Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic,

multisystem autoimmune disease, and renal involvement, which is

referred to as lupus nephritis (LN), occurs in >60% of patients

with SLE (1–3). LN is among the most severe

complications of SLE; if uncontrolled, it can progress to renal

failure and remains a leading cause of mortality in patients with

SLE (4–6). Therefore, elucidating the pathogenic

mechanisms of LN has important clinical significance.

Traditionally, research on LN has focused primarily

on glomerular injury, but growing evidence indicates that

tubulointerstitial pathology plays a key role in both the onset and

progression of LN (7).

Tubulointerstitial lesions are more notably associated with LN

severity than glomerular fibrosis, and markers of tubular injury

(such as tubular proteinuria) often precede microalbuminuria

(8–12). In addition, severe

tubulointerstitial damage has been identified as a major risk

factor for LN progression (13,14).

Mechanistically, epithelial-mesenchymal transition of renal tubular

epithelial cells promotes extracellular matrix deposition and

fibrosis, while infiltration of immune cells (such as macrophages

and lymphocytes) and release of proinflammatory mediators

exacerbate tubular and interstitial injury (14–16).

Multiple signaling pathways, including NF-κB, TGF-β and

Wnt/β-catenin, have been implicated in tubulointerstitial lesion

regulation in LN, underscoring the complex and multifactorial

immune-inflammatory mechanisms involved (17,18).

Fos-related antigen 1 (FRA1) is a member of the

activator protein 1 (AP-1) transcription factor family, which

comprises Fos-family proteins (c-Fos, FosB, FRA1 and FRA2) that

dimerize with Jun-family proteins (19–21).

AP-1 regulates key processes such as cell proliferation,

differentiation and inflammatory responses, and controls cytokine

expression in various immune and inflammatory disorders (22). FRA1 has been implicated not only in

tumorigenesis but also in modulation of inflammatory and autoimmune

diseases, including arthritis, pneumonia, psoriasis, myasthenia

gravis and cardiovascular disorders (22). In immune cells, FRA1 influences

B-cell fate; for example, FRA1 is upregulated in activated B cells

and negatively regulates follicular B-cell differentiation into

plasma cells by suppressing the expression of the key transcription

factor Blimp-1, thereby limiting antibody production (23). In epithelial cells, Li et al

(24) reported that FRA1 disrupts

inflammatory cytokine secretion by medullary thymic epithelial

cells. Thus, the role of FRA1 in immune regulation has received

increasing attention. Promoter regions of numerous inflammatory

cytokines and chemokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-11, IL-8 and

MCP-1, contain AP-1 binding sites, suggesting that FRA1 may

directly regulate their expression (22).

In the context of renal injury, FRA1 also exerts

notable functions; for example, in an acute kidney injury model,

FRA1 expression is upregulated in proximal tubular cells and

mitigates tubular cell damage and inflammation by maintaining

expression of the anti-aging protein Klotho (25). Moreover, a gene-screening study in

IgA nephropathy identified FRA1/2 as novel prognostic biomarkers,

implicating TNF and MAPK signaling pathways in disease progression

(26). Notably, METTL3 has been

shown to exacerbate renal inflammation by enhancing m6A

modification of FRA1 transcripts (27). Nevertheless, the role of FRA1 in LN

and other autoimmune kidney diseases remains unexplored, and its

functions and molecular mechanisms in LN-associated

tubulointerstitial injury remain unclear.

Based on these observations, bioinformatic analysis

of public gene expression datasets was performed to identify FRA1

as a potential key candidate in LN. The present study aimed to

investigate the role of FRA1 in the pathogenesis of LN and to

elucidate its underlying molecular mechanisms. The bioinformatics

analyses were combined with validation in the MRL/lpr mouse model

and in vitro experiments using HK-2 cells to systematically

characterize FRA1 expression patterns and its regulatory effects on

the inflammatory cytokine network in LN. By constructing FRA1

overexpression and knockdown cell models, the impact of FRA1 on

tubular epithelial cell function and inflammatory responses, was

further examined aiming to provide new insights into LN

pathogenesis and to identify potential therapeutic targets.

Materials and methods

Data sources

Gene expression data for renal tubulointerstitial

samples from patients with LN and healthy controls were obtained

from the gene expression omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). A total of

three datasets were included: GSE113342 (47 LN and 10 control

tubulointerstitial samples), GSE200306 (14 LN and 10 control

samples) and GSE127797 (44 LN samples) (28–30).

Probe identifiers were annotated to gene symbols using the platform

annotation file; for genes represented by multiple probes, one

probe was randomly selected to avoid redundancy. Background

correction and normalization were performed with the ‘limma’

package (v3.6.2) (31) in R

(v4.2.1; RStudio, Inc.) to ensure data quality and comparability,

yielding the final gene expression matrices. All analyses adhered

to the principles of The Declaration of Helsinki (2013 revision)

(32).

Identification of differentially

expressed genes (DEGs)

Differential expression analysis between LN and

control tubulointerstitial samples was conducted separately for

GSE113342 and GSE200306 using the ‘limma’ package (31). Genes with |log2fold

change| (|log2FC|)>1 and adjusted P<0.05 were

defined as DEGs. The intersection of DEGs from both datasets was

taken to identify consistently dysregulated genes, and results were

visualized using ggplot2 (v3.3.6; http://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/) and VennDiagram

(v1.7.3).

Functional enrichment analysis

To explore the potential biological roles of DEGs,

gene identifiers were converted using the org.Hs.eg.db package

(v3.22; http://bioconductor.org/packages/org.Hs.eg.db), and

Gene Ontology (GO) (https://geneontology.org/) was used to determine

relevant biological processes (BPs) and molecular functions (MFs)

and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (www.genome.jp/kegg/) for pathway enrichment analyses

were performed with clusterProfiler, with adjusted P<0.05

considered significant (33).

Enrichment results were visualized using ggplot2 (v3.3.6), igraph

(v2.2.1; http://r.igraph.org/) and ggraph

(v2.2.2; http://ggraph.data-imaginist.com/).

Relationship between FRA1 and

immunity

To assess the association between FRA1 expression

and immune cell infiltration in LN tubulointerstitial samples, the

CIBERSORT algorithm was applied, which is a linear support vector

regression-based deconvolution tool that estimates immune cell

proportions from microarray or RNA-seq data (34). In GSE127797, LN samples were

stratified into high- and low-FRA1 expression groups based on the

median, and only samples with CIBERSORT P<0.05 were retained for

subsequent analyses. The correlations between FRA1 expression and

infiltrating immune cell fractions and correlations between FRA1

and tubular epithelial cell-related cytokines were examined; all

visualizations were generated with ggplot2 (v3.3.6).

Animal experiments in MRL/lpr

mice

A total of three female MRL/lpr mice and three

female MRL/MPJ control mice (age, 16 weeks; body weight, 38–46 g)

were obtained from Cavens Biogle (Suzhou) Model Animal Research Co.

Ltd. Mice were maintained under standard housing conditions, which

included a climate-controlled environment at 22±2°C and 50±10%

relative humidity, a 12-h light/dark cycle and free access to food

and water, for 4 weeks and then euthanized for kidney tissue

collection to assess protein expression. All procedures complied

with the AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals (2020) and

approved institutional animal care protocols. Specific humane

endpoints included: Weight loss ≥20% of body weight; inability to

eat or drink; severe dehydration; severe respiratory distress,

paralysis or continuous convulsions; uncontrolled progressive

infection; or unrelievable pain or clinical signs severely

compromised quality of life. Health and behaviour were routinely

monitored, with weekly weighing and observation after enrolment,

and immediate escalation to daily or more frequent monitoring if

abnormalities arose. Mice were deeply anesthetized with

pentobarbital sodium (150–200 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) until loss

of the pedal withdrawal reflex, followed by cervical dislocation to

ensure complete euthanasia. Death was confirmed by the absence of

heartbeat and respiration, dilated pupils and lack of reflex

response. No experimental intervention was performed; MRL/lpr mice,

which spontaneously develop LN (35), were used as the disease model,

whereas MRL/MPJ mice served as healthy controls and were used

solely for terminal tissue collection. The power calculation for

the mouse experiments is shown in Table SI, following the methodology

described by Festing and Altman (36).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Kidney tissues were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered

formalin for 24–48 h at room temperature and were then processed

for paraffin embedding. Paraffin-embedded tissues were cut into

5-µm sections. The sections were dewaxed twice in xylene (15 min

each), rehydrated through a descending ethanol series (100% ethanol

twice, then 95, 85 and 75% ethanol, 5 min each), and rinsed in

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) three times for 5 min each.

Antigen retrieval was performed in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in a

microwave: Medium power for 8 min, rest for 8 min, then low power

for 7 min. Subsequently, the slides were allowed to cool to room

temperature for 20–40 min and then rinsed in PBS (three times, 5

min each). Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by

incubation in 3% hydrogen peroxide at room temperature in the dark

for 25 min, followed by three PBS washes (5 min each). Blocking was

performed using the normal goat serum blocking solution supplied

with the Vectastain ABC Elite HRP Kit (cat. no. SAP-9100; Beijing

Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) according to the

manufacturer's instructions (incubation at room temperature for

10–15 min). For primary antibody incubation, the sections were

incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-FRA1 (cat. no. A5372;

ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.) at a dilution of 1:100 (diluted in PBS)

and incubated overnight at 4°C. After three PBS washes (5 min

each), the sections were incubated with the biotinylated goat

anti-rabbit IgG provided in the Vectastain ABC Elite HRP Kit at a

working dilution of 1:500 for 10–15 min at 37°C, followed by PBS

rinses (3×3 min). The HRP-labeled streptavidin working solution

(provided in the Vectastain ABC Elite HRP Kit) was applied and

incubated for 10–15 min at 37°C according to the manufacturer's

instructions, followed by PBS washes (3×3 min). Chromogenic

detection was performed with DAB substrate (cat. no. ZLI-9017;

Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.); color

development was monitored under the microscope and stopped with

distilled water once an optimal signal was achieved. The sections

were then counterstained with hematoxylin at room temperature for

1–2 min, differentiated in 1% hydrochloric acid-ethanol (~1 sec),

rinsed in running tap water, blued in ammonia water and rinsed

again. Finally, the slides were dehydrated through an ascending

ethanol series (75, 85, 95 and 100%), cleared in xylene and mounted

with neutral resin. The percentage of FRA1-positive area/unit

tissue area was quantified using ImageJ (v2.3.0; National

Institutes of Health). All stained sections were examined and

images were captured using an Olympus BX40 upright light microscope

(Olympus Corporation).

