Introduction

Infertility is a prevalent global reproductive

health problem, affecting ~15% of couples of reproductive ages,

with ~50% of these cases attributed to male factors (1). Idiopathic asthenozoospermia (iAZS)

represents a primary cause of male infertility, yet no optimal

therapeutic strategies for iAZS have been established. Currently,

the non-invasive management of male infertility, including iAZS,

primarily involves changes in lifestyle, oxidative stress therapy,

prebiotic and probiotic supplements, hormone therapy and

enhancement of male gonadal function; however, the efficiency of

these approaches remains unsatisfactory (2–4).

Furthermore, ideal treatment methods (high efficacy with a

favorable safety profile) for asthenozoospermia (AZS) have not been

established. Thus, investigating novel therapeutic methods for male

reproductive disorders is required. The application of traditional

Chinese herbal medicine in reproductive health has garnered notable

attention (5,6). Echinacoside (ECH), a naturally

occurring compound with potentially beneficial biological activity,

has been increasingly recognized for its role in improving sperm

quality (5).

ECH, the most active component extracted from

Cistanche tubulosa (Schrenk) Wight which belongs to the

Asteraceae family, has exhibited extensive biological activities,

such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antitumor effects

(6,7). Notably, ECH positively influences

male reproductive health by enhancing glutathione peroxidase

(GSH-PX) levels and the antioxidant capacity of testicular tissue,

thereby mitigating reproductive toxicity induced by bisphenol A or

lead acetate in male rats (5,8,9).

However, the molecular mechanisms underlying ECH-induced

improvements in sperm quality, particularly sperm motility, remain

poorly understood.

The cation channel of sperm (CatSper), which

comprises a minimum of 11 subunits, including four α subunits that

form the pore region, is specifically expressed in the testis and

localized in the principal section of sperm flagellum (10,11).

This channel mediates Ca2+ influx into the sperm,

thereby promoting capacitation, hyperactivation and participation

in sperm chemotaxis, making CatSper important for male fertility

and human fertilization (12–14).

In human sperm, the expression and function of CatSper channels are

closely linked to progressive motility and may contribute to the

pathogenesis of AZS (15,16). An association has been observed

between single nucleotide polymorphisms in CatSper1 and iAZS, as

well as between CatSper1 protein expression and progressive, total

and hyperactivated sperm motility (17,18).

Similarly, CatSper1 and CatSper3 mRNA expression levels are also

reduced in sperm from asthenoteratozoospermic males (19). In a previous study, we demonstrated

that decreased expression and function of CatSper resulted in

decreased sperm motility, while transcutaneous electrical acupoint

stimulation and electroacupuncture (EA) at a frequency of 2 Hz

exerted therapeutic effects on iAZS by inducing the functional

upregulation of CatSper channels in sperm (16). However, the roles and mechanisms of

CatSper channels in the therapeutic effects of ECH on iAZS remain

unclear.

The sex-determining region Y (Sry)-related

high-mobility-group (HMG)-box (Sox) family comprises a group of

transcription factors that are intricately involved in sex

determination and embryonic development (20). Specifically, Sox4, 8, 9 and 12 are

highly expressed in Sertoli cells, whereas Sox5, 6 and 30 are

predominantly expressed in spermatocytes and spermatozoa. These

transcription factors serve notable roles at distinct stages of

male reproductive development (21). Sox5, 6, 13, 30 and 32 coordinate

the regulation of gene expression within the testes, thereby

promoting spermatogenesis in adult males (22–25).

Sox5 is an important transcription factor implicated in

spermatogenesis and maturation (24). The mutation or aberrant expression

of Sox5 can result in spermatogenic dysfunction, ultimately

contributing to male infertility, and Sox5 has been identified as a

susceptibility gene for non-obstructive azoospermia (26–29).

In addition, the CatSper1 promoter contains four transcriptional

start sites (TSSs) and three functional Sox-binding sites (20). In vivo studies have

demonstrated that Sox5 can enhance the transactivation of the

CatSper1 promoter, suggesting that CatSper1 may serve as a target

gene of Sox5 (30).

The present study aimed to investigate whether ECH

treatment exerted its effects on AZS rats and patients with iAZS

through CatSper channels, as well as whether ECH treatment

upregulated CatSper1 protein expression through the activation of

Sox5.

Materials and methods

Chemicals, reagents and

antibodies

All chemicals, reagents and antibodies used are

listed in Table SI.

High-performance liquid chromatography

(HPLC) analysis

The HPLC was performed using an Agilent 1260

Infinity II system (Agilent Technologies). Separation was achieved

on a Phenomenex Luna 5 µm C18(A) (250.0×4.6 mm, 5 µm) maintained at

30°C. A sample volume of 10 µl was injected into the system. The

mobile phase consisted of two solvents: solvent A (0.1% formic acid

in water) and solvent B (acetonitrile). A gradient elution program

was applied with a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min: solvent B was increased

from 10 to 20% over 14 min.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)

spectroscopic analyses

NMR spectra were measured on a Varian INOVA-500 NMR

spectrometer (Varian Medical Systems Inc., USA), using

methanol-d4 as solvent, and the chemical shifts

were referenced to the solvent residual peak.

Animals

Sexually mature male Sprague-Dawley rats (age, 8

weeks; initial body weight, 200–230 g) were obtained from the

Department of Experimental Animal Sciences at Peking University

Health Science Center (Beijing, China). The rats were individually

kept in a climate-controlled environment at a temperature of 22±2°C

and a relative humidity of 50±10%, with a 12-h light/dark cycle and

free access to food and water. The health and behavior of rats were

monitored every day. A total of 59 rats were used in the present

study. The duration of the experiment was 30 days. Humane endpoints

were as follows: Complete anorexia or signs of depression

accompanied by hypothermia, observable as a body temperature

<37°C, without anesthesia or sedation. The rats were euthanized

by intraperitoneal injection of an overdose of 1% pentobarbital

sodium (300 mg/kg). Animal death was confirmed by respiratory and

cardiac arrest and pupil dilation was observed for ≥10 min. There

were no rats that reached the humane endpoints of the study. All

experimental procedures involving animals were approved by the

Animal Care and Use Committee of Peking University (Beijing, China)

prior to the initiation of the study (approval no. J2024179).

Animal model of AZS

A rat model of AZS was established through

intragastric administration of ornidazole (ORN) to rats, as

previously described with specific modifications (16). In brief, ORN was administered

intragastrically at a dose of 320 mg/kg body weight once daily for

30 consecutive days. Control rats received an equivalent volume of

0.2% carboxymethylcellulose sodium solution, the vehicle of ORN,

throughout the experimental period. On day 32, eight rats were

euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of an overdose of 1%

pentobarbital sodium (300 mg/kg), before their testes and

epididymides were immediately excised for further examination. The

development of the AZS rat model was confirmed by evaluating

epididymal sperm motility and count (16).

ECH treatment for animals

ECH (provided by Professor Yong Jiang) was stored at

room temperature prior to use (6,7). The

AZS model rats (n=35) were intragastrically administered low-dose

ECH (L-ECH; 6 mg/kg/day, 5 rats), middle-dose ECH (M-ECH; 18

mg/kg/day, 4 rats), high-dose ECH (H-ECH; 54 mg/kg/day, 13 rats) or

equal amounts of normal saline (NS; vehicle of ECH, 13 rats) once a

day on days 11–31. Meanwhile, both ECH- and NS-treated AZS model

rats were intragastrically administered ORN (320 mg/kg/d) once a

day to maintain the pathological state of iAZS. On day 32, the rats

were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of an overdose of 1%

pentobarbital sodium (300 mg/kg).

Sperm motility and count

Cauda epididymal sperm were collected and processed

as previously described (31). In

brief, both caudal epididymides were excised and placed in a

modified N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N'-2-ethanesulfonic acid

(HEPES)-buffered medium with the following composition: 120 mM

NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 0.36 mM

NaH2PO4, 25 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM

HEPES, 5.6 mM glucose and 1.1 mM sodium pyruvate. The medium was

supplemented with 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin,

and the pH was adjusted to 7.4 using NaOH. Each cauda epididymis

was carefully dissected into three segments and incubated at 37°C

for 10 min in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Following incubation, the sperm suspension was filtered through a

nylon mesh to remove tissue debris, centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 5

min at room temperature and resuspended in 1 ml of pre-warmed

(37°C) NS. Sperm motility and kinematic parameters were analyzed

using a computer-assisted semen analysis (CASA) system with Olympus

CX33 light microscope (cat. no. WLJY-9000; Beijing Weili New

Century Science and Technology Development Co., Ltd.). Parameters

assessed included the percentage of rapid progressive motile sperm

(grade A; %), progressive motility (grades A + B; %), straight-line

velocity (VSL; µm/s), curve-line velocity (VCL; µm/s), average path

velocity (VAP; µm/s), amplitude of lateral head displacement (ALH;

µm), linearity (LIN; %), straightness (STR; %) and sperm viability

(31). Sperm concentration was

determined using the hemocytometer method with Olympus CX33 light

microscope and expressed as ×106/ml, based on two

independent semen sample preparations (16).

Assessment of sperm hyperactivation

and acrosome reaction

Rat sperm were capacitated in a modified

HEPES-buffered saline solution (HBSS) containing the following: 135

mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 2 mM CaCl2, 20

mM HEPES, 5 mM glucose, 10 mM lactic acid, 1 mM Na-pyruvate, 5

mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), 15 mM

NaHCO3 and 30 mM NH4Cl. The solution was

adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH and sperm were incubated for 90 min at

37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Sperm motility was assessed

using a CASA system, with each analysis based on a minimum of 200

spermatozoa per sample. Sperm hyperactivation was defined as

follows: VCL >100 µm/s, ALH ≥2.0 µm, LIN ≤38.0% and wobble ≥16%

(32).

The NH4Cl-induced acrosome reaction in

rat sperm was evaluated using a previously described method

(33). Briefly, following

capacitation, sperm were pelleted using centrifugation at 2,000 × g

for 5 min at room temperature, washed twice with HBSS buffer and

then spread onto clean glass slides. The samples were air-dried and

fixed with 4% formaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min.

Acrosomes were labeled with 1 µM fluorescein

isothiocyanate-conjugated peanut agglutinin (PNA-FITC;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and nuclei were counterstained with

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for

60 min at room temperature. The acrosome reaction was identified by

the absence of PNA-FITC fluorescence in the sperm head region.

Stained samples were analyzed using a confocal laser scanning

microscope (Leica TCS SP8; Leica Microsystems, Inc.) (33). The percentage of sperm undergoing

the acrosome reaction was determined by analyzing a minimum of 200

sperm cells per sample.

Oxidative stress assessments

Commercial kits procured from the Nanjing Jiancheng

Bioengineering Institute were used to evaluate oxidative stress in

rat testicular tissues and assays were performed according to the

manufacturer's instructions and as previously described (34). The following assays were conducted:

GSH-PX activity was measured using a total GSH-PX assay kit with

NADPH (cat. no. A005); superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was

assessed with a total SOD assay kit utilizing the water-soluble

tetrazolium salt method (cat. no. A001-3); and malondialdehyde

(MDA) levels, an indicator of lipid peroxidation, were determined

using a lipid peroxidation MDA assay kit (cat. no. A003-1)

(34).

ELISA

ELISA kits were used to determine the concentrations

of testosterone (T; cat. no. ml059506, Shanghai Enzyme-linked

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), luteinizing hormone (LH; cat. no.

ml064293, Shanghai Enzyme-linked Biotechnology Co., Ltd.),

estradiol (E2; cat. no. mlc4525, Shanghai Enzyme-linked

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH;

cat. no. ml059034, Shanghai Enzyme-linked Biotechnology Co., Ltd.)

in the plasma of rats according to the instructions of

manufacturer. Optical density (OD) values of each well were

measured at 450 nm using a Multiskan GO Microplate

Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Subsequently,

the concentrations of the analytes in each well were calculated by

referencing their respective OD values to a standard curve derived

from serially diluted standard samples, fitted to a regression

model (35).

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from rat testicular tissues

using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA

using oligo(dT) primers and PrimeScript™ RT reagent kit (Takara

Corporation), according to the instructions of the manufacturers.

