Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a major global

health burden, representing the most common primary liver cancer

and the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide

(1). Most cases are diagnosed at

an intermediate or advanced stage due to the insidious onset of the

disease, and high post-treatment relapse rates further contribute

to a poor overall prognosis (2,3).

While conventional therapies, such as surgical resection, ablation,

transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and kinase inhibitors,

remain central to HCC management, the emergence of cancer

immunotherapy has introduced new therapeutic options. Immune-based

treatments, particularly immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs)

targeting programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/programmed

death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) or cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein

4 (CTLA-4), demonstrate durable clinical responses in several types

of solid tumors, including efficacy in HCC (4,5). For

example, it has been shown that in advanced HCC, single-agent ICIs

can induce objective responses in 15–20% of patients (6).

However, most patients with HCC do not respond

adequately to immunotherapy (7).

This has been attributed, in part, to the distinct tumor immune

microenvironment of HCC, which often renders the tumor

immunologically ‘cold’ or non-inflamed, thereby diminishing

immune-mediated antitumor activity (5,8). The

concept of ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ tumors refers to the degree of immune

cell infiltration and activity in the tumor microenvironment (TME).

Hot HCC tumors are characterized by high densities of

CD8+ T cells infiltrating the tumor the core and margin,

a strong interferon-γ (IFN-γ) gene expression signature indicative

of an active T helper 1 immune response, and the upregulated

expression of checkpoint molecules such as PD-L1 (9,10).

Conversely, cold tumors in general exhibit sparse T-cell

infiltration, diminished levels of IFN-γ-associated inflammatory

cytokines, and minimal checkpoint expression, reflecting an

immunologically inactive microenvironment (9,10).

Several quantitative approaches have been developed

to distinguish between cold and hot tumors in HCC and other solid

cancers. These include immunohistochemical analysis of intratumoral

CD8+T-cell density, commonly using multiplex

immunohistochemistry (11),

IFN-γ-associated immune gene expression profiling, for example

using RNA sequencing or targeted Nanostring panels to generate a

T-cell-inflamed or tumor inflammation signature (12), and spatial immune cell profiling

(13). Composite immune scoring

systems such as the Immunoscore, which quantifies CD3+

and CD8+ T cells in situ, are also used to

stratify tumors immunologically (14).

HCC typically arise in the context of chronic

inflammation, such as that caused by hepatitis B or C infection or

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), but paradoxically often

develops in an immunosuppressive microenvironment (15). Chronic viral antigen exposure and

liver-specific tolerogenic mechanisms contribute to T-cell

exhaustion and immune evasion in HCC (8). Notably, 25–30% of HCC tumors exhibit

an ‘immune-excluded’ phenotype, associated with Wnt/β-catenin

pathway activation and characterized by a lack of T-cell

infiltration, which predicts resistance to ICIs (10).

Converting an immunologically cold HCC into a hot

tumor is a promising strategy to overcome immune resistance and

improve patient responses. In the present review, a condensed

overview of the HCC tumor immune landscape is provided and the

mechanisms underlying its immunologically cold phenotype, including

the roles of various immune cells, cytokines and tumor-intrinsic

pathways in suppressing antitumor immunity are presented. The

established and emerging therapeutic strategies aimed at

reprogramming the HCC microenvironment to a more inflamed,

T-cell-permissive state are also discussed.

Tumor immune landscape in HCC

HCC develops within a complex TME composed of tumor

cells, stromal elements and a diverse array of immune cells. The

baseline immune landscape of HCC is often immunosuppressive and

heterogeneous, contributing to variable immune surveillance and

inconsistent therapeutic responses (16). Chronic liver inflammation,

resulting from viral hepatitis, alcohol or fatty liver disease,

serves as the foundation for immune dysfunction even before

malignant transformation occurs (17). As HCC develops, the intrinsic

tolerogenic milieu of the liver, which normally prevents

overactivation by persistent exposure to gut-derived antigens, is

co-opted by the tumor to escape immune elimination (18). The roles of different cell types in

the TME of HCC are summarized in Table

I (8,16,19–27).

| Table I.Properties of the tumor immune

microenvironment in HCC. |

Table I.

Properties of the tumor immune

microenvironment in HCC.

| Cell type | Marker | Role in HCC tumor

microenvironment | (Refs.) |

|---|

| TAMs | CD68; M2 markers

(CD163, CD206); M1 markers (CD80, CD86) | Often polarized to

immunosuppressive M2 phenotype; secrete IL-10, TGF-β and other

factors that suppress T cell activity. High TAM density is

associated with reduced CD8+ T cell infiltration and

poor prognosis | (8,19) |

| TANs | CD15, CD66b; high

PD-L1 and arginase-1 expression | Can inhibit CTL

function by releasing reactive oxygen species and expressing

immunosuppressive molecules, such as PD-L1. TANs blunt

CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity in HCC and are associated with

aggressive disease | (20) |

| cDCs | cDC1:

CLEC9A+ XCR1+;cDC2:

CD1c+CD11b+ | Primary

antigen-presenting cells that prime T cells. In HCC, cDCs are often

functionally impaired or present in insufficient numbers, limiting

effective anti-tumor T-cell priming | (16) |

| pDCs | BDCA-2, CD303 | Tend to accumulate

in HCC and promote tolerance. pDC infiltration is associated with

Treg expansion and poorer outcomes, suggesting pDCs contribute to

immunosuppressive networks in HCC | (8) |

| NK cells and

ILCs | NK:

CD56+CD16+ (cytotoxic NK); ILCs:

CD127+ (ILC1-3) | NK cells can

directly kill HCC cells, and are associated with improved survival,

but often functionally suppressed in HCC. Certain ILC subsets (ILC2

and ILC3) mimic Th2/Th17 functions and secrete IL-13, IL-17,

promoting tumor growth and suppressing immunity | (21) |

| CTLs | CD8, granzyme B,

IFN-γ | Essential effectors

for tumor clearance. Active, granzyme B-positive CD8 T cells

indicate a hot tumor and are associated with a favorable prognosis.

However, numerous HCCs exhibit low CD8 infiltration or

dysfunctional CTLs due to chronic antigen stimulation and

inhibitory checkpoint signaling | (22) |

| Exhausted T

cells |

PD-1+TIM-3+CTLA-4+

CD8 T cells | High levels of

exhausted T cells (expressing markers such as PD-1 and TIM-3) are

characteristic of HCC. They have impaired effector function and

their enrichment is associated with shorter progression-free and

overall survival | (19). |

| TRM cells | CD69, CD103 | TRM cells reside in

liver tissue and provide local immune surveillance. In HCC,

CD69+CD103+ TRM cells are associated with

improved response to ICIs and superior outcomes, suggesting a

pre-existing local immunity | (22) |

| Tregs |

CD4+FOXP3+, often

CTLA-4+ high | Abundant in HCC and

the surrounding liver. Tregs suppress anti-tumor T-cell responses

via IL-10, TGF-β and checkpoint molecules. Elevated intratumoral

Tregs are associated with CD8 dysfunction and poor survival | (23) |

| Th cells | Th1: IFN-γ, IL-2;

Th2: IL-4, IL-5; Th17: IL-17 | Th1 cells support

antitumor immunity by producing IFN-γ, whereas Th2 and Th17-skewed

responses can aid tumor progression. HCC with a dominant Th2/Th17

cytokine profile tends to have poor immune-mediated control | (24) |

| B cells | CD19, CD20 (plasma

cells: CD138) | Can form TLS in

HCC. TLS with B cells and follicular helper T cells are associated

with an enhanced immune response and improved prognosis. Some B

cells, however, may act as regulatory B cells producing IL-10 | (25) |

| CAFs | α-SMA, collagen I,

FAP | Create dense stroma

and physical barriers to immune cells. CAFs secrete TGF-β and other

factors that foster Treg differentiation and exclude T cells. They

directly interact with immune cells to mediate immune evasion and

are associated with poor immunotherapy responses | (26) |

| ECs |

VEGFR+CD31+

(VEGF-responsive vasculature) | Abnormal tumor

endothelium limits lymphocyte infiltration. VEGF from HCC drives

angiogenesis and suppresses DC and T-cell function. Anti-VEGF

therapy normalizes vessels and improves T-cell entry. ECs in HCC

can express immune checkpoint ligands such as PD-L1, contributing

to local T-cell suppression | (27) |

One hallmark of the HCC immune landscape is the

abundance of immunosuppressive and tumor-promoting immune cells

relative to effector cells (28).

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), which are often skewed toward

an M2-like phenotype, are typically the most abundant immune

infiltrates in HCC and are associated with a poor prognosis

(29). TAMs promote tumor growth

by secreting immunosuppressive cytokines, such as IL-10 and

transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), promoting angiogenesis and

directly inhibiting T cell activity (30).

Similarly, tumor-associated neutrophils in HCC can

suppress T cell cytotoxicity by expressing PD-L1 and arginase-1,

which contribute to the exhaustion of local T cells (20). Dendritic cells (DCs) are present in

the HCC microenvironment but are often functionally impaired:

Conventional DCs may be reduced in number or exhibit dysfunctional

antigen-presenting capacity, whereas plasmacytoid DCs tend to

induce immune tolerance and are associated with the accumulation of

regulatory T cells (Tregs) (8).

Crucially, cytotoxic T lymphocytes, the primary

effectors targeted by immunotherapies, are often excluded from HCC

tumor nests or rendered anergic or functionally exhausted (31). While a subset of HCCs exhibit an

‘immune-active’ phenotype characterized by substantial

CD8+ T-cell infiltration and IFN signaling, most HCC

tumors are categorized as ‘immune-exhausted’ or ‘immune-excluded’.

