Introduction

Overactive bladder (OAB) is a common, benign urinary

disorder. It causes lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). It is

characterized by urinary urgency, often accompanied by increased

frequency and nocturia, with or without urinary incontinence,

excluding urinary tract infections and other pathological changes

(1–3). The primary distinction between the

diagnosis of OAB and other lower urinary tract disorders causing

LUTS is the presence of urinary urgency. In the Asia-Pacific

region, the overall prevalence of OAB is as high as 20.8% and

prevalence rises with age (4).

Among Chinese women aged 31–40, the rate already exceeds 20%

(5). OAB, often referred to as

‘social cancer’, markedly affects the physical and mental

well-being of affected individuals.

The etiology of OAB is incompletely understood, with

neurogenic, myogenic, epitheliogenic and urogenic hypotheses

proposed. Established risk factors include advanced age, elevated

BMI, pelvic surgery, vaginal delivery, diabetes and chronic

constipation (6,7). Psychological factors such as

depression and anxiety also play a role (8,9).

Research on the OAB-anxiety link is scarce and inconclusive. The

underlying mechanisms of OAB remain inadequately understood,

leading to limited efficacy of various treatment modalities,

including behavioral therapy, pharmacotherapy and sacral

neuromodulation. Consequently, investigating the mechanisms

underlying OAB is of substantial clinical importance for the

prevention and treatment of this condition.

Anxiety is one of the commonest mental disorders. It

can both trigger and worsen OAB, and severe OAB can intensify

anxiety (10–12). An in vivo study conducted by

Tanyeri et al (13)

demonstrated that administration of mirabegron, a first-line

treatment for OAB, to anxious mice resulted in a significant

reduction in anxiety levels. This finding suggested the potential

relationship between anxiety and OAB. Anxiety also provoked

oxidative stress. It activated the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal

axis, raising glucocorticoids and damaging mitochondria, leading to

malondialdehyde (MDA) rise, while superoxide dismutase (SOD) and

glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) fell (14,15).

Furthermore, oxidative stress can induce neuroinflammation and the

release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-1β and

TNF-α, which influence neuronal excitability and synaptic

transmission, thereby exacerbating anxiety (16,17).

In colitis, multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer models, oxidative

stress turns on the NF-κB pathway, amplifying inflammation and

tissue injury (18–20). Although research suggests a

correlation between anxiety, oxidative stress and NF-κB activation,

the relationship between these factors and OAB remains unclear.

At present, no clinical research has investigated

the causal relationship between anxiety and OAB, nor the potential

mechanisms involved in anxiety-induced OAB in vivo. The

mechanism of anxiety-induced OAB is categorized under the

aforementioned neurogenic hypothesis. The present study aimed to

explore the possibility of anxiety-induced OAB and identify key

genes in vivo, with the objective of offering new

perspectives and foundational research for the diagnosis of this

condition.

Materials and methods

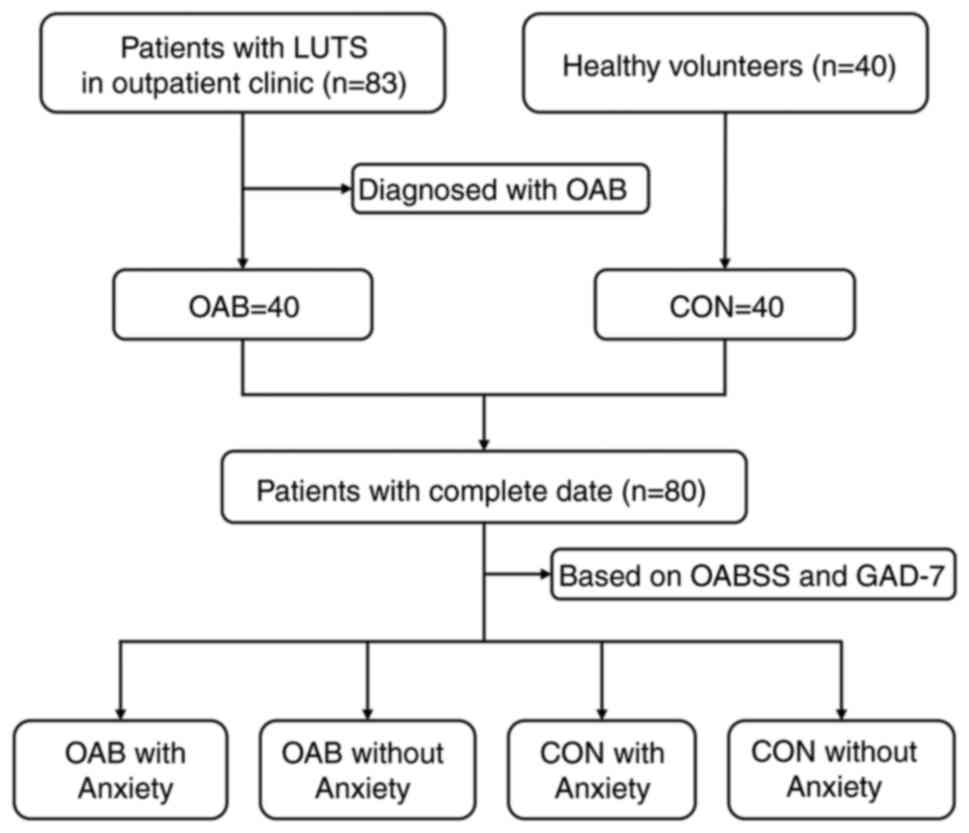

Research design and clinical data

collection

The present study was conducted at Fujian Provincial

Hospital and received approval from the Ethics Committee (approval

no. K2024-10-019). Informed written consent was obtained from all

participants. Inclusion criteria: All patients who meet the

diagnostic criteria for OAB and healthy volunteers. Patients with

any one of the following conditions were ineligible: urinary tract

infection, various cystitis, urinary urogenital cancer, urinary

tract stones, neurogenic bladder, pelvic organ prolapse, pregnancy

and reluctance to participate in the present study. Between July

2023 and July 2024, a total of 83 patients presenting with LUTS and

40 healthy volunteers serving as controls were recruited from

Fujian Provincial Hospital. Of the 83 patients, 43 were excluded

due to LUTS resulting from other causes, leaving 40 patients who

were diagnosed with OAB and included in the disease cohort.

Comprehensive clinical data were successfully collected for 80

participants, encompassing the overactive bladder symptom scores

(OABSS; Table SI) and the

generalized anxiety disorder scale-7 (GAD-7; Table SII). Based on the OABSS scale, a

diagnosis of OAB is made when urinary urgency has a score of ≥2 and

the overall OABSS score is ≥3. When OABSS with a total score range

of 3–5, mild OAB; 6–11, moderate OAB; ≥12, severe OAB. When GAD-7

with a total score range of 0–4, normal; 5–9, mild anxiety; 10–13,

moderate anxiety; 14–18, moderately severe anxiety; 19–21 points,

severe anxiety. These assessment tools are primarily utilized for

the screening and evaluation of OAB severity and anxiety levels,

respectively (21). Based on the

OABSS and GAD-7 results, participants were categorized into four

groups: OAB with anxiety (n=33), OAB without anxiety (n=7), control

with anxiety (n=5), and control without anxiety (n=35). The

recruitment process for the study participants is illustrated in

Fig. 1.

Animal anxiety model

Animal experiments were conducted at the Nanfang

Hospital's Animal Research Center, approved by its Institutional

Animal Ethical Care Committee (approval no. NFYY-2021-0572) and

followed the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and

Use of Laboratory Animals (22). A

total of 60 female C57BL/6 mice (5–8 weeks old, 16–19 g) were

obtained from SPF Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Mice were maintained

under specific pathogen-free conditions in individually ventilated

cages with 0.22-µm filter tops at 21–23°C, 40–55% humidity, under a

12-h light/dark cycle, with autoclaved food and water available

ad libitum. All handling was performed under HEPA-filtered

air conditions to maintain barrier integrity. Before the

establishment of the model, all the animals were first marked on

their ears for identification and then randomly assigned to groups.

For three weeks, mice underwent chronic restraint stress (CRS) by

being immobilized in a transparent cylinder for six hours daily,

from 09:00 to 15:00, without access to food or water (n=6). The

control group could move, eat, and drink freely (n=6) (23). Prior to the tests, the groups were

randomly shuffled and unrelated staff were invited to perform the

operations. All behavioral tests were repeated three times per

mouse. Humane endpoints were predetermined and approved by the

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, including >20%

weight loss, severe dehydration, persistent hunched posture,

inability to ambulate, or any signs of restraint-induced injury.

Animals were monitored twice daily; no animals reached these

endpoints. Mice were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital (60–80

mg/kg, intraperitoneal) and subsequently euthanized by cervical

dislocation.

Elevated plus maze (EPM) test

The EPM test consists of two open and two closed

arms, each measuring 50×10 cm, elevated 50 cm above the ground. The

closed arms have 30 cm high opaque walls, and the intersection of

the arms forms a 10×10 cm center area. Mice are placed in the

center facing an open arm, and their movements are recorded for 5

min using a video system (Shanghai Jiliang Software Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.). Anxiety-like behavior is indicated by

increased entries and prolonged time spent in the closed arms.

Open field (OF) test

The OF test involves a 60×60×40 cm open box with a

video system (Shanghai Jiliang Software Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.) to track movement. The box is divided into 25 squares,

with 9 central and 16 peripheral squares. During the 5-min test,

the total distance traveled, distance in the central area, and time

spent in the central area are recorded. A significant reduction in

these measures indicates anxiety in mice.

Cystometry

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (3.0–4.0% for

induction, 1.0–1.5% for maintenance) and placed in a supine

position. A midline incision exposed the lower abdomen, and a

0.6×15 mm needle was inserted into the bladder to remove residual

urine. Bladder pressure was measured using the BL-420N BioSignal

Acquisition System (Chengdu Techman Software Co., Ltd.), with

sterile saline infused at 1 ml/h. Once a stable micturition

waveform was achieved, intravesical pressure data were recorded for

30 min or at least five voiding cycles. Urine outflow was

monitored, and bladder contractions were identified by increased

intravesical pressure, indicating micturition. Bladder contractions

without urination were labeled as non-micturition contractions, it

reflects the involuntary contraction of the bladder and is one of

the core indicators for diagnosing and describing OAB (24). The peak intravesical pressure

during urination was measured and maximum bladder capacity was

determined by multiplying infusion time by infusion rate.

