Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a

progressive, largely irreversible lung disorder driven by genetic

or environmental factors that is characterized by a complex

inflammatory response and the destruction of lung parenchyma,

leading to emphysema formation (1). From a genetic standpoint, a single

amino acid substitution in the Z allele of the SERPINA1 gene

results in reduced levels of α-1 antitrypsin (AAT) in the

bloodstream of homozygous or loss-of-function homozygous

individuals, which constitutes the primary pathogenesis of COPD

(2). Environmental risk factors,

particularly prolonged exposure to cigarette smoke and harmful

particulate matter (PM), are key contributors, with cigarette smoke

identified as a notable environmental risk factor for COPD

(3).

The inhalation of carbon monoxide, nicotine and

other components of cigarette smoke damages lung epithelial cells,

thereby triggering the release of various inflammatory mediators.

These mediators subsequently recruit circulating monocytes,

mesophilic granulocytes and T cells into lung tissue, thereby

initiating a complex inflammatory response (4). The recruited immune cells further

release inflammatory mediators, which increase pulmonary vascular

permeability, induce pulmonary edema and secrete elastases, which

damage lung tissue and promote airway remodeling (5). As COPD advances, patients face an

increased risk of cor pulmonale (also known as pulmonary heart

disease) and respiratory failure (6). Current treatments are primarily

symptomatic, comprising inhaled bronchodilators, glucocorticoids or

oxygen therapy to alleviate dyspnea in individuals with persistent

airflow limitation (7).

Consequently, the molecular mechanisms underlying COPD and the

development of higher-quality drug delivery systems require further

research to improve the current the treatment of COPD.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are nanoscale lipid

bilayer vesicles secreted by living cells, which are present in

various body fluids, including blood, urine and ascites (8). Upon release into the extracellular

space, EVs facilitate the efficient transfer of bioactive

molecules, including proteins, microRNAs (miRNAs/miRs) and DNA,

making them important mediators of intercellular communication

(9). In previous years, EVs have

been increasingly associated with the progression of various

diseases, including malignant tumors, diabetes mellitus, stroke and

lung inflammation (10,11). Furthermore, based on their

widespread presence in biofluids, high biocompatibility, small

particle size and other physiological properties, EVs have both

been applied as a marker for disease diagnosis and developed as a

platform for drug-targeted therapeutic carriers (12). The present review aims to explore

the molecular mechanisms underlying COPD pathogenesis, with a focus

on the potential role of EVs in COPD development. The present

review also summarizes current approaches to using EVs as

biomarkers for COPD prediction. Finally, the present review

highlights previous advances that have been made in the development

of EV-based therapies and their potential as drug delivery systems

for COPD treatment, with the aim of offering novel research avenues

for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of COPD. Literature

searches were conducted in PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Scopus (https://www.scopus.com/), and Web of Science

(https://www.webofscience.com/) using the

following search terms: ‘Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease’ AND

‘Extracellular vesicles’. After further filtering based on article

content, 97 relevant articles were ultimately retained.

Molecular mechanisms of COPD

pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of COPD is both complex and

multifactorial, involving airway epithelial cell (AEC) damage from

cigarette smoke inhalation, a dysregulated inflammatory response

driven by an imbalance between oxidation and antioxidation, and the

recruitment of immune cells to lung tissue that release various

proteases, leading to protease/antiprotease imbalance and

subsequent airway remodeling.

Imbalance of oxidation and

anti-oxidation

An important factor in the pathogenesis of COPD is

the imbalance between oxidant sources and sinks in the airways.

Patients with COPD are exposed to exogenous oxidants, such as

cigarette smoke and airborne PM, which trigger an endogenous

inflammatory response (13). This

response recruits neutrophils and mononuclear macrophages to the

lungs, where they release superoxide anions, hydrogen peroxide and

reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby inducing oxidative stress in

the airways (14). These ROS

further amplify the inflammatory response by regulating

redox-sensitive transcription factors, including nuclear factor κB

(NF-κB), activator protein-1 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)

(15). Additionally, ROS promote

mucous membrane metaplasia and the expression of the mucin genes

MUC5AC and MUC5B, leading to increased mucus

production (16). Notably,

oxidative stress can damage DNA, and patients with COPD often fail

to repair double-stranded DNA breaks promptly, which has the effect

of raising their susceptibility to lung cancer (17).

Nuclear factor erythroid-2 counteracts oxidative

reactions by regulating related factors, such as nuclear factor

erythroid-2-related factor-2 (Nrf2), reducing cellular oxidative

damage. In oxidative stress responses, Nrf2 undergoes

phosphorylation and decouples from Kelch-like ECH-associated

protein 1, subsequently entering the cell nucleus to participate in

gene transcription, where it can activate the transcription of

various antioxidant factors (including heme oxygenase 1,

N-acetyl-L-tyrosine oxidoreductase and glutathione S-transferase)

(18). However, in patients with

COPD, reduced levels of this factor lead to an impairment of

endogenous antioxidant production, thereby weakening the

self-protective mechanisms of the body (19). Collectively, the residual effects

of oxidative stress contribute to lung cell damage, excessive mucus

secretion, protease inactivation and enhanced lung inflammation via

activation of redox-sensitive transcription factors, thereby

facilitating COPD progression. Additionally, cigarette smoke

induces mitophagy in AECs in COPD, which both impairs oxidative

phosphorylation, and leads to decreases in intracellular ATP levels

and increases in mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) production. This

mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to cellular senescence,

further exacerbating the progression of COPD (20).

Chronic inflammation

COPD is characterized by chronic inflammation, with

patients exhibiting distinctive inflammatory profiles in the lungs

marked by increases in the numbers of macrophages, neutrophils,

eosinophils and T lymphocytes (21). Inhalation of cigarette smoke, PM or

other oxidants activates AECs and macrophages, stimulating them to

release a range of inflammatory mediators, including leukotriene B4

(LTB4), interleukin (IL)-6, granulocyte-macrophage

colony-stimulating factor, CXCL8, CXCL1, ROS and tumor necrosis

factor α (TNF-α) (22). Even after

smoking cessation, the inflammatory response persists, suggesting

that COPD inflammation is maintained by self-sustaining mechanisms

(21). The aforementioned

inflammatory mediators not only exacerbate lung tissue damage and

amplify the inflammatory response, but also serve to recruit

monocytes, neutrophils and lymphocytes from the peripheral blood to

the lungs (23). CXCL1 primarily

recruits monocytes, whereas LTB4, CXCL1, CXCL5 and CXCL8 facilitate

the recruitment of neutrophils. The recruited neutrophils and

macrophages, activated by oxidative stress, contribute to the

metaplasia of goblet cells and increased mucus secretion (24). The release of proteases, including

matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), tissue proteases and neutrophil

elastase, degrades the extracellular matrix and alveolar elastin,

leading to localized and generalized alveolar emphysema (25). Notably, collagen and elastin

breakdown products act as chemotactic factors for inflammatory

cells, further perpetuating the inflammatory cycle in patients with

COPD (26).

Protease-antiprotease imbalance

In response to oxidative stress and inflammatory

mediators, macrophages and neutrophils are recruited to the lungs,

where they secrete various proteases (such as inherited deficiency

of α1-antitrypsin, neutrophil elastase and MMPs) that degrade the

structural components of the lungs, contributing to tissue

remodeling (26). For example,

macrophage secretions of MMP-2 and MMP-9 disrupt the elastic

framework of the alveoli, leading to emphysema formation (27). MMP-12 is involved in pulmonary

vascular remodeling through regulating the migration, proliferation

and release of mitogens and growth factors from smooth muscle cells

(28). In COPD, the endogenous MMP

inhibitor, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases, is cleaved by

neutrophil elastase and MMPs, resulting in elevated MMP-2 levels in

lung tissue (29). Additionally,

mutations in the AAT gene, particularly the Z allele, have been

found to cause a marked deficiency in AAT, leading to the

accumulation of the misfolded protein in hepatocytes (30). In addition, a deficiency of

circulating AAT results in an imbalance between proteases and

inhibitors in the lung tissue, promoting airway remodeling and

airflow limitation (31).

EV involvement in COPD pathogenesis

General overview of EVs

EVs are non-replicating, nanoscale vesicles

originally recognized for their role in maintaining homeostasis and

eliminating waste, which has attracted notable research interest

(31). During biogenesis, EVs

effectively encapsulate nucleic acids, proteins, lipids and other

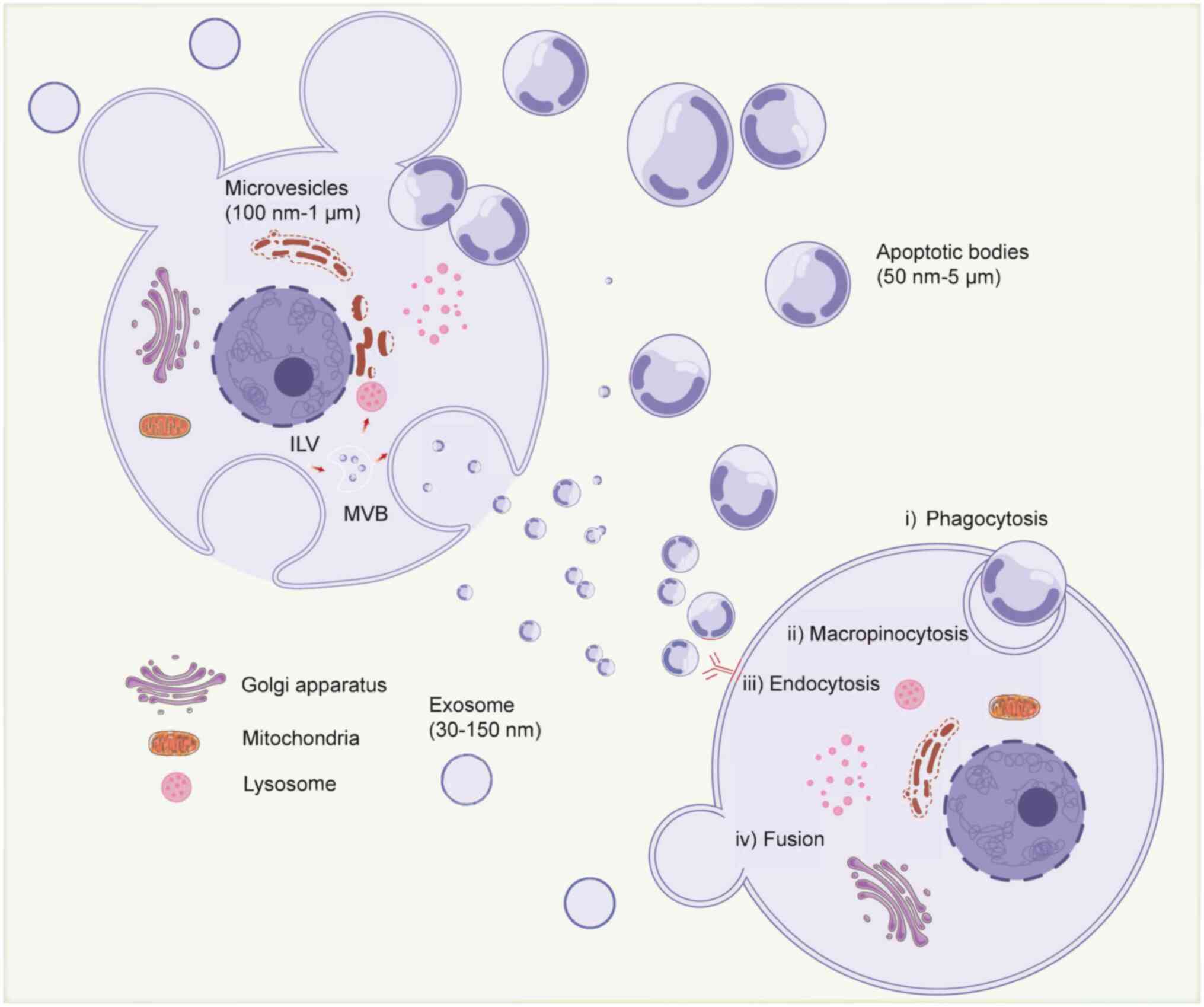

cellular components from the donor cell (32). On the basis of their biogenesis

pathways and particle sizes, EVs are classified into three

categories: Exosomes (30–150 nm), microvesicles (MVs; 100 nm-1 µm)

and apoptotic bodies (50 nm-5 µm) (33,34).

