Introduction

Cholestasis is characterized by the obstruction of

bile formation, secretion and excretion in hepatocytes or bile duct

epithelial cells, due to various intrahepatic or extrahepatic

causes. This condition prevents bile from entering the duodenum and

results in its direct entry into the bloodstream (1,2). A

previous study indicated that 35% patients newly diagnosed with

chronic liver disease will typically develop cholestasis (3). Cholestasis presents as initial

clinical assessments revealing elevated serum alkaline phosphatase

(ALP) and γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) activity; however, 56% of

patients do not achieve normal serum biochemical levels of ALP and

GGT upon discharge (4). Without

appropriate treatment, these abnormalities can substantially

increase the risk of hyperbilirubinemia, liver fibrosis, cirrhosis

and liver failure, posing a notable threat to patient survival

(5). Therefore, investigating safe

and effective treatments for cholestasis is of clinical

importance.

Ferroptosis, first identified by Dixon et al

(6) in 2012, is a form of cell

death characterized by iron and reactive oxygen species (ROS)

involvement. Unlike traditional cell death mechanisms, ferroptosis

results from iron-dependent lipid peroxidation and exhibits

distinct ultrastructural features. Elevated lipid peroxidation

levels serve as a key indicator of ferroptosis occurrence (7).

Persistent cholestasis exacerbates damage to bile

duct epithelial cells and hepatocytes, triggering an inflammatory

response (8). Inflammation is

strongly associated with oxidative stress (9,10).

During inflammation, pro-inflammatory factors stimulate phagocytes

and non-phagocytic cells to produce various ROS, such as

O2−, H2O2 and OH−, to

eliminate pathogens (11).

Excessive intracellular ROS then overwhelm glutathione peroxidase 4

(GPX4), disrupting the balance between ROS production and

scavenging, leading to ferroptosis (12). Additionally, inflammatory changes

in hepatocytes, including chronic viral hepatitis, acute hepatitis

and cholestatic hepatitis, can cause intracellular ferritin efflux

(13). Ferritin binds

Fe2+, whereas its depletion increases free

Fe2+ levels. Excess Fe2+ can react with

H2O2 through the Fenton reaction, producing

OH− and hydroxyl radicals with strong oxidizing

properties, thereby promoting ferroptosis (14). Therefore, molecules and signals

involved in iron metabolism and lipid peroxidation are crucial in

the initiation and progression of ferroptosis (15).

The specific link between α-naphthyl isothiocyanate

(ANIT)-induced cholestasis and iron metabolism dysregulation

warrants emphasis. Chronic cholestasis is associated with a

persistent inflammatory response, which can disrupt the hepatic

expression of hepcidin, a master regulator of iron homeostasis

(16,17). Reduced hepcidin levels can lead to

increased iron absorption and mobilization, resulting in hepatic

iron overload (18). This

iron-rich environment, coupled with ANIT-induced oxidative stress,

creates a favorable condition for the Fenton reaction and lipid

peroxidation, thereby priming hepatocytes for ferroptosis (19,20).

Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) remain quiescent in

healthy liver. By contrast, upon cholestatic liver damage,

persistent intrahepatic inflammation can activate HSCs,

transforming them from vitamin A-storing cells into proliferative,

contractile, inflammatory and chemotactic myofibroblasts that

produce extracellular matrix proteins (21). Ferroptosis in hepatocytes

accelerates this transformation (22). Following ferroptosis activation,

hepatocytes lose their normal functions, weakening their inhibitory

effect on nearby HSCs. The release of free iron ions and ROS from

dead hepatocytes further stimulates HSC activation, perpetuating

ferroptosis. This vicious cycle exacerbates inflammation, enhances

HSC activation and increases extracellular matrix synthesis,

including type IV collagen and laminin, thereby advancing

cholestatic disease progression (23).

Deferoxamine (DFO) is a Food and Drug

Administration-approved iron chelator that has been extensively

applied for treating iron overload disorders such as β-thalassemia

and myelodysplastic syndrome (24). It can effectively reduce free iron

ion levels by chelating them within cells to directly inhibit the

Fenton reaction, thereby preventing cell ferroptosis (25).

Given the intrinsic link between cholestasis and

ferroptosis, it has been hypothesized that hepatocyte ferroptosis

serves as a key driver in the progression of chronic cholestasis.

Therefore, the present study aimed to assess this hypothesis using

the iron chelator DFO to investigate whether the inhibition of

ferroptosis through iron chelation could attenuate the progression

of chronic cholestatic liver injury.

Materials and methods

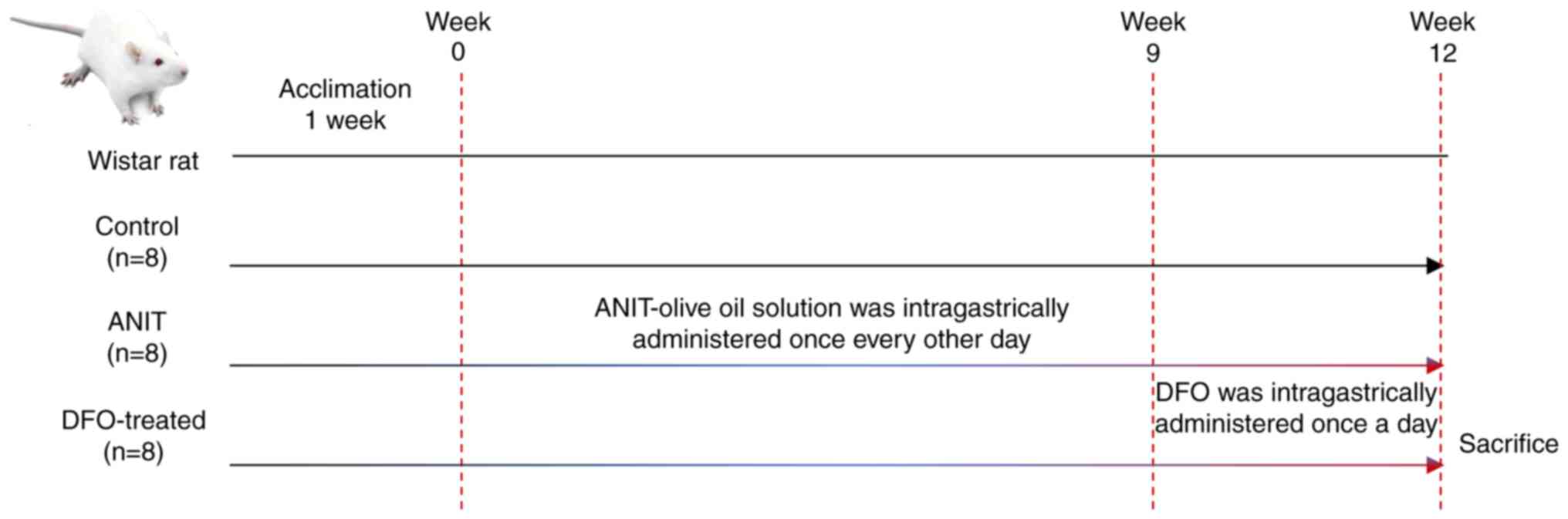

Animal models and experimental

design

Animal welfare and ethical considerations

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal

Care and Utilization Committee of Shanghai University of

Traditional Chinese Medicine (approval no. PZSHUTCM210715019;

Shanghai, China) and were conducted in strict accordance with the

National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of

Laboratory Animals (26).

Animal housing

A total of 24 6-week-old male Wistar rats (batch no.

0054518) were purchased from Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co.,

Ltd. [license no. SCXK (Shanghai) 2017–0005]. The rats weighed

160–180 g upon arrival. They were housed under specific

pathogen-free conditions at 23–24°C with 60±10% humidity, under a

12-h light/12-h dark cycle. After 1 week of acclimation, the rats

were randomly divided into a control group (n=8) and a model group

(n=16).

Dosages

The control group received daily intragastric

administration of an equivalent volume of olive oil (3 ml/kg) and

standard laboratory chow diet. The model group received

intragastric administration of a 2% ANIT (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA)-olive oil solution (3 ml/kg) every other day (27) for 12 weeks. From week 9, the model

group was subdivided into the ANIT (n=8) and DFO-treated (n=8)

groups. The DFO-treated group received daily DFO treatment

(MedChemExpress; 100 mg/kg) (28)

for 4 weeks (weeks 9–12). All animals were sacrificed at the end of

week 12 (Fig. 1).

Health monitoring and humane

endpoints

The health and behavior of all animals were

monitored at least twice daily (morning and evening) throughout the

study. Pre-established humane endpoints were strictly adhered to in

order to minimize suffering. Any animal exhibiting one or more of

the following severe clinical signs was sacrificed immediately: i)

>20% loss of initial body weight; ii) prolonged lethargy or

inability to reach food or water; iii) signs of severe pain or

distress (such as persistent vocalization, self-mutilation); iv)

severe dyspnea or cyanosis; v) paralysis or other neurological

deficits that impeded normal mobility. No animals reached these

endpoints prior to the scheduled termination.

Euthanasia, anesthesia and terminal

blood collection

At the end of week 12, all animals were euthanized

for terminal blood collection and tissue harvesting. Euthanasia was

performed by intraperitoneal injection of an overdose of sodium

pentobarbital (150 mg/kg). A total of 6–8 ml of blood was

aseptically collected from the inferior vena cava. Death was

confirmed by the absence of a heartbeat and cessation of

respiration

Analgesia

No additional analgesics were administered during

the chronic model establishment, as the ANIT-induced injury is not

considered to cause notable pain that requires such intervention

and the administration of analgesics could potentially interact

with the study endpoints. Following confirmation of death, liver

tissue was harvested for subsequent analysis.

Biochemical analysis

Detection method of serum liver function and

blood lipids

Blood was collected from the inferior vena cava and

centrifuged (1,000 × g, 20 min and 4°C) to obtain the serum. Serum

alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (cat. no. KF749; Fujifilm Wako Pure

Chemical Corporation), aspartate aminotransferase (AST; cat. no.

KK718; Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation), ALP (cat. no.

EH360; Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) and GGT (cat. no.

010260; Yantai Ausbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) activities, as well

as total bilirubin (TBIL; cat. no. KK678; Fujifilm Wako Pure

Chemical Corporation), direct bilirubin (DBIL; cat. no. FF870;

Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation), total bile acid (TBA;

cat. no. 210428; Yantai Ausbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd.),

triglyceride (TG) (cat. no. L068; Sekisui Medical Co., Ltd.), total

cholesterol (TCH) (cat. no. L979; Sekisui Medical Co., Ltd.) and

low-density lipoprotein (LDL) (cat. no. EG582; Fujifilm Wako Pure

Chemical Corporation) were measured using the automatic biochemical

analyzer (TK-40FR; Canon Medical Systems Corporation).

Detection method of iron ions in serum

and the liver

For serum analysis, 500 µl serum was introduced into

the measurement tube, whereas 500 µl double-distilled water was

placed in the blank tube. A standard application solution (500 µl;

Iron Assay Kit (cat. no. ab83366; Abcam) was added to the standard

tube. Subsequently, 1.5 ml iron chromogenic reagent was added to

each tube according to the manufacturer's instructions and the

tubes were incubated at 100°C for 5 min, before being allowed to

return to room temperature. Subsequently, the samples were

centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 10 min at room temperature. The

optical density (OD) was measured at 520 nm using a microplate

reader (Infinite M200 PRO; Tecan Group, Ltd.) and the total iron

concentration was calculated based on the standard curve and is

expressed as mM. Briefly, the iron content (in nmol) derived from

the standard curve was divided by the sample volume (500 µl) and

multiplied by the sample dilution factor.

Liver tissue samples (10 mg) were homogenized in 90

µl iron assay buffer (cat. no. ab83366; Abcam) and centrifuged at

16,000 × g for 10 min, according to the manufacturer's

instructions. The supernatant was transferred to a 96-well plate.

For standard wells, 100 µl standard diluent was added, whereas

sample wells received 35 µl sample and 65 µl iron assay buffer.

