Sepsis is a life-threatening systemic-inflammatory

response syndrome triggered by viral, bacterial, fungal or

immunogenic pathogens. This condition initiates a cascade of

reactions culminating in multiorgan dysfunction syndrome. Current

epidemiological data indicate sepsis as the leading cause of

mortality in intensive care units worldwide, with an overall

mortality rate of 25–30% in global cohorts (1–4).

Severe sepsis may induce organ-specific injuries affecting the

kidneys, lungs, brain and heart (5–8).

Notably, sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy (SIC) represents a frequent

complication, occurring in 10–70% of sepsis or septic shock cases

(9). A 2023 cohort study reported

a 20% prevalence of SIC among septic patients, associating with

markedly elevated short-term mortality (10). SIC is defined as an acute,

reversible myocardial depression syndrome during early septic

shock, characterized by infection-driven cardiac dysfunction. While

typically resolving within 7–10 days, SIC may accelerate

cardiovascular collapse (11).

Diagnostic criteria remain non-standardized, but key features

include: i) Left ventricular dilation with normal or reduced

filling pressure; ii) impaired contractility; and iii)

biventricular systolic/diastolic dysfunction manifesting as reduced

ejection fraction (12).

Progressive SIC induces myocardial impairment, as evidenced by

biventricular dilation and decreased left ventricular ejection

fraction (12,13). Notably, myocardial dysfunction

affects 40% of septic patients, with myocardial

dysfunction-associated mortality reaching 70% (14–16),

establishing SIC as a notable threat to patient survival.

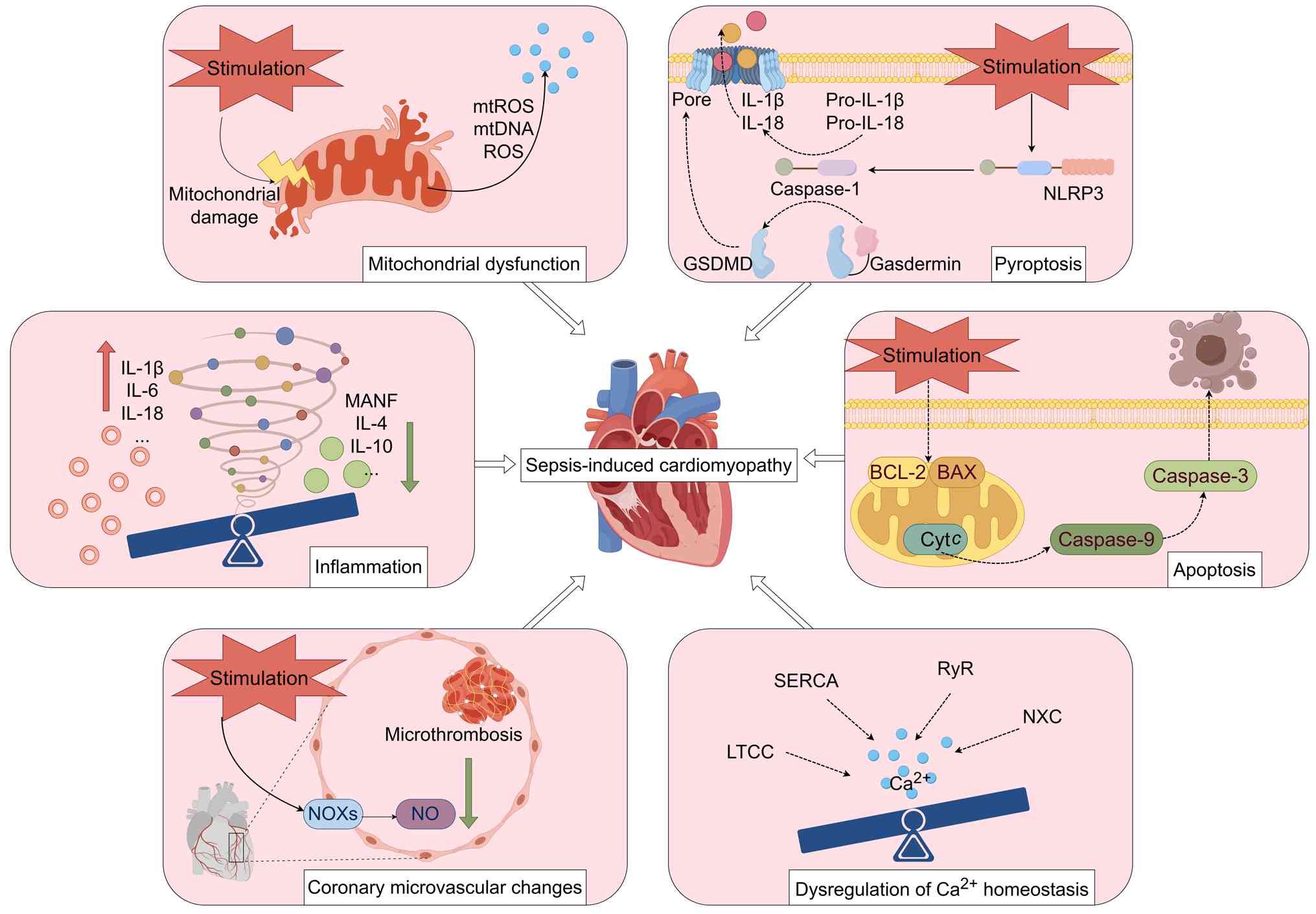

The precise pathogenesis of SIC remains incompletely

elucidated. Current evidence implicates multifactorial mechanisms,

including dysregulated inflammatory responses, programmed cell

death (PCD) mechanisms, such as apoptosis and pyroptosis,

mitochondrial structural or functional impairment, aberrant

calcium-handling protein regulation, endothelial dysfunction and

metabolic disturbances (17–19).

During SIC progression, pathogenic microorganisms and endotoxins

enter systemic circulation, directly activating immune cells. This

triggers excessive cytokine production that amplifies inflammatory

cascades and induces cardiomyocyte cell death. Concurrently,

mitochondrial dysfunction generates an overload of reactive oxygen

species (ROS) and pathological calcium efflux. These interconnected

pathways converge through synergistic amplification, ultimately

impairing myocardial contractility and exacerbating SIC

pathogenesis (Fig. 1).

Previous years have witnessed an intensified

research focus on SIC. Emerging evidence identifies the NOD-like

receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome as a notable innate immune

sensor important for maintaining homeostasis, with its

dysregulation implicated in the pathogenesis of diverse chronic

inflammatory and metabolic disorders (20–24).

During SIC development, the NLRP3 inflammasome is activated by

pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and

damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which triggers

caspase-1-dependent cytokine release, pyroptosis, apoptotic protein

accumulation and mitochondrial injury. These events collectively

drive cardiomyocyte dysfunction and SIC progression (25). Notably, pharmacological inhibition

or genetic downregulation of NLRP3 attenuates SIC-induced cardiac

impairment and improves survival in experimental models (26). Zhu et al (27) demonstrated that the specific NLRP3

inhibitor 5-methoxyindole-3-carboxaldehyde suppresses inflammasome

assembly by disrupting NLRP3-apoptosis-associated speck-like

protein containing a CARD (ASC) interactions. Similarly, MCC950, a

selective small-molecule inhibitor, binds to the NACHT domain of

NLRP3, which prevents the activation of caspase-1 and the resulting

maturation of IL-1β and IL-18, thereby mitigating inflammation and

pyroptosis (28). Although MCC950

demonstrated notable preclinical efficacy, its clinical development

for inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, was halted

during phase II trials due to off-target liver toxicity related to

carbonic anhydrase inhibition (29). Nevertheless, MCC950 remains a

prototypical and widely used research tool, and its chemical

scaffold continues to inform the design of next-generation NLRP3

inhibitors with improved safety profiles (30). These findings establish NLRP3 as a

central node in the SIC pathological network that coordinates

multiple injury mechanisms, including inflammatory cascades, PCD

and impaired mitophagy. Consequently, NLRP3 represents a promising

therapeutic target for SIC intervention.

Due to the absence of comprehensive reviews

addressing NLRP3 inflammasome signaling in SIC, the present review

provided a systematic analysis of its pathogenic role. The present

review elucidated NLRP3 inflammasome priming and activation

mechanisms, discussing clinical and experimental evidence from

previous studies. Notable emphasis was placed on delineating

molecular pathways through which NLRP3 mediates myocardial injury

in SIC, including inflammatory cascades, pyroptosis, apoptosis and

dysregulated mitophagy. Furthermore, the present review catalogued

chemical compounds and pharmacological agents targeting

NLRP3-associated signaling networks. As such, the present review

consolidated current understanding of the central role of NLRP3 in

SIC pathogenesis and identified promising molecular targets for

therapeutic intervention, thereby informing future research

directions.

