Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory

bowel disease (IBD) primarily affecting the colon which is

characterized by mucosal inflammation. Its incidence is gradually

increasing worldwide, with rates in China reaching 11.6 per 100,000

individuals (1,2). If left untreated UC can progress to

colorectal cancer or result in systemic complications (3). The pathogenesis of UC involves immune

dysregulation, excessive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines

and gut microbiota imbalance (4).

Current first-line therapies include aminosalicylates, such as

mesalazine, corticosteroids and immunomodulators. However, up to

50% of patients experience treatment-related adverse events, such

as glucose intolerance and hepatotoxicity (5), highlighting the need for safer and

more effective therapeutic alternatives. Natural products have

therefore attracted growing attention as potential candidates

(6,7).

The intestinal barrier serves an important role in

the pathogenesis of UC. Disruption of its structural and functional

integrity contributes to increased intestinal permeability,

microbial translocation and sustained immune activation. Growing

evidence suggests that enhancing intestinal barrier function

represents a promising therapeutic strategy for UC (8–14).

Among the signaling mechanisms implicated, the Janus kinase 2

(JAK2)/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)

pathway has been extensively studied. Hyperactivation of this

pathway is a hallmark of UC, contributing to both inflammation and

barrier dysfunction (15,16). The preliminary data of the present

study (data not shown), together with prior reports (17,18),

have suggested that naringin, a natural flavonoid, may exert

anti-inflammatory effects through modulation of kinase signaling

pathways. The present study therefore focused on the JAK2/STAT3

pathway to elucidate the mechanism underlying its protective

activity.

Citrus aurantium L., a member of the Rutaceae

family also known as bitter orange, is widely consumed in China as

both a food and traditional medicine, owing to its

anti-inflammatory properties (18). Previous studies have demonstrated

that Citrus aurantium L. alleviates trintrobenzene sulfonic

acid (TNBS)-induced IBD in rats, while its major flavonoid naringin

reduces the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS),

cytochrome c oxidase subunit 2 (COX-2) and TNF-α (17,18).

Naringin has also been shown to ameliorate clinical symptoms in

murine models of IBD (17,18). Given that the JAK2/STAT3 pathway is

hyperactivated in UC and promotes inflammation (15,16),

its pharmacological inhibition has emerged as a promising

therapeutic approach (19–21). However, the role of naringin in

modulating UC through this pathway remains undefined. The present

study aimed to investigate the effects of naringin on sodium

sulfate dextran (DSS)-induced colitis and its influence on the

JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway.

Materials and methods

Materials

Naringin (cat. no. B21594-1g; Shanghai Yuanye

Bio-Technology Co., Ltd.) and fluorescein isothiocyanate dextrose

4000 (FD-4; molecular weight, 3,000-5,000 kDa; cat. no. FD4-250MG)

were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. Mesalazine (cat. no.

20230605) was obtained from Heilongjiang Tianhong Pharmaceutical

Co., Ltd. DSS (molecular weight, 36,000-50,000 kDa; cat. no.

02160110-CF) was purchased from MP Biomedicals, LLC. Caco-2 cells

were obtained from Cell Resource Center, Peking Union Medical

College. Cell culture reagents (HyClone™; Cytiva)

included modified Eagle's medium (MEM; cat. no. SH30024.01), fetal

bovine serum (FBS; cat. no. SH30071.03) and penicillin-streptomycin

(cat. no. SV30010).

Animals

Healthy male BALB-c mice (aged 6–8 weeks; 18–22 g)

were obtained from Sbeifu (Beijing) Biotechnology Co., Ltd.

(certificate of conformity no. 110324210106095731). Mice were

housed in cages with controlled temperature (22±2°C), relative

humidity (40–60%) and a 12-h light/dark cycle throughout the study.

All mice were fed a standard diet (crude protein 16%, crude fat 4%,

crude fiber 12% and ash 8%) and had free access to water. Animal

experiments were approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of Hebei

North University (Zhangjiakou, China; approval no. HBNV20240223003)

and performed according to institutional guidelines.

DSS-induced colitis mice

A total of 32 mice were randomly divided into four

groups, each consisting of eight mice: The normal, control,

mesalazine control and naringin groups. Intragastric administration

volumes were 0.3 ml per 10 g body weight. Mesalazine and naringin

were suspended in 5% acacia gum (cat. no. V900768-500G;

MilliporeSigma; Merck KgaA) and the final doses were 0.2 g/kg and

40 mg/kg, respectively. The dose of 40 mg/kg naringin was selected

based on previous studies demonstrating efficacy in rodent models

of colitis (17,18). Similarly, the mesalazine dose of

0.2 g/kg is a standard dose used in DSS murine models (22,23).

Except for the normal group, all the other groups were freely

administered 3% DSS (dissolved in drinking water) to establish the

UC mouse model, which was administered alongside other treatments

(22,23). The naringin and mesalazine groups

received their respective drug suspensions (in 5% acacia gum) by

oral gavage once daily for 10 days. The normal and control groups

received an equivalent volume of the vehicle (5% acacia gum

solution) on the same schedule. Diet and hydration, body movement,

body weight, diarrhea incidence and bloody stool were recorded

daily throughout the present study.

Disease activity index (DAI) and

analysis of colon injury

Body weight, stool character and incidence of bloody

stools were recorded daily after models were established. The DAI

was determined using a previously established scoring system

(Table I) (24). On day 11, mice were anesthetized

via inhaled isoflurane (induction, 4%; maintenance, 1.5–2% in

oxygen) delivered by a precision vaporizer for final blood

collection from the retro-orbital plexus. A terminal blood sample

not exceeding 10% of total blood volume (0.6–0.8 ml) was collected.

Following this, pentobarbital sodium (40 mg/kg) was administered by

intraperitoneal injection to ensure a surgical plane of anesthesia,

confirmed by the loss of pedal reflex, before euthanasia was

performed via cervical dislocation. This approach guaranteed the

absence of pain or distress throughout the procedure. Death was

verified by the cessation of cardiac and respiratory activity. All

animal procedures were strictly performed in accordance with the

approved animal protocol. The colon segment was resected to

evaluate the macroscopic colon injury, which was scored according

to the method reported in the literature (Table II) (18). Routine hematoxylin and

eosin-stained colon sections, according to previously described

morphological criteria and observed colon tissue damage, were

assessed blindly by two investigators according to a modified

histological grading scale, which considered both inflammatory cell

infiltration and tissue damage (Table III) (18). Any discrepant scores were resolved

through a joint re-evaluation of the slide under a multi-head

microscope to reach a consensus. If a consensus could not be

reached, a third experienced pathologist was consulted for a final

decision.

| Table I.Evaluation of DAI scores. |

Table I.

Evaluation of DAI scores.

| DAI score | Weight loss, % | Stool

consistency | Occult or gross

bleeding |

|---|

| 0 | None | None | None |

| 1 | 1-5 | Loose | Hemoccult

positive |

| 2 | 5-10 | Loose | Hemoccult

positive |

| 3 | 10-15 | Diarrhea | Gross bleeding |

| 4 | >15 | Diarrhea | Gross bleeding |

| Table II.Evaluation of macroscopic scores. |

Table II.

Evaluation of macroscopic scores.

| Colon damage | Score |

|---|

| No damage | 0 |

| Hyperemia with

ulcers | 1 |

| Hyperemia and wall

thickening without ulcers | 2 |

| One ulceration site

without wall thickening | 3 |

| Two or more

ulceration sites | 4 |

| 0.5 cm extension of

inflammation or major damage | 5 |

| 1 cm extension of

inflammation or severe damage | 6-10 |

| Table III.Evaluation of histological

scores. |

Table III.

Evaluation of histological

scores.