Exosome biogenesis begins with the formation of plasma membrane

indentations that encapsulate cell proteins and soluble proteins

from the extracellular environment, creating a cup-shaped

structure. These early endosomes undergo further sorting,

development and maturation into late endosomes, which invaginate to

form multivesicular bodies (MVBs). MVBs subsequently fuse with

lysosomes or autophagosomes, releasing exosomes (35). The biogenesis of MVs involves

localized accumulation of actin filaments and the flipping of

phosphatidylserine from the inner to the outer leaflet of the

membrane, altering membrane curvature and inducing vesicle budding

(36). Apoptotic bodies are

generated through the rupture of the plasma membrane in apoptotic

cells, followed by continuous volume reduction and actinin-driven

contraction, which causes the accumulation of cellular contents and

an increase in hydrostatic pressure, ultimately leading to vesicle

formation. The nucleus then fragments, resulting in the formation

of apoptotic bodies (37). Once

released into the extracellular space, EVs can be internalized by

recipient cells via mechanisms such as granzyme-independent

endocytosis, macropinocytosis and phagocytosis, where they release

their cargo, including nucleic acids, proteins and other molecules,

thereby facilitating intercellular communication (38) (Fig.

1).

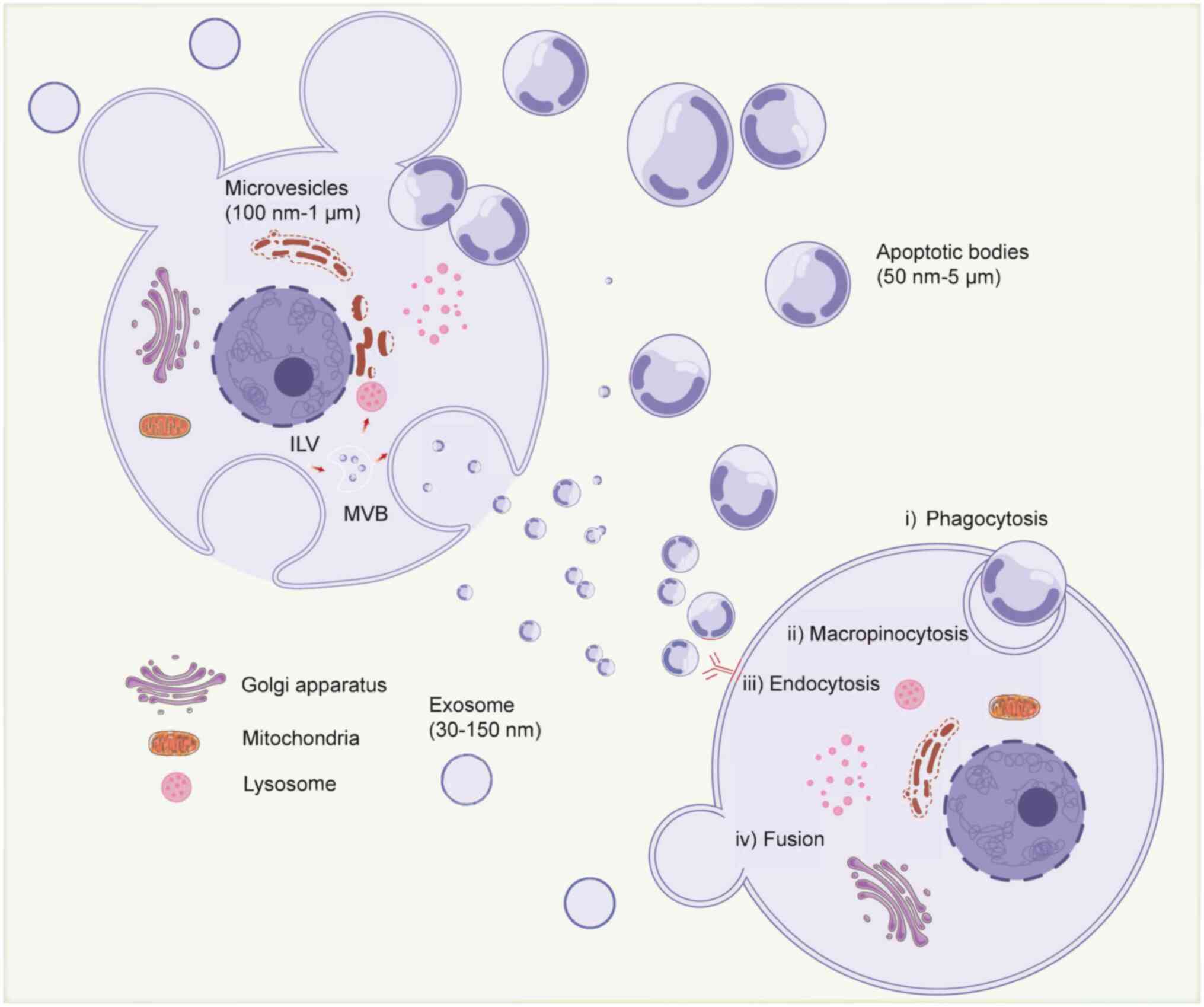

| Figure 1.Biogenesis, secretion and cell entry

of EVs. EVs are categorized into exosomes, apoptotic bodies and MVs

based on their biological origin and size. Exosomes produce ILVs

through inward budding of early endosomes to form MVBs, which

subsequently fuse with lysosomes or cell membranes and are released

into the extracellular environment of the exosome. MVs are produced

by outward budding from the plasma membrane. Apoptotic bodies are

released during cell death through plasma membrane vesicles. EVs

can deliver cargo to recipient cells through phagocytosis,

megakaryocytosis, endocytosis, direct fusion and other means, and

subsequently modulate biological behavior. Created with

BioRender.com (https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/692ee7fb97717aa47f30567d?slideId=76ff231c-5a96-4f30-a8e7-0972073ada7c).

EVs, extracellular vesicles; MVs, microvesicles; MVBs,

multivesicular bodies; ILV, intraluminal vesicle. |

Role of EVs in the pathogenesis of

COPD

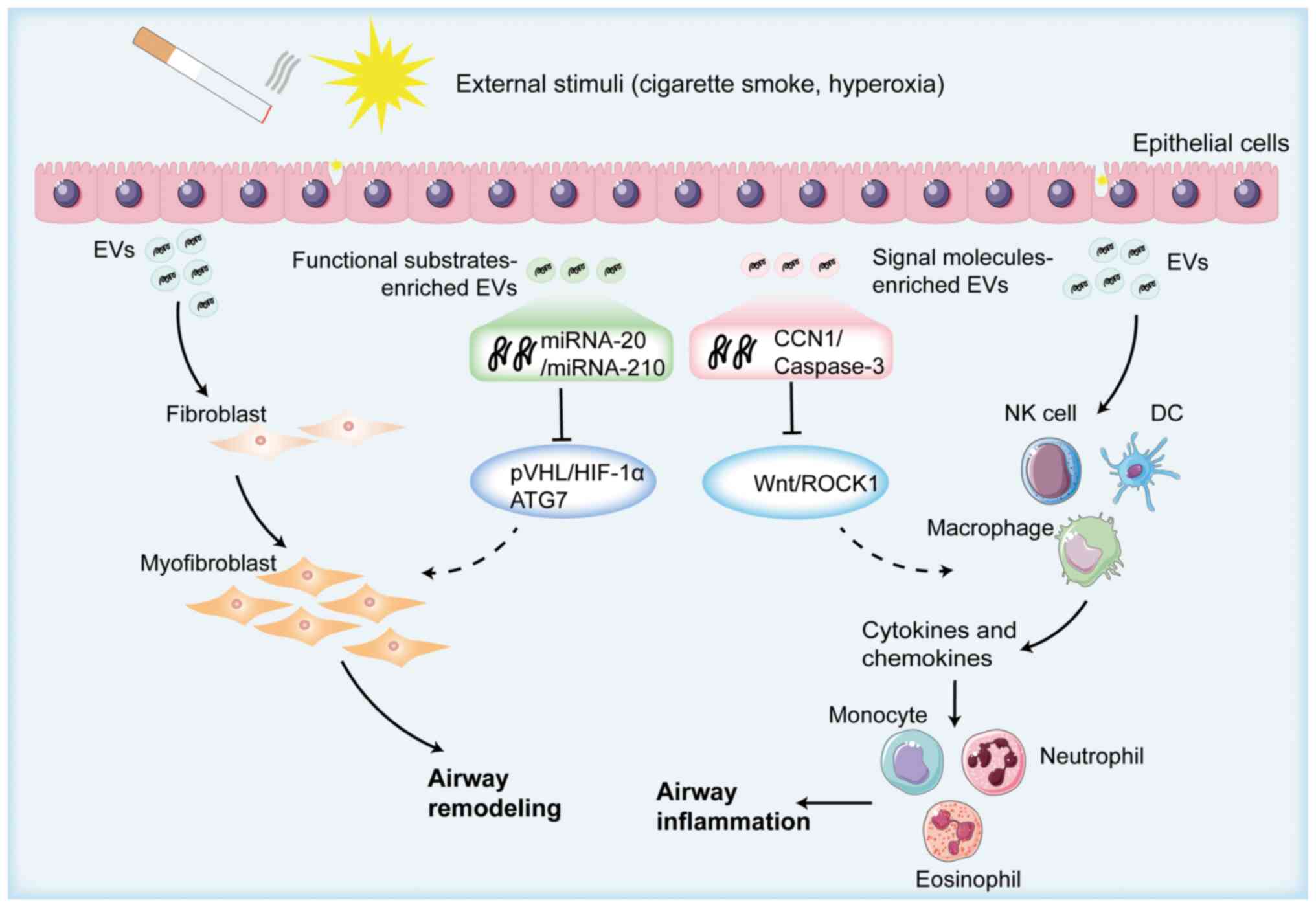

Prolonged exposure to irritants such as cigarette

smoke leads to the destruction of the structural integrity of the

lungs and their dysfunction (39).

In response to such irritants, AECs secrete a variety of EVs,

containing components such as miR-210, miR-21 and cellular

communication network factor 1 (CCN1) (40). Among these, CCN1-containing EVs

activate the Wnt signaling pathway, which induces the secretion of

pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-8 and monocyte

chemoattractant protein 1, by epithelial cells. This activation

promotes the recruitment of circulating T lymphocytes, neutrophils

and monocytes to the lungs, further exacerbating the inflammatory

response (41). Neutrophils and

monocytes release matrix proteases that degrade the structural

integrity of alveoli, contributing to the development of pulmonary

emphysema. Furthermore, T lymphocytes secrete EVs that, through a

positive feedback mechanism, stimulate epithelial cells to release

IL-6 and inhibit the secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine

IL-10, further damaging the airways (42).