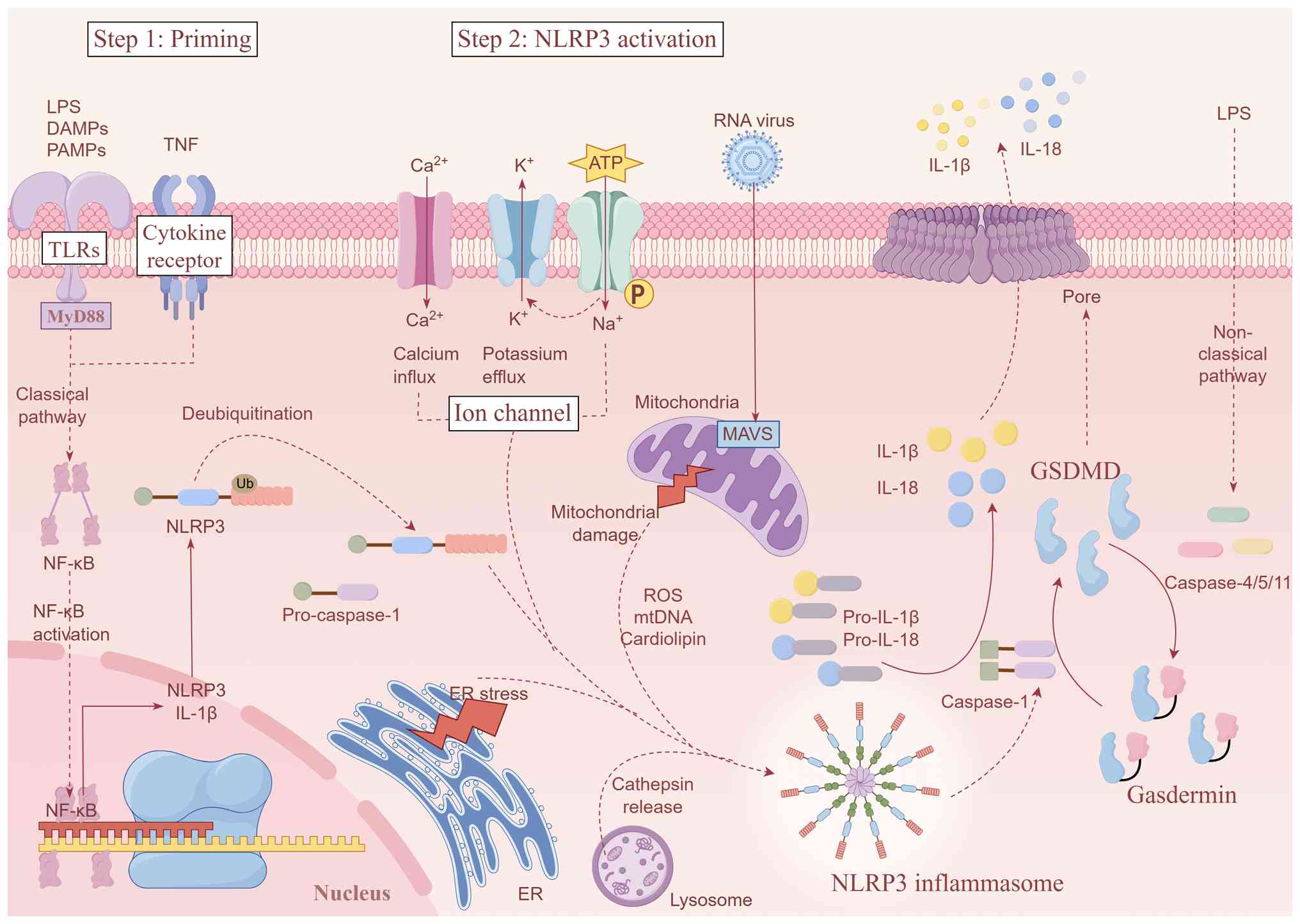

NOD-like receptors, a subclass of pattern

recognition receptors, recognize not only PAMPs but also DAMPs such

as adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and mitochondrial ROS (mtROS)

(31). Among the most extensively

studied inflammasomes, the NLRP3 inflammasome comprises three core

components: Pro-caspase-1, ASC and NLRP3 (32). The NLRP3 protein features three

distinct domains: i) A C-terminal leucine-rich repeat domain; ii)

an N-terminal pyrin domain (PYD); and iii) a central NACHT domain

with ATPase activity (33).

Mutations in the NACHT domain impair NLRP3 oligomerization, thereby

reducing caspase-1 activation, IL-1β and IL-18 secretion and

pyroptosis (34). ASC serves as an

important adaptor protein that bridges the PYD of NLRP3 to the CARD

of pro-caspase-1, facilitating inflammasome assembly (34).

The NLRP3 inflammasome serves as a core regulator of

inflammatory pathways, requiring two distinct signals for canonical

activation: i) A priming signal: Ligands of Toll-like receptors

(TLRs) or cytokine receptors activate the myeloid differentiation

primary response gene 88 (MyD88)/nuclear factor

κ-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) pathway,

inducing transcriptional upregulation of NLRP3 and the

pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 (26); and ii) an activation signal:

Diverse PAMPs, such as bacterial flagellin, lipopolysaccharide

(LPS) and viral RNA, or DAMPs trigger oligomerization of ASC and

pro-caspase-1, culminating in NLRP3 inflammasome complex assembly

(35).

During SIC, multiple pathways converge to activate

the NLRP3 inflammasome through distinct mechanisms. Intracellular

K+ depletion constitutes an important upstream event of

NLRP3 inflammasome activation. ATP-mediated purinergic ligand-gated

ion channel 7 receptor activation triggers K+ efflux,

inducing NLRP3 assembly (36). LPS

induces endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, promoting

Ca2+ release via inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors

and subsequent NLRP3 activation (37). SIC causes mitochondrial structural

and functional impairment (38),

increasing mtROS and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) release. These

components facilitate NLRP3 oligomerization and exacerbate

myocardial injury, with mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein

also contributing to inflammasome activation (39). Endocytosed crystalline or

particulate matter, such as silica and cholesterol crystals,

rupture lysosomes, releasing cathepsin B to promote NLRP3

oligomerization (40). Notably,

crosstalk exists between NLRP3 priming and activation mechanisms.

mtROS serves dual roles: As DAMPs activating TLR/MyD88/NF-κB

signaling and as direct promoters of NLRP3 oligomerization

(41). In addition to mtROS, ER

stress and Ca2+ release constitute another crucial

upstream event that orchestrates NLRP3 activation. Specifically, ER

Ca2+ overload induces mitochondrial Ca2+

uptake; this increased mitochondrial Ca2+ load in turn

amplifies mtROS production, thereby establishing a sustained

pathological feedback loop that exacerbates inflammasome activation

(25).

Upon oligomerization and activation, the NLRP3

inflammasome recruits ASC via PYD-PYD interactions. The resulting

complex facilitates pro-caspase-1 autocleavage, generating active

caspase-1 that processes pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into mature

cytokines (42). Concurrently,

activated caspase-1 cleaves gasdermin D (GSDMD), liberating the

GSDMD N-terminal (GSDMD-NT) domain that subsequently translocates

to the plasma membrane, forming pores that mediate the release of

inflammatory mediators, including IL-1β and IL-18, and drive

pyroptosis, a mode of lytic inflammatory cell death (43). In SIC, pyroptosis releases DAMPs,

such as IL-1β, IL-18 and mtDNA, amplifying inflammation and NLRP3

activation through positive feedback. Notably, the inflammatory

milieu and DAMPs (e.g., mtDNA) released during pyroptosis can also

modulate other cell death and clearance pathways, including

apoptosis and mitophagy (44).

This cascade ultimately induces myocardial dysfunction and

structural damage, representing a core pathogenic mechanism in SIC

(45). Pharmacologically, fatty

acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) inhibitors disrupt NLRP3-FAAH

interactions, promoting NLRP3 degradation (46). This evidence indicates that

targeting NLRP3 attenuates inflammatory responses by modulating

interconnected pathways involving inflammation, pyroptosis,

apoptosis and mitophagy. Nevertheless, the precise molecular

targets governing these pathways require further elucidation

(Fig. 2).

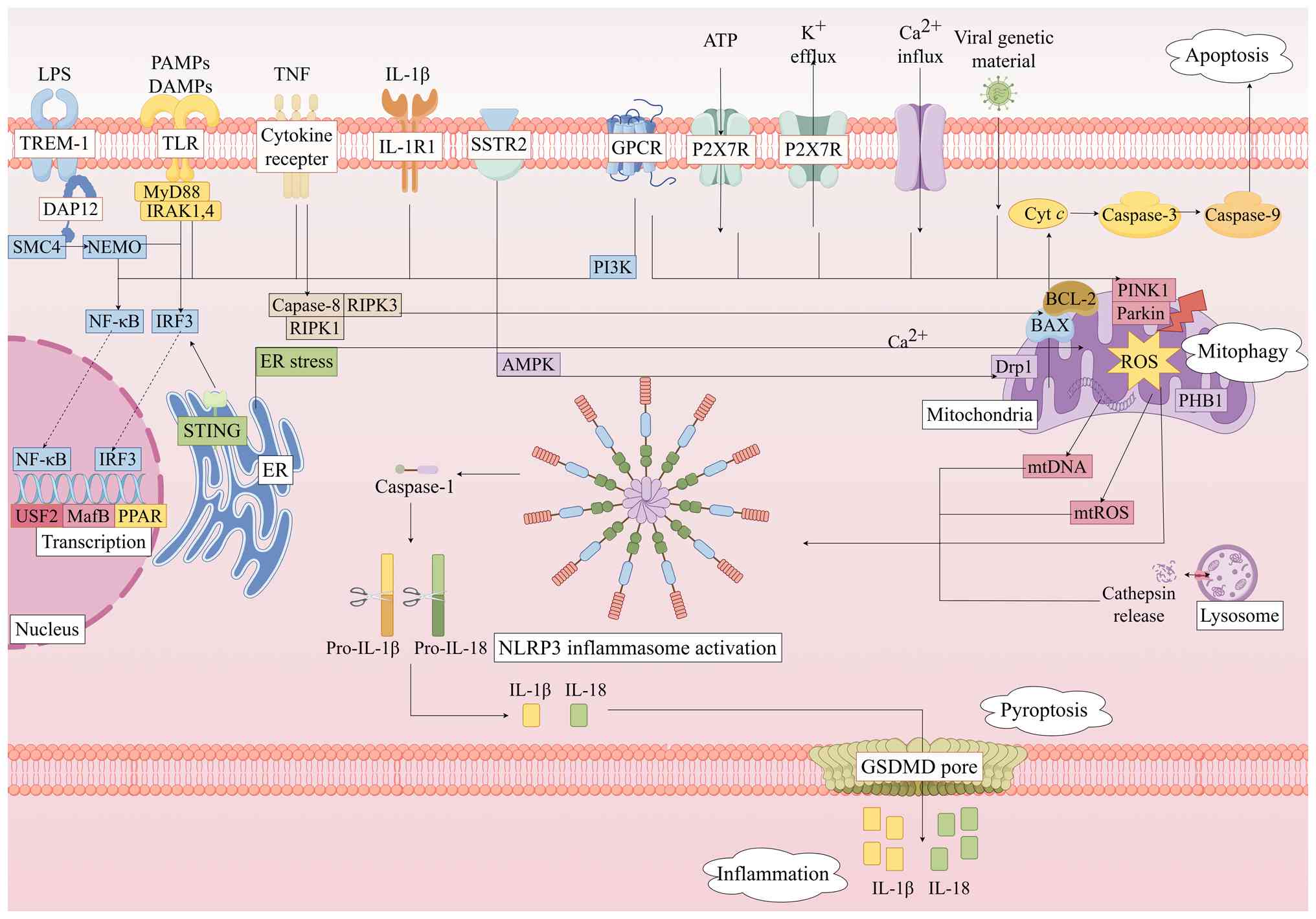

The central pathology of SIC involves a

self-amplifying cascade initiated by NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