| A, Inflammatory

cell infiltration |

|---|

|

|---|

| Pathological

characteristic | Score |

|---|

| No

infiltration | 0 |

| Increased number of

inflammatory cells in the lamina propria | 1 |

| Inflammatory cells

extending into the submucosa | 2 |

| Transmural

inflammatory cell infiltration | 3 |

|

| B, Tissue

damage |

|

| Pathological

characteristic | Score |

|

| No mucosal

damage | 0 |

| Discrete epithelial

lesions | 1 |

| Erosion or focal

ulcerations | 2 |

| Severe mucosal

damage with extensive ulceration extending into the bowel wall | 3 |

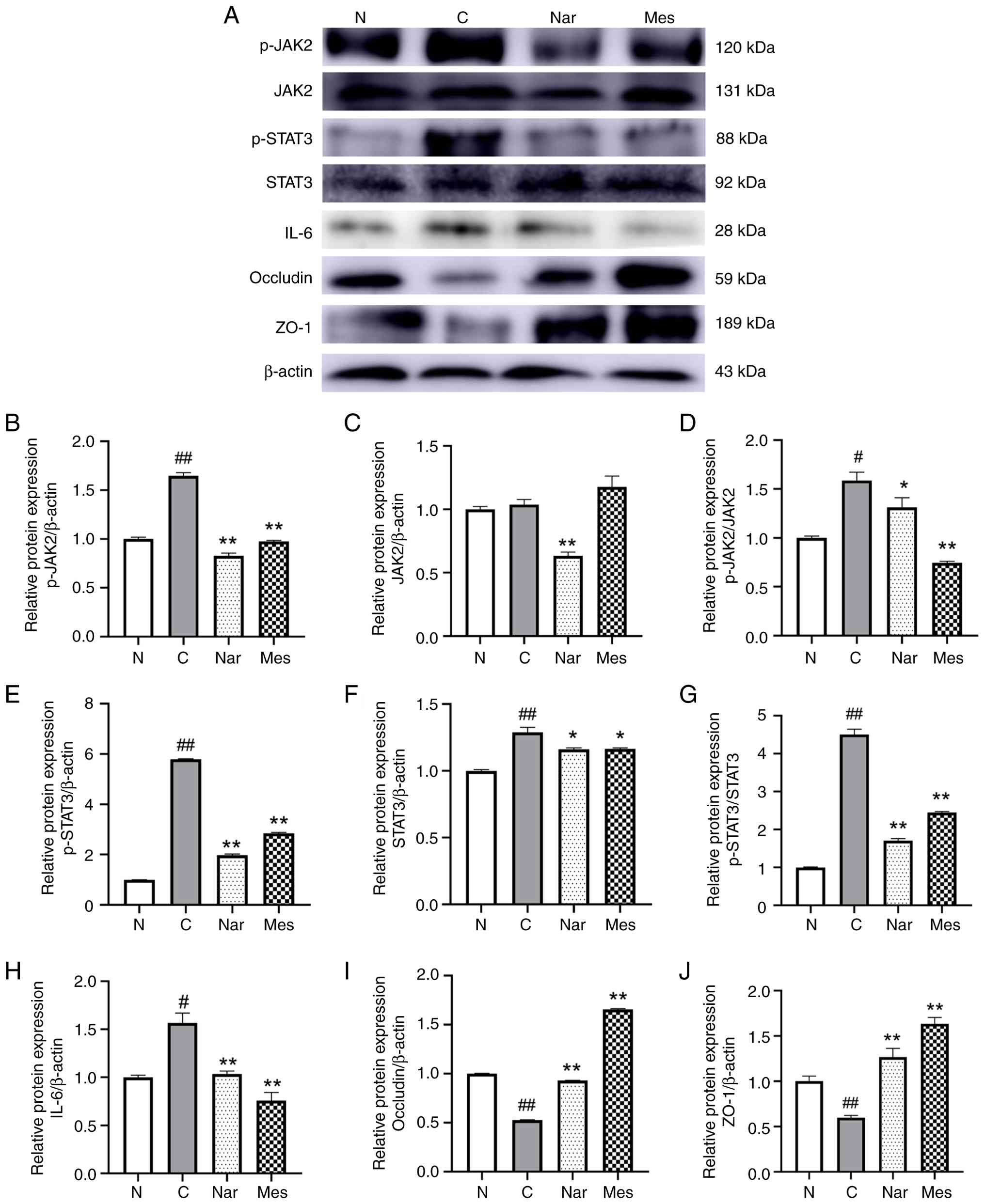

Western blot analysis for JAK2/STAT3

signaling pathway-related proteins from colon tissues

To determine the protective effect of naringin,

western blot analysis was performed. Colon tissues were homogenized

in RIPA buffer (cat. no. P0013B; Beyotime Biotechnology)

supplemented with 1% (v/v) Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor

Cocktail (cat. no. P1050; Beyotime Biotechnology). Protein

concentrations were measured using Cytation 5 (BioTek; Agilent

Technologies, Inc.) using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay

kit (cat. no. PC0020; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.). A total of 60 µg protein were mixed with 4X loading

dye, as well as Laemmli buffer and 2-mercapto ethanol, and were

heated at 95°C for 5 min. The proteins were resolved by 8–12%

SDS-PAGE and transferred to immunoblot PVDF membranes (cat. no.

IPVH00010; Merck KGaA). The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat

dry milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST)

for 2 h at room temperature, then incubated at 4°C overnight with

primary antibodies against IL-6 (1:1,000; cat. no. Bs-0782R;

BIOSS), phosphorylated (p-)JAK2 (1:1,000; cat. no. bs-2485R;

BIOSS), JAK2 (1:1,000; cat. no. bs-0908R; BIOSS), p-STAT3 (1:1,000;

cat. no. bs-1658R; BIOSS), STAT3 (1:1,000; cat. no. bs-55208R;

BIOSS), occludin (1:1,000; cat. no. A2601; ABclonal Biotech Co.,

Ltd.), zona occludens-1 (ZO-1; 1:1,000; cat. no. A0659; ABclonal

Biotech Co., Ltd.) and β-actin (1:1,000; cat. no. ab8227; Abcam).

The membranes were washed with TBST three times for 10 min each and

incubated with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled secondary

goat anti-rabbit (1:5,000; cat. no. ab6721; Abcam) antibodies for 1

h at room temperature. After washing three times with TBST, bands

were detected using ECL Plus Ultra-Sensitive Substrate (cat. no.

PE0010; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) and

visualized using the ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.) after washing three times. The band intensities

were semi-quantified using ImageJ v1.53 gel analysis software

(National Institutes of Health).

IL-6-induced Caco-2 barrier injury

model

Caco-2 cells were cultured in MEM supplemented with

20% FBS, penicillin (100 units/ml), streptomycin (100 µg/ml),

L-glutamine (4.5 mg/ml) and glucose (4.5 mg/ml), and incubated at

37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The

medium was refreshed every other day. A total of 2×106

cells/ml Caco-2 cells were then seeded into a 24-well plate and

incubated overnight at 37°C. The following day, the medium was

changed to a new medium containing 20 ng/ml IL-6 (cat. no. P05231;

Boster Biological Technology) and cells were incubated for 45 min

at 37°C. This resulted in the formation of mucosal barrier damage

in the Caco-2 cells.

Measurement of transepithelial

electrical resistance (TEER) and FD-4 permeability

As described in previously published protocols

(18) with slight modification,

1.5×105 cells/ml Caco-2 cells were seeded in Transwell

cell culture chambers (6.5 mm diameter inserts; 3.0 mm pore size;

Costar; Corning, Inc.), and the growth medium was changed every 2

days. A monolayer of Caco-2 cells was formed after cells were

cultured for 10 days. Subsequently, cells were incubated with or

without IL-6 (20 ng/ml) for 45 min at 37°C and incubated with

naringin (40 µmol/l for 2 h at 37°C. The cell culture was replaced

with serum-free medium and incubated for another 30 min at 37°C

before the sample TEER (Ω/cm2) was assessed.

After the detection of TEER, 100 ml of 1 mg/ml FD-4

was added into the Transwell upper chambers before the cells were

incubated in 37°C for 30 min. After that, 100 ml medium from the

lower chamber of the Transwell was added into a black well to

detect the fluorescence content at an excitation wavelength of 480

nm and emission wavelength of 520 nm using SpectraMax®

M5 (Molecular Devices, LLC) as reported in a previous study

(25).

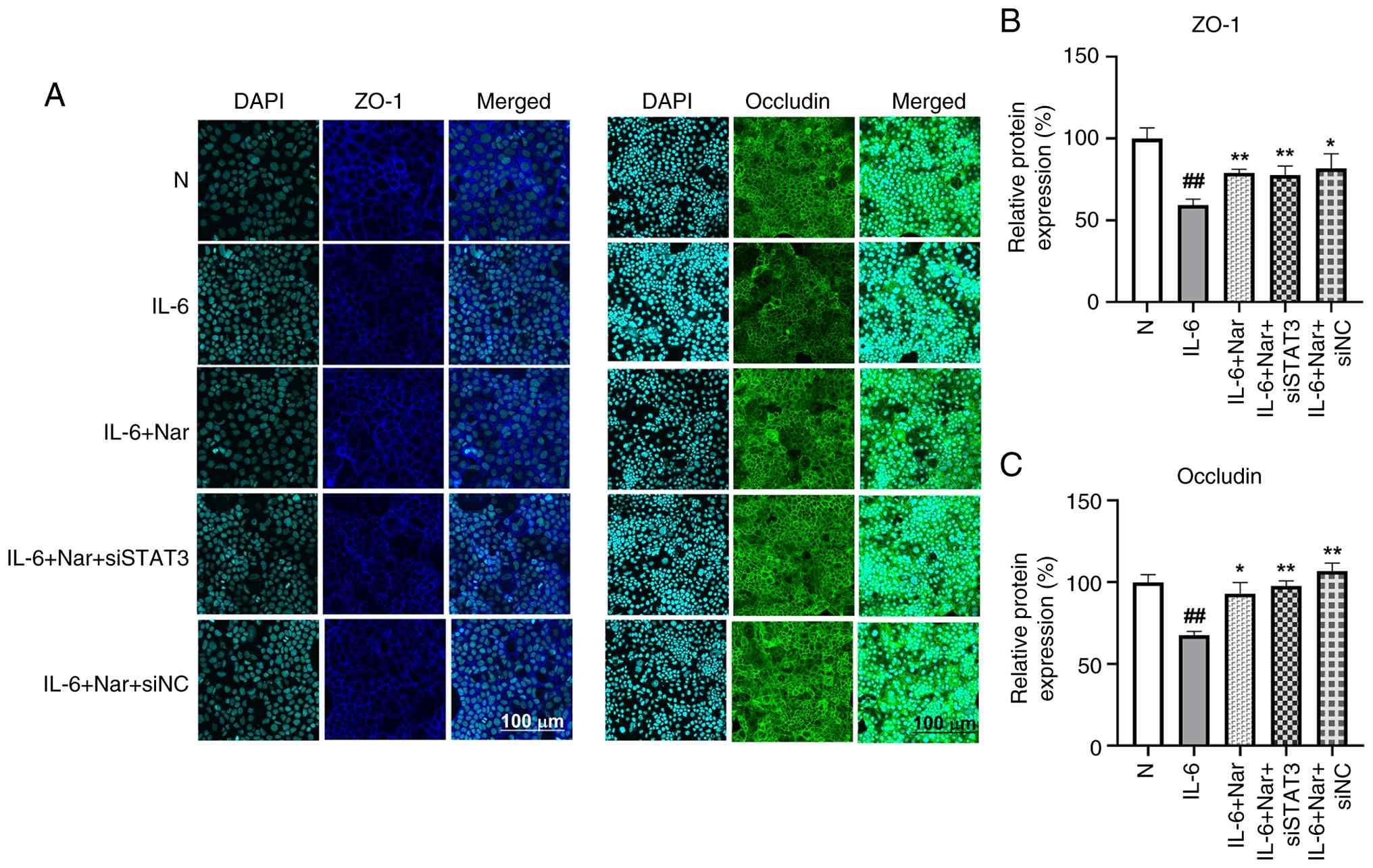

Immunofluorescence assay

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (cat. no.

