200.

In vivo animal experiments

Subcutaneous xenograft models were established in

the right axillary subcutaneous region of male BALB/c nude mice

(Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd.) by

single axillary implantation of 786-O cells (5×106

cells/mouse in total) with stable SF3A2 knockdown or control

constructs (n=5 mice/group). A total of 10 6-week-old male nude

mice with a body weight of ~20 g were used in total. The 786-O

cells were resuspended in PBS at a density of 5×107

cells/ml. A 100-µl aliquot of the cell suspension was injected

subcutaneously into the ventral region of the right anterior armpit

of nude mice. All animals were housed at a suitable temperature

(22–24°C) and humidity (40–70%) under a 12/12-h light/dark cycle

with unrestricted access to food and water. Tumor growth was

monitored biweekly using digital calipers, and tumor volumes were

calculated according to the formula: (Length ×

width2)/2. After 6 weeks, mice were euthanized by

anesthesia with isoflurane (5%), followed by cervical dislocation.

Death was confirmed both by cessation of respiration and heartbeat,

and by the absence of pedal reflexes, prior to tissue collection.

Excised tumors were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h at 4°C

and were processed for subsequent immunohistochemical analyses. The

animal experiments were performed at The First Affiliated Hospital

of Nanchang University (Nanchang, China), which is a certified

facility authorized to conduct laboratory animal research. All

experiments were performed according to the standard Guidelines for

the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (17). All procedures adhered to the

guidelines of the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of

Laboratory Animal Care International, and the experimental protocol

was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use

Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University

[animal license number: SYXK (Gan) 2021-0003; approval no.

CDYFY-IACUC-202212QR030]. Official protocol approval for the

present study was also obtained from the Ethics Committee of The

First Hospital of Putian City(approval no. 2022-036).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad

Prism 9.0 (Dotmatics). All experiments were performed with three

independent biological replicates, parametric data were analyzed

using a paired or unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test (for

two-group comparisons) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test

(for multi-group comparisons). Overall survival analysis was

performed using the TCGA-KIRC cohort. Kaplan-Meier survival curves

were generated using the survival (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival;

version 3.3–1) and survminer (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survminer; version