Culture of HK-2 cells and retroviral

infection

HK-2 cells (Pricella; Elabscience Bionovation Inc.)

were maintained in DMEM/F12 (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Beijing

Baiao Leibo Technology Co., Ltd.). A total of four groups were

established: FRA1 overexpression (FRA1-OE), FRA1 knockdown

(FRA1-shRNA) and their respective empty-vector controls (control-OE

and control-shRNA). The FRA1 overexpression vector

(pCDH_CMV_MCS_EF1_copGFP-FRA1) and shRNA vector

(pMAGic7.1-FRA1-shRNA) were constructed at the Clinical Laboratory,

Boai Hospital of Zhongshan (Zhongshan, China); plasmid maps and

sequences are provided in Fig. S1

and Table SII. For retroviral

packaging, 293T cells (Pricella; Elabscience Bionovation Inc.) were

co-transfected with 4 µg total plasmids using

Lipofectamine® 3000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C for 48 h. Specifically, the packaging

system consisted of the packaging plasmid (psPAX2), the envelope

plasmid (pMD2.G) and one of the four aforementioned transfer

plasmids (FRA1-OE, FRA1-shRNA, control-OE or control-shRNA) at a

mass ratio of 4:3:2. For gene manipulation, 2×105 HK-2

cells were infected with retroviral particles [2×107

transducing units/ml; multiplicity of infection=30; supplemented

with 6 µg/ml polybrene (MedChemExpress); infection efficiency

≥85%]. The infection was performed at 37°C for 24 h, after which

the medium was replaced with fresh complete medium. For the

FRA1-shRNA and control-shRNA groups, stably transduced cells were

selected using 3.0 µg/ml puromycin (MedChemExpress) starting 48 h

post-infection for 4 days. No additional selection was performed

for the FRA1-OE and control-OE groups, as the high transduction

efficiency was sufficient for subsequent experiments. All groups

were harvested for further analysis at 144 h post-transduction.

Western blotting

Kidney tissues or HK-2 cells were homogenized in

RIPA buffer (Biosharp Life Sciences), and protein concentrations

were determined using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd.). For HK-2 experiments, cells were harvested

at 144 h post-transduction to allow time for lentiviral reverse

transcription, genomic integration and establishment of stable

transgene expression and for accumulation of downstream protein and

secreted cytokine changes. Lentiviral-mediated expression commonly

requires on the order of 5–7 days to reach stable levels, and

molecular-kinetic studies indicate that reverse transcription and

integration occur during the first few days post-transduction (~3

days) (37,38). Prior studies have documented

progressively increased reporter expression at 48-, 96- and 144-h

post-transduction, and have selected 144 h post-transduction as the

endpoint for subsequent mRNA and protein analyses of FRA1 effects

(24,39,40);

inflammatory mediators in renal cell models are also commonly

measured at ~5 days or later following perturbation (41). Equal amounts of protein (40

µg/lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% gels and were

transferred to PVDF membranes (MilliporeSigma). Protein molecular

weight markers (10–180 kDa; cat. no. 20350ES90; Shanghai Yeasen

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) were run alongside samples to confirm

target sizes. Membranes were blocked in 5% skim milk at 37°C for 1

h, incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight, then washed

with TBS-0.1% Tween-20 (TBST). The primary antibodies used in the

present study included: β-actin (1:5,000; cat. no. bs-0061R;

BIOSS), FRA1 (1:1,000; cat. no. A5372; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.),

IL-1β (1:1,000; cat. no. HA601002; clone no. A7F9; HUABIO), IL-8

(1:1,000; cat. no. ab289967; clone no. EPR26511-74; Abcam), RANTES

(1:1,000; cat. no. 36467; CST Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.), IL-6

(1:2,000; cat. no. DF6087; Affinity Biosciences, Ltd.), MCP-1

(1:2,000; cat. no. A7277; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.), TNF-α

(1:2,000; cat. no. 17590-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), and TGF-β

(1:2,000; cat. no. 81746-2-RR; clone no. 230544B7; Proteintech

Group, Inc.). The membranes were then incubated with HRP-conjugated

secondary antibodies at a 1:50,000 dilution for 30 min at room

temperature. The secondary antibodies use dincluded HRP-Goat anti

Rabbit (cat. no. 5220-0336) and HRP-Goat anti Mouse (cat. no.

5220-0341; SeraCare; LGC Clinical Diagnostics). After further

washing with TBST, bands were visualized using an ECL

Chemiluminescence Detection Kit (Dalian Meilun Biology Technology

Co., Ltd.) with the JS-1070P imaging system (Shanghai Peiqing

Technology Co., Ltd.) and densitometric analysis was performed with

IPWIN60 software (v6.0; Media Cybernetics, Inc.).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed in R (v4.0.3). For

two-group comparisons of continuous variables the following tests

were used: Unpaired Student's t-test for normally distributed data

with equal variances; Welch's t-test for normal data with unequal

variances; and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-normal data. For

multi-group comparisons, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's Honestly

Significant Difference was applied to normal data with equal

variances and the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's post hoc

test was applied for non-normal data. Pearson's correlation was

used for normally distributed variables, and Spearman's correlation

otherwise. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis was

employed to evaluate the predictive performance of upregulated DEGs

for the disease. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Identification of DEGs in LN