These are characterized by high expression of checkpoint receptors,

including PD-1 and T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain

containing protein 3 (TIM-3), on T cells, or by the physical

exclusion of T cells from the tumor parenchyma (10,32).

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and endothelial

cells in HCC further shape the immune landscape. CAFs produce

extracellular matrix proteins and desmoplastic stroma, which act as

physical barriers to immune cell infiltration (33,34).

They also secrete TGF-β and cytokines including IL-6, IL-8, IL-10,

CXCL12, prostaglandin E2 and vascular endothelial growth factor

(VEGF), which promote Treg differentiation and inhibit effector T

cell activity, thereby facilitating immune evasion (33,34).

The tumor endothelium in HCC is often abnormal, expressing

molecules such as PD-L1, Fas ligand and vascular cell adhesion

molecule-1, which can impair lymphocyte trafficking or induce

T-cell apoptosis, a phenomenon termed the endothelial checkpoint

(35,36). Elevated vascular endothelial growth

factor (VEGF) levels in HCC not only drive angiogenesis but also

directly suppress DC maturation and T-cell responses, contributing

further to immune exclusion (37).

Despite the generally immunosuppressive landscape,

HCC retains a degree of immunogenicity, as evidenced by occasional

spontaneous tumor regression and the observed efficacy of donor

lymphocyte infusions following liver transplantation (38). It is reported that 15–25% of HCC

tumors exhibit a more inflamed, hot phenotype, characterized by

higher CD8+ T-cell infiltration and IFN signaling. These

tumors are associated with an improved prognosis and greater

responsiveness to immunotherapy (5).

Mechanisms of immune ‘coldness’ in HCC

Multiple interrelated mechanisms contribute to the

immunologically cold phenotype of HCC tumors, acting at the tumor

cell-intrinsic level, within the broader liver microenvironment,

and at the systemic level.

Tumor-intrinsic immune evasion

pathways

Genetic and epigenetic alterations in HCC cells can

contribute to an immune-deserted microenvironment. Notably,

activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is observed in

30–50% of HCCs and is strongly associated with the exclusion of T

cells from the tumor (10,39). β-catenin activation in tumor cells

downregulates the expression of C-C motif chemokine ligand (CCL) 4,

which impairs DC recruitment and thereby prevents the effective

priming of anti-tumor T cells. This creates an immunologically cold

tumor niche. Clinically, HCC tumors with catenin β-1 gene mutations

that activate β-catenin rarely respond to ICIs, making this pathway

a recognized driver of immune resistance (40).

Other oncogenic pathways frequently altered in HCC

also contribute to immunosuppression; for example, MYC oncogene

overexpression, which is detected in ~50% of HCCs, upregulates

PD-L1 in tumor cells and modulates cell metabolism to favor an

immunosuppressive milieu (39).

Similarly, the loss-of-function of phosphatase and tensin homologs

or activation of PI3K-AKT signaling can promote an immunoresistant

environment by increasing the expression of inhibitory molecules

and recruiting suppressive myeloid cells (41).

HCC cells actively upregulate immune checkpoint

ligands and other immunoinhibitory molecules. HCCs frequently

express PD-L1 on their surfaces of their cells, especially those

with upregulated MYC expression or enriched in progenitor-like

traits. PD-L1 can directly bind to PD-1 on T cells, thereby

promoting T-cell exhaustion (16).

In addition, some HCC cells express galectin-9, an

immunosuppressive lectin that interacts with TIM-3 on T cells,

further contributing to T-cell exhaustion (42).

Immunosuppressive cellular

constituents

The immune infiltrate in HCC is skewed toward cell

types that sustain an immunosuppressive, cold TME (28). Tregs are often enriched in the

blood and tumor tissues of patients with HCC, where they suppress

antitumor immunity by secreting IL-10 and TGF-β, and by consuming

IL-2, which limits the proliferation of effector T cells (43,44).

TAMs of the M2 phenotype produce high levels of

IL-10 and prostaglandins, and express immune checkpoint molecules

such as PD-1, which suppress phagocytosis and innate immune

responses (45). These TAMs also

recruit Tregs via CCL22 and promote tissue remodeling, which

impairing or inactivating effector T cell functions.

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), a heterogeneous

population of immature monocytes and neutrophils with

immunosuppressive activity, are also present in HCC. MDSCs release

arginase and inducible nitric oxide synthase, which metabolically

starve T cells of L-arginine and produce nitric oxide, thereby

causing T-cell dysfunction (44).

Cytokine and metabolic milieu

The TME of HCC is enriched with immunosuppressive

cytokines (40,46). TGF-β, often abundant due to

cirrhosis and CAF activity, is a key driver of immune exclusion. It

inhibits the proliferation and effector functions of T cells and

natural killer (NK) cells, while promoting the differentiation of

Tregs and M2 macrophages (46). A

high-TGF-β signature in HCC is associated with an immune-excluded

phenotype and resistance to immune checkpoint blockade (40).

HCC tumors are frequently hypoxic due to their rapid

growth and abnormal vasculature (47). Hypoxia induces hypoxia-inducible

factor-1α, which upregulates adenosine production and VEGF

expression, both of which suppress antitumor immunity. Adenosine

accumulates in the TME via CD39/CD73 ectonucleotidase activity in

cancer and stromal cells. It potently inhibits T- and NK-cell

activity through A2A adenosime receptors, while promoting the

expansion and functional activation of Tregs and the polarization

of macrophages to the M2 phenotype (48).

Liver-specific tolerogenic

factors

The unique immune environment of the liver plays a

central role in the immune evasion of HCC. Under normal conditions,

the liver is constantly exposed to food antigens and microbial

products from the gut via the portal circulation. Therefore,

non-immunogenic (tolerogenic) mechanisms have evolved in the liver

to prevent unnecessary immune activation. Kupffer cells, which are

liver-resident macrophages, and liver sinusoidal endothelial cells

(LSECs) constitutively express inhibitory molecules, including

PD-L1 and Fas ligand, and secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines such

as IL-10 and TGF-β, which induce T-cell tolerance (49–51).

Naïve T cells encountering antigens in the liver often become

anergic or differentiate into Tregs (52,53).

HCC exploits these tolerogenic pathways: Kupffer

cells may present tumor antigens in a tolerogenic manner, while

LSECs can induce the deletion of tumor-reactive T cells, thereby

preventing effective antitumor immune priming (54). In addition, cirrhotic livers

exhibit expanded populations of immunosuppressive myeloid and

stellate cells, contributing to an immunosuppressive fibrotic

microenvironment, even before malignant transformation (55).

Immune editing and antigen loss

During HCC development, immune editing can occur,

whereby the adaptive immune system initially eliminates highly

immunogenic tumor cell clones, leading to the selection of tumor

cells that are less detectable by T cells (56). Over time, HCC tumors may exhibit

the downregulation or loss of certain tumor-associated antigens.

For example, tumor variants that no longer express common antigens,

such as α-fetoprotein (AFP) or glypican-3 (GPC3), may evade T-cell-

or antibody-based therapies targeting these antigens (57). Similarly, the loss of major

histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecule expression due to

β2-microglobulin mutations or defects in the antigen presentation

machinery can impair cytotoxic T-cell recognition, although this

may potentially increase the susceptibility of the tumor to NK

cells (58,59).

