Introduction

The present review aimed to provide a comprehensive

analysis of prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) enzymes, detailing

their subtypes, localization, regulatory mechanisms and functional

roles, as well as their involvement in erythropoiesis and the

development of related pharmacological agents. Under hypoxic

conditions, the body initiates a cascade of adaptive biological

responses, numerous of which are mediated by transcriptional

complexes of the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) family. The precise

equilibrium among HIF-1α, HIF-2α and HIF-3α is essential for

orchestrating the transcriptional regulation of genes associated

with erythropoiesis, angiogenesis, vascular homeostasis, metabolic

pathways, and cellular proliferation and survival. Simultaneously,

HIF exerts indirect inhibitory effects on the transcription of

genes linked to other biological processes (1,2).

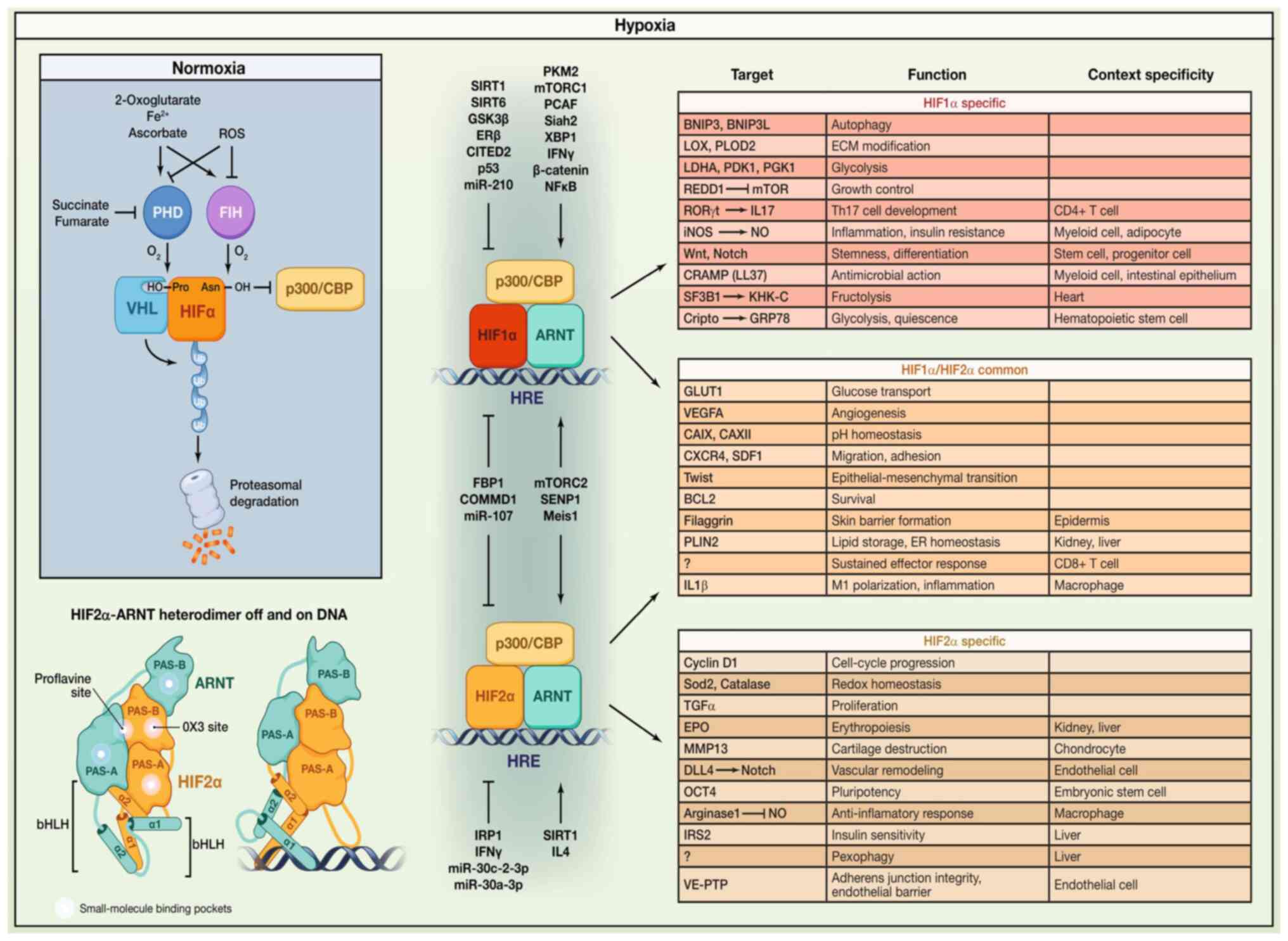

Functionally, the HIF transcription factor exists as a heterodimer

consisting of an oxygen-sensitive α and β subunit. The α subunit

interacts with the nuclear transporter of the constitutively active

aromatic hydrocarbon receptor and its activity is suppressed under

normoxic conditions by the dioxygenase family, which requires

oxygen, Fe, and 2-oxoglutarate (2-OG) for enzymatic function

(3).

In response to hypoxia, HIF-1α levels rise rapidly,

playing a pivotal role in acute hypoxic adaptation, particularly in

regulating erythropoietin (EPO) synthesis, while HIF-2α

predominantly governs long-term hypoxic responses (1,4).

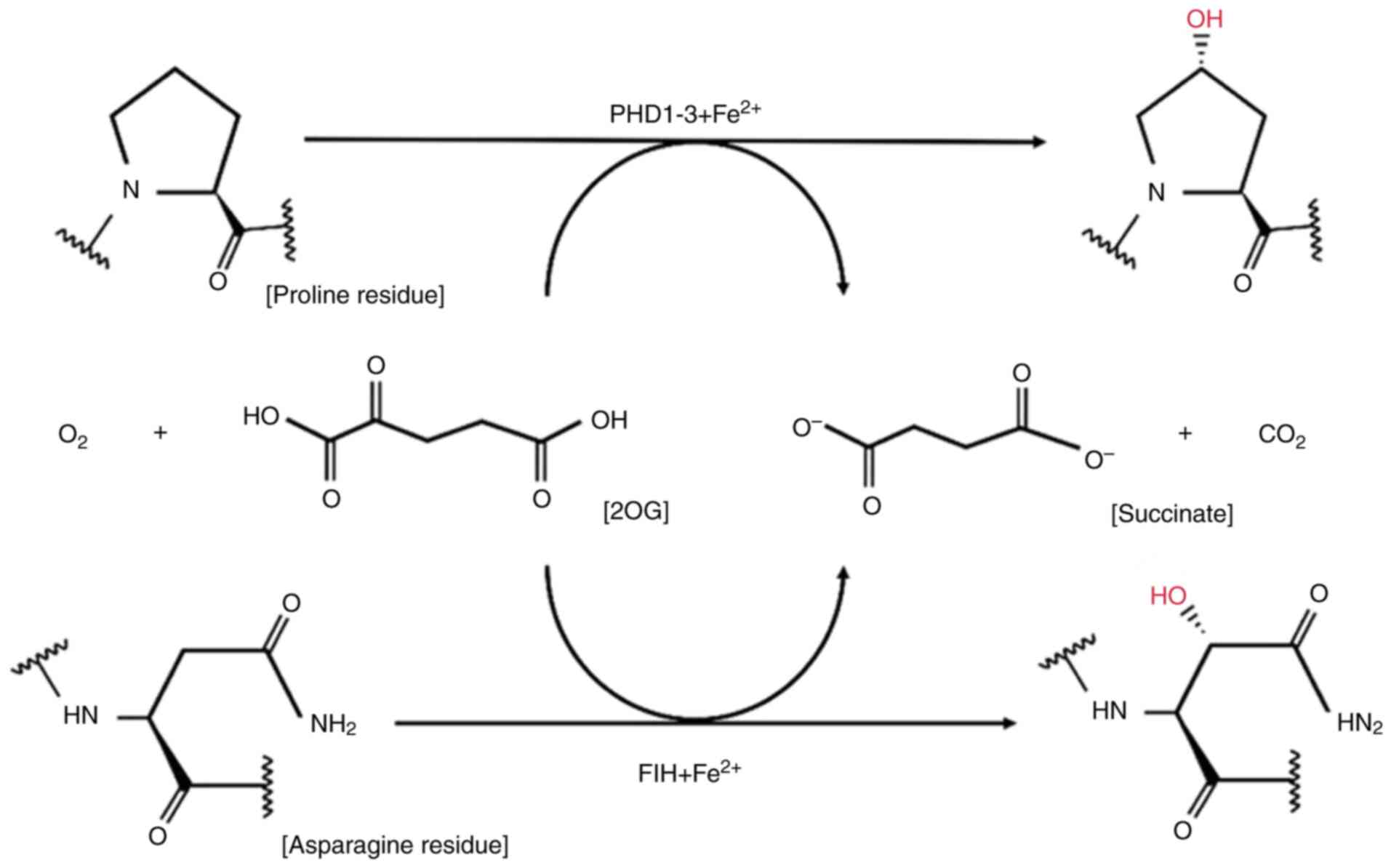

Hydroxylation of two conserved prolyl residues within the HIF-α

subunit by PHD1-3 facilitates its recognition by the von

Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor protein E3 ubiquitin ligase

complex, leading to polyubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal

degradation. In humans, three distinct PHD isoenzymes (PHD1-3) and

an asparaginyl hydroxylase, known as factor-inhibiting HIF (FIH),

have been identified. Hydroxylation of asparagine residues within

the C-terminal transactivation domain (C-TAD) of HIF-α directly

inhibits its interaction with the co-activator p300, thereby

preventing the transcriptional activation of its target genes

(5,6). Moreover, post-translational

modifications such as acetylation and phosphorylation have been

reported to further regulate HIF-α activity, adding additional

layers of complexity to its control mechanisms (6).