Pathogen-derived DAMPs or PAMPs activate the TLR4/NF-κB signaling

pathway, priming NLRP3 expression. This process triggers

mitochondrial dysfunction and impairs mitophagy, leading to the

release of mtROS and mtDNA that directly promote NLRP3

oligomerization. Concurrently, the mitochondrial permeability

transition facilitates the release of cytochrome c (Cyt

c) into the cytoplasm, which is a pivotal event that bridges

mitochondrial damage with downstream programmed cell death (PCD)

pathways (47). Regarding PCD

convergence, these released mitochondrial components, such as Cyt

c, not only initiate intrinsic apoptosis but also contribute to a

complex interplay between apoptosis, pyroptosis, and inflammation

(48). In this context, extrinsic

apoptosis is initiated when TNF-α binds to TNF receptor (TNFR)1,

activating caspase-8, while intrinsic apoptosis occurs as a result

of Cyt c forming apoptosomes to activate caspase-9. Both

pathways converge on caspase-3 of apoptosis-executing factors

(e.g., endonucleases) and other proteins, culminating in apoptosis

(49). In the

pyroptosis-inflammation feedback loop, NLRP3-activated caspase-1

cleaves GSDMD, generating pore-forming GSDMD-NT fragments that

induce pyroptosis in myocardial cells and can further exacerbate

mitochondrial damage (50). This

releases pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and IL-18, which

disseminate systemically to amplify inflammation and generate

secondary DAMPs, thereby reactivating the NLRP3 inflammasome.

The NLRP3 inflammasome exhibits distinct expression

patterns and functional roles across different cardiac cell types,

collectively contributing to the complex pathological network of

SIC. In macrophages, early septic insults induce the expression of

glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related protein on their surface, which

potentiates NLRP3 inflammasome activation and promotes

pro-inflammatory macrophage polarization by modulating the

post-translational modifications of the NLRP3 inflammasome, thereby

amplifying the inflammatory cascade (51). In cardiomyocytes, NLRP3 activation

directly induces pyroptosis through GSDMD pore formation,

compromising membrane integrity and leading to the release of

intracellular contents. The released inflammatory mediators not

only exacerbate autocrine dysregulation of calcium homeostasis but

also recruit and activate macrophages, perpetuating a

pro-inflammatory microenvironment and impairing cardiomyocyte

contractile function, representing a primary mechanism of acute

cardiac injury in SIC (52).

Furthermore, cardiomyocytes can communicate directly with cardiac

fibroblasts via membrane nanotubes, transmitting inflammasome

activation signals that drive fibroblasts toward a pro-inflammatory

and pro-fibrotic phenotype. This intercellular crosstalk results in

excessive extracellular matrix production, exacerbating acute

injury and laying the foundation for long-term myocardial fibrosis

and diastolic dysfunction in survivors of sepsis (53). In summary, the NLRP3 inflammasome

serves heterogeneous roles across different cardiac cell types,

which collectively constitute the complex pathological network of

SIC. These interconnected mechanisms form a notable cycle:

Mitochondrial damage induces NLRP3 activation, which promotes

inflammation, pyroptosis and apoptosis, resulting in secondary

mitochondrial injury. Targeted disruption of any nodal point in

this cycle represents a promising therapeutic strategy for SIC, as

the overlapping pathways converge on NLRP3 inflammasome activation

to sustain myocardial injury (Fig.

3).

Dysregulated inflammation represents a notable

pathophysiological process wherein pro-inflammatory cytokines

activate immune cells and mediate tissue damage, while

anti-inflammatory cytokines counteract these responses. SIC, an

acute cardiac dysfunction syndrome stemming from systemic infection

and inflammation, accelerates cardiovascular collapse by

exacerbating microcirculatory dysfunction and hypoperfusion. Its

pathogenesis involves complex interactions between the immune and

cardiovascular systems, prominently featuring inflammatory

activation (54). Excessive

cytokine production triggers a cytokine storm that amplifies tissue

injury and organ dysfunction (55). During SIC, PAMPs and DAMPs activate

the NLRP3 inflammasome via TLRs (56). This leads to caspase-1-mediated

proteolytic maturation of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18. Mature IL-1β and

IL-18 further activate downstream pathways, such as the NF-κB

pathway, inducing secondary inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α,

IL-6 and IL-1β, that establish a cytokine storm, ultimately causing

cardiomyocyte dysfunction (57).

Notably, NLRP3-knockout murine SIC models exhibit markedly reduced

expression of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18 and TNF-α, with concomitant

improvement in cardiac function and attenuated myocardial injury

(58). These findings suggest that

combined targeting of NLRP3-derived IL-1β and IL-18 represents a

novel therapeutic approach for SIC.

Upstream stimulatory factor 2 (USF2), a basic

helix-loop-helix leucine zipper transcription factor, regulates

NLRP3 expression in multiple disease contexts (59,60).

A study reported by Dong et al (61) demonstrated that USF2 silencing

attenuates NLRP3 inflammasome activation in experimental SIC models

by targeting the microRNA (miR/miRNA)-206/Rho-related GTP-binding

protein RhoB/Rho-associated protein kinase signaling axis, thereby

reducing inflammatory responses and cardiac dysfunction.

Conversely, in lupus nephritis, USF2 does not operate through this

miRNA axis but rather directly binds to the NLRP3 promoter to drive

its transcription and exacerbate podocyte injury (60). These findings underscore that the

pathophysiological role of USF2 is not universal but is determined

by specific cellular milieu.

The TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway serves as the dominant

upstream regulator of NLRP3 activation. During SIC, LPS upregulates

NLRP3, IL-18 and IL-1β expression through this pathway,

exacerbating myocardial inflammation. Notably, NF-κB inhibition

with BAY 11-7082, a selective IκBα phosphorylation blocker,

suppresses SIC-induced inflammation in cellular models (62). Myo-inositol oxygenase (MIOX), a key

enzyme in inositol catabolism, functions as both a biomarker and

therapeutic target in renal diseases (63,64).

Notably, MIOX enhances NLRP3 inflammasome activity by inhibiting

its degradation, aggravating infection-induced cardiac inflammation

and dysfunction in SIC models (65).

PCD represents a conserved mechanism for eliminating

damaged cells. Major PCD modalities include apoptosis, autophagy,

ferroptosis, necroptosis and pyroptosis (66). Apoptosis, as a predominant PCD

form, contributes notably to cellular injury during sepsis.

SIC-induced mitochondrial dysfunction alters membrane permeability,

triggering the activation of pro-apoptotic B-cell lymphoma 2

(BCL-2) family proteins, such as BCL-2-associated X protein (BAX),

while suppressing anti-apoptotic members, such as BCL-2. This

facilitates Cyt c release and caspase-3 activation (67). Similarly, TNF-α binding to TNFR1

activates caspase-8, which cleaves and activates the executioner

protein caspase-3. Nuclear translocation of caspase-3 initiates

substrate proteolysis, DNA fragmentation and apoptotic execution

(68). Myocardial apoptosis

severity associates with cardiac damage in sepsis. SIC models

demonstrate impaired cardiac function coincident with the elevated

expression of apoptosis-related proteins, including cleaved

caspase-3 (69). The NLRP3

inflammasome indirectly regulates apoptosis via inflammatory

signaling and cellular stress in SIC. Specifically, TNFR engagement

activates NLRP3 through the receptor-interacting serine/threonine

kinase (RIPK) 1/RIPK3 signaling axis (70), which promotes the release of

pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and IL-18, and induces

mitochondrial damage and ROS production. ROS trigger BAX

oligomerization via compromising mitochondrial outer membrane

integrity by impairing the anti-apoptotic function of BCL-2, which

normally sequesters BAX (71).

This mitochondrial membrane damage facilitates Cyt c release

into the cytoplasm, where it forms apoptosomes that activate

caspase-3 (72). Concurrently,

NLRP3-driven ROS production also activates downstream caspase-8,

which converges with the caspase-3 pathway to induce nuclear

translocation of endonucleases, culminating in DNA fragmentation

and apoptotic cell death (73).

Several upstream regulators have been shown to modulate this

process: Stimulator of interferon genes knockout attenuates

cardiomyocyte injury by suppressing NLRP3 via an interferon

regulatory factor 3-dependent pathway (74); poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1

(PARP1) overexpression decreases BCL-2 while elevating BAX and

cleaved caspase-3, a cascade reversed by atractylenolide I

targeting the PARP1/NLRP3 pathway (75); and oxysterols receptor LXR-α

knockout exacerbates apoptosis by enhancing NLRP3 expression

(76).

Pyroptosis represents a pro-inflammatory PCD

distinct from apoptosis, mediated by GSDM family proteins that form

transmembrane pores in the plasma membrane. These pores facilitate

IL-18 and IL-1β release while disrupting ionic homeostasis,

ultimately causing cellular swelling and lysis (77,78).

The NLRP3 inflammasome exemplifies a ‘double-edged sword’ in the

pathogenesis of SIC. As an important component of the innate immune

system, NLRP3 inflammasome activation is necessary for host defense

(79). Moderate pyroptosis, driven

by NLRP3, facilitates the clearance of intracellular pathogens in

SIC by eliminating their replicative niche and exposing them to

extracellular immune surveillance, thereby preserving cardiac

function in the early stages of sepsis (80). Conversely, excessive and

uncontrolled NLRP3 activation triggers an excessive release of

pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β and IL-18, and

widespread pyroptotic cell death, which exacerbates myocardial

injury and contributes to cardiac dysfunction (81). While inhibition of NLRP3 represents

a promising strategy to mitigate septic cardiomyopathy, complete

and long-term suppression may inadvertently compromise the ability

of the patient to clear infections. Therefore, future therapeutic

paradigms should not aim to abolish NLRP3 activity entirely, but to

precisely modulate it, therefore suppressing its pathological

overactivation while preserving its beneficial role in pathogen

clearance.