Each 20 µl reaction contained 1 µl dNTP Mixture, 1 µl Oligo dT

Primer, 1 µl Random 6 Primer, 1 µg Total RNA and was brought to

final volume using diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water. RT-qPCR was

performed using GoTaq qPCR Master Mix (Promega Corporation) on an

ABI 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR Detection System (Applied Biosystems;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Each 20 µl reaction contained 1 µl

cDNA template, 10 µl GoTaq qPCR Master Mix and 0.2 µM of each

primer and was brought to final volume using

diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water. β-actin was amplified

concurrently as an endogenous reference gene for normalization.

Primer sequences were described in a previous study (16). Thermal cycling conditions were as

follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min; followed by 40

cycles of 95°C for 10 sec, 58°C for 20 sec and 72°C for 10 sec.

Relative mRNA expression levels were calculated using the

2−ΔΔCq method (16).

Western blotting

Rat sperm suspensions or testicular tissue fragments

were immediately homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer [50 mM Tris

(pH 8.0); 150 mM NaCl; 1% NP-40; 0.5% sodium deoxycholate; 0.1%

SDS; and 1 mM PMSF]. Protein concentrations were determined using a

BCA assay kit (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Equal

protein aliquots (60 µg) were denatured, separated by 10% SDS-PAGE

and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline

with Tween 20 [20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5); 150 mM NaCl; and 0.05%

Tween 20] for 1 h at room temperature, followed by overnight

incubation at 4°C with primary antibodies: Rabbit anti-rat

phosphotyrosine (1:1,000; cat. no. ab179530; Abcam), rabbit

anti-rat CatSper1 (1:100; cat. no. sc-33153; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.), rabbit anti-rat CatSper2 (1:100; cat. no.

sc-98539; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), rabbit anti-rat CatSper3

(1:100; cat. no. sc-98818; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), goat

anti-rat CatSper4 (1:100; cat. no. sc-83126; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.), mouse anti-rat Sox5 (1:100; cat. no.

sc-293215; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), mouse anti-β-actin

(1:2,000; cat. no. sc-47778; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) and

mouse anti-α-tubulin (1:2,000; cat. no. sc-32293; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.). Membranes were then incubated for 1 h at room

temperature with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies: Goat

anti-rabbit IgG (1:2,000; cat. no. sc-2004; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.), goat anti-mouse IgG (1:2,000; cat. no.

sc-2005; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) and rabbit anti-goat IgG

(1:2,000; cat. no. sc-2768; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.).

Protein bands were visualized using ECL Western Blotting Substrate

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), captured by autoradiography

(Hyperfilm MP; GE Healthcare) and quantified with ImageJ software

2.16.0 (National Institutes of Health) (16,36).

Calcium imaging analysis

Sperm calcium imaging was performed as described

(16); the protocol was performed

at 37°C. Rat sperm were isolated from cauda epididymides by

swim-out in HBSS, washed and resuspended in HBSS supplemented with

5 mg/ml BSA (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) (HBSS+). Human sperm were

purified using discontinuous Percoll® density gradients

(40–80% in Earle's balanced salt solution, Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) centrifuged at 600 × g for 20 min (room

temperature), then washed and resuspended in human tubal fluid

(HTF+) [97.8 mM NaCl, 4.69 mM KCl, 4 mM NaHCO3, 0.37 mM

KH2PO4, 2.04 mM CaCl2, 0.2 mM

MgCl2, 21.4 mM lactic acid, 21 mM HEPES, 2.78 mM glucose

and 0.33 mM Na-pyruvate (pH 7.3)] containing 3 mg/ml human serum

albumin (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). Sperm were loaded with 5 µM

fura-2-acetoxymethyl ester (Fura-2-AM) and 0.05%

Pluronic® F-127 for 30 min in 5% CO2 in the

dark, washed and resuspended in HBSS (rat) or HTF (human;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and adhered for 20 min to Cell-Tak™

(Corning, Inc.)-coated glass-bottom dishes (Wuxi Nice Life Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.). Rat sperm were pre-incubated in HBSS+

with or without 10 µM NNC 55–0396 for 5 min; human sperm were

incubated in HTF+ with or without 0.06 mg/ml ECH for 30 min.

Imaging was performed using a Polychrome V

monochromator at 340 nm excitation on an Olympus IX-71 inverted

microscope with ×40 (rat) or ×100 (human) objectives. Emissions

(515–565 nm) were filtered using a HQ540/50 filter and captured

every 100 msec at 5-sec intervals using a CoolSNAP HQ CCD camera. F

was monitored before and after the application of 30 mM

NH4Cl. Fura-2-AM signals were expressed as

background-subtracted F340/F380 ratios normalized to the baseline

(Fbaseline, mean intensity pre-treatment).

Ftreatment and Fbefore represented

intensities after and before NH4Cl application. Images

were analyzed using MetaFluor v7 software (Molecular Devices, LCC)

(16,37,38).

Immunofluorescent staining

To prepare testis tissues for immunofluorescence

staining, rats were anesthetized using 1% pentobarbital sodium (50

mg/kg) and underwent intracardiac perfusion with 300 ml of 0.1 M

phosphate buffer (PBS) followed by 300 ml 4% paraformaldehyde.

Testes were harvested and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (in 0.1

M PBS; pH 7.4) at 4°C for 18 h (16). Following fixation, tissues were

paraffin-embedded and sectioned (5 µm). Paraffin-embedded samples

were dewaxed by xylene followed by immersing in 100% ethanol for

three times (5 min/time). Later, slides were sequentially immersed

in 95, 80, and 70% ethanol and finally washed by double distilled

water (36). Sections underwent

antigen retrieval by heating at 95°C in EDTA buffer (cat. no.

ZLI-9071; Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for 30

min, followed by cooling to room temperature. Subsequently, samples

were blocked with 10% donkey serum (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA)

containing 0.3% Triton X-100 in 0.1 M PBS for 1 h at room

temperature, sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit

anti-rat CatSper1 (1:100) and mouse anti-rat Sox5 (1:100) primary

antibodies diluted in 1% donkey serum and PBS. Following three PBS

washes, sections were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with

secondary antibodies: Cy™3-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (H+L)

and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (1:500;

Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.) (34). Details of secondary antibodies are

listed in Table SI. Nuclei were

counterstained with DAPI (100 ng/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) at room

temperature for 10 min. After three final PBS washes, slides were

mounted in Gel-Mount medium. Imaging was performed using a confocal

microscope (Zeiss LSM880; Zeiss AG) with excitation wavelengths of

488 (green), 555 (red) and 405 nm (blue) (34).

Sequence analysis

Briefly, multiple CatSper1 promoter sequences from

different species were aligned using T-coffee

(tcoffee.crg.eu/apps/tcoffee/do:regular). Sox motifs were then

identified using ConSite (http://consite.genereg.net/) under default settings,

revealing putative binding sites for transcription factors

containing HMG DNA-binding domains. For each promoter, predicted

binding sites were filtered using a transcription factor score

cutoff of 80% to ensure specificity and reliability.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

(ChIP)

ChIP was performed as previously described (39,40)

with minor modifications. Briefly, DNA and associated proteins were

cross-linked in homogenized rat testicular tissues by incubation

with 1% formaldehyde at room temperature for 30 min. The reaction

was quenched by adding glycine to a final concentration of 125 mM.

Following washing twice with ice-cold PBS containing protease

inhibitors (cOmplete™ ULTRA tablets, Mini, EASYpack, Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA), the samples were pelleted by centrifugation (12,000 ×

g for 10 min at 4°C) and resuspended in 1X SDS lysis buffer [1%

SDS, 10 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.1), 10 µl/ml protease

inhibitor cocktail and 10 µl/ml phosphatase inhibitor (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.)]. The lysates were incubated for 15 min at

4°C (39,40). Chromatin was sheared by sonication

(6×10-sec pulses) to generate 250–1,000 bp DNA fragments, confirmed

by agarose gel electrophoresis. Following centrifugation at 3,000 ×

g for 10 min at 4°C, the chromatin-containing supernatant was

collected and diluted 10-fold in ChIP dilution buffer [1% Triton

X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.1), 10 µl/ml

protease inhibitor cocktail and 10 µl/ml phosphatase inhibitor] and

an aliquot was saved as input DNA (39,40).

Samples were pre-cleared with protein G agarose at

4°C overnight and then incubated with the corresponding antibodies

(10 µg each; 1:50 or 1:200 mouse anti-Sox5 or IgG, respectively.

Mouse anti-Sox5: Cat. no. sc-293215, Santa Cruz Biotechnology,

Inc.; IgG: Cat. no. A7028, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China)

on a rocker at 4°C overnight. The complexes were washed three times

with lysis buffer [50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1%

SDS, 1% NP-40 and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate]. The beads were then

resuspended in lysis buffer and digested with proteinase K at 45°C

for 45 min. Co-precipitated DNA was purified using the TIANquick

Maxi Purification Kit (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.) and eluted in 50

µl nuclease-free water (39,40).

For normalization, 10% of total chromatin was

retained as input material prior to immunoprecipitation.

Immunoprecipitated DNA was quantified using RT-qPCR as

aforementioned following elution and purification, normalizing all

values to the input. For ChIP-qPCR, primers targeting the CatSper1

promoter region (Table SII) were

used under standard RT-qPCR protocol. PCR product quality was

assessed using 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis and data was

analyzed using the percent input method, with normal IgG used as

the negative control (41).

Participants

A total of 6 infertile male patients with iAZS (age

range, 25–35 years old; median age, 29.5 years old) and 7 healthy

control subjects (age range, 25–30 years old; median age, 28 years

old) with normal sperm quality and a successful reproductive

history within the past 2 years were enrolled from the Reproductive

Medicine Center of Peking University Third Hospital (Beijing,

China) from January 2023 to January 2024. The diagnosis of iAZS was

established according to the following criteria (42): i) A sexually active,

non-contracepting couple failing to achieve pregnancy after 12

months due to male factor infertility; ii) two or more semen

analyses, with an abstinence period of 3–7 days each time,

demonstrating AZS: Progressive motility (grade A + B sperm) <32%

or total motility (grade A + B + C sperm) <40%; iii) sperm

concentration >15×106 sperm/ml; iv) proportion of

morphologically normal sperm ≥4%; v) no identifiable underlying

causes of infertility, including congenital testicular or genital

dysplasia or deformity, reproductive system infections, positive

serum anti-sperm antibodies, drug exposure, abnormal sex hormone

levels, abnormal seminal plasma biochemistry or a family history of

fertility issues; and vi) a physical examination revealing no

abnormalities in height, weight, secondary sexual characteristics,

testicular size, external genitalia, spermatic veins or mental

status. The present study was approved by the Institutional Review

Board of Peking University Third Hospital (approval no.

IRB00006761-M2022692). All participants provided written voluntary

informed consent prior to enrollment.

Semen analysis for patients

The semen parameters, including semen volume, sperm

motility, sperm concentration and sperm morphology, were evaluated

in human participants according to pre-established guidelines

(42). To evaluate the direct

effect of ECH on human sperm motility in vitro, 1 ml human

semen was incubated with 0.06 mg/ml ECH at 37°C in a water bath and

sperm motility parameters were analyzed using CASA at four time

points: Immediately (0 min) and at 10-, 20- and 30-min

post-incubation with ECH (42).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad

Prism 9.0 for Windows (Dotmatics). All quantitative biochemical

data were representative of at least three independent experiments.

