Introduction

High-mobility group (HMG) nucleosomal-binding domain

2 (HMGN2) is an abundant conserved protein that acts as a

non-histone nuclear DNA-binding protein. Studies have suggested

that HMGN2 interacts with transcription factors and chromatin,

leading to the modulation of gene transcription (1–4). A

previous study revealed that the HMGN2 protein is secreted by

activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells, CD8+ T

cells and γδ T cells, where it induces tumour cell apoptosis

(5,6). However, the precise mechanism of

action of HMGN2 remains to be elucidated. Cytolytic T lymphocytes

(CTLs) are key antitumour immune cells that are rich in cytoplasmic

granules. Upon degranulation, CTLs secrete cytotoxic molecules,

such as TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-2, against target cells (7). Cytoplasmic granules in CTLs contain

perforin, granzymes, granulysin and other effector molecules

involved in the antitumour response (8,9).

A study by Li et al (10) reported that the N-terminal

structure of HMGN2 can recognize and adhere to tumour cells. In

addition, Fan et al (11)

revealed that HMGN2 can modulate DNA transcription and translation,

thus inducing tumour cell apoptosis. Despite these findings, the

detailed mechanism by which HMGN2 affects tumour cells remains to

be elucidated.

The oligosaccharyltransferase (OST) subunit STT3

(STT3) protein is an important enzyme of the OST complex, which

consists of two isoforms in mammalian cells: STT3A and STT3B. As

the catalytic subunits of the OST complex, STT3 isoforms can

initiate N-glycosylation by catalysing the transfer of a 14-sugar

core glycan from dolichol to the asparagine residues of substrates

(12). Evidence indicates that the

expression of STT3 isoforms, including STT3A and STT3B, which are

upregulated during epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), is

important for the glycosylation and stabilization of programmed

cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1), thus facilitating immune evasion in

tumour cells (13).

The present study aimed to identify the receptors of

HMGN2 on tumour cell membranes and to investigate the underlying

mechanisms of HMGN2 in human tongue squamous carcinoma CAL-27

cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The human tongue squamous cell carcinoma cell line

CAL-27 was obtained from the Biobank of West China Hospital of

Stomatology Sichuan University (Chengdu, China). The cells were

cultured in DMEM (cat. no. 10-013-CVRC; Corning, Inc.) supplemented

with 10% foetal bovine serum (cat. no. A5256701; Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in a cell culture dish at 37°C in a

humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Effect of HMGN2 on CAL-27 cells

Recombinant HMGN2 with an N-terminal His-tag

expressed in Escherichia coli and purified to >90% purity

(cat. no. RPB057Hu01) was purchased from CLOUD-CLONE CORP., and

diluted with PBS.

A total of ~1×105 CAL-27 cells were

seeded and cultured in 12-well plates until sub-confluent, after

which His-tagged HMGN2 (0, 5, 10 and 20 µg/ml) was added and the

cells were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The control group was

treated with PBS. After the cells were washed with 1X PBS, a

FLUOVIEW FV3000 bright-field microscope (Olympus Corporation) was

used to observe the cellular state and images were captured.

A total of 20 µg/ml fluorescein isothiocyanate

(FITC)-labelled HMGN2 was added for incubation with CAL-27 cells at

37°C for 10 min, 1 and 2 h, as described in a previous study

(5). Nuclear staining of CAL-27

cells was performed using Hoechst 33258 (cat. no. A3466; APExBIO

Technology LLC) at room temperature for 10 min. After the cells

were washed with 1X PBS, a FLUOVIEW FV3000 confocal laser scanning

microscope (Olympus Corporation) was used to observe the cellular

state and images were captured.

Apoptosis analysis

An Annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection kit (cat. no.

K2003; APExBIO Technology LLC) was used to detect apoptosis

according to the manufacturer's instructions. A total of

~1×105 CAL-27 cells were seeded and cultured in 12-well

plates until sub-confluent, after which His-tagged HMGN2 (20 µg/ml)

was added for incubation at 37°C for 12 or 24 h. The cells were

then washed with 1X PBS and resuspended in 500 µl 1X binding buffer

(cat. no. K2003; APExBIO Technology LLC). Subsequently, 5 µl

Annexin V-FITC and 5 µl PI were added, and the samples were

incubated in the dark at room temperature for 20 min. A CytoFLEX

flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc.) was used for apoptosis

analysis. The flow cytometry data were analyzed using Kaluza

Analysis software (version 2.4.0; Beckman Coulter, Inc.).

Immunoprecipitation and mass

spectrometry (IP/MS)

After washing with 1X PBS, ~1×107 CAL-27

cells cultured in 100-mm culture dishes were incubated with 20

µg/ml His-tagged HMGN2 at 37°C for 60 min. Cells were harvested by

scraping in 1X PBS, and membrane proteins were isolated using a

commercial membrane protein extraction kit (cat. no. EX1110;

Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) with the

following steps: The cells were centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min at

4°C, washed twice with 1X PBS, and resuspended in chilled Membrane

Protein Extraction Buffer A. The suspension was shaken at 4°C for

30 min, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C.

The supernatant was collected, incubated in a 37°C water bath for

10 min, and then centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 5 min at 37°C. The

lower phase was retained, mixed with chilled Membrane Protein

Extraction Buffer B, incubated on ice for 2 min and then at 37°C

for 5 min, and centrifuged again at 1,000 × g for 5 min at 37°C.

After removing the upper liquid, the pelleted membrane proteins

were dissolved in chilled Membrane Protein Solubilization Buffer C.

Protease Inhibitor D was added to all extraction and solubilization

buffers prior to use. Total protein was extracted from cells lysed

in RIPA buffer (cat. no. HY-K1001; MedChemExpress) supplemented

with a protease inhibitor cocktail (cat. no. K1019; APExBIO

Technology LLC). The protein extracts (500 µl) were then incubated

with rabbit anti-HMGN2 antibody (dilution, 1:250; cat. no.

10953-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) or control IgG (dilution,

1:250; cat. no. B30011; Abmart Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd.)

at room temperature for 2 h, after which 20 µl protein A/G beads

(cat. no. K1305; APExBIO Technology LLC) were added and incubated

at room temperature for 1 h. After elution with IP eluent (cat. no.

T10007; Abmart Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd.), the

antibody-protein complex was resolved via SDS-PAGE and Coomassie

blue staining was performed at room temperature for 2 h. The

SDS-PAGE gel and beads binding the antibody-protein complex of the

membrane protein were processed for protein identification by PTM

BIO LLC using in-gel tryptic digestion and liquid

chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis.

For in-gel tryptic digestion, gel slices were

destained, reduced with dithiothreitol, alkylated with

iodoacetamide, and digested overnight with trypsin (37°C). Peptides

were extracted and dried under a stream of nitrogen gas at 320°C,

and subsequently analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Peptides were separated on a

home-made reversed-phase analytical column (15 cm × 75 µm) using an

EASY-nLC 1000 UPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The

mobile phase consisted of solvent A (0.1% formic acid and 2%

acetonitrile in water) and solvent B (0.1% formic acid and 98%

acetonitrile in water). The following gradient was applied at a

flow rate of 400 nl/min with the column temperature set to 60°C:

0–16 min, 6–23% B; 16–24 min, 23–35% B; 24–27 min, 35–80% B; 27–30

min, 80% B. The injection volume was 3 µl, corresponding to 1.5 µg

of peptides, and no internal standards were employed. MS was

performed on a Q Exactive Plus (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

with a nanospray ionization source in positive ion mode (2.0 kV).

Full MS scans (350–1,800 m/z) were acquired at a resolution of

70,000, followed by data-dependent MS/MS scans (NCE 28; resolution,

17,500) of the top 20 ions with dynamic exclusion of 15.0 sec.

Automatic gain control was set to 5×104. MS/MS data were

searched using the MaxQuant search engine (version 1.6.15.0;

http://www.maxquant.org/maxquant/)

with trypsin/P as enzyme (≤2 missed cleavages). The precursor

tolerance was 10 ppm and the fragment tolerance was 0.02 Da.

Carbamidomethylation of cysteine was set as a fixed modification,

and methionine oxidation was included as a variable modification.

Peptide confidence was set to high with an ion score >20.