BL539A; Beijing Lanjieke Technology Co., Ltd.) at room temperature

for 30 min. After discarding the fixative, the cells were washed

with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline and blocked with 5%

bovine serum albumin sealing solution at room temperature for 2 h.

For immunofluorescence experiments, cells were incubated with the

primary antibodies ZO-1 (cat. no. A0659; ABclonal Biotech Co.,

Ltd.) and occludin (cat. no. A2601; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.) at

1:200 dilution overnight at 4°C after blocking. Cells were then

washed with PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 and subsequently incubated

with goat anti-rabbit-Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500; cat. no. 4412S; CST

Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.) and goat anti-rabbit-Alexa Fluor 647

(1:500; cat. no. 4414S, CST Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.)

fluorescent secondary antibodies at room temperature for 2 h in the

absence of light. Finally, cells were counter-stained with DAPI

(cat. no. D1306; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 10 min, and

the images were collected and analyzed using a laser confocal

microscope (FV3000; Olympus Corporation).

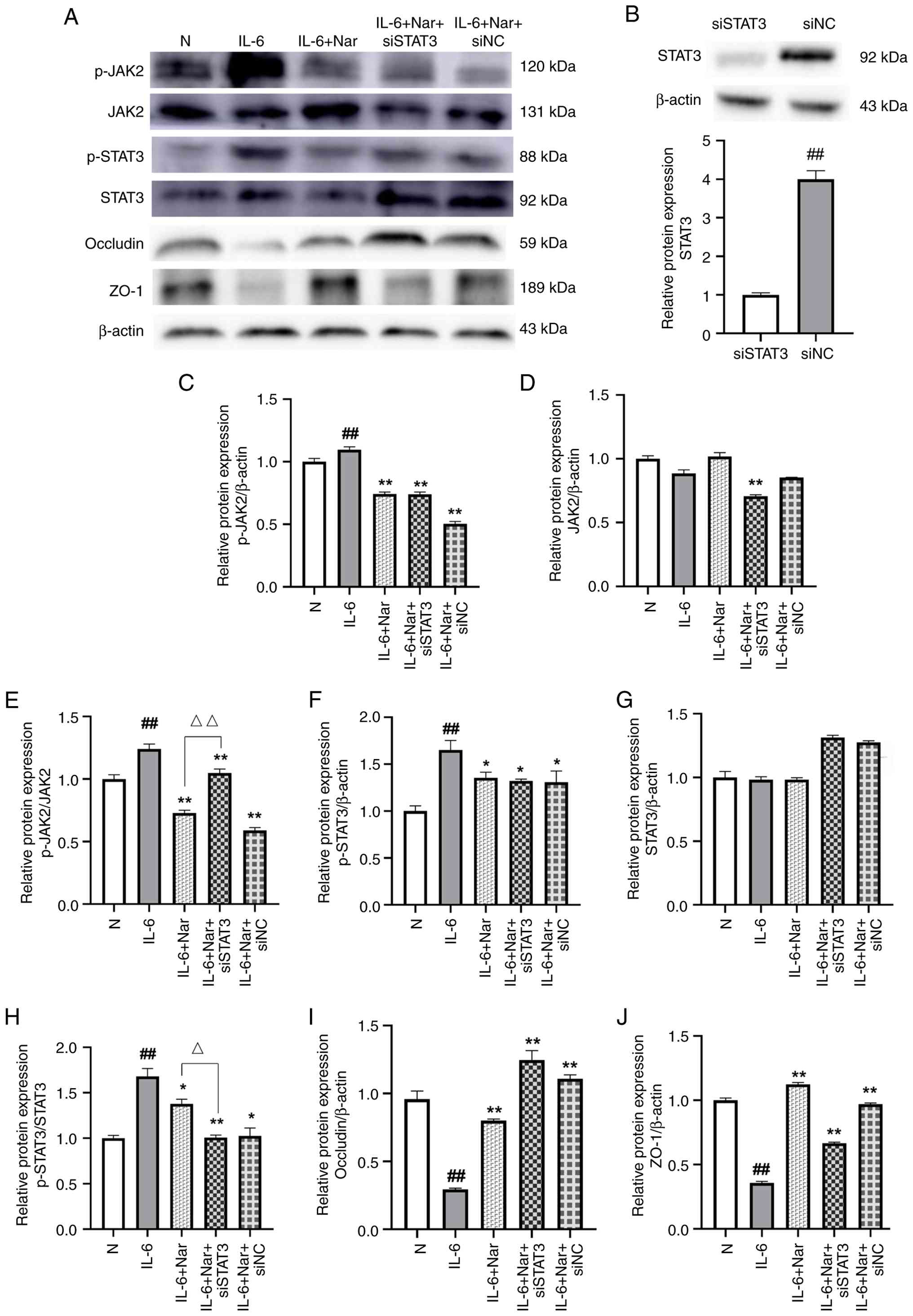

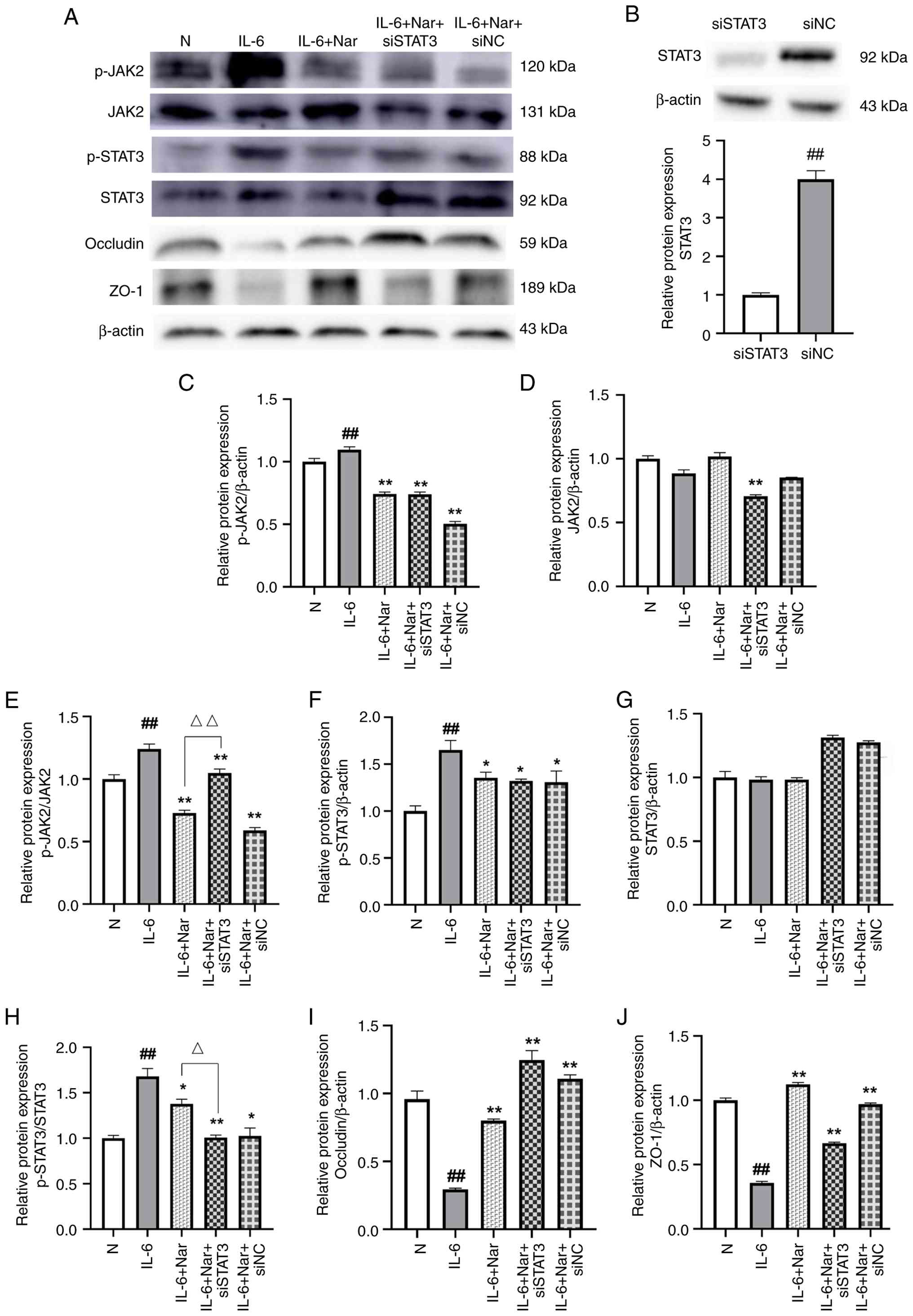

Small interfering RNA (siRNA)

transfection and western blot analysis in Caco-2 cells

siRNA targeting STAT3 (siSTAT3) and negative control

siRNA (siNC) were purchased from Suzhou GenePharma Co., Ltd. The

sequences were as follows: siSTAT3, sense

5′-CCCGGAAAUUUAACAUUCUTT-3′, antisense 5′-AGAAUGUUAAAUUUCCGGGTT-3′;

and siNC, sense 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′, antisense