Multiple pathways converge on NLRP3 to regulate

pyroptosis: TLR4 activation initiates NLRP3 priming via the

MyD88/NF-κB pathway, while pharmacological inhibition of NF-κB

suppresses the resulting caspase-1 expression and pyroptosis

(62,82). Protective factors such as heat

shock protein 70 (83), apelin via

adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK)

signaling (84) and cortistatin

via somatostatin receptor 2 (SSTR2)/AMPK signaling (85) inhibit NLRP3 activation and

downregulate pyroptosis-executing proteins such as GSDMD and

caspase-1. Conversely, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate

3-kinase catalytic subunit γ promotes NLRP3 assembly via G

protein-coupled receptor (GPCR)-induced NF-κB activation,

exacerbating pyroptosis (86,87).

Mitochondria serve as important energy-producing

organelles that regulate cellular functions and maintain

homeostasis, being particularly abundant in cardiomyocytes and

notably vulnerable during sepsis. Autophagy is a lysosomal

degradation process that eliminates damaged macromolecules and

organelles, sustaining intracellular homeostasis (88,89).

Mitophagy specifically targets impaired mitochondria for autophagic

clearance (90), operating

primarily through parkin-dependent and -independent mechanisms. The

PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1)/parkin pathway represents

the canonical mitophagy route: Upon mitochondrial damage or

depolarization, PINK1 accumulates on the mitochondrial outer

membrane and recruits Parkin to ubiquitinate damaged mitochondria,

marking them for autophagosomal engulfment (91–94).

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), a

cytokine-responsive transcription factor, modulates this process;

STAT3 inhibition in macrophages induces PINK1-dependent mitophagy

(95), which clears dysfunctional

mitochondria, restores mitochondrial membrane potential, suppresses

mtROS release and inactivates the NLRP3 inflammasome (96).

During SIC, the pathogen-activated NLRP3

inflammasome inhibits mitophagy via caspase-1-mediated cleavage of

autophagy-related proteins, such as beclin-1, leading to

mitochondrial structural and functional damage (97). This results in a notable release of

mtROS and mtDNA, which act as DAMPs in a positive feedback loop

that activates the NLRP3 inflammasome, establishing a cycle of

autophagy inhibition and exacerbated inflammation (98). Mitophagy, the selective clearance

of damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria, has been shown to reduce

mtROS levels, suppress NLRP3 inflammasome activation and

consequently mitigate septic cardiomyopathy injury (99). A recent study indicated that

inhibiting pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase suppresses NLRP3

inflammasome activation, reduces downstream caspase-1 cleavage and

IL-1β secretion and diminishes ROS production by enhancing

autophagy (100). Dual

specificity phosphatase 1, a regulator of angiotensin II signaling

(101), has been shown to enhance

FUN14 domain-containing protein 1-dependent mitophagy, thereby

reducing NLRP3 inflammasome formation and the generation of

specific inflammatory cytokines, ultimately attenuating the

inflammatory response (102–104). SSTR2, a GPCR, is an important

functional receptor expressed in cardiomyocytes. The activity of

dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), a GTPase primarily regulating

mitophagy, is modulated by phosphorylation (105). During SIC, the neuropeptide

cortistatin can activate SSTR2/Drp1-mediated mitophagy to reduce

ROS production, thereby inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation

and pyroptosis, alleviating SIC-induced myocardial injury (85). Prohibitin 1 (PHB1), a key protein

in the mitochondrial inner membrane, is involved in maintaining

mitochondrial structure, regulating metabolism and inhibiting mtROS

generation. Research demonstrates that PHB1 suppresses mtROS

accumulation by enhancing mitophagy, consequently blocking NLRP3

inflammasome assembly; conversely, PHB1 deficiency exacerbates

mitochondrial damage and inflammation (106). Additionally, autophagy can

directly suppress inflammatory responses by clearing NLRP3

inflammasome components, such as ASC specks, or degrading active

caspase-1 (107,108).

Mitophagy deficiency amplifies mitochondrial danger

signals, including mtROS and mtDNA, which serve as important

triggers and amplifiers for the NLRP3 inflammasome (109). The level of cardiomyocyte

mitophagy is closely associated with the outcome and prognosis of

septic cardiomyopathy; while damaged mitochondria acting as DAMPs

induce NLRP3 inflammasome activation, the activated NLRP3

inflammasome conversely impairs autophagic capacity, establishing a

detrimental positive feedback loop of inflammation and autophagy

imbalance that exacerbates septic cardiomyopathic injury (110). Adaptor protein containing PH

domain, PTB domain and leucine zipper motif 1 (APPL-1), a dynamic

protein of the early endosome, translocates between cellular

organelles under various stress conditions (111). A recent study indicated that

APPL-1 deficiency suppresses mitophagy, consequently triggering

excessive NLRP3 inflammasome activation (112). Additionally, v-maf

musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog B, a protein

belonging to the transcription factor MAF subfamily that is

responsible for binding specific DNA element motifs (113), has been shown to promote NLRP3

inflammasome-mediated mitochondrial damage upon its knockdown in

SIC models, which also display consequent mtROS production and

mtDNA release (114).

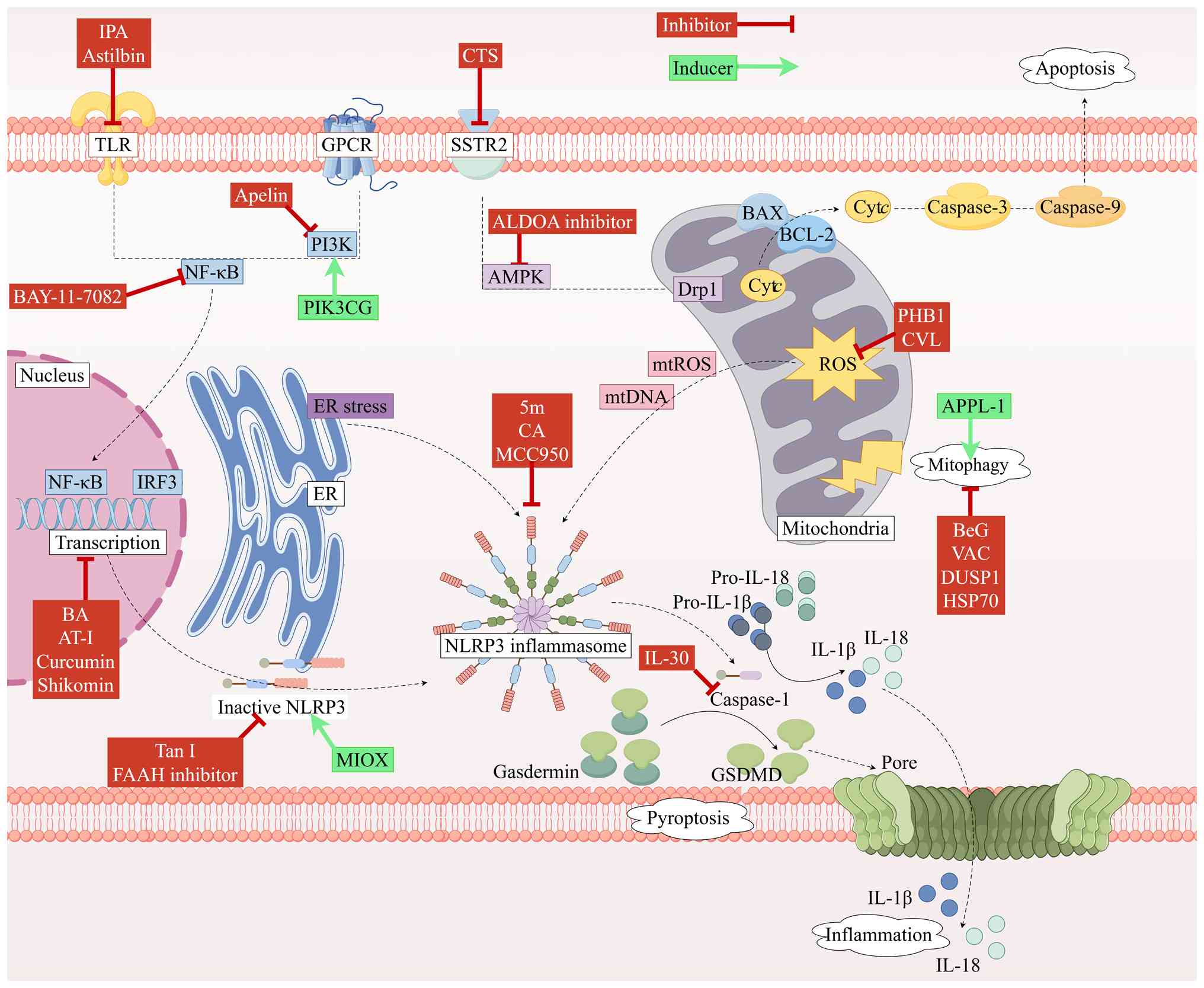

The pathological progression of SIC is driven by the

NLRP3 inflammasome as a central hub, establishing self-amplifying

injury through a triple amplification cascade: i) NLRP3 activation

induces caspase-1-mediated maturation of IL-1β and IL-18,

triggering inflammatory cascades (115); ii) concurrently, caspase-1

cleaves GSDMD to initiate pyroptosis, with resultant pore formation

releasing DAMPs that further activate the TLR4/NLRP3 axis; and iii)

pyroptosis and apoptosis pathways converge at the

caspase-8/BH3-interacting domain death agonist (Bid)/truncated Bid

node, where caspase-8 activation promotes BAX-mediated

mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization, resulting in

mitochondrial Cyt c release and amplified apoptosis.