Additionally, miR-210-containing EVs target the

autophagy-related 7 gene in lung fibroblasts (LFs), inhibiting

autophagosome formation (42).

This impairment in autophagy leads to the increased expression of

type I collagen and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) in LFs, promoting

myofibroblast differentiation and airway wall thickening (43). Similarly, miR-21-containing EVs

promote myofibroblast differentiation by targeting von

Hippel-Lindau protein (pVHL), stabilizing hypoxia-inducible factor

1α, thus facilitating airway remodeling (44). EVs from inhaled bacteria or viruses

also serve a role in COPD pathogenesis. For example, bacterial

outer-membrane vesicles (OMVs) from Moraxella catarrhalis

contribute to pulmonary inflammation (45). OMVs derived from Pseudomonas

aeruginosa inhibit chloride secretion mediated by cystic

fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator, reducing pathogen

clearance through mucociliary action and amplifying the

inflammatory response (46).

Although the exact mechanisms via which EVs influence COPD have yet

to be fully elucidated, their involvement in the pathogenesis of

COPD is notable (Fig. 2).

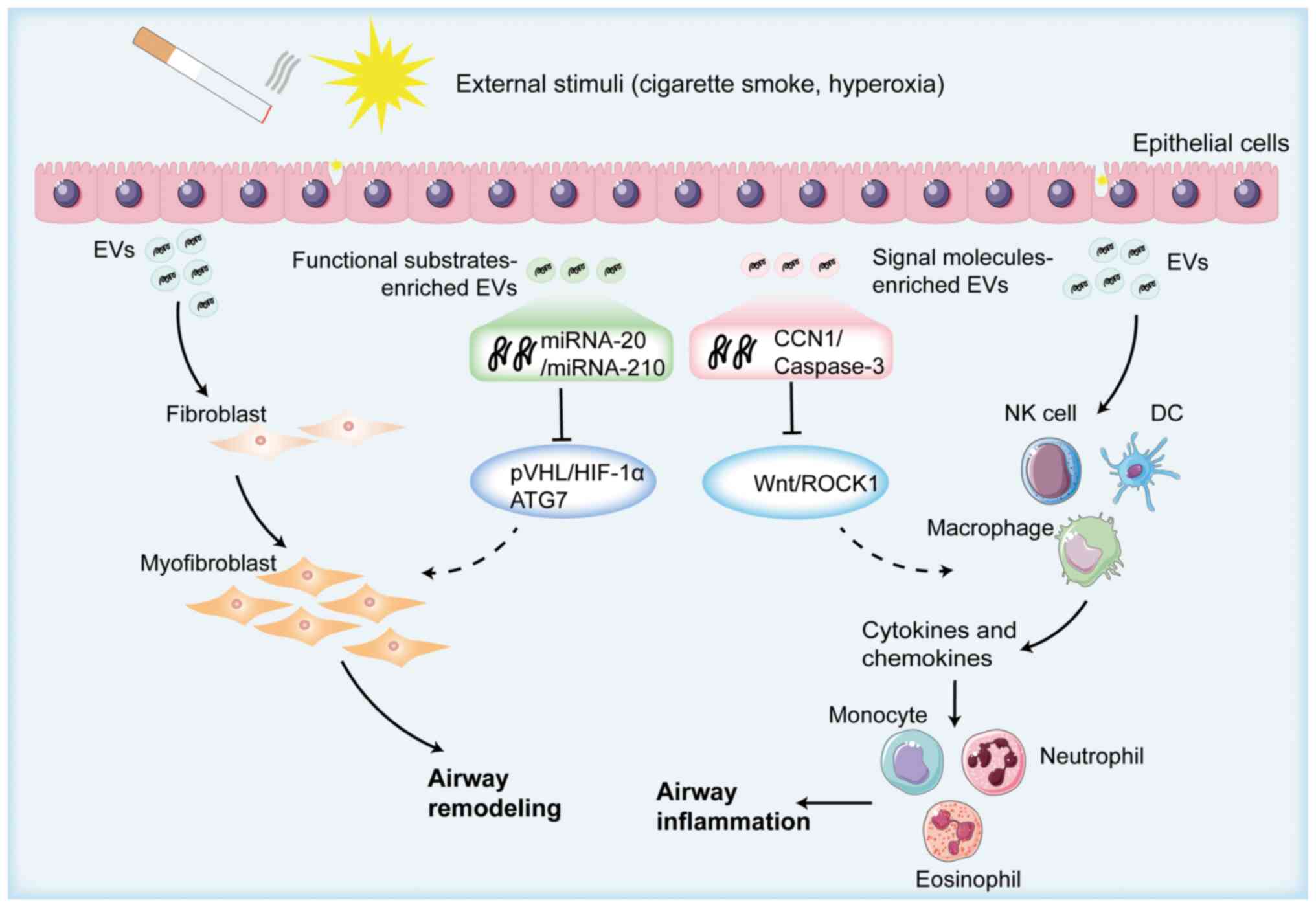

| Figure 2.Schematic overview of epithelial

EV-induced airway remodeling. Epithelial cells secrete a large

number of EVs after being stimulated by the external environment,

and miR-210, miR-21, cellular communication network factor 1 and

other components contained in EVs induce the increased expression

of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-8 and monocyte

chemoattractant protein-1, secreted by activated epithelial cells.

This is achieved by activating the Wnt signaling pathway/hypoxia

inducible factor-1α pathway, which enhances the differentiation of

fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, the contraction of smooth muscle

cells and the accumulation of extracellular matrix proteins,

ultimately promoting airway remodeling. Created with BioRender.com

(https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/692eed2c2bdb071cce996f3d?slideId=f9661b16-c75e-4ba9-a385-974bcfbc0a16).

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; EVs, extracellular

vesicles; CCN1, cellular communication network factor 1; miRNA,

microRNA; NK, natural killer; DC, dendritic cell; ROCK1,

Rho-associated protein kinase 1; PVHL, von Hippel-Lindau tumor

suppressor; HIF-1α, hypoxia inducible factor-1α; ATG7, autophagy

related 7. |

EVs in the diagnosis and treatment of

COPD

Application of EVs in COPD

diagnosis

Patients with COPD typically present with one or

more symptoms such as exertional dyspnea, cough, sputum production,

chest tightness or fatigue (47).

Clinically, COPD diagnosis involves assessing lung function [using

the ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 sec (FEV1) to forced

vital capacity (FVC) post-bronchodilator, with a ratio <0.70

indicating a positive COPD diagnosis], along with chest X-rays,

chest CT scans, and serum markers such as soluble receptors for

advanced glycation end products (48,49).

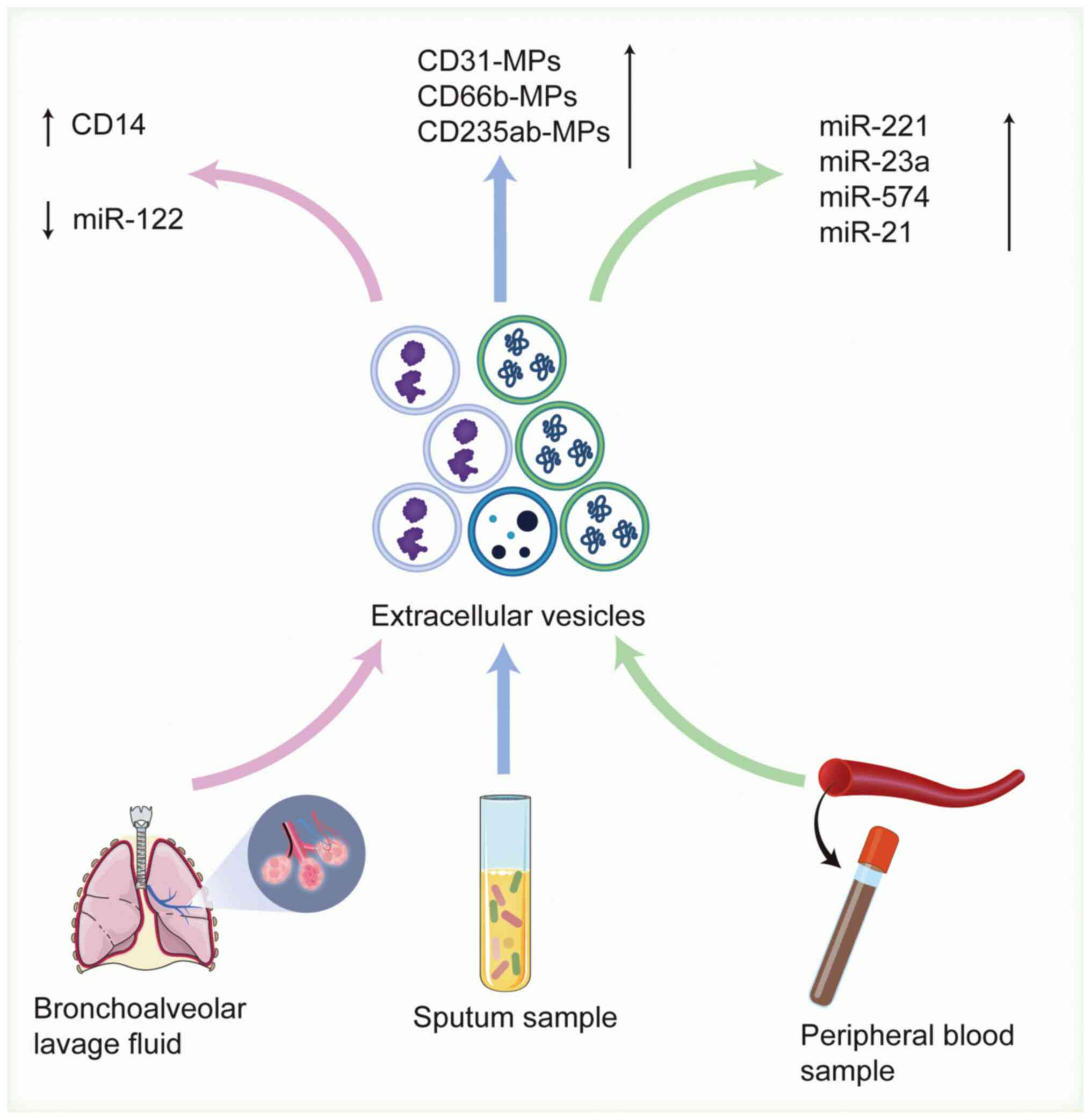

The heterogeneity of EVs is associated with the type and state of

the cells from which they originate. Analyzing the number or

specific content of EVs in peripheral blood, bronchoalveolar lavage

fluid (BALF) or sputum offers new diagnostic possibilities for COPD

(50) (Fig. 3).