Each well was treated with 5 µl iron reducing agent, followed by

the addition of 100 µl iron probe after a 30-min incubation at

37°C. Following incubation at 37°C for 60 min in the dark, the

absorbance was measured at 520 nm at room temperature. A standard

curve was generated from the OD values of the standard wells and

total iron content in the sample wells was calculated accordingly.

To measure Fe2+ content, 100 µl standard diluent and 5

µl iron reducing agent were added to the standard wells, whereas 35

µl sample and 70 µl iron analysis buffer were added to the sample

wells, with all other conditions unchanged.

Detection method of hydroxyproline

(HYP) in the liver

Liver tissue samples (70 mg) were homogenized in 1

ml RIPA buffer (cat. no. SD006; Shanghai Sidings BioTech Co.,

Ltd.). Following hydrolysis at 95°C for 20 min, 10 µl indicator was

added, and the pH was adjusted until the solution turned

yellow-green. The volume of each tube was then increased to 10 ml

with double-distilled water; from this, 4 ml diluted hydrolysate

was combined with 20 mg activated carbon and centrifuged at 1,500 ×

g for 10 min at room temperature. A 1-ml aliquot of the supernatant

was then used as the measurement sample. For controls, 1 ml

double-distilled water was added to the blank tube, with 1 ml

standard solution to the standard tube. Each tube then received 0.5

ml reagents 1, 2 and 3, was mixed thoroughly and was incubated at

60°C for 15 min. After centrifuging at 1,500 × g for 10 min at room

temperature, 200 µl supernatant was taken to measure the OD at 550

nm (cat. no. A030-2; Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering

Institute).

Detection method of malondialdehyde

(MDA) in the liver

Liver tissue samples were accurately weighed (50 mg)

and homogenized in 450 µl 0.9% NaCl, followed by centrifugation at

16,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected for

protein concentration analysis using the BCA method. A working

solution was prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions

(cat. no. A003-1; Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute), and

4 ml was added to each tube. To the blank tube, 1 ml absolute

ethanol was added, whereas 1 ml standard solution was added to the

standard tube. To the assay tube, 1 ml sample was added. The tubes

were then incubated in a 95°C water bath for 40 min, cooled to room

temperature and centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min at room

temperature. The OD was measured at 532 nm. The MDA content in

liver tissue was calculated and expressed as nmol/mg of protein

(nmol/mg prot) based on the measured OD values and the known

standard concentration (10 nmol/ml), normalized to the protein

concentration of the tissue homogenate (cat. no. A003-1; Nanjing

Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute).

Detection method of glutathione (GSH)

in the liver

Liver GSH content was determined using a commercial

Glutathione Assay kit (cat. no. A006-2-1; Nanjing Jiancheng

Bioengineering Institute). Liver tissues were processed as

aforementioned for the MDA assay. Subsequently, 60 µl reagent 1 was

added to the blank well, whereas 60 µl standard was added to the

standard well and 60 µl sample was added to the assay well; 60 µl

reagent 2 and 15 µl reagent 3 were then added to each well. The

mixtures were allowed to form natural precipitates for 5 min at

37°C, before the OD was measured at 405 nm. The GSH concentration

was calculated according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Detection method of glutathione

peroxidase (GSH-PX) in the liver

GSH-PX activity was determined using a commercial

Glutathione Peroxidase Assay kit (cat. no. A005; Nanjing Jiancheng

Bioengineering Institute). The liver tissues were processed as

aforementioned for the MDA assay. To the non-enzymatic tube, 40 µl

1 mmol/l GSH was added, whereas 20 µl 1 mmol/l GSH and 20 µl

homogenate were added to the enzymatic tube. Following the

enzymatic reaction, 200 µl supernatant was extracted for the

colorimetric reaction. In total, 200 µl GSH standard solvent was

added to the blank tube, 200 µl 20 µmol/l GSH standard solution was

added to the standard tube and 200 µl supernatant was added to both

the non-enzymatic and enzymatic tubes. To each tube, 200 µl reagent

3, 50 µl reagent 4 and 10 µl reagent 5 were added. After allowing

natural sedimentation for 15 min at 37°C, the OD value was measured

at 412 nm.

Histopathological evaluation

Liver tissues were sectioned into 0.5×0.5 cm pieces,

fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 24–48 h. The

fixed tissue was dehydrated through a graded ethanol series,

cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin. Subsequently, 4-µm

thick sections were prepared. H&E staining was performed

according to standard protocols. Sirius red and Prussian blue

staining were performed according to the manufacturers'

instructions, with incubations at room temperature (1 h for Sirius

red and 30 min for Prussian blue). Digital slide scanning and

panoramic imaging of all stained sections were conducted using a

Panoramic Scanning and Analysis System (LEICA SCN 400; Leica

Microsystems GmbH, Germany) equipped with its Leica SCN Slide

Scanner Software, version 2.5; Leica Microsystems). For

quantitative analysis of collagen deposition, the Sirius

red-positive area (representing collagen fibers) was measured in

five randomly selected fields of view/section at 200× magnification

using ImageJ software (version 2.14.0; National Institutes of

Health). The collagen-positive area ratio was calculated as (Sirius

red-positive area/total tissue area) ×100%. Similarly, the Prussian

blue-positive area (representing iron deposition) was quantified

(five random fields at 200× magnification), and the iron

deposition-positive area ratio was calculated.

Ultrastructural pathology

evaluation

Liver tissue was sectioned into 0.1×0.1 cm pieces

and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4°C for 4–6 h. Samples

underwent standard dehydration through a graded ethanol series,

followed by embedding in acetone overnight. Subsequently, 50-nm

ultrathin sections were subjected to double staining with 3% uranyl

acetate and lead citrate at room temperature, each for 15–20 min.

The samples were examined using a transmission electron microscope

(TK-40FR; FEI; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Image acquisition

and initial analysis were performed using the microscope's

proprietary software (Tecnai Imaging and Analysis (TIA) Software,

version 4.7; FEI/Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Western blot analysis

Liver tissue lysates were prepared using ice-cold

RIPA Lysis Buffer (cat. no. SD006) supplemented with a protease

inhibitor cocktail (cat. no. SD001; both Shanghai Sidings BioTech

Co., Ltd.). Protein concentrations were measured using a BCA

protein assay kit. Equal protein amounts (20 µg/lane) were

separated by SDS-PAGE on 10%, 7.5%, or 12.5% polyacrylamide gels

and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes The membranes were

blocked at room temperature for 15 min using QuickBlock™ Western

blocking solution (cat. no. P0239; Beyotime Biotechnology). The

membranes were then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary

antibodies as follows: anti-Nrf2 (1:1,000), anti-COX2 (1:1,000),

anti-GPX4 (1:5,000), anti-TFR1 (1:5,000), anti-ASCL4 (1:50,000),

anti-HO-1 (1:50,000), anti-Steap3 (1:10,000), anti-α-SMA (1:2,000),

anti-FPN1 (1:1,000), anti-DMT1 (1:1,000), anti-FTH1 (1:2,000),

anti-XCT (1:2,000), and anti-Keap1 (1:2,000). This was followed by

a 1 h incubation at room temperature with horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit IgG,

cat. no. A0208, and goat anti-mouse IgG, cat. no. A0216; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology; 1:1,000). β-actin (1:10,000; cat. no.

66009-1; Proteintech) served as an internal control. Antibodies

against nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2 (Nrf2; cat. no.

ab137550), cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2; cat. no. ab52237), GPX4 (cat.

no. ab125066), transferrin receptor 1 (TFR1; cat. no. ab269513),

acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ASCL4; cat. no.

ab155282), heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1; cat. no. ab68477),

six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate 3 (Steap3;

cat. no. ab151566) and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; cat. no.

ab7817) were purchased from Abcam. Ferroportin 1 (FPN1; cat. no.

26601-1-AP) and divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1; cat. no.

20507-1-AP) antibodies were purchased from Proteintech Group, Inc.

Ferritin heavy chain 1 (FTH1; cat. no. PA4412) and

cystine/glutamate transporter (XCT; cat. no. T57046) antibodies

were purchased from Abmart Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd. The

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) antibody (cat. no.

bs-3648R) was purchased from BIOSS. Protein bands were visualized

using Clarity Western ECL Substrate (cat. no. 1705061; Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.). Images of the blots were then captured and the

band intensities were semi-quantified using ImageJ software

(version 1.54p; National Institutes of Health).

Statistical analysis

The sample size (n=8 per group) was determined a

priori using a power analysis conducted with G*Power software

(version 3.1.9.7; gpower.hhu.de/). The effect size was estimated

from preliminary data obtained from a pilot experiment with 6

rats/group, with an α level of 0.05 (two-sided) and a power (1-β)

of 0.8, ensuring adequate statistical power to detect significant

effects. All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

The normality of data distribution was confirmed using the

Shapiro-Wilk test, and the homogeneity of variances was verified

using Levene's test. For data that satisfied both assumptions,

one-way ANOVA was performed, followed by Tukey's honestly

significant difference post hoc test for multiple comparisons. For

data that violated the assumption of normality or homogeneity of

variances, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was applied,

followed by Dunn's post hoc test for multiple comparisons. All

statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version

25.0; IBM Corp.). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Liver function of rats with chronic