Mitochondrial damage releases mtROS and mtDNA that directly

activate NLRP3, while conversely, NLRP3 suppresses

PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy via caspase-1 cleavage of beclin-1.

The resulting mitophagy deficiency causes accumulation of damaged

mitochondria and mtROS overproduction, further activating NLRP3 to

establish a cycle of autophagy inhibition and inflammatory

exacerbation (116). Key

molecular targets mediating these interactions include: i)

TNFR-associated factor 2, which bidirectionally regulates the NF-κB

inflammatory pathway and the RIPK1-mediated apoptosis/survival

switch in SIC; and ii) AMPK, an important cellular energy sensor

that concurrently inhibits NLRP3 assembly and enhances

PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy during SIC (117). Notably, mtROS released from

damaged mitochondria in SIC cardiomyocytes serve as a common

trigger that interconnect inflammatory activation, BAX

oligomerization and autophagy suppression (118) (Fig.

4).

As aforementioned, pharmacological agents and

compounds targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome and its upstream or

downstream pathways exhibit notable therapeutic potential for

mitigating myocardial injury and treating SIC, potentially forming

the foundation for future therapeutic strategies. The present

section broadly categorizes the mechanisms of action of currently

investigated compounds.

Several pharmacological agents ameliorate

SIC-induced myocardial dysfunction by directly inhibiting NLRP3

inflammasome assembly and activation. Tanshinone I (Tan I), an

active constituent of Salvia miltiorrhiza with established

therapeutic potential across multiple pathologies (119,120), suppresses inflammasome assembly

and downstream caspase-1 activation in SIC model by targeting the

NLRP3 PYD to disrupt its interaction with ASC; this mechanism

positions Tan I and its derivatives as promising next-generation

NLRP3-targeted therapeutics (121). Cinnamyl alcohol, a bioactive

component of cinnamon demonstrating anti-inflammatory and

antioxidant properties (122,123), reduces tissue inflammation and

downregulates inflammatory cytokine expression via NLRP3

inflammasome inhibition, highlighting its therapeutic potential for

sepsis (124). Genetic ablation

of NLRP3 markedly attenuates IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18 and TNF-α

expression while improving cardiac function and mitigating

myocardial injury in SIC model (58). These findings indicate that

combinatorial NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition represents a viable

therapeutic strategy for SIC.

Several agents indirectly mitigate NLRP3

inflammasome-mediated myocardial injury and dysfunction in SIC by

targeting upstream signaling pathways regulating its priming and

activation. NF-κB, a central regulator of NLRP3 priming,

facilitates inflammasome activation via the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB

pathway (125); a recent study

demonstrated that the NF-κB antagonist BAY 11-7082 reduces

pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, such as that of TNF-α, IL-6

and IL-1β, and suppresses pyroptosis (62). Shikonin, an anti-inflammatory

phytochemical, exerts inhibitory effects on NLRP3

inflammasome-mediated inflammation and pyroptosis via

AMPK/NAD-dependent protein deacetylase sirtuin-1 pathway modulation

when formulated as Zn2+-shikonin nanoparticles (126). Astilbin, a protective flavonoid

(127–131), markedly attenuates inflammatory

marker concentrations and reduces TLR4/NF-κB pathway expression in

septic cardiomyopathy model, indicating that its cardioprotective

mechanism involves TLR4/NF-κB pathway inhibition to suppress NLRP3

inflammasome activation (132).

Brevilin A, an anti-inflammatory sesquiterpene lactone derived from

Centipeda minima, effectively suppresses NF-κB and NLRP3

protein expression in both cellular and animal models of septic

cardiomyopathy, highlighting its promise as a natural therapeutic

for SIC (133).

Indole-3-propionic acid, an anti-inflammatory gut microbiota

metabolite (134–137), inhibits NLRP3 and downstream

caspase-1 expression via TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway suppression in

SIC models (62).

Specific pharmacological agents ameliorate SIC by

inhibiting downstream signaling or effector proteins of the NLRP3

inflammasome. Curcumin, the primary active constituent of turmeric

with demonstrated pleiotropic pharmacological activities (138), reduces NLRP3, ASC and caspase-1

expression in septic animal models when delivered via

arginine-glycine-aspartic acid-anchored liposomal encapsulation,

identifying this as a novel therapeutic strategy for SIC (139). The translational promise of this

strategy is underscored by a phase II randomized controlled trial,

where intervention with nano-curcumin in a cohort of patients with

severe sepsis not only confirmed its safety and feasibility as a

therapeutic but also mechanistically demonstrated a marked

downregulation of NF-κB and NLRP3 mRNA expression in patients

following treatment, thereby providing robust support for its

future application in targeted SIC therapy and prognostic

assessments (140). Furthermore,

IL-30 exhibits anti-inflammatory properties across multiple

pathologies (141–143); a study by Zhao et al

(144) demonstrated that IL-30

treatment effectively suppresses the expression of

pyroptosis-associated proteins, including IL-1β, IL-18, NLRP3 and

GSDMD, in SIC murine models.

Several pharmacological agents mitigate myocardial

injury resulting from SIC by enhancing mitophagy to disrupt the

cycle of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and mitophagy inhibition.

Carvacrol, a monoterpenoid phenol with anti-inflammatory properties

(145), reduces ROS generation

and enhances autophagy to suppress NLRP3 inflammasome formation in

SIC (146). Vaccarin, a bioactive

flavonoid derived from Vaccaria segetalis seeds (147–149), attenuates inflammatory cytokine

expression and modulates mitophagy to confer cardioprotection in

SIC (150). Bergapten, a

bioactive coumarin (151–153), inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome

activation by promoting mitophagy, suggesting therapeutic potential

for SIC (154). Additionally, the

aldolase A inhibitor LYG-202 suppresses activation of the NLRP3

inflammasome and attenuates inflammation in SIC through

AMPK/mitophagy pathway activation (155).

Despite the compelling therapeutic potential of

targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome in SIC, its translation from

promising preclinical data to clinical reality faces numerous

challenges. A critical and expanded analysis of these hurdles,

informed by lessons from broader NLRP3 inhibitor development, is

important for guiding future research.

A defining feature of SIC is its potential

reversibility following sepsis control (161). This characteristic implies a

narrow therapeutic window for NLRP3 inhibition. The

hyperinflammatory phase of early sepsis, when NLRP3 is most active

(162), likely represents the

optimal period for effective intervention to mitigate myocardial

injury and improve patient outcomes. By contrast, administration of

inhibitors during the later immunoparalytic phase may exacerbate

immune imbalance and increase the risk of secondary infections

(163). However, most current

cellular and animal models of NLRP3 inhibition employ prophylactic

or early treatment regimens (164). Therefore, future clinical trials

of NLRP3 inhibitors must carefully define appropriate monitoring

indicators and rigorously evaluate the therapeutic window.

Although several NLRP3 inhibitors have advanced to

clinical trials, current guidelines and clinical experience

emphasize that conventional therapies, including early antibiotic

administration and supportive care, remain the cornerstone of

sepsis management (165). NLRP3

inhibitors are not intended to replace but rather to complement the

existing standard of care, such as antibiotics, fluid resuscitation

and vasopressors. For instance, by mitigating endothelial injury

and capillary leakage (166),

NLRP3 inhibitors may enhance hemodynamic stability achieved through

fluid resuscitation and vasoactive agents. However, potential

antagonistic interactions must be carefully considered in future

clinical use. Certain antibiotics can induce mitochondrial stress

or alter immune cell function, which may indirectly influence NLRP3

inflammasome activation pathways (167). As early and appropriate

antimicrobial therapy is important (168), NLRP3 inhibition must not

interfere with antimicrobial efficacy or the ability of septic

patients to clear bacteria. Furthermore, patients with sepsis

frequently experience acute renal or hepatic dysfunction (169), which can markedly alter the

pharmacokinetics and safety profile of any adjunctive treatment,

including NLRP3 inhibitors. Therefore, integrating NLRP3 inhibitors

into septic care remains challenging and requires rigorous

evaluation in relevant disease-state models. This includes

determining the optimal timing of inhibitor administration relative

to antibiotics, understanding the impact of NLRP3 inhibitors on

hemodynamic management and conducting detailed pharmacokinetic

studies in septic patients exhibiting varying degrees of organ

failure to ensure both the safety and synergistic efficacy of these

inhibitors.

Valuable lessons can be drawn from the clinical

development of NLRP3-targeting agents in other inflammatory

diseases, offering notable insights for SIC clinical trial design

and risk management (170).

Primarily, the clinical development of pioneering compounds such as

MCC950 and GDC-2394 was halted due to hepatotoxicity, with

MCC950-associated liver injury linked to its off-target inhibition

of carbonic anhydrase 2 (171).

This underscores the necessity for thorough hepatic safety

profiling of any SIC therapeutic candidate. Secondly, while the

anti-IL-1β monoclonal antibody canakinumab has demonstrated

cardiovascular benefits in the Canakinumab Anti-Inflammatory

Thrombosis Outcome Study trial, it concurrently increased the

incidence of fatal infections and hematological toxicities,

highlighting the inherent immunosuppressive risks associated with

broad anti-cytokine therapy in patient populations, such as

patients with SIC (172).

Finally, although glyburide supported the potential of NLRP3

inhibition in preclinical models, its clinical utility was notably

constrained by dose-limiting hypoglycemia and other off-target

effects, serving as a cautionary tale that the therapeutic benefit

of drug repurposing must be carefully weighed against its inherent

polypharmacology (173).

Collectively, these experiences mandate that future SIC clinical

trial designs prioritize hepatic safety, cautiously evaluate the

consequences of immunosuppression and rigorously select therapeutic

agents with high specificity. The compounds reported to target the

NLRP3 inflammasome for the treatment of SIC are summarized in

Table I (27).

Future investigations should prioritize: i)

Cell-specific NLRP3 functions using conditional knockout/knock-in

models; ii) interorganellar communication mechanisms between NLRP3

and ER/golgi networks; iii) rational optimization of natural

compound-derived inhibitors through structure-activity relationship

studies; and iv) clinical translation initiatives. These

initiatives may include: i) Advanced SIC models with improved

clinical relevance; ii) preclinical development of principal

compounds, such as MCC950; iii) predictive biomarker discovery; iv)

novel drug delivery systems, such as nanoparticle encapsulation;

and v) combination therapies with antibiotics, mitochondrial

protectants or anti-apoptotic agents.