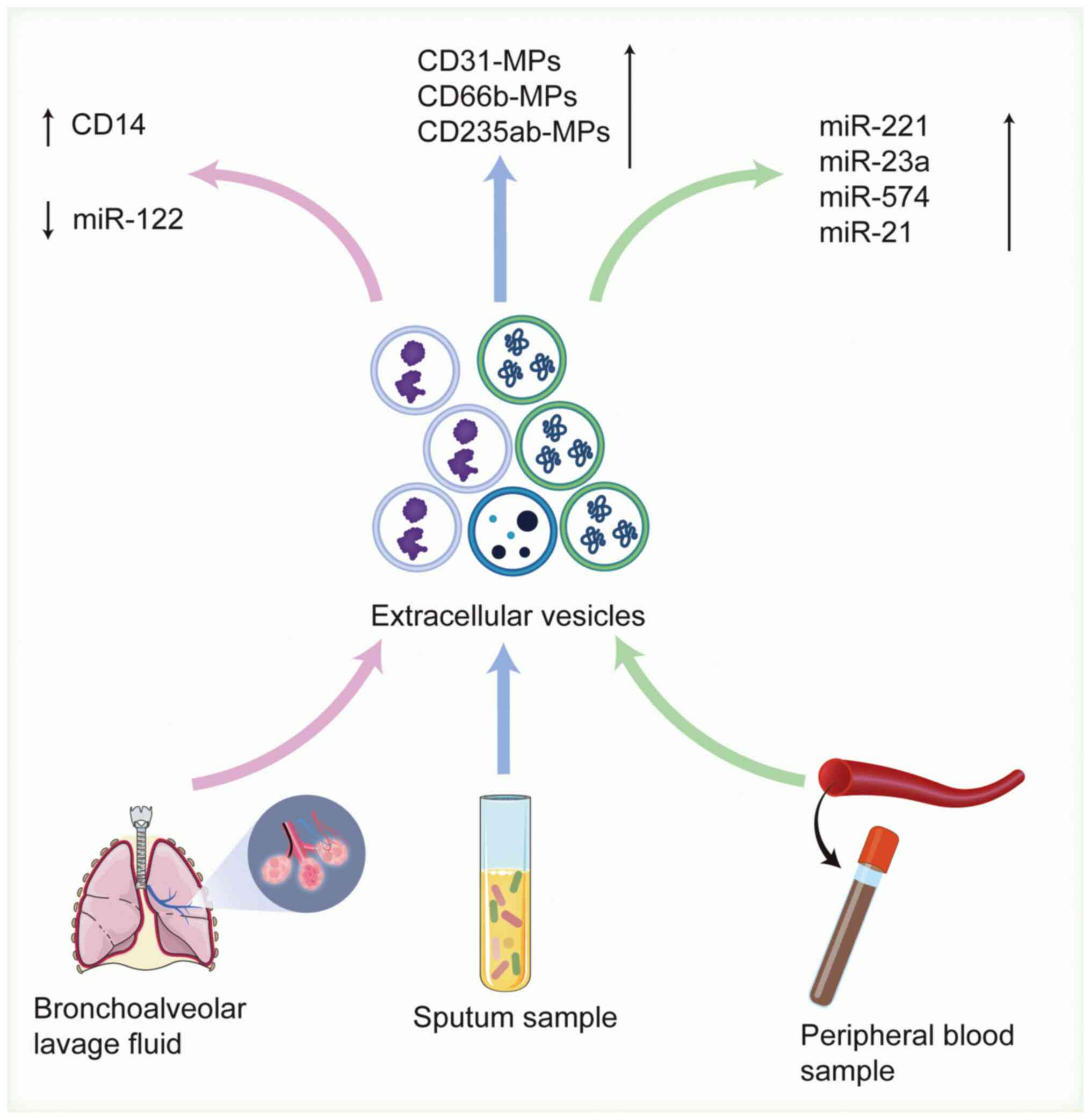

| Figure 3.Schematic overview of EV-based

biomarkers in COPD diagnosis. By detecting sputum, bronchoalveolar

lavage fluid and EVs in blood samples as markers for the diagnosis

of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, the concentrations of

CD31-MPs, CD66b-MPs, CD235ab-MPs and total protein in sputum

sample-derived EVs are notably increased, the levels of miR-122 in

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid are decreased, and the expression

levels of EV miR-221, miR-23a and miR-574 in blood samples are also

notably increased. Created with BioRender.com (https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/692eeccc235f309bfe04b81d?slideId=44a0ee63-27a9-433b-8188-676b7956b82a).

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; miR, microRNA; EVs,

extracellular vesicles; MPs, microparticles. |

EVs derived from sputum

Sputum, a secretion from the respiratory tract, is a

vital diagnostic tool for lung diseases such as COPD, lung cancer,

tuberculosis and chronic pneumonia. The analysis of sputum

supernatant media or sputum cells can provide important diagnostic

information (51). For example,

miR-21, miR-155 and miR-210 levels are markedly elevated in sputum

from patients with lung cancer, while detecting Mycobacterium

tuberculosis in sputum is key for diagnosing pulmonary

tuberculosis (52). However,

spontaneous sputum samples often have poor quality, and hypertonic

or isotonic saline containing salbutamol is typically used to

induce sputum production (53).

Sputum testing is less invasive and easier to perform compared with

testing BALF (54). Recent

research has successfully isolated and purified EVs from sputum

samples of 20 patients with COPD, revealing a notable increase in

the general protein concentration in COPD sputum samples

(106.70±60.56 µg/ml) compared with the healthy control group

(56.82±11.99 µg/ml) (55). Another

study identified that EVs containing CD31, CD66b and CD235 in

sputum are associated with COPD progression (56). Although few studies have been

published on the physicochemical properties of sputum EVs, these

findings suggest that analyzing EVs in sputum components could be a

valuable diagnostic approach for COPD.

BALF

BALF is a standard clinical method for diagnosing

infectious diseases, non-infectious immune diseases and malignant

conditions in the lungs (57). The

procedure involves introducing saline into the alveoli via a

bronchoscope, and then aspirating alveolar cells and biochemical

components under negative pressure (58). Compared with more invasive

procedures, such as lung tissue or bronchial biopsies, BALF is less

invasive and has fewer complications. BALF detects a variety of

components, including cells, proteins, genes, microorganisms and

EVs, making this procedure a more comprehensive reflection of lung

pathology (59). Given the

heterogeneity of EVs and their close association with the biology

of their donor cells, analyzing EVs in BALF can provide a valuable

basis for diagnosing COPD. For example, one study found that the

expression of miR-122-5p in pulmonary EVs from patients with COPD

was significantly downregulated compared with that in healthy

smokers and non-smokers (57). A

metabolomics database of BALF comprising 117 individuals, including

non-smokers, smokers and patients diagnosed with COPD, revealed the

presence of >11,000 lipids and ~650 water-soluble substances in

BALF. Among these, one-tenth of the substances were present in all

samples (60).

Blood-derived EVs

Peripheral blood contains millions of EVs, and the

nucleic acids, proteins and other components within these vesicles

can reflect the biological behavior of their donor cells (58). Consequently, analyzing the

expression levels of nucleic acids and proteins in blood-derived

EVs from patients with COPD compared with healthy individuals

offers a promising foundation for diagnosing COPD. miRNAs are key

regulators in gene expression networks, having roles in cell

differentiation, apoptosis, inflammatory responses, tissue

remodeling and angiogenesis. Profiling miRNA expression using miRNA

microarrays or panel-based quantitative PCR technologies holds

potential as a biomarker for COPD (61). A study comparing circulating miRNA

and cytokine levels between 103 patients with COPD and 25 control

patients found that miR-1 and miR-499 levels were 2.5 and 1.5 times

higher, respectively, in the COPD group compared with in controls

(62). However, one challenge of

this detection method is that miRNAs in circulation are susceptible

to degradation by endogenous RNA enzymes, which could lead to an

inaccurate reflection of the miRNA expression levels in the donor

cells (63). By contrast, EVs, as

natural carriers of signal molecules, are encased in a phospholipid

bilayer that protects miRNAs and proteins from degradation by

proteases and nucleases in the blood. Therefore, analyzing miRNAs

and proteins in blood-derived EVs offers a more reliable approach

for COPD diagnosis (61). For

example, a previous study found that the levels of miR-221, miR-23a

and miR-574 in blood-derived EVs from 41 patients with COPD and 29

healthy individuals were negatively correlated with the FEV1/FVC

ratio, with 95% confidence intervals of 0.776, 0.688 and 0.842,

respectively (64). Another study

identified a notable increase in miR-21 levels in blood-derived EVs

from cigarette smoke-induced COPD, where miR-21 targets pVHL to

regulate α-SMA gene expression, thereby contributing to airway

remodeling. Furthermore, during acute COPD exacerbations, the

number of plasma exosomes, along with the levels of plasma

C-reactive protein and soluble TNF receptor-1, have been found to

increase (65). Although

differential detection of blood-derived EVs is not yet a routine

diagnostic tool in clinical practice, their potential as a

prospective biomarker for predicting COPD is increasingly evident

(Table I) (55–57,61,62,64,65).

| Table I.Potential markers for the diagnosis

of EV-based chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. |

Table I.