tubulointerstitium

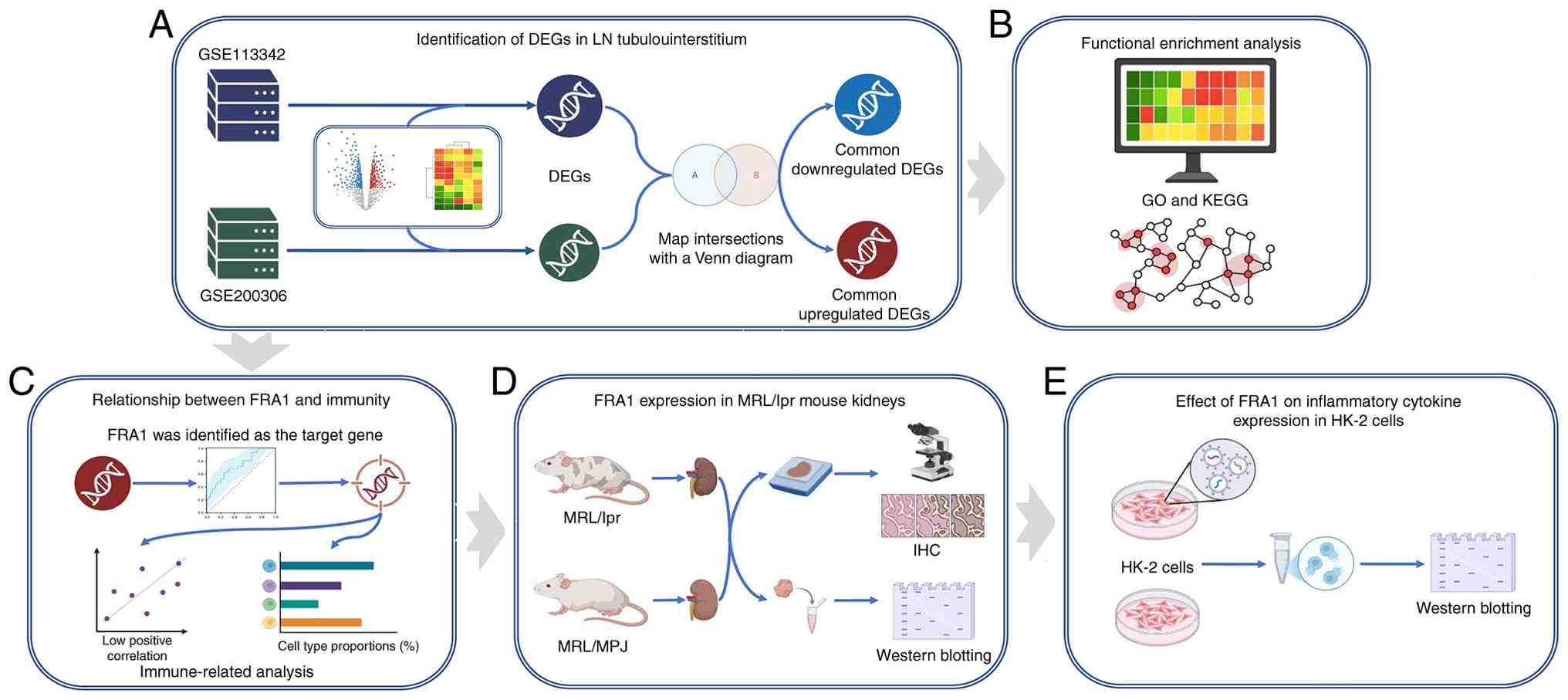

Design of the present study is illustrated in

Fig. 1. To determine gene

expression differences between LN and healthy controls

tubulointerstitial samples, the datasets GSE113342 and GSE200306

from GEO were analyzed. Using |log2FC|>1 and adjusted

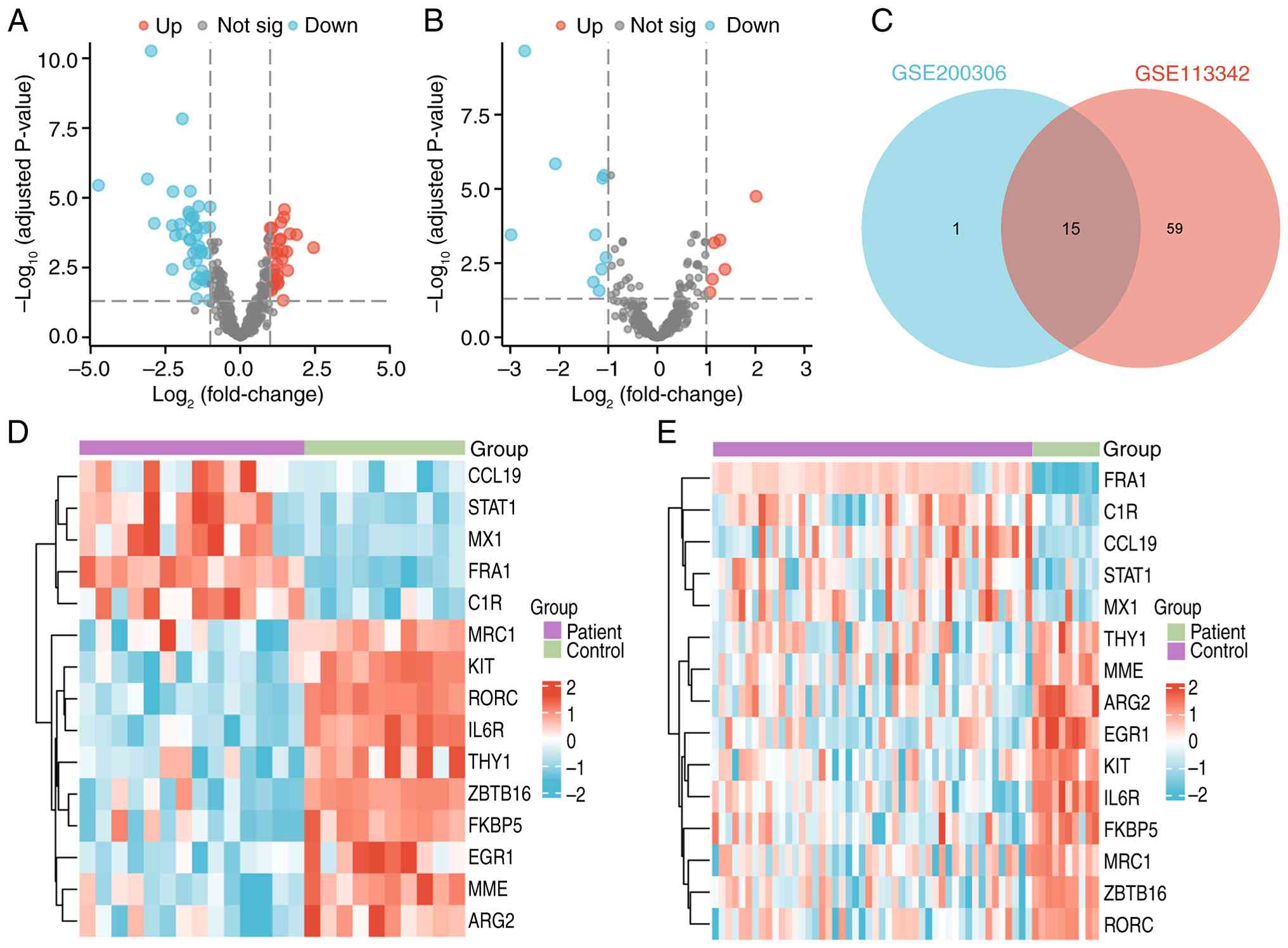

P<0.05, 74 DEGs were identified in GSE113342 (Fig. 2A) and 16 DEGs were identified in

GSE200306 (Fig. 2B). The

intersection of these yielded 15 common DEGs (Fig. 2C), of which FRA1, C1R, CCL19, STAT1

and MX1 were upregulated in LN, whereas THY1, MME, ARG2, EGR1, KIT,

IL6R, FKBP5, MRC1, ZBTB1 and RORC were downregulated. A heatmap

illustrates their expression patterns across both datasets

(Fig. 2D and E).

Functional enrichment of DEGs

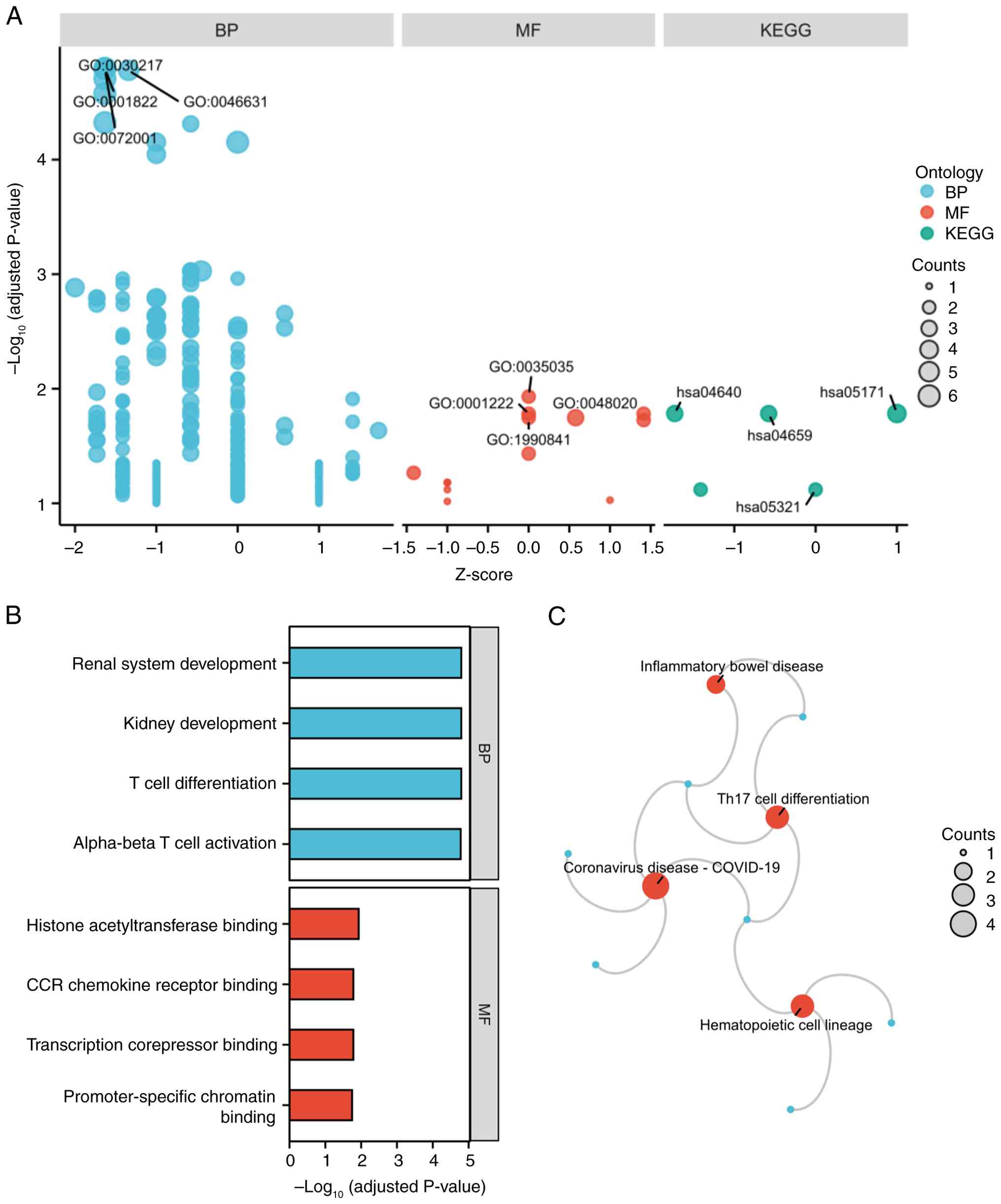

GO and KEGG enrichment analyses of the 15 shared

DEGs revealed significant associations with immune and

developmental processes (Fig. 3A).

In GO-BP, DEGs were enriched in ‘T cell differentiation’, ‘kidney

development’, ‘renal system development’ and ‘alpha-beta T cell

activation’ (Fig. 3B). In GO-MF,

terms included ‘histone acetyltransferase binding’, ‘transcription

corepressor binding’, ‘CCR chemokine receptor binding’,

‘promoter-specific chromatin binding’ (Fig. 3B). KEGG pathways highlighted

‘Coronavirus disease-COVID-19’, ‘Hematopoietic cell lineage’, ‘Th17

cell differentiation’ and ‘Inflammatory bowel disease’ as pathways

significantly associated with the DEGs (Fig. 3C).