5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3′. Caco-2 cells were transfected with

siRNA using Lipofectamine® 3000 reagent (Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's

protocol. Briefly, Caco-2 cells were seeded at a density of

2×106 cells/well in a 6-well plate. In each well, 100

pmol siRNA was complexed with Lipofectamine 3000 reagent. The

transfection mixture was incubated with the cells for 6 h at 37°C,

after which it was replaced with fresh complete medium. A total of

24 h after transfection, the transfected cells were treated with

IL-6 (20 ng/ml) for 45 min at 37°C, followed by naringin (40

µmol/l) treatment for 2 h at 37°C, prior to protein extraction. For

protein detection, Caco-2 cells were lysed using ice-cold RIPA

buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and centrifuged 12,000 × g

for 5 min at 4°C. Protein concentrations were determined using a

BCA assay (Beyotime Biotechnology). Total proteins (20 mg/lane)

were subjected to electrophoresis in a 12% polyacrylamide gel and

transferred onto a PVDF membrane. Subsequently, the membrane was

blocked at 37°C for 1 h with 5% non-fat milk in TBS, with 0.05%

Tween-20. Membranes were subsequently incubated separately with

primary antibodies for p-JAK2 (1:1,000; cat. no. bs-2485R; BIOSS),

JAK2 (1:1,000; cat. no. bs-0908R; BIOSS), p-STAT3 (1:1,000; cat.

no. bs-1658R; BIOSS), STAT3 (1:1,000; cat. no. bs-55208R; BIOSS),

occludin (1:1,000; cat. no. A2601; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.),

ZO-1 (1:1,000; cat. no. A0659; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.) and

β-actin (1:1,000; cat. no. ab8227; Abcam), and then with

HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:5,000;

cat. no. ab6721; Abcam). Signals were detected by enhanced

chemiluminescence (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Western blot

images were semi-quantified using ImageJ v1.53 software, Inc.).

Relative band intensities were normalized to β-actin.

Statistical analysis

Experiments were performed with multiple independent

replicates as indicated in the figure legends (typically, n=8 for

in vivo studies and n=3 for in vitro assays). Data

are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed

using SPSS v11.0 (SPSS, Inc.). One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's

post-hoc test was applied. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Naringin ameliorates clinical symptoms

of UC in DSS-induced mice

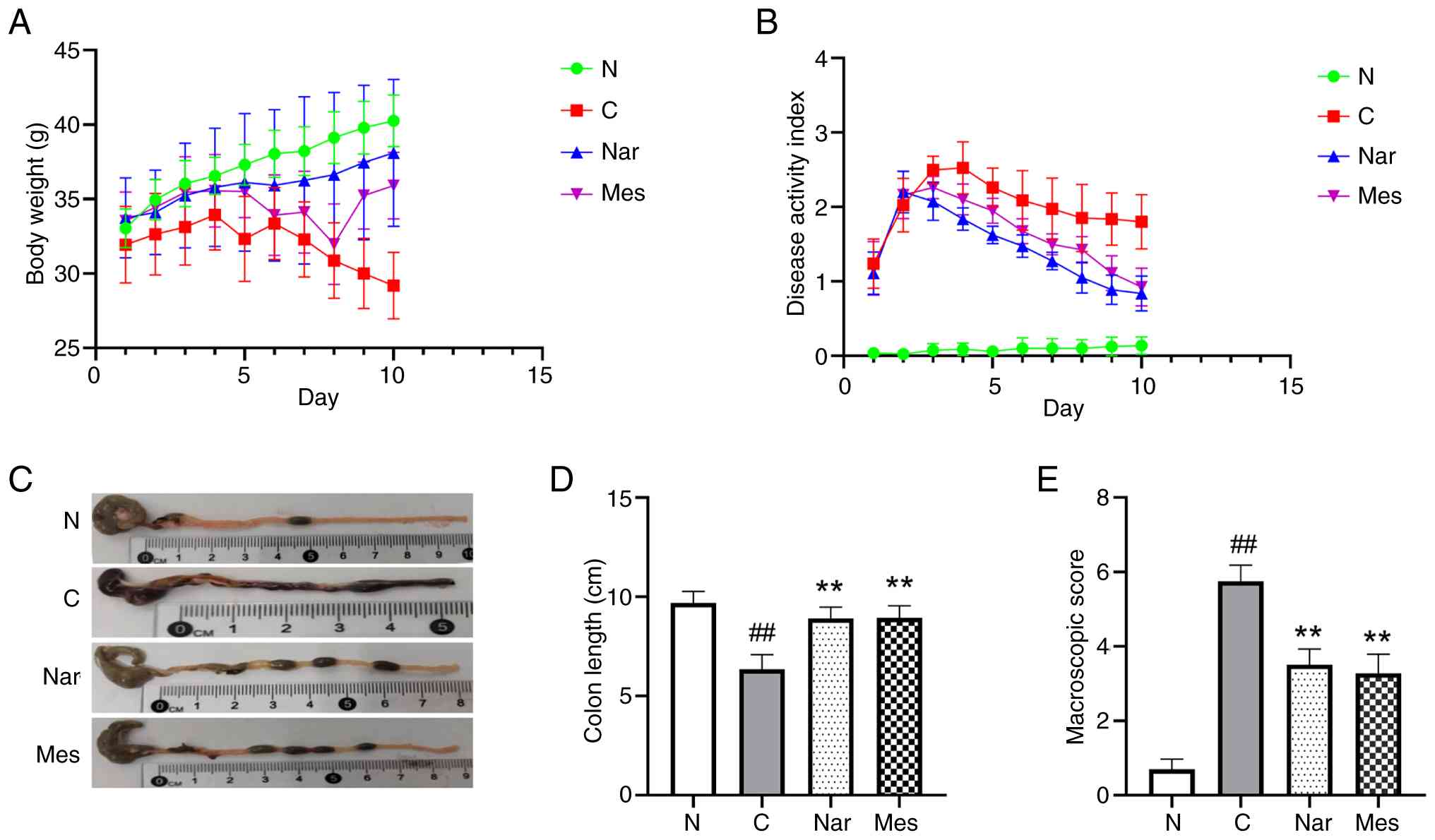

To evaluate whether oral administration of naringin

could ameliorate intestinal damage in UC mice, the present study

established a DSS-induced colitis model and assessed clinical and

pathological indicators, including body weight, diarrhea,

bloody-stool incidence colon length and macroscopic injury.

Compared with the normal group, DSS-treated mice in the control

group exhibited a notable reduction in body weight (Fig. 1A) and a marked increase in DAI

(Fig. 1B). In addition, DSS

administration caused significant colon shortening (P<0.01;

Fig. 1C and D) and a significant

increase in macroscopic injury score (P<0.01; Fig. 1E). Notably, naringin treatment

effectively alleviated these pathological changes (P<0.01),

indicating its protective effect against DSS-induced UC. The

positive control drug, mesalazine, showed a comparable protective

efficacy in ameliorating these clinical symptoms (Fig. 1A-E).

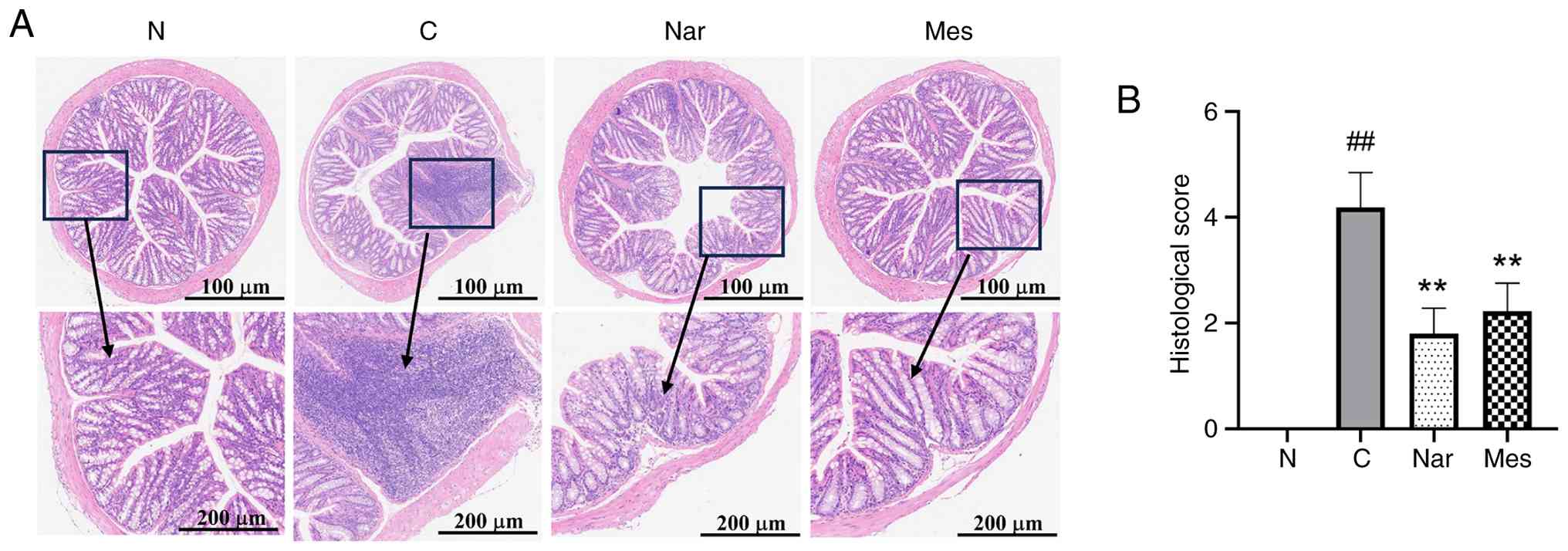

Naringin suppresses histological

injury in DSS-induced colitis in mice

The present study subsequently evaluated the effects

of naringin on colorectal histopathology in mice with DSS-induced

UC (Fig. 2A). Compared with in the

normal group, DSS-treated mice exhibited severe mucosal damage,

including epithelial disruption, erosion, crypt abscesses and

extensive inflammatory cell infiltration (primarily neutrophils and

lymphocytes). Both naringin and mesalazine treatments markedly

ameliorated these pathological features, preserving mucosal and

crypt architecture.