A two-tailed paired or unpaired Student's t-test was used to

compare differences between two groups, while one-way ANOVA

followed by Sidak's post-hoc test was used for multiple

comparisons. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the

mean and P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Improvement of sperm quality in AZS

rats via ECH treatment

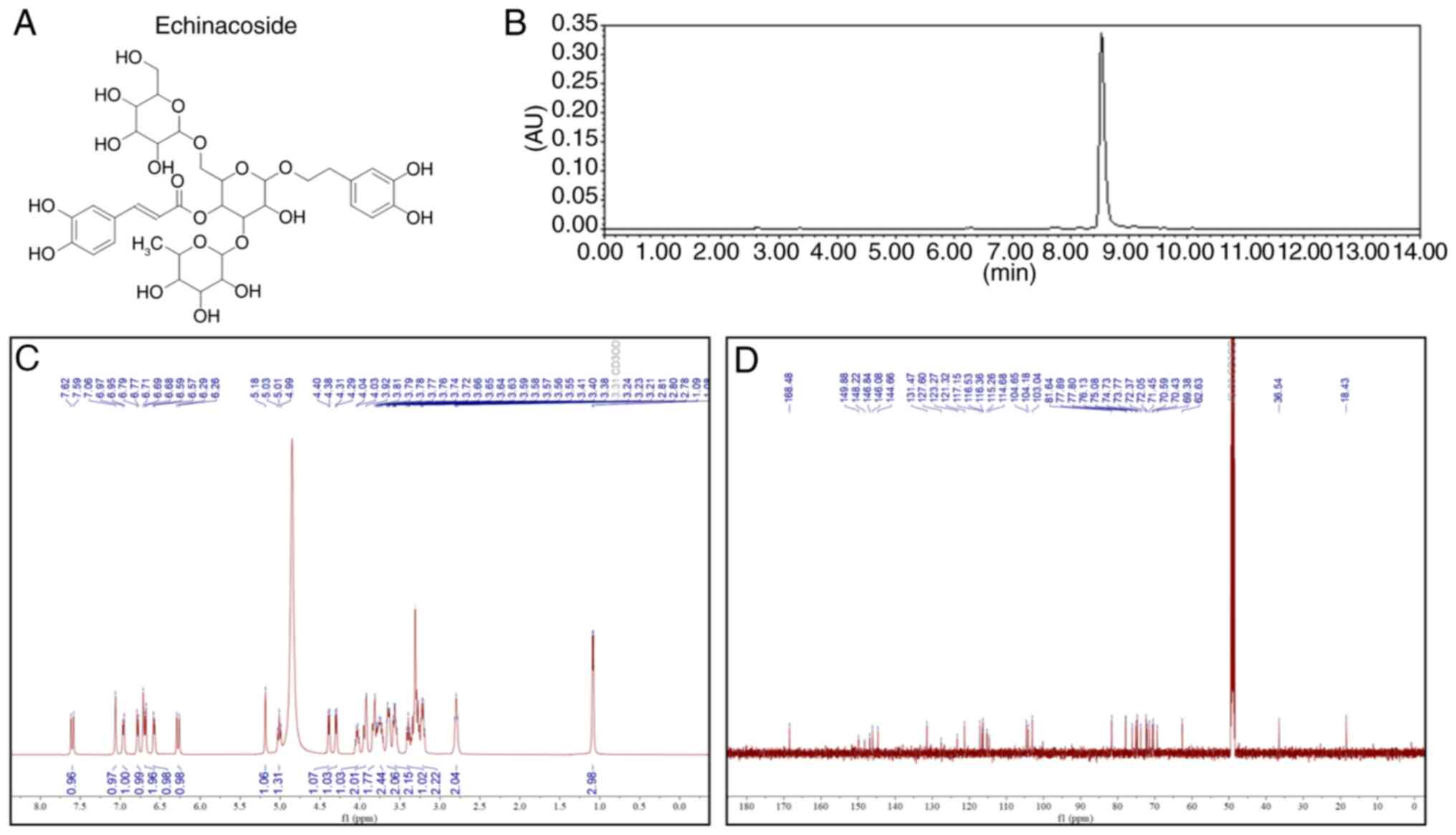

The chemical structure of ECH is illustrated in

Fig. 1A. Subsequently,

high-performance liquid chromatography (Fig. 1B) was used to assess the purity of

ECH. 1H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance

spectroscopic analyses (Fig. 1C and

D) were performed to identify the structure of ECH. As

previously reported (8,9), the effective dosage and treatment

protocol of ECH was first determined via sperm quality in AZS rats

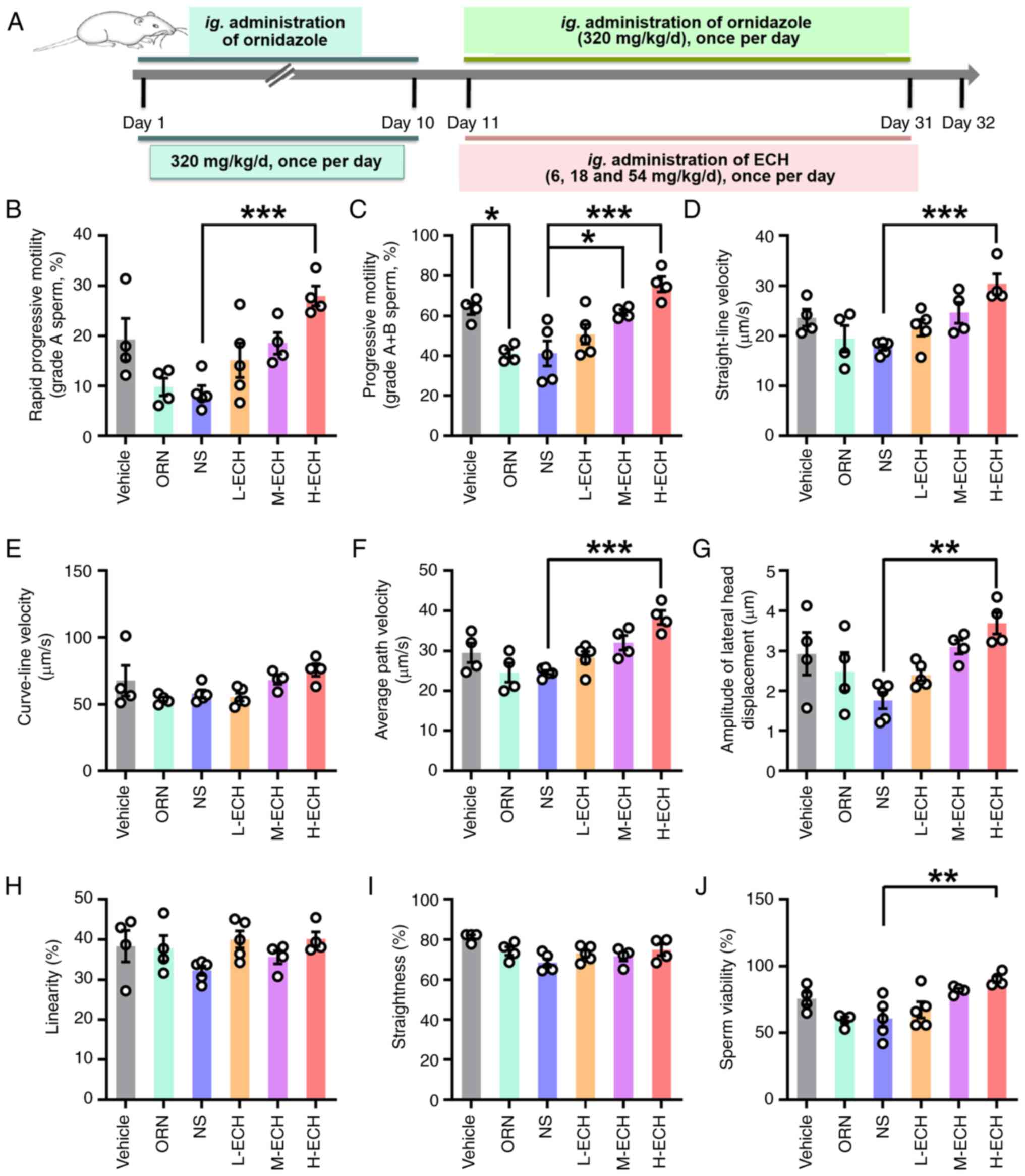

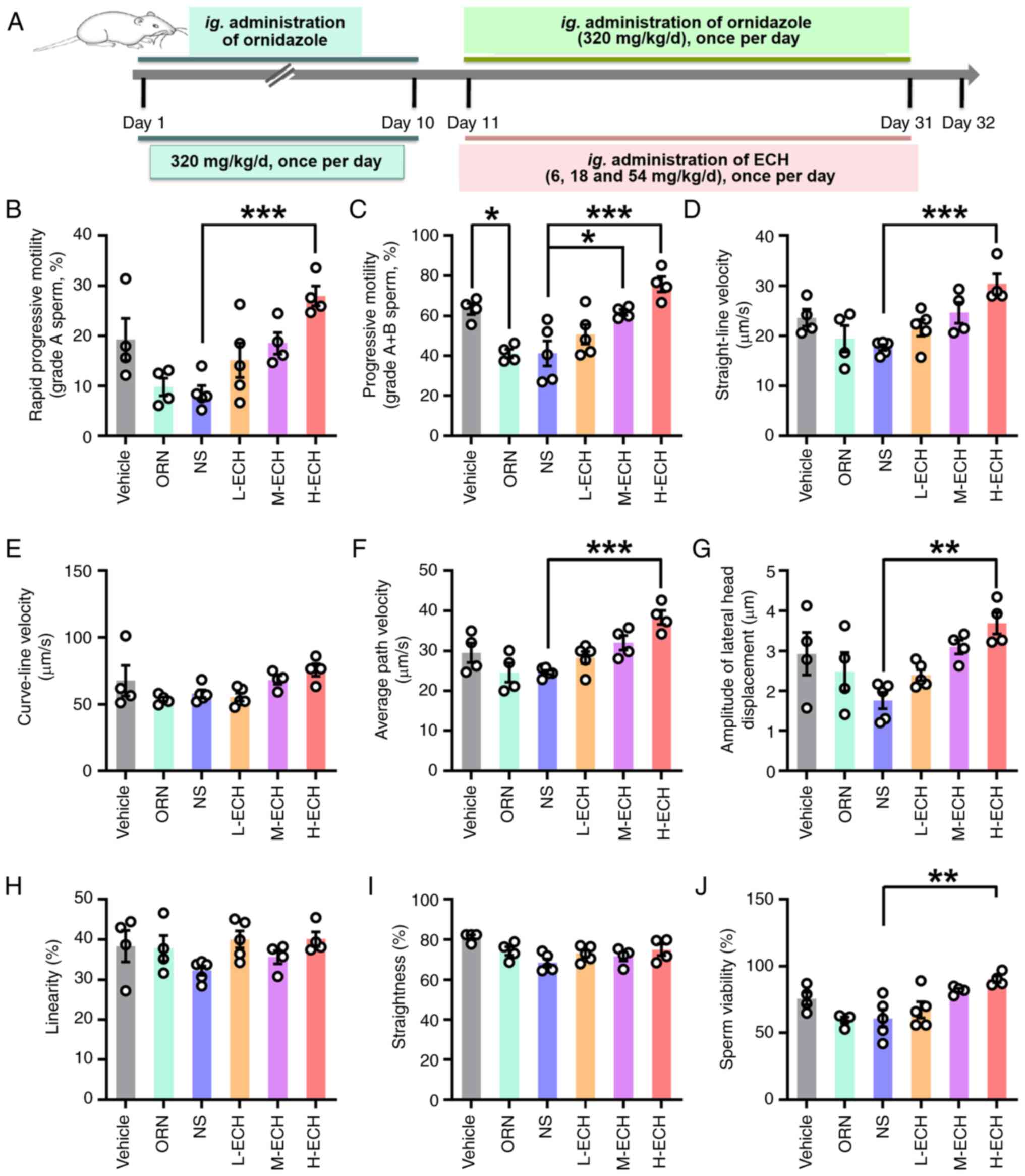

(Fig. 2A). The results

demonstrated that L-ECH treatment had no significant effect on

sperm quality in AZS rats (Fig.