0.4.9) packages in R (version 4.2.1; R Foundation for Statistical

Computing, Vienna, Austria; http://www.r-project.org/). Patients were stratified

into high and low SF3A2 expression groups based on the median

expression value, which was used as the cutoff. Curve fitting was

performed using the survfit function, and statistical significance

between groups was assessed using the log-rank test. Data are

presented as the mean ± SD. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

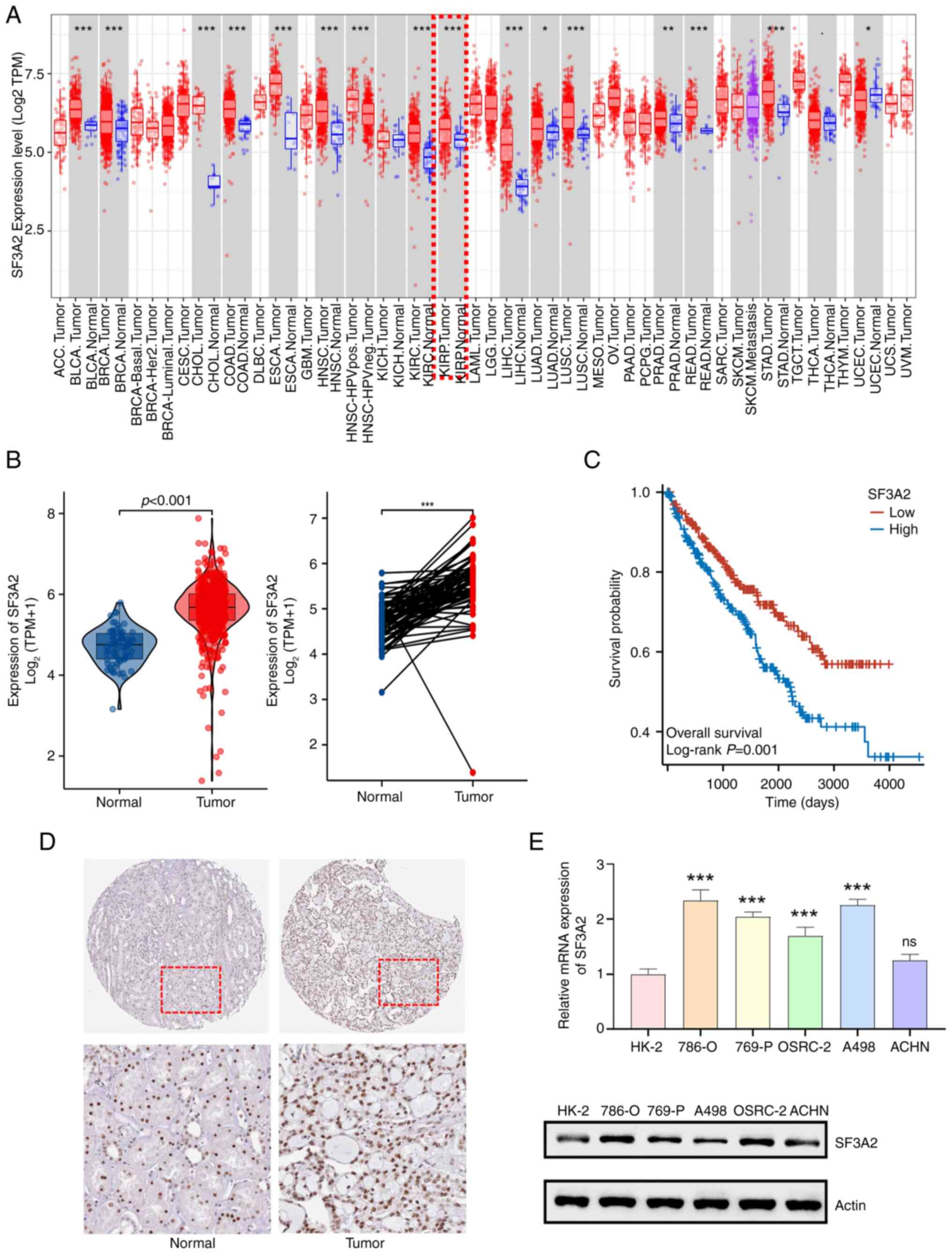

High SF3A2 expression predicts poor

prognosis in ccRCC

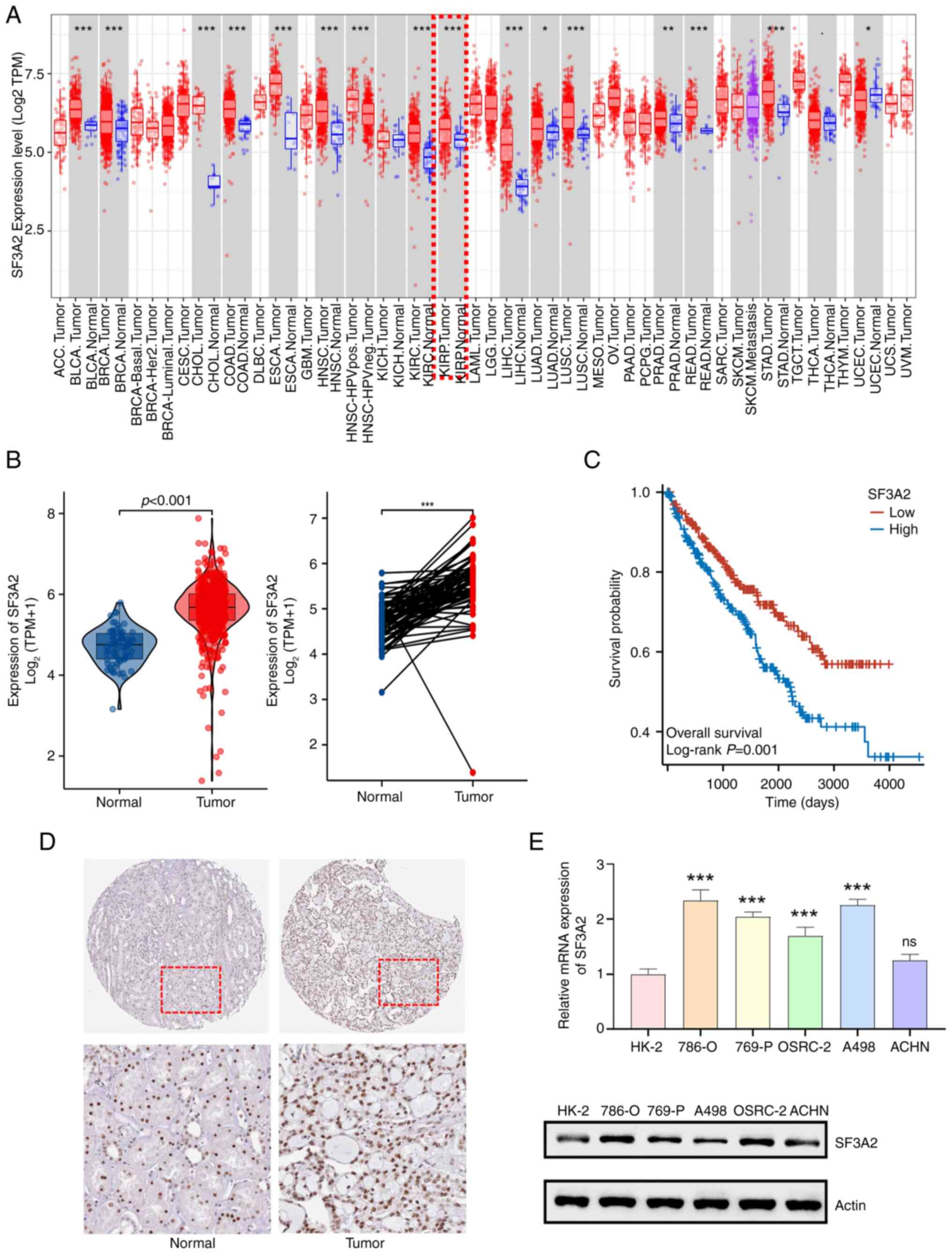

Integrative analysis of TCGA and GTEx datasets

revealed significant dysregulation of SF3A2 in ccRCC.

Transcriptomic profiling demonstrated marked upregulation of SF3A2

mRNA in tumor tissues compared with normal tissues (P<0.001),

with paired-sample validation confirming tumor-specific

upregulation (Fig. 1A and B). High

SF3A2 expression was associated with poor overall survival in

patients in the TCGA-KIRC dataset (log-rank P=0.001). Kaplan-Meier

curves stratified by median expression are shown in Fig. 1C. Furthermore, immunohistochemical

characterization of normal kidney tissues and ccRCC tissues

revealed a nuclear-enriched localization of SF3A2 protein in ccRCC

specimens from HPA (Fig. 1D).

Further orthogonal validation across five ccRCC cell lines (namely,

the 786-O, 769-P, OSRC-2, A498 and ACHN cell lines) compared with

HK-2 control cells confirmed significant increases in SF3A2

expression at the mRNA levels, with statistical significance

maintained across all cell lines with the exception of ACHN cells

(Fig. 1E).

| Figure 1.SF3A2 is highly expressed in ccRCC

and is associated with poorer prognosis. (A) Pan-cancer analysis of

SF3A2 mRNA expression (according to The Cancer Genome

Atlas/Genotype-Tissue Expression databases). ccRCC tissues

(indicated by the red box) exhibited significant upregulation

compared with normal tissues (*P<0.05, **P<0.01

***P<0.001; unpaired t-test). (B) Violin plot comparing SF3A2

mRNA levels in ccRCC tumor tissues vs. normal tissues (unpaired

t-test). Paired analysis confirmed increased SF3A2 expression in

ccRCC tumor tissues compared with matched normal tissues

(***P<0.001; paired t-test). (C) Kaplan-Meier overall survival

curves of patients from The Cancer Genome Atlas Kidney Renal Clear

Cell Carcinoma dataset stratified by SF3A2 expression (median

cut-off). Survival differences were evaluated using the log-rank

test. (D) Immunohistochemical staining, showing weak SF3A2

expression in normal kidney tissues and strong nuclear localization

of SF3A2 in ccRCC tumors. All images were captured at ×200

magnification. (E) Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR analysis