Strategies to reprogram the immune

microenvironment in HCC

Given the array of mechanisms that render HCC an

immunologically cold tumor, various therapeutic strategies have

been developed to modulate the TME and warm it up, thereby

enhancing the efficacy of immunotherapies. These strategies involve

combining ICIs with other treatments, targeting specific

immunosuppressive pathways or cell populations, and introducing

proinflammatory stimuli into the tumor milieu. A summary of these

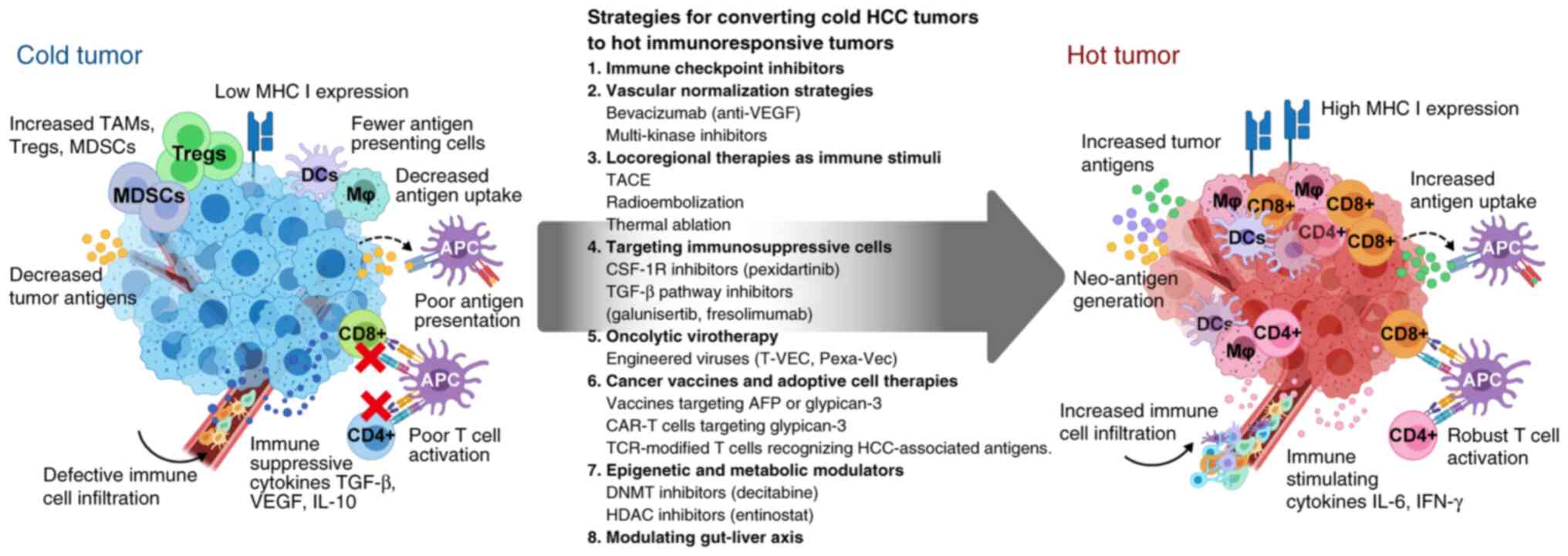

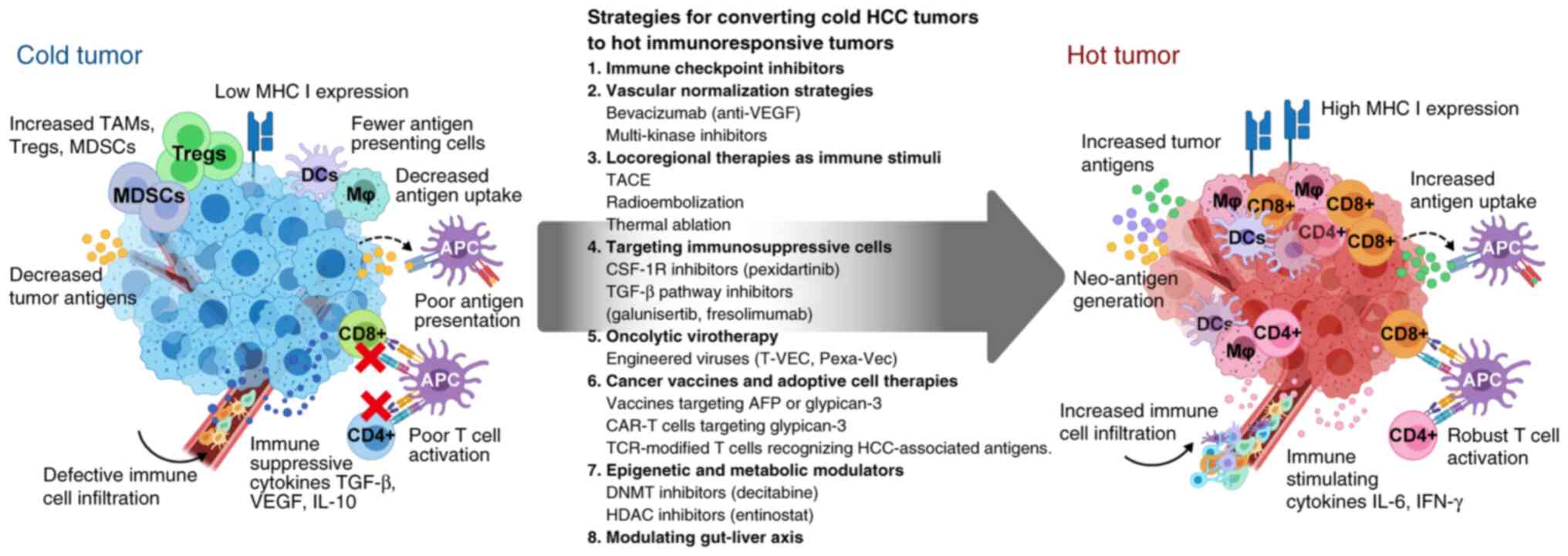

strategies is presented in Fig. 1.

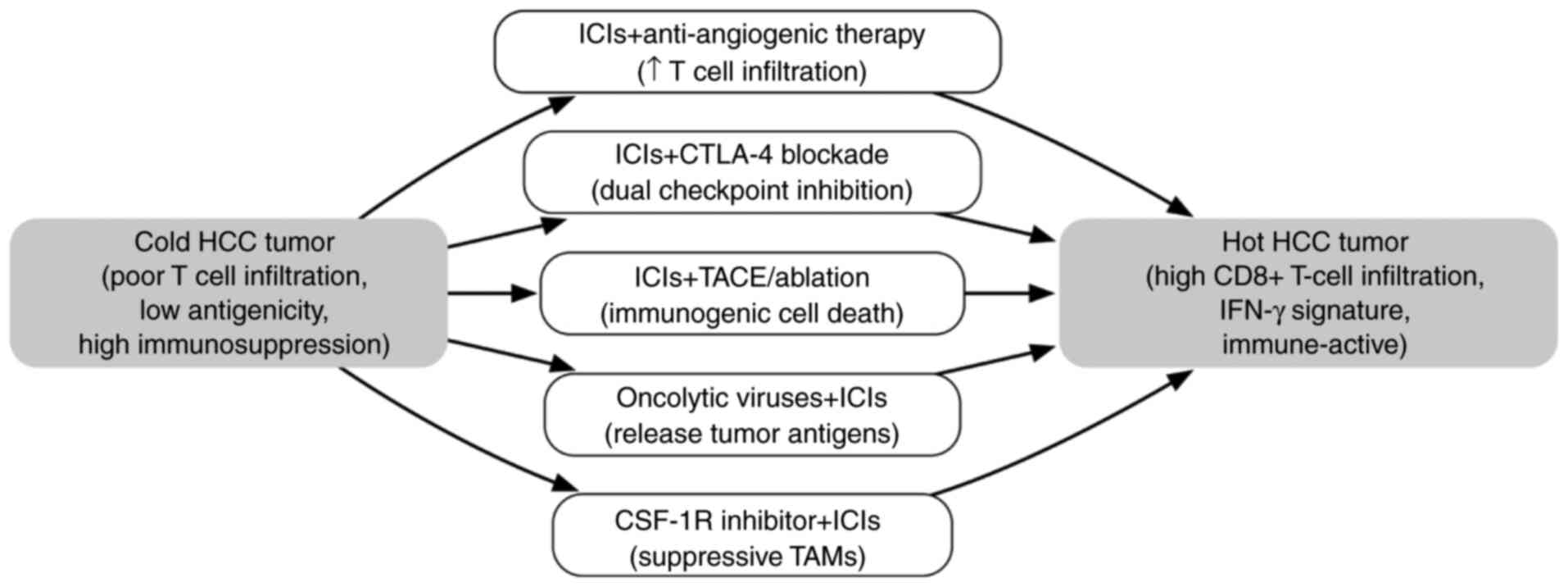

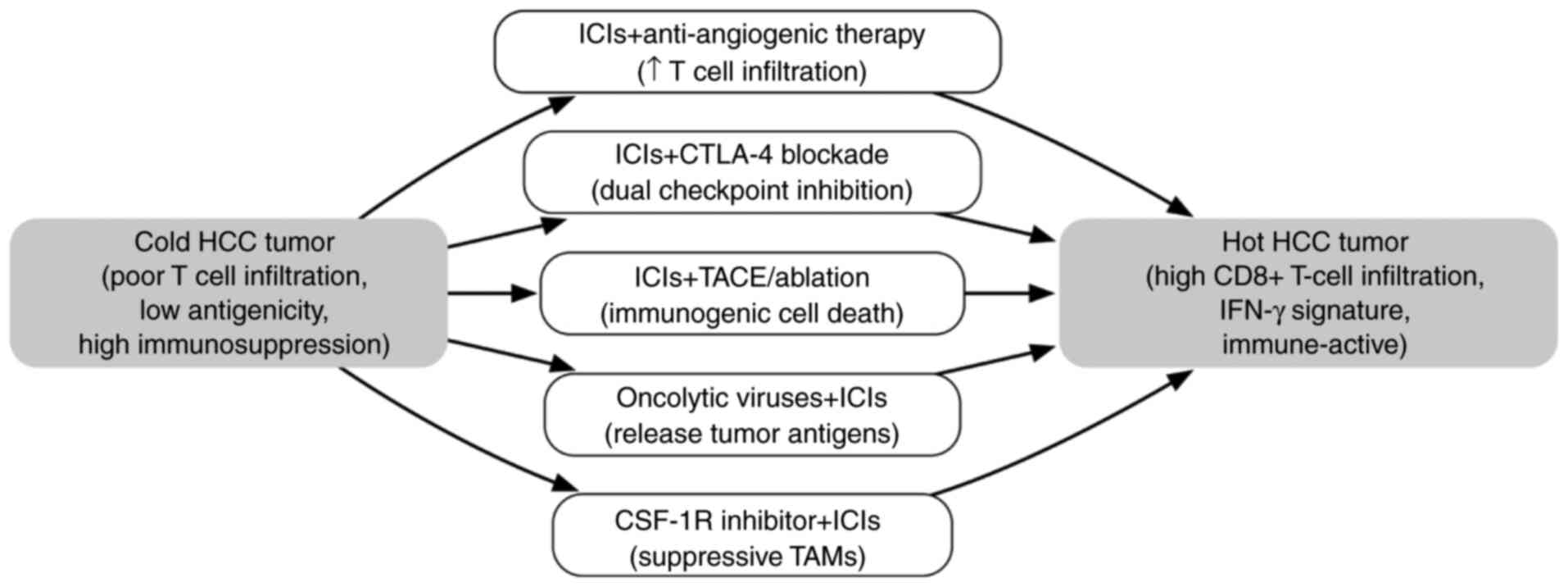

In addition, a flowchart illustrating key combination therapies

used to convert an immunologically cold HCC tumor into a hot tumor

is shown in Fig. 2.