2B-J). By contrast, M-ECH treatment significantly increased the

motility of grade A + B sperm in AZS rats (Fig. 2C). Notably, H-ECH treatment,

hereafter referred to as ECH treatment, significantly improved

sperm quality in AZS rats, as evidenced by enhanced sperm motility,

evident in both grade A and grade A + B sperm groupings, and

significant increases in other parameters of sperm motility such as

VSL, VAP and ALH, as well as sperm viability (Fig. 2B-J). Collectively, these results

suggest that high-dose ECH treatment in AZS rats improves the

motility of epididymal sperm.

| Figure 2.ECH treatment improves sperm motility

in AZS rats. (A) Experimental protocol for ECH administration in

AZS rats. Sperm motility parameters, including percentage of (B)

grade A and (C) grade A + B sperm, as well as (D) straight-line

velocity, (E) VCL, (F) average path velocity, (G) amplitude of

lateral head displacement, (H) linearity, (I) straightness and (J)

sperm viability. Vehicle group: 0.2% carboxymethylcellulose sodium;

NS group: Ornidazole + normal saline; L-ECH group: Ornidazole +

low-dose ECH; M-ECH group: Ornidazole + medium-dose ECH; H-ECH

group: Ornidazole + high-dose ECH. Data are presented as mean ±

standard error of the mean. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001. One-way ANOVA with Sidak's post hoc test; n=4–5 rats

per group. ECH, echinacoside; AZS, asthenozoospermia; VSL,

straight-line velocity; VCL, curve-line velocity; VAP, average path

velocity; ALH, amplitude of lateral head displacement; LIN,

linearity; STR, straightness; ORN, ornidazole; ig.,

intragastric. |

Improvement of sperm function of AZS

rats by ECH treatment

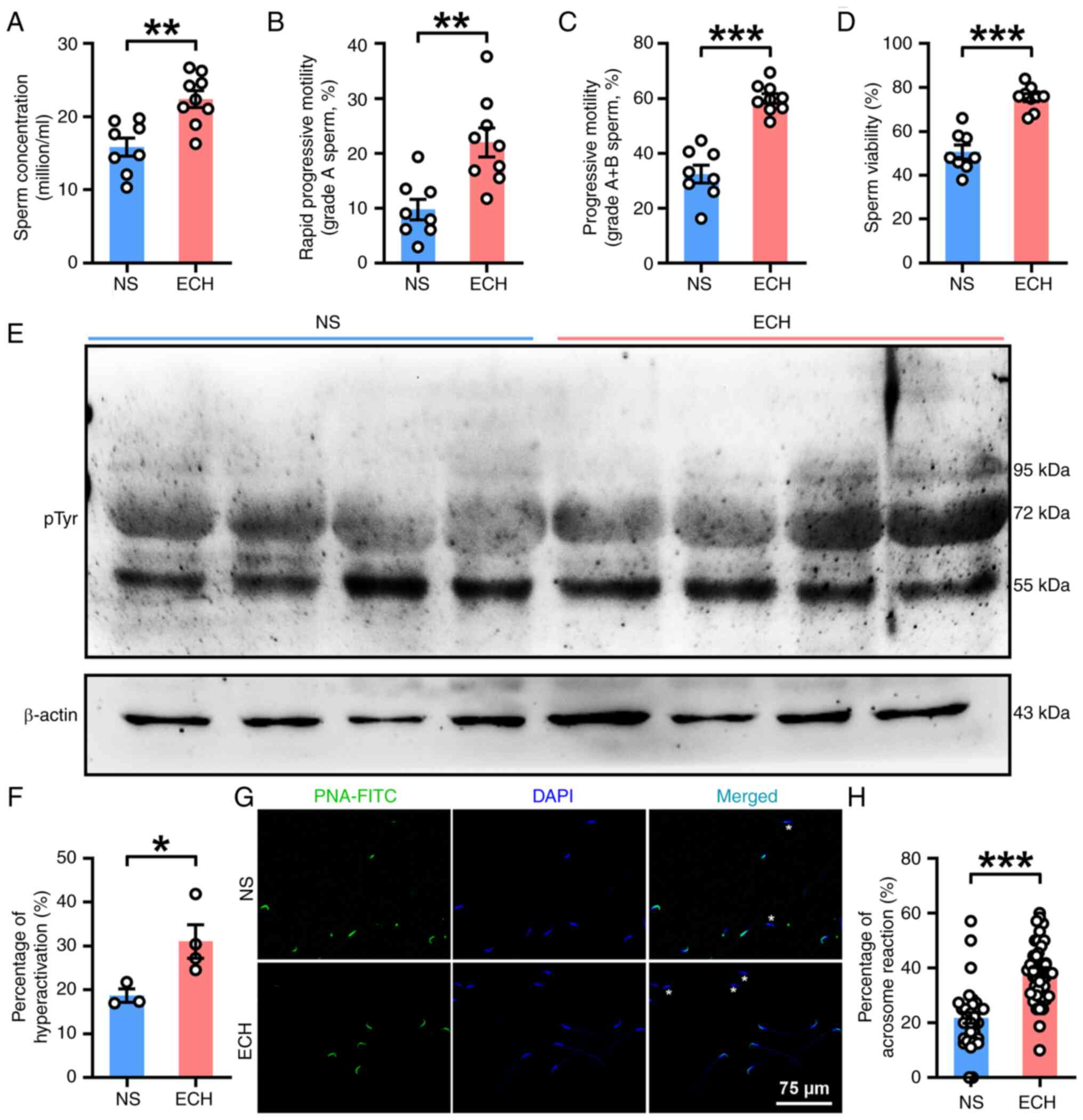

As shown in the aforementioned data (Fig. 2), H-ECH treatment improved sperm

motility in AZS rats. In the present study, the effects of H-ECH

treatment on sperm quality was first determined in AZS rats. ECH

treatment significantly improved sperm quality, as exhibited by

significant increases in sperm concentration and motility in both

grade A and grade A + B sperm (Fig.

3A-C), as well as other sperm motility parameters such as VSL,

VAP, LIN and STR (Figs. S1A-F).

Additionally, ECH treatment demonstrated significantly elevated

sperm viability (Fig. 3D).

Subsequently, the effects of ECH treatment on sperm function were

investigated. The results demonstrated that ECH treatment

effectively reversed the impaired sperm functionality observed in

AZS rats, including a significant increase in protein tyrosine

phosphorylation, increased hyperactivation and increased acrosome

reaction in epididymal sperm, as assessed by PNA-FITC staining

(Fig. 3E-H). In combination, these

results suggest that ECH treatment in AZS rats improved the sperm

quality and functional characteristics of epididymal sperm.

Functional upregulation of CatSper

channels in the sperm of AZS rats by ECH treatment

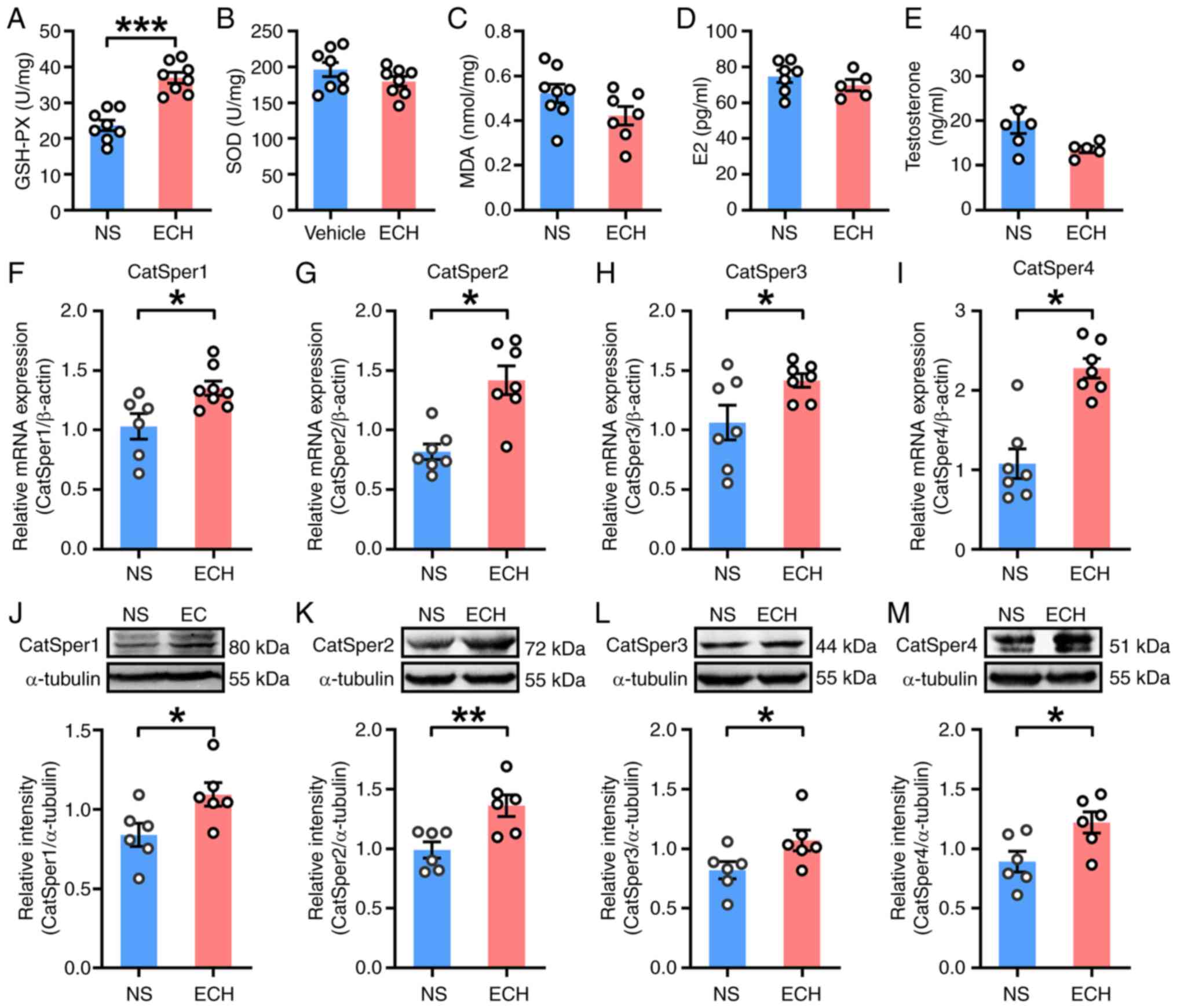

To investigate how ECH improved sperm quality in AZS

rats, testicular oxidative stress was first assessed. ECH treatment

significantly increased GSH-PX levels compared with vehicle

controls (Fig. 4A), while SOD and

MDA levels showed no statistically significant differences between

experimental groups (Fig. 4B and

C). This indicates partial

alleviation of testicular oxidative stress by ECH. The analysis of

plasma hormones revealed no significant changes in E2, T and FSH

levels (Figs. 4D, E and S1G), but significant reduction of LH in

ECH-treated rats (Fig. S1H).

| Figure 4.ECH treatment enhances CatSper

channel expression in testis tissues of rats with

asthenozoospermia. Levels of oxidative stress markers in testis

tissues: (A) GSH-PX, (B) SOD and (C) MDA; n=7–8 rats per group.

Plasma levels of (D) E2 and (E) testosterone; n=5–7 rats per group.

mRNA expression of (F) CatSper1, (G) CatSper2, (H) CatSper3, (I)

CatSper4. Protein expression levels of (J) CatSper1, (K) CatSper2,

(L) CatSper3, (M) CatSper4 in testis tissues; n=6–8 rats per group.

NS group: Ornidazole + normal saline; ECH group: Ornidazole +

high-dose ECH. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the

mean. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. NS, normal saline;

ECH, echinacoside; GSH-PX, glutathione peroxidase; SOD, superoxide

dismutase; MDA, malondialdehyde; E2, estradiol; CatSper, cation

channel of sperm. |

Due to the ECH-mediated enhancement of sperm

motility, CatSper channel expression was examined. In testicular

tissues, ECH significantly increased mRNA (Fig. 4F-I) and protein (Fig. 4J-M) levels of CatSper1-4, as

compared with vehicle controls. Epididymal sperm also showed

significantly increased CatSper1-4 protein expression (Fig. 5A-D). CatSper-mediated

Ca2+ influx was subsequently evaluated (Figs. 5E-K). ECH treatment significantly

enhanced NH4Cl-evoked intracellular calcium levels

[Ca2+]i responses in the sperm of AZS rats at

the single-cell (Fig. 5I),

population (Fig. 5J) and mean

intensity levels (Fig. 5K)

compared with the NS group. Notably, the CatSper inhibitor NNC

55–0396 blocked NH4Cl-induced Ca2+ signals in

both groups (Fig. 5I-K),

supporting CatSper mediation. Collectively, these findings

demonstrate that the functional upregulation of CatSper channels

markedly mediated ECH-induced sperm motility improvement in AZS

rats.