Immunofluorescence

A total of ~1×105 CAL-27 cells were

seeded on microscope coverslips in 12-well plates and cultured at

37°C. The cells were then washed with 1X PBS, fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 20 min, permeabilized with

0.01% Triton X-100 and blocked with 5% BSA (cat. no. AWB-6015;

Abmart Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd.) at room temperature for

1 h, before they were incubated with primary antibodies against

STT3B (dilution, 1:100; cat. no. 15323-1-AP; Proteintech Group,

Inc.) or PD-L1 (dilution, 1:100; cat. no. A27937; ABclonal Biotech

Co., Ltd.) at 4°C overnight. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (cat.

no. C3362; APExBIO Technology LLC). After being washed three times

with 1X PBS, the cells were incubated with an FITC-conjugated

secondary antibody (dilution, 1:100; cat. no. AS011; ABclonal

Biotech Co., Ltd.) at room temperature for 2 h. The cells were

subsequently visualized using a FLUOVIEW FV3000 confocal laser

scanning microscope (Olympus Corporation) and images were

captured.

Western blot analysis

The downstream validation of the IP/MS results was

conducted by western blotting, as outlined subsequently. After

incubation with 20 µg/ml His-tagged HMGN2 at 37°C for 10 and 60

min, proteins were extracted from CAL-27 cells using RIPA buffer

(cat. no. HY-K1001; MedChemExpress), which primarily consists of 50

mM Tris (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium

deoxycholate and 0.1% SDS, as well as sodium orthovanadate and

EDTA. Protein quantification was performed using the Enhanced BCA

Protein Assay Kit (cat. no. P0010S; Beyotime Biotechnology)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. The protein extracts

were subsequently separated by 10% SDS-PAGE (10 µg per lane),

before being transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were

blocked with 5% fat-free milk at room temperature for 1 h and were

subsequently incubated with primary antibodies against HMGN2

(dilution, 1:1,000; cat. no. 10953-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.),

STT3B (dilution, 1:1,000; cat. no. 15323-1-AP; Proteintech Group,

Inc.), PD-L1 (dilution, 1:1,000; cat. no. A27937; ABclonal Biotech

Co., Ltd.), gasdermin D (GSDMD; dilution, 1:1,000; cat. no.

ab210070; Abcam), caspase-1 (dilution, 1:1,000; cat. no. 2225; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.) and GAPDH (dilution, 1:5,000; cat. no.

AC002; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.) at 4°C overnight. The antibodies

against caspase-1 and GSDMD were also used to detect their

respective cleaved forms (cleaved caspase-1 and GSDMD-N). After

being washed, the membranes were incubated at room temperature for

2 h with a horseradish peroxidase-labelled secondary antibody

(dilution, 1:5,000; cat. nos. AS014 and AS003; ABclonal Biotech

Co., Ltd.). Protein bands were subsequently visualized using an

enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (cat. no. WBULS0500;

MilliporeSigma; Merck KGaA) and imaged with a ChemiDoc MP Imaging

system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Protein expression levels were

semi-quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.8.0; National

Institutes of Health).

Depletion of STT3B

Antibody-mediated depletion is an established method

for selectively eliminating cell populations expressing target

proteins, as documented in previous literature (14). Antibody-dependent cell-mediated

cytotoxicity is a recognized consideration, with certain

therapeutic antibodies, such as PD-L1 inhibitors, demonstrating

potent efficacy in cancer treatment through their depletion

mechanisms (15). In 2014, our

laboratory demonstrated that ~50% of HMGN2 was depleted from the

supernatant of FITC-labelled activated CD8+ T cells

using an anti-human HMGN2 antibody (5). In addition, the tumour-killing

capacity of γδ T cells can be functionally blocked by anti-human

HMGN2 antibodies (6). Building

upon this methodology, CAL-27 cells incubated with 10 µg/ml

anti-STT3B antibody (cat. no. 15323-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.)

at 37°C for 2 h in the present study were designated the

‘STT3B-depleted’ group.

Fluorescence-labelled HMGN2

transmembrane transport assay with anti-STT3B antibodies

A total of ~1×105 CAL-27 cells were

seeded in 35-mm glass bottom dishes with 10-mm microwells. After

being washed with PBS, the cells were divided into three groups:

The control, HMGN2 and STT3B-depleted groups. Cells in the depleted

group were treated with 10 µg/ml anti-STT3B antibody (cat. no.

15323-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) at 37°C for 2 h. Subsequently,

20 µg/ml FITC-labelled HMGN2 was added and the cells were incubated

at 37°C for 10 min. Nuclear staining of CAL-27 cells was performed

using Hoechst 33258 (cat. no. A3466; APExBIO Technology LLC) at

room temperature for 10 min. Cells not treated with anti-STT3B

antibody were used as a positive control (HMGN2 group). The control

group was treated with PBS. Imaging was performed using a FLUOVIEW

FV3000 confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus

Corporation).

Protein-protein docking between STT3B

and HMGN2

The Protein Data Bank (PDB) format and FASTA

sequences of the STT3B protein structural domain were downloaded

from the PDB database (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/6S7T). The protein

structure of HMGN2 was predicted using Swiss-Model (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/) according to the

FASTA sequence obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology

Information database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/3151).

The rigid protein-protein docking module ZDOCK

(version 3.0.2; http://zdock.umassmed.edu/) was used to identify the

docking sites between STT3B and HMGN2, and ZDOCK scores were

calculated. Using AlphaFold3 (16)

(https://www.alphafoldserver.com), the 3D

structure of STT3B was simulated with HMGN2. The predictive

structures were visualized using Discovery Studio 2019 Client

(BIOVIA; Dassault Systèmes S.E.).

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism software (version 8.0.1; Dotmatics)

was used for all statistical analyses. Experiments were performed

in three independent biological replicates. The quantitative data

are shown as the mean ± SEM. Comparisons between two groups were

performed using unpaired Student's two-tailed t-tests, whereas

statistical comparisons among more than two groups were performed

by one-way analysis of variance followed by a Bonferroni post hoc

correction. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Functional identification of the

antitumour activity of the HMGN2 protein in CAL-27 cells

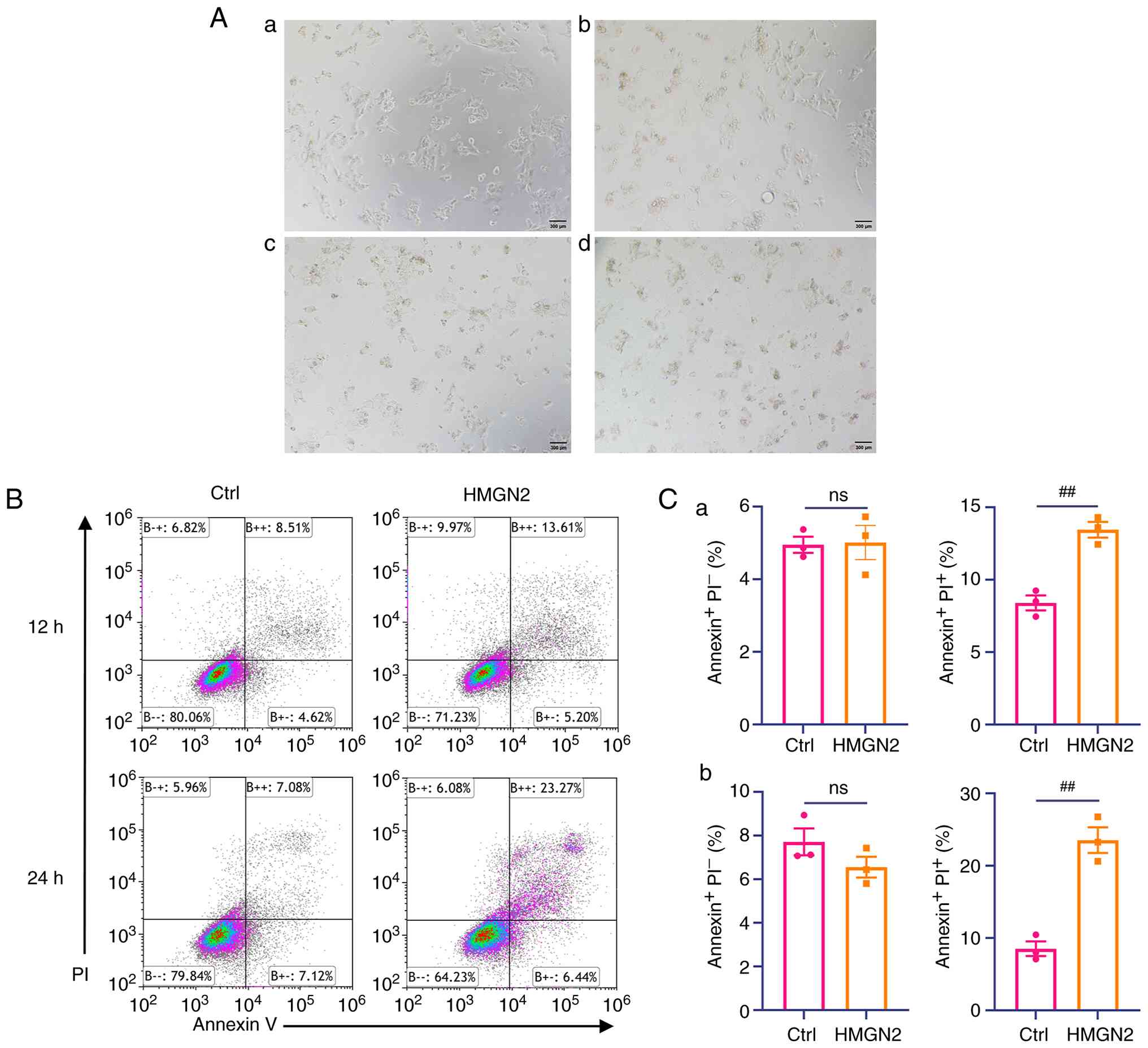

After the cells were incubated with various

concentrations of HMGN2 for 24 h, the apoptotic response of CAL-27

cells was assessed by bright-field microscopy (Fig. 1A). In addition, the HMGN2 protein