cholestasis is impaired and histopathological examination of liver

tissue reveals inflammation

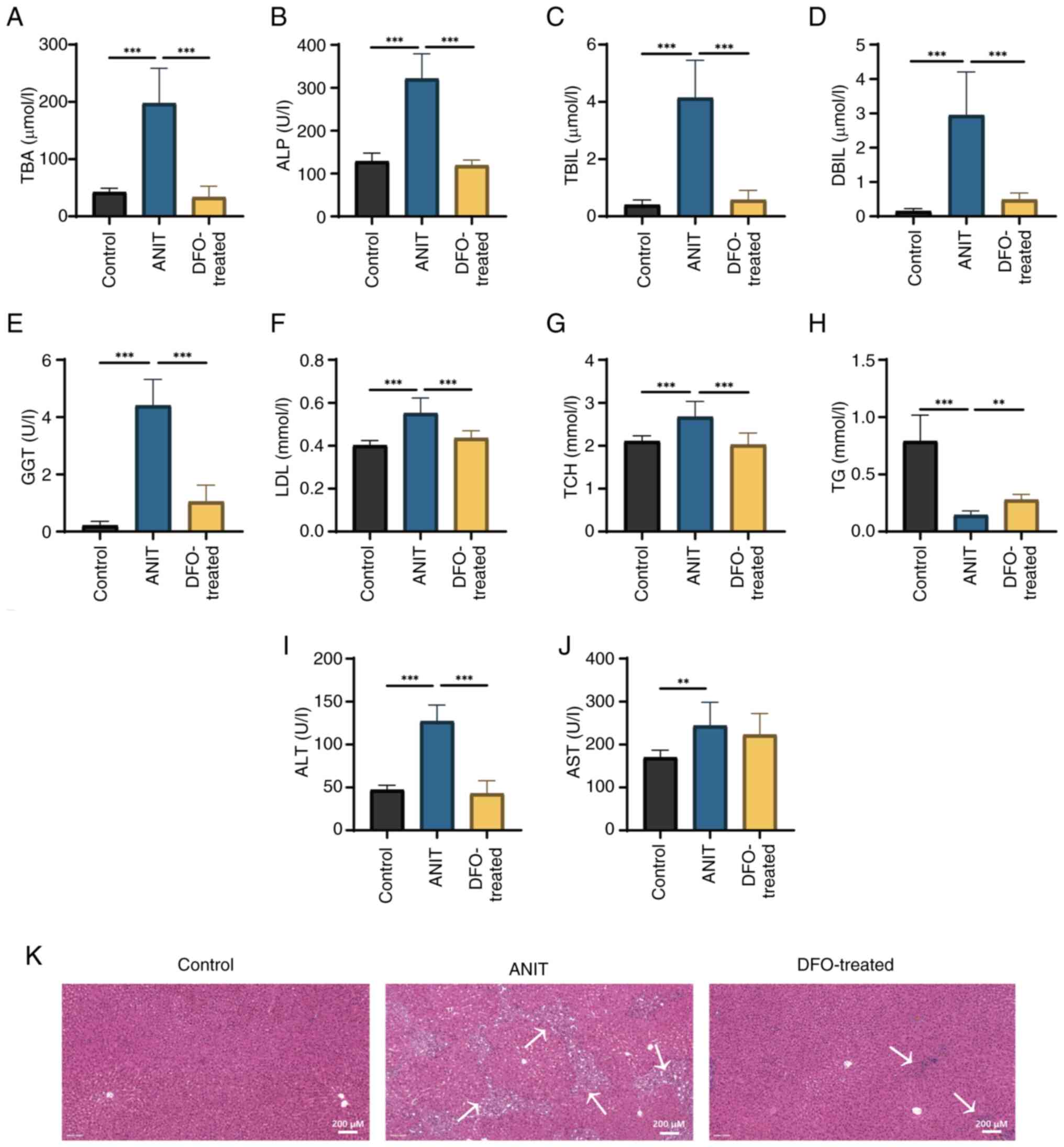

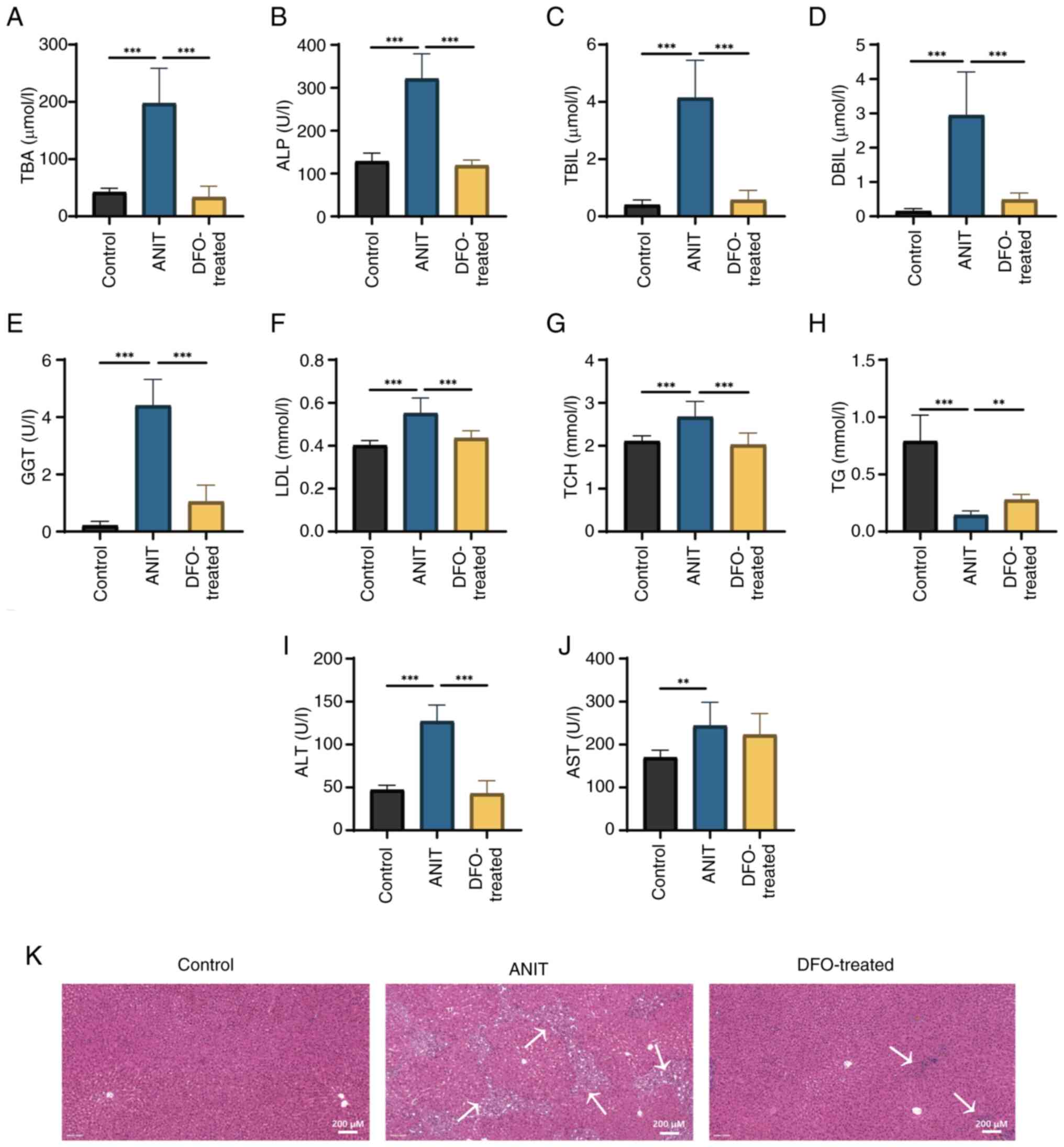

ANIT-induced cholestasis led to significant

increases in serum ALT, AST, ALP and GGT activities, and TBIL,

DBIL, TBA, TCH and LDL levels, whereas TG levels were significantly

decreased compared with those in the control group (Fig. 2A-J). DFO significantly restored

serum ALT, ALP and GGT activities, and TBIL, DBIL, TBA, TCH, LDL

and TG levels, compared with those in the ANIT group. H&E

staining revealed bile duct hyperplasia and inflammatory cell

infiltration in the portal area of rats in the ANIT group, which

were markedly inhibited by DFO treatment (Fig. 2K).

| Figure 2.Liver function of rats with chronic

cholestasis is impaired and histopathological analysis of liver

tissue reveals inflammation. The control group was fed a chow diet,

and the ANIT and DFO-treated groups were intragastrically

administered ANIT olive oil solution with or without DFO

(n=8/group). (A) TBA, (B) ALP, (C) TBIL, (D) DBIL, (E) GGT, (F)

LDL, (G) TCH, (H) TG, (I) ALT and (J) AST were measured.

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. (K) Hematoxylin and eosin staining

(scale bar, 200 µm). Arrows indicate bile duct hyperplasia and

inflammatory cell infiltration in the portal area. ANIT, α-naphthyl

isothiocyanate; DFO, deferoxamine; TBA, total bile acid; ALP,

alkaline phosphatase; TBIL, total bilirubin; DBIL, direct

bilirubin; GGT, γ-glutamyl transferase; LDL, low-density

lipoprotein; TCH, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; ALT, alanine

aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase. |

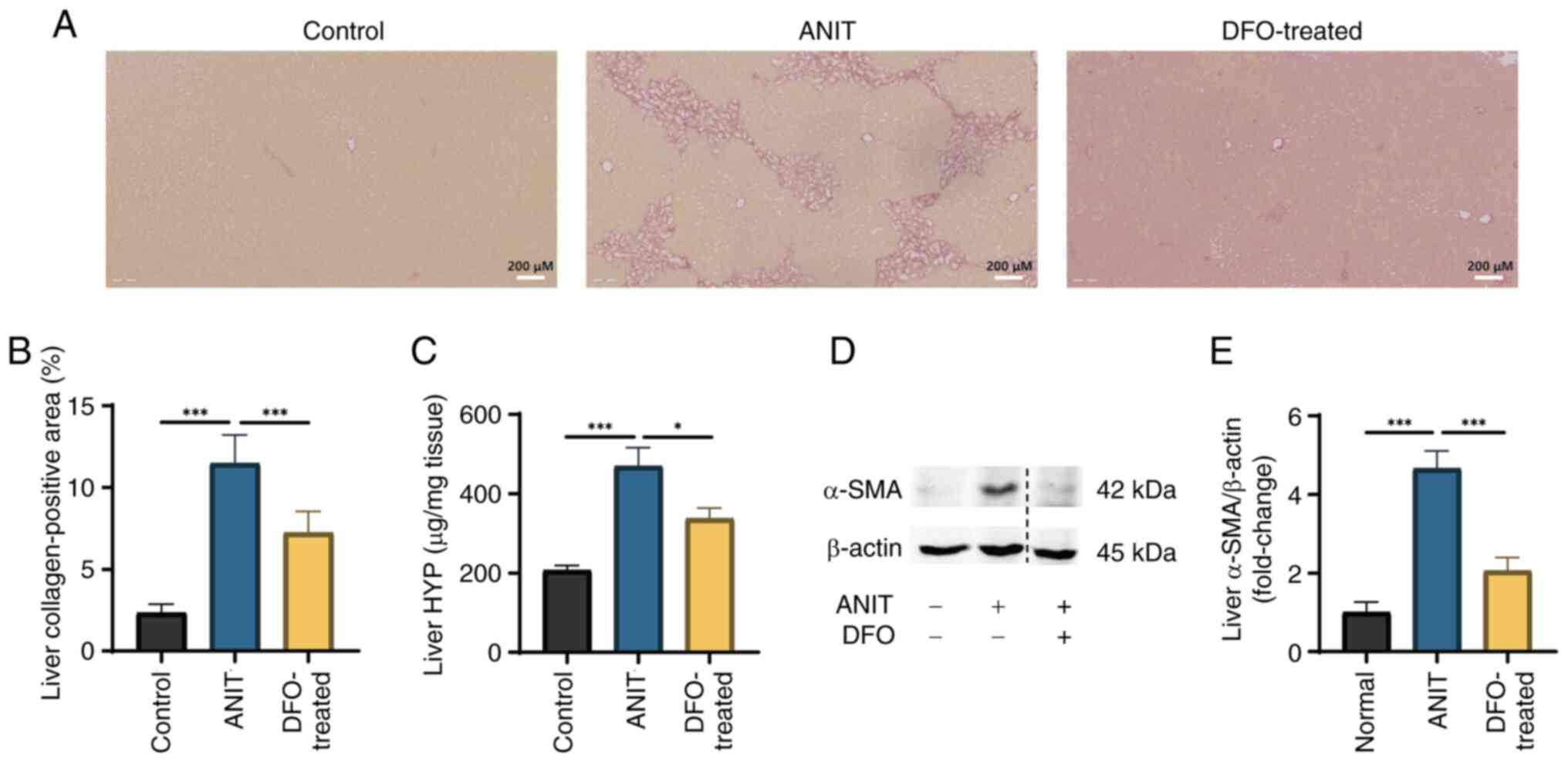

Intrahepatic collagen fiber deposition

is increased in rats with chronic cholestasis

Sirius red staining revealed significant collagen

fiber deposition at the periphery of rat hepatic lobules following

ANIT-induced cholestasis (Fig. 3A and

B). DFO treatment, by reducing iron overload, was shown to

markedly improve ductular function and inflammatory cell

infiltration (Fig. 2K, while

significantly reducing intrahepatic collagen fiber deposition; as

evidenced by a decreased Sirius red-positive staining area ratio

(Fig. 3A and B). HYP levels were

significantly elevated in samples from rats with ANIT-induced

cholestasis compared with those in the control group, whereas DFO

treatment substantially restored HYP levels (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, liver α-SMA protein

expression was significantly increased in the ANIT group, whereas

it was significantly reversed by DFO treatment (Fig. 3D and E).