![ECH treatment upregulates functional

expression of CatSper channels in spermatozoa from rats with

asthenozoospermia. (A) CatSper1, (B) CatSper2, (C) CatSper3 and (D)

CatSper4 protein abundance in sperm; n=5–6 rats per group.

Representative fura-2-acetoxymethyl ester fluorescence images of

sperm before and after 30 mM NH4Cl stimulation in (E)

NS, (F) ECH, (G) NS + NNC and (H) ECH + NNC group. Arrows indicate

[Ca2+]i fluorescent signals in response to

NH4Cl. Scale bar, 10 µm. (I) Representative single-sperm

fluorescence traces. (J) Normalized [Ca2+]i

responses in all tested sperm. (K) Summary plot of normalized

[Ca2+]i signals after NH4Cl

treatment (n=27–33 sperm per group from 5–6 rats). NS group:

Ornidazole + normal saline; ECH group: Ornidazole + ECH. Data are

presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001; Unpaired t-test. ECH, echinacoside;

NS, normal saline; NNC, NNC 55-0396; CatSper, cation channel of

sperm; [Ca2+]i, intracellular calcium levels;

F340, fluorescence at 340 nm; F380, fluorescence at 380 nm.](/article_images/mmr/33/3/mmr-33-03-13794-g04.jpg) | Figure 5.ECH treatment upregulates functional

expression of CatSper channels in spermatozoa from rats with

asthenozoospermia. (A) CatSper1, (B) CatSper2, (C) CatSper3 and (D)

CatSper4 protein abundance in sperm; n=5–6 rats per group.

Representative fura-2-acetoxymethyl ester fluorescence images of

sperm before and after 30 mM NH4Cl stimulation in (E)

NS, (F) ECH, (G) NS + NNC and (H) ECH + NNC group. Arrows indicate

[Ca2+]i fluorescent signals in response to

NH4Cl. Scale bar, 10 µm. (I) Representative single-sperm

fluorescence traces. (J) Normalized [Ca2+]i

responses in all tested sperm. (K) Summary plot of normalized

[Ca2+]i signals after NH4Cl

treatment (n=27–33 sperm per group from 5–6 rats). NS group:

Ornidazole + normal saline; ECH group: Ornidazole + ECH. Data are

presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001; Unpaired t-test. ECH, echinacoside;

NS, normal saline; NNC, NNC 55-0396; CatSper, cation channel of

sperm; [Ca2+]i, intracellular calcium levels;

F340, fluorescence at 340 nm; F380, fluorescence at 380 nm. |

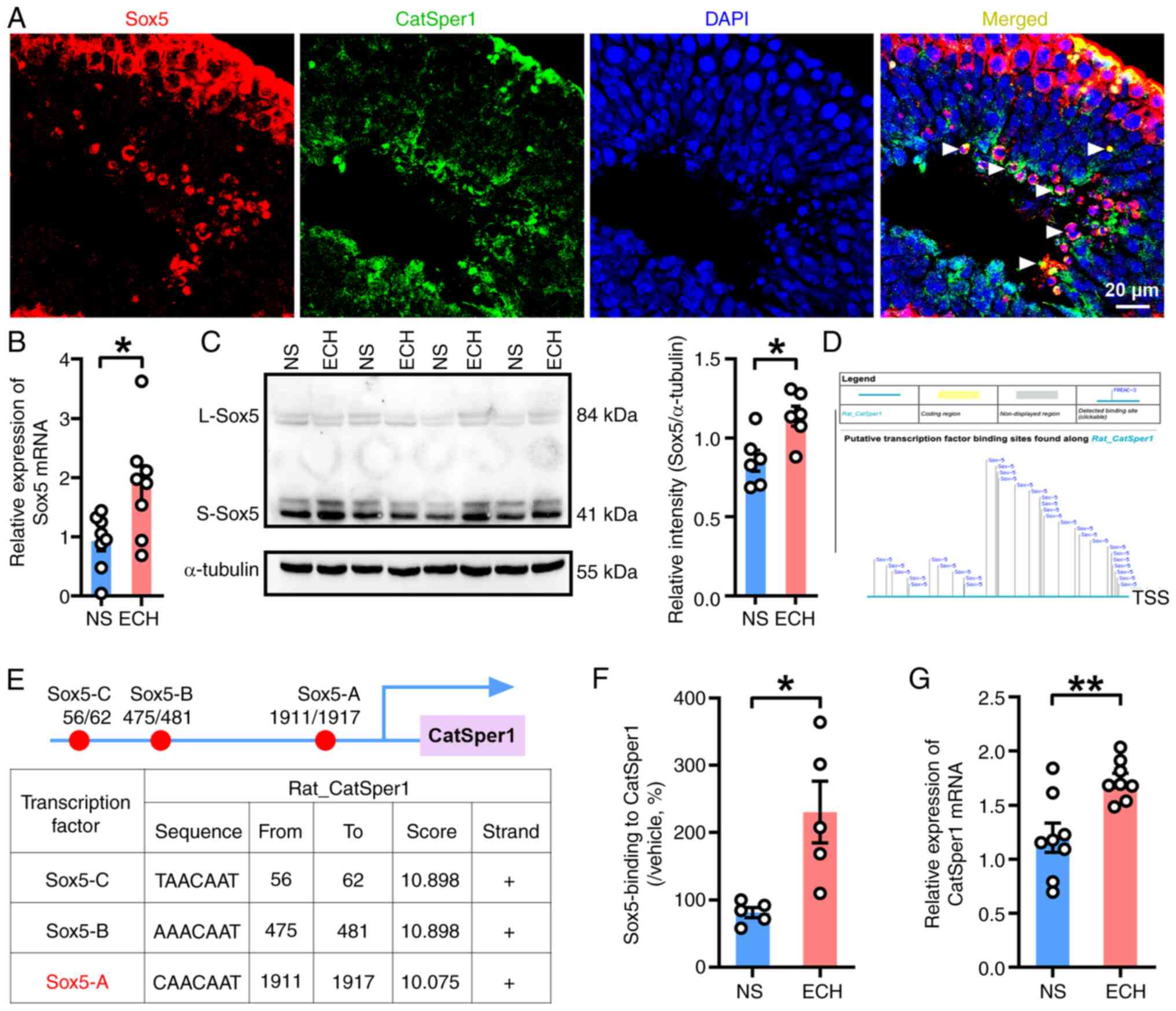

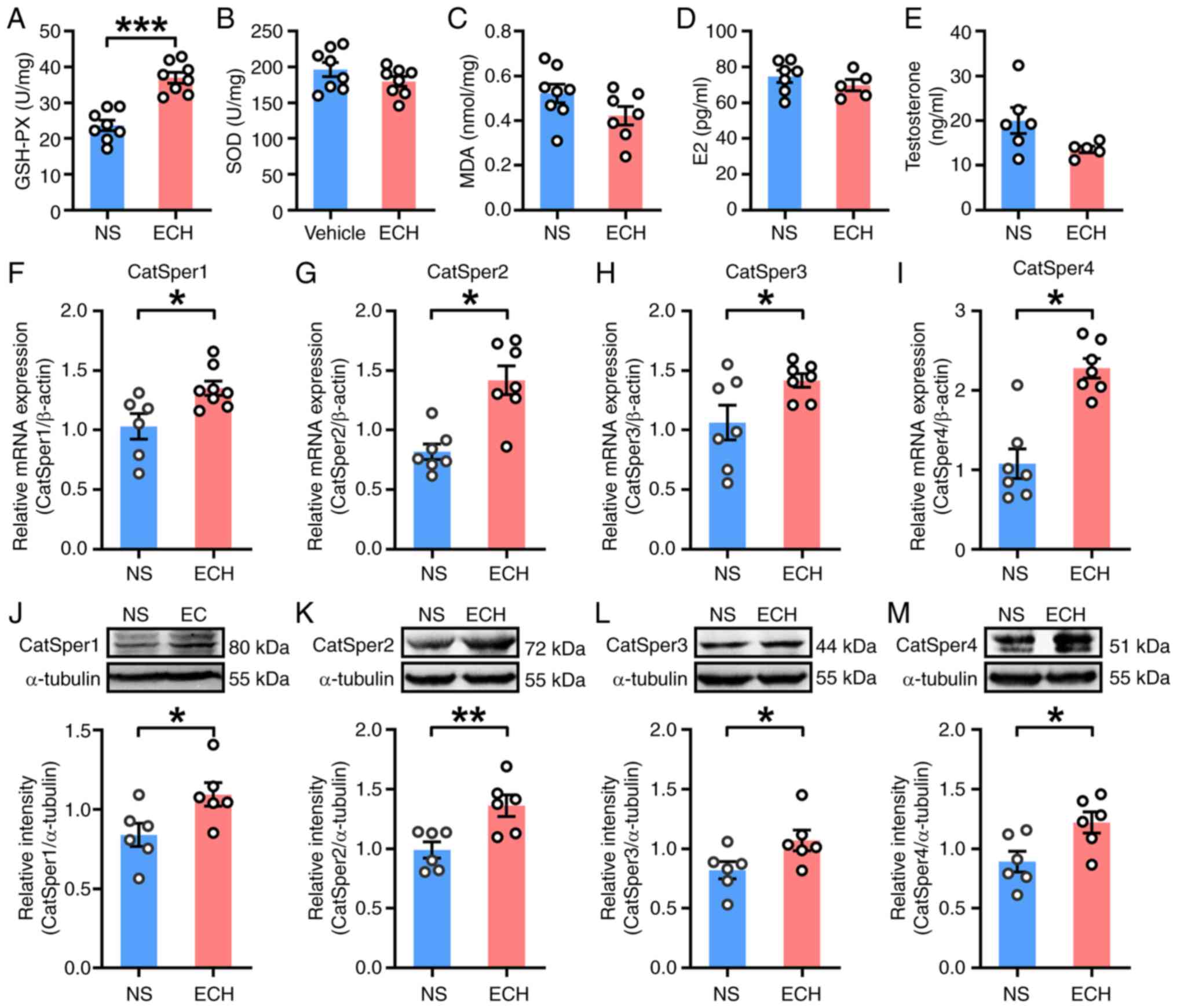

ECH treatment enhances the

Sox5-mediated transcriptional activation of CatSper1 channels in

the testes of AZS rats

Numerous studies have indicated that the Sox family

can coordinate the regulation of gene expression within the testes

(22–25). Specifically, Sox5 has been shown to

enhance the transactivation of the Catsper1 promoter in vivo

(30). To investigate whether Sox5

activated the transcription of CatSper1 in the rat testis, the

co-localization of Sox5 and CatSper1 was examined in testicular

tissues. As expected, immunofluorescent staining revealed that Sox5

co-localized with CatSper1 in testicular tissues (Fig. 6A). In the testis, Sox5 was

predominantly located in cell nuclei, whereas CatSper1 exhibited a

broader distribution, being present in both cytoplasm and nuclei

(Fig. 6A). Subsequently, RT-qPCR

and western blotting were performed on testicular tissues from

vehicle- and ECH-treated rats. Consistently, a significant increase

in the mRNA levels of Sox5 was observed in the ECH-treated group

compared with the control group (Fig.

6B). Notably, the short isoform of Sox5 (S-Sox5), rather than

the long isoform, was identified as the predominant form of Sox5

expressed in the testis. ECH treatment selectively enhanced the

protein expression of S-Sox5 in the testes of AZS rats (Fig. 6C). These findings provide notable

evidence supporting the involvement of Sox5-mediated

transcriptional activation of CatSper1 within the testis.

| Figure 6.ECH treatment enhances Sox5-mediated

transcriptional activation of CatSper1 in testis tissues of AZS

rats. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images showing

co-localization of Sox5 (red) and CatSper1 (green) in testis

tissues of naïve rats (n=3 rats per group). Merged signals are

indicated by triangles. Scale bar, 20 µm. (B) Sox5 mRNA and (C)

S-Sox5 protein expression in testis tissues of ECH-treated AZS

rats. (D and E) In silico analysis of Sox5 binding sites in

the CatSper1 promoter: Sox5-A (−1911 to −1917 bp), Sox5-B (−475 to

−481 bp) and Sox5-C (−56 to −62 bp) relative to the transcriptional

start site. (F) ChIP-qPCR analysis of Sox5 binding at the Sox5-A

site in the CatSper1 promoter. (G) CatSper1 mRNA expression; n=5–8

rats per group. NS group: Ornidazole + normal saline; ECH group:

Ornidazole + high-dose ECH. Data are presented as mean ± standard

error of the mean. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. Unpaired t-test.