RNA-seq analysis

Bladder tissues were stored at −80°C. Total RNA was

extracted with the Eastep Super Kit (cat. no. LS1040; Promega

Corporation). Poly-A mRNA was selected on oligo(dT) beads and

converted to cDNA with the NEBNext Ultra kit (cat. no. 7530; New

England Biolabs, Inc.). The cDNA was amplified and sequenced on the

Illumina Novaseq6000 instrument (Illumina, Inc.), which was owned

by Gene Denovo Biotechnology Co. The specific parameters can be

found in Appendix S1.

To identify differential gene expression, a

comparative analysis was performed using the DESeq2 software

package v 1.48.1 (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html).

Genes with FDR ≤0.05 and |fold change|≥1.5 were called significant

(25).

Analysis of gene ontology (GO) and

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG)

This part of the analysis was conducted using

clusterProfiler software v 3.81 (26).GO enrichment analysis connects

differentially expressed genes (DEGs) to significant biological

functions by identifying enriched GO terms compared with the genome

background (27).

After Bonferroni correction, P-values were adjusted

using FDR correction, with a threshold of FDR ≤0.05. KEGG aids in

understanding gene functions through pathway-based analysis. After

using the same multiple testing corrections, the Q-value, which is

the P-value after FDR correction, defined as the markedly enriched

pathways.

Generation of protein-protein

interaction (PPI) and discovery of key genes

The PPI network was built with STRING v10

(http://string-db.org), with genes as nodes and

interactions as edges (28).

Cytoscape v3.7.1 visualized the network, highlighting core and hub

genes (www.cytoscape.org) (29). Bioinformatics analyses were

conducted using Omicsmart, an online platform for data analysis

(http://www.omicsmart.com). The details

of analysis parameters are listed in Appendix S2.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

(RT-q) PCR

The primers used in the present study are listed in

Table SIII. cDNA synthesis and

qPCR were performed according to the manufacturer's protocols. RNA

was extracted from the bladder using the Animal Total RNA Isolation

Kit (Foregene Co., Ltd.) following the manufacturer's instructions.

cDNA was synthesized from total RNA with HiScript III RT SuperMix

for qPCR (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) at 50°C for 15 min and 85°C for

5 sec. RT-qPCR was conducted on a LightCycler480 system (Roche

Diagnostics, Ltd.) using ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme Biotech

Co., Ltd.) at 95°C for 30 sec; followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 10

sec and 60°C for 30 sec; and a final melt curve analysis at

60–95°C. GAPDH was the internal reference, and gene

expression was measured using the 2−∆∆Cq method

(30).

Determining the levels of oxidative

stress and pro-inflammatory cytokines

Each mouse had a blood sample of ~1 ml collected by

cardiac puncture. Serum and bladder levels of MDA (cat. no.

S0131S), total superoxide dismutase (T-SOD; cat. no. S0101S) and

GSH (cat. no. S0052) were measured using specific assay kits from

Beyotime Biotechnology. ELISA kits from R&D Systems, Inc. were

used to assess IL-6 (cat. no. M6000B), IL-1β (cat. no. MLB00C) and

TNF-α (cat. no. MTA00B) levels. All procedures followed the

provided instructions.

Immunohistochemistry

Bladder tissues were immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde

for fixation at 4°C for 8 h, and sequentially underwent dehydration

with an ethanol gradient (25°C, 5 h), permeabilization with 0.3%

Triton X (25°C, 20 min), paraffin dipping (58°C, 1.5 h) and

embedding (58°C to 4°C, 30 min); after which, the tissues were cut

into 4-µm sections. The sections were cleaned and sealed with drops

of goat serum (cat. no. BL210A; Biosharp Life Sciences) for 30 min

at room temperature. Subsequently, the blocking solution was

discarded and diluted rabbit anti-Hsp90aa1 (1:200; cat. no.

BF0084-50; Affinity Biosciences), anti-Hsp90ab1 (1:200; cat. no.

BF0215; Affinity Biosciences), anti-Hsp90b1 (1:200; cat. no.

AF5287; Affinity Biosciences) and anti-NF-κB (1:200; cat. no.

YM8209; ImmunoWay Biotechnology Company) antibodies were added

dropwise to the sections and incubated overnight at 4°C. The next

day, goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:200; cat. no. LF102;

Epizyme; Ipsen Pharma) was dropped into the sections and incubated

at 37°C for 30 min. DAB chromogen concentrate was mixed with

diluent to prepare a working solution according to the instructions

of the DAB kit (cat. no. BL732A; Biosharp Life Sciences) and

applied to the tissue sections, which were washed, re-stained with

hematoxylin at room temperature for 3 min and washed again.

Finally, the sections were dehydrated, permeabilized with xylene

and sealed. Scanning and viewing of the images was performed using

NanoZoomer Digital slide scanner (Hamamatsu Photonics K.K.) and NDP

View2 Plus Image viewing software (version U12388-01; Hamamatsu

Photonics K.K.). The average optical density was quantified using

Image-Pro Plus software (version 6.0; Media Cybernetics, Inc.),

with measurements taken from three randomly selected fields of view

at ×10 magnification for every sample.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining

Paraffin-embedded sections (4 µm) were dewaxed in

xylene (3×5 min) and rehydrated through a descending ethanol series

(100, 95 and 70%, 2 min each). Nuclei were stained with Mayer's

hematoxylin (cat. no. MHS16-100ML; MilliporeSigma) for 90 sec at

room temperature, differentiated in 1% acid alcohol (1 sec), blued

in 0.2% ammonia water (30 sec) and counterstained with 1% eosin Y

(cat. no. 318906-25G; MilliporeSigma) for 45 sec. After dehydration

in ethanol (95 and 100%, 2 min each) and permeabilization in xylene

(2×3 min), slides were mounted with neutral balsam (cat. no.

10050041; Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.). Digital images

were acquired at ×20 magnification using a NanoZoomer S60 scanner

(Hamamatsu Photonics K.K.).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were summarized as mean ±

standard deviation or median (Q1-Q3) for normal and non-normal

distributions, respectively, while categorical variables were shown

as frequency and percentage (GraphPad Prism software version 10;

Dotmatics). When comparing the difference in means between two

samples, the unpaired Student's t-test was used when data had a

normal distribution, whereas the Mann-Whitney U test was employed

when data had a non-normal distribution. χ2 or Fisher's

exact tests compared categorical variables. Correlations were

analyzed using Pearson's or Spearman's coefficients. Stepwise

multivariate logistic regression identified key predictors,

reporting odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Model fit was checked with the Hosmer-Lemeshow test, and predictive

ability was evaluated using the ROC curve. All candidate variables

with P<0.10 in univariate analysis were entered into the initial

model. Multicollinearity was assessed by variance inflation factor

(VIF); all retained variables showed VIF <5. The final model

exhibited good calibration (Hosmer-Lemeshow test P=0.616). All the

data underwent normality tests before being subjected to

statistical analysis. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the

participants

Demographic characteristics of participants were

assessed in a study involving 40 patients with OAB and 40 healthy

controls (CON). As shown in Table

I, there were no significant differences in age, BMI, sex,

history of pelvic surgery, diabetes, or hypertension between the

groups. OABSS were markedly higher in the OAB group; intriguingly,

GAD-7 was notably elevated at 7.18±3.56 compared with 2.00 (1.00,

3.00) in the CON group, indicating a potential link between anxiety

and OAB.

| Table I.Comparisons of characteristics

between OAB group and CON group. |

Table I.

Comparisons of characteristics

between OAB group and CON group.