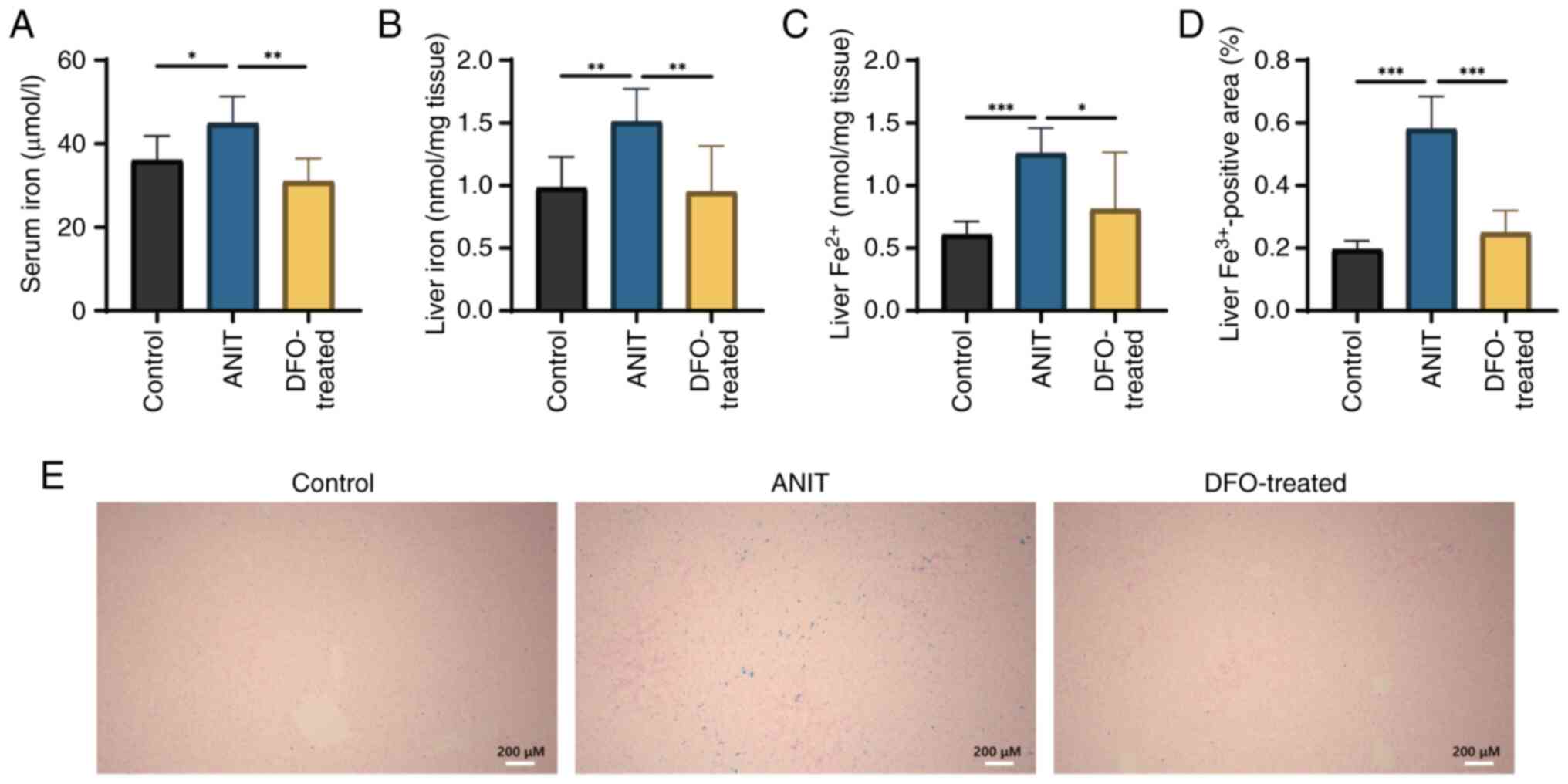

Free iron ions in serum and liver are

aberrantly increased in rats with chronic cholestasis

Serum total iron, liver total iron and

Fe2+ content were significantly elevated in rats with

ANIT-induced cholestasis compared with those in the control group;

however, DFO treatment significantly decreased these levels

compared with those in the ANIT group (Fig. 4A-C). Furthermore, DFO treatment

significantly reduced hepatic iron deposition, as evidenced by the

decreased positive Prussian blue staining area ratio (Fig. 4D). Prussian blue staining revealed

extensive blue staining in the liver of rats with chronic

cholestasis, indicating increased iron deposition (Fig. 4E).

Lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis

marker levels are increased in the livers of rats with and the

liver ultrastructure is affected in a DFO-reversible manner

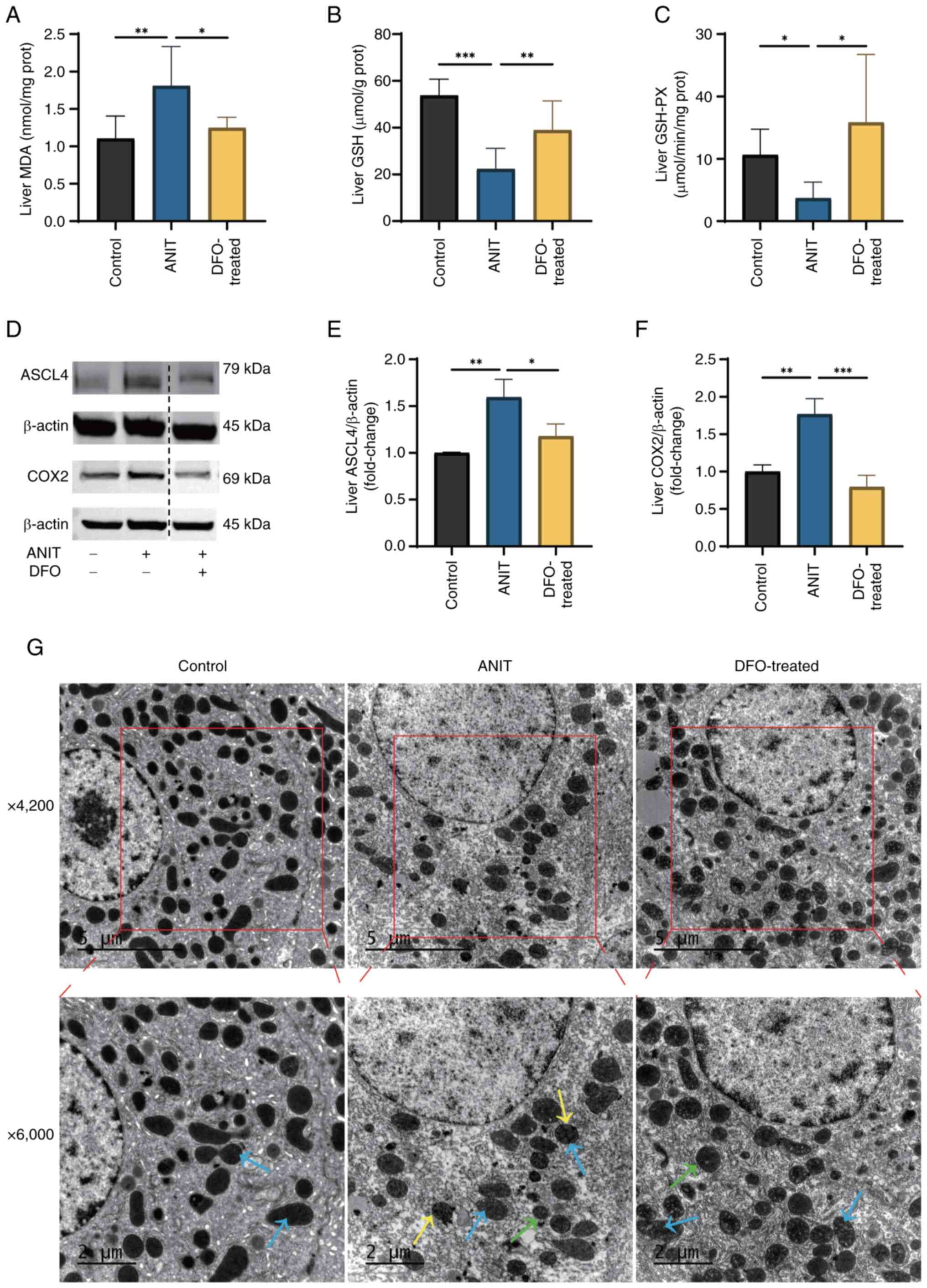

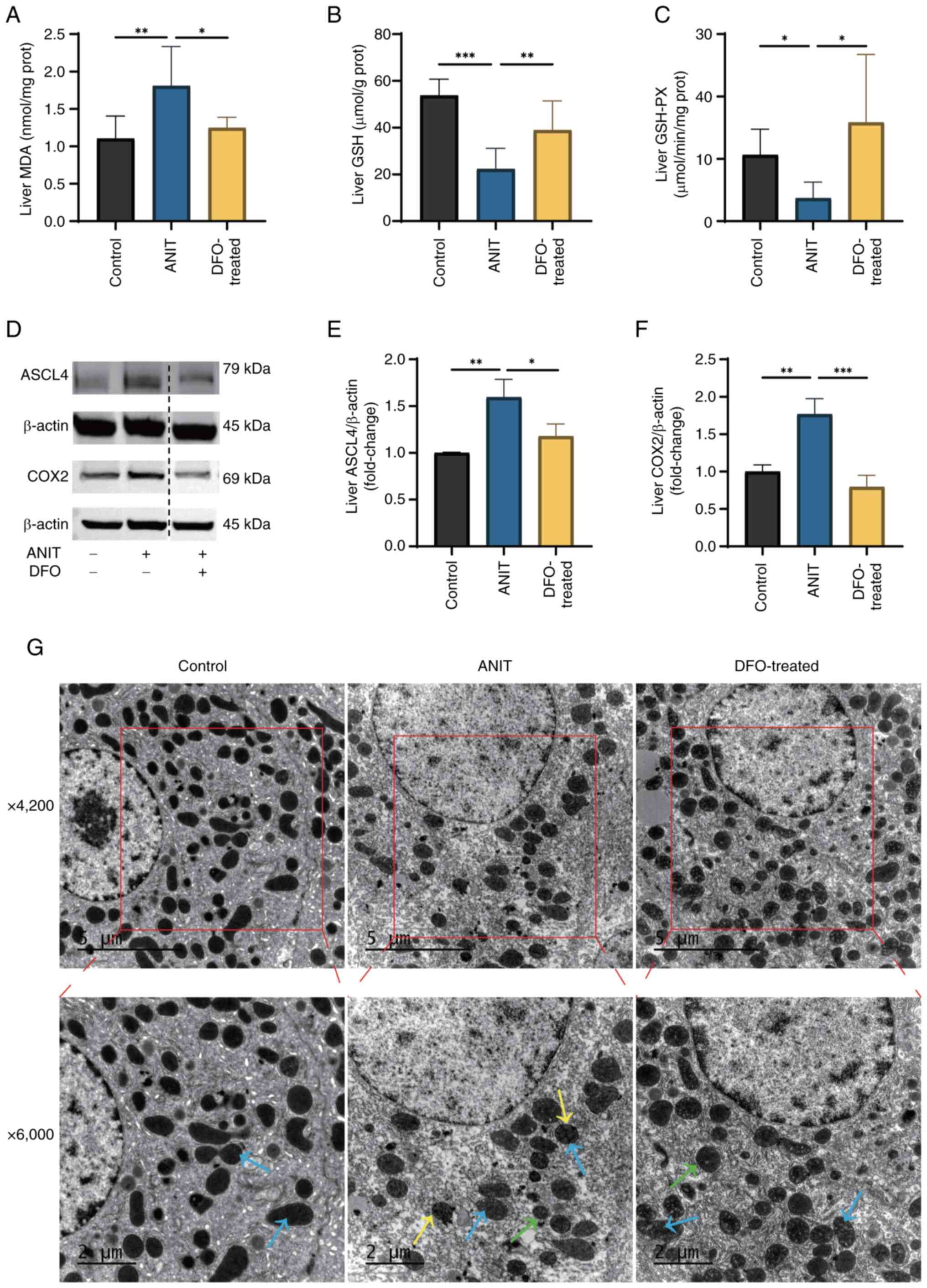

In rats with ANIT-induced cholestasis, liver MDA

levels were significantly increased, whereas GSH content and GSH-PX

activity were significantly decreased, compared with those in the

control group (Fig. 5A-C). DFO

treatment, through its iron-chelating action, notably restored

liver GSH-PX activity and MDA and GSH levels compared with those in

the ANIT group. Furthermore, the protein expression levels of ASCL4

and COX2 were significantly elevated in the liver of rats with

ANIT-induced cholestasis compared with those in the control group

(Fig. 5D-F). By contrast, DFO

treatment significantly reversed the aberrant expression of these

aforementioned ferroptosis markers compared with those in the ANIT

group. Transmission electron microscopy revealed that hepatocytes

from rats with chronic cholestasis exhibited intact nuclei but

characteristic mitochondrial abnormalities, including reduced size,

blurred and fused cristae, and increased bilayer membrane density

(Fig. 5G). By contrast,

DFO-treated rats exhibited intact hepatocyte nuclei and

morphologically normal mitochondrial cristae. Furthermore, the

mitochondrial size in the DFO group appeared increased compared

with that in the ANIT group, indicating a partial restoration of

mitochondrial morphology towards a normal state.