Potential markers for the diagnosis

of EV-based chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

| First author,

year | EV test sample

source | Detection

indicators | Trends in detection

indicators | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Liu et al,

2025 | Sputum | EVs containing

CD31, CD66b and CD235 | Upregulated | (56) |

| Kotsiou et

al, 2024 | Sputum | Total protein

concentration | Upregulated | (55) |

| Kaur et al,

2021 | Bronchoalveolar

lavage fluid | miR-122-5p | Downregulated | (57) |

| Gon et al,

2020 | Bronchoalveolar

lavage fluid | Microvesicles

containing CD14 | Upregulated | (61) |

| Donaldson et

al, 2013 | Blood | miR-1 and

miR-499 | Upregulated | (62) |

| Shen et al,

2021 | Blood | miR-221, miR-23a

and miR-574 | Upregulated | (64) |

| Tan et al,

2017 | Blood | EV number and blood

plasma C-reactive protein and soluble tumor necrosis factor

receptor-1 | Upregulated | (65) |

Application of EVs in COPD

treatment

In addition to the promising potential of liquid

biopsy technology for diagnosing COPD, EVs also offer a new avenue

for treatment. There are two current strategies for utilizing EVs

in COPD treatment. Primarily, the removal of EVs containing nucleic

acids or proteins associated with disease pathogenesis can be

achieved by: i) Inhibiting the secretion of EVs that promote COPD

progression; ii) blocking the effective binding of EVs to recipient

cells; or iii) capturing circulating EVs that contribute to disease

progression (66). For example,

treatment with the EV-production inhibitor GW4869 has been shown to

reduce miR-125a-5p expression in cigarette smoke-induced EV

secretion from AECs. miR-125a-5p promotes M1 macrophage

polarization by downregulating IL-1 receptor antagonist protein,

thereby activating the Toll-like receptor (TLR)4/myeloid

differentiation primary response 88/TNF receptor-associated factor

6/NF-κB signaling pathway and enhancing its pro-inflammatory

effects (67). Alternatively, EVs

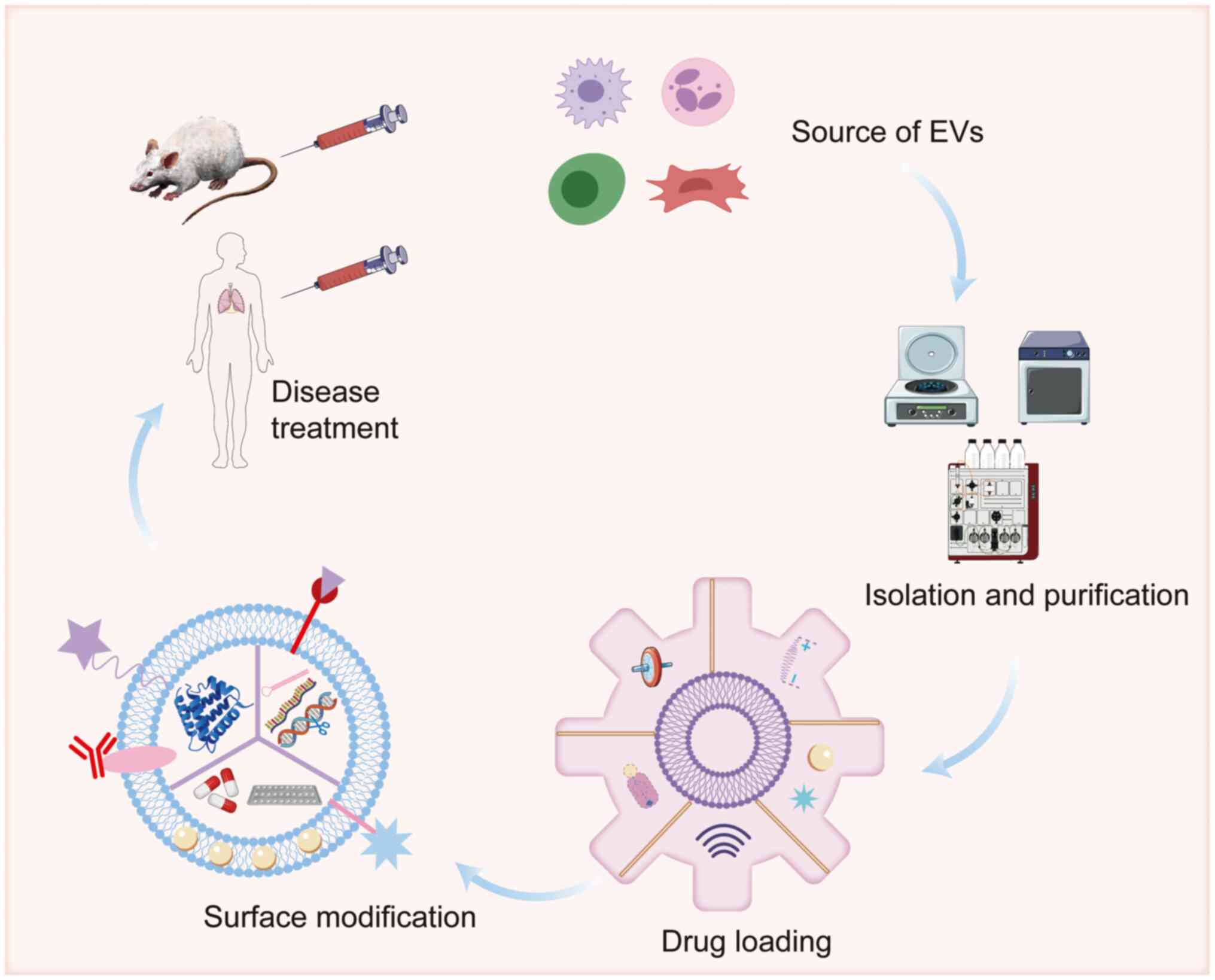

can be used as therapeutic agents or as vehicles for delivering

therapeutic agents to the lungs of patients with COPD. Mesenchymal

stem cell (MSC)-derived EVs, in particular, have been explored for

their therapeutic potential in COPD (Fig. 4) (68).

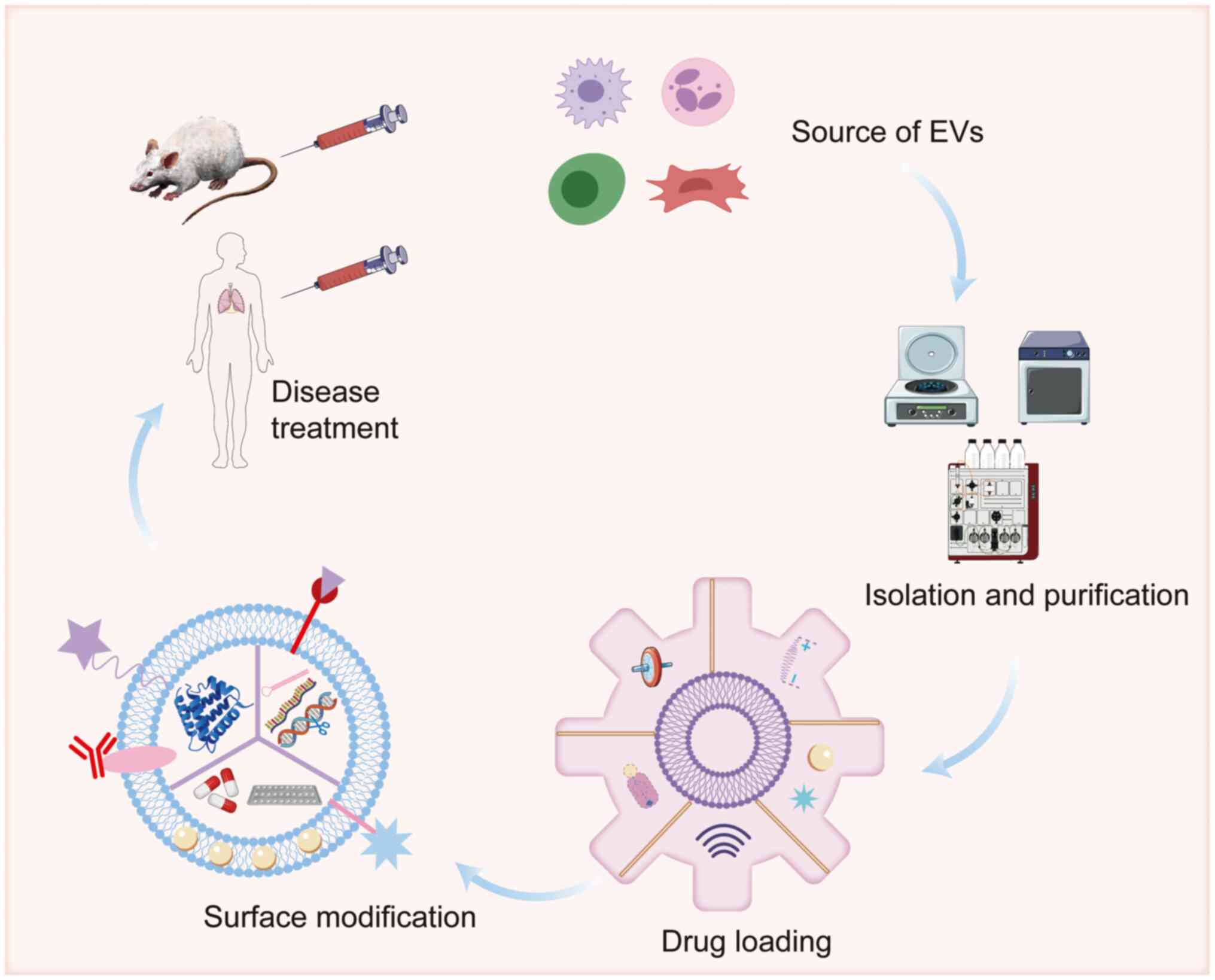

| Figure 4.Therapeutic applications of

engineered extracellular vesicles in COPD. EVs extracted from

different cells, including mesenchymal stem cells, macrophages and

DCs, by methods such as differential centrifugation, size exclusion

chromatography, immunoaffinity capture, microfluidics or

precipitation, can be used in the treatment of COPD. These EVs are

loaded with drugs endogenously and/or exogenously, and their

membrane surfaces are modified to improve lung tissue targeting.

Created with BioRender.com (https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/692ee91969efa5da6646019a?slideId=15732dc8-116e-49fa-a545-6343ae7d7599).

miR, microRNA; EVs, extracellular vesicles. |

Application of MSC-derived EVs in

therapy

MSCs are multipotent adult stem cells that can be

isolated from various human tissues, including bone marrow (BM),

adipose tissue, umbilical cord and placenta (69). MSCs secrete numerous

anti-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-13, neurotrophin 3,

ciliary neurotrophic factor and IL-10, and growth factors that aid

tissue repair (70). Due to their

anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties, MSCs have been

investigated for COPD treatment. A previous study has shown that

BM-derived MSCs are able to inhibit p38 mitogen-activated protein

kinase (MAPK) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase

phosphorylation and activation, thereby reducing the production of

prostaglandin E2 and cyclooxygenase 2 in macrophages and

alleviating airway inflammation and emphysema in a COPD mouse model

(71). Adipose-derived stem cells

have been found to reduce chronic cigarette smoke-induced

activation of JNK1 and protein kinase B (AKT) by eliminating p38

MAPK phosphorylation, which, in turn, mitigates lung inflammation

and cysteine aspartate activity, protecting alveolar structural

integrity in patients with COPD (72). A clinical trial assessing the

systemic administration of allogeneic MSCs in patients with

moderate-to-severe COPD evaluated inflammatory markers, including

TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-2 and TGF-β, pulmonary function and

electrocardiographic parameters. The study confirmed the safety of

systemic MSC infusion in individuals with impaired lung function,

and demonstrated that MSCs may inhibit inflammation and reduce or

reverse emphysematous changes (73). However, the clinical application of

MSCs is limited by challenges such as the difficulty in obtaining

high-quality MSCs, issues with proper storage, potential

tumorigenicity and the ethical complexities of the infusion

process. These factors constrain the broader therapeutic use of

MSCs for patients with COPD (74).

Consequently, there is a growing need to develop MSC-based

cell-free therapies that overcome these limitations.

EVs derived from MSCs retain the anti-inflammatory,

immunomodulatory and tissue-regenerative properties of their parent

cells, effectively transporting proteins, lipids, DNA fragments,

mRNA and other molecules to recipient cells, thereby facilitating

intercellular communication and regulating the biological functions

of these cells (75). Compared

with the donor cells, MSC-derived EVs are enriched with functional

cargo, including signaling molecules and growth factors, and offer

advantages such as long-term stability for storage and transport,

ethical acceptance for infusion, deep-tissue penetration and

versatile administration methods (76). Furthermore, c-Myc gene

transfection, hydrogen peroxide and lipopolysaccharide pretreatment

can further enhance EV secretion from MSCs (77,78).

Over time, MSC-derived EVs have emerged as a promising cell-free

therapeutic alternative.

The bioactive substances contained within EVs

contribute towards COPD treatment through promoting lung cell

proliferation and reducing systemic inflammatory-mediator

production (79). Chronic exposure

to harmful particles or gases triggers a complex inflammatory

response, driving the characteristic pathological features of COPD,

including emphysematous destruction, alveolar remodeling and

narrowing of small airways (80).

A key event in this process is endothelial cell apoptosis in the

lung parenchyma, which is closely associated with emphysema

development. Notably, patients with COPD exhibit reduced expression

levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and VEGF

receptor 2 (VEGFR2) in their bodies, and this leads to extensive

endothelial cell death and microvascular damage upon exposure to

cigarette smoke extract, accelerating emphysema progression

(81). MSC-derived EVs retain ~70%

of the beneficial effects of MSCs and can effectively deliver

signaling molecules and growth factors to lung tissue, reducing

inflammation and promoting the restoration of damaged lung function

(82). Human umbilical cord MSC

exosomes (hUCMSC-Exos) contain hsa-miR-10a-5p and hsa-miR-146a-5p,

which inhibit endothelial cell apoptosis by facilitating the

specific binding of VEGF to VEGFR2 on endothelial cells, thereby

activating the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway (83). Additionally, hUCMSC-Exo treatment

can reduce the lung tissue inflammation score in COPD model mice,

decreasing the influx of peripheral blood neutrophils, eosinophils,

lymphocytes and macrophages into the lungs, while also reducing the

number of mucus-secreting goblet cells. Mechanistically,

hUCMSC-Exos exert their therapeutic effects by inhibiting the

phosphorylation of the pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB

subunit p65 (84).