ECH, echinacoside; AZS, asthenozoospermia; ChIP, chromatin

immunoprecipitation; qPCR, quantitative PCR; Sox5, sex-determining

region Y-related high-mobility-group box family, member 5; CatSper,

cation channel of sperm; TSS, transcriptional start site; L-Sox5,

long isoform-Sox5; S-Sox5, short isoform Sox5. |

Subsequently, in silico analysis was employed

to predict potential binding sites of Sox5 in the promoter region

of the CatSper1 gene. The analysis revealed three distinct

Sox5-binding sites in the CatSper1 gene promoter: i) Sox5-A, −1911

to −1917 bp upstream of the TSS; ii) Sox5-B, −475 to −481 bp

upstream of the TSS; and iii) Sox5-C, located −56 to −62 bp

upstream of the TSS (Fig. 6D and

E). To validate these predictions, ChIP-qPCR was performed to

assess the binding of Sox5 to the CatSper1 gene promoter at the

Sox5-A site. A significant increase in the relative enrichment of

Sox5 was observed at the Sox5-A site in the testicular tissues of

the ECH-treated group compared with the vehicle-treated group

(Fig. 6F). Furthermore, RT-qPCR

analysis demonstrated a significant increase in CatSper1 mRNA

expression in the ECH-treated group compared with the control group

(Fig. 6G). These results suggest

that ECH treatment enhances Sox5 expression, thereby promoting

Sox5-mediated transcriptional activation of CatSper1 in the

testicular tissues of AZS rats. Taken together, this cascade

ultimately improved sperm motility and acrosome reaction capability

in AZS rats.

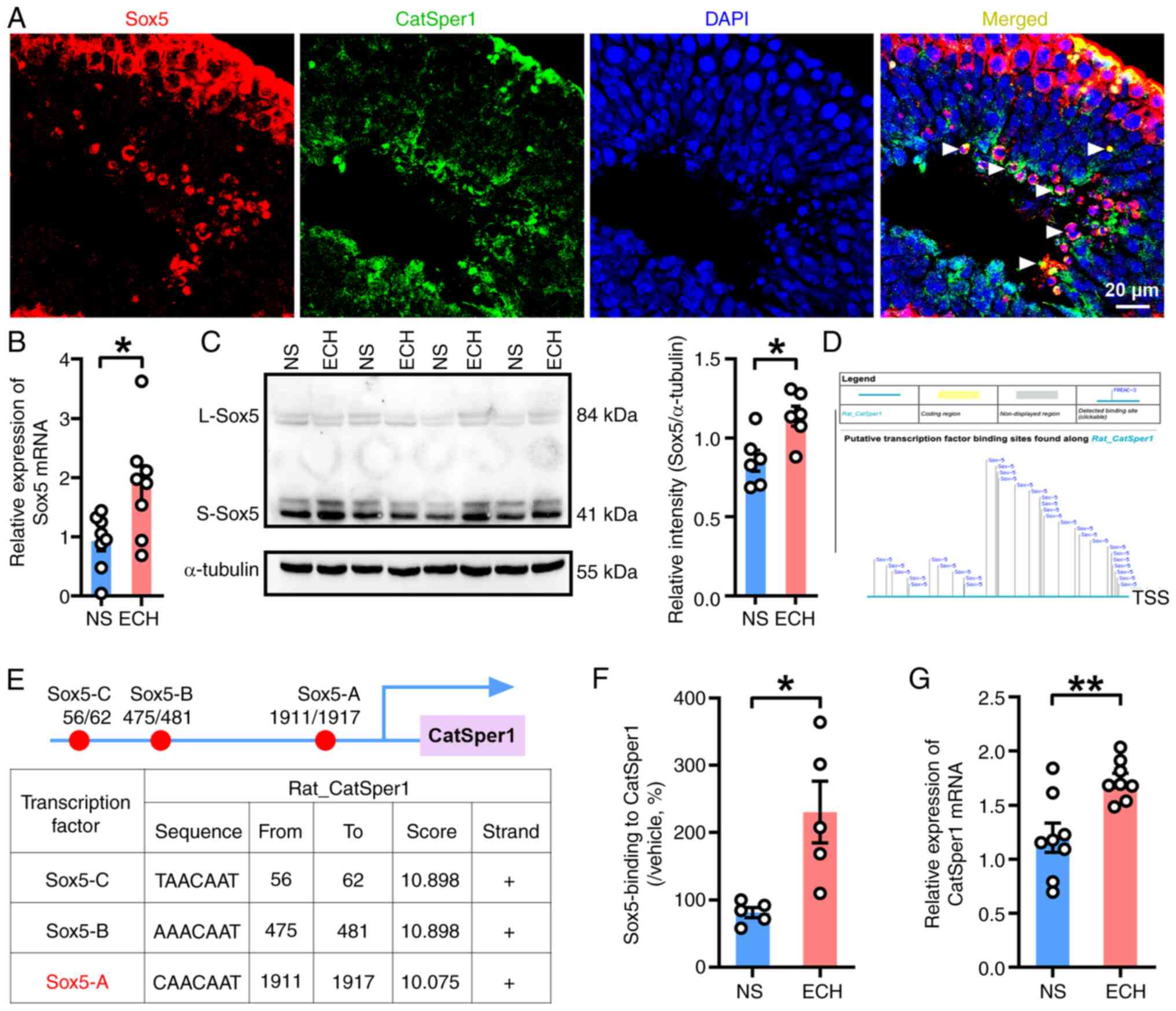

Functional upregulation of CatSper

channels in the human sperm by ECH treatment

To validate the findings obtained from AZS rats, the

present study investigated whether ECH treatment induced the

functional upregulation of CatSper channels in human sperm. In

vitro experiments were first performed to determine whether

sperm motility was increased when ECH was directly added to human

semen. Spermatozoa from healthy subjects (HS) or patients with iAZS

were incubated with ECH prior to sperm motility analysis at 0-,

10-, 20- and 30-min post-incubation. The results demonstrated that

ECH incubation significantly increased the progressive motility

(grade A + B sperm) at 20 min and total motility (grade A + B + C

sperm) at 30 min in sperm from HS (Fig. 7A-C). Notably, 20-min ECH incubation

significantly improved sperm motility in samples from patients with

iAZS, enhancing rapid progressive motility (grade A sperm),

progressive motility and total motility (Fig. 7D-F). Subsequently, the effects of

ECH incubation on CatSper-mediated Ca2+ influx in human

sperm were examined. Notably, a marked increase in

NH4Cl-evoked [Ca2+]i fluorescent

signals was observed in sperm from both HS and patients with iAZS

after 30-min incubation with ECH (Fig.

7G-J). In summary, a consistent enhancement of

NH4Cl-evoked [Ca2+]i fluorescent

signals was observed in the ECH-treated groups compared with their

control counterparts in single spermatozoa (Fig. 7K) and in all tested sperm (Fig. 7L), as well as significant increases

in the mean fluorescence intensity of all tested sperm

post-NH4Cl exposure (Fig.

7M). These findings suggest that ECH incubation may have

increased intracellular calcium levels

[Ca2+]i in human sperm, thereby enhancing

sperm motility.

![Functional activation of CatSper

channels in human sperm by ECH treatment. Sperm motility parameters

in healthy subjects: (A) Grade A, (B) grade A + B and (C) grade A +

B + C sperm. Sperm motility parameters in patients with AZS: (D)

Grade A, (E) grade A + B and (F) grade A + B + C sperm. n=6–7

subjects per group. (G-J) Representative fura-2-acetoxymethyl ester

fluorescence images of human sperm before and after 30 mM

NH4Cl stimulation. Arrows indicate

[Ca2+]i responses. Scale bar, 10 µm. (K)

Representative single-sperm fluorescence traces. (L) Normalized

[Ca2+]i responses in all tested sperm. (M)

Summary plot of normalized [Ca2+]i signals

after NH4Cl treatment (n=33–36 sperm per group from 5–6

subjects). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. Paired t-test for (A-F),

unpaired t-test for (M). ECH, echinacoside; AZS, asthenozoospermia;

[Ca2+]i, intracellular calcium levels; NS,

normal saline; HS, healthy subjects; F340, fluorescence at 340 nm;

F380, fluorescence at 380 nm.](/article_images/mmr/33/3/mmr-33-03-13794-g06.jpg) | Figure 7.Functional activation of CatSper

channels in human sperm by ECH treatment. Sperm motility parameters

in healthy subjects: (A) Grade A, (B) grade A + B and (C) grade A +

B + C sperm. Sperm motility parameters in patients with AZS: (D)

Grade A, (E) grade A + B and (F) grade A + B + C sperm. n=6–7

subjects per group. (G-J) Representative fura-2-acetoxymethyl ester

fluorescence images of human sperm before and after 30 mM

NH4Cl stimulation. Arrows indicate

[Ca2+]i responses. Scale bar, 10 µm. (K)

Representative single-sperm fluorescence traces. (L) Normalized

[Ca2+]i responses in all tested sperm. (M)

Summary plot of normalized [Ca2+]i signals

after NH4Cl treatment (n=33–36 sperm per group from 5–6

subjects). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. Paired t-test for (A-F),

unpaired t-test for (M). ECH, echinacoside; AZS, asthenozoospermia;

[Ca2+]i, intracellular calcium levels; NS,

normal saline; HS, healthy subjects; F340, fluorescence at 340 nm;

F380, fluorescence at 380 nm. |

Discussion

The present study provides evidence that ECH exerts

therapeutic effects on iAZS by functionally upregulating CatSper

channels in sperm. This mechanism was mediated through increased

expression of the testicular transcription factor Sox5, which

transcriptionally activated CatSper1. These findings suggest that

CatSper represents a promising therapeutic target for iAZS. In

addition, ECH may serve as a potential complementary and

alternative medicine (CAM) for treating male infertility associated

with iAZS in clinical settings.

ECH is the primary bioactive compound derived from

Cistanche deserticola (Schrenk) Wight. and exhibits a wide

range of pharmacological effects. It suppresses the P2X

purinoceptor 7/fractalkine/C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor 1

pathway to exert neuroprotective effects (43,44),

inhibits the microglial α-synuclein/toll like receptor 2/NF-κB/NLR

family pyrin domain containing 3 axis for antinociception (43), activates the brain derived

neurotrophic factor (BDNF)/neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase 2

or BDNF/cAMP responsive element binding protein 1 pathways for

antidepressant effects (45,46)

and blocks the activin A receptor type 2A-mediated TGF-β1/Smad

signaling pathway to exert anti-hepatic fibrosis effects (47). ECH also suppresses the PI3K/AKT

pathway to inhibit tumor metastasis (48) and targets the Janus kinase 1/signal

transducer and activator of transcription 1/interferon regulatory

factor 1 pathway for antitumor activity (49,50).

Additionally, ECH reduces the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines

such as TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 (50), demonstrating potent

anti-inflammatory properties. ECH also protects against testicular

injury by restoring T synthesis pathways (51–53).

However, the molecular mechanisms through which ECH improves sperm

quality, particularly motility, remain to be fully elucidated.

In addition to Sheng-Jing-San (SJS) and EA, several

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) formulations have been shown to

enhance sperm motility in AZS rats (16,31).

In the present study, the administration of a high-dose of ECH (54

mg/kg) for 21 consecutive days significantly improved sperm

motility, hyperactivation and acrosome reaction in AZS rats.

Previous studies have shown that ECH mitigates oxidative stress by

activating antioxidant enzymes and MAPK signaling components, such

as p38 and JNK, thereby increasing sperm count, reducing deformity

rates, improving progressive motility and alleviating

spermatogenesis dysfunction in mouse testes (9,12).