of SF3A2 expression in ccRCC cell lines (786-O, 769-P, OSRC-2, A498

and ACHN) compared with HK-2 normal cells, showing increased SF3A2

mRNA expression in four of the tested cell lines (***P<0.001; ns

in the ACHN cell line; one-way ANOVA). Western blot analysis

confirmed that SF3A2 protein was upregulated in 786-O and OSRC-2

cell lines compared to the HK-2 cell line. ccRCC, clear cell renal

cell carcinoma; ns, not significant; SF3A2, splicing factor 3a

subunit 2; TPM, transcripts per million. |

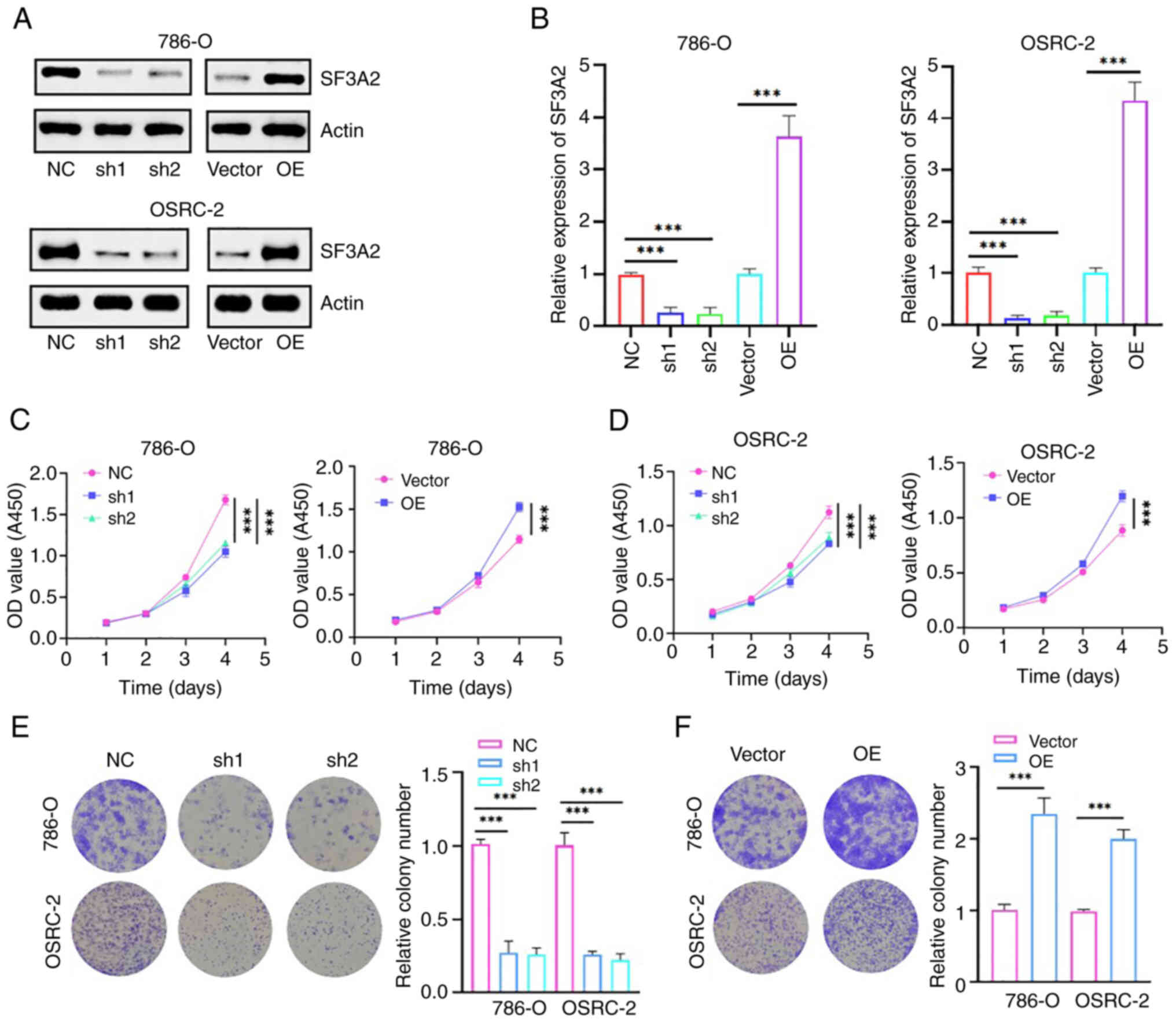

High SF3A2 expression promotes the

proliferation of ccRCC cells

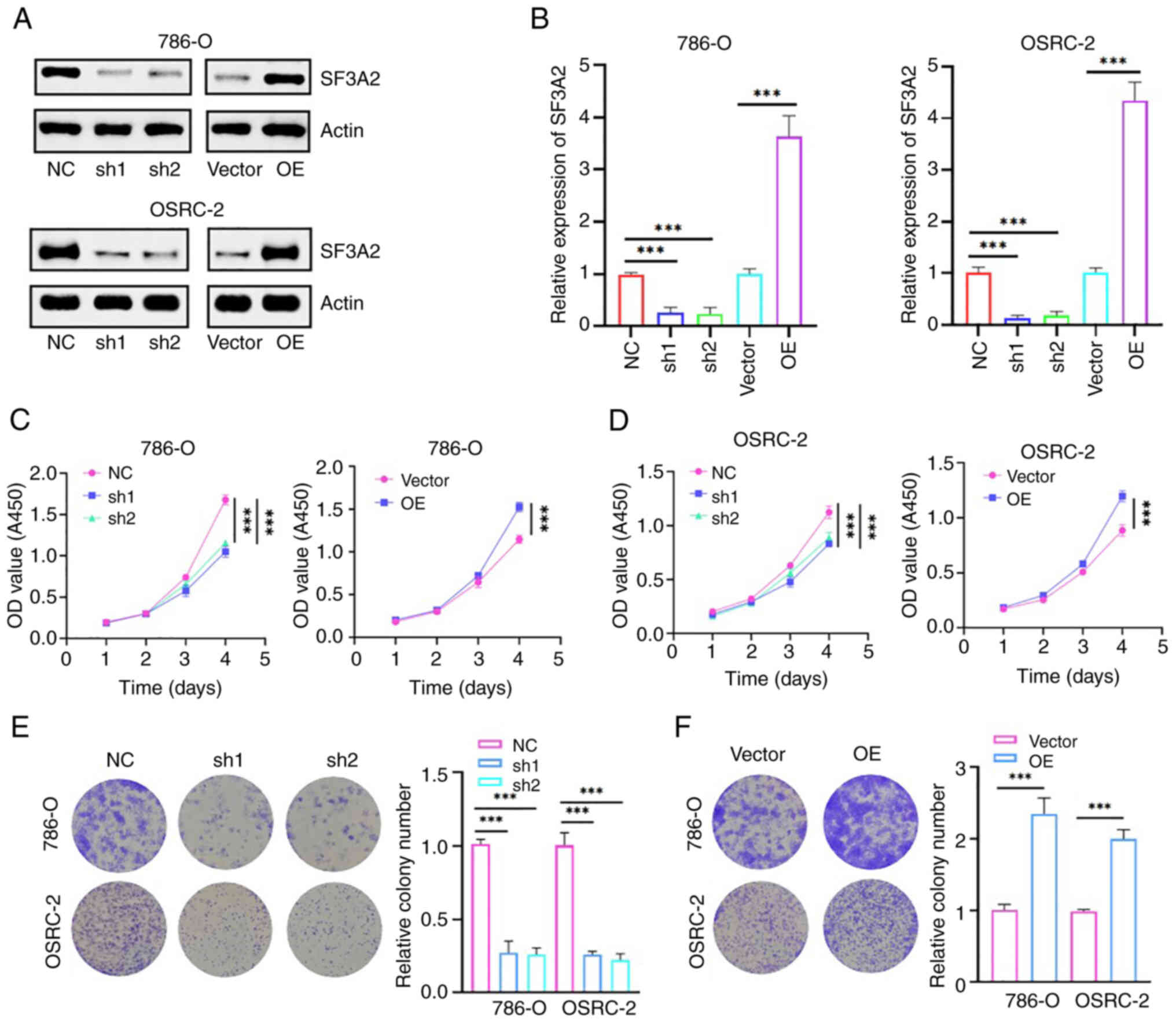

A stable gene intervention model was subsequently

developed via lentiviral transduction to elucidate the functional

role of SF3A2 in ccRCC. Western blotting and RT-qPCR analyses

confirmed the successful SF3A2 knockdown and overexpression at both

the protein and mRNA levels (Fig. 2A

and B). Functional assays revealed SF3A2 regulated the

proliferation of the cells: CCK-8 assays demonstrated an

attenuation of proliferation of the 786-O and OSRC-2 cells upon

SF3A2 silencing, whereas SF3A2 overexpression led to an enhancement

of the cell replicative potential (Fig. 2C and D). Colony formation assays

further validated these results, showing a significant reduction in

the number of clones formed in the sh-SF3A2 groups compared with

the control, whereas the overexpression group exhibited a

significant enhancement in the numbers of colonies formed (Fig. 2 and F). Taken together, these

findings suggested that SF3A2 may act as an oncogenic driver in

ccRCC, promoting cell proliferation, and thereby establishing its

therapeutic susceptibility for targeted intervention.