| Characteristic | OAB (n=40) | CON (n=40) | P-value |

|---|

| Age | 35.90±7.65 | 37.45±12.70 | 0.51 |

| BMI | 21.74±2.43 | 22.65±2.72 | 0.12 |

| Sex |

|

| 0.82 |

|

Male | 21 (53) | 20 (50) |

|

|

Female | 19 (47) | 20 (50) |

|

| History of pelvic

surgery | 8 (20) | 6 (15) | 0.56 |

| Diabetes | 7 (17.5) | 8 (20) | 0.76 |

| Hypertension | 9 (22.5) | 8 (20) | 0.79 |

| GAD-7 | 7.18±3.56 | 2.00 (1.00,

3.00) | <0.001 |

| OABSS | 7.00 (4.25,

8.00) | 1.00 (0.00,

2.00) | <0.001 |

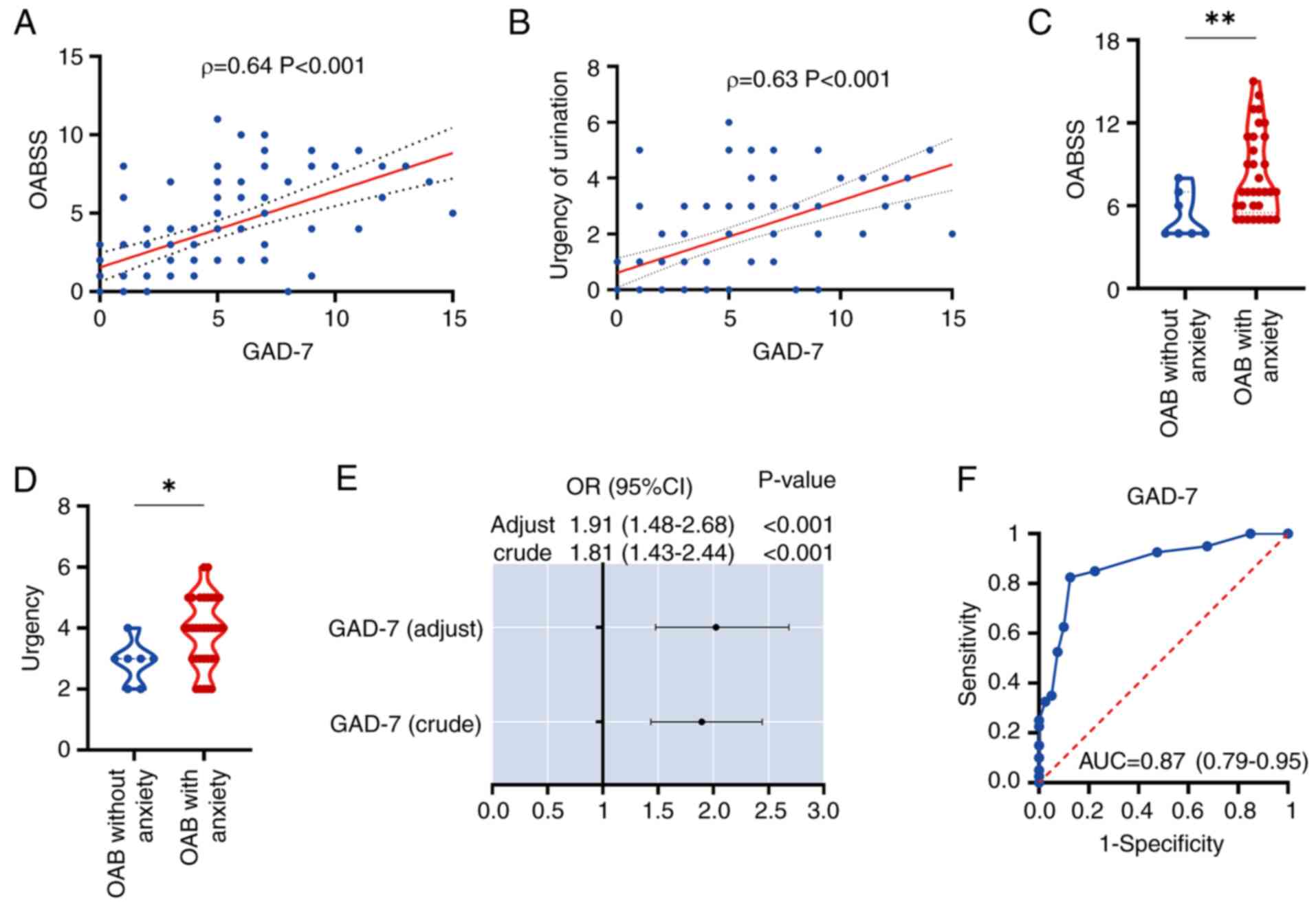

The relationship between anxiety and

OAB

To elucidate the relationship between anxiety and

OAB, and to determine whether anxiety can induce OAB, the present

study conducted correlation and regression analyses. The findings

indicated a positive correlation between OABSS and the GAD-7

(Fig. 2A). Additionally, urinary

urgency, a key symptom of OAB, was positively correlated with GAD-7

(Fig. 2B). Subsequently, all OAB

patients were categorized into two groups based on the presence or

absence of anxiety and compared their OABSS and urinary urgency

scores. The results demonstrated that OAB patients with anxiety

exhibited markedly higher OABSS and urinary urgency levels compared

with those without anxiety (Fig. 2C

and D). To further explore the causal relationship between

anxiety and OAB, the present study initially performed a univariate

logistic regression analysis on GAD-7, which yielded an odds ratio

(OR) of 1.81 (95% CI: 1.43–2.44), with a crude P-value of

<0.001. This was followed by a multivariate logistic regression

analysis, incorporating all baseline variables, which resulted in

an adjusted OR of 1.91 (95% CI: 1.48–2.68), with an adjusted

P-value of <0.001 (Fig. 2E). In

conclusion, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were

used to evaluate the potential of anxiety as an independent risk

factor for predicting the occurrence of OAB. The GAD-7 demonstrated

a notably high predictive accuracy, with an area under the curve

(AUC) of 0.87 (95% CI: 0.79–0.95) (Fig. 2F), the specificity was 0.875, the

sensitivity was 0.825 and the Youden's index was 1.7. This aspect

of the present study effectively demonstrated, at a clinical level,

that anxiety can be employed as an independent risk factor for

forecasting the onset of OAB.

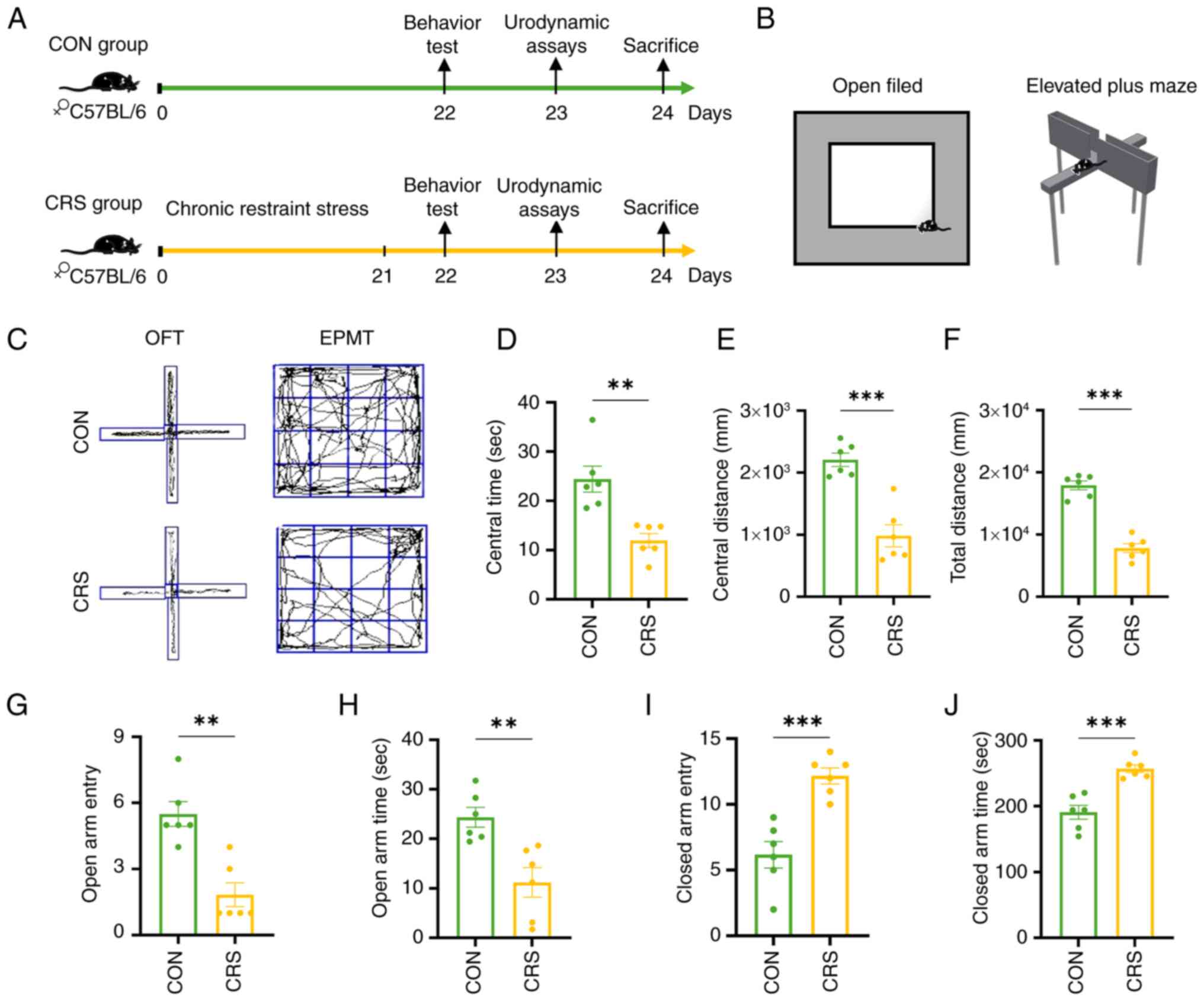

Anxiety can induce OAB-like symptoms

in vivo

In the present study, an anxiety model was developed

using 21 days of CRS (Fig.

3A).

In the open-field (OF) test (Fig. 3B and C), the time spent (11.98±1.41

sec) by the CRS mice in the central area, the distance traveled

(983±179 mm) during activity, and the total distance traveled

(7,803±727.10 mm) were all markedly lower than those of the control

group (24.41±2.63 sec), (2,209±106.80 mm), (1,7926±722.10 mm),

(Fig. 3D-F). In the elevated-plus

maze (EPM), The number of times the CRS mice entered the open arm

(1.83±0.54)and the duration they stayed (11.20±2.97 sec) there were

markedly lower than those of the control group (5.50±0.56),

(24.35±2.00 sec) while the number of times they entered the closed

arm (12.17±0.60) and the duration they stayed (257.10± 5.83 sec)

there were markedly higher than those of the control group

(6.16±1.01), (190.90±10.60 sec), (Fig.

3G-J). These changes confirmed that CRS induced anxiety-like

behavior, as the mice exhibited behaviors resembling anxiety, such

as reduced exploration desire and avoidance of conflicts.