PHDs exhibit substrate specificity and differential

tissue distribution, particularly in their hydroxylation of HIF

proline residues. By modulating intracellular metabolism, reactive

oxygen species (ROS) generation, iron (Fe), homeostasis, nitric

oxide (NO) signaling, and redox balance, PHDs serve as critical

regulators of HIF activity, influencing a broad spectrum of

physiological processes under hypoxic conditions. Although

inhibitors targeting the HIF/PHD axis have been successfully

integrated into clinical practice, the development of HIF/PHD

activators or functional restorers remains limited due to

significant technical hurdles. To date, no studies have reported

the successful discovery of HIF/PHD activators, highlighting a

major gap in current research and a potential avenue for future

therapeutic advancements.

Therefore, the present review aimed to

comprehensively summarize the subtypes, localization, regulatory

mechanisms and biological functions of PHDs, along with the

research and development of related pharmacological agents and

their role in erythropoiesis. Activators or functional restorers

targeting the HIF/PHD pathway represent a promising avenue for

therapeutic intervention, particularly in addressing conditions

such as polycythemia and chronic mountain sickness. Advancing

research in this area could pave the way for groundbreaking

developments, offering novel strategies to enhance clinical

management and improve patient outcomes.

PHD subtypes and localization

PHD enzymes function as critical oxygen sensors,

belonging to a family of oxygen-dependent enzymes responsible for

facilitating the proteasomal degradation of HIF-1α under normoxic

conditions (7). The hydroxylation

of HIF-1α is highly dependent on molecular oxygen, making these

enzymes essential regulators of cellular oxygen homeostasis.

Currently, three PHD isoforms, PHD1, PHD2 and PHD3, have been

identified, each exhibiting distinct oxygen-sensing properties

(8). In vitro studies

suggest a hierarchical hydroxylation efficiency among these

isoforms, with PHD2 demonstrating the highest activity, followed by

PHD3 and then PHD1.

PHDs exhibit both substrate specificity and

tissue-specific expression in their hydroxylation of HIFs. PHD2

preferentially hydroxylates HIF-1α over HIF-2α and HIF-3α, whereas

PHD1 and PHD3 display higher efficiency in hydroxylating HIF-2α.

Their expression patterns also vary across tissues: PHD2 is

predominantly found in adipose tissue, PHD1 is highly expressed in

testicular cells, and PHD3 is primarily located in cardiac cells

(8). In terms of subcellular

localization, PHD2 is mainly cytoplasmic, PHD3 is predominantly

nuclear, and PHD1 is distributed in both the cytoplasm and nucleus.

Encoded by the EGLN1 gene, PHD2 serves as the principal oxygen

sensor responsible for modulating HIF-2α activity (9,10).

Among the three PHD isoforms, PHD2 was initially

identified as the most functionally significant hydroxylase in most

cell types (11). Differences in

their intracellular distribution have been elucidated through

studies involving the overexpression of labeled proteins (12,13).

Specifically, fusion protein analyses have revealed that GFP-tagged

EGLN1/HPH-2/PHD2 localizes predominantly to the cytoplasm, whereas

EGLN2/HPH-3/PHD1 is primarily nuclear. Conversely, EGLN3/HPH-1/PHD3

is distributed across both the nucleus and cytoplasm in a

relatively balanced manner (13).

Notably, PHD expression has been implicated in

inflammatory conditions such as ulcerative colitis (UC), a subtype

of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). In patients with UC, PHD1 and

PHD2 are highly expressed in the lamina propria and colonic

epithelium, while PHD3 is predominantly localized to the vascular

endothelium. Moreover, PHD3 expression is significantly elevated in

inflamed biopsy samples and is positively correlated with

inflammatory cytokines such as IL-8 and TNF-α, as well as the

apoptotic marker caspase-3 (14).

HIF proteins are heterodimeric transcription factors

consisting of a tightly regulated α subunit (HIF-1α, HIF-2α, or

HIF-3α) and a constitutively expressed β subunit. Under normoxic

conditions, HIF-α subunits undergo oxygen-dependent hydroxylation

by PHDs, allowing their recognition by the VHL tumor suppressor

protein, a key component of an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. This

interaction marks HIF-α for ubiquitination and subsequent

degradation via the proteasome pathway (15,16).

However, under hypoxic conditions, hydroxylation is suppressed,

preventing VHL-mediated degradation and enabling HIF-α to

accumulate and exert its transcriptional effects (12).

Within mammalian cells, the functions of the PHD

protein family (PHD1, PHD2 and PHD3) are diverse, with PHD2

emerging as the predominant oxygen sensor regulating HIF-1α

stability and degradation. In addition to PHDs, FIH-1, an

oxygen-dependent asparaginyl hydroxylase, plays a critical role in

regulating the C-TAD of HIF. FIH-1 provides a direct mechanistic

link between oxygen sensing and HIF-mediated transcription, further

modulating cellular responses to hypoxia (17).

HIF-1α exhibits dynamic nucleocytoplasmic shuttling,

whereas HIF-1β remains permanently localized within the nucleus.

The VHL tumor suppressor protein (pVHL) is distributed across both

the nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments. The nuclear translocation

of PHD1 is mediated by classical nuclear localization signals

(NLS), utilizing the importin α/β receptor pathway. By contrast,

PHD2 nuclear import relies on a non-classical NLS, following an

alternative import pathway, which results in PHD2-mediated

hydroxylation of HIF-1α predominantly occurring within the nucleus.

The nuclear export of PHD2 is facilitated by an N-terminal nuclear

export signal and requires the export receptor chromosome region

maintenance 1. Meanwhile, the nuclear import of PHD3 is regulated

via the importin α/β receptor pathway and also depends on a

non-classical NLS (18).

In the central nervous system, NG2 cells represent a

fourth class of glial cells alongside astrocytes, microglia, and

oligodendrocytes. HIF-2 activation in NG2 cells plays a pivotal

role in promoting neurovascular expansion and remodeling

independently of EPO. The regulatory control of HIF-2 activity in

NG2 cells involves both PHD2 and PHD3. Under conditions where PHD2

and PHD3 are inactive, PHD1 assumes a compensatory role in

regulating the HIF-2 transcriptional response, thereby facilitating

vascular expansion and remodeling. However, the simultaneous

inactivation of PHD1, PHD2 and PHD3 leads to robust HIF-2

activation, further enhancing neurovascular remodeling independent

of EPO signaling (19).

The genetic inactivation of PHD1, PHD2 and PHD3

results in HIF activation, triggering the reprogramming of

myofibroblast-transformed renal EPO-producing cells (MF REPs) to

resume EPO secretion. Specifically, the loss of PHD2 in REPs

restores EPO gene expression in damaged renal tissue, leading to

erythrocytosis. By contrast, the simultaneous deletion of PHD1 and

PHD3 prevents the suppression of EPO expression without inducing

erythrocytosis (20). These

findings underscore the predominant role of PHD2 in EPO regulation

and red blood cell (RBC) production. Given the tissue-specific

regulatory mechanisms of HIF by different PHD isoforms, their

physiological roles vary significantly across organ systems. As

research progresses, pharmacological agents targeting angiogenesis

and EPO synthesis have been integrated into clinical practice for

the treatment of related disorders. Therefore, further

investigation into PHD enzyme functions holds substantial clinical

significance.

The study of PHD enzyme localization primarily

involves the fusion of PHD to the N-terminus of a fluorescent

protein, followed by transient transfection of the fusion construct

into human osteosarcoma (U2OS) cells. Subsequent visualization is

performed using three-dimensional two-photon confocal fluorescence

microscopy (13).

PHDs belong to the family of α-ketoglutarate

(α-KG)-dependent dioxygenases and serve as key regulators of

cellular oxygen sensing and metabolic control. They play a crucial

role in maintaining oxygen homeostasis by mediating the

hydroxylation of target proteins, thereby influencing their

stability and function. A summary of the major PHD isoforms,

subcellular localization, tissue distribution, substrates, and

biological functions is provided in Table I.

| Table I.Isoforms, subcellular localization,

tissue expression, substrates, and biological functions of

PHDs. |

Table I.