| Figure 2.SF3A2 promotes the proliferation and

colony formation of renal cancer cells. (A) Western blot analysis

of SF3A2 modulation in 786-O and OSRC-2 cells is shown. Effective

knockdown (sh1/sh2) and overexpression of SF3A2 was demonstrated

compared with the controls (NC/Vector). (B) Reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR assays were performed, confirming

SF3A2 transcriptional regulation in 786-O/OSRC-2 cells

(***P<0.001; two-group comparisons were analyzed using unpaired

t-tests, and three-group comparisons were evaluated using one-way

ANOVA). (C) Cell Counting Kit-8 assay, demonstrating

SF3A2-dependent proliferation. (D) sh1/sh2-SF3A2 groups exhibited

suppressed proliferation, whereas the overexpression group

exhibited enhanced proliferation rates (***P<0.001; two-group

comparisons were analyzed using unpaired t-tests, and three-group

comparisons were evaluated using one-way ANOVA). (E) Colony

formation assay showed that SF3A2 expression regulated clonogenic

growth. sh-SF3A2 reduced colony formation. (F) OE promoted

clonogenicity (quantified as relative colony counts; ***P<0.001;

unpaired t-test). NC, negative control; OD, optical density; OE,

overexpression vector; SF3A2, splicing factor 3a subunit 2; sh,

short hairpin RNA. |

SF3A2 serves an important role in

ccRCC via promotion of the migration and invasion of ccRCC

cells

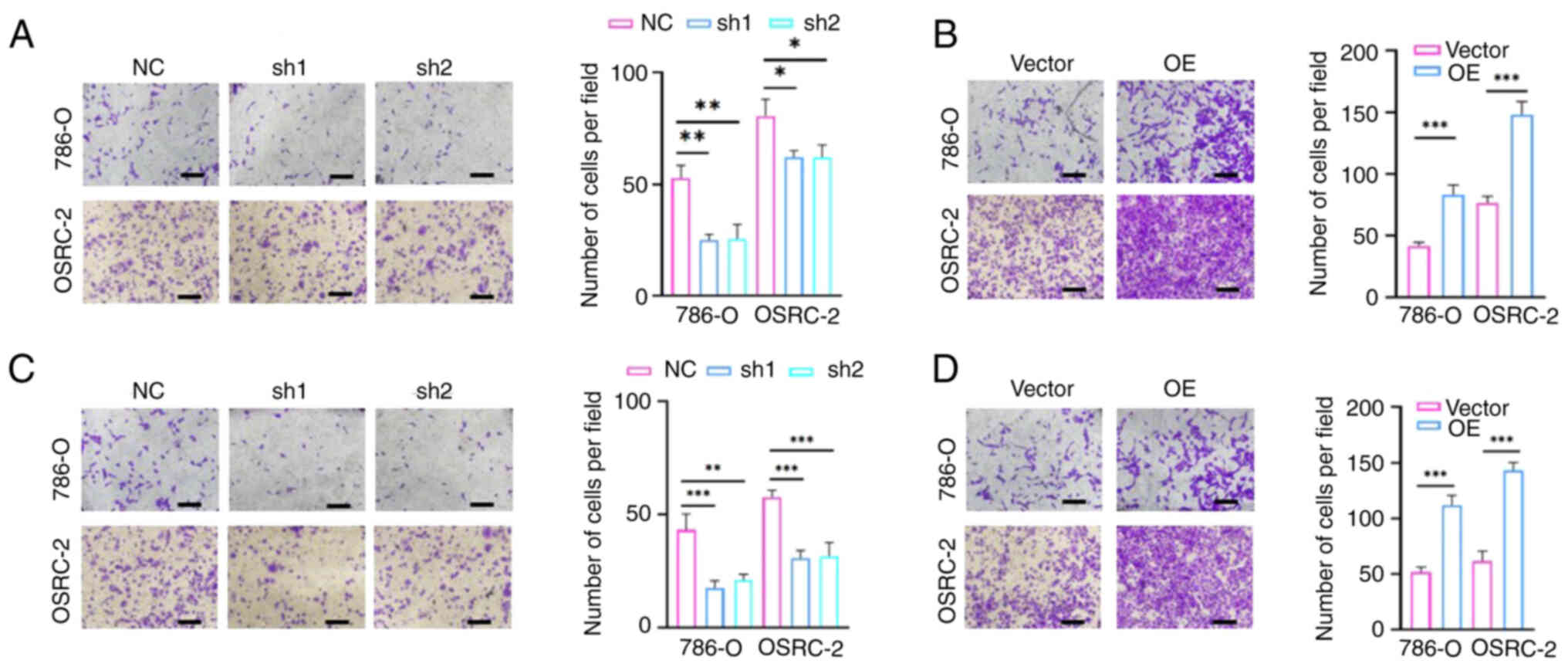

To assess the regulatory role of SF3A2 in terms of

the invasive phenotype of ccRCC cells, Transwell assays were

performed. SF3A2 knockdown (sh1/sh2-SF3A2) led to a marked

impairment of migration and invasion in the 786-O and OSRC-2 cells,

whereas overexpression of SF3A2 produced an enhancement of these

malignant traits. Quantitative analysis subsequently confirmed a

significant reduction in the numbers of migratory and invasive

cells in the knockdown groups compared with the control group,

whereas the overexpression groups exhibited significantly increased

levels of cell migration and invasion (Fig. 3A-D). Taken together, these results

underscored that SF3A2 acts as a master regulator of ccRCC

metastasis, and its upregulation serves as a driver for tumor

progression by enhancing cell motility. The combined impact on cell

proliferation and invasion further designates SF3A2 as a potential

dual-functional therapeutic target for ccRCC intervention.