| Figure 1.Transformation of immunologically

cold HCC tumors into hot immunoresponsive tumors by various

therapeutic strategies. The left panel depicts a cold tumor

microenvironment characterized by low MHC I expression, low levels

of tumor antigens, defective immune cell infiltration and

immunosuppressive features, including abundant TAMs, Tregs and

MDSCs. These tumors show poor antigen presentation, decreased

antigen uptake by DCs, and ineffective T-cell activation due to

immunosuppressive cytokines TGF-β, VEGF and IL-10. The right panel

shows a successfully converted hot tumor with high MHC I

expression, increased tumor antigen levels and uptake, and robust

immune cell infiltration. This environment features activated

CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, functional APCs, and

immune-stimulating cytokines IL-6 and IFN-γ. The central arrow

outlines eight key strategic approaches for this conversion. Each

strategy includes specific therapeutic examples currently being

investigated for HCC treatment. AFP, α-fetoprotein; APC,

antigen-presenting cell; CAR-T, chimeric antigen receptor-T;

CSF-1R, colony stimulating factor-1 receptor; DC, dendritic cell;

DNMT, DNA methyltransferase; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HDAC,

histone deacetylase; Mj, macrophage; MDSC, myeloid-derived

suppressor cell; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; Pexa-Vec,

pexastimogene devacirepvec; T-VEC, talimogene laherparepvec; TACE,

transarterial chemoembolization; TAMs, tumor-associated

macrophages; TCR, T cell receptor; TGF-β, transforming growth

factor-β; Tregs, regulatory T cells; VEGF, vascular endothelial

growth factor. |

| Figure 2.Flowchart illustrating key

combination therapies to convert an immunologically cold HCC tumor

into a hot tumor. Cold tumors exhibit low T-cell infiltration and

strong immunosuppressive factors, whereas hot tumors have abundant

CD8+ T cells and an inflamed microenvironment. Each

arrow represents a combination strategy designed to overcome a

specific barrier to antitumor immunity. ICIs (e.g., PD-1/PD-L1

inhibitor) + anti-angiogenic therapy (e.g., bevacizumab): Targeting

angiogenesis normalizes VEGF-driven abnormal tumor vasculature and

reduces VEGF-mediated immunosuppression, thereby increasing T-cell

infiltration into the tumor. ICIs (e.g., PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor) +

CTLA-4 inhibitor: Dual checkpoint blockade enhances T-cell priming

and reverses T-cell exhaustion, thereby reducing Treg-mediated

suppression. ICI + TACE or ablation: Locoregional treatments such

as TACE or ablation induce immunogenic cell death, the release of

neoantigens and antigen presentation, thereby promoting T-cell

priming and infiltration. Oncolytic viruses + ICIs: Viral oncolysis

triggers innate immune sensing, tumor antigen release and

inflammatory signals, which are sustained and amplified by ICIs.

CSF-1R inhibitor + ICIs: CSF-1R inhibitors deplete or reprogram

immunosuppressive tumor-associated macrophages, relieving

macrophage-induced T cell suppression. In combination with

anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy, this increases cytotoxic T cell activity.

CSF-1R, colony stimulating factor-1 receptor; CTLA-4, cytotoxic

T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma;

ICIs, immune checkpoint inhibitors; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; PD-1,

programmed cell death protein 1; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1;

TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; TAMs, tumor-associated

macrophages; Treg, regulatory T cell; VEGF, vascular endothelial

growth factor. |

ICIs: Foundation for combination

therapies

ICIs include anti-PD-1 antibodies, such as nivolumab

and pembrolizumab, anti-PD-L1 antibodies, such as atezolizumab and

durvalumab, and anti-CTLA-4 antibodies, such as ipilimumab and

tremelimumab. These agents form the foundation of immunotherapy

strategies in HCC, and are able to activate T-cell responses if

primed T cells are already present in the TME. However,

single-agent ICIs have shown limited overall response rates in HCC

(~15%), indicating that numerous tumors lack preexisting active T

cells (60,61). Therefore, ICIs are commonly

combined with other agents that can initiate or amplify antitumor

immunity. One such approach is dual checkpoint blockade, such as

PD-1 plus CTLA-4 inhibition, where CTLA-4 blockade primarily acts

on the lymphoid organs to expand T-cell clonal diversity and reduce

Treg-mediated suppression, whereas PD-1/PD-L1 blockade reactivates

exhausted T cells in the tumor (62).

In HCC, the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab

has demonstrated manageable toxicity and a notably higher response

rate compared with nivolumab monotherapy, indicating that dual

blockage can convert a subset of immunologically cold tumors into

responsive ones (6). Similarly, a

combination of tremelimumab and durvalumab was evaluated in the

phase III HIMALAYA trial, using a single priming dose of

tremelimumab followed by ongoing durvalumab treatment. This regimen

induced an immunogenic boost in patients with unresectable HCC that

improved survival compared with that of patients treated with

sorafenib (63).

Anti-angiogenic and vascular

normalization strategies

Abnormal blood vessels in HCC contribute to immune

evasion by promoting hypoxia and serving as physical barriers to

immune cell trafficking. Anti-angiogenic therapies, including the

anti-VEGF antibody bevacizumab and multi-kinase inhibitors, such as

sorafenib, lenvatinib, cabozantinib and regorafenib, not only

inhibit tumor angiogenesis but also modulate the TME (37). VEGF blockade has immunomodulatory

effects; it can normalize tumor vasculature, thereby enhancing

lymphocyte infiltration and alleviating the VEGF-mediated

suppression of DCs and T cells (37).

The combination of PD-L1 inhibitor atezolizumab with

bevacizumab in the IMbrave150 phase III trial significantly

improved response as well as overall survival (OS) and

progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with unresectable HCC

compared with those of patients treated with sorafenib (60). This exemplifies how combining

immune checkpoint blockade with angiogenesis inhibition can convert

a cold tumor into a more immune-active one. However, the results of

the IMbrave050 trial, a follow-up study of adjuvant treatment with

atezolizumab plus bevacizumab after resection or ablation in

high-risk HCC showed that the benefit in recurrence-free survival

was not sustained, and the effect on OS remained non-significant

(64). The IMbrave150 trial

succeeded because advanced HCC presents abundant neoantigens and

ongoing immune activity that respond to PD-L1 and VEGF blockade,

whereas the adjuvant IMbrave050 setting involved minimal residual

disease and immune quiescence, limiting checkpoint and angiogenesis

inhibition efficacy in preventing recurrence. It is suggested that

bevacizumab enhances T-cell access to the tumor and reduces

VEGF-induced immunosuppression, thereby allowing

atezolizumab-activated T cells to function more effectively

(65).

Locoregional therapies as immune

stimuli

Traditional locoregional treatments for HCC,

including TACE, radioembolization with yttrium-90 and thermal

ablation, including radiofrequency or microwave ablation, can exert

immunological effects that may be exploited to ignite antitumor

immunity (66). These treatments

cause tumor cell death and promote the release of tumor antigens

and damage-associated molecular patterns into the environment, a

process known as immunogenic cell death (66).

TACE induces ischemic and chemotherapeutic stress in

tumor cells, potentially triggering a surge in neoantigen and

proinflammatory cytokine release that attracts immune cells

(67). Evidence suggests that TACE

or ablation can lead to transient increases in T-cell activation

and clonal expansion targeting tumor antigens (68). Radiation therapy upregulates MHC

class I expression on tumor cells and increases chemokine levels

for T-cell recruitment, while also inducing an abscopal effect,

whereby localized radiation leads to systemic antitumor immunity

(69).

Clinical trials have combined ICIs with locoregional

therapies. For example, tremelimumab combined with ablation has

been shown to enhance T-cell responses and induce objective tumor

regression in patients with advanced HCC (67). Ongoing trials, such as EMERALD-1

and −2, are evaluating the PD-L1 inhibitor durvalumab in

combination with TACE for patients with intermediate-stage HCC

(70,71). Selected clinical trials and

combination immunotherapy strategies for advanced HCC are

summarized in Table II (6,60,67,72–77).

| Table II.Selected clinical trials and

combination immunotherapy strategies in advanced HCC. |

Table II.

Selected clinical trials and

combination immunotherapy strategies in advanced HCC.

| Therapy/trial | Regimen | Key outcomes | Implications | (Refs.) |

|---|

| IMbrave150, phase

III | Atezolizumab

(anti-PD-L1) + bevacizumab (anti-VEGF) vs. sorafenib in

unresectable HCC, 1st line | Improved median OS

(19.2 vs. 13.4 months), ORR (27 vs. 12%) and 1-year OS (~67 vs.

55%). Achieved first regulatory approval for an ICI combination in

HCC. | VEGF inhibition +

PD-L1 blockade synergistically converts HCCs to responsive tumors;

new standard of care for front-line therapy. However, updated

results in patients with more advanced disease showed that the

initial benefit in recurrence-free survival was not sustained, and

the change in OS remained non-significant | (60) |

| HIMALAYA, phase

III | Durvalumab

(anti-PD-L1) + tremelimumab (anti-CTLA-4). Single high-dose

tremelimumab + durvalumab maintenance vs. sorafenib, 1st line | Improved median OS

(16.4 vs. 13.8 months) with 3-year OS ~30% and ORR ~20%. Durvalumab

monotherapy was non-inferior to sorafenib. FDA-approved in Oct

2022 | Short CTLA-4

blockade pulse + PD-L1 inhibition can induce durable immunity;

offers an alternative 1st-line regimen, particularly for patients

unsuitable for bevacizumab | (72) |

| CheckMate-040,

phase II | Nivolumab +

ipilimumab in advanced HCC post-sorafenib; 3 dosing arms | Best arm (nivolumab

1 mg/kg + ipilimumab 3 mg/kg at 3 weekly intervals, 4 doses in

total) had an ORR of 32%, CR rate of 8% and median OS of 22 months.