The NLRP3 inflammasome has emerged as a central

molecular hub in SIC pathogenesis. By driving cytokine storms,

inducing cardiomyocyte pyroptosis and apoptosis, disrupting

mitochondrial homeostasis and suppressing protective autophagy, the

NLRP3 inflammasome establishes a self-perpetuating cycle of

inflammation and PCD that culminates in myocardial dysfunction.

Pharmacological targeting of NLRP3 signaling pathways represents a

promising therapeutic strategy for SIC. Therefore, further

elucidating the multifaceted roles of NLRP3 in SIC will accelerate

the development of mechanistically-grounded therapeutic

interventions.

Not applicable.

The present work was supported by Beijing Natural Science

Foundation (grant no. 7232126), the Special Scientific Research

Project of Beijing Critical Care Ultrasound Research Association

(grant no. 2023-CCUSG-A-03), the Medical Health Research Project of

Yichang (grant no. A24-2-011) and the Health Promotion

Project-Academic construction project of adsorption

engineering-Scientific research and academic promotion project for

critical and severe diseases (grant no. QS-XFGCJWZZ-0049).

Not applicable.

The original draft of the manuscript and the figures

were produced by YC. ZZ and GZ were responsible for reviewing and

editing the manuscript and supervision of the study. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW,

Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche

JD, Coopersmith CM, et al: The third international consensus

definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA.

315:801–810. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP,

Fein AM, Knaus WA, Schein RM and Sibbald WJ: Definitions for sepsis

and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative

therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM consensus conference committee.

American college of chest physicians/society of critical care

medicine. Chest. 101:1644–1655. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Cecconi M, Evans L, Levy M and Rhodes A:

Sepsis and septic shock. Lancet. 392:75–87. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Gheen N: Sepsis-3 definitions. Ann Emerg

Med. 68:784–785. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Gong T, Fu Y, Wang Q, Loughran PA, Li Y,

Billiar TR, Wen Z, Liu Y and Fan J: Decoding the multiple functions

of ZBP1 in the mechanism of sepsis-induced acute lung injury.

Commun Biol. 7:13612024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Li Y, Hu C, Zhai P, Zhang J, Jiang J, Suo

J, Hu B, Wang J, Weng X, Zhou X, et al: Fibroblastic reticular

cell-derived exosomes are a promising therapeutic approach for

septic acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 105:508–523. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Song YQ, Lin WJ, Hu HJ, Wu SH, Jing L, Lu

Q and Zhu W: Sodium tanshinone IIA sulfonate attenuates

sepsis-associated brain injury via inhibiting NOD-like receptor

3/caspase-1/gasdermin D-mediated pyroptosis. Int Immunopharmacol.

118:1101112023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Xu JQ, Zhang WY, Fu JJ, Fang XZ, Gao CG,

Li C, Yao L, Li QL, Yang XB, Ren LH, et al: Viral sepsis:

Diagnosis, clinical features, pathogenesis, and clinical

considerations. Mil Med Res. 11:782024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Werdan K, Schmidt H, Ebelt H, Zorn-Pauly

K, Koidl B, Hoke RS, Heinroth K and Müller-Werdan U: Impaired

regulation of cardiac function in sepsis, SIRS, and MODS. Can J

Physiol Pharmacol. 87:266–274. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hasegawa D, Ishisaka Y, Maeda T,

Prasitlumkum N, Nishida K, Dugar S and Sato R: Prevalence and

prognosis of sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. J Intensive Care Med. 38:797–808. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Antonucci E, Fiaccadori E, Donadello K,

Taccone FS, Franchi F and Scolletta S: Myocardial depression in

sepsis: From pathogenesis to clinical manifestations and treatment.

J Crit Care. 29:500–511. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Parker MM, Shelhamer JH, Bacharach SL,

Green MV, Natanson C, Frederick TM, Damske BA and Parrillo JE:

Profound but reversible myocardial depression in patients with

septic shock. Ann Intern Med. 100:483–490. 1984. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

MacLean LD, Mulligan WG, McLean AP and

Duff JH: Patterns of septic shock in man-a detailed study of 56

patients. Ann Surg. 166:543–562. 1967. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Parrillo JE: Pathogenetic mechanisms of

septic shock. N Engl J Med. 328:1471–1477. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Abraham E and Singer M: Mechanisms of

sepsis-induced organ dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 35:2408–2416.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Levy RJ and Deutschman CS: Cytochrome c

oxidase dysfunction in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 35 (9

Suppl):S468–S475. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Mebazaa A, De Keulenaer GW, Paqueron X,

Andries LJ, Ratajczak P, Lanone S, Frelin C, Longrois D, Payen D,

Brutsaert DL and Sys SU: Activation of cardiac endothelium as a

compensatory component in endotoxin-induced cardiomyopathy: role of

endothelin, prostaglandins, and nitric oxide. Circulation.

104:3137–3144. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Hobai IA, Edgecomb J, LaBarge K and

Colucci WS: Dysregulation of intracellular calcium transporters in

animal models of sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy. Shock. 43:3–15.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Miranda M, Balarini M, Caixeta D and

Bouskela E: Microcirculatory dysfunction in sepsis:

Pathophysiology, clinical monitoring, and potential therapies. Am J

Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 311:H24–H35. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Henedak NT, El-Abhar HS, Soubh AA and

Abdallah DM: NLRP3 Inflammasome: A central player in renal

pathologies and nephropathy. Life Sci. 351:1228132024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Tao S, Fan W, Liu J, Wang T, Zheng H, Qi

G, Chen Y, Zhang H, Guo Z and Zhou F: NLRP3 inflammasome: An

Emerging therapeutic target for Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers

Dis. 96:1383–1398. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Tengesdal IW, Dinarello CA and Marchetti

C: NLRP3 and cancer: Pathogenesis and therapeutic opportunities.

Pharmacol Ther. 251:1085452023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Sayaf K, Battistella S and Russo FP: NLRP3

inflammasome in acute and chronic liver diseases. Int J Mol Sci.

25:45372024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wang Y, You YK, Guo J, Wang J, Shao B, Li

H, Meng X, Lan HY and Chen H: C-reactive protein promotes diabetic

kidney disease via Smad3-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

Mol Ther. 33:263–278. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wen Y, Liu Y, Liu W, Liu W, Dong J, Liu Q,

Hao H and Ren H: Research progress on the activation mechanism of

NLRP3 inflammasome in septic cardiomyopathy. Immun Inflamm Dis.

11:e10392023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Toldo S and Abbate A: The role of the

NLRP3 inflammasome and pyroptosis in cardiovascular diseases. Nat

Rev Cardiol. 21:219–237. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhu W, Bao X, Yang Y, Xing M, Xiong S,

Chen S, Zhong Y, Hu X, Lu Q, Wang K, et al: Peripheral evolution of

tanshinone IIA and cryptotanshinone for discovery of a potent and

specific NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor. J Med Chem. 68:3460–3479.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zheng Y, Zhang X, Wang Z, Zhang R, Wei H,

Yan X, Jiang X and Yang L: MCC950 as a promising candidate for

blocking NLRP3 inflammasome activation: A review of preclinical

research and future directions. Arch Pharm (Weinheim).

357:e24004592024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Li H, Guan Y, Liang B, Ding P, Hou X, Wei

W and Ma Y: Therapeutic potential of MCC950, a specific inhibitor

of NLRP3 inflammasome. Eur J Pharmacol. 928:1750912022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Cabral JE, Wu A, Zhou H, Pham MA, Lin S

and McNulty R: Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome for inflammatory

disease therapy. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 46:503–519. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Takeuchi O and Akira S: Pattern

recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 140:805–820. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Chen Y, Ye X, Escames G, Lei W, Zhang X,

Li M, Jing T, Yao Y, Qiu Z, Wang Z, et al: The NLRP3 inflammasome:

Contributions to inflammation-related diseases. Cell Mol Biol Lett.

28:512023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Fu J and Wu H: Structural mechanisms of

NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and activation. Annu Rev Immunol.

41:301–316. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Yu X, Matico RE, Miller R, Chauhan D, Van

Schoubroeck B, Grauwen K, Suarez J, Pietrak B, Haloi N, Yin Y, et

al: Structural basis for the oligomerization-facilitated NLRP3

activation. Nat Commun. 15:11642024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Jo EK, Kim JK, Shin DM and Sasakawa C:

Molecular mechanisms regulating NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell

Mol Immunol. 13:148–159. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Martínez-García JJ, Martínez-Banaclocha H,

Angosto-Bazarra D, de Torre-Minguela C, Baroja-Mazo A, Alarcón-Vila

C, Martínez-Alarcón L, Amores-Iniesta J, Martín-Sánchez F, Ercole

GA, et al: P2X7 receptor induces mitochondrial failure in monocytes

and compromises NLRP3 inflammasome activation during sepsis. Nat

Commun. 10:27112019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Wu QR, Yang H, Zhang HD, Cai YJ, Zheng YX,

Fang H, Wang ZF, Kuang SJ, Rao F, Huang HL, et al: IP3R2-mediated

Ca2+ release promotes LPS-induced cardiomyocyte

pyroptosis via the activation of NLRP3/Caspase-1/GSDMD pathway.

Cell Death Discov. 10:912024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zeng Y, Cao G, Lin L, Zhang Y, Luo X, Ma

X, Aiyisake A and Cheng Q: Resveratrol attenuates sepsis-induced

cardiomyopathy in rats through anti-ferroptosis via the Sirt1/Nrf2

pathway. J Invest Surg. 36:21575212023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Liu S, Bi Y, Han T, Li YE, Wang Q, Wu NN,

Xu C, Ge J, Hu R and Zhang Y: The E3 ubiquitin ligase MARCH2

protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury through

inhibiting pyroptosis via negative regulation of PGAM5/MAVS/NLRP3

axis. Cell Discov. 10:242024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Karasawa T and Takahashi M: The

crystal-induced activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes in

atherosclerosis. Inflamm Regen. 37:182017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Ye T, Wang C, Yan J, Qin Z, Qin W, Ma Y,

Wan Q, Lu W, Zhang M, Tay FR, et al: Lysosomal destabilization: A

missing link between pathological calcification and osteoarthritis.