Furthermore, ECH prevents oligospermia and AZS by inhibiting

hypothalamic androgen receptor activity (8). In combination, these findings support

the conclusion that ECH effectively enhances sperm motility and

increases sperm count in AZS rats.

Human fertilization, both in vivo and in

vitro, relies on the CatSper channel to trigger sperm

hyperactivation (14). The CatSper

channel consists of at least 11 subunits, including four

pore-forming α subunits, and is specifically expressed in the

testis, localized to the principal piece of the sperm flagellum

(10,11). This channel serves an important

role in sperm functions such as hyperactivation and the acrosome

reaction, which are important for male fertility (13). Microarray analyses have revealed

that CatSper1 and CatSper3 mRNA levels are reduced in men with AZS,

and mRNA levels of CatSper1 and CatSper3 are positively associated

with sperm motility, mitochondrial membrane potential,

capacitation, fertilization rate, cleavage rate and embryo quality

(19). In human sperm, CatSper

expression and function have been shown to be closely associated

with progressive motility and may contribute to the pathogenesis of

AZS (15,16). Notably, TCM interventions such as

SJS and EA have been shown to improve sperm motility in AZS rats by

upregulating CatSper channels (16,31).

Consistent with these findings, the present study demonstrated that

ECH enhanced both CatSper mRNA and protein expression and increases

antioxidant capacity in the testicular tissue of AZS rats. In

addition, CatSper function was upregulated in sperm from

ECH-treated AZS rats and in human sperm incubated with ECH.

Furthermore, the indole derivative

N'-(4-dimethylaminobenzylidene)-2-1-(4-(methylsulfinyl)

benzylidene)-5-fluoro-2-methyl-1H-inden-3-yl) acetohydrazide has

been shown to restore impaired sperm motility and concentration in

cis-diamminedichloroplatinum (II)-treated rats by upregulating

CatSper expression and reducing oxidative stress and inflammation

(54). Taxifolin and the hexane

fraction of Prunus japonica seed also enhance sperm motility

in boars by increasing the expression of α-2-glycoprotein 1,

zinc-binding, protein kinase A), CatSper and ERK phosphorylated ERK

(55–59). These findings, together with the

present results, indicate that natural compounds such as ECH and

taxifolin could improve sperm quality across various animal

models.

Transcription factors regulate gene expression by

binding to specific DNA sequences in response to intracellular

signals (60,61). The Sox family, a group of

evolutionarily conserved transcription factors, serves a number of

important roles in cell fate determination, tissue homeostasis and

embryonic development (62). The

term ‘Sox’ stands for ‘Sry-related HMG box’, referring to the

shared DNA-binding domain among these proteins (62). Based on sequence homology and

structural conservation, the Sox family is classified into 11

subfamilies from SoxA to SoxK (22). Sox proteins are important for male

embryonic development, particularly in sex determination and

Sertoli cell differentiation (24). Among the Sox family members, Sox30,

Sox32 and Sox5 are involved in testicular development and

spermatogenesis, serving key roles in maintaining fertility

(22–25). Sox5 is an important transcription

factor in spermatogenesis and maturation (24), and its mutation or dysregulation

can lead to spermatogenic dysfunction and male infertility

(27,29). The present findings showed that ECH

significantly increased Sox5 protein expression in the testes of

AZS rats. Sox5 has been shown to enhance CatSper1 promoter activity

in vivo (30) and elevated

Sox5 levels were shown to regulate transcription by binding to the

promoter regions of genes such as CatSper1. Therefore, ECH may have

enhanced Sox5 expression and functional activity, promoting the

expression of key genes such as CatSper1 and thereby improving

sperm motility and fertilization capacity in male rats. Notably,

data from healthy individuals and patients with iAZS suggested that

ECH may have also enhanced sperm motility in clinical settings.

These findings position ECH as a promising CAM candidate for

improving sperm function and managing iAZS in clinical

practice.

The present study had limitations merit

consideration. First, species differences may limit direct

translation from the rat model to humans with AZS. Second, key

clinical parameters, such as ECH dosages and treatment duration,

remain undefined. Thus, well-designed clinical trials are needed to

validate the translational potential of the ECH/Sox5/CatSper

pathways in male subfertility.

In conclusion, the data in the present study

indicated that ECH improved sperm motility and fertilization

capacity through multiple mechanisms, including enhanced

antioxidant activity, as demonstrated by elevated GSH-PX levels,

upregulated CatSper mRNA and protein expression and increased

Sox5-mediated transactivation of the CatSper gene in AZS rats

(Fig. S2). These findings provide

novel insights into the role of plant-derived compounds in

enhancing male reproductive health and have identified potential

candidates for the development of new therapies for male

infertility.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present work was supported by grants from the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 82371227, 82171226,

81974169, 82450110, 82101676 and 82104543), the Natural Science

Foundation of Beijing Municipality (grant nos. 7222105 and

L256061), the National Key Research and Development Program of

China (grant no. 2019YFC1712104) and the Key Research and

Development Project of Xinjiang (grant nos. 2022B02012 and

2022E02122).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

GGX, ZRJ and YJ conceived and designed the

experiments. ZRJ and YWH performed the experiments. ZRJ, HJ and JC

revised the manuscript. HJ and JC made substantial contributions to

conception and design. BHL, HT, SY, YT and KX analyzed and

interpreted the data. YWH wrote the manuscript. All authors read

and approved the final manuscript. GGX and YJ confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All experimental procedures involving animals were

approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Peking University

(Beijing, China; approval no. J2024179). The present study was

approved by the Institutional Review Board of Peking University

(approval no. IRB00006761-M2022692). All participants provided

voluntary written informed consent.

Patient consent for publication

All participants provided voluntary written

informed consent for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

ALH

|

amplitude of lateral head

displacement

|

|

AZS

|

asthenozoospermia

|

|

CAM

|

complementary and alternative

medicine

|

|

CASA

|

computer-assisted semen analysis

|

|

CatSper

|

cation channel of sperm

|

|

ChIP-qPCR

|

chromatin

immunoprecipitation-quantitative PCR

|

|

ECH

|

echinacoside

|

|

EA

|

electroacupuncture

|

|

ELISA

|

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

|

|

E2

|

estradiol

|

|

PNA-FITC

|

fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated

peanut agglutinin

|

|

FSH

|

follicle-stimulating hormone

|

|

GSH-PX

|

glutathione peroxidase

|

|

HS

|

healthy subjects

|

|

HTF

|

human tubal fluid

|

|

LIN

|

linearity

|

|

LH

|

luteinizing hormone

|

|

MDA

|

malondialdehyde

|

|

NS

|

normal saline solution

|

|

OD

|

optical density

|

|

ORN

|

ornidazole

|

|

RT-qPCR

|

reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR

|

|

Sox5

|

sex-determining region Y-related

high-mobility-group-box family, member 5

|

|

STR

|

straightness

|

|

SOD

|

superoxide dismutase

|

|

T

|

testosterone

|

|

TCM

|

Traditional Chinese Medicine

|

|

VAP

|

average path velocity

|

|

VCL

|

curve-line velocity

|

|

VSL

|

straight-line velocity

|

References

|

1

|

Cox CM, Thoma ME, Tchangalova N, Mburu G,

Bornstein MJ, Johnson CL and Kiarie J: Infertility prevalence and

the methods of estimation from 1990 to 2021: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. Human Reprod Open. 12:hoac0512022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Minhas S, Boeri L, Capogrosso P, Cocci A,

Corona G, Dinkelman-Smit M, Falcone M, Jensen CF, Gül M, Kalkanli

A, et al: European association of urology guidelines on male sexual

and reproductive health: 2025 Update on male infertility. Eur Urol.

87:601–615. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Yang C, Li P and Li Z: Clinical

application of aromatase inhibitors to treat male infertility. Hum

Reprod Update. 28:30–50. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Shahrokhi SZ, Salehi P, Alyasin A,

Taghiyar S and Deemeh MR: Asthenozoospermia: Cellular and molecular

contributing factors and treatment strategies. Andrologia.

52:e134632020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Li Z, Li J, Li Y, Guo L, Xu P, Du H, Lin N

and Xu Y: The role of Cistanches Herba and its ingredients in

improving reproductive outcomes: A comprehensive review.

Phytomedicine. 129:1556812024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Jiang Y and Tu PF: Analysis of chemical

constituents in Cistanche species. J Chromatogr A. 1216:1970–1979.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Song Y, Zeng K, Jiang Y and Tu P:

Cistanches Herba, from an endangered species to a big brand of

Chinese medicine. Med Res Rev. 41:1539–1577. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Jiang Z, Zhou B, Li X, Kirby GM and Zhang

X: Echinacoside increases sperm quantity in rats by targeting the

hypothalamic androgen receptor. Sci Rep. 8:38392018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zhao G, Wang Y, Lai Z, Zheng L and Zhao D:

Echinacoside protects against dysfunction of spermatogenesis

through the MAPK signaling pathway. Reprod Sci. 29:1586–1596. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Cavarocchi E, Whitfield M, Saez F and

Touré A: Sperm ion transporters and channels in human

asthenozoospermia: Genetic etiology, lessons from animal models,

and clinical perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 23:39262022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Hwang JY and Chung JJ: CatSper calcium

channels: 20 years on. Physiology (Bethesda). 38:02023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zhang X, Liang M, Song D, Huang R, Chen C,

Liu X, Chen H, Wang Q, Sun X, Song J, et al: Both protein and

non-protein components in extracellular vesicles of human seminal

plasma improve human sperm function via CatSper-mediated calcium

signaling. Hum Reprod. 39:658–673. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hwang JY, Wang H, Lu Y, Ikawa M and Chung

JJ: C2cd6-encoded CatSperτ targets sperm calcium channel to Ca(2+)

signaling domains in the flagellar membrane. Cell Rep.

38:1102262022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Young S, Schiffer C, Wagner A, Patz J,

Potapenko A, Herrmann L, Nordhoff V, Pock T, Krallmann C,

Stallmeyer B, et al: Human fertilization in vivo and in vitro

requires the CatSper channel to initiate sperm hyperactivation. J

Clin Invest. 134:e1735642024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Tamburrino L, Marchiani S, Minetti F,

Forti G, Muratori M and Baldi E: The CatSper calcium channel in

human sperm: Relation with motility and involvement in

progesterone-induced acrosome reaction. Hum Reprod. 29:418–428.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Jin ZR, Fang D, Liu BH, Cai J, Tang WH,

Jiang H and Xing GG: Roles of CatSper channels in the pathogenesis

of asthenozoospermia and the therapeutic effects of

acupuncture-like treatment on asthenozoospermia. Theranostics.

11:2822–2844. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Shu F, Zhou X, Li F, Lu D, Lei B, Li Q,

Yang Y, Yang X, Shi R and Mao X: Analysis of the correlation of

CATSPER single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with idiopathic

asthenospermia. J Assist Reprod Genet. 32:1643–1649. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Tamburrino L, Marchiani S, Vicini E,

Muciaccia B, Cambi M, Pellegrini S, Forti G, Muratori M and Baldi

E: Quantification of CatSper1 expression in human spermatozoa and

relation to functional parameters. Hum Reprod. 30:1532–1544. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Jalalabadi FN, Cheraghi E, Janatifar R and

Momeni HR: The detection of CatSper1 and CatSper3 expression in men

with normozoospermia and asthenoteratozoospermia and its

association with sperm parameters, fertilization rate, embryo

quality. Reprod Sci. 31:704–713. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Daigle M, Roumaud P and Martin LJ:

Expressions of Sox9, Sox5, and Sox13 transcription factors in mice

testis during postnatal development. Mol Cell Biochem. 407:209–221.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Roumaud P, Haché J and Martin LJ:

Expression profiles of Sox transcription factors within the

postnatal rodent testes. Mol Cell Biochem. 447:175–187. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Wang M, Ding H, Liu M, Gao Y, Li L, Jin C,

Bao Z, Wang B and Hu J: Genome wide analysis of the sox32 gene in

germline maintenance and differentiation in leopard coral grouper

(Plectropomus leopardus). Comp Biochem Physiol Part D Genomics

Proteomics. 54:1014022024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Han F, Yin L, Jiang X, Zhang X, Zhang N,

Yang JT, Ouyang WM, Hao XL, Liu WB, Huang YS, et al: Identification

of SRY-box 30 as an age-related essential gatekeeper for male

germ-cell meiosis and differentiation. Aging Cell. 20:e133432021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Diawara M and Martin LJ: Regulatory

mechanisms of SoxD transcription factors and their influences on

male fertility. Reprod Biol. 23:1008232023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wei L, Tang Y, Zeng X, Li Y, Zhang S, Deng

L, Wang L and Wang D: The transcription factor Sox30 is involved in

Nile tilapia spermatogenesis. J Genet Genomics. 49:666–676. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Cerván-Martín M, Bossini-Castillo L,

Rivera-Egea R, Garrido N, Luján S, Romeu G, Santos-Ribeiro S;

IVIRMA Group and Lisbon Clinical Group and Castilla JA, ; et al:

Effect and in silico characterization of genetic variants

associated with severe spermatogenic disorders in a large Iberian

cohort. Andrology. 9:1151–1165. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Gu X, Li H, Chen X, Zhang X, Mei F, Jia M

and Xiong C: PEX10, SIRPA-SIRPG, and SOX5 gene polymorphisms are

strongly associated with nonobstructive azoospermia susceptibility.