SF3A2 promotes the proliferation of

ccRCC cells by activating the AKT signaling pathway

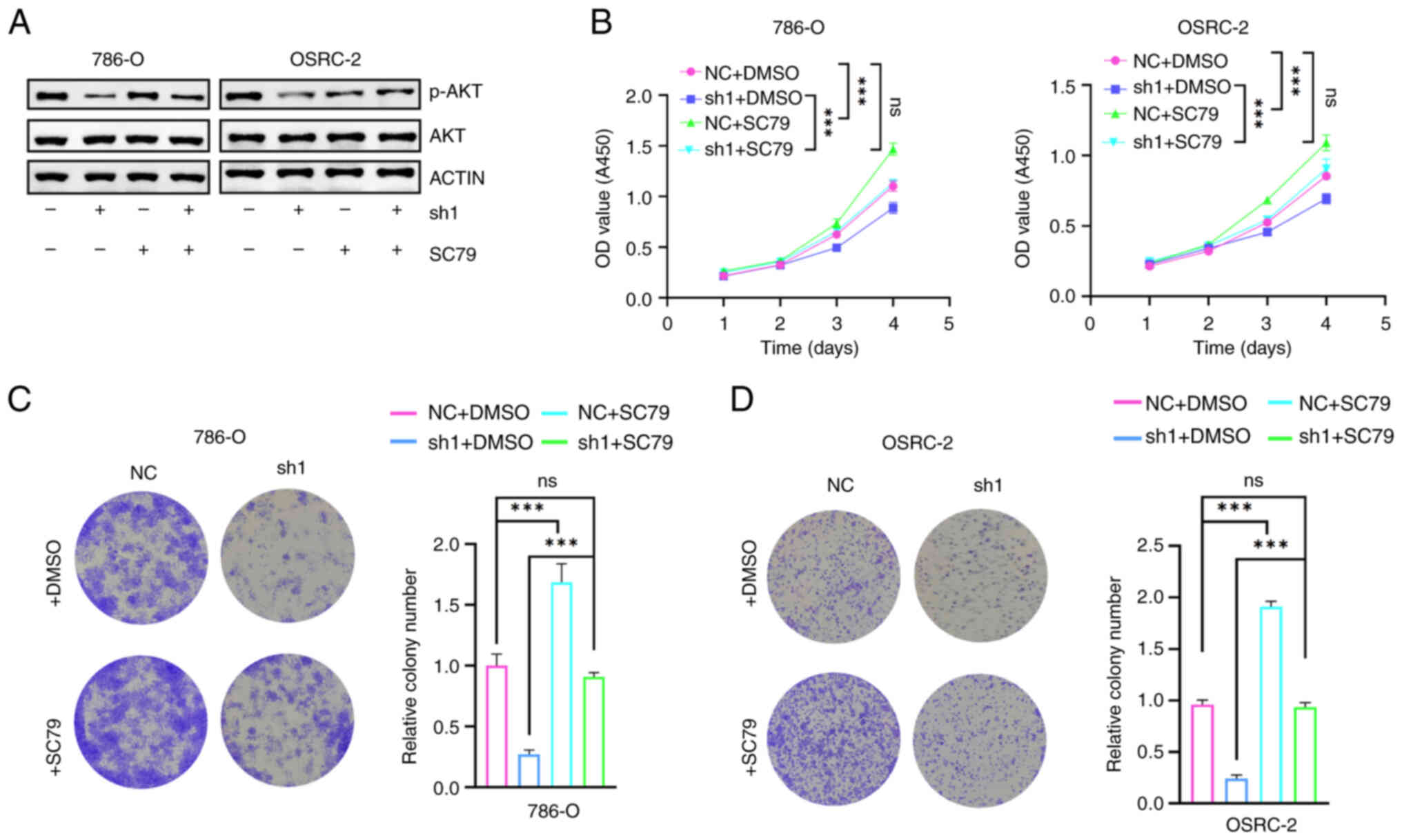

Subsequently, the activation status of the AKT

signaling axis was systematically analyzed to elucidate the

underlying molecular mechanism via which SF3A2 regulates the

malignant phenotype of ccRCC. Western blotting revealed that SF3A2

knockdown led to a reduction in the level of p-AKT (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, functional CCK-8

assays revealed that SF3A2 silencing inhibited the proliferation of

786-O/OSRC-2 cells, whereas treatment of the cells with SC79

restored their proliferative capacity (Figs. 2C and D and 4B). The results from the colony formation

assays further confirmed this oncogenic dependence: SF3A2 depletion

led to a significant reduction in colony formation, whereas SC79

treatment rescued the clonogenic potential (Figs. 2E, F, 4C and D). Taken together, these findings

established a mechanistic link between SF3A2 and AKT pathway

activation, positioning this axis as a potential therapeutic target

for ccRCC.

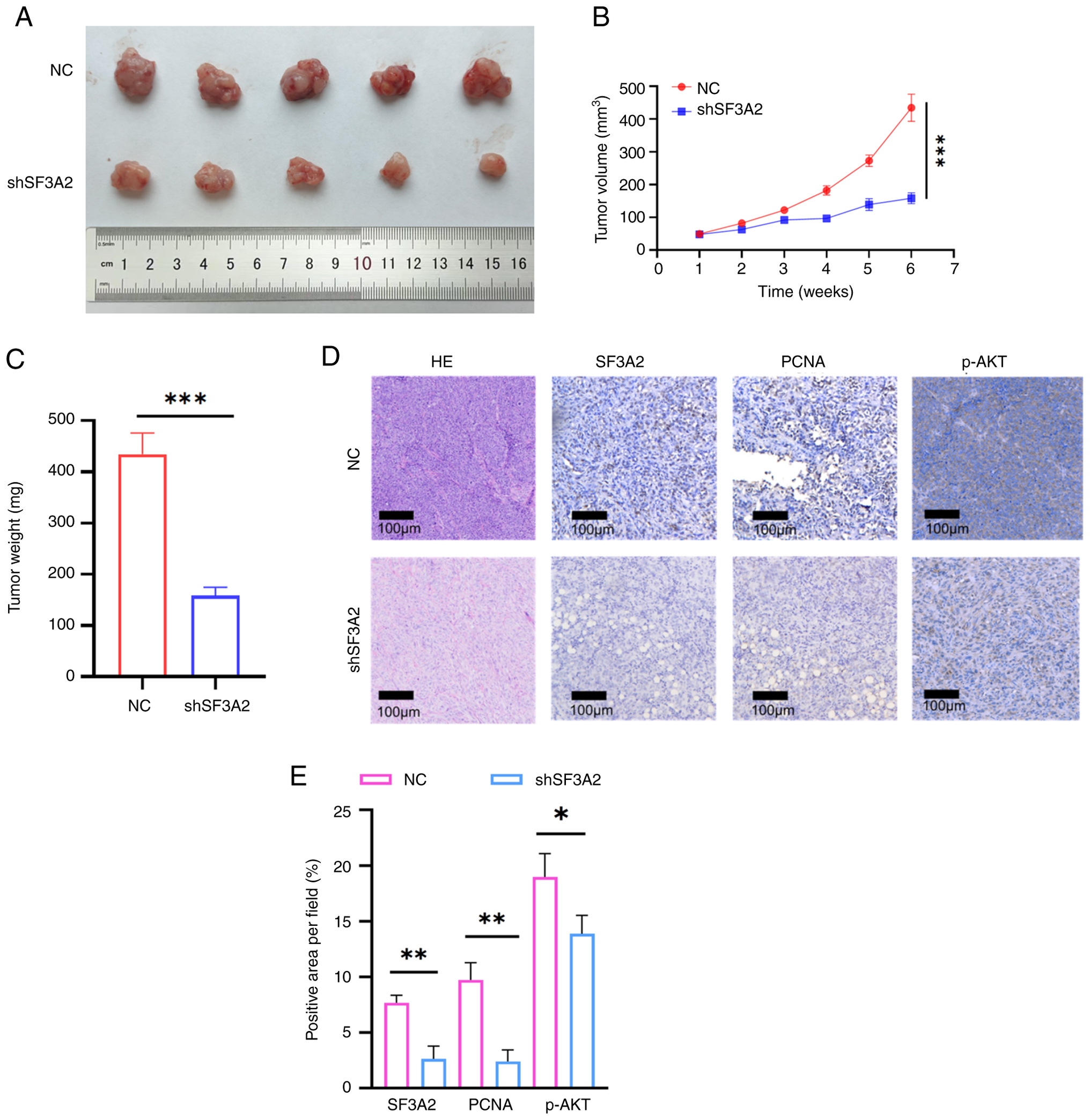

SF3A2 promotes the malignant

biological functions of ccRCC in vivo

To further evaluate the in vivo oncogenic

potential of SF3A2, a ccRCC xenograft tumor model was constructed.