Association between FRA1 and immune

cell infiltration

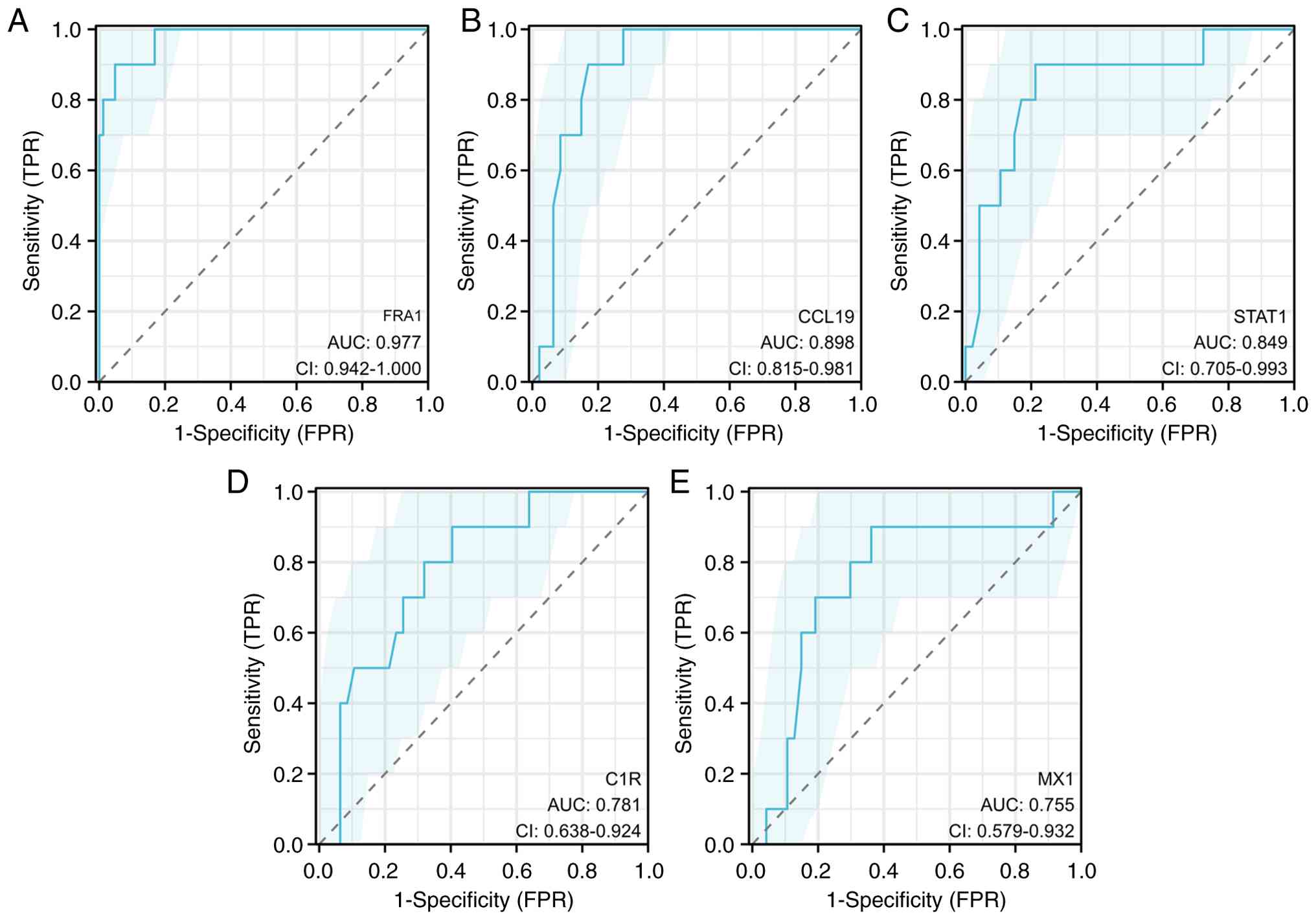

To prioritize candidates for functional follow-up,

the diagnostic performance of five upregulated DEGs was assessed,

and FRA1 was identified as the top performer (AUC=0.977; Fig. 4); therefore, downstream analyses

focused on FRA1. In addition, further analysis of the datasets

showed that the trend of FRA1 remained stable across different

subgroups and after exclusion of outliers, indicating that the

upregulation of FRA1 in LN is robust and minimally affected by

dataset heterogeneity (Fig. S2).

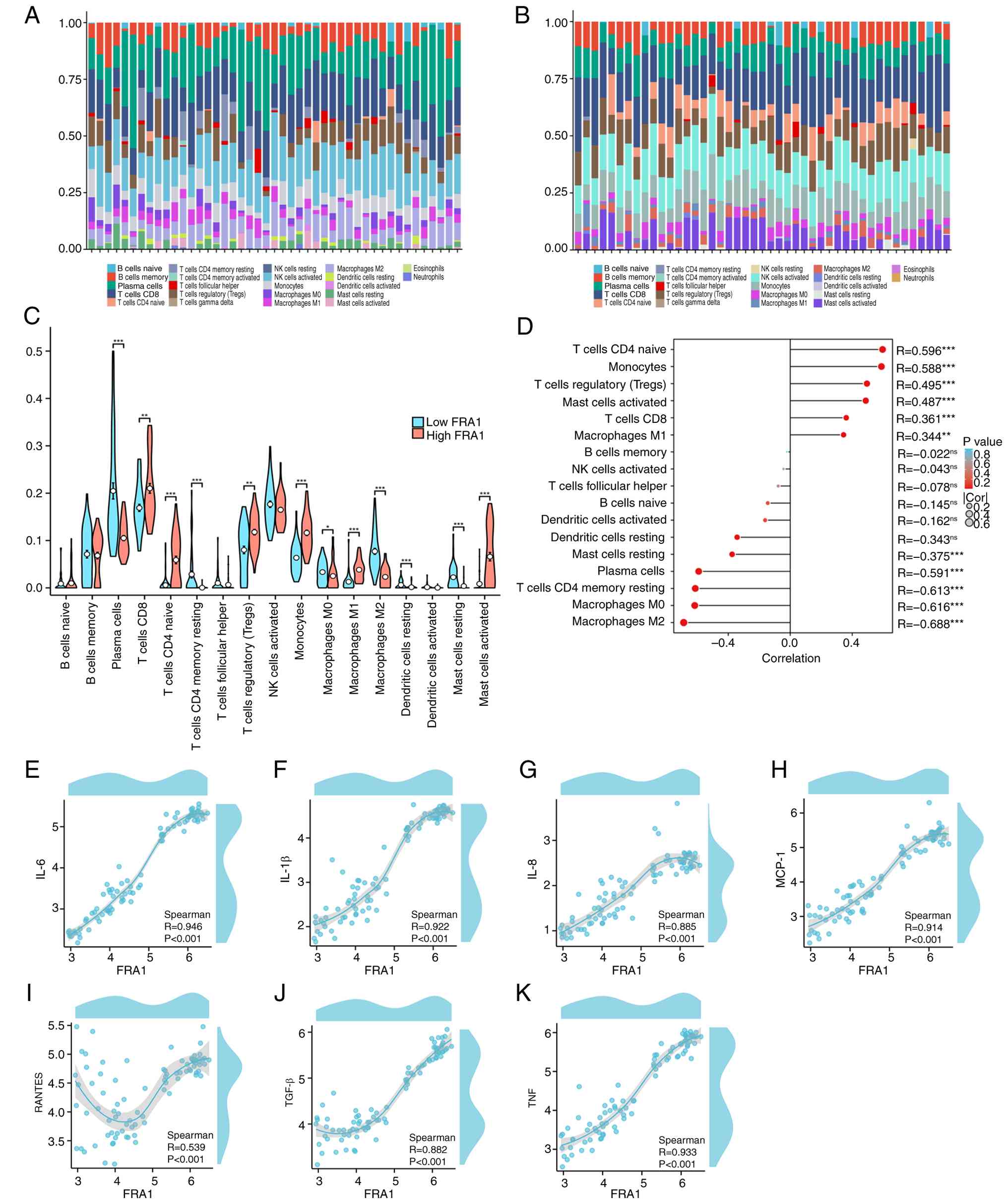

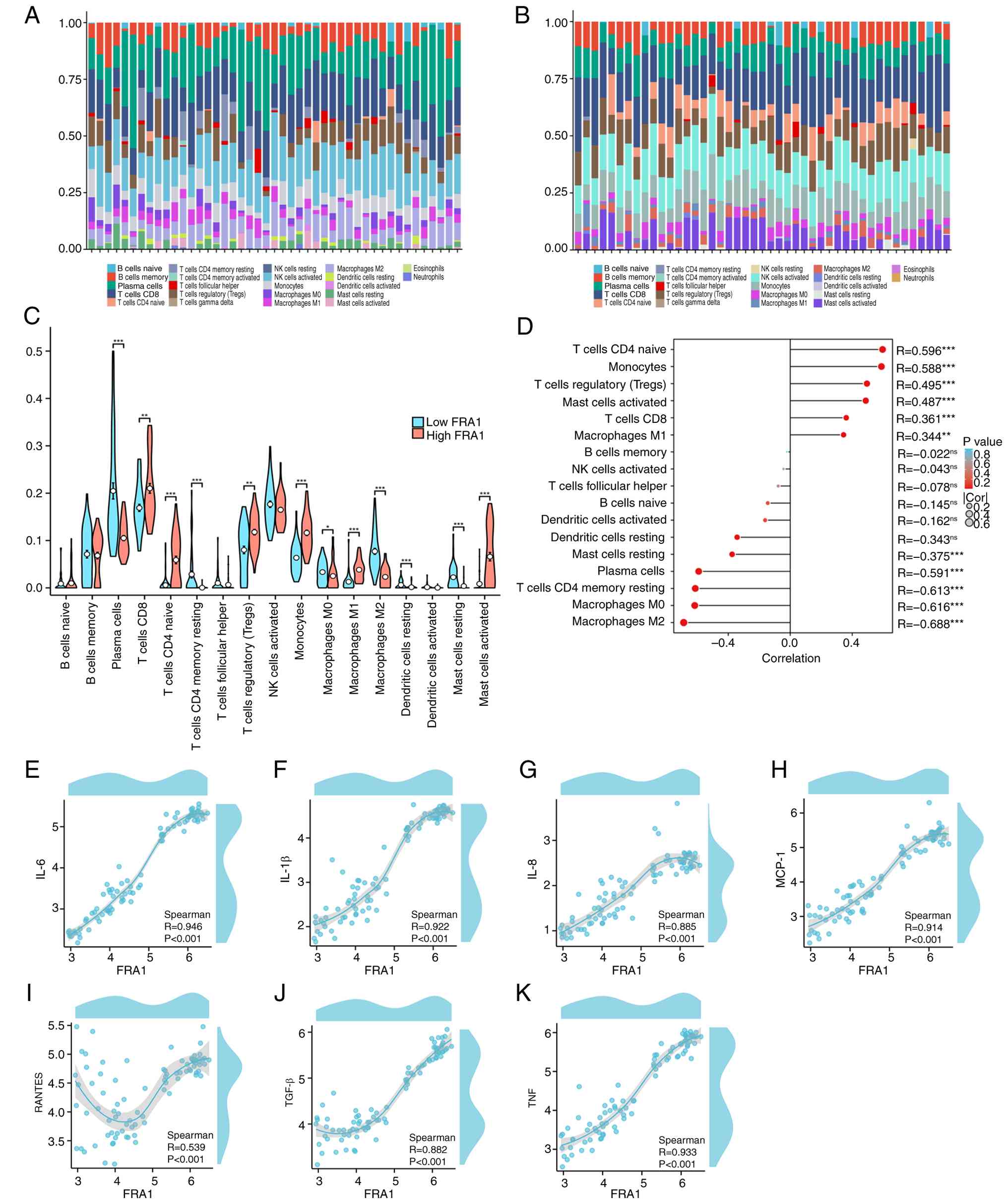

Next, the relationship between FRA1 expression and immune cell

infiltration in LN tubulointerstitial samples was explored using

CIBERSORT on dataset GSE127797.