was incubated with CAL-27 cells at 37°C for 12 and 24 h, and the

cells were subject to flow cytometry. Analysis of flow cytometry

results revealed that compared with that in the control group, the

relative percentage of CAL-27 cells undergoing late apoptosis was

significantly greater following HMGN2 incubation. A total of ~14

and 23% of the CAL-27 cells treated with HMGN2 for 12 and 24 h,

respectively, were Annexin V+ and propidium

iodide+ (Fig. 1B and

C). This was significantly higher than the values observed in

the control group. The present results suggested that HMGN2 induced

the apoptosis of CAL-27 cells.

HMGN2 binds to the membrane and is

transported into tumour cells

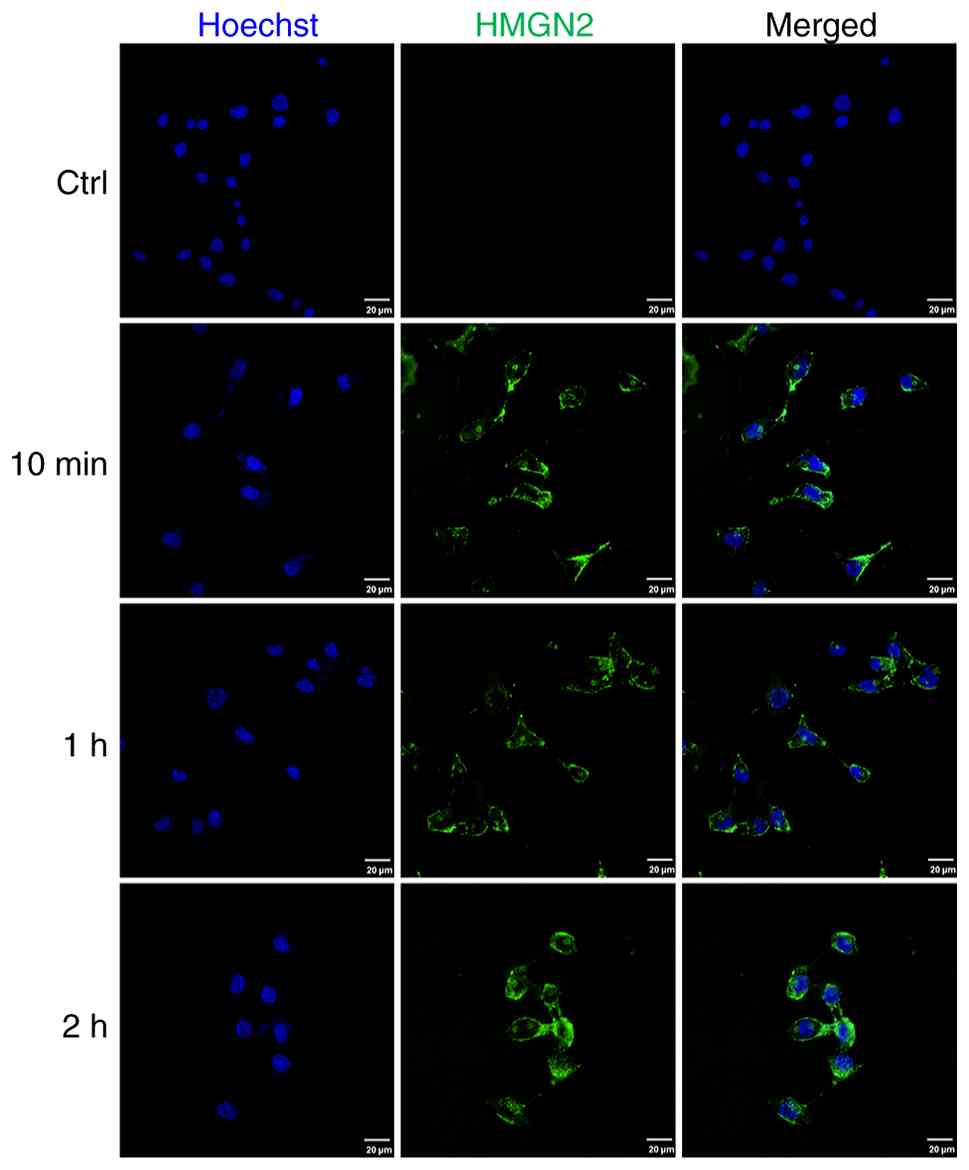

CAL-27 cells were incubated with FITC-labelled HMGN2

for 10 min, 1 and 2 h, and were subsequently detected by confocal

laser scanning microscopy. The results revealed that FITC-labelled

HMGN2 was localised to the membranes of CAL-27 cells and could be

transported into the cells (Fig.

2).