Isoforms, subcellular localization,

tissue expression, substrates, and biological functions of

PHDs.

| Isoforms | Subcellular

localization | Tissue

expression | Substrates | Biological

functions | Disease

associations |

|---|

| PHD1 | Primarily

localized | Highly expressed

in | Substrate

specificity of PHDs depends on isoform | Primarily involved

in | Primarily localized

in the |

| (EGLN2) | in the nucleus

and | skeletal

muscle, | and physiological

context. | fundamental oxygen

sensing | nucleus and

mitochondria, |

|

| mitochondria, | heart, and

kidneys. | Classical

substrates: | and energy

metabolism | associated with

energy |

|

| associated

with |

| – HIF-1α/2α: All

PHD isoforms hydroxylate proline | regulation. | metabolism. |

|

| energy

metabolism. |

| residues in HIF-α

subunits (e.g., Pro402/Pro564 | Closely linked

to |

|

|

|

|

| in HIF-1α),

triggering ubiquitin-mediated | mitochondrial

function |

|

|

|

|

| degradation. | and may modulate

metabolic |

|

|

|

|

| – PHD2 is the

predominant hydroxylase for HIF-1α, | adaptation in

muscle. |

|

|

|

|

| while PHD3 plays a

more prominent role in HIF-2α |

|

|

| PHD2 | Mainly

cytoplasmic | Ubiquitously | regulation. | Hypoxia adaptation:

PHD2 | Mainly cytoplasmic

but |

| (EGLN1) | but can associate

with | expressed, with

high | Non-classical

substrates: | restricts tumor

angiogenesis | can associate with

the |

|

| the plasma

membrane | activity in

vascular | – PHD3 specifically

hydroxylates CRTC2 at | via HIF-1α

degradation. | plasma membrane

or |

|

| or endoplasmic | endothelial cells

and | Pro129/Pro625,

facilitating its nuclear translocation | PHD2

inhibitors | endoplasmic

reticulum, |

|

| reticulum,

dynamically | the tumor

micro- | and activation of

gluconeogenic genes (particularly | (for example,

roxadustat) | dynamically

relocalizing |

|

| relocalizing in

response | environment. | under fasting or

diabetic conditions). | are used to treat

renal | in response to

oxygen |

|

| to oxygen

fluctuations. |

| Other

substrates: | anemia. | fluctuations. |

| PHD3 | Resides in the | Highly expressed

in | – Nuclear factor κB

(NF-κB), RNA polymerase II, | Neuroprotection:

PHD3 | Resides in the

cytoplasm, |

| (EGLN3) | cytoplasm, where

it | the liver,

adipose | among others,

suggesting PHD involvement in | contributes to

ischemic | where it interacts

with |

|

| interacts with

substrates | tissue, and

nervous | inflammation and

transcriptional regulation. | preconditioning in

neurons | substrates such as

CRTC2 |

|

| such as CRTC2

and | system. | The principal

hydroxylase of HIF (HIF-1α), | via HIF-2α

regulation. | and HIF-1α, but

can |

|

| HIF-1α, but

can |

| facilitating its

ubiquitin-mediated degradation, | Metabolic

disorders: The | translocate to the

nucleus |

|

| translocate to

the |

| thereby regulating

hypoxic responses | PHD3-CRTC2 axis

is | under specific

conditions. |

|

| nucleus under

specific |

| (e.g.,

angiogenesis, erythropoiesis). PHD2 knockout | aberrantly

activated in type |

|

|

| conditions. |

| is embryonically

lethal, underscoring its critical role | 2 diabetes, and

PHD3 |

|

|

|

|

| in HIF

regulation. | inhibition has been

shown to |

|

|

|

|

| Beyond its role in

HIF regulation, PHD3 is involved in metabolic control (e.g.,

gluconeogenesis). It hydroxylates CRTC2 (CREB-regulated

transcriptional coactivator), modulating the expression of hepatic

gluconeogenic genes such as PEPCK and G6Pase. | lower blood glucose

levels. |

|

Functions of PHD enzymes

The oxygen-dependent hydroxylation of HIF-α subunits

serves as a key signal for ubiquitination and subsequent

proteasomal degradation, playing a crucial role in regulating HIF

protein abundance and maintaining oxygen homeostasis (21–25).

All three PHD isoforms (PHD1-3) are capable of hydroxylating HIF-α

subunits, although their functional significance varies (12,26).

Among them, genetic studies have highlighted PHD2 as the most

critical regulator of HIF-1α stability. Notably, PHD2 expression is

upregulated under hypoxic conditions, establishing an

HIF-1-mediated autoregulatory feedback loop that fine-tunes

oxygen-dependent responses (11).

Beyond their role in HIF-α hydroxylation, PHDs can

also modulate HIF activity through hydroxylase-independent

pathways. While these enzymes primarily control the stability of

HIF-α proteins, PHD2 and PHD3 themselves are subject to

upregulation via HIF-dependent feedback mechanisms. Functionally,

different PHD isoforms contribute to distinct physiological and

pathological processes, including angiogenesis, erythropoiesis,

tumorigenesis, cell proliferation, differentiation and survival. As

a result, disruptions in PHD expression or function can lead to

diverse biological consequences, reflecting the unique regulatory

roles of each isoform (27). The

selectivity of PHD isoforms toward different HIF-α subunits

exhibits a degree of specificity. PHD2 is preferentially induced by

HIF-1α, whereas PHD3 responds to both HIF-1α and HIF-2α (28). Each PHD isoform regulates the HIF

system in a functionally distinct, non-redundant manner. Under

specific experimental conditions, the relative contribution of each

PHD enzyme depends significantly on its expression levels, with the

hydroxylation rate being directly correlated with the abundance of

active PHD proteins (29). The

oxygen-dependent hydroxylation of specific proline residues in

HIF-1α allows recognition by the VHL tumor suppressor complex, a

key component of the E3 ubiquitin ligase system. This interaction

leads to the polyubiquitination of HIF-1α, triggering its rapid

degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (26,30–32).

All three PHD isoforms contribute to HIF regulation,

and their cell-type specificity and inducibility provide HIF with

the flexibility to fine-tune hypoxia responses across different

tissues. The relative specificity of pharmacological PHD inhibition

presents an opportunity for selective modulation of the HIF system,

which holds considerable clinical significance. For instance,

inhibiting PHD2 broadly enhances HIF activation across multiple

cell types, even under normoxic conditions. By contrast, selective

inhibition of PHD3 predominantly amplifies the hypoxic response in

tissues where this enzyme is highly expressed (29). This approach could be leveraged to

activate the HIF system for treating ischemic or hypoxic diseases.

Future research must further elucidate the in vivo

specificity of PHD effects on different HIF-α subunits, as well as

the distinct roles of PHD isoforms in various biological processes.

A deeper understanding of these mechanisms is essential for

minimizing adverse effects associated with PHD inhibitors and

optimizing their therapeutic efficacy.

When PHD function is inhibited, the oxygen-dependent

degradation of VHL and HIFα is disrupted. Similar to PHDs, the

HIF-associated regulatory factor FIH, an asparaginyl hydroxylase,

suppresses the transactivation function of HIFα by hydroxylating

its TAD, thereby inhibiting the p300/CBP signaling pathway, which

plays a crucial role in cell cycle regulation and apoptosis.

Although the pVHL/PHD/HIF axis is one of the most extensively

studied oxygen-sensing mechanisms, numerous aspects remain to be

elucidated (33). The mechanistic

action of the pVHL/PHD/HIF pathway, the alterations in HIF2α-ARNT

dimerization under hypoxia, and the downstream targets of HIF are

illustrated in Fig. 1.

Regulation of PHD-catalyzed hydroxylation

reactions

PHD1 and PHD2 are large enzymes, each consisting of

>400 amino acids (407 and 426, respectively, in humans), with a

highly conserved hydroxylase domain located in their C-terminal

region, sharing ~55% sequence identity in this region. By contrast,

their N-terminal regions exhibit greater sequence diversity and

comparatively lower activity (26). PHD3, the shortest of the three

isoforms, contains only 239 amino acids in humans. Although it

retains a hydroxylase domain, its N-terminal region is markedly

distinct, comprising only a short, unique segment.

Oxygen dependence

Oxygen serves as a fundamental substrate for

PHD-catalyzed hydroxylation reactions. The Km values for oxygen

across the three PHD isoforms range from 230 to 250 µM, which

slightly exceeds the oxygen concentration in aqueous solutions

equilibrated with ambient indoor air. Since intracellular oxygen

levels are typically lower, this higher Km ensures that hydroxylase

activity remains strictly oxygen-dependent, as long as other

essential substrates and cofactors are adequately available

(34). Under hypoxic conditions

(0.5–2% oxygen), HIF-1α levels increase, a process that requires

functional mitochondria. Notably, inhibition of cytochrome c

oxidase using respiratory chain inhibitors such as NO leads to the

destabilization of HIF-1α, even in low-oxygen environments

(21). This phenomenon is likely

attributed to the rapid mitochondrial oxygen consumption during

oxidative phosphorylation, which significantly reduces cytoplasmic

O2 availability (35).

Intracellular Fe(II)

concentration

PHD enzymes belong to the Fe(II)/2-OG-dependent

dioxygenase family, with PHD2 displaying particularly slow

reactivity with O2, a feature linked to its role in

hypoxia sensing. When PHD2 forms a stable complex with Fe(II) and

2-OG, the water molecules coordinated to Fe(II) remain tightly

bound at the enzyme's active site. Before O2 can bind,

these water molecules must be displaced. A single amino acid

substitution, replacing glutamic acid (D315E) with aspartic acid,

which directly interacts with Fe(II), significantly reduces PHD2's

affinity for Fe(II). However, this modification simultaneously

enhances the reaction rate with O2 by 5-fold, thereby

maintaining PHD2's catalytic efficiency (36).

Competitive inhibition by 2-OG

analogs

2-OG plays a crucial role as an intermediate in the

tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and serves as an essential

co-substrate for PHD activity, aiding in the coordination of Fe(II)

within the catalytic center (26).

The hydroxylation of HIF-α proline residues by Fe(II)- and

2-OG-dependent PHD enzymes is essential for cellular oxygen

sensing. Notably, premature 2-OG binding or prolyl hydroxylation of

HIF-α can drastically reduce the affinity of HIF-α for PHD2, by

nearly 50-fold, thereby inhibiting its interaction with the enzyme.