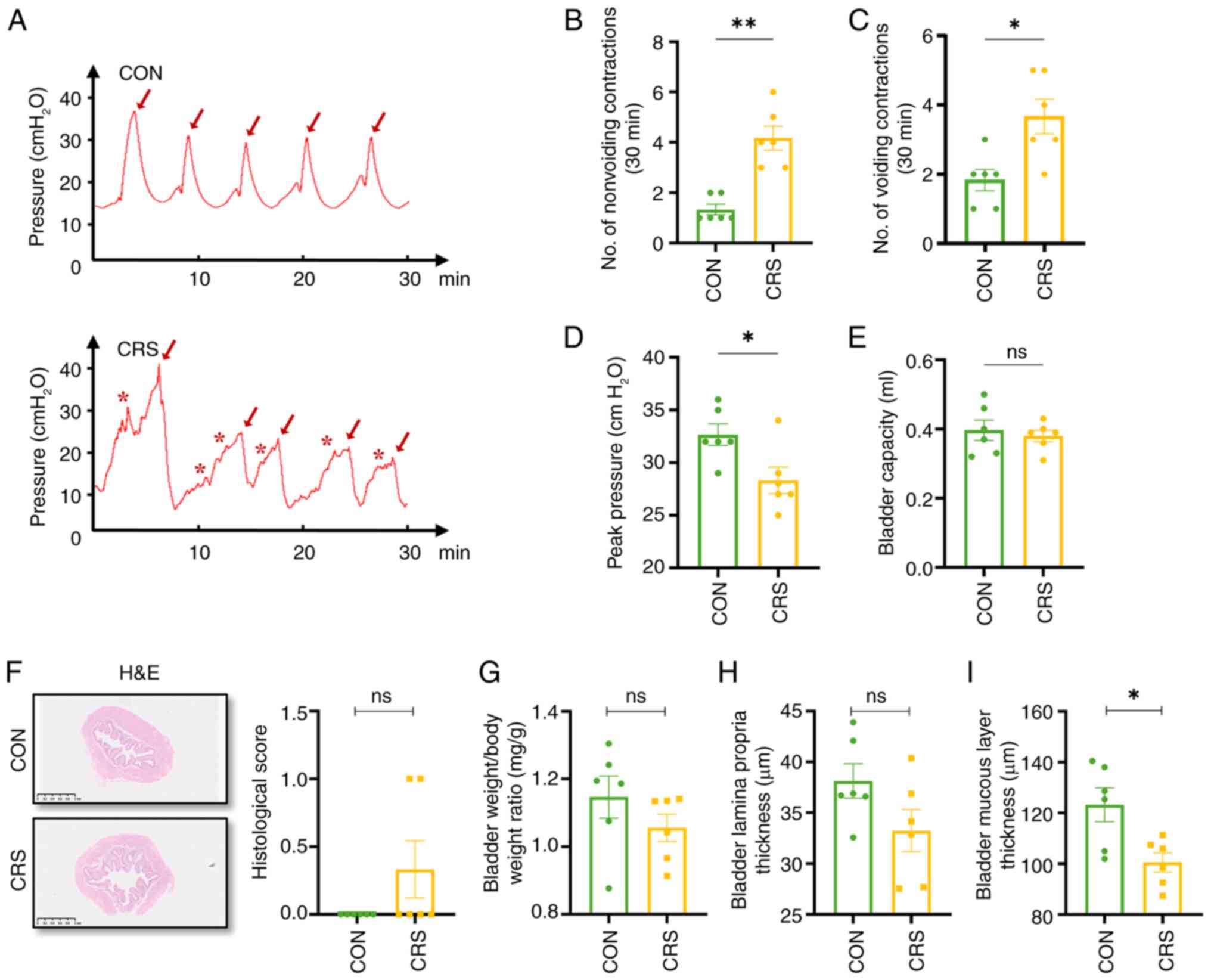

Furthermore, cystometry was conducted to assess

bladder function (Fig. 4A) and it

was and found that CRS mice had more non-voiding (4.16±0.47 vs.

1.33±0.21), voiding contractions (3.67±0.95 vs. 1.83±0.31) and

lower peak pressure (28.33±1.26 vs. 32.67±1.02 cm H2O),

whereas bladder capacity was unchanged (0.38±0.02 vs. 0.39±0.03

ml), (Fig. 4B-E). These results

indicate that CRS-induced anxiety may cause OAB-like symptoms in

mice through involuntary contractions of the detrusor muscle.

Subsequently, the present study conducted hematoxylin and eosin

staining on bladders and calculated the bladder-to-body weight

ratio, finding no difference in bladder-to-body weight ratio or

lamina propria thickness between groups, mirroring human OAB

(31) (Fig. 4F-H). The bladder mucosal layer was

thinner in CRS mice compared with controls (Fig. 4I), suggesting that mucosal layer

changes might contribute to OAB symptoms.

Exploration of differentially

expressed genes (DEGs)

The present study conducted RNA-seq analysis to

identify DEGs between CRS mice and control mice. After processing

and normalizing the raw data, 551 DEGs were found, with 58

upregulated and 493 downregulated (Fig. S1). This meant that certain

pathways are activated, while numerous others are suppressed.

Enrichment analysis of function and

pathways in DEGs

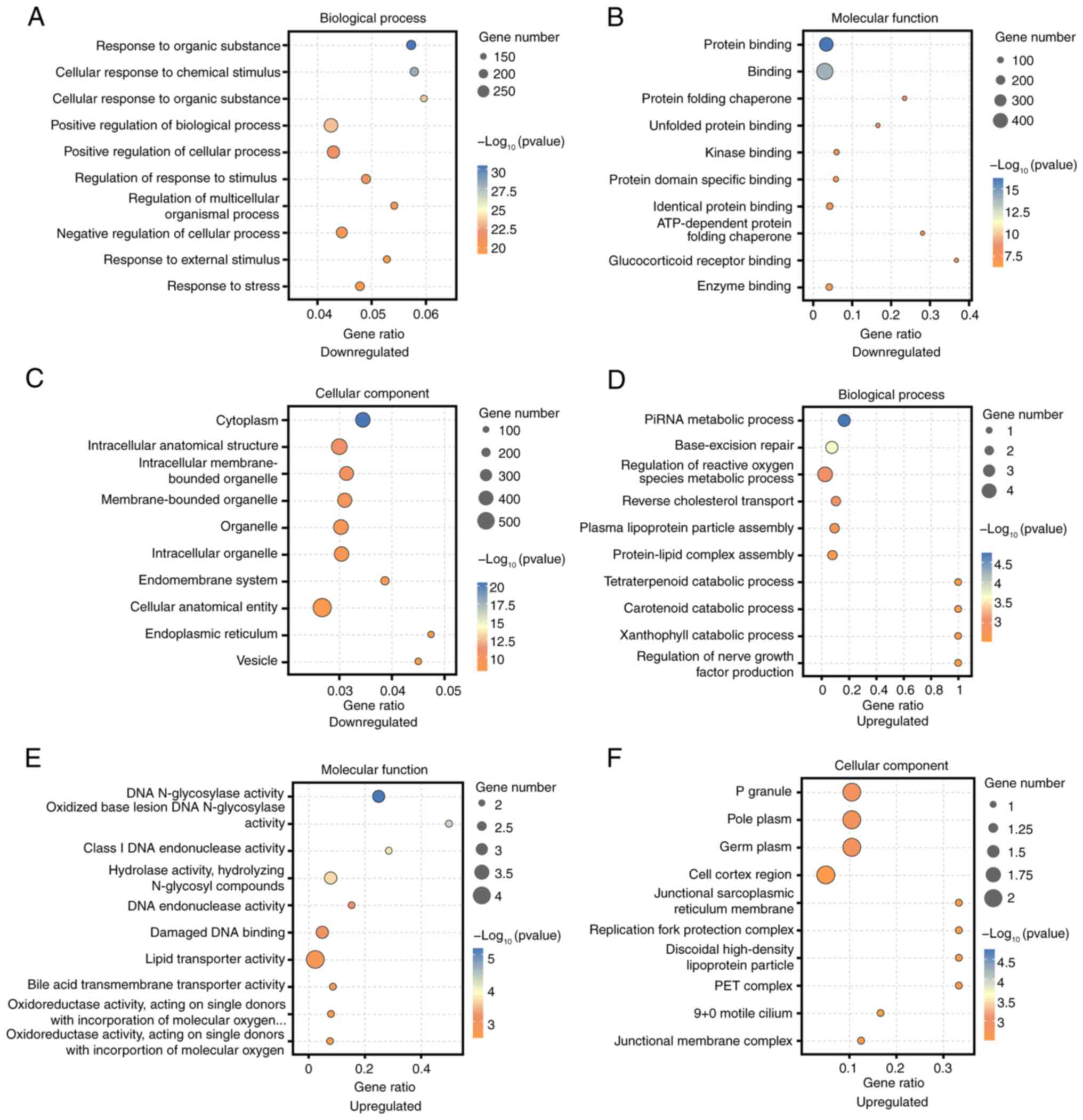

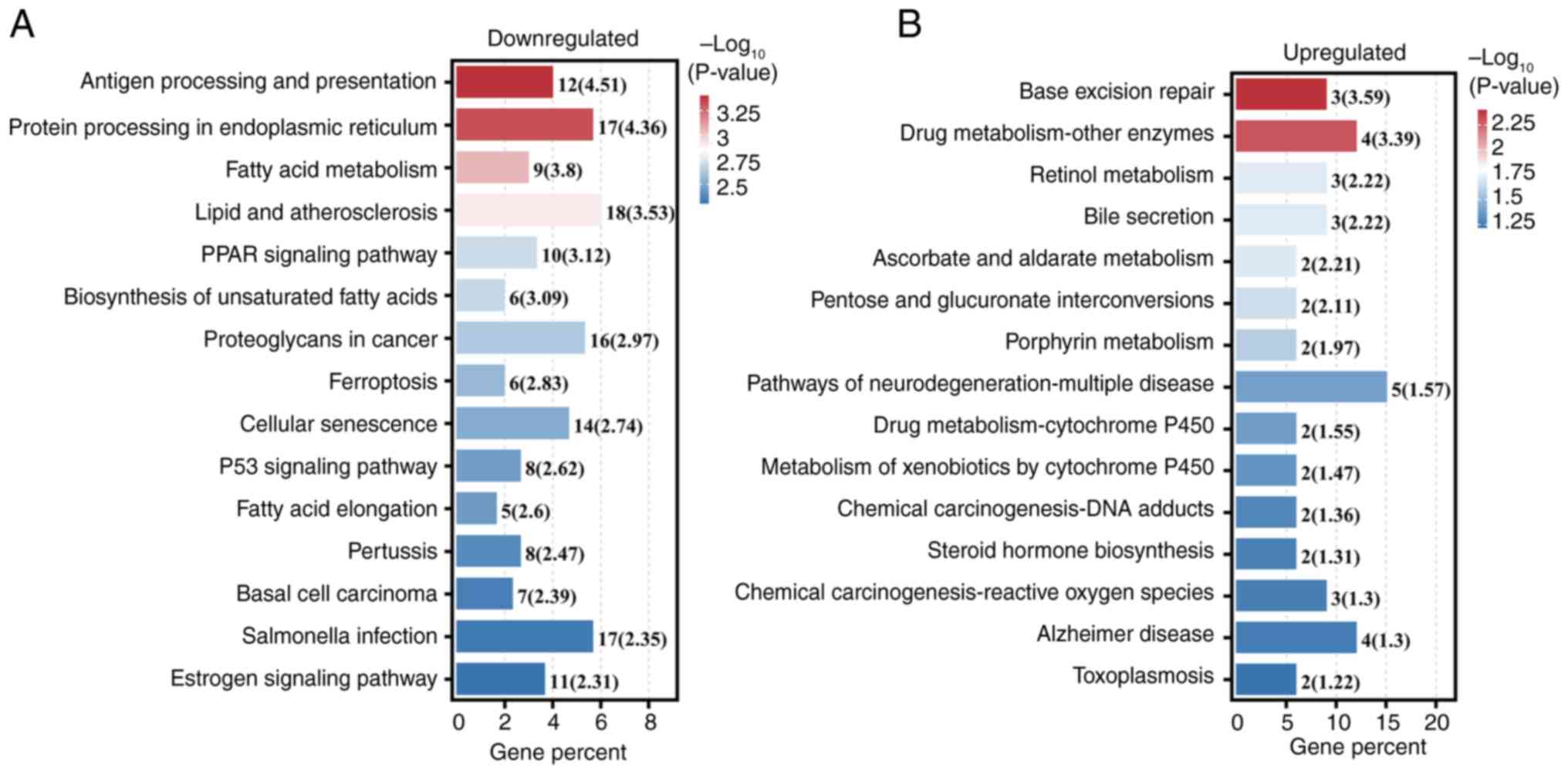

GO analysis identified the most enriched categories

among downregulated DEGs as ‘positive regulation of biological

process’, ‘Binding’, and ‘Cellular anatomical entity’ (Fig. 5A-C). For upregulated DEGs, the top

categories were ‘Regulation of reactive oxygen species metabolic

process’, ‘lipid transporter activity’, and ‘P granule’ (Fig. 5D-F). KEGG pathway analysis revealed

‘Antigen processing and presentation’ as the most markedly

associated with downregulated DEGs (Fig. 6A), while ‘Base excision repair’ was

most significant for upregulated DEGs (Fig. 6B).