| Figure 5.Levels of lipid peroxidation and

ferroptosis markers are increased in the liver of rats with chronic

cholestasis and the liver ultrastructure is affected in a

DFO-reversible manner. Control group was fed a chow diet, whereas

ANIT and DFO-treated groups were intragastrically administered ANIT

olive oil solution with or without DFO (n=8/group). Levels of (A)

MDA, (B) GSH and (C) GSH-PX were detected. (D) Changes in

ferroptosis marker protein expression. The blots shown are

representative of three independent experiments. A dotted line

indicates that the lanes were non-adjacent on the original gel. All

target protein bands and their corresponding loading control bands

shown side-by-side were derived from the same membrane. Relative

expression levels of (E) ASCL4 and (F) COX2. Data are presented as

the mean ± SD. P-values were determined by one-way ANOVA.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. (G) Transmission electron

microscope sections, blue arrows indicate mitochondrial cristae,

yellow arrows indicate outer mitochondrial membrane and green

arrows point to mitochondria (scale bars, 5 and 2 µ m). DFO,

deferoxamine; ANIT, α-naphthyl isothiocyanate; MDA,

malondialdehyde; GSH, glutathione; GSH-PX, glutathione peroxidase;

ASCL4, acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4; COX2,

cyclooxygenase 2. |

Abnormal expression of antioxidant and

iron metabolism-related proteins in liver samples of rats with

chronic cholestasis

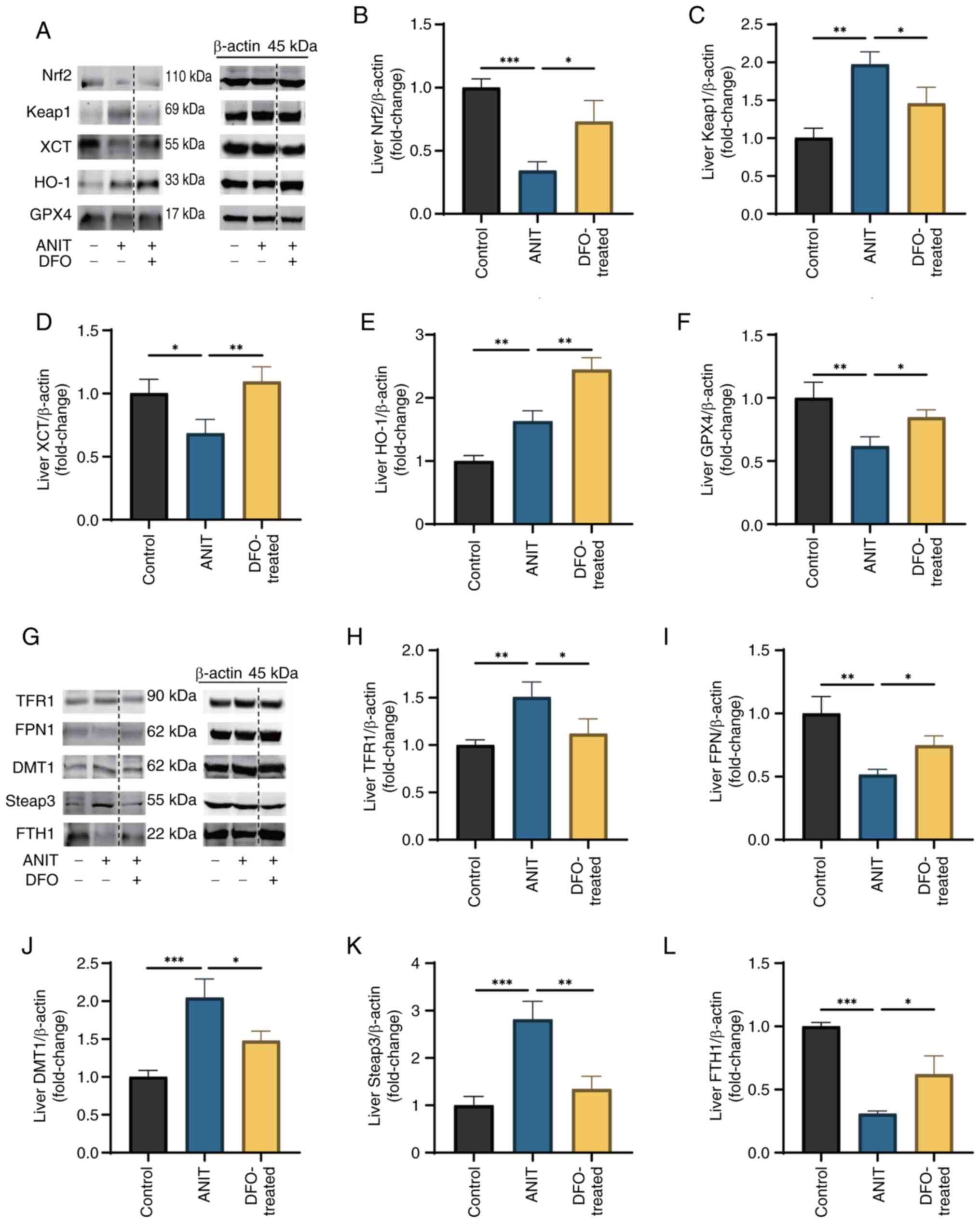

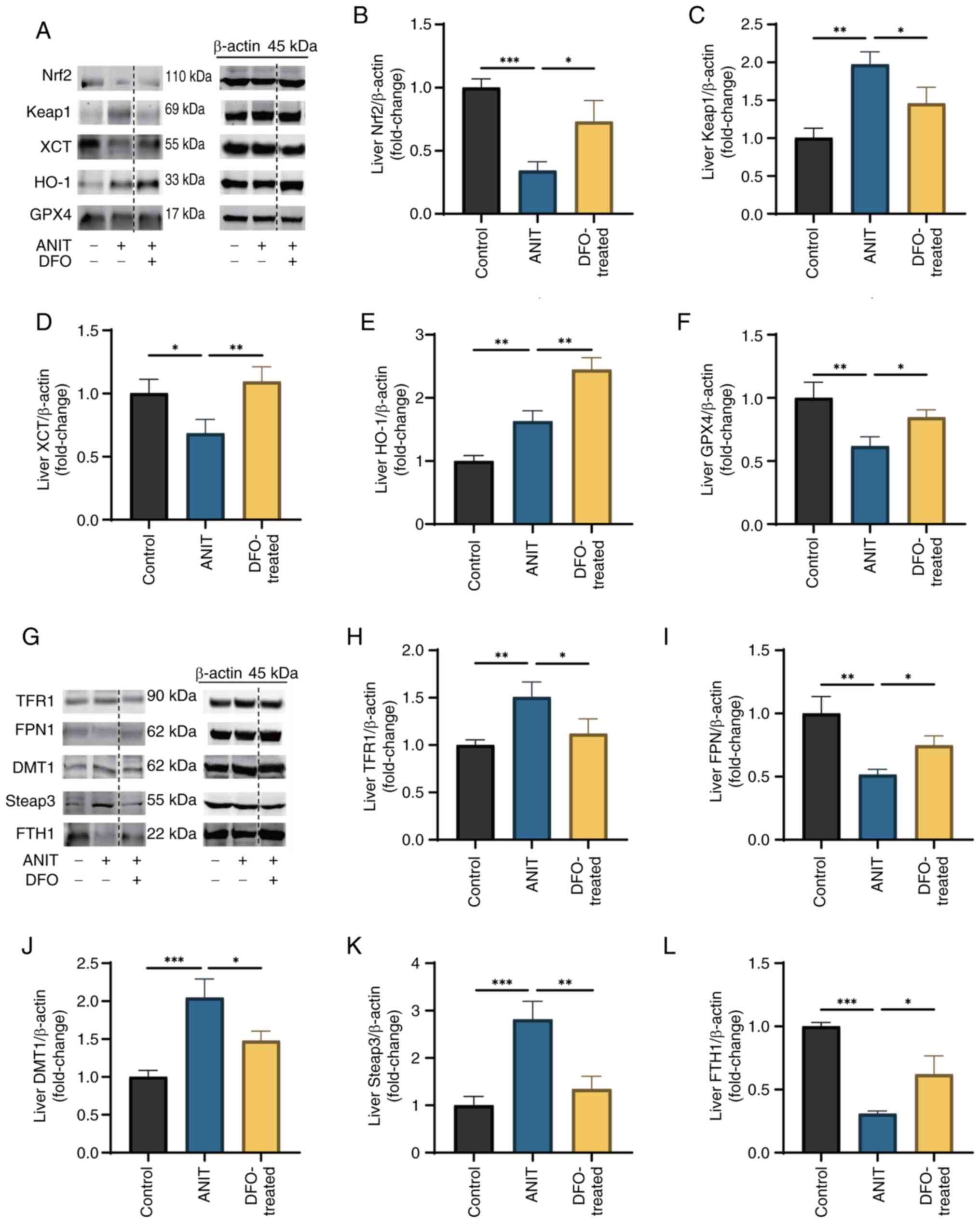

In rats with ANIT-induced cholestasis, liver protein

expression levels of Nrf2, XCT and GPX4 were significantly reduced,

whereas those of Keap1 and HO-1 were increased, compared with those

in rats in the control group (Fig.

6A-F). DFO treatment notably increased the expression of Nrf2,

XCT and GPX4, decreased Keap1 expression and further enhanced HO-1

expression. Similarly, the protein expression levels of liver FPN1

and FTH1 were significantly decreased, whereas those of TFR1, DMT1

and Steap3 were elevated in cholestasis-affected rats (Fig. 6G-L). DFO treatment effectively

normalized these disruptions in the expression of iron

metabolism-related proteins.

| Figure 6.Abnormal expression of antioxidant

and iron metabolism-related proteins in liver samples of rats with

chronic cholestasis. Control group was fed a chow diet, whereas the

ANIT and DFO-treated groups were intragastrically administered ANIT

olive oil solution with or without DFO (n=8/group). (A) Changes in

ferroptosis antioxidant-related protein expression. The blots shown

are representative of three independent experiments. A dotted line

indicates that the lanes were non-adjacent on the original gel. All

target protein bands and their corresponding loading control bands

shown side-by-side were derived from the same membrane. Relative

expression levels of (B) Nrf2, (C) Keap1, (D) XCT, (E) HO-1 and (F)

GPX4. (G) Changes in iron metabolism-related protein expression.

The blots shown are representative of three independent

experiments. A dotted line indicates that the lanes were

non-adjacent on the original gel. All target protein bands and

their corresponding loading control bands shown side-by-side were

derived from the same membrane. Relative expression levels of (H)

TFR1, (I) FPN1, (J) DMT1, (K) Steap3 and (L) FTH1. Data are

presented as the mean ± SD. P-values were determined by one-way

ANOVA. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. ANIT, α-naphthyl

isothiocyanate; DFO, deferoxamine; Nrf2, nuclear factor

erythroid-2-related factor 2; Keap1, Kelch-like ECH-associated

protein 1, XCT, cystine/glutamate transporter; HO-1, heme oxygenase

1; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; TFR1, transferrin receptor 1;

FPN1, ferroportin 1; DMT1, divalent metal transporter 1; Steap3,

six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate 3; FTH1,

ferritin heavy chain 1. |

Discussion

Cholestasis is a pathological condition that

suppresses bile formation and excretion, which is influenced by

various factors affecting the liver (29). During cholestatic liver disease

progression, sustained cholestasis can trigger inflammation in bile

duct cells and hepatocytes (30).