Mesenchymal stem cells, potent mitochondrial donors,

exhibit elevated levels of the mitochondrial fission protein

dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1) upon exposure to cigarette smoke,

leading to impaired mitochondrial function. Prolonged exposure

reduces the expression of fusion proteins such as mitofusin (MFN)1,

MFN2 and optic atrophy 1 (OPA1), causing mitochondrial damage, and

ultimately triggers mitophagy (85). Disrupted mitophagy results in the

accumulation of perinuclear mitochondria in lung epithelial cells

and fibroblasts, impaired oxidative phosphorylation and an increase

in mtROS, all of which exacerbate COPD progression (86). To address COPD induced by

mitochondrial damage, a previous study employed BM-derived MSCs and

exosomes (MSC + EXO) in a COPD mitochondrial Keima mouse model

induced by acute cigarette smoke exposure over a period of 10 days

(87). The combination therapy

markedly upregulated the expression of MFN1, MFN2 and OPA1, whereas

the levels of damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) markers,

including MMP9 and high mobility group box 1, were markedly

increased, supporting the hypothesis that MSC + EXO therapy

protects against lung mitochondrial dysfunction. By contrast, MSC

or EXO treatments alone exhibited limited effects (87). These results highlight MSC-derived

EVs as promising cell-free therapeutic agents capable of addressing

COPD through multiple mechanisms.

Treatment of COPD with EVs as a drug

delivery vehicle

The current standard of care for COPD involves

triple therapy, combining inhaled corticosteroids, long-acting β-2

agonists and long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonists (88). However, steroid resistance in a

number of patients necessitates the administration of higher doses,

which increase the risk of pneumonia and a range of side effects

that negatively impact the function of normal cells, including

osteoporosis, metabolic disorders, cardiac arrhythmias and

hyperglycemia (89). This

underscores the notable need for the development of a high-quality

drug-delivery platform that targets lung tissue to enhance COPD

treatment efficacy.

EVs have been engineered to deliver a wide range of

drugs for the treatment of various diseases (90). For example, EVs loaded with

miR-451a can target MMP10 to inhibit the proliferation, migration

and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma (91). EVs carrying gemcitabine (GEM)

enhance the therapeutic effect of GEM treatment on pancreatic

ductal carcinoma, while reducing GEM-induced toxicity to the liver

and kidneys (92). Curcumin-loaded

EVs mitigate ischemic stroke by suppressing the expression of

phosphorylated-p65 and caspase-3 (93). Similarly, EVs as a drug delivery

platform show notable potential in COPD treatment. Drug-loaded EVs

can regulate key signaling pathways involved in COPD pathogenesis

to inhibit disease progression. For example, CD24-overexpressing

EVs can block the activation of the NF-κB pathway by binding to

DAMPs, preventing their interaction with pattern recognition

receptors, such as TLRs and NOD-like receptors, thereby dampening

the excessive inflammatory response in COPD (94). Furthermore, nebulized human

platelet-derived exosome products have been shown to reduce

smoke-induced emphysema in mice by inhibiting NF-κB activation,

inflammatory cytokine production and apoptotic protein expression,

while promoting an increase in CD4+/forkhead box

P3+ regulatory T cells in lung tissue, thereby

alleviating oxidative lung injury, inflammation and apoptotic

alveolar epithelial cell death (95). In addition, artificial nanovesicles

derived from adipose-derived stem cells expressing fibroblast

growth factor 2 have been shown to enhance the differentiation

potential of type II alveolar cells into type I alveolar cells,

thereby inhibiting emphysema formation (96). Some practical applications of

EV-based treatments for COPD are summarized in Table II (83,84,87,95,96).

| Table II.Practical application of EV-based

treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. |

Table II.

Practical application of EV-based

treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

| First author,

year | Sources of EVs | Cargo | Mechanism of

action | Effect of

action | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Chen et al,

2022 | Human umbilical

cord mesenchymal stem cells | miR-10a and

miR-146a | Promotes specific

binding of VEGF to VEGF receptor 2 of endothelial cells to activate

the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B pathway | Inhibition of

endothelial cell apoptosis | (83) |

| Ridzuan et

al, 2021 | Human umbilical

cord mesenchymal stem cells | Not applicable | Inhibits

phosphorylation of the pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB

subunit p65 | Reduces influx of

neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes and macrophages into lung

tissue | (84) |

| Maremanda et

al, 2019 | Bone marrow

mesenchymal stem cells | Not applicable | Increases the

expression levels of MFN1, MFN2 and optic atrophy 1 | Strengthens

protection against pulmonary mitochondrial dysfunction | (87) |

| Xuan et al,

2024 | Platelets | Not applicable | Inhibits NF-κB

activation, inflammatory cytokine production and apoptotic protein

expression | Inhibits oxidative

lung injury, inflammation and apoptotic alveolar epithelial cell

death | (95) |

| Kim et al,

2017 | Adipose-derived

stem cells | Fibroblast growth

factor 2 | Enhances type II

alveolar cell proliferation and differentiation potential to type I

alveolar cells | Inhibits the

formation of emphysema | (96) |

Achieving the therapeutic effects of drug-loaded EVs

targeting lung tissue involves several important steps: i)

Isolation and purification of EVs; ii) loading of therapeutic

agents into EVs; and iii) artificial modification of EVs to enhance

targeting efficiency. The first step, the isolation and

purification of EVs, primarily utilizes methods based on the

physicochemical properties of EVs such as size, density and surface

marker proteins (97). Techniques

used include differential centrifugation, size-exclusion

chromatography, immunoadsorption capture, microfluidics and

precipitation (98). Among these,

differential centrifugation is considered the ‘gold standard’ for

EV isolation in laboratories, and remains the predominant method

for extracting EVs from biofluids. The second step is the effective

loading of therapeutic drugs into EVs, which can occur either

before or after EV isolation (98,99).

The third important step is modifying EVs to improve their

targeting capability. Natural EVs typically exhibit poor targeting

properties and are rapidly cleared from circulation, primarily

accumulating in the liver and kidneys following intravenous

administration (100). To address

this limitation, artificial modification of EVs is necessary to

enhance their tissue- or cell-specific delivery. A key approach

involves using genetic engineering to transfect plasmids encoding

targeting peptides or proteins, such as lysosomal-associated

membrane protein 2B (LAMP2B) and tetraspanins, into EVs. These

targeting peptides are either incorporated into the biogenesis

pathway of the EVs or directly loaded onto the EV membrane surface,

improving the ability of the EVs to target and deliver cargo to

specific tissues or cells (101).

For example, the fusion of neuron-specific rabies virus

glycoprotein with the N-terminus of LAMP2B enables the targeted

delivery of GAPDH small interfering RNA (siRNA) to neurons,

microglia and oligodendrocytes in the brain. Furthermore, other

tissues do not absorb GAPDH siRNA in this treatment (102).

The route of administration for EVs targeting lung

tissue has garnered notable interest from researchers. Currently,

the primary methods of EV-based COPD treatment involve intravenous

administration and intratracheal delivery. Intravenous

administration is the most widely used method (103), with therapeutic EVs reaching the

lungs through the circulatory system to exert their effects. In

studies performed in isolated cells, typical injection doses of EV

therapeutics range from 2–40 µg/ml (104). However, intravenous

administration carries a risk of microcirculation aggregation,

potentially leading to mutagenicity and carcinogenicity (105). Intratracheal delivery, which

directly targets the airways, reduces systemic side effects

compared with intravenous administration, although the complexity

of the procedure markedly increases (106).

Previous review summaries and novelty of the

present review

A recent review summarized the current understanding

of EV-miRNAs in conditions such as COPD, asthma, lung cancer and

COVID-19, highlighting their potential as both biomarkers and

therapeutic targets in these respiratory diseases (107). The previous work emphasized the

crucial role of EV-miRNAs in regulating immune cell function,

chronic airway inflammation and disease progression. Additionally,

the previous work largely focused on EVs as biomarkers and

therapeutic targets, whereas the present review provides a more

detailed analysis of bacteria-derived OMVs and their impact on

COPD, linking impaired mucociliary clearance and inflammation.

Furthermore, the current review uniquely addresses EV engineering

strategies for targeted drug delivery in COPD, including pre- and

post-isolation drug-loading methods and genetic modifications to

enhance targeting efficiency, topics not as extensively covered in

previous reviews (1,8). A previous study also emphasized the

importance of EVs in regulating immune cell function, chronic

inflammation and disease progression (108). However, the present review

introduces novel insights by exploring mitochondrial dysfunction as

a key mechanism in COPD progression, a topic not deeply covered in

the prior study. Furthermore, while the previous review discussed

EVs as biomarkers detected in biological fluids, such as blood and

sputum, the current review offers a more detailed quantitative

analysis of miRNA expression in various fluids. Additionally, this

review expands on EV engineering strategies for targeted drug

delivery in COPD, including both pre- and post-isolation

drug-loading methods and genetic modifications, which is a more

focused exploration compared with the broader discussions in the

previous review.

Furthermore, another review highlighted the

involvement of EVs in COPD pathogenesis, particularly their

influence on inflammation, immune responses and airway remodeling

(109). However, the present

review introduces novel insights by exploring mitochondrial

dysfunction as a key mechanism in COPD progression, specifically

through mitochondrial fission/fusion proteins, which were not

extensively covered in the referenced review. Furthermore, while

both reviews have discussed EVs as biomarkers, the current review

provides a more detailed quantitative analysis of miRNAs in various

biological fluids, offering deeper insights into their diagnostic

potential. Additionally, this review expands on EV engineering

strategies for targeted drug delivery in COPD, which is more

thoroughly explored than in the previous review, which provided a

broader discussion of EVs as biomarkers and therapeutic

targets.

The present review has provided novel insights into

EV-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction, characterized by imbalances

in key regulators such as DRP1/MFN/OPA1 and increased mtROS

production, as a key driver of COPD progression, a mechanism

frequently overlooked in previous reviews (107–109). Furthermore, the present review

has broadened the perspective of current EV-based research by

linking bacteria-derived OMVs, for example from Moraxella

and Pseudomonas, to impaired mucociliary clearance and

inflammatory responses, thereby establishing a notable association

between microbiology and EV biology.

In terms of diagnostic value, the present review has

systematically compared and evaluated potential EV biomarkers in

blood, BALF and sputum, supplemented with quantitative data. For

example: i) The general protein concentration of sputum EVs in

patients with COPD is higher compared with that in healthy controls

(55); ii) the expression levels

of miR-122-5p in EVs from the lungs of patients with COPD are

significantly downregulated, and a structured dataset of

BALF-derived EV particles, encompassing particle size distribution

and concentration, has been established and analyzed (57,60);

and iii) the expression levels of miR-1 and miR-499 are higher in

the blood of patients with COPD, and the diagnostic confidence

intervals of miR-23a, miR-221 and miR-574-5p have been analyzed

(62,64). These have filled in several gaps in

previous studies.

Regarding therapeutic applications, the present

review has detailed EV engineering strategies for targeted drug

delivery in COPD, including both pre-isolation and post-isolation

drug-loading methods, modification technologies such as genetically

engineered fusion targeting peptides, and their specific processes.

The present review has also objectively analyzed the limitations

and challenges of using EVs as drug delivery systems, and discussed

the therapeutic potential of stem cell-derived EVs, such as the

effects of hUCMSC-Exos and combined therapy with BM-derived MSC +

EXO treatment.