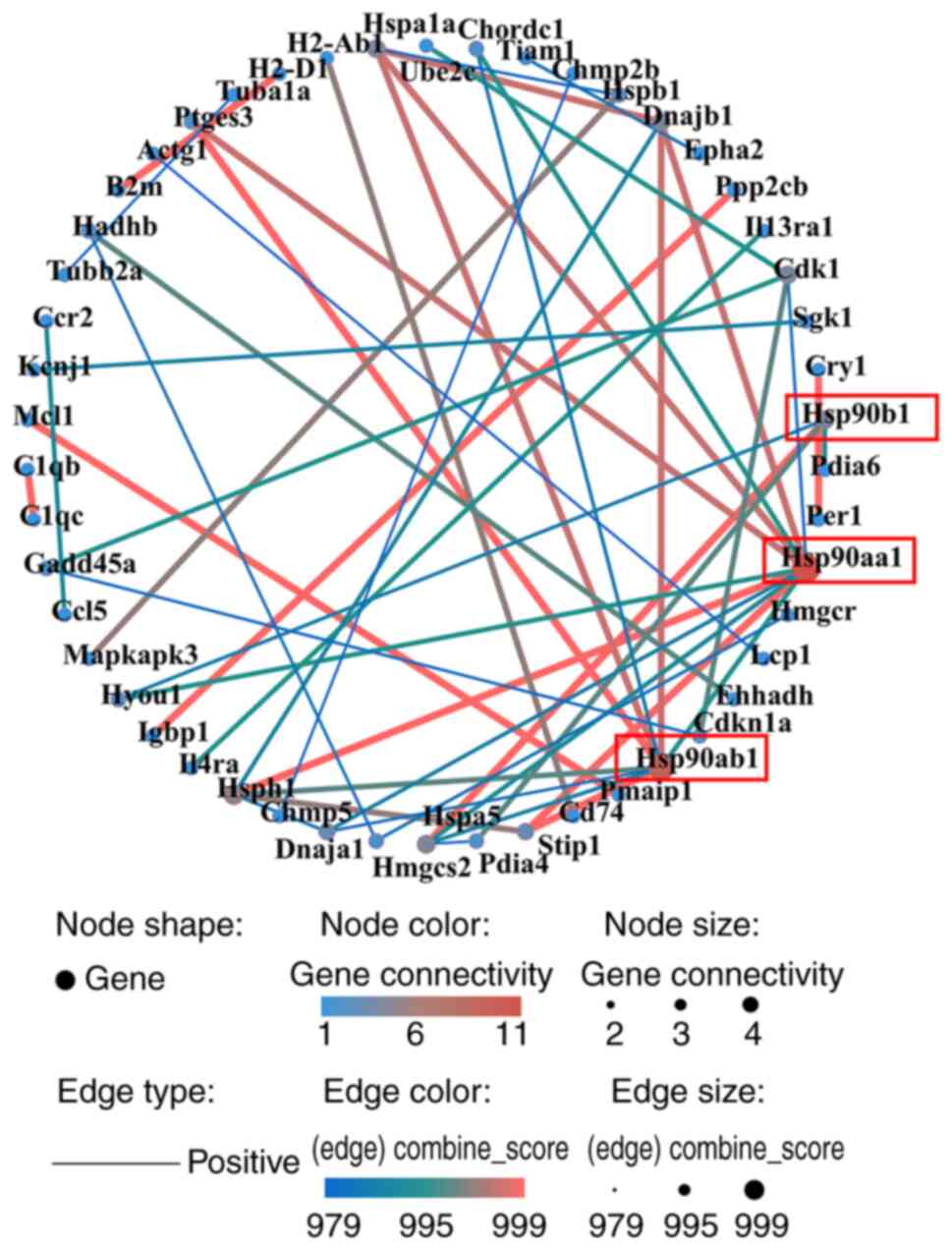

Construction of a PPI network and

identification of key hub genes

The PPI network comprised 50 nodes and 533 edges

(Fig. 7). The top three hub genes,

identified by combined score, were Hsp90aa1, Hsp90ab1, and

Hsp90b1, all from upregulated DEGs.