J Assist Reprod Genet. 36:759–768. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Tu W, Liu Y, Shen Y, Yan Y, Wang X, Yang

D, Li L, Ma Y, Tao D, Zhang S and Yang Y: Genome-wide Loci linked

to non-obstructive azoospermia susceptibility may be independent of

reduced sperm production in males with normozoospermia. Biol

Reprod. 92:412015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Zou S, Li Z, Wang Y, Chen T, Song P, Chen

J, He X, Xu P, Liang M, Luo K, et al: Association study between

polymorphisms of PRMT6, PEX10, SOX5, and nonobstructive azoospermia

in the Han Chinese population. Biol Reprod. 90:962014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Mata-Rocha M, Hernández-Sánchez J,

Guarneros G, de la Chesnaye E, Sánchez-Tusié AA, Treviño CL, Felix

R and Oviedo N: The transcription factors Sox5 and Sox9 regulate

Catsper1 gene expression. FEBS Lett. 588:3352–3360. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wang YN, Wang B, Liang M, Han CY, Zhang B,

Cai J, Sun W and Xing GG: Down-regulation of CatSper1 channel in

epididymal spermatozoa contributes to the pathogenesis of

asthenozoospermia, whereas up-regulation of the channel by

Sheng-Jing-San treatment improves the sperm motility of

asthenozoospermia in rats. Fertil Steril. 99:579–587. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Aguirre-Arias MV, Velarde V and Moreno RD:

Effects of ascorbic acid on spermatogenesis and sperm parameters in

diabetic rats. Cell Tissue Res. 370:305–317. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Wang T, Yin Q, Ma X, Tong MH and Zhou Y:

Ccdc87 is critical for sperm function and male fertility. Biol

Reprod. 99:817–827. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Jin Z, Yang Y, Cao Y, Wen Q, Xi Y, Cheng

J, Zhao Q, Weng J, Hong K, Jiang H, et al: The gut metabolite

3-hydroxyphenylacetic acid rejuvenates spermatogenic dysfunction in

aged mice through GPX4-mediated ferroptosis. Microbiome.

11:2122023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Jin Z, Cao Y, Wen Q, Zhang H, Fang Z, Zhao

Q, Xi Y, Luo Z, Jiang H, Zhang Z and Hang J: Dapagliflozin

ameliorates diabetes-induced spermatogenic dysfunction by

modulating the adenosine metabolism along the gut microbiota-testis

axis. Sci Rep. 14:6412024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Lin SC, Lee HC, Hsu CT, Huang YH, Li WN,

Hsu PL, Wu MH and Tsai SJ: Targeting Anthrax toxin receptor 2

ameliorates endometriosis progression. Theranostics. 9:620–632.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Kelly MC, Brown SG, Costello SM,

Ramalingam M, Drew E, Publicover SJ, Barratt CLR and Martins Da

Silva S: Single-cell analysis of [Ca2+]i signalling in sub-fertile

men: Characteristics and relation to fertilization outcome. Hum

Reprod. 33:1023–1033. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Yin C, Liu B, Li Y, Li X, Wang J, Chen R,

Tai Y, Shou Q, Wang P, Shao X, et al: IL-33/ST2 induces

neutrophil-dependent reactive oxygen species production and

mediates gout pain. Theranostics. 10:12189–12203. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Song C, Han Y, Luo H, Qin Z, Chen Z, Liu

Y, Lu S, Sun H and Zhou C: HOXA10 induces BCL2 expression, inhibits

apoptosis, and promotes cell proliferation in gastric cancer.

Cancer Med. 8:5651–5661. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Zhang ZX, Tian Y, Li S, Jing HB, Cai J, Li

M and Xing GG: Involvement of HDAC2-mediated kcnq2/kcnq3 genes

transcription repression activated by EREG/EGFR-ERK-Runx1 signaling

in bone cancer pain. Cell Commun Signal. 22:4162024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Kim TH and Dekker J: ChIP-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (ChIP-qPCR). Cold Spring Harb Protoc. May

1–2018.(Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

World Health Organization, . WHO

laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human

semen. Fifth Edition. World Health Organization; Geneva: pp. 26–44.

2010, https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/6fcf020b-c7f9-48ea-b3ee-c13402d7328e/contentFebruary

16–2023

|

|

43

|

Liu N, Zhang GX, Zhu CH, Lan XB, Tian MM,

Zheng P, Peng XD, Li YX and Yu JQ: Antinociceptive and

neuroprotective effect of echinacoside on peripheral neuropathic

pain in mice through inhibiting P2X7R/FKN/CX3CR1 pathway. Biomed

Pharmacother. 168:1156752023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Yang XP, Huang JH, Ye FL, Yv QY, Chen S,

Li WW and Zhu M: Echinacoside exerts neuroprotection via

suppressing microglial α-synuclein/TLR2/NF-κB/NLRP3 axis in

Parkinsonian models. Phytomedicine. 123:1552302024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Yang Z, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Liu X, Jiang Y,

Jiang Y, Liu T, Hu Y and Chang H: Echinacoside ameliorates

post-stroke depression by activating BDNF signaling through

modulation of Nrf2 acetylation. Phytomedicine. 128:1554332024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Lu R, Zhang L, Wang H, Li M, Feng W and

Zheng X: Echinacoside exerts antidepressant-like effects through

enhancing BDNF-CREB pathway and inhibiting neuroinflammation via

regulating microglia M1/M2 polarization and JAK1/STAT3 pathway.

Front Pharmacol. 13:9934832022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Liang J, Chen T, Xu H, Wang T, Gong Q, Li

T, Liu X, Wang J, Wang Y and Xiong L: Echinacoside exerts

antihepatic fibrosis effects in high-fat mice model by modulating

the ACVR2A-smad pathway. Mol Nutr Food Res. 68:e23005532024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Wei J, Zheng Z, Hou X, Jia F, Yuan Y, Yuan

F, He F, Hu L and Zhao L: Echinacoside inhibits colorectal cancer

metastasis via modulating the gut microbiota and suppressing the

PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 318:1168662024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Wang X, Tan B, Liu J, Wang J, Chen M, Yang

Q, Zhang X, Li F, Wei Y, Wu K, et al: Echinacoside inhibits tumor

immune evasion by downregulating inducible PD-L1 and reshaping

tumor immune landscape in breast and colorectal cancer.

Phytomedicine. 135:1561882024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Yi Q, Sun M, Jiang G, Liang P, Chang Q and

Yang R: Echinacoside promotes osteogenesis and angiogenesis and

inhibits osteoclast formation. Eur J Clin Invest. 54:e141982024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Jiang Z, Wang J, Li X and Zhang X:

Echinacoside and Cistanche tubulosa (Schenk) R. Wight ameliorate

bisphenol A-induced testicular and sperm damage in rats through

gonad axis regulated steroidogenic enzymes. J Ethnopharmacol.

193:321–328. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Kong ZL, Johnson A, Ko FC, He JL and Cheng

SC: Effect of cistanche tubulosa extracts on male reproductive

function in streptozotocin-nicotinamide-induced diabetic rats.

Nutrients. 10:15622018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Guo Y, Wang L, Li Q, Zhao C, He P and Ma

X: Enhancement of kidney invigorating function in mouse model by

cistanches herba dried rapidly at a medium high temperature. J Med

Food. 22:1246–1253. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Afsar T, Razak S, Trembley JH, Khan K,

Shabbir M, Almajwal A, Alruwaili NW and Ijaz MU: Prevention of

testicular damage by indole derivative MMINA via upregulated StAR

and CatSper channels with coincident suppression of oxidative

stress and inflammation: In silico and in vivo validation.

Antioxidants (Basel). 11:20632022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Cooray A, Chae MR, Wijerathne TD, Kim DG,

Kim J, Kim CY, Lee SW and Lee KP: Hexane fraction of Prunus

japonica thunb. Seed extract enhances boar sperm motility via

CatSper ion channel. Heliyon. 9:e136162023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Zhou Y, Chen L, Han H, Xiong B, Zhong R,

Jiang Y, Liu L, Sun H, Tan J, Cheng X, et al: Taxifolin increased

semen quality of Duroc boars by improving gut microbes and blood

metabolites. Front Microbiol. 13:10206282022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Mohammadi S, Jalali M, Nikravesh MR, Fazel

A, Ebrahimzadeh A, Gholamin M and Sankian M: Effects of vitamin-E

treatment on CatSper genes expression and sperm quality in the

testis of the aging mouse. Iran J Reprod Med. 11:989–998.

2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Mohammadi S, Movahedin M and Mowla SJ:

Up-regulation of CatSper genes family by selenium. Reprod Biol

Endocrinol. 7:1262009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Park EH, Kim DR, Kim HY, Park SK and Chang

MS: Panax ginseng induces the expression of CatSper genes and sperm

hyperactivation. Asian J Androl. 16:845–851. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Lambert SA, Jolma A, Campitelli LF, Das

PK, Yin Y, Albu M, Chen X, Taipale J, Hughes TR and Weirauch MT:

The human transcription factors. Cell. 172:650–665. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Zeng L, Zhu Y, Moreno CS and Wan Y: New

insights into KLFs and SOXs in cancer pathogenesis, stemness, and

therapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 90:29–44. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Jasim SA, Farhan SH, Ahmad I, Hjazi A,

Kumar A, Jawad MA, Pramanik A, Altalbawy MAF, Alsaadi SB and

Abosaoda MK: A cutting-edge investigation of the multifaceted role

of SOX family genes in cancer pathogenesis through the modulation

of various signaling pathways. Funct Integ Genomics. 25:62025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

![ECH treatment upregulates functional

expression of CatSper channels in spermatozoa from rats with

asthenozoospermia. (A) CatSper1, (B) CatSper2, (C) CatSper3 and (D)

CatSper4 protein abundance in sperm; n=5–6 rats per group.

Representative fura-2-acetoxymethyl ester fluorescence images of

sperm before and after 30 mM NH4Cl stimulation in (E)

NS, (F) ECH, (G) NS + NNC and (H) ECH + NNC group. Arrows indicate

[Ca2+]i fluorescent signals in response to

NH4Cl. Scale bar, 10 µm. (I) Representative single-sperm

fluorescence traces. (J) Normalized [Ca2+]i

responses in all tested sperm. (K) Summary plot of normalized

[Ca2+]i signals after NH4Cl

treatment (n=27–33 sperm per group from 5–6 rats). NS group:

Ornidazole + normal saline; ECH group: Ornidazole + ECH. Data are

presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001; Unpaired t-test. ECH, echinacoside;

NS, normal saline; NNC, NNC 55-0396; CatSper, cation channel of

sperm; [Ca2+]i, intracellular calcium levels;

F340, fluorescence at 340 nm; F380, fluorescence at 380 nm.](/article_images/mmr/33/3/mmr-33-03-13794-g04.jpg)

![Functional activation of CatSper

channels in human sperm by ECH treatment. Sperm motility parameters

in healthy subjects: (A) Grade A, (B) grade A + B and (C) grade A +

B + C sperm. Sperm motility parameters in patients with AZS: (D)