Other arms with a lower ipilimumab dose had an ORR of 27%, and OS

of 12 months. Accelerated FDA approval (second-line setting) | Dual checkpoint

blockade yields high response rates and some cures, at cost of

increased immune toxicity. CTLA-4 dose intensity appears critical

for maximal efficacy | (6) |

| KEYNOTE-240, phase

III | Pembrolizumab

(anti-PD-1) vs. placebo in advanced HCC post-sorafenib, 2nd

line | Did not meet

P<0.0175, despite a trend of increased OS (13.9 vs. 10.6 months;

P=0.023) and improved PFS. ORR was 18 vs. 4% for placebo. Generally

well tolerated | Single-agent PD-1

blockade shows activity but under-powered survival benefit;

indicates requirement for combination in most patients. Led to

exploration of pembro-lizumab in combinations, e.g., with

lenvatinib | (60) |

| LEAP-002, phase

III | Pembrolizumab +

lenvatinib vs. lenvatinib alone, 1st line | Median OS increase

(21.2 vs. 19.0 months; HR, 0.84; P=0.0227), did not meet required

P<0.017. ORR (26.1 vs. 17.5%) and PFS (8.2 vs. 8.1 months; HR,

0.87). No new safety signals observed | No significant

improvement in OS, likely due to the efficacy of lenvatinib

monotherapy. However, higher response rate with the combination

suggests certain patients derived added benefit; highlights the

challenge of improving upon strong TKI performance | (73) |

| RESCUE, phase

III | Camrelizumab

(anti-PD-1) + apatinib (VEGFR2 TKI) vs. sorafenib, 1st line | Median OS (22.1 vs.

15.2 months; HR, ~0.62), ORR (25 vs. 5%) and PFS (5.6 vs. 3.7

months). Manageable toxicities, including hand-foot skin reaction

and hypertension. Approved in China | Reinforces class

effect of PD-1 + anti-angiogenic synergy in HCC. Achieved one of

the longest OS reported, albeit in a selected population | (74) |

| Locoregional + ICI,

phase Ib/II | Tremelimumab

(single dose) + computed tomography-guided tumor ablation (30%

tumor volume) in advanced HCC | ORR 26%

(unirradiated lesions) with disease control 89%. Post-treatment,

increased CD8+ T cells and PD-1+ T cells in

blood; 20% had >30% tumor necrosis in non-ablated lesions

(abscopal effect). | Feasible and

promising immunogenic synergy between ablation and CTLA-4 blockade,

priming T cells that attack distant tumors. Supports larger trials

of ICI + RFA/TACE | (67) |

| KEYNOTE-524, phase

Ib | Pembrolizumab +

lenvatinib in advanced unresectable HCC with no prior systemic

treatment | ORR 36% according

to modified RECIST, including 1 CR. Median PFS 9.7 months and OS 22

months. No additive toxicity beyond known profiles | Early sign that

PD-1 + multi-kinase inhibitor yields a high response rate,

justifying phase III (LEAP-002). PFS/OS were encouraging in the

single-arm setting | (75) |

| Oncolytic

virotherapy + ICI, phase Ib | Intratumoral T-VEC

(modified HSV-1 GM-CSF virus) + pembrolizumab in advanced liver

tumors, including HCC | Among patients with

HCC, responses were observed in injected and non-injected lesions.

Overall response rate ~23% across the cohort. Treatment well

tolerated, with no grade 4 or 5 events | Provides clinical

evidence that an oncolytic virus can inflame the TME and improve

responses to PD-1 blockade. Injection approach is viable in liver

tumors | (76) |

| TIL therapy,

pilot | Autologous TIL

infusion + IL-2 after partial hepatectomy, adjuvant setting | Feasibility

demonstrated: TILs were expanded from resected tumor and infused.

1-year recurrence rate appeared lower than the historical value

(~33 vs. 50%), but the sample was very small | Suggests TIL

therapy is feasible for HCC and may help eliminate microscopic

disease. Larger studies are necessary, and combining TILs with ICIs

may enhance the persistence of infused TILs | (77) |

Targeting immunosuppressive cell

populations

Another approach to convert cold tumors into more

immunogenic ones is to deplete or reprogram immunosuppressive cells

in the TME. Colony stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF-1R)

inhibitors, such as pexidartinib, can reduce TAM numbers or alter

TAMs from an immunosuppressive M2-like phenotype toward a more

proinflammatory, antitumor M1-like phenotype (78). In HCC mouse models, the inhibition

of CSF-1/CSF-1R signaling, which is critical for

monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and survival, decreases TAM

infiltration and promotes a shift toward a pro-inflammatory

environment, thereby sensitizing tumors to anti-PD-1 therapy

(79).

C-C motif chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) antagonists

also show promise by preventing the recruitment of monocytes with

high expression of lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus C, a key

surface glycoprotein marker used to distinguish functional subsets

of monocytes, that are precursors for MDSCs and TAMs (80). The inhibition of CCL2-CCR2

signaling reduces the accumulation of intratumoral macrophages and

leads to T-cell-dependent tumor regression in preclinical HCC

models (81).

Tregs are more challenging to target selectively,

but low-dose cyclophosphamide or anti-CD25 antibodies have been

used in solid tumors such as ovarian, breast cancer, prostate

cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and melanoma to transiently deplete

Treg populations (82).

Finally, TGF-β pathway inhibitors are another class

of compounds used to remove a major suppressive influence.

Inhibitors such as galunisertib, a TGF-β receptor kinase inhibitor,

or fresolimumab, an anti-TGF-β antibody, have been investigated in

patients with HCC (83,84). Although these agents have not yet

been tested in phase III trials in combination with ICIs,

preclinical analysis suggests that blocking TGF-β signaling

enhances the penetration of T cells into tumors and is a promising

mechanism for use in combinations that aim to convert cold tumors

into hot ones (85).

Oncolytic virotherapy

Oncolytic viruses (OVs) are engineered or naturally

occurring viruses that selectively replicate in and lyse cancer

cells while stimulating an antitumor immune response (86). This lytic process releases tumor

antigens and viral pathogen signals, effectively transforming the

tumor into a vaccine depot. Several OVs have been evaluated for the

treatment of HCC.

Talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC), a modified herpes

simplex virus type-1 that encodes granulocyte-macrophage (GM)-CSF,

has been approved for melanoma treatment and tested via

intratumoral injection in liver tumors (87). Early trials combining T-VEC with

ICIs have shown increased local immune cell infiltration in HCC and

demonstrated the feasibility of generating a localized autitumor

immune response (88).

Pexastimogene devacirepvec (Pexa-Vec; JX-594), an

oncolytic vaccinia virus expressing GM-CSF, has also been evaluated

in HCC. A phase II trial showed signs of improved survival in a

subset of patients (89), In

addition, a phase III trial (PHOCUS), evaluating Pexa-Vec combined

with sorafenib, was conducted in advanced HCC (86). The PHOCUS phase III trial showed

that adding Pexa-Vec to sorafenib does not improve overall survival

in advanced HCC, leading to early study termination, though

Pexa-Vec was well tolerated with manageable safety (90).

Cancer vaccines and adoptive cell

therapies

Active immunization strategies aim to stimulate the

immune system to recognize HCC-specific antigens, thereby enhancing

T-cell priming against the tumor. Although past vaccine trials in

HCC targeting antigens such as AFP (91), GPC3 (92) or multi-peptide mixtures (93) have shown only modest success, they

all have demonstrated immunogenicity, indicating that T cells

targeting these antigens can be expanded in patients. A summary of

emerging immunotherapeutic approaches for HCC is provided in

Table III (21,23,35,67,79,89,94–101). Certain approaches-particularly

cancer vaccines, oncolytic viruses, and certain adoptive cell

therapies-have shown evidence of inducing tumor-specific immune

responses in clinical or preclinical studies, whereas others

(metabolic, microbiome, and TAM-targeting strategies) are still at

the investigational or early-trial stage and remain to be validated

for immunogenic effects.

| Table III.Emerging immunotherapeutic approaches

in HCC. |

Table III.

Emerging immunotherapeutic approaches

in HCC.

| Strategy | Description | Evidence | Status | (Refs.) |

|---|

| TAM targeting | CSF-1R inhibitors,

including pexidartinib and cabiralizumab | CSF-1R blockade

decreases M2 TAMs and synergized with PD-L1 inhibition, increasing

T cell activity | Phase I trials

ongoing with CSF-1R mAb + nivolumab; biomarkers required for

TAM-high tumors | (79) |

| Treg targeting | CTLA-4 inhibitors;

anti-CD25 antibodies | Tremelimumab

reduced Tregs and increased effector T cells; improved CD8:Treg

ratios are associated with tumor control | CTLA-4 inhibitors

are included in approved combinations; cyclophosphamideanti-CD25

trials underway; however, autoimmunity is a risk factor | (23,67) |

| Neutrophil/MDSC

targeting | CXCR2 inhibitors;

ARG1 inhibitors; IL-8 blockers | CXCR2 antagonist +

PD-1 blockade reduced TANs, and improved the T-cell response; high

neutrophils predict poor ICI outcomes | CXCR2 inhibitor +

durvalumab/bevacizumab trial ongoing; IL-8 antibodies in ongoing

clinical trials | (60,94) |

| OVs | JX-594

(vaccinia-GM-CSF); T-VEC (HSV-GM-CSF); AFP-targeting HDV | JX-594 increased

immune infiltration in tumors. OVs upregulate IFN genes and enhance

antigen presentation | Pexastimogene

devacirepvec + sorafenib, phase III, negative; OV + ICI

combinations in phase I/II; T-VEC + pembrolizumab, ~20%

response | (89,101) |

| CAR T/NK cells | Engineered cells

targeting GPC3, AFP and EpCAM admini- stered intravenously or via

the hepatic artery | GPC3-CAR T induced

tumor necrosis, IFN-γ secretion; PD-1 knockout CAR-Ts overcame

exhaustion | Early trials,

GPC3-CAR T/ NK and AFP-TCR T cells; next-generation, IL-15

secretion and TGF-β resistance | (35,100) |

| Cancer

vaccines | Peptide/neoantigen

vaccines; DC vaccines; oncolytic vaccines | DC vaccine improved

recurrence-free survival post-surgery; neoantigen vaccines induced

tumor- infiltrating T cells | OVAX + nivolumab,

GPC3 peptide + ICI trials ongoing; optimum effect for minimal

disease or with checkpoints | (92,99) |

| Epigenetic

modulators + ICIs | DNMT inhibitors;