Anxiety-induced OAB activated

oxidative stress and NF-κB pathways in vivo

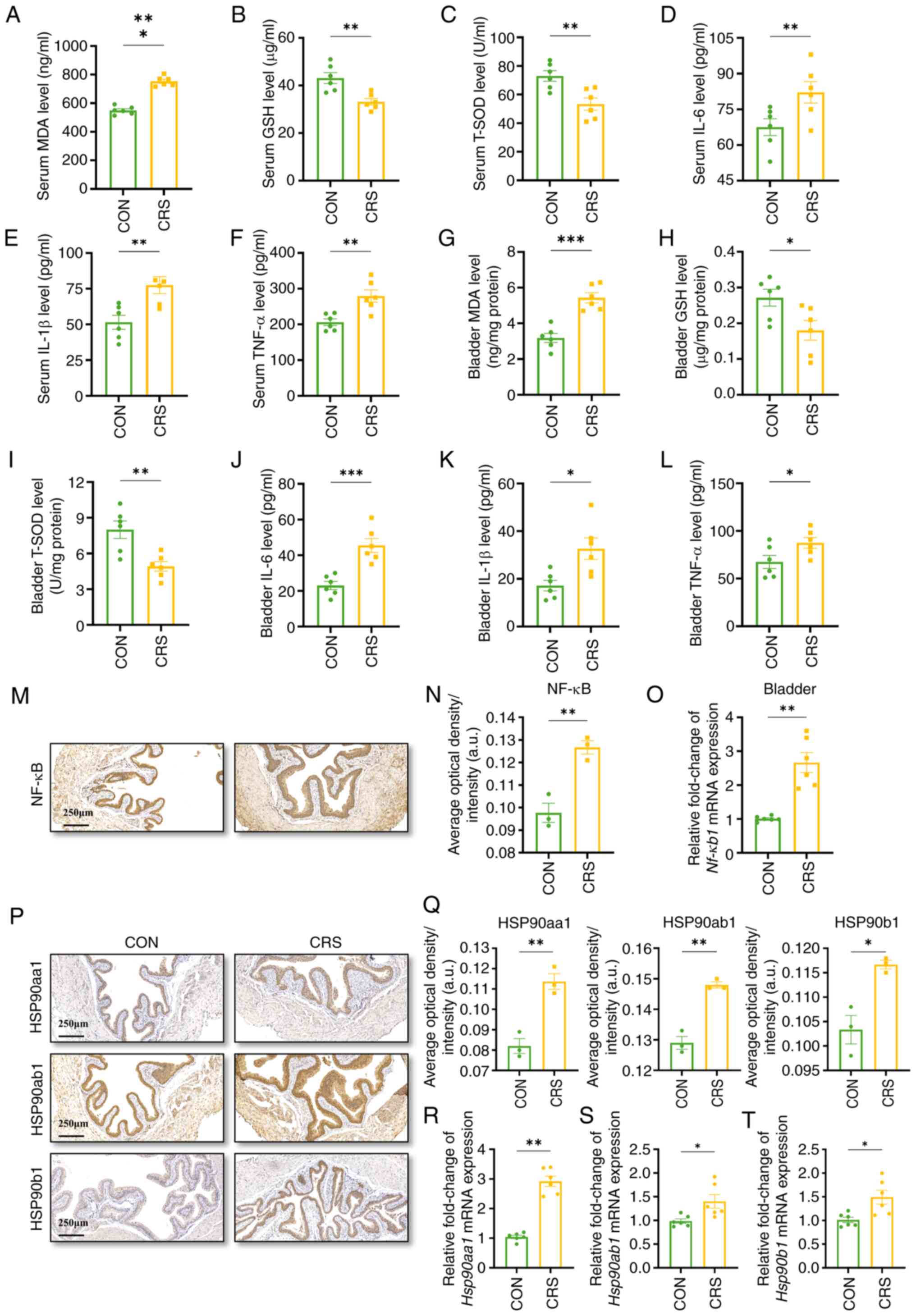

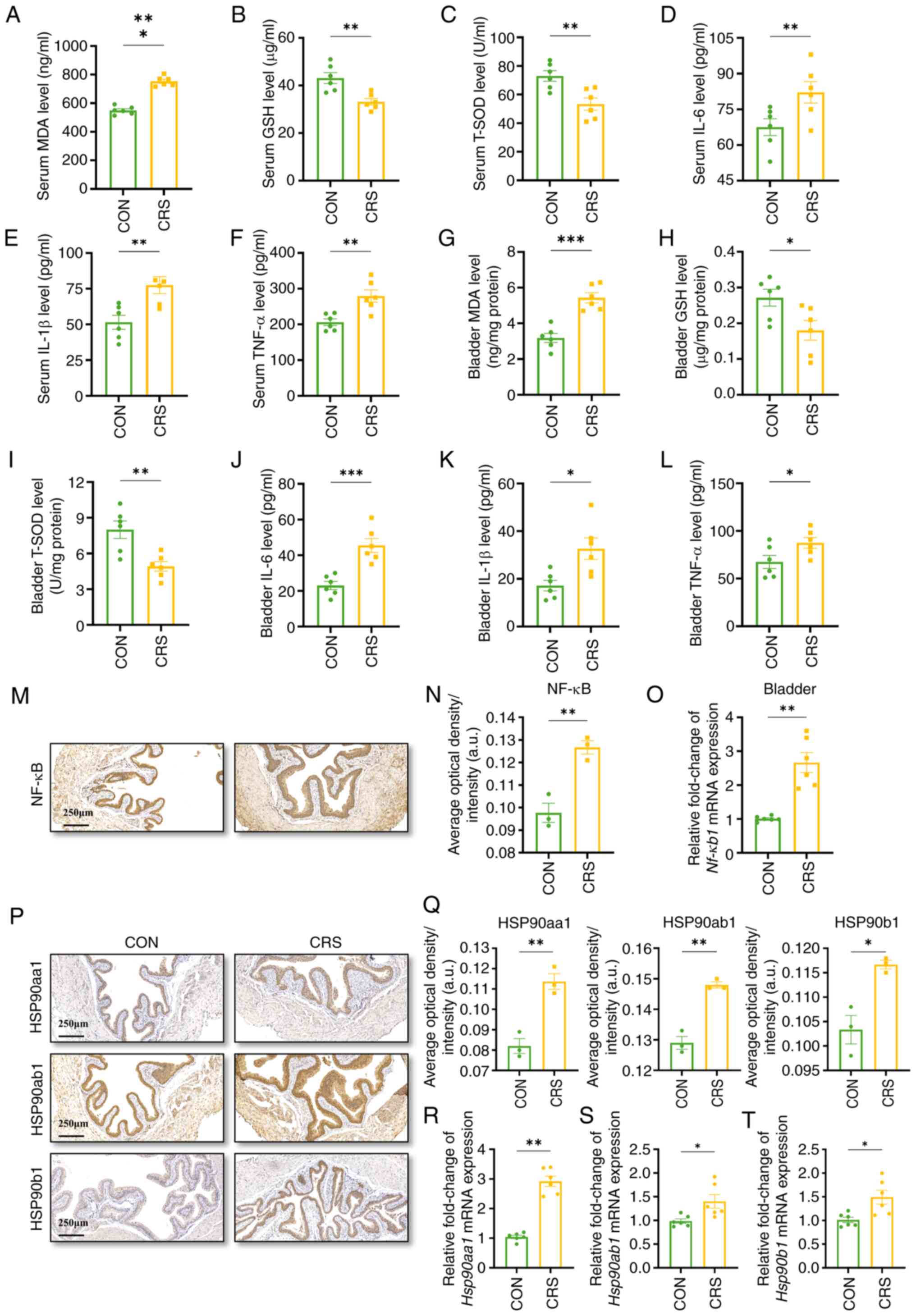

Based on GO analysis and previous studies, it was

hypothesized that the disease mechanism might involve oxidative

stress, which could activate the NF-κB pathway (32,33).

To investigate, the present study measured serum levels of MDA,

GSH, and T-SOD in mice, as these indicate oxidative stress

activation. Serum MDA was higher in CRS mice, whereas GSH and T-SOD

were lower (Fig. 8A-C). The same

pattern was seen in bladder tissue (Fig. 8G-I). Next, we examined downstream

inflammation. Serum IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α were all elevated

(Fig. 8D-F), and identical

increases were found in the bladder (Fig. 8J-L).

| Figure 8.Anxiety active oxidative stress and

NF-κB signaling. The concentration of (A) MDA, (B) GSH, (C) T-SOD,

(D) IL-6, (E) IL-1β and (F) TNF-α in the serum. The concentration

of (G) MDA, (H) GSH, (I) T-SOD, (J) IL-6, (K) IL-1β and (L) TNF-α

in the bladder. (M) Representative images of NF-κB in the bladder,

scale bar, 250 µm. (N) Average optical density of NF-κB in the

bladder. (O) Relative mRNA level of Nf-κb1 in the

bladder. (P) Representative immunohistochemistry of Hsp90aa1,

Hsp90ab1 and Hsp90b1 in the bladder, scale bar, 250 µm. (Q) The

average optical density analysis results of Hsp90aa1, Hsp90ab1 and

Hsp90b1 in the bladder. (R) Relative mRNA levels of Hsp90aa1

in bladder tissues. (S) Relative mRNA levels of Hsp90ab1 in

bladder tissues. (T) Relative mRNA levels of Hsp90b1 in

bladder tissues. Data were presented as the mean ± SD. n=3

in M, N, P and Q, n=6 in A-L, O and R-T for each group.

P-values were calculated using a two-tailed unpaired Student's

t-test (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001). MDA,

malondialdehyde; GSH, glutathione; T-SOD, total superoxide

dismutase. |

To further verify the status of NF-κB in the

bladder, the gene and protein expression of NF-κB in the bladder of

each group were examined and the results showed that the gene

expression of Nf-κb1 and the protein expression levels of

NF-κB as well as IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α were markedly increased in

the CRS group compared with the control group (Fig. 8M-O). These findings might indicate

that anxiety could trigger the NF-κB pathway through oxidative

stress and pro-inflammatory mediators, causing bladder

overactivity.

Identification of key genes and

proteins in bladder

Hsp90 has been linked to NF-κB in various

disease models (34,35). In the present study, Hsp90

genes were identified during PPI network construction. The present

study used qPCR and IHC on mouse bladder tissue to confirm Hsp90

mRNA and protein levels. Results (Fig.

8P-T) showed significant upregulation of Hsp90aa1, Hsp90ab1,

and Hsp90b1 in the OAB group compared with controls, with protein

expression mainly in the mucosal layer.

Discussion

OAB is a common cause of LUTS. It markedly affects

patients' quality of life, leading to mobility issues, urinary

tract infections, anxiety, depression and loss of self-confidence

(36). The unclear pathogenesis of

OAB results in a lack of targeted treatments. Thus, understanding

OAB's underlying mechanisms is crucial for effective prevention and

treatment.

Studies have established a positive correlation

between OAB and factors such as age and BMI (37–39).

Additionally, conditions such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension,

history of pelvic surgery and reproductive history can lead to the

onset or progression of OAB (40,41).

Regarding psychological factors, limited research suggests a

correlation between the severity of OAB and anxiety (42–44).

Nonetheless, there is insufficient evidence to conclude whether

anxiety independently induces OAB or serves as a standalone risk

factor for its development. The current study identified a positive

correlation between the level of anxiety and the severity of OAB

and urinary urgency, corroborating previous findings. Furthermore,

through multivariate logistic regression analysis and the

construction of ROC curves, it established that anxiety serves as

an independent risk factor for the development of OAB.

To explore anxiety-induced OAB mechanisms, the

present study conducted in vivo experiments after analyzing

clinical data. OAB modeling methods include drug injection and

bladder outlet obstruction (BOO), with BOO being the most common

(45–47). BOO can lead to issues such as

collagen redistribution, muscle hypertrophy and changes in bladder

capacity, potentially skewing OAB mechanism studies (48–50).

The present study uniquely applied CRS, typically used for anxiety

models, to induce OAB in mice (51). This method minimized surgical

impact on bladder physiology, reducing confounding factors and

realistically replicated anxiety-induced OAB showed in clinical

settings.

Having confirmed anxiety as an independent OAB risk

factor and generated a murine anxiety-OAB model, the present study

performed bladder transcriptomics to dissect mechanisms, biomarkers

and targets. RNA-seq revealed 551 DEGs, with 58 upregulated and 493

downregulated. It was hypothesized that this transcriptional

imbalance represents a cellular ‘functional trade-off’, where the

extensive downregulation of homeostatic pathways serves to conserve

energy under chronic anxiety stress. Concurrently, the selective

upregulation of genes related to ROS metabolism and base excision

repair indicated a prioritization of essential survival mechanisms

over routine physiological functions, such as antigen presentation.

GO analysis highlighted enriched terms such as ‘regulation of

reactive oxygen species metabolic process’, ‘lipid transporter

activity’, and ‘P granule’ among the upregulated genes. Reactive

oxygen species (ROS) are highly reactive compounds involved in

various biological processes (52). The excessive accumulation of ROS

induces oxidative stress within cells, resulting in damage to DNA,

proteins and lipids. This damage is implicated in the pathogenesis

of various diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular diseases and

neurodegenerative disorders. Furthermore, ROS accumulation has been

associated with NF-κB signaling and ferroptosis, as documented in

several studies (53–55). These findings establish a molecular

framework for mechanistic inquiry. Notably, KEGG pathway analysis

revealed a significant enrichment of upregulated genes in the ‘Base

Excision Repair’ pathway. Base excision repair is a crucial

mechanism by which cells address DNA damage and preserve genomic

stability, thereby playing an essential role in maintaining

cellular health and preventing disease progression (56).

Through GO analysis and literature review, the

present study concentrated on oxidative stress and the NF-κB

signaling pathway. Anxiety boosts ROS by stimulating the

neuroendocrine, autonomic and inflammatory systems (57). Excess ROS damages DNA, proteins and

mitochondria, depletes SOD/GSH and raises MDA, IL-6, IL-1β and

TNF-α (58–60). Oxidative stress switches on NF-κB,

releasing inflammatory mediators and neurotransmitters that amplify

anxiety. In bladder ischemia-reperfusion models, the same ROS burst

sensitives bladder nerves and triggered overactivity (61). Our previous study found that both

oxidative stress and NF-κB are involved in OAB models induced by a

high-salt diet (62). The present

study confirmed oxidative stress and NF-κB pathway activation in an

anxiety-induced OAB model, aligning with previous findings.

To identify DEGs, a PPI network was constructed

through data mining and integration. The present study found that

the upregulated DEGs Hsp90aa1, Hsp90ab1, and

Hsp90b1 were markedly elevated in the bladder tissues of the

CRS group, confirmed by q-PCR, with increased protein levels.

Heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) is a key molecular

chaperone involved in protein folding, stability, and signal

transduction. The main homologs in the Hsp90 family are Hsp90aa1,

Hsp90ab1, and Hsp90b1 (63).