Bioact Mater. 34:37–50. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Du G, Healy LB, David L, Walker C, El-Baba

TJ, Lutomski CA, Goh B, Gu B, Pi X, Devant P, et al: ROS-dependent

S-palmitoylation activates cleaved and intact gasdermin D. Nature.

630:437–446. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Huang Y, Xu W and Zhou R: NLRP3

inflammasome activation and cell death. Cell Mol Immunol.

18:2114–2127. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Saller BS, Wöhrle S, Fischer L, Dufossez

C, Ingerl IL, Kessler S, Mateo-Tortola M, Gorka O, Lange F, Cheng

Y, et al: Acute suppression of mitochondrial ATP production

prevents apoptosis and provides an essential signal for NLRP3

inflammasome activation. Immunity. 58:90–107.e11. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Ting JP, Lovering RC, Alnemri ES, Bertin

J, Boss JM, Davis BK, Flavell RA, Girardin SE, Godzik A, Harton JA,

et al: The NLR gene family: A standard nomenclature. Immunity.

28:285–287. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Zhu Y, Zhang H, Mao H, Zhong S, Huang Y,

Chen S, Yan K, Zhao Z, Hao X, Zhang Y, et al: FAAH served a key

membrane-anchoring and stabilizing role for NLRP3 protein

independently of the endocannabinoid system. Cell Death Differ.

30:168–183. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Yu S, Fu J, Wang J, Zhao Y, Liu B, Wei J,

Yan X and Su J: The influence of mitochondrial-DNA-driven

inflammation pathways on macrophage polarization: A new perspective

for targeted immunometabolic therapy in cerebral

ischemia-reperfusion injury. Int J Mol Sci. 23:1352021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Zheng X, Zhong T, Ma Y, Wan X, Qin A, Yao

B, Zou H, Song Y and Yin D: Bnip3 mediates doxorubicin-induced

cardiomyocyte pyroptosis via caspase-3/GSDME. Life Sci.

242:1171862020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Rodrigue-Gervais IG and Saleh M: Caspases

and immunity in a deadly grip. Trends Immunol. 34:41–49. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Miao R, Jiang C, Chang WY, Zhang H, An J,

Ho F, Chen P, Zhang H, Junqueira C, Amgalan D, et al: Gasdermin D

permeabilization of mitochondrial inner and outer membranes

accelerates and enhances pyroptosis. Immunity. 56:2523–2541.e8.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Gritte RB, Souza-Siqueira T, Borges da

Silva E, Dos Santos de Oliveira LC, Cerqueira Borges R, Alves HHO,

Masi LN, Murata GM, Gorjão R, Levada-Pires AC, et al: Evidence for

monocyte reprogramming in a long-term postsepsis study. Crit Care

Explor. 4:e07342022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Jin Y, Fleishman JS, Ma Y, Jing X, Guo Q,

Shang W and Wang H: NLRP3 inflammasome targeting offers a novel

therapeutic paradigm for sepsis-induced myocardial injury. Drug Des

Devel Ther. 19:1025–1041. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Shen J, Wu JM, Hu GM, Li MZ, Cong WW, Feng

YN, Wang SX, Li ZJ, Xu M, Dong ED, et al: Membrane nanotubes

facilitate the propagation of inflammatory injury in the heart upon

overactivation of the β-adrenergic receptor. Cell Death Dis.

11:9582020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Wiersinga WJ, Leopold SJ, Cranendonk DR

and van der Poll T: Host innate immune responses to sepsis.

Virulence. 5:36–44. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Fajgenbaum DC and June CH: Cytokine storm.

N Engl J Med. 383:2255–2273. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Blevins HM, Xu Y, Biby S and Zhang S: The

NLRP3 inflammasome pathway: A review of mechanisms and inhibitors

for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Front Aging Neurosci.

14:8790212022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Napodano C, Carnazzo V, Basile V, Pocino

K, Stefanile A, Gallucci S, Natali P, Basile U and Marino M: NLRP3

inflammasome involvement in heart, liver, and lung diseases-A

lesson from cytokine storm syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 24:165562023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Fujimura K, Karasawa T, Komada T, Yamada

N, Mizushina Y, Baatarjav C, Matsumura T, Otsu K, Takeda N,

Mizukami H, et al: NLRP3 inflammasome-driven IL-1β and IL-18

contribute to lipopolysaccharide-induced septic cardiomyopathy. J

Mol Cell Cardiol. 180:58–68. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Sun J, Ge X, Wang Y, Niu L, Tang L and Pan

S: USF2 knockdown downregulates THBS1 to inhibit the TGF-β

signaling pathway and reduce pyroptosis in sepsis-induced acute

kidney injury. Pharmacol Res. 176:1059622022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Xie Y, Li X, Deng W, Nan N, Zou H, Gong L,

Chen M, Yu J, Chen P, Cui D and Zhang F: Knockdown of USF2 inhibits

pyroptosis of podocytes and attenuates kidney injury in lupus

nephritis. J Mol Histol. 54:313–327. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Dong W, Liao R, Weng J, Du X, Chen J, Fang

X, Liu W, Long T, You J, Wang W and Peng X: USF2 activates

RhoB/ROCK pathway by transcriptional inhibition of miR-206 to

promote pyroptosis in septic cardiomyocytes. Mol Cell Biochem.

479:1093–1108. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Zhang Y, Li S, Fan X and Wu Y:

Pretreatment with indole-3-propionic acid attenuates

lipopolysaccharide-induced cardiac dysfunction and inflammation

through the AhR/NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway. J Inflamm Res. 17:5293–5309.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Konvalinka A: myo-Inositol oxygenase: A

novel kidney-specific biomarker of acute kidney injury? Clin Chem.

60:708–710. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Wang Y, Lu J, Lin B, Chen J, Lin F, Zheng

Q, Xue X, Wei Y, Chen S and Xu N: Integrated analysis of MIOX gene

in prognosis of clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Cell Death Dis.

16:3682025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Zhou W, Yu C and Long Y: Myo-inositol

oxygenase (MIOX) accelerated inflammation in the model of

infection-induced cardiac dysfunction by NLRP3 inflammasome. Immun

Inflamm Dis. 11:e8292023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Vitale I, Pietrocola F, Guilbaud E,

Aaronson SA, Abrams JM, Adam D, Agostini M, Agostinis P, Alnemri

ES, Altucci L, et al: Apoptotic cell death in disease-current

understanding of the NCCD 2023. Cell Death Differ. 30:1097–1154.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Fu Y, Zhang HJ, Zhou W, Lai ZQ and Dong

YF: The protective effects of sophocarpine on sepsis-induced

cardiomyopathy. Eur J Pharmacol. 950:1757452023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Mahidhara R and Billiar TR: Apoptosis in

sepsis. Crit Care Med. 28 (4 Suppl):N105–N113. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Maluleke TT, Manilall A, Shezi N, Baijnath

S and Millen AME: Acute exposure to LPS induces cardiac dysfunction

via the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Sci Rep.

14:243782024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Speir M and Lawlor KE: RIP-roaring

inflammation: RIPK1 and RIPK3 driven NLRP3 inflammasome activation

and autoinflammatory disease. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 109:114–124.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Zhou Y, Chai Z, Pandeya A, Yang L, Zhang

Y, Zhang G, Wu C, Li Z and Wei Y: Caspase-11 and NLRP3 exacerbate

systemic Klebsiella infection through reducing mitochondrial ROS

production. Front Immunol. 16:15161202025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Yang Y, Lei W, Qian L, Zhang S, Yang W, Lu

C, Song Y, Liang Z, Deng C, Chen Y, et al: Activation of NR1H3

signaling pathways by psoralidin attenuates septic myocardial

injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 204:8–19. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Qu M, Wang Y, Qiu Z, Zhu S, Guo K, Chen W,

Miao C and Zhang H: Necroptosis, pyroptosis, ferroptosis in sepsis

and treatment. Shock. 57:161–171. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Li N, Zhou H, Wu H, Wu Q, Duan M, Deng W

and Tang Q: STING-IRF3 contributes to lipopolysaccharide-induced

cardiac dysfunction, inflammation, apoptosis and pyroptosis by

activating NLRP3. Redox Biol. 24:1012152019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Wang D, Lin Z, Zhou Y, Su M, Zhang H, Yu L

and Li M: Atractylenolide I ameliorates sepsis-induced

cardiomyocyte injury by inhibiting macrophage polarization through

the modulation of the PARP1/NLRP3 signaling pathway. Tissue Cell.

89:1024242024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Deng C, Liu Q, Zhao H, Qian L, Lei W, Yang

W, Liang Z, Tian Y, Zhang S, Wang C, et al: Activation of NR1H3

attenuates the severity of septic myocardial injury by inhibiting

NLRP3 inflammasome. Bioeng Transl Med. 8:e105172023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

D'Souza CA and Heitman J: Dismantling the

cryptococcus coat. Trends Microbiol. 9:112–113. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Yu P, Zhang X, Liu N, Tang L, Peng C and

Chen X: Pyroptosis: Mechanisms and diseases. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 6:1282021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Zheng X, Chen W, Gong F, Chen Y and Chen

E: The role and mechanism of pyroptosis and potential therapeutic

targets in sepsis: A review. Front Immunol. 12:7119392021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Coll RC, Schroder K and Pelegrín P: NLRP3

and pyroptosis blockers for treating inflammatory diseases. Trends

Pharmacol Sci. 43:653–668. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Yarovinsky TO, Su M, Chen C, Xiang Y, Tang

WH and Hwa J: Pyroptosis in cardiovascular diseases: Pumping

gasdermin on the fire. Semin Immunol. 69:1018092023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Fan Y, Guan B, Xu J, Zhang H, Yi L and

Yang Z: Role of toll-like receptor-mediated pyroptosis in

sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy. Biomed Pharmacother. 167:1154932023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Song C, Zhang Y, Pei Q, Zheng L, Wang M,

Shi Y, Wu S, Ni W, Fu X, Peng Y, et al: HSP70 alleviates

sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy by attenuating mitochondrial

dysfunction-initiated NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis in

cardiomyocytes. Burns Trauma. 10:tkac0432022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Cao Z, Li W, Shao Z, Liu X, Zeng Y, Lin P,

Lin C, Zhao Y, Li T, Zhao Z, et al: Apelin ameliorates

sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction via inhibition of

NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis of cardiomyocytes. Heliyon.