HDAC inhibitors + ICIs | DNMT inhibition

increased MHC-I and antigen presentation; HDAC blockade

reprogrammed macrophages and enhanced ICI efficacy | Durvalumab +

tremelimumab + guadecitabine and nivolumab + entinostat trials

ongoing to ‘unmask’ tumors | (98) |

| Metabolic

modulation | A2A antagonists;

IDO inhibitors; lactate modulators | A2A blockade

restored T cell function in hypoxia; IDO inhibition + PD-1 blockade

showed synergy in preclinical models | A2A antagonist

trial (CPI-444) in phase I; metformin showing promise in

NASH-HCC | (21,97) |

| Microbiome

modulation | Probiotics; FMT;

antibiotic management | Akkermansia

and Bifidobacterium are associated with improved outcomes;

FMT from responders improved response in resistant models | Early FMT trials

promising; HCC-specific probiotic interventions in development | (95,96) |

Combining cancer vaccines with ICIs or other TME

modulators is a rational strategy. For example, DC vaccines pulsed

with HCC tumor antigens can generate a wave of tumor-specific T

cells, and concurrent PD-1 blockade can prevent their exhaustion,

allowing them to penetrate and exert cytotoxic activity within

tumors (102).

Adoptive cell therapy supplies effector cells

directly to patients. In HCC, efforts have focused on engineering T

cells to target tumor antigens. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T

cells specific for GPC3, an oncofetal antigen expressed in HCC

cells, have been tested in early-phase trials (102). A phase I study of CAR-GPC3 T

cells in advanced HCC showed some partial responses; however, it

also revealed that the immunosuppressive TME limited CAR-T

persistence and function (100).

A preclinical study used murine and xenograft HCC

models to show that CAR-T cells engineered to secrete IL-12 upon

antigen engagement could remodel the TME and enhance systemic

antitumor activity (103).

Researchers isolated and characterized high-affinity TCRs specific

for AFP peptides presented by HLA-A*02:01. These engineered TCR-T

cells recognize AFP-expressing HCC cells and exhibited potent,

antigen-specific cytotoxicity in vitro and in mouse

xenograft models. Follow-up studies using the same AFP TCR

construct led to a first-in-human phase I trial (NCT03971747) in

HCC patients (104). These TCR-T

cells can recognize intracellular antigens presented on MHC

molecules, potentially broadening targetable proteins beyond

surface markers.

Epigenetic and metabolic

modulators

An emerging strategy to enhance antitumor immunity

involves modulating epigenetic or metabolic pathways to render

tumor and immune cells more immunogenic. Epigenetic drugs,

including DNA methyltransferase inhibitors such as decitabine or

histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors such as entinostat, can

restore the expression of silenced tumor-associated antigens and

increase MHC molecule presentation on cancer cells, thereby

enhancing their recognition by T cells (105).

In addition to their effects on tumor cells,

epigenetic modulators can also alter the differentiation of immune

cells. For example, HDAC inhibition has been shown to promote a

pro-inflammatory macrophage phenotype and reduce the accumulation

of MDSCs, effectively boosting immune responses (106). Furthermore, in HCC models,

combining HDAC inhibitors with PD-1 blockade increased intratumoral

T-cell infiltration and led to tumor regression (106).

Modulating the gut-liver axis

The gut microbiome has a major influence on systemic

immunity and has been shown to affect the response to ICIs in

melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer and renal cell carcinoma.

Therefore, researchers are interested in modulating the gut

microbiota to shift the TME in HCC to a hotter immune state

(95). Certain bacterial

metabolites in the gut can enhance antitumor immunity. Fecal

microbiota transplantation from ICI-responsive patients has been

shown to improve therapeutic responses in melanoma and may hold

promise for application in HCC (95).

Clinical and preclinical evidence

ICI combinations in advanced HCC

The first wave of phase III trials of single-agent

ICIs for advanced HCC has yielded mixed results. In the

CheckMate-459 trial, nivolumab showed durable responses in a subset

of patients when used as a first-line treatment compared with

sorafenib, but it did not significantly improve OS in the primary

analysis (107). Similarly, in

the second-line setting of the KEYNOTE-240 trial, pembrolizumab

yielded a modest improvement in survival compared with placebo in

the second-line setting, however this was not significant (108).

Atezolizumab + bevacizumab (anti-PD-L1

+ anti-VEGF)

The IMbrave150 trial demonstrated that combining

atezolizumab with bevacizumab significantly improved OS and the

objective response rate (ORR) in treatment-naïve patients with

advanced HCC. The median OS was 19.2 months in the combination arm

compared with 13.4 months in patients treated with sorafenib, while

the ORR was ~ 27% compared with ~12%, respectively (60). Numerous responders showed

substantial tumor shrinkage, and some achieved durable remission

(60).

Durvalumab + tremelimumab (anti-PD-L1

+ anti-CTLA-4)

In the phase III HIMALAYA trial, a single high dose

of tremelimumab (300 mg) combined with chronic dosing of durvalumab

achieved a superior OS compared with that of sorafenib in

front-line advanced HCC (63).

This Single Tremelimumab Regular Interval Durvalumab (STRIDE)

regimen capitalized on an initial wave of broad T-cell activation

from CTLA-4 blockade, followed by sustained PD-L1 blockade. The

median OS was 16.4 months compared with 13.8 months in patients

treated with sorafenib. A subset of patients treated with the

STRIDE regimen achieved long-term survival >2 years (63).

Nivolumab + ipilimumab (anti-PD-1 +

anti-CTLA-4)

In the CheckMate-040 cohort 4 phase II study, three

different regimens combining nivolumab with ipilimumab were

evaluated in patients who had progressed on sorafenib. An ORR of

32% and median OS of 22 months was obtained in the arm with higher

ipilimumab dosage (6).

Approximately 8% of patients achieved a CR (6).

Locoregional and multimodal therapy

evidence

A pilot trial combining the CTLA-4 inhibitor

tremelimumab with subtotal radiofrequency ablation in patients with

advanced HCC whose tumors were suitable for partial ablation

reported that 26% of patients had a partial response in non-ablated

lesions, and disease control was achieved in 89% of patients

(67). Notably, an increase in

intratumoral CD8+ T cells and a reduction in viral load

in hepatitis B virus (HBV)-infected patients were observed after

treatment, indicating a systemic immune effect (67). These findings support the concept

that local tumor destruction can synergize with checkpoint

blockade.

Retrospective analyses also suggest that patients

receiving radiotherapy or TACE shortly before or during nivolumab

therapy have improved response rates compared with those receiving

nivolumab alone (109). For

example, one study found an abscopal response in ~20% of patients

who received radiotherapy for a single lesion while receiving

nivolumab treatment compared with <10% in those treated with

nivolumab alone (110).

Adoptive cell therapy and

vaccines

CAR T cells

A phase I trial of CAR T cells targeting GPC3 in

patients with advanced HCC reported a partial response in 2 of 13

patients, with disease stabilization observed in seven patients

(100). Although the clinical

response was modest, tumor biopsies following CAR T infusion

demonstrated the accumulation of CAR T cells at tumor sites, and

some patients exhibited substantial tumor necrosis. These findings

indicate that CAR T cells are able to traffic to and attack HCC

lesions (111). However, the

expansion and persistence of CAR T cells in vivo is limited,

possibly due to immunosuppressive checkpoints and the dense

TME.

TCR-engineered T cells

A first-in-human study of T cells engineered with a

TCR against an AFP peptide presented by HLA-A2 in patients with

AFP-positive HCC showed that the treatment was safe and resulted in

transient reductions in serum AFP levels and tumor shrinkage in

certain patients (112). Although

no objective responses were observed according to RECIST criteria,

one patient exhibited a measurable decrease in tumor burden that

does not meet the threshold for a partial response (PR), and others

achieved stable disease (112).

DC vaccines

A randomized phase II trial of patients with

early-stage HCC compared a tumor lysate-activated autologous DC

vaccine with a control group of patients treated with best

supportive care following curative resection or ablation (113). The vaccinated group experienced a

significantly longer median time to recurrence than the control

group (36 vs. 25 months, respectively) and a higher recurrence-free

survival at 1 year (75.6 vs. 61.1%, respectively) (113).

Preclinical insights

Several mouse model studies have directly

demonstrated the benefits of reprogramming the HCC

microenvironment:

NASH-HCC model

A study of mice with diet-induced NASH revealed that

PD-1 blockade did not protect against liver cancer and instead

promoted the incidence and progression of HCC due to activated, but

dysfunctional, CD8+ T cells producing TNF-α. However,

when those CD8+ T cells were depleted or TNF-α was

neutralized, checkpoint blockade efficacy improved (15).

Osteopontin (OPN)/CSF-1R axis

In a chemically-induced HCC mouse model, it was

revealed that tumor-derived OPN recruits TAMs through the CSF-1

pathway. The blockade of CSF-1R not only reduced TAM infiltration

but also led to increased CD8+ T-cell activity and

responsiveness to anti-PD-L1 therapy (79).