The results showed statistically increased

proportions of CD8+ T cells, regulatory T cells (Tregs),

monocytes, M1 macrophages and activated mast cells in the high-FRA1

group, whereas plasma cells, resting CD4+ memory T

cells, M0/M2 macrophages, resting dendritic cells and resting mast

cells were reduced (Fig. 5A-C).

Correlation analyses further confirmed these associations.

Specifically, Fig. 5D illustrates

that FRA1 expression was significantly and positively correlated

with several immune cell types, most notably naive CD4+

T cells, monocytes and Tregs. Conversely, FRA1 showed strong

negative correlations with M0/M2 macrophages, resting

CD4+ memory T cells and plasma cells. Furthermore, FRA1

expression was positively correlated with key tubular

epithelial-related cytokines, including IL-6, IL-1β, IL-8, MCP-1,

RANTES, TGF-β and TNF (Fig. 5E-K).

Collectively, these findings underscore the diagnostic potential of

FRA1 among upregulated DEGs and also suggest a key immunomodulatory

role for FRA1 in the tubulointerstitial microenvironment of LN.

| Figure 5.Association between FRA1 and immune

cell infiltration. CIBERSORT-estimated immune cell proportions in

each sample stratified by FRA1 expression (median split): (A)

Low-Fra1 group; (B) high-Fra1 group. (C) Bar plots comparing the

proportions of immune cell types between high- and low-FRA1 groups.

Cells significantly increased in the high-FRA1 group included

CD8+ T cells, T regulatory cells, monocytes, M1

macrophages and activated mast cells; cells reduced in the

high-FRA1 group included plasma cells, resting CD4+

memory T cells, M0/M2 macrophages, resting dendritic cells and

resting mast cells (mean ± SEM; n=44; group comparisons were

performed using two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum tests; *P<0.05;

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001). (D) Spearman correlation analyses

showing associations between FRA1 expression and immune cell

fractions, as well as tubular epithelial-related cytokines,

including (E) IL-6, (F) IL-1β, (G) IL-8, (H) MCP-1 (CCL2), (I)

RANTES (CCL5), (J) TGF-β and (K) TNF. All correlation tests are

two-sided Spearman rank tests; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001. |

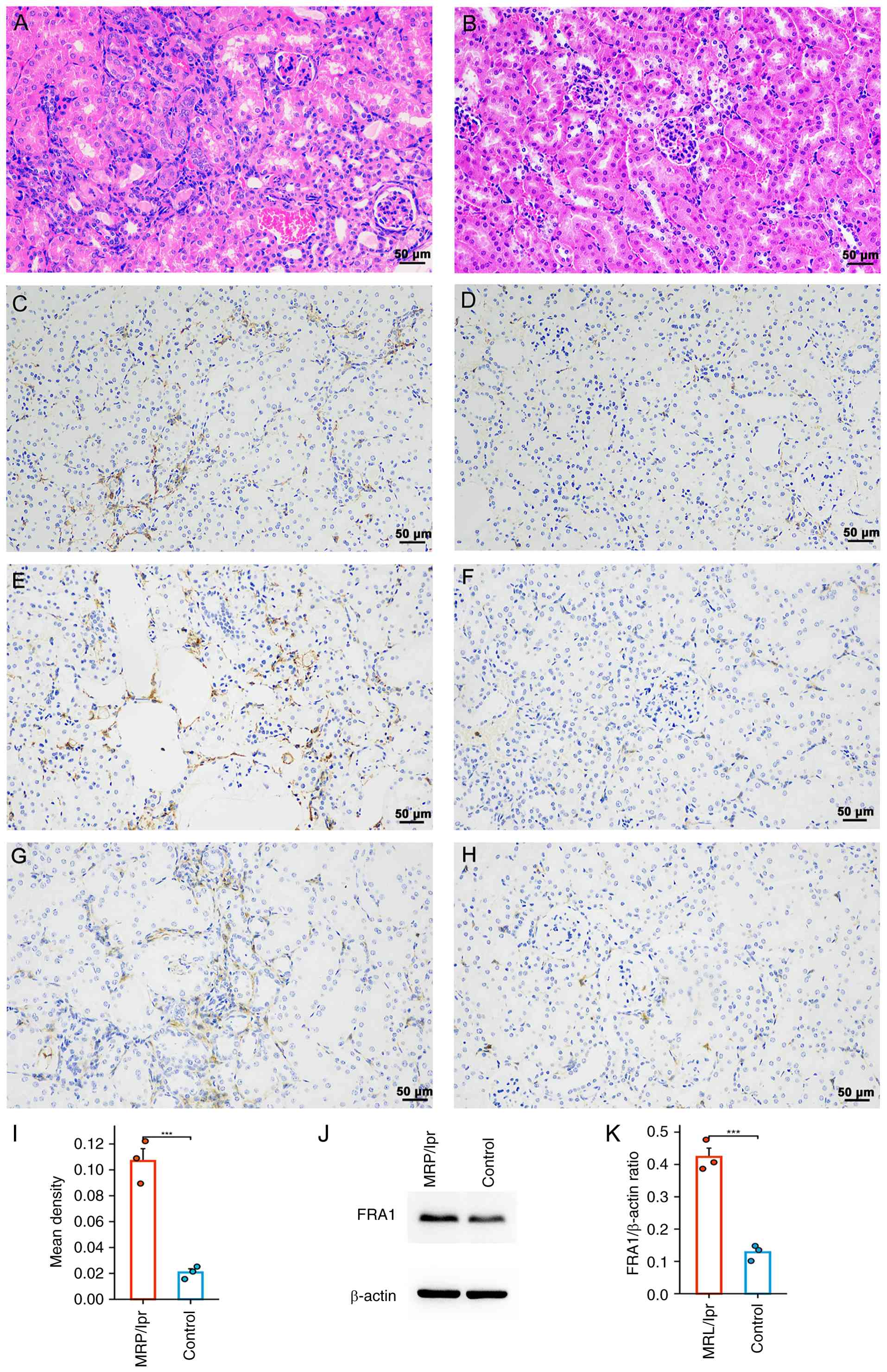

FRA1 expression in MRL/lpr mouse

kidneys

To verify the expression of FRA1 in LN kidneys,

kidneys from 20-week-old MRL/lpr mice were used. Compared with the

control group, H&E staining of MRL/lpr mouse kidneys showed

marked inflammatory infiltration (Fig.

6A and B), and tubulointerstitial injury was a distinctive and

prominent feature of the diseased kidneys. Moreover, IHC revealed

significantly increased FRA1 expression in tubular epithelial cells

of MRL/lpr kidneys compared with the control (Fig. 6C-I), which was corroborated by

elevated protein levels in western blot analysis (Fig. 6J and K).