SF3A2 knockdown (shSF3A2) notably inhibited tumorigenic

progression, as evidenced by reduced tumor volume and decreased

final tumor mass (Fig. 5A-C). The

maximum tumor diameter and volume observed in the present study

were 16 mm and 493.96 mm3, respectively. Subsequently,

immunohistochemical analysis revealed a concomitant reduction in

the proportion of proliferating cell nuclear antigen

(PCNA)-positive cells in tumor tissues (P<0.01), linking

SF3A2-driven tumor growth to increased proliferative activity

(Fig. 5D, E). Additionally, p-AKT

staining was also found to be diminished in the SF3A2 knockdown

group (Fig. 5D, E).

Discussion

ccRCC, a highly heterogeneous malignancy, is closely

associated with the dysregulation of critical driver genes.

Increasing evidence has highlighted the role of single-gene

regulatory mechanisms in ccRCC pathogenesis, thereby presenting

potential therapeutic targets for patients with the disease in its

advanced stages (18–20). The present study identified

significantly increased levels of SF3A2 expression in ccRCC tissues

compared with their normal counterparts, and the statistical

significance of these increases was confirmed through both unpaired

and paired analyses. Survival analysis revealed that patients with

high SF3A2 expression had notably shorter OS times compared with

those with low expression. Consistent upregulation at both the

transcriptional and translational levels suggested the involvement

of SF3A2 in ccRCC tumorigenesis, which warranted further

exploration of its molecular functions and the underlying

mechanistic roles in ccRCC pathogenesis.

Located on chromosome 17q21.33, the SF3A2 gene

encodes a core component of the spliceosomal SF3a complex (11). This evolutionarily conserved gene

has been shown to serve a pivotal role in RNA splicing regulation

(21). Mechanistically, SF3A2

directly interacts with NLR family pyrin domain containing 3

(NLRP3), forming indirect associations with neural precursor cell

expressed developmentally downregulated 4 (NEDD4), and establishing

a tripartite regulatory axis. NEDD4 mediates the proteasomal

degradation of NLRP3 through SF3A2 stabilization, with subsequent

NLRP3 depletion impairing the execution of pyroptosis by

suppressing caspase cascade activation (22,23).

Genetic alterations and dysregulated acetylation of SF3A2

compromise its splicing fidelity, leading to pathogenic errors that

disrupt heterodimer assembly in mitochondrial regulators, such as

FSCN1. Post-translational modifications, especially lysine

acetylation, fulfill a crucial role in regulating SF3A2

functionality (12).

The overexpression of SF3A2 has been shown to be

associated with increased radiotherapy sensitivity in cervical

cancer, thereby positioning the splicing factor SF3A2 as a dual

biomarker for predicting therapeutic responses and clinical

outcomes (24,25). Notably, SF3A2 upregulation in TNBC

has been shown to be strongly associated with reduced overall

survival and disease-free survival (14). In the same study, genetic silencing

of SF3A2 was found to potentiate cisplatin chemosensitivity by

suppressing the MKRN1-FAS-associated death domain signaling

pathway, attenuating both exogenous and intrinsic apoptosis, and

impairing the DNA damage response (14). Furthermore, the DHX9-SF3A2 axis has

been shown to drive ES aggressiveness by orchestrating

spliceosome-mediated oncogenic splicing programs (13). In the functional analyses in the

present study, including CCK-8 proliferation assays, colony

formation assays and Transwell cell migration/invasion experiments,

SF3A2 knockdown led to significant impairment of ccRCC cell

proliferation and migration. Conversely, SF3A2 overexpression

markedly accelerated oncogenic progression. These in vitro

findings were validated through animal experiments in vivo,

with constructed xenograft models confirming the tumor-promoting

effect of SF3A2 during ccRCC malignant evolution. Collectively,

this experimental evidence established SF3A2 as a critical

oncogenic driver in ccRCC pathogenesis, underscoring its potential

as both a novel therapeutic target and prognostic biomarker.

Furthermore, the present study aimed to investigate

the underlying mechanisms associated with the role of SF3A2 during

ccRCC malignant evolution. These mechanistic investigations

revealed the involvement of SF3A2 in the AKT signaling axis in

ccRCC pathogenesis. Genetic ablation of SF3A2 specifically reduced

the levels of AKT phosphorylation without affecting total AKT

protein levels. Pharmacological rescue using the AKT pathway

agonist SC79 successfully restored the levels of p-AKT in

SF3A2-depleted cells. Functional assays confirmed that SF3A2

depletion caused impaired cellular proliferation and clonogenic

potential, although these effects were reversed upon treating the

cells with SC79 and inducing SC79-mediated activation of the AKT

pathway. The AKT signaling axis has been shown to be a central

oncogenic driver regulating cellular survival, proliferation and

metabolic homeostasis (26–29).

Reducing AKT pathway stability has also been shown to promote

cuproptosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells (30). In another study, zinc finger E-box

binding homeobox 1-induced depletion of the long non-coding RNA

MIR497HG was shown to inhibit PI3K-AKT signaling, whereas PI3K-AKT

inhibition in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells restored

tamoxifen responsiveness (31).

Mechanistically, the AKT-mediated phosphorylation of its canonical

substrate, GSK3β, causes the inactivation of this multifunctional

kinase, which thereby modulates numerous downstream effectors

(32–35). In ccRCC, dysregulation of this

pathway has been shown to be critical for tumor initiation and

progression, and therapeutic resistance (36–38).

Furthermore, S-palmitoylation of acylglycerol kinase (AGK) mediated

by the palmitoyltransferase ZDHHC2AGK has been shown to promote AGK

translocation to the plasma membrane, which activated the

PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling pathway in ccRCC, thereby modulating

sensitivity to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) sunitinib

(39). Furthermore, Liu et

al showed that ovarian tumor domain-containing deubiquitinase 1

inhibits the AKT pathway in renal cancer cells, which thereby

suppresses tumor growth and modulates resistance to TKIs (40). Additionally, the zinc finger

protein ZIC2 has been shown to positively regulate ubiquitin

conjugating enzyme E2 C, thereby activating the AKT pathway, and

consequently promoting tumor cell proliferation, invasion and

migration, and G2/M phase blockade, ultimately enhancing

tumor formation and lung metastasis (41). Considered altogether, these studies

have collectively reinforced the hypothesis that SF3A2 may exert a

pro-oncogenic role through the AKT signaling pathway in ccRCC.