This inflammatory response can then prompt immune cells to generate

abundant ROS in the presence of proinflammatory factors to combat

pathogens. However, failure to promptly eliminate the excessive ROS

results in their accumulation, serving as a pathogenic stimulus to

culminate in hepatocyte cell death (12).

A hallmark of ferroptosis is the decreased uptake of

intracellular cystine and synthesis of cysteine, which limits GSH

biosynthesis and reduces GSH-PX activity (31). GSH and GSH-PX scavenge free

radicals and ROS-induced lipid peroxides in vivo, thereby

mitigating oxidative damage within the organism (32,33).

MDA is a primary toxic byproduct of lipid peroxidation, serving as

an indicator of tissue peroxidative damage (34). Serum and liver tissue total iron,

in addition to Fe2+ and Fe3+ levels, indicate

potential iron overload in the organism. Excess free

Fe2+ reacts with intracellular

H2O2 through the Fenton reaction, producing

Fe3+ and potent oxidants. These oxidants damage cell

membranes and facilitate cellular ferroptosis. Strong oxidants can

damage cell membranes and induce ferroptosis (14). As described in previous studies

(13,35), transmission electron microscopy

hallmarks of ferroptosis include hepatocyte mitochondria with

reduced size, increased bilayer density, ruptured and crumpled

outer membranes, and diminished or absent cristae, whilst the

nuclei remain intact. Consistent with these established features,

our ultrastructural analysis revealed characteristic mitochondrial

abnormalities in cholestatic rats, including reduced size, blurred

and fused cristae, and increased bilayer membrane density),

supporting the occurrence of ferroptosis in our model. ASCL4 and

COX2 are key proteins involved in detecting ferroptosis. ASCL4

catalyzes the formation of polyunsaturated fatty acid-acyl coenzyme

A derivatives (36), which bind to

phospholipids in cell membranes through the action of

lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3, increasing membrane

susceptibility to oxidation and lipid peroxide-induced damage

(37,38). By contrast, COX2 enhances

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 1-mediated

lipid peroxidation to elevate intracellular ROS levels (39).

In the present study, rats with chronic cholestasis

exhibited significantly reduced GSH content and GSH-PX activity,

alongside a marked increase in MDA content in liver tissue,

indicating a severe deficiency in antioxidant capacity and

substantial lipid peroxidation damage due to lipid peroxide

accumulation. Total serum iron, total iron and Fe2+

levels in liver tissue were significantly elevated in these model

rats. Prussian blue staining revealed extensive blue staining in

liver tissue, signifying abnormal iron accumulation, particularly

Fe3+, in cholestatic rats. Transmission electron

microscopy also demonstrated indistinct hepatocyte boundaries,

intact nuclei, reduced mitochondrial size, blurred and fused

mitochondrial cristae, with increased bilayer membrane density.

These ultrastructural and morphological alterations in hepatocytes

align with the characteristics of ferroptosis. Western blotting

revealed markedly increased expression levels of ASCL4 and COX2 in

the liver tissue of model rats, signifying a substantial rise in

lipid peroxide levels and the occurrence of ferroptosis. These

findings suggest that ferroptosis of hepatocytes may occur during

ANIT-induced chronic cholestasis in rats.

Although the present study was conducted in an

animal model, the relevance of ferroptosis to human cholestatic

liver diseases has been recognized. Previous studies have reported

iron accumulation and dysregulation of ferroptosis-related genes

(such as GPX4 and SLC7A11) in liver tissues from patients with

intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy or cholestatic drug-induced

liver injury (40,41). This converging evidence suggests

that the ferroptotic pathway identified in the present study may

have translational importance in human cholestatic conditions.

In the ferroptosis antioxidant pathway, System Xc-

is comprised of two proteins, XCT and 4F2 cell-surface antigen

heavy chain, facilitating a 1:1 exchange of extracellular cystine

for intracellular glutamate (42).

Cystine serves as a vital precursor for intracellular cysteine

synthesis, positioning XCT as a key component in this pathway. GPX4

is a selenoprotein that reduces lipid peroxides to lipid alcohols,

thereby preventing ferroptosis by scavenging excess intracellular

lipid peroxides. This enzyme is the most potent antioxidant enzyme

in the GPX family, which serves as a pivotal target within the

antioxidant pathway (43). The

Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1 axis constitutes a key intracellular antioxidant

pathway (44). Keap1 inhibits Nrf2

by retaining it in the cytoplasm (45), thereby preventing its nuclear

translocation and subsequent antioxidant activity (46). Nrf2 is a central component in the

antioxidant system, regulating the upstream factor HO-1 (47), which enhances the expression of

both HO-1 and GPX4 (48). HO-1

exhibits antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, mitigating

mitochondrial and lipid peroxidation damage (49).

In the present study, Keap1 protein expression was

elevated, whereas XCT, GPX4 and Nrf2 protein expression levels were

reduced, in the liver tissues of rats following ANIT-induced

chronic cholestasis. This indicated that the System Xc- transporter

was inhibited during cholestasis, resulting in cysteine deficiency

and limited GPX4 synthesis, which failed to efficiently scavenge

excessive ROS. The Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway was suppressed,

impairing antioxidant activity. The observed upregulation of HO-1

in the present model appeared paradoxical to the overall

suppression of the Nrf2 axis. However, this can be interpreted as a

compensatory stress response to severe oxidative injury. The

initial induction of HO-1 may represent the attempt of the liver to

mitigate damage. In the face of sustained cholestatic insult, this

compensatory mechanism ultimately proved insufficient to prevent

the progression of ferroptosis, as evidenced by the downregulation

of other key antioxidants, such as GPX4 (50,51).

Consequently, the antioxidant capacity of the body was diminished

and excessive intracellular lipid peroxides were not effectively

eliminated, leading to ferroptosis.

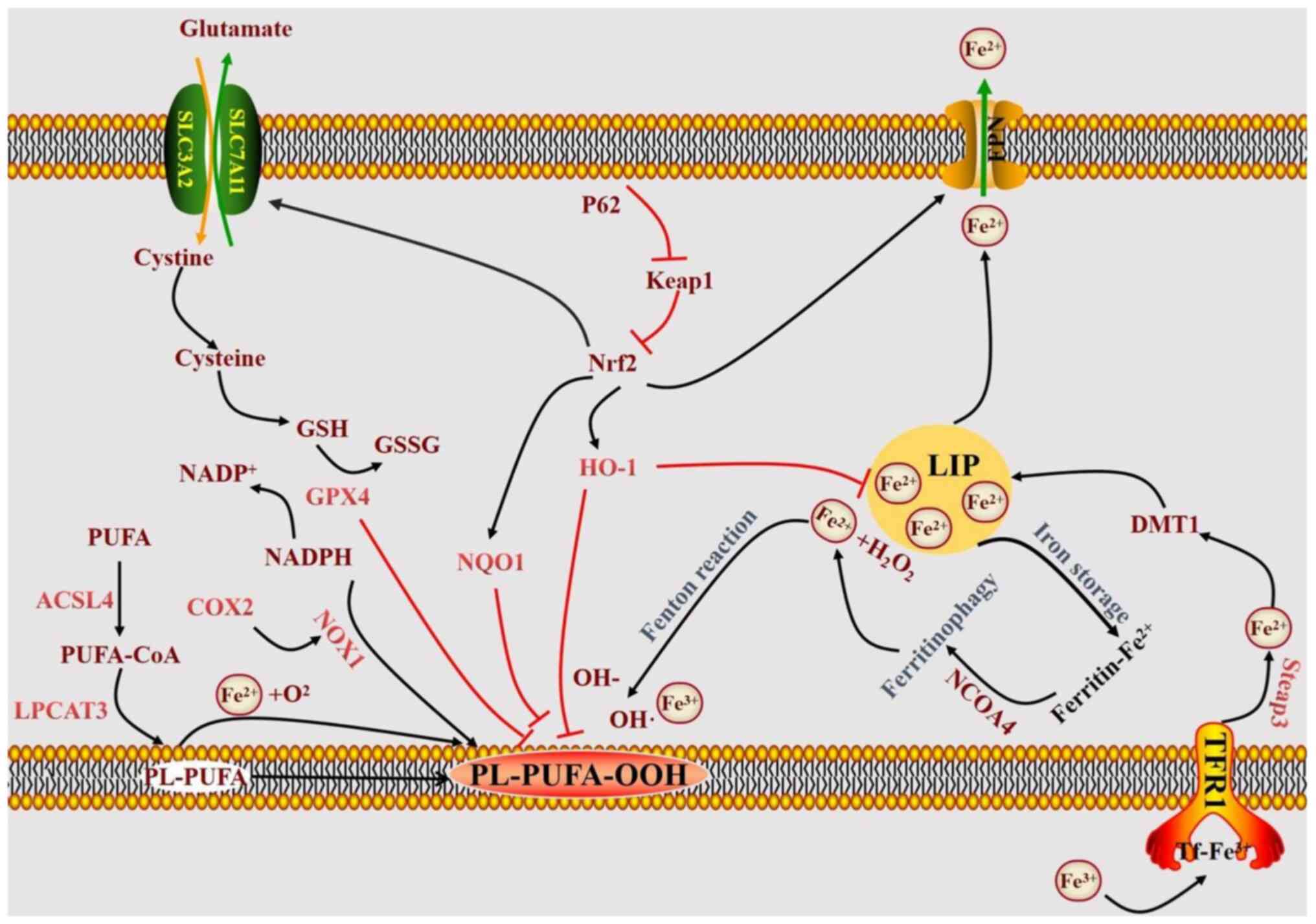

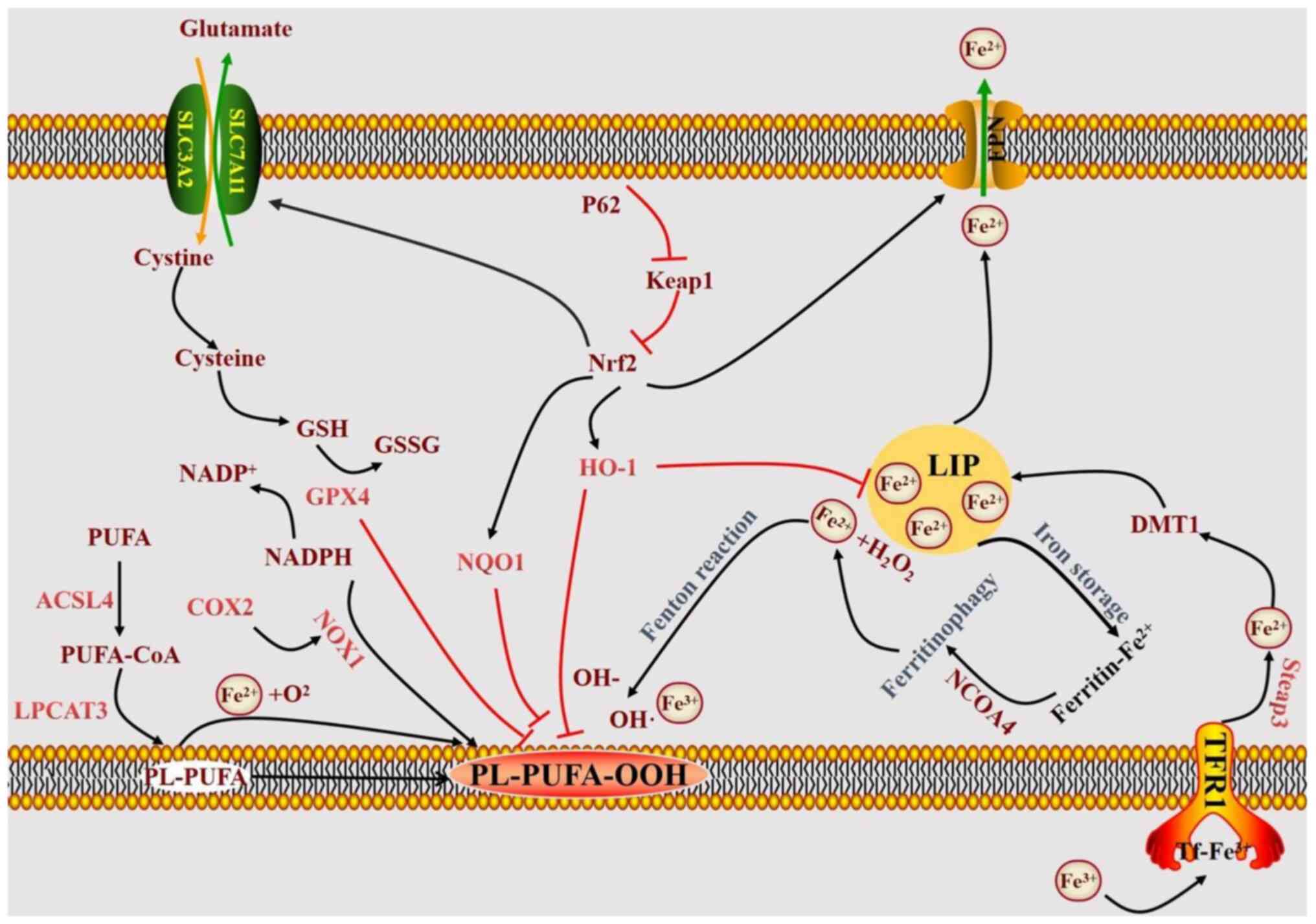

In the iron metabolism pathway, TFR1 on the cell

membrane facilitates the intracellular transport of iron ions by

binding to the extracellular Tf-Fe complex (52). Steap3 reduces transferrin-bound