IP/MS indicates that STT3B is a

receptor of HMGN2 on CAL-27 cell membranes

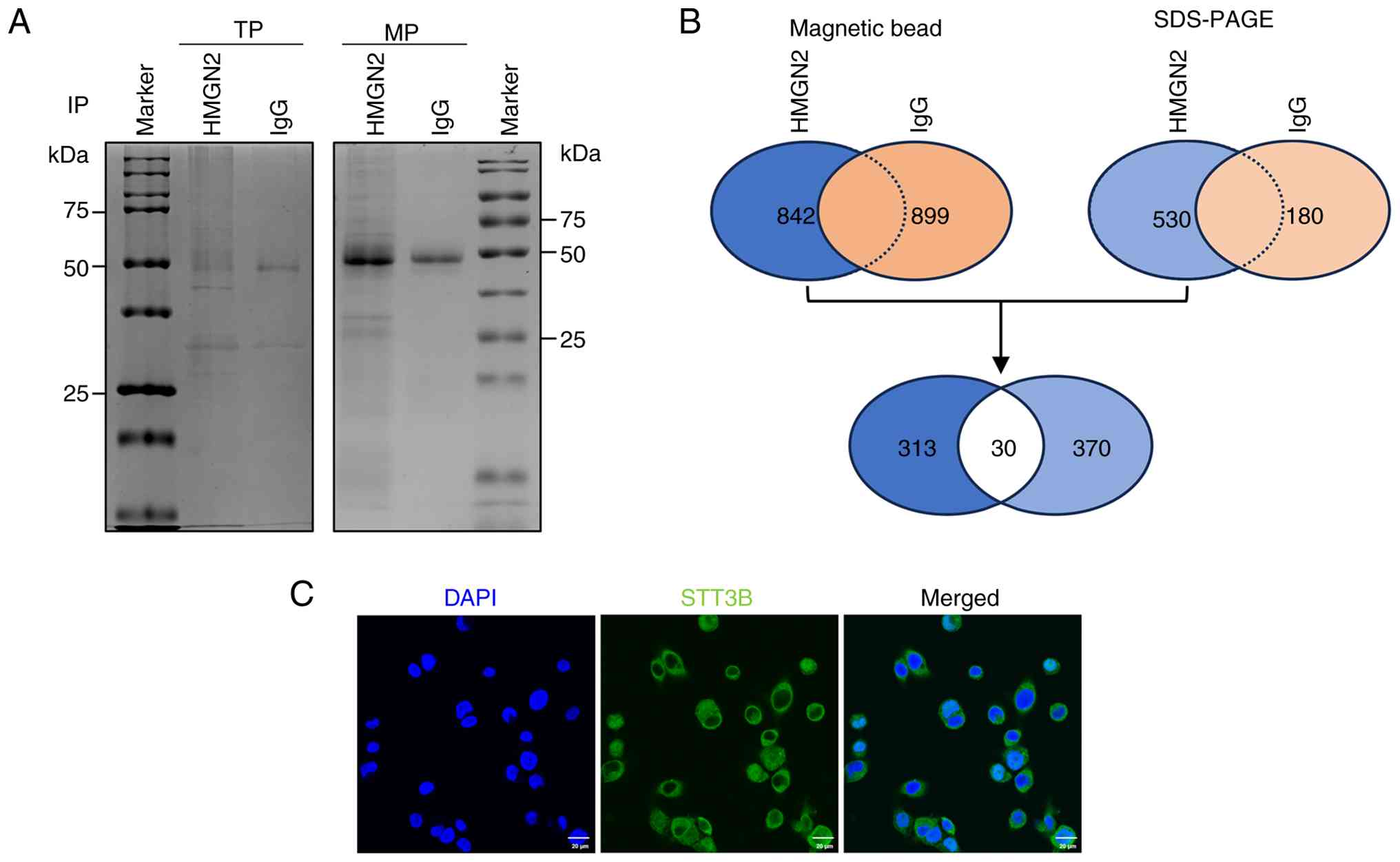

The present study performed IP/MS to identify the

notable receptors associated with HMGN2. After incubation with

HMGN2, the total proteins and membrane proteins of CAL-27 cells

were extracted and immunoprecipitated using magnetic beads so that

the interacting proteins could be visualized by Coomassie blue

staining after SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3A).

Membrane proteins were subsequently identified via mass

spectrometry.

The results of magnetic bead analysis revealed 842

proteins that were immunoprecipitated by the anti-HMGN2 antibody

and 530 proteins identified via SDS-PAGE. The results of magnetic

bead analysis revealed 899 proteins that were immunoprecipitated by

the anti-IgG antibody and 180 proteins identified via SDS-PAGE.

However, only 313 proteins were detected after immunoprecipitation

with the anti-HMGN2 antibody and not with anti-IgG according to the

results of magnetic bead analysis. Similarly, only 370 proteins

exclusive to the anti-HMGN2 antibody were detected via SDS-PAGE.

The results from magnetic bead and gel analyses were subsequently

combined to obtain the 30 top proteins that interact with HMGN2

(Fig. 3B). Only 6 of the 30

proteins screened were located on the membranes of cells, among

which STT3B had the highest protein score and propensity score

matching (PSM) value (Table I).

Immunofluorescence staining supported the subcellular localization

of STT3B on cell membranes (Fig.

3C).

| Table I.Screened proteins identified by mass

spectrometry. |

Table I.

Screened proteins identified by mass

spectrometry.

| Gene name | Molecular weight,

kDa | Protein score | Unique

peptides | Propensity score

matching | Subcellular

localization |

|---|

| STT3B | 93.6 | 94 | 3 | 3 | Plasma

membrane |

| SSR3 | 21.1 | 66 | 3 | 1 | Plasma

membrane |

| ERMP1 | 100.2 | 41 | 2 | 2 | Plasma

membrane |

| TMEM41B | 32.5 | 39 | 1 | 1 | Plasma

membrane |

| MMP14 | 65.9 | 33 | 1 | 1 | Plasma

membrane |

| STX5 | 39.6 | 25 | 1 | 1 | Plasma

membrane |

STT3B is an important receptor of

HMGN2 on CAL-27 cell membranes

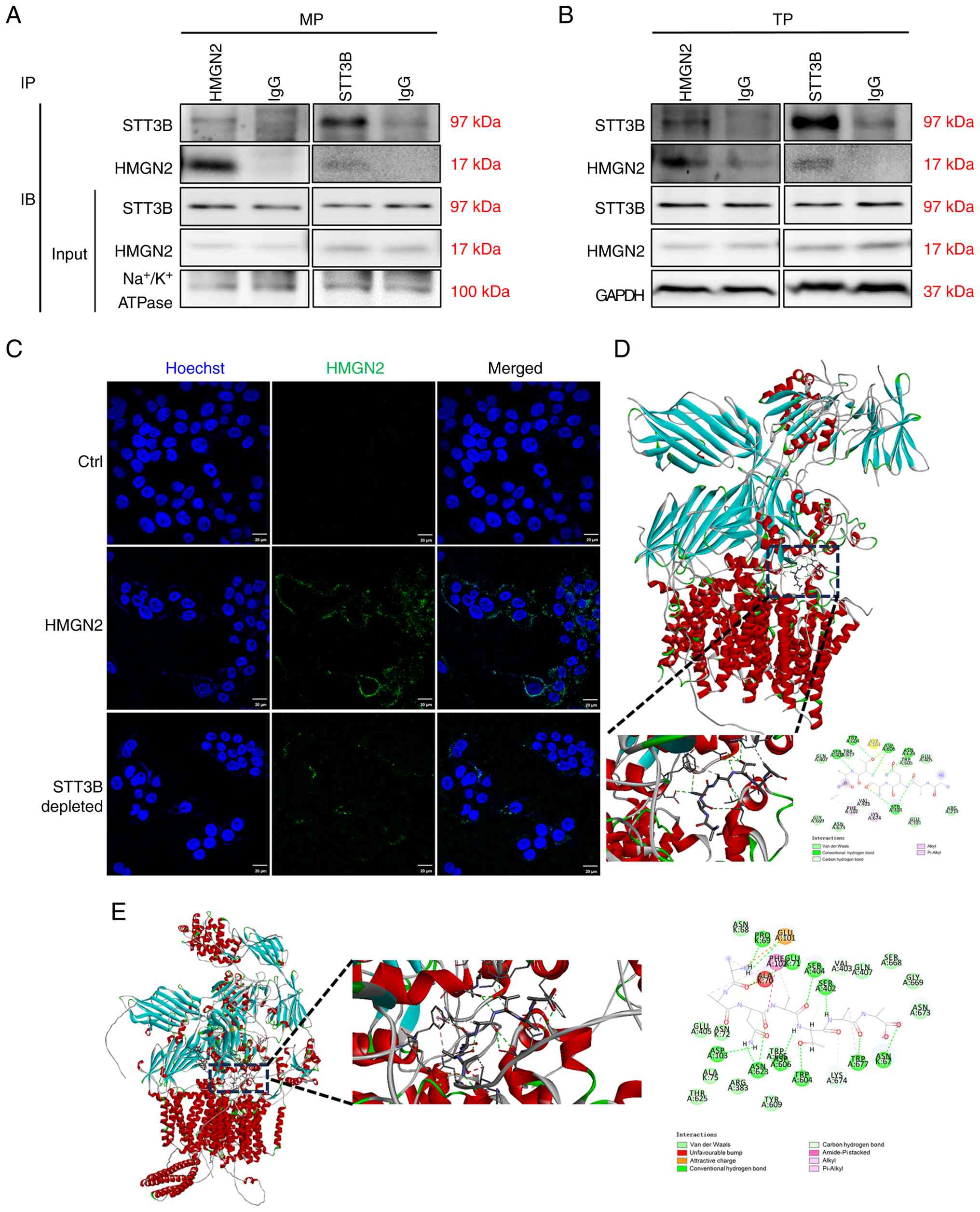

Given that CAL-27 cells respond to HMGN2, the

present study examined the interaction effects of HMGN2 and STT3B

on total protein and membrane proteins in CAL-27 cells.

Immunoprecipitation results indicated that STT3B physically

interacted with HMGN2 (Fig. 4A and

B). To determine whether STT3B was important for HMGN2

translocation into CAL-27 cells, STT3B was blocked on the membrane

using an anti-STT3B antibody, and the results revealed that

compared with that of the positive control, which was incubated

with the FITC-labelled HMGN2 protein, the level of FITC-labelled

HMGN2 protein on the membranes of CAL-27 cells visibly decreased in

the presence of the anti-STT3B antibody (Fig. 4C).

The present study also predicted the best position

for the interaction between HMGN2 and STT3B using rigid

protein-protein docking (Fig. 4D and

E). The highest ZDOCK score for an interaction was 1,846.143.

Furthermore, simulated HMGN2 formed hydrogen bonds at amino acid

sites such as Asn3-Asp103, Asn3-Asn623 and Ala4-Ser404 (Table II). AlphaFold3 simulated the

interaction structure of STT3B and HMGN2 in which hydrogen bonds

were shown to have formed, including at sites such as Ala7-Asn67,

Ala7-Trp677 and Ala6-Ser402. The interface predicted template

modeling score and predicted template modeling score were 0.78 and

0.80, respectively (Table III),

indicating a good predictive power regarding the aforementioned

binding structure. Comprehensive analysis revealed that the

proteins HMGN2 and STT3B formed a stable protein docking model.

| Table II.Analysis of ZDOCK results. |

Table II.