Conclusion

In conclusion, EVs represent a ‘double-edged sword’

in COPD treatment. On one hand, the substances they carry can

contribute to the progression of COPD by regulating key signaling

pathways. On the other hand, liquid biopsy technologies that detect

EVs in sputum, blood and alveolar lavage fluid, along with their

associated cargo, may offer valuable diagnostic markers for early

COPD detection. Additionally, EVs derived from MSCs or used as drug

delivery vehicles for COPD treatment present a promising new

cell-free therapeutic strategy. Therefore, further research into

the role of EVs in COPD progression is important for advancing

preventative measures. Simultaneously, extensive preclinical

studies and clinical trials are required to validate the

therapeutic applications of EVs or therapeutic vectors in COPD.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present work was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 8180150490).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

YZ, ZG and CF conceived and designed the review. TR,

JX and YY retrieved the relevant literature, acquired relevant

references, screened data, and analyzed and organized reference

data. XZ, XH and WY critically revised and edited the manuscript.

YZ, ZG and CF created figures and reviewed the article. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

COPD

|

chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease

|

|

EVs

|

extracellular vesicles

|

|

AAT

|

α-1 antitrypsin

|

|

PM

|

particulate matter

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

|

NF-κB

|

nuclear factor κB

|

|

JNK

|

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

|

|

IL

|

interleukin

|

|

MMPs

|

matrix metalloproteinases

|

|

MVB

|

multivesicular bodies

|

|

LFs

|

lung fibroblasts

|

|

HIF-1α

|

hypoxia-inducible factor 1α

|

|

OMVs

|

outer-membrane vesicles

|

|

FVC

|

forced vital capacity

|

|

BALF

|

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

|

|

AECs

|

airway epithelial cells

|

|

MSCs

|

mesenchymal stem cells

|

|

BM

|

bone marrow

|

|

DAMPs

|

damage-associated molecular

patterns

|

References

|

1

|

Wang C, Zhou J, Wang J, Li S, Fukunaga A,

Yodoi J and Tian H: Progress in the mechanism and targeted drug

therapy for COPD. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 5:2482020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Silverman EK: Genetics of COPD. Annu Rev

Physiol. 82:413–431. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Christenson SA, Smith BM, Bafadhel M and

Putcha N: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet.

399:2227–2242. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Abbaszadeh H, Ghorbani F, Abbaspour-Aghdam

S, Kamrani A, Valizadeh H, Nadiri M, Sadeghi A, Shamsasenjan K,

Jadidi-Niaragh F, Roshangar L and Ahmadi M: Chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease and asthma: Mesenchymal stem cells and their

extracellular vesicles as potential therapeutic tools. Stem Cell

Res Ther. 13:2622022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Wei YY, Chen TT, Zhang DW, Zhang Y, Li F,

Ding YC, Wang MY, Zhang L, Chen KG and Fei GH: Microplastics

exacerbate ferroptosis via mitochondrial reactive oxygen

species-mediated autophagy in chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease. Autophagy. 21:1717–1743. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Dumas G, Arabi YM, Bartz R, Ranzani O,

Scheibe F, Darmon M and Helms J: Diagnosis and management of

autoimmune diseases in the ICU. Intensive Care Med. 50:17–35. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Billington CK, Penn RB and Hall IP:

β2 agonists. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 237:23–40. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Trappe A, Donnelly SC, McNally P and

Coppinger JA: Role of extracellular vesicles in chronic lung

disease. Thorax. 76:1047–1056. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kalita-de Croft P, Sharma S, Sobrevia L

and Salomon C: Extracellular vesicle interactions with the external

and internal exposome in mediating carcinogenesis. Mol Aspects Med.

87:1010392022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Akhmerov A and Parimon T: Extracellular

vesicles, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. Cells.

11:22292022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Marar C, Starich B and Wirtz D:

Extracellular vesicles in immunomodulation and tumor progression.

Nat Immunol. 22:560–570. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Tian J, Han Z, Song D, Peng Y, Xiong M,

Chen Z, Duan S and Zhang L: Engineered exosome for drug delivery:

Recent development and clinical applications. Int J Nanomedicine.

18:7923–7940. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Schaberg T, Klein U, Rau M, Eller J and

Lode H: Subpopulations of alveolar macrophages in smokers and

nonsmokers: Relation to the expression of CD11/CD18 molecules and

superoxide anion production. Am J Respir Crit Care Med.

151:1551–1558. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chen J, Wang T, Li X, Gao L, Wang K, Cheng

M, Zeng Z, Chen L, Shen Y and Wen F: DNA of neutrophil

extracellular traps promote NF-κB-dependent autoimmunity via

cGAS/TLR9 in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 9:1632024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Barnes PJ: Oxidative stress-based

therapeutics in COPD. Redox Biol. 33:1015442020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Nwozor KO, Hackett TL, Chen Q, Yang CX,

Aguilar Lozano SP, Zheng X, Al-Fouadi M, Kole TM, Faiz A, Mahbub

RM, et al: Effect of age, COPD severity, and cigarette smoke

exposure on bronchial epithelial barrier function. Am J Physiol

Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 328:L724–Ll737. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agustí AG, Jones PW,

Vogelmeier C, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Fabbri LM, Martinez FJ,

Nishimura M, et al: Global strategy for the diagnosis, management,

and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD

executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 187:347–365. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Cui W, Zhang Z, Zhang P, Qu J, Zheng C, Mo

X, Zhou W, Xu L, Yao H and Gao J: Nrf2 attenuates inflammatory

response in COPD/emphysema: Crosstalk with Wnt3a/β-catenin and AMPK

pathways. J Cell Mol Med. 22:3514–3525. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Guo P, Li R, Piao TH, Wang CL, Wu XL and

Cai HY: Pathological mechanism and targeted drugs of COPD. Int J

Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 17:1565–1575. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Barnes PJ, Burney PG, Silverman EK, Celli

BR, Vestbo J, Wedzicha JA and Wouters EF: Chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 1:150762015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Barnes PJ: Inflammatory mechanisms in

patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin

Immunol. 138:16–27. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Brightling C and Greening N: Airway

inflammation in COPD: Progress to precision medicine. Eur Respir J.

54:19006512019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Xu J, Zeng Q, Li S, Su Q and Fan H:

Inflammation mechanism and research progress of COPD. Front

Immunol. 15:14046152024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Upadhyay P, Wu CW, Pham A, Zeki AA, Royer

CM, Kodavanti UP, Takeuchi M, Bayram H and Pinkerton KE: Animal

models and mechanisms of tobacco smoke-induced chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease (COPD). J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev.

26:275–305. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

DI Stefano A, Gnemmi I, Dossena F,

Ricciardolo FL, Maniscalco M, Lo Bello F and Balbi B: Pathogenesis

of COPD at the cellular and molecular level. Minerva Med.

113:405–423. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Shapiro SD: Proteolysis in the lung. Eur

Respir J Suppl. 44:30s–32s. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Abboud RT and Vimalanathan S: Pathogenesis

of COPD. Part I. The role of protease-antiprotease imbalance in

emphysema. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 12:361–367. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Haq I, Chappell S, Johnson SR, Lotya J,

Daly L, Morgan K, Guetta-Baranes T, Roca J, Rabinovich R, Millar

AB, et al: Association of MMP-2 polymorphisms with severe and very

severe COPD: A case control study of MMPs-1, 9 and 12 in a European

population. BMC Med Genet. 11:72010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

D'Armiento JM, Goldklang MP, Hardigan AA,

Geraghty P, Roth MD, Connett JE, Wise RA, Sciurba FC, Scharf SM,

Thankachen J, et al: Increased matrix metalloproteinase (MMPs)

levels do not predict disease severity or progression in emphysema.

PLoS One. 8:e563522013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Lomas DA: Does protease-antiprotease

imbalance explain chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Ann Am

Thorac Soc. 13 (Suppl 2):S130–S137. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Xin XF, Zhao M, Li ZL, Song Y and Shi Y:

Metalloproteinase-9/tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 in

induced sputum in patients with asthma and chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease and their relationship to airway inflammation and

airflow limitation. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 30:192–196.

2007.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wickman G, Julian L and Olson MF: How

apoptotic cells aid in the removal of their own cold dead bodies.

Cell Death Differ. 19:735–742. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Du S, Guan Y, Xie A, Yan Z, Gao S, Li W,

Rao L, Chen X and Chen T: Extracellular vesicles: A rising star for

therapeutics and drug delivery. J Nanobiotechnology. 21:2312023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Tenchov R, Sasso JM, Wang X, Liaw WS, Chen

CA and Zhou QA: Exosomes-nature's lipid nanoparticles, a rising

star in drug delivery and diagnostics. ACS Nano. 16:17802–17846.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Liu J, Ren L, Li S, Li W, Zheng X, Yang Y,

Fu W, Yi J, Wang J and Du G: The biology, function, and

applications of exosomes in cancer. Acta Pharm Sin B. 11:2783–2797.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Antonyak MA and Cerione RA: Microvesicles

as mediators of intercellular communication in cancer. Methods Mol

Biol. 1165:147–173. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Xu X, Lai Y and Hua ZC: Apoptosis and

apoptotic body: Disease message and therapeutic target potentials.

Biosci Rep. 39:BSR201809922019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Liu Q, Li D, Pan X and Liang Y: Targeted

therapy using engineered extracellular vesicles: Principles and

strategies for membrane modification. J Nanobiotechnology.

21:3342023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Hallstrand TS, Hackett TL, Altemeier WA,

Matute-Bello G, Hansbro PM and Knight DA: Airway epithelial

regulation of pulmonary immune homeostasis and inflammation. Clin

Immunol. 151:1–15. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Yang Y, Yuan L, Du X, Zhou K, Qin L, Wang

L, Yang M, Wu M, Zheng Z, Xiang Y, et al: Involvement of

epithelia-derived exosomes in chronic respiratory diseases. Biomed

Pharmacother. 143:1121892021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Xu H, Ling M, Xue J, Dai X, Sun Q, Chen C,

Liu Y, Zhou L, Liu J, Luo F, et al: Exosomal microRNA-21 derived

from bronchial epithelial cells is involved in aberrant

epithelium-fibroblast cross-talk in COPD induced by cigarette

smoking. Theranostics. 8:5419–5433. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Qiu Q, Dan X, Yang C, Hardy P, Yang Z, Liu

G and Xiong W: Increased airway T lymphocyte microparticles in

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease induces airway epithelial

injury. Life Sci. 261:1183572020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Fujita Y, Araya J, Ito S, Kobayashi K,

Kosaka N, Yoshioka Y, Kadota T, Hara H, Kuwano K and Ochiya T:

Suppression of autophagy by extracellular vesicles promotes

myofibroblast differentiation in COPD pathogenesis. J Extracell

Vesicles. 4:283882015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Hernández-Díazcouder A, Romero-Nava R,

Del-Río-Navarro BE, Sánchez-Muñoz F, Guzmán-Martín CA,

Reyes-Noriega N, Rodríguez-Cortés O, Leija-Martínez JJ,

Vélez-Reséndiz JM, Villafaña S, et al: The Roles of MicroRNAs in

asthma and emerging insights into the effects of vitamin

D3 supplementation. Nutrients. 16:3412024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Augustyniak D, Roszkowiak J, Wiśniewska I,

Skała J, Gorczyca D and Drulis-Kawa Z: Neuropeptides SP and CGRP

diminish the Moraxella catarrhalis outer membrane

vesicle-(OMV-) triggered inflammatory response of human a549

epithelial cells and neutrophils. Mediators Inflamm.