Hsp90aa1, found on chromosome 14, encodes a chaperone that forms a

homodimer to assist in protein folding using ATPase activity

(64,65). Hsp90ab1 stabilizes various proteins

in the cytoplasm, maintaining cell homeostasis under stress

(66). Hsp90b1, located in the

endoplasmic reticulum (ER), aids in protein folding and secretion,

crucial during ER stress for maintaining protein balance (67). In cancers such as osteosarcoma and

breast cancer, NF-κB, JAK/STAT and autophagy pathways often

upregulate Hsp90 and fuel tumor growth (68–72).

However, few studies connect Hsp90 to urologic diseases such as

bladder cancer and acute kidney injury, with unclear mechanisms

(73,74). While HSP90 is important in various

diseases, its connection to OAB has not been reported until now.

The present study is the first, to the best of the authors'

knowledge, to show increased Hsp90 expression in an anxiety-induced

OAB model, potentially linked to oxidative stress and the NF-κB

signaling pathway. Perhaps in the future, we may be able to predict

the occurrence and severity of OAB by detecting the content of

HSP90 in the patient's bladder tissue or develop drugs that inhibit

the expression of HSP90 to treat OAB.

The present study successfully identified anxiety as

an independent risk factor for the onset of OAB for the first time

to the best of the authors' knowledge, developed an in vivo

model of anxiety-induced OAB, and made preliminary discoveries

regarding the underlying mechanisms. However, several limitations

must be acknowledged. First, the sample sizes collected from

clinical settings were relatively small, limiting the

generalizability of the findings. Although the overall sample

(n=80) provided 88% power to detect a medium-to-large main effect

of anxiety on OAB (partial ρ2 ≥0.20, α=0.05), post-hoc

analysis revealed that pairwise comparisons within the smallest

subgroups (OAB without anxiety, n=7; controls with anxiety, n=5)

remain under-powered (<50%). Consequently, negative findings in

these strata should be interpreted cautiously and future

prospective studies with pre-specified balanced allocation are

warranted. Second, the conclusions derived from the animal model

may not accurately represent the human condition, and it is

recommended that tissue samples be obtained via cystoscopic biopsy

to further validate these findings. Additionally, the results of

the present study cannot conclusively prove the causality between

anxiety and OAB. Further research using pharmacologic inhibition or

genetic knockdown are needed to confirm causal relationship.

The present study was the first, to the best of the

authors' knowledge, to identify anxiety as an independent risk

factor for OAB, using in vivo experiments to create an

anxiety-induced OAB model. Bioinformatic analyses, qPCR and IHC

confirmed increased Hsp90 expression in the bladder. The study also

suggested that anxiety-induced OAB activates oxidative stress and

the NF-κB pathway. Hsp90 could become a potential biomarker

and target for diagnosing and treating anxiety-induced OAB, pending

clinical trial confirmation.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by the Natural Science Foundation

of Fujian Province, China (grant no. 2024J011023) and the Startup

Fund for Scientific Research at Fujian Medical University (grant

no. 2022QH1057).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author. The raw sequence data

generated in the present study may be found in the Genome Sequence

Archive (Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics 2025), National

Genomics Data Center (Nucleic Acids Res 2025), China National

Center for Bioinformation/Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese

Academy of Sciences under accession number GSA: CRA034777 or at the

following URL: https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA034777.

Authors' contributions

HH conceived and designed the study. ZZ and LX

conducted experiments and prepared samples, with ZZ and HW handling

RNA-seq analysis. ZZ and HW confirmed the authenticity of all the

raw data. HW verified the data. ZZ and LX wrote the paper, while HH

and HW offered critical advice and revised it extensively. All

authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study received ethical clearance from

the Institutional Review Board of Fujian Provincial Hospital, with

the protocol number K2024-10-019. Informed consent was obtained in

writing from all participants. Animal experiments were performed at

the Animal Research Center of the Nanfang hospital, following

approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee

(approval no. NFYY-2021-0572).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Nambiar AK, Arlandis S, Bø K,

Cobussen-Boekhorst H, Costantini E, de Heide M, Farag F, Groen J,

Karavitakis M, Lapitan MC, et al: European association of urology

guidelines on the diagnosis and management of female non-neurogenic

lower urinary tract symptoms. Part 1: Diagnostics, overactive

bladder, stress urinary incontinence, and mixed urinary

incontinence. Eur Urol. 82:49–59. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Peyronnet B, Mironska E, Chapple C,

Cardozo L, Oelke M, Dmochowski R, Amarenco G, Gamé X, Kirby R, Van

Der Aa F and Cornu JN: A comprehensive review of overactive bladder

pathophysiology: On the way to tailored treatment. Eur Urol.

75:988–1000. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Chen LC and Kuo HC: Current management of

refractory overactive bladder. Low Urin Tract Symptoms. 12:109–116.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Chow PM, Liu SP, Chuang YC, Lee KS, Yoo

TK, Liao L, Wang JY, Liu M, Sumarsono B and Jong JJ: The prevalence

and risk factors of nocturia in China, South Korea, and Taiwan:

Results from a cross-sectional, population-based study. World J

Urol. 36:1853–1862. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Huang S, Guo C, Tai S, Ding H, Mao D,

Huang J and Qian B: Prevalence of overactive bladder in Chinese

women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One.

18:e02903962023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Ninomiya S, Naito K, Nakanishi K and

Okayama H: Prevalence and risk factors of urinary incontinence and

overactive bladder in Japanese Women. Low Urin Tract Symptoms.

10:308–314. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Mckellar K, Bellin E, Schoenbaum E and

Abraham N: Prevalence, risk factors, and treatment for overactive

bladder in a racially diverse population. Urology. 126:70–75. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Liu L: Exploring the association between

overactive bladder (OAB) and Cognitive decline: Mediation by

depression in elderly adults, a NHANES weighted analysis. Sci Rep.

15:36692025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Van den Ende M, Apostolidis A, Sinha S,

Kheir GB, Mohamed-Ahmed R, Selai C, Abrams P and Vrijens D: Should

We Be treating affective symptoms, like anxiety and depression

which may be related to LUTD in patients with OAB? ICI-RS 2024.

Neurourol Urodyn. 44:661–667. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Akkoç Y, Bardak AN, Yıldız N, Özlü A,

Erhan B, Yürü B, Öztekin SNS, Türkoğlu MB, Paker N, Yumuşakhuylu Y,

et al: The relationship between severity of overactive bladder

symptoms and cognitive dysfunction, anxiety and depression in

female patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord.

70:1044762023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zuluaga L, Caicedo JI, Mogollón MP,

Santander J, Bravo-Balado A, Trujillo CG, Diaz Ritter C, Rondón M

and Plata M: Anxiety and depression in association with lower

urinary tract symptoms: Results from the COBaLT study. World J

Urol. 41:1381–1388. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Sakakibara R, Ito T, Yamamoto T, Uchiyama

T, Yamanishi T, Kishi M, Tsuyusaki Y, Tateno F, Katsuragawa S and

Kuroki N: Depression, anxiety and the bladder. Low Urin Tract

Symptoms. 5:109–120. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Tanyeri MH, Buyukokuroglu ME, Tanyeri P,

Mutlu O, Ozturk A, Yavuz K and Kaya RK: Effects of mirabegron on

depression, anxiety, learning and memory in mice. An Acad Bras

Cienc. 93 (Suppl 4):e202106382021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Bouayed J and Soulimani R: Evidence that

hydrogen peroxide, a component of oxidative stress, induces

high-anxiety-related behaviour in mice. Behav Brain Res.

359:292–297. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Showraki M, Showraki T and Brown K:

Generalized anxiety disorder: Revisited. Psychiatr Q. 91:905–914.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Sheng L, Yao X, Ye J, Wang Z, Chen Y, Li J

and Li M: Eriocitrin alleviates inflammation and oxidative stress

in subarachnoid hemorrhage by regulating DUSP14. Discov Med.

35:1134–1146. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Song J, Han K, Wang Y, Qu R, Liu Y, Wang

S, Wang Y, An Z, Li J, Wu H and Wu W: Microglial activation and

oxidative stress in PM2.5-induced neurodegenerative disorders.

Antioxidants (Basel). 11:14822022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wang Y, Tang Q, Duan P and Yang L:

Curcumin as a therapeutic agent for blocking NF-κB activation in

ulcerative colitis. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 40:476–482.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Bai R, Guo J, Ye XY, Xie Y and Xie T:

Oxidative stress: The core pathogenesis and mechanism of

Alzheimer's disease. Ageing Res Rev. 77:1016192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Sanabria-Castro A, Alape-Girón A,

Flores-Díaz M, Echeverri-McCandless A and Parajeles-Vindas A:

Oxidative stress involvement in the molecular pathogenesis and

progression of multiple sclerosis: A literature review. Rev

Neurosci. 35:355–371. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Toussaint A, Hüsing P, Gumz A, Wingenfeld

K, Härter M, Schramm E and Löwe B: Sensitivity to change and

minimal clinically important difference of the 7-item Generalized

Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD-7). J Affect Disord.

265:395–401. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

National Research Council, . Committee for

the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals:

Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th edition.

National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2011

|

|

23

|

Campos AC, Fogaça MV, Aguiar DC and

Guimarães FS: Animal models of anxiety disorders and stress. Braz J

Psychiatry. 35 (Suppl 2):S101–S111. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wang Q, Wu Q, Wang J, Chen Y, Zhang G,

Chen J, Zhao J and Wu P: Ketamine analog methoxetamine induced

inflammation and dysfunction of bladder in rats. Int J Mol Sci.

18:1172017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Love MI, Huber W and Anders S: Moderated

estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with

DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15:5502014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y and He QY:

clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among

gene clusters. OMICS. 16:284–287. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein

D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT,

et al: Gene Ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. The gene

ontology consortium. Nat Genet. 25:25–29. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Wyder S,

Forslund K, Heller D, Huerta-Cepas J, Simonovic M, Roth A, Santos

A, Tsafou KP, et al: STRING v10: Protein-protein interaction

networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res.