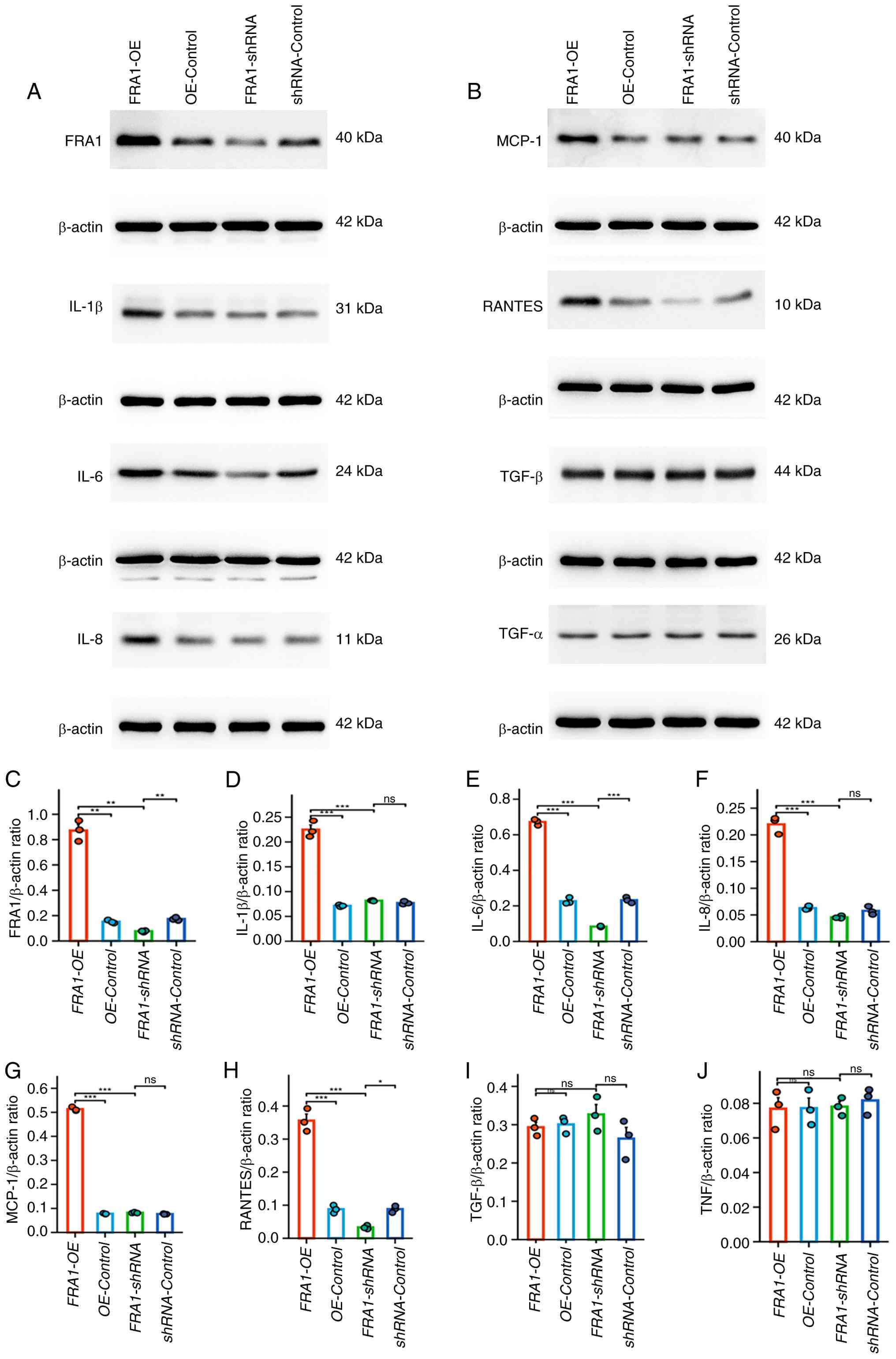

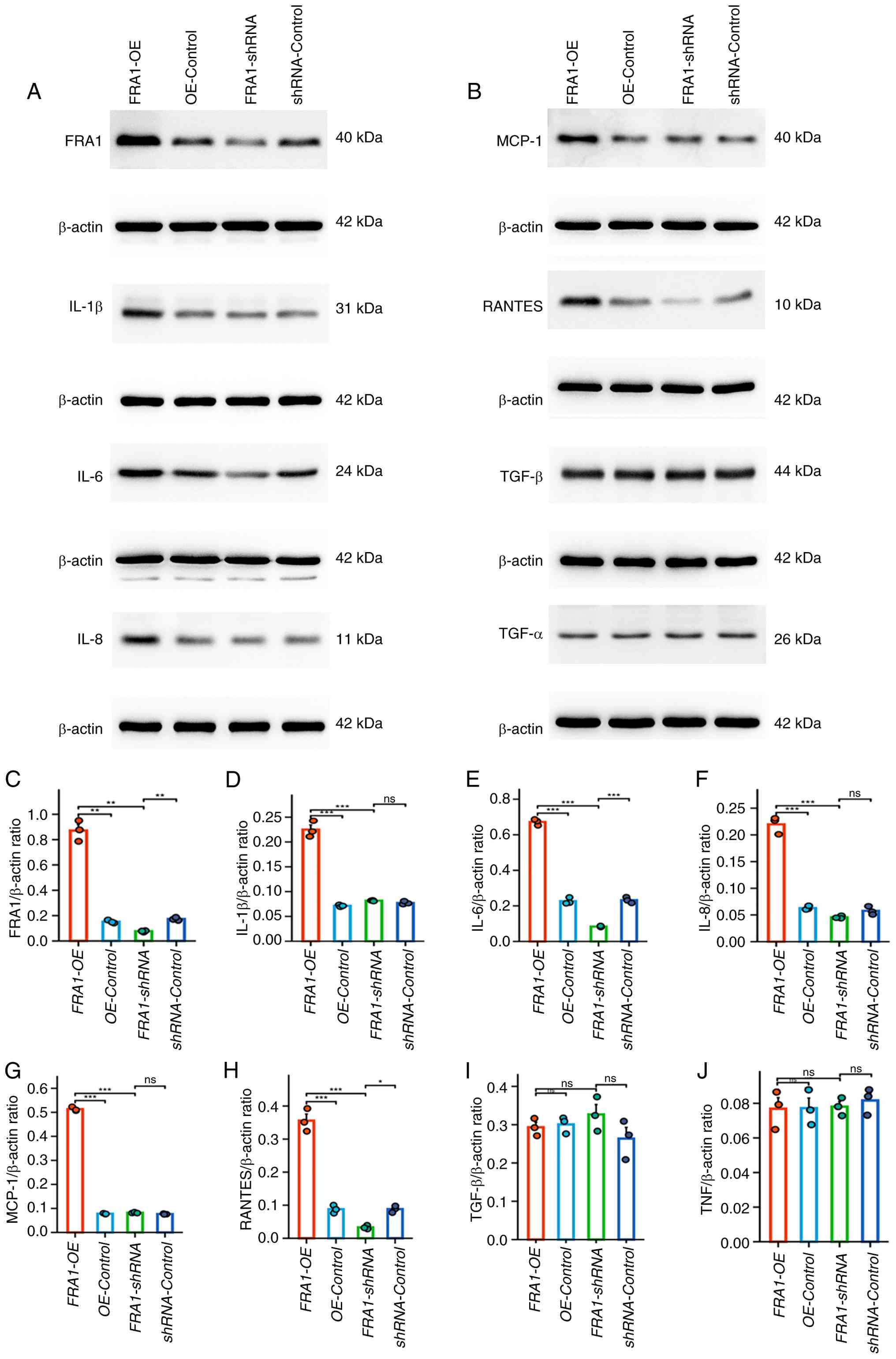

Effect of FRA1 on inflammatory

cytokine expression in HK-2 cells

To investigate the functional role of FRA1 in renal

tubular epithelial cells, the expression of key cytokines were

measured in HK-2 cells following lentivirus-mediated FRA1

overexpression (FRA1-OE) or knockdown (FRA1-shRNA). Western blot

analysis at 144 h post-infection showed that IL-6, IL-1β, IL-8,

MCP-1 and RANTES were significantly upregulated in the FRA1-OE

group, whereas IL-6 and RANTES levels were decreased in the

FRA1-shRNA group (Fig. 7). TNF-α

and TGF-β expression remained unchanged in both FRA1-OE and

FRA1-shRNA cells. These results demonstrate that FRA1 modulates

multiple proinflammatory cytokines in human renal tubular

epithelial cells, suggesting its potential role as a regulator of

the tubulointerstitial immune microenvironment in LN.

| Figure 7.Effect of FRA1 on inflammatory

cytokine expression in HK-2 cells. (A) Representative western blots

of FRA1 and inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8) in HK-2

cells 144 h after transduction with FRA1-OE, FRA1-shRNA or their

corresponding controls. (B) Representative western blots of MCP-1,

RANTES, TGF-β and TNF-α in HK-2 cells following the same

transduction conditions. Densitometric semi-quantification of

protein bands normalized to β-actin for: (C) FRA1, (D) IL-1β, (E)

IL-6, (F) IL-8, (G) MCP-1, (H) RANTES, (I) TGF-β and (J) TNF-α.

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM; n=3 per group; comparisons

among subgroups were assessed using the two-sided Kruskal-Wallis

test; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. OE, over

expression; ns, not significant; sh, short hairpin. |

Discussion

In the present study, an integrated analysis of FRA1

expression and its association with the immune microenvironment in

the renal tubulointerstitium of patients with LN was performed.

Bioinformatic analyses revealed significant upregulation of FRA1 in

LN tubulointerstitial samples, and CIBERSORT deconvolution

demonstrated that high FRA1 expression coincided with increased

infiltration of CD8+ T cells, Tregs, monocytes, M1

macrophages and activated mast cells, alongside decreased

proportions of plasma cells, resting CD4+ memory T

cells, M0/M2 macrophages, resting dendritic cells and resting mast

cells. These correlations suggest that FRA1 contributes to shaping

a proinflammatory microenvironment in LN. Consistent with the

bioinformatics analysis of GEO datasets, kidneys from MRL/lpr mice

exhibited elevated tubular epithelial FRA1 expression. In

vitro, FRA1 overexpression in HK-2 cells markedly increased

levels of IL-6, IL-1β, IL-8, MCP-1 and RANTES, whereas FRA1

knockdown resulted in reduced expression of IL-6 and RANTES.

Collectively, these data indicate that FRA1 may promote

tubulointerstitial inflammation in LN by modulating key

proinflammatory cytokines.

Prior research has indicated that LN renal tissue

exhibits abundant immune cell infiltration and a pro-inflammatory

cytokine environment, and that the renal microenvironment can

bidirectionally regulate immune cell recruitment, survival and

function (42). M1 macrophages in

LN are considered to be associated with disease activity, whereas

M2 macrophages are more commonly associated with the remission

phase (43). In the present study,

an increase in M1 macrophages and a decrease in M2 macrophages in

the FRA1-high group was observed, consistent with the

proinflammatory and alleviating roles attributed to these subsets

in LN (43). Additionally, the

increased monocyte infiltration may also promote macrophage

proliferation and activation (44). Notably, Tregs were also increased

in the FRA1-high group, despite their canonical role as suppressors

of SLE/LN inflammation (43); this

apparent paradox can be explained by several non-exclusive

considerations: i) Increased Foxp3+Treg infiltration has

been reported in active/proliferative LN and lupus-prone mouse

models and may reflect compensatory recruitment or expansion in

response to intense local inflammation rather than restored

suppressive function (45,46); ii) inflammatory milieus,

characterized by cytokines such as IL-6, can impair Treg stability

and suppressive capacity and promote phenotypic plasticity toward

exhausted or effector-like states (such as IL-17 production)

(46,47); and iii) CIBERSORT estimates only

relative cell proportions from bulk transcriptomes and cannot

determine Treg functional status. Thus, the increased Treg

frequency observed in the FRA1-high group may represent numerically

expanded but functionally compromised Tregs that fail to restrain

local LN inflammation (46,48).

The reduction in plasma cells in the FRA1 high-expression group may

reflect the fact that plasma cell aggregation and antibody

production mainly occur in the glomerular region (23,49),

whereas the present analysis focused on interstitial infiltration.

Overall, upregulation of FRA1 is consistent with increased

proinflammatory cell infiltration and aligns with the inflammatory

phenotype of LN renal tissue.

FRA1, as a member of the AP-1 transcription factor

family, regulates the expression of various inflammation-related

genes, including pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-6 and TNF),

chemokines (such as MCP-1 and CXCL1) and matrix metalloproteinases

(22). Prior research has

indicated that the promoter regions of several pro-inflammatory

cytokines contain AP-1 binding sites, suggesting that AP-1 can

directly participate in the transcriptional regulation of these

genes (22). FRA1 can both form

heterodimers with the Jun family to activate gene expression and

may also suppress target genes under specific contexts (50–52).