Consequently, when 2-OG availability is limited, PHD enzymatic

activity decreases, preventing HIF-α degradation and stabilizing

the hypoxic response (37).

Proline substrate specificity

The stabilization of HIF proteins under hypoxic

conditions represents a key adaptive mechanism in oxygen-deprived

environments. The degradation of HIF-α subunits is tightly

regulated by the three PHD isoenzymes (PHD1-3), which catalyze

proline hydroxylation (38). To

date, no proline hydroxylase activity has been detected in non-HIF

proteins or peptides under conditions relevant to HIF-α

hydroxylation (39). Among PHDs,

the C-terminal oxygen-dependent degradation domain (C-ODD) exhibits

higher activity than the N-terminal oxygen-dependent degradation

domain (N-ODD), with the latter being largely inactive in PHD3.

Interestingly, PHD2 demonstrates greater efficiency in

hydroxylating the N-ODD of HIF-2α than that of HIF-1α (40). However, the hydroxylation

efficiency of HIF-2α N-ODD by PHD2 remains lower than that of

HIF-1α N-ODD (40). It has been

suggested that an antiparallel structural motif spanning residues

197 to 380 in PHD2 plays a role in interacting with the ODD domain,

with hydrophobic amino acids contributing to substrate recognition

(41). Furthermore, certain

mutations in PHD2 are associated with altered HIF-2 stability. For

instance, a heterozygous germline mutation at residue H374 leads to

PHD2 destabilization and loss of enzymatic function, ultimately

resulting in upregulated HIF-2α activity (9).

The hydroxylation regulation of PHDs is illustrated

in Fig. 2. Once synthesized, HIF-α

is rapidly degraded if sufficient non-mitochondrial oxygen is

available. HIF PHD1, PHD2 and PHD3 confer oxygen-dependent

proteasomal degradation to the HIF-α subunit. Identifying

alternative targets of HIF hydroxylases is crucial for fully

elucidating the pharmacology of prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors

(PHIs) (42).

Despite significant technological advancements,

screening, detecting, and validating alternative functional targets

of PHD and FIH remain challenging. A major limitation is the lack

of high selectivity for PHD isoform-specific inhibitors, which can

lead to a range of adverse effects. The most successful clinical

application to date is in the treatment of anemia associated with

chronic kidney disease (CKD), where PHD inhibitors have been widely

used. However, research on PHD activators or agonists remains in

its early stages.

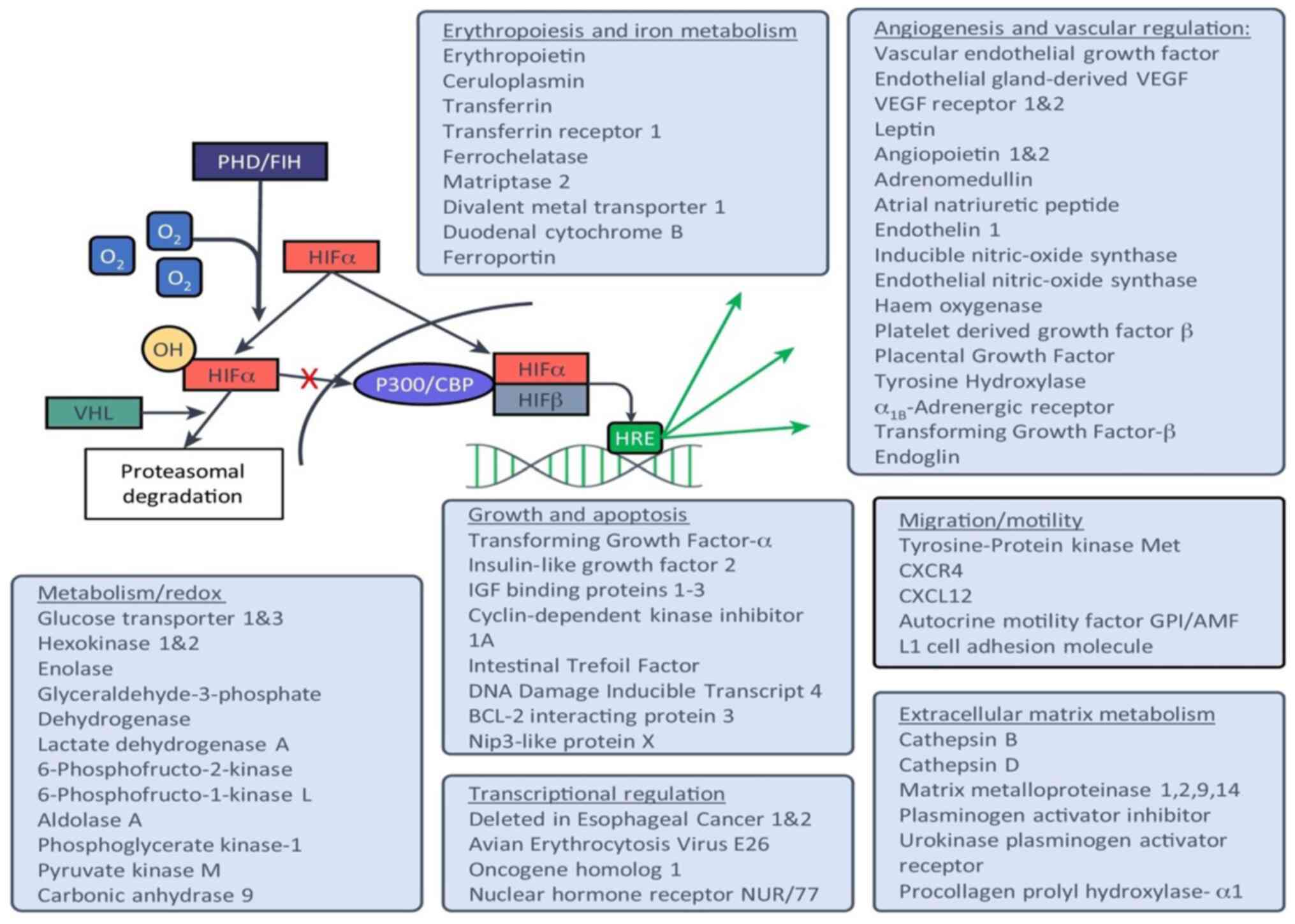

Biological efficacy of PHDs

Transition metal ions, particularly Fe, play a

pivotal role in the hypoxia-regulated PHD-HIF-EPO signaling axis,

which governs erythropoiesis, angiogenesis, anaerobic metabolism,

adaptation, cell survival and proliferation, thereby maintaining

cellular and systemic homeostasis (43). The regulation of HIF is primarily

mediated by the highly conserved EGLN/PHD family, which

hydroxylates HIF in an oxygen-dependent manner. This hydroxylation

facilitates recognition by VHL family proteins, leading to

ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of HIF. Interestingly,

PHD3 has been found to enhance HIF signaling through the

hydroxylation of the glycolytic enzyme pyruvate kinase muscle

subtype 2 (PKM2). Beyond its role in the HIF pathway, PHD also

influences synaptic transmission by modulating

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropanoic acid (AMPA)

receptor trafficking and regulating transient receptor potential

cation channel member A1 (TRPA1) activity in response to oxygen

levels in sensory neurons. Moreover, PHD activation is modulated by

poly(rC)-binding protein 1 (PCBP1), which functions as an Fe

chaperone, as well as by the (R)-enantiomer of 2-hydroxyglutarate

(2-HG), highlighting the intricate interplay between multiple

regulatory pathways in PHD function (8).

Regulation of lifespan and renal

adaptability

In Caenorhabditis elegans, the activity of

EGL-9, a PHD homolog, is regulated by the hydrogen sulfide-sensing

cysteine synthase-like protein CYSL-1, which, in turn, is modulated

by the acyltransferase RHY-1. Notably, mutations in vhl-1

significantly extend lifespan through a HIF-1-dependent mechanism.

The long-lived phenotype of vhl-1 mutants is suppressed by

mutations in egl-9 and rhy-1, whereas RNA

interference targeting rhy-1 extends the lifespan of

wild-type worms while shortening that of vhl-1 mutants

(44). Additionally, in renal

physiology, the downregulation of PHD by high salt exposure

triggers the activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor α (PPARα). This PHD/HIF-1α regulatory axis introduces a

novel transcriptional control mechanism, engaging downstream

signaling pathways of NO synthase and heme oxygenase to promote

adaptive renal responses (45).

PHD regulation of EPO production

Renin-expressing cells can be categorized into two

subgroups: Classic glomerular renin-producing cells and mesenchymal

renin-positive cells. The latter population functions as a

reservoir of natural EPO-producing cells, displaying a rapid EPO

response under acute hypoxia via the stabilization of HIF-2.

Interestingly, it is the combined deficiency of PHD2 and PHD3,

rather than PHD2 loss alone, that induces EPO expression in

glomerular renin-positive cells. Sustained HIF-2 activation in

these cells transforms them into EPO-producing cells. The strong

expression of PHD3 in glomerular renin-positive cells serves to

prevent this HIF-2-driven transformation, suggesting that PHD3

plays a crucial role in maintaining the functional stability of the

renin-expressing cell phenotype (43).