Pathological scoring further supported these

observations (P<0.01; Fig. 2B).

Compared with the normal group, DSS treatment significantly

increased histological scores. Treatment with either naringin or

mesalazine significantly reduced these scores compared with the DSS

group.

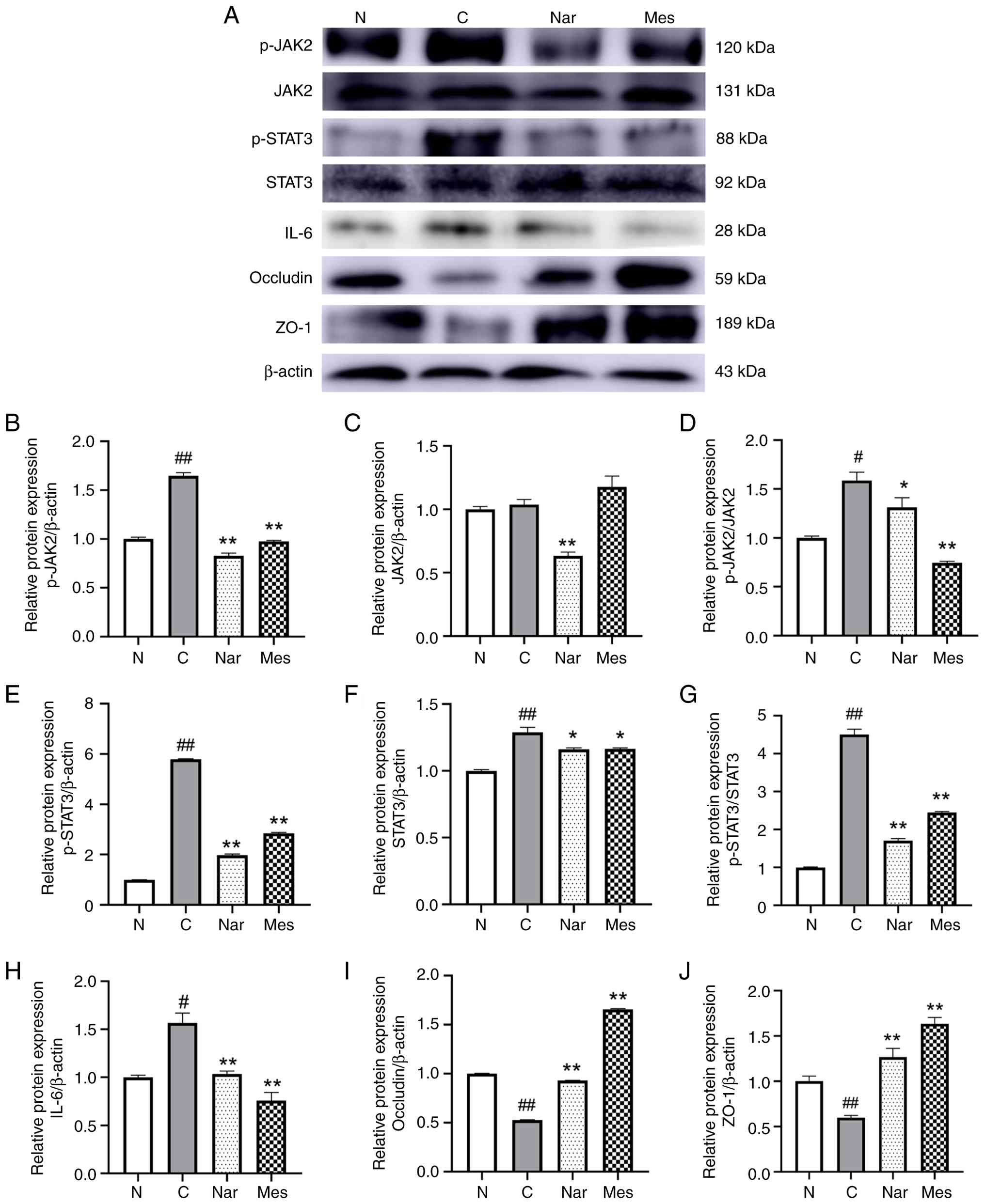

Naringin repairs intestinal mucosa and

decreases JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway-related protein expression

in DSS-induced colitis in mice

The JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway is abnormally

activated in patients with UC and is known to exacerbate colonic

inflammation and compromise mucosal barrier function (26,27).

Consistent with this, western blot analysis revealed a significant

upregulation of p-JAK2 and p-STAT3, as well as significantly

elevated IL-6 expression, in DSS-induced mice compared with the

normal group. Notably, treatment with naringin or mesalazine

significantly suppressed the activation of JAK2/STAT3, as evidenced

by reduced p-JAK2 and p-STAT3 levels, and significantly reduced

IL-6 expression, showing a clear difference compared with the model

group (P<0.05; Fig. 3B-H).

| Figure 3.Naringin inhibits JAK2/STAT3

signaling and restores tight junction proteins in dextran sulfate

sodium-induced colitis. (A) Representative western blotting images

of p-JAK2, JAK2, p-STAT3, STAT3, IL-6, occludin, ZO-1 and β-actin

expression in colon tissues. Densitometric semi-quantification of

the relative protein expression levels of (B) p-JAK2/β-actin, (C)

JAK2/β-actin, (D) p-JAK2/JAK2, (E) p-STAT3/β-actin, (F)

STAT3/β-actin, (G) p-STAT3/STAT3, (H) IL-6/β-actin, (I)

occludin/β-actin and (J) ZO-1/β-actin. Data are presented as mean ±

SEM. n=3. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. control group;

#P<0.05 and ##P<0.01 vs. normal group.

One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test was applied. N,

normal group; C, control group; Nar, naringin group; Mes,

mesalazine group; p-, phosphorylated; JAK2, Janus kinase 2; STAT3,

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; IL-6, ZO-1,

zona occludens-1. |

Tight junction proteins are important structural

components of the intestinal mucosal barrier and are closely linked

to the pathogenesis of UC. Among these, ZO-1 and occludin serve

important roles in maintaining epithelial integrity (28,29).

To further investigate the protective effects of naringin, the

present study assessed their expression in colonic tissues.

Naringin treatment significantly increased the expression of both

ZO-1 and occludin in UC mice, with levels significantly higher than

those in the DSS model group (P<0.01; Fig. 3I and J). Similarly, mesalazine

treatment significantly upregulated the expression of these tight

junction proteins compared with the DSS group. As expected, the

expression levels of ZO-1 and occludin in the DSS control group

were significantly lower than those in the normal group.

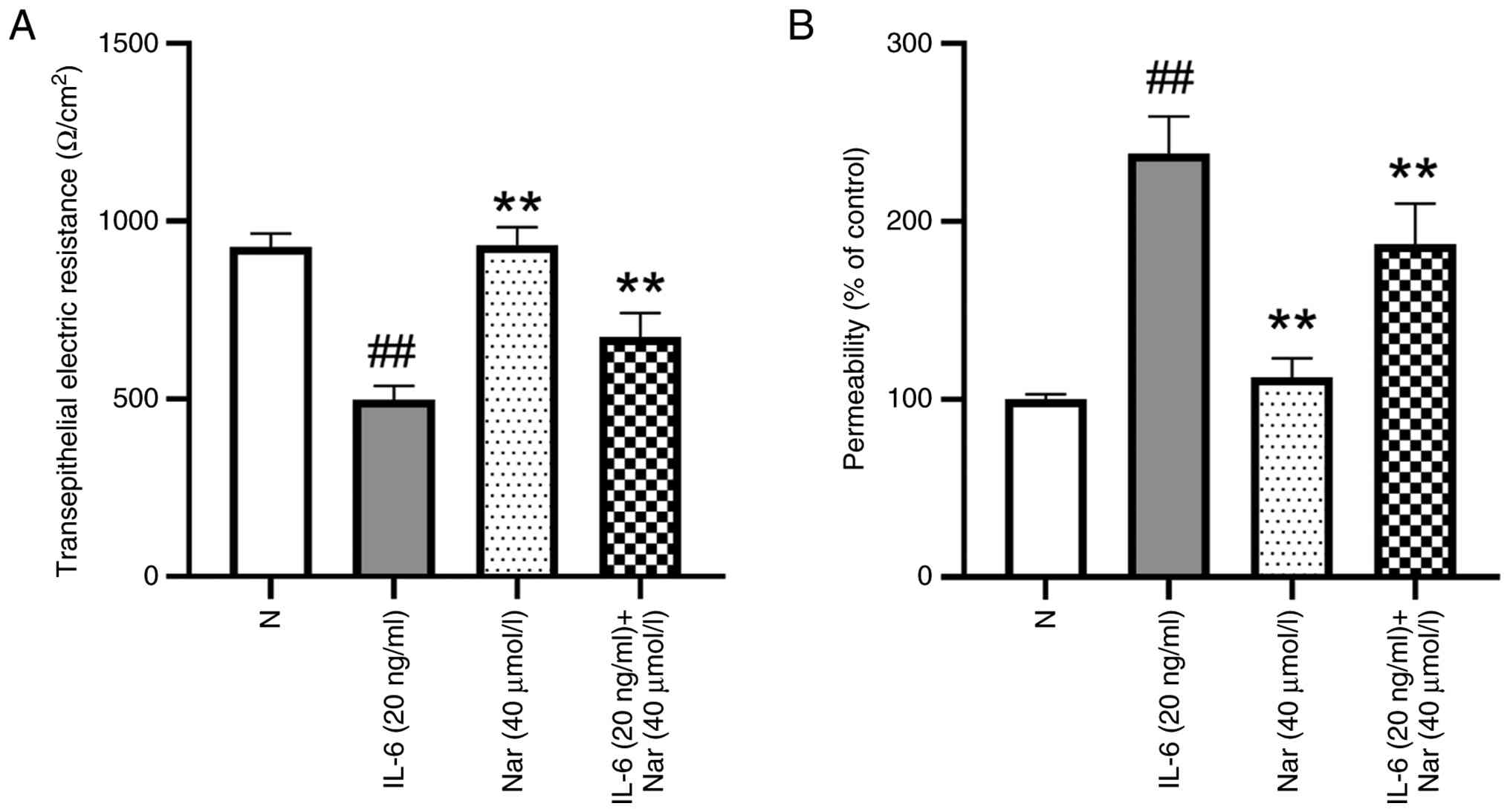

Naringin repairs IL-6-induced barrier

injury in Caco-2 cells

The intestinal mucosal barrier is an important

component of host defense, and its disruption in patients with UC

leads to impaired barrier function and pathological immune

activation. A decrease in TEER is widely recognized as an indicator

of barrier dysfunction (30,31).