2018:48472052018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Bomberger JM, Ye S, Maceachran DP, Koeppen

K, Barnaby RL, O'Toole GA and Stanton BA: A Pseudomonas

aeruginosa toxin that hijacks the host ubiquitin proteolytic

system. PLoS Pathog. 7:e10013252011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Riley CM and Sciurba FC: Diagnosis and

outpatient management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A

review. JAMA. 321:786–797. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Ferrera MC, Labaki WW and Han MK: Advances

in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Annu Rev Med. 72:119–134.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Kahnert K, Jörres RA, Behr J and Welte T:

The diagnosis and treatment of COPD and its comorbidities. Dtsch

Arztebl Int. 120:434–444. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Beetler DJ, Di Florio DN, Bruno KA, Ikezu

T, March KL, Cooper LT Jr, Wolfram J and Fairweather D:

Extracellular vesicles as personalized medicine. Mol Aspects Med.

91:1011552023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Brightling CE: Clinical applications of

induced sputum. Chest. 129:1344–1348. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Jin Y, Chen Z, Chen Q, Sha L and Shen C:

Role and significance of bioactive substances in sputum in the

diagnosis of lung cancer. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 24:867–873.

2021.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Guiot J, Demarche S, Henket M, Paulus V,

Graff S, Schleich F, Corhay JL, Louis R and Moermans C: Methodology

for sputum induction and laboratory processing. J Vis Exp.

566122017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Pastor L, Vera E, Marin JM and Sanz-Rubio

D: Extracellular vesicles from airway secretions: New insights in

lung diseases. Int J Mol. 22:5832021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Kotsiou OS, Katsanaki K, Tsiggene A,

Papathanasiou S, Rouka E, Antonopoulos D, Gerogianni I, Balatsos

NAA, Gourgoulianis KI and Tsilioni I: Detection and

characterization of extracellular vesicles in sputum samples of

COPD patients. J Pers Med. 14:8202024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Liu Y, Huang J, Li E, Xiao Y, Li C, Xia M,

Ke J, Xiang L and Lei M: Analysis of research trends and hot spots

on COPD biomarkers from the perspective of bibliometrics. Respir

Med. 240:1080302025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Kaur G, Maremanda KP, Campos M, Chand HS,

Li F, Hirani N, Haseeb MA, Li D and Rahman I: Distinct exosomal

miRNA profiles from BALF and lung tissue of COPD and IPF patients.

Int J Mol Sci. 22:118302021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Wu J, Ma Y and Chen Y: Extracellular

vesicles and COPD: Foe or friend? J Nanobiotechnology. 21:1472023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Roth K, Hardie JA, Andreassen AH, Leh F

and Eagan TM: Predictors of diagnostic yield in bronchoscopy: A

retrospective cohort study comparing different combinations of

sampling techniques. BMC Pulm Med. 8:22008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Walmsley S, Cruickshank-Quinn C, Quinn K,

Zhang X, Petrache I, Bowler RP, Reisdorph R and Reisdorph N: A

prototypic small molecule database for bronchoalveolar lavage-based

metabolomics. Sci Data. 5:1800602018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Gon Y, Shimizu T, Mizumura K, Maruoka S

and Hikichi M: Molecular techniques for respiratory diseases:

MicroRNA and extracellular vesicles. Respirology. 25:149–160. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Donaldson A, Natanek SA, Lewis A, Man WD,

Hopkinson NS, Polkey MI and Kemp PR: Increased skeletal

muscle-specific microRNA in the blood of patients with COPD.

Thorax. 68:1140–1149. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

McDonald JS, Milosevic D, Reddi HV, Grebe

SK and Algeciras-Schimnich A: Analysis of circulating microRNA:

Preanalytical and analytical challenges. Clin Chem. 57:833–840.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Shen Y, Wang L, Wu Y, Ou Y, Lu H and Yao

X: A novel diagnostic signature based on three circulating exosomal

mircoRNAs for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Exp Ther Med.

22:7172021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Tan DBA, Armitage J, Teo TH, Ong NE, Shin

H and Moodley YP: Elevated levels of circulating exosome in COPD

patients are associated with systemic inflammation. Respir Med.

132:261–264. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Park KS, Lässer C and Lötvall J:

Extracellular vesicles and the lung: from disease pathogenesis to

biomarkers and treatments. Physiol Rev. 105:1733–1821. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Wang R, Zhu Z, Peng S, Xu J, Chen Y, Wei S

and Liu X: Exosome microRNA-125a-5p derived from epithelium

promotes M1 macrophage polarization by targeting IL1RN in chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease. Int Immunopharmacol. 137:1124662024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Hade MD, Suire CN and Suo Z: Mesenchymal

stem cell-derived exosomes: applications in regenerative medicine.

Cells. 10:19592021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Chen L, Qu J, Kalyani FS, Zhang Q, Fan L,

Fang Y, Li Y and Xiang C: Mesenchymal stem cell-based treatments

for COVID-19: Status and future perspectives for clinical

applications. Cell Mol Life Sci. 79:1422022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Pierro M, Ionescu L, Montemurro T, Vadivel

A, Weissmann G, Oudit G, Emery D, Bodiga S, Eaton F, Péault B, et

al: Short-term, long-term and paracrine effect of human umbilical

cord-derived stem cells in lung injury prevention and repair in

experimental bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Thorax. 68:475–484. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Gu W, Song L, Li XM, Wang D, Guo XJ and Xu

WG: Mesenchymal stem cells alleviate airway inflammation and

emphysema in COPD through down-regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 via

p38 and ERK MAPK pathways. Sci Rep. 5:87332015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Schweitzer KS, Johnstone BH, Garrison J,

Rush NI, Cooper S, Traktuev DO, Feng D, Adamowicz JJ, Van Demark M,

Fisher AJ, et al: Adipose stem cell treatment in mice attenuates

lung and systemic injury induced by cigarette smoking. Am J Respir

Crit Care Med. 183:215–225. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Weiss DJ, Casaburi R, Flannery R,

LeRoux-Williams M and Tashkin DP: A placebo-controlled, randomized

trial of mesenchymal stem cells in COPD. Chest. 143:1590–1598.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Lowenthal J and Sugarman J: Ethics and

policy issues for stem cell research and pulmonary medicine. Chest.

147:824–834. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Mohammadipoor A, Antebi B, Batchinsky AI

and Cancio LC: Therapeutic potential of products derived from

mesenchymal stem/stromal cells in pulmonary disease. Respir Res.

19:2182018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Tan F, Li X, Wang Z, Li J, Shahzad K and

Zheng J: Clinical applications of stem cell-derived exosomes.

Signal Transduct Target Ther. 9:172024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Sung DK, Chang YS, Sung SI, Ahn SY and

Park WS: Thrombin preconditioning of extracellular vesicles derived

from mesenchymal stem cells accelerates cutaneous wound healing by

boosting their biogenesis and enriching cargo content. J Clin Med.

8:5332019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Lai RC, Yeo RW, Padmanabhan J, Choo A, de

Kleijn DP and Lim SK: Isolation and characterization of exosome

from human embryonic stem cell-derived C-Myc-immortalized

mesenchymal stem cells. Methods Mol Biol. 1416:477–494. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Miethe S, Potaczek DP, Bazan-Socha S,

Bachl M, Schaefer L, Wygrecka M and Garn H: The emerging role of

extracellular vesicles as communicators between adipose tissue and

pathologic lungs with a special focus on asthma. Am J Physiol Cell

Physiol. 324:C1119–C1125. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Manisalidis I, Stavropoulou E,

Stavropoulos A and Bezirtzoglou E: Environmental and health impacts

of air pollution: A review. Front Public Health. 8:142020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Chen YT, Miao K, Zhou L and Xiong WN: Stem

cell therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chin Med J

(Engl). 134:1535–1545. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Ji HL, Liu C and Zhao RZ: Stem cell

therapy for COVID-19 and other respiratory diseases: Global trends

of clinical trials. World J Stem Cells. 12:471–480. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Chen Q, Lin J, Deng Z and Qian W: Exosomes

derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells protect

against papain-induced emphysema by preventing apoptosis through

activating VEGF-VEGFR2-mediated AKT and MEK/ERK pathways in rats.

Regen Ther. 21:216–224. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Ridzuan N, Zakaria N, Widera D, Sheard J,

Morimoto M, Kiyokawa H, Mohd Isa SA, Chatar Singh GK, Then KY, Ooi

GC and Yahaya BH: Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem

cell-derived extracellular vesicles ameliorate airway inflammation

in a rat model of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Stem Cell Res Ther. 12:542021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Las G and Shirihai OS: Miro1: New wheels

for transferring mitochondria. EMBO J. 33:939–941. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Lerner CA, Sundar IK and Rahman I:

Mitochondrial redox system, dynamics, and dysfunction in lung

inflammaging and COPD. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 81:294–306. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Maremanda KP, Sundar IK and Rahman I:

Protective role of mesenchymal stem cells and mesenchymal stem

cell-derived exosomes in cigarette smoke-induced mitochondrial

dysfunction in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 385:1147882019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Calzetta L, Matera MG, Rogliani P and

Cazzola M: The role of triple therapy in the management of COPD.

Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 13:865–874. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Wang N, Wang Q, Du T, Gabriel ANA, Wang X,

Sun L, Li X, Xu K, Jiang X and Zhang Y: The potential roles of

exosomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Front Med

(Lausanne). 7:6185062021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Yang Y, Hong Y, Cho E, Kim GB and Kim IS:

Extracellular vesicles as a platform for membrane-associated

therapeutic protein delivery. J Extracell Vesicles. 7:14401312018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Xu Y, Lai Y, Cao L, Li Y, Chen G, Chen L,

Weng H, Chen T, Wang L and Ye Y: Human umbilical cord mesenchymal

stem cells-derived exosomal microRNA-451a represses

epithelial-mesenchymal transition of hepatocellular carcinoma cells

by inhibiting ADAM10. RNA Biol. 18:1408–1423. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Li YJ, Wu JY, Wang JM, Hu XB, Cai JX and

Xiang DX: Gemcitabine loaded autologous exosomes for effective and

safe chemotherapy of pancreatic cancer. Acta Biomater. 101:519–530.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Tian T, Zhang HX, He CP, Fan S, Zhu YL, Qi

C, Huang NP, Xiao ZD, Lu ZH, Tannous BA and Gao J: Surface

functionalized exosomes as targeted drug delivery vehicles for

cerebral ischemia therapy. Biomaterials. 150:137–149. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Shapira S, Schwartz R, Tsiodras S,

Bar-Shai A, Melloul A, Borsekofsky S, Peer M, Adi N, MacLoughlin R

and Arber N: Inhaled CD24-enriched exosomes (EXO-CD24) as a novel

immune modulator in respiratory disease. Int J Mol Sci. 25:772023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Xuan W, Wang S, Alarcon-Calderon A,

Bagwell MS, Para R, Wang F, Zhang C, Tian X, Stalboerger P,

Peterson T, et al: Nebulized platelet-derived extracellular

vesicles attenuate chronic cigarette smoke-induced murine

emphysema. Transl Res. 269:76–93. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Kim YS, Kim JY, Cho R, Shin DM, Lee SW and

Oh YM: Adipose stem cell-derived nanovesicles inhibit emphysema

primarily via an FGF2-dependent pathway. Exp Mol Med. 49:e2842017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Staubach S, Bauer FN, Tertel T, Börger V,

Stambouli O, Salzig D and Giebel B: Scaled preparation of

extracellular vesicles from conditioned media. Adv Drug Deliv Rev.

177:1139402021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Jia Y, Yu L, Ma T, Xu W, Qian H, Sun Y and

Shi H: Small extracellular vesicles isolation and separation:

Current techniques, pending questions and clinical applications.

Theranostics. 12:6548–6575. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Araldi RP, Delvalle DA, da Costa VR,

Alievi AL, Teixeira MR, Dias Pinto JR and Kerkis I: Exosomes as a