The present data demonstrated that FRA1 overexpression upregulates

IL-6, a cytokine implicated in promoting antibody-mediated renal

inflammation; IL-6 deficiency delays LN onset and reduces renal

macrophage and T-cell infiltration in MRL/lpr mice (53). Therefore, FRA1-mediated

upregulation of IL-6 may exacerbate LN pathogenesis. MCP-1 is a key

chemokine in LN, produced by renal intrinsic cells and extensively

attracting monocytes/macrophages to inflammatory sites (54); the present study revealed that FRA1

overexpression induced MCP-1 upregulation, which may explain the

increased monocyte and M1 macrophage infiltration in the high-FRA1

group. Similarly, RANTES recruits immune cells such as T cells and

natural killer cells, and research has reported elevated urinary

RANTES levels in patients during active LN (55); FRA1-driven upregulation of RANTES

may also promote T cell (including CD8+ T cells and Tregs)

chemotaxis to the kidney (56–58).

IL-8 is a known neutrophil chemokine that is upregulated in various

nephritis conditions, and its pro-inflammatory effects may

indirectly affect other cell types through interactions (59). FRA1 can exert context-dependent

regulatory effects on IL-6 and other cytokines, influenced by cell

type, microenvironmental stimuli and dimer composition (60–62).

Future work should investigate whether the selective effects of

FRA1 knockdown on IL-6 and RANTES involve distinct AP-1 dimer

configurations or specific co-factor interactions.

FRA1 appears to carry out context-dependent roles

across different forms of renal injury. In an acute kidney injury

model, FRA1 was reported to be protective by preserving expression

of the anti-aging protein Klotho, thereby mitigating tubular damage

and inflammation (25). By

contrast, a bioinformatic screen in IgA nephropathy identified

FRA1/2 among prognostic candidates associated with TNF and MAPK

signaling, consistent with an inflammatory/prognostic association

(26); the present data in LN

align more closely with a proinflammatory role. These apparently

divergent roles may reflect several non-exclusive,

context-dependent factors, for example, acute vs. chronic injury

dynamics, differences in the principal affected cell types,

variation in upstream signaling milieus that influence AP-1

dimerization and post-transcriptional or epigenetic modulation

(such as m6A) of FRA1 expression or activity (27). These factors can alter the partner

selection, co-factor recruitment and promoter occupancy of FRA1,

thereby producing disease-specific transcriptional outputs.

The present study has several limitations; first,

the present data are primarily correlative and derived from in

vitro and ex vivo analyses. Definitive causal roles for

FRA1 in LN pathogenesis will require in vivo manipulation

(such as tubular epithelial-specific FRA1 knockout or

pharmacological inhibition) with larger sample sizes to assess its

effects on renal inflammation and function. Although empty-vector

controls were used to minimize non-specific viral effects,

potential vector integration and shRNA off-target effects cannot be

completely excluded. Second, although the present study

demonstrated that FRA1-dependent changes in selected cytokines, the

direct transcriptional targets of FRA1 in tubular cells remain to

be identified; chromatin immunoprecipitation or promoter-reporter

assays were not performed to confirm FRA1 binding at putative AP-1

sites, and these experiments constitute a clear next step. Third,

the different AP-1 dimer combinations were not distinguished or the

contributions of other Fos/Jun family members were not evaluated,

which may modulate FRA1 activity and selectivity. Fourth, the

present focus on the tubulointerstitium warrants complementary

studies in glomerular compartments and in additional cell types; in

particular, functional interrogation of FRA1 in LN-relevant immune

cells (such as macrophages and T cells) and in glomerular cells

would help determine cell-type-specific roles. Moreover,

species-specific differences between rodent models and human LN

necessitate analyses of human clinical samples to confirm the

translational relevance of FRA1 as a potential biomarker or

therapeutic target. Further investigation of classical profibrotic

and epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers (such as fibronectin,

collagen I and α-SMA) in FRA1 overexpression and knockdown models

would be valuable. Finally, it is worth considering the

translational potential of targeting FRA1/AP-1; for example,

small-molecule AP-1 inhibitors have shown efficacy in preclinical

kidney disease models: The selective c-Fos/AP-1 inhibitor T-5224

ameliorates renal inflammation and fibrosis in murine injury

models, and other AP-1 pathway blockers (such as the JNK inhibitor

SP600125) exhibit protective effects in inflammatory disease

(63). Thus, FRA1-directed

therapies or biomarker strategies, leveraging existing AP-1

modulators, could be explored in future studies of LN.

In conclusion, the present integrative analysis and

experimental validation revealed that FRA1 was upregulated in LN

tubulointerstitium and likely contributes to a proinflammatory

immune microenvironment by driving expression of key cytokines.

These findings position the FRA1/AP-1 axis as a novel regulator of

renal inflammation in LN and highlight its potential as a target

for therapeutic intervention. Further mechanistic and in

vivo studies are warranted to exploit FRA1 modulation for LN

treatment.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by the Social Welfare and Basic

Research Project Fund of Zhongshan City (grant no. 2021B1088).

Availability of data and materials

The gene expression datasets analyzed in the present

study are publicly available from the Gene Expression Omnibus

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/)

under accession numbers GSE113342, GSE200306 and GSE127797. All

other data generated during the present study may be requested from

the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

WN, JH, ZZ, JK, RL and GG contributed to the

research conception and design. WN, JH, ZZ, JK and RL performed the

experiments and drafted the manuscript. LW, YC, CZ, YL, JP and KD

analyzed and interpreted the raw data. WN, JH, ZZ, JK, RL, GG, JP

and KD confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal studies were approved by the ethics

committee of Boai Hospital of Zhongshan (approval no.

WHMYS-20250096). All animal operations were performed in compliance

with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use

of Laboratory Animals.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

LN

|

lupus nephritis

|

|

AP-1

|

Activator Protein 1

|

|

FRA1

|

Fos-related antigen 1

|

|

GEO

|

Gene Expression Omnibus

|

|

Tregs

|

regulatory T cells

|

|

SLE

|

systemic lupus erythematosus

|

|

DEGs

|

differentially expressed genes

|

|

GO

|

Gene Ontology

|

|

KEGG

|

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes

|

|

IHC

|

immunohistochemistry

|

References

|

1

|

Singh S, Saxena R and Palmer BF: Lupus

nephritis. Am J Med Sci. 337:451–460. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Pons-Estel GJ, Serrano R, Plasín MA,

Espinosa G and Cervera R: Epidemiology and management of refractory

lupus nephritis. Autoimmun Rev. 10:655–663. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Guimarães JAR, Furtado SDC, Lucas ACDS,

Mori B and Barcellos JFM: Diagnostic test accuracy of novel

biomarkers for lupus nephritis-An overview of systematic reviews.

PLoS One. 17:e02750162022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Qi J, Wu T, Wang J, Zhang J, Chen L, Jiang

Z, Li Y, Jiang H, Sun Q, Gu Q and Ying Z: Research trends and

frontiers in lupus nephritis: A bibliometric analysis from 2012 to

2022. Int Urol Nephrol. 56:781–794. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kostopoulou M, Pitsigavdaki S and Bertsias

G: Lupus nephritis: Improving treatment options. Drugs. 82:735–748.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Parodis I, Rovin BH, Tektonidou MG, Anders

HJ, Malvar A, Mok CC and Mohan C: Lupus nephritis. Nat Rev Dis

Primers. 11:692025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Cen B, Liao W, Wang Z, Gao L, Wei Y, Huang

W, He S, Wang W, Liu X, Pan X and Ji A: Gelofusine attenuates

tubulointerstitial injury induced by cRGD-conjugated siRNA by

regulating the TLR3 signaling pathway. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids.

11:300–311. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Parikh SV, Madhavan S, Shapiro J, Knight

R, Rosenberg AZ, Parikh CR, Rovin B and Menez S; Kidney Precision

Medicine Project, : Characterization of glomerular and

tubulointerstitial proteomes in a case of nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory drug-attributed acute kidney injury: A clinical

pathologic molecular correlation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol.

18:402–410. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Hong S, Healy H and Kassianos AJ: The

emerging role of renal tubular epithelial cells in the

immunological pathophysiology of lupus nephritis. Front Immunol.

11:5789522020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Gomes MF, Mardones C, Xipell M, Blasco M,

Solé M, Espinosa G, García-Herrera A, Cervera R and Quintana LF:

The extent of tubulointerstitial inflammation is an independent

predictor of renal survival in lupus nephritis. J Nephrol.

34:1897–1905. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Rijnink EC, Teng YKO, Wilhelmus S,

Almekinders M, Wolterbeek R, Cransberg K, Bruijn JA and Bajema IM:

Clinical and histopathologic characteristics associated with renal

outcomes in lupus nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 12:734–743.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Tesch GH: Review: Serum and urine

biomarkers of kidney disease: A pathophysiological perspective.

Nephrology (Carlton). 15:609–616. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hill GS, Delahousse M, Nochy D, Mandet C

and Bariéty J: Proteinuria and tubulointerstitial lesions in lupus

nephritis. Kidney Int. 60:1893–1903. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Pamfil C, Makowska Z, De Groof A, Tilman

G, Babaei S, Galant C, Montigny P, Demoulin N, Jadoul M, Aydin S,

et al: Intrarenal activation of adaptive immune effectors is

associated with tubular damage and impaired renal function in lupus

nephritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 77:1782–1789. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Wang S and Lan HY:

Macrophages promote renal fibrosis through direct and indirect

mechanisms. Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 4:34–38. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Chen H, Liu N and Zhuang S: Macrophages in

renal injury, repair, fibrosis following acute kidney injury and

targeted therapy. Front Immunol. 13:9342992022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wang XD, Huang XF, Yan QR and Bao CD:

Aberrant activation of the WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway in lupus

nephritis. PLoS One. 9:e848522014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Gröne EF, Federico G, Nelson PJ, Arnold B

and Gröne HJ: The hormetic functions of Wnt pathways in tubular

injury. Pflugers Arch. 469:899–906. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Shaulian E and Karin M: AP-1 as a

regulator of cell life and death. Nat Cell Biol. 4:E131–E136. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Madrigal P and Alasoo K: AP-1 takes centre

stage in enhancer chromatin dynamics. Trends Cell Biol. 28:509–511.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Gozdecka M and Breitwieser W: The roles of

ATF2 (activating transcription factor 2) in tumorigenesis. Biochem

Soc Trans. 40:230–234. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

He YY, Zhou HF, Chen L, Wang YT, Xie WL,

Xu ZZ, Xiong Y, Feng YQ, Liu GY, Li X, et al: The Fra-1: Novel role

in regulating extensive immune cell states and affecting

inflammatory diseases. Front Immunol. 13:9547442022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Grötsch B, Brachs S, Lang C, Luther J,

Derer A, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, Bozec A, Fillatreau S, Berberich

I, Hobeika E, et al: The AP-1 transcription factor Fra1 inhibits

follicular B cell differentiation into plasma cells. J Exp Med.