Analysis of ZDOCK results.

| Receptor | Ligand | ZDOCK score | Hydrogen bond

interaction | Hydrophobic

interaction |

|---|

| STT3B | HMGN2 | 1,846.143 | Asn3-Asp103;

Asn3-Asn623; Ala2-Ser404; Ala4-Ser404; Thr5-Trp604;

Thr5-Asp606 | Ala4-Phe102;

Ala7-Lys674 |

| Table III.Analysis of AlphaFold3 results. |

Table III.

Analysis of AlphaFold3 results.

| Receptor | Ligand | ipTM score | pTM score | Hydrogen bond

interaction | Hydrophobic

interaction |

|---|

| STT3B | HMGN2 | 0.78 | 0.80 | Ala7-Asn67;

Ala7-Trp677; Ala6-Ser402; Thr5-Trp604; Thr5-Asp606; Ala4-Ser404;

Asn3-Asn623; Asn3-Asp103; Asn3-Asn623; Ala1-Pro69; Ala1-Glu71 | Ala6-Trp677;

Ala4-Phe102; Asn3-Phe102; Ala2-Phe102 |

HMGN2 promotes the nuclear

translocation of membrane PD-L1, activating the

PD-L1/caspase-1/GSDMD axis

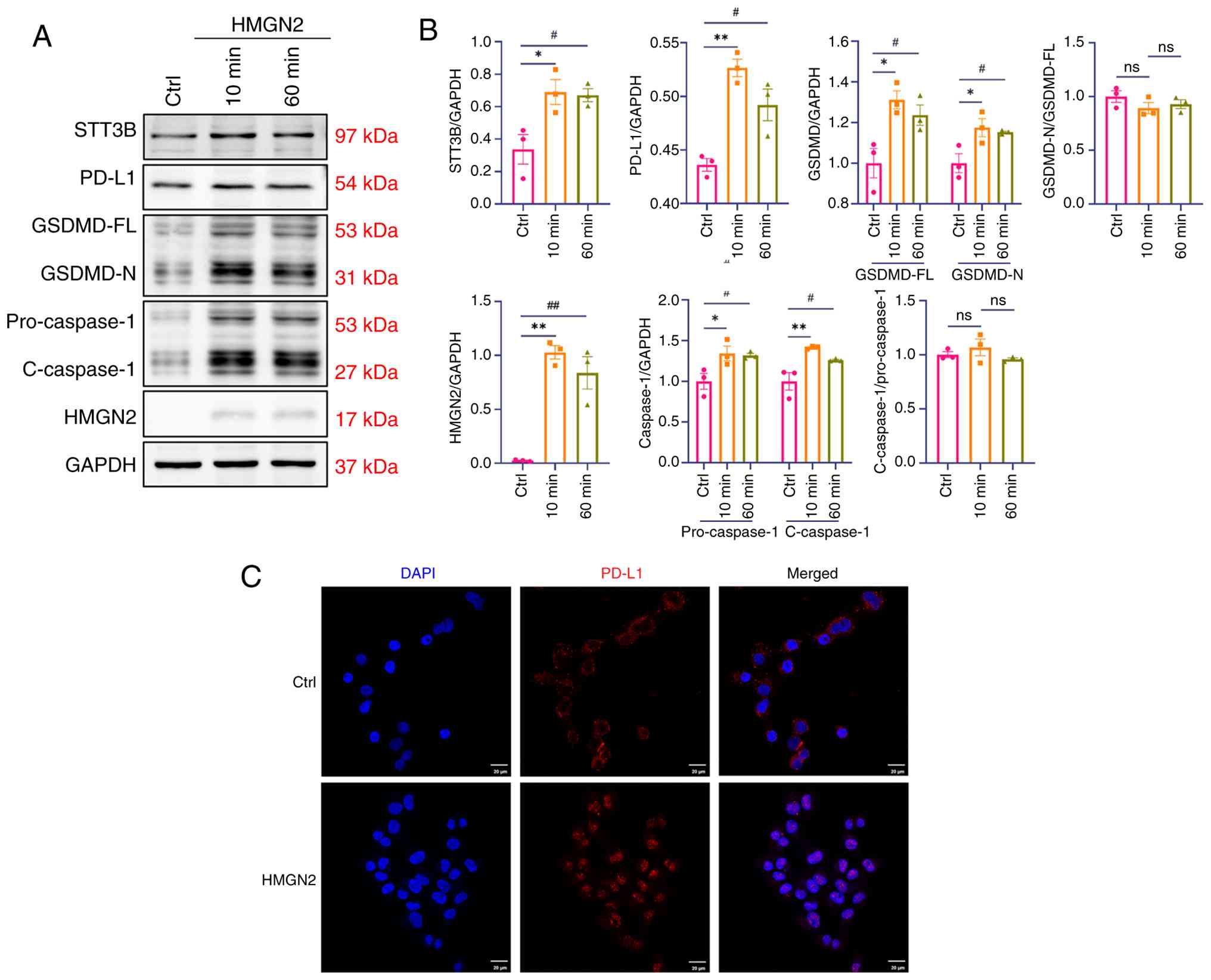

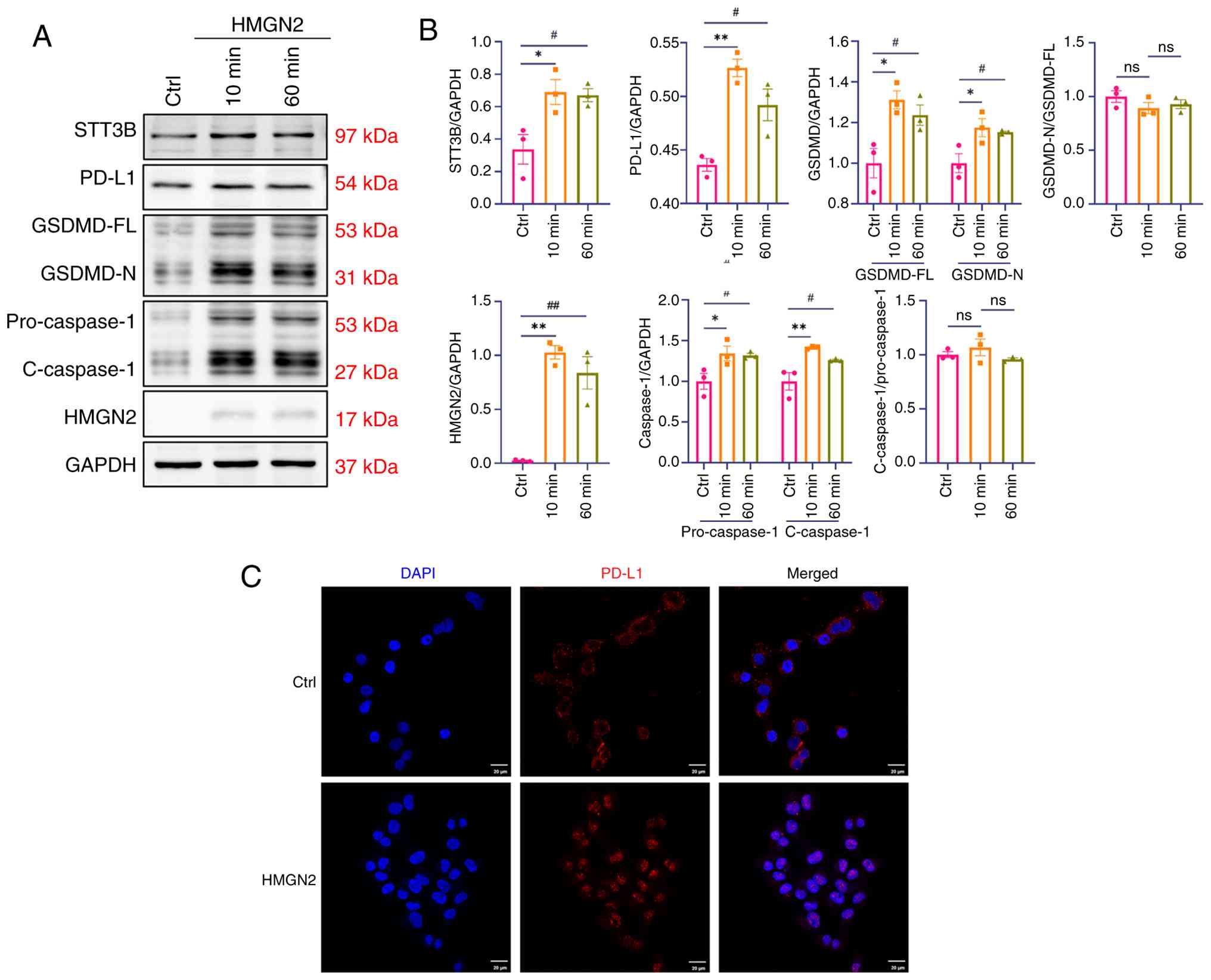

After incubation with HMGN2, the expression of STT3B

was upregulated, which further supported the association between

STT3B and HMGN2 (Fig. 5A and B).