Neuroprotection and PHD-mediated

regulation of HIF

In an in vitro hypoxia-ischemia (HI) model

using oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) in rat pheochromocytoma

(PCC) (PC-12) cells differentiated with nerve growth factor, EPO

treatment has been found to enhance PHD2 transcription and

translation. This upregulation of PHD2 inhibits HIF-1α expression,

reduces ROS formation, and decreases matrix metalloproteinase-9

(MMP-9) activity, ultimately improving cell survival following

OGD-induced injury. Conversely, silencing PHD2 with small

interfering RNA (siRNA) reverses the neuroprotective effects of

EPO, indicating that PHD2 serves as a key mediator in EPO-induced

HIF-1α suppression and neuroprotection in HI conditions (46).

PHD deficiency and metabolic

consequences

The absence of PHD3 leads to increased blood lipid

levels and elevated hematocrit without affecting atherosclerotic

plaque size in low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice

(47). Additionally, studies have

shown that the complete loss of PHD1, PHD2 and PHD3 in the liver

results in severe fatty liver disease and erythrocytosis due to

excessive hepatic EPO production. Mice with hepatocyte-specific

deletion of all three PHD isoforms (PHD1/2/3hKO) exhibit a

1246-fold increase in hepatic EPO expression while renal EPO levels

drop to 6.7% of normal. These mice also develop hematocrit levels

reaching 82.4%, accompanied by severe vascular malformations and

liver steatosis (48).

By contrast, mice with dual liver-specific deletions

of PHD2 and PHD3 (PHD2/3hKO) also show increased hepatic EPO

production and reduced renal EPO expression, but the magnitude of

these changes is significantly lower than in PHD1/2/3hKO mice.

Unlike the triple knockout model, PHD2/3hKO mice maintain normal

hematocrit levels, vascular integrity and hepatic lipid homeostasis

(48). These findings indicate

that overall PHD activity, rather than the function of any single

isoform, plays a dominant role in regulating hepatic EPO production

through the PHD-HIF2α-EPO signaling cascade in vivo

(49).

Impact of PHDs on bone adaptation and

metabolism

The expression levels of negative regulatory

factors, including PHD2, FIH, and histone deacetylase sirtuin-6

(SIRT6), are significantly elevated in the skeletal muscle tissue

of elite athletes, whereas the expression of the hypoxia response

gene pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK-1) is reduced. This

suggests that exercise-induced training enhances HIF inhibition,

thereby downregulating PDK-1 and contributing to skeletal muscle

adaptation to physical activity (50). In bone cells, the disruption of

PHD2, which is highly expressed in osteoblasts, results in severe

osteoporosis. Notably, treatment with ascorbic acid effectively

suppresses PHD2 expression without affecting PHD1 levels (51). However, when osteoblasts are

treated with PHD inhibitors such as dimethyloxalylglycine (DMOG) or

3,4-dihydroxybenzoate ethyl, the ascorbic acid-mediated modulation

of osteoblast differentiation markers is entirely abolished

(52).

Osteoprotegerin (OPG), a direct target gene of HIF,

plays a crucial role in regulating bone homeostasis. The

inactivation of PHD2 and PHD3 enhances HIF activity, thereby

promoting bone accumulation through the direct modulation of OPG

balance between osteoblasts and osteoclasts. However, the

simultaneous inactivation of all three PHD isoforms (PHD1, PHD2 and

PHD3) leads to excessive angiogenesis-osteogenesis coupling,

resulting in severe erythrocytosis and pathological bone overgrowth

due to extreme HIF activation. Interestingly, the dual knockout of

PHD2 and PHD3 is sufficient to prevent bone loss without

compromising hematopoietic homeostasis in ovariectomized mice

(53).

Additionally, PHD3 expression plays a distinct role

in muscle cell migration. Rhodiola glycoside has been shown to

promote skeletal muscle cell migration and paracrine signaling by

selectively inhibiting the transcription of PHD3 without affecting

PHD1 or PHD2 (54). By contrast,

increased α-KG levels suppress osteoclastogenesis by inhibiting the

NF-κB signaling pathway, which is activated by RANKL, in a

PHD1-dependent manner (55).

Regulation of angiogenesis

PHD enzymes also play a significant role in vascular

remodeling and angiogenesis. The endothelial cell-specific deletion

of PHD2 results in severe pulmonary hypertension characterized by

increased right ventricular systolic pressure and extensive

muscular hypertrophy of the peripheral pulmonary arteries. However,

this phenotype does not involve erythrocytosis. Studies on

endothelial-specific PHD2 mutants with concurrent HIF-1α or HIF-2α

inactivation have demonstrated that pulmonary hypertension is

primarily driven by HIF-2α, rather than HIF-1α. The pathological

effects of HIF-2α in this condition are largely mediated by

upregulated expression of the vasoconstrictor endothelin-1 and

diminished apelin receptor signaling, which normally promotes

vasodilation (56). In HI models,

the expression of PHD proteins exhibits dynamic changes over time.

Following 24 h of HI, PHD3 protein levels, along with HIF-1α

expression, are significantly elevated. However, after 72 h of HI,

PHD3 protein levels decline, while PHD1 and PHD2 levels remain

unchanged throughout the hypoxic period (57).

Role of PHDs in tumor progression and

metabolism

PHD enzymes play a complex and context-dependent

role in cancer, significantly influencing tumor growth and

metabolism (58). The primary

mechanism underlying this effect is the regulation of HIF-1α, which

drives a metabolic shift from oxidative phosphorylation to

anaerobic glycolysis, thereby promoting tumor adaptation to hypoxic

microenvironments. This metabolic reprogramming alters oxidative

stress responses and results in the accumulation of tumor-specific

metabolites that contribute to cancer progression.

In clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), the loss

of pVHL leads to the accumulation of HIF-α isoforms and their

downstream target genes. Interestingly, in contrast to most cell

types where PHD3 negatively regulates HIF-1α, ccRCC tumors exhibit

a strong positive correlation between PHD3 and HIF2A mRNA

expression. High PHD3 expression in these tumors sustains elevated

HIF-1α levels and enhances the expression of HIF target genes,

potentially increasing the invasive potential of ccRCC cells

(59).

In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the

downregulation of PHD1 and PHD2 is associated with tumor initiation

and progression. The loss of these PHD isoforms correlates with

increased activity of downstream HIF pathway genes such as HIF-1α,

PKM2 and PDK1. However, PHD3 does not appear to play a significant

role in NSCLC tumor biology (60).

In colorectal cancer models with varying levels of

drug resistance, silencing PHD1, but not PHD2 or PHD3, prevents p53

activation and impairs DNA repair mechanisms, ultimately leading to

cancer cell death. PHD1 facilitates p53 activation through

hydroxylation-dependent interactions with p38α kinase, enabling

phosphorylation of p53 at serine 15. This modification enhances

p53-mediated nucleotide excision repair by promoting interactions

with the DNA helicase XPB, thereby protecting tumor cells from

chemotherapy-induced apoptosis (61).

Current research suggests that PHD enzymes exhibit

both tumor-promoting and tumor-suppressing functions, depending on

their expression profiles in different cancer types and cellular

contexts. The precise role of each PHD isoform in tumorigenesis

remains an area of active investigation, with implications for the

development of targeted cancer therapies (62).

Regulation in inflammation and glucose

metabolism

PHD1 has been found to be overexpressed in pouchitis

biopsies from patients with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for UC,

with its expression levels correlating directly with disease

activity. Notably, treatment with the small-molecule PHD inhibitor

DMOG has demonstrated the ability to restore intestinal epithelial

barrier integrity by upregulating the tight junction proteins zona

occludens-1 and claudin-1. Additionally, DMOG alleviates intestinal

epithelial cell apoptosis, thereby mitigating inflammation in the

pouch and improving disease outcomes (63).

In a mouse model of IBD, the expression of PHD1 and

PHD2 progressively increases as the disease advances, whereas PHD3

levels remain unchanged. This suggests that inhibiting all three

PHD subtypes may not be an optimal therapeutic strategy for IBD, as

normal intestinal function appears to rely on the presence of PHD3

(64).

Beyond inflammation, PHD3 also plays a significant

role in glucose metabolism. A sudden loss of PHD3 (also known as

Egln3) in the liver has been shown to enhance insulin sensitivity

by selectively stabilizing HIF-2α. This stabilization promotes the

transcription of insulin receptor substrate 2 (Irs2), which in turn

enhances insulin-stimulated Akt activation. The beneficial

metabolic effects of PHD3 knockout on glucose tolerance and insulin

signaling are entirely dependent on HIF-2α and Irs2, as their

elimination negates these improvements (65).

Additionally, α-KG, a key respiratory substrate, has

been implicated in insulin secretion. Cytoplasmic PHD enzymes

regulate α-KG metabolism, and inhibition of PHDs using ethyl

dihydroxybenzoate (EDHB) significantly suppresses

glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) in pancreatic β-cells

(832/13 clone), as well as in rat and human islets. This

suppression occurs due to reduced glucose metabolism, a lower

ATP/ADP ratio, and diminished levels of critical TCA cycle

intermediates, including pyruvate, citrate, fumarate and malate.

Interestingly, silencing PHD1 and PHD3 with siRNA impairs GSIS,

whereas PHD2 knockdown has no impact, suggesting that PHD1 and PHD3

are key regulators of glucose metabolism in pancreatic β-cells

(66).