211:2199–2212. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Li QR, Ni WP, Lei NJ, Yang JY, Xuan XY,

Liu PP, Gong GM, Yan F, Feng YS, Zhao R and Du Y: The

overexpression of Fra1 disorders the inflammatory cytokine

secretion by mTEC of myasthenia gravis thymus. Scand J Immunol.

88:e126762018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Cuarental L, Ribagorda M, Ceballos MI,

Pintor-Chocano A, Carriazo SM, Dopazo A, Vazquez E, Suarez-Alvarez

B, Cannata-Ortiz P, Sanz AB, et al: The transcription factor Fosl1

preserves Klotho expression and protects from acute kidney injury.

Kidney Int. 103:686–701. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Qian W, Wang X and Zi Y: Screening and

bioinformatics analysis of IgA nephropathy gene based on GEO

databases. Biomed Res Int. 2019:87940132019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Liu T, Zhuang XX, Li Zhu X, Wu X, Juan Qin

X, Bing Wei L, Chen Gao Y and Rong Gao J: Inhibition of METTL3

promotes mesangial cell mitophagy and attenuates glomerular damage

by alleviating FOSL1 m6A modifications via IGF2BP2-dependent

mechanisms. Biochem Pharmacol. 236:1168672025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Parikh SV, Malvar A, Song H, Shapiro J,

Mejia-Vilet JM, Ayoub I, Almaani S, Madhavan S, Alberton V, Besso

C, et al: Molecular profiling of kidney compartments from serial

biopsies differentiate treatment responders from non-responders in

lupus nephritis. Kidney Int. 102:845–865. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Mejia-Vilet JM, Parikh SV, Song H, Fadda

P, Shapiro JP, Ayoub I, Yu L, Zhang J, Uribe-Uribe N and Rovin BH:

Immune gene expression in kidney biopsies of lupus nephritis

patients at diagnosis and at renal flare. Nephrol Dial Transplant.

34:1197–1206. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Almaani S, Prokopec SD, Zhang J, Yu L,

Avila-Casado C, Wither J, Scholey JW, Alberton V, Malvar A, Parikh

SV, et al: Rethinking lupus nephritis classification on a molecular

level. J Clin Med. 8:15242019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW,

Shi W and Smyth GK: limma powers differential expression analyses

for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res.

43:e472015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

World Medical Association, . World medical

association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical

research involving human subjects. JAMA. 310:2191–2194. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y and He QY:

clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among

gene clusters. OMICS. 16:284–287. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, Gentles AJ,

Feng W, Xu Y, Hoang CD, Diehn M and Alizadeh AA: Robust enumeration

of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods.

12:453–457. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Li Y, Ding T, Chen J, Ji J, Wang W, Ding

B, Ge W, Fan Y and Xu L: The protective capability of Hedyotis

diffusa Willd on lupus nephritis by attenuating the IL-17

expression in MRL/lpr mice. Front Immunol. 13:9438272022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Festing MFW and Altman DG: Guidelines for

the design and statistical analysis of experiments using laboratory

animals. ILAR J. 43:244–258. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Wang RN, Wen Q, He WT, Yang JH, Zhou CY,

Xiong WJ and Ma L: Optimized protocols for γδ T cell expansion and

lentiviral transduction. Mol Med Rep. 19:1471–1480. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Uchida N, Green R, Ballantine J, Skala LP,

Hsieh MM and Tisdale JF: Kinetics of lentiviral vector transduction

in human CD34(+) cells. Exp Hematol. 44:106–115. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Sanber KS, Knight SB, Stephen SL, Bailey

R, Escors D, Minshull J, Santilli G, Thrasher AJ, Collins MK and

Takeuchi Y: Construction of stable packaging cell lines for

clinical lentiviral vector production. Sci Rep. 5:90212015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Malhotra D: Targeting epitope-specific T

cells and modelling protein hypercitrullination in rheumatoid

arthritis. [Master's thesis]. Hamilton (ON): McMaster University;

2024, Available from:. https://macsphere.mcmaster.ca/bitstream/11375/30359/2/Malhotra_Devon_2024August_MedicalSciences.pdf

|

|

41

|

Jian J, Liu Y, Zheng Q, Wang J, Jiang Z,

Liu X, Chen Z, Wan S, Liu H and Wang L: The E3 ubiquitin ligase

TRIM39 modulates renal fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteral

obstruction through regulating proteasomal degradation of PRDX3.

Cell Death Discov. 10:172024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Chernova I: Lupus nephritis: Immune cells

and the kidney microenvironment. Kidney360. 5:1394–1401. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Cheng Y, Liu L, Ye Y, He Y, Hu W, Ke H,

Guo ZY and Shao G: Roles of macrophages in lupus nephritis. Front

Pharmacol. 15:14777082024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Sun L, Rautela J, Delconte RB,

Souza-Fonseca-Guimaraes F, Carrington EM, Schenk RL, Herold MJ,

Huntington ND, Lew AM, Xu Y and Zhan Y: GM-CSF quantity has a

selective effect on granulocytic vs. monocytic myeloid development

and function. Front Immunol. 9:19222018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Shakweer MM, Behairy M, Elhefnawy NG and

Elsaid TW: Value of Foxp3 expressing T-regulatory cells in renal

tissue in lupus nephritis; an immunohistochemical study. J

Nephropathol. 5:105–110. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Kalim H, Pratama MZ, Nugraha AS,

Prihartini M, Chandra A, Sholihah AI, Qonita F and Handono K:

Regulatory T cells compensation failure cause the dysregulation of

immune response in pristane induced lupus mice model. Malays J Med

Sci. 25:17–26. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Wu Y, Zhang W, Liao Y, Sun T and Liu Y and

Liu Y: Immune cell aberrations in systemic lupus erythematosus:

Navigating the targeted therapies toward precision management. Cell

Mol Biol Lett. 30:732025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Jiang C, Wang H, Xue M, Lin L, Wang J, Cai

G and Shen Q: Reprograming of peripheral Foxp3+

regulatory T cell towards Th17-like cell in patients with active

systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Immunol. 209:1082672019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Espeli M, Bökers S, Giannico G, Dickinson

HA, Bardsley V, Fogo AB and Smith KG: Local renal autoantibody

production in lupus nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 22:296–305. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Cao S, Schnelzer A, Hannemann N, Schett G,

Soulat D and Bozec A: The transcription factor FRA-1/AP-1 controls

lipocalin-2 expression and inflammation in sepsis model. Front

Immunol. 12:7016752021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Hannemann N, Cao S, Eriksson D, Schnelzer

A, Jordan J, Eberhardt M, Schleicher U, Rech J, Ramming A, Uebe S,

et al: Transcription factor Fra-1 targets arginase-1 to enhance

macrophage-mediated inflammation in arthritis. J Clin Invest.

129:2669–2684. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Mittelstadt ML and Patel RC: AP-1 mediated

transcriptional repression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 by

recruitment of histone deacetylase 1 in response to interferon β.

PLoS One. 7:e421522012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Cash H, Relle M, Menke J, Brochhausen C,

Jones SA, Topley N, Galle PR and Schwarting A: Interleukin 6 (IL-6)

deficiency delays lupus nephritis in MRL-Faslpr mice: the IL-6

pathway as a new therapeutic target in treatment of autoimmune

kidney disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol.

37:60–70. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Alharazy S, Kong NC, Mohd M, Shah SA,

Ba'in A and Abdul Gafor AH: Urine monocyte chemoattractant

protein-1 and lupus nephritis disease activity: Preliminary report

of a prospective longitudinal study. Autoimmune Dis.

2015:9620462015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Chan RWY, Lai FMM, Li EKM, Tam LS, Chow

KM, Li PKT and Szeto CC: Messenger RNA expression of RANTES in the

urinary sediment of patients with lupus nephritis. Nephrology

(Carlton). 11:219–225. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Roh YS, Park S, Lim CW and Kim B:

Depletion of Foxp3+ Regulatory T cells promotes profibrogenic

milieu of cholestasis-induced liver injury. Dig Dis Sci.

60:2009–2018. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Ahnstedt H, Roy-O'Reilly M, Spychala MS,

Mobley AS, Bravo-Alegria J, Chauhan A, Aronowski J, Marrelli SP and

McCullough LD: Sex differences in adipose tissue CD8+ T

cells and regulatory T cells in middle-aged mice. Front Immunol.

9:6592018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Rovin BH, Lu L and Zhang X: A novel

interleukin-8 polymorphism is associated with severe systemic lupus

erythematosus nephritis. Kidney Int. 62:261–265. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Scheller J, Chalaris A, Schmidt-Arras D

and Rose-John S: the pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of the

cytokine interleukin-6. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1813:878–888. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Mishra RK, Potteti HR, Tamatam CR,

Elangovan I and Reddy SP: c-Jun is required for nuclear

factor-κB-dependent, LPS-stimulated fos-related antigen-1

transcription in alveolar macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol.

55:667–674. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Wang Q, Ni H, Lan L, Wei X, Xiang R and

Wang Y: Fra-1 protooncogene regulates IL-6 expression in

macrophages and promotes the generation of M2d macrophages. Cell

Res. 20:701–712. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Reck M, Baird DP, Veizades S, Sutherland

C, Bell RMB, Hur H, Cairns C, Janas PP, Campbell R, Nam A, et al:

Multiomic analysis of human kidney disease identifies a tractable

inflammatory and pro-fibrotic tubular cell phenotype. Nat Commun.

16:47452025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Song D, Lian Y and Zhang L: The potential

of activator protein 1 (AP-1) in cancer targeted therapy. Front

Immunol. 14:12248922023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|