To evaluate the protective effect of naringin, the present study

established an IL-6-induced barrier injury model in Caco-2

monolayers. After 10 days of culture, confluent Caco-2 cells formed

a resistant monolayer with a baseline TEER of 927.9

Ω/cm2. IL-6 stimulation caused a significant decrease in

TEER, providing evidence of impaired barrier integrity. Treatment

of IL-6 stimulated cells with naringin significantly restored TEER

values compared with the IL-6 group, whereas naringin alone did not

alter TEER in unstimulated cells compared with the normal group

(P<0.01; Fig. 4A).

To further assess barrier permeability, FD-4 was

added to the upper chamber of Transwell inserts. In IL-6-treated

cells, FD-4 transport into the lower chamber increased 2.3-fold

compared with the normal group, indicating elevated paracellular

permeability. Naringin co-treatment significantly reduced FD-4 flux

compared with the IL-6 group (P<0.01; Fig. 4B). Together, these results

demonstrate that naringin effectively repairs IL-6-induced barrier

damage in Caco-2 cells.

Naringin enhances fluorescent

expression of tight junction proteins in Caco-2 cells

A previous study has shown that naringin can enhance

the mRNA expression of tight junction proteins ZO-1 and occludin in

Caco-2/RAW264.7 co-culture systems (18). To further clarify whether the

mucosal protective effect of naringin was related to the JAK2/STAT3

signaling pathway, the present study used IL-6 to induce mucosal

damage in cells and used STAT3 gene silencing to examine the

mechanism of action of naringin. Tight junction protein expression

was assessed using immunofluorescence (Fig. 5), and JAK2/STAT3 pathway activation

was evaluated using western blot analysis (Fig. 6).

| Figure 6.Naringin suppresses JAK2/STAT3

activation in IL-6-stimulated Caco-2 cells with STAT3 silencing.

(A) Western blot analysis of p-JAK2, JAK2, p-STAT3, STAT3, occludin

and ZO-1 in Caco-2 cells under indicated treatments. (B) Validation

of STAT3 knockdown efficiency: Relative STAT3 expression in cells

transfected with siSTAT3 vs. siNC. ##P<0.01 vs. siNC.

Densitometric semi-quantification of relative protein expression

levels of (C) p-JAK2/β-actin, (D) JAK2/β-actin, (E) p-JAK2/JAK2,

(F) p-STAT3/β-actin, (G) STAT3/β-actin, (H) p-STAT3/ STAT3, (I)

occludin/β-actin, (J) ZO-1/β-actin. Data are presented as mean ±

SEM. n=3. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. IL-6 group;

##P<0.01 vs. normal group; ΔP<0.05 and

ΔΔP<0.01 IL-6 + Nar group vs. IL-6 + Nar + siSTAT3

group. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test was applied.

N, normal group; Nar, naringin group; Mes, mesalazine group; p-,

phosphorylated; JAK2, Janus kinase 2; STAT3, signal transducer and

activator of transcription 3; ZO-1, zona occludens-1; si, small

interfering RNA; NC, negative control. |

Immunofluorescence analysis revealed that in the

normal group, ZO-1 (blue) and occludin (green) displayed strong,

continuous fluorescence signals along cell-cell junctions,

reflecting intact tight junctions. IL-6 stimulation significantly

reduced the fluorescence intensity of both proteins compared with

the normal group (P<0.01), indicating barrier disruption.

Naringin treatment significantly alleviated this reduction,

restoring ZO-1 (P<0.01) and occludin (P<0.05) expression at

cell borders. Notably, the combination of STAT3 silencing and

naringin treatment (IL-6 + Nar + siSTAT3 group) also significantly

restored the fluorescence intensities of ZO-1 and occludin compared

with those in the IL-6 group (P<0.01), to a level comparable

with that achieved by naringin alone (Fig. 5). This supports the conclusion that

naringin-induced protection of tight junctions is mediated, at

least in part, through the inhibition of JAK2/STAT3 signaling

(Fig. 5).

Western blot analysis showed that IL-6 stimulation

significantly increased the expression of p-JAK2 (P<0.01;

Fig. 6C and E) and p-STAT3

(P<0.01; Fig. 6F and H) in

Caco-2 cells compared with the normal group, while JAK2 and STAT3

levels remained largely unchanged (P>0.05; Fig. 6D and G). Transfection with siSTAT3

alone significantly reduced total STAT3 protein levels compared

with siNC transfection (P<0.01; Fig. 6B), confirming knockdown efficiency.

Naringin treatment significantly reduced the expression of p-JAK2

and p-STAT3 relative to the IL-6 group (P<0.05; Fig. 6C, E, F, H). The present study

subsequently examined the effect of STAT3 silencing in the context

of IL-6 and naringin treatment. Compared with in the IL-6 group,

the combination treatment of naringin and STAT3 siRNA (IL-6 + Nar +

siSTAT3) led to a significant reduction in both p-JAK2 (P<0.01;

Fig. 6C and E) and p-STAT3 levels

(P<0.05; Fig. 6F and H).

However, when compared specifically to the IL-6 +

Nar group, the combination treatment (IL-6 + Nar + siSTAT3)

significantly decreased p-STAT3 levels (P<0.05; Fig. 6H). By contrast, p-JAK2 levels were

significantly increased in the IL-6 + Nar + siSTAT3 group relative

to the IL-6 + Nar group (P<0.01; Fig. 6E). An increase in total STAT3

protein was observed in both siRNA co-treatment groups (IL-6 + Nar

+ siSTAT3 and IL-6 + Nar + siNC) compared with that in the normal,

IL-6 and IL-6 + Nar groups (P>0.05; Fig. 6G), which may represent a

compensatory cellular response. Despite this increase in total

STAT3, JAK2/STAT3 pathway activity (i.e., the phosphorylation

levels of JAK2 and STAT3, semi-quantified as p-JAK2/JAK2 and

p-STAT3/STAT3 ratios) in the IL-6 + Nar + siSTAT3 group remained

significantly suppressed compared with in the IL-6 group

(P<0.01; Fig. 6E and H).

Furthermore, analysis of tight junction proteins showed that

naringin treatment (IL-6 + Nar) increased the expression of both

occludin and ZO-1 compared with in the IL-6 group (P<0.01;

Fig. 6I and J). Notably, the

combination treatment with STAT3 silencing (IL-6 + Nar + siSTAT3)

differentially affected the two proteins: It further enhanced

occludin expression but reduced ZO-1 expression relative to the

IL-6 + Nar group. This suggests a complex regulatory role of STAT3

in modulating distinct tight junction components.

Discussion

UC is a chronic, non-specific inflammatory disease

of the gastrointestinal tract that primarily affects the colon and

rectum, and is commonly characterized by abdominal pain, diarrhea

and bloody stool (32,33). Current pharmacological

interventions, such as sulfonamides, corticosteroids and

immunosuppressive agents, can alleviate UC symptoms; however, high

recurrence rates and limited long-term efficacy remain notable

clinical challenges (34,35). Consequently, the development of

effective strategies for treating and preventing UC has attracted

considerable attention globally (34,36).

Citrus aurantium L., dried immature orange, possesses both

nutritional and medicinal value, with flavonoids representing its

principal bioactive constituents. Naringin, the dominant flavonoid,

exhibits multiple pharmacological activities (17,37).

Previous studies have shown that naringin suppresses jejunal

contractions, alleviates intestinal spasms (19), enhances the repair of TNBS-induced

intestinal mucosal barrier damage in experimental mice,

downregulates inflammatory factors such as iNOS, COX-2 and TNF-α,

and preserves cellular permeability and integrity (18) in IBD models. These findings suggest

that naringin may exert protective effects in UC, thereby

supporting its clinical potential as a food-derived therapeutic

agent.

In experimental UC models, the DAI provides a

comprehensive measure of disease severity by integrating weight

loss, stool consistency and presence of blood (38,39).

Colon shortening is another hallmark of DSS-induced UC and serves

as a reliable morphological indicator of disease severity (33,40).

In the present study, DSS administration markedly increased DAI

scores and significantly reduced colon length compared with the

normal group. Naringin treatment ameliorated these parameters,

indicating a protective effect. Histopathological analysis further

revealed that naringin alleviated epithelial necrosis, goblet cell

loss, crypt destruction and inflammatory infiltration in

DSS-treated mice.

Mechanistically, the present study demonstrated that

naringin protected against UC by inhibiting the JAK2/STAT3

signaling pathway and enhancing intestinal barrier integrity. Tight

junction proteins such as ZO-1 and occludin are important for

barrier function, and their disruption leads to increased

permeability, microbial translocation and sustained inflammation

(8–11). The data of the present study showed

that naringin upregulated ZO-1 and occludin expression while

suppressing phosphorylation of JAK2 and STAT3 in colon tissue and

IL-6-stimulated Caco-2 cells. These findings suggest that naringin

restores intestinal barrier integrity through JAK2/STAT3

inhibition.

The JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway serves a dual role

in UC. In inflamed intestinal tissues of patients with UC, this

pathway is excessively activated and serves as a key driver of

disease progression. However, in healthy intestinal epithelial

cells, the activation of STAT3 can promote the repair of the

intestinal mucosal barrier (15,23,41).

The present study focused on UC mouse intestinal tissue and Caco-2

cells, which are fundamentally different from intestinal epithelial

cells; thus, the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway observed in Caco-2

primarily reflected its role in promoting inflammatory reactions.

This interpretation was consistent with multiple previous reports

(22,42,43).

ZO-1 and occludin are important proteins in the tight junction

structures of the intestinal barrier, and their expression and

distribution are usually used to assess the function of the

intestinal barrier in the colon (12–14).

The present data demonstrated that naringin upregulated ZO-1 and

occludin expression while suppressing phosphorylation of JAK2 and

STAT3, highlighting its potential as a dietary intervention for UC.

Future studies are warranted to explore the efficacy of the

clinical translation of naringin.

JAK2 is an important tyrosine protein kinase that

serves an important role in the inflammatory cascade of UC, while

STAT3 is a key transcription factor involved in cell proliferation,

differentiation, apoptosis and the immune and inflammatory response

(44). Accumulating evidence

indicates that activation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway exacerbates UC

symptoms (45,46). In the present study, IL-6 was

selected to induce mucosal barrier damage and inflammatory

responses in Caco-2 cells, as it is a primary activator of the

JAK2/STAT3 pathway (15,45). Although lipopolysaccharide is

commonly used to model inflammation, it primarily activates

Toll-like receptor 4/NF-κB signaling; therefore, IL-6 was more

appropriate for studying JAK2/STAT3-specific effects. Furthermore,

IL-6 is elevated in patients with UC and contributes to barrier

dysfunction. By silencing the STAT3 gene the protective effect of

naringin on this pathway was explored. IL-6 binds to its soluble

receptor, forms a complex with membrane-bound glycoprotein 130,

activates JAK2, induces STAT3 phosphorylation and activates

downstream transcription factors, regulating the expression of

inflammatory cytokines and thus mediating the occurrence of

inflammatory responses (15).

The results of the present study showed that

naringin significantly reduced the levels of p-JAK2 and p-STAT3 in

the colon tissue of UC mice and inhibited JAK2/STAT3 activation in

IL-6-stimulated Caco-2 cells. The enhanced suppression of pathway

activation in the IL-6 + Nar + siSTAT3 group compared with the IL-6

group confirmed the involvement of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway in

mediating the effects of naringin. Although the combination

treatment (IL-6 + Nar + siSTAT3) reduced p-STAT3 compared with that

in the IL-6 + Nar group, it did not lead to a further reduction in

p-JAK2 levels, indicating a complex interaction. Nevertheless, the

significant reduction in both p-JAK2 and p-STAT3 in the IL-6 + Nar

+ siSTAT3 group compared with the IL-6 group underscores that the

therapeutic action of naringin is mediated, at least in part,

through the suppression of JAK2/STAT3 signaling. Notably, in the

siRNA-treated groups (IL-6 + Nar + siSTAT3 and IL-6 + Nar + siNC)

under IL-6 stimulation, an increase in total STAT3 protein was

observed, which may represent a compensatory cellular response to

STAT3 knockdown. Furthermore, despite this increase in total STAT3

protein, the combination treatment (IL-6 + Nar + siSTAT3) still

achieved notable suppression of JAK2/STAT3 phosphorylation compared

with the IL-6 group. This effective uncoupling of pathway

activation from total STAT3 protein levels underscored that the

therapeutic benefit of naringin was achieved through suppressing

the activation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway.

Laser confocal microscopy revealed that IL-6

stimulation significantly decreased ZO-1 and occludin expression in

Caco-2 cells, whereas naringin treatment significantly restored

their expression. This restorative effect persisted even after

STAT3 silencing, reinforcing the conclusion that naringin enhances

tight junction protein expression primarily through JAK2/STAT3

inhibition, thereby repairing the intestinal mucosal barrier and

exerting therapeutic effects in UC.

Inflammatory responses were evaluated indirectly

through histological scoring of inflammatory cell infiltration and

directly through activation assessment of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway,

which functions upstream of multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines.

However, direct measurement of cytokine levels, such as those of

TNF-α and IL-1β, would provide additional validation. The effects

of naringin on other inflammatory factors require further

elucidation in subsequent studies.

Although JAK2 inhibition would provide more

comprehensive mechanistic insights, experimental focus was placed

on STAT3 due to resource constraints. Previous investigations on

Citrus aurantium (17,18)

have demonstrated inhibitory effects on JAK2 downstream pathways,

including key inflammatory factors such as TNF-α and NF-κB. Given

that naringin represents a major active component of Citrus

aurantium (47), these

findings provide biological plausibility for the approach in the

present study. The direct targeting of JAK2 by naringin requires

further investigation in future studies. Additionally, while

naringin may potentially interact with other inflammatory pathways

such as the NF-κB, MAPK or NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing

protein 3 pathways, the present experimental design specifically

focused on the JAK2/STAT3 axis based on prior evidence from

Citrus aurantium (17,18).

These limitations indicate important directions for future

research. Studies employing molecular docking or surface plasmon

resonance could strengthen mechanistic claims and are recommended

for subsequent investigations. Further studies are warranted to

explore additional mechanisms and validate direct molecular targets

of naringin with the ultimate goal of comprehensively elucidating

its therapeutic potential for UC.

In summary, integrated in vitro and in

vivo evidence indicates that naringin, a flavonoid from the

edible fruit Citrus aurantium L., significantly ameliorates

DSS-induced UC in mice. Its therapeutic effects are mediated

through suppression of the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway, leading to

both anti-inflammatory effects and enhanced tight junction protein

expression. These findings support the potential of naringin as a

food-based intervention for UC and provide a molecular basis for

further mechanistic investigation. Although the JAK2/STAT3 pathway

serves a notable role in UC pathogenesis, the precise mechanisms

underlying naringin-induced modulation of this pathway require

further elucidation.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present research was supported by the Hebei Youth Fund for

Science and Technology Research in Colleges and Universities (grant

no. QN2022014).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

WH was responsible for funding acquisition,

experimental design, conceptualization, writing the original draft

and supervision. YaW contributed to the experimental design,

assisted in the interpretation of data and critically revised the

manuscript for important intellectual content. MW was contributed

towards writing the original draft, reviewing and editing the

manuscript, formal analysis and data curation. YA contributed to

writing the original draft, reviewing and editing the manuscript,

formal analysis and data curation. YL contributed towards

experimental design and formal analysis. YiW was responsible for

validation and data curation. CW contributed towards validation and

formal analysis. MW and YA confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Animal experiments were approved by the Animal

Welfare Committee of Hebei North University (approval no.

HBNV20240223003) and performed according to institutional

guidelines.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

JAK2

|

Janus kinase 2

|

|

STAT3

|

signal transducer and activator of

transcription 3

|

|

UC

|

ulcerative colitis

|

References

|

1

|

Gros B and Kaplan GG: Ulcerative colitis

in adults: A review. JAMA. 330:951–965. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Segal JP, LeBlanc JF and Hart AL:

Ulcerative colitis: An update. Clin Med (Lond). 21:135–139. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Pabla BS and Schwartz DA: Assessing

severity of disease in patients with ulcerative colitis.

Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 49:671–688. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wangchuk P, Yeshi K and Loukas A:

Ulcerative colitis: Clinical biomarkers, therapeutic targets, and

emerging treatments. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 45:892–903. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Lee SD: Health maintenance in ulcerative

colitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 49:xv–xvi. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Cheng WW, Liu BH, Hou XT, Meng H, Wang D,

Zhang CH, Yuan S and Zhang QG: Natural products on inflammatory

bowel disease: Role of gut microbes. Am J Chin Med. 52:1275–1301.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zobeiri M, Momtaz S, Parvizi F, Tewari D,

Farzaei MH and Nabavi SM: Targeting mitogen-activated protein

kinases by natural products: A novel therapeutic approach for

inflammatory bowel diseases. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 21:1342–1353.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Li YY, Wang XJ, Su YL, Wang Q, Huang SW,

Pan ZF, Chen YP, Liang JJ, Zhang ML, Xie XQ, et al: Baicalein

ameliorates ulcerative colitis by improving intestinal epithelial

barrier via AhR/IL-22 pathway in ILC3s. Acta Pharmacol Sin.

43:1495–1507. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wu X, Wei S, Chen M, Li J, Wei Y, Zhang J

and Dong W: P2RY13 exacerbates intestinal inflammation by damaging

the intestinal mucosal barrier via activating IL-6/STAT3 pathway.

Int J Biol Sci. 18:5056–5069. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wang X, Xie X, Li Y, Xie X, Huang S, Pan

S, Zou Y, Pan Z, Wang Q, Chen J, et al: Quercetin ameliorates

ulcerative colitis by activating aryl hydrocarbon receptor to

improve intestinal barrier integrity. Phytother Res. 38:253–264.

2024. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Niu C, Hu XL, Yuan ZW, Xiao Y, Ji P, Wei

YM and Hua YL: Pulsatilla decoction improves DSS-induced colitis

via modulation of fecal-bacteria-related short-chain fatty acids

and intestinal barrier integrity. J Ethnopharmacol. 300:1157412023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zong Y, Meng J, Mao T, Han Q, Zhang P and

Shi L: Repairing the intestinal mucosal barrier of traditional

Chinese medicine for ulcerative colitis: A review. Front Pharmacol.

14:12734072023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Guo H, Guo H, Xie Y, Chen Y, Lu C, Yang Z,

Zhu Y, Ouyang Y, Zhang Y and Wang X: Mo3Se4

nanoparticle with ROS scavenging and multi-enzyme activity for the

treatment of DSS-induced colitis in mice. Redox Biol.