Although SF3A2 has been traditionally recognized as

a core component of the spliceosomal SF3a complex, the present

study primarily focused on its role in downstream oncogenic

signaling via the AKT signaling pathway. Recent studies have

demonstrated that SF3A2 is able to influence splicing events in key

regulators, thereby contributing to chemoresistance and aggressive

tumor phenotypes (13,14). The nuclear localization of SF3A2

may facilitate the regulation of splicing networks that indirectly

activate either the AKT signaling axis or other oncogenic pathways.

Due to funding and time limitations, large-scale RNA-seq or

splicing microarray analyses were not performed in the present

study; however, the absence of these analyses is acknowledged as

one of its limitations, and future work will aim to systematically

establish the profile of SF3A2-dependent splicing events and their

association with AKT pathway regulation. Additionally, the

nuclear-enriched localization of splicing factors, including SF3A2,

has been shown to serve a unique role in coordinating

transcriptional and post-transcriptional processes that drive

malignant transformation (11).

In spite of this limitation, the present

investigation systematically characterized the oncogenic function

of SF3A2 in ccRCC through in functional validation (both in

vitro and in vivo) and a mechanistic exploration of its

signaling axis. Although the present findings have highlighted the

pathological relevance of SF3A2, there are methodological

constraints that still need to be addressed. First, validation

across expanded clinical cohorts is required to confirm expression

patterns. Secondly, a deeper mechanistic interrogation of

SF3A2-mediated spliceosomal regulation and its impact on AKT

signaling will be required to further delineate its molecular role

in ccRCC. Lastly, given that the present study focused on the

genetic modulation of SF3A2, future studies will need to assess the

potential of small-molecule inhibitors, such as E7107, in order to

validate SF3A2 as a druggable target in ccRCC.

In conclusion, the present study identified SF3A2

upregulation as a clinically significant prognostic marker in

ccRCC, which was associated with poor clinical outcomes and

accelerated tumor progression. Mechanistically, SF3A2 was shown to

promote tumor growth through activation of the AKT signaling

pathway. Collectively, these findings have positioned SF3A2 as a

dual-functional biomarker with translational relevance, offering

both prognostic stratification and actionable therapeutic targeting

opportunities in ccRCC management.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Fujian Provincial Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant no. 2023J011724).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JX designed the study, analyzed the data and wrote

the manuscript. RC collected the data and prepared the figures. JX

and RC both contributed to the data analysis, conceived the study,

and critically revised the manuscript. JX and RC confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal experiments were approved by the

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The First Affiliated

Hospital of Nanchang University (Nanchang, Jiangxi, China)

(approval no. CDYFY-IACUC-202212QR030) and were conducted in

accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory

Animals. The present study involved animal experiments only. The

research protocol was administratively reviewed and approved by The

First Hospital of Putian City (approval no. 2022-036), which served

as the primary institutional oversight body for this project.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

AS

|

alternative splicing

|

|

CCK-8

|

Cell Counting Kit-8

|

|

RCC

|

renal cell carcinoma

|

|

ccRCC

|

clear cell RCC

|

|

DHX9

|

DExH-box helicase 9

|

|

ES

|

Ewing sarcoma

|

|

FSCN1

|

fascin actin-bundling protein 1

|

|

GTEx

|

Genotype-Tissue Expression

|

|

MKRN1

|

makorin ring finger protein 1

|

|

NEDD4

|

neural precursor cell expressed

developmentally downregulated 4

|

|

NLRP3

|

NLR family pyrin domain containing

3

|

|

RNA-seq

|

RNA-sequencing

|

|

SF3A2

|

splicing factor 3a subunit 2

|

|

TCGA

|

The Cancer Genome Atlas

|

|

TNBC

|

triple-negative breast cancer

|

|

TKI

|

tyrosine kinase inhibitor

|

|

RT-qPCR

|

reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR

|

References

|

1

|

Rose TL and Kim WY: Renal cell carcinoma:

A review. JAMA. 332:1001–1010. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Barata P, Gulati S, Elliott A, Hammers HJ,

Burgess E, Gartrell BA, Darabi S, Bilen MA, Basu A, Geynisman DM,

et al: Renal cell carcinoma histologic subtypes exhibit distinct

transcriptional profiles. J Clin Invest. 134:e1789152024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Young M, Jackson-Spence F, Beltran L, Day

E, Suarez C, Bex A, Powles T and Szabados B: Renal cell carcinoma.

Lancet. 404:476–491. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Atkins MB and Tannir NM: Current and

emerging therapies for first-line treatment of metastatic clear

cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 70:127–137. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Powles T, Albiges L, Bex A, Comperat E,

Grunwald V, Kanesvaran R, Kitamura H, McKay R, Porta C, Procopio G,

et al: Renal cell carcinoma: ESMO clinical practice guideline for

diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 35:692–706. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Bedke J, Ghanem YA, Albiges L, Bonn S,

Campi R, Capitanio U, Dabestani S, Hora M, Klatte T, Kuusk T, et

al: Updated European association of urology guidelines on the use

of adjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitors and subsequent therapy for

renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 87:491–496. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Marasco LE and Kornblihtt AR: The

physiology of alternative splicing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

24:242–254. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Bradley RK and Anczukow O: RNA splicing

dysregulation and the hallmarks of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer.

23:135–155. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Bian Z, Yang F, Xu P, Gao G, Yang C, Cao

Y, Yao S, Wang X, Yin Y, Fei B and Huang Z: LINC01852 inhibits the

tumorigenesis and chemoresistance in colorectal cancer by

suppressing SRSF5-mediated alternative splicing of PKM. Mol Cancer.

23:232024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Meng K, Li Y, Yuan X, Shen HM, Hu LL, Liu

D, Shi F, Zheng D, Shi X, Wen N, et al: The cryptic lncRNA-encoded

microprotein TPM3P9 drives oncogenic RNA splicing and

tumorigenesis. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 10:432025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhang X, Zhan X, Bian T, Yang F, Li P, Lu

Y, Xing Z, Fan R, Zhang QC and Shi Y: Structural insights into

branch site proofreading by human spliceosome. Nat Struct Mol Biol.

31:835–845. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Huang Q, Yao Y, Wang Y, Li J, Chen J, Wu

M, Guo C, Lou J, Yang W, Zhao L, et al: Ginsenoside Rb2 inhibits

p300-mediated SF3A2 acetylation at lysine 10 to promote Fscn1

alternative splicing against myocardial ischemic/reperfusion

injury. J Adv Res. 65:365–379. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Frezza V, Chellini L, Riccioni V,

Bonvissuto D, Palombo R and Paronetto MP: DHX9 helicase impacts on

splicing decisions by modulating U2 snRNP recruitment in Ewing

sarcoma cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 53:gkaf0682025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Deng L, Liao L, Zhang YL, Yang SY, Hu SY,

Andriani L, Ling YX, Ma XY, Zhang FL, Shao ZM and Li DQ: SF3A2

promotes progression and cisplatin resistance in triple-negative

breast cancer via alternative splicing of MKRN1. Sci Adv.