Few studies have examined the function of STT3B in cancer cell

death, but STT3B has been shown to mediate the glycosylation of

PD-L1, which induces immune evasion (13). PD-L1, an immune checkpoint

regulator, shields cancer cells from host immune responses

(17). However, PD-L1 can also

trigger pyroptosis in cancer cells, indicating that PD-L1 is a

signalling mediator that affects tumour outcomes (18). In addition to apoptosis,

ferroptosis and necrosis, pyroptosis serves an important role in

tumour cell death and is characterized as a GSDM-mediated mode of

programmed cell death. In terms of the molecular mechanism of

pyroptosis, caspase-1, −4, −5, −11 and −3 have been shown to cleave

GSDMD or GSDME to induce pyroptosis (19). The results of the present study

revealed that the expression of PD-L1/caspase-1/GSDMD axis

components was significantly upregulated in response to HMGN2

stimulation (Fig. 5A and B), while

the cleavage ratios of both caspase-1 and GSDMD showed no

statistically significant alterations. In addition, treatment with

HMGN2 was shown to induce the nuclear translocation of PD-L1 from

the membranes of cancer cells (Fig.

5C).

| Figure 5.HMGN2 induces pyroptosis in CAL-27

cells through the PD-L1/caspase-1/GSDMD axis. (A) Representative

western blot analysis of the PD-L1/caspase-1/GSDMD axis, and the

HMGN2 and STT3B proteins in CAL-27 cells after incubation with 20

µg/ml HMGN2 for 10 or 60 min. The Ctrl group was treated with PBS.

(B) Semi-quantitative analyses of the PD-L1/caspase-1/GSDMD axis,

and the HMGN2 and STT3B proteins in CAL-27 cells (n=3). (C)

Representative images showing PD-L1 translocation in CAL-27 cells

treated with HMGN2. The Ctrl group was treated with PBS. Scale bar,

20 µm. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P<0.05 and

**P<0.01; #P<0.05 and ##P<0.01.

Ctrl, control; ns, not significant; HMGN2, high-mobility group

nucleosomal-binding domain 2; PD-L1, programmed cell death 1 ligand

1; GSDMD-N, N-terminal domain of gasdermin D; GSDMD-FL, full-length

gasdermin D; STT3B, oligosaccharyltransferase subunit STT3B;

C-caspase-1, cleaved caspase-1. |

Discussion

HMG proteins constitute an abundant family of

non-histone proteins localised in the cell nuclei of vertebrates

and invertebrates (5). The HMG

protein family comprises three subfamilies: HMGB, HMGA and HMGN,

which each perform a distinct nuclear function (11). However, other peptides in the HMG

protein family also have important roles. For example, as an

abundant, highly conserved cellular protein, HMGB1 is considered a

nuclear DNA-binding protein (20).

A decade-long search revealed HMGB1 as a late toxic cytokine of

endotoxaemia (21–23). Upon release by macrophages in

response to endotoxins, HMGB1 triggers the activation of various

proinflammatory mediators, which can be fatal to healthy animals

(24). Additionally, HMGB1-3

operate as universal sentinel proteins for nucleic acid-mediated

innate immune responses (25).

HMGA proteins modulate the transcription of a number

of genes through interactions with transcription factors and

altering the structure of chromatin. HMGA proteins have been shown

to be involved in both benign and malignant neoplasia via numerous

pathways. A number of benign human mesenchymal tumours show HMGA

gene rearrangements. Conversely, malignant tumours exhibit

wild-type HMGA protein upregulation, which is frequently a cause of

neoplastic cell transformation (26,27).

The HMGN family comprises five chromatin

architectural proteins present in higher vertebrates (28). HMGN5, located on human chromosome

Xq13.3, is a prominent member of the HMGN family, and exhibits a

functional nucleotide-binding domain and a negatively charged

C-terminus (28). The HMGN5

protein can rapidly translocate into the nucleus and interact with

nucleosomes, thereby affecting transcription (29). Previous studies have indicated that

the expression of the HMGN5 gene is upregulated in numerous human

tumours and that HMGN5 is activated in tumour models (30,31).

HMGN2 is one of the most abundant non-histone

nuclear proteins in both vertebrates and invertebrates, which

participates in chromatin remodelling and transcriptional

activation (1–4). Additionally, HMGN2 is associated with

the recognition of various types of tumour cells (32–34),

antineoplastic activity (5,35,36)

and the prediction of various tumours (37–40).

Previous studies have demonstrated that HMGN2 expressed by

CD8+ T cells has strong antitumour effects through rapid

recognition and transport into tumour cells (5,41).

For example, a study performed by Li et al (42) demonstrated that T cells engineered

to express HMGN2, designated ‘HMGN2-T cells’, effectively kill

cancer cells and enhance the secretion of IL-2 and TNF-α.

Similarly, Su et al (5)

showed that HMGN2 released by CD8+ T cells can enter

tumour cells and induce cell death. However, the specific mechanism

by which HMGN2 affects tumour cells remains to be fully elucidated,

raising the important question of how HMGN2 identifies and

interacts with tumour cells. The present study aimed to detect

receptors of HMGN2 on tumour cell membranes and to elucidate the

mechanism through which HMGN2 molecule induces tumour cell

apoptosis.

To provide evidence of the antitumour effect of

HMGN2, the present study first incubated CAL-27 cells with HMGN2

and assessed their degree of apoptosis via flow cytometry. Given

the precise location of FITC-labelled HMGN2 on the membranes of

CAL-27 cells, the present study hypothesized that the presence of a

specific receptor on the cell membrane was responsible for

mediating signal communication between HMGN2 and CAL-27 cells,

leading to tumour cell death. In the present study, six proteins

were identified to be localized to the cytoplasmic membrane through

qualitative screening via IP/MS, in which STT3B emerged as the

preferred protein, exhibiting the highest protein score, unique

peptide count and PSM value.

The immunoprecipitation results verified the

interaction between HMGN2 and STT3B; however, the evidence was not

significant enough to establish the notable role of STT3B in the

communication between HMGN2 and CAL-27 cells. To further validate

the importance of STT3B, the present study blocked the STT3B

protein on the membranes of CAL-27 cells with an anti-STT3B

antibody. The resulting findings underscored the importance of

STT3B in the interaction between HMGN2 and CAL-27 cells.

Additionally, the present study predicted binding conformations and

binding sites of HMGN2 to STT3B using ZDOCK and AlphaFold3. Both

models revealed numerous hydrogen bond interactions, including

Thr5-Trp604, Thr5-Asp606, Ala4-Ser404, Asn3-Asn623 and Asn3-Asp103,

indicating that HMGN2 interacted with CAL-27 cells by binding to

the membrane protein STT3B. However, the predicted binding residues

for the HMGN2-STT3B interaction, as generated by ZDOCK and

AlphaFold3, require further validation through site-directed

mutagenesis studies.

Research has shown that upregulation of the STT3

isoforms STT3A and STT3B during EMT acts as a key mediator of

tumour immune evasion by promoting PD-L1 glycosylation and

stabilization (13). In the

present study, the expression levels of STT3B and PD-L1 were found

to be upregulated following incubation with HMGN2, which was

consistent with the findings of the previous study; these results

suggested that the upregulation of STT3B expression stimulated by

HMGN2 resulted in the glycosylation and stabilization of PD-L1,

thus leading to tumour cell death. This observation conflicted with

the notion that stabilization of PD-L1 by STT3B promotes immune

evasion (43,44). However, this discrepancy can be

addressed by considering STT3B/PD-L1 as a dual-function signalling

mediator that may simultaneously trigger pyroptosis while also

facilitating immune evasion (17,45).

Notably, the precise mechanism governing this dual STT3B/PD-L1

functionality remains to be elucidated, thereby constraining a more

comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted roles of PD-L1 in

tumour biology.

Pyroptosis is defined as a GSDM-mediated form of

programmed necrosis (46,47). Numerous studies have established

that caspase-1-mediated pyroptosis serves as an important innate

immune defence mechanism (46–49).

Notably, GSDMD has been identified as a key substrate of both

inflammatory caspases, such as caspase-1, and non-canonical

caspases, such as caspase-4, −5 and −11, and is considered the

primary executor of pyroptotic cell death (49–51).