Regulation of erythropoiesis

A heterozygous PHD2 c.1121A → G (p.H374R) mutation

has been identified in patients with familial polycythemia, though

it is not directly associated with tumor development. However,

individuals with PHD2 mutations linked to polycythemia have been

later diagnosed with recurrent paragangliomas (PGL), suggesting a

potential predisposition. The pathogenic mechanism underlying these

conditions involves dysregulated hypoxia sensitivity, leading to

the stabilization and accumulation of HIF-2α, which creates a

pseudo-hypoxic state. This state, in turn, may contribute to the

development of both polycythemia and hypoxia-associated endocrine

tumors, including PCC and PGL (9).

VHL-associated diseases also result in the

stabilization of HIFs, frequently observed in endocrine tumors such

as PCC and PGL. The aberrant upregulation of HIF not only directly

promotes tumor growth but also reduces apoptosis in endocrine tumor

cells, further exacerbating disease progression. Based on the

classification, localization and functions of PHDs, it is evident

that excessive erythrocytosis is primarily driven by dysregulation

of PHD2, which leads to unchecked HIF-2α accumulation. This, in

turn, results in the overexpression of downstream target genes,

particularly through the hyperactivation of the EPO pathway.

Chuvash polycythemia, a well-characterized genetic

disorder, is associated with a homozygous 598C>T germline

mutation in the VHL gene. This mutation leads to aberrant HIF-1α

upregulation, even under normoxic conditions, driving the excessive

production of EPO and several other hypoxia-responsive genes. The

C>T missense mutation in VHL causes an arginine-to-tryptophan

substitution at residue 200 (Arg200Trp), weakening the interaction

between VHL and HIF-1α. This defective interaction reduces HIF-1α

degradation, thereby leading to the persistent overexpression of

EPO, SLC2A1 (GLUT1, encoding solute carrier family 2), TF (encoding

transferrin), TFRC (encoding transferrin receptors CD71/p90), and

VEGF (encoding vascular endothelial growth factor) (67,68).

Overall, the HIF/PHD axis plays a complex and

multifaceted role in diverse physiological and pathological

processes (Fig. 3). Significant

progress has been made in the development of PHD inhibitors for

clinical applications (69).

However, different PHD subtypes exert distinct effects across

various biological functions, including angiogenesis,

erythropoiesis, cancer progression, cellular growth,

differentiation and survival. Therefore, further investigations are

required to elucidate the precise impact of PHD enzymes on HIF-α

subtype specificity in in vivo models, as well as their

individual contributions to distinct biological pathways (27).

Pharmaceutical development and therapeutic

applications of PHD inhibitors

The hydroxylation of HIF-α proline residues is

catalyzed by Fe- and 2-OG-dependent dioxygenase enzymes known as

PHDs, whose activity is strictly oxygen-dependent. As a result,

inhibiting PHD function leads to the stabilization of HIF-α,

thereby activating hypoxia-associated signaling pathways even under

normoxic conditions. This mechanism has been leveraged for

therapeutic purposes, with small-molecule PHD inhibitors developed

as clinical treatments for renal anemia. Beyond their application

in anemia management, recent research has highlighted the broader

medical potential of PHD inhibitors in various disease contexts.

Emerging evidence suggests that modulating PHD activity may have

therapeutic implications for ischemic disorders, chronic

inflammatory diseases, metabolic syndromes and even

neurodegenerative conditions. These findings underscore the

expanding role of PHD-targeted therapies and warrant further

investigation into their diverse clinical applications (70).

PHD inhibitors have also been reported in the

treatment of various other diseases (70). There is increasing evidence

supporting the potential of targeting the HIF pathway in acute

myeloid leukemia (AML) therapy. Studies suggest that the selective

PHD2 inhibitor IOX5 exerts its effects by stabilizing HIF-1α,

thereby triggering a cascade of events detrimental to AML cells. By

stabilizing HIF-1α, IOX5 disrupts pro-leukemogenic signaling

pathways, shifts metabolic processes to a state less favorable for

cancer cells and induces apoptosis through BNIP3 upregulation,

highlighting its potential as a non-toxic therapeutic strategy for

AML. Furthermore, when combined with BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax,

which is already used in clinical settings, IOX5 enhances anti-AML

efficacy. Notably, IOX5 selectively targets PHD without interfering

with other enzymes such as FIH-1, a key feature for minimizing

off-target effects (71).

Roxadustat, another PHD inhibitor, has shown promise

in alleviating anemia in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic

syndrome, reducing their dependence on RBC transfusions.

Additionally, roxadustat has been identified as a novel therapeutic

candidate for Fe-refractory Fe-deficiency anemia (IRIDA). In mouse

models of IRIDA, it activates the HIF-2α-ferroportin (FPN) axis,

demonstrating significant therapeutic efficacy and clinical

translation potential. Mechanistically, roxadustat stabilizes

HIF-2α in the duodenum, leading to FPN transcriptional activation

and increased intestinal Fe absorption, independent of hepcidin

levels, ultimately ameliorating hepcidin-activated anemia (72).

Moreover, in ischemia/reperfusion injury models,

roxadustat preconditioning has been shown to induce ischemic

tolerance by shifting aerobic respiration to anaerobic metabolism,

thereby maintaining ATP production under hypoxic conditions and

reducing myocardial ischemic damage (73). Additionally, roxadustat activates

the HIF-1α/VEGF/VEGFR2 pathway, promoting angiogenesis, and has

demonstrated therapeutic potential in diabetic wound healing in rat

models (74). Furthermore,

roxadustat induces the accumulation of HIF-1α and WNT7a in the

tibialis anterior muscle, facilitating muscle regeneration

following cyclophosphamide-induced muscle injury and promoting the

formation of significantly larger muscle fibers (75). These findings suggest that

roxadustat could be a promising drug for diabetic wound healing and

the prevention of age-related skeletal muscle atrophy, though

clinical validation is still required.

Given the broad biological functions of HIF,

roxadustat's ability to stabilize HIF has opened new avenues for

treating hypoxia-related diseases, including neuroprotection in

nerve injury (76), oxygen-induced

retinopathy (77), pulmonary

fibrosis (78), acute lung injury

(79), fracture healing (80) and radiation-induced apoptosis

(81).

The therapeutic development of HIF-PHD modulators

has primarily focused on inhibitors designed to elevate hemoglobin

(Hb) levels, particularly for the treatment of renal anemia. To

date, no studies have reported on optimal recovery doses or the

development of PHD activators.

A comprehensive meta-analysis encompassing 30

studies and a total of 13,146 patients has assessed the long-term

efficacy and safety of HIF-PHD inhibitors, including roxadustat,

daprodustat, vadadustat, molidustat, desidustat and enarodustat, in

the management of anemia associated with CKD. The findings

demonstrate that HIF-PHD inhibitors significantly enhance Hb

levels, total Fe-binding capacity, and transferrin concentrations

compared with placebo or erythropoiesis-stimulating agent (ESA)

treatments. Additionally, these inhibitors contribute to a

reduction in cholesterol levels, indicating potential metabolic

benefits.

Regarding safety, patients receiving HIF-PHD

inhibitors exhibit a higher incidence of serious adverse events

compared with those in the placebo group. However, the overall risk

profile is comparable to that observed with ESA therapy. Adverse

effects commonly associated with HIF-PHD inhibitors include

diarrhea, nausea, peripheral edema, hyperkalemia and hypertension,

with a higher likelihood of vomiting, headaches and thrombotic

events when compared with ESA treatment. Despite these risks,

HIF-PHD inhibitors remain effective in elevating Hb levels,

optimizing Fe metabolism, and demonstrating favorable long-term

tolerability in CKD-associated anemia. To mitigate adverse effects

related to excessive Fe utilization, it is recommended that HIF-PHD

inhibitors be administered in conjunction with Fe supplementation

for extended treatment regimens (82).

The research studies on HIF-PHD inhibitors for renal

anemia are as follows [Table

II;(83–94)]: Beyond clinical trials,

investigations have explored the pharmacokinetic interactions of

HIF-PHD inhibitors both in vitro and in healthy volunteers.

In vitro studies have demonstrated that the formation of

chelates between vadadustat and Fe-containing compounds varies

depending on the specific type of Fe reagent in aqueous and

simulated intestinal fluid environments. Notably, when vadadustat

is co-administered with oral Fe supplements, its area under the

plasma concentration-time curve (AUC0-∞) and maximum

plasma concentration (Cmax) are reduced due to

gastrointestinal chelation. This interaction suggests that Fe

supplements may impair vadadustat absorption, necessitating a

dosing interval to optimize its therapeutic efficacy (95).

| Table II.Clinical studies of hypoxia-inducible

factor-PHD inhibitors for renal anemia. |

Table II.