43:D447–D452. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS,

Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B and Ideker T: Cytoscape: A

software environment for integrated models of biomolecular

interaction networks. Genome Res. 13:2498–2504. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, Griffiths D,

Rosier P, Ulmsten U, Van Kerrebroeck P, Victor A and Wein A;

Standardisation Sub-Committee of the International Continence

Society, : The standardisation of terminology in lower urinary

tract function: Report from the standardisation sub-committee of

the International Continence Society. Urology. 61:37–49. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Obaidul Islam M, Bacchetti T, Berrougui H,

Abdelouahed Khalil and Ferretti G: Effect of glycated HDL on

oxidative stress and cholesterol homeostasis in a human bladder

cancer cell line, J82. Exp Mol Pathol. 126:1047772022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Chen J, Li Q, Hong Y, Zhou X, Yu C, Tian

X, Zhao J, Long C, Shen L, Wu S and Wei G: Inhibition of the NF-κB

signaling pathway alleviates pyroptosis in bladder epithelial cells

and neurogenic bladder fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci. 24:111602023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Fang T, Xiong J, Huang X, Fang X, Shen X,

Jiang Y and Lu H: Extracellular Hsp90 of Candida albicans

contributes to the virulence of the pathogen by activating the

NF-κB signaling pathway and inducing macrophage pyroptosis.

Microbiol Res. 290:1279642025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Cheng HM, Xing M, Zhou YP, Zhang W, Liu Z,

Li L, Zheng Z, Ma Y, Li P, Liu X, et al: HSP90β promotes

osteoclastogenesis by dual-activation of cholesterol synthesis and

NF-κB signaling. Cell Death Differ. 30:673–686. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Knight S, Luft J, Nakagawa S and Katzman

WB: Comparisons of pelvic floor muscle performance, anxiety,

quality of life and life stress in women with dry overactive

bladder compared with asymptomatic women. BJU Int. 109:1685–1689.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Bou Kheir G, Verbakel I, Hervé F, Bauters

W, Abou Karam A, Holm-Larsen T, Van Laecke E and Everaert K: OAB

supraspinal control network, transition with age, and effect of

treatment: A systematic review. Neurourol Urodyn. 41:1224–1239.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zhu J, Hu X, Dong X and Li L: Associations

between risk factors and overactive bladder: A Meta-analysis.

Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 25:238–246. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zhong M and Wang Z: The Association

between anthropometric indices and overactive bladder (OAB): A

Cross-sectional study from the NHANES 2005–2018. Neurourol Urodyn.

44:345–359. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Karjalainen PK, Tolppanen A-M, Mattsson

NK, Wihersaari OAE, Jalkanen JT and Nieminen K: Pelvic organ

prolapse surgery and overactive bladder symptoms-a population-based

cohort (FINPOP). Int Urogynecol J. 33:95–105. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Palma T, Raimondi M, Souto S, Fozzatti C,

Palma P and Riccetto C: Prospective study of prevalence of

overactive bladder symptoms and child-bearing in women of

reproductive age. J Obstet Gynaecol. 39:1324–1329. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Lai HH, Rawal A, Shen B and Vetter J: The

relationship between anxiety and overactive bladder or urinary

incontinence symptoms in the clinical population. Urology.

98:50–57. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Melotti IGR, Juliato CRT, Tanaka M and

Riccetto CLZ: Severe depression and anxiety in women with

overactive bladder. Neurourol Urodyn. 37:223–228. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Mehr AA, Kreder KJ, Lutgendorf SK, Ten

Eyck P, Greimann ES and Bradley CS: Daily symptom associations for

urinary urgency and anxiety, depression and stress in women with

overactive bladder. Int Urogynecol J. 33:841–850. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Sezginer EK, Yilmaz-Oral D, Lokman U,

Nebioglu S, Aktan F and Gur S: Effects of varying degrees of

partial bladder outlet obstruction on urinary bladder function of

rats: A novel link to inflammation, oxidative stress and hypoxia.

Low Urin Tract Symptoms. 11:O193–O201. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Dunton CL, Purves JT, Hughes FM and

Nagatomi J: BOO induces fibrosis and EMT in urothelial cells which

can be recapitulated in vitro through elevated storage and voiding

pressure cycles. Int Urol Nephrol. 53:2007–2018. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Niemczyk G, Fus L, Czarzasta K, Jesion A,

Radziszewski P, Gornicka B and Cudnoch-Jedrzejewska A: Expression

of toll-like receptors in the animal model of bladder outlet

obstruction. Biomed Res Int. 2020:66323592020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Wishahi M, Hassan S, Kamal N, Badawy M and

Hafiz E: Is bladder outlet obstruction rat model to induce

overactive bladder (OAB) has similarity to human OAB? Research on

the events in smooth muscle, collagen, interstitial cell and

telocyte distribution. BMC Res Notes. 17:222024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Kang YJ, Jin LH, Park CS, Shin HY, Yoon SM

and Lee T: Early sequential changes in bladder function after

partial bladder outlet obstruction in awake Sprague-Dawley rats:

Focus on the decompensated bladder. Korean J Urol. 52:835–841.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Shen JD, Chen SJ, Chen HY, Chiu KY, Chen

YH and Chen WC: Review of animal models to study urinary bladder

function. Biology (Basel). 10:13162021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Ye F, Dong MC, Xu CX, Jiang N, Chang Q,

Liu XM and Pan RL: Effects of different chronic restraint stress

periods on anxiety- and depression-like behaviors and

tryptophan-kynurenine metabolism along the brain-gut axis in

C57BL/6N mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 965:1763012024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Brieger K, Schiavone S, Miller FJ and

Krause KH: Reactive oxygen species: From health to disease. Swiss

Med Wkly. 142:w136592012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Rauf A, Khalil AA, Awadallah S, Khan SA,

Abu-Izneid T, Kamran M, Hemeg HA, Mubarak MS, Khalid A and

Wilairatana P: Reactive oxygen species in biological systems:

Pathways, associated diseases, and potential inhibitors-A review.

Food Sci Nutr. 12:675–693. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Wang P, Liu WC, Han C, Wang S, Bai MY and

Song CP: Reactive oxygen species: Multidimensional regulators of

plant adaptation to abiotic stress and development. J Integr Plant

Biol. 66:330–367. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Ahola S and Langer T: Ferroptosis in

mitochondrial cardiomyopathy. Trends Cell Biol. 34:150–160. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Gohil D, Sarker AH and Roy R: Base

excision repair: Mechanisms and impact in biology, disease, and

medicine. Int J Mol Sci. 24:141862023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Murphy MP, Bayir H, Belousov V, Chang CJ,

Davies KJA, Davies MJ, Dick TP, Finkel T, Forman HJ,

Janssen-Heininger Y, et al: Guidelines for measuring reactive

oxygen species and oxidative damage in cells and in vivo. Nat

Metab. 4:651–662. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Burtscher J, Niedermeier M, Hüfner K, van

den Burg E, Kopp M, Stoop R, Burtscher M, Gatterer H and Millet GP:

The interplay of hypoxic and mental stress: Implications for

anxiety and depressive disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev.

138:1047182022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Martinez-Moral MP and Kannan K: Analysis

of 19 urinary biomarkers of oxidative stress, nitrative stress,

metabolic disorders, and inflammation using liquid

chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem.

414:2103–2116. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Chaudhary P, Janmeda P, Docea AO,

Yeskaliyeva B, Abdull Razis AF, Modu B, Calina D and Sharifi-Rad J:

Oxidative stress, free radicals and antioxidants: Potential

crosstalk in the pathophysiology of human diseases. Front Chem.

10:11581982023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Wu YH, Chueh KS, Chuang SM, Long CY, Lu JH

and Juan YS: Bladder hyperactivity induced by oxidative stress and

bladder ischemia: A review of treatment strategies with

antioxidants. Int J Mol Sci. 22:60142021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Xue J, Zhou Z, Zhu Z, Sun Q, Zhu Y and Wu

P: A high salt diet impairs the bladder epithelial barrier and

activates the NLRP3 and NF-κB signaling pathways to induce an

overactive bladder in vivo. Exp Ther Med. 28:3622024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Chen B, Piel WH, Gui L, Bruford E and

Monteiro A: The HSP90 family of genes in the human genome: Insights

into their divergence and evolution. Genomics. 86:627–637. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Yang S, Nie T, She H, Tao K, Lu F, Hu Y,

Huang L, Zhu L, Feng D, He D, et al: Regulation of TFEB nuclear

localization by HSP90AA1 promotes autophagy and longevity.

Autophagy. 19:822–838. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Zuehlke AD, Beebe K, Neckers L and Prince

T: Regulation and function of the human HSP90AA1 gene. Gene.

570:8–16. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Sharma S and Kumar P: Dissecting the

functional significance of HSP90AB1 and other heat shock proteins

in countering glioblastomas and ependymomas using omics analysis

and drug prediction using virtual screening. Neuropeptides.

102:1023832023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Huang X, Zhang W, Yang N, Zhang Y, Qin T,

Ruan H, Zhang Y, Tian C, Mo X, Tang W, et al: Identification of

HSP90B1 in pan-cancer hallmarks to aid development of a potential

therapeutic target. Mol Cancer. 23:192024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Liu C, Zhao W, Su J, Chen X, Zhao F, Fan

J, Li X, Liu X, Zou L, Zhang M, et al: HSP90AA1 interacts with CSFV

NS5A protein and regulates CSFV replication via the JAK/STAT and

NF-κB signaling pathway. Front Immunol. 13:10318682022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Liu H, Zhang Z, Huang Y, Wei W, Ning S, Li

J, Liang X, Liu K and Zhang L: Plasma HSP90AA1 predicts the risk of

breast cancer onset and distant metastasis. Front Cell Dev Biol.

9:6395962021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Tang F, Li Y, Pan M, Wang Z, Lu T, Liu C,

Zhou X and Hu G: HSP90AA1 promotes lymphatic metastasis of

hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma by regulating

epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncol Res. 31:787–803. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Xiao X, Wang W, Li Y, Yang D, Li X, Shen

C, Liu Y, Ke X, Guo S and Guo Z: HSP90AA1-mediated autophagy

promotes drug resistance in osteosarcoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

37:2012018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Wei D, Tian X, Zhu L, Wang H and Sun C:

USP14 governs CYP2E1 to promote nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

through deubiquitination and stabilization of HSP90AA1. Cell Death

Dis. 14:5662023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Li S, Zhou H, Liang Y, Yang Q, Zhang J,

Shen W and Lei L: Integrated analysis of transcriptome-wide

m6A methylation in a Cd-induced kidney injury rat model.

Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 256:1149032023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Pichler R, Diem G, Hackl H, Koutník J,

Mertens LS, D Andrea D, Pradere B, Soria F, Mari A, Laukhtina E, et

al: Intravesical BCG in bladder cancer induces innate immune

responses against SARS-CoV-2. Front Immunol. 14:12021572023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|