A previous in vitro study revealed that GSDMD cleavage is

increased in CTLs and contributes to the antitumour function of

CD8+ T cells, indicating that GSDMD is important for the

ability of CTLs to kill tumour cells (52). Therefore, the present study

hypothesized that GSDMD may have been involved in HMGN2-induced

tumour cell death. The findings of the present study revealed that

HMGN2 upregulated the expression of caspase-1/GSDMD pathway

components, revealing an underlying signalling pathway through

which HMGN2 may have induced tumour cell death via activation of

the canonical pyroptosis pathway. HMGN2 upregulated caspase-1 and

GSDMD protein levels but did not significantly alter their cleavage

ratios. This ‘priming’ phenotype is not uncommonly observed in

immune-related cell death pathways, suggesting a priming mechanism

in which protein accumulation precedes proteolytic activation

(53,54). Additionally, PD-L1 was translocated

from the plasma membrane to the nucleus; this translocation has

been previously reported to mediate GSDMC expression and caspase-8

activation, leading to pyroptosis of tumour cells (18). However, the regulatory effect of

PD-L1 on the GSDM family remains to be fully elucidated. Further

questions arise regarding how HMGN2 activated STT3B expression and

whether HMGN2 influenced the gene expression of the GSDM family.

Given that HMGN2 has been confirmed to regulate the activity of

transcriptional regulatory factors (1,4) and

chromatin (2,3), additional studies are required to

elucidate its precise role in these processes.

There are several limitations of the present study

that merit consideration. Primarily, while the observed

upregulation of GSDMD, a key mediator of pyroptosis, resulted in

the conclusion that observed cell death was consistent with

pyroptotic processes, direct visualization of characteristic

morphological features through live-cell imaging, such as membrane

pore formation, cell swelling or large bubble formation, is

required to provide additional evidence of this.

Additionally, although the present investigation

built upon existing literature and focused primarily on the role of

HMGN2 in promoting pyroptosis, the mechanistic basis by which PD-L1

may have concurrently mediated pyroptosis and immune escape has not

been fully explored. To improve understanding of this dual

functionality, future studies involving STT3B and PD-L1 knockdown

or neutralization, combined with detailed analysis of downstream

signalling events, would be highly informative.

Furthermore, while the findings of the present study

demonstrated coordinated protein-level changes along the

STT3B/PD-L1/caspase-1/GSDMD axis, the precise sequence of events

and causal relationships within this signalling cascade remain to

be fully established. Further studies employing specific inhibitors

or systematic loss-of-function approaches may help to clarify the

regulatory hierarchy of this pathway and establish mechanistic

causality.

From a methodological standpoint, the antibody-based

STT3B depletion approach employed in the present study was based on

established protocols and the present specific experimental

context. Nevertheless, the use of genetic perturbation methods,

such as CRISPR/Cas9 or stable RNA interference, in future work

could offer more definitive mechanistic insights.

Finally, all experimental findings in the present

study are based on the CAL-27 tongue squamous cell carcinoma model.

Further validation across a broader range of cancer models,

including additional squamous cell carcinoma subtypes and

non-squamous malignancies, would help to assess the

generalizability of the proposed mechanism. In addition, in

vivo studies using immunocompetent mouse models would be

valuable to validate the physiological relevance of this pathway

and to more comprehensively evaluate the therapeutic potential of

HMGN2 within an intact tumour microenvironment.

In conclusion, extracellular HMGN2 may induce

pyroptosis in tumour cells through the STT3B/PD-L1/caspase-1/GSDMD

axis, indicating the capacity of HMGN2 in antitumour immunotherapy,

as well as a new mechanism through which CTLs induce antitumour

effects.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation

of Sichuan Province (grant no. 2022YFS0118) and the

Interdisciplinary Research Project of the State Key Laboratory of

Oral Diseases (grant no. 2022KXK0402).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

WH was responsible for the conceptualization and

methodology of the present study, as well as contributing to the

investigation, formal analysis and composition of the original

draft. HC, BC and JC contributed towards the formal analysis of the

present study. PZ contributed towards the conceptualization,

funding acquisition, and reviewing and editing the manuscript. YF

was responsible for conceptualization of the study, as well as

reviewing and editing the manuscript. WH and YF confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Craig JM, Turner TH, Harrell JC and

Clevenger CV: Prolactin drives a dynamic STAT5A/HDAC6/HMGN2

Cis-regulatory landscape exploitable in ER+ breast cancer.

Endocrinology. 162:bqab0362021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

He B, Zhu I, Postnikov Y, Furusawa T,

Jenkins L, Nanduri R, Bustin M and Landsman D: Multiple epigenetic

factors co-localize with HMGN proteins in A-compartment chromatin.

Epigenetics Chromatin. 15:232022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zhang S, Postnikov Y, Lobanov A, Furusawa

T, Deng T and Bustin M: H3K27ac nucleosomes facilitate HMGN

localization at regulatory sites to modulate chromatin binding of

transcription factors. Commun Biol. 5:1592022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Eliason S, Su D, Pinho F, Sun Z, Zhang Z,

Li X, Sweat M, Venugopalan SR, He B, Bustin M and Amendt BA: HMGN2

represses gene transcription via interaction with transcription

factors Lef-1 and Pitx2 during amelogenesis. J Biol Chem.

298:1022952022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Su L, Hu A, Luo Y, Zhou W, Zhang P and

Feng Y: HMGN2, a new anti-tumor effector molecule of

CD8+ T cells. Mol Cancer. 13:1782014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Chen J, Fan Y, Cui B, Li X, Yu Y, Du Y,

Chen Q, Feng Y and Zhang P: HMGN2: An antitumor effector molecule

of γδT cells. J Immunother. 41:118–124. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Xia A, Zhang Y, Xu J, Yin T and Lu XJ: T

cell dysfunction in cancer immunity and immunotherapy. Front

Immunol. 10:17192019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Mahaki H, Ravari H, Kazemzadeh G, Lotfian

E, Daddost RA, Avan A, Manoochehri H, Sheykhhasan M, Mahmoudian RA

and Tanzadehpanah H: Pro-inflammatory responses after peptide-based

cancer immunotherapy. Heliyon. 10:e322492024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Najafi M, Farhood B and Mortezaee K:

Contribution of regulatory T cells to cancer: A review. J Cell

Physiol. 234:7983–7993. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Li Q, Chen J, Li X, Cui B, Fan Y, Geng N,

Chen Q, Zhang P and Feng Y: Increased expression of high-mobility

group nucleosomal-binding domain 2 protein in various tumor cell

lines. Oncol Lett. 15:4517–4522. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Fan B, Shi S, Shen X, Yang X, Liu N, Wu G,

Guo X and Huang N: Effect of HMGN2 on proliferation and apoptosis

of MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 17:1160–1166.

2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Breitling J and Aebi M: N-linked protein

glycosylation in the endoplasmic reticulum. Cold Spring Harb

Perspect Biol. 5:a0133592013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hsu JM, Xia W, Hsu YH, Chan LC, Yu WH, Cha

JH, Chen CT, Liao HW, Kuo CW, Khoo KH, et al: STT3-dependent PD-L1

accumulation on cancer stem cells promotes immune evasion. Nat

Commun. 9:19082018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Sutton MS, Bucsan AN, Lehman CC, Kamath M,

Pokkali S, Magnani DM, Seder R, Darrah PA and Roederer M:

Antibody-mediated depletion of select leukocyte subsets in blood

and tissue of nonhuman primates. Front Immunol. 15:13596792024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Chen Z, Kankala RK, Yang Z, Li W, Xie S,

Li H, Chen AZ and Zou L: Antibody-based drug delivery systems for

cancer therapy: Mechanisms, challenges, and prospects.

Theranostics. 12:3719–3746. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Abramson J, Adler J, Dunger J, Evans R,

Green T, Pritzel A, Ronneberger O, Willmore L, Ballard AJ, Bambrick

J, et al: Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular

interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature. 630:493–500. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Xiong W, Gao Y, Wei W and Zhang J:

Extracellular and nuclear PD-L1 in modulating cancer immunotherapy.

Trends Cancer. 7:837–846. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Hou J, Zhao R, Xia W, Chang CW, You Y, Hsu

JM, Nie L, Chen Y, Wang YC, Liu C, et al: PD-L1-mediated gasdermin

C expression switches apoptosis to pyroptosis in cancer cells and

facilitates tumour necrosis. Nat Cell Biol. 22:1264–1275. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Liu W, Peng J, Xiao M, Cai Y, Peng B,

Zhang W, Li J, Kang F, Hong Q, Liang Q, et al: The implication of

pyroptosis in cancer immunology: Current advances and prospects.