Fe3+ to Fe2+ (53), which is then translocated into the

intracytoplasmic labile iron pool (LIP) through DMT1. DMT1 is

crucial for the intracellular transport of ferric ions and serves

as an essential metal ion transporter in the iron metabolism

pathway (54). Cytoplasmic

ferritin as a multimer can decrease intracellular free iron ion

levels by binding to free iron ions in the LIP. FPN is the sole

protein facilitating iron efflux in mammals, enabling the transfer

of iron ions out of cells and thereby reducing intracellular free

iron ion concentrations (55). The

mechanism of iron-induced cell death is illustrated in Fig. 7.

| Figure 7.Diagram of the mechanism of

ferroptosis. ASCL4, acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4;

COX2, cyclooxygenase 2; DMT1, divalent metal transporter 1; FPN,

ferroportin; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; GPX4, glutathione

peroxidase 4; GSH, glutathione; HO-1, heme oxygenase 1; Keap1,

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1; LIP, labile iron pool; LPCAT3,

lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3; NCOA4, nuclear receptor

coactivator 4; NOX1, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

oxidase 1; NQO1, NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1; Nrf2, nuclear

factor erythroid-2-related factor 2; PL-PUFA-OOH,

phospholipid-polyunsaturated fatty acid hydroperoxide; SLC7A11,

solute carrier family 7 member 11; Steap3, six-transmembrane

epithelial antigen of the prostate 3; TFR1, transferrin receptor

1. |

The present study revealed that in liver tissues of

rats after ANIT-induced chronic cholestasis, TFR1, Steap3 and DMT1

protein expression increased, whereas FTH1 and FPN1 expression

decreased. This suggests that cholestasis can enhance cellular iron

ion uptake, reduce ferritin storage function, diminish iron

exclusion capacity, elevate intracellular free iron levels,

intensify the Fenton reaction and promote excessive ROS, leading to

lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis in hepatocytes.

In summary, these aforementioned observations

suggested that decreased antioxidant and iron metabolism in

hepatocytes, resulting in iron-induced cell death, is a key

pathological mechanism in chronic cholestasis.

DFO is a potent iron chelator that is extensively

used in clinical settings to treat iron overload disorders such as

β-thalassemia and myelodysplastic syndrome (24). In the present study, the protective

effect of DFO was shown to be primarily mediated through its

capacity to chelate iron. DFO treatment significantly reduced serum

and hepatic total iron levels as well as Fe2+ content,

and markedly decreased hepatic iron deposition. Furthermore, DFO

alleviated indices of iron-dependent oxidative damage, including

lowering lipid peroxidation (MDA) and restoring antioxidant

capacity (GSH and GSH-PX). In addition, DFO normalized the

expression of key proteins involved in iron metabolism (TFR1, FPN1,

etc., Fig. 6G-L) and ferroptosis

(ASCL4, COX2). By reducing intracellular and systemic iron load,

DFO can limit the substrates available for the Fenton reaction

(56), thereby decreasing the

generation of hydroxyl radicals and subsequent lipid peroxidation

(57,58). This reduction in iron-driven

oxidative stress ultimately mitigates the process of ferroptosis

(59).

The present study investigated the role of the

ferroptosis inhibitor DFO in addressing ANIT-induced chronic

cholestasis in rats, aiming to test the hypothesis that

hepatocellular ferroptosis is a key pathogenic mechanism in chronic

cholestasis and that targeting it may be therapeutic. The findings

indicated that DFO may markedly ameliorate cholestasis.

Biochemically, DFO reduced serum levels of TBA, TBIL, DBIL, LDL and

TCH, decreased GGT, ALP and ALT activities, increased serum TG

levels and mitigated hepatocyte dysfunction in cholestatic rats. In

hepatic tissues, DFO enhanced GSH content and GSH-PX activity,

boosted antioxidant capacity, lowered MDA content, reduced lipid

peroxidation and decreased HYP content in the liver of model rats.

Biochemical analysis demonstrated that DFO effectively reduced

serum total iron, liver tissue total iron and Fe2+

levels in model rats. Hepatic histopathology revealed that DFO

decreased small bile duct proliferation in the hepatic portal

areas, reduced inflammatory cell infiltration and diminished

collagen fiber deposition and Fe3+ accumulation.

Transmission electron microscopy indicated that hepatocyte nuclei

in the DFO group remained intact, with normal mitochondrial

morphology, size and clear cristae. Western blotting showed that

DFO downregulated the protein expression of α-SMA, a classical

marker of activated HSCs, in the rat liver tissue, indicating the

inhibition of HSC activation. This contributed to the deceleration

of hepatic fibrosis progression in cholestasis. DFO downregulated

ASCL4 and COX2 protein expression in liver tissues, and inhibited

ANIT-induced ferroptosis in chronically cholestatic rats. After

intervention, DFO reduced Keap1, TFR1, DMT1 and Steap3 protein

levels, whereas it upregulated Nrf2, XCT, HO-1, GPX4, FPN1 and FTH1

in liver tissues. This suggested that DFO can mitigate ferroptosis

by enhancing hepatocyte iron storage and excretion, reducing

extracellular ferric iron translocation and decreasing free ferric

iron content, thereby boosting antioxidant capacity and preventing

ferroptosis.

However, it is important to acknowledge that DFO is

a pleiotropic agent with biological effects beyond iron chelation.

These include intrinsic antioxidant properties and potential

modulatory effects on non-parenchymal cells, such as HSCs (60,61).

While the present data strongly supported iron chelation as the

primary mechanism, the contribution of these additional pleiotropic

effects to the overall hepatoprotection observed cannot be ruled

out.

The present study has several limitations. The

findings are based on a single animal model of cholestasis.

Validation in additional models would strengthen the

generalizability of the conclusions. In addition, the use of DFO,

though effective, prevents the unequivocal attribution of all

protective effects solely to the reduction of ferroptosis through

iron chelation, due to its pleiotropic nature. Future studies using

more specific ferroptosis inhibitors (such as ferrostatin-1)

(62) or genetic approaches to

manipulate key ferroptosis regulators (including GPX4) would be

invaluable. The lack of in vitro data also limited the

mechanistic depth. Establishing in vitro models of bile

acid-induced hepatocyte injury will be essential for dissecting the

precise molecular sequence of events.

In conclusion, the present findings demonstrated

that ferroptosis, driven by the concurrent disruption of hepatocyte

antioxidant and iron metabolism capacities, is a key pathological

mechanism in chronic cholestasis. The iron chelator DFO alleviated

cholestatic liver injury, an effect likely mediated by the

reduction of iron overload and the subsequent ferroptotic process.

The present study highlighted the ferroptosis pathway as a

promising therapeutic target for cholestatic liver diseases.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 81774196), the Natural Science

Foundation of Shanghai Municipality of China (grant no.

22ZR1459200) and the Luzhou Science and Technology Innovation City

Development Fund of China (grant no. 2024RQN226).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

XW designed the present study. ZG performed

experiments. JW performed data interpretation. YW performed data

analysis. XL, YX, LQ, JL and PL assisted in collecting the samples.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript. XW and ZG

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The animal protocol was approved by the Animal Care

and Utilization Committee of Shanghai University of Traditional

Chinese Medicine (Ethics Review Number: PZSHUTCM210715019) and was

conducted following the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory

Animals (26).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Karpen SJ, Kelly D, Mack C and Stein P:

Ileal bile acid transporter inhibition as an anticholestatic

therapeutic target in biliary atresia and other cholestatic

disorders. Hepatol Int. 14:677–689. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Pollock G and Minuk GY: Diagnostic

considerations for cholestatic liver disease. J Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 32:1303–1309. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Bortolini M, Almasio P, Bray G, Budillon

G, Coltorti M, Frezza M, Okolicsanyi L, Salvagnini M and Williams

R: Multicentre survey of the prevalence of intrahepatic cholestasis

in 2520 consecutive patients with newly diagnosed chronic liver

disease. Drug Invest. 4 (Suppl 4):S83–S89. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Xie W, Cao Y, Xu M, Wang J, Zhou C, Yang

X, Geng X, Zhang W, Li N and Cheng J: Prognostic significance of

elevated cholestatic enzymes for fibrosis and hepatocellular

carcinoma in hospital discharged chronic viral hepatitis patients.

Sci Rep. 7:102892017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ibrahim SH, Kamath BM, Loomes KM and

Karpen SJ: Cholestatic liver diseases of genetic etiology: Advances

and controversies. Hepatology. 75:1627–1646. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta

R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS,

et al: Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell

death. Cell. 149:1060–1072. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Bayir H, Dixon SJ, Tyurina YY, Kellum JA

and Kagan VE: Ferroptotic mechanisms and therapeutic targeting of

iron metabolism and lipid peroxidation in the kidney. Nat Rev

Nephrol. 19:315–336. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Yang W: Iron turns to wild when the

transferrin is away. Blood. 136:649–650. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Buckley CD, Barone F, Nayar S, Benezech C

and Caamano J: Stromal cells in chronic inflammation and tertiary

lymphoid organ formation. Annu Rev Immunol. 33:715–745. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Forrester SJ, Kikuchi DS, Hernandes MS, Xu

Q and Griendling KK: Reactive oxygen species in metabolic and

inflammatory signaling. Circ Res. 122:877–902. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhang WB, Yang F, Wang Y, Jiao FZ, Zhang

HY, Wang LW and Gong ZJ: Inhibition of HDAC6 attenuates LPS-induced

inflammation in macrophages by regulating oxidative stress and

suppressing the TLR4-MAPK/NF-ĸB pathways. Biomed Pharmacother.

117:1091662019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Xie Y, Hou W, Song X, Yu Y, Huang J, Sun

X, Kang R and Tang D: Ferroptosis: Process and function. Cell Death

Differ. 23:369–379. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Han C, Liu Y, Dai R, Ismail N, Su W and Li

B: Ferroptosis and its potential role in human diseases. Front

Pharmacol. 11:2392020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wang Y and Tang M: PM2.5 induces

ferroptosis in human endothelial cells through iron overload and

redox imbalance. Environ Pollut. 254:1129372019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Jiang X, Stockwell BR and Conrad M:

Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 22:266–282. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Lyberopoulou A, Chachami G, Gatselis NK,

Kyratzopoulou E, Saitis A, Gabeta S, Eliades P, Paraskeva E, Zachou

K, Koukoulis GK, et al: Low serum hepcidin in patients with

autoimmune liver diseases. PLoS One. 10:e01354862015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Marques O, Horvat NK, Zechner L, Colucci

S, Sparla R, Zimmermann S, Neufeldt CJ, Altamura S, Qiu R, Mudder

K, et al: Inflammation-driven NF-kappab signaling represses

ferroportin transcription in macrophages via HDAC1 and HDAC3.