10:eadj40092024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Karlsson M, Zhang C, Mear L, Zhong W,

Digre A, Katona B, Sjostedt E, Butler L, Odeberg J, Dusart P, et

al: A single-cell type transcriptomics map of human tissues. Sci

Adv. 7:eabh21692021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Council N.R, . Guide for the Care and Use

of Laboratory Animals. National Academies Press; Washington, DC:

2010, PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Miao D, Wang Q, Shi J, Lv Q, Tan D, Zhao

C, Xiong Z and Zhang X: N6-methyladenosine-modified DBT alleviates

lipid accumulation and inhibits tumor progression in clear cell

renal cell carcinoma through the ANXA2/YAP axis-regulated Hippo

pathway. Cancer Commun (Lond). 43:480–502. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Xu Y, Li L, Yang W, Zhang K, Zhang Z, Yu

C, Qiu J, Cai L, Gong Y, Zhang Z, et al: TRAF2 promotes

M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophage infiltration, angiogenesis

and cancer progression by inhibiting autophagy in clear cell renal

cell carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 42:1592023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Huang B, Ren J, Ma Q, Yang F, Pan X, Zhang

Y, Liu Y, Wang C, Zhang D, Wei L, et al: A novel peptide

PDHK1-241aa encoded by circPDHK1 promotes ccRCC progression via

interacting with PPP1CA to inhibit AKT dephosphorylation and

activate the AKT-mTOR signaling pathway. Mol Cancer. 23:342024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Pellacani C, Bucciarelli E, Renda F,

Hayward D, Palena A, Chen J, Bonaccorsi S, Wakefield JG, Gatti M

and Somma MP: Splicing factors Sf3A2 and Prp31 have direct roles in

mitotic chromosome segregation. Elife. 7:e403252018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Sun W, Lu H, Cui S, Zhao S, Yu H, Song H,

Ruan Q, Zhang Y, Chu Y and Dong S: NEDD4 ameliorates myocardial

reperfusion injury by preventing macrophages pyroptosis. Cell

Commun Signal. 21:292023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Hirokawa M, Morita H, Tajima T, Takahashi

A, Ashikawa K, Miya F, Shigemizu D, Ozaki K, Sakata Y, Nakatani D,

et al: A genome-wide association study identifies PLCL2 and

AP3D1-DOT1L-SF3A2 as new susceptibility loci for myocardial

infarction in Japanese. Eur J Hum Genet. 23:374–380. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wang Y, Ouyang Y, Cao X and Cai Q:

Identifying hub genes for chemo-radiotherapy sensitivity in

cervical cancer: A bi-dataset in silico analysis. Discov Oncol.

15:4342024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Long G and Li Z, Gao Y, Zhang X, Cheng X,

Daniel IE, Zhang L, Wang D and Li Z: Ferroptosis-related

alternative splicing signatures as potential biomarkers for

predicting prognosis and therapy response in gastric cancer.

Heliyon. 10:e343812024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Song M, Bode AM, Dong Z and Lee MH: AKT as

a therapeutic target for cancer. Cancer Res. 79:1019–1031. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhang HL, Hu BX, Ye ZP, Li ZL, Liu S,

Zhong WQ, Du T, Yang D, Mai J, Li LC, et al: TRPML1 triggers

ferroptosis defense and is a potential therapeutic target in

AKT-hyperactivated cancer. Sci Transl Med. 16:eadk03302024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Martin F, Alcon C, Marin E,

Morales-Sanchez P, Manzano-Munoz A, Diaz S, Garcia M, Samitier J,

Lu A, Villanueva A, et al: Novel selective strategies targeting the

BCL-2 family to enhance clinical efficacy in ALK-rearranged

non-small cell lung cancer. Cell Death Dis. 16:1942025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Yu L, Wei J and Liu P: Attacking the

PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway for targeted therapeutic treatment

in human cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 85:69–94. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Yu W, Yin S, Tang H, Li H, Zhang Z and

Yang K: PER2 interaction with HSP70 promotes cuproptosis in oral

squamous carcinoma cells by decreasing AKT stability. Cell Death

Dis. 16:1922025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Tian Y, Chen ZH, Wu P, Zhang D, Ma Y, Liu

XF, Wang X, Ding D, Cao XC and Yu Y: MIR497HG-Derived miR-195 and

miR-497 mediate tamoxifen resistance via PI3K/AKT signaling in

breast cancer. Adv Sci (Weinh). 10:e22048192023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Li Y, Huang J, Wang J, Xia S, Ran H, Gao

L, Feng C, Gui L, Zhou Z and Yuan J: Human umbilical cord-derived

mesenchymal stem cell transplantation supplemented with curcumin

improves the outcomes of ischemic stroke via AKT/GSK-3β/β-TrCP/Nrf2

axis. J Neuroinflammation. 20:492023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Liu J, Li SM, Tang YJ, Cao JL, Hou WS,

Wang AQ, Wang C and Jin CH: Jaceosidin induces apoptosis and

inhibits migration in AGS gastric cancer cells by regulating

ROS-mediated signaling pathways. Redox Rep. 29:23133662024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Liu X, Song J, Zhang H, Liu X, Zuo F, Zhao

Y, Zhao Y, Yin X, Guo X, Wu X, et al: Immune checkpoint

HLA-E:CD94-NKG2A mediates evasion of circulating tumor cells from

NK cell surveillance. Cancer Cell. 41:272–287. e92023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Jiang Q, Zheng N, Bu L, Zhang X, Zhang X,

Wu Y, Su Y, Wang L, Zhang X, Ren S, et al: SPOP-mediated

ubiquitination and degradation of PDK1 suppresses AKT kinase

activity and oncogenic functions. Mol Cancer. 20:1002021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhang Z, Zhang Y and Zhang R: P4HA3

promotes clear cell renal cell carcinoma progression via the

PI3K/AKT/GSK3β pathway. Med Oncol. 40:702023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Mao H, Zhao Y, Lei L, Hu Y, Zhu H, Wang R,

Ni D, Liu J, Xu L, Xia H, et al: Selenoprotein S regulates

tumorigenesis of clear cell renal cell carcinoma through

AKT/GSK3β/NF-ĸB signaling pathway. Gene. 832:1465592022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zhou Z, Li Y, Chai Y, Zhang Y and Yan P:

Analysis of mRNA pentatricopeptide repeat domain 1 as a prospective

oncogene in clear cell renal cell carcinoma that accelerates tumor

cells proliferation and invasion via the Akt/GSK3β/β-catenin

pathway. Discov Oncol. 16:222025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Sun Y, Zhu L, Liu P, Zhang H, Guo F and

Jin X: ZDHHC2-Mediated AGK palmitoylation activates AKT-mTOR

signaling to reduce sunitinib sensitivity in renal cell carcinoma.

Cancer Res. 83:2034–2051. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Liu W, Yan B, Yu H, Ren J, Peng M, Zhu L,

Wang Y, Jin X and Yi L: OTUD1 stabilizes PTEN to inhibit the

PI3K/AKT and TNF-alpha/NF-kappaB signaling pathways and sensitize

ccRCC to TKIs. Int J Biol Sci. 18:1401–1414. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Lv Z, Wang M, Hou H, Tang G, Xu H, Wang X,

Li Y, Wang J and Liu M: FOXM1-regulated ZIC2 promotes the malignant

phenotype of renal clear cell carcinoma by activating UBE2C/mTOR

signaling pathway. Int J Biol Sci. 19:3293–3306. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|