Fibroblast growth factor receptor 4

(FGFR4) and Tregs

A study of lenvatinib demonstrated that the

inhibition of FGFR4, a protein that is overexpressed in some HCC

tissues, not only affected tumor cell growth but also reduced

intratumoral Treg accumulation in mouse xenografts and PD-L1

expression in tumor cells. This dual effect was associated with

improved anti-PD-1 antibody efficacy and tumor rejection in mouse

models (114).

CAR T cells with checkpoint

knockout

In an orthotopic HCC model in mice, PD-1

gene-deleted CAR T cells targeting GPC3 outperformed conventional

CAR T cells, as they were more persistent and infiltrated the

tumors more deeply. In addition, these modified CAR T cells

resulted in complete tumor eradication in a higher proportion of

the mice (35).

Other therapeutical targets

Preclinical findings have revealed new targets,

including CSF-1R (78), CXCR2

(115) and adenosine (116), and confirmed mechanisms such as

Wnt-mediated exclusion, that can be therapeutically targeted

(116).

Future directions

The field of HCC immunotherapy is rapidly evolving,

and the paradigm of converting cold tumors into hot ones will

continue to guide future research and clinical practice. Several

key directions are anticipated.

Personalized immunotherapy and

biomarker-driven treatment

As our understanding of HCC immune biology deepens,

there is growing recognition that not all patients should receive

the same immunotherapy regimen. Future treatment algorithms will

likely incorporate biomarkers to stratify patients. For example,

tumors with Wnt/β-catenin mutations or an immune-excluded phenotype

may be prioritized for trials evaluating Wnt pathway inhibitors or

other T-cell-recruiting strategies (39).

A robust immune score for HCC could be developed,

analogous to the Immunoscore used in colorectal cancer (117). This could help to determine the

required intensity of immunotherapy. Liquid biopsies, including

circulating tumor DNA and immune cell profiling assays, may enable

the early assessment of whether a tumor is becoming hotter or

remains immunologically cold, allowing for adaptive treatment

adjustments.

Next-generation checkpoint

targets

While PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 are the current targets,

several other inhibitory pathways are being explored in clinical

trials and could be integrated into HCC treatment (5). Antibodies targeting

lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3), known as relatlimab, were

recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the

treatment of melanoma and are of interest in HCC, as LAG-3 is

upregulated in exhausted T cells in the liver (118).

T-cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains

(TIGIT) is another checkpoint protein expressed on T and NK cells;

anti-TIGIT antibodies, such as tiragolumab, combined with anti-PD-1

therapy are in trials for HCC following promising results in other

cancer types (119). These

emerging checkpoint inhibitors may help to revive exhausted T cells

in HCC when PD-1 blockade alone is inadequate.

Triplet therapies and beyond

Building on the success of doublet regimens, such as

atezolizumab + bevacizumab and durvalumab + tremelimumab, the next

wave of studies is testing triplet combinations to further convert

cold tumors into a hot state. For example, the COSMIC-312 trial has

evaluated a triplet of PD-1 + CTLA-4 + tyrosine kinase inhibitors,

namely nivolumab + ipilimumab + cabozantinib, to simultaneously

target T cells, Tregs and tumor angiogenesis (120). The COSMIC-312 phase III trial

reported that cabozantinib + atezolizumab significantly improved

progression-free survival vs. sorafenib (6.8 vs 4.2 months; HR

0.63) but did not improve overall survival (121). However, the nivolumab +

ipilimumab + cabozantinib triplet remains under investigation, with

no published efficacy results yet for this regimen.

However, as toxicity and cost increase with each

added agent, future research must identify which patient subsets

truly require multilayered therapy. Sequential approaches, such as

an induction phase followed by a maintenance phase, rather than

concurrent triple therapy, may also mitigate toxicity.

Immunotherapy in earlier-stage

HCC

Although most immunotherapy trials have focused on

advanced HCC, there is a strong rationale for applying these

strategies in earlier stages of the disease, when immune function

is less impaired and the tumor burden is lower. Neoadjuvant

immunotherapy prior to surgery is being investigated, and small

studies administering ICIs or combinations prior to resection have

shown that some patients achieve significant tumor necrosis and

robust pathologic responses, which might translate to a lower

recurrence risk (40).

In the adjuvant setting, after curative resection or

ablation, the goal is to eradicate residual disease and prevent

recurrence. The CheckMate-9DX phase III trial of adjuvant nivolumab

did not meet the primary endpoint of recurrence-free survival

(122), possibly due to trial

design considerations or insufficient treatment duration. However,

other adjuvant trials are ongoing, including the KEYNOTE-937 trial

of pembrolizumab and the EMERALD-2 trial of durvalumab ±

bevacizumab (123,124).

Addressing etiology-specific immune

contexts

As already noted, NASH-related HCC has a suppressive

immune milieu that may require tailored therapeutic strategies

(15). One future approach is to

treat underlying liver conditions in parallel with the cancer

itself. In NASH, this could involve therapies that reduce hepatic

inflammation, such as farnesoid X receptor agonists, acetyl-CoA

carboxylase inhibitors or anti-IL-1β agents, administered in

conjunction with immunotherapy, to prevent the non-productive

activation of T cells. For HBV-associated HCC, continuing antiviral

therapy is crucial, and additional strategies, such as therapeutic

HBV vaccines or TCR-based approaches targeting HBV antigens, may

boost antitumor immunity, given that some HCC tumor cells express

HBV-derived proteins.

Novel delivery systems

Accessibility of the liver via the hepatic artery

allows for innovative strategies for the delivery of

immunotherapies directly to the tumor or liver, thereby maximizing

local immune activation effects while minimizing systemic toxicity.

Ongoing trials are currently examining the locoregional delivery of

IL-12 plasmids (125), toll-like

receptor 9 agonists (126), and

CAR T cells through hepatic artery infusion (127). Nanotechnology-based approaches

may enable nanoparticles carrying immune stimulants, such as

stimulators of IFN gene agonists, or small interfering RNAs

targeting immune checkpoints, to be delivered selectively to liver

tumors (96). Such approaches can

convert the tumor site into an immune-reactive zone without

exposing the whole body to high cytokine or drug levels, thereby

potentially reducing systemic side effects.

Monitoring and managing immune-related

toxicity

As immunotherapy strategies are intensified to

convert cold tumors into hot ones, the risk of collateral damage to

normal liver tissue increases. Future protocols will require robust

monitoring procedures for immune-related adverse events and

potentially prophylactic measures. For example, patients with

cirrhosis are at risk of decompensation if immunotherapy triggers

autoimmune hepatitis (128,129). Gut microbiome manipulation is

being considered as a means of improving efficacy and also

mitigating toxicity, since certain microbiome profiles are

associated with the risk of colitis (130,131). Researchers are also exploring

selective immunosuppressants capable of controlling toxicity

without completely compromising antitumor immunity (132,133).

Integration of artificial intelligence

and systems biology

As data from genomic, transcriptomic, imaging and

clinical sources accumulate, artificial intelligence and machine

learning will likely play a role in the identification of features

that define cold and hot tumors and in guiding treatment selection.

For example, deep learning applied to histological images can

quantify immune infiltrates and their spatial distribution, thereby

potentially predicting outcomes (115). Multiomics analysis may identify

new therapeutic targets, for example, by identifying that a certain

chemokine is the key factor limiting T-cell infiltration in a

subset of patients, which could be targeted by drugs. Systems

biology approaches may be used to model complex interactions within

the HCC immune ecosystem, simulate the performance of a given

combination and guide the rational design of treatment

regimens.

Conclusions

HCC has long been considered an immunologically

cold tumor, posing a formidable challenge for immunotherapy. In the

present review, numerous factors, including immunosuppressive cell

populations, inhibitory cytokines, tumor-intrinsic pathways and

liver-induced tolerance are described that are able to blunt

antitumor immunity in HCC. Crucially, it is emphasized that these

barriers are not insurmountable. Through various strategies,

researchers and clinicians have demonstrated that the active

transformation of cold HCC tumors into hot, immune-reactive tumors

is possible.

Combination therapies combining ICIs with agents

such as anti-angiogenic drugs or CTLA-4 blockers have already

yielded significantly improved clinical outcomes, validating the

principle that immune silencing in HCC can be reversed. Emerging

modalities, including locoregional therapy combined with

immunotherapy, OVs, CAR T/NK-cell approaches, and metabolic or

epigenetic modulators, have further expanded the therapeutic

options for reprogramming the TME.

As the immune landscape of HCC is progressively

understood and manipulated, it is anticipated that what was once

considered a non-immunogenic cancer may become routinely

manageable, and potentially even curable, by harnessing the immune

system of the patient. The journey from cold to hot HCC (Fig. 1) exemplifies a paradigm shift in

oncology: Rather than treating the tumor alone, the TME and the

host immune response are also targeted, creating a situation in

which the immune system contributes to HCC eradication.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was funded by the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (grant

nos. CMRPG8Q0181 and CORPG8N0241).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

CHH was responsible for study conceptualization and

writing the original draft of the manuscript. PCC contributed to

study methodology, and the review and editing of the manuscript.