Clinical studies of hypoxia-inducible

factor-PHD inhibitors for renal anemia.

| First author/s,

year | Stage trial | Study design | Object | Medicine | Results | Conclusion | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Kansagra et

al, | Phase I | Randomized, | 100 healthy | ZYAN1 | Maximum

concentration (Cmax) ranged from | Single (10–300 mg)

and | (83) |

| 2018 | clinical | double-blind, | volunteers |

| 566.47±163.03 to

17,858.33±2,899.19 ng/ml. | multiple (100–300

mg) doses |

|

|

| trial | placebo- |

|

| After a single

incremental dose of 10–300 mg | of Zyany1 were safe

and |

|

|

|

| controlled |

|

| The median time

(t/MAX) to Cmax with a | well tolerated in

healthy |

|

|

|

| (evaluation |

|

| 300 mg oral dose of

Zyan1 was ~2.5 h. | volunteers. |

|

|

|

| of safety, |

|

| The mean

Cmax and area (AUC T) area values | The mean C Max

and |

|

|

|

| tolerability, |

|

| under the

concentration-time curve from time | AUCt increased

almost |

|

|

|

| and pharma- |

|

| 0 to time t showed

a dose-proportional increase | proportionally with

the |

|

|

|

| cokinetics |

|

| regardless of

single or multiple dosing. | dose of Zyan

1. |

|

|

|

| after oral |

|

| The average

elimination half-life (t½) is | The average

concentration |

|

|

|

|

administration) |

|

| 6.9–13 h and the

cumulative dose was | of serum EPO showed

a |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| negligible. | dose-response

trend. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| After a single dose

of Zyany1, the maximum | Zyan 1 once every 2

days |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| mean serum EPO

showed a dose-response | was recommended

for |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (i.e., 10 and 300

mg Zyany1 doses were | Phase II study

based on |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 6.6 and 79.9 Miu/l,

respectively), and the | the data of T 1FI

2, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| average maximum

serum EPO | pharmacodynamic

activity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| concentration

ranged from 10 to 72 h. | and drug

accumulation. |

|

| Singh et al,

2021 | Phase 3 | Randomized, | 2964 patients | Daprodustat | The mean (±SD)

baseline Hb level was | In CKD patients

with | (84) |

|

| clinical | open-label | with dialysis |

| 10.4±1.0 g per

deciliter overall. The mean | dialysis, the

daprodustat |

|

|

| trial | (1,487 cases

of | CKD patients |

| (±SE) change in the

Hb level from baseline | group is not

inferior to the |

|

|

|

| daprodustat

oral | of Hb levels |

| to weeks 28 through

52 was 0.28±0.02 g | ESAs group in

changes |

|

|

|

|

administration; | ranging from |

| per deciliter in

the daprodustat group and | in Hb levels since

baseline |

|

|

|

| 1,477 cases of | 80 to 115 g/l |

| 0.10±0.02 g per

deciliter in the ESA group | and outcomes of

cardio- |

|

|

|

| ESA) |

|

| [difference, 0.18 g

per deciliter; 95% | vascular adverse

events. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| confidence interval

(CI), 0.12 to 0.24], |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| which met the

prespecified noninferiority |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| margin of −0.75 g

per deciliter. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| During a median

follow-up of 2.5 years, a |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| major adverse

cardiovascular event occurred |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| in 374 of 1487

patients (25.2%) in the |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| daprodustat group

and in 394 of 1477 (26.7%) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| in the ESA group

(hazard ratio, 0.93; 95% CI, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0.81 to 1.07),

which also met the prespecified |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| noninferiority

margin for daprodustat. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The percentages of

patients with other adverse |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| events were similar

in the two groups. |

|

|

| Singh et

al, | Phase 3 | Randomized, | 3872 patients | Daprodustat | The mean (±SE)

change in the Hb level from | In non-dialysis

CKD | (85) |

| 2021 | clinical | open labe | with non- |

| baseline to weeks

28 through 52 was | patients with

anemia, the |

|

|

| trial | (daprodustat: | dialysis CKD |

| 0.74±0.02 g per

deciliter in the daprodustat | daprodustat group

was not |

|

|

|

| darbepoetin | stage 3–5 |

| group and 0.66±0.02

g per deciliter in the | inferior to the

dapepoetin |

|

|

|

| alfa 1:1) |

|

| darbepoetin alfa

group [difference, 0.08 g per | alpha group in

terms of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| deciliter; 95%

confidence interval (CI), 0.03 to | Hb levels changes

since |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0.13], which met

the prespecified noninferiority | baseline and

outcomes of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| margin of −0.75 g

per deciliter. | cardiovascular

adverse |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| During a median

follow-up of 1.9 years, the | events. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| first MACE occurred

in 378 of 1937 patients |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (19.5%) in the

daprodustat group and in 371 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| of 1935 patients

(19.2%) in the darbepoetin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| alfa group (hazard

ratio, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.89 to |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1.19), which met

the prespecified noninferiority |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| margin of

1.25. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The percentages of

patients with adverse events |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| were similar in the

two groups. |

|

|

| Fishbane et

al, | Phase 3 | Randomized, | 2133 patients | Roxadustat | Mean (95%

confidence interval) Hb change | Roxadustat

effectively | (86) |

| 2022 | clinical | open label | with dialysis- |

| from baseline was

0.77 (0.69 to 0.85) g/dl with | increased Hb in

patients |

|

|

| trial | (roxadustat: | dependent |

| roxadustat and 0.68

(0.60 to 0.76) g/dl with | with DD-CKD, with

an |

|

|

|

| epoetin alfa

1:1) | (DD) CKD |

| epoetin alfa,

demonstrating noninferiority | AE profile

comparable to |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [least squares mean

difference (95% CI), | epoetin alfa. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0.09 (0.01 to

0.18); P<0.001]. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The proportion of

patients experiencing ≥1 AE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| and ≥1 serious AE

was 85.0 and 57.6% with |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| roxadustat and 84.5

and 57.5% with epoetin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| alfa,

respectively. |

|

|

| Fishbane et

al, | Phase 3 | Double-blind | CKD stages | Roxadustat | The mean change in

Hb from baseline was | Roxadustat

effectively | (87) |

| 2021 | clinical | randomization | 3–5 of Hb |

| 1.75 g/dl [95%

confidence interval (95% CI), | increased Hb in

patients with |

|

|

| trial | (roxadustat: | <10.0 g/dl |

| 1.68 to 1.81] with

roxadustat vs. 0.40 g/dl |

non-dialysis-dependent CKD |

|

|

|

| placebo 1:1) |

|

| (95% CI, 0.33 to

0.47) with placebo, (P<0.001). | and reduced the

need for |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Among 411 patients

with baseline elevated | RBC transfusion,

with |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| high-sensitivity

C-reactive protein, the mean | an adverse event

profile |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| change in Hb from

baseline was 1.75 g/dl | comparable to that

of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (95% CI, 1.58 to

1.92) with roxadustat vs. | placebo. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0.62 g/dl (95% CI,

0.44 to 0.80) with placebo, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (P<0.001).

Roxadustat reduced the risk of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| RBC transfusion by

63% (hazard ratio, 0.37; |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 95% CI, 0.30 to

0.44). The most common |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| adverse events with

roxadustat and placebo, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| respectively, were

ESKD (21.0% vs. 20.5%), |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| urinary tract

infection (12.8% vs. 8.0%), |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| pneumonia (11.9%

vs. 9.4%), and hypertension |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (11.5% vs.

9.1%). |

|

|

| Chen et

al, | Phase 3 | Double-blind | 154 patients | Roxadustat | During the primary

analysis period, the mean | The roxadustat

group had | (88) |

| 2019 | clinical | randomization | with non- |

| (±SD) change from

baseline in the Hb level | a higher mean Hb

level |

|

|

| trial | (Roxadustat: | dialysis CKD |

| was an increase of

1.9±1.2 g per deciliter in the | than those in the

placebo |

|

|

|

| placebo= 2:1) | in 29 regions |

| roxadustat group

and a decrease of 0.4±0.8 g | group after 8

weeks. |

|

|

|

|

| of China |

| per deciliter in

the placebo group (P<0.001). | Hyperkalemia and

metabolic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The mean reduction

from baseline in the | acidosis occurred

more |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| hepcidin level

(associated with greater Fe | frequently in the

roxadustat |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| availability) was

56.14±63.40 ng per milliliter | group than in the

placebo |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| in the roxadustat

group and 15.10±48.06 ng per | group. The efficacy

of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| milliliter in the

placebo group. The reduction | roxadustat in Hb

correction |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| from baseline in

the total cholesterol level was | and maintenance

was |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 40.6 mg per

deciliter in the roxadustat group | maintained during

the |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| and 7.7 mg per

deciliter in the placebo group. | 18-week open-label

period. |

|

| Perkovic et

al, | The | Randomized | 3872 cases | Daprodustat | The median baseline

Hb was 9.9 g/dl, blood | Hb

efficacy,cardiovascular | (89,90) |

| 2022; | American | Open-label

trial | of non- |

| pressure was 135/74

mmHg, and the estimated | (CV) safety and

secondary |

|

| Testi et

al, | CKD | (daprodustat: | dialysis CKD |

| glomerular

filtration rate was 18 ml/min/1.73 m2. | efficacy

outcomes, |

|

| 2023 | anemia | darbepoetin | anemia in |

| Among randomized

patients, 53% were ESA | daprodustat is not

inferior |

|

|

| study | alfa 1: 1) | 38 countries |

| non-users, 57% had

diabetes, and 37% had a | to the control

substance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| history of CV

disease. At baseline, 61% of | darboetin

alpha. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| participants were

using renin-angiotensin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| system blockers,

55% were taking statins, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| and 49% were taking

oral iron. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Baseline

demographics were similar to those |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| in other large

non-dialysis anemia trials. |

|

|

| Kurata et

al, | Phase III |

| Non-dialysis- | Roxadustat | Roxadustat

effectively increases and maintains | Roxadustat

effectively | (91) |

| 2022 | clinical |

| dependent |

| Hb levels in both

non-dialysis-dependent and | increases and

maintains |

|

|

| trial |

| and dialysis- |

| dialysis-dependent

CKD patients. Roxadustat | Hb levels.