10:e245682024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Duan F, Li L, Liu S, Tao J, Gu Y, Li H, Yi

X, Gong J, You D, Feng Z, et al: Cortistatin protects against

septic cardiomyopathy by inhibiting cardiomyocyte pyroptosis

through the SSTR2-AMPK-NLRP3 pathway. Int Immunopharmacol.

134:1121862024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Lu C, Liu J, Escames G, Yang Y, Wu X, Liu

Q, Chen J, Song Y, Wang Z, Deng C, et al: PIK3CG regulates

NLRP3/GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis in septic myocardial injury.

Inflammation. 46:2416–2432. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Liu Q, Dong Y, Escames G, Wu X, Ren J,

Yang W, Zhang S, Zhu Y, Tian Y, Acuña-Castroviejo D and Yang Y:

Identification of PIK3CG as a hub in septic myocardial injury using

network pharmacology and weighted gene co-expression network

analysis. Bioeng Transl Med. 8:e103842022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Liu S, Yao S, Yang H, Liu S and Wang Y:

Autophagy: Regulator of cell death. Cell Death Dis. 14:6482023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Ren C, Zhang H, Wu TT and Yao YM:

Autophagy: A potential therapeutic target for reversing

sepsis-induced immunosuppression. Front Immunol. 8:18322017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Wang S, Long H, Hou L, Feng B, Ma Z, Wu Y,

Zeng Y, Cai J, Zhang DW and Zhao G: The mitophagy pathway and its

implications in human diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

8:3042023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Shan X, Tao W, Li J, Tao W, Li D, Zhou L,

Yang X, Dong C, Huang S, Chu X and Zhang C: Kai-Xin-San ameliorates

Alzheimer's disease-related neuropathology and cognitive impairment

in APP/PS1 mice via the mitochondrial autophagy-NLRP3 inflammasome

pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 329:1181452024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Lei X, Wang J, Zhang F, Tang X, He F,

Cheng S, Zou F and Yan W: Micheliolide ameliorates

lipopolysaccharide-induced acute kidney injury through suppression

of NLRP3 activation by promoting mitophagy via Nrf2/PINK1/Parkin

axis. Int Immunopharmacol. 138:1125272024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Zhou F, Lian W, Yuan X, Wang Z, Xia C, Yan

Y, Wang W, Tong Z, Cheng Y, Xu J, et al: Cornuside alleviates

cognitive impairments induced by Aβ1-42 through

attenuating NLRP3-mediated neurotoxicity by promoting mitophagy.

Alzheimers Res Ther. 17:472025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Ajoolabady A, Chiong M, Lavandero S,

Klionsky DJ and Ren J: Mitophagy in cardiovascular diseases:

Molecular mechanisms, pathogenesis, and treatment. Trends Mol Med.

28:836–849. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Zhu L, Wang Z, Sun X, Yu J, Li T, Zhao H,

Ji Y, Peng B and Du M: STAT3/Mitophagy axis coordinates macrophage

NLRP3 inflammasome activation and inflammatory bone loss. J Bone

Miner Res. 38:335–353. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Luo L, Wang F, Xu X, Ma M, Kuang G, Zhang

Y, Wang D, Li W, Zhang N and Zhao K: STAT3 promotes NLRP3

inflammasome activation by mediating NLRP3 mitochondrial

translocation. Exp Mol Med. 56:1980–1990. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Nedel W, Deutschendorf C and Portela LVC:

Sepsis-induced mitochondrial dysfunction: A narrative review. World

J Crit Care Med. 12:139–152. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Jing J, Yang F, Wang K, Cui M, Kong N,

Wang S, Qiao X, Kong F, Zhao D, Ji J, et al: UFMylation of NLRP3

prevents its autophagic degradation and facilitates inflammasome

activation. Adv Sci (Weinh). 12:e24067862025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Yang S, Huang G and Ting JP: Mitochondria

and NLRP3: To die or inflame. Immunity. 58:5–7. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Meyers AK, Wang Z, Han W, Zhao Q, Zabalawi

M, Duan L, Liu J, Zhang Q, Manne RK, Lorenzo F, et al: Pyruvate

dehydrogenase kinase supports macrophage NLRP3 inflammasome

activation during acute inflammation. Cell Rep. 42:1119412023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Thorburn J, Xu S and Thorburn A: MAP

kinase- and Rho-dependent signals interact to regulate gene

expression but not actin morphology in cardiac muscle cells. EMBO

J. 16:1888–1900. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Tan Y, Zhang Y, He J, Wu F, Wu D, Shi N,

Liu W, Li Z, Liu W, Zhou H and Chen W: Dual specificity phosphatase

1 attenuates inflammation-induced cardiomyopathy by improving

mitophagy and mitochondrial metabolism. Mol Metab. 64:1015672022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Li FJ, Hu H, Wu L, Luo B, Zhou Y, Ren J,

Lin J, Reiter RJ, Wang S, Dong M, et al: Ablation of mitophagy

receptor FUNDC1 accentuates septic cardiomyopathy through

ACSL4-dependent regulation of ferroptosis and mitochondrial

integrity. Free Radic Biol Med. 225:75–86. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Nie J and Qiu H: DUSP1 mitigates

MSU-induced immune response in gouty arthritis reinforcing

autophagy. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 29:2222024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Jiang H, Chen F, Song D, Zhou X, Ren L and

Zeng M: Dynamin-related protein 1 is involved in mitochondrial

damage, defective mitophagy, and NLRP3 inflammasome activation

induced by MSU crystals. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022:50644942022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Chen S, Ma J, Yin P and Liang F: The

landscape of mitophagy in sepsis reveals PHB1 as an NLRP3

inflammasome inhibitor. Front Immunol. 14:11884822023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Song D, Tao W, Liu F, Wu X, Bi H, Shu J,

Wang D and Li X: Lipopolysaccharide promotes NLRP3 inflammasome

activation by inhibiting TFEB-mediated autophagy in NRK-52E cells.

Mol Immunol. 163:127–135. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Zhang R, Guan S, Meng Z, Zhang D and Lu J:

Ginsenoside Rb1 alleviates 3-MCPD-induced renal cell pyroptosis by

activating mitophagy. Food Chem Toxicol. 186:1145222024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Hu D, Sheeja Prabhakaran H, Zhang YY, Luo

G, He W and Liou YC: Mitochondrial dysfunction in sepsis:

Mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Crit Care. 28:2922024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Silva RCMC: Mitochondria, autophagy and

inflammation: Interconnected in aging. Cell Biochem Biophys.

82:411–426. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Miaczynska M, Christoforidis S, Giner A,

Shevchenko A, Uttenweiler-Joseph S, Habermann B, Wilm M, Parton RG

and Zerial M: APPL proteins link Rab5 to nuclear signal

transduction via an endosomal compartment. Cell. 116:445–456. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Wu KKL and Cheng KKY: A new role of the

early endosome in restricting NLRP3 inflammasome via mitophagy.

Autophagy. 18:1475–1477. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Yu WM, Appler JM, Kim YH, Nishitani AM,

Holt JR and Goodrich LV: A Gata3-Mafb transcriptional network

directs post-synaptic differentiation in synapses specialized for

hearing. Elife. 2:e013412013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Cui H, Banerjee S, Xie N, Dey T, Liu RM,

Sanders YY and Liu G: MafB regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation

by sustaining p62 expression in macrophages. Commun Biol.

6:10472023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Wang J, Wu M, Magupalli VG, Dahlberg PD,

Wu H and Jensen GJ: Human NLRP3 inflammasome activation leads to

formation of condensate at the microtubule organizing center.

bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2024.09.12.612739. 2024.

|

|

116

|

Chen X, Yuan T, Zheng D, Li F, Xu H, Ye M,

Liu S and Li J: Cardiomyocyte mitochondrial mono-ADP-ribosylation

dictates cardiac tolerance to sepsis by configuring bioenergetic

reserve in male mice. Nat Commun. 16:81192025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Wan C and Wang Y: Integrated multi-omics

of mitophagy-related molecular subtype characterization and

biomarker identification in sepsis. Sci Rep. 16:7012025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Mohd S, Sharma V, Harish V, Kumar R and

Pilli G: Exploring thiazolidinedione-naphthalene analogues as

potential antidiabetic agents: Design, synthesis, molecular docking

and in-vitro evaluation. Cell Biochem Biophys. 83:2213–2226. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Hu C, He X, Zhang H, Hu X, Liao L, Cai M,

Lin Z, Xiang J, Jia X, Lu G, et al: Tanshinone I limits

inflammasome activation of macrophage via docking into Syk to

alleviate DSS-induced colitis in mice. Mol Immunol. 173:88–98.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Liang D, Tang S, Liu L, Zhao M, Ma X, Zhao

Y, Shen C, Liu Q, Tang J, Zeng J and Chen N: Tanshinone I

attenuates gastric precancerous lesions by inhibiting epithelial

mesenchymal transition through the p38/STAT3 pathway. Int

Immunopharmacol. 124:1109022023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Zhao J, Liu H, Hong Z, Luo W, Mu W, Hou X,

Xu G, Fang Z, Ren L, Liu T, et al: Tanshinone I specifically

suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome activation by disrupting the

association of NLRP3 and ASC. Mol Med. 29:842023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Dai Y, Zhang X, Xu Y, Wu Y and Yang L: The

protective effects of cinnamyl alcohol against hepatic steatosis,

oxidative and inflammatory stress in nonalcoholic fatty liver

disease induced by childhood obesity. Immunol Invest. 52:1008–1022.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|