56:1024412022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wang Y, Zhang J, Zhang B, Lu M, Ma J, Liu

Z, Huang J, Ma J, Yang X, Wang F and Tang X: Modified Gegen Qinlian

decoction ameliorated ulcerative colitis by attenuating

inflammation and oxidative stress and enhancing intestinal barrier

function in vivo and in vitro. J Ethnopharmacol. 313:1165382023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhao Y, Luan H, Jiang H, Xu Y, Wu X, Zhang

Y and Li R: Gegen Qinlian decoction relieved DSS-induced ulcerative

colitis in mice by modulating Th17/Treg cell homeostasis via

suppressing IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 signaling. Phytomedicine.

84:1535192021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wang Y, Lai W, Zheng X, Li K, Zhang Y,

Pang X, Gao J and Lou Z: Linderae Radix extract attenuates

ulcerative colitis by inhibiting the JAK/STAT signaling pathway.

Phytomedicine. 132:1558682024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

He W, Liu M, Li Y, Yu H, Wang D, Chen Q,

Chen Y, Zhang Y and Wang T: Flavonoids from Citrus aurantium

ameliorate TNBS-induced ulcerative colitis through protecting

colonic mucus layer integrity. Eur J Pharmacol. 857:1724562019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

He W, Li Y, Liu M, Yu H, Chen Q, Chen Y,

Ruan J, Ding Z, Zhang Y and Wang T: Citrus aurantium L. and

its flavonoids regulate TNBS-induced inflammatory bowel disease

through anti-inflammation and suppressing isolated jejunum

contraction. Int J Mol Sci. 19:30572018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wu Q, Liu Y, Liang J, Dai A, Du B, Xi X,

Jin L and Guo Y: Baricitinib relieves DSS-induced ulcerative

colitis in mice by suppressing the NF-κB and JAK2/STAT3 signalling

pathways. Inflammopharmacology. 32:849–861. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Puppala ER, Aochenlar SL, Shantanu PA,

Ahmed S, Jannu AK, Jala A, Yalamarthi SS, Borkar RM, Tripathi DM

and Naidu VGM: Perillyl alcohol attenuates chronic restraint stress

aggravated dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis by

modulating TLR4/NF-κB and JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathways.

Phytomedicine. 106:1544152022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yang NN, Yang JW, Ye Y, Huang J, Wang L,

Wang Y, Su XT, Lin Y, Yu FT, Ma SM, et al: Electroacupuncture

ameliorates intestinal inflammation by activating α7nAChR-mediated

JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway in postoperative ileus. Theranostics.

11:4078–4089. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

He Z, Liu J and Liu Y: Daphnetin

attenuates intestinal inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis

in ulcerative colitis via inhibiting REG3A-dependent JAK2/STAT3

signaling pathway. Environ Toxicol. 38:2132–2142. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wen J, Yang Y, Li L, Xie J, Yang J, Zhang

F, Duan L, Hao J, Tong Y and He Y: Magnoflorine alleviates dextran

sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis via inhibiting JAK2/STAT3

signaling pathway. Phytother Res. 38:4592–4613. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Duan B, Hu Q, Ding F, Huang F, Wang W, Yin

N, Liu Z, Zhang S, He D and Lu Q: The effect and mechanism of

Huangqin-Baishao herb pair in the treatment of dextran sulfate

sodium-induced ulcerative colitis. Heliyon. 9:e230822023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wang J, Zhang C, Guo C and Li X: Chitosan

ameliorates DSS-induced ulcerative colitis mice by enhancing

intestinal barrier function and improving microflora. Int J Mol

Sci. 20:57512019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Bao X, Tang Y, Lv Y, Fu S, Yang L, Chen Y,

Zhou M, Zhu B, Ding Z and Zhou F: Tetrastigma hemsleyanum

polysaccharide ameliorated ulcerative colitis by remodeling

intestinal mucosal barrier function via regulating the

SOCS1/JAK2/STAT3 pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 137:1124042024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Deng B, Wang K, He H, Xu M, Li J, He P,

Liu Y, Ma J, Zhang J and Dong W: Biochanin A mitigates colitis by

inhibiting ferroptosis-mediated intestinal barrier dysfunction,

oxidative stress, and inflammation via the JAK2/STAT3 signaling

pathway. Phytomedicine. 141:1566992025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Ouyang F, Li B, Wang Y, Xu L, Li D, Li F

and Sun-Waterhouse D: Attenuation of palmitic acid-induced

intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction by 6-shogaol in Caco-2

cells: The role of MiR-216a-5p/TLR4/NF-κB axis. Metabolites.

12:10282022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Qu Y, Li X, Xu F, Zhao S, Wu X, Wang Y and

Xie J: Kaempferol alleviates murine experimental colitis by

restoring gut microbiota and inhibiting the LPS-TLR4-NF-κB axis.

Front Immunol. 12:6798972021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Wu XX, Huang XL, Chen RR, Li T, Ye HJ, Xie

W, Huang ZM and Cao GZ: Paeoniflorin prevents intestinal barrier

disruption and inhibits lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced

inflammation in Caco-2 cell monolayers. Inflammation. 42:2215–2225.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Spalinger MR, Sayoc-Becerra A, Santos AN,

Shawki A, Canale V, Krishnan M, Niechcial A, Obialo N, Scharl M, Li

J, et al: PTPN2 regulates interactions between macrophages and

intestinal epithelial cells to promote intestinal barrier function.

Gastroenterology. 159:1763–1777.e14. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Xiong T, Zheng X, Zhang K, Wu H, Dong Y,

Zhou F, Cheng B, Li L, Xu W, Su J, et al: Ganluyin ameliorates

DSS-induced ulcerative colitis by inhibiting the enteric-origin

LPS/TLR4/NF-κB pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 289:1150012022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Yuan SN, Wang MX, Han JL, Feng CY, Wang M,

Wang M, Sun JY, Li NY, Simal-Gandara J and Liu C: Improved colonic

inflammation by nervonic acid via inhibition of NF-κB signaling

pathway of DSS-induced colitis mice. Phytomedicine. 112:1547022023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Wu Y, Jha R, Li A, Liu H, Zhang Z, Zhang

C, Zhai Q and Zhang J: Probiotics (Lactobacillus plantarum HNU082)

supplementation relieves ulcerative colitis by affecting intestinal

barrier functions, immunity-related gene expression, gut

microbiota, and metabolic pathways in mice. Microbiol Spectr.

10:e01651222022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Jeong DY, Kim S, Son MJ, Son CY, Kim JY,

Kronbichler A, Lee KH and Shin JI: Induction and maintenance

treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: A comprehensive review.

Autoimmun Rev. 18:439–454. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Wang M, Fu R, Xu D, Chen Y, Yue S, Zhang S

and Tang Y: Traditional Chinese Medicine: A promising strategy to

regulate the imbalance of bacterial flora, impaired intestinal

barrier and immune function attributed to ulcerative colitis

through intestinal microecology. J Ethnopharmacol. 318:1168792024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Alam F, Mohammadin K, Shafique Z, Amjad ST

and Asad MHHB: Citrus flavonoids as potential therapeutic agents: A

review. Phytother Res. 36:1417–1441. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Mirsepasi-Lauridsen HC: Therapy used to

promote disease remission targeting gut dysbiosis, in UC patients

with active disease. J Clin Med. 11:74722022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Wu Y, Ran L, Yang Y, Gao X, Peng M, Liu S,

Sun L, Wan J, Wang Y, Yang K, et al: Deferasirox alleviates

DSS-induced ulcerative colitis in mice by inhibiting ferroptosis

and improving intestinal microbiota. Life Sci. 314:1213122023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Ruan Y, Zhu X, Shen J, Chen H and Zhou G:

Mechanism of Nicotiflorin in San-Ye-Qing rhizome for

anti-inflammatory effect in ulcerative colitis. Phytomedicine.

129:1555642024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Tang L, Liu Y, Tao H, Feng W, Ren C, Shu

Y, Luo R and Wang X: Combination of Youhua Kuijie Prescription and

sulfasalazine can alleviate experimental colitis via

IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 pathway. Front Pharmacol. 15:14375032024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Shalaby M, Abdelaziz RR, Ghoneim HA and

Suddek GM: Imatinib mitigates experimentally-induced ulcerative

colitis: Possible contribution of NF-kB/JAK2/STAT3/COX2 signaling

pathway. Life Sci. 321:1215962023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Yu T, Li Z, Xu L, Yang M and Zhou X:

Anti-inflammation effect of Qingchang suppository in ulcerative

colitis through JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway in vitro and in vivo.

J Ethnopharmacol. 266:1134422021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Jiang M, Zhong G, Zhu Y, Wang L, He Y, Sun

Q, Wu X, You X, Gao S, Tang D and Wang D: Retardant effect of

dihydroartemisinin on ulcerative colitis in a JAK2/STAT3-dependent

manner. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 53:1113–1123. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Wang X, Huang S, Zhang M, Su Y, Pan Z,

Liang J, Xie X, Wang Q, Chen J, Zhou L and Luo X: Gegen Qinlian

decoction activates AhR/IL-22 to repair intestinal barrier by

modulating gut microbiota-related tryptophan metabolism in

ulcerative colitis mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 302:1159192023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Voshagh Q, Anoshiravani A, Karimpour A,

Goodarzi G, Tehrani SS, Tabatabaei-Malazy O and Panahi G:

Investigating the association between the tissue expression of

miRNA-101, JAK2/STAT3 with TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-10 cytokines

in the ulcerative colitis patients. Immun Inflamm Dis.

12:e12242024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Miles EA and Calder PC: Effects of citrus

fruit juices and their bioactive components on inflammation and

immunity: A narrative review. Front Immunol. 12:7126082021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|