Blood. 145:866–880. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Xie X, Chang L, Zhu X, Gong F, Che L,

Zhang R, Wang L, Gong C, Fang C, Yao C, et al: Rubiadin mediates

the upregulation of hepatic hepcidin and alleviates iron overload

via BMP6/SMAD1/5/9-signaling pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 26:13852025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Delesderrier E, Monteiro JDC, Freitas S,

Pinheiro IC, Batista MS and Citelli M: Can iron and polyunsaturated

fatty acid supplementation induce ferroptosis? Cell Physiol

Biochem. 57:24–41. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Liu C, Liu Z, Dong Z, Liu S, Kan H and

Zhang S: Multifaceted interplays between the essential players and

lipid peroxidation in ferroptosis. J Genet Genomics. 52:1071–1081.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Tsuchida T and Friedman SL: Mechanisms of

hepatic stellate cell activation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

14:397–411. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yu Y, Jiang L, Wang H, Shen Z, Cheng Q,

Zhang P, Wang J, Wu Q, Fang X, Duan L, et al: Hepatic transferrin

plays a role in systemic iron homeostasis and liver ferroptosis.

Blood. 136:726–739. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zhang Q, Qu Y, Zhang Q, Li F, Li B, Li Z,

Dong Y, Lu L and Cai X: Exosomes derived from hepatitis b

virus-infected hepatocytes promote liver fibrosis via mir-222/TFRC

axis. Cell Biol Toxicol. 39:467–481. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Yang L, Xie P, Wu J, Yu J, Li X, Ma H, Yu

T, Wang H, Ye J, Wang J and Zheng H: Deferoxamine treatment

combined with sevoflurane postconditioning attenuates myocardial

ischemia-reperfusion injury by restoring HIF-1/BNIP3-mediated

mitochondrial autophagy in GK rats. Front Pharmacol. 11:62020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Duscher D, Neofytou E, Wong VW, Maan ZN,

Rennert RC, Inayathullah M, Januszyk M, Rodrigues M, Malkovskiy AV,

Whitmore AJ, et al: Transdermal deferoxamine prevents

pressure-induced diabetic ulcers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

112:94–99. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

National RCUC, . Guide for the Care and

Use of Laboratory Animals. National Academies Press; Washington,

DC: 2011

|

|

27

|

Liu X, Wang J, Li M, Qiu J, Li X, Qi L,

Liu J, Liu P, Xie G and Wang X: Farnesoid × receptor is an

important target for the treatment of disorders of bile acid and

fatty acid metabolism in mice with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

combined with cholestasis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 38:1438–1446.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Wang H, Jiang C, Yang Y, Li J, Wang Y,

Wang C and Gao Y: Resveratrol ameliorates iron overload induced

liver fibrosis in mice by regulating iron homeostasis. PeerJ.

10:e135922022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Xiang D, Liu Y, Zu Y, Yang J, He W, Zhang

C and Liu D: Calculus bovis sativus alleviates estrogen

cholestasis-induced gut and liver injury in rats by regulating

inflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and bile acid profiles.

J Ethnopharmacol. 302:1158542023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zhuang Y, Ortega-Ribera M, Thevkar Nagesh

P, Joshi R, Huang H, Wang Y, Zivny A, Mehta J, Parikh SM and Szabo

G: Bile acid-induced IRF3 phosphorylation mediates cell death,

inflammatory responses, and fibrosis in cholestasis-induced liver

and kidney injury via regulation of ZBP1. Hepatology. 79:752–767.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Yang WS and Stockwell BR: Ferroptosis:

Death by lipid peroxidation. Trends Cell Biol. 26:165–176. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Alajbeg IZ, Lapic I, Rogic D, Vuletic L,

Andabak Rogulj A, Illes D, Knezović Zlatarić D, Badel T, Vrbanovic

E and Alajbeg I: Within-subject reliability and between-subject

variability of oxidative stress markers in saliva of healthy

subjects: A longitudinal pilot study. Dis Markers.

2017:26974642017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Hakkoymaz H, Nazik S, Seyithanoglu M,

Guler O, Sahin AR, Cengiz E and Yazar FM: The value of

ischemia-modified albumin and oxidative stress markers in the

diagnosis of acute appendicitis in adults. Am J Emerg Med.

37:2097–2101. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Tangvarasittichai S: Oxidative stress,

insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and type 2 diabetes mellitus.

World J Diabetes. 6:456–480. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Moore DD, Kato S, Xie W, Mangelsdorf DJ,

Schmidt DR, Xiao R and Kliewer SA: International union of

pharmacology. LXII. The NR1h and NR1i receptors: Constitutive

androstane receptor, pregnene × receptor, farnesoid × receptor

alpha, farnesoid × receptor beta, liver × receptor alpha, liver ×

receptor beta, and vitamin d receptor. Pharmacol Rev. 58:742–759.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Kagan VE, Mao G, Qu F, Angeli JP, Doll S,

Croix CS, Dar HH, Liu B, Tyurin VA, Ritov VB, et al: Oxidized

arachidonic and adrenic PEs navigate cells to ferroptosis. Nat Chem

Biol. 13:81–90. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Panzilius

E, Kobayashi S, Ingold I, Irmler M, Beckers J, Aichler M, Walch A,

et al: ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular

lipid composition. Nat Chem Biol. 13:91–98. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Yang WS, Kim KJ, Gaschler MM, Patel M,

Shchepinov MS and Stockwell BR: Peroxidation of polyunsaturated

fatty acids by lipoxygenases drives ferroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 113:E4966–E4975. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Daiber A, Di Lisa F, Oelze M,

Kroller-Schon S, Steven S, Schulz E and Munzel T: Crosstalk of

mitochondria with NADPH oxidase via reactive oxygen and nitrogen

species signalling and its role for vascular function. Br J

Pharmacol. 174:1670–1689. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

You Y, Qian Z, Jiang Y, Chen L, Wu D, Liu

L, Zhang F, Ning X, Zhang Y and Xiao J: Insights into the

pathogenesis of gestational and hepatic diseases: The impact of

ferroptosis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 12:14828382024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Teschke R: Treatment of drug-induced liver

injury. Biomedicines. 11:152022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Lewerenz J, Hewett SJ, Huang Y, Lambros M,

Gout PW, Kalivas PW, Massie A, Smolders I, Methner A, Pergande M,

et al: The cystine/glutamate antiporter system x(c)(−) in health

and disease: From molecular mechanisms to novel therapeutic

opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 18:522–555. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Kan X, Yin Y, Song C, Tan L, Qiu X, Liao

Y, Liu W, Meng S, Sun Y and Ding C: Newcastle-disease-virus-induced

ferroptosis through nutrient deprivation and ferritinophagy in

tumor cells. iScience. 24:1028372021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Sun X, Ou Z, Chen R, Niu X, Chen D, Kang R

and Tang D: Activation of the p62-keap1-NRF2 pathway protects

against ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatology.

63:173–184. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Yoo S, Kim M, Bae JY, Lee SA and Koh G:

Bardoxolone methyl inhibits ferroptosis through the Keap1-Nrf2

pathway in renal tubular epithelial cells. Mol Med Rep. 32:2672025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Ichimura Y, Waguri S, Sou YS, Kageyama S,

Hasegawa J, Ishimura R, Saito T, Yang Y, Kouno T, Fukutomi T, et

al: Phosphorylation of p62 activates the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway during

selective autophagy. Mol Cell. 51:618–631. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Chen Y, Ma L, Yan Y, Wang X, Cao L, Li Y

and Li M: Ophiopogon japonicus polysaccharide reduces

doxorubicin-induced myocardial ferroptosis injury by activating

Nrf2/GPX4 signaling and alleviating iron accumulation. Mol Med Rep.

31:362025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Xiao P, Huang H, Zhao H, Liu R, Sun Z, Liu

Y, Chen N and Zhang Z: Edaravone dexborneol protects against

cerebral ischemia/reperfusion-induced blood-brain barrier damage by

inhibiting ferroptosis via activation of nrf-2/HO-1/GPX4 signaling.

Free Radic Biol Med. 217:116–125. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Hu T, Wei G, Xi M, Yan J, Wu X, Wang Y,

Zhu Y, Wang C and Wen A: Synergistic cardioprotective effects of

danshensu and hydroxysafflor yellow a against myocardial

ischemia-reperfusion injury are mediated through the Akt/Nrf2/HO-1

pathway. Int J Mol Med. 38:83–94. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Lin Q, Li S, Jin H, Cai H, Zhu X, Yang Y,

Wu J, Qi C, Shao X, Li J, et al: Mitophagy alleviates

cisplatin-induced renal tubular epithelial cell ferroptosis through

ROS/HO-1/GPX4 axis. Int J Biol Sci. 19:1192–1210. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Choi AM and Alam J: Heme oxygenase-1:

Function, regulation, and implication of a novel stress-inducible

protein in oxidant-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol.

15:9–19. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Fisher AL, Wang CY, Xu Y, Joachim K, Xiao

X, Phillips S, Moschetta GA, Alfaro-Magallanes VM and Babitt JL:

Functional role of endothelial transferrin receptor 1 in iron

sensing and homeostasis. Am J Hematol. 97:1548–1559. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Deng P, Li J, Lu Y, Hao R, He M, Li M, Tan

M, Gao P, Wang L, Hong H, et al: Chronic cadmium exposure triggered

ferroptosis by perturbing the STEAP3-mediated glutathione redox

balance linked to altered metabolomic signatures in humans. Sci

Total Environ. 905:1670392023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Gao X, Hu W, Qian D, Bai X, He H, Li L and

Sun S: The mechanisms of ferroptosis under hypoxia. Cell Mol

Neurobiol. 43:3329–3341. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Nairz M, Fritsche G, Brunner P, Talasz H,

Hantke K and Weiss G: Interferon-gamma limits the availability of

iron for intramacrophage salmonella typhimurium. Eur J Immunol.

38:1923–1936. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Ge W, Jie J, Yao J, Li W, Cheng Y and Lu

W: Advanced glycation end products promote osteoporosis by inducing

ferroptosis in osteoblasts. Mol Med Rep. 25:1402022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Chen GH, Song CC, Pantopoulos K, Wei XL,

Zheng H and Luo Z: Mitochondrial oxidative stress mediated

Fe-induced ferroptosis via the NRF2-ARE pathway. Free Radic Biol

Med. 180:95–107. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Holden P and Nair LS: Deferoxamine: An

angiogenic and antioxidant molecule for tissue regeneration. Tissue

Eng Part B Rev. 25:461–470. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Zeng Z, Huang H, Zhang J, Liu Y, Zhong W,

Chen W, Lu Y, Qiao Y, Zhao H, Meng X, et al: HDM induce airway

epithelial cell ferroptosis and promote inflammation by activating

ferritinophagy in asthma. FASEB J. 36:e223592022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Mohammed A, Abd Al Haleem EN, El-Bakly WM

and El-Demerdash E: Deferoxamine alleviates liver fibrosis induced

by CCl4 in rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 43:760–768. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Liu MX, Gu YY, Nie WY, Zhu XM, Qi MJ, Zhao

RM, Zhu WZ and Zhang XL: Formononetin induces ferroptosis in

activated hepatic stellate cells to attenuate liver fibrosis by

targeting NADPH oxidase 4. Phytother Res. 38:5988–6003. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Xie J, Ye Z, Li L, Xia Y, Yuan R, Ruan Y

and Zhou X: Ferrostatin-1 alleviates oxalate-induced renal tubular

epithelial cell injury, fibrosis and calcium oxalate stone

formation by inhibiting ferroptosis. Mol Med Rep. 26:2562022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|