Data authentication is not applicable. Both authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

AFP

|

α-fetoprotein

|

|

CAF

|

cancer-associated fibroblast

|

|

CAR

|

chimeric antigen receptor

|

|

CCL

|

C-C motif chemokine ligand

|

|

CCR

|

C-C motif chemokine receptor

|

|

CR

|

complete response

|

|

CSF

|

colony stimulating factor

|

|

CTL

|

cytotoxic T lymphocyte

|

|

CTLA-4

|

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated

protein 4

|

|

DC

|

dendritic cell

|

|

FGFR

|

fibroblast growth factor receptor

|

|

GM-CSF

|

granulocyte-macrophage

colony-stimulating factor

|

|

GPC3

|

glypican-3

|

|

HBV

|

hepatitis B virus

|

|

HCC

|

hepatocellular carcinoma

|

|

HDAC

|

histone deacetylase

|

|

HLA

|

human leukocyte antigen

|

|

ICI

|

immune checkpoint inhibitor

|

|

IFN-γ

|

interferon-γ

|

|

IL

|

interleukin

|

|

LAG-3

|

lymphocyte-activation gene 3

|

|

LSEC

|

liver sinusoidal endothelial cell

|

|

MDSC

|

myeloid-derived suppressor cell

|

|

MHC

|

major histocompatibility complex

|

|

NASH

|

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

|

|

NK

|

natural killer

|

|

OPN

|

osteopontin

|

|

ORR

|

objective response rate

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

|

OV

|

oncolytic virus

|

|

PD-1

|

programmed cell death protein 1

|

|

PD-L1

|

programmed death-ligand 1

|

|

T-VEC

|

talimogene laherparepvec

|

|

TACE

|

transarterial chemoembolization

|

|

TAM

|

tumor-associated macrophage

|

|

TCR

|

T cell receptor

|

|

TGF-β

|

transforming growth factor-β

|

|

TIGIT

|

T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and

ITIM domains

|

|

TIM-3

|

T cell immunoglobulin and

mucin-domain containing protein 3

|

|

TME

|

tumor microenvironment

|

|

Treg

|

regulator T cell

|

|

VEGF

|

vascular endothelial growth

factor

|

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Villanueva A: Hepatocellular carcinoma. N

Engl J Med. 380:1450–1462. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Ker CG: Hepatobiliary surgery in Taiwan:

The past, present, and future. Part I; biliary surgery. Formos J

Surg. 57:1–10. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Sangro B, Gomez-Martin C, de la Mata M,

Iñarrairaegui M, Garralda E, Barrera P, Riezu-Boj JI, Larrea E,

Alfaro C, Sarobe P, et al: A clinical trial of CTLA-4 blockade with

tremelimumab in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and chronic

hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 59:81–88. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Llovet JM, Castet F, Heikenwalder M, Maini

MK, Mazzaferro V, Pinato DJ, Pikarsky E, Zhu AX and Finn RS:

Immunotherapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol.

19:151–172. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Yau T, Kang YK, Kim TY, El-Khoueiry AB,

Santoro A, Sangro B, Melero I, Kudo M, Hou MM, Matilla A, et al:

Efficacy and safety of nivolumab plus ipilimumab in patients with

advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with

sorafenib: The checkmate 040 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol.

6:e2045642020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Childs A, Aidoo-Micah G, Maini MK and

Meyer T: Immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. JHEP Rep.

6:1011302024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Ho DW, Tsui YM, Chan LK, Sze KM, Zhang X,

Cheu JW, Chiu YT, Lee JM, Chan AC, Cheung ET, et al: Single-cell

RNA sequencing shows the immunosuppressive landscape and tumor

heterogeneity of HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat

Commun. 12:36842021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Galon J and Bruni D: Approaches to treat

immune hot, altered and cold tumours with combination

immunotherapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 18:197–218. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Pinyol R, Sia D and Llovet JM: Immune

exclusion-Wnt/CTNNB1 class predicts resistance to immunotherapies

in HCC. Clin Cancer Res. 25:2021–2023. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Giraud J, Chalopin D, Blanc JF and Saleh

M: Hepatocellular carcinoma immune landscape and the potential of

immunotherapies. Front Immunol. 12:6556972021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

De Marchi P, Leal LF, da Silva LS, Cavagna

RO, da Silva FAF, da Silva VD, da Silva EC, Saito AO, de Lima VCC

and Reis RM: Gene expression profiles (GEPs) of immuno-oncologic

pathways as predictors of response to checkpoint inhibitors in

advanced NSCLC. Transl Oncol. 39:1018182024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hernandez S, Lazcano R, Serrano A, Powell

S, Kostousov L, Mehta J, Khan K, Lu W and Solis LM: Challenges and

opportunities for immunoprofiling using a spatial high-plex

technology: The NanoString GeoMx(®) digital spatial

profiler. Front Oncol. 12:8904102022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Bruni D, Angell HK and Galon J: The immune

contexture and Immunoscore in cancer prognosis and therapeutic

efficacy. Nat Rev Cancer. 20:662–680. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Pfister D, Núñez NG, Pinyol R, Govaere O,

Pinter M, Szydlowska M, Gupta R, Qiu M, Deczkowska A, Weiner A, et

al: NASH limits anti-tumour surveillance in immunotherapy-treated

HCC. Nature. 592:450–456. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zhang Q, He Y, Luo N, Patel SJ, Han Y, Gao

R, Modak M, Carotta S, Haslinger C, Kind D, et al: Landscape and

dynamics of single immune cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell.

179:829–845.e20. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Yi Q, Yang J, Wu Y, Wang Y, Cao Q and Wen

W: Immune microenvironment changes of liver cirrhosis: Emerging

role of mesenchymal stromal cells. Front Immunol. 14:12045242023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Montella L, Sarno F, Ambrosino A, Facchini

S, D'antò M, Laterza M, Fasano M, Quarata E, Ranucci RAN, Altucci

L, et al: The role of immunotherapy in a tolerogenic environment:

Current and future perspectives for hepatocellular carcinoma.

Cells. 10:19092021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Shu QH, Ge Y, Hua X, Gao XQ, Pan JJ, Liu

DB, Xu GL, Ma JL and Jia WD: Prognostic value of polarized

macrophages in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after

curative resection. J Cell Mol Med. 20:1024–1035. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Xue R, Zhang Q, Cao Q, Kong R, Xiang X,

Liu H, Feng M, Wang F, Cheng J, Li Z, et al: Liver tumour immune

microenvironment subtypes and neutrophil heterogeneity. Nature.

612:141–147. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ghaedi M and Ohashi P: ILC

transdifferentiation: Roles in cancer progression. Cell Res.

30:562–563. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kim HD, Song G, Park S, Jung M, Kim MH,

Kang H, Yoo C, Yi K, Kim KH, Eo S, et al: Association between

expression level of PD1 by tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells and

features of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology.

155:1936–1950. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Fu J, Xu D, Liu Z, Shi M, Zhao P, Fu B,

Zhang Z, Yang H, Zhang H, Zhou C, et al: Increased regulatory T

cells correlate with CD8 T-cell impairment and poor survival in

hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Gastroenterology. 132:2328–2239.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Yan J, Liu XL, Xiao G, Li NL, Deng YN, Han

L, Yin LC, Ling LJ and Liu LX: Prevalence and clinical relevance of

T-Helper cells, Th17 and Th1, in hepatitis B virus-related

hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 9:e960802014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Hu C, You W, Kong D, Huang Y, Lu J, Zhao

M, Jin Y, Peng R, Hua D, Kuang DM and Chen Y: tertiary lymphoid

structure-associated B cells enhance CXCL13+CD103+CD8+

tissue-resident memory T-Cell response to programmed cell death

protein 1 blockade in cancer immunotherapy. Gastroenterology.

166:1069–1084. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Ford K, Hanley C, Mellone M, Szyndralewiez

C, Heitz F, Wiesel P, Wood O, Machado M, Lopez MA, Ganesan AP, et

al: NOX4 inhibition potentiates immunotherapy by overcoming

cancer-associated fibroblast-mediated CD8 T-cell exclusion from

tumors. Cancer Res. 80:1846–1860. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Deng HJ, Kan A, Lyu N, Mu L, Han Y, Liu L,

Zhang Y, Duan Y, Liao S, Li S, et al: Dual vascular endothelial

growth factor receptor and fibroblast growth factor receptor

inhibition elicits antitumor immunity and enhances programmed cell

death-1 checkpoint blockade in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver

Cancer. 9:338–357. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yin Y, Feng W, Chen J, Chen X, Wang G,

Wang S, Xu X, Nie Y, Fan D, Wu K and Xia L: Immunosuppressive tumor

microenvironment in the progression, metastasis, and therapy of

hepatocellular carcinoma: From bench to bedside. Exp Hematol Oncol.

13:722024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Yeung O, Lo C, Ling C, Qi X, Geng W, Li C,

Ng KT, Forbes SJ, Guan XY, Poon RT, et al: Alternatively activated

(M2) macrophages promote tumour growth and invasiveness in

hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 62:607–616. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Mantovani A, Allavena P, Marchesi F and

Garlanda C: Macrophages as tools and targets in cancer therapy. Nat

Rev Drug Discov. 21:799–820. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Zhu Y, Tan H, Wang J, Zhuang H, Zhao H and

Lu X: Molecular insight into T cell exhaustion in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Pharmacol Res. 203:1071612024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Sia D, Jiao Y, Martinez-Quetglas I, Kuchuk

O, Villacorta-Martin C, de Moura MC, Putra J, Camprecios G,

Bassaganyas L, Akers N, et al: Identification of an immune-specific

class of hepatocellular carcinoma, based on molecular features.

Gastroenterology. 153:812–826. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Guo T and Xu J: Cancer-associated

fibroblasts: A versatile mediator in tumor progression, metastasis,

and targeted therapy. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 43:1095–1116. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Gao D, Fang L, Liu C, Yang M, Yu X, Wang

L, Zhang W, Sun C and Zhuang J: Microenvironmental regulation in

tumor progression: Interactions between cancer-associated

fibroblasts and immune cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 167:1156222023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Liu ZL, Zhu LL, Liu JH, Pu ZY, Ruan ZP and

Chen J: Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 and its

association with tumor immune regulatory gene expression in