Roxadustat is an |

|

|

| expert |

| dependent |

| also improved Fe

metabolism and reduced | attractive

alternative |

|

|

| opinion |

| CKD patients |

| intravenous (IV) Fe

requirements. However, | treatment

especially for |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| pooled analyses of

phase 3 studies have | patients with

ESA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| revealed frequent

thromboembolic events in | hyporesponsive due

to |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| the roxadustat

group, which might be attributed | impaired Fe

utilization. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| to rapid changes in

Hb and inadequate Fe | So, the appropriate

selection |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| supplementation.

Roxadustat is an attractive | of target patients

and its |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| alternative

treatment especially for patients | proper use are

crucially |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| with ESA

hyporesponsive due to impaired Fe | important. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| utilization. |

|

|

| Eckardt et

al, | Phase 3 | Random, open- | 3,923 patients | Vadadustat | In the pooled

analysis, the first MACE occurred | vadadustat was

noninferior | (92) |

| 2021 | clinical | label, non- | with |

| in 355 patients

(18.2%) in the vadadustat group | to darbepoetin alfa

with |

|

|

| trial | inferiority | occasional |

| and in 377 patients

(19.3%) in the darbepoetin | respect to

cardiovascular |

|

|

|

| (vadadustat: | or dialysis- |

| alfa group [hazard

ratio, 0.96; 95% confidence | safety and

correction and |

|

|

|

| darbepoetin | dependent |

| interval (CI), 0.83

to 1.11]. The mean | maintenance of

Hb |

|

|

|

| alfa) | (DD-CKD) |

| differences between

the groups in the change |

concentrations. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| in Hb concentration

were −0.31 g per deciliter |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (95% CI, −0.53 to

−0.10) at weeks 24 to 36 and |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| −0.07 g per

deciliter (95% CI, −0.34 to 0.19) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| at weeks 40 to 52

in the incident DD-CKD |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| trial and −0.17 g

per deciliter (95% CI, −0.23 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| to −0.10) and −0.18

g per deciliter (95% CI, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| −0.25 to −0.12),

respectively, in the prevalent |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DD-CKD trial. The

incidence of serious adverse |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| events in the

vadadustat group was 49.7% in |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| the incident DD-CKD

trial and 55.0% in the |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| prevalent DD-CKD

trial, and the incidences |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| in the darbepoetin

alfa group were 56.5% and |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 58.3%,

respectively. |

|

|

| Provenzano et

al, | Phase 1b | Double-blind | 17 patients | Roxadustat | Maximum plasma

concentration and area | Peak median

endogenous | (93) |

| 2020 | clinical | placebo | with hemo- | (FG-4592) | under the plasma

concentration-time curve | EPO levels were 96

mIU/ml |

|

|

| trial | randomized | dialysis |

| for patients

receiving roxadustat were slightly | and 268 mIU/ml for

the 1- |

|

|

|

| controlled

study | end-stage |

| more than dose

proportional and elimination | and 2-mg/kg

doses, |

|

|

|

| (roxadustat: | renal disease |

| half-life ranged

from 14.7–19.4 h. Roxadustat | respectively,

within |

|

|

|

| Placebo = 3:1) |

|

| was highly protein

bound (99%) in plasma, and | physiologic range

of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| dialysis

contributed a small fraction of the total | endogenous EPO

responses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| clearance: only

4.56 and 3.04% of roxadustat | to hypoxia at high

altitude or |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| recovered from the

1 and 2 mg/kg dose groups, | after blood loss.

No serious |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| respectively.

Roxadustat induced transient | adverse events were

reported, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| elevations of

endogenous EPO that peaked | and there were no

treatment- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| between 7 and 14 h

after dosing and returned to | or dose-related

trends in |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| baseline by 48 h

after dosing. | adverse event

incidence. |

|

| Akizawa et

al, | Phase 3 | Open-label, | Non-dialysis | roxadustat | Either the

roxadustat or DA comparative group | The roxadustat dose

required | (94) |

| 2021 | clinical | partially | dependent |

| received treatment

(roxadustat, n=131; DA, | to maintain target

Hb in NDD |

|

|

| trial | random | (NDD) |

| n=131). Higher mean

(standard deviation) | patients in Japan

with anemia |

|

|

|

| (roxadustat

and | patients |

| doses of both

roxadustat [63.15 (24.84) mg] | of CKD relative to

DA dose |

|

|

|

| darbepoetin | with CKD |

| and DA [47.33

(29.79) µg] were required in the | may not be impacted

by |

|

|

|

| alfa 1: 1) | anemia |

| highest ESA

resistance index (≥6.8) quartile | low-grade

inflammation. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (P=0.003 and

P<0.001, respectively). Patients | Roxadustat may be

beneficial |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| with adequate Fe

repletion had the lowest doses | for

ESA-hyporesponsive |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| for both roxadustat

[45.54 (18.01) mg] and DA | NDD CKD

patients. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [28.13 (20.98) µg].

High-sensitivity C-reactive |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| protein ≥28.57

nmol/l and the estimated |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| glomerular

filtration rate <15 ml/min/1.73 m2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| were associated

with requiring higher DA but |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| not roxadustat

doses. |

|

|

Additionally, pharmacokinetic evaluations in healthy

volunteers have assessed the interaction between roxadustat and

warfarin. The combination has been found to be well-tolerated, with

only mild treatment-related adverse events. Importantly,

co-administration does not necessitate warfarin dose adjustments,

indicating that roxadustat does not significantly alter warfarin

metabolism or anticoagulant activity (96).

The potential impact of HIF-PHIs on tumor

development and progression has been a subject of significant

concern, particularly given their close association with VHL

disease. VHL disease is a syndrome characterized by detectable

genetic abnormalities in the VHL gene, frequently associated with

tumor formation (97). HIF

regulates the transcription of numerous target genes, including

VEGF, a key factor that promotes tumor growth. Additionally, two

Phase 3 clinical trials conducted in China have reported a higher

incidence of hyperkalemia in the roxadustat group. However, further

analysis of potassium levels measured by central laboratories does

not confirm an increased risk of hyperkalemia in patients treated

with Roxadustat (88,98).

In the TREAT trial, patients in the darbepoetin alfa

group (target Hb 130 g/l) exhibit a higher risk of fatal or

non-fatal stroke, venous thromboembolism, and arterial

thromboembolism compared with the placebo group (where darbepoetin

alfa is only administered when Hb levels fell below 90 g/l)

(99). Furthermore, in 2019, the

first reported case of roxadustat-induced pulmonary arterial

hypertension is documented (100).

Beyond its role as an HIF prolyl hydroxylase

inhibitor, roxadustat has been suggested to exert HIF-independent

effects, indicating the presence of potential off-target

activities. Notably, it may increase the risk of pulmonary arterial

hypertension and vascular calcification, as well as exacerbate

inflammation and infection (101). Although no significant off-target

effects have been observed in clinical trials or real-world

applications thus far, HIF regulates a vast array of genes and has

pleiotropic effects. Therefore, strict control of HIF activation

levels and duration is essential, and careful consideration of

roxadustat's dosage and treatment regimen is warranted to minimize

unintended side effects resulting from excessive HIF

activation.

PHDs and erythrocytosis

Human survival depends on a continuous and adequate

oxygen supply to meet cellular metabolic demands, primarily through

oxidative phosphorylation, which generates ATP. HIFs play a central

role in regulating gene transcription to maintain oxygen

homeostasis by balancing oxygen supply and demand. The activity of

HIFs is tightly regulated through oxygen-dependent hydroxylation,

primarily mediated by PHD proteins and VHL proteins. Mutations in

VHL, HIF-2α and PHD2 genes can lead to hereditary polycythemia, a

condition characterized by excessive RBC production and PHA due to

aberrantly elevated HIF activity. Furthermore, genetic adaptations

involving variations in PHD2 and HIF-2 contribute to high-altitude

acclimatization by reducing erythropoiesis and pulmonary vascular

reactivity to hypoxia, enabling improved survival in low-oxygen

environments (102).

Population genomic studies have identified EPAS1

(HIF-2α) and EGLN1 (PHD2) as the primary genes responsible for

high-altitude adaptation. These genes exhibit strong associations

with lower Hb levels in the Tibetan population, suggesting an

evolutionary advantage in hypoxic environments (103). PHD2, encoded by EGLN1, functions

as a critical oxygen sensor, facilitating HIF-α hydroxylation and

subsequent degradation under normoxic conditions. In addition to

its catalytic domain, PHD2 contains a highly conserved zinc finger

domain, which independently interacts with HIF-α in vitro. A

C36S/C42S EGLN1 knockout mutation, which disrupts the zinc finger

function, leads to increased EPO gene expression, excessive

erythropoiesis, and an enhanced hypoxic ventilatory response in

vivo. These physiological effects are attributed to

loss-of-function mutations in EGLN1, resulting in prolonged HIF

stabilization and activation (104).

A gain-of-function mutation in EGLN1 (PHD2 D4E:

C127S), along with polymorphisms in EPAS1 (HIF-2α), contributes to

reduced Hb levels among Tibetan highlanders. While the influence of

EGLN1 haplotypes on Hb concentration varies with age in

low-altitude populations, Tibetan highlanders consistently exhibit

lower Hb levels due to adaptation to the EPAS1 rs142764723 C/C

allele. The high-altitude-adapted EGLN1 haplotypes, c.12C>G and