Genes Dis. 10:2339–2350. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Yang Z, Simovic MO, Edsall PR, Liu B,

Cancio TS, Batchinsky AI, Cancio LC and Li Y: HMGB1 inhibition to

ameliorate organ failure and increase survival in trauma.

Biomolecules. 12:1012022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Tang D, Kang R, Xiao W, Zhang H, Lotze MT,

Wang H and Xiao X: Quercetin prevents LPS-induced high-mobility

group box 1 release and proinflammatory function. Am J Respir Cell

Mol Biol. 41:651–660. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Tang Y, Lv B, Wang H, Xiao X and Zuo X:

PACAP inhibit the release and cytokine activity of HMGB1 and

improve the survival during lethal endotoxemia. Int

Immunopharmacol. 8:1646–1651. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Czura CJ, Wang H and Tracey KJ: Dual roles

for HMGB1: DNA binding and cytokine. J Endotoxin Res. 7:315–321.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wang S and Zhang Y: HMGB1 in inflammation

and cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 13:1162020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yanai H, Ban T, Wang Z, Choi MK, Kawamura

T, Negishi H, Nakasato M, Lu Y, Hangai S, Koshiba R, et al: HMGB

proteins function as universal sentinels for nucleic-acid-mediated

innate immune responses. Nature. 462:99–103. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

De Martino M, Fusco A and Esposito F: HMGA

and cancer: A review on patent literatures. Recent Pat Anticancer

Drug Discov. 14:258–267. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Meireles Da Costa N, Ribeiro Pinto LF,

Nasciutti LE and Palumbo A Jr: The prominent role of HMGA proteins

in the early management of gastrointestinal cancers. Biomed Res

Int. 2019:20595162019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Nanduri R, Furusawa T and Bustin M:

Biological functions of HMGN chromosomal proteins. Int J Mol Sci.

21:4492020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Rochman M, Postnikov Y, Correll S, Malicet

C, Wincovitch S, Karpova TS, McNally JG, Wu X, Bubunenko NA,

Grigoryev S and Bustin M: The interaction of NSBP1/HMGN5 with

nucleosomes in euchromatin counteracts linker histone-mediated

chromatin compaction and modulates transcription. Mol Cell.

35:642–656. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Mou J, Huang M, Wang F, Xu X, Xie H, Lu H,

Li M, Li Y, Kong W and Chen J: HMGN5 escorts oncogenic STAT3

signaling by regulating the chromatin landscape in breast cancer

tumorigenesis. Mol Cancer Res. 20:1724–1738. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Yao K, He L, Gan Y, Liu J, Tang J, Long Z

and Tan J: HMGN5 promotes IL-6-induced epithelial-mesenchymal

transition of bladder cancer by interacting with Hsp27. Aging

(Albany NY). 12:7282–7298. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

He B, Deng T, Zhu I, Furusawa T, Zhang S,

Tang W, Postnikov Y, Ambs S, Li CC, Livak F, et al: Binding of HMGN

proteins to cell specific enhancers stabilizes cell identity. Nat

Commun. 9:52402018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Nanduri R, Furusawa T, Lobanov A, He B,

Xie C, Dadkhah K, Kelly MC, Gavrilova O, Gonzalez FJ and Bustin M:

Epigenetic regulation of white adipose tissue plasticity and energy

metabolism by nucleosome binding HMGN proteins. Nat Commun.

13:73032022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Morande PE, Borge M, Abreu C, Galletti J,

Zanetti SR, Nannini P, Bezares RF, Pantano S, Dighiero G, Oppezzo

P, et al: Surface localization of high-mobility group

nucleosome-binding protein 2 on leukemic B cells from patients with

chronic lymphocytic leukemia is related to secondary autoimmune

hemolytic anemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 56:1115–1122. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Wu Z, Huang Y, Yuan W, Wu X, Shi H, Lu M

and Xu A: Expression, tumor immune infiltration, and prognostic

impact of HMGs in gastric cancer. Front Oncol. 12:10569172022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Liang G, Xu E, Yang C, Zhang C, Sheng X

and Zhou X: Nucleosome-binding protein HMGN2 exhibits antitumor

activity in human SaO2 and U2-OS osteosarcoma cell lines. Oncol

Rep. 33:1300–1306. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Lin J, Cai Y, Wang Z, Ma Y, Pan J, Liu Y

and Zhao Z: Novel biomarkers predict prognosis and drug-induced

neuroendocrine differentiation in patients with prostate cancer.

Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 13:10059162023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Bin-Alee F, Arayataweegool A,

Buranapraditkun S, Mahattanasakul P, Tangjaturonrasme N, Hirankarn

N, Mutirangura A and Kitkumthorn N: Transcriptomic analysis of

peripheral blood mononuclear cells in head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma patients. Oral Diseases. 27:1394–1402. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Yu B, Geng C, Wu Z, Zhang Z, Zhang A, Yang

Z, Huang J, Xiong Y, Yang H and Chen Z: A CIC-related-epigenetic

factors-based model associated with prediction, the tumor

microenvironment and drug sensitivity in osteosarcoma. Sci Rep.

14:13082024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Antony F, Deantonio C, Cotella D, Soluri

MF, Tarasiuk O, Raspagliesi F, Adorni F, Piazza S, Ciani Y, Santoro

C, et al: High-throughput assessment of the antibody profile in

ovarian cancer ascitic fluids. Oncoimmunology. 8:e16148562019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Hu A, Dong X, Liu X, Zhang P, Zhang Y, Su

N, Chen Q and Feng Y: Nucleosome-binding protein HMGN2 exhibits

antitumor activity in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Lett.

7:115–120. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Li H, Wu X, Bu D, Wang L, Xu X, Wang Y,

Liu Y and Zhu P: Recombinant jurkat cells (HMGN2-T cells) secrete

cytokines and inhibit the growth of tumor cells. J Mol Histol.

53:741–751. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Sun Z, Ma X, Zhao C, Fan L, Yin S and Hu

H: Delta-tocotrienol disrupts PD-L1 glycosylation and reverses

PD-L1-mediated immune suppression. Biomed Pharmacother.

170:1160782024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Xu S, Wang H, Zhu Y, Han Y, Liu L, Zhang

X, Hu J, Zhang W, Duan S, Deng J, et al: Stabilization of EREG via

STT3B-mediated N-glycosylation is critical for PDL1 upregulation

and immune evasion in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J

Oral Sci. 16:472024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Blasco MT and Gomis RR: PD-L1 controls

cancer pyroptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 22:1157–1159. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Anderson MJ, den Hartigh AB and Fink SL:

Molecular mechanisms of pyroptosis. Methods Mol Biol. 2641:1–16.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Shi J, Gao W and Shao F: Pyroptosis:

Gasdermin-mediated programmed necrotic cell death. Trends Biochem

Sci. 42:245–254. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Li Y and Jiang Q: Uncoupled pyroptosis and

IL-1β secretion downstream of inflammasome signaling. Front

Immunol. 14:11283582023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Zuo Y, Chen L, Gu H, He X, Ye Z, Wang Z,

Shao Q and Xue C: GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis: A critical mechanism

of diabetic nephropathy. Expert Rev Mol Med. 23:e232021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Huang Y, Wang S, Huang F, Zhang Q, Qin B,

Liao L, Wang M, Wan H, Yan W, Chen D, et al: c-FLIP regulates

pyroptosis in retinal neurons following oxygen-glucose

deprivation/recovery via a GSDMD-mediated pathway. Ann Anat.

235:1516722021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Chen Y, Long T, Chen J, Wei H, Meng J,

Kang M, Wang J, Zhang X, Xu Q, Zhang C and Xiong K: WTAP

participates in neuronal damage by protein translation of NLRP3 in

an m6A-YTHDF1-dependent manner after traumatic brain injury. Int J

Surg. 110:5396–5408. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Xi G, Gao J, Wan B, Zhan P, Xu W, Lv T and

Song Y: GSDMD is required for effector CD8+ T cell responses to

lung cancer cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 74:1057132019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Yan H, Luo B, Wu X, Guan F, Yu X, Zhao L,

Ke X, Wu J and Yuan J: Cisplatin induces pyroptosis via activation

of MEG3/NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD pathway in Triple-negative breast

cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 17:2606–2621. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Liu Y, Fang Y, Chen X, Wang Z, Liang X,

Zhang T, Liu M, Zhou N, Lv J, Tang K, et al: Gasdermin E-mediated

target cell pyroptosis by CAR T cells triggers cytokine release

syndrome. Sci Immunol. 5:eaax79692020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|